Wei Gu, Institute for Cancer Genetics, and Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center, Vagelos College of Physicians & Surgeons, Columbia University, New York NY 10032, USA. E-mail: wg8@cumc.columbia.edu

Abstract

Oxidative stress, characterized by an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cellular antioxidant defenses, is a critical driver of various pathological states. The transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) serves as the master regulator of redox homeostasis, counteracting oxidative stress by orchestrating the expression of genes involved in glutathione biosynthesis, iron metabolism, and lipid peroxidation detoxification. Recently, the specific induction of lipid peroxidation has been identified as the hallmark of ferroptosis, a form of regulated cell death that represents a promising vulnerability for cancer therapy. However, cancer cells frequently hijack the NRF2 pathway to suppress ferroptosis, thereby promoting tumor survival, metastasis, and therapy resistance. Here, we comprehensively summarize the multi-layered regulatory mechanisms of NRF2, spanning transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and post-translational modifications, within the specific context of the ferroptosis-cancer axis. We further discuss how aberrant NRF2 signaling confers ferroptosis resistance in malignancy and highlight emerging therapeutic strategies that target the NRF2 pathway to reignite ferroptotic cell death in tumors. A deeper understanding of these regulatory networks is essential for the development of precision ferroptosis-based cancer therapies.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are chemically reactive molecules that are essential for the survival of living organisms[1]. Owing to the distinct regulatory mechanisms and metabolism rewiring, cancer cells exhibit increased endogenous ROS levels, rendering them more vulnerable to ROS-mediated stress compared to normal cells[2,3]. Consequently, manipulating ROS levels represents a potential therapeutic strategy to induce tumor cell death while sparing normal tissues[4]. However, redox imbalance in cancer cells is highly complicated because of the various regulators that are involved in. In response to oxidative stress, cells adapt by modulating the activity and expression of multiple transcription factors. These factors constitute an antioxidant barrier that mitigates potential damage caused by ROS overload. A key player in this process is nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2; encoded by NFE2L2), the master transcriptional regulator of the antioxidant response, as the majority of its downstream targets are dedicated to maintaining redox homeostasis.

The most critical signaling protein within the NRF2-regulated pathway is Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1), which functions as a repressor and degrader of NRF2. KEAP1 contains multiple cysteine residues that act as sensors for oxidative or electrophilic stress, inducing conformational changes that lead to NRF2 escape from ubiquitin-proteasome degradation[5,6]. Under physiological conditions, this mechanism maintains cellular homeostasis. However, in the context of malignancy, the system is frequently hijacked. Notably, advanced-stage cancer cells frequently harbor gain-of-function mutations in NFE2L2 or loss-of-function mutations in KEAP1, leading to the constitutive activation of NRF2. These mutations are prevalent across various cancer types, particularly in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)[7]. The inactivation of KEAP1 or the expression of mutant NRF2 results in the nuclear accumulation of NRF2 and the subsequent upregulation of its target genes. While this reduces intracellular ROS levels and enhances ROS-scavenging capacity to promote cell survival, the implications of constitutive NRF2 activation extend far beyond oxidative stress management. This phenomenon, often described as the “dark side” of NRF2, fosters a permissive environment for tumorigenesis through several distinct mechanisms, with a particular emphasis on the evasion of ferroptotic cell death[8].

Iron-dependent ROS accumulation promotes ferroptosis, a novel form of regulated cell death triggered by an overload of lipid peroxides. Notably, many proteins and enzymes involved in preventing lipid peroxidation, and thus inhibiting the initiation of ferroptosis, are encoded by NRF2 target genes. Consequently, NRF2 plays an indispensable role in regulating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis[9]. Although ferroptosis was initially identified through high-throughput screening of anti-tumor agents, mounting evidence indicates that it represents a targetable vulnerability in cancer[10-13]. Given that NRF2 activity is directly linked to ferroptosis sensitivity, NRF2 itself, its regulators, and its downstream targets offer promising avenues for ferroptosis-based cancer therapies. The following sections review the direct non-genomic regulatory mechanisms of NRF2 activation. Furthermore, we highlight the potential roles of NRF2 regulators in oxidative stress and ferroptosis, discussing their impact on tumorigenesis and implications for cancer therapy.

2. KEAP1-NRF2 Signaling Pathway

NRF2 activity is strictly controlled by internal and external stimuli associated with oxidative stress. Under basal conditions, KEAP1 acts as an adaptor linking NRF2 to the Cullin-3 (CUL3)-based E3 ligase complex, mediating NRF2 degradation via the

Nuclear NRF2 forms heterodimers with small musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (sMAF) proteins (MAFF, MAFG, and MAFK) and binds to antioxidant response elements (AREs), specifically the core sequence 5’-TGACNNNGC-3’, to activate the expression of a broad spectrum of cytoprotective genes[16-19]. These target genes are involved in diverse cellular processes, including the antioxidant response, detoxification, cellular metabolism, survival, proliferation, autophagy, DNA repair, and mitochondrial physiology[20-22]. Although significant scientific progress has been made, challenges remain in effectively targeting NRF2, its regulators, or its downstream effectors.

3. Genomic Dysregulation of the KEAP1-NRF2 Pathway

The KEAP1-NRF2 signaling pathway is frequently co-opted by cancer cells, where constitutive NRF2 activation confers advantages in tumor growth, metastasis, and chemoresistance[23,24]. Although NFE2L2 or KEAP1 mutations occur less frequently than common drivers like KRAS or TP53, genetic alterations in this pathway are found in approximately 20% of lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and

4. The Role of NRF2-Regulated Ferroptosis in Cancer Progression

Ferroptosis, first identified by Dixon et al. in 2012, is a form of regulated cell death characterized by excessive lipid peroxidation of cellular membranes, resulting from a disrupted antioxidant defense system and/or imbalanced cellular metabolism. To date, several ferroptosis defense mechanisms have been discovered, with the cyst(e)ine/glutathione (GSH)/glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) axis serving as the core system. GPX4 protects cells from ferroptosis by reducing lipid hydroperoxides to lipid alcohols, utilizing GSH as a cofactor[28]. Ferroptosis induced by GPX4 inhibition depends on the activity of acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4), which acylates free fatty acids, such as polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Subsequently, lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) incorporates these acylated fatty acids into phospholipids[29,30].

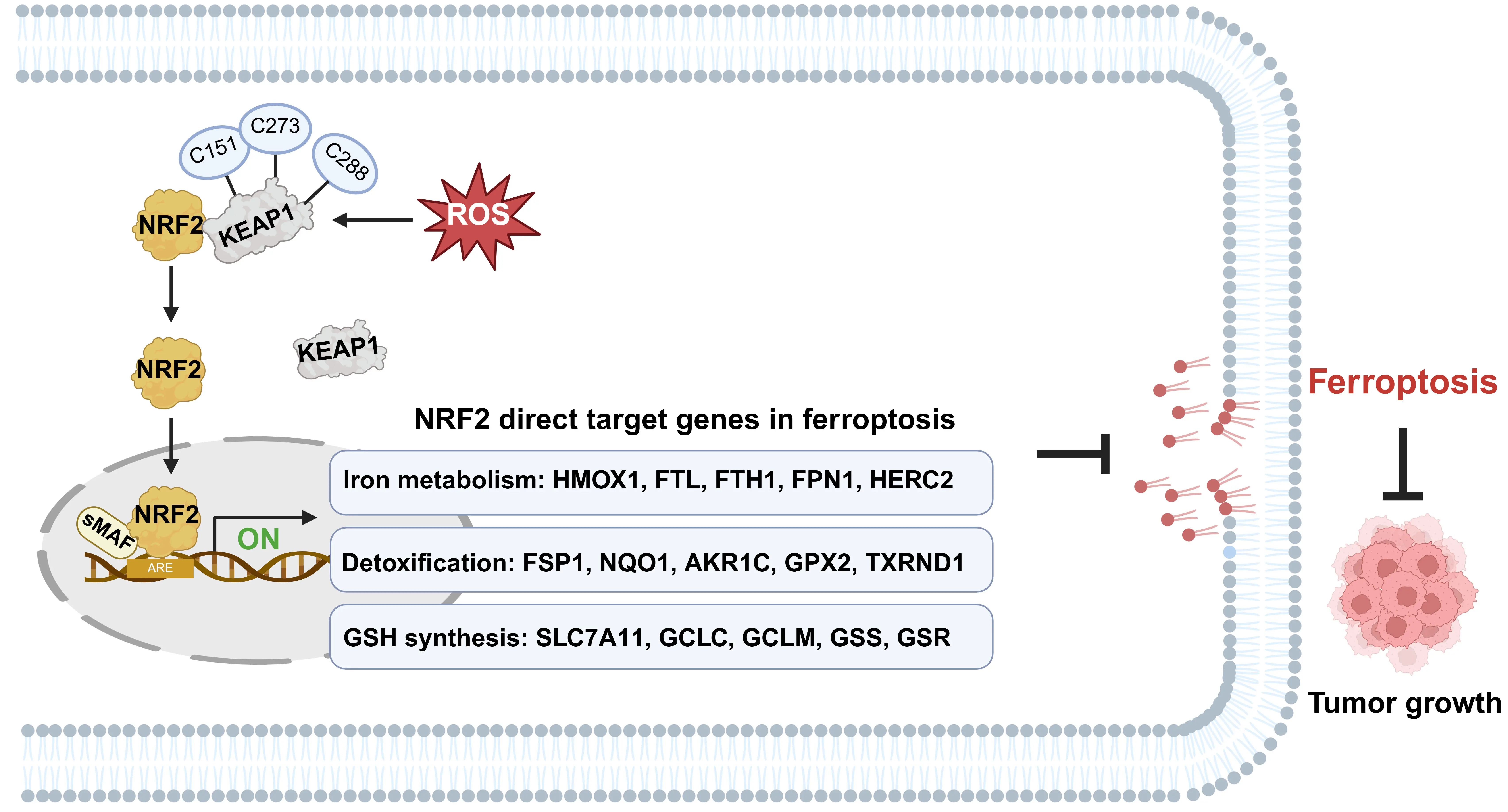

NRF2 acts as a master regulator coordinating multiple aspects of ferroptosis, including iron metabolism, GSH synthesis, and ROS detoxification, through the transcriptional upregulation of numerous genes[9,31] (Figure 1). Extensive studies have demonstrated that most direct target genes of NRF2 function as ferroptosis suppressors to promote cancer progression.

Figure 1. The crucial role of NRF2 in ferroptosis defense. Upon exposure to ROS-induced oxidative stress, NRF2 protein is stabilized in KEAP1-dependent manner and translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Nuclear NRF2 heterodimerizes with sMAF proteins and binds to AREs within the promoter regions of target genes. This transcriptional program orchestrates a multi-layered defense against ferroptosis by upregulating genes governing iron metabolism, detoxification, and GSH synthesis. Created in BioRender.com. ROS: reactive oxygen species; NRF2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; sMAF: small musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma; AREs: antioxidant response elements; GSH: glutathione; KEAP1: Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1.

4.1 Iron metabolism

Heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1; encoded by HMOX1) plays a dual role in ferroptosis, contingent upon its level of activation. Excessive HO-1 activation catalyzes heme degradation, producing large amounts of free iron. This iron overload induces lipid peroxidation and accelerates ferroptosis via the Fenton reaction, as observed in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells[32,33]. Conversely, HO-1 can also exert antioxidant effects that inhibit ferroptosis, contributing to radioresistance in glioblastoma (GBM), through the production of heme metabolic byproducts, including biliverdin and carbon monoxide[34,35]. Thus, the activation of HO-1 may play distinct,

4.2 Detoxification

GPX4 is a critical molecule preventing lipid peroxidation and the occurrence of ferroptosis. It is established that the ferroptotic response induced by GPX4 inhibitors is ACSL4-dependent[29]. Interestingly, deficiency of tumor ACSL4 accelerates tumor progression by impairing spontaneous anti-tumor immunity, suggesting that a natural ferroptosis-inducing mechanism functions during tumor development[36]. It is worth noting that while GPX4 is commonly considered an NRF2 target gene, NRF2 chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) (ENCODE portal: ENCFF390TMR) and Cleavage Under Targets and Release Using Nuclease (CUT & RUN) data indicate that NRF2 is not significantly enriched at the GPX4 genomic region[37,38]. Furthermore, NRF2 knockdown has been shown to upregulate GPX4 expression in lung tumor spheroid cells[39]. Therefore, GPX4 may not be a direct transcriptional target of NRF2.

It is well-established that NRF2-null mice show a significantly reduced ability to detoxify aldehydes, leading to an accumulation of toxic metabolites. NRF2 induces the expression of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), which prevents radical generation and ferroptosis[40]. In addition, aldo-keto reductases (AKRs, such as AKR1A1-3, AKR1B10, et al.) are a superfamily of enzymes that serve as critical downstream targets in the NRF2-mediated detoxification pathway[41,42]. Due to their broad substrate specificity, AKRs not only neutralize lipid peroxidation products like 4-Hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and methylglyoxal, but also degrade xenobiotic and chemotherapeutic agents, thereby contributing to chemoresistance in cancer cells[43].

4.3 GSH synthesis

GSH, the primary cofactor for GPX4, mitigates lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. The synthesis process begins with the cystine/glutamate antiporter System xc (comprising SLC7A11 and SLC3A2), which imports cystine that is subsequently reduced to cysteine. Next, glutamate and cysteine are ligated by glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCLC/GCLM) to produce the dipeptide

The essential role of SLC7A11 in providing intracellular cysteine, influencing kynurenine metabolism, and maintaining lysosomal pH homeostasis is critical for preventing ferroptosis and tumor progression[45-47]. However, ferroptosis sensitivity induced by SLC7A11 expression is context-dependent[48]. While Slc7a11 knockout mice are phenotypically normal, embryonic fibroblasts derived from these animals fail to survive in culture without β-mercaptoethanol supplementation, which facilitates cellular cysteine uptake[49]. Moreover, prolonged treatment with SLC7A11 inhibitors induces ferroptosis resistance in ovarian cancer cells via activation of the transsulfuration pathway, catalyzed by cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) (another direct NRF2 target)[50]. Since intracellular cysteine can be synthesized via compensatory pathways (such as from methionine via the transsulfuration pathway) in addition to

Given the high frequency of NFE2L2/KEAP1 mutations leading to constitutive NRF2 activation in cancer, the protective effect of NRF2 overexpression against ferroptosis implies its potential as a biomarker. The involvement of NRF2 activation in regulating ferroptosis was first elucidated in hepatocellular carcinoma cells in 2016[52]. Treatment with SLC7A11 inhibitors (e.g., erastin) enhances the suppression of NRF2-mediated ferroptosis defense. Over the past decade, research has revealed crucial NRF2-regulated mechanisms in ferroptosis and established its key role in cancer progression. While lipid peroxidation products, including 4-HNE and malondialdehyde (MDA), and expression levels of signature genes, including prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2), ChaC glutathione-specific gamma-glutamylcyclotransferase 1 (CHAC1), transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1)[53], and peroxiredoxin 3 (PRDX3)[54] are currently regarded as detection markers for ferroptosis, these markers are context-dependent and subject to other regulatory influences. Notably, there remains a lack of specific biomarkers for definitively detecting ferroptosis in vivo, hindering the monitoring of dynamic changes in ferroptosis during cancer progression.

5. Upstream Regulators of NRF2 Activation

Changes in NFE2L2 mRNA expression and stability contribute to NRF2 overexpression and the induction of its downstream targets. Cellular NRF2 transcript levels are tightly regulated by transcription factors and non-coding RNA (ncRNA) events through transcriptional, epigenetic, post-transcriptional, or post-translational modification pathways.

5.1 Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation

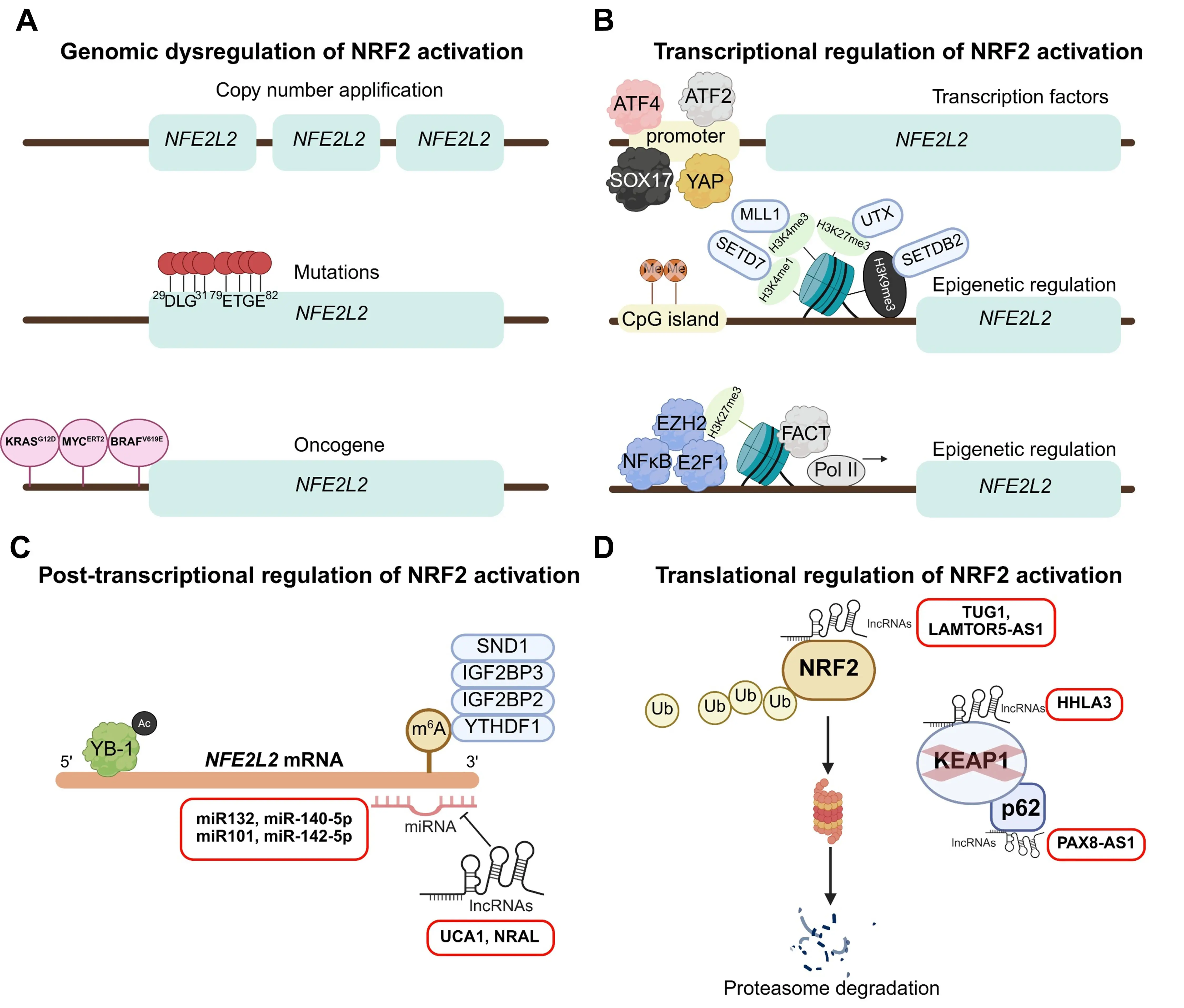

Genomic variations can constitutively elevate NRF2 activity in cancer by augmenting NFE2L2 mRNA levels (Figure 2A). Additionally, activation of endogenous oncogenes, such as myelocytomatosis oncogene (MYC)ERT2, b-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF)V619E, and Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS)G12D, directly increases the transcription and activity of NRF2 during tumorigenesis[55]. MYC can directly bind to the NFE2L2 promoter and activate NRF2 transcription to counteract oxidative stress and drive tumor progression of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC)[56]. Of note, inhibition of SLC7A11, a critical NRF2 target involved in cystine import and GSH synthesis, resulted in tumor suppression and improved overall survival in a KrasG12D mutant LUAD mouse model. This model drives the rewiring of GSH metabolism by upregulating NRF2 expression[57]. Therefore, targeting NRF2-mediated ferroptosis resistance provides a vital avenue for cancer therapy.

Figure 2. Genomic and upstream transcriptional regulation for NRF2 activation. (A) Genomic alterations driving NFE2L2 mRNA upregulation. Mechanisms include NFE2L2 copy number amplification, gain-of-function mutations (predominantly within the DLG and ETGE motifs), and oncogene-induced NRF2 activation; (B) Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of NFE2L2. Transcription factors such as ATF4, ATF2, YAP, and SOX17 modulate NRF2 activation. Epigenetic mechanisms, including CpG island demethylation, histone modifications at the promoter region, and enhanced transcriptional elongation, promote NFE2L2 mRNA expression; (C) Post-transcriptional regulation of NFE2L2 mRNA. This includes suppression by microRNAs (miR-132, miR-140-5p, miR-101, miR-142-5p, and miR-144), modulation by long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs UCA1 and NRAL), m6A RNA methylation readers (SND1, IGF2BP2, IGF2BP3, and YTHDF1), and stabilization by the RNA-binding protein YB-1; (D) Post-translational regulation of NRF2 protein. LncRNAs such as TUG1, LAMTOR5-AS1, HHLA3, and PAX8-AS1 disrupt the NRF2-KEAP1 complex, thereby preventing NRF2 degradation. Created in BioRender.com. NRF2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; ATF4: activating transcription factor 4; ATF2: activating transcription factor 2; YAP: Yes-associated protein; YB-1: deacetylated Y-box protein 1; SOX17: SRY (sex determining region Y)-box 17; CpG: cytosine-phosphodiester bond-guanin; UCA1: Urothelial cancer associated 1;

Activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) directly upregulates NRF2 expression in response to the integrated stress response (ISR), which plays a central role in cancer plasticity[58]. Moreover, activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2) has been found to suppress the anti-tumor effects of bromodomain and extraterminal domain (BET) inhibitors by significantly upregulating NRF2 levels, thereby attenuating ferroptosis[59]. Yes-associated protein (YAP), a major transcriptional coactivator in the Hippo pathway, also increases NRF2 transcription to bolster tumor cell defense against ferroptosis[60]. Additionally, deacetylated Y-box protein 1 (YB-1), an

5.2 Epigenetic regulation

Oxidative stress response can also be influenced by epigenetic events, which modulate chromatin structure or RNA stability to regulate gene transcription[63,64] (Figure 2B). Cytosine-phosphodiester bond-guanine (CpG) methylation in NFE2L2 promoter region is involved in programming NRF2 expression. A recent pilot study indicated that CpG methylation of the NFE2L2 promoter could serve as a risk factor for age-related lung cancer[65].

Histone methylation and demethylation at the NEF2L2 promoter region regulate its transcriptional activity, thereby modulating ROS generation to contribute to drug resistance or carcinogenesis[66-69] (Figure 2B). A recently reported study demonstrated that Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 (EZH2), a transcriptional repressor that catalyzes histone H3K27 trimethylation, maintains H3K27ac marks and recruits transcription factor occupancy at NFE2L2 promoters to stimulate NFE2L2 transcription and maintain malignancy[70]. Inactivation of the facilitates chromatin transcription (FACT) complex, a histone chaperone that facilitates rapid nucleosome disassembly, reduces the transcription elongation of NFE2L2 and its downstream antioxidant genes, thereby increasing chemosensitivity[71]. Furthermore, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) methylation is a reversible epigenetic mark that modulates mRNA stability and translation. m6A readers can directly bind and stabilize NFE2L2 mRNA in an m6A-dependent manner to promote ferroptosis resistance and tumor suppression[72-75].

5.3 Non-coding RNA

Given the diversity of physiological processes controlled by NRF2, findings indicate that NRF2 regulation is also guided by ncRNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs) and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), during cancer progression. Although ncRNAs can function as both downstream targets and upstream regulators of NRF2, we focus here on upstream regulators (Figure 2C,D).

miRNAs are single-stranded ncRNAs of approximately 22 nucleotides that typically modulate the translation or stability of NFE2L2 mRNA by binding to specific sequences via complementary base pairing. In the following section, we summarize direct miRNA mediators of NRF2 that contribute to carcinogenesis in response to ROS-induced stress. miR-132, miR-140-5p, miR-101, miR-142-5p, and miR-144 act as oncogenic negative regulators of NRF2 by targeting the 3’UTR of NFE2L2, reducing NRF2 expression and thereby regulating tumor metastasis and chemoresistance[76-83]. Thus, dysregulation of the miRNA-NRF2 machinery significantly influences oxidative stress and tumorigenesis.

LncRNAs (> 200 nucleotides) regulate NRF2 expression through varied mechanisms, including acting as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) for proteins or as miRNA sponges, recruiting chromatin modifiers and transcription factors, or mediating translational repression/degradation. Several lncRNAs act as regulators of the NRF2-oxidative stress system. Urothelial cancer associated 1 (UCA1) upregulates NRF2 expression by sponging miR-495, contributing to chemoresistance in NSCLC[84]. Nrf2 regulation-associated lncRNA (NRAL) acts as a ceRNA for NRF2, binding miR340-5p to activate NRF2, leading to drug resistance in HCC[85]. Moreover, late endosomal/lysosomal adaptor, MAPK and MTOR activator 5-antisense RNA 1 (LAMTOR5-AS1) or taurine upregulated gene 1 (TUG1) directly binds and stabilizes NRF2 protein, associating with chemoresistance[86,87]. Meanwhile, KEAP1-mediated degradation of NRF2 is indirectly attenuated by HERV-H LTR-associating 3 (HHLA3) or paired box 8-antisense RNA 1 (PAX8-AS1) to promote cancer progression[88,89]. Collectively, lncRNA-NRF2 regulation is characterized by tissue specificity, which is relevant to the development of targeted therapies for specific cancer subtypes.

6. Co-Factors of NRF2 Transcriptional Activity

Although NRF2 serves as the master transcription factor directly regulating a series of genes in response to antioxidant stress, studies report that several proteins, including epigenetic regulators and chromatin remodeling complexes, act as co-factors for NRF2. These co-factors modulate specific subsets of target genes without altering the mRNA or protein levels of NRF2.

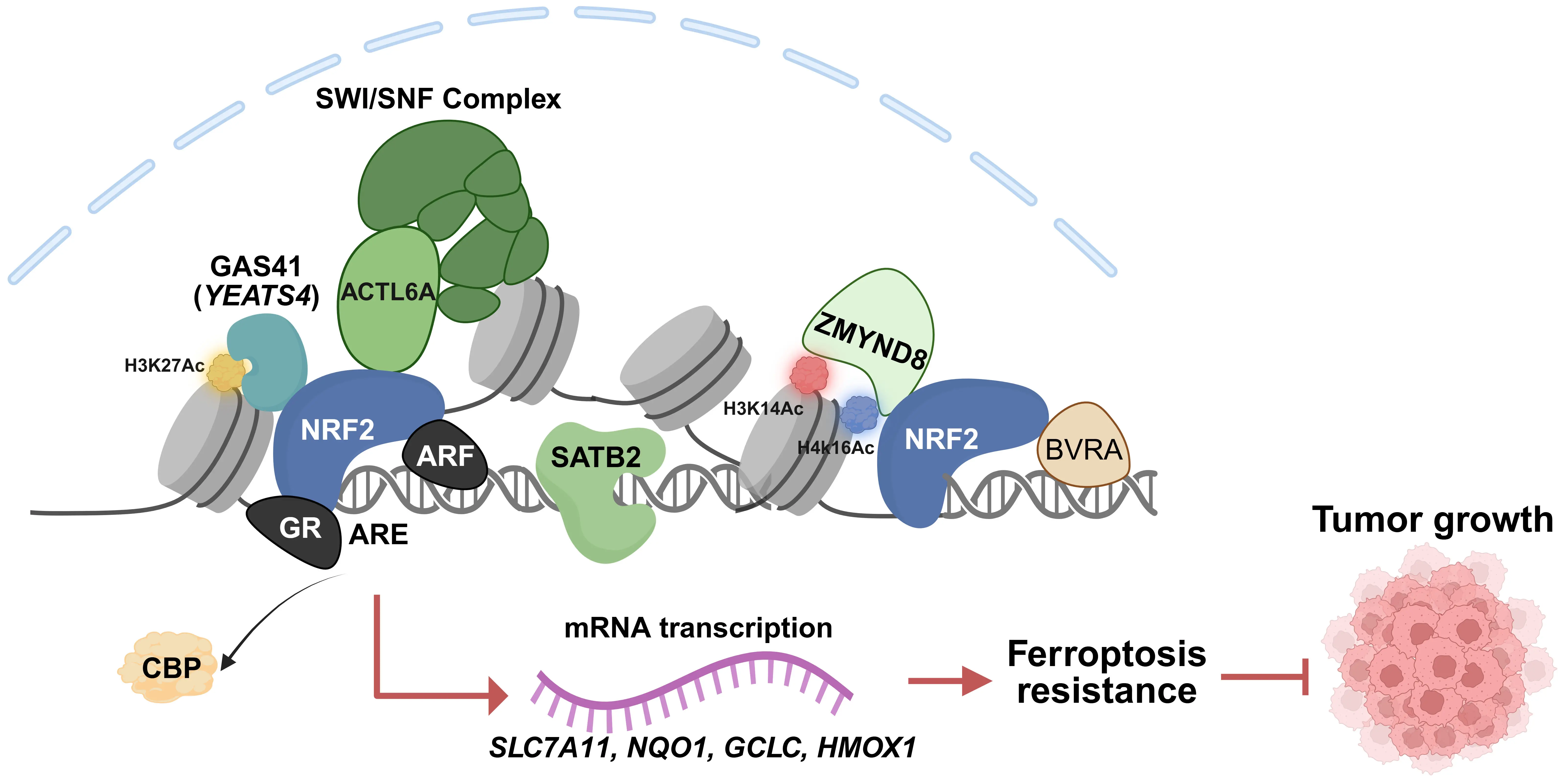

NRF2 contains seven highly conserved domains known as NRF2-ECH homology (Neh) domains. Among these, the Neh4, Neh5, and Neh3 regions are critical for NRF2 transcriptional activity through binding components of the transcriptional apparatus[90], such as CBP/p300[91,92] and CHD6[93]. Recently, many unexpected co-factors of NRF2 have been identified (Figure 3). These factors cooperate with NRF2 to protect cells from ferroptosis and maintain cell survival.

Figure 3. Co-factors modulating NRF2 transcriptional activity. Illustration of the diverse chromatin-associated proteins that interact with NRF2 to fine-tune its transcriptional output. These include transcriptional activators (GAS41, ACTL6A, and ZMYND8), chromatin loop organizers (SATB2), and transcriptional suppressors (ARF and GR), which bind to NRF2 to either enhance or inhibit its transactivation potential. Created in BioRender.com. NRF2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; GAS41: Glioma Amplified Sequence 41; ACTL6A: actin-like protein 6A; ZMYND8: Zinc finger MYND-type containing 8; SATB2: special AT-rich binding protein-2; ARF: alternative reading frame;

We identified Glioma Amplified Sequence 41 (GAS41, encoded by YEATS4) as a transcriptional regulator that anchors NRF2 on chromatin. GAS41 enhances the DNA-binding activity of NRF2, regulated by histone markers (H3K27Ac), to promote ferroptosis resistance and tumor progression in NSCLC[37]. Similarly, actin-like protein 6A (ACTL6A), encoding a SWI/SNF subunit, acts as a

Besides mutual recruitment between NRF2 and co-factors, some chromatin-associated proteins function as chromatin organizers for NRF2 transcription. Special AT-rich binding protein-2 (SATB2) co-localizes with NRF2 to drive enhancer-promoter interactions and recruits SWI/SNF complex. This coordination between SATB2 and NRF2 enhances NRF2 transcriptional activity, amplifying resistance to oxidative stress in renal cell carcinoma[97]. Moreover, deficiency of double PHD fingers 2 (DPF2), subunit of the canonical SWI/SNF complex, leads to the displacement of the catalytic subunit brahma-related gene 1 (BRG1) from NRF2-occupied enhancers, decreasing the expression of anti-inflammatory and antioxidant genes in hematopoietic stem cells[98]. However, BRG1 may exert divergent or opposing roles in NRF2 signaling depending on tissue context, BRG1 expression status, or mutation frequency. For instance, BRG1 knockdown leads to increased NRF2 binding specifically at the HMOX1 promoter, but not at other targets in NSCLC[99]. Conversely, Yamamoto et al. demonstrated that NRF2-mediated HMOX1 expression is BRG1-dependent in colorectal carcinoma cells (CRC)[100].

Beyond co-activators, transcription factors can also function as suppressors of NRF2 activity. The tumor suppressor alternative reading frame (ARF) inhibits NRF2 transcription potential by directly binding to NRF2, thereby sensitizing cancer cells to ferroptosis in both p53-independent and p53-dependent manners[101]. Moreover. nuclear receptors, whose conformation is altered by ligand binding, have been identified as negative regulators of the NRF2-ARE pathway. For example, upon glucocorticoids stimulation, the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) binds to NRF2 and is recruited to AREs. This interaction represses NRF2 transcriptional activity by reducing NRF2-dependent histone acetylation mediated by cAMP responsive element binding protein binding protein (CBP), a mechanism that may underlie certain side effects of glucocorticoids therapy[102].

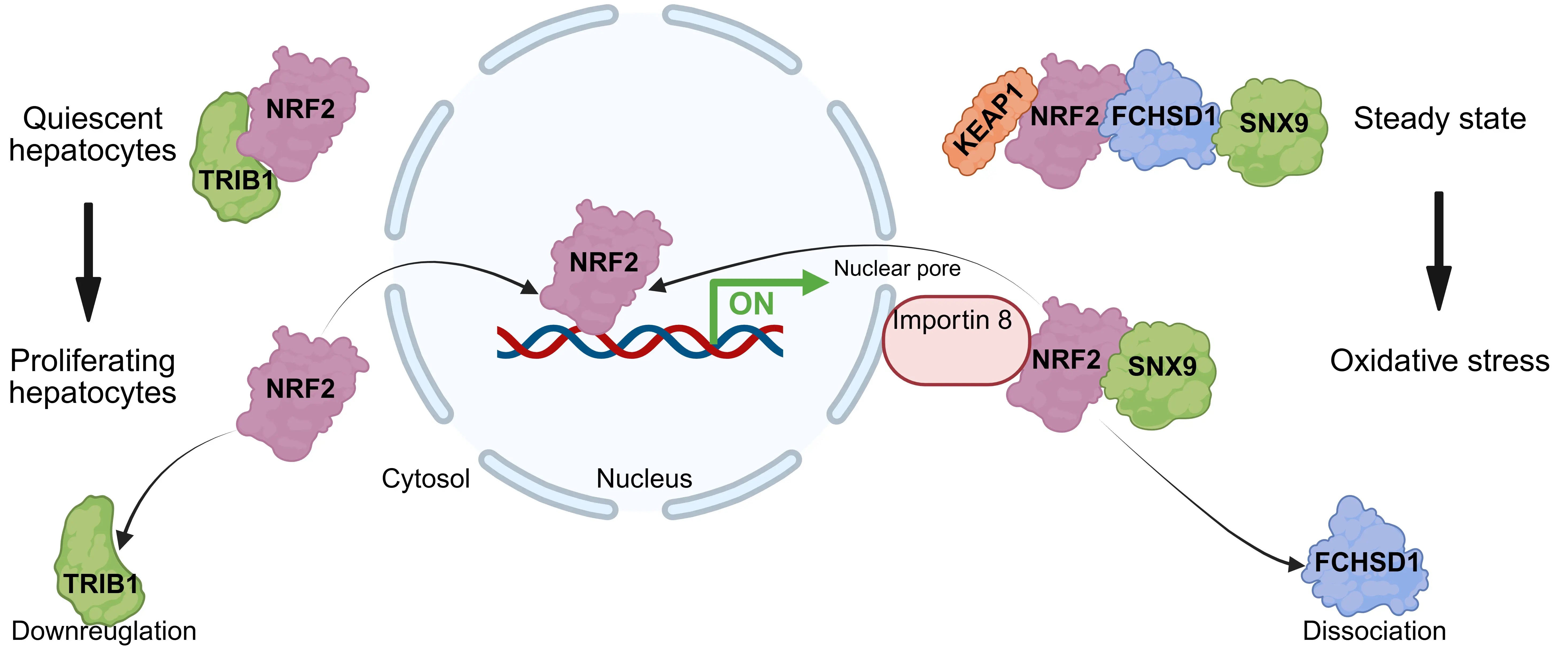

Additionally, several regulators modulate NRF2 activation by physically restricting its nuclear translocation (Figure 4). Tribbles homolog 1 (TRIB1) interacts with NRF2 to block its nuclear entry, thereby inhibiting target gene expression and restraining liver cell proliferation[103]. Similarly, FCH and double SH3 domains 1 (FCHSD1) forms a cytosolic complex with NRF2 and sorting nexin 9 (SNX9), preventing NRF2 nuclear translocation and promoting the initiation of emphysema[104]. Conversely, TP53 induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator (TIGAR), a regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis, binds to NRF2 and facilitates its nuclear translocation to confer chemotherapy resistance by maintaining redox balance[105].

Figure 4. Regulators restricting NRF2 nuclear translocation. Schematic depicting proteins that interact with NRF2 in the cytoplasm to inhibit its nuclear entry. Regulators such as TRIB1 and FCHSD1 bind to NRF2, thereby sequestering it in the cytosol or preventing its translocation to the nucleus, consequently suppressing NRF2-mediated transcriptional activation under oxidative stress. Created in BioRender.com. NRF2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; TRIB1: tribbles homolog 1; FCHSD1: FCH and double SH3 domains.

In summary, the transcriptional output of NRF2 is finely tuned by a complex network of chromatin remodelers like BRG1, suppressive transcription factors, and translocation modulators, highlighting the context-dependent nature of NRF2 regulation in cancer progression and therapy response.

7. The Post Translational Modifications (PTMs) in NRF2 Regulation

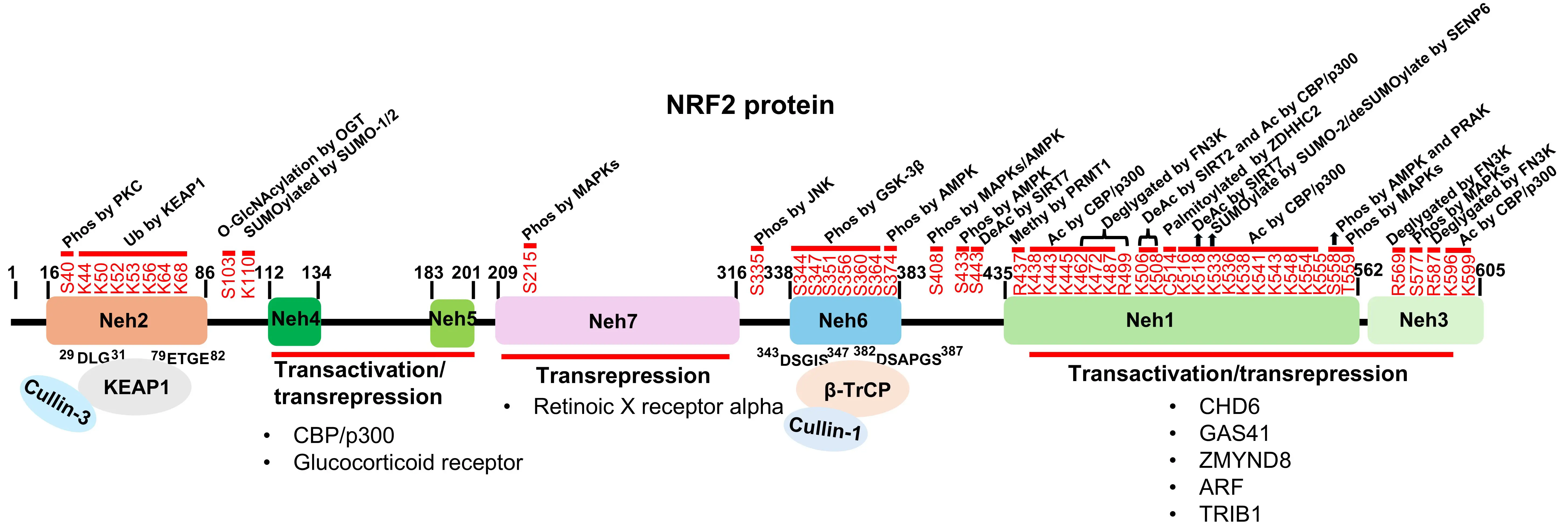

Protein stability and nuclear accumulation of NRF2 are dynamically regulated by post-translational modifications, including acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and methylation[106]. Evaluating these processes across various cancer types is crucial for determining their impact on NRF2 transcriptional activity (Figure 5).

Figure 5. The PTMs, transactivation and domain-specific interactions regulating NRF2 stability and activity. Schematic map of NRF2 protein domains (Neh1–Neh6) highlighting key PTMs and binding partners. The Neh4, Neh5, Neh1, and Neh3 domains serve as docking sites for co-factors that either activate or suppress NRF2 transcriptional activity. Ubiquitination: KEAP1 and β-TrCP target the Neh2 and Neh6 domains, respectively, to mediate ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation; Acetylation: CBP/p300 mediates acetylation at multiple lysine residues within the Neh1 and Neh3 domains (K438, K443, K445, K462, K472, K487, K506, K508, K516, K518, K533, K536, K538, K541, K543, K548, K554, K555, K596, and K599), while SIRT2 deacetylates specific sites (K506, K508); Methylation: PRMT1 methylates NRF2 at arginine residue R437; Phosphorylation: Various kinases phosphorylate NRF2 at distinct sites to regulate its function, including PKC (S40), MAPKs (S215, S408, S558, T559, and S577), AMPK (S374, S408, S433, and S558), PRAK (S558), JNK (S335), and GSK-3β (S344, S347, S351, S356, S360, and S364); Other PTMs: SUMOylation by SUMO-1/2 occurs at K110 and K533. FN3K mediates deglycation at multiple sites including K462, K472, K487, R499, R569, and R587. NRF2 is palmitoylated by ZDHHC2 at C514 and O-GlcNAcylated at S103. Neh: NRF2-ECH homology; NRF2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; PTMs: post translational modifications; KEAP1: Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1;

7.1 De/ubiquitination

Under basal conditions, the KEAP1-CUL3 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex targets NRF2 for cytoplasmic degradation. Recently, Ingersoll et al. identified thyroid hormone receptor interactor protein 12 (TRIP12) as a ubiquitin chain elongation factor within the KEAP1-CUL3 complex, dynamically controlling NRF2 degradation in response to ROS[107]. In a KEAP1-independent manner, β-transducin

Given the critical role of KEAP1 and β-TrCP in NRF2 stability, numerous proteins impair the KEAP1-NRF2 interaction to modulate redox homeostasis. Many proteins promote the dissociation of NRF2 from the KEAP1-CUL3 complex, allowing NRF2 to evade degradation. This stabilization supports tumor growth by preventing ferroptosis[110-128]. Similarly, growth differentiation factor 15 (GDF15), peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 (PIN1), peptidylprolyl isomerase A (PPIA), and HECT domain and ankyrin repeat containing E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 1 (HACE1) directly interact with NRF2, competing with KEAP1 binding and compromising NRF2 ubiquitination[129-132]. Circular RNA produced by β-TrCP encodes a novel β-TrCP isoform, which competitively binds to NRF2 and blocks β-TrCP-mediated degradation[133]. These mechanisms enhance NRF2 transcriptional activity, favoring cancer progression and radioresistance. Consequently, the overexpression of these competitive inhibitors can lead to constitutive NRF2 activation.

Besides KEAP1 and β-TrCP, one study demonstrates that mind bomb 1 (MIB1) overexpression sensitizes lung cancer cells to ferroptosis by inducing NRF2 proteasomal degradation[134]. Meanwhile, STAM binding protein-like 1 (STAMBPL1) stabilizes NRF2 through K63 deubiquitination, thereby impeding ferroptosis and cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) progression[135]. However, deubiquitination can also reverse this process. Deubiquitinase 3 (DUB3) promotes NRF2 activation and transcriptional activity, conferring chemotherapy resistance in colon cancer[136]. Additionally, ubiquitin specific peptidase 11 (USP11) stabilizes NRF2 via deubiquitination, contributing to ferroptosis resistance and cell growth in NSCLC[137]. In KRAS-mutated LUAD, ubiquitin specific peptidase 13 (USP13) catalyzes NRF2 deubiquitination, facilitating a switch from autophagy to ferroptosis resistance, thereby promoting tumor progression[138]. While the proteasome is the primary degradation machinery, alternative pathways exist. Activation of transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1), a receptor potential ion channel, promotes the trafficking of NRF2 to lysosomes for degradation, a process independent of the canonical ubiquitin-proteasome system[139]. Collectively, these precise regulator mechanisms govern NRF2 stability, where the disruption of this equilibrium by competing proteins or specific enzymes serves as a pivotal switch in determining tumor cell susceptibility to ferroptosis.

7.2 Sumoylation

Sumoylation involves the covalent attachment of Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier (SUMO) proteins to specific lysine residues on target proteins. NRF2 can be modified by SUMO-1 and SUMO-2/3, with SUMO-2/3 being the predominant modifiers[140,141]. SUMO-1 modification at lysine 110 of NRF2 has been shown to sustain hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth[142]. Meanwhile, SUMO-2-mediated sumoylation at lysine 110 and lysine 533 promotes NRF2 nuclear localization and transcriptional activity[143]. Conversely, Sentrin/SUMO-specific protease 6 (SENP6) acts as a negative regulator; by desumoylating NRF2, SENP6 enhances NRF2 ubiquitination and degradation, thereby inducing oxidative stress[141].

7.3 De/acetylation

NRF2 acetylation by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) p300/CBP is essential for its transcriptional response to oxidative stress, augmenting DNA-binding activity in a promoter-specific manner[92]. Additionally, Lysine acetyltransferase 8 (MOF)-mediated acetylation increases NRF2 nuclear retention and downstream gene transcription, regulating anti-drug responses in NSCLC[144]. Conversely, Sirtuins, NAD-dependent deacetylases (HDACs), deacetylate NRF2, leading to either nuclear export or altered stability, thereby modulating antioxidant gene expression[145-150]. HATs and deacetylases not only modify NRF2 directly but also act as

7.4 Methylation

Protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1) is implicated as a co-activator within the p300/CBP complex. Liu et al. discovered that PRMT1 methylates NRF2 at arginine 437. This methylation enhances NRF2 DNA-binding and transcriptional activity, protecting cells against ROS-induced ferroptosis[151]. In contrast, PRMT4 overexpression in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy promotes ferroptosis by methylating NRF2 in a manner that restricts its nuclear translocation and suppresses GPX4 expression[152].

7.5 Phosphorylation

Phosphorylation plays a vital role in regulating the subcellular distribution and activity of NRF2. Kinases such as casein kinase 2 (CK2), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), protein kinase C (PKC), PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), and c-Jun

Adenosine 5'-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase (AMPK)-mediated phosphorylation of NRF2 yields site-specific effects. Phosphorylation at Serine 558 by AMPK accelerates NRF2 nuclear accumulation[163]. Interestingly, AMPK also phosphorylates NRF2 at Serine 374, Serine 408, and Serine 433, which affects the transactivation of specific target genes without altering NRF2 protein levels or nuclear accumulation[164]. Conversely, protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) dephosphorylates NRF2, promoting its nuclear export and enhancing tumor cell sensitivity to ferroptosis[165]. Collectively, the phosphorylation landscape of NRF2 is highly complex and

7.6 Other PTM

Apart from classical modifications, NRF2 is regulated by a complex array of PTMs that drive malignancy. Glutarylation of NRF2 has been shown to increase its stability and DNA-binding activity, thereby modulating cell viability and promoting tumor growth[166]. Similarly, Fructosamine-3-kinase (FN3K)-mediated deglycation is essential for NRF2 transcriptional competence, acting as a catalyst for NRF2-driven tumorigenesis[167]. Nuclear retention and stability are further orchestrated by PARylation and O-GlcNAcylation: PARP2-mediated PARylation retains NRF2 in the nucleus to sustain antioxidant gene expression[168], while O-GlcNAcylation at Serine 103 disrupts KEAP1-dependent ubiquitination, promoting nuclear accumulation and cancer malignancy[169]. Finally, palmitoylation at Cysteine 514 protects NRF2 from proteasomal degradation, and its interruption significantly suppresses tumor development[170].

8. Association of NRF2 with Core Histone Modifications

As noted, NRF2 cooperates with chromatin-binding proteins (HATs, HDACs, readers, and remodelers) to alter chromatin conformation and recruit transcriptional machinery. This indicates that histone status is integral to NRF2 regulation. Conversely, histone modifications can be directly regulated by NRF2. For instance, the linker histone variant H1.2 interacts with NRF2 to promote its nuclear accumulation, while NRF2 transcriptionally upregulates H1.2. This H1.2-NRF2 feedforward loop drives tumor progression in NSCLC[171].

Metabolic intermediates also link NRF2 to epigenetics. In the HCC mouse model, NRF2 ablation impairs metabolic pathways, reducing acetyl-CoA generation and suppressing histone acetylation in tumors (but not in normal tissue), thereby disrupting transcription complex assembly at antioxidant genes[172]. Furthermore, 2-oxoglutarate (2OG), a cofactor for JmjC domain-containing histone demethylases, is regulated by NRF2 via the metabolic enzyme L-2-hydroxyglutarate dehydrogenase (L2HGDH)[173,174]. NRF2-mediated production of 2OG affects histone methylation and modulates the ROS-induced ferroptosis response. Therefore, a bidirectional regulatory axis exists between NRF2 and the epigenetic landscape, mediated by direct protein interactions and metabolic signaling, which coordinates the sustained antioxidant program required for tumorigenesis.

9. Clinical Applications of NRF2 Inhibitors Induced-Ferroptosis for Cancer Therapy

NRF2 is the master regulator of the antioxidant response, and its role in cancer initiation and progression is well-established[20]. However, the function of NRF2 in oncology is Janus-faced. While NRF2 inducers are desirable for suppressing early-stage carcinogenesis by alleviating inflammation and oxidative stress, constitutive NRF2 activation in malignant cells protects against

Although numerous NRF2 inhibitors have shown tumor-suppressive effects, few have successfully progressed through the drug development pipeline. A major hurdle is the intrinsically disordered nature of the NRF2 protein and its lack of druggable binding pockets. However, the convergence of drug repurposing strategies and cutting-edge Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras (PROTAC) technology expands the horizon of NRF2-targeted therapies, promising to overcome the “undruggable” nature of NRF2 and deliver effective ferroptosis-inducing treatments to the clinic (Table 1).

| Drug | Mechanism of action | Cancer types | Functions in ferroptosis | Reference |

| PZM | Decrease NRF2 transcriptional activity | ESCC | Increase ferroptosis sensitivity | [193] |

| AEM1 | Decrease NRF2 transcriptional activity | NSCLC | Not reported | [189] |

| ML385 | Decrease NRF2 transcriptional activity | AML; CRC | Increase ferroptosis sensitivity | [190] |

| ARE-PROTAC | Decrease NRF2 transcriptional activity | NSCLC | Increase ferroptosis sensitivity | [201] |

| CR-1-31B | Block NRF2 translation | Osteosarcoma | Not reported | [192] |

| Clobetasol propionate | Inhibit nuclear translocation of NRF2 | NSCLC | Increase ferroptosis sensitivity | [196] |

| triptolide | Inhibit nuclear translocation of NRF2 | NSCLC; Leukemia | Increase ferroptosis sensitivity | [182,183] |

| Trigonelline | Inhibit nuclear translocation of NRF2 | HNC; NSCLC | Increase ferroptosis sensitivity | [180,181] |

| Sirolimus | Inhibit nuclear translocation of NRF2 | SCC | Not reported | [195] |

| Brusatol | Enhanced NRF2 ubiquitination | NSCLC; EAC; Ovarian cancer | Increase ferroptosis sensitivity | [177,179] |

| VVD-065 | Enhanced NRF2 ubiquitination | NSCLC; ESCC; HNSCC | No reported | [186] |

| R16 | Enhanced NRF2 ubiquitination | NSCLC; BAC | Not reported | [187] |

| CX-5461 | Enhanced NRF2 ubiquitination | CRC | Increase ferroptosis sensitivity | [194] |

| Pyrimethamine | Enhanced NRF2 ubiquitination | ESCC; NSCLC | Not reported | [197,198] |

| ZVI-NP | Enhanced NRF2 ubiquitination | NSCLC; ESCC | Increase ferroptosis sensitivity | [188] |

| 2-(3-methylbenzyl) succinic acid | Restrain NRF2 activation | Melanoma; PDAC | Increase ferroptosis sensitivity | [184] |

NRF2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; PZM: pizotifen malate; ESCC: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer; CRC: colorectal carcinoma cells; HNSCC: head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; ZVI-NP: zero-valent-iron nanoparticle; ESCC: esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; HNC: head and neck cancer; SCC: squamous cell carcinoma; EAC: esophageal adenocarcinoma; AML: acute myeloid leukemia; BAC: bronchioloalveolar carcinoma; PDAC: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

9.1 Natural compounds

Brusatol, a natural product, was the first identified potent NRF2 inhibitor that enhances NRF2 ubiquitination and degradation to combat chemoresistance[176]. Combining brusatol with ferroptosis inducers sensitizes cancer cells to death, offering a potential therapeutic strategy[177-179]. Trigonelline reduces NRF2 nuclear accumulation via epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling and cooperates with ferroptosis inducers to restore chemosensitivity[180,181]. Similarly, Triptolide inhibits NRF2 downstream targets by affecting nuclear localization and exerts robust synergistic effects with ferroptosis inducers[182,183]. Furthermore, targeting the tumor microenvironment (TME) reveals that the itaconate transporter SLC13A3 endows tumors with ferroptosis resistance via the

9.2 Synthetic inhibitors

VVD-065 is a first-in-class covalent inhibitor that engages Cysteine151 on KEAP1 to induce KEAP1-CUL3 complex formation, enhancing NRF2 degradation and suppressing tumor growth[186]. Meanwhile, R16 selectively binds KEAP1 mutants to restore the NRF2 and KEAP1 interaction, downregulating NRF2 and reducing chemoresistance in KEAP1-mutant tumor cells[187]. Although the direct impact of VVD-065 and R16 on ferroptosis remains to be fully elucidated, they hold significant potential for treating cancers with KEAP1 somatic mutations. Meanwhile, zero-valent-iron nanoparticle (ZVI-NP) can induce cancer-specific cytotoxicity and anti-cancer immunity. Mechanically, ZVI-NP inhibits NRF2 expression by enhancing β-TrCP-dependent degradation or recovering SOX17/NRF2 axis to induce lung cancer ferroptosis and tumor growth[62,188]. Additionally, synthetic compounds like ML385 and AEM1 decrease NRF2 transcriptional activity and show promise in ferroptosis-based therapy[189-191]. Beyond transcriptional control, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A1 (EIF4A1) inhibitors like CR-1-31B and the clinical-grade eFT226 (NCT04092673) block NRF2 translation, reducing metastatic burden[192].

9.3 Drug repurposing

Drug repurposing offers an efficient route to identify NRF2 inhibitors. Pizotifen malate (PZM), an FDA-approved medication, binds to the Neh1 domain of NRF2 and prevents NRF2 protein binding to the ARE motif of target genes, suppressing the transcriptional activity of NRF2 to induce ferroptosis and inhibit tumor growth[193]. CX-5461, an RNA polymerase I inhibitor approved for breast cancer susceptibility gene 1/2 (BRCA1/2)-mutant cancers, promotes NRF2 ubiquitination and induces ferroptosis in colorectal cancer[194]. Sirolimus (Rapamycin), an mTORC1 inhibitor and immunosuppressant, suppresses NRF2 expression and nuclear localization, restraining tumor growth in kidney transplant patients[195]. Clobetasol propionate (CP), a corticosteroid, enhances radiosensitization by inhibiting NRF2 nuclear translocation and inducing ferroptosis[196]. Pyrimethamine (PYR), an anti-parasitic drug, acts as a signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) inhibitor and has shown indirect NRF2 inhibitory activity by promoting ubiquitination[197,198]. PYR and its derivative WCDD115 effectively suppress NRF2-driven cancers, with clinical trials in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma already completed (NCT05678348). These repurposed drugs hold immediate translational value for oncology.

9.4 PROTAC technology

Given the difficulties in developing direct NRF2 inhibitors, PROTACs offer an alternative by eliminating the target protein[199]. A recently published PROTAC NRF2 degrader demonstrates anti-cancer effects in cells with constitutive NRF2 activation[200]. Furthermore, Ji et al. reported an ARE-PROTAC that degrades NRF2-MAFG heterodimers via ubiquitination, sensitizing NSCLC cells to ferroptosis[201]. However, the clinical translation of NRF2-targeting PROTACs requires overcoming challenges related to off-target effects and drug delivery.

10. Conclusion and Future Perspective

In conclusion, the NRF2-KEAP1 signaling axis acts as a pivotal guardian of cellular redox homeostasis and tumorigenesis. While NRF2 provides cytoprotection in normal physiology, its constitutive activation, driven by somatic mutations in NFE2L2/KEAP1, oncogenic signaling, and epigenetic rewiring, is frequently hijacked by advanced malignancies to circumvent oxidative stress and suppress ferroptosis. As highlighted in this review, the regulation of NRF2 extends far beyond the canonical KEAP1-dependent degradation machinery. A complex regulatory network, comprising epigenetic modifiers, non-coding RNAs, and chromatin-associated co-factors, orchestrates the fine-tuning of NRF2 transcriptional output. This intricate interplay confers robustness to cancer cells, enabling metabolic adaptability and resistance to ferroptosis-inducing therapies.

Looking forward, several critical avenues warrant further investigation to translate these mechanistic insights into clinical benefits. First, given the “undruggable” structural nature of NRF2 itself, targeting the distinct upstream regulators and co-factors identified herein offers a promising alternative. Moreover, identification of the undescribed downstream targets of NRF2 may also provide additional paths to kill tumors by triggering ferroptosis. Second, as current biomarkers for monitoring ferroptosis in vivo remain elusive, the identification of reliable, non-invasive signatures reflecting NRF2-dependent ferroptosis resistance will be instrumental in stratifying patients who are most likely to benefit from NRF2-targeted interventions. Ultimately, unraveling the multi-layered regulation of the NRF2-ferroptosis axis holds the potential to unlock novel therapeutic vulnerabilities in refractory cancers.

Acknowledgements

We thank the ENCODE Consortium and the ENCODE production laboratory (Michael Snyder, Stanford) generating the ENCSR584GHV dataset.

Author contribution

Wang Z: Conceptualization, manuscript writing-original draft, and writing-reviewing.

Geng Z: Manuscript writing-original draft.

Gu W: Writing-reviewing.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

The project was supported by Soochow University Research Development Funding (Grant No. NH24500125); the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BK20250818); and Jiangsu Specially-Appointed Professor Funding (Grant No. SR24500125).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Sies H, Belousov VV, Chandel NS, Davies MJ, Jones DP, Mann GE, et al. Defining roles of specific reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cell biology and physiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23(7):499-515.[DOI]

-

2. Liu S, Qiu Y, Xiang R, Huang P. Characterization of H2O2-induced alterations in global transcription of mRNA and lncRNA. Antioxidants. 2022;11(3):495.[DOI]

-

3. Perillo B, Di Donato M, Pezone A, Di Zazzo E, Giovannelli P, Galasso G, et al. ROS in cancer therapy: The bright side of the Moon. Exp Mol Med. 2020;52(2):192-203.[DOI]

-

4. Yang X, Wang Z, Samovich SN, Kapralov AA, Amoscato AA, Tyurin VA, et al. PHLDA2-mediated phosphatidic acid peroxidation triggers a distinct ferroptotic response during tumor suppression. Cell Metab. 2024;36(4):762-777.[DOI]

-

5. Kobayashi A, Kang MI, Okawa H, Ohtsuji M, Zenke Y, Chiba T, et al. Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(16):7130-7139.[DOI]

-

6. Dayalan Naidu S, Muramatsu A, Saito R, Asami S, Honda T, Hosoya T, et al. C151 in KEAP1 is the main cysteine sensor for the cyanoenone class of NRF2 activators, irrespective of molecular size or shape. Sci Rep. 2018;8:8037.[DOI]

-

7. Hellyer JA, Padda SK, Diehn M, Wakelee HA. Clinical implications of KEAP1-NFE2L2 mutations in NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16(3):395-403.[DOI]

-

9. Zhang DD. Ironing out the details of ferroptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2024;26(9):1386-1393.[DOI]

-

10. Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, et al. Ferroptosis: An iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060-1072.[DOI]

-

11. Yang WS, Stockwell BR. Synthetic lethal screening identifies compounds activating iron-dependent, nonapoptotic cell death in oncogenic-RAS-harboring cancer cells. Chem Biol. 2008;15(3):234-245.[DOI]

-

12. Dolma S, Lessnick SL, Hahn WC, Stockwell BR. Identification of genotype-selective antitumor agents using synthetic lethal chemical screening in engineered human tumor cells. Cancer Cell. 2003;3(3):285-296.[DOI]

-

13. Lei G, Zhuang L, Gan B. Targeting ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(7):381-396.[DOI]

-

14. Takaya K, Suzuki T, Motohashi H, Onodera K, Satomi S, Kensler TW, et al. Validation of the multiple sensor mechanism of the Keap1-Nrf2 system. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;53(4):817-827.[DOI]

-

15. Yamamoto T, Suzuki T, Kobayashi A, Wakabayashi J, Maher J, Motohashi H, et al. Physiological significance of reactive cysteine residues of Keap1 in determining Nrf2 activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28(8):2758-2770.[DOI]

-

16. Fujiwara KT, Kataoka K, Nishizawa M. Two new members of the maf oncogene family, mafK and mafF, encode nuclear b-Zip proteins lacking putative trans-activator domain. Oncogene. 1993;8(9):2371-2380.[PubMed]

-

17. Rushmore TH, Morton MR, Pickett CB. The antioxidant responsive element. Activation by oxidative stress and identification of the DNA consensus sequence required for functional activity. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(18):11632-11639.[DOI]

-

18. Hirotsu Y, Katsuoka F, Funayama R, Nagashima T, Nishida Y, Nakayama K, et al. Nrf2–MafG heterodimers contribute globally to antioxidant and metabolic networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(20):10228-10239.[DOI]

-

19. Itoh K, Chiba T, Takahashi S, Ishii T, Igarashi K, Katoh Y, et al. An Nrf2/small maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236(2):313-322.[DOI]

-

20. Rojo de la Vega M, Chapman E, Zhang DD. NRF2 and the hallmarks of cancer. Cancer Cell. 2018;34(1):21-43.[DOI]

-

21. Zhang DD. Thirty years of NRF2: Advances and therapeutic challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2025;24(6):421-444.[DOI]

-

22. Hayes JD, Dinkova-Kostova AT. The Nrf2 regulatory network provides an interface between redox and intermediary metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39(4):199-218.[DOI]

-

23. Jeong Y, Hoang NT, Lovejoy A, Stehr H, Newman AM, Gentles AJ, et al. Role ofKEAP1/NRF2andTP53Mutations in lung squamous cell carcinoma development and radiation resistance. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(1):86-101.[DOI]

-

24. Guan L, Nambiar DK, Cao H, Viswanathan V, Kwok S, Hui AB, et al. NFE2L2Mutations enhance radioresistance in head and neck cancer by modulating intratumoral myeloid cells. Cancer Res. 2023;83(6):861-874.[DOI]

-

25. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489(7417):519-525.[DOI]

-

26. HYPERLINK "https://www.nature.com/articles/nature13385" \l "group-1" The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511(7511):543-550.[DOI]

-

27. Sasaki H, Shitara M, Yokota K, Hikosaka YU, Moriyama S, Yano M, et al. Increased NRF2 gene (NFE2L2) copy number correlates with mutations in lung squamous cell carcinomas. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6(2):391-394.[DOI]

-

28. Ingold I, Berndt C, Schmitt S, Doll S, Poschmann G, Buday K, et al. Selenium utilization by GPX4 is required to prevent hydroperoxide-induced ferroptosis. Cell. 2018;172(3):409-422.[DOI]

-

29. Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(1):91-98.[DOI]

-

30. Dixon SJ, Winter GE, Musavi LS, Lee ED, Snijder B, Rebsamen M, et al. Human haploid cell genetics reveals roles for lipid metabolism genes in nonapoptotic cell death. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10(7):1604-1609.[DOI]

-

31. Anandhan A, Dodson M, Schmidlin CJ, Liu P, Zhang DD. Breakdown of an ironclad defense system: The critical role of NRF2 in mediating ferroptosis. Cell Chem Biol. 2020;27(4):436-447.[DOI]

-

32. Zheng C, Zhang B, Li Y, Liu K, Wei W, Liang S, et al. Donafenib and GSK-J4 synergistically induce ferroptosis in liver cancer by upregulating HMOX1 expression. Adv Sci. 2023;10(22):2206798.[DOI]

-

33. Menon AV, Liu J, Tsai HP, Zeng L, Yang S, Asnani A, et al. Excess heme upregulates heme oxygenase 1 and promotes cardiac ferroptosis in mice with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2022;139(6):936-941.[DOI]

-

34. Qiao M, Zhou L, Zhou M, Fang Y, Mai H, Cao L, et al. ERM inhibition confers ferroptosis resistance through ROS-induced NRF2 signaling. Adv Sci. 2026;e13310.[DOI]

-

35. Zhou Y, Zeng L, Cai L, Zheng W, Liu X, Xiao Y, et al. Cellular senescence-associated gene IFI16 promotes HMOX1-dependent evasion of ferroptosis and radioresistance in glioblastoma. Nat Commun. 2025;16:1212.[DOI]

-

36. Liao P, Wang W, Wang W, Kryczek I, Li X, Bian Y, et al. CD8+ T cells and fatty acids orchestrate tumor ferroptosis and immunity via ACSL4. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(4):365-378.e6.[DOI]

-

37. Wang Z, Yang X, Chen D, Liu Y, Li Z, Duan S, et al. GAS41 modulates ferroptosis by anchoring NRF2 on chromatin. Nat Commun. 2024;15:2531.[DOI]

-

38. Luo Y, Hitz BC, Gabdank I, Hilton JA, Kagda MS, Lam B, et al. New developments on the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) data portal. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(D1):D882-D889.[DOI]

-

39. Takahashi N, Cho P, Selfors LM, Kuiken HJ, Kaul R, Fujiwara T, et al. 3D culture models with CRISPR screens reveal hyperactive NRF2 as a prerequisite for spheroid formation via regulation of proliferation and ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2020;80(5):828-844.e6.[DOI]

-

40. Yuan Z, Wang X, Qin B, Hu R, Miao R, Zhou Y, et al. Targeting NQO1 induces ferroptosis and triggers anti-tumor immunity in immunotherapy-resistant KEAP1-deficient cancers. Drug Resist Updat. 2024;77:101160.[DOI]

-

41. Shi Y, Fan S, Wu M, Zuo Z, Li X, Jiang L, et al. YTHDF1 links hypoxia adaptation and non-small cell lung cancer progression. Nat Commun. 2019;10:4892.[DOI]

-

42. Gagliardi M, Cotella D, Santoro C, Corà D, Barlev NA, Piacentini M, et al. Aldo-keto reductases protect metastatic melanoma from ER stress-independent ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(12):902.[DOI]

-

43. Penning TM, Jonnalagadda S, Trippier PC, Rižner TL. Aldo-keto reductases and cancer drug resistance. Pharmacol Rev. 2021;73(3):1150-1171.[DOI]

-

44. Kang YP, Mockabee-Macias A, Jiang C, Falzone A, Prieto-Farigua N, Stone E, et al. Non-canonical glutamate-cysteine ligase activity protects against ferroptosis. Cell Metab. 2021;33(1):174-189.e7.[DOI]

-

45. Zhou N, Chen J, Hu M, Wen N, Cai W, Li P, et al. SLC7A11 is an unconventional H+ transporter in lysosomes. Cell. 2025;188(13):3441-3458.e25.[DOI]

-

46. Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang SJ, Su T, Hibshoosh H, et al. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 2015;520(7545):57-62.[DOI]

-

47. Fiore A, Zeitler L, Russier M, Groß A, Hiller MK, Parker JL, et al. Kynurenine importation by SLC7A11 propagates anti-ferroptotic signaling. Mol Cell. 2022;82(5):920-932.e7.[DOI]

-

48. Yan Y, Teng H, Hang Q, Kondiparthi L, Lei G, Horbath A, et al. SLC7A11 expression level dictates differential responses to oxidative stress in cancer cells. Nat Commun. 2023;14:3673.[DOI]

-

49. Sato H, Shiiya A, Kimata M, Maebara K, Tamba M, Sakakura Y, et al. Redox imbalance in cystine/glutamate transporter-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(45):37423-37429.[DOI]

-

50. Liu N, Lin X, Huang C. Activation of the reverse transsulfuration pathway through NRF2/CBS confers erastin-induced ferroptosis resistance. Br J Cancer. 2020;122(2):279-292.[DOI]

-

51. Zhu J, Berisa M, Schwörer S, Qin W, Cross JR, Thompson CB. Transsulfuration activity can support cell growth upon extracellular cysteine limitation. Cell Metab. 2019;30(5):865-876.e5.[DOI]

-

52. Sun X, Ou Z, Chen R, Niu X, Chen D, Kang R, et al. Activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway protects against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):173-184.[DOI]

-

53. Feng H, Schorpp K, Jin J, Yozwiak CE, Hoffstrom BG, Decker AM, et al. Transferrin receptor is a specific ferroptosis marker. Cell Rep. 2020;30(10):3411-3423.e7.[DOI]

-

54. Cui S, Ghai A, Deng Y, Li S, Zhang R, Egbulefu C, et al. Identification of hyperoxidized PRDX3 as a ferroptosis marker reveals ferroptotic damage in chronic liver diseases. Mol Cell. 2023;83(21):3931-3939.e5.[DOI]

-

55. DeNicola GM, Karreth FA, Humpton TJ, Gopinathan A, Wei C, Frese K, et al. Oncogene-induced Nrf2 transcription promotes ROS detoxification and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2011;475(7354):106-109.[DOI]

-

56. Tang YC, Hsiao JR, Jiang SS, Chang JY, Chu PY, Liu KJ, et al. C-MYC-directed NRF2 drives malignant progression of head and neck cancer via glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and transketolase activation. Theranostics. 2021;11(11):5232-5247.[DOI]

-

57. Hu K, Li K, Lv J, Feng J, Chen J, Wu H, et al. Suppression of the SLC7A11/glutathione axis causes synthetic lethality in KRAS-mutant lung adenocarcinoma. J Clin Investig. 2020;130(4):1752-1766.[DOI]

-

58. Kreß JKC, Jessen C, Hufnagel A, Schmitz W, Xavier da Silva TN, Ferreira dos Santos A, et al. The integrated stress response effector ATF4 is an obligatory metabolic activator of NRF2. Cell Rep. 2023;42(7):112724.[DOI]

-

59. Wang L, Chen Y, Mi Y, Qiao J, Jin H, Li J, et al. ATF2 inhibits ani-tumor effects of BET inhibitor in a negative feedback manner by attenuating ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;558:216-223.[DOI]

-

60. Zhang X, Zhang J, Peng H, Liu X, Zhang H. SLC38A5 drives colorectal cancer ferroptosis resistance through the Hippo-YAP/Nrf2 axis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2026;244:367-379.[DOI]

-

61. El-Naggar AM, Somasekharan SP, Wang Y, Cheng H, Negri GL, Pan M, et al. Class IHDACinhibitors enhanceYB-1 acetylation and oxidative stress to block sarcoma metastasis. EMBO Rep. 2019;20(12):e48375.[DOI]

-

62. Hsieh CH, Kuan WH, Chang WL, Kuo IY, Liu H, Shieh DB, et al. Dysregulation of SOX17/NRF2 axis confers chemoradiotherapy resistance and emerges as a novel therapeutic target in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Biomed Sci. 2022;29:90.[DOI]

-

63. Shimazu T, Hirschey MD, Newman J, He W, Shirakawa K, Le Moan N, et al. Suppression of oxidative stress by β-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenous histone deacetylase inhibitor. Science. 2013;339(6116):211-214.[DOI]

-

64. Chen Y, Liu X, Li Y, Quan C, Zheng L, Huang K. Lung cancer therapy targeting histone methylation: Opportunities and challenges. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2018;16:211-223.[DOI]

-

65. Hong KJ, Choi YJ, Kim J, Cho MC, Kim JH. Pilot study on CpG methylation of the NRF2 promoter across different ages and sexes in healthy and lung cancer prediagnostic individuals. Free Radic Biol Med. 2025;235:86-94.[DOI]

-

66. Yuan G, Hu B, Ma J, Zhang C, Xie H, Wei T, et al. Histone lysine methyltransferase SETDB2 suppresses NRF2 to restrict tumor progression and modulates chemotherapy sensitivity in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Med. 2023;12(6):7258-7272.[DOI]

-

67. Choi J, Lee H. MLL1 histone methyltransferase and UTX histone demethylase functionally cooperate to regulate the expression of NRF2 in response to ROS-induced oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2024;217:48-59.[DOI]

-

68. Zhang Y, Yu R, Li Q, Song S, Fu Y, Shen X, et al. Epigenetic suppression of Nrf2–Slc40a1 axis induces ferroptosis and enhances immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13(10):e013269.[DOI]

-

69. Wang C, Shu L, Zhang C, Li W, Wu R, Guo Y, et al. Histone methyltransferase Setd7 regulates Nrf2 signaling pathway by phenethyl isothiocyanate and ursolic acid in human prostate cancer cells. Molecular Nutrition Food Res. 2018;62(18):1700840.[DOI]

-

70. Antonucci L, Li N, Duran A, Cobo I, Nicoletti C, Watari K, et al. Self-amplifying NRF2–EZH2 epigenetic loop converts KRAS-initiated progenitors to invasive pancreatic cancer. Nat Cancer. 2025;6(7):1263-1282.[DOI]

-

71. Shen J, Chen M, Lee D, Law CT, Wei L, Tsang FH, et al. Histone chaperone FACT complex mediates oxidative stress response to promote liver cancer progression. Gut. 2020;69(2):329-342.[DOI]

-

72. Wang K, Wang G, Li G, Zhang W, Wang Y, Lin X, et al. M6A writer WTAP targets NRF2 to accelerate bladder cancer malignancy via M6A-dependent ferroptosis regulation. Apoptosis. 2023;28(3-4):627-638.[DOI]

-

73. Zhu JF, Guo DP, Lv HN, Liang ZY, Song J, Zeng W. Histone lactylation-mediated up-regulation of IGF2BP2 enhances ferroptosis resistance via Nrf2 in colorectal cancer. Clinical & Translational Med. 2025;15(12):e70551.[DOI]

-

74. Lu Y, Zhu J, Zhang Y, Li W, Xiong Y, Fan Y, et al. Lactylation-driven IGF2BP3-mediated serine metabolism reprogramming and RNA M6A: Modification promotes lenvatinib resistance in HCC. Adv Sci. 2024;11(46):2401399.[DOI]

-

75. Zheng J, Zhang Q, Zhao Z, Qiu Y, Zhou Y, Wu Z, et al. Epigenetically silenced lncRNA SNAI3-AS1 promotes ferroptosis in glioma via perturbing the M6A-dependent recognition of Nrf2 mRNA mediated by SND1. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2023;42:127.[DOI]

-

76. Mao M, Yang L, Hu J, Liu B, Zhang X, Liu Y, et al. Oncogenic E3 ubiquitin ligase NEDD4 binds to KLF8 and regulates the microRNA-132/NRF2 axis in bladder cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2022;54(1):47-60.[DOI]

-

77. Mahajan M, Sitasawad S. miR-140-5p attenuates hypoxia-induced breast cancer progression by targeting Nrf2/HO-1 axis in a Keap1-independent mechanism. Cells. 2022;11(1):12.[DOI]

-

79. Xiao S, Liu N, Yang X, Ji G, Li M. Polygalacin D suppresses esophageal squamous cell carcinoma growth and metastasis through regulating miR-142-5p/Nrf2 axis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;164:58-75.[DOI]

-

80. Jadeja RN, Jones MA, Abdelrahman AA, Powell FL, Thounaojam MC, Gutsaeva D, et al. Inhibiting microRNA-144 potentiates Nrf2-dependent antioxidant signaling in RPE and protects against oxidative stress-induced outer retinal degeneration. Redox Biol. 2020;28:101336.[DOI]

-

81. Shi L, Chen ZG, Wu LL, Zheng JJ, Yang JR, Chen XF, et al. miR-340 reverses cisplatin resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines by targeting Nrf2-dependent antioxidant pathway. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;15(23):10439-10444.[DOI]

-

82. Zhou S, Ye W, Zhang Y, Yu D, Shao Q, Liang J, et al. miR-144 reverses chemoresistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines by targeting Nrf2-dependent antioxidant pathway. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8(7):2992-3002.

-

83. Singh B, Ronghe AM, Chatterjee A, Bhat NK, Bhat HK. microRNA-93 regulates NRF2 expression and is associated with breast carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(5):1165-1172.[DOI]

-

84. Li C, Fan K, Qu Y, Zhai W, Huang A, Sun X, et al. Deregulation of UCA1 expression may be involved in the development of chemoresistance to cisplatin in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer via regulating the signaling pathway of microRNA-495/NRF2. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(4):3721-3730.[DOI]

-

85. Wu LL, Cai WP, Lei X, Shi KQ, Lin XY, Shi L. NRAL mediates cisplatin resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma via miR-340-5p/Nrf2 axis. J Cell Commun Signal. 2019;13(1):99-112.[DOI]

-

86. Zhang Z, Xiong R, Li C, Xu M, Guo M. LncRNA TUG1 promotes cisplatin resistance in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells by regulating Nrf2. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2019;51(8):826-833.[DOI]

-

87. Pu Y, Tan Y, Zang C, Zhao F, Cai C, Kong L, et al. LAMTOR5-AS1 regulates chemotherapy-induced oxidative stress by controlling the expression level and transcriptional activity of NRF2 in osteosarcoma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(12):1125.[DOI]

-

88. Zhang C, Liang X, Wang M, Wang K, Liu J, Li C, et al. HHLA3 transcriptionally promotes GPX2 to enhance anti-oxidative capacity by attenuating KEAP1-mediated NRF2 ubiquitination in lung adenocarcinoma. Free Radic Biol Med. 2026;244:482-495.[DOI]

-

89. Chen ZW, Shan JJ, Chen M, Wu Z, Zhao YM, Zhu HX, et al. Targeting GPX4 to induce ferroptosis overcomes chemoresistance mediated by thePAX8-AS1/GPX4 axis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Adv Sci. 2025;12(30):e01042.[DOI]

-

91. Katoh Y, Itoh K, Yoshida E, Miyagishi M, Fukamizu A, Yamamoto M. Two domains of Nrf2 cooperatively bind CBP, a CREB binding protein, and synergistically activate transcription. Genes Cells. 2001;6(10):857-868.[DOI]

-

92. Sun Z, Chin YE, Zhang DD. Acetylation of Nrf2 by p300/CBP augments promoter-specific DNA binding of Nrf2 during the antioxidant response. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29(10):2658-2672.[DOI]

-

93. Nioi P, Nguyen T, Sherratt PJ, Pickett CB. The carboxy-terminal Neh3 domain of Nrf2 is required for transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25(24):10895-10906.[DOI]

-

94. Yang Z, Zou S, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Zhang P, Xiao L, et al. ACTL6A protects gastric cancer cells against ferroptosis through induction of glutathione synthesis. Nat Commun. 2023;14:4193.[DOI]

-

95. Luo M, Bao L, Xue Y, Zhu M, Kumar A, Xing C, et al. ZMYND8 protects breast cancer stem cells against oxidative stress and ferroptosis through activation of NRF2. J Clin Investig. 2024;134(6):e171166.[DOI]

-

98. Mas G, Man N, Nakata Y, Martinez-Caja C, Karl D, Beckedorff F, et al. The SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling subunit DPF2 facilitates NRF2-dependent antiinflammatory and antioxidant gene expression. J Clin Investig. 2023;133(13):e158419.[DOI]

-

99. Song S, Nguyen V, Schrank T, Mulvaney K, Walter V, Wei D, et al. Loss of SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling alters NRF2 signaling in non–small cell lung carcinoma. Mol Cancer Res. 2020;18(12):1777-1788.[DOI]

-

100. Zhang J, Ohta T, Maruyama A, Hosoya T, Nishikawa K, Maher JM, et al. BRG1 interacts with Nrf2 to selectively mediate HO-1 induction in response to oxidative stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(21):7942-7952.[DOI]

-

101. Chen D, Tavana O, Chu B, Erber L, Chen Y, Baer R, et al. NRF2 is a major target of ARF in p53-independent tumor suppression. Mol Cell. 2017;68(1):224-232.e4.[DOI]

-

102. Alam MM, Okazaki K, Nguyen LTT, Ota N, Kitamura H, Murakami S, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor signaling represses the antioxidant response by inhibiting histone acetylation mediated by the transcriptional activator NRF2. J Biol Chem. 2017;292(18):7519-7530.[DOI]

-

103. Sun X, Wang S, Miao X, Zeng S, Guo Y, Zhou A, et al. TRIB1 regulates liver regeneration by antagonizing the NRF2-mediated antioxidant response. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(6):372.[DOI]

-

104. Kawasaki T, Sugihara F, Fukushima K, Matsuki T, Nabeshima H, Machida T, et al. Loss of FCHSD1 leads to amelioration of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(26):e2019167118.[DOI]

-

105. Wang H, Wang Q, Cai G, Duan Z, Nugent Z, Huang J, et al. Nuclear TIGAR mediates an epigenetic and metabolic autoregulatory loop via NRF2 in cancer therapeutic resistance. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12(4):1871-1884.[DOI]

-

106. Yang X, Liu Y, Cao J, Wu C, Tang L, Bian W, et al. Targeting epigenetic and post-translational modifications of NRF2: Key regulatory factors in disease treatment. Cell Death Discov. 2025;11:189.[DOI]

-

107. Ingersoll AJ, McCloud DM, Hu JY, Rape M. Dynamic regulation of the oxidative stress response by the E3 ligase TRIP12. Cell Rep. 2025;44(9):116262.[DOI]

-

108. Rada P, Rojo AI, Chowdhry S, McMahon M, Hayes JD, Cuadrado A. SCF/β-TrCP promotes glycogen synthase kinase 3-dependent degradation of the Nrf2 transcription factor in a Keap1-independent manner. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31(6):1121-1133.[DOI]

-

109. Chowdhry S, Zhang Y, McMahon M, Sutherland C, Cuadrado A, Hayes JD. Nrf2 is controlled by two distinct β-TrCP recognition motifs in its Neh6 domain, one of which can be modulated by GSK-3 activity. Oncogene. 2013;32(32):3765-3781.[DOI]

-

111. Li L, Xie D, Yu S, Ma M, Fan K, Chen J, et al. WNK1 interaction with KEAP1 promotes NRF2 stabilization to enhance the oxidative stress response in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2024;84(17):2776-2791.[DOI]

-

112. Wu H, Zhu G, Zhu Q, Ma J, Mao S, Ding M, et al. TCF3 activates super-enhancer-driven TRIB2 overexpression to suppress ferroptosis and promote hepatoblastoma proliferation. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2025;44:329.[DOI]

-

113. Wang S, Zhang C, Zhou S, Liu S, Li Q, Cheng X, et al. RNF217-KEAP1-NRF2 feedback loop confers therapeutic resistance by inhibiting ferroptosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Drug Resist Updat. 2025;83:101296.[DOI]

-

114. Hua C, Zhang G, Yu W, Zhou J, Ru L, Xue G, et al. CROT overactivation within peroxisomes confers chemoresistance to non-small cell lung cancer by targeting fatty acid oxidation-Nrf2-ferroptosis resistance axis. Pharmacol Res. 2025;220:107911.[DOI]

-

115. Wang Y, Liang Y, Luo D, Ye F, Jin Y, Wang L, et al. EDEM1 inhibits endoplasmic reticulum stress to induce doxorubicin resistance through accelerating ERAD and activating Keap1/Nrf2 antioxidant pathway in triple-negative breast cancer. Research. 2025;8:797.[DOI]

-

116. Guo M, Chen S, Sun J, Xu R, Qi Z, Li J, et al. PIP5K1A suppresses ferroptosis and induces sorafenib resistance by stabilizing NRF2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Adv Sci. 2025;12(30):e04372.[DOI]

-

117. Huang C, Zeng Q, Chen J, Wen Q, Jin W, Dai X, et al. TMEM160 inhibits KEAP1 to suppress ferroptosis and induce chemoresistance in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16:287.[DOI]

-

118. Dong R, Fei Y, He Y, Gao P, Zhang B, Zhu M, et al. Lactylation-driven HECTD2 limits the response of hepatocellular carcinoma to lenvatinib. Adv Sci. 2025;12(15):2412559.[DOI]

-

119. Song Y, Wang X, Sun Y, Yu N, Tian Y, Han J, et al. PRDX1 inhibits ferroptosis by binding to Cullin-3 as a molecular chaperone in colorectal cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2024;20(13):5070-5086.[DOI]

-

120. Lu K, Alcivar AL, Ma J, Foo TK, Zywea S, Mahdi A, et al. NRF2 induction supporting breast cancer cell survival is enabled by oxidative stress–induced DPP3–KEAP1 interaction. Cancer Res. 2017;77(11):2881-2892.[DOI]

-

121. Ma J, Cai H, Wu T, Sobhian B, Huo Y, Alcivar A, et al. PALB2 interacts with KEAP1 to promote NRF2 nuclear accumulation and function. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32(8):1506-1517.[DOI]

-

122. Camp ND, James RG, Dawson DW, Yan F, Davison JM, Houck SA, et al. Wilms tumor gene on X chromosome (WTX) inhibits degradation of NRF2 protein through competitive binding to KEAP1 protein. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(9):6539-6550.[DOI]

-

123. Tamberg N, Tahk S, Koit S, Kristjuhan K, Kasvandik S, Kristjuhan A, et al. Keap1–MCM3 interaction is a potential coordinator of molecular machineries of antioxidant response and genomic DNA replication in Metazoa. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12136.[DOI]

-

124. Wang Q, Ma J, Lu Y, Zhang S, Huang J, Chen J, et al. CDK20 interacts with KEAP1 to activate NRF2 and promotes radiochemoresistance in lung cancer cells. Oncogene. 2017;36(37):5321-5330.[DOI]

-

125. Tian W, Rojo de la Vega M, Schmidlin CJ, Ooi A, Zhang DD. Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) differentially regulates nuclear factor erythroid-2–related factors 1 and 2 (NRF1 and NRF2). J Biol Chem. 2018;293(6):2029-2040.[DOI]

-

126. Komatsu M, Kurokawa H, Waguri S, Taguchi K, Kobayashi A, Ichimura Y, et al. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12(3):213-223.[DOI]

-

127. Ge W, Zhao K, Wang X, Li H, Yu M, He M, et al. iASPP is an antioxidative factor and drives cancer growth and drug resistance by competing with Nrf2 for Keap1 binding. Cancer Cell. 2017;32(5):561-573.e6.[DOI]

-

128. Fan L, Guo D, Zhu C, Gao C, Wang Y, Yin F, et al. LRRC45 accelerates bladder cancer development and ferroptosis inhibition via stabilizing NRF2 by competitively KEAP1 interaction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2025;226:29-42.[DOI]

-

129. Feng W, Liu Y, Zhang Q, Hu S, Xie D, Tan P, et al. GDF15 drives glioblastoma radioresistance by inhibiting ferroptosis and remodeling the immune microenvironment. Int J Biol Sci. 2025;21(15):6794-6807.[DOI]

-

130. Saeidi S, Kim SJ, Guillen-Quispe YN, Jagadeesh ASV, Han HJ, Kim SH, et al. Peptidyl-prolylcis-transisomerase NIMA-interacting 1 directly binds and stabilizes Nrf2 in breast cancer. FASEB J. 2022;36:e22068.[DOI]

-

131. Lu W, Cui J, Wang W, Hu Q, Xue Y, Liu X, et al. PPIA dictates NRF2 stability to promote lung cancer progression. Nat Commun. 2024;15:4703.[DOI]

-

132. Da C, Pu J, Liu Z, Wei J, Qu Y, Wu Y, et al. HACE1-mediated NRF2 activation causes enhanced malignant phenotypes and decreased radiosensitivity of glioma cells. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:399.[DOI]

-

133. Wang S, Wang Y, Li Q, Li X, Feng X, Zeng K. The novel β-TrCP protein isoform hidden in circular RNA confers trastuzumab resistance in HER2-positive breast cancer. Redox Biol. 2023;67:102896.[DOI]

-

134. Wang H, Huang Q, Xia J, Cheng S, Pei D, Zhang X, et al. The E3 ligase MIB1 promotes proteasomal degradation of NRF2 and sensitizes lung cancer cells to ferroptosis. Mol Cancer Res. 2022;20(2):253-264.[DOI]

-

135. Wang Z, Zhang Y, Shen Y, Zhu C, Qin X, Gao Y. Liquidambaric acid inhibits cholangiocarcinoma progression by disrupting the STAMBPL1/NRF2 positive feedback loop. Phytomedicine. 2025;136:156303.[DOI]

-

136. Zhang Q, Zhang ZY, Du H, Li SZ, Tu R, Jia YF, et al. DUB3 deubiquitinates and stabilizes NRF2 in chemotherapy resistance of colorectal cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26(11):2300-2313.[DOI]

-

137. Meng C, Zhan J, Chen D, Shao G, Zhang H, Gu W, et al. The deubiquitinase USP11 regulates cell proliferation and ferroptotic cell death via stabilization of NRF2 USP11 deubiquitinates and stabilizes NRF2. Oncogene. 2021;40(9):1706-1720.[DOI]

-

138. Chen L, Ning J, Li L, Tang J, Liu N, Long Y, et al. USP13 facilitates a ferroptosis-to-autophagy switch by activation of the NFE2L2/NRF2-SQSTM1/p62-KEAP1 axis dependent on the KRAS signaling pathway. Autophagy. 2025;21(3):565-582.[DOI]

-

139. Eskandari N, Delisi D, Vakili Saatloo M, Keceli G, Pinheiro N, Eblen S, et al. TRPA1 activation prompts lysosome-mediated Nrf2 degradation enhancing the killing of colorectal cancer cells. Redox Biol. 2025;88:103942.[DOI]

-

140. Malloy MT, McIntosh DJ, Walters TS, Flores A, Goodwin JS, Arinze IJ. Trafficking of the Transcription Factor Nrf2 to Promyelocytic Leukemia-Nuclear Bodies implications for degradation of nrf2 in the nucleus. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(20):14569-14583.[DOI]

-

141. Xia Q, Que M, Zhan G, Zhang L, Zhang X, Zhao Y, et al. SENP6-mediated deSUMOylation of Nrf2 exacerbates neuronal oxidative stress following cerebral ischemia and reperfusion injury. Adv Sci. 2025;12(7):2410410.[DOI]

-

142. Guo H, Xu J, Zheng Q, He J, Zhou W, Wang K, et al. NRF2 SUMOylation promotes de novo serine synthesis and maintains HCC tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett. 2019;466:39-48.[DOI]

-

144. Chen Z, Ye X, Tang N, Shen S, Li Z, Niu X, et al. The histone acetylranseferase hMOF acetylates Nrf2 and regulates anti-drug responses in human non-small cell lung cancer. British J Pharmacology. 2014;171(13):3196-3211.[DOI]

-

145. Kawai Y, Garduño L, Theodore M, Yang J, Arinze IJ. Acetylation-deacetylation of the transcription factor Nrf2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) regulates its transcriptional activity and nucleocytoplasmic localization. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(9):7629-7640.[DOI]

-

146. Yang X, Park SH, Chang HC, Shapiro JS, Vassilopoulos A, Sawicki KT, et al. Sirtuin 2 regulates cellular iron homeostasis via deacetylation of transcription factor NRF2. J Clin Investig. 2017;127(4):1505-1516.[DOI]

-

147. Yu T, Ding C, Peng J, Liang G, Tang Y, Zhao J, et al. SIRT7-mediated NRF2 deacetylation promotes antioxidant response and protects against chemodrug-induced liver injury. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16:232.[DOI]

-

148. Liu F, Zhang H, Feng Y. SIRT6AttenuatesERStress-associated mucus hypersecretion via regulation ofNRF2in asthma models. FASEB J. 2025;39(15):e70926.[DOI]

-

149. Sheng B, Chen X, Tao T, Sun J, Li W, Wu L, et al. SIRT2 Inhibition promotes microglia LC3-associated phagocytosis via NRF2/CD36 after the experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neuroinflammation. 2026;23:26.[DOI]

-

150. Cui M, An Y, Zhao J, Hui M, Xiong Z, Guan B, et al. Dahuang Gancao decoction suppresses ferroptosis via SIRT3-mediated NRF2 deacetylation in acute kidney injury. Phytomedicine. 2026;150:157724.[DOI]

-

151. Liu X, Li H, Liu L, Lu Y, Gao Y, Geng P, et al. Methylation of arginine by PRMT1 regulates Nrf2 transcriptional activity during the antioxidative response. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA Mol Cell Res. 2016;1863(8):2093-2103.[DOI]

-

152. Wang Y, Yan S, Liu X, Deng F, Wang P, Yang L, et al. PRMT4 promotes ferroptosis to aggravate doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy via inhibition of the Nrf2/GPX4 pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29(10):1982-1995.[DOI]

-

153. Apopa PL, He X, Ma Q. Phosphorylation of Nrf2 in the transcription activation domain by casein kinase 2 (CK2) is critical for the nuclear translocation and transcription activation function of Nrf2 in IMR-32 neuroblastoma cells. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2008;22(1):63-76.[DOI]

-

154. Sun Z, Huang Z, Zhang DD. Phosphorylation of Nrf2 at multiple sites by MAP kinases has a limited contribution in modulating the Nrf2-dependent antioxidant response. PLoS One. 2009;4(8):e6588.[DOI]

-

155. Huang HC, Nguyen T, Pickett CB. Phosphorylation of Nrf2 at ser-40 by protein kinase C regulates antioxidant response element-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(45):42769-42774.[DOI]

-

156. Cullinan SB, Zhang D, Hannink M, Arvisais E, Kaufman RJ, Diehl JA. Nrf2 is a direct PERK substrate and effector of PERK-dependent cell survival. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(20):7198-7209.[DOI]

-

157. Küper A, Baumann J, Göpelt K, Baumann M, Sänger C, Metzen E, et al. Overcoming hypoxia-induced resistance of pancreatic and lung tumor cells by disrupting the PERK-NRF2-HIF-axis. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:82.[DOI]

-