Pu Chen, Eastern Institute of Technology, Ningbo 315200, Zhejiang, China; Department of Chemical Engineering and Waterloo Institute for Nanotechnology, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1, Canada. E-mail: puchen@eitech.edu.cn

Abstract

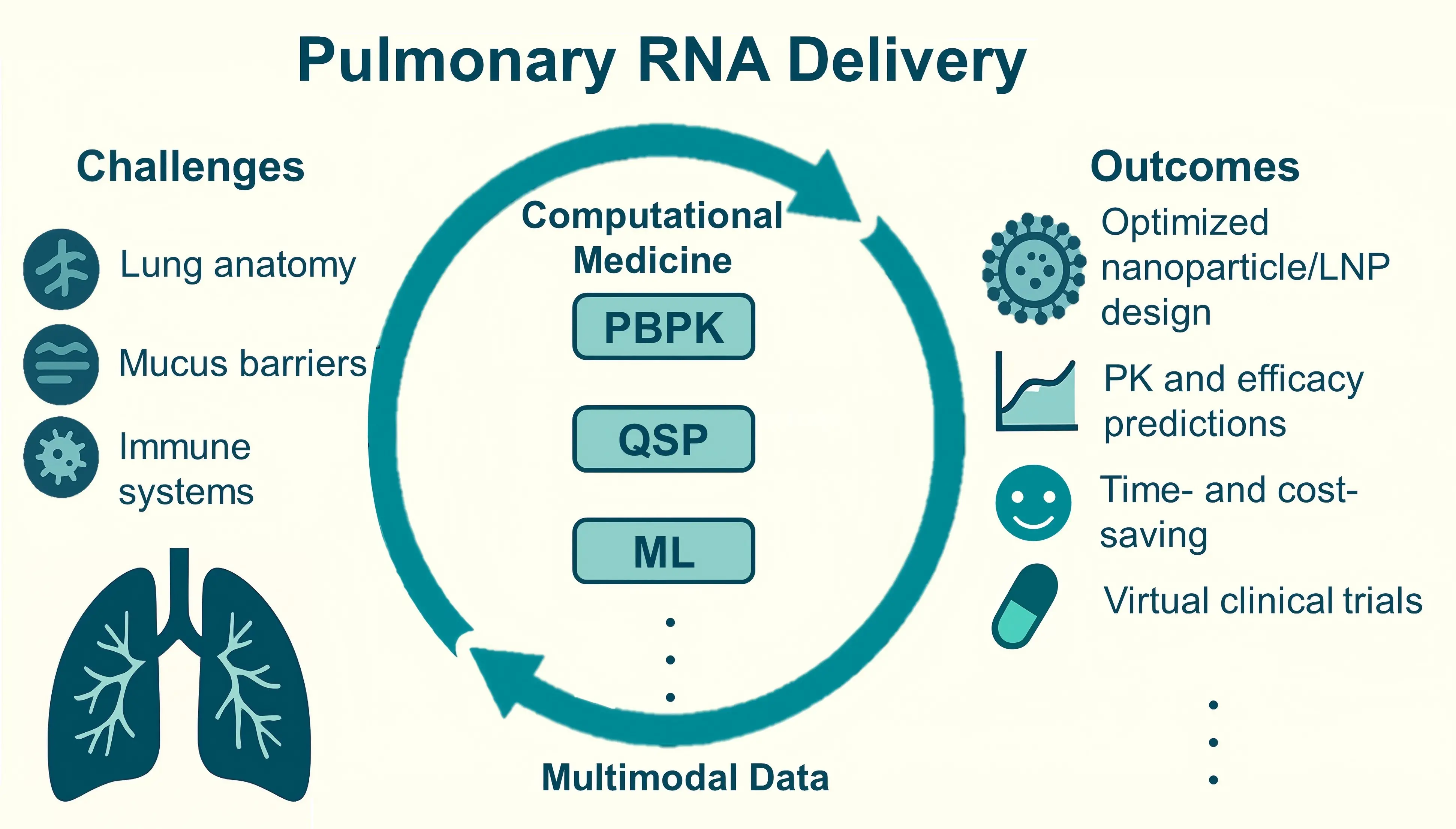

Targeted delivery of RNA-based therapeutics to the lungs remains a substantial challenge due to the unique anatomy of lung tissue and its complex immune barriers. In recent years, the convergence of physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models, quantitative systems pharmacology approaches, and machine learning algorithms has led to the development of computational medicine frameworks, providing intelligent tools for addressing the aforementioned challenges in efficient pulmonary delivery. By integrating experimental data with predictive computational models, these approaches have advanced the development of RNA therapies for pulmonary diseases. The deep integration of multimodal data is expected to further accelerate drug discovery and clinical translation. In this review, we systematically summarize these computational approaches in designing and optimizing pulmonary RNA delivery systems. We particularly highlight the mechanism-based rational design of RNA therapies through simulations and predictions of biodistribution, cellular targeting, and intracellular transport processes.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

1. Introduction

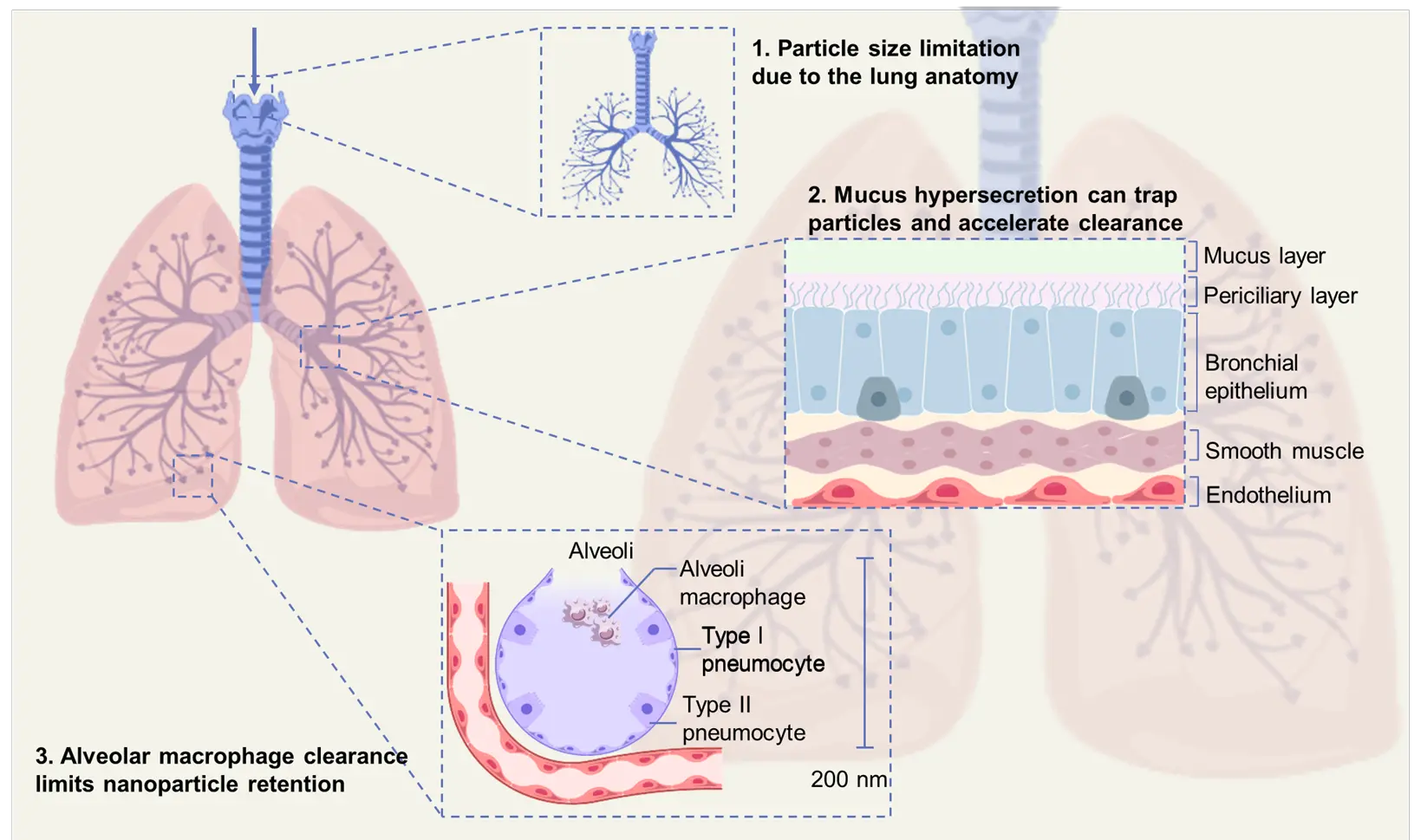

Lung disease represents a major global health issue and places substantial strain on healthcare systems, causing around 7.6 million deaths each year. Diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pneumonia, and lung cancer contribute significantly to this burden[1]. Furthermore, some rare lung disorders, which often involve complex and incomplete pathological mechanisms, can pose challenges for clinical diagnosis and have so far lacked effective clinical treatment[2]. RNA-based therapeutics have shown great potential in treating the lung diseases and disorders described above. By regulating disease-related gene expression at the molecular level and specifically intervening in biological pathways, RNA-based therapeutics offer substantial potential for diagnosing, preventing, and treating these conditions. Specifically, antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), and microRNAs (miRNAs) interact with mRNAs and non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) through Watson-Crick base pairing to elicit explicit regulatory effects[3-5]. However, multiple obstacles hinder efficient pulmonary RNA delivery due to the unique anatomical and physiological barriers of the lungs (Figure 1). These include the dense and dynamic mucus layer[6], efficient mucociliary clearance[7], tight junctions of epithelial cells[8], and rapid immune recognition and degradation of exogenous RNA[9-11]. Therefore, the development of delivery strategies that can effectively overcome these intrinsic biological barriers is critical for the successful clinical translation of pulmonary RNA therapeutics[12]. Currently, siRNA and ASO therapies have achieved the most significant progress in inhaled pulmonary delivery, particularly in the treatment of airway diseases. This success is attributed to their relatively small molecular size and the availability of stabilizing chemical modifications (such as 2'-O-methylation or thiophosphate backbones). For example, inhaled ASO strategies have been used to reduce excessive mucus secretion (an ASO targeting Jagged1 has reduced goblet cell metaplasia and mucus production in an asthma model), while an inhaled siRNA therapy for treating pulmonary fibrosis (TRK-250 targeting TGF-β1) recently completed a Phase I clinical trial without significant adverse events. However, RNA therapies typically require suitable vectors with strong endosomal escape capabilities and surface modifications to avoid innate immune activation[13-15].

Recently, nanomaterial-based delivery systems, such as lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and polymeric nanocarriers, have been widely investigated for pulmonary RNA delivery due to their adaptable design[16], excellent biocompatibility[17], and versatile structural properties[18]. By manipulating their physicochemical properties, nanocarriers can protect RNA from degradation and ensure targeted delivery to specific cells or regions within the lungs[19-21]. Moreover, computational medicine has become a powerful tool that can assist in and accelerate the rational design and optimization of nanocarriers[22]. By combining multidimensional experimental data (e.g., single-cell sequencing, live-cell imaging, and organ-on-a-chip models) with advanced computational modeling techniques, the capability of designing RNA delivery systems can be significantly enhanced[23]. Among the approaches, physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models can effectively simulate the distribution characteristics and interactions of nanocarriers within the complex lung microenvironment[24]. Meanwhile, quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) methods can further quantitatively characterize key events, such as endosomal escape efficiency and intracellular degradation kinetics during RNA delivery, providing complementary mechanistic guidance for vector optimization[25]. In addition, data-driven computational methods, including machine learning (ML) and its subset deep learning (DL) have been applied to nanoparticle formulation and delivery optimization[26].

This review highlights recent advances in using computational methods to improve pulmonary RNA delivery, encompassing pharmacokinetic (PK) evaluation models, computational optimization of nanoparticle formulations, and detailed simulations of pulmonary delivery. We also discuss emerging trends and future directions based on representative research (Table 1). The reviewed computational strategies may also guide the design and optimization of RNA therapies for organs beyond the lungs, thereby supporting broader advancements in RNA-based medicine.

| RNA type | Therapeutic scenario | Carrier | Key modelable parameters | Results | Examples |

| siRNA | Viral lower respiratory tract infections; mucus-driven phenotypes, etc. | Polymeric/lipid nanoparticles; nebulized/oronasal inhalation | MMAD 2–4 µm; GSD; mucus Deff; cellular uptake rate constant k; endosomal escape % | In vitro/in vivo: % gene knockdown, tissue distribution; human safety/PK | [27] |

| mRNA | Protein replacement/immunomodulation (e.g., CFTR, reporter genes) | LNP; inhalation or systemic dosing (for comparison); nebulization process parameters | Endosomal escape %; mRNA stability/translation rate; tissue distribution parameters; innate-immune trigger proxies | PBPK/QSP-fitted tissue expression profiles; in vivo expression/protein readouts; cross-dataset validation | [28-30] |

| miRNA mimic / anti-miR | Multigene pathway modulation (COPD/bronchiectasis as potential indications) | Polymeric/lipid carriers; inhalation | Mucus Deff; off-target risk proxies; dose rate; pathway-level PD parameters | In vitro/in vivo: pathway readouts and tissue distribution; target-network analysis where available | [31] |

MMAD: mass median aerodynamic diameter; GSD: geometric standard deviation; PK: pharmacokinetic; CFTR: cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator; LNP: lipid nanoparticle; PBPK: physiologically based pharmacokinetic; QSP: quantitative systems pharmacology; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PD: pharmacodynamic; siRNA: small interfering RNA; mRNA: messenger RNA; miRNA: microRNA.

2. Methodology

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus for studies published from Jan 2015 to Oct 2025 using: (“pulmonary” OR “lung”) AND (“RNA” OR “siRNA” OR “mRNA” OR “antisense” OR “oligonucleotide”) AND (“delivery” OR “nanoparticle” OR “inhalation”) AND (“model” OR “PBPK” OR “QSP” OR “computational”).

Inclusion: therapeutic RNA for pulmonary delivery with pharmacodynamic/biodistribution outcomes and/or an explicit computational component (PBPK/QSP/ML).

Exclusion: non-pulmonary delivery, non-therapeutic RNAs only, purely theoretical work without biological data, conference abstracts without full text, non-English studies.

Selection flow (PRISMA-style, text): records identified = 103; after deduplication = 92; title/abstract screened = 93 (excluded = 26); full-text assessed = 67; excluded with reasons (non-pulmonary = 3; no computational component = 2; insufficient data = 1; non-English/no full text = 1; other = 0); included in qualitative synthesis = 60.

3. Modeling and Simulation of Pulmonary Delivery Systems

3.1 Multi-scale PK modeling

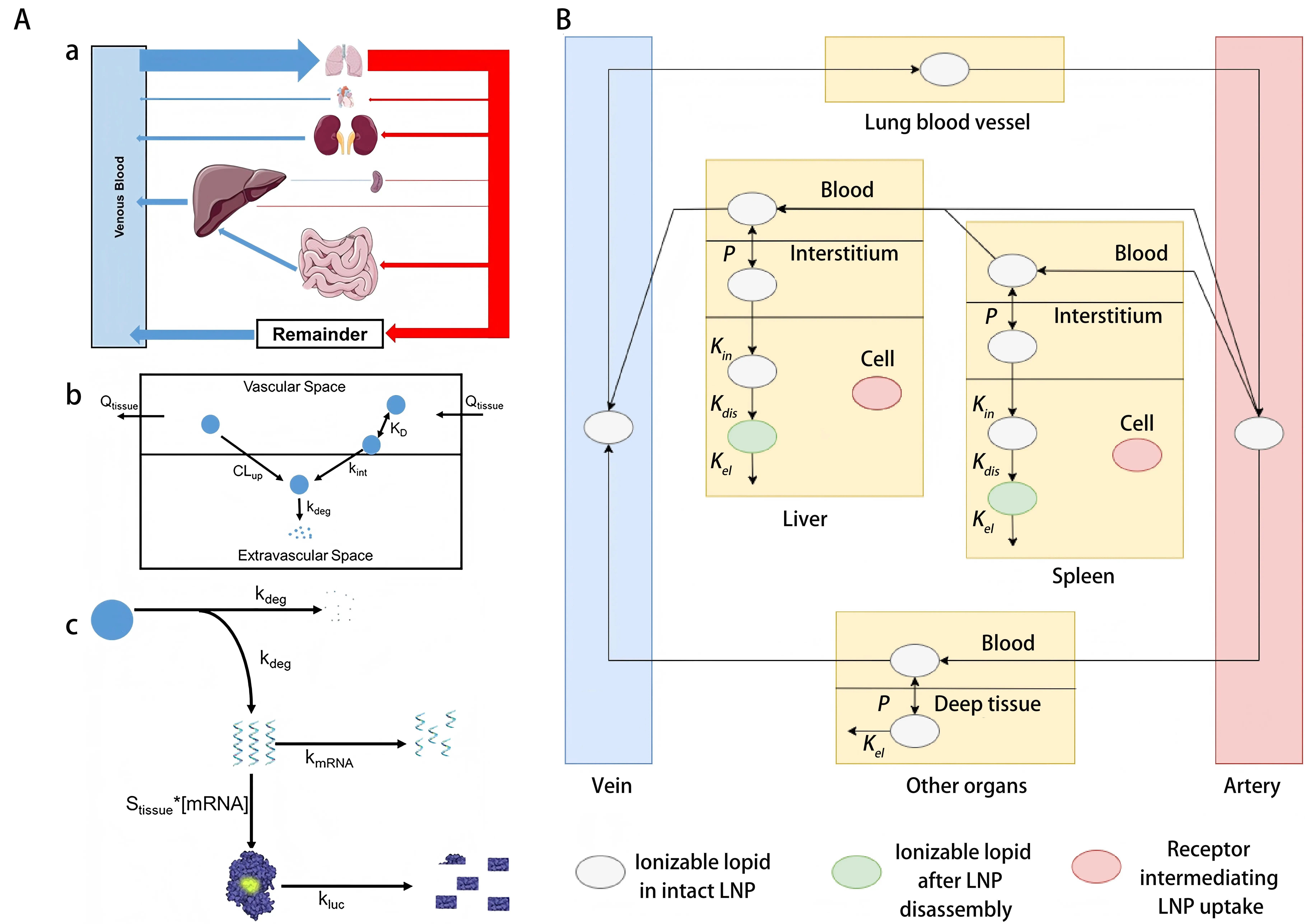

The pharmacokinetics (PK) of drug delivery systems describes how a drug moves through the body over time[32]. It depends on the physicochemical properties of the vector and the payload and on physiological and pathological barriers in the lung, such as mucus, inflammation, and fibrosis. It is also shaped by system level interactions in the body, for example protein corona formation and phagocytosis. PK analysis helps to show how well a delivery system reaches the target site and limits off target exposure. In most models, PK behavior is summarized by the processes of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. In pulmonary RNA delivery, these PK processes are strongly influenced by local lung barriers and thus create both challenges and opportunities for model-based optimization[28,33]. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling is now a standard tool to simulate and predict organ and tissue exposure to drug delivery systems. These models can reduce the need for animal experiments and can lower development costs. In the context of pulmonary RNA delivery, PBPK models can describe the time course of nanocarriers in the lung and in other organs[29,30,34]. A combined PBPK and pharmacodynamic (PD) framework has been used to analyze mRNA loaded lipid nanoparticles in mice after systemic administration. Such models link exposure to pharmacodynamic response and can support dose selection and safety evaluation for pulmonary RNA therapies (Figure 2A)[35]. The model reproduces the PK profiles and luciferase expression in several tissues, including the lung. It was validated with two independent experimental datasets and showed high predictive accuracy. This level of agreement supports the use of the model to guide LNP design and optimization before large animal studies. A related study reported a multiscale modeling strategy that links PBPK models and quantum mechanical simulations to predict in vivo LNP distribution across species (Figure 2B). In this framework, ordinary differential equations describe receptor mediated uptake, endosomal transport, and overall LNP disposition[27].

Figure 2. (A) PBPK model schematic for LNPs[35]. (a) Whole-body circulation highlighting key organ blood flow; (b) Tissue-level uptake, internalization, and degradation processes of LNPs; (c) Intracellular mRNA release from degraded LNPs, leading to tissue-specific protein (luciferase) expression; (B) Optimized PBPK model illustrating ionizable lipid PK in RNA-LNP systems. Model depicts LNP circulation, tissue permeation, cellular uptake, particle disassembly, and lipid metabolism[27]. PBPK: physiologically based pharmacokinetic; LNPs: lipid nanoparticles; PK: pharmacokinetic.

In addition to traditional PBPK models, QSP frameworks can also perform comprehensive simulations to more accurately capture the biodistribution and pharmacodynamic responses of RNA drugs in the body. An integrated PBPK-QSP platform specifically designed for enzyme replacement therapy was validated[36]. The model showed that intracellular mRNA stability and translation efficiency strongly influence the amount of target protein produced in the lung. In some cases, these factors had a stronger effect than the efficiency of nanoparticle uptake by cells. These findings suggest that strategies which extend the intracellular half-life of mRNA, for example by nucleoside modification, can improve therapeutic effects more than approaches that only increase nanoparticle uptake. This is particularly relevant for indications that require sustained and stable protein expression inside lung cells.

3.2 Non-deep ML integrating with experimental approaches

In this section, we focus on classical, non-deep ML methods such as random forests, gradient boosting machines, and support vector machines. We refer to these models as “non-deep ML” because they operate on hand-crafted molecular descriptors or fingerprints and consist of shallow decision trees or kernel machines rather than deep neural networks. Such models are particularly suitable for small to medium sized, structured datasets, where the features are well defined physicochemical properties and the available number of experimental formulations is limited.

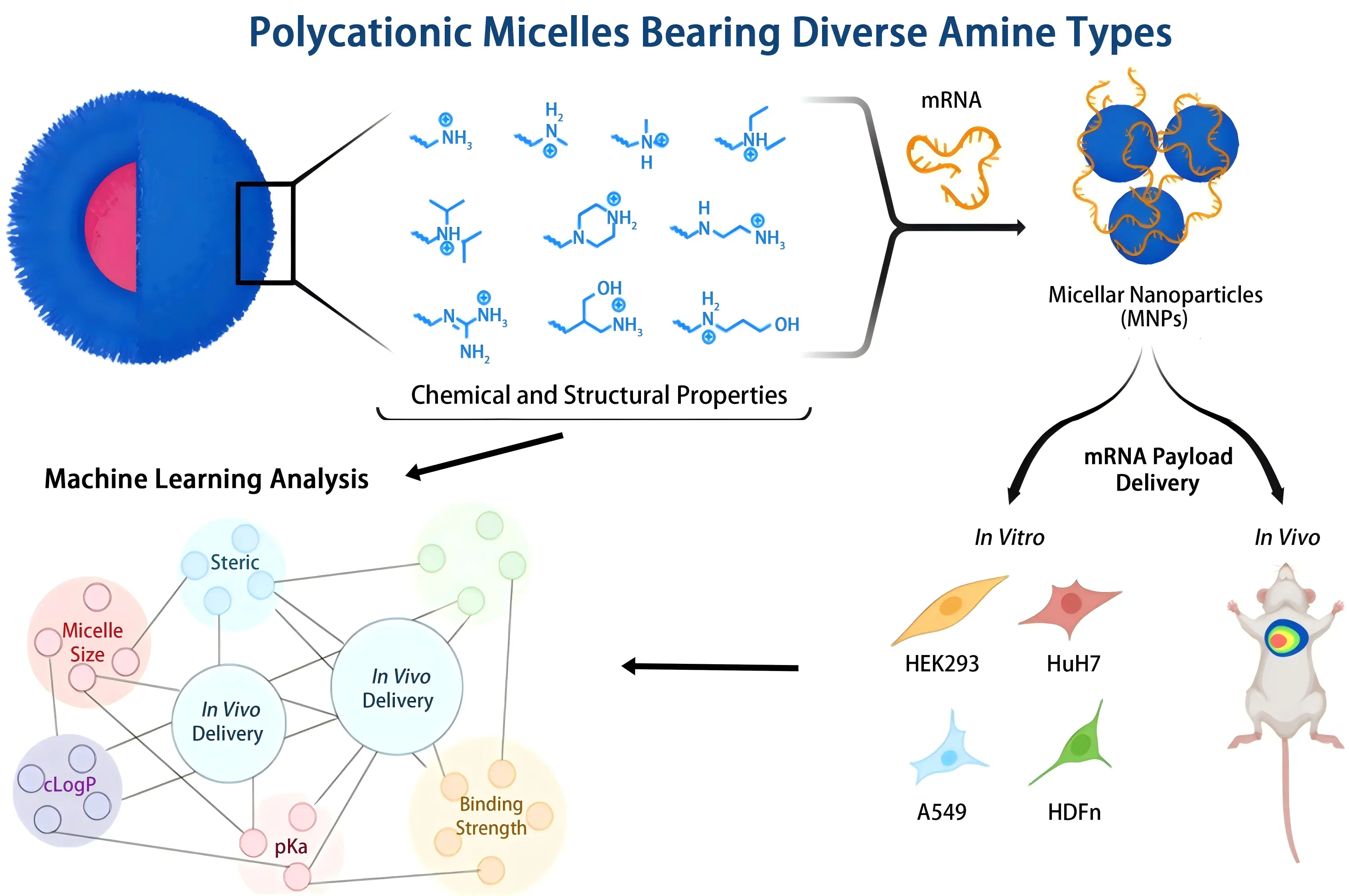

ML approaches have been employed as powerful tools to optimize nanoparticle formulations . For tabular tasks with small sample sizes, recipe optimization is preferred using simpler non-deep ML[37]. In one study[38] researchers optimized lung mRNA delivery using cationic micelles formed from amphiphilic block copolymers. They systematically varied the amine side chain chemistry and built a structure performance dataset for each formulation. The researchers analyzed this dataset with a tree-based machine learning pipeline. The models used gradient boosted decision trees (LightGBM) with K-fold cross validation and Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) based attribution. Model inputs included amine class, predicted pKa, hydrophobicity (cLogP), and N over P ratio. Particle size and zeta potential were also used, and the outputs were mRNA binding and cellular delivery readouts. The analysis highlighted amine chemical properties and binding strength as the main contributors to micelle performance. Among the tested systems, micelles A7 that contained both primary and secondary amines achieved the highest specific delivery to lung tissue in vitro and in vivo. These results show the value of data-driven structural design for lung RNA delivery, and they support schematic frameworks that link polymer structure, biophysical properties, and in vivo performance[38] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Schematic overview of the synthesis of diblock cationic amphiphiles, micelle–mRNA complexation, and biophysical characterization, followed by performance evaluation using in vitro/in vivo assays and SHAP-based structure–activity analysis[38]. mRNA: messenger RNA.

In addition, non-deep machine learning can improve the triage of lung delivery polymers. In one study, Sieber Schäfer et al.[39] trained a LightGBM classifier on a curated literature dataset of about 605 polyester based siRNA formulations. The model used RDKit descriptors and fingerprints with block wise encoding and also included molecular weight and cell line as one hot encoded features. Vector formulations were grouped into two classes based on a binary threshold of 50% gene knockdown efficiency. This simple binning strategy improved the robustness and interpretability of models that integrate heterogeneous data sources. Together, these results illustrate how non-deep learning tools can provide a practical framework for early screening of candidate vectors in pulmonary RNA delivery[39]. Eleven key features were first screened out using a tree model, then SMOTEEN was used for sample resampling, and hyperopt was used to adjust hyperparameters to build a more stable and accurate model. Under 100 stratified training-test splits of 80/20, the model performed stably, with an average balanced accuracy of ≈ 0.846. Furthermore, SHAP was introduced to analyze variable contributions, clarifying the relative impact of key features on prediction. Based on the screening results provided by the model, six candidate PBAEs were synthesized and tested, of which 5/6 (≈ 0.833) were validated, ultimately pointing to SP/TDA-BG as a high-potential carrier, thus reducing the workload of subsequent synthesis and screening. Data-driven ML can reduce the synthesis and screening space for delivery vectors and can lower both costs and ethical burdens. It also provides a reusable framework for the rational design of polymer carriers in pulmonary RNA delivery.

Non-deep machine learning models that use explicit molecular fingerprints and physicochemical descriptors are often more efficient and more reproducible in settings with small sample size, high noise, and well defined features. Methods such as gradient boosting trees and random forests need less training data, show strong robustness, and are easier to tune and interpret. For structured tasks with limited data, classic ML models such as ladder random forests are often more suitable. However, when the formulation space becomes high dimensional and combinatorial, with strong interactions between multiple lipid or polymer components, classical models may struggle to extrapolate to unseen chemotypes. In these cases, representation learning with deep neural networks can become advantageous, as discussed in the next section.

3.3 DL integrating with experimental approaches

While DL has shown strong modeling ability in many fields, its benefits do not apply to all tasks. Current evidence does not support clear and stable gains for DL on structured and low-dimensional tabular problems. In these cases, traditional ML methods such as random forests and gradient boosting are often more reliable. They are efficient, interpretable, and suitable for small datasets. DL models become useful when the input space is high-dimensional and complex. These spaces often show strong feature interactions and combinatorial diversity. In such tasks, the goal is often to move beyond known chemical space. The model may try to discover new molecular structures or pick the best ones from a large set. In these situations, DL can learn complex nonlinear patterns between input parts. It helps improve generalization and can support flexible feature learning. It may also reduce the need for repeated synthesis or testing.

Still, DL models come with high training costs and a strong need for data. If the data are small or features are not abstract enough, DL may not beat simpler models. Roccetti et al. studied how models behaved during the COVID-19 pandemic[40]. They showed that complex models may fail without careful planning and good task matching. These risks apply to lung delivery systems as well. Whether a deep model should be used depends on many factors. These include input types, feature sizes, learning goals, and generalization needs. While classical ML remains strong for low-dimensional and structured problems, DL can outperform it under high complexity.

Recent studies have expanded the role of DL in pulmonary drug delivery by addressing varied modeling challenges and data types. One investigation examined dry powder inhalers containing Arformoterol[41]. Instead of using only pre-calculated surface descriptors, a convolutional neural network was trained directly on scanning electron microscopy images. The model achieved better performance than traditional models like support vector machines in predicting key aerosol metrics such as fine particle fraction and emitted dose. This success was attributed to the CNN’s capacity to extract subtle spatial patterns from raw images. However, the model required a large and diverse training set and involved high computational costs. It also lacked transparency, which could limit its use in early development stages.

In another effort[42], researchers developed a multimodal strategy for optimizing inhalable dry powders. Structured formulation descriptors were combined with microscopy images from 134 thin-film freeze-dried samples. Random forests were effective in predicting fine particle fraction. Still, deep neural networks performed better when modeling median aerodynamic diameter. A CNN used for particle classification achieved over 83% accuracy. Deep learning was key in capturing visual features that structured data could not represent. Yet, the method demanded precise annotation and high-performance computing, which may hinder broader application in resource-limited settings.

Large-scale analysis of nanoparticle distribution across murine organs was also pursued. Data from many published experiments were aggregated to evaluate prediction accuracy across different ML models[43]. Deep neural networks produced the highest accuracy, with R-squared values above 0.8 in the lungs and spleen. These models enabled the identification of new nanoparticle candidates with improved tumor targeting. DL helped manage noisy and heterogeneous datasets without needing extensive manual feature engineering. Nevertheless, the need for significant data processing and model tuning was a barrier for smaller labs. Transformer-based architectures have also been introduced to address more complex formulation tasks. In one study, researchers developed a DL model named COMET to predict the delivery performance of LNPs. The model uses a Transformer architecture and encodes each formulation as a readable sequence. This sequence combines simplified structural fingerprints and molar ratios for ionic lipids, cholesterol, helper lipids, and PEG lipids. COMET also takes preparation and characterization features such as particle size and zeta potential as inputs and outputs standardized measures of delivery and protein expression. The model is trained on the experimentally generated LANCE dataset with separate training, validation, and test sets that are split by formulation and by batch. This datadriven, closed loop design cycle reduces blind synthesis and screening effort and shows the practical value of DL for complex multi component formulation design in pulmonary RNA delivery. These elements can be shown in a schematic that links formulation encoding to model prediction and experimental validation. In such extrapolative regimes, tree-based models with fixed tabular descriptors become less effective, whereas sequence based Transformers can leverage shared substructures across formulations, providing an architectural advantage over classical ML[44]. In another study, researchers introduced a DL design strategy for ionizable lipids named LiON, which stands for Lipid Optimization using Neural Networks. They compiled a dataset with more than nine thousand lipid nanoparticle activity measurements and trained a directed message passing neural network (D-MPNN) to predict nucleic acid delivery for different lipid structures. Model training and evaluation used both random data splits and stricter headgroup scaffold-based splits to test generalization. The authors tuned model hyperparameters with Bayesian and grid search and applied early stopping and L2 regularization to limit overfitting and to improve generalization. Using in silico enumeration and ranking, the model virtually screened about 1.6 million candidate lipids and selected a small set of top ranked structures. This screen identified new ionizable lipids such as FO 32 and FO 35, which showed efficient mRNA delivery in mouse muscle and nasal mucosa. FO 32 reached state-of-the-art performance in nebulized lung delivery in mice, and both FO 32 and FO 35 achieved efficient delivery in a ferret whole lung model. These findings show that a D MPNN based deep learning framework can improve the efficiency of lipid nanoparticle design and optimization even when data are limited and chemical structures are diverse. Such frameworks can support systematic discovery and validation of lung nucleic acid delivery materials and can be summarized in a schematic that links virtual design, experimental testing, and in vivo performance. By operating directly on molecular graphs, the D-MPNN can better capture subtle changes in headgroup and tail structures, which is difficult to encode manually in fixed fingerprints. This provides a concrete example where a DL architecture offers added value beyond established non-deep ML techniques[45].

Combining high-throughput experimental screening with computational analyses enhances the reliability of pulmonary RNA-delivery system design. A DNA-barcoding strategy[46] was used to screen 96 chemically distinct LNP formulations and to evaluate their quantitative pulmonary delivery performance. Computational analyses employing ML algorithms such as random forests and support vector machines identified key physicochemical parameters, including particle size, zeta potential, and lipid pKa, as predictors of pulmonary-targeting efficiency. Overall, these predictive capabilities not only expedite design and optimization, but also significantly reduce experimental costs and timelines, underscoring the indispensable role of computational methods in advancing pulmonary RNA therapeutics.

Deep models work well when the input includes molecular graphs or complex sequences. They are also useful when the design space is large and has many parts. Deep learning becomes more helpful when the goal is to find new chemical types and test new structures. However, many studies still use small datasets with simple features. In these cases, deep models are not always better than traditional methods. Without strong comparisons to other models, their advantage is unclear. This review does not suggest that DL is always the best choice. Instead, it shows when these models are useful and when they are not.

3.4 Cellular-level delivery mechanisms

Beyond organ level pharmacokinetics, computational medicine is increasingly used to study the cellular mechanisms of RNA delivery in the lung. The lung epithelium contains a heterogeneous mix of alveolar type I and type II epithelial cells, airway epithelial cells, and alveolar macrophages. These epithelial cell types differ in their uptake routes, endocytic behavior, and intracellular processing. A major challenge is to overcome barriers between cell types and to achieve efficient cytoplasmic delivery in target pulmonary cells such as alveolar epithelial cells, macrophages, and fibroblasts. Despite progress with lipid nanoparticles and polymer carriers, cell type selective uptake and endosomal escape remain poorly understood and need further study. Recent modeling studies[47] have used QSP models that integrate live cell imaging data to examine the dynamics of endosomal escape. Stochastic modeling schemes and Bayesian parameter estimation have been applied to describe the probability, timing, and efficiency of escape events at the single particle level. These computational methods increase the accuracy of intracellular RNA delivery models and provide guidance for the optimization of nanoparticle formulations. Together, these insights highlight how cellular heterogeneity and endosomal trafficking shape the efficiency of pulmonary RNA delivery.

At the same time, systems biology methods are gradually being incorporated into the development of RNA therapeutics. Although some studies focus on liver-targeted LNPs[48-50], the cross-species RNA sequencing and bioinformatics analysis methods applied in these studies also provide important insights and reference value for pulmonary delivery research. In recent years, researchers have begun to combine single-cell transcriptome analysis (scRNA-seq) with lung organoid models to more precisely identify the heterogeneous characteristics of different lung cell types in barrier function and endocytic pathways[51]. Based on this, some studies have begun to explore how to systematically model the lung delivery process using a multi-scale simulation framework to supplement experimental data and assist in the prediction of delivery efficiency. For example, one study proposed a hierarchical modeling workflow[52], which first predicts aerosol deposition patterns using computational fluid dynamics, and then connects this with tissue-level PK simulations and cellular-level transfection simulations. This tiered modeling approach allows optimization across multiple biological scales, from aerosol behavior within the airways to bioavailability within target cells. This modeling approach promises to enable multi-level optimization from aerosol physical behavior to intracellular availability in target cells, providing more predictive and regulatory design tools for lung RNA delivery. Beyond these mechanistic models and classical ML methods, DL-based approaches have also been explored at the cellular level.

Finally, DL-based on large experimental datasets enhances the generalization ability of the prediction model. For instance, convolutional neural networks trained on barcoded nanoparticle libraries were developed to predict biological distribution and cell targeting, improving prediction accuracy and increasing design efficiency. (Figure 4A)[53].

Figure 4. (A) Regression analysis of literature-extracted nanoparticle data using random forest and ANN methods. Key features and interactions identified via TBRFA guide nanoparticle optimization[53]; (B) Schematic for training the supervised ML model to generate an efficacy prediction algorithm for a single threshold combination[54]. ANN: artificial neural network; TBRFA: tree-based random forest analysis; ML: machine learning; NP: nanoparticle.

Similarly, a deep neural network–driven platform was reported that can differentiate between the uptake of malignant and healthy lung cells using molecular descriptors and in vitro analysis, enabling the design of nanocarriers for selective accumulation in diseased lung tissue[55]. These advances highlight the critical role of computational medicine in gaining a deeper understanding of pulmonary-targeted delivery at cellular levels.

4. ML and DL for Nanocarrier Design and Optimization

Combining multiscale computational modeling with ML is accelerating the rational design of lung-targeted RNA nanocarriers[56]. At the same time, data-driven ML supports formulation screening and parameter optimization by predicting the physicochemical properties and biological properties of LNP formulations, ultimately driving the design of efficient lung delivery vectors[57]. Integrating these computational strategies with experimental data establishes a data-driven framework, reducing reliance on trial-and-error experimentation and accelerating the development of effective pulmonary RNA nanomedicines. For example, AGILE[58] is an AI-based lipid design platform that uses a deep graph neural network encoder to learn lipid representations from molecular structures and experimental data. Concretely, AGILE warm starts a graph neural encoder with MolCLR and contrastively pretrains on ~60,000 virtual lipids, then fine-tunes on an experimentally measured set of ~1,200 ionizable lipids (mRNA transfection potency) with a scaffold-based 80/10/10 split while concatenating learned graph embeddings with Mordred descriptors. The top models are ensembled to rank a curated 12,000-compound candidate library by headgroup-tail combinations, after which a small set is synthesized and tested, closing a rapid design-build-test loop for cell-type-adaptable LNPs. With this model, AGILE can rapidly and accurately screen the best potential candidates from millions of virtual lipid molecules. Through the iteration of “AI prediction-experimental verification”, the researchers finally discovered new lipids with significantly improved performance compared to traditional ones, which enhanced the effect of mRNA drug delivery. By contrastively pretraining on ~60,000 virtual lipids and then fine-tuning on an experimentally measured set of ~1,200 ionizable lipids, the graph-based DL encoder can exploit structural similarity across chemotypes, enabling efficient screening of millions of candidates that would be intractable to explore experimentally.

5. Future Directions and Clinical Translation

5.1 Digital twins for pulmonary RNA therapeutics

Notably, the emerging concept of digital twin technology integrates high-dimensional biological data into computational models that simulate lung physiology[59]. Current research efforts focus on developing a “virtual lung”, a comprehensive, patient-specific predictive model incorporating detailed anatomical structures, cellular dynamics, and molecular pathways[60]. By simulating perturbations within the digital twin, researchers can efficiently evaluate RNA delivery strategies and predict individual treatment responses, enabling personalized therapeutic approaches. Initial studies have underscored that the successful creation of accurate lung digital twins critically depends on a multidisciplinary convergence of detailed biological mechanisms, such as lung development and disease progression, and sophisticated mathematical modeling techniques. Recently, a patient-specific “digital lung” was successfully constructed by matching a high-fidelity lung computational model with bedside ventilation parameters and arterial blood gas data from 98 ARDS patients[61]. Digital twin simulation results showed that the optimized APRV significantly reduced mechanical stress associated with VILI and the risk of circulatory lung recruitment/collapse, while maintaining gas exchange, thus exhibiting a stronger lung-protective effect. The model also determined the parameter optimization range for balancing lung protection and ventilation efficiency at the individual level. This study demonstrates that digital twins can serve as an alternative to in vivo VILI indices that cannot be directly measured and can be used to screen ventilation strategies with greater lung-protective potential.

5.2 ML prediction of RNA therapeutic efficacy

ML also shows outstanding potential for predicting efficacy in the development of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) and other RNA therapeutic strategies. One study[54] demonstrated that the random-forest algorithm remained effective in classifying highly efficient siRNA candidates with limited training data (only a few hundred samples) (Figure 4B). The study described a framework for applying ML to a small dataset (356 modified sequences) for siRNA efficacy prediction. To overcome noise and biological limitations inherent in siRNA datasets, a third-party, double-threshold partitioning approach was employed, generating several combinations of classification-threshold pairs. The impact of different thresholds on the performance of random-forest ML models was subsequently tested using a novel evaluation metric designed to measure category imbalances. Threshold models with high predictive power were identified and experimentally validated, and they outperformed linear models derived from the same data. By adopting an improved feature-extraction method, the underlying importance and preferences of the target sites were consistent with the current understanding of siRNA-mediated silencing mechanisms. The resolution provided by the random-forest model was higher than that of linear models[54].

5.3 Virtual clinical trials for pulmonary RNA therapeutics

Advanced computer models now support safety testing for RNA therapies and virtual trials in lung diseases. These virtual trials help test clinical plans and drug strategies before real studies begin. This lowers risks, improves efficiency, and supports ethical research.

One modeling study focused on COVID-19[62]. It used a QSP model built from clinical data to simulate how the immune system responds to infection. The data included virus levels in the lungs and blood, as well as immune signals. The model matched patient results seen in real trials with antiviral and antibody drugs. It showed how virus levels are connected with immune strength. It also confirmed that antibody therapy works best within five days after symptoms start. After that time, the effect drops quickly.

6. Conclusion

Computational tools and nanomedicine are improving RNA delivery to the lungs. Simulations now guide how RNA drugs are taken up and processed by lung cells. Models like PBPK and QSP can predict where and how well these drugs work. This saves time and cost and helps guide clinical decisions. The traditionally trial-and-error-based R & D paradigm is being replaced by an intelligent “simulate-first, experiment-later” design framework. The core of this shift lies in leveraging multiscale computational models and algorithms to simulate cell-type-specific uptake, endosomal escape, and intracellular kinetics across different pulmonary cells, thereby accelerating the design, optimization, and screening of lung-targeted RNA delivery carriers.

Still, big problems remain. In lung diseases, the lung barrier changes. This makes RNA delivery harder. In asthma, airway cells thicken and scar, which blocks drug entry. In infections, inflammation damages lung cells and makes drug action less stable. Current models cannot fully predict these effects. They also do not track how RNA drugs reach different lung cells. Better models are still needed to handle these complex steps in drug delivery. The success of pulmonary RNA delivery is primarily influenced by three factors: deposition, mucus, and intracellular delivery. First, aerosol particle size distribution (common target ranges: MMAD 2-4 μm; GSD 1.82.2) determines peripheral deposition activity. Second, the effective diffusion coefficient of mucus (Deff) and ciliary clearance parameters determine the available flux reaching the epithelium. Third, endosome escape efficiency and intracellular stability determine the conversion efficiency between RNA deposition and the effective dose. In different delivery systems, the protein expression of mRNA-LNPs is generally more sensitive to intracellular stability and translation rate than to uptake rate. However, in siRNA systems, cellular uptake, RISC loading, and endosome escape remain the main rate-limiting factors. For computational methods, non-deep ML (tree models + SHAP) is more robust and interpretable for small-sample, structured formulation data. A deeper investigation into this area centers on a pivotal question: how to accurately simulate endosomal escape and intracellular kinetics in RNA delivery. Alternatively, a promising approach involves leveraging deep learning-enhanced super-resolution microscopy (e.g., SMLM, SIM) to enable high spatiotemporal dynamic tracking of RNA delivery. This would allow quantitative analysis of key rate-limiting steps, such as endosomal escape, thereby fully elucidating the underlying mechanisms of RNA delivery. Subsequent development of pulmonary therapeutics and nanocarriers based on these insights could substantially advance RNA delivery systems—not only for the lungs but also for other organs. Conversely, DL (Transformer/graph networks) has greater cross-formulation extrapolation capabilities for multi-component LNP design and large-scale virtual screening. Therefore, future research should focus on developing more comprehensive multiscale computational models to enhance the predictive capability and generalization performance of the models. At the same time, developing adaptive nanoscale carrier systems to achieve precise and personalized pulmonary RNA drug delivery strategies should also become an important research focus in the next phase. Overall, the in-depth development of computational medicine will further promote the optimal design of pulmonary RNA drug delivery systems and effectively improve the delivery efficiency and targeting specificity of RNA drugs, providing important technical support and theoretical guidance for the precision treatment of pulmonary diseases.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the Ningbo EIT Industrial Technology Institute.

Authors contribution

Li X: Writing-original draft.

Wang J, Chen P: Writing-review & editing.

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Sauler M, McDonough JE, Adams TS, Kothapalli N, Barnthaler T, Werder RB, et al. Characterization of the COPD alveolar niche using single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):494.[DOI]

-

2. Saetta M, Turato G, Maestrelli P, Mapp CE, Fabbri LM. Cellular and structural bases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(6):1304-1309.[DOI]

-

3. Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(26):2645-2653.[DOI]

-

4. Xu S, Xu Y, Solek NC, Chen J, Gong F, Varley AJ, et al. Tumor-tailored ionizable lipid nanoparticles facilitate IL-12 circular RNA delivery for enhanced lung cancer immunotherapy. Adv Mater. 2024;36(29):2400307.[DOI]

-

5. Wu H, Yu Y, Huang H, Hu Y, Fu S, Wang Z, et al. Progressive pulmonary fibrosis is caused by elevated mechanical tension on alveolar stem cells. Cell. 2020;180(1):107-121.[DOI]

-

6. Xi Y, Kim T, Brumwell AN, Driver IH, Wei Y, Tan V, et al. Local lung hypoxia determines epithelial fate decisions during alveolar regeneration. Nat Cell Biol. 2017;19(8):904-914.[DOI]

-

7. Zacharias WJ, Frank DB, Zepp JA, Morley MP, Alkhaleel FA, Kong J, et al. Regeneration of the lung alveolus by an evolutionarily conserved epithelial progenitor. Nature. 2018;555(7695):251-255.[DOI]

-

8. Zepp JA, Zacharias WJ, Frank DB, Cavanaugh CA, Zhou S, Morley MP, et al. Distinct mesenchymal lineages and niches promote epithelial self-renewal and myofibrogenesis in the lung. Cell. 2017;170(6):1134-1148.[DOI]

-

9. Rafii S, Cao Z, Lis R, Siempos II, Chavez D, Shido K, et al. Platelet-derived SDF-1 primes the pulmonary capillary vascular niche to drive lung alveolar regeneration. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(2):123-136.[DOI]

-

10. Niethamer TK, Stabler CT, Leach JP, Zepp JA, Morley MP, Babu A, et al. Defining the role of pulmonary endothelial cell heterogeneity in the response to acute lung injury. eLife. 2020;9:e53072.[DOI]

-

11. Parekh KR, Nawroth J, Pai A, Busch SM, Senger CN, Ryan AL. Stem cells and lung regeneration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2020;319(4):C675-C693.[DOI]

-

12. Penkala IJ, Liberti DC, Pankin J, Sivakumar A, Kremp MM, Jayachandran S, et al. Age-dependent alveolar epithelial plasticity orchestrates lung homeostasis and regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(10):1775-1789.[DOI]

-

13. Zhang J, Ji K, Ning Y, Sun L, Fan M, Shu C, et al. Biological hyperthermia-inducing nanoparticles for specific remodeling of the extracellular matrix microenvironment enhance pro-apoptotic therapy in fibrosis. ACS Nano. 2023;17(11):10113-10128.[DOI]

-

14. Carrer M, Crosby JR, Sun C, Jiang X, Castanotto D, Berraondo P, et al. Antisense oligonucleotides targeting Jagged 1 reduce house dust mite–induced goblet cell metaplasia in the adult murine lung. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2020;63(1):46-56.[DOI]

-

15. Man HSJ, Moosa VA, Singh A, Wu L, Granton JT, Juvet SC, et al. Unlocking the potential of RNA-based therapeutics in the lung: current status and future directions. Front Genet. 2023;14:1281538.[DOI]

-

16. Praskova M, Xia F, Avruch J. MOBKL1A/MOBKL1B phosphorylation by MST1 and MST2 inhibits cell proliferation. Curr Biol. 2008;18(5):311-321.[DOI]

-

17. Zhao B, Wei X, Li W, Udan RS, Yang Q, Kim J, et al. Inactivation of YAP oncoprotein by the Hippo pathway is involved in cell contact inhibition and tissue growth control. Genes Dev. 2007;21(21):2747-2761.[DOI]

-

18. Zhao R, Wang Z, Wang G, Geng J, Wu H, Liu X, et al. Sustained amphiregulin expression in intermediate alveolar stem cells drives progressive fibrosis. Cell Stem Cell. 2024;31(9):1344-1358.[DOI]

-

19. Zhou B, Flodby P, Luo J, Castillo DR, Liu Y, Yu F-X, et al. Claudin-18–mediated YAP activity regulates lung stem and progenitor cell homeostasis and tumorigenesis. J Clin Invest. 2018;128(3):970-984.[DOI]

-

20. Zheng GXY, Terry JM, Belgrader P, Ryvkin P, Bent ZW, Wilson R, et al. Massively parallel digital transcriptional profiling of single cells. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):14049.[DOI]

-

21. Zilionis R, Engblom C, Pfirschke C, Savova V, Zemmour D, Saatcioglu HD, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics of human and mouse lung cancers reveals conserved myeloid populations across individuals and species. Immunity. 2019;50(5):1317-1334.[DOI]

-

22. Green J, Endale M, Auer H, Perl A-KT. Diversity of interstitial lung fibroblasts is regulated by platelet-derived growth factor receptor α kinase activity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016;54(4):532-545.[DOI]

-

23. Gustine JN, Jones D. Immunopathology of hyperinflammation in COVID-19. Am J Pathol. 2021;191(1):4-17.[DOI]

-

24. Haga Y, Sakamoto Y, Kajiya K, Kawai H, Oka M, Motoi N, et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals the molecular implications of the stepwise progression of lung adenocarcinoma. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):8375.[DOI]

-

25. Han G, Sinjab A, Rahal Z, Lynch AM, Treekitkarnmongkol W, Liu Y, et al. Author correction: An atlas of epithelial cell states and plasticity in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2024;628:E1.[DOI]

-

26. He P, Lim K, Sun D, Pett JP, Jeng Q, Polanski K, et al. A human fetal lung cell atlas uncovers proximal-distal gradients of differentiation and key regulators of epithelial fates. Cell. 2022;185(25):4841-4860.[DOI]

-

27. Wang W, Deng S, Lin J, Ouyang D. Modeling on in vivo disposition and cellular transportation of RNA lipid nanoparticles via quantum mechanics/physiologically-based pharmacokinetic approaches. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2024;14(10):4591-4607.[DOI]

-

28. Öztürk K, Kaplan M, Çalış S. Effects of nanoparticle size, shape, and zeta potential on drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2024;666:124799.[DOI]

-

29. Na YG, Byeon JJ, Kim MK, Han MG, Cho CW, Baek JS, et al. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling to predict the antiplatelet effect of the ticagrelor-loaded self-microemulsifying drug delivery system in rats. Mol Pharm. 2020;17:1079-1089.[DOI]

-

30. Marques L, Vale N. Prediction of CYP-mediated drug interaction using physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling: A case study of salbutamol and fluvoxamine. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15:1586.[DOI]

-

31. Kim RY, Sunkara KP, Bracke KR, Jarnicki AG, Donovan C, Hsu AC, et al. A microRNA-21–mediated SATB1/S100A9/NF-κB axis promotes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease pathogenesis. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13(621):eaav7223.[DOI]

-

32. Miao Y, Li L, Wang Y, Wang J, Zhou Y, Guo L, et al. Regulating protein corona on nanovesicles by glycosylated polyhydroxy polymer modification for efficient drug delivery. Nat Commun. 2024;15:1159.[DOI]

-

33. Ozbek O, Genc DE, Ülgen KÖ. Advances in Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling of Nanomaterials. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2024;7(8):2251-2279.[DOI]

-

34. Chou WC, Chen Q, Yuan L, Cheng YH, He C, Monteiro-Riviere NA, et al. An artificial intelligence-assisted physiologically based pharmacokinetic model to predict nanoparticle delivery to tumors in mice. J Control Release. 2023;361:53-63.[DOI]

-

35. Parhiz H, Shuvaev VV, Li Q, Papp TE, Akyianu AA, Shi R, et al. Physiologically based modeling of LNP-mediated delivery of mRNA in the vascular system. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2024;35(2):102175.[DOI]

-

36. Hamilton S, Kingston BR. Development of a minimal PBPK-QSP modeling platform for LNP-mRNA based therapeutics to study tissue disposition and protein expression dynamics. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2024;85:103043.[DOI]

-

37. Jovic D, Liang X, Zeng H, Lin L, Xu F, Luo Y. Single-cell RNA sequencing technologies and applications: a brief overview. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12(3):e694.[DOI]

-

38. Panda S, Eaton EJ, Muralikrishnan P, Stelljes EM, Seelig D, Leyden MC, et al. Machine learning reveals amine type in polymer micelles determines mrna binding, in vitro, and in vivo performance for lung-selective delivery. JACS Au. 2025;5(4):1845-1861.[DOI]

-

39. Sieber-Schäfer F, Jiang M, Kromer A, Nguyen A, Molbay M, Pinto Carneiro S, et al. Machine learning-enabled polymer discovery for enhanced pulmonary siRNA delivery. Adv Funct Mater. 2025;e02805.[DOI]

-

40. Roccetti M, Delnevo G. Modeling CoVid-19 diffusion with intelligent computational techniques is not working. What are we doing wrong? In: Janusz Kacprzyk, editor. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 479-484.[DOI]

-

41. Jiang J, Peng H, Yang Z, Ma X, Sahakijpijarn S, Moon C, et al. The applications of machine learning (ML) in designing dry powder for inhalation by using thin-film-freezing technology. Int J Pharm. 2022;626:122179.[DOI]

-

42. Jiang T, Xu W, Zheng Y, Song Y, Jin K, He Y, et al. A multimodal machine learning strategy for modeling aerosol performance of inhalable dry powders. Int J Pharm. 2023;636:122824.[DOI]

-

43. Mi K, Chou WC, Chen Q, Yuan L, Kamineni VN, Kuchimanchi Y, et al. Predicting tissue distribution and tumor delivery of nanoparticles in mice using machine learning models. J Control Release. 2024;374:219-229.[DOI]

-

44. Chan A, Kirtane AR, Qu QR, Huang X, Woo J, Subramanian DA, et al. Designing lipid nanoparticles using a transformer-based neural network. Nat Nanotechnol. 2025;20(10):1491-1501.[DOI]

-

45. Witten J, Raji I, Manan RS, Beyer E, Bartlett S, Tang Y, et al. Artificial intelligence-guided design of lipid nanoparticles for pulmonary gene therapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2025;43(11):1790-1799.[DOI]

-

46. Xue L, Hamilton AG, Zhao G, Xiao Z, El-Mayta R, Han X, et al. High-throughput barcoding of nanoparticles identifies cationic, degradable lipid-like materials for mRNA delivery to the lungs in female preclinical models. Nat Commun. 2024;15:1884.[DOI]

-

47. Yadav N, Boulos J, Alexander-Bryant A, Cook K. Stochastic model of siRNA endosomal escape mediated by fusogenic peptides. Math Biosci. 2025;387:109476.[DOI]

-

48. Radmand A, Lokugamage MP, Kim H, Dobrowolski C, Zenhausern R, Loughrey D, et al. The transcriptional response to lung-targeting lipid nanoparticles in vivo. Nano Lett. 2023;23(3):993-1002.[DOI]

-

49. Zenhausern R, Jang B, Schrader Echeverri E, Gentry K, Calkins R, Curran EH, et al. Lipid nanoparticle screening in nonhuman primates with minimal loss of life. Nat Biotechnol. 2025;1-9:[DOI]

-

50. Hatit MZ, Lokugamage MP, Dobrowolski CN, Paunovska K, Ni H, Zhao K, et al. Species-dependent in vivo mRNA delivery and cellular responses to nanoparticles. Nat Nanotechnol. 2022;17(3):310-318.[DOI]

-

51. Kopan R, Ilagan MXG. The canonical Notch signalling pathway: Unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell. 2009;137(2):216-233.[DOI]

-

52. Islam MS, Larpruenrudee P, Rahman MM, Li G, Husain S, Munir A, et al. Pharmaceutical aerosol transport in airways: A combined machine learning (ML) and discrete element model (DEM) approach. Powder Technol. 2024;448:120271.[DOI]

-

53. Yu F, Wei C, Deng P, et al. Deep exploration of random forest model boosts the interpretability of machine learning studies of complicated immune responses and lung burden of nanoparticles. Sci Adv. 2021;7(22):eabf4130.[DOI]

-

54. Kathryn R. Monopoli, Dmitry Korkin, Anastasia Khvorova. Asymmetric trichotomous partitioning overcomes dataset limitations in building machine learning models for predicting siRNA efficacy. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2023, 33(1);93-109.[DOI]

-

55. La Manno G, Soldatov R, Zeisel A, Braun E, Hochgerner H, Petukhov V, et al. RNA velocity of single cells. Nature. 2018;560(7719):494-498.[DOI]

-

56. Castillo-Hair SM, Seelig G. Machine learning for designing next-generation mRNA therapeutics. Acc Chem Res. 2022;55(1):24-34.[DOI]

-

57. Wang W, Chen K, Jiang T, Wu Y, Ying H, Yu H, et al. Artificial intelligence-driven rational design of ionizable lipids for mRNA delivery. Nat Commun. 2024;15:10804.[DOI]

-

58. Xu Y, Ma S, Cui H, Chen J, Xu S, Gong F, et al. AGILE platform: A deep learning powered approach to accelerate LNP development for mRNA delivery. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):6305.[DOI]

-

59. Lam T, Quach HT, Hall L, Abou Chakra M, Wong AP. A multidisciplinary approach towards modeling of a virtual human lung. npj Syst Biol Appl. 2025;11(1):38.[DOI]

-

60. Sadée C, Testa S, Barba T, Hartmann K, Schuessler M, Thieme A, et al. Medical digital twins: Enabling precision medicine and medical artificial intelligence. Lancet Digit Health. 2025;7(7):100864.[DOI]

-

61. Joy W, Albanese B, Oakley D, Mistry S, Nikulina K, Schuppert A, et al. Digital twins to evaluate the risk of ventilator-induced lung injury during airway pressure release ventilation compared with pressure-controlled ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2025;10.1097.[DOI]

-

62. Rao R, Musante CJ, Allen R. A quantitative systems pharmacology model of the pathophysiology and treatment of COVID-19 predicts optimal timing of pharmacological interventions. npj Syst Biol Appl. 2023;9(1):13.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite