Peter E. Thomas, Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Copenhagen University Hospital - Herlev and Gentofte, Copenhagen 2730, Denmark. E-mail: peter.engel.thomas@regionh.dk

Abstract

Lipoprotein(a) is an established risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), with strong evidence of causality from genetic and epidemiological studies. This recognition has led to the development of multiple potent lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapies, four of which are currently in phase 3 cardiovascular outcomes trials. Despite this progress, several critical knowledge gaps remain. Notably, the potential role of high lipoprotein(a) in non-coronary vascular diseases, specifically peripheral arterial disease, major adverse limb events, and abdominal aortic aneurysms, has not been adequately investigated, despite the considerable morbidity and mortality associated with these conditions. Furthermore, recent findings suggest that systemic low-grade inflammation, as measured by high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP), may modify the ASCVD risk attributable to high lipoprotein(a). This raises the possibility that future lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapies may only benefit individuals with concomitantly elevated hsCRP. This review summarizes the current knowledge of lipoprotein(a) as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and aortic valve stenosis, outlines the emerging evidence linking lipoprotein(a) with peripheral arterial disease, major adverse limb events, and abdominal aortic aneurysms, and examines whether high lipoprotein(a) independently predicts the risk of ASCVD and aortic valve stenosis regardless of the presence or absence of systemic low-grade inflammation. By placing recent studies within a broader scientific landscape, we will thus attempt to clarify the vascular relevance of high lipoprotein(a) beyond coronary disease and inform precision targeting of future lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapies.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death globally[1], with atherosclerosis accounting for the majority of clinical events[2]. Atherosclerosis develops from the accumulation of cholesterol in the arterial intima, triggering inflammation, necrosis, and ultimately plaque rupture, which leads to vascular occlusion and ischemic events such as myocardial infarction and ischemic

A key contributor to this residual risk is lipoprotein(a)[7,8], a genetically determined LDL-like particle in which apolipoprotein B100 (apoB) is covalently bound to the unique plasminogen-like apolipoprotein(a)[9]. Lipoprotein(a) is hypothesized to possess prothrombotic, proatherogenic, and proinflammatory properties[8-11]. Extensive epidemiological and genetic data support its role as an independent and causal risk factor for myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and aortic valve stenosis, as well as all-cause and cardiovascular mortality[7,8,10,12-16]. As a result, many international guidelines now recommend lipoprotein(a) measurement for

In this review, we will summarize the current knowledge of lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor, outline the emerging evidence linking high lipoprotein(a) with peripheral arterial disease, major adverse limb events, and abdominal aortic aneurysms, and summarize findings on whether high lipoprotein(a) independently predicts ASCVD risk regardless of the presence or absence of systemic low-grade inflammation.

2. Lipoprotein(a)

2.1 Discovery and identification as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease

Lipoprotein(a) was first identified in 1963 by the Norwegian scientist Kåre Berg[32]. Interest in lipoprotein(a) was limited until 1987, when the LPA gene, encoding apolipoprotein(a), was sequenced[33]. It was found that apolipoprotein(a) shares marked homology with plasminogen, leading to early hypotheses implicating lipoprotein(a) in thrombogenesis through competitive inhibition of plasminogen[11,34,35]. Initial smaller studies did find higher plasma lipoprotein(a) levels in individuals with cardiovascular disease when compared to controls[11,13]. Nonetheless, the first larger prospective cohort studies did not find a clear association of high lipoprotein(a) levels with risk of cardiovascular disease, resulting in diminished research focus[11]. As later became clear, these prospective studies were likely constrained by suboptimal assays and a failure to account for regression dilution bias, and therefore came to the wrong conclusion and unfortunately delayed the interest in lipoprotein(a) research for years[10,11].

Interest in lipoprotein(a) was first restored in 2008-2009 with findings from the Copenhagen General Population Study and the Copenhagen City Heart Study, where high lipoprotein(a) and LPA genetic variants (i.e., genetically determined high lipoprotein(a)) were found to be associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction[14,15]. Later in 2009, the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration published data showing that plasma lipoprotein(a) was continuously and independently associated with cardiovascular disease[36], and in a study of 2,100 genetic variants, LPA emerged as the strongest genetic determinant of cardiovascular risk[12].

Taken together, these findings firmly established lipoprotein(a) as a causal risk factor for ASCVD and catalyzed the development of targeted lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapies.

2.2 Structure and synthesis of lipoprotein(a)

Lipoprotein(a) is synthesized in hepatocytes and consists of an LDL-like particle where apoB is covalently bound through a disulfide bridge to apolipoprotein(a)[9]. Apolipoprotein(a) is closely homologous to plasminogen, and both contain so-called “Kringle” domains, which are folding protein structures named after the Danish pastry which they resemble[9]. Only plasminogen contains Kringles I-III, while apolipoprotein(a) and plasminogen both contain Kringles IV, V, and a protease domain, which is inactive in apolipoprotein(a), unlike in plasminogen[9]. Further, compared to the one type of Kringle IV in plasminogen, apolipoprotein(a) has ten subtypes and Kringle IV subtype 2 (KIV-2) has a copy number variation, ranging from 2 to > 40 copies[9]. The isoform size of apolipoprotein(a) therefore varies greatly, and this isoform size is strongly, but inversely, correlated with the plasma concentrations of lipoprotein(a). Thus, the KIV-2 number of repeats is the strongest determinant of plasma lipoprotein(a) levels, and individuals with a low number of KIV-2 repeats, on average, have high plasma lipoprotein(a) levels, whereas individuals with a high number of KIV-2 repeats have low levels[8,9,11]. This difference is thought to be due to large isoforms being more susceptible to degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes, a longer transit time in hepatocytes, and an overall higher production of smaller versus larger apolipoprotein(a) isoforms[9]. The structure and synthesis of lipoprotein(a) and the influence of apolipoprotein(a) isoform size on plasma levels are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Structure and synthesis of lipoprotein(a) and influence of intraindividual apolipoprotein(a) isoform size variation on plasma lipoprotein(a) levels. LDL: low-density lipoprotein; mRNA: messenger ribonucleic acid.

2.3 Determinants of plasma lipoprotein(a) levels and distribution by age, sex, and ethnicity

Plasma levels are more than 90% genetically determined in both sexes and all ethnicities[8], primarily through the LPA gene, which directly determines the number of KIV-2 repeats as described above. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in and around the LPA locus modify the association of KIV-2 repeats with lipoprotein(a) levels, and a few SNPs influence lipoprotein(a) levels independently of KIV-2[9]. As levels are mainly genetically determined, they are generally unaffected by conventional cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, smoking, or socioeconomic status[7,8]. Nonetheless, a diet high in saturated fat and low in carbohydrate content decreases lipoprotein(a) levels by ~15% and individuals with chronic kidney disease have higher levels[7,37]. Plasma levels approach adulthood levels already at 15 months and are generally ~5-10% higher in women than in men[38,39]. In men, levels are relatively constant throughout life, whereas in women plasma levels increase slightly after menopause[39].

Lipoprotein(a) levels also vary with ethnicity, with individuals of Black ethnicity having the highest levels, individuals from Latin America, the Middle East, and South Asia having intermediate levels, and individuals from East and Southeast Asia and Europe having the lowest levels[7,8,40]. In ethnicities with low or intermediate levels, the population distribution is highly skewed with a tail towards high levels, whereas in ethnicities with high levels, the distribution approximates a normal distribution, though still with a tail towards higher levels[8].

2.4 Effects of current and future treatments

Statins, the cornerstone therapy for managing hypercholesterolemia, exert minimal to no influence on lipoprotein(a) levels[41]. In contrast, more recently developed agents such as proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors have been shown to lower lipoprotein(a) levels by approximately 14-35%[42,43]. Post hoc analyses from large cardiovascular outcome trials suggest that individuals with high lipoprotein(a) may derive greater relative benefit from PCSK9 inhibition; however, these analyses were exploratory and post-hoc, and predominantly included participants with modest baseline lipoprotein(a) levels. Niacin has demonstrated a 20-30% reduction in lipoprotein(a) levels, but randomized trials in statin-treated individuals have not shown cardiovascular risk reduction with its use, though these trials did not specifically enrol patients with high lipoprotein(a)[42]. Lipoprotein apheresis, a process in which lipoprotein(a) and other lipoproteins are physically removed from plasma via filtration, can reduce lipoprotein(a) levels by an average of 35%, and up to 60% in some cases[44]. Clinical studies have reported lower event rates with apheresis in patients with high lipoprotein(a) and recurrent atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; however, the procedure’s high cost, need for weekly or biweekly sessions, and time-intensive nature (2-4 hours per session) constrain its broader

In sum, there are no randomized clinical trials that have shown that a specific therapy to lower lipoprotein(a) reduces the risk of ASCVD. However, there are five therapies under development, which lower lipoprotein(a) levels by 80-98%[23-27] These work by silencing the expression of LPA through either antisense oligonucleotides or small interfering RNAs, or by inhibiting the binding of apolipoprotein(a) to LDL using small molecules[8,43]. Notably, these therapies have negligible effects on reducing inflammation[23-27]. Four of these therapies are in phase 3 cardiovascular outcomes trials, with results expected in 2026-2029 (NCT04023552, NCT05581303, NCT06292013, NCT07157774).

3. Lipoprotein(a) and Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease

3.1 Evidence from cohort studies in primary and secondary prevention

The first meta-analyses of population-based cohorts from the 2000s indicated that individuals who developed ischemic heart disease had higher lipoprotein(a) levels than those who did not[13]. Nevertheless, the role of high lipoprotein(a) as a causal risk factor for ASCVD was not firmly established until 2009, when Mendelian randomization analyses from the Copenhagen City Heart Study and the Copenhagen General Population Study demonstrated a stepwise increase in myocardial infarction risk with genetically determined higher lipoprotein(a) levels[15]. Numerous subsequent studies have confirmed these findings and extended the association of high lipoprotein(a) to the risk of other cardiovascular diseases, including ischemic stroke, heart failure, and cardiovascular mortality[8], but also to aortic valve stenosis, peripheral arterial disease, and abdominal aortic aneurysms as detailed later.

Importantly, a publication from the UK Biobank of 460,506 individuals included ethnicities other than white, with 8,940 (1.9%) of South Asian origin, 7,144 (1.6%) of Black origin, and 1,435 (0.3%) of Chinese origin[40], and confirmed findings from the Copenhagen studies. In that study, there was a log-linear association between higher lipoprotein(a) levels and increased risk of ASCVD, with hazard ratios of 1.11 (95% CI: 1.10-1.12) per 50 nmol/L higher lipoprotein(a) in the overall population. Similar estimates were found when stratifying by ethnicity, with corresponding estimates of 1.11 (1.10-1.12) for Whites, 1.10 (1.04-1.16) for South Asians, and 1.07 (1.00-1.15) for Blacks, while there were too few Chinese individuals to calculate meaningful risk estimates.

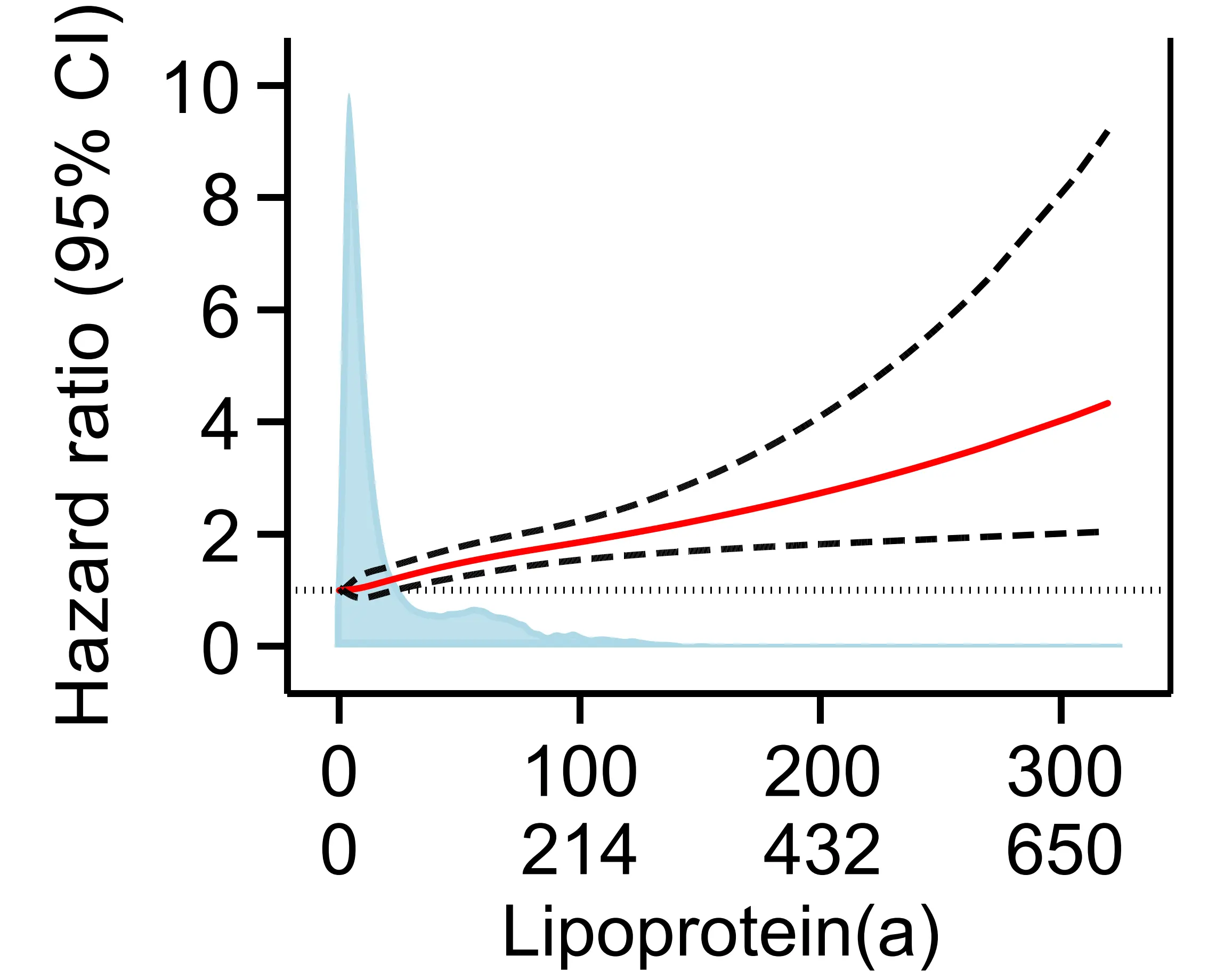

We recently updated previously published data from the Copenhagen General Population Study (N = 68,090, ASCVD = 5,104) on the association of high lipoprotein(a) with risk of ASCVD, and as expected, found that continuous higher lipoprotein(a) was associated with an increased risk of ASCVD (Figure 2)[30].

Figure 2. Risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease by plasma lipoprotein(a)[30]. Restricted cubic splines using multivariable adjusted Cox proportional hazards regressions with hazard ratios (solid red line) and 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines). Density plots of population distribution (blue) are made as kernel density estimation. Based on individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study. CI: Confidence interval.

Nonetheless, our study and most other previous studies were conducted in primary prevention, whereas ongoing phase 3 trials are primarily conducted in individuals with ASCVD, i.e., secondary prevention. Until recently, few large studies had investigated the association of lipoprotein(a) with risk of recurrent cardiovascular disease in secondary prevention, though most did find high lipoprotein(a) as a risk factor also for recurrent cardiovascular events[7,8,10]. However, in a recent study from the US Family Heart database including 273,770 individuals with baseline ASCVD, higher lipoprotein(a) levels were associated with continuously higher risk of recurrent ASCVD regardless of sex and ethnicity, providing the strongest evidence to date that lipoprotein(a) is a risk factor for ASCVD also in secondary prevention[45].

Taken together, there is robust evidence from both observational and genetic epidemiology that high lipoprotein(a) is a causal risk factor for ASCVD in both primary and secondary prevention. Importantly, observational cohort studies cannot generally be used to establish causality, as they are affected by confounding and reverse causation[46]. However, for lipoprotein(a), where levels are 80-90% genetically determined, it can be argued that even observational epidemiological studies support causality[8], in accordance with the principles of a Mendelian randomization study[46]. Nonetheless, exactly how lipoprotein(a) causes ASCVD remains unclear.

3.2 Lipoprotein(a) in atherogenesis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

Most studies on atherogenesis have been conducted using remnant cholesterol (β-very-low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) and LDL cholesterol in animal or in vitro models[3]. The evidence from preclinical studies for remnant and LDL cholesterol as a cause of atherogenesis is briefly outlined below. However, whether these findings are directly applicable to lipoprotein(a) is unknown, as there are few good mouse or other animal models for lipoprotein(a) available, limiting the evidence from animal studies[47].

LDL is the main carrier of cholesterol in the blood and the main contributor to atherosclerosis[2]. Lipoproteins with a diameter

As lipoprotein(a) is an LDL-like molecule, it is reasonable to hypothesize that part of the ASCVD caused by high lipoprotein(a) is via proatherogenic mechanisms similar to those of LDL[7]. Notably, lipoprotein(a) is usually present in the circulation in far lower concentrations than LDL, and while measurements of LDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, and apoB all contain contributions from lipoprotein(a), the cardiovascular risk from high lipoprotein(a) is minimally explained by elevations of these parameters[48]. Furthermore, on a per-particle basis, lipoprotein(a) appears to entail six times more risk of ASCVD than LDL[8,48,49].

Taken together, the mechanism by which high lipoprotein(a) causes ASCVD most likely differs from that of LDL, and lipoprotein(a) appears to cause ASCVD beyond its cholesterol content. While the exact mechanisms are unknown, it is hypothesized to be due to both prothrombotic, proatherosclerotic, or proinflammatory mechanisms, as illustrated in Figure 3[3,7,8,11,34,35,50].

Figure 3. Illustration of hypothesized mechanisms of lipoprotein(a) as a cause of cardiovascular disease.

The rate-limiting step in atherosclerotic development is not the influx of lipoproteins into the arterial intima, but rather whether these particles are retained within the arterial intima[3]. Apolipoprotein(a) possibly binds to extracellular matrix components, which may result in an increased retention of lipoprotein(a) particles versus LDL particles in atherosclerotic plaques[3,10,51]. Kinetic studies have indicated a preferential accumulation of lipoprotein(a) in the vessel wall at sites of tissue injury, that is, where fibrin clots develop following injury, indirectly supporting this hypothesis[52]. Yet, this could also be explained by the fact that lipoprotein(a) attaches to fibrin, possibly within the area of wound healing, delivering cholesterol and other components to repair tissue

While apolipoprotein(a) appears to inhibit plasmin-mediated fibrinolysis in vitro, these results have not been convincingly replicated in vivo[3,34]. Furthermore, high lipoprotein(a) is not convincingly associated with the risk of venous thromboembolisms[7], a disease where clots are fibrin rich but platelet poor when compared to arterial clots, and where plasmin inhibition by apolipoprotein(a) therefore theoretically should be more important[34]. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the mechanism of thrombosis in the venous and arterial systems is very different, not the least because of the huge difference in blood pressure and the speed at which blood flows in veins and arteries. Thus, whether lipoprotein(a) particles are in fact directly prothrombotic remains unclear. Lipoprotein(a) is also a preferential carrier of oxidized phospholipids, leading to the hypotheses that lipoprotein(a) causes ASCVD at least partly through proinflammatory pathways[50].

Nonetheless, as apolipoprotein(a) has developed independently twice in evolution (in hedgehogs and old-world monkeys, apes, and humans)[9], it has been suggested that apolipoprotein(a) may confer a survival advantage[8,11,35]. This could possibly be through the inhibition of fibrinolysis and subsequent better wound healing, which may impart a survival advantage in e.g., childbirth[8,11,35]. However, this hypothesis should be regarded as speculative.

In summary, the exact mechanisms by how lipoprotein(a) causes ASCVD are unclear, but could be due to both prothrombotic, proatherosclerotic, and/or proinflammatory mechanisms, or a combination of all three. Nevertheless, there is evidence to suggest that this mechanism may be different for other noncardiac vascular diseases such as peripheral arterial disease, abdominal aortic aneurysms, and aortic valve stenosis[28].

4. Peripheral Arterial Disease

4.1 Clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and epidemiology

Peripheral arterial disease is caused by the progressive narrowing of the arteries due to the buildup of atherosclerotic plaques, and most commonly affects the lower extremities[53]. Many patients are initially asymptomatic but eventually develop claudication, which, if left untreated, may progress to rest pain and chronic ulcers[54]. Diagnosis is often noninvasive through the measurement of the ankle brachial index (ABI), which is calculated as the blood pressure in the posterior tibialis artery or the dorsalis pedis artery divided by the blood pressure in the brachial artery, with an ABI < 0.9 generally considered diagnostic[55].

Peripheral arterial disease is associated with higher cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and shares risk factors with coronary artery disease, including age, male sex, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes mellitus[54]. Yet, the underlying mechanisms likely differ, as myocardial infarctions are generally caused by thrombosis in a vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque, whereas in peripheral arterial disease thrombosis may occur independently of the extent of atherosclerosis[56,57]. Thus, it is not a given that high lipoprotein(a) is a risk factor for peripheral arterial disease to the same extent as for myocardial infarction.

4.2 Lipoprotein(a) as a causal risk factor for peripheral arterial disease

Multiple studies have investigated the relationship between high lipoprotein(a) and the risk of peripheral arterial disease[58]. While most earlier investigations were limited by small sample sizes or cross-sectional designs, they generally supported an association between high lipoprotein(a) and increased risk of peripheral arterial disease[28,29,58]. The largest of these, conducted in 283,540 cardiovascular disease-free participants from the UK Biobank, found that each 120 nmol/L (~57 mg/dL) higher plasma lipoprotein(a) was associated with a hazard ratio of 1.25 (95% CI: 1.19-1.31) for peripheral arterial disease[59]. Given that individuals with the highest lipoprotein(a) levels experience substantially greater ASCVD risk, it is essential to analyse lipoprotein(a) stratified into separate risk categories for the highest levels[28,29]. Therefore, we assessed the association between high lipoprotein(a) and peripheral arterial disease in 70,317 participants from the Copenhagen General Population Study, categorizing lipoprotein(a) into predefined percentile groups: < 50th, 50th– < 75th, 76th – < 95th, 96th– < 99th, and ≥ 99th[29]. We observed a stepwise increase in risk with higher lipoprotein(a), with a multivariable-adjusted hazard ratio of 2.99 (95% CI: 2.09-4.30) for those at or above the 99th percentile compared with those below the 50th percentile (Figure 4). These findings were corroborated by cross-sectional analyses, in which peripheral arterial disease was defined by an ankle-brachial index < 0.9 or self-reported claudication, yielding corresponding odds ratios of

Figure 4. Risk of peripheral arterial disease by lipoprotein(a) and LPA Kringle IV type 2 number of repeats. Multivariable (observational estimates) and age and sex (genetic estimates) adjusted Cox regression analyses. Lipoprotein(a) values according to genotype are median and interquartile range. Based on individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study. Republished with permission from[29]. CI: Confidence interval.

Next, in genetic analyses using LPA KIV-2 number of repeats, hazard ratios were 1.39 (95% CI: 1.17-1.64) for LPA KIV-2 repeats < 5th percentile (associated with high lipoprotein(a) levels) versus LPA KIV-2 repeats > 50th percentile (associated with low lipoprotein(a) levels) (Figure 4). Further, in instrumental variable analyses, a 50 mg/dL (105 nmol/L) genetically determined higher lipoprotein(a) was associated with a causal risk ratio of 1.39 (1.24-1.56). These genetic findings were supported by similar previous findings from studies of the UK Biobank and the Million Veterans Program[60,61].

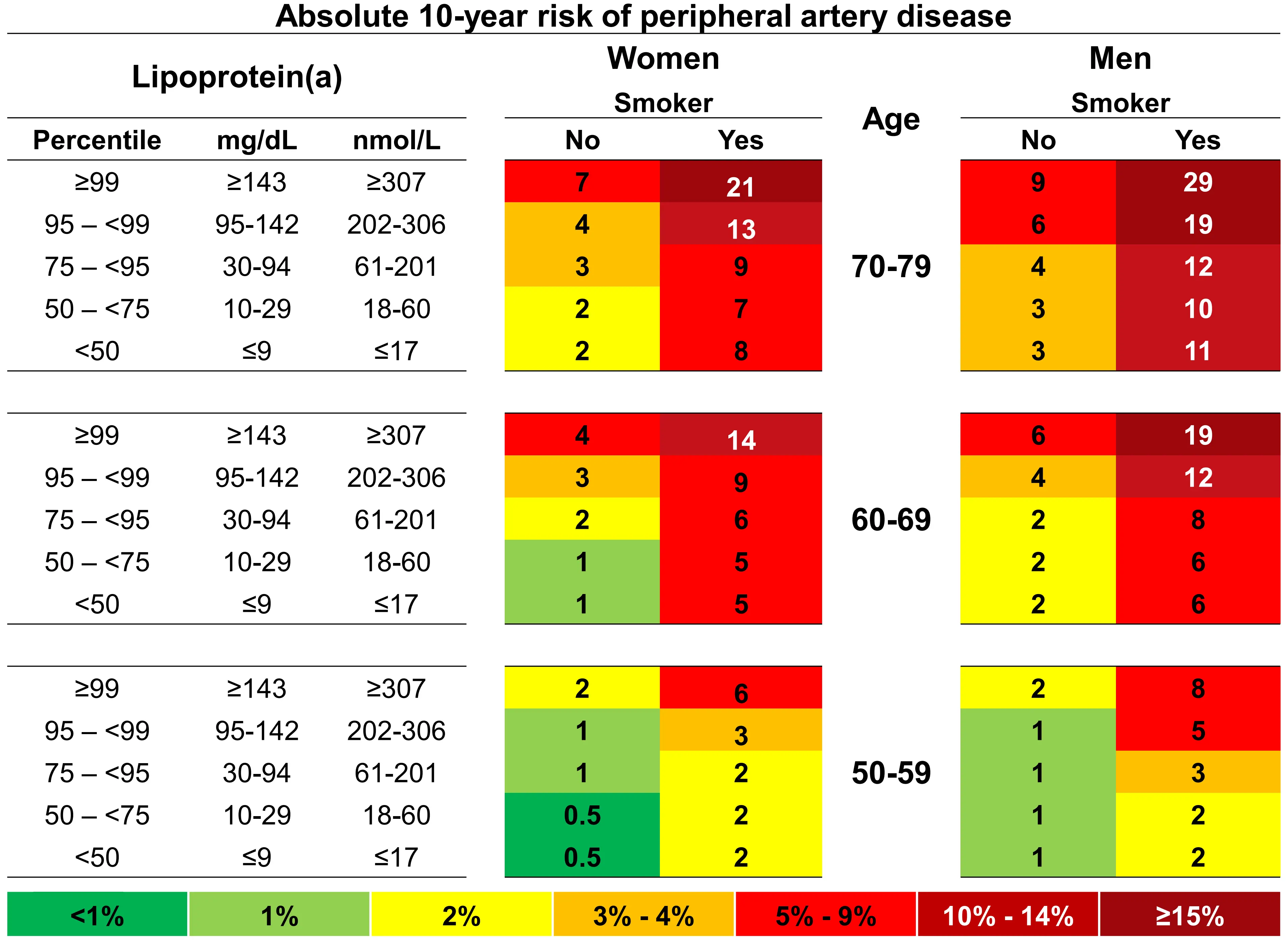

Finally, we estimated 10-year absolute risks of peripheral arterial disease stratified by age, sex, and smoking status (Figure 5). In women smokers, aged 70 to 79 years with lipoprotein(a) < 50th and ≥ 99th percentile, absolute 10-year risks of peripheral arterial disease were 8% and 21%, and equivalent risks in men were 11% and 29%.

Figure 5. 10-year absolute risk of peripheral arterial disease by lipoprotein(a), age, sex and smoking status. Risk estimates are based on Fine and Gray competing risk models with categories of age, sex, lipoprotein(a), and smoking status. Based on individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study. Republished with permission from[29].

In summary, there is strong evidence from both observational and genetic epidemiology that high lipoprotein(a) is a causal risk factor for peripheral arterial disease. However, some individuals with peripheral arterial disease progress to chronic limb-threatening ischemia, which may require lower extremity amputation and/or revascularization, also known as major adverse limb events[53,54].

4.3 Lipoprotein(a) as a risk factor for major adverse limb events

Approximately 1-3% of individuals with peripheral arterial disease eventually progress to requiring lower extremity revascularizations or amputations, and many individuals require multiple procedures[57]. These procedures are associated with substantial morbidity and mortality and are costly, both in terms of direct surgical costs and associated economic costs in the form of disabilities and loss of ability to work[1,53,54].

High lipoprotein(a) could contribute to the progression of peripheral arterial disease to major adverse limb events through a prothrombotic effect, in accordance with the idea that high lipoprotein(a) may indirectly lead to thrombus growth through inhibition of thrombolysis and fibrinolysis[8,11,34-36]. Nonetheless, most previous studies on lipoprotein(a) and risk of major adverse limb events were small and/or cross-sectional and conducted in hospitalized patients with peripheral arterial disease[28]. Thus, in a study of 16,513 hospitalized patients, of which 572 developed major adverse limb events during follow-up, individuals with lipoprotein(a) > 95th percentile had higher risks of major adverse limb events when compared with individuals with lipoprotein(a) < 50 mg/dL[62]. Similarly, in 1,472 patients with peripheral arterial disease, individuals with lipoprotein(a) > 30 mg/dL versus < 30 mg/dL had a greater requirement for peripheral arterial disease operations (hazard ratio: 1.20 [95% CI: 1.02-1.41]) and lower limb revascularization (hazard ratio: 1.33 [1.06-1.66])[63]. These findings were supported in other smaller studies[64-67].

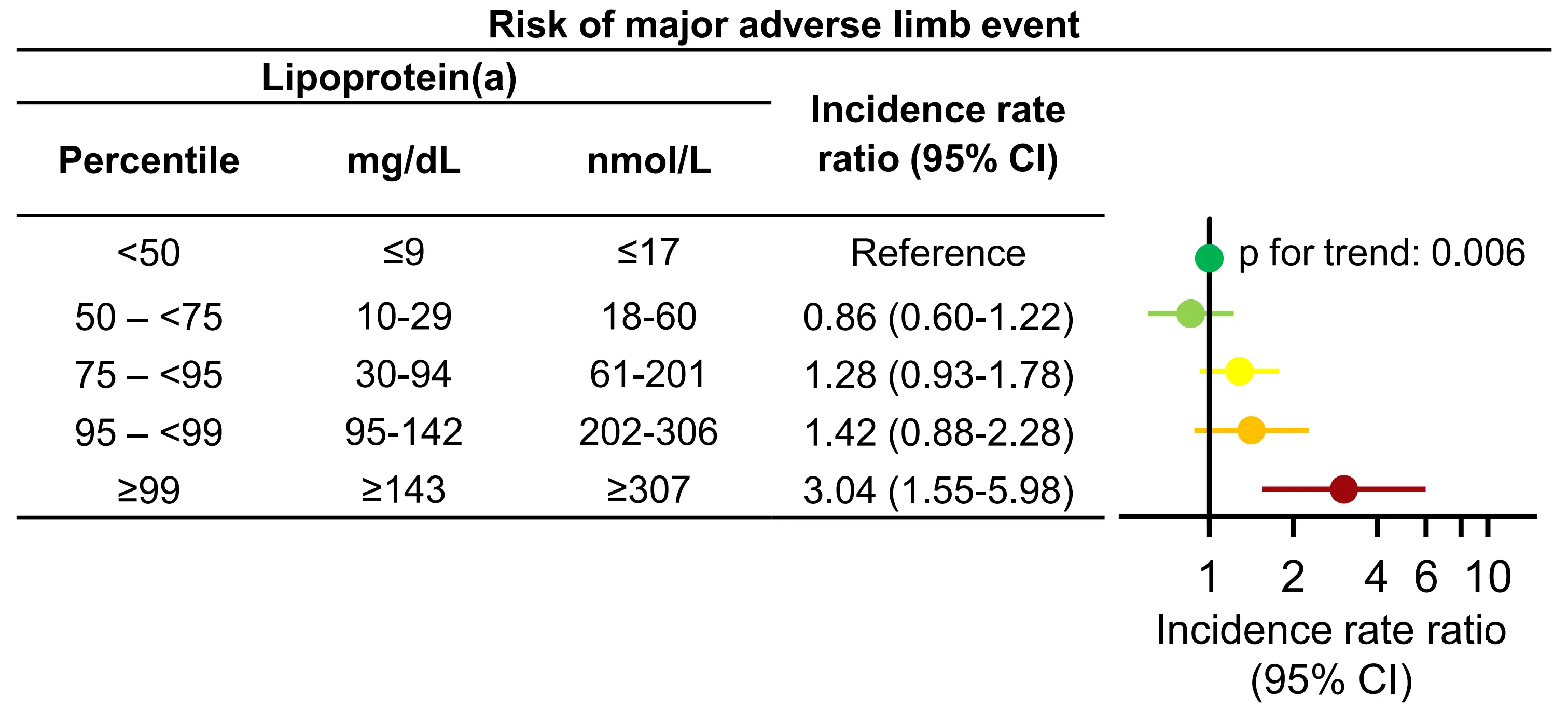

The strongest evidence from a general population cohort came from combined analyses of individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study and the Copenhagen City Heart Study with peripheral arterial disease (N = 4,747)[29]. Here, high lipoprotein(a) was associated with a stepwise higher incidence rate ratio for major adverse limb events (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Risk of major adverse limb events by lipoprotein(a) in individuals with peripheral artery disease. Multivariable adjusted Poisson regression. Based on individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study and the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Republished with permission from[29]. CI: Confidence interval.

In individuals with lipoprotein(a) > 99th versus < 50th percentile, incidence rate ratios were 3.04 (95% CI: 1.55-5.98) for major adverse limb events. Notably, individuals could have multiple major adverse limb events during follow-up, as often seen for this patient

Taken together, despite major adverse limb events being rare in the general population[53,54], there is evidence from multiple cohort studies implicating high lipoprotein(a) as a risk factor for the progression of peripheral arterial disease to major adverse limb events.

5. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm

5.1 Clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and epidemiology

Abdominal aortic aneurysms are focal dilations of the abdominal aorta > 50% greater than the normal diameter (typically > 3 cm)[69]. They are caused by the degradation of the arterial vascular wall and subsequent decrease in wall strength, and aneurysms therefore tend to get larger with age[70]. It is a relatively common disease, with an estimated prevalence of 7% in individuals above age 50[71], but most individuals have no symptoms, and diagnosis is therefore often an incidental finding following radiography of the abdomen[69]. Risk factors include age, male sex, smoking, family history, and hypertension, and the main complication is the risk of aortic rupture, with a mortality of more than 50%[71]. The risk of rupture is dependent mainly on the size of the aneurysm, but smokers, individuals with hypertension, and women have a higher rupture risk[69].

Thus, while there is a considerable overlap of the risk factors for ASCVD and abdominal aortic aneurysms, atherosclerosis per se is not sufficient to cause abdominal aortic aneurysms[70]. Nevertheless, high lipoprotein(a) could contribute to abdominal aortic aneurysm development through both prothrombotic, proatherosclerotic and proinflammatory mechanisms[28,70].

5.2 Lipoprotein(a) as a causal risk factor for abdominal aortic aneurysms

The association of high lipoprotein(a) with the risk of abdominal aortic aneurysms has been less investigated than for other cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial infarction or peripheral arterial disease[28]. Nevertheless, in a study from the UK Biobank, a 50 mg/dL higher genetically predicted lipoprotein(a) was associated with an odds ratio of 1.42 (95% CI: 1.28-1.59) for abdominal aortic aneurysms[61]. Additionally, in a Mendelian randomization analysis of the UK Biobank and the Million Veterans Program cohorts combined, a 1-SD higher genetically determined lipoprotein(a) was associated with an odds ratio for aortic aneurysms of 1.28

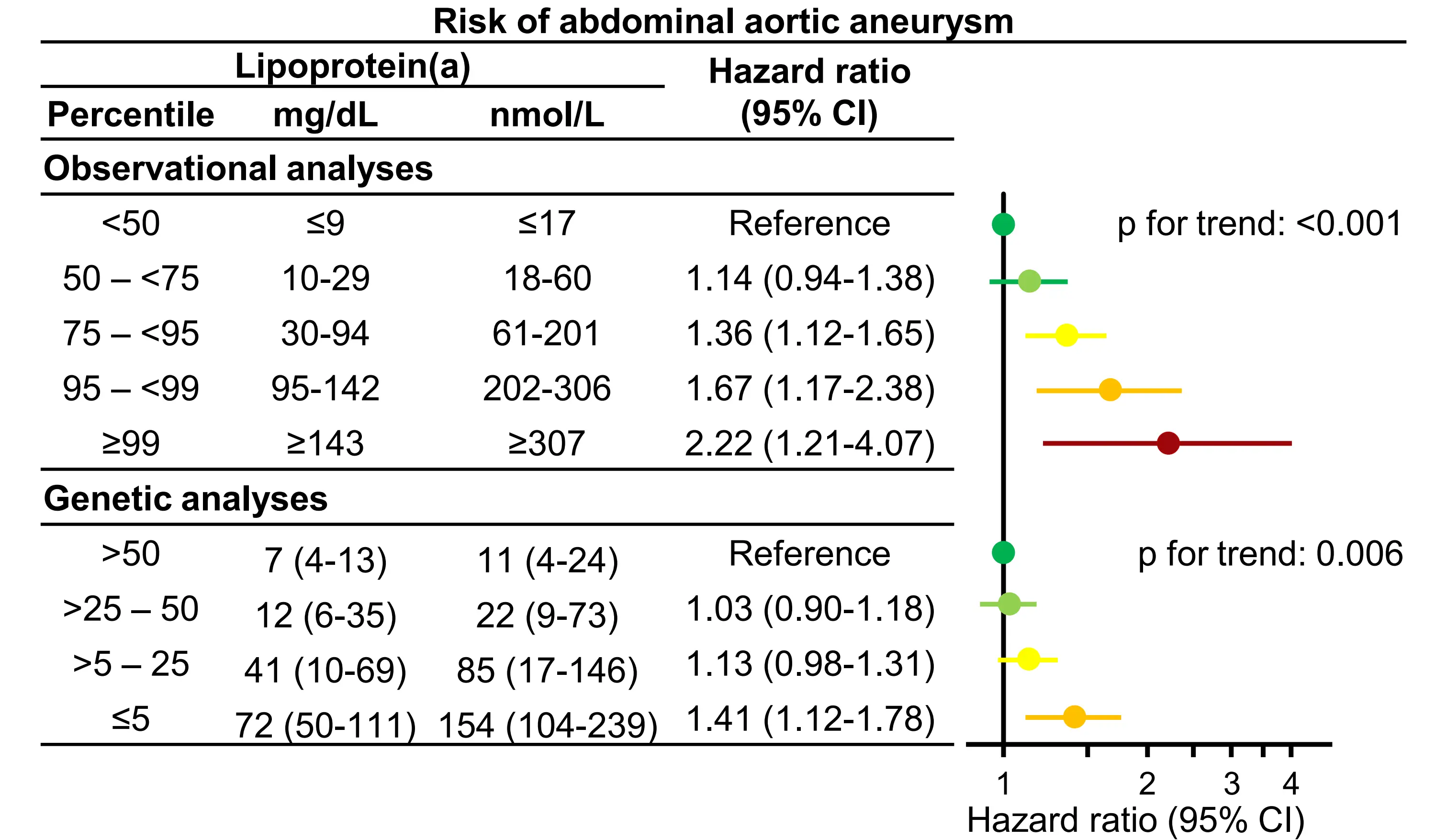

Yet, the strongest evidence for lipoprotein(a) as a causal risk factor for abdominal aortic aneurysms comes from data based on the Copenhagen General Population Study[29]. In the study, we used similar categories for lipoprotein(a) as those previously presented for peripheral arterial disease and found a stepwise higher risk of abdominal aortic aneurysms with higher lipoprotein(a) (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Risk of abdominal aortic aneurysms by lipoprotein(a) and LPA Kringle IV type 2 number of repeats. Multivariable (observational estimates) and age and sex (genetic estimates) adjusted Cox regression analyses. Lipoprotein(a) values according to genotype are median and interquartile range. Based on individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study. Republished with permission from[29]. CI: Confidence interval.

Thus, multivariable adjusted hazard ratios were 2.22 (95% CI: 1.21-4.07) for lipoprotein(a) ≥ 99th versus < 50th percentile and were, in genetic analyses, 1.41 (1.12-1.78) for KIV-2 repeats < 5th versus KIV-2 repeats > 50th percentile. Finally, in instrumental variable analyses, a 50 mg/dL (105 nmol/L) higher genetically determined lipoprotein(a) was associated with a causal risk ratio of

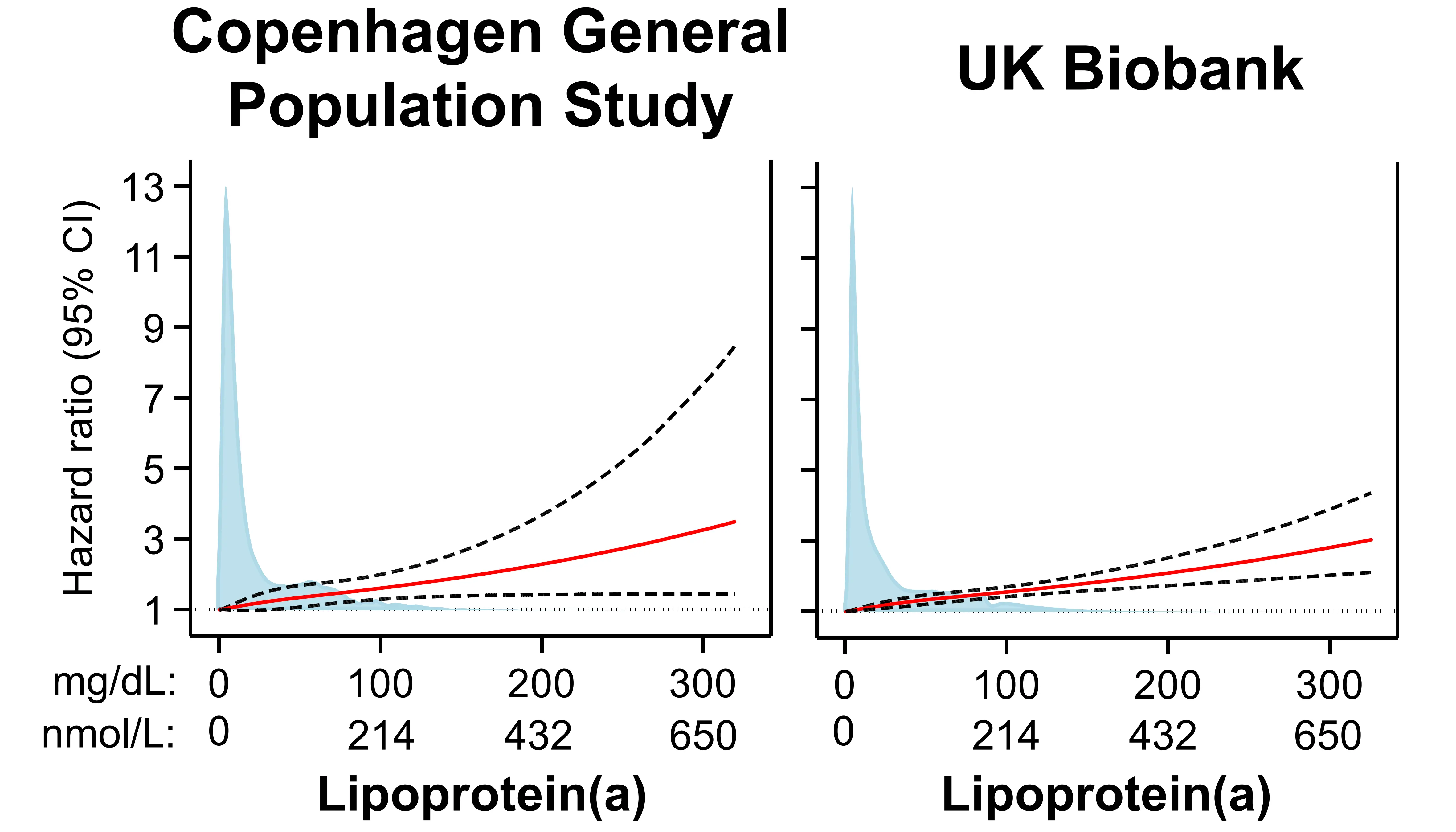

We additionally published estimates for lipoprotein(a) and risks of abdominal aortic aneurysms based on data from the UK Biobank and reported similar findings to those from the Copenhagen General Population Study (Figure 8)[28].

Figure 8. Risk of abdominal aortic aneurysms by plasma lipoprotein(a) in the Copenhagen General Population Study and the UK Biobank. Restricted cubic splines using multivariable adjusted Cox proportional hazards regressions with hazard ratios (solid red line) and 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines). Density plots of population distribution (blue) are made as kernel density estimation. Republished with permission from[28].CI: Confidence interval.

Taken together, there is strong evidence from multiple cohorts using both observational and genetic epidemiology that high lipoprotein(a) is a causal risk factor also for abdominal aortic aneurysms.

6. Aortic Valve Stenosis

6.1 Clinical presentation, pathophysiology and epidemiology

Aortic valve stenosis is the most common cause of left ventricular outflow obstruction[74], with the three principal causes being: 1) rheumatic valve disease, following acute rheumatic fever; 2) stenosis and calcification of a congenitally abnormal valve (often bicuspid); and 3) progressive calcification of a tricuspid valve. Calcific aortic valve stenosis is by far the most common form in Western countries, and only calcific aortic disease is therefore the focus of the present review[75].

Calcific aortic valve disease is a degenerative disease that progresses with age and where individuals with congenital anomalies generally progress faster[74]. The natural history of the disease begins with aortic valve thickening, termed aortic valve sclerosis, where there are no hemodynamic effects, which eventually progresses to mild symptomatic/asymptomatic stenosis and subsequently to severe symptomatic stenosis. Late-stage symptoms include dyspnea, heart failure, chest pain, and syncope, but most patients are initially asymptomatic or have mild symptoms at diagnosis[74,76]. Treatment is limited to surgical intervention, including transcatheter aortic valve implantation[76], and while treatment is largely successful in patients who have not yet developed heart failure, identifying modifiable risk factors prior to symptom manifestation would allow for primary prevention, hereby reducing the need for surgery.

Established risk factors overlap with those of ASCVD, and include age, male sex, hypertension, smoking, and obesity[77-79]. Furthermore, both plasma and genetically determined high LDL cholesterol are associated with an increased risk of aortic valve stenosis[80-82], though randomized trials of statins have been unable to reduce the risk of aortic valve stenosis progression[77]. Nonetheless, it remains unclear if lowering LDL cholesterol may reduce the risk of aortic valve stenosis development.

In summary, as risk factors for ASCVD and aortic valve stenosis overlap and high LDL cholesterol is a probable risk factor, investigating the association of high lipoprotein(a) with risk of aortic valve stenosis is meaningful.

6.2 Lipoprotein(a) as causal a risk factor for aortic valve stenosis

Early cross-sectional studies indicated that high lipoprotein(a) could be a risk factor for aortic valve stenosis, but it was not until a 2013 publication by Thanassoulis et al. that high lipoprotein(a) was firmly established as a causal risk factor for aortic valve

Figure 9. Risk of aortic valve stenosis by plasma lipoprotein(a) in the Copenhagen General Population Study[30]. Restricted cubic splines using multivariable adjusted Cox proportional hazards regressions with hazard ratios (solid red line) and 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines). Density plots of population distribution (blue) are made as kernel density estimation. CI: Confidence interval.

There is thus strong evidence from both genetic and observational epidemiology that high lipoprotein(a) is a risk factor for aortic valve stenosis.

More recently, high lipoprotein(a) has also been implicated as a risk factor for aortic valve disease progression, and a clinical trial investigating the potential of reducing the progression of aortic valve stenosis by lowering lipoprotein(a) with the antisense oligonucleotide pelacarsen has been initiated (NCT05646381)[84].

7. Systemic Low-Grade Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease

Systemic low-grade inflammation is now firmly established as a key contributor to the pathogenesis of ASCVD[85,86]. High-sensitivity

We recently reaffirmed these findings using data from the Copenhagen General Population Study, demonstrating an association between elevated hsCRP and risk of ASCVD[30]. Notably, elevated hsCRP was also associated with an increased risk of aortic valve stenosis, a novel finding, emphasizing that the impact of systemic inflammation extends beyond classical ASCVD.

Together, these studies, and others, confirm systemic low-grade inflammation as a modifiable risk factor and potential therapeutic target in cardiovascular disease prevention and management[91]. Nonetheless, the joint effects of systemic low-grade inflammation and lipoprotein(a) on risks of cardiovascular disease have been the subject of considerable debate[31,92].

7.1 Effect modification of lipoprotein(a)-associated risk of cardiovascular disease by systemic low-grade inflammation

Whether systemic low-grade inflammation modifies the risk of ASCVD from high lipoprotein(a) has important implications for cardiovascular risk stratification and for the therapeutic targeting of future lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapy[92]. Thus, while inflammation and lipoprotein(a) both contribute to ASCVD development, the extent of their interaction is debated[31,92].

The hypothesis that high lipoprotein(a) confers cardiovascular risk only in individuals with concomitant systemic low-grade inflammation was proposed based on secondary analyses from the ACCELERATE trial[93]. In the study of 10,503 statin-treated individuals with established cardiovascular disease, high lipoprotein(a) was only associated with risk of ASCVD in individuals with concomitant hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L, suggesting that lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapy may only benefit those with concurrent systemic

A similar finding was observed in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (N = 4,679; ASCVD = 684), where high lipoprotein(a) predicted incident cardiovascular disease only in those with hsCRP ≥ 2 mg/L[94]. These findings, now also from a primary prevention cohort, further supported the interaction hypothesis.

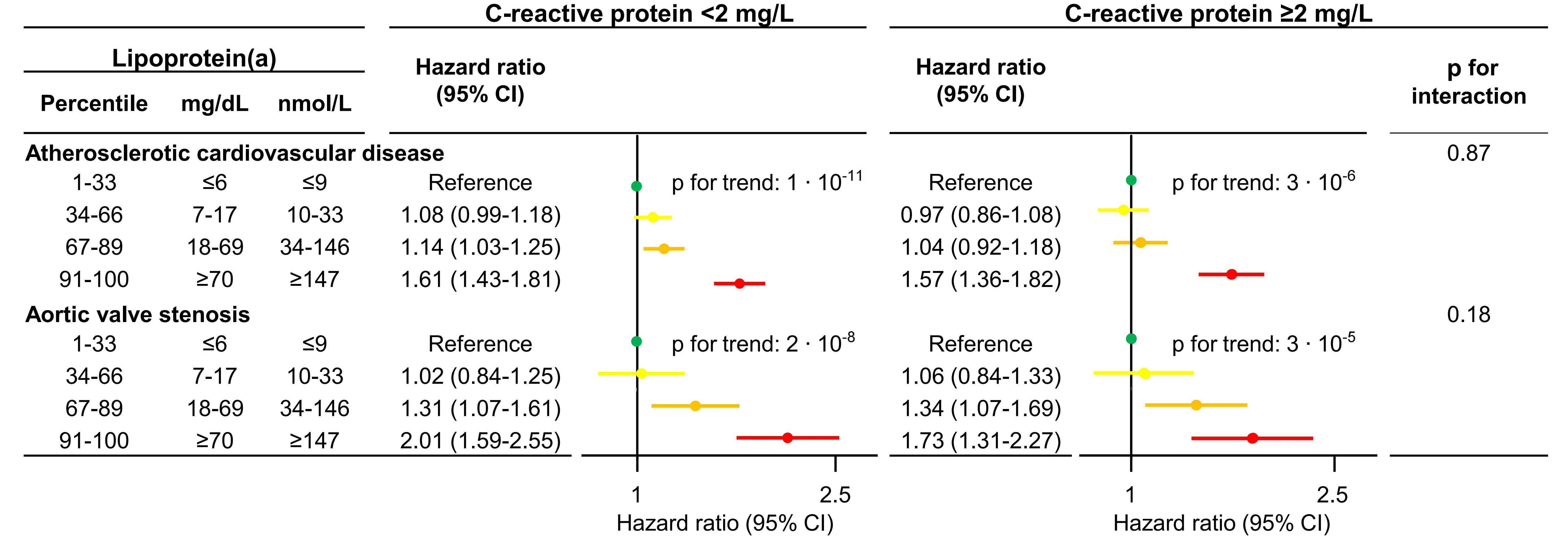

However, in 68,090 individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study (ASCVD = 5,104), high lipoprotein(a) was consistently associated with ASCVD and aortic valve stenosis across all hsCRP levels, with no significant interaction observed (Figure 10)[30].

Figure 10. Risk of ASCVD and aortic valve stenosis by categories of lipoprotein(a) stratified by levels of C-reactive protein[30]. Multivariable adjusted Cox regression, Interactions were tested for by continuous values of both lipoprotein(a) and C-reactive protein. Based on individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study.

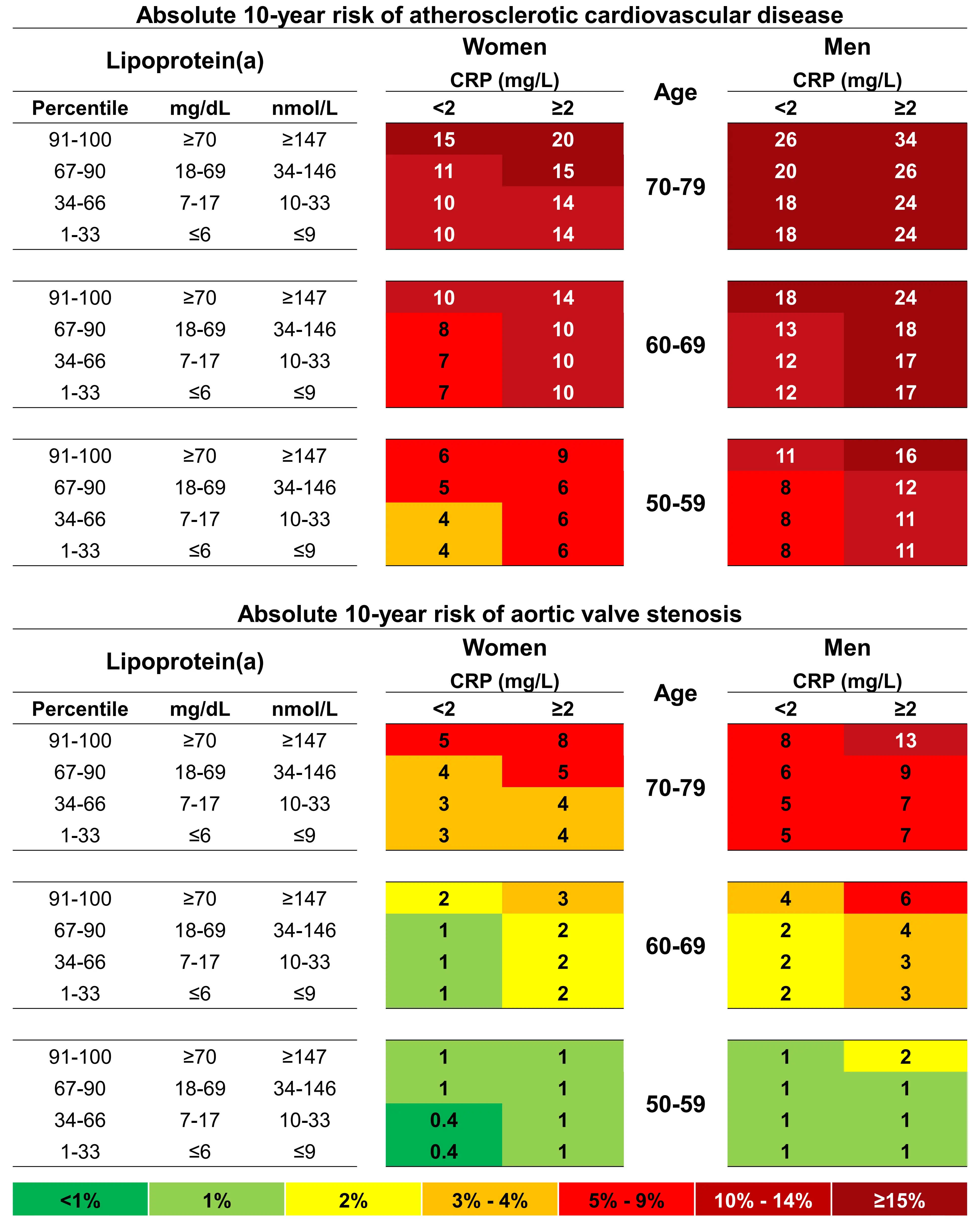

In this, the largest study to date at that time, we provided strong evidence that systemic low-grade inflammation does not modify the cardiovascular risk conferred by high lipoprotein(a). As expected, we did find that individuals with concomitant elevations of both lipoprotein(a) and hsCRP had the highest absolute risks of ASCVD and aortic valve stenosis, indicating that these individuals may gain the most benefit from future lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapies (Figure 11).

Figure 11. 10-year absolute risk of ASCVD and aortic valve stenosis by lipoprotein(a), age, sex and C-reactive protein[30]. Risk estimates are based on Fine and Gray competing risk models with categories of age, sex, lipoprotein(a), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. Based on individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study.

Our findings were subsequently supported by a pooled analysis of eight European cohort studies, which showed similar results in primary prevention[95]. However, in secondary prevention in individuals with low hsCRP, there was no statistically significant association for recurrent ASCVD for the top vs. bottom lipoprotein(a) quintiles (HR 1.29; 95% CI 0.98-1.71). Further, a study by

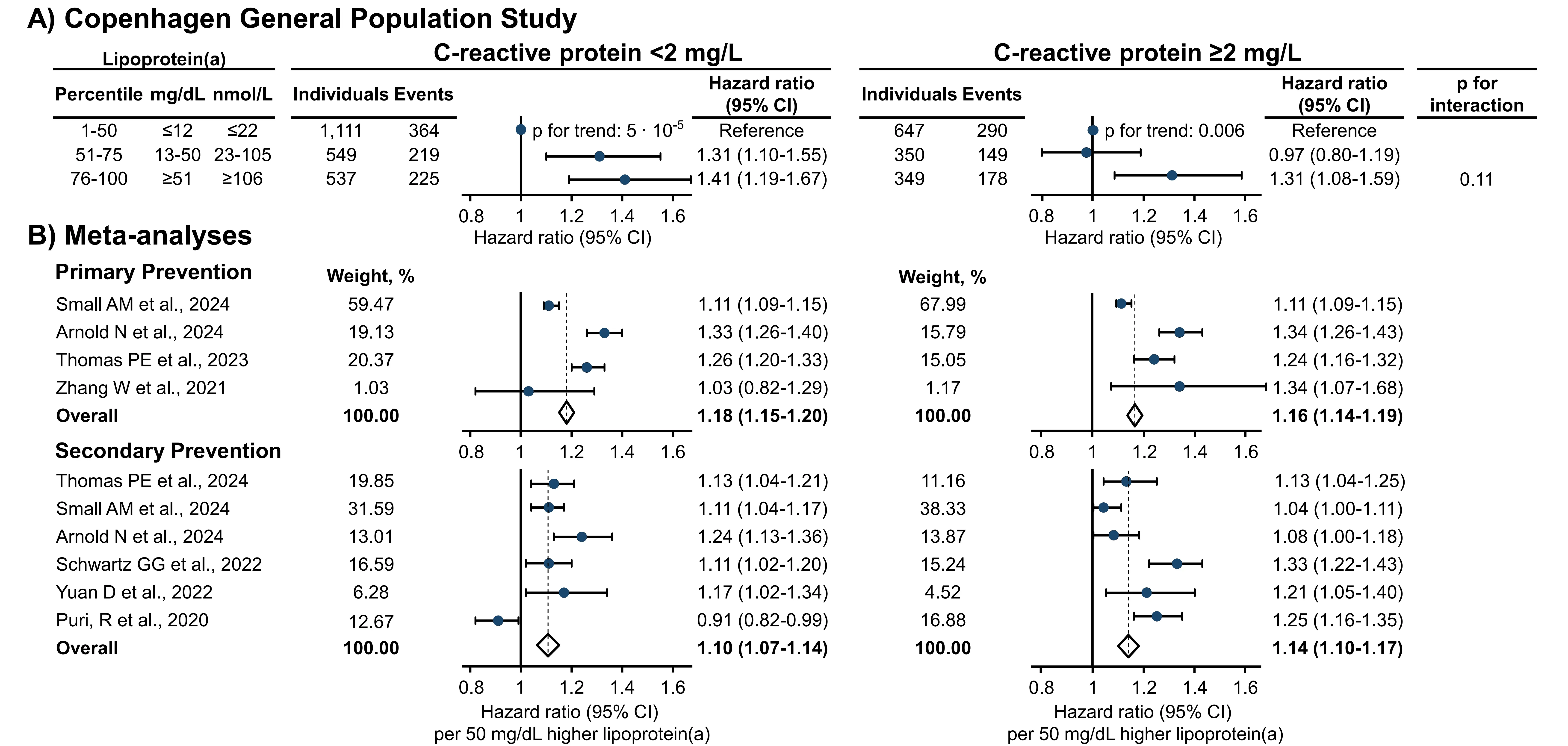

To address these inconsistencies, we conducted a second investigation within the Copenhagen General Population Study to assess whether the cardiovascular risk associated with high lipoprotein(a) persists independently of hsCRP levels in individuals with established cardiovascular disease[31]. In parallel, we conducted a meta-analysis of existing studies evaluating the association between high lipoprotein(a) and ASCVD risk stratified by hsCRP levels, encompassing both primary and secondary prevention populations. Findings from both analyses indicated that high lipoprotein(a) confers increased cardiovascular risk irrespective of the degree of low-grade inflammation (Figure 12). A subsequent meta-analysis conducted by another group reported similar results[92].

Figure 12. Risk of ASCVD by high lipoprotein(a) stratified by high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels[31]. (A) Multivariable adjusted Cox regression analyses with interactions tested for by using likelihood ratio testing and continuous values of both lipoprotein(a) and C-reactive protein. Based on individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study with ASCVD prior to baseline; (B) Meta-analyses of studies in primary and secondary prevention settings on the risk of ASCVD per 50 mg/dL higher lipoprotein(a) levels stratified by C-reactive protein. CI: Confidence interval; ASCVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

In summary, although both systemic low-grade inflammation and high lipoprotein(a) are important contributors to cardiovascular risk, current evidence shows that lipoprotein(a)-associated risk is independent of hsCRP in both primary and secondary prevention. Thus, if lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapies are shown to reduce cardiovascular events, their benefit is likely to extend across levels of low-grade systemic inflammation, though individuals with concomitant high lipoprotein(a) and systemic low-grade inflammation have the potential to achieve the highest absolute risk reductions.

8. Conclusion

High lipoprotein(a) is now firmly established as a causal and independent risk factor for ASCVD. Genetic and observational evidence consistently demonstrate an association between higher plasma concentrations of lipoprotein(a) and increased risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and aortic valve stenosis[8]. Importantly, clinical trials targeting lipoprotein(a) with highly potent lowering therapies are ongoing, aiming to evaluate whether reducing lipoprotein(a) concentrations can decrease cardiovascular events in primarily secondary prevention[23-27]. As these therapies approach potential clinical introduction, several key questions have arisen concerning their therapeutic scope and optimal use.

First, the burden of atherosclerotic disease extends beyond the coronary and cerebral arteries. In the present review, we summarize the evidence of high lipoprotein(a) as a likely causal risk factor also for peripheral arterial disease, major adverse limb events, and abdominal aortic aneurysms[29]. Findings from the Copenhagen General Population Study, along with supporting findings from other studies as presented in Table 1, suggest a broader spectrum of vascular conditions where future lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapy may be beneficial[28].

| Study design | Peripheral artery disease | Abdominal aortic aneurysm | Major adverse limb event |

| Case-control or cross-sectional studies | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Large prospective observational studies | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Meta-analyses of prospective observational studies | Not examined | Not examined | Not examined |

| Large genome-wide association studies | Yes | Yes | Not examined |

| Large Mendelian randomization studies | Yes | Yes | Not examined |

| Randomized double-blind Lp(a) lowering trials | Not examined | Not examined | Not examined |

In particular, given the high morbidity and cost associated with peripheral arterial disease and subsequent major adverse limb

Second, another priority is to define which patients are most likely to benefit from lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapy. While international guidelines increasingly recommend lipoprotein(a) measurement for risk stratification[7,17-22,42], patient selection for future treatment remains uncertain. There is now a preponderance of evidence that high lipoprotein(a) is associated with risk of ASCVD independently of systemic low-grade inflammation, as measured by elevated hsCRP. However, individuals with concomitant elevations of both lipoprotein(a) and hsCRP appear to have the highest absolute risks of ASCVD and aortic valve stenosis. This suggests that, while systemic low-grade inflammation does not modify the relative risk conferred by high lipoprotein(a), it contributes to absolute risk of ASCVD and aortic valve stenosis and may help identify individuals who could benefit the most from future therapies.

In conclusion, current evidence strongly supports high lipoprotein(a) as a key therapeutic target for cardiovascular risk reduction. As phase 3 outcome trials progress, attention must also turn to refining treatment indications and maximizing clinical benefit. Future studies should explore the efficacy of lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapies for peripheral arterial disease and major adverse limb events, and further define subgroups most likely to derive benefit. Ultimately, whether high lipoprotein(a) can be integrated into clinical treatment requires confirmation of cardiovascular risk reduction from specific lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapies; results of ongoing phase 3 trials are therefore eagerly awaited.

Acknowledgments

We thank participants, staff, and funders of the Copenhagen General Population Study, the Copenhagen City Heart Study, and UK Biobank for their important work and contributions. Figures were made partly using Biorender.com.

Authors contribution

Thomas PE: Conceptualization, project administration, validation, writing-original draft.

Vedel-Krogh S, Kamstrup PR: Conceptualization, writing-review & editing.

Nordestgaard BG: Conceptualization, supervision, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Peter E. Thomas has received lecture honoraria from Amgen and Novo Nordisk. Børge G. Nordestgaard has received lecture honoraria or consultancies with Abbott, Akcea, Amarin, Amgen, Arrowhead, AstraZeneca, Denka, Esperion, Kowa, Lilly, Mankind, Marea Therapeutics, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Regeneron, Sanofi, Silence Therapeutics, and Ultragenyx. Pia R. Kamstrup has received lecture honoraria or consultancies from the American Heart Association, Physicians’ Academy for Cardiovascular Education, PCSK9 Forum, MedScape, Silence Therapeutics, Novartis, Amgen, and Lilly. Signe Vedel-Krogh reports no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was founded by Copenhagen University Hospital - Herlev and Gentofte, Gangstedfonden, and supported by a research grant from the Danish Cardiovascular Academy (Grant No 2022007-HF), which is funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation (Grant No. NNF20SA0067242) and The Danish Heart Foundation (Grant No. 2022007-HF).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Mensah GA, Fuster V, Murray CJL, Roth GA. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and risks, 1990-2022. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82:2350-2473.[DOI]

-

2. Libby P, Buring JE, Badimon L, Hansson GK, Deanfield J, Bittencourt MS, et al. Atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:56.[DOI]

-

3. Borén J, Packard CJ, Binder CJ. Apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins in atherogenesis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2025;22:399-413.[DOI]

-

4. Ference BA, Ginsberg HN, Graham I, Ray KK, Packard CJ, Bruckert E, et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2459-2472.[DOI]

-

5. Chou R, Cantor A, Dana T, Wagner J, Ahmed AY, Fu R, et al. Updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2022;328(8):754-771.[DOI]

-

6. Global Cardiovascular Risk Consortium. Global effect of modifiable risk factors on cardiovascular disease and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1273-1285.[DOI]

-

7. Kronenberg F, Mora S, Stroes ES, Ference BA, Arsenault BJ, Berglund L, et al. Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: A European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:3925-3946.[DOI]

-

8. Nordestgaard BG, Langsted A. Lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2024;404:1255-1264.[DOI]

-

9. Schmidt K, Noureen A, Kronenberg F, Utermann G. Structure, function, and genetics of lipoprotein (a). J Lipid Res. 2016;57(8):1339-1359.[DOI]

-

10. Kamstrup PR. Lipoprotein (a) and cardiovascular disease. Clin Chem. 2021;67:154-166.[DOI]

-

11. Nordestgaard BG, Langsted A. Lipoprotein (a) as a cause of cardiovascular disease: insights from epidemiology, genetics, and biology. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:1953-1975.[DOI]

-

12. Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, Kyriakou T, Goel A, Heath SC, et al. Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2518-2528.[DOI]

-

13. Danesh J, Collins R, Peto R. Lipoprotein(a) and coronary heart disease: Meta-analysis of prospective studies. Circulation. 2000;102:1082-1085.[DOI]

-

14. Kamstrup PR, Benn M, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Extreme lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of myocardial infarction in the general population: The Copenhagen City Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:176-184.[DOI]

-

15. Kamstrup PR, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Steffensen R, Nordestgaard BG. Genetically elevated lipoprotein(a) and increased risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2009;301:2331-2339.[DOI]

-

16. Langsted A, Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG. High lipoprotein(a) and high risk of mortality. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:2760-2770.[DOI]

-

17. Koschinsky ML, Bajaj A, Boffa MB, Dixon DL, Ferdinand KC, Gidding SS, et al. A focused update to the 2019 NLA scientific statement on use of lipoprotein(a) in clinical practice. J Clin Lipidol. 2024;18(3):e308-e319.[DOI]

-

18. Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, Badimon L, et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk: The Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J. 2020;41:111-188.[DOI]

-

19. Pearson GJ, Thanassoulis G, Anderson TJ, Barry AR, Couture P, Dayan N, et al. 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37:1129-1150.[DOI]

-

20. Ward NC, Watts GF, Bishop W, Colquhoun D, Hamilton-Craig C, Hare DL, et al. Australian Atherosclerosis Society Position Statement on lipoprotein (a): Clinical and implementation recommendations. Heart Lung Circ. 2023;32:287-296.[DOI]

-

21. Reyes-Soffer G, Ginsberg HN, Berglund L, Duell PB, Heffron SP, Kamstrup PR, et al. Lipoprotein (a): A genetically determined, causal, and prevalent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022;42(1):e48-e60.[DOI]

-

22. Mach F, Koskinas KC, Roeters van Lennep JE, Tokgözoğlu L, Badimon L, Baigent C, et al. 2025 Focused Update of the 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Developed by the task force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). European Heart Journal. 2025;46(42):4359-4378.[DOI]

-

23. Nicholls SJ, Ni W, Rhodes GM, Nissen SE, Navar AM, Michael LF, et al. Oral muvalaplin for lowering of lipoprotein (a): A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2024;333(3):222-231.[DOI]

-

24. Nissen SE, Linnebjerg H, Shen X, Wolski K, Ma X, Lim S, et al. Lepodisiran, an extended-duration short interfering RNA targeting lipoprotein (a): A randomized dose-ascending clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330:2075-2083.[DOI]

-

25. Nissen SE, Wang Q, Nicholls SJ, Navar AM, Ray KK, Schwartz GG, et al. Zerlasiran—a small-interfering RNA targeting lipoprotein (a): a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2024;332(23):1992-2002.[DOI]

-

26. O’Donoghue ML, Rosenson RS, Gencer B, López JAG, Lepor NE, Baum SJ, et al. Small interfering RNA to reduce lipoprotein(a) in cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1855-1864.[DOI]

-

27. Tsimikas S, Karwatowska-Prokopczuk E, Gouni-Berthold I, Tardif JC, Baum SJ, Steinhagen-Thiessen E, et al. Lipoprotein(a) reduction in persons with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:244-255.[DOI]

-

28. Thomas PE, Vedel-Krogh S, Kamstrup PR. High lipoprotein(a) is a risk factor for peripheral artery disease, abdominal aortic aneurysms, and major adverse limb events. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2024;39:511-519.[DOI]

-

29. Thomas PE, Vedel-Krogh S, Nielsen SF, Nordestgaard BG, Kamstrup PR. Lipoprotein (a) and risks of peripheral artery disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and major adverse limb events. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82:2265-2276.[DOI]

-

30. Thomas PE, Vedel-Krogh S, Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG. Lipoprotein(a) is linked to atherothrombosis and aortic valve stenosis independent of C-reactive protein. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:1449-1460.[DOI]

-

31. Thomas PE, Vedel-Krogh S, Afzal S, Nordestgaard BG, Kamstrup PR. Lipoprotein(a)-associated risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is independent of C-reactive protein. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2024;32(9):783-785.[DOI]

-

32. Berg K. new serum type system in man—the Lp system. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1963;59(3):369-382.[DOI]

-

33. McLean JW, Tomlinson JE, Kuang WJ, Eaton DL, Chen EY, Fless GM, et al. cDNA sequence of human apolipoprotein(a) is homologous to plasminogen. Nature. 1987;330:132-137.[DOI]

-

34. Boffa MB. Beyond fibrinolysis: The confounding role of Lp(a) in thrombosis. Atherosclerosis. 2022;349:72-81.[DOI]

-

35. Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Teaching old dogmas new tricks. Nature. 1987;330:113-114.[DOI]

-

36. Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Lipoprotein (a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. JAMA. 2009;302(4):412-423.[DOI]

-

37. Bay Simony S, Rørbæk Kamstrup P, Bødtker Mortensen M, Afzal S, Grønne Nordestgaard B, Langsted A. High lipoprotein (a) as a cause of kidney disease: a population-based mendelian randomization study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;84:2407-2410.[DOI]

-

38. Strandkjær N, Hansen MK, Nielsen ST, Frikke-Schmidt R, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG, et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels at birth and in early childhood: The COMPARE study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(2):324-335.[DOI]

-

39. Simony SB, Mortensen MB, Langsted A, Afzal S, Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG. Sex differences of lipoprotein(a) levels and associated risk of morbidity and mortality by age: The Copenhagen General Population Study. Atherosclerosis. 2022;355:76-82.[DOI]

-

40. Patel AP, Wang M, Pirruccello JP, Ellinor PT, Ng K, Kathiresan S, et al. Lp (a)(lipoprotein [a]) concentrations and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: new insights from a large national biobank. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41(1):465-474.[DOI]

-

41. Greco A, Finocchiaro S, Spagnolo M, Faro DC, Mauro MS, Raffo C, et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a pharmacological target: Premises, promises, and prospects. Circulation. 2025;151(6):400-415.[DOI]

-

42. Thomas PE, Vedel-Krogh S, Nordestgaard BG. Measuring lipoprotein(a) for cardiovascular disease prevention - in whom and when? Curr Opin Cardiol. 2024;39(1):39-48.[DOI]

-

43. Wulff AB, Nordestgaard BG, Langsted A. Novel therapies for lipoprotein (a): Update in cardiovascular risk estimation and treatment. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2024;26:111-118.[DOI]

-

44. Roeseler E, Julius U, Heigl F, Spitthoever R, Heutling D, Breitenberger P, et al. Lipoprotein apheresis for lipoprotein (a)-associated cardiovascular disease: Prospective 5 years of follow-up and apolipoprotein (a) characterization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36:2019-2027.[DOI]

-

45. MacDougall DE, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Knowles JW, Stern TP, Hartsuff BK, McGowan MP, et al. Lipoprotein(a) and recurrent atherosclerotic cardiovascular events: The US Family Heart Database. Eur Heart J. 2025;46(44):4762-4775.[DOI]

-

46. Smith GD, Ebrahim S. ‘Mendelian randomization’: Can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:1-22.[DOI]

-

47. Yeang C, Cotter B, Tsimikas S. Experimental animal models evaluating the causal role of lipoprotein (a) in atherosclerosis and aortic stenosis. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2016;30:75-85.[DOI]

-

48. Thomas PE V-KS, Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG. Lipoprotein(a) cardiovascular risk explained by LDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, apoB, or hsCRP is minimal. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2025;85(21):2046-2051.[DOI]

-

49. Björnson E, Adiels M, Taskinen M-R, Burgess S, Chapman MJ, Packard CJ, et al. Lipoprotein (a) is markedly more atherogenic than LDL: An apolipoprotein B-based genetic analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83:385-395.[DOI]

-

50. Koschinsky ML, Boffa MB. Oxidized phospholipid modification of lipoprotein(a): Epidemiology, biochemistry and pathophysiology. Atherosclerosis. 2022;349:92-100.[DOI]

-

51. D’Angelo A, Geroldi D, Hancock MA, Valtulina V, Cornaglia AI, Spencer CA, et al. The apolipoprotein(a) component of lipoprotein(a) mediates binding to laminin: Contribution to selective retention of lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic lesions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1687(1-3):1-10.[DOI]

-

52. Nielsen LB, Stender S, Kjeldsen K, Nordestgaard BG. Specific accumulation of lipoprotein (a) in balloon-injured rabbit aorta in vivo. Circ Res. 1996;78(4):615-626.[DOI]

-

53. Aboyans V, Ricco JB, Bartelink MEL, Björck M, Brodmann M, Cohnert T, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral arterial diseases, in collaboration with the European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:763-816.[DOI]

-

54. Criqui MH, Matsushita K, Aboyans V, Hess CN, Hicks CW, Kwan TW, et al. Lower extremity peripheral artery disease: Contemporary epidemiology, management gaps, and future directions: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;144:e171-e191.[DOI]

-

55. Curry SJ, Krist AH, Owens DK, Barry MJ, Caughey AB, Davidson KW, et al. Screening for peripheral artery disease and cardiovascular disease risk assessment with the ankle-brachial index: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:177-183.[DOI]

-

56. Narula N, Olin JW, Narula N. Pathologic disparities between peripheral artery disease and coronary artery disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:1982-1989.[DOI]

-

57. Narula N, Dannenberg AJ, Olin JW, Bhatt DL, Johnson KW, Nadkarni G, et al. Pathology of peripheral artery disease in patients with critical limb ischemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2152-2163.[DOI]

-

58. Thanigaimani S, Kumar M, Golledge J. Lipoprotein(a) and peripheral artery disease: Contemporary evidence and therapeutic advances. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2025;36(5):258-267.[DOI]

-

59. Trinder M, Uddin MM, Finneran P, Aragam KG, Natarajan P. Clinical utility of lipoprotein (a) and LPA genetic risk score in risk prediction of incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6:287-295.[DOI]

-

60. Klarin D, Lynch J, Aragam K, Chaffin M, Assimes TL, Huang J, et al. Genome-wide association study of peripheral artery disease in the Million Veteran Program. Nat Med. 2019;25:1274-1279.[DOI]

-

61. Larsson SC, Gill D, Mason AM, Jiang T, Bäck M, Butterworth AS, et al. ipoprotein (a) in Alzheimer, atherosclerotic, cerebrovascular, thrombotic, and valvular disease: Mendelian randomization investigation. Circulation. 2020;141:1826-1828.[DOI]

-

62. Guédon AF, De Freminville JB, Mirault T, Mohamedi N, Rance B, Fournier N, et al. Association of lipoprotein (a) levels with incidence of major adverse limb events. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2245720.[DOI]

-

63. Golledge J, Rowbotham S, Velu R, Quigley F, Jenkins J, Bourke M, et al. Association of serum lipoprotein (a) with the requirement for a peripheral artery operation and the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events in people with peripheral artery disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015355.[DOI]

-

64. Hishikari K, Hikita H, Nakamura S, Nakagama S, Mizusawa M, Yamamoto T, et al. Usefulness of lipoprotein (a) for predicting clinical outcomes after endovascular therapy for aortoiliac atherosclerotic lesions. J Endovasc Ther. 2017;24:793-799.[DOI]

-

65. Sanchez Muñoz-Torrero JF, Rico-Martín S, Álvarez LR, Aguilar E, Alcalá JN, Monreal M. Lipoprotein (a) levels and outcomes in stable outpatients with symptomatic artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2018;276:10-14.[DOI]

-

66. Tomoi Y, Takahara M, Soga Y, Kodama K, Imada K, Hiramori S, et al. Impact of high lipoprotein (a) levels on clinical outcomes following peripheral endovascular therapy. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:1466-1476.[DOI]

-

67. Verwer MC, Waissi F, Mekke JM, Dekker M, Stroes ESG, de Borst GJ, et al. High lipoprotein(a) is associated with major adverse limb events after femoral artery endarterectomy. Atherosclerosis. 2022;349:196-203.[DOI]

-

68. Bellomo TR, Bramel EE, Lee J, Urbut S, Flores A, Yu Z, et al. Evaluation of lipoprotein (a) as a prognostic marker of extracoronary atherosclerotic vascular disease progression. Circulation. 2025;152:585-598.[DOI]

-

69. Sakalihasan N, Michel JB, Katsargyris A, Kuivaniemi H, Defraigne JO, Nchimi A, et al. Abdominal aortic aneurysms. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:34.[DOI]

-

70. Quintana RA, Taylor WR. Cellular mechanisms of aortic aneurysm formation. Circ Res. 2019;124:607-618.[DOI]

-

71. Karthikesalingam A, Holt PJ, Vidal-Diez A, Ozdemir BA, Poloniecki JD, Hinchliffe RJ, et al. Mortality from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms: Clinical lessons from a comparison of outcomes in England and the USA. Lancet. 2014;383:963-969.[DOI]

-

72. Satterfield BA, Dikilitas O, Safarova MS, Clarke SL, Tcheandjieu C, Zhu X, et al. Associations of genetically predicted Lp (a)(lipoprotein [a]) levels with cardiovascular traits in individuals of European and African Ancestry. Circ Genom Precis Med. 2021;14:e003354.[DOI]

-

73. Chou EL, Pettinger M, Haring B, Mell MW, Hlatky MA, Wactawski-Wende J, et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of abdominal aortic aneurysm in the Women’s Health Initiative. J Vasc Surg. 2021;73:1245-1252.[DOI]

-

74. Otto CM, Prendergast B. Aortic-valve stenosis—from patients at risk to severe valve obstruction. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:744-756.[DOI]

-

75. Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, Delahaye F, Gohlke-Bärwolf C, Levang OW, et al. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: The Euro Heart Survey on Valvular Heart Disease. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1231-1243.[DOI]

-

76. Henkel DM, Malouf JF, Connolly HM, Michelena HI, Sarano ME, Schaff HV, et al. Asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with severe aortic stenosis: Characteristics and outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2325-2329.[DOI]

-

77. Chen HY, Engert JC, Thanassoulis G. Risk factors for valvular calcification. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2019;26:96-102.[DOI]

-

78. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases: A population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368:1005-1011.[DOI]

-

79. Kaltoft M, Langsted A, Nordestgaard BG. Obesity as a causal risk factor for aortic valve stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:163-176.[DOI]

-

80. Smith JG, Luk K, Schulz CA, Engert JC, Do R, Hindy G, et al. Association of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol-related genetic variants with aortic valve calcium and incident aortic stenosis. JAMA. 2014;312:1764-1771.[DOI]

-

81. Nazarzadeh M, Rahimi K. Mendelian randomization of plasma lipids and aortic valve stenosis: the importance of outlier variants and population stratification. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2714-2715.[DOI]

-

82. Thanassoulis G, Campbell CY, Owens DS, Smith JG, Smith AV, Peloso GM, et al. Genetic associations with valvular calcification and aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:503-512.[DOI]

-

83. Kamstrup PR, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated lipoprotein(a) and risk of aortic valve stenosis in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:470-477.[DOI]

-

84. Arsenault BJ, Loganath K, Girard A, Botezatu S, Zheng KH, Tzolos E, et al. Lipoprotein (a) and calcific aortic valve stenosis progression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2024;9:835-842.[DOI]

-

85. Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135-1143.[DOI]

-

86. Libby P. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Vasc Pharmacol. 2024;154:107255.[DOI]

-

87. Ridker PM. From C-reactive protein to interleukin-6 to interleukin-1: moving upstream to identify novel targets for atheroprotection. Circ Res. 2016;118:145-156.[DOI]

-

88. Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, MacFadyen JG, Chang WH, Ballantyne C, et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1119-1131.[DOI]

-

89. Tardif JC, Kouz S, Waters DD, Bertrand OF, Diaz R, Maggioni AP, et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2497-2505.[DOI]

-

90. d’Entremont M-A, Poorthuis MHF, Fiolet ATL, Amarenco P, Boczar KE, Buysschaert I, et al. Colchicine for secondary prevention of vascular events: A meta-analysis of trials. Eur Heart J. 2025;46:2564-2575.[DOI]

-

91. Nguyen MT, Fernando S, Schwarz N, Tan JT, Bursill CA, Psaltis PJ. Inflammation as a therapeutic target in atherosclerosis. J Clin Med. 2019;8(8):1109.[DOI]

-

92. Alebna Pamela L, Han Chin Y, Ambrosio M, Kong G, Cyrus John W, Harley K, et al. Association of lipoprotein (a) with major adverse cardiovascular events across hs-CRP: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JACC Adv. 2024;3:101409.[DOI]

-

93. Puri R, Nissen SE, Arsenault BJ, St John J, Riesmeyer JS, Ruotolo G, et al. Effect of C-reactive protein on lipoprotein (a)-associated cardiovascular risk in optimally treated patients with high-risk vascular disease: A prespecified secondary analysis of the ACCELERATE trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1136-1143.[DOI]

-

94. Zhang W, Speiser JL, Ye F, Tsai MY, Cainzos-Achirica M, Nasir K, et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein modifies the cardiovascular risk of lipoprotein (a) multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:1083-1094.[DOI]

-

95. Arnold N, Blaum C, Goßling A, Brunner FJ, Bay B, Ferrario MM, et al. C-reactive protein modifies lipoprotein (a)-related risk for coronary heart disease: The BiomarCaRE project. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:1043-1054.[DOI]

-

96. Small AM, Pournamdari A, Melloni GEM, Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Raz I, et al. Lipoprotein (a), C-reactive protein, and cardiovascular risk in primary and secondary prevention populations. JAMA Cardiol. 2024;9:385-391.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite