Abstract

Ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death driven by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, has emerged as a crucial tumor suppressive mechanism and a promising therapeutic target in oncology. This review synthesizes the current understanding of its core molecular machinery, encompassing lipid metabolism, iron homeostasis, and multi-layered cellular defense systems. We highlight the unique metabolic and genetic vulnerabilities that render specific cancer cell types intrinsically susceptible to ferroptosis. Furthermore, we discuss the dynamic propagation of ferroptotic signals within the tumor microenvironment and their complex immunomodulatory effects. Central to this review is a strategic framework for targeting ferroptosis, synthesizing recent advances in the development of specific ferroptosis inducers and evaluating their synergistic potential when combined with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. By integrating mechanistic insight with translational perspectives, this work provides a systematic guide for rationally exploiting ferroptosis in cancer treatment.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Regulated cell death (RCD) plays crucial roles in maintaining tissue homeostasis and eliminating abnormal cells, with its dysregulation commonly observed in various diseases, including cancer[1]. Among the diverse forms of RCD, ferroptosis has gained increasing attention as a unique, iron-dependent, and lipid peroxidation-driven cell death modality. Ferroptosis is characterized by the accumulation of iron and the excessive peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acid-containing phospholipids (PUFA-PLs) on biological membranes, ultimately leading to membrane damage and cell demise[2,3].

In recent years, our understanding of the intricate molecular mechanisms regulating ferroptosis has advanced significantly. In this review, we summarize the latest insights into the molecular mechanisms of ferroptosis, encompassing its prerequisites (the critical roles of lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism) and its sophisticated defense systems. We then delve into a comprehensive analysis of the mechanistic basis of ferroptosis in tumor biology. Beyond intracellular events, recent evidence further indicates that ferroptosis can propagate both within and between cells, influencing the tumor microenvironment and neighboring cells.

The burgeoning interest in ferroptosis stems from its profound implications in tumor biology. Given the inherent or acquired ferroptosis vulnerabilities present in refractory cancers and within the tumor microenvironment, this process is increasingly recognized as a novel therapeutic target for cancer treatment[4,5]. We attempt to summarize potential targets that can be exploited to modulate the ferroptosis sensitivity of tumor cells and propose a conceptual framework for strategically targeting this vulnerability in cancer therapy. Furthermore, we highlight various current therapeutic strategies aimed at inducing ferroptosis in cancer cells and underscore their synergistic potential when combined with traditional cancer treatment modalities. By integrating existing knowledge, this review aims to provide researchers and clinicians with novel perspectives and insights on activating ferroptosis to combat cancer.

2. Molecular Mechanisms of Ferroptosis

2.1 Lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism

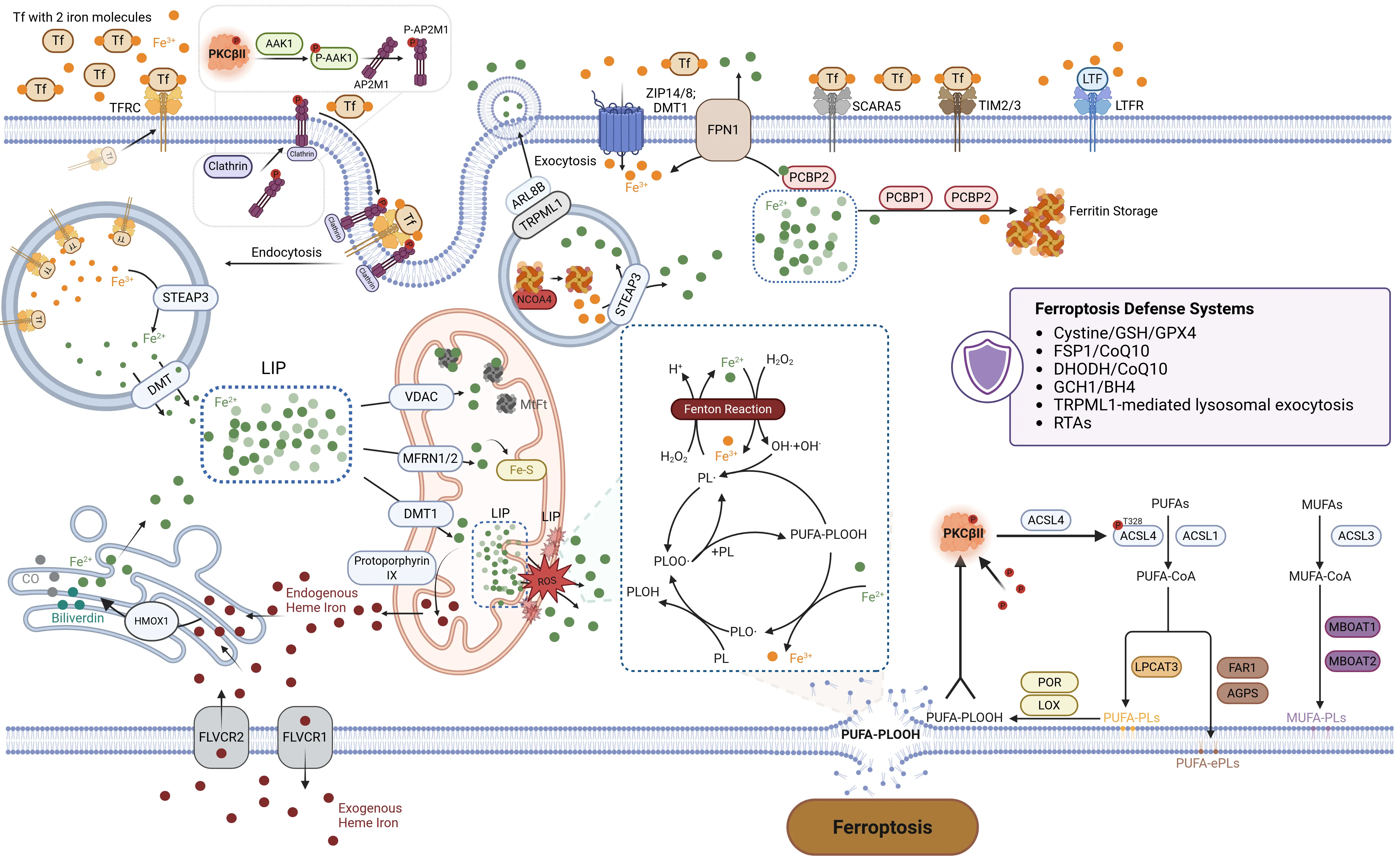

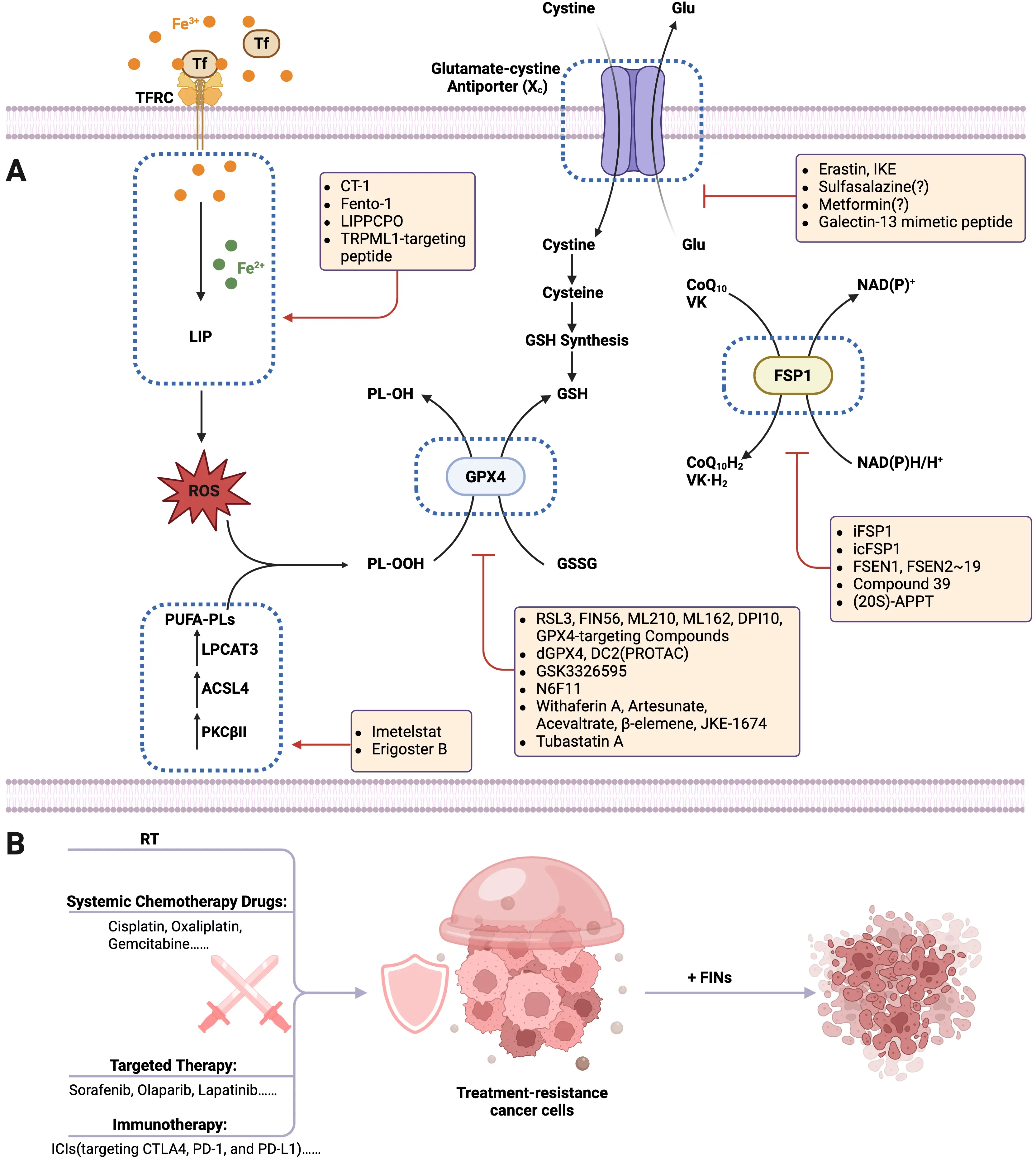

Lipid peroxidation is a process driven by iron-dependent oxidative damage to polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in cellular membranes. Many oxidizable lipids are involved in the process, particularly PUFA-PLs, which are esterified and incorporated into membranes via Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3). When such peroxidation reactions exceed the buffering capacity of the ferroptosis defense system (Section 3), they induce the lethal accumulation of lipid peroxides. This ultimately results in plasma membrane rupture and cell death. Iron is an essential yet potentially toxic trace element, existing as Fe2+ and Fe3+ to enable redox reactions critical for cellular metabolism[6]. Iron homeostasis dynamically regulates ferroptosis by controlling the labile iron pool (LIP) through balanced absorption, storage, utilization, and excretion. Both lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism are prerequisites for ferroptosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism of ferroptosis. The hallmark of ferroptosis is the iron-dependent accumulation of ROS that drives the peroxidation of PUFAs, ultimately leading to plasma membrane rupture and cell death. Lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism are essential prerequisites for the initiation, progression, and execution of ferroptosis. The balance between iron-driven lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis defense systems determines ferroptosis occurrence. Created in BioRender.com. Tf: transferrin; TFRC: transferrin receptor; DMT: divalent metal transporter; DMT1: divalent metal transporter 1; AAK1: AP2-associated protein kinase 1; AP2M1: adaptor related protein complex 2 subunit mu 1; TRPML1: Transient Receptor Potential Mucolipin 1; ARL8B: adenosine 5′-diphosphate Ribosylation factor–like GTPase 8B;

2.1.1 Oxidizable lipids in ferroptosis

2.1.1.1 Fatty acids: the basis of lipid metabolism

Lipids are not only important energy storage molecules but also key biomolecules that regulate cellular structure, mediate intercellular communication, and coordinate genetic programs. Fatty acids (FAs), which primarily include saturated fatty acids (SFAs), monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs), and PUFAs, are fundamental components of cellular lipid metabolism. On one hand, mammals require dietary intake of essential PUFAs, namely α-linolenic acid (18:3 n-3) and linoleic acid (18:2 n-6). These exogenous fatty acids can enter cells through a series of transporters, such as the fatty acid transporter family, CD36, and plasma membrane fatty acid binding protein, to participate in metabolism[7]. On the other hand, SFAs and MUFAs can be synthesized de novo intracellularly. De novo synthesis of SFAs begins with acetyl-CoA in the cytoplasm. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase mediates the conversion of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA, which is subsequently utilized by fatty acid synthase (FASN) to generate the long-chain SFA palmitic acid (PA, 16:0). PA can be further elongated to stearic acid (SA, 18:0) by elongases, while PA and SA can be desaturated to palmitoleic acid and oleic

2.1.1.2 PUFA-PLs: the “engine” of ferroptosis

PUFAs contain more than one double bond and are particularly prone to peroxidation due to the bisallylic groups (–CH=CH–CH2–CH=CH–). The C–H bonds at the bisallylic positions, such as C-7, C-10, and C-13 in arachidonate, are the weakest bonds in the molecules, and the hydrogen atoms at these positions are preferentially abstracted by a peroxyl radical to generate lipid radicals[9]. The composition and asymmetrical distribution of fatty acyl chains in individual phospholipids are modified after their de novo synthesis by a remodeling process known as Lands’ cycle, which results in the incorporation of PUFAs at the sn-2 position of PLs by undergoing a series of deacylation and reacylation reactions[10].

PUFAs must be activated and esterified into membrane phospholipids to function as the essential peroxidation substrates for ferroptosis. Ferroptosis is mechanistically driven by the peroxidation of specific phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)-containining PUFAs, particularly arachidonic acid (AA, C20:4 n-6) and adrenic acid (AdA, C22:4 n-6) species[11]. ACSL4 has a strong preference for AA and AdA, and catalyzes the formation of fatty acyl-CoA by inserting CoA into PUFAs[11,12]. PUFA-CoA is then incorporated into phospholipids primarily in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) by LPCAT3, which preferentially targets acetylated AA[13]. The glycerol backbone of most phospholipids contains a SFAs chain at the sn1 position, while the sn2 position may harbor SFAs, MUFAs, or PUFAs[14].

ACSL4 is an essential component for ferroptosis execution. IFNγ induces the upregulation of ACSL4 expression via the JAK/STAT1 signaling pathway, leading to increased incorporation of PUFAs-CoA into membrane PLs and inducing immunogenic tumor ferroptosis[17]. A recent study found that ACSL4 enhances membrane fluidity and cellular invasiveness, and ACSL4/enoyl-CoA hydratase 1 co-inhibition suppress cancer metastasis[18]. In contrast, α6β4-mediated activation of Src and STAT3 suppresses expression of ACSL4, therefore protecting cells from ferroptosis[19]. Unlike ACSL4, ACSL3, another member of the ACSL family, exhibits expression patterns associated with ferroptosis resistance[20]. Mechanistically, ACSL3 contributes to intracellular lipid metabolism by facilitating the biogenesis and maturation of lipid droplets. Under LD-deficient conditions, ACSL3 predominantly localizes to the ER. Upon cellular uptake of exogenous fatty acids, ACSL3 orchestrates LD growth and maturation via ER-derived budding processes[21]. Crucially, ACSL3 is essential for activating MUFAs, and synergistically, exogenous MUFAs with ACSL3 activity confer cellular protection against ferroptosis[22].

Acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase 3 (AGPAT3) is also found to be a pro-ferroptotic hit. AGPAT3 exhibited acyltransferase activity with a preference for PUFA-CoA, such as arachidonoyl(20:4n-6)-CoA and docosahexanoyl(22:6n-3)-CoA, and it was shown to be involved in the formation of PUFA-containing PC[23,24]. But the AGPAT family does not appear to have a specific substrate preference toward fatty acyl-CoAs at the sn-2 position. Furthermore, AGPAT3 functions in the ER to synthesize polyunsaturated ether phospholipids (PUFA-ePLs) in the downstream of the peroxisomal pathway, thereby promoting the occurrence of ferroptosis[25]. In contrast, LPCAT1 enhances membrane phospholipid saturation through the Lands cycle, which reduces PUFA levels in membrane, protecting cells from phospholipid peroxidation-induced membrane damage, and ultimately inhibits ferroptosis[26].

2.1.1.3 MUFAs: the “brake” of ferroptosis

Contrary to PUFAs, MUFAs, activated by ACSL3, can displace PUFAs from PLs located at the plasma membrane, thus preventing the accumulation of lipid ROS in the plasma membranes, and effectively inhibit the process of iron-dependent oxidative cell death[22]. MUFAs, such as oleic acid, contain only one double bond, endowing them with potent antiperoxidative activity. The synthesis of MUFAs initiates with SCD1. By converting SFAs to MUFAs, SCD1 increases MUFA availability on one hand and reduces SFAs substrates available for the synthesis of ferroptosis-promoting PUFA-containing phospholipids on the other hand. Subsequently,

2.1.1.4 Ether phospholipids: another disruptor of membrane homeostasis

Ether PLs are a specialized class of glycerophospholipids. Unlike diacyl-containing PLs, these lipids are characterized by a unique ether linkage between the glycerol backbone and the acyl chain at the sn-1 position. Their sn-2 position, particularly in plasmalogens, tends to be esterified with long-chain PUFAs. This sn-2 position also frequently serves as a direct target for lipid peroxidation[25,59]. The unique ether linkage structure protects them from easy degradation but renders their oxidation-sensitive PUFAs “explosive”, that continuously trigger membrane damage[30].

Transmembrane protein 189 introduces vinyl-ether double bond into alkyl-ether lipids to generate plasmalogens, rendering the cells resistant to ferroptosis by inhibiting of fatty acyl CoA reductase (FAR1)[31]. Similarly, TMEM164 acts as an acyltransferase with a conserved cysteine (C123) to selectively transfer C20:4 acyl chains from PC to lyso-ePLs to produce PUFA-ePLs. Genetic deletion of TMEM164 resulted in robust decreases in C20:4 ePE lipids with minimal changes in C20:4 diacyl PEs, therefore protecting cells from ferroptosis[32].

2.1.1.5 Cholesterol and its intermediates: Sterol contributions to ferroptosis

Cholesterol and multiple intermediate metabolites generated during its biosynthetic pathway are closely associated with ferroptosis. On the one hand, cholesterol itself is susceptible to auto-oxidation, leading to the formation of cholesterol hydroperoxides, and its high abundance in the plasma membrane of eukaryotic cells renders it a potential substrate for lipid peroxidation[33]. On the other hand, aberrantly elevated cholesterol levels within the tumor microenvironment have been shown to disrupt lipid metabolic homeostasis in CD8+ T cells and induce endoplasmic reticulum stress, thereby impairing their antitumor function and altering cellular sensitivity to ferroptosis[34]. Cholesterol is generated from isoprenoid precursors produced by the mevalonate pathway, together with several essential intermediate metabolites, including isopentenyl pyrophosphate, squalene, and CoQ10. Using statins to inhibit HMG-CoA reductase, a rate limiting enzyme in the mevalonate pathway, might induce ferroptosis by inactivating glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4)[35]. In ALK+ anaplastic large cell lymphoma cell lines, squalene is elevated by the loss of squalene monooxygenase and prevents damage to membrane PUFAs under oxidative stress, to protect cancer cells from ferroptotic cell death[36].

2.1.2 The process of lipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation refers to the process by which oxidants, such as free radicals or non-radical substances, attack lipids containing carbon-carbon double bonds, particularly PUFAs.

2.1.2.1 Enzymatic lipid peroxidation

Enzymatic lipid peroxidation is mainly accomplished by lipoxygenases (LOXs), which are a family of non-heme iron-containing dioxygenases that directly catalyze the dioxygenation of PUFAs containing at least two isolated cis-double bonds. There are six isoforms that exist in humans, including ALOX5, ALOX12, ALOX12B, ALOX15, ALOX15B, and ALOXE3[39]. AA and LA are the most common substrates of LOXs. These enzymes oxidize PUFAs to their corresponding hydroperoxy derivatives, which serve as precursors for bioactive lipid mediators such as eicosanoids[40]. LOX‐catalyzed lipid hydroperoxides in cellular membranes were found to promote susceptibility to ferroptosis[41].

Inhibition or knockout of ALOX12 or ALOX15 can block the ferroptosis process in various pathological contexts, including neurodegenerative diseases and cancer[42]. ALOX12 and ALOX15 can not only synthesize 12-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic

2.1.2.2 Non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation

Non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation is mediated by the spontaneous generation of free radicals and catalyzed by redox active iron. Briefly, the lipid peroxidation mechanism consists of three steps: initiation, propagation, and termination. In the initial stage, free ferrous labile iron reacts with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), known as the Fenton reaction, generating oxidative free radicals like hydroxyl radical (•OH) to initiate the oxidation of PUFAs. PUFAs lose one molecule of hydrogen at the carbon atom in the middle of the bisallylic groups and form phospholipid radical(L•). Once L• is formed, it can be further oxidized to lipid peroxide radical (LOO•) under the action of oxygen and other substances. LOO• can continue to seize a hydrogen atom on the central carbon atom of the diallyl group on the adjacent PUFAs, thereby forming a new L• and a lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH). Like H2O2, LOOH can undergo an

2.1.2.3 The products of lipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation produces a diverse array of oxidation byproducts such as reactive aldehydes within cells. LO• undergo

2.1.2.4 Other metabolites and associated enzymes modulating ferroptosis

Beyond lipid metabolism, alcohol- and aldehyde-related metabolites generated during lipid peroxidation, together with their associated detoxifying enzymes, have emerged as important modulators of ferroptosis in cancer. Enhanced expression of alcohol dehydrogenase exacerbates ethanol-evoked lipid peroxidation, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and ferroptotic signaling[56]. Genetic dysfunction of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2), which detoxifies reactive aldehyde metabolites, leads to an “aldehyde storm” with glutathione depletion and heightened lipid peroxidation[57]. In cancer cells, ALDH2 deficiency increases ferroptosis susceptibility by promoting the accumulation of lipid-derived reactive aldehydes and weakening the antioxidant defense[58]. Purine metabolism has also been confirmed to be involved in the regulation of ferroptosis. Purine synthesis and its key metabolic enzymes in tumor cells can support the stability of mitochondria and membrane-related antioxidant systems by maintaining the supply of nucleotides and reducing equivalents, thereby indirectly suppressing lipid peroxidation to reduce ferroptosis susceptibility[59]. mTORC1-mediated purine catabolism was shown to regulate the intracellular purine pool in tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, and suppression of this catabolic axis by DEPDC5 protected these T cells from ferroptosis[60].

2.1.3 Cellular sensing of lipid peroxides

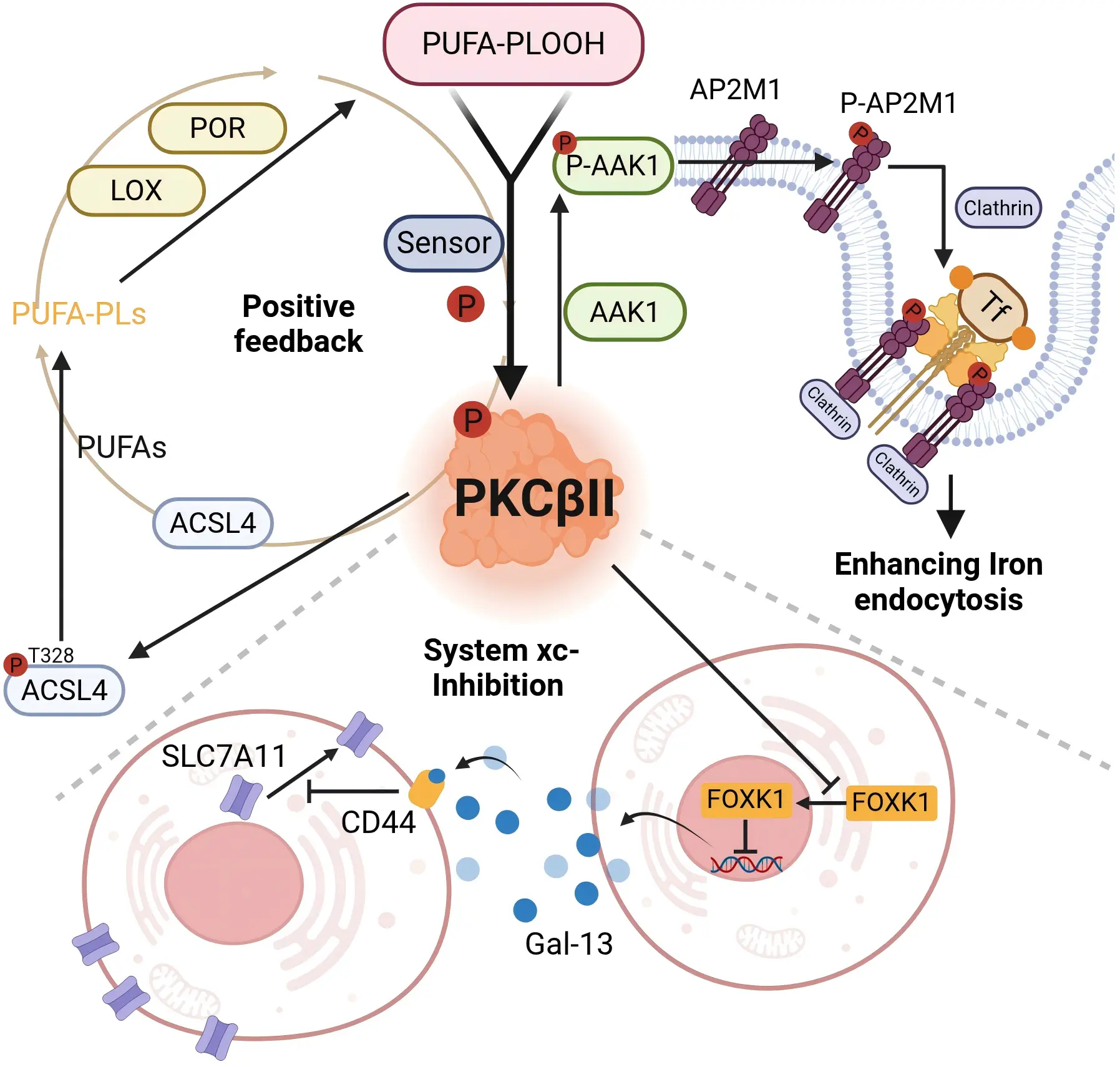

Although lipid peroxidation is a well-established hallmark of ferroptosis, the precise mechanisms by which lipid peroxidation is sensed and triggers ferroptosis are not fully understood to date. In our study, we found that protein kinase C β II (PKCβII) acts as a sensor for lipid peroxidation during ferroptosis. Ferroptosis inducers promote a slight accumulation of lipid peroxides. PKCβII senses the initial lipid peroxides by directly interacting with and phosphorylating ACSL4 at Thr328, which leads to ACSL4 activation, triggering PUFA-containing lipid biosynthesis and promoting the abundant generation of lipid-peroxidation products. The

Figure 2. PKCβII as a pleiotropic lipid peroxide sensor. PKCβII functions not merely as an isolated kinase but as a pleiotropic signaling integrator, strategically positioned at the critical junctions of both lipid peroxidation and iron metabolism—two core pathways governing ferroptosis. This unique positioning enables PKCβII to coordinate death signals from distinct molecular origins, thereby playing an indispensable role in the initiation and propagation of ferroptosis. Created in BioRender.com. Tf: transferrin;

PKCβII acts as a central regulatory hub in ferroptosis. Beyond its role as a lipid peroxide sensor, it simultaneously compromises cellular defense systems (ferroptosis defense system) and amplifies offensive signals (iron metabolism), thereby precisely governing the execution of ferroptosis. Our findings demonstrate a dual mechanism: first, PKCβII impairs SLC7A11 plasma membrane localization by suppressing FOXK1 transcriptional activity, thereby disrupting intracellular glutathione synthesis and lipid peroxide clearance. Second, PKC-mediated AP2-associated protein kinase 1 (AAK1) activation promotes transferrin receptor endocytosis, consequently elevating cellular total iron and ferrous iron levels (see subsequent sections). (Figure 2).

2.1.4 Absorption, intake and export of iron

In the human diet, iron exists primarily in three forms: heme, ferritin, and ferric iron. Heme iron and non-heme iron, the latter encompassing ferritin and free iron, are absorbed through distinct physiological mechanisms[62,63].

2.1.4.1 Absorption and intake of iron

Non-heme iron is primarily absorbed as Fe2+ via divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) at the apical brush border of enterocytes in the small intestine. The absorption of dietary iron requires both the acidic environment provided by gastric acid and the enzymatic reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+ by duodenal cytochrome B. After export from enterocytes, Fe2+ is oxidized to Fe3+ by enzymes such as hephaestin and ceruloplasmin, binds to transferrin (TF), and is transported to other tissues via blood circulation[64,65].

In addition to small intestinal epithelial cells, other cell types predominantly acquire iron through several pathways. For example, transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1/TFRC)-mediated iron endocytosis is considered a critical process in the progression of ferroptosis[66]. Saturated TF, which binds two Fe3+ ions in plasma, is recognized by TFR1/TFRC on target cells, forming an Fe3+-TF-TFR1/TFRC complex.

This complex is internalized via clathrin-mediated endocytosis, forming an intracellular vesicle termed a siderosome[67]. According to our study, this process is also closely associated with PKCβII. Specifically, PKCβII phosphorylates and activates AAK1, which in turn phosphorylates adaptor related protein complex 2 subunit mu 1 (AP2M1). This facilitates the recruitment of clathrin to mediate the endocytosis of TFR1, increasing the levels of both cellular total iron and ferrous iron and thereby promoting ferroptosis. We have identified the PKCβII-AAK1-AP2M1 pathway as a crucial mechanism for the regulation of cellular iron uptake during ferroptosis, which is correlated with the survival prognosis of breast cancer patients (unpublished) (Figure 1, Figure 2). Within the acidic siderosomal environment, Fe3+ dissociates from TF and is reduced to Fe2+ by the metalloreductase STEAP3 or lysosomal cytochrome B, then transported into the cytoplasmic LIP via DMT1. Subsequently, TFR1/TFRC is recycled to the cell membrane, while TF re-enters circulation[64,68]. Lactoferrin, structurally analogous to TF, serves as another critical pathway for iron uptake[69,70]. Upon binding to multiple Fe3+, the lactoferrin receptor or other receptors, form a complex that is subsequently internalized through endocytosis for cellular transport[71].

Cells also acquire iron through heme metabolism, supplementing sources beyond extracellular free iron. These sources include exogenous and recycled intracellular heme. The uptake of exogenous heme relies on membrane transporters such as the Feline Leukemia Virus Subgroup C Receptor and heme transporter HRG1/SLC48A1, coupled with cytoplasmic heme oxygenase activity[67]. FLVCR1 facilitates heme export, whereas FLVCR2 mediates heme import[72]. Both exogenous and endogenous heme are degraded in the ER, where heme oxygenase 1 (HMOX1) catalyzes heme breakdown into carbon monoxide, biliverdin, and Fe2+. HMOX1-mediated heme degradation releases Fe2+ into the LIP, fueling Fenton reaction-derived ROS. ROS accumulation exacerbates lipid peroxidation, driving ferroptosis[73]. Paradoxically, HMOX1 also suppresses ferroptosis by upregulating SLC7A11 and glutathione (GSH) levels[74,75]. Its dual role hinges on intracellular iron and ROS levels: elevated iron/ROS shifts HMOX1 from anti- to pro-ferroptotic activity[76]. Moreover, the expression of HMOX1 is also affected by erastin[74], polydopamine[77] or hypoxia[78].

2.1.4.2 Export of iron

Multiple pathways mediate extracellular iron efflux. Cytosolic poly(rC) binding protein 2 (PCBP2) acquires iron from DMT1(SLC11A2) and delivers it to ferroportin 1 (FPN1/SLC40A1) on the cell membrane[79-81]. As the primary iron efflux transporter, FPN1 oxidizes cytoplasmic Fe2+ to Fe3+ and releases it into the bloodstream, where it binds TF for systemic distribution. This oxidation process requires oxygen-dependent ferroxidases, including hephaestin, zyklopen, and ceruloplasmin, to enable Fe3+ loading onto TF[82]. Without ferroxidase activity, Fe2+ accumulates in the cytoplasm rather than being exported[83,84]. FPN1-mediated iron export is tightly regulated by hepcidin. During iron overload, hepcidin secretion increases significantly, suppressing FPN1 activity and enhancing iron import proteins such as TFRC/TFR1 and FTH1. This leads to greater intracellular iron retention and promotes ferroptosis[85-87].

Under conditions of intracellular iron overload, multivesicular bodies undergo fusion with the plasma membrane, resulting in the release of exosomes containing ferritin into the extracellular space. This mechanism serves to decrease cytoplasmic iron levels and reduce the potential for iron-induced cellular toxicity[88,89]. Conversely, when cellular iron export is impaired, the LIP accumulates within the cytoplasm. This accumulation promotes glutathione depletion, inhibits GPX4 activity, compromises the clearance of lipid peroxides, and ultimately leads to the induction of ferroptosis.

2.1.5 Iron metabolism within the mitochondria and cytoplasm

2.1.5.1 Iron metabolism within the mitochondria

The majority of free Fe2+ in the cytoplasm is transported into mitochondria via a coordinated mechanism involving DMT1[90], mitochondrial iron importers MFRN1 (SLC25A37) and MFRN2 (SLC25A28)[91], and the mitochondrial calcium uniporter[92]. In addition to these transporters, the mitochondrial membrane harbors the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC), a porin responsible for ion and metabolite exchange across the outer membrane. Three VDAC isoforms, VDAC1, VDAC2, and VDAC3, have been identified. The stabilization of VDAC1 to preserve mitochondrial homeostasis has been shown to inhibit ferroptosis in prostate and breast cancer cells. Conversely, erastin directly binds to VDAC2 and/or VDAC3, altering outer mitochondrial membrane permeability, which reduces NADH oxidation rates and promotes ferroptosis[93,94]. Despite these findings, the precise mechanisms underlying VDAC-mediated regulation of ferroptosis remain incompletely understood.

Within mitochondria, Fe2+ participates in critical physiological processes, including iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster and heme biosynthesis, as well as storage in mitochondrial ferritin (MtFt)[95].

Heme, a prosthetic group in proteins such as hemoglobin and cytochromes, serves a vital role in the electron transport chain (ETC) as a component of protein complexes embedded in the inner mitochondrial membrane. Heme biosynthesis proceeds through a conserved enzymatic pathway, wherein iron is incorporated into protoporphyrin IX to form heme, with key steps localized to the mitochondrial matrix and inner membrane[96]. Fe-S clusters act as essential cofactors for mitochondrial enzymes involved in the TCA cycle and ETC, as well as cellular processes like DNA repair. Mitochondrial Fe-S cluster assembly is mediated by specialized proteins, including FDX2, NFS1, frataxin, and ISCU. Any event that interferes with the biosynthesis of heme or Fe-S clusters can lead to mitochondrial iron overload[97-99]. For instance, doxorubicin primarily accumulates in mitochondria through integration into mtDNA, which disrupts the heme biosynthesis pathway and promotes mitochondrial iron accumulation in cardiomyocytes[100,101].

MtFt is an iron storage protein localized in mitochondria, sharing high structural and functional homology with the cytosolic ferritin H-chain. Unlike cytosolic ferritin, MtFt expression is not regulated by the canonical iron-responsive element/iron-regulatory protein system. Its primary role involves modulating ROS generation by controlling iron distribution between the cytosol and mitochondria, as well as mitochondrial iron bioavailability, thereby maintaining mitochondrial iron homeostasis[102]. Studies demonstrate that MtFt overexpression redistributes iron from cytosolic ferritin to mitochondria, thereby depleting the cytoplasmic labile iron pool. However, iron sequestered within MtFt shows reduced chelation accessibility, leading to mitochondrial iron accumulation. This pathological iron deposition disrupts mitochondrial dynamics, impairs respiratory chain complexes I and III, and ultimately enhances ROS production and ferroptosis through impaired electron transport[103,104].

In addition to regulating MtFt, Heme, and Fe-S synthesis, mitochondria also coordinate the maintenance of iron homeostasis and functional stability through other mechanisms such as mitophagy. Mitophagy, a selective degradation pathway for dysfunctional mitochondria, serves as a critical mitochondrial quality control system that preserves intracellular homeostasis[105]. During early stages of cytoplasmic LIP overload, excess free iron translocates into mitochondria, activating the PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy pathway. This process sequesters free iron within mitophagosomes to restore cellular homeostasis[106,107]. However, mitochondrial free iron can participate in the Fenton reaction, oxidizing PUFAs on mitochondrial membranes and destabilizing their structure. The subsequent release of sequestered iron drives ROS and lipid peroxide overproduction, thereby promoting ferroptosis[108].

2.1.5.2 Iron metabolism within the cytoplasm

Ferritin, a critical iron storage protein primarily localized in the cytoplasm, consists of heavy (FTH1) and light (FTL) chain subunits. FTH1 uniquely contains an iron oxidase center essential for iron loading[109]. FTH1 oxidizes cytosolic LIP-associated Fe2+ to Fe3+, forming stable iron oxides/hydroxides that are stored non-toxically and mobilized as needed. This process is mediated by the cytosolic iron chaperones PCBP1 and PCBP2[110-112], alongside endophilin A2, encoded by the SH3GL1 gene[113]. PCBP1-deficient hepatocytes exhibit elevated unchelated iron and redox activity, triggering ferroptosis due to Fe2+ instability. Excess Fe2+ acts as both a substrate and a catalyst in the Fenton reaction with H2O2, generating cytotoxic ROS that induce oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and biomolecules, culminating in cell death[110,114].

When cellular iron demand increases, NCOA4 binds to FTH1 and directs its transport to autophagosomes and subsequently to lysosomes for degradation, a process mediated by autophagy-related proteins (ATG) such as GABARAP and GABARAPL1. Within lysosomes, Fe3+ stored in ferritin is reduced to Fe2+ by STEAP3 and released into the cytoplasm as bioavailable iron. This selective degradation mechanism is termed ferritinophagy[115]. In addition to the classical ATG-dependent pathway, the NCOA4-FTH1 complex can also be tightly regulated for lysosomal degradation through the ESCRT machinery[116]. Perturbation of these regulatory pathways disrupts cytoplasmic iron homeostasis.

2.2 The propagation of ferroptosis

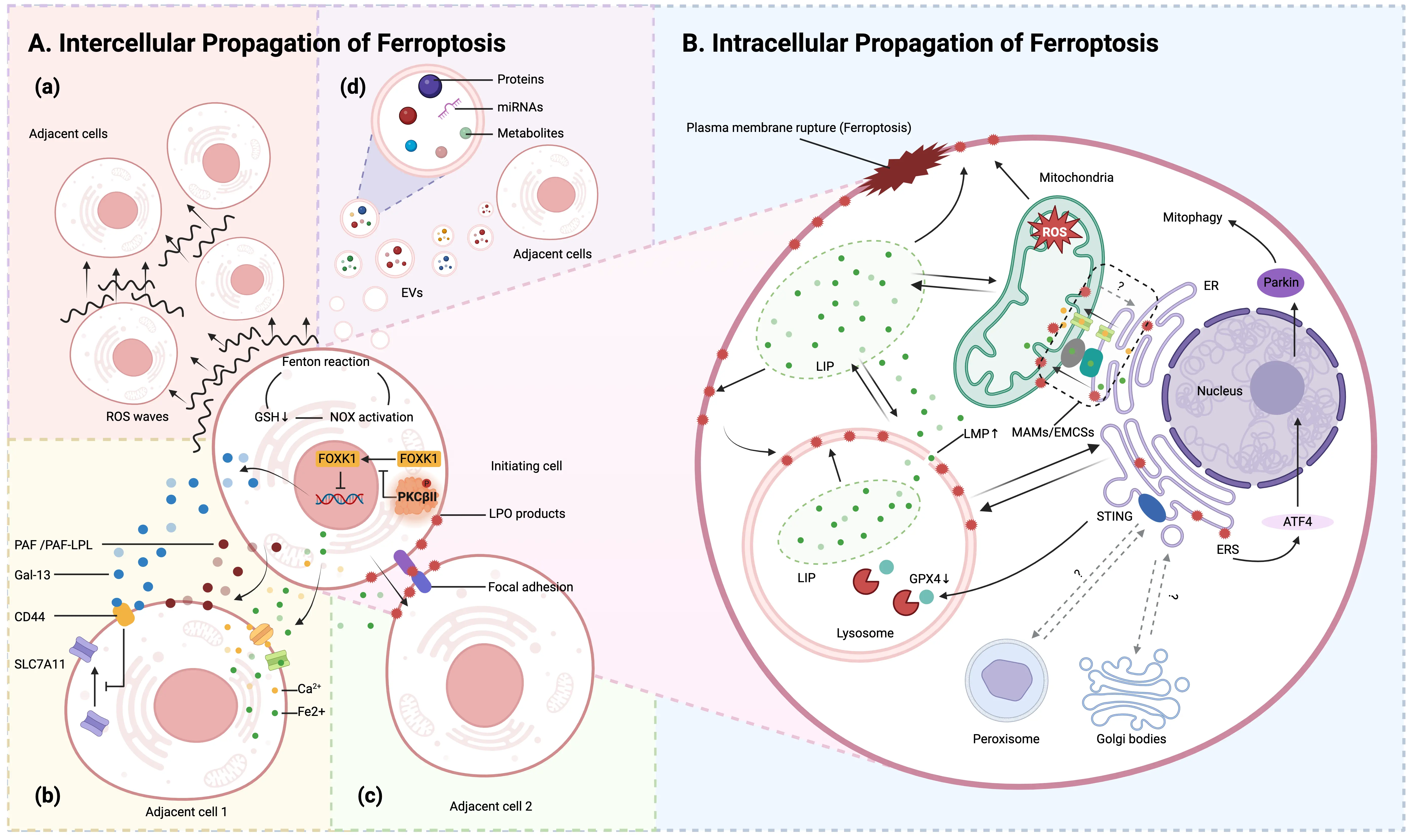

Ferroptosis is not a standalone process but rather a tightly regulated form of cell death that relies on coordinated interactions and precise signal transduction among specific organelles. Organelles such as lysosomes, the ER, and mitochondria play pivotal roles in modulating ferroptosis through essential biological functions, including the regulation of iron homeostasis, lipid metabolism, and redox balance. The intrinsic mechanisms within these organelles ultimately dictate whether a ferroptotic signal can be effectively initiated.

Of particular significance is the fact that these organelles not only function as central regulators of ferroptosis but also constitute key components in the signaling network that mediates this process. Upon initiation, the ferroptosis signal does not disseminate uniformly throughout the cell; instead, it progresses along a precisely orchestrated and spatially confined pathway, propagating in a directional fashion across distinct intracellular compartments and potentially extending beyond the cellular boundary to affect neighboring cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Intercellular and Intracellular Propagation of Ferroptosis. (A) Intercellular propagation of ferroptosis; (a) In the initiating cell, a tripartite positive feedback loop, comprising Fenton reaction induction, NOX activation, and inhibition of glutathione synthesis, is established, facilitating the dissemination of ferroptosis across the cell population via ROS waves; (b) The initiating cell promotes ferroptosis spread through the secretion of soluble mediators: PKCβII senses LPO and becomes activated, thereby inhibiting nuclear translocation of FOXK1 and suppressing transcription, resulting in upregulated expression and secretion of Gal13. Extracellular Gal13 binds to CD44, impairing plasma membrane localization of SLC7A11, reducing intracellular glutathione levels, and increasing cellular susceptibility to ferroptosis, thus promoting its propagation. Additionally, the initiating cell releases PAF/PAF-LPL, which integrates into the membranes of adjacent cells, disrupts membrane integrity, and initiate ferroptosis. Prior to plasma membrane rupture, the initiating cell also leaks low-molecular-weight species such as Fe2+ and Ca2+ into neighboring cells, contributing to ferroptotic induction; (c) Through α-catenin-mediated adherens junctions, the initiating cell facilitates the relay-like transfer of lipid peroxidation products to adjacent cells, a process potentiated by extracellular iron ions, thereby enabling coordinated propagation of ferroptosis; (d) Ferroptotic cells can communicate with surrounding cells by releasing EVs, which carry bioactive molecules such as miRNAs, proteins, or lipid metabolites; (B) Intracellular propagation of ferroptosis. The intracellular progression of ferroptosis is highly compartmentalized and fundamentally involves the directional spread of lipid peroxidation chain reactions along cellular membranes. Lysosomes serve as the initial trigger sites for this process. The ER and mitochondria function as central hubs for signal transmission and amplification. MAMs/EMCSs constitute dynamic physical and functional interfaces between the ER and mitochondria, playing a pivotal role in coordinating interorganellar crosstalk during ferroptosis regulation. Created in BioRender.com. PKCβII: protein kinase C β II; FOXK1: forkhead box protein K1; Gal13: galectin-13; SLC7A11: solute carrier family 7 member 11; PAF/PAF-LPL: platelet-activating factor or PAF-like phospholipids; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; MAMs/EMCSs: mitochondria-associated membranes or ER–mitochondria contact sites;

2.2.1 Intercellular propagation of ferroptosis

Upon crossing the single-cell boundary, ferroptotic death signals display complex population-level dynamics during inter-cellular propagation. Research has demonstrated that ferroptosis can propagate in a wave-like manner across cell populations, giving rise to a distinct spatiotemporal pattern of cell death, a phenomenon not observed in other forms of programmed cell death[117,118]. This long-range propagation mechanism fundamentally relies on reactive ROS-triggered waves. The underlying driving force of this propagation is a redox bistability switch induced by glutathione depletion. Moreover, a triple positive feedback loop comprising the Fenton reaction, NADPH oxidase activation, and inhibition of glutathione synthesis collectively enables cell populations to function as a “biological conductor” for sustained ROS propagation[119]. Within the local microenvironment, direct cell–cell contact provides an additional pathway for ferroptosis propagation: α-catenin-mediated adherens junctions, together with extracellular iron ions, facilitate the transmembrane relay transfer of lipid peroxidation products[120].

Although the ultimate outcome of ferroptosis is plasma membrane rupture, nanoscale pores can form prior to complete membrane disintegration. These pores facilitate the exchange of substances between the intracellular and extracellular environments, permitting the leakage of small molecules (e.g., Fe2+, Ca2+) while retaining large proteins. Released small molecules can infiltrate adjacent cells not yet undergoing ferroptosis, inducing intracellular calcium oscillations or elevated LIP levels. This process activates downstream signaling, initiates lipid peroxidation, and ultimately promotes ferroptosis in neighboring cells[118].

Notably, soluble factors critically mediate ferroptosis signal propagation within the tumor microenvironment. Our study reveals that during ferroptosis in initiating cells, PKCβII acts as a lipid peroxide sensor and is activated, triggering phosphorylation of FOXK1 at the Ser441 residue. This post-translational modification results in the cytoplasmic retention of FOXK1, preventing its nuclear translocation and abolishing its ability to repress Galectin-13 (Gal-13) transcription. Consequently, Gal-13 expression is upregulated, and the protein is robustly secreted into the extracellular milieu. Extracellular Gal-13 binds to CD44 on adjacent cells, impairing the plasma membrane localization of SLC7A11, leading to reduced intracellular glutathione synthesis. The depletion of this essential antioxidant compromises cellular redox homeostasis, thereby increasing susceptibility to ferroptosis and facilitating the coordinated propagation of ferroptotic cell death across the cell population[121]. Concurrently, platelet-activating factor (PAF) and PAF-like phospholipids accumulate during early ferroptosis and are actively secreted extracellularly, establishing a foundation for ferroptotic signal diffusion. These lipids embed into adjacent cell membranes, where their short acyl chains disrupt lipid bilayer organization, increasing membrane defects and water permeability. This cascade leads to ion imbalance (e.g., Ca2+ influx) and subsequent ferroptosis[122].

Ferroptotic cells can communicate with surrounding cells by releasing extracellular vesicles (EVs), which carry bioactive molecules such as miRNAs, proteins, or lipid metabolites. These molecules can be taken up by neighboring cells and induce ferroptosis or modulate ferroptosis sensitivity in recipient cells[123-126]. For instance, during the transition from acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease, proximal tubular epithelial cells undergo ferroptosis under hypoxic conditions and release EVs containing specific miRNAs that trigger lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis in adjacent cells[123]. Another study showed that doxorubicin-stimulated breast cancer cells release small EVs delivering specific miRNAs to cardiomyocytes, thereby exacerbating ferroptosis sensitivity in the latter[124]. Furthermore, ferroptotic cells may release inflammatory mediators. For example, M1 macrophages under inflammatory conditions release mitochondrial contents via EVs, which are taken up by pancreatic β-cells and promote ferroptosis, contributing to β-cell dysfunction in acute pancreatitis[125]. Additionally, EVs derived from ferroptotic cells can carry iron ions or ferritin, which may alter cellular iron metabolism in recipient cells and promote ferroptosis[126]. This EV-mediated propagation of ferroptosis has also been explored for precise cancer therapy. For instance, an engineered EV platform has been developed to selectively target melanoma and induce YAP-dependent ferroptosis[127].

However, existing research continues to reveal critical gaps in our understanding of ferroptosis. Key unresolved issues include the potential selectivity of the propagation of ferroptosis; the impact of cellular heterogeneity, particularly differences in antioxidant capacity, on the dynamics and magnitude of ferroptotic propagation; and the involvement of or regulatory role of stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment in mediating ROS wave transmission or soluble factor diffusion (Figure 2, Figure 3A).

2.2.2 Intracellular propagation of ferroptosis

Ferroptosis follows a highly compartmentalized pattern during its intracellular propagation, characterized fundamentally by the directional diffusion of lipid peroxidation chain reactions across cellular membrane systems. Lysosomes function as the initial trigger hub. Lipid peroxidation within lysosomes increases lysosomal membrane permeability, resulting in iron release and subsequent widespread intracellular lipid peroxidation. This process not only facilitates ferroptosis but also amplifies lysosomal lipid peroxidation, thereby establishing a self-reinforcing positive feedback mechanism[128-131]. As lysosomal oxidative damage intensifies, free radical reactions transcend individual compartment boundaries and propagate to adjacent membrane structures, such as the

Subsequently, the ER functions as a central hub for the transmission and amplification of death signals. Accumulating evidence indicates that the ER not only serves as the primary site for the accumulation of peroxidized lipids, but also represents the initial subcellular compartment where lipid peroxidation markers exhibit significant accumulation, prior to their dissemination to the plasma membrane and other organelles[132]. ER stress has been shown to induce mitochondrial autophagy via ATF4-mediated transcriptional activation of Parkin, which subsequently reduces the generation of lipid peroxidation products and inhibits ferroptosis by limiting the accumulation of mitochondrial ROS[133]. Furthermore, the ER plays a central role in orchestrating an intricate inter-organelle communication network through its resident proteins, such as the stimulator of interferon genes and SLC39A7, thereby modulating the initiation and propagation of ferroptosis[134,135].

Mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs) or ER-mitochondria contact sites (EMCSs), functioning as a dynamic interface between the ER and mitochondria, serve as a critical interorganellar platform for coordinating the regulation of ferroptosis[136]. Inhibiting the activity of the resident protein sigma-1 receptor on MAMs interferes with calcium transport between the ER and mitochondria, resulting in the accumulation of lipid peroxidation in both the ER and mitochondria[137,138]. Moreover, EMCSs operate as “hotspot amplifiers” for phospholipid peroxidation, enabling the targeted transfer of oxidative damage to mitochondria through specialized membrane interfaces, thereby ultimately initiating ferroptosis[139].

This sequential propagation cascade, from lysosomes → ER → MAMs/EMCSs → mitochondria, demonstrates that ferroptosis is governed by precise spatial programming at the subcellular level. However, several critical questions remain unresolved regarding the aforementioned propagation network: whether it encompasses multiple initiation points, whether its transmission follows a strictly unidirectional pattern, and whether feedback mechanisms are present that either enhance or suppress the propagation process (Figure 3B).

2.3 Ferroptosis defense systems

2.3.1 Cystine/GSH/GPX4 axis

Ferroptosis was originally described as a non-apoptotic form of cell death induced by the inhibition of cystine transport by cystine/system xc− to create a void in the antioxidant defenses of the cell, which can be rescued by Fer-1[2]. System xc– is a member of the heteromeric amino acid transporter family acting as a cystine importer and glutamate exporter, which consists of heterodimers of the catalytic subunit SLC7A11 and the partner subunit SLC3A2[140]. As the most abundant small molecule intracellular antioxidant, the synthesis of intracellular GSH depends on system xc−-mediated cystine uptake. GSH serves as the reductive co-substrate for the non-heme enzyme GPX4. Functioning as the primary enzyme catalyzing the reduction of PLOOHs in mammalian cells, GPX4 reduces PL-OOH to alcohols. This reaction is accompanied by the spontaneous oxidation of its selenocysteine residue and the oxidation of GSH to glutathione disulfide (GSSG), thereby establishing GPX4 as a central regulator of ferroptosis. Subsequently, GSSG is regenerated to GSH by glutathione reductase utilizing the two electrons provided by NADPH, completing the redox cycle[141-143]. In this process, cysteine serves as the rate-limiting substrate for GSH synthesis, being synthesized from serine and homocysteine mainly via the trans-sulfuration pathway. Furthermore, cysteine facilitates the protein synthesis of GPX4 by promoting selenium uptake and utilization.

2.3.2 Ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1)/CoQ10 system

FSP1 (used to be known as apoptosis-inducing factor mitochondria-associated 2, AIFM2) confers protection against ferroptosis elicited by GPX4 deletion. Physiologically, FSP1 is a lipid droplet-associated protein highly enriched in brown adipose tissue and contains a flavoprotein NADH oxidoreductase domain[144]. The reduced form of ubiquinone (also known as coenzyme Q10, CoQ10), ubiquinol (CoQH2), traps lipid peroxyl radicals while FSP1 catalyzes the regeneration of ubiquinone using NAD(P)H. CoQH2 can additionally regenerate α-tocopherol and therefore enabling sustained radical scavenging[145]. This process requires the

2.3.3 Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (quinone) (DHODH)/CoQ10 system

DHODH, a mitochondrial enzyme involved in pyrimidine biosynthesis, inhibits ferroptosis in the mitochondrial inner membrane through reducing CoQ to CoQH2[150]. DHODH shares a function analogous to FSP1, as both proteins reduce CoQ10 to prevent lipid peroxidation. The studies exploiting the effects of DHODH inhibitors, such as brequinar, revealed that these inhibitors surprisingly also suppressed FSP1. This indicates that the ferroptosis-sensitizing effect of DHODH inhibitors may be mediated through the inhibition of FSP1, rather than being directly attributable to DHODH itself[151].

2.3.4 GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1)/tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) system

BH4 shows great radical-trapping antioxidant activity by increasing ubiquinol and protecting cells from ferroptosis[152]. Within the GCH1/BH4 pathway, GCH1 is recognized as the rate-limiting enzyme for BH4 synthesis, catalyzing the conversion of dihydrobiopterin (BH2) to BH4 upon NAD(P)H consumption. GCH1 and its metabolic derivatives BH4/BH2 drive lipid remodeling in GCH1-expressing cells alone or in synergy with α-tocopherol (vitamin E), suppressing ferroptosis through selective prevention of phospholipid depletion with two PUFA tails[152-154].

2.3.5 Transient Receptor Potential Mucolipin 1 (TRPML1)-mediated lysosomal exocytosis

Through a CRISPR-Cas9 activation screen to identify factors conferring resistance to ferroptosis, we discovered an enrichment of genes associated with lysosomal exocytosis. Among these, TRPML1 emerged as a potent suppressor of ferroptosis. Further investigation revealed that AKT directly phosphorylates TRPML1 at serine 343, which in turn inhibits K552 ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of TRPML1. This post-translational stabilization promotes the interaction between TRPML1 and ribosylation factor–like GTPase 8B (ARL8B), triggering lysosomal exocytosis. This pathway suppresses ferroptosis via two primary mechanisms. On the one hand, it can expel intracellular Fe2+ to diminish Fenton reaction-driven lipid peroxidation. On the other hand, it will secrete acid sphingomyelinase to bolster plasma membrane repair capacity, thereby countering oxidative damage[155].

2. 3.6. Radical-trapping antioxidants (RTAs)

In addition to the enzymatic defense systems, a diverse array of endogenous RTAs suppresses ferroptosis by directly donating hydrogen atoms to lipid peroxyl radicals, thereby halting the propagation of phospholipid peroxidation. Beyond the previously discussed BH4, CoQ10, and vitamin K, other crucial RTAs include vitamin E, which quenches lipid peroxyl radicals within membranes, albeit with activity modulated by its interaction with phospholipid head groups[42,156]. Key intermediates of the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway, such as squalene[36] and 7-DHC[37,38], also function as potent lipophilic RTAs. Furthermore, hydropersulfides inhibit ferroptosis through radical scavenging and autocatalytic regeneration, a pathway dependent on cysteine availability but distinct from the canonical GPX4 axis[157,158]. Finally, several tryptophan metabolites, including serotonin, 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid, trans-3-indoleacrylic acid, and kynurenine, act as effective RTAs or modulate ferroptosis sensitivity through direct radical trapping or indirect metabolic regulation[159-161], highlighting the breadth of endogenous antioxidant mechanisms that can counteract lipid peroxidation.

3. Ferroptosis-Associated Targets in Cancer

3.1 Ferroptosis vulnerability in certain cancers

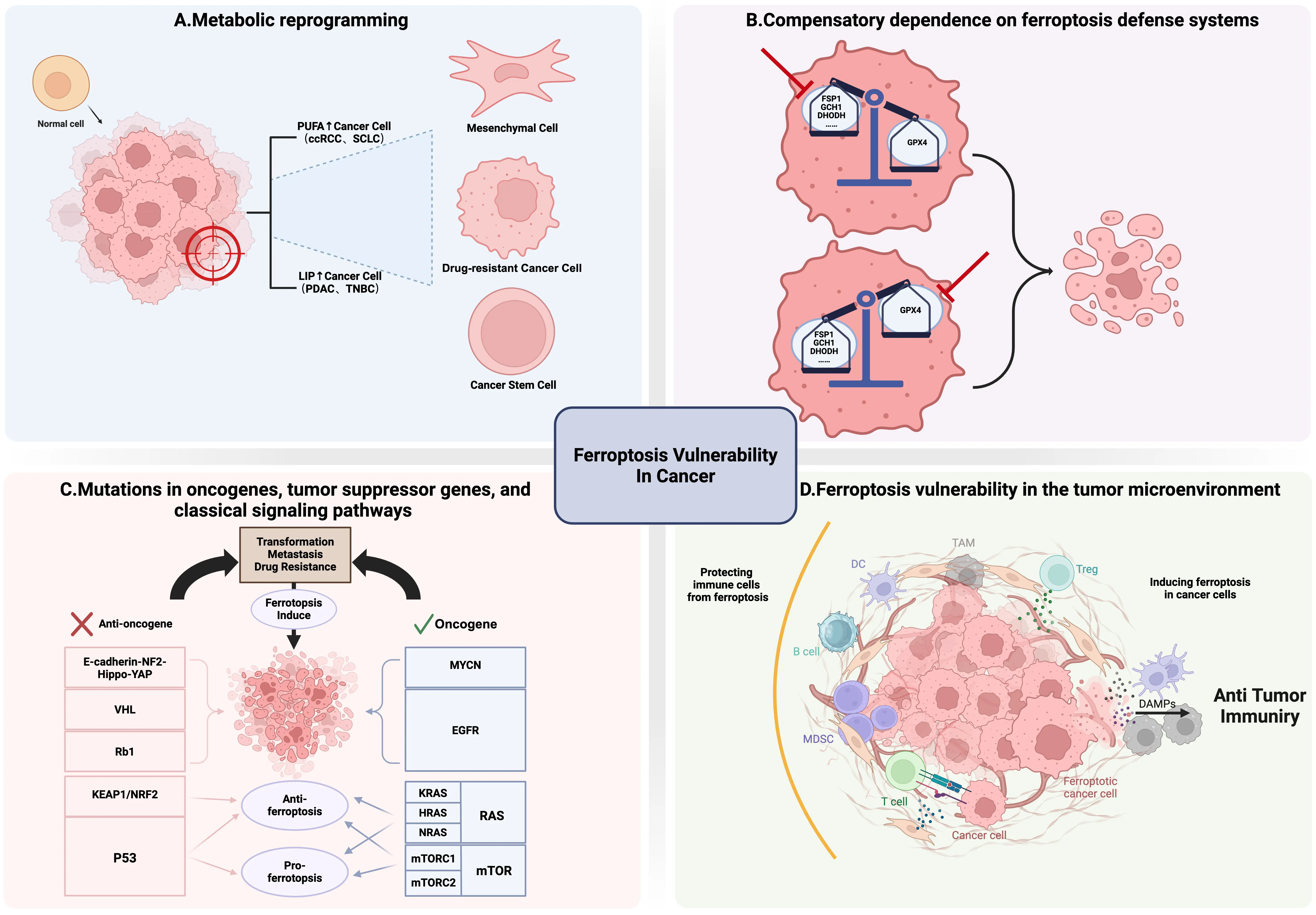

Inducing ferroptosis has emerged as a novel strategy for cancer therapy. Numerous studies have demonstrated that various oncoproteins, tumor suppressor genes, and oncogenic signal transduction pathways can regulate ferroptosis. To cope with survival pressures and meet their increasing nutritional demands, cancer cells remodel their metabolic networks and adjust the tumor microenvironment to maintain survival, proliferation, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance. Such adaptations often endow specific cancer types with new vulnerabilities, such as heightened sensitivity to ferroptosis. In-depth research to identify the types, characteristics, and biomarkers of these tumor cells is therefore crucial for treating these “refractory” tumors[162]. For instance, clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), clear cell ovarian carcinoma, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, all exhibit inherently high sensitivity to ferroptosis. In this section, we systematically elaborate on several characteristic alterations in these tumor cells that confer significant susceptibility to ferroptosis (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Characteristic Alterations in Cancer leading to Ferroptosis Vulnerability. (A) Metabolic reprogramming. Some cancer cells possess unique lipid metabolic features, such as high PUFA content or elevated levels of labile iron pools, rendering them more susceptible to ferroptosis; (B) Compensatory dependence on ferroptosis defense systems. Ferroptosis defense systems mainly include GPX4-dependent and GPX4-independent systems. Specific inhibition of the remaining major defense pathways that cancer cells depend on will trigger intense ferroptosis due to the lack of effective compensatory mechanisms; (C) Mutations in oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, and classical signaling pathways. Mutations in oncogenes and anti-oncogenes often help tumor cells cope with survival pressure but may also lead to their vulnerability to ferroptosis, providing potential intervention windows for targeted therapy. Meanwhile, cancer cells may have differential responses to ferroptosis in the face of the same gene or pathway mutation; (D) Ferroptosis vulnerability in the tumor microenvironment. Ferroptosis and the TME, especially the immune system, interact in complex ways. On the one hand, mediators released by ferroptotic tumor cells can be transmitted to immune cells, triggering anti-tumor immune responses. On the other hand, mediators released by immune cells can regulate the sensitivity of tumor cells to ferroptosis, and the sensitivity of immune cells themselves to ferroptosis can also affect their functions. Created in BioRender.com. PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acid; LIP: labile iron pool; ccRCC: clear cell renal cell carcinoma; SCLC: small cell lung cancer; PDAC: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer; GPX4: glutathione peroxidase 4; FSP1: ferroptosis suppressor protein 1; DHODH: dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (quinone); GCH1: GTP cyclohydrolase 1; DAMPs: damage-associated molecular patterns; MDSC: myeloid-derived suppressor cell; TAM: tumor-associated macrophage;

3.1.1 Metabolic reprogramming

Certain tumor cells often possess unique lipid metabolic features, such as high PUFA content or elevated levels of labile iron pools. Their overall metabolism is more active, and ROS load is higher, rendering them more susceptible to ferroptosis (Figure 4A).

As substrates for lipid peroxides, the abundance of PUFAs (e.g., AA or LA) is one of the key factors determining ferroptosis sensitivity. In ccRCC, HIF-2α has been found to selectively enrich polyunsaturated lipids by activating the expression of hypoxia-inducible lipid droplet-associated protein[163]. Meanwhile, this type of cell highly expresses alkylglycerone phosphate synthase, a key enzyme involved in the synthesis of PUFA-ePLs, leading to the accumulation of large amounts of PUFA-ePLs and subsequent increase in lipid peroxidation[25]. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma primarily maintains extremely high intracellular levels of GSH and GSSG through the XC system. These tumor cells are highly sensitive to cystine uptake and catabolism. Compared with clear cell renal cell carcinoma, they are more sensitive to ferroptosis[164]. Metastatic tumors, particularly metastatic ovarian cancer cells, also exhibit higher PUFA levels and lower MUFA levels. Moreover, metastatic tumor cells can utilize high ACSL4 and abundant PUFAs to better promote cancer metastasis and in vivo survival[18].

The level of intracellular labile iron pools is another key factor determining ferroptosis sensitivity. Compared with normal cells, cancer cells rely strongly on iron for growth and are therefore more prone to ferroptosis occurrence. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), the BACH1 gene regulates EMT and ferroptosis sensitivity through multiple mechanisms. Specifically, it inhibits the NRF2 pathway by binding to NRF2, promoting an increase in labile iron within tumor cells and leading to ferroptosis. BACH1 links EMT to ferroptosis, providing new insights for the treatment of these malignant tumors[165]. TNBC cells have long been found to be highly sensitive to ferroptosis, which stems from their unique metabolic features, including abundant PUFAs, elevated labile iron pool levels, and impairment of the GPX4-GSH defense system[12,166]. Notably, there is heterogeneity in ferroptosis-related metabolites and metabolic pathways among different TNBC subtypes. The luminal androgen receptor subtype of TNBC is particularly susceptible to ferroptosis induced by GPX4 inhibition[167,168].

Mesenchymal cancer cells typically refer to tumor cells that have undergone EMT and possess high invasiveness, drug resistance, and stem cell-like properties. However, these tumor cells often have more abundant phospholipids containing PUFAs and higher levels of labile iron pools. Increased synthesis of phospholipids containing PUFAs is closely associated with the high expression of zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1). ZEB1 is a transcription factor associated with EMT and a driver of lipid biosynthesis. It promotes the accumulation of PUFA-PLs by directly activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, thereby rendering cells highly dependent on GPX4[169]. In mesenchymal cancer cells, enhanced CD44-mediated chondroitin sulfate-dependent iron endocytosis and iron accumulation caused by decreased FPN expression also contribute to ferroptosis susceptibility[170,171]. Similarly, mesenchymal gastric cancer shows elevated levels of amino acids and adenylates due to high expression of ELOVL5 and FADS1 involved in PUFA synthesis[172].

Drug-tolerant persister (DTP) cells with similar mesenchymal characteristics also exhibit inherent sensitivity to ferroptosis and high dependence on GPX4 due to their unique and analogous metabolic features[173]. These cells develop tolerance to traditional drugs through metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic modifications, therefore entering a state of suspended proliferation with enhanced survival capacity. Therapy-resistant dedifferentiated subpopulations in melanoma cells exhibit their susceptibility to ferroptosis, which may be due to the accumulation of PUFAs and decreased glutathione levels[174]. Gefitinib-resistant lung cancer cells can also increase susceptibility to ferroptosis by downregulating apoptosis-associated tyrosine kinase, which promotes endosomal recycling and iron accumulation[175]. Additionally, most DTP cells exhibit upregulation of CD44 to promote the uptake of redox-active iron to meet metabolic demands. The newly developed Fento-1 can effectively target these CD44-highly expressing DTP cells to induce ferroptosis[130]. Through epigenetic regulation, DTP cells, on one hand, resist external survival pressure, and on the other hand, indirectly induce susceptibility to ferroptosis. For example, erlotinib-resistant DTP cells can inhibit glutaminolysis and retain their mesenchymal characteristics through histone lysine demethylase 5A-mediated inhibition of mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 1, resulting in enhanced susceptibility to ferroptosis both in vitro and in vivo[176].

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are a group of cells with self-renewal ability, differentiation potential, and unlimited proliferative capacity, capable of generating heterogeneous tumor cells. CSCs lead to the failure of traditional radiotherapy and chemotherapy as well as tumor metastasis and recurrence. Dysregulated iron homeostasis is a hallmark feature of CSCs. To meet the demands of their tumor microenvironment and the energy requirements for self-renewal, CSCs typically exhibit stronger iron absorption capacity[177,178]. Numerous studies have found a significant association between CSCs of different cancer types and abnormal iron metabolism. For example, glioblastoma and breast cancer CSCs show significantly increased expression of transferrin receptor 1 and ferritin[179,180]. This alteration in iron metabolism is crucial for maintaining CSC stemness and increases their susceptibility to ferroptosis inducers, providing a new approach for targeted elimination. Studies have also found that enhancing stem cell characteristics of tumor cells can increase their sensitivity to ferroptosis, which may be due to their lack of antioxidant capacity and abundant iron storage. However, although CSCs have increased levels of labile iron pools due to massive iron uptake, they still employ various ways to resist potentially induced ferroptosis, including maintaining low ROS levels[181], inhibiting ACSL4[182], or enhancing SLC7A11 expression[183] and so on. Future studies need to further investigate issues such as heterogeneity of CSCs and the complexity of the tumor microenvironment to better induce ferroptosis in CSCs in vivo.

In summary, these changes in metabolic reprogramming render the aforementioned tumor cells susceptible to ferroptosis and provide promising therapeutic strategies for addressing these challenging malignant tumors.

3.1.2 Compensatory dependence on ferroptosis defense systems

As mentioned earlier, ferroptosis defense systems mainly include GPX4-dependent and GPX4-independent systems. Tumor cells usually possess multiple ferroptosis defenses, but when one of them (such as FSP1) is congenitally deficient, has low expression, or is functionally impaired, cells are forced to over-rely on the remaining major pathways (such as GPX4) to maintain survival. This “putting all eggs in one basket” state creates fatal metabolic vulnerabilities in certain tumor cells. Specific inhibition of the remaining major defense pathways that cancer cells depend on will trigger intense ferroptosis due to the lack of effective compensatory mechanisms (Figure 4B).

In some cancer cells, if GPX4 expression is low or partially inactive, cells are highly dependent on GPX4-independent defense systems to resist ferroptosis. For example, studies have found that inhibition of DHODH in NCI-H226 cells (with low GPX4 expression) results in a more significant lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis compared to cells with normal GPX4 expression. Additionally, the use of DHODH inhibitors can better suppress the growth and proliferation of GPX4-low-expressing xenograft tumors[150]. Similarly, tumor cells with low GPX4 expression also exhibit high sensitivity to FSP1 inhibitors[145]. Germinal center B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with low GPX4 expression is more sensitive to ferroptosis induced by dimethyl fumarate, which primarily functions by rapidly depleting GSH by succination[184].

It is worth noting that there may be a therapeutic time window for acquired inactivation of a ferroptosis defense pathway. For example, after continuous inhibition of FSP1, tumor cells can develop resistance to ferroptosis through cholesterol synthesis[37]. If GPX4-independent defense systems are lowly expressed or inactive, cells will also be highly dependent on the GPX4 system to resist ferroptosis. For example, studies have found that certain tumor cells with low FSP1 expression or FSP1 knockout are more sensitive to ferroptosis induced by GPX4 inhibitors (such as RSL3). Additionally, GPX4 knockout significantly inhibits tumor growth more in FSP1-knockout xenografts than in FSP1 wild-type tumors, and this reduction in tumor growth is attributed to more intense ferroptosis[145,146].

GCH1 is an important component of the ferroptosis defense system. Cancer cells with low GCH1 expression are also more sensitive to GPX4 inhibitors (such as RSL3) and FSP1 inhibitors (such as iFSP1)[153]. Therefore, a deep understanding of which ferroptosis defense pathways are active, absent, or weakened in specific tumor cells is crucial for selecting the most effective single-agent therapy and designing rational combination therapy strategies.

3.1.3 Mutations in oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, and classical signaling pathways

A growing body of research supports the view that ferroptosis acts as a natural anti-tumor mechanism. In general, the interaction of multiple tumor suppressor genes with ferroptosis (such as KEAP1[185], BAP1[186]) can exert their tumor-suppressive effects, while activation of specific genes can endow cancer cells with the ability to evade ferroptosis (such as OTUB1[187], CKB[188]) to promote tumor growth. Specific targeted activation of these tumor suppressor genes or inhibition of oncogene expression is an important

Mutations in tumor suppressor genes are often associated with malignant transformation, metastasis, drug resistance, poor prognosis, and ferroptosis resistance in cancer. However, cancer cells with some tumor suppressor gene mutations are also more sensitive to ferroptosis, exposing unusual weaknesses. The E-cadherin-NF2-Hippo-YAP pathway is one of the most notable examples. E-cadherin (ECAD), mainly responsible for maintaining cell polarity, acts as an upstream regulator of the Hippo pathway. Its mediated cell-cell interactions activate the Hippo tumor suppressor signaling pathway in an NF2-dependent manner, inhibiting the transcriptional activity of YAP and transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif (TAZ), thereby regulating tumor cell proliferation[189]. Antagonizing this signaling pathway allows YAP to promote ferroptosis by upregulating various ferroptosis regulators, including ACSL4 and TFRC[190]. Meanwhile, loss-of-function mutations in ECAD, NF2, and Hippo pathway components LATS1/2, or overexpression of YAP, often occur in cancers such as gastric cancer, breast cancer, and mesothelioma. These mutations make it possible to treat them with ferroptosis inducers. ccRCC, the most common type of kidney cancer, is inherently highly sensitive to ferroptosis. ccRCC is mainly caused by the deletion of the tumor suppressor gene VHL, which in turn leads to the selective accumulation of PUFAs and impairment of fatty acid degradation, making tumor cells particularly sensitive to cystine deprivation or GPX4 inhibition[191,192]. The RB1 tumor suppressor gene inactivation is common in various therapy-resistant cancers. Studies have found that RB1 deletion and E2F activation can sensitize tumor cells to ferroptosis by upregulating ACSL4 levels and the content of phospholipids containing PUFAs. The use of the GPX4 inhibitor JKE-1674 can efficiently block the growth and metastasis of

The transcription factor p53 has long been a star molecule in the field of cancer treatment. p53 is one of the most frequently mutated genes in cancer, and its mutation predicts poor prognosis in various cancer types. p53 itself can regulate the key substrates of lipid peroxidation, executors of lipid peroxidation, and anti-ferroptosis systems, which have been elaborated in relevant reviews[194-196]. Interestingly, p53 activation plays a dual role in ferroptosis: p53 can sensitize tumor cells to ferroptosis by promoting ROS production, catalyzing lipid peroxidation, and inhibiting SLC7A11 transcription, while also resisting ferroptosis through transactivation of iPLA2β and restriction of membrane-bound dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4). This implies that p53 regulation of ferroptosis is a complex environment-dependent and pathway-specific network. As a guardian of cell fate and responder to stress, it regulates the delicate balance between death and survival. Similarly, p53 mutations in cancer also have dual effects on ferroptosis regulation. On the one hand, p53 mutations can promote certain antioxidant stress proteins and ferroptosis defense systems

Beyond the classical tumor suppressor genes, mutations in the core cellular antioxidant stress-response pathway, the KEAP1/NRF2/CUL3 axis, are also intimately linked to tumor ferroptosis sensitivity and therapy resistance. Under physiological conditions, KEAP1 acts as a sensor for oxidative stress. By binding to the CUL3 ubiquitin ligase complex, it facilitates the continuous ubiquitination and degradation of the transcription factor NRF2, thereby restricting its activity[202]. However, in various cancers

Activation of some proto-oncogenes in tumor cells may also expose sensitivity to ferroptosis by enhancing their dependence on the GPX4 pathway. For example, MYCN-amplified neuroblastomas are highly invasive. Due to the regulation of cell proliferation, iron uptake, and other cellular activities by MYCN, high iron content in these tumor cells enhances their dependence on cysteine/cystine. These cells mainly rely on trans-sulfuration-mediated cysteine supply and LRP8-mediated organic selenium absorption to resist inherent ferroptosis susceptibility[211]. Triple therapy with co-inhibition of GPX4, cystine uptake, and trans-sulfuration pathways has been confirmed to effectively inhibit the growth of MYCN-amplified neuroblastomas[212,213]. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a key driver gene in solid tumors such as lung cancer. The EGFR signaling pathway significantly upregulates SLC7A11 expression by activating key downstream effectors including PI3K/AKT and RAS/MAPK[214]. This creates an abnormal dependency of mutant EGFR cells on extracellular cystine uptake to support their rapid proliferation and antioxidant stress response, concurrently rendering them highly susceptible to SLC7A11 inhibitors and cystine deprivation-induced ferroptosis[214].

The RAS family is one of the most frequently mutated oncogenes in human cancers and the first oncogene found to be closely associated with ferroptosis[141]. RAS mainly includes three mutants, including KRAS, HRAS, and NRAS, and different RAS mutation types have different effects on ferroptosis[215]. For example, HRAS-mutant cells show increased clearance of lysophospholipids and resistance to SCD1 inhibition[216]. The KRAS gene plays a pivotal role in regulating diverse intracellular signaling pathways and cellular activities, including the activation of the MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathways[141]. Tumors harboring KRAS mutations manifest a distinct metabolic profile. On one hand, their accelerated metabolism generates substantial ferroptosis pressure; on the other hand, this is counterbalanced by the activation of robust compensatory defense networks[141]. KRAS mutations drive the Warburg effect and glutaminolysis, leading to persistently elevated intracellular ROS levels, thereby creating a pro-oxidative stress microenvironment[217]. Concurrently, KRAS-mutant cells have evolved multi-layered, redundant ferroptosis defense systems. KRAS mutations can evade ferroptosis through ACSL3-dependent FASN-mediated increased synthesis of saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids in the Lands cycle[218]. Downstream of FASN, ACSL3 is crucial for tumorigenesis in KRAS-mutant lung cancer[219]. In addition, KRAS-mutant cells can also exhibit increased GSH synthesis and FSP1 expression driven by NRF2 and MAPK signaling[217,220], and can protect tumor cells from ferroptosis by upregulating the NRF2/SLC7A1 axis[217]. Combined use of SLC7A11 inhibitors or FSP1 inhibitors with traditional treatments is an effective strategy for treating KRAS-mutant tumors. KRAS can also resist ferroptosis by affecting lactate levels in the tumor microenvironment. Specifically, KRAS mutation-induced lactate promotes acylation of the glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL) modifier subunit mediated by acetyl-CoA acyltransferase 2 (ACAT2). This modification reduces GCL enzyme activity, inhibits GSH synthesis through targeting ACAT2, and thereby overcomes tumor ferroptosis resistance[221]. Recent studies have also found that KRAS-mutant pancreatic cancer can develop ferroptosis resistance by inducing ALOX15B depalmitoylation and membrane translocation to promote its degradation[222].

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a serine/threonine protein kinase, is involved in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway and plays an important role in regulating cell growth, proliferation, and death[223]. mTOR can form two functional complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2, and their effects on ferroptosis depend not only on the complex type but also on the tissue microenvironment. mTORC2 can promote ferroptosis in tumor cells by phosphorylating serine 26 of SLC7A11 to inhibit the activity of the system xc−[224]. Studies using a mouse model of acute lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection found that mTORC2 can also activate the AKT/GSK3β/NRF2 signaling axis to resist ferroptosis in memory CD4+ T cells and prolong the survival of antigen-specific memory T cells[225]. In most tumor cells, mTORC1 inhibits ferroptosis mainly through three ways: inhibiting autophagy, promoting GPX4 protein synthesis, and promoting MUFA synthesis. mTORC1 can phosphorylate and inhibit ULK1 of ATG complexes, thereby effectively suppressing autophagy. For example, knockdown of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase can promote redox homeostasis, trigger phosphorylation activation of AMPK, and reduce mTORC1 activity, thereby effectively activating the autophagy pathway[226]. Under high cell density, the Hippo pathway is activated, leading to phosphorylation activation of mTORC1, which in turn inhibits

Mutations in oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, and certain signaling pathways often help tumor cells cope with survival pressure but may also lead to their vulnerability to ferroptosis, providing potential intervention windows for targeted therapy of specific tumor types. Meanwhile, the above studies also imply that cancer cells may have differential responses to ferroptosis in the face of the same gene or pathway mutation. Future studies need to further clarify the impact of cell-specific differences on ferroptosis sensitivity.

3.1.4 Ferroptosis vulnerability in the tumor microenvironment

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a dynamic and complex system composed of tumor cells, immune cells, stromal cells, vascular systems, and other non-cellular components. In the TME, these components coexist and interact with each other, playing an important role in tumor growth and proliferation[229]. Ferroptosis and the TME, especially the immune system, interact in complex ways. On the one hand, mediators released by dying tumor cells can be transmitted to immune cells, triggering anti-tumor immune responses. On the other hand, mediators released by immune cells can regulate the sensitivity of tumor cells to ferroptosis in the TME, and the sensitivity of immune cells themselves to ferroptosis can also affect their functions, thereby reshaping tumor development in the TME (Figure 4D).

3.1.4.1 Immunogenicity of ferroptosis

ICD refers to the process by which cells activate the immune system during death, triggering a specific immune response in the body against antigens related to dying cells[230]. Exploring methods to induce immunogenic cell death is a new approach to cancer treatment, because the treatment itself kills tumor cells, and the immunostimulatory signals released by dead cells can further activate the adaptive immune system, thereby synergistically inhibiting tumors. Due to the lack of observation of specific, effective, and orderly release of danger signals to strongly activate adaptive immune responses in early studies, ferroptosis was generally regarded as a low-immunogenic death mode. In recent years, increasing evidence has shown that ferroptosis does not necessarily lead to immune silence, especially in the TME. Efimova et al. first demonstrated that ferroptosis is immunogenic in vitro and in vivo, and found that early ferroptotic cells with intact membrane structures can promote the phenotypic maturation of bone

It should be noted that the immunogenicity of ferroptosis is highly environment-dependent, affected by multiple factors such as cell type, ferroptosis induction method, and tumor microenvironment. For example, studies have shown that ferroptotic cancer cells can impair the maturation of dendritic cells, and their derived damage-associated molecular patterns may have negative effects on adaptive immune responses[241]. Moreover, ferroptosis induced by RSL3 or erastin cannot expose calreticulin before complete rupture of the plasma membrane, indicating that certain specific ferroptosis induction methods and environments affect the immunogenicity of ferroptosis[241]. Ferroptosis of various immune cells is also associated with immune dysfunction in mouse cancer models[242]. Meanwhile, ferroptosis-induced immune responses focus more on strong innate immune activation, and more exploration is needed on how to initiate effective adaptive immunity. Future studies need to further understand and optimize how to utilize the immunostimulatory potential of ferroptosis and overcome its potential immunosuppressive effects.

3.1.4.2 Ferroptotic immune cells and immune cells on cancer cells ferroptosis

In addition to specifically inducing ferroptosis in tumor cells to generate adaptive immune responses, protecting immune cells from ferroptosis is also crucial. Ferroptosis inducers show good tumor-killing effects in in vitro experiments but are relatively less effective in animal models, except in immunodeficient mice. Ferroptosis of immune cells affects not only their survival but also their functions. Their sensitivity to ferroptosis varies significantly with the environment.

T cells, especially CD8+ T cells, are the main executors of anti-tumor immunity in the TME. IFNγ derived from immune-activated CD8+ T cells can combine with AA in the TME to form endogenous ferroptosis inducers and synergistically induce ferroptosis in tumor cell through ACSL4[17]. Activated CD8+ T cells can also deplete intracellular GSH in tumor cells by inhibiting SLC7A11 mediated by TNFγ to promote ferroptosis[243]. CD8+ T cells appear to be more susceptible to GPX4 inhibitor-induced ferroptosis than ordinary cancer

The characteristic high dependence on GPX4 also extends to CD4+ T cells. Follicular helper T cells (TFH) are a specialized subset of CD4+ T cells, mainly supporting germinal center responses. Deletion of GPX4 in T cells selectively eliminates TFH numbers and germinal center responses in mouse models, suggesting that TFH are highly dependent on GPX4[249]. Regulatory T (Treg) cells are a subset with immunosuppressive activity and an important barrier to prevent autoimmunity. Treg cells have inherently high GPX4 expression, so GPX4-deficient Treg cells show high sensitivity to ferroptosis and promote the production of IL-1β and the response of helper T cell 17, thereby enhancing the body’s anti-tumor immune capacity[250]. Notably, T cell populations are more dependent on GPX4 than SLC7A11. Deletion of SLC7A11 in mouse models does not affect the growth and anti-tumor immunity of T cells in vivo and even enhances the efficacy of ICIs[251]. This may be due to the low and non-essential expression of SLC7A11 in T cells[252]. Recent studies on the lipid profile of immune system cells have shown differences in PUFA-PLs abundance, which explain and support the susceptibility of T cells to ferroptosis[253].

B cells are another pillar of anti-tumor immunity and exhibit significant heterogeneity. Different B cells subset exert complex and interrelated effects in the TME. Innate-like B cells (including B1 cells and marginal zone B cells) exhibit more active lipid metabolic characteristics compared with follicular B2 cells and are more susceptible to GPX4 inhibition-induced ferroptosis. These studies highlight the importance of ferroptosis in B cell survival and function, but the impact of ferroptosis on tumor-infiltrating B cells and B cell-mediated tumor immunity remains to be further studied[254]. B cells and T cells have very similar PUFA-PLs compositions, but B cells are more resistant to ferroptosis than T cells, possibly due to differences in peroxidized PLs components or undiscovered protective mechanisms[253]. However, studies on the impact of ferroptosis on tumor-infiltrating B cells and B cell-mediated humoral immunity are relatively few and still need further exploration.

The innate immune system also plays a role in regulating ferroptosis in tumor cells, and its own functions are affected by both ferroptosis and secretions from related cells. For example, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) can differentiate into immunostimulatory M1 phenotypes and immunosuppressive M2 phenotypes. During treatment, we tend to eliminate M2 phenotype cells or promote their conversion to M1 phenotype. M1 TAMs show significantly enhanced resistance to ferroptosis compared with M2 TAMs. On the one hand, M1 TAMs have higher expression of nitric oxide synthase and production of nitric oxide radicals (NO·), which can neutralize lipid radicals produced by 15-LOX[255]. On the other hand, M1 TAMs have increased ferritin heavy chain 1 expression and decreased iron exporter expression, which may lead to relatively stable intracellular iron content and resistance to ferroptosis[256]. Immunosuppressive M2 TAMs are relatively sensitive to ferroptosis. Moreover, multiple studies have confirmed that applying ferroptosis stimulation can reprogram M2 TAMs into M1 phenotype, thereby further inhibiting tumor progression[257-259]. Targeting ferroptosis in TAMs is expected to specifically eliminate M2 TAMs that promote tumor growth or promote the production of M1 TAMs, providing a promising strategy for immunotherapy. Pathologically activated neutrophils, also known as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (PMN-MDSCs), are another relevant immune cell type in the TME, with significant immunosuppressive capacity and heterogeneity. PMN-MDSCs are prone to ferroptosis and can even undergo spontaneous ferroptosis in the TME. Meanwhile, accumulated peroxidized lipids and release of PEG2 affect the activity of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and tumor-associated macrophages, making them more immunosuppressive[260]. Studies based on mouse hepatocyte models have also found that GPX4 deficiency leads to increased CXCL10-dependent CD8+ T cell infiltration, elevated PD-L1 expression, and promotes PMN-MDSC infiltration into the TME. Here, PMN-MDSCs do not show susceptibility to ferroptosis, and the strategy of combining GPX4 blockade with blocking MDSC recruitment significantly enhances the efficacy of immune checkpoint therapy and improves the survival of

These studies collectively reveal the complex interrelationship between ferroptosis and both adaptive and innate immunity in the TME. To improve cancer immunotherapy strategies, it is crucial to further clarify the heterogeneity of these immune cells in the TME and their connection with ferroptosis.