Rajiv R. Ratan, Burke Neurological Institute, White Plains, NY 10605, USA. E-mail: rrr2001@med.cornell.edu

Abstract

Ferroptosis, a non-apoptotic regulated cell death culminating in iron-dependent lipid peroxidation, has rapidly emerged as an additional mechanism of neuronal death after stroke. Yet, despite converging molecular features, such as the collapse of antioxidant systems and oxidation of lipids, the upstream biochemical landscapes that trigger ferroptosis differ across ischemic and hemorrhagic injury. In this review, we examine ferroptosis as an emergent property of redox network failure, where the transcriptional, metabolic, and oxidative circuits that normally sustain neuronal resilience are interrupted. Cells continuously operate within a spectrum of oxidative eustress and distress, balancing reactive species that serve as physiological signals and limiting their ability to inflict irreversible damage. Within this continuum, eustress supports adaptive redox signaling, metabolic coupling, and repair, whereas distress reflects exhaustion of reducing power and a shift toward self-propagative oxidation. Drawing on evidence from our lab and others, we explore how distinct stress inputs drive neurons and glia along this continuum toward ferroptotic collapse following each stroke subtype; much of this work originated within reductionist in vitro ferroptotic models and has since been extended to in vivo models. Understanding ferroptosis after stroke not only as a graded failure of redox homeostasis but also an evolutionarily adapted mechanism to couple neuronal injury to the reparative immune response is essential. Effective neuroprotective strategies will therefore depend on identifying and targeting the context-specific triggers and temporal windows that define each stroke subtype.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Stroke remains a leading cause of death and long-term disability worldwide[1], yet effective neuroprotective therapies remain elusive. Stroke can be broadly categorized into ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke. Focal ischemia is caused by a vascular occlusion that restricts blood flow and oxygen delivery to downstream brain tissue[2], while intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) occurs due to extravasation of blood into the brain parenchyma from a ruptured cerebral arteriole[3]. Of the 12 million new strokes that occur globally each year, ~65% are ischemic, ~29% are ICH, and the remainder are subarachnoid hemorrhages, which are not addressed here[1]. While reperfusion strategies have transformed outcomes in a subset of ischemic stroke patients, they remain time-limited[2]. Additionally, the abrupt restoration of blood flow can itself precipitate reperfusion injury, amplifying oxidative and inflammatory damage[2]. Most ICH patients can receive only supportive medical management[3]. While recent trials of minimally invasive hematoma evacuation have shown benefit, this has largely been confined to lobar ICH, representing a minority of cases[4]. In both stroke subtypes, the molecular processes that dictate whether neurons survive or degenerate remain uncontrolled, leading to progressive secondary injury within penumbral or perihematomal tissue.

Among these molecular processes, ferroptosis has emerged as a compelling mechanism linking dyshomeostasis of reactive lipids to cellular degeneration after stroke. First characterized by Dixon et al. in 2012[5], ferroptosis is a regulated form of cell death driven by a failure of cellular antioxidant reserves, resulting in iron-dependent lipid peroxidation and terminal membrane failure[6]. While ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke engage ferroptotic pathways in both animal models and patients[7-14], each does so via distinct upstream mechanisms. During an ischemic stroke, deprivation of oxygen and glucose halts mitochondrial respiration and antioxidant regeneration, predisposing penumbral neurons to oxidative injury upon reperfusion[15]. By contrast, ICH results in oxidation of extravasated hemoglobin from lysed red blood cells, liberating iron-containing heme species that ultimately catalyze neuronal lipid peroxidation within hematomal and perihematomal tissue[16,17].

Despite these diverging biochemical environments, the occurrence of ferroptotic death in both ischemia and ICH reflects a shared failure of dynamic redox homeostasis, in which neurons cannot adequately adapt to insult-specific stressors. Neurons continuously balance oxidation and reduction reactions to sustain their function and plasticity, a dynamic homeostasis maintained through coordinated metabolic and transcriptional programs[18,19]. Stroke pathology overwhelms these homeostatic responses, rendering them insufficient, mistimed, or misdirected. This allows oxidative species to accumulate, shifting their normally modulatory role into a lethal force[20] capable of driving lipid peroxidation and membrane failure. Effective therapeutic strategies will require us to understand how neurons attempt to adapt to insult-specific conditions, why these adaptations fail, and how this failure funnels diverse upstream stressors into ferroptotic death.

Our investigations into the mechanisms underlying neuronal ferroptosis in vitro have demonstrated consistent translational relevance to in vivo stroke models. We employ two in vitro models of ferroptotic neuronal death (Figure 1), one of which originated at Johns Hopkins in the late 1980s through work done by Murphy, Coyle, and colleagues[21]. In this review, we discuss how these in vitro models of ferroptosis have advanced our understanding of therapeutic strategies to mitigate neuronal death after ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.

Figure 1. To model ferroptosis in neurons following ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, our laboratory isolates primary cortical neurons from E16 rat pups, which are incubated for at least 24 hours. After DIV-1, immature neurons are treated with glutamate, HCA, erastin, or RSL3 to model ischemic stroke. Alternatively, cultures are treated with hemin or hemoglobin to model hemorrhagic stroke. Neurons are assayed within 24 hours of treatment for viability, transcriptional responses, and other endpoints. DIV: days in vitro; HCA: homocysteic acid; RSL3: RAS-selective lethal 3.

2. The Emergence of Ferroptosis: Lessons from In Vitro Models

Glutamate is well established as a neurotoxin capable of inducing neuronal death through receptor-mediated excitotoxicity, a framework that has guided decades of neuroprotection research in stroke[22]. However, many candidate therapies have failed in clinical translation[22].

The reasons for these shortcomings are multifactorial, but a key limitation of excitotoxicity-based culture models is their rapid progression: injury occurs so swiftly[22] that causative events cannot be easily distinguished from secondary consequences. Other oxidative stress-based models relevant to stroke often rely on the exogenous application of non-physiological concentrations of oxidants (e.g., H2O2)[23,24], further constraining their translational relevance.

In the late 1980s, Murphy and Coyle observed that glutamate-induced cytotoxicity in the neuroblastoma-retinal hybrid cell line N18-RE-105 could be modulated by cystine availability in the medium[21]. Like immature cortical neurons, N18-RE-105 cells lack N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, revealing a receptor-independent mechanism of glutamate cytotoxicity[21,25]. This and subsequent work demonstrated that excess extracellular glutamate can kill neurons by blocking the cystine/glutamate antiporter system Xc-, depriving cells of cystine required for glutathione (GSH) synthesis[21,25,26]. As a key co-factor for antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase-4 (GPX4; the only known selenoenzyme that can detoxify lipid peroxides), GSH depletion results in progressive lipid peroxidation and neuronal death[26]. In 2001, Tan et al. defined this as a distinct form of cell death termed “oxytosis”[27]. Unlike apoptosis, this NMDA receptor-independent oxidative death proceeds slowly (over the course of ~24 hours), features necrotic membrane rupture rather than caspase activation, and is exacerbated, not rescued, by growth factor withdrawal[28]. Instead of an abrupt execution phase, neuronal demise is driven by a progressive erosion of redox balance, with GSH depletion reaching a steady state by ~6 hours. This delay between the onset of death and terminal execution is a defining ferroptotic feature that reflects the gradual collapse of antioxidant capacity over time.

Together, these ideas foreshadowed what would later be recognized as ferroptosis, as defined by Dixon and Stockwell in 2012[5]. While screening for compounds selectively lethal to oncogenic RAS-mutant tumor cells, Stockwell’s group identified erastin, a small molecule that reproduced the same cystine-starvation and glutathione depletion observed in glutamate-induced death by directly inhibiting system Xc-. The same screen revealed RAS-selective lethal 3 (RSL3), which acts downstream of erastin by directly inhibiting GPX4[5]. By introducing pharmacologically tractable tools and a unified biochemical framework, Dixon and Stockwell’s definition of ferroptosis quickly gained widespread acceptance. Together, the discovery of erastin and RSL3 established ferroptosis as a hierarchical process that is initiated by depletion of reducing power and amplified by loss of enzymatic peroxide control.

This conceptual foundation proved essential for translating ferroptosis into models of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Following ischemia, ferroptosis is likely driven by a combination of glutamate-mediated inhibition of system Xc- and bioenergetic stress, as oxygen and glucose deprivation within oligemic or hypo-perfused tissue work in parallel to diminish nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and glutathione regeneration, a situation exacerbated by reperfusion[29]. Therefore, application of glutamate, erastin, or RSL3 can be used to model ferroptosis following ischemia in vitro by exhausting reducing capacity through cystine starvation or GPX4 inhibition (Figure 1). In contrast, ICH introduces an exogenous source of catalytic stress. The rupture of small arterioles floods the parenchyma with erythrocytes, whose lysis releases hemoglobin and hemin (the oxidized form of heme)[30]. Both promote ferroptosis through iron-catalyzed lipid peroxidation and consumption of GSH and NADPH[30,31]. Hemin intercalates into lipid membranes and undergoes redox cycling, while hemoglobin degradation liberates ferrous iron, expanding the labile iron pool and overwhelming antioxidant defenses[30,31]. Accordingly, hemin and hemoglobin can be applied to primary neurons in vitro to model ferroptosis after ICH (Figure 1).

Together, the conceptual evolution from glutamate-induced cytotoxicity to erastin, RSL3, and finally to hemin and hemoglobin mirrors growing recognition of ferroptosis as a spectrum of redox network collapse induced by heterogeneous upstream stimuli.

3. Redox Networks as Determinants of Ferroptotic Susceptibility

By coupling energy production to redox signaling, cells are able to sense and adapt to fluctuations in oxygen, nutrients, and metabolic status. In neurons and other aerobic cells, these redox signals arise primarily from the mitochondrial electron transport chain, where a small fraction of electrons reduce oxygen to superoxide during oxidative phosphorylation. Additional oxidants come from regulated enzyme systems (e.g., NADPH oxidases, nitric oxide synthases, and peroxisomal metabolism), creating a baseline “redox tone” that is buffered via thiol metabolism (e.g., glutathione and thioredoxin systems)[18,19]. The reversible oxidation of cysteine and thiol-based switches within cytosolic and nuclear proteins transduce these redox signals, coordinating gene expression, protein synthesis, antioxidant defence, and energy metabolism via a series of feedback loops- a concept known as dynamic homeostasis[18,32]. Yet these same reactions can become destructive when regulation fails[32].

The dual capacity of oxidants to serve as both signaling molecules/modifiers and as agents of injury is referred to as the “redox paradox”[33]. In biological systems, low-level oxidative activity (e.g., “oxidative eustress”) sustains signaling and cellular plasticity, whereas excessive or unbuffered oxidative activity (e.g., “oxidative distress”) drives molecular damage (Figure 2). As an illustrative example, we have found that low-level H2O2 produced in astrocytes over a defined period (~7 hours) induces protective antioxidant signaling in neighbouring neurons, whereas high-level H2O2 production results in neuronal death[23]. This protective effect is dependent on intracellular generation of H2O2, and correlates with selective, reversible oxidation of protein tyrosine phosphatases[23].

Figure 2. In order to balance physiological oxidative pressure and maintain growth and plasticity (e.g., oxidative eustress), the “three pillars” of oxidative metabolism must remain intact: cellular iron control, thiol metabolism (e.g., cysteine and GSH), and regulation of PUFAs. Loss of any one pillar under supraphysiological oxidative pressure (such as following stroke) disrupts regulation of the others, resulting in maladaptive transcriptional programs that sway neurons towards uncontrolled oxidative distress, and eventually, cellular degeneration and ferroptosis. Following ischemic stroke, thiol metabolism is the first “lost pillar”, as energetic deficits impair GSH synthesis and recycling, which in turn disrupts labile iron control and allows lipid peroxidation to proceed unchecked. In hemorrhagic stroke, the first “lost pillar” is cellular iron control, as excessive iron from blood breakdown products overwhelms antioxidant defenses, permitting runaway lipid peroxidation. GSH: glutathione; PUFAs: polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Whether a cell experiences oxidative eustress or distress depends not only on absolute oxidant levels, but also on the source, duration, and pre-existing cellular state[34]. Resistance to oxidative pressure relies on how electrons are distributed and recycled among competing reactions. This redox economy is sustained by a network of reducing systems that together define the cell’s nucleophilic tone (e.g. the collective ability to donate electrons and maintain macromolecules in a reduced functional state). In this manner, ferroptosis can be understood as a systemic failure of three different “pillars” of metabolism (Figure 2), as described by Bayír and colleagues: iron control, the cysteine-glutathione axis (e.g., thiol metabolism), and regulation of polyunsaturated phospholipids (PUFAs)[35]. Normally, these systems operate together to sustain redox homeostasis: iron shuttles electrons, the cysteine-glutathione axis buffers them, and phospholipids act as both substrates and sensors of oxidative activity[35]. The integrity of these pillars feeds forward to transcriptional programs, as redox-sensitive signaling translates metabolic cues into gene expression and post-translational modifications that reinforce antioxidant defences. When this coordination is lost, adaptive signaling (e.g., oxidative eustress) collapses into self-propagating oxidative distress, maladaptive transcriptional responses emerge, and neurons are primed for ferroptotic death (Figure 2).

To dissect how this integrated neuronal redox network fails following stroke, our laboratory has examined the actions of canonical ferroptosis inhibitors that stabilize discrete control points[14,17]. Deferoxamine (DFO) limits iron-catalyzed radical formation and preserves NADPH-dependent buffering, while N-acetylcysteine (NAC) replenishes cystine-derived thiols and supports GSH synthesis. Radical trapping antioxidants (RTAs) such as vitamin E and ferrostatin-1 intercept lipid radicals to preserve membrane integrity. Finally, the MEK-ERK inhibitor U0126 reduces the activity of cMyc and transglutaminases, regulating iron import genes and epigenetically modulating homeostatic gene programs. Building on the mechanisms of these canonical inhibitors, we have explored additional strategies to stabilize these key nodes within the redox network and refine potential therapeutic targets. Together, this work has made it clear that neuronal ferroptotic death arises not from a single cellular event, but from the coordinated collapse of numerous different metabolic and transcriptional defences. Understanding these vulnerabilities will provide a roadmap for interventions aimed at restoring redox balance and protecting neurons after stroke.

3.1 Iron chelation and catalytic control

By definition, ferroptosis is iron-dependent, suppressed by structurally diverse iron chelators such as DFO[5]. To understand why iron plays such a decisive role, it must be viewed within its broader biological context. Across nearly all known life forms, the ability of iron to shuttle electrons has made it a cornerstone of metabolism, driving mitochondrial respiration, DNA synthesis, and lipid metabolism. Yet the same redox flexibility that makes iron indispensable also renders it hazardous when unregulated.

Within cells, controlled iron redox cycling supports oxidative eustress: localized, transient oxidation that tunes enzymatic activity, transcription, and metabolic flux. Indeed, these transient fluctuations in labile iron are not inherently harmful to neurons. Iron-mediated signaling facilitates neuronal growth, myelination, structural plasticity, synaptic plasticity, and a myriad of other physiological processes through transient modification of redox-sensitive enzymes and transcription factors[36-40]. When iron regulation escapes control, however, the same chemistry drives a shift toward oxidative distress, in which uncontrolled electron transfer drives lipid peroxidation and metabolic failure. Therefore, iron homeostasis is tightly maintained through a coordinated cycle of uptake, utilization, and storage[41]. Within the interstitium of the central nervous system (CNS), ferric iron (Fe3+) is bound by transferrin, which is synthesized by the choroid plexus and circulates within blood[42,43]. The transferrin-iron complex enters cells via transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1)-mediated endocytosis (Figure 3a), where it is reduced to ferrous iron (Fe2+) by STEAP (six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate) oxidoreductases and released into the cytosol through divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1)[41]. This Fe2+ replenishes the labile iron pool (LIP), a metabolically active but potentially cytotoxic reservoir supplying iron for heme synthesis, mitochondrial iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster assembly, and other essential reactions[41,44,45]. To prevent uncontrolled redox activity, Fe2+ within the cytosol is transiently buffered by poly(rC)-binding protein 1 (PCBP1), a GSH-dependent iron chaperone that delivers Fe2+ safely to ferritin or metalloenzymes (Figure 3a)[46-50].

Figure 3. (a) Under normal physiological circumstances, ferrous iron (Fe3+) is imported into neurons via transferrin-mediated endocytosis. Inside the endosome, ferric iron is reduced to ferrous iron (Fe2+) by STEAP3 and exported into the cytosol via DMT1, contributing to the LIP. The LIP is tightly regulated; ferrous iron within the LIP is stabilized by forming a complex with GSH, with excess ferrous iron exported via PCBP2 and ferroportin. Iron chaperone PCBP1 delivers ferrous iron from the LIP either to ferritin for storage, to the mitochondria for iron-sulfur cluster formation, or to metalloenzymes such as the hypoxia-inducible factor. Under normal circumstances, HIF PHDs hydroxylate HIF-1α, tagging it for proteasomal degradation upon ubiquitination by VHL; (b) When neurons undergo hypoxia, the lack of oxygen inactivates HIF PHDs, leaving them unable to hydroxylate HIF-1α. This prevents the degradation of HIF-1α, allowing it to translocate to the nucleus where it binds to HIF-1β to form the HIF-1 complex. The HIF-1 complex binds to hypoxia response elements, promoting expression of a coordinated gene program that allows the cell to adapt to hypoxic conditions- as long as thiol metabolism remains intact. Because the HIF PHDs require iron as a co-factor, iron chelation also permits HIF-1α stabilization; (c) When thiol metabolism is compromised and GSH is depleted, control of the LIP is lost, tipping neurons into oxidative distress. Ferrous iron export is downregulated, and import is upregulated. Ferritinophagy and dissociation of the Fe-S clusters further expands the LIP, loading PCBP1 with ferrous iron and redirecting it to the HIF PHDs. Once loaded with iron within an oxidative environment, the HIF PHDs (likely HIF PHD1) preferentially hydroxylate ATF4, resulting in the transcription of a pro-ferroptotic gene cassette. STEAP3: six-membrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3; DMT1: divalent metal ion transporter 1; LIP: labile iron pool; GSH: glutathione; PCBP2: poly(rc)-binding protein 2; PCBP1: poly(rc)-binding protein 1; HIF PHDs: hypoxia-inducible prolyl hydroxylases; VHL: von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein; HIF-1α: hypoxia-inducible factor 1α; HIF-1β: hypoxia-inducible factor 1β.

Under physiological conditions, most intracellular iron is tightly sequestered within ferritin, cytochromes, or Fe-S enzymes, maintaining the LIP within a narrow range[51]. When mitochondrial redox balance is preserved, Fe-S clusters remain stable (Figure 3a)[40,52]. However, following ischemia, the impaired electron transport chain limits NADPH regeneration and GSH synthesis[29], creating an oxidizing mitochondrial environment that directly destabilizes Fe-S clusters (Figure 3c)[40]. The loss of Fe-S clusters reduces the activity of associated metalloenzymes, weakening cellular redox buffering[52-54]. In hemorrhagic stroke, heme degradation and ferrireductase activity introduce additional Fe2+ to the LIP[30], fueling mitochondrial oxidative dysfunction and compounding Fe-S cluster instability. As the Fe-S clusters disassemble, Fe2+ is released back into the LIP, expanding the pool of redox-active iron (Figure 3c). Since IRP1 and IRP2 (iron response protein 1/2) sense iron status through Fe-S cluster integrity rather than total iron[55], Fe-S loss is misinterpreted as iron deficiency. Iron uptake is increased via upregulation of TfR1 and DMT1, iron export via ferroportin is blocked, and ferritin storage is suppressed despite an increasing LIP (Figure 3c)[56]. Concurrently, ferritin is targeted for nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4)-mediated ferritinophagy, further reinforcing LIP expansion (Figure 3c)[57,58]. This feed-forward sequence aligns with elevated total iron observed within peri-infarct regions of focal ischemia patients on neuroimaging[59,60]. Consistent with this model, proteins associated with Fe-S cluster stability and coordination, such as CDGSH iron sulfur domain 2 (CISD2) decline after ischemia[61,62], and CISD2 overexpression preserves Fe-S integrity and limits ferroptosis in both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke models[62,63].

Once the LIP exceeds the cell’s buffering capacity, Fe2+ catalyzes Fenton reactions with peroxides, producing hydroxyl radicals and ferryl intermediates that attack membrane lipids (Figure 4a)[35,64]. These reactions are not random; local intracellular iron coordination and redox conditions determine whether oxidation occurs diffusely or at specific sites[34]. Thus, ferroptosis arises not from chance oxidation but through a collapse in iron handling and peroxide metabolism. Only later did such mechanistic understanding clarify what early interventions like DFO had already exploited: the therapeutic potential of stabilizing redox-active iron in the CNS. Originally derived from the microbial siderophore ferrioxamine B, DFO was first used clinically in 1962 to treat thalassemia and later shown to reverse aluminum-induced dialysis encephalopathy[65-67], demonstrating the importance of iron homeostasis within the CNS.

Figure 4. (a) In astrocytes and immature neurons, cystine is imported into the cell in exchange for glutamate via the system Xc- transporter. Cystine is converted to cysteine, which is then converted to γ-glutamylcysteine by glutamate-cysteine ligase. Glutathione synthetase then acts on γ-glutamylcysteine and glycine to produce GSH. GPX4 uses GSH as a reducing agent to neutralize toxic lipid hydroperoxides, forming GSSG. Glutathione reductase then recycles GSSG back into GSH in an NADPH-dependent reaction; (b) Upon depletion of cellular cysteine supply, uncharged tRNA builds up within the neuron, activating GCN2, which in turn activates eIF2. Activation of eIF2α triggers the integrated stress response, globally reducing protein synthesis, and redirects cysteine away from translation towards glutathione production. While the upstream ferroptotic triggers for ATF4 activation in neurons are incompletely understood, they may include eIF2α phosphorylation or association with an unidentified co-factor. Data from other models (e.g., immortalized neuronal cell lines, non-neuronal cells) suggest that transient ATF4 activation is beneficial, resulting in expression of antioxidant gene programs which act to increase cellular cysteine and GSH levels. Chronic ATF4 activation, however, results in pro-ferroptotic transcription and eventual death. Notably, delivering cysteine to the cell in the form of N-acetylcysteine prevents neuronal ferroptosis. GSH: glutathione; GPX4: glutathione peroxidase 4; GSSG: glutathione disulfide; NADPH: nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; GCN2: general control nonderepressible 2; eIF2α: eukaryotic initiation factor 2 subunit 1; ATF4: activating transcription factor 4.

Our laboratory first demonstrated that iron chelators such as DFO prevent ferroptotic death in immature cortical neurons not only by quenching hydroxyl radicals or interrupting Fenton chemistry, but also by activating the transcriptional response normally triggered by hypoxia (Figure 3b)[68]. Structurally diverse iron chelators enhanced activation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), a master transcription factor that orchestrates cellular adaptation to low oxygen by inducing genes involved in glycolysis, erythropoiesis, angiogenesis, and antioxidant defense (Figure 3b)[68]. Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α is continuously synthesized but rapidly degraded: HIF prolyl hydroxylase domain (PHD) enzymes hydroxylate proline residues on HIF-1α in an iron- and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent reaction, marking it for recognition by the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) E3 ubiquitin ligase (Figure 3a)[69-71]. In turn, VHL ubiquitinates HIF-1α and targets it for proteasomal degradation[69]. This work by Kaelin, Ratcliffe, and Semenza provided the mechanistic foundation for this phenomenon, revealing how these oxygen- and iron-sensing PHDs couple metabolic state to HIF-1α stability (winning them the Nobel Prize in 2019)[69-71]. By chelating ferrous iron and limiting expansion of the LIP, DFO inhibits PHD activity (Figure 3c). This effectively prevents HIF-1α hydroxylation and degradation, thereby mimicking hypoxia and activating a coordinated transcriptional program that can enhance neuronal redox resilience and survival (Figure 3b)[68,70]. Subsequent work from our laboratory revealed that the neuroprotective actions of iron chelators arise from selective inhibition of HIF PHD1. Genetic or pharmacologic suppression of PHD1, but not PHD2 or PHD3, protected neurons from death by glutathione depletion, identifying PHD1 as a key redox-sensitive regulator of metabolic resilience even under normoxic conditions[72].

Yet, as we later found, HIF-1α activation is not uniformly protective in a ferroptotic context. Forced expression of an oxygen-stabilized HIF-1α in a hippocampal neuroblast (HT-22) cell line enhanced resistance to DNA damage and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, but unexpectedly potentiated ferroptotic death, indicating that the outcome of HIF stabilization depends on the nature of the stressor and the ongoing cellular context[73]. This paradox arises when oxidative stress and iron loading convert HIF-1α from an adaptive transcription factor into a pro-death effector by inducing the apoptotic proteins BNIP3 (BCL2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDA protein-interacting protein 3) and p53 upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA)[74]. These genes are canonical HIF targets, as they contain hypoxia-response elements, yet their induction alone is not lethal; a secondary oxidative signal (e.g., GSH depletion) activates their mitochondrial death functions[74]. Importantly, antioxidants or pharmacologic inhibition of HIF PHDs prevents this switch, suggesting that active, iron-loaded PHDs are permissive for HIF to engage its pro-death transcriptional program, whereas apo (iron-free) PHDs favor canonical HIF signaling[74].

Together, these findings posit that the iron-loading state of the HIF PHDs dictates their regulatory control over transcriptional pathways. Under conditions of iron chelation or hypoxia, HIF PHDs remain in their apo (iron-free) form, favouring HIF stabilization (Figure 3b)[24]. In contrast, during normoxic oxidative stress, the expansion of the LIP appears to preferentially load the HIF PHDs (via iron chaperone PCBP1; Figure 3c)[49], redirecting their activity to non-HIF substrates such as activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4)[24]. Normally, ATF4 functions as part of the integrated stress response (ISR), which serves to balance protein synthesis, metabolism, and redox homeostasis when the cell is under stress[75]. Transient activation of the ISR pathway supports adaptive cellular responses to redox stress. However, our model suggests that under sustained oxidative or metabolic stress, iron-loaded HIF PHDs hydroxylate ATF4, enhancing its stability and transcriptional output toward pro-ferroptotic death genes such as C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), tribbles homolog 3 (TRIB3), cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase 1 (CARS), regulated in development and DNA damage 1 (REDD1), and cation transport regulator-like 1 (CHAC1; Figure 3c)[17,76].

To block this maladaptive loop, our laboratory developed adaptaquin, a brain-penetrant 8-hydroxyquinoline that binds the catalytic iron center of HIF PHDs and inhibits their hydroxylase activity[77,78]. Unlike broad chelators, adaptaquin spares bulk iron metabolism while suppressing ATF4-dependent transcription (Figure 3c)[77]. In primary cortical neurons, adaptaquin potently suppressed ferroptotic death triggered by glutathione depletion, hemin toxicity, or excitotoxic oxidative stress. Protective concentrations (~1 μM) were several-fold lower than those needed to stabilize HIF-1α, and transcriptomic analyses revealed suppression of an ATF4-dependent gene cassette (e.g., CHOP, TRIB3, and CHAC1) rather than activation of canonical HIF targets[77]. These genes likely amplify oxidative injury by promoting degradation of Parkin and degrading intracellular glutathione, respectively, thereby reinforcing redox and mitochondrial collapse[17,76,79]. In vivo, adaptaquin recapitulated the effects of genetic HIF PHD knockdown, improving neuronal survival and behavioral recovery in collagenase- and autologous blood-induced models of intracerebral hemorrhage[77], as well as ischemic stroke (unpublished data, Ratan lab). Post-injury treatment reduced perihematomal degeneration without altering total brain iron or zinc, confirming selective PHD inhibition rather than wholesale metal chelation as the mechanism of protection. Notably, adaptaquin remained effective when delivered up to six hours after hemorrhage onset[77].

By contrast, systemic chelators like DFO, though protective in vitro, exhibit poor brain penetration and narrow safety margins, a consequence of wholesale iron chelation. While numerous preclinical studies have found neuroprotective efficacy with DFO treatment following both focal ischemia and hemorrhage, others found no benefit or evidence of harm[80-88]. Randomized controlled trials in ICH have been similarly mixed; the Phase II i-DEF trial did not meet their efficacy endpoint[89], while the Phase II Hi-DEF trial (e.g., high dose DFO) was terminated early due to evidence of harm[90]. Post-hoc analyses of the i-DEF trial have since indicated that DFO may accelerate recovery trajectories[91,92], but there remains room for therapeutic refinement. Deferiprone has been posited as a more bioavailable alternative to DFO in the treatment of CNS disorders; however, recent clinical findings indicating potential harm in both patients with Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease warrant extreme caution[93-95]. Our findings regarding adaptaquin have established targeted inhibition of iron-dependent dioxygenases as a potential alternative to global iron chelation, intercepting maladaptive ATF4 signaling while preserving physiological iron metabolism.

Over the past three decades, this work has collectively illustrated that disturbances in iron handling set the stage for neuronal ferroptosis by transcriptionally altering the cell’s redox balance. When iron-driven reactions diminish glutathione recycling, redox homeostasis falters. In this manner, the boundary between oxidative eustress and distress is defined by the efficiency of cellular thiol metabolism, which plays a major role in buffering the reactivity of iron.

3.2 Thiol metabolism and the cystine-glutathione axis

At the center of cellular redox control is GSH, the most abundant endogenous antioxidant that establishes the baseline redox potential of the cell[96]. GSH is synthesized from glutamate, cysteine, and glycine via glutathione-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit/glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit (GCLC/GCLM) and glutathione synthetase (Figure 4a)[97]. Its core function is to provide reducing equivalents for GPX4, enabling detoxification of lipid hydroperoxides and thereby limiting ferroptotic lipid damage (Figure 4a)[98]. Beyond supporting GPX4, GSH maintains protein cysteine redox states through reversible S-glutathionylation and fuels glutaredoxin-dependent Fe-S cluster assembly and repair[54,99]. Through glutathione S-transferases, GSH also conjugates electrophilic lipid aldehydes formed during membrane peroxidation, preventing secondary oxidative injury[16]. In addition, GSH can directly bind Fe2+ within the labile iron pool, forming a complex that PCBP1 chaperones toward Fe-S cluster synthesis (Figure 4a)[48]. Sustaining a robust GSH pool is metabolically demanding, and highly dependent on NADPH availability. In most cells, NADPH is primarily generated via the pentose phosphate pathway, with cytosolic malic enzyme 1 (ME1) and NADP⁺-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenases (IDH1/2) providing auxiliary sources that couple mitochondrial and cytosolic metabolism to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle[100].

Neurons and astrocytes, however, differ markedly in how they balance these reactions. Neurons prioritize oxidative phosphorylation and ATP generation to meet the energetic demands of firing action potentials, whereas astrocytes maintain high glycolytic flux and robust pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) activity, producing abundant NADPH[101]. Accordingly, the burden of GSH production is shared asymmetrically. Astrocytes, with their strong capacity for NADPH production and abundant expression of system Xc-, are able to sustain cystine import and cysteine reduction under oxidative load (e.g., eustress), releasing GSH and GSH-derived dipeptides that neurons can import via γ-glutamyl or amino-acid transporters[102,103]. This division of labor preserves neuronal redox balance under normal conditions but becomes precarious when energy metabolism falters (e.g., due to stroke). In this scenario, astrocytes must use their own GSH supply to combat oxidative distress; increased astrocytic GSH consumption reduces their rate of GSH export to neurons and other cell types[103]. The resulting depletion of neuronal GSH supply weakens iron coordination (as discussed above), accelerating Fe-S cluster instability and the expansion of the labile iron pool (Figure 3c).

Beyond its direct metabolic consequences, cystine depletion also initiates a distinct cellular stress program (Figure 4b). When cystine import fails, and/or GSH stores decline, cells interpret this loss as a signal of amino acid starvation[104]. As cysteine becomes scarce, uncharged tRNAs bind to the general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2) kinase, activating this sensor of amino acid deprivation[105]. Once engaged, GCN2 phosphorylates eukaryotic initiation factor 2 subunit (eIF2α), triggering the integrated stress response and globally reducing protein synthesis (Figure 3)[106]. Transient activation of this circuit is likely adaptive, as it conserves amino acid supply while permitting selective translation of ATF4, which in turn upregulates amino-acid transporters, GSH-synthesis enzymes, and other stress response genes (Figure 4b)[75,107]. However, if cysteine scarcity persists, ATF4 signaling appears to transition from restorative to destructive, driving a pro-death transcriptional cassette that accelerates ferroptosis (Figure 4b; as discussed above in Section 3.1)[76]. Indeed, early studies from our lab showed that inhibition of macromolecular synthesis rescues neurons from glutamate-induced oxidative death by redirecting cysteine flux away from protein synthesis and toward glutathione production, reinforcing antioxidant defense[108-110], as similarly corroborated by others[111].

Together, these mechanisms define the cystine-glutathione axis as a key inflection point that determines whether redox stress remains adaptive or becomes fatal. When cystine uptake and NADPH supply are adequate, neurons can sustain oxidative eustress that supports signaling and plasticity. Once this coordination fails, however, cysteine depletion, iron dysregulation, and the resulting lipid peroxidation form a self-reinforcing cycle of oxidative distress. Encouragingly, this trajectory can be intercepted after hemorrhagic stroke by restoring cysteine availability. We have shown that treatment with NAC, a clinically approved cysteine prodrug, bypasses system Xc- to replenish intracellular cysteine (Figure 4b)[16]. This restores GSH synthesis and enables GPX4-dependent detoxification of oxidized lipids, independent of iron modulation[16]. In primary cortical cultures exposed to hemin, NAC prevents ferroptotic cell death by neutralizing arachidonate-derived lipid species produced by 5-lipoxygenase (LOX-5), an enzyme also upregulated in human ICH brain tissue samples[16]. Systemic NAC administration initiated two hours post-stroke improved behavioral outcomes after collagenase ICH, a phenotype mirrored by LOX-5 deletion[16].

These findings emphasize that sustaining thiol metabolism (and by extension, the antioxidant economy) restrains ferroptosis. When this control fails, LOX and other lipid-oxidizing enzymes begin to execute the terminal phases of ferroptosis, opposed only by the membrane-associated and radical-trapping antioxidant systems described below in Section 3.3.

3.3 Membrane integrity and radical trapping antioxidants

Once the buffering capacity of thiol metabolism is exhausted, cellular membranes become the final “battleground” of ferroptosis. The same polyunsaturated phospholipids (PUFAs) that endow neuronal membranes with fluidity and signaling versatility also render them intrinsically vulnerable to oxidation[112,113]. Each PUFA chain contains bis-allylic hydrogens (e.g., chemically fragile sites with low bond-dissociation energy)[35]. When a reactive species abstracts one of these hydrogens, the resulting lipid radical reacts with oxygen to form lipid peroxyl radicals that propagate across the membrane in a chain reaction (Figure 4a)[35]. Under physiological conditions, these transient oxidation events are tightly regulated and contribute to redox signaling, membrane remodeling, and prostanoid synthesis[35,112]. During oxidative distress, however, this chemistry becomes self-propagating, driving structural disintegration, ionic collapse, and cell death[35].

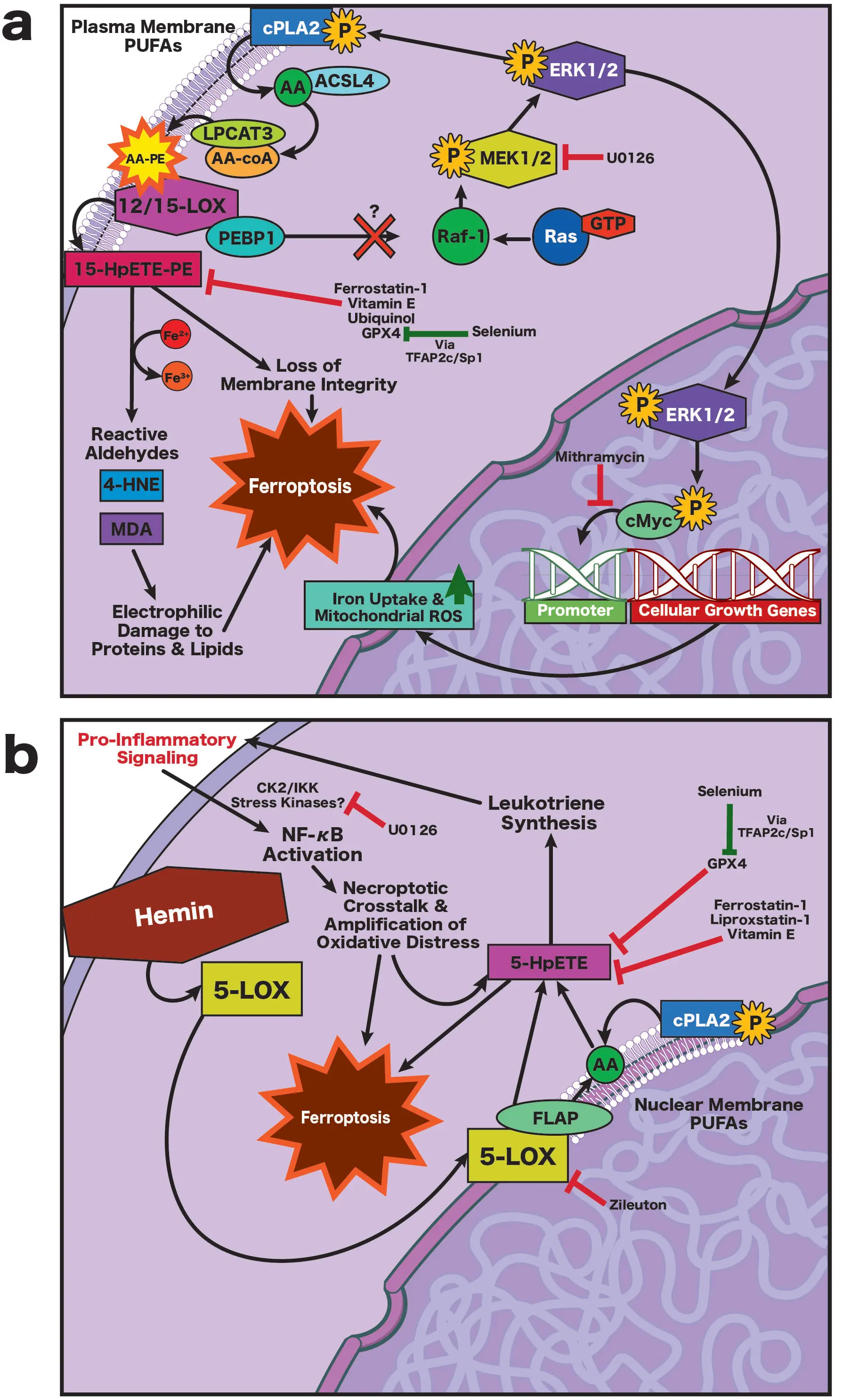

As described above, ferroptotic lipid peroxidation is not random but enzyme-directed, shaped by the same iron-dependent dioxygenases that regulate normal lipid signaling. Among these, the lipoxygenases (LOXs) play a central role[35]. Under basal conditions, LOXs act on free arachidonic acid (AA) released by cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) to generate hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HPETEs), intermediates in prostaglandin and leukotriene biosynthesis[35,112]. During ferroptotic stress, substrate preference shifts from free AA to membrane-bound phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) species, a transition thought to be orchestrated by phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 1 (PEBP1; also known as Raf-kinase inhibitory protein, or RKIP; Figure 5a)[35,114]. When oxidative distress and mitochondrial dysfunction trigger Ca2+ transients, ERK1/2-phosphorylated cPLA2 hydrolyzes membrane phospholipids, releasing AA that is rapidly re-esterified by ACSL4 and LPCAT3 into arachidonoyl-PE (AA-PE), enriching membranes with oxidizable phospholipids[115-117]. As oxidative load escalates, PEBP1 is thought to disengage from Raf-1 and bind 12/15-lipoxygenase (12/15-LOX), forming a PEBP1-15-LOX complex that converts AA-PE to 15-HpETE-PE (15-hydroperoxy-eicosatetraenoyl-PE; Figure 5a)[114,116,118].

Figure 5. (a) Ischemia-induced ferroptosis. Oxidative stress dissociates PEBP1 from Raf-1, enabling Ras-Raf-MEK1/2-ERK1/2 signaling that activates cPLA2, releasing AA from membrane PUFAs. AA is reincorporated into PE by ACSL4 and LPCAT3 and oxidized by 12/15-LOX to form 15-HpETE-PE, compromising membrane integrity and generating toxic aldehydes (4-HNE, MDA). ERK1/2 also activates cMyc, promoting iron overload and mitochondrial ROS, thereby accelerating ferroptosis. This pathway is inhibited by U0126 and mithramycin; (b) Hemorrhage-induced ferroptosis. Hemin inserts into membranes, promoting formation of a 5-LOX/FLAP complex at the nuclear envelope, where free AA is converted to 5-HpETEs and leukotrienes, amplifying inflammation via CK2/IKK-NF-κB signaling, lipid peroxidation, and generation of toxic aldehydes. This process is independent of ERK1/2 activity; the protective effect of U0126 in this context reflects off-target inhibition of CK2/IKK signaling. In both models, ferroptosis is suppressed by radical-trapping antioxidants or upregulation of GPX4, which is enhanced by selenium via TFAP2c/Sp1-dependent GPX4 induction. AA: arachidonic acid; ACSL4: long-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase 4; cMyc: cellular Myc proto-oncogene; cPLA2: cytosolic phospholipase A2; CK2: casein kinase 2; ERK1/2: extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2; FLAP: 5-lipoxygenase–activating protein; GPX4: glutathione peroxidase 4; 4-HNE: 4-hydroxynonenal; IKK: IκB kinase; LPCAT3: lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3; LOX: lipoxygenase; 12/15-LOX: 12/15-lipoxygenase; 5-LOX: 5-lipoxygenase; MDA: malondialdehyde; MEK1/2: mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 and 2; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; PE: phosphatidylethanolamine; PEBP1: phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 1; PUFAs: polyunsaturated fatty acids; Raf-1: proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase Raf-1; Ras: rat sarcoma; ROS, reactive oxygen species; TFAP2c: transcription factor AP-2 gamma; Sp1: specificity protein 1; 15-HpETE-PE: 15-hydroperoxy-eicosatetraenoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine; 5-HpETE: 5-hydroperoxy-eicosatetraenoic acid.

The dominant LOX isoform that mediates neuronal ferroptotic damage depends on the injury context: during ischemia, an increase in oxidative tone activates 12/15-LOX-PEBP1 complexes at the plasma membrane, oxidizing PE to 15-HpETE-PE and effectively coupling membrane rupture to antioxidant failure (Figure 5a)[119]. Inhibition of 12/15-LOX with LOXBlock-1 or newer compounds like ML351 is protective across both permanent and transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) models[120-122]. In contrast, after ICH, hemin and other iron-rich hemoglobin products preferentially activate 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) at the nuclear envelope (Figure 5b)[16]. Once activated, 5-LOX acts on free AA to generate 5-HpETE, a highly unstable lipid hydroperoxide. The 5-HpETEs are the precursors for leukotrienes that amplify oxidative distress indirectly via NADPH oxidase activation, cytokine release, and inflammatory recruitment (Figure 5b)[123,124]; together, this cascade sustains lipid peroxidation and promotes ferroptosis in surrounding cells[16]. Therefore, ischemia and hemorrhage drive ferroptotic membrane injury through distinct spatial and biochemical routes, though both converge on oxidative collapse. In support of this, we find that structurally diverse 5-LOX inhibitors (e.g., zileuton) are protective against hemin-induced neurotoxicity in vitro, while selective inhibitors of 12/15-LOX are not[16]. While zileuton is found to be protective following collagenase ICH in mice[125], it also confers benefit after transient and permanent MCAO in mice[126-129], an effect likely reflective of attenuated leukotriene-driven neuroinflammation rather than direct suppression of ferroptotic lipid peroxidation.

The core enzymatic defense against lipid peroxidation is GPX4, the only enzyme capable of directly reducing membrane-embedded phospholipid hydroperoxides (PUFA-OOH) into lipid alcohols (Figure 4a)[98,130]. GPX4 defines the decisive checkpoint of ferroptosis, analogous to Bcl-2 in apoptosis[17]. Genetic deletion or inhibition of GPX4 (e.g., with RSL3) commits cells to oxidative death, whereas forced GPX4 expression fortifies neurons against ferroptosis in vitro and in vivo following stroke[131]. Under physiological conditions, GPX4 allows controlled lipid oxidation to support signaling and membrane dynamics; when its activity declines, lipid peroxides accumulate, increasing membrane permeability and generating reactive aldehydes such as 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and malondialdehyde (MDA)[132,133]. At low concentrations, these products induce plasticity and adaptive transcriptional responses (e.g., endogenous antioxidant programs); at high concentrations, however, they form adducts with histones, induce inflammatory and pro-death signaling, and cross-link proteins, resulting in stiff membranes, osmotic failure, and ferroptotic collapse[133,134]. The threshold at which peroxidation becomes irreversible likely depends on the spatial extent and kinetics of oxidation within different intracellular compartments, as well as events occurring in adjacent cells[34]. It is intriguing to note that ferroptosis in one cell can propagate to adjacent bystanders, potentially via cell-cell contacts[135]; future work may help us understand how this phenomenon may be leveraged therapeutically.

Although GPX4 is the principal defense against lipid peroxidation, cells deploy additional antioxidant circuits that act directly at the membrane interface (Figure 5a,b). One such pathway involves ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1), which regenerates ubiquinol (CoQ10H2) at the plasma membrane to trap lipid peroxyl radicals and preserve membrane integrity in parallel to GPX4 (Figure 4)[136]. Structural studies indicate that FSP1 can use NADPH as an electron donor, aligning it with the GSH-GPX4 axis[137]. However, recent work also suggests that a membrane-associated NADH pool, regulated in part by ALDH7A1, can support FSP1 activity under ferroptotic stress, implying that cofactor usage may be compartmentalized or contextually-dependent[138,139]. This FSP1-CoQ10 circuit could be particularly vital in neurons, whose PUFA-rich membranes and limited GSH turnover heighten vulnerability[113]. Another recently discovered endogenous RTA system is the GCH1 (GTP-cyclohydrolase 1)-BH4 axis, which supplies the antioxidant BH4 in an NADPH-dependent process[140]. While these mechanisms are yet to be exploited to treat stroke in vivo, they represent important areas for future investigation.

Other RTAs, including vitamin E (α-tocopherol), liproxstatin-1, and ferrostatin-1 (Figure 4) act through similar radical-quenching chemistry[141]. While vitamin E and its derivatives potently inhibit ferroptosis in vitro[141], there is mixed preclinical evidence regarding their benefit when administered prior to stroke[142-146], and few have investigated efficacy with treatment delay following stroke. Additionally, the increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke with vitamin E supplementation substantially limits translational potential for stroke neuroprotection[147,148]. Interestingly, the canonical ferroptosis inhibitor ferrostatin-1 acts not only as an RTA but also inhibits formation of the 12/15-LOX/PEBP1 complex (Figure 5a), limiting formation of 15-HpETE-PE[149]. Administration of ferrostatin-1 following rodent ICH and focal ischemia has shown neuroprotective efficacy[7,9,150-152], but the translational feasibility of ferrostatin-1 is currently limited by its short half-life and limited CNS penetrance[153]. Work on similar alternatives is ongoing[153,154], as the efficacy of lipophilic RTAs both in vitro and in preclinical models thus far has validated lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis as tractable therapeutic targets following stroke.

While RTAs buy time, they act transiently at the end stage of oxidative injury. A potentially more durable approach is to enhance endogenous enzymatic repair, especially those governed by selenoproteins that restore antioxidant capacity from within. As an essential micronutrient, selenium is incorporated as selenocysteine into a family of selenoproteins, such as GPX4, thioredoxin reductase 1 (TXNRD1), and Selenoprotein P (SelP)[131,155]. Collectively, these selenoproteins sustain redox balance under ferroptotic stress. Our group demonstrated that ferroptotic stimuli such as hemin or glutamate analogues elicit a frustrated adaptive transcriptional response in neurons, characterized by modest upregulation of these same selenoproteins[131]. We found that selenium supplementation amplifies this response, driving a broad selenome transcriptional network via coordinated activation of the transcription factors transcription factor AP-2 Gamma (TFAP2c) and Specificity Protein 1 (Sp1)[131]. This adaptive pathway increases expression of both nuclear and mitochondrial GPX4 isoforms (Figure 5a,b), expanding the cellular capacity to detoxify lipid hydroperoxides and suppressing ferroptosis even when initiated hours after insult. Following collagenase ICH in mice, a single intracerebroventricular dose of selenium or systemic delivery of a brain-penetrant selenocysteine peptide (Tat-SelPep) upregulated GPX4, reduced neuronal death, and restored behavioral function without affecting hematoma size[131]. Following transient MCAO, Tat-SelPep also reduced infarct volume independently of excitotoxicity when delivered two hours post-stroke[131]. Mechanistically, this selenium-driven transcriptional reinforcement counterbalances the pro-ferroptotic ATF4 axis activated during sustained glutathione depletion (Figure 3c, Figure 4b), converging with nuclear factor erythroid 2- related factor 2 (Nrf2)-dependent antioxidant gene expression to restore redox equilibrium.

Together, these antioxidant systems illustrate that the outcome of ferroptosis depends not only on the chemistry of lipid peroxidation, but also on the capacity of the cell to coordinate both enzymatic and transcriptional responses to oxidative stress.

3.4 Transcriptional control of redox tone

When antioxidant defenses begin to falter, the cell must decide whether to restore redox balance or commit to degeneration. This decision is governed by transcriptional hierarchies that sense oxidative pressure and redistribute metabolic resources toward either recovery or collapse. At the apex of this system is Nrf2, the principal transcriptional regulator of dynamic redox homeostasis[17]. Under basal conditions, Nrf2 maintains constitutive expression of genes that preserve redox tone. Normally sequestered by Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) and targeted for proteasomal degradation, Nrf2 is released when electrophiles oxidize Keap1’s cysteine residues. Freed Nrf2 then translocates to the nucleus, where it activates antioxidant-response elements (AREs), orchestrating a broad cytoprotective program. This includes upregulation of GCLC and GCLM (for glutathione synthesis), SLC7A11 (the cystine importer of system Xc⁻), NQO1 (which prevents quinone redox cycling), HO-1 (which catabolizes heme), and ferritin subunits FTH1 and FTL1, which sequester iron[17]. Collectively, this program stabilizes iron homeostasis and reinforces NADPH production through induction of the pentose-phosphate pathway and ME1, coupling antioxidant defenses to metabolic supply[156].

When oxidative pressure rises, Nrf2 activity is amplified through stabilization and nuclear accumulation, expanding metabolic and antioxidant capacity. Therefore, while Nrf2 maintains dynamic basal antioxidant tone, it also acts as a rapid-response sensor when redox balance tips toward oxidation. Importantly, within the CNS, Nrf2 expression is cell-type specific. Mature neurons exhibit low basal Nrf2 levels, but astrocytes and microglia have robust expression, allowing them to dynamically adjust to local oxidative load[102,157]. Astrocytic Nrf2 activation enhances glutathione synthesis and export (along with glutathione precursors), which are taken up by neurons to support antioxidant defence[102,158]. Experimental data support this compartmentalization: in primary cultures, the forced expression of Nrf2 in astrocytes protects against neuronal ferroptosis, even when constituting less than 2% of the total culture population[102].

This cell-type specific expression likely has developmental origins: low levels of Nrf2 activation enhance the capacity for oxidative eustress, which is required for neuronal differentiation, neurite outgrowth, and synapse formation[159-161]. Similarly, in post-mitotic neurons, oxidative eustress plays an important role in shaping structural plasticity via JNK/c-Jun signaling[159]. Therefore, compared to astrocytes, neurons must maintain a relatively oxidized intracellular state (via higher expression of Keap1)[157], while astrocytes retain their stress-inducible Nrf2 signaling into adulthood. In this manner, Nrf2 links transcriptional control to metabolic supply, ensuring that antioxidant defenses and NADPH regeneration scale with redox demand. Under normal conditions, this coordination maintains oxidative eustress within a physiological range. During acute injuries such as stroke, however, oxidative load overwhelms metabolic capacity.

As Nrf2-dependent programs fail to meet rising oxidative demand, secondary signaling cascades such as stress-activated MAPKs are recruited in an attempt to restore homeostasis. In particular, the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway plays a pivotal role in this transition (Figure 5a). Initially, transient ERK activation supports metabolic compensation and cytoprotective gene expression, but sustained activation becomes maladaptive when reducing power is exhausted[162,163]. This concept became apparent in early ferroptosis studies, which demonstrated that unlike apoptosis[164], growth factor stimulation enhanced neuronal susceptibility to ferroptotic death[28]. As discussed above, under normal physiological conditions, PEBP1 (RKIP) binds to Raf-1 and prevents its association with Ras, restraining ERK activation. During canonical growth factor signaling, protein kinase C (PKC) is activated by tyrosine receptor kinases, phosphorylating PEBP1 and dissociating the PEBP1-Raf-1 complex; together, these events activate the downstream MEK-ERK1/2 cascade[165]. In the setting of ferroptosis, an analogous shift appears to occur, though the precise trigger remains uncertain (Figure 5a). Oxidative modifications of PEBP1, phospholipid interactions, or PKC-dependent phosphorylation could each contribute to Raf-1 release, freeing PEBP1 to associate with 12/15-LOX. This effectively links stress-activated kinase signaling to the onset of lipid peroxidation.

Once activated, ERK1/2 translocates to the nucleus to phosphorylate its transcriptional targets, including cMyc, Elk1, and cfos (Figure 5a)[166]. Under normal conditions, this activity is transient, terminated by the phosphatase MKP3, which dephosphorylates ERK1/2 and returns it to the cytoplasm. During oxidative distress, however, MPK3 itself is vulnerable, as its redox-sensitive residues can be oxidized or covalently modified by lipid hydroperoxides such as 15-HpETE-PE, rendering the enzyme inactive[167]. The resulting persistence of nuclear ERK1/2 sustains phosphorylation of c-Myc, stabilizing it as a pro-ferroptotic transcriptional amplifier (Figure 5a)[168,169]. Normally, c-Myc coordinates energy metabolism and ribosome biogenesis, matching neuronal activity with metabolic demand. Many of its canonical targets enhance iron uptake and turnover to sustain oxidative metabolism, such as the ferritin subunits, Trf1, natural resistance-associated macrophage protein-1 (Nramp1) and iron-regulatory protein-2 (IRP2), among others[170]. When reducing power is sufficient, this response is adaptive and self-limiting. Yet under sustained ERK1/2 activation and redox imbalance, the same program drives excessive iron import and mitochondrial ROS production, outpacing antioxidant capacity[168]. This creates a feed-forward loop of lipid peroxidation and iron-driven oxidative stress (Figure 5a), further committing neurons to ferroptotic death.

Sustained oxidative stress also triggers chromatin remodeling (e.g., histone glutamylation, acetylation, and methylation), altering the accessibility of antioxidant and metabolic gene promoters[171]. These epigenetic shifts likely determine whether redox signals are resolved through adaptive transcription or a transition to ferroptotic commitment, coupling metabolic state to chromatin configuration. Indeed, pharmacologic dissection of the ferroptotic transcriptional programs discussed in this section has revealed several points of intervention. Mithramycin, an antibiotic that binds to GC-rich motifs of the c-Myc promoter, prevents cofactor Sp1 from binding and silences the ERK/c-Myc amplification loop that drives iron-handling and metabolic genes during oxidative stress (Figure 5a), which we have found to protect neurons from glutamate-induced ferroptosis in vitro[172]. While we have not tested mithramycin following stroke in vivo, others have found that it confers cytoprotective benefit following transient global ischemia[173], though its translational potential is low due to a high risk of toxicity, thrombocytopenia, and platelet dysfunction[174].

Evidence from our lab and others indicates that Sp1 acts in a contextually and temporally dependent manner via post-translational modifications[175]; pro-survival when acetylated early after the onset of oxidative stress, to sustain antioxidant tone, but pro-death when engaged downstream of ERK during sustained oxidative distress. For instance, pan-histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors such as trichostatin A or suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA; also known as vorinostat) enhance p300-mediated Sp1 acetylation, promoting expression of adaptive antioxidant genes like MnSOD and HO-1 in vitro during glutamate-induced ferroptosis[176,177]. Additionally, we have found that inhibition of specific HDAC isoforms, such as HDAC6, may confer not only neuroprotection, but also encourage neurite extension in vitro[178]. Beyond transcriptional modulation, sustained ERK activation engages an additional layer of regulation through transglutaminases. Dramatically upregulated both following ischemic stroke in vivo and glutamate exposure in vitro, transglutaminase inhibitors block ferroptosis up to 14 hours after exposure onset in vitro, while U0126 does not prevent death mediated by forced transglutaminase expression, placing transglutaminase activity functionally downstream of ERK signaling[179].

In vivo, both pan-HDAC inhibitors and class 1 HDAC inhibitors reduce cell death and provide functional benefit when administered both immediately and up to several days following MCAO or focal cortical stroke[180,181]. Selective class 1 HDAC inhibitors also confer benefit when administered immediately following autologous whole blood ICH[182]. However, selective class IIa HDAC inhibition has been shown to impair remodeling, exacerbate lesion volume, and increase mortality following transient MCAO in rats[183]. Therefore, despite strong mechanistic rationale, the delivery of HDAC inhibitors as stroke therapeutics remains translationally challenging due to their complex pharmacodynamics, contextual dependence, narrow temporal window of efficacy, and risk of adverse and off-target effects (including metal chelation)[184,185].

While erastin- and glutamate-induced ferroptosis activate the ERK/c-Myc axis, we find that hemin-induced ferroptosis proceeds independently of ERK (Figure 5b)[14]. Yet ferroptosis triggered by erastin, glutamate, and hemin are blocked by U0126, a nominally MEK-selective inhibitor (Figure 5b), even though other ERK inhibitors fail to protect against hemin toxicity. This apparent contradiction prompted us to conduct a comparative phosphoproteomic analysis of neurons exposed to erastin or hemin (with or without U0126), revealing distinct kinase signatures: erastin promotes the canonical proline-directed MAPK motifs characteristic of ERK activation, whereas hemin exposure is associated with Ca2+- and CK2/IKK-type signatures, implicating a broader stress-kinase network[14]. These data suggest that U0126 protects against hemin toxicity not by directly inhibiting ERK, but by dampening alternative phosphorylation cascades that link lipid peroxidation to inflammatory signaling. Although the precise downstream mediators remain uncertain, enrichment of CK2/IKK motifs strongly suggest NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain enhancer of activated B cells) involvement[186], a pathway known to intersect with both redox and lipid metabolism across numerous cell types[187]. Consistent with this interpretation, we find that hemin-induced neuronal death in vitro and after hemorrhage in vivo uniquely displays features of both ferroptosis and necroptosis, with protection achieved by inhibitors of either pathway, including U0126[14,188].

As discussed above, hemin exposure and 5-LOX-mediated lipid peroxidation result in neuronal synthesis and release of leukotrienes, which can act in an autocrine or paracrine manner, activating their cognate G-protein coupled receptors on neighbouring neurons and glia. Leukotriene signaling is known to engage NF-κB either directly through their cognate receptors or indirectly via amplification of cytokines associated with NF-κB activation and necroptosis, such as TNF-α[124,189,190]. Although the precise upstream signaling cascade responsible for CK2/IKK stress kinase activation following neuronal hemin exposure must be further explored, it is possible that leukotriene signaling promotes IKK-dependent phosphorylation of IκBα, permitting nuclear translocation of NF-κB[191]. Once in the nucleus, NF-κB engages a transcriptional program that primes key components of the necroptotic machinery (e.g., “the necrosome”), including RIPK1, RIPK3, and MLKL[191], licensing neurons for execution via crosstalk between necroptotic and ferroptotic processes- a phenomenon that must be explored further.

Within this framework, ferroptotic lipid peroxidation constitutes the initiating insult, while leukotriene-driven inflammatory signaling provides the molecular bridge to necroptosis, functionally coupling these two pathways. Depending on the cellular context, the convergence of ferroptotic and necroptotic signals may push neurons beyond a shared threshold for necrotic death. Consistent with this model, inhibition of either pathway alone during hemin exposure is sufficient to restore survival, though hemin-induced death can still be operationally defined as ferroptosis given its sensitivity to ferroptosis-selective inhibitors[14]. While further experimental exploration is required, analogous crosstalk between ferroptosis and necroptosis has been reported in other pathological contexts, including acute kidney injury[192]. More broadly, the integration of lipid peroxidation with NF-κB dependent inflammatory signaling raises the possibility that ferroptosis evolved not only as a mode of cell death, but also as a mechanism to convert oxidative collapse into signals that promote tissue repair and immune recruitment[15,158], a concept we explore further below.

Taken together, these findings point to transcriptional reprogramming as a potential inflection point between adaptive redox responses and ferroptotic collapse. As antioxidant reserves wane, signaling networks that normally sustain recovery instead appear to reinforce oxidative and inflammatory stress. Although the precise hierarchy of these pathways remains uncertain, their interplay suggests a gradual shift from metabolic coordination to loss of homeostatic control. Clarifying when and where this transition occurs across neurons, astrocytes, and immune cells will be key to identifying therapeutic windows in which ferroptosis remains reversible after each stroke subtype.

4. Translational Frontiers: Timing, Spatial Dynamics, and Cellular Crosstalk

Importantly, ferroptosis does not occur in isolation; it evolves within a shifting tissue landscape where neurons and glia are weathering rapid changes on numerous fronts, from intracellular metabolic instability to an ongoing and dynamic inflammatory response. Despite major advances in defining the molecular framework of ferroptosis, its translation into effective stroke therapies remains constrained by a limited understanding of how, when, and where it unfolds in animal models and patients.

4.1 Divergent redox trajectories in ischemia and hemorrhage

Although the temptation to categorize ischemia and hemorrhage together as insults that cause “oxidative stress” is understandable, this oversimplification obscures their distinct biochemical trajectories. Both focal ischemia and ICH share a common initiation phase in which damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released by acute necrotic cell death immediately begin to shape redox and inflammatory signaling[193-195]. This early DAMP signaling triggers NADPH-oxidase dependent superoxide generation, primes microglia for cytokine release, and establishes an oxidizing extracellular milieu that spreads into surrounding viable tissue[196]. However, against this shared backdrop, ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes diverge in how they sustain, amplify, and resolve oxidative injury.

Within penumbral tissue ranging from oligemic (cerebral blood flow in the range of 22-60 mL/100 g/min) to ischemic (below 22 mL/100 g/min)[197], partial oxygen and glucose deprivation slows mitochondrial respiration, diminishes ATP and NADPH generation, increases lactate production, and produces a hyper-reduced redox state (“reductive stress”) due to mitochondrial accumulation of reduced electron carriers[96,198-200]. Upon reperfusion, accumulated reducing equivalents generate reactive oxygen species (ROS)[15], and intracellular calcium levels rise[201], rapidly transforming reductive stress into oxidative distress. Transient activation of transcriptional programs by HIF-1α and ATF4 initially supports adaptation by promoting glycolytic metabolism, but the concurrent suppression of the PPP reduces neuronal NADPH regeneration, impairs glutathione cycling, and expands the labile iron pool (LIP)[75,202-204]. Together, this creates a delayed ferroptotic vulnerability at the ischemic penumbra that is likely exacerbated by development of edema, given the sensitivity of ferroptotic processes to osmoprotectants in non-CNS cell types[205]. Therefore, following focal ischemia, ferroptosis appears to emerge around the time of reperfusion[13,206], likely within penumbral tissue where oxidative flux suddenly returns and outpaces the restoration of cellular NADPH and GSH pools.

In contrast, following ICH, neurons in the perihematomal zone that escape necrosis from direct mechanical injury experience early and intense oxidative distress driven by iron toxicity, shifting hydrostatic pressure, osmotic gradients, thrombin release, and complement activation[3]. Preclinical models indicate that early limited erythrocyte lysis within the hematoma begins immediately following ICH, reaching a peak by ~24-48 hours post-stroke[207-209]. Given average hemoglobin levels within whole blood[31], a conservative estimate of the hemoglobin within the hematoma is ~2.3 mM. Erythrocytes must lyse for hemoglobin to be released. Of note, Hgb induces death of cortical and striatal neurons in vitro at concentrations of 1.5 mM[14,188], suggesting that only 1 out of 2,000 erythrocytes need to lyse in order to trigger local cell death. These results may explain why anti-ferroptotic agents are efficacious early after ICH onset.

It is clear that ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes impose distinct redox trajectories that converge on the same endpoints: exhaustion of reducing power, collapse of glutathione and NADPH systems, and lipid peroxidation-driven membrane failure. The challenge is to determine which components of this cascade are causative, reversible, or adaptive, their timing, and whether they represent feasible therapeutic targets. To tackle this challenge, we must better understand the interplay between acute metabolic status and the spatiotemporal progression of ferroptosis within the penumbral and perihematomal zones, along with the relationships between constituent cell types. Recent evidence suggests that the vascular compartment is an early and critical site of injury following focal ischemia: brain endothelial cells highly express 12/15-LOX, which directly contributes to blood-brain barrier breakdown, vasogenic edema, and subsequent neuroinflammation, along with hemorrhagic transformation[120]. Astrocytes can buffer oxidative stress and deliver glutathione precursors, along with healthy mitochondria, to neurons, yet this protective capacity may convert to pro-oxidant signaling under sustained activation[102,158,210]. Compensatory ischemic glycolysis, iron overload, and lipid peroxidation in microglia can drive them toward a pro-inflammatory state, amplifying cell death and limiting plasticity and repair following stroke through the release of cytokines and reactive oxygen species[210,211]. Oligodendrocytes, rich in iron-handling and lipid-synthesis machinery, are particularly vulnerable to secondary ferroptotic degeneration once local redox buffering collapses[10,212-214]. It is likely that cell-type specific antioxidant capacities also vary across regions, shaping susceptibility to ferroptosis as a function of local redox tone and activity level[215]. Future work using spatial transcriptomics, in vivo redox imaging, and single-cell metabolomics could define how ferroptotic vulnerability propagates across tissue compartments.

Many other unresolved questions remain. What is the precise timing of ferroptotic death relative to reperfusion or red blood cell lysis? How long does the reversible window of ferroptosis remain open in vivo? What molecular cues determine where/when ferroptosis begins within peri-infarct or peri-hematoma tissue, and what are the irreversible terminal events? Clarifying such kinetic parameters is needed to align mechanistic insights with realistic treatment windows.

4.2 Crosstalk and immunological context

Ferroptosis exists within a broader network of oxidative and inflammatory death programs that co-occur after stroke. It overlaps mechanistically and functionally with autophagy, necroptosis, parthanatos, pyroptosis, and apoptosis, dependent on the cellular context in which the inducing stimuli occur. In ischemic tissue, PARP-1 activation and NAD⁺ depletion bridge ferroptosis to parthanatos, while MLKL-dependent necroptosis often co-occurs downstream of TNF-α and RIPK1/3 signaling[216,217]. As discussed above, in hemorrhagic stroke models, we have found ferroptosis and necroptosis to coincide[14], suggesting shared metabolic checkpoints involving mitochondrial dysfunction, iron dysregulation, and amplification of reactive oxygen species. Others have demonstrated possible overlap between necroptosis and ferroptosis upon ischemic reperfusion following transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice[13].

Intriguingly, in innate immune cells, induction of NF-κB signaling via toll-like receptors (TLRs) increases intracellular iron sequestration by ferritin, resulting in HIF PHD inhibition and HIF1α stabilization[218]. This helps dictate their pro-inflammatory function under both hypoxic and normoxic circumstances[218,219]. While it is unclear whether such a relationship exists in neurons, sustained NF-κB signaling is shown to suppress Nrf2 in neurons and glial cells (and vice versa); conversely, acute/activity-dependent NF-κB induction signals oxidative eustress and induces plasticity in healthy cells[20,32,220-223]. It is possible that the frustrated Nrf2 response after stroke and other acute CNS injuries reflects astrocytic sensitivity to sustained NF-κB signals, impairing their antioxidant support to other cell types and amplifying neuroinflammation[220-222,224]. Such crosstalk between these and other pathways is simultaneously influenced by ongoing changes in the mechanical and osmotic environment (e.g., edema, ionic imbalance, and elevated intracranial pressure) that occur following stroke in both preclinical models and patients[225-229]. These biomechanical forces distort oxygen delivery and redox flux, both triggering and amplifying inflammatory signaling, ferroptosis and other forms of cell death[205,230,231].

Indeed, a theorized evolutionary function of ferroptosis is to act as a source of bioactive inflammatory signals, providing a warning to the immune system that redox homeostasis has been lost within a given region[232]. Following stroke, the DAMPs released from acutely necrotic cells in the infarct core or hematoma initiate early oxidative distress through TLRs, RAGE, and inflammasome activation[193-195]. As ferroptosis progresses in penumbral or perihematomal cells, secondary release of oxidized phospholipids and aldehydes such as 4-HNE and MDA further propagate this inflammatory circuit. These lipid peroxidation products function as immunotransmitters that signal the failure of local redox homeostasis, recruiting and polarizing microglia and infiltrating macrophages to contain the damage and protect wider organ integrity[233].

Some lipid peroxidation products can also help resolve the inflammatory response[123]. The membrane 12/15-LOX activity characteristic of focal ischemia yields 15-HpETE-PE, but when redox balance recovers, this pathway can shift toward production of pro-resolving lipoxins and prostaglandins that guide tissue repair[233]. Conversely, in ICH pathology, nuclear 5-LOX activity dominates, producing leukotrienes that massively amplify neutrophil extravasation and sustain chronic inflammation and oxidative distress[233]. These distinct repertoires of lipid mediators may explain why ischemic injury more readily transitions toward resolution, whereas hemorrhagic injury often results in chronic, ongoing cell death. Yet how and when these oxidized lipids serve primarily as pro-death signals or as adaptive cues for debris clearance and tissue remodeling remains unclear. Disentangling how ferroptotic signaling interfaces with innate immunity, mechanical/osmotic stress, and parallel death programs will be necessary to determine how and when ferroptosis should be suppressed, modulated, or repurposed as part of a controlled injury-resolution process following stroke.

5. Conclusion: The Path to Translation

It is striking that many anti-ferroptotic agents that inhibit cell death induced by ferroptotic stimuli in vitro also reduce cell death and improve behavioral outcomes following ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke in vivo (Table 1). This suggests that anti-ferroptotic agents protect the brain in a manner that preserves integrated functional benefit. Therefore, there is hope that blocking ferroptosis in the first days following stroke could reduce neuronal and glial cell loss, preserve functional circuits, and promote improved motor, cognitive, and sensory recovery in patients- though for many therapeutic agents, translational challenges remain (Table 1). Additionally, while our understanding of ferroptosis is advancing rapidly, there are numerous therapeutic “nodes” that are yet to be exploited in the context of stroke.

| Therapeutic Agent | Therapeutic Target | Mechanism of Action | Representative Preclinical/Clinical Evidence | Translational Considerations/Challenges |

| Deferoxamine | LIP | Chelates intracellular iron, reducing iron-driven lipid peroxidation by limiting expansion of the LIP; reduced intracellular iron can relieve HIF-1α inhibition (contextually dependent effects). | Preclinical: Reduced peri-hematomal edema, iron deposition, cell death, and provided functional benefit in multiple porcine/rodent ICH models with 0-6 h treatment delay[81,86-88], though evidence of benefit is mixed in the collagenase model[80]. Functional benefit and reduced infarct volume, neuronal death, and BBB disruption when administered 1-3 h[85] or 24 h[83] following reperfusion upon transient MCAO in rodents. Others find evidence of harm, impeding repair and prolonging neurological deficits following permanent rodent MCAO with subacute administration (72 h treatment delay)[84]. Clinical: Evaluated in Phase II i-DEF trial for ICH; failed to reach primary endpoint of functional improvement[89], though post-hoc analyses suggest earlier and more rapid recovery trajectories in treated patients[91,92]. A Phase I trial for high dose treatment (HI-DEF) in ICH patients was terminated early due to evidence of harm[90]. Evaluated in Phase I trials for focal ischemic stroke patients alongside tPA infusion; found to be safe[242] | FDA-approved for iron overload; poor CNS penetrance (requires high doses), short half-life, and risk of systemic hypotension/toxicity. Trial failures suggest a need for better CNS-targeting, or alternatives to wholesale iron chelation. |

| Adaptaquin | HIF PHDs | Selective inhibition of HIF PHDs suppresses ATF4-driven pro-ferroptotic transcription while sparing bulk iron metabolism. | Functional benefit and reduced cell death in multiple mouse ICH models (2 h treatment delay)[77]. | Unknown pharmacokinetic and safety profile in humans. |

| Zileuton | 5-LOX | Suppresses hemin-mediated production of 5-HpETE lipid hydroperoxides by 5-LOX and leukotriene-driven inflammatory amplification. | Functional benefit, reduced levels of leukotriene B4, and attenuated neutrophil infiltration after collagenase ICH (3 h treatment delay)[125]. | FDA-approved for asthma; possible risk of hepatotoxicity at doses required for CNS penetrance in humans; short half-life; poor solubility. Likely restricted to acute treatment window due to risk of interfering with the lipid mediators that help resolve inflammation during the sub-acute recovery phase (e.g., lipoxins). |