Abstract

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD), primarily driven by dysfunction of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), is the leading cause of irreversible blindness in the elderly. As the central hub for photoreceptor support, nutrient transport, and waste clearance, the RPE is particularly vulnerable to age-related stressors that disrupt proteostasis and mitochondrial quality control. Autophagy and mitophagy are essential regulators of RPE and retinal longevity, ensuring the turnover of damaged proteins and organelles while maintaining energy homeostasis. In AMD, these pathways become compromised, contributing to lipofuscin accumulation, oxidative stress, inflammation, and progressive cell death. This review examines the physiological roles of autophagy and mitophagy in retinal homeostasis, their dysregulation in AMD, and emerging therapeutic approaches aimed at restoring these protective processes. Targeting autophagy and mitophagy is a promising strategy to preserve vision and delay the progression of AMD.

Keywords

1. Introduction

The retina is the light-sensitive tissue located in the posterior region of the eye. Its function involves capturing photons and converting them into electrical impulses, which are subsequently transmitted to the brain to facilitate vision. Recent advances in single-cell sequencing have identified 69 distinct cell types within the human retina[1]. These cells are organized into 10 specific layers, including the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE); the outer nuclear layer (ONL), which contains photoreceptors (PRs); the inner nuclear layer (INL), that contains bipolar, horizontal, and amacrine neurons; and the ganglion cell layer (GCL), where signals converge and from which axons extend to form the optic nerve, transmitting information to the brain. Interposed between the ONL, INL, and GCL are the plexiform layers, which serve as the primary sites for synaptic transmission and signal processing[2]. In addition to neural cells, the retina contains non-neural cells such as Müller glia, astrocytes, and microglia, which are distributed throughout the tissue to provide metabolic and trophic support, structural integrity, and synaptic modulation.

Given that many retinal cells are post-mitotic, robust quality-control mechanisms are essential to maintain their viability, as these cells cannot dilute toxic cellular byproducts through cell division. Lysosomes, the principal intracellular degradative organelles, are therefore crucial for preserving cellular homeostasis. Degradation of intracellular cargo within lysosomes, mediated by the autophagy machinery, enables retinal cells to eliminate deleterious materials, sustain their metabolism, and ensure visual function[3]. In the retina, which has high energetic demands, optimal mitochondrial function is maintained through mitophagy, which is the selective degradation of mitochondria via autophagy and eliminates excess or damaged mitochondria[4].

Retinal diseases are conditions that disrupt the processing of visual signals, leading to vision loss. These diseases are broadly categorized as either genetic or multifactorial. The inherited retinal diseases (IRDs), such as retinitis pigmentosa, are a diverse group caused by specific genetic mutations. In contrast, age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a multifactorial disease where both genetic and environmental factors contribute to its development. In AMD, the combination and effects of various risk factors, including aging, diet, lifestyle, and genetic predisposition, are recognized triggers for disease onset[5]. AMD is characterized by the degeneration of the macula, the region of the primate retina responsible for detailed color vision. Extensive research indicates that disruption of RPE cell function and integrity is a key contributor to AMD pathogenesis[5-7]. Evidence strongly implicates autophagy and mitophagy, or dysregulation thereof, in the progression of retinal diseases[4,8]. Consequently, modulation of the corresponding regulatory pathways represents a novel therapeutic approach for these diseases[9]. In this review, we specifically focus on AMD and the alterations observed in the autophagy pathway within RPE cells. We review evidence from cell and animal models supporting the therapeutic potential of strategies that modulate these pathways in AMD and other retinal diseases.

2. The RPE and Aging

2.1 How does the RPE sustain retinal function?

The RPE is a monolayer of post-mitotic cells. Its apical side faces the PR outer segments (POS), while its basal membrane faces the choroid, a highly vascularized layer external to the retina that metabolically supports the outer retina. RPE cells are characterized by their polarity and tight junctions, maintained by an extensive cytoskeletal network. This cellular organization facilitates the creation of gradients for ions, metabolites, macromolecules, and organelles, leading to compartmentalization and coordination of specific functions within these epithelial cells[10]. RPE cells are critical for maintaining outer retinal homeostasis, performing key functions including visual chromophore recycling, POS renewal, light absorption, metabolic and trophic support, maintenance of ionic and molecular gradients, and contribution to the structural integrity of the blood-retinal barrier (BRB)[10].

PRs (cones and rods) are situated in the outer retina, where phototransduction occurs. This cascade begins with the excitation of the visual chromophore within the POS by light, initiating a signaling pathway that results in the hyperpolarization of the PR membrane potential. This event leads to changes in synaptic transmission among retinal neurons, which, upon processing and transmission to the brain cortex, generates a visual image 2. Synthesis, shuttling, and recycling of the active form of the visual chromophore are a primary function of the RPE and ensure the light-detection capacity of PRs[10,11]. Phototransduction relies on membrane potential and ion transport that must be extracellularly compensated: the RPE maintains this equilibrium, as demonstrated in studies of light-evoked electrophysiological responses[12]. Furthermore, the RPE synthesizes the pigment melanin, which accumulates in melanosomes. Melanin absorbs light to maintain visual acuity by reducing light reflection and scattering. Melanosomes also quench metal ions and free oxidative radicals[13].

Due to the high physiological activity of PRs, POS are renewed daily through the formation of new disks and transfer of their tips into the RPE, where they will be degraded[10]. Heterophagy, the process by which POS are degraded, involves POS recognition and binding, internalization through phagocytosis, and degradation within lysosomes, underlining all previous steps as key for proper cellular function[3]. Given that RPE cells interact with multiple PRs, heterophagy must be coordinated with other cellular activities, including metabolism and autophagy[10]. Thus, lysosomes are vital for RPE homeostasis and play a central role in POS degradation and in the elimination and recycling of intracellular components through autophagy[3]. The RPE relies on autophagy-mediated degradation of superfluous or damaged intracellular components, thereby acting under normal conditions as a homeostatic process or under stress to mitigate the damage[8]. Upstream autophagic regulators such as mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) sense different triggers and converge on core autophagy machinery activation. Nevertheless, each stimulus gives rise to differential activation of autophagy mediators, diversifying the response and enabling the cell to cope with specific alterations[14].

The RPE is a fundamental component of the BRB, which establishes the necessary gradients for metabolites and oxygen that are actively transported to fuel the PRs. This metabolic interface therefore requires fine-tuned compartmentalization of specific metabolic pathways, which is crucial to sustain cellular homeostasis but also creates cell type-specific vulnerabilities[10]. While PRs and RPE exhibit distinct yet complementary metabolic regulation, both cell types rely on mitochondrial metabolism to maintain their viability[4,15].

2.2 RPE alterations during aging

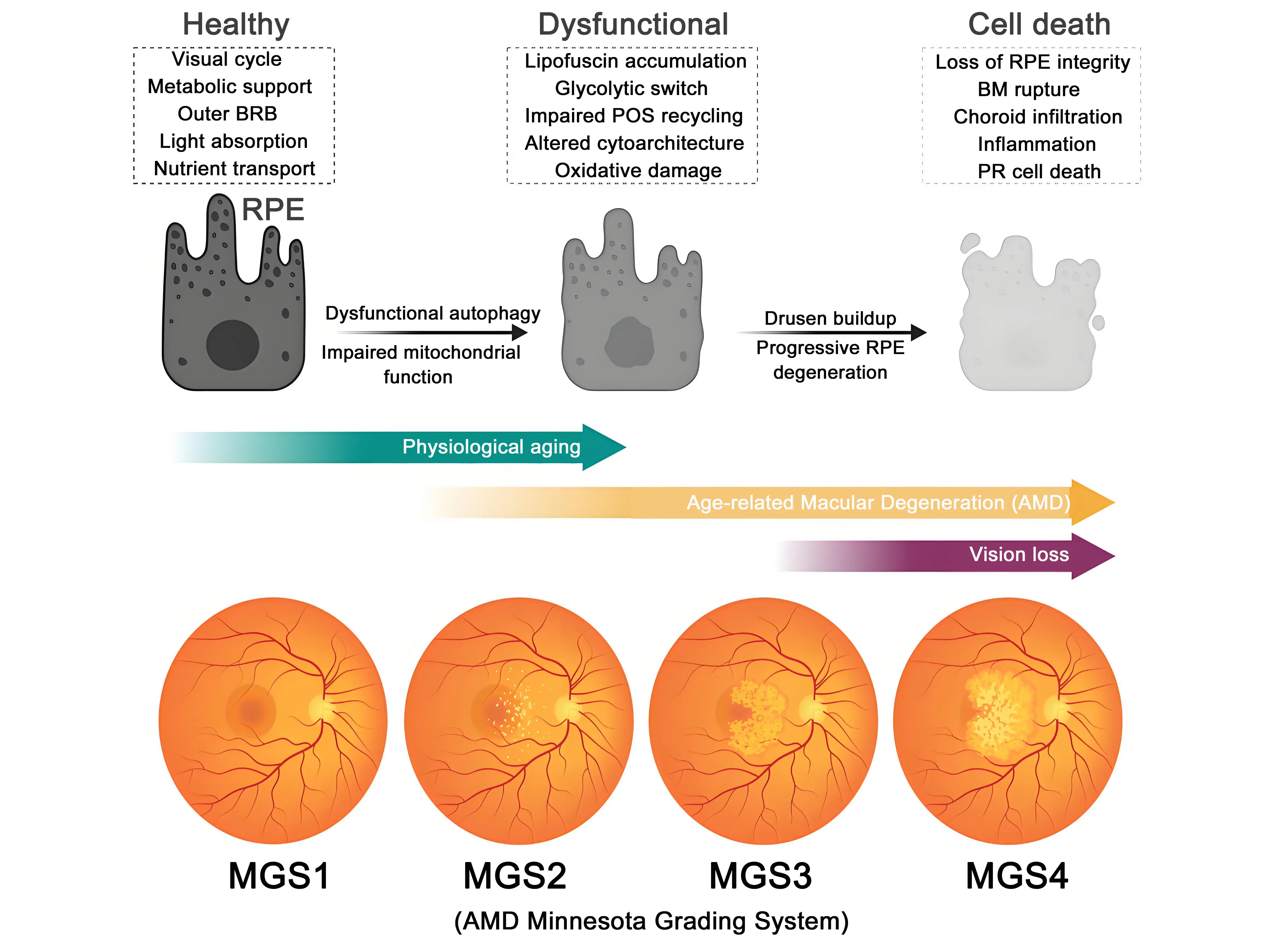

Increased age is associated with functional, cellular, and molecular changes that impact visual processes[16,17]. In both humans and mice, the RPE undergoes age-associated atrophy, characterized by a decrease in cell number alongside an increase in cell area and nuclear count[18,19]. This is accompanied by morphological changes in organelles and dysregulation of signaling pathways, which further impair cell function[20] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Progression of RPE dysfunction and AMD. Healthy RPE provides visual cycle activity, metabolic support, BRB function, light absorption, and nutrient transport. With aging, dysfunctional autophagy and impaired mitochondrial function lead to lipofuscin accumulation, defective phagocytosis of POS, oxidative stress, and progressive RPE degeneration, accompanied by BM rupture and drusen buildup. Advanced dysfunction culminates in RPE cell death, characterized by barrier breakdown, chronic inflammation, and photoreceptor degeneration. The lower panel shows how the disease progresses using the Minnesota Grading System (MGS1–MGS4). Grading is given after performing fundus imaging and histology and ranks severity in terms of drusen buildup, changes in RPE pigmentation, and the presence of geographic atrophy spots. RPE: retinal pigment epithelium; AMD: age-related macular degeneration; BRB: blood retina barrier; POS: photoreceptor outer segments; BM: Bruch’s membrane.

The coordinated phagosome-lysosome axis is fundamental for maintaining RPE homeostasis, a process frequently compromised during aging in the RPE[9,21,22]. In aged mice, the downregulation of genes critical for POS phagocytosis and degradation leads to the accumulation of undigested POS material within RPE lysosomes, forming lipofuscin[23]. These lipofuscin aggregates are primarily composed of various bisretinoids, which are generated following light exposure of the visual chromophore[24]. Increased lipofuscin levels lead to the formation of degradation-resistant solid crystals. Their continued accumulation can cause lysosomal membrane permeabilization and subsequent cell death due to the release of lysosomal proteases into the cytosol[25,26]. Furthermore, lipofuscin accumulation alters the cholesterol composition of late endosomes and lysosomes[27], which in turn increases ceramide levels and impairs autophagosome formation and trafficking. These detrimental effects are observed in both mouse (Abca4 KO) and cellular (A2E) models of RPE lipofuscin accumulation[28]. Additional evidence demonstrates mTOR overactivation in response to RPE lipofuscin accumulation[29], a characteristic also noted in aged human RPE[30]. Moreover, genetic manipulation of mTOR upstream regulators, such as LST8 (knock-in) and TSC1 (knock-out), results in an age-dependent reduction in visual function and photoreceptor degeneration[30]. Recently, Chowdhury et al. demonstrated that mTOR overactivation in the RPE diminishes the expression of autophagy genes and autophagy flux, leading to decreased mitophagy and impaired glucose metabolism and mitochondrial ATP production[31]. Therefore, the proper functioning of the phagosome-lysosome axis in the RPE is critical for maintaining retinal health and preventing age-related pathology.

Physiological aging induces metabolic alterations in the retina and RPE, evidenced by altered levels of metabolites, including nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), which is reduced in aged RPE[32]. These metabolic shifts, coupled with other factors, contribute to mitochondrial defects in the RPE, which can be aggravated by lipofuscin buildup, complement activation, and targeted inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase[33-35]. Indeed, aging is associated with mitochondrial defects in morphology and mass within the RPE[17], a phenomenon attributable to the age-related decline in proteins implicated in mitochondrial transcription and biogenesis, as observed in aged retinas[35]. Consistently, genetic ablation of mitochondrial transcription and biogenesis regulators, such as TFAM and PGC-1, results in loss of RPE cell markers, accumulation of lipofuscin-like deposits, photoreceptor loss, and diminished visual function[36,37]. Moreover, whole-body depletion of autophagy and mitophagy proteins in mice leads to defects in RPE mitochondria, metabolism, and redox balance, thereby rendering the RPE highly vulnerable, akin to the state observed in primary human aged RPE[38-40]. Intriguingly, recent evidence reveals a pathway in which mitophagy is selectively upregulated in the aging retina and RPE to mitigate oxidative stress-associated neuroinflammation[16]. Crucially, pharmacological enhancement of mitophagy in aged animals not only reduces neuroinflammation but also ameliorates age-related functional decline in vision and neurological function[16]. Collectively, these data suggest that age-associated mitochondrial dysfunction in the RPE can be counteracted by enhancing mitochondrial fitness.

3. The Roles of Autophagy and Mitophagy in Retinal Homeostasis

As post-mitotic cells, retinal neurons and the RPE require cellular quality-control mechanisms to maintain homeostasis throughout the individual’s lifespan. Detecting and responding to light stimuli places high energy demands on PRs, resulting in the generation of metabolic intermediates and reactive oxygen species (ROS), which create an oxidative environment that can damage organelles and cell membranes[41]. PRs therefore need robust and redundant strategies to remove metabolic byproducts, misfolded proteins and damaged organelles. This occurs in a cell-autonomous manner, mediated by autophagy[42], or through their release into the extracellular space as extracellular vesicles, where they can be taken up and recycled by Müller glia and the RPE, which act as scavengers, processing waste and subsequently nourishing the retina[43].

Autophagy and mitophagy play essential roles in maintaining retinal homeostasis in both health and disease, an area extensively studied by our group[4,8,9]. The complexity and high-level specialization of the retina can compensate for cell-specific impairments in autophagy and deficiencies in downstream components of the autophagy cascade. Consequently, the main degeneration phenotypes arise when upstream modulators of the autophagy pathways are disrupted in the whole tissue, as demonstrated in different genetic mouse models deficient in autophagy proteins.

The autophagy machinery plays a crucial role in POS degradation through LC3-associated phagocytosis, which is necessary to maintain retinal homeostasis. Dysregulation of this process can lead to debris accumulation and retinal degeneration[10]. This is a feature of both AMD and aging, in which lysosomal damage impairs autophagosome degradation, in turn leading to the extracellular release of autophagosomes via secretory autophagy, contributing to drusen formation[44]. This decline in autophagy leads to the accumulation of damaged organelles such as mitochondria, which impairs lipid metabolism and mitochondrial respiration and makes them less resistant to cellular stress[22]. Indeed, in situations of autophagy disruption due to lysosomal impairment, pharmacological promotion of lysophagy with Urolithin A restores autophagic flux in the RPE, thereby preserving visual function[45].

Recent data indicate that induction of mitophagy in aging retinas reduces mtDNA-cGAS-STING-mediated inflammation, promoting the elimination of damaged mitochondria, which improves visual function, preserves synaptic integrity, and reduces the inflammatory and oxidative stress response[16]. Elimination of damaged mitochondria during aging is driven by the PINK1-Parkin-mediated pathway[16]. Interestingly, during retinal development a peak of PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitophagy is followed by a peak of oxidative stress[46]. In addition, PINK1 deletion causes an increase in ROS that activates a transcriptional program to driving RPE cell dedifferentiation, highlighting the relevance of oxidative stress and mitochondria fitness in the retina[38].

Consistent with these findings, accumulation of autophagosomes and mitophagosomes in PR synaptic terminals, along with swollen mitochondria in the outer segments, has been observed in aged human retinal samples[47]. Underscoring the importance of mitochondrial quality control, a study in zebrafish found that in conditions of stress, cones release damaged mitochondria that are taken up and degraded by the Müller glia in a process called transmitophagy[48].

Studies in two different animal models of IRDs (retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator [RPGR] mutant and phosphodiesterase 6B [Pd6B] mutant) show that degeneration is preceded by an increase in mitochondrial stress and the accumulation of autophagosomes and autolysosomes. PRs increase autophagy to degrade misfolded or mislocalized proteins and damaged mitochondria, but due to incomplete flux, the pathway collapses[49]. These observations are consistent with previous findings showing that lysosomal alterations and blockade of autophagic flux contribute to PR cell death in various retinitis pigmentosa models[50].

4. Dysregulation of Autophagy-Mitophagy in AMD

AMD is characterized by a progressive loss of PRs and deterioration of the macula, affecting visual acuity. It is the most prevalent retinal disease in the elderly population, and population aging has seen the number of affected individuals worldwide double over the past 30 years[51,52]. Epidemiological data indicate that it affects both sexes equally, although prevalence in the 60-64 age group is higher in women, suggesting faster progression or earlier diagnosis[51]. Environmental factors, including smoking and hypertension, and genetic factors, like the CFHY402H and ARMS2A69S polymorphisms, have been linked to a higher AMD incidence, although aging remains the primary contributor to disease development[53]. One of the main challenges in AMD management is the frequently late diagnosis of this disease, which often coincides with the onset of vision loss, at which stage AMD can be further classified as “dry” or “wet”. Wet AMD is characterized by angiogenic events in the choroid that lead to neovascularization, disruption of Bruch’s membrane, RPE displacement, and cell death. Vascular invasion of the neuroretina triggers edema, local inflammation, and eventually PR cell death due to the lack of trophic support from the RPE and the inflammatory microenvironment. Wet AMD accounts for approximately 10% of cases, while dry AMD, the etiology of which remains unclear, accounts for the remaining 90%[51,52]. Progression of dry AMD is characterized by the accumulation of extracellular debris known as drusen (consisting of lipids, oxidized proteins, apolipoproteins, complement components, trace elements, and extracellular vesicles) between the RPE and Bruch’s membrane. Drusen also disrupt the RPE monolayer, causing geographic atrophy (GA) and subsequent cell death of adjacent PRs, including both cones and rods[5].

AMD research has been hindered by a lack of animal models that present an anatomical macula and recapitulate the slow progression of the disease[54]. Donor tissue has thus emerged as a valuable tool to elucidate the cellular alterations in the RPE that lead to AMD[6]. Standardized diagnostic criteria and sample grading are crucial aspects of the use of donor biopsies: the best-known classification is the AMD Minnesota Grading System (MGS), which differentiates between healthy tissue (MGS1) and early (MGS2), intermediate (MGS3), and late (MGS4) AMD[55,56] (Figure 1).

The RPE of AMD donors displays marked accumulation of autophagosomes and abnormal mitochondria, indicative of impaired autophagy and, specifically, mitophagy[57,58]. Cultured human adult RPE cells (haRPE) from donors with AMD show reduced autophagic flux, as evaluated by LC3-II levels in the presence of lysosomal inhibitors[57]. Other features of AMD haRPE include the accumulation of the selective autophagy substrate p62/SQSTM1 and swollen lysosomes, suggesting that defective lysosomal degradation may underlie the observed impairment of autophagy[57]. The sodium iodate (SI) model is another traditionally used pharmacological model (in vitro and in vivo) of selective oxidative stress-driven RPE degeneration[59]. Autophagy is also impaired in this model in vitro[60], and mechanistic studies have shown that inhibiting autophagy further sensitizes human ARPE-19 cells to SI-induced cell death[61], while treatment with the autophagy inducer rapamycin is protective[60,62]. Blockade of autophagy in this model appears to stem from impaired lysosomal function, as evidenced by lipofuscin accumulation, enlarged lysosomes, and impaired degradation of autophagic substrates in SI-treated cells[60]. Indeed, our group recently demonstrated that lysosomal membrane permeabilization is a driver of RPE collapse during SI-induced GA, and that this effect can be counteracted by promoting p62-dependent lysosomal recycling via lysophagy[45].

Mitochondrial dysfunction has also been identified as a driver of the pathophysiological processes underlying AMD. haRPE cells from AMD donors show an increased reliance on glycolysis for ATP production and an increase in lipid droplets, indicating decreases in fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial function[57]. Studies using microplate respirometry of AMD haRPE have validated this decrease in mitochondria-coupled ATP production[63]. Using the mitophagy fluorescent reporter mt-Keima, Fisher et al. demonstrated increased fission upon mitochondrial depolarization in AMD haRPE, as well as increased receptor-mediated mitophagy in response to cobalt chloride[64]. Crucially, treatment with the autophagy inducer rapamycin can restore mitochondrial respiration in AMD haRPE to the levels seen in healthy donors[65]. Interestingly, the RPE of donors with the high-risk CFHY402H variant shows increased mtDNA damage[66] and alterations in the mitochondrial proteome[67]. Induced pluripotent stem cells differentiated into RPE (iPSC-RPE) are a useful tool to study the contribution of high-risk polymorphisms and donor genetic makeup to RPE malfunction[67]. iPSC-RPE from CFHY402H donors display reduced mitochondrial function[67], as well as increased susceptibility to, and an impaired antioxidant response to, cigarette smoke extract[68] and hydroquinone[69]. The impact of the CFHY402H variant on mitophagy and autophagy remains to be determined. We previously reported impaired mitophagy in vitro[70] and in vivo[45] in the SI model of RPE degeneration, leading to the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria and ROS production. However, as previously mentioned, aberrant mitochondria turnover may be a direct consequence of defective lysosomal function. Drugs known to modulate mitophagy, such as rapamycin[60] and A769662[71], have shown protective effects against SI insult in RPE cells, but further research is needed to determine whether this effect is mitophagy-dependent.

5. Therapeutic Modulation of Autophagy-Mitophagy in AMD

Recent therapeutic advances in AMD have revealed considerable potential for the treatment of both wet (neovascular) and dry (GA) forms. For wet AMD, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents such as aflibercept (Eylea), ranibizumab, and brolucizumab remain the standard of care, effectively reducing neovascularization and fluid leakage by targeting VEGF pathways[72]. Investigational therapies include gene therapy approaches—currently in clinical trials—that seek durable VEGF suppression from a single administration, as well as tyrosine kinase inhibitors and combination therapies to enhance efficacy in refractory cases[73].

Treatments for dry AMD include recently FDA-approved therapies that target the complement system: pegcetacoplan (Syfovre) inhibits C3, while avacincaptad pegol (Izervay) targets C5, and both molecules slow GA progression without reversing existing atrophy. Emerging therapeutic strategies for dry AMD include complement inhibition by gene therapy (e.g., KRIYA-825, currently in Phase 1/2 trials for a single suprachoroidal injection) and RPE stem cell replacement strategies that have shown promise in small patient cohorts[74].

Pharmacological activation of autophagy has emerged as a promising therapeutic approach across diverse diseases, including neurodegeneration, cancer, and metabolic disorders[75]. Among the most established autophagy inducers are rapalogs—mTORC1 inhibitors such as rapamycin, everolimus, and temsirolimus—which promote autophagy by relieving mTOR-mediated suppression. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that rapamycin reduces β-amyloid accumulation and improves cognitive function in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease[75]. Rapamycin has also shown protective effects in the SI mouse model of RPE degeneration, preserving retinal structure, reducing apoptosis, and mitigating oxidative stress and inflammation[62]. Although rapalogs are FDA-approved for other indications, direct evidence based on autophagy measurements in human tissues remains limited[76].

AMPK is a cellular energy sensor that promotes autophagy by inhibiting mTORC1 and directly phosphorylating autophagy-initiating proteins[77]. Metformin is the most widely used AMPK activator. Metformin and other AMPK activators induce autophagy in various cell types and tissues[78]. Metformin is also extensively used in diabetes; indirect evidence suggests it may modulate autophagy in humans, although direct evidence is lacking[79]. AMPK activation declines with age, and its deletion accelerates retinal aging and PR degeneration, underscoring its importance in the pathogenesis of AMD[80]. Preclinical studies investigating AMPK modulation in AMD models are limited, but stimulation of its activity using metformin has been suggested to preserve retinal integrity and function by stimulating mitochondrial biogenesis in photoreceptor degeneration models, such as light-induced damage and Rd10, as well as in the selective RPE impairment model of SI[81]. Evidence from human studies (primarily retrospective cohort and case-control studies) suggests that metformin use may be associated with a reduced risk of developing AMD[82]. A meta-analysis of five retrospective studies found a trend toward lower AMD risk in metformin users, with one large Taiwanese cohort showing a substantial risk reduction, although statistical significance was not reached in the overall meta-analysis[82]. Prospective clinical trials are underway, but no results have yet been reported. Evidence of metformin’s beneficial effect in AMD is thus suggestive, but not definitive.

Increasing age leads to a drop in the levels of specific metabolites such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), which has a crucial role in sustaining cellular metabolism, autophagy, and signaling cascades that are activated in response to stress[83]. While decreasing NAD+ levels results in photoreceptor degeneration, supplementation with a NAD+ precursor rescues visual function in a mouse model of degeneration[84]. Replenishing NAD+ levels is being evaluated in clinical trials for neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer Disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Multiple Sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease[85]. NAD+ supplementation restores mitochondrial quality control and mitophagy and attenuates AMD-related features in both animal models and human iPSC-derived RPE cells from AMD donors[86]. NAD+ has also been shown to reduce drusen formation and complement-driven inflammation, as well as correct mitochondrial dysfunction and modulate VEGF expression in these models[86]. In RPE cells, nicotinamide, a precursor of NAD+, also suppresses pathological signaling pathways that are implicated in AMD and prevents epithelial–mesenchymal transition, another process involved in AMD progression[86]. While these findings point to potential therapeutic applications of NAD+ supplementation, no corresponding clinical evidence in AMD patients has been reported to date.

Urolithin A (UA) supplementation has shown protective effects in human aging studies, improving mitochondrial health, muscle function, and biomarkers of cellular fitness in older adults and elderly populations[87]. UA has demonstrated therapeutic potential, with studies in human muscle samples suggesting that its mechanism involves increased mitophagy and reduced inflammation[88]. In the context of AMD, recent mechanistic investigations provide compelling evidence for UA’s neuroprotective role. Specifically, UA restores autophagic flux and promotes the selective clearance of damaged lysosomes (lysophagy) via a p62/SQSTM1-dependent mechanism in AMD models[45]. In murine and ex vivo models of SI-induced AMD, UA treatment ameliorated neurodegeneration, preserved visual function, reduced oxidative damage, and prevented photoreceptor (PR) cell death by sustaining proteostasis and supporting RPE survival[45]. Furthermore, UA can modulate Ca2+ transfer between organelles, specifically from the endoplasmic reticulum to mitochondria and lysosomes, thereby regulating mitophagy activity[89]. It would be pertinent to investigate whether UA’s positive effects in the SI model are linked to calcium regulation across cellular organelles and how this might influence mtDNA release into the cytosol and subsequent cell death[90]. Collectively, these findings strongly support the therapeutic potential of UA in AMD, aging, and other age-related diseases.

Nutritional intervention with the AREDS2 supplement (lutein, zeaxanthin, vitamins C/E, zinc, and copper) remains a widely recommended preventive measure for intermediate AMD. As clinical trials continue to progress, the therapeutic landscape is shifting toward longer-lasting interventions and more precise targeting of the mechanisms underlying AMD[91,92].

6. Conclusion, Future Direction, and Open Questions

While recent advances in AMD therapy reflect important progress in this field, therapeutic options for both wet and dry forms of the disease remain limited. Anti-VEGF agents and complement inhibitors have transformed disease management, but they primarily slow progression. Emerging strategies highlight novel avenues to preserve retinal function and include approaches targeting autophagy, mitochondrial quality control, and cellular metabolism. Meanwhile, promising data obtained with rapalogs, AMPK activators, NAD+ boosters, and urolithin A underscore the therapeutic potential of modulating proteostasis and energy homeostasis in the RPE.

A critical future step will be to translate promising preclinical findings into rigorously designed clinical trials, with standardized biomarkers to directly measure autophagy and mitochondrial function in patients. Combining autophagy-targeting therapies with gene therapy or regenerative approaches, such as RPE stem-cell replacement, may offer synergistic benefits. Furthermore, personalized interventions guided by the patient’s genetic risk, metabolic status, and lifestyle factors could ultimately shift AMD treatment from damage control to true disease modification.

Authors contribution

Noorbergen IJ: Writing–original draft, writing– review & editing, conceptualization.

Jimenez-Garcia C, Jimenez-Loygorri JI: Writing –original draft, conceptualization.

Boya P: Writing–original draft, writing–review & editing, conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision.

Conflicts of interest

Patricia Boya is an Editorial Board Member of Geromedicine. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable,

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

Research in the P.B. lab is supported by grants 310030_215271 Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF)

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Liang Q, Cheng X, Wang J, Owen L, Shakoor A, Lillvis JL, et al. A multi-omics atlas of the human retina at single-cell resolution. Cell Genom. 2023;3(6):100298.[DOI]

-

2. Grossniklaus HE, Geisert EE, Nickerson JM. Introduction to the retina. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2015;134:383-396.[DOI]

-

3. Boya P, Kaarniranta K, Handa JT, Sinha D. Lysosomes in retinal health and disease. Trends Neurosci. 2023;46(12):1067-1082.[DOI]

-

4. Jiménez-Loygorri JI, Benítez-Fernández R, Viedma-Poyatos Á, Zapata-Muñoz J, Villarejo-Zori B, Gómez-Sintes R, et al. Mitophagy in the retina: Viewing mitochondrial homeostasis through a new lens. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2023;96:101205.[DOI]

-

5. Deng Y, Qiao L, Du M, Qu C, Wan L, Li J, et al. Age-related macular degeneration: Epidemiology, genetics, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and targeted therapy. Genes Dis. 2022;9(1):62-79.[DOI]

-

6. Fisher CR, Ferrington DA. Perspective on amd pathobiology: A bioenergetic crisis in the RPE. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(4):AMD41-AMD47.[DOI]

-

7. Kaarniranta K, Blasiak J, Liton P, Boulton M, Klionsky DJ, Sinha D. Autophagy in age-related macular degeneration. Autophagy. 2023;19(2):388-400.[DOI]

-

8. Boya P, Esteban-Martínez L, Serrano-Puebla A, Gómez-Sintes R, Villarejo-Zori B. Autophagy in the eye: Development, degeneration, and aging. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2016;55:206-245.[DOI]

-

9. Villarejo-Zori B, Jiménez-Loygorri JI, Zapata-Muñoz J, Bell K, Boya P. New insights into the role of autophagy in retinal and eye diseases. Mol Aspects Med. 2021;82:101038.[DOI]

-

10. akkaraju A, Umapathy A, Tan LX, Daniele L, Philp NJ, Boesze-Battaglia K, et al. The cell biology of the retinal pigment epithelium. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2020;78:100846.[DOI]

-

11. Strauss O. The retinal pigment epithelium in visual function. Physiol Rev. 2005;85(3):845-881.[DOI]

-

12. Wu J, Peachey NS, Marmorstein AD. Light-evoked responses of the mouse retinal pigment epithelium. J Neurophysiol. 2004;91(3):1134-1142.[DOI]

-

13. Kaufmann M, Han Z. RPE melanin and its influence on the progression of AMD. Ageing Res Rev. 2024;99:102358.[DOI]

-

14. Boya P, Reggiori F, Codogno P. Emerging regulation and functions of autophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(7):713-720.[DOI]

-

15. Hurley JB. Retina Metabolism and Metabolism in the Pigmented Epithelium: A Busy Intersection. Annu Rev Vis Sci. 2021;7:665-692.[DOI]

-

16. Jiménez-Loygorri JI, Villarejo-Zori B, Viedma-Poyatos Á, Zapata-Muñoz J, Benítez-Fernández R, Frutos-Lisón MD, et al. Mitophagy curtails cytosolic mtDNA-dependent activation of cGAS/STING inflammation during aging. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):830.[DOI]

-

17. Yako T, Nakamura M, Otsu W, Nakamura S, Shimazawa M, Hara H. Mitochondria dynamics in the aged mice eye and the role in the RPE phagocytosis. Exp Eye Res. 2021;213:108800.[DOI]

-

18. Gao H, Hollyfield JG. Aging of the human retina. Differential loss of neurons and retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33(1):1-17.[PubMed]

-

19. Chen M, Rajapakse D, Fraczek M, Luo C, Forrester JV, Xu H. Retinal pigment epithelial cell multinucleation in the aging eye–a mechanism to repair damage and maintain homoeostasis. Aging Cell. 2016;15(3):436-445.[DOI]

-

20. Tong Y, Zhang Z, Wang S. Role of mitochondria in retinal pigment epithelial aging and degeneration. Front Aging. 2022;3:926627.[DOI]

-

21. Rodríguez-Muela N, Koga H, García-Ledo L, de la Villa P, de la Rosa EJ, Cuervo AM, et al. Balance between autophagic pathways preserves retinal homeostasis. Aging Cell. 2013;12(3):478-488.[DOI]

-

22. Cox K, Shi G, Read N, Patel MT, Ou K, Liu Z, et al. Age-associated decline in autophagy pathways in the retinal pigment epithelium and protective effects of topical trehalose in light-induced outer retinal degeneration in mice. Aging Cell. 2025;24(7):e70081.[DOI]

-

23. Ma JYW, Greferath U, Wong JHC, Fothergill LJ, Jobling AI, Vessey KA, et al. Aging induces cell loss and a decline in phagosome processing in the mouse retinal pigment epithelium. Neurobiol Aging. 2023;128:1-16.[DOI]

-

24. Sparrow JR, Gregory-Roberts E, Yamamoto K, Blonska A, Ghosh SK, Ueda K, et al. The bisretinoids of retinal pigment epithelium. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012;31(2):121-135.[DOI]

-

25. Wang F, Gomez-Sintes R, Boya P. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization and cell death. Traffic. 2018;19(12):918-931.[DOI]

-

26. Pan C, Banerjee K, Lehmann GL, Almeida D, Hajjar KA, Benedicto I, et al. Lipofuscin causes atypical necroptosis through lysosomal membrane permeabilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2021;118(47):e2100122118.[DOI]

-

27. Lakkaraju A, Finnemann SC, Rodriguez-Boulan E. The lipofuscin fluorophore A2E perturbs cholesterol metabolism in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2007;104(26):11026-11031.[DOI]

-

28. Toops KA, Tan LX, Jiang Z, Radu RA, Lakkaraju A. Cholesterol-mediated activation of acid sphingomyelinase disrupts autophagy in the retinal pigment epithelium. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26(1):1-14.[DOI]

-

29. Kaur G, Tan LX, Rathnasamy G, La Cunza N, Germer CJ, Toops KA, et al. Aberrant early endosome biogenesis mediates complement activation in the retinal pigment epithelium in models of macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2018;115(36):9014-9019.[DOI]

-

30. Huang J, Gu S, Chen M, Zhang SJ, Jiang Z, Chen X, et al. Abnormal mTORC1 signaling leads to retinal pigment epithelium degeneration. Theranostics. 2019;9(4):1170-1180.[DOI]

-

31. Chowdhury O, Bammidi S, Gautam P, Babu VS, Liu H, Shang P, et al. Activated mTOR signaling in the RPE drives EMT, autophagy, and metabolic disruption, resulting in AMD-like pathology in mice. Aging Cell. 2025;24(6):e70018.[DOI]

-

32. Wang Y, Grenell A, Zhong F, Yam M, Hauer A, Gregor E, et al. Metabolic signature of the aging eye in mice. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;71:223-233.[DOI]

-

33. Shaban H, Gazzotti P, Richter C. Cytochrome c oxidase inhibition by N-retinyl-N-retinylidene ethanolamine, a compound suspected to cause age-related macula degeneration. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;394(1):111-116.[DOI]

-

34. Vives-Bauza C, Anand M, Shirazi AK, Magrane J, Gao J, Vollmer-Snarr HR, et al. The age lipid A2E and mitochondrial dysfunction synergistically impair phagocytosis by retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(36):24770-24780.[DOI]

-

35. Ramírez-Pardo I, Villarejo-Zori B, Jiménez-Loygorri JI, Sierra-Filardi E, Alonso-Gil S, Mariño G, et al. Ambra1 haploinsufficiency in CD1 mice results in metabolic alterations and exacerbates age-associated retinal degeneration. Autophagy. 2023;19(3):784-804.[DOI]

-

36. Zhao C, Yasumura D, Li X, Matthes M, Lloyd M, Nielsen G, et al. mTOR-mediated dedifferentiation of the retinal pigment epithelium initiates photoreceptor degeneration in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(1):369-83.[DOI]

-

37. Rosales MAB, Shu DY, Iacovelli J, Saint-Geniez M. Loss of PGC-1α in RPE induces mesenchymal transition and promotes retinal degeneration. Life Sci Alliance. 2019;2(3):e201900436.[DOI]

-

38. Datta S, Cano M, Satyanarayana G, Liu T, Wang L, Wang J, et al. Mitophagy initiates retrograde mitochondrial-nuclear signaling to guide retinal pigment cell heterogeneity. Autophagy. 2023;19(3):966-983.[DOI]

-

39. Ramírez-Pardo I, Villarejo-Zori B, Jiménez-Loygorri JI, Sierra-Filardi E, Alonso-Gil S, Mariño G, et al. Ambra1 haploinsufficiency in CD1 mice results in metabolic alterations and exacerbates age-associated retinal degeneration. Autophagy. 2023;19(3):784-804.[DOI]

-

40. Rohrer B, Bandyopadhyay M, Beeson C. Reduced metabolic capacity in aged primary retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is correlated with increased susceptibility to oxidative stress. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;854:793-798.[DOI]

-

41. Chen Y, Zizmare L, Calbiague V, Wang L, Yu S, Herberg FW, et al. Retinal metabolism displays evidence for uncoupling of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation via Cori-, Cahill-, and mini-Krebs-cycle. Elife. 2024;12:RP91141.[DOI]

-

42. Liton PB. The autophagic lysosomal system in outflow pathway physiology and pathophysiology. Exp Eye Res. 2016;144:29-37.[DOI]

-

43. Spencer WJ. Extracellular vesicles highlight many cases of photoreceptor degeneration. Front Mol Neurosci. 2023;16:1182573.[DOI]

-

44. Ghosh S, Sharma R, Bammidi S, Koontz V, Nemani M, Yazdankhah M, et al. The AKT2/SIRT5/TFEB pathway as a potential therapeutic target in non-neovascular AMD. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):6150.[DOI]

-

45. Jimenez-Loygorri JI, Viedma-Poyatos A, Gomez-Sintes R, Boya P. Urolithin A promotes p62-dependent lysophagy to prevent acute retinal neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener. 2024;19(1):49.[DOI]

-

46. Zapata-Muñoz J, Jiménez-Loygorri JI, Stumpe M, Villarejo-Zori B, Alonso-Gil S, Terešak P, et al. The developing retina undergoes mitochondrial remodeling via PINK1/PRKN-dependent mitophagy. J Mol Biol. 2025;437(18):169263.[DOI]

-

47. Nag TC. Accumulation of autophagosomes in aging human photoreceptor cell synapses. Exp Eye Res. 2025;251:110240.[DOI]

-

48. Hutto RA, Rutter KM, Giarmarco MM, Parker ED, Chambers ZS, Brockerhoff SE. Cone photoreceptors transfer damaged mitochondria to Muller glia. Cell Rep. 2023;42(2)[DOI]

-

49. Newton F, Halachev M, Nguyen L, McKie L, Mill P, Megaw R. Autophagy disruption and mitochondrial stress precede photoreceptor necroptosis in multiple mouse models of inherited retinal disorders. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):4024.[DOI]

-

50. Rodríguez-Muela N, Hernández-Pinto AM, Serrano-Puebla A, García-Ledo L, Latorre SH, de la Rosa EJ, et al. Lysosomal membrane permeabilization and autophagy blockade contribute to photoreceptor cell death in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(3):476-487.[DOI]

-

51. Davari A, Piroozkhah M, Iranpour A, Nejadghaderi SA. The burden of age-related macular degeneration and its socioeconomic associates in the Eastern Mediterranean Region from 1990 to 2021. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):21950.[DOI]

-

52. Wong WL, Su X, Li X, Cheung CMG, Klein R, Cheng CY, et al. Global prevalence of age-related macular degeneration and disease burden projection for 2020 and 2040: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(2):e106-e116.[DOI]

-

53. Landowski M, Kelly U, Klingeborn M, Groelle M, Ding JD, Grigsby D, et al. Human complement factor H Y402H polymorphism causes an age-related macular degeneration phenotype and lipoprotein dysregulation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2019;116(9):3703-3711.[DOI]

-

54. Soundara Pandi SP, Ratnayaka JA, Lotery AJ, Teeling JL. Progress in developing rodent models of age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Exp Eye Res. 2021;203:108404.[DOI]

-

55. Olsen TW, Feng X. The Minnesota Grading System of eye bank eyes for age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(12):4484-4490.[DOI]

-

56. Olsen TW, Liao A, Robinson HS, Palejwala NV, Sprehe N. The nine-step Minnesota grading system for eyebank eyes with age related macular degeneration: A systematic approach to study disease stages. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(12):5497-5506.[DOI]

-

57. Golestaneh N, Chu Y, Xiao YY, Stoleru GL, Theos AC. Dysfunctional autophagy in RPE, a contributing factor in age-related macular degeneration. Cell Death Dis. 2018;8(1):e2537.[DOI]

-

58. Mitter SK, Song C, Qi X, Mao H, Rao H, Akin D, et al. Dysregulated autophagy in the RPE is associated with increased susceptibility to oxidative stress and AMD. Autophagy. 2014;10(11):1989-2005.[DOI]

-

59. Upadhyay M, Bonilha VL. Regulated cell death pathways in the sodium iodate model: Insights and implications for AMD. Exp Eye Res. 2024;238:109728.[DOI]

-

60. Lin YC, Horng LY, Sung HC, Wu RT. Sodium iodate disrupted the mitochondrial-lysosomal axis in cultured retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2018;34(7):500-511.[DOI]

-

61. Chan CM, Huang DY, Sekar P, Hsu SH, Lin WW. Reactive oxygen species-dependent mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy confer protective effects in retinal pigment epithelial cells against sodium iodate-induced cell death. J Biomed Sci. 2019;26(1):40.[DOI]

-

62. Niu Z, Shi Y, Li J, Qiao S, Du S, Chen L, et al. Protective effect of rapamycin in models of retinal degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2021;210:108700.[DOI]

-

63. Ferrington DA, Ebeling MC, Kapphahn RJ, Terluk MR, Fisher CR, Polanco JR, et al. Altered bioenergetics and enhanced resistance to oxidative stress in human retinal pigment epithelial cells from donors with age-related macular degeneration. Redox biology. 2017;13:255-265.[DOI]

-

64. Fisher CR, Shaaeli AA, Ebeling MC, Montezuma SR, Ferrington DA. Investigating mitochondrial fission, fusion, and autophagy in retinal pigment epithelium from donors with age-related macular degeneration. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):21725.[DOI]

-

65. Ebeling MC, Polanco JR, Qu J, Tu C, Montezuma SR, Ferrington DA. Improving retinal mitochondrial function as a treatment for age-related macular degeneration. Redox Biol. 2020;34:101552.[DOI]

-

66. Ferrington DA, Kapphahn RJ, Leary MM, Atilano SR, Terluk MR, Karunadharma P, et al. Increased retinal mtDNA damage in the CFH variant associated with age-related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2016;145:269-277.[DOI]

-

67. Shen S, Kapphahn RJ, Zhang M, Qian S, Montezuma SR, Shang P, et al. Quantitative proteomics of human retinal pigment epithelium reveals key regulators for the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):3252.[DOI]

-

68. Shang P, Ambrosino H, Hoang J, Geng Z, Zhu X, Shen S, et al. The Complement Factor H (Y402H) risk polymorphism for age-related macular degeneration affects metabolism and response to oxidative stress in the retinal pigment epithelium. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;225:833-845.[DOI]

-

69. Armento A, Sonntag I, Almansa-Garcia AC, Sen M, Bolz S, Arango-Gonzalez B, et al. The AMD-associated genetic polymorphism CFH Y402H confers vulnerability to Hydroquinone-induced stress in iPSC-RPE cells. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1527018.[DOI]

-

70. Jiménez-Loygorri JI, Jiménez-García C, Viedma-Poyatos Á, Boya P. Fast and quantitative mitophagy assessment by flow cytometry using the mito-QC reporter. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024;12:1460061.[DOI]

-

71. Chan CM, Sekar P, Huang DY, Hsu SH, Lin WW. Different effects of metformin and A769662 on sodium iodate-induced cytotoxicity in retinal pigment epithelial cells: Distinct actions on mitochondrial fission and respiration. Antioxidants. 2020;9(11):1057.[DOI]

-

72. Kumar A, Ferro Desideri L, Ting MYL, Anguita R. Perspectives on the currently available pharmacotherapy for wet macular degeneration. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2024;25(6):755-767.[DOI]

-

73. Cheung CMG. Age-related macular degeneration in 2025- opportunities and challenges. Eye. 2025;39(7):1231-1232.[DOI]

-

74. Wheeler S, Mahmoudzadeh R, Randolph J. Treatment for dry age-related macular degeneration: where we stand in 2024. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2024;35(5):359-364.[DOI]

-

75. Galluzzi L, Bravo-San Pedro JM, Levine B, Green DR, Kroemer G. Pharmacological modulation of autophagy: therapeutic potential and persisting obstacles. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(7):487-511.[DOI]

-

76. Sargeant TJ, Bensalem J. Human autophagy measurement: An underappreciated barrier to translation. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27(12):1091-1094.[DOI]

-

77. Jang M, Park R, Kim H, Namkoong S, Jo D, Huh YH, et al. AMPK contributes to autophagosome maturation and lysosomal fusion. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):12637.[DOI]

-

78. Kruczkowska W, Gałęziewska J, Buczek P, Płuciennik E, Kciuk M, Śliwińska A. Overview of metformin and neurodegeneration: A comprehensive review. Pharmaceuticals. 2025;18(4):486.[DOI]

-

79. Bharath LP, Agrawal M, McCambridge G, Nicholas DA, Hasturk H, Liu J, et al. Metformin enhances autophagy and normalizes mitochondrial function to alleviate aging-associated inflammation. Cell Metab. 2020;32(1):44-55.[DOI]

-

80. Dieguez HH, Romeo HE, Alaimo A, Bernal Aguirre NA, Calanni JS, Adán Aréan JS, et al. Mitochondrial quality control in non-exudative age-related macular degeneration: From molecular mechanisms to structural and functional recovery. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;219:17-30.[DOI]

-

81. Xu L, Kong L, Wang J, Ash JD. Stimulation of AMPK prevents degeneration of photoreceptors and the retinal pigment epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2018;115(41):10475-10480.[DOI]

-

82. Romdhoniyyah DF, Harding SP, Cheyne CP, Beare NAV. Metformin, a potential role in age-related macular degeneration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmol Ther. 2021;10(2):245-260.[DOI]

-

83. Jadeja RN, Thounaojam MC, Bartoli M, Martin PM. Implications of NAD+ metabolism in the aging retina and retinal degeneration. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020(1):2692794.[DOI]

-

84. Lin JB, Kubota S, Ban N, Yoshida M, Santeford A, Sene A, et al. NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis is essential for vision in mice. Cell Rep. 2016;17(1):69-85.[DOI]

-

85. Zhang J, Wang H-L, Lautrup S, Nilsen HL, Treebak JT, Watne LO, et al. Emerging strategies, applications and challenges of targeting NAD+ in the clinic. Nat Aging. 2025;5(9):1704-1731.[DOI]

-

86. Cimaglia G, Votruba M, Morgan JE, André H, Williams PA. Potential therapeutic benefit of NAD+ supplementation for glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration. Nutrients. 2020;12(9):2871.[DOI]

-

87. D’Amico D, Andreux PA, Valdés P, Singh A, Rinsch C, Auwerx J. Impact of the natural compound urolithin a on health, disease, and aging. Trends Mol Med. 2021;27(7):687-699.[DOI]

-

88. Singh A, D’Amico D, Andreux PA, Fouassier AM, Blanco-Bose W, Evans M, et al. Urolithin A improves muscle strength, exercise performance, and biomarkers of mitochondrial health in a randomized trial in middle-aged adults. Cell Rep Med. 2022;3(5):100633.[DOI]

-

89. Roussos A, Kitopoulou K, Borbolis F, Ploumi C, Gianniou DD, Li Z, et al. Urolithin Α modulates inter-organellar communication via calcium-dependent mitophagy to promote healthy ageing. Autophagy. 2025;21(12):3097-3122.[DOI]

-

90. Zhang A, Wei TT, Yin H, Tan CY, Han C, Yao Y, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling prompts ZBP1-mediated RPE cell PANoptosis in age-related macular degeneration. Commun Biol. 2025;8(1):1118.[DOI]

-

91. Saigal K, Salama JE, Pardo AA, Lopez SE, Gregori NZ. Modifiable lifestyle risk factors and strategies for slowing the progression of age-related macular degeneration. Vision. 2025;9(1):16.[DOI]

-

92. Li X, Zhao L, Zhang B, Wang S. Berries and their active compounds in prevention of age-related macular degeneration. Antioxidants. 2024;13(12):1558.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite