Zhen Li, Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Light Field Manipulation Physics and Applications & School of Physics and Optoelectronics, Shandong Normal University, Jinan 250358, Shandong, China. E-mail: lizhen19910528@163.com

Chao Zhang, Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Light Field Manipulation Physics and Applications & School of Physics and Optoelectronics, Shandong Normal University, Jinan 250358, Shandong, China. E-mail: czsdnu@126.com

Abstract

The development of surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) technology is critically reliant on the effective modulation of the electromagnetic mechanism and chemical mechanism. In this paper, we conduct a systematic review of the recent advancements in the modulation of SERS by multi-physical fields (light field, magnetic field, and electric field) and their cooperative modulation. Light field modulation enhances the intensity and area of hotspots by optimizing the matching between the local surface plasmon resonance of nanostructures and the parameters of incident light (wavelength, polarization, and pulse). Moreover, the photo-induced plasmonic thermal effect dynamically regulates the phase transition between the nanogap and the material, achieving the synergistic enhancement of SERS. Magnetic field modulation capitalizes on the magnetic induction of magnetic materials and the magnetic resonance behavior of non-magnetic structures. It enables an external magnetic field to control the aggregation and spatial organization of nanoparticles, thereby generating high-density hotspots and enhancing the detection sensitivity and selectivity. Electric field modulation can adjust the band structure, carrier density, and molecular orientation of the substrate through an external electric field or the spontaneous electric field of functional materials (such as piezoelectric, triboelectric, thermoelectric, and pyroelectric materials), thus enhancing the charge transfer efficiency and the local electromagnetic field strength. The multi-field cooperative modulation strategy overcomes the static limitations of traditional SERS substrates and further provides a crucial theoretical and technical approach for realizing a high-performance, intelligent, and reconfigurable SERS sensing platform.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) is a distinctive, non-destructive fingerprint identification technique predominantly founded on the inelastic light scattering of molecules[1-8]. It provides outstanding Raman signal discrimination for molecular structures. Owing to its high specificity and ultra-sensitivity capabilities, it finds extensive application in molecular characterization and analytical testing. To further expand and optimize the application of SERS technology, it is essential to commence from the principle and mechanism. Currently, the enhancement of the SERS response depends on the construction strategy of the substrate. Based on this, the electromagnetic mechanism (EM) and chemical mechanism (CM) have emerged as the two modes of SERS enhancement[9-11].

The EM mainly stems from noble metal structures, such as gold, silver, and copper. These structures are engineered to generate gaps where strong electromagnetic fields can be excited, also referred to as “hotspots”. The SERS enhancement is realized by coupling the hotspots to molecules. Through light irradiation, the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) of the metal structures is excited, thereby amplifying the inelastic scattering strength of the molecules[12-15]. The CM mechanism primarily relies on the charge transfer (CT) between the substrate and molecules. Most of the materials employed are semiconductors and two-dimensional materials, which renders it insensitive to changes in the local electromagnetic field. The cause of this type of SERS enhancement effect is that the CT between the molecule and the substrate induces a change in the polarization rate of the molecule, which further modifies the Raman scattering cross-section[16,17].

In the past history of development, SERS technology has gradually penetrated into the fields of biosensing, food safety, and environmental monitoring[18-22]. Although the applicability of SERS technology in various fields has been verified, its further dissemination still confronts numerous challenges. The primary cause lies in the fact that traditional construction strategies substantially restrict the possibilities of substrate modulation. The characteristics of SERS are determined when the plasticity of the material itself transitions into solidity. Once traditional SERS substrates are fabricated, their physical structure and chemical properties tend to be fixed, which is essentially a steady-state limitation. This leads to the non-uniformity and uncontrollability of hot spot distribution, making it difficult to ensure signal reproducibility[23-25]. Additionally, solid substrates are difficult to regenerate or reuse after detection. These factors severely restrict the reliability and universality of SERS technology in complex and dynamic real-world scenarios.

In order to break through the above limitations of traditional static substrates, in recent years, the strategy of using external physical fields (such as light, magnetic and electric fields) to dynamically regulate SERS performance has emerged and rapidly developed into the frontier of the field. Unlike the static substrate, the multi-physics field modulation endows the SERS substrate with reversible changes[26-29]. Light-field modulation is the most direct approach. It not only optimizes the initial excitation by precisely aligning laser parameters with the LSPR of nanostructures, but also induces the plasmonic thermal effect, which triggers the thermal expansion of nanoparticles, phase transitions, or deformation of gel materials, thereby enabling the dynamic and reversible adjustment of nanogaps to create “transient hotspots”. Additionally, pulsed lasers can induce crystal structural transformations in two-dimensional materials or phase-change materials, fundamentally altering their electronic properties and offering new pathways for the CM enhancement[30-33].

Magnetic field modulation provides unique non-contact spatial manipulation capabilities for SERS. For magnetic nanomaterials, an external magnetic field can govern their aggregation, dispersion, and directional arrangement. The magnetic enrichment of the analyte and the in-situ assembly of hot spots are realized, and the detection sensitivity and selectivity are significantly enhanced. For non-magnetic metal nanostructures (metal dimers, slotted nanospheres, and core-shell structures), their special magnetic resonance modes can generate local magnetic field enhancement in specific spectral regions, contributing an additional dimension to the EM[34,35].

Electric field modulation focuses on the band engineering and charge transfer level. The applied electric field can directly modify the electric potential of the metal/semiconductor interface, as well as the adsorption orientation and dipole moment of the molecules. More ingeniously, the spontaneous electric field effects (such as piezoelectric effect, thermoelectric effect, triboelectric effect, and pyroelectric effect) inherent in functional materials can be effectively controlled. Specifically, through simple stimuli such as mechanical force, temperature changes, and even friction, a powerful internal electric field can be generated within the substrate without the need for complex electrodes. This electric field can effectively modulate the Schottky barrier of the heterojunction, the carrier concentration of the semiconductor, and the LSPR characteristics of the metal, further achieving the synergistic enhancement of EM and CM[36,37]. These field modulation technologies not only overcome the limitations of static substrates but also provide novel insights for the synergistic optimization of EM and CM.

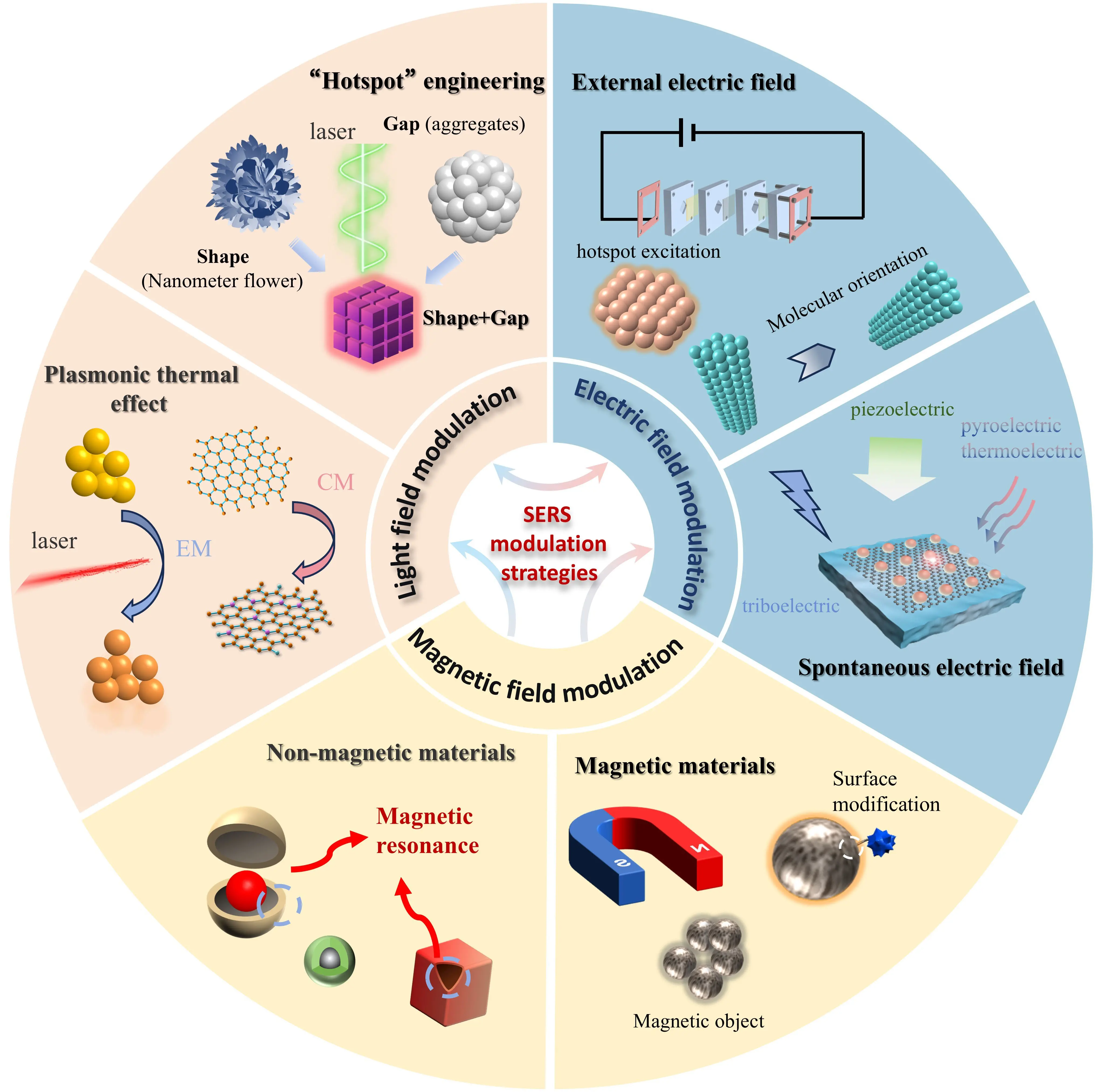

This paper will conduct a systematic review of the most recent substantial advancements in the modulation of SERS by multi-physical fields, encompassing optical, magnetic, and electric fields. The contents are shown in Figure 1. First, it will expound on how light-field modulation enhances SERS mechanisms through hot-spot engineering and plasmonic thermal effects. Second, it will conduct an in-depth analysis of the magnetic plasmon resonance in non-magnetic structures and the controllable assembly mechanisms of magnetic nanoscale components under magnetic-field modulation. Subsequently, it will explore electric-field modulation, including the precise adjustment of SERS performance by applied electric fields and various spontaneous electric-field effects (piezoelectric, thermoelectric, triboelectric, pyroelectric). Finally, this paper will forecast future trends in multi-field coupling and synergistic modulation, highlighting that integrating responses to multiple physical fields to develop “smart SERS” platforms with high sensitivity, environmental adaptability, and functional reconfigurability is crucial for promoting the technology towards more extensive applications.

Figure 1. Overview of light-field and external-field modulation in SERS. SERS: surface-enhanced Raman scattering.

2. Light Field Modulation for SERS Research

Hotspot engineering, as the most direct approach for modulating the EM contribution, which involves optimizing the size and shape of metal nanostructures. In this context, parameters such as the surface morphology, proximity gap, and composition method of noble-metal nanoparticles are precisely tuned to maximize the intensity of the local electromagnetic field[38]. Traditional hotspot engineering projects can be mainly classified into two categories: plasmonic media engineering and metal construction engineering[39]. Plasmonic media engineering involves coating a dielectric substrate with metal nanostructures to generate potent hotspots. This process mainly depends on the structural composition of the substrate to form hotspots. This method allows for the independent adjustment of the morphology of the dielectric core and the performance of the metal coating, offering greater degrees of freedom for realizing complex three-dimensional (3D) hotspot structures[40,41]. Nevertheless, its process is relatively intricate, and the uniformity and stability of the metal coating pose key challenges for its further development.

Another approach focuses on manipulating metal structures, for instance, creating hotspots through techniques such as nanostructures and porous materials. Generally, this type of structure is relatively straightforward to construct, and can also generate a strong LSPR effect[42,43]. However, the selection of materials is restricted to easily adjustable precious metals, and it is arduous to uniformly and precisely control the morphology. After extensive research, the hotspot construction problem has been effectively resolved. However, the hotspot excitation problem has gradually emerged. These problems impose extremely stringent requirements on the wavelength of the incident light, polarization degree, incidence angle, etc. This has led to the study of the coupling between light-field modulation and hotspot excitation.

In the engineering of light-field regulation hotspots, the primary consideration is the matching issue or size discrepancy between the laser wavelength and the substrate plasmonic. In SERS, the electromagnetic enhancement predominantly stems from LSPR. When the laser wavelength aligns with the LSPR peak of the nanostructure, it can trigger a larger-scale or more intense hotspot[44,45]. Consequently, it is of great significance to select the appropriate excitation wavelength based on the LSPR peak of the SERS substrate, and the frequency of plasmonic resonance (ωLSPR) can be expressed as[46]:

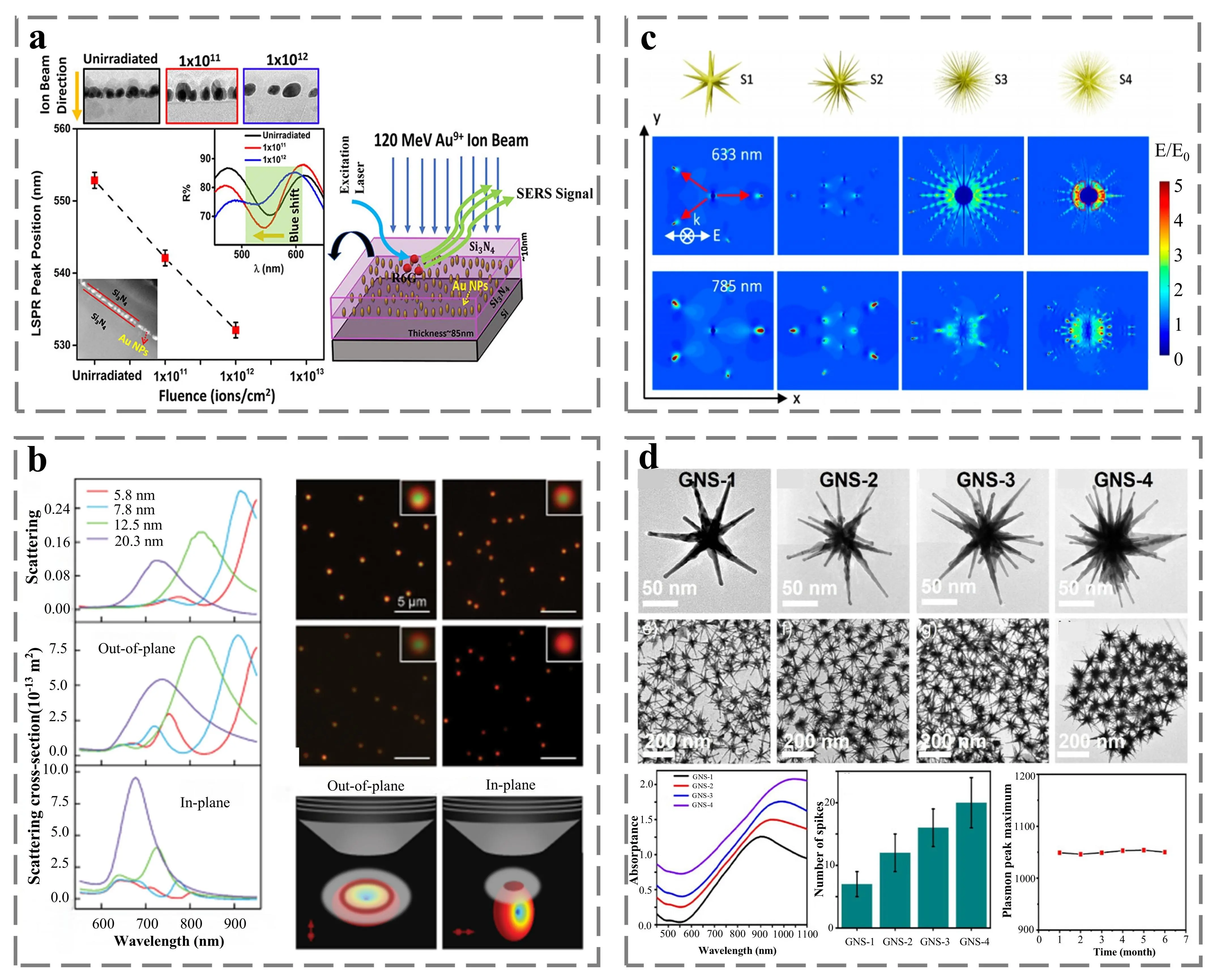

Where N is the free carrier density, ε0 is the permittivity of free space, εm is the dielectric constant of the surrounding medium, and m is the effective mass of the free carrier. Alternatively, actual measurements can be conducted using a UV-visible spectrophotometer, which subsequently selects the appropriate excitation wavelength for field simulation. Certain straightforward methods (such as modifying the shape, size, and material of the nanostructure) can be employed to adjust the LSPR peak. For instance, Ghosh et al. modulated the optical and structural properties of Au NPs embedded in a thin Si3N4 by the intense electronic excitation induced by ultra-fast heavy ion irradiation. Under the influence of the ion beam, the shape and size of Au NPs undergo changes, resulting in a blue-shift of the LSPR resonance peak[47]. Wu et al. respectively investigated the electromagnetic field effects of Ag NPs, Cu2O and their composites. Resonance peaks corresponding to the 532 nm laser were observed in the Cu2O@Ag composite, indicating that the effective electromagnetic field resonance region of the Ag NPs lies in the inter-particle gap, while that of Cu2O is at the bottom contact surface[48]. Wang et al. coupled the Au nanocrystals encapsulated by ZIF-8 with the Au film. By adjusting the thickness of ZIF-8, they altered the crystal size and further affected the gap with the Au film. As the gap increased from 5.8 nm to 20.3 nm, the scattering resonance peak of the substrate exhibited a significant blue-shift, and the corresponding excitation light was further utilized to demonstrate excellent SERS detection performance[49]. Vo-Dinh et al. successfully fabricated Au nanostar structures with varying numbers of tips. The research indicates that as the number of tips increases, the overall plasmonic resonance peak shifts towards the infrared band, and the intensity gradually rises. The above findings effectively prove the effective coupling between the laser wavelength and the substrate LSPR[50]. The above content is shown in Figure 2. In this manner, the substrate is anticipated to generate a broader hot-spot area and higher hot-spot intensity, thereby further enhancing the electromagnetic contribution in SERS.

Figure 2. (a) Schematic representation of the LSPR formant as a function of Au NPs size under ion impact. Republished with permission from[47]; (b) The left side shows the single-particle dark-field scattering spectra of the experiment, out-of-plane excitation, and in-plane excitation, respectively. The top right panel shows the dark field scattering images for different gap distances, and the bottom panel shows the out-of-plane (left) and in-plane (right) scattering schemas[49]; (c) S1 to S4 show the computational model images of nano-star based on SEM images, and the simulated images show the local electric field under excitation at 633 nm (top) and 785 nm (bottom), respectively[51]; (d)The top panel shows TEM images of different GNS samples, the middle panel shows TEM images of expanded areas, and the bottom panel shows absorption map, spike number statistics, and temporal stability map from left to right[50]. LSPR: local surface plasmon resonance; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; GNS: gold nanostars.

In addition, there is an aspect frequently neglected by researchers, which is the disparities in material system properties under the irradiation of different laser wavelengths. For example, Wang et al. conducted a study on the silver sphere system with gaps and found that at longer excitation wavelengths, the absolute value of the silver dielectric function decreased, which would influence the intensity variation of the hot-spot and thus achieve a higher signal-to-noise ratio[52]. Wen et al. fabricated silver particle-wire nanostructures and verified the hot-spot distribution at the junction of the particles and wires. It was revealed that the hot-spot distribution was highly sensitive to the excitation wavelength, and the position of the hot-spot could be altered by the wavelength of the incident laser.

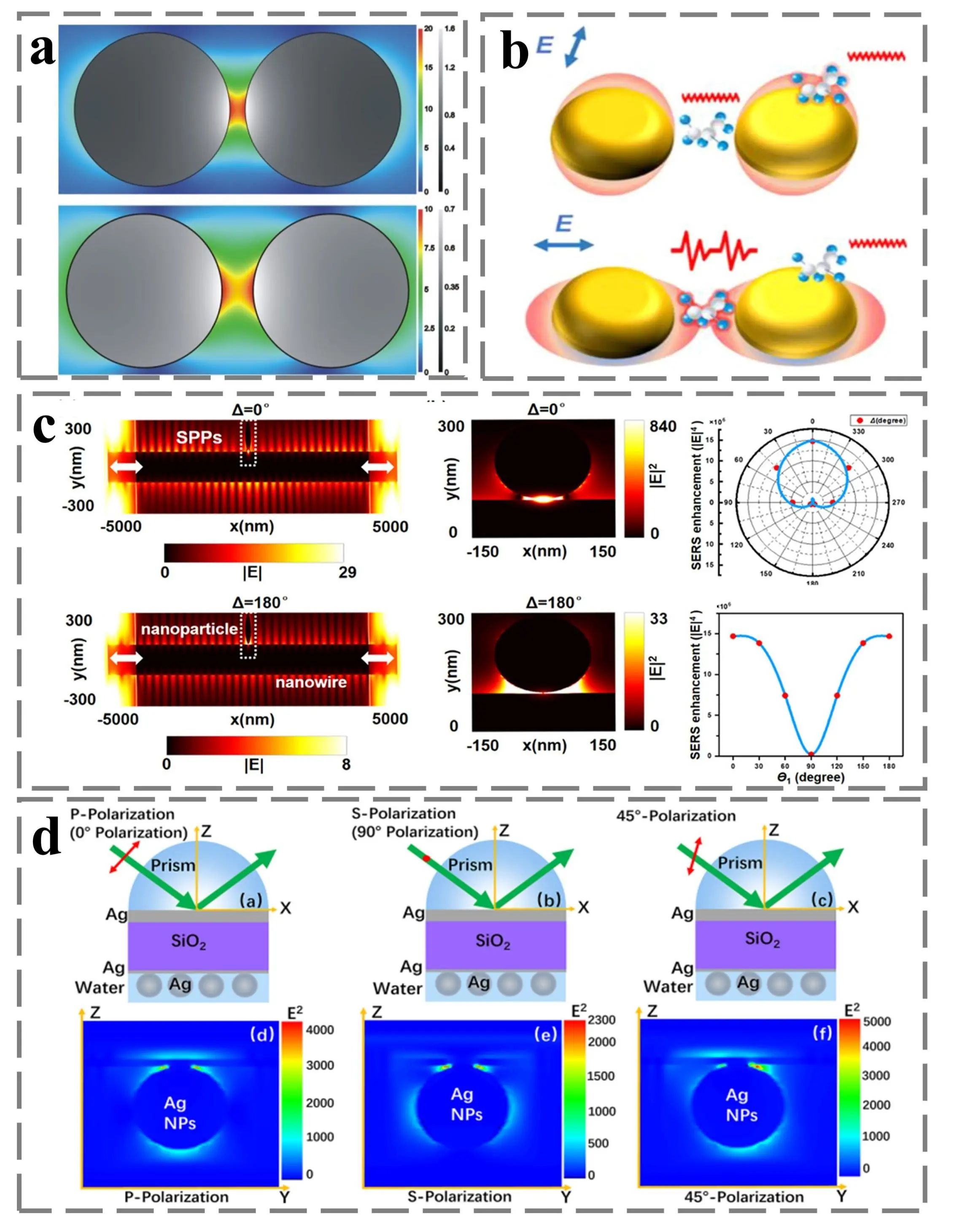

For some anisotropic hotspot structures (such as nanorod gaps, tips, and asymmetrically arranged nanotube arrays), their electromagnetic enhancement demonstrates a strong polarization dependence[53]. By rotating the polarization direction of the incident light, specific hotspots can be selectively excited in specific directions. For instance, Shang et al. discovered through their research on cross-shaped Ag nanowires that the hotspots were highly sensitive to the polarization direction of the incident light. When the polarization direction of the incident light was parallel to the bottom nanowire, the field enhancement and SERS intensity reached their maximum values[54]. Wang et al. prepared hexagonal close-packed nanoscale periodic silver array structures with different symmetries and found that the signal strength and area generated by S-polarization were superior to those excited by P-polarization. This confirmed that the hotspot distribution of the symmetrical structure was the fundamental cause of the polarization dependence[55]. Geng et al. developed a 5-layer structure composed of prisms, silver, silica, silver, and water. When 45° polarized light was incident on this structure, more hotspots and higher hotspot intensities were generated within the structure[56]. Research on the formation of hotspots triggered by the incident angle generally only modifies the formation area of the hotspots or the position of the resonance peaks. Only in special array-type inclined sedimentary structures will the intensity of the hotspots change. For example, Wu et al. used the template method to synthesize silica porous hollow spheres with an ultra-low refractive index (n = 1.05). When the incident angle was adjusted, the resonance peak of the substrate exhibited a significant blue-shift[57]. Jiang et al. combined the microsphere lens array with the dual gold nanopores (MLA/2-AuNHs) and found that different incident angles would generate hotspots in different areas, but the intensity of the hotspots would not change[58]. However, Chen et al. successfully fabricated gold nanocone arrays through oblique deposition. By coupling the deposition angle and the incident angle, it was found that changing the incident angle of the light source could increase the number of hotspots and yield more significant SERS signals[59]. The above content is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. (a) Schematic of the electric field for different particle spacing. Republished with permission from[52]; (b) Schematic of polarization-selective Raman measurement using metal dimers[60]; (c) The left side shows the simulated optical power distribution at Δ = 0° (top) and Δ = 180° (bottom) incidence, the middle shows the SERS enhancement of the simulated table at Δ = 0° (top) and Δ = 180° (bottom) interfaces, and the right side shows the relationship between the phase difference (top) and the input polarization Angle (bottom)[61]; (d) From left to right, the diagram of the incident laser with P polarization, S polarization and 45° polarization, and the local electromagnetic field simulation are shown[56].

In conclusion, the combination of precise nanostructures and flexible light field control strategies is the key focus of hot engineering. It not only meets the various requirements of the electromagnetic enhancement mechanism but also enhances the sensitivity and reliability of SERS detection.

3. Plasmonic thermal Effect for SERS Research

The photo-field-induced plasmonic thermal effect pertains to the phenomenon wherein, upon the interaction of a laser with metal nanostructures, the latter are excited to generate the LSPR effect. Subsequently, due to the non-radiative relaxation process, the energy of plasmonic oscillation is transformed into lattice thermal vibration. As a result, the temperature inside the nanostructure and surrounding environment increases[62]. Specifically, the plasmonic thermal effect stems from the relaxation process of plasmonic excitation, which encompasses radiative decay and non-radiative decay. The relaxation process can be characterized by the decay rate (Γ)[63]:

Here, ΓRad represents radiative decay into photons, and ΓBulk and ΓSurf represent non-radiative decay by electron bulk scattering and surface scattering, respectively. During the processes of electron scattering and surface scattering, the regulation of the light field exerts a notable enhancement effect on the plasmonic thermal effect. For instance, Han et al. accomplished the precise measurement of the plasmonic surface temperature by integrating Au NPs, carbon nanotubes, and Ag films as SERS probes. It has been discovered that when the dielectric spacer is excessively thin to support the Fabry-Perot mode in the visible region, the disordered plasmonic system would manifest broadband absorption characteristics. At this juncture, the majority of photons are confined within the surface. The non-radiative attenuation of hot electrons within the nanocluster can result in significant heating of the nanocluster itself and its surrounding environment through “Landau damping” to generate hot electrons. Most crucially, the position of the resonant peak is influenced by altering the thickness of the dielectric layer, and thermal excitation is effectively achieved by matching the excitation wavelengths of different bands[64]. Polman et al. conducted a comprehensive exploration of the thermodynamic theoretical basis for the electrical effects of plasmonics through the analysis of a simplified model system consisting of a single Ag NP. It was discovered that the electrochemical potential displayed a monotonic, wavelength independent upward tendency with the increase in electron density. Simultaneously, the entropy remained relatively constant, with only minor modulation as a function of the logarithm of the particle temperature. The most crucial factor, temperature, exhibited a strong dependence on the wavelength and showed a good fit to the LSPR resonance. Specifically, when the wavelength of the incident light resonated with the plasmonic frequency, it would generate extremely strong light absorption and local field enhancement, and subsequently achieve efficient conversion to heat. It can be deduced that wavelength regulation determines the resonance position where the plasmonic thermal effect takes place[62]. Moreover, the polarization state of light also exerts an influence on the excitation of the plasmonic thermal effect, especially in the case of anisotropic plasmonic structures. The variation of plasmonic absorption (Abs.) with polarization Angle can be expressed as follows[65]:

Here, Abs.90 denotes the peak absorption intensity for the polarization angle of 90°, and θ denotes the polarization angle. Meanwhile, Wang et al. experimentally fabricated one-dimensional Te nanoribbons to achieve the plasmonic thermal effect under polarization angle control. By effectively converting polarization-sensitive absorption into substantial temperature gradients and integrating the size effect of the plasmonic absorber, the thermal performance is notably enhanced. Specifically, the plasmonic resonance absorption band is influenced by altering the incident polarization angle, thereby driving the overall thermal effect. It has been discovered that the temperature is correlated with the polarization angle and exhibits a linear relationship with the laser power. Yin et al. synthesized a plasmonic composite of mixed ferric oxide/Ag nanorods, accomplished anisotropic nanorod orientation, plasmonic excitation, and photothermal conversion. When the laser polarization is coupled with the nanorod orientation, the plasmonic thermal effect of the substrate is efficiently excited[66].

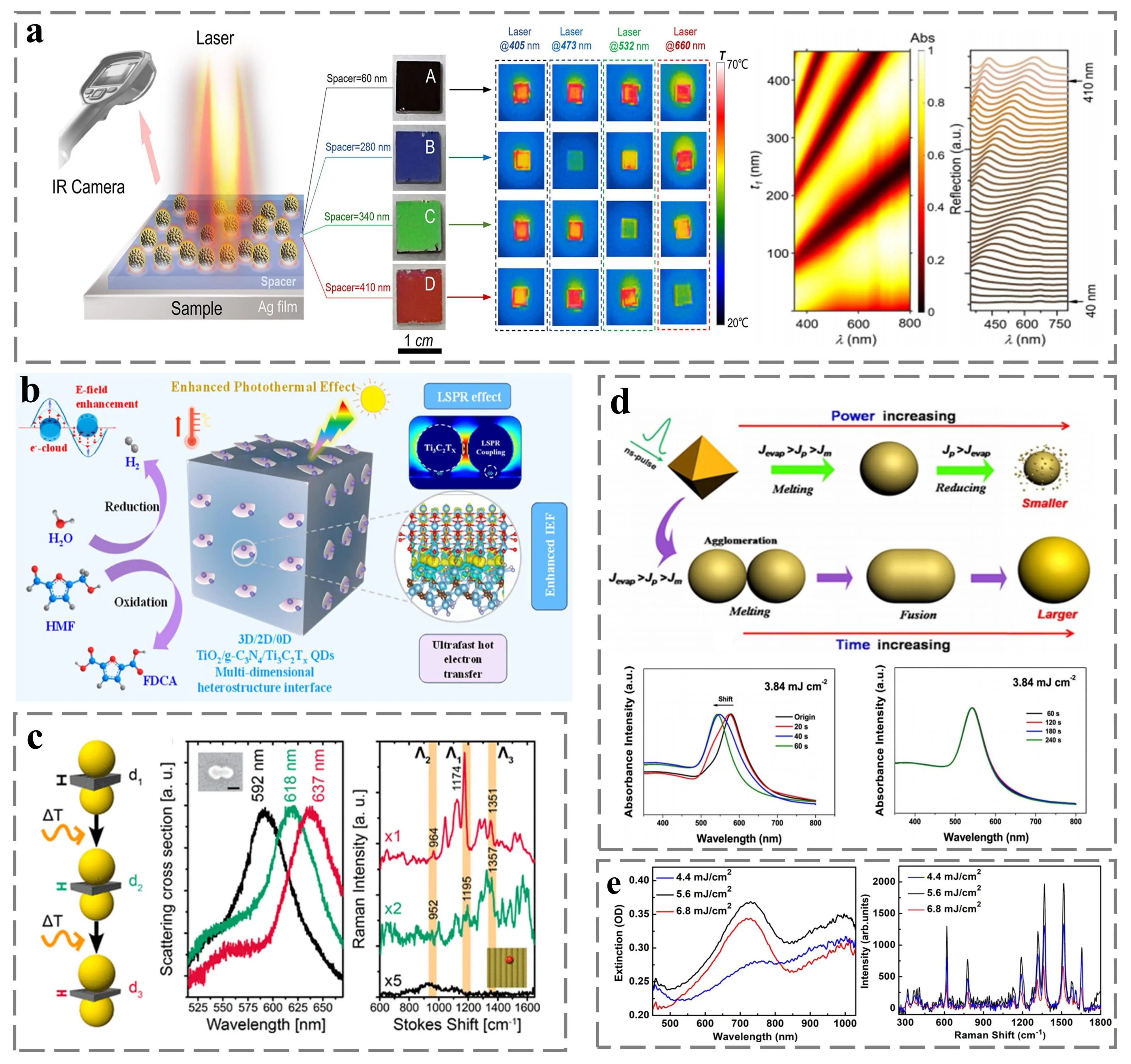

In addition, the development of pulsed lasers has gradually demonstrated its regulatory effect on the thermal effect and achieved SERS enhancement. For instance, Li et al. prepared large-scale single-crystal gold nano-octahedra with uniform dimensions via the polyols synthesis route and employed the photothermal fusion-evaporation model to conduct an in-depth analysis of the morphological transformation mechanism of the nanosecond pulsed laser excitation system. It was found that the LSPR frequency of the substrate changes under different laser energy densities and pulse irradiation times. Through the electromagnetic coupling of the laser, a large number of SERS hotspots are formed between adjacent gold nanospheres in the array, which further improves the SERS performance[67]. Zhang et al. prepared homogeneous aggregated SERS substrates based on the strong interaction between femtosecond (fs) laser pulses and colloidal gold nanoparticles (Au NPs) films. These substrates exhibit different LSPR responses under different power pulse laser aggregations. This phenomenon is attributed to the inconsistent thermal effects generated under different pulse energies, which further impact the size of Au NPs. As the pulse energy increases, the resonance spectrum shifts towards the long - wavelength direction and simultaneously strengthens and broadens[68]. The above content is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. (a) Left: Schematic diagram of the infrared thermal imaging process of the sample. Middle: Photographs of four metasurface samples and thermal images under laser irradiation at 405, 473, 532, and 633 nm. Right: absorption and reflection spectra as a function of spacer thickness. Republished with permission from[64; (b) Schematic diagram of photothermal induced hotspot excitation and realization of catalytic reaction[69]; (c) Illustration of laser-induced gap size shrinkage at different wavelengths (left), spectral comparison between Rayleigh scattering (middle) and Raman scattering (right) at the hotspot[70]; (d) The top figure shows the shape transformation of octahedral gold nanoparticles induced by nanosecond laser irradiation in water. The lower figure shows the absorption spectra of Au NPs under laser irradiation with irradiation times of 20-60s (left) and 60-240 s (right), respectively[67]; (e) Extinction spectra (left) and SERS spectra (right) at different laser energy densities. Republished with permission from[68].SERS: surface-enhanced Raman scattering.

In addition, it is a more effective strategy to directly change the hotspot area and intensity by photoinduced plasmonic thermal effects[71]. The principle is that laser causes thermal expansion among the nanostructures, or induce thermal swimming forces. This enables the width of the nanoscale gap to be dynamically adjusted. When the irradiation power increases, the gap may temporarily narrow, forming a transient and extremely intense “dynamic hotspot”; after the irradiation power is turned off or reduced, the structure cools down and returns to its original state. For example, Choi et al. detected robust SERS signals regardless of the size of the liquid analyte by photothermally driven co-assembly with colloidal plasmonic nanoparticles, which act as signal enhancers. Under resonant light irradiation, plasmonic nanoparticles and analytes in solution can be rapidly assembled on the focused surface region without surface modification through convective motion induced by photothermal heating. By adjusting the optical density, surface charge, solvent viscosity and illumination time of the nanoparticles, the collective assembly of plasmonic nanoparticles and analytes could be optimized to maximize SERS signal[72]. Wu et al. developed a dynamic "hotspot" hybrid plasmonic platform based on the assembly of gold nanospheres (Au NSs) on a temperature sensitive bacterial cellulose (BC) film. The plasmonic photothermal effect of Au NSs is used to regulate the “hot spot” structure and simplify the heating process. This hotspot structure is regulated in situ by local conformational contraction of heat-responsive PNIPAM around the BC skeleton of grafted poly (n-isopropyl acrylamide) without changing the overall morphology of the substrate[73]. Li et al. developed a photothermally modulated SERS platform to achieve high sensitivity and stable analysis of target substances by utilizing stimulation-responsive gold nanoparticles (GNPs) modified polyvinyl alcohol hydrogels (GPH). Importantly, the proposed GPH is able to accurately control the 3D hot spot region by adjusting the surrounding temperature and humidity. This tunable GPH can not only be used as a stable matrix for high-density GNPs, but also can be used as an adsorption domain to enrich target analytes at hotspots, so as to realize the synchronous regulation of 3D nanostructures and the capture of target analytes in the plasmonic region. The key point is that due to reversible nanostructures and nano-plasmonic properties, GPH can remove adsorbate after exposure to bromide solutions, thus enabling reproducible and reliable in situ SERS detection of complex media[74]. It is well established that, in the field of optical control, the changes in the light field are also very important. For example, Lertsiriyothin et al. proposed a micro-scale resonator with dipole antenna structure on silicon aerogel as a SERS platform, and found that LSPR would be generated at the interface between the array layer and the dielectric material layer. The hot spot excitation of the plasma array was different with different laser wavelengths[75]. Liu et al. analyzed the near-field distribution and photothermal temperature distribution of nanoparticle arrays when considering the scattered light field between particles. They found that when the polarization direction of incident light, particle spacing and particle size are different, “hotspot” representing strong electric field enhancement will be formed. At the same time, the direction of the near-field enhancement region will rotate with the illumination polarization Angle, and the rotation direction of the individual nanoparticles is completely synchronized. In particular, when the direction of linearly polarized light is parallel to the long axis of gold nanorods, the efficiency of light-to-heat conversion is the highest[76]. The above content is shown in Figure 5. Utilizing this fact, specific-polarized controlled light can be used to selectively heat a certain orientation of the nanorods in the array, causing them to expand thermally, thereby changing the gap between it and the adjacent structures in only that direction, creating dynamic hotspots. By rotating the polarization direction, hotspots can be scanned and activated at different spatial positions.

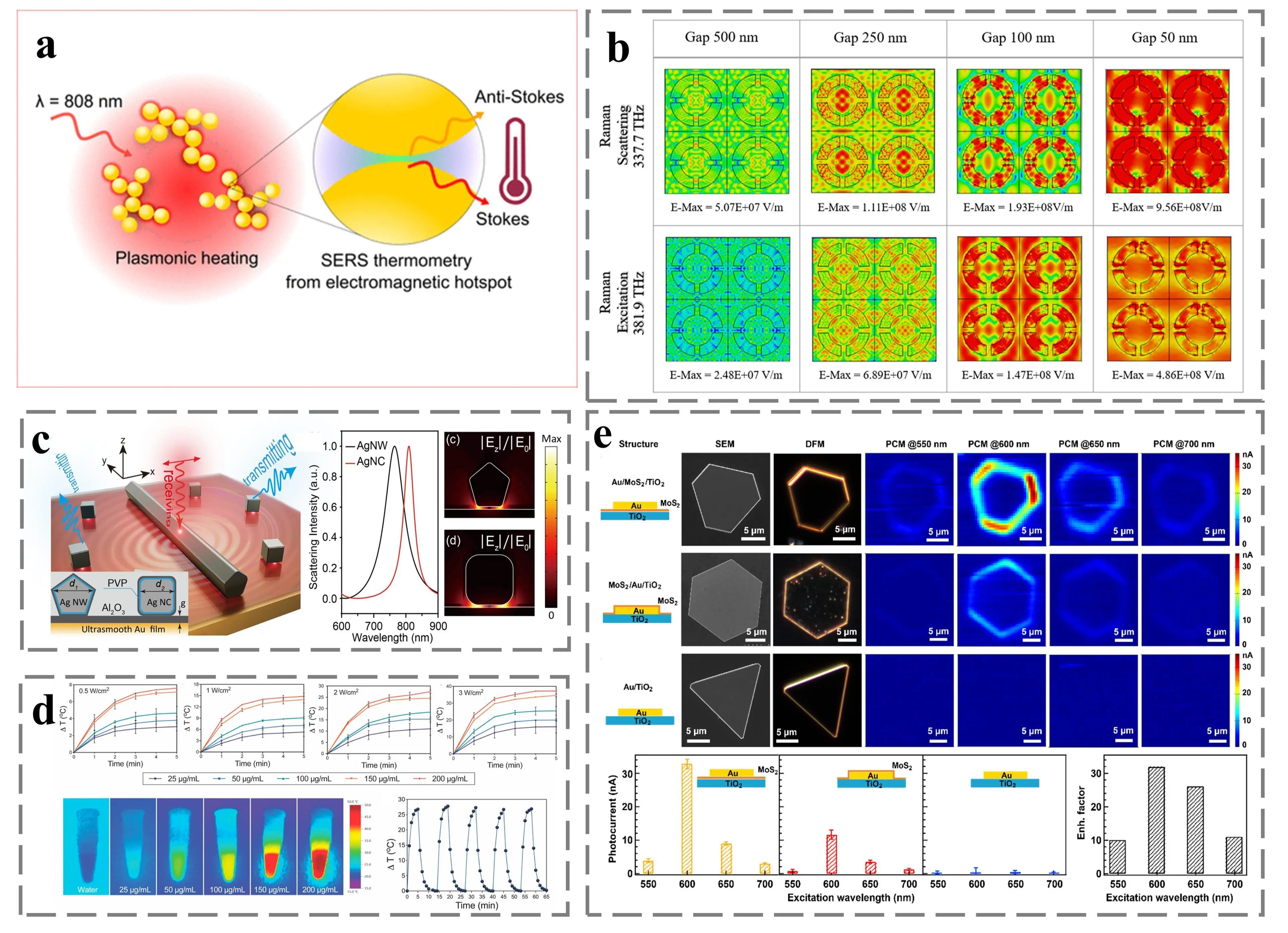

Figure 5. (a) Schematic illustration of the photoinduced plasma thermal effect[77]; (b) From left to right are the effects of structures with gaps of 500, 250, 100, 50 nm on the electric field distribution at 337.7 (top) and 381.9 THz (bottom) around the array[75]; (c) Left: Schematic of the excitation -collection separation spectrum for the nanoantenna pair. Middle: Scattering spectra of Ag NW and Ag NC. Right: plasma-mode electric field distribution of Ag Ag NW (top) and Ag NC (bottom) in the Au film system[78]; (d) Top: From left to right, the temperature change curves of Au DB NRTs with different concentrations at laser power densities of 0.5, 1, 2, 3 W/cm2 are shown. Bottom: From left to right are thermal images of Au DB NRT with different concentrations and thermal stability diagram[79]; (e) From left to right, the structure schematic diagram of Au/MoS2/TiO2 (top), MoS2/Au/TiO2 (middle) and Au/TiO2 (bottom), SEM, DFM diagram, current region under light irradiation at 550, 600, 650 and 700 nm. Republished with permission from[63]. NW: nanowire; NC: nanocube; DB: double-branched; NRTs: nanorattles; DFM: dark-field microscopy; THz: Terahertz; SEM: scanning electron microscopy.

Moreover, laser-induced plasmonic can also initiate the phase transformation of two-dimensional excess metal compounds. This transformation significantly modifies the electronic characteristics, electrical conductivity, surface defect density, and molecular interaction mode of the material, thus profoundly affecting the enhancement effect of SERS. In the case of two-dimensional materials, the photonic-induced plasmonic thermal effect is highly likely to cause phase transitions, particularly under conditions of high laser density and pulse power[80]. For instance, Yan et al. fabricated an Au/two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide hybrid SERS sensor. By exciting the plasmonic structure with a 343-nm femtosecond laser, they achieved the phase transition of MoTe2 from the 2H phase to the 1T phase. The study revealed that the efficient charge transfer among Au, 2H-MoTe2, and methylene blue (MB) also contributes to the SERS effect[81]. Xu et al. induced a single-crystal phase transformation of 2M-WS₂ to the 2H phase through laser heating. They found that, in contrast to the CT mechanism dominated by the Fermi level in the metallic phase 2M-WS2, the reduction and recombination of the band gap resulting from vacancy enrichment during the phase transformation of 2M-WS2 significantly accelerated the CT process[82]. Lu et al. prepared Ag-dimolybdenum disulfide and Pt-dimolybdenum disulfide nanohybrid materials. They achieved a high-performance SERS response by inducing electrons on the substrate using femtosecond laser pulses. This can be attributed to the phase transition of molybdenum disulfided from the 1T phase to the 2H phase, as well as the doping effect of metals on molybdenum disulfide, which can increase its free-carrier concentration[83].

For semiconductors, phase transition represents a relatively stable improvement. For example, VO2 exists as a monoclinic semiconductor at low temperatures and transforms into a rutile-phase metal when the temperature rises. This phase transition is accompanied by abrupt changes in conductivity and permittivity. Li et al. fabricated periodic arrays of three-dimensional composite structures composed of vanadium dioxide shells covered with gold nanoparticles on self - assembled highly ordered silica microspheres. When the semiconductor-metal phase transition of VO2 is triggered by the photoinduced plasmonic thermal effect, the plasmonic coupling between AuNPs and the vanadium dioxide shell is enhanced, which further strengthens the SERS signal. At this stage, VO₂ can support LSPR, and the SERS enhancement mechanism shifts to being dominated by the EM effect. Through this phase transition, the same substrate can switch between being dominated by the CM and the EM mechanism, potentially achieving an optimal response for different molecules or different excitation wavelengths[84]. The above content is shown in Figure 6. Another distinctive phenomenon is the transition between the amorphous and crystalline states. Certain materials can transform from an amorphous state to a crystalline state under laser induction[85]. Crystalline states generally exhibit higher carrier mobility and more well-defined energy-band structures, which may be more favorable for the CT process and thus enhance the contribution of the CM mechanism.

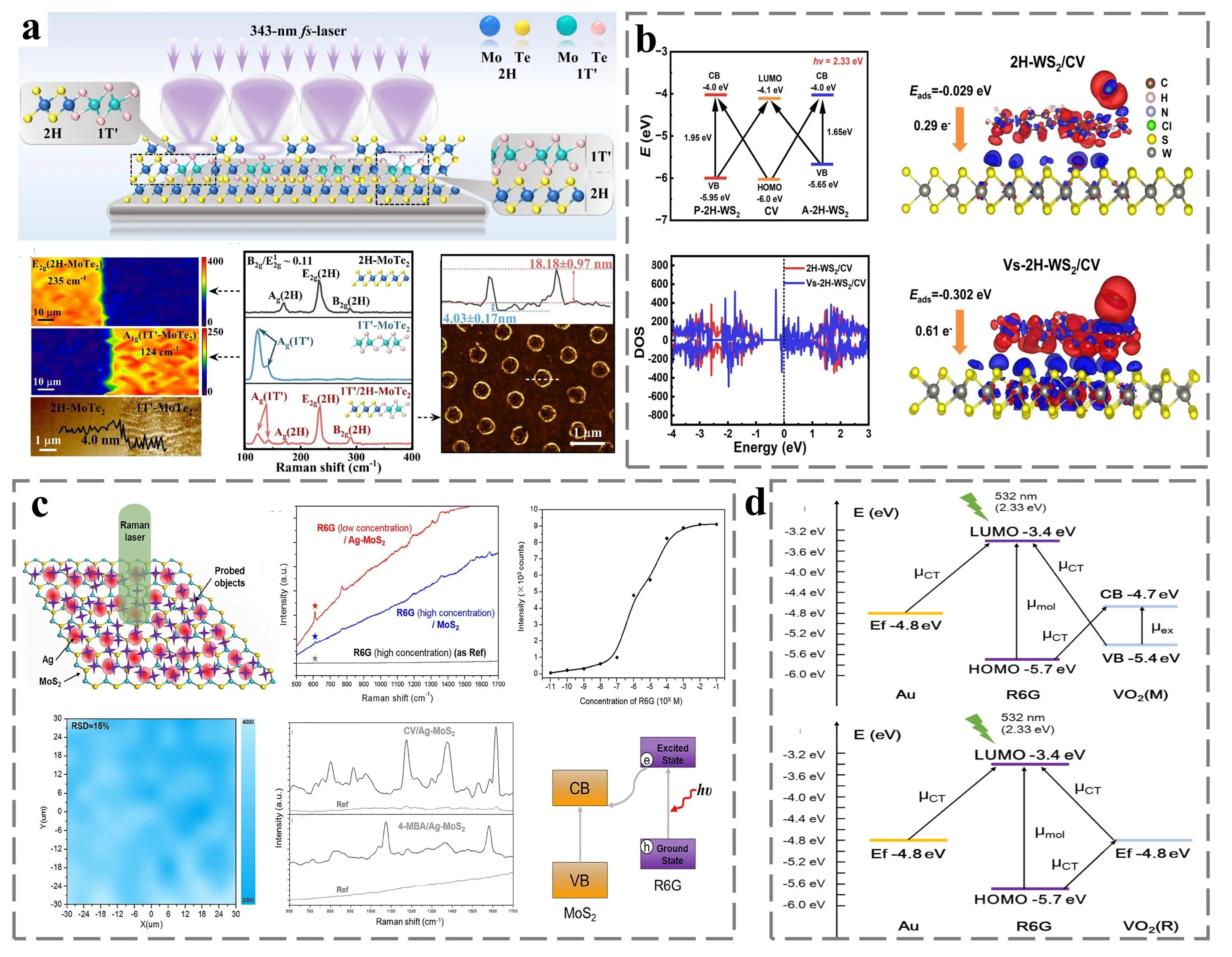

Figure 6. (a) Top: Schematic diagram of femtosecond laser-induced phase transition. Bottom: From left to right are the analysis of the 2H phase and 1T-MoTe2 nanodot edges, Raman spectral comparison, and AFM plots of 1T-MoTe2. Republished with permission from[81]; (b) Left: CT transitions (top) and density of states (bottom) in CV/A-2H-WS2 versus CV/P-2H-WS2. Right: Difference in charge density between CV molecules on 2H-WS2 (top) and Vs-2H-WS2 (bottom). Republished with permission from[82]; (c) Left: Schematic illustration of SERS test (top) and Raman mapping image (bottom). Middle: Raman spectra of R6G, R6G on MoS2 and R6G on Ag−MoS2 (top), Raman maps of CV and 4-MBA molecules (bottom). Right: Curve of Raman intensity as a function of R6G concentration (top) and CT process between R6G and MoS2 (bottom). Republished with permission from[83]; (d) CT process of R6G with VO2 at 20 °C (top) and 80 °C (bottom)[86]. AFM: atomic force microscopy; CT: charge transfer; CV: crystal violet.

The plasmonic thermal effect induced by light field is an important part to realize the synergistic enhancement of SERS performance. The essence is that the LSPR can be optimized by precisely adjusting the wavelength, polarization, pulse and other parameters of the incident light, so that the light energy can be efficiently converted into local thermal energy of the nanostructure and its surrounding microenvironment. This controllable thermal effect synergistically enhances SERS through two main ways: First, dynamic EM, which uses thermal expansion, thermophoretic force or smart material response to adjust nanogaps in situ and reversibly to create and scan “dynamic hotspot”, which greatly enhances the local electric field strength. Second, profound influence CM, that is, the use of laser-induced high temperature to trigger the crystalline phase transition of two-dimensional materials or phase change materials, thereby changing the energy band structure, carrier concentration and charge transfer efficiency of materials, and optimizing the CM contribution. Finally, through the fine manipulation of plasmonic thermal effect by light field, the dual regulation of SERS substrate “hotspot” structure and material intrinsic properties is realized, so that EM and CM effects can be coordinated, which provides a key theoretical basis and technical path for the development of high-performance, intelligent and reconfigurable SERS sensing platform.

4. Magnetic Field Modulation for SERS Research

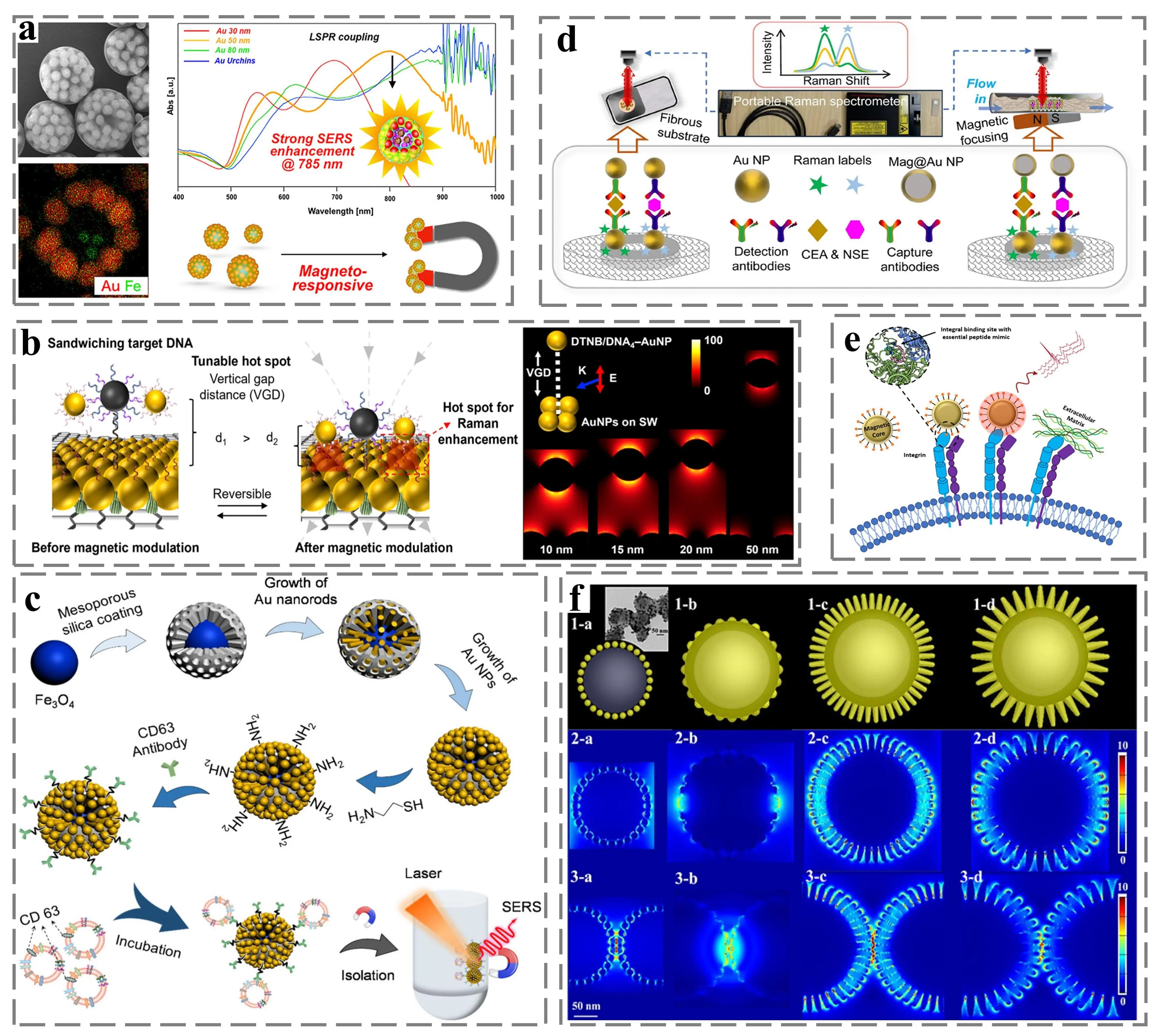

Magnetic field induced SERS (M-SERS) is a dynamic modulation technique that employs an external magnetic field as a stimulus to actively and dynamically manipulate the physical structure of the SERS substrate (e.g., the spatial arrangement and aggregation state of nanoparticles) or to influence the properties of the magnetic substrate itself, thereby altering its SERS performance[87,88]. Given that SERS is highly reliant on the substrate, magnetically induced non-magnetic and magnetic material structures have attracted extensive attention. Magnetically induced magnetic entities, including magnetic beads (MBs), magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), and magnetic nanocomposites, generally exhibit a high degree of magnetic responsiveness and are prone to magnetic enrichment, magnetic segregation, and magnetic resonance when excited by a magnetic field. Simultaneously, the surface of magnetic entities can be effectively modified using the “targeted binding” strategy, such as chemical bonding, linking functional groups, and specific recognition substances (e.g., DNA, antibodies). This enables excellent capture of specific biological targets and significantly improves the detection limits of SERS[89,90].

Moreover, magnetic entities can be composited with materials possessing functionalization properties (e.g., graphene and silicon). Depending on the nature of the combined materials, nanocomposites with more prominent specific properties are formed. On the other hand, the magnetic resonance behavior of some metal-modified structures (e.g., core-shell structures and grooved structures) on non-magnetic materials has been demonstrated to have enhanced magnetic field excitation and hot-spot generation capabilities. This leads to a particularly diverse range of combinations of substrate materials, and a number of non-magnetic magnetic resonance structures are gradually being expanded.

4.1 Magnetic field modulating SERS without magnetic materials

For non-magnetic structures capable of magnetic modulation, which involve plasmonic, the induced electromagnetic fields exhibit two coupling modes: electric resonance and magnetic resonance. Across the field, the majority of electromagnetic enhancement is induced by electric resonance modes, while the magnetic modulation consistent with non-magnetic materials is dominated by magnetic resonance modes. Notably, in an electric resonance dipole mode, the direction of the potential displacement vector aligns with the direction of the incident electric field. In contrast, in the magnetic resonance dipole mode, the potential shift vector responds in a vortex-like pattern[91,92]. Magnetic resonance is an essential component of the electromagnetic field enhancement contribution, and magnetic resonance-guided electromagnetic field enhancement is consistent with magnetic modulation.

Simultaneously, non-magnetic dimers, which are closely spaced metal nanostructures (e.g., particle-to-particle and particle-to-film), have been comprehensively investigated due to their high susceptibility to the generation of LSPR). Tian et al. designed a simple and practical plasmonic Au NP/4-MBA/Au film. By studying the electromagnetic field between the plasmonic and the film, they discovered that the hotspots excited in the magnetic field coupling mode were more concentrated, which was classified as plasmonic-induced magnetic resonance. This ultimately provided novel insights into the enhancement mechanism of plasmonic-enhanced spectroscopy[93]. Burak et al. designed an Au dimer/Au thin film connection structure and proposed two modes which are shielded bonded dimer (SBD) plasmonic resonance and charge transfer plasmonic (CTP) resonance, through electromagnetic field simulation. In the lower energy CTP mode, the magnetically coupled modes make the main contribution to the excitation of the electromagnetic field, which is attributed to the current loop of the magnetic dipole moment that reduces the influence of the electric dipole moment[94]. Zhao et al. constructed a periodic array of non - linear optical elements (NLNOEs) composed of multilayered Au/SiO2 with connected Au layers at the edges of the multilayered structure. Further, through magnetic field simulation, they found that the region of magnetic resonance-amplified magnetic field coincided with the region of effective coupling between Au and SiO2, thus explaining the mechanism of nano-plasmonic-enhanced metal luminescence in the context of SERS spectroscopy[95].

The electrical and magnetic coupling modes of non-magnetic dimer structures are influenced by different variables. For example, in metal particle-film systems, the electrical coupling mode depends on the particle diameter, while the magnetic coupling mode depends on the effective coupling length between the particle and the film. Hence, the existence of an effective coupling length is one of the conditions for non-magnetic material structures to achieve magnetic resonance. It is worth noting that non-magnetic dimer substrates of non-magnetic materials can efficiently excite magnetic resonance and may even exhibit better field enhancement than electric resonance. With the in-depth development of nanosized materials, researchers are not only focused closely on spaced dimer structures but also on modifying the metal particles themselves to stimulate electromagnetic fields and on finding modified structures of non-magnetic nanoparticles capable of exciting strong magnetic resonance. Lee et al. performed grooving treatment on gold nanospheres, simulated the electromagnetic field based on the position of the absorption band of the grooved gold nanospheres, and clearly distinguished the resonance coupling mode to which the absorption band belonged. It was proven that the absorption peak excited by magnetic resonance at the edge of the slot had higher absorption efficiency[91]. Liu et al. developed a gain-assisted SiO2-Si core-shell structure to evaluate the amplification ability of magnetic resonance through the SERS enhancement factor of different dipole magnetic modes, effectively demonstrating the weak background radiation and excellent magnetic resonance excitation of this core-shell structure[96]. Chen et al. designed gold nano-ingots with notched core-shell structures. It was found that the gold nano-ingots with the largest shell opening size had the strongest magnetic field and the highest photocatalytic activity. This tunable cavity structure exhibits strong plasmonic coupling, tunable magnetic plasmon resonance, and excellent SERS properties[97]. The above content is shown in Figure 7. The material structure of the nanoparticles is stable and simple. After modification, the difference between the peaks of electric resonance and magnetic resonance can be clearly distinguished in the absorption band of the structure, which is further verified by electromagnetic field simulations. After grooving treatment, Ag NPs exhibit a new absorption band in the near infrared band. Through coupled laser excitation in the absorption band, it was found that the electric displacement vector of Ag NPs shows a vortex back flow and only generates a strong magnetic resonance at the edge of its internal groove (effective coupling length). Therefore, an effective coupling laser is one of the effective conditions for exciting the structure of non-magnetic materials.

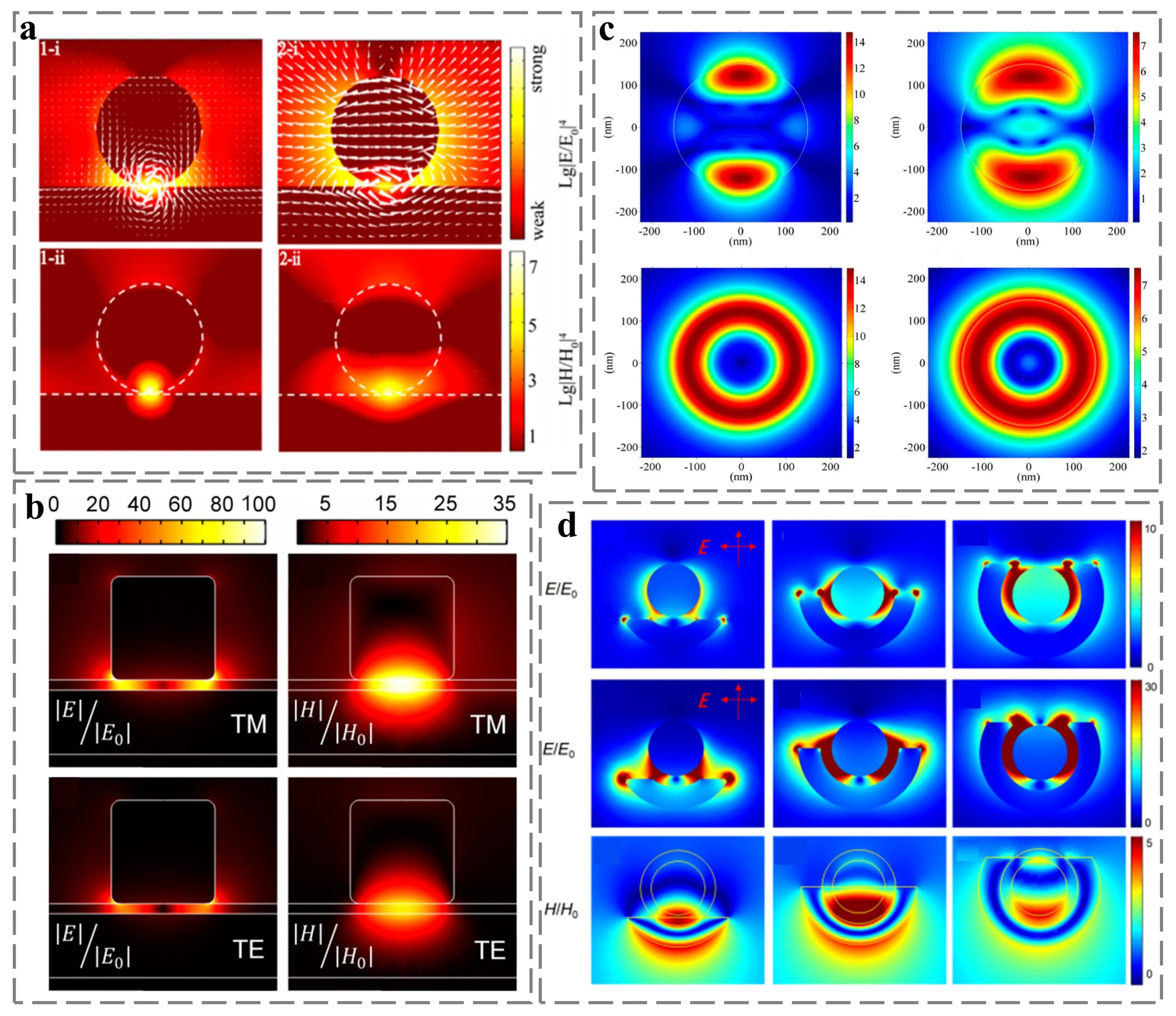

Figure 7. (a) Electric field distribution (top) and magnetic field distribution (bottom) in magnetoelectric dipole mode. Republished with permission from[93]; (b) Distribution of electric intensity (left) and magnetic field (right) for TM (top) versus TE (bottom) polarization modes[98]; (c) The electric field distributions in the y-z plane (top) and x-z plane (bottom) under octupolar (left) and quadrupolar (right) magnetic resonance[96]; (d)The electric field (top) at the electric resonance wavelength, the electric field (middle) at the magnetic resonance wavelength, and the magnetic field (bottom) at the magnetic resonance wavelength for the Au nano-irons wrapped in 1/4 (left), 1/2 (middle), and 3/4 (right)[97]. TM: transverse magnetic; TE: transverse electric.

In conclusion, after effective modification of metal particles, magnetic resonance can further contribute to the electromagnetic field, and there is a distinct difference in the absorption spectrum compared to electric resonance. Overall, non-magnetic dimers and modified structures of non-magnetic nanoparticles have been proven to possess good magnetic resonance excitation ability.

4.2 Magnetic field modulating SERS based on magnetic materials

Currently, the magnetically regulated SERS of magnetic materials has garnered extensive attention owing to its highly sensitive magnetic response, flexible tunability, and non-invasive stability. The magnetic regulation of SERS is founded on the excitation behavior of magnetic materials under a magnetic field to effectively augment the contribution to SERS. Magnetic materials encompass MBs, MNPs, magnetic composite materials, etc. These materials have been adequately fabricated on M-SERS substrates and can be categorized into three types[99-102].

The first type is the functionalized magnetic media and metal - bonded substrate. This refers to substrates which are composed of functionally modified magnetic materials joined to metallic structures (e.g., metal particles, metal cavities, and metal thin films). It aims to address the issues of easy oxidation of bare magnetic media, low acid-base tolerance, and poor SERS signal recognition ability. For instance, Kim et al. accomplished targeted SERS detection of E. coli by utilizing immunization with surface-functionalized specific antibodies on AuNP@SMBs[103]. Ye et al. modified biotin on the surface of magnetic beads and obtained accurate SERS signals of biological proteins after magnetic field aggregation in a microfluidic channel constructed with PDMS[104].

The second type is the magnetic bonded material substrate which consists of structures formed by combining a magnetic material with a solid material (such as oxides, two-dimensional materials, and metal-organic frameworks) possessing unique properties. For example, Wang et al. prepared Fe3O4 nanoparticles via a water-bath heating method, then added an SiO2 solvent, stirred and dissolved it, and mixed it with silver nanoparticles to fabricate the mixed Fe3O4@SiO2/Ag substrate. The addition of SiO2 regulated the concentration and distance between the magnetic component and the “hotspot” region, effectively preventing the agglomeration and adhesion of silver nanoparticles, thereby attaining the optimal collection efficiency and SERS signal enhancement[105].

The third type is the core-shell magnetic substrate which is predominantly composed of magnetic nanocomposites with a core-shell structure formed by MBs or MNPs. This approach not only triggers core-shell magnetic resonance at the nanoscale but also excites magnetic responses within the effective area, ensuring magnetic field excitation and magnetic resonance behavior within the nanoscale range. For example, Che et al. successfully synthesized core-shell structured Fe/Fe4N@Pd/C (FFPC) nanocomposites through interfacial polymerization and annealing treatment. Due to the coupling effect of the intrinsic magnetic field and electromagnetic field in the plasma region, SERS enhancement was successfully realized[106]. The above content is shown in Figure 8. The application of core-shell structures has effectively promoted the development of magnetic SERS detection. Such effective magnetic resonance-modified structures are not restricted to core-shell structures; they can also be achieved through methods like grooving and etching. However, other modification methods are rarely employed at present, primarily because the cost of nano-scale modification for each magnetic medium is excessively high, and the magnetic resonance excitation intensity after modification shows no significant difference compared to the core-shell structure. On the other hand, the principles of these magnetic resonance structures lack systematic analysis, making it challenging to clearly comprehend the specific role of the magnetic resonance structure in the magnetic response. Therefore, this core-shell magnetic substrate is the most commonly used structure for high-sensitivity detection.

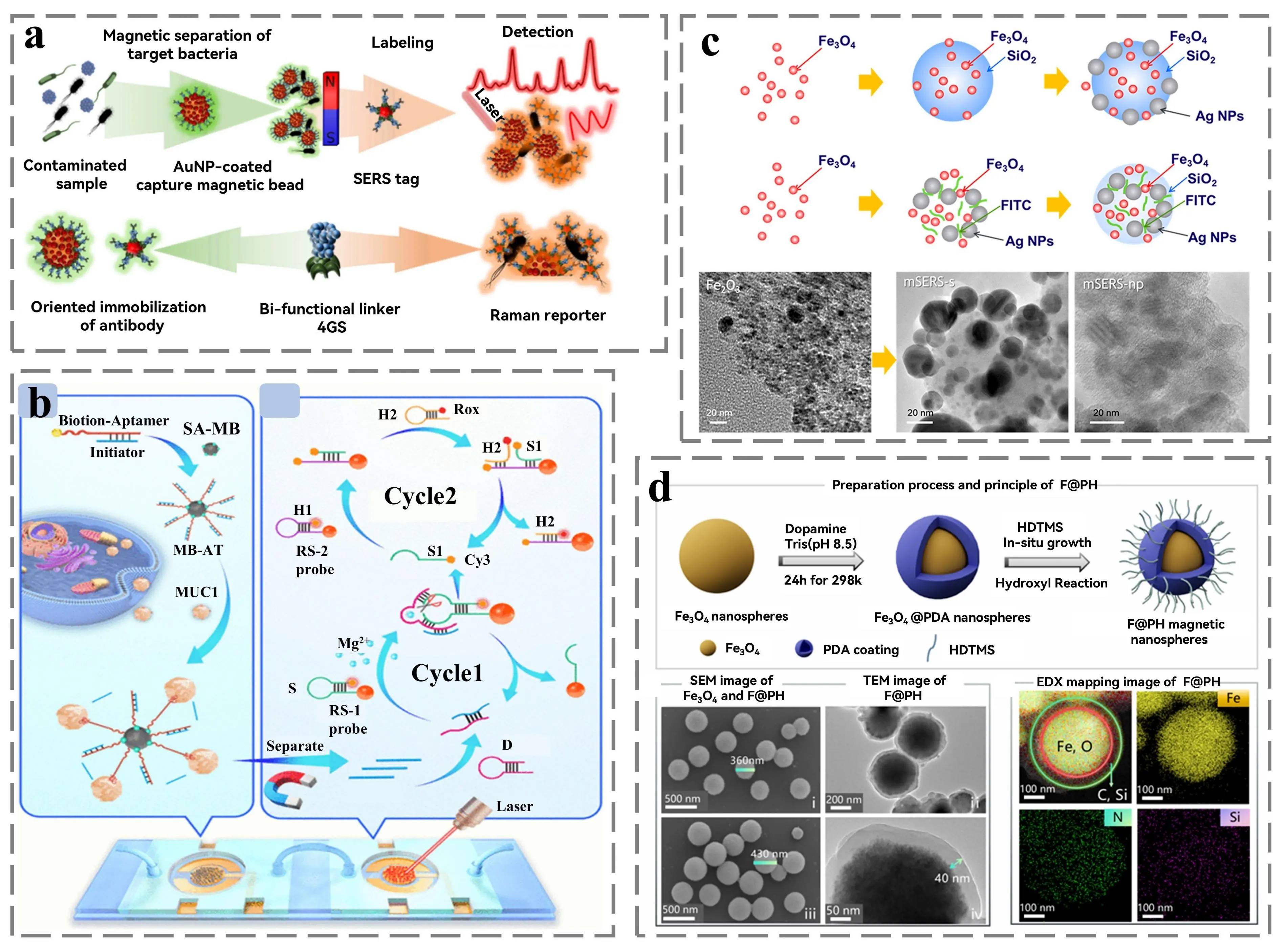

Figure 8. (a) Schematic diagram of magnetic beads used for SERS detection[103]; (b) Schematic representation of the combination of magnetic separation with microfluidic techniques used for detection[104]; (c)Top: Fe3O4@SiO2/Ag and conjugated SERS nanoparticle tracers are schematic. Bottom: TEM images of Fe3O4 (left) and Fe3O4@SERS-np (right)[105]; (d) Top: Preparation of F@PH. Bottom: SEM and TEM images of F@PH (left), EDX mapped images (right)[107]. TEM: transmission electron microscopy; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; SERS: surface-enhanced Raman scattering.

These types of substrates effectively utilize the magnetic response and magnetic resonance behavior, jointly constituting the basis of magnetic field-controlled SERS. In brief, each of the three types of substrates has its own characteristics. The functionalized magnetic media and metal - bonded substrate possess abundant surface functional groups (such as carboxyl (-COOH) and amino (-NH2), hydroxyl (-OH), etc.) and high-intensity hotspots, yet their structures are unstable after coupling and are prone to agglomeration. The magnetically bonded solid material substrate has sufficient adhesion sites and a fixed base plate, but there is some interference with the magnetic response behavior of the magnetic medium. The core-shell magnetic substrate has an extremely robust core-shell structure, and can excite magnetic resonance at the nanoscale, which effectively guarantees the magnetic response behavior under magnetic field excitation. However, the time and steps involved in the preparation of such structures are more costly. Selecting an appropriate substrate construction strategy for a specific detection environment is the key issue in M-SERS.

In the context of magnetic field-regulated SERS mechanisms, the primary influence lies in EM contribution. The magnetic materials change the SERS signal by relying on the magnetic behavior of the material under a magnetic field. This is mainly manifested in the aggregation of hotspots affected by magnetic enrichment, the excitation of surface-bound hotspots, and the coupling of the magnetic field with LSPR. Specifically, the magnetic response behavior of magnetic media under magnetic field excitation encompasses phenomena such as magnetization, magnetostriction, and permeability variations induced in materials by an external magnetic field. When magnetically excited, magnetic materials display magnetization characteristics due to interactions among magnetic dipoles. The alignment and magnetic moment magnitude of these dipoles directly determine the magnetization intensity of the material. This approach effectively couples the inter-particle gaps of magnetic nanoparticles, influencing the LSPR and hotspot coupling of the substrate.

For instance, Yabu et al. successfully integrated magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles into Au NP-based core–shell structures through a self-assembly method, achieving a broad redshift in the LSPR peak. Under an applied magnetic field, nanoparticle aggregation was induced, generating hot-spots and enhancing SERS detection performance[108]. Yang et al. reported a magnetically responsive substrate composed of heterogeneous nanostructures, which enabled ultrasensitive and highly selective detection of the SARS-CoV-2 N gene by controlling the coupling distance. In the AuNPs model, when the magnetic field reduced the coupling distance from 50 nm to 15 nm, stronger hot-spot excitation was achieved, leading to approximately 2-fold and 1.5-fold increases in the enhancement factor and electric field intensity, respectively[109].

Furthermore, the integration of molecular targeting techniques with magnetic media facilitates the rapid and precise extraction of analytes in SERS detection. Common functional recognition strategies include antigen–antibody interactions, aptamers, polymers, and chemical bonding. For example, Schultz et al. demonstrated peptide–protein interactions between integrin-binding peptides and cyclic conjugated onto gold-coated magnetic nanoparticles. The coupling of surface-targeting strategies with SERS technology enabled the effective detection of colorectal cancer cells expressing target integrins[110]. To further enhance the efficiency of surface modification strategies, Sun et al. fabricated a novel multilayered core–shell composite, Fe3O4@Au@Ag@Au (DFAAA), whose densely packed and uniform spiky arrays provided abundant hot-spots, significantly enhancing sensitivity, uniformity, and reproducibility[111]. The above content is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9. (a) Schematic of the magnetic enrichment strategy for magnetic beads. Republished with permission from[108]; (b) The magnetic field controls the distance between the magnetic particles and the substrate and its electric field distribution. Republished with permission from[109]; (c) Schematic of the SERS detection method for exosome with magnetic core-shell nanometallic structure. Republished with permission from[112]; (d)Schematic of the surface modified plasma probe used for SERS detection. Republished with permission from[113]; (e) Schematic representation of surface targeting binding. Republished with permission from[110]; (f) Electric field distribution of different surface modified structures. Republished with permission from[111]. SERS: surface-enhanced Raman scattering.

It is worth noting that the magnetic field can couple with the intrinsic LSPR or localized electromagnetic fields of the material, thereby further amplifying the EM contribution[114]. Wang et al. synthesized Co–Pt NPs smaller than 10 nm with an ultrathin shell (~2 nm) via a solution - based method. The SERS performance of these NPs could be tuned by an external magnetic field. Specifically, the SERS signal intensity exhibited an approximately linear increase with the rising strength of the external magnetic field, which was attributed to the enhanced plasmonic coupling resonance among nanoparticles under the field. The synergistic effect between electric and magnetic fields improved the SERS response[115]. Additionally, Zhang et al. modulated the distribution of hot-spot locations by influencing the growth of Ag NPs under a magnetic field. Under the influence of the magnetic field, the Lorentz force acting on charged particles or the Faraday rotation affecting the magnetic vector of light collectively altered particle trajectories. This resulted in varied Ag NP morphologies, which changed the hot-spot distribution and further improved the EM contribution in SERS[116]. In conclusion, magnetic fields can effectively assist in the construction and regulation of hot-spots, significantly enhancing the electromagnetic contribution in SERS.

5. Electric Field Modulation for SERS Research

Electric field-induced surface-enhanced Raman scattering (E-SERS) is a strategy grounded in the SERS principle, which modifies the physical and chemical properties of the substrate via an electric field. Typically, E-SERS is realized by applying an external electric field to the substrate or activating the substrate’s inherent electric field. Specifically, through the interaction between external fields and intrinsic electric field excitation, the local electromagnetic field within the substrate’s metallic nanostructures is modified, the band tilting of the semiconductor’s valence band and conduction band is disrupted, and the Fermi level of the metal is adjusted. Moreover, the accumulation of molecules can also be achieved through the electrophoretic migration of metal nanoparticles and probe molecules within the electric field[117,118]. Herein, E-SERS is classified into two primary categories based on the principle, namely, applied electric field and self-generated electric field. The former category includes various forms such as applied direct current and applied alternating current. Conversely, the latter category involves methods leveraging material-induced piezoelectric effects, thermoelectric effects, pyroelectric effects, and triboelectric effects.

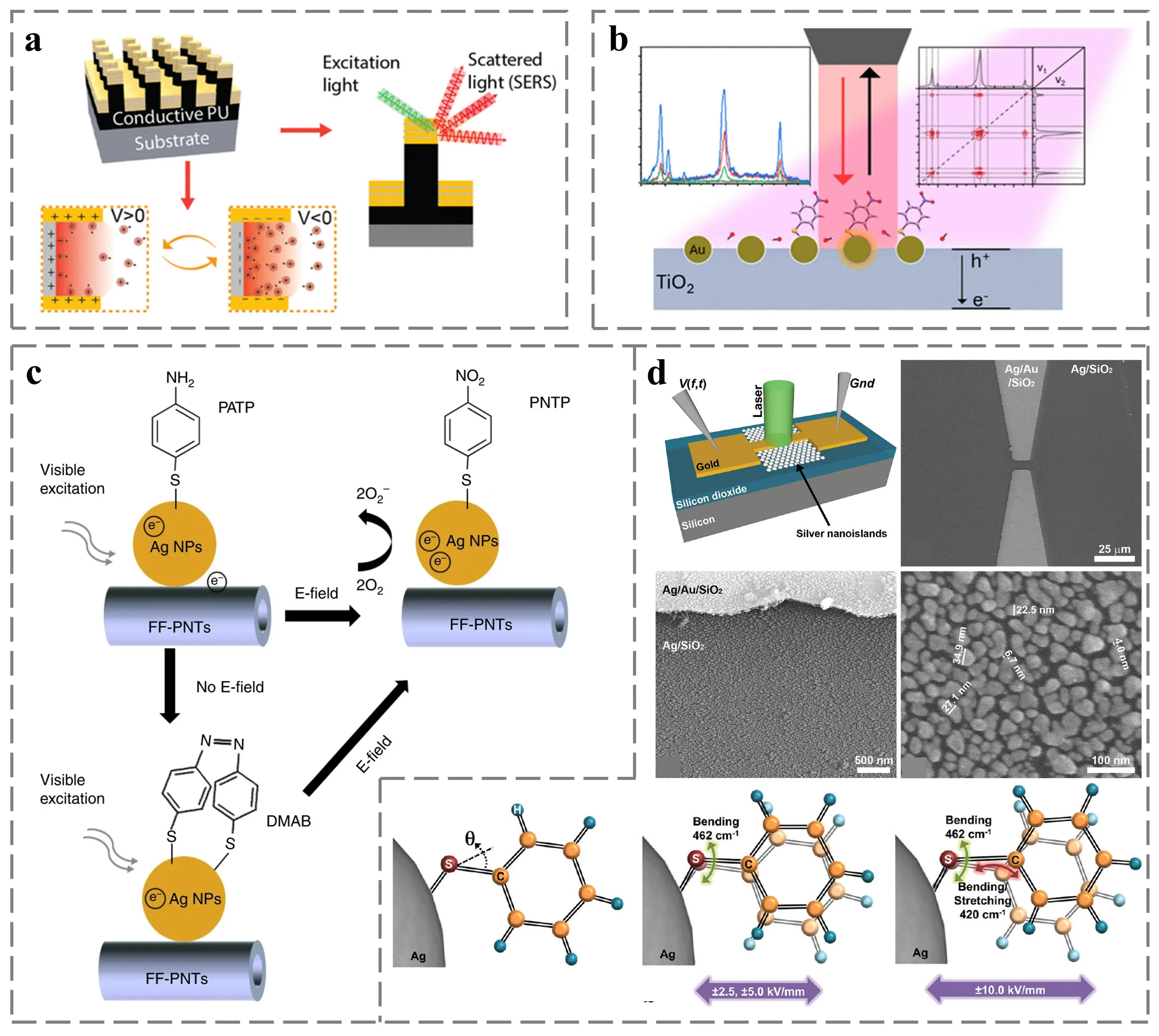

5.1 External electric field modulating SERS

The external electric field control involves directly applying voltage or current to the SERS substrate via an external circuit, thereby establishing a controllable electric field environment. This represents the most direct and flexible approach for electrical regulation. Under the influence of the electric field, a larger quantity of free electrons is attracted, actively participating in the charge transfer between the substrate and molecules, which substantially enhances the Raman signal. The application of an external electric field is the most direct and effective modulation method. The electric field affects the local electromagnetic field and free electron density at the substrate surface, thereby inducing a shift in the plasmon resonance peak. Moreover, applying a potential to specific structures can induce dielectrophoresis and dipole-dipole interactions, facilitating the enrichment of nanoparticles in high-electric-field regions and forming high-density hotspot zones. Conversely, the free electrons driven by the electric field participate in the charge transfer process between the substrate and the molecules, significantly modifying the charge transfer efficiency and further resulting in the enhancement of the Raman signal[119].

The effective action of the applied electric field is fundamentally contingent upon the modification of metal nanostructures and molecules. The superior electrical conductivity of metals facilitates efficient electric-field response and conduction, thereby augmenting the electromagnetic contribution in SERS. Simultaneously, alterations in molecular orientation and electron density further influence the chemical contribution. For instance, Zhou et al. explored the impact of double-layer nanolaminate nano-photoelectrode arrays (NL-NOEAs) on the direct current (DC) and alternating current (AC) of charged analyte molecules for SERS measurements in ionic solutions. The concentration and orientation of R6G molecules on the electrode surface can be regulated through the application of DC and AC voltages. Under AC voltage modulation, when the voltage is negative, the response pattern of R6G is largely consistent with the DC scenario. Nevertheless, when the voltage turns positive, in the absence of a depletion region, R6G molecules can directly migrate from the electrode surface to the bulk of the solution, resulting in a more rapid concentration equilibrium[120].

Chen et al. designed a controllable array of Au NPs deposited on a TiO2 template substrate. It was discovered that the electric field affects the angle and height of the adsorbed 4-NTP molecule, leading to a change in the effective dipole moment of the molecule. Specifically, as the surface charge decreases, the high electron density of the nitro group is repelled by the surface charge, causing the 4-NTP molecule to stand upright on the surface[121]. Rice et al. successfully assembled Ag NP-loaded peptide nanotubes onto microfabricated chips. The study posits that metal substrates serve as ideal charge-exchange sources, and when combined with semiconductor materials, they effectively impede hot-electron leakage, achieving temporal separation of charge equilibrium. Control experiments indicated that an applied electric field exerted minimal perturbation on the Si/Ag NPs substrate without altering its band position. In contrast, the FF-PNT/Ag NPs substrate demonstrated a four-fold enhancement in SERS, accompanied by intense spectral scintillation. This suggests that the charge effect in the FF-PNT/Ag NP composite stems from electric-field interaction[122]. Moreover, the application of a longitudinal electric field significantly stimulates field-induced coupling between low-energy electrons and Ag NPs, thereby promoting charge transfer between templates. The enhancement of the local electric field around Ag NPs induced by the external electric field, in conjunction with thermal electron migration, collectively gives rise to fluctuations in the Raman signal, providing compelling evidence for the role of external electric fields in SERS.

Naturally, the influencing factors were also further investigated. Mitchell et al. utilized microfabricated silver nanostructured electrode pairs to conduct in-situ observations of the effects of low-frequency (5 mHz-1 kHz) oscillating electric fields on the SERS of thiophenol molecules. Experiments demonstrated that the applied electric field not only modulated SERS peak intensities but also regulated specific vibrational modes of the analytes[123]. The above content is shown in Figure 10. Electric-field perturbations induced polarity changes in charged analytes, thereby altering scattering cross-sections. Peaks, which are associated with the sulfur-related bond that binds the molecule to the silver nanotexture, exhibit strong and distinguishable responses to the applied field, attributable to varying bending and stretching mechanics. Additionally, the oscillating electric field (alternating field) can induce synchronous vibration in adsorbed molecules, altering their dipole moment and the orientation of chemical bonds. This not only changes the scattering cross-section of the molecules but also enables molecular-specific recognition based on the vibration-frequency response.

Figure 10. (a) Schematic illustration of the effect of an applied electric field on molecular aggregation[120]; (b) Schematic illustration of the effect of an applied electric field on the adsorption Angle of a 4-NTP molecule. Republished with permission from[121]; (c) Schematic diagram of the electric field affecting the molecular transformation[122]; (d) Top: Micromachined SERS measurement device and its SEM images. Bottom: Electric field induced thiophenol molecular kinetics. Republished with permission from[123]. SERS: surface-enhanced Raman scattering; SEM: scanning electron microscopy.

This approach of applying an external electric field can achieve highly precise and real-time reversible electric-field regulation, which holds significant importance for enhancing the SERS signal. However, due to issues associated with additional devices, the stability of the entire system requires improvement, which restricts its further expansion in practical applications.

5.2 Spontaneous electric field modulating SERS

The spontaneous electric field regulation skillfully exploits the property of specific functional materials to generate built-in electric fields under external physical stimuli (force, heat, magnetism, and friction), thereby realizing the enhancement of SERS. Distinct from the direct application of an electric field, the thermoelectric effect, pyroelectric effect, piezoelectric effect, triboelectric effect, and flexoelectric effect all necessitate external stimuli to trigger the electric field. These stimulating elements encompass, but are not restricted to, temperature gradients, mechanical stress, and electromagnetic forces.

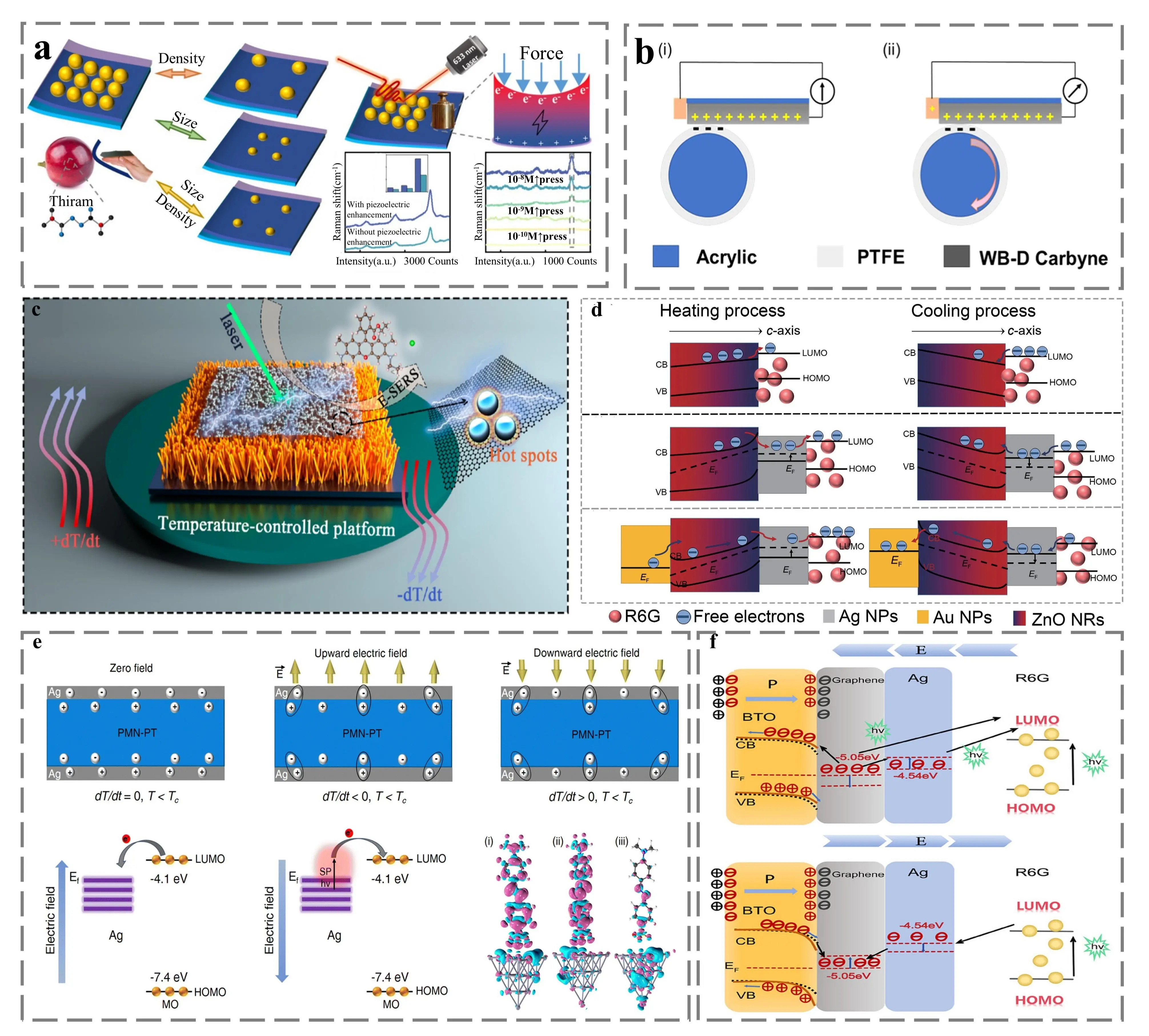

The piezoelectric effect pertains to the phenomenon in which non-centrosymmetric crystal materials generate polarized charges and electric potentials upon the application of external forces[124,125]. This phenomenon is attributed to the displacement of ions within the crystal structure during mechanical deformation. The generated polarized charges are highly likely to transfer to adjacent metals or two-dimensional materials, thereby altering their electron cloud density and LSPR properties, and consequently enhancing the SERS signal. The amplitude of signal enhancement exhibits a nonlinear relationship with the magnitude of strain, and an optimal value exists. Simultaneously, this effect can be classified into the direct piezoelectric effect and the inverse piezoelectric effect. The former refers to the generation of an electric field by mechanical stress, while the latter denotes the mechanical deformation caused by an externally applied electric field. This classification depends on the non-centrosymmetry of the crystal structure. Zhang et al. employed the polydopamine (PDA) layer as a mild and controllable reducing medium to optimize the size and spatial distribution of silver nanowires (Ag NWs) on the polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) nanofibers. This approach enabled relatively precise control over the size and density of the Ag NWs, creating an effectively dense-distributed hotspot. On the other hand, by leveraging the inherent piezoelectric properties of PVDF nanofibers, the LSPR effect in SERS testing was further enhanced, resulting in a flexible dual-enhancement composite SERS substrate with superior sensitivity[126]. Lu et al. designed a novel type of piezoelectric-enhanced zinc oxide/silver microcavity SERS substrate. Through the piezoelectric enhancement method, an enhancement factor of 1.05 × 1011 was achieved, and trace detection of dopamine molecules was realized[127].

The triboelectric effect refers to the phenomenon where, due to the disparity in electron affinity between two distinct materials, the surfaces of these materials will carry equal amounts of opposite charges[128-130]. When they come into contact and then separate, an electric charge is generated as a result of electron transfer at the material interface. The formation mechanism is primarily influenced by the dual effects of contact electrification and charge redistribution at the material interface. An et al. proposed a SERS substrate for tribo-electroactive Au-Ag binary metal nanostructures. Triboelectricity can be readily generated by simply rubbing the SERS substrate with copper foil. The generated electric field will enhance the hotspot intensity within the noble metal structure, leading to a three-fold increase in the SERS signal. The advantage over piezoelectric E-SERS substrates lies in the fact that the charge generation process is induced by gentle frictional motion during Raman measurements, which does not cause diffusion of laser irradiation due to film deformation and simplifies the measurement operation. The SERS substrate is expected to detect dye contaminants in simulated industrial oxidation solutions[131].

The thermoelectric effect refers to the bidirectional conversion between temperature gradient and electric potential in specific materials (i.e., thermoelectric materials). Its essence is the Seebeck effect, when a temperature gradient exists between the two ends of a thermoelectric material, charge carriers will diffuse from the hot end to the cold end, generating a thermoelectric potential[132-134]. This electric potential can modulate the Schottky barrier height and band bending between the semiconductor and metal nanoparticles, thereby regulating the interface charge transfer efficiency and the Fermi level of the metal, and significantly enhancing the contribution of CM. Li et al. combined the thermoelectric semiconductor material gallium nitride with Ag NPs to fabricate an electric field induced SERS substrate. By altering the temperature gradient, it was found that the thermoelectric potential can regulate the charge exchange between GaN and Ag NPs, thus shifting the Fermi level of Ag over a wide range and increasing the resonant electron transition probability with the detected molecule. Based on the principle of charge exchange, real-time monitoring of the catalytic reduction reaction of PATP to DMAB was achieved by changing the temperature[37]. In the same year, Li et al. proposed a thermoelectrically induced SERS substrate composed of a ZnO nanorod array and Ag NPs. The SERS signal intensity is further enhanced by applying the thermoelectric potential. Through analysis of the enhancement mechanism, it was discovered that the SERS signal enhancement induced by thermoelectricity should be classified as a chemical contribution. Meanwhile, it also provides a theoretical support for the real-time monitoring of PATP to DMAB reaction. It illustrates the possibility of applying thermoelectric effect to environmental monitoring[135]. Subsequently, Zhang et al. coupled the silver nanostructure of graphene as a spacer layer with the thermoelectric semiconductor P-type GaN. A thermoelectric field induced SERS substrate with graphene was then added, successfully achieving the double enhancement of EM and CM. The thermoelectric field enables rapid and repeatable doping of graphene, thereby adjusting its Fermi level over a wide range. The thermoelectric field also regulates the position of the plasmonic resonance peak of the silver nanocavity structure, which realizes the synchronous double regulation of electromagnetism and chemistry[136]. Additionally, graphene was added to the interlayer of ZnO and Ag NPs to achieve further SERS enhancement. It was also confirmed that the thermoelectric potential can simultaneously modulate the Fermi level of graphene and the plasmon resonance peak of Ag NPs to achieve double enhancement. Based on this double enhancement effect, the in-situ detection of SARS-CoV-2 virus is realized, and further combined with wearable devices to realize an actual detector using the temperature difference of human breathing[137].

The pyroelectric effect is that when the temperature changes, the spontaneous polarization intensity of polar crystal materials (such as PMN-PT, PVDF, and BaTiO3) changes, breaking the surface charge balance and generating a surface pyroelectric field[138-140]. This field can be used to instantaneously enhance the local electromagnetic field or drive charge transfer. This phenomenon occurs in materials lacking an inversion center in their crystal structure, resulting in a net electric dipole moment. At the beginning of the study, Li et al. constructed Ag/Gr/WTe2 heterostructures according to the principle of energy level matching, and attempted to excite the pyroelectric properties of two-dimensional ferroelectric materials. The charge transfer process in SERS is further enhanced by introducing the pyroelectric field, and the enhancement factor reaches 1.34 × 1012[141]. Subsequently, the pyroelectric crystals with excellent ferroelectric properties were explored. Li et al. presented a pyroelectric effect assisted SERS signal amplification platform combining PMN-PT with plasmonic silver nanostructures. The SERS signal intensity was further enhanced by more than 100 times after applying positive or negative thermoelectric potentials, confirming that CT induced CM is the main cause of enhanced E-SERS. This effective enhancement lies in the CT interaction between the molecule and the substrate, specifically the effective response of the electrons in the molecule to the applied electric field. Compared with the case without electric field, when the upward electric field is applied, the electrons migrate to the bottom atoms of the Ag cluster, while when the electric field is applied downward, the holes are localized on the Ag cluster. At the same time, the effective energy conversion of pyroelectric materials is used to realize the application scenario of light energy conversion to heat energy[142]. In addition, Li et al. utilized BaTiO3 as a pyroelectric field generator, and further incorporated graphene and Ag NPs as an effective platform for SERS. The local electromagnetic field simulation in the case of variable temperature shows that the electromagnetic field changes weakly under different temperature changes, confirming that the pyroelectric mainly improves the chemical contribution. The thermoelectric field drives the charge transfer between the SERS substrate and the molecules. For R6G, the driving electrons transfer from the Fermi energy level of Ag to the LUMO energy level during the heating process, and from the LUMO to the Fermi energy level of Ag during the cooling process. This charge transfer pathway guided by the pyroelectric field effectively excites SERS performance. Through this efficient charge transfer, the degradation of molecules under cyclic temperature variations was achieved, which stimulated the self-cleaning property of the substrate and further opened up new avenues for environmental monitoring[143]. The above content is shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. (a) Schematic representation of the SERS response enhanced by the piezoelectric effect. Republished with permission from[126]; (b) Schematic diagram of the triboelectric effect[144]; (c) Schematic diagram of the SERS performance enhanced by thermoelectric effect[137]; (d) CT process analysis based on Seebeck effect[135]; (e) Top: Pyroelectric schematic diagram. Bottom: CT process analysis (left) and charge density difference under electric field (right)[142]; (f) Pyroelectric induced CT process during heating (top) and cooling (bottom)[143]. SERS: surface-enhanced Raman scattering; CT: charge transfer.

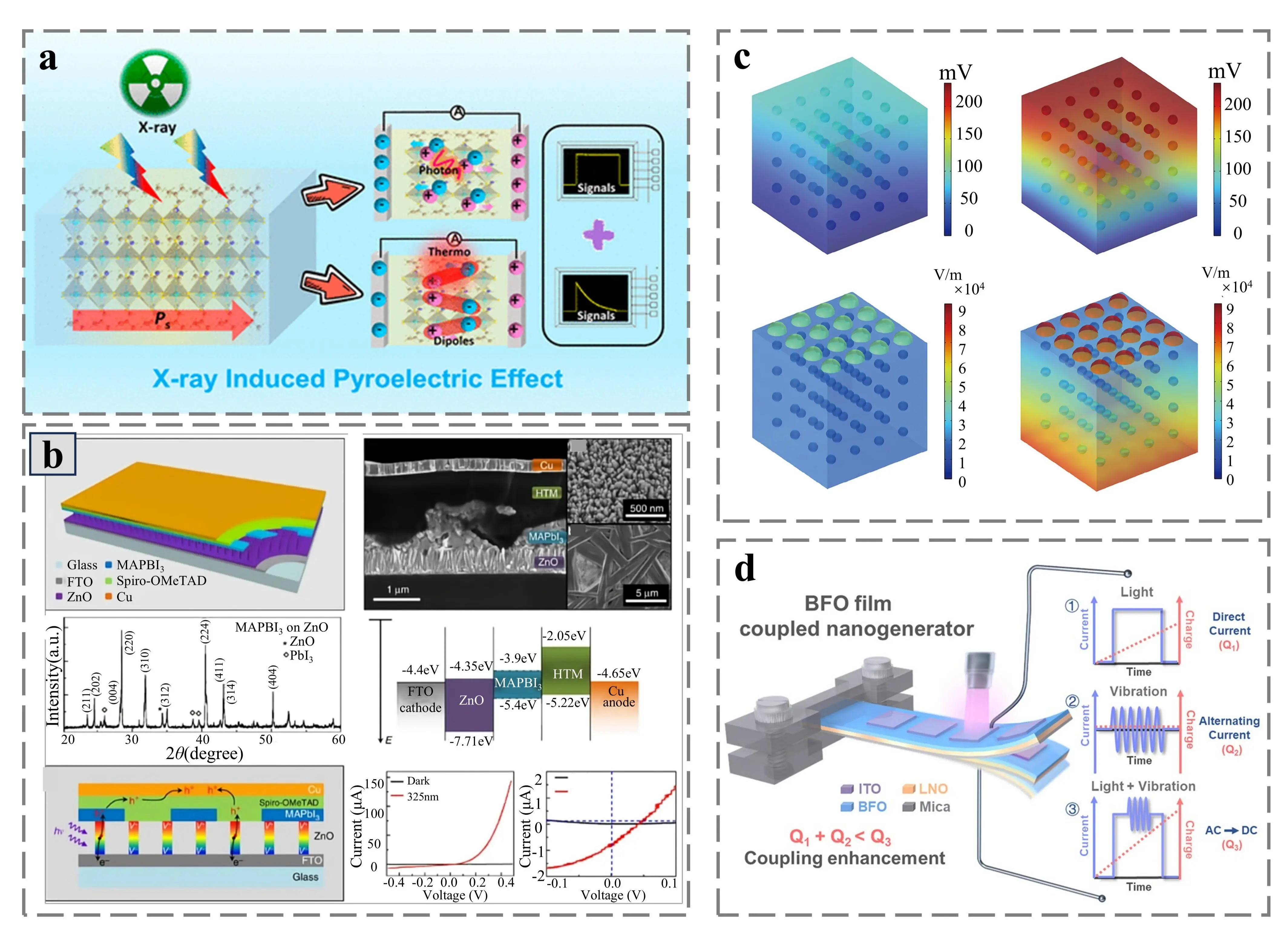

Undoubtedly, the aforementioned electrical regulation does not confine itself to a single regulatory means; instead, it exhibits diverse coupling regulation characteristics. For instance, Xu et al. employed the electrospinning technique to integrate the BiFeO3 pyroelectric functional layer with CNFs for the fabrication of a plasmonic metal/ferroelectric hybrid SERS substrate. Leveraging the photoinduced pyroelectric effect, the photoinduced thermal energy is efficiently converted into pyroelectric charge, subsequently adjusting the electron density of silver to enhance the electromagnetic field within the hotspot region[145]. In this manner, the photoinduced excitation and pyroelectric effect are effectively combined to achieve the coupling regulation of the SERS signal. Meanwhile, the real-time in situ monitoring of the photocatalytic reduction of p-nitrophenol (P-NTP) to 4,4'-dimercaptoazoben (DMAB) was achieved by multi-physical field regulation. It is promising to achieve further environmental monitoring of pollutant molecules.

Man et al. put forward a magnetoelectric composite film with SERS characteristics, the performance of which can be actively regulated through the remote application of a magnetic field. Here, the magnetoelectric coupling effect serves as the fundamental mechanism for realizing the SERS effect, which is generally regarded as the combined effect of the piezoelectric effect of the ferroelectric phase and the magnetostrictive effect of the ferromagnetic phase. Specifically, when an external magnetic field is applied, the ferromagnetic material undergoes stress due to the magnetostriction effect. This stress acts on the ferroelectric material, leading to a change in its self-polarized electric field. Based on this effect, the external magnetic field can alter the surface electric potential of the composite film, thereby adjusting the local electric field intensity of the silver nanoparticles on the membrane surface. At the same time, with the help of this remote magnetic field control, the detection limit of dopamine in aqueous solution is effectively improved. Furthermore, the composition of human sweat was identified, which was reflected in the accurate identification of urea and lactic acid. This multi-physical field control makes the process of analyzing complex components in sweat more convenient and accurate[146].

Moreover, apart from the several types of electrically regulated SERS that have been extensively investigated, there exist numerous other electrical effects with development potential (such as the flexoelectric effect and the photoelectric effect), whose outstanding electrical response characteristics form the basis for the application of electrically regulated SERS. For example, Yang et al. successfully constructed a novel type of coupling nanogenerator based on a flexible BiFeO3 ferroelectric thin film. The device effectively harnessed the flexoelectric effect to achieve the efficient collection of light energy and vibration energy[147]. Mishra et al. prepared a bulk Mn3O4 film, and by reducing the thickness of the oxide film, the activation of the bending mode was enhanced, which in turn resulted in a significant flexural response. At the same time, the material was successfully applied to self-powered paper-based flexible devices[148]. The above content is shown in Figure 12. Nevertheless, the mechanism of its re-SERS field still requires further exploration.

Figure 12. (a) Schematic illustration of the X-ray induced pyroelectric effect[149]; (b) Top: Schematic representation of the substrate structure (left) and SEM image (right). Middle: XRD profile of MAPbI3 (left) and band pattern of the substrate (right). Bottom: self-powered substrate mechanism diagram, left, and I-V characteristics in the dark or with a 325 nm laser[150]; (c) Local electromagnetic field distribution without Ag (top) and with Ag (bottom) in the absence (left) and presence (right) of the magnetic field[146]; (d) Schematic diagram of the flexoelectric effect. Republished with permission from[147]. SEM: scanning electron microscopy.

6. Prospects and Conclusions