Abstract

This review summarizes our current knowledge and understanding of the biosynthesis and assembly of lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] with a focus on diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Lp(a) is composed of a low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-like particle and the covalently bound apolipoprotein(a) [apo(a)]. Our understanding of the physiology and pathophysiology of the atherogenic Lp(a) has considerably increased over the past decades. The precise mechanisms regulating the biosynthesis, secretion, and assembly of Lp(a) have been extensively investigated but are, nevertheless, still incompletely understood or, at least, controversially discussed. Lp(a) plasma concentrations are mainly determined by synthesis and, to a minor extent, also by catabolism. Assembly of Lp(a) occurs in a complex 2-step procedure, starting with an intracellular non-covalent association between lysine-binding sites on apo(a) and lysine residues on apoB-100, the two major protein components of Lp(a). The final assembly of Lp(a) occurs extracellularly and/or transiently associated with the cell membrane by covalent disulfide bonding from newly synthesized apolipoprotein(a) and circulating LDL. Lp(a)-lowering therapies have been developed that specifically inhibit apo(a) biosynthesis and Lp(a) particle assembly. The inhibition of Lp(a) assembly raises interesting questions regarding the quantification of Lp(a) since it leads to the release of substantial amounts of LDL-unbound apo(a), which is co-measured by routine laboratory assays. The complex biosynthesis and assembly pathway of Lp(a) has been intensively investigated since its discovery more than 60 years ago. It is not only of basic-scientific interest but also concerns actual issues of diagnosis and therapy of elevated plasma concentrations of this enigmatic lipoprotein.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Although lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] was first described more than 60 years ago as an antigen variant of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) by the Norwegian human geneticist Kare Berg[1], fundamental knowledge of Lp(a) biology remains incomplete. Lp(a) has been an attractive study target for clinical and theoretical investigations since elevated blood concentrations of Lp(a) have been identified as an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic diseases such as coronary artery disease, aortic valve calcifications, peripheral vascular disease, and stroke[2,3]. Despite considerable research efforts over the past decades, crucial questions concerning the physiological as well as the pathophysiological function of Lp(a), its biosynthesis and particle assembly, removal, and degradation have remained incompletely understood[4-6]. This article summarizes our current knowledge of the biogenesis of this enigmatic lipoprotein with particular focus on the Lp(a) assembly process and its possible implications for the diagnosis and treatment of elevated Lp(a) concentrations.

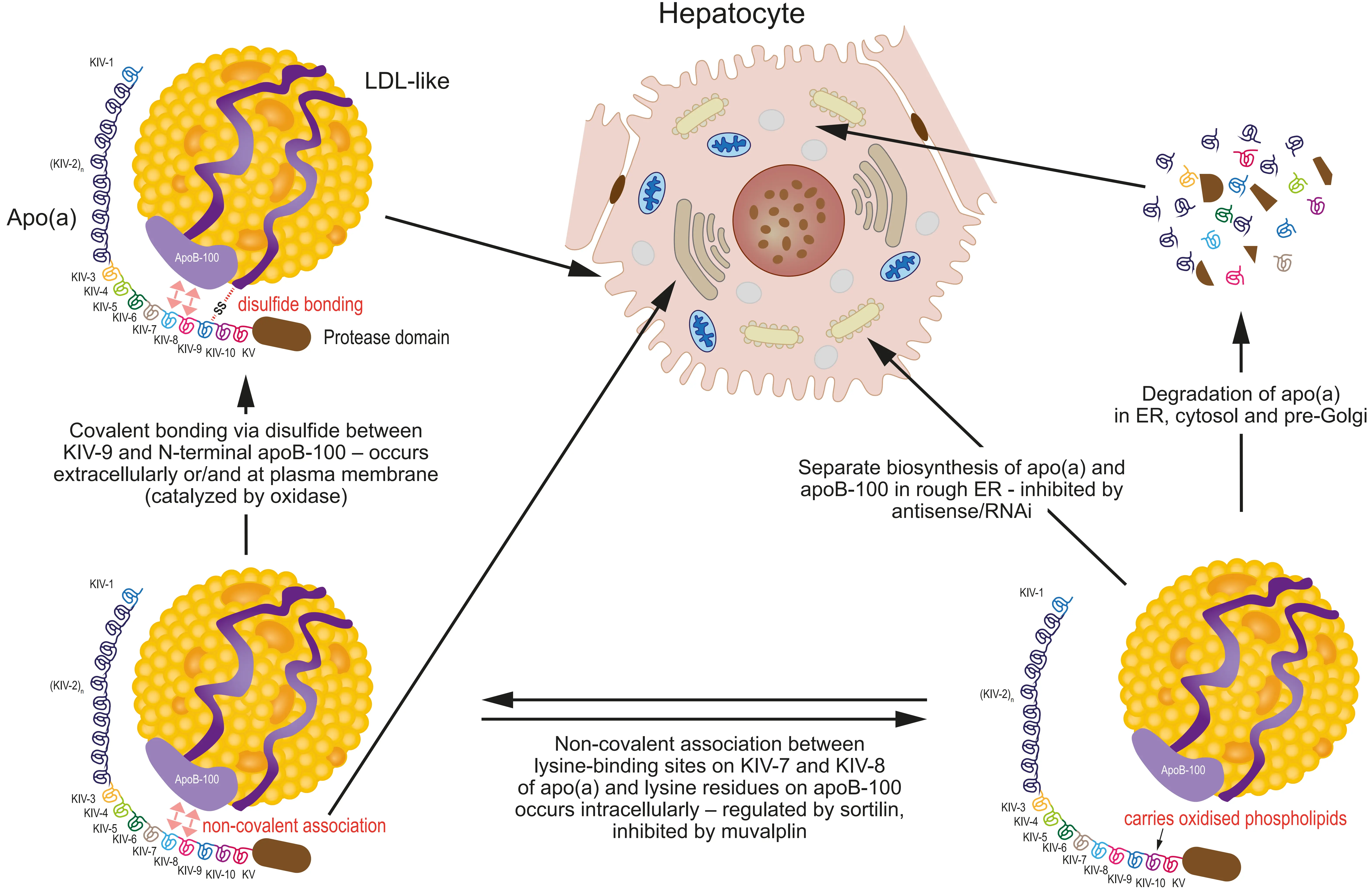

Lp(a) consists of an LDL-like particle and the large, highly glycosylated, and hydrophilic apolipoprotein(a) [apo(a)] that is covalently linked via a single disulfide bond to the apolipoprotein B (apoB)-100 moiety of LDL (Figure 1). The lipid composition of Lp(a) is very similar but not identical to that of LDL; therefore, it is often referred to as an “LDL-like” particle[7]. Its hydrated density is higher due to the presence of apo(a) (1.040 g/mL - 1.125 g/mL)[8]. The seminal sequencing work of McLean et al. led to the discovery of a high degree of homology between apo(a) and the fibrinolytic proenzyme plasminogen[9].

Figure 1. Lipoprotein(a) assembly is a complex multi-step pathway. Lp(a) consists of an LDL-like particle and the covalently linked apo(a), which is built of an inactive protease domain, a Kringle V domain, and identical (KIV-2) as well as non-identical (KIV-1 and KIV-3-to-KIV-10) repeats of Kringle IV domains. The number of identical KIV-2 repeats differs largely between individuals (from 3 to > 40-fold) and represents the basis of the remarkable size polymorphism of apo(a). After biosynthesis in the rough ER, apo(a) undergoes presecretory degradation in the ER, cytosol, and pre-Golgi compartments as an important determinant of secretion and, finally, circulating plasma concentration of Lp(a). The non-repetitive KIV-10 domain has been shown to possess a carrier function for OxPl, which are believed to play a crucial role in the pathogenicity of Lp(a). Apo(a)/Lp(a) synthesis can be specifically inhibited by antisense/RNAi medication against apo(a). The first assembly step is a non-covalent association between lysine-binding sites on Kringles IV-7 and IV-8 and lysine residues of apolipoprotein B-100, taking place intracellularly within the secretory pathway. This association can be inhibited by substances such as muvalaplin by interfering with lysine-binding sites on apo(a), which results in diminished secretion and subsequent plasma concentrations of Lp(a). The intracellular sorting receptor sortilin plays a further role by interfering in a complex fashion with the non-covalent association between apo(a) and apoB. The final step of assembly to the mature Lp(a) particle occurs by disulfide linkage between Cys4057 on Kringle IV-9 on apo(a) and Cys4326 on apolipoprotein B-100. This process may take place either on the plasma membrane (with apo(a) still transiently bound to the cell surface) or in the circulation. LDL: low-density lipoprotein; Apo(a): apolipoprotein(a); apoB: apolipoprotein B; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; OxPl: oxidized phospholipids.

Plasminogen is composed of five different kringle domains (KI–KV) linearly arranged in the form of a pearl string. Kringles are cysteine-rich protein structures formed by three intramolecular disulfide bonds (“bridges”) resulting in tri-loop structures that resemble a Danish pretzel. Apo(a) is considerably larger than plasminogen due to multiple copies of the KIV domains (1-10) that are 75%-85% homologous to those of plasminogen. KIV encoding domains KIV-1 and KIV-3 to KIV-10 occur only once and differ by minor variations in amino acid composition, whereas KIV-2 motifs vary in copy number (from 3 to > 40-fold) and are completely identical at the amino acid sequence level[10]. This KIV-2 copy number variation results in a remarkable apo(a) isoform, and hence Lp(a) particle size heterogeneity among populations[11]. The KIV domains are followed by a KV domain highly homologous to a respective domain in plasminogen. The C-terminus of apo(a) contains a region with high sequence homology to the protease domain of plasminogen, which is catalytically inactive in apo(a)[12].

Lp(a) concentrations vary widely within populations, from less than 1 nmol/L to more than 300 nmol/l, and are extremely non-normally distributed[3,11]. More than 90% of the variance in Lp(a) plasma concentrations is under genetic control and determined primarily by the apo(a) gene[12]. Lp(a) plasma concentrations are inversely correlated with the number of KIV-2 repeats in the gene and, hence, with the molecular weight of the apo(a) isoform. Individuals carrying alleles with a low copy number of KIV-2 repeats on average (thus with a low-molecular weight isoform) have high Lp(a) plasma concentrations, whereas those with high KIV-2 copy number alleles (resulting in high molecular weight isoforms) express lower Lp(a) plasma concentrations[13,14].

2. Biogenesis of Apo(a)

Early kinetic studies using radiolabeled lipoproteins suggested that Lp(a) represents an “independent” lipoprotein species and not a metabolic product of other apoB-containing lipoproteins such as very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL)[15]. However, more recent kinetic studies described a more complex metabolic scenario, as apolipoprotein E from VLDL seems to determine, to a substantial extent, Lp(a) production[16].

Several in vivo kinetic studies in humans have shown that Lp(a) plasma concentrations are almost exclusively determined by Lp(a)/apo(a) synthesis and not by degradation. Individuals with different Lp(a) concentrations and apo(a) isoforms have different production rates but similar catabolic rates of Lp(a)[17-19]. More recently, a large in vivo turnover study in humans using stable isotopes corroborated and extended the earlier findings by reporting an exclusive association between apo(a) production rates and Lp(a) concentrations only in individuals with small apo(a) isoforms, whereas in those with large apo(a) isoforms, the association was found with both production and, to a smaller extent, catabolic rates[20]. Another recent kinetic study in humans confirmed the results of Chan et al. by showing again significant associations of Lp(a) concentrations with both production AND catabolic rates[21]. This indicates that Lp(a)/apo(a) catabolism may play a minor but significant role in determining Lp(a) concentrations in individuals with large apo(a) isoform size, in line with reports of elevated Lp(a) concentrations in patients with chronic kidney disease, preferably in carriers of large apo(a) isoforms[22]. Based on these studies and findings of renovascular arteriovenous differences in Lp(a) concentrations, a substantial role of the human kidney for the removal of Lp(a) from circulation has been postulated[23,24].

The determination of apo(a) isoforms before and after therapeutic liver transplantation in humans elegantly demonstrated that circulating plasma apo(a)/Lp(a) is derived almost exclusively from the liver[25]. Since apo(a) is not expressed in classic animal models such as mice, rats, and rabbits and is barely produced by cultured transformed human cell lines like HepG2[26,27], alternative in vitro cell model systems, such as primary cultures of baboon hepatocytes and human HepG2 cells transfected with different recombinant apo(a) constructs, have been developed to examine the biosynthesis of apo(a)/Lp(a). Finally, work on transgenic mice expressing both human apo(a) and apoB, as well as cell culture studies on primary hepatocytes from such animals, added significantly to our knowledge about the biogenesis of Lp(a)[28,29].

Studies in primary baboon hepatocytes[30], primary hepatocytes from mice transgenic for human apo(a) and apoB-100, and in the human hepatoma cell line HepG2 recombinantly expressing apo(a)[31,32] revealed that post-translational mechanisms largely influence the Lp(a) production rate and subsequently also its plasma concentration. As with most secretory proteins, apo(a) is synthesized, not surprisingly, as a precursor, which is processed to its mature form by glycosylation and folding in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where it is retained for a prolonged period. Proper N-linked glycosylation in the ER and interactions with chaperons such as calnexin and calreticulin are required for apo(a) maturation and secretion. Nascent apo(a) undergoes extensive presecretory degradation in the ER, post-ER/pre-Golgi compartment[29,33,34], and, possibly, also in the cytosol (Figure 1). Residence time in the ER is apo(a) size-dependent: large isoforms are retained longer than smaller ones. This complex maturation process can at least partly explain the correlation between apo(a) size and plasma Lp(a) concentrations in humans and baboons[35]. To investigate the mechanisms underlying this prolonged and isoform-dependent ER retention of apo(a), the influence of glycosylation, folding, and intracellular degradation on apo(a) secretion was examined in the baboon hepatocyte and various transfected cell models. N-glycosylation of apo(a) is required for its proper intracellular processing since secretion of apo(a) from N-glycosylation-defective cells is blocked or significantly reduced, depending on the apo(a) size[36,37]. White and coworkers investigated the presecretory degradation of apo(a) and demonstrated a role of the cytosolic proteasome machinery for a regulatory apo(a) degradation[34,38]. The authors observed an accumulation of the intracellular apo(a) precursor as well as an increased secretion of mature apo(a) when proteasomal degradation was blocked by specific inhibitors. A number of secretory and membrane proteins are now known to undergo quality control, including retention in the ER, retrotranslocation into the cytosol, and subsequent proteasomal degradation[39]. Surprisingly, apo(a) degradation was inhibited by brefeldin A, and the accumulating apo(a) remained sensitive to endoglucosaminidase H, suggesting that an unusual transport of apo(a) to a post-ER, pre-medial Golgi compartment followed by retrotranslocation into cytosol might be required for this process[34]. An accumulation in an ER-to-Golgi intermediate compartment with subsequent degradation by the proteasome complex has been described for misfolded membrane proteins[40], but so far never for secretory proteins.

Taken together, these results suggest that Lp(a) plasma concentrations are controlled to a significant extent by complex apo(a) isoform-dependent intracellular processing at several “stations” along the secretory pathway, representing a rather unique cellular basis for a strictly genetically controlled secretory protein complex.

3. Sites and Mechanisms of Lp(a) Assembly

The sites and mechanisms of Lp(a) particle assembly from apo(a) and apoB-100 have received significant scientific attention for three decades and have been investigated in transfected HepG2 and baboon cell model systems, but also in transgenic mice and by in vivo turnover studies in humans. Depending on the strategy used, these studies came to partly disagreeing conclusions[4,5,41].

3.1 In vitro cell culture studies

There is overwhelming evidence and general agreement that Lp(a) particle assembly is a two-step process (Figure 1). The assembly starts with a non-covalent interaction via weak lysine binding sites between apo(a) KIV-7/KIV-8 and specific lysine residues of apoB-100, followed by covalent bond formation between the two molecules[42]. The key question, which has also therapeutic relevance, is where these two processes occur (intracellularly, extracellularly, or both). The answers were partially controversial and, as said above, depended on the used systems of investigation.

The majority of earlier studies in HepG2 cells recombinantly expressing apo(a) have revealed that Lp(a) assembly occurs extracellularly with secreted apo(a) and extracellularly available LDL. Covalently formed apo(a)-apoB complexes could not be detected intracellularly[43-45]. These findings were supported by analysis of homogenates from human livers, which contained apoB and apo(a) but no complexes thereof[46]. Furthermore, it has been shown in transfected Chinese hamster ovary cells that recombinantly expressed and secreted apo(a) is able to assemble into Lp(a) in the culture medium with exogenously added human LDL[37]. Similar assembly experiments in transfected glycosylation-defective cells revealed that neither N-linked nor O-linked glycosylation of apo(a) is necessary for Lp(a) assembly[36,37].

After adding anti-apo(a) antiserum to baboon hepatocyte culture medium, White et al. did not detect any assembled Lp(a), which excludes an intracellularly formed and covalently linked apo(a)-apoB complex[47]. Similar experiments were also performed in HepG2 cells and led to the same results[44]. Non-covalent intracellular associations between apo(a) and apo B, as described more recently[48], could not have been detected with these methods. In the baboon hepatocyte model, it was demonstrated that extracellular assembly takes place, at least in part, on the surface of the plasma membrane, involving apo(a), which is transiently associated with the plasma membrane[47]. The same authors demonstrated that antibiotics like neomycin are able to inhibit the release of apo(a) from the baboon hepatocyte plasma membrane[49]. Neomycin has been shown to be one of the few drugs capable of reducing Lp(a) concentrations in vivo[50]. An enzyme with oxidase activity, present in culture supernatants from hepatocytes, responsible for extracellular bond formation between apo(a) and apoB-100, was described by Becker et al.[51], and argues for a final extracellular assembly of Lp(a).

An exclusively extracellular assembly of Lp(a) was also strongly suggested in stably transfected HepG2 cells[32]. Aside from other approaches, the authors investigated transfected HepG2 cells to see if they would form intracellular apo(a)/apoB complexes under conditions where the secretory pathway was inhibited at restricted temperatures. These experiments showed that neither at 15 °C (where secretory proteins accumulate in the ER) nor at 20 °C (which blocks the secretory pathway at the trans-Golgi-network level) could covalent apo(a)/apoB complexes be observed. Mature Lp(a) was detected only in cell culture medium after incubation at 37 °C. Again, initial non-covalent intracellular associations between apo(a) and apoB would not have been seen under those conditions.

Besides these seemingly clear data, the literature also contains reports suggesting an intracellular assembly of Lp(a) in humans. Edelstein et al. found apo(a)-apoB-containing particles in cell lysates from primary human hepatocytes[52]. Oleate stimulated apoB secretion and the formation of such particles, suggesting that apo(a) secretion is coupled to triglyceride synthesis and secretion. Similar results were obtained in transfected HepG2 cells[53]. An intracellular apo(a)-apoB complex was also observed in HepG2 cells transfected with an apo(a) minigene[54]. The physiological relevance of these findings, however, remains questionable, since the transfected apo(a) consisted of only the signal sequence, six non-identical KIV domains, the KV and the protease domain, and completely lacked the repetitive KIV-2 domains. Although this domain is not essential for Lp(a) assembly, an Lp(a) particle with such a small apo(a) isoform has never been observed in humans and may be structurally totally different from a native Lp(a) particle.

In a more recent study, Youssef et al. demonstrated lysine-dependent non-covalent apo(a)-apoB-100 complexes throughout the whole secretory pathway within hepatocytes[48]. This intracellular non-covalent interaction was investigated by immunoprecipitation, immunofluorescence, and proximity ligation assays. This first step in the Lp(a) assembly process precedes specific disulfide bond formation between the free cysteine in apo(a) KIV-9 and the unpaired cysteine at amino acid 4326 within the N-terminal domain of human apoB-100, which occurs extracellularly and/or on the hepatocyte membrane (Figure 1). The authors used HepG2 cells stably expressing apo(a) carrying mutations at the two lysine-binding sites in KIV-7 and KIV-8 and could demonstrate non-covalent complexes between apo(a)/apoB in lysates from wild-type cells but not from those transfected with the lysine-binding deficient mutant. These findings have important implications for therapeutic strategies regarding the development of Lp(a)-lowering substances interfering with Lp(a) assembly. Inhibitors of the non-covalent interaction between apo(a) and apoB, which are in development and already at various stages of clinical trials, such as muvalaplin, may have to be taken up into the liver to be effective[55].

The above-described intracellular initial non-covalent association between apo(a) and apoB seems to be also regulated in a complex fashion by sortilin, acting as a sorting receptor involved in Golgi-to-lysosome trafficking[56]. Overexpression of sortilin increased and its inhibition decreased apo(a) secretion in genetically modified HepG2 cells, without binding to either apo(a) or Lp(a), indicating that this effect was likely indirect via the availability of apoB.

Taken together, the majority of investigations in various in vitro cellular models reveal an extracellular assembly process of Lp(a). The assembly occurs, however, in two subsequent steps, starting as an intracellular non-covalent association between distinct lysine-binding sites on apo(a) and lysine residues on the apoB-100 moiety of LDL, followed by covalent disulfide bonding between the two proteins, which takes place, at least partly, by transient attachment to the plasma membrane of hepatocytes.

3.2 Studies in transgenic mice

Metabolic studies in transgenic mice were shown to be compatible with both an intracellular and extracellular assembly of Lp(a). Double transgenic human-apo(a)/apoB-100 mice produced mature Lp(a) in the circulation, whereas free apo(a) was virtually absent, supporting the intracellular assembly of Lp(a)[28]. In apo(a) transgenic animals, most apo(a) circulates as lipoprotein-free protein and does not bind mouse LDL, which evidently lacks structural requirements for association with human apo(a)[57]. Intravenous injection of human LDL, but not of mouse LDL, into the mice resulted in the formation of human Lp(a), suggesting an extracellular assembly, albeit under very non-physiological conditions[58]. These results, therefore, have to be considered with caution, since the used animal models are highly artificial, because wild-type mice do not produce apo(a)/Lp(a).

3.3 In vivo human kinetic studies

Human kinetic studies using the stable isotope enrichment technology have provided results supporting intra- as well as extracellular assembly, or were compatible with processes in both locations[59-64]. The first study (unfortunately being only published as a congress abstract) in ten normolipidemic subjects strongly argues for an intracellular assembly of Lp(a)[63]. Production rates for apo(a) and apoB in Lp(a) were very similar and significantly different from those of apoB in LDL, which argues for separate apoB pools for LDL and Lp(a) secretion and an intracellular assembly process of Lp(a). These data were later supported by a similar investigation in 12 female probands and by Frischmann et al., who investigated nine normolipidemic, healthy probands[61-64]. The authors again found a tracer enrichment at similar rates for both protein components of Lp(a), resulting in nearly identical fractional synthetic rates comparable to published results from turnover studies with radiolabeled Lp(a).

There are, however, also reports from in vivo kinetic studies in support of extracellular Lp(a) assembly processes[59,64]. The discrepancies are not fully understandable but could be due to different study groups and different modeling strategies.

3.4 Lp(a) in hypo-, abetalipoproteinemia (ABL) and lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) deficiency

Several investigations in patients diagnosed with various rare genetic dyslipidemias have demonstrated that additional structural and compositional properties of LDL are required for proper Lp(a) biosynthesis and assembly.

Hypobetalipoproteinemia, caused by mutations in the gene for apoB and leading to various truncated forms of apoB, has been shown to result in normal or reduced plasma concentrations of Lp(a), depending on the resulting size of apoB[65,66].

In contrast, very low plasma levels of apo(a) have been reported in patients with autosomal recessive ABL[67]. Apo(a) was found in the plasma of these patients as a lipid-poor complex with trace amounts of apoB, as well as in free, uncomplexed form. These data therefore suggest that a defectively assembled apoB-containing lipoprotein is barely secreted and only poorly assembles with apo(a) to form Lp(a).

Lp(a) assembly is also impaired in patients diagnosed with the rare deficiency of LCAT, an enzyme which is responsible for the esterification of cholesterol in plasma and, subsequently, for the lipid composition of all major lipoproteins[68]. The authors investigated two families with five members homozygous for LCAT deficiency, who completely lacked Lp(a) and apo(a). The LDL fraction of the patients was unable to form Lp(a) with recombinant apo(a) in vitro. Treatment of LCAT-deficient plasma with exogenously added active LCAT restored the ability of LDL to assemble Lp(a) normally. From these results, the authors concluded that conformational properties of LDL, in this case depending on the lipid composition of LDL, are also required for proper Lp(a) assembly.

3.5 Reasons for reported discrepancies

The conflicting results regarding the sites of Lp(a) assembly are most likely due to the quite different research models and experimental approaches used. As an example, let us look at the various cellular models: Almost all investigated hepatocytes produce a lipoprotein pattern which differs substantially from that in human plasma. For example, primary cultures of baboon hepatocytes secrete 80% of their apoB as VLDL[69], which does not associate with apo(a) (see Section 3.2). As a consequence, a large portion of apo(a) is found in free, non-lipoprotein-bound form in the cell culture media. HepG2 cells, on the other hand, secrete triglyceride-rich lipoprotein particles with LDL density[70], that do not exist at all in human plasma. Nevertheless, they do bind secreted apo(a) in vitro to assemble Lp(a) extracellularly[43-45]. Since such particles, however, do not form Lp(a) intracellularly, they may not meet there or, alternatively, the nascent lipoproteins undergo specific processing and modulation that enables extracellular Lp(a) formation. Very few reports demonstrate a direct synthesis of LDL by cultured human hepatocytes[71,72]. Only in one of them, were the secreted lipoproteins characterized in detail: hepatocytes secreted VLDL, LDL, and HDL particles; their protein moiety represented 44%, 20%, and 36%, respectively, of the total secreted lipoprotein protein[71]. These in vitro data were challenged by several in vivo kinetic studies in humans and can be summarized as follows: ApoB-containing lipoproteins are secreted by the liver as a heterogeneous spectrum of VLDL particles which, in a stepwise process, are converted in plasma to LDL by lipolytic enzymes[73]. Although this metabolic cascade generates the majority of circulating LDL, direct secretion of LDL particles by human hepatocytes is not explicitly excluded.

Very recently, apo(a) secretion was reported from human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived liver organoids (hiPSCs)[74]. These organoids were developed as a new in vitro model to study human lipoprotein metabolism in the liver and resemble very closely the in vivo situation. Although the authors did not characterize the secreted apo(a) (for example, whether it is secreted as lipoprotein or in free, non-LDL-bound form), this model certainly offers an opportunity to study a number of unsolved metabolic questions, including the topic of this review article.

4. Implication for Diagnosis and Therapy of Elevated Lp(a) Concentrations

Since Lp(a) concentrations are almost exclusively determined by their hepatic synthesis, all major recent attempts to specifically reduce elevated concentrations of Lp(a), independently of other lipids/lipoproteins, have been pursued by pharmacologically interfering with the biosynthesis of apo(a) in the liver[75]. Initial studies with novel therapeutic approaches demonstrated that Lp(a) concentrations were lowered by 80% with an antisense oligonucleotide[76] and by up to 98% with RNA interference[77,78] (Figure 1). These agents are currently being investigated in large clinical trials to evaluate the effect of Lp(a) on cardiovascular disease reduction. According to their mode of action, this treatment leads to decreased formation of apo(a), with subsequent reduction in Lp(a) particle concentrations.

More recently, a novel oral small molecule therapy for lowering increased Lp(a) concentrations has been developed as an alternative to the injectable antisense/RNAi approaches[55,79,80]. The mode of action of these substances differs completely from that described above. Muvalaplin, its best-known representative so far, is a small-molecule inhibitor of Lp(a) formation by inhibiting the intracellular non-covalent association between the lysine-binding sites on KIV-7 and KIV-8 and lysine residues on the N-terminal apoB-100 moiety of LDL[48] (Figure 1). This compound has been initially successfully tested in transgenic mice and cynomolgus monkeys and is also already at the stage of clinical trials. Muvalaplin has been reported to reduce plasma Lp(a) concentrations by 90%[75].

The results from studies with inhibitors of Lp(a) assembly have raised a few interesting questions, which are intensively discussed at the moment:

(1) Assuming that the non-covalent association between apo(a) and apoB-100 that was shown in a hepatocyte model[48] occurs also intracellularly in humans, the results with muvalaplin provide a very strong argument for an intracellular assembly of Lp(a)–at least regarding its initial, most likely rate-limiting, first step of a non-covalent association between the two protein components of Lp(a). This conclusion can, however, be drawn only if muvalaplin is able to cross cellular membranes to act intracellularly. This has, to our knowledge, not been demonstrated so far.

(2) The administration of compounds that inhibit Lp(a) assembly (wherever it occurs) also has far-reaching consequences for measuring Lp(a) concentrations. Due to its mode of action, it does neither inhibit biosynthesis of apo(a) nor of apoB-100, but leads instead to substantial amounts of circulating “free” (= LDL-unbound) apo(a), together with the (drastically diminished) remaining properly assembled Lp(a)[81]. Most commercial Lp(a) assays (including those used in clinical routine laboratories) are based on immunoturbidimetric methods that employ anti-apo(a) polyclonal antibodies and therefore measure both apo(a) in the Lp(a) particle as well as “unbound” apo(a)[82]. In healthy individuals, “unbound” apo(a) circulates at very low concentrations (less than 5% of total apo(a)), is heavily fragmented, and is excreted into the urine[83-86]. In situations/patients under muvalaplin treatment, modified Lp(a) assays have therefore to be applied that measure only LDL-bound apo(a). Such an assay was recently reported and consists of a double-antibody strategy using, for example, ELISAs with anti-apo(a) and anti-B antibodies[81]. With this Lp(a)-particle-specific assay, it could be shown by comparison with commercial double-anti-apo(a)-sandwich strategies that commercial assays underestimate the efficacy of Lp(a) lowering of muvalaplin by 17-18%.

(3) The substantial generation of free (= non-LDL-bound) apo(a) by muvalaplin raises, however, new interesting questions. First of all, how does this “free” apo(a) look like? Is it intact or, as in healthy, untreated individuals, also fragmented/degraded? If intact, is it still able to bind and carry OxPl, which are believed to be a key element for the pathogenicity of Lp(a)[87]? Unfortunately, no information regarding the molecular structure of the “free” apo(a) in treated patients has been provided so far. In healthy, untreated individuals, a substantial fraction of the OxPl on Lp(a) is covalently bound to the KIV-10 domain of apo(a); the remaining OxPl stays bound to the lipid moiety of Lp(a) (Figure 1)[88]. It is tempting to speculate that, assuming substantial amounts of OxPl on intact LDL-unbound apo(a) generated by treatment with muvalaplin, it would be difficult to seriously measure the “truly” pathological concentrations of Lp(a). It remains to be seen in further studies whether these considerations have any clinically relevant consequences.

5. Conclusion

Cellular, transgenic animal expression systems using wild-type and mutated forms of apo(a) and apoB, as well as human in vivo kinetic studies, have significantly enhanced our understanding of the complex mechanisms of the biosynthesis, secretion, and assembly of Lp(a). The secretory pathway of apo(a) is strictly regulated by intracellular retention and partial degradation. Lp(a) assembly has been demonstrated in most model systems in two steps, starting with a non-covalent attachment of several kringle domains to lysine-rich regions on apoB within hepatocytes. The second step represents membrane-associated and/or extracellular covalent disulfide linkage between the only unpaired cysteine residue on KIV-9 and a cysteine at the C-terminal domain of apoB. Further research will be required to completely identify the precise, complex mechanisms of Lp(a) assembly. This knowledge has undoubtedly helped to develop strategies for lowering the atherogenic plasma concentrations of Lp(a), but has raised new, interesting questions regarding its diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to a large number of coworkers in their respective laboratories over many years as well numerous national and international collaborators having tremendously contributed to the described work.

Authors contribution

Dieplinger B, Dieplinger H: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft, writing-review &editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Berg K. A new serum type system in man—the LP system. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1963;59:369-382.[DOI]

-

2. Kronenberg F, Mora S, Stroes ESG, Ference BA, Arsenault BJ, Berglund L, et al. Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: A European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(39):3925-3946.[DOI]

-

3. Patel AP, Wang M, Pirruccello JP, Ellinor PT, Ng K, Kathiresan S, et al. Lp(a) (lipoprotein[a]) concentrations and incident atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: New insights from a large national biobank. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2021;41(1):465-474.[DOI]

-

4. Boffa MB, Koschinsky ML. Understanding the ins and outs of lipoprotein (a) metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2022;33(3):185-192.[DOI]

-

5. Dieplinger H, Utermann G. The seventh myth of lipoprotein(a): Where and how is it assembled? Curr Opin Lipidol. 1999;10(3):275-283.[DOI]

-

6. Schmidt K, Noureen A, Kronenberg F, Utermann G. Structure, function, and genetics of lipoprotein (a). J Lipid Res. 2016;57(8):1339-1359.[DOI]

-

7. Fless GM, ZumMallen ME, Scanu AM. Physicochemical properties of apolipoprotein(a) and lipoprotein(a-) derived from the dissociation of human plasma lipoprotein (a). J Biol Chem. 1986;261(19):8712-8718.[DOI]

-

8. Kraft HG, Sandholzer C, Menzel HJ, Utermann G. Apolipoprotein (a) alleles determine lipoprotein (a) particle density and concentration in plasma. Arterioscler Thromb. 1992;12(3):302-306.[DOI]

-

9. McLean JW, Tomlinson JE, Kuang WJ, Eaton DL, Chen EY, Fless GM, et al. cDNA sequence of human apolipoprotein(a) is homologous to plasminogen. Nature. 1987;330(6144):132-137.[DOI]

-

10. Haibach C, Kraft HG, Köchl S, Abe A, Utermann G. The number of kringle IV repeats 3–10 is invariable in the human apo(a) gene. Gene. 1998;208(2):253-258.[DOI]

-

11. Utermann G, Menzel HJ, Kraft HG, Duba HC, Kemmler HG, Seitz C. Lp(a) glycoprotein phenotypes. Inheritance and relation to Lp(a)-lipoprotein concentrations in plasma. J Clin Invest. 1987;80(2):458-465.[DOI]

-

12. Kronenberg F, Utermann G. Lipoprotein(a): Resurrected by genetics. J Intern Med. 2013;273(1):6-30.[DOI]

-

13. Cohen JC, Chiesa G, Hobbs HH. Sequence polymorphisms in the apolipoprotein (a) gene. Evidence for dissociation between apolipoprotein(a) size and plasma lipoprotein(a) levels. J Clin Invest. 1993;91(4):1630-1636.[DOI]

-

14. Sandholzer C, Hallman DM, Saha N, Sigurdsson G, Lackner C, Császár A, et al. Effects of the apolipoprotein(a) size polymorphism on the lipoprotein(a) concentration in 7 ethnic groups. Hum Genet. 1991;86(6):607-614.[DOI]

-

15. Krempler F, Kostner G, Bolzano K, Sandhofer F. Lipoprotein (a) is not a metabolic product of other lipoproteins containing apolipoprotein B. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;575(1):63-70.[DOI]

-

16. Croyal M, Blanchard V, Ouguerram K, Chétiveaux M, Cabioch L, Moyon T, et al. VLDL(very-low-density lipoprotein)-Apo E (apolipoprotein E) may influence Lp(a) (Lipoprotein [a]) synthesis or assembly. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40(3):819-829.[DOI]

-

17. Krempler F, Kostner GM, Bolzano K, Sandhofer F. Turnover of lipoprotein (a) in man. J Clin Invest. 1980;65(6):1483-1490.[DOI]

-

18. Rader DJ, Cain W, Ikewaki K, Talley G, Zech LA, Usher D, et al. The inverse association of plasma lipoprotein(a) concentrations with apolipoprotein(a) isoform size is not due to differences in Lp(a) catabolism but to differences in production rate. J Clin Invest. 1994;93(6):2758-2763.[DOI]

-

19. Rader DJ, Cain W, Zech LA, Usher D, Brewer HB. Variation in lipoprotein(a) concentrations among individuals with the same apolipoprotein (a) isoform is determined by the rate of lipoprotein(a) production. J Clin Invest. 1993;91(2):443-447.[DOI]

-

20. Chan DC, Watts GF, Coll B, Wasserman SM, Marcovina SM, Barrett PHR. Lipoprotein(a) particle production as a determinant of plasma lipoprotein(a) concentration across varying apolipoprotein(a) isoform sizes and background cholesterol-lowering therapy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(7):e011781.[DOI]

-

21. Matveyenko A, Matienzo N, Ginsberg H, Nandakumar R, Seid H, Ramakrishnan R, et al. Relationship of apolipoprotein(a) isoform size with clearance and production of lipoprotein(a) in a diverse cohort. J Lipid Res. 2023;64(3):100336.[DOI]

-

22. Dieplinger H, Lackner C, Kronenberg F, Sandholzer C, Lhotta K, Hoppichler F, et al. Elevated plasma concentrations of lipoprotein(a) in patients with end-stage renal disease are not related to the size polymorphism of apolipoprotein(a). J Clin Invest. 1993;91(2):397-401.[DOI]

-

23. Frischmann ME, Kronenberg F, Trenkwalder E, Schaefer JR, Schweer H, Dieplinger B, et al. In vivo turnover study demonstrates diminished clearance of lipoprotein(a) in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2007;71(10):1036-1043.[DOI]

-

24. Kronenberg F, Trenkwalder E, Lingenhel A, Friedrich G, Lhotta K, Schober M, et al. Renovascular arteriovenous differences in Lp[a] plasma concentrations suggest removal of Lp[a] from the renal circulation. J Lipid Res. 1997;38(9):1755-1763.[PubMed]

-

25. Kraft HG, Menzel HJ, Hoppichler F, Vogel W, Utermann G. Changes of genetic apolipoprotein phenotypes caused by liver transplantation. Implications for apolipoprotein synthesis. J Clin Invest. 1989;83(1):137-142.[DOI]

-

26. Koschinsky ML, Tomlinson JE, Zioncheck TF, Schwartz K, Eaton DL, Lawn RM. Apolipoprotein(a): Expression and characterization of a recombinant form of the protein in mammalian cells. Biochemistry. 1991;30(20):5044-5051.[DOI]

-

27. Vu H, Cianflone K, Zhang Z, Kalant D, Sniderman AD. Characterization and modulation of LP(a) in human hepatoma HEPG2 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1349(2):97-108.[DOI]

-

28. Chiesa G, Hobbs HH, Koschinsky ML, Lawn RM, Maika SD, Hammer RE. Reconstitution of lipoprotein(a) by infusion of human low density lipoprotein into transgenic mice expressing human apolipoprotein(a). J Biol Chem. 1992;267(34):24369-24374.[DOI]

-

29. White AL. Biogenesis of Lp(a) in transgenic mouse hepatocytes. Clin Genet. 1997;52(5):326-337.[DOI]

-

30. White AL, Lanford RE. Biosynthesis and metabolism of lipoprotein (a). Curr Opin Lipidol. 1995;6(2):75-80.[DOI]

-

31. Brunner C, Lobentanz EM, Pethö-Schramm A, Ernst A, Kang C, Dieplinger H, et al. The number of identical kringle IV repeats in apolipoprotein(a) affects its processing and secretion by HepG2 cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(50):32403-32410.[DOI]

-

32. Lobentanz EM, Krasznai K, Gruber A, Brunner C, Müller HJ, Sattler J, et al. Intracellular metabolism of human apolipoprotein(a) in stably transfected hep G2 cells. Biochemistry. 1998;37(16):5417-5425.[DOI]

-

33. Wang J, White AL. Role of N-linked glycans, chaperone interactions and proteasomes in the intracellular targeting of apolipoprotein(a). Biochem Soc Trans. 1999;27(4):453-458.[DOI]

-

34. White AL, Guerra B, Wang J, Lanford RE. Presecretory degradation of apolipoprotein[a] is mediated by the proteasome pathway. J Lipid Res. 1999;40(2):275-286.[DOI]

-

35. White AL, Hixson JE, Rainwater DL, Lanford RE. Molecular basis for “null” lipoprotein(a) phenotypes and the influence of apolipoprotein(a) size on plasma lipoprotein(a) level in the baboon. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(12):9060-9066.[DOI]

-

36. Bonen DK, Nassir F, Hausman AML, Davidson NO. Inhibition of N-linked glycosylation results in retention of intracellular apo[a] in hepatoma cells, although nonglycosylated and immature forms of apolipoprotein[a] are competent to associate with apolipoprotein B-100 in vitro. J Lipid Res. 1998;39(8):1629-1640.[DOI]

-

37. Frank S, Krasznai K, Durovic S, Lobentanz EM, Dieplinger H, Wagner E, et al. High-level expression of various apolipoprotein(a) isoforms by “transferrinfection”: The role of kringle IV sequences in the extracellular association with low-density lipoprotein. Biochemistry. 1994;33(40):12329-12339.[DOI]

-

38. Wang J, White AL. 6-Aminohexanoic acid as a chemical chaperone for apolipoprotein(a). J Biol Chem. 1999;274(18):12883-12889.[DOI]

-

39. Bonifacino JS, Weissman AM. Ubiquitin and the control of protein fate in the secretory and endocytic pathways. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:19-57.[DOI]

-

40. Raposo G, van Santen HM, Leijendekker R, Geuze HJ, Ploegh HL. Misfolded major histocompatibility complex class I molecules accumulate in an expanded ER-Golgi intermediate compartment. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1403-1419.[DOI]

-

41. Reyes-Soffer G, Ginsberg HN, Ramakrishnan R. The metabolism of lipoprotein (a): An ever-evolving story. J Lipid Res. 2017;58(9):1756-1764.[DOI]

-

42. Koschinsky ML, Marcovina SM. Structure-function relationships in apolipoprotein(a): Insights into lipoprotein(a) assembly and pathogenicity. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2004;15(2):167-174.[DOI]

-

43. Brunner C, Kraft HG, Utermann G, Müller HJ. Cys4057 of apolipoprotein(a) is essential for lipoprotein(a) assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 1993;90(24):11643-11647.[DOI]

-

44. Ernst A, Brunner C, Petho A, Helmhold M, Armstrong V, Mu HJ. Assembly and lysine binding of recombinant lipoprotein(a). Atherosclerosis. 1994;109(1):346.[DOI]

-

45. Koschinsky ML, Côté GP, Gabel B, van der Hoek YY. Identification of the cysteine residue in apolipoprotein(a) that mediates extracellular coupling with apolipoprotein B-100. J Biol Chem. 1993;268(26):19819-19825.[DOI]

-

46. Wilkinson J, Munro LH, Higgins JA. Apolipoprotein[a] is not associated with apolipoprotein B in human liver. J Lipid Res. 1994;35(10):1896-1901.[DOI]

-

47. White AL, Lanford RE. Cell surface assembly of lipoprotein(a) in primary cultures of baboon hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(46):28716-28723.[DOI]

-

48. Youssef A, Clark JR, Marcovina SM, Boffa MB, Koschinsky ML. Apo(a) and apoB interact noncovalently within hepatocytes: Implications for regulation of Lp(a) levels by modulation of apoB secretion. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022;42(3):289-304.[DOI]

-

49. Lanford RE, Estlack L, White AL. Neomycin inhibits secretion of apolipoprotein [a] by increasing retention on the hepatocyte cell surface. J Lipid Res. 1996;37(10):2055-2064.[PubMed]

-

50. Gurakar A, Hoeg JM, Kostner G, Papadopoulos NM, Brewer HB. Levels of lipoprotein Lp(a) decline with neomycin and niacin treatment. Atherosclerosis. 1985;57:293-301.[DOI]

-

51. Becker L, Webb BA, Chitayat S, Nesheim ME, Koschinsky ML. A ligand-induced conformational change in apolipoprotein(a) enhances covalent Lp(a) formation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(16):14074-14081.[DOI]

-

52. Edelstein C, Davidson NO, Scanu AM. Oleate stimulates the formation of triglyceride-rich particles containing apoB100-apo(a) in long-term primary cultures of human hepatocytes. Chem Phys Lipids. 1994;67-68:135-143.[DOI]

-

53. Nassir F, Bonen DK, Davidson NO. Apolipoprotein(a) synthesis and secretion from hepatoma cells is coupled to triglyceride synthesis and secretion. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(28):17793-17800.[DOI]

-

54. Bonen DK, Hausman AM, Hadjiagapiou C, Skarosi SF, Davidson NO. Expression of a recombinant apolipoprotein(a) in HepG2 cells. Evidence for intracellular assembly of lipoprotein(a). J Biol Chem. 1997;272(9):5659-5667.[DOI]

-

55. Diaz N, Perez C, Escribano AM, Sanz G, Priego J, Lafuente C, et al. Discovery of potent small-molecule inhibitors of lipoprotein(a) formation. Nature. 2024;629(8013):945-950.[DOI]

-

56. Clark JR, Gemin M, Youssef A, Marcovina SM, Prat A, Seidah NG, et al. Sortilin enhances secretion of apolipoprotein(a) through effects on apolipoprotein B secretion and promotes uptake of lipoprotein(a). J Lipid Res. 2022;63(6):100216.[DOI]

-

57. Trieu VN, McConathy WJ. The binding of animal low-density lipoproteins to human apolipoprotein(a). Biochem J. 1995;309:899-904.[DOI]

-

58. Purcell-Huynh DA, Farese RV, Johnson DF, Flynn LM, Pierotti V, Newland DL, et al. Transgenic mice expressing high levels of human apolipoprotein B develop severe atherosclerotic lesions in response to a high-fat diet. J Clin Invest. 1995;95(5):2246-2257.[DOI]

-

59. Demant T, Seeberg K, Bedynek A, Seidel D. The metabolism of lipoprotein(a) and other apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins: A kinetic study in humans. Atherosclerosis. 2001;157(2):325-339.[DOI]

-

60. Diffenderfer MR, Lamon-Fava S, Marcovina SM, Barrett PH, Lel J, Dolnikowski GG, et al. Distinct metabolism of apolipoproteins (a) and B-100 within plasma lipoprotein(a). Metabolism. 2016;65(4):381-390.[DOI]

-

61. Frischmann ME, Ikewaki K, Trenkwalder E, Lamina C, Dieplinger B, Soufi M, et al. In vivo stable-isotope kinetic study suggests intracellular assembly of lipoprotein(a). Atherosclerosis. 2012;225(2):322-327.[DOI]

-

62. Jenner JL, Seman LJ, Millar JS, Lamon-Fava S, Welty FK, Dolnikowski GG, et al. The metabolism of apolipoproteins (a) and B-100 within plasma lipoprotein (a) in human beings. Metabolism. 2005;54(3):361-369.[DOI]

-

63. Gaubatz JW, Nava MN, Guyton JR, Hoffman AS, Opekun AR, Hachey DL, et al. Metabolism of apo(a) and apoB-100 in human lipoprotein(a). In: Catapano AL, Gotto AM, Smith LC, Paoletti R, editors. Drugs affecting lipid metabolism. Dordrecht: Springer; 1993. p. 161-167.[DOI]

-

64. Su W, Campos H, Judge H, Walsh BW, Sacks FM. Metabolism of Apo(a) and ApoB100 of lipoprotein(a) in women: Effect of postmenopausal estrogen replacement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(9):3267-3276.[DOI]

-

65. Averna M, Marcovina SM, Noto D, Cole TG, Krul ES, Schonfeld G. Familial hypobetalipoproteinemia is not associated with low levels of lipoprotein(a). Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15(12):2165-2175.[DOI]

-

66. Giammanco A, Noto D, Nardi E, Gagliardo CM, Scrimali C, Brucato F, et al. Do genetically determined very high and very low LDL levels contribute to Lp(a) plasma concentration? Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2025;35(2):103723.[DOI]

-

67. Menzel HJ, Dieplinger H, Lackner C, Hoppichler F, Lloyd JK, Muller DR, et al. Abetalipoproteinemia with an ApoB-100-lipoprotein(a) glycoprotein complex in plasma. Indication for an assembly defect. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(2):981-986.[DOI]

-

68. Steyrer E, Durovic S, Frank S, Giessauf W, Burger A, Dieplinger H, et al. The role of lecithin: Cholesterol acyltransferase for lipoprotein (a) assembly. Structural integrity of low density lipoproteins is a prerequisite for lp(a) formation in human plasma. J Clin Invest. 1994;94(6):2330-2340.[DOI]

-

69. White AL, Rainwater D, Lanford RE. Intracellular maturation of apolipoprotein [a] and assembly of lipoprotein [a] in primary baboon hepatocytes. J Lipid Res. 1993;34(3):509-517. Available from: https://www.jlr.org/article/S0022-2275(20)40742-4/fulltext

-

70. Dashti N, Koren E, Alaupovic P. Identification and partial characterization of discrete apolipoprotein A-containing lipoprotein particles secreted by human hepatoma cell line HepG2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;163(1):574-580.[DOI]

-

71. Bouma ME, Pessah M, Renaud G, Amit N, Catala D, Infante R. Synthesis and secretion of lipoproteins by human hepatocytes in culture. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1988;24(2):85-90.[DOI]

-

72. Salhanick AI, Schwartz SI, Amatruda JM. Insulin inhibits apolipoprotein B secretion in isolated human hepatocytes. Metabolism. 1991;40(3):275-279.[DOI]

-

73. Millar JS, Packard CJ. Heterogeneity of apolipoprotein B-100-containing lipoproteins: What we have learnt from kinetic studies. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1998;9(3):197-202.[DOI]

-

74. Roudaut M, Caillaud A, Souguir Z, Bray L, Girardeau A, Rimbert A, et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cells-derived liver organoids grown on a biomimesys® hyaluronic acid-based hydroscaffold as a new model for studying human lipoprotein metabolism. Bioeng Transl Med. 2024;9(4):e10659.[DOI]

-

75. Pirillo A, Catapano AL. Lipoprotein (a): A new target for pharmacological research and an option for treatment. Eur J Intern Med. 2025;139:106425.[DOI]

-

76. Tsimikas S, Karwatowska-Prokopczuk E, Gouni-Berthold I, Tardif JC, Baum SJ, Steinhagen-Thiessen E, et al. Lipoprotein(a) reduction in persons with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(3):244-255.[DOI]

-

77. Nissen SE, Wolski K, Balog C, Swerdlow DI, Scrimgeour AC, Rambaran C, et al. Single ascending dose study of a short interfering RNA targeting lipoprotein(a) production in individuals with elevated plasma lipoprotein(a) levels. JAMA. 2022;327(17):1679-1687.[DOI]

-

78. O’Donoghue ML, Rosenson RS, Gencer B, López JAG, Lepor NE, Baum SJ, et al. Small interfering RNA to reduce lipoprotein(a) in cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(20):1855-1864.[DOI]

-

79. Nicholls SJ, Nelson AJ, Michael LF. Oral agents for lowering lipoprotein(a). Curr Opin Lipidol. 2024;35(6):275-280.[DOI]

-

80. Nicholls SJ, Nissen SE, Fleming C, Urva S, Suico J, Berg PH, et al. Muvalaplin, an oral small molecule inhibitor of lipoprotein(a) formation: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(11):1042-1053.[DOI]

-

81. Swearingen CA, Sloan JH, Rhodes GM, Siegel RW, Bivi N, Qian Y, et al. Measuring Lp(a) particles with a novel isoform-insensitive immunoassay illustrates efficacy of muvalaplin. J Lipid Res. 2025;66(1):100723.[DOI]

-

82. Scharnagl H, Stojakovic T, Dieplinger B, Dieplinger H, Erhart G, Kostner GM, et al. Comparison of lipoprotein (a) serum concentrations measured by six commercially available immunoassays. Atherosclerosis. 2019;289:206-213.[DOI]

-

83. Kostner KM, Maurer G, Huber K, Stefenelli T, Dieplinger H, Steyrer E, et al. Urinary excretion of apo(a) fragments. Role in apo(a) catabolism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16(8):905-911.[DOI]

-

84. Mooser V, Marcovina SM, White AL, Hobbs HH. Kringle-containing fragments of apolipoprotein(a) circulate in human plasma and are excreted into the urine. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(10):2414-2424.[DOI]

-

85. Trenkwalder E, Gruber A, König P, Dieplinger H, Kronenberg F. Increased plasma concentrations of LDL-unbound apo(a) in patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 1997;52(6):1685-1692.[DOI]

-

86. Gries A, Nimpf J, Nimpf M, Wurm H, Kostner GM. Free and Apo B-associated Lpa-specific protein in human serum. Clin Chim Acta. 1987;164(1):93-100.[DOI]

-

87. Koschinsky ML, Boffa MB. Oxidized phospholipid modification of lipoprotein(a): Epidemiology, biochemistry and pathophysiology. Atherosclerosis. 2022;349:92-100.[DOI]

-

88. Leibundgut G, Scipione C, Yin H, Schneider M, Boffa MB, Green S, et al. Determinants of binding of oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein (a) and lipoprotein (a). J Lipid Res. 2013;54(10):2815-2830.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite