Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become a central driver in healthy longevity medicine (HLM), offering new tools to characterize biological aging trajectories, identify preclinical physiological decline, and optimize interventions aimed at preserving function throughout the lifespan by targeting age-related processes. HLM is increasingly recognized as a specialty focusing on the multidimensional process of aging, encompassing molecular, physiological, cognitive, and behavioral components, all of which generate complex, high-dimensional datasets that exceed the analytical capacity of traditional clinical approaches. AI methodologies, including machine learning and deep learning models capable of integrating large, multimodal data streams, provide the computational infrastructure required to produce actionable insights. In the clinical practice of HLM, AI further facilitates integration of converging domains, including continuous digital phenotyping enabled by wearables and sensors, advanced biomarker modeling, predictive modeling capable of forecasting risk trajectories and personalized intervention optimization through life models and digital twins. These models support anticipatory clinical management, shifting care from reactive disease treatment toward continuous preservation of physiological resilience. Despite rapid progress, the integration of AI into routine healthy longevity care requires careful consideration of data quality, algorithmic transparency, regulatory frameworks, population diversity, and clinical interpretability. Nonetheless, AI-driven healthy longevity management is beginning to allow biological aging to be quantified, targeted, and longitudinally monitored in clinical practice.

Keywords

1. Introduction

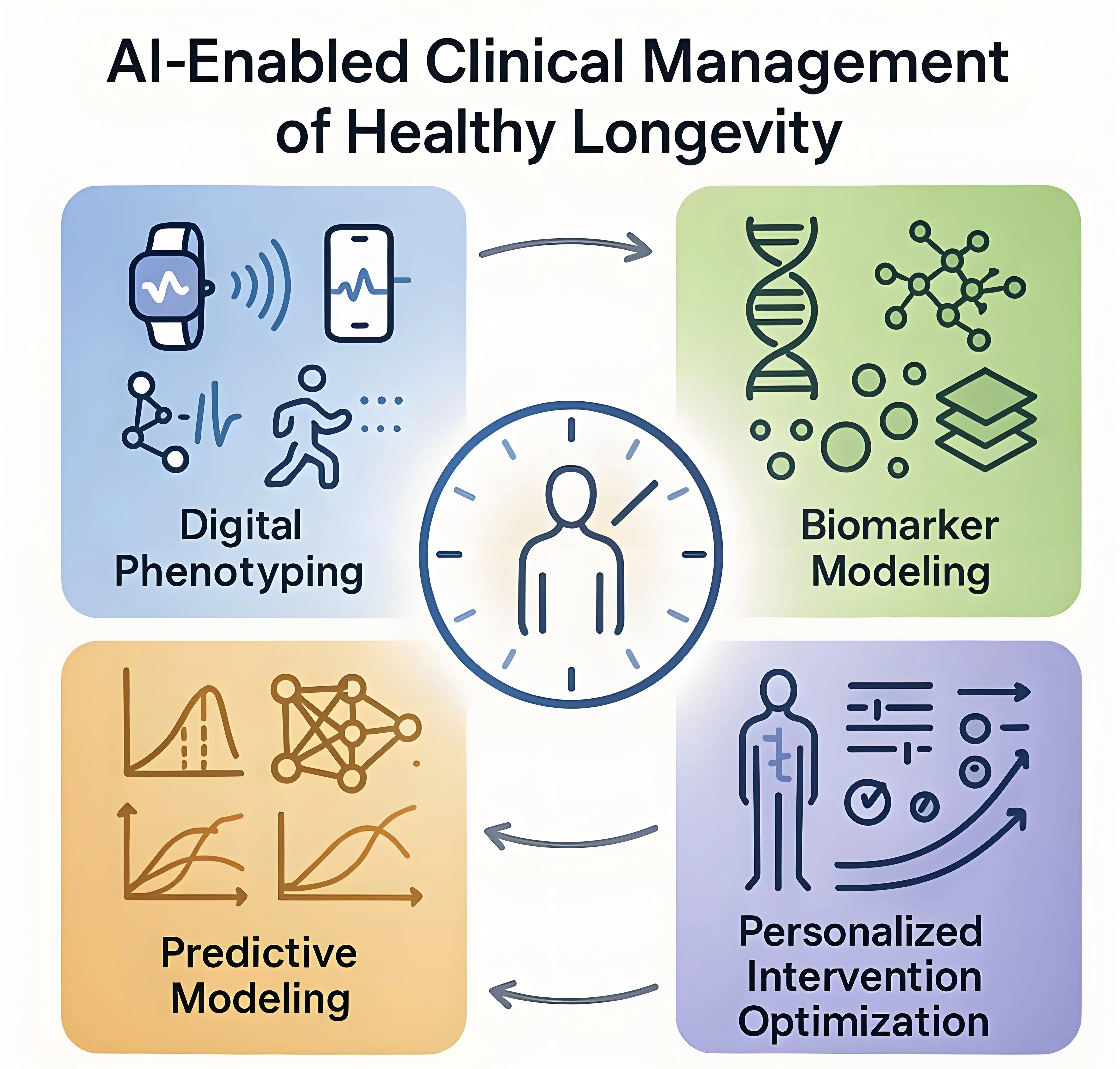

Healthy longevity medicine (HLM) is an emerging clinical approach driven by AI integration to analyze and interpret longitudinal data oriented around longevity-related domains[1,2]. The clinical aim of HLM is to provide care based on measurable anticipation of health trajectories rather than on solely the prevention of diseases, maintaining physiological reserve, decelerating pathological functional decline and optimizing healthspan[3]. This approach requires the capacity to detect trends in metabolic, cardiovascular, cognitive, and functional systems at stages when interventions can bring meaningful outcomes. Traditional physicians’ approaches and available medical tools, however, remain limited in their ability to integrate diverse, high-volume datasets, such as multi-omics analyses, imaging markers, wearable-derived digital signals, and longitudinal clinical information. As represented in Figure 1, AI continues to offer solutions for data integration which traditional diagnostics would not grasp and interpretation which would not be achievable by healthcare professionals alone.

Figure 1. Outcomes of AI integration in HLM. AI: artificial intelligence; HLM: healthy longevity medicine.

2. Digital Phenotyping and Continuous Monitoring

Continuous physiological monitoring has become a central component of AI-enabled healthy longevity[4]. Wearables, smartphones, ambient sensors, point-of-care tests, and digital platforms now enable real-time collection of diverse physiological signals, like heart rate variability, physical activity, gait characteristics, sleep architecture, thermal patterns, photoplethysmography signals, stress indicators and more[5-8]. Beyond within-person measurements, such monitoring can be extended to capture how environmental factors shape individual physiology, requiring technologies that assess environmental exposure markers and correlate them with wearable-derived data to support exposome mapping[9].

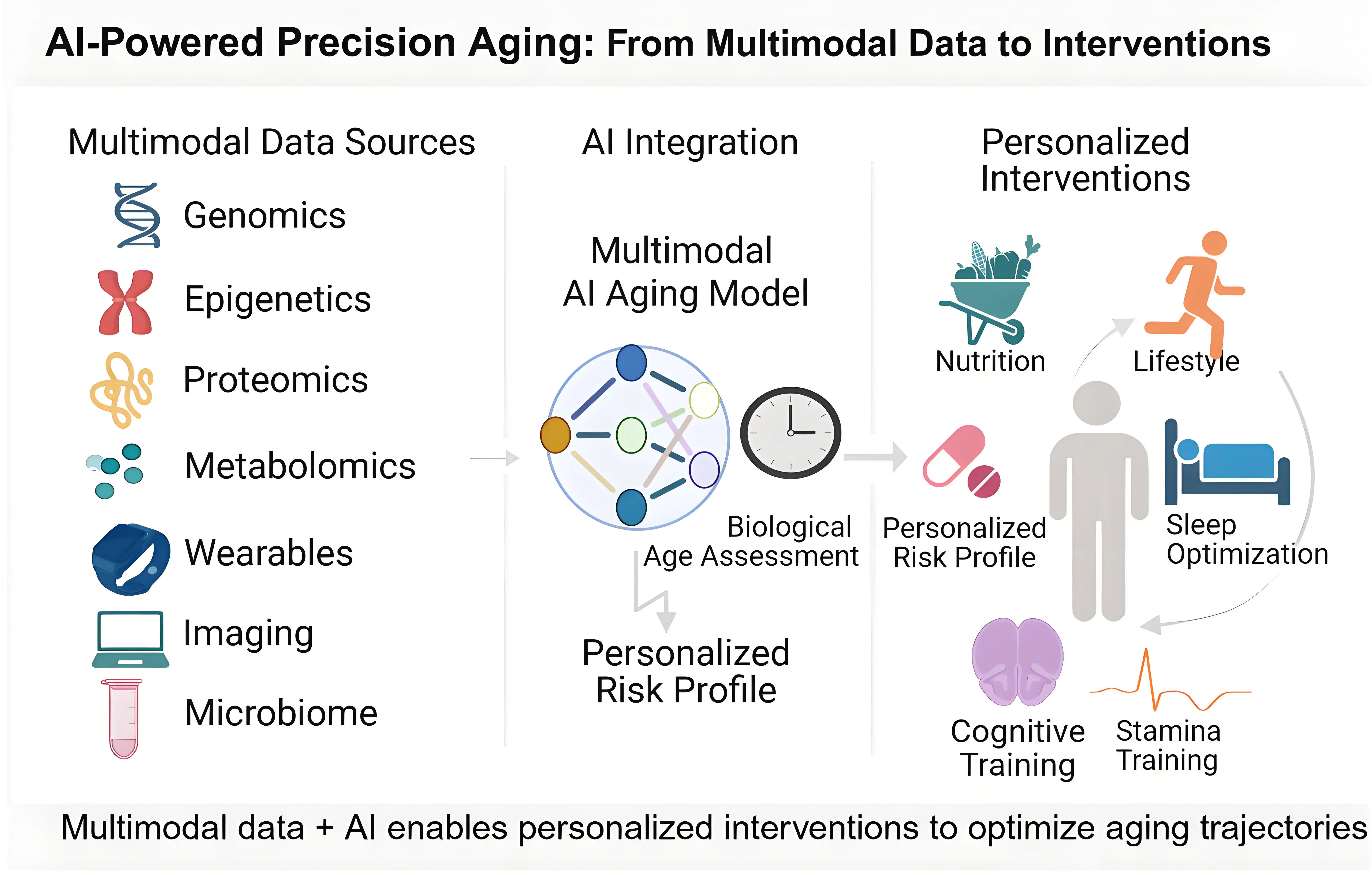

AI methods, such as machine learning models, including deep learning–based time-series and representation learning approaches, enable continuous integration and correlation of such diverse data streams, transforming discrete measurements into a coherent, longitudinal representation of individual physiology. This enables identification of subtle deviations from an individual’s baseline that often emerge before clinical deterioration becomes apparent, supporting preventive strategies. Daily examples in HLM departments illustrating the above-mentioned approach are changes in heart rate variability, which reflect early autonomic dysfunction associated with cardiometabolic aging[10], or micro-irregularities in mobility patterns, which could signal evolving frailty or neurodegenerative processes[11]. Other examples include sleep architecture monitoring and modeling to capture circadian misalignment, strongly associated with metabolic decline, depression and cognitive impairment[12]. Such deep and continuous analysis allows clinicians to intervene early through behavioral, or pharmacologic strategies. As represented in Figure 2, digital phenotyping thus forms a continuous biomarker stream that reflects physiological aging in real time, providing a foundation for proactive intervention rather than episodic clinical encounters.

Figure 2. AI-powered precision aging: From multimodal data to interventions. Created in BioRender. AI: artificial intelligence.

3. AI-Enabled Biomarkers of Aging and Aging Clocks

Numerous biomarkers of aging have been identified and validated across multiple biological domains[13-15]. AI methods have made it possible to translate these biomarkers into practical tools for HLM, such as biological aging clocks: computational models that estimate an individual’s biological age or aging rate by learning patterns in high-dimensional biological data that correlate with morbidity, mortality, and functional decline[16]. In current practice, aging clocks are primarily used to support research and within-person longitudinal monitoring rather than as stand-alone clinical decision tools, although they have already been implemented across clinics and centers practicing or studying HLM. Initially, aging clocks were framed within the broader concept of deep biomarkers of aging, emphasizing their role as components of AI-guided precision medicine for biological age estimation and intervention evaluation[1]. However, practitioners should recognize that aging clocks differ not only in data modality but also in modeling assumptions and therefore should not be used interchangeably. Population shifts, assay differences, and temporal data drift can introduce systematic bias, particularly in longitudinal applications[16]. Traditional machine learning based clocks typically rely on predefined feature sets derived from biological measurements and are trained to optimize population-level age prediction. Deep learning-based clocks extend this approach by learning internal data representations directly from raw or minimally processed inputs. While this can improve performance in some settings, it also increases model complexity and can complicate interpretability, calibration, and longitudinal stability in clinical use. Reliable deployment, therefore requires recalibration, stratified performance evaluation, and governance over model updates, including monitoring for performance drift.

Representative examples of aging clocks include first-generation epigenetic aging clocks, in which machine learning algorithms derive DNA methylation patterns that correlate with morbidity, mortality and physiological decline[17], as well as deep learning based hematological aging clocks that were trained on routine blood measures across multiple populations[18,19]. Proteomic and metabolomic aging clocks rely on thousands of circulating molecules that reflect systemic inflammation, metabolic function, immune aging and oxidative stress[20,21]. Deep learning-based microbiome profiling reveals patterns of microbial diversity and metabolic potential associated with immune status[22,23]. Deep aging clocks based on imaging-based biomarkers, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-derived brain age[24], computed tomography (CT)-derived vascular age, dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA)-derived musculoskeletal age, and electrocardiogram (ECG)-derived cardiac age[25-27], identify structural and functional patterns associated with accelerated or decelerated aging[16]. Therefore, HLM is equipped with multiple AI-based tools to detect accelerated aging and to monitor the effects of nutritional, behavioral, pharmacological or regenerative interventions in real time.

4. AI for Early Risk Identification and Preventive Stratification

Conventional risk scores rely on a limited number of linear predictors and generally detect risk at preclinical stages. Machine learning models integrate nonlinear patterns across high-dimensional clinical, molecular, and digital data, allowing earlier identification of disease susceptibility and earlier implementation of preventive strategies such as lifestyle modification[28]. Current clinical examples include integrating data such as glucose [29] or lipidomic signatures[30] to identify individuals at high risk for developing insulin resistance or dyslipidemia even when individual laboratory markers remain normal. In cognitive health, AI models incorporating neuroimaging, linguistic analysis, reaction time variability, and digital behavioral patterns can predict conversion time from mild to moderate cognitive impairment, which is difficult to achieve with neuropsychological testing[31,32]. Frailty models using gait kinetics, standard clinical biomarkers, inflammation markers, or biological age determined by aging clocks detect early physiological vulnerability[33-36]. Such predictive tools support the transition toward anticipatory care by enabling earlier deployment of preventive and longevity-oriented interventions.

While these approaches support personalized, longitudinal care at the individual level, their broader public health value lies in scalable risk stratification. Aggregated biomarkers, composite risk scores, and AI-derived phenotypic clusters can be used to inform population-level screening thresholds, early-intervention policies, and targeted prevention programs[37,38]. In this way, data-intensive precision approaches complement traditional public health strategies by improving identification of at-risk subpopulations and enabling more efficient allocation of preventive resources. When properly validated and standardized, AI-based risk models may be deployed at relatively low marginal cost across health systems, facilitating translation from specialized centers to primary care and community-based settings.

Older adults with frailty, sensory limitations, or cognitive impairment might seem to be at particular risk of exclusion from digitally driven healthcare innovations. However, AI tools can be used as one of the most important resources through human-centered design to address this exclusion issue[39]. AI enables simplified user interfaces, passive data collection (e.g., ambient sensors or clinician-entered data), and the use of proxy informants, such as caregivers or healthcare professionals, where appropriate. Those tools are being used already in various countries, such as in smart hospitals in China where elderly patients can converse with a chat bot to book appointments or arrange refills of their medication[40,41]. Hybrid care models, combining AI-supported digital tools with in-person clinical assessment and human oversight, are likely to be especially effective in this population.

5. AI for Intervention Modeling and Longitudinal Decision Support

It is important to distinguish between measurement-oriented AI systems, such as aging clocks, and modeling-oriented systems designed to support intervention planning. Aging clocks provide scalar summaries of physiological state that are primarily used for longitudinal monitoring and feedback, but they do not model biological dynamics or simulate the effects of potential interventions. Modeling-oriented approaches address this gap by representing how biological systems evolve over time and respond to perturbation. Within this category, digital twins have emerged as a promising tool for reducing the trial-and-error dynamics that often characterize lifestyle and pharmacological management in healthy longevity medicine. Digital twins are computational representations of an individual’s biological state that are continuously refined as new clinical, molecular, or sensor-derived data are incorporated, enabling simulation of how alternative management strategies may influence healthspan trajectories over time[42,43].

Life models extend this individualized simulation paradigm by embedding biological aging explicitly as a temporal process[44]. Unlike traditional disease models that treat biological measurements as static snapshots, these multimodal, transformer-based architectures generalize across tissues, data modalities, and omics layers to predict age-associated change and to address data limitations in geroscience[45,46]. At the core of these models is their ability to simulate real-world biological experiments through natural language prompting, functioning as a “digital laboratory” for researchers. In translational and early clinical contexts, life models can generate differential omics signatures for age-related conditions, simulate intervention effects where mechanistic plausibility exists, and prioritize candidate geroprotective or dual-purpose therapeutics, effectively functioning as a computational testbed for intervention design.

Complementing these simulation-based approaches, AI-driven stratification methods translate model outputs into actionable clinical decisions, e.g., by identifying individuals more or less likely to benefit from interventions with putative gerotherapeutic effects, including metformin[47], GLP-1 receptor agonists[48,49], statins[50], thereby limiting unnecessary exposure and improving the probability of achieving a clinically meaningful effect Together, these approaches offer a pragmatic route toward individualized intervention strategies: they rely on empirical patterns in real-world clinical data, simulate intervention effects only where mechanistic plausibility exists, and adjust recommendations as a patient’s physiological profile evolves over time.

6. Integration of AI Into Clinical Workflow

Translating AI-enabled decision support into routine clinical practice requires embedding these systems within existing clinical workflows rather than introducing parallel analytic layers. In contemporary healthcare settings, the electronic health record (EHR) serves as the primary operational backbone, providing longitudinal clinical depth across years of routine care and enabling AI models to contextualize patient-specific physiological trajectories beyond snapshot-based assessments[51,52]. Within this EHR-centered framework, AI systems (currently most commonly large language models) are deployed to support specific, well-defined clinical tasks, such as medical history summarization, pre-visit chart review, assistance with differential diagnosis formulation, treatment planning support, and clinical documentation[53-56].

In practice, this integration supports a continuous workflow across time. Prior to a scheduled preventive follow-up visit, an AI system integrated within the EHR could synthesize longitudinal patient information (including physician notes from prior visits, previously implemented interventions, recent laboratory and diagnostic test results with their timing, and wearable-derived data collected between visits) and highlight deviations from the individual’s established baseline. Clinicians would retain full access to the underlying raw data. In selected cases, life model-based tools could be used to contextualize intervention decisions by simulating how alternative strategies might influence longer-term physiological trajectories, supporting scenario exploration rather than automated decision-making. Furthermore, AI could assist with clinical documentation by drafting visit notes and updating structured fields within existing order sets.

The same workflow extends beyond episodic encounters through AI-enabled remote monitoring pipelines that integrate longitudinal physiological data from wearables. Such systems should generate alerts only when within-person variability exceeds clinically meaningful thresholds, while preserving continuous data access for clinician review. Patient-facing layers play a complementary role by translating clinician-reviewed model outputs into interpretable summaries that support shared decision-making, sustained adherence, and patient education[57]. Importantly, these interfaces should not deliver autonomous medical recommendations, ensuring that clinical judgment and responsibility remain with the treating physician.

7. Challenges

Despite significant promise, the implementation of AI in HLM raises several interconnected challenges that span clinical integration, model reliability, data governance, and ethical deployment. At the level of clinical workflow, effective deployment requires AI outputs to be explainable, interoperable with existing order sets and documentation pathways, and aligned with established clinical decision logic, so as to avoid increasing cognitive burden or fragmenting care delivery[58]. Structured training of healthcare professionals in this domain is therefore essential to ensure ethical interpretation and responsible use of AI-generated insights in routine care.

At the model level, data quality and representativeness remain critical limitations. Measurements derived from wearables, laboratories, and digital platforms vary substantially across devices, protocols, and populations, necessitating harmonization and standardization to ensure clinically reliable aging assessments. Algorithmic bias represents another challenge, as models trained on narrow populations may perform poorly in underrepresented groups, necessitating diverse datasets and ongoing monitoring for fairness[59,60]. Interpretability remains a multi-layered concern, as clinicians require explanations for algorithmic decisions before trusting AI recommendations in clinical practice.

These technical challenges intersect with broader concerns around data governance, privacy, and consent, particularly given the continuous monitoring and longitudinal data collection inherent to many AI-enabled HLM approaches. Emerging frameworks, such as the Global Patient co-Owned Cloud (GPOC), which is a blockchain-secured, decentralized platform for personal health records, propose patient co-ownership models that enhance data interoperability, privacy, and equitable access, while also serving as a substrate for ethical AI integration in global healthcare[61,62].

The integration of AI into clinical decision support raises important questions regarding liability and accountability. In current and foreseeable implementations, AI systems function as advisory tools rather than autonomous decision-makers, and ultimate clinical responsibility for the applied procedures remains with the treating physician[63-65]. Clinicians retain authority to accept, modify, or reject AI-generated suggestions, and liability for clinical decisions continues to be governed by existing standards of medical practice. This includes the clinician’s obligation to integrate AI outputs with clinical examination and contextual judgment derived from direct patient interaction. Health institutions bear responsibility for appropriate system selection, validation, monitoring, and governance, while developers are accountable for model performance, transparency, and post-deployment surveillance within their intended use. Clear documentation of AI involvement, well-defined oversight mechanisms, and alignment with evolving regulatory guidance are essential to ensure that responsibility is appropriately allocated across clinicians, healthcare organizations, and technology providers.

8. Conclusion

In HLM, AI-based analysis of longitudinal clinical, molecular, and sensor data enables three clinically relevant functions: early detection of within-person physiological deviation before guideline thresholds are crossed; stratification of near-term risk across cardiometabolic, neurocognitive, and frailty domains; and individualized adjustment of lifestyle and pharmacologic regimens as new measurements are obtained. To translate these functions into routine care, implementation should prioritize standardized data capture and quality control, external validation in diverse cohorts, explicit documentation of model scope and limitations, and full interoperability with existing EHR order sets and decision pathways to avoid additional workload. As multimodal aging models mature, they are expected to yield clinically useful surrogate endpoints for clinical trials, improve identification of likely responders and non-responders to geroprotectors, and support dose and timing optimization in both practice and trials. AI in HLM allows for physiology-centered care with measurable targets, earlier intervention windows, and clearer criteria for monitoring treatment effect across the lifespan.

Acknowledgements

During the preparation of this manuscript, ChatGPT 5.2 was briefly explored during the early stages of figure conceptualization. The authors subsequently reviewed the content as necessary and assume full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the published work.

Authors contribution

Evelyne B: Conceptualization, writing-original draft.

Chaim H: Visualization, writing-original draft.

Niklas L: Writing-review & editing.

Dominika W: Writing-original draft.

Conflicts of interest

Evelyne Bischof is an Editorial Board Member of Geromedicine. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Zhavoronkov A, Bischof E, Lee KF. Artificial intelligence in longevity medicine. Nat Aging. 2021;1(1):5-7.[DOI]

-

2. Radenkovic D, Zhavoronkov A, Bischof E. AI in Longevity Medicine. In: Lidströmer N, Ashrafian H, editors. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 1-13.[DOI]

-

3. Bonnes SLR, Strauss T, Palmer AK, Hurt RT, Island L, Goshen A, et al. Establishing healthy longevity clinics in publicly funded hospitals. GeroScience. 2024;46(5):4217-4223.[DOI]

-

4. Czaja SJ, Ceruso M. The promise of artificial intelligence in supporting an aging population. J Cogn Eng Decis Mak. 2022;16(4):182-193.[DOI]

-

5. Maan P, Kumar M, Kumar A, Komaragiri R. Cuffless monitoring of blood pressure using photoplethysmography signal: A comprehensive review of artificial intelligence and edge computing solutions. Arch Computat Methods Eng. 2025;32:1-30.[DOI]

-

6. Lombardi S, Bocchi L, Francia P. Photoplethysmography and artificial intelligence for blood glucose level estimation in diabetic patients: A scoping review. IEEE Access. 2024;12:178982-178996.[DOI]

-

7. Menassa M, Wilmont I, Beigrezaei S, Knobbe A, Arita VA, Valderrama JFV, et al. The future of healthy ageing: Wearables in public health, disease prevention and healthcare. Maturitas. 2025;196:108254.[DOI]

-

8. Babu M, Lautman Z, Lin X, Sobota MHB, Snyder MP. Wearable devices: Implications for precision medicine and the future of health care. Annu Rev Med. 2024;75:401-415.[DOI]

-

9. Woods T, Palmarini N, Corner L, Barzilai N, Maier AB, Sagner M, et al. Cities, communities and clinics can be testbeds for human exposome and aging research. Nat Med. 2025;31(4):1066-1068.[DOI]

-

10. Stein PK, Barzilay JI, Chaves PHM, Domitrovich PP, Gottdiener JS. Heart rate variability and its changes over 5 years in older adults. Age Ageing. 2009;38(2):212-218.[DOI]

-

11. Albites-Sanabria J, Palumbo P, Bandinelli S, D’Ascanio I, Mellone S, Paraschiv-Ionescu A, et al. Walking into aging: Real-world mobility patterns and digital benchmarks from the InCHIANTI Study. npj Aging. 2025;11(1):60.[DOI]

-

12. Huang T. Sleep irregularity, circadian disruption, and cardiometabolic disease risk. Circ Res. 2025;137(5):709-726.[DOI]

-

13. Moqri M, Herzog C, Poganik JR, Justice J, Belsky DW, Higgins-Chen A, et al. Biomarkers of aging for the identification and evaluation of longevity interventions. Cell. 2023;186(18):3758-3775.[DOI]

-

14. Moqri M, Herzog C, Poganik JR, Ying K, Justice JN, Belsky DW, et al. Validation of biomarkers of aging. Nat Med. 2024;30(2):360-372.[DOI]

-

15. Ren J, Song M, Zhang W, Cai JP, Cao F, Cao Z, et al. The Aging Biomarker Consortium represents a new era for aging research in China. Nat Med. 2023;29(9):2162-2165.[DOI]

-

16. Wilczok D. Deep learning and generative artificial intelligence in aging research and healthy longevity medicine. Aging. 2025;17(1):251-275.[DOI]

-

17. Horvath S, Raj K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19(6):371-384.[DOI]

-

18. Mamoshina P, Vieira A, Putin E, Zhavoronkov A. Applications of deep learning in biomedicine. Mol Pharm. 2016;13(5):1445-1454.[DOI]

-

19. Mamoshina P, Zhavoronkov A. Deep integrated biomarkers of aging. In Moskalev A, editor. p. 281-291.[DOI]

-

20. Argentieri MA, Xiao S, Bennett D, Winchester L, Nevado-Holgado AJ, Ghose U, et al. Proteomic aging clock predicts mortality and risk of common age-related diseases in diverse populations. Nat Med. 2024;30(9):2450-2460.[DOI]

-

21. Huang H, Chen Y, Xu W, Cao L, Qian K, Bischof E, et al. Decoding aging clocks: New insights from metabolomics. Cell Metab. 2025;37(1):34-58.[DOI]

-

22. Galkin F, Mamoshina P, Aliper A, Lane E, Moskalev V, Gladyshev VN, et al. Human gut microbiome aging clock based on taxonomic profiling and deep learning. iScience. 2020;23(6):101199.[DOI]

-

23. Chen Y, Wang H, Lu W, Wu T, Yuan W, Zhu J, et al. Human gut microbiome aging clocks based on taxonomic and functional signatures through multi-view learning. Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1):2025016.[DOI]

-

24. Lee J, Burkett BJ, Min HK, Senjem ML, Lundt ES, Botha H, et al. Deep learning-based brain age prediction in normal aging and dementia. Nat Aging. 2022;2(5):412-424.[DOI]

-

25. Lima EM, Ribeiro AH, Paixão GMM, Ribeiro MH, Pinto-Filho MM, Gomes PR, et al. Deep neural network-estimated electrocardiographic age as a mortality predictor. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5117.[DOI]

-

26. Libiseller-Egger J, Phelan JE, Attia ZI, Benavente ED, Campino S, Friedman PA, et al. Deep learning-derived cardiovascular age shares a genetic basis with other cardiac phenotypes. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):22625.[DOI]

-

27. Siontis G, Le Goallec A, Prost JB, Collin S, Diai S, Vincent T, et al. Multi-modality deep learning prediction of heart age: Insights from UK-Biobank. Eur Heart J. 2024;45(Supplement_1):ehae666.3442.[DOI]

-

28. Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25(1):44-56.[DOI]

-

29. Huang X, Schmelter F, Seitzer C, Martensen L, Otzen H, Piet A, et al. Digital biomarkers for interstitial glucose prediction in healthy individuals using wearables and machine learning. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):30164.[DOI]

-

30. Mishkin IA, Koncevaya AV, Drapkina OM. Prediction of cardiovascular events with using proportional risk models and machine learning algorithms: A systematic review. Eur Phys J Spec Top. 2025;234(15):4505-4526.[DOI]

-

31. García-Gutiérrez F, Hernández-Lorenzo L, Cabrera-Martín MN, Matias-Guiu JA, Ayala JL. Predicting changes in brain metabolism and progression from mild cognitive impairment to dementia using multitask Deep Learning models and explainable AI. NeuroImage. 2024;297:120695.[DOI]

-

32. Cornacchia E, Bonvino A, Scaramuzzi GF, Gasparre D, Simeoli R, Marocco D, et al. Digital screening for early identification of cognitive impairment: A narrative review. WIREs Cogn Sci. 2025;16(4):e70009.[DOI]

-

33. Zheng X, Zeng Z, S van Schooten K, Yang Y. Machine learning approach for frailty detection in long-term care using accelerometer-measured gait and daily physical activity: Model development and validation study. JMIR Aging. 2025;8:e77140.[DOI]

-

34. Velazquez-Diaz D, Arco JE, Ortiz A, Pérez-Cabezas V, Lucena-Anton D, Moral-Munoz JA, et al. Use of artificial intelligence in the identification and diagnosis of frailty syndrome in older adults: Scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e47346.[DOI]

-

35. Wang X, Ji J. Explainable machine learning framework for biomarker discovery by combining biological age and frailty prediction. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):13924.[DOI]

-

36. Olugbenga SS, Aashiq M, Ahmad SA, Pin TM, Zhao Y, Rokhani FZ. Artificial intelligence-based prediction of cognitive frailty: A clinical data approach. IEEE Access. 2025;13:161529-161540.[DOI]

-

37. Sharma A, Adekunle BI, Ogeawuchi JC, Abayomi AA, Onifade O. AI-driven patient risk stratification models in public health: Improving preventive care outcomes through predictive analytics. Int J Multidiscip Res Growth Eval. 2023;4(3):1123-1130.[DOI]

-

38. Basu S, Bermudez-Canete P, Hall TC, Rajpurkar P. Optimizing ai solutions for population health in primary care. npj Digit. Med. 2025;8(1):434.[DOI]

-

39. Tzimourta KD. Human-centered design and development in digital health: Approaches, challenges, and emerging trends. Cureus. 2025;17(6):e85897.[DOI]

-

40. Chen J, Zhang Q. DeepSeek reshaping healthcare in China’s tertiary hospitals. arXiv:2502.16732 [Preprint]. 2025.[DOI]

-

41. Yang Y, Liu S, Lei P, Huang Z, Liu L, Tan Y. Assessing usability of intelligent guidance chatbots in Chinese hospitals: Cross-sectional study.Digit Health. 2024;10:20552076241260504.[DOI]

-

42. Murshid GA. The rise of healthy longevity and healthspan in saudi arabia: From funding geroscience research to precision medicine and personalized digital twins. Discov Med. 2024;1(1):83.[DOI]

-

43. Su C, Wang P, Foo N, Ho D. Optimizing metabolic health with digital twins. npj Aging. 2025;11(1):20.[DOI]

-

44. Galkin F, Naumov V, Pushkov S, Sidorenko D, Urban A, Zagirova D, et al. Precious3GPT: Multimodal multi-species multi-omics multi-tissue transformer for aging research and drug discovery. BioRxiv [Preprint]. 2024.[DOI]

-

45. Urban A, Sidorenko D, Zagirova D, Kozlova E, Kalashnikov A, Pushkov S, et al. Precious1GPT: multimodal transformer-based transfer learning for aging clock development and feature importance analysis for aging and age-related disease target discovery. Aging. 2023;15(11):4649.[DOI]

-

46. Sidorenko D, Pushkov S, Sakip A, Leung GHD, Lok SWY, Urban A, et al. Precious2GPT: the combination of multiomics pretrained transformer and conditional diffusion for artificial multi-omics multi-species multi-tissue sample generation. npj Aging. 2024;10(1):37.[DOI]

-

47. Zaizar-Fregoso SA, Lara-Esqueda A, Hernández-Suarez CM, Delgado-Enciso J, Garcia-Nevares A, Canseco-Avila LM, et al. Using artificial intelligence to develop a multivariate model with a machine learning model to predict complications in mexican diabetic patients without arterial hypertension (national nested case-control study): Metformin and elevated normal blood pressure are risk factors, and obesity is protective. J Diabetes Res. 2023;2023(1):8898958.[DOI]

-

48. Are GLP-1s the first longevity drugs? Nat Biotechnol. 2025;43(11):1741-1742.[DOI]

-

49. Landau J, Tiram Y, Ilan Y. Employing an artificial intelligence platform to enhance treatment responses to glp-1 agonists by utilizing metabolic variability signatures based on the constrained disorder principle. Biomedicines. 2025;13(11):2645.[DOI]

-

50. Costa F, Gomez Doblas JJ, Díaz Expósito A, Adamo M, D’Ascenzo F, Kołtowski L, et al. Artificial intelligence in cardiovascular pharmacotherapy: Applications and perspectives. Eur Heart J. 2025;46(37):3616-3627.[DOI]

-

51. Moen H, Raj V, Vabalas A, Perola M, Kaski S, Ganna A, et al. Towards modeling evolving longitudinal health trajectories with a transformer-based deep learning model. Ann Epidemiol. 2025;111:30-43.[DOI]

-

52. Miotto R, Li L, Kidd BA, Dudley JT. Deep patient: An unsupervised representation to predict the future of patients from the electronic health records. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):26094.[DOI]

-

53. Griot M, Vanderdonckt J, Yuksel D. Implementation of large language models in electronic health records. PLOS Digit Health. 2025;4(12):e0001141.[DOI]

-

54. Song JW, Park J, Kim JH, You SC. Large language model assistant for emergency department discharge documentation. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(10):e2538427.[DOI]

-

55. Olson KD, Meeker D, Troup M, Barker TD, Nguyen VH, Manders JB, et al. Use of ambient ai scribes to reduce administrative burden and professional burnout. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(10):e2534976.[DOI]

-

56. Gaber F, Shaik M, Allega F, Bilecz AJ, Busch F, Goon K, et al. Evaluating large language model workflows in clinical decision support for triage and referral and diagnosis. npj Digit Med. 2025;8(1):263.[DOI]

-

57. Elkefi S. Supporting patients’ workload through wearable devices and mobile health applications, a systematic literature review. Ergonomics. 2024;67(7):954-970.[DOI]

-

58. Ye J, Hai J, Song J, Wang Z. The role of artificial intelligence in the application of the integrated electronic health records and patient-generated health data. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2024.[DOI]

-

59. Georgievskaya A, Tlyachev T, Danko D, Chekanov K, Corstjens H. How artificial intelligence adopts human biases: The case of cosmetic skincare industry. AI Ethics. 2025;5(1):105-115.[DOI]

-

60. Zhang J, Zhang Z. Ethics and governance of trustworthy medical artificial intelligence. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2023;23(1):7.[DOI]

-

61. Lidströmer N, Kanters JK, Herlenius E. Systematic review of ethics and legislation of a Global Patient co-Owned Cloud (GPOC). Bioeth Open Res 2025;2:3.[DOI]

-

62. Lidströmer N, Davids J, ElSharkawy M, Ashrafian H, Herlenius E. Necessity for a global patient co-owned cloud (GPOC). BMC Digit Health. 2024;2(1):76.[DOI]

-

63. Jones C, Thornton J, Wyatt JC. Artificial intelligence and clinical decision support: clinicians’ perspectives on trust, trustworthiness, and liability. Med Law Rev. 2023;31(4):501-520.[DOI]

-

64. Bernstein MH, Sheppard B, Bruno MA, Lay PS, Baird GL. Randomized study of the impact of AI on perceived legal liability for radiologists. NEJM AI. 2025;2(6):AIoa2400785.[DOI]

-

65. Gerke S, Simon DA, Roman BR. Liability risks of ambient clinical workflows with artificial intelligence for clinicians, hospitals, and manufacturers. JCO Oncol Pract. 2025;2:3.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite