Abstract

Topology, a cornerstone of modern condensed matter physics, has in the past decade played a crucial role in diverse wave systems. As a powerful wave system, light can be sculpted into an even richer variety of topological structures, including vortices, skyrmions, Möbius strips, etc., leading to advanced photonic technologies from optical trapping to imaging, across quantum and classical regimes. A recent breakthrough demonstrated that topologically structured water waves can manipulate particles with intricate spin-orbital motion, and similar principles have enabled topological control in acoustofluidics, opening new insights in wave-matter interactions. Therefore, we argue that topological light waves possess an analogous potential, offering a route beyond the scalar-field limitations of conventional optical tweezers and establishing a new paradigm of multidimensional, vectorial control over matter. This article starts with brief introductions to optical tweezer technologies and topological light waves, then focuses on their emerging combination: particle trapping and sorting. It follows with perspectives on how topologies can couple to new degrees of freedom for manipulating complex particle motions previously inaccessible, and finally discusses potential applications.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Topology, a branch of mathematics concerned with properties that remain invariant under continuous deformations, has become a profound physical principle, revolutionizing our understanding of matter and waves. Its introduction to physics led to the discovery of exotic phenomena such as topological phase transitions and topological stability, a breakthrough recognized by the 2016 Nobel Prize in Physics[1,2].

This powerful concept has since expanded beyond its origins in condensed matter, sparking a revolution in wave physics. The past decade has witnessed a surge of innovation as researchers have learned to sculpt topological structures into various wave fields. Notable milestones include the observation of optical and acoustic skyrmions[3-5], the realization of polarization Möbius strips[6-8], and the generation of vortex states in electron and atomic waves[9-12]. Nowhere has this progress been more dramatic than in optics, where the ability to engineer topological textures—from skyrmions and merons to hopfions—has profoundly expanded the landscape of topological light waves[13-15]. These structures can be imprinted onto various degrees of freedom (DoF) of the light field, including its electromagnetic vectors[3,16,17], spin[4,18-21], Stokes[22-24], and Poynting vectors[25,26], and have even been extended into the ultrafast spatiotemporal domain[27-29], creating unprecedentedly rich structures of topological waves.

Having mastered the generation of such a diverse set of topological structures, the crucial question arises: how can we harness these intricate structures to interact with and manipulate matter? A compelling answer has recently emerged from a parallel physical domain: water waves. There, the controllable generation of topological water-wave structures was predicted and experimentally confirmed[30-32], revealing that skyrmion and Möbius-strip structures can be transferred to matter to manipulate floating particles.

This milestone provides a powerful proof of concept and raises an even more compelling prospect in optics. The principle of transferring topology to manipulate particles becomes profoundly more significant when applied to light, given the unparalleled advantages of optical tweezers (OTs): their non-contact, non-invasive, and highly precise control. Moreover, the importance of this technology has already been recognized with the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics[33-38]. Therefore, can we sculpt these topologies into optical fields to control particle dynamics in ways beyond the reach of classical beams?

To answer this question, we must first consider the technology at the heart of the field. The classic OT typically uses the gradient force from a tightly focused Gaussian laser beam to create a stable “single-point trapping”, a breakthrough that has enabled decades of research across physics, biology, and medicine[39-43]. The field’s capabilities were significantly expanded with the advent of structured light, where engineering the spatial profiles of light beams enabled more complex, multidimensional manipulation[44-47]. Landmark demonstrations include using the orbital angular momentum (OAM) of Laguerre–Gaussian (LG) beams to induce controlled rotation in trapped particles[48] and employing Airy beams for transport along curved trajectories[49]. However, despite these significant advances, the classical paradigm, which primarily relies on sculpting the intensity and phase of scalar fields, is facing significant challenges in meeting the demands for higher-dimensional and parallelized control.

This perspective will chart the emergence of the powerful synergy between topological light waves and optical manipulation. We begin by outlining the limitations of the classical paradigm, and then introduce the transformative “Topological Toolkit”, review pioneering experiments that translate this principle into the optical domain, demonstrating functionalities beyond the reach of classical methods. Finally, we look to the future, arguing that the convergence of topological principles with optical manipulation will unlock unprecedented control over matter, and we dissect the grand challenges that must be overcome to realize this ambitious vision.

2. Technical Reviews

To appreciate the potential of topological light, one must first understand the limitations of the classical paradigm.

2.1 The classical paradigm and its limitations

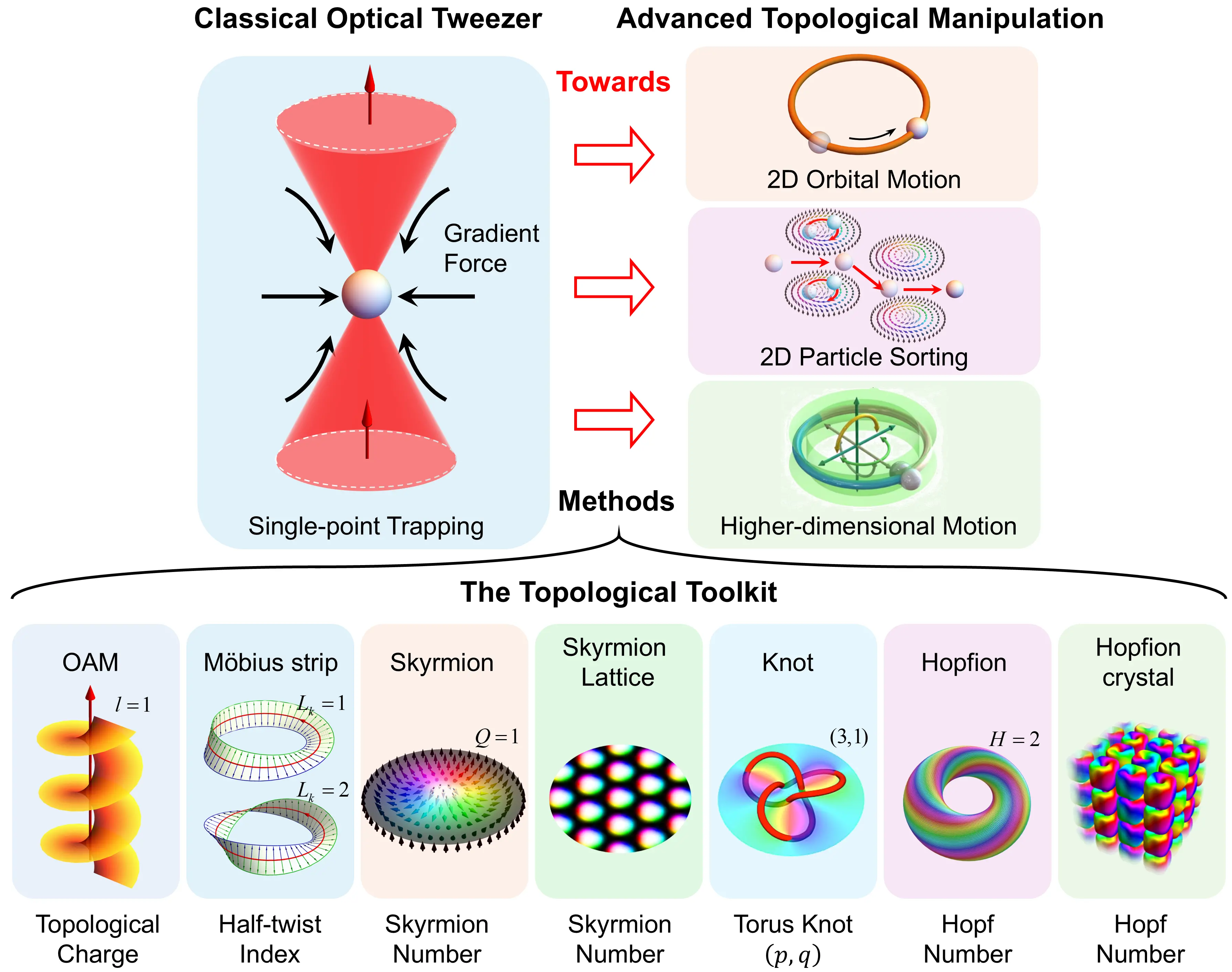

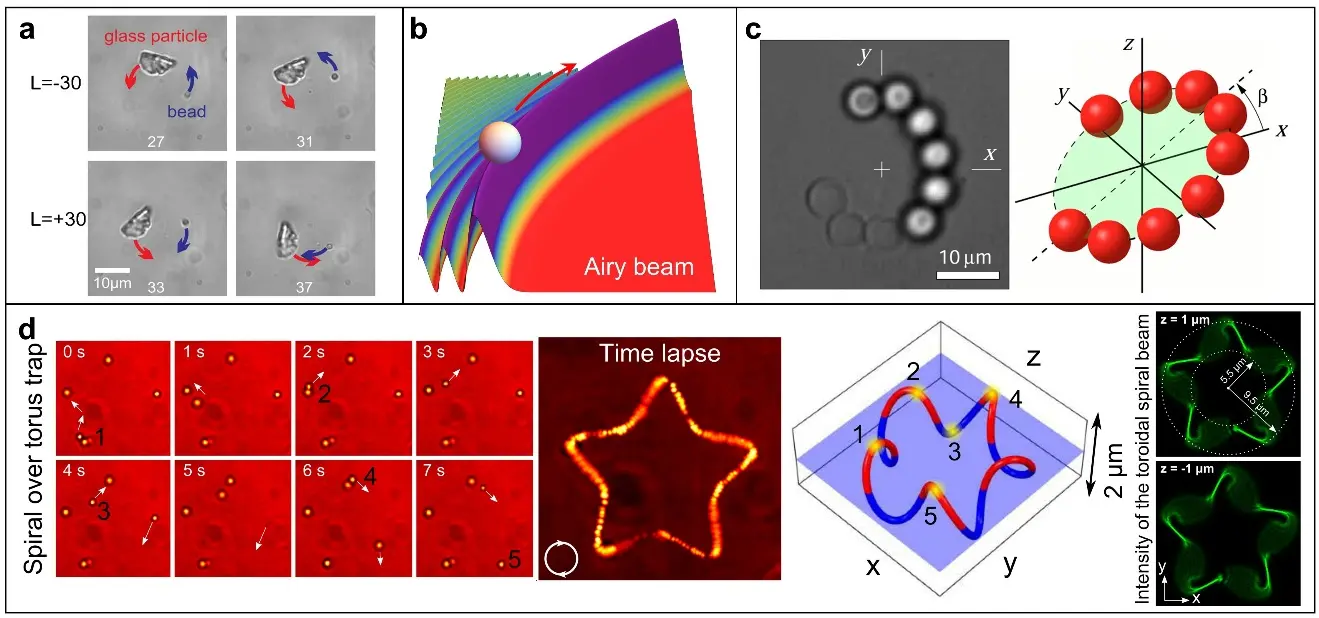

As illustrated in the left panel of Figure 1, the primary mechanism of OTs is the gradient force, which draws a dielectric particle toward the region of highest light intensity, creating a stable three-dimensional trap. However, the classical OT, based on a simple Gaussian beam, is fundamentally a “single-point trapping” with limited functionality. The first major advance beyond the classical paradigm was the emergence of structured light, where the spatial, phase, and polarization profiles of the beam are deliberately engineered[44-46,50,51]. This enabled a leap from single-point trapping to multidimensional manipulation[47]. Early demonstrations used LG beams carrying OAM to impart controlled rotation to trapped particles (Figure 2a)[48], while Airy beams enabled curved particle transport[49] (Figure 2b). Furthermore, dynamic holographic techniques have unlocked real-time control over particle trajectories in three dimensions, including trapping along complex paths like rings and toroidal spirals (Figure 2c,d)[52,53]. Nevertheless, the paradigm of classical structured light, which relies on engineering the intensity and phase of scalar fields, is constrained by the intrinsic principles of scalar-field optics. These approaches, while versatile, suffer from several critical limitations that hinder the next generation of optical control:

Figure 1. The evolution from classical OTs to advanced topological manipulation. The classical OT (left panel) utilizes the gradient force from a tightly focused laser beam to achieve stable “single-point trapping”. This contrasts with advanced manipulation techniques (right panel) enabled by a transformative “Topological Toolkit” (bottom panel). This toolkit provides a rich set of structures for sculpting light, including optical vortices carrying OAM characterized by the topological charge l; Möbius strips with a half-twist indexLk; and skyrmionic textures defined by the skyrmion number Q. The toolkit also extends to complex three-dimensional structures such as optical knots and hopfions, described by knot invariants (p, q) and the Hopf number H, respectively. These topological structures enable functionalities far beyond simple trapping, such as inducing orbital motion, creating complex force landscapes for parallel particle sorting, and guiding particles along higher-dimensional trajectories. OTs: optical tweezers; OAM: orbital angular momentum.

Figure 2. Optical trapping with classical structured light. (a) Rotation of a polystyrene bead and a glass sliver trapped using a LG mode[48]; (b) Transport of particles using an Airy beam; (c) Optical trapping and transport of microparticles along three-dimensional parametrized trajectories: (left) particles trapped along a single ring in three-dimension; (right) schematic representation of the trapping configuration[52]; (d) Optical trapping with 3D toroidal-spiral beams. The time-lapse image shows particle flow forming a starfish shape, matching the structure of the trapping beam[53]. LG: Laguerre-Gaussian. Republished with copyright permission from[48,52,53].

Restricted Degrees of Freedom: A classical tweezer provides precise 3D positional control but offers minimal command over a particle’s orientation. While structured light can induce simple rotation, achieving full six-degree-of-freedom (6-DoF) control is largely out of reach, as scalar potentials are not designed to generate the sophisticated torques required.

Inefficient Sorting and Separation: Classical methods excel at creating localized potential wells for trapping. However, they are ill-suited for generating the complex, large-area vector force fields needed for advanced functions like high-throughput sorting of particles based on intrinsic properties (e.g., size, refractive index, or chirality) or large-scale parallel processing.

Generating Arbitrary Trajectories: While holographic traps can create complex paths, designing the required optical field becomes exceptionally challenging when the desired particle trajectories are arbitrary or not easily described parametrically.

These challenges highlight the need for a more powerful and robust framework, motivating the search for a new principle in designing light–matter interactions. Topology is poised to fill this role. It provides a new toolkit based not on sculpting scalar intensity but on imprinting robust vectorial properties into the light field itself.

2.2 The topological toolkit

The paradigm shift from scalar intensity to topological vectorial fields empowers optical manipulation through a diverse set of topological structures, each protected by a robust topological invariant that ensures stability against perturbations[13,14]. The bottom panel of Figure 1 illustrates several of the most important tools in this toolkit, which range from vortices to complex 3D topologies. These topologies are constructed using different DoF of light, such as its phase and polarization. The most prominent examples include:

· Optical Vortex: These are phase singularities around which the phase of the light field winds, characterized by an integer topological charge ℓ, famously endowing the light beam with OAM[44-47,54-57]. Figure 1 illustrates a vortex with a topological charge of ℓ = 1.

· Möbius Strip: A 2D topology written into the polarization of light, where the polarization vector field undergoes a half-twist along a closed path[6-8,58,59]. It is characterized by the half-twist index Lk. Figure 1 shows examples of Möbius strips with half-twist indices of Lk = 1 and Lk = 2.

· Skyrmion: A 2D topological texture, typically formed in a vector field of light (e.g., spin, Stokes, or Poynting vector)[13,14,24,28,60]. It is described by an integer skyrmion number Q, which quantifies how the vector field wraps a unit sphere. Mathematically, this corresponds to a mapping from a 2D plane in real space to the 2D surface of an order-parameter sphere (e.g., the Poincaré sphere for polarization states). The example in Figure 1 has a skyrmion number of Q = 1. These individual skyrmions can be arranged into periodic structures, forming a skyrmion lattice[3,19,61,62].

· Knot: Complex 3D structures where lines of constant phase or polarization are tied into nontrivial knots[63-68]. A primary example is the torus knot, which is characterized by a pair of integer knot invariants (p, q) describing its windings on a torus surface. The specific torus knot visualized in Figure 1 is a (3, 1) knot.

· Hopfion: A 3D topological structure whose fundamental invariant is the integer Hopf number H[21,23,69-73]. This number describes the linking of any pair of fiber-like preimages within the field. While these preimages can form specific linked structures, the Hopf number H is the global invariant that characterizes the entire Hopfion structure. Figure 1 depicts a Hopfion with a Hopf number of H = 2. Like skyrmions, hopfions can also be organized into crystalline structures, forming a hopfion crystal[74].

These topological structures can be generated and controlled on two primary platforms. Free-space systems, using wavefront shaping technologies like digital holography, offer maximum flexibility and reconfigurability for the generation of topological light waves[75-79]. In parallel, on-chip platforms, based on plasmonic systems, have enabled the realization of diverse photonic topological textures, not only electric-field[3] and spin skyrmions[18], but also novel topologies like optical skyrmion bag[80,81]. Collectively, these topological structures provide unprecedented components for next-generation light-matter interactions and optical manipulation.

3. Topological Light Waves for Particle Manipulation

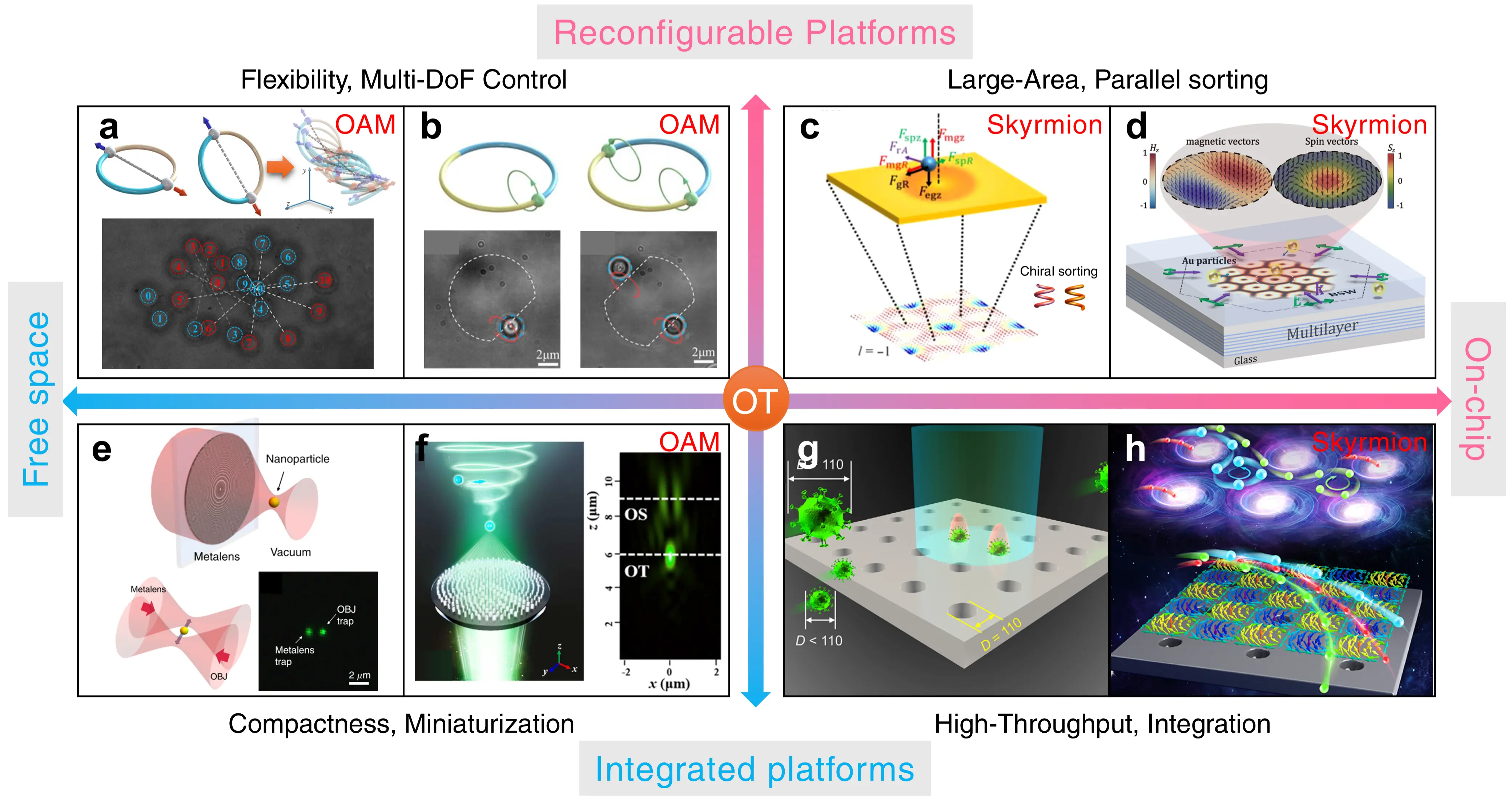

The theoretical promise of the topological toolkit is now being realized in a series of pioneering experiments that overcome the limitations of classical optical manipulation. The development of these advanced platforms is advancing along two primary strategic thrusts, as categorized in the framework of Figure 3.

Figure 3. A framework for topological optical manipulation platforms, categorized by two primary strategic thrusts: reconfigurable systems for flexibility and integrated systems for compactness and robustness. (a, b) Reconfigurable free-space systems for advanced control, including (a) 6-DoF manipulation[82] and (b) transverse OAM generation[83]; (c, d) Reconfigurable on-chip platforms for parallel sorting using (c) tunable plasmonic lattices[84] and (d) lossless all-dielectric magnetic lattices[85]; (e, f) Integrated free-space systems for compactness, featuring (e) a metalens for vacuum levitation[86] and (f) a single metasurface combining trapping and rotation[87]; (g, h) Integrated on-chip devices for high-throughput, precision manipulation, such as (g) virus trapping with nanocavities[88] and (h) subwavelength sorting with optical merons[26]. Relevant subfigures (a-d, f, h) are labeled in their upper-right corners to link them to the corresponding concepts from the ‘Topological Toolkit’ (Figure 1). 6-DoF: six-degree-of-freedom; OAM: orbital angular momentum. Republished with copyright permission from[26,82-88].

On the one hand, the first strategy prioritizes reconfigurable systems to achieve flexible and multifunctional topological manipulation. This approach leverages dynamic technologies—such as holography in free space or tunable elements on-chip—to provide flexible control over topological fields. On the other hand, the second strategy focuses on integrated platforms, using technologies like metasurfaces and photonic crystals to create compact, robust, and scalable devices. This path is essential for translating topological manipulation from laboratory setups to practical, miniaturized applications.

3.1 Reconfigurable free-space systems for advanced control

Following the first strategy, reconfigurable platforms in free space offer unparalleled flexibility for complex manipulation. A significant advance is the development of 6-DoF OTs that emulate rigid-body mechanics, enabling full control over a particle’s position and orientation (surge, sway, heave, roll, pitch, and yaw), as shown in Figure 3a[82]. Another innovative technique involves shaping a beam into an “optical skipping rope” to generate transverse OAM, which induces previously inaccessible orbital motions parallel to the optical axis, such as along an oblique coil (Figure 3b)[83].

3.2 Reconfigurable on-chip platforms for parallel sorting

On-chip platforms are an emerging frontier for applications requiring flexible and parallel manipulation. One approach uses surface plasmon polaritons to create tunable optical lattices (Figure 3c), where adjusting the input polarization and phase can transform the topological structure of the lattice, enabling functions like sorting chiral particles[84]. However, these plasmonic systems suffer from high ohmic loss and thermal effects[89]. To overcome this, a promising direction is to use all-dielectric platforms. As shown in Figure 3d, interfering Bloch surface waves on a transparent multilayer can create robust topological lattices in the magnetic field and spin vector, offering markedly reduced heating and enabling large-scale, size-dependent sorting of nanoparticles[85].

3.3 Integrated free-space systems for compactness

In complement to the reconfigurable systems described above, and inspired by advances in metasurface tweezers[39], we envision a new frontier. This approach would trade real-time reconfigurability for major gains in compactness, robustness, and functionality, realized through highly integrated platforms. Although the following examples do not yet demonstrate complex topological manipulations, they represent crucial foundational manipulations. In the free-space domain, this has led to ultrathin, metalens-based OTs[90-93]. As shown in Figure 3e, a single high-numerical-aperture metalens can achieve stable optical levitation of nanoparticles in a vacuum, paving the way for sensing and portable systems[86]. Furthermore, functionality can be integrated by designing a single metasurface that simultaneously acts as an OT for trapping and an optical spanner for imparting rotation, as shown in Figure 3f[87].

3.4 Integrated on-chip devices for high throughput

For on-chip applications, the frontier lies in creating integrated devices for functional and high-throughput tasks. One such platform uses engineered arrays of nanocavities to enhance optical forces, enabling the efficient trapping, patterning, and sorting of large quantities of nanoparticles, including viruses as small as 40 nm (Figure 3g)[88]. For even higher precision, another approach utilizes a photonic crystal to generate topological textures in the Poynting vector, such as merons and antimerons (Figure 3h). These structures create complex optical force fields that can sort nanoparticles with 10 nm precision, demonstrating deep-subwavelength manipulation in a lossless environment[26].

4. Outlook

The experiments and platforms discussed so far show a clear shift in the field. The powerful combination of topological light waves and optical manipulation is not just a small step forward; it represents a new paradigm. Looking forward, the central challenge and opportunity lie in the synthesis of specific topological structures with advanced manipulation schemes. For instance, it is envisioned that integrating skyrmionic beams with OTs could offer new ways to rotate particles, with the ultimate goal of achieving full 6-DoF control while also controlling an object’s spin[94]. In parallel, exploring the rich physics of novel on-chip topologies, such as the recently discovered optical skyrmion bags[80], could open a new frontier for studying near-field particle dynamics. Such physics-driven approaches, which focus on using the unique properties of each topological feature, will likely lead the field toward truly higher-dimensional and versatile optical manipulation.

4.1 Transformative applications on the horizon

Researchers are quickly learning to use a wide range of complex light–matter interactions, from novel spin-gradient and curl torques to counterintuitive optical backflow and long-range pulling forces, enabling sophisticated vectorial control over 3D trajectories and torques[95-99]. These fundamental discoveries are inspiring new platforms and functionalities, ranging from all-optical particle blasters to integrated imaging systems[100-103]. Building on these trends, we can see several key areas where combining topological light waves with optical manipulation will be transformative:

Advanced Biomedical and Diagnostic Tools. The unique capabilities of topological light waves hold the potential to drive significant advances in biology and medicine. We envision the development of dedicated metasurface sorters for high-throughput applications, like diagnostic chips or microfluidic processors. A particularly exciting frontier is the sorting of chiral molecules (enantiomers), where the tailored chirality of topological fields could enable highly sensitive separation—a task of immense importance in pharmacology and biochemistry[104]. Because many topological fields possess intrinsic chirality and complex 3D vector structures, they could enable precise enantiomer separation in ways that are impossible with conventional scalar fields[105-108].

To realize these applications, we envision two primary experimental platforms. First, for free-space manipulation (e.g., advanced 6-DoF control), a versatile setup would combine a generation stage with a high-NA focusing stage. The topological beam, such as an optical skyrmion, could be generated dynamically using digital holography[21,22] or statically using compact elements like metasurfaces[76,77] or designed wave plates[109-112]. This beam would then be focused by a high-numerical-aperture objective to concentrate its topological properties and enhance the localized optical forces. Second, for on-chip topological manipulation, we propose two concrete approaches: (a) fabricating dedicated metasurfaces designed to excite specific topological near-fields, such as optical merons or skyrmion lattices, for high-precision sorting; or (b) integrating holographic control with optical surface-wave systems, where a shaped beam excites a topological surface-wave field on a specific substrate.

Frontiers in Quantum and Atomic Physics. The ability to transfer topology from light to matter opens up important applications in other fields, like quantum physics. For instance, the topology of a light field can be directly imprinted onto a quantum fluid, such as a Bose–Einstein condensate, to create, control, and study topological excitations[113,114]. This technique can also be applied to manipulate the quantum states of atoms, offering new tools for fundamental research[115,116].

Hybrid Manipulation Platforms. Looking beyond purely optical systems, the programmability of topological light waves can be merged with other manipulation techniques. By leveraging photoacoustic effects, for example, the precision of OTs can be combined with the potent, large-scale manipulation capabilities of acoustic waves[117]. This opens the door to harnessing the growing library of acoustic topological structures for advanced particle control.

4.2 Grand challenges

However, to turn these exciting possibilities into reality, the field must first overcome several major challenges:

Understanding the Mechanisms of Topology Transfer to Matter. To move from successful experiments to designing from basic principles, a deeper, quantitative understanding of the interaction between complex topological fields and particles is essential. This requires developing complete theoretical models that can accurately predict the forces and torques on particles of arbitrary size, shape, and material composition. Mastering these mechanisms will be the key to optimizing and tailoring topological light waves for highly specific and efficient manipulation tasks.

Enhancing Nanoscale Light-Matter Interaction. A primary hurdle, particularly for the goal of sorting chiral molecules, is the weak interaction between light and nanoscale objects. As a particle’s size decreases, its scattering and absorption cross sections quickly decrease. A critical challenge is therefore to develop methods to significantly enhance the optical forces exerted on nano-objects. This will require novel strategies, perhaps combining topological fields with plasmonic or resonant dielectric nanostructures to amplify the local fields and forces to a level where the experimental sorting of individual molecules becomes possible.

Dynamic Generation and Characterization. Many advanced applications will require the ability to dynamically reconfigure complex 3D topological fields in real-time. Recently, mind-controlled optical manipulation based on human-computer interaction has emerged, offering a novel interactive operation scheme[118]. It has also been demonstrated that the confinement volume during trapping can be effectively reduced by using a wavefront-shaping-inspired strategy[119]. In addition, by integrating artificial intelligence (AI) or deep-learning technology, it is possible to effectively improve their design, calibration, and real-time control[120]. For instance, deep-learning models can solve the complex inverse-design problem, rapidly generating the required holographic patterns to produce arbitrary 3D topological fields. Furthermore, AI-driven algorithms can be used for real-time aberration correction and to implement feedback loops that dynamically adjust the optical field, enabling the stable and precise manipulation of particles even in fluctuating environments[121,122].

In conclusion, the field of optical manipulation stands at the threshold of a new era. By embracing the robust principles of topology, we are poised to develop tools that can control matter with a finesse and complexity that was previously unattainable. The path forward is challenging, but the potential rewards—from new diagnostic tools to fundamental discoveries in physics and biology—are immense.

Authors contribution

Shen Y: Conceptualization, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Xie X: Writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Singapore Ministry of Education (MOE) AcRF Tier 1 grants (Grant Nos. RG157/23 & RT11/23), the Singapore Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) MTC Individual Research Grants (Grant No. M24N7c0080), and the Nanyang Assistant Professorship Start Up grant.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Kosterlitz JM. Nobel lecture: Topological defects and phase transitions. Rev Mod Phys. 2017;89(4):040501.[DOI]

-

2. Haldane FD. Nobel lecture: Topological quantum matter. Rev Mod Phys. 2017;89(4):040502.[DOI]

-

3. Tsesses S, Ostrovsky E, Cohen K, Gjonaj B, Lindner NH, Bartal G. Optical skyrmion lattice in evanescent electromagnetic fields. Science. 2018;361(6406):993-996.[DOI]

-

4. Dai Y, Zhou Z, Ghosh A, Mong RS, Kubo A, Huang CB, et al. Plasmonic topological quasiparticle on the nanometre and femtosecond scales. Nature. 2020;588(7839):616-619.[DOI]

-

5. Ge H, Xu XY, Liu L, Xu R, Lin ZK, Yu SY, et al. Observation of acoustic skyrmions. Phys Rev Lett. 2021;127(14):144502.[DOI]

-

6. Bauer T, Banzer P, Karimi E, Orlov S, Rubano A, Marrucci L, et al. Observation of optical polarization Möbius strips. Science. 2015;347(6225):964-966.[DOI]

-

7. Bauer T, Neugebauer M, Leuchs G, Banzer P. Optical polarization Möbius strips and points of purely transverse Spin density. Phys Rev Lett. 2016;117(1):013601.[DOI]

-

8. Muelas-Hurtado RD, Volke-Sepúlveda K, Ealo JL, Nori F, Alonso MA, Bliokh KY, et al. Observation of polarization singularities and topological textures in sound waves. Phys Rev Lett. 2022;129(20):204301.[DOI]

-

9. Verbeeck J, Tian H, Schattschneider P. Production and application of electron vortex beams. Nature. 2010;467(7313):301-304.[DOI]

-

10. McMorran BJ, Agrawal A, Anderson IM, Herzing AA, Lezec HJ, McClelland JJ, et al. Electron vortex beams with high quanta of orbital angular momentum. Science. 2011;331(6014):192-195.[DOI]

-

11. Clark CW, Barankov R, Huber MG, Arif M, Cory DG, Pushin DA. Controlling neutron orbital angular momentum. Nature. 2015;525(7570):504-506.[DOI]

-

12. Luski A, Segev Y, David R, Bitton O, Nadler H, Barnea AR, et al. Vortex beams of atoms and molecules. Science. 2021;373(6559):1105-1109.[DOI]

-

13. Shen Y, Zhang Q, Shi P, Du L, Yuan X, Zayats AV. Optical skyrmions and other topological quasiparticles of light. Nat Photon. 2023;18(1):15-25.[DOI]

-

14. Shen Y, Wang H, Fan S. Free-space topological optical textures: Tutorial. Adv Opt Photon. 2025;17(2):295.[DOI]

-

15. Yang A, Kong A, Meng F, Chen X, Lin M, Shi P, et al. Optical skyrmions: From fundamentals to applications. J Opt. 2025;27(4):043002.[DOI]

-

16. Davis TJ, Janoschka D, Dreher P, Frank B, Meyer zu Heringdorf FJ, Giessen H. Ultrafast vector imaging of plasmonic skyrmion dynamics with deep subwavelength resolution. Science. 2020;368(6489):eaba6415.[DOI]

-

17. Deng ZL, Shi T, Krasnok A, Li X, Alù A. Observation of localized magnetic plasmon skyrmions. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):8.[DOI]

-

18. Du L, Yang A, Zayats AV, Yuan X. Deep-subwavelength features of photonic skyrmions in a confined electromagnetic field with orbital angular momentum. Nat Phys. 2019;15(7):650-654.[DOI]

-

19. Lei X, Yang A, Shi P, Xie Z, Du L, Zayats AV, et al. Photonic spin lattices: symmetry constraints for skyrmion and meron topologies. Phys Rev Lett. 2021;127(23):237403.[DOI]

-

20. Yang A, Lei X, Shi P, Meng F, Lin M, Du L, et al. Spin‐manipulated photonic skyrmion‐pair for pico‐metric displacement sensing. Adv Sci. 2023;10(12):2205249.[DOI]

-

21. Wu H, Mata-Cervera N, Wang H, Zhu Z, Qiu C, Shen Y. Photonic torons with 3D topology transitions and tunable spin monopoles. Phys Rev Lett. 2025;135(6):063802.[DOI]

-

22. Shen Y, Martínez EC, Rosales-Guzmán C. Generation of optical skyrmions with tunable topological textures. Acs Photonics. 2022;9(1):296-303.[DOI]

-

23. Shen Y, Yu B, Wu H, Li C, Zhu Z, Zayats AV. Topological transformation and free-space transport of photonic hopfions. Adv Photon. 2023;5(1):015001.[DOI]

-

24. Mata-Cervera N, Sharma DK, Shen Y, Paniagua-Dominguez R, Porras MA. Skyrmionic polarization texture around the phase singularity of optical vortices. Phys Rev Lett. 2025;135(3):033805.[DOI]

-

25. Wang S, Zhou Z, Zheng Z, Sun J, Cao H, Song S, et al. Topological structures of energy flow: Poynting vector skyrmions. Phys Rev Lett. 2024;133(7):073802.[DOI]

-

26. Lu C, Wang B, Fang X, Tsai DP, Zhu W, Song Q, et al. NNanoparticle deep-subwavelength dynamics empowered by optical meron–antimeron topology. Nano Lett. 2023;24(1):104-113.[DOI]

-

27. Shen Y, Hou Y, Papasimakis N, Zheludev NI. Supertoroidal light pulses as electromagnetic skyrmions propagating in free space. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5891.[DOI]

-

28. Teng H, Liu X, Zhang N, Fan H, Chen G, Cao Q, et al. Construction of optical spatiotemporal skyrmions. Light Sci Appl. 2025;14(1):324.[DOI]

-

29. Liu X, Zhang N, Cao Q, Liu J, Liang C, Zhan Q, et al. Dynamics of photonic toroidal vortices mediated by orbital angular momenta. Sci Adv. 2025;11(39):eadz0843.[DOI]

-

30. Smirnova DA, Nori F, Bliokh KY. Water-wave vortices and skyrmions. Phys Rev Lett. 2024;132(5):054003.[DOI]

-

31. Bliokh KY, Alonso MA, Sugic D, Perrin M, Nori F, Brasselet E. Polarization singularities and Möbius strips in sound and water-surface waves. Phys Fluids. 2021;33(7):077122.[DOI]

-

32. Wang B, Che Z, Cheng C, Tong C, Shi L, Shen Y, et al. Topological water-wave structures manipulating particles. Nature. 2025;638(8050):394-400.[DOI]

-

33. Grier DG. A revolution in optical manipulation. Nature. 2003;424(6950):810-816.[DOI]

-

34. Li H, Cao Y, Zhou LM, Xu X, Zhu T, Shi Y, et al. Optical pulling forces and their applications. Adv Opt Photon. 2020;12(2):288-366.[DOI]

-

35. Xin H, Li Y, Liu YC, Zhang Y, Xiao YF, Li B. Optical forces: From fundamental to biological applications. Adv Mater. 2020;32(37):2001994.[DOI]

-

36. Gieseler J, Gomez-Solano JR, Magazzù A, Pérez Castillo I, Pérez García L, Gironella-Torrent M, et al. Optical tweezers—from calibration to applications: A tutorial. Adv Opt Photon. 2021;13(1):74-241.[DOI]

-

37. Bustamante CJ, Chemla YR, Liu S, Wang MD. Optical tweezers in single-molecule biophysics. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2021;1(1):25.[DOI]

-

38. Li M, Yan S, Zhang Y, Zhou Y, Yao B. Orbital angular momentum in optical manipulations. J Opt. 2022;24(11):114001.[DOI]

-

39. Shi Y, Song Q, Toftul I, Zhu T, Yu Y, Zhu W, et al. Optical manipulation with metamaterial structures. Appl Phys Rev. 2022;9(3):031303.[DOI]

-

40. Zhou LM, Shi Y, Zhu X, Hu G, Cao G, Hu J, et al. Recent progress on optical micro/nanomanipulations: Structured forces, structured particles, and synergetic applications. ACS Nano. 2022;16(9):13264-13278.[DOI]

-

41. Volpe G, Maragò OM, Rubinsztein-Dunlop H, Pesce G, Stilgoe AB, Volpe G, et al. Roadmap for optical tweezers. J Phys Photonics. 2023;5(2):022501.[DOI]

-

42. Xu H, Xie X, Chen S, Fu Y, Zhang Y, Yuan X, et al. Optical nanotweezers based on all-dielectric resonant structures. Adv Devices Instrum. 2025;6:0078.[DOI]

-

43. Yang M, Shi Y, Song Q, Wei Z, Dun X, Wang Z, et al. Optical sorting: Past, present and future. Light Sci Appl. 2025;14(1):103.[DOI]

-

44. Shen Y, Wang X, Xie Z, Min C, Fu X, Liu Q, et al. Optical vortices 30 years on: OAM manipulation from topological charge to multiple singularities. Light Sci Appl. 2019;8(1):90.[DOI]

-

45. Forbes A, de Oliveira M, Dennis MR. Structured light. Nat Photonics. 2021;15(4):253-262.[DOI]

-

46. Wang J, Liang Y. Generation and detection of structured light: A review. Front Phys. 2021;9:688284.[DOI]

-

47. Yang Y, Ren YX, Chen M, Arita Y, Rosales-Guzmán C. Optical trapping with structured light: A review. Adv Photon. 2021;3(3):034001.[DOI]

-

48. Jesacher A, Fürhapter S, Maurer C, Bernet S, Ritsch-Marte M. Reverse orbiting of microparticles in optical vortices. Opt Lett. 2006;31(19):2824.[DOI]

-

49. Christodoulides DN. Riding along an Airy beam. Nat Photonics. 2008;2(11):652-653.[DOI]

-

50. Xie X, Wang X, Min C, Ma H, Yuan Y, Zhou Z, et al. Single-particle trapping and dynamic manipulation with holographic optical surface-wave tweezers. Photon Res. 2021;10(1):166-173.[DOI]

-

51. He M, Liang Y, Yun X, Wang Z, Zhao T, Wang S, et al. Generalized perfect optical vortices with free lens modulation. Photonics Res. 2022;11(1):27-34.[DOI]

-

52. Shanblatt ER, Grier DG. Extended and knotted optical traps in three dimensions. Opt Express. 2011;19(7):5833-5838.[DOI]

-

53. Rodrigo JA, Alieva T. Freestyle 3d laser traps: Tools for studying light-driven particle dynamics and beyond. Optica. 2015;2(9):812-815.[DOI]

-

54. Allen L, Beijersbergen MW, Spreeuw RJC, Woerdman JP. Orbital angular momentum of light and the transformation of laguerre-gaussian laser modes. Phys Rev A. 1992;45(11):8185-8189.[DOI]

-

55. O’Neil AT, MacVicar I, Allen L, Padgett MJ. Intrinsic and extrinsic nature of the orbital angular momentum of a light beam. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;88(5):053601.[DOI]

-

56. Aiello A, Banzer P, Neugebauer M, Leuchs G. From transverse angular momentum to photonic wheels. Nature Photon. 2015;9(12):789-795.[DOI]

-

57. Chen J, Wan C, Zhan Q. Engineering photonic angular momentum with structured light: A review. Adv Photon. 2021;3(6):064001.[DOI]

-

58. Garcia-Etxarri A. Optical polarization möbius strips on all-dielectric optical scatterers. ACS Photonics. 2017;4(5):1159-1164.[DOI]

-

59. Wan C, Zhan Q. Generation of exotic optical polarization Möbius strips. Opt Express. 2019;27(8):11516-11524.[DOI]

-

60. Lei X, Yang A, Chen X, Du L, Shi P, Zhan Q, et al. Skyrmionic spin textures in nonparaxial light. Adv Photonics. 2025;7(1):016009.[DOI]

-

61. Zhang Q, Xie Z, Shi P, Yang H, He H, Du L, et al. Optical topological lattices of bloch-type skyrmion and meron topologies. Photonics Res. 2022;10(4):947-957.[DOI]

-

62. Zhang Q, Yang A, Xie Z, Shi P, Du L, Yuan X. Periodic dynamics of optical skyrmion lattices driven by symmetry. Appl Phys Rev. 2024;11:011409.[DOI]

-

63. Dennis MR, King RP, Jack B, O’holleran K, Padgett MJ. Isolated optical vortex knots. Nature Phys. 2010;6(2):118-121.[DOI]

-

64. Larocque H, Sugic D, Mortimer D, Taylor AJ, Fickler R, Boyd RW, et al. Reconstructing the topology of optical polarization knots. Nature Phys. 2018;14(11):1079-1082.[DOI]

-

65. Pires DG, Tsvetkov D, Barati Sedeh H, Chandra N, Litchinitser NM. Stability of optical knots in atmospheric turbulence. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):3001.[DOI]

-

66. Zhong J, Teng H, Zhan Q. Generation of high-order optical vortex knots and links. ACS Photonics. 2025;12(3):1683-1688.[DOI]

-

67. Gao J, Barati Sedeh H, Tsvetkov D, Pires DG, Vincenti MA, Xu Y, et al. Topology-imprinting in nonlinear metasurfaces. Sci Adv. 2025;11(24):eadv5190.[DOI]

-

68. Wang Z, Lu X, Chen Z, Cai Y, Zhao C. Topological links and knots of speckled light mediated by coherence singularities. Light Sci Appl. 2025;14(1):1-9.[DOI]

-

69. Wan C, Shen Y, Chong A, Zhan Q. Scalar optical hopfions. eLight. 2022;2(1):22.[DOI]

-

70. Tamura R, Allam SR, Litchinitser NM, Omatsu T. Three-dimensional projection of optical hopfion textures in a material. ACS Photonics. 2024;11(11):4958-4965.[DOI]

-

71. Lyu Z, Fang Y, Liu Y. Formation and controlling of optical hopfions in high harmonic generation. Phys Rev Lett. 2024;133(13):133801.[DOI]

-

72. Ehrmanntraut D, Droop R, Sugic D, Otte E, Dennis MR, Denz C. Optical second-order skyrmionic hopfion. Optica. 2023;10(6):725-731.[DOI]

-

73. Li C, Wang S, Li X. Spatiotemporal pulse weaving scalar optical hopfions. Light Sci Appl. 2023;12(1):54.[DOI]

-

74. Lin W, Mata-Cervera N, Ota Y, Shen Y, Iwamoto S. Space-time optical hopfion crystals. Phys Rev Lett. 2025;135(8):083801.[DOI]

-

75. Teng H, Zhong J, Chen J, Lei X, Zhan Q. Physical conversion and superposition of optical skyrmion topologies. Photon Res. 2023;11(12):2042-2053.[DOI]

-

76. He T, Meng Y, Wang L, Zhong H, Mata-Cervera N, Li D, et al. Optical skyrmions from metafibers with subwavelength features. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):10141.[DOI]

-

77. Mata-Cervera N, Xie Z, Li C, Yu H, Ren H, Shen Y, et al. Tailoring propagation-invariant topology of optical skyrmions with dielectric metasurfaces. Nanophotonics. 2025;14(23):4069-4077.[DOI]

-

78. Zhang Z, Xie X, Zhuang C, Wu B, Liu Z, Wu B, et al. Topological protection degrees of optical skyrmions and their electrical control. Photon Res. 2025;13(9):B1-B11.[DOI]

-

79. Chen J, Shen X, Zhan Q, Qiu CW. Gouy phase induced optical skyrmion transformation in diffraction limited scale. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025;19(2):2400327.[DOI]

-

80. Schwab J, Neuhaus A, Dreher P, Tsesses S, Cohen K, Mangold F, et al. Skyrmion bags of light in plasmonic moiré superlattices. Nat Phys. 2025;21:988-994.[DOI]

-

81. Tsesses S, Dreher P, Janoschka D, Neuhaus A, Cohen K, Meiler TC, et al. Four-dimensional conserved topological charge vectors in plasmonic quasicrystals. Science. 2025;387(6734):644-648.[DOI]

-

82. Zhu L, Tai Y, Li H, Hu H, Li X, Cai Y, et al. Multidimensional optical tweezers synthetized by rigid-body emulated structured light. Photon Res. 2023;11(9):1524-1534.[DOI]

-

83. Zhu L, Zhang X, Rui G, He J, Gu B, Zhan Q. Optical skipping rope induced transverse oam for particle orbital motion parallel to the optical axis. Nanophotonics. 2023;12(23):4351-4359.[DOI]

-

84. Tang X, Kuai Y, Fan Z, Lu F, Zang H, Chen J, et al. Achiral and chiral optical force within topological optical lattices generated with plasmonic metasurfaces and tunable incident beam. Phys Rev Applied. 2023;19(5):054016.[DOI]

-

85. Xu H, Xie X, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Yuan X, Shen Y, et al. Topological magnetic lattices for on-chip nanoparticle trapping and sorting. Nano Letters. 2025;25(26):10611-10618.[DOI]

-

86. Shen K, Duan Y, Ju P, Xu Z, Chen X, Zhang L, et al. On-chip optical levitation with a metalens in vacuum. Optica. 2021;8(11):1359-1362.[DOI]

-

87. Li T, Xu X, Fu B, Wang S, Li B, Wang Z, et al. Integrating the optical tweezers and spanner onto an individual single-layer metasurface. Photonics Res. 2021;9(6):1062-1068.[DOI]

-

88. Shi Y, Wu Y, Chin LK, Li Z, Liu J, Chen MK, et al. Multifunctional virus manipulation with large‐scale arrays of all‐dielectric resonant nanocavities. Laser Photonics Rev. 2022;16(5):2100197.[DOI]

-

89. Zhang Y, Min C, Dou X, Wang X, Urbach HP, Somekh MG, et al. Plasmonic tweezers: For nanoscale optical trapping and beyond. Light Sci Appl. 2021;10(1):59.[DOI]

-

90. Chantakit T, Schlickriede C, Sain B, Meyer F, Weiss T, Chattham N, et al. All-dielectric silicon metalens for two-dimensional particle manipulation in optical tweezers. Photon Res. 2020;8(9):1435-1440.[DOI]

-

91. Plidschun M, Ren H, Kim J, Förster R, Maier SA, Schmidt MA. Ultrahigh numerical aperture meta-fibre for flexible optical trapping. Light Sci Appl. 2021;10(1):57.[DOI]

-

92. Li X, Zhou Y, Ge S, Wang G, Li S, Liu Z, et al. Experimental demonstration of optical trapping and manipulation with multifunctional metasurface. Opt Lett. 2022;47(4):977-980.[DOI]

-

93. Yang D, Zhang J, Zhang P, Liang H, Ma J, Li J, et al. Optical trapping and manipulating with a transmissive and polarization-insensitive metalens. Nanophotonics. 2024;13(15):2781-2789.[DOI]

-

94. O’Donnell MJ, Hanna S. Optical forces and torques in skyrmionic beams. In: Dholakia K, Rubinsztein-Dunlop H, Volpe G, editors. Optical Trapping and Optical Micromanipulation XXI; 2024 Oct 2; California, United States. Bellingham: SPIE; 2024. p. 74-81.[DOI]

-

95. Xu X, Nieto-Vesperinas M, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Li M, Rodríguez-Fortuño FJ, et al. Gradient and curl optical torques. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):6230.[DOI]

-

96. Huang H, Wu PC, Wei Z, Yi W, Lai C, Wu X, et al. Optical torques on dielectric spheres in a spin-gradient light field. Laser Photonics Rev. 2025;19(13):2500386.[DOI]

-

97. Xie X, Shi P, Min C, Yuan X. Optical backflow for the manipulations of dipolar nanoparticles. Photon Res. 2025;13(8):2033-2045.[DOI]

-

98. Wu YJ, Zhuang JH, Yu PP, Liu YF, Wang ZQ, Li YM, et al. Time-varying 3d optical torque via a single beam. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):593.[DOI]

-

99. Zhang J, Liu K, Wang P, Tong L, Guo X. Ultra-long-range optical pulling with an optical nanofibre. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):7424.[DOI]

-

100. Ussembayev Y, Arakawa Y, Beunis F, Spoelstra AB, Bus T, Schenning APHJ, et al. Optical blaster: Launching nanostructured microrockets out of an optical trap by a single laser beam. ACS Nano. 2025;19(31):28460-28468.[DOI]

-

101. Li X, Dan D, Zavatski S, Gao W, Zhang Q, Zhou Y, et al. Optical tweeze-sectioning microscopy for 3D imaging and manipulation of suspended cells. Sci Adv. 2025;11(27):eadx3900.[DOI]

-

102. Dong Y, Wang Y, He D, Wang T, Zeng J, Wang J. Nearfield observation of spin-orbit interactions at nanoscale using photoinduced force microscopy. Sci Adv. 2024;10(51):eadp8460.[DOI]

-

103. Chen Y, Xie X, Zhou J, Ju Z, Zhang C, Min C, et al. Switchable graphene‐based opto‐thermoelectric tweezers with ultralow‐power operation. Adv Opt Mater. 2025;13(29):e01601.[DOI]

-

104. Smirnova O. A new age of molecular chirality. Science. 2025;389(6757):232-233.[DOI]

-

105. Mayer N, Ayuso D, Decleva P, Khokhlova M, Pisanty E, Ivanov M, et al. Chiral topological light for detection of robust enantiosensitive observables. Nat Photon. 2024;18(11):1155-1160.[DOI]

-

106. Fang L, Wang J. Optical trapping separation of chiral nanoparticles by subwavelength slot waveguides. Phys Rev Lett. 2021;127(23):233902.[DOI]

-

107. Man Z, Zhang Y, Cai Y, Yuan X, Urbach HP. Construction of chirality-sorting optical force pairs. Phys Rev Lett. 2024;133(23):233803.[DOI]

-

108. Lai C, Shi Y, Huang H, Yi W, Mazzulla A, Cipparrone G, et al. Observation of intricate chiral optical force in a spin-curl light field. Phys Rev Lett. 2024;133(23):233802.[DOI]

-

109. Hakobyan V, Brasselet E. Q-plates: From optical nortices to optical skyrmions. Phys Rev Lett. 2025;134(8):083802.[DOI]

-

110. Hakobyan V, Shen Y, Brasselet E. Unitary spin-orbit optical-skyrmionic wave plates. Phys Rev Appl. 2024;22(5):054038.[DOI]

-

111. He C, Chen B, Song Z, Zhao Z, Ma Y, He H, et al. A reconfigurable arbitrary retarder array as complex structured matter. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):4902.[DOI]

-

112. Wang AA, Ma Y, Zhang Y, Zhao Z, Cai Y, Qiu X, et al. Perturbation-resilient integer arithmetic using optical skyrmions. Nat Photon. 2025.[DOI]

-

113. Chen Z, Haber E, Bigelow NP. Imprinting knots in a spinor bose-einstein condensate via a raman process without knotted optical fields. Phys Rev Research. 2022;4(4):043109.[DOI]

-

114. Leanhardt AE, Görlitz A, Chikkatur AP, Kielpinski D, Shin YI, Pritchard DE, et al. Imprinting vortices in a Bose-Einstein condensate using topological phases. Phys Rev Lett. 2002 Nov 4;89(19):190403.[DOI]

-

115. Bégin J-L, Karimi E, Corkum P, Brabec T, Bhardwaj R. Orbital angular momentum control of strong-field ionization in atoms and molecules. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):2467.[DOI]

-

116. Mitra C, Madasu CS, Gabardos L, Kwong CC, Shen Y, Ruostekoski J, et al. Topological optical skyrmion transfer to matter. APL Photonics. 2025;10(4):046113.[DOI]

-

117. Zhang R, Zhao X, Li J, Zhou D, Guo H, Li Z, et al. Programmable photoacoustic patterning of microparticles in air. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):3250.[DOI]

-

118. Peng L, Yao J, Bai Y, Sun Y, Zeng J, Ren YX, et al. Mind-controlled optical manipulation. ACS Photonics. 2024;11(3):1213-1220.[DOI]

-

119. Būtaitė UG, Sharp C, Horodynski M, Gibson GM, Padgett MJ, Rotter S, et al. Photon-efficient optical tweezers via wavefront shaping. Sci Adv. 2024;10(27):eadi7792.[DOI]

-

120. Wetzstein G, Ozcan A, Gigan S, Fan S, Englund D, Soljačić M, et al. Inference in artificial intelligence with deep optics and photonics. Nature. 2020;588(7836):39-47.[DOI]

-

121. Ciarlo A, Ciriza DB, Selin M, Maragò OM, Sasso A, Pesce G, et al. Deep learning for optical tweezers. Nanophotonics. 2024;13(17):3017-3035.[DOI]

-

122. Shen Z, Liu N. Optical tweezers with optical vortex based on deep learning. ACS Photonics. 2025;12(4):2212-2218.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite