Abstract

BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficiencies are classically defined by impaired homologous recombination–mediated DNA repair; however, their pathological consequences extend far beyond cell-autonomous genomic instability. Accumulating evidence indicates that BRCA deficiency is accompanied by iron dysregulation and persistent lipid peroxidation, placing cells under chronic ferroptotic pressure. Studies using BRCA1/2 rat models demonstrate that ferroptosis functions as a decisive biological checkpoint with gene-specific outcomes. Under BRCA1 haploinsufficiency, iron-driven oxidative stress accelerates carcinogenesis by selecting for ferroptosis-resistant clones, whereas BRCA2 haploinsufficiency enhances ferroptotic execution, thereby preventing iron-induced cancer promotion. In contrast, reproductive tissues lacking adaptive escape capacity manifest BRCA deficiency as a direct ferroptosis-driven cellular loss, resulting in male and female infertility. Importantly, ferroptosis is not a silent, cell-confined event. Experimental evidence from asbestos-induced carcinogenesis demonstrates that macrophages undergoing ferroptosis after asbestos phagocytosis release CD63-positive, ferritin-containing extracellular vesicles (EVs) that induce oxidative stress in recipient mesothelial cells, establishing EVs as active mediators of ferroptotic stress propagation. We propose that BRCA deficiency generates a state of ferroptotic priming in which oxidized lipids, iron-related factors, and nucleic acids are disseminated via EVs, thereby shaping tissue- and organ-level pathology. From an evolutionary perspective, the persistence of pathogenic BRCA variants may reflect adaptive advantages conferred by haploinsufficiency in iron-limited, short-lived ancestral environments; under modern conditions of iron abundance and extended lifespan, this once-adaptive state becomes maladaptive, predisposing carriers to cancer and degenerative disorders beyond the cell.

Keywords

1. Introduction

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are essential guardians of genome integrity through their roles in homologous recombination–mediated DNA repair[1,2]. Pathogenic variants in these genes predispose carriers to cancer[3] and reproductive dysfunction[4], yet the molecular basis underlying the tissue specificity of these disorders remains incompletely understood. Increasing evidence indicates that BRCA deficiency is accompanied by iron dysregulation, persistent oxidative stress, and enhanced lipid peroxidation[5,6], collectively placing affected cells under chronic ferroptotic pressure[7,8]. Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death driven by lipid peroxidation[9], therefore represents a central pathological axis in BRCA-associated disorders.

Importantly, ferroptosis is not merely a terminal intracellular event. Persistent DNA damage and oxidative stress are now recognized to activate extracellular vesicle (EV)–based secretory programs that enable stressed cells to communicate with their cellular microenvironment[10]. This review integrates evidence from BRCA1/2 rat models with emerging concepts in ferroptosis and EV biology, proposing a unifying framework in which BRCA-associated pathologies extend beyond the cell through EV-mediated propagation of ferroptotic stress.

2. Cancer: Ferroptosis as a Selective Pressure under BRCA Deficiency

Experimental studies using BRCA1 haploinsufficient rat models have demonstrated that iron-driven oxidative stress markedly accelerates renal carcinogenesis[7]. In these models, iron overload induces intense lipid peroxidation, imposing strong ferroptotic pressure on renal epithelial cells. Tumors that eventually arise do so not by succumbing to ferroptosis but by acquiring resistance mechanisms involving iron handling, antioxidant capacity, and redox adaptation[7]. Similar principles operate in BRCA1-associated mesothelial carcinogenesis, where chronic iron exposure shapes tumor evolution through selection under ferroptotic stress[11].

Importantly, this carcinogenic acceleration by iron is not uniformly observed across BRCA genes. In contrast to BRCA1 deficiency, BRCA2 haploinsufficiency does not enhance iron-induced renal carcinogenesis, as demonstrated in our recent study[8]. In

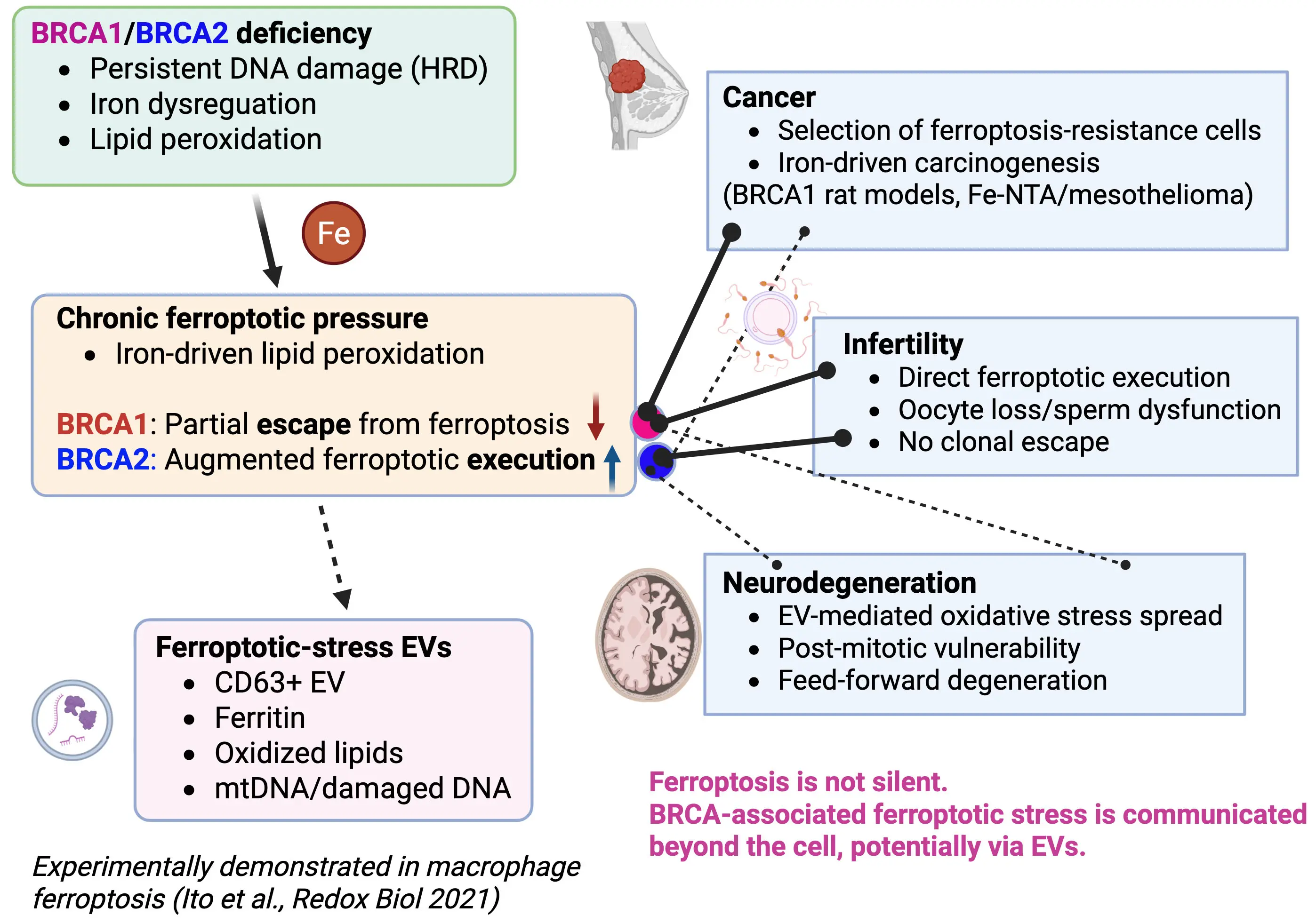

Figure 1. Ferroptotic-stress extracellular vesicles link BRCA deficiency to non–cell-autonomous pathology. BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficiencies induce persistent DNA damage and iron dysregulation, resulting in chronic lipid peroxidation and ferroptotic pressure. Under BRCA1 haploinsufficiency, iron-driven oxidative stress promotes carcinogenesis by selecting for ferroptosis-resistant clones, whereas BRCA2 haploinsufficiency enhances ferroptotic execution, thereby preventing iron-induced cancer promotion. Before overt cell death, cells under ferroptotic stress actively release CD63-positive EVs containing oxidized lipids, ferritin, and nucleic acids. Experimental evidence from macrophages undergoing ferroptosis after asbestos phagocytosis demonstrates that ferritin-containing EVs induce oxidative stress and DNA damage in recipient mesothelial cells. We propose that such “ferroptotic-stress EVs” disseminate iron-dependent oxidative signals beyond the cell, driving divergent BRCA-associated outcomes including cancer, male and female infertility, and neurodegeneration. Created in BioRender. EVs: extracellular vesicles; HRD: homologous recombination deficiency; Fe-NTA: ferric nitrilotriacetate.

Together, these in vivo data establish a critical gene-specific divergence in how ferroptotic pressure shapes cancer risk under BRCA deficiency. While BRCA1 haploinsufficiency promotes tumorigenesis through selection of ferroptosis-resistant clones, BRCA2 deficiency biases cells toward ferroptotic elimination, preventing iron-driven cancer promotion. This distinction underscores ferroptosis as a decisive biological checkpoint that differentially governs malignant evolution in BRCA-associated carcinogenesis.

3. Reproductive Failure as Direct Execution of Ferroptosis

3.1 Female infertility

In contrast to cancer, reproductive tissues lack the capacity for clonal selection and adaptive escape. Studies using BRCA2 heterozygous rat models have revealed a significant reduction in ovarian reserve, accompanied by increased oxidative stress in granulosa cells[12]. These findings indicate that oocytes and their supporting cells are intrinsically vulnerable to lipid peroxidation. Furthermore, BRCA1-deficient rat models demonstrate heightened sensitivity to chemotherapy-induced ovarian damage, consistent with an inability to tolerate additional oxidative and ferroptotic stress[13].

Collectively, these data position female infertility in BRCA deficiency as a manifestation of direct ferroptotic execution, rather than a process shaped by selective survival (Figure 1).

3.2 Male infertility

Male reproductive dysfunction provides a parallel example. BRCA2 heterozygous rats exhibit age-dependent declines in sperm quality, reflecting cumulative oxidative damage in spermatogenic cells[14]. Given the abundance of polyunsaturated fatty acids in sperm membranes[15], these cells are particularly susceptible to lipid peroxidation. The absence of malignant transformation in this context further underscores that BRCA-associated reproductive failure is driven by ferroptosis-prone tissue vulnerability rather than by neoplastic selection.

4. Neurodegeneration: Ferroptosis-Sensitive Post-Mitotic Cells and EV-Mediated Stress Spread

Neurons represent a unique cellular context in which BRCA-associated ferroptotic stress is expected to manifest as degeneration rather than malignant transformation. Post-mitotic neurons are intrinsically vulnerable to lipid peroxidation due to their high polyunsaturated fatty acid content, intense mitochondrial activity, and limited regenerative capacity[16,17]. Iron accumulation and oxidative lipid damage are well-established features of multiple neurodegenerative disorders, including Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA)[18,19].

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are expressed in the nervous system and contribute to DNA damage repair and mitochondrial homeostasis[20,21]. Persistent DNA damage resulting from BRCA deficiency is therefore predicted to exacerbate neuronal oxidative stress and ferroptotic vulnerability[22-24]. Unlike cancer cells, neurons cannot escape ferroptotic pressure through clonal selection, rendering them susceptible to progressive functional decline.

Emerging evidence further implicates EVs as critical mediators of neurodegenerative spread[25]. Under injury/oxidative inflammatory stress, neurons and astrocytes release EVs that reshape microglial activation states and neuroinflammatory signaling in recipient cells[26]. In addition, DNA damage in microglia can drive the release of DNA-containing EVs that promote neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration[27,28]. EVs carrying oxidized lipids, iron-related proteins, or mitochondrial nucleic acids have been suggested to amplify ferroptosis sensitivity in recipient neurons and glia, creating a feed-forward loop of degeneration (Figure 1).

Within this framework, BRCA deficiency may represent a condition in which ferroptosis-primed EVs disseminate oxidative stress across neural networks. This model parallels the macrophage–mesothelial EV axis observed in asbestos-induced carcinogenesis[10] and supports a broader principle in which ferroptotic stress is communicated beyond the originating cell to shape organ-level pathology.

5. Beyond Cell Death: EV-Mediated Propagation of Ferroptotic stress

Persistent DNA damage is increasingly recognized to activate EV–based secretory programs that export harmful intracellular components[29,30]. Beyond damaged DNA, EVs can carry iron-handling proteins, oxidized lipids, and redox-active cargo, thereby functioning as vectors of oxidative stress rather than as inert byproducts of cellular injury[10,31,32].

A compelling experimental demonstration of this concept is provided by Ito et al., who showed that macrophages undergoing ferroptosis after asbestos phagocytosis actively release CD63-positive extracellular vesicles enriched in ferritin[10], building on earlier studies demonstrating the involvement of extracellular vesicles in iron metabolism[33]. These EVs are efficiently taken up by adjacent mesothelial cells—the principal targets of asbestos-induced carcinogenesis—where they induce oxidative stress and DNA damage[10]. Importantly, this process occurs independently of direct asbestos exposure of mesothelial cells, establishing EV-mediated iron transfer as a non–cell-autonomous driver of pathology.

This macrophage–mesothelial EV axis provides a mechanistic blueprint for how ferroptotic stress can be propagated across cell types and tissues. In the context of BRCA deficiency, where unresolved DNA damage and iron dysregulation coexist, similar EV-mediated dissemination of ferroptotic signals is likely to operate. Thus, EVs should be viewed not merely as biomarkers of cellular stress, but as active effectors that translate intracellular ferroptotic pressure into tissue-level disease processes.

6. Working Hypothesis: Ferroptotic Priming and Non–Cell-Autonomous Stress Propagation

Accumulating evidence indicates that BRCA deficiency is accompanied by persistent DNA damage, iron dysregulation, and enhanced lipid peroxidation, collectively placing cells under chronic ferroptotic pressure[7,8]. We refer to this condition as a state of ferroptotic priming, in which cells are poised near the threshold of ferroptotic execution but do not necessarily undergo immediate cell death.

Independent studies have established that sustained DNA damage and oxidative stress can activate EV–based secretory programs that export redox-active cargo[29,30-32]. In addition, experimental evidence from asbestos-induced carcinogenesis demonstrates that macrophages undergoing ferroptosis release CD63-positive, ferritin-containing EVs capable of inducing oxidative stress in recipient cells[10]. Together, these observations provide a mechanistic rationale for EV-mediated, non–cell-autonomous propagation of ferroptotic stress.

Based on this framework, we propose that BRCA deficiency–associated ferroptotic priming may similarly engage EV-mediated stress export, although direct experimental evidence in BRCA-deficient systems is currently lacking. The pathological consequences of such EV-mediated signaling are expected to diverge in a gene- and tissue-specific manner. In cancer-prone tissues under BRCA1 haploinsufficiency, EV-mediated stress propagation may contribute to microenvironmental remodeling that favors the selection of ferroptosis-resistant clones. In contrast, in reproductive tissues and the nervous system—where adaptive escape is not

This working hypothesis integrates cancer, infertility, and neurodegeneration as distinct outcomes arising from a shared BRCA–ferroptosis–EV axis, while explicitly distinguishing established evidence from testable speculation.

7. Discussion and Perspectives

7.1 Gene-specific ferroptotic checkpoints beyond the cell

The studies discussed in this Mini-Review collectively position ferroptosis not as a uniform outcome of BRCA deficiency, but as a gene- and tissue-specific checkpoint that critically determines disease manifestation. Importantly, emerging in vivo evidence demonstrates that BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficiencies are not functionally equivalent with respect to iron-driven oxidative stress and ferroptotic pressure[7,8].

BRCA1 haploinsufficient rat models consistently show that chronic iron overload accelerates carcinogenesis by imposing ferroptotic stress that selects for resistant clones[7]. In this setting, ferroptosis functions as an evolutionary filter rather than a terminal fate, allowing cells that acquire adaptive redox resistance to survive and expand. By contrast, recent findings in BRCA2 haploinsufficient rats reveal a fundamentally different response: iron loading enhances lipid peroxidation and ferroptotic execution, resulting in efficient elimination of damaged renal epithelial cells and a failure to promote iron-driven carcinogenesis[8]. This dichotomy highlights ferroptosis as a decisive biological bifurcation point, separating malignant escape from cellular elimination.

This gene-specific divergence provides a unifying explanation for the contrasting disease spectra observed in BRCA-associated disorders. Tissues capable of clonal selection, such as epithelia prone to cancer development, may exploit partial ferroptosis resistance—particularly under BRCA1 deficiency—to fuel tumorigenesis. In contrast, tissues lacking regenerative or selective capacity, including germ cells and neurons, manifest BRCA deficiency predominantly as ferroptosis-driven functional loss. The reproductive phenotypes observed in both female and male BRCA1/2 rat models exemplify this principle[12-14], where enhanced oxidative stress directly translates into cellular attrition rather than malignant transformation.

Beyond these cell-intrinsic outcomes, accumulating evidence underscores the importance of non–cell-autonomous propagation of ferroptotic stress via extracellular vesicles (EVs). A key experimental precedent is provided by our demonstration that macrophages undergoing ferroptosis after asbestos phagocytosis release CD63-positive, ferritin-containing EVs that are internalized by mesothelial cells, inducing oxidative stress and DNA damage independently of direct asbestos exposure[10]. This macrophage–mesothelial EV axis establishes that ferroptosis can actively remodel tissue microenvironments through EV-mediated iron and redox signaling.

From a broader perspective, this framework challenges the traditional view of ferroptosis as a silent, cell-autonomous event. Instead, ferroptosis emerges as a communicative state in which stressed cells broadcast their redox imbalance to surrounding tissues. Within this paradigm, BRCA deficiency acts as a chronic generator of ferroptotic stress, while EVs serve as the conduit that extends its pathological reach beyond the originating cell.

Future studies should aim to define the molecular signatures of ferroptotic-stress EVs in BRCA1- versus BRCA2-deficient contexts and to determine how these vesicles influence recipient cell fate decisions. Such efforts will not only clarify the systemic consequences of BRCA-associated ferroptosis but may also identify EV-based biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Ultimately, integrating ferroptosis with extracellular vesicle biology offers a conceptual framework that unifies cancer, infertility, and neurodegeneration as divergent outcomes of a shared redox-driven pathology that extends beyond the cell.

7.2 Evolutionary implications of BRCA1/2 haploinsufficiency

An evolutionary perspective suggests that the persistence of pathogenic BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants in human populations may be compatible with, or partially explained by, adaptive contexts in which haploinsufficiency was advantageous under ancestral conditions. Throughout most of human evolution, food availability was limited, systemic iron deficiency was common, and life expectancy was short. In such environments, the long-term risk of cancer would have exerted minimal selective pressure[34-37]. Instead, traits that enhanced survival to reproductive age and preserved developmental robustness would have been favored regarding iron metabolism.

Partial reduction of BRCA1/2 function may have provided increased tolerance to environmental stress by relaxing stringent genome surveillance and cell elimination pathways. Under iron-limited conditions, where ferroptosis was unlikely to be frequently triggered, BRCA haploinsufficiency could have permitted stressed cells to survive developmental and metabolic challenges without incurring immediate pathological consequences. This increased cellular persistence may have supported tissue development, reproductive success, and population survival despite chronic nutritional stress.

Notably, BRCA2 is evolutionarily conserved across eukaryotes[38], consistent with its fundamental role in homologous recombination, whereas BRCA1 appears later in vertebrate evolution as a regulatory integrator of DNA repair, redox signaling, and cell fate

Acknowledgments

ChatGPT (OpenAI) was used solely to assist with English grammar, wording, and clarity. The authors take full responsibility for the content, interpretation, and conclusions of the manuscript.

Authors contribution

Toyokuni S: Article conception and design.

Kong K, Maeda Y, Ohara Y, Motooka Y: Interpretation of data and substantial revision.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by JST CREST (Grant Number JPMJCR19H4) and JSPS Kakenhi (Grant Number JP19H05462 and JP20H05502) to ST.

References

-

1. Narod SA, Foulkes WD. BRCA1 and BRCA2: 1994 and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(9):665-676.[DOI]

-

2. Huen MSY, Sy SMH, Chen J. BRCA1 and its toolbox for the maintenance of genome integrity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(2):138-148.[DOI]

-

3. Momozawa Y, Sasai R, Usui Y, Shiraishi K, Iwasaki Y, Taniyama Y, et al. Expansion of cancer risk profile for BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathogenic variants. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(6):871.[DOI]

-

4. Daum H, Peretz T, Laufer N. BRCA mutations and reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2018;109(1):33-38.[DOI]

-

5. Gorrini C, Baniasadi PS, Harris IS, Silvester J, Inoue S, Snow B, et al. Gauthier, BRCA1 interacts with Nrf2 to regulate antioxidant signaling and cell survival, J Exp Med. 2013;210(8):1529-1544.[DOI]

-

6. Renaudin X, Lee M, Shehata M, Surmann EM, Venkitaraman AR. BRCA2 deficiency reveals that oxidative stress impairs RNaseH1 function to cripple mitochondrial DNA maintenance. Cell Rep. 2021;36(5):109478.[DOI]

-

7. Kong Y, Akatsuka S, Motooka Y, Zheng H, Cheng Z, Shiraki Y, et al. BRCA1 haploinsufficiency promotes chromosomal amplification under Fenton reaction-based carcinogenesis through ferroptosis-resistance. Redox Biol. 2022;54:102356. [DOI:10.1016/j.redox.2022.102356] HYPERLINK "http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2022.102356" \o "自助复核"

-

8. Maeda Y, Motooka Y, Akatsuka S, Tanaka H, Mashimo T, Toyokuni S. Iron-catalyzed oxidative stress compromises cancer promotional effect of BRCA2 haploinsufficiency through mitochondria-targeted ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2025;85:103739.[DOI]

-

9. Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, et al. Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 2017;171(2):273-285.[DOI]

-

10. Ito F, Kato K, Yanatori I, Murohara T, Toyokuni S. Ferroptosis-dependent extracellular vesicles from macrophage contribute to asbestos-induced mesothelial carcinogenesis through loading ferritin. Redox Biol. 2021;47:102174.[DOI]

-

11. Luo Y, Akatsuka S, Motooka Y, Kong Y, Zheng H, Mashimo T, et al. BRCA1 haploinsufficiency impairs iron metabolism to promote chrysotile-induced mesothelioma via ferroptosis resistance. Cancer Sci. 2023;114(4):1423-1436.[DOI]

-

12. Tanaka H, Motooka Y, Maeda Y, Sonehara R, Nakamura T, Kajiyama H, et al. Brca2(p.T1942fs/+)dissipates ovarian reserve in rats through oxidative stress in follicular granulosa cells. Free Radic Res. 2024;58(2):130-143.[DOI]

-

13. Kaseki S, Sonehara R, Motooka Y, Tanaka H, Nakamura T, Osuka S, et al. Susceptibility of Brca1(L63X/+) rat to ovarian reserve dissipation by chemotherapeutic agents to breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2025;116(4):1139-1152.[DOI]

-

14. Motooka Y, Tanaka H, Maeda Y, Katabuchi M, Mashimo T, Toyokuni S. Heterozygous mutation in BRCA2 induces accelerated age-dependent decline in sperm quality with male subfertility in rats. Sci Rep. 2025;15:447.[DOI]

-

15. Collodel G, Castellini C, Lee JC, Signorini C. Relevance of fatty acids to sperm maturation and quality. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:7038124.[DOI]

-

16. Kole AJ, Annis RP, Deshmukh M. Mature neurons: Equipped for survival. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4(6):e689.[DOI]

-

17. Shichiri M. The role of lipid peroxidation in neurological disorders. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2014;54(3):151-160.[DOI]

-

18. Ward RJ, Zucca FA, Duyn JH, Crichton RR, Zecca L. The role of iron in brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(10):1045-1060.[DOI]

-

19. Levi S, Ripamonti M, Moro AS, Cozzi A. Iron imbalance in neurodegeneration. Mol Psychiatry. 2024;29(4):1139-1152.[DOI]

-

20. Frappart PO, Lee Y, Lamont J, McKinnon PJ. BRCA2 is required for neurogenesis and suppression of medulloblastoma. EMBO J. 2007;26(11):2732-2742.[DOI]

-

21. Suberbielle E, Djukic B, Evans M, Kim DH, Taneja P, Wang X, et al. DNA repair factor BRCA1 depletion occurs in Alzheimer brains and impairs cognitive function in mice. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8897.[DOI]

-

22. Genova A, Dix O, Thakur M, Dhillon MS. A review on the mutations of the BRCA 1 gene on neurocognitive disorders. Eur J Biomed. 2020;7:385-392. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Mala-Arguello/publication/339024586_A_REVIEW_ON_THE_MUTATIONS_OF_THE_BRCA_1_GENE_ON_NEUROCOGNITIVE_DISORDERS/links/5f4c7feda6fdcc14c5f22599/A-REVIEW-ON-THE-MUTATIONS-OF-THE-BRCA-1-GENE-ON-NEUROCOGNITIVE-DISORDERS.pdf

-

23. Lei G, Mao C, Horbath AD, Yan Y, Cai S, Yao J, et al. BRCA1-mediated dual regulation of ferroptosis exposes a vulnerability to GPX4 and PARP co-inhibition in BRCA1-deficient cancers. Cancer Discov. 2024;14(8):1476-1495.[DOI]

-

24. Lorenz SM, Wahida A, Bostock MJ, Seibt T, Mourão AS, Levkina A, et al. A fin-loop-like structure in GPX4 underlies neuroprotection from ferroptosis. Cell. 2026;189(1):287-306.[DOI]

-

25. Thompson AG, Gray E, Heman-Ackah SM, Mäger I, Talbot K, El Andaloussi S, et al. Extracellular vesicles in neurodegenerative disease: Pathogenesis to biomarkers. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12(6):346-357.[DOI]

-

26. Jiang D, Gong F, Ge X, Lv C, Huang C, Feng S, et al. Neuron-derived exosomes-transmitted miR-124-3p protect traumatically injured spinal cord by suppressing the activation of neurotoxic microglia and astrocytes. J Nanobiotechnol. 2020;18:105.[DOI]

-

27. Ruan J, Miao X, Schlüter D, Lin L, Wang X. Extracellular vesicles in neuroinflammation: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Mol Ther. 2021;29(6):1946-1957.[DOI]

-

28. Arvanitaki ES, Goulielmaki E, Gkirtzimanaki K, Niotis G, Tsakani E, Nenedaki E, et al. Microglia-derived extracellular vesicles trigger age-related neurodegeneration upon DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121(17):e2317402121.[DOI]

-

29. Takahashi A, Okada R, Nagao K, Kawamata Y, Hanyu A, Yoshimoto S, et al. Exosomes maintain cellular homeostasis by excreting harmful DNA from cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15287.[DOI]

-

30. Goulielmaki E, Ioannidou A, Tsekrekou M, Stratigi K, Poutakidou IK, Gkirtzimanaki K, et al. Tissue-infiltrating macrophages mediate an exosome-based metabolic reprogramming upon DNA damage. Nat Commun. 2020;11:42.[DOI]

-

31. Wu Q, Zhang H, Sun S, Wang L, Sun S. Extracellular vesicles and immunogenic stress in cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(10):894.[DOI]

-

32. Han J, Xu K, Xu T, Song Q, Duan T, Yang J. The functional regulation between extracellular vesicles and the DNA damage responses. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 2025;795:108532.[DOI]

-

33. Yanatori I, Richardson DR, Dhekne HS, Toyokuni S, Kishi F. CD63 is regulated by iron via the IRE-IRP system and is important for ferritin secretion by extracellular vesicles. Blood. 2021;138(16):1490-1503.[DOI]

-

34. Eaton SB, Konner M. Paleolithic nutrition: A consideration of its nature and current implications. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(5):283-289.[DOI]

-

35. Stoltzfus RJ. Iron deficiency: Global prevalence and consequences. Food Nutr Bull. 2003;24(4_suppl2):S99-S103.[DOI]

-

36. Greaves MF. Cancer: the evolutionary legacy. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

-

37. Toyokuni S, Kong Y, Cheng Z, Sato K, Hayashi S, Ito F, et al. Carcinogenesis as side effects of iron and oxygen utilization: From the unveiled truth toward ultimate bioengineering. Cancers. 2020;12(11):3320.[DOI]

-

38. Chanteau A, Quilleré S, Crouset A, Allipra S, Tuquoi U, Perroud PF, et al. Moss BRCA2 lacking the canonical DNA-binding domain promotes homologous recombination and binds to DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025;53(17):gkaf856.[DOI]

-

39. Lou DI, McBee RM, Le UQ, Stone AC, Wilkerson GK, Demogines AM, et al. Rapid evolution of BRCA1 and BRCA2in humans and other Primates. BMC Evol Biol. 2014;14:155.[DOI]

-

40. Arcas A, Fernández-Capetillo O, Cases I, Rojas AM. Emergence and evolutionary analysis of the human DDR network: Implications in comparative genomics and downstream analyses. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31(4):940-961.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite