Abstract

The decline in brown adipose tissue (BAT) activity is a hallmark of aging and is believed to contribute significantly to the loss of cold tolerance and the increased propensity for obesity with age. Paradoxically, unlike in many other tissues and organs, available evidence suggests that macroautophagy increases in BAT with aging. This aligns with observations of a negative correlation between thermogenic activity and macroautophagy in response to environmental factors such as ambient temperature, with evidence showing that macroautophagy is suppressed in thermogenically active BAT under cold conditions, and conversely, increased in warmer environments. Moreover, the activation of macroautophagy, particularly mitophagy, has been shown to be essential for the “whitening” process, whereby brown or beige adipose tissue loses its thermogenic phenotype and adopts characteristics of energy-storing white adipose tissue. In contrast, recent findings suggest that chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) is directly associated with BAT thermogenesis. In male mice, CMA tends to decline with age in BAT, and pharmacological activation of CMA can restore thermogenic activity. This may be due to a specific role of CMA in degrading thermogenesis-inhibiting factors that accumulate in aging BAT because of diminished CMA activity. Given the critical role of BAT in metabolic health, especially during aging, autophagic processes, and their potential druggability, emerge as a promising strategy to preserve thermogenic capacity and improve metabolic health in the elderly.

Keywords

1. Introduction

The thermogenic capacity of adipose tissues refers to the ability of fat depots to show an energy-expending phenotype rather than an energy-storing phenotype. This is currently known to be a crucial factor in protecting against multiple cardiometabolic diseases, the prevalence of which increases with aging. Traditionally, adipose tissue was viewed primarily as a passive energy reservoir, but we currently know that it is a highly adaptive organ capable of regulating systemic metabolism.

White, brown, and beige adipocytes display distinct metabolic programs that reflect their specialized physiological functions. White adipocytes present in white adipose tissue (WAT) are primarily dedicated to energy storage and exhibit low mitochondrial content, limited fatty acid oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation, the absence of uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) expression, and a metabolic bias toward insulin-dependent glucose uptake and de novo lipogenesis, supporting triglyceride accumulation and endocrine adipokine secretion. In contrast, brown adipocytes present in brown adipose tissue (BAT) are optimized for energy dissipation through adaptive thermogenesis, characterized by very high mitochondrial density, elevated fatty acid oxidation, strong tricarboxylic acid cycle and electron transport chain flux, and constitutive UCP1 expression that uncouples respiration from ATP synthesis; these cells are highly responsive to sympathetic stimulation and secrete distinct batokines that contribute to systemic metabolic regulation[1]. Beige adipocytes represent a metabolically plastic population that resembles white adipocytes under basal conditions but, upon cold exposure or adrenergic activation, increase mitochondrial biogenesis, induce UCP1, enhance glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation, and acquire a brown-like thermogenic phenotype[2].

Importantly, the thermogenic activity of adipose tissues is a finely regulated biological process. External stimuli such as cold exposure, certain dietary components, and pharmacologic agents (e.g., β-adrenergic agonists, PPARγ activators) can activate BAT and promote the browning of WAT, enhance mitochondrial function, and reduce ectopic fat deposition[3-5], all of which are critical for maintaining cardiovascular and metabolic health. Moreover, the secretion of brown adipokines (the so-called batokines) from thermogenically active BAT and beige adipose depots has systemic anti-inflammatory and insulin-sensitizing effects[6].

As will be discussed below, there is evidence that BAT activity and the browning capacity of WAT decline with aging. Considering the increased prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases with aging, preserving or enhancing thermogenic activity in adipose tissues represents a promising therapeutic strategy. Given the powerful association between BAT activity and cardiometabolic protection found in extensive cohort studies[7], promoting thermogenic adipose tissue activity can potentially mitigate the risks of metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, and cardiac dysfunction. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the age-dependent decline in thermogenic adipose tissues, its impact on aging-related health issues, and how this decline might be reversed remains a key challenge in aging research.

2. Alterations of Brown and Beige Adipose Tissue Adipose Tissues in Aging

The progressive decline in BAT levels with aging is a common observation across all mammals, although it manifests differently depending on the species. In small mammals, despite evidence of a gradual decrease in BAT with age, significant levels are maintained throughout the entire lifespan. In contrast, larger mammals such as cows or ovine species experience a sharp reduction in both the quantity and activity of BAT shortly after birth, rendering it virtually undetectable in aged adults[1].

However, the case of humans is particularly notable, as it highlights the potential metabolic implications of BAT decline with aging. Historically, it was believed that BAT in humans was present and active only during the neonatal and early childhood stages, disappearing almost entirely in adulthood[8]. Nonetheless, decades ago, Heaton conducted a systematic histological study of human autopsies across various ages and found that, although BAT nearly disappeared from certain anatomical regions, such as the interscapular area, by adulthood, it persisted in other locations, including the neck and areas surrounding certain blood vessels, even into the seventh decade of life[9]. These findings have been confirmed by studies using positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) scans, the current “gold-standard” for the measurement of BAT activity in humans[10], which have demonstrated the presence of metabolically active BAT in adults, as well as its age-related decline[11].

BAT loss appears to plateau around the sixth decade of life and decreases further in advanced age, as active BAT is rarely detected in individuals over sixty[12-14]. This reduction likely contributes to diminished cold tolerance and impaired thermoregulation commonly observed in the elderly. There are also indications that BAT decline with aging is more pronounced in men than in women[15].

Similarly, the prevailing consensus regarding beige adipocytes is that aging leads to a progressive shift toward a prevalent white adipocyte phenotype in WAT depots, hindering the browning process in both aged mice and older humans. As a result, many, if not all, forms of adipose tissue may gradually transition toward a WAT phenotype with age[16].

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the age-related regression in BAT activity. These include reductions in sympathetic nerve output and mitochondrial function, altered expression of key regulatory proteins, diminished function of brown adipogenic progenitors, and age-associated changes in endocrine signaling and the secretion profile of batokines.

The sympathetic nervous system is the primary regulator of both BAT activity and its recruitment in response to thermogenic stimuli, as well as the main inducer of WAT browning. Noradrenergic signaling via β-adrenergic receptor stimulation induces both the activation of existing brown adipocytes and the proliferation and differentiation of precursor cells to increase BAT mass. β3 receptor-adrenergic signaling prevails in BAT stimulation in rodents[1], whereas there are indications of a major role of the β1 and β2 adrenergic pathways in human thermogenic activation of BAT[17,18].

In rodent models, some data suggest that under basal conditions, sympathetic tone to BAT is not significantly altered with aging[19]. However, the capacity of cold exposure and norepinephrine to activate BAT is impaired[20], suggesting that reduced responsiveness to activation rather than diminished sympathetic tone is responsible for the age-related decline in BAT function. This is supported by reports showing reduced β-adrenergic receptor expression in BAT with aging[21]. In humans, there is also evidence that cold-induced BAT activity is diminished in aged individuals[22,23]. In this case, additional data indicate that sympathetic nerve activity is significantly reduced in elderly men[24], emphasizing the role of reduced sympathetic activation in the age-related decline of BAT function.

Non-sympathetic regulators of BAT activity may also contribute to the decline of BAT during aging. For instance, although levels of fibroblast growth factor-21 (FGF21), a hormonal factor known to activate BAT and promote the browning of WAT, increase with age in humans[25], a state of FGF21 resistance similar to that occurring in obesity and involving BAT, but not WAT, has been hypothesized to develop in aged individuals[26]. Thyroid hormones are also well-established regulators of BAT activity, acting both through indirect central mechanisms and directly within BAT by promoting the transcription of UCP1 and other genes involved in the thermogenic program[27]. Aging is associated with a decline in circulating thyroid hormone levels and a reduced conversion of thyroxine (T4) to its active form, triiodothyronine (T3), partly due to an age-related reduction in the expression of the deiodinase 2 enzyme in adipose tissues[28].

On the other hand, the maintenance of active brown adipocytes and their recruitment in response to thermogenic stimuli depend on the proliferation and differentiation of brown adipocyte precursor cells present within the tissue[29,30]. Evidence suggests that aging affects both the population of these precursor cells in BAT and their ability to sustain BAT function in advanced age. Huang et al.[31] reported a reduced capacity of brown adipose precursor cells from aged rabbits to differentiate into brown adipocytes following β3-adrenergic stimulation. This is of particular relevance because rabbit BAT exhibits age-dependent involution, plasticity, and sensitivity to ambient temperature and metabolic state, more closely mirroring human BAT physiology than mouse BAT[1,32,33].

Similarly, an age-related decline in the proliferation and differentiation potential of beige adipocyte precursor cells has been observed[34,35], which may contribute to the age-associated reduction in beige adipocyte biogenesis.

Other phenomena may contribute to the aging-associated decline in BAT activity. For example, the production of pro-inflammatory mediators and the infiltration of immune cells in adipose tissue increase with age, a phenomenon commonly referred to as “inflammaging”[36]. Inflammatory signals are known to impair BAT activity in metabolic conditions such as obesity[37]. Although direct evidence of their role in aging is limited, it is plausible that an elevated pro-inflammatory state within BAT contributes to its age-related decline. However, a recent report also showed that an age-dependent progressive infiltration of senescent immune cells, primarily T cells and neutrophils, induces aging- like BAT dysfunction[38]. Another recent report points to a potential mechanism underlying the age-related decline in BAT: the accumulation, within aging BAT, of a population of pyroptotic brown adipocytes that exhibit reduced expression of the longevity gene syntaxin-4, leading to the loss of BAT mass and thermogenic dysfunction characteristic of aged BAT[39].

Several molecules with putative anti-aging activity exert beneficial effects on BAT function. Examples include metformin[40], senolytic agents[41], and NAD+ boosters[42]. However, these effects have been only minimally explored in the specific context of age-associated BAT decline. Notably, a recent study reported that metformin delays the loss of thermogenic capacity in BAT in a mouse model of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome[43]. Comparable evidence in humans remains scarce. Although nicotinamide riboside has been shown to activate BAT in mice, a six-month intervention in young, lean individuals did not increase BAT activity[42]. Caloric restriction, one of the most robust interventions known to slow aging in model organisms, has also been linked to the preservation of BAT activity during aging[44]. However, it remains unclear whether BAT activation is a primary driver of the anti-aging effects of caloric restriction. Evidence further suggests that BAT mass and/or activity is increased in several experimental models of genetic interventions that extend lifespan, particularly those involving inactivation of components of the growth hormone/IGF-1 axis (see Darcy and Tseng, 2019 for a review)[45]. In these models, BAT activation is clearly associated with improved cardiometabolic phenotypes accompanying delayed aging, but it is not yet known whether BAT activation contributes directly to lifespan extension per se[46].

3. A differential Role of Autophagy in White and Brown Adipogenesis

Although our understanding of autophagy’s role in adipobiology, and especially in the thermogenic plasticity of adipose tissues, remains limited, several studies have shed light on this process. Current knowledge primarily focuses on macroautophagy, with considerably less information available regarding other forms of autophagy, such as chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA). Throughout this review, the term “autophagy” will be used to refer to macroautophagy unless otherwise specified or when macroautophagy is specifically contrasted with CMA, in accordance with common practice in the field to improve readability and avoid unnecessary complexity.

Basal autophagy differs markedly among adipocyte subtypes and plays a central role in maintaining their metabolic identity. White adipocytes display moderate to relatively high basal autophagy, which is required for adipocyte differentiation, lipid droplet remodeling via lipophagy, and organelle quality control, thereby facilitating lipid storage and adipose tissue expansion[47-49]. Brown adipocytes, in contrast, maintain comparatively low basal autophagy and tightly suppress mitophagy to preserve their high mitochondrial content and sustain thermogenic capacity; excessive activation of autophagy in these cells leads to mitochondrial loss, BAT whitening, and impaired heat production[50,51]. Beige adipocytes exhibit an intermediate and highly regulated autophagic tone that functions as a reversible phenotypic switch: increased autophagy and mitophagy promote beige-to-white conversion, whereas autophagy suppression stabilizes mitochondrial content and maintains inducible thermogenic competence[50,51](see below).

The role of autophagy in adipocyte biology was evidenced through experimental models in which key macroautophagy genes, such as ATG7 or ATG5, were selectively deleted in adipocytes[47-49]. These studies showed that macroautophagy is progressively activated during white adipocyte differentiation, as evidenced by increased autophagosome formation. Conversely, loss of autophagy impaired white adipogenesis, reduced lipid accumulation, and increased apoptosis during differentiation. Pharmacological inhibition of autophagy (e.g., with chloroquine) further confirmed that active autophagy is essential for proper adipogenic differentiation.

More recent findings suggest that CMA also regulates adipogenesis. CMA, a selective autophagy pathway in which individual proteins are recognized by chaperones and directly delivered to lysosomes for degradation, has been proposed to control adipogenesis through the timely degradation of signaling molecules and transcription factors involved in critical processes such as proliferation (Myc), energy metabolism adaptation (glycolytic enzymes), and transcriptional regulation (SMAD2/3)[52]. Termination of TGFβ/SMAD3 signaling has been proposed as one of the main mechanisms behind the regulatory effect of CMA on adipocyte differentiation. Through modulation of these pathways, CMA supports adipogenesis and helps maintain cellular homeostasis.

Despite these advances, the mechanisms linking autophagy to adipogenesis are not fully understood, although some evidence point to a role of autophagy in controlling the expression of key transcriptional regulators of adipogenesis, including C/EBPβ, C/EBPα, and PPARγ[48,53].

Interestingly, disrupting autophagy in adipose tissue profoundly alters the balance between brown and white adipocyte differentiation. For example, macroautophagy impairment increases BAT mass and upregulates thermogenic genes such as UCP1 and PGC1α, while also promoting the emergence of beige adipocytes within WAT[48]. These changes enhance thermogenesis and fatty acid β-oxidation, ultimately reducing overall fat mass.

Although the precise mechanisms underlying these contrasting outcomes remain unclear, they may stem from differences in the transcriptional programs that govern white versus brown/beige adipocyte development[54]. Moreover, recent evidence suggests that autophagy plays distinct roles depending on the developmental stage of brown/beige adipocytes. For example, deletion of ATG7 in Myf5+ precursor cells, which give rise to brown but not white adipocytes, disrupts BAT development, particularly during late embryonic and early postnatal stages[55]. However, in adult mice, autophagy impairment enhances beige adipocyte formation and increases β-oxidation in BAT[48,50].

Recently, the autophagy cargo receptor Ncoa4 has emerged as a key regulator of both BAT and WAT function. In BAT, Ncoa4 is required for full activation of thermogenic gene expression, including UCP1, and for a proper response to cold. In WAT, Ncoa4 influences PPARγ‑dependent gene expression during adipocyte differentiation and metabolic adaptation. Adipose‑specific loss of Ncoa4 impairs BAT thermogenesis and alters WAT gene expression programs, highlighting its role in coordinating autophagy and adipocyte function[56].

In summary, while the loss of autophagy more significantly disrupts white adipogenesis, it appears to promote the development of a brown adipocyte phenotype characterized by enhanced oxidative metabolism and thermogenic capacity.

4. Autophagy in Brown and Beige Adipose Tissue Thermogenic Regulation

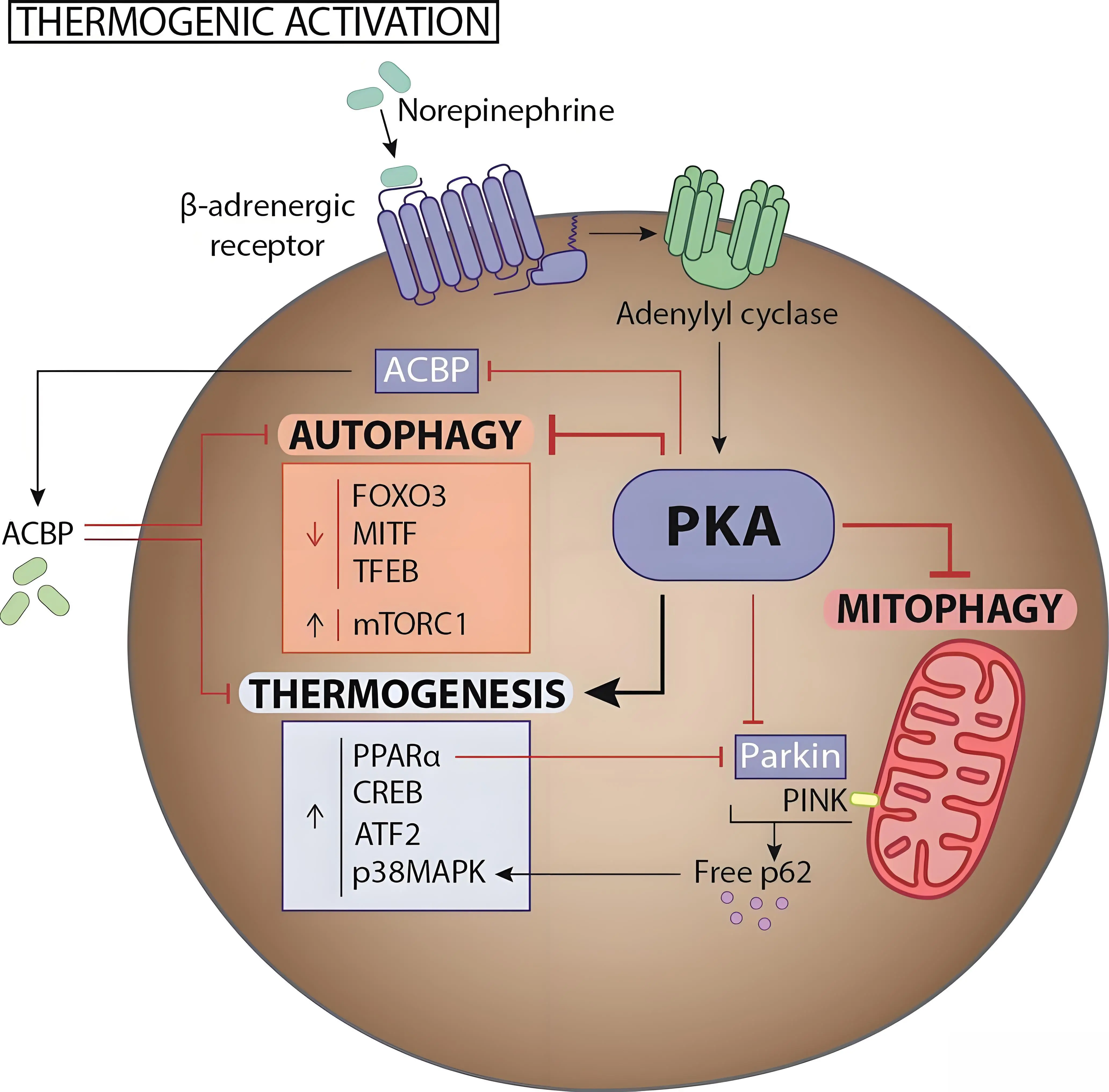

In addition to the differential role of autophagy in the brown/beige/white differentiation processes, it appears also to be a fundamental mechanism for adaptive brown and beige adipose tissue function in response to thermogenic requirements. During thermogenic activation (e.g. under conditions of cold stress) macroautophagy degradative processes in BAT are suppressed[50,57,58], largely through the action of adrenergic stimuli inducing protein kinase A (PKA), which simultaneously promotes thermogenesis and inhibits autophagy. Pharmacological blockade of PKA with H89 prevents the cAMP-driven downregulation of autophagy-related genes and activity in brown and beige adipocytes, highlighting the close interplay between these pathways[50,57,58].

PKA enhances thermogenic gene expression through CREB and also via p38MAPK phosphorylation, which activates ATF2[54]. However, the mechanisms by which PKA represses autophagy-related transcription remain unresolved. Several transcription factors have been implicated: Altshuler-Keylin et al.[50] identified Mitf and FOXO3 as autophagy regulators downregulated by cAMP–PKA signaling, while we reported that TFEB, a master controller of autophagy and lysosomal biogenesis, is also reduced during thermogenic activation[57]. Interestingly, p38MAPK appears dispensable for this suppression[57], suggesting alternative PKA downstream effectors. CREB is also a candidate transcription factor to mediate PKA effects on the BAT thermogenic machinery, as it is also known to regulate autophagy in the liver[59,60]. PKA may also act indirectly via mTORC1, a central energy sensor and autophagy inhibitor[61].

Beyond repression, autophagy may also enable BAT function via the suppression of the transcriptional repressor Nuclear Receptor Corepressor 1 (NCOR1). NCOR1 interacts with nuclear receptors and transcription factors that are central to BAT function, including thyroid receptors, PPARγ, PPARα, and ERRα. By recruiting histone deacetylase-3 (HDAC3), NCOR1 maintains a repressive chromatin state at thermogenic enhancers[62]. Notably, NCOR1 degradation via autophagy and the subsequent activation of the PPARγ pathway have been reported as essential for brown adipocyte maturation and function[63].

However, prolonged cold exposure has been reported to increase autophagy[64], which might indicate temporal differences in the regulation of autophagy across thermogenic phases. Further studies are needed to delineate how PKA, mTORC1, and transcriptional regulators converge to control autophagy during BAT activation and the time-course of concomitant thermogenic activation and autophagy repression.

On the other hand, autophagic activity in BAT and its relationship with thermogenic function may involve a specific regulatory mechanism mediated by acyl-CoA–binding protein (ACBP), also known as diazepam-binding inhibitor (DBI). ACBP is a regulatory protein secreted via an autophagy-dependent pathway[65]. Recent findings indicate that both the expression and autophagy-dependent secretion of ACBP by brown adipocytes are inversely regulated according to the level of thermogenic activation[66]. In turn, ACBP acts to suppress BAT activity. These observations suggest the existence of an autocrine feedback loop, in which increased autophagic activity, such as under warm ambient temperatures, leads to ACBP secretion, thereby contributing to the repression of thermogenesis.

In studies examining how autophagy influences thermogenesis in brown and beige adipose tissue, special focus has been placed on specific macroautophagy pathways such as mitophagy and lipophagy. These processes are essential for maintaining mitochondrial quality and for controlling lipid handling within the cell, two functions that are central to the thermogenic capacity and metabolic activity of brown and beige adipocytes.

4.1 Mitophagy in adipose tissue thermogenic plasticity

Mitophagy, the selective degradation of mitochondria, preserves cellular homeostasis by removing damaged organelles. The best-characterized molecular pathway controlling mitophagy involves the PINK1/Parkin system, which is activated upon mitochondrial depolarization[67,68]. PINK1 protein accumulates on dysfunctional mitochondria, recruits and phosphorylates Parkin, and together they promote ubiquitination of outer membrane proteins, attracting autophagy receptors such as p62, OPTN, NDP52, NBR1, and TAX1BP1[69-71]. Additional receptors (BNIP3, NIX, FUNDC1) are also implicated, though their tissue-specific roles remain unclear[68]. In adipocytes, BNIP3 is induced during adipogenesis under PPARγ and C/EBPα regulation, influencing mitochondrial dynamics and metabolism, though it appears dispensable for mitochondrial turnover[72,73].

In brown/beige adipocytes, PINK1/Parkin regulation is key for balancing mitochondrial expansion and thermogenesis. Parkin expression rises during general adipogenic differentiation[58,74,75], but Parkin-deficient adipocytes differentiate normally[75,76]. Strikingly, Parkin-KO mice show enhanced BAT thermogenesis, increased browning, and resistance to diet-induced obesity[58,74,77]. PINK1, instead, is mainly regulated post-transcriptionally and kept at low levels by mitochondrial proteases[75].

Upon thermogenic activation in BAT, because UCP1 activity causes partial mitochondrial depolarization as part of the heat production mechanism[78], PINK1 can accumulate on mitochondria, but Parkin is strongly repressed in response to thermogenic activation of brown adipocytes, both transcriptionally via PPARα and functionally by PKA[58]. This likely prevents degradation of active mitochondria when thermogenesis is active. Additionally, autophagy adaptor accumulation, especially p62, promotes thermogenic gene expression through p38MAPK signaling, while its loss impairs BAT mitochondrial function[79] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The role and regulation of autophagy in brown/beige adipogenesis and thermogenesis: in mature brown and beige adipocytes, thermogenic stimulation via β-adrenergic receptors suppresses autophagy through PKA activation. PKA promotes the transcription of thermogenic and mitochondrial biogenesis genes while repressing those related to lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy. It also activates mTORC1 and downregulates autophagy-related transcription factors via mechanisms that are still unclear. ACBP stands as a nexus between thermogenesis and autophagy activity. Moreover, PKA impairs mitophagy by blocking Parkin translocation to depolarized mitochondria, and PKA-driven lipolysis further suppresses Parkin expression via PPARα. PKA: protein kinase A; ACBP: acyl-CoA–binding protein; PKA: protein kinase A.

Functionally, PINK1, but not Parkin, is required for BAT mitochondrial integrity in response to thermogenic induction such as cold stress[58,74,75,80]. Redundant mitophagy pathways likely compensate for Parkin absence[71], while PINK1-independent processes contribute to basal mitochondrial quality control in high-energy tissues[81].

Moreover, active mitophagy regulated by the PINK1/Parkin system has been identified as a key mechanism in the “whitening” of beige adipocytes, namely the loss of their thermogenic phenotype and transition to a white, non-thermogenic state. The induction of mitophagy is essential for degrading the abundant mitochondrial content characteristic of beige adipocytes during this “whitening” process[50,74].

4.2 Lipophagy and CMA in adipose tissue lipid catabolism

On the other hand, lipophagy, another specialized form of macroautophagy, degrades intracellular lipids, complementing hormone-driven lipolysis, and has been mainly studied in the liver[82]. In hepatocytes, lipid turnover involves lipolysis, macroautophagy, and also CMA, which directly translocates proteins into lysosomes, enabling perilipin (PLIN) degradation, thus facilitating lipolysis and lipophagy[83,84].

CMA selectively targets PLIN2 and PLIN3 to control lipid droplet accessibility and lipolysis, whereas PLIN1 largely escapes CMA and is regulated by alternative degradation and remodeling pathways. In WAT, CMA-mediated degradation of PLIN2 and PLIN3 contributes to the controlled initiation of lipolysis by removing lipid droplet-shielding proteins and allowing hormone-sensitive lipase and adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) access to triglycerides, particularly during fasting or nutrient deprivation. Because WAT primarily functions as an energy reservoir, this CMA-PLIN axis operates as a regulated gatekeeping mechanism that balances lipid storage and mobilization[83].

In BAT, lipolysis is more tightly and rapidly coupled to mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation to fuel thermogenesis[85]. BAT lipid droplets are predominantly coated by PLIN1, which is largely resistant to CMA and instead regulated by β-adrenergic signaling, dependent phosphorylation and cofactor exchange. As a result, BAT relies less on CMA-driven PLIN removal and more on acute sympathetic control for lipolytic activation, ensuring rapid and reversible substrate supply for UCP1-dependent heat production[86]. Thus, in brown adipocytes, lipid mobilization relies mainly on cytosolic lipases. The noradrenergic stimulation of PKA leads to the phosphorylation of perilipins, granting access to ATGL, hormone-sensitive lipase, and monoacylglycerol lipase, which hydrolyze triglycerides into fatty acids for β-oxidation and thermogenesis[87]. Although lipophagy occurs in BAT, it is secondary to lipolysis. It has been reported that very short-term cold exposure (1 hour) can induce lipophagy in BAT, as in the liver and hypothalamic neurons, with lipid droplets appearing in autophagosomes[88]. However, unlike hepatocytes, where chronic lipophagy defects cause steatosis[48,83], autophagy loss in brown/beige adipocytes enhances β-oxidation, suggesting that lipolysis predominates in the regulation of lipid catabolism associated with thermogenesis[48].

5. The Paradoxical Role of Autophagy in the Decline of BAT Activity and WAT Browning During Aging.

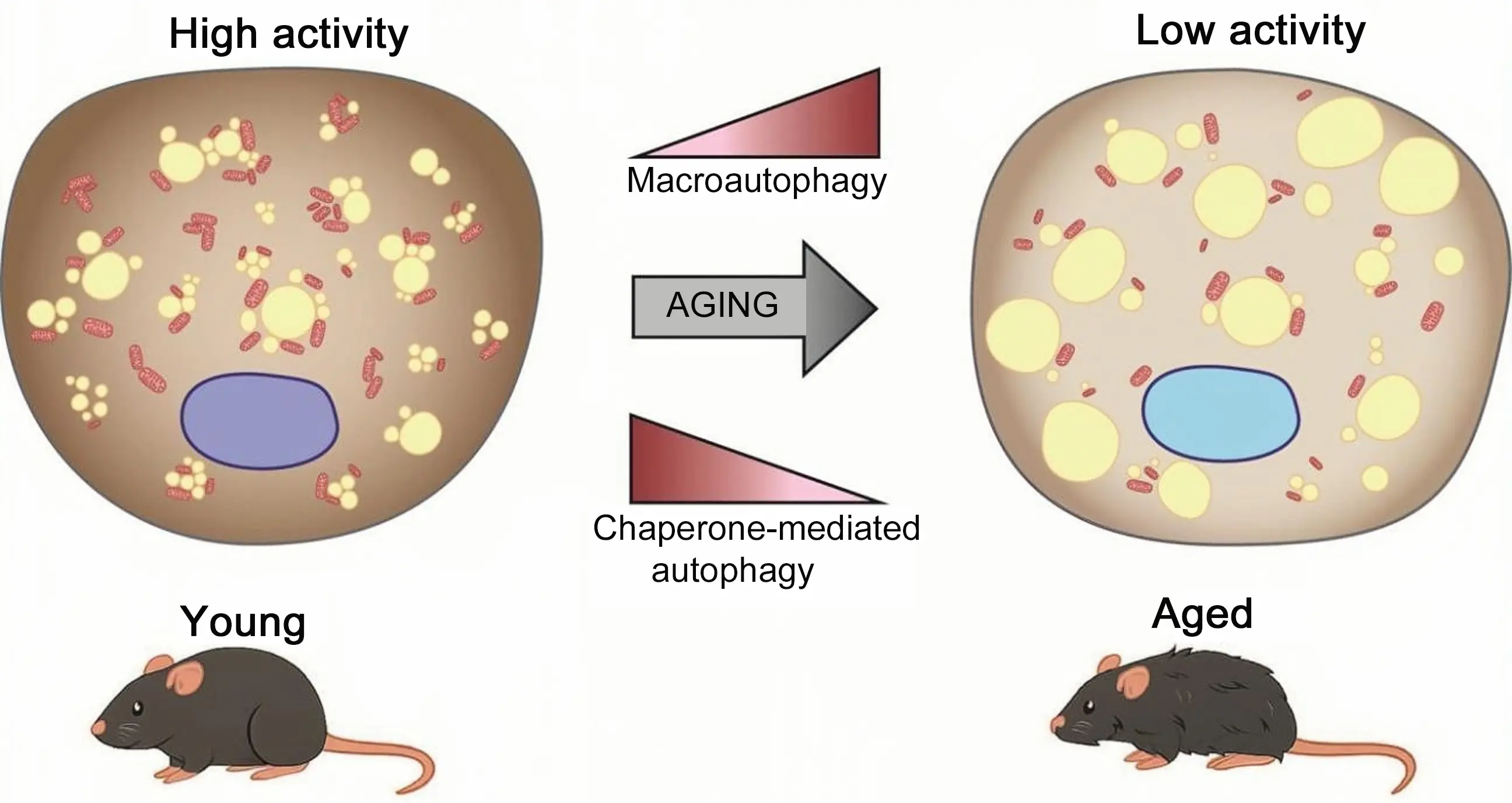

A comprehensive assessment of how aging affects macroautophagy in BAT and the browning capacity of WAT is still lacking. Current assumptions are largely derived from observations of a reciprocal relationship between macroautophagy and thermogenic activity in adipose tissue. During adipogenic differentiation, inhibition of macroautophagy is associated with enhanced brown and beige adipocyte differentiation. Moreover, during cold-induced thermogenic activation, increased thermogenic function correlates with reduced macroautophagy. Based on these findings, it has been proposed that macroautophagy is likely to increase in aging BAT, a condition characterized by diminished thermogenic capacity. Although transcriptional data provide only a partial view of macroautophagy activity[89], analysis of up to 20 gene transcripts involved in autophagosome initiation, maturation, and fusion within a dataset examining BAT transcriptomic changes across mouse aging[90] showed a significant trend toward increased expression. Increased autophagy in aging BAT has also been proposed based on elevated expression of ATG7 and LC3-II in BAT from older compared with younger mice[91]. This increase has been postulated to contribute to the age-related decline in mitochondrial content in BAT through enhanced mitochondrial degradation. Indeed, evidence shows that Parkin expression increases with age in both BAT and WAT in mice, which has been interpreted as an indication of increased mitophagy[92]. Genetic deletion of Parkin in mice prevents the age-related decline in WAT browning[92] and concurrently mitigates the age-associated increases in whole body adiposity and inflammation[92,93].

Overall, the evidence suggesting a potential increase in autophagy during aging in BAT and in relation to WAT browning may initially appear counterintuitive, given that a general decline in autophagic capacity has traditionally been considered a hallmark of aging[94]. However, this assumption is challenged by recent studies demonstrating cases where autophagy actually increases with age. For instance, macroautophagy has been shown to rise in aging WAT[95], as well as in both mouse and human leukocytes[96,97]. It has been proposed that this age-related increase may represent a compensatory response to the accumulation of cellular damage over time. Thus, while basal autophagic activity may appear elevated with age, the overall capacity to respond effectively to autophagy-inducing stimuli could still be impaired[98]. Further research is needed to fully understand how autophagy changes with age in BAT and beige adipose tissue, and to clarify the implications of these changes in the context of age-associated systemic cardiometabolic dysfunction, considering the growing evidence for a positive association between BAT activity and cardiometabolic health[7].

On the other hand, recent studies suggest a somewhat different scenario for CMA. Similarly to macroautophagy, it is often assumed that CMA activity tends to decline with advanced aging[99] but there are indications that age-related changes in CMA activity may be highly dependent on the genetic background of experimental models, the tissue or cell type under consideration, and the ages at which CMA is evaluated[100]. A recent assessment of CMA activity in mouse tissues revealed a trend toward reduced CMA activity in BAT from aged C57BL/6 male mice, whereas an increase was observed in aged females[101]. Also, in C57BL/6 male mice, the levels of Lamp2A (the molecular biomarker of CMA) and the transcriptional CMA network were also found to decline with aging, and pharmacological intervention to increase CMA activity in aged male mice restored BAT thermogenic activity[102]. In brown adipocytes, CMA activation increased thermogenic activity and metabolic oxidative activity, whereas Lamp2A invalidation caused the opposite effects. In male mice, Lamp2A expression increases as part of the thermogenic induction program of BAT in response to cold, and it has been proposed that CMA would play a role in the selective degradation of cellular inhibitors of the thermogenic machinery, so being a key process to maintain active BAT[102]. Thus, while general macroautophagic activity in BAT appears to increase with aging, an age-related decline in CMA may result in the accumulation of undegraded repressors of BAT function, thereby contributing to the reduced thermogenic capacity observed in aging BAT (Figure 2). However, this phenomenon has been observed in males, and it remains unclear whether it occurs similarly in females. Pronounced sex differences in BAT thermogenic function are well established, particularly in rodent models[103] raising the possibility that CMA regulation and its trajectory during aging may contribute to these disparities. These observations highlight the critical need for further investigation into sex-specific differences in CMA activity within BAT. Furthermore, the fact that CMA is considerably less studied than macroautophagy in the context of adipose tissues, combined with the methodological limitations of its in vivo assessment, often relying on indirect measurements, highlights the clear need for more in-depth investigation. Moreover, the fact that current tools for pharmacological activation of CMA (i.e. the CA77.1 compound) rely on repressing retinoic acid receptor-α activity[104] underscores the need for further research, considering the importance of retinoic acid in the control of BAT thermogenic activity[105].

Figure 2. The age-related decline in BAT activity is accompanied by an increase in macroautophagy in experimental models. In contrast, available data indicate a distinct pattern for CMA, which, at least in C57BL/6 male mice, tends to decline in BAT with aging. CMA: chaperone-mediated autophagy; BAT: brown adipose tissue.

6. Conclusion

Available evidence indicates that distinct autophagy pathways play a complex role in the age-related decline of BAT activity and its associated health consequences. Based on current findings, it seems unlikely that systemic, non–tissue-specific induction of macroautophagy as an anti-aging strategy would be beneficial, and it might even be counterproductive, in preventing the age-related decline of BAT function. Instead, targeting specific forms of autophagy may offer more effective approaches to preserving BAT activity and its cardiometabolic benefits, which are mediated through its thermogenic and secretory functions. Notably, emerging strategies aimed at inducing CMA appear particularly promising for preventing BAT dysfunction, according to preclinical evidence. However, most of the current knowledge regarding the contribution of autophagy to age-associated BAT decline is derived from mouse models. Given the substantial differences in body size, thermogenic demands, and lifespan between mice and humans, caution is warranted when extrapolating findings from experimental models to human physiology, particularly in the context of aging. Consequently, further studies are required to validate, in humans, the complex and multifaceted relationships between distinct autophagy pathways and BAT function during aging that have been identified in preclinical models.

Authors contribution

Villarroya J: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, visualization, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Franco-Bordés C, Blasco-Roset A: Conceptualization, software, visualization, writing-review & editing.

Villarroya F: Conceptualization, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was partially supported by grant CNS2022-135516 (JV) from the State Agency of Research (AEI) of the Spanish Ministry of Science (MICIN/AEI/10.13039/50110 0011033 and FEDER, UE).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: Function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev. 2004;84(1):277-359.[DOI]

-

2. Satheesan A, Kumar J, Leela KV, Lathakumari RH, Angelin M, Murugesan R, et al. The multifaceted regulation of white adipose tissue browning and their therapeutic potential. J Physiol Biochem. 2025;81(4):925-947.[DOI]

-

3. Villarroya F, Vidal-Puig A. Beyond the sympathetic tone: The new brown fat activators. Cell Metab. 2013;17(5):638-643.[DOI]

-

4. Osuna-Prieto FJ, Martinez-Tellez B, Segura-Carretero A, Ruiz JR. Activation of brown adipose tissue and promotion of white adipose tissue browning by plant-based dietary components in rodents: A systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2021;12(6):2147-2156.[DOI]

-

5. Collins S. β-adrenergic receptors and adipose tissue metabolism: Evolution of an old story. Annu Rev Physiol. 2022;84:1-16.[DOI]

-

6. Gavaldà-Navarro A, Villarroya J, Cereijo R, Giralt M, Villarroya F. The endocrine role of brown adipose tissue: An update on actors and actions. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2022;23(1):31-41.[DOI]

-

7. Becher T, Palanisamy S, Kramer DJ, Eljalby M, Marx SJ, Wibmer AG, et al. Brown adipose tissue is associated with cardiometabolic health. Nat Med. 2021;27(1):58-65.[DOI]

-

8. Trayhurn P. Brown adipose tissue: A short historical perspective. In: Guertin DA, Wolfrum C, editors. Secondary Brown adipose tissue: A short historical perspective. New York: Springer; 2022. p. 1-18.[DOI]

-

10. Chen KY, Cypess AM, Laughlin MR, Haft CR, Hu HH, Bredella MA, et al. Brown Adipose Reporting Criteria in Imaging STudies (BARCIST 1.0): Recommendations for standardized FDG-PET/CT experiments in humans. Cell Metab. 2016;24(2):210-222.[DOI]

-

11. Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Matsushita M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Kameya T, Kawai Y, et al. Age-related decrease in cold-activated brown adipose tissue and accumulation of body fat in healthy humans. Obesity. 2011;19(9):1755-1760.[DOI]

-

12. Lee P, Greenfield JR, Ho KKY, Fulham MJ. A critical appraisal of the prevalence and metabolic significance of brown adipose tissue in adult humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2010;299(4):E601-E606.[DOI]

-

13. Ouellet V, Routhier-Labadie A, Bellemare W, Lakhal-Chaieb L, Turcotte E, Carpentier AC, et al. Outdoor temperature, age, sex, body mass index, and diabetic status determine the prevalence, mass, and glucose-uptake activity of 18F-FDG-detected BAT in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(1):192-199.[DOI]

-

14. Yoneshiro T, Ogawa T, Okamoto N, Matsushita M, Aita S, Kameya T, et al. Impact of UCP1 and β3AR gene polymorphisms on age-related changes in brown adipose tissue and adiposity in humans. Int J Obes. 2013;37(7):993-998.[DOI]

-

15. Pfannenberg C, Werner MK, Ripkens S, Stef I, Deckert A, Schmadl M, et al. Impact of age on the relationships of brown adipose tissue with sex and adiposity in humans. Diabetes. 2010;-59(7):1789-1793.[DOI]

-

16. Wu C, Yu P, Sun R. Adipose tissue and age-dependent insulin resistance: New insights into WAT browning. Int J Mol Med. 2021;47(5):71.[DOI]

-

17. Riis-Vestergaard MJ, Richelsen B, Bruun JM, Li W, Hansen JB, Pedersen SB. Beta-1 and not beta-3 adrenergic receptors may be the primary regulator of human brown adipocyte metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(4):e994-e1005.[DOI]

-

18. Blondin DP, Nielsen S, Kuipers EN, Severinsen MC, Jensen VH, Miard S, et al. Human brown adipocyte thermogenesis is driven by β2-AR stimulation. Cell Metab. 2020;32(2):287-300.e287.[DOI]

-

19. Kawate R, Talan MI, Engel BT. Aged C57BL/6J mice respond to cold with increased sympathetic nervous activity in interscapular brown adipose tissue. J Gerontol. 1993;48(5):B180-B183.[DOI]

-

20. McDonald RB, Horwitz BA. Brown adipose tissue thermogenesis during aging and senescence. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1999;31(5):507-516.[DOI]

-

21. Scarpace PJ, Mooradian AD, Morley JE. Age-associated decrease in beta-adrenergic receptors and adenylate cyclase activity in rat brown adipose tissue. J Gerontol. 1988;43(3):B65-B70.[DOI]

-

22. Saito M, Okamatsu-Ogura Y, Matsushita M, Watanabe K, Yoneshiro T, Nio-Kobayashi J, et al. High incidence of metabolically active brown adipose tissue in healthy adult humans: effects of cold exposure and adiposity. Diabetes. 2009;58(7):1526-1531.[DOI]

-

23. Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Matsushita M, Kayahara T, Kameya T, Kawai Y, et al. Recruited brown adipose tissue as an antiobesity agent in humans. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(8):3404-3408.[DOI]

-

24. Bahler L, Verberne HJ, Admiraal WM, Stok WJ, Soeters MR, Hoekstra JB, et al. Differences in sympathetic nervous stimulation of brown adipose tissue between the young and old, and the lean and obese. J Nucl Med. 2016;57(3):372-377.[DOI]

-

25. Hanks LJ, Gutiérrez OM, Bamman MM, Ashraf A, McCormick KL, Casazza K. Circulating levels of fibroblast growth factor-21 increase with age independently of body composition indices among healthy individuals. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2015;2(2):77-82.[DOI]

-

26. Villarroya J, Gallego-Escuredo JM, Delgado-Anglés A, Cairó M, Moure R, Gracia Mateo M, et al. Aging is associated with increased FGF21 levels but unaltered FGF21 responsiveness in adipose tissue. Aging Cell. 2018;17(5):e12822.[DOI]

-

27. Sabatino L, Vassalle C. Thyroid hormones and metabolism regulation: Which role on brown adipose tissue and browning process? Biomolecules. 2025;15(3):361.[DOI]

-

28. Gonçalves LF, Machado TQ, Castro-Pinheiro C, de Souza NG, Oliveira KJ, Fernandes-Santos C. Ageing is associated with brown adipose tissue remodelling and loss of white fat browning in female C57BL/6 mice. Int J Exp Pathol. 2017;98(2):100.[DOI]

-

29. Sanchez-Gurmaches J, Guertin DA. Adipocytes arise from multiple lineages that are heterogeneously and dynamically distributed. Nat Commun. 2014;5(1):4099.[DOI]

-

30. Lee YH, Petkova AP, Konkar AA, Granneman JG. Cellular origins of cold-induced brown adipocytes in adult mice. FASEB J. 2015;29(1):286-299.[DOI]

-

31. Huang Z, Zhang Z, Moazzami Z, Heck R, Hu P, Nanda H, et al. Brown adipose tissue involution associated with progressive restriction in progenitor competence. Cell Rep. 2022;39(2)[DOI]

-

32. Du K, Bai X, Yang L, Shi Y, Chen L, Wang H, et al. De novo reconstruction of transcriptome identified long non-coding RNA regulator of aging-related brown adipose tissue whitening in rabbits. Biology. 2021;10(11):1176.[DOI]

-

33. Li L, Wan Q, Long Q, Nie T, Zhao S, Mao L, et al. Comparative transcriptomic analysis of rabbit interscapular brown adipose tissue whitening under physiological conditions. Adipocyte. 2022;11(1):529-549.[DOI]

-

34. Khanh VC, Zulkifli AF, Tokunaga C, Yamashita T, Hiramatsu Y, Ohneda O. Aging impairs beige adipocyte differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells via the reduced expression of Sirtuin 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;500(3):682-690.[DOI]

-

35. Tajima K, Ikeda K, Chang HY, Chang CH, Yoneshiro T, Oguri Y, et al. Mitochondrial lipoylation integrates age-associated decline in brown fat thermogenesis. Nat Metab. 2019;1(9):886-898.[DOI]

-

36. Zhang YX, Ou MY, Yang ZH, Sun Y, Li QF, Zhou SB. Adipose tissue aging is regulated by an altered immune system. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1125395.[DOI]

-

37. Villarroya F, Cereijo R, Gavaldà-Navarro A, Villarroya J, Giralt M. Inflammation of brown/beige adipose tissues in obesity and metabolic disease. J Intern Med. 2018;284(5):492-504.[DOI]

-

38. Feng X, Wang L, Zhou R, Zhou R, Chen L, Peng H, et al. Senescent immune cells accumulation promotes brown adipose tissue dysfunction during aging. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):3208.[DOI]

-

39. Yu X, Benitez G, Wei PT, Krylova SV, Song Z, Liu L, et al. Involution of brown adipose tissue through a Syntaxin 4 dependent pyroptosis pathway. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):2856.[DOI]

-

40. Karise I, Bargut TC, Del Sol M, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Metformin enhances mitochondrial biogenesis and thermogenesis in brown adipocytes of mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;111:1156-1165.[DOI]

-

41. de Oliveira Silva T, Lunardon G, Lino CA, de Almeida Silva A, Zhang S, Irigoyen MCC, et al. Senescent cell depletion alleviates obesity-related metabolic and cardiac disorders. Mol Metab. 2025;91:102065.[DOI]

-

42. Nascimento EBM, Moonen MPB, Remie CME, Gariani K, Jörgensen JA, Schaart G, et al. Nicotinamide riboside enhances in vitro beta-adrenergic brown adipose tissue activity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(5):1437-1447.[DOI]

-

43. Xiang X, Feng Y, Li H, Li W, Li J, Xia Z, et al. Metformin delays the decline in thermogenic function of brown adipose tissue in a mouse model of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Exp Gerontol. 2025;201:112702.[DOI]

-

44. Corrales P, Vivas Y, Izquierdo-Lahuerta A, Horrillo D, Seoane-Collazo P, Velasco I, et al. Long-term caloric restriction ameliorates deleterious effects of aging on white and brown adipose tissue plasticity. Aging Cell. 2019;18(3):e12948.[DOI]

-

45. Darcy J, Tseng YH. ComBATing aging-does increased brown adipose tissue activity confer longevity? Geroscience. 2019;41(3):285-296.[DOI]

-

46. Zhang J, Kibret BG, Vatner DE, Vatner SF. The role of brown adipose tissue in mediating healthful longevity. J Cardiovasc Aging. 2024;4(2):17.[DOI]

-

47. Baerga R, Zhang Y, Chen PH, Goldman S, Jin S. Targeted deletion of autophagy-related 5 (atg5) impairs adipogenesis in a cellular model and in mice. Autophagy. 2009;5(8):1118-1130.[DOI]

-

48. Singh R, Xiang Y, Wang Y, Baikati K, Cuervo AM, Luu YK, et al. Autophagy regulates adipose mass and differentiation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(11):3329-3339.[DOI]

-

49. Zhang Y, Goldman S, Baerga R, Zhao Y, Komatsu M, Jin S. Adipose-specific deletion of autophagy-related gene 7 (atg7) in mice reveals a role in adipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2009;106(47):19860-19865.[DOI]

-

50. Altshuler-Keylin S, Shinoda K, Hasegawa Y, Ikeda K, Hong H, Kang Q, et al. Beige adipocyte maintenance is regulated by autophagy-induced mitochondrial clearance. Cell Metab. 2016;24(3):402-419.[DOI]

-

51. Lu X, Altshuler-Keylin S, Wang Q, Chen Y, Henrique Sponton C, Ikeda K, et al. Mitophagy controls beige adipocyte maintenance through a Parkin-dependent and UCP1-independent mechanism. Sci Signal. 2018;11(527):eaap8526.[DOI]

-

52. Kaushik S, Juste YR, Lindenau K, Dong S, Macho-González A, Santiago-Fernández O, et al. Chaperone-mediated autophagy regulates adipocyte differentiation. Sci Adv. 2022;8(46):eabq2733.[DOI]

-

53. Guo L, Huang JX, Liu Y, Li X, Zhou SR, Qian SW, et al. Transactivation of Atg4b by C/EBP β promotes autophagy to facilitate adipogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33(16):3180-3190.[DOI]

-

54. Harms M, Seale P. Brown and beige fat: Development, function and therapeutic potential. Nat Med. 2013;19(10):1252-1263.[DOI]

-

55. Martinez-Lopez N, Athonvarangkul D, Sahu S, Coletto L, Zong H, Bastie CC, et al. Autophagy in Myf5+ progenitors regulates energy and glucose homeostasis through control of brown fat and skeletal muscle development. EMBO Rep. 2013;14(9):795-803.[DOI]

-

56. Rowland LA, Santos KB, Guilherme A, Munroe S, Lifshitz LM, Nicoloro S, et al. The autophagy receptor Ncoa4 controls PPARγ activity and thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. BioRxiv [Preprint]. 2025.[DOI]

-

57. Cairó M, Villarroya J, Cereijo R, Campderrós L, Giralt M, Villarroya F. Thermogenic activation represses autophagy in brown adipose tissue. Int J Obes. 2016;40(10):1591-1599.[DOI]

-

58. Cairó M, Campderrós L, Gavaldà-Navarro A, Cereijo R, Delgado-Anglés A, Quesada-López T, et al. Parkin controls brown adipose tissue plasticity in response to adaptive thermogenesis. EMBO Rep. 2019;20(5):EMBR201846832.[DOI]

-

59. Lee JM, Wagner M, Xiao R, Kim KH, Feng D, Lazar MA, et al. Nutrient-sensing nuclear receptors coordinate autophagy. Nature. 2014;516(7529):112-115.[DOI]

-

60. Seok S, Fu T, Choi SE, Li Y, Zhu R, Kumar S, et al. Transcriptional regulation of autophagy by an FXR-CREB axis. Nature. 2014;516(7529):108-111.[DOI]

-

61. Mavrakis M, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Stratakis CA, Bossis I. MTOR kinase and the regulatory subunit of protein kinase A (PRKAR1A) Spatially and functionally interact during autophagosome maturation. Autophagy. 2007;3(2):151-153.[DOI]

-

62. Richter HJ, Hauck AK, Batmanov K, Inoue SI, So BN, Kim M, et al. Balanced control of thermogenesis by nuclear receptor corepressors in brown adipose tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U. A. 2022;119(33):e2205276119.[DOI]

-

63. Sabaté-Pérez A, Romero M, Sànchez-Fernàndez-de-Landa P, Carobbio S, Mouratidis M, Sala D, et al. Autophagy-mediated NCOR1 degradation is required for brown fat maturation and thermogenesis. Autophagy. 2023;19(3):904-925.[DOI]

-

64. Yau WW, Wong KA, Zhou J, Thimmukonda NK, Wu Y, Bay BH, et al. Chronic cold exposure induces autophagy to promote fatty acid oxidation, mitochondrial turnover, and thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. iScience. 2021;24(5)[DOI]

-

65. Montégut L, Lambertucci F, Moledo-Nodar L, Fiuza-Luces C, Rodríguez-López C, Serra-Rexach JA, et al. Acyl coenzyme A binding protein (ACBP): An aging- and disease-relevant “autophagy checkpoint”. Aging Cell. 2023;22(9):e13910.[DOI]

-

66. Blasco-Roset A, Quesada-López T, Mestres-Arenas A, Villarroya J, Godoy-Nieto FJ, Cereijo R, et al. Acyl CoA-binding protein in brown adipose tissue acts as a negative regulator of adaptive thermogenesis. Mol Metab. 2025;96:102153.[DOI]

-

67. Nguyen TN, Padman BS, Lazarou M. Deciphering the Molecular Signals of PINK1/Parkin Mitophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26(10):733-744.[DOI]

-

68. Pickles S, Vigié P, Youle RJ. Mitophagy and quality control mechanisms in mitochondrial maintenance. Curr Biol. 2018;28(4):R170-R185.[DOI]

-

69. Matsuda N, Sato S, Shiba K, Okatsu K, Saisho K, Gautier CA, et al. PINK1 stabilized by mitochondrial depolarization recruits Parkin to damaged mitochondria and activates latent Parkin for mitophagy. J Cell Biol. 2010;189(2):211-221.[DOI]

-

70. Narendra DP, Jin SM, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Gautier CA, Shen J, et al. PINK1 is selectively stabilized on impaired mitochondria to activate Parkin. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(1):e1000298.[DOI]

-

71. Lazarou M, Sliter DA, Kane LA, Sarraf SA, Wang C, Burman JL, et al. The ubiquitin kinase PINK1 recruits autophagy receptors to induce mitophagy. Nature. 2015;524(7565):309-314.[DOI]

-

72. Tol MJ, Ottenhoff R, van Eijk M, Zelcer N, Aten J, Houten SM, et al. A PPARγ-Bnip3 axis couples adipose mitochondrial fusion-fission balance to systemic insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. Diabetes. 2016;65(9):2591-2605.[DOI]

-

73. Choi JW, Jo A, Kim M, Park HS, Chung SS, Kang S, et al. BNIP3 is essential for mitochondrial bioenergetics during adipocyte remodelling in mice. Diabetologia. 2016;59(3):571-581.[DOI]

-

74. Altshuler-Keylin S, Kajimura S. Mitochondrial homeostasis in adipose tissue remodeling. Sci Signal. 2017;10(468):eaai9248.[DOI]

-

75. Taylor D, Gottlieb RA. Parkin-mediated mitophagy is downregulated in browning of white adipose tissue. Obesity. 2017;25(4):704-712.[DOI]

-

76. Corsa CAS, Pearson GL, Renberg A, Askar MM, Vozheiko T, MacDougald OA, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase parkin is dispensable for metabolic homeostasis in murine pancreatic β cells and adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(18):7296-7307.[DOI]

-

77. Kim KY, Stevens MV, Akter MH, Rusk SE, Huang RJ, Cohen A, et al. Parkin is a lipid-responsive regulator of fat uptake in mice and mutant human cells. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(9):3701-3712.[DOI]

-

78. Wikstrom JD, Mahdaviani K, Liesa M, Sereda SB, Si Y, Las G, et al. Hormone-induced mitochondrial fission is utilized by brown adipocytes as an amplification pathway for energy expenditure. EMBO J. 2014;33(5):418-436.[DOI]

-

79. Müller TD, Lee SJ, Jastroch M, Kabra D, Stemmer K, Aichler M, et al. P62 Links β-adrenergic input to mitochondrial function and thermogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(1):469-478.[DOI]

-

80. Lu Y, Fujioka H, Joshi D, Li Q, Sangwung P, Hsieh P, et al. Mitophagy is required for brown adipose tissue mitochondrial homeostasis during cold challenge. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):8251.[DOI]

-

81. McWilliams TG, Prescott AR, Montava-Garriga L, Ball G, Singh F, Barini E, et al. Basal mitophagy occurs independently of PINK1 in mouse tissues of high metabolic demand. Cell Metab. 2018;27(2):439-449.[DOI]

-

82. Singh R, Cuervo AM. Lipophagy: Connecting autophagy and lipid metabolism. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012(1):282041.[DOI]

-

83. Kaushik S, Cuervo AM. Degradation of lipid droplet-associated proteins by chaperone-mediated autophagy facilitates lipolysis. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(6):759-770.[DOI]

-

84. Sathyanarayan A, Mashek MT, Mashek DG. ATGL promotes autophagy/lipophagy via SIRT1 to control hepatic lipid droplet catabolism. Cell Rep. 2017;19(1):1-9.[DOI]

-

85. Bartelt A, Heeren J. Adipose tissue browning and metabolic health. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10(1):24-36.[DOI]

-

86. Najt CP, Devarajan M, Mashek DG. Perilipins at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2022;135(5):jcs259501.[DOI]

-

87. Li Y, Li Z, Ngandiri DA, Llerins Perez M, Wolf A, Wang Y. The molecular brakes of adipose tissue lipolysis. Front Physiol. 2022;13:826314.[DOI]

-

88. Martinez-Lopez N, Garcia-Macia M, Sahu S, Athonvarangkul D, Liebling E, Merlo P, et al. Autophagy in the CNS and periphery coordinate lipophagy and lipolysis in the brown adipose tissue and liver. Cell Metab. 2016;23(1):113-127.[DOI]

-

89. Klionsky DJ, Abdel-Aziz AK, Abdelfatah S, Abdellatif M, Abdoli A, Abel S, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (4th edition)1. Autophagy. 2021;17(1):1-382.[DOI]

-

90. Xu Y, Li M, Hu C, Luo Y, Gao X, Li X, et al. Developing a novel aging assessment model to uncover heterogeneity in organ aging and screening of aging-related drugs. Genome Med. 2025;17(1):83.[DOI]

-

91. Kim D, Kim JH, Kang YH, Kim JS, Yun SC, Kang SW, et al. Suppression of brown adipocyte autophagy improves energy metabolism by regulating mitochondrial turnover. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(14):3520.[DOI]

-

92. Delgado-Anglés A, Blasco-Roset A, Godoy-Nieto FJ, Cairó M, Villarroya F, Giralt M, et al. Parkin depletion prevents the age-related alterations in the FGF21 system and the decline in white adipose tissue thermogenic function in mice. J Physiol Biochem. 2024;80(1):41-51.[DOI]

-

93. Moore TM, Cheng L, Wolf DM, Ngo J, Segawa M, Zhu X, et al. Parkin regulates adiposity by coordinating mitophagy with mitochondrial biogenesis in white adipocytes. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):6661.[DOI]

-

94. López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell. 2023;186(2):243-278.[DOI]

-

95. Yamamuro T, Kawabata T, Fukuhara A, Saita S, Nakamura S, Takeshita H, et al. Age-dependent loss of adipose Rubicon promotes metabolic disorders via excess autophagy. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):4150.[DOI]

-

96. Dang LVP, Martin A, Carosi JM, Gore J, Singh S, Sargeant TJ. Cell-type-specific autophagy in human leukocytes. FASEB J. 2025;39(12):e70708.[DOI]

-

97. Carosi JM, Martin A, Hein LK, Hassiotis S, Hattersley KJ, Turner BJ, et al. Autophagy across tissues of aging mice. PLoS One. 2025;20(6):e0325505.[DOI]

-

98. Singh S, Carosi JM, Dang L, Sargeant TJ. Autophagy does not always decline with ageing. Nat Cell Biol. 2025;27(5):712-715.[DOI]

-

99. Kaushik S, Cuervo AM. The coming of age of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(6):365-381.[DOI]

-

100. Endicott SJ. Chaperone-mediated autophagy as a modulator of aging and longevity. Front Aging. 2024;5:1509400.[DOI]

-

101. Khawaja RR, Martín-Segura A, Santiago-Fernández O, Sereda R, Lindenau K, McCabe M, et al. Sex-specific and cell-type-specific changes in chaperone-mediated autophagy across tissues during aging. Nat Aging. 2025;5(4):691-708.[DOI]

-

102. Mestres-Arenas A, Quesada-López T, Blasco-Roset A, Gavaldà-Navarro A, Godoy-Nieto FJ, Cereijo R, et al. Chaperone-mediated autophagy controls brown adipose tissue thermogenic activity. Sci Adv. 2025;11(44):eady0415.[DOI]

-

103. Gómez-García I, Trepiana J, Fernández-Quintela A, Giralt M, Portillo MP. Sexual dimorphism in brown adipose tissue activation and white adipose tissue browning. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(15):8250.[DOI]

-

104. Gomez-Sintes R, Xin Q, Jimenez-Loygorri JI, McCabe M, Diaz A, Garner TP, et al. Targeting retinoic acid receptor alpha-corepressor interaction activates chaperone-mediated autophagy and protects against retinal degeneration. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4220.[DOI]

-

105. Villarroya F, Iglesias R, Giralt M. Retinoids and retinoid receptors in the control of energy balance: novel pharmacological strategies in obesity and diabetes. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11(6):795-805.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite