Minpeng Xu, Academy of Medical Engineering and Translational Medicine, Medical School of Tianjin University, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China; State Key Laboratory of Advanced Medical Materials and Devices, Tianjin International Joint Research Centre for Neural Engineering, Tianjin 300072, China; Haihe Laboratory of Brain-computer Interaction and Human-machine Integration, Tianjin 300392, China. E-mail: xmp52637@tju.edu.cn

Abstract

Aims: Neural networks capable of capturing temporal dependencies in electroencephalogram (EEG) signals hold considerable potential for seizure prediction by modeling the progressive evolution of preictal EEG changes. However, redundant or less informative temporal features may obscure critical preictal patterns, limiting seizure prediction performance. To address this, we developed a neural architecture that effectively leverages informative temporal features to enhance seizure prediction capability.

Methods: We designed a bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) network enhanced with a channel attention mechanism, termed Attention-BiLSTM, which adaptively emphasizes informative temporal features while reducing information redundancy. We further analyze the model’s attention weights and feature distributions to provide interpretable insights into its decision-making process.

Results: Evaluation on the CHB-MIT scalp EEG dataset demonstrates that Attention-BiLSTM achieves significant performance improvements over the baseline BiLSTM, with an average accuracy of 94.77%, sensitivity of 94.58%, specificity of 94.97%, and an area under the curve of 98.38%. Furthermore, visualization results indicate that the proposed model progressively enhances feature discriminability and directs attention to the most relevant temporal features for seizure prediction.

Conclusion: The proposed Attention-BiLSTM achieves improved performance and interpretability, offering valuable insights to support future development of scalable and generalizable seizure prediction systems.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Epilepsy is a chronic brain disorder caused by abnormal hypersynchronous neuronal discharges[1,2], affecting approximately 50 million people worldwide[3]. Patients with epilepsy face a premature mortality rate that is two to three times higher than that of the general population, imposing a profound burden on individuals, families, and society[4,5]. Therefore, accurate seizure prediction is crucial, enabling timely intervention and helping reduce or prevent seizure-related harm. Electroencephalography (EEG) captures abnormal brain rhythms associated with epilepsy, including spikes, slow waves, sharp waves, spike-slow wave complexes, and sharp-slow wave complexes, etc[6]. EEG-based seizure prediction systems can detect these patterns during the preictal period, enabling timely and accurate seizure forecasting[7-10].

Numerous methods have emerged for EEG-based seizure prediction, broadly falling into traditional machine learning and deep learning categories. Traditional machine learning approaches[11,12] for seizure prediction rely on manually designed features and conventional classifiers such as Bayesian classifiers[13], support vector machines[5], and k-nearest neighbors[14]. In recent years, deep learning approaches have been widely adopted due to their data-driven feature learning capability and improved performance[15-20]. Representative studies include convolutional neural network (CNN)-based frameworks using handcrafted time–frequency or spectral features, such as wavelet packet decomposition with common spatial patterns[18] and topology-based image encoding of spectral and statistical features[19].

Despite these advances, seizure prediction performance using CNNs remains limited, primarily due to their reliance on local convolution operations, which restricts their ability to capture global temporal dependencies in EEG signals[21]. Preictal EEG, however, evolves gradually, exhibiting patterns such as spikes, low-voltage fast discharges (LFD), and high-frequency oscillations (HFOs) that may emerge tens of minutes before seizure onset[22-24]. To capture such long-range temporal dynamics, bidirectional long short-term memory (BiLSTM) networks have been introduced into seizure prediction tasks[25]. Nevertheless, existing BiLSTM-based methods still show suboptimal performance[26,27], partly because redundant or less informative temporal features may obscure critical preictal patterns.

To address these issues, we propose a BiLSTM model enhanced with a channel attention mechanism, termed Attention-BiLSTM. This architecture enables the model to capture global temporal dependencies in preictal EEG while adaptively emphasizing informative temporal features, thereby improving seizure prediction performance. We employ a dense feature transformation at the input stage to provide high-quality EEG representations for effective attention learning. Furthermore, to enhance model interpretability, we analyze the attention weights and feature distribution of the proposed model. Our findings demonstrate that Attention-BiLSTM not only progressively enhances feature discriminability but also directs the attention to the temporal features most relevant to seizure prediction.

2. Methods

2.1 CHB-MIT dataset

We evaluated the proposed model on the CHB-MIT dataset, a widely used and well-established public collection of scalp EEG recordings from Boston Children’s Hospital for seizure prediction[28-30]. The dataset contains recordings from 23 pediatric patients with refractory epilepsy (5 males, 17 females, and one patient with missing gender/age information). The EEG recordings form 24 cases, as case chb21 comes from re-monitoring the same patient from case chb01 after 1.5 years. A Nihon Kohden EEG-1100A system recorded 23 differential electrode voltages at a sampling rate of 256 Hz with 16-bit resolution. Electrodes were placed according to the International 10-20 system. Table 1 provides detailed information on the CHB-MIT dataset.

| Case | No. of seizures | Dur. of preictal (/h) | Dur. of interictal (/h) | Case | No. of seizure | Dur. of preictal (/h) | Dur. of interictal (/h) |

| chb01 | 7 | 3.5 | 17 | chb14 | 5 | 2.5 | 5 |

| chb02 | 3 | 1.5 | 20 | chb15 | 9 | 4.5 | 2 |

| chb03 | 6 | 3 | 22 | chb16 | 5 | 2.5 | 6 |

| chb04 | 3 | 1.5 | 31 | chb17 | 3 | 1.5 | 10 |

| chb05 | 5 | 2.5 | 14 | chb18 | 6 | 3 | 24 |

| chb06 | 9 | 4.5 | 21 | chb19 | 3 | 1.5 | 25 |

| chb07 | 3 | 1.5 | 55 | chb20 | 5 | 2.5 | 20 |

| chb08 | 5 | 2.5 | 3 | chb21 | 4 | 2 | 22 |

| chb09 | 4 | 2 | 40 | chb22 | 2 | 1 | 17 |

| chb10 | 6 | 3 | 26 | chb23 | 5 | 2.5 | 12.5 |

| chb11 | 3 | 1.5 | 31 | Total | 101 | 50.5 | 423.5 |

2.2 Pre-processing

In general, the interictal period is defined as the time interval starting at least 4 hours after the end of the last seizure and ending at least 4 hours before the start of the next seizure[31]. For cases chb12 and chb13, the electrode types, sequences, and numbers, and reference schemes varied multiple times. Therefore, we excluded cases chb12 and chb13 from the analysis. Following the recommendation of Maiwald et al.[32], we set the preictal horizon to 30 minutes to ensure sufficient time for seizure prediction. Within the preictal and interictal periods, EEG signals were segmented into non-overlapping 3-second windows to increase the number of samples[33]. For each patient included in this study, a total of 23 differential electrode voltages were recorded: FP1–F7, F7–T7, T7–P7, P7–O1, FP1–F3, F3–C3, C3–P3, P3–O1, FP2–F4, F4–C4, C4–P4, P4–O2, FP2–F8, F8–T8, T8–P8, P8–O2, FZ–CZ, CZ–PZ, P7–T7, T7–FT9, FT9–FT10, FT10–T8, and T8–P8. As the channel T8–P8 appeared twice, duplicate channels were removed, resulting in 22 channels corresponding to the maximum set of commonly available channels shared across 21 subjects. To suppress power-line interference introduced during EEG acquisition, a notch filter centered at 60 Hz was applied to remove line noise and its harmonics.

2.3 Attention-BiLSTM model

In our data-driven seizure prediction approach, let

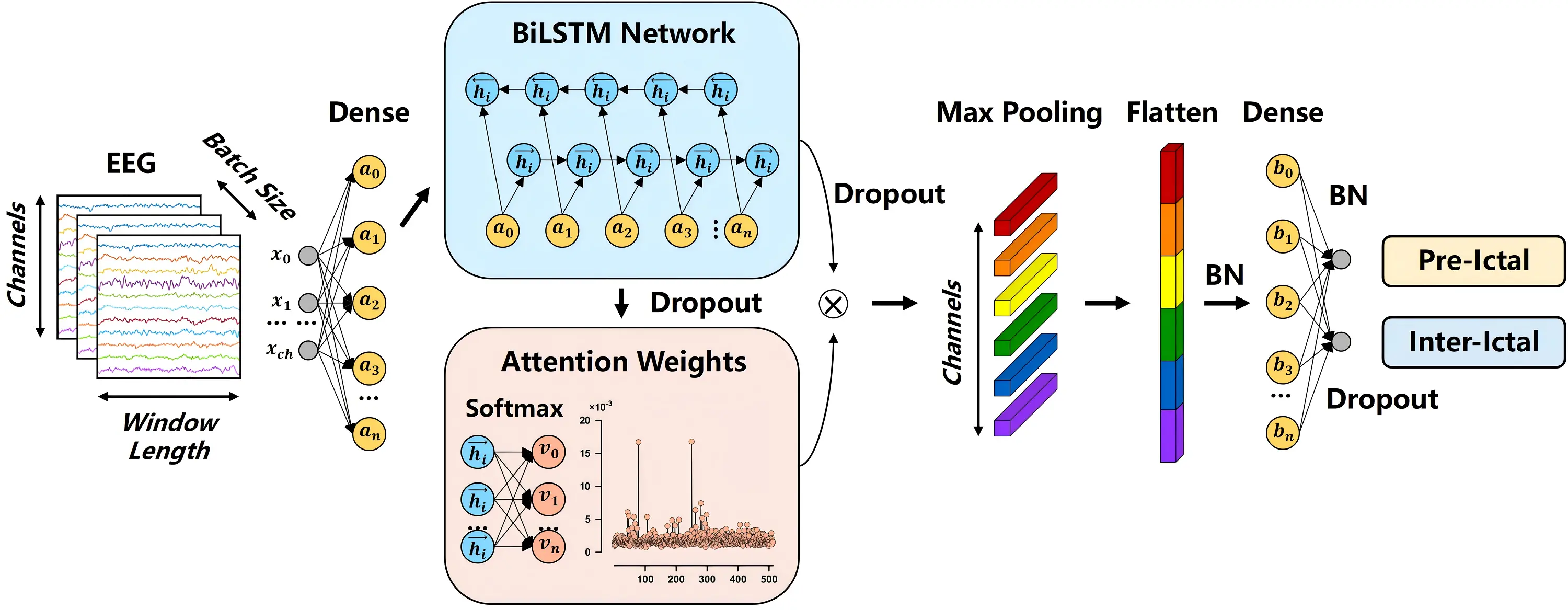

Figure 1. Flow chart of the Attention-BiLSTM architecture. BiLSTM: bidirectional long short-term memory; EEG: electroencephalogram; BN: batch normalization.

2.3.1 BiLSTM

LSTM is a type of recurrent neural network designed to capture long-term dependencies in sequential data and time-series prediction. BiLSTM extends LSTM by processing sequences in both forward and backward directions, enabling it to capture temporal dependencies from both past and future EEG signals, which is particularly important for modeling gradual preictal changes that precede seizures. The BiLSTM module incorporates both forward and backward LSTM layers, each with 256 hidden units. The core component of an LSTM layer is the memory unit, which stores information across time steps via three gating mechanisms: the input gate it, the forget gate ft, and the output gate ot. These gates determine what information to add, retain, or output at each time step. By combining the memory unit with gating mechanisms, LSTM can selectively retain, update, and propagate information over long sequences, enabling effective modeling of long-term temporal dependencies. The gating mechanisms and memory state updates of LSTM can be expressed as follows:

where

2.3.2 Channel attention

The channel attention module enhances the representation of discriminative features by modeling interdependencies among BiLSTM hidden units. It adaptively assigns importance weights to individual feature channels according to their relevance to seizure prediction, thereby emphasizing informative patterns while maintaining parameter efficiency. Unlike generic attention mechanisms that treat all features equally or attend only across time steps, channel attention explicitly models interdependencies among feature channels, allowing the network to weight feature channels according to their relevance for the task. Specifically, the BiLSTM outputs

where

where

Through this process, the channel attention module amplifies feature channels that contribute most to seizure prediction while suppressing less relevant or redundant ones. During training, the attention weights are iteratively refined via backpropagation, enabling the model to dynamically focus on the most discriminative temporal characteristics. As a result, this module complements the BiLSTM by enhancing the extraction of salient temporal features from EEG signals, supporting more effective modeling of both short-term and long-term dependencies essential for accurate seizure prediction.

2.3.3 Attention-BiLSTM

At the beginning of the proposed model, we employ dense preprocessing to provide high-quality EEG representations for subsequent effective attention learning. Then, the Attention-BiLSTM module integrates the refined temporal representations from the BiLSTM layer with the feature-wise emphasis provided by the channel attention mechanism. This integration creates optimized feature representations specifically tailored for seizure prediction. The processing pipeline begins by applying a 1D max-pooling layer to the weighted feature representation, which reduces feature dimensionality while preserving the most salient activations. The pooled features are then flattened into a vector format suitable for subsequent fully connected layers. To stabilize training and accelerate convergence, batch normalization is applied, ensuring more stable feature distributions. A dense layer performs a non-linear transformation and dimensionality reduction, projecting the normalized features into a compact representation space optimized for classification. Finally, the network concludes with an output layer that generates predictions for the two target classes: preictal and interictal states. This integrated architecture enables the model to effectively combine long-range temporal dependencies captured by the BiLSTM with the feature-channel-wise discriminative information emphasized by the attention mechanism. The complete model architecture, including output shapes and parameter settings for each layer, is summarized in Table 2.

| Module | Output shape | Parameters |

| Input | (768, 22) | – |

| Dense 1 | (768, 256) | Hidden units = 256 |

| BiLSTM | (768, 512) | Hidden units = 512 |

| Dropout 1 | (768, 512) | Rate = 0.3 |

| Channel attention | (768, 512) | Self-attention |

| Max-Pooling 1D | (768, 22) | Pool size = 24 |

| Flatten | 16,896 | – |

| Batch Normalization 1 | 16,896 | – |

| Dense 2 | 64 | Hidden units = 64 |

| Dropout 2 | 64 | Rate = 0.3 |

| Batch Normalization 2 | 64 | – |

| Dense 3 | 2 | Hidden units = 2 |

BiLSTM: bidirectional long short-term memory.

2.4 Network training and evaluation

We implemented the proposed approach using the TensorFlow framework with the Keras API. Model training was conducted on a computing system equipped with an Intel Core i5-13600KF CPU and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU. We optimized the model parameters using the Adam optimizer with a cross-entropy loss function. To prevent overfitting, we employed an early stopping strategy and retained the model weights from the epoch with the lowest validation loss for final evaluation. For performance assessment, we evaluated accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC) using subject-specific ten-fold cross-validation. For each subject, the preictal and interictal data were first divided into 10 folds separately and then combined for cross-validation. We report the mean and standard deviation of these metrics across 21 patients. The evaluation metrics were calculated as follows:

where TP, TN, FP, and FN represent true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively. We used paired t-tests to assess the statistical significance of performance differences between compared methods.

3. Results

Table 3 presents the stratified classification performance on the CHB-MIT dataset. Mean represents the average value, and SD represents the standard deviation. We conducted a stratified analysis by dividing patients into high- and low-seizure-frequency groups based on the average number of seizures in the dataset. The results indicate that the high-seizure-frequency group achieves higher average accuracy and sensitivity, whereas the low-seizure-frequency group exhibits relatively higher specificity and AUC, suggesting that seizure frequency influences different aspects of classification performance.

| High-seizure-frequency group | Low-seizure-frequency group | ||||||||

| Case | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC | Case | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC |

| chb01 | 0.9914 | 0.9895 | 0.9933 | 0.9997 | chb02 | 0.9442 | 0.8978 | 0.9906 | 0.9992 |

| chb03 | 0.9792 | 0.9783 | 0.9800 | 0.9979 | chb04 | 0.9600 | 0.9489 | 0.9711 | 0.9914 |

| chb05 | 0.9632 | 0.9623 | 0.9640 | 0.9940 | chb07 | 0.9875 | 0.9878 | 0.9872 | 0.9976 |

| chb06 | 0.7826 | 0.8135 | 0.7517 | 0.8724 | chb09 | 0.9454 | 0.9500 | 0.9408 | 0.9883 |

| chb08 | 0.9915 | 0.9913 | 0.9917 | 0.9993 | chb11 | 0.9484 | 0.9000 | 0.9969 | 0.9999 |

| chb10 | 0.8822 | 0.8989 | 0.8656 | 0.9577 | chb17 | 0.9903 | 0.9878 | 0.9928 | 0.9988 |

| chb14 | 0.9025 | 0.8987 | 0.9063 | 0.9669 | chb19 | 0.9525 | 0.9406 | 0.9644 | 0.9919 |

| chb15 | 0.9931 | 0.9904 | 0.9958 | 0.9988 | chb21 | 0.8842 | 0.9217 | 0.8467 | 0.9540 |

| chb16 | 0.9650 | 0.9653 | 0.9647 | 0.9944 | chb22 | 0.9100 | 0.9217 | 0.8983 | 0.9674 |

| chb18 | 0.9678 | 0.9644 | 0.9711 | 0.9949 | Mean | 0.9469 | 0.9396 | 0.9543 | 0.9876 |

| chb20 | 0.9772 | 0.9723 | 0.9820 | 0.9978 | SD | 0.0336 | 0.0332 | 0.0512 | 0.0161 |

| chb23 | 0.9838 | 0.9797 | 0.9880 | 0.9984 | Non-stratified dataset | ||||

| Mean | 0.9483 | 0.9504 | 0.9462 | 0.9810 | Mean | 0.9477 | 0.9458 | 0.9497 | 0.9838 |

| SD | 0.0629 | 0.0536 | 0.0727 | 0.0369 | SD | 0.0512 | 0.0453 | 0.0630 | 0.0294 |

BiLSTM: bidirectional long short-term memory; AUC: area under the curve; SD: standard deviation.

Across 21 patients, the model achieved an average accuracy of 94.77%, sensitivity of 94.58%, specificity of 94.97%, and AUC of 98.38%. The model exhibited particularly strong performance for patient chb15, reaching 98.31% accuracy, 99.04% sensitivity, 99.58% specificity, and 99.88% AUC. Relatively inferior performance observed in a small number of patients (e.g., chb06, chb10, chb14, and chb21) was not attributed to channel-related factors, as no channel selection was performed and an identical set of EEG channels was used for all patients. Instead, this variability is more likely due to inter-subject differences in seizure characteristics and the discriminability between preictal and interictal EEG patterns.

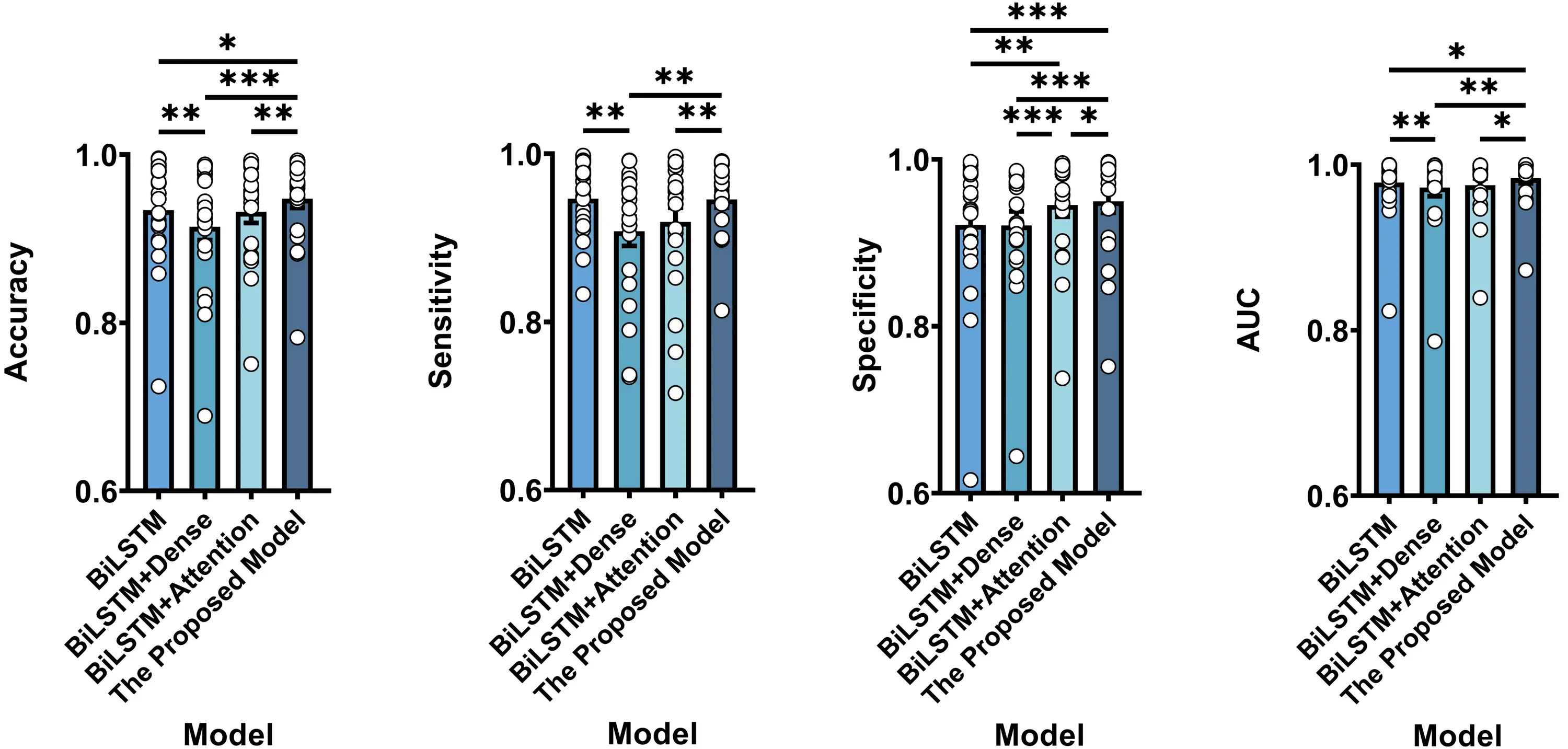

To further assess the effectiveness of the main component, we performed ablation studies involving BiLSTM (without dense1 + channel attention), BiLSTM + Dense (without channel attention), BiLSTM + Attention (without dense1), and the proposed model, as illustrated in Figure 2. Table 4 presents the results under different ablation conditions. Specifically, paired t-tests revealed that the proposed model showed significant enhancements over BiLSTM on accuracy (p = 0.0189 < 0.05), specificity (p = 0.0005 < 0.001), and AUC (p = 0.0152 < 0.05). The proposed model achieved significant improvements over BiLSTM + Dense across all metrics, including accuracy (p = 0.0002 < 0.001), sensitivity (p = 0.0071 < 0.01), specificity (p = 0.0004 < 0.001), and AUC (p = 0.0056 < 0.01). Similarly, the proposed model significantly outperformed BiLSTM + Attention in terms of accuracy (p = 0.0020 < 0.01), sensitivity (p = 0.0063 < 0.01), specificity (p = 0.0268 < 0.05), and AUC (p = 0.0228 < 0.05). Overall, these comparative results demonstrate the effectiveness of the main components in the network design.

Figure 2. Classification performance comparison between BiLSTM, BiLSTM + Dense, BiLSTM + Attention, and the proposed model. Results represent averages across patients. Note that * represents p < 0.05, ** represents p < 0.01, *** represents p < 0.001 according to paired t-tests. Error bars indicate standard errors. BiLSTM: bidirectional long short-term memory.

| Architecture | Accuracy | Sensitivity | Specificity | AUC |

| BiLSTM | 0.9341 ± 0.0137 | 0.9467 ± 0.0096 | 0.9214 ± 0.0191 | 0.9782 ± 0.0085 |

| BiLSTM + Dense | 0.9144 ± 0.0161 | 0.9079 ± 0.0174 | 0.9208 ± 0.0169 | 0.9722 ± 0.0103 |

| BiLSTM + Attention | 0.9321 ± 0.0133 | 0.9189 ± 0.0171 | 0.9453 ± 0.0139 | 0.9752 ± 0.0082 |

| The proposed model | 0.9477 ± 0.0112 | 0.9458 ± 0.0099 | 0.9497 ± 0.0138 | 0.9838 ± 0.0064 |

BiLSTM: bidirectional long short-term memory; AUC: area under the curve.

Table 5 provides a comprehensive comparison between our method and recently published seizure prediction approaches using CNNs on the CHB-MIT dataset[18,19,26,34-36]. While no single method consistently outperforms all others across every metric, our Attention-BiLSTM achieves the highest values in accuracy, specificity, and AUC, demonstrating its competitive advantage in seizure prediction tasks.

| Method | EEGdatasets | Interictal distance | Preictal horizon | Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC (%) |

| CSP + CNN[18] | 23 patients | – | 30 min | 90.00 | 92.00 | – | 90.00 |

| STFT + GAN[34] | 13 patients | 4 h | 35 min | – | – | – | 77.68 |

| CNN + BiLSTM[26] | 7 patients | 2 h | 35 min | 77.60 | 82.70 | 72.40 | – |

| 3D-CNN[19] | 16 patients | 4 h | 60 min | – | 85.71 | – | 88.60 |

| RDANet[35] | 13 patients | 4 h | 30 min | 92.07 | 89.25 | 92.67 | 91.30 |

| ST-MLPs[36] | 18 patients | 4 h | 30 min | – | 96.60 | 86.70 | 93.80 |

| This work | 21 patients | 4 h | 30 min | 94.77 | 94.58 | 94.97 | 98.38 |

CNN: convolutional neural network; EEG: electroencephalogram; AUC: area under the curve; CSP: common spatial pattern; STFT: short-time fourier transform; GAN: generative adversarial network; BiLSTM: bidirectional long short-term memory; RDAnet: dual self-attention residual network; MLPs: multi-layer perceptrons.

3.1 Visualization analysis

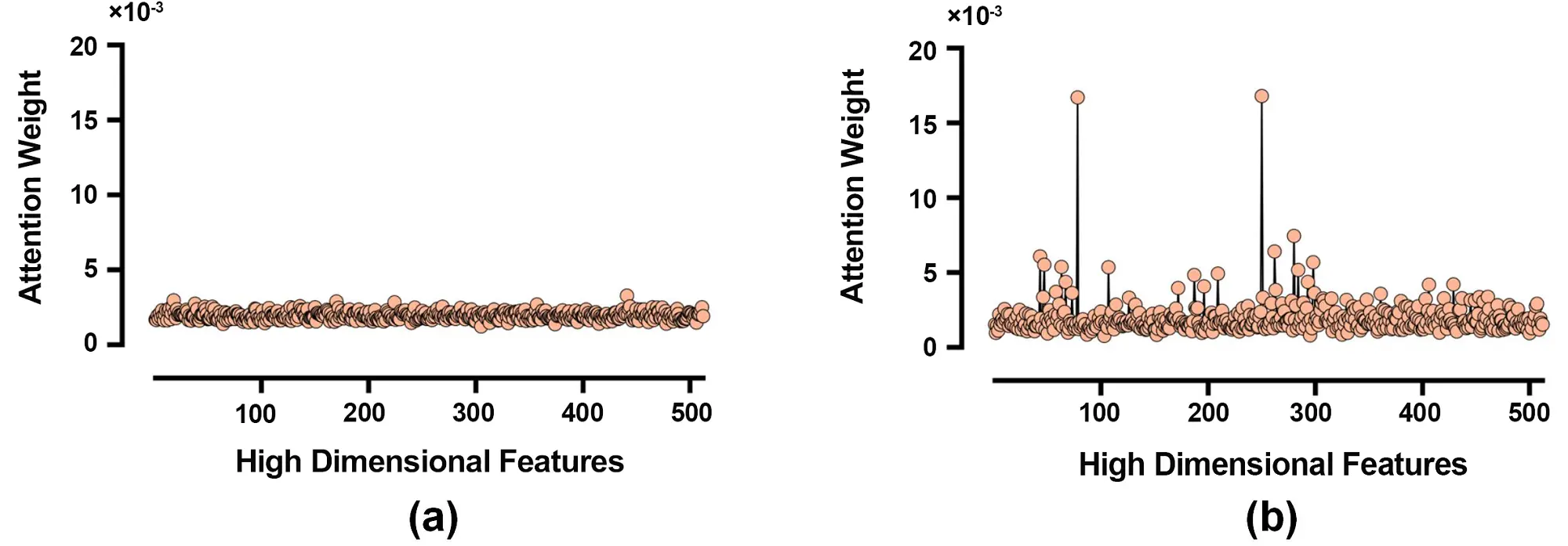

To gain deeper insights into the model’s behavior, we performed visualization analysis focusing on the attention weight distribution learned by the channel attention module. Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of feature selection across 512 hidden units.

Figure 3. Analysis of attention weight distributions. (a) Initial distribution at the beginning of training; (b) Optimized distribution after training.

Figure 3a shows the initial attention weight distribution at the beginning of training, which appears nearly uniform, indicating no inherent preference for specific feature channels. In contrast, Figure 3b displays the optimized attention weight distribution after training, revealing a more heterogeneous pattern where the model selectively emphasizes discriminative feature channels while suppressing less informative ones. This contrast demonstrates the channel attention module’s capability to enhance feature representation for seizure prediction.

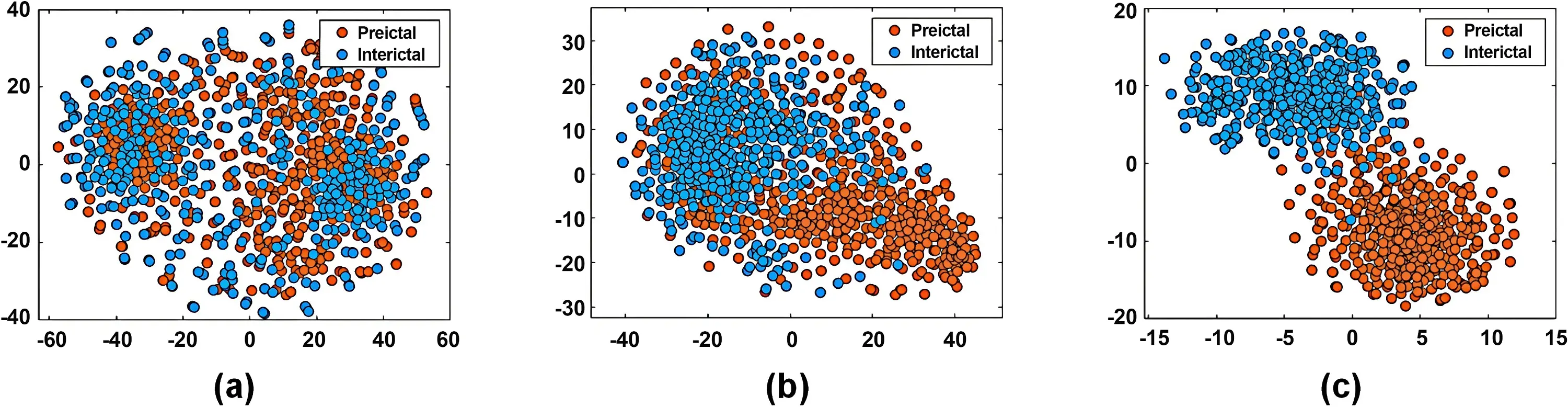

We further employed t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) to visualize the feature distribution learned by different model components, as shown in Figure 4. Each point represents an EEG sample, with orange indicating preictal and blue indicating interictal states. Figure 4a displays the embeddings derived from raw EEG samples, showing substantial overlap between the two classes. Figure 4b presents the feature embeddings learned by the BiLSTM layer, which exhibit more organized clustering with tighter intra-class grouping and increased inter-class separation. Figure 4c shows the embeddings from the complete Attention-BiLSTM, demonstrating further improved separation between preictal and interictal samples, with more compact and distinct clusters. These visualizations collectively illustrate the progressive enhancement in class separability achieved by our approach.

Figure 4. t-SNE visualization of feature embeddings: (a) embeddings derived from raw EEG samples; (b) Embeddings learned by BiLSTM layer; (c) Embeddings learned by Attention-BiLSTM. t-SNE: t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding; EEG: electroencephalogram; BiLSTM: bidirectional long short-term memory.

3.2 Complexity analysis

We further present the parameter count, floating-point operations per second (FLOPs), memory usage, training time, and inference latency of the proposed model, evaluated in Python on a hardware platform equipped with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) Platinum 8352V CPU@2.10 GHz and 24.0 GB RAM. As summarized in Table 6, the proposed model contains 2.47 M parameters. The average training time per batch is 107.2 ms. The inference latency is 39.7 ms per batch and 0.155 ms per sample. The per-sample inference latency is shorter than the duration of the input EEG segment (3 s). In addition, the computational cost of the proposed model is 416.55 M FLOPs. For reference, the classic MobileNet network deployed on mobile devices has 569 M FLOPs[37].

| Models | Parameters (× 106) | FLOPs (× 106) | Memory usage (MB) | Training time (ms) | Inference latency (ms) |

| BiLSTM | 1.72 | 2.3 | 6.56 | 92.81 | 38.95 |

| BiLSTM + Dense | 2.21 | 11.15 | 8.41 | 93.45 | 38.44 |

| BiLSTM + Attention | 1.98 | 407.7 | 7.57 | 105.26 | 38.58 |

| The proposed model | 2.47 | 416.55 | 9.42 | 107.20 | 39.70 |

FLOPs: floating-point operations per second; BiLSTM: bidirectional long short-term memory.

4. Discussion

4.1 Temporal neural mechanism of preictal EEG

Our study introduces a BiLSTM-enhanced architecture designed to capture temporal dependencies in EEG signals, leveraging the progressive dynamics of preictal EEG as biomarkers for seizure prediction. Substantial evidence indicates that EEG network alterations evolve across multiple timescales prior to seizure onset[38,39]. On longer timescales, Medina et al.[38] observed that recurrent, short-lasting (0.6 s) high-connectivity network configurations emerging hours prior to seizures, suggesting that preictal network reorganization may commence well in advance. On shorter timescales closer to onset, both degree and betweenness centrality increase in seizure onset zone channels approximately 37.0 ± 2.8 s before seizure initiation, followed by a rise in degree across all channels about 8.2 ± 2.2 s prior to onset, indicating a gradual intensification of network connectivity[39]. Concurrently, EEG recordings reveal widespread oscillatory alterations[22-24,40-42], most commonly manifesting as LFD. Preceding LFD, EEG changes may include preictal spikes, spike-wave trains, or slow-wave complexes[22]. Additionally, short-duration (< 100 ms) HFOs above 80 Hz have emerged as crucial preictal biomarkers over the past decade[40-42], with certain HFO characteristics evolving within 30 minutes before seizure onset in specific individuals[23,24]. Together, these findings demonstrate that the temporally progressive dynamics of preictal EEG provide rich, multiscale information that can significantly enhance accurate seizure prediction.

4.2 Effectiveness of the channel attention mechanism

Existing seizure prediction studies focusing on temporal dependencies, including Wang et al.[26], Li et al.[43], and Daoud et al.[44], frequently overlook the presence of redundant temporal information within the extracted features. While some models achieve relatively high seizure prediction performance, they often suffer from overfitting and lack interpretability. For instance, Li et al. developed an STS-HGCN-AL model to capture spatio-temporal dynamics across different cortical rhythms, but its reliance on temporal spectral information necessitates a highly complex network architecture that compromises interpretability. To address these limitations, we incorporated a channel attention mechanism that provides targeted improvements in both feature representation and model interpretability. This mechanism adaptively emphasizes informative temporal features through a simple yet efficient architecture, effectively reducing information redundancy. Simultaneously, the explicit attention weights enhance interpretability by quantifying the importance of different temporal components. Our experimental results validate these advantages.

Evaluation on the CHB-MIT dataset demonstrates that Attention-BiLSTM achieves significant improvements over the baseline BiLSTM without channel attention across all metrics: accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and AUC. Analysis of attention weight distributions further reveals that the Attention-BiLSTM adaptively assigns higher weights to discriminative feature channels while suppressing less relevant ones, indicating effective selective feature representation. Corresponding t-SNE visualizations show progressively improved separation between preictal and interictal samples, from raw inputs to BiLSTM features and further to Attention-BiLSTM features. Together, these findings confirm that the channel attention mechanism not only reduces information redundancy and enhances feature discriminability but also provides clearer insights into the model’s decision-making process. The improved separation between preictal and interictal samples could guide dynamic, patient-specific thresholds in real-world seizure prediction systems, providing a basis for early warning decisions. Furthermore, by capturing temporal dependencies in EEG signals, the proposed model also holds potential for extension to other biomedical signal classification tasks relying on time-resolved features, such as Alzheimer’s disease detection[45,46], driver fatigue evaluation[47], sleep stage detection[48], mental state classification[49], and heart disease monitoring[50,51].

4.3 Limitations and future directions

Although the proposed seizure predictor achieves a promising forecasting performance, two limitations still remain in the current work. First, classification performance in this study may be overestimated due to temporal autocorrelation. Second, preictal EEG patterns are highly patient-specific, influenced by factors such as epileptogenic zone location, seizure types, and disease severity, the proposed subject-specific approach may overfit to individual patients and struggle to capture these heterogeneous preictal signatures, which makes it not directly applicable to cross-subject scenarios. To address these limitations, future work will focus on developing cross-subject adaptive or domain-generalizable frameworks, incorporating personalized feature adaptation or meta-learning strategies, evaluating the approach on larger and more diverse datasets, and investigating the effects of different signal-level normalization strategies (e.g., z-score, min–max, per-channel versus global) on model performance. These efforts aim to better capture patient-specific preictal patterns and heterogeneous preictal signatures, ultimately improving the practical applicability of seizure prediction systems.

5. Conclusion

This study proposes a BiLSTM architecture enhanced with a channel attention mechanism for seizure prediction. The proposed architecture adaptively captures key temporal features in preictal EEG signals while effectively suppressing redundant information. Comprehensive evaluation on the CHB-MIT dataset demonstrated that Attention-BiLSTM outperforms the baseline BiLSTM without channel attention, achieving an average accuracy of 94.77%, sensitivity of 94.58%, specificity of 94.97%, and an AUC of 98.38%. Beyond these quantitative improvements, an analysis of attention weights and feature distributions confirms that the model successfully directs computational focus toward the most relevant temporal features while progressively enhancing feature discriminability. These findings provide valuable insights to support the future development of scalable and generalizable seizure prediction systems.

Authors contribution

Yu H: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing-original draft, funding acquisition.

Shan B: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing-original draft.

Shi Q: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft.

Meng J, Yi W, Huang Y, He F, Jung TP: Formal analysis, writing-review & editing.

Xu M, Ming D: Conceptualization, investigation, writing-review & editing, supervision, funding acquisition.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data could be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant No. 2023YFF1203700, the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 62406220, No. 62576242, No. 82330064, China Postdoctoral Science Foundation under Grant No. 2023M742604, and Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF under Grant No. GZC20231916.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Fisher RS, Acevedo C, Arzimanoglou A, Bogacz A, Cross JH, Elger CE, et al. ILAE official report: A practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55(4):475-482.[DOI]

-

2. Rakhade SN, Jensen FE. Epileptogenesis in the immature brain: emerging mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(7):380-391.[DOI]

-

3. Singh G, Sander JW. The global burden of epilepsy report: Implications for low- and middle-income countries. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;105:106949.[DOI]

-

4. Iasemidis LD, Shiau DS, Chaovalitwongse W, Sackellares JC, Pardalos PM, Principe JC, et al. Adaptive epileptic seizure prediction system. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2003;50(5):616-627.[DOI]

-

5. Park Y, Luo L, Parhi KK, Netoff T. Seizure prediction with spectral power of EEG using cost-sensitive support vector machines. Epilepsia. 2011;52(10):1761-1770.[DOI]

-

6. Jaseja H, Jaseja B. EEG spike versus EEG sharp wave: Differential clinical significance in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;25(1):137.[DOI]

-

7. Affes A, Mdhaffar A, Triki C, Jmaiel M, Freisleben , B . Personalized attention-based EEG channel selection for epileptic seizure prediction. Expert Syst Appl. 2022;206:117733.[DOI]

-

8. Horvath AA, Csernus EA, Lality S, Kaminski RM, Kamondi A. Inhibiting epileptiform activity in cognitive disorders: Possibilities for a novel therapeutic approach. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:557416.[DOI]

-

9. Zurdo-Tabernero M, Canal-Alonso Á, de la Prieta F, Rodríguez S, Prieto J, Corchado JM. An overview of machine learning and deep learning techniques for predicting epileptic seizures. J Integr Bioinform. 2023;20(4):20230002.[DOI]

-

10. Wang Y, Shi Y, Cheng Y, He Z, Wei X, Chen Z, et al. A spatiotemporal graph attention network based on synchronization for epileptic seizure prediction. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2023;27(2):900-911.[DOI]

-

11. Firpi H, Goodman E, Echauz J. On prediction of epileptic seizures by means of genetic programming artificial features. Ann Biomed Eng. 2006;34(3):515-529.[DOI]

-

12. Shahidi Zandi A, Tafreshi R, Javidan M, Dumont GA. Predicting epileptic seizures in scalp EEG based on a variational Bayesian Gaussian mixture model of zero-crossing intervals. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2013;60(5):1401-1413.[DOI]

-

13. Behnam M, Pourghassem H. Real-time seizure prediction using RLS filtering and interpolated histogram feature based on hybrid optimization algorithm of Bayesian classifier and Hunting search. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2016;132:115-136.[DOI]

-

14. Hasan MK, Ahamed MA, Ahmad M, Rashid MA. Prediction of epileptic seizure by analysing time series EEG signal using k-NN classifier. Appl Bionics Biomech. 2017;2017(1):6848014.[DOI]

-

15. Usman SM, Khalid S, Aslam MH. Epileptic seizures prediction using deep learning techniques. IEEE Access. 2020;8:39998-40007.[DOI]

-

16. Wu D, Shi Y, Wang Z, Yang J, Sawan M. C2SP-Net: Joint compression and classification network for epilepsy seizure prediction. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2023;31:841-850.[DOI]

-

17. Ji H, Xu T, Xue T, Xu T, Yan Z, Liu Y, et al. An effective fusion model for seizure prediction: GAMRNN. Front Neurosci. 2023;17:1246995.[DOI]

-

18. Zhang Y, Guo Y, Yang P, Chen W, Lo B. Epilepsy seizure prediction on EEG using common spatial pattern and convolutional neural network. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2020;24(2):465-474.[DOI]

-

19. Ozcan AR, Erturk S. Seizure prediction in scalp EEG using 3D convolutional neural networks with an image-based approach. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2019;27(11):2284-2293.[DOI]

-

20. Ahmad I, Zhu M, Liu Z, Shabaz M, Ullah I, Tong MCF, et al. Multi-feature fusion-based convolutional neural networks for EEG epileptic seizure prediction in Consumer Internet of Things. IEEE Trans Consum Electron. 2024;70(3):5631-5643.[DOI]

-

21. Ma X, Chen W, Pei Z, Zhang Y, Chen J. Attention-based convolutional neural network with multi-modal temporal information fusion for motor imagery EEG decoding. Comput Biol Med. 2024;175:108504.[DOI]

-

22. Lagarde S, Bonini F, McGonigal A, Chauvel P, Gavaret M, Scavarda D, et al. Seizure-onset patterns in focal cortical dysplasia and neurodevelopmental tumors: Relationship with surgical prognosis and neuropathologic subtypes. Epilepsia. 2016;57(9):1426-1435.[DOI]

-

23. Jacobs J, Zelmann R, Jirsch J, Chander R, Dubeau CÉCF, Gotman J. High frequency oscillations (80–500 Hz) in the preictal period in patients with focal seizures. Epilepsia. 2009;50(7):1780-1792.[DOI]

-

24. Pearce A, Wulsin D, Blanco JA, Krieger A, Litt B, Stacey WC. Temporal changes of neocortical high-frequency oscillations in epilepsy. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110(5):1167-1179.[DOI]

-

25. Tsiouris ΚΜ, Pezoulas VC, Zervakis M, Konitsiotis S, Koutsouris DD, Fotiadis DI. A long short-term memory deep learning network for the prediction of epileptic seizures using EEG signals. Comput Biol Med. 2018;99:24-37.[DOI]

-

26. Wang Z, Yang J, Wu H, Zhu J, Sawan M. Power efficient refined seizure prediction algorithm based on an enhanced benchmarking. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):23498.[DOI]

-

27. Yan K, Shang J, Wang J, Xu J, Yuan S. Seizure prediction based on hybrid deep learning model using scalp electroencephalogram. In: Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Computing Technology and Applications(ICIC); 2023 Aug 10-13; Zhengzhou, China. Singapore: Springer; 2023. p. 272-282.[DOI]

-

28. Thuwajit P, Rangpong P, Sawangjai P, Autthasan P, Chaisaen R, Banluesombatkul N, et al, EEGWaveNet: Multiscale CNN-based spatiotemporal feature extraction for EEG seizure detection. IEEE Trans Ind Informat. 2022;18(8):5547-5557.[DOI]

-

29. Zeng D, Huang K, Xu C, Shen H, Chen Z. Hierarchy graph convolution network and tree classification for epileptic detection on electroencephalography signals. IEEE Trans Cogn Dev Syst. 2020;13(4):955-968.[DOI]

-

30. Dissanayake T, Fernando T, Denman S, Sridharan S, Fookes C. Geometric deep learning for subject independent epileptic seizure prediction using scalp EEG signals. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2022;26(2):527-538.[DOI]

-

31. Truong ND, Nguyen AD, Kuhlmann L, Bonyadi MR, Yang J, Ippolito S, et al. Convolutional neural networks for seizure prediction using intracranial and scalp electroencephalogram. Neural Netw. 2018;105:104-111.[DOI]

-

32. Maiwald T, Winterhalder M, Aschenbrenner-Scheibe R, Voss HU, Schulze-Bonhage A, Timmer J. Comparison of three nonlinear seizure prediction methods by means of the seizure prediction characteristic. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenom. 2004;194:357-368.[DOI]

-

33. Aghababaei MH, Azemi G, O’Toole JM. Detection of epileptic seizures from compressively sensed EEG signals for wireless body area networks. Expert Syst Appl. 2021;172:114630.[DOI]

-

34. Truong ND, Kuhlmann L, Bonyadi MR, Querlioz D, Zhou L, Kavehei O. Epileptic seizure forecasting with generative adversarial networks. IEEE Access. 2019;7:143999-144009.[DOI]

-

35. Yang X, Zhao J, Sun Q, Lu J, Ma X. An effective dual self-attention residual network for seizure prediction. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng. 2021;29:1604-1613.[DOI]

-

36. Li C, Shao C, Song R, Xu G, Liu X, Qian R, et al. Spatio-temporal MLP network for seizure prediction using EEG signals. Measurement. 2023;206:112278.[DOI]

-

37. Howard AG, Zhu M, Chen B, Kalenichenko D, Wang W, Weyand T, et al. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv:1704.04861v1 [Preprint]. 2017.[DOI]

-

38. Medina N, Vila-Vidal M, Tost A, Khawaja M, Carreño M, Roldán P, et al. Preictal high-connectivity states in epilepsy: evidence of intracranial EEG, interplay with the seizure onset zone and network modeling. J Neural Eng. 2025;22(4):046035.[DOI]

-

39. Sumsky S, Greenfield Jr LJ. Network analysis of preictal iEEG reveals changes in network structure preceding seizure onset. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):12526.[DOI]

-

40. Frauscher B, Bartolomei F, Kobayashi K, Cimbalnik J, van’t Klooster MA, Rampp S, et al. High-frequency oscillations: The state of clinical research. Epilepsia. 2017;58(8):1316-1329.[DOI]

-

41. Jacobs J, Zijlmans M. HFO to measure seizure propensity and improve prognostication in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Curr. 2020;20(6):338-347.[DOI]

-

42. Scott JM, Gliske SV, Kuhlmann L, Stacey WC. Viability of preictal high-frequency oscillation rates as a biomarker for seizure prediction. Front Hum Neurosci. 2021;14:612899.[DOI]

-

43. Li Y, Liu Y, Guo YZ, Liao XF, Hu B, Yu T. Spatio-temporal-spectral hierarchical graph convolutional network with semisupervised active learning for patient-specific seizure prediction. IEEE Trans Cybern. 2022;52(11):12189-12204.[DOI]

-

44. Daoud H, Bayoumi MA. Efficient epileptic seizure prediction based on deep learning. IEEE Trans Biomed Circuits Syst. 2019;13(5):804-813.[DOI]

-

45. Shan X, Cao J, Huo S, Chen L, Sarrigiannis PG, Zhao Y. Spatial-temporal graph convolutional network for Alzheimer classification based on brain functional connectivity imaging of electroencephalogram. Hum Brain Mapp. 2022;43(17):5194-5209.[DOI]

-

46. Tufail AB, Ullah I, Rehman AU, Khan RA, Khan MA, Ma YK, et al. On disharmony in batch normalization and dropout methods for early categorization of Alzheimer’s disease. Sustainability. 2022;14(22):14695.[DOI]

-

47. Gao Z, Wang X, Yang Y, Mu C, Cai Q, Dang W, et al. EEG-based spatio-temporal convolutional neural network for driver fatigue evaluation. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst. 2019;30(9):2755-2763.[DOI]

-

48. Cheng YH, Lech M, Wilkinson RH. Simultaneous sleep stage and sleep disorder detection from multimodal sensors using deep learning. Sensors. 2023;23(7):3468.[DOI]

-

49. Rahman AU, Ali S, Wason R, Aggarwal S, Abohashrh M, Daradkeh YI, et al. Emotion-based mental state classification using EEG for brain-computer interface applications. Comput Intell. 2025;41(4):e70112.[DOI]

-

50. Devarajan MV, Yallamelli ARG, Yalla RKMK, Mamidala V, Ganesan T, Sambas A. An enhanced IOMT and blockchain-based heart disease monitoring system using BS-THA and OA-CNN. Trans Emerg Telecommun Technol. 2025;36(2):e70055.[DOI]

-

51. Ahmed MJ, Afridi U, Shah HA, Khan H, Bhatt MW, Alwabli A, et al. CardioGuard: AI-driven ECG authentication hybrid neural network for predictive health monitoring in telehealth systems. Slas Technol. 2024;29(5):100193.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite