Abstract

Neurons exist at the intersection of two essential yet hazardous metabolic demands: iron-driven bioenergetics and lipid-dependent membrane remodeling. Their reliance on mitochondrial iron for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) generation, combined with the requirement for polyunsaturated fatty acids to sustain synaptic plasticity, creates a biochemical environment primed for ferroptosis. This Perspective examines how the interplay between iron and lipid metabolism defines neuronal vulnerability in neurodegenerative diseases, focusing on apolipoprotein E (ApoE) as a metabolic gatekeeper coordinating those pathways. Beyond its canonical function in lipid transport, ApoE acts as a potent anti-ferroptotic factor by inhibiting ferritinophagy and restraining the release of labile iron, thereby coupling lipid trafficking with iron homeostasis. Dysregulation of this axis in Alzheimer’s disease amplifies lipid peroxidation and compromises antioxidant defenses. Parallel mechanisms are observed in Neurodegeneration with Brain Iron Accumulation disorders, where mutations in lipid-metabolic genes paradoxically lead to brain iron accumulation, underscoring the genetic entanglement of these pathways. Collectively, these findings support a unifying model in which neuronal ferroptosis arises not from isolated iron overload or lipid imbalance, but from the breakdown of a coordinated iron-lipid defense network. We propose that restoring this equilibrium through modulation of ApoE function, preservation of mitochondrial iron utilization, and suppression of lipid peroxidation represents a promising avenue for therapeutic intervention in neurodegenerative disease.

Keywords

1. The Double-Edged Demands of Neurons

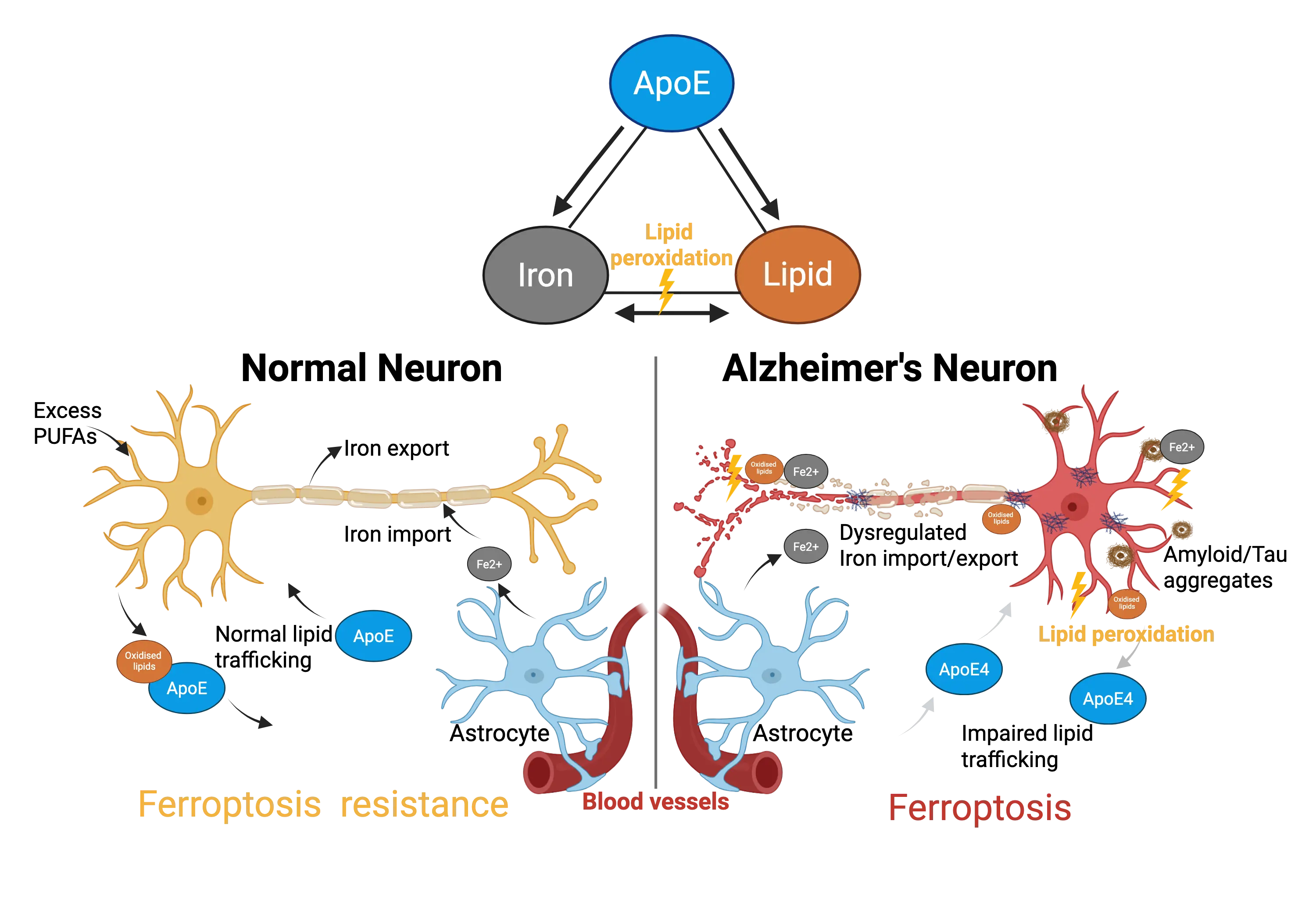

Neurons occupy a unique position in the metabolic landscape of the brain, requiring continuous synthesis of both energy and membrane lipids to sustain their function. Their reliance on oxidative phosphorylation demands a constant supply of iron for mitochondrial enzymes such as cytochromes and iron-sulfur proteins, while their need for membrane remodeling mandates abundant polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs)[1,2]. These dual requirements are metabolically indispensable yet inherently hazardous: iron catalyzes the Fenton reaction, generating highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and ferryl/oxyl species that initiate lipid peroxidation[3,4]. Together, these features create an environment inherently prone to ferroptosis, the iron-dependent, lipid-driven form of regulated cell death (Figure 1)[5].

Figure 1. ApoE: Gatekeeper of the Iron-Lipid Axis in Neuronal Ferroptosis. Schematic illustration shows how ApoE coordinates iron and lipid metabolism to maintain neuronal resistance to ferroptosis. In healthy neurons (left), ApoE supports lipid trafficking and limits labile iron, preventing lipid peroxidation. In contrast, ApoE4 dysfunction (right) disrupts this balance, promoting iron accumulation, oxidized lipid formation, and ferroptotic neuronal degeneration. Created in BioRender.com. ApoE: apolipoprotein E; PUFAs: polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Astrocytes and neurons cooperate in managing these risks. Astrocytes synthesize and export cholesterol and PUFAs via apolipoprotein E (ApoE)-containing lipoproteins and detoxify oxidized lipids, while neurons, which lack robust lipid storage and β-oxidation capacity, depend on astrocytic support (Figure 1)[6]. Perturbations in this lipid shuttle lead to activity-induced lipotoxicity and dendritic loss[6,7]. Moreover, specific phospholipids enriched in PUFAs such as arachidonic and adrenic acids are essential substrates for ferroptosis[4]. Their incorporation into cellular membranes, mediated by acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain 4 and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3, determines a cell’s sensitivity to ferroptotic death[8]. Consequently, neurons’ physiological membrane composition and iron-intensive bioenergetics create a structural vulnerability to ferroptosis.

2. Ferroptosis as a Neuronal Liability

Ferroptosis is defined by the accumulation of lipid peroxides and iron-dependent cell death that can be rescued by iron chelators and ferroptosis inhibitors, including ferrostatin-1 or liproxstatin-1[9]. Although these inhibitors possess radical-trapping activity in cell-free systems, emerging evidence demonstrates additional biological mechanisms, including iron-binding and lysosomal iron modulation, as shown for liproxstatin-1[10]. Neuron-specific deletion of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), the selenoenzyme that reduces lipid hydroperoxides, leads to rapid neurodegeneration in mice, establishing ferroptosis as a bona fide neuronal death mechanism[11-15]. Ferroptosis can be initiated enzymatically, through 15-lipoxygenase-PEBP1 complexes that oxidize membrane PUFAs, or non-enzymatically by iron-driven free-radical reactions[16].

Cellular iron handling sets the threshold for this process. Transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) mediates uptake, ferroportin exports iron, and ferritin stores it[17]. In addition to TfR1, CD44 has recently emerged as a regulator of iron endocytosis and ferroptosis sensitivity, particularly through hyaluronan-CD44 interactions[18,19]. Selective autophagic degradation of ferritin, known as ferritinophagy, releases redox-active Fe(II) and sensitizes cells to ferroptosis[20,21]. Recent findings indicate that lysosomal iron activation is a key driver of ferroptosis, and that suppression of lysosomal Fe3+ prevents lipid peroxidation and cell death[10]. Lysosomal iron sequestration can also trigger ferritinophagy and global disruption of iron homeostasis, promoting ferroptosis[22]. Excessive neuronal activity or impaired lipid shuttling to astrocytes disrupts vesicle cycling, leading to lipid peroxide buildup and degeneration[6]. Thus, ferroptosis in neurons is not simply a toxic by-product of oxidative stress but a distinct metabolic failure, in which energy generation, antioxidant capacity, and membrane integrity collapse together.

3. ApoE as a Gatekeeper of the Iron-Lipid Axis

3.1 ApoE isoforms and Alzheimer’s disease

ApoE exists in three common human isoforms: ApoE2, ApoE3, and ApoE4 that arise from single amino acid substitutions at residues 112 and 158[23]. ApoE3 is the most prevalent and is considered the “neutral” reference isoform, whereas ApoE4 is the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, increasing risk approximately threefold in heterozygotes and up to twelvefold in homozygotes[24]. In contrast, ApoE2 is protective, with both heterozygous and homozygous genotypes associated with a substantially reduced incidence of Alzheimer’s disease[25]. The ApoE isoforms differ markedly in structure and function, leading to distinct affinities for key receptors, including LDLR, LRP1, ApoER2, and TREM2 that regulate lipid transport, intracellular signaling, and cellular homeostasis[26-28]. These structural differences also influence downstream biological processes such as microglial activation, synaptic remodeling, regenerative responses, and the clearance of aggregated proteins[23]. Together, these isoform-specific effects help explain the divergent roles of ApoE variants in neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative disease.

3.2 ApoE as a modulator of neuronal ferroptosis

Among brain proteins, ApoE occupies a unique niche at the intersection of lipid and iron homeostasis[23]. Classically recognized as the principal lipid carrier of the central nervous system, ApoE also exerts potent anti-ferroptotic effects by blocking ferritinophagy, thereby restraining the release of labile iron[29]. This dual function enables ApoE to coordinate two ferroptosis-relevant pathways: lipid transport and iron storage into a single defense system[30]. The existence of multiple isoform differences and disease-relevant variants adds another layer of complexity. The ApoE4 isoform displays reduced lipid-binding capacity, impaired astrocyte-neuron lipid transfer, and heightened lipid peroxidation compared to ApoE3[7,31,32]. Conversely, microglial expression of another ApoE variant named Christchurch confers protection against tau pathology and ferroptosis[33,34]. In cerebrospinal fluid, ApoE levels correlate closely with ferritin concentrations, underscoring ApoE’s dual role in regulating both iron release and lipid peroxidation[35,36]. Collectively, these findings portray ApoE as a biochemical integrator of neuronal lipid and iron balance, where isoform-specific dysfunction directly increases ferroptotic vulnerability. Beyond the CNS, ApoE has been implicated in ferroptosis across multiple tissues: ApoE-deficient mice display ferroptosis-like changes that are alleviated by ferroptosis inhibitors in atherosclerotic lesions, and ApoE expression modulates ferroptotic signaling in tumor and immune cells, underscoring a broader role for ApoE in iron- and lipid-dependent cell death pathways outside the brain.

4. Iron-Lipid Convergence in Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease exemplifies the pathological convergence of disrupted lipid and iron metabolism. Magnetic resonance imaging using quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) reveals focal iron accumulation in cortical and subcortical regions that correlates with cognitive decline[37,38]. Parallel lipidomic analyses identify extensive remodeling of neuronal membranes and accumulation of oxidized phospholipids in postmortem cortex of Alzheimer’s patients[31]. Measurements of iron content and stable lipid peroxidation products in postmortem tissue are generally robust, whereas other redox-sensitive metabolites can be more challenging to interpret due to their susceptibility to the post-mortem interval and handling conditions. Amyloid-β aggregates bind redox-active iron and copper, catalyzing Fenton-like reactions that generate lipid-oxidizing radicals. Tau aggregates can disrupt membranes, promote PUFA exposure, and enhance local reactive oxygen species production. Both proteins therefore amplify lipid peroxidation through metal-dependent and membrane-perturbing mechanisms[39,40].

Energetic failure provides a mechanistic link: mitochondrial dysfunction reduces ATP availability and thus limits glutathione synthesis, undermining the glutathione-GPX4 axis that restrains ferroptosis[41]. In this context, mitochondrial iron and glutathione metabolism are tightly interdependent, as elevated Fe2+ increases oxidative pressure on the GSH-GPX4 system while glutathione depletion further amplifies iron-driven lipid peroxide formation[2,9]. This energy crisis explains why iron chelation therapy, effective against labile iron toxicity in vitro, worsened cognitive outcomes in Alzheimer’s clinical trials[42]. Instead of alleviating oxidative stress, chelation deprives mitochondria of essential iron required for respiration, inadvertently weakening ferroptosis defenses. Therefore, Alzheimer’s pathology reflects not a simple iron overload or lipid imbalance, but a failure of the iron-lipid defense network in which ApoE plays a pivotal role.

5. Genetic Evidence from Neurodegeneration with Brain Iron Accumulation (NBIA)

The intersection between iron and lipid metabolism is most clearly revealed in NBIA disorders, a group of rare inherited diseases characterized by basal ganglia iron deposition and mutations in lipid-metabolic genes. In PLA2G6-associated neurodegeneration, loss of the calcium-independent phospholipase A2β impairs membrane phospholipid remodeling and repair, leading to axonal spheroids, lipid storage pathology, and early iron accumulation[43,44]. Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration arises from mutations in PANK2, which disrupt coenzyme A biosynthesis, limiting acyl-CoA supply for β-oxidation and phospholipid synthesis. Patient cells exhibit mitochondrial dysfunction and iron accumulation despite the primary lesion residing in lipid metabolism[45,46].

Similarly, C19orf12 mutations in Mitochondrial Membrane Protein-Associated Neurodegeneration alter phospholipid and fatty-acid homeostasis, causing lipid droplet accumulation and oxidative stress[47]. Mutations in FA2H affect sphingolipid hydroxylation, while COASY mutations disrupt the final step of coenzyme A synthesis, both resulting in combined lipid and iron pathology[48,49]. Finally, WDR45-related BPAN, though classified as an autophagy disorder, also shows lysosomal lipid dysregulation with secondary iron deposition[50,51]. Across NBIA syndromes, primary mutations in lipid remodeling, coenzyme A metabolism, or membrane maintenance consistently manifest with secondary iron accumulation, illustrating the genetic entanglement of iron and lipid homeostasis in neurodegeneration.

6. Therapeutic Implications: Targeting the Mix, Not the Pieces

Despite a strong oxidative stress rationale, interventions aimed at modulating iron, lipids, or antioxidant capacity in Alzheimer’s disease have not delivered clinical benefit. The brain-permeable iron chelator deferiprone showed target engagement on QSM-MRI (reduced hippocampal susceptibility) yet was associated with accelerated cognitive decline over 12 months in amyloid-confirmed early Alzheimer’s patients[42]. Similarly, statins, despite epidemiological hints, have not slowed cognitive decline or altered disease trajectory in large, randomized trials[52]. High-dose vitamin E supplementation (2,000 IU/day) produced only a modest delay in functional decline in one study but no consistent cognitive advantage across trials[53-56]. On the contrary, meta-analyses link high-dose vitamin E to increased all-cause mortality and prostate cancer risk[57,58]. Similar to previous trials, other antioxidants showed early signals of benefit that did not translate into meaningful or lasting clinical improvement[59,60]. Collectively, these outcomes underscore that broad antioxidant, lipid-lowering, or iron-chelating approaches are insufficient and potentially maladaptive when not targeted to neuronal redox biology. By targeting the intersection, not the pieces, it may be possible to restore the fragile equilibrium neurons require to survive. Future therapies should instead focus on: (1) enhancing ApoE function or mimicking its anti-ferroptotic activity; (2) developing brain-permeable ferroptosis inhibitors and interventions that restore iron-lipid homeostasis within the CNS, to more precisely mitigate the ferroptotic drive that underlies neuronal vulnerability; and (3) developing metabolic support strategies that bolster glutathione synthesis and mitochondrial resilience, ensuring antioxidant capacity keeps pace with neuronal demand.

7. Concluding Remarks

Neurodegeneration is often viewed through the lens of misfolded proteins or isolated metabolic defects. Yet neurons’ greatest liability may be their metabolic design: a compulsory dependence on iron and lipids that creates an ever-present ferroptotic risk. Maintaining equilibrium between these forces requires tight coordination, for which ApoE provides a central safeguard. When this coordination fails, through ApoE4 isoform effects, metabolic stress, or lipid gene mutations as seen in NBIA, neurons succumb to ferroptotic vulnerability. Framing Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders as failures of iron-lipid co-regulation unifies disparate observations from genetic risk to biochemical pathology under a common mechanistic principle and opens a path toward therapies that stabilize, rather than sever, the partnership between iron and lipids.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the support of the Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health and the Victorian Government, particularly through the Operational Infrastructure Support Grant.

Authors contribution

The author contributed solely to the article.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by funds from the Alzheimer’s Association (AARGD-21-850785, AARGD-24-1294531).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Bazinet RP, Layé S. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in brain function and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(12):771-785.[DOI]

-

2. Ward DM, Cloonan SM. Mitochondrial iron in human health and disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2019;81:453-482.[DOI]

-

3. Dixon SJ, Stockwell BR. The role of iron and reactive oxygen species in cell death. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10(1):9-17.[DOI]

-

4. Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, Angeli JP, Doll S, Croix CS, et al. Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic PEs navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(1):81-90.[DOI]

-

5. Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060-1072.[DOI]

-

6. Ioannou MS, Jackson J, Sheu SH, Chang CL, Weigel AV, Liu H, et al. Neuron-astrocyte metabolic coupling protects against activity-induced fatty acid toxicity. Cell. 2019;177(6):1522-1535.[DOI]

-

7. Qi G, Mi Y, Shi X, Gu H, Brinton RD, Yin F. ApoE4 impairs neuron-astrocyte coupling of fatty acid metabolism. Cell Rep. 2021;34(1):108572.[DOI]

-

8. Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(1):91-98.[DOI]

-

9. Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, et al. Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 2017;171(2):273-285.[DOI]

-

10. Cañeque T, Baron L, Müller S, Carmona A, Colombeau L, Versini A, et al. Activation of lysosomal iron triggers ferroptosis in cancer. Nature. 2025;642(8067):492-500.[DOI]

-

11. Seiler A, Schneider M, Förster H, Roth S, Wirth EK, Culmsee C, et al. Glutathione peroxidase 4 senses and translates oxidative stress into 12/15-lipoxygenase dependent- and AIF-mediated cell death. Cell Metab. 2008;8(3):237-248.[DOI]

-

12. Friedmann Angeli JP, Schneider M, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Hammond VJ, et al. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(12):1180-1191.[DOI]

-

13. Hambright WS, Fonseca RS, Chen L, Na R, Ran Q. Ablation of ferroptosis regulator glutathione peroxidase 4 in forebrain neurons promotes cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration. Redox Biol. 2017;12:8-17.[DOI]

-

14. Chen L, Hambright WS, Na R, Ran Q. Ablation of the ferroptosis inhibitor glutathione peroxidase 4 in neurons results in rapid motor neuron degeneration and paralysis. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(47):28097-28106.[DOI]

-

15. Yan HF, Zou T, Tuo QZ, Xu S, Li H, Belaidi AA, et al. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms and links with diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):49.[DOI]

-

16. Shah R, Shchepinov MS, Pratt DA. Resolving the role of lipoxygenases in the initiation and execution of ferroptosis. ACS Cent Sci. 2018;4(3):387-396.[DOI]

-

17. Belaidi AA, Bush AI. Iron neurochemistry in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: Targets for therapeutics. J Neurochem. 2016;139:179-197.[DOI]

-

18. Müller S, Sindikubwabo F, Cañeque T, Lafon A, Versini A, Lombard B, et al. CD44 regulates epigenetic plasticity by mediating iron endocytosis. Nat Chem. 2020;12(10):929-938.[DOI]

-

19. Rodriguez R, Müller S, Colombeau L, Solier S, Sindikubwabo F, Cañeque T. Metal ion signaling in biomedicine. Chem Rev. 2025;125(2):660-744.[DOI]

-

20. Gryzik M, Asperti M, Denardo A, Arosio P, Poli M. NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy promotes ferroptosis induced by erastin, but not by RSL3 in Hela cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2021;1868(2):118913.[DOI]

-

21. Hou W, Xie Y, Song X, Sun X, Lotze MT, Zeh III HJ, et al. Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by degradation of ferritin. Autophagy. 2016;12(8):1425-1428.[DOI]

-

22. Mai TT, Hamaï A, Hienzsch A, Cañeque T, Müller S, Wicinski J, et al. Salinomycin kills cancer stem cells by sequestering iron in lysosomes. Nat Chem. 2017;9(10):1025-1033.[DOI]

-

23. Belaidi AA, Bush AI, Ayton S. Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease: Molecular insights and therapeutic opportunities. Mol Neurodegener. 2025;20(1):47.[DOI]

-

24. Troutwine BR, Hamid L, Lysaker CR, Strope TA, Wilkins HM. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12(2):496-510.[DOI]

-

25. Reiman EM, Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Quiroz YT, Huentelman MJ, Beach TG, Caselli RJ, et al. Exceptionally low likelihood of Alzheimer’s dementia in APOE2 homozygotes from a 5,000-person neuropathological study. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):667.[DOI]

-

26. Guo JL, Braun D, Fitzgerald GA, Hsieh YT, Rougé L, Litvinchuk A, et al. Decreased lipidated APOE-receptor interactions confer protection against pathogenicity of APOE and its lipid cargoes in lysosomes. Cell. 2025;188(1):187-206.[DOI]

-

27. Zhao N, Liu CC, Qiao W, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E, receptors, and modulation of Alzheimer’s disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83(4):347-357.[DOI]

-

28. Herz J, Strickland DK. LRP: A multifunctional scavenger and signaling receptor. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(6):779-784.[DOI]

-

29. Belaidi AA, Masaldan S, Southon A, Kalinowski P, Acevedo K, Appukuttan AT, et al. Apolipoprotein E potently inhibits ferroptosis by blocking ferritinophagy. Mol Psychiatry. 2024;29(2):211-220.[DOI]

-

30. Mahoney-Sanchez L, Belaidi AA, Bush AI, Ayton S. The complex role of Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease: An overview and update. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;60(3):325-335.[DOI]

-

31. He S, Xu Z, Han X. Lipidome disruption in Alzheimer’s disease brain: Detection, pathological mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Mol Neurodegener. 2025;20(1):11.[DOI]

-

32. Lefterov I, Wolfe CM, Fitz NF, Nam KN, Letronne F, Biedrzycki RJ, et al. APOE2 orchestrated differences in transcriptomic and lipidomic profiles of postmortem AD brain. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):113.[DOI]

-

33. Sun GG, Wang C, Mazzarino RC, Perez-Corredor PA, Davtyan H, Blurton-Jones M, et al. Microglial APOE3 christchurch protects neurons from Tau pathology in a human iPSC-based model of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Rep. 2024;43(12):114982.[DOI]

-

34. Ralhan I, Do AD, Bae JY, Feringa FM, Cai W, Chang J, et al. Protective ApoE variants support neuronal function by effluxing oxidized phospholipids. Neuron. 2025.[DOI]

-

35. Ayton S, Faux NG, Bush AI. Ferritin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid predict Alzheimer’s disease outcomes and are regulated by APOE. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6760.[DOI]

-

36. Ayton S, Janelidze S, Kalinowski P, Palmqvist S, Belaidi AA, Stomrud E, et al. CSF ferritin in the clinicopathological progression of Alzheimer’s disease and associations with APOE and inflammation biomarkers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2023;94(3):211-219.[DOI]

-

37. Ayton S, Faux NG, Bush AI. Association of cerebrospinal fluid ferritin level with preclinical cognitive decline in APOE-ε4 carriers. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(1):122-125.[DOI]

-

38. Ayton S, Wang Y, Diouf I, Schneider JA, Brockman J, Morris MC, et al. Brain iron is associated with accelerated cognitive decline in people with Alzheimer pathology. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(11):2932-2941.[DOI]

-

39. Chai B, Wu Y, Yang H, Fan B, Cao S, Zhang X, et al. Tau aggregation-dependent lipid peroxide accumulation driven by the hsa_circ_0001546/14-3-3/CAMK2D/Tau complex inhibits epithelial ovarian cancer peritoneal metastasis. Adv Sci. 2024;11(23):e2310134.[DOI]

-

40. Lermyte F, Everett J, Brooks J, Bellingeri F, Billimoria K, Sadler PJ, et al. Emerging approaches to investigate the influence of transition metals in the proteinopathies. Cells. 2019;8(10):1231.[DOI]

-

41. Alves F, Lane D, Wahida A, Jakaria M, Kalinowski P, Southon A, et al. Aberrant mitochondrial metabolism in Alzheimer’s disease links energy stress with ferroptosis. Adv Sci. 2025;12(37):e04175.[DOI]

-

42. Ayton S, Barton D, Brew B, Brodtmann A, Clarnette R, Desmond P, et al. Deferiprone in Alzheimer disease: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2025;82(1):11-18.[DOI]

-

43. Beck G, Sugiura Y, Shinzawa K, Kato S, Setou M, Tsujimoto Y, et al. Neuroaxonal dystrophy in calcium-independent phospholipase A2β deficiency results from insufficient remodeling and degeneration of mitochondrial and presynaptic membranes. J Neurosci. 2011;31(31):11411-11420.[DOI]

-

44. Kinghorn KJ, Castillo-Quan JI, Bartolome F, Angelova PR, Li L, Pope S, et al. Loss of PLA2G6 leads to elevated mitochondrial lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction. Brain. 2015;138(7):1801-1816.[DOI]

-

45. Brunetti D, Dusi S, Giordano C, Lamperti C, Morbin M, Fugnanesi V, et al. Pantethine treatment is effective in recovering the disease phenotype induced by ketogenic diet in a pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration mouse model. Brain. 2014;137(1):57-68.[DOI]

-

46. Zhou B, Westaway SK, Levinson B, Johnson MA, Gitschier J, Hayflick SJ. A novel pantothenate kinase gene (PANK2) is defective in Hallervorden-Spatz syndrome. Nat Genet. 2001;28(4):345-349.[DOI]

-

47. Venco P, Bonora M, Giorgi C, Papaleo E, Iuso A, Prokisch H, et al. Mutations of C19orf12, coding for a transmembrane glycine zipper containing mitochondrial protein, cause mis-localization of the protein, inability to respond to oxidative stress and increased mitochondrial Ca2+. Front Genet. 2015;6:185.[DOI]

-

49. Kruer MC, Paisán-Ruiz C, Boddaert N, Yoon MY, Hama H, Gregory A, et al. Defective FA2H leads to a novel form of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA). Ann Neurol. 2010;68(5):611-618.[DOI]

-

50. Ebrahimi-Fakhari D, Saffari A, Wahlster L, Lu J, Byrne S, Hoffmann GF, et al. Congenital disorders of autophagy: An emerging novel class of inborn errors of neuro-metabolism. Brain. 2016;139(2):317-337.[DOI]

-

51. Saitsu H, Nishimura T, Muramatsu K, Kodera H, Kumada S, Sugai K, et al. De novo mutations in the autophagy gene WDR45 cause static encephalopathy of childhood with neurodegeneration in adulthood. Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):445-449.[DOI]

-

52. Feldman HH, Doody RS, Kivipelto M, Sparks DL, Waters DD, Jones RW, et al. Randomized controlled trial of atorvastatin in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: LEADe. Neurology. 2010;74(12):956-964.[DOI]

-

53. Dysken MW, Sano M, Asthana S, Vertrees JE, Pallaki M, Llorente M, et al. Effect of vitamin E and memantine on functional decline in Alzheimer disease: The TEAM-AD VA cooperative randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(1):33-44.[DOI]

-

54. Farina N, Llewellyn D, Isaac M, Tabet N. Vitamin E for Alzheimer’s dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4(4):CD002854.[DOI]

-

55. Kryscio RJ, Abner EL, Caban-Holt A, Lovell M, Goodman P, Darke AK, et al. Association of antioxidant supplement use and dementia in the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease by vitamin E and selenium trial (PREADViSE). JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(5):567-573.[DOI]

-

56. Petersen RC, Thomas RG, Grundman M, Bennett D, Doody R, Ferris S, et al. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(23):2379-2388.[DOI]

-

57. Klein EA, Thompson IM Jr, Tangen CM, Crowley JJ, Lucia MS, Goodman PJ, et al. Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: The Selenium and Vitamin E cancer prevention trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2011;306(14):1549-1556.[DOI]

-

58. Miller III ER, Pastor-Barriuso R, Dalal D, Riemersma RA, Appel LJ, Guallar E. Meta-analysis: High-dosage vitamin E supplementation may increase all-cause mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(1):37-46.[DOI]

-

59. DeKosky ST, Williamson JD, Fitzpatrick AL, Kronmal RA, Ives DG, Saxton JA, et al. Ginkgo biloba for prevention of dementia: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300(19):2253-2262.[DOI]

-

60. Yuan Q, Wang CW, Shi J, Lin ZX. Effects of Ginkgo biloba on dementia: An overview of systematic reviews. J Ethnopharmacol. 2017;195:1-9.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite