Abstract

It is becoming increasingly clear that the tumour microenvironment (TME) adopts a changing and increasingly complex landscape as tumours evolve. Central to the TME, and alongside malignant cells, are tissue resident and recruited macrophages, other immune cells, and endothelial cells, with the latter critical for angiogenesis and tumour development. Tumour vessels provide oxygen and nutrients and are portals for immune cells. Tumour cells, immune cells and endothelial cells engage in multi-directional crosstalk that untimately influence tumour progression and treatment responses. Adding to complexity, the TME often consists of oxygenated, and oxygen deprived or hypoxic regions, with the latter significantly contributing to disease progression and treatment resistance. However, the function of immune cells and endothelial cells change with ageing, and this underexplored area likely influences the aged TME and disease outcomes in the elderly. Solid cancers such as mesothelioma with known carcinogen exposure (asbestos) take decades to reach a diagnosable size, often emerging in people aged 60 years or more. Here, we discuss the influence of ageing on the function of tumour-associated immune cells, focussing on macrophages, and their possible interactions with endothelial cells, and how this might impact the evolving mesothelioma TME in elderly people.

Keywords

1. The Carcinogenic Process in Mesothelioma

Many cancers do not yet have identifiable carcinogens that can be used to track initial exposure and long-term disease aetiology. In contrast, the carcinogen (asbestos fibres) that causes mesothelioma, confirmed in the 1960s by Wagner[1], is trackable. It is now well established that there is a lengthy latency period (over 30 years) between known asbestos exposure and detectable mesothelioma[2], meaning this disease mostly emerges in people over 60 years old. This is confirmed by age-response relationship studies that report a slow increase in mesothelioma diagnosis until people reach 50 years old, after which a sharp increase is seen[3-5]. This lengthy timeframe provides ample opportunity for multiple genetic, molecular, and cellular changes, including changes associated with ageing.

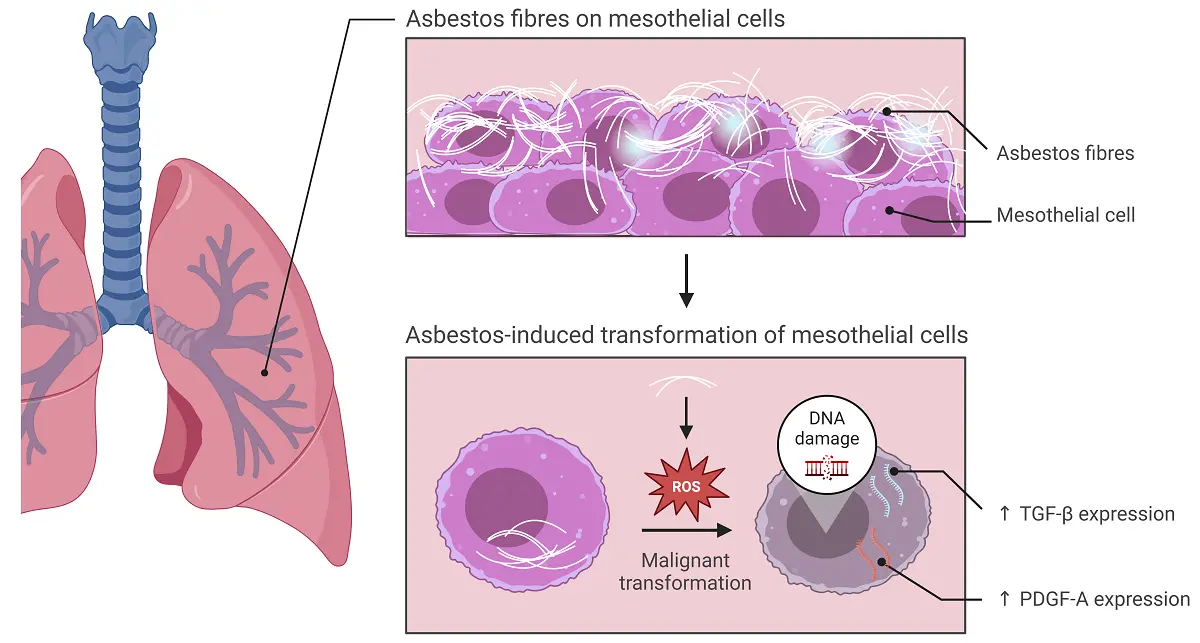

The underlying genetic mechanisms leading to carcinogenesis in mesothelioma are not yet fully understood, but there is evidence that it starts with mesothelial cells phagocytosing asbestos fibres[6], summarized in Figure 1. Asbestos fibres induce production of reactive oxygen metabolites that could be responsible for causing DNA point mutations, as well as strand and chromosomal breaks, in combination with mitotic damage ADDIN ENRfu ADDIN ENRfu and increased cell division, all resulting in cell survival and neoplastic transformation[7,8]. Genetic changes of mesothelial cells as they differentiate into malignancy include upregulating transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-A transcripts[9,10]. Whilst these events may happen relatively quickly in-vitro (between one to six weeks depending on the cell line tested[11,12]), it is not known how long genetic and molecular changes take in asbestos-exposed humans, with type of asbestos fibre, dose, and duration of exposure affecting disease outcomes. However, there is also evidence that local acute and chronic inflammatory responses contribute to the carcinogenetic process and, in this regard, it is possible that age-associated changes, such as low level inflammation, or inflammageing[13,14] in the local environment contribute to the ultimate emergence of immune-resistant mesothelioma.

Figure 1. The effect of asbestos fibres on mesothelial cells. Inhaled asbestos fibres induce production of ROS and initiate malignant transformation of mesothelial cells. Malignant mesothelial cells upregulate TGF-β and PDGF-A. Created in BioRender.com. ROS: reactive oxygen species; TGF-β: transforming growth factor beta; PDGF: platelet-derived growth factor; ↑: increased.

The potential role of the ageing process in mesothelioma aetiology is further highlighted by the fact that universal driver mutations have not been found, and that mesothelioma is generally regarded as having a low tumour mutation burden with unusual genetic aberrations[15]. Deletion of the cyclin D dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) gene and the co-located methylthioadenosine phosphorylase (MTAP) gene on chromosome 9 are the most common mutations, both affect cell cycle. Other common mutations are seen in the BRCA1-associated protein-1 (BAP1), neurofibromin2 (NF2), and tumour protein (TP)53 genes[16-18]. Early events occurring after asbestos exposure, including an increasingly inflammatory environment, likely drive aberrant activation of intracellular pathways and transcriptional processes that induce malignant transformation[19], with the distinct possibility that some of these processes occur with, and perhaps because of, age-related changes.

2. Macrophages and Mesothelioma Carcinogenesis

Macrophages may be crucial players in mesothelioma development. Our in-vivo studies in mice show that macrophages are required for mesothelioma growth, as co-inoculation of macrophages with mesothelioma tumour cells leads to faster tumour growth, whilst depleting macrophages using the anti-F4/80 antibody induces tumour regression in young and elderly mice[20].

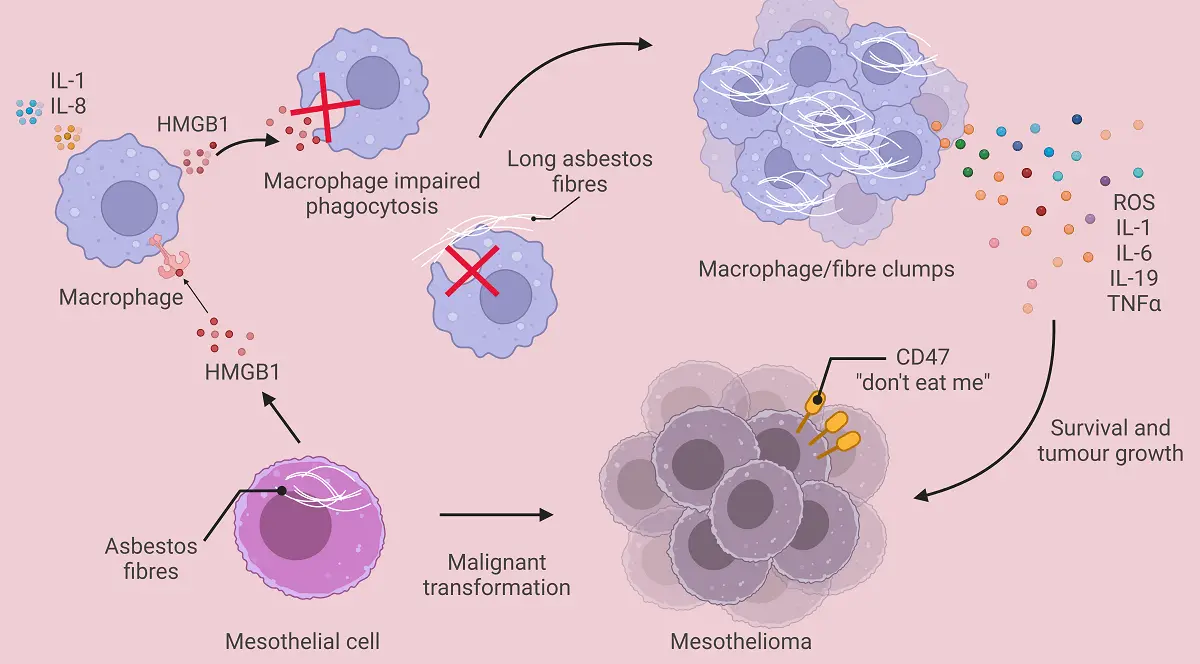

Early events induced by inhaled asbestos fibres lodged in the lungs include haemorrhage, destruction of the elastic membrane under visceral pleura, and inflammation[21]. The early inflammatory response is characterised by a polymorphonuclear infiltrate[22,23] that cannot clear lodged asbestos fibres. Whilst most asbestos fibres in the lungs are phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages, long asbestos fibres cannot be readily phagocytosed, resulting in persistent abnormal macrophage/fibre clumps. Macrophages unable to eliminate asbestos fibres, have been termed ‘frustrated’[24]. Asbestos fibres activate macrophages in-vitro[25,26], and increased numbers of macrophages have been recovered from bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL) of asbestos-exposed and asbestosis patients[27,28], as well as from the BAL of experimental animals after asbestos injury[29]. These activated frustrated macrophages display increased expression of IgG Fc receptors, surface ruffles, and filopodia[30]. Up to six months later, fibre clusters partially covered by mesothelium are surrounded by macrophages, and regenerating mesothelial cells are visible[31]. Frustrated macrophages produce nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), reactive oxygen species (ROS)[32] and pro-inflammatory factors including interleukin-1

Figure 2. The effect of asbestos fibres on macrophages. This figure summarises the cross talk between mesothelial cells and macrophages injured by asbestos fibres. Activated macrophages may clump due to an inability to breakdown asbestos fibres and release inflammatory factors such as ROS and IL-6 that induce upregulation of CD47 on transforming mesothelial cells, thereby creating immune-resistant mesothelioma. Created in BioRender.com. ROS: reactive oxygen species; IL: interleukin; TNF-α: transforming growth factor alpha; HMGB1: high-mobility group protein box 1.

High-mobility group protein box 1 (HMGB1), an endogenous damage-associated molecular pattern (DAMP) ‘danger’ molecule that binds DNA and possesses pro-inflammatory properties[35], is released by mesothelial cells upon asbestos exposure[36]. HMGB1 can activate macrophages via multiple pattern recognition receptors including Toll Like Receptor (TLR)4[35]. When HMGB1 binds TLR4 on macrophages the NLRP3 (nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich-containing family, pyrin domain-containing-3) inflammasome is activated, resulting in secretion of IL-1, IL-18, and HMGB1, thereby establishing a chronic inflammatory loop[37]. HMGB1 activation further impairs macrophage phagocytosis and induces TNF-α secretion that protects mesothelial cells from death signals, concomitantly sustaining chronic inflammation[38,39]. Transforming mesothelioma cells proliferate[38] and express CD47, a “don’t eat me” signal, helping them avoid macrophage phagocytosis[40].

3. Mesothelioma-Associated Macrophages

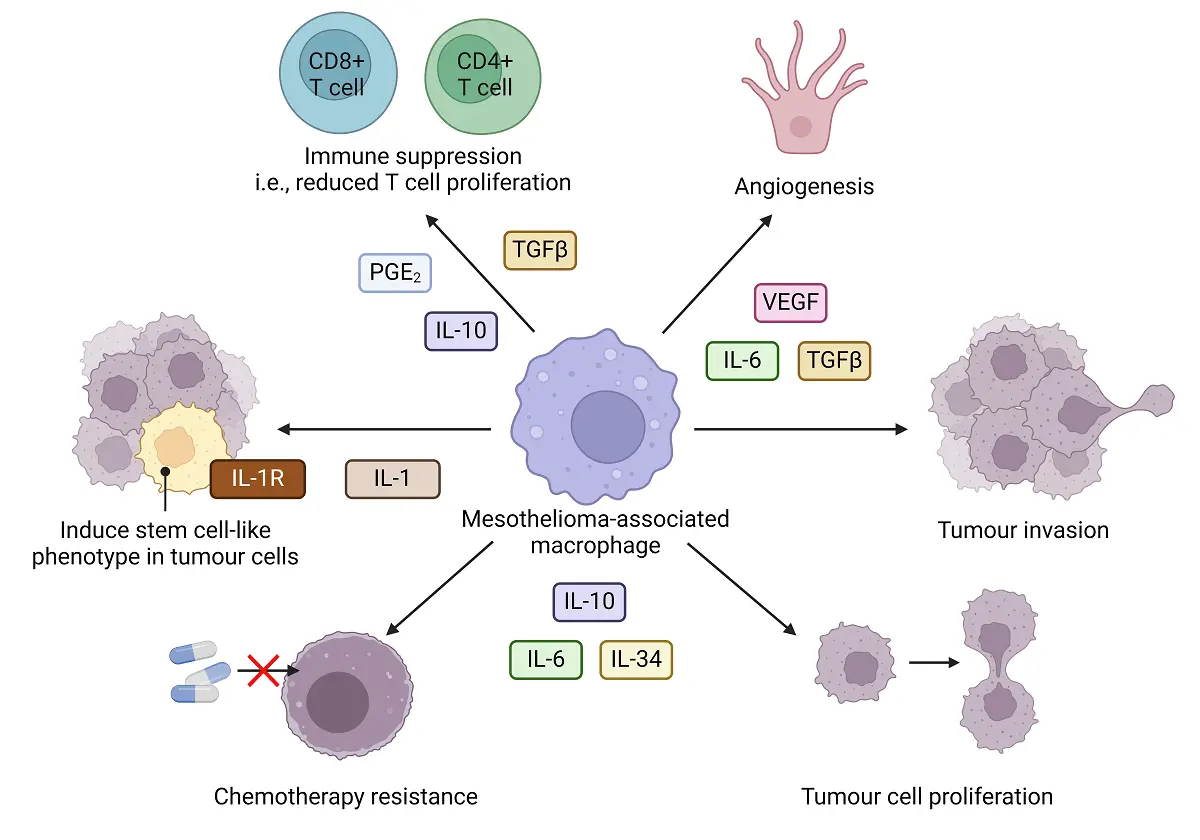

Mesothelioma cells produce high levels of the monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-1; also known as C-C motif chemokine ligand 2, CCL2), to recruit monocytes[41] and induce tumour-promoting macrophages (that have also been referred to as alternatively activated, M2 or M2-like macrophages) by secreting IL-10, TGF-β and macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF), these factors are seen in patient pleural effusions (PE)[42]. Increased numbers of tumour-associated macrophages (TAMs) that express CD68 (a scavenger receptor for the hemoglobin-haptoglobin complex) and display an immunosuppressive, tumour-promoting phenotype, that includes the high affinity scavenger receptor (CD163), the mannose receptor (CD206) and the IL-4R receptor (IL-4R), have been reported in human mesothelioma[41,43]. The presence of these tumour-promoting TAMs that release IL-6, IL-10 and IL-34 has been linked to increased tumour cell proliferation and chemotherapy resistance[41]. TAMs, in turn, induce a cancer stem cell-like phenotype in tumour cells via IL-1/IL-1R activation[44].

Human and murine mesotheliomas are heavily infiltrated by macrophages, which can comprise greater than 20% of total

Mesothelioma TAMs play a major role in tumour development by providing factors that promote matrix components, tumour cell proliferation and angiogenesis. TAMs also suppress the anti-tumour immune response via multiple mechanisms including production of TGF-β, nitric oxide (NO) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)[49]. PE-derived macrophages, used as surrogate mesothelioma TAMs, were shown to display an immune suppressive phenotype that released high levels of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and suppressed CD4+ and

Figure 3. The role of mesothelioma-associated macrophages in tumor progression. Mesothelioma-associated macrophages support disease progression by secreting factors that drive angiogenesis, tumour cell proliferation, tumour invasion, contribute to treatment resistance and induce stem-like cells and immune suppression. Created in BioRender.com. TGF-β: transforming growth factor beta; PGE2: prostaglandin E2; IL-1R: interleukin 1 receptor; IL: interleukin; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

4. The Mesothelioma Tumour Microenvironment

The human mesothelioma TME also contains regulatory T cells (Tregs) that supress the function of effector T cells, such CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs)[51,52]. High levels of programmed death protein ligand-1 (PD-L1, or CD274) are expressed in the TME[46] by immune cells, particularly macrophages, as well as by mesothelioma cells, although the latter is contestable[34]. Macrophages may be responsible for reprogramming T helper (Th)-1 cells into Tregs via TGF-β and IL-10. Dysfunctional CTLs and tissue-resident memory (Trm) cells have been described in mesothelioma, their dysfunction likely due to pre-existing Tregs and expression of the Eomes transcriptional factor, a regulator of CD8+ T cell function[53]. Patient PE also contain activated CTLs and Th cells that express exhaustion (checkpoint) molecules, such as programmed death protein-1 (PD-1) or CD279. PD-1 on CD8+ T cells binds its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 which suppress effector T cell function (i.e., their tumour killing capacity). Other checkpoint molecules found in PEs include T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3 (TIM-3, or CD366) and lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3, CD223 or FDC protein) that suppress T cell activity[54]. Natural killer (NK) cells with an immunosuppressive profile and lower cytotoxic function are also present in mesothelioma samples[55]. However, it should be noted that the mesothelioma TME differs between patients and histological subtypes[56]. An association between the aged environment and different mesothelioma TEMs has yet to be identified.

Murine mesothelioma models display similar infiltrating M2-like cells[20,48] and Treg[57], as well as low numbers of dendritic cells (DCs), T cells, B cells and NK cells[58]. DCs are the most likely antigen presenting cell (APC) to take up mesothelioma antigens as they traverse the tumour site and move to draining lymph nodes to cross-present tumour antigen. We have shown, using transfection/transgenic models, that mesothelioma growth in young and elderly mice is associated with constitutive tumour antigen cross-presentation and CTL induction, meaning that DCs retain their APC function in the aged and cancerous setting, however, these CTLs fail to prevent disease progression suggesting a severe defect in DCs and/or T cells[59,60].

We have reported defects in human DCs with healthy ageing[61], and in humans with mesothelioma[62]. For example, we found that circulating elderly blood myeloid (m)DC1s, mDC2s, and plasmacytoid (p)DCs numbers diminished with ageing. We also found that whilst lipopolysaccharide (LPS)/IFNγ or CD40Ligand(L) stimulation induced elderly blood mDC1s, mDC2s, and plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) to up-regulate comparable levels of T cell co-stimulatory molecules (CD40, CD80 and/or CD86), pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFNγ, TNF-α, IL-6 and/or IL-12), and induce CD8+ and CD4+ T cell proliferation, they maintained their antigen processing ability, implying incomplete maturation. Moreover, elderly LPS/IFNγ-activated mDC1s and pDCs adopted a regulatory phenotype, due to greater expression of PD-L1 and TGF-β than their younger counterparts, that may impact the efficacy of immune responses in the elderly[63].

In mesothelioma-bearing mice, we found that elderly tumour antigen-specific CTLs lost their ability to lyse target cells, whereas young CTLs did not[59]. Whilst this might explain why tumours in elderly hosts continued to progress, it does not explain why tumours in young hosts also continued to progress. Nonetheless, it does help explain why chemotherapy is not as effective in elderly hosts, as even though there is likely elevated tumour antigen presentation, on account of increased tumour cell death, CTL functionality remained compromised in elderly mice[59]. In contrast, chemotherapy enhanced CTL function in young mice; CD8+ T cell depletion studies confirmed that these CTLs were responsible for chemotherapy-induced mesothelioma regression[59,64].

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are recruited into tumours, likely by frustrated macrophages. CAFs further enhance the migratory and invasive abilities of mesothelioma tumour cells, recruit immune and vascular cells, and remodel the extra cellular matrix (ECM)[65].

5. Mesothelioma, Macrophages and Ageing

We have data suggesting that macrophages in older hosts function differently to those from younger hosts. Our intra-tumoural

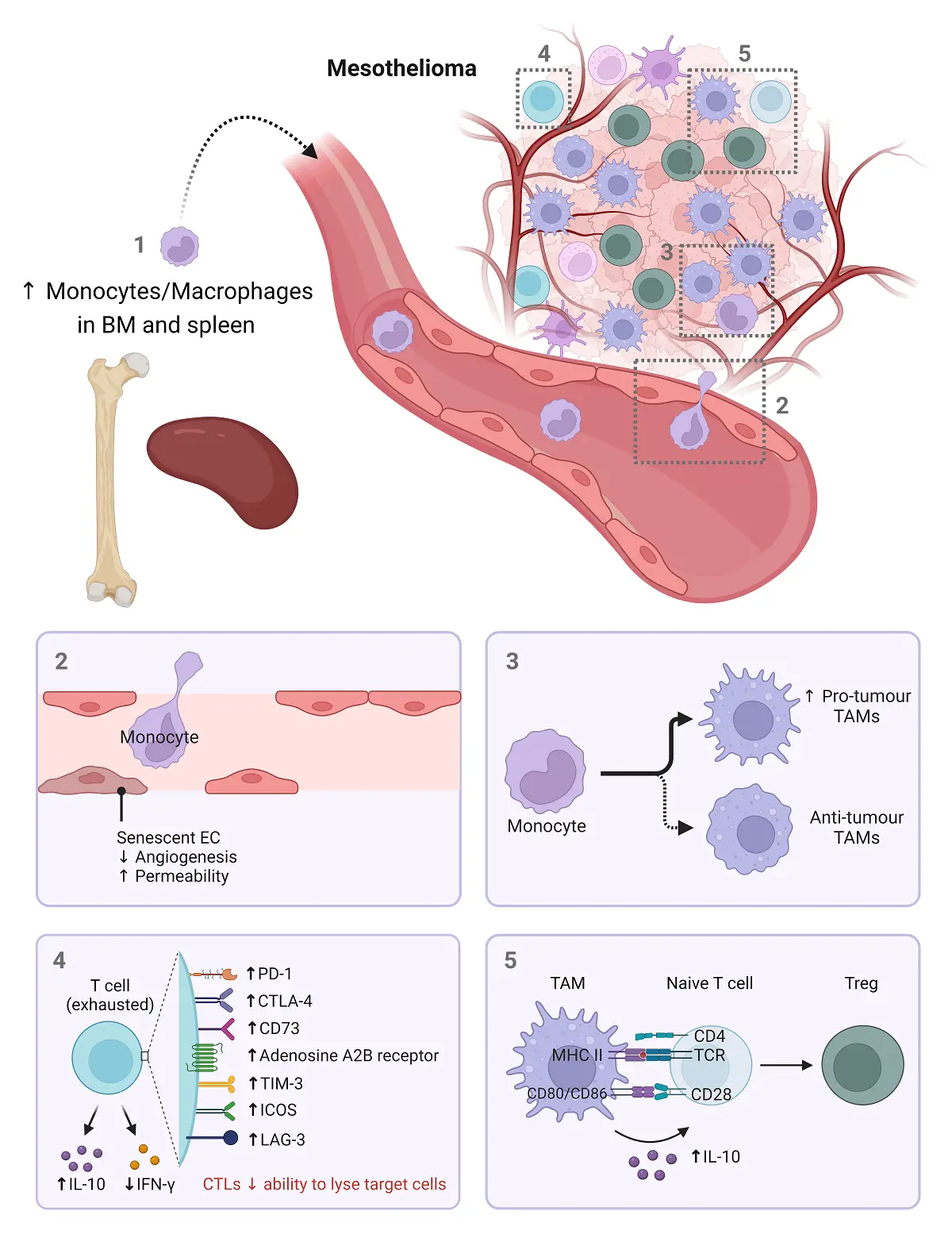

Our data show that mesothelioma tumours grow faster in elderly compared with young mice, and this that corresponds with an increase in TAMs[61]. We also reported that macrophages increase in bone marrow (BM) and spleens during healthy ageing, suggesting these sites have an increased potential to supply cancer-promoting macrophages[61]. Furthermore, we found that all tumour-bearing elderly, but not young, mice demonstrated signs of cachexia such as decreased body weight, which was exacerbated by immunotherapy. Interestingly, macrophage depletion prevented therapy-induced cachexia[61], suggesting macrophages play a key role in driving cancer cachexia in the elderly, particularly during therapy, and likely sabotage elderly anti-tumour immune responses.

Age-associated macrophage dysregulation has been shown in in-vitro studies using splenic macrophages from Balb/c mice; elderly macrophages produced less TNF-α and IL-1β than their younger counterparts in response to LPS[67]. Yet, BM-derived macrophages from elderly C57BL/6J mice produced more TNF-α and IL-6 than those from younger mice in response to LPS[68]. In contrast, elderly-derived peritoneal macrophages from Balb/c and C57BL/6J mice displayed elevated production of anti-inflammatory IL-10 and TGF-β in response to IL-4[69,70]. Macrophages from the eye, muscles, lymph nodes, spleen and BM have also been shown to release increased IL-10 with ageing[69-71]. However, liver and adipose tissue macrophages from elderly C57BL/6J mice produced more IL-6 and

6. Endothelial Cells, Immune Cells, Cancer and Ageing

The endothelium is made up of a single cell layer of ECs that line vascular and lymphatic systems. ECs play essential physiological roles including vascular stabilization, hemostasis, modulating vascular permeability, and regulating the movement of cells into and out of the circulatory system[12]. Under normal healthy physiological conditions, ECs are non-proliferating quiescent cells that allow diffusion of solutes to underlying cells, and do not interact with immune cells. ECs only engage with immune cells after activation by pro-angiogenic signals, hypoxia and inflammation. Activated ECs up-regulate adhesion molecules, chemokines and integrins that interact with, and activate, immune cells so that they up-regulate relevant ligands enabling the multi-step process that follows. ECs sequentially express selectins. The first is E-selectin, that ligates sialofucosylated glycan determinants on protein and lipid scaffolds of immune cells, enabling their tethering and slow rolling on the EC surface. Immune cells are then exposed to chemokines immobilized by glycosaminoglycans on ECs leading to engagement of G-protein-coupled chemokine receptors on immune cells. In response, immune cells up-regulate integrins, particularly very late activation protein 4 (VLA-4) and lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1), that bind vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) on ECs, leading to firm adhesion[76]. Transendothelial migration (or diapedesis) is facilitated via transient dismantling of EC junctions (paracellular migration) or migration through individual EC (transcellular migration).

It is becoming widely accepted that ECs are key regulators of the immune response[14,35,

7. Endothelial Cells and Vascular Ageing

ECs change with the ageing process, referred to as vascular ageing. For example, EC proliferation decreases with age, meaning ECs adopt a senescent profile[36,90]. Accumulating senescent ECs in vessels, such as the aortic wall of aged mammals, induces EC dysfunction, and increased permeability. Senescent ECs lose their ability to produce NO, leading to decreased vasodilation during ageing. Furthermore, senescent ECs exhibit increased expression and secretion of various cytokines, known as the Senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)[90-92]. SASP cytokines cause low-grade chronic inflammation, cellular fibrosis and apoptosis, and stimulate macrophage, T and B cell infiltration which together exacerbate vascular ageing.

Vascular ageing appears to be the result of interactions with multiple cell types and their secreted products over time leading to endothelial injury. More recently, the potential role of mitochondria in multicellular interactions and vascular ageing has been revealed[93-95]. Mitochondria are the main source of intracellular ROS, but are also targets of ROS damage. An imbalance between mitochondrial ROS ((mt)ROS) leads to overproduction and/or decreased antioxidant enzymes in the mitochondria and cytosol, causing oxidative stress, which is closely associated with cell senescence, vascular inflammation, arterial stiffness and vascular ageing.

MtDNA contain unmethylated cytosine-phosphate-guanine motifs, similar to bacterial DNA, this may be because mitochondria evolved from ancient eubacteria. This means that mtDNA can be identified as foreign once outside cells, and function as a DAMP resulting in immune activation and inflammation[96]. Increased levels of circulating mtDNA with ageing[97] has been correlated with elevated inflammatory factors, such as TNF-α, IL-6, regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES), also known as CCL5, and the IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra) to promote vascular ageing. Excessive or prolonged increases in vessel permeability, may contribute to the chronic inflammation and cancer seen in the elderly.

8. Immune Cells, Fibroblasts and Vascular Ageing

Macrophages play a key role in vascular ageing on account of their ability to release pro- and anti-inflammatory factors, as well as their role in lipid metabolism. Mitochondria in macrophages are reported to be crucial effectors in vascular ageing[49,98,99]. Mitochondria represent the energy powerhouse for macrophages under inflammatory conditions such as hypoxia and hyperglycemia via glycolysis or fatty acid oxidation. The latter are seen in ageing due to vascular and metabolic dysfunction. Vascular ageing has been best characterised in atherogenesis and starts when accumulating lipids or lipoproteins are modified in the vascular sub-endothelium, resulting in macrophage recruitment and activation. Macrophages then take lipids up via scavenger receptors such as CD36, and excess lipid that cannot be degraded leads to the formation of foam cells[100,101]. In early atherogenesis development, mitochondria in macrophages from coronary artery disease plaques consume more oxygen and produce more energy (ATP) than their healthy counterparts[102]. Moreover, these M2-like macrophages demonstrate higher mitochondrial content, including increased levels of mtDNA and have a higher oxygen consumption rate than their pro-inflammatory M1-like counterparts[103]. Interestingly, enhanced mitochondrial respiration improves lipid metabolism in M2-like macrophages[104] that may provide a protective effect on vascular ageing[95,105]. However, with disease progression lipid-loaded foamy macrophages reduce oxygen consumption leading to apoptosis. Overexpression of mtROS in macrophages can aggravate atherosclerosis by stimulating NF-kB pathway activation and recruiting monocytes that exacerbate the vascular inflammatory cascade[106].

Neutrophils, plasma cells, and mast cells are elevated in aged arteries, along with elevated IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 in plasma[106-109]. These cells, as well as fibroblasts, secrete factors associated with vascular ageing. Fibroblasts in the aortic adventitia layer demonstrate excessive proliferation and differentiation in aged vessels which exacerbate vascular sclerosis and fibrosis[110]. Moreover, activated fibroblasts secrete cytokines and chemokines to recruit immune cells and modulate ECs, driving endothelial dysfunction, and aggravating vascular ageing.

9. Endothelial Cells, Angiogenesis and Ageing

Angiogenesis, the process of vessel formation from pre-existing vascular beds, supports tissues during high metabolic demand such as growth, physiological stress, and tissue injury[111]. Angiogenesis is guided by proliferating ECs. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) A binding VEGF receptor 2 (VEGFR2) on ECs triggers the development of navigating tip ECs and proliferating stalk ECs that form new vascular sprouts by following the VEGFA gradient[112,113].

Aged individuals appear to have impaired angiogenesis and to be at higher risk of pathological vessel formation[114-116]. Age-related changes in angiogenesis likely result from vascular ageing and/or endothelial cell senescence[117,118]. This is supported by data showing that endothelial cells from aged mice show decreased proliferation and migration[46,119] contributing to delayed wound healing. Moreover, elderly patients are reported to have reduced capillary density[116,

The ageing process is associated with accumulating exposure to harmful stimuli. Oxidative stress is increased in ageing and is associated with increases in oxidatively damaged proteins, lipids, and DNA that affect blood vessel growth. Multiple mechanisms contribute to age-related increases in oxidative stress, including increased production in endogenous antioxidant/oxidant pathways[37,124,125]. Mitochondrial production of ROS is increased in ageing animals. Mitochondria-derived H2O2 aggravates NFκB activation in aged ECs, elevating low-grade vascular inflammation and further promoting oxidative stress by activating NADPH oxidases, matrix metalloproteinase, and TGF-β expression. As a result, elastin fragments and collagen content increases in aged arteries[126-130], contributing to arterial stiffness and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

EC senescence can be induced by stimuli associated with ageing[131], such as hypoxia, disturbed flow and oxidative stress, including ROS, high glucose, β-amyloid peptides and inflammation[132-134]. Senescent EC accumulate in ageing tissues and contribute to tissue dysfunction[90]. These senescent ECs adopt a pro-inflammatory SASP phenotype[91,92]. Structural and functional changes in senescent ECs include vascular leak, thrombosis and immune dysregulation. Senescent ECs stop proliferating and undergo other functional changes. Superoxide, a ROS produced by immune cells and generated by mitochondria inhibits angiogenesis by acting as a NO scavenger that inhibits endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity. Thus, increased superoxide in aged endothelium impairs vasodilation and vessel formation. However, somewhat confusingly, Coleman et al. showed that age-related stress can also induce non-activated, anti-inflammatory senescent ECs[135] mediated by NFκB inhibition[136,137]. It is possible that the proportion of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory senescent ECs in aged hosts determines inflammatory responses, and when dysregulated, drives pathological outcomes such as cancer. Age-related changes in monocytes/macrophages, endothelial cells and T cells are summarised in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Age-related changes in monocytes/macrophages, endothelial cells and T cells. Ageing is associated with an increase in monocytes and macrophages in the bone marrow and spleen which can be a source of TAMs (1). The migration of these cells to the tumour site may be impacted by aged vessels, as senescent endothelial cells exhibiting decreased angiogenesis and increased permeability (2). In the tumour, the ageing environment drives the development of pro-tumor TAMs (3) and exhausted T cells (4). Furthermore, the presence of pro-tumour TAMs promotes Treg differentiation. Created in BioRender.com. BM: bone marrow; EC: endothelial cell; PD-1: programmed death ligand-1; CTLA-4: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4; TIM-3: T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3; ICOS: inducible T-cell co-stimulator; LAG-3: lymphocyte activation gene-3; CTL: cytotoxic T lymphocyte; MHC: major histocompatibility complex, TAMs: tumour-associated macrophages; TCR: T cell receptor; Treg: regulatory T cell; IL: interleukin; IFN-γ: interferon gamma; ↓: decreased; ↑: increased.

10. Angiogenesis and Cancer

Angiogenesis plays a major role in tumor growth, and the elderly are at increased risk of most forms of cancer. Relevant to cancer and ageing, one of the pathways central to angiogenesis is hypoxia. Hypoxia increases expression of transcription factors or co-activators such as hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) and PPARγ coactivator (PGC)-1α that induce production of angiogenic factors, such as VEGF and eNOS. A common factor for most angiogenic pathways is that they intersect with ageing-related pathways, particularly regulators of cell senescence, such as telomere length, sirtuins, and the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, p16 (Ink4a), p19 (Arf). Senescent ECs and slowed angiogenesis may account for the observation that in some cancers, disease progression is slower in elderly compared with younger patients. For example, studies in aged mice showed that B16 melanoma growth was slower[138] and associated with decreased tumour vasculature relative to younger mice[138,139,140,141]. Moreover, young mice with B16 pulmonary metastases had a poorer prognosis than 12 month old mice[141]. The Lewis lung carcinoma model has been shown to grow more slowly in older mice[142]. 4TI breast tumours also grew slower in elderly mice[135,136] and reduced tumour microvessel counts may also account for slower disease progression and lower grade tumours in elderly breast cancer patients[143,144]. Similarly, colorectal cancer is more aggressive in younger people, who nonetheless have a higher survival rates than their older counterparts[145,146]; this is replicated in murine CT26 and MC38 colon cancer with tumours progressing faster in younger mice[136]. However, others have reported the opposite, with CT26 colon tumours growing slower in younger mice[147].

We found that mesothelioma grows faster in older mice[61]. This appears similar to people with mesothelioma, as younger pleural mesothelioma patients at 40 years old live between 4-9 years, whilst life expectancy diminishes to 1-3 years at 80 years old, suggesting older people experience a more aggressive, immune-evasive, treatment-resistant cancer[148]. Similarly, prostate cancer in older men is more aggressive than in younger men[149]. The differences in cancer progression in the elderly might be accounted for by the type and location of tumours. For example, cancers with a higher hypoxic load might progress faster than those with higher oxygenated environments, noting that the elderly are already susceptible to the development of hypoxic regions due to vascular ageing.

11. Tumour Endothelial Cells, Hypoxia and Cancer

The TME represents a complex and changing network of cancer and stromal cell types that interact with, and modulate, each other over time. At the early stages of development, tumour cells rely on diffusion of oxygen and nutrients from surrounding tissue. However, as tumour cells proliferate this becomes inadequate with the TME becoming hypoxic. Cancer cells respond to this hypoxic environment by expressing angiogenic factors such as HIF, VEGFA, PDGF and/or angiopoietin 2 (ANGPT2), as well as pro-angiogenic chemokines and receptors to initiate neoangiogenesis in a process termed the “angiogenic switch”[111,150].

Tumor vessels develop differently to normal vessels and are excessively branched, disorganized and leaky[85,151]. Unlike normal ECs (NECs), tumour ECs (TECs) are characterized by an irregular multi-layered endothelial lining, a discontinuous basement membrane and an inconsistent smooth muscle and pericyte sheath[152,12]. Unstable vessel walls promote leakiness leading to higher interstitial pressure, poor perfusion and inconsistent blood flow, causing hypoxic regions[153] that foster neo-angiogenesis[85,154].

Single cell RNA-Seq and bioinformatic analyses have shown that TECs are genetically, phenotypically, functionally and metabolically different to NECs[155,156]. TECs demonstrate chromosomal instability and abnormality, including aneuploic karyotypes, deletions, translocations or supernumerary centrosomes, all likely due to hypoxia, redox alterations, and epigenetic modulation (e.g., demethylations)[157,158]. Unlike NECs, TECs show increased potential of self-renewal and are highly proliferative. This is because TECs are highly transcriptionally active (with up to four-fold higher RNA content), are hyper-glycolytic and mostly use aerobic glycolysis to meet their energy demands[154,159]. TEC show high gene expression heterogeneity. Single cell RNA-Seq data reveal numerous TEC subtypes, such as tip and stalk ECs that are involved in neo-angiogenesis, or postcapillary venous and activated postcapillary ECs that display immunoregulatory capacity[154,155,160]. TEC phenotypes may be determined by the tumour milieu, hypoxia-induced ROS and cellular stress, as well as by vascular ageing in the elderly.

12. TECs and Their Immunoregulatory Properties

TECs represent the first-line encounter for immune cells and tumour cells[154] and can activate, inhibit or selectively barricade effector immune cells[155,161,162]. Tumour cells up-regulate VEGF, fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), EGF-like domain-containing protein 7 (EGFL7) and NO that regulate blood flow[163] and prevent rolling and adhesion of immune cells by inhibiting up-regulation of adhesion molecules on TECs, even under inflammatory stimulation[19,

NECs and TECs can express MHC class I and II molecules and select and activate antigen-specific T cells. However, they do not express the T cell costimulatory molecules, CD80 and CD86[161], meaning they can only present processed antigens to antigen experienced memory T cells. Moreover, TECs acting as APCs have been shown to control the formation of tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) within tumours, which are associated with positive responses to checkpoint antibody therapy[176]. However, TECs can down-regulate MHC I/II molecules in response to the local milieu and lose their antigen presenting function[155].

ECs can upregulate checkpoint molecules to inhibit T cell activation[177]. For example, ECs in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IFNg and TNF-α, can elevate PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression[178,179]. Moreover, Fas ligand (FasL) expression can be induced on TECs by VEGF-A, IL-10 and PGE2. TECs expressing FasL have been shown to selectively reduce effector CD8+ T cell, but not Treg, tumour infiltration[180]. The enzyme indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) prevents T cell proliferation, induces T cell apoptosis and promotes Treg activation via tryptophan metabolism[181]. TECs up-regulate IDO in response to IFN stimulation, to promote an immunosuppressive microenvironment[182]. The effect of ageing on TEC expression of checkpoint molecules in mesothelioma has yet to be fully elucidated, however we have shown that lymph node CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in healthy elderly mice express higher levels of several checkpoint molecules than their younger counterparts including CD73, the adenosine A2B receptor, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4 or CD152), PD-1, inducible T-cell co-stimulator (ICOS, or CD278), LAG-3, and IL-10, compared to young mice; the presence of mesothelioma did not change their expression levels[182]. Therefore, T cells expressing high levels of checkpoint molecules interacting with TECs expressing their ligands are likely to experience loss of function in mesothelioma tumours in elderly people. Indeed, we found decreased IFN-γ by elderly CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in mesothelioma, compared to their younger counterparts, implying loss of function[182].

13. Mesothelioma, Angiogenesis and Ageing

Angiogenesis plays a key role in mesothelioma progression with blood and PE samples from patients demonstrating up to three-fold higher serum VEGF levels compared to other malignancies or healthy volunteers, and high serum VEGF levels are a negative prognostic factor[183-185]. Harada et al. showed that IL-6 secreted by mesothelioma cells promoted increased VEGF expression in mesothelioma cell lines via the signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)3 pathway[186]. Others have shown that mesothelioma CAFs and TAMs also release VEGF to amplify VEGF production by mesothelioma cells and further promote EC recruitment and angiogenesis[187,188]. Recent papers using single cell RNA-Seq confirmed the presence of a large proportion of endothelial cells and angiogenic molecules in human mesothelioma samples; age was not addressed[189,190]. The influence of age on VEGF release and its downstream effects has not yet been addressed in mesothelioma.

Human mesothelioma tumours consist of significant areas of hypoxia, particularly in dominant tumour masses, these hypoxic regions positively correlated with intensity of metabolic activity[191]; the data were not stratified for age. An in-vitro study showed that culturing human mesothelioma cell lines under hypoxic conditions upregulated HIF-1α/2α as well as the glucose transporter (Glut)-1 target relative to normoxic controls[192]. Therefore, the hypoxic regions likely further induced VEGF release by tumour cells and ECs thereby promoting tumour growth and augmenting aggressive behaviour by mesothelioma cells, because their clonogenicity, mobility and invasive characteristics were significantly elevated, as was resistance to cisplatin[193]. Furthermore, a higher microvessel density (MVD) has been reported in mesothelioma biopsies compared to other malignancies[194] which was independently related to poor survival, even when adjusted for other known prognostic factors, including age. These data prompted testing of several antiangiogenic drugs with or without chemotherapy in mesothelioma patients, but the effects were unremarkable and sometimes led to significant toxicity[157,64,

14. Summary and Conclusions

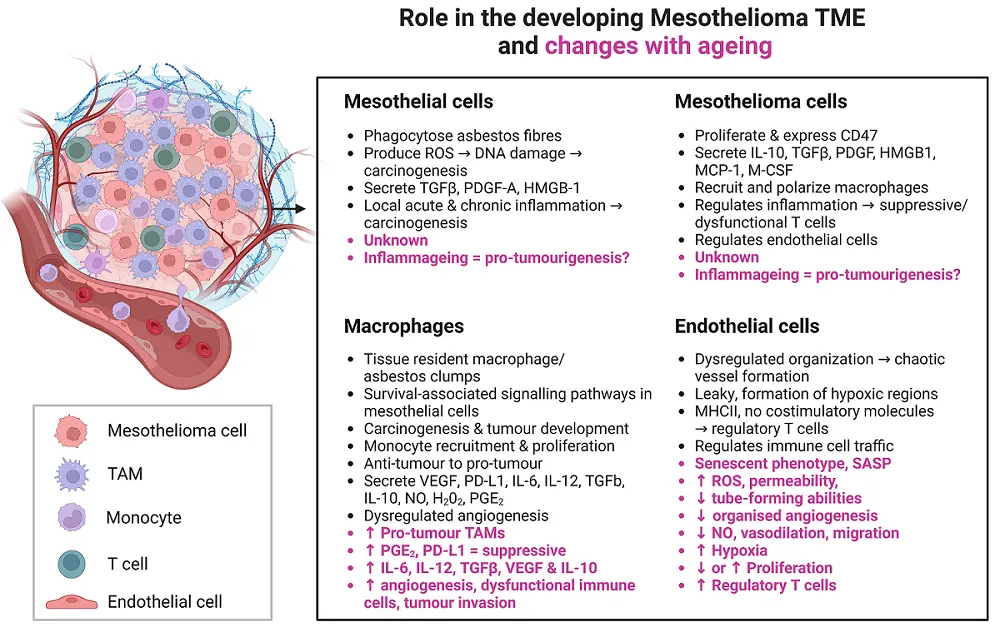

The vascular and the immune systems are intimately linked, both share metabolic and growth factor stimuli and are responsive to their local milieu, particularly hypoxia. Both systems are altered during healthy ageing, and more so in response to factors released by cancer cells, yet there are few studies examining the links between ageing, cancer, the immune and vascular systems. Here, we argue that mesothelioma is an especially useful model for understanding the impact of ageing and cancer on TECs and immune cells. This is because there is a lengthy latency period of over 30 years between known asbestos exposure and detectable mesothelioma, meaning this disease mostly emerges in elderly people. Like other cancers with less well-defined carcinogens and unknown latency periods, mesothelioma sabotages normal endothelial and immune cell physiological functions by releasing factors such as VEGF, and by recruiting and modulating suppressive cell types including TAMS, and Tregs that amplify EC recruitment and modulate their function (Figure 5). There is a clear gap in knowledge, as we do not yet understand the role ageing plays in mesothelioma aetiology and disease progression, this is true in many cancers.

Figure 5. The influence of ageing on interactions between mesothelial cells, mesothelioma cells, macrophages and endothelial cells in the developing tumor microenvironment. Created in Biorender.com. TAM: tumour-associated macrophage; TME: tumour microenvironment; ROS: reactive oxygen species; TGF-β: transforming growth factor beta; PDGF-A: platelet-derived growth factor-A; HMGB-1: high-mobility group protein box 1; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; PGE2: prostaglandin E2; PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1; IL: interleukin; NO: nitric oxide; MCP-1: monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; M-CSF: macrophage-colony stimulating factor; MHC: major histocompatibility complex; SASP: senescence-activated secretory phenotype; ↓: decreased; ↑: increased.

Acknowledgements

Lelinh Duong was supported by a PhD top up scholarship from Cancer Council Western Australia.

Authors contribution

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Conflicts of interest

Nelson DJ is a research academic at Curtin University and is involved in a number of research projects. One project is funded by an immunotherapy start-up company, Selvax. Selvax played no role in the preparation, or generation of data described in this manuscript. Nelson DJ is an Editorial Board member of Ageing and Cancer Research & Treatment.

Other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Wagner JC, Sleggs CA, Marchand P. Diffuse pleural mesothelioma and asbestos exposure in the North Western Cape Province. Br J Ind Med. 1960;17(4):260-271.[DOI]

-

2. Girardi P, Bressan V, Merler E. Past trends and future prediction of mesothelioma incidence in an industrialized area of Italy, the Veneto Region. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;38(5):496-503.[DOI]

-

3. Gariazzo C, Gasparrini A, Marinaccio A. Asbestos consumption and malignant mesothelioma mortality trends in the major user countries. Ann Glob Health. 2023;89(1):11.[DOI]

-

4. Moolgavkar SH, Meza R, Turim J. Pleural and peritoneal mesotheliomas in SEER: age effects and temporal trends, 1973-2005. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(6):935-944.[DOI]

-

5. Reid A, de Klerk NH, Magnani C, Ferrante D, Berry G, Musk AW, et al. Mesothelioma risk after 40 years since first exposure to asbestos: a pooled analysis. Thorax. 2014;69(9):843-850.[DOI]

-

6. Yamashita K, Nagai H, Toyokuni S. Receptor role of the annexin A2 in the mesothelial endocytosis of crocidolite fibers. Lab Investig. 2015;95(7):749-764.[DOI]

-

7. Hiltbrunner S, Mannarino L, Kirschner MB, Opitz I, Rigutto A, Laure A, et al. Tumor immune microenvironment and genetic alterations in mesothelioma. Front Oncol. 2021;11:660039.[DOI]

-

8. Hylebos M, Van Camp G, van Meerbeeck JP, Op de Beeck K. The genetic landscape of malignant pleural mesothelioma: results from massively parallel sequencing. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(10):1615-1626.[DOI]

-

9. Gerwin BI, Lechner JF, Reddel RR, Roberts AB, Robbins KC, Gabrielson EW, et al. Comparison of production of transforming growth factor-beta and platelet-derived growth factor by normal human mesothelial cells and mesothelioma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1987;47(23):6180-6184.[PubMed]

-

10. Fujii M, Toyoda T, Nakanishi H, Yatabe Y, Sato A, Matsudaira Y, et al. TGF-beta synergizes with defects in the Hippo pathway to stimulate human malignant mesothelioma growth. J Exp Med. 2012;209(3):479-494.[DOI]

-

11. Thompson JK, MacPherson MB, Beuschel SL, Shukla A. Asbestos-induced mesothelial to fibroblastic transition is modulated by the inflammasome. Am J Pathol. 2017;187(3):665-678.[DOI]

-

12. Aird WC. Endothelial cell heterogeneity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(1):a006429.[DOI]

-

13. Teissier T, Boulanger E, Cox LS. Interconnections between inflammageing and immunosenescence during ageing. Cells. 2022;11(3):359.[DOI]

-

14. Cevenini E, Monti D, Franceschi C. Inflamm-ageing. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16(1):14-20.[DOI]

-

15. Cersosimo F, Barbarino M, Lonardi S, Vermi W, Giordano A, Bellan C, et al. Mesothelioma malignancy and the microenvironment: molecular mechanisms. Cancers. 2021;13(22):5664.[DOI]

-

16. Guo G, Chmielecki J, Goparaju C, Heguy A, Dolgalev I, Carbone M, et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals frequent genetic alterations in BAP1, NF2, CDKN2A, and CUL1 in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 2015;75(2):264-269.[DOI]

-

17. Bueno R, Stawiski EW, Goldstein LD, Durinck S, De Rienzo A, Modrusan Z, et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of malignant pleural mesothelioma identifies recurrent mutations, gene fusions and splicing alterations. Nat Genet. 2016;48(4):407-416.[DOI]

-

18. Hmeljak J, Sanchez-Vega F, Hoadley KA, Shih J, Stewart C, Heiman D, et al. Integrative molecular characterization of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(12):1548-1565.[DOI]

-

19. Mossman BT, Shukla A, Heintz NH, Verschraegen CF, Thomas A, Hassan R. New insights into understanding the mechanisms, pathogenesis, and management of malignant mesotheliomas. Am J Pathol. 2013;182(4):1065-1077.[DOI]

-

20. Jackaman C, Yeoh TL, Acuil ML, Gardner JK, Nelson DJ. Murine mesothelioma induces locally-proliferating IL-10+TNF-alpha+CD206-CX3CR1+ M3 macrophages that can be selectively depleted by chemotherapy or immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(6):e1173299.[DOI]

-

21. Hill RJ, Edwards RE, Carthew P. Early changes in the pleural mesothelium following intrapleural inoculation of the mineral fibre erionite and the subsequent development of mesotheliomas. J Exp Pathol. 1990;71(1):105-118.[PubMed]

-

22. Schoenberger CI, Hunninghake GW, Kawanami O, Ferrans VJ, Crystal RG. Role of alveolar macrophages in asbestosis: modulation of neutrophil migration to the lung after acute asbestos exposure. Thorax. 1982;37(11):803-809.[DOI]

-

23. Lewczuk E, Owczarek H, Staniszewska G. Contribution and role of polymorphonuclear leucocytes in inflammatory reactions of asbestosis. Med Pr. 1994;45(6):547-550.[PubMed]

-

24. Ishida T, Fujihara N, Nishimura T, Funabashi H, Hirota R, Ikeda T, et al. Live-cell imaging of macrophage phagocytosis of asbestos fibers under fluorescence microscopy. Genes Environ. 2019;41:1-11.[DOI]

-

25. Driscoll KE, Higgins JM, Leytart MJ, Crosby LL. Differential effects of mineral dusts on the in vitro activation of alveolar macrophage eicosanoid and cytokine release. Toxicol In Vitro. 1990;4(4-5):284-288.[DOI]

-

26. Holian A, Kelley K, Jr RFH. Mechanisms associated with human alveolar macrophage stimulation by particulates. Environ Health Perspect. 1994;102(Suppl 10):69-74.[DOI]

-

27. Kokkinis FP, Bouros D, Hadjistavrou K, Ulmeanu R, Serbescu A, Alexopoulos EC. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid cellular profile in workers exposed to chrysotile asbestos. Toxicol Ind Health. 2011;27(9):849-856.[DOI]

-

28. Keskitalo E, Varis L, Bloigu R, Kaarteenaho R. Bronchoalveolar cell differential count and the number of asbestos bodies correlate with survival in patients with asbestosis. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(10):765-771.[DOI]

-

29. Beno M, Hurbankova M, Dusinska M, Volkovova K, Staruchova M, Cerna S, et al. Some lung cellular parameters reflecting inflammation after combined inhalation of amosite dust with cigarette smoke by rats. Central Eur J Public Health. 2004;12:S11-S13.[PubMed]

-

30. Takemura T, Rom WN, Ferrans VJ, Crystal RG. Morphologic characterization of alveolar macrophages from subjects with occupational exposure to inorganic particles. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140(6):1674-1685.[DOI]

-

31. Moalli PA, MacDonald JL, Goodglick LA, Kane AB. Acute injury and regeneration of the mesothelium in response to asbestos fibers. Am J Pathol. 1987;128(3):426-445.[PubMed]

-

32. Benedetti S, Nuvoli B, Catalani S, Galati R. Reactive oxygen species a double-edged sword for mesothelioma. Oncotarget. 2015;6(19):16848-16865.[DOI]

-

33. Nishimura Y, Nishiike-Wada T, Wada Y, Miura Y, Otsuki T, Iguchi H. Long-lasting production of TGF-beta1 by alveolar macrophages exposed to low doses of asbestos without apoptosis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2007;20(4):661-671.[DOI]

-

34. Desage AL, Karpathiou G, Peoc’h M, Froudarakis ME. The immune microenvironment of malignant pleural mesothelioma: a literature review. Cancers. 2021;13(13):3205.[DOI]

-

35. Kim S, Kim SY, Pribis JP, Lotze M, Mollen KP, Shapiro R, et al. Signaling of high mobility group box 1 (HMGB1) through toll-like receptor 4 in macrophages requires CD14. Mol Med. 2013;19(1):88-98.[DOI]

-

36. Goveia J, Rohlenova K, Taverna F, Treps L, Conradi LC, Pircher A, et al. An integrated gene expression landscape profiling approach to identify lung tumor endothelial cell heterogeneity and angiogenic candidates. Cancer Cell. 2020;37(1):21-36.[DOI]

-

37. Cohen AA, Ferrucci L, Fulop T, Gravel D, Hao N, Kriete A, et al. A complex systems approach to aging biology. Nat Aging. 2022;2(7):580-591.[DOI]

-

38. Carbone M, Yang H. Molecular pathways: targeting mechanisms of asbestos and erionite carcinogenesis in mesothelioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(3):598-604.[DOI]

-

39. Hiraku Y, Guo F, Ma N, Yamada T, Wang S, Kawanishi S, et al. Multi-walled carbon nanotube induces nitrative DNA damage in human lung epithelial cells via HMGB1-RAGE interaction and Toll-like receptor 9 activation. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2015;13:1-21.[DOI]

-

40. Schurch CM, Forster S, Bruhl F, Yang SH, Felley-Bosco E, Hewer E. The “don’t eat me” signal CD47 is a novel diagnostic biomarker and potential therapeutic target for diffuse malignant mesothelioma. Oncoimmunology. 2017;7(1):e1373235.[DOI]

-

41. Chene AL, d’Almeida S, Blondy T, Tabiasco J, Deshayes S, Fonteneau JF, et al. Pleural effusions from patients with mesothelioma induce recruitment of monocytes and their differentiation into M2 macrophages. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(10):1765-1773.[DOI]

-

42. Cornelissen R, Lievense LA, Maat AP, Hendriks RW, Hoogsteden HC, Bogers AJ, et al. Ratio of intratumoral macrophage phenotypes is a prognostic factor in epithelioid malignant pleural mesothelioma. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e106742.[DOI]

-

43. Burt BM, Rodig SJ, Tilleman TR, Elbardissi AW, Bueno R, Sugarbaker DJ. Circulating and tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells predict survival in human pleural mesothelioma. Cancer. 2011;117(22):5234-5244.[DOI]

-

44. Horio D, Minami T, Kitai H, Ishigaki H, Higashiguchi Y, Kondo N, et al. Tumor-associated macrophage-derived inflammatory cytokine enhances malignant potential of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Sci. 2020;111(8):2895-2906.[DOI]

-

45. Salaroglio IC, Kopecka J, Napoli F, Pradotto M, Maletta F, Costardi L, et al. Potential diagnostic and prognostic role of microenvironment in malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(8):1458-1471.[DOI]

-

46. Giurisato E, Lonardi S, Telfer B, Lussoso S, Risa-Ebri B, Zhang J, et al. Extracellular-regulated protein kinase 5-mediated control of p21 expression promotes macrophage proliferation associated with tumor growth and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2020;80(16):3319-3330.[DOI]

-

47. Wu L, Kohno M, Murakami J, Zia A, Allen J, Yun H, et al. Defining and targeting tumor-associated macrophages in malignant mesothelioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2023;120(9):e2210836120.[DOI]

-

48. Colin DJ, Cottet-Dumoulin D, Faivre A, Germain S, Triponez F, Serre-Beinier V. Experimental model of human malignant mesothelioma in athymic mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(7):1881.[DOI]

-

49. Duan M, Chen H, Yin L, Zhu X, Novak P, Lv Y, et al. Mitochondrial apolipoprotein A-I binding protein alleviates atherosclerosis by regulating mitophagy and macrophage polarization. J Cell Commun Signal. 2022;20(1):60.[DOI]

-

50. Lievense LA, Cornelissen R, Bezemer K, Kaijen-Lambers ME, Hegmans JP, Aerts JG. Pleural effusion of patients with malignant mesothelioma induces macrophage-mediated T Cell suppression. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(10):1755-1764.[DOI]

-

51. Hegmans JP, Hemmes A, Hammad H, Boon L, Hoogsteden HC, Lambrecht BN. Mesothelioma environment comprises cytokines and T-regulatory cells that suppress immune responses. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(6):1086-1095.[PubMed]

-

52. Needham DJ, Lee JX, Beilharz MW. Intra-tumoural regulatory T cells: a potential new target in cancer immunotherapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343(3):684-691.[DOI]

-

53. Klampatsa A, O’Brien SM, Thompson JC, Rao AS, Stadanlick JE, Martinez MC, et al. Phenotypic and functional analysis of malignant mesothelioma tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8(9):e1638211.[DOI]

-

54. Marcq E, Waele J, Audenaerde JV, Lion E, Santermans E, Hens N, et al. Abundant expression of TIM-3, LAG-3, PD-1 and PD-L1 as immunotherapy checkpoint targets in effusions of mesothelioma patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8(52):89722-89735.[DOI]

-

55. Nishimura Y, Kumagai-Takei N, Matsuzaki H, Lee S, Maeda M, Kishimoto T, et al. Functional alteration of natural killer cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes upon asbestos exposure and in malignant mesothelioma patients. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:238431.[DOI]

-

56. Minnema-Luiting J, Vroman H, Aerts J, Cornelissen R. Heterogeneity in immune cell content in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(4):1041.[DOI]

-

57. Ireland DJ, Kissick HT, Beilharz MW. The role of regulatory T cells in mesothelioma. Cancer Microenv. 2012;5(2):165-172.[DOI]

-

58. Harber J, Kamata T, Pritchard C, Fennell D. Matter of TIME: the tumor-immune microenvironment of mesothelioma and implications for checkpoint blockade efficacy. J Immuno Ther Cancer. 2021;9(9):e003032.[DOI]

-

59. Jackaman C, Gardner JK, Tomay F, Spowart J, Crabb H, Dye DE, et al. CD8+ cytotoxic T cell responses to dominant tumor-associated antigens are profoundly weakened by aging yet subdominant responses retain functionality and expand in response to chemotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8(4):e1564452.[DOI]

-

60. Jackaman C, Bundell CS, Kinnear BF, Smith AM, Filion P, van Hagen D, et al. IL-2 intratumoral immunotherapy enhances CD8+ T cells that mediate destruction of tumor cells and tumor-associated vasculature: a novel mechanism for IL-2. J Immunol. 2003;171(10):5051-5063.[DOI]

-

61. Duong L, Radley-Crabb HG, Gardner JK, Tomay F, Dye DE, Grounds MD, et al. Macrophage depletion in elderly mice improves response to tumor immunotherapy, increases anti-tumor T cell activity and reduces treatment-induced cachexia. Front Genet. 2018;9:526.[DOI]

-

62. Cornwall SM, Wikstrom M, Musk AW, Alvarez J, Nowak AK, Nelson DJ. Human mesothelioma induces defects in dendritic cell numbers and antigen-processing function which predict survival outcomes. Oncoimmunology. 2016;5(2):e1082028.[DOI]

-

63. Gardner JK, Jackaman C, Mamotte CDS, Nelson DJ. The regulatory status adopted by lymph node dendritic cells and T cells during healthy aging is maintained during cancer and may contribute to reduced responses to immunotherapy. Front Med. 2018;5:337.[DOI]

-

64. Jackaman C, Majewski D, Fox SA, Nowak AK, Nelson DJ. Chemotherapy broadens the range of tumor antigens seen by cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in vivo. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61(12):2343-2356.[DOI]

-

65. Ohara Y, Enomoto A, Tsuyuki Y, Sato K, Iida T, Kobayashi H, et al. Connective tissue growth factor produced by cancer-associated fibroblasts correlates with poor prognosis in epithelioid malignant pleural mesothelioma. Oncol Rep. 2020;44(3):838-848.[DOI]

-

66. Jackaman C, Lew AM, Zhan Y, Allan JE, Koloska B, Graham PT, et al. Deliberately provoking local inflammation drives tumors to become their own protective vaccine site. Int Immunol. 2008;20(11):1467-1479.[DOI]

-

67. Mahbub S, Deburghgraeve CR, Kovacs EJ. Advanced age impairs macrophage polarization. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2012;32(1):18-26.[DOI]

-

68. Bouchlaka MN, Sckisel GD, Chen M, Mirsoian A, Zamora AE, Maverakis E, et al. Aging predisposes to acute inflammatory induced pathology after tumor immunotherapy. J Exp Med. 2013;210(11):2223-2237.[DOI]

-

69. Jackaman C, Radley-Crabb HG, Soffe Z, Shavlakadze T, Grounds MD, Nelson DJ. Targeting macrophages rescues age-related immune deficiencies in C57BL/6J geriatric mice. Aging Cell. 2013;12(3):345-357.[DOI]

-

70. Jackaman C, Dye DE, Nelson DJ. IL-2/CD40-activated macrophages rescue age and tumor-induced T cell dysfunction in elderly mice. Age. 2014;36(3):9655.[DOI]

-

71. Kelly J, Ali Khan A, Yin J, Ferguson TA, Apte RS. Senescence regulates macrophage activation and angiogenic fate at sites of tissue injury in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(11):3421-3426.[DOI]

-

72. Lumeng CN, Liu J, Geletka L, Delaney C, Delproposto J, Desai A, et al. Aging is associated with an increase in T cells and inflammatory macrophages in visceral adipose tissue. J Immunol. 2011;187(12):6208-6216.[DOI]

-

73. Fontana L, Klein S. Aging, adiposity, and calorie restriction. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;297(9):986-994.[DOI]

-

74. Campbell RA, DochertyM-H , Ferenbach DA, Mylonas KJ. The role of ageing and parenchymal senescence on macrophage function and fibrosis. Front Immunol. 2021;21:700790.[DOI]

-

75. Blériot C, Svetoslav C, Ginhoux F. Determinants of resident tissue macrophage identity and function. Immunity. 2020;52:957-970.[DOI]

-

76. Ley K, Laudanna C, Cybulsky MI, Nourshargh S. Getting to the site of inflammation: the leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(9):678-689.[DOI]

-

77. Taflin C, Charron D, Glotz D, Mooney N. Regulation of the CD4+ T cell allo-immune response by endothelial cells. Hum Immunol. 2012;73(12):1269-1274.[DOI]

-

78. Al-Soudi A, Kaaij MH, Tas SW. Endothelial cells: from innocent bystanders to active participants in immune responses. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16(9):951-962.[DOI]

-

79. Ebeling S, Kowalczyk A, Perez-Vazquez D, Mattiola I. Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by the crosstalk between innate immunity and endothelial cells. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1171794.[DOI]

-

80. Dauphinee SM, Karsan A. Lipopolysaccharide signaling in endothelial cells. Lab Invest. 2006;86(1):9-22.[DOI]

-

81. Austrup F, Vestweber D, Borges E, Lohning M, Brauer R, Herz U, et al. P- and E-selectin mediate recruitment of T-helper-1 but not T-helper-2 cells into inflammed tissues. Nature. 1997;385(6611):81-83.[DOI]

-

82. Ritzman AM, Hughes-Hanks JM, Blaho VA, Wax LE, Mitchell WJ, Brown CR. The chemokine receptor CXCR2 ligand KC (CXCL1) mediates neutrophil recruitment and is critical for development of experimental Lyme arthritis and carditis. Infect Immun. 2010;78(11):4593-4600.[DOI]

-

83. Maus TP. Imaging of the spine and nerve roots. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2002;13(3):487-544.[DOI]

-

84. Savinov AY, Wong FS, Stonebraker AC, Chervonsky AV. Presentation of antigen by endothelial cells and chemoattraction are required for homing of insulin-specific CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197(5):643-656.[DOI]

-

85. Rothermel AL, Wang Y, Schechner J, Mook-Kanamori B, Aird WC, Pober JS, et al. Endothelial cells present antigens in vivo. BMC Immunol. 2004;5:5.[DOI]

-

86. Marelli-Berg FM, Scott D, Bartok I, Peek E, Dyson J, Lechler RI. Antigen presentation by murine endothelial cells. Transplant Proc. 2001;33(1-2):315-316.[DOI]

-

87. Angelot F, Seillès E, Biichlé S, Berda Y, Gaugler B, Plumas J, et al. Endothelial cell-derived microparticles induce plasmacytoid dendritic cell maturation: potential implications in inflammatory diseases. Haematologica. 2009;94(11):1502-1512.[DOI]

-

88. Klein D. The tumor vascular endothelium as decision maker in cancer therapy. Front Oncol. 2018;8:367.[DOI]

-

89. He H, Xu J, Warren CM, Duan D, Li X, Wu L, et al. Endothelial cells provide an instructive niche for the differentiation and functional polarization of M2-like macrophages. Blood. 2012;120(15):3152-3162.[DOI]

-

90. Wienke J, Veldkamp SR, Struijf EM, Yousef Yengej FA, van der Wal MM, van Royen-Kerkhof A, et al. T cell interaction with activated endothelial cells primes for tissue-residency. Front Immunol. 2022;13:827786.[DOI]

-

91. Tang SQ, Yao WL, Wang YZ, Zhang YY, Zhao HY, Wen Q, et al. Improved function and balance in T cell modulation by endothelial cells in young people. Clin Exp Immunol. 2021;206(2):196-207.[DOI]

-

92. Ting KK, Coleman P, Zhao Y, Vadas MA, Gamble JR. The aging endothelium. Vasc Biol. 2021;3(1):R35-R47.[DOI]

-

93. Basisty N, Kale A, Jeon OH, Kuehnemann C, Payne T, Rao C, et al. A proteomic atlas of senescence-associated secretomes for aging biomarker development. PLoS Biol. 2020;18(1):e3000599.[DOI]

-

94. Sun X, Feinberg MW. Vascular endothelial senescence: pathobiological insights, emerging long noncoding RNA targets, challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Front Physiol. 2021;12:693067.[DOI]

-

95. Rossman MJ, Santos-Parker JR, Steward CAC, Bispham NZ, Cuevas LM, Rosenberg HL, et al. Chronic supplementation with a mitochondrial antioxidant (MitoQ) improves vascular function in healthy older adults. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1056-1063.[DOI]

-

96. Tracy EP, Hughes W, Beare JE, Rowe G, Beyer A, LeBlanc AJ. Aging-induced impairment of vascular function: mitochondrial redox contributions and physiological/clinical implications. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2021;35(12):974-1015.[DOI]

-

97. Li YJ, Jin X, Li D, Lu J, Zhang XN, Yang SJ, et al. New insights into vascular aging: emerging role of mitochondria function. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;156:113954.[DOI]

-

98. Grazioli S, Pugin J. Mitochondrial damage-associated molecular patterns: from inflammatory signaling to human diseases. Front Immunol. 2018;9:832.[DOI]

-

99. Pinti M, Cevenini E, Nasi M, De Biasi S, Salvioli S, Monti D, et al. Circulating mitochondrial DNA increases with age and is a familiar trait: implications for “inflamm-aging”. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44(5):1552-1562.[DOI]

-

100. Dumont A, Lee M, Barouillet T, Murphy A, Yvan-Charvet L. Mitochondria orchestrate macrophage effector functions in atherosclerosis. Mol Aspects Med. 2021;77:100922.[DOI]

-

101. Karunakaran D, Thrush AB, Nguyen MA, Richards L, Geoffrion M, Singaravelu R, et al. Macrophage mitochondrial energy status regulates cholesterol efflux and is enhanced by anti-miR33 in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2015;117(3):266-278.[DOI]

-

102. Watanabe T, Hirata M, Yoshikawa Y, Nagafuchi Y, Toyoshima H, Watanabe T. Role of macrophages in atherosclerosis. Sequential observations of cholesterol-induced rabbit aortic lesion by the immunoperoxidase technique using monoclonal antimacrophage antibody. Lab Invest. 1985;53(1):80-90.[PubMed]

-

103. Farahi L, Sinha SK, Lusis AJ. Roles of macrophages in atherogenesis. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:785220.[DOI]

-

104. Zeisbrich M, Yanes RE, Zhang H, Watanabe R, Li Y, Brosig L, et al. Hypermetabolic macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis and coronary artery disease due to glycogen synthase kinase 3b inactivation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(7):1053-1062.[DOI]

-

105. Tavakoli S, Asmis R. Reactive oxygen species and thiol redox signaling in the macrophage biology of atherosclerosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;17(12):1785-1795.[DOI]

-

106. Dorighello GG, Assis LHP, Rentz T, Morari J, Santana MFM, Passarelli M, et al. Novel role of CETP in macrophages: reduction of mitochondrial oxidants production and modulation of cell immune-metabolic profile. Antioxid. 2022;11(9):1734.[DOI]

-

107. Collins T, Cybulsky MI. NF-κB: pivotal mediator or innocent bystander in atherogenesis? J Clin Invest. 2001;107(3):255-264.[DOI]

-

108. Trott DW, Henson GD, Ho MHT, Allison SA, Lesniewski LA, Donato AJ. Age-related arterial immune cell infiltration in mice is attenuated by caloric restriction or voluntary exercise. Exp Gerontol. 2018;109:99-107.[DOI]

-

109. Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Koller A, Edwards JG, Kaley G. Aging-induced proinflammatory shift in cytokine expression profile in coronary arteries. FASEB J. 2003;17(9):1183-1185.[DOI]

-

110. Belmin J, Bernard C, Corman B, Merval R, Esposito B, Tedgui A. Increased production of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 by arterial wall of aged rats. Am J Physiol. 1995;268(6):H2288-H2293.[DOI]

-

111. Lesniewski LA, Durrant JR, Connell ML, Henson GD, Black AD, Donato AJ, et al. Aerobic exercise reverses arterial inflammation with aging in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301(3):H1025-H1032.[DOI]

-

112. Mackay CDA, Jadli AS, Fedak PWM, Patel VB. Adventitial fibroblasts in aortic aneurysm: unraveling pathogenic contributions to vascular disease. Diagnostics. 2022;12(4):871.[DOI]

-

113. Lahteenvuo J, Rosenzweig A. Effects of aging on angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2012;110(9):1252-1264.[DOI]

-

114. Potente M, Gerhardt H, Carmeliet P. Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell. 2011;146(6):873-887.[DOI]

-

115. De Palma M, Biziato D, Petrova TV. Microenvironmental regulation of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17(8):457-474.[DOI]

-

116. Swift ME, Kleinman HK, DiPietro LA. Impaired wound repair and delayed angiogenesis in aged mice. Lab Invest. 1999;79(12):1479-1487.[PubMed]

-

117. Reed MJ, Corsa A, Pendergrass W, Penn P, Sage EH, Abrass IB. Neovascularization in aged mice: delayed angiogenesis is coincident with decreased levels of transforming growth factor beta1 and type I collagen. Am J Pathol. 1998;152(1):113-123.[PubMed]

-

118. Rivard A, Fabre JE, Silver M, Chen D, Murohara T, Kearney M, et al. Age-dependent impairment of angiogenesis. Circulation. 1999;99(1):111-120.[DOI]

-

119. Uryga AK, Bennett MR. Ageing induced vascular smooth muscle cell senescence in atherosclerosis. J Physiol. 2016;594(8):2115-2124.[DOI]

-

120. Moriya J, Minamino T. Angiogenesis, cancer, and vascular aging. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2017;4:65.[DOI]

-

121. Hohensinner PJ, Kaun C, Buchberger E, Ebenbauer B, Demyanets S, Huk I, et al. Age intrinsic loss of telomere protection via TRF1 reduction in endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863(2):360-367.[DOI]

-

122. Parizkova J, Eiselt E, Sprynarova S, Wachtlova M. Body composition, aerobic capacity, and density of muscle capillaries in young and old men. J Appl Physiol. 1971;31(3):323-325.[DOI]

-

123. Helmbold P, Lautenschlager C, Marsch W, Nayak RC. Detection of a physiological juvenile phase and the central role of pericytes in human dermal microvascular aging. J Investig Dermatol. 2006;126(6):1419-1421.[DOI]

-

124. Ambrose CT. Pro-angiogenesis therapy and aging: a mini-review. Gerontology. 2017;63(5):393-400.[DOI]

-

125. Sadoun E, Reed MJ. Impaired angiogenesis in aging is associated with alterations in vessel density, matrix composition, inflammatory response, and growth factor expression. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51(9):1119-1130.[DOI]

-

126. Tan BL, Norhaizan ME, Liew WP, Sulaiman Rahman H. Antioxidant and oxidative stress: a mutual interplay in age-related diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1162.[DOI]

-

127. Liguori I, Russo G, Curcio F, Bulli G, Aran L, Della-Morte D, et al. Oxidative stress, aging, and diseases. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:757-772.[DOI]

-

128. Hosoda Y, Kawano K, Yamasawa F, Ishii T, Shibata T, Inayama S. Age-dependent changes of collagen and elastin content in human aorta and pulmonary artery. Angiology. 1984;35(10):615-621.[DOI]

-

129. Hall DA. The ageing of connective tissue. Exp Gerontol. 1968;3(2):77-89.[DOI]

-

130. Cattell MA, Hasleton PS, Anderson JC. Increased elastin content and decreased elastin concentration may be predisposing factors in dissecting aneurysms of human thoracic aorta. Cardiovasc Res. 1993;27(2):176-181.[DOI]

-

131. Giudici A, Li Y, Yasmin , Cleary S, Connolly K, McEniery C, et al. Time-course of the human thoracic aorta ageing process assessed using uniaxial mechanical testing and constitutive modelling. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2022;134:105339.[DOI]

-

132. Franceschi C, Bonafe M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, De Luca M, Ottaviani E, et al. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;908:244-254.[DOI]

-

133. Liu B, Ren KD, Peng JJ, Li T, Luo XJ, Fan C, et al. Suppression of NADPH oxidase attenuates hypoxia-induced dysfunctions of endothelial progenitor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;482(4):1080-1087.[DOI]

-

134. Rogers SC, Zhang X, Azhar G, Luo S, Wei JY. Exposure to high or low glucose levels accelerates the appearance of markers of endothelial cell senescence and induces dysregulation of nitric oxide synthase. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(12):1469-1481.[DOI]

-

135. Bertelli PM, Pedrini E, Hughes D, McDonnell S, Pathak V, Peixoto E, et al. Long term high glucose exposure induces premature senescence in retinal endothelial cells. Front Physiol. 2022;13:929118.[DOI]

-

136. Coleman PR, Chang G, Hutas G, Grimshaw M, Vadas MA, Gamble JR. Age-associated stresses induce an anti-inflammatory senescent phenotype in endothelial cells. Aging. 2013;5(12):913-924.[DOI]

-

137. Powter EE, Coleman PR, Tran MH, Lay AJ, Bertolino P, Parton RG, et al. Caveolae control the anti-inflammatory phenotype of senescent endothelial cells. Aging Cell. 2015;14(1):102-111.[DOI]

-

138. Ershler WB, Stewart JA, Hacker MP, Moore AL, Tindle BH. B16 murine melanoma and aging: slower growth and longer survival in old mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1984;72(1):161-164.[DOI]

-

139. Oh J, Magnuson A, Benoist C, Pittet MJ, Weissleder R. Age-related tumor growth in mice is related to integrin alpha 4 in CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest Insight. 2018;3(21):e122961.[DOI]

-

140. Pettan-Brewer C, Morton J, Coil R, Hopkins H, Fatemie S, Ladiges W. B16 melanoma tumor growth is delayed in mice in an age-dependent manner. Pathobiol Aging Age-related Dis. 2012;2(1):19182.[DOI]

-

141. Chen YM, Wang PS, Liu JM, Hsieh YL, Tsai CM, Perng RP, et al. Effect of age on pulmonary metastases and immunotherapy in young and middle-aged mice. J Chinese Med Assoc. 2007;70(3):94-102.[DOI]

-

142. Beheshti A, Benzekry S, McDonald JT, Ma L, Peluso M, Hahnfeldt P, et al. Host age is a systemic regulator of gene expression impacting cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2015;75(6):1134-1143.[DOI]

-

143. Schonberg MA, Marcantonio ER, Li D, Silliman RA, Ngo L, McCarthy EP. Breast cancer among the oldest old: tumor characteristics, treatment choices, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(12):2038-2045.[DOI]

-

144. Lodi M, Scheer L, Reix N, Heitz D, Carin AJ, Thiebaut N, et al. Breast cancer in elderly women and altered clinico-pathological characteristics: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;166(3):657-668.[DOI]

-

145. Hemminki K, Forsti A, Hemminki A. Survival in colon and rectal cancers in Finland and Sweden through 50 years. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2021;8(1):e000644.[DOI]

-

146. O’Connell JB, Maggard MA, Livingston EH, Yo CK. Colorectal cancer in the young. Am J Surg. 2004;187(3):343-348.[DOI]

-

147. Ishikawa S, Matsui Y, Wachi S, Yamaguchi H, Harashima N, Harada M. Age-associated impairment of antitumor immunity in carcinoma-bearing mice and restoration by oral administration of Lentinula edodes mycelia extract. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2016;65(8):961-972.[DOI]

-

148. Shavelle R, Vavra-Musser K, Lee J, Brooks J. Life expectancy in pleural and peritoneal mesothelioma. Lung Cancer Int. 2017;2017(1):2782590.[DOI]

-

149. Pettersson A, Robinson D, Garmo H, Holmberg L, Stattin P. Age at diagnosis and prostate cancer treatment and prognosis: a population-based cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(2):377-385.[DOI]

-

150. Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407(6801):249-257.[DOI]

-

151. Tilki D, Kilic N, Sevinc S, Zywietz F, Stief CG, Ergun S. Zone-specific remodeling of tumor blood vessels affects tumor growth. Cancer. 2007;110(10):2347-2362.[DOI]

-

152. Morikawa S, Baluk P, Kaidoh T, Haskell A, Jain RK, McDonald DM. Abnormalities in pericytes on blood vessels and endothelial sprouts in tumors. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(3):985-1000.[DOI]

-

153. Cantelmo AR, Conradi LC, Brajic A, Goveia J, Kalucka J, Pircher A, et al. Inhibition of the glycolytic activator PFKFB3 in endothelium induces tumor vessel normalization, impairs metastasis, and improves chemotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2016;30(6):968-985.[DOI]

-

154. Tilki D, Hohn HP, Ergun B, Rafii S, Ergun S. Emerging biology of vascular wall progenitor cells in health and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15(11):501-509.[DOI]

-

155. Lambrechts D, Wauters E, Boeckx B, Aibar S, Nittner D, Burton O, et al. Phenotype molding of stromal cells in the lung tumor microenvironment. Nat Med. 2018;24(8):1277-1289.[DOI]

-

156. Hida K, Hida Y, Amin DN, Flint AF, Panigrahy D, Morton CC, et al. Tumor-associated endothelial cells with cytogenetic abnormalities. Cancer Res. 2004;64(22):8249-8255.[DOI]

-

157. Deeb G, Vaughan MM, McInnis I, Ford LA, Sait SN, Starostik P, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha protein expression is associated with poor survival in normal karyotype adult acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia Res. 2011;35(5):579-584.[DOI]

-

158. Croix BS. Vaccines targeting tumor vasculature: a new approach for cancer immunotherapy. Cytotherapy. 2007;9(1):1-3.[DOI]

-

159. Maishi N, Annan DA, Kikuchi H, Hida Y, Hida K. Tumor endothelial heterogeneity in cancer progression. Cancers. 2019;11(10):1511.[DOI]

-

160. Buckanovich RJ, Facciabene A, Kim S, Benencia F, Sasaroli D, Balint K, et al. Endothelin B receptor mediates the endothelial barrier to T cell homing to tumors and disables immune therapy. Nat Med. 2008;14(1):28-36.[DOI]

-

161. Kambayashi T, Laufer TM. Atypical MHC class II-expressing antigen-presenting cells: can anything replace a dendritic cell? Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(11):719-730.[DOI]

-

162. Fukumura D, Kashiwagi S, Jain RK. The role of nitric oxide in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(7):521-534.[DOI]

-

163. De Caterina R, Libby P, Peng HB, Thannickal VJ, Rajavashisth TB, Gimbrone MA Jr, et al. Nitric oxide decreases cytokine-induced endothelial activation. Nitric oxide selectively reduces endothelial expression of adhesion molecules and proinflammatory cytokines. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(1):60-68.[DOI]

-

164. Griffioen AW, Damen CA, Mayo KH, Barendsz-Janson AF, Martinotti S, Blijham GH, et al. Angiogenesis inhibitors overcome tumor induced endothelial cell anergy. Int J Cancer. 1999;80(2):315-319.[DOI]

-

165. Dirkx AE, Oude Egbrink MG, Kuijpers MJ, van der Niet ST, Heijnen VV, Bouma-ter Steege JC, et al. Tumor angiogenesis modulates leukocyte-vessel wall interactions in vivo by reducing endothelial adhesion molecule expression. Cancer Res. 2003;63(9):2322-2329.[PubMed]

-

166. Flati V, Pastore LI, Griffioen AW, Satijn S, Toniato E, D’Alimonte I, et al. Endothelial cell anergy is mediated by bFGF through the sustained activation of p38-MAPK and NF-kappaB inhibition. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2006;19(4):761-773.[DOI]

-

167. Delfortrie S, Pinte S, Mattot V, Samson C, Villain G, Caetano B, et al. Egfl7 promotes tumor escape from immunity by repressing endothelial cell activation. Cancer Res. 2011;71(23):7176-7186.[DOI]

-

168. Spinella F, Rosano L, Di Castro V, Natali PG, Bagnato A. Endothelin-1 induces vascular endothelial growth factor by increasing hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in ovarian carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(31):27850-27855.[DOI]

-

169. Rossi E, Smadja DM, Boscolo E, Langa C, Arevalo MA, Pericacho M, et al. Endoglin regulates mural cell adhesion in the circulatory system. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(8):1715-1739.[DOI]

-

170. Stalin J, Nollet M, Garigue P, Fernandez S, Vivancos L, Essaadi A, et al. Targeting soluble CD146 with a neutralizing antibody inhibits vascularization, growth and survival of CD146-positive tumors. Oncogene. 2016;35(42):5489-5500.[DOI]

-

171. Griffioen AW, Damen CA, Blijham GH, Groenewegen G. Tumor angiogenesis is accompanied by a decreased inflammatory response of tumor-associated endothelium. Blood. 1996;88(2):667-673.[DOI]

-

172. Nummer D, Suri-Payer E, Schmitz-Winnenthal H, Bonertz A, Galindo L, Antolovich D, et al. Role of tumor endothelium in CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cell infiltration of human pancreatic carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(15):1188-1199.[DOI]

-

173. Karikoski M, Marttila-Ichihara F, Elima K, Rantakari P, Hollmen M, Kelkka T, et al. Clever-1/stabilin-1 controls cancer growth and metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(24):6452-6464.[DOI]

-

174. De Sanctis F, Ugel S, Facciponte J, Facciabene A. The dark side of tumor-associated endothelial cells. Semin Immunol. 2018;35:35-47.[DOI]

-

175. Nagl L, Horvath L, Pircher A, Wolf D. Tumor endothelial cells (TECs) as potential immune directors of the tumor microenvironment - new findings and future perspectives. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:766.[DOI]

-

176. Georganaki M, van Hooren L, Dimberg A. Vascular targeting to increase the efficiency of immune checkpoint blockade in cancer. Front Immunol. 2018;9:3081.[DOI]

-

177. Valenzuela NM. IFNγ, and to a Lesser Extent TNFα, Provokes a Sustained Endothelial Costimulatory Phenotype. Front Immunol. 2021;12:648946.[DOI]

-

178. Rodig N, Ryan T, Allen JA, Pang H, Grabie N, Chernova T, et al. Endothelial expression of PD-L1 and PD-L2 down-regulates CD8+ T cell activation and cytolysis. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33(11):3117-3126.[DOI]

-

179. Motz GT, Santoro SP, Wang LP, Garrabrant T, Lastra RR, Hagemann IS, et al. Tumor endothelium FasL establishes a selective immune barrier promoting tolerance in tumors. Nat Med. 2014;20(6):607-615.[DOI]

-

180. Curti A, Trabanelli S, Salvestrini V, Baccarani M, Lemoli RM. The role of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in the induction of immune tolerance: focus on hematology. Blood. 2009;113(11):2394-2401.[DOI]

-

181. Georganaki M, Ramachandran M, Tuit S, Nunez NG, Karampatzakis A, Fotaki G, et al. Tumor endothelial cell up-regulation of IDO1 is an immunosuppressive feed-back mechanism that reduces the response to CD40-stimulating immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9(1):1730538.[DOI]

-

182. Gardner JK, Cornwall SMJ, Musk AW, Alvarez J, Mamotte CDS, Jackaman C, et al. Elderly dendritic cells respond to LPS/IFN-gamma and CD40L stimulation despite incomplete maturation. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0195313.[DOI]

-

183. Demirag F, Unsal E, Yilmaz A, Caglar A. Prognostic significance of vascular endothelial growth factor, tumor necrosis, and mitotic activity index in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Chest. 2005;128(5):3382-3387.[DOI]

-

184. Hirayama N, Tabata C, Tabata R, Maeda R, Yasumitsu A, Yamada S, et al. Pleural effusion VEGF levels as a prognostic factor of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Respir Med. 2011;105(1):137-142.[DOI]

-

185. Yasumitsu A, Tabata C, Tabata R, Hirayama N, Murakami A, Yamada S, et al. Clinical significance of serum vascular endothelial growth factor in malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5(4):479-483.[DOI]

-

186. Harada A, Uchino J, Harada T, Nakagaki N, Hisasue J, Fujita M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor promoter-based conditionally replicative adenoviruses effectively suppress growth of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(1):116-123.[DOI]

-

187. Kumar-Singh S, Weyler J, Martin MJ, Vermeulen PB, Van Marck E. Angiogenic cytokines in mesothelioma: a study of VEGF, FGF-1 and -2, and TGF beta expression. J Pathol. 1999;189(1):72-78.[DOI]

-

188. Chia PL, Russell P, Asadi K, Thapa B, Gebski V, Murone C, et al. Analysis of angiogenic and stromal biomarkers in a large malignant mesothelioma cohort. Lung Cancer. 2020;150:1-8.[DOI]

-

189. Obacz J, Valer JA, Nibhani R, Adams TS, Schupp JC, Veale N, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of human pleura reveals stromal heterogeneity and informs in vitro models of mesothelioma. Eur Respir J. 2024;63(1):2300143.[DOI]