Abstract

Aims: This article aims to create a taxonomy of evidence-based medical eXtended Reality (MXR) applications, including Virtual Reality (VR), Augmented Reality (AR), Mixed Reality (MR), and 360-degree photo/video technologies, to identify best practices for designing and evaluating user experiences and interfaces (UX/UI). The goal is to assist researchers, developers, and practitioners in comparing and extrapolating the best solutions for high-precision MXR tools in medical and wellness contexts.

Methods: To develop the taxonomy, a review of medical and MXR publications was conducted, followed by three systematic mapping studies. Applications were categorized by end-users and purposes. The first mapping cross-referenced digital health technology classifications. The second validated the structure by incorporating over 350 evidence-based MXR apps, with input from twenty XR-HCI researchers. The third, ongoing mapping adds emerging apps, refining the taxonomy further.

Results: The taxonomy is presented in a dynamic database and 3D interactive graph, allowing international researchers to visualize and discuss developed evidence-based medical and wellness XR applications. This formalizes prior efforts to distinguish validated MXR solutions from speculative ones.

Conclusion: The taxonomy focuses solely on evidence-based applications, highlighting areas where VR, AR, and MR have been successfully implemented. It serves as a tool for stakeholders to analyze and understand best practices in MXR design, promoting the development of safe, effective, and user-friendly medical and wellness applications.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Medical, health, and wellness innovations are experiencing exponential growth, driven by virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), mixed reality (MR), 360-degree video, photo, and volumetric reality technologies, collectively known as MXR. When combined with the Internet of Health/Medical Things (IoHT/IoMT), advanced cloud computing, and rapid breakthroughs in artificial intelligence (AI), MXR is set to further accelerate the rollout of cutting-edge medical, health, and wellness solutions into society at an unprecedented pace.

Our collective understanding of how to design and evaluate safe new MXR tools needs to keep pace with this exponential growth too. To address these challenges, we need to foster international interdisciplinary collaboration to identify best practices for the design and evaluation of MXR tools. We want to know what design solutions and evaluation methods for the development of high-precision, high-dexterity, and high-empathy MXR tools. We need to collectively analyze the most effective solutions based on insights from empirical tests of MXR tools with representative end-users that demonstrated positive effects. For MXR tools, this means studying the so-called evidence-based MXR applications.

Including speculative MXR application proposals based on predictions and hype, would be counterproductive, as it would hinder our ability to analyze best design and evaluation practices. Therefore, the term "evidence-based" in the context of this taxonomy signifies applications that demonstrably work with positive effect assessed via empirical research, irrespective of their regulatory status. This focus allows us to identify and describe the most effective design solutions and measurement approaches for MXR applications. For example, the much-publicized but ultimately fraudulent claims around Theranos' blood-testing technology illustrate the dangers of basing conclusions on unproven, hyped-up medical solutions.

Analyzing best design and evaluation practices begins with developing a comprehensive overview of proven solutions. This process starts by constructing a taxonomy to systematically organize current evidence. Our envisioned taxonomy serves as the foundation for identifying best practices in MXR design and evaluation, offering valuable insights to researchers, developers, and practitioners. Unlike previous efforts, our taxonomy focuses exclusively on evidence-based MXR apps, distinguishing them from speculative future applications and other taxonomies that primarily categorize XR technologies for medical or educational purposes. With this resource, researchers can pinpoint effective designs, developers can build precise applications, and practitioners can adopt validated tools for medical, health, and wellness uses.

The results presented here include a significant number of MXR applications, with a current total of 350 evidence-based MXR apps identified. To manage this extensive dataset, the information was moved from a static table to a dynamic database. This solution addresses the impracticality of managing a massive table and accommodates the rapidly expanding number of evidence-based MXR apps. Some areas of the taxonomy remain granular, others are more populated, reflecting both the diversity and growth of the field. This dynamic database allows for continuous updates and more effective categorization as new apps emerge. Additionally, this specific database allows for community management around analyzing and curating the various topics involved in MXR design and evaluation of best practices.

Recent advancements in Generative AI (GenAI) present unprecedented opportunities for AI-assisted disease recognition and physical resistance or assistance through haptic feedback integrated into MXR device hardware and software. Moreover, developments in Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) R&D may lead to AI-assisted medical implants, prostheses, and exoskeletons, as well as remote-controlled robotic treatments.

The Internet of Health Things (IoHT) comprises interconnected devices that enhance patient care and practitioner efficiency through data sharing. Machine learning (ML) is a powerful tool in healthcare, enabling IoHT devices to analyze data and provide intelligent solutions in contexts ranging from big-data cloud computing to smart sensors[1]. McKinsey[2] predicted that by 2025, IoHT could have an annual financial impact of $11.1 trillion[3].

However, many researchers have noted a lack of interdisciplinary guidelines for systematically developing and evaluating these technologies[4-11]. In medical research, "evidence-based research and evaluation" refers to the rigorous process through which applications are tested and validated using clinical evidence.

To address the need for best practices in MXR app design and evaluation, we researched evidence-based MXR apps. Our goal is to understand the most effective UX/UI design solutions for various stakeholders in the MXR ecosystem. Building on previous technical and scientific developments[11], our work aims to:

• Standardize evidence-based MXR terminology;

• Accelerate time to market for MXR solutions;

• Create Best Practice Guidelines for MXR app development;

• Contribute to discussions on risk prevention, high-precision design, long-term data collection, and privacy concerns.

Our MXR taxonomy is structured around the user journey in healthcare - Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Care - and three core dimensions: Purpose, Users, and XR Technology type. Given the rapid growth of MXR apps, we transitioned from a static table to a dynamic database, enabling interactive visualizations that allow users to explore Purpose, Users, and XR Technology combinations. This ensures our taxonomy remains comprehensive and adaptable to ongoing advancements in the field.

The next sections describe the background research (section 2), the method we used to develop our evidence-based MXR app taxonomy (section 3), the results from our research and the analyses we conducted (section 4), followed by a discussion of the results of the new MXR app taxonomy (section 5), and the conclusions (section 6) in which we review the development of evidence-based MXR app taxonomy, including the limitations of our study, and the future directions for further research and development of successful and safe MXR apps.

2. Background Research

This section introduces five key topics that outline the complexities and considerations in interdisciplinary MXR product development, user experience evaluation, and evidence-based medical app taxonomy creation. Section 2.1 explores the challenges of developing a shared vocabulary for international MXR collaboration, addressing communication issues due to varied specialized terminologies across subfields. Section 2.2 delves into the regulatory approval process, focusing on randomized controlled trials as a key method for validating MXR applications. The subsequent sections cover the challenge of defining best practices in MXR development (2.3), the role of real-world data in MXR development and MXR applications (2.4), and the creation of a taxonomy of evidence-based MXR applications for global interdisciplinary collaboration (2.5).

2.1 Breaking barriers: Creating a unified MXR vocabulary for seamless collaboration

Prof. Greenleaf, a neuroscientist at Stanford University's Virtual Human Interaction Lab and MXR pioneer[12,13], identified communication challenges in interdisciplinary MXR development due to specialized vocabularies and limited cross-disciplinary knowledge among stakeholders. These challenges stem from the complexities of MXR-related subfields.

Researchers have also noted ambiguity and confusion in XR terminology across industry and academia[14]. Developers use inconsistent labels for technologies, and the boundaries between AR, VR, and MR remain unclear, prompting calls for reorganization[14]. MXR is rapidly evolving, driven by technology companies aiming to differentiate themselves, while consultants, academics, and media figures shape the discipline with their interpretations[14]. Greenleaf[15] and Yang[16] stress the need for cross-disciplinary dialogue to integrate MXR into healthcare ecosystems while minimizing errors.

2.2 Navigating the maze: Randomized controlled trials and regulatory approval for MXR

For medical and health products, regulatory approval requires demonstrating positive effects, typically through randomized clinical trials (RCTs). These trials must show improvements in outcomes like reduced morbidity, mortality, and enhanced quality of life. MXR apps are particularly suited for measuring long-term effects such as better health literacy, healthcare access, adherence to treatments, and coordination of care. These outcomes are assessed by:

• Collecting multiple measurements over time;

• From representative end-users;

• Using a series of organized trials.

The user's experience must be tracked over time through various metrics, as treatment, education, and training effects take time to manifest. Longitudinal studies, with multiple trials and regular or continuous measurements, are essential for this purpose.

Ongoing efforts aim to standardize RCT protocols for evaluating MXR interventions. For example, Rawlins[17] developed protocols for assessing VR treatment for US veterans, advocating for shared resources to combine data from different researchers. The British National Health Service (NHS) also developed the Global Digital Exemplar (GDE) guidelines to improve digital capabilities and services[18]. Sharing standardized protocols globally for digital health solutions, including MXR apps, is crucial, as uniform testing protocols enable easier data comparison and collaboration across regions.

2.3 Designing the future: Best practices for MXR UX/UI in healthcare

A systematic review of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) techniques for training and learning in medicine, healthcare, and engineering found that 3D design and evaluation methods for XR-HCI are part of a new, emerging approach that enhances skills, safety, reduces costs, and shortens learning periods[19]. However, the researchers identified a lack of comprehensive research categorization in XR-HCI, with only 69 publications available[19]. A transdisciplinary approach is needed to improve user experiences through 3D HCI design and evaluation methods[20]. This highlights the necessity for a holistic UX/UI framework that integrates best practices from HCI[21], participatory design, information modeling, and computational methods to support XR creation[22] and the broader development of XR systems and the Metaverse[23-25]. Design Thinking, developed by IDEO, offers a valuable human-centered approach by balancing user needs, technological capabilities, and business requirements[26,27]. A quote from two medical MXR pioneers[5] illustrates the urgency of addressing UXUI standards in MXR apps:

" Some of the biggest medical advances of the last few decades have been in diagnostic imaging [..]. Yet, while the imaging has radically evolved, how the images are displayed is basically the same as it was in 1950. [..] It is not that different modes of imaging really require special displays but that the current economic model is to sell whole systems with incompatible imaging devices. [This requires] hospitals to buy entire systems, each with their own display. The systems can cost upwards of hundreds of thousands of dollars each"[5].

2.4 Unlocking insights: Leveraging real-world data for smarter MXR development

There is increasing recognition of the value and the opportunity of using AI to collect real-world data (RWD) to analyze large data sets. This has multiple massive implications for improving data processing and data security, including for MXR apps.

With RWD derived from the analyses of medical, health, and safety measurements, we can rapidly produce real-world evidence (RWE) and this could improve the time to market for MXR applications. The regulatory landscape for RWE and mobile medical, health, and wellness applications is rapidly changing and evolving due to these new RWE opportunities[8]. Further research is needed for the seamless integration of smart devices, data analytics, data security, privacy, interoperability, scalability, flexibility, interoperability, and the need for more user-centered designs for AI tools in healthcare systems[1].

2.5 Building bridges: Crafting an evidence-based MXR application taxonomy for global innovation

Taxonomies are essential for analyzing the scope and structure of a field. They are now being applied in emerging areas like AI, blockchain, fintech, design science, Health Information Technology (HIT), m-health, and XR. However, most taxonomies are constructed either ad-hoc or through intuitive reasoning, and researchers[28-30] have found that these taxonomies:

• Lack a solid conceptual, theoretical, or empirical foundation[28,29];

• Lead to confusion in terminology and meaning[30].

Experts must organize all facets of a topic into a hierarchical taxonomy structure for further analysis. Facets are widely applied in various indexing and retrieval systems, from traditional classifications to ontologies, thesauri, and discovery tools[31].

Over time, taxonomies have been developed to categorize digital health and XR technologies. The taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays[32] is a well-known effort to categorize MR-enabling display types. However, additional attempts have been made to create more inclusive taxonomies as interactive 3D technology rapidly evolves. Relevant taxonomies for our evidence-based MXR app taxonomy task include: a taxonomy of medical MR[4], a VR taxonomy for healthcare[33], a survey of 200 medical VR/AR companies identifying 20 clinical sectors for XR[34], XR display taxonomies[35], VR/AR applications in education[27,30], AR/MR for medical rehabilitation[36], mobile health evaluation[29], and the MXR Field taxonomy[37].

3. Method

A taxonomy of evidence-based MXR applications could help create clear differentiations between different types of MXR technologies, users, and use case scenarios. It should be able to differentiate between various use cases and related MXR solutions within the MXR taxonomy and for a search within the MXR database. For instance, between a VR app for medical students based on an imitation of an endoscope coupled with a screen for training purposes, such as MIST VR[38], and a simulator with 3D capabilities for endoscope training purposes[30], or to identify the difference between an educational mobile phone VR game app such as Chilly Mo[36], a mobile game for children to experience cultural heritage in VR[36], from another playful mobile phone VR app for example, Pengunaut Trainer[39], which prepares children for MRIs.

As mentioned in the introduction our research only includes "evidence-based MXR apps". To be precise, we included all applications that had been empirically tested with representative end-users, as evidenced by public reports and scientific publications, ensuring their effectiveness and reliability. Only these evidence-based apps were selected from the broader pool of scientific publications about speculative MXR applications and application area proposals, identified in our searches. Some of these apps are MXR prototypes tested with representative end-users, some are on the path to governmental regulatory clearance, some already obtained it and are on the market, and some are wellness apps that do not require clearance from governmental bodies, but had positive effects reported. Positive effects are measured by longitudinal studies of positive health and wellness improvements, self-reports of improvements experienced by the users, and measurements of task or psychophysical changes that are better than without the use of the MXR app. We made a note of the status of development of the apps. The regulatory landscape for MXR apps is still evolving, with many governments still uncertain about the specifics of what they will regulate.

As our collective understanding of a new field expands, the need to define terms more precisely becomes more pressing. In line with the taxonomy-building methodologies used by previous researchers[29,30,36], the MXR apps taxonomy was structured using the taxonomy-building principles of facet analysis[39]. We created a glossary of terms alongside our taxonomy building work.

We now turn to the development of the evidence-based MXR applications taxonomy. Section 3.1 describes the central research question guiding our work. Section 3.2 discusses the guidelines used for constructing the taxonomy, followed by section 3.3, which covers the sample size and selection process. Section 3.4 details the search and selection strategy, while section 3.5 explains the criteria for inclusion. Section 3.6 introduces the researchers involved in the study, and section 3.7 provides an overview of our ongoing efforts to monitor innovations and expand the MXR app database.

3.1 Research question for the development of the MXR applications taxonomy

Our research question is: How do MXR apps intersect with the broader health journey? We want to include all medical, health, or wellness XR apps and digital health services that apply, extend, or have an impact on the digital health and wellness of humans. Additionally, we want to know how and where MXR apps fit into the entire health-journey.

3.2 Guidelines for the MXR taxonomy construction

Guidelines were created for selecting which new medical, health, or wellness app is in-scope and out-of-scope for our data collection, based on criteria outlined by Vargas[40]: the a priori identification and explicit formulation of the research question, search strategy, selection procedure, data extraction strategy, and data synthesis, in advance of the start of the search and selection process. See Table 1 for an overview of our Search and Selection Strategy.

| Database searched | Anything available online |

| Target Item | Evidence-based MXR apps |

| Search applied to | Keywords, Title, Abstract, Publication |

| Publication period | Up to July 2022, with some newer additions |

| Inclusion criteria | Publications that fulfill the search string, written in English, published up to July 2022 |

| Exclusion criteria | Publications that present future possibilities rather than evidence-based MXR apps |

MXR: medical eXtended reality.

3.3 Sample size and selection

Due to the fact that the MXR app field is rapidly growing, the items for the taxonomy categorization will expand accordingly. For this reason, it was decided to take two bounded samples from the landscape of available MXR apps and select only the evidence-based ones to create a hierarchical list of unique labels in order to start the construction of the taxonomy structure. The authors acknowledge that a taxonomy of MXR apps should be considered an evolving construct that needs to be updated on a regular basis as long as the MXR app field continues to develop. Due to the huge number of MXR apps being developed, this needs to be an ongoing, open-source effort.

3.4 Search and selection strategy for the MXR applications research

Search keywords are derived from the research question, and related terms that are found during the analysis should be utilized in further searches to enhance search comprehensiveness in the following way:

• Use the Boolean OR to include alternative spelling, labeling, synonyms, and related keywords;.

• Use the Boolean AND to link the main keywords.

The search and selection strategies are summarized in Table 1.

3.5 Criteria for inclusion

Three selection criteria utilized for the inclusion of the specific MXR apps in the selection for the MXR app taxonomy were defined as follows:

Criteria 1: Medical, Health, or Wellness XR product or service publicly available?

Criteria 2: Underwent one or more published successful evaluations with end-users?

Criteria 3: If required, in the process or achieved medical device regulation approval?

Criteria 3 allowed us to keep track of the regulatory status of the app in our database. Not all MXR apps, such as wellness apps, need regulatory approval. However, it is important to record regulatory approval status in general, as this is a lengthy process measuring positive effects multiple times. In order to test medical apps real end-users need to be using the devices over time. The taxonomy development process followed a top-down analysis to research previously developed taxonomies and their relevance to the selection of facets and categories for the development of our MXR app taxonomy. A top-down analysis is recommended to create an overarching system of data collection and analysis before developing the subsystems under it.

We subsequently used a bottom-up data collection method to collect the evidence-based MXR apps from online publications. A bottom-up analysis involves piecing together elements of the domain and adding any necessary subsystems to the initial system to achieve the final design for the structure of the taxonomy being built. This requires labeling the elementary categories of the taxonomy in unique detail and wording before it can be mapped with any matching facet or category of the MXR-related taxonomies developed by others, which we found during our top-down analysis of our literature research.

During this mapping process, all overlapping or ambiguous terminology has to be eliminated from the descriptive labels of the facets and categories. For example, the Motigravity app[41] would be labeled "VR-based Performance and Safety Training in Rehabilitation Medicine (for Space Operations)" and placed under the MXR Training facet in our MXR taxonomy because it is a VR-based training app for performance and safety for practitioners of rehabilitation medicine for space operations.

The bottom-up analytical process was useful for finding the currently available evidence-based MXR apps from the literature, analyzing the descriptions of the MXR apps, and creating unique labels to name each of the MXR app facets and categories we identified. The development of these facet and category labels adhered to the guiding principles of parsimony, comprehensiveness, and utility, and we selected the relevant information from the papers according to these guidelines:

Parsimonious: If there is no facet or category that the MXR app logically fits under, create a new one, either as top-level or sub-level, non-overlapping category labels if an evidence-based MXR app has been identified, without introducing unnecessary categories.

Comprehensive: Include all aspects of the MXR app purpose, i.e., user journey for which one or more evidence-based MXR apps have been identified.

Usefulness: Only include evidence-based MXR apps, not predictions of future apps, so that we get a clear picture of what exists and what has been underexplored.

Following these standard taxonomy-building practices allows us to collaborate internationally and avoids confusion during decision making, when taxonomy labeling and naming options are to be decided.

3.6 Background of the researchers who mapped the evidence-based MXR applications

The study was organized by the lead XR-HCI researcher, who has 30+ years of experience in the XR-HCI development field, a Ph.D. in systematic high-precision collaborative XR usability design and evaluation, a master's in clinical psychology and social informatics, and a Bachelor in Design. Twenty people conducted the second study: nineteen 1st year and 2nd year HCI Master's students with diverse educational and professional backgrounds such as Computer Science, Psychology, Design, Architecture, etc., and their XR-HCI professors.

3.7 Two samples and an ongoing monitor of innovations in MXR app space

We conducted three studies, which are described below. The first two studies consisted of sampling the available MXR apps and identifying the evidence-based MXR apps. The third study is ongoing, as we develop the database for the evidence-based MXR apps and find more items to include. In summary:

Study 1: searches were performed during March and April 2022.

Study 2: searches during two weeks in September 2022.

Study 3: the evidence-based MXR app search is ongoing.

We included all the evidence-based MXR apps that we have found so far.

4. Results

Our literature review identified three existing taxonomies with informative overlap for the design of the structure of our MXR app taxonomy. These three taxonomies have the most topics that are similar to our evidence-based MXR apps and application areas. This means that we could use them to inform the facets and categories of the MXR app taxonomy. These three taxonomies were: i) the medical MR taxonomy[4], ii) the UK healthcare XR review[34], and iii) the MXR field taxonomy[11]. The literature research for evidence-based MXR applications helped inform the structure of our evidence-based MXR application taxonomy. We present the results from our studies below.

4.1 First sample of evidence-based MXR apps

The first sample of MXR apps was categorized and placed in the order in which XR applications support medicine, health, and wellness service providers, practitioners, patients, and clients through their health journey by the lead XR-HCI researcher. During the initial MXR app taxonomy development phase, 62 evidence-based MXR categories were identified through a detailed analysis of the available literature, starting with the description of the keywords, title, and abstract. The first MXR apps taxonomy structure was based on three main facets of MXR application development, i.e. 1) the technology stack, 2) the purpose (where in the user-journey is it used), and 3) the users:

• The newly emerging MXR app technologies: VR, AR, MR, 360, etc.

• The purpose, aka medical, health, and wellness user journey : Prevention, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Care.

• The various MXR ecosystem stakeholders : Clients/Patients, Practitioners, Developers, Regulators, etc.

These three main facets can encompass all medical, health, and wellness XR apps, all the different types of potential end users, and all MXR use case scenarios. MXR apps represent a wide variety of use case scenarios. To illustrate the wide variety of use cases: MXR apps can be used for training and education of patients and practitioners or as a tool for practitioners, patients, and clients. Additionally, the MXR apps can be used for different treatment purposes by different types of practitioners and for different types of goals, including people doing self-treatments. Furthermore, MXR apps can be used for all kinds of information-collection and information-sharing purposes that can benefit the practitioner, the patient, or the client, and for informing the logistics of the care system. This data can be used before, during, and after doing the medical, health, or wellness work.

The first sample was based on the evidence-based MXR apps from the collection of 19 medical apps with FDA clearance, or in the process of obtaining it, listed in the first internal MXR device Working Group 2022 report by MDIC of which one of the authors is a member; 20 MXR application areas from the report about emerging XR Healthcare apps in the United Kingdom, a collaboration between NHSX, Health Education England Technology Enhanced Learning Team; and a 100-hour literature search by the authors. The 56 evidence-based MXR apps were analyzed in terms of health and wellness application area, and labeled and placed in the user-journey structure, formatted in a hierarchical taxonomy order (Table 2).

| Top Facets | Main Categories | Sub-Categories | Variations of Subcategories |

| Prevention | VR-based Wellness | VR-based Community Outreach after Disaster | |

| XR-based Fitness Training | XR-based Fitness Training Motivator for Physically/Intellectually Disabled | ||

| 360o Video-based Nature-Karaoke Therapeutic Singalong to Group Singing | |||

| Multi-User VR-based Emotional Connectedness to Alleviate Loneliness | |||

| XR-based Healthy Aging Skills Training for Patients and Medical Practitioners | |||

| VR-based Therapeutic Mindfulness | XR-based Interventions to Improve Self-Compassion for Women of Color in Workplace | ||

| XR for Youth Wellbeing: Positive Realities | |||

| AR/MR-based Transition of Care Support | |||

| VR-enhanced Therapeutic Meditation | VR-enhanced Therapeutic Meditation for Students with Complex Needs | ||

| VR-based Training of De-escalation Techniques and Strategies for Challenging Behaviors in Youth with a Focus on Racial/Gender Bias | |||

| VR-based Medical Practitioner Training | VR-based Medical Staff Wellbeing Treatment during Pandemic | ||

| 360 video-based Training Enhancing Empathy, Connectivity, and Humanistic Skills for Healthcare Staff | |||

| MR-based Virtual Ward Rounds Remote Access Medical Teaching | |||

| 360 video-based Virtual Tour of the Pathology Laboratories | |||

| AR-based Training for Pediatric Pandemic Preparedness/Disaster Preparedness | |||

| VR-based Clinician Procedural Education | |||

| VR-based Infection Control Training | |||

| Diagnostics and Pre-operative uses | VR Navigation test for Early Detection of Alzheimer's Disease by Differentiation of Mild Cognitive Impairment in the Entorhinal Cortex | ||

| VR-based Pre-Surgical Treatment Visualization for Patient Education | |||

| MR-based Presurgical Visualization for Surgeons and Surgery Teamwork Planning | |||

| XR-based Surgery Training | Volumetric OR Surgery Training | ||

| XR-based Training Simulation of Surgical Knot and Suturing Techniques | |||

| AR-based Medical Simulation for Pediatric Practitioner Training | |||

| XR-based Treatment and Interoperative Use | XR-based Remote Surgery for Long-Distance Surgery Assistance | ||

| XR Pain Management | VR-based Chronic Pain Management | VR-based Body Mapping Therapy for Chronic Pain Management | |

| VR-based Acute Pain Management | VR-based Pain, Fear, and Anxiety Stress Management during Treatment | ||

| VR-based Non-Pharmaceutical Analgesic | VR-based Pain Management during Dressing Changes for Burn Victims | ||

| VR-based Treatment Distraction for Podiatry Treatments | |||

| XR Anxiety Management | VR-based Therapy for Social Prescribing | ||

| VR-based Clinical Therapy for PTSD | |||

| XR-based Tools for Anxiety Regulation for Use within School | |||

| VR-based Clinical Exposure Therapy for Phobias | VR-based Fear of Heights Clinical Exposure Therapy | ||

| VR-based Clinical Exposure Therapy for Social Anxiety | |||

| VR-based Clinical Exposure Therapy for Fear of Flying | |||

| VR-based Autism Patient Skills Development Training | |||

| AR-based Communications Skills Training for Parents of Autistic Children | |||

| VR-based Clinical Treatment of Psychosis | |||

| VR-based Clinical Treatment of Depression | VR-based Psychedelic Simulation for Treatment of Depression | ||

| VR-based Clinical Treatment of Eating Disorders | |||

| VR-based Therapy with Virtual Embodiment Treatment for Auditory Hallucinations | |||

| VR-based Client/Patient Embodying, at Different Times, an Adult and Child Version of Themselves | |||

| Automated Therapy with Virtual Agents trained as Therapists | |||

| VR-enhanced Therapeutic Meditation for rehabilitation of patients with COPD | |||

| VR-based Art Therapy | |||

| VR-Based Pediatric Virtual Sandtray Play Therapy | |||

| XR-based Physical Rehabilitation | XR-based Neurorehabilitation for Neurological Conditions: Stroke, Spinal Injury and Multiple Sclerosis | ||

| XR-based Reinforced Feedback for Adult Stroke Patient Upper Limb Rehabilitation | |||

| VR-based Clinical Physiotherapy for Children with Upper Limb Motor Impairment | |||

| Intraoperative 3D Hologram Visualization for Surgical Teamwork Assistance | |||

| AR-based Intraoperative Guided Photoplethysmographic Visualization of Tissue Perfusion | MR-based Vein Visualization for Best Needle Injection Point Localization | ||

| Care and post-operative use | VR-based Fall Prevention Training for the Elderly | ||

| 360 video-based Virtual Reminiscing for Geriatric Activation in Care Home Settings | |||

| VR-based End-of-Life Existential Suffering Alleviation Solutions | |||

| VR-enhanced Therapeutic Meditation for Patients in Palliative Care |

MXR: medical eXtended reality; VR: virtual reality; AR: augmented reality; MR: mixed reality; 3D: three dimensions; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

4.2 The second sample of evidence-based MXR applications

The second study was undertaken to populate the taxonomy further and validate the construction of the new evidence-based MXR app taxonomy. This second sample study was conducted three months after the initial study. A systematic search and comprehensive analysis of the medical XR app domain was undertaken by nineteen HCI design and evaluation experts over a period of two weeks. Their assignment was to search for a minimum of 20 MXR apps. They examined the existing medical, HCI, and XR publications and commercial evidence-based MXR apps. They were asked to include evidence-based MXR products from companies and developers anywhere around the world. The facet analysis mapping methodology was explained to the students. Based on their analysis of the functionality of the evidence-based MXR apps, they identified the best category for the evidence-based MXR app. If the category already existed, they added the name and details to the initial MXR app taxonomy under the existing category, or if there was no appropriate category for the MXR app yet, they added a new category to the initial taxonomy outline. They used the precisely defined selection guidelines and the unique labeling scheme described in the Method section. They identified over 350 unique MXR apps. Their XR-HCI professor checked their entries for correctness and completeness. In total, 350 apps were found, and more than 20 new categories for the evidence-based MXR app taxonomy structure were added to the hierarchy during Study 2. Due to the exponential growth of the field of MXR apps, the categories are still expanding and being refined to cover all newly emerging types. The new version, of the extended taxonomy, can be seen in Table S1.

4.3 The third sample of evidence-based MXR applications

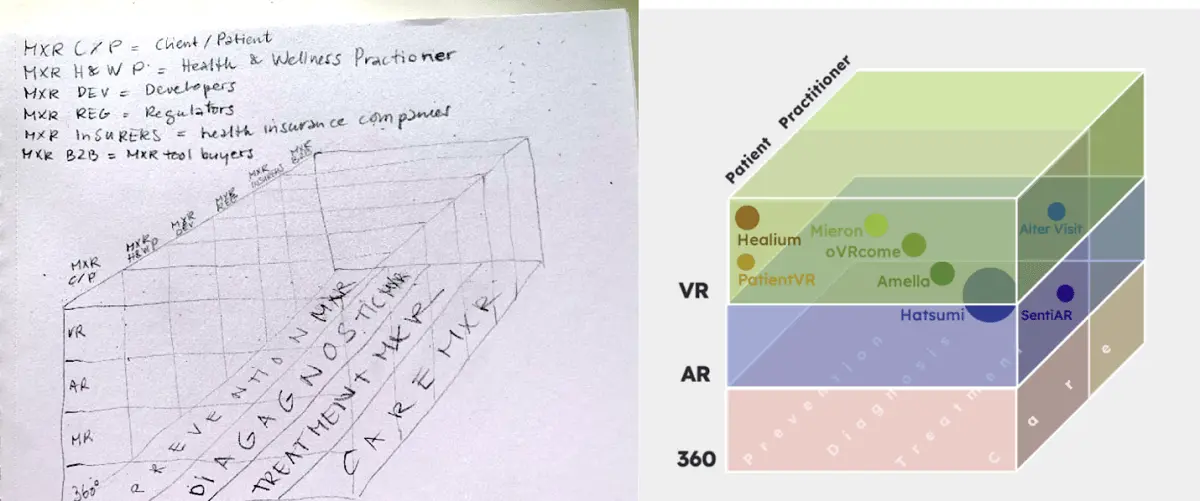

During the third study we created a MXR stakeholder analysis, a new MXR apps database and an interactive 3D graph of the MXR app space. The data in the database can be used for visualization of the MXR app landscape in a 3D computer-generated interactive multi-user space. We created several prototypes for the construction of a 3D graph. See Figure 1 for the first paper sketch and computer graphics sketch for the 3D visualization of MXR app space.

Figure 1. Sketches for the 3D visualization of evidence-based MXR apps: a paper and pencil sketch (left) and a digital depiction, using some commercial MXR apps to populate the 3D graph for example purposes (right). MXR: medical eXtended reality; VR: virtual reality; AR: augmented reality; MR: mixed reality; 3D: three dimensions.

Visualizations in 3D space can be very helpful for understanding the subsets within a large set of data. One of the properties of XR, which is the ability to provide multi-user digital information viewing spaces, is especially attractive for complex data visualizations and interactive 3D analysis. These multi-user interactive visualizations can be particularly valuable for MXR developers and users to share best practice data and for cross-disciplinary collaboration purposes. It was decided to use some time during our third study to create a multi-user interactive version of this graph in 3D computer graphics in a VR space, using Unity3Dtm to develop it.

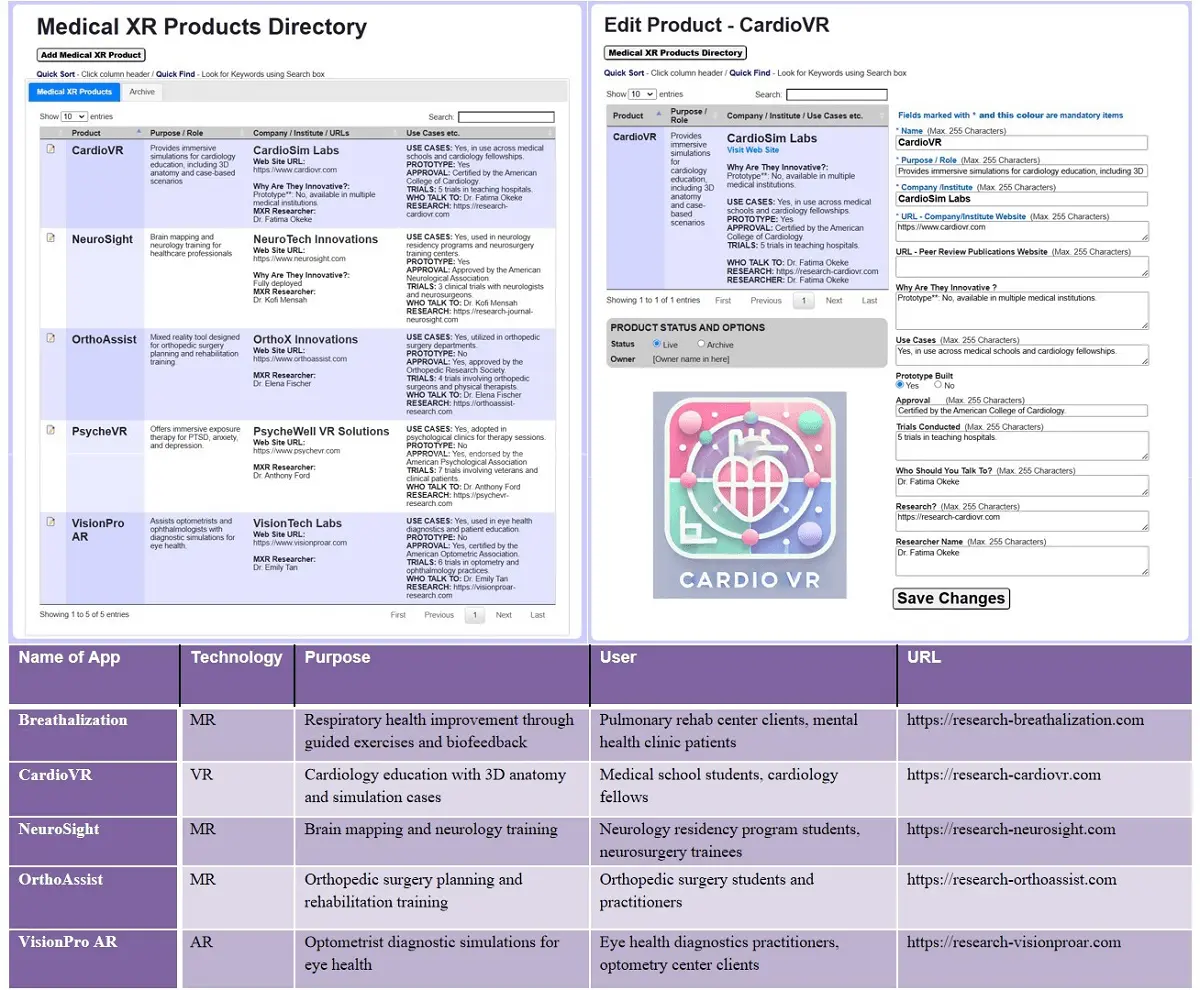

The third study is ongoing due to the rapid expansion of the MXR app field. We needed to focus on creating a bespoke database to organize and systematically keep track of all the collected information regarding MXR app development in this rapidly expanding field. The large amount of relevant data about MXR app development rather than MXR apps that we came across during our search for evidence-based MXR apps reinforced our need to create a structured database that can be used by all stakeholders of the MXR ecosystem. We created a pilot for this database using a community management system to be able to assign the different branches of the MXR app taxonomy to different curators, share the record of the MXR apps with the app owners, and connect aspiring MXR human factors expert reviews with the respective MXR app developers. See Figure 2 for two screenshots of the pilot database (left), the MXR app record editor of the database (right), and the output of a search query below (bottom) - please note these are fictional records to showcase the database functionality.

Figure 2. Screenshots of the MXR database design: Overview of MXR apps (top-left); Adding a new MXR app record to the database (top-right), and example query output from MXR database (bottom). MXR: medical eXtended reality; VR: virtual reality; AR: augmented reality; MR: mixed reality; 3D: three dimensions.

The database is built on a system called Agoria, see http://www.agoria.co.uk /, which allows the organization of people and topics into groups and subgroups. We found this community management solution an important additional functionality for our MXR community building purposes, because it will allow us to assign curators and members to specific MXR app topical groups and give them the ability to read, write and organize information, including events, within their group's topic for all members or selected members with access to the database.

The Agoria platform is robust and has been used by a wide variety of general community groups, resident associations, and social clubs (e.g. Basingstoke Science Cafe since 2013; the Association of Inter-Varsity Clubs UK since 2010; and ~50 other user groups around the UK, such as the Rugby Football Union and England Rugby Supporters Club with 1,750 clubs and around 500,000 members, and the World Institute For Pain Prevention (WIPP). The WIPP used the Agoria system between 2008 and 2019 for their 35+ chapters of pain researchers and anesthetists around the world. This enabled the WIPP to communicate with the pain research, anesthetics, and pain relief practitioner community to propose and advertise events, conferences, etc. Our mission is similar in that we want to enable MXR experts to curate the different branches of evidence-based MXR app types. Due to the exponential increase of MXR apps being developed and the need to distill best practices from the evidence generated by the user testing of these novel MXR apps, a systematic analysis is urgent.

During our research studies, we found a rich collection of information from diverse MXR development resources during our search for the evidence-based MXR apps. We decided to make a note of any information, even if not directly related to MXR apps themselves if there was any relevance to the MXR field in general. The following additional mappings were made if we came across anything relevant:

• Hardware: the technology provided for the medical XR experience.

• Software: the content presented to the different user groups.

• User Types: the different types of users and user groups.

• Developers: small, medium & large XR practitioners, companies, and projects.

• Resources: developers' tools, guidelines, frameworks & standards.

• Glossary of terms: disambiguation and definition of MXR terminology.

We started adding this information and the resources that we found relevant to the MXR app developers and stakeholder ecosystem to our MXR app database.

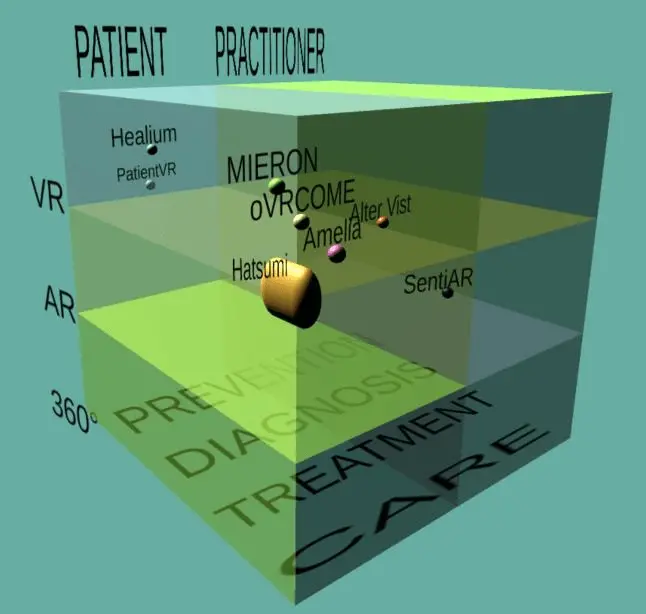

4.5 Dynamically visualizing evidence-based MXR applications in shared 3D space

During our MXR apps taxonomy analysis, we found that there are three dominant facets and a growing number of categories, with which we could place all MXR apps within a 3D space in a specific location based on their X, Y, and Z dimensions. Firstly, on the x-axis, for what purpose was the MXR app made: Prevention, Diagnostics, Treatment, or Care. Secondly, on the Y-axis, which XR technology is based on, a rapidly expanding technology stack: VR or AR, 360 photo/video, and other combinations of newly emerging technologies. Thirdly, on the Z-axis, by whom is it intended to be used: is it a tool catering to medicine, health, or wellness clients, patients, students, practitioners, healthcare providers, etc. Figure 3 visualizes in 3D the landscape of MXR apps, positioning them based on their intended purpose, technology, and target users. It depicts the evidence-based MXR application space in a 3D interactive computer-generated multi-user environment and shows some of the MXR apps in their location on the continuums.

Figure 3. Screenshot of the first 3D graph of MXR apps in a multi-user interactive MXR app 3D space, made in Unity3Dtm, by Jolanda Tromp and Mario Roman Blanco. MXR: medical eXtended reality; VR: virtual reality; AR: augmented reality; MR: mixed reality; 3D: three dimensions.

This 3D graph allows us to view the MXR app visualization of these characteristics in one dynamic interactive computer-generated 3D space. By locating the 3D icons for each MXR app within the computer-generated interactive 3D digital multi-user space, we can dynamically search and analyze the various MXR apps and their UXUI solutions for all the various stages of the health and wellness journey. The 3D graph can be dynamically adjusted by eliminating certain categories to view the different topics in the selected data in focused searches. For instance, to see only MXR apps that are made for medical practitioners to relax more efficiently between shifts, or only all VR apps that are for patients' self-healing exercises that patients use by themselves, or only all AR apps that are used by surgeons during surgery.

4.6 MXR ecosystem stakeholder analysis for evidence-based MXR development

Designing and implementing medical XR UXUI solutions effectively requires an understanding of the various needs, demands, and perspectives of different stakeholders. In the development of medical XR products/services, different stakeholders play pivotal roles in informing the best design choices. Aside from the developers, UX/UI designers, and testers, these other types of stakeholders encompass a broad spectrum, including regulation experts, insurers, clients, patients, students, teachers, and practitioners. The stakeholders involved in medical XR development can be categorized into at least seven groups (Table 3). We present an analysis of the degree of influence and importance of the different stakeholders during the four phases of the development process: design, test, build, and deploy. The stakeholder analysis shows the importance of each of the identified MXR stakeholder groups during each of the MXR development phases and when and why they need to be included and consulted during MXR development.

| STAKEHOLDERS | DESIGN PHASE | TESTING PHASE | BUILD PHASE | DEPLOY PHASE |

| Wellness clients | Influence: Moderate to high; user feedback can significantly impact app features and usability improvements. | Influence: Moderate; their feedback helps identify usability issues and ensures the app meets user expectations. | Influence: Low; direct involvement is minimal, though their needs guide the development priorities. | Influence: High; their adoption and reviews will determine the app's market success. |

| Wellness practitioners | Influence: High; their expertise and feedback can guide app development to better serve end-user needs. | Influence: High; their professional feedback is crucial for validating the app's effectiveness and usability in real-world scenarios. | Influence: Moderate; their requirements and expertise shape the development of features and functionalities. | Influence: High; their endorsement can drive client adoption, and their ongoing feedback helps refine the app post-launch. |

| Medical patients : | Influence: High; patient feedback is critical for ensuring safety and efficacy of medical XR applications. | Influence: High; their feedback is essential for ensuring safety, efficacy, and user-friendliness of the medical application. | Influence: Moderate; their needs and potential feedback influence design decisions and priorities. | Influence: High; their acceptance and usage determine the app's clinical success and market penetration. |

| Medical practitioners | Influence: High; their professional insights are crucial for clinical effectiveness and safety. | Influence: High; their clinical insights and validation are crucial for ensuring the medical reliability of the app. | Influence: High; their input is vital for developing accurate and reliable diagnostic and therapeutic tools. | Influence: High; their recommendations and integration into clinical practice can significantly impact the app's success and credibility. |

| Medical XR device developers | Influence: High; they are responsible for the technical feasibility and innovation of XR solutions. | Influence: High; they conduct testing, troubleshoot issues, and incorporate feedback from all stakeholders. | Influence: Very High; they are responsible for translating design requirements into functional and reliable applications. | Influence: High; they ensure the app is correctly deployed, and provide support and updates post-launch. |

| Medical XR device regulators | Influence: Very high; they have the authority to approve or reject devices and applications. | Influence: High; their approvals and certifications are necessary for moving the app from testing to deployment. | Influence: Moderate; their guidelines and requirements influence the development process to ensure compliance. | Influence: Very High; their final approval is essential for the app to be legally available to users. |

| Medical XR device healthcare insurers | Influence: High; their policies can influence user adoption and market success. | Influence: Moderate; their interest in efficacy and cost-effectiveness can influence the focus of testing efforts. | Influence: Low; they have minimal direct involvement, though their eventual coverage decisions can impact design considerations. | Influence: High; their coverage policies and endorsements can significantly affect user adoption and market success. |

MXR: medical eXtended reality.

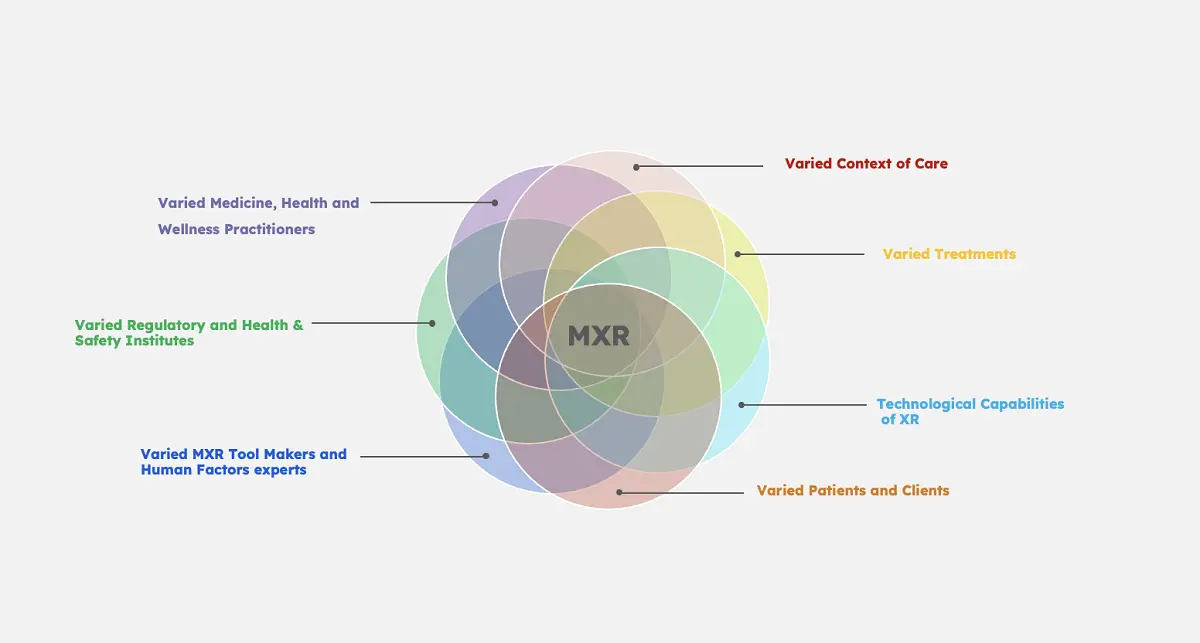

For MXR app users: clients, patients, and practitioners, there are three broad use case scenarios: training, education, and treatment. Additionally, some MXR apps are made for users to treat themselves, while other MXR apps are made for practitioners, to learn or train, or to use on their clients/patients. As more MXR apps are being conceived, there will be an influx of new types of MXR apps, leading to new subgroups being added to the taxonomy. There are also potential increases in terms of new types of end-users with diverging requirements that will require the addition of new sections within the main stakeholder categories, such as whether it is intended for training providers, teachers, medical managers, or nurses, physicians, medical device policymakers, etc.

These categories are expected to expand with the arrival of additional newly developed unique MXR application technology types on the market. The varied stakeholders in the MXR app ecosystem have different needs and expectations, and they all have to be considered for the safe and successful introduction of new MXR apps. Our MXR interdisciplinary stakeholder ven-diagram reveals the large gamut of desirable transdisciplinary expertise areas, and further diversification is expected to continue for a while. The ven-diagram is shown in Figure 4 as an impression of the varied stakeholders involved in MXR app design. The overlapping areas of the circles show the different combinations and permutations of required overlapping knowledge areas involved and what type of multi-disciplinary MXR experts are needed. These knowledge workers need to be enabled to engage in the best collaboration practices available to create the necessary and essential evidence-based MXR apps from which the best practices guidelines for MXR app tool makers can be derived.

Figure 4. The varied stakeholders of the MXR Ecosystem (image by: Shojaei). MXR: medical eXtended reality.

To successfully design MXR apps, designers and researchers have to analyze and intimately understand the user goals of the varied users, as well as the essential task steps each of these representative user types needs to take to achieve their goal[42]. Therefore, understanding each stakeholder's needs, issues, and requirements for using an MXR app is of the utmost importance. Understanding the complex user needs for high-precision and high-risk tools is clearly very important and can be greatly facilitated by using HCI user requirements research methods created to canvas the needs of the varied MXR ecosystem stakeholders listed in Figure 4.

5. Discussion

The MXR taxonomy was crafted to systematically classify and analyze evidence-based MXR applications through a structured framework based on three primary dimensions: the purpose, aka user journey through the medical, health, and wellness field, which we will label Purpose in our formula below, the Users, and the different XR Technologies. This framework ensures a detailed and adaptable classification system suitable for a rapidly evolving field.

Purpose: This dimension categorizes MXR applications according to their primary objectives within healthcare. The top-level categories include: Prevention, Diagnostics, Treatment, Care. Within each category, specific medical, health, and wellness specialties are incorporated, providing additional granularity. For example, under Treatment, categories might include Oncology or Cardiology.

Users: This dimension identifies the types of stakeholders who interact with MXR applications. Key user types include: Patients, Practitioners, Students. While these are the primary user types considered in this taxonomy, it is important to recognize that numerous other stakeholders are involved in the development and deployment of MXR applications, including developers, regulators, trainers, and more.

XR Technology: This dimension encompasses the types of XR technologies utilized in applications, specifically: VR, AR, MR. Additionally, emerging technologies like 360-Degree Photo and Video and Holograms exemplify the need for the taxonomy to be flexible and adaptable as new advancements in technology arise.

The taxonomy integrates these dimensions to create a detailed classification system. Each MXR application is categorized based on its purpose, the type of user it serves, and the XR technology it employs. This integration facilitates a thorough understanding of each application's role and functionality.

To enhance granularity, the taxonomy includes detailed aspects such as specific medical specialties and types of content within each purpose category. While this adds layers of detail, it does not introduce new dimensions but rather provides deeper specificity within the existing dimensions.

To quantify the number of potential categories and facets, we use the following formula:

Total Combinations = Purposes * Users * XR Technologies

Where:

Purposes: 4 (Prevention, Diagnostics, Treatment, Care); Users: 3 (Patients, Practitioners, Students); XR Technologies: 3 (VR, AR, MR).

Facets per Category = Users * XR Technologies

For each top-level Purpose category: Facets per Category = 3 * 3 = 9

Thus, for the entire taxonomy: Total Facets = 9 facets per category * 4 categories = 36 facets.

The MXR taxonomy's 36 unique facets are further detailed through sub-sections based on specific MXR tools for each of the medical, health, and wellness specialties. Each facet, representing a combination of Purpose, User, and XR Technology, includes multiple subcategories to capture the diversity within each area. For instance, within the Treatment + Practitioners + VR facet, there are subcategories for MXR tools for the various medical specialties such as Cardiology, Oncology, Neurology, and more. This hierarchical structure allows for detailed analysis and precise categorization of MXR applications, facilitating targeted research and development within specific medical, health, and wellness domains.

In contrast, there are at least 78 medical categories in the MXR Field taxonomy[11], encompassing a wide range of medical specialties. This ensures that the taxonomy provides a comprehensive and granular medical classification system. However, in the MXR Field taxonomy MXR apps are not yet labeled nor identifiable in terms of specific Purpose, User, or XR Technology type. Using 78 top categories we calculate the number of facets using 78[11] top categories instead of 4 (Purpose), while keeping the same users: 3 (Patients, Practitioners, Students) and the same number of XR technologies: 3 (VR, AR, MR), using the same formula as above:

Total Subcategories (facets) = 78 * 3 * 3 = 702

Thus, using 78 top categories, each combined with 3 user types and 3 XR technologies, results in a total of 702 unique facets in their MXR Field taxonomy[11], which creates a rather more unwieldy amount of options to place MXR apps in, and requires a deep medical background to be able to place the MXR apps correctly. While we acknowledge it is important for medical experts to check the allocation of MXR apps to the taxonomy, it should also be feasible for other MXR stakeholders to contribute to this task. The new evidence-based MXR app taxonomy approach presented here allows for a structured yet flexible taxonomy that captures the diversity of MXR applications while remaining adaptable to future technological advancements and evolving stakeholder needs.

With the rapid expansion of the evidence-based MXR app field, newly emerging categories and subcategories will have to be added to the MXR app taxonomy. To continue sampling the types of MXR apps available, another snapshot of available evidence-based MXR apps could be repeated on a regular basis or even continuously. MXR pioneers Yang & Varshney note that a categorization system is helpful when creating actionable suggestions for MXR researchers and practitioners[29].

The lack of a common overview of MXR apps in terms of what has been made so far, who is doing what, and the MXR terminology used to describe it creates difficulties in discussing the various opportunities between the experts from the different disciplines involved in medical XR solution development.

The time and resource-consuming effort of developing evidence-based MXR apps for digital health and wellness requires the global digital health community to take a more deliberate and coordinated approach to further identify and address MXR research and development gaps. It is recommended to make this a global action plan trail blazed by the Ministries of Health[43], the MXR researchers and developers, and informed by the medical practitioners[11], medical tool makers, and regulatory review specialists. Some early adopter examples are the recommendations report by the XRSI group to the Biden-Harris USA administration to advise them about the pressing issues that need regulations regarding building responsible, safe, and inclusive XR ecosystems[44] and the report on human rights in the age of neurotechnology, covering the impact, opportunities and recommended measures[45].

The evidence-based MXR app taxonomy analysis presented here, identified the current evidence-based MXR applications made by small, medium and large businesses, including information regarding the MXR standardization activities and MXR developers in the current MXR app development landscape. It was created to support and facilitate a multi-disciplinary dialog and provide a vocabulary for improving and accelerating communication and collaboration between all stakeholders.

6. Conclusion

MXR apps are poised to provide significant value in healthcare by promoting more decentralized, preventive, and therapeutic solutions in future healthcare ecosystems[16]. These innovations are crucial for meeting the evolving needs of global healthcare, aligning with Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG #3): "Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages," particularly SDG Target 3.8: "Achieve universal health coverage, including access to quality, affordable healthcare services" and medicines.

Global initiatives are addressing healthcare challenges described in the SDGs, focusing on improving regulatory pathways, expanding the use of Real-World Evidence (RWE) collection, and employing the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) for data collection. The advent of 5G/6G networks enables rapid data transfer, enhancing collaboration for remote MXR-supported interactions using IoMT and cloud computing. Continued development is needed to make MXR devices more affordable, user-friendly, and effective[46].

XR's advantages for medical, health, and wellness include 3D visualizations, touch-free interfaces for sterile environments[47], remote consultations, and easy capture of real-world data to personalize treatments. Additional value includes the ability to project multiple media on one display, richer 3D data fidelity, and more cognitively intuitive interpretations. Opportunities also exist to innovate device form factors, enhance viewing angles and magnifications, and improve XR UX/UI solutions[48-50].

6.1 Bridging borders: Overcoming global challenges in MXR app adoption and integration

Cross-national differences in medical, health and wellness classifications, terminology and licensing pose significant challenges to the global use and acceptance of evidence-based MXR apps. Key issues include:

• Terminology Variations: Different countries use distinct terms to describe similar medical, health and wellness issues and treatments, leading to problems for integration of evidence-based MXR app best design and evaluation practices and research data.

• Licensing Discrepancies: Licensing requirements for software, including MXR apps, vary greatly between countries. This includes differences in regulatory standards, intellectual property laws, and evidence-based certification processes and insurance-cover, making it difficult for developers to create universally compliant apps.

• Data Privacy and Security: Different nations have varying standards for data privacy and security, affecting how MXR apps handle user data. Compliance with one country's regulations does not guarantee compliance with another's, complicating global deployment.

• Cultural and Educational Contexts: MXR apps designed with a specific cultural or educational framework in mind may not be effective or relevant in another country. Local context is crucial for medical, health, and wellness user engagement and the perceived value of MXR apps.

• Healthcare and Clinical Standards: For MXR apps used in healthcare, different countries have unique clinical regulatory institutions, guidelines, and standards for what constitutes "evidence-based" practice. This can hinder the acceptance and integration of such apps into healthcare systems across borders.

These challenges require global efforts to integrate MXR app design, evaluation, and regulation best practices. Careful consideration of differences in local regulations and vocabulary, culturally appropriate contexts of use, and international collaboration and insurance coverage must be emphasized.

Our work involved building a taxonomy of evidence-based MXR apps. We created a database and a 3D visualization of the evidence-based MXR apps in a 3D interactive environment. Our mission is to help create a sustainable global MXR resource to keep track of the rapidly expanding MXR app field. We developed the MXR app taxonomy and database to facilitate the collaboration of all MXR stakeholders. Our vision is that specialized vocabulary and 3D multi-user visualizations of MXR apps will help identify and discuss the latest research outcomes of best practices. Additionally, the evidence-based MXR app taxonomy will help to identify the still unsolved innovation challenges for MXR app development.

6.2 Limitations of this study

While the scope of the analysis periods between February and September 2022 was relatively short, we have been working on another study to validate the structure of the MXR app taxonomy. It is clear that with the current exponential expansion of the field[11], to efficiently keep up with the new developments of MXR apps and best practices for UXUI, it is necessary to create an ongoing effort to collect the data to provide an up-to-date overview of the landscape. For this reason, we used a timestamp (a snapshot of what is available at a given time) approach to data collection. Rather than developing an exhaustive search which would have no end-point due to the exponential growth of MXR apps, using a timestamp of MXR apps available at that time provides a means to continue expanding the MXR app data collection into a semi-automated ongoing effort to collect data as it becomes available. Spiegel and colleagues’ new MXR Field overview has paved the way for a comprehensive overview of the issues that must be addressed for successful MXR app development and a way to organize MXR publications for the new Journal (https://home.liebertpub.com/publications/journal-of-medical-extended-reality/680/for-authors) for MXR[11]. Our findings for the MXR app taxonomy provided on the one hand, corroboration of the categories and on the other hand, additional new, evidence-based MXR application area labels, making the overview of MXR application areas more fine-grained and informative.

6.3 Future directions

Future work should focus on best practices and the most advantageous design and evaluation practices for developing successful MXR apps. Finding the best design practices for MXR app UXUI design and evaluation best practices to demonstrate the positive effects of using MXR apps is essential. Collectively, we need to prioritize and systematically analyze the data of different MXR app UX/UI solutions and the evidence-based evaluation results for different MXR app designs in different scenarios of use and for each of the various user types. The shared goal for the global MXR ecosystem is to find the best UXUI designs for the varied MXR technologies and stakeholders produced so far around the world.

Important areas for further MXR design research and innovation can be found in the realms of:

• Multimodal UXUI solutions : for task effectiveness, predictive modeling of human-computer interactions supportive of cognitive load management, and error reduction[51].

• Gamification : embedded in the UXUI of MXR apps for motivation and adherence.

• Integrating AI and ML : for dynamic, predictive modeling and personalized MXR app functionality of interface, task support, and treatment.

Exploring the range of existing and emerging immersive devices and technologies is essential, as they offer diverse solutions for interaction mappings and system architectures[52]. The plethora of different immersive devices and scenarios of use results in a lack of interoperability standards, a staggered workflow for content producers, and a less seamless and effective experience for the end-user[53,54]. Given the current exponential increase in MXR apps being created, it is vital to maintain an overview of the best practices and best approach for achieving rapid, incremental innovation, and this starts by mapping out the current evidence-based MXR apps.

For successful interdisciplinary collaboration and evidence-based regulatory reviews, it is vital to have a cross-disciplinary common best practice or standard for issues that need to be clarified to do empirical user tests and evaluations of the usability of MXR apps, such as how to formulate user study end-points, how to handle missing data, how to create control groups, developing the study question, equity considerations, generalizability of the data collected from samples, interoperability functional components if manufactured by different companies, and faster ways to establish fitness for continue to be urgent.

The overarching concern for the stakeholders in the national and international MXR ecosystem is to clarify how to achieve high-precision usability UXUI solutions for MXR apps, protect the privacy, health, and safety of the users, and identify the best evidence-based design and evaluation principles that have been tried and tested for MXR apps so far. It is important to identify best practices for MXR app development and share the evidence-based MXR app data labeling scheme to help create an internationally agreed ontology and to achieve international interoperable MXR technology components, best UXUI design and evaluation solutions, evidence-based positive care results, and homogenized, standardized, globalized end-point data comparisons.

Given a shared efficient vocabulary and overview of best MXR design and evaluation practices, multi-disciplinary teams can enhance healthcare interventions, improve medicine, health and wellness education and training, achieve universal health coverage, and promote well-being for all. Importantly, MXR apps can assist in addressing solutions for the challenges expressed in the 17 global sustainable health development goals.

The main challenge in the next two decades will be to tap the potential of multidimensional evidence generation by extracting, collating, and mining large sets of natural history data, genomics, and all other omics analyses, all published clinical studies, RWD, data from ubiquitous smart devices and amassed data from the IoMT and IoHT to provide next-generation evidence for deep medicine[54].

RWD collection and the development of shared MXR study end-points and globally applicable RCT guidelines for MXR, combining the research results in a shared data pool, should include testing the human experience as a whole, as the MXR device or service is used in situ, with actual representative end-users. It needs to include HCI-informed assessments of best design and evaluation practices for MXR apps in realistic use scenarios for the varied stakeholders. However, the data can only be used for scientific comparisons in a reliable empirical manner if there is an internationally agreed, homogenized, and accepted data format and a shared, accessible database.

What is needed to help formulate best practices for high MXR usability is similar to the International Medical Interventions Classification (ICHI)[55]. This is a standard tool for reporting and analyzing health interventions for clinical and statistical purposes, maintained by the World Health Organization (WHO), and the International Classification of Wellness (IWC)[56]. These international classification categories are relevant for the creation of the database of evidence-based MXR apps.

We presented our MXR app taxonomy findings above. The MXR app taxonomy labels were captured and stored in our database. The database allows groups and group leaders to organize events around a certain topic, which they can populate and curate relevant MXR design and evaluation best practices research findings. Our research provided additional insights into the landscape of MXR app developers and product stakeholders, and it enables the collaboration between "who is doing what" in the MXR field related to evidence-based MXR app development, standardization, regulation, sales, safety, and ethical long-term use.

Supplementary materials

The supplementary material for this article is available at: Supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the HCI Master students on the HCI 505 2022 course run by Assistant Prof. Tromp for the State University of New York in Oswego, USA, who participated in the MXR app research for their insightful findings and constructive contributions to the database of MXR apps. Fatemehalsadat Shojaei created the 3D MXR App sketch (Figure 1). Mario Roman Blanco created the MXR App multi-user interactive graph in Unity3Dtm (Figure 3). The database is being constructed by Bob Clifford and Dr. Tromp. The authors wish to express their gratitude and special appreciation to Sandra for her generous support and great editing feedback, Steven Max Patterson, Professor Greenleaf, John Bottoms, and Bob Clifford for their kind support and feedback.

The MDIC MXR WG documents and the Growing Value of XR Healthcare in the United Kingdom report, published online on May 18, 2021, have been valuable input for the evidence-based MXR application taxonomy.

This MXR app taxonomy research is dedicated to the memory of Mario Roman Blanco.

Authors contribution

Tromp JG: Conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing - original draft, review & editing, supervision, funding acquisition, validation, data curation, visualization, project administration.

Raeisian Parvari P: Visualization.

Le CV: Project administration, validation, data curation, writing - review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Tromp is on the journal's Editorial Board and an observing MDIC MXR Working Group member. Mr. Raeisian Parvari P is an alumnus of Dr. Tromp on the Master in HCI at the State University of New York in Oswego, NY, USA. Dr. Le is the director of the Company for Visualization and Simulation (CVS), at Duy Tan University (DTU) in Da Nang, Vietnam. Dr. Tromp is the Chief Metaverse Officer at CVS-DTU.

Ethical approval

The human data in our research is secondary data, which is already publicly available via scientific publications of the survey data, meaning that the ethics requirement for the research published here can be waived.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials could be obtained from the corresponding author.

Funding

The research and writing of this document were partially financed by Grassroots (Steven Max Patterson) (a small part of the work for sample 1) and wholly funded by Global Teamwork 3D (Dr. Jolanda Tromp) (all of the work for samples 1, 2, 3, and the evidence-based MXR App database development). ActivityForum (Bob Clifford, Bsc.) funded the Agoria database development.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2024.

References

-

1. Nasr M, Islam MM, Shehata S, Karray F, Quintana Y. Smart Healthcare in the Age of AI: Recent Advances, Challenges, and Future Prospects. IEEE Access. 2021;9:145248-145270.

[DOI] -

2. Manyika J, Chui M, Bisson P, Woetzel J, Dobbs R, Bughin J, et al. Unlocking the Potential of the Internet of Things. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com

-

3. Yee L, Chui M, Roberts R, Issler M. McKinsey Technology Trends Outlook 2024. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital

-

4. Chen L, Day TW, Tang W, John NW. Recent Developments and Future Challenges in Medical Mixed Reality. In: 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR); 2017 Oct 9-13; Nantes, France. Piscataway: IEEE; 2017. p. 123-135.

[DOI] -

5. Murthi S, Varshney A. Innovation: How Augmented Reality Will Make Surgery Safer. Harvard Business Review. 2018. Available from: https://hbr.org/2018/03/how-augmented-reality-will-make-surgery-safer

-

6. Kowatsch T, Otto L, Harperink S, Cotti A, Schlieter H. A Design and Evaluation Framework for Digital Health Interventions. IT Inf Technol. 2019;61(5-6):253-263.

[DOI] -

7. Venkatesan M, Mohan H, Ryan JR, Schürch CM, Nolan GP, Frakes DH, et al. Virtual and augmented reality for biomedical applications. Cell Rep Med. 2021;2(7):100348.

[DOI] -

8. Stern AD, Brönneke J, Debatin JF, Hagen J, Matthies H, Patel S, et al. Advancing Digital Health Applications: Priorities for Innovation in Real-World Evidence Generation. Lancet Digit Health. 2022;4(3):e200-e206.

[DOI] [PubMed] -

9. Evans J. The IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Extended Reality (XR) Report: Extended Reality (XR) Ethics in Medicine. In: Evans J, editor. The IEEE Global Initiative on Ethics of Extended Reality (XR) Report. 2022 Feb 14. Piscataway: IEEE; 2022. p. 1-31. Available from: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/servlet/opac?punumber=9714057

-

10. Greenleaf W, Roberts L, Fine R. Applied virtual reality in healthcare: Case studies and perspectives. 1st ed. Washington: Cool Blue Media; 2021.

-

11. Spiegel BMR, Rizzo A, Persky S, Liran O, Wiederhold B, Woods S, et al. What is medical extended reality? A taxonomy defining the current breadth and depth of an evolving field. J Med Ext Reality. 2024;1(1):4-12.

[DOI] -

12. Greenleaf W. How VR technology will transform healthcare. In: SIGGRAPH'16: Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques Conference; 2016 Jul 24-28; Anaheim, California. New York: ACM; 2016. p. 1-2.

[DOI] -

13. Greenleaf W, Roberts L, Fine R. Applied virtual reality in healthcare: Case studies and perspectives. Cham: Springer; 2021.

-

14. Rauschnabel PA, Reto F, Christian H, Shahab H, Alt F. What is XR? Towards a Framework for Augmented and Virtual Reality. Comput Hum Behav. 2022;133:107289.

[DOI] -

15. Greenleaf W. Walter Greenleaf on digital therapeutics, AR/VR, and sensor-driven health [Internet]. California: ApplySci Silicon Valley. 2020 Mar. Available from: https://vrforhealth.com

-

16. Yang E. Implications of immersive technologies in the healthcare sector and its built environment. Front Med Technol. 2023;5:1184925.

[DOI] -

17. Rawlins C, Dans M. 2019 Pathway Award® winner. Nurs Manag. 2020;51(10):9-14.

[DOI] -

18. NHS England. Global Digital Exemplars. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk

-

19. Milania AS, Cecil-Xavierb A, Gupta A, Cecila J, Kennisond S. A Systematic Review of Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) Research in Medical and Other Engineering Fields. Int J Hum-Comput Interact. 2022;40(3):515-536.

[DOI] -

20. Yang E, Colloca L. Implications of immersive technologies in healthcare sector and its built environment. Front Med Technol. 2023;5:1184925.

[DOI] -

21. Persky S, Colloca L. Medical extended reality trials: Building robust comparators, controls, and sham. J Med Internet Res. 2023;22:e45821.

[DOI] -

22. Gupta A, Cecil J, Pirela-Cruz M, Kennison S, Hicks NA. Need for Human Extended Reality Interaction (HXRI) framework for the design of extended reality-based training environments for surgical contexts. In: 2022 IEEE 10th International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH); 2022 Aug 10-12; Sydney, Australia. New York: IEEE; 2022. p. 1-8.

[DOI] -

23. Liu ZH. State-of-the-Art Human-Computer-Interaction in Metaverse. Int J Hum-Comput Interact. 2023;40(21):6690-6708.

[DOI] -

24. Chengoden R, Victor N, Huynh-The T, Yenduri G, Jhaveri RH, Alazab M, et al. Metaverse for Healthcare: A Survey on Potential Applications, Challenges and Future Directions. arXiv:2209.04160 [Preprint]. 2022

[DOI] -

25. Sun M, Xie L, Liu Y, Li K, Jiang B, Lu Y, et al. The Metaverse in Current Digital Medicine. Clin eHealth. 2022;5:52-57.

[DOI] -

26. Shojaei F, Shojaei F, Desai AP, Long E, Mehta J, Fowler NR, et al. The Feasibility of AgileNudge+ Software to Facilitate Positive Behavioral Change: A Mixed Methods Design. JMIR Form Res. 2024;8:e57390.

[DOI] -

27. Shojaei F. Exploring Traditional and Tech-Based Toddler Education: A Comparative Study and VR Game Design for Enhanced Learning. In: Arai K, editor. Advances in Information and Communication. Proceedings of the Future of Information and Communication Conference; 2024 Apr 4-5; Berlin, Germany. Cham: Springer; 2024. p. 448-460.

[DOI] -

28. Nickerson RC, Varshney U, Muntermann J. A method for taxonomy development and its application in information systems. Eur J Inf Syst. 2013;22:336-359.

[DOI] -

29. Yang A, Varshney U. Mobile health evaluation: Taxonomy development and cluster analysis. Healthc Analyt. 2022;2:100022.

[DOI] -

30. Motejlek J, Alpay E. Taxonomy of virtual and augmented reality applications in education. IEEE Trans Learn Technol. 2021;14(3):415-429.

[DOI] -

31. Broughton V. Facet Analysis: The Evolution of an Idea. Cat Classif Q. 2023;61(5-6):411-438.

[DOI] -