Abstract

Phonon hydrodynamics is a theoretical framework for predicting nondiffusive heat transport processes in solids at the nanoscale or under high-frequency excitations. This article presents the microscopic and thermodynamic foundations of the theory and reviews its applications. First, we discuss historical and modern derivations of hydrodynamic heat transport equations from the phonon Boltzmann transport equation (BTE), and highlight advanced methods to predict hydrodynamic effects from direct solutions of the BTE beyond the Relaxation Time Approximation. Then, we review the main experiments that uncovered nondiffusive heat transport effects and their interpretation from the hydrodynamic perspective. Overall, the developments summarized in this work establish phonon hydrodynamics as a vital tool for understanding and engineering thermal transport at the nanoscale in data-processing and energy-conversion devices.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

1. Introduction

Traditionally, heat conduction is described as a diffusive process in terms of Fourier’s law, where the energy flux is proportional to the local thermal gradient. In nonmetallic crystalline solids, this description is valid only if phonons—the quantized vibrational modes that carry heat—locally and instantaneously perceive the inhomogeneity in the thermal field. Microscopically, this corresponds to situations where the characteristic size and timescale under consideration are significantly larger than the phonon mean free paths and scattering times, respectively[1,2]. Therefore, Fourier’s law is generally inadequate to describe the thermal response in current electronic devices, where the inclusion of thin multilayered structures and miniaturized components introduce characteristic scales in the nanometer range[3,4], two orders of magnitude smaller than the average room-temperature phonon mean free path in standard semiconductors such as silicon[5].

To develop advanced heat transport models beyond diffusion and including boundary conditions, the usual starting point is the linearized Boltzmann transport equation (BTE) for phonons,

where fλ is the phonon distribution function of the λ-phonon mode (λ stands for the wave-vector

Phonon hydrodynamics constitutes an alternative route to treat the BTE with special attention to the conservation laws and phonon mode correlations at the nanoscale and predicts the emergence of collective phonon evolution in a range of non-equilibrium conditions[19]. Accordingly, phonon evolution is best understood not as a random walk of independent particles, but as a correlated phonon gas that can sustain transport phenomena akin to fluid-like viscosity or thermal waves. This description bridges microscopic (particle-based) and macroscopic (continuum) descriptions, providing new insights and a unified framework for modeling thermal transport. The hydrodynamic and RTA-based interpretations of nanoscale heat transport differ fundamentally in their description of phonon dynamics and lead to contrasting predictions, including the number of intrinsic phonon length scales expected to directly manifest in experiments[18]. Determining which approach provides a deeper understanding of phonon evolution at the nanoscale remains an outstanding question and is essential for incorporating the key transport mechanisms beyond diffusion into predictive modeling tools. Ultimately, adequate theoretical treatment of the BTE for phonons will influence a broad range of engineering applications, including improved heat dissipation in nanoelectronics and enhanced performance in thermoelectric devices.

Extensive literature reviewing the topic of phonon hydrodynamics and its applications is available, including but not limited to previous studies[19-23]. This manuscript is a complementary review aimed at unifying the different perspectives and flavors that this theoretical framework has adopted historically. We focus on illustrating the general applicability of the hydrodynamic approach as a tool to understand phonon evolution out of equilibrium, from both theoretical and experimental perspectives, and we critically revise restrictive applicability criteria that are commonly assumed. First, we review the diversity of routes to derive hydrodynamic-like equations from microscopic grounds and the BTE. Then, we discuss the key features and general thermodynamic robustness of the resulting phonon hydrodynamic models. Finally, we briefly but comprehensively review the experiments where hydrodynamic descriptions have successfully provided interpretations of non-diffusive effects. In this last section, we emphasize studies in which all the parameters of the hydrodynamic equations are quantified using ab initio calculations associated with specific averages over the phonon properties, as derived from the BTE.

2. Microscopic Foundation

The deviation from equilibrium of the phonon distribution can be expanded in terms of an arbitrary perturbation,

where εk is the phonon energy and Φλ generally depends on a set of macroscopic variables, such as the thermal gradient, weighted by mode-dependent coefficients. From the point of view of the variational principle, the solution of the linearized BTE, Eq. (1), for a given non-equilibrium situation corresponds to the phonon distribution function that optimizes the entropy production rate while accommodating all the boundary conditions and conservation laws. In other words, the BTE can be formulated as an optimization problem for a function directly related to entropy production and that only depends on Φλ and the collision operator. This interpretation was carefully discussed by J. M. Ziman in Chapters 7.7 and 7.8 of the previous study[1]. Accordingly, it is crucial to select adequate macroscopic variables to expand Φλ depending on the non-equilibrium conditions under consideration. Otherwise, entropy production is optimized within a sub-space of solutions that does not accommodate sufficient complexity, and the resulting solution can be arbitrarily far from the true solution. This is particularly relevant in complex non-equilibrium situations, such as those in the presence of non-homogeneous heat flux profiles at the nanoscale. In light of this general variational principle, phonon hydrodynamic theory is a method to obtain refined heat transport models from specific macroscopic characterizations of Φλ, which are specifically designed to capture the main non-equilibrium features emerging at the nanoscale. As discussed in the remainder of this article, the analogy with fluid dynamics is pertinent in this context because an adequate choice of the expansion for Φλ in terms of slowly-evolving thermodynamic variables generally leads to hydrodynamic-like heat transport equations.

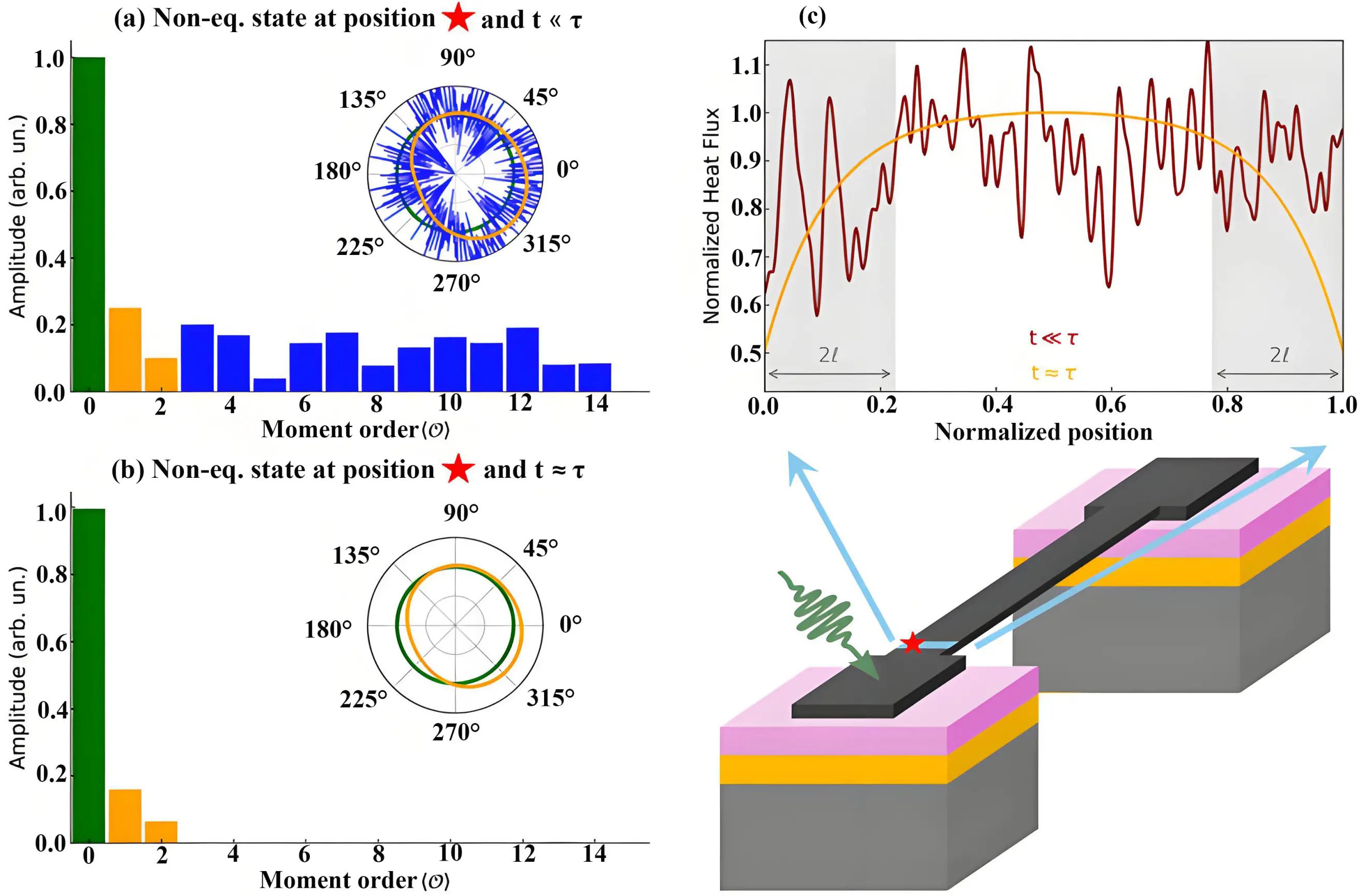

The development and implementation of the hydrodynamic interpretation of phonon transport has a long and rich history. Originally, hydrodynamic behavior was predicted to manifest at ultra-low temperatures in specific materials where momentum-conserving (Normal) phonon collisions are much more frequent than resistive ones[24-28]. Not only are Normal phonon-phonon collisions analogous to molecular collisions in fluids, but the first derivation of a hydrodynamic heat transport equation resembling the Navier-Stokes equation was derived from the BTE using the dominance of Normal collisions as a central hypothesis[26]. More recently, a substantial body of work has shown that the abundance of Normal collisions is a sufficient but not necessary condition for the emergence of phonon hydrodynamics[29-38]. A more fundamental necessary condition for the emergence of hydrodynamic transport effects at the nanoscale is the comparatively slow relaxation of the phonon distribution perturbation associated with the heat flux, relative to higher-order nonequilibrium perturbations[39-41]. This condition is not restricted to situations where most phonon interactions conserve the phonon momentum, but is generally satisfied at length or time scales comparable to the average mean free path or scattering time associated with resistive phonon interactions. Phenomenologically, this implies that the heat flux profile cannot locally or instantaneously align with the thermal gradient, thus leading to non-local and memory transport effects[42]. This view, schematically illustrated in Figure 1, extends the significance of hydrodynamic descriptions to a wide range of semiconductor materials and temperatures. The applicability of current hydrodynamic models, however, has been shown to be limited to moderately small Knudsen numbers, which prevents predictive modeling at arbitrary small length and timescales[30,43].

Figure 1. Illustration of non-equilibrium phonon evolution. We consider a nanoscale constriction connecting a heat source terminal subjected to a pulsed injection of thermal energy and a heat sink terminal at constant temperature. (a,b) Schematic representation of a possible non-equilibrium phonon distribution function in terms of the amplitude of its statistical moments at the position denoted by the red star. The insets show the phonon population as a function of the wave-vector direction. At time scales much smaller than the heat flux relaxation time τ after pulsed excitation, the deviation from equilibrium is arbitrarily complex and the distribution function accommodates high-order statistical moments. At time scales comparable to τ, all the non-equilibrium statistical moments have already relaxed due to phonon scattering except the ones directly related to energy and heat flux. This intermediate non-equilibrium state, which is generally established before thermal equilibrium is recovered, displays hydrodynamic-like transport features that can be modeled using the GKE; (c) Representative heat flux profiles along the cross-section denoted by the blue line at the different time scales. The hydrodynamic signature manifests here as a viscous non-local correlation of the heat flux profile restricted to the heat flux boundary layers (denoted in gray color). GKE: Guyer-Krumhansl equation.

In this section, we briefly review some of the key derivations of hydrodynamic-like heat transport models from the BTE. We focus on the different expansions for the non-equilibrium phonon distribution assumed in each case, which limit the applicability of the resulting models to different scenarios, and highlight the generality of this methodology to interpret nondiffusive thermal transport effects.

2.1 Guyer and Krumhansl derivation and historic perspective

In the collective limit, where Normal phonon interactions are much more frequent than resistive ones, an arbitrary non-equilibrium phonon state rapidly decays toward the displaced phonon distribution—the maximum entropy state that accommodates the total crystalline momentum in the absence of boundaries—before ultimately decaying to equilibrium via momentum-relaxing resistive interactions[24]. This displaced distribution reads,

where ωλ is the phonon frequency, T is the temperature, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and

To investigate the implications of collective phonon evolution, a hydrodynamic heat transport equation was originally derived from the BTE in the seminal work of Guyer and Krumhansl[26]. They first decomposed the collision operator into terms of Normal and resistive interactions, C = N + R. Instead of the phonon-mode basis, they expanded the distribution function in terms of the eigenvectors of the Normal collision operator N. Some of these eigenvectors, which are specific linear combinations of phonon modes, can be related to key thermodynamic quantities such as the energy and the crystalline momentum. When formulated in this basis, the BTE can be substantially simplified by enforcing thermodynamic constraints. For instance, energy conservation implies that the first N-eigenvector does not relax under the action of either R or N, while momentum conservation imposes that the three N-eigenvectors associated with the crystal momentum remain invariant under N. In this picture, the bulk thermal conductivity can be decomposed in terms of collective and kinetic contributions, thus providing physical intuition about the phonon transport mechanisms[26,50-52]. Most importantly, the BTE can be projected into the form of a hydrodynamic-like heat transport equation by assuming the dominance of Normal collisions

where κ is the bulk thermal conductivity, τ is the heat flux relaxation time, ℓ is the non-local length, and ζ is a dimensionless viscosity coefficient, all resulting from specific averages of the phonon group velocities, specific heats, and relaxation times.

The GKE, in combination with appropriate boundary conditions[30,53] and the energy conservation equation (

The Guyer and Krumhansl framework represents the starting point for the implementation of hydrodynamic heat transport modeling. According to the original derivation, this treatment is restricted to the collective limit, where in principle the GKE can be extended to very small length scales due to the small Knudsen number associated with abundant Normal collisions. Early experimental efforts identified signatures of strong hydrodynamic effects in this limit at ultra-low temperatures[56,57], and more recent ones in graphite at higher temperatures, including fully developed Poiseuille profiles[58,59] and damped thermal waves[60,61].

2.2 Perturbation expansion

More recently, the regime of applicability of Eq. (4) has been extended into weak hydrodynamic regimes beyond the collective limit, analogous to fluid dynamics in rarefied gases[62]. The first modern derivation of phonon hydrodynamics was introduced in the previous work[30]. The derivation considers the BTE with a single scattering time (gray-model) and a single group velocity (Debye approximation), and employs a Perturbation Expansion around a nonequilibrium solution characterized by four phonon moments,

where

The heat transport equation resulting from the BTE and the distribution in Eq. (5) is formally equivalent to the GKE, Eq. (4). Thus, this modern derivation expands the applicability of phonon hydrodynamics beyond the traditional low-temperature regime, and highlights the significance of phonon hydrodynamics in nanoscale crystalline semiconductors even at ambient conditions in semiconductors such as silicon. In addition, the nonequilibrium distribution function in Eq. (5) can be used to derive consistent boundary conditions by imposing microscopic energy and heat flux balance constraints[30]. The resulting boundary conditions are formulated at the level of integrated variables—temperature and heat flux—rather than individual phonon modes, thereby enabling implementation in complex geometries and nanostructures, including interfaces[53,54,63,64].

It is worth stressing that the Perturbation Expansion assumes an average relaxation time for all phonon modes, as reflected in Eq. (5), and does not provide a microscopic expression to quantify the non-local length ℓ and the flux relaxation time τ using first principles calculations of the spectral phonon transport properties[5,65,66].

2.3 Flux derivatives formalism

An alternative derivation of Eq. (4) from the BTE was later presented in the studies[32,67], which introduced a formalism that systematically solves the BTE for arbitrary materials and temperatures at moderately small Knudsen numbers. The phonon distribution is assumed to be well approximated by an expansion in terms of the heat flux and its spatial and time derivatives, which are treated as independent variables,

and the BTE is used to determine the mode-dependent prefactors weighting each term in the expansion. Once this distribution function is fully characterized using ab initio inputs, the energy and momentum projections of the BTE can be used to recover the GKE. Crucially, this approach provides explicit expressions for the transport parameters κ, ℓ, τ, and ζ as averages over the spectral properties of the complete phonon distribution, thereby going beyond the gray-model approximation, and accounting for realistic phonon dispersion relations beyond the Debye approximation[32]. The transport parameters values from ab initio calculations for graphene, silicon, germanium, and diamond across a range of temperatures are provided in the studies[32,52].

The Flux Derivatives Formalism generalizes the approach of the previous work[68], in which the perturbation is expanded in terms of a constant temperature gradient, to the nanoscale, where inhomogeneous and rapidly varying perturbations occur. This framework implicitly assumes that, at the nanoscale, arbitrary non-equilibrium distribution functions rapidly decay to the intermediate non-equilibrium state described by Eq. (6), rather than directly relaxing back to equilibrium. As illustrated in Figure 1, this hierarchical relaxation of the statistical moments of the phonon distribution is the key microscopic reason behind the manifestation of hydrodynamic effects at small scales. From a thermodynamic perspective, the choice of the heat flux as the key magnitude to characterize the non-equilibrium state is motivated by its slower relaxation compared to other non-equilibrium features under spontaneous phonon dynamics and interactions at moderately small Knudsen numbers. Microscopically, this approximation captures the limited phase space for phonon evolution restricted by the boundary conditions and conservation laws.

Importantly, this approach does not implicitly assume the gray-model approximation for the phonon scattering landscape. Instead, the microscopic expressions for the transport parameters depend on the phonon properties of all modes, and can be calculated via iterative methods by accounting for the full collision operator[32]. Therefore, the inclusion of a single characteristic non-local length ℓ and relaxation time τ in the GKE to model the influence of boundaries and heat sources on thermal evolution is not an approximation, but rather a defining feature of phonon hydrodynamic behavior[37,69]. This characteristic distinguishes the hydrodynamic framework from RTA-based descriptions, in which each phonon mode interacts with boundaries independently and the multiscale mean free path spectrum explicitly manifests[18].

Finally, we note that non-local and memory effects at the nanoscale compatible with the GKE have recently been predicted using alternative methodologies[38,41,70], wherein the GKE can be obtained as a limiting case of more general transport equations. Future work should aim to reconcile the different derivations from first principles, and identify the significance of higher-order and non-linear transport effects beyond the ones captured by the GKE[38,71-73].

2.4 Viscous heat equation

As illustrated by the analysis of Guyer and Krumhansl, the eigenvectors of the collision operator constitute a useful basis for studying the BTE for phonons. In contrast to the phonon mode basis, the C-eigenvectors decay exponentially toward equilibrium with well-defined relaxation times. The only exception is the eigenvector associated with the energy density, which does not relax under collisions. Since different C-eigenvectors remain uncorrelated under phonon interactions, this change of basis implicitly captures collective phonon behavior while reducing the collision operator in the BTE to a diagonal form. This advantage was exploited in a series of seminal works by Robert Hardy and coauthors[25,39], which distinguished between odd eigenvectors with a non-null contribution to the heat flux and even eigenvectors, which represent symmetric non-equilibrium perturbations and therefore do not contribute to the net heat flux. Under spatially homogeneous perturbations, the relaxation time of the odd C-eigenvectors is therefore directly related to the timescale for the decay of energy currents in the system[41].

This perspective was later adopted in recent work[74], where the decay times of the C-eigenvectors, denoted as relaxons, were quantified from first-principles calculations for different materials. In addition, this approach enabled solving the BTE in the presence of a homogeneous thermal gradient and computing the bulk thermal conductivity without requiring iterative methods. However, despite the usefulness of the relaxon basis to model simple non-equilibrium situations, relaxons are not eigenvectors of the drift operator, as they evolve into other relaxons due to phonon propagation. Therefore, describing complex non-equilibrium situations beyond homogeneous thermal gradients using the relaxon basis has remained elusive, requiring further approximations to account for boundary effects[75].

To address these limitations, a mesoscopic hydrodynamic-like heat equation was later derived from the BTE using the relaxon basis[76]. The key assumption here is to expand the non-equilibrium state in terms of linear perturbations of the displaced distribution, Eq. (3):

where ∆T refers to the local temperature deviation from global equilibrium,

The mesoscopic transport equation consistent with Eq. (7) and the BTE contains terms analogous to viscous effects in fluids, but exhibits significant qualitative differences compared to the GKE. The Viscous Heat Equation predicts the existence of a diffusive heat flux background that obeys Fourier’s law with the bulk conductivity, combined with an additional heat flux contribution that displays hydrodynamic behavior[76]. In contrast to the GKE, this equation thus predicts that hydrodynamic effects induce an increase in apparent thermal conductivity relative to the diffusive background, rather than a reduction. Consequently, this formalism does not attempt to capture the non-local reduction of the heat current caused by the presence of boundaries, but instead aims to model strong hydrodynamic effects in the collective limit, such as the Knudsen minimum[45]. To model the reduction in conductivity with respect to the diffusive limit generally observed at the nanoscale, the transport parameters of the viscous heat equation must be corrected by using reduced phonon mode scattering times[76].

2.5 Direct BTE solvers

The construction of mesoscopic hydrodynamic-like heat transport equations is not the only possibility to describe heat flux correlations and collective phonon effects. Phonon hydrodynamics can also be studied by directly solving the linearized BTE, Eq. (1), with a collision operator fully characterized from ab initio inputs. Since this approach seeks to capture the full microscopic complexity of phonon dynamics, it is worth emphasizing a few general considerations to ensure a physically meaningful description. First and foremost, it is necessary to avoid the RTA, which explicitly suppresses collective behavior and correlations between different phonon modes in direct microscopic solvers. Second, the macroscopic variables to expand the phonon distribution in Eq. (2) need to be carefully selected depending on the non-equilibrium conditions under consideration. This is particularly important beyond local equilibrium and in the presence of inhomogeneous heat flux profiles, where the local thermal gradient is not sufficient to characterize the non-equilibrium constraints. Third, low-frequency phonon modes play an important role in determining the hydrodynamic length and timescales. Hence, direct BTE solutions must be meticulously converged in terms of the phonon wave-vector space discretization.

In recent years, a variety of methods have been developed to solve the linearized BTE beyond the RTA. Under homogeneous thermal gradients, the distribution function and the associated bulk thermal conductivity can be obtained by iterative methods[65,77]. These iterative solutions demonstrate that the displaced distribution described by Eq. (3) can be approached in some materials such as graphene even at relatively high temperatures[48,49,52]. This is an indication that some materials and temperatures can host the collective limit and the associated strong hydrodynamic regime, leading to pronounced non-diffusive responses in the presence of boundaries[59] or rapid excitations[60]. Nevertheless, under complex non-equilibrium conditions and nanoscale boundary constraints, iterative solutions of the BTE are generally not feasible. To address this, direct solvers of the BTE usually simplify the collision operator. Beyond the RTA, the Callaway approximation is commonly employed[12],

where

However, Eq. (8) does not inherently capture the complexity of intermediate non-equilibrium states established at the nanoscale, such as those described by Eq. (5) and Eq. (6), or Eq. (7), which can cause discrepancies with more sophisticated solvers using the full form of the collision operator[80]. Beyond Callaway’s approximation, the BTE can be solved using a deviational Monte Carlo approach[16,61] or the Green’s function approach[81]. These techniques have been successfully implemented to describe the emergence of second sound under ring-shaped[61] and transient grating[60] optical excitations in the absence of boundaries. Hence, these direct BTE solvers constitute alternative routes for predicting phonon hydrodynamic effects relative to mesoscopic heat transport equations such as the GKE.

3. Thermodynamic Foundation

The fundamental condition underlying the emergence of collective phonon behavior in the form of hydrodynamic effects is the slow relaxation of the non-equilibrium part of the distribution accommodating the heat flux[39]. The implicit existence of this slowly-relaxing variable constitutes the common necessary condition across all approaches to derive phonon hydrodynamic models.

In formalisms where the heat transport equation is derived from the BTE by expanding the phonon distribution function in terms of the heat flux and related variables, such as the Perturbation Expansion or the Flux Derivatives Formalism, this condition is explicitly imposed by assuming that the non-equilibrium state mainly depends on the shape of the heat flux vector field. This directly implies that other forms of non-equilibrium perturbations relax much faster and can be neglected when approximating the phonon mode populations. As illustrated in Figure 1, this is a reasonable hypothesis at relatively short length or timescales, where the limited phase space for phonon interactions reveals a hierarchical decay of the non-equilibrium state[1].

In formalisms assuming the collective limit, such as the original derivation of the GKE, the abundance of Normal collisions slows down the relaxation of the total crystal momentum compared to other potentially excited mesoscopic variables. Microscopically, this corresponds to a slow decay of the asymmetric features of the distribution function, which in turn entails a slow relaxation of the total heat flux. Consequently, the collective limit assumption constitutes a sufficient condition for the emergence of phonon hydrodynamics. It is important to emphasize, however, that this is not a necessary condition, particularly at the nanoscale where the heat flux does not evolve locally or instantaneously.

In summary, the slow relaxation of the heat flux implies non-local and memory effects on the thermal evolution, reminiscent of fluid-like behavior. These effects are captured in the GKE by introducing a single characteristic decay length ℓ and timescale τ, which directly quantify the relaxation dynamics of the heat flux. This is in stark contrast with RTA-based descriptions of nanoscale heat transport, where the full spectrum of decay timescales associated with each phonon mode manifests explicitly[6,9]. Thus, the existence of a single interaction scale characterizing nanoscale dynamics represents the primary and most general signature of phonon hydrodynamics, rather than any specific microscopic criterion. This crucial aspect of hydrodynamic theory underlies the similarities between the GKE and alternative models based on the existence of a single interaction scale in time and space, such as the Dual Phase Lag model[82,83].

Finally, we note that hydrodynamic equations derived from the BTE, such as the GKE, are fully consistent with the thermodynamic principles[23,84]. The energy conservation constraint is explicitly satisfied in the formalisms described above. Moreover, the second law can also be reconciled with hydrodynamic-like equations by considering advanced non-equilibrium thermodynamic formulations. For instance, Extended Irreversible Thermodynamics[85] proposes the generalization of the Gibbs equation by including dissipative fluxes as independent variables characterizing the local non-equilibrium state. This generalized thermodynamic relation can be combined with conservation laws to demonstrate that the GKE predicts a positive entropy production under arbitrary non-equilibrium conditions[84]. Notably, the idea of using the heat flux as a key variable to describe the non-equilibrium thermodynamic state motivates the variational treatment of the phonon distribution in the Perturbation Expansion method or the Flux Derivatives Formalism described above.

4. Experiments and Phenomenology

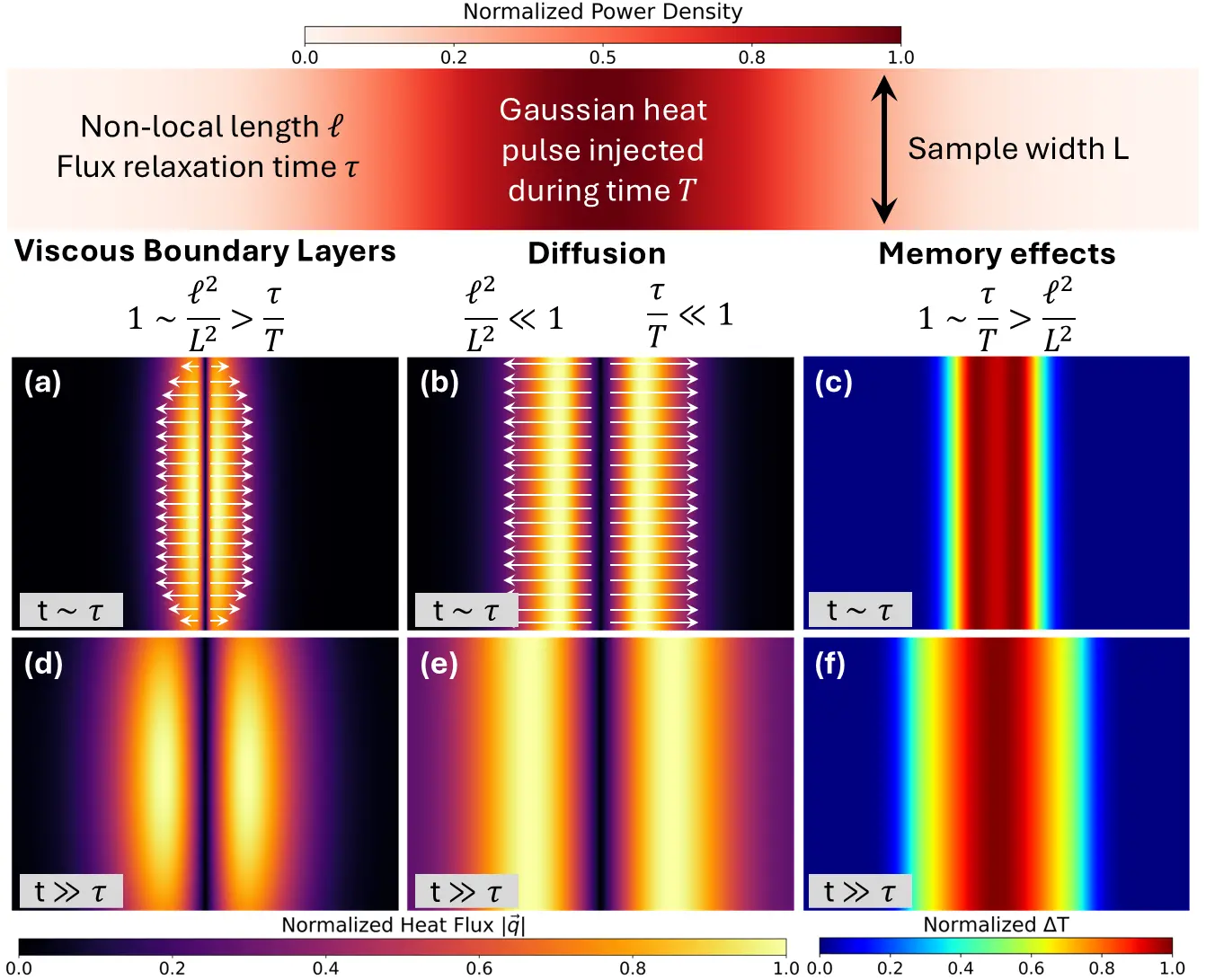

Hydrodynamic phonon transport manifests in the form of viscous-like non-local correlations of the heat flux, or memory and thermal waves[27,36,42]. The emergence of these effects requires that the relevant length and timescales under consideration approach the nonlocal length ℓ and the heat flux relaxation time τ, respectively. Hydrodynamic phenomena are therefore amplified at low temperatures, where scattering rates decrease, or in materials where resistive processes such as Umklapp, phonon-defect, isotope, or alloy scattering are weak, allowing the distribution function to deviate from local equilibrium and increasing ℓ and τ. The interplay of heat viscosity, memory, and diffusion at different scales, as predicted by the GKE under a simple non-equilibrium situation, is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Emergence and interplay of weak hydrodynamic transport effects at different length and time scales. We consider a pulsed excitation with a Gaussian-shape injecting heat during a time window T within a thin film with thickness L. Three different situations are shown both at early and late times t after excitation. (b, e) At length scales L and time scales T larger than the non-local length ℓ and the relaxation time τ, respectively, non-local and memory effects are negligible and the heat flux and temperature fields evolve following standard diffusion; (a, d) For L~ℓ and long timescales with respect to τ, the heat flux is reduced close to the film boundaries, which reduces the total energy current and delays thermal relaxation. This viscous effect tends to prevent the propagation of thermal waves; (c, f) Finally, if the excitation time T and the observation time t are comparable to τ, a fraction of the thermal energy propagates as a damped wave.

Experimental identification of hydrodynamic effects and quantitative comparison between theory and experiments requires characterizing the specific heat capacities and group velocities of all the phonon modes along with the phonon-phonon transition rates from first principles calculations[66]. These inputs can be used either to directly model the experiment by solving the linearized BTE[60,61,86], or to evaluate the transport parameters of mesoscopic hydrodynamic models, such as κ, ℓ and τ in the GKE[30,35,87]. A systematic comparison of measured versus calculated GKE parameters in a variety of experiments is provided in the previous work[32].

In this section, we review the experimental methods that have been used to detect phonon hydrodynamic behavior, and we identify the range of predictive applicability of hydrodynamic models with ab initio calculated inputs across different experiments. Overall, this section shows that the hydrodynamic perspective provides a unifying framework for predicting a variety of experimental configurations where Fourier’s law breaks down.

4.1 Stationary heat flow in nanostructures

4.1.1 Heat flux boundary layers

The energy current established in response to a thermal gradient across a semiconductor nanostructure is generally smaller than the diffusive prediction based on Fourier’s law[88-90]. This reduction in apparent thermal conductivity is associated with the momentum-destroying phonon-boundary scattering events. For a free surface, the microscopic balance of the flux of heat flux according to the non-equilibrium distribution functions in Eq. (5) or Eq. (6) results in a slip boundary condition[1,30,43]. This condition, combined with the GKE, predicts a reduced energy transfer rate and a non-uniform heat flux profile near the structure edges that accommodates a slip boundary flux, in analogy to fluid flow in rarefied gases[42,55,91]. In general, resistive phonon-phonon interactions limit the heat flux correlations in space and time. Consequently, the curvature of the flux profile is confined to a region next to the boundaries, known as the heat flux boundary layer, with a characteristic size comparable to the non-local length (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Although the flux profile is not directly accessible in experiments, predictions of the apparent thermal conductivity in steady-state can be directly compared with measurements. In contrast to standard fluid dynamics, the GKE with slip boundary flux predicts a linear dependence of the apparent conductivity on system size[92]. Experiments show good agreement with the hydrodynamic predictions for moderate Knudsen numbers in standard semiconductors such as silicon[30,43,93]. In particular, the reduced conductivity observed experimentally is accurately predicted by the GKE with parameter values obtained from ab initio calculations[32] across different geometries and a wide range of temperatures for L down to 2ℓ (i.e., Kn = ℓ/L ≤ 1/2), where L is the smallest characteristic size of the nanostructure and ℓ is the non-local length in the GKE[43]. Accordingly, the applicability of current hydrodynamic models in standard semiconductors is limited to relatively large inter-boundary distances (a few hundreds of nanometers at 300 K), which precludes the use of this description with ab initio inputs to model ultrathin layers present in nanoelectronic devices. Moreover, thermal conductivity measurements in alloy nanostructures reveal a gradual reduction of the conductivity as the device length scale is decreased over multiple orders of magnitude[94]. This multiscale onset of non-diffusive behavior observed in alloys can be described using various implementations of the RTA[9,15,95], and is incompatible with the hydrodynamic description based on a single interaction scale .

4.1.2 Poiseuille flow

In certain materials and temperatures, such as monolayer graphene around 100 K, the collective limit is approached because a large fraction of phonon-phonon interactions conserve momentum[48,49,96]. In these conditions, phonon momentum is almost exclusively destroyed in the boundaries, and the heat flux profile becomes strongly correlated across the full nanostructure. Due to the rapid redistribution of phonon momentum via Normal collisions, the slip heat flux in the boundary decays to zero, and the GKE predicts a fully correlated quadratic heat flux profile, analogous to Poiseuille flow in standard fluid dynamics. This is a signature of strong collective phonon evolution, which is phenomenologically different from the presence of slip flux and boundary layers confining the viscous effect close to the system edges.

The manifestation of Poiseuille flow has traditionally been associated with specific trends in thermal conductivity as a function of temperature T[27]. At sufficiently high temperatures, the mean free path of both resistive (ΛR) and Normal (ΛN) phonon-phonon interactions can become significantly smaller than the sample characteristic size L. In this limit of bulk diffusion, the thermal conductivity follows a T-1 trend, reflecting the temperature-dependence of the resistive scattering time. In contrast, at ultra-low temperatures, both ΛN and ΛR can easily become much larger than the device size L. In this ballistic limit, the mean free paths are geometrically confined, and the thermal conductivity follows a T3 trend, reflecting the temperature dependence of the specific heat capacity. Deviations from these trends at intermediate temperatures can be associated with strong phonon hydrodynamic behavior. By increasing the temperature above the ballistic limit, a temperature dependence of the conductivity with an exponent larger than 3 can be established if ΛN < L < ΛR This is a manifestation of Poiseuille heat flow, which increases the maximum flux in the internal regions of the nanostructure relative to the ballistic limit. Finally, in between the Poiseuille regime and the diffusion limit, an exponential trend of conductivity versus temperature can also be observed. This effect is a signature of the Ziman limit[27] and reflects the dominance of Normal collisions with respect to resistive ones in situations where the mean free paths are not geometrically confined. Indications of Poiseuille flow and the Ziman limit regimes have been observed in some materials, including isotopically purified graphite[59], black phosphorus[58], and even sapphire[97]. Additionally, in the collective limit, the complex interplay between phonon-boundary and phonon-phonon interactions can induce a minimum in the thermal conductivity as a function of the device size, which is known as the Knudsen minimum[45,98]. However, direct experimental evidence for this effect is scarce[22]. The particular temperature and size dependence of the conductivity in the collective limit has been successfully described using direct solutions of the BTE under Callaway’s approximation[13]. To precisely capture collective phonon behavior within this microscopic framework, careful consideration of isotope scattering, surface roughness and grain-boundary effects is required[86,99].

At this point, it is worth stressing that the manifestation of hydrodynamic behavior is not limited to materials and temperatures that accommodate the Poiseuille flow and the Ziman limit. Viscous heat flux correlations generally emerge across a broader range of materials, temperatures, and nanoscale conditions, at length and time scales comparable to the resistive mean free path and scattering times. Accordingly, we emphasize that the relevance of including hydrodynamic corrections to the diffusive transport equation is not limited to the collective limit.

4.2 Nanostructured heat sources

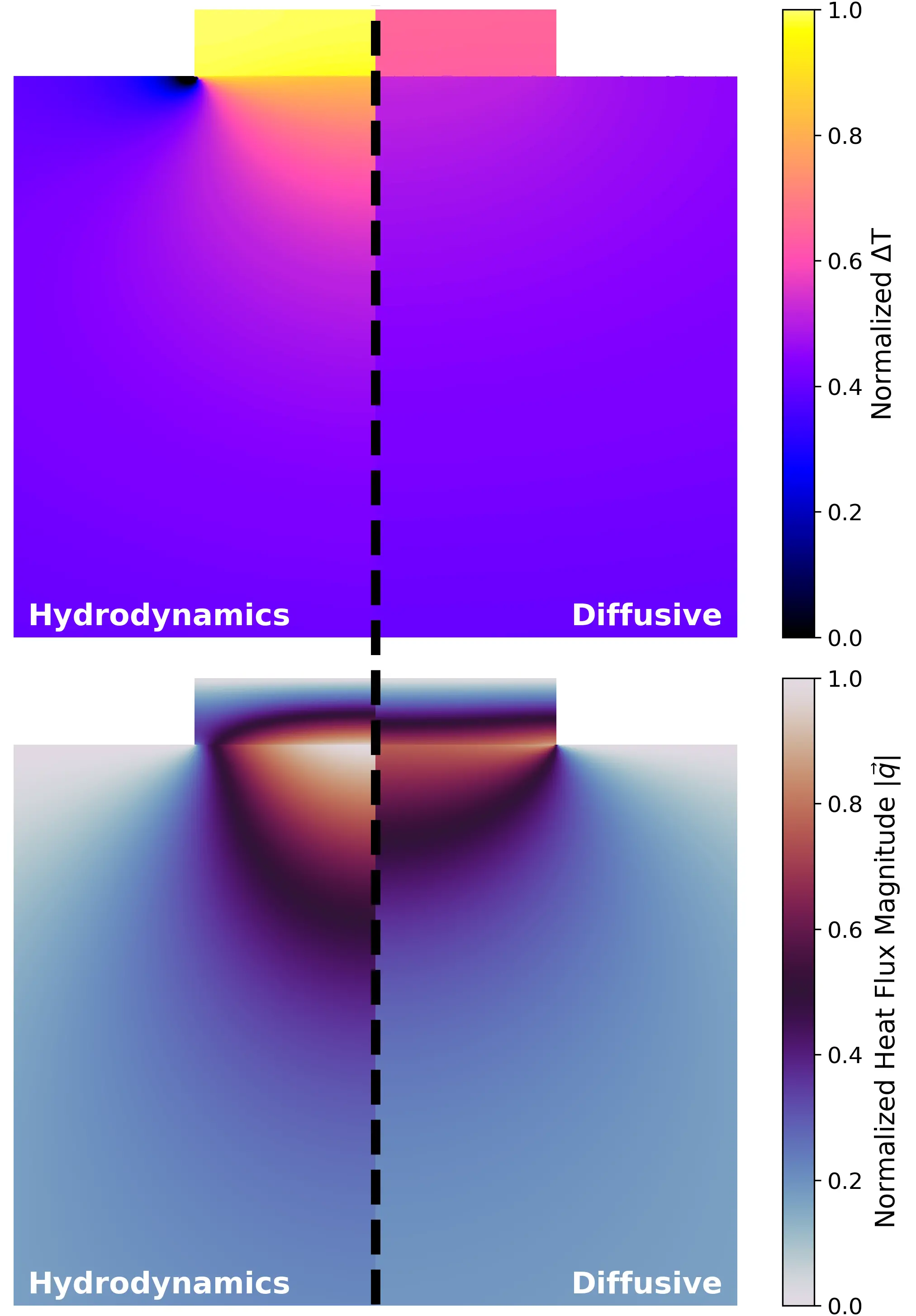

A crucial case of study is the process of heat release from nanoscale structures toward a semiconductor substrate[100-102]. The heat flux profile underneath nanoscale interfaces cannot immediately and locally align with the thermal gradient due to the lack of resistive phonon collisions, leading to inefficient thermal energy evacuation compared to the diffusive prediction. The resulting thermal relaxation of the nanoscale heat sources cannot be described using an effective Fourier’s law with a fitted conductivity or a fitted interfacial thermal resistance[87,101]. From the hydrodynamic perspective, this is a consequence of the emergence of heat vorticity near the corners of the interfaces, where

According to the GKE, the regions that accommodate vorticity display a well-defined characteristic size ℓ (cf. Figure 3). This provides a unified explanation for the transition from diffusive to non-diffusive behavior by reducing the characteristic size of the heat source, as has been observed using different experimental techniques. First, the GKE with ab initio parameters[32] accurately predicts the stationary thermoreflectance profile measured around electrically-excited gold nanostructures with different sizes and shapes on top of a silicon substrate[40,103]. In contrast, the full temperature profile cannot be reproduced using Fourier’s law even with effective parameters[101,103]. Second, the same hydrodynamic modeling and parameter values also capture the thermoelastic relaxation of nanoscale heat sources on silicon following pulsed optical excitation[87]. Remarkably, the temperature decay in these experiments displays a double-exponential function form, with the first time scale associated to the interfacial thermal resistance and the second to the non-local length scale. Hence, these results provide direct evidence of a single characteristic phonon interaction scale, strongly supporting the occurrence of hydrodynamic phonon evolution in silicon at room temperature[87].

Figure 3. Illustration of the temperature and heat flux profiles in a metallic nanostructure releasing heat toward a semiconductor substrate. We consider a stationary situation where a constant and homogeneous power density is injected in the nanostructures. The left side of the figures show a hydrodynamic shape as predicted by the GKE, which is representative of situations where the interface width is comparable to the non-local length ℓ. The right side shows a diffusive shape corresponding to an interface width much larger than ℓ. GKE: Guyer-Krumhansl equation.

Although hydrodynamic modeling shows general agreement with experiments for nanoscale heat sources with characteristic sizes down to tens of nanometers, it has been shown to fail where the spacing between adjacent heat sources is smaller than ~2ℓ. In these cases, non-local heat flux correlations and vorticity effects appear to be geometrically constrained, leading to faster thermal relaxation compared to isolated heat sources[104]. This counter-intuitive effect is not captured by the GKE with ab initio inputs, but can be reproduced by geometrically constraining the non-local length value[87].

4.3 Transient grating experiments

The Transient Grating (TG) technique is a popular experimental method to investigate the onset of non-diffusive transport effects at the nanoscale. Here, two optical pulses interfere to generate a sinusoidal power density pattern in the sample, and the subsequent relaxation is measured to identify the transport mechanisms during the temperature field homogenization[105,106]. This technique enables identifying a reduction of the apparent thermal conductivity at high temperatures by reducing the transient grating period in a variety of materials, including silicon[106] and graphite[60].

Within the hydrodynamic framework, this apparent reduction in conductivity is interpreted as a viscous effect arising from a strongly non-uniform heat flux profile. In situations where the grating period P approaches the ab initio value of the non-local length ℓ, the GKE predicts the emergence of viscosity and a highly impeded heat flow, in good agreement with experiments in silicon[107]. However, similar to the experiments in nanostructures, the predictive power of the GKE with ab initio inputs is limited to relatively small ratios ℓ/P, preventing accurate predictions of thermal relaxation under nanometer scale optical excitations[108]. Moreover, the viscous effect based on a characteristic non-local length scale, as predicted by the GKE, is inadequate to explain TG experiments in alloys, where the apparent thermal conductivity decreases over multiple orders of magnitude with decreasing grating period[109,110].

Transient grating experiments have also been employed to investigate the other form of hydrodynamic behavior, namely memory effects or second sound. Specifically, an oscillating, wave-like evolution of the thermal field has been observed at temperatures ranging from 100 to 200 K in graphite under small grating period excitations[60,111]. This phenomenon, and other signatures of second sound propagation in similar conditions[61], have been directly predicted using numerical solutions of the BTE with the full collision operator[60,81]. According to the GKE, second sound propagation is only possible in the absence of strong viscous effects[83]. In this regime, where the viscous contribution is small compared to the diffusive and memory terms, the GKE solutions resemble those of the hyperbolic heat equation[112,113], thereby capturing second sound propagation in the TG configuration[52].

4.4 Time- and frequency-domain thermoreflectance

Time- and Frequency-Domain thermoreflectance experiments[114] have been established as one of the main experimental techniques not only to measure intrinsic thermal properties of a wide range of materials, but also to uncover non-diffusive thermal transport mechanisms emerging at the nanoscale[115,116]. Here, the sample is subjected to a time-modulated optical excitation, and the thermal response is monitored by measuring the optical reflectivity of the sample[117]. The ability of the sample to dissipate heat from the transducer or surface region where the energy is injected affects both the amplitude of the thermoreflectance oscillations and their phase relative to the laser power, thus informing about the underlying transport mechanisms within the semiconductor. Once again, experimental measurements at small scales cannot be described using effective Fourier descriptions with a fitted conductivity or interfacial resistance[53,116]. These non-diffusive signatures are a consequence of the same mechanisms inducing the slow relaxation of the nanoheaters discussed above. Indeed, the GKE with the same ab initio calculated inputs can describe non-Fourier signatures in both time-domain[35] and frequency-domain[53] thermoreflectance experiments in silicon and germanium over a wide range of temperatures.

Furthermore, this experimental configuration in the absence of metallic transducers can be used to investigate thermal evolution in response to highly confined energy density sources injecting heat directly into the semiconductor. Similar to nanoscale heat source relaxation experiments, in these conditions the non-local length can become geometrically limited by the penetration depth of the optical excitation. Consequently, the viscous term in the GKE is attenuated, which unlocks the propagation of thermal waves under high-frequency excitations[33,118]. The emergence of second sound in transducerless FDTR experiments can be distinguished from ballistic transport effects because the non-diffusive behavior can be predicted using a single heat flux relaxation time-scale τ, rather than a multiscale phonon scattering spectrum. The observation of this single-scale feature in experiments unambiguously indicates that a fraction of the thermal energy can propagate as a wave even at high temperatures in standard semiconductors, such as germanium[33].

4.5 Molecular dynamics

As evidenced by multiple experiments, the applicability of hydrodynamic modeling with ab initio parameter values is generally limited to length scales comparable or larger than the intrinsic non-local length ℓ, characteristic of a given material and temperature. In principle, this prevents interpretation of molecular dynamics simulations of standard semiconductors such as silicon, which typically consider very small nanostructures due to computational limitations. Nevertheless, a growing body of research shows that some non-equilibrium features observed in molecular dynamics simulations are reminiscent of hydrodynamic behavior, including non-local[119-122] and memory[33,119,123,124] effects. In particular, the heat flux profile established in structures down to a few tens of nanometers size displays a hydrodynamic-like shape that can be accurately fitted using the GKE with effective parameters[120,125,126], suggesting that the phonon population remains strongly correlated even at extremely high Knudsen numbers. This, in turn, indicates that current formulations of hydrodynamic theory with ab initio inputs could be refined and extended to extraordinarily small length scales, down to tens of nanometers.

5. Concluding Remarks and Outstanding Questions

Hydrodynamic models derived directly from the BTE, such as the GKE, represent a powerful framework to connect the ab initio characterization of the phonon transport properties with macroscopic, continuum-level descriptions. As demonstrated by a variety of experiments, this approach is useful to identify the breakdown of Fourier’s law of heat diffusion and predict the thermal response of devices at moderately small length and time scales. Nevertheless, the predictive capabilities of hydrodynamic models with ab initio inputs are generally limited to length or time scales comparable to or larger than the intrinsic value of the non-local length ℓ and the flux relaxation time τ. Although recent theoretical and experimental studies suggest that the applicability of this framework could be extended to smaller scales, a robust connection with ab initio calculations and molecular dynamics simulations is still missing at high Knudsen numbers. In particular, understanding the apparent reduction of the non-local length observed in experiments and molecular dynamics simulations at high Knudsen numbers[87,120] stands as a key objective to push the applicability limits of the GKE with ab initio inputs to smaller scales.

From a phenomenological or experimental point of view, the most-defining feature of hydrodynamic phonon transport is the manifestation of single intrinsic phonon length and time scales, ℓ and τ, characterizing the interaction with boundaries and external heat sources, rather than uncorrelated phonon mode evolution associated with the multiscale phonon mean free path spectrum[18]. This single-scale characteristic is compatible with a wide range of experimental observations in semiconductors such as graphite and silicon. In contrast, a variety of heat transport experiments in alloy semiconductors, such as SiGe, reveal a gradual onset of non-diffusive transport effects spanning multiple orders of magnitude in length scale that is not generally observed in the absence of alloy scattering. Therefore, elucidating and incorporating the role of alloy scattering within the phonon hydrodynamic framework remains as an important outstanding question.

Another crucial open question concerns the fundamental non-equilibrium conditions underlying the emergence of second sound. Experiments reporting this effect involve extremely confined heat sources within the material sample, which effectively attenuate viscosity and enable the manifestation of memory effects. A deeper understanding of the interplay between non-local and memory effects in the presence of extremely confined volumetric heat sources is therefore essential to establish the general conditions necessary for second sound propagation. To address this, further development of direct numerical solvers of the BTE in complex non-equilibrium situations represents a promising option to benchmark hydrodynamic modeling.

More generally, the efforts discussed in this review to identify phonon hydrodynamic behavior and to validate generalized hydrodynamic descriptions of phonon transport at the nanoscale parallel a growing body of work on electron hydrodynamics[44,127-130]. Establishing clear analogies between these two domains, and uncovering possible coupled phonon-electron hydrodynamic regimes[131,132], stands among the most promising directions for advancing our fundamental understanding of nanoscale transport phenomena.

In conclusion, the generalized hydrodynamic perspective presented in this review suggests that nanoscale thermal evolution can be interpreted using fluid-dynamics concepts such as viscosity and vorticity across a broad range of conditions beyond the restrictive applicability limitations that have been traditionally assumed. Since hydrodynamic modeling tools such as the GKE are formulated at the continuum level of description, they can be easily solved in complex conditions using finite elements[43,113] or alternative numerical and analytical methods[29,63]. This framework thus provides a robust theoretical basis for developing advanced thermal management strategies that leverage fluid-dynamics analogies, with potential applications to increase the efficiency and lifetime of energy-conversion and data-processing devices[3,4,113].

Authors contribution

Beardo A: Conceptualization, writing-original draft, writing review & editing.

Tur-Prats J: Conceptualization, visualization, writing review & editing.

Camacho J, Alvarez FX: Conceptualization, writing review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work is supported by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovacion y Universidades under Grant No.PID2021-122322NB-I00 and TED2021-129612B-C22 (MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER UE) and the AGAUR-Generalitat de Catalunya under Grant No.2021-SGR-00644.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Ziman JM. Electrons and phonons. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1963. Available from: https://global.oup.com/electrons-and-phonons

-

2. Chen G. Nanoscale energy transport and conversion: A parallel treatment of electrons, molecules, phonons, and photons. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/book/54665

-

3. Waldrop MM. The chips are down for Moore’s law. Nature. 2016;530(7589):144.[DOI]

-

4. Warzoha RJ, Wilson AA, Donovan BF, Donmezer N, Giri A, Hopkins PE, et al. Applications and impacts of nanoscale thermal transport in electronics packaging. J Electron Packag. 2021;143(2):020804.[DOI]

-

5. Esfarjani K, Chen G, Stokes HT. Heat transport in silicon from first-principles calculations. Phys Rev B. 2011;84(8):085204.[DOI]

-

6. Casimir HBG. Note on the conduction of heat in crystals. Physica. 1938;5(6):495-500.[DOI]

-

7. Chen G. Ballistic-diffusive heat-conduction equations. Phys Rev Lett. 2001;86(11):2297-2300.[DOI]

-

8. Lacroix D, Joulain K, Lemonnier D. Monte Carlo transient phonon transport in silicon and germanium at nanoscales. Phys Rev B. 2005;72(6):064305.[DOI]

-

9. Minnich AJ, Johnson JA, Schmidt AJ, Esfarjani K, Dresselhaus MS, Nelson KA, et al. Thermal conductivity spectroscopy technique to measure phonon mean free paths. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;107(9):095901.[DOI]

-

10. Maznev AA, Johnson JA, Nelson KA. Onset of nondiffusive phonon transport in transient thermal grating decay. Phys Rev B. 2011;84(19):195206.[DOI]

-

11. Vermeersch B, Carrete J, Mingo N, Shakouri A. Superdiffusive heat conduction in semiconductor alloys. I. Phys Rev B. 2015;91(8):085202.[DOI]

-

12. Callaway J. Model for lattice thermal conductivity at low temperatures. Phys Rev. 1959;113(4):1046-1051.[DOI]

-

13. Guo Y, Wang M. Heat transport in two-dimensional materials by directly solving the phonon Boltzmann equation under Callaway’s dual relaxation model. Phys Rev B. 2017;96(13):134312.[DOI]

-

14. Péraud JPM, Hadjiconstantinou NG. Efficient simulation of multidimensional phonon transport using energy-based variance-reduced Monte Carlo formulations. Phys Rev B. 2011;84(20):205331.[DOI]

-

15. Vermeersch B, Carrete J, Mingo N, Shakouri A. Superdiffusive heat conduction in semiconductor alloys. I. Phys Rev B. 2015;91(8):085202.[DOI]

-

16. Landon CD, Hadjiconstantinou NG. Deviational simulation of phonon transport in graphene ribbons with ab initio scattering. J Appl Phys. 2014;116(16):163502.[DOI]

-

17. Fu B, Parrish KD, Kim HY, Tang G, McGaughey AJH. Phonon confinement and transport in ultrathin films. Phys Rev B. 2020;101(4):045417.[DOI]

-

18. Beardo A, Chen W, McBennett B, Karimzadeh Sabet T, Nelson EE, Culman TH, et al. Nanoscale confinement of phonon flow and heat transport. npj Comput Mater. 2025;11(1):172.[DOI]

-

19. Guo Y, Wang M. Phonon hydrodynamics and its applications in nanoscale heat transport. Phys Rep. 2015;595:1-44.[DOI]

-

20. Lee S, Li X. Hydrodynamic phonon transport: Past, present and prospects. In: Liao B, editor. Nanoscale energy transport: Emerging phenomena, methods and applications. Bristol: IOP Publishing; 2020. p. 1-26. Available from: https://iopscience.iop.org/book/edit/978-0-7503-1738-2/chapter/bk978-0-7503-1738-2ch1#bk978-0-7503-1738-2ch1s1-7

-

21. Benenti G, Donadio D, Lepri S, Livi R. Non-Fourier heat transport in nanosystems. Riv Nuovo Cimento. 2023;46(3):105-161.[DOI]

-

22. Ghosh K, Kusiak A, Battaglia JL. Phonon hydrodynamics in crystalline materials. J Phys Condens Matter. 2022;34(32):323001.[DOI]

-

23. Kovács R. Heat equations beyond Fourier: From heat waves to thermal metamaterials. Phys Rep. 2024;1048:1-75.[DOI]

-

24. Sussmann J, Thellung A. Thermal conductivity of perfect dielectric crystals in the absence of Umklapp processes. Proc Phys Soc. 1963;81(6):1122.[DOI]

-

25. Hardy RJ, Albers DL. Hydrodynamic approximation to the phonon Boltzmann equation. Phys Rev B. 1974;10(8):3546-3551.[DOI]

-

26. Guyer RA, Krumhansl JA. Solution of the linearized phonon boltzmann equation. Phys Rev. 1966;148(2):766-778.[DOI]

-

27. Guyer RA, Krumhansl JA. Thermal conductivity, second sound, and phonon hydrodynamic phenomena in nonmetallic crystals. Phys Rev. 1966;148(2):778-788.[DOI]

-

28. Beck H, Meier PF, Thellung A. Phonon hydrodynamics in solids. Phys Status Solidi A. 1974;24(1):11-63.[DOI]

-

29. Kovács R, Ván P. Generalized heat conduction in heat pulse experiments. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2015;83:613-620.[DOI]

-

30. Guo Y, Wang M. Phonon hydrodynamics for nanoscale heat transport at ordinary temperatures. Phys Rev B. 2018;97(3):035421.[DOI]

-

31. Shang MY, Zhang C, Guo Z, Lü JT. Heat vortex in hydrodynamic phonon transport of two-dimensional materials. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):8272.[DOI]

-

32. Sendra L, Beardo A, Torres P, Bafaluy J, Alvarez FX, Camacho J. Derivation of a hydrodynamic heat equation from the phonon Boltzmann equation for general semiconductors. Phys Rev B. 2021;103(14):L140301.[DOI]

-

33. Beardo A, López-Suárez M, Pérez LA, Sendra L, Alonso MI, Melis C, et al. Observation of second sound in a rapidly varying temperature field in Ge. Sc Adv. 2021;7(27):eabg4677.[DOI]

-

34. Raya-Moreno M, Carrete J, Cartoixà X. Hydrodynamic signatures in thermal transport in devices based on two-dimensional materials: An ab initio study. Phys Rev B. 2022;106(1):014308.[DOI]

-

35. Xiang Z, Jiang P, Yang R. Time-domain thermoreflectance (TDTR) data analysis using phonon hydrodynamic model. J Appl Phys. 2022;132(20):205104.[DOI]

-

36. Shang MY, Mao WH, Yang N, Li B, Lü JT. Unified theory of second sound in two-dimensional materials. Phys Rev B. 2022;105(16):165423.[DOI]

-

37. Tur-Prats J, Gutiérrez-Pérez M, Bafaluy J, Camacho J, Alvarez FX, Beardo A. Microscopic origin of heat vorticity in quasi-ballistic phonon transport. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2024;226:125464.[DOI]

-

38. Yadav U, Goutham CNS, Meshram K, Pathak A, Bansal D, Agrawal A. Derivation of the generalized heat transport equation and comparison with existing models. Phys Rev Appl. 2025;24(3):034024.[DOI]

-

39. Hardy RJ. Phonon Boltzmann equation and second sound in solids. Phys Rev B. 1970;2(4):1193-1207.[DOI]

-

40. Beardo A, Alajlouni S, Sendra L, Bafaluy J, Ziabari A, Xuan Y, et al. Hydrodynamic thermal transport in silicon at temperatures ranging from 100 to 300 K. Phys Rev B. 2022;105(16):165303.[DOI]

-

41. Crawford DE, Zeng Y, Vidal J, Dong J. Time-domain theory of transient heat conduction in the local limit. Phys Rev B. 2025;112(11):115201.[DOI]

-

42. Alvarez FX, Jou D. Memory and nonlocal effects in heat transport: From diffusive to ballistic regimes. Appl Phys Lett. 2007;90(8):083109.[DOI]

-

43. Beardo A, Calvo-Schwarzwälder M, Camacho J, Myers T, Torres P, Sendra L, et al. Hydrodynamic heat transport in compact and holey silicon thin films. Phys Rev Appl. 2019;11(3):034003.[DOI]

-

44. Gurzhi RN. Hydrodynamic effects in solids at low temperature. Sov Phys Usp. 1968;11(2):255.[DOI]

-

45. Ding Z, Zhou J, Song B, Chiloyan V, Li M, Liu TH, et al. Phonon hydrodynamic heat conduction and knudsen minimum in graphite. Nano Lett. 2018;18(1):638-649.[DOI]

-

46. Xu M. Thermal oscillations, second sound and thermal resonance in phonon hydrodynamics. Proc R Soc A. 2021;477(2247):20200913.[DOI]

-

47. Yu C, Ouyang Y, Chen J. A perspective on the hydrodynamic phonon transport in two-dimensional materials. J Appl Phys. 2021;130(1):010902.[DOI]

-

48. Lee S, Broido D, Esfarjani K, Chen G. Hydrodynamic phonon transport in suspended graphene. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):6290.[DOI]

-

49. Cepellotti A, Fugallo G, Paulatto L, Lazzeri M, Mauri F, Marzari N. Phonon hydrodynamics in two-dimensional materials. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):6400.[DOI]

-

50. Torres P, Torelló A, Bafaluy J, Camacho J, Cartoixà X, Alvarez FX. First principles kinetic-collective thermal conductivity of semiconductors. Phys Rev B. 2017;95(16):165407.[DOI]

-

51. Ghosh K, Kusiak A, Battaglia JL. Effect of characteristic size on the collective phonon transport in crystalline GeTe. Phys Rev Mater. 2021;5(7):073605.[DOI]

-

52. Tur-Prats J, Han Z, Beardo A, Ruan X, Alvarez FX. High-order anharmonicities shape phonon hydrodynamic effects in graphene. Nano Lett. 2025;25(29):11203-11209.[DOI]

-

53. Beardo A, Hennessy MG, Sendra L, Camacho J, Myers TG, Bafaluy J, et al. Phonon hydrodynamics in frequency-domain thermoreflectance experiments. Phys Rev B. 2020;101(7):075303.[DOI]

-

54. Both S, Czél B, Fülöp T, Gróf G, Gyenis Á, Kovács R, et al. Deviation from the Fourier law in room-temperature heat pulse experiments. J Non-Equilib Thermodyn. 2016;41(1):41-48.[DOI]

-

55. Sellitto A, Cimmelli VA, Jou D. Mesoscopic theories of heat transport in nanosystems Cham: Springer; 2016.[DOI]

-

56. Jackson HE, Walker CT, McNelly TF. Second sound in NaF. Phys Rev Lett. 1970;25(1):26-28.[DOI]

-

57. Narayanamurti V, Dynes RC. Observation of second sound in bismuth. Phys Rev Lett. 1972;28(22):1461-1465.[DOI]

-

58. Machida Y, Subedi A, Akiba K, Miyake A, Tokunaga M, Akahama Y, et al. Observation of Poiseuille flow of phonons in black phosphorus. Sci Adv. 2018;4(6):eaat3374.[DOI]

-

59. Huang X, Guo Y, Wu Y, Masubuchi S, Watanabe K, Taniguchi T, et al. Observation of phonon Poiseuille flow in isotopically purified graphite ribbons. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):2044.[DOI]

-

60. Huberman S, Duncan RA, Chen K, Song B, Chiloyan V, Ding Z, et al. Observation of second sound in graphite at temperatures above 100 K. Science. 2019;364(6438):375-379.[DOI]

-

61. Jeong J, Li X, Lee S, Shi L, Wang Y. Transient hydrodynamic lattice cooling by picosecond laser irradiation of graphite. Phys Rev Lett. 2021;127(8):085901.[DOI]

-

62. HYPERLINK "https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/3-540-32386-4" \l "author-0-0" Struchtrup H. Macroscopic transport equations for rarefied gas flows. Heidelberg: Springer; 2005.[DOI]

-

63. Sellitto A, Carlomagno I, Jou D. Two-dimensional phonon hydrodynamics in narrow strips. Proc R Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2015;471(2182):200150376.[DOI]

-

64. Rezgui H, Nasri F, Ali ABH, Guizani AA. Analysis of the ultrafast transient heat transport in sub 7-nm SOI FinFETs technology nodes using phonon hydrodynamic equation. IEEE Trans Electron Devices. 2021;68(1):10-16.[DOI]

-

65. Broido DA, Malorny M, Birner G, Mingo N, Stewart DA. Intrinsic lattice thermal conductivity of semiconductors from first principles. Appl Phys Lett. 2007;91(23):231922.[DOI]

-

66. Lindsay L, Hua C, Ruan XL, Lee S. Survey of ab initio phonon thermal transport. Mater Today Phys. 2018;7:106-120.[DOI]

-

67. Sendra L, Beardo A, Bafaluy J, Torres P, Alvarez FX, Camacho J. Hydrodynamic heat transport in dielectric crystals in the collective limit and the drifting/driftless velocity conundrum. Phys Rev B. 2022;106(15):155301.[DOI]

-

68. Broido DA, Ward A, Mingo N. Lattice thermal conductivity of silicon from empirical interatomic potentials. Phys Rev B. 2005;72(1):014308.[DOI]

-

69. Sun Y, Liu W, Guo Y, Yi HL. Heat dissipation from nanoscale heat sources by phonon hydrodynamic model. Int J Therm Sci. 2026;222:110597.[DOI]

-

70. Sobolev SL. Discrete heat conduction equation: Dispersion analysis and continuous limits. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2024;221:125062.[DOI]

-

71. Dong Y, Cao BY, Guo ZY. Generalized heat conduction laws based on thermomass theory and phonon hydrodynamics. J Appl Phys. 2011;110(6):063504.[DOI]

-

72. Sciacca M, Jou D. Nonlinear Guyer-Krumhansl equation and its boundary conditions in nanolayers. Z Angew Math Phys. 2025;76(3):105.[DOI]

-

73. Struchtrup H. Phonon hydrodynamics revisited. In: Fuhrmann J, Hömberg D, Müller WH, Weiss W, editors, editor. Advances in continuum physics: In Memoriam Wolfgang Dreyer. Cham: Springer; 2025. p. 795-822.[DOI]

-

74. Cepellotti A, Marzari N. Thermal transport in crystals as a kinetic theory of relaxons. Phys Rev X. 2016;6(4):041013.[DOI]

-

75. Cepellotti A, Marzari N. Boltzmann transport in nanostructures as a friction effect. Nano Lett. 2017;17(8):4675-4682.[DOI]

-

76. Simoncelli M, Marzari N, Cepellotti A. Generalization of Fourier’s law into viscous heat equations. Phys Rev X. 2020;10(1):011019.[DOI]

-

77. Omini M, Sparavigna A. An iterative approach to the phonon Boltzmann equation in the theory of thermal conductivity. Physica B Condens Matter. 1995;212(2):101-112.[DOI]

-

78. Li X, Lee S. Role of hydrodynamic viscosity on phonon transport in suspended graphene. Phys Rev B. 2018;97(9):094309.[DOI]

-

79. Nie BD, Cao BY. Thermal wave in phonon hydrodynamic regime by phonon Monte Carlo simulations. Nanoscale Microscale Thermophys Eng. 2020;24(2):94-122.[DOI]

-

80. Malviya N, Ravichandran NK. Callaway approximation to the Boltzmann equation fails to predict phonon hydrodynamics. J Phys Condens Matter. 2025.[DOI]

-

81. Chiloyan V, Huberman S, Ding Z, Mendoza J, Maznev AA, Nelson KA, et al. Green’s functions of the Boltzmann transport equation with the full scattering matrix for phonon nanoscale transport beyond the relaxation-time approximation. Phys Rev B. 2021;104(24):245424.[DOI]

-

82. Tzou DY. A unified field approach for heat conduction from macro- to micro-scales. J Heat Transf. 1995;117(1):8-16.[DOI]

-

83. Gandolfi M, Benetti G, Glorieux C, Giannetti C, Banfi F. Accessing temperature waves: A dispersion relation perspective. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2019;143:118553.[DOI]

-

84. Guo Y, Jou D, Wang M. Nonequilibrium thermodynamics of phonon hydrodynamic model for nanoscale heat transport. Phys Rev B. 2018;98(10):104304.[DOI]

-

85. Jou D, Casas-Vazquez J, Lebon G. Extended irreversible thermodynamics. Rep Prog Phys. 1988;51(8):1105.[DOI]

-

86. Liu W, Guo Y. Basal-plane heat transport in three-dimensional graphite ribbons. Phys Rev B. 2024;110(15):155429.[DOI]

-

87. Beardo A, Knobloch JL, Sendra L, Bafaluy J, Frazer TD, Chao W, et al. A general and predictive understanding of thermal transport from 1D- and 2D-confined nanostructures: Theory and experiment. ACS Nano. 2021;15(8):13019-13030.[DOI]

-

88. Asheghi M, Kurabayashi K, Kasnavi R, Goodson KE. Thermal conduction in doped single-crystal silicon films. J Appl Phys. 2002;91(8):5079-5088.[DOI]

-

89. Song D, Chen G. Thermal conductivity of periodic microporous silicon films. Appl Phys Lett. 2004;84(5):687-689.[DOI]

-

90. Poudel B, Hao Q, Ma Y, Lan Y, Minnich A, Yu B, et al. High-thermoelectric performance of nanostructured bismuth antimony telluride bulk alloys. Science. 2008;320(5876):634-638.[DOI]

-

91. Xu M. Slip boundary condition of heat flux in Knudsen layers. Proc R Soc A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2014;470(2161):20130578.[DOI]

-

92. Alvarez FX, Jou D, Sellitto A. Phonon hydrodynamics and phonon-boundary scattering in nanosystems. J Appl Phys. 2009;105(1):014317.[DOI]

-

93. Zhu CY, You W, Li ZY. Nonlocal effects and slip heat flow in nanolayers. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):9568.[DOI]

-

94. Cheaito R, Duda JC, Beechem TE, Hattar K, Ihlefeld JF, Medlin DL, et al. Experimental investigation of size effects on the thermal conductivity of silicon-germanium alloy thin films. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;109(19):195901.[DOI]

-

95. Wang Z, Mingo N. Diameter dependence of SIGe nanowire thermal conductivity. Appl Phys Lett. 2010;97(10):101903.[DOI]

-

96. Sjakste J, Markov M, Sen R, Fugallo G, Paulatto L, Vast N. Occurrence of the collective Ziman limit of heat transport in cubic semiconductors Si, De, AlAs and AlP: Scattering channels and size effects. Nano Express. 2024;5(3):035018.[DOI]

-

97. Kawabata T, Shimura K, Ishii Y, Koike M, Yoshida K, Yonehara S, et al. Phonon hydrodynamic regimes in sapphire. Phys Rev Res. 2025;7(3):033017.[DOI]

-

98. Liu W, Yuan WZ, Guo Y. Size effect on phonon Knudsen minimum in three-dimensional graphite ribbons. J Appl Phys. 2025;138(10):104303.[DOI]

-

99. Jeon W, Pei Y, Li X, Lindsay L, Lee S, Chen R. Grain boundary-limited thermal transport in suspended thin graphite across an unexplored thickness regime. Nano Lett. 2025;25(38):14074-14081.[DOI]

-

100. Siemens ME, Li Q, Yang R, Nelson KA, Anderson EH, Murnane MM, et al. Quasi-ballistic thermal transport from nanoscale interfaces observed using ultrafast coherent soft X-ray beams. Nat Mater. 2010;9(1):26-30.[DOI]

-

101. Ziabari A, Torres P, Vermeersch B, Xuan Y, Cartoixà X, Torelló A, et al. Full-field thermal imaging of quasiballistic crosstalk reduction in nanoscale devices. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):255.[DOI]

-

102. Hu Y, Zeng L, Minnich AJ, Dresselhaus MS, Chen G. Spectral mapping of thermal conductivity through nanoscale ballistic transport. Nat Nanotechnol. 2015;10(8):701-706.[DOI]

-

103. Alajlouni S, Beardo A, Sendra L, Ziabari A, Bafaluy J, Camacho J, et al. Geometrical quasi-ballistic effects on thermal transport in nanostructured devices. Nano Res. 2021;14(4):945-952.[DOI]

-

104. Hoogeboom-Pot KM, Hernandez-Charpak JN, Gu X, Frazer TD, Anderson EH, Chao W, et al. A new regime of nanoscale thermal transport: Collective diffusion increases dissipation efficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112(16):4846-4851.[DOI]

-

105. Eichler H, Salje G, Stahl H. Thermal diffusion measurements using spatially periodic temperature distributions induced by laser light. J Appl Phys. 1973;44(12):5383-5388.[DOI]

-

106. Johnson JA, Maznev AA, Cuffe J, Eliason JK, Minnich AJ, Kehoe T, et al. Direct measurement of room-temperature nondiffusive thermal transport over micron distances in a silicon membrane. Phys Rev Lett. 2013;110(2):025901.[DOI]

-

107. Torres P, Ziabari A, Torelló A, Bafaluy J, Camacho J, Cartoixà X, et al. Emergence of hydrodynamic heat transport in semiconductors at the nanoscale. Phys Rev Mater. 2018;2(7):076001.[DOI]

-

108. Bencivenga F, Mincigrucci R, Capotondi F, Foglia L, Naumenko D, Maznev AA, et al. Nanoscale transient gratings excited and probed by extreme ultraviolet femtosecond pulses. Sci Adv. 2019;5(7):eaaw5805.[DOI]

-

109. Vermeersch B, Mohammed AMS, Pernot G, Koh YR, Shakouri A. Superdiffusive heat conduction in semiconductor alloys. II. Phys Rev B. 2015;91(8):085203.[DOI]

-

110. Huberman S, Chiloyan V, Duncan RA, Zeng L, Jia R, Maznev AA, et al. Unifying first-principles theoretical predictions and experimental measurements of size effects in thermal transport in SiGe alloys. Phys Rev Mater. 2017;1(5):054601.[DOI]

-

111. Ding Z, Chen K, Song B, Shin J, Maznev AA, Nelson KA, et al. Observation of second sound in graphite over 200 K. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):285.[DOI]

-

112. Rogolino P, Kovács R, Ván P, Cimmelli VA. Generalized heat-transport equations: Parabolic and hyperbolic models. Contin Mech Thermodyn. 2018;30(6):1245-1258.[DOI]

-

113. Rezgui H. Phonon hydrodynamic transport: Observation of thermal wave-like flow and second sound propagation in graphene at 100 K. ACS Omega. 2023;8(26):23964-23974.[DOI]

-

114. Mohan R, Khan S, Wilson RB, Hopkins PE. Time-domain thermoreflectance. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2025;5(1):55.[DOI]

-

115. Regner KT, Sellan DP, Su Z, Amon CH, McGaughey AJH, Malen JA. Broadband phonon mean free path contributions to thermal conductivity measured using frequency domain thermoreflectance. Nat Commun. 2013;4(1):1640.[DOI]

-

116. Wilson RB, Cahill DG. Anisotropic failure of Fourier theory in time-domain thermoreflectance experiments. Nat Commun. 2014;5(1):5075.[DOI]

-

117. Jiang P, Qian X, Yang R. Tutorial: Time-domain thermoreflectance (TDTR) for thermal property characterization of bulk and thin film materials. J Appl Phys. 2018;124(16):161103.[DOI]

-

118. Camacho de la Rosa A, Esquivel-Sirvent R, Becerril D. Relaxation times of non-fourier materials using frequency-domain thermoreflectance. J Appl Phys. 2025;137(15):155103.[DOI]

-

119. Melis C, Fugallo G, Colombo L. Room temperature second sound in cumulene. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2021;23(28):15275-15281.[DOI]

-

120. McBennett B, Beardo A, Nelson EE, Abad B, Frazer TD, Adak A, et al. Universal behavior of highly confined heat flow in semiconductor nanosystems: From nanomeshes to metalattices. Nano Lett. 2023;23(6):2129-2136.[DOI]

-

121. Dionne CJ, Thakur S, Scholz N, Hopkins P, Giri A. Enhancing the thermal conductivity of semiconductor thin films via phonon funneling. npj Comput Mater. 2024;10(1):177.[DOI]

-

122. Xu K, Li Y, Ding D, Liang T, Wu J, Xu J. Critical size transitions in silicon nanowires: Amorphization, phonon hydrodynamics, and thermal conductivity. J Phys Chem Lett. 2025;16(33):8580-8587.[DOI]

-

123. Savin AV, Kivshar YS. Modeling of second sound in carbon nanostructures. Phys Rev B. 2022;105(20):205414.[DOI]

-

124. Schelling PK, Margolles AM, Echazabal LP. Thermal response functions and second sound in single-layer hexagonal boron nitride. Phys Rev B. 2025;112(2):024307.[DOI]

-

125. Melis C, Rurali R, Cartoixà X, Alvarez FX. Indications of phonon hydrodynamics in telescopic silicon nanowires. Phys Rev Appl. 2019;11(5):054059.[DOI]

-

126. Desmarchelier P, Beardo A, Alvarez FX, Tanguy A, Termentzidis K. Atomistic evidence of hydrodynamic heat transfer in nanowires. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2022;194:123003.[DOI]

-

127. Qi M, Lucas A. Distinguishing viscous, ballistic, and diffusive current flows in anisotropic metals. Phys Rev B. 2021;104(19):195106.[DOI]

-

128. Varnavides G, Yacoby A, Felser C, Narang P. Charge transport and hydrodynamics in materials. Nat Rev Mater. 2023;8(11):726-741.[DOI]

-

129. Aharon-Steinberg A, Völkl T, Kaplan A, Pariari AK, Roy I, Holder T, et al. Direct observation of vortices in an electron fluid. Nature. 2022;607(7917):74-80.[DOI]

-

130. Estrada-Álvarez J, Salvador-Sánchez J, Pérez-Rodríguez A, Sánchez-Sánchez C, Clericò V, Vaquero D, et al. Superballistic conduction in hydrodynamic antidot graphene superlattices. Phys Rev X. 2025;15(1):011039.[DOI]

-

131. Huang X, Lucas A. Electron-phonon hydrodynamics. Phys Rev B. 2021;103(15):155128.[DOI]

-

132. Quan Y, Liao B. Coupled electron-phonon hydrodynamics in two-dimensional semiconductors. Phys Rev Lett. 2025;134(22):226301.[DOI]

-

133. Esfarjani K, Shiomi J. Fundamentals and advances in thermal transport in thermoelectric materials. MRS Bull. 2025;50(8):935-944.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite