Abstract

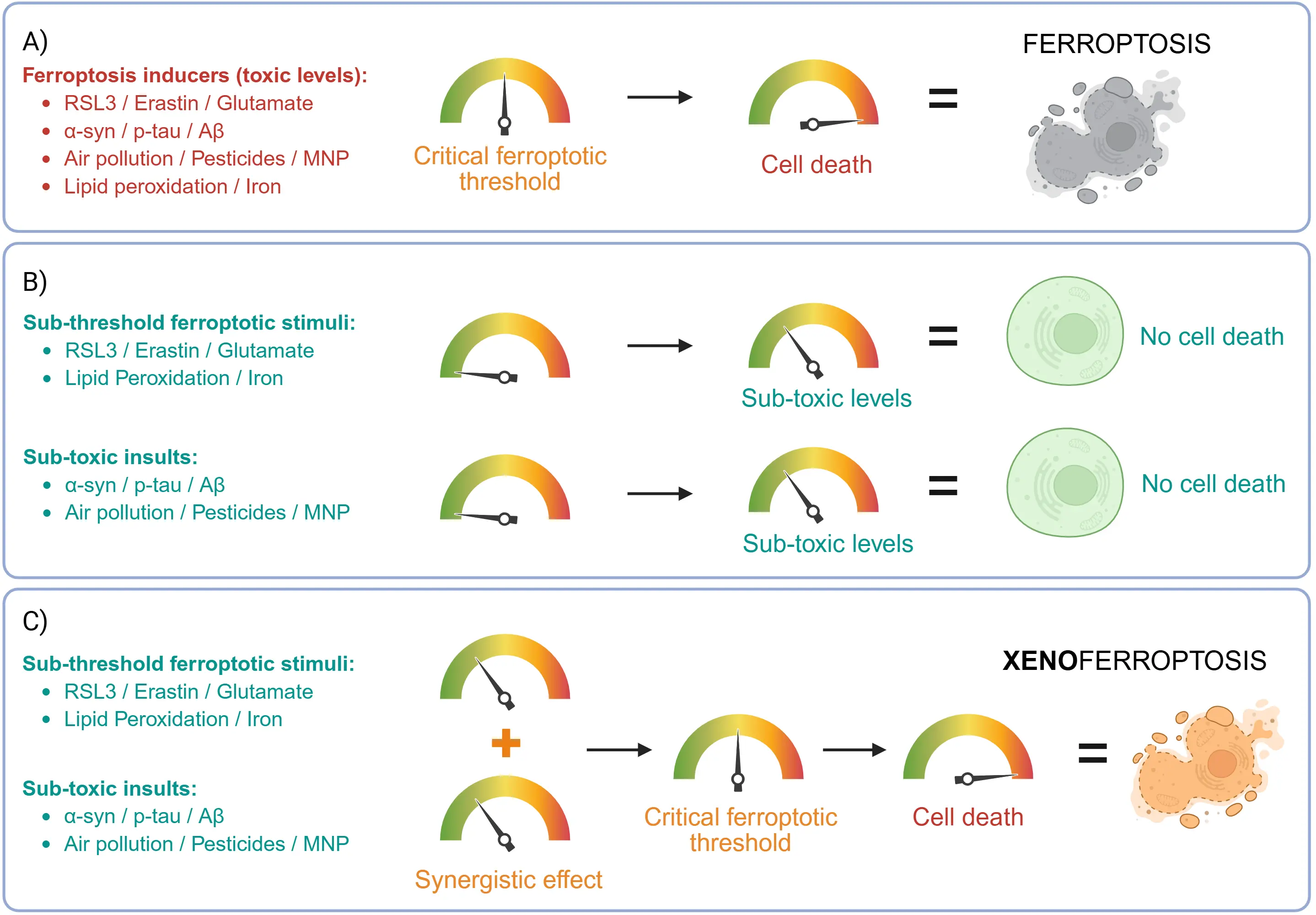

Ferroptosis is a regulated form of cell death driven by iron-dependent lipid peroxidation. Recent evidence indicates that ferroptosis is a critical player associated with cell death and inflammatory processes in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, as well as in chronic inflammation. In addition, during aging, the expression and activity of various proteins and cellular processes associated with the ferroptotic pathway, such as lipid peroxidation, have been shown to be altered. In this review, we introduce the concept of xenoferroptosis, a process in which ferroptotic signalling is amplified through the combined action of distinct challenges: one involving sub-threshold ferroptosis-related mechanisms, and another involving sub-toxic levels of exogenous or endogenous stressors. Exogenous challenges, such as air pollutants, pesticides, and micro- or nanoplastics, can disrupt redox balance through increased reactive oxygen species production, and impaired antioxidant defences. Endogenous triggers could include misfolded, aggregated proteins, such as amyloid-beta, hyperphosphorylated tau, and alpha-synuclein, which sensitize cells by promoting redox imbalance and mitochondrial dysfunction. While each individual stressor, either endogenous/exogenous or ferroptotic-associated process, may be sublethal, their convergence would initiate a synergistic cascade that accelerates cell death. We propose that xenoferroptosis represents a distinct pathogenic axis at the intersection of molecular pathology and environmental exposure, offering new perspectives for therapeutic interventions that target its dual-trigger mechanisms.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Programmed cell death is a regulated process, whereby cells “self-destruct” in the presence of insults, in order to maintain tissue health. Apoptosis is a common form of programmed cell death which could involve a caspase- or non-caspase-mediated process that clears damaged cells[1]. Apoptosis is especially associated with cell death in neurodegenerative disorders where it could act as a protective mechanism to preserve neuronal integrity[2,3]. In Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the presence of proteopathic inclusions foreign to healthy cells triggers neuronal cell death[3]. Other external risk factors, such as environmental pollutants and micro(nano)plastics (MNPs), have been studied as they also contribute to these cell death pathways. However, mounting evidence has pointed to the involvement of another form of regulated cell death in the brain, ferroptosis. Ferroptosis is a form of non-apoptotic cell death characterised by lipid peroxidation of cell membranes potentially resulting from iron accumulation and oxidative stress[4-7]. Ferroptotic cell death can be initiated by a single-hit stimulus; however, sub-toxic lipid peroxidation conditions alone do not result in cell death. We observed that an additional second challenge in the form of either environmental pollutants (e.g. diesel exhaust particles (DEP), pesticides or plastics, acting as “external” or “exogenous” stimuli) or misfolded aggregated proteins (e.g. amyloid-beta (Aβ) or alpha-synuclein aggregates, acting as “internal” or “endogenous” stimuli) could act as catalysts for induction of cell death. This double-hit challenge could be driving ferroptotic cell death, thus this process is termed xenoferroptosis (“xeno” = “foreign”).

The first key step in xenoferroptosis is the presence of multiple sub-threshold ferroptotic stimuli, such as modest increases in lipid peroxides, and/or iron, that individually remain below the level required to trigger cell death. The second key step is the synergistic exposure to additional subtoxic exogenous and/or endogenous insults together with the existing subthreshold ferroptotic challenges. This combined action drives oxidative damage beyond a critical threshold of ferroptosis, thereby accelerating cell death, in a distinct xenoferroptotic process.

In the present review, we explore how exogenous and/or endogenous insults foreign to cells’ healthy environment may lead to the double-hit challenge hypothesis of xenoferroptosis, whereby a combination of sub-toxic levels of lipid peroxidation or components of the ferroptosis pathway in combination with sub-toxic concentrations of various external/internal stimuli may result in ferroptotic cell death[8,9].

There are two main pathways by which ferroptosis may be initiated in cells[10]: 1) by increasing free intracellular iron, and 2) inhibition of the cysteine-glutamate antiporter system (Xc-) and antioxidant systems. Free iron promotes the Fenton reaction which, in turn, produces free radicals, namely, reactive oxygen species (ROS). As a result, inhibiting antioxidant pathways leads to the build-up of lipid peroxides, which could be incorporated into the phospholipid bilayer and contribute to the break-down of the cellular membrane[11,12]. Ferroptosis’ main players are labile iron and Fenton chemistry, antioxidant defence via the glutathione (GSH)/glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) axis, and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) abundance. First, to prevent the increase of iron, there are several proteins that can help keep a “healthy” balance of iron intracellularly: 1) transferrin as an iron transporter, enabling iron entry into the cell[13]; 2) ferritin as an intracellular iron store, preventing damage by free iron that would otherwise be toxic[14]; and 3) ferroportin (Fpn) as an iron exporter, that could transport free iron to the extracellular space[15]. Failure to establish this iron homeostasis could lead to excessive intracellular levels of iron that can catalyse the Fenton reaction, leading to the generation of hydroxyl radicals and lipid peroxidation propagation[16]. These free radicals interact with neuronal membrane PUFAs, thereby promoting lipid peroxidation. However, at the antioxidant level, the Xc- system plays an important role by exchanging glutamate for cystine, supporting the generation of GSH[5]. GPX4 utilises GSH to detoxify peroxides and prevent membrane lipid peroxidation.

When studying ferroptosis, several “classic” inducers have been extensively used, which we explore in this review as the “single-hit” challenge of ferroptosis which targets the Xc- system, the GSH/GPX4 axis and lipid peroxidation, and thus, directly or indirectly results in ROS and lipid peroxidation accumulation. Interestingly, changes in mitochondrial size and membrane dynamics are also associated with ferroptosis, as well as accumulation of ROS under stress conditions[5,17]. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases (NOX) enable intracellular ROS formation and use products of lipid peroxidation, such as 4-Hydroxynonenal (4HNE) and malondialdehyde (MDA) to further induce the activation of NOX and amplify ROS production[18,19].

Oxidative stress, caused by an imbalance of free radical production and antioxidants, contributes to ferroptotic cell death[5,20,21]. In addition to the classic ferroptosis inducers, there are other factors stimulating ferroptotic cell death in a “single-hit” mechanism, namely, mutations leading to increased lipid peroxidation, cellular stress, and ultimately disease phenotypes. For example, i) GPX4 mutations can lead to Sedaghatian-type spondylometaphyseal dysplasia, which causes lipid peroxidation in tissues and dysfunctional mitochondria, resulting in malformations of bones and the central nervous system (CNS)[22]; ii) Autosomal-recessive congenital ichthyosis caused by lipoxygenase (ALOX)12B/ALOXE3 mutations, results in aberrant lipid oxidation in the epidermis and consequent skin scaling[23]. Inhibition of 12/15LOX activity has been proven to lead to neuroprotective effects in the presence of ferroptotic stimuli and oxidative stress conditions such as glutamate or erastin[24]. iii) Mutations in Ferrodoxin Reductase can lead to severe mitochondrial disease that is associated with neuropathy due to excessive ROS production and accumulated iron resulting from impaired mitochondrial redox balance[25]. Interestingly, other ferroptosis-related mutations are also associated with (age-related) neurodegenerative diseases, such as familial PD, including PARK7 (DJ-1), PARK2 (PINK1/Parkin) and PARK9 (ATP13A2) mutations, known to induce PD as a result of impaired redox cycling, mitochondrial function and lysosomal/iron homeostasis[26,27], respectively, and collectively leading to enhanced lipid peroxidation and/or ROS accumulation and neuronal death. Similarly, Presenilin (PSEN)1 and PSEN2 mutations associated with familial AD are thought to be involved in decreased GPX4 activity[28], while apolipoprotein E ε4, a risk allele for developing sporadic AD, has been associated with lipid peroxidation and increased susceptibility to ferroptosis[29,30].

In this review, we explore the double-hit challenge in xenoferroptosis. First, we will discuss findings showing the combination of sub-lethal doses of exogenous factors (including DEP, pesticides, MNPs, as well as other metals), with ferroptotic-associated processes exacerbating the ferroptosis pathway[31-36]. Then, we explore the combination of internal (endogenous) proteopathic inclusions, such as α-synuclein (α-syn) in PD, Aβ in AD and hyperphosphorylated tau (p-tau) in tauopathies (including progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), but also AD, a secondary tauopathy), with sub-threshold ferroptotic-associated processes.

Despite several diseases being linked to an upregulated ferroptosis profile[37,38], it remains unknown how exposure to certain insults may exacerbate this form of cell death and predispose certain individuals to developing chronic diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases. We will further discuss several pathologies thought to be affected by xenoferroptosis, primarily focusing on age-related neurodegeneration, including PD, AD and PSP. Exploring the xenoferroptotic underpinnings of disease progression is pivotal in understanding its aetiology and furthering research into better treatments.

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of cell death characterized by excessive lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress. In various pathological conditions, increased levels of lipid peroxides, iron, and/or free radicals may drive a critical threshold of ferroptosis, required to initiate cell death. However, in conditions of a sub-threshold ferroptotic state, simultaneous exposure to additional factors may amplify oxidative damage, thereby lowering the ferroptotic resilience of the cell or the critical ferroptotic threshold, leading to cell death. Exposure to these multiple-hit stimuli, each with a sub-threshold ferroptotic state, leads to an increased vulnerability to cell death, a cellular process referred to as xenoferroptosis.

2. Inducers of Ferroptosis

2.1 Traditional ferroptosis inducers

Since its discovery, ferroptosis has attracted increasing attention due to its critical role in various pathological processes, including cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and tissue injury[38,39]. As ferroptosis has become a rapidly expanding field of study, a large number of small molecule compounds that can specifically trigger this cell death process have been discovered, providing important tools for further analysing its molecular mechanism and exploring treatment strategies[40]. Based on the different targets, we summarize representative ferroptosis inducers based on their molecular mechanisms and pathways of action.

2.2 Targeting system Xc-

System Xc- is a sodium-independent cysteine/glutamate antiporter system located on the plasma membrane[41]. It consists of the light chain subunit SLC7A11 (xCT) and the heavy chain subunit SLC3A2 (also known as CD98hc or 4F2hc)[42]. SLC7A11 is responsible for substrate-specific recognition and transmembrane transport, whereas SLC3A2 serves as an accessory subunit that forms a heterodimeric complex with SLC7A11, contributing to its proper folding, membrane localization, and structural stability[43]. The primary function of System Xc- is to mediate an equimolar exchange between intracellular glutamate and extracellular cystine, thereby importing cystine into the cell[44]. Once transported into the cell, cystine is rapidly reduced to cysteine within a reducing intracellular environment, maintaining the intracellular cysteine supply. This process is crucial for cellular redox homeostasis, as cysteine is a precursor for various antioxidant molecules, such as GSH[45]. Inhibition of System Xc- restricts the intracellular availability of cysteine, resulting in impaired antioxidant defence and excessive lipid peroxidation, which ultimately triggers ferroptotic cell death. Several ferroptosis inducers have been identified to target the System Xc- antiporter.

Glutamate has been extensively used as a cell death inducer to mimic oxidative stress in cells lacking NMDA/AMPA receptors, via a process termed oxytosis[46-49]. Oxytosis and ferroptosis share common characteristics, including inhibition of the Xc- antiporter, decreased levels of GSH, mitochondrial dysfunction with Bid proteins being highly relevant to this dysfunction, alterations in mitochondrial Ca2+, and increased levels of lipid peroxidation[50]. Another ferroptosis inducer, erastin, was initially identified in 2003 through a synthetic lethal high-throughput screen for anticancer compounds and represents the most extensively studied small-molecule ferroptosis inducer that directly inhibits SLC7A11, thereby promoting lipid peroxidation and cell death[51,52]. Erastin exhibits selective cytotoxicity across multiple tumour cell lines, particularly those harbouring small T (ST) and RAS oncogenic mutations. Studies have shown that after 18 hours of erastin treatment, BJ-TERT/LT/ST/RASV12 tumorigenic cells showed a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential, reduced cell size, and aggregation and detachment. In addition, erastin effects could involve the RAS–RAF–MEK pathway[52,53]. Upon erastin treatment, the intracellular ROS and MDA levels significantly increase, while the superoxide dismutase and GSH levels markedly decrease, accompanied by mitochondrial morphological damage. Similar cell death pathways induced by erastin have been reported in various cell types, including human DLBCL cell lines (OCI-Ly3 and DB)[54], murine hippocampal cells HT22[55], human cervical cancer cells (HeLa and SiHa)[56], and human neuroblastoma cells SH-SY5Y[57]. Erastin has been widely used in in vitro research, and also in vivo research to model ferroptosis. For example, activation of small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels could prevent erastin-induced ferroptotic cell death in neuronal cells[58]. Intraperitoneal injection of erastin in healthy C57BL/6 mice increased serum iron levels and MDA levels in tissues such as the kidney and liver, while also inhibiting the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4[59]. Consistent with these results, in the mouse xenograft model, erastin treatment triggered ferroptosis, characterized by reduced tumour growth, elevated lipid peroxidation, and depletion of GSH in tumour tissues[60]. However, its poor metabolic stability and limited in vivo bioavailability have constrained its clinical application.

To overcome these limitations, imidazole ketone erastin (IKE), that has better potency, metabolic stability, and water solubility, has been developed. Hepatoma cell lines (Hep G2, Hep 3B, HCCLM3, and Huh-7) all responded to IKE-induced ferroptosis in a concentration-dependent manner, with Hep G2 cells being the most sensitive and HCCLM3 cells being the least sensitive. However, inhibition of lipid peroxidation with ferrostatin 1 (Fer-1) inhibited IKE-induced cell death. Furthermore, intraperitoneal injection of IKE increased iron deposition in subcutaneous tumour sections of nude mice[61]. In line with the above, IKE also can significantly induce changes in mitochondrial membrane potential, promote the production of intracellular ROS, and upregulate the p53 gene expression in osteosarcoma cell lines[62].

In addition, clinically approved drugs like sulfasalazine (SAS) have been found to suppress System Xc- activity and induce ferroptosis in certain cancer cell types[63]. Studies have shown that SAS treatment significantly reduced the expression of ferroptosis-related proteins (such as GPX4, SLC7A11, and ferritin heavy chain) in fibroblast-like synoviocytes and promoted the accumulation of lipid peroxides. The addition of the iron chelator Deferoxamine (DFO) significantly attenuated the adverse effects of SAS on cells. Further studies demonstrated that SAS-induced ferroptosis was closely associated with downregulation of ERK1/2 expression and upregulation of P53[64]. Similar results showed that SAS induced ferroptosis in osteosarcoma cells by promoting iron accumulation, lipid peroxidation, and ROS production, while simultaneously reducing antioxidant defence mechanisms. Ferroptosis inhibitors (DFO, Fer-1, and Liproxstatin-1 (Lip-1)) can reverse SAS-induced cell death. Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is responsible for maintaining redox homeostasis by regulating different antioxidant expression, including GPX4 and GSH, therefore regulating ferroptosis. Mechanistically, SAS inhibits the Nrf2/SLC7A11/GPX4 signalling pathway, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction and decreased cell viability[65].

The oncogenic kinase inhibitor sorafenib has been identified as an inducer of ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells and has been shown to trigger ferroptosis across various cancer cell lines. Notably, it is the only kinase inhibitor known to exhibit ferroptotic activity[66]. In hepatocellular carcinoma, sorafenib induced ferroptosis by causing GSH depletion and lipid peroxidation. Metallothionein MT-1G was upregulated through Nrf2 activation, conferring resistance by inhibiting ferroptosis. Conversely, knockdown of MT-1G by RNA interference enhanced the ferroptosis and antitumor effects of sorafenib[67]. Recently, Zheng et al. found that sorafenib does not induce ferroptosis in many cancer cell lines (such as the human fibrosarcoma cell line HT1080), making the role of sorafenib as a ferroptosis inducer controversial. Moreover, it was shown that Lip-1 and deferiprone could not rescue sorafenib-induced cell death[68].

In addition to these direct effects on System Xc- inducers of ferroptosis, the expression of this system is regulated by a variety of transcription factors. For example, p53 and activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) can negatively regulate SLC7A11, thereby indirectly increasing the sensitivity of cells to ferroptosis under certain contexts. However, accumulating evidence indicates that the role of ATF3 in ferroptosis is highly context-dependent rather than uniformly pro-ferroptotic. Previous studies have provided evidence that both factors participate in the regulation of ferroptosis through distinct cellular pathways. p53-null mouse embryonic fibroblasts exhibited reduced sensitivity to erastin, with lower cell death compared to wild-type cells, whereas the ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 completely prevented erastin-induced cell death in wild-type cells, inhibiting lipid peroxidation and protecting cellular membranes from oxidative damage[69]. Several studies have demonstrated a pro-ferroptotic function of ATF3. For instance, knockout of ATF3 expression in retinal pigment epithelial cells significantly suppressed erastin-induced ferroptosis and lipid peroxide accumulation. ATF3 has also shown a role in promoting erastin-induced ferroptosis in other cancer cell lines, such as DU145 and U2OS[70]. Conversely, overexpression of ATF3 attenuated erastin-induced ferroptosis in neonatal mouse cells by enhancing cell viability, reducing ROS and MDA levels, upregulating GPX4, and downregulating cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX2) expression[71]. Overall, pharmacological inhibition of System Xc- represents a key strategy to initiate ferroptosis through disruption of cystine uptake and redox homeostasis[30,72].

2.3 Targeting GSH/GPX4

One of the most critical downstream pathways of the Xc- system is the GSH/GPX4 axis[73]. GPX4 is the only glutathione peroxidase capable of directly reducing membrane lipid peroxides, using GSH as a reducing agent to convert lipid peroxides into their corresponding alcohols and thereby protecting cellular membranes from oxidative damage[38]. Its activity is highly dependent on intracellular cysteine availability and GSH synthesis. When GPX4 is inhibited or absent, lipid peroxides accumulate rapidly, compromising membrane integrity and ultimately triggering ferroptosis[74]. Given its central role in cellular defence, GPX4 is widely recognized as the primary molecular target in ferroptosis[75]. (1S,3R)-RSL3 (RSL3) is a small molecule first discovered in 2009, and later was shown to induce ferroptosis by inhibiting GPX4[76]. RSL3 has been shown to consistently induce ferroptosis in cell lines from diverse sources[76-80]. For example, it induces cell death in human colorectal carcinoma cell lines (HCT116, LoVo, and HT29) in a dose- and time-dependent manner, accompanied by an increase in the labile iron pool and accumulation of ROS. Additionally, RSL3 treatment in cells such as SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells[77], HT22 mouse hippocampal neuronal cells[78], and human colorectal cancer cells[80] led to elevated ROS levels, increased cytosolic and mitochondrial calcium, enhanced lipid peroxidation, and ultimately cell death[78]. Inhibition of mitochondrial calcium uniporter pathways could prevent cell death induced by RSL3 in HT-22 cells[78,81]. RSL3-induced ferroptosis has also been widely studied in vivo models. RSL3 significantly exacerbated liver damage in mice with acute-on-chronic liver failure, including increased levels of the lipid peroxidation end product MDA, decreased levels of GSH and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), and upregulation of prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase 2 (Ptgs2) mRNA expression[82]. Furthermore, in mouse xenograft models of glioblastoma, RSL3 administration reduced tumour volume[83,84] and increased intracellular iron, lipid ROS, and GSH levels[83]. Similarly, in an AD mouse model, RSL3 administration reduced xCT, Gpx4, and Fpn mRNA expression, as well as decreased total antioxidant status and increased total oxidant status in the mouse brain tissue[85].

Another inducer of ferroptosis, N2,N7-Dicyclohexyl-9-(hydroxyimino)-9H-fluorene-2,7-disulfonamide, has a slightly different mechanism from the above-mentioned small molecules. It not only promotes GPX4 degradation but also inhibits coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), thereby doubly damaging cellular antioxidant defences and accelerating lipid peroxidation accumulation[86]. A large-scale screening of ferroptosis-inducing (FIN) compounds discovered DPI7 and DPI10. A systematic comparison of the response characteristics of FIN compounds with non-FIN compounds in HT-1080 cells demonstrated that FIN-like small molecules induce ferroptosis by promoting lipid peroxidation and inhibiting GPX4 function. Fat-soluble antioxidants have a significant rescue effect on it. Furthermore, when glutathione was depleted by buthionine sulfoximine treatment, indirectly inhibiting GPX4, FIN-induced ferroptosis was significantly enhanced. However, overexpression of GPX4 suppressed FIN-induced cell death[76]. Among the various ferroptosis inducers targeting GPX4, ML162 has also been identified as a potent compound[87]. ML162 exhibits a mechanism similar to that of RSL3, though it differs slightly in its chemical structure, cell-type selectivity, and potency. At the molecular level, ML162 upregulates the expression of acyl-CoA-synthetase (ACSL4) and lysophospholipid acyltransferase 5 (LPCAT3), two key enzymes involved in phospholipid remodelling, thereby promoting the accumulation of lipid peroxides[88]. Functionally, ML162 induced cell death in KBM7 cells, which can be effectively rescued by the lipophilic antioxidant Fer-1 and the iron chelator ciclopirox olamine (CPX), further confirming that the cytotoxic effect of ML162 is mediated by ferroptosis[11].

2.4 Targeting lipid metabolism

Lipid metabolism plays a pivotal role in the initiation and execution of ferroptosis, with lipid peroxidation serving as its most direct biochemical hallmark[89]. Ferroptosis is driven by the accumulation and oxidation of PUFAs incorporated into membrane phospholipids, which act as critical substrates for oxidative stress-induced membrane damage[90]. ACSL4 facilitates the activation of PUFAs and their esterification into membrane phospholipids, primarily phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), promoting their participation in the lipid peroxidation process, thereby accelerating ferroptosis. During ferroptosis, these PE species undergo selective oxidation, accompanied by the oxidation of phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidylinositol (PI)[91]. The accumulation of these oxidized phospholipids amplifies membrane lipid peroxidation and ultimately leads to ferroptotic cell death. Exogenous supplementation of PUFAs, such as arachidonic acid (AA) or adrenic acid (AdA), can further increase the content of readily oxidizable substrates in membrane lipids, significantly enhancing cellular susceptibility to ferroptosis[92]. Conversely, inhibiting the activity of key enzymes involved in lipid metabolism can effectively block this process. For example, genetic ablation and inhibition of ACSL4 by triacsin C can reduce the incorporation of PUFAs into membrane phospholipids, thereby reducing lipid peroxidation and counteracting RSL3-induced cell death[93]. Studies have shown that in gastric cancer cells NCI-N87 and SNU-719 with low AA and AdA content, exogenous supplementation of AA significantly enhances ferroptosis sensitivity, accompanied by increased PE levels in membrane phospholipids and enhanced lipid peroxidation. Furthermore, AA supplementation promotes ferroptosis in response to RSL3 treatment, confirming that elevated intracellular AA levels accelerate ferroptosis by promoting the accumulation of lipid peroxidation[94]. As the role of AA in ferroptosis has become increasingly evident, recent studies have focused on developing fatty acid–based ferroptosis inducers. Among them, GS-9, an AA-derived compound, exhibits improved solubility and potent FIN activity. GS-9 is composed of AA and L-lysine, which increases the solubility of fatty acids in aqueous solutions. Functionally, GS-9 effectively induces ferroptosis in various cancer cell lines, an effect independent of apoptosis and necroptosis pathways. Furthermore, GS-9 treatment promotes lipid peroxidation and MDA accumulation, a process completely blocked by Fer-1[95].

3. Evidence of Single-Hit Ferroptosis in Disease

3.1 External risk factors associated with ferroptosis in chronic and neurodegenerative diseases

3.1.1 Air pollutants and ferroptosis

Air pollution represents one of the most serious environmental challenges worldwide due to its profound impact on public health and ecological stability[72]. Air pollutants consist of a complex mixture of gases and particulate matter (PM) originating from vehicle traffic, combustion activities (biomass, industrial, and waste burning), and road dust in urban areas[96]. Common atmospheric pollutants include PM, particularly PM2.5 and PM10; gaseous pollutants such as ozone (O3), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), sulphur dioxide (SO2), and carbon monoxide (CO); and complex organic compounds and metal elements released during combustion[97]. Air pollutants not only contribute to climate change, but also to a broad spectrum of human diseases[98,99]. Indeed, numerous epidemiological and experimental studies have confirmed that long-term or high-level exposure to air pollutants is closely associated with the development and progression of a variety of diseases, including respiratory illnesses (such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)), cardiovascular diseases, and neurodegenerative disorders[100-103]. Emerging evidence suggests that ferroptosis serves as a unifying molecular mechanism underlying many of these pollution-induced pathologies[104].

Due to their small particle size and complex composition, these pollutants can be deeply deposited in the respiratory tract and penetrate the bloodstream, even crossing the blood brain barrier (BBB) and causing systemic toxic effects[105]. Air pollution is strongly linked to respiratory diseases, including asthma[106], COPD[107], and lung cancer[108]. Inhalation of PM induces airway inflammation, oxidative stress, and impaired lung function. Evidence of iron overload and redox imbalance in asthma[109] and COPD[110] suggests activation of ferroptosis during disease progression. Epithelial bronchial cells (Beas-2B) exposed to PM2.5 showed a significant reduction in cell viability and increased lipid peroxides, which were both reverted with Fer-1[109]. Furthermore, PM2.5 induced the ferroptotic pathway in rat lungs by increasing iron levels and reducing antioxidant defence by reducing the expression of SLC7A11 and GPX4[111]. In addition, PM2.5 could cause damage to MLE-12 lung epithelial cells and to in vivo lung tissue by blocking both mRNA and protein expression of GPX4 and SLC7A11 through the downregulation of NRF2[112].

Beyond the respiratory system, numerous epidemiological studies have demonstrated associations between air pollution and cardiovascular diseases[113,114]. These effects are largely driven by the stimulation of an inflammatory response and oxidative stress, suggesting a mechanistic role for ferroptosis in PM2.5-mediated cardiovascular injury[115-117]. Inhibiting ferroptosis with Fer-1 could attenuate lipid peroxidation induced by the pollutant and could also preserve the expression of GPX4 and SLC7A11 in mouse aortic endothelial cells[118]. More recently, increasing evidence suggests that air pollution also contributes to metabolic disorders such as diabetes and obesity[119]. Pollutants may disrupt metabolic homeostasis by triggering chronic low-grade inflammation, altering lipid and glucose metabolism, and promoting insulin resistance[120].

In addition, emerging studies highlight the impact of air pollution on the CNS[121,122]. Ultrafine particles and neurotoxic components can cross the BBB or reach the brain via the olfactory pathway, leading to neuroinflammation, microglial activation, and neuronal damage[72]. Such mechanisms have been implicated in the development or progression of neurodegenerative diseases, including AD[123], PD[124], and other forms of dementia. In neuronal cell models (Neuro-2a, SH-SY5Y), PM2.5 triggers ferroptosis by downregulating GPX4 and modulating iron-handling proteins such as ferritin heavy and light chains (FTH/FTL) and transferrin receptor (TFRC), effects reversible by Fer-1[125]. Moreover, in the lung epithelial MLE-12 cell line, exposure to PM2.5 (100 μg/ml, 24 h) decreased Slc7a11, Gpx4, and Ptgs2 gene expression and GSH levels, and in mouse lung tissue exposed to PM2.5 (100 μg/kg, 4 weeks), NRF2 protein and mRNA expression was decreased[112]. PM2.5 exposure could also cause neurobehavioral impairment in mice, and increase the vulnerability to ferroptosis through increased expression of COX2 and ACSL4 and downregulation of GPX4 and SCL7A11[126]. Interestingly, exposure of the BV2 microglia cell line to PM2.5 (5-20 μg/cm2, 24 h) increased Nrf2 mRNA and protein expression, which regulates the Hmox1 gene responsible for iron release[126]. Using pharmacological inhibition of HMOX1 and NRF2 with Zinc Protoporphyrin (ZnPP) and ML385, respectively, cell death was rescued and cytosolic iron was decreased in the PM2.5-challenged BV2 cells. The effect of ZnPP on heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) expression is controversial, depending on the cell type[126-128]. These results indicate that PM2.5 can trigger cellular damage in a ferroptosis-dependent manner, however the involved pathways may be tissue and concentration dependent.

3.1.2 Pesticides and ferroptosis

Recent studies have shown that pesticides widely used in agriculture are involved in multiple disorders. Increasing evidence indicates that several chemical classes of pesticides, including botanicals[129-131], bipyridyls[132,133], phosphonate herbicides[134-136], macrocyclic lactones[137,138], and organophosphates[139,140], can induce ferroptosis. Pesticide exposure usually triggers ferroptosis by disrupting redox homeostasis and iron metabolism, and by inhibiting GPX4, which promotes lipid peroxidation.

Many studies demonstrate that various pesticides downregulate the core GPX4-GSH antioxidant system. One study reported that glyphosate induces ferroptosis in human hepatic L02 cells and mouse livers by suppressing the Nrf2/GSH/GPX4 axis, exacerbating hepatotoxicity. Interestingly, Fer-1 rescued this mouse liver damage[134]. Similarly, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid induced ferroptosis in human neuroblastoma cells SH-SY5Y cells through the Xc-/GSH/GPX4 axis, which could be alleviated by Fer-1 or Beclin 1 knockdown[141]. However, inhibition of the GPX4-GSH axis may not be the initial event directly impacted by pesticides. Some studies suggest that pesticides could increase intercellular Fe2+ levels, leading to ferroptosis. For example, atrazine activates cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase, facilitating Fe2+ accumulation and lipid peroxidation, ultimately causing ferroptosis in mouse hepatocytes[142]. Deltamethrin, an insecticide, activates the phospholipase C/inositol triphosphate 3 receptor pathway and disrupts calcium homeostasis in the hippocampus, inducing ferroptosis accompanied by iron accumulation and redox imbalance associated with ferroptosis[143].

As a form of cell death characterized by redox imbalance and lipid peroxidation, ferroptosis is considered to be modulated by the cellular oxidative status. One study reported that paraquat (PQ) downregulated Nrf2 expression and upregulated Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) expression in the rat lung, inducing ferroptosis[144]. Nrf2 is a key transcription factor that generally protects against oxidative damage[145]. In many models of pesticide exposure, Nrf2 activation reduces ferroptosis induced by pesticide exposure. Natural compounds such as chitosan oligosaccharide[146], grape seed-derived procyanidin[135], silybin[138] and vitamin E[147] have been shown to protect against ferroptosis induced by deoxynivalenol, glyphosate, avermectin, and chlorpyrifos, respectively. These compounds activate Nrf2 and its downstream targets, such as HO-1 and NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1), enhancing GSH synthesis and reducing lipid peroxidation.

However, as previously discussed, NRF2 may not always be protective against ferroptosis. One study found that diquat induces ferroptosis by activating HO-1, a downstream target of Nrf2, in a diquat dibromide-induced testis injury mouse model, in which HO-1 activation degraded heme into ferrous ions, driving ferroptosis[132]. Although HO-1 is a classical antioxidant downstream target of NRF2, excessive HO-1 activation can lead to the release of excessive ferrous ions and generate oxidative overload beyond the antioxidation capacity of the NRF2 pathway, resulting in a shift from protection to initiation of ferroptosis.

Other signalling pathways besides NRF2 could also contribute to pesticide-induced ferroptosis. For example, the Adenosine 5′-monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK)-unc-51-like autophagy-activating kinase 1 (ULK1) pathway is involved in chlorpyrifos-induced autophagy and ferroptosis, suggesting that activation of the AMPK-ULK1 axis promotes autophagy, inducing iron release and lipid peroxidation, and ultimately leading to ferroptosis[140]. However, a different study showed that AMPK can also suppress ferroptosis when activated by energy stress, as it reduces the levels of lipid peroxidation-susceptible PUFAs AA and AdA[148]. This suggests that, depending on the cellular context, AMPK can have a dual effect on ferroptosis regulation. Endoplasmic reticulum stress also plays a role in the ferroptosis regulation in PQ-exposed mouse liver cells (NCTC1469 cells), where ChaC glutathione specific gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 1, ATF3, TFRC, and SLC7A11 are key molecules during the cell death[149]. In addition, p53 mediates chlorpyrifos-induced ferroptosis in mouse hepatocytes through mitochondrial ROS-modulation of cell death pathways[150]. Together, these studies indicate that pesticide-induced ferroptosis involves multiple interconnected signalling networks.

Ferritinophagy, a type of selective autophagy that releases Fe2+ by degradation of ferritin heavy and light chains, is also important in pesticide-induced ferroptosis. A study suggested that glyphosate can mobilize intracellular iron stores by activating organelle degradation pathways, linking autophagy to ferroptosis[136]. Therefore, the mechanistic framework of pesticide-induced ferroptosis has expanded from a simple GPX4-centered axis to a broader network involving iron metabolism, oxidative stress, calcium homeostasis, the regulatory Nrf2 pathway, and autophagy.

Most studies have used in vitro cell line models such as HepG2[151], A549[152,153], or SH-SY5Y cells[130,141,154], or acute high-dose of pesticides in animal models[144,153,155,156]. These models help identify molecular mechanisms, but differ from real-world situations of long-term and low-dose exposure in humans. For example, one study exposed Wistar rats to nine subcutaneous injections of 1 mg/kg rotenone administered every 48 hours, which induced ferroptosis[129], while the reference dose (RfD) for chronic exposure to rotenone established by the United States Environmental Protection Agency is 0.004 mg/kg/d[157]. Only a few studies have investigated more realistic conditions. One study investigated ferroptosis in male offspring after maternal exposure to different concentrations of deltamethrin throughout the entire gestational period, also using pregnant Wistar rats, which provides valuable insight into environmentally relevant exposure and evidence of transgenerational effects[143].

Toxicological data from the European Food Safety Authority reported that the acceptable daily intake (ADI) for glyphosate is 0.5 mg/kg body weight (bw) per day and the acceptable operator exposure level (AOEL) is 0.1 mg/kg bw per day, based on studies in dogs and rabbits, respectively[158]. Notably, ADI and AOEL, as toxicological reference values, are usually much higher than real-world exposure levels. Two recent studies used oral gavage of 2, 50, and 250 mg/kg each day for 8 weeks in male specific pathogen-free BALB/c mice to study glyphosate-triggered hepatocyte ferroptosis[134]. The doses of these two studies were based on the median lethal dose (LD50) from a previous study in Wistar rats[159] and the RfD of 2 mg/kg/d from the United States Environmental Protection Agency[157]. Although these doses are still higher than the real human exposure through oral intake or skin absorption, the 8-week treatment provides valuable information about the long-term effects of chronic glyphosate exposure. By comparison, in vitro studies also apply high concentrations, such as 1 mM glyphosate in TM3 mouse Leydig cells[136]. Although studying the mechanism of pesticide-induced ferroptosis under acute high-dose exposure can be helpful to some extent, its relevance under chronic low-dose exposure is questionable, especially regarding risks for some chronic diseases, such as neurodegenerative disorders. Under chronic low-dose conditions, adaptive responses, epigenetic modifications, and chronic immune activation may play additional roles, which are often missed in acute models.

In addition, studies on the protective effects of compounds such as lycopene[141] and silybin[137] mostly remain at the animal experimental stage. Translating these findings into clinical therapy or preventive strategies for exposed populations still requires more research. Furthermore, early biomarkers of ferroptosis in populations at high risk of pesticides exposure have not yet been identified, highlighting the need for population-based studies to support risk assessment and intervention.

3.1.3 MNPs and ferroptosis

A review summarized that 8 out of 12 organ systems show evidence of MNP contamination[160], including the cardiovascular, digestive, endocrine, integumentary, lymphatic, respiratory, reproductive, and urinary systems. Early studies on MNPs mainly focused on physical damage, inflammatory responses, and oxidative stress, which are too general to explain how MNPs cause cellular dysfunction and organ injury[161-163]. The discovery of MNP-induced ferroptosis has given a new perspective on this topic.

Several studies have shown that MNPs, as exogenous stressors, disrupt redox balance and promote ferroptosis. MNP exposure increases intracellular ROS levels[164,165]. On one hand, excessive ROS directly affects PUFAs in membranes. On the other hand, ROS led to the depletion of GSH, the major intracellular antioxidant, and indirectly reduce GPX4 activity.

The size of MNPs is one of the key factors for their biological effects. Nanoplastics, smaller than 1 μm[166], are generally considered to have stronger bioactivity and penetration ability due to their smaller size and larger surface area. However, it is still unclear if nanoplastics induce ferroptosis through different mechanisms compared with microplastics (smaller than 5 mm[167]). High-dose exposure to 0.5 mg/mL of 50 μm polystyrene microplastics for 48 hours induced ROS in alpha mouse liver 12 cells without triggering ferroptosis, while many studies have shown that nanoplastics can induce ferroptosis in different models[168-173]. This suggests that nanoplastics may trigger ferroptosis more efficiently through specific mechanisms. Yet, the small number of studies and differences in experimental designs make it difficult to compare results directly. More controlled studies are needed to compare microplastics and nanoplastics under the same conditions.

Besides particle size, the surface characteristics such as surface charge also influence the biological effects of MNPs. Bivalves are widely used in toxicity assays because of their filter-feeding mechanism, contaminant vulnerability, and their role as an exposure route of MNPs for humans[174]. In one study, Ruditapes philippinarum was exposed to both positively charged nanoplastics (p-NPs) and negatively charged nanoplastics (n-NPs) at environmentally relevant levels for 35 days. The results showed that p-NP induced mitochondrial injury and ferroptosis, while n-NPs mainly activated innate immune responses[175]. This indicates that surface charge can alter the cellular response pattern.

Although much progress has been made in understanding MNP-induced ferroptosis, there are still problems in mimicking relevant experimental design. Most studies use commercial, spherical, and uniform plastic particles, especially polystyrene, which differ greatly from irregular and aged plastic mixtures in the real environment. Moreover, humans are often co-exposed to multiple pollutants, and MNPs have been shown to act as carriers for heavy metals[176,177] and chemical contaminants[178-180], even enhancing their absorption in humans. Combined effects of nanoplastics and absorbed iron in aging mouse brains resulted in aggravated cognitive decline dependent on the ferroptosis pathway[181]. Other studies have also reported co-exposure with other metals such as cadmium[182,183], silver[184], lead, and arsenic[185], which were also related to ferroptosis. In addition to heavy metals, co-exposure of MNPs with pesticides and aromatic hydrocarbons has also been shown to lead to ferroptosis[179,186-189]. However, studies on MNPs as carriers inducing ferroptosis under co-exposure conditions are still limited, although such models are more relevant to real-world situations.

3.2 Risk factors associated with ferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases

3.2.1 AD and ferroptosis

AD is the most common neurodegenerative disease, affecting millions of individuals worldwide[190]. It is characterized by progressive deterioration and loss of neurons in brain regions responsible for memory, language, and other cognitive functions[191]. The main pathological features of AD include the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) resulting from hyperphosphorylation of tau protein within neurons, as well as the abnormal extracellular accumulation and deposition of Aβ plaques. Yet, disruptions in iron metabolism, oxidative stress, and lipid peroxidation, hallmarks of ferroptosis, have been observed in AD[192], supporting the idea of ferroptosis being an important contributor to AD progression.

Elevated levels of iron and/or lipid peroxides have been observed in brain regions abundant in Aβ oligomers or NFTs. While iron is essential for oxygen transport and cellular energy metabolism, its dysregulated homeostasis in AD leads to the production of ROS and oxidative stress, which can promote or aggravate Aβ aggregation, as well as p-tau and NFT formation[190]. Furthermore, it has been shown that impaired mitochondrial metabolism in AD leads to ferroptosis through oxidative stress-induced lipid peroxidation. PUFAs contribute to alterations in tau protein conformation and polymerization. PUFAs affected by ROS in neuronal membranes generate lipid hydroperoxides, characteristic of ferroptosis[190]. As oxidative stress increases, so does ROS production, followed by lipid peroxidation and, therefore, cell damage[190]. A decrease in antioxidants such as GPX4 and GSH reduces the defence potential of neurons, making them more vulnerable to ferroptotic cell death[191]. In fact, GPX4 expression is downregulated[193], and multiple ferroptosis-related genes have also been found to be differentially expressed in AD[194].

Because brain tissue has a high lipid content, it is especially susceptible to oxidative stress; hence, neurons in AD brains become more susceptible to ferroptosis and ultimately to neuronal loss[191,193,194]. MDA and 4-HNE, commonly used biomarkers to identify ferroptosis, lipid peroxidation, and oxidative stress in AD, have been found to be increased in post-mortem AD tissue analyses together with elevated iron accumulation in brain regions like the cortex and hippocampus[190-192,195,196].

Other studies analysing lipid-raft-enriched human AD tissue found iron-associated lipid peroxidation to be increased, together with a reduction in ferroptosis suppressors[190]. Furthermore, these changes were observed colocalised with Aβ and tau pathology, further supporting a link between protein aggregates and ferroptosis in AD. A major limitation to using post-mortem tissue is that it represents late or end-stage disease; therefore, it does not reveal whether ferroptosis causes AD or occurs as a consequence of it[196,197].

3.2.2 PD and ferroptosis

PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disease, characterized by the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (SN). Although there are familial and idiopathic forms of PD, regardless of the aetiology, the molecular pathological manifestation of the disease shares common hallmarks including mitochondrial dysfunction, calcium homeostasis, ROS generation, protein misfolding (α-syn aggregation), neuroinflammation, and disturbances in iron (and other metals) homeostasis[198]. These hallmarks are not independent, but interact with each other, resulting in a complex disease that culminates in the characteristic neurodegeneration. The alteration in iron homeostasis and increased ROS suggest that ferroptosis might be a relevant mechanism of cell death in PD.

Although the term “ferroptosis” was only coined in 2012, as early as 1987 there was already evidence of ferroptosis in the SN of post-mortem parkinsonian brains, detected as altered PUFA composition, elevated lipid peroxidation, and increased iron levels. In the meantime, there is substantial research carried out in different PD models that identified different markers of ferroptosis, including altered iron homeostasis, ROS, and lipid peroxidation, being associated with the pathological hallmarks of PD, such as protein aggregates of α-syn[199].

The deposition of iron in the CNS has been extensively studied. As reviewed by Zheng et al., MRI images of PD patients reveal increased iron content in the parkinsonian brain in different brain areas, including the SN[200,201]. Moreover, gene expression analysis identified the genes responsible for iron accumulation in patients with PD and revealed a spatial expression profile which correlates with the increased iron levels[200]. Nevertheless, the correlation with disease progression is unclear. Some studies detected increased iron accumulation during the disease progression, closely correlated with the neuronal loss[200,202], while other findings showed no association with the severity of the pathology[201]. Proteins involved in iron homeostasis have been proposed to be used as markers of ferroptosis. For instance, ferritin was positively correlated with disease duration and severity[203]. Furthermore, the transferrin/transferrin receptor 2 system is disrupted in PD dopaminergic neurons, leading to transferrin accumulation in the mitochondria of dopaminergic neurons and being associated with increased iron levels[204]. A commonly used model for PD is 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) as it leads to symptoms of PD by killing dopaminergic neurons. Deletion of the transferrin receptor 2 in mice protected against MPTP and α-syn-induced dopaminergic neuronal loss[205].

Iron accumulation is also connected to inflammation, an important characteristic of PD pathology. In fact, inhibition of iron accumulation in microglia through different strategies of iron chelation and inhibition of iron-dependent ROS production prevented neuroinflammation[206]. Additionally, plasma interleukin 6 was correlated with ferritin levels[203], indicative of pro-inflammatory processes upon iron storage in brain cells.

Another important pillar of ferroptosis is the generation of ROS and lipid peroxidation. There is ample evidence of increased ROS in PD; however the underlying mechanisms connecting this to ferroptosis still have to be investigated in detail. In models of PD and human PD samples, a reduction of GPX4 levels has been reported[199,207]. Additionally, loss of GSH has also been reported in dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra of autopsied brains from PD patients. The increased levels of ROS in PD could be a result of the lack of GSH, this could also lead to decreased mitochondrial function eventually culminating in neuronal loss[208]. Moreover, given that the NRF2 pathway can regulate GPX4 and GSH expression, its modulation could also increase vulnerability to ferroptosis. In fact, inhibition of Nrf2 promoted α-syn aggregation, and overexpression of synthetic activation of NRF2 delayed α-syn-mediated degradation of dopaminergic neurons[199,209]. Moderate activation of NRF2 could be a potential defence mechanism against ferroptosis-associated neurodegeneration in PD.

Chemical inducers of PD, like PQ, rotenone, 6-hydroxydopamine, and MPTP, induce neurotoxicity via mitochondrial dysfunction and/or production of ROS[210], and the neuronal loss can be partially prevented with ferroptosis inhibitors[199,210], indicating that chemically-induced models of PD also develop ferroptosis due to increased ROS. Moreover, the presence of lipid peroxidation has been found in post-mortem brains of synucleinopathies. PD brains show an increase in PUFAs, which would increase the susceptibility to undergo peroxidation; in fact, products of lipid peroxidation like aldehyde and MDA levels are increased in synucleinopathies[211]. Additionally, 4HNE, an aldehyde product of PUFA peroxidation, has been detected in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of PD patients at higher levels compared to the CSF of healthy individuals[212]. 4HNE is neurotoxic due to the formation of adducts with proteins, which have been identified in the CSF and in Lewy bodies in the SN of PD patients[213]. Increased 4HNE is also observed in different models of PD, including those with Leucine Rich Repeat Kinase 2 (LRRK2) mutation, rotenone, and MPTP[213].

Several reports have shown that α-syn could interact with lipids. This interaction could further facilitate α-syn aggregation. The binding of α-syn to membrane lipids depends on the lipid composition, which in turn is affected by lipid peroxidation[211]. Several studies have identified alterations in lipids and lipid metabolism in different genetic models of PD, particularly those where mutations in Glucoceramidase Beta 1, LRRK2, and SYNJ1 of PD patients or murine models contribute to the pathology of the disease[199]. Some reports indicate that the observed alterations in lipids could precede PD α-syn pathology[214].

3.2.3 Inflammatory-related diseases and ferroptosis

Inflammatory mediators such as cytokines, nitric oxide, and ROS profoundly alter both lipid metabolism and iron homeostasis, thereby sensitizing cells to ferroptotic death[215]. In chronic inflammatory states, persistent activation of immune cells leads to the sustained release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like tumour necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-1 beta, and interferon gamma. These cytokines upregulate enzymes such as ACSL4 and LPCAT3, which facilitate the incorporation of PUFAs into cellular membranes[216]. Simultaneously, inflammatory signals disrupt iron regulatory pathways by upregulating TFRC and divalent metal transporter 1, while suppressing ferritin and Fpn expression, resulting in labile iron accumulation[217]. Many studies, in a variety of both in vitro and in vivo models, have identified different inflammation-related signalling pathways, such as Janus kinases and Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription, nuclear factor-κB, inflammasome, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase-stimulator of interferon genes, and mitogen-activated protein kinase, which can lead to activation of the ferroptosis pathway by disrupting iron metabolism and redox balance[218].

In infectious diseases, pathogens and host responses can perturb iron handling and lipid metabolism (e.g., by releasing iron, altering PUFA availability, or generating ROS), creating conditions that favour ferroptosis; some pathogens may even exploit or trigger ferroptosis to aid dissemination or immune evasion[219].

In sepsis, multiple studies have demonstrated that ferroptosis contributes to organ injury and systemic inflammation[220]. This process affects various cell types, including epithelial cells, endothelial cells, and immune cells, exacerbating the pathophysiology of sepsis. Conversely, inhibition of ferroptosis has been shown to protect against sepsis-induced organ injury and reduce organ damage in animal sepsis models. Reduced lipid peroxidation by puerarin also decreased ROS levels and inhibited ferroptosis in sepsis-induced lung injury in LPS-treated A549 human alveolar epithelial cells[221]. Moreover, transcriptional regulator PRD1-BF1-RIZ1 homeodomain protein 16 protected against sepsis-induced multi-organ injury by inhibiting ferroptosis via upregulation of the NRF2/GPX4 axis[222]. This implicates ferroptosis as a contributor to sepsis pathology and as a potential therapeutic target candidate[219,223].

4. Evidence of Double Hit Challenge and Xenoferroptosis in Disease

4.1 Evidence of external challenges in xenoferroptosis

4.1.1 The contribution of air pollutants to xenoferroptosis

Air pollutants have received increasing attention in recent years as one of the top environmental health risks globally[224]. Numerous studies have shown that exposure to air pollutants can significantly exacerbate the occurrence of cell death in cells that are already sensitive to ferroptosis or have enhanced lipid peroxidation. For example, in BEAS-2B cells with Nrf2 knockdown, PM2.5 can act as a second hit to further accelerate the occurrence of lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Furthermore, in a glutamate-induced excitotoxicity model, glutamate inhibits System Xc- and reduces GSH levels, indirectly suppressing GPX4 activity, promoting lipid peroxidation and ROS accumulation; thereby, the addition of PM2.5 further inhibited the NRF2/GPX4 pathway, exacerbating the imbalance between oxidative stress and antioxidant defence, and synergistically amplifying ferroptosis[225]. Similarly, Beclin1 overexpression resulted in BEAS-2B cells being highly sensitive to ferroptosis, with PM2.5 exposure further enhancing the induction of ferroptosis by directly inhibiting System Xc-. This cellular process weakened the cellular antioxidant capacity and accelerated the accumulation of lipid peroxidation. Ultimately, as GPX4 serves as a crucial antioxidant enzyme preventing lipid peroxidation, its absence significantly increased cellular sensitivity to ferroptosis[226]. In this vulnerable state, exposure to PM2.5 further exacerbated lipid peroxidation and cell death in airway epithelial cells, suggesting a cumulative effect of air pollutants that exacerbates the ferroptotic response[227].

Extending this framework, our recent work was the first to propose the concept of xenoferroptosis, which characterizes the amplification of ferroptotic cell death by xenobiotic agents such as airborne particulate matter. We observed that diverse air pollutants-including DEP, biodiesel exhaust particles, and black carbon-enhanced ferroptosis triggered by established inducers (RSL-3, erastin, and glutamate), even though these pollutants alone at low concentrations did not reduce cell viability[8]. Mechanistically, DEP exposure at low concentrations in combination with an RSL-3 challenge exacerbated lipid peroxidation, disturbed calcium homeostasis, and led to mitochondrial fragmentation accompanied by excessive ROS generation[9].

Several reports have shown that PM2.5 could either reduce cell viability or have minimal effects on cell survival pathways. This discrepancy is likely due to differences in exposure concentration, treatment duration, and the specific cell types used, highlighting that the cytotoxic effects of PM2.5 are highly context-dependent. Based on lung particle dose calculations, 0-100 μg/mL corresponded to low, moderate, and high oxidative stress conditions, respectively[228]. Although there are limitations to extrapolating these findings to brain particle accumulation, most previous studies on PM-induced brain injury used PM2.5 concentrations above physiological exposure levels (100-400 μg/mL) and observed cell death[229-231], while DEP particles in concentrations lower than 100 μg/mL did not affect neuronal-like HT-22 cells[8,9]. However, DEP particles (at low concentrations such as 100 μg/mL) in combination with ferroptotic stimuli (such as erastin or RSL-3 in subtoxic concentrations) led to accelerated cell death[8,9].

In summary, these results consistently suggest that air pollutants can synergistically amplify the occurrence of ferroptosis by enhancing lipid peroxidation and inhibiting antioxidant pathways in a ferroptosis-sensitive context (such as impaired antioxidant defence, GPX4/Nrf2 inhibition, or Beclin1 activation), revealing the potential mechanism by which pollutants exacerbate cell damage (Figure 1).

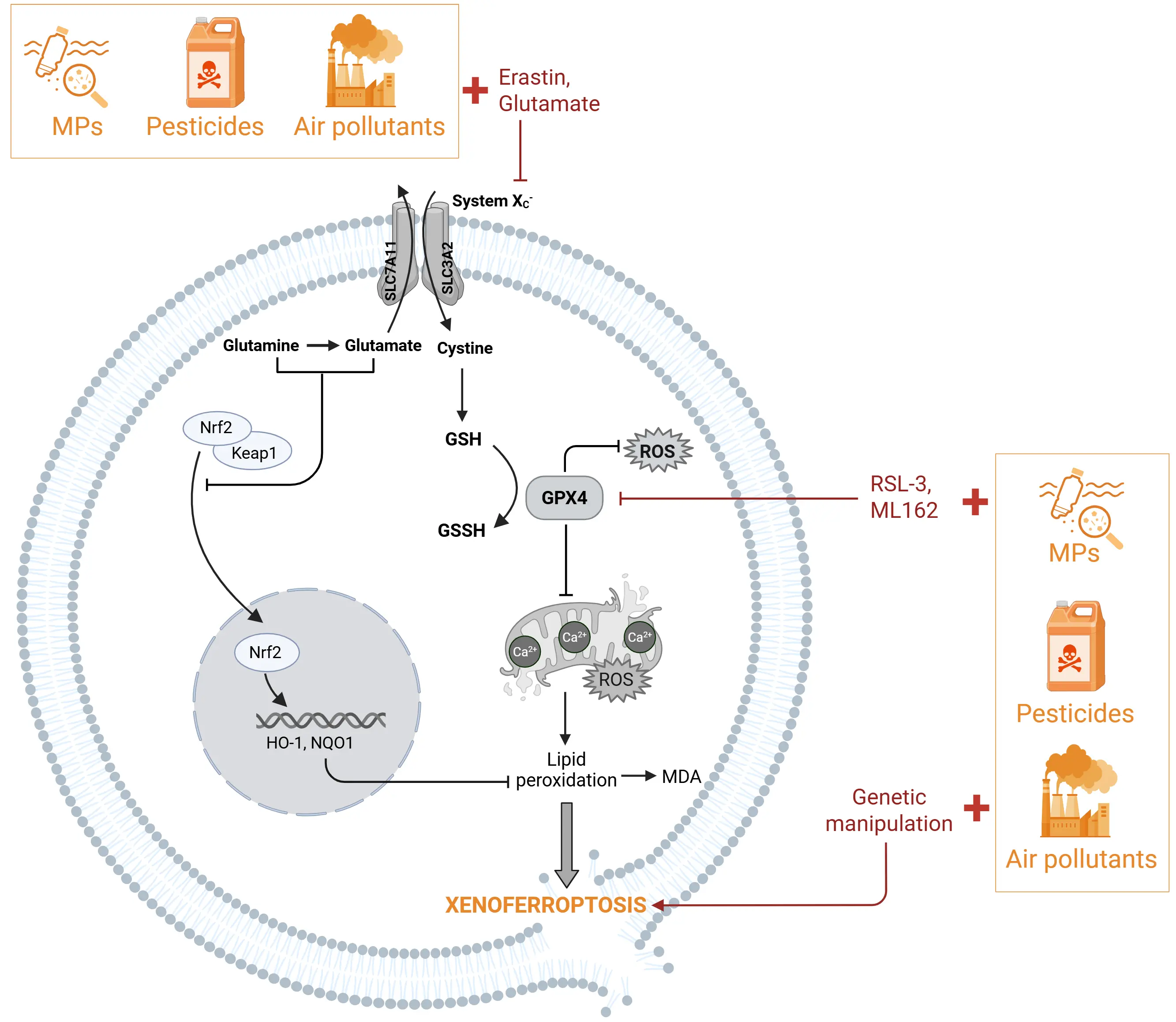

Figure 1. Xenoferroptosis can be induced by external environmental challenges. Xenoferroptosis is initiated by a combination of sub-lethal concentrations of environmental challenges, such as particulate matters (air pollution), pesticides, or MNPs with sub-toxic doses of ferroptosis inducers or low expression of ferroptotic-associated proteins. Environmental stressors (shown in yellow) in cells primed to ferroptosis by specific inducers (shown in red) like glutamate or erastin will initiate and accelerate the cell death through inhibition of the NRF2 pathway. In addition, environmental stressors in the presence of sub-toxic doses of ferroptosis inducers (RSL3, Erastin, ML162) initiate cell death through inhibition of GPX4. Eventually these double-hit challenges converge in aggravated ferroptotic changes like increased lipid peroxidation leading to xenoferroptotic cell death. Created in BioRender. MNPs: micro(nano)plastics; NRF2: nuclear factor E2-related factor 2; RSL3: RAS-selective lethal 3; ML162: molecule library 162; GPX4: glutathione peroxidase 4; MPs: microplastics.

4.1.2 The contribution of pesticides to xenoferroptosis

Several studies have focused on pesticide-involved double-hit inducers of ferroptosis cell death, as it has practical significance for many pathological conditions. For example, rotenone, a widely used pesticide and a well-known mitochondrial complex I inhibitor, is often employed to establish PD models[232], and it is widely accepted that PD is associated with ferroptosis[233]. This highlights the importance of investigating the combined effects of ferroptosis and pesticide exposure for potential clinical applications. While some pesticides alone can induce ferroptosis in various models, humans are typically exposed to multiple stressors in the real world. Therefore, recent studies have started to examine the co-exposure effects of pesticides and classical ferroptosis inducers, providing new insights into the mechanisms of pesticide-related ferroptosis and the impact of double hit scenarios.

A recent study showed that LUHMES dopaminergic neurons are sensitized to rotenone by GPX4 inhibitor RSL3[234]. This study laid the groundwork for subsequent research on pesticide-related double-hit hypotheses, as the GPX4 inhibitor RSL3 increases the susceptibility to ferroptosis in neurons. Based on this, another study used a lipid peroxidation-induced neuronal damage model in which differentiated neuronal cells derived from human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells were exposed to 0.05-1 μM rotenone alone, leading to lipid peroxidation, which was exacerbated when combined with RSL3. This study also demonstrated that the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin can reverse mitochondrial oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, thereby alleviating neuronal xenoferroptosis[235], suggesting that carotenoids exert protective effects against pesticide-aggravated xenoferroptosis. In addition, a study using GPX4 low-expression cancer cells, including Huh7 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) and NCI-H23 (human non-small cell lung adenocarcinoma) cells, showed that treatment with classical ferroptosis inducers RSL3 or ML162 combined with 50 μM rotenone resulted in greater ferroptosis levels compared with either agent alone. Interestingly, this double-hit effect was more pronounced in GPX4 high-expression cancer cells such as SKOV3 (human ovarian carcinoma) and Hep3B (human hepatocellular carcinoma), where rotenone enhanced the ferroptosis sensitivity to GPX4 inhibition[236]. This comparison suggests a potential therapeutic strategy for inducing xenoferroptosis in cancer treatment based on GPX4 expression levels inthe cancer cells.

However, rotenone in nM concentrations could induce neuroprotection in conditions of glutamate-induced oxytosis/ferroptosis in a neuronal-like HT22 cell line[237]. In another study, 10 μM rotenone was protective against ferroptosis induced by erastin or cystine deprivation in human fibrosarcoma HT1080 cells[238], possibly due to the inhibition of the electron transport chain, which diminishes mitochondria-derived lipid peroxidation. Notably, this protective effect did not occur in ferroptosis induced by GPX4 inhibition or knockout, which is consistent with findings from the studies discussed above[235,236], as GPX4 dysfunction bypasses the mitochondrial contribution to lipid peroxidation, and phospholipid hydroperoxides generated from any source can propagate via radical chain reactions, triggering ferroptosis.

Moreover, the novel fungicide SYP-14288 could induce ferroptosis in Phytophthora capsici, a destructive plant oomycete pathogen. Ferroptosis can be further enhanced by the classical ferroptosis inducer erastin, relieving the resistance against SYP-14288 in resistant Phytophthora capsici mutants[239]. Although this finding provides an interesting example of pesticide-related xenoferroptosis, it is derived from Phytophthora capsici, a plant pathogen model. The effective concentration of SYP-14288 for antifungal activity is far higher than the exposure levels relevant to humans. Also, ferroptosis regulatory pathways in oomycetes may differ from those in humans.

Overall, pesticides can serve as a second hit together with classical ferroptosis inducers, while age-related increases in lipid peroxidation may also sensitize cells to ferroptosis. Several convergent mechanisms across different models were documented, such as the impairment of the mitochondrial electron transport chain and the lipid antioxidant defence system (Figure 1). However, study numbers on pesticide-involved double-hit ferroptosis are limited, so it is still premature to draw conclusions about shared mechanisms.

4.1.3 The contribution of MNPs to xenoferroptosis

MNPs have been widely detected in various human organs. A recent study using pyrolysis gas chromatography–mass spectrometry on human post-mortem tissues reported MNPs in human kidney, liver, and brain, with the highest level in the brain. Notably, MNP levels were even higher in a cohort with dementia[240], highlighting a potential link between MNP exposure and mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases. Microplastic exposure induced liver metabolic disorders in chickens by a mechanism involving glutamine and glutamate synthesis. The excess glutamine and glutamate cooperated with microplastics to inhibit the NRF2-Keap1-HO-1/NQO1 signalling pathway, triggering cell death. The study also found that microplastics impaired the integrity of the BBB through microplastic-induced downregulation of tight junction proteins, including Occludin, Claudin 3, and ZO-1, potentially allowing the excessively synthesized glutamine and glutamate to enter the brain and cause damage[241]. Therefore, in this study, the combination of microplastics exposure and elevated glutamine and glutamate created a double-hit condition, suggesting that microplastics can act both as a direct toxic stressor and as a promoter for other FIN stressors (Figure 1).

4.2 Evidence of endogenous challenges in xenoferroptosis

4.2.1 Aβ protein aggregates and xenoferroptosis

In AD pathology, several mechanisms converge as synergistic hits which ultimately lower the threshold for ferroptotic cell death initiation. These mechanisms include Aβ-iron interactions, mitochondrial dysfunction, ROS, and antioxidant failure. The cumulative effect of these mechanisms effectively pushes vulnerable neurons over the ferroptotic threshold. In the context of the brain, certain features such as the high PUFA content, elevated oxygen consumption, and iron concentration, that could be altered during aging or due to chronic pathologies, could make neurons vulnerable to ferroptotic-cell death. Here, we will examine how Aβ (and misfolded p-tau) in combination with mitochondrial dysfunction and antioxidant failure contribute as double-hits to trigger ferroptosis in AD.

PSEN mutations are linked to familial forms of AD and lead to increased Aβ aggregation. In iPSC-derived neurons, knockout of PSEN (which can mimic the effects of PSEN mutations), was shown to enhance ferroptosis vulnerability[28]. This further strengthens the connection between ferroptosis and AD, possibly exacerbated by the build-up of aggregated Aβ. These studies show that ferroptosis is connected to AD, and that iron builds up in the brains of AD patients[242,243]. Furthermore, Aβ-like aggregates were observed in 50-day old brain organoids with PSEN1 mutations, paralleled by a higher 4HNE and lower heavy chain ferritin expression profile, in comparison to isogenic brain organoids[194], and these changes were rescued by Fer-1. These findings indicate that Aβ deposition drives the production of peroxides. Interestingly, at day 100, where pathology became advanced and Aβ burden higher, while 4HNE remained higher in AD organoids, heavy chain ferritin expression increased compared to control (isogenic), which suggests that changes in ferritin may be dependent on the level of Aβ present and disease development. Thus, it is tempting to speculate that incremental Aβ levels and changes in ferroptosis pathways may converge synergistically to push the critical threshold for xenoferroptosis and potentiate neuronal death seen in AD.

Other in vitro studies using intra- or extra-cellular Aβ reported mitochondrial changes, neuronal metabolic reprogramming, increased ROS production, and lipid peroxidation, as well as an increased sensitivity to ferroptosis-like cell death[191,244]. Specifically, a multi-omics analysis was performed using MC65 nerve cells, a cell line which expresses the C99 fragment of amyloid precursor protein (APP) under a tetracycline-sensitive promoter. When tetracycline is removed, C99 expression resumes and is subsequently processed by γ-secretase into Aβ, resulting in rapid Aβ accumulation and aggregation within the cells. After only two days the cells showed an upregulation of ferroptosis- and oxytosis-related genes and proteins, accompanied by downregulation of several genes associated with mitochondrial pathways, thereby suggesting that intracellular Aβ mediates these redox- and ferroptosis-related changes[244]. In vitro, these cells with Aβ also show increased lipid peroxidation, ROS formation (both cellular and mitochondrial), along with reduced GSH levels. Importantly, pre-incubation of the nerve cells with toxic Aβ rendered them more vulnerable to RSL3 and glutamate-induced cell death, which was prevented by several ferroptosis inhibitors, including Fer-1, Lip-1, and iron chelators. These findings support the hypothesis that proteopathic inclusions in combination with subtoxic concentrations of ferroptosis insults push the system towards xenoferroptotic cell death. Moreover, it was reported that these nerve cells die three days after Aβ induction due to its toxic aggregation and accumulation[244]. This further suggests that the cell death seen at day three could result from the upregulation of ferroptosis-related pathways in combination with the Aβ (and p-tau) deposition leading to Aβ-triggered xenoferroptosis.

Specific genetic mutations leading to lipid peroxidation, iron dysfunction, or mitochondrial dysfunction could render cells vulnerable to additional stressors. The potential involvement of Aβ as a second hit inducer of xenoferroptosis in AD pathology was also observed in vivo in mouse models with specific genetic mutations. Bao et al. studied the impact of Aβ and deficiency of Fpn on primary neurons and mouse brains. Deficiency of Fpn in mice resulted in several ferroptosis hallmarks, including dysregulated iron homeostasis, altered expression of ferroptosis-related genes such as GPX4 downregulation and mitochondrial fragmentation, brain atrophy, and impaired learning and cognition of the mice, all of which are characteristic of AD pathology. Restoration of Fpn ameliorated ferroptosis by restoring iron levels in the brain, reversing the aberrant ferroptosis-related gene expression and improving mouse memory[245]. The presence of the aggregates reduced cell viability and increased PI staining uptake indicative of cell death. However, this was rescued by ferroptosis inhibitors, Fer-1 and Lip-1, indicative of the interaction between Aβ aggregates and the ferroptotic pathway. Interestingly, it appears that the Aβ-induced ferroptosis damage occurs through Fpn downregulation, as the protein expression was downregulated in the hippocampus of mice exposed to Aβ aggregates[245]. Additionally, 5xFAD mice are widely used as AD models due to the progressive deposition of Aβ. These mice present increased levels of lipid peroxidation and decreased GPX4 expression and activity, indicative of ferroptosis potentially triggered by Aβ[246]. Previous studies determined that conditional GPX4 knockout models showed hippocampal neuron loss and cognitive defects[247,248]. To test the interaction between Aβ and the ferroptosis pathways, GPX4 was overexpressed in the Aβ-prone AD 5xFAD mice. These 5xFAD/GPX4 mice reverted the ferroptotic hallmarks by decreasing ROS and lipid peroxidation, preventing neurodegeneration, and rescuing of memory deficits and cognition, but also significantly reduced Aβ deposition[246]. Altogether, these results indicate that Aβ aggregates may exacerbate the ferroptosis-induced damage through downregulation of Fpn and GPX4, and therefore could represent the second hit that triggers xenoferroptosis in AD pathology[191,245,246].

CNS cells other than neurons are also affected by ferroptosis and may also contribute to Aβ-induced xenoferroptosis. For example, pericytes exposed to Aβ undergo mitophagy-dependent ferroptosis[249], a process associated with BBB dysfunction. Furthermore, upregulated NOX4 (an enzyme responsible for ROS production) in astrocytes enhanced ferroptosis, while NOX4 knockdown reduced p-tau, Aβ aggregation, and cognitive deficits in APP AD mouse models[250]. Additionally, administration of the natural iron chelator lactoferrin (Lf) reduced Aβ accumulation in APP/PS1 AD mice and prevented cognitive deficits[251]. Of particular interest, astrocyte-derived Lf also had a protective role by preventing ferroptosis-induced neurodegeneration through the reduction of iron levels and maintaining GPX4 expression[252], reinforcing the aggravating effect of Aβ in the ferroptotic pathway.

Accumulating evidence from human post-mortem brain tissue, cell culture models, and AD mouse models suggest that alterations in iron homeostasis and lipid peroxidation create conditions favourable for ferroptotic neuronal cell death, and together with Aβ aggregation could aggravate the ferroptotic-induced damage, consequently leading to Aβ-triggered xenoferroptosis (Figure 2).

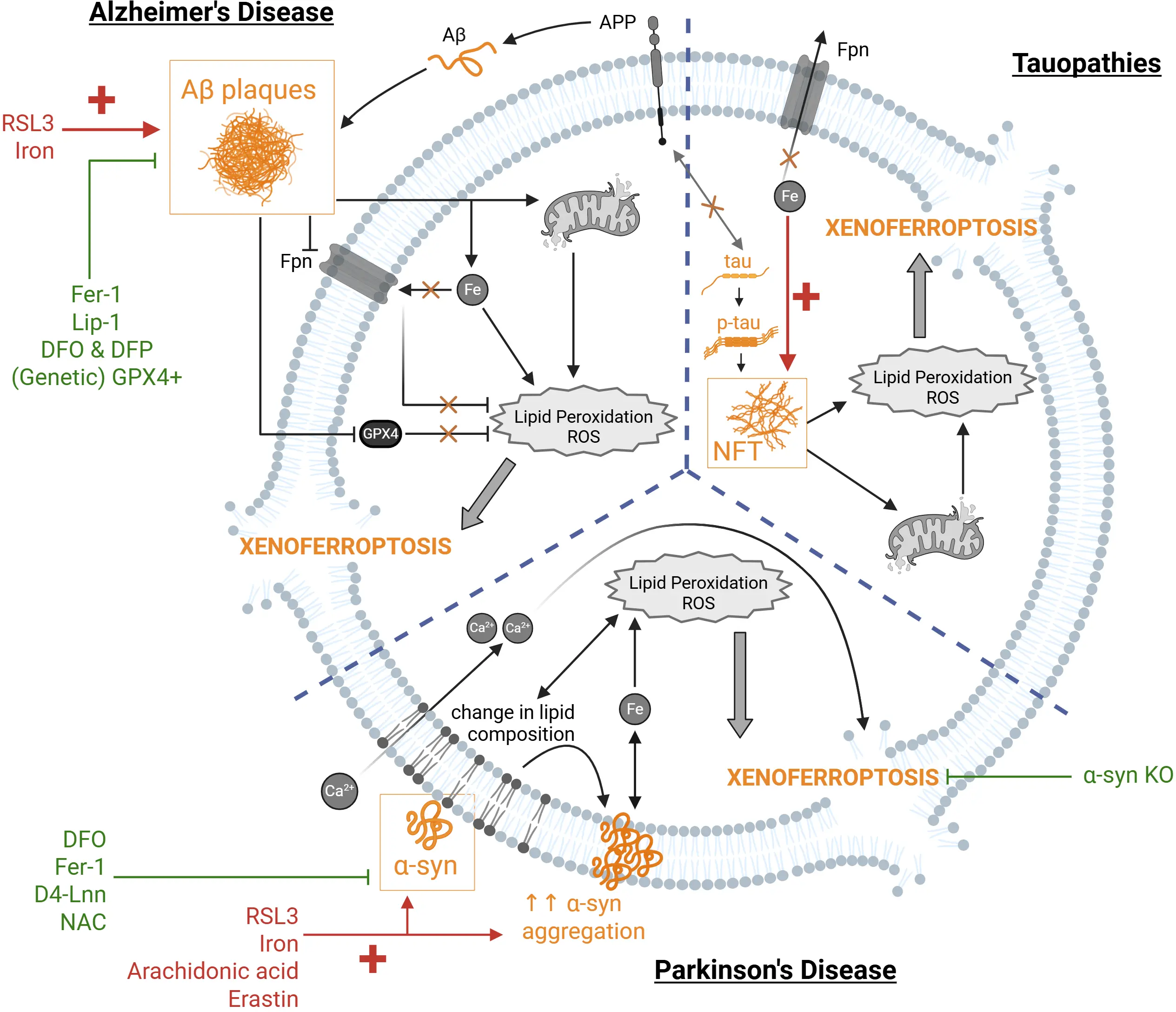

Figure 2. Xenoferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases triggered by protein aggregates. Protein aggregates (shown in yellow) can represent the second hit trigger as endogenous stimuli for xenoferroptosis. In the context of AD, Aβ aggregates, formed as a result of impaired APP function, in combination with ferroptosis inducers, such as RSL3 or increased iron (shown in red) can synergistically trigger xenoferroptosis by aggravating the ferroptotic pathway. This has been observed via further dysregulation of iron homeostasis, metabolic reprogramming, mitochondrial dysfunction, and increased lipid peroxidation and ROS. Moreover, Aβ downregulates GPX4 and Fpn further exacerbating the increased lipid peroxidation and ROS. This synergistic effect can be rescued with ferroptosis inhibitors (green), such as Fer-1 and Lip-1, iron chelation using DFO and DFP, or genetic overexpression of GPX4. In tauopathies, p-tau aggregation into NFTs can exacerbate the ferroptosis-associated cellular changes induced by iron dysregulation, thereby acting as a second challenge to trigger xenoferroptosis. Similarly, loss of soluble (monomeric) tau to NFT formation can impair Fpn trafficking to the membrane due to absence of the physiological tau interaction with APP. Similarly, increasing soluble (healthy) tau can attenuate iron-dysregulation damage induced by p-tau toxicity. In the context of PD, α-syn becomes the second-hit challenge in xenoferroptosis when combined with ferroptosis synthetic inducers (RSL3, erastin) or endogenous ones (iron, arachidonic acid). α-syn aggravates the ferroptotic pathway by interacting with membrane lipids, altering the lipid composition and increasing lipid peroxidation, which allows calcium (Ca2+) influx and further promotes α-syn aggregation and iron homeostasis dysregulation. α-syn-induced xenoferroptosis can be attenuated with ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1, iron chelator DFO, lipid peroxidation inhibitor D4-Lnn, and antioxidant N-acetylcysteine (NAC), as well as genetic knockout of α-syn. Created in BioRender. AD: Alzheimer’s disease; Aβ: amyloid-beta; APP: amyloid precursor protein; RSL3: RAS-selective lethal 3; ROS: reactive oxygen species; GPX4: glutathione peroxidase 4; Fpn: ferroportin; Fer-1: ferrostatin-1; Lip-1: liproxstatin-1; DFO: deferoxamine; DFP: deferiprone; p-tau: hyperphosphorylated tau; NFTs: neurofibrillary tangles; PD: Parkinson’s disease; α-syn: α-synuclein.

4.2.2 α-syn protein aggregates and xenoferroptosis

As previously summarised, it is widely established that ferroptosis plays a key role in PD. However, whether ferroptosis is the cause of the neurodegeneration or a consequence of the α-syn aggregates remains unknown. α-syn has been observed to co-localise with iron in Lewy bodies indicative of the connection between these two elements to ferroptosis[253]. The mRNA of α-syn has an iron binding domain, suggesting that its expression is responsive to iron cellular changes[253]. Furthermore, α-syn is associated with increased lipid peroxidation and lipid dysfunction[254], making neurons more vulnerable to cell death[233]. In SH-SY5Y cells, increasing iron concentration also decreased cell viability and increased α-syn protein expression. The knockdown of α-syn was able to protect against the iron-induced cell death[57]. Another study showed that the aggregation of α-syn results in free radical production and neuronal toxicity. Although both oligomeric and fibrillar forms of α-syn produced free radicals, only the oligomers could lower GSH levels and activate cell death pathways. Furthermore, ROS production, lipid peroxidation and cell death are dependent on the presence of iron, as these readouts were significantly decreased upon addition of different iron chelators, also in an SNCA triplication iPSC model of endogenous α-syn production[255].