Abstract

Aims: Medical image translation is widely used for data augmentation and cross-domain adaptation in clinical image analysis. However, the nature of medical imaging makes it challenging to collect high-quality samples for the training of translation models. Because of the limited access to and costly expense of medical images, distribution bias is commonly observed between the source and target samples, and this finally leads the models to mismatch the target domain.

Methods: To promote medical image translation, a bias correction method, named content adaptation, has been proposed in this study to align the training samples in the data space. Based on the invariant medical topological structure, paired samples are constructed from weakly paired and unpaired data using content adaptation to correct the distribution bias and promote the image-to-image translation.

Results: Experiments on retinal fundus image translation and COVID-19 CT synthesis demonstrate that the proposed method effectively suppresses structural hallucination and improves both visual quality and quantitative performance. Consistent gains are observed across multiple backbone models under different supervision settings. The results suggest that explicit anatomical alignment provides an effective and model-agnostic way to mitigate distribution bias in medical image translation. By bridging weakly paired data with paired translation paradigms, the proposed approach enhances structural fidelity without requiring strong supervision.

Conclusion: This work presents a topology-guided content adaptation strategy that improves robustness and reduces hallucination in medical image translation. The proposed framework is general and can be readily integrated into existing translation models, offering a practical solution for data-scarce medical imaging scenarios.

Keywords

1. Introduction

The goal of image-to-image translation is to learn the mapping from a given image to a specific target image. Learning the mapping from one visual representation to another entails a deep understanding of the underlying features[1]. With the advent of generative adversarial networks (GANs), generative tasks have gained a lot of attention in the computer vision community[2-4]. Thanks to their capability of data generation without explicitly modeling the probability density function, GANs and their extensions have carved out new ways to bridge the gap between supervised learning and image generation. The adversarial loss provided by the discriminator breaks an unprecedented path for incorporating unlabeled samples into training and imposing higher-order consistency. The

Many tasks involving computer vision and computer graphics can be transferred to the image-to-image translation problems, which learn to map one visual representation of a given image to another representation in the target domain[9-11]. Conditional GANs are used as the protocol in image-to-image translation[12]. A given image from the source domain is treated as a conditional input to control the generation of images belonging to the target domain. The underlying features that are shared between these domains are identified as domain-independent or domain-specific. Then the domain-independent features are preserved during translation, while the domain-specific features are transformed[1]. These properties of image-to-image translation attracted researchers to import it to the medical imaging community.

Due to its general applicability, image-to-image translation is very popular in medical scenarios[13,14]. Considering noise reduction as translating an image with noise to one with reduced noise, novel solutions for medical image enhancement were presented using image-to-image translation[15-18]. To aid the diagnosis and treatment of brain tumors, the cross-modality synthesis between MR and CT data was proposed based on the image-to-image translation models[19-21]. As an addition to the manual labeling from radiologists, medical images were synthesized according to the segmentation mask by image-to-image translation[22-24]. Despite the promising potential, image-to-image translation encounters challenges in medical scenarios.

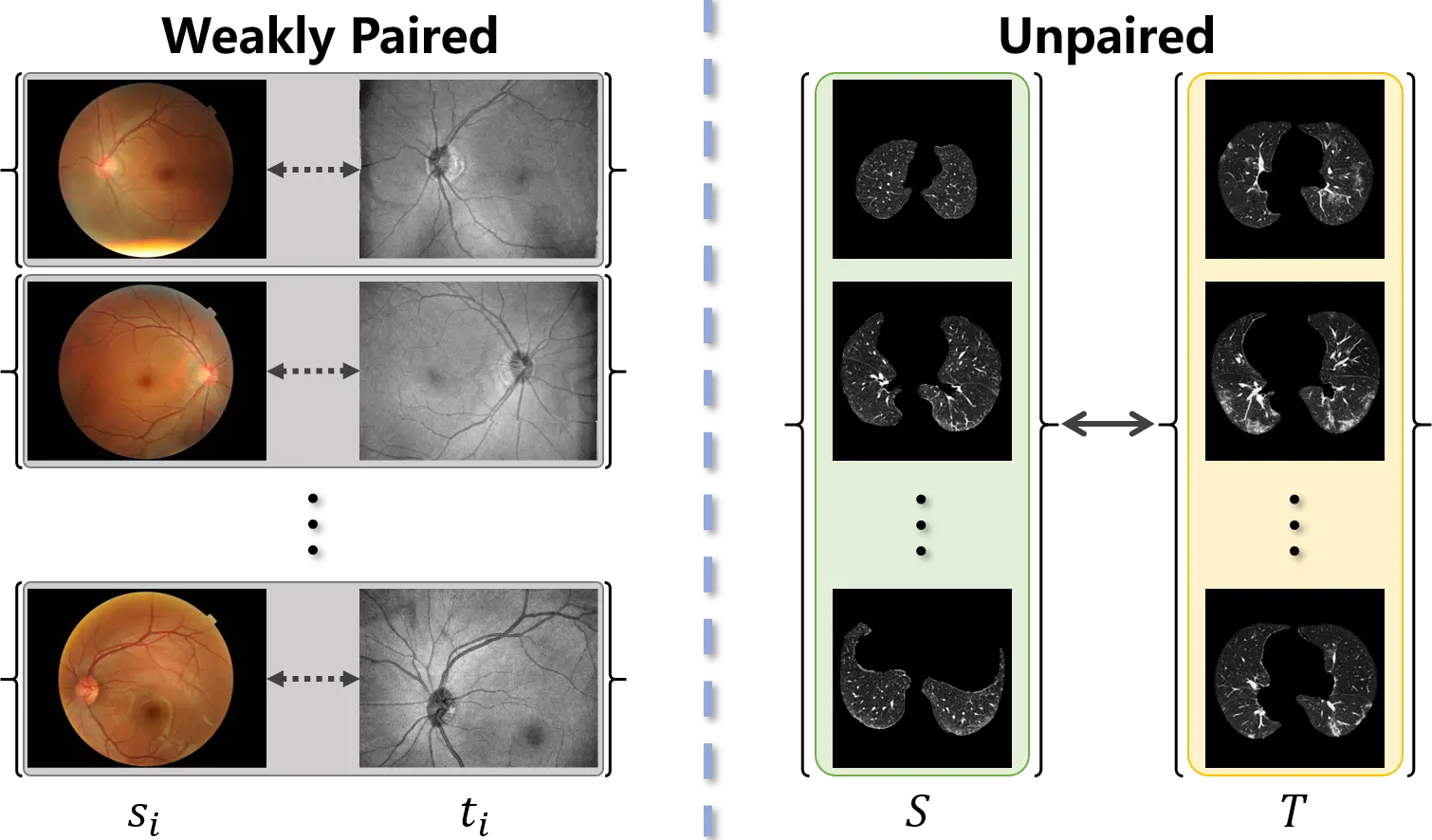

The acquisition of training data for image-to-image translation is a formidable task in medical scenarios. Most of the applications based on image-to-image translation follow one of two fundamental frameworks, namely pix2pix[5] and CycleGAN[6], depending on whether the training data are paired or unpaired. As pix2pix is trained under supervision, paired input-output samples are necessary for its implementation. However, such a training set is hard to obtain in practice. Many factors, such as divergence between individuals, changes with time, and differences in imaging mechanisms, will lead to misalignment of the images. Consequently, as shown in Figure 1, weakly paired data (pairwise captured and sharing an overlapping field of view) and unpaired data (independently collected) are more common in medical images. To mitigate the limitation of image-to-image translation and make full use of available data, CycleGAN was proposed to translate an image from a source domain to a target domain in the absence of paired examples. Although weakly paired and unpaired data have been successfully utilized to perform image-to-image translation, the distribution bias between the source and target samples has not been overcome.

Figure 1. Weakly paired dataset (left) consists of training examples

Current research using image-to-image translation often operate on data whose modes of distribution are well-matched. Once the data distributions are not well-matched, the translation models do not work well[25]. This mode imbalance confuses the identification of domain-independent and domain-specific features and results in a mismatch of semantics between source samples and generated samples in the target distribution. Furthermore, due to legal concerns regarding patient privacy, the labor-intensive annotation process, and the rare nature of some pathologies, the chronic scarcity of high-quality annotated data is an essential problem in the medical imaging community[14]. The mode of medical datasets is thus prone to imbalance. Finally, the training of translation models is hindered by the bias between the data distribution and the sampling distribution, which is caused by the mode imbalance[26]. Cohen et al.[27] empirically demonstrated the argument that the composition of the source and target domains can bias the medical image translation to fall into an unwanted feature hallucination. In contrast, our method explicitly corrects this bias by constructing paired samples through content matching and adaptive sampling, improving robustness under mode imbalance.

In this paper, we aim to align the distributions of the source and target samples such that the modes of medical data are

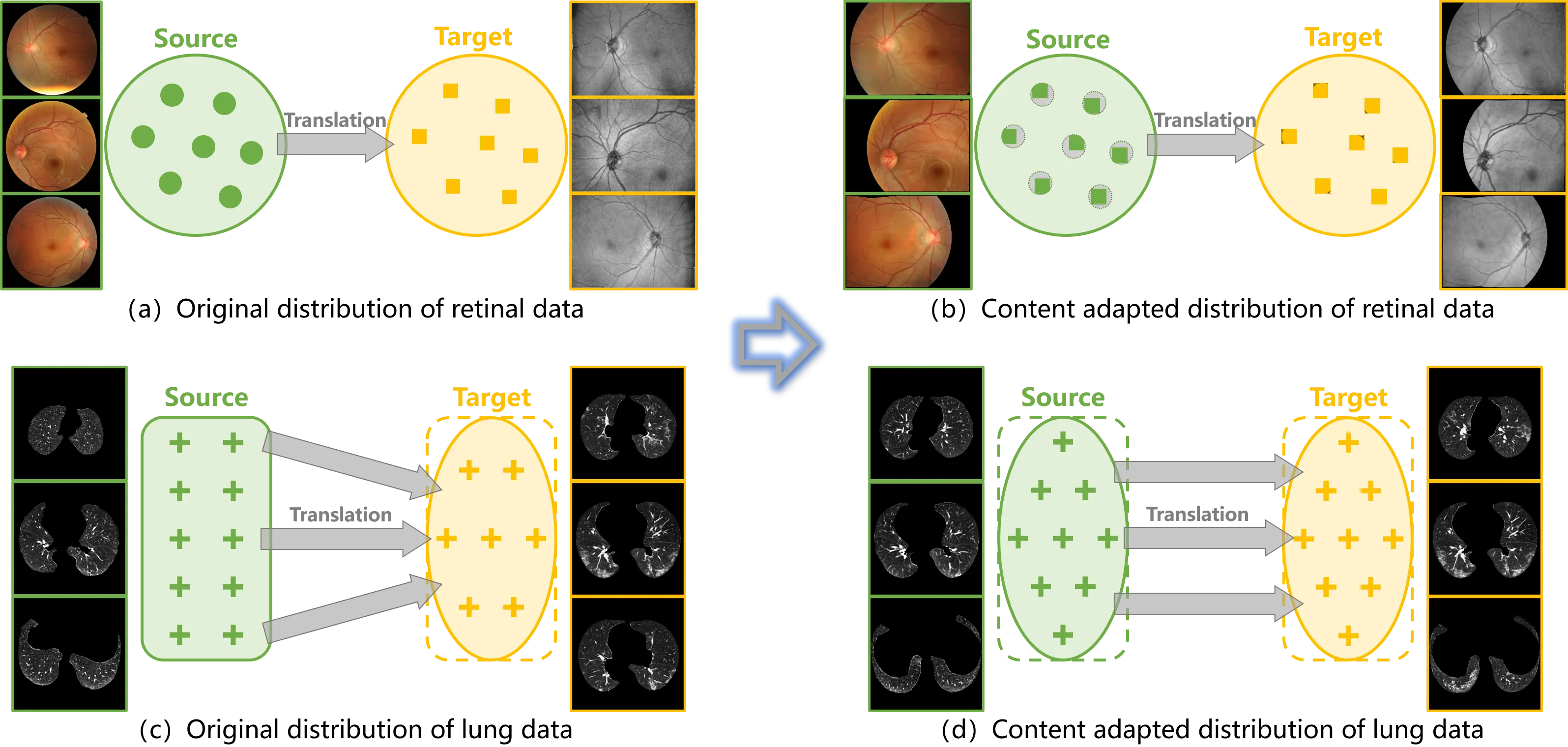

Figure 2. (a) (c) Distribution bias is embedded in the original data and misleads the training of translation models; (b) (d) Content adaptation corrects the distribution bias between the source and target samples, such that the translation models are properly trained.

Inspired by the algorithm of atlas-based segmentation, a straightforward method, named content adaptation, is proposed to correct the distribution bias between the source and target samples (Figure 2b,d). The invariance of topological structure in medical datasets is leveraged to match the source and target samples. Unbiased training samples are hence provided to image-to-image translation in medical scenarios. The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows.

(1) To circumvent the limitation of image-to-image translation in medical scenarios, a content adaptation method has been proposed to correct the distribution bias in medical translation samples.

(2) Content adaptation matches the samples from the source and target domains based on the invariance of topological structure in medical images and collects samples with the balanced distributions using adaptive sampling.

(3) As the sampling distribution is aligned in data space and paired samples are acquired from the weakly paired and unpaired data, content adaptation not only offers balanced training samples for image-to-image translation, but also enables the implementation of the paired translation framework.

(4) The medical applications of cross-modality translation and pathological image synthesis are implemented in the experiment using the retinal data of color fundus photography and En-face OCT, as well as the CT data of lung. Remarkable progress has been achieved by content adaptation, as the quality of the synthesized images has been significantly improved.

The remaining sections of the paper are organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the proposed content adaptation to align the distributions of the source and target samples. Its cooperation with the frameworks of image-to-image translation is described as well. Experimental results are given in Section 3 to demonstrate the effectiveness of content adaptation to promote the proper construction of translation mapping. The last section concludes the paper.

2. Methods

The distribution bias in the training samples misleads the image-to-image translation models and results in a mismatch of semantics between source samples and generated samples of the target distribution. To promote image-to-image translation in medical scenarios, content adaptation is proposed to correct the distribution bias between the source and target samples. Inspired by the algorithm of atlas-based segmentation, the invariance of topological structure in medical images is leveraged in content adaptation to match the source and target samples. The distribution bias is thus constrained during the training of the image-to-image translation models.

2.1 Content adaptation

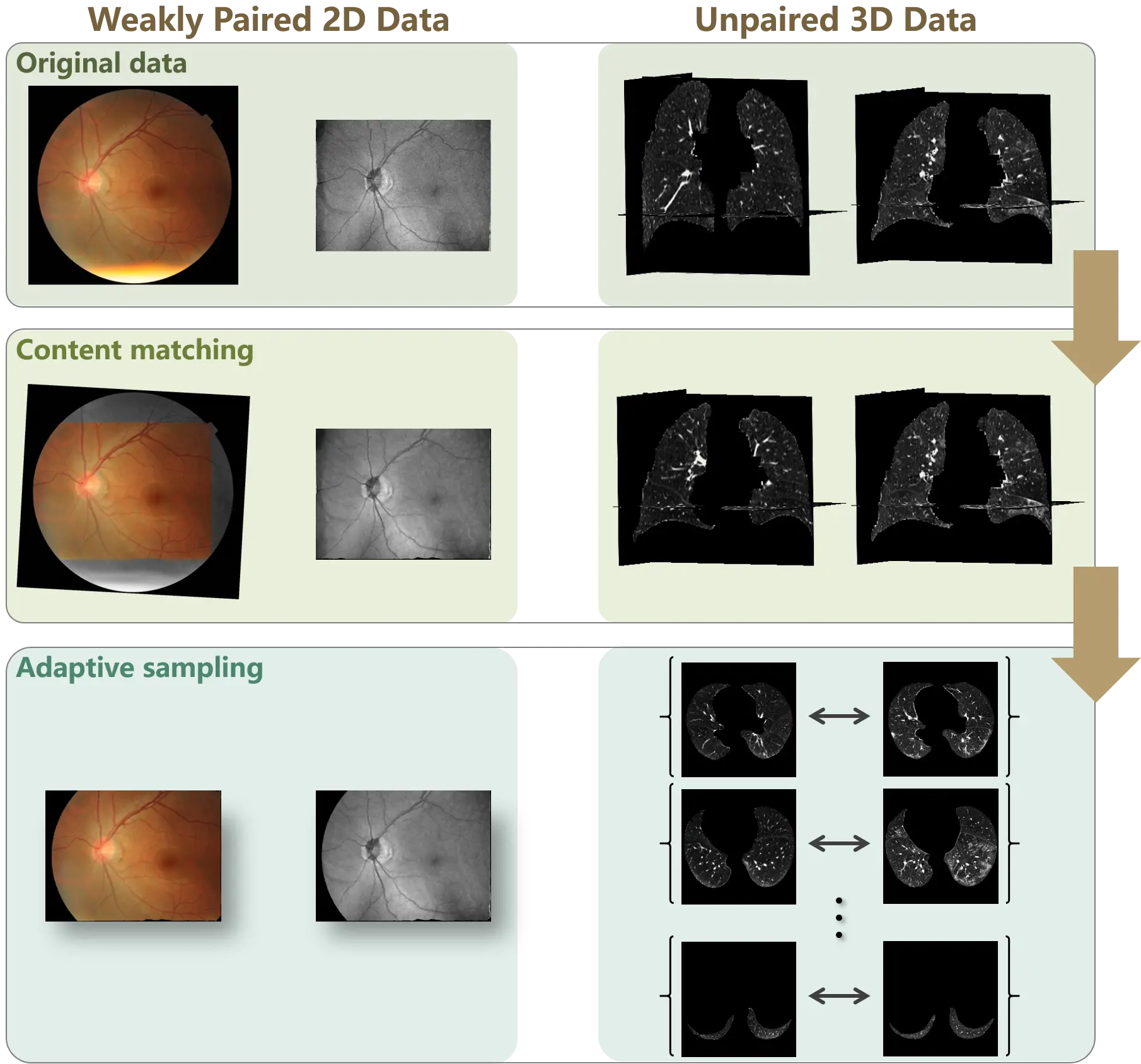

The proposed content adaptation constructs paired samples from unpaired (weakly paired) data to correct the distribution bias. As illustrated in Figure 3, the proposed method consists of two stages: content matching and adaptive sampling.

Figure 3. Workflow of content adaptation on weakly paired and unpaired data. Content adaptation consists of content matching and adaptive sampling. The content matching registers the source and target samples to align the data spaces, and the adaptive sampling corrects the distribution bias by symmetrically collects samples from the aligned data spaces.

2.1.1 Content matching

The distribution bias in medical images derives from the content variation between the source and target samples. Following the routine of atlas-based algorithms, we develop a scheme to match the source and target samples and construct paired samples. The assumption underlying atlas-based segmentation is that a certain level of coarse anatomical topology of non-pathological organs or tissue remains invariant among subjects. Based on this assumption, image registration aligns the global anatomical structures into a common space, thereby preserving the underlying topological relationships while allowing local pathological or intensity variations.

For obtaining accurate and plausible results in medical segmentation, atlas-based algorithms provide a paradigm to tackle the variability in the medical images by incorporating prior anatomical knowledge. Compared with other segmentation methods,

An atlas comprises of a reference image and the corresponding segmentation labels. The spatial relationships between segmentation labels and anatomical structures are established using the mapping from the reference image in the atlas to the input image to be segmented. Therefore, the atlas-based segmentation is decomposed into image registration and label propagation.

Denote the input image as αI(θ), where θ ∈ Rd represents a point in the coordinates and d is the dimension of the image space. The reference image and the segmentation labels in the atlas are defined as βI(θ) and βL(θ). During image registration, the transformation that maps βI(θ) to αI(θ) is computed to encode the relationships between anatomical structures. The transformation

Subsequently, the final segmentation is achieved by the label propagation, which assigns the segmentation labels to each point in the input image. Once the transformation

Following atlas-based algorithms, content matching is accomplished by modeling the spatial relationship between the source and target samples. For the image-to-image translation, denote the image sample in the source domain as sI(θ) and the sample in the target domain as tI(θ). The registered images are given by as follows:

where

Using the above pipeline, the spatial relationships between the source and target samples are established (shown in Figure 3). Thus, two image pairs are respectively constructed by sI(θ) and tP, as well as tI(θ) and sP. To simplify the manuscript, we only use the first pair as an instance in the following part.

2.1.2 Adaptive sampling

Content matching aligns the global structure between the source and target samples. Then, adaptive sampling is conducted to collect paired samples without distribution bias.

For medical image data, the translation models can be directly applied to 2D image data, while the 3D image data are commonly decomposed into 2D scans for the translation. Therefore, 2D and 3D medical image data are respectively processed in adaptive sampling.

For weakly paired 2D data, each individual sample obeys the characteristic of the corresponding domain. Therefore, after aligning the global structure using content matching, adaptive sampling is implemented by straightforwardly capturing the overlapping field of the source and target samples to construct paired samples.

If θ ∈ R2, the constructed paired samples are defined as:

where V(·) denotes the field of view,

For unpaired 3D data, the scans in a case may not obey the characteristic of the case domain. For instance, in the CT or MR data of tumor patients, tumor tissue only exists in a portion of scans[19]. Consequently, the pathological data is composed of the scans containing tumor tissue, and the scans without tumor are discarded.

To adaptively sample the scans of 3D data, the overlapping field of the aligned 3D images is extracted. If θ ∈ R3, the paired 3D data

Subsequently, the paired samples

Where j denotes the index of scans. DS and DT represent the domains of source and target.

Through content matching and adaptive sampling, paired samples are constructed from the weakly paired and unpaired data. Content adaptation corrects the distribution bias in the original data, since aligned distributions are provided in the paired samples. As demonstrated in Figure 2b, the distribution bias in the image space of the weakly paired 2D data and the scan sampling from the unpaired 3D data are corrected using content adaptation. Specifically, the deformable registration algorithms proposed in our previous study[30] and advanced normalization tools (ANTs)[31] are separately introduced to conduct content matching. For ANTs-based registration, an ElasticSyN deformable transformation is adopted, together with a multi-resolution optimization strategy with four iteration levels. Nearest-neighbor interpolation is applied when warping images to preserve discrete anatomical structures.

2.2 Cooperation with image-to-image translation

Using the paired samples obtained by content adaptation, both paired and unpaired image-to-image translation models are able to be performed on the unpaired (weakly paired) data.

2.2.1 Paired image-to-image translation

Paired data is the foundation of the paired image-to-image translation. However, there is little access to collect paired data in the medical imaging community. The proposed content adaptation enables paired image-to-image translation on unpaired data.

A conditional discriminator is adopted in the paired image-to-image translation of pix2pix[5] to model the joint distribution from the source and target pairs. The adversarial loss of pix2pix is given by

And L1 distance is used in the generate loss to minimize the pixel wise error between the source and target samples. The generate loss is expressed as:

It should be noted that according to the definitions in Equation (9) and in Equation (10), the adversarial loss and generator loss of pix2pix are calculated from the pixel-level paired source and target samples. From the weakly paired data, the pixel-level paired samples are acquired by content adaptation. However, the performance of pix2pix heavily depends on the registration accuracy of the source and target samples. Furthermore, pixel-level pairs are not available in the paired samples constructed from unpaired data, since content adaptation only matches the global structure. In this circumstance, the conditional discriminator is degraded to a normal discriminator for local content.

2.2.2 Unpaired image-to-image translation

CycleGAN[6] is the most commonly used unpaired image-to-image translation model in medical imaging community. Cycle consistency is proposed in the CycleGAN[6] to enforce the mapping between the domains.

Using the paired samples obtained by content adaptation, the adversarial loss of CycleGAN is modified as

And the generator loss with cycle consistency is given by Equation (13).

In concert with the above equations, instead of building the joint distribution from pairs in the adversarial loss, CycleGAN minimizes the difference between the source and the synthesized image through cycle consistency in the generator loss. Therefore, paired samples are unessential in the installation of CycleGAN. Even so, the correction of the distribution bias is necessary to properly match the synthesized images to the target domain.

Content adaptation provides the paired samples to the translation models, ensuring that distribution bias has been obstructed from the training samples. In addition, since pixel-level pairs are unnecessary with cycle-consistency, CycleGAN is robust to the misregistration and local variations, which are inevitable in content adaptation.

The main goal of the image-to-image translation problem is to import features from the target domain into the output while retaining the content of the specific input. Utilizing content adaptation, the distribution bias embedded in the source and target samples are corrected to promote the proper translation. The paired translation model is enabled by the paired samples provided by content adaptation. Cooperating with CycleGAN, an unbiased translation mapping can be robustly established using content adaptation.

3. Results

With the intent to evaluate the performance of the proposed content adaptation, two applications of medical image translation are adopted in the experiments. Specifically, content adaptation is introduced for the cross-modality translation of retinal images and the pathological image synthesis of CT scans. Subsequently, qualitative and quantitative evaluation metrics are provided to comprehensively assess the efficiency of the proposed method.

3.1 Implementation details

3.1.1 Datasets

The cross-modality translation is performed on the retinal image dataset of color fundus photography and En-face OCT images. Fifty paired samples of these two modalities were captured pairwise from identical patients. The color fundus images were captured by Topcon TRC-NW8, and the OCT images were captured by a Topcon Maestro1. In the experiment, 35 paired samples were used to train the translation models, and the rest 15 paired samples were used as the test data.

The outbreak of COVID-19 in December 2019 drew much attention to the computer-aided diagnosis of the infection. To aid clinicians on screening and diagnosis with radiological images, researchers are making efforts to develop AI solutions to detect lung abnormalities caused by COVID-19[32-35]. As the foundation of developing AI algorithms, a sufficient database is necessary. In the experiments, pathological image synthesis was presented by translating from non-COVID-19 cases to COVID-19 ones. The twenty COVID-19 cases from CORONACASES.ORG[36] were used as the target data, while 20 cases from LUNA16[37] were as the source data.

Each 3D CT volume was decomposed into 328 axial 2D slices for training. The source scans were uniformly sampled, while the target scans were collected from infected slices. Sixteen cases are randomly selected from each dataset as the training data, and the rest four cases are used for testing.

3.1.2 Translation models

The most popular image-to-image translation models of pix2pix and CycleGAN were implemented in the experiments. A recently proposed translation model, contrastive unpaired translation (CUT)[38,39], was also presented. The unpaired translation models, including CycleGAN and CUT, were applied to the original data as well as the data that underwent content adaptation. However, as strictly paired data are unavailable in the experiment, the paired translation model, pix2pix, was only performed on the content adapted data. The Adam optimizer was used for both generators and discriminators, with an initial learning rate of 2 × 10-4 and a batch size of 4. Models were trained for 50 epochs with a fixed learning rate, followed by another 50 epochs with a linearly decayed learning rate to zero. All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU. Training a single translation model required approximately 4-6 hours, depending on the dataset size.

3.2 Cross-modality translation

Cross-modality translation of retinal images was first implemented on the weakly paired data of color fundus photography and

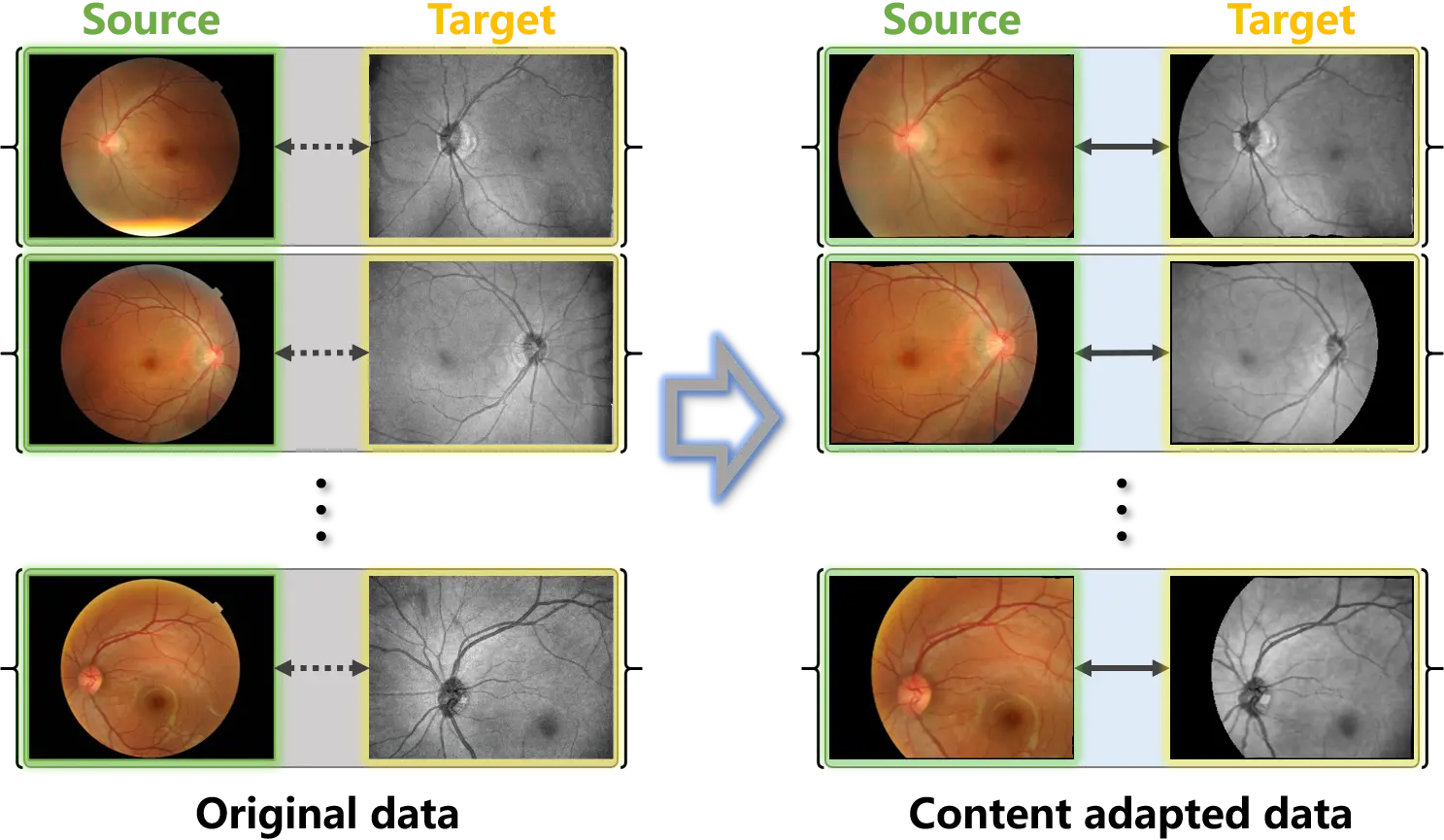

Figure 4. Examples of the original weakly paired retinal data and the content adapted data. Content adaptation matches the source and target samples and constructs paired samples.

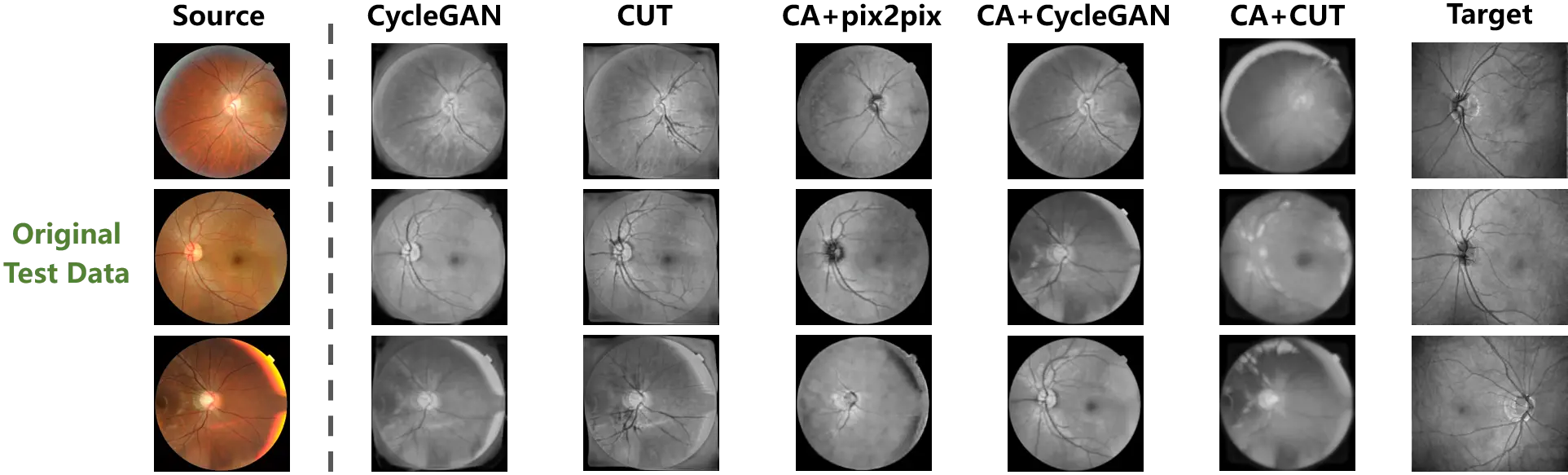

3.2.1 Evaluation with original data

The synthesized outputs of the original test data are exhibited in Figure 5, and the source and target samples are respectively presented in the first and last columns. Although the mappings from the source to the target domain could be learned by the unpaired translation models from the original data, these mappings improperly match the domains. Specifically, the foreground is distributed throughout the entire images of the target samples, while the foreground of the source samples is a circular area in the center. This distribution bias in the training data is regarded as an intrinsic domain shift from the source to the target domain by the translation models. Consequently, as shown in the second and third columns of Figure 5, the learned mappings tried to match the target samples by filling the background of the source samples at the corners. The synthesized outputs of CycleGAN and CUT, which were trained on the original data, thus suffer severely from hallucination in the corner background.

Figure 5. The cross-modality translation tested on the original weakly paired retinal data. The distribution bias misleads the learning of translation mapping to fill up the background of the source samples. And Content adaptation enhances the translation models by correcting the bias.

On the other hand, the proposed method is designed to correct the distribution bias between the source and target samples. In accordance with the fourth to the sixth columns of Figure 5, once the sample distribution is aligned by content adaptation, the mappings between domains are more effectively established by the translation models. The hallucination in the outputs has been significantly constrained by the models trained on the content adapted data. Additionally, using content adaptation, the pix-level correspondence is constructed on the weakly paired data. The paired image translation model of pix2pix is enabled. Furthermore, content adaptation endowed versatility to the translation models, such that superior performances are presented on the original test data.

In order to quantitatively compare the hallucination in the background of the outputs, the evaluation metrics of pixel accuracy (PA) and mean intersection over union (MIoU) were imported from image segmentation to quantify the background hallucination. Specifically, to measure the foreground and background consistency between the source and synthesized samples, the samples were binarized according to the non-zero pixels. Then, PA and MIoU were calculated between the binary masks of the source and synthesized samples. The higher value of PA and MIoU represent less hallucination in the background. The quantitative results are provided in Table 1. The models performed with content adapted data are denoted by ‘CA+’.

| Models | PA | mIoU |

| pix2pix | - | - |

| CycleGAN | 0.8178 | 0.5360 |

| CUT | 0.8013 | 0.4979 |

| CA + pix2pix | 0.9892 | 0.9712 |

| CA + CycleGAN | 0.9894 | 0.9718 |

| CA + CUT | 0.8661 | 0.6564 |

PA: pixel accuracy; mIoU: mean intersection over union; GAN: generative adversarial network; CUT: contrastive unpaired translation; CA: channel attention.

As pix2pix is not able to be trained on the original data, the corresponding values are absent in Table 1. Content adaptation provided aligned training samples to the translation models, such that pix2pix was enabled and the performances of the unpaired translation models were remarkably improved. The comparison between the results of the original and content adapted data indicates that through correcting the distribution bias in the training data, superior translation mappings were discovered by identical models.

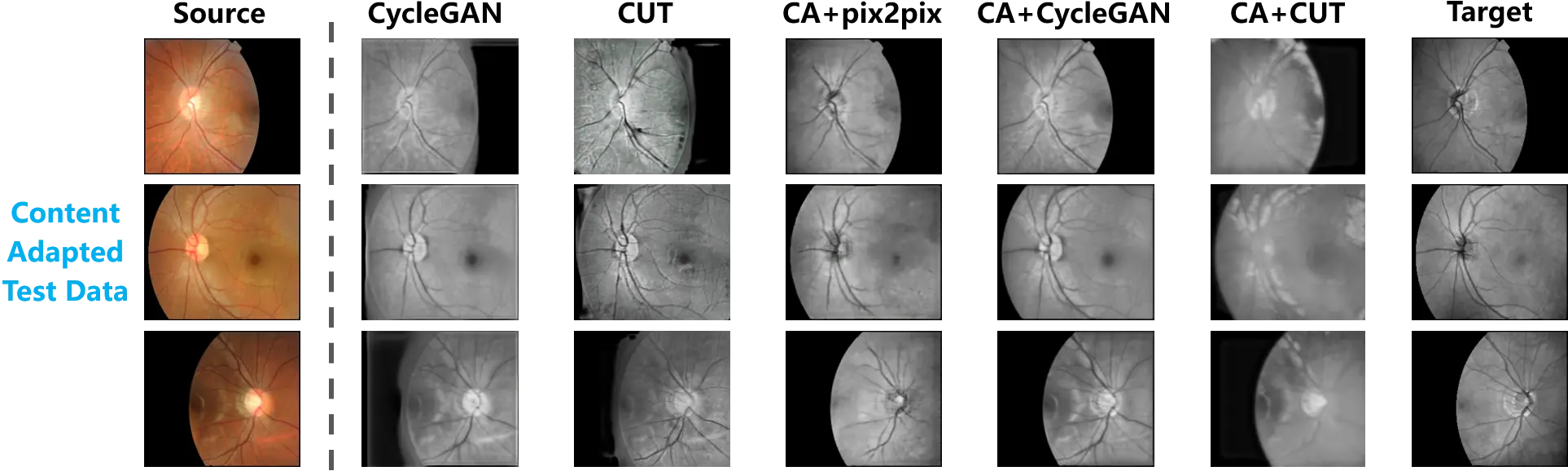

3.2.2 Evaluation with content adapted data

To further investigate the influence of training samples, the test data that underwent content adaptation was also used for the evaluation. Figure 6 exhibits the synthesized outputs based on the content adapted test data. In the first and last columns, the source and target samples are respectively presented.

Figure 6. The cross-modality translation tested on the content adapted retinal data. The paired test data are provided by content adaptation. A comparison between the translation outputs and the target samples is thus presented.

Consistent with the observation in Figure 5, the translation mapping learned from the original data still tried to fill the background of the source samples, while the foreground and background in the source samples were satisfactorily preserved by the models trained on the content adapted data.

Following the above-mentioned evaluation, Table 2 summarizes the quantitative measurement of hallucination. PA and MIoU were computed from the content adapted test data. According to the quantitative comparison between the models trained on the original and content adapted data, significant progress can be observed.

| Models | PA | mIoU |

| pix2pix | - | - |

| CycleGAN | 0.8964 | 0.6440 |

| CUT | 0.8471 | 0.4783 |

| CA+pix2pix | 0.9825 | 0.9273 |

| CA+CycleGAN | 0.9884 | 0.9572 |

| CA+CUT | 0.9050 | 0.7039 |

PA: pixel accuracy; mIoU: mean intersection over union; GAN: generative adversarial network; CUT: contrastive unpaired translation; CA: channel attention.

Based on the comprehensive evaluation of Figure 5 and Figure 6, as well as Table 1 and Table 2, unbiased training data is critical to correctly learn the translation mappings from the source to the target domain. Because of the distribution bias, the real shift between the source and target domains was distorted, and as a result of this distortion, the translation models made efforts to import the bias into the source samples during the training stage, with the purpose of matching the target domain. In this experiment, the distribution bias of the foreground in the original training data led the translation models to attempt to synthesize data of the target domain by filling the background. Therefore, no matter whether the original data or the content adapted data was employed in the test, hallucination appeared in the synthesized images.

Content adaptation helps to align the source and target samples, which constrains the distribution bias. The aligned training samples allow the translation models to properly estimate the domain shift and learn a mapping from the source to the target domain. Accordingly, the mappings learned from the content adapted data were immune to the distribution bias of the foreground. They did not fill the background in the source samples with hallucinations. Moreover, the mappings correctly learned from content adapted data were robust with respect to the test data, since hallucination was equally limited on the original test data.

3.2.3 Quality assessment of synthesized data

Evaluation of hallucination is only a part of the assessment of the generative models. To investigate the quality of the synthesized images, the evaluation metrics of image quality, including structural similarity (SSIM) and peak signal to noise ratio (PSNR), were applied to this cross-modality translation experiment.

As shown in Figure 4, pixel-level paired data were obtained from the original weakly paired data by content adaptation. Consequently, SSIM and PSNR are carried out with the content adapted test data (as shown in Figure 6) to quantify the quality of the synthesized images. Table 3 summarizes the values of SSIM and PSNR calculated from the synthesized images and the target samples.

| Models | SSIM | PSNR |

| pix2pix | - | - |

| CycleGAN | 0.7020 | 15.96 |

| CUT | 0.5538 | 14.22 |

| CA+pix2pix | 0.7831 | 21.05 |

| CA+CycleGAN | 0.8034 | 19.01 |

| CA+CUT | 0.6236 | 14.95 |

SSIM: structural similarity; PSNR: peak signal to noise ratio; GAN: generative adversarial network; CUT: contrastive unpaired translation; CA: channel attention.

As described in Section 3.1, only 35 sample pairs were available for the training the translation models. Hence, there is no surprise that the translation models were incapable of learning a satisfying mapping. The mediocre values in Table 3 denote the models were not yet fully trained. However, the gap between the original training data and the content adapted ones is distinguished. The performances of all translation models were improved after content adaptation was applied. Coherent with the analysis given in Section 2.2, cycle consistency made CycleGAN robust to the local mismatch between the sample pairs, which is inevitable in image registration. Using the content adapted data, CycleGAN achieved the top performance in the synthesis quality.

Furthermore, there is a conflicting observation in the metrics of the SSIM and PSNR. Trained on the content adapted data, CycleGAN outperformed other models in the metric of SSIM, while pix2pix achieved the highest value of PSNR. To interpret this conflicting observation, we refer to the definitions of SSIM and PSNR. Given a reference image $p$ and a test image $q$, SSIM is expressed by:

where l(p,q) is the luminance comparison function, c(p,q) is the contrast comparison function, and s(p,q) is the structure comparison function. For 8-bit grey-level images, the PSNR is given by

where

Based on Equation (14), SSIM provides the measurement of the SSIM between two images. The highest score of SSIM reflects that CycleGAN enjoyed superior capacity for structure synthesis, which is consistent with the inference from Figure 6. Equation (15) and (10) demonstrate that both PSNR and the generator loss in pix2pix are calculated from the pixel-level differences between the source (test) and target (reference) image.

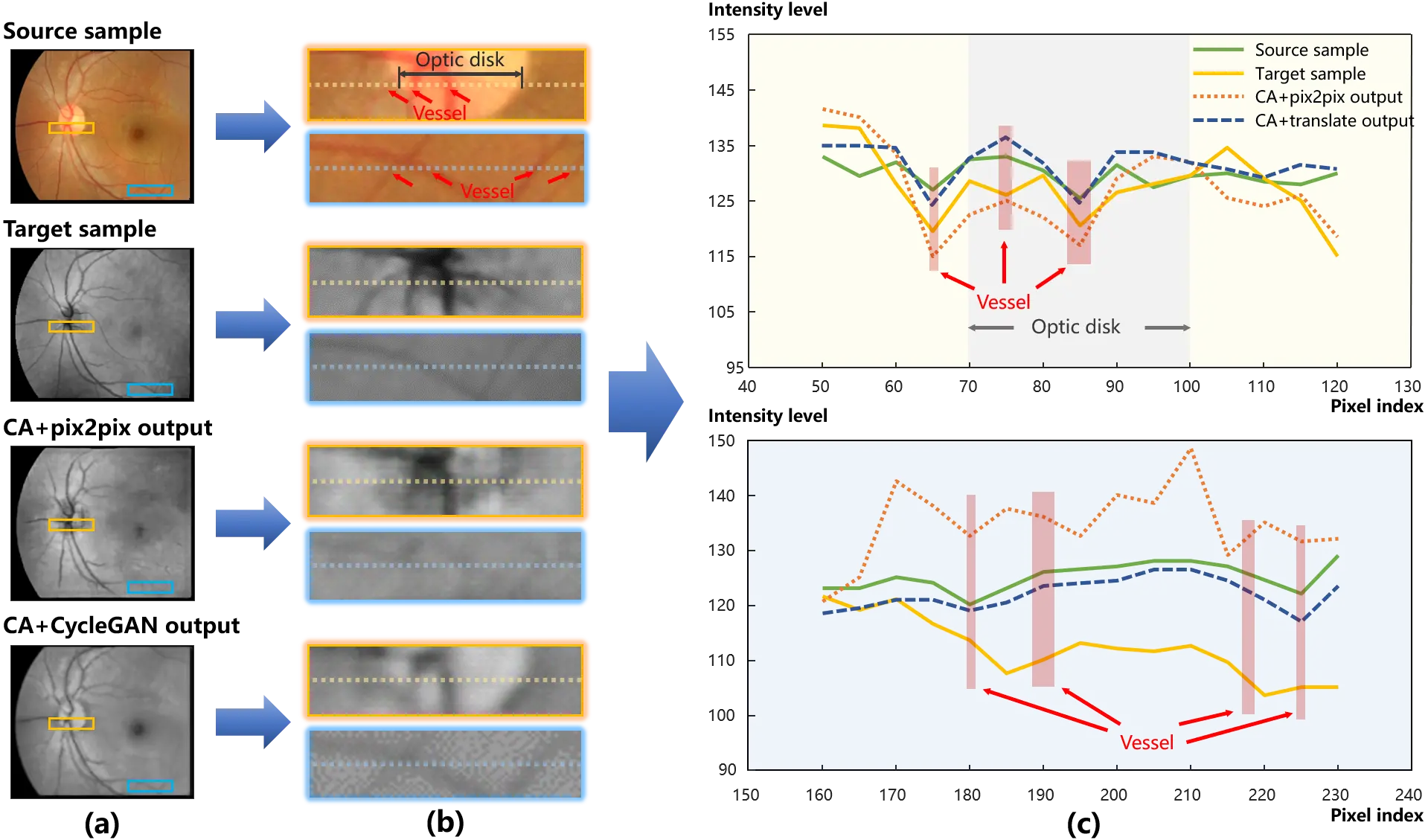

Therefore, considering the models were not fully trained on the limited data volume, it is reasonable that pix2pix had advantages in the metric of PSNR. A deep insight into the comparison of pix2pix and CycleGAN is presented in Figure 7, in which the translation of the optic disk and vessels in the retina is exhibited. Figure 7a shows the global images of the training and synthesized samples. The intensity curve of the pixels along the middle line in Figure 7b is plotted in Figure 7c, where the top one corresponds to the orange patches, and the bottom one corresponds to the aqua patches. In the patches of the source sample in Figure 7b,c, the optic disk area is marked in grey and vessel areas are in red.

Figure 7. An example of synthesized results. (a) presents the global images of the training samples and the outputs. And two local patches are displayed in (b) to provide deep insights into structure details. The pix level transformation is plotted in (c) that the intensity curve of pixels is compared. As a result of the local mismatch, affine transformations can be detected between the source and target samples in the aqua patches. And compared with the curve of the source sample in (c), the target curve decreases progressively, which indicates an illumination bias from the left to right.

As illuminated in Figure 7a,b, in contrast to the light area in the source sample, the optic disk is observed as a dark area in the target one. Pix2pix successfully transferred the optic disk area from high intensity in the source sample to dark in the target one. More evidences are presented in Figure 7c. The optic disk area expresses a convexity in the intensity curve of the source sample (the green solid line), while a concavity for the target (the yellow solid line). Following the green solid line, the intensity curve of pix2pix output (the orange dotted line) goes down at the optic disk area.

On the other hand, CycleGAN with the content adapted data outperformed pix2pix in the structure consistency between the inputs and outputs. Specifically, the vessels are perceptible in the intensity curve of CycleGAN (the blue dash line) in Figure 7c. In Figure 7b,c, local mismatch and illumination bias can be detected from the comparison of the aqua patches between the source and target samples. Due to these interferences from mismatch and illumination bias, the structure was blurred by the pix-level translation of pix2pix, while cycle consistency was robust to the interferences and effectively preserved the structure during the translation.

In summary, content adaptation corrected the distribution bias between the source and target samples, thus promoting the training of the translation models. Superior translation mappings were learned, and hallucination was limited. In addition, the model of pix2pix was enabled by content adaptation, while cycle consistency made content adaptation robust to the local mismatch in image registration.

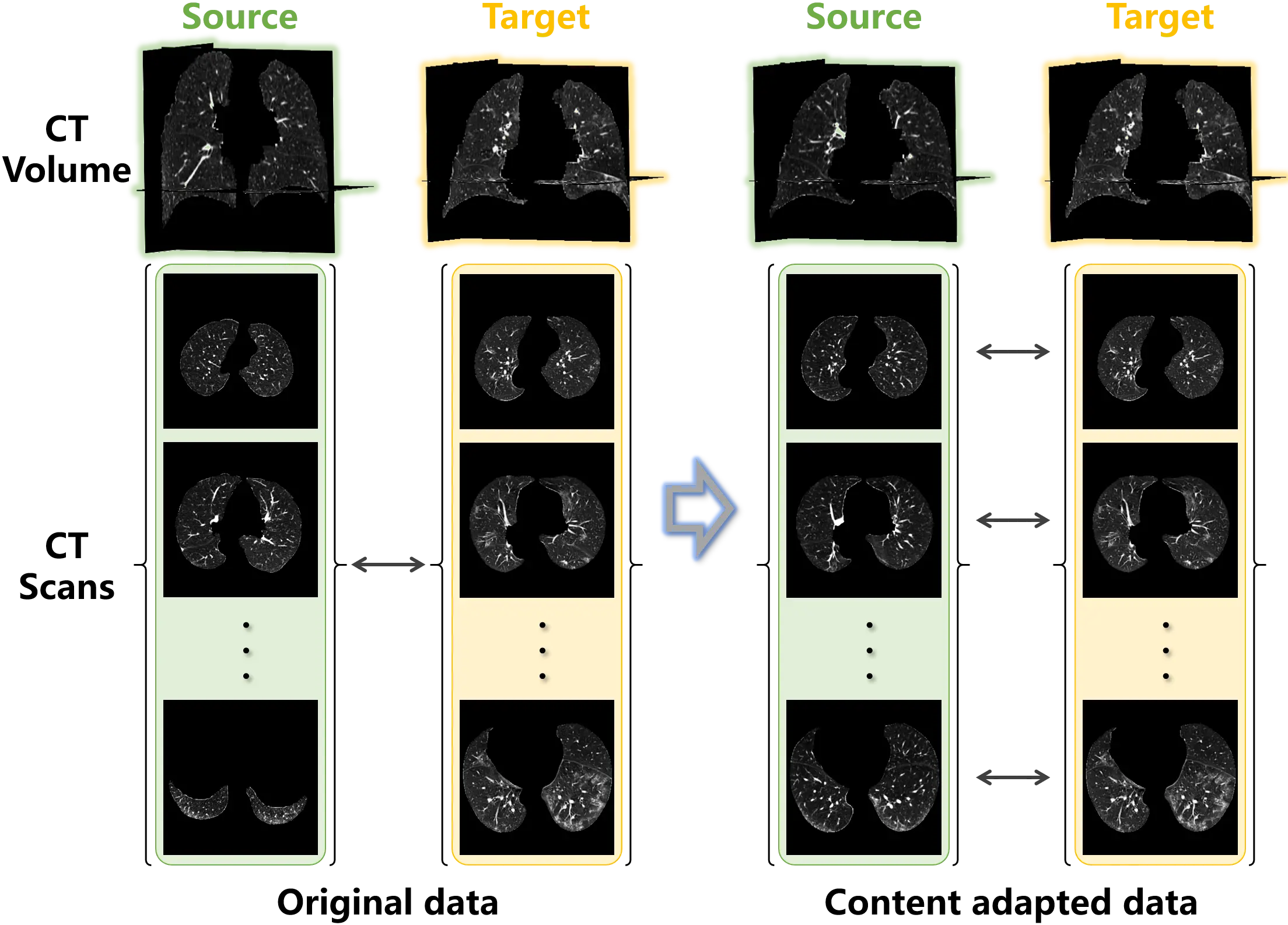

3.3 Pathological image synthesis

Pathological image synthesis is a popular application scenario of GAN in the medical imaging community. There is a consensus that pathological medical images can be plausibly generated by translating the medical images from healthy to ill. To promote the development of diagnostic algorithms for COVID-19, translation models were applied to the synthesis of CT scans of COVID-19 infected lung. The CT scans with and without COVID-19 were respectively sampled from the cases in CORONACASES.ORG[36] and LUNA16[37].

As no paired data was available in this scenario, unpaired translation models were used in the conventional paradigm. The models of CycleGAN and CUT were thus implemented using the original training data.

Considering the sampling bias between the source and target training samples shown in Figure 2, content adaptation was introduced to align the training samples. Specifically, the CT samples in the source and target datasets were registered using ANTs[31] to match the lung region. Then, following the scheme given in Equation (8), CT scans were symmetrically captured from the registered volume samples of the source and target data. Figure 8 demonstrates the original and content adapted samples for the pathological image synthesis of COVID-19.

Figure 8. Examples of the original unpaired lung data and the content adapted data. Paired samples are obtained from the unpaired data using content adaptation.

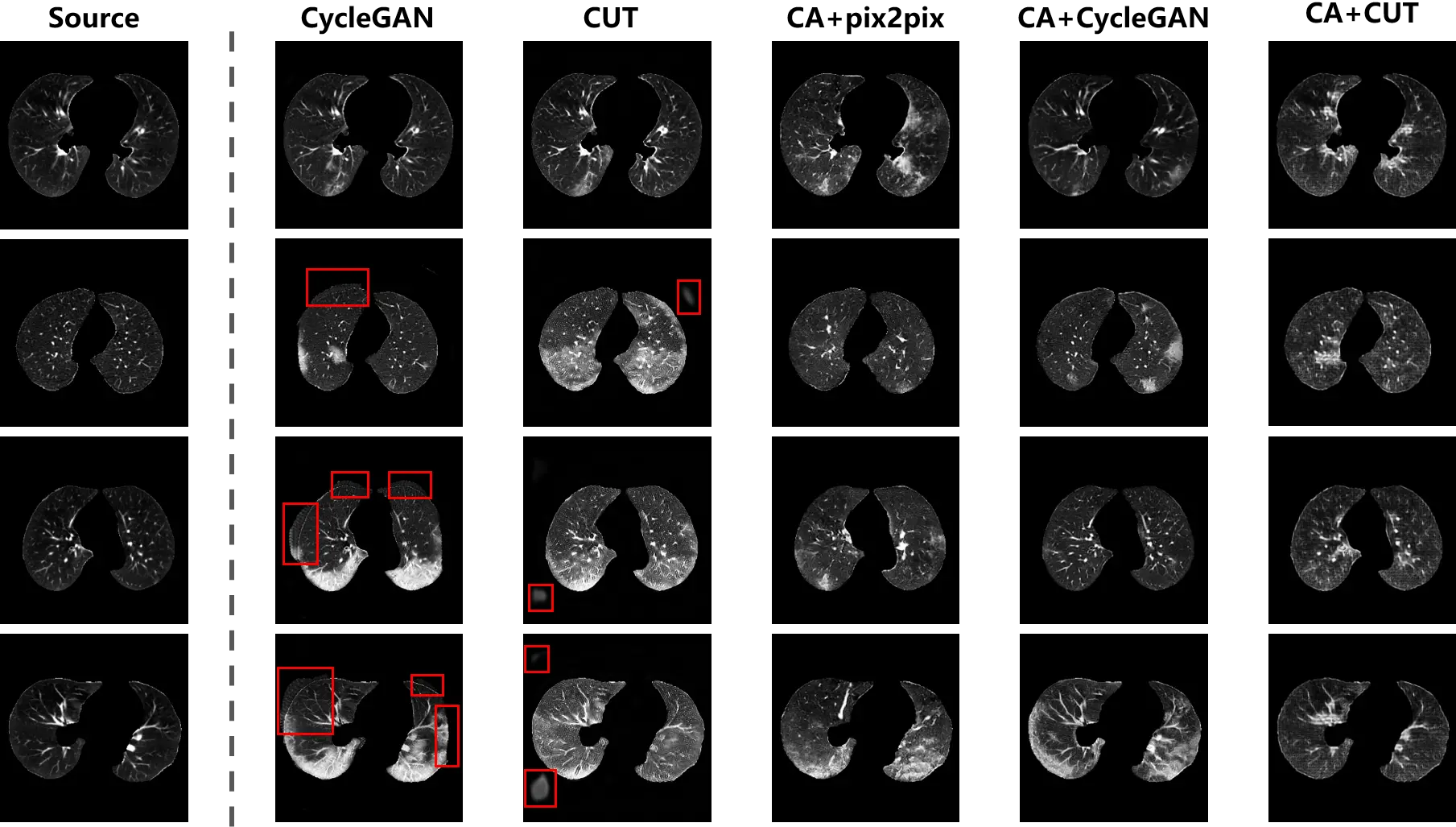

CycleGAN and CUT were implemented using both types of training data, while pix2pix was able to be executed using the paired data collected by content adaptation. The synthesis outputs are exhibited in Figure 9. As shown in the second and third columns, the distribution bias in training samples leads to hallucinations (highlighted in red boxes) in the background of the outputs. Similar to the phenomenon in Figure 5 and Figure 6, the translation models attempted to match the outputs to target samples by revamping the foreground and background. The unbiased samples provided by content adaptation enabled the translation models to focus on the desirable translation mapping, such that in the fourth to sixth columns of Figure 9 the foreground was intact and the lesions were generated. Furthermore, the bias distracted the attention of the models that the diversity of the outputs from the original data were not as good as the content adapted ones. Especially, in the third column, analogical lesion patterns were shared among the outputs of CUT.

Figure 9. The synthesis of CT scans with COVID-19 infection. The distribution bias in the original data leads to hallucinations (i.e. spurious non-anatomical artifacts or unrealistic background structures), as shown by the red boxes. The hallucination has disappeared in the outputs of the translation models trained on content adapted data.

From the fourth column of Figure 9, the content variant in the lung region is observed between the outputs and the source samples. The reason is that with the content adapted data, pix2pix learned to preserve the global structure, while ignoring local content. For the unpaired data, content adaptation only matched the global structure between the source and target samples to correct the distribution bias, but local characteristics of each individual patient remained in the samples. Because of this circumstance, the conditional discriminator of pix2pix (formulated as a formula in Equation (9)) just constrained the global consistency of the translation mapping. But for the local content, it was degraded to a normal discriminator as used in a vanilla GAN. Accordingly, global consistency was incorporated into pix2pix, while local consistency was ignored by the pix-level translation.

Compared with pix2pix, the unpaired translation models were robust to the local variant between the content adapted source and target samples. The pathological scans were properly synthesized so that that the characteristics in the source samples were preserved, while lesions were integrated into the outputs.

3.3.1 Quantitative evaluation of hallucination

The metrics of PA and mIoU were also employed to quantitatively evaluate the hallucination in the synthesized images. The binary masks of the source and synthesized images were obtained from the non-zero pixels, and then the hallucination was assessed based on the PA and mIoU between the masks. The quantitative evaluation is provided in Table 4.

| Models | PA | mIoU |

| pix2pix | - | - |

| CycleGAN | 0.9641 | 0.9095 |

| CUT | 0.9176 | 0.8352 |

| CA+pix2pix | 0.9925 | 0.9765 |

| CA+CycleGAN | 0.9946 | 0.9846 |

| CA+CUT | 0.9862 | 0.9618 |

PA: pixel accuracy; mIoU: mean intersection over union; GAN: generative adversarial network; CUT: contrastive unpaired translation; CA: channel attention.

The translation models trained on original data suffered from hallucination in the outputs. Resulting from the distribution characteristics of CT scans with COVID-19, sampling bias was embedded in the training samples. The bias distorted the real shift between the source and target domains. The translation models attempted to match this distorted domain shift to synthesize samples belonging to the target domain, and hallucination was hence generated.

By circumventing the bias embedded in the domain shift, content adaptation allowed the translation models to synthesize plausible images. As displayed in Figure 8, to correct the bias imported from the sampling, content adaptation matched the sample distribution through symmetrically collecting the source and target scans. The models trained on content adapted data effectively limited hallucinations. Thanks to cycle consistency, CycleGAN provided a prominent mapping consistency with the highest PA and mIoU.

3.3.2 Quality assessment by classification

Because there was no translation ground truth for the synthesis of COVID-19 CT scans, reference images were unavailable to calculate the quality metrics of SSIM and PSNR. Following the evaluation scheme[40,41], a classification task was designed to quantitatively evaluate how interpretable the synthesized CT scans were according to off-the-shelf algorithms. The hypothesis was that once the scans were plausibly synthesized, universal discriminative pathological features would be learned by the off-the-shelf classifiers from the synthesized scans. Specifically, the translation models were implemented for data augmentation in the classification task, and the quality of the synthesized images was assessed by the capacity for COVID-19 identification with classification models.

The CNN models of AlexNet, VGG16, and ResNet18 were adopted as the classifiers, and initialized with parameters pre-trained on ImageNet. In the training stage, the batch size was set to 32, and 50 echoes were performed. Subsequently, to objectively verify the classification models, the test data were obtained from another COVID-19 CT dataset[42], where the scans with COVID-19 infection were labeled. The classification models were used to identify the COVID-19 infected scans, and the identification accuracy was calculated by comparison with the labels.

As interpreted in Section 3.1, the CT scans from LUNA16[37] and CORONACASES.ORG[36] were used as the source and target samples to train the translation models. The classification baseline was demarcated by the classification models trained on real data. Subsequently, to evaluate the quality of the synthesized images, the positive training samples from CORONACASES.ORG were replaced by the synthesized ones for the training of the classification models.

Table 5 summarizes the accuracy of the classification models. The classification baseline refers to Real Data, in which the models were trained on the original real data. The data augmented image registration is also adopted in the classification, which is denoted by Registered in Table 5. As content adaptation enabled pix2pix with the unpaired data, it was performed with the proposed scheme, while the unpaired translation models of CycleGAN and CUT were carried out with both types of training data.

| Models | AlexNet | VGG16 | ResNet18 |

| Real Data | 0.8383 | 0.8533 | 0.8623 |

| Registered | 0.8478 | 0.7595 | 0.8125 |

| pix2pix | - | - | - |

| CycleGAN | 0.9198 | 0.8111 | 0.8302 |

| CUT | 0.8713 | 0.8438 | 0.8193 |

| CA + pix2pix | 0.8954 | 0.8709 | 0.8849 |

| CA + CycleGAN | 0.9552 | 0.9027 | 0.9059 |

| CA + CUT | 0.8802 | 0.8715 | 0.8737 |

GAN: generative adversarial network; CUT: contrastive unpaired translation; CA: channel attention.

Content adaptation improved the translation models in the accuracy of the classification task. When only original data was available, ResNet18 was the most potent model to identify infected scans. Once data augmentation was installed, the power of AlexNet was significantly enhanced, and the accuracy increased stably. Nevertheless, a converse effect could be caused by data augmentation for VGG16 and ResNet18.The real data contained the entire original information. The augmentation with image registration extended the volume of the dataset, but provided no additional information. The translation models estimated the feature space according to the real data, and synthesized samples to augment the dataset. The most meaningful information was provided by CycleGAN that underwent content adaptation, that endowed the most precise classification parameters to AlexNet.

From the performance of VGG16 and ResNet18, the limitation of data augmentation was evident. The deeper networks allowed VGG16 and ResNet to mine latent information from the training data. Consequently, inferior data augmentation could mislead the training of VGG16 and ResNet18, instead of enhancing the classification. Although registration extended the data volume, the redundant information exacerbated the overfitting. The mismatching of target data caused by distribution bias impacted the performance of CycleGAN and CUT. In spite of better performance than registration, the outputs of CycleGAN and CUT still introduced negative information to the classifiers of VGG16 and ResNet18, such that their performances were not as good as when trained on real data. Because content adaptation counteracted the distribution bias of samples, the translation models were able to properly match the target domain distribution. Therefore, the synthesized data outperformed the real data in tuning the classifiers.

3.4 Limitation discussion

While the proposed framework demonstrates consistent improvements across multiple medical image translation tasks, several aspects merit further investigation. First, the effectiveness of content matching is inherently conditioned on the quality of

4. Conclusion

Image-to-image translation provides novel routines to solve the problems in the medical imaging community. How to obtain

Authors contribution

Li H, Lin H: Conceptualization, methodology, software, data curation, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Li H, Ou M, Lin J: Investigation, visualization, data curation, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study used publicly available anonymized datasets; therefore, no additional ethical approval was required.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62401246), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2514050003407), and Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (Grant No. JCYJ20250604185805008 and No. JCYJ20240813095112017).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Brahmi W, Jdey I, Drira F. Exploring the role of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) in dental radiography segmentation: A comprehensive Systematic Literature Review. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2024;133:108510.[DOI]

-

2. Mi J, Ma C, Zheng L, Zhang M, Li M, Wang M. WGAN-CL: A Wasserstein GAN with confidence loss for small-sample augmentation. Expert Syst Appl. 2023;233:120943.[DOI]

-

3. Karras T, Laine S, Aila T. A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks. In: 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2019 Jun 15-20; Long Beach, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2019. p. 4396-4405.[DOI]

-

4. Choi Y, Choi M, Kim M, Ha JW, Kim S, Choo J. StarGAN: Unified generative adversarial networks for multi-domain image-to-image translation. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018 Jun 19-21; Salt Lake City, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2018. p. 8789-8797.[DOI]

-

5. Isola P, Zhu JY, Zhou T, Efros AA. Image-to-image translation with conditional adversarial networks. In: 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017 Jul 21-26; Honolulu, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2017. p. 5967-5976.[DOI]

-

6. Zhu JY, Park T, Isola P, Efros AA. Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks. In: 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2017 Oct 22-29; Venice, Italy. Piscataway: IEEE; 2017. p. 2242-2251.[DOI]

-

7. Bengesi S, El-Sayed H, Sarker MK, Houkpati Y, Irungu J, Oladunni T. Advancements in generative AI: A comprehensive review of GANs, GPT, autoencoders, diffusion model, and transformers. IEEE Access. 2024;12:69812-69837.[DOI]

-

8. Bandi A, Adapa PVSR, Kuchi YEVPK. The power of generative AI: A review of requirements, models, input–output formats, evaluation metrics, and challenges. Future Internet. 2023;15(8):260.[DOI]

-

9. Wang Q, Fink O, Van Gool L, Dai D. Continual test-time domain adaptation. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18-24; New Orleans, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2022. p. 7191-7201.[DOI]

-

10. Wang Z, Yuan Z, Wang X, Li Y, Chen T, Xia M, et al. MotionCtrl: A unified and flexible motion controller for video generation. In: ACM SIGGRAPH 2024 Conference Papers; 2024 Jul 27-Aug 1; Denver, USA. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2024. p. 1-11.[DOI]

-

11. Wang Y, Yang W, Chen X, Wang Y, Guo L, Chau LP, et al. SinSR: Diffusion-based image super-resolution in a single step. In: 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2024 Jun 16-22; Seattle, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2024. p. 25796-25805.[DOI]

-

12. Mirza M, Osindero S. Conditional generative adversarial nets. arXiv:1411.1784 [Preprint]. 2014.[DOI]

-

13. van Breugel B, Liu T, Oglic D, van der Schaar M. Synthetic data in biomedicine via generative artificial intelligence. Nat Rev Bioeng. 2024;2(12):991-1004.[DOI]

-

14. Asgari Taghanaki S, Abhishek K, Cohen JP, Cohen-Adad J, Hamarneh G. Deep semantic segmentation of natural and medical images: A review. Artif Intell Rev. 2021;54(1):137-178.[DOI]

-

15. Koetzier LR, Mastrodicasa D, Szczykutowicz TP, van der Werf NR, Wang AS, Sandfort V, et al. Deep learning image reconstruction for CT: Technical principles and clinical prospects. Radiology. 2023;306(3):e221257.[DOI]

-

16. Yi X, Babyn P. Sharpness-aware low-dose CT denoising using conditional generative adversarial network. J Digit Imaging. 2018;31(5):655-669.[DOI]

-

17. Bhati A, Gour N, Khanna P, Ojha A. Discriminative kernel convolution network for multi-label ophthalmic disease detection on imbalanced fundus image dataset. Comput Biol Med. 2023;153:106519.[DOI]

-

18. Shen Z, Fu H, Shen J, Shao L. Modeling and Enhancing Low-quality Retinal Fundus Images. arXiv:2005.05594 [Preprint]. 2020.[DOI]

-

19. Shamshad F, Khan S, Zamir SW, Khan MH, Hayat M, Khan FS, et al. Transformers in medical imaging: A survey. Med Image Anal. 2023;88:102802.[DOI]

-

20. Dayarathna S, Islam KT, Uribe S, Yang G, Hayat M, Chen Z. Deep learning based synthesis of MRI, CT and PET: Review and analysis. Med Image Anal. 2024;92:103046.[DOI]

-

21. Wang J, Wang K, Yu Y, Lu Y, Xiao W, Sun Z, et al. Self-improving generative foundation model for synthetic medical image generation and clinical applications. Nat Med. 2025;31(2):609-617.[DOI]

-

22. Li W, Zhong X, Shao H, Cai B, Yang X. Multi-mode data augmentation and fault diagnosis of rotating machinery using modified ACGAN designed with new framework. Adv Eng Inform. 2022;52:101552.[DOI]

-

23. Han C, Rundo L, Araki R, Nagano Y, Furukawa Y, Mauri G, et al. Combining noise-to-image and image-to-image GANs: Brain MR image augmentation for tumor detection. IEEE Access. 2019;7:156966-156977.[DOI]

-

24. Guan H, Yap PT, Bozoki A, Liu M. Federated learning for medical image analysis: A survey. Pattern Recognit. 2024;151:110424.[DOI]

-

25. Liu W, Durasov N, Fua P. Leveraging self-supervision for cross-domain crowd counting. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18-24; New Orleans, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2022. p. 5331-5342.[DOI]

-

26. Xie S, Gong M, Xu Y, Zhang K. Unaligned image-to-image translation by learning to reweight. In: 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021 Oct 10-17; Montreal, Canada. Piscataway: IEEE; 2021. p. 14154-14164.[DOI]

-

27. Lipkova J, Chen RJ, Chen B, Lu MY, Barbieri M, Shao D, et al. Artificial intelligence for multimodal data integration in oncology. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(10):1095-1110.[DOI]

-

28. Lundervold AS, Lundervold A. An overview of deep learning in medical imaging focusing on MRI. Z Med Phys. 2019;29(2):102-127.[DOI]

-

29. Chen J, Liu Y, Wei S, Bian Z, Subramanian S, Carass A, et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image registration: New technologies, uncertainty, evaluation metrics, and beyond. Med Image Anal. 2025;100:103385.[DOI]

-

30. Xu C, Yu C, Zhang S. Lightweight multi-scale dilated U-Net for crop disease leaf image segmentation. Electronics. 2022;11(23):3947.[DOI]

-

31. Avants B, Tustison NJ, Song G. Advanced normalization tools (ANTS). Insight J. 2009;2(365):1-35.[DOI]

-

32. Nabavi S, Ejmalian A, Moghaddam ME, Ali Abin A, Frangi AF, Mohammadi M, et al. Medical imaging and computational image analysis in COVID-19 diagnosis: A review. arXiv:2010.02154 [Preprint]. 2020.[DOI]

-

33. Wang Z, Liu Q, Dou Q. Contrastive cross-site learning with redesigned net for COVID-19 CT classification. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2020;24(10):2806-2813.[DOI]

-

34. Aslani S, Jacob J. Utilisation of deep learning for COVID-19 diagnosis. Clin Radiol. 2023;78(2):150-157.[DOI]

-

35. Li H, Hu Y, Li S, Lin W, Liu P, Higashita R, et al. CT scan synthesis for promoting computer-aided diagnosis capacity of COVID-19. In: Huang DS, Jo KH, editors. Intelligent computing theories and application. Cham: Springer; 2020. p. 413-422.[DOI]

-

36. Cohen JP, Morrison P, Dao L. Covid-19 image data collection. arXiv:2003.11597 [Preprint]. 2020.[DOI]

-

37. Adams SJ, Stone E, Baldwin DR, Vliegenthart R, Lee P, Fintelmann FJ. Lung cancer screening. Lancet. 2023;401(10374):390-408.[DOI]

-

38. Tumanyan N, Geyer M, Bagon S, Dekel T. Plug-and-play diffusion features for text-driven image-to-image translation. In: 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2023 Jun 17-24; Vancouver, Canada. Piscataway: IEEE; 2023. p. 1921-1930.[DOI]

-

39. Tang Y, Yang D, Li W, Roth HR, Landman B, Xu D, et al. Self-supervised pre-training of swin transformers for 3D medical image analysis. In: 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022 Jun 18-24; New Orleans, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2022. p. 20730-20740.[DOI]

-

40. Dou B, Zhu Z, Merkurjev E, Ke L, Chen L, Jiang J, et al. Machine learning methods for small data challenges in molecular science. Chem Rev. 2023;123(13):8736-8780.[DOI]

-

41. Kim HE, Cosa-Linan A, Santhanam N, Jannesari M, Maros ME, Ganslandt T. Transfer learning for medical image classification: A literature review. BMC Med Imaging. 2022;22:69.[DOI]

-

42. Artificial Intelligence AS. COVID-19 CT segmentation dataset [dataset]. 2020 Apr 13. Available from: http://medicalsegmentation.com/covid19/

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite