Abstract

Skin diseases affect nearly one quarter of the global population, with prevalence rising sharply among older adults. By 2050, the number of individuals over 60 years will double, making age-related dermatological conditions an increasing public health concern. A central process underlying aging is cellular senescence, a stable form of growth arrest induced by diverse stressors, including DNA damage, telomere attrition, and oncogenic signaling. Senescent keratinocytes, fibroblasts, melanocytes, and immune cells accumulate in the skin with age and secrete a pro-inflammatory senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) that actively shapes the cutaneous immune landscape. Although senescence can promote tissue repair and tumour suppression, the persistence of senescent cells drives inflammation, impairs immunity function, and contributes to pathology, a concept now termed senopathy. In this review, we first examine the crosstalk between senescent stromal and immune cells in human skin. Then we discuss how SASP from senescent fibroblasts inhibits the function of resident T cell, while senescent T cells adopt a paradoxical state, hyperfunctional yet non-proliferative, that can accelerate tissue damage. We further highlight the immune evasion strategies which enable senescent cells to persist and drive inflammaging. Insights from patients with Familial Melanoma Syndrome (germline CDKN2A mutations) illustrate how defective senescence pathways across multiple cell types impair cutaneous immunosurveillance and increase melanoma risk. Finally, we explore evidence for stromal- and immune-mediated cutaneous senopathies, including psoriasis, lupus, vitiligo, and leishmaniasis, where senescent cells actively drive the diseases’ progression. Based on the analysis, we propose that the skin represents a powerful and accessible model for investigating the interplay between senescent immune and non-immune cells across the lifespan, with therapeutic implications for aging and age-related pathologies.

Keywords

1. Introduction

At any given time, nearly a quarter of the global population is living with skin diseases[1]. The conditions span from inflammatory and infectious disorders to malignancies, affecting individuals at all stages of life. The skin undergoes profound structural and immunological changes during aging; after the age of 65 years, the prevalence of skin diseases rises sharply, with 50-80% of older adults affected by at least one dermatological disease[2,3]. By 2050, the number of people over 60 is expected to double and those over 80 years to triple[1]. Therefore, the burden of skin diseases will increase dramatically in the future, underscoring an urgent need to elucidate mechanisms that underpin declines in skin health.

Cellular senescence is central to the process of skin aging. It represents a stable form of cell cycle arrest in multiple cell types triggered by various intrinsic and extrinsic stressors, including DNA damage, telomere attrition, oxidative stress, and oncogenic signaling[4,5]. Initially considered a tumour-suppressive mechanism, cellular senescence is now recognized as a dynamic regulator of tissue homeostasis[6]. In the skin, senescent keratinocytes, fibroblasts, melanocytes, and immune cells increase with age[7,8]. These senescent cells can influence immune cell recruitment[9,10], tissue remodelling[11] and inflammatory signaling[9,12] through the secretion of a mixture of cytokines, chemokines, proteases and growth factors, collectively referred to as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)[13]. As such, the accumulation of diverse senescent cells actively shapes the immune landscape of the skin[14-17]. It also raises key questions on whether these cells are beneficial (promote repair) or detrimental (drive chronic inflammation). Furthermore, clarification is needed on whether senescent stromal cells influence the function and fate of aging immune cells in this tissue, and vice versa.

Recent work suggests that senescent structural cells in the skin are not merely remnants of damage, but actively contribute to immune regulation by creating an inflammatory environment that inhibits cutaneous immunity[9,12]. In addition, our study of skin from individuals having heterozygous defects in the CDKN2A gene that encodes the senescence associated protein p16Ink4a, has provided valuable insights into the regulation of cellular senescence across different cell types within the same human skin samples. In this review, we will explore how cellular senescence influences cutaneous immunity and its role in cutaneous ‘senopathy’ (i.e., dermatopathology caused by the accumulation of senescent cells).

2. Senescence: Physiology and Detection

Cellular senescence was originally described by Hayflick and Moorhead in the context of replicative exhaustion[18]. Senescent cells are characterized by the cessation of proliferation, resistance to apoptosis and a highly secretory nature[13]. These physiologic alterations are induced by metabolic reprogramming, including enhanced glycolytic flux, mitochondrial dysfunction, altered lipid metabolism and disrupted autophagy[19]. These cells also exhibit numerous features that facilitate their identification, including enlarged cell size, increased expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (such as p16Ink4a and p21CIP1[10,20], persistent DNA damage response foci (e.g., γH2AX)[21,22], epigenetic changes[23], expression of senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-Gal)[24], and altered mitochondrial dynamics[25].

The potential role of these cells in organ dysfunction and disease emphasizes the critical importance of their identification for ongoing research. At present, no single marker or combination of markers can detect senescence with complete sensitivity and specificity across all cell types in tissues and experimental approaches. The consensus is for multi-parameter profiling using cytoplasmic, nuclear and SASP/cell-type-specific markers for detection in all cell/tissue types including skin[26]. However, many conventional senescence markers have inherent limitations. For instance, cell cycle inhibitors can be upregulated in both quiescent and senescent cells[5,27], and marker expression varies depending on the employed senescence stimulus[10]. As demonstrated in Table 1, studies have reported variable, and sometimes opposing senescence marker expressions within the same cell type. This may reflect differences in experimental protocols, including senescence modality, technological advancements and experimental limitations. Moreover, the most widely used markers for identification (enlarged cell size, permanent cell cycle arrest, SA-β-Gal expression) are largely restricted to cells studied in vitro. Detection of senescent cells in the skin follows the same above-mentioned limitations[5,26]. Table 1 summarises both in vitro and in vivo senescence markers in human cutaneous research.

| Senescence Marker | Keratinocyte | Melanocyte | Fibroblast | Endothelial Cells |

| p16INK4a | Increased[28,29] Not detected[30,31] | Increased[10,31-34] | Increased[22,35-37,38] | Increased[39-42] |

| p21CIP1 | Increased[30,31,43] Reduced[28] | Increased[33] Unchanged[10,31,32] | Increased[36-38] | Increased[40-42] |

| p53 | Reduced[28] | Increased[33,44] Not detected[10] | Increased[36,37,45] | Increased[42] Unchanged[40] |

| SA-β-Gal | Increased[24,30,46-48] | Increased[31,33,34] | Increased[10,22,24,36,37,49,50] | Increased[39,42,51] |

| Lamin B1 | Reduced[47,52] | Reduced[53] Not detected[10] | Reduced[52-54] | Unknown |

| HMGB1 | Reduced[31] | Reduced[10,31] | Reduced[49,55] | Unknown |

| TAF (telomere associated DNA damage foci) | Increased[31] | Increased[31] | Increased[22] | Unknown |

| Ki67 | Reduced[48,56] | Reduced[22,33] | Reduced[10,22,49] | Unknown |

| Lipofuscin | Unknown | Unknown | Increased[38,57] | Increased[39,51] |

| Proliferation assay | Reduced[24,31,46] | Reduced[31] | Reduced[10,36,37,50] | Reduced[51] |

| SASP | Increased[48] | Increased[31,58,59] Unchanged[10] | Increased[10,13,22,60-62] | Unknown |

SASP: senescence-associated secretory phenotype; SA-β-Gal: senescence-associated β-galactosidase.

Several machine learning tools have recently been developed to define senescence-associated signatures. For instance, SENESCopedia identifies common transcriptomic profiles of senescent cancer cells[63], while SenPred is an emerging machine learning tool that utilizes single-cell transcriptomics to detect in vitro replicative senescence in human dermal fibroblasts[64,65]. SenMayo offers a gene set for identifying senescence across multiple in vitro cell types[66]. However, the generalizability of these tools across diverse cell types, tissues, and experimental platforms has yet be fully validated. In 2021, the SenNet Consortium was launched with the goal of mapping senescent cells and their associated SASP across 18 healthy human tissues throughout the lifespan. By integrating genomic, proteomic and lipidomic data, it aims to build a comprehensive senescent cell atlas[67]. Although it remains uncertain whether a universal method for senescence detection will emerge, such an atlas would provide a valuable resource for tailoring senescence detection approaches to specific experimental contexts.

Despite the limitations, two methods have been successfully used to detect senescent non-lymphoid cells in human skin, namely the expression of p16INK4a, and the expression of telomere associated DNA damage (TAF)[22]. Both these methods correlate strongly with each other and indicate that senescent cells, particularly fibroblasts, increase in the skin with age[22]. The reliability of these methods was further supported by studies in individuals heterozygous for defects in the CDKN2A gene encoding p16Ink4a, who show significantly reduced expression of both p16Ink4a and TAF expressing cells in the skin[10]. The functional consequences of altered cellular senescence in different populations of skin-derived cells from these individuals will be discussed more detailed below.

2.1 Immune senescence

In addition to structural cells such as fibroblasts, immune cells can also become senescent. These changes are most extensively characterized in T cells[68-72], but are increasingly being studied in other immune cell subsets, including macrophages[73,74] and B cells[75]. In humans, senescent T cells can be identified by a wide range of cell surface markers, including loss of co-stimulatory receptors such as CD28 and CD27, and upregulation of CD57 and KLRG1[68,76]. Functionally, these cells exhibit shortened telomeres, reduced telomerase activity, and profound deficits in antigen responsiveness, including reduced TCR signaling, defective calcium flux, and impaired synapse formation and proliferation after activation[68,77-79]. They rely on glycolysis for energy and display mitochondrial dysfunction with increased reactive oxygen species production[80]. they also exhibit persistent DNA damage signaling, often accompanied by upregulation of p16INK4a and p21CIP1[80]. This led to earlier assumptions that senescent T cells were dysfunctional[81]. However, despite their impaired proliferative capacity, senescent T cells still secrete high levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α upon activation, and express numerous cytotoxic molecules such as granzyme B and perforin. This paradoxical non-proliferative but hyper-functional profile is considered a unique SASP signature of senescent T cells[68,76]. Table 2 outlines the markers commonly used to detect senescent T cells in blood and skin. While certain cell surface markers, such as KLRG1 and CD57, can identify these cells in resting peripheral blood of healthy individuals, they are not reliable for detecting those in the skin[89]. In contrast, in patients with inflammatory conditions such as cutaneous leishmaniasis, where large numbers of T cells infiltrate the tissue, these markers can identify senescent populations. For this reason, senescence markers detecting senescent cells across cell types (p16, p21, γH2AX; Table 2), are used to detect senescent T cells in the skin.

| Senescence Marker | Senescent Peripheral T Cells | Senescent Cutaneous T Cells |

| p16INK4a | Increased[82-85] | Increased[86,87] |

| p21CIP1 | Increased[82,85] | Increased[86,87] |

| CD27 | Absent[68,88] | Absent[88,89] |

| CD28 | Absent[69,88] | Unknown |

| CD45RA | Increased[69] | Increased[88,89] |

| TCR-mediated proliferation | Reduced[79,80,90] | Unknown |

| CCR7 | Reduced[91-94] | Unknown |

| CD62L | Reduced[95] | Unknown |

| CD57 | Increased[96] | Increased[88,96,97] |

| KLRG1 | Increased[90,94,98] | Increased[87] |

| NKG2A/C | Increased[78,87,99] | Increased[88] |

| NKG2D | Increased[79,99,100] | Increased[88] |

| DAP12 | Increased[79] | Unknown |

| Proliferative capacity | Reduced[69] | Unknown |

| Telomere length | Reduced[101] | Unknown |

| Telomerase | Reduced[101] | Unknown |

| BCL-2 | Reduced[93,102,103] | Unknown |

| yH2AX | Increased[104,105] | Unknown |

| DDR | Increased[76,79] | Increased[87] |

| Sestrins | Increased[78,79] | Increased[87] |

| P38MAPK | Increased[76,79,80] | Increased[87] |

| SASP | Increased[76] | Increased[87] |

| Cytotoxic granules (perforin, granzyme) | Increased[91] | Increased[88] Reduced[89] |

SASP: senescence-associated secretory phenotype.

Recent studies have shown that senescent human T cells express a group of stress-sensing molecules known as sestrins, which regulate their reduced proliferative capacity and senescence characteristics[78,79]. Notably, senescent CD8+ T cells exhibit a sestrin-dependent shift toward natural killer (NK) receptor expression (e.g., NKG2D, NKG2C) and MHC-unrestricted cytotoxicity against NK target cells, such as the K562 cell line[79]. CD8+ T cells can recognize and eliminate senescent non-lymphoid cells expressing MICA/B, the ligand for the activating NK receptor NKG2D[22]. Therefore, beyond their established role in eradicating malignant and infected cells, NK and CD8+ T cells can also recognize and eliminate senescent non-lymphoid cells, thus identifying a novel form of immunosurveillance in vivo. Altered interactions between senescent immune and non-immune cells in different tissue compartments during aging or in inflammatory diseases, may contribute to the disease pathophysiology[22,72].

2.2 The accumulation of senescent lymphoid and non-lymphoid cells in the skin during aging

The skin is anatomically divided into three principal tissue compartments: the epidermis, dermis, and subcutis (or hypodermis). Each layer contains distinct populations of structural and immune cells, and provides a unique microenvironment in which cellular senescence can arise and exert context-dependent effects.

The epidermis, composed primarily of keratinocytes, serves as the frontline barrier against environmental insults. Immunologically, it hosts resident Langerhans cells and a population of skin-homing memory T cells[106,107]. The dermis beneath is rich in fibroblasts, vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells, macrophages, mast cells and dermal T cells, functioning as a connective tissue and an immunological interface[106,107]. The subcutis, consisting of adipocytes, blood vessels, and a diffuse population of immune cells, is increasingly recognized as a critical regulator of the metabolic environment for leukocytes. This role is highlighted by studies showing that how adipokines (cytokines derived from adipocytes) influence immune cell metabolism and systemic metabolic outcomes such as thermogenesis[108-111].

Several studies have quantified the proportion of senescent cells in the skin, but the values are markedly different due to experimental differences, markers employed, and units used to quantitate. For instance, in the epidermis, Victorelli et al. identified 6% of senescent cells based on the p21 expression but 30% based on TAF[31]. Another study showed 4% p16-positive cells and 6% p21-positive cells in the aged epidermis[112]. In the dermis, Ressler et al. reported a mean of seven p16-positive senescent cells per visual field in aged skin[20], while Pereira et al. observed 20-65% TAF-positive senescent cells per visual field in aged dermis[22]. Despite the variations in markers, methods and quantification, a consistent finding is the accumulation of senescent cells in the skin with age.

Senescent cells have been identified in all these compartments of aged skin[20,22,31,112]. Melanocytes and fibroblasts, in particular, exhibit clear hallmarks of senescence in response to replicative stress, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, pollution and inflammation[113]. These cells adopt a SASP that can profoundly alter the local immune landscape by recruiting, activating, or even dysregulating immune cells. Senescence has been best characterized in fibroblasts, and senescent dermal fibroblasts actually remodel the extracellular matrix, impair fibroblast-keratinocyte crosstalk, and secrete SASP factors that drive chronic low-grade inflammation and matrix degradation[114]. These changes contribute to hallmark features of cutaneous aging, such as dermal thinning, wrinkle formation, delayed wound healing, and reduced tensile strength. Melanocytes similarly undergo senescence with age[31,115].

While the classic regulators of senescence are the p53/p21 and p16/Rb pathways, melanocyte senescence appears to be at least partially distinct from other studied cell types, more dependent on p16 relative to the other pathways[10,32,116]. Melanocytes secrete melanin, which protects the skin from the UV-induced damage by mitigating reactive oxygen species production[117,118]. Indeed melanocytes accumulate more DNA damage than dermal fibroblasts in vivo[10], and after UVA irradiation in vitro[117]. Few studies have explored the nature of melanocyte SASP. Gene-level analyses have revealed the upregulation of inflammatory and SASP signatures in a model of oncogene-induced melanocyte senescence, including TGFβ regulators, MMP7 and VEGF[58]. Senescent melanocyte-derived IP-10 can induce paracrine senescence in neighbouring keratinocytes, contributing to epidermal thinning[31], a key feature of aged skin. Although melanin is actively secreted via extracellular vesicles, it does not seem to constitute a component of the SASP. In fact, senescent melanocytes display impaired melanin secretion[115].

Senescent stromal-immune interactions in the skin under normal homeostatic conditions remain poorly understood. Tissue-resident memory T cells, having growing proportions with age, can adopt a dysfunctional, pro-inflammatory phenotype, secreting IFN-γ and TNF-α while exhibiting reduced proliferation and antigen-specific capacity[17,119,120]. The shift promotes an inflammatory microenvironment that is no longer protective but exhaustive and maladaptive. Despite this, long-lived resident memory T-cells (Trm) are not obviously “senescent” in healthy human skin. For instance, CD8 Trm cells typically show low CD57/KLRG1 and lack immediate cytotoxicity[89]. Aging changes the Trm functional diversity rather than abundance, resulting in an age-related shift toward cytotoxicity through CD49a+ expression in CD8 Trm[17]. Evidence of classically defined senescent T-cells, characterized by expression of p16/p21+ and SASP-like features, remains scarce. This contrasts with the evidence in human blood, where a sharp rise in such T-cells is observed in a steady state during aging[121]. Nevertheless, increased numbers of senescent T cells defined by loss of CD28- and gain of CD57+ expression are found in the skin of patients with systemic sclerosis[122]; psoriasis[123] and cutaneous infections such as leishmaniasis[124].

2.3 Immune evasion by senescent cells in tissues

It is paradoxical that despite the immune system’s capacity to eliminate senescent cells[125,126] the cells accumulate in many tissues during aging. This is because senescent cells can evade the immune system by expressing inhibitory NK ligands such as HLA-E and PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) on their surface in vitro and in vivo[22,127]. HLA-E binds to the inhibitory NK receptor NKG2A on NK and senescent CD8+ T cells, thereby inhibiting their cytotoxic activity[22], while PD-L1 engages PD1 on T cells to inhibit their functions [22,128,129]. Senescent cells can also employ other strategies to evade the immune system, including the secretion of soluble MICA/B, the ligand for the activating NK receptor NKG2D expressed on NK and T cells[130].

Similarly, protease/exosome-mediated loss of NKG2D ligands can occur in the context of cellular stress and senescence, with MICA/B lost in an ADAM10/17-dependent manner due to its metalloproteinase activity. The loss of NK/T-cell activating ligands results in clearance-evasion in specific microenvironmental contexts[131].

In a human skin model, it was shown that senescent fibroblasts recruit inflammatory monocytes that produce prostaglandin E2, which subsequently suppresses tissue T-cell responses to antigen-recall challenge in a p38MAPK-dependent manner[9]. Likewise, in senescence-rich tumours, tumour-associated macrophages expressing CD73, drive adenosine accumulation, thus inhibiting NK/T-cell activity via A2A receptors[132].

More recently, ganglioside-mediated immune checkpoints have been found to be upregulated on senescent cells and can hence inhibit NK cytotoxicity[130,133,134]. Collectively, these evasion strategies may enable senescent cells to persist in tissues during aging, and contribute to increased inflammation with deleterious consequences.

2.4 Senescent non-lymphoid cells regulate decreased cutaneous immune responses during aging

The lack of suitable human models for investigating immunity in vivo prompted the development of an experimental system, where recall antigens were injected into the skin of volunteers, followed by the biopsy of the injection site[120,135-138]. The biopsied tissue was then investigated using immunohistological and transcriptional platforms, while leukocytes and other cell types were also isolated for functional analyses in vitro[12,120,138,139]. These studies demonstrated that older adults respond significantly weaker to cutaneous challenge with bacterial (tuberculin PPD), fungal (candida albicans) and viral (varicella-zoster virus; VZV) recall antigens[9,12,120]. This was not attributable to diminished immune memory, since the responses to these antigens by T cells in the peripheral blood were similar to those in both young (> 40 years) and older (> 65 years old) subjects[120]. Furthermore, the number of skin resident T cells and their responses to recall antigen after isolation were similar across both age groups[139]. This suggested that the factors within the skin environment during antigen challenge inhibited the local response to the challenge.

Elevated baseline inflammation in the skin of older individuals was found to be strongly correlated with the diminished responsiveness to recall antigen challenge[9,12]. The inflammation arose from the recruitment of inflammatory myeloid cells by senescent fibroblasts, driven by their secretion of monocyte chemoattractant molecules such as CCL2[9]. Therefore, the fibroblast-derived SASP creates an inflammatory environment that inhibits resident memory T cell responses[9]. As senescent cells, particularly fibroblasts, accumulate in the skin and other organs during aging[22,114,140-144], they may contribute to broader age-associated immune decline by promoting sterile inflammatory responses, a manifestation of inflammaging[145,146]. As proof of this regulatory axis, the inhibition of the cutaneous SASP in older adults using an oral p38 MAP kinase inhibitor (Losmapimod) for 4 days in vivo significantly enhanced the recall responses to antigen challenge in these subjects[9,12]. Accordingly, the accumulation of senescent stromal cells can inhibit resident memory T cell activation in the skin and may exert similar effects in other organs.

However, resident memory CD8⁺ T cells themselves can also become senescent and studies in mice demonstrated that these cells can accelerate tissue aging and contribute to physiological decline[147,148]. Although senescent non-lymphoid cells generate inflammatory, immunosuppressive environments, senescent T cells, via their NK-like cytotoxic functions, can directly induce tissue damage[72,148]. In support of this contention, senescent T cells have been identified in the skin of humans and mice with systemic lupus erythematosus[72,149] and psoriasis[87] based on the expression of p16Ink4a and p21CIP1. The use of a topical Bcl-2 inhibitor (senolytic therapy) reduces the numbers of these senescent T cells in mice, reducing disease severity[72,87,149]. Senescence in both lymphoid and non-lymphoid cells may occur simultaneously, and their interactions may synergistically induce pathology in aging and inflamed tissue[72]. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the co-evolution of senescence across different cellular compartments, as this may be induced by a shared mechanism that leads to pathology in inflamed and aging tissues.

2.5 A skin model of crosstalk between senescent immune and non-immune cells: Familial Melanoma Syndrome (FMS)

Our understanding of cellular senescence remains compartmentalized, focusing on isolated cell types, individual signaling pathways, or specific SASP components[113,150]. However, senescence in human tissue is a multi-cellular, spatially integrated process, shaped by the dynamic interactions among structural cells, immune populations, and the aged tissue microenvironment. An integrated overview of senescence in both immune and non-immune compartments of the skin has emerged from analyses of skin and blood samples of patients with the FMS[10]. These patients carry autosomal dominant heterozygous germline mutations in the CDKN2A gene, which encodes the tumour suppressor p16INK4a[10]. Despite surviving to adulthood, they exhibit phenotypic features, including multiple atypical melanocytic naevi, increased susceptibility to melanoma, often developing early and repeatedly, and, less commonly, pancreatic cancer[151]. Their tissues offer a unique window into how defective senescence pathways shape cutaneous immunity and tumour risk prior to overt tumour development.

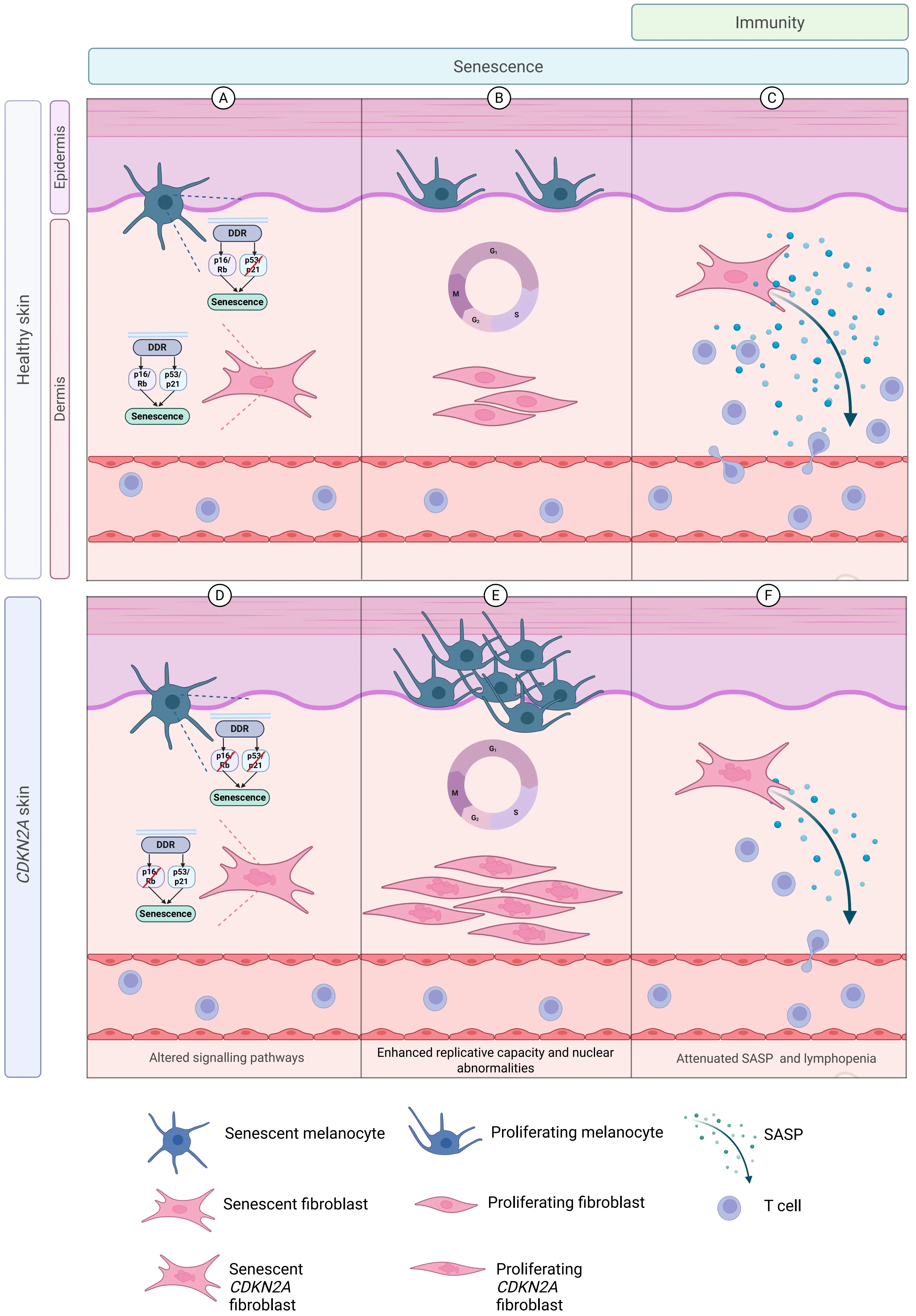

Both melanocytes and fibroblasts in FMS patients fail to undergo normal p16-mediated senescence[10,152]. Notably, melanocytes in these patients are particularly vulnerable to the loss of p16 as they do not upregulate p21 during senescence induction to compensate for this deficit, while senescent fibroblasts can upregulate both p16 and p21 (Figure 1A,D)[10]. In addition to this intrinsic senescence defect in melanocytes, senescent dermal fibroblasts in FMS patients exhibit attenuated SASP secretion, which is associated with a marked reduction in resident memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations in the skin (Figure 1C,F)[10]. This increased risk of melanoma in CDKN2A-deficient individuals may result from the reliance of senescent melanocytes on p16 for growth arrest after DNA damage, rendering them susceptible to malignant transformation. This susceptibility is further exacerbated by senescence-related defects in fibroblasts, especially reduced SASP secretion, which hinders recruitment of T cells[10].

Figure 1. The germline CDKN2A mutation leads to multiple cutaneous abnormalities in senescence and immunity. Schematic showing alterations in the skin of individuals with the germline CDKN2A mutation. In skin from healthy individuals (A) Melanocytes preferentially recruit the p16 pathway to execute senescence, while fibroblasts can flexibly use both the p16 and p21 pathways; (B) Melanocytes and fibroblasts proliferate with normal nuclear architecture; (C) Senescent fibroblasts secrete a SASP rich in inflammatory proteins, chemokines and cytokines, with preserved numbers of resident memory T cells. Differences exist in baseline skin from individuals with the germline CDKN2A mutation in which (D) Both melanocytes and fibroblasts fail to upregulate p16 to effect senescence, while fibroblasts are able to recruit the p21 pathway in the context of p16 pathway redundancy; (E) Melanocytes and fibroblasts have increased replicative capacity, fibroblasts showing nuclear morphological abnormalities in pre-senescent and senescent states; (F) Senescent fibroblasts secrete less SASP with an associated reduction in numbers of cutaneous CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Created in Biorender.com. SASP: senescence-associated secretory phenotype.

When either melanocytes[10,152] or fibroblasts[10] were isolated from the skin of FMS patients and cultured continuously toward replicative senescence in vitro, further evidence of senescence-associated defect in these cells was observed. These cell types showed substantially increased replicative capacity before reaching senescence compared to age- and sex-matched controls (Figure 1B,E)[10]. Of note, pre-senescent fibroblasts from FMS patients could proliferate despite harboring DNA damage, ultimately developing abnormal nuclei upon entry into replicative senescence (Figure 1E)[10]. The study of FMS patients has thus enabled the simultaneous assessment of the integrated dysregulation of senescence across multiple cell types in the skin of humans in vivo. Consequently, the susceptibility of these patients to melanoma is multi-faceted.

2.6 Senopathy: when senescence causes disease

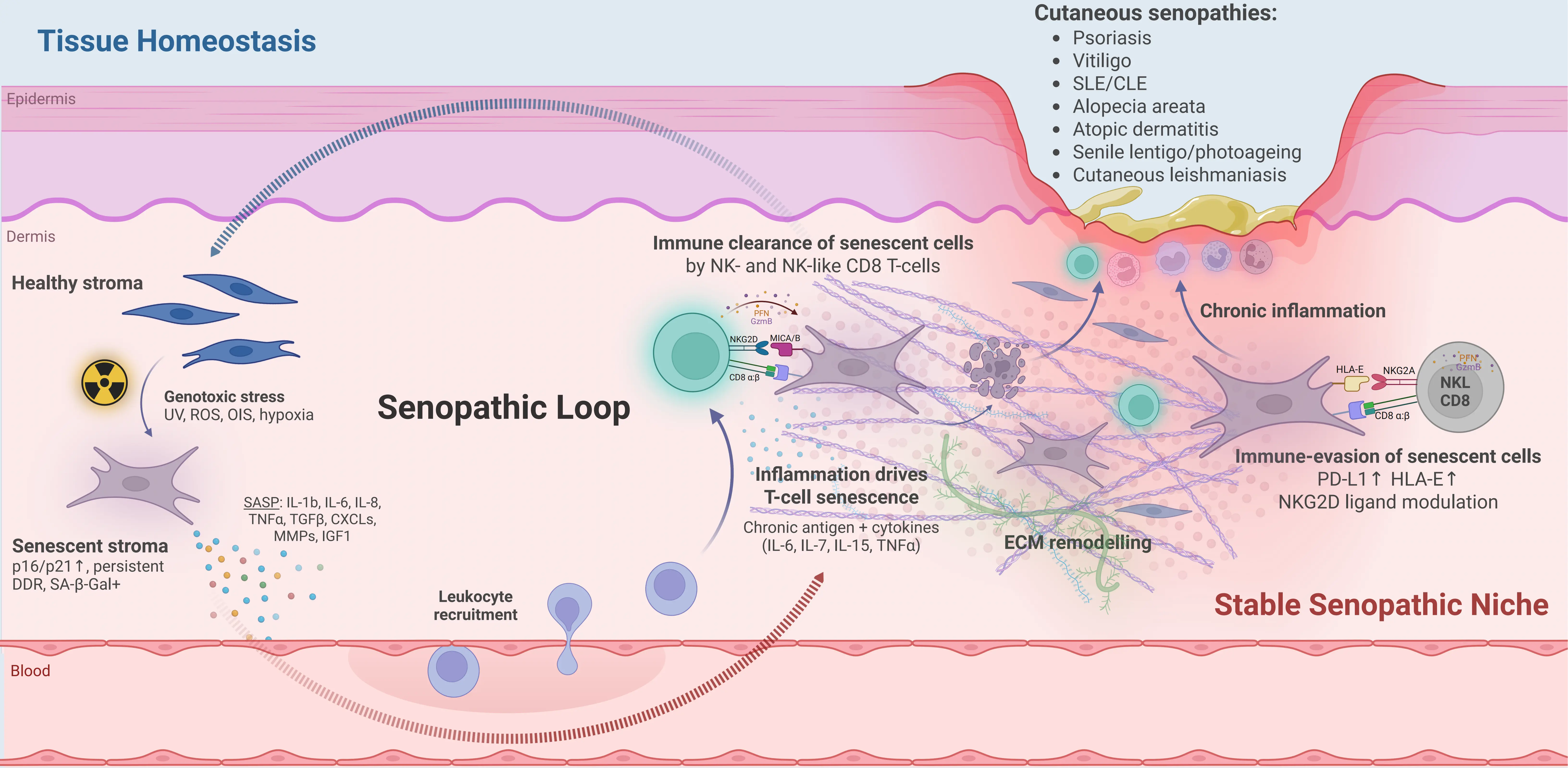

The term “senopathy” has emerged to describe a class of diseases where the accumulation and persistence of senescent cells actively contribute to pathology[153]. Senescence can play a beneficial role in processes such as wound healing[11], tumour suppression[154-156] and tissue remodelling[157]. In contrast, senopathy is a maladaptive state where senescent cells are not effectively cleared and instead exert chronic effects on their surrounding environment. These effects are primarily mediated by the SASP that disrupts local tissue homeostasis[158], promotes secondary senescence in neighbouring cells[159], and fosters a microenvironment conducive to inflammation[13], fibrosis[160], and degeneration[161]. Therefore, senescent cells can act as active drivers of age-associated disease, with broad relevance across multiple organ systems. In the skin, we propose that senopathy reflects the establishment of a ‘stable senopathic niche’, where senescent stromal and immune cells persist within a remodelled microenvironment and fail to return to homeostasis. Across the diseases discussed below, SASP-driven inflammation, secondary senescence and impaired clearance cooperate in a self-reinforcing ‘senopathic loop’, converting transient, physiological senescence into a chronic driver of cutaneous pathology (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The senopathic loop and formation of a stable senopathic niche in human skin. Schematic cross-section of skin illustrating how cellular senescence in stromal and immune compartments regulates cutaneous immunity. Left: tissue homeostasis is disrupted by environmental and intrinsic genotoxic stressors—such as UV radiation, reactive oxygen species, oncogene-induced stress and hypoxia—which drive senescence in stromal cells (for example dermal fibroblasts)[21,25,162-166]. Senescent stromal cells are characterised by p16/p21 up-regulation, persistent DNA damage responses and SA-β-Gal activity[20,21,24,35]. These cells secrete a SASP rich in inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, growth factors and matrix metalloproteinases—for example IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-15, TGF-β, CXCL chemokines, MMPs and, under hypoxia, IGF-1—which recruit leukocytes from the circulation and remodel the extracellular matrix[45,60-62,114,167,168]. In human skin models, senescent dermal fibroblasts promote leukocyte recruitment and low-grade inflammation, reinforcing this loop[9,12]. Under effective immunosurveillance, NK and NK-like CD8⁺ T cells expressing activating NK receptors such as NKG2D recognise ligands including MICA/B on senescent stromal cells and mediate their clearance, thereby returning the tissue towards homeostasis[22,71,79,124-126]. Right: when SASP-driven inflammation is chronic, recruited T cells themselves acquire senescent, NK-like phenotypes in response to persistent antigen and cytokine exposure (for example IL-6, IL-7, IL-15, TNF-α), amplifying tissue damage[22,71,76,79,87,169]. Senescent stromal cells up-regulate immune checkpoint ligands such as PD-L1 and HLA-E[22,127,128,170], and senescent or stressed cells modulate NKG2D ligands—including shedding of MICA/B—creating an immunosuppressive, immune-evasive microenvironment that permits survival of both senescent stromal and lymphoid cells within a remodelled ECM[125,127,131,171,172]. This self-sustaining configuration constitutes a stable senopathic niche, in which persistent senescent cells and chronic inflammation reinforce one another, and is proposed to underlie “cutaneous senopathies” such as psoriasis[173-176], vitiligo[177], systemic/cutaneous lupus erythematosus[149,178], alopecia areata[179], atopic dermatitis/eczema[180], senile lentigo/photoageing[141], and cutaneous leishmaniasis, where stromal and/or T-cell senescence are directly linked to lesion burden and tissue injury[124,169,181]. Created in Biorender.com. SASP: senescence-associated secretory phenotype; UV: ultraviolet; SA-β-Gal: senescence-associated β-galactosidase.

2.6.1 Non-immune-mediated cutaneous senopathy

Environmental insults, such as UV radiation[162,163], mechanical injury[182], infection[164], and pollution[165], as well as intrinsic factors such as metabolic stress, hypoxia[167] and nutrient imbalance, are capable of driving senescence in fibroblasts, keratinocytes, melanocytes, and endothelial cells. Senescent stromal cells have been shown to accumulate in inflammatory dermatoses, contributing to disease pathology. In psoriasis, mid and upper epidermal keratinocytes exhibit features of senescence, including elevated expression of p16 and p21 in both in vivo and in vitro studies[173-175]. These cells also demonstrate reduced proliferation[174], resistance to apoptosis[176], and enhanced SASP secretion, even relative to senescent keratinocytes from non-psoriatic individuals[174]. Though psoriasis is traditionally considered a disease of hyperproliferative keratinocytes, the presence of senescent keratinocytes within psoriatic plaques has been proposed to be protective against keratinocyte malignancies. However, this benefit is offset by increased immune activation and basal keratinocyte proliferation driven by excessive SASP secretion[175].

Stromal senescence has further been implicated in cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). In lesional epidermis from CLE patients, diffuse expression of p16 and p21 is observed, in contrast to unaffected skin from the same individuals[178]. Comparisons across other inflammatory skin diseases reveal increased p16 and p21 expression in the basal epidermis, particularly in conditions characterized by dermo-epidermal junction inflammation[178]. While direct causality has not been established, this spatial correlation between senescent cell accumulation and sites of inflammation suggests a potential mechanistic link. Similarly, senescent fibroblasts and their SASP-driven activation of innate immunity may contribute to eczema in older subjects[180]. In vitiligo, the presence of senescent dermal fibroblasts has raised the possibility that SASP-mediated CD8+ T cell recruitment may play a role in melanocyte destruction[177,179].

2.6.2 Immune-mediated cutaneous senopathy

Senescent T cells may play a crucial role in mediating senopathy across various dermatological diseases. In cutaneous leishmaniasis, Leishmania braziliensis is inoculated into human skin via sandfly bites. In untreated patients, peripheral blood shows increased senescent CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, characterised by CD57 and KLRG1 expression, along with other hallmarks of senescence, including DNA damage, elevated pp38 activity, and shortened telomeres[181]. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from these patients exhibit a more pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic profile compared to healthy controls, with enhanced skin-homing potential due to increased expression of the CLA. Notably, the abundance of these senescent T cells positively correlates with cutaneous lesion size[181]. At the tissue level, lesional skin is enriched with senescent CD8+ T lymphocytes and NK cells[88]. The severity of cutaneous disease also links strongly to the presence of these CD8+ lymphocytes, independent of the low parasite burden in the skin[70,169]. This observation has led to the hypothesis that extensive skin damage in leishmaniasis results from non-specific NK-like cytotoxicity exhibited by senescent T cells[70,124].

A broad role of senescence in other cutaneous diseases has also been identified. In alopecia areata, a subset of highly differentiated memory CD8+ T cells (senescent) displays innate-like cytotoxic behaviour mediated by NKG2D[179], which may cause hair follicle destruction. In human psoriasis patients and murine psoriasis models, numerous senescent CD4+ T cells are observed in both the epidermis and dermis. Topical treatment of the senolytic BCL-2 inhibitor ABT-737 in psoriatic mice significantly reduces the number of senescent CD4+ T cells and mitigates the inflammatory milieu, lowering the levels of key cytokines implicated in psoriasis pathogenesis, including IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-12, and IFN-γ[87]. Furthermore, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and in SLE mouse models, increased numbers of senescent CD4+ CD57+ lymphocytes were observed in peripheral blood and skin compared with both healthy individuals and those with other rheumatological conditions[149,180]. The abundance of these cells and the intensity of CD57 expression, correlate positively with disease activity and cutaneous involvement. Treatment with the BCL-2 inhibitor ABT-263 (navitoclax) reduces senescent T cell numbers in peripheral blood samples from SLE donors in vitro and in a lupus mouse model in vivo. This reduction is accompanied by an alleviation of lupus-like phenotype and improved renal function[148]. Additionally, the gene expression analysis of senescent CD4+ lymphocytes from SLE patients highlights their proinflammatory signature, supporting the notion that these cells contribute to the inflammatory pathology of lupus.

2.7 Senotherapeutics in skin: immune or stromal modulation?

The prospect of halting or reversing age-related decline has long been a focus of interest. Pharmacological targeting of senescence, either through senolytic (cell-killing) or senomorphic (SASP-suppressing) therapies, has increasingly become viable and extensively reviewed elsewhere[86,183,184]. There is growing interest in leveraging these approaches to treat age-related skin dysfunction and inflammatory dermatoses. Both lymphoid and non-lymphoid senescent cells contribute to cutaneous pathology, representing the potential therapeutic targets. In the skin, senescent stromal cells, notably fibroblasts, exert immune-suppressive effects by producing excessive SASP, impairing local immunity[9,12,185]. They also induce immune checkpoint molecules on T cells and ligands on stromal cells (e.g., PD-L1, HLA-E)[22,128], and cleave immune-stimulatory molecules[130], collectively inhibiting their own clearance. Meanwhile, chronic inflammation upregulates activating NK ligands, such as MICA/B, on non-senescent stromal cells[171,172,186], rendering them susceptible to NK-like cytotoxicity of senescent T cells. This duality raises a therapeutic paradox: in skin diseases, should interventions target senescent stromal cells, senescent T cells, or both?

2.7.1 Evidence for targeting stromal cells

Senolytic agents, dasatinib and quercetin, can eliminate senescent human dermal fibroblasts in vitro and in vivo, resulting in increased collagen deposition and suppressed SASP in the skin[187]. Systemic dasatinib monotherapy in systemic sclerosis improves skin thickness in a subset of patients, accompanied by a reduction in cutaneous SASP and senescence-associated gene expression[187,188]. Furthermore, the combined dasatinib-quercetin treatment alleviates radiation-induced cutaneous ulcers in mice through the clearance of senescent stromal cells[189].

Several senomorphic agents have demonstrated efficacy in modulating cutaneous immunity by targeting dermal fibroblasts. The p38 MAPK inhibitors losmapimod with vitamin D3 reduces systemic inflammation, and improves cutaneous T cell infiltration and antigen-specific immunity in aged human skin by suppressing senescent dermal fibroblast SASP[9,12]. The mTOR inhibitor rapamycin is a powerful SASP suppressor in humans[190,191], effectively working on human dermal fibroblasts in vitro[192] and reducing objective measures of human skin aging in vivo[193]. Although its efficacy in dermatopathology has yet to be proven, aberrant mTOR activity has been implicated in psoriasis, eczema, and pemphigus[194]. This suggests that rapamycin may have potential to modulate cutaneous immunity through its senomorphic activity in these conditions.

Multiple other agents have been shown to modulate senescent stromal cells in the skin, such as BCL-2 inhibitor ABT-737, which selectively removes senescent melanocytes in a 3D co-culture model, restoring epidermal thickness[31,194]. Another BCL-2 inhibitor, navitoclax (ABT-263), eliminates senescent human fibroblasts grafted onto mice, improving collagen density of grafted skin and reducing SASP production[195].

Numerous plant-derived extracts have exhibited senomorphic activity in human stromal cells in vitro. Acting on human dermal fibroblasts, flavonoids apigenin, quercetin, kaempferol and wogonin reduce SASP (Lim, Park, and Kim 2015). Ferulic acid reduces p16, MMP1/3 mRNA and SA-β-Gal expression after UVA exposure[196], while nectandin B attenuates SA-β-Gal, p21, p53 and p16 expression in aged fibroblasts[196,197]. Reseveratrol, a SIRT1 activator, mitigates the effects of senescence in human epidermal keratinocytes in vitro[198], and also modulates senescence in dermal papillae cells in vitro, reducing SA-β-Gal expression, SASP cytokine and cell cycle inhibitor mRNA levels, and p16/p21 protein levels[199]. Emerging technologies such as extracellular vesicles have similarly demonstrated efficacy in mitigating human dermal fibroblast[200-202] and epidermal keratinocyte[200] senescence in vitro, and in reducing inflammatory cytokines in the skin to improve psoriasis and eczema in mouse models[203]. Several other second-generation senotherapeutics, such as nanoparticles and drug antibody conjugates, have shown early in vitro potential in dermal fibroblasts[204]. Although the impact of these interventions on cutaneous immune profile and function has not yet been evaluated, they hold potential as the basis for novel treatments of dermatoses with dysregulated cutaneous immunity.

2.7.2 Evidence for targeting T cells

Evidence supporting the targeting of senescent T cells to beneficially modulate the cutaneous environment remains limited; however, BCL-2 inhibitors have yielded encouraging results. Topical ABT-737 improves psoriasis in mice by reducing senescent dermal CD4+ T cells and cutaneous inflammatory cytokines[86], and further improves histological and clinical features in a mouse model of cutaneous lupus erythematosus[205]. Similarly, ABT-263 selectively eliminates senescent T cells in vitro from both healthy human and SLE patient PBMCs. These effects were replicated in a murine lupus model, with associated attenuation of lupus disease activity in multiple organs, including the skin[205,206].

2.7.3 Dual action

Metformin directly regulates mTOR-STAT3 signaling in dermal fibroblasts in vitro[206], and significantly reduces levels of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-8, IFN-γ, TNF-α, in lesional skin explants from both hidradenitis suppurativa and psoriasis patients[207]. Metformin improves skin fibrosis in a mouse model of scleroderma, reducing infiltration of lymphocytes and inflammatory cytokine burden in the skin[207]. It also reduces the burden of inflammatory cytokines in patients with inflammatory skin disease[207], directly impacting immunosenescence through the reduced numbers and IFN-γ secretion of senescent CD8+ T cells and increasing the frequency of naive T cells in aged humans[208].

Metformin, a first-line diabetes medication, can increase lifespan[209] and reduce all-cause mortality[209,210] in diabetic patients compared with non-diabetic controls. Its dual action on senescent lymphoid and non-lymphoid compartments indicates that targeting multiple sources of senescence may not only benefit the cutaneous landscape but overall organism health.

Emerging data suggests that targeting senescence in the skin may restore immune homeostasis, particularly in diseases with combined stromal and immune dysfunction. However, interventions aimed at one cell type may exacerbate dysfunction in others. For instance, stromal senolysis could relieve immunosuppressive barriers but may also destabilize tissue structure; immune cell senolysis may reduce inflammation but impair host defense. Future therapies must carefully balance these opposing effects. This paradox underscores the necessity to better understand the immune-stromal crosstalk in health and disease.

3. Concluding Remarks

Skin acts as a window into systemic aging: as the body’s largest immune–stromal organ, it is uniquely exposed to environmental and mechanical stress.

Natural human experiments provide the clearest route to causality. Cohorts carrying CDKN2A (familial melanoma) or TP53 (Li-Fraumeni) germline variants, alongside well-characterized progeroid paediatric syndromes, can reveal how defective senescence control shapes immunity and tissue architecture over time. In parallel, controlled human models, including standardised UV exposure, tape-stripping, suction blisters and recall-antigen challenge, can connect senescence programs to skin-organ function and immune responses in situ.

Successful translation depends on discrimination. We need robust biomarkers to separate physiological from pathological senescence across epidermis, dermis, and subcutis, and across ages, phototypes and anatomical sites. A composite Skin Senescence Index could integrate canonical markers (p16/p21, Lamin B1 loss), SASP/chemokine profiles, immune checkpoint ligands (HLA-E, PD-L1, sialoglycans), SCAP dependence and dermal-adipose immunometabolism, while anchoring these to patient-centered functional readouts such as barrier recovery, wound closure, infection-free days, vaccine responsiveness, thermoregulation, itch/pain and activity metrics.

Therapeutically, the goal remains to integrate senostatics/senomorphics to dampen harmful SASP (e.g., p38MAPK blockers), senolytics (e.g., BCL-2 inhibitors) to eliminate persistent senescent cells, and immune/metabolic modulators to restore surveillance and resilience (e.g., NKG2A/PD-1 or anti-sialoglycan strategies with SCAP sensitisation). Delivery should be local first (topical or intradermal) to maximise on-target effects while preserving beneficial, transient senescence elsewhere. Patient selection, dosing and endpoints should be driven by the biomarker framework outlined above, with safety and function (not just histology) outcomes.

By treating skin as an accessible sentinel of systemic aging, we can preserve physiological senescence while selectively targeting its pathological counterpart, guided by discriminatory biomarkers. The ultimate goal is to convert descriptive maps into actionable, tissue-specific interventions that restore barrier, immunity and function. In short, this represents the beginning of precision senescence medicine for the skin.

Authors contribution

Subramanian P: Conceptualization, investigation, data curation, writing-original draft, visualization.

Devine O: Conceptualization, writing-original draft, visualization.

Akbar AN: Conceptualization, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Arne N. Akbar is an Editorial Board Member of Geromedicine. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was funded by Dermatrust, Medical Research Council (MR/T030534/1) and LEO Foundation grant (LF-OC-19-000192) to Arne N. Akbar.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Ageing and health [Internet]. [cited 2025 Apr 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health

-

2. Lim H, Park H, Kim HP. Effects of flavonoids on senescence-associated secretory phenotype formation from bleomycin-induced senescence in BJ fibroblasts. Biochem Pharmacol. 2015;96(4):337-348.[DOI]

-

3. Sinikumpu SP, Jokelainen J, Haarala AK, Keränen MH, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Huilaja L. The high prevalence of skin diseases in adults aged 70 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(11):2565-2571.[DOI]

-

4. Di Micco R, Krizhanovsky V, Baker D, d’Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence in ageing: From mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22(2):75-95.[DOI]

-

5. Gorgoulis V, Adams PD, Alimonti A, Bennett DC, Bischof O, Bishop C, et al. Cellular senescence: Defining a path forward. Cell. 2019;179(4):813-827.[DOI]

-

6. Muñoz-Espín D, Serrano M. Cellular senescence: From physiology to pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(7):482-496.[DOI]

-

7. Chin T, Lee XE, Ng PY, Lee Y, Dreesen O. The role of cellular senescence in skin aging and age-related skin pathologies. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1297637.[DOI]

-

8. Thau H, Gerjol BP, Hahn K, von Gudenberg RW, Knoedler L, Stallcup K, et al. Senescence as a molecular target in skin aging and disease. Ageing Res Rev. 2025;105:102686.[DOI]

-

9. Chambers ES, Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Shih BB, Trahair H, Subramanian P, Devine OP, et al. Recruitment of inflammatory monocytes by senescent fibroblasts inhibits antigen-specific tissue immunity during human aging. Nat Aging. 2021;1(1):101-113.[DOI]

-

10. Subramanian P, Sayegh S, Laphanuwat P, Devine OP, Fantecelle CH, Sikora J, et al. Multiple outcomes of the germline p16INK4a mutation affecting senescence and immunity in human skin. Aging Cell. 2025;24(2):e14373.[DOI]

-

11. Demaria M, Ohtani N, Youssef Sameh A, Rodier F, Toussaint W, Mitchell James R, et al. An essential role for senescent cells in optimal wound healing through secretion of PDGF-AA. Dev Cell. 2014;31(6):722-733.[DOI]

-

12. Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Chambers ES, Suárez-Fariñas M, Sandhu D, Fuentes-Duculan J, Patel N, et al. Enhancement of cutaneous immunity during aging by blocking p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase–induced inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(3):844-856.[DOI]

-

13. Coppé JP, Patil CK, Rodier F, Sun YU, Muñoz DP, Goldstein J, et al. Senescence-associated secretory phenotypes reveal cell-nonautonomous functions of oncogenic RAS and the p53 tumor suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(12):e301.[DOI]

-

14. Pilkington SM, Barron MJ, Watson REB, Griffiths CEM, Bulfone-Paus S. Aged human skin accumulates mast cells with altered functionality that localize to macrophages and vasoactive intestinal peptide-positive nerve fibres. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(4):849-858.[DOI]

-

15. Gather L, Nath N, Falckenhayn C, Oterino-Sogo S, Bosch T, Wenck H, et al. Macrophages are polarized toward an inflammatory phenotype by their aged microenvironment in the human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142(12):3136-3145.[DOI]

-

16. Gunin AG, Kornilova NK, Vasilieva OV, Petrov VV. Age-related changes in proliferation, the numbers of mast cells, eosinophils, and cd45-positive cells in human dermis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66A(4):385-392.[DOI]

-

17. Koguchi-Yoshioka H, Hoffer E, Cheuk S, Matsumura Y, Vo S, Kjellman P, et al. Skin T cells maintain their diversity and functionality in the elderly. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):13.[DOI]

-

18. Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp Cell Res. 1961;25(3):585-621.[DOI]

-

19. Wiley CD, Campisi J. The metabolic roots of senescence: Mechanisms and opportunities for intervention. Nat Metab. 2021;3(10):1290-1301.[DOI]

-

20. Ressler S, Bartkova J, Niederegger H, Bartek J, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Jansen-Dürr P, et al. p16INK4A is a robust in vivo biomarker of cellular aging in human skin. Aging Cell. 2006;5(5):379-389.[DOI]

-

21. Hewitt G, Jurk D, Marques FDM, Correia-Melo C, Hardy T, Gackowska A, et al. Telomeres are favoured targets of a persistent DNA damage response in ageing and stress-induced senescence. Nat Commun. 2012;3(1):708.[DOI]

-

22. Pereira BI, Devine OP, Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Chambers ES, Subramanian P, Patel N, et al. Senescent cells evade immune clearance via HLA-E-mediated NK and CD8+ T cell inhibition. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2387.[DOI]

-

23. Aird KM, Zhang R. Detection of senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF). In: Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Kepp O, Kroemer G, editors. Cell senescence: Methods and protocols. Totowa: Humana Press; 2013. p. 185-196.[DOI]

-

24. Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, Acosta M, Scott G, Roskelley C, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 1995;92(20):9363-9367.[DOI]

-

25. Passos JF, Nelson G, Wang C, Richter T, Simillion C, Proctor CJ, et al. Feedback between p21 and reactive oxygen production is necessary for cell senescence. Mol Syst Biol. 2010;6(1):MSB20105.[DOI]

-

26. Ogrodnik M, Carlos Acosta J, Adams PD, d’Adda di Fagagna F, Baker DJ, Bishop CL, et al. Guidelines for minimal information on cellular senescence experimentation in vivo. Cell. 2024;187(16):4150-4175.[DOI]

-

27. Mitra M, Ho LD, Coller HA. An in vitro model of cellular quiescence in primary human dermal fibroblasts. In: Lacorazza HD, editor. Secondary An in vitro model of cellular quiescence in primary human dermal fibroblasts. New York: Springer; 2018. p. 27-47.[DOI]

-

28. Kim RH, Kang MK, Kim T, Yang P, Bae S, Williams DW, et al. Regulation of p53 during senescence in normal human keratinocytes. Aging Cell. 2015;14(5):838-846.[DOI]

-

29. Rheinwald JG, Hahn WC, Ramsey MR, Wu JY, Guo Z, Tsao H, et al. A two-stage, p16INK4A- and p53-dependent keratinocyte senescence mechanism that limits replicative potential independent of telomere status. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(14):5157-5172.[DOI]

-

30. Lewis DA, Yi Q, Travers JB, Spandau DF. UVB-induced senescence in human keratinocytes requires a functional insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and p53. Biol Cell. 2008;19(4):1346-1353.[DOI]

-

31. Victorelli S, Lagnado A, Halim J, Moore W, Talbot D, Barrett K, et al. Senescent human melanocytes drive skin ageing via paracrine telomere dysfunction. EMBO J. 2019;38(23):EMBJ2019101982.[DOI]

-

32. Gray-Schopfer VC, Cheong SC, Chong H, Chow J, Moss T, Abdel-Malek ZA, et al. Cellular senescence in naevi and immortalisation in melanoma: A role for p16? Br J Cancer. 2006;95(4):496-505.[DOI]

-

33. Haferkamp S, Tran SL, Becker TM, Scurr LL, Kefford RF, Rizos H. The relative contributions of the p53 and pRb pathways in oncogene-induced melanocyte senescence. Aging. 2009;1(6):542-556.[DOI]

-

34. Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LCW, Soengas MS, Denoyelle C, Kuilman T, van der Horst CMAM, et al. BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi. Nature. 2005;436(7051):720-724.[DOI]

-

35. Waaijer MEC, Parish WE, Strongitharm BH, van Heemst D, Slagboom PE, de Craen AJM, et al. The number of p16INK4a positive cells in human skin reflects biological age. Aging Cell. 2012;11(4):722-725.[DOI]

-

36. Chen W, Kang J, Xia J, Yang B, Chen B, Sun W, Song X, Xiang W, Wang X, Wang F, Wan Y. p53-related apoptosis resistance and tumor suppression activity in UVB-induced premature senescent human skin fibroblasts. Int J Mol Med. 2008;21(5):645-653.[DOI]

-

37. Debacq-Chainiaux F, Borlon Cl, Pascal T, Royer Vr, Eliaers Fo, Ninane Nl, et al. Repeated exposure of human skin fibroblasts to uvb at subcytotoxic level triggers premature senescence through the TGF-β1 signaling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(4):743-758.[DOI]

-

38. Hasegawa T, Oka T, Son HG, Oliver-García VS, Azin M, Eisenhaure TM, et al. Cytotoxic CD4+ T cells eliminate senescent cells by targeting cytomegalovirus antigen. Cell. 2023;186(7):1417-1431.[DOI]

-

39. Lee JH, Hong IA, Oh SH, Kwon YS, Cho SH, Lee KH. The effect of moesin overexpression on ageing of human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18(11):997-999.[DOI]

-

40. Watanabe Y, Lee SW, Detmar M, Ajioka I, Dvorak HF. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor (VPF/VEGF) delays and induces escape from senescence in human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Oncogene. 1997;14(17):2025-2032.[DOI]

-

41. Tang J, Gordon GM, Nickoloff BJ, Foreman KE. The helix–loop–helix protein Id-1 delays onset of replicative senescence in human endothelial cells. Lab Invest. 2002;82(8):1073-1079.[DOI]

-

42. Lee JH, Chung KY, Bang D, Lee KH. Searching for aging-related proteins in human dermal microvascular endothelial cells treated with anti-aging agents. Proteomics. 2006;6(4):1351-1361.[DOI]

-

43. McCart EA, Thangapazham RL, Lombardini ED, Mog SR, Panganiban RAM, Dickson KM, et al. Accelerated senescence in skin in a murine model of radiation-induced multi-organ injury. J Radiat Res. 2017;58(5):636-646.[DOI]

-

44. Choi SY, Bin BH, Kim W, Lee E, Lee TR, Cho EG. Exposure of human melanocytes to UVB twice and subsequent incubation leads to cellular senescence and senescence-associated pigmentation through the prolonged p53 expression. J Dermatol Sci. 2018;90(3):303-312.[DOI]

-

45. Gerasymchuk M, Robinson GI, Kovalchuk O, Kovalchuk I. Modeling of the senescence-associated phenotype in human skin fibroblasts. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(13):7124.[DOI]

-

46. Rivetti di Val Cervo P, Lena AM, Nicoloso M, Rossi S, Mancini M, Zhou H, et al. p63–microRNA feedback in keratinocyte senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2012;109(4):1133-1138.[DOI]

-

47. Wang AS, Ong PF, Chojnowski A, Clavel C, Dreesen O. Loss of lamin B1 is a biomarker to quantify cellular senescence in photoaged skin. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):15678.[DOI]

-

48. Xu LW, Sun YD, Fu QY, Wu D, Lin J, Wang C, et al. Unveiling senescence-associated secretory phenotype in epidermal aging: Insights from reversibly immortalized keratinocytes. Aging. 2024;16(18):12651-12666.[DOI]

-

49. Biran A, Zada L, Abou Karam P, Vadai E, Roitman L, Ovadya Y, et al. Quantitative identification of senescent cells in aging and disease. Aging Cell. 2017;16(4):661-671.[DOI]

-

50. Chainiaux F, Magalhaes J-P, Eliaers F, Remacle J, Toussaint O. UVB-induced premature senescence of human diploid skin fibroblasts. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2002;34(11):1331-1339.[DOI]

-

51. Ha MK, Chung KY, Lee JH, Bang D, Park YK, Lee KH. Expression of psoriasis-associated fatty acid-binding protein in senescent human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Exp Dermatol. 2004;13(9):543-550.[DOI]

-

52. Dreesen O, Chojnowski A, Ong PF, Zhao TY, Common JE, Lunny D, et al. Lamin B1 fluctuations have differential effects on cellular proliferation and senescence. J Cell Biol. 2013;200(5):605-617.[DOI]

-

53. Ivanov A, Pawlikowski J, Manoharan I, van Tuyn J, Nelson DM, Rai TS, et al. Lysosome-mediated processing of chromatin in senescence. J Cell Biol. 2013;202(1):129-143.[DOI]

-

54. Freund A, Laberge R-M, Demaria M, Campisi J. Lamin B1 loss is a senescence-associated biomarker. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23(11):2066-2075.[DOI]

-

55. Davalos AR, Kawahara M, Malhotra GK, Schaum N, Huang J, Ved U, et al. p53-dependent release of Alarmin HMGB1 is a central mediator of senescent phenotypes. J Cell Biol. 2013;201(4):613-629.[DOI]

-

56. Rübe CE, Bäumert C, Schuler N, Isermann A, Schmal Z, Glanemann M, et al. Human skin aging is associated with increased expression of the histone variant H2A.J in the epidermis. npj Aging Mech Dis. 2021;7(1):7.[DOI]

-

57. Sitte N, Merker K, Grune T, von Zglinicki T. Lipofuscin accumulation in proliferating fibroblasts in vitro: An indicator of oxidative stress. Exp Gerontol. 2001;36(3):475-486.[DOI]

-

58. Pawlikowski JS, McBryan T, van Tuyn J, Drotar ME, Hewitt RN, Maier AB, et al. Wnt signaling potentiates nevogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2013;110(40):16009-16014.[DOI]

-

59. Park YJ, Kim JC, Kim Y, Kim YH, Park SS, Muther C, et al. Senescent melanocytes driven by glycolytic changes are characterized by melanosome transport dysfunction. Theranostics. 2023;13(12):3914-3924.[DOI]

-

60. Rodier F, Coppé JP, Patil CK, Hoeijmakers WAM, Muñoz DP, Raza SR, et al. Persistent DNA damage signalling triggers senescence-associated inflammatory cytokine secretion. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(8):973-979.[DOI]

-

61. Waldera Lupa DM, Kalfalah F, Safferling K, Boukamp P, Poschmann G, Volpi E, et al. Characterization of skin aging–associated secreted proteins (SAASP) produced by dermal fibroblasts isolated from intrinsically aged human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(8):1954-1968.[DOI]

-

62. Freund A, Patil CK, Campisi J. p38MAPK is a novel DNA damage response-independent regulator of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. EMBO J. 2011;30(8):1536-1548.[DOI]

-

63. Jochems F, Thijssen B, De Conti G, Jansen R, Pogacar Z, Groot K, et al. The cancer SENESCopedia: A delineation of cancer cell senescence. Cell Rep. 2021;36(4):109441.[DOI]

-

64. Hughes BK, Davis A, Milligan D, Wallis R, Mossa F, Philpott MP, et al. Senpred: A single-cell RNA sequencing-based machine learning pipeline to classify deeply senescent dermal fibroblast cells for the detection of an in vivo senescent cell burden. Genome Med. 2025;17(1):2.[DOI]

-

65. Hughes BK, Davis A, Milligan D, Wallis R, Philpott MP, Wainwright LJ, et al. SenPred: A single-cell RNA sequencing-based machine learning pipeline to classify senescent cells for the detection of an in vivo senescent cell burden. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2023.[DOI]

-

66. Saul D, Kosinsky RL, Atkinson EJ, Doolittle ML, Zhang X, LeBrasseur NK, et al. A new gene set identifies senescent cells and predicts senescence-associated pathways across tissues. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4827.[DOI]

-

67. Lee PJ, Benz CC, Blood P, Börner K, Campisi J, Chen F, et al. NIH SenNet consortium to map senescent cells throughout the human lifespan to understand physiological health. Nat Aging. 2022;2(12):1090-1100.[DOI]

-

68. Akbar AN, Henson SM, Lanna A. Senescence of T lymphocytes: Implications for enhancing human immunity. Trends Immunol. 2016;37(12):866-876.[DOI]

-

69. Henson SM, Riddell NE, Akbar AN. Properties of end-stage human T cells defined by CD45RA re-expression. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24(4):476-481.[DOI]

-

70. Covre LP, De Maeyer RPH, Gomes DCO, Akbar AN. The role of senescent T cells in immunopathology. Aging Cell. 2020;19(12):e13272.[DOI]

-

71. Pereira BI, Akbar AN. Convergence of innate and adaptive immunity during human aging. Front Immunol. 2016;7:445.[DOI]

-

72. Laphanuwat P, Gomes DCO, Akbar AN. Senescent T cells: Beneficial and detrimental roles. Immunol Rev. 2023;316(1):160-175.[DOI]

-

73. Behmoaras J, Gil J. Similarities and interplay between senescent cells and macrophages. J Cell Biol. 2020;220(2):e202010162.[DOI]

-

74. Haston S, Gonzalez-Gualda E, Morsli S, Ge J, Reen V, Calderwood A, et al. Clearance of senescent macrophages ameliorates tumorigenesis in KRAS-driven lung cancer. Cancer Cell. 2023;41(7):1242-1260.[DOI]

-

75. Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Garcia D, Blomberg BB. B cell immunosenescence. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2020;36(36):551-574.[DOI]

-

76. Callender LA, Carroll EC, Beal RWJ, Chambers ES, Nourshargh S, Akbar AN, et al. Human CD8+ EMRA T cells display a senescence-associated secretory phenotype regulated by p38 MAPK. Aging Cell. 2018;17(1):e12675.[DOI]

-

77. Lanna A, Henson SM, Escors D, Akbar AN. The kinase p38 activated by the metabolic regulator AMPK and scaffold TAB1 drives the senescence of human T cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(10):965-972.[DOI]

-

78. Lanna A, Gomes DCO, Muller-Durovic B, McDonnell T, Escors D, Gilroy DW, et al. A sestrin-dependent Erk–Jnk–p38 MAPK activation complex inhibits immunity during aging. Nat Immunol. 2017;18(3):354-363.[DOI]

-

79. Pereira BI, De Maeyer RPH, Covre LP, Nehar-Belaid D, Lanna A, Ward S, et al. Sestrins induce natural killer function in senescent-like CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2020;21(6):684-694.[DOI]

-

80. Henson SM, Lanna A, Riddell NE, Franzese O, Macaulay R, Griffiths SJ, et al. p38 signaling inhibits mTORC1-independent autophagy in senescent human CD8+ T cells. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(9):4004-4016.

-

81. Akbar AN, Henson SM. Are senescence and exhaustion intertwined or unrelated processes that compromise immunity? Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(4):289-295.[DOI]

-

82. Scheuring UJ, Sabzevari H, Theofilopoulos AN. Proliferative arrest and cell cycle regulation in CD8+CD28− versus CD8+CD28+ T cells. Hum Immunol. 2002;63(11):1000-1009.[DOI]

-

83. Janelle V, Neault M, Lebel MÈ, De Sousa DM, Boulet S, Durrieu L, et al. p16INK4a regulates cellular senescence in PD-1-expressing human T cells. Front Immunol. 2021;12:698565.[DOI]

-

84. Villanueva-Romero R, Lamana A, Flores-Santamaría M, Carrión M, Pérez-García S, Triguero-Martínez A, et al. Comparative study of senescent Th biomarkers in healthy donors and early arthritis patients. Analysis of VPAC receptors and their influence. Cells. 2020;9(12):2592.[DOI]

-

85. Martínez-Zamudio RI, Dewald HK, Vasilopoulos T, Gittens-Williams L, Fitzgerald-Bocarsly P, Herbig U. Senescence-associated β-galactosidase reveals the abundance of senescent CD8+ T cells in aging humans. Aging Cell. 2021;20(5):e13344.[DOI]

-

86. Zhu H, Jiang J, Yang M, Zhao M, He Z, Tang C, et al. Topical application of a BCL-2 inhibitor ameliorates imiquimod-induced psoriasiform dermatitis by eliminating senescent cells. J Dermatol Sci. 2024;115(2):54-63.[DOI]

-

87. Fantecelle CH, Covre LP, Garcia de Moura R, Guedes HLdM, Amorim CF, Scott P, et al. Transcriptomic landscape of skin lesions in cutaneous leishmaniasis reveals a strong CD8+ T cell immunosenescence signature linked to immunopathology. Immunology. 2021;164(4):754-765.[DOI]

-

88. Covre LP, Fantecelle CH, Garcia de Moura R, Oliveira Lopes P, Sarmento IV, Freire-de-Lima CG, et al. Lesional senescent CD4+ T cells mediate bystander cytolysis and contribute to the skin pathology of human cutaneous leishmaniasis. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1475146.[DOI]

-

89. Seidel JA, Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Muller-Durovic B, Patel N, Fuentes-Duculan J, Henson SM, et al. Skin resident memory CD8+ T cells are phenotypically and functionally distinct from circulating populations and lack immediate cytotoxic function. Clin Exp Immunol. 2018;194(1):79-92.[DOI]

-

90. Henson SM, Franzese O, Macaulay R, Libri V, Azevedo RI, Kiani-Alikhan S, et al. Klrg1 signaling induces defective Akt (ser473) phosphorylation and proliferative dysfunction of highly differentiated CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2009;113(26):6619-6628.[DOI]

-

91. Appay V, van Lier RAW, Sallusto F, Roederer M. Phenotype and function of human T lymphocyte subsets: Consensus and issues. Cytometry A. 2008;73A(11):975-983.[DOI]

-

92. Slaets H, Veeningen N, de Keizer PLJ, Hellings N, Hendrix S. Are immunosenescent T cells really senescent? Aging Cell. 2024;23(10):e14300.[DOI]

-

93. Libri V, Azevedo RI, Jackson SE, Di Mitri D, Lachmann R, Fuhrmann S, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection induces the accumulation of short-lived, multifunctional CD4+ CD45RA+ CD27− T cells: The potential involvement of interleukin-7 in this process. Immunology. 2011;132(3):326-339.[DOI]

-

94. Voehringer D, Koschella M, Pircher H. Lack of proliferative capacity of human effector and memory T cells expressing killer cell lectinlike receptor G1 (KLRG1). Blood. 2002;100(10):3698-3702.[DOI]

-

95. Rodríguez IJ, Parra-López CA. Markers of immunosenescence in CMV seropositive healthy elderly adults. Front Aging. 2025;5:1436346.[DOI]

-

96. Brenchley JM, Karandikar NJ, Betts MR, Ambrozak DR, Hill BJ, Crotty LE, et al. Expression of CD57 defines replicative senescence and antigen-induced apoptotic death of CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2003;101(7):2711-2720.[DOI]

-

97. Batista MD, Tincati C, Milush JM, Ho EL, Ndhlovu LC, York VA, et al. CD57 expression and cytokine production by T cells in lesional and unaffected skin from patients with psoriasis. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e52144.[DOI]

-

98. Ouyang Q, Wagner WM, Voehringer D, Wikby A, Klatt T, Walter S, et al. Age-associated accumulation of cmv-specific CD8+ T cells expressing the inhibitory killer cell lectin-like receptor G1 (KLRG1). Experimental Gerontology. 2003;38(8):911-920.[DOI]

-

99. Tarazona R, DelaRosa O, Casado JG, Torre-Cisneros J, Villanueva JL, Galiani MD, et al. NK-associated receptors on CD8 T cells from treatment-naive HIV-infected individuals: defective expression of CD56. AIDS. 2002;16(2):197-200.[DOI]

-

100. Alonso-Arias R, Moro-García MA, López-Vázquez A, Rodrigo L, Baltar J, García FMS, et al. Nkg2d expression in CD4+ T lymphocytes as a marker of senescence in the aged immune system. AGE. 2011;33(4):591-605.[DOI]

-

101. Plunkett FJ, Franzese O, Finney HM, Fletcher JM, Belaramani LL, Salmon M, et al. The loss of telomerase activity in highly differentiated CD8+CD28−CD27− T cells is associated with decreased Akt (Ser473) phosphorylation1. J Immunol. 2007;178(12):7710-7719.[DOI]

-

102. Akbar AN, Borthwick N, Salmon M, Gombert W, Bofill M, Shamsadeen N, et al. The significance of low bcl-2 expression by CD45RO T cells in normal individuals and patients with acute viral infections. The role of apoptosis in T cell memory. J Exp Med. 1993;178(2):427-438.[DOI]

-

103. Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Proliferation and differentiation potential of human CD8+ memory T-cell subsets in response to antigen or homeostatic cytokines. Blood. 2003;101(11):4260-4266.[DOI]

-

104. Callender LA, Carroll EC, Bober EA, Akbar AN, Solito E, Henson SM. Mitochondrial mass governs the extent of human T cell senescence. Aging Cell. 2020;19(2):e13067.[DOI]

-

105. Henson SM, Macaulay R, Riddell NE, Nunn CJ, Akbar AN. Blockade of PD-1 or p38 MAP kinase signaling enhances senescent human CD8+ T-cell proliferation by distinct pathways. Eur J Immunol. 2015;45(5):1441-1451.[DOI]

-

106. Zhang C, Merana GR, Harris-Tryon T, Scharschmidt TC. Skin immunity: Dissecting the complex biology of our body’s outer barrier. Mucosal Immunol. 2022;15(4):551-561.[DOI]

-

107. Richmond JM, Harris JE. Immunology and skin in health and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4(12):a015339.[DOI]

-

108. Ziadlou R, Pandian GN, Hafner J, Akdis CA, Stingl G, Maverakis E, et al. Subcutaneous adipose tissue: Implications in dermatological diseases and beyond. Allergy. 2024;79(12):3310-3325.[DOI]

-

109. Fantuzzi G. Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(5):911-919.[DOI]

-

110. Liu C, Li X. Role of leptin and adiponectin in immune response and inflammation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;161:115082.[DOI]

-

111. Man K, Kallies A, Vasanthakumar A. Resident and migratory adipose immune cells control systemic metabolism and thermogenesis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022;19(3):421-431.[DOI]

-

112. Idda ML, McClusky WG, Lodde V, Munk R, Abdelmohsen K, Rossi M, et al. Survey of senescent cell markers with age in human tissues. Aging. 2020;12(5):4052-4066.[DOI]

-

113. Dorf N, Maciejczyk M. Skin senescence—from basic research to clinical practice. Front Med. 2024;11:1484345.[DOI]

-

114. Zhang J, Yu H, Man MQ, Hu L. Aging in the dermis: Fibroblast senescence and its significance. Aging Cell. 2024;23(2):e14054.[DOI]

-

115. Hughes BK, Bishop CL. Current understanding of the role of senescent melanocytes in skin ageing. Biomedicines. 2022;10(12):3111.[DOI]

-

116. Bandyopadhyay D, Timchenko N, Suwa T, Hornsby PJ, Campisi J, Medrano EE. The human melanocyte: A model system to study the complexity of cellular aging and transformation in non-fibroblastic cells. Exp Gerontol. 2001;36(8):1265-1275.[DOI]

-

117. Marrot L, Belaidi JP, Meunier JR, Perez P, Agapakis-Causse C. The human melanocyte as a particular target for uva radiation and an endpoint for photoprotection assessment. Photochem Photobiol. 1999;69(6):686-693.[DOI]

-

118. Jenkins NC, Grossman D. Role of melanin in melanocyte dysregulation of reactive oxygen species. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013(1):908797.[DOI]

-

119. Akbar AN, Reed JR, Lacy KE, Jackson SE, Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Rustin MHA. Investigation of the cutaneous response to recall antigen in humans in vivo. Clin Exp Immunol. 2013;173(2):163-172.[DOI]

-

120. Agius E, Lacy KE, Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Jagger AL, Papageorgiou AP, Hall S, et al. Decreased TNF-α synthesis by macrophages restricts cutaneous immunosurveillance by memory CD4+ T cells during aging. J Exp Med. 2009;206(9):1929-1940.[DOI]

-

121. Liu Y, Sanoff HK, Cho H, Burd CE, Torrice C, Ibrahim JG, et al. Expression of p16INK4a in peripheral blood T-cells is a biomarker of human aging. Aging Cell. 2009;8(4):439-448.[DOI]

-

122. Li G, Larregina AT, Domsic RT, Stolz DB, Medsger TA, Jr. , Lafyatis R, et al. Skin-resident effector memory CD8+ CD28– T cells exhibit a profibrotic phenotype in patients with systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(5):1042-1050.[DOI]

-

123. De Rie MA, Catro I, Van Lier RA, Bos JD. Expression of the T-cell activation antigens CD27 and CD28 in normal and psoriatic skin. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21(2):104-111.[DOI]

-

124. Covre LP, Devine OP, Garcia de Moura R, Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Dietze R, Ribeiro-Rodrigues R, et al. Compartmentalized cytotoxic immune response leads to distinct pathogenic roles of natural killer and senescent CD8+ T cells in human cutaneous leishmaniasis. Immunology. 2020;159(4):429-440.[DOI]

-

125. Majewska J, Krizhanovsky V. Immune surveillance of senescent cells in aging and disease. Nat Aging. 2025;5(8):1415-1424.[DOI]

-

126. Kale A, Sharma A, Stolzing A, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Role of immune cells in the removal of deleterious senescent cells. Immun Ageing. 2020;17(1):16.[DOI]

-

127. Majewska J, Agrawal A, Mayo A, Roitman L, Chatterjee R, Sekeresova Kralova J, et al. p16-dependent increase of PD-L1 stability regulates immunosurveillance of senescent cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2024;26(8):1336-1345.[DOI]

-

128. Onorati A, Havas AP, Lin B, Rajagopal J, Sen P, Adams PD, et al. Upregulation of PD-L1 in senescence and aging. Mol Cell Biol. 2022;42(10):e00171-22.[DOI]

-

129. Wang TW, Johmura Y, Suzuki N, Omori S, Migita T, Yamaguchi K, et al. Blocking PD-L1–PD-1 improves senescence surveillance and ageing phenotypes. Nature. 2022;611(7935):358-364.[DOI]

-

130. Muñoz DP, Yannone SM, Daemen A, Sun Y, Vakar-Lopez F, Kawahara M, et al. Targetable mechanisms driving immunoevasion of persistent senescent cells link chemotherapy-resistant cancer to aging. JCI Insight. 2019;4(14):e124716.[DOI]

-

131. Zingoni A, Vulpis E, Loconte L, Santoni A. NKG2D ligand shedding in response to stress: Role of ADAM10. Front Immunol. 2020;11:447.[DOI]

-

132. Deng Y, Chen Q, Yang X, Sun Y, Zhang B, Wei W, et al. Tumor cell senescence-induced macrophage CD73 expression is a critical metabolic immune checkpoint in the aging tumor microenvironment. Theranostics. 2024;14(3):1224-1240.[DOI]

-

133. Iltis C, Moskalevska I, Debiesse A, Seguin L, Fissoun C, Cervera L, et al. A ganglioside-based immune checkpoint enables senescent cells to evade immunosurveillance during aging. Nat Aging. 2025;5(2):219-236.[DOI]

-

134. van der Haar Àvila I, Windhouwer B, van Vliet SJ. Current state-of-the-art on ganglioside-mediated immune modulation in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2023;42(3):941-958.[DOI]

-

135. Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Reed JR, Lacy KE, Rustin MHA, Akbar AN. Mantoux Test as a model for a secondary immune response in humans. Immunol Lett. 2006;107(2):93-101.[DOI]

-

136. Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Agius E, Booth N, Dunne PJ, Lacy KE, Reed JR, et al. The kinetics of CD4+ Foxp3+ T cell accumulation during a human cutaneous antigen-specific memory response in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(11):3639-3650.[DOI]

-

137. Orteu CH, Poulter LW, Rustin MHA, Sabin CA, Salmon M, Akbar AN. The role of apoptosis in the resolution of T cell-mediated cutaneous inflammation. J Immunol. 1998;161(4):1619-1629.[DOI]

-

138. Reed JR, Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Fletcher JM, Soares MVD, Cook JE, Orteu CH, et al. Telomere erosion in memory T cells induced by telomerase inhibition at the site of antigenic challenge in vivo. J Exp Med. 2004;199(10):1433-1443.[DOI]

-

139. Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Sandhu D, Seidel JA, Patel N, Sobande TO, Agius E, et al. The characterization of varicella zoster virus–specific T cells in skin and blood during aging. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135(7):1752-1762.[DOI]

-

140. Meguro S, Johmura Y, Wang TW, Kawakami S, Tanimoto S, Omori S, et al. Preexisting senescent fibroblasts in the aged bladder create a tumor-permissive niche through CXCL12 secretion. Nat Aging. 2024;4(11):1582-1597.[DOI]

-

141. Yoon JE, Kim Y, Kwon S, Kim M, Kim YH, Kim JH, et al. Senescent fibroblasts drive ageing pigmentation: A potential therapeutic target for senile lentigo. Theranostics. 2018;8(17):4620-4632.[DOI]

-

142. Ganguly S, Sakane S, Hokutan K, Zhang V, Miciano C, Wang A, et al. Aging and aging-related senescence in liver. Semin Liver Dis. 2025;45(04):549-566.[DOI]

-