Abstract

Sulfur, like oxygen, belongs to group 16 of the periodic table and exhibits remarkable versatility in both electron donation and acceptance, as well as in its wide range of oxidation states. These properties enable sulfur to participate in diverse redox reactions, while also serving as a critical component of enzyme active sites and redox sensors. Moreover, sulfur is the only element capable of forming stable linear homonuclear chains, a property known as catenation, which gives rise to a rich array of naturally occurring allotropes with complex chemical architectures. Recent advances in analytical technologies have uncovered the in vivo existence of supersulfides, molecules containing catenated sulfur atoms, whose physiological functions and pathological relevance are now beginning to be elucidated. In this review, we highlight the unique chemical features and biological functions of supersulfur species, with a particular focus on their roles in cancer. Furthermore, we discuss the therapeutic implications of supersulfur-driven “reductive stress,” a distinct imbalance in redox homeostasis that may be exploited for cancer treatment.

Keywords

1. Introduction

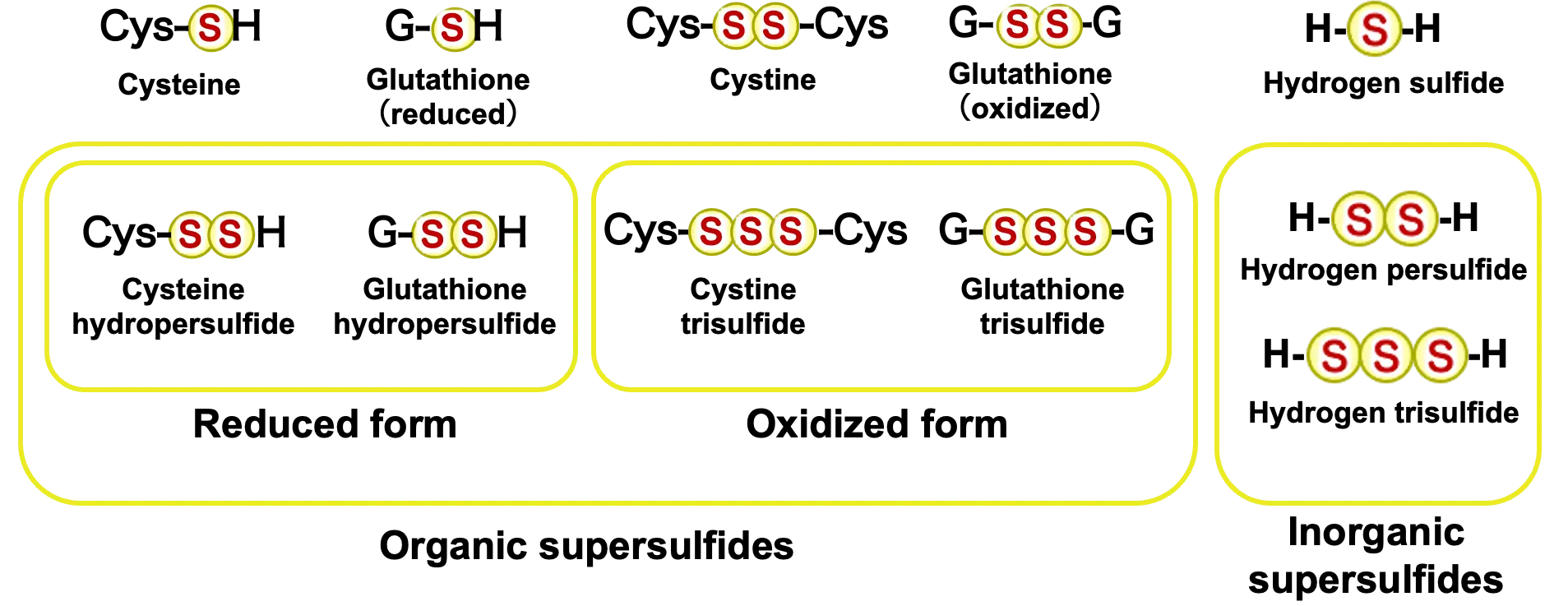

Recent advances in mass spectrometry-based analytical technologies have revealed supersulfides as a previously unrecognized class of bioactive molecules[1-3]. Supersulfides are defined by sulfur-sulfur catenation, in which multiple sulfur atoms are linearly connected. This category encompasses metabolites such as cysteine hydropersulfide (CysSSH) and glutathione hydropersulfide (GSSH), in which excess sulfur atoms are appended to thiol groups, as well as supersulfidated proteins bearing additional sulfur atoms on cysteine residues (Figure 1). Phenomena once attributed to hydrogen sulfide (H2S) signaling are now increasingly recognized as functions mediated by supersulfides[4]. In fact, much of what was previously detected as H2S in biological samples is now understood to be artifactual decomposition products of supersulfides generated during sample processing. Consequently, the physiological and pathological significance of supersulfides has recently attracted considerable attention as a novel dimension of redox biology. In this section, we first outline the chemical characteristics and biosynthetic pathways of supersulfides. We then introduce their biological functions, with particular emphasis on our recent discovery of the PNPO–PLP regulatory axis as an oxygen-sensing mechanism that drives supersulfide production and suppresses inflammation. Finally, we discuss how supersulfides and the KEAP1–NRF2 oxidative stress response pathway cooperatively regulate redox balance in cancer progression, and we explore the therapeutic potential of targeting supersulfide metabolism and its biosynthetic machinery in NRF2-addicted malignancies.

Figure 1. Various supersulfides. Supersulfides are molecules that contain catenated sulfur moieties in each molecular structure, e.g., H–Sn–H, R-Sn-H, R-SSn-R’, cyclo-SSn (n > 1). They can be either low molecular weight metabolites or proteins.

2. Chemical Properties of Supersulfides

Sulfur, like oxygen, belongs to group 16 of the periodic table, yet its chemical properties are markedly distinct. Most notably, sulfur is highly flexible in both donating and accepting electrons, and it can adopt a wide range of oxidation states, from -2 to +6. This versatility underlies sulfur’s pivotal role in biological redox reactions. Indeed, sulfur frequently serves as a catalytic center in enzymes or as a sensor molecule that detects shifts in redox states, thereby regulating diverse biological processes. In addition to these redox properties, sulfur possesses a unique structural capacity not observed in other elements: the ability to form catenation, or linear and cyclic chains of sulfur atoms bonded to each other. Such catenation generates a remarkable structural diversity, which in turn gives rise to the wide-ranging chemical properties of sulfur compounds.

In living systems, sulfur-containing metabolites can broadly be classified as either organic or inorganic (Figure 1). Organic sulfur compounds include sulfur-containing amino acids such as cysteine and methionine and their derivatives, whereas inorganic compounds encompass hydrogen sulfide (H2S), sulfite (SO32-), and sulfate (SO42-). Within proteins, cysteine thiol groups (–SH) are known to undergo stepwise oxidation, yielding disulfides (–SS–), sulfenic acids (–SOH), sulfinic acids (–SO2H), and ultimately sulfonic acids (–SO3H). Beyond these conventional oxidation products, the advent of advanced mass spectrometry and high-sensitivity chemical probes has revealed the in vivo existence of a new class of molecules containing sulfur catenation, collectively termed supersulfides[5] (Figure 1). Supersulfides are defined as molecular species containing catenated sulfur atoms within their structures, including H-Sn-H, R-Sn-H, R-SSn-R′, and cyclo-SSn species (n > 1)[5]. Among these, H-S-S-H and R-S-SH are classified as persulfides, whereas species with longer sulfur chains, such as H-Sn-H and R-Sn-H (n > 2), as well as R-SSn-R′ and cyclic S-Sn (n > 1), are referred to as polysulfides. These molecules exhibit chemical properties distinct from classical thiols and disulfides. Representative examples include CysSSH, GSSH, and inorganic polysulfides (e.g., HSSH, HSSSH).

Glutathione (GSH) is widely recognized as a major endogenous antioxidant. However, its pKa is approximately 9, meaning that under physiological pH (~7), GSH exists predominantly in its protonated form, which limits its nucleophilic reactivity. Consequently, conjugation of GSH to electrophilic xenobiotics generally requires enzymatic catalysis, such as that provided by glutathione S-transferases (GSTs). In contrast, GSSH exhibits a substantially lower pKa (approximately 6-7), and thus exists largely in the deprotonated thiolate form (GSS-) under intracellular conditions[6,7]. This confers GSSH with strong nucleophilic activity, enabling it to spontaneously conjugate with electrophilic toxicants without enzymatic assistance. In this sense, GSSH functions as a unique driver of non-enzymatic detoxification reactions. Indeed, GSSH has been detected in mouse tissues at physiologically relevant concentrations: > 100 μM in the brain, and ~50 μM in other major organs such as the heart and liver. Although these levels represent only 1-10% of the abundant millimolar concentrations of GSH, the amount of reactive thiolate species derived from GSSH (GSS-), as predicted from its pKa, exceeds that of GS- by 10-100 fold. Thus, despite its lower abundance, GSSH dominates intracellular nucleophilic reactivity and functions as a more potent antioxidant and detoxifying factor than GSH itself[1].

3. Biosynthetic Pathways of Supersulfides in Cells

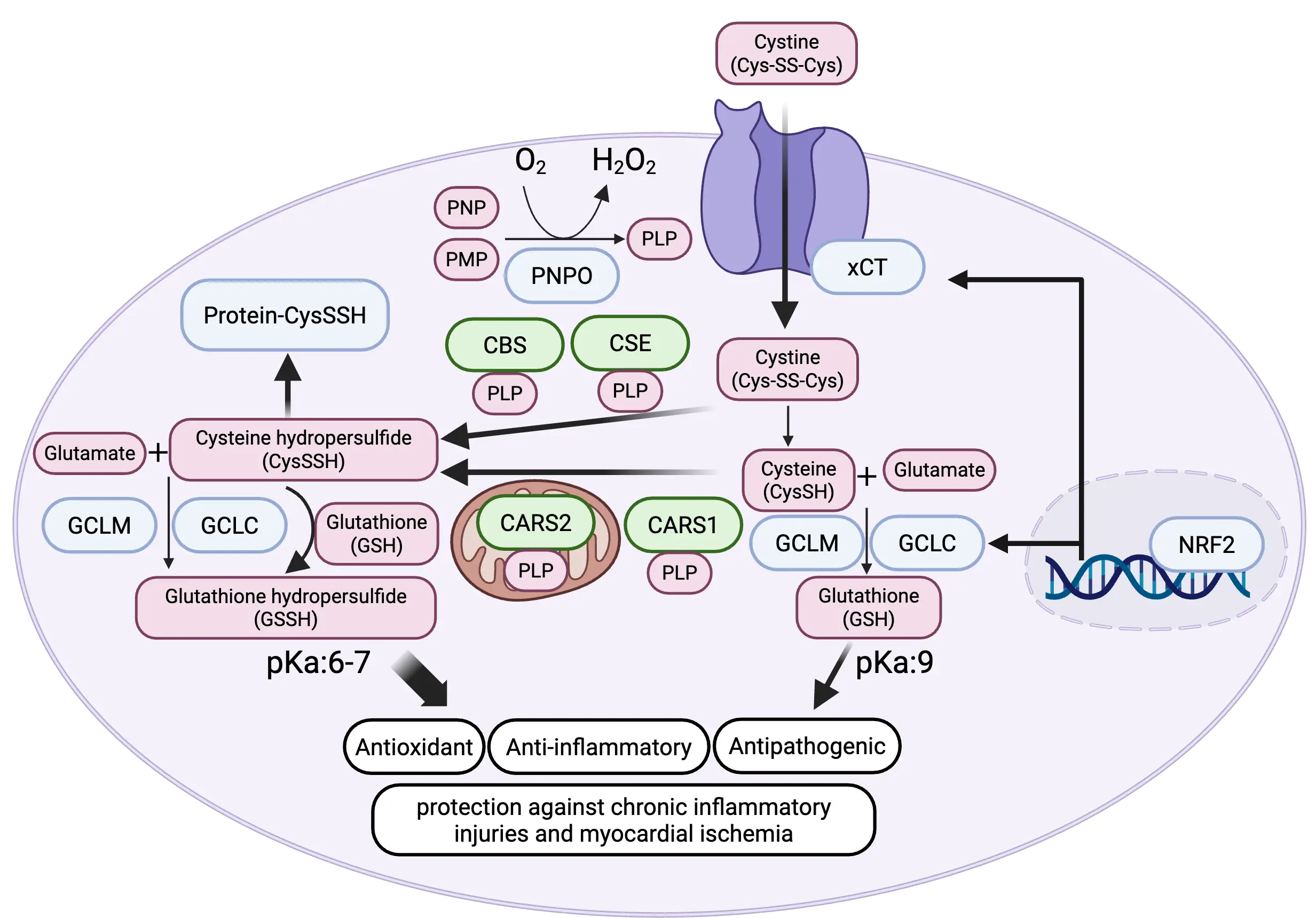

Multiple pathways exist for the intracellular generation of CysSSH, which is a primary supersulfide synthesized in cells (Figure 2). First, cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) can utilize cystine (CysSSCys) as a substrate to produce CysSSH[1]. Second, cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase 1 (CARS1) and CARS2 catalyze the conversion of two cysteine molecules (CysSH) into one molecule of CysSSH[2]. Both pathways require pyridoxal phosphate (PLP), the active form of vitamin B6, as a cofactor. In addition to these enzymatic mechanisms, supersulfides may also be generated through non-enzymatic reactions, such as the oxidation of H2S or its interaction with nitric oxide (NO). However, analyses of Cars2-deficient mice strongly suggest that enzyme-dependent pathways make the predominant contribution[2,8]. Enzymatically synthesized CysSSH spontaneously reacts with GSH to form GSSH and higher-order polysulfides such as GSSSH. This non-enzymatic sulfur transfer establishes a cascade that continually expands the intracellular supersulfide network (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Regulation of cysteine hydro persulfide synthesis by NRF2 and PNPO. NRF2 enhances cysteine hydro persulfide production by upregulating xCT, a cystine transporter, thereby increasing intracellular cysteine availability. PNPO elevates pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (PLP), an essential coenzyme required for all cysteine hydro persulfide-synthesizing enzymes. In addition, NRF2 promotes glutathione biosynthesis through induction of GCLC and GCLM, which in turn facilitates the formation of glutathione hydro persulfide as a downstream supersulfide species. Created in BioRender.com. PNPO: pyridoxine phosphate oxidase; PLP: pyridoxal 5′-phosphate; CBS: β-synthase; CARS1: cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase 1; CARS2: cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase 2; NRF2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; GCLC: glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic subunit; GCLM: glutamate-cysteine ligase modifier subunit; PNP: pyridoxine 5′-phosphate; CES: cystathionine γ-lyase; PMP: pyridoxamine 5′-phosphate.

The biosynthesis of supersulfides is tightly coupled to the supply of sulfur-containing amino acids such as cystine, cysteine, and methionine[9]. Intriguingly, the master transcription factor of the oxidative stress response, NRF2, has been shown to increase intracellular levels of supersulfides by transcriptionally activating SLC7A11, the gene encoding the cystine transporter xCT[9]. In addition, NRF2 is known to promote GSH synthesis by transcriptionally inducing expressions of γ-glutamylcysteine ligase catalytic and regulatory subunits, GCLC and GCLM, respectively. Thus, part of NRF2’s cytoprotective function may be mediated through the augmentation of supersulfide production.

Our recent work revealed that cellular oxygen tension dynamically regulates PLP abundance, thereby fine-tuning CysSSH synthesis and supersulfide production[10]. In oxygen-rich environments, elevated PLP levels promote CysSSH generation and broaden the supersulfide pool. Under such conditions, the potent antioxidant activity of supersulfides mentioned above may endow cells with a distinct adaptive advantage. In addition, supersulfides possess mitochondria-activating activity as well. Within mitochondria, CARS2 catalyzes the synthesis of CysSSH from CysSH. Electrons supplied from the electron transport chain reduce supersulfides, generating hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and reduced polysulfides. H₂S and reduced polysulfides are rapidly oxidized by sulfide-quinone oxidoreductase (SQOR), transferring electrons to ubiquinone and returning them to the respiratory chain. In this process, H2S is re-oxidized to persulfides and polysulfides, enabling the regeneration of supersulfides. Conversely, the oxidative degradation of supersulfides involves enzymes such as ethylmalonic encephalopathy protein 1 (ETHE1), thiosulfate sulfurtransferase (TST), and sulfite oxidase (SUOX), ultimately yielding oxidized metabolites including thiosulfate, sulfite, and sulfate. These findings highlight that mitochondrial sulfur metabolism—encompassing synthesis, conversion, and degradation—is dynamically and stringently regulated[2]. Of note, under hypoxic conditions, enhancing SQOR activity in the brain promotes the metabolism of H2S, thereby sustaining mitochondrial respiration and conferring resistance to hypoxemia[11].

4. Biological Functions of Supersulfides

Supersulfides exhibit strong antioxidant activity by virtue of their high nucleophilicity, which enables them to efficiently scavenge reactive oxygen species. Functional studies of supersulfides, conducted by our group and others, have revealed their critical contributions to antioxidant defense and redox-dependent signaling pathways[3,5]. For example, supersulfidation of protein cysteine residues has been shown to confer metabolic plasticity. Under endoplasmic reticulum stress, as many as 827 proteins in pancreatic β-cells become supersulfidated, resulting in profound reprogramming of glucose metabolism[12]. This process is regulated by ATF4-dependent activation of the cystine transporter xCT, which enhances cystine uptake and increases the pool of supersulfidated proteins. Similarly, supersulfidation of the α-subunit of ATP synthase has been reported to enhance enzymatic activity, thereby stimulating mitochondrial energy metabolism[13].

The anti-inflammatory functions of supersulfides are also increasingly recognized. Analyses using supersulfide donors have demonstrated that supersulfides strongly suppress lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory responses in macrophages by inhibiting Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling[14]. Our group further discovered that endogenous supersulfide production exerts anti-inflammatory effects in macrophages[15]. Upon LPS stimulation, macrophages upregulate xCT expression and cystine uptake, leading to an increase in intracellular supersulfides, which in turn dampens excessive inflammation. Consistently, knockout of xCT in mice exacerbates macrophage inflammatory responses, which can be rescued by administration of supersulfide donors.

We also identified a novel oxygen-sensing system, the PNPO–PLP axis, as a key regulator of supersulfide metabolism and inflammation[10]. As noted earlier, all enzymes catalyzing de novo supersulfide synthesis are PLP-dependent. PLP is generated from pyridoxine and pyridoxamine through the activity of pyridoxine phosphate oxidase (PNPO), a reaction that requires molecular oxygen. Under hypoxic conditions, reduced PNPO activity lowers PLP levels, thereby suppressing supersulfide synthesis and other PLP-dependent metabolic pathways. We showed that chronic hypoxia decreases PLP in macrophages, leading to diminished supersulfide metabolism and delayed resolution of inflammation[10]. Beyond their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, supersulfides also exert direct antiviral effects against pathogens such as influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2, thereby contributing to host defense[8]. In addition, their anti-inflammatory functions help protect the lung against chronic inflammatory injuries, including COPD, pulmonary fibrosis, and aging-associated lung damage[8].

Supersulfides have also been implicated in organ dysfunction. In cardiomyocytes under hypoxic conditions, supersulfides are converted into hydrogen sulfide (H2S; HS-), and this catabolic shift has been correlated with cardiac impairment[16]. Interestingly, the same group reported that oxidized glutathione (GSSG)—traditionally considered a mere oxidative stress marker without intrinsic antioxidant activity—exerts a protective effect against myocardial ischemia by suppressing excessive Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission in cardiomyocytes[17].

5. Redox Imbalance and Acquisition of Antioxidant Capacity in Cancer Malignancy

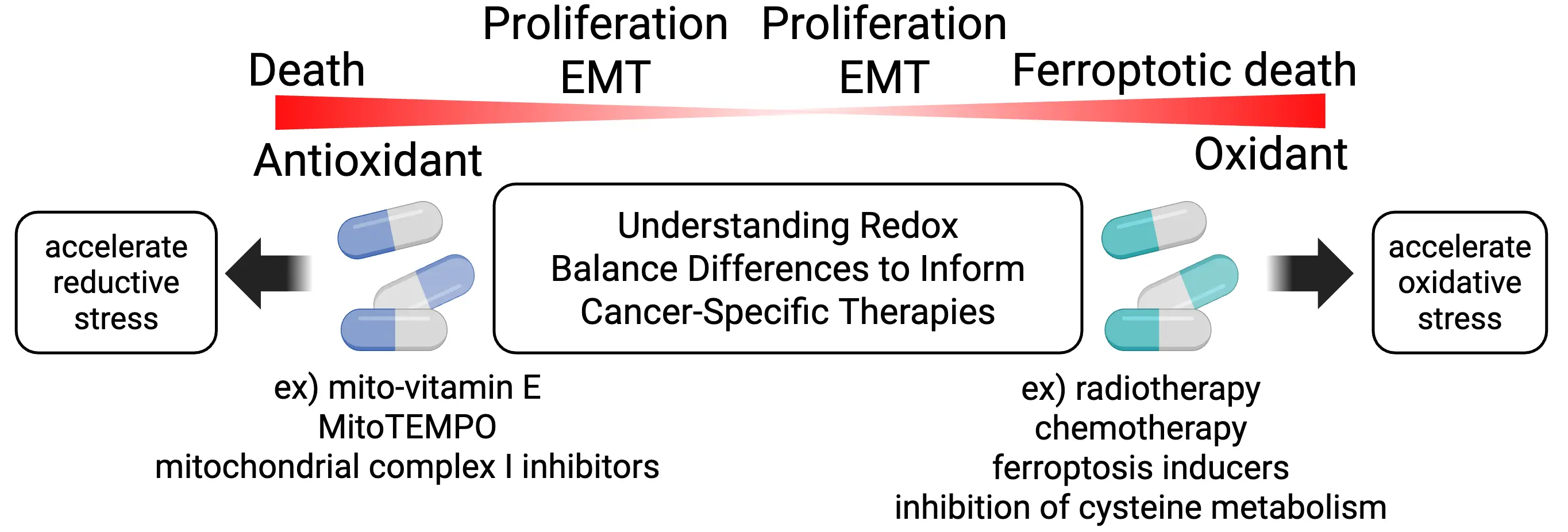

Tumorigenesis and cancer progression are intimately linked to disruptions in redox balance (Figure 3). To sustain their hallmark rapid proliferation, cancer cells exhibit heightened metabolic demands and consequently generate elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Depending on their abundance, ROS can exert either tumor-promoting or cytotoxic effects. At moderate levels, ROS activate multiple oncogenic signaling pathways, including the RAS-MAPK, PI3K-AKT, and IKK-NFκB cascades[18]. During the metastatic process, for instance, elevated ROS contributes to the acquisition of invasive phenotypes in KRAS-mutant pancreatic cancer. Inhibition of the antioxidant protein TIGAR enhances ROS accumulation, delaying early tumor growth but paradoxically accelerating metastatic progression at later stages[19]. Conversely, excessive ROS production is detrimental to cancer cells, necessitating the activation of robust antioxidant defense systems to mitigate oxidative damage and maintain redox homeostasis. Two major mechanisms exemplify this defense: the KEAP1-NRF2 system and the action of supersulfides[20].

Figure 3. Redox balance in cancer cells and therapeutic strategies. Cancer cell vulnerability frequently arises from disturbances in redox balance. Under conditions of oxidative stress, excess oxidants further exacerbate oxidation, driving cells toward ferroptosis. Conversely, in a reductive environment, excess antioxidants intensify reductive stress, which can also result in cancer cell death. EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition; MitoTEMPO: (2-(2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl-4-ylamino)-2-oxoethyl)triphenylphosphonium chloride.

While NRF2 is a master transcription factor that orchestrates a broad spectrum of cytoprotective responses and serves as a central regulator of oxidative stress defense[21], somatic mutations in KEAP1 or NFE2L2 (encoding NRF2) in cancer cells lead to constitutive NRF2 activation, dramatically enhancing the antioxidant capacity of cancer cells and enabling their survival under conditions of high oxidative stress[22]. NRF2-addicted cancers exhibit strong induction of target genes that increase GSH biosynthesis, elevate NADPH production, and upregulate detoxifying enzymes and antioxidant proteins, conferring resistance to oxidative stress and radiotherapy[23-25]. In addition, sustained NRF2 activation drives malignant traits by altering transcription factor networks and remodeling the epigenome, thereby promoting cancer stemness and drug resistance[26-27]. Consequently, constitutive NRF2 activation is associated with extremely poor prognosis[28,29].

NRF2 activation also promotes supersulfide synthesis by increasing cystine and cysteine availability through upregulation of xCT[9]. In parallel, NRF2 induces expression of the thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase system, which has been implicated in depersulfidation reactions[30]. Thus, supersulfide levels in cancer cells with persistent NRF2 activation are likely determined by the dynamic balance between supersulfide production and degradation. Collectively, these observations suggest that sulfur turnover is markedly accelerated in NRF2-addicted cancer cells.

Supersulfides are likewise elevated in various cancers, including breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and esophageal cancers, concomitant with increased expression of CBS and/or CSE (Table 1)[31-34]. Many earlier studies reported elevated sulfide levels in cancer cells; however, a substantial fraction of these observations likely reflects the presence of supersulfide species, owing to limitations in sample processing and analytical methodologies available at the time, particularly in the context of colon cancer where CBS and CSE expression is markedly upregulated (Table 1)[35-41]. Owing to their strong nucleophilicity, supersulfides efficiently neutralize radical species such as lipid radicals generated during hyperactive metabolism, thereby exerting potent antioxidant effects that protect cancer cells from oxidative damage[42-44]. Notably, supersulfides safeguard cancer cells against ferroptosis, a form of cell death triggered by lipid peroxidation, thus strongly supporting tumor survival and progression. In addition, supersulfides have been implicated in the promotion of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis[33]. Supersulfide-generating enzymes also contribute to malignant signaling: for example, CBS has been reported to promote supersulfidation of PHD2, suppressing its activity and leading to activation of the HIF pathway[45]. It is therefore plausible that part of the HIF activation observed in cancer arises from this supersulfide-mediated mechanism.

| Cancer type | Specific alteration | functional consequences | Reference |

| Basal-like breast cancer | CBS elevation, protein persulfidation increase, GSSH/GSH ratio decrease | Resistance to ferroptosis | [31] |

| Breast cancer | CBS elevation, H2S increase | Protection from tumoricidal macrophage | [35] |

| Ovariay cancer (clear cell carcinoma) | CSE elevation, polysulfide increase | Poor overall survival | [32] |

| Ovarian cancer | CBS elevation, H2S elevation | Promotion of tumor growth, drug resistance acquisition | [36] |

| Metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | CBS elevation | Enhancement of metastatic dissemination of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma | [33] |

| Esophageal cancer | CysSSH increase in plasma and exhaled breath condensates, homoCysSSH increase in plasma | Diagnostic marker for early stage, stage I & II | [34] |

| Colon cancer | CBS elevation, H2S increase | Stimulation of colon cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion in vitro. Tumor xenograft growth, angiogenesis, and peritumoral vascular tone | [37] |

| Colon cancer | SQOR, TST, ETHE1 elevation. Production of supersulfides | Protection from toxicity of sulfide derived from gut microbiota | [38] |

| Colon cancer | H2S elevation | Decrease in CD8 T cells/Treg | [39] |

| Colon cancer | xCT elevation, H2S elevation | Avoidance of ferroptosis and apoptosis | [40] |

| Melanoma | CSE, CBS, 3-MST elevation | Inhibition of melanoma cell proliferation | [41] |

GSSH: glutathione hydropersulfide; CysSSH: cysteine hydropersulfide; CBS: β-synthase; CSE: cystathionine γ-lyase; GSH: glutathione; SQOR: sulfide-quinone oxidoreductase; TST: thiosulfate sulfurtransferase; ETHE1: Ethylmalonic encephalopathy protein 1 (mitochondrial sulfur dioxygenase); 3-MST: 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase.

6. Therapeutic Targeting of Redox Imbalance in Cancer

Redox imbalance in cancer not only supports malignant progression but also creates context-dependent vulnerabilities that may be therapeutically exploited. While many anticancer therapies rely on ROS to induce tumor cell death, excessive antioxidant capacity can promote tumor growth and therapeutic resistance. Indeed, dietary supplementation with antioxidants such as N-acetylcysteine (NAC) or vitamin E has been shown to accelerate tumor progression and metastasis in multiple mouse cancer models, underscoring the complex role of redox balance in cancer biology[46-48].

Importantly, redox states vary substantially among cancer types. In particular, NRF2-activated cancers exhibit a pronounced shift toward a highly reduced intracellular environment. Although this enhanced reducing capacity confers robust protection against oxidative stress, it can also give rise to reductive stress, a pathological condition characterized by excess reducing equivalents such as NADH, NADPH, and low-molecular weight thiols[49]. Reductive stress has been shown to induce protein misfolding and aggregation, triggering endoplasmic reticulum stress and impairing cellular functions including neurogenesis and myogenesis[50,51].

In cancer cells, reductive stress may disrupt key metabolic and signaling pathways essential for proliferation and survival[49]. Excess NADH can over-reduce the mitochondrial NADH/NAD+ pool, thereby limiting oxidized NAD+ availability and perturbing tricarboxylic acid cycle flux, which impairs de novo nucleotide synthesis by limiting aspartate production[52]. Moreover, excessive reducing power interferes with redox-dependent signaling and enzymatic reactions, including those regulated by thiol oxidation-reduction cycles. In NRF2-addicted cancers, mitochondrial complex I inhibitors have been shown to exacerbate NADH-driven reductive stress, selectively inducing cancer cell death[53].

Supersulfides, owing to their strong nucleophilicity and electron-donating capacity, are likely to play a critical role in shaping this reductive redox landscape[1,2]. Elevated supersulfide levels can further buffer oxidative stress but may also intensify reductive pressure by reinforcing electron-rich states and suppressing lipid radical propagation[42-44]. While increased supersulfide production in cancer cells contributes to malignant behavior through its potent antioxidant function[31], it remains an open and important question whether such elevation simultaneously creates vulnerabilities to dysfunction arising from an excessively reductive redox environment. Notably, given the dual chemical nature of supersulfides, exhibiting both nucleophilic and electrophilic reactivity depending on context[54], it is also plausible that supersulfides may function as buffers that mitigate excessively reductive redox states.

Therapeutically, these insights suggest that supersulfide-producing cancers may be selectively targeted by strategies that exploit disrupted sulfur metabolism. Suppression of supersulfide production or function is expected to facilitate lipid radical accumulation, enhance ferroptosis sensitivity, and promote cancer cell death. Consistent with this concept, ferroptosis inducers targeting lipid peroxide-detoxifying systems, such as GPX4 inhibitors (RSL3, ML210, DPI) and FSP1 inhibitors (iFSP1, icFSP1), as well as agents that inhibit cysteine metabolism (sulfasalazine, erastin, cyst(e)inase), have demonstrated potent anticancer activity[55-59]. Interestingly, in the in vivo context, FSP1 inhibition rather than GPX4 inhibition exhibits much better anticancer effects[60,61]. Future therapeutic approaches may further benefit from the development of drugs that act selectively under reductive conditions, thereby exploiting a unique metabolic liability of reductively stressed cancers.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of Department of Medical Biochemistry and Department of Environmental Medicine and Molecular Toxicology at Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine for continuous supports. ChatGPT 5.2 was used to polish the language of the manuscript. The authors reviewed the final content and take all responsibilities for this article.

Authors contribution

Pan S, Kawaguchi M: Visualization, writing-original draft

Akaike T, Motohashi H: Conceptualization, writing-original draft.

Conflicts of interest

Hozumi Motohashi is an Editorial Board Member of Ferroptosis and Oxidative Stress. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS [Grant numbers 25K18868 (M.K.), 21H05263 (T.A.), 22K19397 (T.A.), 23K20040 (H.M. & T.A.), 24H00063 (T.A.), 21H04799 (H.M.), 21H05258 (T.A. & H.M.), 21H05264 (H.M.) and 24H00605 (H.M.)]. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or manuscript preparation.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Ida T, Sawa T, Ihara H, Tsuchiya Y, Watanabe Y, Kumagai Y, et al. Reactive cysteine persulfides and S-polythiolation regulate oxidative stress and redox signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(21):7606-7611.[DOI]

-

2. Akaike T, Ida T, Wei FY, Nishida M, Kumagai Y, Alam MM, et al. Cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase governs cysteine polysulfidation and mitochondrial bioenergetics. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1177.[DOI]

-

3. Sekine H, Akaike T, Motohashi H. Oxygen needs sulfur, sulfur needs oxygen: A relationship of interdependence. EMBO J. 2025;44(12):3307-3326.[DOI]

-

4. Kasamatsu S, Ida T, Koga T, Asada K, Motohashi H, Ihara H, et al. High-precision sulfur metabolomics innovated by a new specific probe for trapping reactive sulfur species. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2021;34(18):1407-1419.[DOI]

-

5. Akaike T, Morita M, Ogata S, Yoshitake J, Jung M, Sekine H, et al. New aspects of redox signaling mediated by supersulfides in health and disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;222:539-551.[DOI]

-

6. Benchoam D, Semelak JA, Cuevasanta E, Mastrogiovanni M, Grassano JS, Ferrer-Sueta G, et al. Acidity and nucleophilic reactivity of glutathione persulfide. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(46):15466-15481.[DOI]

-

7. Zhang T, Akaike T, Sawa T. Redox regulation of xenobiotics by reactive sulfur and supersulfide species. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2024;40(10-12):679-690.[DOI]

-

8. Matsunaga T, Sano H, Takita K, Morita M, Yamanaka S, Ichikawa T, et al. Supersulphides provide airway protection in viral and chronic lung diseases. Nat Commun. 2023;14:4476.[DOI]

-

9. Alam MM, Kishino A, Sung E, Sekine H, Abe T, Murakami S, et al. Contribution of NRF2 to sulfur metabolism and mitochondrial activity. Redox Biol. 2023;60:102624.[DOI]

-

10. Sekine H, Takeda H, Takeda N, Kishino A, Anzawa H, Isagawa T, et al. PNPO-PLP axis senses prolonged hypoxia in macrophages by regulating lysosomal activity. Nat Metab. 2024;6(12):2391.[DOI]

-

11. Marutani E, Morita M, Hirai S, Kai S, Grange RMH, Miyazaki Y, et al. Sulfide catabolism ameliorates hypoxic brain injury. Nat Commun. 2021;12:3108.[DOI]

-

12. Gao XH, Krokowski D, Guan BJ, Bederman I, Majumder M, Parisien M, et al. Quantitative H2S-mediated protein sulfhydration reveals metabolic reprogramming during the integrated stress response. eLife. 2015;4:e10067.[DOI]

-

13. Módis K, Ju Y, Ahmad A, Untereiner AA, Altaany Z, Wu L, et al. S- Sulfhydration of ATP synthase by hydrogen sulfide stimulates mitochondrial bioenergetics. Pharmacol Res. 2016;113:116-124.[DOI]

-

14. Zhang T, Ono K, Tsutsuki H, Ihara H, Islam W, Akaike T, et al. Enhanced cellular polysulfides negatively regulate TLR4 signaling and mitigate lethal endotoxin shock. Cell Chem Biol. 2019;26(5):686-698.e4.[DOI]

-

15. Takeda H, Murakami S, Liu Z, Sawa T, Takahashi M, Izumi Y, et al. Sulfur metabolic response in macrophage limits excessive inflammatory response by creating a negative feedback loop. Redox Biol. 2023;65:102834.[DOI]

-

16. Tang X, Nishimura A, Ariyoshi K, Nishiyama K, Kato Y, Vasileva E, et al. Echinochrome prevents sulfide catabolism-associated chronic heart failure after myocardial infarction in mice. Mar Drugs. 2023;21(1):52.[DOI]

-

17. Nishimura A, Ogata S, Tang X, Hengphasatporn K, Umezawa K, Sanbo M, et al. Polysulfur-based bulking of dynamin-related protein 1 prevents ischemic sulfide catabolism and heart failure in mice. Nat Commun. 2025;16:276.[DOI]

-

18. Wu K, El Zowalaty AE, Sayin VI, Papagiannakopoulos T. The pleiotropic functions of reactive oxygen species in cancer. Nat Cancer. 2024;5(3):384-399.[DOI]

-

19. Cheung EC, DeNicola GM, Nixon C, Blyth K, Labuschagne CF, Tuveson DA, et al. Dynamic ROS control by TIGAR regulates the initiation and progression of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;37(2):168-182.e4.[DOI]

-

20. Hayashi M, Okazaki K, Papgiannakopoulos T, Motohashi H. The complex roles of redox and antioxidant biology in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2024;14(11):a041546.[DOI]

-

21. Yamamoto M, Kensler TW, Motohashi H. The KEAP1-NRF2 system: A thiol-based sensor-effector apparatus for maintaining redox homeostasis. Physiol Rev. 2018;98(3):1169-1203.[DOI]

-

22. Kitamura H, Takeda H, Motohashi H. Genetic, metabolic and immunological features of cancers with NRF2 addiction. FEBS Lett. 2022;596(16):1981-1993.[DOI]

-

23. Shibata T, Kokubu A, Gotoh M, Ojima H, Ohta T, Yamamoto M, et al. Genetic alteration of Keap1 confers constitutive Nrf2 activation and resistance to chemotherapy in gallbladder cancer. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(4):1358-1368.[DOI]

-

24. Mitsuishi Y, Taguchi K, Kawatani Y, Shibata T, Nukiwa T, Aburatani H, et al. Nrf2 redirects glucose and glutamine into anabolic pathways in metabolic reprogramming. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(1):66-79.[DOI]

-

25. Jeong Y, Hoang NT, Lovejoy A, Stehr H, Newman AM, Gentles AJ, et al. Role of KEAP1/NRF2 and TP53 mutations in lung squamous cell carcinoma development and radiation resistance. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(1):86-101.[DOI]

-

26. Okazaki K, Anzawa H, Liu Z, Ota N, Kitamura H, Onodera Y, et al. Publisher Correction: Enhancer remodeling promotes tumor-initiating activity in NRF2-activated non-small cell lung cancers. Nat Commun. 2021;12:506.[DOI]

-

27. Okazaki K, Anzawa H, Katsuoka F, Kinoshita K, Sekine H, Motohashi H. CEBPB is required for NRF2-mediated drug resistance in NRF2-activated non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Biochem. 2022;171(5):567-578.[DOI]

-

28. Shibata T, Ohta T, Tong KI, Kokubu A, Odogawa R, Tsuta K, et al. Cancer related mutations inNRF2impair its recognition by Keap1-Cul3 E3 ligase and promote malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(36):13568-13573.[DOI]

-

29. Inoue D, Suzuki T, Mitsuishi Y, Miki Y, Suzuki S, Sugawara S, et al. Accumulation of p62/SQSTM1 is associated with poor prognosis in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2012;103(4):760-766.[DOI]

-

30. Braunstein I, Engelman R, Yitzhaki O, Ziv T, Galardon E, Benhar M. Opposing effects of polysulfides and thioredoxin on apoptosis through caspase persulfidation. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(11):3590-3600.[DOI]

-

31. Erdélyi K, Ditrói T, Johansson HJ, Czikora Á, Balog N, Silwal-Pandit L, et al. Reprogrammed transsulfuration promotes basal-like breast tumor progression via realigning cellular cysteine persulfidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(45):e2100050118.[DOI]

-

32. Honda K, Hishiki T, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto T, Miura N, Kubo A, et al. On-tissue polysulfide visualization by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy benefits patients with ovarian cancer to predict post-operative chemosensitivity. Redox Biol. 2021;41:101926.[DOI]

-

33. Czikora Á, Erdélyi K, Ditrói T, Szántó N, Jurányi EP, Szanyi S, et al. Cystathionine β-synthase overexpression drives metastatic dissemination in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma via inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation of cancer cells. Redox Biol. 2022;57:102505.[DOI]

-

34. Asamitsu S, Ozawa Y, Okamoto H, Ogata S, Matsunaga T, Yoshitake J, et al. Supersulfide metabolome of exhaled breath condensate applied as diagnostic biomarkers for esophageal cancer. Cancer Sci. 2025;116(4):1023-1033.[DOI]

-

35. Sen S, Kawahara B, Gupta D, Tsai R, Khachatryan M, Roy-Chowdhuri S, et al. Role of cystathionine β-synthase in human breast Cancer. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;86:228-238.[DOI]

-

36. Bhattacharyya S, Saha S, Giri K, Lanza IR, Nair KS, Jennings NB, et al. Cystathionine beta-synthase (CBS) contributes to advanced ovarian cancer progression and drug resistance. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79167.[DOI]

-

37. Szabo C, Coletta C, Chao C, Módis K, Szczesny B, Papapetropoulos A, et al. Tumor-derived hydrogen sulfide, produced by cystathionine-β-synthase, stimulates bioenergetics, cell proliferation, and angiogenesis in colon cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(30):12474-12479.[DOI]

-

38. Libiad M, Vitvitsky V, Bostelaar T, Bak DW, Lee HJ, Sakamoto N, et al. Hydrogen sulfide perturbs mitochondrial bioenergetics and triggers metabolic reprogramming in colon cells. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(32):12077-12090.[DOI]

-

39. Yue T, Li J, Zhu J, Zuo S, Wang X, Liu Y, et al. Hydrogen sulfide creates a favorable immune microenvironment for colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2023;83(4):595-612.[DOI]

-

40. Chen S, Bu D, Zhu J, Yue T, Guo S, Wang X, et al. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide regulates xCT stability through persulfidation of OTUB1 at cysteine 91 in colon cancer cells. Neoplasia. 2021;23(5):461-472.[DOI]

-

41. Panza E, De Cicco P, Armogida C, Scognamiglio G, Gigantino V, Botti G, et al. Role of the cystathionine γ lyase/hydrogen sulfide pathway in human melanoma progression. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2015;28(1):61-72.[DOI]

-

42. Wu Z, Khodade VS, Chauvin JR, Rodriguez D, Toscano JP, Pratt DA. Hydropersulfides inhibit lipid peroxidation and protect cells from ferroptosis. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144(34):15825-15837.[DOI]

-

43. Kaneko T, Mita Y, Nozawa-Kumada K, Yazaki M, Arisawa M, Niki E, et al. Antioxidant action of persulfides and polysulfides against free radical-mediated lipid peroxidation. Free Radic Res. 2022;56(9-10):677-690.[DOI]

-

44. Barayeu U, Schilling D, Eid M, Xavier da Silva TN, Schlicker L, Mitreska N, et al. Hydropersulfides inhibit lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis by scavenging radicals. Nat Chem Biol. 2023;19(1):28-37.[DOI]

-

45. Dey A, Prabhudesai S, Zhang Y, Rao G, Thirugnanam K, Hossen MN, et al. Cystathione β-synthase regulates HIF-1α stability through persulfidation of PHD2. Sci Adv. 2020;6(27):eaaz8534.[DOI]

-

46. Kashif M, Yao H, Schmidt S, Chen X, Truong M, Tüksammel E, et al. ROS-lowering doses of vitamins C and A accelerate malignant melanoma metastasis. Redox Biol. 2023;60:102619.[DOI]

-

47. Sayin VI, Ibrahim MX, Larsson E, Nilsson JA, Lindahl P, Bergo MO. Antioxidants accelerate lung cancer progression in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(221):e3007653.[DOI]

-

48. Le Gal K, Ibrahim MX, Wiel C, Sayin VI, Akula MK, Karlsson C, et al. Antioxidants can increase melanoma metastasis in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(308):eaad3740.[DOI]

-

49. Ge M, Papagiannakopoulos T, Bar-Peled L. Reductive stress in cancer: Coming out of the shadows. Trends Cancer. 2024;10(2):103-112.[DOI]

-

50. Narasimhan KKS, Devarajan A, Karan G, Sundaram S, Wang Q, van Groen T, et al. Reductive stress promotes protein aggregation and impairs neurogenesis. Redox Biol. 2020;37:101739.[DOI]

-

51. Rajasekaran NS, Connell P, Christians ES, Yan LJ, Taylor RP, Orosz A, et al. Human αB-crystallin mutation causes oxido-reductive stress and protein aggregation cardiomyopathy in mice. Cell. 2007;130(3):427-439.[DOI]

-

52. Birsoy K, Wang T, Chen WW, Freinkman E, Abu-Remaileh M, Sabatini DM. An essential role of the mitochondrial electron transport chain in cell proliferation is to enable aspartate synthesis. Cell. 2015;162(3):540-551.[DOI]

-

53. Weiss-Sadan T, Ge M, Hayashi M, Gohar M, Yao CH, de Groot A, et al. NRF2 activation induces NADH-reductive stress, providing a metabolic vulnerability in lung cancer. Cell Metab. 2023;35(3):487-503.[DOI]

-

54. Switzer CH. How super is supersulfide Reconsidering persulfide reactivity in cellular biology. Redox Biol. 2023;67:102899.[DOI]

-

55. Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, et al. Ferroptosis: A regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 2017;171(2):273-285.[DOI]

-

56. Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M, da Silva MC, Ingold I, et al. FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature. 2019;575(7784):693-698.[DOI]

-

57. Nakamura T, Hipp C, Santos Dias Mourão A, Borggräfe J, Aldrovandi M, Henkelmann B, et al. Phase separation of FSP1 promotes ferroptosis. Nature. 2023;619(7969):371-377.[DOI]

-

58. Cramer SL, Saha A, Liu J, Tadi S, Tiziani S, Yan W, et al. Systemic depletion of L-cyst(e)ine with cyst(e)inase increases reactive oxygen species and suppresses tumor growth. Nat Med. 2017;23(1):120-127.[DOI]

-

59. Badgley MA, Kremer DM, Maurer HC, DelGiorno KE, Lee HJ, Purohit V, et al. Cysteine depletion induces pancreatic tumor ferroptosis in mice. Science. 2020;368(6486):85-89.[DOI]

-

60. Wu K, Vaughan AJ, Bossowski JP, Hao Y, Ziogou A, Kim SM, et al. Targeting FSP1 triggers ferroptosis in lung cancer. Nature. 2026;649(8096):487-495.[DOI]

-

61. Palma M, Chaufan M, Breuer CB, Müller S, Sabatier M, Fraser CS, et al. Lymph node environment drives FSP1 targetability in metastasizing melanoma. Nature. 2026;649(8096):477-486.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite