Abstract

Radiative thermal management (RTM) smart windows represent an emerging class of adaptive building-envelope technologies that combine dynamic spectral regulation with passive heat dissipation through the atmospheric window. By simultaneously modulating visible light (VIS), near-infrared solar radiation (NIR), and mid-infrared thermal emission (MIR), these systems enable year-round thermal regulation with reduced building energy consumption. This review systematically summarizes recent progress and mechanisms of RTM smart windows. Compared with existing reviews that mainly focus on static radiative cooling materials or single-mode smart windows, this review emphasizes integrated RTM smart windows featuring tri-band (VIS/NIR/MIR) spectral regulation and dual-responsive mechanisms. Firstly, the fundamental principles of radiative thermal management and intelligent response mechanisms are introduced, followed by an overview of key performance. Secondly, the latest progress in electrochromic, thermochromic, and photochromic RTM smart windows is comprehensively reviewed. Particular attention is devoted to dual-responsive mechanism RTM smart windows, which integrate passive and active control to achieve synergistic performance. In summary, this review presents an overview of recent advances and underlying mechanisms in intelligent windows for radiative heat management.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Global climate change and the continued growth of energy demand have posed significant challenges to the sustainable development of modern society[1,2]. Among all energy-consuming sectors, buildings account for approximately 30-40% of global energy consumption[3], with windows responsible for a substantial fraction of heat exchange between indoor and outdoor environments[4]. Owing to their direct exposure to solar radiation and thermal emission, windows play a decisive role in regulating building energy flows and indoor thermal comfort[5].

Conventional glazing systems provide daylighting and visual transparency but inherently suffer from poor thermal selectivity[6]. Excessive solar heat gain during summer increases cooling loads, while insufficient solar utilization during winter leads to elevated heating demands[7]. This fundamental trade-off has driven extensive research into smart window technologies capable of dynamically modulating optical properties in response to environmental conditions[8,9]. In recent years, radiative cooling has emerged as a powerful strategy to address this challenge. By leveraging the high atmospheric transmittance within the mid-infrared (MIR) atmospheric window (8-13 μm), radiative cooling enables passive heat dissipation to outer space without external energy input, offering a fundamentally different pathway for thermal regulation[10-12].

Early radiative cooling materials were primarily based on static designs, including porous polymers and multilayer photonic structures[13-15], which exhibited high cooling efficiency under specific conditions[16]. However, their fixed optical and thermal properties limited adaptability to diurnal and seasonal variations, potentially resulting in undesired heat loss under cold conditions[17]. To overcome these limitations, radiative thermal management (RTM) smart windows have been developed by integrating dynamic spectral regulation with radiative heat dissipation, enabling adaptive and on-demand thermal management[18,19]. RTM smart windows are distinguished by their ability to dynamically modulate visible (VIS) light transmission, near-infrared (NIR) solar radiation, and MIR thermal emission in response to external stimuli such as temperature, light, electric fields, or mechanical deformation. This multiband spectral control allows simultaneous optimization of daylighting, solar heat gain, and radiative cooling, thereby enabling year-round energy-efficient operation across diverse climatic conditions[17]. Recent advances, including tri-band electrochromic systems and hybrid stimulus-responsive architectures, have further expanded the modulation bandwidth and functional versatility of these systems[20].

In this review, we systematically summarize the mechanisms and thermal management performance of RTM smart windows. We first introduce the fundamental principles of spectral regulation and intelligent response mechanisms, followed by an overview of key performance. We then critically review recent progress in electrochromic, thermochromic, photochromic, other multifunctional, and emerging hybrid RTM smart windows, as shown in Figure 1. Several review articles have previously summarized smart window technologies or radiative cooling materials from material or device perspectives. In contrast, this review integrates RTM with intelligent smart window technologies, with particular emphasis on tri-band spectral regulation and dual-responsive mechanisms that combine passive and active control. This integrated perspective provides new insights into achieving year-round adaptive thermal management.

2. Overview of RTM Smart Windows

RTM smart windows can be broadly classified into passive and active systems according to their triggering stimuli and energy input requirements[24]. Passive systems respond autonomously to environmental variations without external power, whereas active systems rely on user-controlled or externally applied stimuli to achieve precise modulation. Recent advances have further extended these concepts toward self-powered operation, cooperative control, and multi-stimuli responsiveness, forming a more comprehensive and flexible regulation framework. As shown in Figure 1, based on the nature of the external stimuli, intelligent response mechanisms can be generally categorized into thermochromic (TC) systems based on phase-transition materials such as VO2[25], electrochromic (EC) systems relying on ion insertion/extraction under an applied electric field[26], photochromic (PC) systems activated by light irradiation[27], and emerging multi-responsive modes integrating multiple stimuli[28].

Thermo-responsive systems exploit the intrinsic phase-transition behavior of thermosensitive materials, such as VO2, which undergo abrupt changes in optical properties when the temperature exceeds a critical threshold[29-32]. These transitions occur spontaneously without external energy input, enabling fully passive regulation and inherent energy savings. However, their practical applicability is often constrained by fixed switching temperatures, limited spectral tunability, and relatively slow response kinetics. In contrast, electro-responsive systems achieve dynamic optical modulation through externally applied electric fields. In typical electrochromic materials such as WO3 and NiO, reversible ion insertion and extraction reactions induce controllable changes in optical transmittance and reflectance[33,34]. This mechanism enables high modulation precision, rapid response, and user-defined control over optical states, making electro-responsive windows particularly attractive for adaptive building envelopes, albeit at the expense of additional power requirements. Photo-responsive systems rely on reversible structural or electronic transitions of photosensitive materials under light irradiation. These responses are intrinsically self-driven and energy-free, offering a passive modulation pathway that directly couples optical behavior with ambient illumination conditions. Nevertheless, compared with electrically driven systems, photo-responsive windows typically exhibit narrower modulation ranges, slower reversibility, and limited controllability, which may restrict their adaptability under complex and rapidly changing environments.

To provide a systematic understanding of the progress in RTM smart windows, Figure 2 presents a roadmap summarizing the key stages of technological evolution. The roadmap reflects a transition from static traditional windows to mono-responsive smart windows, followed by the emergence of multiband architectures enabling independent VIS/NIR/MIR regulation, and ultimately to dual-responsive systems that combine passive and active control. This progression underscores the shift from single-function thermal regulation toward adaptive, climate-responsive smart window platforms.

2.1 Spectral regulation mechanisms

The spectral regulation mechanism of RTM smart windows encompasses broadband management ranging from the solar spectrum to the MIR region, demanding selective control over multiple wavelength bands, far more complex than that of conventional energy-saving windows[37,38]. An effective design must simultaneously satisfy three optical criteria: (i) moderate transmittance in the VIS range (0.4-0.8 μm) to ensure visual comfort and natural illumination, while preventing excessive solar heat gain; (ii) low transmittance in the NIR range (0.8-2.5 μm) to suppress solar-induced thermal gain; and (iii) high emissivity within the atmospheric window (8-13 μm) to facilitate efficient radiative heat dissipation[39].

As illustrated in Figure 3, an ideal RTM smart windows exhibits low VIS transmittance, strong NIR blocking, and high MIR emissivity under cooling mode, whereas under heating mode, it demonstrates high VIS transmittance, high NIR transmission, and reduced MIR emissivity[40].

Figure 3. Spectral characteristics of an ideal RTM smart windows. RTM: radiative thermal management.

The defining feature of RTM smart windows is their dynamic spectral tunability. According to the specific spectral regions being modulated, these systems can be broadly categorized into three functional types as follows.

(1) VIS Regulation (0.4-0.8 μm)

VIS transmittance directly determines indoor lighting quality and visual comfort. It can be adjusted through absorption, reflection, scattering, or interference effects[41]. For smart windows, both the maximum transmittance in the transparent state and the minimum transmittance in the tinted state are critical, as well as the modulation amplitude between them. The solar-weighted VIS transmittance TVis is defined as:

where λ denotes the wavelength, Isun(λ) represents the global solar spectral irradiance (AM 1.5G), and T(λ) is the spectral transmittance of the material.

VIS modulation is typically achieved by altering the optical state of the material. For instance, electrochromic materials enable reversible switching between colored and bleached states. Ding et al. developed a dynamically photothermal-regulating smart window capable of modulating VIS transmittance over a remarkable range of 92%, allowing transitions from nearly fully transparent to almost completely opaque[42]. This broad modulation capability expands its practical applicability and enables effective management of solar heat gain through mode switching.

(2) NIR Regulation (0.8-2.5 μm)

The NIR region plays a decisive role in managing solar heat gain and thus directly influences indoor thermal conditions[43]. Its modulation relies on mechanisms such as Mie scattering, wavelength-selective reflection, absorption filtering, nanoscale structural design, and multilayer interference[44]. An ideal smart window can adaptively adjust its NIR transmittance with seasonal variations, lowering it during summer to minimize heat gain, and increasing it during winter to utilize solar energy for passive heating.

(3) Atmospheric Window Regulation (8-13 μm)

The emissivity control in the atmospheric transparency window directly determines radiative cooling performance. It depends primarily on the material’s molecular vibrational characteristics and crystal structure, and is further influenced by thin-film interference and surface morphology[45]. By dynamically tuning the emissivity in this spectral region, RTM smart windows can adapt to different environmental conditions, enhancing emissivity under hot conditions to promote cooling, and reducing it under cold climates to minimize heat loss[46].

The MIR emissivity εLWIR is defined as the ratio of the spectral radiance of a material to that of an ideal blackbody at the same temperature T:

where IBB(T, λ) represents the blackbody spectral radiance at temperature T, and ε(λ) is the spectral emissivity of the material.

From these definitions, it is evident that independent modulation across the three spectral regions-VIS, NIR, and MIR-is the ultimate goal of RTM smart windows design. Cao et al. pioneered a tri-band electrochromic smart window for building energy efficiency that successfully achieved this objective[20]. By employing a VO2/WO3 multilayer structure and controlling Li⁺ ion insertion depth, they realized independent modulation of VIS and NIR spectra. Furthermore, by designing a low-emissivity PE/ITO layer (facing indoors) and a high-emissivity quartz substrate (facing outdoors), they optimized radiative heat exchange between interior and exterior environments. This architecture enables flexible switching among bright, cool, and dark modes, allowing the system to adapt to diverse weather conditions and energy demands.

2.2 Key performance

Beyond the response mechanisms, the dynamic modulation performance of RTM smart windows is a critical criterion for evaluating their practical applicability in building environments. For most isotropic smart window materials under natural illumination, polarization effects can be neglected[47], allowing performance assessment to focus on intrinsic optical-thermal modulation behaviors. In general, three key performance indicators are used to characterize smart windows: response time[48,49], cycling stability[50], and driving conditions[40,51,52].

Response time refers to the time required for a smart window to reversibly switch between distinct optical or thermal states under an external or environmental stimulus, such as electrical bias, temperature variation, or light irradiation. It is typically evaluated by monitoring the temporal evolution of spectral transmittance, reflectance, or emissivity during the switching process. Response time is particularly important for applications requiring rapid adaptation to transient environmental changes, such as fluctuating solar irradiation or intermittent user control.

Cycling stability describes the ability of a smart window to maintain consistent optical and thermal modulation performance over repeated switching operations. It is commonly assessed through long-term cycling tests, in which variations in modulation depth, baseline transmittance, or emissivity are tracked as a function of switching number. High cycling stability is essential for ensuring long service lifetimes and reliable operation under real-world conditions involving frequent environmental or user-driven state transitions. Driving conditions encompass the nature and intensity of the stimulus required to activate the modulation process, as well as the associated energy consumption. Depending on the response mechanism, driving conditions may involve applied electrical voltage, thermal input, optical irradiation, or mechanical deformation. From an application perspective, minimizing driving energy while maintaining stable and controllable modulation is a key consideration for achieving energy-efficient and sustainable smart window systems.

Importantly, these intelligent response characteristics are closely coupled with the overall thermal management performance of RTM smart windows. Metrics such as radiative cooling power and temperature reduction relative to ambient conditions are commonly used to quantify their real-world energy-saving potential[41]. Establishing standardized and comparative evaluation protocols under controlled environmental conditions is therefore crucial for linking material- and device-level response characteristics with system-level thermal outcomes, enabling meaningful comparison across different smart window technologies and guiding future material design and device optimization.

3. RTM Smart Windows with Various Mechanisms

Based on distinct responsive mechanisms, RTM smart windows have evolved into multiple technological pathways, each corresponding to specific material systems and device architectures. These approaches exhibit differentiated advantages in regulation precision, energy consumption, and environmental adaptability. The following subsections provide a categorized overview.

3.1 Electrochromic

EC technology achieves spectral modulation by driving ion insertion/extraction under an applied voltage. It represents one of the primary strategies for precise control of RTM smart windows and is currently the only active approach capable of simultaneously regulating VIS, NIR, and MIR spectra. The core material systems are typically based on metal oxides and their composite structures[53]. These materials exhibit excellent electro-optical modulation performance, low driving voltage, and rapid switching speed, making them widely applicable in smart windows/glass, electrochromic batteries, and display devices, with great potential in RTM.

As shown in Figure 4a, Deng et al. developed an electrically controlled passive radiative cooling-polymer dispersed liquid crystal (PRC-PDLC) smart window that remains opaque at 0 V (Rsolar≈90%, εLWIR = 92.6%), enabling radiative cooling, and becomes transparent at 50 V (Tsolar≈55%), activating solar heating. Its VIS transmittance can be tuned from 0.19% (0 V) to 48.5% (50 V), achieving nighttime cooling 4.2 °C below ambient temperature[23]. Deng et al. further developed the multimode PDLC (MPDLC) smart window integrating a SiO2@PRC PDLC layer with a CNT heating layer. In MPDLC smart windows, multimode heating arises from the synergistic contribution of photothermal heating (PRH), solar heating (SH), and electrothermal heating (EH). PRH originates from light absorption by embedded photothermal agents, SH is associated with enhanced solar absorption in the opaque state, while EH is induced by Joule heating under an applied electric field. Figure 4b illustrates its ability to achieve actively adjustable PRC and multi-mode heating (PRH/SH/EH). Under 700 W m-2 irradiation, the window maintains near-ambient temperature, and at 500 W m-2 achieves a 2.3 °C temperature reduction. The PRC state can be rapidly adjusted via voltage, with all-climate energy performance surpassing Low-E glass[54].

Figure 4. Electrochromic RTM smart windows. (a) Schematic illustration of the working principle and layered structure of the PRC-PDLC film, showing voltage-controlled transparency switching and high LWIR emissivity for radiative cooling. Republished with permission from[23]; (b) Schematic illustration of the MPDLC smart window, highlighting the integration of PDLC, radiative cooling layer, and heating components that enable PRC, SH, and EH modes. Republished with permission from[54]; (c) Structural schematic of the tri-band electrochromic device with a low-e inner surface and high-emissivity outer surface, designed for independent VIS/NIR/MIR regulation; (d) Measured optical transmittance spectra (0.35-2.5 μm) under different electrochromic states and corresponding MIR emissivity spectra (2.5-20 μm) of the inner and outer surfaces, illustrating tri-band modulation capability; (e) Schematic illustration of the operating principles of the electrochromic window under cold weather, hot weather, and nighttime conditions, emphasizing adaptive solar and thermal radiation control. Republished with permission from[20]; (f) Functional design of the LHE-ED device, showing the electrode configuration and spectral regulation strategy leveraging both solar irradiation and thermal radiation; (g) Experimental spectral transmittance (380-1,600 nm) and emissivity/absorption characteristics (2.5-25 μm) of the LHE-ED under high-radiative-cooling and low-emissivity warming states; (h) Schematic diagrams of the LHE-ED smart window illustrating six electro-controlled working states enabled by reversible ion transport and silver deposition processes. Republished with permission from[55]. RTM: radiative thermal management; PRC-PDLC: passive radiative cooling-polymer dispersed liquid crystal; MPDLC: multimode PDLC; SH: solar heating; EH: electrothermal heating; MIR: mid-infrared; low-e: low-emissivity.

For tri-band electrochromic radiative cooling windows, Shao et al. developed a WO3/VO2 thin-film system capable of three optical states by controlling lithium-ion intercalation depth, allowing independent modulation of VIS and NIR transmittance (Figure 4c). Utilizing a high-emissivity quartz outer layer and a low-emissivity PE/ITO inner layer, the design suppresses indoor–outdoor radiative heat exchange and maintains optical states for over 4 hours without applied voltage (Figure 4d). This system can switch modes according to weather patterns and demonstrates superior heating and cooling energy performance across global climate zones compared with Low-E glass (Figure 4e)[20]. Zeng et al. developed a dynamic tri-band smart window (LHE-ED) that integrates internal (ion insertion/silver deposition) and external (reversible silver deposition) electrodes to achieve six electro-controlled states under a single electric field (Figure 4f,g,h). The device allows independent regulation across 0.38-25 μm, with VIS modulation (ΔTVis = 41.24%), NIR modulation (ΔTNIR = 53.95%), and LWIR emissivity modulation (Δε8-13μm = 35%), marking the first unified tri-band electro-control suitable for multi-climate building energy management[55].

3.2 Thermochromic

TC smart windows rely on phase-transition materials that can spontaneously regulate their optical properties in response to ambient temperature, without external energy input. As a result, TC systems represent a passive and self-adaptive approach for dynamic thermal management. This technology exploits temperature-induced phase transitions to achieve automatic regulation. Among inorganic thermochromic materials, vanadium dioxide (VO2) is the core representative, whose performance in balancing solar absorption and infrared emissivity has been substantially improved through doping modification and micro/nanostructural design[30,31,35]. Meanwhile, thermochromic hydrogels provide macroscopic phase transitions with continuous modulation of optical and thermal properties, and recent developments have extended their application to microscale systems.

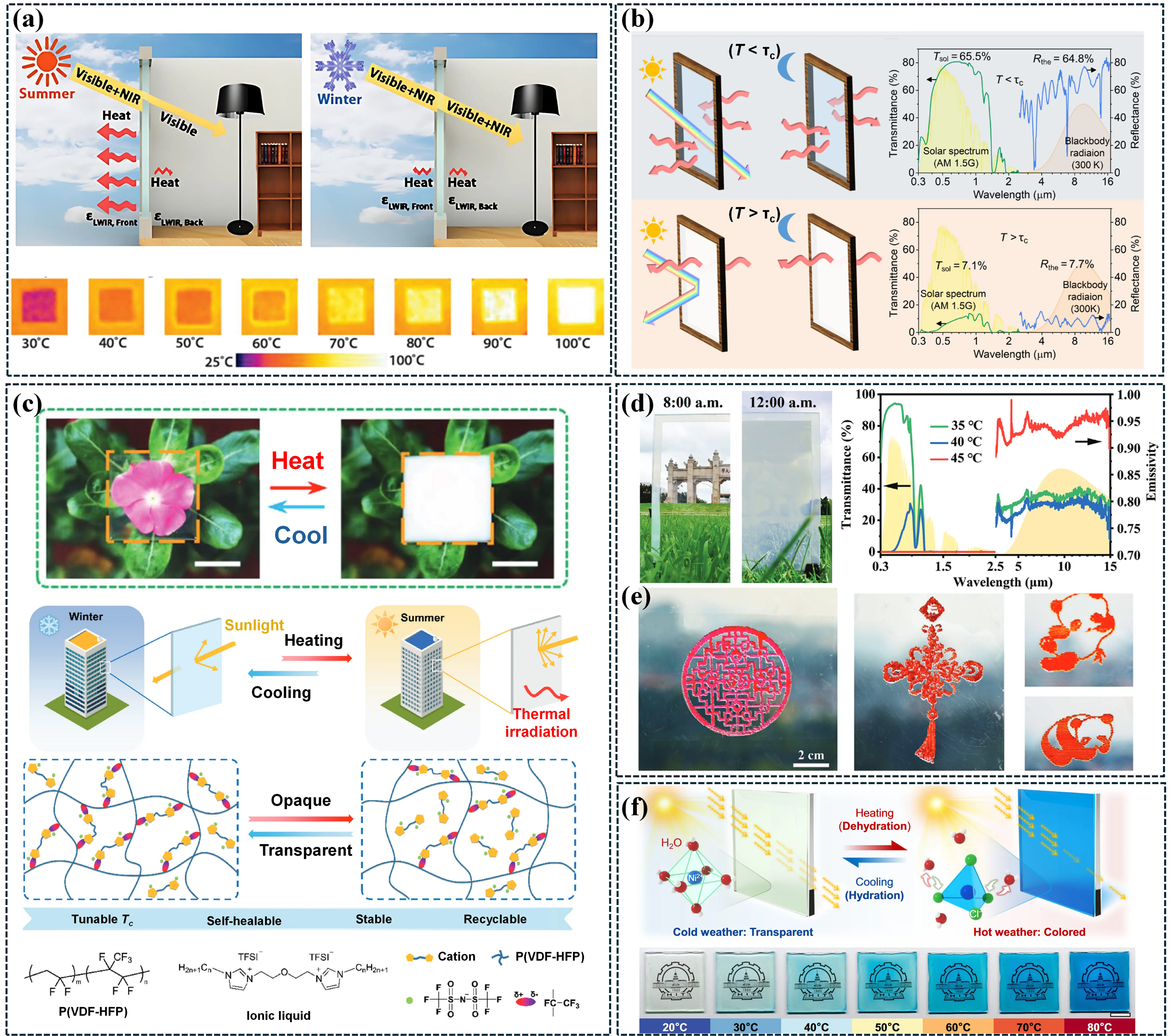

Wang et al. first proposed a VO2-based thermochromic radiative cooling window that utilizes the Fabry-Perot resonance to achieve significant modulation of long-wave infrared emissivity (ΔεLWIR = 40%) near the phase-transition temperature (~60 °C) (Figure 5a). This work introduced a new concept for phase-transition-based radiative cooling regulation, although its VIS transmittance remained limited (~27%)[35]. Lin et al. developed a pNIPAm/AgNW composite STR smart window that synchronously modulates solar transmittance (ΔTsolar = 58.4%) and thermal emissivity (Δε = 57.1%) through a temperature-triggered water capture/release mechanism, achieving all-day thermal management with scalability potential (Figure 5b). However, its opacity at elevated temperatures may restrict certain applications[56]. Liu et al. reported an ion–dipole-interaction-based thermochromic coating (TPC thermochromic coating) with tunable transition temperature (33-43 °C), wide thermal stability range (-20 to 70 °C), self-healing capability, and intrinsic radiative cooling performance (Figure 5c). The dynamic polymer network provides outstanding environmental durability and long-term operational stability[57]. Chen et al. fabricated a thermochromic hydrogel window (PND Smart Window) with adjustable transition temperature (32.5-43.5 °C), achieving a solar modulation efficiency of up to 88.84% and an intrinsic transmittance of 91.30% without external energy input (Figure 5d). The device provided a 7.3 °C summer cooling effect and supported 3D-printed structural optimization for tailored optical control and aesthetic design (Figure 5e)[58]. Wang et al. developed a hydrated ionic polymer-based thermochromic window (HIP thermochromic window) that undergoes a reversible transparent-to-blue transition between 25-42 °C via hydration/dehydration processes (Figure 5f). The device demonstrates 30.5% solar modulation and 87.7% transmittance, achieving an experimentally verified 10 °C temperature drop. When integrated with Low-E glass, the combined system reached a maximum energy-saving efficiency of 17.7%, making it highly suitable for energy-efficient building applications in warm climates[59].

Figure 5. Thermochromic RTM smart windows. (a) Device structure, working concept, and infrared thermal images of the RCRT window based on VO2 phase transition[35]; (b) Structural design, operating mechanism, and optical spectra of the pNIPAm/AgNW composite STR smart window, illustrating synchronous modulation of solar transmittance and thermal emissivity[56]; (c) Photographs of the TPC at 25 °C and 60 °C, corresponding chemical structures, and schematic representation of the reversible phase-transition mechanism. Republished with permission from[57]; (d) Photographs of the printable thermochromic hydrogel-based PND smart window at different temperatures and times, together with temperature-dependent optical spectra (35-45 °C); (e) Demonstration of patterned structures fabricated by 3D printing of the PND hydrogel, highlighting structural and aesthetic tunability. Republished with permission from[58]; (f) Fabrication process and structural schematic of the HIP thermochromic smart window, illustrating hydration/dehydration-induced optical switching[59]. RTM: radiative thermal management; RCRT: radiative cooling-regulating thermochromic; STR: solar-thermal regulation; TPC: thermochromic polymer coating; HIP: hydrated ionic polymer.

3.3 Photochromic

PC technology enables zero-energy spectral modulation by triggering material structural isomerization or electron transfer under ultraviolet/VIS light[60,61]. Material systems include inorganic oxides, organic compounds, and composite gels. The principal advantage of photochromic materials lies in their ability to respond directly to ambient illumination without external power[62]. However, their application in RTM smart windows remains relatively limited, primarily because photochromism typically affects only the VIS spectrum, with minimal impact on MIR radiative properties.

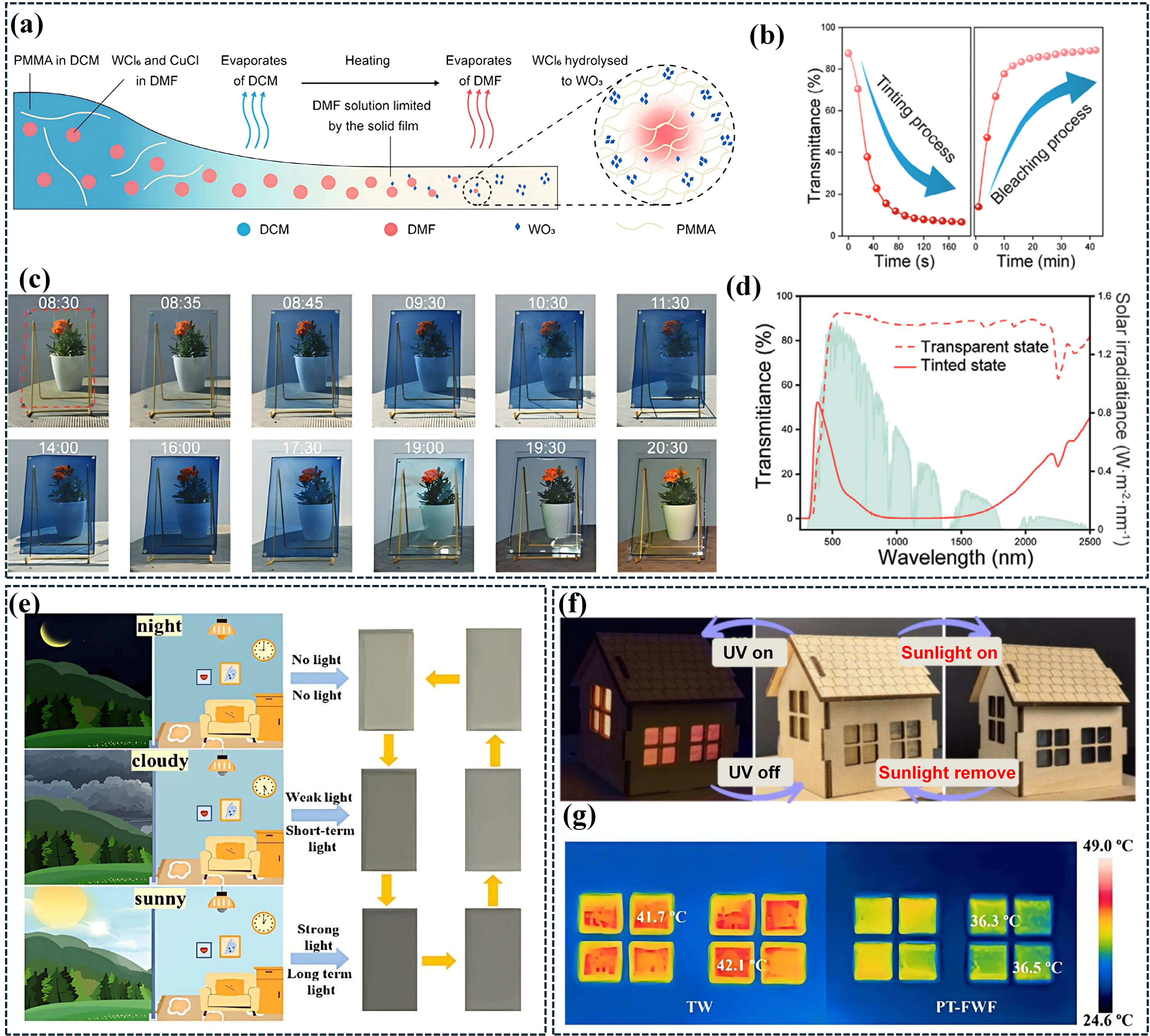

Meng et al. introduced a novel strategy to in situ grow copper-doped WO₃ nanoparticles within a poly(methyl methacrylate) matrix (Figure 6a), successfully fabricating large-area (30 × 40 cm2), highly transparent (Tlum = 91%) photochromic Cu-W-PC films (Figure 6b,c). These films exhibit VIS-light transmittance modulation of ΔTlum = 73%, solar transmittance modulation of ΔTsolar = 73%, and solar heat gain coefficient modulation of ΔSHGC (solar heat gain coefficient) = 0.5, substantially improving indoor visual comfort and energy efficiency. The response speed of Cu-W-PC films is exceptionally rapid: T1,050nm was reduced from 90% to 9% in ≈100 s of irradiation and recovered to a large extent (T1,050nm = 85%) in as fast as 20 min in room light, and the value recovered completely to its original state in ≈40 min (Figure 6d)[6]. Cheng et al. developed a photochromic smart window by immobilizing BiOCl nanosheets within a calcium alginate hydrogel matrix, achieving adaptive optical modulation and thermal management. Under solar irradiation, light-induced oxygen vacancies synergize with bismuth ions to dynamically regulate solar radiation (Figure 6e). The system provides complete UV blocking and maintains 50% VIS-light transmittance in the colored state, effectively balancing glare control and daylighting. When combined with a double-glass structure, the window reduces indoor heat by 5.6 °C in summer and significantly mitigates heat loss in winter, achieving year-round energy-efficient regulation[63]. Yang et al. designed a flexible photochromic transparent fluorescent wood composite film via molecular-scale engineering (Figure 6f). This material exhibits 88% optical transparency, a water contact angle of 107.5°, and approximately 5.5 °C heat insulation. Its dual-mode optical response enables instantaneous fluorescence under UV illumination and reversible VIS-light coloration/bleaching (transmittance switching between 88% and 5%), with a VIS-light modulation rate of ΔTlum = 83% and over 90% UV-blocking efficiency (Figure 6g). This smart window not only enables dynamic daylight management and energy saving but also establishes a novel multifunctional platform for architectural energy efficiency and information encryption[62].

Figure 6. Photochromic RTM smart windows. (a) Schematic illustration of the fabrication process of the Cu-W-PC photochromic film, showing in situ growth of Cu-doped WO3 nanoparticles within a polymer matrix (b) Dynamic transmittance variation at 1,050 nm during photo-induced tinting and spontaneous bleaching processes; (c) Photographs of large-area Cu-W-PC films deployed outdoors under natural sunlight; (d) Optical transmittance spectra of the Cu-W-PC films in transparent and tinted states. Republished with permission from[6]; (e) Schematic diagram of the working mechanism and schematic diagram of the operational performance of BiOCl/CA hydrogel-based photochromic smart window. Republished with permission from[63]; (f) Application demonstrations of the PT-FWF in smart window configurations; (g) Infrared thermal images comparing temperature distributions of conventional TW and PT-FWF under identical heating conditions, highlighting enhanced thermal insulation[62]. RTM: radiative thermal management; PC: photochromic; PT-FWF: photochromic transparent fluorescent wood film; TW: transparent wood.

3.4 Dual-responsive mechanism

Recent research has centered on hybrid or multifunctional smart windows integrating multiple chromic properties, thereby improving both energy efficiency and adaptability, as demonstrated by representative electrochromic-thermochromic and Janus-type smart window architectures[64,65]. Such systems further extend to dual-response configurations, including TC/EC, PC/EC, and PC/TC smart windows, which have been conceptually and experimentally explored in recent studies[66,67]. The following sections delineate the most prominent dual-response systems currently under intensive investigation.

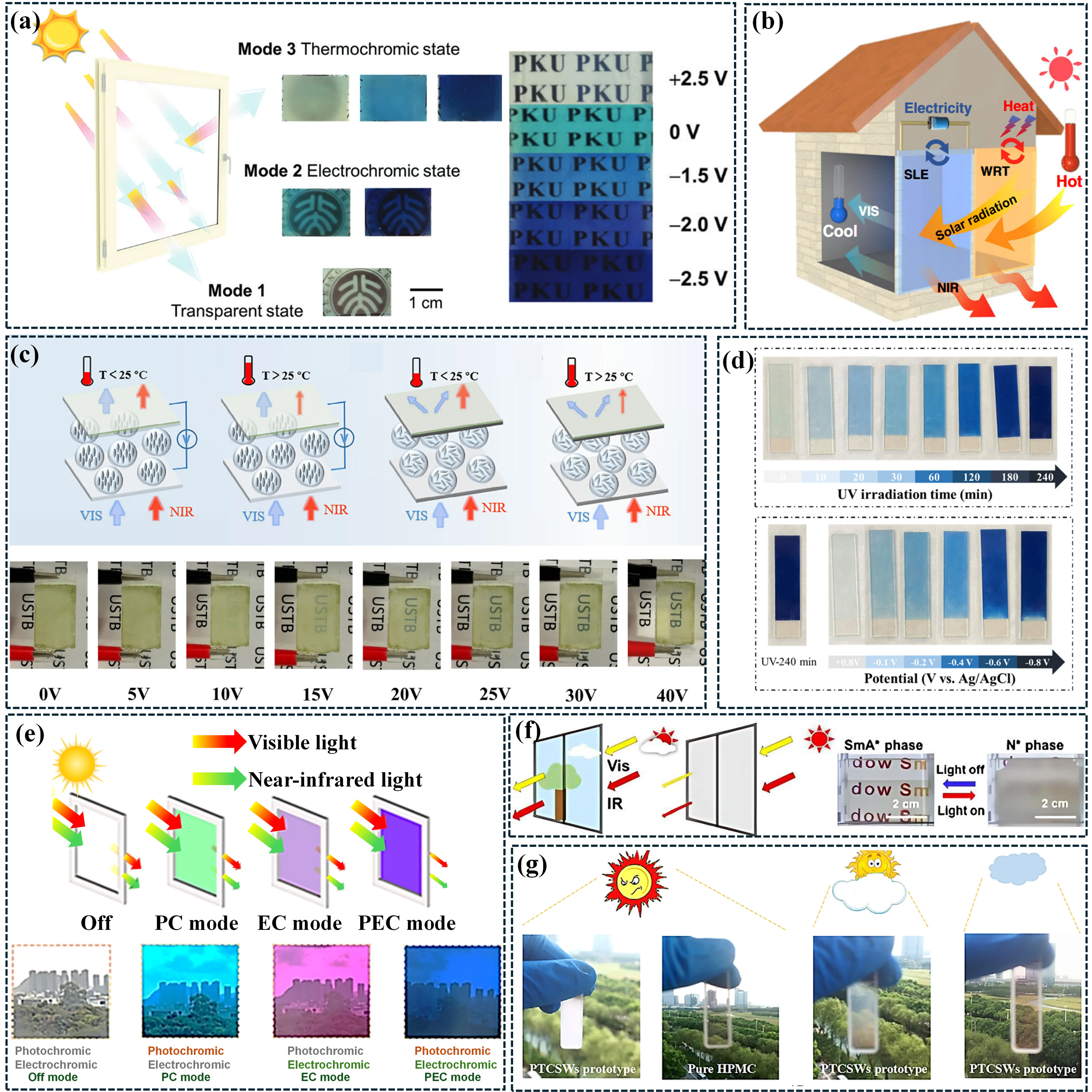

TC/EC smart windows combine temperature- and voltage-induced responses to modulate light and heat transfer. By integrating the passive temperature regulation of thermochromic materials with the active control of electrochromic systems, these devices minimize energy loss while maintaining indoor comfort, representing an ideal solution for sustainable building design. Deng et al. developed a TC/EC smart window, in which the novel EC device synergizes with a thermochromic gel electrolyte to achieve ultrafast optical modulation and multiple operational modes (Figure 7a). The EC unit exhibited coloring/bleaching times of 0.53/0.16 s and a transmittance modulation range of 21-99%, while the TC unit responded to temperature changes with transmittance ranging from 0-80% and provided 6.4 °C thermal insulation. The integrated window achieved switching speeds of 0.82/0.60 s across multiple modes, offering an innovative blueprint for next-generation fast-response energy-saving windows[68]. To effectively improve the sunlight modulation and heat management capability of smart windows, here, Sheng et al. propose a co-assembly strategy to fabricate the TC/EC smart windows with tunable components and ordered structures for the dynamic regulation of solar radiation (Figure 7b). By tuning the aspect ratio and composition of Au nanorods to cooperate with W18O49 nanowires, 90% NIR attenuation across 760-1,360 nm and 5 °C cooling under one-sun illumination was achieved. Further, doping and ordered assembly of W-VO2 nanowires extended the TC response range to 30-50 °C while reducing haze, enhancing both VIS-light transparency and comprehensive light-thermal regulation[36]. Jing et al. designed a PDLC/W-VO2 composite film, where EC-modulated PDLC adjusted VIS light, and W-VO2 thermochromic phase transition modulated NIR transmission (Figure 7c). The film achieved 13.90% solar modulation and 54.77% VIS transmittance, with high MIR emissivity in the atmospheric window (8-13 μm) enabling radiative cooling. Tests showed maximum temperature reduction of 12.5 °C, with outdoor temperature 2.3 °C below ambient[69].

Figure 7. Dual-responsive mechanism RTM smart windows. (a) Photographs and operational modes of the TC/EC device, illustrating multi-state optical modulation under different voltages. Republished with permission from[68]; (b) Schematic illustration of the modulation mechanism of TC/EC smart windows based on nanowire assemblies, enabling synergistic VIS and NIR regulation[36]; (c) Working principle of the PDLC/W-VO2 composite film, showing voltage-controlled visible light modulation and temperature-induced NIR regulation, together with transparency changes under applied voltages. Republished with permission from[69]; (d) EC/PC response behavior of OV-WO3-x/ZnO composite films under electrical bias and light irradiation. Republished with permission from[70]; (e) System diagram of the PECD smart window with four distinct operating modes (off, PC, EC, and PC/EC), illustrating combined passive and active regulation strategies. Republished with permission from[22]; (f) Schematic illustration and photographs of a photo-thermal dual-responsive smart window based on liquid crystal systems. Republished with permission from[71]; (g) Photographs of the photo-thermochromic smart window (PTCSW) prototype and pure HPMC under different weather conditions, demonstrating autonomous light-thermal regulation. Republished with permission from[72]. RTM: radiative thermal management; TC: thermochromic; EC: electrochromic; PC: photochromic; PDLC: polymer dispersed liquid crystal; PTCSW: photo-thermochromic smart window.

PC/EC smart windows responses represent a promising strategy for reducing building energy consumption while enhancing occupant comfort. PC/EC windows integrate light- and voltage-driven mechanisms, providing dual-response solar modulation: autonomous color adjustment under ultraviolet light and active control via electric field. A key challenge remains the scarcity of materials responsive to both stimuli simultaneously. Chen et al. developed an inorganic, all-solid-state dual-responsive smart window based on an OV-WO3-x/ZnO composite. The device exhibits pronounced electrochromic modulation of 85.9% at 633 nm and 74.5% at 1,000 nm, with rapid coloring/bleaching times of 3.1/5.5 s. In addition, a photochromic modulation depth of 86.1% is achieved, leading to notable indoor temperature reductions of 5.3 °C under electrochromic operation and 4.7 °C under photochromic regulation (Figure 7d)[70]. Sun et al. constructed a four-mode smart window (the PECD smart window) based on violanthrone derivatives (off, PC, EC, and synergistic mode), with PC states maintained for ~4 hours and EC response being rapid and low-power (Figure 7e)[22]. While both devices enhance building light-thermal control and energy-saving potential, they face stability challenges from oxygen vacancy oxidation and photodegradation of violanthrone. Overall, PC/EC dual-mode smart windows reduce reliance on HVAC systems, integrate passive and active indoor environment control, and offer aesthetic flexibility, establishing themselves as sustainable solutions for modern architecture.

PC/TC smart windows integrate photochromic and thermochromic properties, autonomously adjusting light and heat transmittance in response to solar radiation and ambient temperature, offering dynamic indoor environment regulation. Meng et al. developed a photo-thermal dual-responsive window based on isobutyl-substituted diimmonium borate molecules and liquid crystal composites, capable of self-regulating between near-crystalline (~70% transmittance) and cholesteric (~20% transmittance) phases without external power (Figure 7f). In the NIR range (800-1,200 nm), the material exhibits strong absorption and efficient photothermal conversion, reducing transmittance by 50% during phase transition, effectively blocking infrared radiation and stabilizing indoor temperature[71]. Cao et al. proposed a passive photothermal window composed of gold nanocrystals embedded in HPMC, where the AuNCs’ photothermal effect triggers conformational changes in HPMC chains, reducing transparency to 1% at 49 °C with fully reversible adjustment. The device exhibits significant modulation in both VIS and NIR regions, autonomously regulating indoor lighting and thermal gain based on sunlight intensity, without external power. Consequently, it adapts to varying weather conditions (Figure 7g)[72]. PC/TC smart windows represent an innovative class of dynamic glazing, autonomously responding to environmental cues-light intensity and temperature-to regulate optical and thermal properties, offering energy-saving solutions for indoor climate control. Their self-adaptive capability provides unique value in daytime and seasonal light-thermal management, maintaining optimal indoor conditions. Compared with single-responsive systems, dual-responsive smart windows offer enhanced adaptability by integrating passive environmental response with active control. This synergistic regulation enables improved seasonal energy efficiency and broader operational flexibility under complex climatic conditions.

4. Summary and Perspective

RTM smart windows are emerging adaptive building-envelope technologies that integrate dynamic spectral regulation (VIS, NIR, MIR) with passive radiative cooling via the 8-13 μm atmospheric window. They address the thermal selectivity limitations of conventional glazing, offering a viable solution to reduce building energy consumption and optimize indoor comfort. Mechanistically, these windows have evolved from static materials to dynamically tunable platforms, with tri-band modulation (independent control of VIS, NIR, and MIR spectra) representing a key breakthrough that resolves the trade-off between summer cooling and winter heating. Technologically, diverse pathways have advanced: electrochromic systems provide precise, rapid multi-band control; thermochromic materials offer passive temperature adaptation; photochromic designs achieve zero-energy light-driven regulation; and dual-responsive mechanisms (TC/EC, PC/EC, and PC/TC) synergize active and passive regulation to enhance adaptability.

From a forward-looking perspective, future research on RTM smart windows should move beyond proof-of-concept demonstrations toward scalable, standardized, and application-oriented designs. Materials and device innovations have substantially improved core performance, including faster response times, enhanced cycling stability (exceeding 10,000 cycles for optimized electrochromic devices), and expanded modulation ranges. However, challenges remain, such as the long-term stability of photochromic/hybrid systems, high manufacturing costs, and scalable production of high-performance materials. Existing research on smart windows largely focuses on small-area, planar prototypes and lacks comprehensive discussion of the effects of size and geometry, necessitating the development of standardized evaluation methods. Standardized evaluation protocols for radiative cooling power and energy efficiency are also needed for comparative assessment. Future research should focus on optimizing stability, reducing costs, and scaling production. For example, light-resistant protective coatings and molecular stabilization strategies are being explored to mitigate photodegradation in photochromic materials, while optimizing crosslinking density and network design has proven effective in enhancing the durability of thermochromic hydrogels. As hybrid synergy and performance optimization advance, these smart windows are poised to become a cornerstone technology for sustainable, net-zero energy buildings amid global climate change and rising energy demand.

Authors contribution

Ma R: Supervision, conceptualization, writing-review & editing.

Xia Y, Zhou Y: Writing-original draft.

Zhang Y, Zhang B, Zhang Y: Writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52473215, No. 52273248, and No. 52303238), the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (Grant No. 24JCJQJC00230 and No. 25JCLZJC00660), the Young Scientific and Technological Talents (Level One) in Tianjin (Grant No. QN20230102), and the Scientific Research Innovation Capability Support Project for Young Faculty (Grant No. ZYGXQNJSKYCXNLZCXM-M16).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Akhmat G, Zaman K, Tan S, Sajjad F. Does energy consumption contribute to climate change? Evidence from major regions of the world. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2014;36:123-134.[DOI]

-

2. Wang J, Azam W. Natural resource scarcity, fossil fuel energy consumption, and total greenhouse gas emissions in top emitting countries. Geosci Front. 2024;15(2):101757.[DOI]

-

3. Ko WH, Schiavon S, Zhang H, Graham LT, Brager G, Mauss I, et al. The impact of a view from a window on thermal comfort, emotion, and cognitive performance. Build Environ. 2020;175:106779.[DOI]

-

4. Mesloub A, Ghosh A, Touahmia M, Albaqawy GA, Alsolami BM, Ahriz A. Assessment of the overall energy performance of an SPD smart window in a hot desert climate. Energy. 2022;252:124073.[DOI]

-

5. Hee WJ, Alghoul MA, Bakhtyar B, Elayeb O, Shameri MA, Alrubaih MS, et al. The role of window glazing on daylighting and energy saving in buildings. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2015;42:323-343.[DOI]

-

6. Meng W, Kragt AJJ, Gao Y, Brembilla E, Hu X, van der Burgt JS, et al. Scalable photochromic film for solar heat and daylight management. Adv Mater. 2024;36(5):e2304910.[DOI]

-

7. Lantonio NA, Krarti M. Simultaneous design and control optimization of smart glazed windows. Appl Energy. 2022;328:120239.[DOI]

-

8. Cao S, Zhang S, Zhang T, Yao Q, Lee JY. A visible light-near-infrared dual-band smart window with internal energy storage. Joule. 2019;3(4):1152-1162.[DOI]

-

9. Zhai Y, Li J, Shen S, Zhu Z, Mao S, Xiao X, et al. Recent advances on dual-band electrochromic materials and devices. Adv Funct Mater. 2022;32(17):2109848.[DOI]

-

10. Fan S, Li W. Photonics and thermodynamics concepts in radiative cooling. Nat Photonics. 2022;16(3):182-190.[DOI]

-

11. Zhao D, Aili A, Zhai Y, Xu S, Tan G, Yin X, et al. Radiative sky cooling: Fundamental principles, materials, and applications. Appl Phys Rev. 2019;6(2):021306.[DOI]

-

12. Zhai Y, Ma Y, David SN, Zhao D, Lou R, Tan G, et al. Scalable-manufactured randomized glass-polymer hybrid metamaterial for daytime radiative cooling. Science. 2017;355(6329):1062-1066.[DOI]

-

13. Zhao X, Li T, Xie H, Liu H, Wang L, Qu Y, et al. A solution-processed radiative cooling glass. Science. 2023;382(6671):684-691.[DOI]

-

14. Mandal J, Fu Y, Overvig AC, Jia M, Sun K, Shi NN, et al. Hierarchically porous polymer coatings for highly efficient passive daytime radiative cooling. Science. 2018;362(6412):315-319.[DOI]

-

15. Li X, Peoples J, Yao P, Ruan X. Ultrawhite BaSO4 paints and films for remarkable daytime subambient radiative cooling. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(18):21733-21739.[DOI]

-

16. Tian J, Cheng W, Xiu M, Zhang H, Han C, Ye F, et al. Multifunctional smart windows: Development and integration for smart net-zero buildings–A state-of-the-art review. Constr Build Mater. 2025;495:143524.[DOI]

-

17. Li G, Wang J, Zhao X, Su Y, Zhao D. Simultaneous modulation of solar and longwave infrared radiation for smart window applications. Mater Today Phys. 2023;38:101284.[DOI]

-

18. Wang J, Tan G, Yang R, Zhao D. Materials, structures, and devices for dynamic radiative cooling. Cell Rep Phys Sci. 2022;3(12):101198.[DOI]

-

19. An Y, Fu Y, Dai JG, Yin X, Lei D. Switchable radiative cooling technologies for smart thermal management. Cell Rep Phys Sci. 2022;3(10):101098.[DOI]

-

20. Shao Z, Huang A, Cao C, Ji X, Hu W, Luo H, et al. Tri-band electrochromic smart window for energy savings in buildings. Nat Sustain. 2024;7(6):796-803.[DOI]

-

21. Hu L, Wang C, Zhu H, Zhou Y, Li H, Liu L, et al. Adaptive thermal management radiative cooling smart window with perfect near-infrared shielding. Small. 2024;20(30):e2306823.[DOI]

-

22. Sun F, Cai J, Wu H, Zhang H, Chen Y, Jiang C, et al. Novel extended viologen derivatives for photochromic and electrochromic dual-response smart windows. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cells. 2023;260:112496.[DOI]

-

23. Deng Y, Yang Y, Xiao Y, Xie HL, Lan R, Zhang L, et al. Ultrafast switchable passive radiative cooling smart windows with synergistic optical modulation. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33(35):2301319.[DOI]

-

24. Zhang Z, Zhang L, Zhou Y, Cui Y, Chen Z, Liu Y, et al. Thermochromic energy efficient windows: Fundamentals, recent advances, and perspectives. Chem Rev. 2023;123(11):7025-7080.[DOI]

-

25. Tian J, Den Z, Ma X, Ye F, Huang Y. Self-supported MXene V4C3-derived VO2 thermochromic smart window materials: In situ synthesis and performance enhancement. Cryst Growth Des. 2025;25(10):3354-3364.[DOI]

-

26. Goei R, Ong AJ, Hao TJ, Yi LJ, Kuang LS, Mandler D, et al. Novel Nd–Mo Co-doped SnO2/α-WO3 electrochromic materials (ECs) for enhanced smart window performance. Ceram Int. 2021;47(13):18433-18442.[DOI]

-

27. Tällberg R, Jelle BP, Loonen R, Gao T, Hamdy M. Comparison of the energy saving potential of adaptive and controllable smart windows: A state-of-the-art review and simulation studies of thermochromic, photochromic and electrochromic technologies. Sol Energy Mater Sol Cells. 2019;200:109828.[DOI]

-

28. Wu S, Sun H, Duan M, Mao H, Wu Y, Zhao H, et al. Applications of thermochromic and electrochromic smart windows: Materials to buildings. Cell Rep Phys Sci. 2023;4(5):101370.[DOI]

-

29. Bhupathi S, Wang S, Ke Y, Long Y. Recent progress in vanadium dioxide: The multi-stimuli responsive material and its applications. Mater Sci Eng R Rep. 2023;155:100747.[DOI]

-

30. Cui Y, Ke Y, Liu C, Chen Z, Wang N, Zhang L, et al. Thermochromic VO2 for energy-efficient smart windows. Joule. 2018;2(9):1707-1746.[DOI]

-

31. Zhou J, Gao Y, Zhang Z, Luo H, Cao C, Chen Z, et al. VO2 thermochromic smart window for energy savings and generation. Sci Rep. 2013;3:3029.[DOI]

-

32. Luo JJ, Sun YH, Zhou GZ, Li HX, Zhang HF. Thermally tunable nonreciprocal broadband octave absorber based on anapole modes. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2026;172:110356.[DOI]

-

33. Huang R, Xie Y, Cao N, Jia X, Chao D. Self-powered electrochromic smart window helps net-zero energy buildings. Nano Energy. 2024;129:109989.[DOI]

-

34. Liu T, Liu B, Wang J, Yang L, Ma X, Li H, et al. Smart window coating based on F-TiO2-KxWO3 nanocomposites with heat shielding, ultraviolet isolating, hydrophilic and photocatalytic performance. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27373.[DOI]

-

35. Wang S, Jiang T, Meng Y, Yang R, Tan G, Long Y. Scalable thermochromic smart windows with passive radiative cooling regulation. Science. 2021;374(6574):1501-1504.[DOI]

-

36. Sheng SZ, Wang JL, Zhao B, He Z, Feng XF, Shang QG, et al. Nanowire-based smart windows combining electro- and thermochromics for dynamic regulation of solar radiation. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):3231.[DOI]

-

37. Zhang C, Zhang X, Shen H, Shuai D, Xiong X, Wang Y, et al. Superior self-cleaning surfaces via the synergy of superhydrophobicity and photocatalytic activity: Principles, synthesis, properties, and applications. J Clean Prod. 2023;428:139430.[DOI]

-

38. Shen W, Li G. Recent progress in liquid crystal-based smart windows: Materials, structures, and design. Laser Photonics Rev. 2023;17:2200207.[DOI]

-

39. Yu S, Zhang Q, Liu L, Ma R. Thermochromic conductive fibers with modifiable solar absorption for personal thermal management and temperature visualization. ACS Nano. 2023;17(20):20299-20307.[DOI]

-

40. Zhang Q, Wang Y, Lv Y, Yu S, Ma R. Bioinspired zero-energy thermal-management device based on visible and infrared thermochromism for all-season energy saving. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(38):e2207353119.[DOI]

-

41. Yoo MJ, Pyun KR, Jung Y, Lee M, Lee J, Ko SH. Switchable radiative cooling and solar heating for sustainable thermal management. Nanophotonics. 2024;13(5):543-561.[DOI]

-

42. Ding Y, Mei Z, Zhang W, Wu X, Zhang Y, Gao D, et al. Intelligent electrochromic photothermal regulation for integrated building energy saving. Energy Environ Sci. 2025;18(23):10088-10101.[DOI]

-

43. Yang S, Tang S, Yuan X, Zou X, Zeng H, Song Y, et al. Advances in tunable radiative cooling materials: Design, mechanisms, and applications. Adv Funct Mater. 2026;36(4):e11552.[DOI]

-

44. Lin C, Li Y, Chi C, Kwon YS, Huang J, Wu Z, et al. A solution-processed inorganic emitter with high spectral selectivity for efficient subambient radiative cooling in hot humid climates. Adv Mater. 2022;34(12):e2109350.[DOI]

-

45. Li T, Zhai Y, He S, Gan W, Wei Z, Heidarinejad M, et al. A radiative cooling structural material. Science. 2019;364(6442):760-763.[DOI]

-

46. Fei J, Han D, Ge J, Wang X, Koh SW, Gao S, et al. Switchable surface coating for bifunctional passive radiative cooling and solar heating. Adv Funct Mater. 2022;32(27):2203582.[DOI]

-

47. Huang G, Yengannagari AR, Matsumori K, Patel P, Datla A, Trindade K, et al. Radiative cooling and indoor light management enabled by a transparent and self-cleaning polymer-based metamaterial. Nat Commun. 2024;15:3798.[DOI]

-

48. Yin H, Zhou X, Zhou Z, Liu R, Mo X, Chen Z, et al. Switchable kirigami structures as window envelopes for energy-efficient buildings. Research. 2023;6:0103.[DOI]

-

49. Yang S, Wan MP, Ng BF, Dubey S, Henze GP, Chen W, et al. Model predictive control for integrated control of air-conditioning and mechanical ventilation, lighting and shading systems. Appl Energy. 2021;297:117112.[DOI]

-

50. Chen M, Deng J, Zhang H, Zhang X, Yan D, Yao G, et al. Advanced dual-band smart windows: Inorganic all-solid-state electrochromic devices for selective visible and near-infrared modulation. Adv Funct Mater. 2025;35(3):2413659.[DOI]

-

51. Li X, Sun B, Sui C, Nandi A, Fang H, Peng Y, et al. Integration of daytime radiative cooling and solar heating for year-round energy saving in buildings. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6101.[DOI]

-

52. Zhao H, Sun Q, Zhou J, Deng X, Cui J. Switchable cavitation in silicone coatings for energy-saving cooling and heating. Adv Mater. 2020;32(29):e2000870.[DOI]

-

53. Azens A, Granqvist C. Electrochromic smart windows: Energy efficiency and device aspects. J Solid State Electrochem. 2003;7(2):64-68.[DOI]

-

54. Deng Y, Yang Y, Xiao Y, Zeng X, Xie HL, Lan R, et al. Annual energy-saving smart windows with actively controllable passive radiative cooling and multimode heating regulation. Adv Mater. 2024;36(27):e2401869.[DOI]

-

55. Zeng Y, Liu Y, Jiang T, Zhao F, Wang L, Ma S, et al. A multimodal smart window with visible-NIR-LWIR electro-modulation for all weather. Adv Mater. 2026;38(1):e12029.[DOI]

-

56. Lin C, Hur J, Chao CYH, Liu G, Yao S, Li W, et al. All-weather thermochromic windows for synchronous solar and thermal radiation regulation. Sci Adv. 2022;8(17):eabn7359.[DOI]

-

57. Liu Y, Zhang Y, Chen T, Jin Z, Feng W, Li M, et al. A stable and self-healing thermochromic polymer coating for all weather thermal regulation. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33(49):2307240.[DOI]

-

58. Chen G, Wang K, Yang J, Huang J, Chen Z, Zheng J, et al. Printable thermochromic hydrogel-based smart window for all-weather building temperature regulation in diverse climates. Adv Mater. 2023;35(20):e2211716.[DOI]

-

59. Wang H, Lu Y, Wang J, Qi T, Tian X, Yang C, et al. Hydrated ionic polymer for thermochromic smart windows in buildings. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):6509.[DOI]

-

60. Sui J, Yao T, Zou J, Liao S, Zhang HF. A switchable dual-mode integrated photonic multilayer film with highly efficient wide-angle radiative cooling and thermal insulation for year-round thermal management. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2025;241:126783.[DOI]

-

61. Du M, Li C. Engineering supramolecular hydrogels via reversible photoswitching of cucurbit[8]uril-spiropyran complexation stoichiometry. Adv Mater. 2024;36(40):e2408484.[DOI]

-

62. Yang X, Duan G, Liu Y, Han J, Han X, Fu H, et al. Next-generation photochromic smart window: Wood-derived cellulose flexible composites integrated thermal insulation, UV-shielding, and anti-counterfeiting. InfoMat. 2026;8:e70049.[DOI]

-

63. Cheng X, Zhang B, Lei G, Su Y, Gao L, Du K, et al. Solar-tunable reversible photochromic smart window based on BiOCl/CA hydrogel. Adv Opt Mater. 2025;13(24):01228.[DOI]

-

64. Zhang Z, Yu M, Ma C, He L, He X, Yuan B, et al. A Janus smart window for temperature-adaptive radiative cooling and adjustable solar transmittance. Nanomicro Lett. 2025;17(1):233.[DOI]

-

65. Xie G, Li Y, Wu C, Cao M, Chen H, Xiong Y, et al. Dual response multi-function smart window: An integrated system of thermochromic hydrogel and thermoelectric power generation module for simultaneous temperature regulation and power generation. Chem Eng J. 2024;481:148531.[DOI]

-

66. Yu P, Liu J, Zhang W, Zhao Y, He Z, Ma C, et al. Ionic liquid-doped liquid crystal/polymer composite for multifunctional smart windows. Dyes Pigm. 2023;208:110817.[DOI]

-

67. Ke Y, Chen J, Lin G, Wang S, Zhou Y, Yin J, et al. Smart windows: Electro-, thermo-, mechano-, photochromics, and beyond. Adv Energy Mater. 2019;9(39):1902066.[DOI]

-

68. Deng B, Zhu Y, Wang X, Zhu J, Liu M, Liu M, et al. An ultrafast, energy-efficient electrochromic and thermochromic device for smart windows. Adv Mater. 2023;35(35):e2302685.[DOI]

-

69. Jing F, Zhang Z, Zhang L, Zhou F, Qin J, Zou C, et al. A dual-band smart window with electrical-thermal control for visible and near-infrared light modulation. Small. 2025;21(39):e06780.[DOI]

-

70. Chen M, Zhang X, Sun W, Xiao Y, Zhang H, Deng J, et al. A dual-responsive smart window based on inorganic all-solid-state electro- and photochromic device. Nano Energy. 2024;123:109352.[DOI]

-

71. Meng W, Gao Y, Hu X, Tan L, Li L, Zhou G, et al. Photothermal dual passively driven liquid crystal smart window. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(24):28301-28309.[DOI]

-

72. Cao D, Xu C, Lu W, Qin C, Cheng S. Sunlight-driven photo-thermochromic smart windows. Sol RRL. 2018;2(4):1700219.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite