Abstract

Aging is characterized by systemic dysregulation of intercellular communication, with extracellular vesicles (EVs) serving as key mediators that transport bioactive molecules, including long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), to modulate tissue homeostasis and aging processes. In this review, we summarize how EVs selectively package and deliver lncRNAs between cells, thereby transmitting senescence-related signals. These EV-associated lncRNAs regulate core aging-related signaling pathways such as p53, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), and sirtuins, influencing cellular senescence, stress adaptation, and systemic aging. In age-related diseases, including neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, and metabolic disorders, as well as osteoarthritis, EV-lncRNAs play significant pathophysiological roles by mediating inflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and tissue repair. Owing to the protection provided by the vesicular membrane and the selectivity of their loading, EV-lncRNAs exhibit exceptional stability and cell-type specificity in biofluids, positioning them as candidate biomarkers for aging clocks and disease risk stratification. Furthermore, they also hold potential as vehicles for therapeutic delivery. However, progress in this field is constrained by methodological heterogeneity in EV isolation and characterization, a lack of causal in vivo validation, and an incomplete understanding of lncRNA sorting mechanisms. Emerging advances in experimental and analytical technologies are expected to overcome these bottlenecks and facilitate the translation of EV-lncRNA regulatory networks into precision diagnostics and aging-targeted therapeutic strategies.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Aging is a systemic process driven by disrupted intracellular regulation and altered intercellular communication. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) play a central regulatory role in aging[1], showing pronounced age-dependent expression changes across tissues and participating in aging-related pathways[2]. Recent evidence indicates that aging-associated lncRNAs can be selectively packaged into extracellular vesicles (EVs) and transmitted between cells, rather than being passively released[3,4]. Functional roles of EV-associated lncRNAs secreted by senescent cells remain unclear, representing an important knowledge gap in aging research[5]. Moreover, circulating EV-lncRNA profiles correlate closely with chronological age and age-related diseases, underscoring their potential as sensitive biomarkers for systemic aging[6]. Collectively, EV-associated lncRNAs constitute an emerging regulatory axis linking intracellular gene regulation to systemic aging processes. Their stability, specificity, and regulatory richness highlight EV-lncRNAs as promising biomarkers and therapeutic targets for precision aging, although standardized EV methodologies and rigorous tissue-specific validation remain essential for clinical translation.

In this review, “EVs-mediated” refers to the intercellular communication process involving EVs, whereas “EV-derived lncRNAs” specifically denotes the lncRNA molecules that are selectively packaged and transported by EVs.

Aging is an inevitable and multifactorial biological process. It is characterized by a progressive decline in physiological functions, regenerative capacity, and stress resistance. Aging arises from the cumulative effects of molecular, cellular, and systemic perturbations, which gradually disrupt tissue homeostasis. The fundamental hallmarks of aging include genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, disabled macroautophagy, deregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, altered intercellular communication, chronic inflammation, and dysbiosis[7]. Increasing evidence indicates that aging is not solely driven by intracellular damage accumulation, but also by the propagation of stress signals between cells and tissues. Senescent and stressed cells actively remodel their microenvironment through the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), releasing cytokines, chemokines, metabolites, and EVs. EVs serve as a key component of the SASP, facilitating the protected and targeted transfer of bioactive cargos beyond soluble factors to neighboring or distant cells[8,9], thereby amplifying inflammatory signaling, metabolic imbalance, and tissue dysfunction at the organismal level[10,11].

EVs are nanosized, membrane-bound particles released by nearly all cell types and represent key mediators of intercellular communication[12]. According to their biogenesis and size, EVs are broadly categorized into exosomes (≈30-150 nm, endosomal origin), microvesicles (≈100-1,000 nm, plasma-membrane budding), and apoptotic bodies (≈500-2,000 nm, derived from dying cells)[13]. They transport diverse bioactive molecules, including proteins, lipids, DNA, mRNAs, microRNAs, and lncRNAs, that can reprogram transcriptional states, metabolism, and cellular fate in recipient cells[14]. In the context of aging, EVs have attracted increasing attention not only as circulating biomarkers that reflect tissue status, but also as functional effectors and therapeutic vehicles, particularly those derived from young or stem cells with regenerative and anti-inflammatory properties[15].

Among EV cargos, lncRNAs, which are transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides lacking protein-coding potential, have emerged as particularly compelling regulators due to their high cell-type specificity and versatile regulatory functions. lncRNAs can act as molecular scaffolds, decoys, or guides to modulate chromatin states, transcriptional programs, and post-transcriptional regulation[16,17]. Compared with proteins and microRNAs, lncRNAs display greater cell-type specificity and regulatory versatility, enabling them to act as scaffolds, decoys, or guides. When transferred via EVs, these properties allow lncRNAs to serve as stable and selective signals that propagate aging-associated regulatory states across tissues[18]. EV-associated lncRNAs can be categorized based on genomic context, structural determinants of vesicular loading[19], functional mechanisms in recipient cells, and cellular origin, highlighting their capacity to act as potent intercellular regulators of epigenetic and transcriptional programs[20,21].

During aging, senescent cells secrete EVs containing diverse bioactive cargos, including oxidized proteins, inflammatory mediators, and lncRNAs. Direct in vivo evidence for EV lncRNA-mediated propagation of aging signals remains limited. However, studies in cancer and stem cell models show that EV-derived lncRNAs can be delivered to neighboring or distant cells, where they modulate signaling pathways such as NF-κB, Wnt, and inflammatory cascades[22]. These findings support the mechanistic plausibility that EV-lncRNAs could propagate senescence- or inflammation-related signals in a paracrine or endocrine manner, potentially contributing to systemic tissue dysfunction. In contrast, EVs released from young or stem cells convey rejuvenating lncRNAs and other bioactive cargos that help restore mitochondrial homeostasis, suppress inflammatory pathways, and mitigate senescence-associated signaling[23,24]. Encapsulation within EVs protects lncRNAs from enzymatic degradation, enabling their stable presence in body fluids and supporting their potential as noninvasive biomarkers of biological aging[15,24]. Circulating EV microRNAs exhibit age-dependent expression patterns, showing promise for constructing molecular aging clocks that may provide noninvasive estimates of biological age[25,26]. Given that lncRNAs can be selectively packaged into EVs and exhibit broad regulatory versatility[27], EV-associated lncRNAs may similarly reflect biological aging processes. This raises the possibility that EV-lncRNAs could be exploited to develop lncRNA-based aging clocks, although validation in large-scale longitudinal studies is still required. Beyond aging models, EV-lncRNAs also hold potential in precision aging medicine. However, their application will depend on a deeper understanding of the mechanisms governing selective lncRNA packaging into EVs. At present, these mechanisms remain largely undefined.

In summary, the interaction between intrinsic cellular damage and EV-mediated lncRNA signaling represents a regulatory axis contributing to aging initiation and systemic propagation. Elucidating how EV-lncRNAs couple intracellular stress responses with intercellular communication may provide a molecular basis for lncRNA-guided diagnostics and interventions in age-related decline.

2. EV-Derived lncRNAs in the Regulation of Aging Processes

EVs are key mediators of intercellular communication, capable of transmitting both protective and regulatory signals that help maintain tissue homeostasis. In the context of aging, EV-associated lncRNAs may play dual roles, contributing to adaptive cellular responses while also influencing the onset and propagation of senescence. As cells enter a senescent state, EV secretion is markedly increased, exceeding canonical SASP factors[28,29]. Senescent or late-passage cells release substantially higher numbers of EVs than proliferating cells. These EVs are enriched in lncRNAs whose expression is associated with cellular senescence, as well as other regulatory molecules, suggesting a potential role in propagating aging-related signals[30]. By transferring their cargo (which may include regulatory lncRNAs, miRNAs, and proteins), senescent cell-derived EVs can modulate key senescence signaling pathways in recipient cells, thereby potentially promoting a senescent phenotype. While senescent EV-associated lncRNAs are biologically plausible mediators, their specific and necessary role in this process awaits direct experimental validation[31,32]. This intercellular communication can drive both localized and systemic senescence, exemplifying a “bystander effect” in tissue aging[33]. These observations indicate that EVs from senescent cells function not only as conveyors of senescence signals but also as modulators of critical aging-related pathways. They provide a conceptual framework for exploring their molecular cargo and functional impacts in future studies[34,35].

2.1 Mechanistic considerations for EV-lncRNA transfer in aging contexts

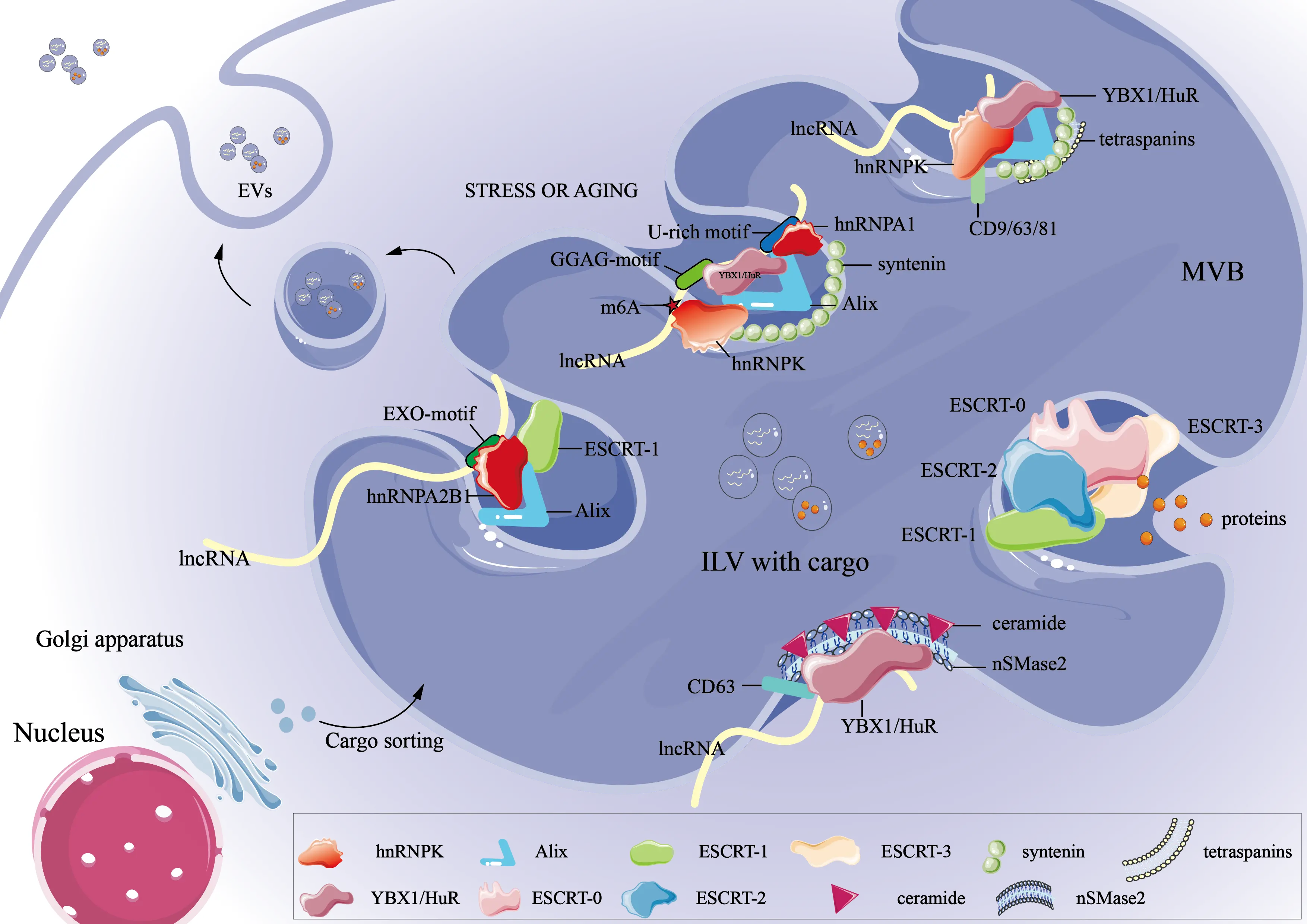

The functional involvement of EV-associated lncRNAs in aging depends on two tightly coupled processes: their selective incorporation into EVs and their subsequent delivery to recipient cells. As summarized in Figure 1, these steps together constitute an integrated transmission axis that provides the mechanistic foundation for aging-related intercellular communication.

Figure 1. Mechanisms of lncRNA loading into EVs. EV: extracellular vesicle; lncRNAs: long non-coding RNAs; MVB: multivesicular body; ESCRT: endosomal sorting complexes required for transport; m6A: N6-methyladenosine; EXO: exosome; RNA: ribonucleic acid.

Selective lncRNA incorporation into EVs is governed by coordinated interactions between RNA sequence or structural features, RNA-binding proteins (RBPs), and vesicle biogenesis machinery (Figure 1). Emerging evidence indicates that lncRNAs with shorter length, higher structural stability, or defined secondary structures are preferentially loaded into EVs, while specific RNA regions, including elements within the 3’ untranslated region (UTR), further contribute to selective sorting[19]. Additionally, the 3’UTR of RNA may also contain loading signals, with specific segments or elements (such as fewer A/U-rich regions) aiding in guiding lncRNA into EVs[19,36]. These sequence features typically interact with RBPs to recognize specific motifs or structures on RNA, forming RNA–RBP complexes that enable selective transport. As illustrated in Figure 1, hnRNPA2B1 acts as a molecular adaptor that recognizes cytoplasmic lncRNAs containing the EXO-motif (e.g., GGAG). It facilitates their recruitment to sites of intraluminal vesicle formation within multivesicular bodies[37]. Mechanistic insights into RBP-mediated lncRNA sorting have largely been derived from cancer and other model systems. For example, in renal cell carcinoma, the drug resistance-associated LncARSR has been shown to rely on hnRNPA2B1 for its incorporation into EVs, and depletion of hnRNPA2B1 markedly reduces LncARSR levels within EVs[38]. Although specific studies in senescent or aged cells are still emerging, RBP-mediated sorting mechanisms observed in other cellular contexts may similarly contribute to the packaging of lncRNAs into EVs during aging, considering the conserved nature of RBPs and RNA motif recognition[19]. Similarly, as summarized in Figure 1, the lncRNA H19 carries a GGAG sequence at its 5’ end, which binds to hnRNPA2B1 and enables its selective packaging into EVs. Mutating this motif or knocking down hnRNPA2B1 both impedes its loading[39]. Other RBPs shown in Figure 1 regulate lncRNA fate through distinct recognition modes. Human antigen R (HuR, encoded by ELAVL1) binds AU-rich elements and modulates RNA stability and transport[40]; LncRNA PDCD4-AS1 influences PDCD4 mRNA stability by interfering with HuR binding via double-stranded RNA formation[41]. Y-box binding protein 1 (YBX1) binds to CA-rich or UC-rich elements and mediates the exosomal loading of specific lncRNAs such as lncRNAAC073352.1. This process is closely associated with metastasis and angiogenesis in breast cancer[42,43].

RNA chemical modifications add an additional regulatory layer to selective lncRNA sorting, with m5C marks recognized by YBX1 and NSUN2 enhancing the stability and EV-mediated signaling capacity of lncRNA H19[44], and m6A modification facilitating hnRNPA2B1-dependent loading of lncRNAs into EVs[45,46]. Environmental and cellular states similarly influence lncRNA loading, as illustrated in Figure 1. When cells experience hypoxia, inflammation, or aging-related stress, RBP expression and membrane lipid composition change, thereby indirectly regulating the selective loading of lncRNAs[47,48]. When cells select suitable lncRNAs, ceramide enriched by lipid rafts promotes negative curvature formation in endosomal membranes via nSMase2, thereby promoting the formation of intraluminal vesicles (ILVs)[49]. At the same time, ALIX (ALG-2-interacting protein X)[50,51] and CD63[19,52] serve as Membrane-anchored factors. They accumulate in specialized membrane microdomains, providing space and structural support and spatial niches for the entry of RNA–RBP complexes[53]. Additionally, aging or stress stimuli can modulate EV secretion by regulating the expression of components such as Rab GTPases[54] or the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT)[55]. As captured schematically in Figure 1, the ESCRT complex contributes to the inward budding and scission of ILVs, thereby enabling the incorporation of lncRNA–RBP complexes into nascent EVs, which in turn affect EV release levels[56]. Collectively, these processes establish a highly regulated, multi-level framework that governs the selective loading of lncRNAs into EVs.

This figure provides a mechanistic framework rather than aging-specific pathways. Under stress or aging conditions, specific RBPs such as hnRNPA1, hnRNPA2B1, and hnRNPK recognize lncRNAs through sequence motifs (e.g., GGAG, U-rich, or EXO-motifs) and facilitate their sorting into ILVs via ESCRT-dependent or tetraspanin/ceramide-mediated pathways. The multivesicular body subsequently fuses with the plasma membrane to release EVs containing lncRNA cargo.

Beyond their selective packaging into EVs, lncRNAs also actively influence subsequent stages of EV communication. EV uptake by recipient cells occurs primarily via endocytosis (clathrin-, caveolin-mediated, or macropinocytosis) or membrane fusion, with receptor-mediated signaling also contributing to intracellular pathway activation without full internalization[51,57]. Certain EV-derived lncRNAs enhance reuptake through feedback signaling; for instance, lncARSR activates the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor/Protein Kinase B (AKT) pathway in recipient cells, establishing a positive feedback loop that promotes EVs’ internalization[38,58]. Other lncRNAs indirectly influence uptake by regulating the expression of Rab GTPases or integrins, thereby modulating vesicle trafficking and membrane adhesion[59]. Moreover, specific lncRNAs such as H19 and LincRNA01703 can remodel lipid rafts and the actin cytoskeleton of target cells, facilitating EV adhesion and internalization[59,60]. Overall, these findings delineate a reciprocal regulatory model in which EVs deliver lncRNAs as functional signaling cargo, while lncRNAs actively reshape the molecular landscape governing EV recognition, entry, and release. This dynamic feedback mechanism not only fine-tunes intercellular communication but also provides a conceptual framework for developing lncRNA-guided EV-based diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Importantly, in the context of aging, age-related changes in stress responses, RBP expression, and membrane dynamics may alter EV-mediated lncRNA communication, highlighting the potential role of EVs in aging processes and age-associated pathologies.

2.2 EVs-mediated lncRNA regulation of cellular aging pathways

Following their established roles in EV packaging and uptake, EV-derived lncRNAs further modulate key signaling pathways in recipient cells, thereby influencing cellular aging processes. Cellular senescence, a state of irreversible cell-cycle arrest, is a fundamental contributor to organismal aging and age-related pathologies. The signaling pathways governing senescence, most notably p53, mTOR, and sirtuins, are frequently dysregulated during aging. Emerging evidence suggests that EV-derived lncRNAs may function as intercellular messengers to modulate these pathways in recipient cells and thereby influence senescence-associated processes. This section focuses on evidence from aging and senescence models, while noting that mechanistic understanding is partly informed by studies from related fields, including cancer biology.

The p53 pathway is a master regulator of genomic stability and cellular stress responses and plays a dual role in tumor suppression and aging. Transient activation of p53 promotes DNA repair and cell survival, whereas chronic or excessive p53 signaling induces senescence or apoptosis and is associated with tissue degeneration and reduced regenerative capacity during aging[61]. Evidence from Aging and Age-Related Disease Models: Direct evidence linking EV-lncRNAs to p53 regulation in aging tissues is still emerging. However, instructive parallels are provided by studies in age-related disease models. For instance, in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (an age-exacerbated condition), EVs carrying LINC00174 suppress p53-mediated autophagy and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes, mitigating injury[62]. This finding suggests that EV-lncRNAs may be capable of delivering functional p53-modulatory signals under age-related stress conditions. Mechanistic Insights from Cancer Models: To further explore potential mechanisms, insights can be drawn from extensively characterized cancer systems. In p53-mutated ovarian cancer, cisplatin-induced EVs carrying lncRNA PANDAR modulate p53-associated stress responses to enhance cell survival[63,64]. Although these findings arise in a distinct pathological context, they reveal molecular principles by which EV-lncRNAs interface with the core p53 pathway. Such conserved mechanisms suggest testable models for EV–lncRNA-mediated modulation of p53 in senescence and tissue aging.

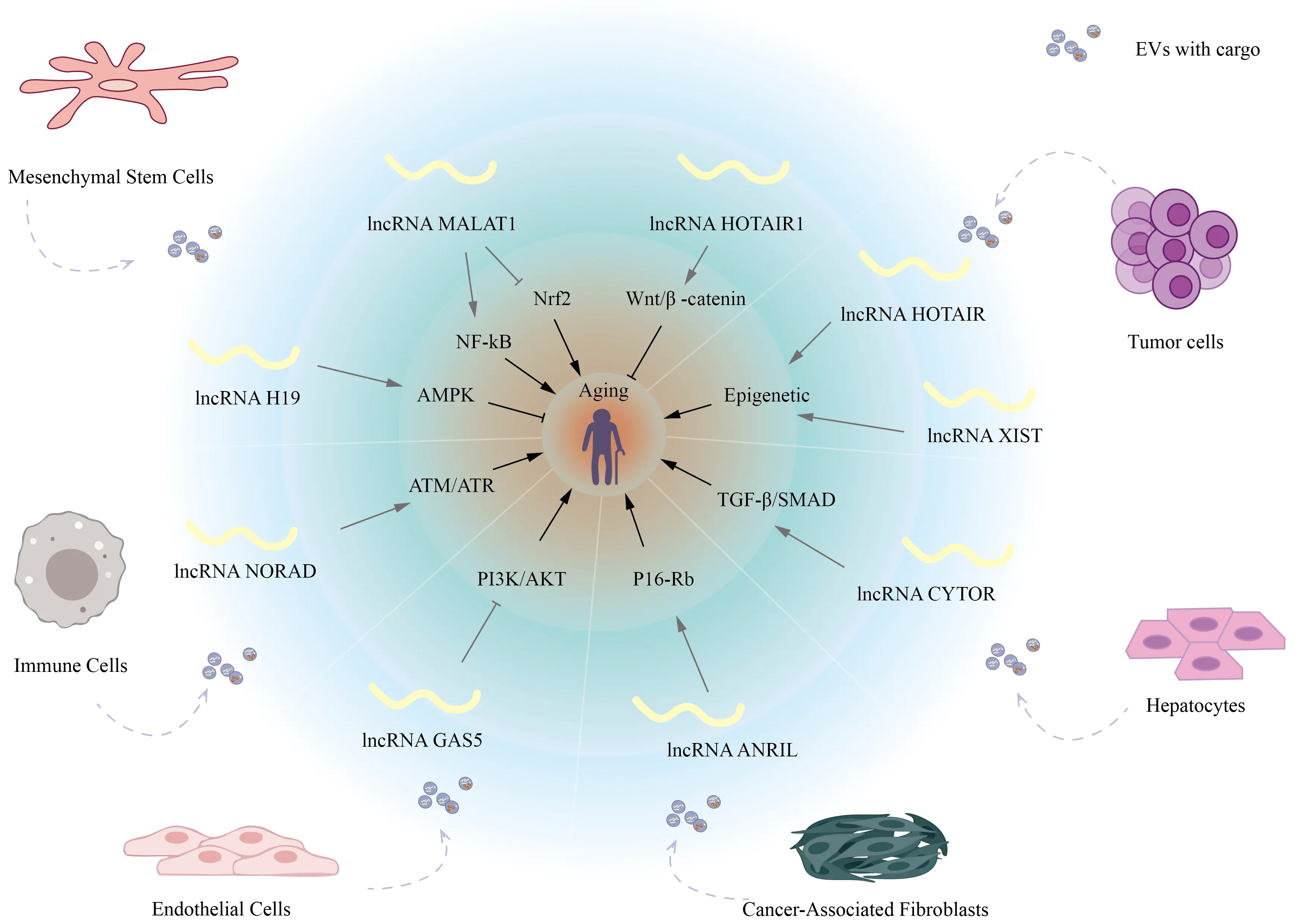

mTOR is a central regulator of cellular growth, metabolism, and aging. Its chronic activation accelerates aging by suppressing autophagy and promoting metabolic imbalance[65]. Evidence Linking EV-lncRNAs to mTOR in Aging Contexts: Excessive mTOR activation in aged tissues is closely associated with impaired autophagy and diminished cellular homeostasis[24]. EV-lncRNAs such as MALAT1[66,67] and GAS5[68] have been shown to regulate inflammatory responses and autophagy through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (Figure 2), suggesting a potential role in age-associated metabolic reprogramming. Mechanistic Insights from Disease Models: In non-small cell lung cancer, EVs containing lncRNA-UFC1 suppress PTEN transcription via EZH2, thereby activating mTOR signaling in recipient cells[69]. This exemplifies how EV-derived lncRNAs can reinforce mTOR signaling to alter cellular fate decisions, a mechanism relevant to age-associated mTOR hyperactivation.

Figure 2. Schematic overview of EV-associated lncRNAs in aging-related signaling networks. EV: extracellular vesicle; lncRNAs: long non-coding RNAs; GAS5: growth arrest–specific 5 RNA; MALAT1: metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; AKT: protein kinase B; Wnt/β-catenin: canonical signaling pathway regulating osteogenesis.

Sirtuins are NAD+-dependent deacetylases that coordinate redox balance, genomic stability, and metabolic homeostasis. Their functional decline is a hallmark of cellular aging[70,71]. Research has revealed that lncRNAs within EVs can influence cellular senescence by regulating the expression and activity of sirtuins, thereby modulating aging-related stress adaptation at the intercellular level. These lncRNAs typically act through two principal mechanisms: modulating miRNA targeting of sirtuin mRNAs (primarily SIRT1 or SIRT2) via a “sponge” or competitive endogenous RNA mechanism, or regulating sirtuin protein stability, for example, through deubiquitinating enzymes such as USP22. Through these mechanisms, EV-derived lncRNAs serve as upstream modulators of sirtuin-dependent aging pathways. EV-lncRNAs in Sirtuin-Mediated Protection: EVs carrying lncNEAT1 can sequester miR-221-3p, thereby promoting SIRT2 expression and mitigating doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte senescence[72] (Table 1). This provides evidence that EV-lncRNA–mediated activation of sirtuin signaling can counteract stress-induced cellular aging. Similarly, EVs from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) carrying lnc-KLF3-AS1 can increase SIRT1 protein stability via USP22, improving outcomes in brain injury models[90]. Modulation of Aging Phenotypes: LncRNA H19 within EVs can adsorb miR-138 to upregulate SIRT1, reducing UVB-induced DNA damage and photoaging phenotypes[91] (Table 1). These findings highlight how EV-lncRNAs can serve as upstream modulators of sirtuin-dependent aging pathways across different tissues.

| Pathway | Main Function | Representative LncRNA | Potential EV-Mediated Effect |

| p16–Rb | Cell cycle arrest | ANRIL | Induces senescence in neighboring cells[73,74] |

| ATM/ATR | DNA damage response | NORAD | Paracrine transmission of DNA damage signals[75,76] |

| AMPK–PGC1α | Energy homeostasis | H19 | Regulates mitochondrial metabolism[77,78] |

| NF-κB | mitigating inflammation | a1 | prevention and repair of aging-induced damage[79,80] |

| JAK/STAT | SASP secretion | LincRNA-p21 | Activates STAT3 signaling[81] |

| TGF-β/SMAD | Fibrosis and EMT | CYTOR | Promotes tissue aging[82] |

| Nrf2–Keap1 | Antioxidant defense | MALAT1 | Attenuates oxidative senescence[83,84] |

| Wnt/β-catenin | Stem cell renewal | HOTAIR, NEAT1 | Causes imbalance in tissue regeneration[85,86] |

| PI3K/AKT | Metabolic/apoptotic balance | GAS5 | Inhibits survival signaling[68,87] |

| Epigenetic | Chromatin regulation | XIST, HOTAIR | Drives epigenetic remodeling[88,89] |

EV: extracellular vesicle; lncRNAs: long non-coding RNAs; ANRIL: antisense non-coding RNA in the INK4 locus; DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; H19: imprinted maternally expressed lncRNA involved in growth control; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; MALAT1: metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1; SASP: senescence-associated secretory phenotype; PI3K: phosphoinositide 3-kinase; AKT: protein kinase B; Wnt/β-catenin: canonical signaling pathway regulating osteogenesis; HOTAIR: HOX transcript antisense RNA.

These EV-derived lncRNAs regulate intracellular processes and mediate intercellular signaling, thereby potentially affecting the senescence of neighboring and distant tissues (Figure 2). A summary of additional key aging-related pathways influenced by EV-derived lncRNAs is provided in Table 1. Targeting these EV-lncRNA axes may offer promising strategies for delaying tissue aging and developing novel anti-aging therapies.

EV-derived lncRNAs from senescent or tumor cells participate in key regulatory axes of aging, including the representative pathways. Dysregulation of these signaling cascades influences autophagy, apoptosis, and DNA repair, ultimately determining cellular fate, tissue regeneration capacity, and age-associated pathophysiological processes.

2.3 Epigenetic functions of lncRNAs

Given their established roles in modulating aging-associated signaling pathways, EV-derived lncRNAs may further influence cellular phenotypes through epigenetic regulation. By altering chromatin states and gene expression patterns in recipient cells, these lncRNAs can reinforce or modulate aging-related responses, highlighting an additional layer through which EV-lncRNAs contribute to the aging process. lncRNAs have emerged as central epigenetic regulators in diverse physiological and pathological contexts, including tumorigenesis and aging. Within the nucleus, lncRNAs can directly modulate chromatin architecture. For instance, the well-characterized HOTAIR lncRNA recruits the PRC2 complex and the histone demethylase LSD1 to mediate H3K27 trimethylation and H3K4 demethylation[92], thereby reshaping chromatin architecture and regulating gene expression with high specificity[22,93]. Evidence shows that lncRNAs such as H19, LNMAT2, and AL139294.1 can be selectively packaged into EVs and delivered to recipient cells, where they epigenetically silence target genes through DNA methylation or histone modifications, thereby promoting tumor progression[22,94]. EV-packaged lncRNAs mediate intercellular communication, extending their epigenetic regulation beyond individual cells and highlighting their potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets in aging and disease.

3. EV-Derived lncRNAs as Emerging Mediators in Age-Related Diseases

3.1 Neurodegenerative diseases

In neurodegenerative diseases, lncRNAs within EVs are believed to play a crucial role in inter-neuronal signaling, neuroinflammation regulation, and maintenance of cellular homeostasis. Taking Alzheimer’s disease as an example, studies reveal that the EV-derived lncRNA BACE1-AS stabilizes BACE1 mRNA, promoting excessive Aβ production and thereby exacerbating neurotoxicity and amyloid plaque deposition[95,96]. Interestingly, MALAT1 displays neuroprotective properties, limiting neuronal apoptosis and oxidative stress while dampening inflammatory processes[97]. In Parkinson’s disease, EV-derived lncRNAs NEAT1 regulate α-synuclein aggregation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammasome activation, contributing to dopaminergic neuronal degeneration[98]. Notably, aging significantly alters the lncRNA loading profile of EVs, transforming these molecules into potential biomarkers for early diagnosis beyond their role as pathological signal carriers in the nervous system. Future strategies targeting the expression and loading of EV–lncRNAs, or utilizing engineered EVs to deliver protective lncRNAs, may provide novel therapeutic avenues for intervening in neurodegenerative diseases.

3.2 Cardiovascular disease

Recent studies have highlighted the therapeutic potential of EV-encapsulated lncRNAs in cardiovascular diseases. Ischemia/reperfusion (I/R)-treated cardiomyocytes release EVs enriched with lncRNA KLF3-AS1, which enhances IGF-1 secretion by MSCs to mitigate myocardial injury[99]. Similarly, MSCs pretreated with macrophage migration inhibitory factor secrete EVs containing lncRNA NEAT1, which is transferred to cardiomyocytes to alleviate doxorubicin-induced cardiac senescence[72]. Reviews have further emphasized that exosomal lncRNAs exert cardioprotective effects across myocardial infarction, myocardial fibrosis, and I/R injury by regulating apoptosis, fibrosis, and inflammation[100,101]. In addition, atorvastatin has been shown to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of MSC-derived EVs in acute myocardial infarction, partly by upregulating exosomal lncRNA H19, thereby improving cardiac repair[102]. Collectively, these findings indicate that EV-associated lncRNAs not only function as intercellular signaling mediators but also hold promise as therapeutic agents in cardiovascular disease management.

3.3 Immune aging and metabolic syndrome

Exosomal lncRNAs play a pivotal role in linking the vicious cycle of immune senescence and metabolic syndrome by mediating precise organ-cell dialogues. EVs released by senescent or stressed immune cells, such as macrophages rich in lncRNAs like NEAT1 and MALAT1, act as inflammatory messengers[103,104]. By activating pathways like NF-κB, they drive M1 polarization of macrophages and stimulate secretion of inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and TNF-α[103,105], thereby establishing systemic inflammatory senescence. Simultaneously, these lncRNAs exacerbate T-cell exhaustion and dysfunction by regulating immune checkpoint molecules like PD-1[106]. Regarding metabolic syndrome, adipose tissue-derived extracellular lncRNAs in obesity directly transmit metabolic disturbance signals to insulin-sensitive tissues like liver and muscle[107]. By interfering with critical nodes in the IRS-1/Akt insulin signaling pathway, they induce systemic insulin resistance[108]. Concurrently, lncRNAs like H19 promote de novo hepatic lipid synthesis by regulating transcription factors such as SREBP-1c[109], thereby exacerbating hepatic steatosis[68]. Exosomal lncRNAs establish an efficient signaling bridge between immune aging and metabolic syndrome. They convert metabolic stress signals from energy excess into immune inflammatory signals and transmit the aged and dysfunctional state of the immune system to metabolic tissues, thereby driving a mutually reinforcing vicious pathological cycle.

3.4 Osteoarthritis regeneration

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a prevalent age-related degenerative joint disease characterized by cartilage degradation, synovial inflammation, and subchondral bone remodeling. Its incidence increases sharply with aging, making it a major contributor to pain and disability in elderly populations. Recent studies suggest that intercellular communication mediated by EVs and their lncRNA cargo plays critical roles in OA pathogenesis and therapy. EVs carrying lncRNAs have been shown to modulate cellular functions relevant to OA progression and joint repair. For instance, H19 promotes osteogenesis and angiogenesis by binding miR-106 and activating the Lnc-H19/Tie2-NO axis[80]; MALAT1 enhances osteoblast function via the miR-34c/SATB2 axis[110]; and osteoclast-derived LOC103691165 promotes bone repair by binding Osterix to reduce its ubiquitination and degradation[111]. These findings indicate that EVs not only serve as lncRNA delivery vehicles but also coordinate multi-cellular, multi-gene networks and signaling pathways. In OA research, synovial mesenchymal stem cell-derived EVs carrying lncRNA SNHG14[112] promote cartilage matrix synthesis, repair cartilage damage, and alleviate pain in OA rat models, demonstrating potent anti-inflammatory and chondroprotective effects. Engineered delivery systems, such as hydrogel sustained-release[113], prolong EVs’ retention within the joint cavity, enabling continuous release[114]. Collectively, these findings underscore the pivotal role of EV-lncRNA complexes in age-related joint degeneration and repair, providing a mechanistic and translational foundation for EV-based OA therapies.

4. EV-Derived lncRNAs as Biomarkers and Precision Indicators of Aging

Compared with traditional circulating lncRNAs or protein biomarkers, exosomal lncRNAs exhibit exceptional stability and high specificity, making them highly promising candidates for biomarkers of aging and age-related diseases. Their stability stems from a dual mechanism: the EVs’ lipid bilayer protects RNAs from RNase degradation in the bloodstream, and the intracellular microenvironment preserves RNA integrity during storage and circulation, supporting reliable clinical detection[115,116]. Crucially, their loading is not random but reflects a selective “molecular snapshot” of the parent cell’s physiological or pathological state[24]. Their lncRNA profiles have the potential to serve as precise “molecular signatures,” revealing cellular origin and functional status[117,118]. As enriched and stable carriers of biomarkers, EVs hold immense potential for the diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring of malignant and non-malignant diseases[119].

4.1 Biomarkers for systemic aging

Population studies reveal that EV-lncRNA profiles undergo systematic changes with age, contributing to molecular models that predict biological age, such as lncRNA-based aging clocks[23,120]. Although independent validations have demonstrated their practicality and potential causal associations, large-scale longitudinal cohorts are still required[121]. Direct clinical evidence is emerging: in a study of 155 elderly individuals, a three-plasma-EV-lncRNA signature (LINC001380, ENST00000484033, ENST00000531087) differentiated those with mild cognitive impairment with an AUC of ~0.70[6]. Complementary primate studies confirm that lncRNAs exhibit dynamic, stage-specific expression patterns during critical aging windows, distinct from other RNA species[122]. Compared with individual markers, these EV-lncRNAs offer enhanced sensitivity through combinatorial signatures, tissue- and cell-type specificity, and stability conferred by vesicle encapsulation, supporting their utility as reliable biomarkers for early detection, monitoring, and risk stratification. Beyond their value as biomarkers of aging, EVs can also function as delivery platforms for functional lncRNAs.

4.2 Diagnostic and prognostic applications in age-related diseases

Multiple patient-based studies have demonstrated that tissue-enriched EV-derived lncRNAs can be detected in circulation and serve as non-invasive biomarkers. In neurodegenerative disease, elevated levels of brain-derived, EV-associated BACE1-AS in plasma correlate with Alzheimer’s pathology[95]. In cardiovascular aging, plasma EV-ANRIL and H19 levels are linked to disease severity and prognosis[101,123]. For metabolic disorders, adipose tissue-derived EV-lncRNA MEG3 shows an association with insulin resistance, potentially serving as an early indicator[108]. In age-related diseases, distinct EV-derived lncRNAs signatures allow patient stratification and prediction of treatment response, as shown in hepatocellular carcinoma and advanced cancer[124]. Circulating EV-derived lncRNAs also reflect disease activity in systemic autoimmune disorders and cardiovascular aging, supporting individualized risk assessment[125]. These combinatorial signatures consistently demonstrate superior diagnostic performance over single markers[126,127].

4.3 Therapeutic potential and translational challenges

Notably, EV-mediated transfer of lncRNA H19 splice variants to cardiac cells promotes cardiac repair, providing proof-of-concept for EV-lncRNA-based strategies targeting age-associated functional decline[128]. Their dynamic expression changes during treatment render them sensitive tools for real-time monitoring of therapeutic efficacy[129,130]. However, therapeutic translation remains nascent. Major hurdles include methodological standardization to control for batch effects, establishing robust normalization protocols for quantification, addressing significant inter-individual variability, and navigating evolving regulatory pathways for EV-based products.

5. Methodological Considerations and Technical Perspectives

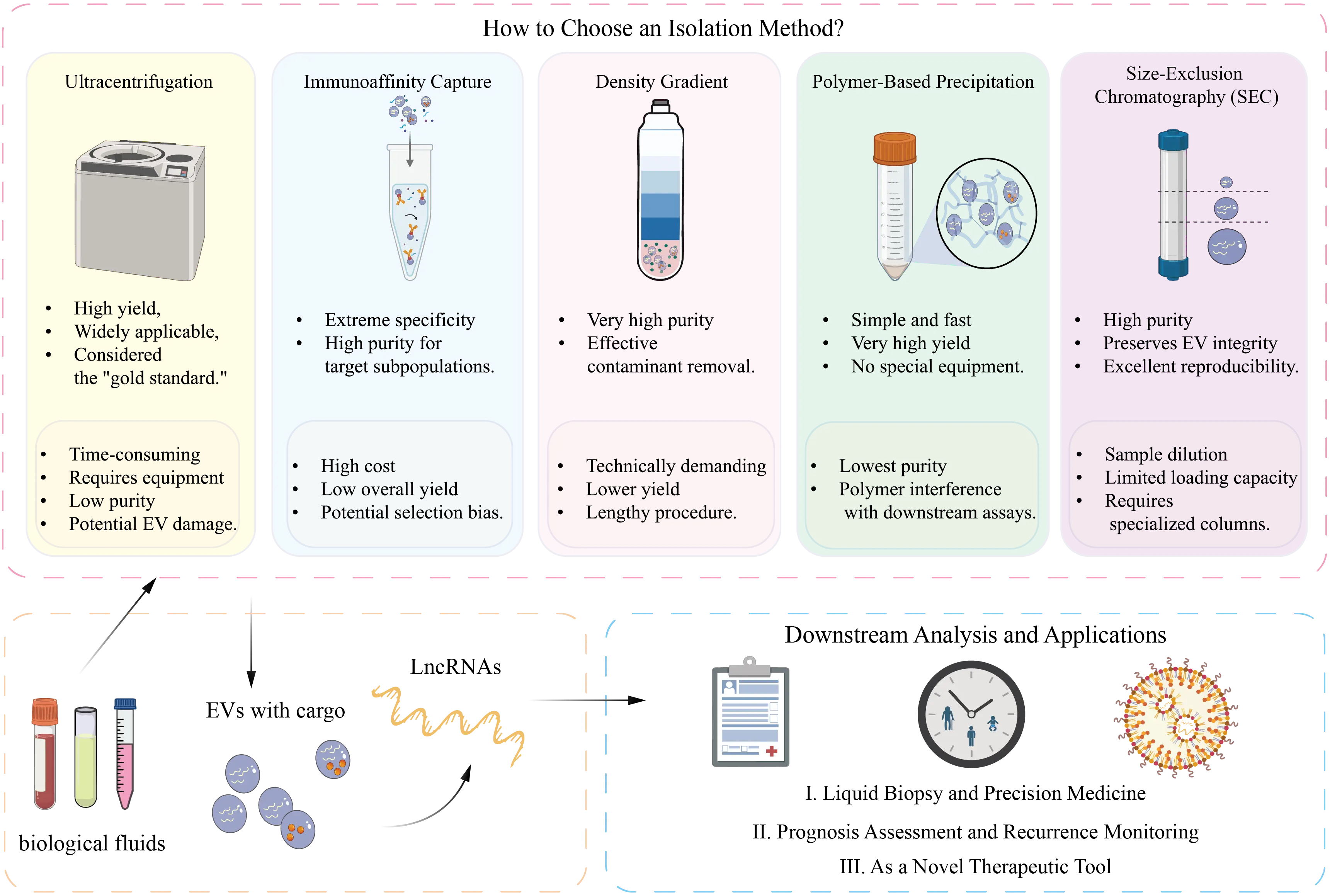

Although EV-derived lncRNAs are promising non-invasive biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring, their clinical translation is still limited by three major methodological challenges: isolation and purification, detection and analysis, and standardization (Figure 3). Ultracentrifugation remains the classical gold standard for EV isolation but is labor-intensive and may damage vesicle integrity. Alternative approaches, including differential centrifugation, density gradient centrifugation, polymer-based precipitation, and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), each involve trade-offs between purity, yield, scalability, and downstream compatibility. Differential centrifugation often results in contaminant co-precipitation, density gradients provide high purity but low yield, and polymer-based methods may introduce interfering residues. Emerging platforms such as SEC, microfluidic systems, and the EXODUS system offer improved purity, throughput, and preservation of biological activity and are summarized in Table 2[137]. Detection of EV-derived lncRNAs is further hindered by their low abundance (≈3.36% of total exosomal RNA) and complex structural features, which limit the sensitivity of conventional qPCR. Current strategies include pre-amplification, selection of stable lncRNAs, and complementary validation using RNA immunoprecipitation and dual-luciferase reporter assays. In parallel, the lack of standardized protocols contributes to substantial inter-laboratory variability; therefore, the Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles guidelines recommend the use of multiple positive and negative EV markers to ensure data comparability.

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Ultracentrifugation | Widely recognized as the gold standard; capable of processing large sample volumes; does not require chemical reagents | Time-consuming and equipment-intensive; high centrifugal force may damage EVs structures; limited purity[131] |

| Precipitation | Simple and rapid operation; suitable for parallel processing of multiple samples | Co-precipitation of non-exosomal proteins or lipids; reduced purity; potential interference with downstream analyses[132] |

| Density Gradient Centrifugation | High purity and low contamination; enables separation of different EV subtypes | Complex and time-consuming; limited sample volume[133] |

| SEC | Maintains EVs integrity and bioactivity; no chemical contamination | Slow separation speed; limited sample volume[134] |

| Immunoaffinity Capture | High specificity and purity; enables isolation of EVs from specific sources or with defined functions | Some EVs lack target surface markers; magnetic bead detachment may affect downstream assays[135] |

| Microfluidic Technology | Requires minimal sample volume | Limited throughput; potential device clogging[136] |

EV: extracellular vesicle; SEC: size exclusion chromatography.

Recent advances are progressively overcoming these limitations. Combined isolation strategies (e.g., SEC plus density gradients) improve EV purity and RNA fidelity[138], while low-input library preparation, Unique Molecular Identifier-based quantification, and long-read sequencing substantially enhance sensitivity and quantitative accuracy[139,140]. Moreover, single-EV RNA sequencing and multi-omics integration have revealed pronounced transcriptomic heterogeneity among individual vesicles, enabling more precise molecular characterization and accelerating the application of EV lncRNAs in precision medicine[141].

Overall, continued optimization of isolation methods, detection technologies, and standardization frameworks is expected to further improve the reproducibility and clinical translational potential of EV-derived lncRNA research.

The schematic summarizes five commonly used EV isolation methods, including ultracentrifugation, immunoaffinity capture, density gradient centrifugation, polymer-based precipitation, and SEC. Each method differs in yield, purity, equipment requirements, and downstream compatibility. Ultracentrifugation remains the gold standard, while SEC provides superior EV integrity and reproducibility.

6. Discussion

Although EV-associated lncRNAs have garnered attention, their classification and functional study face significant challenges. Most studies still classify EV-associated lncRNAs based on their genomic location or the size and origin of EVs, yet a unified framework integrating vesicle origin, molecular function, and selective loading mechanisms remains lacking. Current investigations also tend to focus on individual lncRNAs rather than conducting systematic or comparative analyses. EVs are highly heterogeneous, with different sources and isolation methods strongly affecting RNA cargo, while packaging mechanisms remain complex and only partially understood, with RBPs such as hnRNPA2B1 implicated. Isolation approaches, including ultracentrifugation, precipitation, density gradient centrifugation, size exclusion chromatography, immunoaffinity capture, and microfluidics, differently impact vesicle integrity and RNA content. Future studies should comprehensively map aging-specific EV-lncRNA repertoires, combine single-EV or single-cell sequencing with functional validation, and advance clinical translation, including liquid biopsy biomarkers and EV-based therapeutic strategies. Integration with multi-omics and AI may enable precise aging prediction models and mechanistic insights.

7. Conclusion

In summary, EV-associated lncRNAs represent a promising yet still emerging area of research with significant translational potential. Advancing this field will require the establishment of standardized EV-isolation and characterization protocols, the implementation of rigorous in vivo functional studies, and the integration of large longitudinal human cohorts to validate candidate biomarkers and develop reliable lncRNA-based aging clocks. Addressing these challenges is essential to move beyond correlative observations and achieve clinically meaningful applications in aging research and regenerative medicine.

Authors contribution

Yan M: Conceptualization, writing-original draft, visualization.

Zhu S, Li J: Conceptualization, writing-review & editing.

Han JDJ: Conceptualization, writing-review & editing, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32088101, Grant No. 92374207, Grant No. 32330017, Grant No. 82361148130, Grant No. 92049302), the China Ministry of Science and Technology (Grant No. 2020YFA0804000) and Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. IS23077) to Jing-Dong J. Han.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Ugalde AP, Roiz-Valle D, Moledo-Nodar L, Caravia XM, Freije JMP, López-Otín C. Noncoding RNA contribution to aging and lifespan. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2024;79(4):glae058.[DOI]

-

2. Dolati S, Shakouri SK, Dolatkhah N, Yousefi M, Jadidi-Niaragh F, Sanaie S. The role of exosomal non-coding RNAs in aging-related diseases. BioFactors. 2021;47(3):292-310.[DOI]

-

3. Spanos M, Gokulnath P, Chatterjee E, Li G, Varrias D, Das S. Expanding the horizon of EV-RNAs: LncRNAs in EVs as biomarkers for disease pathways. Extracell Vesicle. 2023;2:100025.[DOI]

-

4. Fabbiano F, Corsi J, Gurrieri E, Trevisan C, Notarangelo M, D’Agostino VG. RNA packaging into extracellular vesicles: An orchestra of RNA-binding proteins? J Extracell Vesicles. 2020;10(2):e12043.[DOI]

-

5. Putri PHL, Alamudi SH, Dong X, Fu Y. Extracellular vesicles in age-related diseases: Disease pathogenesis, intervention, and biomarker. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2025;16(1):263.[DOI]

-

6. Gao J, Chen P, Li Z, Zhong W, Huang Q, Zhang X, et al. Identification of lncRNA in circulating exosomes as potential biomarkers for MCI among the elderly. J Affect Disord. 2025;370:401-411.[DOI]

-

7. López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell. 2023;186(2):243-278.[DOI]

-

8. Childs BG, Durik M, Baker DJ, van Deursen JM. Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: From mechanisms to therapy. Nat Med. 2015;21(12):1424-1435.[DOI]

-

9. Wallis R, Mizen H, Bishop CL. The bright and dark side of extracellular vesicles in the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Mech Ageing Dev. 2020;189:111263.[DOI]

-

10. Mansfield L, Ramponi V, Gupta K, Stevenson T, Mathew AB, Barinda AJ, et al. Emerging insights in senescence: Pathways from preclinical models to therapeutic innovations. npj Aging. 2024;10(1):53.[DOI]

-

11. Li X, Li C, Zhang W, Wang Y, Qian P, Huang H. Inflammation and aging: Signaling pathways and intervention therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):239.[DOI]

-

12. van Niel G, D’Angelo G, Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(4):213-228.[DOI]

-

13. Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): A position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018;7(1):1535750.[DOI]

-

14. Jeppesen DK, Fenix AM, Franklin JL, Higginbotham JN, Zhang Q, Zimmerman LJ, et al. Reassessment of exosome composition. Cell. 2019;177(2):428-445.[DOI]

-

15. Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367(6478):eaau6977.[DOI]

-

16. Wang KC, Chang HY. Molecular mechanisms of long noncoding RNAs. Mol Cell. 2011;43(6):904-914.[DOI]

-

17. Xie Y, Dang W, Zhang S, Yue W, Yang L, Zhai X, et al. The role of exosomal noncoding RNAs in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):37.[DOI]

-

18. Kim GD, Shin SI, Jung SW, An H, Choi SY, Eun M, et al. Cell type- and age-specific expression of lncRNAs across Kidney cell types. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2024;35(7):870-885.[DOI]

-

19. O’Grady T, Njock MS, Lion M, Bruyr J, Mariavelle E, Galvan B, et al. Sorting and packaging of RNA into extracellular vesicles shape intracellular transcript levels. BMC Biol. 2022;20(1):72.[DOI]

-

20. Papoutsoglou P, Morillon A. Extracellular vesicle lncRNAs as key biomolecules for cell-to-cell communication and circulating cancer biomarkers. Noncoding RNA. 2024;10(6):54.[DOI]

-

21. Padilla JA, Barutcu S, Malet L, Deschamps-Francoeur G, Calderon V, Kwon E, et al. Profiling the polyadenylated transcriptome of extracellular vesicles with long-read nanopore sequencing. BMC Genomics. 2023;24(1):564.[DOI]

-

22. Ma X, Chen Z, Chen W, Chen Z, Shang Y, Zhao Y, et al. LncRNA AL139294.1 can be transported by extracellular vesicles to promote the oncogenic behaviour of recipient cells through activation of the Wnt and NF-κB2 pathways in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024;43(1):20.[DOI]

-

23. Grigorian Shamagian L, Rogers RG, Luther K, Angert D, Echavez A, Liu W, et al. Rejuvenating effects of young extracellular vesicles in aged rats and in cellular models of human senescence. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):12240.[DOI]

-

24. Cao Q, Guo Z, Yan Y, Wu J, Song C. Exosomal long noncoding RNAs in aging and age-related diseases. IUBMB Life. 2019;71(12):1846-1856.[DOI]

-

25. Havelka M, Satomura A, Yamaguchi H, Cortal A, Ando Y, Mikami M, et al. A urinary microRNA aging clock accurately predicts biological age. npj Aging. 2025;12(1):14.[DOI]

-

26. Kuiper LM, Mens MMJ, Wu JW, Goudsmit J, Ma Y, Liang L, et al. Plasma microRNA signatures of aging and their links to health outcomes and mortality: Findings from a population-based cohort study. Genome Med. 2025;17(1):70.[DOI]

-

27. Kern F, Kuhn T, Ludwig N, Simon M, Gröger L, Fabis N, et al. Ageing-associated small RNA cargo of extracellular vesicles. RNA Biol. 2023;20(1):482-494.[DOI]

-

28. Misawa T, Tanaka Y, Okada R, Takahashi A. Biology of extracellular vesicles secreted from senescent cells as senescence-associated secretory phenotype factors. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20(6):539-546.[DOI]

-

29. Tanaka Y, Takahashi A. Senescence-associated extracellular vesicle release plays a role in senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) in age-associated diseases. J Biochem. 2021;169(2):147-153.[DOI]

-

30. Oh C, Koh D, Jeon HB, Kim KM. The role of extracellular vesicles in senescence. Mol Cells. 2022;45(9):603-609.[DOI]

-

31. Montes M, Lubas M, Arendrup FS, Mentz B, Rohatgi N, Tumas S, et al. The long non-coding RNA MIR31HG regulates the senescence associated secretory phenotype. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2459.[DOI]

-

32. Chiba M, Miyata K, Okawa H, Tanaka Y, Ueda K, Seimiya H, et al. YBX1 regulates satellite II RNA loading into small extracellular vesicles and promotes the senescent phenotype. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(22):16399.[DOI]

-

33. Nelson G, Wordsworth J, Wang C, Jurk D, Lawless C, Martin-Ruiz C, et al. A senescent cell bystander effect: Senescence-induced senescence. Aging Cell. 2012;11(2):345-349.[DOI]

-

34. Yin Y, Chen H, Wang Y, Zhang L, Wang X. Roles of extracellular vesicles in the aging microenvironment and age-related diseases. J Extracell Vesicles. 2021;10(12):e12154.[DOI]

-

35. Jeon OH, Wilson DR, Clement CC, Rathod S, Cherry C, Powell B, et al. Senescence cell-associated extracellular vesicles serve as osteoarthritis disease and therapeutic markers. JCI Insight. 2019;4(7):e125019.[DOI]

-

36. Oka Y, Tanaka K, Kawasaki Y. A novel sorting signal for RNA packaging into small extracellular vesicles. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):17436.[DOI]

-

37. Villarroya-Beltri C, Gutiérrez-Vázquez C, Sánchez-Cabo F, Pérez-Hernández D, Vázquez J, Martin-Cofreces N, et al. Sumoylated hnRNPA2B1 controls the sorting of miRNAs into exosomes through binding to specific motifs. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2980.[DOI]

-

38. Qu L, Ding J, Chen C, Wu ZJ, Liu B, Gao Y, et al. Exosome-transmitted lncARSR promotes sunitinib resistance in renal cancer by acting as a competing endogenous RNA. Cancer Cell. 2016;29(5):653-668.[DOI]

-

39. Lei Y, Guo W, Chen B, Chen L, Gong J, Li W. Tumor-released lncRNA H19 promotes gefitinib resistance via packaging into exosomes in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 2018;40(6):3438-3446.[DOI]

-

40. Ding Y, Yin R, Zhang S, Xiao Q, Zhao H, Pan X, et al. The combined regulation of long non-coding RNA and RNA-binding proteins in atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:731958.[DOI]

-

41. Jadaliha M, Gholamalamdari O, Tang W, Zhang Y, Petracovici A, Hao Q, et al. A natural antisense lncRNA controls breast cancer progression by promoting tumor suppressor gene mRNA stability. PLoS Genet. 2018;14(11):e1007802.[DOI]

-

42. Kong X, Li J, Li Y, Duan W, Qi Q, Wang T, et al. A novel long non-coding RNA AC073352.1 promotes metastasis and angiogenesis via interacting with YBX1 in breast cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(7):670.[DOI]

-

43. Ma L, Singh J, Schekman R. Two RNA-binding proteins mediate the sorting of miR223 from mitochondria into exosomes. eLife. 2023;12:e85878.[DOI]

-

44. Yu M, Cai Z, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Fu J, Cui X. Aberrant NSUN2-mediated m5C modification of exosomal LncRNA MALAT1 induced RANKL-mediated bone destruction in multiple myeloma. Commun Biol. 2024;7(1):1249.[DOI]

-

45. Wang Z, He J, Bach DH, Huang YH, Li Z, Liu H, et al. Induction of m6A methylation in adipocyte exosomal LncRNAs mediates myeloma drug resistance. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2022;41(1):4.[DOI]

-

46. Li K, Gong Q, Xiang XD, Guo G, Liu J, Zhao L, et al. HNRNPA2B1-mediated m6A modification of lncRNA MEG3 facilitates tumorigenesis and metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer by regulating miR-21-5p/PTEN axis. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):382.[DOI]

-

47. Wang W, Qiao S, Kong X, Zhang G, Cai Z. The role of exosomes in immunopathology and potential therapeutic implications. Cell Mol Immunol. 2025;22(9):975-995.[DOI]

-

48. Zhu P, He F, Hou Y, Tu G, Li Q, Jin T, et al. A novel hypoxic long noncoding RNA KB-1980E6.3 maintains breast cancer stem cell stemness via interacting with IGF2BP1 to facilitate c-Myc mRNA stability. Oncogene. 2021;40(9):1609-1627.[DOI]

-

49. Lee YJ, Shin KJ, Chae YC. Regulation of cargo selection in exosome biogenesis and its biomedical applications in cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2024;56(4):877-889.[DOI]

-

50. Cone AS, Hurwitz SN, Lee GS, Yuan X, Zhou Y, Li Y, et al. Alix and Syntenin-1 direct amyloid precursor protein trafficking into extracellular vesicles. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21(1):58.[DOI]

-

51. Kołat D, Hammouz R, Bednarek AK, Płuciennik E. Exosomes as carriers transporting long non-coding RNAs: Molecular characteristics and their function in cancer (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2019;20(2):851-862.[DOI]

-

52. van Niel G, Charrin S, Simoes S, Romao M, Rochin L, Saftig P, et al. The tetraspanin CD63 regulates ESCRT-independent and -dependent endosomal sorting during melanogenesis. Dev Cell. 2011;21(4):708-721.[DOI]

-

53. Horbay R, Hamraghani A, Ermini L, Holcik S, Beug ST, Yeganeh B. Role of ceramides and lysosomes in extracellular vesicle biogenesis, cargo sorting and release. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(23):15317.[DOI]

-

54. Park H, Seo YK, Arai Y, Lee SH. Physicochemical modulation strategies for mass production of extracellular vesicle. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2025;22(5):569-591.[DOI]

-

55. Marie PP, Fan SJ, Mason J, Wells A, Mendes CC, Wainwright SM, et al. Accessory ESCRT-III proteins are conserved and selective regulators of Rab11a-exosome formation. J Extracell Vesicles. 2023;12(3):e12311.[DOI]

-

56. Linnemannstöns K, Karuna MP, Witte L, Choezom D, Honemann-Capito M, Lagurin AS, et al. Microscopic and biochemical monitoring of endosomal trafficking and extracellular vesicle secretion in an endogenous in vivo model. J Extracell Vesicles. 2022;11(9):e12263.[DOI]

-

57. Dragomir M, Chen B, Calin GA. Exosomal lncRNAs as new players in cell-to-cell communication. Transl Cancer Res. 2018;7:S243-S252.[DOI]

-

58. Li X, Huang X, Chang M, Lin R, Zhang J, Lu Y. Updates on altered signaling pathways in tumor drug resistance. Vis Cancer Med. 2024;5:6.[DOI]

-

59. Huang Y, Guo S, Lin Y, Huo L, Yan H, Lin Z, et al. LincRNA01703 facilitates CD81+ exosome secretion to inhibit lung adenocarcinoma metastasis via the Rab27a/SYTL1/CD81 complex. Cancers. 2023;15(24):5781.[DOI]

-

60. Sasaki N, Toyoda M, Yoshimura H, Matsuda Y, Arai T, Takubo K, et al. H19 long non-coding RNA contributes to sphere formation and invasion through regulation of CD24 and integrin expression in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2018;9(78):34719-34734.[DOI]

-

61. Rufini A, Tucci P, Celardo I, Melino G. Senescence and aging: The critical roles of p53. Oncogene. 2013;32(43):5129-5143.[DOI]

-

62. Su Q, Lv XW, Xu YL, Cai RP, Dai RX, Yang XH, et al. Exosomal LINC00174 derived from vascular endothelial cells attenuates myocardial I/R injury via p53-mediated autophagy and apoptosis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021;23:1304-1322.[DOI]

-

63. Pal S, Garg M, Pandey AK. Deciphering the mounting complexity of the p53 regulatory network in correlation to long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in ovarian cancer. Cells. 2020;9(3):527.[DOI]

-

64. Wang H, Li Y, Wang Y, Shang X, Yan Z, Li S, et al. Cisplatin-induced PANDAR-Chemo-EVs contribute to a more aggressive and chemoresistant ovarian cancer phenotype through the SRSF9-SIRT4/SIRT6 axis. J Gynecol Oncol. 2024;35(2):e13.[DOI]

-

65. Saxton RA, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell. 2017;168(6):960-976.[DOI]

-

66. Xu J, Xiao Y, Liu B, Pan S, Liu Q, Shan Y, et al. Exosomal MALAT1 sponges miR-26a/26b to promote the invasion and metastasis of colorectal cancer via FUT4 enhanced fucosylation and PI3K/Akt pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39(1):54.[DOI]

-

67. Huang C, Han J, Wu Y, Li S, Wang Q, Lin W, et al. Exosomal MALAT1 derived from oxidized low-density lipoprotein-treated endothelial cells promotes M2 macrophage polarization. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18(1):509-515.[DOI]

-

68. Chen L, Yang W, Guo Y, Chen W, Zheng P, Zeng J, et al. Exosomal lncRNA GAS5 regulates the apoptosis of macrophages and vascular endothelial cells in atherosclerosis. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0185406.[DOI]

-

69. Zang X, Gu J, Zhang J, Shi H, Hou S, Xu X, et al. Exosome-transmitted lncRNA UFC1 promotes non-small-cell lung cancer progression by EZH2-mediated epigenetic silencing of PTEN expression. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(4):215.[DOI]

-

70. Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature. 2000;403(6771):795-800.[DOI]

-

71. Imai S, Guarente L. NAD+ and sirtuins in aging and disease. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24(8):464-471.[DOI]

-

72. Zhuang L, Xia W, Chen D, Ye Y, Hu T, Li S, et al. Exosomal LncRNA-NEAT1 derived from MIF-treated mesenchymal stem cells protected against doxorubicin-induced cardiac senescence through sponging miR-221-3p. J Nanobiotechnol. 2020;18(1):157.[DOI]

-

73. Qiu J, Hua K. Circulating exosomal ANRIL is a novel prognostic marker for epithelial ovarian cancer. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(7):S3.[DOI]

-

74. Zhang B, Huang R, Tang Z, Hu Y. CAF-derived exosomal LncRNA ANRIL promotes glycolytic metabolism and proliferation in non-small cell lung cancer via the miR-186-5p/HIF-1α axis. Discov Oncol. 2025;16(1):1638.[DOI]

-

75. Zhao Q, Li B, Zhang X, Zhao H, Xue W, Yuan Z, et al. M2 macrophage-derived lncRNA NORAD in EVs promotes NSCLC progression via miR-520g-3p/SMIM 22/GALE axis. npj Precis Oncol. 2024;8(1):185.[DOI]

-

76. Lee S, Kopp F, Chang TC, Sataluri A, Chen B, Sivakumar S, et al. Noncoding RNA NORAD regulates genomic stability by sequestering PUMILIO proteins. Cell. 2016;164(1):69-80.[DOI]

-

77. Gui W, Zhu WF, Zhu Y, Tang S, Zheng F, Yin X, et al. LncRNAH19 improves insulin resistance in skeletal muscle by regulating heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1. Cell Commun Signal. 2020;18(1):173.[DOI]

-

78. Behera J, Kumar A, Voor MJ, Tyagi N. Exosomal lncRNA-H19 promotes osteogenesis and angiogenesis through mediating Angpt1/Tie2-NO signaling in CBS-heterozygous mice. Theranostics. 2021;11(16):7715-7734.[DOI]

-

79. Ma J, Lei P, Chen H, Wang L, Fang Y, Yan X, et al. Advances in lncRNAs from stem cell-derived exosome for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:986683.[DOI]

-

80. Zhu B, Zhang L, Liang C, Liu B, Pan X, Wang Y, et al. Stem cell-derived exosomes prevent aging-induced cardiac dysfunction through a novel exosome/lncRNA MALAT1/NF-κB/TNF-α signaling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:9739258.[DOI]

-

81. Castellano JJ, Marrades RM, Molins L, Viñolas N, Moises J, Canals J, et al. Extracellular vesicle lincRNA-p21 expression in tumor-draining pulmonary vein defines prognosis in NSCLC and modulates endothelial cell behavior. Cancers. 2020;12(3):734.[DOI]

-

82. Xu W, Mo W, Han D, Dai W, Xu X, Li J, et al. Hepatocyte-derived exosomes deliver the lncRNA CYTOR to hepatic stellate cells and promote liver fibrosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2024;28(8):e18234.[DOI]

-

83. Gan L, Dai A, He Y, Liu S, Ni Q, Hu Y, et al. Exosomal LncRNA MALAT1 derived from hepatocytes in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease regulates the miR-579-3p/Keap1/NRF2 pathway to exacerbate obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Mol Biotechnol. 2025.[DOI]

-

84. Vahidinia Z, Azami Tameh A, Barati S, Izadpanah M, Seyed Hosseini E. Nrf2 activation: A key mechanism in stem cell exosomes-mediated therapies. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2024;29(1):30.[DOI]

-

85. Liu R, Jiang C, Li J, Li X, Zhao L, Yun H, et al. Serum-derived exosomes containing NEAT1 promote the occurrence of rheumatoid arthritis through regulation of miR-144-3p/ROCK2 axis. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:2040622321991705.[DOI]

-

86. Born LJ, Chang KH, Shoureshi P, Lay F, Bengali S, Hsu ATW, et al. HOTAIR-loaded mesenchymal stem/stromal cell extracellular vesicles enhance angiogenesis and wound healing. Adv Healthc Mater. 2022;11(5):e2002070.[DOI]

-

87. Liu J, Chen M, Ma L, Dang X, Du G. LncRNA GAS5 suppresses the proliferation and invasion of osteosarcoma cells via the miR-23a-3p/PTEN/PI3K/AKT pathway. Cell Transplant. 2020;29:963689720953093.[DOI]

-

88. Wang J, Wang N, Zheng Z, Che Y, Suzuki M, Kano S, et al. Exosomal lncRNA HOTAIR induce macrophages to M2 polarization via PI3K/p-AKT/AKT pathway and promote EMT and metastasis in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):1208.[DOI]

-

89. Gao B, Wang L, Wen T, Xie X, Rui X, Chen Q. Colon cancer-derived exosomal LncRNA-XIST promotes M2-like macrophage polarization by regulating PDGFRA. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(21):11433.[DOI]

-

90. Xie X, Cao Y, Dai L, Zhou D. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal lncRNA KLF3-AS1 stabilizes Sirt1 protein to improve cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury via miR-206/USP22 axis. Mol Med. 2023;29(1):3.[DOI]

-

91. Gao W, Zhang Y, Yuan L, Huang F, Wang YS. Long non-coding RNA H19-overexpressing exosomes ameliorate UVB-induced photoaging by upregulating SIRT1 via sponging miR-138. Photochem Photobiol. 2023;99(6):1456-1467.[DOI]

-

92. Amicone L, Marchetti A, Cicchini C. The lncRNA HOTAIR: A pleiotropic regulator of epithelial cell plasticity. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2023;42(1):147.[DOI]

-

93. Shin TJ, Lee KH, Cho JY. Epigenetic mechanisms of lncRNAs binding to protein in carcinogenesis. Cancers. 2020;12(10):2925.[DOI]

-

94. Samuels M, Jones W, Towler B, Turner C, Robinson S, Giamas G. The role of non-coding RNAs in extracellular vesicles in breast cancer and their diagnostic implications. Oncogene. 2023;42(41):3017-3034.[DOI]

-

95. Wang D, Wang P, Bian X, Xu S, Zhou Q, Zhang Y, et al. Elevated plasma levels of exosomal BACE1-AS combined with the volume and thickness of the right entorhinal cortex may serve as a biomarker for the detection of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Med Rep. 2020;22(1):227-238.[DOI]

-

96. Fotuhi SN, Khalaj-Kondori M, Hoseinpour Feizi MA, Talebi M. Long non-coding RNA BACE1-AS may serve as an Alzheimer’s disease blood-based biomarker. J Mol Neurosci. 2019;69(3):351-359.[DOI]

-

97. Gao H, Wang X, Lin C, An Z, Yu J, Cao H, et al. Exosomal MALAT1 derived from ox-LDL-treated endothelial cells induce neutrophil extracellular traps to aggravate atherosclerosis. Biol Chem. 2020;401(3):367-376.[DOI]

-

98. Wei XB, Jiang WQ, Zeng JH, Huang LQ, Ding HG, Jing YW, et al. Exosome-derived lncRNA NEAT1 exacerbates sepsis-associated encephalopathy by promoting ferroptosis through regulating miR-9-5p/TFRC and GOT1 axis. Mol Neurobiol. 2022;59(3):1954-1969.[DOI]

-

99. Chen G, Yue A, Wang M, Ruan Z, Zhu L. The exosomal lncRNA KLF3-AS1 from ischemic cardiomyocytes mediates IGF-1 secretion by MSCs to rescue myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:671610.[DOI]

-

100. Sufianov A, Kostin A, Begliarzade S, Kudriashov V, Ilyasova T, Liang Y, et al. Exosomal non coding RNAs as a novel target for diabetes mellitus and its complications. Non-coding RNA Res. 2023;8(2):192-204.[DOI]

-

101. Zhao L, Gu M, Sun Z, Shi L, Yang Z, Zheng M, et al. The role of exosomal lncRNAs in cardiovascular disease: Emerging insights based on molecular mechanisms and therapeutic target level. Non-coding RNA Res. 2025;10:198-205.[DOI]

-

102. Huang P, Wang L, Li Q, Tian X, Xu J, Xu J, et al. Atorvastatin enhances the therapeutic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells-derived exosomes in acute myocardial infarction via up-regulating long non-coding RNA H19. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116(2):353-367.[DOI]

-

103. Zhang RX, Zhang ZX, Zhao XY, Liu YH, Zhang XM, Han Q, et al. Mechanism of action of lncRNA-NEAT1 in immune diseases. Front Genet. 2025;16:1501115.[DOI]

-

104. Ruan L, Mendhe B, Parker E, Kent A, Isales CM, Hill WD, et al. Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 is depleted with age in skeletal muscle in vivo and MALAT1 silencing increases expression of TGF-β1 in vitro. Front Physiol. 2021;12:742004.[DOI]

-

105. Shin JJ, Park J, Shin HS, Arab I, Suk K, Lee WH. Roles of lncRNAs in NF-κB-mediated macrophage inflammation and their implications in the pathogenesis of human diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(5):2670.[DOI]

-

106. Wu P, Mo Y, Peng M, Tang T, Zhong Y, Deng X, et al. Emerging role of tumor-related functional peptides encoded by lncRNA and circRNA. Mol Cancer. 2020;19(1):22.[DOI]

-

107. Lin A, He W. LINC01705 derived from adipocyte exosomes regulates hepatocyte lipid accumulation via an miR-552-3p/LXR axis. J Diabetes Investig. 2023;14(10):1160-1171.[DOI]

-

108. Yang W, Lyu Y, Xiang R, Yang J. Long noncoding RNAs in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(24):16054.[DOI]

-

109. Son T, Jeong I, Park J, Jun W, Kim A, Kim OK. Adipose tissue-derived exosomes contribute to obesity-associated liver diseases in long-term high-fat diet-fed mice, but not in short-term. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1162992.[DOI]

-

110. Yang X, Yang J, Lei P, Wen T. LncRNA MALAT1 shuttled by bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells-secreted exosomes alleviates osteoporosis through mediating microRNA-34c/SATB2 axis. Aging. 2019;11(20):8777-8791.[DOI]

-

111. Wang D, Liu Y, Diao S, Shan L, Zhou J. Long non-coding RNAs within macrophage-derived exosomes promote BMSC osteogenesis in a bone fracture rat model. Int J Nanomedicine. 2023;18:1063-1083.[DOI]

-

112. Zheng D, Yang K, Chen T, Lv S, Wang L, Gui J, et al. Inhibition of LncRNA SNHG14 protects chondrocyte from injury in osteoarthritis via sponging miR-137. Autoimmunity. 2023;56(1):2270185.[DOI]

-

113. Fan MH, Pi JK, Zou CY, Jiang YL, Li QJ, Zhang XZ, et al. Hydrogel-exosome system in tissue engineering: A promising therapeutic strategy. Bioact Mater. 2024;38:1-30.[DOI]

-

114. Wan J, He Z, Peng R, Wu X, Zhu Z, Cui J, et al. Injectable photocrosslinking spherical hydrogel-encapsulated targeting peptide-modified engineered exosomes for osteoarthritis therapy. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21(1):284.[DOI]

-

115. Koga Y, Yasunaga M, Moriya Y, Akasu T, Fujita S, Yamamoto S, et al. Exosome can prevent RNase from degrading microRNA in feces. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;2(4):215-222.[DOI]

-

116. Wang J, Yue BL, Huang YZ, Lan XY, Liu WJ, Chen H. Exosomal RNAs: Novel potential biomarkers for diseases-A review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5):2461.[DOI]

-

117. Fang S, Zhang L, Guo J, Niu Y, Wu Y, Li H, et al. NONCODEV5: A comprehensive annotation database for long non-coding RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D308-D314.[DOI]

-

118. Uszczynska-Ratajczak B, Lagarde J, Frankish A, Guigó R, Johnson R. Towards a complete map of the human long non-coding RNA transcriptome. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19(9):535-548.[DOI]

-

119. Delshad M, Sanaei MJ, Mohammadi MH, Sadeghi A, Bashash D. Exosomal biomarkers: A comprehensive overview of diagnostic and prognostic applications in malignant and non-malignant disorders. Biomolecules. 2025;15(4):587.[DOI]

-

120. Schoger E, Bleckwedel F, Germena G, Rocha C, Tucholla P, Sobitov I, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveal extracellular vesicles secretion with a cardiomyocyte proteostasis signature during pathological remodeling. Commun Biol. 2023;6(1):79.[DOI]

-

121. Jiao Z, Yu A, Rong W, He X, Zen K, Shi M, et al. Five-lncRNA signature in plasma exosomes serves as diagnostic biomarker for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Aging. 2020;12(14):15002-15010.[DOI]

-

122. Liu Y, Lu S, Yang J, Yang Y, Jiao L, Hu J, et al. Analysis of the aging-related biomarker in a nonhuman primate model using multilayer omics. BMC Genomics. 2024;25(1):639.[DOI]

-

123. Gareev I, Kudriashov V, Sufianov A, Begliarzade S, Ilyasova T, Liang Y, et al. The role of long non-coding RNA ANRIL in the development of atherosclerosis. Non-coding RNA Res. 2022;7(4):212-216.[DOI]

-

124. Zhong F, Yao F, Wang XL, Wang Z, Huang B, Liu J, et al. Plasma exosomal lncRNA-related signatures define molecular subtypes and predict survival and treatment response in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1663943.[DOI]

-

125. Peng XC, Ma LL, Miao JY, Xu SQ, Shuai ZW. Differential lncRNA profiles of blood plasma-derived exosomes from systemic lupus erythematosus. Gene. 2024;927:148713.[DOI]

-

126. Yang Z, Zhang X, Zhan N, Lin L, Zhang J, Peng L, et al. Exosome-related lncRNA score: A value-based individual treatment strategy for predicting the response to immunotherapy in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2024;13(11):e7308.[DOI]

-

127. Wei Y, Hu X, Yuan S, Zhao Y, Zhu C, Guo M, et al. Identification of plasma exosomal lncRNA as a biomarker for early diagnosis of gastric cancer. Front Genet. 2024;15:1425591.[DOI]

-

128. Vilaça A, Jesus C, Lino M, Hayman D, Emanueli C, Terracciano CM, et al. Extracellular vesicle transfer of lncRNA H19 splice variants to cardiac cells. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2024;35(3):102233.[DOI]

-

129. Ghani MU, Du L, Moqbel AQ, Zhao E, Cui H, Yang L, et al. Exosomal ncRNAs in liquid biopsy: A new paradigm for early cancer diagnosis and monitoring. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1615433.[DOI]

-

130. Ma L, Guo H, Zhao Y, Liu Z, Wang C, Bu J, et al. Liquid biopsy in cancer current: Status, challenges and future prospects. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):336.[DOI]

-

131. Coughlan C, Bruce KD, Burgy O, Boyd TD, Michel CR, Garcia-Perez JE, et al. Exosome isolation by ultracentrifugation and precipitation and techniques for downstream analyses. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2020;88(1):e110.[DOI]

-

132. Martins TS, Vaz M, Henriques AG. A review on comparative studies addressing exosome isolation methods from body fluids. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2023;415(7):1239-1263.[DOI]

-

133. Yakubovich EI, Polischouk AG, Evtushenko VI. Principles and problems of exosome isolation from biological fluids. Biochem (Mosc) Suppl Ser A Membr Cell Biol. 2022;16(2):115-126.[DOI]

-

134. Sidhom K, Obi PO, Saleem A. A review of exosomal isolation methods: Is size exclusion chromatography the best option? Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(18):6466.[DOI]

-

135. Gao J, Li A, Hu J, Feng L, Liu L, Shen Z. Recent developments in isolating methods for exosomes. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:1100892.[DOI]

-

136. Gorgzadeh A, Nazari A, Ali Ehsan Ismaeel A, Safarzadeh D, Hassan JAK, Mohammadzadehsaliani S, et al. A state-of-the-art review of the recent advances in exosome isolation and detection methods in viral infection. Virol J. 2024;21(1):34.[DOI]

-

137. Chen Y, Zhu Q, Cheng L, Wang Y, Li M, Yang Q, et al. Exosome detection via the ultrafast-isolation system: EXODUS. Nat Methods. 2021;18(2):212-218.[DOI]

-

138. Kong F, Upadya M, Wong ASW, Dalan R, Dao M. Isolating Small Extracellular Vesicles from Small Volumes of Blood Plasma using size exclusion chromatography and density gradient ultracentrifugation: A comparative study. BioRxiv 564707 [Preprint]. 2025.[DOI]

-

139. Miceli RT, Chen TY, Nose Y, Tichkule S, Brown B, Fullard JF, et al. Extracellular vesicles, RNA sequencing, and bioinformatic analyses: Challenges, solutions, and recommendations. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024;13(12):e70005.[DOI]

-

140. Padilla JA, Barutcu S, Deschamps-Francoeur G, Lécuyer E. Exploring extracellular vesicle transcriptomic diversity through long-read nanopore sequencing. Methods Mol Biol. 2025;2880:227-241.[DOI]

-

141. Luo T, Chen SY, Qiu ZX, Miao YR, Ding Y, Pan XY, et al. Transcriptomic features in a single extracellular vesicle via single-cell RNA sequencing. Small Methods. 2022;6(11):e2200881.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite