Abstract

In the evolving landscape of digital childhood, ensuring safe environments within the Extended Verse (XV) is essential for preventing trauma and fostering positive experiences. This paper proposes a conceptual framework for the integration of advanced emotion recognition systems and physiological sensors with virtual and augmented reality technologies to create secure spaces for children. The author presents a theoretical architecture and data flow design that could enable future systems to perform real-time monitoring and interpretation of emotional and physiological responses. This design architecture lays the groundwork for future research and development of adaptive, empathetic interfaces capable of responding to distress signals and mitigating trauma. The paper addresses current challenges, proposes innovative solutions, and outlines an evaluation framework to support an empathic, secure and nurturing virtual environment for young users.

Keywords

1. Introduction

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child stands as a cornerstone in safeguarding the well-being of children worldwide. With its 54 articles encompassing every aspect of a child's life, the Convention establishes a comprehensive framework of civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights[1]. These rights, universal and indivisible, apply to every child without discrimination and place a responsibility on adults and governments to ensure their fulfilment. As we venture into the realm of extended reality and virtual worlds, it becomes imperative to translate these fundamental rights - including the right to play, freedom of expression, safety from violence, and protection of identity - into new digital landscapes.

The Extended Verse's (XV) immersive nature amplifies user experiences, both positive and negative. Its heightened sense of presence can deepen learning and social connections, but it also intensifies the impact of harmful encounters, potentially leading to lasting trauma[2,3]. This dichotomy necessitates a proactive approach to safeguarding children in these digital realms.

This research explores innovative solutions at the intersection of technology and child protection within the XV and proposes integrating advanced emotion recognition systems with physiological sensors to create intelligent, responsive, empathic environments. The framework aims to detect and mitigate potential threats in real-time, fostering a safe space for young users to explore, learn, and interact.

By leveraging machine learning and adaptive interfaces, we envision a framework that not only shields children from harm but also enhances their digital experiences. This paper outlines a methodology for developing and evaluating a protective system, considering both the technical challenges and the ethical implications of implementing such technologies in children's digital lives.

Through this research, we aim to contribute to the creation of a more secure and enriching XV, where the potential of immersive technologies can be harnessed for the benefit of young users, without compromising their safety or well-being.

2. Related Works

The rapid advancement of digital technologies has given rise to a complex landscape of immersive experiences, blending physical and virtual realities. This text explores the concept of the XV, situating it within the broader context of virtual, augmented, and mixed realities, as well as spatial computing technologies. This exploration serves as a foundation for understanding the challenges and opportunities presented by these evolving digital environments.

This complex landscape necessitates a clear definition of the XV[4]. XV is contextualized within the broader spectrum of virtual, augmented, mixed, realities and spatial computing technology, providing a framework to explore the future of digital interactions. Virtual Reality (VR) immerses users in fully digital environments through specialized equipment[5]. Augmented Reality (AR) overlays digital content onto the real world without physical interaction[6]. Mixed Reality (MR) enables interaction between real and virtual objects[7].

XR, commonly known as extended reality, serves as a broad term encompassing various concepts, AR and VR[8]. According to the framework presented by Rauschnabel et al., XR is more accurately used to denote xReality, with "x" representing a spectrum of realities such as augmented, assisted, mixed, virtual, atomistic virtual, holistic virtual, or diminished[8,9]. In this framework, VR involves creating an artificial, user-centric environment that is enclosed in a 3D space, distinct from the physical world[8]. Users' experiences in VR range between atomistic and holistic virtual realities[8]. AR is described as a hybrid experience where virtual elements are contextually integrated with the user's real-time physical environment through computing devices. This integration results in a coexistence of digital and physical content, closely tied to the user's surroundings[6,8].

Furthermore, the metaverse, as a concept, has emerged as a collective virtual shared space, created by the convergence of virtually enhanced physical reality and physically persistent virtual space[10,11]. The World Economic Forum defines the metaverse as a future persistent and interconnected virtual environment where social and economic elements mirror reality. Users can interact with it and each other simultaneously across devices and immersive technologies while engaging with digital assets and property[12]. Mann et al. introduced the "XV" to describe a comprehensive vision of the digitally enabled realities, including VR, AR, MR and XR experiences. The concept of XV, uses the analogy of "atoms versus bits" to highlight a significant paradigm shift[4]. This shift reflects the transition from a world dominated by physical atoms to one increasingly defined by digital bytes. The term XV provides a broader framework for understanding the future of virtual worlds as a blend of organic (atoms) and computer-generated (bits) realities in which the physical and the digital are blurred. The concept of XV is of value because it encompasses not only immersive technologies AR, VR, MR, XR and the metaverse, but also a wider range of shared perceptual experiences, such as shared events, share experiences, visceral movement, non-verbal communication, and emotional resonance of the human experience[4]. It suggests an expansive, collaborative sensory realm that mirrors the potential of shared experiences. In the context of children's experiences, the shared digital environment of the XV can enhance the ways they connect and play with others, regardless of physical location[13]. Additionally, in these shared virtual spaces, children can use their bodies as direct interfaces for communication. With facial and full-body tracking, interactions in the digital environment can mimic face-to-face communication, making it easier and more natural for them to connect and express emotions. This includes the ability to express emotions and social engagement in social VR, as well as use nonverbal communication methods like gestures, on one end such as fist bumps, high-fives, poking, to more personal shoulder touches[14], embraces, physical intimacy and sexual activities. The immersive nature of XV can make experiences feel more real and impactful[15,16].

Every day, millions engage with XV technologies, and projections indicate that the VR sector will expand to $20.9 billion by 2025, while AR is expected to reach $77 billion. In 2022, global sales of VR headsets reached 8.8 million units, with Meta producing about 80% and ByteDance's Pico headsets accounting for 10%. Other significant contributors to global sales include DPVR, HTC, iQIYI, and Xreal[17].

The demand for both VR and AR headsets is substantial. Meta has sold nearly 20 million Quest VR headsets to date[18]. In May 2023, Sony announced that its PSVR 2, a next-generation VR gaming headset, sold approximately 600,000 units in the first six weeks post-launch, an 8% increase over its predecessor's 450,000 units[19]. In the AR market, Xreal sold 100,000 devices in 2022 alone, solidifying its status as the leading AR device company, with total sales exceeding 150,000 units[20].

Ownership of VR devices among children and young people is also on the rise. A Piper Sandler study from spring 2023, involving over 5,600 adolescents with an average age of 16.2 years, found that 29% owned a VR device[21]. This figure represents a 3% increase from the previous year and a 12% rise since 2021, when a Common Sense Media survey reported that 17% of minors aged 8 to 18 owned a VR headset[22].

The Institution of Engineering and Technology's 2022 study also reveals that more than a fifth of 5 to 10-year-olds (21%) already have a VR headset of their own or have asked for a similar tech present for their birthday or Christmas. Further, 15% of them were recorded as saying they have already tried VR, while 6% said they use it on a regular basis[2].

Despite some scepticism regarding consumer engagement, interest in VR technologies continues to rise[23]. Meta, a dominant force in the VR space, reported approximately 200,000 monthly active users in its virtual world, Horizon Worlds, by late 2022[18]. Although this figure was below their internal goal of 500,000 users, it reflects a substantial user base exploring virtual environments. Meta has been attempting to increase teenage XR usage in part by opening Horizon Worlds to children aged 13 to 17 - children over the age of 13 are already able to use Meta's Quest headset[24].

AR is gaining traction, particularly in e-commerce with Snap's AR-powered "Shopping Lens" have seen adoption, with over 250 million users interacting with these features more than 5 billion times between January 2021 and February 2022[25]. Pinterest's "Try On" feature has also experienced growth, allowing users to visualize home decor items in their spaces before purchasing, with its popularity more than doubling from 2020 to 2021[26]. Users can engage with avatars, discuss products, and view items from multiple angles, enhancing the shopping experience. AI-generated avatars capable of multilingual interactions further enrich this immersive environment[27].

Interest in virtual worlds such as Roblox, Minecraft and Fortnite continues to surge, with 350 million, 175 million and 75 million monthly active users respectively[10]. This growth is indicative of a broader trend where virtual worlds are becoming integral to digital socialization and entertainment, particularly among younger demographics. The platforms' success is mirrored by their revenue generation and developer earnings, highlighting the economic potential of virtual worlds. Moreover, the launch of Roblox on Meta Quest in October 2023[28] further underscores the increasing demand for accessible and immersive virtual experiences.

Additionally, the collaboration between Disney and Epic Games marks a significant expansion in the realm of virtual entertainment, as they aim to create an expansive game and entertainment universe connected to Fortnite. Disney's investment of $1.5 billion in Epic Games underscores the strategic importance of this partnership, which will leverage Epic's Unreal Engine, a versatile 3D computer graphics game used for creating video games, films, architectural visualizations, and other real-time applications, to integrate Disney franchises such as Marvel, Star Wars, and Pixar into a persistent, open ecosystem. This initiative not only enhances the gaming experience but also allows fans to engage with Disney's stories and characters in innovative ways, reflecting the growing trend of immersive digital worlds. The partnership builds on previous successful collaborations, including the Marvel Nexus War event in Fortnite, and highlights Disney's commitment to expanding its digital footprint through strategic alliances and cutting-edge technology preparing to take, even its youngest users, into the XV[29].

Electronic Arts (EA), a prominent entity in the digital entertainment industry, has established a substantial global presence in the interactive gaming sector[30] with successful VR gaming offerings including EA SPORTS FC, Madden NFL, and Need for Speed contributing to sports fandom[31]. Recent data indicate that EA's user base has reached approximately 500 million individuals worldwide[32]. EA reports 150 million monthly active users and 50 million daily active users, the average play time per user is estimated at 2 hours per day. EA's approach to virtual worlds encompasses persistent online environments, user-generated content platforms, and evolving game ecosystems. These statistics underscore EA's substantial market reach and provide context for the company's ambitious goal to double its global audience to over one billion users within a five-year timeframe[33].

Furthermore, the child's experience of education has been significantly transformed by the rapid evolution of technology in recent years. The advancements in VR, which have introduced novel methods for content engagement for both educators and students[9,34]. The potential benefits of these technologies have been well-documented in academic literature. For instance, they have been shown to alleviate speaking anxiety among language learners[35], foster creative and critical thinking skills[36], and enhance overall engagement in the learning process[37].

There is a growing body of academic literature exploring the use of XV in paediatric healthcare. Studies have demonstrated that VR can effectively reduce pain and anxiety in pediatric intensive care units (PICUs), offering immersive distractions during medical procedures and facilitating engagement in physical therapy for children[38]. MR applications have been found to improve engagement and therapeutic outcomes in paediatric patients, enhancing the overall healthcare experience[39]. Additionally, XV technologies are increasingly utilized in medical education, enhancing training and patient education not only improving medical education for healthcare providers but also offering interactive and engaging forms of patient education tailored to children[40-42].

The integration of XV technologies in these areas of children's lives suggests a future where digital and physical realities seamlessly blend, offering enhanced learning experiences, improved healthcare outcomes, and potentially new forms of social interaction and entertainment. As these technologies continue to evolve, they are likely to become increasingly integral to children's daily experiences, shaping their understanding of and interaction with the world around them.

2.1 Regulator landscape and challenges

The global regulatory landscape for XV technologies presents numerous challenges for governments worldwide. One primary obstacle is the lack of consensus on defining these technologies, particularly the "metaverse." A recent study revealed over thirty distinct definitions, highlighting the complexity of regulating a concept that lacks a unified understanding[43]. Another significant hurdle is the issue of jurisdiction. XV platforms operate across borders, while regulations are typically confined to specific jurisdictions. This discrepancy results in uneven legal protections for users globally. For instance, European citizens benefit from robust data privacy laws, whereas residents in certain U.S. states with limited data privacy legislation have minimal safeguards[44]. The question of legal jurisdiction over XR-related offenses, especially when perpetrators are in different countries, further complicates matters[45].

At the federal level in the United States, there is a growing appetite to regulate XV technology, with over 60 bills containing references to virtual, augmented, or mixed reality introduced in Congress. However, there are currently no comprehensive laws or regulations specifically addressing the unique privacy and content moderation challenges posed by XV technologies[46]. The federal privacy framework in the United States is characterized by a collection of domain-specific statutes, such as the Fair Credit Reporting Act, HIPAA, COPPA, GLBA, and FERPA. These laws are limited in scope, focusing on specific types of data and purposes rather than providing comprehensive protection for all information types. For instance, while XV technologies can gather extensive sensitive health-related data, HIPAA does not cover this data unless it is used within healthcare or insurance contexts. Consequently, many XV hardware and software companies, including health and wellness apps, fall outside HIPAA's jurisdiction, leaving the data they collect unprotected[47]. Similarly, federal computer crimes law provides little recourse for harms like sexual harassment and bullying in virtual worlds[48]. Experts argue that Congress should reinforce the Federal Trade Commission's mandate to protect consumers against unfair and deceptive practices by XV platforms or create a new specialized federal body to regulate the technology[49].

Recent congressional efforts to protect children online have led to the introduction of several bills, including the Protecting Kids On Social Media Act, the EARN IT Act, and the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA)[50-52]. While KOSA makes some explicit references to XV environments, the applicability of content moderation provisions to XV platforms remains unclear due to potential limitations in the definitions of "content" and "covered platforms"[52]. These proposed regulations may conflict with existing children's privacy rights under the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA), potentially exposing children to further privacy risks through age verification or content scanning processes[53].

The United Kingdom's approach to regulating XV technologies and metaverse-like environments is primarily centred around the Online Safety Act (OSA), which targets social media companies and user-generated content platforms, "user-to-user service[s]," defined as "internet service[s] by means of which content that is generated directly on the service by a user of the service, or uploaded to or shared on the service by a user of the service, may be encountered by another user, or other users, of the service," but it is unclear if XR services like social VR worlds meet this definition[54]. However, the bill's applicability to XV platforms remains ambiguous. The Institution of Engineering and Technology has argued that while the act applies to immersive environments, its current content definition fails to adequately address the breadth of live activities occurring in XV spaces or protect users from harmful immersive digital experiences[55]. Even if the OSA is deemed applicable to XV environments, compliance with certain provisions may prove challenging, particularly in moderating inherently visceral and ephemeral experiences within the complexity of XV spaces.

Australia's regulatory approach to XR technologies is primarily driven by the eSafety Commissioner[56]. The Commissioner has identified various risks associated with XV, including cyberbullying, privacy intrusions, addiction, and potential sexual harassment in immersive experiences[56]. In response, the Commissioner's Office has launched several initiatives: public awareness campaigns to educate parents about safe gaming environments, a "Safety by Design" program requiring XV developers to prioritize user safety, and resources for individuals affected by virtual harms[57].

The European Union's Better Internet for Kids (BIK+) strategy, adopted in May 2022 as the digital arm of the 2021 EU Strategy on the Rights of the Child, outlines a comprehensive approach to enhancing online safety for children[58]. This multifaceted strategy encompasses several key initiatives: the development of an EU code of conduct on age-appropriate design, aligned with existing regulations such as the Digital Services Act, General Data Protection Regulation, and Audiovisual Media Services Directive; the establishment of a European standard for online age verification; the enhancement of child helpline services to address cyberbullying; the promotion of media literacy campaigns targeting children, parents, and teachers; and the co-funding of Safer Internet Centres in Member States to raise awareness and foster digital literacy[58].

Ultimately as the landscape of XV technologies continues to evolve, policymakers face ongoing challenges in balancing child protection with privacy concerns, suggesting a need for further refinement of proposed legislation[44].

2.2 Potential risks in the XV

Children may be drawn to non-child-friendly VR spaces within platforms due to curiosity, peer influence, and the allure of social interaction, despite the minimum age requirement of 13 years. Platforms often lack strict age verification processes, allowing underage access to environments that are for adult usage and exposing children to significant safety and privacy risks, including inappropriate content and cyberbullying[14]. As participation in XV environments continues to rise among younger populations, it is imperative to implement robust safety protocols and parental controls to ensure a secure and positive experience for children[59]. Additionally, understanding the perspectives of parents and guardians on the appropriateness of social VR for children is crucial in developing effective safeguarding measures[60].

To uphold the rights of children as outlined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), it is crucial to prevent trauma in both physical and virtual environments. As we extend these protections into the realm of XV worlds, we must address the potential sources of trauma that can compromise these fundamental rights[61].

Trauma can be defined as psychological or emotional harm resulting from negative experiences[62]. Several potential sources of trauma in the XV. These include sexual grooming, harassment, and assault in XV multi-user spaces, exposure to inappropriate content such as underage access to VR pornography, and child sexual abuse simulations in VR, and child exploitation[63]. Additionally, avatar-based child sexual exploitation in VR environments poses a significant risk. Furthermore, the physical body disassociation and avatar transference experienced by users[64-67], which can amplify harm to children and offenders.

Despite the potential of XV, several challenges are apparent. One of the primary challenges is the current limitations for safety. Many existing platform safeguards rely on user-driven reporting and community moderation, which are often insufficient to protect from harm[68,69] and a lack of support for parents and educators to support prevention[70,71,2].

By recognizing and addressing these potential sources of trauma, we can better ensure that children's rights are preserved in digital landscapes. This proactive approach aligns with the Convention's mandate to protect children's rights universally and without discrimination. Recent studies have shown the potential of digital games and virtual reality applications in child abuse prevention and education[72]. Additionally, online education for healthcare and social service providers has been developed to improve recognition and response to child maltreatment[73]. Implementing trauma-informed practices in virtual environments, similar to those used in schools[74], can further support children's well-being in these new digital frontiers.

2.3 Framework for safe XV experiences

XV technologies offer innovative solutions for trauma prevention in virtual environments through advanced emotion recognition systems[75,76]. These systems utilize algorithms to analyze facial expressions, voice tones, and physiological signals, identifying and responding to distress in real-time. The integration of physiological sensors, such as heart rate monitors and galvanic skin response sensors, with machine learning algorithms enhances accuracy and enables adaptive responses to mitigate potential trauma[77,78]. Machine learning algorithms also analyze patterns of behavior and interactions within virtual environments, identifying potential risks and flagging them for investigation[79,80]. By leveraging large datasets of user interactions, these algorithms can recognize subtle indicators of harmful behavior, such as grooming or harassment, and take proactive measures. For instance, studies have explored the use of wearable devices that monitor emotional states by analyzing physiological data in real-time, enabling applications in various settings, including workplace stress management and mobile advertising[81-83]. This integration of physiological signals with user interfaces aims to create responsive systems that can adapt to users' emotional states, thereby improving user experience and emotional well-being[84]. This approach not only enhances safety but also provides valuable insights into user interactions, informing the development of effective safety measures and supporting crime investigation in immersive environments[63].

Incorporating features that promote positive social interactions and skill development further enhances children's safety and well-being in XV[59]. This includes designing activities and experiences that encourage cooperation, empathy, and resilience, as well as providing tools and resources for children to learn and practice healthy coping strategies. By fostering a supportive and nurturing virtual environment, children can build the skills and confidence needed to navigate the challenges of the XV safely[71].

Integrating XV safety into educational resources and training programs for professionals, such as teachers and law enforcement, is crucial to address the multifaceted influences of key stakeholders. Facilitating cross-sector collaboration across domains like education, health, criminal justice, academia, and industry helps develop a collective understanding and response to XV-related risks[71].

Designing adaptive and empathetic interfaces supports the creation of safe and supportive XV for children[5,71]. One strategy for mitigating distress and potential trauma is implementing adaptive content moderation using AI-driven systems to monitor interactions and identify harmful behaviour. When such behaviour is detected, the system can intervene by removing offending content, issuing warnings to perpetrators, or providing support to affected users[70].

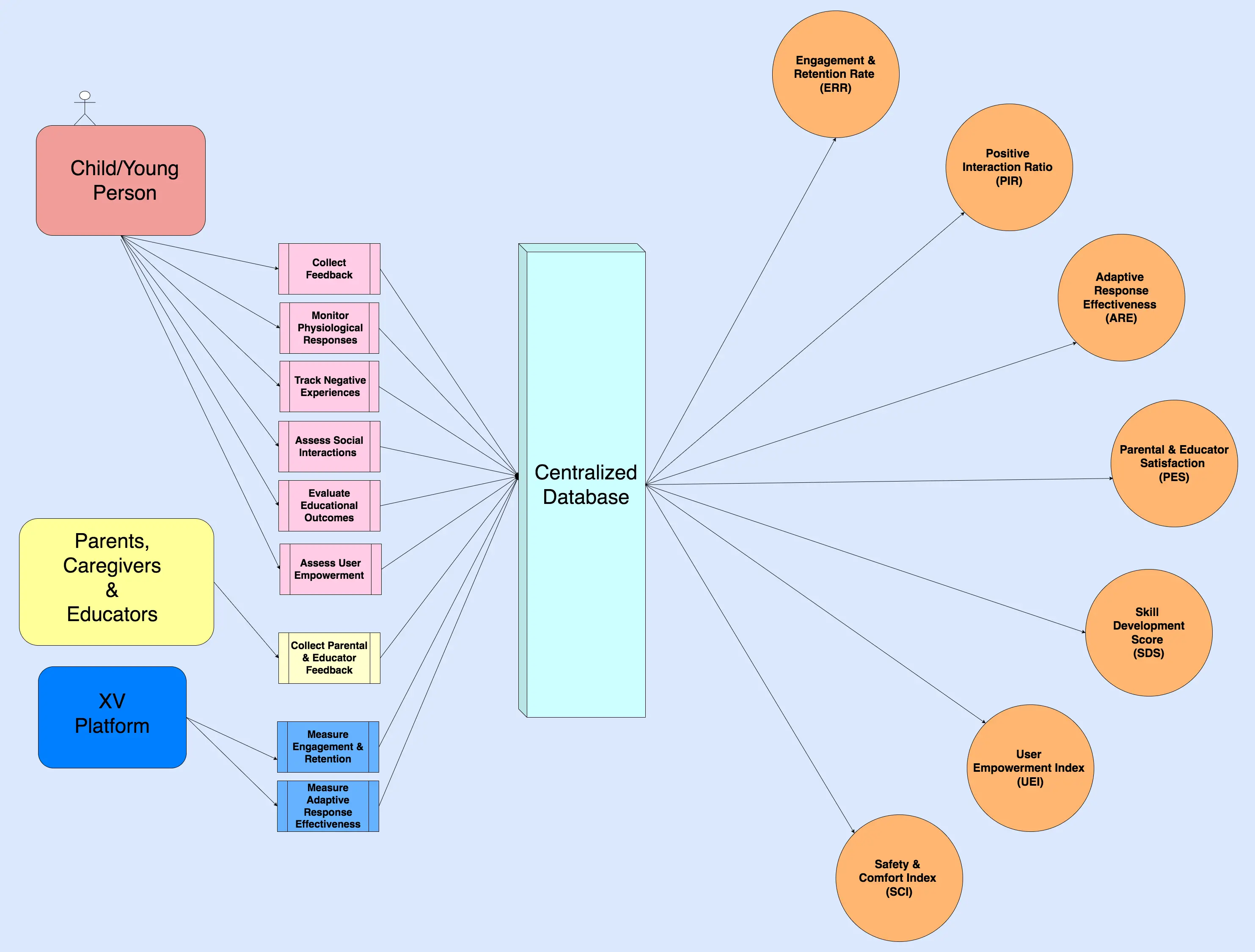

This framework integrates cutting-edge technologies, such as emotion recognition and adaptive content moderation, with user-centric design principles and cross-sector collaboration[85,86] Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 are original contributions developed by the author to address gaps in existing evaluation frameworks for children's safety in XV environments. Figure 1 presents a comprehensive visual representation of the XV Framework, designed to evaluate and enhance the experience of children in extended virtual environments. At its core, the framework emphasizes a holistic approach to XV interaction, balancing safety measures with user empowerment. Key elements include mechanisms for collecting and integrating feedback from multiple stakeholders, including parents and educators, ensuring a well-rounded perspective on the child's virtual experience. The framework's structure illustrates the complex interplay between various factors influencing a child's engagement with XV platforms, from initial interaction to long-term developmental impacts. By visualizing these relationships, Figure 1 sets the stage for a nuanced understanding of how different aspects of virtual environments contribute to overall user safety, comfort, and positive outcomes. This diagram serves as a foundational tool for researchers, developers, and policymakers working to create and assess child-friendly virtual spaces, offering a structured approach to navigating the multifaceted challenges and opportunities presented by emerging XV technologies.

Figure 1. Data flow diagram, interconnected components of the XV evaluation framework for children. XV: Extended Verse.

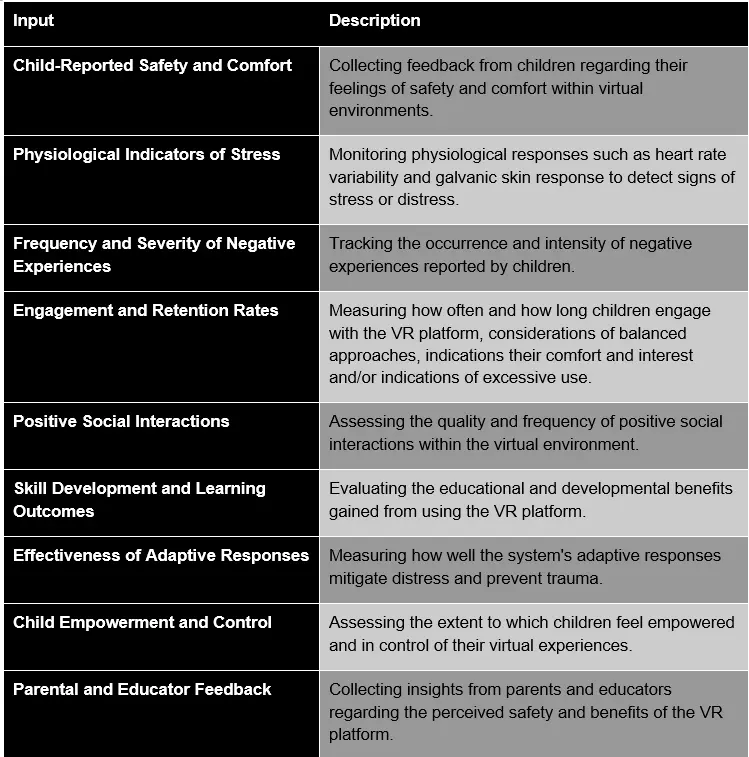

Figure 2. Key performance inputs for assessing child safety and well-being in XV platforms. XV: Extended Verse.

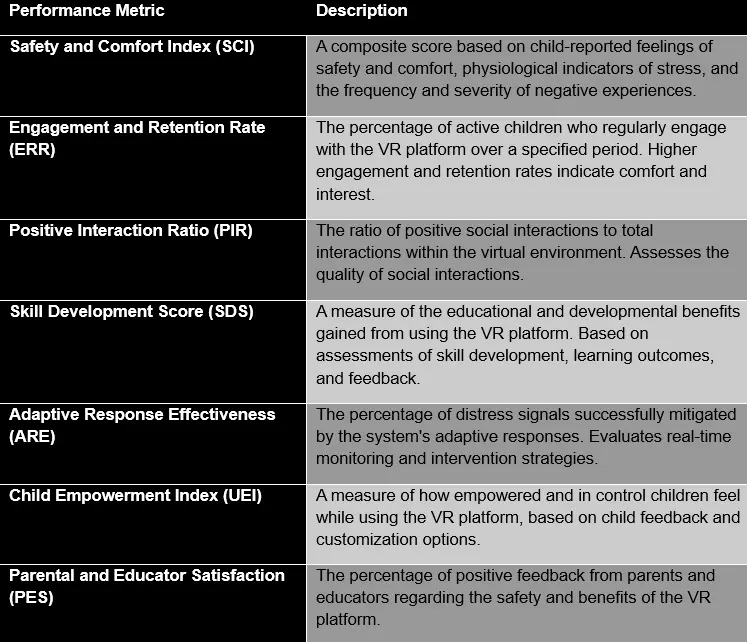

Figure 3. Performance metrics for evaluating child safety in XV platforms. XV: Extended Verse.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate key performance inputs and metrics designed to assess child safety and well-being in XV platforms. The development process involved identifying critical inputs such as children's feedback on safety, physiological stress indicators, and engagement rates, as well as synthesizing these into metrics. This proposed framework is adaptable and scalable, evolving with the understanding of children's experiences in XV.

Figure 2 details the inputs that focus on evaluating children's experiences within virtual environments. They include gathering feedback on how safe and comfortable children feel, monitoring physiological stress indicators like heart rate and skin conductivity, and tracking the frequency and severity of negative experiences. Additionally, inputs measure engagement and retention rates to gauge children's interest, assess the quality of positive social interactions, and evaluate the educational and developmental benefits gained. The effectiveness of the system's adaptive responses in mitigating distress is also measured, along with assessing children's sense of control and empowerment in the virtual space. Lastly, inputs incorporate feedback from parents and educators on the perceived safety and benefits of the platform for children.

Figure 3 presents a proposed framework of novel composite metrics, designed to quantitatively assess the efficacy, safety, and developmental impact of virtual environments for children. These metrics synthesize established methodologies with innovative evaluative constructs to provide a multidimensional analysis. The Safety and Comfort Index (SCI) integrates self-reported safety data, physiological stress biomarkers, and negative experiential indicators, drawing on trauma-informed diagnostic frameworks[62] and VR risk assessment methodologies[70,71]. The Engagement and Retention Rate (ERR) quantifies platform usage frequency and consistency, informed by studies on user engagement dynamics[30] and retention optimization strategies in digital ecosystems[33]. The Positive Interaction Ratio (PIR) evaluates the quality and frequency of social interactions, leveraging research on children's behavioral patterns in VR[14] and parent-aware social VR frameworks[60]. The Skill Development Score (SDS) measures educational and developmental outcomes, grounded in evidence-based research on XR-enhanced pedagogical interventions[34] and therapeutic applications in paediatric healthcare[38]. The Adaptive Response Effectiveness (ARE) assesses the system's capacity to mitigate distress, incorporating advancements in affective computing and emotion recognition within immersive environments[76] and real-time adaptive emotional interfaces[80]. The User Empowerment Index (UEI) quantifies perceived agency and control, informed by principles of human-computer interaction and digital autonomy[13] and frameworks for children's digital rights[61]. Finally, the Parental and Educator Satisfaction (PES) captures stakeholder approval, integrating insights from studies on perspectives of VR[60] and the conceptualization of child-friendly XV environments[69].

The method and integration into a cohesive evaluation framework presented represent a novel approach in the field of trauma prevention in virtual worlds. As the complexities of child safety in increasingly immersive digital environments are navigated, these metrics aim to provide researchers, developers, and policymakers with a tool for measuring the well-being of children in the XV.

Conceptual Use Case 1: Virtual Classroom Safety Enhancement

In an XV classroom setting, the framework's emotion recognition systems are integrated to monitor students' emotional states. When a student exhibits signs of distress, such as increased heart rate or negative facial expressions, the system alerts the teacher and provides real-time interventions, such as calming exercises or one-on-one support. This approach can be improved over time to understand the students' ideal support plan. This proactive approach helps maintain a supportive learning environment, reducing anxiety and improving student engagement and retention.

Conceptual Use Case 2: Safe Social Interaction in Online Gaming/Virtual Worlds

An online gaming platform or social virtual world for children implements the framework's adaptive content moderation and positive interaction metrics. The system identifies and mitigates harmful behaviors, such as bullying or harassment, by issuing warnings and providing support to affected users. By promoting positive social interactions and skill development, the platform enhances children's safety and well-being, leading to higher user satisfaction and parental approval.

Conceptual Use Case 3: Trauma Support in Virtual Therapy Sessions

An XV program for children uses the framework's physiological monitoring and adaptive response systems to tailor sessions to individual needs. By continuously assessing stress indicators, the system adjusts the virtual environment to create a calming atmosphere, facilitating effective therapy. This personalized approach empowers children, improves therapeutic outcomes, and increases satisfaction among parents and therapists.

While the proposed conceptual use cases highlight the benefits of the framework, it is important to consider how monitoring might influence user behavior and adoption. Research in emotion recognition systems suggests that continuous monitoring can affect the authenticity of emotional responses[82,86]. Younger children may perceive the system as supportive, but older children and teenagers might view it as intrusive, potentially leading to altered behaviour or attempts to circumvent the system. Studies on physiological signal-based emotion recognition highlight the importance of balancing detection accuracy with user comfort[85]. Future iterations of the framework should explore customizable monitoring levels that consider age-appropriate autonomy while maintaining safety.

2.4 Evaluation metrics and validation

To effectively integrate the proposed system into an existing XV framework, it is necessary to leverage modular design principles that allow for seamless incorporation of emotion recognition systems and physiological sensors[87]. This can be achieved by developing APIs that facilitate communication between the XV platform and the emotion recognition modules, ensuring real-time data exchange and adaptive responses. Additionally, the integration process should include a comprehensive testing phase, where the system is evaluated within controlled environments to assess its performance and reliability[88]. This testing should involve scenarios that mimic real-world interactions, allowing for the identification and resolution of potential issues before full deployment. By utilizing iterative testing and feedback loops, the system can be refined to ensure optimal functionality and user experience[89].

Furthermore, collaboration with stakeholders, including educators and child psychologists, as well as policymakers, regulators and internet crimes against children (ICAC) specialists can provide valuable insights into the system's effectiveness and areas for improvement, ensuring that the integration continually enhances the safety and engagement of the XV environment for children[71]. For designers to incorporate the proposed factors into their systems, designers and researchers should adopt a holistic approach that integrates emotion recognition, physiological monitoring, and machine learning for behaviour analysis, as outlined in the framework. This approach aligns with the principles of Child's Rights by Design[90], emphasizing children's right to protection in digital environments. Implementing adaptive content moderation and fostering positive social interactions supports the Safety by Design framework[91], which prioritizes user safety in the development process. Designers can facilitate skill development and cross-sector collaboration by creating interfaces that respond dynamically to users' needs, embodying the concept of Thriving by Design[92]. Practical implementation could involve developing APIs for emotion recognition integration, creating dashboards for real-time physiological data analysis, and establishing guidelines for adaptive content moderation based on machine learning insights. By incorporating these elements, designers and researchers can create safer, more empathetic digital environments that protect and empower children in XV.

The XV Safety Framework for Children presents a comprehensive approach to creating secure and empowering digital environments for young users. The following steps outline a potential implementation process to support safety measures effectively integrated into XV platforms and continuously improved based on continual feedback and evolving best practices. This approach aligns with the guidelines provided by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) on digital safety and child protection[93].

• Ensure legal compliance: Adhere to data protection and online safety regulations (e.g., GDPR, COPPA) by implementing robust data handling practices, obtaining necessary consent, and ensuring transparency in data collection and usage. Regularly update policies to align with evolving legal standards, protecting children's privacy and maintaining stakeholder trust.

• Foster positive interactions: Create activities and features that encourage cooperation, empathy, and skill development, supported by educational resources.

• Prioritize user empowerment: Develop features that give children appropriate control over their digital experiences, enhancing their sense of agency and safety.

• Provide comprehensive training: Offer educational programs for developers, moderators, and other stakeholders on implementing and maintaining these safety measures.

• Establish cross-sector partnerships: Facilitate collaborations between technology companies, researchers, policymakers, and child protection experts to share knowledge and resources.

• Integrate emotion recognition APIs: Implement robust APIs that seamlessly connect with existing platforms, ensuring real-time processing of emotional data.

• Deploy physiological monitoring: Utilize wearable devices to track key physiological indicators continuously, providing data for adaptive responses.

• Develop behavior analysis algorithms: Create machine learning models that analyze user interactions to identify and mitigate potential risks in real-time.

• Conduct regular safety audits: Implement a system for ongoing evaluation of the framework's effectiveness using the proposed metrics (e.g., Safety and Comfort Index, Engagement and Retention Rate).

• Iterate and improve: Continuously gather feedback from users, parents, and experts to refine and enhance the framework's components.

The strategic implementation process supports legal compliance, fosters positive interactions, and empowers users while continuously refining the framework through feedback and collaboration, in line with OECD guidelines.

3. Ethical Considerations

The integration of advanced emotion recognition systems, physiological sensors, and machine learning algorithms presents a potential approach to creating safer virtual environments for children in the XV. By enabling real-time monitoring and adaptive responses to potential threats, these technologies can help mitigate the risks of trauma and negative experiences in XV. Significant challenges remain, the reliability of proposed data measures is critical to the success of any framework designed to enhance safety in XV. Ensuring accuracy involves rigorous testing and validation of data collection methods, as well as continuous monitoring to identify and correct any discrepancies[94]. The establishment and use of standardized protocols and benchmarks can help maintain consistency and reliability across different platforms and applications[95]. Furthermore, incorporating feedback loops that allow users to report inaccuracies or issues can improve the overall robustness of the data measures[96].

Combining and interpreting data measures effectively will require sophisticated modelling tools, such as causal loop diagrams, which could visualize the relationships between different variables and identify potential feedback loops[97]. The consideration of such tools can help researchers and developers understand the complex interactions within XV and make informed decisions about system design and policy implementation[98]. Additionally, employing machine learning algorithms to analyse large datasets can uncover patterns and insights that inform the development of more effective safety measures[99].

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed framework it will be essential to conduct empirical studies and pilot programs that test its implementation in real-world settings[100]. These studies should measure key performance indicators, such as user satisfaction, safety incident rates, and system responsiveness, to assess the framework's impact[101]. Validation techniques, such as A/B testing or randomized controlled trials, could provide robust evidence of the framework's efficacy and identify areas for improvement[102].

Research indicates that blockchain can preserve the privacy of data providers by implementing privacy-preserving methodologies during data storage, management, and query processing[103]. The relationship between privacy and anonymization in blockchain technologies can be explored for the framework for a decentralized database alternative[104,105]. Research highlights its potential to enhance data security, transparency, and user control through decentralized storage solutions like the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) and smart contracts[106]. Additionally, the convergence of blockchain with VR and AR technologies has been identified as a promising enabling efficient data management and secure interactions[107]. While these applications are still in their early stages, they demonstrate the feasibility of integrating blockchain into XV frameworks, paving the way for future advancements. However, while blockchain can improve user control and usability of data, it raises ethical, legal, and social implications that need to be addressed[108].

4. Technical Challenges

Acknowledging the theoretical nature of the presented framework, the implementation will involve specific technical components and evaluation protocols that are not considered within the breadth of this paper. The proposed framework does not yet exist and presents significant technical challenges that warrant careful consideration by future researchers. The integration of sensors and data collection systems in XV environments requires careful consideration of latency issues and calibration requirements. The processing and analysis of multimodal data streams present substantial technical hurdles, particularly in maintaining real-time performance while ensuring data privacy and security. The system must handle large volumes of physiological and behavioural. These challenges are compounded by the need to balance local processing capabilities with cloud-based solutions. Success in implementing this framework will require collaborative efforts across multiple disciplines, including computer science, psychology, and human-computer interaction[95]. This framework serves as a call to action for researchers to contribute to the development of practical solutions that can effectively protect children in XV environments while maintaining engaging and beneficial experiences.

5. Conclusion and Future Directions

In conclusion, the proposed framework for creating safe environments for children in the XV represents a novel approach for digital safety and empowerment, specifically for child XV experiences. By integrating cutting-edge technologies with a multidisciplinary approach, the framework addresses the critical need to prevent trauma and foster positive development in XV.

The deployment of advanced monitoring and intervention technologies in the XV to enhance child safety necessitates a thorough examination of ethical implications. While the primary objective is to safeguard children, it is imperative to balance this with the preservation of privacy, autonomy, and the child's right to play, explore and learn free from harm[1]. Key ethical considerations include ensuring that the collection and utilization of emotional and physiological data are conducted transparently, securely, and strictly for their intended purposes. Developing age-appropriate methods for obtaining meaningful consent from children and their guardians is essential to uphold ethical standards. Regular audits of AI systems are necessary to prevent and address biases that may unfairly target or overlook specific groups of children. Clear communication with users regarding the operation of safety systems and the circumstances under which interventions occur is vital. Establishing mechanisms for oversight and redress in instances where the system errs or causes unintended harm is critical. Ensuring that safety measures respect diverse cultural norms and values across global user bases will be required.

Incorporating diverse perspectives from children, parents, and educators is crucial for refining and validating the XV safety framework. This user-centric approach will support the implemented solutions to be not only technologically sound but also acceptable to the end-users.

The collaborative efforts of educators, policymakers, industry leaders, and child protection experts are essential in implementing all solutions, ensuring that the XV becomes a secure and enriching environment for young users, for years to come. As society continues to navigate the complexities of the digital frontier, this framework serves as a guide, paving the way for a future where children can explore, learn, and thrive safely in the digital world.

Authors contribution

The author contributed solely to the article.

Conflicts of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. United Nations. Convention on the rights of the child, Treaty no. 27531, United Nations Treaty Series, 1577 [Internet]. New York: United Nations. Available from: https://treaties.un.org/Treaties/1998/05.pdf

-

2. Allen C, McIntosh V. Safeguarding the Metaverse [Internet]. The Institution of Engineering and Technology. Available from: https://www.theiet.org/media/9836/safeguarding-the-metaverse.pdf

-

3. Dwivedi YK, Kshetri N, Hughes L, Rana NP, Baabdullah AM, Kar AK, et al. Exploring the Darkverse: a multi-perspective analysis of the negative societal impacts of the metaverse. Inf Syst Front. 2023;25(5):2071-2114.

[DOI] -

4. Mann S, Yuan Y, Furness TA, Paradiso J, Coughlin TM. Beyond the metaverse: xv (extended meta/uni/verse). Electrical Engineering and Systems Science, Systems and Control. arXiv: 2212.07960 [Preprint]. 2022.

[DOI] -

5. Bailenson J. Experience on Demand: What Virtual Reality Is, How It Works, and What It Can Do. 1st ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company; 2018.

-

6. Azuma RT. A survey of augmented reality. Presence Teleoper Virtual Environ. 1997;6(4):355-385.

[DOI] -

7. Milgram P, Kishino F. A taxonomy of mixed reality visual displays. IEICE Trans Inf Syst. 1994;77(12):1321-1329. Available from: https://cs.gmu.edu/~zduric/cs499/Readings/r76JBo-Milgram_IEICE_1994.pdf

-

8. Rauschnabel P, Felix R, Hinsch C, Shahab H, Alt F. What is XR? Towards a Framework for Augmented and Virtual Reality. Comput Human Behav. 2022;133(1530):107289.

[DOI] -

9. Dwivedi YK, Ismagilova E, Hughes DL, Carlson J, Filieri R, Jacobson J, et al. Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. Int J Inf Manage. 2021;59(1):102168.

[DOI] -

10. Ball M. Roblox is Already the Biggest Game In The World. Why Can't It Make a Profit (And How Can It)? [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://www.matthewball.co/all/roblox2024

-

11. Lee LH, Braud T, Zhou P, Wang L, Xu D, Lin Z, et al. All one needs to know about metaverse: a complete survey on technological singularity, virtual ecosystem, and research agenda. arXiv: 2110.05352 [Preprint]. 2021. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2110.05352

-

12. World Economic Forum [Internet]. Demystifying the consumer metaverse; 2023. Available from: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Demystifying_the_Consumer_Metaverse.pdf

-

13. Ferrari F, Paladino MP, Jetten J. Blurring human-machine distinctions: anthropomorphic appearance in social robots as a threat to human distinctiveness. Int J Soc Robotics. 2016;8(2):287-302.

[DOI] -

14. Maloney D, Freeman G, Robb A. It is complicated: Interacting with children in social virtual reality. In: Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW); 2020 Mar 22-26; Atlanta, USA. New York: IEEE; 2020. p. 343-347.

[DOI] -

15. Slater M, Sanchez-Vives MV. Enhancing our lives with immersive virtual reality. Front Robot AI. 2016;3:74.

[DOI] -

16. Rizzo A, Koenig ST. Is clinical virtual reality ready for primetime? Neuropsychology. 2017;31(8):877-899.

[DOI] [PubMed] -

17. Business Wire [Internet]. Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality Market with COVID-19 Impact Analysis - Global Forecast to 2025-ResearchAndMarkets.Com; c2025. Available from: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210111005575/en

-

18. Heath A [Internet]. Meta's social VR platform Horizon hits 300,000 users. New York: The Verge. 2022. Available from: https://www.theverge.com/2022/2/17/22939297/meta-social-vr-platform-horizon-300000-users

-

19. Hayden S [Internet]. PSVR 2 outsold original PSVR in first 6 weeks, Sony confirms. USA: Road to VR. Available from: https://www.roadtovr.com/psvr-2-sales-figures-units-sony/

-

20. Kharpal A [Internet]. Chinese augmented reality glasses maker Nreal rebrands as Xreal as it takes on tech giants. New Jersey: CNBC. Available from: https://www.cnbc.com/2023/05/25/chinese-augmented-reality-glasses-maker-nreal-rebrands-as-xreal.htm

-

21. Piper Sandler [Internet]. 45th semi-annual Taking Stock with Teens Survey, Spring 2023. Minneapolis: Piper Sandler. Available from: https://www.pipersandler.com/TSWT_Spring23_Infographic.pdf

-

22. Common Sense [Internet]. The common sense census: Media use by tweens and teens. San Francisco: Common Sense; 2021. Available from: https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/the-common-sense-census-media-use-by-tweens-and-teens-2021

-

23. Forbes [Internet]. VR headset sales underperform expectations, what does it mean for the metaverse in 2023? New York: Forbes. Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/qai/2023/01/06/vr-headset-sales-underperform-expectations-what-does-it-mean-for-the-metaverse-in-2023/

-

24. Rodriguez S [Internet]. Meta opens Horizon Worlds VR app to teens as company seeks more VR users. New York: Wall Street Journal; 2023. Available from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/meta-opens-horizon-worlds-vr-app-to-teens-as-company-seeks-more-metaverse-users-2e9deeeb

-

25. Snapchat Inc [Internet]. Transform mobile shopping with AR at scale. Available from: https://forbusiness.snapchat.com/blog/catalog-powered-shopping-lenses

-

26. King J [Internet]. Pinterest introduces AR Try on for home decor for the ultimate online home shopping experience. California: Pinterest Newsroom; 2022. Available from: https://newsroom.pinterest.com/en-gb/news/pinterest-introduces-ar-try-on-for-home-decor-for-the-ultimate-online-home-shopping-experience/

-

27. Arora A, Glaser D, Kluge P, Kim A, Kohli S, Sak N. It's showtime: How live commerce is transforming the shopping experience. New York: McKinsey & Company. Available from: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/mckinsey-digital/our-insights/its-showtime-how-live-commerce-is-transforming-the-shopping-experience

-

28. Roblox Corporation [Internet]. Roblox is now available on Meta Quest! Available from: https://devforum.roblox.com/t/roblox-is-now-available-on-meta-quest/2620624

-

29. The Walt Disney Company [Internet]. Disney and Epic Games to create expansive and open games and entertainment universe connected to Fortnite. California: The Walt Disney Company. Available from: https://thewaltdisneycompany.com/disney-and-epic-games-fortnite/

-

30. Zendle D, Cairns P, Barnet , H , McCall C. The relationship between videogame micro-transactions, problem gaming, and problem gambling: A systematic review. Comput Human Behav. 2022;131(2):107314.

[DOI] -

31. Guschwan M. 'It's in the game': FIFA videogames and the misuse of history. Sport Hist. 2024;44(4):590-611.

[DOI] -

32. Electronic Arts [Internet]. 2024 Impact Report. California: Electronic Arts. Available from: https://s204.q4cdn.com/701424631/files/ElectronicArts_2024ImpactReport-1.pdf

-

33. Takahashi D [Internet]. EA aims to double audience to over 1 billion in 5 years. California: VentureBeat. Available from: https://venturebeat.com/games/ea-unveils-ea-sports-app-to-reach-beyond-gaming-as-it-aims-to-double-audience-in-5-years/

-

34. Hoyer WD, Kroschke M, Schmitt B, Kraume K, Shankar V. Transforming the customer experience through new technologies. J Interact Mark. 2020;51(4):57-71.

[DOI] -

35. Chen MRA, Hwang GJ. Effects of experiencing authentic contexts on English speaking performances, anxiety and motivation of EFL students with different cognitive styles. Interact Learn Environ. 2022;30(9):1619-1639.

[DOI] -

36. Annamalai N, Uthayakumaran A, Zyoud SH. High school teachers' perception of AR and VR in English language teaching and learning activities: A developing country perspective. Educ Inform Technol. 2023;28(16):3117-3143.

[DOI] -

37. Barrett AJ, Pack A, Quaid ED. Understanding learners' acceptance of high-immersion virtual reality systems: Insights from confirmatory and exploratory PLS-SEM analyses. Comput Educ. 2021;169(81):104214.

[DOI] -

38. Goldsworthy A, Chawla J, Baumann O, Birt J, Gough S. Extended Reality Use in Paediatric Intensive Care: A Scoping Review. J Intensive Care Med. 2023;38(9):856-877.

[DOI] [PubMed] [PMC] -

39. Sin JE, Kim AR. Mixed Reality in Clinical Settings for Pediatric Patients and Healthcare Professionals: A Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024;21(9):1185.

[DOI] -

40. Curran VR, Xu X, Aydin MY, Meruvia-Pastor O. Use of Extended Reality in Medical Education: An Integrative Review. Med Sci Educ. 2022;33(1):275-286.

[DOI] [PubMed] [PMC] -

41. Curran VR, Hollett A. The use of extended reality (XR) in patient education: A critical perspective. Health Educ J. 2024;83(4):338-351.

[DOI] -

42. Yeung AWK, Tosevska A, Klager E, Eibensteiner F, Laxar D, Stoyanov J, et al. Virtual and Augmented Reality Applications in Medicine: Analysis of the Scientific Literature. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(2):e25499.

[DOI] -

43. Al-Ghaili AM, Kasim H, Al-Hada NM, Hassan ZB, Othman M, Tharik JH, et al. A review of metaverse's definitions, architecture, applications, challenges, issues, solutions, and future trends. IEEE Access. 2022;10:126662-126682.

[DOI] -

44. Olaizola Rosenblat M [Internet]. Reality check: How to protect human rights in the 3D immersive web. New York: NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights; 2023. Available from: https://bhr.stern.nyu.edu/Sep5ONLINEFINALCOVER1ADA.pdf

-

45. Coleman B [Internet]. Jurisdiction and torts in the metaverse. London: Bristows; 2023. Available from: https://www.bristows.com/news/jurisdiction-and-torts-in-the-metaverse/

-

46. Zhu L. The Metaverse: Concepts and Issues for Congress. Washington: Congressional Research Service; 2022. Available from: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47224

-

47. Theodos K, Sittig S. Health Information Privacy Laws in the Digital Age: HIPAA Doesn't Apply. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2020;18:1l.

[PubMed] [PMC] -

48. US General Services Administration [Internet]. Virtual presence. Technology Transformation Services; 2022. Available from: https://tech.gsa.gov/emergent-technology/virtual-presence/

-

49. Dick E [Internet]. Balancing user privacy and innovation in augmented and virtual reality. Washington: Inform Technol Innov Found; 2021. Available from: https://www2.itif.org/2021-ar-vr-user-privacy.pdf

-

50. Congress Gov [Internet]. S.1291-Protecting Kids on Social Media Act, 118th Congress. Washington: Congress Gov; 2023. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/1291

-

51. Congress Gov [Internet]. S.3663-Kids Online Safety Act, 117th Congress. Washington: Congress Gov; 2022. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/3663.

-

52. Congress Gov [Internet]. S.3538- EARN IT Act of 2022, 117th Congress. Washington: Congress Gov; 2022. Available from: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/3538

-

53. Federal Trade Commission [Internet]. Children's Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA). Washington: Federal Trade Commission; 1998. Available from: https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse

-

54. UK Parliament [Internet]. Online Safety Act 2023. London: UK Parliament; 2023. Available from: https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3137

-

55. Institution of Engineering and Technology. Why the Online Safety Bill needs a 'metaverse' amendment [Internet]. London: PoliticsHome; 2023. Available from: https://www.politicshome.com/article

-

56. eSafety Commissioner [Internet]. Immersive tech: Trends and challenges. Sydney: eSafety Commissioner; 2020. Available from: https://www.esafety.gov.au/industry/tech-trends-and-challenges/immersive-tech

-

57. eSafety Commissioner [Internet]. Safety by Design. Sydney: eSafety Commissioner; 2024. Available from: https://www.esafety.gov.au/industry/safety-by-design

-

58. European Commission [Internet]. A European Strategy for a better Internet for Kids (BIK+) strategy. Brussels: European Commission; 2022. Available from: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu

-

59. Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Metaverse risks and harms among US youth: Experiences, gender differences, and prevention and response measures. New Media Soc. 2024;26(1):3-24.

[DOI] -

60. Fiani C, Saeghe P, McGill M, Khamis M. Exploring the perspectives of social VR-aware non-parent adults and parents on children's use of social virtual reality. Pro ACM Hum-Comput Interact. 2024;8:1-25.

[DOI] -

61. Mukherjee S, Pothong K, Livingstone S [Internet]. Child Rights Impact Assessment: A tool to realise child rights in the digital environment. London: Digital Futures Commission; 2021. Available from: https://digitalfuturescommission.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/CRIA-Report.pdf

-

62. D'Andrea W, Ford J, Stolbach B, Spinazzola J, van der Kolk BA. Understanding interpersonal trauma in children: why we need a developmentally appropriate trauma diagnosis. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82(2):187-200.

[DOI] [PubMed] -

63. Interpol [Internet]. Metaverse: A law enforcement perspective: Use cases, crime, forensics, investigation, and governance. Lyon: Interpol; 2024. Available from: https://www.interpol.int/20828

-

64. Blascovich J, Bailenson J. Infinite Reality: Avatars, Eternal Life, New Worlds, and the Dawn of the Virtual Revolution. New York: William Morrow & Co; 2011.

-

65. Slater M, Spanlang B, Sanchez-Vives MV, Blanke O. First person experience of body transfer in virtual reality. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10564.

[DOI] [PubMed] [PMC] -

66. Fox J, Bailenson JN. Virtual self-modeling: The effects of vicarious reinforcement and identification on exercise behaviors. Media Psychology. 2009;12(1):1-25.

[DOI] -

67. Yee N, Bailenson J. The Proteus effect: The effect of transformed self-representation on behavior. Hum Commun Res. 2007;33(3):271-290.

[DOI] -

68. Sanchez-Vives MV, Slater M. From presence to consciousness through virtual reality. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6(4):334-339.

[DOI] [PubMed] -

69. Vibert S, Bissoondath A [Internet]. A whole new world? Towards a child-friendly metaverse. London: Internet Matters. Available from: https://www.internetmatters.org/uInternet-Matters-Metaverse-Report-Jan-2023.pdf

-

70. Pettifer S, Barrett E, Marsh J, Hill K, Turner P, Flynn S [Internet]. The future of eXtended reality technologies, and implications for online child sexual exploitation and abuse. Manchester: University of Manchester; 2022. Available from: https://documents.manchester.ac.uk/display.aspx?DocID=62042

-

71. Davidson J, Martellozzo E, Farr R, Bradbury P, Meggyesfalvi B. VIRRAC Toolkit Report: Virtual Reality Risks Against Children. London: University of East London; 2024. Available from: https://repository.uel.ac.uk/item/8xz9y

-

72. Asadzadeh A, Shahrokhi H, Shalchi B, Khamnian Z, Rezaei-Hachesu P. Digital games and virtual reality applications in child abuse: A scoping review and conceptual framework. PLoS One. 2022;17(11):e0276985.

[DOI] [PubMed] [PMC] -

73. Kimber M, McTavish JR, Vanstone M, Stewart DE, MacMillan HL. Child maltreatment online education for healthcare and social service providers: Implications for the COVID-19 context and beyond. Child Abuse Negl. 2021;116(Pt 2):104743.

[DOI] [PubMed] [PMC] -

74. Dorado J, Martinez M, McArthur L, Leibovitz T. Healthy environments and response to trauma in schools (HEARTS): A whole-school, multi-level, prevention and intervention program for creating trauma-informed, safe and supportive schools. Sch Ment Health. 2016;8(1):163-176.

[DOI] -

75. Keller-Maples JL, Miller LS, Rothbaum BO. The Use of Virtual Reality Technology in the Treatment of Anxiety and Other Psychiatric Disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2017;25(3):103-113.

[DOI] -

76. Marín-Morales J, Llinares C, Guixeres J, Alcañiz M. Emotion recognition in immersive virtual reality: From statistics to affective computing. Sensors. 2020;20(18):5163.

[DOI] [PubMed] [PMC] -

77. Liao Y, Gao Y, Wang F, Xu Z, Wu Y, Zhang L. Exploring emotional experiences and dataset construction in the era of short videos based on physiological signals. Biomed Signal Process Control. 2024;96(Part A ):106648.

[DOI] -

78. Lin W, Li C. Review of studies on emotion recognition and judgment based on physiological signals. Appl Sci. 2023;13(4):2573.

[DOI] -

79. Olabanji SO, Marquis Y, Adigwe CS, Ajayi SA, Oladoyinbo TO, Olaniyi OO. AI-driven cloud security: Examining the impact of user behavior analysis on threat detection. Asian J Res Comput Sci. 2024;17(3):57-74.

[DOI] -

80. Burrows H, Zarrin J, Babu-Saheer L, Maktab-Dar-Oghaz M. Realtime Emotional Reflective User Interface Based on Deep Convolutional Neural Networks and Generative Adversarial Networks. Electronics. 2022;11(1):118.

[DOI] -

81. Sun Y, Lu T, Wang X, Chen W, Chen S, Chen H, et al. Physiological feedback technology for real-time emotion regulation: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1182667.

[DOI] [PubMed] [PMC] -

82. Bailenson JN, Pontikakis ED, Mauss IB, Gross JJ, Jabon ME, Hutcherson CAC, et al. Real-time classification of evoked emotions using facial feature tracking and physiological responses. Int J Hum-Comput Stud. 2008;66(5):303-317.

[DOI] -

83. Pham P, Wang J. Understanding Emotional Responses to Mobile Video Advertisements via Physiological Signal Sensing and Facial Expression Analysis. In: Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces; 2017 Mar 13-16; Limassol, Cyprus. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2017. p. 67-78.

[DOI] -

84. Khare S, Blanes-Vidal V, Nadimi E, Acharya U. Emotion recognition and artificial intelligence: A systematic review (2014-2023) and research recommendations. Inf Fusion. 2023;102(3):102019.

[DOI] -

85. Jerritta S, Murugappan M, Nagarajan R, Wan K. Physiological signals based human emotion recognition: A review. In: Proceedings of 2011 IEEE 7th International Colloquium on Signal Processing and its Applications; 2011 Mar 4-6; Penang, Malaysia. New York: IEEE; 2011. p. 410-415.

[DOI] -

86. Cowie R, Douglas-Cowie E, Tsapatsoulis N, Votsis G, Kollias S, Fellenz W, et al. Emotion recognition in human-computer interaction. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 2001;18(1):32-80.

[DOI] -

87. Masood T, Egger J. Augmented reality in support of Industry 4.0 - Implementation challenges and success factors. Robot Comput Integr Manuf. 2019;58:181-195.

[DOI] -

88. Bowman DA, Gabbard JL, Hix D. A Survey of Usability Evaluation in Virtual Environments: Classification and Comparison of Methods. Presence Teleoper Virt Environ. 2002;11(4):404-424.

[DOI] -

89. Jerald J. The VR Book: Human-Centered Design for Virtual Reality. New York: ACM and Morgan & Claypool; 2015.

[DOI] -

90. Livingstone S, Third A. Children and young people's rights in the digital age: An emerging agenda. New Media Soc. 2017;19(5):657-670.

[DOI] -

91. OECD. Towards digital safety by design for children [Internet]. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2024.

-

92. Buchanan R, Margolin V. Discovering design: Explorations in design studies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1995.

-

93. OECD. Declaration on a trusted, sustainable and inclusive digital future [Internet]. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2022.

-

94. Salinas D, Muñoz-La Rivera, Mora-Serrano J. Critical analysis of the evaluation methods of extended reality (XR) experiences for construction safety. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(22):15272.

[DOI] [PMC] -

95. Elser A, Lange M, Kopkow C, Schäfer AG. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of virtual reality interventions for people with chronic pain: Scoping review. JMIR XR Spatial Comput. 2024;1:e53129.

[DOI] -

97. Sterman JD. Business dynamics: Systems thinking and modeling for a complex world. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000.

-

98. Mahfoud E, Wegba K, Li Y, Han H, Lu A. Immersive visualization for abnormal detection in heterogeneous data for on-site decision making. In: Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences; 2018 Jan 3-6; Hawaii, USA. New York: IEEE; 2018. p. 1300-1309.

[DOI] -

99. Baker RSJD, Yacef K. The state of educational data mining in 2009: A review and future visions. J Educ Data Min. 2009;1(1):3-16.

[DOI] -

100. Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet. 2003;362(9391):1225-1230.

[DOI] [PubMed] -

101. Kaplan RS, Norton DP. The balanced scorecard: measures that drive performance. Harv Bus Rev. 1992;70(1):71-79.

[PubMed] -

102. Kohavi R, Longbotham R. Online Controlled Experiments and A/B Testing. In: Sammut C, Webb GI, editors. Encyclopedia of Machine Learning and Data Mining. Boston: Springer; 2017. p. 922-929.

[DOI] -

103. Kaaniche N, Laurent M. Data security and privacy preservation in cloud storage environments based on cryptographic mechanisms. Comput Commun. 2017;111:120-141.

[DOI] -

104. Zyskind G, Nathan O, Pentland A. Decentralizing privacy: Using blockchain to protect personal data. In: Proceedings of 2015 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops; 2015 May 21-22; San Jose, USA. New York: IEEE; 2015. p. 180-184.

[DOI] -

105. Lohiya R, Mandowara A, Raolji R. Privacy Preserving Data Mining: A Comprehensive Survey. Int J Comput Appl. 2017;161(6):30-38.

[DOI] -

106. Fraga-Lamas P, Lopes SI, Fernández-Caramés TM. Towards a blockchain and opportunistic edge driven metaverse of everything. arXiv:2410.20594 [Preprint]. 2024. Available from: https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.20594

-

107. Cannavò A, Lamberti F. How blockchain, virtual reality, and augmented reality are converging, and why. IEEE Consum Electron Mag. 2021;10(5):6-13.

[DOI] -

108. Zarchi G, Sherman M, Gady O, Herzig T, Idan Z, Greenbaum D. Blockchains as a means to promote privacy protecting, access availing, incentive increasing, ELSI lessening DNA databases. Front Digit Health. 2013;4:1028249.

[DOI] [PubMed] [PMC]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Share And Cite