Abstract

MXenes, as emerging two-dimensional transition metal carbides/nitrides, have shown considerable potential in multiple fields due to their high electrical conductivity, tunable surface functional groups, and excellent interfacial properties. However, inherent limitations, such as limited band structure modulation, single terminal functionality, and susceptibility to oxidation, hinder their further development in complex application scenarios. Surface modification engineering, which regulates the chemical termination and interfacial microenvironment of MXenes, has become a key strategy to break through these performance boundaries and impart multifunctionality. This review systematically summarizes the latest research advances in surface-modification-driven functionalization of MXenes. It focuses on modification strategies and structural tuning, with particular emphasis on the effects of surface functional group modulation on their electronic structure, interfacial charge distribution, and ion transport behavior. Furthermore, the innovative applications of functionalized MXenes in fields such as optoelectronic detection, electrocatalysis, energy storage, and biomedicine are summarized. Finally, the challenges faced by surface modification are outlined, and prospects for future development toward atomic-level precision control and multifunctional integration are discussed, providing theoretical support and technical guidance for the transition of MXenes from basic research to practical applications.

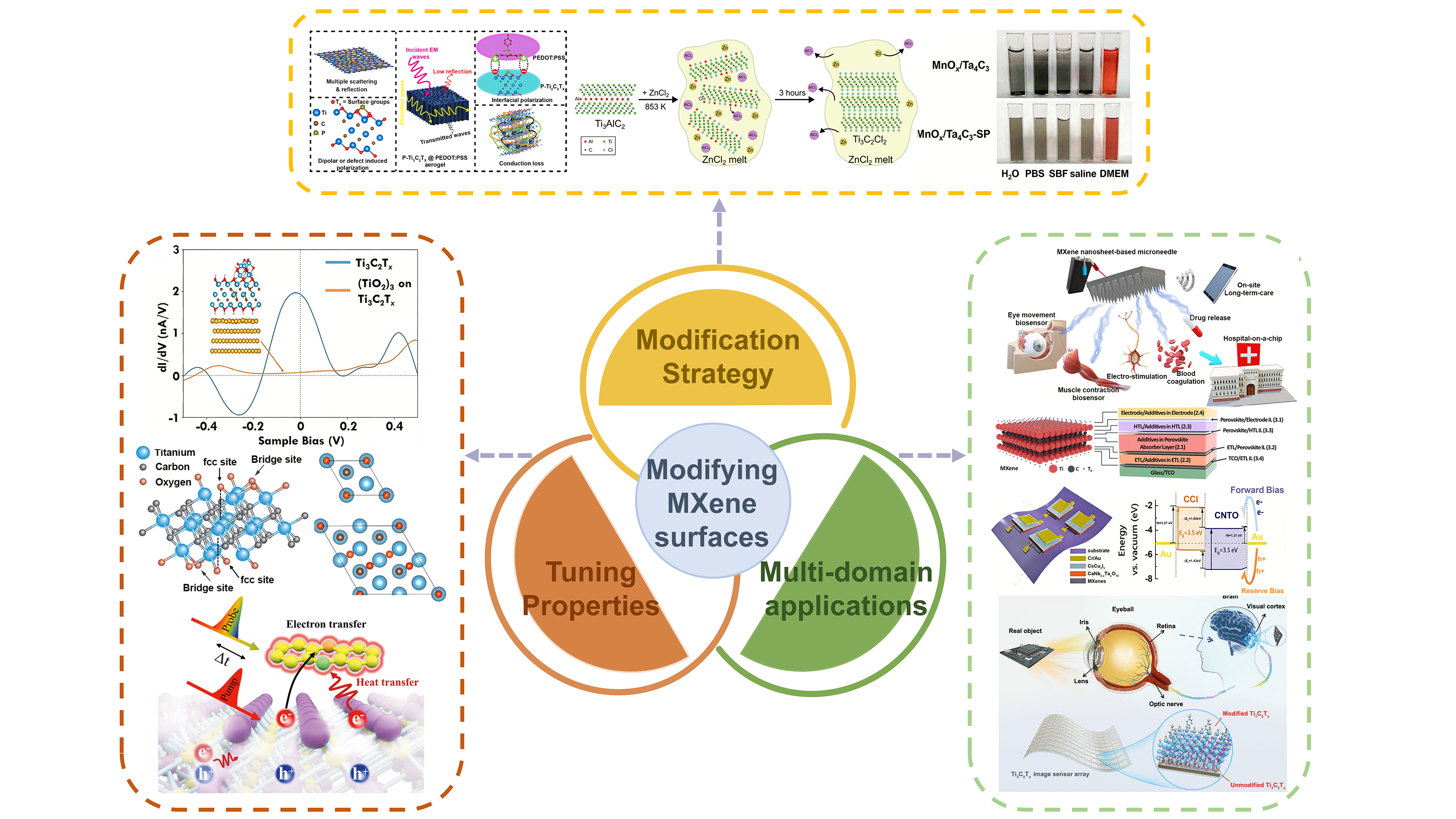

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

1. Introduction

Since the first successful synthesis of MXenes in 2011, two-dimensional transition-metal carbides, nitrides, and carbonitrides derived from this family have rapidly emerged as a major research frontier in functional materials science[1]. Distinct from conventional two-dimensional materials, MXenes exhibit unique characteristics in terms of band-structure features, interfacial polarization behavior, and chemically tunable interlayer interactions. Their metallic electronic nature, combined with highly variable surface terminations, defines an unconventional set of physical property boundaries and provides a fundamental basis for their expansion into applications such as energy conversion, optoelectronics, electrocatalysis, and biomedicine[2-6]. Beyond the intrinsic lattice structure, however, the surface chemistry of MXenes plays an equally critical role. The complexity and tunability of surface terminations constitute one of the most distinctive scientific attributes of this material system. (Herein, the term functional groups is interpreted broadly to encompass not only intrinsic covalent terminations such as -O, -OH, and -F, but also diverse extrinsic organic and inorganic species ranging from small molecules to polymer coatings that are anchored via covalent bonding or non-covalent interactions.) Even subtle variations in surface functional group configurations can induce pronounced changes in the band structure, charge-transport dynamics, interfacial coupling, and structural stability of MXenes, rendering surface functionalization a decisive factor in governing their physical property limits and application accessibility.

Although the metallic nature of MXenes endows them with excellent electrical conductivity and strong interfacial charge-coupling capability, these same characteristics also impose intrinsic constraints on their functional diversification. The limited tunability of the electronic band structure arising from native surface terminations, charge scattering induced by interfacial polarization and defects, rapid structural degradation under humid and oxidative conditions[7,8], and the divergent requirements for electronic structure, stability, and interfacial behavior across different application domains collectively render pristine MXenes insufficient for complex device architectures. Consequently, strategies for structural optimization and performance enhancement have shifted from conventional regulation of layered architectures toward the precise manipulation of surface chemistry. In this context, surface modification has emerged as a central approach for driving MXene functionalization. A broad range of modification strategies, including solution-phase grafting, diazonium-induced covalent functionalization, polymer-mediated interfacial engineering, high-temperature solid-state doping, and molten-salt-enabled termination exchange and interfacial reconstruction, have been developed. These approaches enable profound alterations in fundamental physicochemical properties, such as work-function modulation, bandgap opening, redistribution of interfacial polarization, reconfiguration of ion-transport pathways, and improved environmental stability. As a result, MXenes have evolved from single-function, highly conductive two-dimensional materials into versatile functional platforms capable of supporting applications spanning optoelectronics, catalysis, energy storage, and biomedicine[9-13].

Research on surface-engineered MXenes for applications spanning multiple disciplines has grown rapidly; however, a cohesive and mechanistic framework linking specific surface-modification strategies to the resulting MXenes physicochemical properties is still lacking. To address this gap, this review surveys recent advances in surface-modification-driven functional MXenes and their cross-disciplinary applications. We begin by summarizing representative approaches for regulating surface chemistry and then delineate how these interventions reshape the electronic structure, interfacial processes, and environmental/structural stability of MXenes. Building on these insights, we discuss how the ensuing structure-property evolution underpins performance improvements in key areas including photodetection, electrocatalysis, energy storage, and biomedicine (Figure 1). Finally, we outline the major scientific bottlenecks and practical challenges that currently limit MXene surface modification and propose future directions toward more precise and application-oriented design, aiming to provide guidance that is both fundamentally grounded and technologically relevant for the next phase of MXene materials development.

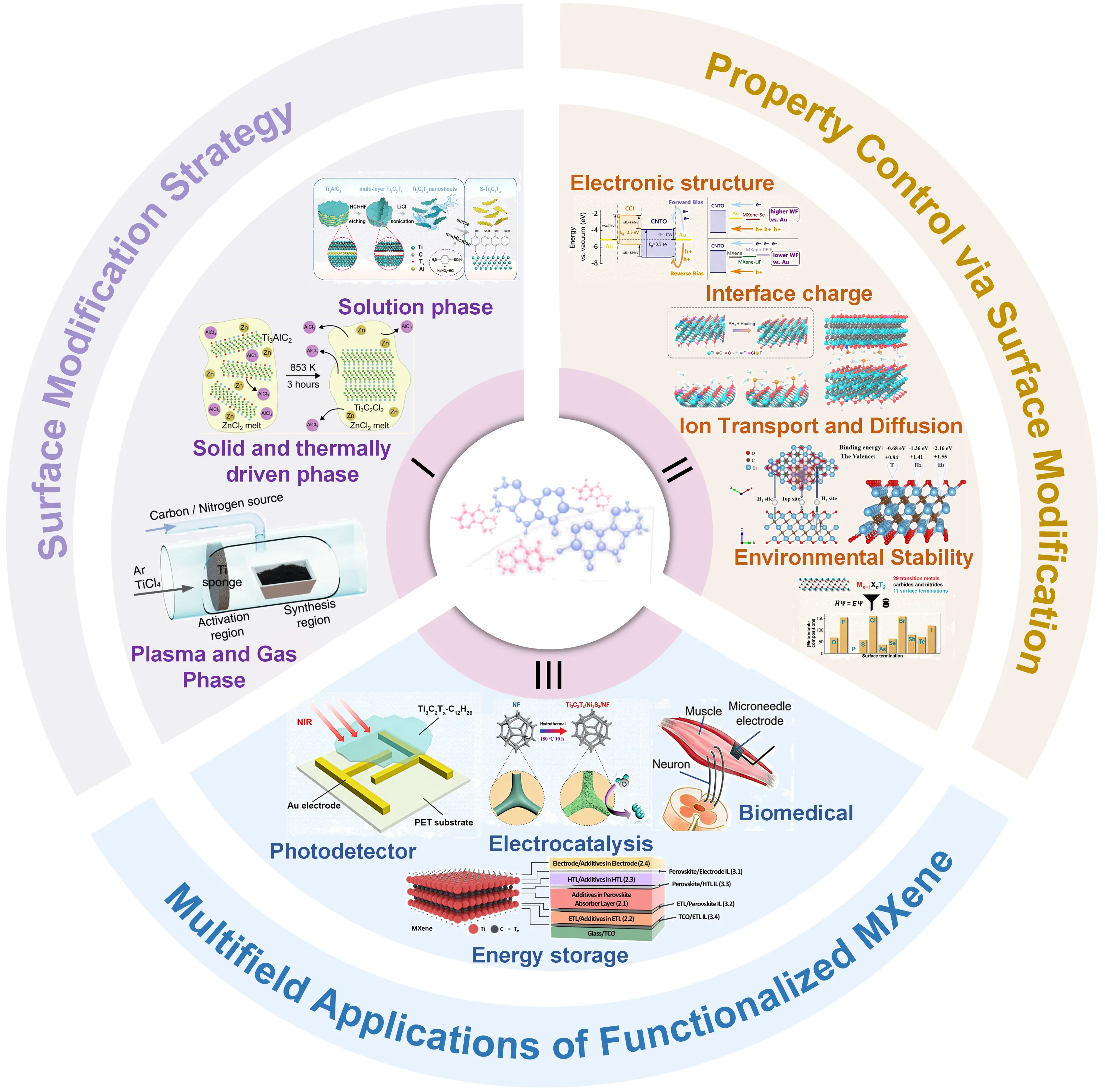

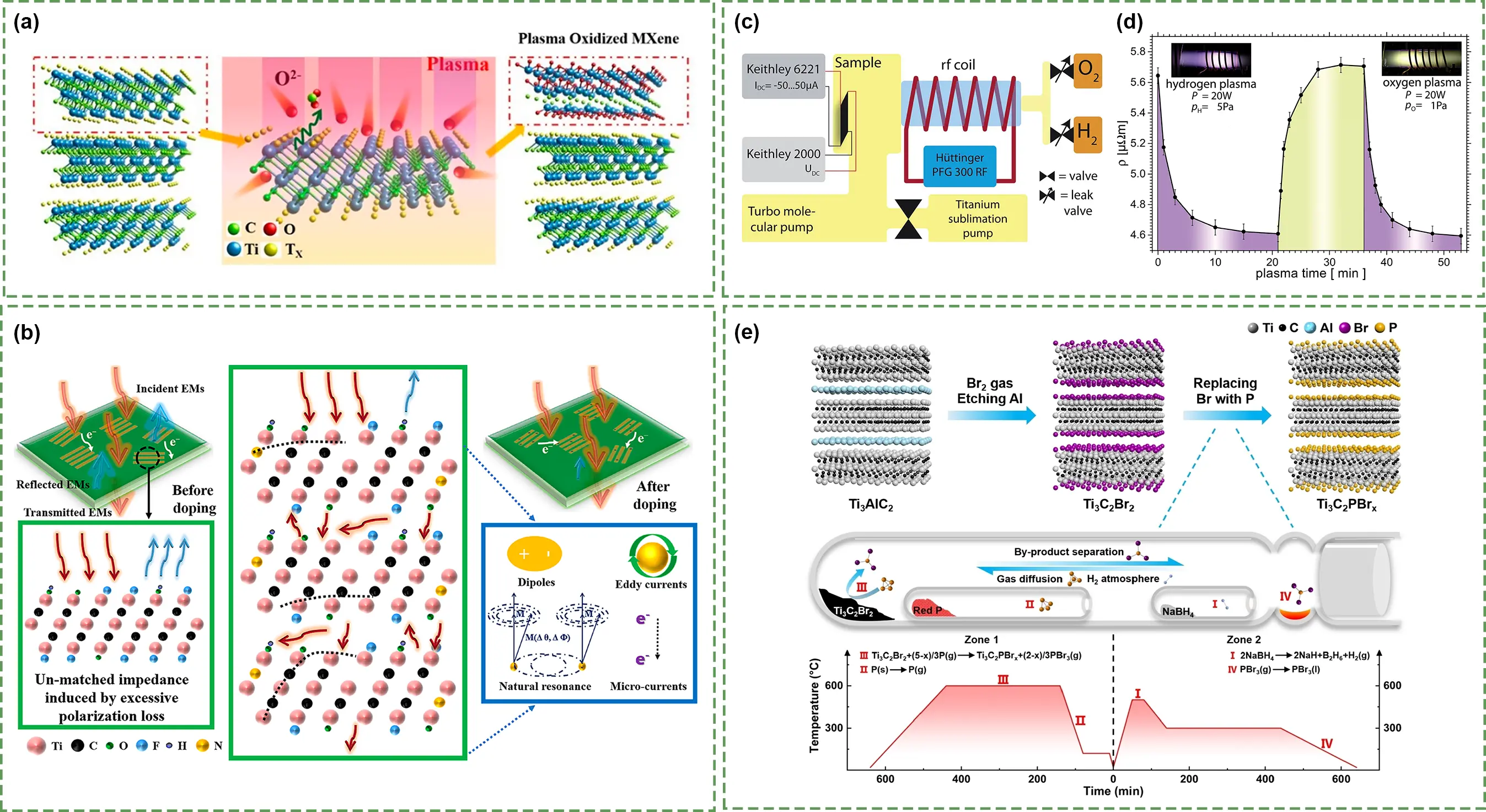

Figure 1. An overview of the multi-field applications of MXene enabled by interfacial regulation. Solution Phase. Republished with permission from[26]. Solid and thermally driven phase. Republished with permission from[55]. Plasma and Gas Phase[65]. Electronic structure. Republished with permission from[86]. Interface charge. Republished with permission from[174]. Ion Transport and Diffusion[115]. Environmental Stability. Republished with permission from[135]. Photodetector[21]. Electrocatalysis. Republished with permission from[27]. Energy storage[6]. Biomedical[5].

2. Surface Modification Strategies for MXenes

The configuration of surface terminations and the associated interfacial chemical states constitute key determinants governing the tunability of MXenes’ physicochemical properties and their performance in practical applications. To modulate these surface chemical characteristics in a controlled manner, the development of systematic and versatile surface-modification strategies is a prerequisite for advancing MXene functionalization. Accordingly, this section focuses on the principal approaches currently employed for MXene surface engineering, including solution-phase chemical grafting, solid-state and thermally driven reconstruction, and plasma- or gas-phase functionalization. These strategies provide a methodological framework for subsequent discussions on how surface modification influences the electronic structure, interfacial behavior, and environmental stability of MXene.

To ensure that surface-engineering protocols are not only synthetically accessible but also chemically verifiable, reliable characterization of surface terminations and interfacial chemical states is indispensable. In practice, the evolution of terminal groups (e.g., -O, -OH, -F, -Cl, -S, -N, and organic moieties) is most commonly evaluated by a combination of surface-sensitive spectroscopy and structural probes. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy is widely adopted to quantify elemental compositions and oxidation-state variations, enabling the deconvolution of Ti-C/Ti-O bonding environments and the tracking of termination substitution or oxidation-induced reconstruction. Vibrational spectroscopies such as Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy are particularly useful for identifying grafted organic functionalities (e.g., Si-O-M, C-N, C=O) and monitoring changes in surface bonding configurations after covalent modification or polymer coating. Solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance, though less frequently applied, provides complementary insights into local bonding motifs (e.g., Si environments in silanization or P-containing terminations), especially when bulk-sensitive confirmation is required. In addition, microscopic and diffraction-based tools including high-resolution transmission electron microscopy, in situ TEM, and electron energy-loss spectroscopy can directly visualize interfacial reconstruction, defect formation, and heteroatom incorporation at the atomic scale, thereby correlating termination evolution with local structural rearrangements. Given that no single technique alone can unambiguously resolve termination chemistry, cross-validation using multiple complementary methods is generally recommended for establishing the reliability of surface functionalization and its structure-property correlations.

2.1 Solution-phase surface functionalization

Solution-phase functionalization represents the most extensively employed and structurally diverse class of MXene surface-modification strategies. These approaches are typically carried out under mild conditions and are compatible with aqueous or organic solvent environments, enabling molecular-level regulation of surface terminations and the interfacial chemical microenvironment while preserving the integrity of the two-dimensional MXene framework.

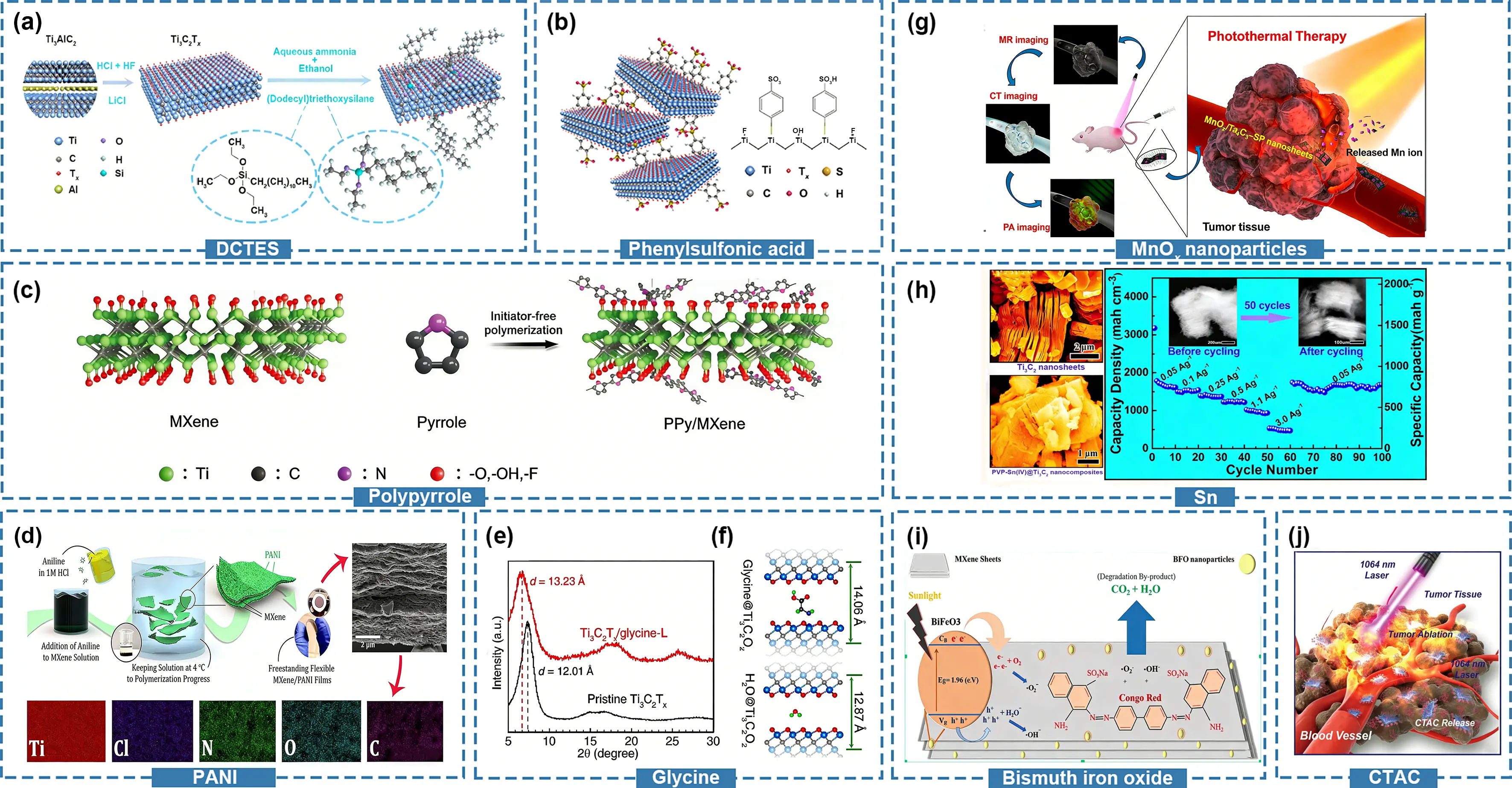

In solution environments, the intrinsic -OH terminations on MXene surfaces are commonly regarded as key reactive sites for constructing covalent interfacial architectures. Following alkaline treatment to increase the surface -OH density, silane coupling agents can be introduced to form robust Si-O-M bonding interfaces on MXenes such as Ti3C2Tx. Silane molecules with different molecular structures give rise to organic surface shells with distinct compositions and polarities[14-17]. For example, through simple stirring at room temperature, (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES), (dodecyl)triethoxysilane (Figure 2a), (methylaniline)triethoxysilane, and (3-methacryloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane can graft -C3H6NH2, -C6H6, -C12H26, and -COOR terminal groups onto the surface of Ti3C2Tx MXene, respectively[18-21]. Alkyl silanes typically generate hydrophobic long-chain hydrocarbon coatings, whereas aromatic silanes construct π-conjugated surface architectures[22-27]. These functional layers not only improve MXene dispersibility in organic solvents and compatibility within composite systems, but also enable fine regulation of the work function and surface potential through modulation of surface dipoles and local charge distributions, thereby facilitating energy-level alignment at subsequent electron and hole injection interfaces. Diazonium-salt-driven covalent grafting provides another important route for introducing aromatic functionalities onto MXene surfaces. For instance, Shen and co-workers diazotized p-aminobenzenesulfonic acid in acidic solution and subsequently induced nucleophilic substitution reactions with active sites on MXene surfaces, achieving the grafting of -phSO3H functional groups onto Ti3C2Tx, as shown in Figure 2b[26]. Related aromatic diazonium systems have also been employed to introduce nitro, carboxyl, and other substituents, enabling precise tuning of the MXene work function and surface coordination capability[28]. In parallel, solution-phase in situ polymerization combined with physical adsorption has been widely adopted to achieve synergistic regulation of interlayer spacing, pore architecture, and interfacial charge-transport behavior in MXenes. Dopamine readily undergoes self-polymerization under mildly alkaline conditions, and the resulting polydopamine (PDA) uniformly coats the Ti3C2Tx surface. The nitrogen- and oxygen-rich interfacial layer enables cooperative modulation of interlayer distance, surface polarity, and local electronic distribution[29]. In situ oxidative polymerization of conductive polymers such as polypyrrole and polyaniline (PANI) on MXene surfaces can further construct continuous conductive networks and flexible interfacial layers, enhancing charge-transport efficiency through π-conjugated coupling, as demonstrated in Figure 2c,d[30-35]. As illustrated in Figure 2e,f, small molecules such as glycine and glutathione can regulate the interlayer spacing and surface charge state of Ti3C2Tx MXene through coordination interactions or hydrogen bonding, thereby enhancing charge permeation and interfacial recognition capabilities[36-38]. For hydrophilic polymers such as polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), surface modification is mainly achieved via solvation layers and noncovalent coordination interactions, which improve environmental stability and colloidal dispersibility while preserving the integrity of the layered structure and the tunability of flexible interfaces[39-44].

Figure 2. (a) Preparation of Ti3C2Tx-C12H26[21]; (b) Schematic diagram of MXene modified by phenylsulfonic acid. Republished with permission from[26]; (c) Preparation of carboxyl terminated aryl diazonium salt-modified Ti3C2Tx. Republished with permission from[30]; (d) Modification of Ti3C2Tx with PANI and SEM images. Republished with permission from[35]; (e) XRD measurement diagram of MXene before and after glycine modification. Republished with permission from[36]; (f) Schematic diagram of glycine grafting. Republished with permission from[36]; (g) Inhibitory effect of MnOx/Ta4C3 composite nanoflakes on tumor growth in photothermal hyperthermia. Republished with permission from[45]; (h) Sn4+ ions uniformly decorate the surface and interlayers of Ti3C2 MXene, delivering a high reversible volumetric capacity and excellent cycling stability over 50 charge-discharge cycles. Republished with permission from[46]; (i) Schematic of the BiFeO3/Ti3C2 MXene nanohybrid for enhanced photocatalytic activity[51]; (j) Schematic illustration of CTAC-mediated codelivery of chemotherapeutics and photothermal agents (via Nb2C) for enhanced synergistic tumor therapy[52]. SEM: scanning electron microscopy; XRD: X-ray diffraction; MR: magnetic resonance; CT: computed tomography; PA: photoacoustic imaging; SP: soybean phospholipid; BFO: BiFeO3.

Solution-based media also provide versatile platforms for grafting inorganic species onto MXene surfaces. For example, treating Ta4C3 in solutions containing oxidizing or reducing agents enables the in situ growth of MnOx nanoparticles on the MXene surface, thereby constructing strongly coupled interfaces between the two-dimensional conductive scaffold and zero-dimensional active sites, as illustrated in Figure 2g[45]. In systems containing metal salts and appropriate chelating agents, impregnation followed by suitable post-treatment can achieve the distributed loading or localized doping of metal species such as Sn4+ on Ti3C2 substrates (Figure 2h)[46-50]. In addition, dual-solvent sol-gel methods offer a controllable and generally applicable route for constructing inorganic coatings on MXenes. In such processes, controlled hydrolysis and condensation of metal alkoxide precursors occur in mixed aqueous/organic solvent environments, leading to the in situ formation of continuous or discretely distributed inorganic oxide networks on MXene surfaces. Owing to the abundance of -OH or -O terminations on MXene sheets such as Ti3C2Tx, these hydrolysis products can be firmly anchored through M-O-Ti bonding, enabling molecular-level regulation of the interfacial chemical environment. For instance, Figure 2i shows that Rizwan et al. successfully modified Ti3C2 using La- and Mn-co-doped bismuth ferrite (BiFeO3) via a dual-solvent sol-gel approach[51]. As shown in Figure 2j, Chen and co-workers sequentially introduced cetyltrimethylammonium chloride and an organosilicon precursor (tetraethyl orthosilicate, TEOS) onto Nb2C using a similar strategy[52]. This multifunctional modification not only generated a mesoporous silica shell (CTAC@Nb2C-MSN) on the MXene surface but also significantly improved its chemical stability and interfacial compatibility under physiological conditions.

2.2 Solid-state and thermally driven surface functionalization

Solid-state and thermally driven surface-modification strategies endow MXenes with the capability for deep chemical reconstruction that is difficult to achieve in solution-based systems. By leveraging high-temperature treatments, molten-salt reactions, or gas-solid interfacial processes, these approaches enable transformations beyond simple terminal exchange or molecular grafting under mild conditions. Elevated temperatures facilitate elemental diffusion, termination substitution, and reorganization of local coordination environments, thereby substantially expanding the accessible surface-chemistry space of MXene. As a result, solid-state and thermally driven modifications represent a powerful route for tailoring the electronic structure of MXenes and unlocking property regimes unattainable through low-temperature processing[53-56].

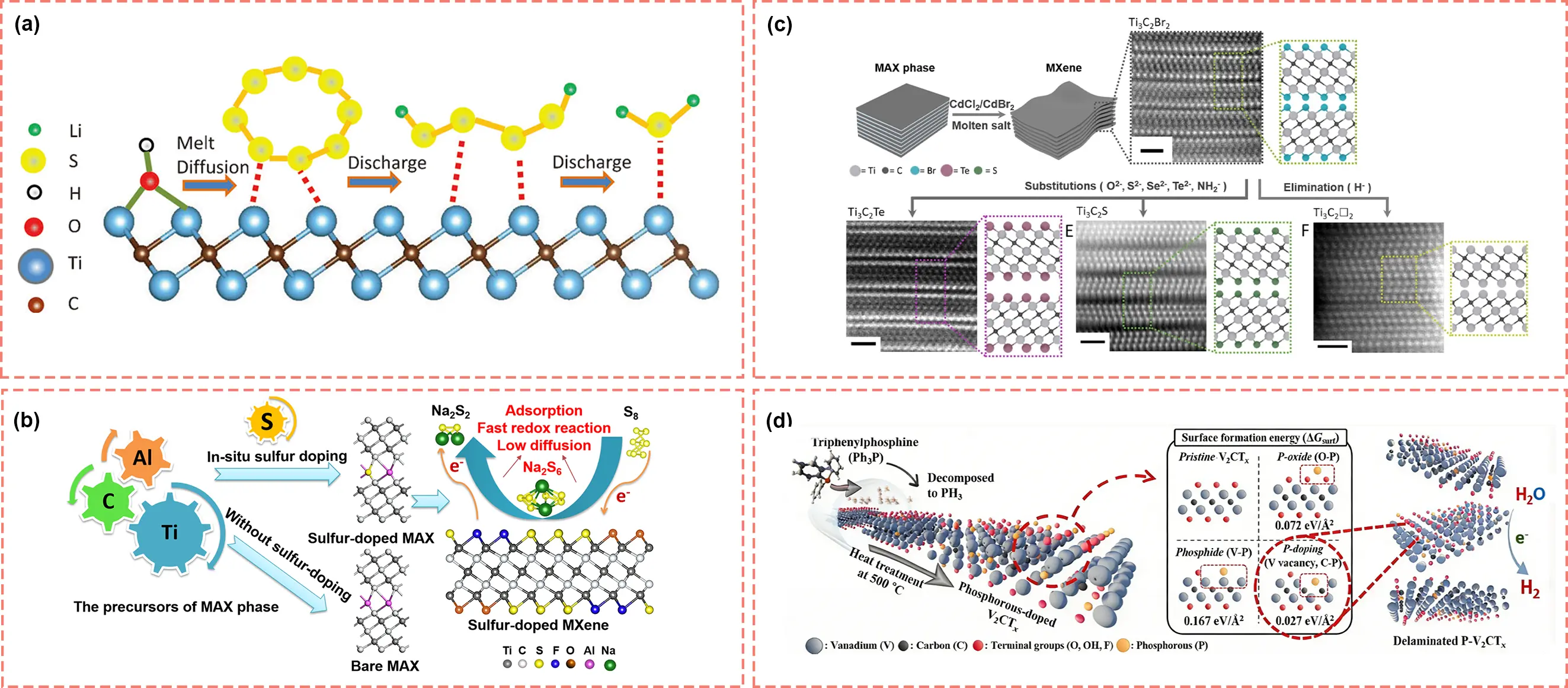

In high-temperature diffusion systems, the migration of elements in the solid state serves as the primary driving force for regulating MXene surface terminations. Molten elements can infiltrate MXene surfaces with strong thermodynamic driving forces, displacing native terminations and forming stable surface coordination structures. For example, Liang et al. reported the solid-state diffusion of sulfur on Ti2C and Ti3C2Tx surfaces under high-temperature conditions, as shown in Figure 3a. By co-heating MXene with elemental sulfur, molten S atoms penetrate surface-active sites at elevated temperatures, partially replacing -O and -F terminations. This process is accompanied by reconstruction of the surface coordination environment, where the introduction of S terminations induces redistribution of surface electron density and leads to the formation of more stable S-Ti bonding configurations[57]. Alternatively, sulfur-containing species can be preintroduced into MAX-phase precursors via solid-state reactions. As demonstrated by Fawzy et al., high-temperature sintering of Al-S mixtures yields sulfur-containing MAX precursors, which subsequently generate sulfur-doped MXene with wrinkled morphologies during etching. This approach enables simultaneous regulation of interlayer architecture and surface morphology, as illustrated in Figure 3b[58].

Figure 3. (a) Schematic diagram of S element grafting on the Ti2C MXene surface. Republished with permission from[57]; (b) Illustrative diagram of the preparation of surface-doped MXene via high-temperature sintering of an Al-S mixture. Republished with permission from[58]; (c) Etching schematic diagram of MAX phase in Lewis acid molten salt and atomic resolution high-angle annular dark-field images of Ti3C2Br2, Ti3C2Te, Ti3C2S, and Ti3C2□2 (□ stands for the vacancy) sheets. Republished with permission from[59]; (d) Schematic diagram of preparation and application of V2CTx with triphenylphosphine as phosphorus source. Republished with permission from[61].

Surface reconstruction in molten-salt systems represents another representative class of thermally driven modification strategies. Owing to the high ionic concentration and low viscosity of molten metal halides, rapid species exchange and coordination rearrangement can be achieved at MXene surfaces. For instance, Xiong et al. treated Ti3AlC2 with molten CoCl2 at approximately 750 °C, during which Co2+ ions directly coordinated with the emerging Ti3C2Tx surface, enabling simultaneous reconstruction of the metal species and the MXene substrate[53]. The strong ionic interactions in molten-salt environments not only accelerate elemental diffusion kinetics but also promote the formation of robust interfacial bonding. Talapin and co-workers further demonstrated that substitution and elimination reactions conducted in molten inorganic salts allow the functionalization of MXene surfaces with a broad range of terminations, including O, NH, S, Cl, Se, Br, and Te (Figure 3c)[59]. Thermodynamically, molten-salt-enabled termination exchange can be understood as an interfacial chemical potential-driven process, in which the relative stability of surface terminations is determined by the free-energy balance between breaking the original M-T bonds and forming new surface coordination with incoming anions or complexing species from the melt. At elevated temperatures, the increased ionic mobility and reduced effective viscosity of the molten medium facilitate mass transport to and from the MXene surface, while the high ionic strength helps sustain a large activity of reactive ions near the interface, collectively lowering the kinetic barriers for exchange. In addition, the ion-exchange kinetics can vary across different molten salt systems because the melt composition governs the activity of the exchanging ions, the strength of ion pairing or complexation, and the interfacial reaction environment, which together influence both the driving force and the rate of termination substitution. Therefore, molten salt selection is expected to affect not only the attainable termination species but also the exchange kinetics and the degree of surface reconstruction under comparable thermal conditions.

High-temperature gas-solid reactions likewise provide an effective route for tailoring MXene surface chemistry. Li et al. investigated the nitridation behavior of V4C3Tx under an ammonia atmosphere and found that high-temperature annealing enabled nitrogen atoms to adsorb as surface terminations. This modification induced changes in surface polarity, local charge redistribution, and termination-state energy levels. Compared with pristine V4C3Tx, NH3-treated V4C3Tx exhibited higher gravimetric capacitance and reduced capacitance loss[60]. In addition, high-temperature treatment of V2CTx with triphenylphosphine under an inert atmosphere results in phosphorus-functionalized MXenes through surface substitution or doping. Phosphorus is incorporated via P-O-Ti or P-Ti bonding, shifting the termination configuration from oxygen-dominated species toward phospho-oxygen or partially phosphidized structures. This transformation is typically accompanied by redistribution of local electron density and modification of the coordination field, as illustrated in Figure 3d[61].

2.3 Plasma and gas-phase surface functionalization

Plasma treatment and gas-phase modification offer complementary routes for MXene surface engineering that are distinct from solution-phase functionalization and high-temperature solid-state approaches. These methods are typically conducted under solvent-free or low-temperature conditions, where high-energy species or volatile gaseous precursors directly interact with MXene surfaces. Such interactions enable reconstruction of surface terminations, regulation of localized defects, incorporation of heteroatoms, or the formation of ultrathin surface layers, while largely preserving the layered framework of MXenes[61-70]. Compared with the dispersion-dependent nature of solution-phase reactions and the pronounced structural rearrangements that may arise from high-temperature treatments, plasma- and gas-phase strategies afford superior precision in reaction uniformity, depth control, and interfacial tunability.

Plasma-based modification strategies exploit the activation effects of high-energy ions, radicals, and electrons present in the plasma to induce controllable structural variations on MXene surfaces, including mild etching, adjustment of functional group ratios, and defect generation[71]. Among these approaches, argon plasma primarily enables surface activation and the introduction of controlled defects through physical bombardment. For example, Pang et al. employed Ar plasma to mildly etch the surface of Ti3C2Tx, thereby exposing additional metal active sites and increasing the interlayer spacing[64]. In oxygen plasma, energetic ions, radicals, and electrons induce gentle etching and surface reconstruction, leading to partial cleavage of Ti-C bonds and the formation of amorphous Ti-O functional species and interfacial defects. This process enables regulation of surface termination ratios, work-function tunability, and suppression of interfacial trap states, thereby significantly improving charge transport and device stability, as illustrated in Figure 4a[63]. Nitrogen plasma, in turn, facilitates the incorporation of nitrogen-related functional groups or partial nitride structures, resulting in reconfiguration of surface chemistry and modulation of the electronic structure. As shown in Figure 4b, Zhou and co-workers achieved nitrogen doping of Ti3C2Tx under low-temperature radio-frequency N₂ plasma, successfully introducing -N terminations and tailoring the surface electronic states[62]. In addition, hydrogen plasma can induce partial surface reduction by removing -F or weakly bonded -O species from MXene surfaces, thereby exposing a greater number of metal-centered active sites and further tuning the surface configuration. As demonstrated by the experimental setup shown in Figure 4c,d, devices exposed to a hydrogen atmosphere exhibit higher electrical conductivity compared with those treated under oxygen-rich conditions[72]. Owing to their short reaction pathways, high selectivity, and precise control over treatment depth, plasma-based approaches are particularly well suited for fine-tuning termination compositions or constructing localized functional regions on MXene surfaces.

Figure 4. (a) Schematic representation of Ti3C2Tx MXene structure before and after oxygen plasma treatment. Republished with permission from[63]; (b) A proposed schematic illustrating microwave absorbing mechanisms of Ti3C2Tx MXene and N-doped products. Republished with permission from[62]; (c) Schematic diagram of the electrical conductivity measurement setup[72]; (d) Time-dependent resistivity evolution under plasma treatment[72]; (e) Schematic diagram of gas-phase preparation of MXene with -P functional groups and specific details of replacing -Br with -P. Republished with permission from[68].

As a complementary strategy, gas-phase processing represents an alternative surface-modification strategy in which volatile precursors or controlled reactive atmospheres interact chemically with MXene surfaces under solvent-free conditions, enabling surface termination exchange or heteroatom incorporation[73,74]. Although studies in this area remain relatively limited, gas-phase approaches have begun to demonstrate distinct advantages for tailoring MXene surface chemistry. In a recent example, Zhu et al. achieved the substitution of -Br with -P surface terminations via a two-step gas-phase reaction, successfully synthesizing -P-functionalized Ti3C2PBrx MXene and revealing a dual redox mechanism in which both Ti and -P cooperatively participate in pseudocapacitive reactions, as illustrated in Figure 4e, highlighting the unique capability of gas-phase surface functionalization for the precise regulation of MXene surface chemistry and electrochemical behavior.

3. Regulation of Physical Properties via Surface Modification

Surface structural engineering extends far beyond changes in morphology or terminal species. More fundamentally, surface modification reshapes a series of key physical parameters, including electronic structure, interfacial charge distribution, ion transport kinetics, and environmental stability, which collectively determine the performance of MXenes in diverse device systems[75-78]. Therefore, this section focuses on the intrinsic physical origins of these effects and discusses the evolution of electronic, interfacial, and kinetic behaviors induced by different surface functionalization strategies.

3.1 Electronic structure

Key electronic characteristics of MXenes, including the density of states (DOS) near the Fermi level, band alignment, and carrier effective mass, are strongly regulated by surface terminations and functional layers through modifications of local coordination environments and charge distribution[79-82]. Consequently, surface chemical engineering is widely recognized as an effective approach for reconstructing the electronic structure of MXenes and expanding their accessible property space.

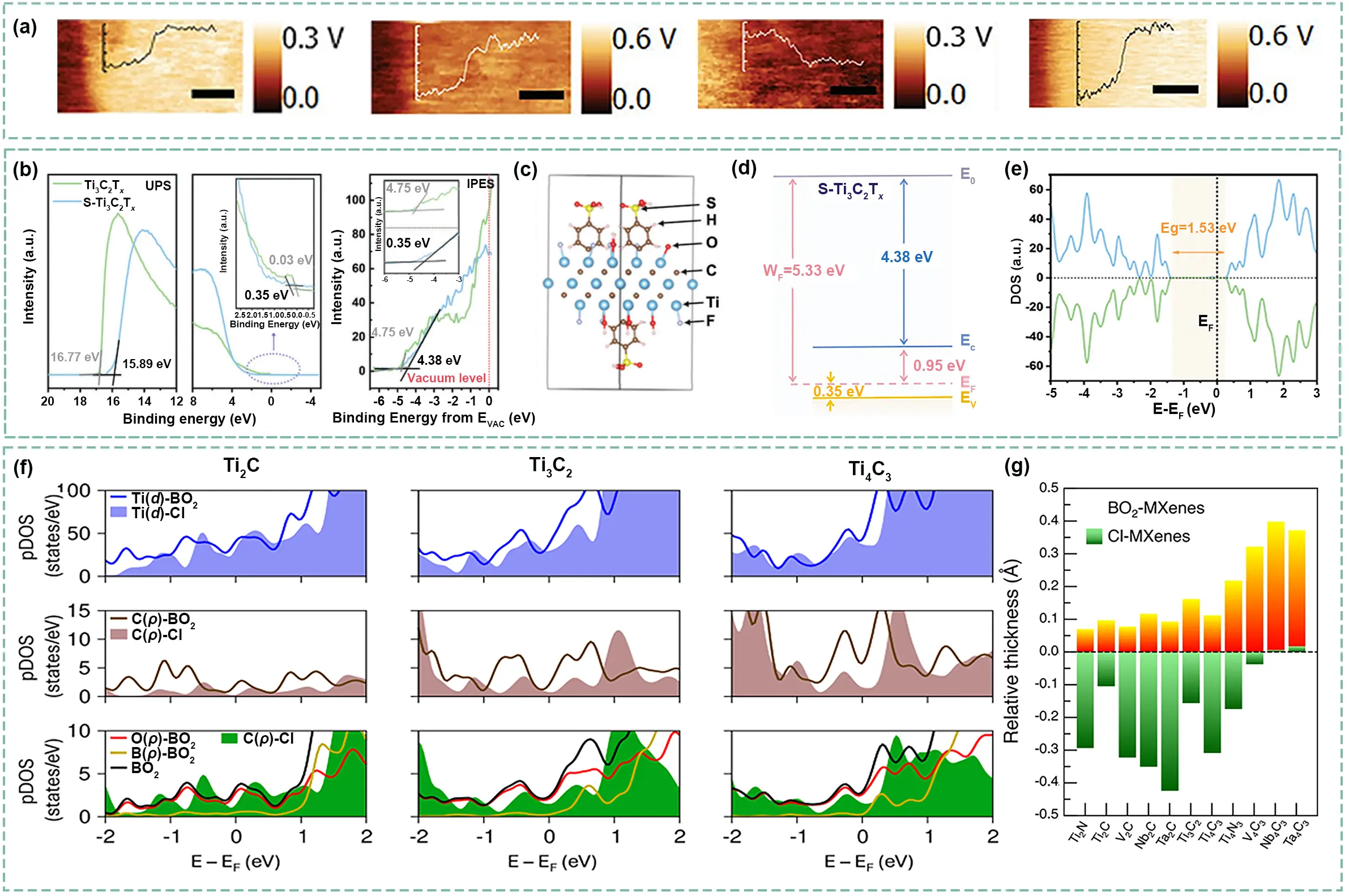

Both theoretical calculations and experimental studies consistently demonstrate that the electronegativity and dipole moment of surface functional groups exert a pronounced influence on the DOS near the Fermi level, leading to systematic variations in work function, band positions, and surface polarity[83]. Importantly, the work function of MXenes is not an intrinsic constant but a tunable parameter governed by surface dipoles and charge transfer. Different surface terminations/molecular modifiers, depending on their electron-donating or electron-withdrawing characteristics, generate oriented dipole layers on the MXene surface, thereby shifting the vacuum level alignment[84,85]. As a result, by tailoring surface termination composition or introducing charged/polar molecules, the work function of MXenes can be continuously tuned over a wide range. For example, Fang and co-workers demonstrated that sequential functionalization of Ti3C2Tx with LiF, Se, and polyethyleneimine ethoxylation (PEIE) progressively shifts the Fermi level and modulates the interfacial energy barrier, enabling work-function tuning from approximately 4.55 eV to 5.25 eV, as shown in Figure 5a[86]. Covalent grafting via diazonium chemistry or aromatic functional groups has also been shown to substantially modify the work function and intrinsic electrical conductivity of MXenes[87,88]. In particular, grafting of 4-nitrophenyl diazonium introduces strong electron-withdrawing moieties that induce surface charge redistribution and enhance surface dipole strength, resulting in a marked increase in the work function from 4.7 eV to 5.28 eV[89]. Work-function modulation is closely correlated with band structure reconstruction, and bandgap opening represents a key mechanism by which surface modification imparts semiconducting behavior to MXene. Although most MXenes are intrinsically metallic, covalent attachment of π-conjugated or strongly polar aromatic groups can introduce new hybridized electronic states and break local symmetry. This leads to a reduction in the DOS near the Fermi level and the emergence of an appreciable bandgap. For instance, Shen and co-workers covalently modified Ti3C2Tx with benzenesulfonic acid groups. Through π-d orbital hybridization and charge localization, a bandgap of approximately 1.53 eV was achieved (Figure 5b,c,d,e)[26].

Figure 5. (a) KPFM results of pristine MXene film, MXene-LiF film, MXene-Se film, and MXene-PEIE film, scale bar: 1 µm. Republished with permission from[86]; (b) UPS and IPES curves of S-Ti3C2Tx and Ti3C2Tx MXene. Republished with permission from[26]; (c) Molecular model of S-Ti3C2Tx. Republished with permission from[26]; (d) Schematic diagram of energy band structure of S-Ti3C2Tx. Republished with permission from[26]; (e) Calculation of density of states of S-Ti3C2Tx by HSE. Republished with permission from[26]; (f) Close-up comparison of the pDOS for each atomic species in BO2-(solid lines) vs Cl-terminated (shaded area) MXene, the black line (bottom panels) shows the total DOS of BO2 units[95]; (g) Relative thickness differences of each MXene[95]. S-Ti3C2Tx: sulfur-modified Ti3C2Tx MXene; UPS: ultraviolet photoelectron spectroscopy; IPES: inverse photoelectron spectroscopy; PDOS: projected density of states; BO2-MXenes: MXene with boron oxide surface terminations; Cl-MXene: MXene with chlorine surface terminations.

Surface termination engineering also alters surface polarity, local charge density, and interfacial electrostatic potential, which are key variables linking electronic structure to interfacial chemical behavior. These changes directly influence adsorption energies, local electron availability, and the structure of the electric double layer[90-92]. Both work-function tuning and bandgap opening are intrinsically accompanied by redistribution of surface polarity and charge density. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations indicate that different terminations, including O, OH, F, Cl, Br, I, NH, and S, induce predictable variations in the DOS and work function through differences in electronegativity, dipole orientation, and metal–termination spacing. Among these, NH terminations are particularly effective in lowering the work function due to their intrinsic dipole moments[93].

In addition, increasing evidence suggests that surface terminations can introduce subtle surface-induced strain and lattice distortion, leading to slight variations in M-X bond lengths, where M denotes the transition metal and X represents carbon or nitrogen. These structural perturbations shift the center of the transition-metal d band and ultimately modify adsorption barriers and electron transport pathways[94]. For example, Rosen and co-workers systematically investigated the influence of triatomic borate terminations on the electronic structures of eleven MXenes, including Ti2N, Ti3C2, and V4C3, using DFT. Their results showed that this strongly coordinating termination induces out-of-plane lattice expansion while significantly enhancing the DOS near the Fermi level and surface charge transfer (Figure 5f,g)[95]. These findings highlight surface termination engineering as an effective strategy for constructing strain-electronic structure coupling in MXenes and for optimizing their electronic properties.

3.2 Interfacial charge

MXenes exhibit interfacial charge redistribution when they form heterostructures with semiconductors, metal oxides, or other two-dimensional materials, driven by differences in work function, termination-induced dipole moments, and modulation of the local DOS. Extensive research has highlighted the critical role of surface terminations in regulating interfacial charge transfer. Early studies on MXenes demonstrated that terminations such as -O and -F not only alter surface polarity but also significantly influence the work function, thus largely determining the direction of charge transfer across heterointerfaces[83,96]. Functionalization with chemical groups that enhance surface dipole moments or polarization modifies the Fermi-level alignment between MXenes and adjacent materials, allowing for effective tuning of the interfacial built-in electric field[97-99].

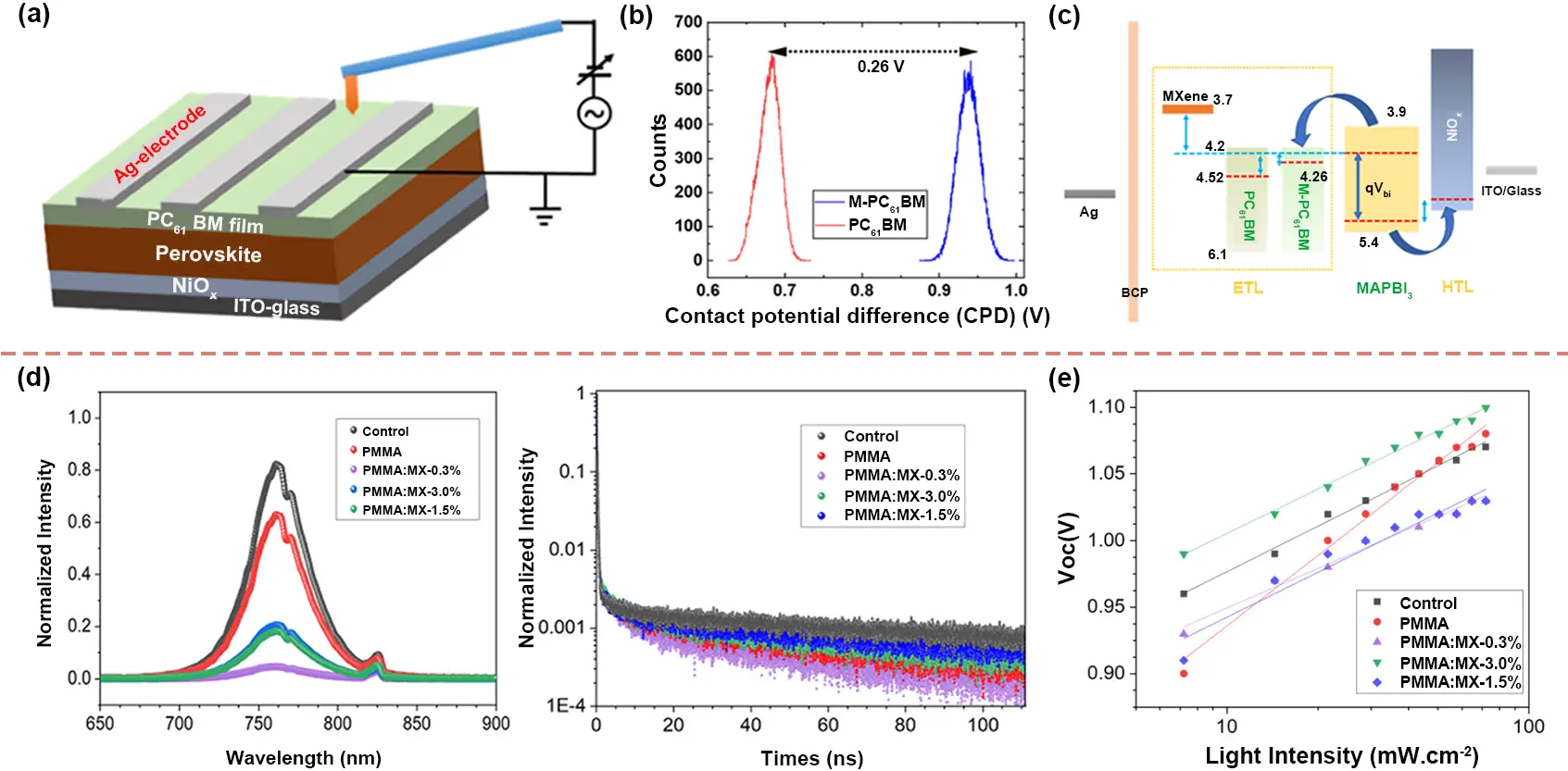

In typical two-dimensional heterostructures, the realignment of the Fermi level drives charge redistribution between MXenes and neighboring components. Surface functionalization adjusts both the work function and surface polarity of MXenes, facilitating the formation of distinct charge transfer pathways with materials of higher or lower work functions. Enhancing the surface dipole via termination engineering significantly modulates the direction of electron transfer, depletion width, and interfacial barrier height[100-102]. The resulting built-in electric field not only governs interfacial charge transport but also alters the occupancy of interfacial states, which profoundly influences subsequent interfacial reaction pathways. For instance, Zou et al. constructed a Ti3C2Tx/MoS2 heterojunction and found that the relatively high work function of Ti3C2Tx promotes electron injection from n-type MoS2 into the MXene, creating a pronounced depletion region and built-in electric field on the MoS2 side, with significant band bending at the interface[103]. This interfacial field accelerates the spatial separation and extraction of photogenerated carriers, significantly improving the photoresponse and directional charge transport in photodetectors. Similarly, as illustrated in Figure 6a,b,c, in MXene/perovskite or MXene/oxide composite devices, work-function modulation and interfacial charge transfer induced by surface terminations and functional layers have been demonstrated to optimize energy-level alignment and built-in electric-field distribution. These effects collectively contribute to improved open-circuit voltage, fill factor, and overall device stability[104,105].

Figure 6. (a) Schematic of a SKPFM measurement setup. Republished with permission from[104]; (b) Histogram of CPD values obtained from the SKPFM mapping for PC61BM and M-PC61BM. Republished with permission from[104]; (c) Energy-level band diagram. Republished with permission from[104]; (d) PL and TRPL spectra of perovskite/PMMA:MX/PCBM. Republished with permission from[106]; (e) Irradiation-intensity-dependent open-circuit potential Voc of the control, PMMA and PMMA:MX (0.3%, 1.5% and 3.0%) perovskite solar cells. Republished with permission from[106]. SKPFM: scanning Kelvin probe force microscopy; PC61BM: 6,6-phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester; NiOx: nickel oxide (non-stoichiometric); ITO: indium tin oxide; BCP: bathocuproine; ETL: electron transport layer; HTL: hole transport layer; MAPbI3: methylammonium lead iodide; PMMA: poly(methyl methacrylate).

Surface functionalization also improves the interfacial chemical environment by reducing trap-state density and passivating interfacial defects. In several MXene-based composite systems, surface terminations, in situ formed oxide layers, or introduced heterophase nanodomains effectively saturate dangling bonds and compensate vacancy defects, redistributing interfacial states from deep traps to shallower traps. This increases carrier lifetime and suppresses nonradiative recombination[6,104]. For example, a Ti3C2Tx-doped PMMA passivation layer significantly reduces interfacial trap-state density and mitigates nonradiative recombination (Figure 6d,e), improving the open-circuit voltage and power-conversion efficiency[106]. HFIP-functionalized MXenes can reconstruct the perovskite surface, suppress defect formation and trap states, and enhance the interfacial dipole, leading to improved carrier transport and device stability[107]. Such interfacial passivation represents a surface/interface reconstruction process, creating a cleaner and more controllable interfacial charge environment and enabling MXenes to exhibit more robust interfacial regulation in electronic and optoelectronic applications.

Furthermore, certain MXenes, such as Mo2CTx, demonstrate significant localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) behavior, with resonance frequency and intensity highly sensitive to surface termination composition, carrier concentration, and flake morphology[91]. When integrated with metallic nanostructures or semiconductor light absorbers, LSPR excitation induces hot-electron injection and transient charge accumulation, enhancing the local built-in electric field and improving charge migration efficiency. This amplifies the regulation of interfacial charge dynamics through coupled photo-electro-thermal effects[108]. Further functionalization to tailor termination distribution and local electronic density is expected to strengthen plasmonic responses at the interface, inducing more pronounced Fermi-level shifts and nonequilibrium carrier accumulation, thus enabling highly tunable interfacial charge responses under varying temporal and optical conditions[109,110]. Therefore, interfacial charge regulation achieved through surface functionalization reconstructs the charge distribution of MXenes at heterointerfaces, endowing them with newly established interfacial potential landscapes, cleaner interfacial states, and tunable coupled photoinduced electric-field response characteristics.

3.3 Ion transport and diffusion

The performance of MXenes in electrochemical energy storage, electrocatalysis, and ion sieving is strongly governed by their ion transport and diffusion properties[111,112]. However, intrinsic MXenes typically exhibit limited interlayer spacing, diverse surface terminations, and a strong tendency toward restacking, which together significantly constrain ion migration pathways. As a result, ion transport rates are reduced and diffusion kinetics are hindered[113]. Consequently, rational and designable regulation strategies focusing on MXene surface chemistry and interlayer structure have emerged as key approaches for enhancing ion transport behavior.

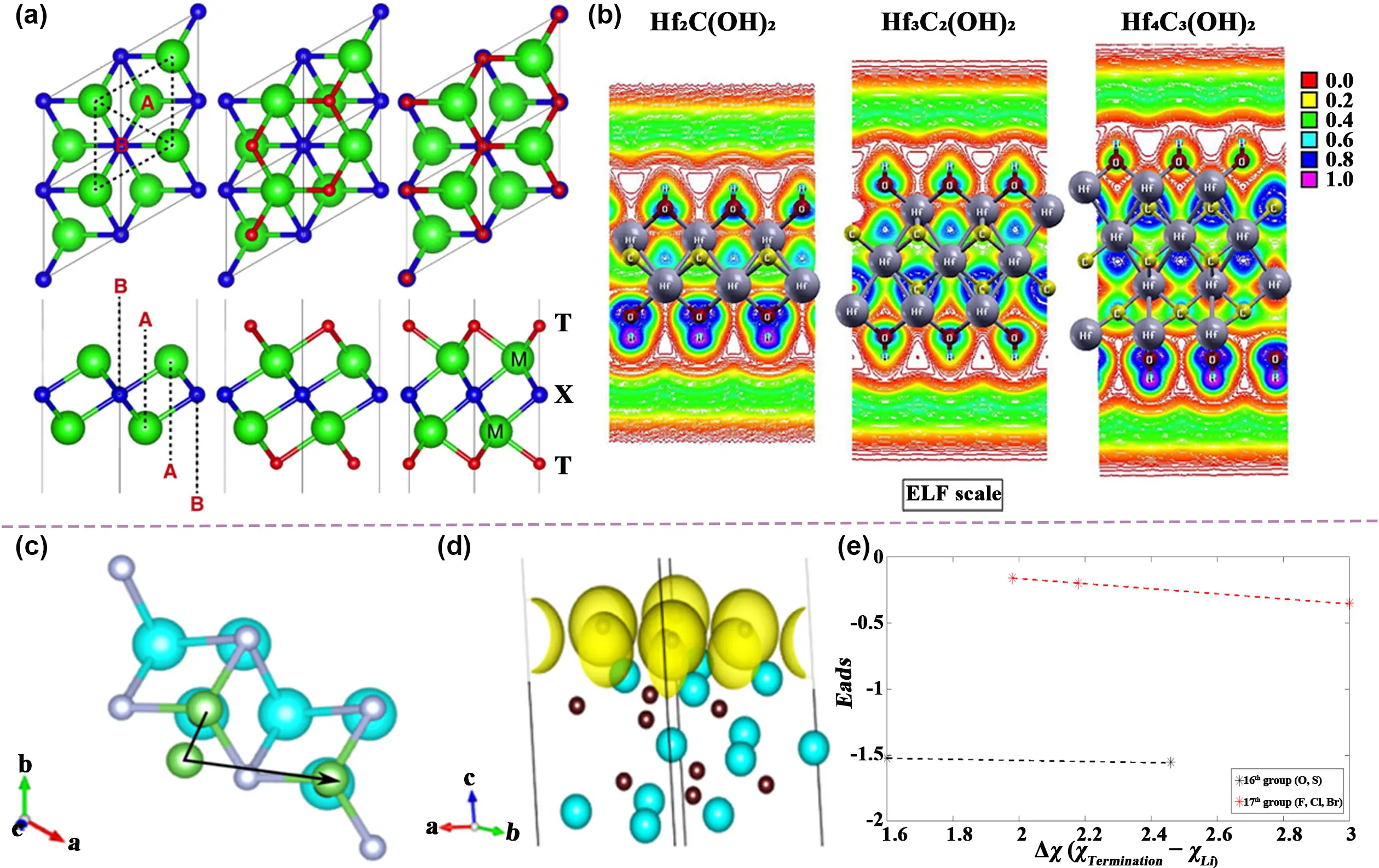

Owing to their unique surface terminations, engineerable interlayer spacing, and highly tunable interfaces, MXenes offer advantages in ion-kinetics modulation that are difficult to achieve simultaneously in other two-dimensional materials[114,115]. Previous studies have demonstrated that different surface terminations induce distinct local charge distributions, leading to pronounced variations in ion migration barriers. As shown in Figure 7a,b, O-terminated MXenes form relatively strong π-d electronic coupling with the metal layers, generating a more uniform electric field environment and reducing the Li+ diffusion barrier to as low as 0.07 eV. This value is substantially lower than that of conventional carbon materials (0.4 eV), highlighting the unique capability of MXenes in regulating in-plane ion migration[116]. In contrast, F terminations, owing to their higher electronegativity, tend to form stronger binding interactions with both the metal layers and migrating ions, resulting in increased diffusion barriers and the formation of localized trapping sites. These effects suppress overall reaction kinetics, as illustrated in Figure 7c,d,e[117]. Accordingly, terminal reconstruction achieved through chemical treatments (such as defluorination and oxygen-enrichment) has become one of the key strategies for improving ion transport and diffusion in MXenes. Beyond intrinsic terminal effects, the interlayer structure of surface-functionalized MXenes is another critical factor governing ion transport behavior. An appropriate interlayer spacing can significantly enhance ion mobility between adjacent layers, whereas excessive collapse or restacking can block ion channels and impede transport[3,118]. The introduction of functional molecules, metal ions, or polymer chains has proven effective in expanding the MXene interlayer spacing. For instance, modification with PDA, PANI, and other polar polymers not only improves surface hydrophilicity but also prevents excessive restacking, thereby maintaining continuous and accessible ion diffusion pathways[119-123]. It should be noted that the restacking of MXene flakes becomes more severe in thick-film electrodes with high areal mass loading, where increased diffusion length and electrode compaction can partially offset the benefits of interlayer expansion achieved in thin films. In this regard, polymer-based surface modification and interlayer bridging can help stabilize lamellar architectures and preserve ion-transport channels across the electrode thickness. However, excessive polymer incorporation may occupy interlayer space and impede ion accessibility, necessitating a careful balance between structural stabilization and transport efficiency. In addition, ions migrating on MXene surfaces or within interlayers typically undergo a desolvation process prior to transport, the associated energy barrier of which is closely related to interfacial charge distribution. Surface functional groups can regulate interfacial polarity and electric-field uniformity, thereby facilitating ion transfer across interfaces. As reported by Soroush et al., surface functionalization improves the interfacial wettability between MXenes and electrolytes, enabling ions to more readily undergo desolvation and overcome interfacial energy barriers, thereby facilitating enhanced interfacial charge-transfer kinetics[124]. Existing studies further indicate that oxygen- or sulfur-containing terminations enhance MXene wettability and homogenize interfacial electric fields, resulting in a marked reduction in interfacial resistance[92,125-127]. The construction of polymeric or organic molecular interfacial layers can also stabilize the interfacial structure of MXene and, by improving interfacial wettability and transport-channel architecture, accelerate ion/molecule exchange and diffusion across the interface[128,129]. Collectively, these surface and interlayer engineering strategies significantly enhance ion transport and diffusion in MXenes, providing a solid foundation for their application in high-performance energy storage systems, electrocatalysis, and ion-sieving devices.

Figure 7. (a) Top and side views of pristine and surface-terminated MXene structures. The pristine MXene (left) shows distinct hollow adsorption sites (A and B), while the functionalized MXenes (middle and right) illustrate the preferred termination configurations, M, X, and T denote transition metal atoms (green), C/N atoms (blue) and surface termination groups, such as F, O and OH (red), respectively. Republished with permission from[116]; (b) ELF for Hfn+1Cn(OH)2 (n = 1, 2, and 3) MXene with different thicknesses. Republished with permission from[116]; (c) Top view of the 2 × 2 × 1 supercell for the Ti3C2-T MXene layer, showing the reactant, TS, and product Li-ion configurations for the F-terminated surface, purple, blue and green spheres denote F, Ti and Li atoms, respectively, arrows indicate the direction of Li-ion diffusion. Republished with permission from[117]; (d) Schematic illustration of Li+ accessible migration regions on an F-terminated MXene surface, the yellow surfaces indicate the spatially confined sites available for Li+ occupation and migration. Blue spheres: titanium atoms; brown spheres: carbon atoms. Republished with permission from[117]; (e) Eads vs the difference in the electronegativities ∆x between the termination atoms and the Li. Republished with permission from[117]. ELF: electron localization function; TS: transition state.

3.4 Stability and environmental tolerance

The highly active surface terminations and exposed transition-metal layers of MXenes endow them with excellent electronic, electrochemical, and interfacial properties, but also render them susceptible to oxidation, hydrolysis, restacking, and environmental perturbations, ultimately leading to structural degradation and performance decay[130-132]. Therefore, targeted regulation of surface termination chemistry and the interfacial microenvironment, aimed at reducing the thermodynamic driving force and kinetic rate of oxidation while strengthening interlayer/interfacial interactions, represents an effective strategy to maintain structural integrity and functional stability under complex environments[78,133].

As illustrated in Figure 8a,b,c,d, oxidation of typical MXenes such as Ti3C2Tx generally initiates at edges or defect sites through Ti-C bond cleavage accompanied by Ti-O bond formation. Water and dissolved oxygen are widely recognized as the primary oxidizing agents, while the oxidation rate is jointly determined by termination composition, defect density, and storage conditions[134]. Both theoretical and experimental studies indicate that surface functional groups are key parameters governing the stability window of MXenes. Moderate terminal reconstruction can reduce the oxidation free energy and increase the oxidation energy barrier. For example, decreasing the fraction of unstable -F/-OH terminations while enriching more stable coordination environments such as -O or halogen terminations (-Cl/-Br) can significantly lower the oxidation driving force and raise the kinetic barrier, thereby suppressing hydrolysis and oxidation processes[75,135,136].

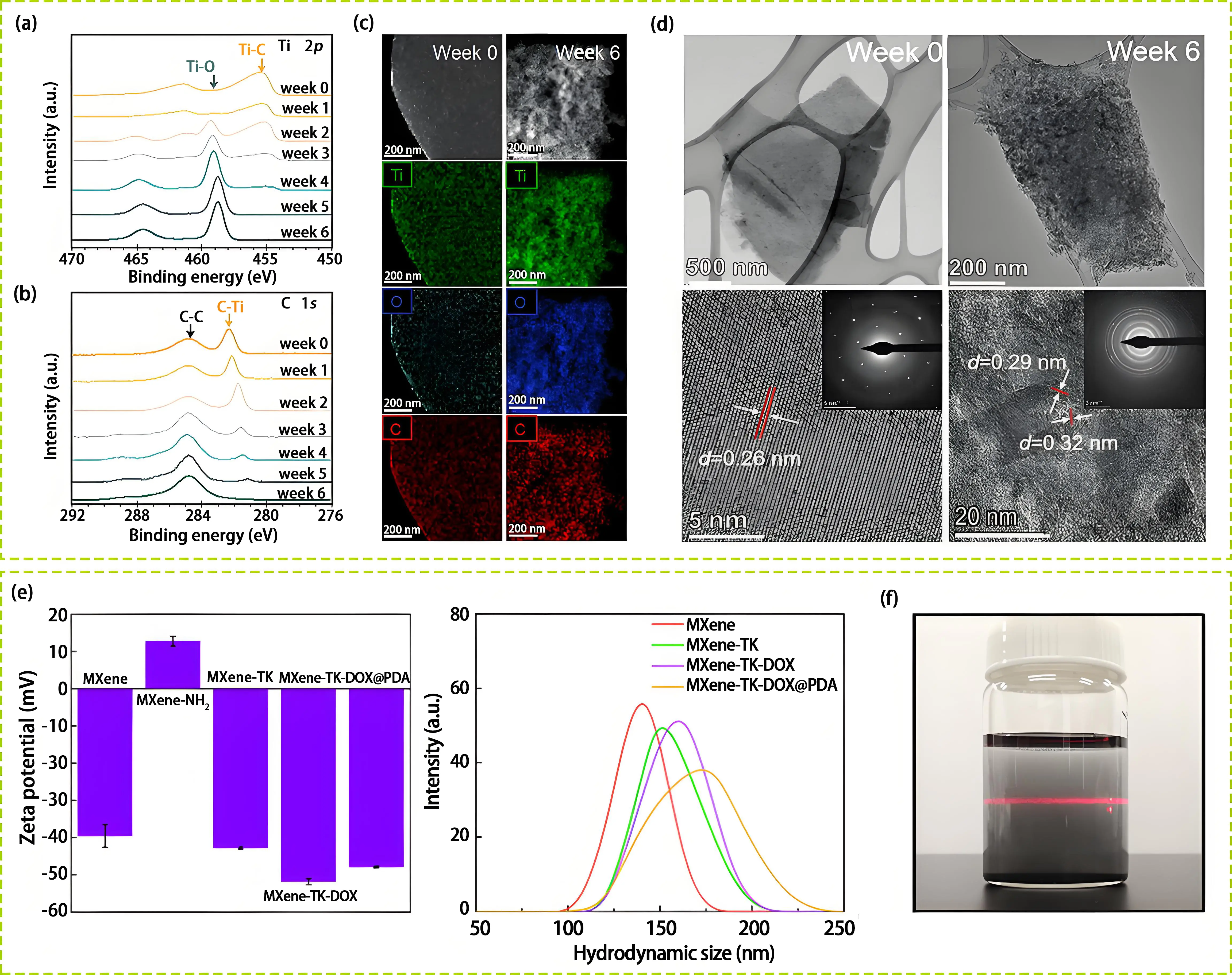

Figure 8. (a) Ti 2p and (b) C 1s XPS spectra of Ti3C2Tx solutions over six weeks. The sample was prepared on a silicon substrate from the MXene solution by drop-casting right before XPS was carried out[134]; (c) HAADF-STEM and the corresponding EDX elemental (Ti, O, and C) mapping images of fresh (at week 0) and oxidized (at week 6) samples[134]; (d) TEM (top) and HRTEM (bottom) images of fresh and aged (six weeks in aqueous solution) Ti3C2Tx flakes. Insets show the corresponding SAED patterns of fresh and oxidized MXene[134]; (e) Zeta potentials and hydrodynamic size distributions of MXene, MXene-TK, MXene-TK-DOX, and MXene-TK-DOX@PDA nanoparticles, illustrating the evolution of surface charge characteristics and colloidal dispersion behavior upon successive surface functionalization[138]; (f) Optical image showing the Tyndall effect of MXene dispersed in an aqueous colloidal solution[138]. XPS: X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy; HRTEM: high-resolution transmission electron microscopy; SAED: selected area electron diffraction; STEM: scanning transmission electron microscope; EDX: energy-dispersive X-ray; DOX: doxorubicin; PDA: polydopamine.

Beyond thermodynamic regulation, kinetic blocking constitutes another critical dimension for enhancing MXene stability. The construction of dense organic molecular layers or polymeric protective coatings can effectively hinder the diffusion of water and oxygen to the MXene surface and stabilize the coordination environment of Ti sites. Biomimetic polymers containing catechol and amine groups, exemplified by PDA, can form coordination bonds, hydrogen bonds, and π-π interactions with Ti-O sites, thereby building a compact and dynamic protective network that markedly improves oxidation resistance and dispersion stability (Figure 8e,f)[137-139]. Similarly, covalent surface functionalization strategies such as silanization have been shown to effectively suppress the spontaneous oxidation of Ti3C2Tx while preserving its electrical conductivity[140]. In addition to chemical oxidation, MXene in practical applications often suffer from restacking, interlayer sliding, and cycling-induced structural collapse. The effectiveness of surface functionalization in enhancing structural robustness arises from its ability to reconstruct interlayer interactions and interfacial binding energies, forming chemically crosslinked or molecular scaffold-like stabilization networks. Specifically, surface-initiated polymerization or in situ growth of conductive polymers (such as PANI and PPy) can generate flexible and conductive interlayer bridges. These polymer chains provide steric hindrance through molecular segments and π-π interactions to suppress dense restacking, while the continuous composite framework redistributes stress and enhances overall mechanical strength, thereby significantly improving long-term structural retention under repeated cycling[124,141,142]. Further polymer composite engineering (such as polyimide and epoxy systems) also commonly relies on surface functional groups to achieve strong interfacial adhesion and efficient stress transfer, thereby endowing the materials with improved fatigue resistance, enhanced hygrothermal stability, and increased resistance to environmental degradation[143-145].

Moreover, under saline, protein-rich, or biologically relevant media, MXenes are exposed to more severe interfacial challenges, such as rapid aggregation, terminal rearrangement, protein adsorption, induced interfacial degradation, and disruption of solvation layers[146-149]. These processes are likewise closely related to surface termination chemistry. Beyond oxidation suppression and structural reinforcement, constructing stable hydration layers using hydrophilic and biocompatible surface functional groups has therefore emerged as a key strategy for maintaining long-term structural and functional stability of MXenes in biological systems. Hydrophilic polymers such as PVP can strongly adsorb onto MXene surfaces through carbonyl and lactam groups, forming dense hydration shells and steric barriers that suppress flake aggregation in high-ionic-strength or protein-containing environments. These hydration layers also partially block water and oxygen diffusion, thereby retarding oxidation[43,150-152]. PVP functionalization significantly enhances the dispersion stability and environmental tolerance of MXene in physiological media, while simultaneously improving biocompatibility and long-term operational stability. A representative example is the Nb2C-PVP composite system, which exhibits superior structural stability and biocompatibility compared with pristine Nb2C under simulated physiological conditions, providing a direct reference for the design of MXene-based biomaterials[153]. Notably, PVP molecules can also act as bridging agents or structural scaffolds, further stabilizing MXene lamellar architectures through chain crosslinking and entanglement. This synergistically enhances oxidation resistance and anti-aggregation capability, as experimentally demonstrated in various MXene-PVP systems, including Ti3C2Tx, Nb2C, and V2C[42,142,154,155]. These findings indicate that hydrophilic functional-layer modification strategies represented by PVP provide essential technical support for achieving long-term structural and functional stability of MXenes in complex biological and solution environments, and represent one of the most promising surface-engineering approaches in current MXene stability research.

4. Applications of Functionalized MXene across Multiple Fields

Surface chemical modification not only alters the local electronic structure, termination-induced dipole moments, and surface polarity of MXenes, but also profoundly influences their interfacial charge distribution, energy-level alignment, ion diffusion pathways, and environmental stability[91,156]. As a result, functionally modified MXene systems no longer serve merely as highly conductive frameworks or inert supports; instead, through the multiscale coupling effects of “structure-electronics-interface”, they exhibit functional performances that far exceed those of intrinsic MXenes across a wide range of key applications[157]. Accordingly, this section focuses on representative applications of functionalized MXenes in photodetection, electrocatalysis, energy storage, and bio-related environments. Emphasis is placed on how surface functionalization enhances device or system performance by regulating key parameters such as work function, band structure, interfacial charge behavior, and chemical stability.

4.1 Photodetectors

Given that the DOS near the Fermi level, work function, and surface polarity of MXenes are strongly dependent on their terminal configurations, photodetectors represent one of the application platforms that most directly reflect the effects of surface modification[158]. The introduction of surface functional groups or molecular layers can significantly tune the energy-level position, bandgap opening or narrowing, interfacial charge-separation behavior, and environmental stability of MXenes. As a result, MXenes can simultaneously function as tunable electrodes, interfacial regulation layers, or even photosensitive layers in optoelectronic devices[159-161].

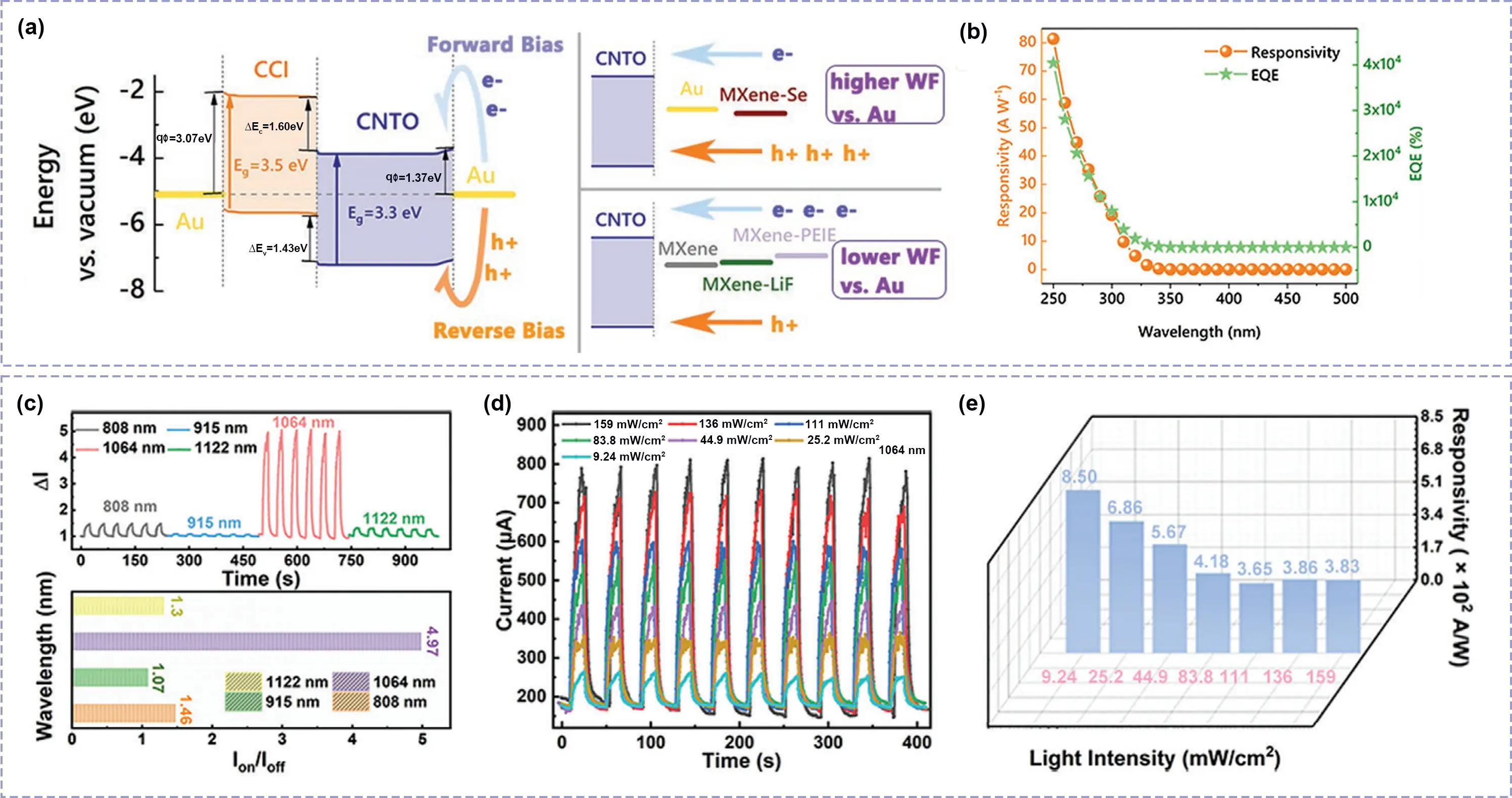

Work-function modulation via surface modification is the most direct strategy for improving the interfacial performance of MXene-based photodetectors. Fang et al. achieved a wide work-function tuning window ranging from 4.55 eV (MXene-PEIE) to 5.25 eV (MXene-Se) by introducing LiF, Se, and PEIE onto the surface of Ti3C2Tx[86]. Owing to the reduced work function induced by LiF and PEIE modification, photodetectors employing modified MXenes as electrodes in vertical p-CsCu2I3/n-Ca2Nb3-xTaxO10 inorganic perovskite junctions exhibited improved rectification behavior under dark conditions. In particular, the use of MXene-PEIE as the electrode resulted in a lower Schottky barrier, which optimized the built-in electric field and carrier separation efficiency in the junction while maintaining good electrical conductivity. Consequently, the device achieved a rectification ratio of 16,136 and, under 250 nm ultraviolet illumination, delivered a maximum responsivity (R) of 81.3 A·W-1 and an external quantum efficiency of approximately 4.04 × 104%, which are significantly higher than those of devices based on Au electrodes or pristine MXene electrodes, as shown in Figure 9a,b. For photosensitive layers in photodetectors, certain MXenes such as Mo2CTx exhibit intrinsic semiconducting characteristics and can generate carrier transitions through surface plasmon excitation[162-166]. However, the high electrical conductivity of most MXenes limits their direct application as active layers. To broaden their applicability in optoelectronics, surface modification strategies have been employed to induce semiconducting behavior. For example, Shen et al. grafted benzenesulfonic acid groups (-phSO3H) onto the surface of Ti3C2Tx via a diazonium nucleophilic reaction, transforming its electronic structure from nearly metallic to semiconducting while preserving high carrier mobility and widening the bandgap to 1.53 eV[26]. As shown in Figure 9c,d,e, flexible photodetectors using -phSO3H-modified Ti3C2Tx as the semiconducting photosensitive material exhibited a clear response to near-infrared (NIR) laser illumination in the range of 808-1,122 nm. Under a bias voltage of 0.5 V, the devices delivered photocurrents on the microampere scale, with a maximum responsivity of 8.50 × 102 A·W-1 and a corresponding specific detectivity of approximately 3.69 × 1011 Jones. In addition, functional surface groups such as dodecylsiloxane (-C12H26) have also been employed to modify Ti3C2Tx, yielding devices with favorable photoelectric response characteristics[21].

Figure 9. (a) Energy band diagram of Au/p-CsCu2I3/n-Ca2Nb3-xTaxO10/MXenes device. Republished with permission from[86]; (b) The responsivity and EQE of Au/p-CsCu2I3/n-Ca2Nb3-xTaxO10/MXene-PEIE under illumination of various wavelength under a bias of -5 V. Republished with permission from[86]; (c) Dynamic cycling and on-off ratio patterns of S-Ti3C2Tx/Au PDs at different wavelengths. Republished with permission from[26]; (d) Dynamic I-T curves of S-Ti3C2Tx/Au PDs under irradiation at 1,064 nm with different optical power densities. Republished with permission from[26]; (e) Under the irradiation of 1,064 nm with different optical power densities, the R of the device. Republished with permission from[26]. CCI: charge collection interface; CNTO: (C,N)-codoped titanium oxide; MXene-Se: selenium-functionalized MXene; MXene-PEIE: poly(ethylenimine) ethoxylated modified MXene; MXene-LiF: lithium fluoride modified MXene; WF: work function; EQE: external quantum efficiency.

These studies demonstrate that surface functionalization, particularly through the introduction of additional functional surface terminations, not only substantially expands the accessible bandgap range of MXenes and enhances photogenerated carrier generation efficiency, but also broadens their potential as photosensitive layers in flexible photodetectors. Such advances provide an important theoretical foundation for the development of highly sensitive, high-resolution flexible NIR photodetectors.

4.2 Electrocatalysis

The electrocatalytic activity of MXenes toward the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) is highly dependent on the surface-termination-regulated electronic structure and interfacial reaction pathways. Termination configurations determine the electronic states of metal centers, the binding strength of reaction intermediates, and interfacial charge-transfer behavior. Previous studies have demonstrated that terminal regulation, surface chemical substitution, or the introduction of functional terminations can effectively modify catalytic reaction pathways while preserving the layered structure, enabling MXenes to exhibit enhanced intrinsic activity as standalone two-dimensional catalysts[167].

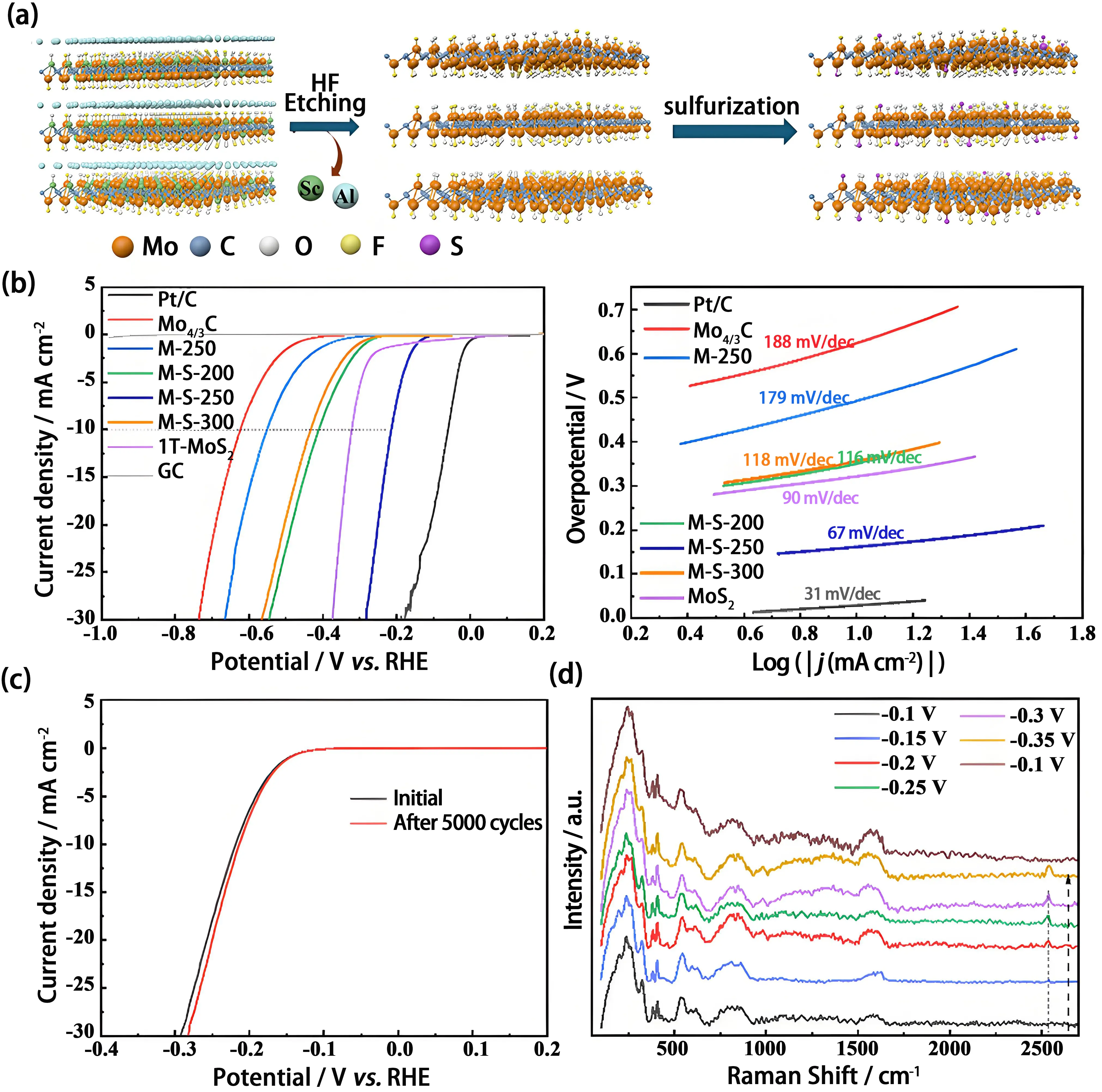

Theoretical calculations indicate that different surface terminations systematically modulate the hydrogen adsorption free energy (∆G_H*), thereby governing the intrinsic HER activity of MXene. -O terminations generally place the metal layers in a more favorable electronic state, bringing ∆G_H* closer to the thermodynamically optimal value; -OH terminations show moderate adsorption strength, whereas strongly electronegative -F terminations weaken hydrogen adsorption and thus reduce intrinsic catalytic efficiency[116]. Experimental results further confirm the critical role of termination engineering in HER performance[27,168]. Although -F terminations are intrinsically unfavorable for hydrogen adsorption, significant enhancement in HER activity can still be achieved in certain systems through coordinated regulation of terminal composition and layer structure. For example, Li et al. investigated Ti2CTx and tuned its surface functional group composition to favor -F terminations within mixed -F/-O/-OH terminations while maintaining an ultrathin structure close to monolayer or few-layer thickness[169]. Electrochemical measurements revealed that F-rich Ti2CTx nanosheets exhibit a low onset overpotential of approximately 75 mV and a relatively high exchange current density of 0.41 mA·cm-2 in acidic electrolyte, significantly outperforming non-optimized samples. Combined theoretical calculations and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy results indicate that F-rich terminations simultaneously accelerate proton adsorption kinetics and reduce charge-transfer resistance, thereby enhancing the intrinsic HER activity of the MXene matrix without introducing additional metallic components. In addition to F terminations, sulfur termination has recently emerged as an effective surface-modification strategy to enhance MXene HER activity. As shown in Figure 10a, Rosen et al. used a one-step sulfurization strategy to replace the native -F on MXene surfaces with stable -S coordination environments, converting Mo4/3C, W4/3C, and Nb1.33C MXenes into sulfur-functionalized nanosheets under mild conditions[170]. Among these, S-Mo4/3C exhibits an overpotential of approximately 210 mV at 10 mA·cm-2 in acidic media with a Tafel slope of about 67 mV·dec-1 (Figure 10b), while maintaining an essentially unchanged current over 120 h of continuous operation (Figure 10c). In situ Raman spectra reveal a reversible S-H bond (approximately 2,542 cm-1) formed by sulfur terminations with protons during catalysis (Figure 10d), indicating that the sulfur sites on the MXene surface directly mediate H+ adsorption/desorption and act as the main active centers for HER.

Figure 10. (a) Schematic illustration of the synthesis of sulfur-functionalized Mo4/3C[170]; (b) Polarization curves and Tafel plots of Mo4/3C MXene, M-250, M-S-200, M-S-250, M-S-300, 1T-MoS2, and commercial Pt/C for HER in 0.5 M H2SO4[170]; (c) The long-term durability tests of M-S-250[170]; (d) In situ Raman spectra of M-S-250 collected at different potentials[170]. RHE: reversible hydrogen electrode; GC: glassy carbon electrode.

4.3 Energy storage

In electrochemical energy storage systems, the charge-storage behavior of MXenes is highly sensitive to the nature of their surface terminations and the interlayer microenvironment[171,172]. Different terminations (such as -F, -O, -OH, halogen, and heteroatom groups) systematically alter surface charge distribution, confined interlayer water, and ion adsorption/desorption kinetics, leading to marked differences in specific capacitance, rate capability, and cycling stability[173]. Accordingly, tuning surface functional groups has become a central strategy to enhance MXene performance in supercapacitors and aqueous batteries.

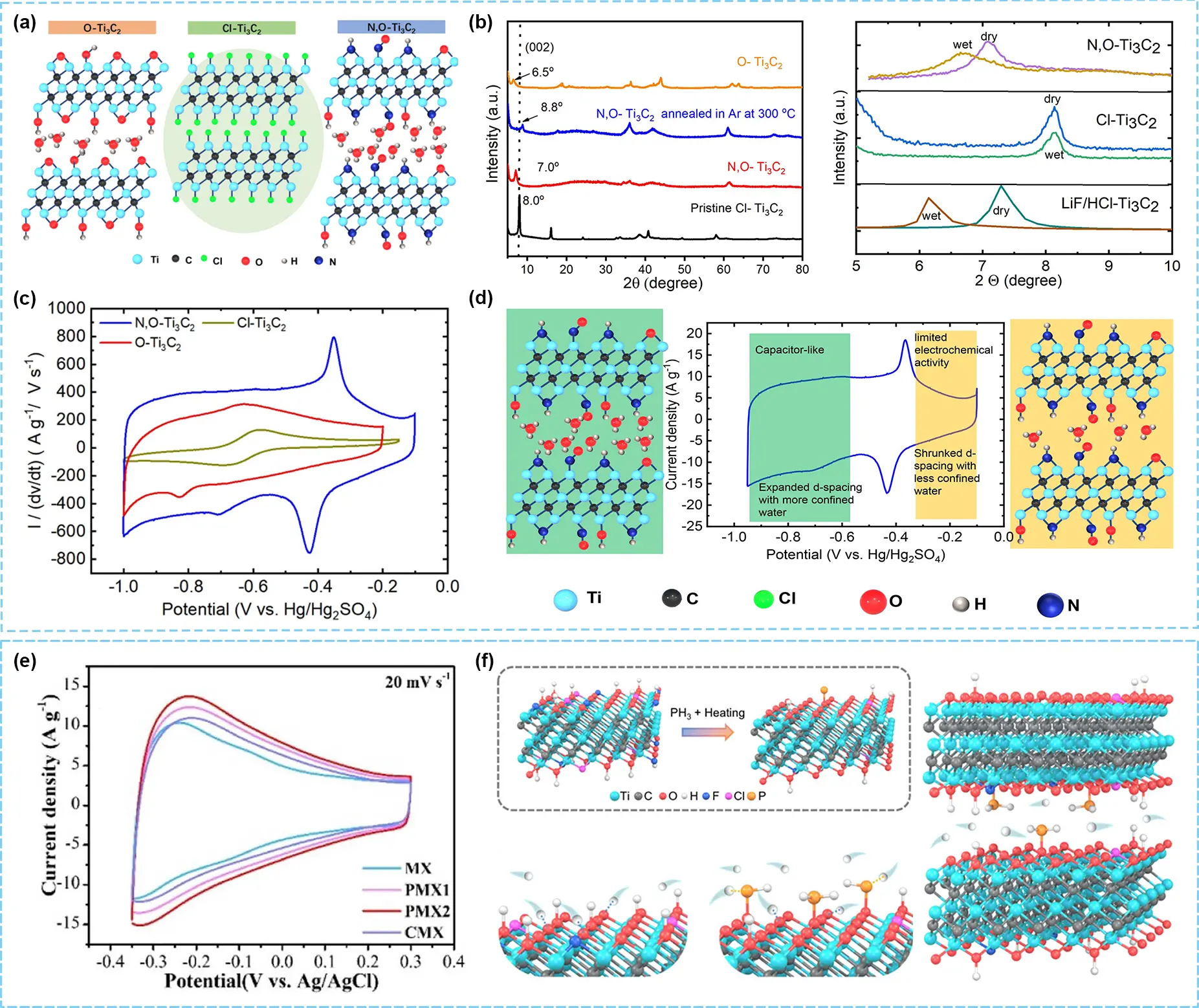

Native surface terminations such as -O and -OH typically strengthen interactions with small ions such as H+ and Li+, whereas moderate incorporation of heteroatom terminations (such as -P or -S) or halogen terminations can expand pseudocapacitive sites and improve interlayer ion transport without compromising the conductivity of the 2D framework. As shown in Figure 11a, Liu and co-workers used Ti3C2Tx as a model and, by tuning the molten-salt system and processing conditions, selectively obtained functionalized MXenes dominated by Cl-, N/O-, and O- terminations while largely preserving the Ti3C2 backbone[126]. Electrochemical measurements show that Cl--modified Ti3C2Tx exhibits almost no obvious pseudocapacitive behavior, whereas the N/O--modified sample maintains nearly rectangular cyclic voltammograms over a wide potential window, indicative of a fast pseudocapacitive response (Figure 11c). The high charge-storage capability and rapid kinetics arise because molten-salt-induced termination reconstruction simultaneously adjusts interlayer spacing and the confined water structure, as shown in Figure 11b,d. Phosphorus modification also effectively enhances MXene energy storage: Huang et al. selectively introduced P-O terminations on Ti3C2Tx via mild post-treatment, generating new proton adsorption/desorption sites in acidic electrolyte (Figure 11f)[174]. As shown in Figure 11e, compared with unmodified Ti3C2Tx, the electrode exhibits an approximately 35% increase in specific capacitance at a scan rate of 2 mV·s-1 and maintains excellent capacitance stability during long-term cycling tests. These results experimentally confirm the central role of surface termination engineering in optimizing MXene energy storage and provide clear structure-property guidelines for high-performance MXene devices through termination design and interlayer microenvironment control.

Figure 11. (a) Schematic illustration of MS-Ti3C2Tx with various surface terminations[126]; (b) XRD patterns of Ti3C2 MXene with various surface terminations, showing the structural evolution induced by annealing and acidic treatment in 3 M H2SO4 for 2 h[126]; (c) Comparison of the cyclic voltammetry data recorded at a potential scan rate of 20 mV·s-1 of Cl-Ti3C2, N,O-Ti3C2, and O-Ti3C2. The electrode mass loading was kept similar for all measurements at about 1 mg·cm-2[126]; (d) Schematic illustrating the transition from limited electrochemical behavior to a fast, capacitive-like charge storage mechanism in N,O-Ti3C2 in 3 M H2SO4[126]; (e) CV curves of MX, PMX1, PMX2 and CMX at a scan rate of 20 mV·s-1. Republished with permission from[174]; (f) Schematic illustration for phosphorus doping strategy, proton interaction with the surface of pristine Ti3C2Tx, and proton interaction with the surface of PMX. Republished with permission from[174]. MX: MXene; PMX: phosphorus-modified MXene; CMX: composite MXene.

4.4 Biomedicine

As MXenes gain traction in biomedical systems, their behavior clearly goes beyond native -O, -OH, or -F terminations. In complex chemical and biological environments, additional surface functionalization is essential to improve stability, bioresponsiveness, and adsorption selectivity[5,175]. Such post-treatment reshapes the interfacial structure and electronic environment and introduces new molecular interaction modes, markedly expanding MXene applications in photothermal therapy, drug delivery, antibacterial activity, and adsorption of environmental pollutants.

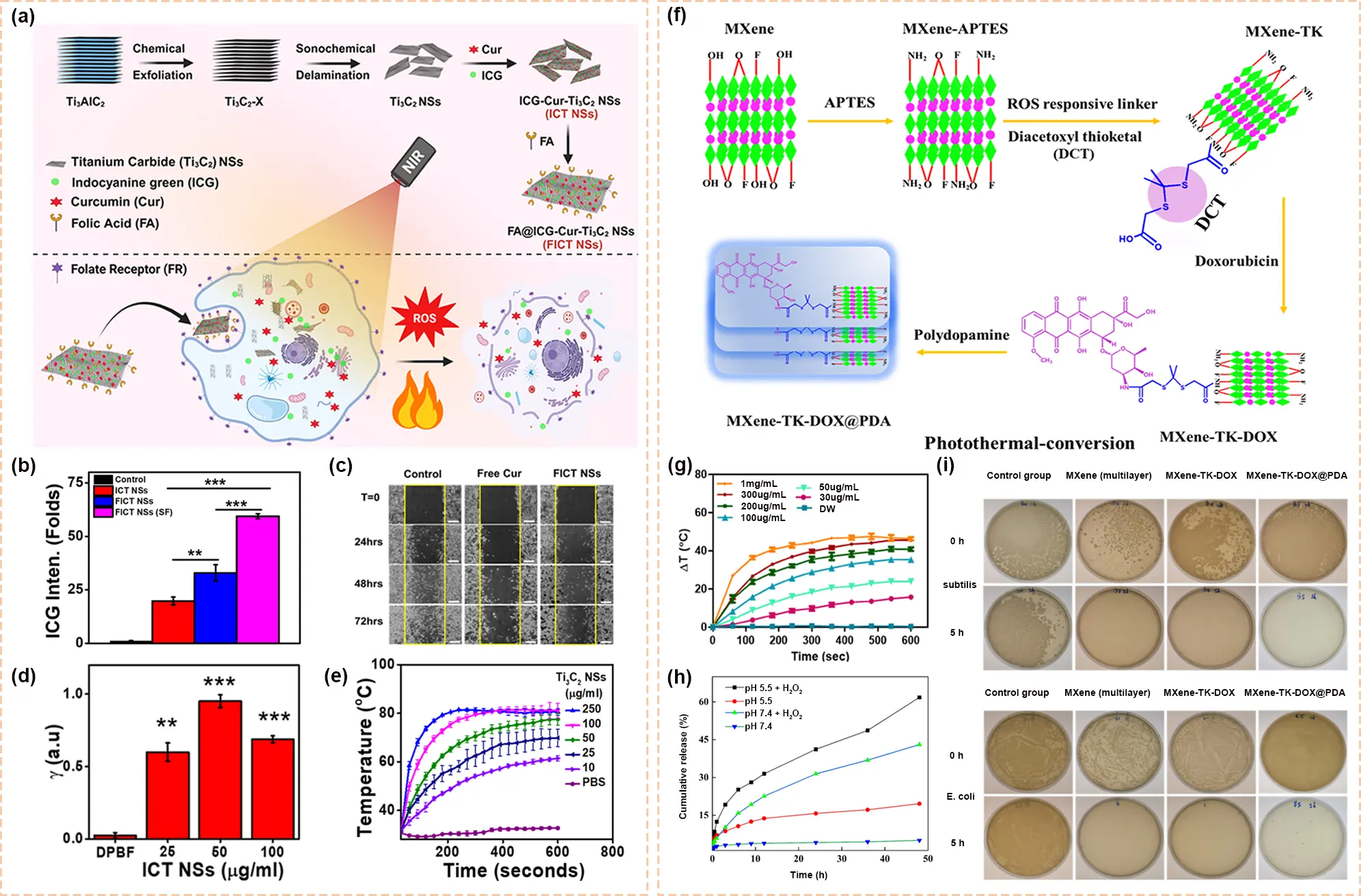

In biomedicine, cooperative functionalization builds multifunctional platforms. Co-decorating Ti3C2 MXene nanosheets with folic acid (FA), indocyanine green (ICG), and curcumin (Cur) produces a NIR responsive system[176]. FA provides tumor targeting, ICG with MXene mediates combined photothermal-photodynamic therapy, and Cur supplies chemo/antioxidant effects, yielding high photothermal efficiency and multimodal treatment, as shown in Figure 12a,b,c,d,e. Metal-polyphenol networks offer another key route. Li et al. coordinated epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) with Fe3+ on small Ti3C2Tx nanosheets to form an EGCG/Fe metal-polyphenol nanoshell (MXene@EGCG)[177]. This functional layer maintains similar photothermal efficiency but significantly improves tumor ablation and mitigates inflammation compared with bare MXene. Additionally, grafting -NH₂ groups onto Ti3C2Tx via APTES, linking doxorubicin (DOX) through a thioketal (TK) cleavable bond, and coating with a PDA pH-responsive shell yields MXene-TK-DOX@PDA particles (synthesis in Figure 12f,g,h,i). These particles deliver higher photothermal conversion and stability, selectively release drug under ROS and mildly acidic conditions, and exhibit strong antibacterial activity against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, clearly outperforming unfunctionalized MXene[138]. Collectively, these studies show that tailored surface functionalization underlies control of MXene biological behavior and is crucial for stability, targeting, and therapeutic efficacy.

Figure 12. (a) Schematic illustration of the synthesis and photoactivation of FICT NSs. Republished with permission from[176]; (b) Quantification of ICG fluorescence intensity analyzed under a flow cytometer in groups (i) control (CM), (ii) ICT NSs (CM), (iii) FICT NSs (CM), and (iv) FICT NSs (SF). Republished with permission from[176]; (c) Microscopic image analysis of scratches in treatment groups (i) control, (ii) Cur, and (iii) FICT NSs for 72 h of incubation at 37 °C and under a 5% CO2-enriched atmosphere. Scale bar: 100 μm. Republished with permission from[176]; (d) 1O2 generation of ICT NSs in a cell-free system under light irradiation, detected using the DPBF probe (at different concentrations). Republished with permission from[176]; (e) Photothermal heating curves of freshly prepared Ti3C2 NSs at different concentrations under laser irradiation for 10 min. Republished with permission from[176]; (f) Illustration of the preparation process of MXene-TK-DOX@PDA nanoparticles by reaction with APTES, thioketal, doxorubicin, and coating with PDA, respectively[138]; (g) Photothermal conversion profile of the MXene-TK-DOX@PDA nanoparticles in an aqueous solution after 808 nm laser irradiation (2 W·cm-2) at elevated concentrations (0, 30, 50, 100, 200, 300 ug·mL-1, and 1 mg·mL-1)[138]; (h) The drug release curves from the MXene-TK-DOX@PDA nanoparticles in different media[138]; (i) Antibacterial activities in aqueous solutions after 5 h of incubation: bacterial suspensions in PBS solution (0.01 mM) acted as the control group, a photograph of the test plates for E. coli and B. subtilis bacteria exposed to the MXene, MXene-TK-DOX, and MXene-TK-DOX@PDA nanoparticles at a concentration of 6.085 mg/mL, respectively, all analyses of the results were performed in triplicate[138]. ICG: indocyanine green; Cur: curcumin; FA: folic acid; NSs: nanosheets; ROS: reactive oxygen species; DOX: doxorubicin; PDA: polydopamine.

5. Challenges and Perspectives

As an emerging class of two-dimensional materials, MXenes have demonstrated remarkable application potential across a wide range of fields owing to their outstanding electrical conductivity, rich surface functional groups, and unique interfacial properties[178-181]. Among these advantages, surface modification strategies have been widely recognized as a key approach for expanding the structural tunability and functional versatility of MXenes. This review systematically summarizes the recent progress in surface-modification-driven functionalized MXenes, with particular emphasis on the profound influence of surface functional group regulation on their electronic structure, interfacial charge distribution, and ion transport behavior. Through a comprehensive analysis of existing surface modification strategies, this work highlights the critical role of surface engineering in enhancing MXene performance and broadening their application scenarios. Specifically, tailoring surface terminations not only enables effective modulation of the work function, band structure, and interfacial polarization of MXenes, but also leads to significant performance improvements in energy storage, photodetection, and electrocatalysis.

Nevertheless, despite the extensive validation of these promising properties, functionalized MXenes still face several challenges in practical applications. As research efforts gradually transition from performance demonstration toward mechanistic understanding and device-level integration, further development of functionalized MXenes places higher demands on the precision of surface chemical control, systematic understanding of structure–property relationships, and scalability across diverse application domains.

(1) Precision Control of Surface Terminations and Chemical Designability: At present, surface-modified MXenes are predominantly characterized by the coexistence of multiple surface terminations. Variations in the type, proportion, and spatial distribution of functional groups result in highly diverse and complex surface chemistries. While such diversity provides MXenes with broad functional tunability, it also introduces uncertainties in performance comparison and mechanistic interpretation among different studies.

Encouragingly, recent advances in gas-phase reactions, molten-salt-induced termination exchange, and plasma-assisted surface engineering have demonstrated promising potential in improving termination selectivity and controllability. With continued progress in understanding reaction pathways and the development of advanced in situ characterization techniques, more precise and predictable regulation of surface terminations is expected to become achievable. These advances will establish a more robust chemical foundation for electronic structure engineering, interfacial modulation, and application-oriented MXene design.

(2) Continuous Optimization of MXene Stability Engineering: The stability of MXenes under humid, oxidative, electrochemical, or complex biological environments remains a central concern in surface engineering research. Previous studies have shown that functional group modification, polymer encapsulation, and interfacial layer construction can effectively retard oxidation processes and enhance structural integrity. However, these approaches primarily rely on interfacial protection, leaving room for further improvement in the intrinsic stability of MXene materials.

Looking forward, stability engineering is expected to evolve from passive protective strategies toward structure-chemistry synergistic design. Approaches such as introducing more stable coordination terminations, constructing self-passivating surface structures, or developing intrinsically more stable MXene compositions may enable improved durability while maintaining functional performance. Such strategies will be crucial for ensuring reliable MXene operation in practical devices and complex environments.

(3) Expansion of Semiconducting MXenes and Bandgap-Tunable Design: Although MXenes are well known for their metallic nature and high electrical conductivity, increasing demand for controllable bandgaps and semiconducting behavior has emerged in applications such as optoelectronics, logic electronics, and sensing. To date, MXenes exhibiting intrinsic semiconducting characteristics remain relatively limited, and their realization often relies on specific surface functional groups or particular structural configurations.

This situation does not indicate an inherent limitation of MXenes. Rather, it underscores the substantial, yet underexplored, potential of surface modification for electronic structure engineering. Future efforts focusing on the synergistic effects of diverse functional groups and interfacial strain on band structure modulation are expected to enable the development of MXene systems with tunable bandgaps and controllable carrier transport behavior, thereby significantly expanding their applicability in optoelectronic and information devices. In this context, High-Entropy MXenes represent a promising frontier platform, where lattice distortion and local strain fields arising from multi-element configurations may interact with surface terminations and interfacial electronic states. Such strain-electronic coupling effects, if rationally leveraged together with surface modification, could broaden the design space for band structure regulation beyond conventional single- or few-component MXenes.

(4) Prospects for Scalable Synthesis and Standardization: As MXene research increasingly advances toward device-level and system-level applications, greater demands are being placed on material uniformity, reproducibility, and scalability. Although multiple mature synthesis and surface modification routes have been established, further harmonization and optimization of fabrication protocols and characterization standards across different experimental systems and application requirements are still desirable.

With continued refinement of synthesis methodologies and progressive maturation of surface modification strategies, scalable production and standardized characterization of MXenes are expected to improve steadily, providing a solid foundation for their broader technological deployment. From an applied perspective, surface-modification strategies differ significantly in environmental and economic feasibility. Thermally driven and molten-salt-based methods enable precise termination control but usually require high temperatures and energy input, whereas solution-phase approaches such as silanization are conducted under milder conditions and are more compatible with scalable processing.

Overall, MXene surface modification strategies are currently transitioning from exploratory functionalization toward refined design and system-level integration. Future advances, including the development of programmable surface termination chemistry, the incorporation of artificial intelligence-assisted functional group prediction, the construction of highly stable MXene families, and the establishment of multiscale interfacial engineering theoretical frameworks, are expected to enable more precise control over MXene structure and properties. Driven by these developments, MXenes are poised to evolve from high-performance two-dimensional materials into versatile functional material platforms with designable surface chemistry and multiphysics coupling capabilities, continuing to demonstrate unique advantages and broad application potential in next-generation optoelectronic devices, energy conversion systems, and biomedical engineering.

Authors contribution

Hu C, Zhang G, Duan Q: Conceptualization, writing-original draft.

Bai Y, Shen L, Jia Y, Zhang Z, Liu J: Writing-review & editing.

Qiu P, Wu D, Fu C, Wang X: Conceptualization, supervision.

Conflicts of interest

Chuqiao Hu is a Youth Editorial Board Member of Smart Materials and Devices. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62504031) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities at Dalian Maritime University (Grant No. 3132025246).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-