Abstract

Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death (RCD) driven by lipid peroxidation, has been extensively studied since its conceptualization in 2012 and has been suggested as a therapeutic target in many cancers and degenerative diseases. However, three fundamental questions remain unanswered about ferroptosis. First, the mechanisms by which cells execute death during ferroptosis remain elusive: The key role of lipid peroxides in triggering ferroptosis is established, but how this results in the death of a cell remains unclear. Second, the physiological role of ferroptosis throughout the human life cycle is unclear; currently, there is evidence for ferroptosis in early development, immunity, aging, and tumor suppression, but not in many other aspects of physiology. Third, and finally, the intersection between ferroptosis and other RCD modalities, such as apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and autophagic cell death, is necessary for understanding how ferroptosis integrates into networks controlling cellular fate. Addressing these gaps in knowledge is essential for building a comprehensive understanding of this mode of cell death, as well as translating ferroptosis knowledge into effective therapeutics.

Keywords

1. Introduction

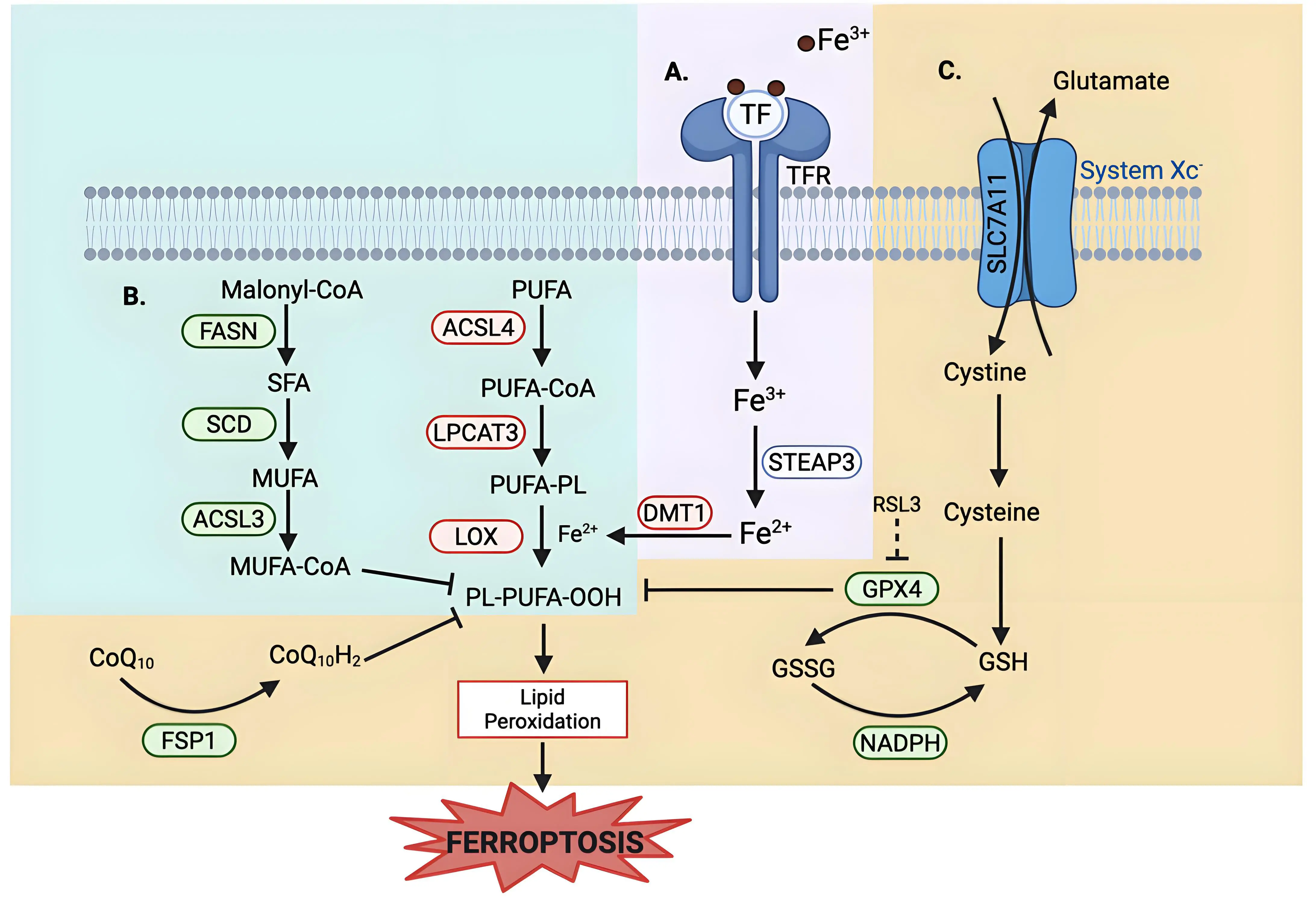

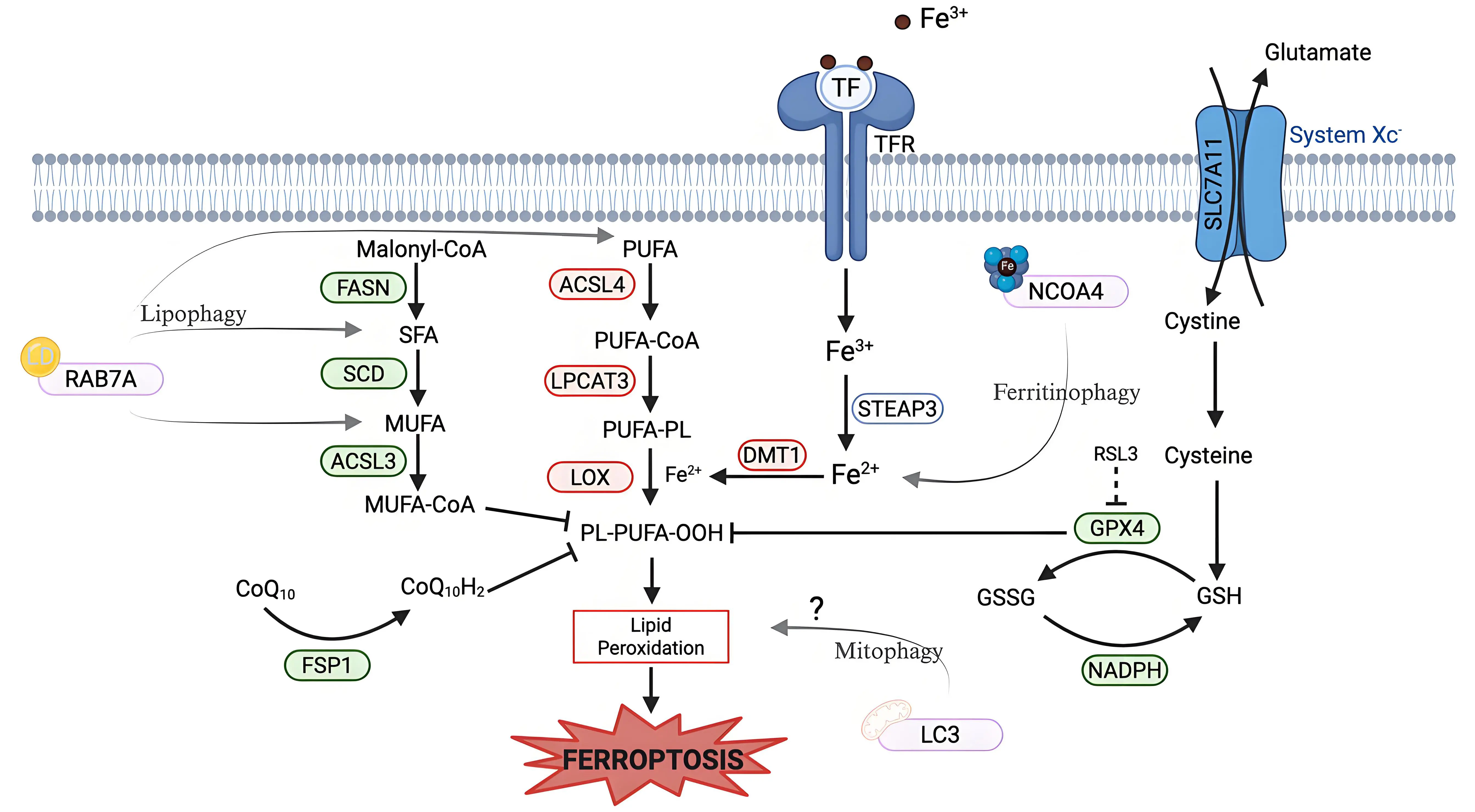

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent form of non-apoptotic cell death characterized by excessive lipid peroxidation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) that result in plasma membrane rupture[1]. The regulation of ferroptosis is multifaceted and involves numerous pathways and biomolecules involved in metabolism, iron regulation, and redox defenses (Figure 1). The primary and most frequently studied pathway involved in ferroptosis prevention is the system Xc-/GSH/GPX4 axis involving Solute Carrier Family 7 Member 11 (SLC7A11), the cystine/glutamate antiporter[2], glutathione (GSH), and glutathione-dependent peroxidase 4 (GPX4)[3]. System Xc- is located in the plasma membrane and aids in the transport of cystine into, and glutamate out of, the cell via SLC7A11[4]. Cystine is reduced to cysteine intracellularly, which is then used in the production of GSH, which is further a cofactor for GPX4 in the reduction of lipid hydroperoxides to repair oxidative damage to lipids[1,5-7]. The FSP1/CoQ10/NAD(P)H axis is a parallel process that suppresses phospholipid peroxidation[8,9]. This pathway uses FSP1 (Ferroptosis Suppressor Protein 1) with its cofactor NAD(P)H to reduce coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) (also known as ubiquinone) to CoQ10H2 (ubiquinol), which then acts as a lipophilic antioxidant[8-10].

Figure 1. Metabolic pathways of ferroptosis regulation. Ferroptosis regulation involves (A)iron uptake and metabolism; (B) lipid metabolism, and (C) multiple antioxidant defense systems. (A) Iron Uptake and Metabolism: Iron metabolism uses TF to deliver extracellular iron (Fe3+) into the cells via the TFR, followed by a reduction to Fe2+ via STEAP3. DMT1, an iron transporter, aids in cytosolic iron import, contributing to the labile iron pool. Excess iron promotes ROS generation via the Fenton reaction, driving lipid peroxidation. (B) Lipid Metabolism: Lipid composition plays a role in regulating ferroptosis sensitivity. Enzymes that promote the synthesis and incorporation of MUFAs into phospholipids, such as FASN, SCD, and ACSL3, confer resistance to ferroptosis, as MUFAs are resistant to peroxidation. Conversely, enzymes that promote the synthesis and incorporation of PUFAs, such as ACSL4 and LPCAT3, sensitize cells to lipid peroxidation. LOX catalyzes the oxidation of PUFA-containing phospholipids, leading to the accumulation of lipid hydroperoxides. (C) Antioxidant Defense System: System Xc-/SLC7A11 imports cystine into the cell and glutamate out of the cells. Cystine is reduced to cysteine and is then used in GSH synthesis. GPX4, a GSH-dependent enzyme, uses reducing equivalents from NADPH to detoxify lipid hydroperoxides. RSL3 is a well-studied inhibitor of GPX4 that induces ferroptosis. An alternate defense is provided by FSP1 via reducing CoQ10 to block lipid peroxidation independent of GPX4. Created in BioRender.com. Red: anti-ferroptotic factors; Green: pro-ferroptotic factors; Gray: context-dependent regulator of ferroptosis; SLC7A11: solute carrier family 7 member 11; STEAP3: six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3; DMT1: divalent metal transporter 1; FASN: fatty acid synthase; SCD: stearoyl-CoA desaturase; ACSL3: acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 3; ACSL4: acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4; LPCAT3: lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3; LOX: lipoxygenase; GPX4: glutathione peroxidase 4; FSP1: ferroptosis suppressor protein 1; TF: transferrin; TFR: transferrin receptor; ROS: reactive oxygen species; MUFAs: monounsaturated fatty acids; PUFAs: polyunsaturated fatty acids; GSH: glutathione; RSL3: RAS-selective lethal 3; CoQ10: coenzyme Q10.

Lipid metabolism also plays a role in the regulation of ferroptosis, as peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acyl tails (PUFAs) in membrane lipids contributes to the triggering of ferroptosis (Figure 1)[11,12]. Because PUFA moieties are more susceptible to lipid peroxidation than monounsaturated fatty acyl (MUFAs) moieties, the proteins involved in the incorporation of PUFAs into membrane lipids, such as Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long-Chain Family Member 4 (ACSL4) and Lysophosphatidylcholine Acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3), are pro-ferroptotic enzymes, while proteins involved in the incorporation of MUFAs into the membrane, such as Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long-Chain Family Member 3 (ACSL3), are anti-ferroptotic[12-15]. Iron metabolism also plays a key role in the regulation of ferroptosis, as iron is used in the Fenton reaction to produce ROS[16]. Therefore, pathways involved in iron storage, iron import and export, and iron turnover impact ferroptosis sensitivity[17,18]. As such, transferrin, a major iron transporter in the body, and its receptors, are important in the regulation of ferroptosis, as is CD44[17,19].

Since its conceptualization in 2012[1], ferroptosis has garnered significant interest, especially within oncology, with about half of ferroptosis-related publications focusing on cancer[20]. While research in the early days of ferroptosis focused on basic mechanisms to elucidate key genes, tools, and pathways, much of ferroptosis research has expanded to its use as a therapeutic target in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, and ischemia–reperfusion injuries[20-26]. While these indications are important, a need remains for continued research into basic ferroptosis mechanisms, as gaps exist. We don’t yet understand how ferroptosis is employed in normal physiology, how cells die during ferroptosis, and how ferroptosis intersects with other forms of cell death. While these topics are fundamental, they also open the possibility for the discovery of new targets and better designed drugs for ferroptosis-related diseases.

2. Question One: What are the Molecular Execution Mechanisms of Ferroptosis?

Cells undergoing ferroptotic cell death have, morphologically, necrosis-like changes—the cell swells and the plasma membrane ruptures; a morphological difference from the blebbing and shrinking seen in apoptotic cells[1,27]. Morphological changes to mitochondria, such as fragmentation, increased membrane density, and loss of cristae, are also observed during ferroptosis[1,28]. Understanding how ferroptosis is executed downstream of lipid peroxidation is currently still not well defined – whether it be membrane damage directly due to lipid peroxidation, a toxic byproduct of peroxidation, lipid peroxide modulation of membrane protein activity, or a still unidentified feature[29,30].

Currently, there is a suggestion that polar lipid hydroperoxides cluster together and cause membrane thinning and bending[31]. This may be a link to the formation of nanometer pores in the plasma membrane which have been identified as a key component in the final plasma membrane disruption[32]. These nanometer sized pores result in an osmotic imbalance due to the influx of water and ions. Specifically, an increase in Ca2+, after lipid peroxidation but prior to cell bursting, has been identified to play a key role in ferroptotic membrane degradation[32,33]. Additionally, truncated lipid-derived electrophile products formed after reaction with iron have been implicated as executioners of ferroptosis by damaging key proteins[34-38]. Moreover, the aldo-keto reductase1 (AKR1) family of aldo-keto reductases can detoxify lipid-derived electrophiles[39]; these genes are upregulated in ferroptosis-resistant cells and drive resistance to ferroptosis[2,40].

Ninjurin-1 (NINJ1) has emerged as a multifunctional protein that is involved in mediating plasma membrane rupture (PMR) in lytic cell death pathways such as apoptosis, necrosis and pyroptosis[41]. The role of NINJ1 in ferroptosis is more complex and less straightforward. NINJ1 has been shown not to be relevant to the early stages of ferroptosis such as lipid peroxidation, calcium influx, or cell swelling; rather, NINJ1 was seen to regulate the late stages of ferroptosis, including membrane integrity loss, cell rupture, and damage-associated molecular pattern release after cell death[42,43]. Interestingly, NINJ1-deficient cells were not protected against PMR and cell death after treatment with ferroptosis inducers, but were able to delay lysis for hours after ferroptosis induction[42,43]. Additionally, the effect of NINJ1 was sensitive to the cell type and ferroptosis inducer used; NINJ1 deficiency has only a minor impact on cell lysis under RAS-selective lethal 3 (RSL3)-induced ferroptosis when compared to other inducers of ferroptosis[42].

In addition to the specific players within the cell that allow for ferroptosis cell rounding and eventual death, understanding as to how ferroptosis is spread to neighboring cells via plasma membrane contact has recently been of interest[44]. Cells in which ferroptosis was induced were able to propagate lipid peroxidation and subsequent cell death to neighboring cells in a wave like pattern[45]. This propagation occurred upstream of cell lysis and only occurred in cells in which ferroptosis was induced via treatments that inhibit GSH and/or increase cellular iron, but not in cells in which ferroptosis was induced via direct GPX4 inhibition[33,44,45].

To date, we don’t know whether morphological changes are a byproduct of how cells die and whether these changes are indicative of how ferroptotic cell death is executed. There is thus an understanding as to the importance of lipid peroxide accumulation in inducing ferroptosis, but how this results in cell death and its ability to propagate remain elusive.

3. Question Two: What are the Physiological Roles of Ferroptosis in Development and Aging?

The majority of the current research related to ferroptosis focuses on disease states; while important, there is still much to learn about how ferroptosis is involved in normal physiology. One area of physiological ferroptosis that has been studied is animal development. Large-scale cell death occurs in embryonic development to eliminate organs and tissues that play a role during a specific phase of development[46,47]. Large-scale ferroptosis during embryogenesis was first observed in the nineteenth century[33,48]. More recent work has explored how ferroptosis may propagate across large cell populations via trigger waves with ROS at the wavefront to aid in the shaping of limbs during development[48]. In both the avian and zeugopod limbs, large-scale cell death by ferroptotic waves was seen, highlighting the potential for ferroptosis to play a functional role in the muscle remodeling occurring during embryogenesis[48].

Additionally, ferroptosis plays a role in the regulation of muscle fibers and the individualization of muscle limbs in muscle development via the removal of excess and improperly positioned myoblasts[48]. Similarly, ferroptosis has been linked to neurogenesis: The level of ROS in developing neurons must be kept within a key range, as ROS are needed in the early stages of brain development, and then suppressed by antioxidants in order to ensure stem cells mature and differentiate properly[49,50]. Moreover, a link between ferroptosis and erythropoiesis is seen when looking at embryonic visceral endoderm[51]. An increase in ferroptosis was described linking it to the differentiation and development of blood vessels[51,52].

Looking at the opposite end of human life, ferroptosis has been implicated in aging. As the body ages, iron accumulates, as there is no excretion pathway for iron in men and post-menopausal women[53]. In multiple parts of the eye in aging individuals, an increase in iron is correlated with an increase in ferroptosis susceptibility[54-56]. The brain sees a similar increase in iron, and potentially ferroptosis, in the aging population[57-58]. This increase in iron-induced ferroptosis in elderly individuals may correlate with an increase in neurodegenerative diseases later in life[59]; however this may also aid in promoting tumor ferroptosis in iron-rich cancers[60].

Increasing evidence has highlighted ferroptosis as an innate mechanism of malignancy suppression[23,61-65]. p53, a well-established tumor suppressor, uses ferroptosis via the transcriptional suppression of SLC7A11[62]. Similarly, cells deficient in fumarate hydratase (FH), a mitochondrial tumor suppressor, are resistant to cysteine deprivation-induced ferroptosis, highlighting that FH uses ferroptosis as a mechanism to suppress tumors[63]. Again, this is seen via BRCA1-associated protein 1 suppression of tumorigenesis through ferroptosis by the repression of SLC7A11[64]. Another occurrence of ferroptosis acting in an anti-cancer role can be seen when looking at skin cancers; specifically, Mixed Lineage Leukemia 4 deficiency, which significantly alters the epidermis, also alters the expression of key markers of ferroptosis, highlighting that ferroptosis is used here in a tumor suppressive role (and that it may play a more global role in differentiation and skin homeostasis)[65]. This phenomenon is seen again when looking at how membrane-bound glycerophospholipid O-acyltransferase 1 (MBOAT1) and membrane-bound glycerophospholipid O-acyltransferase 2 (MBOAT2) suppress ferroptosis by remodeling the cellular phospholipid composition[61]. Interestingly, MBOAT1 and MBOAT2 are transcriptionally upregulated by the estrogen receptor (ER) and androgen receptor (AR), respectively, highlighting differences in ferroptosis sensitivity seen between sexes[61,66]. Understanding the emphasized role of ferroptosis in cancer suppression allows for greater understanding of ways in which we can target ferroptosis to be used in anti-cancer treatments.

Although ferroptosis has been associated with embryonic development and age-related decline, its precise roles and mechanisms in development and aging remain largely unexplored. Additionally, physiological ferroptosis may play important roles at multiple stages of the lifecycle beyond tumor suppression and immunity, which have been implicated as processes depending on ferroptosis[11,67-70]. Understanding where, when, and how the body uses ferroptosis for normal physiology can improve our understanding of the physiological potency and regulation of ferroptosis and the ability to use it as a treatment target in disease models while simultaneously avoiding unwanted side effects in healthy tissues.

4. Question Three: How much Crosstalk is There Between Ferroptosis and Other Regulated Cell Death Modalities?

Regulated cell death (RCD), or programmed cell death, refers to orchestrated death by macromolecules to maintain homeostasis, which is contrasted with accidental cell death, which is an uncontrolled process of cell death triggered by injury[71]. Crosstalk among RCD modalities is of particular interest, as it allows for more efficient and more accurate therapeutic development. How cells decide between one death and another, how cells can switch between the different types of regulated cell death, and if specific cells have a preference for one modality over the other are questions of interest that can work to guide treatment design. Knowledge of the intersections of ferroptosis with other cell deaths is varied among RCDs. Continued research into understanding these crossroads is critical for designing combination treatments (that target two or more death modalities) to improve therapeutic outcomes.

4.1 Ferroptosis and apoptosis

Apoptosis is a mechanism of controlled cell death in which DNA is fragmented and membranes bleb, creating apoptotic bodies that are removed without triggering of an inflammatory response[27,72,73]. Apoptosis and ferroptosis share multiple regulators and upstream stress signals; however, significant differences exist in the mechanisms that induce these two types of cell death. Understanding how these cell death modalities interact and affect each other is still a priority.

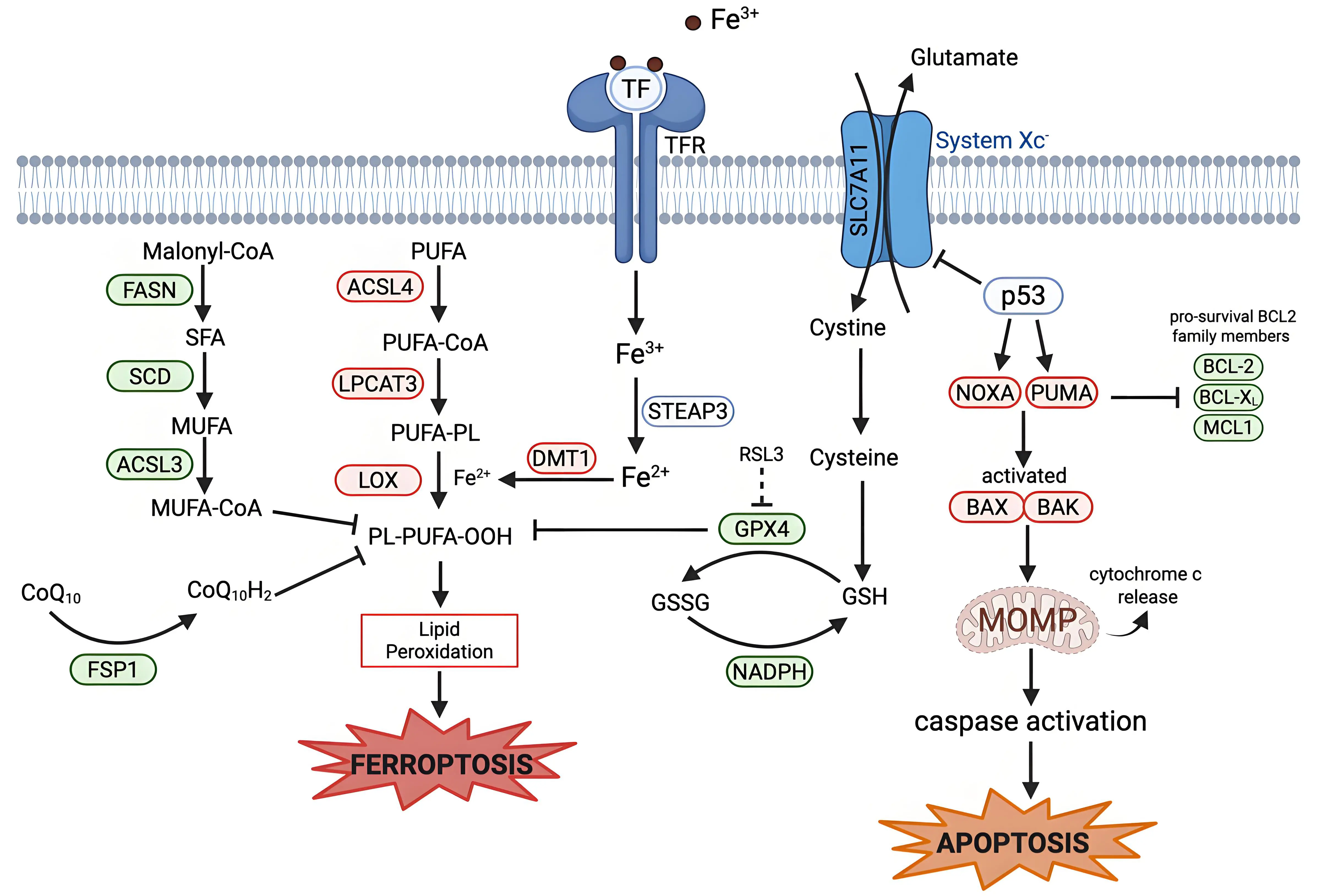

In both apoptosis and ferroptosis, the mitochondria play a significant role. In apoptosis, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) is the point of no return. MOMP allows the release of cytochrome c into the cytosol, which results in caspase activation and eventual apoptotic death (Figure 2)[74-77]. This release is mediated by the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) family of proteins, with specific BCL-2 family proteins such as Bcl-2-associated X protein (BAX) and Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer inserting into the outer membrane of the mitochondria[78,79]. The BCL-2 family of proteins consists of proteins that are pro-apoptotic or pro-survival; the ratio of these two types of BCL-2 family proteins determines apoptosis sensitivity in the cell[80].

Figure 2. Mechanistic crosstalk between ferroptosis and apoptosis. Apoptosis is regulated by BCL-2 family proteins. The tumor suppressor p53 can transcriptionally upregulate pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins (PUMA and NOXA). PUMA and NOXA inhibit anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family proteins (BCL-2, BCL-XL, and MCL1), activating BAX and BAK. BAX/BAK oligomerize to induce MOMP, which leads to release of cytochrome c and eventual caspase-9 activation and apoptotic cell death. P53 links ferroptosis and apoptosis via the suppression of SLC7A11 and induction of PUMA and NOXA. Some BCL-2 family proteins can influence both apoptosis and ferroptosis. Created in BioRender.com. Red: anti-cell death factors; Green: pro-cell death factors; Gray: context-dependent regulator of cell death; SLC7A11: solute carrier family 7 member 11; STEAP3: six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3; DMT1: divalent metal transporter 1; FASN: fatty acid synthase; SCD: stearoyl-CoA desaturase; ACSL3: acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 3; ACSL4: acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4; LPCAT3: lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3; LOX: lipoxygenase; GPX4: glutathione peroxidase 4; FSP1: ferroptosis suppressor protein 1; PUMA: p53-up-regulated modulator of apoptosis; NOXA: phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein; BCL-2: B-cell lymphoma 2; BCL-XL B-cell lymphoma-extra-large; MCL1: myeloid cell leukemia sequence; BAX: Bcl-2-associated X protein; BAK: Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer; MOMP: mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization.

Some BCL-2 family proteins have been linked to ferroptotic cell death[81]. Abivertinib, an epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), was able to induce apoptosis by suppressing BCL-2 and B-cell lymphoma-extra-large and by upregulating Bcl-2 Interacting Mediator of cell death and BAX[82]. Abivertinib was also able to induce iron-and-ROS-induced ferroptosis in breast, cervical, and lung cancers[83]. Abivertinib’s ability to induce apoptosis and ferroptosis has elicited discussions on the role of BCL-2 family proteins as regulators of ferroptosis, but this has been contested, as BCL-2 family proteins can only protect and/or induce ferroptosis in some studies and not others[83-87].

The perplexing role of BCL-2 family proteins in ferroptosis may be tied to the role of the mitochondria in ferroptosis. While the importance of the mitochondria in apoptosis is well documented, their role in ferroptosis is less established, but still important. When ferroptosis was first discovered, an aspect of its characterization by electron microscopy involved the shrinkage of mitochondria with increased membrane density[1]. The role of the mitochondria in ferroptosis, as understood today, is a metabolic one; the Tricarboxylic Acid cycle and electron transport chain produce cellular ROS and promote ferroptosis under cysteine-deprived conditions[63]. This highlights a distinction between these two death modalities: ferroptosis relies on active mitochondrial metabolism, whereas apoptosis is initiated by mitochondrial breakdown. When inducing ferroptosis via pharmacological inhibition or genetic elimination of GPX4, mitochondrial activity does not impact sensitivity to ferroptosis[63]. This suggests that there is a hierarchy of control in which GPX4 is more significant for ferroptosis induction than the mitochondria. This further highlights the question about the impact of one death modality on another. Is there a way to leverage the mitochondria so that it can aid in the induction of both RCD pathways? Mitochondria are also implicated as drivers of the formation of drug-tolerant persister (DTP) cells[88]: Sublethal release of cytochrome c results in a DTP cell state that is resistant to apoptosis-inducing drugs but hypersensitive to ferroptosis[88,89]. Lysosomal iron activation, however, can also trigger ferroptosis in drug-resistant cancer cells, as iron itself can promote cell state transitions in cancer cells[17,90-93].

Other regulators of apoptosis have been connected to ferroptosis: Wildtype p53 is a tumor suppressor that is involved in the regulation of apoptosis and has been linked to ferroptosis[94]. p53 can trigger apoptosis through direct transcriptional activation of PUMA and NOXA, two BH3 only BCL-2 family proteins[95,96]. p53 has also been established to be involved in the cascade that triggers ferroptosis, mostly in a ferroptosis-promoting role, (but p53 has also inhibited ferroptosis in specific contexts)[97]. p53 is involved in the regulation of cellular and systemic metabolism of many of the key pathways involved in ferroptosis regulation. For example, SLC7A11, a key component involved in System Xc-, is a target gene that is suppressed by p53, resulting in less cystine transported into the cell (Figure 2)[62]. Further research is required to understand how p53 expression and mutations affect the interplay between these two forms of cell death, and whether p53 can simultaneously protect from one death modality while inducing another, or act as a switch between these two cell death processes.

Another upstream stress signal that is shared between apoptosis and ferroptosis is endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and oxidative stress. ER stress is characterized by the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER, which results in the disruption of regular cellular processes[98]. ER stress results in the activation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) pathway, which if persistent, morphs into terminal UPR, which can promote upregulation of genes involved in iron uptake, storage, and utilization, and the inhibition of genes involved in the regulation of antioxidant defense and fatty acid metabolism, sensitizing cells to ferroptosis[99-102]. Similarly, when cells experience late-stage UPR, there is upregulation of pro-apoptotic genes with simultaneous downregulation of pro-survival BCL-2 family proteins. Gaining a greater understanding of how and where these two death pathways intersect can reveal targets that can be used to better induce both cell ferroptosis and apoptosis in tumors, while avoiding issues of resistance.

4.2 Ferroptosis and necroptosis

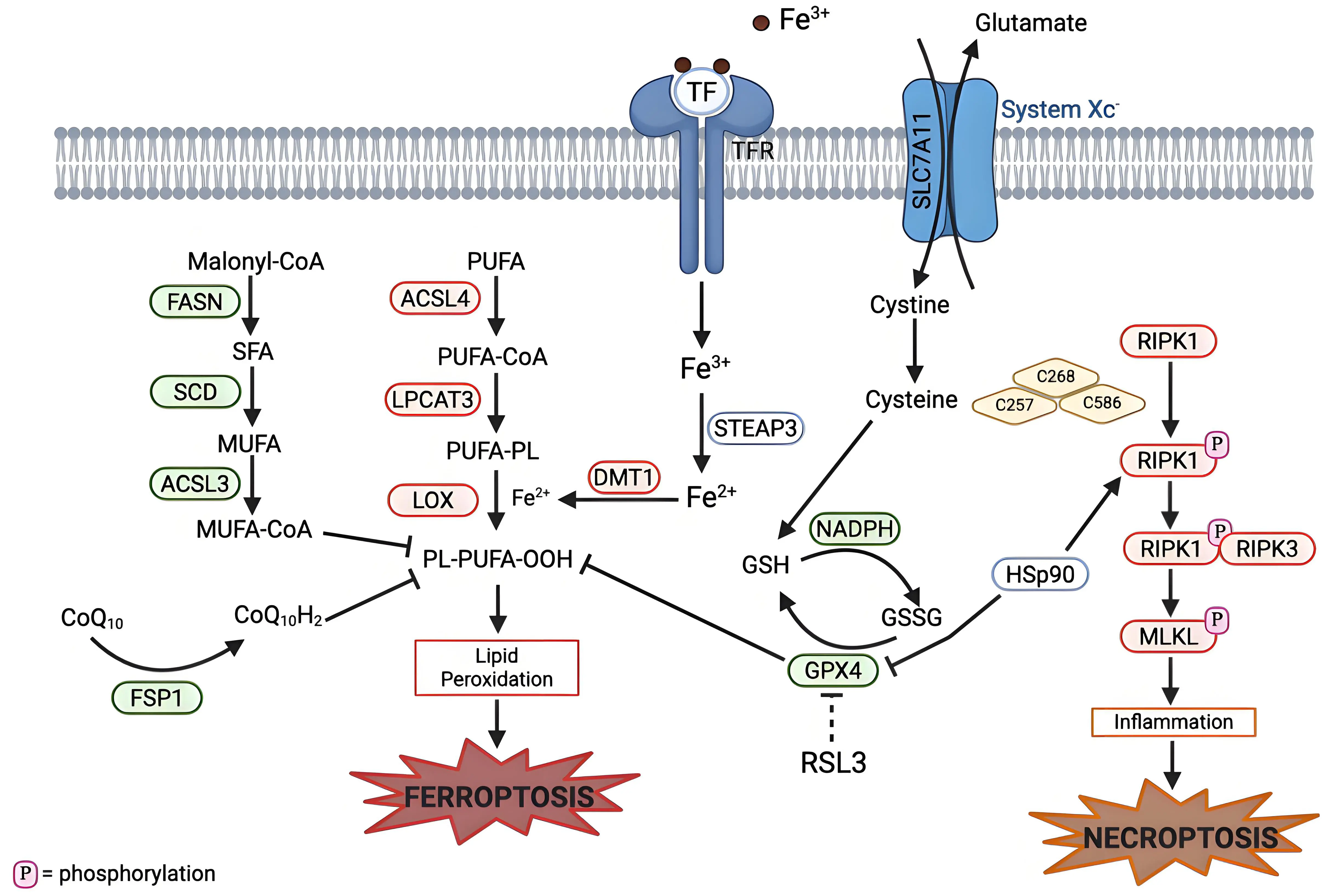

Necroptosis, like ferroptosis, is a non-apoptotic form of RCD[103]. Necroptosis emerged from the discovery that receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) is critical for inducing regulated necrosis, while necrostatin 1 (Nec-1), a potent inhibitor of RIPK1, is able to inhibit necroptotic cell death[104-106]. The activation of RIPK1, receptor-interacting protein kinase 3 (RIPK3), and the tumor necrosis factor signaling pathway is critical for necroptosis (Figure 3)[107].

Figure 3. Mechanistic crosstalk between ferroptosis and necroptosis pathways. Necroptosis can be initiated by the activation of RIPK1 (in response to death receptors), which results in phosphorylation of RIPK1. Phosphorylated RIPK1 forms a complex with RIPK3 (the necrosome complex), which then phosphorylates MLKL. This leads to a pro-inflammatory response and eventual necroptotic cell death. HSP90, a molecular chaperone, links ferroptosis and necroptosis by stabilizing RIPK1 to promote necrosome assembly and also degradation of GPX4. Cysteine plays a role in both ferroptosis and apoptosis: Cysteine is involved in GSH production, which is used as a cofactor for GPX4, and also required for autophosphorylation of RIPK1. Created in BioRender.com. Red: anti-cell death factors; Green: pro-cell death factors; Gray: context dependent regulator of cell death; SLC7A11: solute carrier family 7 member 11; STEAP3: six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3; DMT1: divalent metal transporter 1; FASN: fatty acid synthase; SCD: stearoyl-CoA desaturase; ACSL3: acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 3; ACSL4: acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4; LPCAT3: lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3; LOX: lipoxygenase; GPX4: glutathione peroxidase 4; FSP1: ferroptosis suppressor protein 1; RIPK1: receptor interacting protein kinase 1; RIPK3: receptor interacting protein kinase 3; MLKL: mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein; HSp90: heat shock protein 90.

Some studies examined the intersection between ferroptosis and necroptosis. In cells not sensitive to necroptosis, there is a time and concentration dependent hypersensitization to ferroptosis; the opposite is true as well for cells insensitive to ferroptosis[108]. Where this switch takes place and how these mechanisms interact with each other is unknown.

Cysteine has been highlighted as playing a key role in both these forms of cell death (Figure 3). In necroptosis, three cysteine residues (C257, C268 and C586) in RIPK1 form intermolecular disulfide bonds, which ultimately induce autophosphorylation of serine residue 161 (S161) of RIPK1. Then, the phosphorylated RIPK1 can recruit RIPK3 to form a functional necrosome[109,110]. In ferroptosis, cysteine aids in the production of GSH, which then acts as an antioxidant agent to protect against ferroptosis[5]. The use of cysteine by both these cell death pathways highlights an opportunity to exploit this sensitivity to induce both types of cell death with one treatment.

Similarly, heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) is involved in both necroptosis and ferroptosis (Figure 3). HSP90 plays a key role in the homeostasis of the RIPK1/RIPK3 complex by aiding in the stabilization and folding of RIPK3[111]. HSP90 is also involved in the degradation of GPX4, as it stabilizes the protein and prevents its degradation, but when HSP90 is inhibited, there is greater degradation of ferroptosis[112-115]. Key remaining questions involve: Where this shift from ferroptosis to necroptosis occur? How can these unique features present in both RCD modalities be targeted? Is there a way to target both types of cell death at the same time to create a multitarget treatment to increase results?

4.3 Ferroptosis and pyroptosis

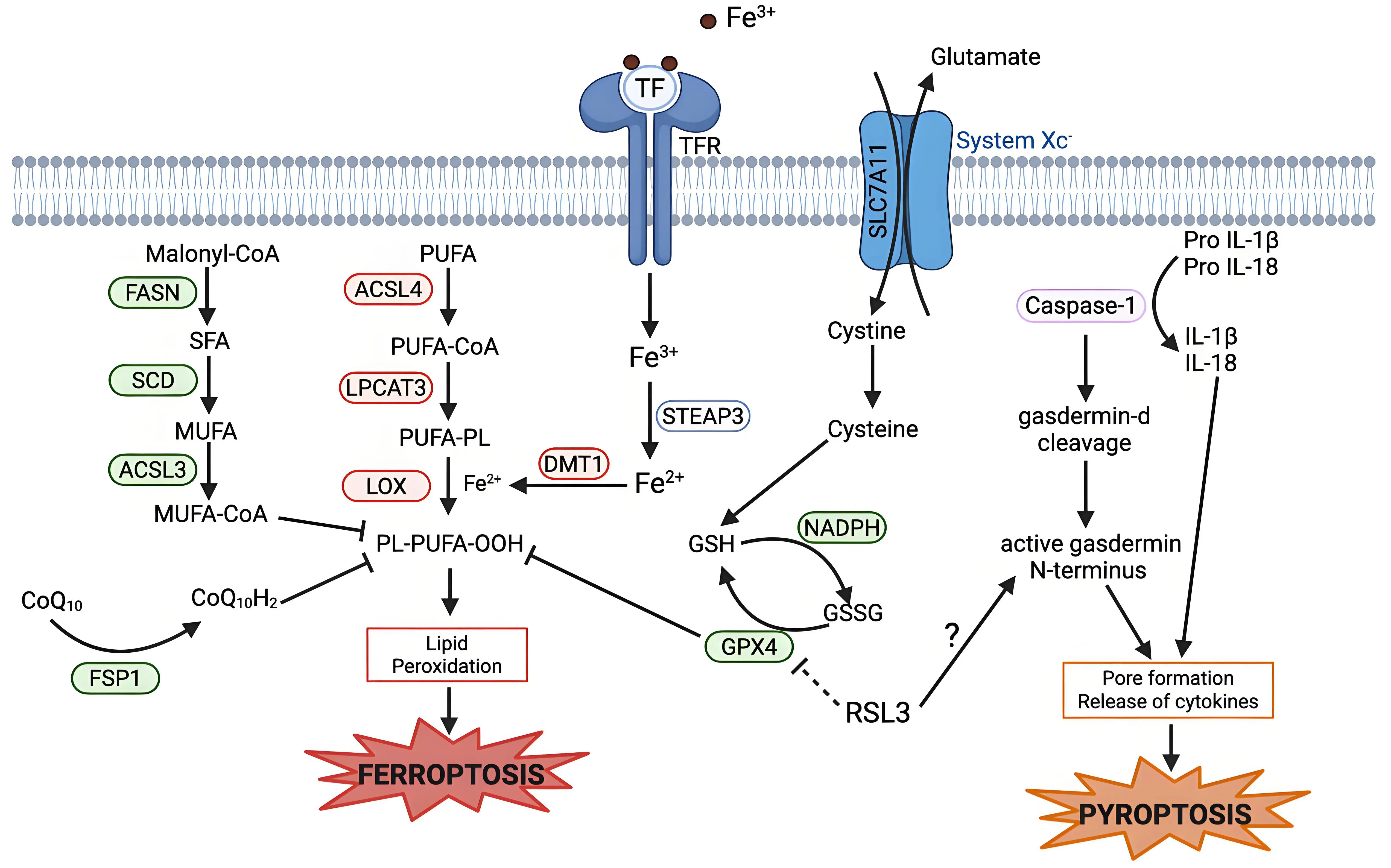

Pyroptosis is an inflammatory type of cell death which involves the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β and interleukin-18[116]. Pyroptosis is triggered when gasdermin proteins are cleaved into N-terminal and C-terminal fragments by proteases, usually caspases, although other proteases can also perform this function. The N-terminal fragments oligomerize to form pores in the cell membrane, which lead to swelling and eventually lysis (Figure 4)[117-119].

Figure 4. Mechanistic crosstalk between ferroptosis and pyroptosis. Pyroptosis is executed by caspase-1 activation, which leads to the cleavage of gasdermin D. The active N-terminal fragment of gasdermin D causes formation of pores in the plasma membrane and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to pyroptotic cell death. RSL3, a ferroptosis inducer, can induce pyroptosis via increasing gasdermin D cleavage in some cases. Created in BioRender.com. Red: anti-cell death factors; Green: pro-cell death factors; Gray: context dependent regulator of cell death; SLC7A11: solute carrier family 7 member 11; STEAP3: six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3; DMT1: divalent metal transporter 1; FASN: fatty acid synthase; SCD: stearoyl-CoA desaturase; ACSL3: acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 3; ACSL4: acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4; LPCAT3: lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3; LOX: lipoxygenase; GPX4: glutathione peroxidase 4; FSP1: ferroptosis suppressor protein; IL-1β: interleukin-1 beta.

Pyroptosis has shown overlap with other cell deaths, such as apoptosis, in which caspases play an important role[120]. But, the overlap with ferroptosis is less clear. RSL3, a potent ferroptosis inducer, can enhance ketamine-induced pyroptosis in the brain and induce pyroptosis in cancer cells via gasdermin cleavage (Figure 4)[121,122]. Similarly, with the depletion of GPX4 in myeloid cells, an increase in caspase-mediated gasdermin-D cleavage is seen[123]. An understanding of how GPX4 regulates both pyroptosis and ferroptosis is lacking, but the potential role of GPX4 in both suggests that lipid peroxidation may accelerate inflammasome activation and hence pyroptosis. There is much to be understood about the intersection between ferroptosis and pyroptosis. Still to be investigated are if proteins, other than GPX4, in the system Xc- axis can show similar impacts on pyroptosis sensitivity as GPX4, and if this effect is bidirectional - do any of the established pyroptosis regulators affect ferroptosis sensitivity in any way?

4.4 Ferroptosis and autophagy

Autophagy is a cellular lysosomal process in which the cell degrades and recycles biomolecules, proteins, and organelles to maintain intracellular homeostasis[124-126]. These macromolecules are degraded by the lysosome into raw materials as a mechanism for adaptation to starvation or stress[124,127]. Autophagy plays an important role in the regulation of ferroptosis and, in most contexts, promotes ferroptosis (Figure 5)[112,128]. Ferritinophagy is a type of autophagy that regulates the distribution and utilization of iron ions in cells[128]. Ferritin, the primary intracellular iron storage protein, undergoes degradation via autophagy, leading to the release of iron from the lysosome, resulting in elevated cytosolic labile iron, facilitating ferroptosis[128-131]. Additionally, lipophagy, the degradation of lipid droplets, results in increased lipid release, leading to lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis[132]. Mitophagy, the selective autophagy of mitochondria, has a more complicated relationship to ferroptosis[133]. Mitophagy can be triggered by ROS but can also reduce mitochondrial ROS, protecting from ferroptosis[134], and GPX4 can be recruited to the mitochondria in the activation of mitophagy, which reduces free GPX4 and can promote ferroptosis[135,136].

Figure 5. Roles of lipophagy, ferritinophagy, and mitophagy in ferroptosis regulation. Lipophagy is mediated by RAB7A, which promotes the breakdown of neutral LD into fatty acids. These fatty acids are incorporated into phospholipids that contribute to lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis sensitivity. Ferritinophagy is mediated by NCOA4, a cargo receptor that directs ferritin to the autophagosome for degradation, releasing redox-active iron into the cytosol. This increases the labile iron pool to promote ROS generation via the Fenton reaction, driving lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Mitophagy requires binding to LC3 on the autophagosome. The role of mitophagy in ferroptosis is not well defined, as mitophagy can both trigger ROS and reduce mitochondrial ROS, while reducing GPX4. Created in BioRender.com. Red: anti-cell death factors; Green: pro-cell death factors; Gray: context dependent regulator of cell death; SLC7A11: solute carrier family 7 member 11; STEAP3: six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3; DMT1: divalent metal transporter 1; FASN: fatty acid synthase; SCD: stearoyl-CoA desaturase; ACSL3: acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 3; ACSL4: acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4; LPCAT3: lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3; LOX: lipoxygenase; FSP1: ferroptosis suppressor protein; NCOA4: nuclear receptor coactivator 4; LC3: microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3; RAB7A: ras-related protein Rab-7a; LD: lipid droplets; ROS: reactive oxygen species; GPX4: glutathione-dependent peroxidase 4.

Thus, autophagy mainly aids in the induction and sensitization to ferroptosis, but mitophagy has a more complicated impact on ferroptosis. A more detailed understanding of how mitophagy regulates mitochondrial ROS and ferroptosis in different contexts is needed.

5. Perspectives and Conclusions

In the years since ferroptosis was conceptualized, it has emerged as a distinct and biologically significant form of regulated cell death, with clear relevance to cancer, neurodegeneration and other disease states[20-26,137-139]. Despite substantial progress in defining its molecular regulators and biochemical hallmarks, fundamental gaps remain in our understanding of how ferroptosis is executed, when and where it functions physiologically, and how it interfaces with other cell death programs. Addressing these questions is essential for the integration of ferroptosis into the framework of cellular fate control and to fully reap its therapeutic potential.

A major priority for future research is to elucidate the final steps and execution of ferroptotic death. While lipid peroxidation and osmotic flux are defining features of ferroptosis the downstream events that result in cellular demise are still undetermined. Future work can look at how the membrane nanopores are formed, if there are specific sites within the membrane that are more susceptible to this pore formation, and how that correlates to the fatty acid content of the membrane. Additionally, determining any biophysical thresholds that trigger ferroptosis can allow for a greater understanding of the critical execution steps of ferroptosis.

Equally important is defining the physiological roles of ferroptosis across tissues and developmental stages. While emerging work highlights the function of ferroptosis in embryogenesis, aging, and tumor suppression, there remains a continued need to map where ferroptosis occurs under normal physiological conditions. Identifying cell-type specific vulnerabilities to ferroptosis and distinguishing physiological from pathological activation are possible next steps in mapping the physiological roles of ferroptosis.

In addition, crosstalk between ferroptosis and other forms of regulated cell death can be leveraged to maximize drug treatments. Ferroptosis interacts with apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and autophagy regulation pathways through shared signaling, dependencies, and stress responses. Dissecting the interplay of these pathways can illuminate more of the cell fate scaffolding and can reveal opportunities for combination therapeutic strategies which can target more than one pathway at a time.

Authors contribution

Feinsod H: Conceptualization, writing-original draft.

Stockwell BR: Supervision, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Brent R. Stockwell is an inventor on patents and patent applications involving ferroptosis, holds equity in and serves as a consultant to ProJenX Inc, and serves as a consultant to Weatherwax Biotechnologies Corporation and Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP. Brent R. Stockwell is also an Editorial Board member of the journal Ferroptosis and Oxidative Stress. The other author declares no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This research related to this article was supported by the National Cancer Institute (P01CA291697 to Brent R. Stockwell) and in part through the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA008748), the Columbia University Digestive and Liver Disease Research Center (funded by NIH grant 5P30DK132710) through use of its Bioimaging Core, Bioinformatic and Single Cell Analysis Core, Organoid and Cell Culture Core and Clinical Biospecimen and Research Core.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060-1072.[DOI]

-

2. Dixon SJ, Patel DN, Welsch M, Skouta R, Lee ED, Hayano M, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine–glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. eLife. 2014;3:e02523.[DOI]

-

3. Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, et al. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 2014;156(1):317-331.[DOI]

-

4. Fotiadis D, Kanai Y, Palacín M. The SLC3 and SLC7 families of amino acid transporters. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34(2):139-158.[DOI]

-

5. Ursini F, Maiorino M. Lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis: The role of GSH and GPx4. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;152:175-185.[DOI]

-

6. Mandal PK, Seiler A, Perisic T, Kölle P, Canak AB, Förster H, et al. System xc− and thioredoxin reductase 1 cooperatively rescue glutathione deficiency. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(29):22244-22253.[DOI]

-

7. Cardoso BR, Hare DJ, Bush AI, Roberts BR. Glutathione peroxidase 4: A new player in neurodegeneration? Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(3):328-335.[DOI]

-

8. Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M, da Silva MC, Ingold I, et al. FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature. 2019;575(7784):693-698.[DOI]

-

9. Bersuker K, Hendricks JM, Li Z, Magtanong L, Ford B, Tang PH, et al. The CoQ oxidoreductase FSP1 acts parallel to GPX4 to inhibit ferroptosis. Nature. 2019;575(7784):688-692.[DOI]

-

10. Hadian K. Ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) and coenzyme Q10 cooperatively suppress ferroptosis. Biochemistry. 2020;59(5):637-638.[DOI]

-

11. Stockwell BR. Ferroptosis turns 10: Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic applications. Cell. 2022;185(14):2401-2421.[DOI]

-

12. Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, Patel M, Shchepinov MS, Stockwell BR. Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2016;113(34):E4966-E4975.[DOI]

-

13. Magtanong L, Ko PJ, To M, Cao JY, Forcina GC, Tarangelo A, et al. Exogenous monounsaturated fatty acids promote a ferroptosis-resistant cell state. Cell Chem Biol. 2019;26(3):420-432.[DOI]

-

14. Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, et al. Acsl4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(1):91-98.[DOI]

-

15. Dixon SJ, Winter GE, Musavi LS, Lee ED, Snijder B, Rebsamen M, et al. Human haploid cell genetics reveals roles for lipid metabolism genes in nonapoptotic cell death. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10(7):1604-1609.[DOI]

-

16. Xie Y, Hou W, Song X, Yu Y, Huang J, Sun X, et al. Ferroptosis: process and function. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23(3):369-379.[DOI]

-

17. Cañeque T, Baron L, Müller S, Carmona A, Colombeau L, Versini A, et al. Activation of lysosomal iron triggers ferroptosis in cancer. Nature. 2025;642(8067):492-500.[DOI]

-

18. Stockwell BR, Angeli JPF, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon S, et al. Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 2017;171(2):273-285.[DOI]

-

19. Gao M, Monian P, Quadri N, Ramasamy R, Jiang X. Glutaminolysis and transferrin regulate ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2015;59(2):298-308.[DOI]

-

20. Fernández-Acosta R, Vintea I, Koeken I, Hassannia B, Vanden Berghe T. Harnessing ferroptosis for precision oncology: Challenges and prospects. BMC Biol. 2025;23(1):57.[DOI]

-

21. Zhang T, Han Y, Wang Y, Wang X, Zhao M, Cheng Z, et al. The interaction between ferroptosis and myocardial ischemia–reperfusion injury: Molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets. Eur J Med Res. 2025;30(1):643.[DOI]

-

22. Chen Y, Wu Z, Li S, Chen Q, Wang L, Qi X, et al. Mapping the research of ferroptosis in Parkinson’s Disease from 2013 to 2023: A scientometric review. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2024;18:1053-1081.[DOI]

-

23. Zhou Q, Meng Y, Li D, Yao L, Le J, Liu Y, et al. Ferroptosis in cancer: From molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):55.[DOI]

-

24. Xu J, Shen R, Qian M, Zhou Z, Xie B, Jiang Y, et al. Ferroptosis in alzheimer’s disease: The regulatory role of glial cells. J Integr Neurosci. 2025;24(4):25845.[DOI]

-

25. Ma H, Dong Y, Chu Y, Guo Y, Li L. The mechanisms of ferroptosis and its role in alzheimer’s disease. Front Mol Biosci. 2022;9:965064.[DOI]

-

26. Lin KJ, Chen SD, Lin KL, Liou CW, Lan MY, Chuang YC, et al. Iron brain menace: The involvement of ferroptosis in parkinson disease. Cells. 2022;11(23):3829.[DOI]

-

27. Kerr JFR, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Apoptosis: A basic biological phenomenon with wideranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer. 1972;26(4):239-257.[DOI]

-

28. Battaglia AM, Chirillo R, Aversa I, Sacco A, Costanzo F, Biamonte F. Ferroptosis and cancer: Mitochondria meet the “iron maiden” cell death. Cells. 2020;9(6):1505.[DOI]

-

29. Saraev DD, Pratt DA. Reactions of lipid hydroperoxides and how they may contribute to ferroptosis sensitivity. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2024;81:102478.[DOI]

-

30. Do Q, Xu L. How do different lipid peroxidation mechanisms contribute to ferroptosis? Cell Rep Phys Sci. 2023;4(12):101683.[DOI]

-

31. Agmon E, Solon J, Bassereau P, Stockwell BR. Modeling the effects of lipid peroxidation during ferroptosis on membrane properties. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):5155.[DOI]

-

32. Pedrera L, Espiritu RA, Ros U, Weber J, Schmitt A, Stroh J, et al. Ferroptotic pores induce Ca2+ fluxes and ESCRT-III activation to modulate cell death kinetics. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28(5):1644-1657.[DOI]

-

33. Riegman M, Sagie L, Galed C, Levin T, Steinberg N, Dixon SJ, et al. Ferroptosis occurs through an osmotic mechanism and propagates independently of cell rupture. Nat Cell Biol. 2020;22(9):1042-1048.[DOI]

-

34. Van Kessel ATM, Karimi R, Cosa G. Live-cell imaging reveals impaired detoxification of lipid-derived electrophiles is a hallmark of ferroptosis. Chem Sci. 2022;13(33):9727-9738.[DOI]

-

35. Amoscato AA, Anthonymuthu T, Kapralov O, Sparvero LJ, Shrivastava IH, Mikulska-Ruminska K, et al. Formation of protein adducts with Hydroperoxy-PE electrophilic cleavage products during ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2023;63:102758.[DOI]

-

36. Chen Y, Liu Y, Lan T, Qin W, Zhu Y, Qin K, et al. Quantitative profiling of protein carbonylations in ferroptosis by an aniline-derived probe. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(13):4712-4720.[DOI]

-

37. Tyurina YY, Kapralov AA, Tyurin VA, Shurin G, Amoscato AA, Rajasundaram D, et al. Redox phospholipidomics discovers pro-ferroptotic death signals in A375 melanoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Redox Biol. 2023;61:102650.[DOI]

-

38. Van Kessel ATM, Cosa G. Lipid-derived electrophiles inhibit the function of membrane channels during ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2024;121(21):e2317616121.[DOI]

-

39. Fujii J, Homma T, Miyata S, Takahashi M. Pleiotropic actions of aldehyde reductase (AKR1A). Metabolites. 2021;11(6):343.[DOI]

-

40. Li X, Qian J, Xu J, Bai H, Yang J, Chen L. NRF2 inhibits RSL3 induced ferroptosis in gastric cancer through regulation of AKR1B1. 2024;442(1):114210.[DOI]

-

41. Kayagaki N, Kornfeld OS, Lee BL, Stowe IB, O’Rourke K, Li Q, et al. NINJ1 mediates plasma membrane rupture during lytic cell death. Nature. 2021;591(7848):131-136.[DOI]

-

42. Ramos S, Hartenian E, Santos JC, Walch P, Broz P. NINJ1 induces plasma membrane rupture and release of damage-associated molecular pattern molecules during ferroptosis. EMBO J. 2024;43(7):1164-1186.[DOI]

-

43. Chen SY, Shyu IL, Chi JT, Chen SY, Shyu IL, Chi JT. NINJ1 in cell death and ferroptosis: Implications for tumor invasion and metastasis. Cancers. 2025;17(5):800.[DOI]

-

44. Roeck BF, Lotfipour Nasudivar S, Vorndran MRH, Schueller L, Yapici FI, Rübsam M, et al. Ferroptosis spreads to neighboring cells via plasma membrane contacts. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):2951.[DOI]

-

45. Nishizawa H, Matsumoto M, Chen G, Ishii Y, Tada K, Onodera M, et al. Lipid peroxidation and the subsequent cell death transmitting from ferroptotic cells to neighboring cells. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(4):332.[DOI]

-

46. Saunders JW. Death in embryonic systems. Science. 1966;154(3749):604-612.[DOI]

-

47. Clarke PGH, Clarke S. Nineteenth century research on naturally occurring cell death and related phenomena. Anat Embryol. 1996;193(2):81-99.[DOI]

-

48. Co HKC, Wu CC, Lee YC, Chen SH. Emergence of large-scale cell death through ferroptotic trigger waves. Nature. 2024;631(8021):654-662.[DOI]

-

49. Tschuck J, Padmanabhan Nair V, Galhoz A, Zaratiegui C, Tai HM, Ciceri G, et al. Suppression of ferroptosis by vitamin A or radical-trapping antioxidants is essential for neuronal development. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7611.[DOI]

-

50. Chui A, Zhang Q, Dai Q, Shi SH. Oxidative stress regulates progenitor behavior and cortical neurogenesis. Development. 2020;147(5):dev184150.[DOI]

-

51. Zheng H, Jiang L, Tsuduki T, Conrad M, Toyokuni S. Embryonal erythropoiesis and aging exploit ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2021;48:102175.[DOI]

-

52. Boucher DM, Pedersen RA. Induction and differentiation of extra-embryonic mesoderm in the mouse. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1996;8(4):765-777.[DOI]

-

53. Andrews NC. Disorders of iron metabolism. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(26):1986-1995.[DOI]

-

54. He X, Hahn P, Iacovelli J, Wong R, King C, Bhisitkul R, et al. Iron homeostasis and toxicity in retinal degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2007;26(6):649-673.[DOI]

-

55. Ugarte M, Geraki K, Jeffery G. Aging results in iron accumulations in the non-human primate choroid of the eye without an associated increase in zinc, copper or sulphur. Biometals. 2018;31(6):1061-1073.[DOI]

-

56. Hahn P, Ying G shuang, Beard J, Dunaief JL. Iron levels in human retina: Sex difference and increase with age. NeuroReport. 2006;17(17):1803-1806.[DOI]

-

57. Zecca L, Stroppolo A, Gatti A, Tampellini D, Toscani M, Gallorini M, et al. The role of iron and copper molecules in the neuronal vulnerability of locus coeruleus and substantia nigra during aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2004;101(26):9843-9848.[DOI]

-

58. Zecca L, Gallorini M, Schünemann V, Trautwein AX, Gerlach M, Riederer P, et al. Iron, neuromelanin and ferritin content in the substantia nigra of normal subjects at different ages: Consequences for iron storage and neurodegenerative processes. J Neurochem. 2001;76(6):1766-1773.[DOI]

-

59. Mazhar M, Din AU, Ali H, Yang G, Ren W, Wang L, et al. Implication of ferroptosis in aging. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7(1):149.[DOI]

-

60. Müller S, Sindikubwabo F, Cañeque T, Lafon A, Versini A, Lombard B, et al. CD44 regulates epigenetic plasticity by mediating iron endocytosis. Nat Chem. 2020;12(10):929-938.[DOI]

-

61. Liang D, Feng Y, Zandkarimi F, Wang H, Zhang Z, Kim J, et al. Ferroptosis surveillance independent of GPX4 and differentially regulated by sex hormones. Cell. 2023;186(13):2748-2764.[DOI]

-

62. Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang SJ, Su T, Hibshoosh H, et al. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 2015;520(7545):57-62.[DOI]

-

63. Gao M, Yi J, Zhu J, Minikes AM, Monian P, Thompson CB, et al. Role of mitochondria in ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2019;73(2):354-363.[DOI]

-

64. Zhang Y, Shi J, Liu X, Feng L, Gong Z, Koppula P, et al. BAP1 links metabolic regulation of ferroptosis to tumor suppression. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20(10):1181-1192.[DOI]

-

65. Egolf S, Zou J, Anderson A, Simpson CL, Aubert Y, Prouty S, et al. MLL4 mediates differentiation and tumor suppression through ferroptosis. Sci Adv. 2021;7(50):eabj9141.[DOI]

-

66. Tonnus W, Maremonti F, Gavali S, Schlecht MN, Gembardt F, Belavgeni A, et al. Multiple oestradiol functions inhibit ferroptosis and acute kidney injury. Nature. 2025;645(8082):1011-1019.[DOI]

-

67. Dai E, Chen X, Linkermann A, Jiang X, Kang R, Kagan VE, et al. A guideline on the molecular ecosystem regulating ferroptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2024;26(9):1447-1457.[DOI]

-

68. Bell HN, Stockwell BR, Zou W. Ironing out the Role of Ferroptosis in Immunity. Immunity. 2024;57(5):941-956.[DOI]

-

69. Berndt C, Alborzinia H, Amen VS, Ayton S, Barayeu U, Bartelt A, et al. Ferroptosis in health and disease. Redox Biol. 2024;75:103211.[DOI]

-

70. Kordi N, Saydi A, Karami S, Bagherzadeh-Rahmani B, Marzetti E, Jung F, et al. Ferroptosis and aerobic training in ageing. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2024;87(3):347-366.[DOI]

-

71. Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, Abrams JM, Adam D, Agostinis P, et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25(3):486-541.[DOI]

-

73. Meagher LC, Savill JS, Baker A, Fuller RW, Haslett C. Phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils does not induce macrophage release of thromboxane B2. J Leukoc Biol. 1992;52(3):269-273.[DOI]

-

74. Sesso A, Belizário J, Marques M, Higuchi M, Schumacher R, Colquhoun A, et al. Mitochondrial swelling and incipient outer membrane rupture in preapoptotic and apoptotic cells. Anat Rec. 2012;295(10):1647-1659.[DOI]

-

75. Petit PX, Susin SA, Zamzami N, Mignotte B, Kroemer G. Mitochondria and programmed cell death: Back to the future. FEBS Lett. 1996;396(1):7-13.[DOI]

-

76. Goldstein JC, Waterhouse NJ, Juin P, Evan GI, Green DR. The coordinate release of cytochrome c during apoptosis is rapid, complete and kinetically invariant. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(3):156-162.[DOI]

-

77. Liu X, Kim CN, Yang J, Jemmerson R, Wang X. Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: Requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell.1996;86(1):147-157.[DOI]

-

78. Cleary ML, Sklar J. Nucleotide sequence of a t(14;18) chromosomal breakpoint in follicular lymphoma and demonstration of a breakpoint-cluster region near a transcriptionally active locus on chromosome 18. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 1985;82(21):7439-7443.[DOI]

-

79. Bakhshi A, Jensen JR, Goldman P, Wright JJ, McBride OW, Epstein AL, et al. Cloning the chromosomal breakpoint of t(14;18) human lymphomas: Clustering around JR on chromosome 14 and near a transcriptional unit on 18. Cell. 1985;41(3):899-906.[DOI]

-

80. Qian S, Wei Z, Yang W, Huang J, Yang Y, Wang J. The role of BCL-2 family proteins in regulating apoptosis and cancer therapy. Front Oncol. 2022;12:985363.[DOI]

-

81. Neitemeier S, Jelinek A, Laino V, Hoffmann L, Eisenbach I, Eying R, et al. BID links ferroptosis to mitochondrial cell death pathways. Redox Biol. 2017;12:558-570.[DOI]

-

82. Yan X, Zhou Y, Huang S, Li X, Yu M, Huang J, et al. Promising efficacy of novel BTK inhibitor AC0010 in mantle cell lymphoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144(4):697-706.[DOI]

-

83. Tang Q, Chen H, Mai Z, Sun H, Xu L, Wu G, et al. Bim- and Bax-mediated mitochondrial pathway dominates abivertinib-induced apoptosis and ferroptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022;180:198-209.[DOI]

-

84. Falco A, Bartolomé-Cabrero R, Gascón S. Bcl-2-assisted reprogramming of mouse astrocytes and human fibroblasts into induced neurons. In: Ahlenius H, editor. Neural Reprogramming: Methods and Protocols. New York: Springer; 2021. p. 57-71.[DOI]

-

85. Liu H, Zhang C, Li S, Wang S, Xiao L, Chen J, et al. Overexpression Bcl-2 alleviated ferroptosis induced by molybdenum and cadmium co-exposure through inhibiting mitochondrial ROS in duck kidneys. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;291:139118.[DOI]

-

86. Glover HL, Schreiner A, Dewson G, Tait SWG. Mitochondria and cell death. Nat Cell Biol. 2024;26(9):1434-1446.[DOI]

-

87. Wang X, Li J, Zhang Y, huang M, Yang P, Huang T, et al. HIF1A/BNIP3 pathway affects ferroptosis in sepsis-induced cardiomyopathy through binding to BCL-2. Redox Rep. 2025;30(1):2544412.[DOI]

-

88. Kalkavan H, Chen MJ, Crawford JC, Quarato G, Fitzgerald P, Tait SWG, et al. Sublethal cytochrome c release generates drug-tolerant persister cells. Cell. 2022;185(18):3356-3374.[DOI]

-

89. Hangauer MJ, Viswanathan VS, Ryan MJ, Bole D, Eaton JK, Matov A, et al. Drug-tolerant persister cancer cells are vulnerable to GPX4 inhibition. Nature. 2017;551(7679):247-250.[DOI]

-

90. Antoszczak M, Müller S, Cañeque T, Colombeau L, Dusetti N, Santofimia-Castaño P, et al. Iron-sensitive prodrugs that trigger active ferroptosis in drug-tolerant pancreatic cancer cells. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144(26):11536-11545.[DOI]

-

91. Rodriguez R, Schreiber SL, Conrad M. Persister cancer cells: Iron addiction and vulnerability to ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2022;82(4):728-740.[DOI]

-

92. Mai TT, Hamaï A, Hienzsch A, Cañeque T, Müller S, Wicinski J, et al. Salinomycin kills cancer stem cells by sequestering iron in lysosomes. Nat Chem. 2017;9(10):1025-1033.[DOI]

-

93. Müller S, Cañeque T, Solier S, Rodriguez R. Copper and iron orchestrate cell-state transitions in cancer and immunity. Trends Cell Biol. 2025;35(2):105-114.[DOI]

-

94. Finlay CA, Hinds PW, Levine AJ. The p53 proto-oncogene can act as a suppressor of transformation. Cell. 1989;57(7):1083-1093.[DOI]

-

95. Aubrey BJ, Kelly GL, Janic A, Herold MJ, Strasser A. How does p53 induce apoptosis and how does this relate to p53-mediated tumour suppression? Cell Death Differ. 2018;25(1):104-113.[DOI]

-

96. Shaw P, Bovey R, Tardy S, Sahli R, Sordat B, Costa J. Induction of apoptosis by wild-type p53 in a human colon tumor-derived cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 1992;89(10):4495-4499.[DOI]

-

97. Liu Y, Gu W. p53 in ferroptosis regulation: the new weapon for the old guardian. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29(5):895-910.[DOI]

-

98. Schwarz DS, Blower MD. The endoplasmic reticulum: structure, function and response to cellular signaling. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73(1):79-94.[DOI]

-

99. Hetz C, Papa FR. The unfolded protein response and cell fate control. Mol Cell. 2018;69(2):169-181.[DOI]

-

100. Liu J, Kuang F, Kroemer G, Klionsky DJ, Kang R, Tang D. Autophagy-dependent ferroptosis: Machinery and regulation. Cell Chem Biol. 2020;27(4):420-435.[DOI]

-

101. Lee YS, Lee DH, Choudry HA, Bartlett DL, Lee YJ. Ferroptosis-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress: Cross-talk between ferroptosis and apoptosis. Mol Cancer Res MCR. 2018;16(7):1073-1076.[DOI]

-

102. Li X, Zhu S, Li Z, Meng YQ, Huang SJ, Yu QY, et al. Melittin induces ferroptosis and ER stress-CHOP-mediated apoptosis in A549 cells. Free Radic Res. 2022;56(5-6):398-410.[DOI]

-

103. Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Chan FKM, Kroemer G. Necroptosis: Mechanisms and relevance to disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2017;12:103-130.[DOI]

-

104. Degterev A, Huang Z, Boyce M, Li Y, Jagtap P, Mizushima N, et al. Chemical inhibitor of nonapoptotic cell death with therapeutic potential for ischemic brain injury. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1(2):112-119.[DOI]

-

105. Degterev A, Hitomi J, Germscheid M, Ch’en IL, Korkina O, Teng X, et al. Identification of RIP1 kinase as a specific cellular target of necrostatins. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4(5):313-321.[DOI]

-

106. Holler N, Zaru R, Micheau O, Thome M, Attinger A, Valitutti S, et al. Fas triggers an alternative, caspase-8–independent cell death pathway using the kinase RIP as effector molecule. Nat Immunol. 2000;1(6):489-495.[DOI]

-

107. Berghe TV, Linkermann A, Jouan-Lanhouet S, Walczak H, Vandenabeele P. Regulated necrosis: The expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(2):135-147.[DOI]

-

108. Müller T, Dewitz C, Schmitz J, Schröder AS, Bräsen JH, Stockwell BR, et al. Necroptosis and ferroptosis are alternative cell death pathways that operate in acute kidney failure. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74(19):3631-3645.[DOI]

-

109. Zhou Y, Liao J, Mei Z, Liu X, Ge J. Insight into crosstalk between ferroptosis and necroptosis: Novel therapeutics in ischemic stroke. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021(1):9991001.[DOI]

-

110. Zhang Y, Su SS, Zhao S, Yang Z, Zhong CQ, Chen X, et al. RIP1 autophosphorylation is promoted by mitochondrial ROS and is essential for RIP3 recruitment into necrosome. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):14329.[DOI]

-

111. Yang CK, He SD. Heat shock protein 90 regulates necroptosis by modulating multiple signaling effectors. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(3):e2126[DOI]

-

112. Zhou B, Liu J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Kroemer G, Tang D. Ferroptosis is a type of autophagy-dependent cell death. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;66:89-100.[DOI]

-

113. Wang Z, Guo L min, Wang Y, Zhou H kang, Wang S chao, Chen D, et al. Inhibition of HSP90α protects cultured neurons from oxygen-glucose deprivation induced necroptosis by decreasing RIP3 expression. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(6):4864-4884.[DOI]

-

114. Fearns C, Pan Q, Mathison JC, Chuang TH. Triad3A regulates ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of RIP1 following disruption of Hsp90 binding. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(45):34592-34600.[DOI]

-

115. Li J, Wu G, Su H, Liang M, Cen S, Liao Y, et al. Hsp90 C-terminal domain inhibition enhances ferroptosis by disrupting GPX4-VDAC1 interaction to increase HMOX1 release from oligomerized VDAC1 channels. Redox Biol. 2025;85:103672.[DOI]

-

116. Tan Y, Chen Q, Li X, Zeng Z, Xiong W, Li G, et al. Pyroptosis: a new paradigm of cell death for fighting against cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2021;40(1):153.[DOI]

-

117. Chen X, He W ting, Hu L, Li J, Fang Y, Wang X, et al. Pyroptosis is driven by non-selective gasdermin-D pore and its morphology is different from MLKL channel-mediated necroptosis. Cell Res. 2016;26(9):1007-1020.[DOI]

-

118. Liu X, Zhang Z, Ruan J, Pan Y, Magupalli VG, Wu H, et al. Inflammasome - activated gasdermin D causes pyroptosis by forming membrane pores. Nature. 2016;535(7610):153-158.[DOI]

-

119. Aglietti RA, Estevez A, Gupta A, Ramirez MG, Liu PS, Kayagaki N, et al. GsdmD p30 elicited by caspase-11 during pyroptosis forms pores in membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2016;113(28):7858-7863.[DOI]

-

120. Fritsch M, Günther SD, Schwarzer R, Albert MC, Schorn F, Werthenbach JP, et al. Caspase-8 is the molecular switch for apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis. Nature. 2019;575(7784):683-687.[DOI]

-

121. Herrick WG, Tran HL, Tomaino FR, Beall B, Govindharajulu J, Esposito D, et al. Potent ferroptosis agent RSL3 induces cleavage of Pyroptosis-Specific gasdermins in Cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):25249.[DOI]

-

122. Bai H, Du S, Qiu D, Li S, Gao R, Zhang Z. GPX4 inhibition contributes to NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis and cognitive impairment in ketamine-exposed neonatal rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2025;62(9):12360-12370.[DOI]

-

123. Kang R, Zeng L, Zhu S, Xie Y, Liu J, Wen Q, et al. Lipid peroxidation drives gasdermin D-mediated pyroptosis in lethal polymicrobial sepsis. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;24(1):97-108.[DOI]

-

124. Yamamoto H, Zhang S, Mizushima N. Autophagy genes in biology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2023;24(6):382-400.[DOI]

-

125. Liu S, Yao S, Yang H, Liu S, Wang Y. Autophagy: Regulator of cell death. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(10):648.[DOI]

-

126. Levine B, Klionsky DJ. Development by self-digestion: Molecular mechanisms and biological functions of autophagy. Dev Cell. 2004;6(4):463-477.[DOI]

-

127. Ryter SW, Cloonan SM, Choi AMK. Autophagy: A critical regulator of cellular metabolism and homeostasis. Mol Cell. 2013;36(1):7-16.[DOI]

-

128. Gao M, Monian P, Pan Q, Zhang W, Xiang J, Jiang X. Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell Res. 2016;26(9):1021-1032.[DOI]

-

129. Zhao P, Yin S, Qiu Y, Sun C, Yu H. Ferroptosis and pyroptosis are connected through autophagy: A new perspective of overcoming drug resistance. Mol Cancer. 2025;24(1):23.[DOI]

-

130. Hou W, Xie Y, Song X, Sun X, Lotze MT, Zeh HJ, et al. Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by degradation of ferritin. Autophagy. 2016;12(8):1425-1428.[DOI]

-

131. Mancias JD, Wang X, Gygi SP, Harper JW, Kimmelman AC. Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature. 2014;509(7498):105-109.[DOI]

-

132. Bai Y, Meng L, Han L, Jia Y, Zhao Y, Gao H, et al. Lipid storage and lipophagy regulates ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;508(4):997-1003.[DOI]

-

133. Youle RJ, Narendra DP. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(1):9-14.[DOI]

-

134. Yamashita S, Sugiura Y, Matsuoka Y, Maeda R, Inoue K, Furukawa K, et al. Mitophagy mediated by BNIP3 and NIX protects against ferroptosis by downregulating mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Cell Death Differ. 2024;31(5):651-661.[DOI]

-

135. Basit F, van Oppen LM, Schöckel L, Bossenbroek HM, van Emst-de Vries SE, Hermeling JC, et al. Mitochondrial complex I inhibition triggers a mitophagy-dependent ROS increase leading to necroptosis and ferroptosis in melanoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(3):e2716.[DOI]

-

136. Bi Y, Liu S, Qin X, Abudureyimu M, Wang L, Zou R, et al. FUNDC1 interacts with GPx4 to govern hepatic ferroptosis and fibrotic injury through a mitophagy-dependent manner. J Adv Res. 2024;55:45-60.[DOI]

-

137. Lei G, Zhuang L, Gan B. Targeting ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(7):381-396.[DOI]

-

138. Zhang C, Liu X, Jin S, Chen Y, Guo R. Ferroptosis in cancer therapy: a novel approach to reversing drug resistance. Mol Cancer. 2022;21(1):47.[DOI]

-

139. Fei Y, Ding Y. The role of ferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Cell Neurosci. 2024;18:1475934.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite