Eryang Mao, Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Dalian 116023, Liaoning, China. E-mail: maoeryang@foxmail.com

Abstract

Electrocatalytic water splitting is a key technology for sustainable hydrogen production, but its efficiency is limited by the slow kinetics of the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER). Spinel oxides (AB2O4) have drawn significant interest due to their electrochemical stability, tunable electronic properties, and low cost. Their catalytic performance is highly influenced by the crystalline phase, which governs charge transport, active site density, and reaction energetics. However, the effects of phase transitions and structural variations on electrocatalysis remain insufficiently explored. This review systematically evaluates the performance of spinel oxides across six primary crystal phases: cubic, hexagonal, tetragonal, orthorhombic, rhombohedral, and monoclinic, discussing how these structural features affect charge transport, intermediate adsorption, and reaction energetics. The review emphasizes the structure-electronic-catalytic performance relationships and covers phase variants, including coordination environment modulation, defect regulation, metastable phase transitions, and strain engineering. It further examines how phase symmetry, oxygen coordination, orbital rearrangement, and interfacial characteristics influence OER and HER kinetics. Challenges in phase engineering, such as controlling phase transitions and stabilizing metastable phases, are also highlighted. This review provides a framework for understanding the electrocatalytic behavior of spinel oxides and offers guidance for designing high-performance catalysts for water splitting.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Electrocatalytic water splitting, as a promising technology for hydrogen production, is widely regarded as a key strategy to address the global energy transition[1]. This process efficiently converts water into hydrogen and oxygen, providing a crucial solution for the advancement of clean energy. In the context of the ongoing transformation of global energy structures, the development of efficient, stable, and low-cost electrocatalysts, particularly for optimizing the catalytic performance in the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) and hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), has become a central challenge to enhance the efficiency of water electrolysis[2,3]. Spinel oxides (AB2O4), due to their excellent electrochemical stability, diverse composition, and relatively low cost, have emerged as promising alternatives to precious metal-based catalysts[4]. They exhibit superior durability in extreme electrochemical environments and can sustain efficient catalytic performance during large-scale hydrogen production processes. Particularly, transition metal ions at the B-site (e.g., Ni, Co, Fe, and Cu) have tunable oxidation-reduction properties, offering a broad potential for optimizing catalytic activity[5,6]. However, despite the advantages in stability, the electrocatalytic performance of spinel oxides is still limited by several inherent challenges. First, spinel oxides typically exhibit low surface area and limited active sites, which restrict their catalytic efficiency in OER and HER[7]. Specifically, in alkaline electrolytes, their charge transfer kinetics and conductivity often fail to meet the demands of high current density, posing a significant bottleneck in practical applications[8,9]. Second, the activation efficiency of reaction intermediates is relatively low, leading to suboptimal reaction pathways and further reducing overall water splitting performance. Although surface defects, such as oxygen vacancies, have shown potential in improving catalytic performance, their precise role, especially in accelerating reaction kinetics and facilitating intermediate adsorption, remains inadequately understood[10,11]. Therefore, addressing these structural and electronic bottlenecks through a deeper understanding of the spinel oxides’ catalytic behavior in various crystal phases and structural variants is essential for advancing their application in electrocatalytic water splitting[12,13].

Spinel oxides exhibit a range of crystal phases, each of which presents distinct structural and electronic properties that influence their catalytic performance in electrocatalytic water splitting[14,15]. The conventional cubic spinel structure, with its high symmetry and stable lattice configuration, provides ideal charge transfer channels and catalytic active sites, making it a commonly used base material for catalysis[16,17]. However, as research advances, increasing evidence suggests that non-cubic spinel phases, such as hexagonal, tetragonal, and metastable phases, can significantly enhance catalytic performance through various lattice distortions and defect modulations[18]. For instance, hexagonal and tetragonal spinel oxides demonstrate higher activity in the OER due to their lower crystal symmetry and defect-rich structures, which facilitate efficient intermediate adsorption and optimization of reaction pathways[19,20]. Furthermore, metastable spinel phases, with their unique structural characteristics and dynamic electronic behaviors, offer more reaction sites and improve reaction kinetics, particularly in the HER, where they exhibit higher catalytic activity[21]. Despite these promising characteristics, several challenges remain in realizing the full potential of non-cubic spinel oxides[22,23]. First, precisely controlling the synthesis conditions of these non-cubic phases and ensuring their stability during electrocatalytic reactions remains a critical challenge. Metastable phases often exist at higher energy states, making them prone to phase transitions under practical reaction conditions, resulting in fluctuating and unstable catalytic performance[24,25]. Additionally, the phase transformation dynamics are complex, and the heterogeneity between different phases may lead to interface mismatches, reducing catalytic efficiency[26,27]. Another challenge lies in the fact that while surface defects have been shown to enhance catalytic performance, the systematic understanding of how these defects optimize catalytic activity is still lacking[28,29]. Most current research is focused on single-phase systems or specific material types, without a comprehensive structural perspective on how different spinel phases and their variants influence catalytic mechanisms[30,31]. Therefore, further exploration of precise structural modulation and phase-engineering strategies, together with a deeper investigation of how structural features govern electronic states and ultimately catalytic performance, is essential for overcoming the inherent performance limitations of spinel oxides[32,33].

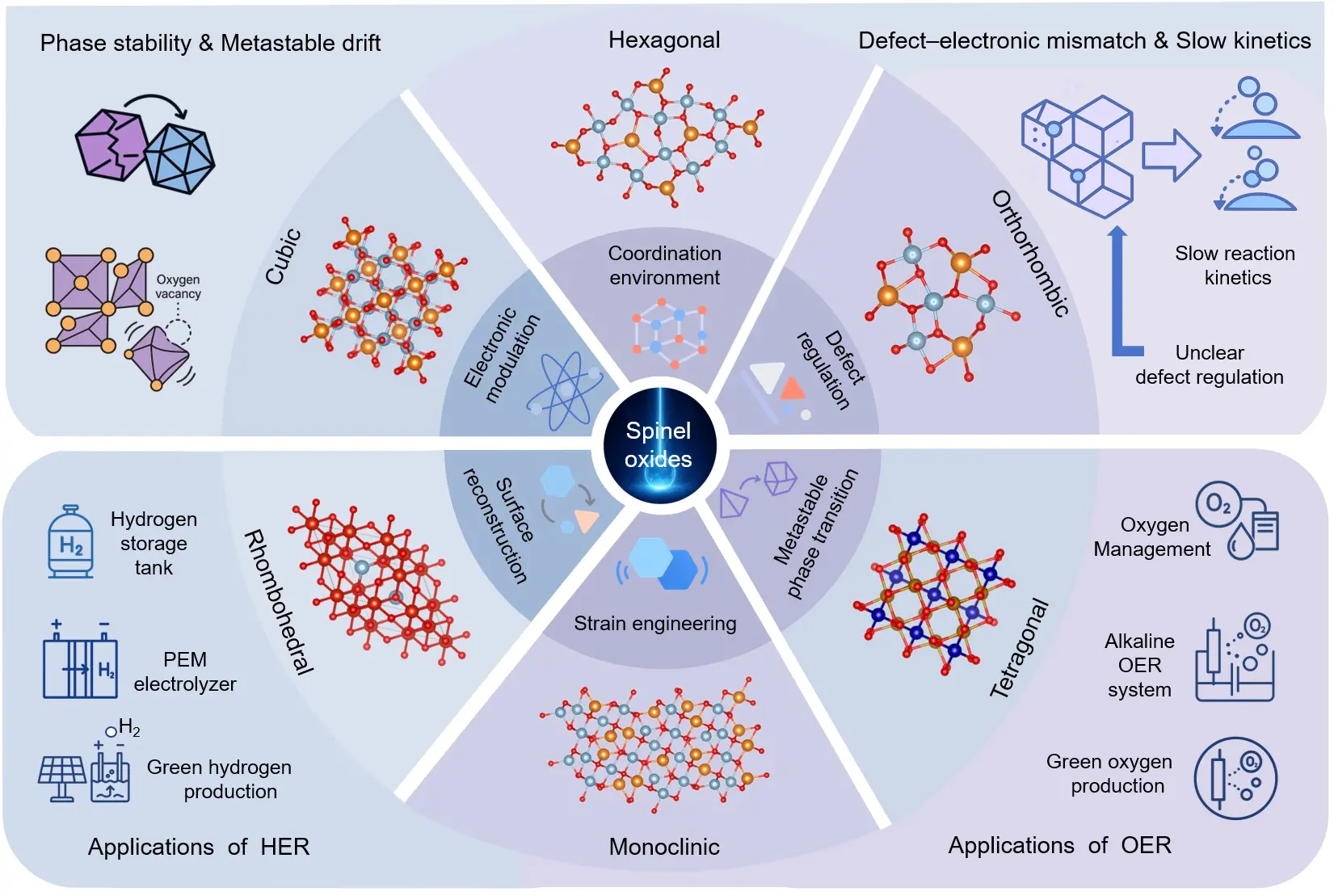

This review aims to comprehensively assess the potential of spinel oxides in electrocatalytic water splitting from a crystallographic perspective, shedding light on the deep relationships between different crystal phases and their catalytic performance. Unlike traditional studies that focus on single-phase or specific material systems, this review systematically discusses the six main crystal phases of spinel oxides (cubic, hexagonal, tetragonal, orthorhombic, rhombohedral, and monoclinic) and their variants, highlighting their distinct impacts on electrocatalytic water splitting performance (Figure 1). It provides an at-a-glance roadmap of this review, linking the major spinel crystal phases and phase-variant regulation strategies to their roles in lattice-coupled OER/HER catalysis and broader energy-conversion applications. By analyzing the lattice symmetry, oxygen coordination environment, orbital rearrangement, and interface properties of these phases, this work provides a comprehensive framework to help readers understand how different crystal structures govern the electrocatalytic behavior of spinel oxides, particularly in OER and HER catalytic dynamics. The novelty of this review lies in its integration of how distinct crystal phases govern electrocatalytic water splitting through a phase-specific classification framework, thereby elucidating the intrinsic coupling among structural features, electronic configurations, and catalytic performance. Through a systematic analysis of how different phases influence charge transfer efficiency, intermediate adsorption, and reaction energy barrier optimization, this review offers new insights for the design of highly efficient electrocatalysts for water splitting. Furthermore, this review addresses the precise control of phase transitions, the stability of metastable phases, and the impact of phase heterogeneity on catalytic performance, proposing key directions for future research. Overall, this work aims to establish a systematic framework for advancing spinel oxide catalysts and guide the future development of high-performance materials for sustainable water electrolysis.

Figure 1. Structural phases, regulation strategies, and energy-conversion applications of spinel oxides.

2. Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms Governing Spinel Oxides for Electrocatalytic Water Splitting

Spinel oxides are widely used in electrocatalytic water splitting due to their excellent electrochemical stability, tunable electronic structures, and abundant active sites. The unique characteristics of the spinel structure contribute to superior performance in charge transport, oxygen vacancy formation, and reaction kinetics, while also ensuring long-term catalytic stability[34,35]. To further enhance their catalytic performance, a comprehensive understanding of the fundamental catalytic mechanisms and structural features of spinel oxides is crucial. In this review, “lattice-coupled water-redox electrocatalysis” denotes a bidirectional coupling in which the catalyst lattice (symmetry/coordination, defects/strain, cation distribution) sets the electronic structure and adsorption energetics for OER/HER, while operating potentials/intermediates can in turn trigger lattice responses (vacancies, cation redistribution, surface reconstruction/phase evolution). This section first explores the underlying principles and advantages of spinel oxides in water splitting, followed by an in-depth analysis of the six major crystal phases of spinel oxides, including cubic, hexagonal, orthorhombic, tetragonal, rhombohedral, and monoclinic, with a focus on how their structural characteristics influence catalytic performance[36,37]. It then discusses the impacts of structural variants, such as coordination environment modulation, defect regulation, metastable phase transitions, and strain engineering. Finally, a summary and analysis of existing research studies are provided, revealing the structure–performance relationships of spinel oxides and offering theoretical guidance for the rational design of high-performance spinel oxide electrocatalysts[38,39].

2.1 Advantages and fundamental mechanisms of spinel oxides for electrocatalytic water splitting

Spinel oxides have attracted significant attention in electrocatalytic water splitting due to their exceptional electrochemical stability, tunable electronic structure, and abundant active sites. These properties enable spinel oxides to exhibit superior catalytic performance in water splitting reactions[40,41]. The AB2O4 consists of metal ions at A and B sites, along with oxygen ions. The A-site typically contains metals with high oxidation states, such as aluminum, magnesium, and zinc, while the B-site hosts transition metals like cobalt, nickel, iron, and copper[42]. Variations in the coordination environment, electronic properties, and ionic radii of these metal ions influence not only catalytic performance but also charge transfer, oxygen vacancy formation, and the adsorption and conversion of reaction intermediates[43,44]. These distinctive structural features make spinel oxides highly promising catalysts for electrocatalytic water splitting.

From a fundamental mechanism perspective, the electrocatalytic performance of spinel oxides is closely linked to their crystalline structure. The high symmetry and stable lattice configuration of spinel oxides facilitate the formation of a high density of active sites, promoting efficient charge transfer[45]. In the OER, the introduction of oxygen vacancies enhances reaction rates by modifying the electronic structure and strengthening the adsorption of intermediates[46,47]. The presence of oxygen vacancies facilitates electron migration and provides additional adsorption sites for oxygen molecules, thus accelerating oxygen generation. In the HER, structural defects and the reduction states of transition metal ions at the B-site play critical roles. The electronic density and redox properties of these metal ions directly impact the rate of hydrogen generation[48]. By adjusting the types of B-site metal ions, the density of oxygen vacancies, and the state of surface defects, the catalytic activity can be significantly improved, optimizing the energy pathway for hydrogen generation during water splitting[49].

Furthermore, spinel oxides offer distinct advantages in terms of their superior stability and low cost compared to precious metal catalysts. Spinel oxides uniquely combine a robust 3D close-packed lattice with dual-site (A/B) cation tunability, enabling phase/defect engineering while maintaining high durability at practically relevant current densities. Unlike noble metal catalysts, spinel oxides maintain long-term stable performance even at high current densities, making them ideal for large-scale applications[50]. Additionally, their relatively low synthesis costs make them more feasible for widespread use in industrial applications. The abundant availability and low cost of transition metal oxides further enhance the sustainability and economic viability of spinel oxides as electrocatalysts. These advantages provide a solid foundation for their application in large-scale water electrolysis systems[51,52].

2.2 Crystal structure of spinel oxides for classification and structural insights

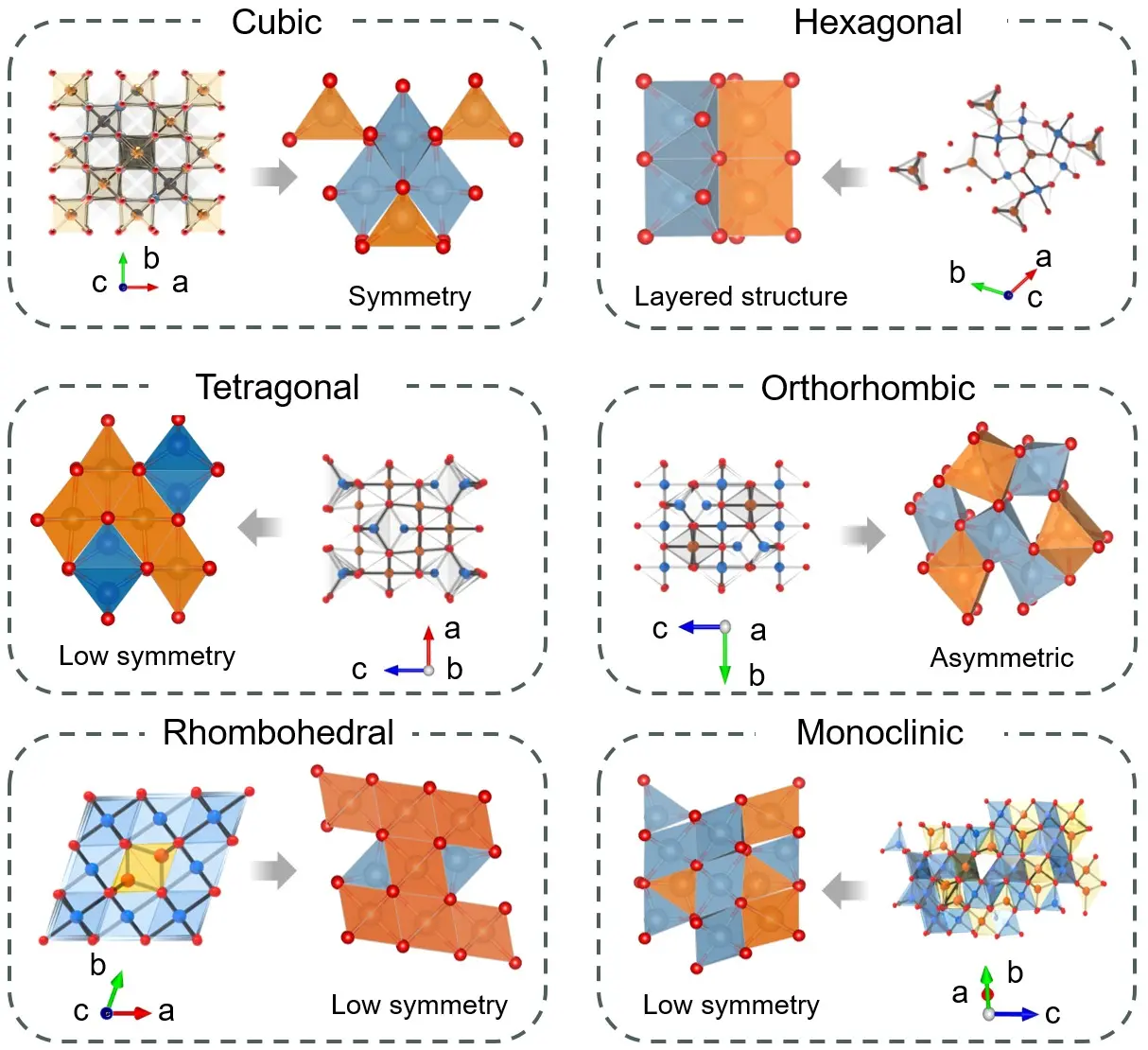

The six main crystal phases of spinel oxides, including cubic, hexagonal, tetragonal, orthorhombic, rhombohedral, and monoclinic, each exhibit unique structural features that, to a large extent, govern their performance in electrocatalytic water splitting (Figure 2). Here, the classification adopted in this section follows a symmetry-lowering progression, where changes in coordination geometry, lattice distortion, and vacancy ordering collectively reshape the electronic structure and thus electrocatalytic activity[53]. Accordingly, phase symmetry, the coordination environment of metal ions, the distribution of oxygen vacancies, and lattice distortions regulate the electronic structure of spinel oxides, subsequently affecting catalytic reaction efficiency and selectivity[54,55]. By analyzing the structural characteristics of these phases, a better understanding can be gained of how spinel oxides perform in various electrocatalytic reactions, providing a theoretical basis for their optimization. Therefore, a detailed exploration of the classification of different crystal phases and their structural features will offer a more systematic theoretical framework for subsequent catalytic performance studies and material design. Unlike prior reviews organized by composition, dimensionality/morphology, or specific applications (OER/HER), we treat the crystal phase (symmetry) as the first-order design variable and unify doping, defects, and morphology as within-phase variants. The lattice-coupled view further emphasizes operando phase/valence evolution as a mechanistic determinant of activity-stability trade-offs.

Figure 2. Representative cubic-to-triclinic phases illustrate symmetry evolution, coordination geometry, lattice distortion, and vacancy ordering, and their roles in determining the electronic structure and electrocatalytic activity.

2.2.1 Cubic phase

The cubic spinel oxide structure exhibits a face-centered cubic (FCC) symmetry, with two types of metal ions, A and B, occupying tetrahedral and octahedral positions, respectively, within the unit cell. Specifically, the larger metal ions, often Ni2+ or Co2+, occupy the tetrahedral positions, while the smaller metal ions, such as Fe3+ or Cr3+, are located in the octahedral sites[56,57]. Oxygen ions are positioned at the face centers and corners of the unit cell, forming a dense three-dimensional network of oxygen ions. This arrangement results in high symmetry within the cubic spinel structure, facilitating efficient charge transfer and contributing to enhanced conductivity and catalytic activity due to its simplified charge transport pathways[58,59]. In this structure, strong charge interactions between the A and B site metal ions are mediated by the oxygen ions, which play a crucial role in both lattice stability and charge conduction. The coordination environment around the B-site metal ions, which form octahedral coordination with oxygen ions, is critical in determining the oxidation-reduction behavior of the metal ions[60]. The typical bond distances between the oxygen ions and metal ions in the octahedral coordination are generally in the range of 1.9-2.2 Å[61]. This specific coordination environment not only influences the metal ions' redox behavior but also governs charge migration and intermediate adsorption during catalysis. The high symmetry and uniform distribution of oxygen ions in the cubic spinel structure also contribute to the material's thermodynamic and kinetic stability[62,63]. Furthermore, the cubic spinel oxide structure typically exhibits low internal stress and high structural stability, which can be attributed to the high symmetry and the well-ordered metal-oxygen coordination. The formation of oxygen vacancies in this structure is relatively flexible, with vacancies primarily occurring near the octahedral B-sites[64,65]. The introduction of oxygen vacancies improves the uniform distribution of charge and enhances both conductivity and catalytic activity. The stability of the cubic spinel structure is further reinforced by the formation of a stable three-dimensional oxygen ion network, which helps maintain the integrity of the structure across varying temperatures and in different acidic or alkaline environments[66]. In summary, the unique crystal structure of cubic spinel oxides imparts exceptional performance in electrocatalytic applications. Its face-centered cubic symmetry, precise metal ion coordination, and ordered oxygen ion arrangement provide high stability and excellent performance in charge transfer and catalytic reactions[67,68].

2.2.2 Hexagonal phase

Hexagonal spinel oxides belong to the hexagonal crystal system, with their unit cell composed of A- and B-site metal cations and oxygen anions, exhibiting a layered structure[69,70].In contrast to the cubic phase, hexagonal spinels exhibit lower symmetry, where A-site metal cations predominantly occupy octahedral sites, while B-site metal cations are primarily distributed in tetrahedral sites[71]. The oxygen anions are arranged in a bilayer stacking pattern within the unit cell, with one layer surrounding the octahedral A-site metal cations, and the other positioned near the tetrahedral B-site cations. In hexagonal spinels, the A-site metal cations have a stronger octahedral coordination, while the B-site cations exhibit looser coordination[72,73]. The metal-oxygen bond lengths typically range between 2.0 and 2.4 Å. This elongated coordination bond enhances electron transfer during redox reactions. Due to the lower symmetry, the electronic structure of the B-site metal cations is more complex, which can further influence the adsorption of reaction intermediates and optimize reaction pathways[74,75]. The lattice distortion in hexagonal spinels creates the potential for oxygen vacancy formation, which typically occurs around the octahedral B-site metal cations. Oxygen vacancies not only facilitate electronic conductivity but also improve the material's stability under extreme conditions[76]. The bilayer oxygen anion stacking also provides more space for oxygen ion migration and metal cation exchange, enhancing performance under high-temperature or high-current-density conditions. The stability of hexagonal spinels is highly dependent on the regulation of lattice distortions[77]. The lower symmetry makes these materials more susceptible to local structural changes or phase transitions under high-temperature or high-current-density conditions. However, by optimizing synthesis conditions, the stability of the hexagonal phase can be improved, preventing unnecessary phase transformations[78]. In conclusion, the unique crystalline architecture of hexagonal spinel oxides, defined by their low structural symmetry, layered stacking motif, intricate metal-oxygen coordination environments, and intrinsic oxygen vacancy formation, provides substantial opportunities for rationally tuning their catalytic performance[79,80].

2.2.3 Tetragonal phase

The tetragonal spinel oxide belongs to the tetragonal crystal system, with structural characteristics that differ notably from the cubic and hexagonal phases, exhibiting relatively lower symmetry. In this structure, A-site metal ions are typically positioned in octahedral coordination, while B-site metal ions are in tetrahedral coordination[81,82]. Compared to the cubic phase, the oxygen ion arrangement in the tetragonal phase is distorted, with oxygen-oxygen distances generally ranging from 2.2 to 2.4 Å, deviating significantly from the regular arrangement seen in the cubic phase[83,84]. This alteration in coordination leads to changes in the electron density around the metal ions, which subsequently influences charge transport and the interactions with reactants. The lattice structure of tetragonal spinel oxides exhibits slight axial or lateral elongation, causing variations in the distance between the A-site and B-site metal ions[85]. Due to the lower symmetry of the tetragonal crystal structure, the position of metal ions in the coordination environment is more susceptible to distortion, particularly under reaction conditions, which may result in local lattice strain. The oxygen-metal-oxygen bond length typically ranges from 2.1 to 2.3 Å, with a slight elongation compared to the cubic phase[86,87]. These changes not only affect the coordination environment of the metal ions but also contribute to the formation of oxygen vacancies and the introduction of lattice defects, which in turn modify the electronic structure and catalytic activity of the phase[88]. Moreover, due to the lower symmetry of the tetragonal phase, local structural distortions are more likely to occur during synthesis or operation, particularly under high current density or high-temperature conditions[89,90]. Although the overall lattice shows good stability, slight distortions in the structure may alter the coordination environment, leading to performance fluctuations under different conditions. Overall, while tetragonal spinel oxides exhibit relatively high stability, structural distortions pose a challenge. To ensure the material’s stability and reliability under various reaction conditions, it is necessary to optimize the synthesis process and conditions, minimizing local strain in the lattice[91].

2.2.4 Orthorhombic phase

Orthorhombic spinel oxides belong to the orthorhombic crystal system, exhibiting low crystal symmetry and a complex lattice configuration. In this structure, A-site metal ions typically occupy octahedral positions, while B-site metal ions are distributed between tetrahedral and octahedral sites, creating an asymmetric coordination environment[92,93]. This non-symmetric coordination results in significant lattice distortion and internal stress. Oxygen ions in the crystal do not exhibit symmetry, typically adopting two different coordination modes, which further complicates the structure[94]. The coordination distance between A-site metal ions and oxygen ions is typically in the range of 2.1 to 2.3 Å, while the distance between B-site metal ions and oxygen ions is slightly larger, usually between 2.3 and 2.5 Å[94]. Due to the differing coordination environments of the metal ions, the interactions between A-site and B-site metal ions are complex, leading to more varied electron density distributions and charge transfer pathways[95]. This lattice distortion influences the conductivity and catalytic behavior. The lattice constants a, b, and c in the orthorhombic phase exhibit anisotropy, with the c-axis typically exhibiting more significant elongation, indicating notable deformation along different lattice[96]. The arrangement of oxygen ions in orthorhombic spinel oxides forms a relatively loose metal-oxygen-metal network. The irregular coordination and variations in the positioning of oxygen ions introduce significant lattice strain, which may lead to the formation of local defects or further lattice distortion, particularly under high-temperature or high-current density conditions[97,98]. Overall, the structural characteristics of orthorhombic spinel oxides are defined by considerable lattice distortion and the asymmetric coordination of metal-oxygen sites, providing considerable flexibility for material performance tuning while also presenting stability challenges[99].

2.2.5 Rhombohedral phase

Rhombohedral spinel oxides belong to the rhombohedral crystal system, characterized by lower symmetry and a more complex coordination environment compared to other phases. In this structure, A-site metal ions typically occupy octahedral coordination, while B-site metal ions are primarily distributed between tetrahedral and octahedral sites, forming an asymmetric coordination[100]. This asymmetry leads to significant lattice strain, and the arrangement of oxygen ions within the unit cell is distorted, adding to the complexity of the structure[101]. The coordination distance between A-site metal ions and oxygen ions typically ranges from 2.3 to 2.5 Å, while the distance between B-site metal ions and oxygen ions is in the range of 2.1 to 2.3 Å[102]. Due to the different coordination environments of the A and B metal ions, the distribution of electron density and charge transport characteristics within the lattice exhibit variations. The complex interactions between A and B metal ions further complicate the electron transfer pathways within the crystal, affecting the material's conductivity and reactivity[103,104]. The unit cell of the rhombohedral phase typically shows significant anisotropy, with varying degrees of elongation or compression along the a, b, and c lattice constants, resulting in lattice distortion in different directions[105,106]. This distortion and increased lattice strain make the rhombohedral spinel oxide more susceptible to structural changes under high-temperature or high-current-density conditions, potentially leading to the formation of local defects[107]. Overall, the crystal structure of rhombohedral spinel oxides, characterized by significant lattice distortion and complex metal-oxygen coordination, exhibits pronounced anisotropy and lower symmetry, offering a large degree of flexibility for tuning the electronic structure and stability, while also presenting stability challenges under extreme conditions[108,109].

2.2.6 Monoclinic phase

Monoclinic spinel oxides belong to the monoclinic crystal system, characterized by low symmetry and significant lattice distortion. In this structure, A-site metal ions are typically situated in octahedral coordination, while B-site metal ions are distributed between tetrahedral and octahedral positions, forming an asymmetric coordination environment that induces considerable internal lattice strain[110,111]. The arrangement of oxygen ions is not symmetric in the monoclinic phase, exhibiting notable displacements and distortions, which further exacerbate the asymmetry of the lattice. The coordination distance between A-site metal ions and oxygen ions typically ranges from 2.3 to 2.5 Å, while the distance between B-site metal ions and oxygen ions is shorter, typically between 2.1 and 2.3 Å[112]. The different coordination environments of the metal ions result in more complex interactions between the A and B site metal ions, affecting the electron density distribution and charge transfer pathways within the crystal[113,114]. The lattice distortion destabilizes the coordination relationship between metal and oxygen, which may lead to the formation of local defects, particularly under high-temperature or high-current density conditions, further impacting the structural stability[115,116]. The unit cell of monoclinic spinel oxides exhibits notable anisotropy, with large differences between the lattice constants a, b, and c, particularly with elongation or compression along the b-axis[117,118]. The irregular arrangement of oxygen ions induces significant directional lattice distortion. Due to its lower symmetry, the crystal exhibits varying stress along different directions, which may lead to structural changes under extreme conditions. Overall, the crystal structure of monoclinic spinel oxides, with its pronounced lattice distortion and complex metal-oxygen coordination, provides significant flexibility for tuning, but also presents higher stability challenges[119,120].

2.2.7 Triclinic phase

In practice, oxide spinels almost never adopt a true triclinic phase because the spinel framework’s inherent topological and geometric constraints are incompatible with such low symmetry[121]. Because the spinel lattice is locked by a densely packed oxygen scaffold, it favors near-orthogonal angles and tolerates only modest shearing, so the three-axis shear required for triclinic symmetry would impose prohibitive metal-oxygen bond strain and AO4/BO6 polyhedral distortion[122]. Therefore, the structure typically reconstructs into a different framework before a stable triclinic spinel can be reached. The spinel structure is based on a close-packed oxygen lattice with translation vectors of similar length and interaxial angles near 90º, so only limited deviations in a,b,c and α,β,γ are tolerated without disrupting close packing[123]. Within this anion scaffold, A- and B-site cations occupy ordered tetrahedral and octahedral voids, forming a three-dimensional network of corner- and edge-sharing AO4 and BO6 polyhedra. In contrast, achieving triclinic symmetry would require all three lattice constants and angles to become inequivalent with strong non-orthogonality, demanding large anisotropic shifts of the oxygen sublattice and severe tilting/distortion of the coordination polyhedra[124]. Such distortion would force unrealistically short or excessively elongated cation–oxygen/cation–cation distances, disrupt the characteristic spinel connectivity, and build elastic strain beyond what the dense oxide lattice can accommodate. From a crystal-chemical perspective, these requirements render a stable triclinic spinel energetically unfavorable: rather than continuously lowering symmetry to a triclinic metric, the lattice is expected to undergo reconstructive transformations into alternative frameworks once distortion exceeds the tolerance of the close-packed anion scaffold and its tetrahedral–octahedral network[125].

2.3 Phase variants of spinel oxides

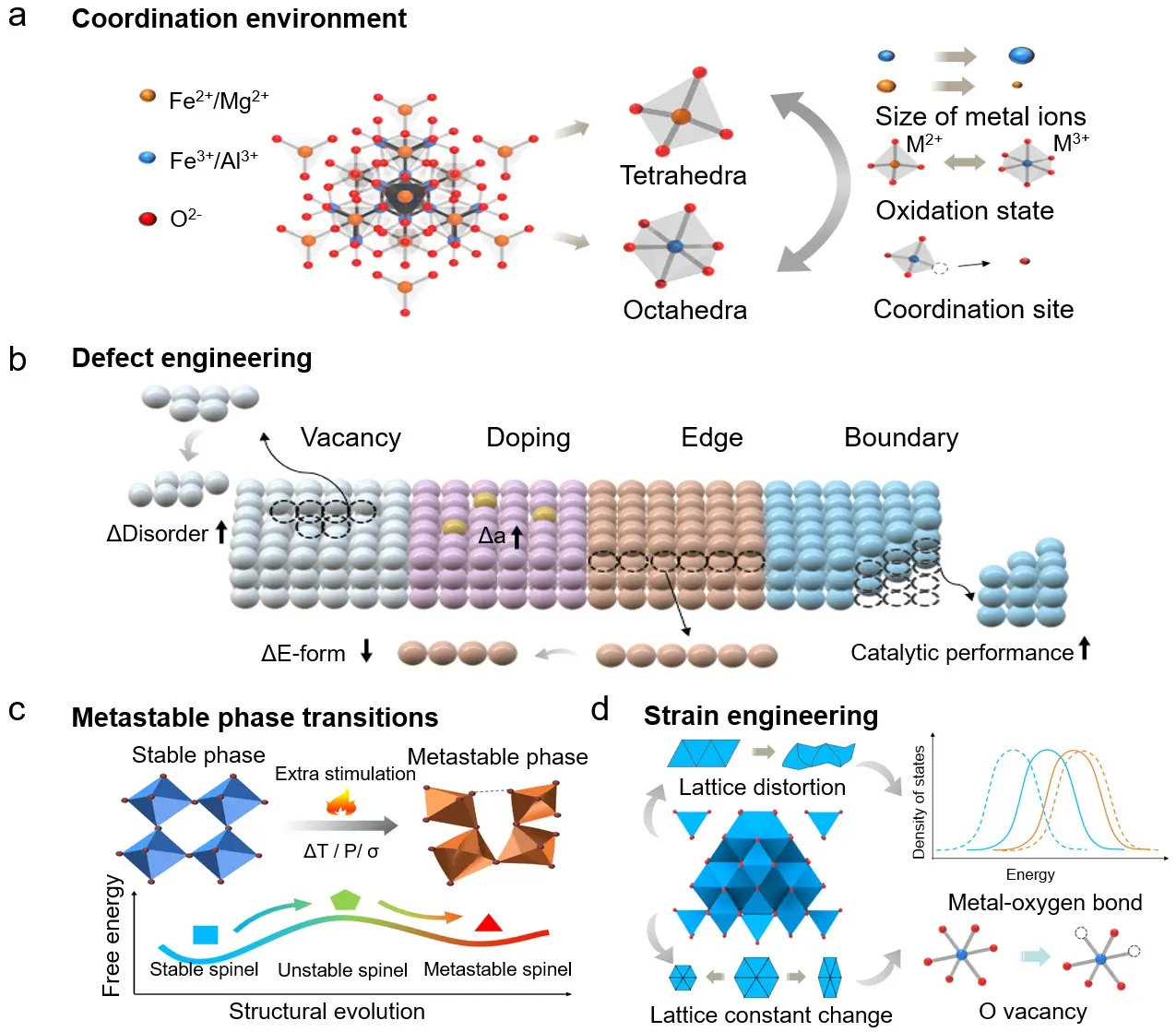

In addition to the six major crystalline phases, spinel oxides in practical applications may also exhibit various phase variants, which present unique characteristics through modifications such as metal-oxygen coordination, defect regulation, metastable phase transitions (i.e., non-equilibrium transformations that yield kinetically trapped, higher-energy structures), and strain engineering. These four are classic approaches to generating such variants (Figure 3)[126]. In this section, “primary crystal phases” denote space-group-defined bulk polymorphs with distinct long-range symmetry, whereas “phase variants” refer to within-phase structural modulations that do not necessarily form a new bulk phase but can substantially alter the electronic structure and electrocatalytic behavior[127]. The formation of these phase variants leads to changes in the electronic structure and physical properties of the material, making the understanding of their structural evolution mechanisms critical for optimizing electrocatalytic performance[128,129]. The regulation of the coordination environment can influence the electronic structure and catalytic behavior by altering the coordination number and geometry of metal ions[130,131]. Defect regulation, by introducing oxygen vacancies or metal vacancies, can modulate conductivity and reaction activity. Metastable phase transitions enable the transformation of different crystalline phases into lower-energy phases under specific conditions, improving catalytic performance[132]. Finally, strain engineering adjusts the lattice structure via external stresses, tuning the material's electronic and catalytic properties. Understanding these phase variants and their relationship with performance is essential for the rational design of more efficient spinel oxide catalysts[133,134].

Figure 3. Structural modulation strategies in spinel oxides. (a) Coordination tuning through metal-ion occupation of tetrahedral and octahedral sites, governed by ionic size, oxidation state, and local geometry; (b) Defect engineering, including vacancies, doping, edge and boundary defects, to tailor lattice disorder, formation energy, and reactivity; (c) Metastable phase transitions induced by thermal, chemical, or mechanical stimuli, leading to structural distortion and modified coordination; (d) Strain engineering to adjust lattice constants, metal-oxygen bonding, and electronic states, thereby enhancing catalytic activity.

2.3.1 Coordination environment

The coordination environment of metal ions in spinel oxides plays a pivotal role in determining both the overall structure and properties of the material. In the spinel structure, metal ions typically occupy two types of coordination sites: octahedral and tetrahedral[135]. Metal ions in octahedral sites are coordinated with six oxygen ions, forming an octahedral structure with sixfold coordination, while those in tetrahedral sites are coordinated with four oxygen ions, forming a tetrahedral structure with fourfold coordination[136,137]. The interactions between metal ions in these two coordination environments govern the local geometry of the material and its macroscopic properties. The coordination environment is influenced by factors such as the size, oxidation state of the metal ions, and the presence of vacancies in the lattice[138,139]. For example, smaller metal ions, such as iron and chromium, tend to occupy tetrahedral sites, while larger metal ions, such as cobalt and nickel, are more likely to occupy octahedral sites. Variations in the oxidation states of the metal ions directly affect their electron density, which in turn alters their electronic interactions with oxygen ions[140]. Furthermore, the introduction of coordination vacancies can disrupt the regularity of the coordination environment, leading to changes in the coordination number and geometry of the metal ions, which further impact the electronic structure and catalytic activity. In certain unconventional spinel phases, the coordination environment of metal ions may exhibit asymmetry or irregularity, resulting in incomplete octahedral or tetrahedral coordination[141,142]. Such irregular coordination can enhance the material's reactivity under specific conditions. Therefore, precise control over the coordination environment is crucial for tuning the structural stability and catalytic properties of spinel oxides[143,144]. In conclusion, the coordination environment of metal ions plays a decisive role in regulating the structure and properties of spinel oxides, influencing not only the redox behavior of metal ions but also the overall electronic conductivity and stability of the material[145,146].

2.3.2 Defect regulation

In the structure of spinel oxides, defect regulation is a crucial factor influencing crystal stability and physical properties. The spinel structure consists of alternating metal ions and oxygen ions, with metal ions typically occupying octahedral and tetrahedral sites, while oxygen ions are located at the face centers of the octahedra and the vertices of the tetrahedra[147]. The introduction of defects, particularly oxygen vacancies, metal ion vacancies, and abnormal coordination, causes lattice distortion and generates localized stress, thereby impacting material stability and reactivity. Oxygen vacancies are common point defects in spinel oxides[148,149]. The presence of oxygen vacancies disrupts the periodic arrangement of oxygen ions, resulting in local lattice distortion and stress concentration, which affects the distribution and oxidation states of metal ions[150]. The concentration and distribution of oxygen vacancies determine the stability of metal ions in higher oxidation states, making precise control of oxygen vacancy formation crucial for optimizing material performance. In addition, metal ion vacancies disrupt lattice symmetry, leading to local instability, while abnormal coordination of metal ions further induces disorder in the lattice, affecting the overall structure[151,152]. The introduction of defects is closely linked to lattice strain, particularly as oxygen vacancies, and metal ion vacancies, cause changes in lattice constants, which in turn affect long-range ordering. The presence of defects not only impacts crystal stability but can also induce subtle fluctuations in lattice constants, altering the overall structural symmetry[153,154]. Therefore, precise regulation of defect types, concentrations, and distributions is essential for enhancing the structural stability and catalytic activity of spinel oxides in material design.

2.3.3 Metastable phase transitions

During phase transitions in spinel oxides, metastable phase transitions represent significant phenomena, especially under non-equilibrium conditions where spinel structures may undergo transitions from stable phases to metastable ones[155,156]. These metastable phases typically form under non-equilibrium conditions and possess lower thermodynamic stability, yet they can maintain certain structural characteristics under specific temperature, pressure, or chemical environments[157]. Such phase transitions involve changes in long-range crystalline order and local structural adjustments, with lattice distortions or minor changes in lattice constants often accompanying the formation of metastable phases in metal oxides[158,159]. Structurally, while metastable spinel oxides retain certain aspects of the spinel framework, there are notable changes in crystal symmetry and the coordination environment of metal ions[160]. In these metastable phases, metal ions may deviate from their ideal octahedral or tetrahedral coordination, leading to local stresses and lattice distortions. For instance, reduction or oxidation reactions of metal ions can alter their positions and coordination modes, further influencing the overall structure of the crystal[161]. Moreover, metastable spinel oxides are often associated with significant lattice strain. The formation of metastable phases is usually triggered by factors such as temperature fluctuations, external pressure, or rapid cooling, causing transitions between different phases and resulting in shifts in atomic positions and redistribution of lattice stresses[162]. Although these metastable phases have poorer thermodynamic stability, they can exhibit unique structural features under certain conditions. A deeper understanding of these phase transition processes not only helps elucidate the structural evolution of spinel oxides in varying environments but also provides a theoretical basis for designing materials with specific properties[163,164]. Under realistic OER/HER conditions, metastable spinels may undergo potential-driven surface reconstruction, so the as-prepared phase often serves as a pre-catalyst, while the steady-state reconstructed surface is the true active phase. This should be verified by correlating electrochemical activation/stability with in situ/operando phase/valence tracking (e.g., XAS/Raman/XRD or microscopy). Metastable-phase evolution can be tracked by changes in OER kinetics and interfacial charge transfer[165], as exemplified by the Li-vacancy–induced disordered phase (≈ 430 mV at 10 mA cm-2, 85.6 mV dec-1, C-dl = 0.39 mF cm-2) indicating accelerated charge transfer and enhanced intrinsic OER kinetics[166].

2.3.4 Strain engineering

Strain engineering plays a crucial role in the structural modulation of spinel oxides, particularly in adjusting their crystal characteristics. By applying external stress or introducing strain during the synthesis process, changes can occur in the lattice constants, atomic distances, and the coordination environment of ions in spinel oxides[167,168]. Strain regulation can be achieved via lattice-coupled architectures, where coherent epitaxial interfaces impose a uniform strain field that tunes metal-oxygen bonding and reaction energetics during catalysis[169]. For example, an interfacial lattice-coupling Ru–Mn–O system (Ru, Mn)2O3-250 delivers 168 mV at 10 mA cm-2 with a 68.7 mV dec-1 Tafel slope and sustains > 40 h stability, indicating that interface-induced strain can concurrently enhance charge transfer and structural robustness in line with general strain effects[170]. These strain-induced structural changes are typically manifested as the disruption of crystal symmetry, fine-tuning of lattice constants, and rearrangement of atomic positions. The geometric distortions caused by strain often lead to alterations in metal-oxygen bond strength, which in turn facilitates the formation of oxygen vacancies, creating new active sites[171,172]. Such structural changes often result in a shift in the coordination number of metal ions, for example, from a standard octahedral coordination to a tetrahedral or other asymmetric coordination[173]. These changes in coordination and structure not only affect the crystal’s stability but may also drive new phase transitions, thereby altering the material's overall structural properties. In certain cases, strain can induce a transition in the crystal’s space group, causing a metastable phase to become the dominant phase, thereby imparting new structural characteristics to the material[174,175]. Precise control over strain provides a means of optimizing the structure of spinel oxides. Through strain-guided phase transitions, it is possible to modify the local geometric and electronic states of the crystal without disrupting its overall integrity. The core of strain engineering lies in the fine-tuning of the stress state within the lattice, enabling the optimization of material properties at the microscopic level[176,177]. This structural modulation approach allows for significant performance enhancement while maintaining material stability, particularly in the design of multifunctional catalytic materials.

2.4 Influence of crystal phases on electrocatalytic water splitting mechanisms and performance

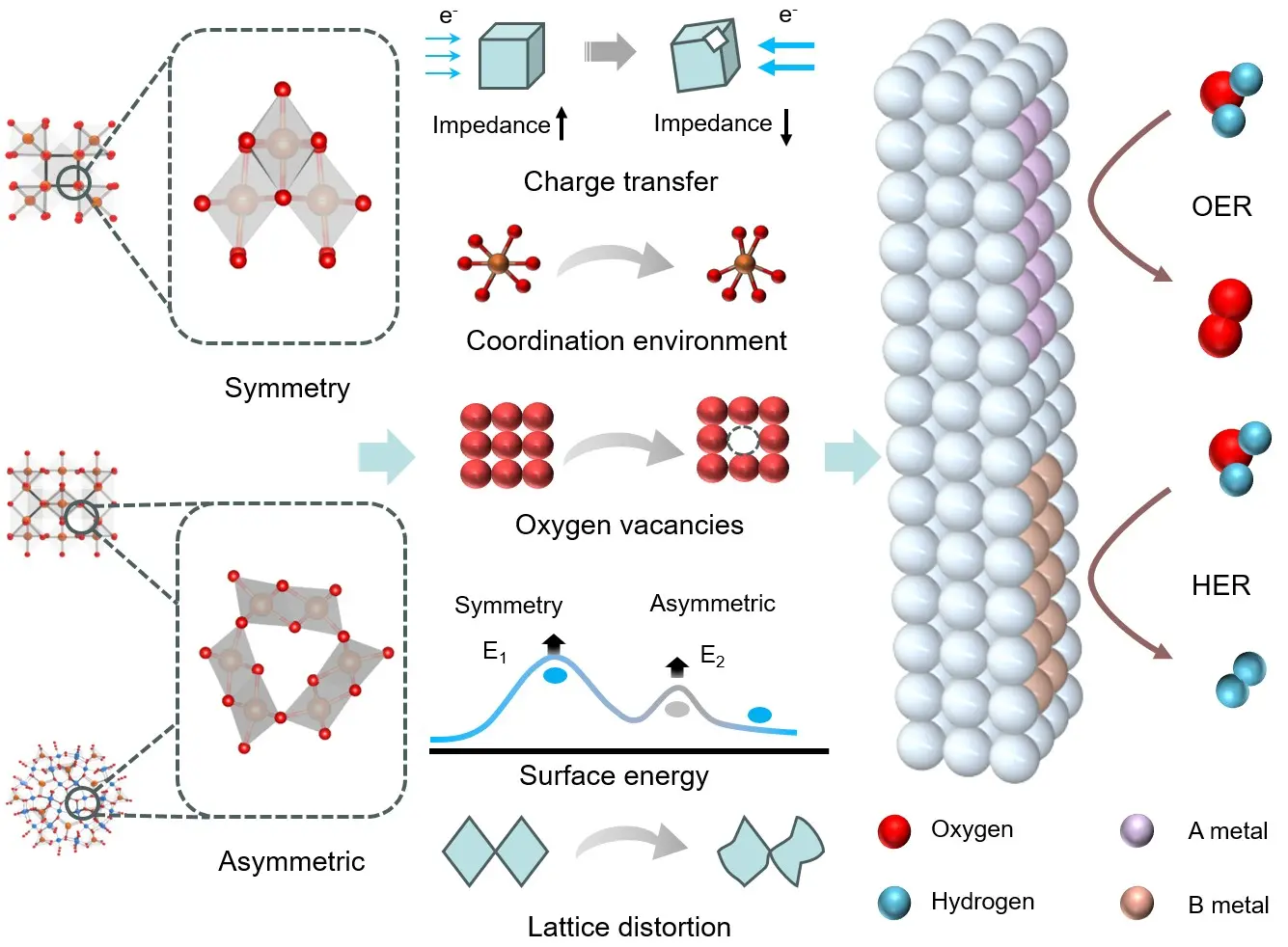

The crystal phase structure of spinel oxides significantly influences their electrocatalytic water splitting performance through various mechanisms, including metal ion coordination environment, oxygen vacancy formation, lattice distortion, surface energy, and charge transfer; these phase-dependent structural descriptors collectively regulate active-site chemistry and metal-oxygen interactions, providing a unified framework for the discussion below (Figure 4). Firstly, the coordination environment of metal ions determines the electronic structure, which directly impacts catalytic activity[178]. In cubic spinel oxides, metal ions are typically located in symmetric octahedral coordination, which ensures high stability and efficient electron conductivity, making cubic phases conducive to charge transfer during catalytic reactions. In contrast, low-symmetry phases such as hexagonal and tetragonal phases feature less symmetric and more distorted coordination environments[179,180]. This irregular coordination enhances interactions between metal ions and oxygen intermediates, lowering reaction energy barriers and improving catalytic activity. For example, reduced symmetry and looser metal coordination in these phases allow better interaction between metal ions and oxygen species, accelerating redox reactions[181,182].

Figure 4. Structural factors regulating water-splitting activity in spinel oxides. Symmetry-dependent coordination environments, oxygen-vacancy formation, lattice distortion, surface-energy variation, and charge-transfer characteristics collectively tune active sites and metal-oxygen interactions, thereby governing OER and HER performance. OER: oxygen evolution reaction; HER: hydrogen evolution reaction.

Secondly, the formation of oxygen vacancies is critical for enhancing catalytic activity in water splitting reactions. Oxygen vacancies act as additional active sites that promote charge transfer and facilitate the reaction[183,184] In high-symmetry structures like the cubic phase, the formation of oxygen vacancies is relatively difficult due to the tight coordination between metal and oxygen ions[185]. However, in lower-symmetry phases such as hexagonal and tetragonal phases, the presence of lattice distortions and asymmetric coordination makes oxygen vacancy formation easier, which effectively lowers reaction barriers, particularly in the OER[186,187]. Oxygen vacancies not only enhance oxygen desorption but also accelerate the formation of reaction intermediates, thereby improving the overall catalytic performance.

Lattice distortion also plays a crucial role in catalysis. This distortion, often caused by irregular metal coordination, oxygen vacancy creation, or external strain, alters the lattice energy distribution, impacting the strength of metal-oxygen bonds and the electron density[188,189]. For instance, in tetragonal and hexagonal phases, the slight changes in the metal-oxygen distance due to lattice distortion strengthen the metal-oxygen bond’s electronic exchange capacity, making metal ions more involved in electron transfer reactions[190]. Lattice distortion may also introduce new catalytic active sites, further enhancing reactivity.

Surface energy is another important factor influencing catalytic efficiency. The surface energy distribution varies between crystal phases, affecting the arrangement of surface active sites. In high-symmetry phases like cubic spinels, surface energy is relatively uniform, and fewer active sites are available, resulting in lower catalytic efficiency[191,192]. However, in lower-symmetry phases like hexagonal and tetragonal phases, lattice distortions and asymmetric coordination lead to more uneven surface energy distribution, creating additional active sites that effectively adsorb and activate reactants, thereby enhancing catalytic activity[193].

Additionally, charge transfer rates are a critical factor in electrocatalytic performance. In lower-symmetry phases, due to lattice irregularities and the presence of oxygen vacancies, the electronic conductivity and charge transfer rates are typically higher, allowing stable catalytic activity even under high current densities[194,195]. Efficient charge transfer in the OER, for example, facilitates the breakdown of water molecules, enhancing the overall reaction rate.

2.5 Summary and statistical analysis of structure–performance relationships in spinel oxide catalysts

The statistical patterns in Table 1 highlight several clear relationships between crystal phases and electrocatalytic performance. We further quantified phase-resolved overpotential–Tafel correlations and phase-wise distributions, noting that protocol heterogeneity may weaken global trends, while phase-dependent shifts remain robust. The phase distribution and metrics in Table 1 are inevitably literature-skewed—cubic spinels are overrepresented because they are thermodynamically favored and readily accessible, whereas low-symmetry phases (e.g., monoclinic) are less frequently and unambiguously reported due to narrower synthesis windows/kinetic stabilization and challenging phase verification under operation; moreover, intrinsic activity descriptors (mass activity, TOF, ECSA-normalized values) are not consistently reported with comparable protocols, so we include/discuss them only when explicitly available and note the resulting limitations for cross-phase comparisons. Cubic spinels, which constitute the largest portion of the dataset, generally exhibit OER overpotentials concentrated near 300 to 360 mV at benchmark current densities in 1.0 M KOH, with Tafel slopes commonly falling in the 50 to 90 mV dec-1 range. Within this phase family, NiCo2O4 and related Co rich compositions repeatedly deliver lower overpotentials, for example values close to 310 mV or 308 mV, while Fe containing cubic systems often occupy the higher end of the range, indicating that B site electronic configuration is a primary contributor to the observed variation. Several cubic entries also display good durability, with operation times such as 20 h at 10 mA cm-2 or stable performance across 1,000 cycles, suggesting that the high symmetry lattice provides consistent structural robustness. In contrast, tetragonal and orthorhombic spinels show a wider but frequently more favorable distribution of activity. For instance, ZnMn2O4 and Mn3O4 exhibit overpotentials near 350 mV or even below 300 mV at comparable current densities, and stability measurements such as 20 h at 10 mA cm-2 or over 300 mA cm-2 conditions imply that lattice distortion or anisotropic bonding can support sustained operation. Hexagonal spinels appear less common in the dataset but show a recognizable pattern of moderate overpotentials, for example values around 370 to 450 mV, combined with strong cycling endurance, often exceeding several hundred cycles. This recurring combination suggests that layered anion and cation arrangements can buffer structural stress during prolonged testing. Monoclinic entries, although fewer, provide activity levels near 270 to 285 mV, accompanied by operation durations such as 12 h at 10 mA cm-2, demonstrating that low symmetry does not necessarily hinder performance when cation distribution is optimized. Across multiple symmetry classes, mixed B site compositions and mild A site doping, such as Li containing Co spinels, appear repeatedly among the better performing entries, with overpotentials near 390 mV or lower and stability values approaching tens of hours, indicating that small perturbations in cation distribution can tune conductivity and intermediate adsorption more effectively than large compositional shifts. Overall, the statistical evidence points to a combined influence of crystallographic symmetry, cation arrangement, and defect related tuning in determining the activity and durability of spinel oxide electrocatalysts, with both high symmetry and symmetry lowered lattices capable of strong performance when supported by optimized electronic and structural environments.

| Crystalline Phases | Material | Electrolyte | Application/Function | Tafel slope (mV dec-1) | Overpotential (mV) | Key structural factor | Stability @Current density | Reference |

| Cubic Spinel Oxides | (R–COO) xσ-Co3O4-x | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 60.9 | η10 = 230 η100 = 330 | Surface functionalization | 100 h @ 20 mA cm-2 | [196] |

| Co2MnO4 | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 65 | η10 = 328 | Mixed-valence Co/Mn | 55 h @ 10 mA cm-2 | [197] | |

| CoMn2O4 | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 92 | η10 = 460 | B-site substitution | 55 h @ 10 mA cm-2 | [197] | |

| Co2MnO4 | H3PO4/H2SO4 | OER | 80 | η500 = 1,700 | Phase robustness under harsh electrolyte | > 1,500 h @ 200 mA cm-2 | [198] | |

| NiCo2O4 | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 58 | η10 = 310 | Mixed-cation conduction network | 100 h @ 10 mA cm-2 | [199] | |

| Co2FeO4 | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 43 | η0.01 = 359 | Fe substitution | 1,000 cycles | [200] | |

| CoFe2O4 | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 79 | η0.01 = 432 | Fe–Co electronic coupling | 1,000 cycles | [200] | |

| Co3O4 | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 65 | η10 = 360 | Baseline cubic framework | 20 h @ 10 mA cm-2 | [201] | |

| Co1.47Rh1.53O4 | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 59.2 | η10 = 301 | Noble-metal substitution | > 24 h @ 10 mA cm-2 | [202] | |

| ZnCo2O4 | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 60 | η10 = 340 | A-site Zn tuning | 1,000 cycles (no η shift) | [201] | |

| CoAl2O4 | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 95 | η10 = 480 | Inactive-site dilution | Stable (low activity) | [201] | |

| Fe1Co1Ox | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 36.8 | η10 = 308 | Fe–Co electronic synergy | > 2.8 h @ 300 mV | [203] | |

| LixCo3-xO4 | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 60-70 | η10 = 390 | Li-induced cation disorder | 60 h @1.62 V | [204] | |

| (Co, Fe, Ni, Cr, Mn)3O4 | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 34.7 | η10 = 307 | High-entropy cation disorder | 168 h @ 10 mA cm-2 | [204] | |

| Mn [Al0.5Mn1.5] O4 | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 60 | η0.025 = 240 | Aliovalent doping | 12 h | [205] | |

| LT-LiCoO2 | 0.1 M KOH | OERORR | 5260 | η10 = 370 | Metastable Li–Co framework | 6 h @1.7 V | [206] | |

| Hexagonal Spinel Oxides | Zn4-xCoxSO4(OH)6·0.5 H₂O | 0.5 M KOH | OER | 60 | η10 = 370 η100 = 450 | Hexagonal open framework | 11 h @380 mV | [207] |

| LiNi0.5Co0.2Mn0.3O2 | 0.1 M KOH | OER | 85.6-241.8 | η10 = 430 | Li-vacancy–induced cation disorder | > 500 cycles | [165] | |

| Co3O4 | 0.05 M KOH | OER | — | — | Hexagonal polymorph | several cycles | [170] | |

| Orthorhombic Spinel Oxides | (Ru, Mn)2O3 | 0.1 M HClO4 | OER | 38 | η10 = 180 | Interface-induced lattice strain | 250 h @ 10 mA cm-2 | [208] |

| Tetragonal Spinel Oxides | Mn3O4 | 0.1 M KOH | OERORR | 8777 | η10 = 410 | Jahn–Teller tetragonal distortion | 2.8 h @1.6 V | [209] |

| CoMn2O4 | —— | OERHER | 8379 | η10 = 252 | Tetragonal distortion | 20 h @ 10 mA cm-2 | [210] | |

| ZnMn2O4 | 1.0 M KOH | OERHER | 84102 | η10 = 350 | Distortion-enabled vacancies | 20 h @ 10 mA cm-2 | [211] | |

| Mn3O4 | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 86 | η10 = 287 | Distortion plus surface reconstruction under high rates | 10 h @ 320 mA cm-2 | [212] | |

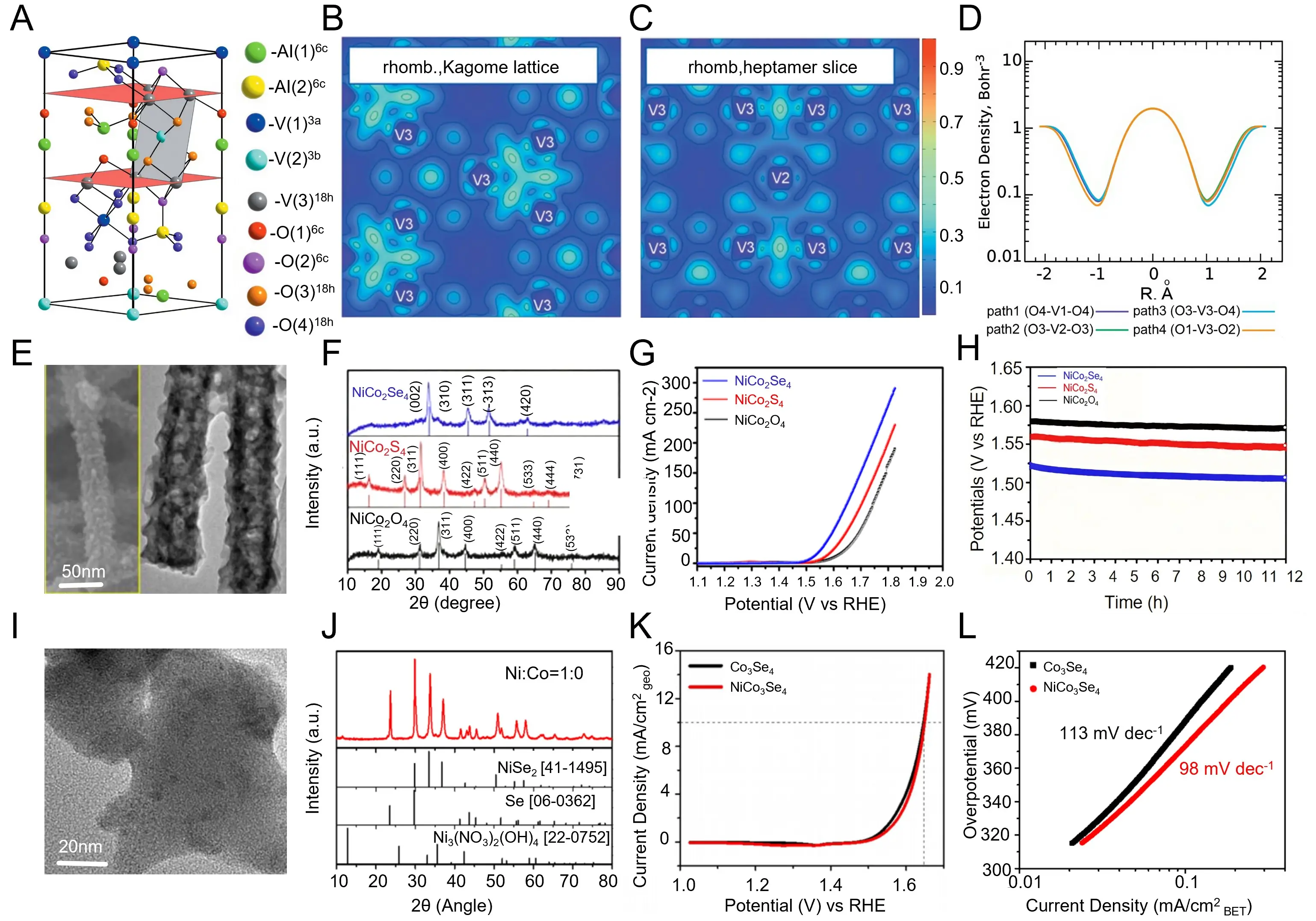

| Monoclinic Spinel Oxides | NiCo2Se4 | 1.0 M KOH | OERHER | 63 | η10 = 270 | Anion substitution (Se) | 12 h @ 10 mA cm-2 | [213] |

| NiCo2Se4/Co3Se4 | 1.0 M KOH | OER | 68 | η10 = 285 | Phase boundary | 20 h @ 10 mA cm-2 | [214] |

3. Crystalline Structure-Dependent Electrocatalytic Behavior of Spinel Oxide

The following sections provide a detailed analysis of the electrocatalytic behavior of spinel oxides across different crystal phases, with emphasis on how each structural motif governs performance in electrocatalytic water splitting. Through an in-depth examination of these crystal phases, a clearer understanding can be established regarding the intrinsic connections between crystal structure and catalytic activity, thereby offering a theoretical foundation for the rational optimization of electrocatalysts. To bridge Section 2 and Section 3, we adopt a concise “material–structure–behavior–performance” linkage: composition, phase, and variants define symmetry/coordination, defects/strain and related structural descriptors, which govern intermediate adsorption/charge transport and possible reconstruction under operating potentials, ultimately determining activity–stability outcomes across the phase-by-phase discussion below.

3.1 Cubic spinel oxides

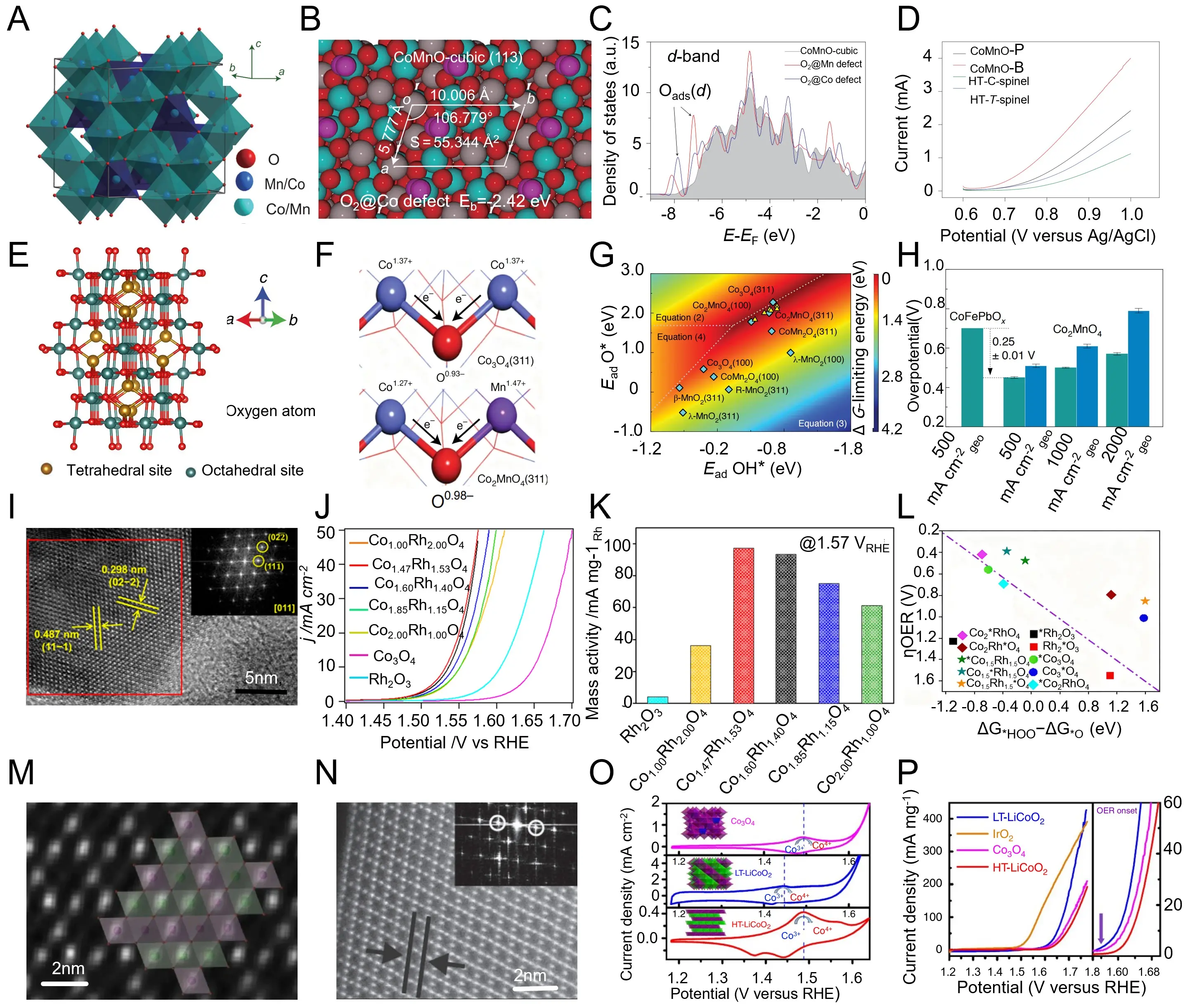

Following the previous discussion on phase-governed activity, Cheng et al. established a rapid room-temperature reduction-recrystallization strategy to synthesize nanocrystalline Co-Mn-O spinels with precisely controllable cubic and tetragonal phases[215]. As illustrated in Figure 5a, the cubic CoMn2O4 lattice consists of corner-sharing [Co/MnO6] octahedra and [Co/MnO4] tetrahedra, forming a highly symmetric three-dimensional framework that enables efficient electron transport. First-principles simulations indicate that the cubic (113) surface exhibits a stronger oxygen adsorption energy (Eb = -2.42 eV), and an Oads-induced d-band upshift toward the Fermi level, revealing intensified metal-oxygen orbital hybridization (i.e., covalent mixing/overlap between transition-metal 3d and O 2p states) compared with the tetragonal (121) surface (Figure 5b,c). Electrochemical characterization further demonstrates that the cubic phase delivers superior oxygen-reduction activity, whereas the tetragonal counterpart favors enhanced oxygen-evolution performance, both outperforming conventionally synthesized high-temperature spinels (Figure 5d). These findings clearly demonstrate that crystallographic symmetry and defect-mediated electronic modulation cooperatively regulate charge transport and intermediate adsorption, underscoring that phase engineering of spinel oxides provides an effective strategy to optimize bifunctional electrocatalysis for overall water splitting. Extending the investigation on Co-Mn-O spinels, Li et al. employed a controlled thermal-decomposition strategy to prepare cubic Co2MnO4 spinel catalysts with enhanced structural stability and acid durability[198]. The catalyst adopts a cubic Fd-3m lattice in which Co2+ occupies tetrahedral sites while Mn3+/4+ resides at octahedral positions (Figure 5e). Charge redistribution across Co-O-Mn coordination units builds a rigid oxygen network that effectively suppresses lattice distortion and prevents structural collapse during oxygen evolution (Figure 5f). First-principles calculations reveal that the dominant (311) surface exhibits near-optimal adsorption energies for OER intermediates (Ead (OH*) ≈ -0.8 eV; Ead (O*) ≈ -0.3 eV), ensuring balanced binding strength and mitigating metal dissolution under acidic conditions (Figure 5g). Electrochemical measurements confirm remarkable activity, showing an overpotential of 0.25 ± 0.01 V at 500 mA cm-2 and stable operation exceeding 1,500 h in pH 1 electrolyte (Figure 5h). These results demonstrate that cation ordering and Mn-mediated Co-O stabilization cooperatively modulate the electronic structure and surface energetics, highlighting that precise crystallographic regulation in cubic spinels can simultaneously achieve high activity and exceptional acid stability for overall water-splitting electrocatalysis.

Figure 5. (a) Crystal structure model of Co-Mn-O spinel showing Mn/Co octahedra; (b) Atomic configuration and oxygen-vacancy formation energy in Co-Mn-O with highlighted local structural parameters; (c) Calculated DOS for Co-Mn-O showing d-band modulation induced by oxygen-vacancy configurations; (d) Electrochemical polarization curves of various Co–Mn–O phases (CoMnO-P, CoMnO-B, HT-C-spinel, HT-T-spinel). Republished with permission from[215]; (e) Crystal structure model of Co2MnO4 showing tetrahedral and octahedral cation sites; (f) Schematic of surface adsorption configurations (OH-, O) on Co2MnO4(311) and Co3O4(311) surfaces; (g) Energy landscape diagram correlating Ead(O) and E3d(O) for different Co-Mn-O surfaces; (h) Comparison of OER overpotentials of Co2MnO4 and Co-Fe-B2O4 under different current densities. Republished with permission from[198,216]; (i) HRTEM image and FFT pattern of CoxRh3-xO4 showing well-ordered spinel lattice; (j) LSV polarization curves of CoxRh3-xO4 spinels showing composition-dependent activity; (k) Mass activity comparison of RhO2, Co3O4, and CoxRh3-xO4 at 1.57 V RHE; (l) Scaling relationship between log(OER activity) and ΔGHOO - ΔGO for various CoxRh3-xO4 compositions. Republished with permission from[202]; (m) Atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM image of LT-LiCoO2 showing the local spinel-like atomic arrangement; (n) HRTEM image and FFT pattern showing lattice ordering and phase transition features in LiCoO2; (o) LSV polarization curves comparing Co3O4, HT-LiCoO2 and LT-LiCoO2; (p) OER polarization and ORR activity comparison of LiCoO2-derived materials and reference Co3O4. Republished with permission from[206]. DOS: density of states; OER: oxygen evolution reaction; HT: high temperature; LT: low temperature; FFT: fast Fourier transform; ORR: oxygen reduction reaction; LSV: linear-sweep voltammograms; RHE: reversible hydrogen electrode; HRTEM: high-resolution transmission electron microscopy; HAADF-STEM: high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy; C-spinel: cubic spinel; T-spinel: tetragonal spinel.

To further elucidate the role of cation modulation in cubic spinels, Zhu et al. constructed a series of CoxRh3-xO4 solid-solution spinels via high-temperature solid-state synthesis, enabling precise control of lattice distortion and electronic configuration through Rh incorporation[202]. As shown in Figure 5i, the catalysts retain a well-defined Fd-3m cubic framework, with high-resolution TEM images revealing distinct (111) and (022) planes (0.487 and 0.298 nm, respectively), confirming homogeneous Co/Rh distribution. Electrochemical polarization curves and mass-activity plots demonstrate that the optimized Co1.85Rh1.15O4 exhibits an overpotential of 270 mV at 10 mA cm-2 and an exceptional mass activity of ≈ 90 mA mg-1Rh @ 1.57 V vs reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE), outperforming Co3O4 and Rh2O3 benchmarks (Figure 5j,k). Theoretical calculations further reveal a volcano-type relationship between overpotential and adsorption-energy difference (ΔG*OOH - ΔG*O), indicating optimized intermediate binding arising from lattice distortion and Co-Rh electronic hybridization (Figure 5l). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that rational lattice engineering and cation substitution within cubic spinels effectively tailor orbital occupancy and reaction thermodynamics, thereby substantially accelerating intrinsic oxygen-evolution kinetics. Building on the preceding advances in cation-engineered spinels, Hong et al. synthesized low-temperature (LT) and high-temperature (HT) LiCoO2 phases through a controlled solid-state reaction, allowing a direct comparison between cubic-like disordered and layered rhombohedral structures[206]. As shown in Figure 5m,n, high-resolution STEM images reveal that LT-LiCoO2 exhibits partially disordered Co-O stacking resembling a spinel-like cubic configuration, while HT-LiCoO2 maintains a well-ordered layered framework with distinct (003) lattice fringes. Such structural divergence markedly alters the electronic configuration and surface coordination, leading to distinct oxygen-adsorption behaviors. Electrochemical measurements demonstrate that LT-LiCoO2 achieves superior oxygen-evolution activity with an overpotential of ≈ 350 mV at 10 mA cm-2, outperforming both HT-LiCoO2 and Co3O4 references (Figure 5o,p). These findings confirm that phase transformation from layered to spinel-like cubic structures enhances active-site accessibility and charge transport, emphasizing that crystal-phase reconstruction is a key pathway to boost the intrinsic OER activity of cobalt-based oxides.

3.2 Hexagonal spinel oxides

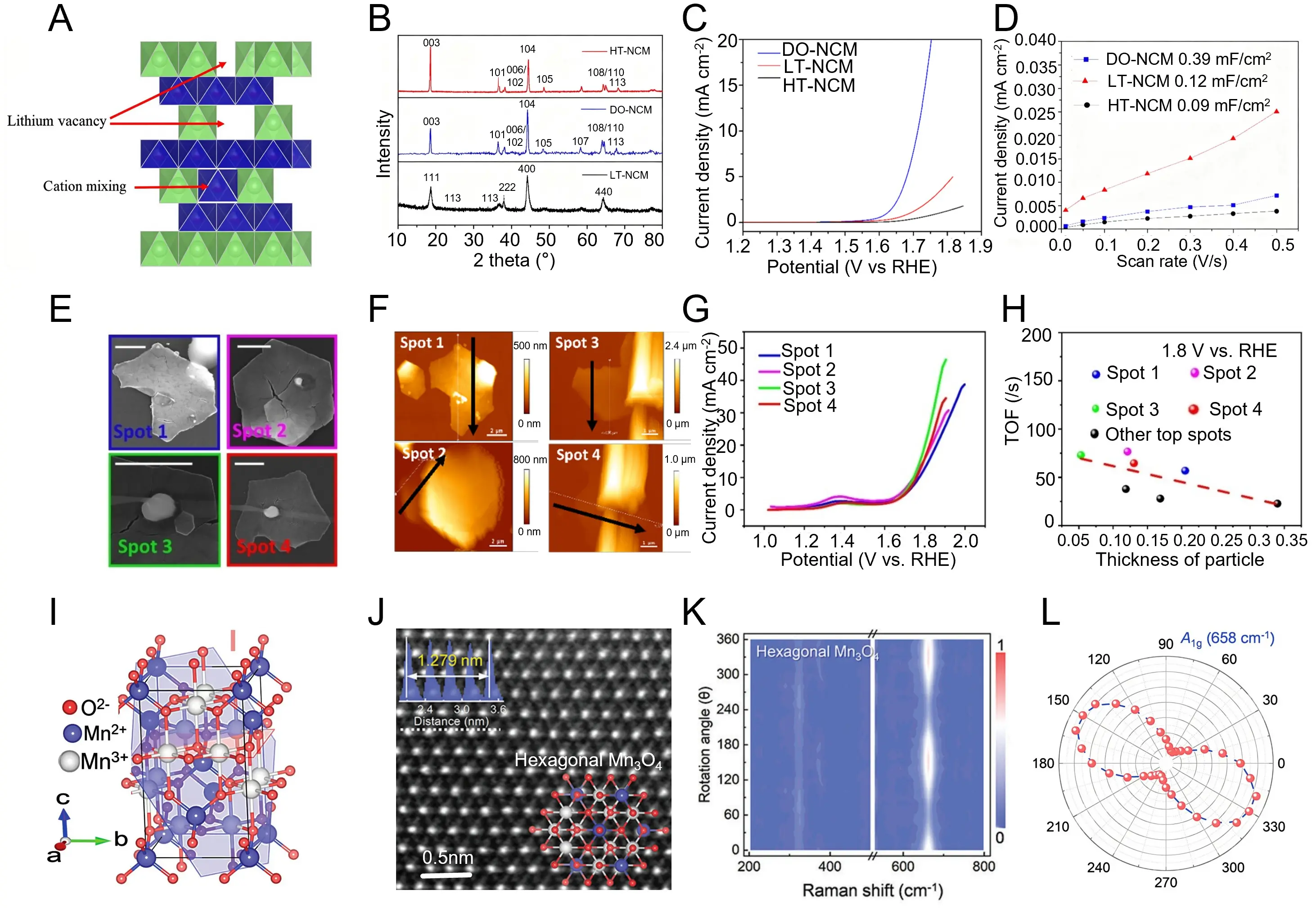

Following the previous discussion on phase-regulated Co-based systems, Huang et al. synthesized LiNi0.5Co0.2Mn0.3O2 (NCM523) with layered (HT-NCM), spinel-like (LT-NCM), and disordered (DO-NCM) phases via a polymer-assisted solution synthesis, aiming to correlate lithium-vacancy formation with oxygen-evolution activity[165]. As illustrated in Figure 6a, schematic analysis depicts that Li deficiency and cation intermixing disrupt the regular stacking of the layered structure, leading to progressive lattice disorder. Figure 6b shows the XRD patterns, where the gradual reduction of the (003)/(104) intensity ratio confirms the transformation from the well-ordered R-3m layered lattice to a disordered hexagonal configuration. Electrochemical measurements reveal that the DO-NCM phase exhibits the highest catalytic activity, with an overpotential of ≈ 430 mV @ 10 mA cm-2 and a Tafel slope of 85.6 mV dec-1, surpassing both LT- and HT-NCM counterparts (Figure 6c). In addition, capacitive response analyses show that DO-NCM possesses the largest double-layer capacitance (0.39 mF cm-2), indicating increased electrochemically active surface area and faster charge transfer (Figure 6d). These results demonstrate that Li-vacancy-induced cation disorder and crystal-phase transformation synergistically enhance electronic delocalization and active-site accessibility, underscoring that phase modulation is a decisive factor governing the intrinsic OER kinetics of layered transition-metal oxides. Building on the preceding insights into phase- and structure-regulated layered oxides, Varhade et al. employed scanning electrochemical cell microscopy (SECCM) to elucidate the facet-dependent electrocatalytic behavior of single hexagonal Co3O4 spinel crystals[170]. As shown in Figure 6e, high-resolution scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images identify individual microcrystals with well-defined (111) top and (110) edge facets, characteristic of the hexagonal spinel lattice. AFM analyses further reveal distinct surface morphologies and facet thicknesses, confirming anisotropic Co-O coordination and crystallographic orientation (Figure 6f). Electrochemical mapping demonstrates that the (111) facets exhibit a thickness-dependent turnover frequency (TOF) of approximately 100 s-1 at 1.8 V vs RHE, whereas the (110) planes achieve a higher and thickness-independent TOF of ≈ 270 ± 68 s-1 (Figure 6g). The corresponding TOF-thickness correlation indicates that enhanced surface Co density and improved electron conductivity along the (110) edges account for the superior oxygen-evolution performance (Figure 6h). These results highlight that crystal-plane anisotropy plays a decisive role in dictating local reaction kinetics, underscoring that facet-level structural regulation is an effective route to optimize the intrinsic activity of hexagonal spinel oxides.

Figure 6. (a) Schematic illustration of cation mixing and lithium-vacancy defects in layered NCM structures; (b) XRD patterns of NCM samples showing the structural evolution associated with heat treatment and cation disorder; (c) LSV of LT-, HT-, and DO-NCM catalysts in 0.1 M KOH; (d) Scan-rate-dependent current responses of LT-, HT-, and DO-NCM electrodes, indicating different capacitive behaviors. Republished with permission from[165]; (e) SEM image of a single hexagonal Co3O4 particle analyzed by SECCM; (f) Cyclic-voltammogram responses at landing spots on particle surfaces and bare carbon; (g) SEM micrograph showing on-top droplet landing spots on the Co3O4 particle used for activity mapping; (h) Corresponding TOF values of the (111) top plane plotted against particle thickness. Republished with permission from[170]; (i) Schematic of the CVD growth of 2D tetragonal and hexagonal Mn3O4 nanosheets; (j) High-resolution TEM images revealing lattice arrangements and thickness of tetragonal and hexagonal Mn3O4 nanosheets; (k) Angle-dependent Raman spectra of hexagonal Mn3O4 showing crystallographic anisotropy; (l) Polar plot of the A1g Raman mode (658 cm-1) confirming the single-crystal symmetry of the Mn3O4 nanosheets. Republished with permission from[166]. LSV: linear-sweep voltammogram; HT: high temperature; LT: low temperature; SEM: scanning electron microscopy; TEM: transmission electron microscopy; SECCM: scanning electrochemical cell microscopy; XRD: X-ray diffraction; LSV: linear sweep voltammetry; TOF: turnover frequency; NCM: nickel-cobalt-manganese; DO: disordered oxide; CVD: chemical vapor deposition.

Following the above study on facet-controlled Co3O4 systems, Feng et al. achieved the phase-engineered synthesis of two-dimensional hexagonal Mn3O4 spinel nanosheets via a van der Waals epitaxial growth strategy, enabling precise control over crystal geometry and orientation[166]. Atomic-resolution structural modeling reveals a well-defined hexagonal spinel lattice composed of alternating Mn2+ and Mn3+ ions within a layered framework (Figure 6i). High-resolution STEM imaging further displays periodically ordered atomic planes with a lattice spacing of ~0.279 nm, confirming the formation of single-phase hexagonal Mn3O4 (Figure 6j). Raman spectroscopy identifies a strong A1g vibration at 658 cm-1 with pronounced angular dependence, indicative of high crystallinity and in-plane symmetry (Figure 6k,l). Compared with conventional tetragonal Mn3O4, the hexagonal phase exhibits enhanced electronic coupling and faster charge transfer, arising from improved metal-oxygen orbital hybridization. These findings highlight that the tetragonal-to-hexagonal phase transformation effectively modulates the electronic configuration and coordination environment, demonstrating the pivotal role of phase engineering in optimizing the catalytic performance of Mn-based spinel oxides.

3.3 Orthorhombic spinel oxides

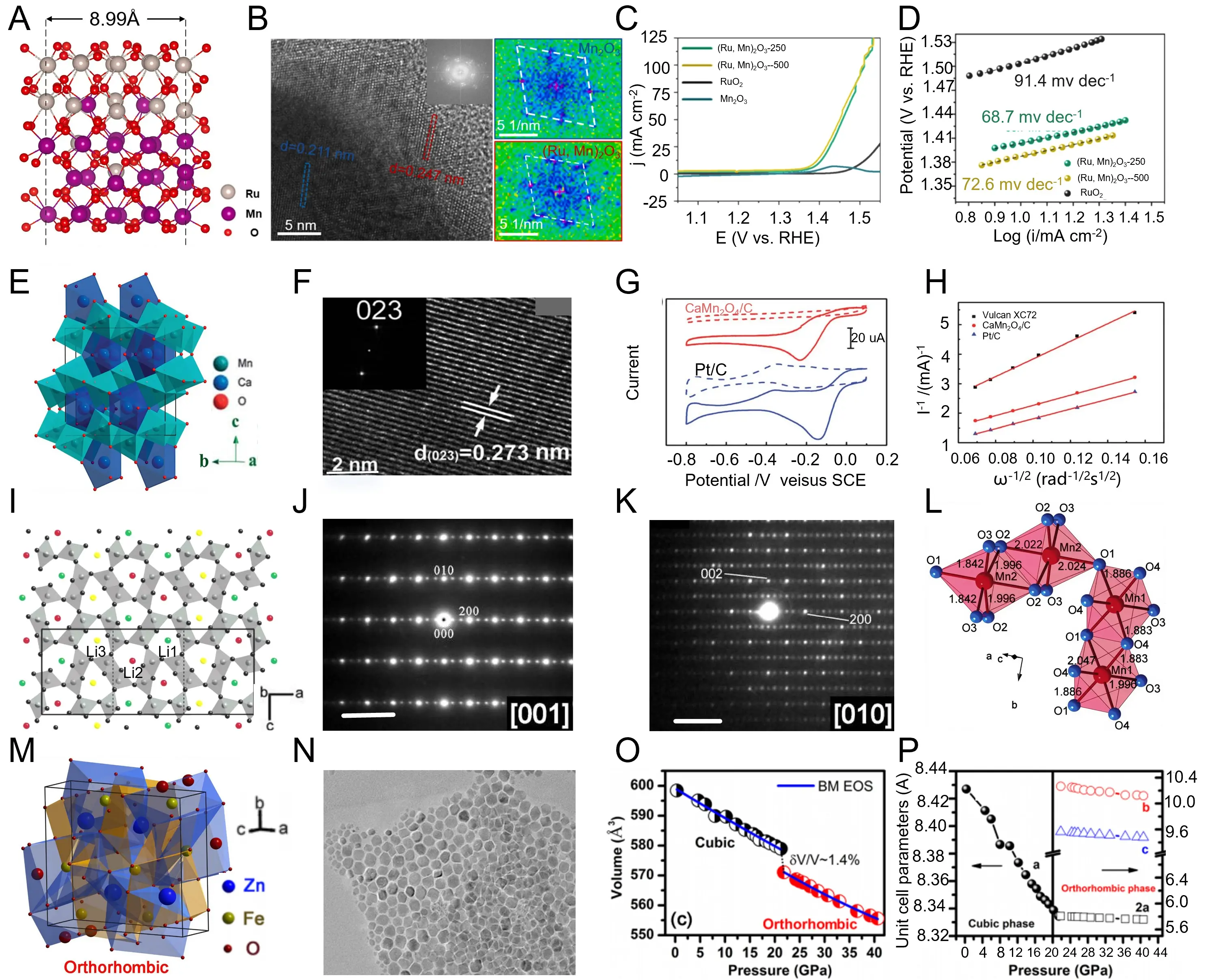

Following the above discussion on oxide-phase engineering, Liu et al. constructed a layered Ru-Mn-O mixed oxide through an interfacial lattice-coupling strategy, enabling atomic-level modulation of metal-oxygen coordination and crystallographic coherence[208]. Structural modeling reveals a layered configuration with an interplanar spacing of 8.99 Å, where alternately arranged RuO6 and MnO6 octahedra form coherent heterointerfaces between RuO2 and Mn2O3 domains (Figure 7a). High-resolution TEM imaging displays lattice fringes of 0.247 nm corresponding to Ru-Mn-O and 0.211 nm for Mn2O3, confirming epitaxial coupling and structural continuity across the phase boundary (Figure 7b). Fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern analysis further corroborates this coherent interface alignment, indicating ordered orientation and uniform lattice strain (Figure 7c). Electrochemical evaluation shows that the optimized (Ru, Mn)2O3-250 catalyst achieves an overpotential of 168 mV @ 10 mA cm-2 and a Tafel slope of 68.7 mV dec-1, maintaining stability for over 40 h (Figure 7d). These results highlight that lattice coupling and phase hybridization effectively tailor the electronic structure and reaction energetics, providing a viable strategy to enhance the intrinsic OER activity of Ru-based mixed oxides. Expanding the exploration of crystallographic modulation in Mn-based systems, Du et al. synthesized orthorhombic post-spinel CaMn2O4 nanorods through a facile solvothermal method, achieving controllable phase formation under moderate conditions[217]. Structural modeling reveals a marokite-type orthorhombic framework composed of distorted MnO6 octahedra and CaO8 polyhedral that assemble into a robust three-dimensional lattice (Figure 7e). High-resolution TEM analysis shows clear (023) lattice fringes with a spacing of 0.273 nm, confirming high crystallinity and preferential orientation along the nanorod axis (Figure 7f). Electrochemical oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) measurements reveal a distinct oxygen-reduction peak around -0.15 V vs SCE for CaMn2O4/C, comparable to Pt/C and indicative of a quasi-four-electron process (Figure 7g). The Koutecký-Levich analysis confirms an electron-transfer number close to 4 with low diffusion resistance, demonstrating efficient oxygen-reduction kinetics (Figure 7h). These findings demonstrate that the orthorhombic post-spinel lattice, stabilized by Ca-Mn coordination and enhanced electron transport, provides an effective route to optimize the intrinsic ORR activity of Mn-based spinel oxides.

Figure 7. (a) Schematic illustration of the orthorhombic (Ru, Mn)2O3 crystal structure showing atomic positions of Ru, Mn, and O; (b) High-resolution TEM image and corresponding FFT patterns revealing lattice expansion and strain distribution in (Ru, Mn)2O3; (c) LSVs of (Ru, Mn)2O3 and RuO2 in 0.5 M H2SO4 comparing OER activities; (d) Tafel plots derived from LSV curves showing improved OER kinetics after Ru incorporation. Republished with permission from[208]; (e) Crystal model of orthorhombic CaMn2O4 illustrating MnO6 octahedral connectivity; (f) High-resolution TEM image showing lattice fringes of the (023) plane in CaMn2O4 nanorods; (g) Cyclic voltammograms of CaMn2O4 compared with Pt/C and Vulcan under identical conditions (h) Koutecky–Levich plots obtained from rotating-disk electrode measurements of CaMn2O4 in 0.1 M KOH. Republished with permission from[217]; (i) Crystal structure of orthorhombic LiMn2O4 derived from high-pressure transformation showing Mn-O network; (j) SAED pattern recorded along the [001] zone axis of CaFe2O4-type LiMn2O4; (k) SAED pattern acquired along the [010] direction showing the orthorhombic symmetry of LiMn2O4 (l) Polyhedral representation of orthorhombic LiMn2O4 showing MnO6 connectivity and crystallographic axes. Republished with permission from[218]; (m) Polyhedral structure of orthorhombic ZnFe2O4 highlighting FeO6 and ZnO6 coordination environments; (n) TEM image of ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles showing morphology and particle distribution; (o) Pressure-dependent volume change of ZnFe2O4 showing a cubic-to-orthorhombic transition fitted by a Birch–Murnaghan equation of state; (p) Evolution of lattice parameters with pressure, confirming cubic-to-orthorhombic transition near 20-25 GPa. Republished with permission from[219]. TEM: transmission electron microscopy; LSV: linear-sweep voltammogram; FFT: fast Fourier transform; OER: oxygen evolution reaction; SAED: selected-area electron diffraction.

Advancing from the study of orthorhombic post-spinel frameworks, Yamaura et al. realized a spinel-to-CaFe2O4-type phase transformation in LiMn2O4 using a high-pressure solid-state reaction (6 GPa, > 1,100 °C), achieving denser lattice packing and altered Mn coordination[218]. The transformed CaFe2O4-type structure exhibits orthorhombic pnma symmetry, composed of edge-shared MnO6 octahedral chains with Li ions occupying interstitial sites along the b-axis (Figure 7i). Electron-diffraction patterns display sharp [001] and [010] zone-axis reflections, confirming a 3a × b × c superstructure associated with ordered Li-vacancy distribution (Figure 7j). High-resolution diffraction mapping further supports coherent phase formation and crystallographic ordering within the reconstructed lattice (Figure 7k). Local structural analysis identifies two distinct Mn coordination environments, with Mn1-O distances of approximately 1.89 Å and Mn2-O distances of roughly 1.99 Å, accompanied by a moderate octahedral distortion of about 9%, consistent with a mixed Mn3+/Mn4+ valence configuration (Figure 7l). The high-pressure-induced reconstruction increases structural density by ~6% and decreases the activation energy from 0.40 to 0.27 eV, reflecting improved electron mobility and enhanced stability. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that pressure-driven orthorhombic transformation of spinel lattices provides an effective route to regulate cation ordering and charge transport, deepening the understanding of structural-phase control in Mn-oxide electrocatalysts. Continuing the investigation of pressure-induced lattice reconstruction, Zhang et al. explored the structural evolution of spinel ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles under compression up to 40 GPa using in-situ synchrotron X-ray diffraction[219]. The material initially exhibits a cubic Fd-3m spinel framework composed of tetrahedral Zn2+ and octahedral Fe3+ sites, which progressively transforms into a denser orthorhombic post-spinel phase with mixed Fe-O coordination (Figure 7m). TEM imaging reveals uniform nanocrystals (~10 nm) whose morphology remains intact throughout compression, ensuring homogeneous strain distribution and structural integrity (Figure 7n). Equation-of-state analysis indicates a discontinuous volume collapse of ≈ 1.4% at ≈ 22-25 GPa, marking the onset of the cubic-to-orthorhombic transition (Figure 7o). The evolution of lattice parameters confirms anisotropic compression dominated along the b-axis, consistent with symmetry reduction and rearranged cation coordination (Figure 7p). The high-pressure orthorhombic phase exhibits enhanced electronic density and improved dielectric stability due to reduced grain-boundary resistance and increased Fe-O overlap. These findings demonstrate that pressure-driven symmetry reduction in spinel ferrites effectively modulates electron transport and polarization behavior, highlighting the pivotal role of phase compression engineering in tuning the functional properties of Fe-based spinel oxides.

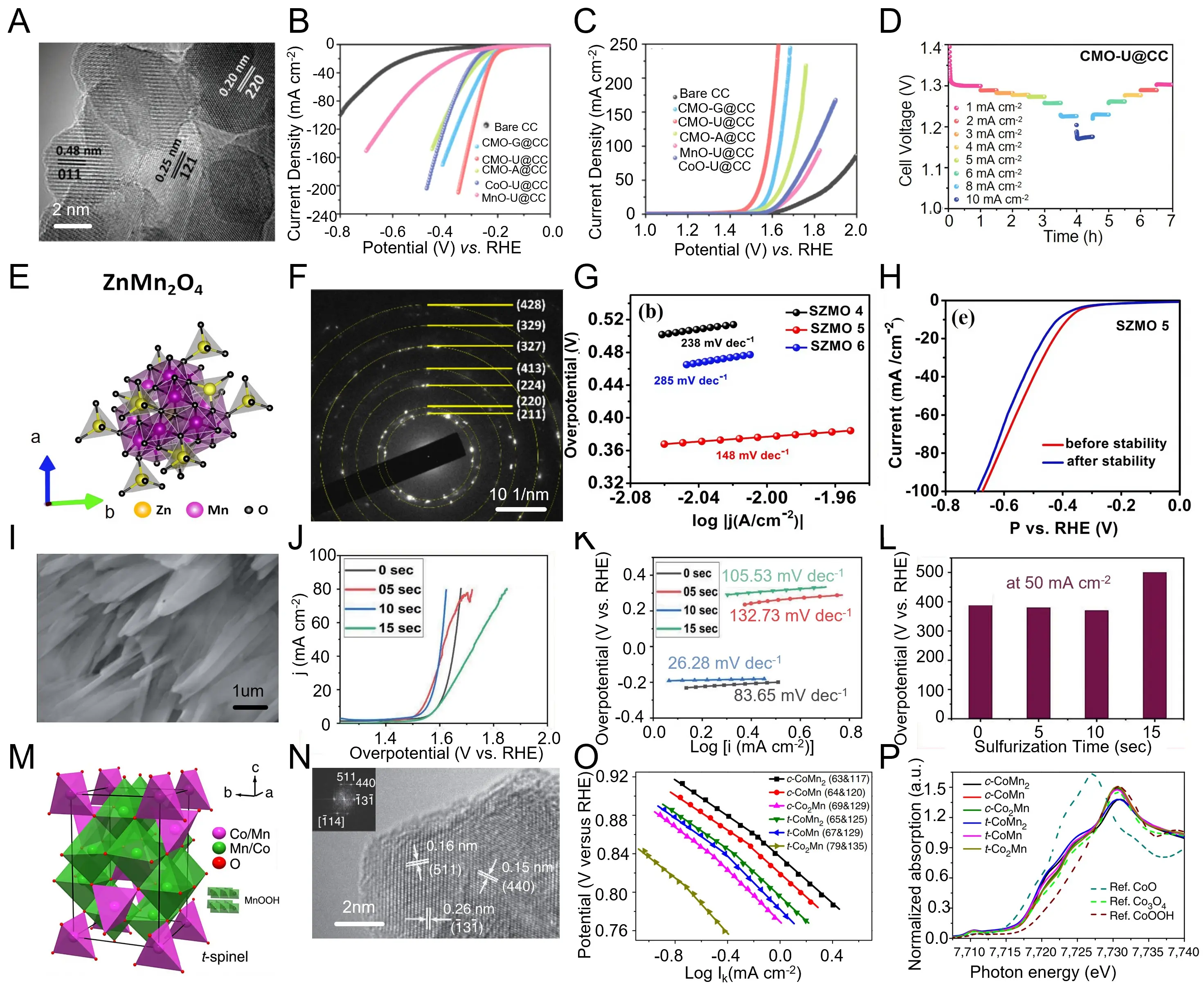

3.4 Tetragonal spinel oxides

Extending the discussion on structural modulation of spinel frameworks, Zhang et al. realized the in-situ growth of tetragonal CoMn2O4 (CMO-U@CC) arrays on conductive carbon cloth through a controlled hydrothermal-annealing process[210]. As shown in Figure 8a, high-resolution TEM reveals distinct lattice fringes corresponding to the (117) and (011) planes, verifying the well-defined tetragonal spinel structure with coherent interfacial contact. Electrocatalytic analyses demonstrate outstanding bifunctional activity, with overpotentials of 252 mV (OER) and 194 mV (HER) at 10 mA cm-2, surpassing cubic and amorphous counterparts (Figure 8b,c). The integrated electrolyzer achieves overall water splitting at 1.61 V to deliver 10 mA cm-2, retaining performance over 20 h of continuous operation. Such enhancement originates from the tetragonal-induced lattice distortion that strengthens Co/Mn-O hybridization and accelerates surface redox transitions (Figure 8d). These results highlight that tetragonal-phase regulation within Co-Mn-oxide spinels provides a rational route to harmonize conductivity, stability, and bifunctional catalytic efficiency for overall water splitting. Building upon the preceding exploration of tetragonal spinel modulation, Wang et al. prepared ZnMn2O4 nanocrystals via a solvothermal synthesis route, enabling precise control over cation ordering and lattice symmetry[211]. As depicted in Figure 8e,f, the obtained material crystallizes in a single‐phase spinel framework where Zn2+ occupies tetrahedral sites and Mn3+ resides in octahedral sites, as confirmed by distinct SAED rings indexed to the (211), (220), and (428) planes. Electrocatalytic evaluation shows that the optimized ZnMn2O4 delivers an overpotential of ≈ 380 mV at 10 mA cm-2 with a Tafel slope of 148 mV dec-1 for the OER (Figure 8g). The corresponding HER polarization curves display negligible degradation after repeated cycling, highlighting its robust bifunctional stability (Figure 8h). Such superior performance arises from the cooperative effect of Mn-O orbital hybridization and the symmetric spinel geometry, which collectively enhance charge transfer and surface redox kinetics. These results underscore that cation-site distribution and spinel symmetry regulation are decisive factors governing the intrinsic activity and durability of Mn-based spinel oxides.