Abstract

Modification with UFM1 (UFMylation) has recently emerged as a versatile signaling system regulating diverse cellular processes, from endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis to genome stability. Recent studies have expanded this landscape by revealing a direct role of UFMylation in the core machinery of DNA replication. Specifically, UFMylation of MCM5 is required for optimal activation of the CDC45–MCM–GINS (CMG) helicase, the molecular engine that governs origin firing and drives replication fork progression. This discovery introduces a previously unrecognized regulatory layer into the DNA replication program and positions UFMylation as an important coordinator of genome duplication, whose disruption provides a mechanistic explanation for developmental disorders such as microcephalic primordial dwarfism (MPD), while more subtle or progressive dysregulation may have important implications for genome stability across ageing and cancer.

Keywords

1. From Genetic Clues to Molecular Mechanisms

Accurate genome duplication is essential for life continuity and the maintenance of genetic stability. DNA replication proceeds through initiation, elongation, and termination, relying on the coordinated actions of numerous replication factors[1,2]. Among them, the CDC45–MCM–GINS (CMG) helicase unwinds the DNA duplex and powers fork progression. In the canonical model, origin licensing during G1 establishes MCM2-7 double hexamers, whereas DDK- and CDK-mediated phosphorylation in early S phase triggers the recruitment of CDC45 and GINS to form the active CMG helicase[3]. Despite this well-defined framework, how post-translational modifications (PTMs) fine-tune CMG activation at the molecular level has remained unclear.

Guided by striking genetic clues, Li et al. noted that mutations in CMG components, such as MCM5, CDC45, or GINS cause microcephalic primordial dwarfism (MPD), a developmental disorder characterized by severe growth retardation and brain hypoplasia[4-6]. Remarkably, mutations in modification with UFM1 (UFMylation) pathway genes, including UFM1, UBA5, UFC1, and UFL1, are associated with highly overlapping phenotypes, characterized by microcephaly and growth retardation[7]. This genetic convergence hints that UFMylation might serve as a pivotal regulatory node for replication initiation. Building on this hypothesis, the authors uncovered the molecular mechanism linking UFMylation to CMG activation[4].

2. UFMylation Promotes Efficient DNA Replication

The authors first established that UFMylation is important for efficient DNA synthesis. Using siRNA-mediated knockdown, CRISPR–Cas9 knockout of the E3 ligase UFL1, and chemical inhibition of the E1 enzyme UBA5 (with DKM 2-93), they consistently observed a sharp reduction in replication efficiency. Importantly, this phenotype occurred independently of replication stress, as γH2AX and pCHK1 levels remained unchanged.

DNA fiber analyses revealed that UFMylation deficiency leads to fewer active origins (increased inter-origin distance) and slower fork progression (shortened IdU tracks). These results demonstrate that UFMylation directly supports both replication initiation and elongation, thereby acting as a core modulator of fork dynamics rather than a secondary stress response.

3. MCM5 as a Key Substrate of UFMylation

Proteomic screening and biochemical assays identified the E3 enzyme UFL1 at replication origins and active replisomes, where it interacts with CDC45, GINS3, and multiple MCM subunits. Among them, MCM5 Lys583 (K583) emerged as the major UFMylation site, undergoing reversible modification by the protease UFSP2.

Cells expressing a UFMylation-deficient mutant (MCM5-K583R) displayed delayed replication initiation and reduced fork speed, phenocopying UFL1 loss or UBA5 inhibition. Moreover, these mutant cells became insensitive to UFMylation inhibition, confirming MCM5 as a principal functional substrate of the pathway. Mechanistically, UFMylation of MCM5 at Lys583 promotes the stable recruitment of CDC45 and GINS to licensed origins. Its absence disrupts CMG assembly, delays S-phase entry, and slows fork movement. Thus, MCM5 UFMylation represents a central molecular switch that controls helicase activation.

4. Structural and Pathological Insights

Structural mapping placed MCM5-K583 within the C-terminal domain near the MCM3 interface, spatially distant from the CDC45- and GINS-binding regions. This suggests that UFMylation may stabilize the MCM ring through allosteric regulation or serve as a scaffold facilitating helicase maturation, rather than introducing a new binding interface. Furthermore, structural modeling indicated that the conjugated UFM1 moiety lies close to POLE2, a subunit of DNA polymerase ε, suggesting a potential role in coordinating helicase–polymerase coupling.

These insights provide a unifying explanation for MPD pathogenesis: defective UFMylation compromises CMG assembly, restricting DNA replication in rapidly dividing embryonic cells, particularly neural progenitors, which results in microcephaly and growth retardation. Patient-derived mutants of UFM1, UBA5, or UFC1 failed to rescue replication defects, underscoring the developmental necessity of this modification. Collectively, these findings integrate genetic and biochemical evidence into a coherent model that links defective replication initiation to human developmental disorders.

5. A Broadening Role for UFMylation in the DNA Replication Cycle

UFMylation, catalyzed by the UBA5–UFC1–UFL1 cascade, is increasingly recognized as a critical regulator of DNA replication and genome integrity, extending beyond its classical roles in ER homeostasis and proteostasis. Consistent with this broader function, the UFMylation system has been implicated in the DNA damage response, where it promotes ATM activation following double-strand breaks through modification of MRE11 and histone H4[8-12]. Moreover, targeting the UFL1-PARP1 axis has been shown to amplify anti-tumor immunity by modulating R-loop stability[13].

Expanding on this landscape, recent studies have revealed distinct functions of UFMylation under replication stress: in BRCA1/2-deficient cells, UFMylation of PTIP promotes MLL3/4–PTIP complex assembly and MRE11 recruitment, thereby modulating fork stability and PARP inhibitor sensitivity[14]. Similarly, Tan et al. recently reported that PTIP UFMylation promotes replication fork degradation in BRCA1-deficient cells[15]. Furthermore, UFMylation of PARP1 enhances its catalytic activity and facilitates CHK1 activation to stabilize stalled forks and preserve genome integrity[16].

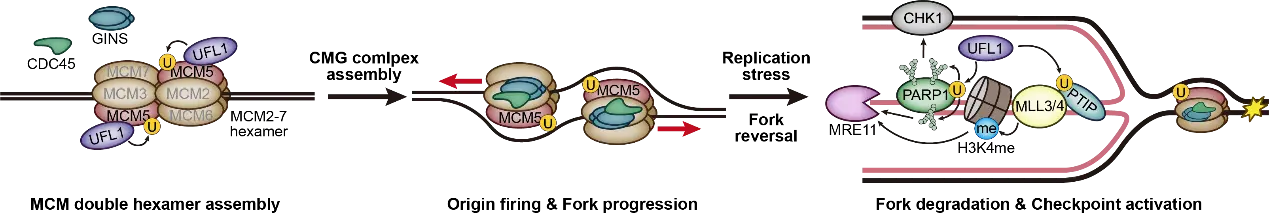

By contrast, Li et al.[4] uncover an upstream function of UFMylation in unperturbed replication, directly promoting CMG helicase activation and origin firing (Figure 1). Together, these findings position UFMylation as a multi-layered regulatory axis that coordinates replication initiation, fork progression, and stress response—safeguarding replication fidelity across diverse cellular contexts.

Figure 1. UFMylation in DNA replication. UFL1 promotes MCM5 UFMylation to facilitate CMG assembly, ensuring proper origin firing and fork progression. Under replication stress, UFL1-mediated UFMylation of PTIP enhances MRE11 recruitment to stalled forks via increased H3K4 methylation. Additionally, UFMylation of PARP1 by UFL1 promotes CHK1 activation, promoting controlled fork processing and degradation. CMG: CDC45–MCM–GINS; PTIP: PAX transcription activation domain-interacting protein; MRE11: meiotic recombination 11 homolog; H3K4: histone H3 lysine 4; CHK1: checkpoint kinase 1; MCM: minichromosome maintenance complex component; GINS: Go-Ichi-Ni-San complex; PARP1: poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1.

6. Significance and Perspectives

Traditionally, replication initiation has been attributed to CDK/DDK-dependent phosphorylation, SUMOylation, and ubiquitination[17-20]. The discovery of MCM5 UFMylation expands this repertoire, revealing a previously unrecognized post-translational checkpoint for helicase activation.

Collectively, the work by Li et al. supports the notion that MCM5 UFMylation exerts two distinct yet interconnected mechanistic roles in DNA replication. First, during replication initiation, UFMylation at K583 promotes the stable recruitment of CDC45 and GINS, thereby facilitating CMG helicase assembly and origin firing. Second, during replication elongation, the same modification contributes to efficient replication fork progression, as evidenced by shortened DNA fiber tracks upon its loss. While the precise mechanism underlying this latter role remains to be fully elucidated and may potentially involve fork stabilization or coordination with other replisome components, it appears mechanistically separable from its function in origin activation.

This finding positions UFMylation as a temporal coordinator of the replication machinery, potentially synchronizing helicase–polymerase coupling and fork dynamics. Importantly, this newly identified regulatory layer is likely to become particularly consequential in pathological contexts characterized by elevated replication demand, such as cancer.

At the disease and translational level, UFMylation represents a double-edged sword. Its loss causes developmental disorders, whereas hyperactivation may sustain tumor proliferation. Cancer cells are frequently exposed to chronic replication stress and depend on efficient origin firing and fork stabilization to sustain rapid proliferation, thereby rendering CMG helicase regulation a potential vulnerability. The next challenge is to define the replicative threshold of UFMylation: how much modification maintains physiological replication versus drives hyperreplication. Future studies utilizing quantitative mass spectrometry could help determine the specific stoichiometric threshold of MCM5 UFMylation required for optimal CMG activation. Therapeutic strategies must therefore be context-dependent. Enhancing MCM5 UFMylation could benefit disorders such as MPD, whereas selective inhibition may suppress replication in cancer. However, because high proliferative capacity is also a defining feature of normal stem and progenitor cells, indiscriminate inhibition of UFMylation could compromise tissue homeostasis and regenerative potential. Notably, in BRCA1/2-deficient tumors, excessive UFMylation inhibition might impair fork degradation and promote PARP inhibitor resistance, highlighting the need for precise modulation.

Mechanistically, much remains to be explored. Beyond CMG assembly and canonical replication processes, UFMylation may contribute to higher-order genome organization. Given its enrichment at active replisomes and the preferential localization of replication origins at the transcription start sites (TSSs) of long, transcriptionally active genes in mammalian cells, UFMylation could also function at replication–transcription interfaces[21]. In these contexts, it may modulate R-loop stability and help resolve transcription–replication conflicts, a notion supported by recent work demonstrating that UFL1-mediated UFMylation of PARP1 regulates R-loop homeostasis and shapes anti-tumor immune responses in cancer[13]. Moreover, although UFMylation is known to function in ER and nuclear processes, the continuity between the ER and nuclear envelope raises the possibility that it could contribute to nuclear envelope integrity and the spatial organization of replication domains, a hypothesis that remains to be tested[22,23].

Future studies integrating cryo-EM, single-molecule imaging, and time-resolved proteomics will be crucial for mapping the spatiotemporal dynamics of UFMylation during replication and for identifying additional substrates that define this signaling network.

Collectively, the discovery of MCM5 UFMylation–driven CMG activation establishes UFMylation as a key regulatory node within the DNA replication program. As this field advances, UFMylation is poised to emerge not only as a guardian of replication fidelity but also as a master integrator linking replication control, developmental homeostasis, and genome stability. While Li et al.[4] demonstrate that MCM5 UFMylation promotes efficient replication initiation and fork progression, further investigation will be required to elucidate how this modification is coordinated with other post-translational modifications of the CMG helicase to fine-tune its activity across distinct stages of the replication cycle, and whether this coordination is dynamically regulated under different physiological or pathological conditions.

Acknowledgements

ChatGPT (GPT-4, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) was used only for language refinement. All scientific content was conceived and written by the authors.

Authors contribution

Song L: Writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Liu T: Conceptualization, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing, supervision.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (32525025 to T.L.; 32500626 to L.Z.S.), Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LD26C070002 to T.L.), Central guidance for local scientific and technological development funding project: “The Construction of Zhejiang Key Laboratory of Geriatrics” (2025ZY01106 to T.L.).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Bell SP, Dutta A. DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:333-374.[DOI]

-

2. Song A, Wang Y, Liu C, Yu J, Zhang Z, Lan L, et al. Replication-coupled inheritance of chromatin states. Cell Insight. 2024;3(6):100195.[DOI]

-

3. Heller RC, Kang S, Lam WM, Chen S, Chan CS, Bell SP. Eukaryotic origin-dependent DNA replication in vitro reveals sequential action of DDK and S-CDK kinases. Cell. 2011;146(1):80-91.[DOI]

-

4. Li Z, Wu X, Liu L, Rao S, Liao Y, Liu M, et al. MCM5 UFMylation regulates replication origin firing and fork progression. EMBO J. 2025;44(21):6019-6050.[DOI]

-

5. Schmit M, Bielinsky AK. Congenital diseases of DNA replication: Clinical phenotypes and molecular mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(2):911.[DOI]

-

6. Nielsen-Dandoroff E, Ruegg MSG, Bicknell LS. The expanding genetic and clinical landscape associated with Meier-Gorlin syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2023;31(8):859-868.[DOI]

-

7. Nahorski MS, Maddirevula S, Ishimura R, Alsahli S, Brady AF, Begemann A, et al. Biallelic UFM1 and UFC1 mutations expand the essential role of ufmylation in brain development. Brain. 2018;141(7):1934-1945.[DOI]

-

8. Wang Z, Gong Y, Peng B, Shi R, Fan D, Zhao H, et al. MRE11 UFMylation promotes ATM activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(8):4124-4135.[DOI]

-

9. Lee L, Perez Oliva AB, Martinez-Balsalobre E, Churikov D, Peter J, Rahmouni D, et al. UFMylation of MRE11 is essential for telomere length maintenance and hematopoietic stem cell survival. Sci Adv. 2021;7(39):eabc7371.[DOI]

-

10. Qin B, Yu J, Nowsheen S, Wang M, Tu X, Liu T, et al. UFL1 promotes histone H4 ufmylation and ATM activation. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1242.[DOI]

-

11. Qin B, Yu J, Nowsheen S, Zhao F, Wang L, Lou Z. STK38 promotes ATM activation by acting as a reader of histone H4 ufmylation. Sci Adv. 2020;6(23):eaax8214.[DOI]

-

12. Panichnantakul P, Aguilar LC, Daynard E, Guest M, Peters C, Vogel J, et al. Protein UFMylation regulates early events during ribosomal DNA-damage response. Cell Rep. 2024;43(9):114738.[DOI]

-

13. Song W, He C, Xing X, Xu G, Yao Y, Li H, et al. Targeting the UFL1-PARP1 axis amplifies anti-tumor immunity. Cell Rep. 2025;44(10):116433.[DOI]

-

14. Tian T, Chen J, Zhao H, Li Y, Xia F, Huang J, et al. UFL1 triggers replication fork degradation by MRE11 in BRCA1/2-deficient cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2024;20(12):1650-1661.[DOI]

-

15. Tan Q, Xu X. PTIP UFMylation promotes replication fork degradation in BRCA1-deficient cells. J Biol Chem. 2024;300(6):107312.[DOI]

-

16. Gong Y, Wang Z, Zong W, Shi R, Sun W, Wang S, et al. PARP1 UFMylation ensures the stability of stalled replication Forks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121(18):e2322520121.[DOI]

-

17. Costa A, Diffley JFX. The initiation of eukaryotic DNA replication. Annu Rev Biochem. 2022;91:107-131.[DOI]

-

18. Quan Y, Zhang QY, Zhou AL, Wang Y, Cai J, Gao YQ, et al. Site-specific MCM sumoylation prevents genome rearrangements by controlling origin-bound MCM. PLoS Genet. 2022;18(6):e1010275.[DOI]

-

19. Regan-Mochrie G, Hoggard T, Bhagwat N, Lynch G, Hunter N, Remus D, et al. Yeast ORC sumoylation status fine-tunes origin licensing. Genes Dev. 2022;36(13-14):807-821.[DOI]

-

20. Han J, Mu Y, Huang J. Preserving genome integrity: The vital role of SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases. Cell Insight. 2023;2(6):100128.[DOI]

-

21. Prioleau MN, MacAlpine DM. DNA replication origins: Where do we begin? Genes Dev. 2016;30(15):1683-1697.[DOI]

-

22. Makhlouf L, Peter JJ, Magnussen HM, Thakur R, Millrine D, Minshull TC, et al. The UFM1 E3 ligase recognizes and releases 60S ribosomes from ER translocons. Nature. 2024;627(8003):437-444.[DOI]

-

23. Komatsu M, Inada T, Noda NN. The UFM1 system: Working principles, cellular functions, and pathophysiology. Mol Cell. 2024;84(1):156-169.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite