Yuri N. Antonenko, Belozersky Institute of Physical-Chemical Biology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow 119991, Russia. E-mail: antonen@belozersky.msu.ru

Abstract

Aims: Non-enzymatic autoxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), generating numerous toxic by-products implicated in neurodegeneration, aging, and other pathologies, is a key process in ferroptosis. Lipid peroxidation (LPO) can be inhibited by deuterated polyunsaturated fatty acids (D-PUFA), as the rate-limiting step of abstraction of bis-allylic hydrogen atoms is slowed down by replacing the bis-allylic hydrogens with deuteriums. Here, we aimed to assess the protective effect of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA), which do not undergo LPO, as compared to that of various D-PUFAs, in a liposomal model of LPO.

Methods: To detect LPO induced by ferrous ions in liposomes, we used the LPO fluorescent probe C11-Bodipy (581/591), in addition to measuring conjugated diene and malondialdehyde accumulation.

Results: By applying the C11-Bodipy (581/591) probe, we found that both 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (POPC) and 1-stearoyl-2-(11,11-d2-linoleoyl)-phosphatidylcholine (D2-Lin-PC) protect non-deuterated 1-stearoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (H-Lin-PC) liposomes from LPO. Similarly, both POPC and 1-stearoyl-2-(11,11,14,14-D4-linolenyl)-phosphatidylcholine (D4-Lnn-PC) protect 1-stearoyl-2-linolenyl-phosphatidylcholine (H-Lnn-PC), and so does 1-stearoyl-2-(6,6,9,9,12,12,15,15,18,18-d10-docosahexaenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (D10-DHA-PC). The conjugated diene and malondialdehyde probes also showed similar protective effects of POPC and D-PUFA on LPO in H-Lnn-PC.

Conclusion: Obviously, the presence of non-oxidizable lipids, such as POPC, similar to the deuterated lipids D2-Lin-PC, D4-Lnn-PC, and D10-DHA-PC, leads to a sharp decrease in the length of lateral propagation of chain reactions in lipid membranes, but they do not participate in LPO themselves.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Many cellular pathologies are associated with oxidative stress. Peroxidation of membrane lipids[1-3] affects a variety of functions including transport along cellular membranes, mitochondrial bioenergetics, vesicular traffic, and autophagy/mitophagy processes[4-13]. Although antioxidants can effectively inhibit ferroptosis in cell culture, administration of antioxidants is usually of little help in vivo because living systems tightly control the antioxidant levels, which cannot be exceeded. Antioxidants cannot stop the lipid peroxidation (LPO) chain for stoichiometric reasons[14]. Besides, excessive amounts of small molecule antioxidants may lead to undesirable pro-oxidant effects.

An alternative approach is the administration of deuterated polyunsaturated fatty acids (D-PUFA), which have been shown to slow down the peroxidation process both in vitro and in vivo[14,15]. The protective effect of D-PUFA relies on the higher energy of hydrogen abstraction from bis-allylic C-D bonds compared to C-H bonds; however, the detailed mechanism of the protection is still not fully understood[16,17] Importantly, the major physicochemical properties of D-PUFA are identical to those of protiated polyunsaturated fatty acids (H-PUFA), which makes their processing and incorporation identical to that of normal H-PUFAs, and ensures their non-toxic nature.

In the present study, we compared the protective effect of D-PUFA with that of oleic acid, a monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA). Oleic acid, which contains one double bond at the ω9 position, does not undergo the LPO reaction due to the absence of bis-allylic hydrogen atoms, which play a major role in the peroxidation of PUFAs[18]. Of note, nonenzymatic oxidation of PUFAs in phospholipids proceeds according to the same basic mechanisms as oxidation of free (nonesterified) PUFAs[19]. It has earlier been shown that adding MUFA to liposomes inhibits LPO of PUFA[20,21]. Furthermore, the presence of oleic acid in the intestinal mucosa has been shown to inhibit LPO[22]. Importantly, MUFA strongly suppress ferroptosis, while PUFA sensitize cells to ferroptosis[23-34]. As shown previously, the oxidation of liposomes from 1,2-dilinoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DLnnPC) is slowed down by the introduction of 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) into the system, and a dose-dependence of the protective effect is observed when varying the ratio of DOPC and the fully saturated lipid 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC)[21]. On the other hand, in experiments with mutant yeast particularly sensitive to oxidative stress, D-PUFA exhibited a protective effect, while oleate did not[16]. In the present work, we continued the study of the protective effect of D-PUFA on the system of liposomes upon initiation of peroxidation by iron[35]. We used the convenient fluorescent reporter of ROS formation, C11-Bodipy (581/591), as well as diene conjugates and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) readouts. The “antioxidant”-like protective effect of D-PUFA observed in this system was similar to that of oleic acid-based lipids, i.e. both D-PUFA and MUFA do not sustain LPO.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

1-stearoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (H-Lin-PC), 1-stearoyl-2-linolenyl-phosphatidylcholine (H-Lnn-PC), 1-stearoyl-2-docosahexaenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (H-DHA-PC), and 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (POPC) were from Avanti Polar Lipids, USA. 1-stearoyl-2-(11,11,14,14-D4-linolenyl)-phosphatidylcholine (D4-Lnn-PC), 1-stearoyl-2-(6,6,9,9,12,12,15,15,18,18-D10-docosahexaenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (D10-DHA-PC), 1-stearoyl-2-(11-D-linoleyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (HD-Lin-PC), and 1-stearoyl-2-(11,11-D2-linoleyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (D2-Lin-PC) were manufactured by Retrotope. C11-BODIPY (581/591) was from Molecular Probes. Other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.2 Preparation of liposomes

Empty and dye-loaded large unilamellar vesicles (LUV) were prepared by the extrusion method as described previously[15].

2.3 C11-BODIPY (581/591) assay

The spectra of C11-BODIPY (581/591) were measured with a CM2203 spectrofluorometer (SOLAR, Minsk, Belarus). The kinetics of C11-BODIPY (581/591) fluorescence were measured with a Panorama Fluorat 02 spectrofluorometer (Lumex, Saint Petersburg, Russia) at 25 °C.

2.4 Conjugated diene assay

The amount of conjugated dienes was estimated from the absorbance at 234 nm with a CM 2203 spectrophotometer (SOLAR, Belarus) as described previously[15]. The data points represented the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments.

2.5 TBARS assay

0.5 mL of liposome suspension (lipid concentration of 300 µg/mL) was incubated under oxidizing conditions (5 µM FeSO4) at room temperature for 10 min. Then 0.5 mL of thiobarbituric acid (0.7%) and 5 µL of HCl (14 M) were sequentially added. The mixture was boiled in a water bath at 100 °C for 30 min. Absorption was measured at 530 nm using a Solar CM2203 spectrophotometer (SOLAR, Belarus). The experiments were repeated three times.

3. Results

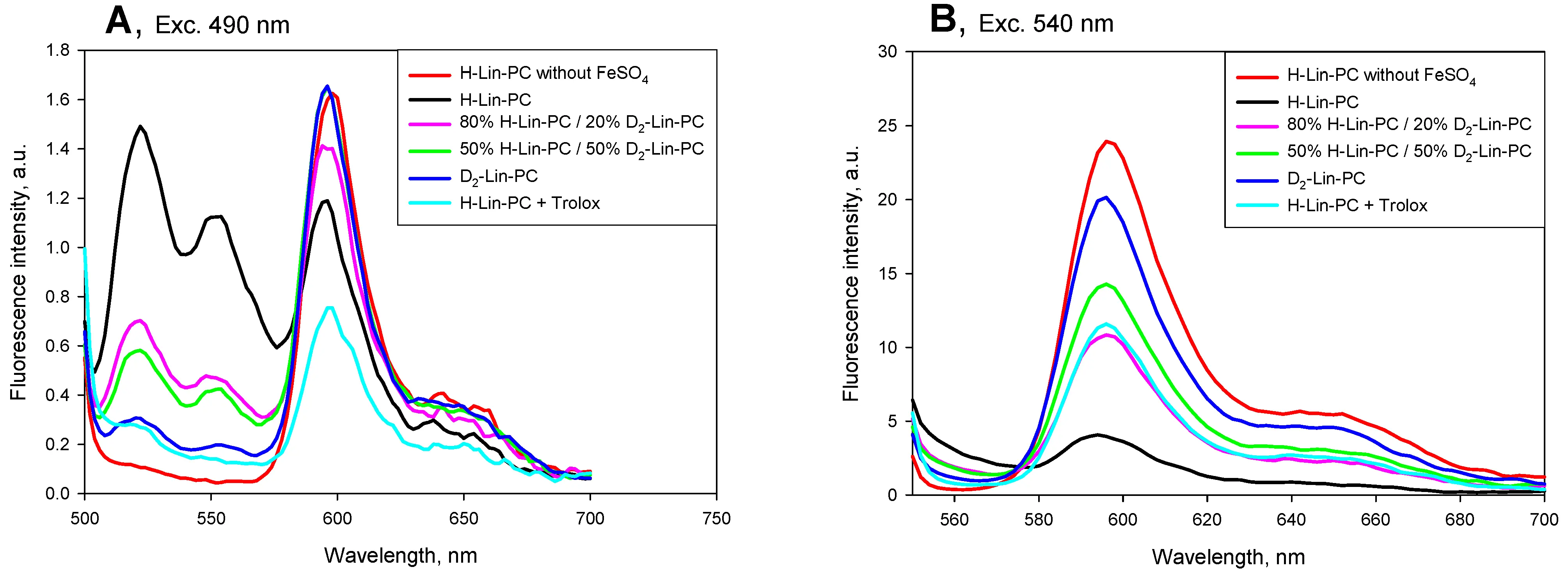

It has been shown previously that the C11-Bodipy dye (581/591) can be successfully used to assess the degree of LPO both in liposomes[36] and in cellular membranes[16,36,37]. One of its advantages is that when the surrounding lipid is oxidized, its fluorescence increases in the green region (520-560 nm), while decreasing in the orange region (580-620 nm). Figure 1 shows typical emission spectra of C11-Bodipy at 490 nm excitation (panel A) and 540 nm excitation (panel B) in a system of liposomes subjected to LPO during 20 minutes in the presence of ferrous ions. We used liposomes of different compositions with variable levels of deuterated linoleic acid: 100% H-Lin-PC (black curve), 80% H-Lin-PC and 20% D2-Lin-PC (pink curve), 50% H-Lin-PC and 50% D2-Lin-PC (green curve), 100% D2-Lin-PC (blue curve), and 100% H-Lin-PC with 100 μM antioxidant trolox (cyan curve). Red curves in Figure 1 are 100% H-Lin-PC controls without ferrous ions. It can be seen that the green channel of C11-Bodipy fluorescence measurement (panel A) was more sensitive to changes in the level of LPO, since it had a larger range of changes and the sensitivity of the fluorescence signal to trolox was higher compared to the orange channel (panel B). However, the signal from the orange channel at 540-nm excitation was significantly higher, ensuring more reliable detection of weak signals. Figure 1 shows the significant protective effect of D2-Lin-PC in both the green channel and the orange channel. This protective effect was studied in detail in the subsequent kinetic experiments with excitation-emission wavelengths of 490/520 nm and 540/594 nm.

Figure 1. Emission spectra of C11-Bodipy (581/591) in lipid vesicles measured after 20-min incubation with 5 µM FeSO4 with the excitation at 490 nm (panel A) and at 540 nm (panel B). The following lipid compositions were used: 100% H-Lin-PC (black curve), 80% H-Lin-PC and 20% D2-Lin-PC (pink curve), 50% H-Lin-PC and 50% D2-Lin-PC (green curve), 100% D2-Lin-PC (blue curve), 100 % H-Lin-PC with the addition of 100 μM antioxidant trolox (cyan curve). Red curves are controls of 100 % H-Lin-PC without ferrous ions. The buffer contained 100 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris, 10 mM MES, pH 7.4. Lipid concentration, 10 μg/ml. The concentration of C11-Bodipy (581/591) was 0.4 µM. H-Lin-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; D2-Lin-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-(11,11-d2-linoleoyl)-phosphatidylcholine; MES: 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid.

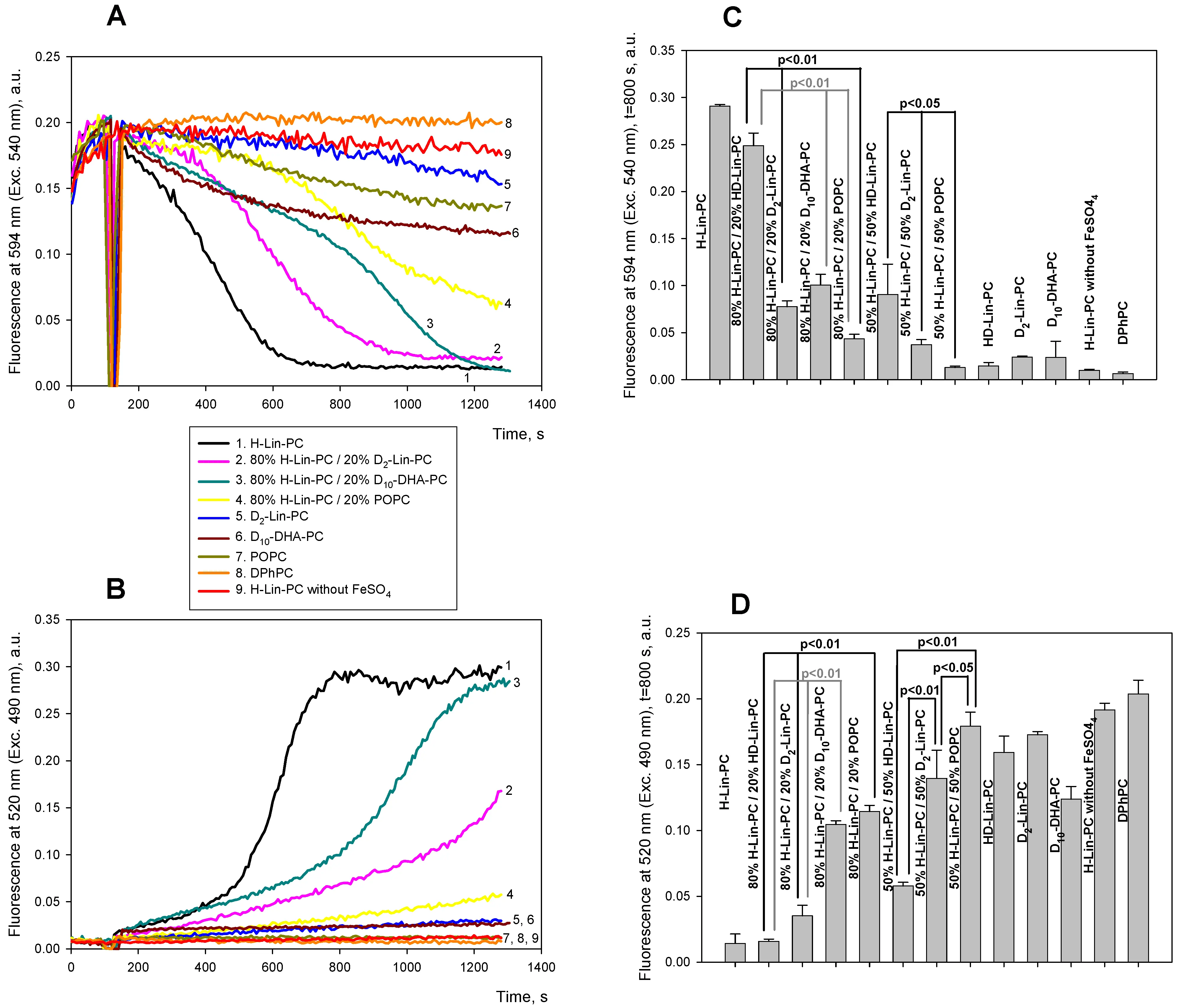

Panels A and B of Figure 2 show typical kinetics of C11-Bodipy fluorescence at 595 nm (panel A, exc. 540 nm) and at 520 nm (panel B, exc. 490 nm) for liposomes from pure H-Lin-PC (black curve), D2-Lin-PC (blue curve), POPC (dark yellow curve), 80% H-Lin-PC/20% D2-Lin-PC (pink curve), and 80% H-Lin-PC/20% POPC (yellow curve). 5 µM FeSO4 was added at 120 s for the induction of LPO (the red curve is a control without FeSO4). In the case of H-Lin-PC liposomes, the addition of ferrous ions resulted in a significant decrease in orange and an increase in green C11-Bodipy fluorescence on a minute time scale (black curve). C11-Bodipy fluorescence showed negligible changes in the case of D2-Lin-PC (blue curve) and POPC (dark yellow curve) liposomes, indicating that no peroxidation occurred in these lipids over this time scale. Comparison of the pink and yellow curves indicates a significantly higher degree of liposome oxidation in the case of 80% H-Lin-PC/20% D2-Lin-PC compared to 80% H-Lin-PC/20% POPC. Panels C and D of Figure 2 show statistical analysis of data, indicating significant differences between them, both in green (C) and orange (D) channels. We also tested liposomes made from HD-Lin-PC, having one deuterium atom at the C11 position, and found the level of LPO to be similar to that of D2-Lin-PC (9th pair of bars in Figure 2C,D). However, the level of oxidation in the case of 80% H-Lin-PC/20% HD-Lin-PC was significantly higher than in the case of 80% H-Lin-PC/20% D2-Lin-PC (second pair of bars in Figure 2C,D). The same series of protection strength (POPC > HD-Lin-PC > D2-Lin-PC) was observed at 50% content of these lipids in H-Lin-PC (5th-7th pairs of bars in Figure 2C,D). Figure 3 shows data on the accumulation of diene conjugates by liposomes of different compositions, which was recorded by an increase in absorption at 234 nm. The higher rate of LPO of 80% H-Lin-PC/20% D2-Lin-PC compared to 80% H-Lin-PC/20% POPC, was also observed using the diene conjugate measurements, but the difference was small and statistically insignificant.

Figure 2. Kinetics of lipid peroxidation in liposomes with various concentrations of deuterated linoleic acid in lipids. A and B. Fluorescence of 0.4 µM C11-Bodipy (581/591) at 595 nm (Exc. 540 nm, panel A) or at 520 nm (Exc. 490 nm, panel B) in the following lipid mixtures: 100% H-Lin-PC (black curve), 80% H-Lin-PC and 20% D2-Lin-PC (pink curve), 80% H-Lin-PC and 20% POPC (yellow curve), 100% D2-Lin-PC (blue curve), 100 % POPC (dark yellow curve), 80% H-Lin-PC and 20% D10-DHA-PC (dark cyan curve), 100% D10-DHA-PC (dark red curve). Red curve is a control of 100 % H-Lin-PC without ferrous ions. C and D. Statistical analysis of the signals at t = 800 s of green (C) and orange (D) channels after the addition of ferrous ions for lipid mixtures shown in panel A and B plus 100 % HD-Lin-PC using Student’s test. H-Lin-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; D2-Lin-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-(11,11-d2-linoleoyl)-phosphatidylcholine; D10-DHA-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-(6,6,9,9,12,12,15,15,18,18-d10-docosahexaenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine.

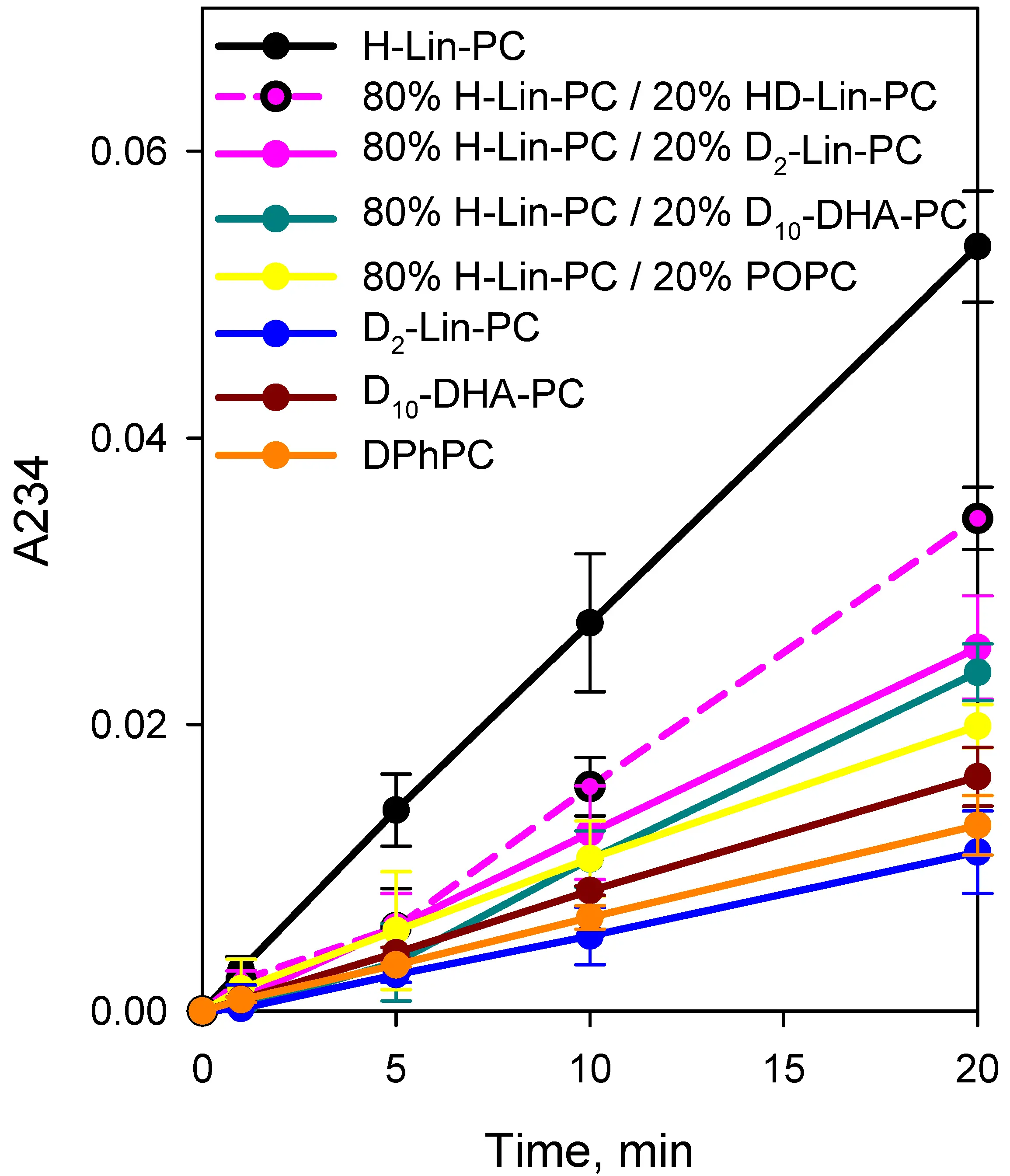

Figure 3. Kinetics of accumulation of diene conjugates in 100% H-Lin-PC (black curve), 80% H-Lin-PC and 20% D2-Lin-PC (pink curve), 80% H-Lin-PC and 20% POPC (yellow curve), 100% D2-Lin-PC (blue curve), 80% H-Lin-PC and 20% D10-DHA-PC (dark cyan curve), 100% D10-DHA-PC (dark red curve). Other experimental conditions were as in the legend to Figure 1. H-Lin-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; POPC: 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine; D2-Lin-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-(11,11-d2-linoleoyl)-phosphatidylcholine; D10-DHA-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-(6,6,9,9,12,12,15,15,18,18-d10-docosahexaenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine.

Figure 2 displays the effect of 1-stearoyl-2-(6,6,9,9,12,12,15,15,18,18-d10-docosahexaenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (D10-DHA-PC) on the level of LPO in a mixture with H-Lin-PC. The protective effect of 20% D10-DHA-PC was similar to that of 20% D2-Lin-PC (dark cyan curve in Figure 2A,B). The diene conjugate data presented in Figure 3 and Table 1 showed similar protective effects of 20% deuterated lipids on the peroxidation of H-Lin-PC-containing liposomes in the following mixtures: 20% D10-DHA-PC/80% H-Lin-PC and 20% D2-Lin-PC/80% H-Lin-PC.

| Lipid compositions | Slope in min-1 |

| 1. H-Lin-PC | 0.00266 ± 0.000021 |

| 2. 80% H-Lin-PC/20% HD-Lin-PC | 0.00172 ± 0.000095 |

| 3. 80% H-Lin-PC/20% D2-Lin-PC | 0.00128 ± 0.000015 |

| 4. 80% H-Lin-PC/20% D10-DHA-PC | 0.00121 ± 0.000072 |

| 5. 80% H-Lin-PC/20% POPC | 0.000984 ± 0.000024 |

| 6. D2-Lin-PC | 0.000562 ± 0.000012 |

| 7. D10-DHA-PC | 0.00082 ± 0.0000072 |

| 8. DPhPC | 0.000646 ± 0.0000041 |

H-Lin-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; D2-Lin-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-(11,11-d2-linoleoyl)-phosphatidylcholine; D10-DHA-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-(6,6,9,9,12,12,15,15,18,18-d10-docosahexaenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine; DPhPC: 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine.

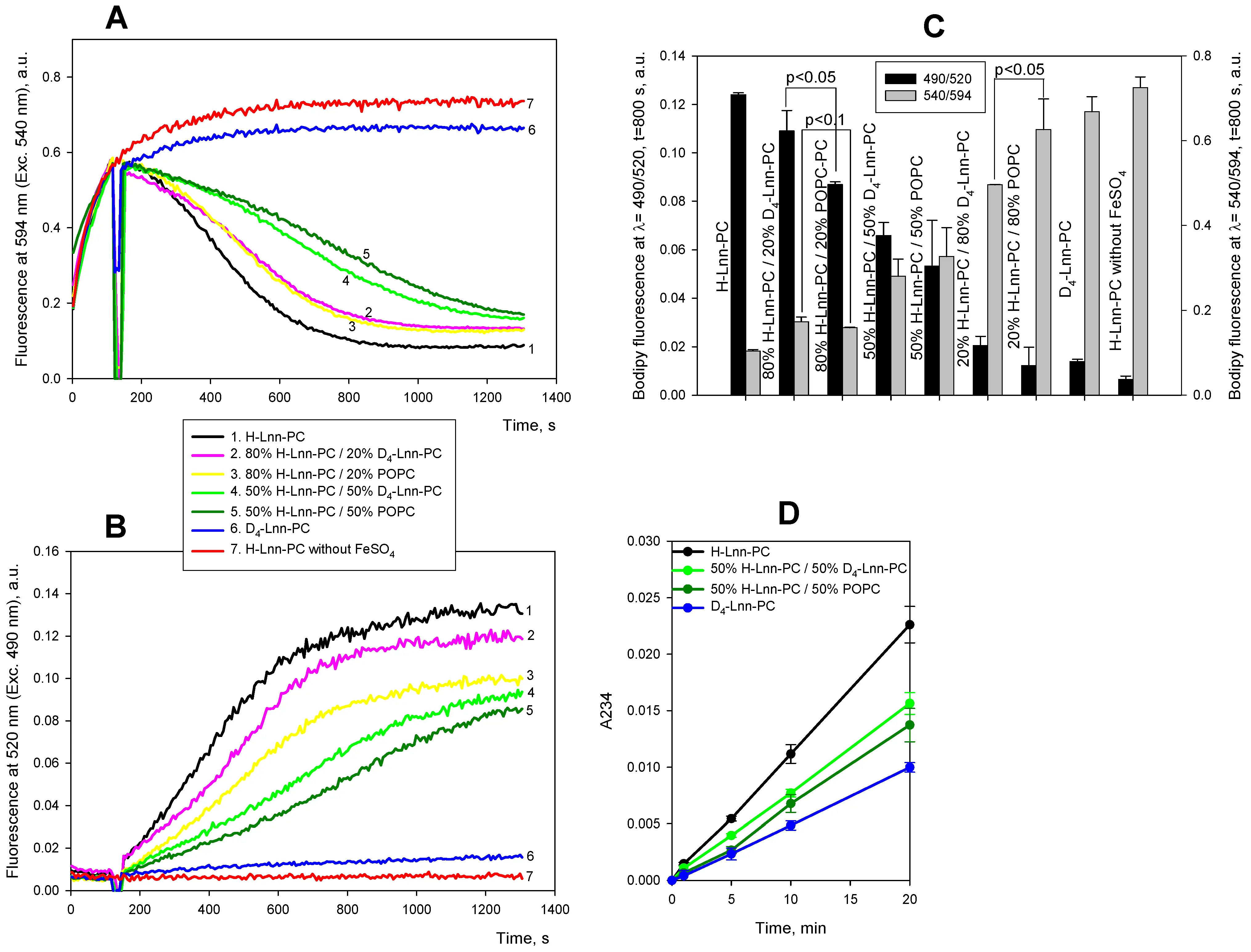

Figure 4 shows a series of results using mixtures of linolenic acid-based lipids having two bis-allylic positions at C11 and C14. Similar to the data shown in Figure 2 for linoleic acid-based lipids, the addition of ferrous ions to H-Lnn-PC resulted in a significant decrease in orange (black curve in panel A) and an increase in green C11-Bodipy fluorescence (black curve in panel B) within a matter of minutes (black curve). The C11-Bodipy fluorescence in D4-Lnn-PC liposomes (blue curves in Figure 4A,B) followed the control curve without the addition of FeSO4 (red curves), suggesting the suppression of lipid peroxidation upon deuteration of bis-allylic C11 and C14. The pink and yellow curves in Figure 4A,B show results of the experiments with 80% H-Lnn-PC/20% D4-Lnn-PC and 80% H-Lnn-PC/20% POPC to H-Lin-PC liposomes. The addition of POPC provided a stronger protection to the liposomes (Figure 4B), although the effect was small and the curves almost overlapped (Figure 4A). The green and dark green curves in Figure 4A,B show results of the experiments with the addition of 50% H-Lnn-PC / 50% D4-Lnn-PC and 50% H-Lnn-PC/50% POPC to H-Lin-PC liposomes. The protective effect of POPC considerably exceeded that of D4-Lnn-PC at the increased concentration. Panel C shows statistical analysis of these data and of the data with 20% H-Lnn-PC/80% D4-Lnn-PC and 20% H-Lnn-PC/80% POPC liposomes. The diene conjugate data presented in Figure 4D and Table 2 also revealed the higher rate of peroxidation of 50% H-Lnn-PC/50% D2-Lin-PC compared to 50% H-Lnn-PC/50% POPC; however, the difference was small and statistically insignificant.

Figure 4. Kinetics of lipid peroxidation in liposomes with different concentration of deuterated linolenic acid in lipids. A and B. Fluorescence of 0.4 µM C11-Bodipy (581/591) at 595 nm (Exc. 540 nm, panel A) or at 520 nm (Exc. 490 nm, panel B) in the following lipid mixtures: 100% H-Lnn-PC (black curve), 80% H-Lnn-PC and 20% D4-Lnn-PC (pink curve), 80% H-Lnn-PC and 20% POPC (yellow curve), 100% D4-Lnn-PC (blue curve), 100% POPC (dark yellow curve). Red curve is a control of 100% H-Lnn-PC without ferrous ions. C. Statistical analysis of the signals at t = 800 s after the addition of ferrous ions using Student’s test. D. Kinetics of accumulation of diene conjugates in 100% H-Lnn-PC (black curve), 50% H-Lnn-PC and 50% D4-Lnn-PC (pink curve), 50% H-Lnn-PC and 50% POPC (yellow curve), 100% D4-Lnn-PC (blue curve). Other experimental conditions were as in the legend to Figure 1. D4-Lnn-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-(11,11,14,14-D4-linolenyl)-phosphatidylcholine; H-Lin-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; POPC: 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine.

| Lipid compositions | Slope in min-1 |

| 1. H-Lnn-PC | 0.00112 ± 0.000014 |

| 2. 50% H-Lnn-PC/50% D4-Lnn-PC | 0.000773 ± 0.0000099 |

| 3. 50% H-Lnn-PC/50% POPC | 0.000692 ± 0.000023 |

| 4. D4-Lnn-PC | 0.000501 ± 0.0000050 |

H-Lin-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; D4-Lnn-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-(11,11,14,14-D4-linolenyl)-phosphatidylcholine; POPC: 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine.

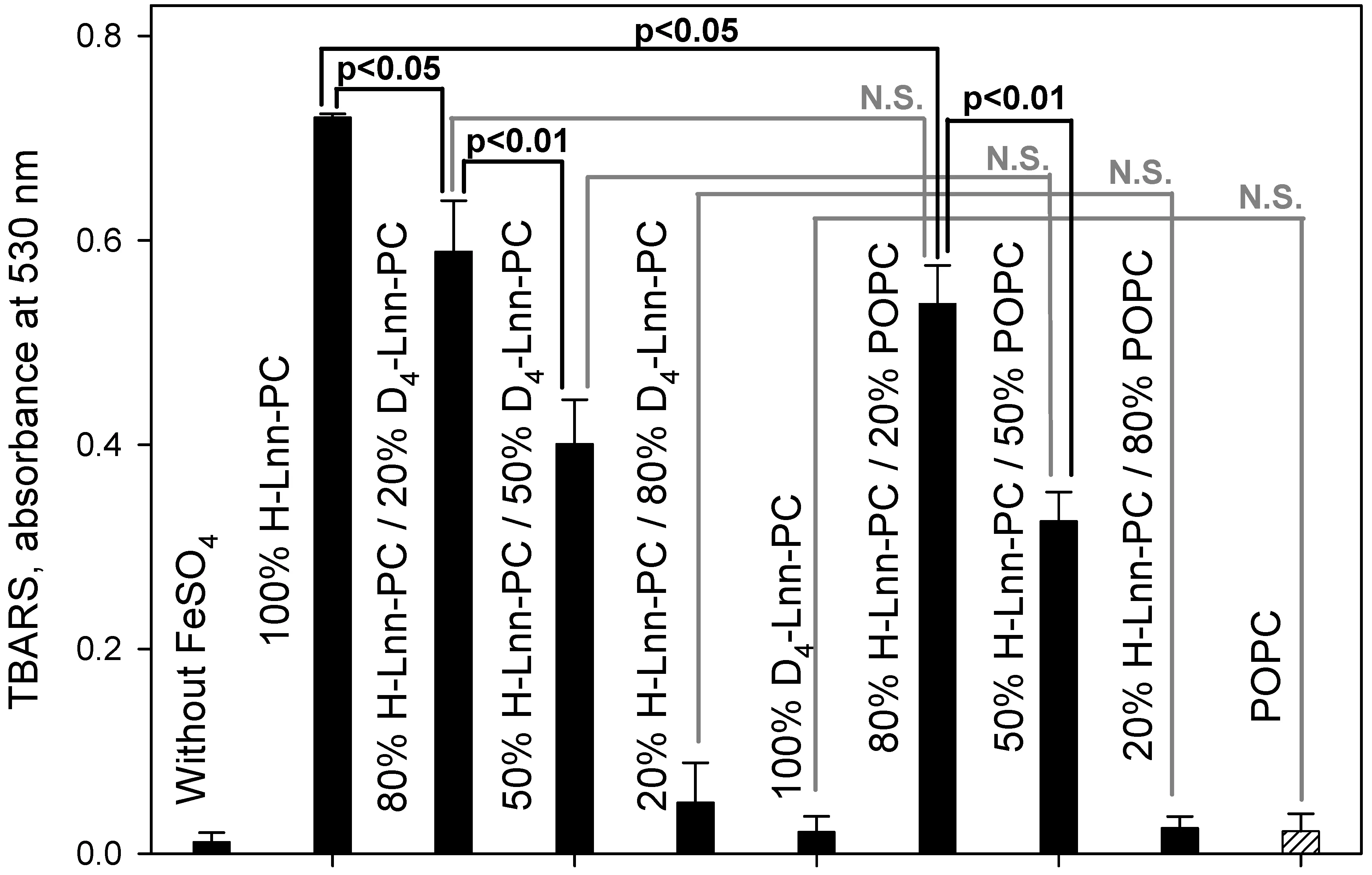

One of the end-products of peroxidation of PUFA is malondialdehyde (MDA), which forms a colored conjugate with thiobarbituric acid (TBARS). Figure 5 presents data comparing the accumulation of TBARS in liposomes made on the basis of linolenic acid. Comparison of bars 3 and 7 (20% D-PUFA or POPC), bars 4 and 8 (50% D-PUFA or POPC), and bars 5 and 9 (80% D-PUFA or POPC) suggests that the effects of D-PUFA and POPC on TBARS accumulation are similar and statistically indistinguishable for H-Lnn-PC-based formulations. These data are consistent with the finding, based on C11-Bodipy fluorescence analysis, that D-PUFAs strongly inhibit the rate of PUFA peroxidation.

Figure 5. Accumulation of malondialdehyde via colored product with thiobarbituric acid (TBARS) in liposomes of H-Lnn-PC/D4-Lnn-PC/POPC. The time of incubation with 5 µM FeSO4 was 10 min. For experimental details see Methods. Statistical analysis of the signals using Student’s test. N.S., not significant. D4-Lnn-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-(11,11,14,14-D4-linolenyl)-phosphatidylcholine; H-Lin-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; POPC: 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine.

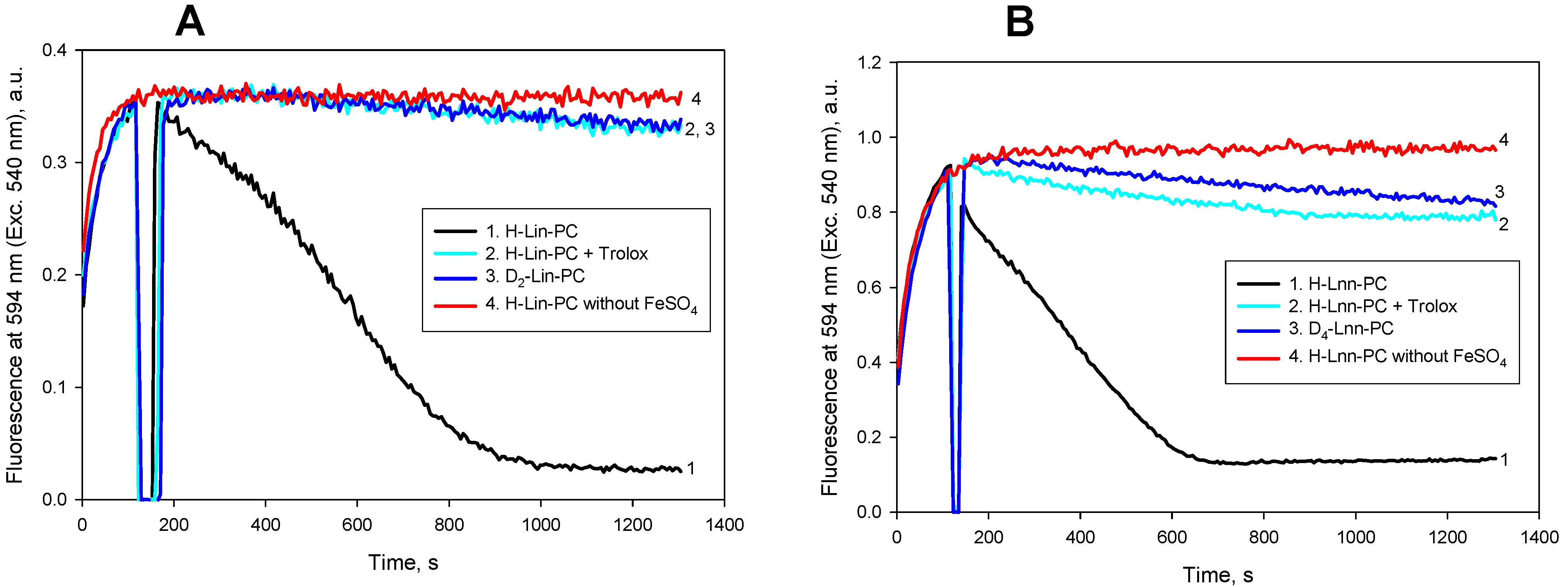

In addition, we studied the effect of antioxidant trolox on the kinetics of LPO measured by the fluorescence of C11-Bodipy induced by FeSO4 for liposomes on the basis of linoleic acid (Figure 6A) and linolenic acid (Figure 6B). In both cases 100 μM trolox almost completely suppressed the development of peroxidation (cyan curves in Figure 6A,B, respectively).

Figure 6. Kinetics of lipid peroxidation of liposomes with linoleic acid (panel A), and linolenic acid (panel B). Fluorescence of 0.4 µM C11-Bodipy (581/591) at 595 nm (Ext 540 nm) was measured for H-PUFA (black curves), 100 % D-PUFA (blue curves) and H-PUFA with 100 µM trolox (cyan curves). Red curves are controls without the addition of ferrous ions. Other experimental conditions were as in the legend to Figure 1. H-Lin-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; H-PUFA: protiated polyunsaturated fatty acids; D-PUFA: deuterated polyunsaturated fatty acids; D2-Lin-PC: 1-stearoyl-2-(11,11-d2-linoleoyl)-phosphatidylcholine.

4. Discussion

The data obtained support the idea that the deuterated lipids D2-Lin-PC, D4-Lnn-PC, and D10-DHA-PC, as well as POPC, do not participate in the process of LPO. Previously, the protective effect of lipid containing oleic acid was observed in a liposome system of a mixture of DPPC, DOPC, and 1,2-dilinolenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine[20,21]. The authors noted that the “antioxidant”-like protective effect of oleic acid in phospholipids was preserved when DOPC was used as a source of oleic acid.

The inhibitory action of MUFA-containing lipids on ferroptosis[24,25], along with its suppression by antioxidants such as vitamin A[38] and D-PUFA[24,39], supports the idea that ferroptosis is based on LPO, which is mechanistically similar in cellular and artificial lipid membranes, although ferroptosis depends on the activity of certain enzymes.

To explain the strong dependence of non-deuterated membrane H-PUFA oxidation on D-PUFA content, a simplified model of a 2D facet surface populated with a selected density of D-PUFA cells (which would “stop” the chain propagation with varying probability) among oxidizable H-PUFA cells has been proposed[16,35]. The model considers a two-dimensional grid with a random distribution of oxidizable and non-oxidizable cells. The "propagation of chain reaction" proceeds from a central cell in accordance with whether there is an oxidizable lipid nearby (one step ahead in the propagation), or a non-oxidizable lipid nearby (a chain break in the reaction). A Monte-Carlo simulation was developed and showed that with an increase in the proportion of non-oxidizable cells, the length of the oxidation chain track decreased, and at a certain small proportion (about 5%), the oxidation chain was terminated. This means that at sufficiently small proportion of non-oxidizable lipid (POPC or D-PUFA), the oxidation chain is terminated after just a few steps of the process due to an encounter with three neighboring non-oxidizable cells that surround the current cell. Clearly, such a model is an extreme simplification of a real process of LPO, but it provides a qualitative answer to the question of why the presence of non-oxidizable lipids can have a strong protective effect.

Various metrics exist for assessing the extent of LPO. Firsov and co-authors used the leakage of fluorophore molecules from liposomes as a measure of membrane integrity[35]. It was demonstrated that this metric is very similar to the UV absorbance measurement at 234 nm, which, by detecting conjugated dienes, evaluates the extent of bulk LPO in PUFA-containing bilayers. While it is arguable which bilayer damage would lead to the liposome membrane failing to contain the molecules trapped inside, the formation of conjugated dienes represents one of the initial steps of the PUFA oxidative damage, immediately following the hydrogen abstraction off a bis-allylic site. In the current work, we assessed different end-points. While C11-BODIPY (581/591) data report on the formation of lipid peroxyl radicals, where the full length of the PUFA backbone would be expected to be intact, the aldehydes detected by TBARS represent a downstream process likely concomitant with the PUFA backbone fragmentation. Therefore, the data obtained here and by Firsov et al.[35] should not be expected to fully match. In a similar way, the industrial methods of seed oil quality control rely on Peroxidation Value (PoV, measurements of peroxides) and Anisidine Value (AV, detection of carbonyls), and the quality assessment relies on both values (PoV may be low because there is no oxidation, or because the peroxides disappear as they are converted into carbonyls).

Liposomes model the lipid bilayer but lack any associated biochemistry, like availability of ROS and antioxidants, repair enzymes, cleanup and waste disposal systems, replenishment of damaged elements, etc. It is therefore likely that the observations reported herein may not directly correlate with cell culture or animal studies and can serve only as a very rough qualitative guide to relative oxidation proclivity of the PUFA-containing membranes.

The major consequence of LPO is the formation of a smorgasbord of toxic reactive carbonyl compounds such as HNE, HHE and MDA, which are not radicals and hence cannot be neutralized by most antioxidants. These diffuse away, cross-linking molecules in membranes and aqueous compartments alike, making up a very substantial part of an LPO-associated damage[40]. The monitoring methods used in this paper – C11-BODIPY (581/591) (detects lipid peroxide species) and TBARS (a low-resolution method unable to distinguish between various carbonyls) – would not report on this aspect of LPO. D-PUFAs were previously shown to reduce the levels of reactive carbonyls[14], and can therefore be recommended as a reliable tool for reducing the LPO-inflicted damage in the natural, in vivo setting.

Finally, supplementing dietary MUFAs to decrease LPO in vivo is impractical. MUFAs are produced by organisms, and so adding them to the diet will not result in a dramatic change in their availability. More importantly, the PUFA composition of the key lipid membranes, such as in the eyes or neurons, is precisely maintained, and changing the dietary intake will not change the PUFA ratios[41]. Membranes of human neurons contain DHA and ARA in an approximate ratio of 55 to 45%, while DHA, at 80%, is the dominant PUFA in the retina[42]. PUFA composition of blood vessels walls, mitochondria, heart, and other compartments is also tightly controlled. The pre-defined PUFA composition rules out the use of more oxidation-resistant FAs, such as SFA or MUFA, as a way of reducing membrane peroxidation. As antioxidants are inefficient for stoichiometric and other reasons, D-PUFAs emerge as the only available method of allaying LPO.

5. Limitations

The main limitation of this study is the reliance on models other than whole organism. This is an important mechanistic step towards an efficient drug. However, practical applications will require animal model experiments to establish to what extent dosing of MUFAs or D-PUFAs can control the MUFA/PUFA composition in key lipid membranes. The animal studies, currently at the planning stage, will involve different models (cancer and neurology) and will be dosed with different combinations of MUFA-D-PUFA oils to establish the therapeutic window for the optimal LPO inhibition, depending on the target organ pathology.

6. Conclusion

Non-oxidizable lipids with less than two double bonds, such as POPC, similar to the deuterated lipids D2-Lin-PC, D4-Lnn-PC, and D10-DHA-PC, inhibit the lateral propagation of the chain reaction of LPO in lipid membranes. They do not participate in LPO themselves. This fact makes D-PUFAs an attractive alternative to antioxidants in addressing various pathologies known to involve lipid peroxidation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Moscow State University Development Program PNR5 for providing access to the CM2203 spectrofluorimeter.

Authors contribution

Antonenko YN, Shchepinov MS: Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, visualization, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Firsov AM, Sharko OL, Shmanai VV: Investigation, formal analysis, visualization, validation.

Kotova EA: Writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the State assignment of Lomonosov Moscow State University (No. АААА-А19-119031390114-5).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Zheng Y, Sun J, Luo Z, Li Y, Huang Y. Emerging mechanisms of lipid peroxidation in regulated cell death and its physiological implications, Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(11):859.[DOI]

-

2. Halliwell B. Understanding mechanisms of antioxidant action in health and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25(1):13-33.[DOI]

-

3. Chandimali N, Bak SG, Park EH, Lim HJ, Won YS, Kim EK, et al. Free radicals and their impact on health and antioxidant defenses: A review. Cell Death Discov. 2025;11(1):19.[DOI]

-

4. Villalón-García I, Povea-Cabello S, Álvarez-Córdoba M, Talaverón-Rey M, Suárez-Rivero JM, Suárez-Carrillo A, et al. Vicious cycle of lipid peroxidation and iron accumulation in neurodegeneration. Neural Regen Res. 2023;18(6):1196-1202.[DOI]

-

5. Farooqui AA, Horrocks LA. Lipid peroxides in the free radical pathophysiology of brain diseases, Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1998;18(6):599-608.[DOI]

-

6. Jahn U, Galano JM, Durand T. Beyond prostaglandins--chemistry and biology of cyclic oxygenated metabolites formed by free-radical pathways from polyunsaturated fatty acids, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47(32):5894-5955.[DOI]

-

7. Lee JCY, Durand T. Lipid peroxidation: Analysis and applications in biological systems. Antioxidants. 2019;8(2):40.[DOI]

-

8. Martins WK, Santos NF, Rocha CdS, Bacellar IOL, Tsubone TM, Viotto AC, et al. Parallel damage in mitochondria and lysosomes is an efficient way to photoinduce cell death. Autophagy. 2019;15(2):259-279.[DOI]

-

9. Rezende LG, Tasso TT, Candido PHS, Baptista MS. Assessing photosensitized membrane damage: Available tools and comprehensive mechanisms. Photochem Photobiol. 2022;98(3):572-590.[DOI]

-

10. Abramova A, Bride J, Oger C, Demion M, Galano JM, Durand T, et al. Metabolites derived from radical oxidation of PUFA: NEO-PUFAs, promising molecules for health? Atherosclerosis. 2024;398:118600.[DOI]

-

11. Sassano ML, Tyurina YY, Diokmetzidou A, Vervoort E, Tyurin VA, More S, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria contacts are prime hotspots of phospholipid peroxidation driving ferroptosis, Nat Cell Biol. 2025;27(6):902-917.[DOI]

-

12. Higashi Y. Roles of oxidative stress and inflammation in vascular endothelial dysfunction-related disease. Antioxidants. 2022;11(10):1958.[DOI]

-

13. Gęgotek A, Skrzydlewska E. Lipid peroxidation products' role in autophagy regulation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;212:375-383.[DOI]

-

14. Shchepinov MS. Polyunsaturated fatty acid deuteration against neurodegeneration. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2020;41(4):236-248.[DOI]

-

15. Firsov AM, Franco MSF, Chistyakov DV, Goriainov SV, Sergeeva MG, Kotova EA, et al. Deuterated polyunsaturated fatty acids inhibit photoirradiation-induced lipid peroxidation in lipid bilayers. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2022;229:112425.[DOI]

-

16. Hill S, Lamberson CR, Xu L, To R, Tsui HS, Shmanai VV, et al. Small amounts of isotope-reinforced polyunsaturated fatty acids suppress lipid autoxidation. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53(4):893-906. [DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.06.004][DOI]

-

17. Elharram A, Czegledy NM, Golod M, Milne GL, Pollock E, Bennett BM, et al. Deuterium-reinforced polyunsaturated fatty acids improve cognition in a mouse model of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. FEBS J. 2017;284(23):4083-4095.[DOI]

-

18. Wagner BA, Buettner GR, Burns CP. Free radical-mediated lipid peroxidation in cells: oxidizability is a function of cell lipid bis-allylic hydrogen content. Biochemistry. 1994;33(15):4449-4453.[DOI]

-

19. Bochkov VN, Oskolkova OV, Birukov KG, Levonen AL, Binder CJ, Stöckl J. Generation and biological activities of oxidized phospholipids. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12(8):1009-1059.[DOI]

-

20. Cortie CH, Else PL. An antioxidant-like action for non-peroxidisable phospholipids using ferrous iron as a peroxidation initiator. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1848(6):1303-1307.[DOI]

-

21. Lee C, Barnett J, Reaven PD. Liposomes enriched in oleic acid are less susceptible to oxidation and have less proinflammatory activity when exposed to oxidizing conditions. J Lipid Res. 1998;39(6):1239-1247.[DOI]

-

22. Balasubramanian KA, Nalini S, Manohar M. Nonesterified fatty acids and lipid peroxidation, Mol Cell Biochem. 1992;111(1):131-135.[DOI]

-

23. Balasubramanian KA, Nalini S, Cheeseman KH, Slater TF. Nonesterified fatty acids inhibit iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1003(3):232-237.[DOI]

-

24. Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, Patel M, Shchepinov MS, Stockwell BR. Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2016;113(34):E4966-E4975.[DOI]

-

25. Magtanong L, Ko PJ, To M, Cao JY, Forcina GC, Tarangelo A, et al. Exogenous monounsaturated fatty acids promote a ferroptosis-resistant cell state. Cell Chem Biol. 2019;26(3):420-432.e429.[DOI]

-

26. Ubellacker JM, Tasdogan A, Ramesh V, Shen B, Mitchell EC, Martin-Sandoval MS, et al Lymph protects metastasizing melanoma cells from ferroptosis, Nature. 2020;585(7823):113-118.[DOI]

-

27. Jiang X, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22(4):266-282.[DOI]

-

28. Stockwell BR. Ferroptosis turns 10: Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic applications. Cell. 2022;185(14):2401-2421.[DOI]

-

29. Liang D, Minikes AM, Jiang X. Ferroptosis at the intersection of lipid metabolism and cellular signaling. Mol Cell. 2022;82(12):2215-2227.[DOI]

-

30. Rodencal J, Dixon SJ. A tale of two lipids: Lipid unsaturation commands ferroptosis sensitivity. Proteomics. 2023;23(6):2100308.[DOI]

-

31. Pope LE, Dixon SJ. Regulation of ferroptosis by lipid metabolism. Trends Cell Biol. 2023;33(12):1077-1087.[DOI]

-

32. Lin Z, Long F, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Yang M, Tang D. The lipid basis of cell death and autophagy. Autophagy. 2024;20(3):469-488.[DOI]

-

33. Li Z, Lange M, Dixon SJ, Olzmann JA. Lipid quality control and ferroptosis: From concept to mechanism. Annu Rev Biochem. 2024;93:499-528.[DOI]

-

34. Shan K, Fu G, Li J, Qi Y, Feng N, Li Y, et al. Cis-monounsaturated fatty acids inhibit ferroptosis through downregulation of transferrin receptor 1. Nutr Res. 2023;118:29-40.[DOI]

-

35. Firsov AM, Fomich MA, Bekish AV, Sharko OL, Kotova EA, Saal HJ, et al. Threshold protective effect of deuterated polyunsaturated fatty acids on peroxidation of lipid bilayers. FEBS J. 2019;286(11):2099-2117.[DOI]

-

36. Drummen GPC, van Liebergen LCM, Op den Kamp JAF, Post JA. C11-BODIPY581/591, an oxidation-sensitive fluorescent lipid peroxidation probe: (micro)spectroscopic characterization and validation of methodology. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;33(4):473-490.[DOI]

-

37. Pap EHW, Drummen GPC, Winter VJ, Kooij TWA, Rijken P, Wirtz KWA, et al. Ratio-fluorescence microscopy of lipid oxidation in living cells using C11-BODIPY581/591. FEBS Lett. 1999;453(3):278-282.[DOI]

-

38. Tschuck J, Padmanabhan Nair V, Galhoz A, Zaratiegui C, Tai HM, Ciceri G, et al. Suppression of ferroptosis by vitamin A or radical-trapping antioxidants is essential for neuronal development. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7611.[DOI]

-

39. von Krusenstiern AN, Robson RN, Qian N, Qiu B, Hu F, Reznik E, et al. Identification of essential sites of lipid peroxidation in ferroptosis, Nat Chem Biol. 2023;19(6):719-730.[DOI]

-

40. Fritz KS, Petersen DR. An overview of the chemistry and biology of reactive aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;59:85-91.[DOI]

-

41. Pilecky M, Závorka L, Arts MT, Kainz MJ. Omega-3 PUFA profoundly affect neural, physiological, and behavioural competences – implications for systemic changes in trophic interactions. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2021;96(5):2127-2145.[DOI]

-

42. Lafuente M, Rodríguez González-Herrero ME, Romeo Villadóniga S, Domingo JC. Antioxidant activity and neuroprotective role of docosahexaenoic acid (dha) supplementation in eye diseases that can lead to blindness: A narrative review. Antioxidants. 2021;10(3):386.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite