Keywords

1. Introduction

Iron’s role as the protagonist in ferroptosis centres on its ability to cycle between ferrous and ferric states, enabling electron transfer and redox coupling with reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation such as hydrogen peroxide[1]. The resultant hydroxyl radicals can initiate a chain reaction of lipid peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acid species that destabilize cellular membranes, leading to cell rupture and death[2]. In addition, iron-containing enzymes, including lipoxygenases, have been shown to accelerate lipid oxidation[3,4]. Even before the term ‘ferroptosis’ was coined, studies demonstrated a link between iron and lipid peroxidation when iron dextran injected into healthy mice caused peroxide formation in adipose tissue that was mitigated by vitamin E, a bona fide anti-ferroptotic radical chain-reaction quencher[5-7].

Cellular ferroptosis susceptibility has also been demonstrated to be tuned by iron-handling pathways, including transferrin uptake (via TFR1 modulation)[8,9], iron export (via ferroportin knockout)[10,11], iron storage in ferritin and ferritin degradation

Indeed, iron chelators have been used in clinical practice for many years to protect patients from complications of iron overload due to blood transfusions to treat thalassemia, sickle cell disease, and myelodysplastic syndromes[19,20]. Because there is no physiological way for excess iron to be actively excreted, iron accumulation within tissues causes progressive organ damage that can be fatal without chelation therapy[21]. The clinical success of iron chelation in this context validated the principle of targeting toxic iron overload. It was therefore a natural extension to investigate whether iron chelators might also be repurposed to reduce iron burden in neurodegenerative diseases characterized by signatures of iron overload and oxidative stress[22].

Localised ‘iron overload’ has been associated with several neurodegenerative diseases (i.e., Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease), based on measurements of elevated brain iron, demonstrated through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) imaging[23-25], ferritin in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)[26,27], and postmortem analyses[28-30]. Using the framework of iron as a catalyst for lipid peroxidation, along with evidence of lipid peroxidation and decreased glutathione (the substrate for the ferroptosis checkpoint inhibitor, glutathione peroxidase 4, GPX4), ferroptosis has been implicated as a pathological contributor promoting neuronal loss[31,32]. Unexpectedly, clinical trials in Parkinson’s[33] and Alzheimer’s disease[34] revealed that iron chelation with deferiprone accelerated disease progression.

This discrepancy of iron chelation worsening neurodegeneration characterised by local iron overload raises a critical question: why does iron chelation block ferroptosis induced by pro-ferroptotic agents such as RSL3 and erastin (where there is no iron elevation in cell culture), yet fail to protect in the context of human neurodegenerative disease where iron is elevated? We propose three explanations:

1. Iron overload may not be a central driver of ferroptosis in these disorders, which challenges current assumptions about the physiological triggers of ferroptosis in vivo[35]. Iron elevation may reflect a homeostatic response to an underlying metabolic disruption, e.g. supplying substrate for Fe-S cluster production[36].

2. Ferroptosis itself may not be a significant mechanism of cell death in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, undermining the use of ‘iron overload’ as a surrogate marker for ferroptosis in human pathology. This may be true since only trace amounts of Fe2+ are needed to drive lipid peroxidation.

3. Iron chelation is effective in preventing ferroptosis, yet iron starvation worsens disease outcomes via other mechanisms, e.g., depriving the formation of Fe–S clusters.

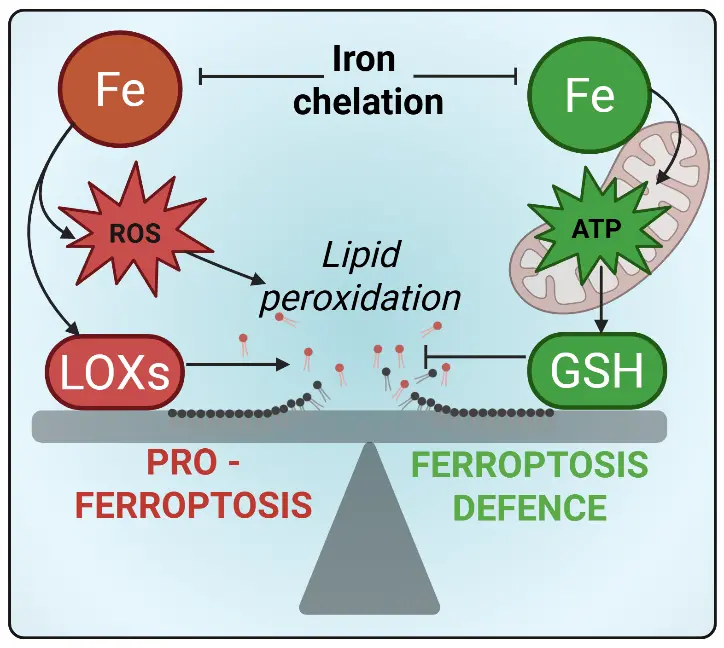

To unpack these potential explanations, we revisited the original experiments defining ferroptosis. When investigating potential bioenergetic similarities with other cell death mechanisms, Dixon et al. highlighted that ferroptosis could not be explained by a simple increase in H2O2-dependent, iron-catalyzed ROS production (i.e., Fenton chemistry), as H2O2, but not erastin (which depletes cellular glutathione), induced substantial depletion of intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP), hinting at different toxic mechanisms[16]. Furthermore, cell death induced by erastin and RSL3 is blocked by iron chelators and radical trapping antioxidants (e.g. ferrostatin) where this is less evident with H2O2-induced toxicity[37]. Instead, Dixon postulated that ferroptosis occurs due to an imbalance in oxidative stress defences (i.e. via erastin induced cystine deficiency), whereby ROS production outweighs antioxidant capacity[16]. Importantly, this imbalance may arise from either increased ROS generation (i.e., via iron) and/or depletion of antioxidant defence (by glutathione depletion), with the latter given less weight in terms of being a cause of ferroptosis in diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s where iron elevation is a signature (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Iron at the crossroads of ferroptosis: Driver of lipid peroxidation or defender of redox homeostasis. ROS: reactive oxygen species; ATP: adenosine triphosphate; LOX: lipoxygenases; GSH: glutathione.

However, iron can act on both sides of this ferroptosis catalysis/defence equation. The same redox flexibility of iron that can amplify oxidative stress is also what makes it indispensable for mitochondrial energy metabolism, which we have recently shown to be a limiting factor for glutathione synthesis required to protect against ferroptosis[29]. This is due to glutathione requiring 2 ATP for its production and, given the high abundance of glutathione (~5 mM) and rapid turnover, a material tax on the ATP pool is required to maintain glutathione antioxidant capacity. So, iron limitation could paradoxically enhance ferroptosis susceptibility if it blunts mitochondrial energy metabolism.

Mitochondria are avid consumers of iron, using as much as 20-50% of total cellular iron depending on cell type[38,39]. Much of this iron is directed to the electron transport chain, including forming iron–sulfur (Fe–S) clusters and heme groups embedded in respiratory complexes I–IV. Beyond oxidative phosphorylation, Fe–S–dependent enzymes such as aconitase, lipoic acid synthase, and biotin synthase sustain tricarboxylic acid cycle flux and key biosynthetic reactions[40]. Mitochondria are also the primary site of heme biosynthesis, where iron insertion into protoporphyrin IX produces heme for cytochromes and other hemoproteins essential for electron transport and redox signalling[40]. Together, these processes have mitochondrial iron metabolism underpinning both energy production and antioxidant capacity, thereby influencing cellular susceptibility to ferroptosis.

This potential link between impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics and ferroptotic vulnerability may not be apparent in short-term in vitro experiments, which are typically conducted in nutrient-rich media that support metabolic flexibility and compensate for transient energy deficits, explaining why iron chelators only suppress ferroptosis in this context. In contrast, chronic iron chelation in vivo, where cells are subject to tighter metabolic constraints, may unintentionally restrict iron availability necessary for mitochondrial energy production. For instance, in a mouse model of muscle atrophy characterized by systemic iron overload and heightened lipid peroxidation, deferiprone treatment further reduced mitochondrial iron-containing proteins without altering ferritin levels[41]. If mitochondrial dysfunction due to iron insufficiency compromises ATP-dependent glutathione biosynthesis, this could shift the balance toward ferroptosis even in the context of diminished labile iron pools. This challenges the prevailing therapeutic rationale for targeting iron as a straightforward anti-ferroptotic strategy and underscores the dual nature of iron, as both an essential antioxidant cofactor and a potential catalyst of ferroptotic cell death. Consequently, in disease states marked by intrinsic energy insufficiency, such as neurodegeneration[42], it may be the failure of metabolic resilience, rather than the presence of excess free iron, which acts as the primary driver of ferroptosis.

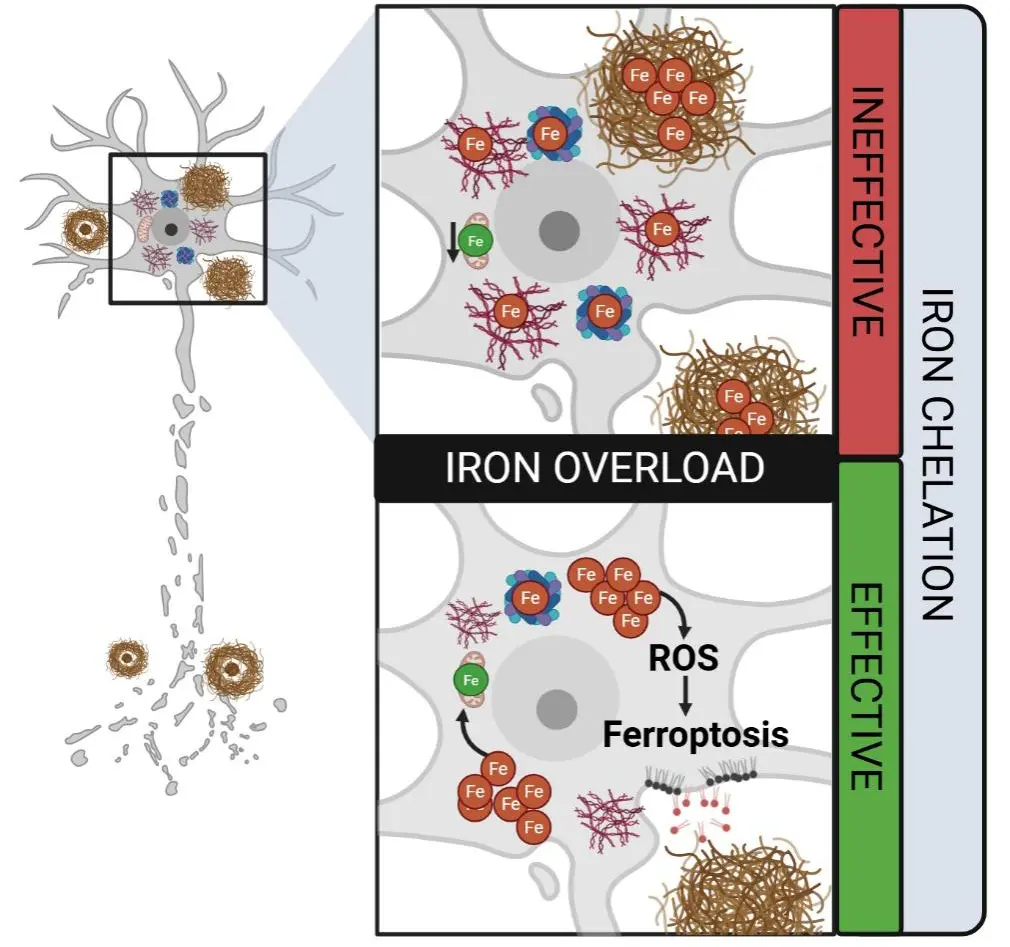

In the case of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, and likely in other conditions marked by energetic insufficiency, iron accumulation may paradoxically coexist with a functional iron deficiency, starving the mitochondria. This concept, proposed in the “Azalea Hypothesis” by Steve LeVine[43], suggests that despite appearing iron overloaded, cells may be unable to access usable iron for mitochondrial processes (Figure 2). Pathological immobilisation of iron by protein aggregates such as amyloid β and tau may sequester iron in a non-bioavailable form, or impaired autophagy may prevent efficient breakdown of ferritin to mobilise iron, thereby impairing mitochondrial ATP production and subsequently glutathione synthesis, an essential component of the ferroptosis defence system[29].

Figure 2. Distinct forms of “iron overload” and their implications for iron-chelation efficacy. Cells may appear iron-overloaded, yet much of the iron can be sequestered in pathological aggregates (such as neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid plaques), or trapped in ferritin, rendering it inaccessible for normal mitochondrial function. In this scenario, chelation is ineffective because the excess iron is not part of the labile iron pool. Conversely, when iron overload reflects an accumulation of labile, redox-active iron, this promotes ROS generation and lipid peroxidation, driving ferroptosis. Under these conditions, iron chelation is likely effective in reducing oxidative stress and mitigating ferroptotic cell death. Created in Biorender.com. ROS: reactive oxygen species.

Under this framework, apparent “iron overload” in neurodegenerative disease does not necessarily signify an excess of freely reactive iron, but rather a breakdown in the dynamic trafficking, localisation, and utilisation of iron that ultimately impairs cellular bioenergetics. Most investigations of iron dysregulation have traditionally relied on the paradigm of iron homeostasis in health; they assume that cells regulate iron through predictable adjustments in import, export, and storage. However, this model is overly reductive in the context of human pathology. Simply lowering total iron has repeatedly failed to ameliorate neurodegenerative changes, indicating that iron quantity alone is not the core problem.

Instead, iron accumulation in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related disorders should be interpreted through the lens of iron stasis (ferrostasis); a state in which iron becomes mislocalised, improperly mobilised, or trapped in dysfunctional compartments. This perspective emphasises not only how much iron is present, but where it resides, in what chemical form, and how it is dynamically regulated within the cell. Within this framework, iron accumulation may signal heightened susceptibility to ferroptosis, reflecting defective iron mobilisation and organellar crosstalk rather than simply a reservoir of pro-oxidant potential. By reframing iron pathology as a problem of iron stasis rather than simple overload, we challenge conventional interpretations of iron in neurodegeneration and highlight the need to consider both iron immobilisation and metabolic insufficiency as central determinants of ferroptosis-related disease mechanisms.

A recent study by Remesal et al. demonstrates this notion using the example of a model of ferritin over-expression[44]. They identified the iron storage protein, ferritin light chain 1 (FTL1), as a pro-ageing neuronal factor: its overexpression in the hippocampus of young mice accelerated cognitive decline, whereas knockdown in aged mice preserved synaptic integrity and prevented cognitive deterioration. Overexpression of FTL1 diminished iron availability, gene expression of mitochondrial/oxidative phosphorylation pathway components, and consequent ATP production. Without sufficiently bioavailable iron, mitochondrial respiration is impaired, leading to reduced ATP synthesis, which is required to fuel glutathione (GSH) synthesis, a key co-factor required for ferroptosis defence[29,44]. Analogously, iron overload apparent in Alzheimer’s[28] and Parkinson’s diseases[45], may in fact be a compensation for the inability of mitochondria to mobilize iron to produce ATP and, hence, GSH. Thus, targeting bioavailable forms of iron via iron chelation in an energy-deprived context could weaken ferroptosis defences, which would explain the paradoxical clinical worsening in iron chelator trials[33,34].

While the central role of labile iron in driving ferroptosis is well established, the presence of excess iron alone does not distinguish between its functional forms, namely, redox-active labile iron versus iron incorporated into metabolic or storage pools. Without this resolution, interpreting “iron overload” as an indication for therapeutic iron chelation becomes problematic. Common iron quantification methods such as Quantitative susceptibility mapping[23,28,46], an MRI modality sensitive to Fe3+, or ICP-MS, that measures total iron[41,47], are not capable of differentiating between pro-ferroptotic labile Fe2+ and functionally essential intracellular iron, such as that required for mitochondrial ATP production. A major unmet need in ferroptosis research is the ability to quantify redox-active iron with spatial, temporal, and oxidation-state resolution in intact tissues. Promising advancements, such as genetically encoded iron sensors (i.e., FEOX[48]), fluorescent probes capable of distinguishing between specific iron species (i.e., FerrOrange, which selectively detects Fe2+ ions[49]), and synchrotron-based nano-x-ray analysis[50], offer a path toward physiologically accurate measurement of labile iron pools. Integration of these emerging tools with lipid peroxidation reporters, ROS probes, and single-cell transcriptomics will be essential for establishing the causal hierarchy of iron dysregulation in pathophysiological ferroptosis.

Consequently, iron chelation is likely to be beneficial only when ferroptosis is the primary driver of neurodegeneration and when the initiating event is an excess of labile iron driving Fenton chemistry and lipid peroxidation. Although ferroptosis is often described as an “iron-dependent” cell death pathway, an explicit increase in the labile iron pool is not universally required as a trigger. As demonstrated recently by Liu et al., an increase in labile iron was required for ferroptosis triggered by cysteine deficiency but not direct inhibition of GPX4[51]. In contrast, in diseases characterised by mitochondrial dysfunction and bioenergetic failure (often reflected by reduced FDG-PET signal), elevated iron may instead represent a compensatory response to functional iron deficiency rather than a pathogenic surplus. In these contexts, iron chelation may fail to address the upstream drivers of cell death and may even activate alternative death pathways. For example, iron chelation has been shown to induce apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells through ROS-dependent MAPK signalling[52]. Recently, cuproptosis in acute myeloid leukemia was shown to be initiated by inhibiting heme biosynthesis[53], therefore it is conceivable that iron chelation limited heme to induce cuproptosis in the clinical trials of deferiprone. The capacity of iron chelation to influence other regulated cell death modalities is less well studied, but this possibility should be carefully considered when evaluating why iron chelators have, in some cases, exacerbated neurodegenerative conditions featuring multiple overlapping cell death mechanisms.

This raises a fundamental challenge for the field: what initiates ferroptosis in neurodegeneration, if ferroptosis is relevant at all? Only with a clearer understanding of disease-specific ferroptotic triggers[35] can we determine whether iron chelation is mechanistically justified. Until then, broad application of chelation strategies risks exacerbating the very vulnerabilities they are intended to treat. Ferroptosis in degenerative diseases is unlikely to be driven by a single event such as iron excess. Rather, it may arise from a progressive erosion of anti-ferroptotic defences, including glutathione depletion, impaired lipid-repair capacity, membrane PUFA remodelling, and mitochondrial energetic failure. In these settings, targeting the lipid peroxidation arm of ferroptosis directly may prove both more effective and less disruptive than manipulating iron itself.

Several strategies fall into this category, including the use of non-chelating radical trapping agents such as liproxstatin-1 or ferrostatin-1, targeting phospholipid remodelling enzyme ACSL4[54,55], promoting GPX4 expression[56], or modulating ether lipids[57]. To date, no classical ferroptosis inhibitors have entered neurodegenerative disease–specific clinical trials but several antioxidant and radical-trapping agents (RTAs) have/are being evaluated in AD or MCI, including vitamin E (NCT00235716: 2000 IU/d of alpha tocopherol compared with placebo resulted in slower functional decline ~19% delay in clinical progression per year[58]; however at a lower dose, 800 IU/d in NCT00117403, results show no meaningful benefit[59]), N-acetylcysteine (NCT01320527: N-acetyl cysteine present in a nutraceutical formulation (NF) along with folate, alpha-tocopherol, B12, S-adenosyl methioinine, and acetyl-L-carnitine. Relative to placebo, NF cohort showed improvements in Clox-1 and Dementia Rating Scale[60]; NCT04740580: result pending), and the phenolic lipid-lowering drug probucol (ACTRN12621000726853: trial in process)[61]. Notably, several factors reported may limit the clinical impact of such agents[62]. RTAs often lack target engagement biomarkers or companion diagnostics, making it difficult to confirm whether they reach and modulate the intended ferroptotic pathways in vivo. In addition, non-enzymatic antioxidants require high local concentrations and rapid reaction kinetics to meaningfully intercept lipid radicals.

If Alzheimer’s disease reflects a state of functional iron deficiency, then an alternative therapeutic paradigm emerges that contrasts sharply with iron-chelation strategies. Iron supplementation, a well-established intervention for restoring systemic iron balance and correcting iron-deficiency anaemia[63], may similarly prove beneficial within the central nervous system. Supporting this concept, a long-term dietary iron supplementation study in rodents showed that co-administration of iron and vitamin B6 markedly enhanced mitochondrial bioenergetics, substantially increasing complex I– and complex II–driven ATP production in intact mitochondria isolated from the brain and skeletal muscle[64]. These findings suggest that targeted iron repletion could help alleviate the bioenergetic deficits contributing to Alzheimer’s disease progression.

Total iron content should not be equated with ferroptotic potential. A functional iron deficiency may paradoxically present as “iron overload” due to homeostasis, sequestration, misdistribution, or oxidation state changes. Bioenergetic dysregulation and mitochondrial dysfunction are signatures of functional iron deficiency[41,65,66]; thus a functional iron deficiency presenting as ‘iron overload’ cannot be excluded by measuring total markers of iron. In this context, iron may be protective, not harmful, supporting ATP synthesis and redox buffering rather than catalyzing lipid peroxidation. Thus, as we have learnt, therapeutic strategies should not rely solely on crude iron measures, but instead incorporate assessments of iron speciation, bioenergetic status, and lipid peroxidation. Iron’s dual nature, as both a vital cofactor and a potential catalyst of oxidative damage, demands a more nuanced appreciation.

Authors contribution

All authors contributed equally to this work.

Conflicts of interest

Ashley I. Bush holds shares in Alterity Ltd, Cogstate Ltd, and a profit-share arrangement with Collaborative Medicinal Development Pty Ltd, and has received travel support from Novonordisk. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia (Grant No. GNT2008359) and by an operational infrastructure support grant to The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health from the Victorian Government.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Dixon SJ, Stockwell BR. The role of iron and reactive oxygen species in cell death. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:9-17.[DOI]

-

2. Fenton HJH. Lxxiii.—oxidation of tartaric acid in presence of iron. J Chem Soc Trans. 1894;65:899-910.[DOI]

-

3. Kagan VE, Mao G, Qu F, Angeli JPF, Doll S, Croix CS, et al. Oxidized arachidonic and adrenic pes navigate cells to ferroptosis. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(1):81-90.[DOI]

-

4. Shah R, Shchepinov MS, Pratt DA. Resolving the role of lipoxygenases in the initiation and execution of ferroptosis. ACS Cent Sci. 2018;4(3):387-396.[DOI]

-

5. Golberg L, Smith JP. Changes associated with the accumulation of excessive amounts of iron in certain organs of the rat. Br J Exp Pathol. 1958;39:59-73.[PubMed]

-

6. Carlson BA, Tobe R, Yefremova E, Tsuji PA, Hoffmann VJ, Schweizer U, et al. Glutathione peroxidase 4 and vitamin e cooperatively prevent hepatocellular degeneration. Redox Biol. 2016;9:22-31.[DOI]

-

7. Zheng J, Conrad M. The metabolic underpinnings of ferroptosis. Cell Metab. 2020;32(6):920-937.[DOI]

-

8. Yi L, Hu Y, Wu Z, Li Y, Kong M, Kang Z, et al. TFRC upregulation promotes ferroptosis in CVB3 infection via nucleus recruitment of Sp1. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(7):592.[DOI]

-

9. Gao M, Monian P, Quadri N, Ramasamy R, Jiang X. Glutaminolysis and transferrin regulate ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2015;59(2):298-308.[DOI]

-

10. Geng N, Shi BJ, Li SL, Zhong ZY, Li YC, Xua WL, et al. Knockdown of ferroportin accelerates erastin-induced ferroptosis in neuroblastoma cells. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22(12):3826-3836.[DOI]

-

11. Li Y, Zeng X, Lu D, Yin M, Shan M, Gao Y. Erastin induces ferroptosis via ferroportin-mediated iron accumulation in endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2021;36(4):951-964.[DOI]

-

12. Gryzik M, Asperti M, Denardo A, Arosio P, Poli M. NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy promotes ferroptosis induced by erastin, but not by RSL3 in HeLa cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2021;1868(2):118913.[DOI]

-

13. Hou W, Xie Y, Song X, Sun X, Lotze MT, Zeh Iii HJ, et al. Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by degradation of ferritin. Autophagy. 2016;12(8):1425-1428.[DOI]

-

14. Belaidi AA, Masaldan S, Southon A, Kalinowski P, Acevedo K, Appukuttan AT, et al. Apolipoprotein e potently inhibits ferroptosis by blocking ferritinophagy. Mol Psychiatry. 2024;29(2):211-220.[DOI]

-

15. Gao M, Monian P, Pan Q, Zhang W, Xiang J, Jiang X. Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell Res. 2016;26(9):1021-1032.[DOI]

-

16. Dixon Scott J, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060-1072.[DOI]

-

17. Zilka O, Shah R, Li B, Friedmann Angeli JP, Griesser M, Conrad M, et al. On the mechanism of cytoprotection by ferrostatin-1 and liproxstatin-1 and the role of lipid peroxidation in ferroptotic cell death. ACS Cent Sci. 2017;3(3):232-243.[DOI]

-

18. Cañeque T, Baron L, Müller S, Carmona A, Colombeau L, Versini A, et al. Activation of lysosomal iron triggers ferroptosis in cancer. Nature. 2025;642(8067):492-500.[DOI]

-

19. Olivieri NF, Brittenham GM. Iron-chelating therapy and the treatment of thalassemia. Blood. 1997;89(3):739-761.[DOI]

-

20. Mobarra N, Shanaki M, Ehteram H, Nasiri H, Sahmani M, Saeidi M, et al. A review on iron chelators in treatment of iron overload syndromes. Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res. 2016;10(4):239-247.[PMC]

-

21. Kohgo Y, Ikuta K, Ohtake T, Torimoto Y, Kato J. Body iron metabolism and pathophysiology of iron overload. Int J Hematol. 2008;88(1):7-15.[DOI]

-

22. Belaidi AA, Bush AI. Iron neurochemistry in alzheimer’s disease and parkinson’s disease: Targets for therapeutics. J Neurochem. 2016;139(S1):179-197.[DOI]

-

23. Ayton S, Fazlollahi A, Bourgeat P, Raniga P, Ng A, Lim YY, et al. Cerebral quantitative susceptibility mapping predicts amyloid-β-related cognitive decline. Brain. 2017;140(8):2112-2119.[DOI]

-

24. Pyatigorskaya N, Sanz-Morère CB, Gaurav R, Biondetti E, Valabregue R, Santin M, et al. Iron imaging as a diagnostic tool for parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2020;11:366.[DOI]

-

25. Gaurav R, Lejeune FX, Santin MD, Valabrègue R, Pérot JB, Pyatigorskaya N, et al. Early brain iron changes in parkinson’s disease and isolated rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder: A four-year longitudinal multimodal quantitative mri study. Brain Commun. 2025;7(3):fcaf212.[DOI]

-

26. Ayton S, Faux NG, Bush AI. Ferritin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid predict Alzheimer’s disease outcomes and are regulated by APOE. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6760.[DOI]

-

27. Ayton S, Janelidze S, Kalinowski P, Palmqvist S, Belaidi AA, Stomrud E, et al. CSF ferritin in the clinicopathological progression of Alzheimer’s disease and associations with APOE and inflammation biomarkers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2023;94(3):211-219.[DOI]

-

28. Ayton S, Wang Y, Diouf I, Schneider JA, Brockman J, Morris MC, et al. Brain iron is associated with accelerated cognitive decline in people with alzheimer pathology. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(11):2932-2941.[DOI]

-

29. Alves F, Lane D, Wahida A, Jakaria M, Kalinowski P, Southon A, et al. Aberrant mitochondrial metabolism in alzheimer's disease links energy stress with ferroptosis. Adv Sci. 2025;12(37):e04175.[DOI]

-

30. Sofic E, Riederer P, Heinsen H, Beckmann H, Reynolds GP, Hebenstreit G, et al. Increased iron (III) and total iron content in post mortem substantia nigra of parkinsonian brain. J Neural Transmission. 1988;74(3):199-205.[DOI]

-

31. Lei P, Walker T, Ayton S. Neuroferroptosis in health and diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2025;26(8):497-511.[DOI]

-

32. Lane DJR, Alves F, Ayton SJ, Bush AI. Striking a NRF2: The rusty and rancid vulnerabilities toward ferroptosis in Alzheimer's disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2023;39(1-3):141-161.[DOI]

-

33. Devos D, Labreuche J, Rascol O, Corvol JC, Duhamel A, Delannoy PG, et al. Trial of deferiprone in parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(22):2045-2055.[DOI]

-

34. Ayton S, Barton D, Brew B, Brodtmann A, Clarnette R, Desmond P, et al. Deferiprone in alzheimer disease: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2025;82(1):11-18.[DOI]

-

35. Nguyen TPM, Alves F, Lane DJR, Bush AI, Ayton S. Triggering ferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci. 2025;48(10):750-765.[DOI]

-

36. Martelli A, Schmucker S, Reutenauer L, Mathieu Jacques RR, Peyssonnaux C, Karim Z, et al. Iron regulatory protein 1 sustains mitochondrial iron loading and function in frataxin deficiency. Cell Metab. 2015;21(2):311-323.[DOI]

-

37. Chen Y, Guo X, Zeng Y, Mo X, Hong S, He H, et al. Oxidative stress induces mitochondrial iron overload and ferroptotic cell death. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):15515.[DOI]

-

38. Jhurry ND, Chakrabarti M, McCormick SP, Holmes-Hampton GP, Lindahl PA. Biophysical investigation of the ironome of human jurkat cells and mitochondria. Biochemistry. 2012;51(26):5276-5284.[DOI]

-

39. Rauen U, Springer A, Weisheit D, Petrat F, Korth H-G, de Groot H, et al. Assessment of chelatable mitochondrial iron by using mitochondrion-selective fluorescent iron indicators with different iron-binding affinities. ChemBioChem. 2007;8(3):341-352.[DOI]

-

40. Ward DM, Cloonan SM. Mitochondrial iron in human health and disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2019;81:453-482.[DOI]

-

41. Alves FM, Kysenius K, Caldow MK, Hardee JP, Chung JD, Trieu J, et al. Iron overload and impaired iron handling contribute to the dystrophic pathology in models of duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13(3):1541-1553.[DOI]

-

42. Wilson DM, III , Cookson MR, Van Den Bosch L, Zetterberg H, Holtzman DM, Dewachter I. Hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases. Cell. 2023;186(4):693-714.[DOI]

-

43. LeVine SM. The azalea hypothesis of Alzheimer disease: A functional iron deficiency promotes neurodegeneration. Neuroscientist. 2024;30(5):525-44.[DOI]

-

44. Remesal L, Sucharov-Costa J, Wu Y, Pratt KJB, Bieri G, Philp A, et al. Targeting iron-associated protein ftl1 in the brain of old mice improves age-related cognitive impairment. Nat Aging. 2025;5(10):1957-1969.[DOI]

-

45. Tambasco N, Paolini Paoletti F, Chiappiniello A, Lisetti V, Nigro P, Eusebi P, et al. T2*-weighted MRI values correlate with motor and cognitive dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;80:91-98.[DOI]

-

46. Guan X, Lancione M, Ayton S, Dusek P, Langkammer C, Zhang M. Neuroimaging of Parkinson's disease by quantitative susceptibility mapping. NeuroImage. 2024;289:120547.[DOI]

-

47. Alves FM, Kysenius K, Caldow MK, Hardee JP, Crouch PJ, Ayton S, et al. Iron accumulation in skeletal muscles of old mice is associated with impaired regeneration after ischaemia–reperfusion damage. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021;12(2):476-492.[DOI]

-

48. Sangokoya C. The genetically encoded biosensor FEOX is a molecular gauge for cellular iron environment dynamics at single cell resolution. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):36596.[DOI]

-

49. Grubwieser P, Brigo N, Seifert M, Grander M, Theurl I, Nairz M, et al. Quantification of macrophage cellular ferrous iron (Fe2+) content using a highly specific fluorescent probe in a plate reader. Bio-protocol. 2024;14(3):e4929.[DOI]

-

50. Brooks J, Everett J, Hill E, Billimoria K, Morris CM, Sadler PJ, et al. Nanoscale synchrotron x-ray analysis of intranuclear iron in melanised neurons of Parkinson’s substantia nigra. Commun Biol. 2024;7(1):1024.[DOI]

-

51. Liu X, Zhao Z, Bian Z, Benthani FA, Hu Y, Liang D, et al. Endocytosis is essential for cysteine-deprivation-induced ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2025;85(17):3333-3342.[DOI]

-

52. Xue Y, Zhang G, Zhou S, Wang S, Lv H, Zhou L, et al. Iron chelator induces apoptosis in osteosarcoma cells by disrupting intracellular iron homeostasis and activating the MAPK pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(13):7168.[DOI]

-

53. Lewis AC, Gruber E, Franich R, Armstrong J, Kelly MJ, Opazo CM, et al. Inhibition of heme biosynthesis triggers cuproptosis in acute myeloid leukaemia. bioRxiv 2024.08.11.607520[Preprint]. 2024.[DOI]

-

54. Huang Q, Ru Y, Luo Y, Luo X, Liu D, Ma Y, et al. Identification of a targeted acsl4 inhibitor to treat ferroptosis-related diseases. Sci Adv. 2024;10(13):eadk1200.[DOI]

-

55. Linghu M, Luo X, Zhou X, Liu D, Huang Q, Ru Y, et al. Covalent inhibition of ACSL4 alleviates ferroptosis-induced acute liver injury. Cell Chem Biol. 2025;32(7):942-954.e945.[DOI]

-

56. Fan S, Wang K, Zhang T, Deng D, Shen J, Zhao B, et al. Mechanisms and therapeutic potential of GPX4 in pain modulation. Pain Ther. 2025;14(1):21-45.[DOI]

-

57. Zou Y, Henry WS, Ricq EL, Graham ET, Phadnis VV, Maretich P, et al. Plasticity of ether lipids promotes ferroptosis susceptibility and evasion. Nature. 2020;585(7826):603-608.[DOI]

-

58. Dysken MW, Sano M, Asthana S, Vertrees JE, Pallaki M, Llorente M, et al. Effect of vitamin E and memantine on functional decline in Alzheimer disease: the TEAM-AD VA cooperative randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(1):33-44.[DOI]

-

59. Galasko DR, Peskind E, Clark CM, Quinn JF, Ringman JM, Jicha GA, et al. Antioxidants for alzheimer disease: A randomized clinical trial with cerebrospinal fluid biomarker measures. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(7):836-841.[DOI]

-

60. Remington R, Bechtel C, Larsen D, Samar A, Doshanjh L, Fishman P, et al. A phase II randomized clinical trial of a nutritional formulation for cognition and mood in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45(2):395-405.[DOI]

-

61. Briyal S, Ranjan AK, Gulati A. Oxidative stress: A target to treat alzheimer’s disease and stroke. Neurochem Int. 2023;165:105509.[DOI]

-

62. Davies AM, Holt AG. Why antioxidant therapies have failed in clinical trials. J Theor Biol. 2018;457:1-5.[DOI]

-

63. Pantopoulos K. Oral iron supplementation: New formulations, old questions. Haematologica. 2024;109(9):2790.[DOI]

-

64. Zhou L, Mozaffaritabar S, Kolonics A, Kawamura T, Koike A, Kéringer J, et al. Long-term iron supplementation combined with vitamin B6 enhances maximal oxygen uptake and promotes skeletal muscle-specific mitochondrial biogenesis in rats. Front Nutr. 2024;10:1335187.[DOI]

-

65. Masini A, Salvioli G, Cremonesi P, Botti B, Gallesi D, Ceccarelli D. Dietary iron deficiency in the rat. I. Biochim Biophys Acta Bioenerg. 1994;1188(1):46-52.[DOI]

-

66. Jarvis JH, Jacobs A. Morphological abnormalities in lymphocyte mitochondria associated with iron-deficiency anaemia. J Clin Pathol. 1974;27(12):973-979.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite