Abstract

Drug-Drug Interaction (DDI) prediction plays a critical role in ensuring clinical medication safety and optimizing therapeutic regimens, while also representing a significant challenge in the drug development process. With the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence technologies, computational methods based on machine learning and deep learning have emerged as the mainstream paradigm in DDI research. In this survey, we systematically review the latest research progress and establish a clear methodological taxonomy that traces the evolution from classical feature engineering to modern deep learning architectures. Beyond detailing foundational molecular representations, we provide a comprehensive overview of DDI prediction techniques, encompassing sequence-based models, graph-based models, Transformers, and Graph Transformers. Our analysis culminates in a dedicated discussion of emerging advanced strategy paradigms, such as multimodal fusion and specialized pre-training and fine-tuning schemes. Furthermore, we synthesize current challenges with contemporary solutions and discuss their practical implications for clinical decision support, providing a forward-looking perspective for the continued development of DDI prediction models.

Keywords

1. Introduction

In the field of modern clinical medicine, drug-drug interactions (DDIs) represent a growing concern. Studies have shown that combination therapies often achieve higher efficacy rates than monotherapies[1]. Consequently, with the aging of the population and advances in the treatment of complex diseases, the concurrent use of multiple medications (polypharmacy)[2] has become a standard clinical practice. However, this also significantly increases patients' risk of exposure to DDIs[3]. These interactions may lead to reduced drug efficacy, enhanced drug toxicity, or even severe adverse drug reactions[4], which not only endanger patients’ health and safety but also impose a substantial economic burden on healthcare systems[5]. A 2007 meta-analysis encompassing 23 clinical studies worldwide indicated that drug interactions annually resulted in approximately 74,000 emergency department visits and 195,000 hospitalizations[6] in the United States. Traditionally, potential DDIs could only be identified through costly clinical trials and

To address this challenge, the use of computational models to identify potential drug interactions has emerged as a mainstream approach and has garnered significant attention in recent years. The advent of the big data era in biomedicine has provided these computational models with a vast amount of data[7], spanning from atomic-level chemical structures of drugs to macro-level

Driven by data, the evolution of the DDI prediction field has been closely intertwined with the advancement of AI technologies. Early research primarily relied on feature engineering-based classical machine learning methods, such as inferring potential interactions by calculating drug structural similarity[9], or utilizing classical algorithms like Random Forest and Support Vector Machines[10-12] to process hand-crafted molecular descriptors. However, the performance of these methods was heavily constrained by the quality of feature engineering. Subsequently, models based on matrix factorization marked a critical transition from manual design to automatic learning by decomposing the interaction matrix to automatically learn latent features of drugs. The development of deep learning later brought about a paradigm shift in DDI prediction. Graph neural networks (GNNs) demonstrated the capability to automatically learn the two-dimensional (2D) topological structures of molecules, achieving accurate representation of drug molecules[13]. Sequence-based models, leveraging architectures such as recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or Transformers, capture the syntactic and semantic information within molecular sequences, effectively mining hidden patterns from large-scale sequence data. However, the message-passing mechanism inherent in traditional GNNs faces limitations due to their limited receptive field, which hinders the capture of long-range dependencies. To address this, Graph Transformer models have emerged. By incorporating a global self-attention mechanism, they enable the direct computation of interactions between any atom pairs, overcoming the neighborhood constraints of traditional GNNs and thereby allowing more flexible capture of global molecular features and complex dependencies. Furthermore, other emerging architectures have opened up unique technical pathways, collectively propelling the DDI prediction field toward more generalized and powerful capabilities.

This survey provides a systematic and structured analysis of deep learning methods for DDI prediction. We begin by outlining foundational molecular representations and key datasets. The core of our review establishes a clear taxonomy that traces the methodological evolution of the field. This taxonomy systematically progresses from classical feature engineering to modern deep learning architectures, encompassing sequence-based, graph-based, Graph Transformer models, and multimodal models. Within the sequence-based category, we further clarify the related research lines of molecule-based prediction and text-based extraction from biomedical literature. The framework culminates in a dedicated analysis of emerging multimodal and advanced strategy paradigms in the DDI field. Finally, we discuss current challenges alongside contemporary solutions and their practical clinical implications, offering a forward-looking perspective to guide future research.

2. Drug Molecule Representation

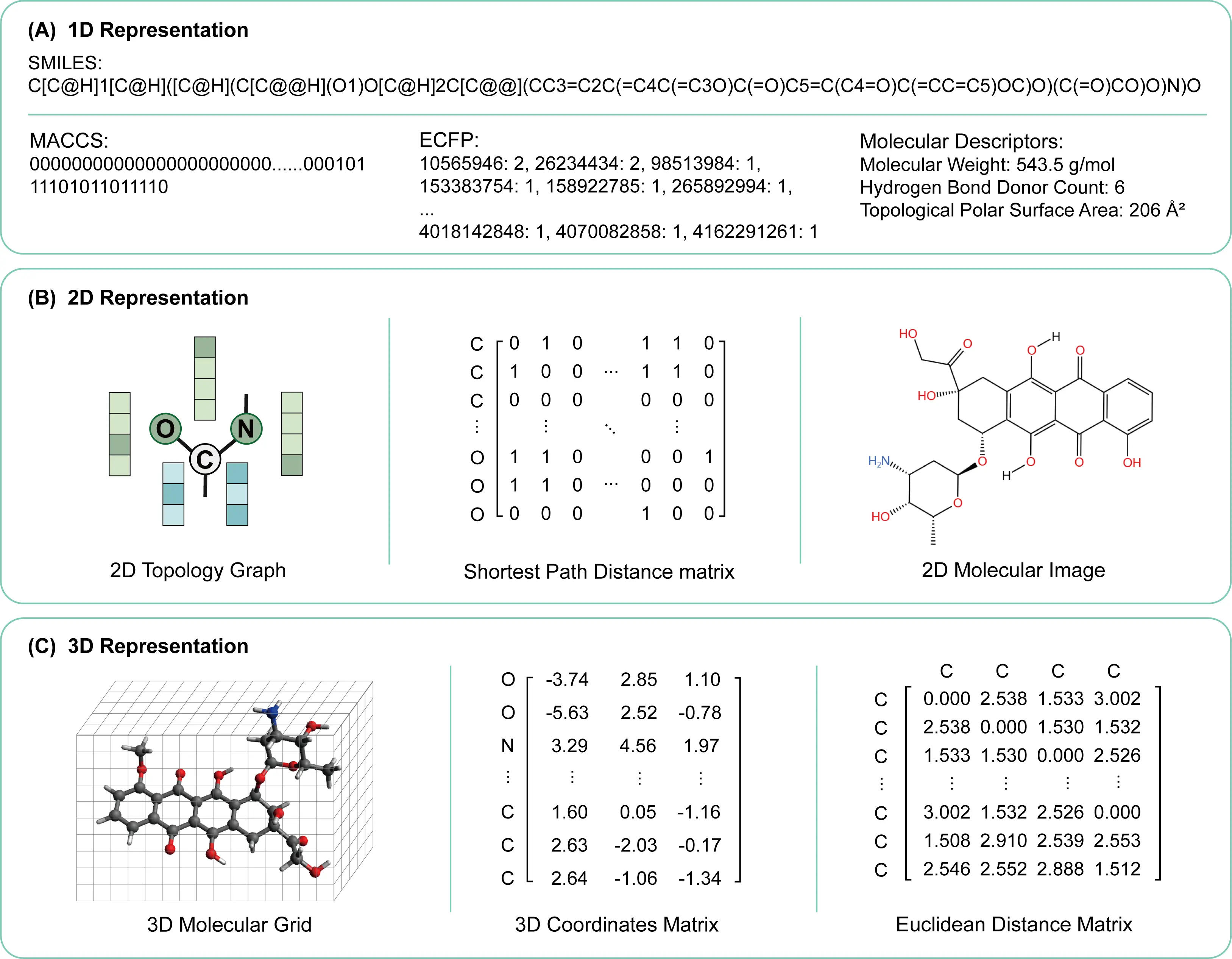

Drug molecules can be represented using various molecular descriptors. As illustrated in Figure 1, these include one-dimensional sequence-based simplified molecular input line entry system (SMILES) strings, 2D molecular graphs, and 3D molecular conformational information. This section will systematically introduce these three categories of drug representation methods.

Figure 1. Molecular representations at different dimensional levels. (A) 1D representations, including the SMILES string, MACCS keys, ECFP fingerprints, and key molecular descriptors; (B) 2D representations, featuring the molecular topology graph, shortest path distance matrix, and a 2D structural image; (C) 3D representations, showing the 3D molecular grid, atomic coordinate matrix, and Euclidean distance matrix. SMILES: simplified molecular input line entry system; MACCS: Molecular ACCess System;

2.1 1D sequence-based molecular representation

SMILES is a linear representation of chemical molecules based on specific grammatical rules. It encodes the structure of a drug molecule into a one-dimensional ordered string using ASCII characters, following a specialized syntax and rule set. This representation facilitates the storage, retrieval, and computational modelling of molecules. However, the relationship between SMILES and a molecule is not strictly one-to-one; a single molecule may correspond to multiple different SMILES expressions, requiring canonicalization to ensure uniqueness. Furthermore, for molecules exhibiting resonance or tautomerism, SMILES must select one specific structure for representation and cannot directly express all delocalized or tautomeric forms[14], which may interfere with molecular learning.

To address these robustness issues, a novel string-based representation called SELFIES has been proposed. SELFIES[15], which stands for SELF-referencing Embedded Strings, guarantees that every possible string corresponds to a syntactically valid molecular structure. The deterministic and constrained nature of SELFIES makes it particularly suitable for generative models in de novo drug design, where exploration of the chemical space without structural violations is essential. Beyond robustness, its representation has been shown to improve the performance and stability of deep learning models. Recent studies[16,17] have successfully leveraged SELFIES in conjunction with Transformer architectures for advanced tasks in molecular property prediction and generation.

In addition to SMILES, one-dimensional representations of drug molecules also include molecular fingerprints and molecular descriptors. Molecular fingerprints map structural features of a molecule into a fixed-length binary bit string via specific algorithms, enabling the vectorization of structural information. For example, the MACCS fingerprint encodes molecules based on a predefined dictionary of functional groups and substructures, while the extended connectivity fingerprint (ECFP) generates data-driven circular fingerprints by capturing the local environment of atoms, effectively characterizing the topological features of drugs. On the other hand, molecular descriptors are computed numerical values representing a series of physicochemical properties, such as molecular weight, the logarithm of the partition coefficient, and polar surface area, quantitatively describing the overall characteristics of a drug from different dimensions.

2.2 2D molecular representation

In 2D representations of drug molecules, molecules are typically represented as undirected graphs, where atoms correspond to nodes and chemical bonds correspond to edges, forming a 2D graph structure. Topological graph structures are particularly effective for capturing the connectivity and structural relationships within molecules, and they can be directly used with graph-based models such as GNNs. However, 2D topological graphs do not contain atomic positional information and cannot capture molecular conformations. It is also possible for multiple molecules to share identical 2D topologies while differing in their 3D structures. Additionally, drug molecules can be represented as molecular images by converting structural formulas into visual data, enabling the application of computer vision techniques for tasks such as drug similarity analysis and pharmacophore identification.

2.3 3D molecular representation

To address the limitations of 1D and 2D representations in capturing complete molecular information, three-dimensional representations incorporate spatial positional information, including the precise coordinates and conformations of atoms. 3D molecular representations can be constructed using atomic coordinate matrices, distance matrices, or Coulomb matrices. Beyond encoding basic structural information, 3D representations also capture atomic spatial coordinates, interatomic distances, and bond angles. Moreover, quantum chemical properties of molecules, such as molecular energy and polarizability, can be calculated to support learning. However, 3D molecular representations are inherently more complex, requiring greater storage space and higher computational costs.

Beyond traditional coordinate-based representations, recent advances have integrated deep learning directly into 3D molecular modeling. These data-driven methods treat molecules as geometric objects in 3D space, often as atomic point clouds. Inspired by breakthroughs in protein structure prediction (e.g., AlphaFold2), methods employing SE(3)-equivariant Transformer networks[18,19] can now directly predict or generate molecular conformations in 3D space, capturing complex quantum chemical properties and enabling end-to-end learning from atomic point clouds. These approaches represent a significant shift towards data-driven, geometric deep learning for 3D molecular representation.

2.4 From static descriptors to learned representations: A paradigm shift

The molecular representations described previously provide a foundational yet static vocabulary for chemistry. Contemporary deep learning overcomes this limitation by learning representations directly from data. Through representation learning, models distill raw structures into task-optimized, high-dimensional embeddings. These learned embeddings are optimized end-to-end, enabling them to dynamically highlight the chemical substructures and complex hierarchical patterns most relevant to predicting drug interactions. The following sections detail three key directions in this paradigm that are central to advancing the field.

A prominent direction is the development of pre-trained chemical language models. These models, such as ChemBERTa[20,21], conceptualize SMILES and SELFIES strings as a specialized chemical language. Through pre-training on vast molecular corpora using objectives like masked token prediction, they acquire a deep, contextual understanding of chemical syntax and semantics. The resulting contextualized SMILES embeddings encapsulate rich, transferable chemical knowledge, serving as powerful input features for downstream DDI prediction and often diminishing reliance on large task-specific datasets. A fundamental shift has also occurred in leveraging 2D molecular graphs. Rather than treating them as static descriptors for predefined fingerprint generation, modern approaches employ graph neural networks to learn graph embeddings directly. These embeddings are optimized end-to-end for the specific prediction task, enabling models to autonomously capture nuanced, task-critical substructures that exceed the representational capacity of fixed fingerprint dictionaries. A distinct advancement focuses on learning geometry-aware 3D representations. Standard neural networks processing 3D coordinates often disregard fundamental physical symmetries, such as rotation and translation. 3D-equivariant GNNs, including architectures like the SE(3)-Transformer[18,19], are designed to overcome this limitation. By construction, they produce 3D embeddings that inherently respect these symmetries, resulting in more physically meaningful and generalizable representations for interactions where spatial conformation is critical.

3. DDI Datasets

The availability of comprehensive and standardized benchmark datasets is fundamental for systematically evaluating the performance and applicability of existing DDI prediction methods. These datasets exhibit substantial heterogeneity across multiple dimensions, such as drug coverage, number of interactions, annotation granularity (e.g. mechanism or severity labels), and data sources. These variations directly influence model design and comparative analysis. To provide a clear foundation for the subsequent discussion of methodologies, Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of widely used public DDI datasets in the field.

| Dataset | Description | Access Link |

| Drugbank | 14,633 drug entries (including 4,563 approved drugs) and over 1.4 million DDIs. | https://go.drugbank.com/ |

| TWOSIDES | 645 drugs with 963 interaction types, providing 4,576,287 positive DDI instances | https://github.com/jcsun-00/TWOSIDES |

| DDInter1.0 | 1972 approved drug entries in 1,833 drugs containing 236,834 interaction drug pairs | https://ddinter.scbdd.com/ |

| DDInter 2.0 | 2,310 approved drug entries in 2122 distinct drugs, with 302,516 DDI records | https://ddinter2.scbdd.com/ |

| DDIMDL | 572 drugs and 37,264 DDI records, involving 65 distinct interaction types. | https://github.com/YifanDengWHU/DDIMDL |

| MecDDI | 1,922 drugs with 109 interaction types, providing 178,406 DDI instances | https://mecddi.idrblab.net/ |

| DrugComb | 2,887 drugs involved in 448,555 combinations | http://drugcombdb.denglab.org/main |

DDI: drug-drug interaction.

3.1 DrugBank dataset

The DrugBank[22] dataset integrates extensive biomedical, clinical, and molecular information, including chemical structures, targets, mechanisms, interactions, metabolism, indications, and adverse effects. According to the latest official release (DrugBank 6.0, 2024), the database contains information on 14,633 drug entries, comprising 4,563 FDA-approved and 6,231 investigational drugs. A major expansion is seen in its interaction data, which now catalogs over 1.4 million drug-drug interactions and 2,475 drug-food interactions. Additionally, it provides experimental or predicted spectral data (MS/MS, NMR, etc.) for thousands of small molecule drugs. Its depth and breadth make it a foundational resource for applications ranging from new drug discovery and chemical informatics to deep learning-based DTI and DDI prediction. DrugBank provides a comprehensive, multi-modal data foundation for computational pharmacology. Due to its broad scope, the annotation depth for specific DDI mechanisms may lag behind specialized databases. It is primarily used as a general-purpose data source for feature engineering and as a benchmark for AI models in drug discovery.

3.2 TWOSIDES dataset

The TWOSIDES dataset, developed by the Tatonetti Lab, complements the OFFSIDES dataset, which focuses on single-drug adverse events. TWOSIDES specifically records side effects arising from the co-administration of two drugs. It contains 645 drugs, approximately 4,649,441 DDI records, and 963 different interaction types, enabling the extraction of drug-target information, indication prediction, and discovery of drug-drug interactions[23]. While valuable for pharmacovigilance screening and computational drug discovery, TWOSIDES is inherently limited by spontaneous reporting biases and unmeasured confounders. Its findings should be treated as preliminary signals requiring clinical or experimental validation.

3.3 DDInter dataset

DDInter[24], released in 2021, is a curated DDI database that includes chemical and pharmacological information of drugs as well as a network of drug-drug interactions. It contains 1,833 approved drugs and 0.24 million DDI pairs. Beyond data analysis and DDI prediction, DDInter provides a web-based prescription checking tool for clinical safety. DDInter 1.0 is accessible at https://ddinter.scbdd.com/. Based on DDInter 1.0, DDInter 2.0[25] was released in 2024 as an enhanced and expanded version. It provides richer resources for clinical decision-making and incorporates additional interaction types, including drug–food interactions, drug-disease interactions, and therapeutic duplications. The updated database contains 2,310 drugs, 203,516 DDI records, 857 DFI records, 8,359 DDSI records, and 6,033 therapeutic duplication records. DDInter 2.0 is accessible at https://ddinter2.scbdd.com/. DDInter is a manually curated database of known drug interactions, useful for clinical reference. Its primary limitation is its reliance on published literature, which may not include recent, rare, or complex real-world interactions. Clinical use should therefore be combined with other evidence sources.

3.4 DDIMDL dataset

The DDIMDL dataset, introduced by Deng et al.[26] in 2020, was used for a multimodal deep learning framework for DDI prediction. DDIs are represented as quadruples of the form (drugA, drugB, mechanism, action), converting natural language descriptions from DrugBank into a standardized structured format. To ensure data clarity, only DDI events with a single interaction type per drug pair are retained, as multiple simultaneous interactions are extremely rare. The final dataset contains 572 drugs and 37,264 DDI records involving 65 types of DDI events, suitable for DDI prediction studies. The DDIMDL dataset is a computationally structured resource derived from DrugBank, which uniquely encodes drug-drug interactions into a normalized four-tuple representation (drug A, drug B, mechanism, action). This structured event-based format distinguishes itself from datasets that primarily provide binary interaction labels or unstructured descriptions

3.5 MecDDI dataset

MecDDI[27], introduced in 2023, uses a dataset collected from the FDA and other large-scale databases such as DrugBank and TTD. DDI data were extracted from FDA drug labels and PubMed literature. The dataset contains 1,922 approved drugs and 178,406 DDI records with mechanism annotations, including interactions related to gastrointestinal absorption, cellular transport, intra-/extra-hepatic metabolism, excretion, pharmacodynamic additive effects, and antagonistic effects. The severity of each DDI is also annotated. The MecDDI database provides a uniquely annotated resource where drug-drug interactions are systematically categorized by pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic mechanisms, with additional clinical severity assessments. This mechanistic granularity differentiates it from interaction datasets that primarily list co-occurrence or clinical associations without explanatory biological pathways.

3.6 DrugComb dataset

DrugCombDB[28] is a comprehensive database integrating data from high-throughput screening (HTS), PubMed publications, FDA Orange Book, and external databases. It contains 448,555 drug combinations derived from HTS assays, involving 2,887 drugs and 124 human cancer cell lines. The database includes over 6 million quantitative dose-response measurements and multiple synergy scores to assess overall synergistic or antagonistic effects of drug combinations. DrugCombDB also provides preprocessed datasets suitable for pre-training models, facilitating computational model development and experimental validation. DrugCombDB provides a distinctive collection of in vitro drug combination data with quantitative dose–response and synergy metrics, supporting computational modeling of combination therapy effects. Its primary value lies in aggregating experimentally measured, rather than clinically reported or predicted, interaction outcomes.

4. DDI Model Architectures

We provided a systematic taxonomy and analysis of computational models for DDI prediction, structured along the methodological evolution from classical to deep learning-based approaches. We began by examining early paradigms reliant on feature engineering, followed by an in-depth discussion of contemporary deep learning architectures categorized by their representational forms. Finally, we reviewed emerging strategies that integrate multimodal data and leverage transfer learning. A chronological synthesis of representative models, encapsulating their methodologies, datasets, and contributions, is presented in Table 2 an a consolidated reference.

| Year | Method | Method Category | Dataset | Key Feature |

| 2012 | Vilar et al.[9] | Similarity-based | DrugBank | Molecular fingerprint structural similarity |

| 2016 | Liu et al.[39] | CNN | DDI Extraction 2013 corpus | CNN for DDI extraction from biomedical literature |

| 2017 | Ferdousi et al.[29] | Similarity-based | DrugBank | Uses CTET for functional similarity |

| 2017 | Abdelaziz et al.[30] (Tiresias) | Similarity-based | DrugBank | Integrates local features and global embeddings |

| 2017 | Ramakanth et al.[42] | RNN | DDI Extraction 2013 corpus | Integrates word-level and character-level RNNs with LSTM |

| 2017 | Huang et al.[43] | LSTM | DDI Extraction 2013 corpus | Two-stage method combining SVM and LSTM |

| 2018 | Zitnik et al.[53] | GCN | Decagon | Multi-modal GCN for polypharmacy side effects |

| 2018 | Sahu et al.[44] | LSTM | MEDLINE and DrugBank | Multiple Bi-LSTM variants for DDI extraction |

| 2019 | Shi et al.[34] (BRSNMF) | Matrix Factorization | DrugBank | Balance regularized semi-nonnegative matrix factorization |

| 2019 | Sun et al.[40] (RHCNN) | CNN | DDI Extraction 2013 dataset | Recurrent hybrid CNN combining RNNs |

| 2020 | Zhu et al.[32] (PDMTF) | Matrix Factorization | DrugBank and TWOSIDES | Probabilistic dependent matrix tri-factorization |

| 2020 | Huang et al.[49] (SkipGNN) | GNN | BIOSNAP-DDI, BIOSNAP-DTI, HuRI-PPI, DisGeNET-GDI | Skip graph for second-order interactions |

| 2020 | Feng et al.[54] (DPDDI) | GCN | DrugBank | Two-layer GCN for drug embeddings |

| 2021 | Nyamabo et al.[58] (SSI-DDI) | GAT | DrugBank | Substructure-substructure interactions with co-attention |

| 2021 | Zaikis et al.[46] (TP-DDI) | Transformer | DDI Extraction 2013 corpus | BioBERT-based end-to-end pipeline |

| 2022 | Zhang et al.[37] (CNN-DDI) | CNN | DrugBank | CNN processing SMILES and multi-source features |

| 2022 | Wang et al.[38] (ACNN) | CNN | DDIMDL | CNN with attention mechanism |

| 2022 | Shao et al.[47] (TBPM-DDIE) | Transformer | ChEMBL24 and DDIMDL | Transformer pretraining for joint latent representations |

| 2022 | Hong et al.[59] (LaGAT) | GAT | KEGG-drug and DrugBank | Link-aware GAT with differential attention paths |

| 2022 | Lin et al.[45] (MDF-SA-DDI) | Transformer | DDIMDL | Multi-source fusion with self-attention mechanism |

| 2022 | Zhang et al.[60] (AI-DDI) | GNN | DrugBank | Two-stage graph merging and attention mechanism |

| 2022 | Nyamabo et al.[61] (GMPNN-CS) | MPNN | DrugBank and TWOSIDES | Learnable edge gating mechanism for dynamic substructure delineation |

| 2022 | Yang et al.[62] (SA-DDI) | MPNN | DrugBank | D-MPNN with substructure attention mechanism |

| 2022 | Zhu et al.[63] (SSF-DDI) | MPNN | DrugBank and TWOSIDES | D-MPNN for substructure features |

| 2022 | Han et al.[50] (SmileGNN) | Multimodal Fusion | DrugBank | Joint learning of SMILES features and KG topology |

| 2023 | Shtar et al.[35] (LAMFP) | Matrix Factorization | DrugBank | Lookup mechanism for cold-start problem |

| 2023 | Yin et al.[55] (DeepDrug) | GCN | DrugBank and TWOSIDES | Residual Graph Convolutional Network |

| 2023 | Xia et al.[68] (MDTips) | Multimodal Fusion | DRKG | Integrates drug-target KGs, gene expression, molecular structures |

| 2024 | Han et al.[33] (CTF-DDI) | Matrix Factorization | DrugBank and TWOSIDES | Constrained tensor factorization |

| 2024 | Tamir et al.[48] (KITE-DDI) | Transformer | DrugBank | KG-integrated Transformer for SMILES and BioKGs |

| 2024 | Yuan et al.[64] | GNN | DrugBank | Self-supervised contrastive learning pretraining |

| 2024 | Chen et al.[65] (DrugDAGT) | Graph Transformer | DrugBank | Dual-attention graph Transformer with contrastive learning |

| 2024 | Jiang et al.[56] (DeepGCL) | GCN | DrugBank | Deep graph contrastive learning framework |

| 2024 | Su et al.[66] (TIGER) | Graph Transformer | DrugBank | Relation-aware heterogeneous graph Transformer |

| 2024 | Lu et al.[69] (MMFDL) | Multimodal Fusion | Delaney, Llinas2020 | Transformer + BiGRU + GCN fusion |

| 2024 | Wang et al.[73] (PTDA) | Prompt Tuning | DDI Extraction 2013 | Prompt tuning + data augmentation for DDI extraction |

| 2025 | Wang et al.[41] (BiRNN-DDI) | RNN | DDIMDL | Graph2Seq and bidirectional RNN |

| 2025 | Qiao et al.[67] (Taco-DDI) | Graph Transformer | DDInter | Dynamic co-attention for key substructure identification |

| 2025 | Liu et al.[51] (HGNN-DDI) | GNN | DrugBank | Heterogeneous graph with pre-trained language model features |

| 2025 | Wang et al.[70] (MMDDI-SSE) | Multimodal Fusion | DDIMDL | Fusion of sequence features and DDI graph topology |

| 2025 | Xie et al.[71] (DDintensity) | Fine-tuning | DrugBank and DDInter | Leverages pre-trained embeddings |

| 2025 | Yu et al.[72] (R-BERT-DDI) | Fine-tuning | DDI Extraction 2013 | BERT fine-tuning with explicit drug entity modeling |

DDI: drug-drug interaction; CNN: convolutional neural network; CTET: carriers, transporters, enzymes and targets; RNN: recurrent neural network; LSTM: long short-term memory; SVM: support vector machine; Bi-LSTM: bidirectional LSTM; BRSNMF: balance regularized semi-nonnegative matrix factorization; RHCNN: recurrent hybrid convolutional neural network; PDMTF: probabilistic dependent matrix tri-factorization; GCN: graph convolutional network; GAT: graph attention network; MPNN: message passing neural network; D-MPNN: directed message-passing neural network; DPDDI: deep predictor of drug-drug interactions; SSI-DDI: substructure–substructure interaction drug-drug interaction; TP-DDI: transformer-based pipeline for drug-drug interaction extraction; CNN-DDI: convolutional neural network for drug-drug interaction prediction; ACNN: attention-based convolutional neural network; TIGER: transformer-based relation-aware graph representation learning framework; MMFDL: multimodal fused deep learning; PTDA: prompt tuning with data augmentation.

4.1 From classical models to deep learning: A methodological evolution

The evolution of DDI prediction methodologies has progressed from classical, feature-engineered approaches to end-to-end deep learning paradigms. Early methods, while foundational, were often limited by the quality of manual feature design or the simplicity of their representations. This section briefly outlines these classical paradigms, specifically similarity-based and matrix factorization methods. This overview provides context for the subsequent deep learning revolution, which overcame many prior limitations through automated representation learning.

4.1.1 Similarity-based models

In DDIs, if there exists an interaction between drug A and drug B, a drug C that is similar to drug A is more likely to exhibit a similar interaction with drug B. Therefore, several similarity measures among drugs can be computed based on biological features, such as drug targets and pathways, to help predict interactions.

Vilar et al.[9] proposed a large-scale DDI prediction method based on molecular structural similarity. Its core innovation lies in using molecular fingerprints (specifically BIT_MACCS) to quantify drug similarity and applying the assumption that structurally similar drugs share interaction profiles. However, its reliance on 2D fingerprints limits the capture of full molecular information. Ferdousi et al.[29] introduced a functional similarity-based method using four biological elements (CTET) to predict DDIs. While it enabled large-scale screening, its accuracy depends on the completeness of CTET databases. Abdelaziz et al.[30] proposed Tiresias, a knowledge

In summary, while similarity-based models offer intuitive and explainable frameworks for DDI prediction, they are fundamentally constrained by two inherent limitations. First, their predictive performance is heavily dependent on the completeness and quality of the pre-defined drug features or databases. Second, their generalization capability is often limited. The core assumption that drug similarity implies interaction similarity does not always hold for complex, non-linear pharmacological effects, which may arise from specific atomic-level interactions. This can result in poor predictive accuracy for drug pairs that are structurally or functionally similar yet interact through distinct mechanisms.

4.1.2 Matrix factorization-based models

Matrix factorization (MF)-based approaches learn latent representations by decomposing the drug interaction matrix, enabling the reconstruction of unknown DDIs. DDI data are typically represented as a matrix, which can be factorized to extract latent features capturing hidden drug-drug relationships for predicting novel interactions. However, these methods often have limited interpretability and require appropriate constraints to incorporate drug features[31].

Zhu et al.[32] designed a dependency network to model the interdependencies among drugs and proposed an attribute-supervised learning model, Probabilistic Dependency Matrix Tri-Factorization, for predicting adverse drug-drug interactions. Han et al.[33] introduced a novel Constrained Tensor Factorization module, incorporating Hessian and L2,1 regularization to enforce constraints. Shi et al.[34] proposed the balance regularized semi-nonnegative matrix factorization (BRSNMF) method which explicitly models the weak balance relationship within DDI networks. BRSNMF leverages this structural property not only to detect pharmacologically meaningful drug communities but also to enhance the prediction of both enhancive and degressive interactions. Shtar et al.[35] proposed LAMFP, an extension of the AMF method designed for preclinical DDI prediction when only chemical structures are available. Its core innovation is a lookup mechanism that uses drug similarity to generalize predictions to new, unseen drugs, addressing the cold-start challenge effectively.

In conclusion, matrix factorization models provide a principled framework for learning latent drug representations from interaction data. However, they exhibit two primary limitations. First, the learned latent factors are often abstract and lack direct biochemical interpretation, making it difficult to trace predictions back to drug features or mechanisms. Second, they cannot handle new unseen drugs that are not present in the original interaction matrix, which is known as the cold-start problem.

4.2 End-to-end deep learning models

Deep learning models for DDI prediction can be broadly categorized by their input representation: sequence-based and graph-based approaches, each with distinct inductive biases and strengths. Sequence-based approaches leverage architectures such as CNNs, RNNs, and Transformers. These models are applied to two primary types of sequential data: (1) molecular representations (notably SMILES strings), where they capture patterns and long-range dependencies akin to natural language; and (2) biomedical text, where they extract known interaction relationships directly from the scientific literature. In contrast, graph-based models, including graph convolutional networks (GCNs), graph attention networks (GATs), and message passing neural networks (MPNNs), explicitly operate on the molecular graph structure. Their primary strength lies in directly modeling the topological connectivity and spatial relationships between atoms and bonds, which often provides a more natural and informative representation for chemical reasoning. Notably, the recent emergence of Graph Transformers represents a significant evolution within the graph-based paradigm, combining the strengths of global self-attention with explicit graph structure to capture both long-range and local interactions. The following subsections detail these paradigms and their evolution.

4.2.1 Sequence-based approaches

Sequence-based deep learning architectures, originally developed for natural language processing, have been adapted to process sequential data in DDI research. The most direct application is the modeling of molecular structures using their textual representations, primarily SMILES strings. Additionally, these architectures have been applied to the task of extracting known drug interaction relationships directly from biomedical literature texts. This section reviews the development and application of CNNs, RNNs, and Transformer models in this context.

In the context of molecular DDI prediction, CNNs are applied to SMILES strings as one-dimensional sequences. Convolutional kernels slide over these sequences to extract local structural patterns, enabling hierarchical feature learning of the entire molecule[36]. For instance, Zhang et al.[37] introduced the CNN-DDI model, which processes SMILES alongside multi-source biological features via a CNN to predict specific interaction types. Focusing solely on structural data, Wang et al.[38] proposed the ACNN model, an end-to-end framework that predicts DDIs using only SMILES sequences. Its core innovation is the integration of a deep CNN for molecular feature extraction with an attention mechanism that explicitly models complex inter-atomic interactions by assigning an attention vector to each atom, leading to improved predictive accuracy. In parallel, the representational power of CNNs has been leveraged for extracting DDI relations from unstructured biomedical literature. Liu et al.[39] pioneered this approach by using CNNs to replace traditional feature-based methods. Their model encodes textual input with word and position embeddings, utilizing sequence and dependency path information. Sun et al.[40] further advanced this line of work with a Recurrent Hybrid CNN model, combining recurrent networks for contextual semantics with CNNs to capture both local and long-range sentence features.

RNNs process SMILES sequences sequentially through their recurrent units, utilizing internal hidden states to transmit information, thereby modeling long-range dependencies between atoms and capturing the dynamic temporal relationships within the sequence. For instance, the BiRNN-DDI model[41] converts drug SMILES into sequences via a Graph2Seq approach and employs a bidirectional RNN to learn contextual representations for predicting DDI event types. For the distinct task of extracting DDIs from biomedical literature, RNNs are leveraged to model sentence context, with long short-term memory (LSTM) networks being a particularly prevalent architecture. Ramakanth et al.[42] proposed a DDI extraction method that integrates word-level and character-level RNNs. This approach embeds 128-dimensional ASCII characters and trains a LSTM network to generate character-level word vectors. Huang et al.[43] introduced a two-stage classification method for DDI extraction. It first employs a feature-based classifier to identify positive instances, followed by an LSTM classifier to perform fine-grained categorization of these positives. Sahu et al.[44] proposed three DDI extraction models based on LSTM architectures, namely B-LSTM, AB-LSTM, and Joint AB-LSTM. These models utilize word embeddings and position embeddings as input features and leverage bidirectional LSTM structures to extract sentence-level features.

The self-attention mechanism of Transformers has revolutionized sequence modeling by capturing global dependencies, finding dual utility in DDI research for both molecular representation and text understanding. In molecular prediction, Transformers directly process SMILES strings to model comprehensive inter-atomic relationships. An example is the MDF-SA-DDI model[45], which employs a multi-source fusion network to extract features from drug pairs and utilizes self-attention for effective feature integration to predict interaction events. Concurrently, in the domain of knowledge extraction from biomedical literature, Transformer-based

In summary, sequence-based models present a clear trade-off between efficiency and representational power for DDI tasks. For molecular prediction, CNNs are efficient but local, RNNs model sequence but are computationally costly, and Transformers offer global context at the expense of higher complexity. In text extraction, pre-trained Transformers dominate due to their transfer learning capability, though they require substantial computational resources. A consistent trend across both domains is the shift towards Transformer-based architectures, driven by their superior ability to model long-range dependencies. The ongoing integration of diverse data types within these models promises better generalization but also introduces new challenges in data fusion and computational demand.

4.2.2 Graph neural network-based models

GNN-based models represent drug information using graph structures and primarily leverage architectures such as GCNs, GAT, and MPNNs. Their typical inputs include 2D molecular topology graphs of drugs and knowledge graphs of biomedical entities. By utilizing message-passing mechanisms between nodes, these models effectively learn the topological relationships of atoms and chemical bonds, achieving accurate modeling of molecular structures. For instance, Huang et al.[49] proposed the SkipGNN model, which introduces second-order interaction information by constructing a skip graph and employs an iterative fusion scheme to combine the original graph with the skip graph for message passing, thereby enhancing the prediction capability for molecular interactions. Han et al.[50] developed the SmileGNN model, which achieves joint representation learning for drug interactions by aggregating drug structural features constructed from SMILES data with drug topological features extracted from knowledge graphs. The HGNN-DDI model[51] predicts DDIs by constructing a heterogeneous graph encompassing drugs, proteins, and their interactions. Its distinctive approach lies in integrating drug-protein and protein-protein interaction information as auxiliary knowledge and utilizing

GCNs learn representations for each node in a graph by aggregating features from its first-order neighbors, thereby smoothing the graph structure[52]. Through multi-layer stacking, they capture both local structural information and long-range dependencies within molecular graphs. Zitnik et al.[53] proposed a multi-modal relational prediction model based on Graph Convolutional Networks. This model employs a GCN encoder to learn node embeddings for drugs, proteins, and side effects, and utilizes a tensor factorization decoder to predict specific types of DDIs. Feng et al.[54] introduced a DDI prediction method based on a two-layer GCN. It learns embedded representations of drugs within a network via GCN and employs a deep neural network (DNN) to accomplish interaction prediction. Yin et al.[55] proposed a DDI prediction approach based on a Residual Graph Convolutional Network. This method takes the drug molecular graph as input and learns topological features by aggregating neighbor information of atom nodes within the molecular graph. DeepGCL[56] introduces a novel deep graph contrastive learning framework for DDI prediction by integrating molecular structure features with network topology features. Unlike existing methods that rely on single-view learning or simple multi-view aggregation, DeepGCL employs a contrastive learning component to enhance consistency between structural and topological representations, effectively balancing and fusing multi-source information.

GAT leverages on the attention mechanism to dynamically compute the importance weights of neighboring nodes, focusing on key inter-atomic interactions within the molecular graph and thereby achieving discriminative representation of molecular structures[57]. Nyamabo et al.[58] proposed the SSI-DDI model, which decomposes DDI prediction into the identification of pairwise interactions between drug substructures. This model learns substructure representations directly from the original molecular graph and employs a co-attention mechanism to evaluate the contribution of different substructure pairs to the final prediction. The LaGAT model[59] introduces a link-aware graph attention mechanism, enabling the generation of differentiated attention paths for different drug pairs. This allows for the dynamic aggregation of the most relevant neighborhood information within the knowledge graph, thereby enhancing DDI prediction performance. In contrast to previous substructure-based DDI models that often depended on predefined molecular fragments or overlooked global intermolecular contexts, AI-DDI[60] innovatively introduces a two-stage graph merging and attention mechanism. This approach dynamically constructs comprehensive intermolecular interactions, thereby achieving superior and interpretable predictions.

MPNNs propagate and aggregate chemical information on molecular graphs through a framework of message passing, node updating, and readout functions. This process learns environment-aware atom representations and captures comprehensive structural features, ranging from local bonding to long-range interactions. The GMPNN-CS[61] model introduces a learnable edge gating mechanism that dynamically delineates chemical substructures by controlling the flow of message propagation within the molecular graph, thereby enabling DDI prediction based on weighted interactions between learned substructure pairs. Yang et al. proposed a SA-DDI[62]. This model employs a D-MPNN with a substructure attention mechanism to capture substructures of varying sizes and shapes, and incorporates a Substructure-Substructure Interaction Module to model interactions between substructures, ultimately improving prediction accuracy by emphasizing critical substructures. The SSF-DDI[63] model comprehensively considers both drug sequence features and substructure features. In this framework, the D-MPNN performs information transmission and updates along directed edges, aggregating information from all neighboring nodes and chemical bonds for each atom to generate substructure representations.

Despite their strengths in structure-aware representation, GNN-based models face notable challenges. A primary computational concern is their scalability when dealing with large molecular graphs or knowledge graphs, as the message-passing mechanism incurs costs that grow with graph size and complexity. More fundamentally, deep GNNs are prone to the over-smoothing issue, where node representations become indistinguishable after multiple rounds of aggregation, causing a loss of discriminative power and hindering the modeling of long-range interactions within molecules. Various architectural innovations, such as residual connections, skip connections, and attention-based gating mechanisms, have been proposed to mitigate these issues. Recent research has also focused on developing more comprehensive representations by jointly modeling drug molecules at multiple levels. For instance, the PHGL-DDI[64] framework employs self-supervised contrastive learning to pretrain GNNs on molecular graphs, thereby enriching node features, and then integrates these features with the topological structure of the DDI network for final prediction.

4.2.3 Graph transformer-based models

Graph Transformer-based DDI prediction models overcome the receptive field limitations inherent in traditional GNNs by incorporating a global self-attention mechanism. This enables direct computation of interaction strengths between any atom pairs in the molecular graph, thereby more effectively capturing long-range dependencies and complex structural features of drug molecules.

Chen et al.[65] proposed the DrugDAGT model, which is based on a dual-attention graph Transformer. It utilizes bond attention and atom attention to capture short-range and long-range intramolecular dependencies, respectively, and introduces graph contrastive learning to enhance the discriminative power of molecular representations, ultimately achieving multi-type DDI prediction. The TIGER[66] model introduces a relation-aware graph Transformer with a dual-pathway architecture that processes the drug molecular graph and the biomedical knowledge graph separately. Through a cross-channel feature interaction mechanism, it performs feature fusion at both the node level and graph level, effectively modeling long-range dependencies and high-order structural relations while preserving drug structural features and incorporating rich biological context. The Taco-DDI[67] model, built upon a graph Transformer architecture, employs a self-attention mechanism to learn atom-level representations of drug molecules and capture global structural features. Innovatively, it incorporates a dynamic co-attention mechanism that can adaptively identify key substructures relevant to interactions within a drug pair.

Collectively, Graph Transformer models represent a significant advancement in DDI prediction by unifying the explicit modeling of molecular graph topology with the power to capture global, long-range dependencies through self-attention. This hybrid capability allows them to learn more expressive and context-aware molecular representations, which is crucial for accurately predicting complex pharmacological interactions that may depend on both local chemical motifs and overall molecular conformation.

4.3 Emerging paradigms and advanced strategies

Beyond the core architectural innovations in processing molecular sequences and graphs, the field of DDI prediction is being reshaped by several advanced methodological paradigms. These strategies often leverage or combine the deep learning architectures discussed previously but focus on harnessing broader biological context, advanced learning schemes, and large-scale structured knowledge. This section explores key emerging paradigms that represent significant frontiers in developing more robust and biologically interpretable DDI prediction systems.

4.3.1 Multimodal integration of drug structure with biological context

Moving beyond models that rely solely on molecular representations, a significant frontier in computational drug discovery involves the integration of multimodal biological data. This paradigm seeks to construct more holistic and context-aware models by combining drug chemical structures with complementary evidence such as target profiles, gene expression data, and protein-protein interaction networks.

The MDTips system[68] exemplifies this approach for the closely related task of DTI prediction by integrating drug-target knowledge graphs, gene expression profiles, and molecular structures. Its design demonstrates that multimodal fusion learning can dynamically weigh the importance of each data source and synthesize information from multiple biological perspectives. Notably, the study found that deep learning-based encoders for processing these modalities consistently outperformed traditional chemical descriptors or fingerprints. The MMFDL model[69] tackles the limitation of single-representation learning by systematically integrating three complementary molecular views. It employs a Transformer-Encoder for SMILES sequences, a BiGRU for ECFP fingerprints, and a Graph Convolutional Network for molecular graphs. This fusion strategy demonstrates that fusing complementary structural views yields more robust predictions than any single representation. The MMDDI-SSE model[70] directly addresses DDI event prediction by fusing sequence-based drug features, such as pharmacodynamic profiles, chemical substructures, target proteins, and enzyme information, with topological features from DDI graphs via a graph autoencoder. This integration of biological context and network structure yields superior predictive performance.

Furthermore, the construction and utilization of large-scale biomedical knowledge graphs that formally link drugs, diseases, genes, and pathways offer a rich, structured context for prediction. Models capable of reasoning over such graphs can potentially uncover explainable interaction mechanisms within a broader biological network, addressing the need for more interpretable and

4.3.2 Pre-training and fine-tuning strategies for DDI models

The paradigm of pre-training models on large-scale datasets followed by task-specific fine-tuning has become a cornerstone of modern deep learning, effectively addressing data scarcity and improving generalization. In DDI research, this paradigm is actively explored. Studies not only investigate which pre-trained models provide the most useful prior knowledge for the task but also develop specialized fine-tuning techniques to better adapt the nuances of drug interaction data.

The DDintensity framework[71] directly tackles the challenge of imbalanced DDI risk level prediction by leveraging embeddings from diverse pre-trained models as transferable features, which are then processed by an LSTM-Attention network for fine-tuning. This approach demonstrates that pre-trained embeddings can significantly boost performance on specialized, data-scarce tasks. For the task of extracting DDIs from biomedical text, models like R-BERT-DDI[72] and PTDA[73] showcase advanced fine-tuning strategies.

Collectively, these works highlight a key methodological shift: the central challenge has evolved from accessing pre-trained knowledge to orchestrating its effective translation for DDI tasks. This progression from generic fine-tuning to domain-calibrated adaptation marks the maturation of pre-training strategies in computational pharmacology, establishing a new standard for building robust DDI models.

5. Future Perspectives

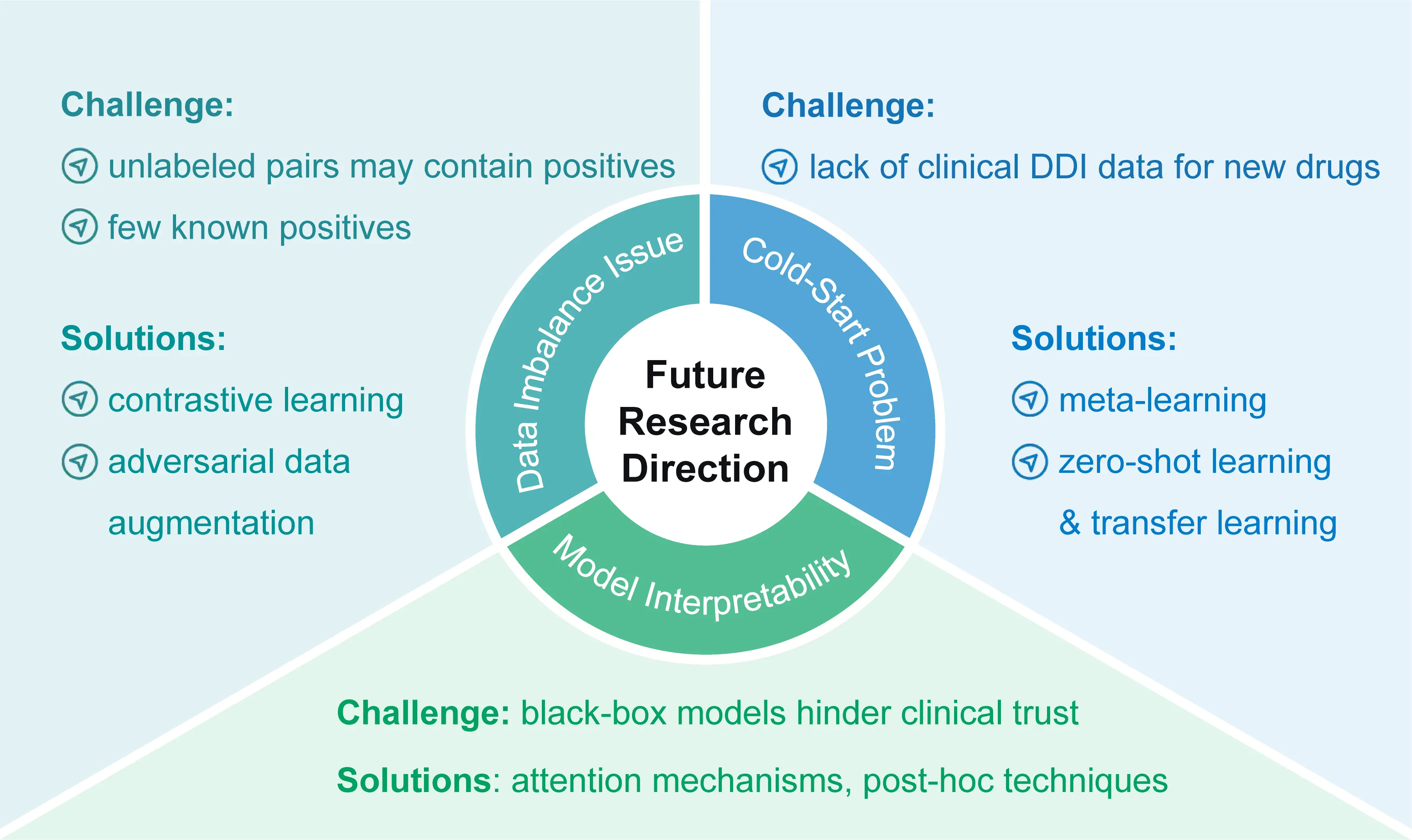

The application of machine learning and deep learning to DDI prediction continues to face challenges arising from data scarcity and model opacity. This section discusses ongoing research directions aimed at addressing these limitations. Specifically, it covers methodological advances for handling severe data imbalance, overcoming the cold-start problem and improving model interpretability. The discussion synthesizes current approaches, such as contrastive learning, data augmentation, few-shot and transfer learning paradigms, as well as techniques from Explainable AI (XAI), and highlights persisting gaps in each area. A conceptual summary of these key future directions is visually outlined in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Key future research directions for DDI prediction. DDI: drug-drug interaction.

5.1 Addressing the DDI data imbalance issue

A severe data imbalance problem exists in DDI research, as the number of known positive interactions is minuscule compared to the vast space of potential drug combinations. Traditional methods that treat all unrecorded pairs as negative samples are problematic, as these sets may contain many unannotated positives.

To tackle this, contrastive learning has emerged as a powerful paradigm for learning robust representations from imbalanced data. By maximizing the similarity between differently augmented views of the same interaction type while distancing different types, models can learn more discriminative features even with limited positive examples. For instance, frameworks as such MCL-DDI[74] explicitly address this challenge by leveraging multi-view contrastive learning. They enforce consistency between different structural and network-based views of drugs, which helps the model learn more discriminative and balanced representations even from an imbalanced set of known interactions, thereby directly mitigating the class imbalance issue.

Beyond representation learning, synthetic data augmentation strategies directly address the scarcity of positive samples. Adversarial learning frameworks are particularly effective in this regard. In a typical setup, a generator and a discriminator engage in a dynamic game to produce chemically plausible yet mechanistically informative synthetic samples. A notable advancement is the integration of such adversarial mechanisms to fuse multimodal features. For example, the RCAN-DDI model[75] employs a cross-adversarial network to explore the correlations and complementarity between different information sources (e.g., structural and topological features), effectively integrating multimodal drug characteristics. Collectively, these approaches refine the data distribution and enhance model generalizability in the face of severe imbalance.

5.2 Addressing the cold-start problem in new drug development

The development of new drugs faces a significant cold-start problem: due to the lack of clinical DDI data for newly launched drugs, traditional data-driven models cannot make effective predictions for them.

Few-shot learning paradigms offer powerful solutions by enabling models to generalize from very limited examples. Meta-learning, a prominent strategy within this paradigm, addresses the cold-start problem by performing meta-optimization across numerous subtasks involving DDIs of known drugs. This process allows the model to acquire a learning-to-learn capability, enabling rapid adaptation and accurate prediction for new drugs with only a handful of DDI samples. Beyond meta-learning, zero-shot learning approaches tackle an even more extreme scenario by predicting interactions for entirely unseen DDI event types without any task-specific training examples. For instance, the ZeroDDI[76] framework employs semantic-enhanced learning and dual-modal alignment to represent and predict novel DDI events, effectively addressing the challenge of unseen classes. In parallel, transfer learning provides a complementary strategy by leveraging knowledge from large, source datasets to boost prediction performance on the data-scarce target task of new drug DDI prediction. By fine-tuning pre-trained models, this approach mitigates the data scarcity issue and has shown significant promise in various pharmacokinetic and pharmacological prediction tasks.

5.3 Interpretability of DDI models

Despite the widespread application of deep learning in DDI prediction, many advanced models operate as black boxes, lacking transparency and hindering clinical adoption. To build trust and enable safe integration into decision support, XAI has become a critical research focus, aiming to make model predictions interpretable. XAI techniques are typically categorized into model-aware and model-agnostic methods.

Intrinsic interpretability is achieved by designing models with transparent reasoning mechanisms. A prominent example is the use of attention mechanisms in architectures like GNNs or Transformers, where the weights assigned to atoms, bonds, or substructures directly highlight the chemical features deemed most relevant for a prediction. For essential high-performance models that are inherently complex, post-hoc interpretation techniques are employed to explain predictions after the fact. These include

6. Conclusion

In this survey, we have systematically reviewed the key technologies and recent advances in computational DDI prediction. We encompassed multi-dimensional molecular representations, from sequences to spatial conformations, categorized prevalent public databases, and analyzed the architectural evolution of predictive models. Our discussion also critically addressed the persistent limitations of current approaches, which must be overcome to ensure their reliability and trustworthiness in real-world clinical decision support and AI-driven drug safety systems.

Ultimately, the translation of computational DDI predictions into tangible clinical impact represents the paramount goal of this field. As discussed, reliable models hold the potential for integration into clinical decision support systems, electronic health records, and pharmacovigilance tools. This integration can empower healthcare providers to pre-empt high-risk interactions, personalize complex therapies, and significantly enhance overall medication safety and therapeutic outcomes.

Looking ahead, the field is poised for transformation by emerging trends such as the integration of large language models to mine unstructured biomedical text, and the move toward multi-modal frameworks that combine molecular, omics, real-world, and imaging data. To realize the full clinical potential, future work must strive to synergize data-driven predictive power with mechanistic models, thereby achieving not only higher accuracy but also the interpretability and biological plausibility essential for gaining clinical trust. We anticipate that this convergent evolution will ultimately cement DDI prediction as an indispensable pillar of precision medicine and rational pharmacotherapy.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used AI tools to assist with language polishing in order to enhance the normative quality and fluency of the text. The core viewpoint and argumentation process of the paper are independently completed by the authors. The authors take full responsibility for the final content of the publication.

Authors contribution

Guo X, Chen S: Investigation, visualization, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Qiao J: Investigation, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Wei L: Supervision, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Leyi Wei is an Editorial Board Member of Computational Biomedicine. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

References

-

1. Walkup JT, Albano AM, Piacentini J, Birmaher B, Compton SN, Sherrill JT, et al Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(26):2753-2766.[DOI]

-

2. Espinal MA, Kim SJ, Suarez PG, Kam KM, Khomenko AG, Migliori GB, et al. Standard short-course chemotherapy for drug-resistant tuberculosis: treatment outcomes in 6 countries. JAMA. 2000;283(19):2537-2545.[DOI]

-

3. Huang J, Niu C, Green CD, Yang L, Mei H, Han JD. Systematic prediction of pharmacodynamic drug-drug interactions through protein-protein-interaction network. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9(3):e1002998.[DOI]

-

4. Agarwal S, Agarwal V, Agarwal M, Singh M. Exosomes: Structure, biogenesis, types and application in diagnosis and gene and drug delivery. Curr Gene Ther. 2020;20(3):195-206.[DOI]

-

5. Moura CS, Acurcio FA, Belo NO. Drug-drug interactions associated with length of stay and cost of hospitalization.; J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2009;12(3):266-272.[DOI]

-

6. Becker ML, Kallewaard M, Caspers PW, Visser LE, Leufkens HG, Stricker BH. Hospitalisations and emergency department visits due to drug–drug interactions: A literature review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(6):641-651.[DOI]

-

7. Percha B, Altman RB. Informatics confronts drug–drug interactions. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2013;34(3):178-184.[DOI]

-

8. Qiao J, Gao W, Jin J, Wang D, Guo X, Manavalan B, et al. Molecular pretraining models towards molecular property prediction. Sci China Inf Sci. 2025;68(7):170104.[DOI]

-

9. Vilar S, Harpaz R, Uriarte E, Santana L, Rabadan R, Friedman C. Drug-drug interaction through molecular structure similarity analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(6):1066-1074.[DOI]

-

10. Wang Y, Zhai Y, Ding Y, Zou Q. SBSM-Pro: Support bio-sequence machine for proteins. Sci China Inf Sci. 2024;67(11):212106.[DOI]

-

11. Kumar Meher P, Hati S, Sahu TK, Pradhan U, Gupta A, Rath SN. SVM-root: Identification of root-associated proteins in plants by employing the support vector machine with sequence-derived features. Curr Bioinform. 2024;19(1):91-102.[DOI]

-

12. Liu B, Gao X, Zhang H. BioSeq-Analysis2. 0: An updated platform for analyzing DNA, RNA and protein sequences at sequence level and residue level based on machine learning approaches. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(20):e127.[DOI]

-

13. Qiao J, Jin J, Wang D, Teng S, Zhang J, Yang X, et al. A self-conformation-aware pre-training framework for molecular property prediction with substructure interpretability. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):4382.[DOI]

-

14. Quirós M, Gražulis S, Girdzijauskaitė S, Merkys A, Vaitkus A. Using SMILES strings for the description of chemical connectivity in the Crystallography Open Database. J Cheminform. 2018;10(1):23.[DOI]

-

15. Krenn M, Ai Q, Barthel S, Carson N, Frei A, Frey NC, et al. SELFIES and the future of molecular string representations. Patterns. 2022;3(10):100588.[DOI]

-

16. Priyadarsini I, Takeda S, Hamada L, Brazil EV, Soares E, Shinohara H. Self-bart: A transformer-based molecular representation model using selfies. arXiv:2410.12348 [Preprint]. 2024.[DOI]

-

17. Priyadarsini I, Takeda S, Hamada L, Brazil EV, Soares E, Shinohara H. SELFIES-TED: A robust transformer model for molecular representation using SELFIES [Internet]. ICLR 2025. Available from: https://openreview.net/pdf/15298d84c67b8fc5e8c01b88add2d7b5a2c6fc1b.pdf

-

18. Liao YL, Smidt T. Equiformer: Equivariant graph attention transformer for 3d atomistic graphs. arXiv:2206.11990 [Preprint].[DOI]

-

19. Huang W, Jiao R, Kong X, Zhang L, Yu Z, Ren F, et al. An equivariant pPretrained transformer for unified 3D molecular representation learning. arXiv:2402.12714 [Preprint]. 2024.[DOI]

-

20. Chithrananda S, Grand G, Ramsundar B. ChemBERTa: Large-scale self-supervised pretraining for molecular property prediction. arXiv:2010.09885 [Preprint]. 2020.[DOI]

-

21. Ahmad W, Simon E, Chithrananda S, Grand G, Ramsundar B. Chemberta-2: Towards chemical foundation models. arXiv:2209.01712[Preprint]. 2022.[DOI]

-

22. Knox C, Wilson M, Klinger Christen M, Franklin M, Oler E, Wilson A, et al. DrugBank 6.0: the DrugBank knowledgebase for 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024;52(D1):D1265-D1275.[DOI]

-

23. Tatonetti NP, Ye PP, Daneshjou R, Altman RB. Data-driven prediction of drug effects and interactions. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4(125):125ra131.[DOI]

-

24. Xiong G, Yang Z, Yi J, Wang N, Wang L, Zhu H, et al. DDInter: An online drug–drug interaction database towards improving clinical decision-making and patient safety. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(D1):D1200-D1207.[DOI]

-

25. Xiong G, Yang Z, Yi J, Wang N, Wang L, Zhu H, et al. DDInter 2.0: An enhanced drug interaction resource with expanded data coverage, new interaction types, and improved user interface. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;50(D1):D1200-D1207.[DOI]

-

26. Deng Y, Xu X, Qiu Y, Xia J, Zhang W, Liu S. A multimodal deep learning framework for predicting drug–drug interaction events. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(15):4316-4322.[DOI]

-

27. Hu W, Zhang W, Zhou Y, Luo Y, Sun X, Xu H, et al. MECDDI: Clarified drug–drug interaction mechanism facilitating rational drug use and potential drug–drug interaction prediction. J Chem Inf Model. 2023;63(5):1626-1636.[DOI]

-

28. Liu H, Zhang W, Zou B, Wang J, Deng Y, Deng L. DrugCombDB: A comprehensive database of drug combinations toward the discovery of combinatorial therapy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;48(D1):D871-D881.[DOI]

-

29. Ferdousi R, Safdari R, Omidi Y. Computational prediction of drug-drug interactions based on drugs functional similarities. J Biomed Inform. 2017;70:54-64.[DOI]

-

30. Abdelaziz I, Fokoue A, Hassanzadeh O, Zhang P, Sadoghi M. Large-scale structural and textual similarity-based mining of knowledge graph to predict drug–drug interactions. J Web Semant. 2017;44:104-117.[DOI]

-

31. Han K, Cao P, Wang Y, Xie F, Ma J, Yu M, et al. A review of approaches for predicting drug–drug interactions based on machine learning. Front Pharmacol. 2022;12:814858.[DOI]

-

32. Zhu J, Liu Y, Zhang Y, Li D. Attribute supervised probabilistic dependent matrix tri-factorization model for the prediction of adverse drug-drug interaction. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2021;25(7):2820-2832.[DOI]

-

33. Han G, Peng L, Ding A, Zhang Y, Lin X. CTF-DDI: Constrained tensor factorization for drug–drug interactions prediction. Future Gener Comput Syst. 2024;161:26-34.[DOI]

-

34. Shi JY, Mao KT, Yu H, Yiu SM. Detecting drug communities and predicting comprehensive drug–drug interactions via balance regularized semi-nonnegative matrix factorization. J Cheminform. 2019;11(1):28.[DOI]

-

35. Shtar G, Solomon A, Mazuz E, Rokach L, Shapira B. A simplified similarity-based approach for drug-drug interaction prediction. PLoS One. 2023;18(11):e0293629.[DOI]

-

36. Szmidt E, Kacprzyk J. A similarity measure for intuitionistic fuzzy sets and its application in supporting medical diagnostic reasoning. In: Rutkowski L, Siekmann JH, Tadeusiewicz R, Zadeh LA, editors. Artificial Intelligence and Soft Computing — ICAISC 2004; 2024 Jun 7-11; Poland. Berlin: Springer; 2024. p. 388-393.[DOI]

-

37. Zhang C, Lu Y, Zang T. CNN-DDI: A learning-based method for predicting drug–drug interactions using convolution neural networks. BMC Bioinform. 2022;23(1):88.[DOI]

-

38. Wang W, Liu H. ACNN: Drug-Drug Interaction prediction through CNN and attention mechanism. In: Huang DS, Jo KH, Jing J, Premaratne P, Bevilacqua V, Hussain A, editors. Intelligent Computing Theories and Application; 2022 Aug 7-11; Xi’an, China. Cham: Springer; 2022. p. 278-288.[DOI]

-

39. Liu S, Tang B, Chen Q, Wang X. Drug‐drug interaction extraction via convolutional neural networks. Comput Math Methods Med. 2016;2016(1):6918381.[DOI]

-

40. Sun X, Dong K, Ma L, Sutcliffe R, He F, Chen S, et al. Drug-drug interaction extraction via recurrent hybrid convolutional neural networks with an improved focal loss. Entropy. 2019;21(1):37.[DOI]

-

41. Wang G, Feng H, Cao C. BiRNN-DDI: A drug-drug interaction event type prediction model based on bidirectional recurrent neural network and Graph2Seq representation. J Comput Biol. 2025;32(2):198-211.[DOI]

-

42. Kavuluru R, Rios A, Tran T. Extracting drug-drug interactions with word and character-level recurrent neural networks. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Healthcare Informatics (ICHI); 2017 Aug 23-26; Park City, USA. New York: IEEE; 2017. p. 5-12.[DOI]

-

43. Huang D, Jiang Z, Zou L, Li L. Drug–drug interaction extraction from biomedical literature using support vector machine and long short term memory networks. Inf Sci. 2017;415-416:100-109.[DOI]

-

44. Sahu SK, Anand A. Drug-drug interaction extraction from biomedical texts using long short-term memory network. J Biomed Inform. 2018;86:15-24.[DOI]

-

45. Lin S, Wang Y, Zhang L, Chu Y, Liu Y, Fang Y, et al. MDF-SA-DDI: Predicting drug–drug interaction events based on multi-source drug fusion, multi-source feature fusion and transformer self-attention mechanism. Brief Bioinform. 2022;23(1):bbab421.[DOI]

-

46. Zaikis D, Vlahavas I. TP-DDI: Transformer-based pipeline for the extraction of drug-drug interactions. Artif Intell Med. 2021;119:102153.[DOI]

-

47. Shao Z, Qian Y, Dou L. TBPM-DDIE: Transformer based pretrained method for predicting drug-drug interactions events. In: 2022 IEEE 46th Annual Computers, Software, and Applications Conference (COMPSAC); Los Alamitos, USA; 2022 Jun 27-Jul 1. New York: IEEE; 2022. P. 229-234.[DOI]

-

48. Tamir A, Yuan JS. KITE-DDI: A knowledge graph integrated transformer model for accurately predicting drug-drug interaction events from drug smiles and biomedical knowledge graph. IEEE Access. 2025;13:40028-40043.[DOI]

-

49. Huang K, Xiao C, Glass LM, Zitnik M, Sun J. SkipGNN: Predicting molecular interactions with skip-graph networks, Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):21092.[DOI]

-

50. Han X, Xie R, Li X, Li J. Smilegnn: Drug–drug interaction prediction based on the smiles and graph neural network. Life. 2022;12(2):319.[DOI]

-

51. Liu H, Li S, Yu Z. Predicting drug-drug interactions using heterogeneous graph neural networks: HGNN-DDI. arXiv:2508.18766 [Preprint]. 2025.[DOI]

-

52. Jiang B, Zhang Z, Lin D, Tang J, Luo B. Semi-supervised learning with graph learning-convolutional networks. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15-20; Long Beach, USA. New York: IEEE; 2019. p. 11305-11312.[DOI]

-

53. Zitnik M, Agrawal M, Leskovec J. Modeling polypharmacy side effects with graph convolutional networks. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(13):i457-i466.[DOI]

-

54. Feng YH, Zhang SW, Shi JY. DPDDI: A deep predictor for drug-drug interactions. BMC Bioinform. 2020;21(1):419.[DOI]

-

55. Yin Q, Fan R, Cao X, Liu Q, Jiang R, Zeng W. Deepdrug: A general graph-based deep learning framework for drug-drug interactions and drug-target interactions prediction. Quant Biol. 2023;11(3):260-274.[DOI]

-

56. Jiang Z, Gong Z, Dai X, Zhang H, Ding P, Shen C. PLoS One. 2024;19(6):e0304798.[DOI]

-

57. Veličković P, Cucurull G, Casanova A, Romero A, Lio P, Bengio Y. Graph attention networks. arXiv:1710.10903 [Preprint]. 2017.[DOI]

-

58. Nyamabo AK, Yu H, Shi JY. SSI–DDI: Substructure–substructure interactions for drug–drug interaction prediction. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22(6):bbab133.[DOI]

-

59. Hong Y, Luo P, Jin S, Liu X. Lagat: Link-aware graph attention network for drug–drug interaction prediction. Bioinformatics. 2022;38(24):5406-5412.[DOI]

-

60. Zhang S, Yang Z, Jin S. AI-DDI: An attention-based substructure interactive model for predicting drug-drug interaction. In: Proceedings of the 2025 5th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Intelligent Computing; 2025 Jan 10-12; Shenyang, China. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2025. p. 396-402[DOI]

-

61. Nyamabo AK, Yu H, Liu Z, Shi JY. Drug–drug interaction prediction with learnable size-adaptive molecular substructures. Brief Bioinform. 2021;23(1):bbab441.[DOI]

-

62. Yang Z, Zhong W, Lv Q, Yu-Chian Chen C. Learning size-adaptive molecular substructures for explainable drug–drug interaction prediction by substructure-aware graph neural network. Chem Sci. 2022;13(29):8693-8703.[DOI]

-

63. Zhu J, Che C, Jiang H, Xu J, Yin J, Zhong Z. SSF-DDI: A deep learning method utilizing drug sequence and substructure features for drug–drug interaction prediction. BMC Bioinform. 2024;25(1):39.[DOI]

-

64. Yuan Y, Yue J, Zhang R, Su W. Phgl-ddi: A pre-training based hierarchical graph learning framework for drug-drug interaction prediction. Expert Syst Appl. 2025;270:126408.[DOI]

-

65. Chen Y, Wang J, Zou Q, Niu M, Ding Y, Song J, et al. Drugdagt: A dual-attention graph transformer with contrastive learning improves drug-drug interaction prediction. BMC Biol. 2024;22(1):233.[DOI]

-

66. Su X, Hu P, You Z-H, Yu PS, Hu L. Dual-channel learning framework for drug-drug interaction prediction via relation-aware heterogeneous graph transformer. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2024;38(1):249-256.[DOI]

-

67. Qiao J, Guo X, Jin J, Wang D, Li K, Gao W, et al. Taco-DDI: Accurate prediction of drug-drug interaction events using graph transformer-based architecture and dynamic co-attention matrices. Neural Netw. 2025;189:107655.[DOI]

-

68. Xia X, Zhu C, Zhong F, Liu L. MDTips: A multimodal-data-based drug–target interaction prediction system fusing knowledge, gene expression profile, and structural data. Bioinformatics. 2023;39(7)[DOI]

-

69. Lu X, Xie L, Xu L, Mao R, Xu X, Chang S. Multimodal fused deep learning for drug property prediction: Integrating chemical language and molecular graph. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2024;23:1666-1679.[DOI]

-

70. Wang G, Chen H, Wang H, Gao H, Hu X, Cao C. MMDDI-SSE: A novel multi-modal feature fusion model with static subgraph embedding for drug-drug interaction event prediction. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2025;29(8):6081-6091.[DOI]

-

71. Xie W, Chen X, Huang L, Zheng Z, Wang Y, Zhang R, et al. DDintensity: Addressing imbalanced drug-drug interaction risk levels using pre-trained deep learning model embeddings. Artif Intell Med. 2025;168:103202.[DOI]

-

72. Yu S, Peng W. R-BERT-DDI: Improving drug-drug interaction prediction via relation grounding and knowledge [Preprint]. SSRN. 2025.[DOI]

-

73. Wang K, Fu X, Liu Y, et al. PTDA: Improving drug-drug interaction extraction from biomedical literature based on prompt tuning and data augmentation. IAENG Int J Comput Sci. 2024;51(5):463-476. Available from: https://openurl.ebsco.com/EPDB%3Agcd%3A10%3A12088042

-

74. Li D, Zhao F, Yang Y, Cui Z, Hu P, Hu L. Multi-view contrastive learning for drug-drug interaction event prediction. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2025;1-12.[DOI]

-

75. Zhang Y, Xu X, Feng B, Zheng H, Zhang Ca, Xu W, et al. RCAN-DDI: Relation-aware cross adversarial network for drug-drug interaction prediction. J Pharm Anal. 2025;15(9):101159.[DOI]

-

76. Wang Z, Xiong Z, Huang F, Liu X, Zhang W. ZeroDDI: A zero-shot drug-drug interaction event prediction method with semantic enhanced learning and dual-modal uniform alignment. arXiv:2407.00891 [Preprint]. 2024.[DOI]

-

77. Uddin SH, Maaz MAS, Azeemuddin E, Nath S, Tiwari A, Upreti K. Interpretable drug interaction forecasting: Leveraging graph neural networks with explainable artificial intelligence. In: Virmani D, Castillo O, Balas VE, Elngar A, editors. Proceedings of International Conference on Generative AI, Cryptography and Predictive Analytics. Singapore; Springer; 2025. p. 59-72.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite