Fei Guo, School of Computer Science and Engineering, Central South University, Changsha 410083, Hunan, China. E-mail: guofei@csu.edu.cn

Jijun Tang, School of Computer Science and Control Engineering, Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, Shenzhen 518055, Guangdong, China. E-mail: jj.tang@siat.ac.cn

Abstract

Aims: Development of robust and effective methods for uncovering herb interactions and constructing herb–disease associations requires the integration of diverse biological and medical information. A key challenge in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) research is to robustly uncover herb interactions and construct reliable herb–disease associations. This task requires handling the inherently high-dimensional, multi-label, and cross-domain nature of prescription data. Existing approaches provide limited representation capacity and insufficient integration of biomedical knowledge, restricting their ability to capture the complex semantics underlying the relationships between herbs and diseases.

Methods: To address the limitations of existing approaches, we propose MediHerb, a multi-modal enhanced framework for disease inference via herbal knowledge. MediHerb unifies five complementary modalities: molecular sequences, fingerprints, physicochemical properties, graphical prescription representations, and the description of TCM prescriptions into a shared latent space. An attention-based fusion mechanism aligns the semantics across molecular, herbal, and diagnostic levels, enabling multi-granularity reasoning. To further promote accessibility, a lightweight graphical interface has been developed to support interaction with both the model and open datasets.

Results: Experimental results on benchmark datasets demonstrate that MediHerb substantially outperforms existing baselines in herb–disease inference. Beyond predictive accuracy, the learned embeddings and model attention patterns reveal meaningful biological and pharmacological insights, confirming that MediHerb captures the mechanistic underpinnings of herb–disease associations.

Conclusion: MediHerb highlights the potential of knowledge-enhanced multi-modal fusion to bridge molecular, herbal, and clinical semantics, offering a more interpretable and holistic approach to understanding TCM prescriptions.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has been practiced for millennia, representing a unique system of medical theory and clinical application[1,2]. In practice, TCM utilizes herbal prescriptions that combine multiple herbs to target complex pathological conditions through synergistic effects. Unlike modern pharmaceuticals, which are typically designed around single active compounds, TCM prescriptions are highly complex. They exhibit a high-dimensional nature, where herbs may contain hundreds of chemical constituents that interact through multiple therapeutic pathways[3]. Consequently, understanding and predicting the disease associations of these prescriptions is a critical, yet challenging problem that requires integrating diverse information sources at both the molecular and semantic levels.

Early computational studies of TCM prescription analysis largely employed statistical or topic-modeling techniques. For example, Yao et al.[4] proposed a probabilistic topic model to uncover latent prescription patterns, and other probabilistic models, such as conditional probabilistic frameworks, have also been applied with promising performance[5]. While these provided useful insights, they were limited by their shallow representation capability. The rise of deep learning has since led to the proposal of more sophisticated frameworks, such as knowledge-driven herb recommendation models based on graph convolutional networks (GCNs)[6-9], Large Language Model (LLM) based frameworks[10-13], and multi-view contrastive learning for herb recommendation[14,15]. While these advances have improved coverage and usability such approaches may face challenges, including relatively low performance or imbalanced precision-recall ratio, i.e., sometimes predicting many labels to enhance recall at the expense of precision. In addition, these methods generally use labels only and place less emphasis on the biochemical perspectives of herb ingredients, which may limit interpretability and hinder deeper reasoning about potential mechanistic interactions.

Parallel to advances in TCM modeling, the machine learning community has made significant progress in molecular representation learning. Sequence-based encoders like BARTSmiles[16] have demonstrated a strong capacity to extract structural information from chemical formulas. At the same time, large-scale pre-trained language models such as SciBERT and PubMedBERT have enabled fine-grained semantic understanding of biomedical texts[17,18]. Despite these advances, studies have yet to bridge these chemical or biomedical views and textual modalities within a unified TCM prescription inference framework, leaving a gap in the development of robust, multi-modal approaches.

Moreover, the inherent challenges of multi-label prediction in TCM persist. Each prescription may be associated with multiple diseases, and herb–disease relationships are rarely one-to-one. Existing LLM-based models have demonstrated the potential of knowledge graph injection and fine-tuned large models for prescription generation. However, issues such as hallucination and limited interpretability remain. Similarly, graph-based methods[7,11] are effective in modeling herb–herb interactions, yet they face challenges in extending these insights to systematic disease inference or broader model generalization.

To overcome these limitations, recent advancements have focused on multi-modal learning frameworks that integrate diverse, complementary data sources for a holistic understanding of TCM mechanisms[19,20]. For example, studies like Multi-ITI[21] utilize a multi-modal approach that combines molecular biological features with network topological features to predict fine-grained relationships, such as herbal ingredient–target interactions. Building upon this philosophy of multi-modal integration, our MediHerb model extends this concept to the high-level task of systematic prescription–disease inference, combining clinical data with derived network features to bridge the gap between high-level clinical records and underlying biological associations.

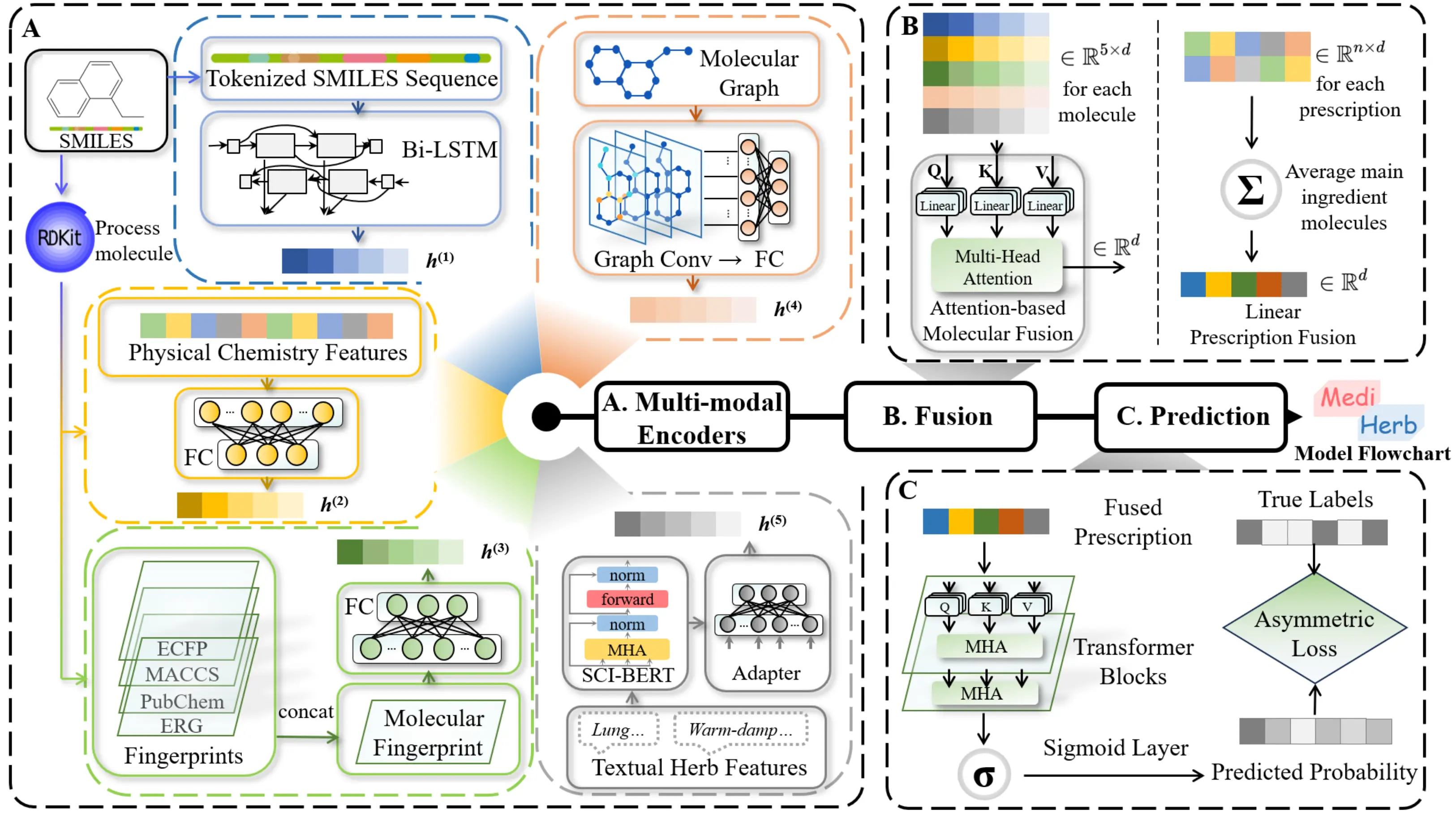

In this study, we address these challenges by proposing MediHerb, a novel multi-modal, attention-based architecture for herb–disease inference, as shown in Figure 1. Our model integrates five complementary modalities of herb information, including chemical formula, molecular fingerprints, physicochemical features, molecular graphical structures, and natural language herb descriptions, through modality-specific encoders and an adaptive attention fusion module. By projecting these heterogeneous embeddings into a unified semantic space and employing a transformer-based self-attention mechanism, our framework dynamically balances the contributions of each modality and captures complex herb–herb interactions within prescriptions to finally predict herb–disease relationships. We also provide extensive experimental validation against strong baselines, ranging from topic modeling and graph-based methods to deep learning and LLM-based approaches. Furthermore, we offer an exploration of potential biomedical insights derived from our attention-based model and a practical, user-friendly software tool implementation with a Graphical User Interface (GUI) on our website, which makes advanced predictive tools accessible to practitioners and researchers without specialized hardware.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the MediHerb model. (A) Input stage: multi-modal encoders represent the main ingredient of each herb using chemical, structural, physiological, and textual features; (B) Fusion stage: five modalities are integrated via attention and aggregated across herbs in a prescription; (C) Prediction stage: fused features are processed by transformer blocks and a sigmoid layer to produce disease probabilities, optimized with an asymmetric loss for imbalanced multi-label data. SMILES: Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System; Bi-LSTM: bidirectional long short-term memory; FC: fully connected; ECFP: extended connectivity fingerprint; MACCS: Molecular Access System; ERG: extended reduced graph; MHA: multi-head attention.

2. Methods

2.1 Dataset and preprocessing

The dataset used in this study was primarily derived from the publicly available Prescription Topic Modeling (PTM) dataset[4], which provides a comprehensive collection of TCM prescriptions. To enhance data completeness and ensure consistent feature representation, we further incorporated auxiliary molecular and textual information from the HERB database[22]. This integration enriched each herb in the PTM dataset with detailed multi-modal attributes, including textual descriptions and chemical representations of key active ingredients.

The HERB database was preprocessed to retain only molecular entries explicitly linked to the main herbal sources and annotated with at least one of the following essential metadata: a valid Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) representation or a complete textual molecular description. Specifically, three steps of data cleaning were adopted. (1) Filtering: Records without explicit herbal provenance or missing both SMILES and textual descriptors were excluded. (2) Handling missing values: For herbs with partially missing molecular metadata, missing SMILES strings were replaced with a special <unk> token during tokenization, while missing textual descriptions were treated as empty strings. These strategies ensured consistent data representation across all herbal entries. (3) De-duplication: Molecular entries sharing identical Chinese, English, or Latin names were merged, in which the record containing more complete information (typically the one with textual annotations) was retained. After these steps, 6,232 out of the original 49,258 molecular entries were preserved.

To harmonize HERB nomenclature between the PTM and herb datasets, we performed fuzzy string matching based on normalized lexical similarity, addressing orthographic variations and synonymous naming conventions. Ambiguous mappings were resolved through a hierarchical matching strategy that prioritized exact Latin binomials, followed by standardized pinyin and common English aliases. Using these correspondences, each prescription in the PTM dataset was enriched with the available molecular and textual features of its constituent herbs, forming a structured multi-modal dataset that integrates chemical, textual, and relational information. The combined dataset also follows rigorous cleaning steps. (1) Within each prescription, herbs lacking both valid molecular and textual information were removed, while other herbs with informative metadata were retained. (2) Prescriptions containing identical sets of valid herbs and corresponding disease labels were merged to remove redundancy. After these steps, a total of 32,920 unique prescriptions were preserved. The final dataset ensures consistent data representation and minimizes the influence of incomplete entries on model training.

During preprocessing, the chemical structures represented in SMILES format[23] were further processed using the RDKit package[24] to extract comprehensive chemical features. This step generated additional multi-modal data, including molecular graphs, quantitative physicochemical properties, and diverse molecular fingerprints. Therefore, a multi-modal dataset systematically links TCM prescriptions to their constituent herbs, associated diseases, and underlying molecular characteristics, providing a comprehensive foundation for subsequent analysis and modeling.

2.2 Problem description

The therapeutic relevance of herbs can be formulated as a multi-label prediction task. Our objective is to predict the set of diseases associated with a given prescription. Each herb is represented by its main ingredient through five modalities: chemical formula, molecular fingerprint, physiological features, structural graph, and textual description, denoted as h(i), i = 1, ..., 5. A prescription, denoted as X, consists of multiple herbs Xi, each encoded into a fused representation Zi. The ground truth label set is y = y1, y2, ..., yC, where yi ∈ {0, 1} corresponds to one of C possible diseases. The aim is to predict all relevant diseases, denoted as

2.3 Compound encoder

MediHerb represents a significant advancement in multi-modal, multi-label learning for herb–disease inference in TCM. It is an attention-based large model meticulously engineered to fuse disparate data types, extracting intricate relationships to predict diseases from complex herb combinations. The architecture is distinguished by its sophisticated handling of multi-modal herb information, followed by an adaptive attention mechanism and a robust prediction layer. The core of our model is an ensemble of five specialized modality-specific encoders, each uniquely designed to extract rich feature representations from a particular data stream associated with an herb.

2.3.1 Sequence representation module

Compounds of herbs’ primary active ingredients are commonly represented as SMILES sequences, which deliver information about the natural compound structure, and are processed by a two-layer bidirectional long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM) network[25]. SMILES sequences are first tokenized and mapped to atom-level embeddings, then fed into the forward and backward LSTM layers. Formally, if S denotes the tokenized SMILES of length T, we compute as follows:

The final hidden states hSMILES from both directions are concatenated and passed through a two-layer Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) to yield the fixed-dimensional SMILES embedding for each molecule.

2.3.2 Fingerprints representation module

Compound fingerprints are employed as binary vectors that encode the presence or absence of specific substructural motifs within a molecule. These pre-computed molecular fingerprints, which provide precise numerical representations of substructural composition, are subsequently processed by an MLP for feature transformation. In this study, multiple fingerprinting strategies are incorporated, including Extended Reduced Graph fingerprints[26], Molecular Access System (MACCS) keys[27], PubChem fingerprints[28], and Extended Connectivity Fingerprints[29], thereby ensuring a diverse and comprehensive characterization of molecular substructures.

Together, these diverse fingerprint types furnish the MLP with a rich and highly informative basis for extracting crucial features h(2) from each molecule’s structural profile. This module effectively distills the essence of molecular topology and connectivity.

2.3.3 Physio-chemical representation module

Analogous to the construction of molecular fingerprints, the preprocessed tensors, which encode a comprehensive set of physicochemical descriptors of the ingredient, are processed by a distinct MLP.

This dedicated head systematically transforms the high-dimensional physical feature space into a compact, continuous embedding vector h(3) that preserves informative structural and chemical characteristics.

2.3.4 Graph representation module

The complex spatial and graphical arrangement of each molecule is represented as a dynamic graph structure[30]. Recognizing that chemical bonds serve as natural neighboring edges and atoms as nodes, we employ a combined GCN[31] as the encoder, which is adept at analyzing localized features within these graphs. Specifically, we first adapt a graph attention network (GAT)[32] to capture the intricate local molecular structure information through a shared self-attention mechanism. The outputs from this GAT, representing neighborhood-aware high-dimensional features, are then passed through a subsequent deep Convolutional Neural Network to further discern complex structural patterns.

This integrated encoder is particularly adept at discerning intricate structural patterns and local environments within the molecular graph.

2.4 Herbal description and representation module

The Herb Description Encoder is designed to extract semantic meaning from the natural language descriptions of each herb. These descriptions, which detail properties, target meridians, and potential functions rather than direct disease associations, offer valuable insights into an herb’s context within a prescription. We utilized the pre-trained SciBERT uncased model[17] for this task, with a maximum context length of 128 tokens. To effectively integrate this textual modality with the others, we first fine-tuned the model by adding a two-layer network to its output. This network was trained to align the resulting high-dimensional vector representations with those of the other modalities, ensuring semantic coherence across the different data streams, as shown in Equation (5).

The output from this fine-tuned BERT model then serves as a powerful representation of the herb’s descriptive information, capturing insights complementary to those derived from its chemical constituents alone.

2.5 Fusion and aggregation module

A critical step lies in the subsequent semantic alignment of the tensor outputs from these five diverse encoders. Cosine similarity is strategically employed to project these high-dimensional embeddings into a unified, semantically coherent feature space. This ensures that representations derived from vastly different modalities (e.g., graphical structure and textual description) are not only comparable but also physically and medically meaningful. The aligned outputs are then intelligently combined via weighted concatenation, yielding a single, comprehensive vector for each individual herb within the prescription.

To create a single, comprehensive representation for a prescription, our model employs a two-stage fusion process that preserves the rich, modality-specific information of each herb. First, for each herb i, we take its five aligned embeddings

This produces a unified vector Zi that dynamically weighs and fuses the different data streams for that herb. Such attention-based fusion yields a more expressive per-herb representation compared to simple averaging, as it allows the model to emphasize the most informative modalities in context.

Following per-herb fusion, we aggregate the resulting vectors for all H herbs in a prescription by element-wise summation, which captures the collective synergistic effect of the herb combination:

Here, Wagg and bagg denote a learned linear layer that transforms the summed vector u into the final prescription embedding r.

2.6 Disease prediction

The resulting prescription vector r encapsulates both the individual characteristics of the herbs and their joint interactions. We pass r through several standard Transformer blocks to enable deeper contextual refinement, culminating in an MLP and a sigmoid activation layer that generates the probability scores across the 390 target disease categories:

Where each component

This architecture (excluding the pre-trained SciBERT module) comprises approximately 20 million trainable parameters, striking a balance between high predictive performance and computational efficiency. As a result, our model can be deployed on typical CPUs, democratizing access to multi-label disease prediction without the need for specialized hardware.

2.7 Training details

Trained on a single NVIDIA 2080 Ti GPU, the training regimen of our model is tailored to the specific complexities of multi-label disease prediction, particularly addressing label imbalance. We employ a modified asymmetric loss for multi-label classification[33] as our loss function. This choice is critical for effectively handling the common challenge of disparate positive and negative label frequencies in medical datasets, ensuring robust learning. The model’s parameters are optimized using the Adam optimizer[34] with an initial learning rate of 8 × 10-6. To ensure stable and efficient convergence, an exponentially decreasing learning rate scheduler is implemented, applying a gamma of 0.995 at each epoch.

3. Results

3.1 Evaluation metrics

To assess the performance of the multi-label prediction task, we employed three standard evaluation metrics: precision, recall, and F1 score. These metrics were computed according to their conventional definitions as follows:

where m denotes the number of samples, yi is the ground-truth label vector, and

3.2 Comparison with other methods

In this section, we compare our model (MediHerb), which formulates disease inference as a multi-label prediction task, with other multi-label prediction models, including a GCN-based method proposed by Baranwal et al.[35], a GAT-based method developed by Yang et al.[36], and a sequence-based model like BARTSmiles[16]. Table 1 presents the performance comparison of MediHerb and these comparable models for disease prediction from herbs. As shown, MediHerb consistently outperforms both GCN and GAT across all evaluation metrics, including area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. In particular, MediHerb achieves the highest AUROC of 0.936, demonstrating its superior ability to distinguish positive disease–herb associations while maintaining high predictive reliability. These results confirm that integrating multi-modal herbal knowledge with graph-based molecular representations substantially enhances the performance of multi-label disease inference compared with conventional graph neural network approaches.

| Methods | AUROC (%) | Accuracy (%) | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1 Score (%) |

| GCN | 91.88 | 14.19 | 17.83 | 21.78 | 19.42 |

| GAT | 91.86 | 15.36 | 19.01 | 25.63 | 21.68 |

| BARTSmiles | 89.39 | 4.90 | 8.30 | 21.01 | 11.90 |

| MediHerb | 93.64 | 20.04 | 23.38 | 37.98 | 28.76 |

AUROC: area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; GCN: graph convolutional network; GAT: graph attention network.

3.3 Ablation studies

We conducted a comprehensive ablation study to rigorously quantify the contribution of each input modality to the overall predictive performance of the MediHerb model. This involved comparing the full framework with several variants that either encoded a single data modality, such as physicochemical properties, graph topological features, text descriptions, fingerprint molecular structure, or SMILES sequence information, or employed the non-fused MediHerb Concatenation approach.

The results, summarized in Table 2, unequivocally demonstrate the necessity of integrating diverse features. Analysis of the unimodal baselines showed that the model relying solely on fingerprint information achieved the highest performance among single-view models, yet its performance remained clearly suboptimal compared to the full MediHerb model. This outcome validates the necessity of incorporating multiple feature views into the prediction process.

| Method | F1 score | Precision | Recall |

| MediHerb (physicochemical) | 0.1263 | 0.1243 | 0.1326 |

| MediHerb (graph) | 0.2601 | 0.2243 | 0.3148 |

| MediHerb (text) | 0.2607 | 0.2227 | 0.3195 |

| MediHerb (fingerprint) | 0.2781 | 0.2293 | 0.3588 |

| MediHerb (SMILES) | 0.2729 | 0.2294 | 0.3427 |

| MediHerb (SMILES + graph + physicochemical + fingerprint) | 0.2773 | 0.2253 | 0.3661 |

| MediHerb (SMILES + graph + physicochemical + text) | 0.2757 | 0.2321 | 0.3449 |

| MediHerb (SMILES + fingerprint + physicochemical + text) | 0.2800 | 0.2238 | 0.3792 |

| MediHerb (SMILES + graph + fingerprint + text) | 0.2803 | 0.2349 | 0.3526 |

| MediHerb (fingerprint + graph + physicochemical + text) | 0.2825 | 0.2294 | 0.3732 |

| MediHerb (w/o text) | 0.2806 | 0.2317 | 0.3611 |

| MediHerb (Concatenation) | 0.2809 | 0.2324 | 0.3605 |

| MediHerb | 0.2876 | 0.2338 | 0.3798 |

SMILES: Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System.

Overall, the MediHerb Concatenation model outperformed the majority of single-view models, highlighting the baseline significance of assembling diverse features. Specifically, compared to the MediHerb physicochemical model, the Concatenation variant improved the F1 score by 15.46%. Similarly, when compared to the MediHerb Text model, it enhanced the F1 score by 2.02%. These substantial gains reinforce the value derived from simply assembling the various data perspectives.

However, merely concatenating these feature representations led to a noticeable performance difference when compared to the full MediHerb framework. The MediHerb model achieved the highest F1 score of 0.2876. Notably, the full MediHerb model outperformed all other variants across all metrics.

These findings not only reinforce the superior performance of the full MediHerb model over concatenated feature sets but also emphasize the critical role that the Hierarchical Multi-Modal Fusion strategy plays in systematic prescription-disease prediction. Therefore, multi-view learning with diverse feature encoders and an optimized fusion module are crucial for accurately capturing the comprehensive therapeutic effects of TCM prescriptions.

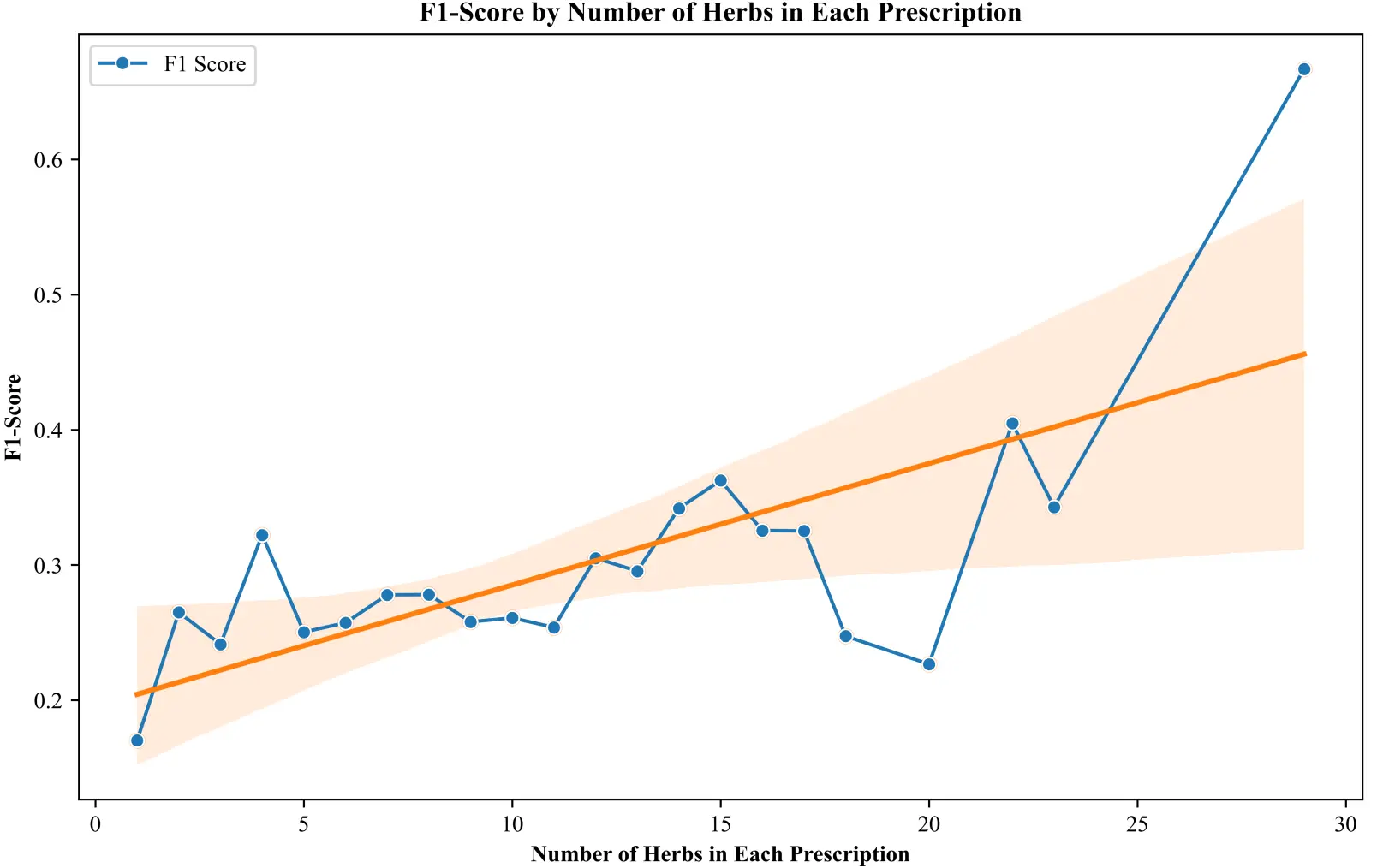

3.4 Assessment of herb count on prediction performance

We examined the influence of prescription complexity on predictive accuracy by analyzing the relationship between the number of herbs in a prescription and the performance of our model. As shown in Figure 2, prescriptions containing only one or two herbs yield relatively low prediction performance, with F1 scores typically around 0.2. In contrast, when prescriptions include twelve or more herbs, most F1 scores exceed 0.3 and often surpass the overall average. This trend is also supported by the regression line, which indicates a clear positive correlation between the number of herbs in a prescription and the corresponding F1-score. This observation suggests that as more herbs are incorporated, the prescription’s therapeutic intent becomes clearer, enabling the model to achieve greater predictive accuracy. This enhanced performance is likely due to the fact that multi-herb formulations provide a higher density of contextual information, manifesting consistent co-occurrence patterns and reinforcing complementary pharmacological interactions within the composite. These findings provide computational support for the traditional principle of herbal synergism, where combined therapeutic effects possess greater specificity than those of isolated components. Consequently, the robust joint representation derived from multi-herb prescriptions yields a stronger, more coherent embedding, substantially enhancing the model’s capacity to generalize across diverse prescription types and accurately infer corresponding diseases.

Figure 2. F1 score as a function of the number of herbs per prescription. A positive correlation shows that predictive accuracy improves with increased herbal complexity.

3.5 Case studies

3.5.1 Identification of potential herb–herb interactions

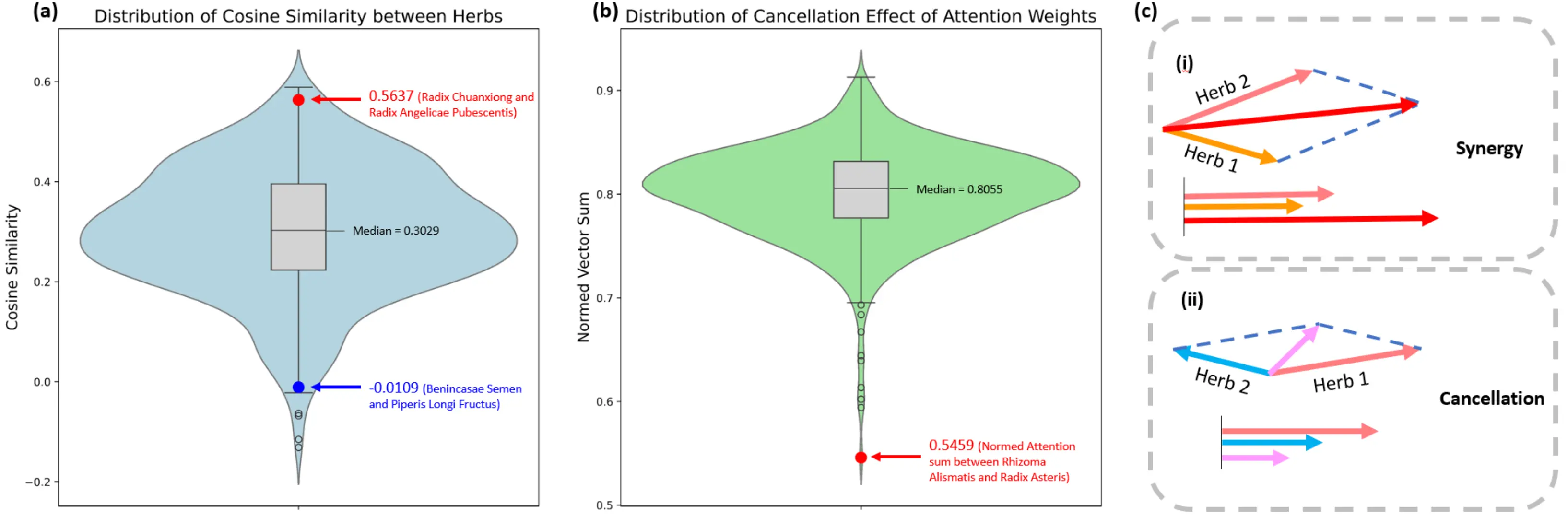

The semantic alignment of the input layers allows the model to find similarities across different data types. For example, an herb with a vague or missing textual description can be aligned with an herb that has similar chemical or physical properties, thereby enabling interference of its potential usage. Cosine similarity is adopted as it measures the angular distance between embedding vectors, emphasizing their semantic orientation rather than magnitude. This property makes it particularly suitable for evaluating relational similarity across modalities.

A representative case is shown in Figure 3a, where Radix Chuanxiong, an herb with no textual description in the dataset, is semantically aligned with Radix Angelicae Pubescentis, whose molecular fingerprint vector shows a high cosine similarity of 0.5637. This value is among the highest across 500 sampled herb pairs, suggesting a strong semantic alignment in the embedded representation. Conversely, Enincasae Semen and Piperis Longi Fructus exhibit low cosine similarity. Such alignment indicates that the model effectively captures cross-modal relationships between molecular features and textual semantics, even when one modality is absent or incomplete. Cross-referencing with the Chinese Pharmacopoeia[2] confirms their overlapping functions: both are indicated for promoting blood circulation and treating rheumatic pain, further validating the semantic inference ability of our model.

Figure 3. Analyzing herb interactions in feature space. (a) Fingerprint similarity across 500 herb pairs, confirming the model captures meaningful relationships. For example, high similarity between Chuanxiong and Angelica indicates synergy, while low similarity between Benincasa seed and Long Pepper reflects distance; (b) Cancellation effects using normalized vector sums. Values near zero indicate stronger cancellation, with the Alismatis-Aster pair showing marked cancellation in this formula context; (c) How vectors represent pharmacological effects: aligned vectors create synergy (longer combined vector), while opposed vectors cause cancellation (shorter combined vector). This demonstrates the mathematical basis of herb interactions.

Beyond improving predictive accuracy, the attention mechanism provides an informative signal that can be leveraged to identify potential adverse herb–herb interactions within a prescription. We observed instances where the vector sum of two specific herb representations,

The cancellation effect can be quantified using the normalized vector sum, expressed as

For example, for Rhizoma Alismatis and Radix Asteris, their normalized attention vector sum is only 0.5459. It is a substantial outlier in the distribution shown in Figure 3b, which strongly suggests a negative interaction signal. The demonstration of the cancellation effect is shown in Figure 3c. When viewing the attention score of each herb as an effect vector, two herbs with vectors pointing in similar directions produce a longer summed vector, representing a synergistic effect. In contrast, if two vectors point in opposite directions, they counteract one another, resulting in a smaller magnitude of the summed vector, corresponding to the cancellation effect illustrated in the figure.

This is consistent with traditional herbology: according to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia[2], Rhizoma Alismatis is characterized as sweet, bland, and cold in nature, whereas Radix Asteris is pungent, bitter, and warm. They are essentially opposites in properties and are therefore typically recommended against concurrent use. This emergent capability offers a data-driven approach to proactively identify and mitigate adverse interactions in complex multi-herb TCM prescriptions, thereby enhancing both safety and efficacy.

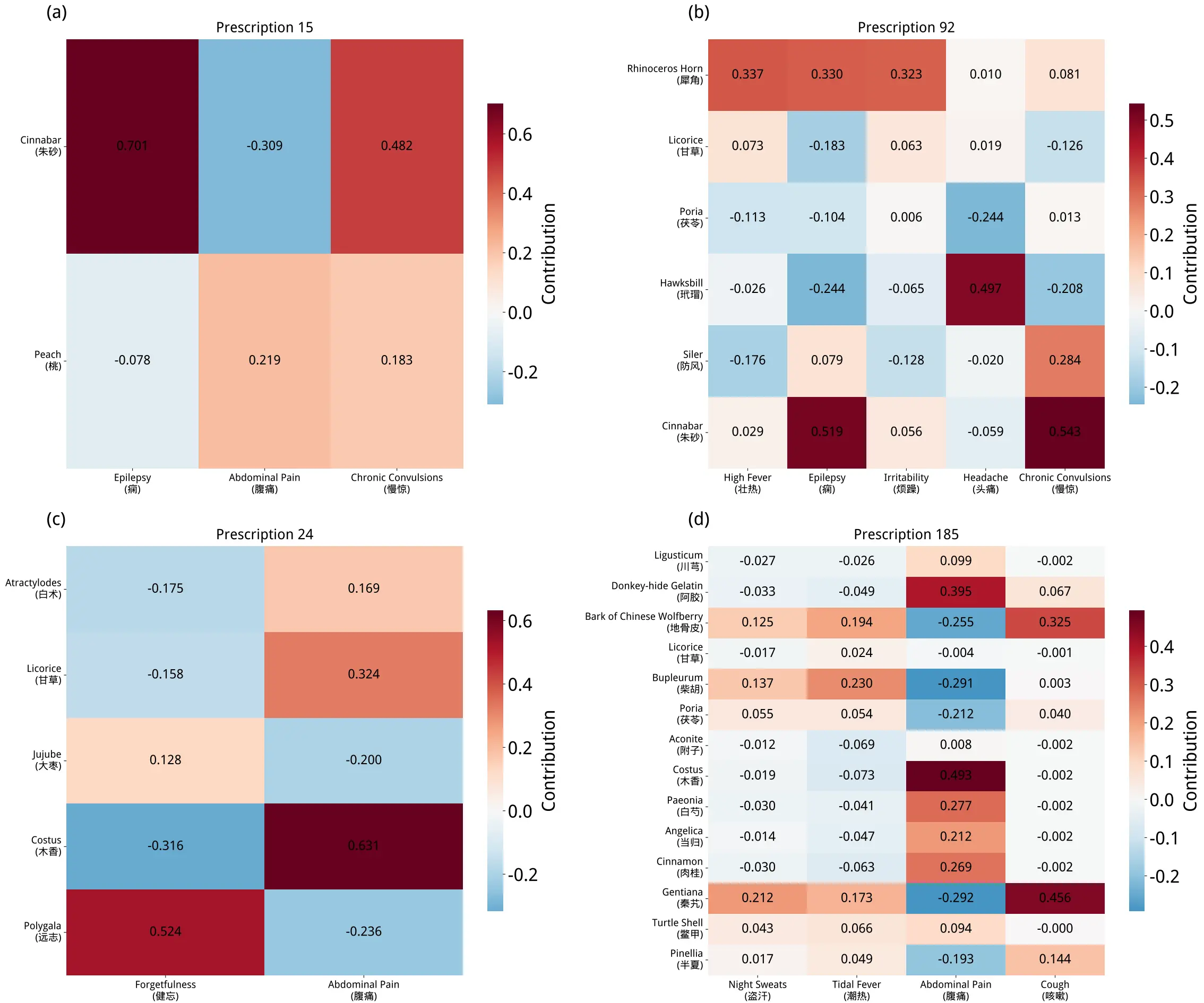

3.5.2 Herb contribution

Figure 4 presents contribution heatmaps for individual herbs within traditional prescriptions against target symptoms. In these heatmaps, rows represent specific herbs, and columns correspond to symptoms for which the model’s prediction probability exceeded a predefined threshold. The color intensity of each cell reflects the magnitude of the contribution value. This value is calculated by subtracting the model’s prediction probability for a symptom after removing a specific herb from the probability with the complete prescription. This metric quantifies the relative contribution of each individual herb to symptom prediction.

Figure 4. The contribution heatmaps of each herb in the prescriptions to positive symptoms.

The results highlight key therapeutic components. For instance, in Figure 4a and Figure 4b, Cinnabar exhibits strong contribution values of 0.701 and 0.519, respectively, for the “Epilepsy” symptom. This finding suggests that Cinnabar may function as a core synergistic component in epilepsy-targeting prescriptions, consistent with its traditional therapeutic application. Similarly, Figure 4c and Figure 4d reveal a high contribution from Costus to abdominal pain, aligning with its known efficacy in relieving such discomfort.

In summary, these heatmaps visually quantify the magnitude and direction of each component’s contribution to target symptoms. This method not only provides partial validation for the rationality of traditional formula compatibility but also offers a valuable analytical tool for modern TCM research, particularly for component screening and formula optimization.

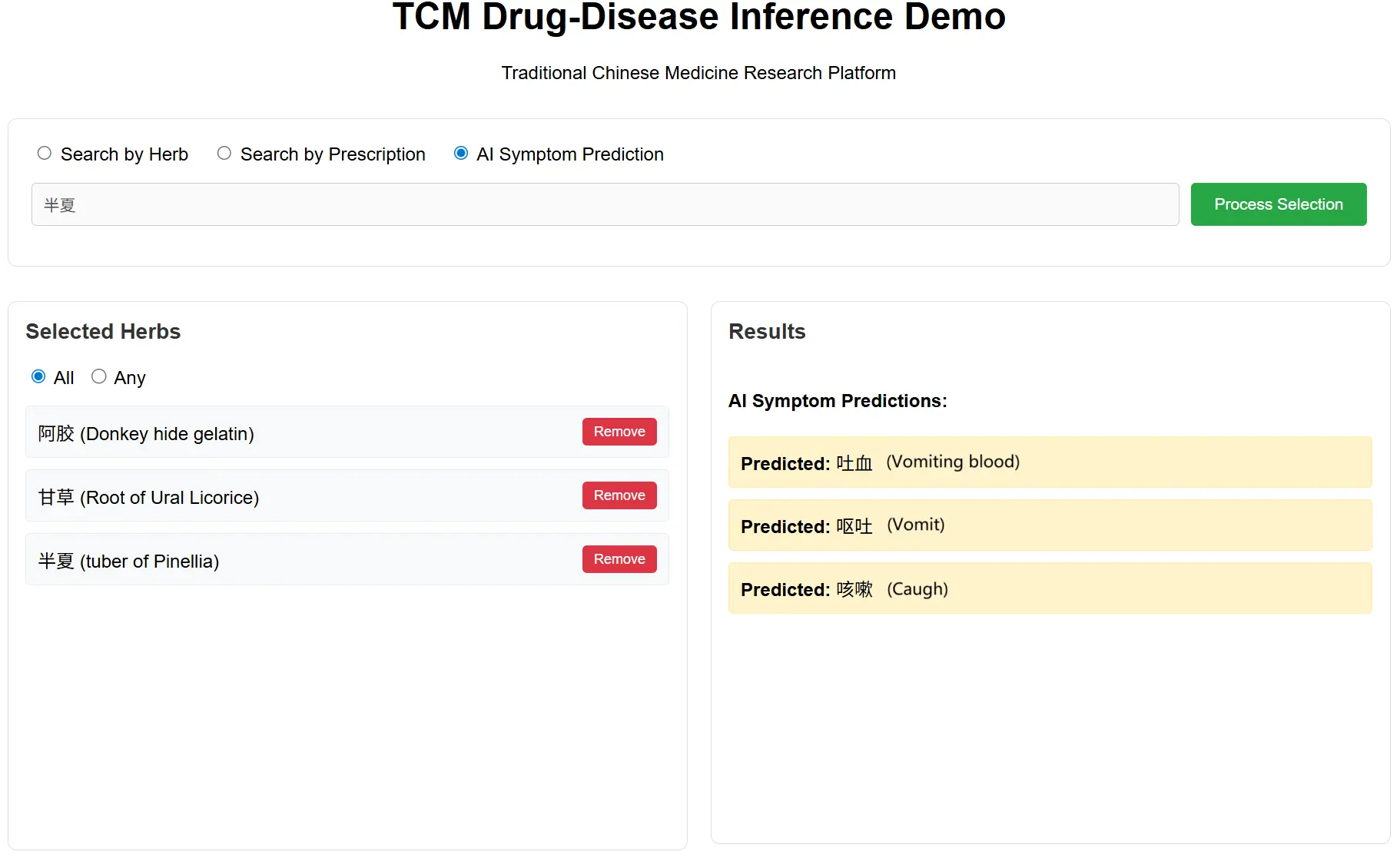

3.6 Development of a web-based computational tool

Recognizing a significant gap in the accessibility and usability of existing TCM datasets, which are often provided in raw formats without user-friendly search interfaces, we developed a web-based software application, as shown in Figure 5. This new tool aims to serve as both a public repository and an interactive platform for our multi-modal model and public datasets. It offers an intuitive interface that allows users to easily search for specific herbs and prescriptions, explore their associated multi-modal data, and even use our trained model for real-time AI herb–disease prediction.

Figure 5. An example of the MediHerb website’s GUI. The interface allows users to select one or more herbs to either query related prescriptions (displayed in the left panel) or predict potential associated diseases using our model (shown in the right panel). GUI: Graphical User Interface.

By providing this software, we aim to democratize access to high-quality TCM data and our predictive model, encouraging further research and practical applications by the wider community. This tool represents a significant contribution to the field by providing a modern and efficient way to interact with TCM data, which was previously a labor-intensive manual process. The software is now available at www.mediherb.lbci.net.

4. Conclusion

In this work, we propose a multi-modal attention framework that integrates five heterogeneous information sources, including chemical structures, molecular properties, and textual descriptions, to improve herb–disease inference in TCM. By unifying complementary modalities, the model enhances predictive accuracy and interpretability compared with text or network-based methods. Nevertheless, this study has certain limitations. The performance of the framework depends on the completeness and quality of external databases, and structural annotations are not consistently available for all herbs. In addition, potential biases in the training data may influence model predictions, necessitating further experimental validation. The multi-modal design also increases computational complexity, which may affect scalability for large-scale applications. Despite these limitations, the proposed framework achieves robust performance and offers practical value for advancing data-driven TCM research through its integration into an accessible web platform.

Authors contribution

Liu X: Data curation, methodology, conceptualization, supervision, formal analysis, investigation, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Chen F: Data curation, methodology, formal analysis, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Pan J: Formal analysis, writing-review & editing, investigation.

Ai C: Writing-review & editing.

Guo F, Tang J: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, formal analysis, writing-review & editing, investigation.

Conflicts of interest

Jijun Tang is an Editorial Board Member of Computational Biomedicine. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data are from publicly available resources. The herb and TCM datasets can be downloaded from https://zenodo.org/records/17141208. The code supporting the findings of this study is freely available on https://github.com/xiaoyiliu-usc/MediHerb repository.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62502050, 62532017, 62322215, U24A20257), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program grant number JCYJ20241202130212016 and KQTD20200820113106007. Also, this work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2025-JYB-XJSJJ008). This study was also supported in part by the High-Performance Computing Clusters (PL-17161) of Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Cheung F. TCM: Made in china. Nature. 2011;480(7378):S82-S83.[DOI]

-

2. Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China. 20th ed. Beijing: China Medical Science Press; 2020.

-

3. Zhang W, Huai Y, Miao Z, Qian A, Wang Y. Systems pharmacology for investigation of the mechanisms of action of traditional Chinese medicine in drug discovery. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:743.[DOI]

-

4. Yao L, Zhang Y, Wei B, Zhang W, Jin Z. A topic modeling approach for traditional Chinese medicine prescriptions. IEEE Trans Knowl Data Eng. 2018;30(6):1007-1021.[DOI]

-

5. Wang S, Huang EW, Zhang R, Zhang X, Liu B, Zhou X, et al. A conditional probabilistic model for joint analysis of symptoms, diseases, and herbs in traditional Chinese medicine patient records. In: 2016 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM); 2016 Dec 15-18; Shenzhen, China. Piscataway: IEEE; 2016. p. 411-418.[DOI]

-

6. Yu T, Li J, Yu Q, Tian Y, Shun X, Xu L, et al. Knowledge graph for TCM health preservation: Design, construction, and applications. Artif Intell Med. 2017;77:48-52.[DOI]

-

7. Yang Y, Rao Y, Yu M, Kang Y. Multi-layer information fusion based on graph convolutional network for knowledge-driven herb recommendation. Neural Netw. 2022;146(6):1-10.[DOI]

-

8. Zhao W, Lu W, Li Z, Zhou C, Fan H, Yang Z, et al. TCM herbal prescription recommendation model based on multi-graph convolutional network. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;297(3):115109.[DOI]

-

9. Gu L, Ma Y, Liu S, Zhang Q, Zhang Q, Ma P, et al. Prediction of herbal compatibility for colorectal adenoma treatment based on graph neural networks. Chin Med. 2025;20(1):1-12.[DOI]

-

10. Zhang H, Zhang J, Ni W, Jiang Y, Liu K, Sun D, et al. Transformer- and generative adversarial network-based inpatient traditional Chinese medicine prescription recommendation: Development study. JMIR Med Inform. 2022;10(5):e35239.[DOI]

-

11. Qi J, Wang X, Yang T. Traditional Chinese medicine prescription recommendation model based on large language models and graph neural networks. In: 2023 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM); 2023 Dec 5-8; Istanbul, Turkiye. Piscataway: IEEE; 2023. p. 4623-4627.[DOI]

-

12. Tan Y, Zhang Z, Li M, Pan F, Duan H, Huang Z, et al. MedChatZH: A tuning LLM for traditional Chinese medicine consultations. Comput Biol Med. 2024;172:108290.[DOI]

-

13. Zhuang Y, Yu L, Jiang N, Ge Y. TCM-KLLaMA: Intelligent generation model for traditional Chinese medicine prescriptions based on knowledge graph and large language model. Comput Biol Med. 2025;189(7378):109887.[DOI]

-

14. Yang Q, Cheng Z, Kang Y, Wang X. A novel multi-view contrastive learning for herb recommendation. Appl Intell. 2024;54(22):11412-11429.[DOI]

-

15. Hu H, Li Y, Zheng Z, Hu W, Lin R, Kang Y. A traditional Chinese medicine prescription recommendation model based on contrastive pre-training and hierarchical structure network. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;268(1):126318.[DOI]

-

16. Chilingaryan G, Tamoyan H, Tevosyan A, Babayan N, Hambardzumyan K, Navoyan Z, et al. BartSmiles: Generative masked language models for molecular representations. J Chem Inf Model. 2024;64(15):5832-5843.[DOI]

-

17. Beltagy I, Lo K, Cohan A. SciBERT: A pretrained language model for scientific text. In: Inui K, Jiang J, Ng V, Wan X. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP); 2019 Nov 03-07; Hong Kong, China. Pittsburgh: Association for Computational Linguistics; 2019. p. 3615-3620.[DOI]

-

18. Gu Y, Tinn R, Cheng H, Lucas M, Usuyama N, Liu X, et al. Domain-specific language model pretraining for biomedical natural language processing. ACM Trans Comput Healthcare. 2021;3(1):1-23.[DOI]

-

19. Hu L, Zhang M, Hu P, Zhang J, Niu C, Lu X, et al. Dual-channel hypergraph convolutional network for predicting herb–disease associations. Brief Bioinform. 2024;25(2):bbae067.[DOI]

-

20. Qiao Y, Hu L, Zhang J, Hu P, Luo X. Identifying novel therapeutic targets of natural compounds in traditional Chinese medicine herbs with hypergraph representation learning. Brief Bioinform. 2025;26(4):bbaf399.[DOI]

-

21. Liang X, Lai G, Yu J, Lin T, Wang C, Wang W. Herbal ingredient-target interaction prediction via multi-modal learning. Inf Sci. 2025;711:122115.[DOI]

-

22. Fang S, Dong L, Liu L, Guo J, Zhao L, Zhang J, et al. HERB: A high-throughput experiment- and reference-guided database of traditional chinese medicine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49(D1):D1197-D1206.[DOI]

-

23. Weininger D. SMILES, a chemical language and information system. 1. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 1988;28(1):31-36.[DOI]

-

24. Landrum G and contributors. RDKit: Open-source Cheminformatics Software [Internet]. 2021. Available from: https://www.rdkit.org/

-

25. Graves A, Schmidhuber J. Framewise phoneme classification with bidirectional LSTM networks. In: Proceedings. 2005 IEEE International Joint Conference on Neural Networks, 2005.; Jul 31-Aug 4; Montreal, Canada. Piscataway: IEEE; 2005. p. 2047-2052.[DOI]

-

26. Stiefl N, Watson IA, Baumann K, Zaliani A. ErG: 2D pharmacophore descriptions for scaffold hopping. J chem inf model. 2006;46(1):208-220.[DOI]

-

27. Durant JL, Leland BA, Henry DR, Nourse JG. Reoptimization of MDL keys for use in drug discovery. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2002;42(6):1273-1280.[DOI]

-

28. Wheeler RA, Spellmeyer D. Annual reports in computational chemistry. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2010.

-

29. Rogers D, Hahn M. Extended-connectivity fingerprints. J Chem Inf Model. 2010;50(5):742-754.[DOI]

-

30. Wang MY. Deep graph library: Towards efficient and scalable deep learning on graphs. In: ICLR Workshop on Representation Learning on Graphs and Manifolds; 2019 May 6; New Orleans, USA. 2019. Available from: https://par.nsf.gov/biblio/10311680

-

31. Zhang S, Tong H, Xu J, Maciejewski R. Graph convolutional networks: A comprehensive review. Comput Soc Netw. 2019;6(1):1-23.[DOI]

-

32. Velickovic P, Cucurull G, Casanova A, Romero A, Lio P, Bengio Y. Graph attention networks. Stat. 2017;1050(20):10-48550.[DOI]

-

33. Ridnik T, Ben-Baruch E, Zamir N, Noy A, Friedman I, Protter M, et al. Asymmetric loss for multi-label classification. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10-17; Montreal, Canada. Los Alamitos: IEEE Computer Society Conference Publishing Services; 2021. p. 82-91.[DOI]

-

34. Kinga D, Adam JB. A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv:1412.6980 [Preprint]. 2014.[DOI]

-

35. Baranwal M, Magner A, Elvati P, Saldinger J, Violi A, Hero AO. A deep learning architecture for metabolic pathway prediction. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(8):2547-2553.[DOI]

-

36. Yang Z, Liu J, Wang Z, Wang Y, Feng J. Multi-class metabolic pathway prediction by graph attention-based deep learning method. In: 2020 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM); 2020 Dec 16-19; Seoul, South Korea. Piscataway: IEEE; 2020. p. 126-131.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite