Shuming Zeng, College of Physics Science and Technology, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou 225009, Jiangsu, China. E-mail: zengsm@yzu.edu.cn

Abstract

We investigate how metallic rattling modes in Sr2HgSn simultaneously suppress particle-like (κp) and enhance wave-like (κc) thermal conductivity via a combined first-principles, force-constant modulation, and Wigner transport analysis. Weak Hg-Sn bonds generate flat phonon bands that relax momentum conservation, intensifying both three- and four-phonon scattering and shortening phonon lifetimes. This dual scattering-coherence mechanism reveals a frequency-selective κp - κc crossover, leading to a weak temperature-dependent κL. Our work establishes rattling as a tunable design strategy for controlling phonon transport in thermoelectrics.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

1. Introduction

Rattling vibrations, which are large-amplitude, localized oscillations of weakly bound atoms, have emerged as a powerful mechanism for suppressing lattice thermal conductivity κL in thermoelectric materials. By disrupting long-range phonon propagation, rattling modes enhance phonon-phonon scattering and induce glass-like thermal transport in otherwise crystalline solids[1,2]. Key signatures of rattling include avoided crossings between acoustic and optical phonon branches, large atomic displacement parameters, and flat, low-frequency vibrational modes[3,6]. Recent high-throughput screening has further revealed that loosely bonded atoms, identified through simple geometric descriptors such as long bond lengths relative to covalent radii, can reliably indicate rattling behavior, underscoring the statistical robustness and generality of rattling as a design principle for low thermal conductivity[7].

Among the materials exhibiting rattling-induced phonon scattering, full-Heusler compounds with the general formula X2YZ have recently attracted attention for their thermoelectric potential[8-11]. These intermetallics combine semimetallic or narrow-gap electronic structures with the possibility of incorporating heavy, weakly bonded elements in a highly symmetric cubic lattice. In analogy to clathrates and skutterudites[4,12,13], full-Heuslers can host internal “rattlers” that strongly reshape phonon dispersions and scattering pathways, yet the mechanisms underlying their heat transport remain less explored.

Traditional analyses based on the Peierls-Boltzmann transport equation (BTE) attribute thermal resistance to three-phonon (3ph) scattering[14]. However, recent studies have shown that in systems with pronounced rattling behavior and flat phonon bands, four-phonon (4ph) scattering[8,15-18] and wave-like, coherent phonon transport[2,19-21] can play critical roles. This renders BTE approaches insufficient and necessitates the frameworks such as the Wigner transport equation to capture phase-coherent heat flow.

While rattling phenomena have been widely investigated in skutterudites, clathrates, and Zintl phases, the role of metallic rattling bonds in full-Heusler compounds, as well as their distinct impact on phonon dispersion and scattering, remains less explored. Moreover, a quantitative and tunable link between rattling strength, band flatness, and multiphonon scattering within a single material system is still lacking. Additionally, how rattling modes selectively enhance both particle-like scattering and wave-like coherence in a frequency-resolved manner requires further clarification.

In this work, we address these gaps by investigating the full-Heusler compound Sr2HgSn as a model system. Using first-principles lattice dynamics combined with force-constant modulation and Wigner transport analysis, we reveal a tunable, frequency-selective crossover between κP and κc driven by Hg rattling. Our work introduces a quantitative flatness descriptor, correlates rattling strength with 3ph/4ph scattering phase spaces, and demonstrates that metallic rattling in a high-symmetry cubic lattice can simultaneously suppress κP and enhance κc, offering a distinct platform for phonon engineering beyond conventional cage-like structures. These findings advance the understanding of rattling-mediated thermal transport and provide new design strategies for tuning both scattering and coherence in thermoelectric materials.

2. Numerical Methods

The calculations are performed using the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package based on density functional theory[22], employing the projector augmented wave method with the PBEsol exchange-correlation functional (a revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof generalized gradient approximation for solids)[23]. A plane-wave cutoff energy of 500 eV is used. Atomic positions are optimized with an energy convergence criterion of 10-5 eV between consecutive steps and a maximum Hellmann-Feynman force tolerance of 10-3 eV/Å. The primitive cell was optimized using a Γ-centered q-mesh of 13 × 13 × 13 in the Brillouin zone.

For the ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations, the 3 × 3 × 3 supercell was constructed by expanding the primitive cell with Γ-centered 1 × 1 × 1 k-mesh. The simulations run for 30 ps with a 1 fs timestep. Interatomic force constants (IFCs) are extracted from AIMD trajectories using the temperature-dependent effective potential method[24]. Cutoff radii for third-order and fourth-order IFCs are set to 6 Å. The lattice thermal conductivity (κL) and related parameters, including phonon relaxation times, are computed using the ShengBTE software[25,26], which implements an iterative solution scheme. A q-mesh of 13 × 13 × 13 is adopted in the first irreducible Brillouin zone, with a Gaussian smearing width of 0.2. The 4ph scattering rate is efficiently calculated using a maximum likelihood estimation method[27] with a sample size of 4 × 105.

3. Results and Discussion

As a full-Heusler compound with stoichiometry X2YZ (space group

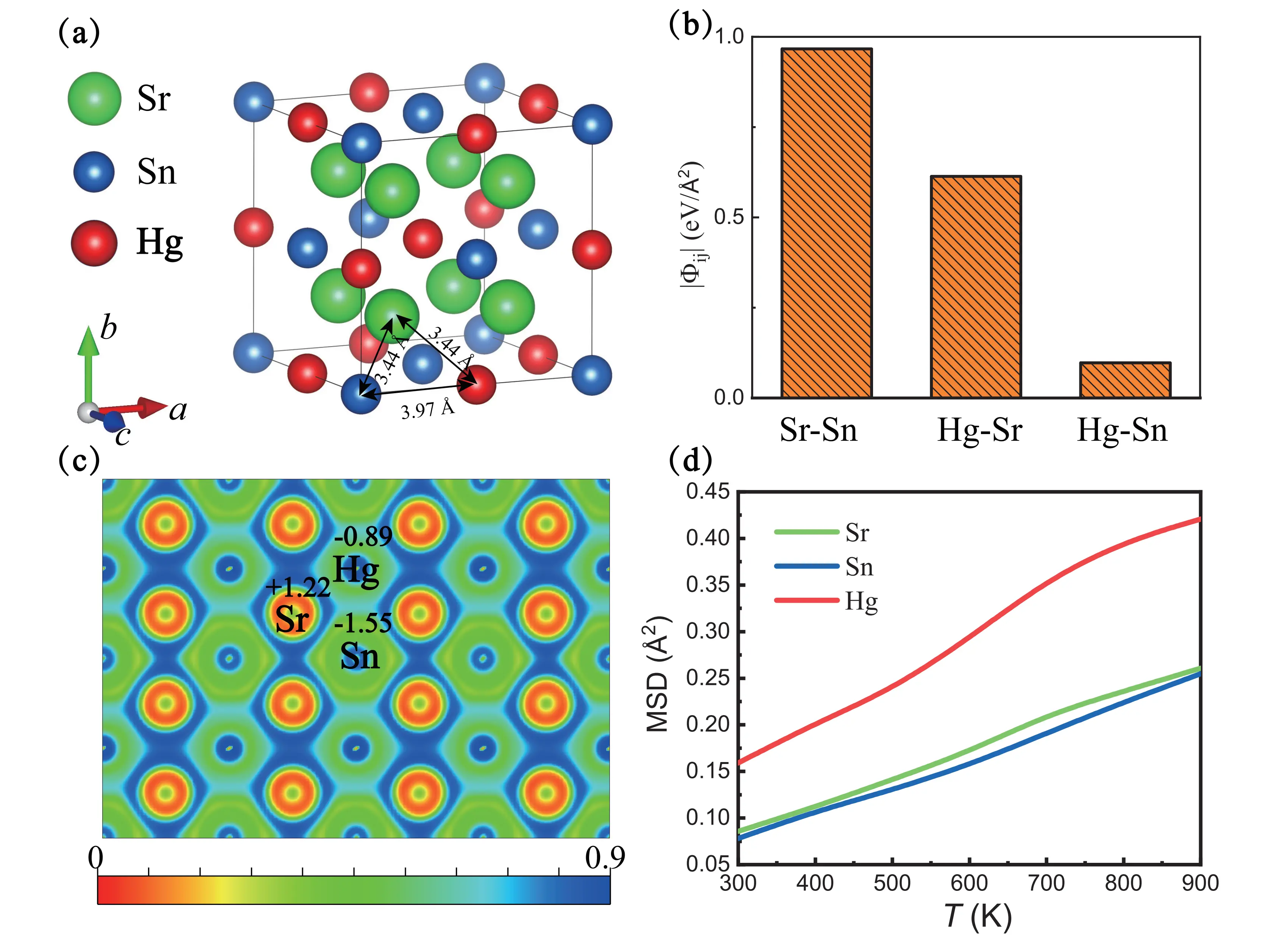

Figure 1. (a) Cubic crystal structure of full-Heusler Sr2HgSn (space group Fm3m) with atomic positions; (b) Interatomic force constants showing bond strengths; (c) ELF and Bader charge analysis revealing the bonding nature; (d) Temperature-dependent atomic MSDs demonstrating lattice dynamics. ELF: electron localization function; MSDs: mean square displacements.

Figure 1d shows the temperature-dependent atomic mean square displacements (MSDs). The weak metallic bonding between Hg and Sn, combined with the overall weak interactions around Hg, results in significantly larger MSDs for Hg compared to Sr and Sn. This rattling-dominated lattice dynamics has important implications for the thermal transport properties discussed in the following sections.

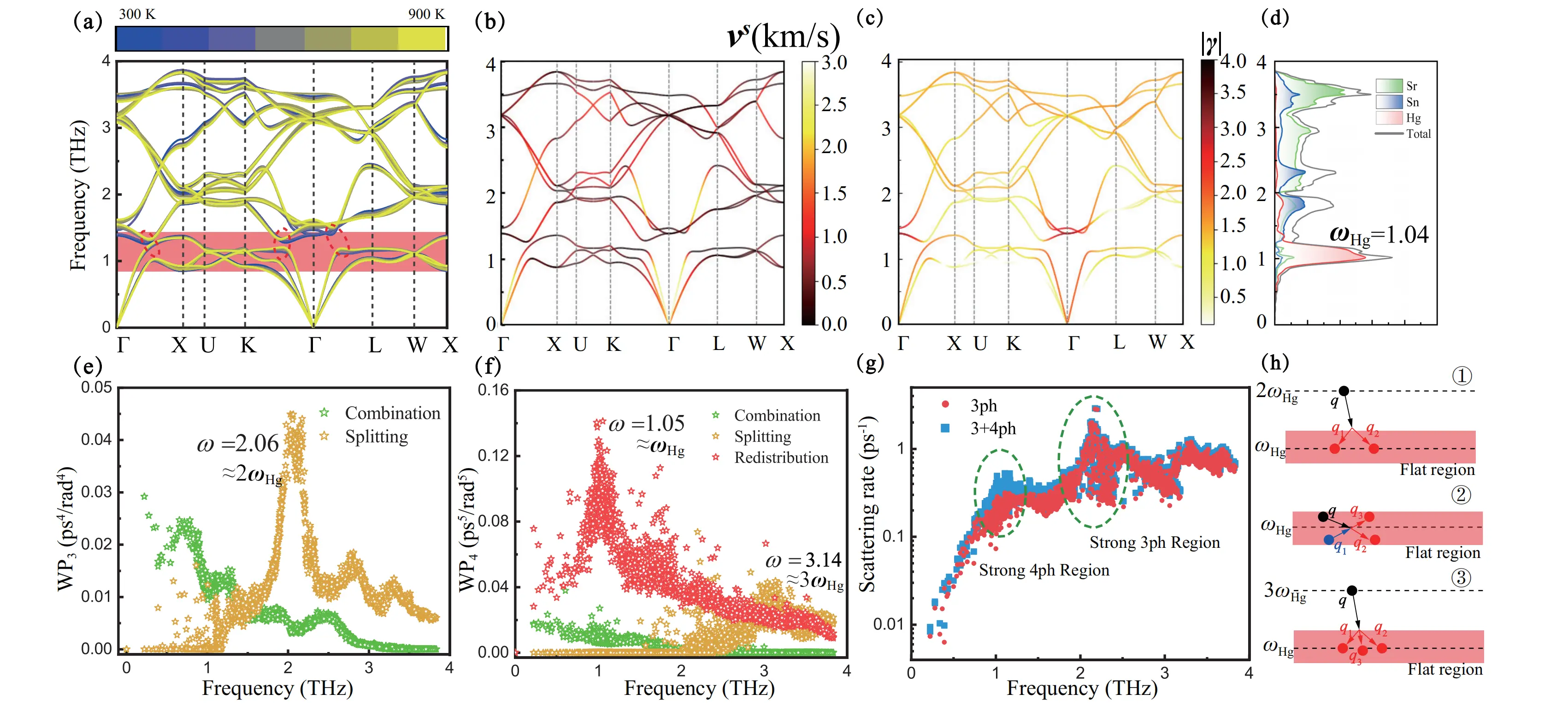

As revealed in Figure 2a, the temperature-evolved phonon dispersion displays characteristic avoided-crossing features between acoustic and optical branches (dashed circles), where the low-frequency optical modes generated by weakly bonded Hg atoms interact with propagating acoustic modes. This dynamic coupling induces phonon branch repulsion while simultaneously exhibiting abnormal hardening with temperature - a fingerprint of rattling behavior where guest atoms oscillate in a weakly constrained potential[5,28,29].

Figure 2. (a) Temperature-dependent phonon dispersion. Red rectangles mark flat phonon band regions and red dashed lines mark avoided crossings; (b) Group velocity-projected phonon dispersion; (c) Grüneisen parameter-projected phonon dispersion; (d) Atom-projected phonon density of states; (e) 3ph scattering phase space showing 2ωHg emission peak; (f) 4ph scattering phase space with ωHg redistribution peak and 3ωHg splitting peak; (g) Total phonon scattering rates with 3ph and processes; (h) Schematic of dominant scattering mechanisms.

The profound impact on thermal transport is quantified in Figure 2b, where group velocity projections expose dramatically flattened dispersions (< 0.5 km/s) near the avoided-crossing region. These sluggish phonon modes, visualized as near-horizontal bands, create intrinsic bottlenecks for heat propagation. Complementary anharmonicity analysis in Figure 2c reveals giant Grüneisen parameters (> 3) localized at the interaction zones, confirming the rattling mechanism generates exceptional bond stiffness variations during atomic vibrations.

The vibrational decomposition in Figure 2d reveals the unique nature of rattling dynamics: while the sharp, Hg-dominated peak at 1.04 THz indicates localized vibrations in momentum space (flat dispersion), the avoided-crossing in Figure 2a demonstrates their delocalized character in real space through hybridization with acoustic phonons. This dual behavior - localized in energy but extended in spatial influence - is a hallmark of rattling systems, where weakly bonded atoms maintain distinct vibrational signatures while strongly perturbing the host lattice dynamics.

The phonon scattering phase space analysis in Figure 2e,f reveals two characteristic peaks originating from the flat rattling modes at 1.04 THz (ωHg). Figure 2e shows a pronounced 3ph emission peak at 2ωHg, resulting from the decay process q → q1 + q2, where energy conservation requires ωq = ωq1 + ωq2 ≈ 2ωHg while momentum selection is relaxed due to the flat dispersion of Hg-derived modes. This enables efficient decay of high-energy phonons into pairs of rattling modes[14].

Similarly, Figure 2f exhibits a 4ph redistribution peak at ωHg from processes q + q1 → q2 + q3 where the flat bands again facilitate momentum conservation[17]. Moreover, a small 4ph splitting peak near 3ωHg from processes q → q1 + q2 + q3 is observed. The combined scattering effects are quantified in Figure 2g, where the total scattering rate displays twin peaks with a lower-frequency peak near ωHg (strong 4ph) and a higher-frequency peak near 2ωHg (strong 3ph).

The microscopic scattering mechanisms are illustrated in Figure 2h, contrasting the 3ph emission (above) and 4ph redistribution (below) processes that dominate at their respective characteristic frequencies. The 3ph process shows a high-frequency phonon splitting into two rattling modes, while the 4ph process depicts the redistribution of phonon populations through collisions between rattling modes.

According to the Wigner transport equation, as derived from the Wigner phase-space formulation of quantum mechanics, the lattice thermal conductivity (κL) in complex crystals consists of two distinct contributions: the particle-like thermal conductivity (κP), describing propagating phonons, and the glass-like coherence term (κc), accounting for wave-like tunneling between phonon modes[30-32].

The particle-like component κP is given by:

Where V is the volume of the primitive unit cell, and Nq represents the number of sampled q-points in the first Brillouin zone,

The glass-like contribution κc emerges from phonon mode interference:

Where h is the reduced Planck constant, κB the Boltzmann constant,

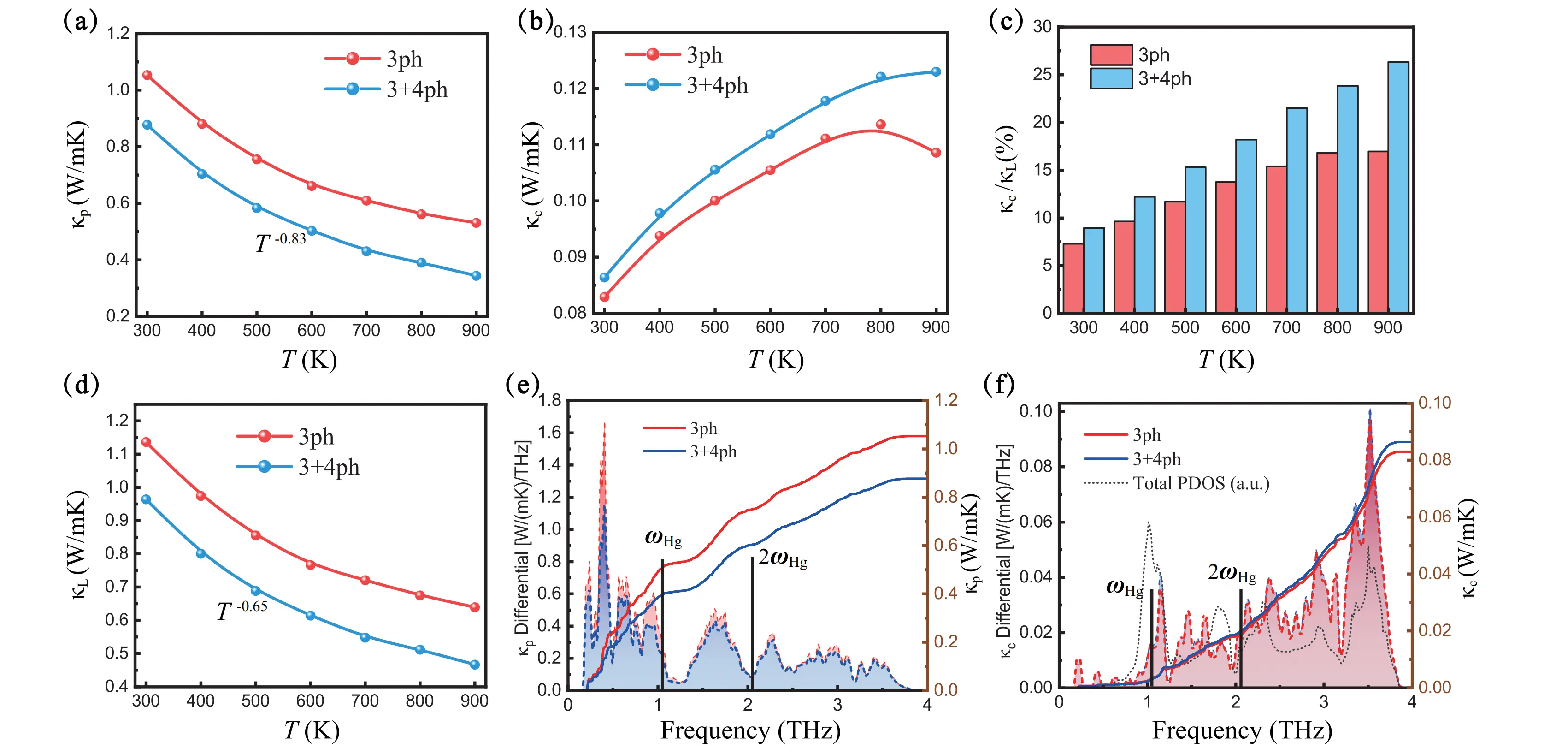

Figure 3 reveals the distinct temperature dependence of thermal transport components. As shown in Figure 3a, κp exhibits a gradual decrease with rising temperature, dropping from 1.05 W/mK at 300 K (considering only 3ph scattering) to 0.88 W/mK when 4ph interactions are included, representing a 16% reduction.

Figure 3. Calculated temperature-dependent (a) κp (b) κc considering 3ph and 3+4ph scattering; (c) The relative contribution of κc to total thermal conductivity κL; (d) Temperature-dependent total lattice thermal conductivity κL; (e) Cumulative and differential κp versus phonon frequency at 300 K; (f) Cumulative and differential κc versus phonon frequency at 300 K.

In contrast, Figure 3b demonstrates that κc follows an increasing trend with temperature. The 4ph effects enhance this contribution, elevating κc from 0.11 W/mK (3ph only) to 0.12 W/mK at 900 K, representing a 9% increase.

The competing temperature dependencies of these components lead to important consequences for the overall thermal transport, as illustrated in Figure 3c. The relative contribution kc/kL grows substantially with temperature, reaching 26% at 900 K when both 3ph and 4ph processes are considered. This enhancement of the glass-like contribution by 4ph scattering highlights the growing importance of wave-like thermal transport at elevated temperatures. Figure 3d presents the temperature evolution of total lattice thermal conductivity κL, which exhibits a weaker temperature dependence

The frequency-resolved analysis in Figure 3e reveals that phonons below 1 THz dominate κp contributions, accounting for 45% of the total κp when including 4ph processes. This predominance stems from their combination of high group velocities and relatively long lifetimes. Two distinct minima appear in the differential κp spectrum. Near ωHg (1.04 THz), the κp suppression results from both the ultralow group velocities of flat rattling modes and enhanced 4ph scattering through redistribution processes (q + q1 → q2 + q3). At 2ωHg (2.08 THz), the minimum arises from 3ph emission (q → q1 + q2) facilitated by the dense, flat Hg-derived rattling modes that provide abundant final states.

Figure 3f demonstrates a complementary relationship between κc and κp. The κc spectrum shows maximum enhancement at ωHg due to 4ph-assisted wave tunneling through the overdamped rattling modes. The peak near 2ωHg arises from enhanced wave-like tunneling between the flat phonon branches induced by Hg rattling modes. Both features correlate strongly with the phonon density of states, as the abundant phonon pairs with small

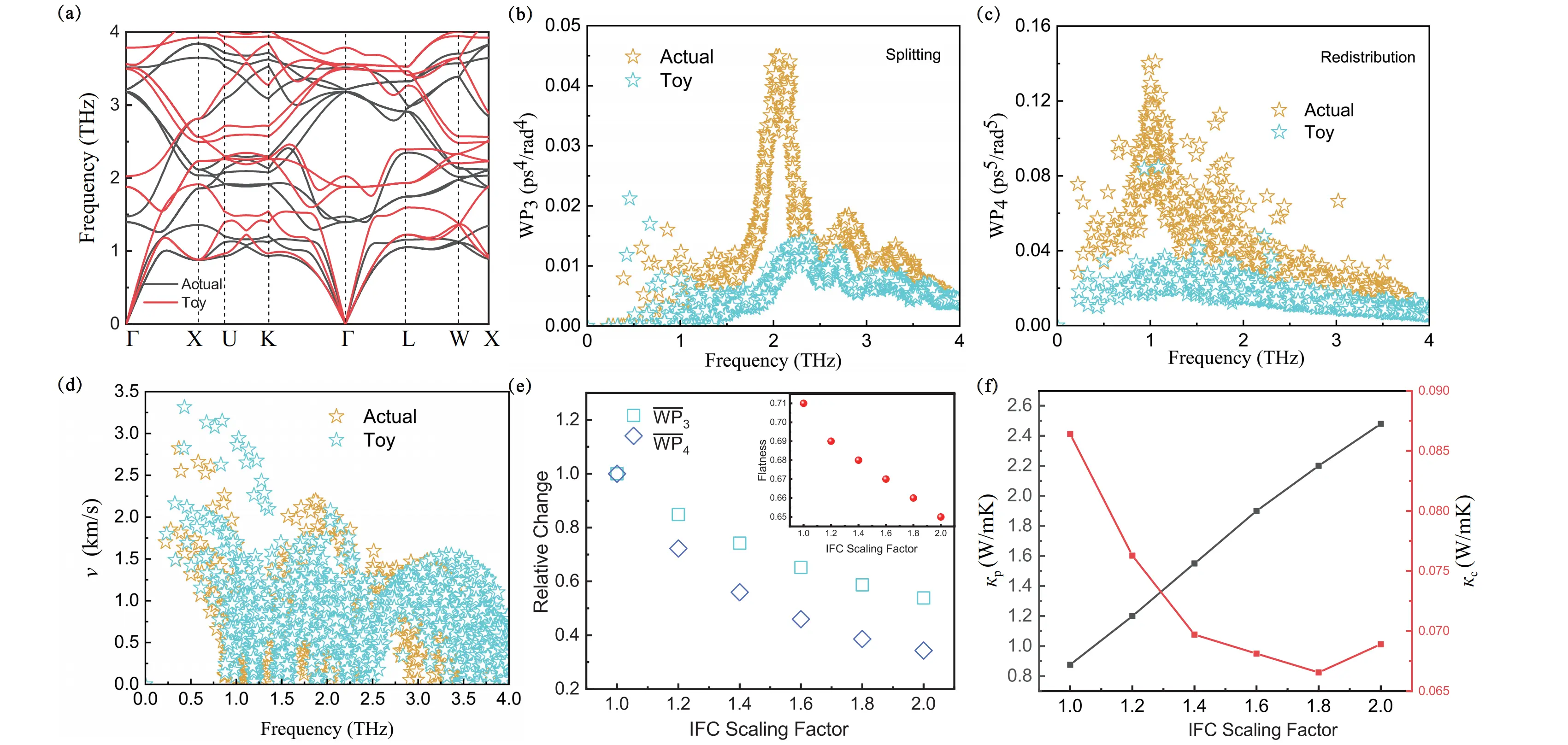

To further validate the causal link between rattling modes and phonon scattering, we systematically tuned the Hg-neighbor force constants and examined the resulting changes in phonon dispersion, scattering phase space, and thermal transport. As shown in Figure 4a, doubling the force constants (“Toy” model) significantly hardens the low-frequency flat phonon bands compared to the natural system (“Actual”), indicating suppressed rattling. Correspondingly, the characteristic peaks in the three-phonon emission (Figure 4b) and four-phonon redistribution (Figure 4c) phase spaces nearly vanish, confirming that these scattering channels are intrinsically tied to rattling-induced band flatness.

Figure 4. Modulation of Hg-neighbor force constants in Sr2HgSn. (a) Phonon dispersion: Actual (black) vs. Toy (red); (b) Three-phonon emission phase space comparison; (c) Four-phonon redistribution phase space comparison; (d) Phonon group velocity remains largely unchanged; (e) Evolution of

Figure 4d shows that phonon group velocities remain largely unchanged, implying that the thermal conductivity variation stems primarily from scattering modulation rather than velocity suppression. The quantitative decrease in band flatness, together with the reduction in average three-phonon

Where σωac and <ωac> denote the standard deviation and mean of acoustic phonon frequencies, respectively. Finally, Figure 4f demonstrates that stiffening the rattling bonds leads to an increase in κp and a decrease in κc, directly correlating rattling softness with the suppression of lattice thermal conductivity.

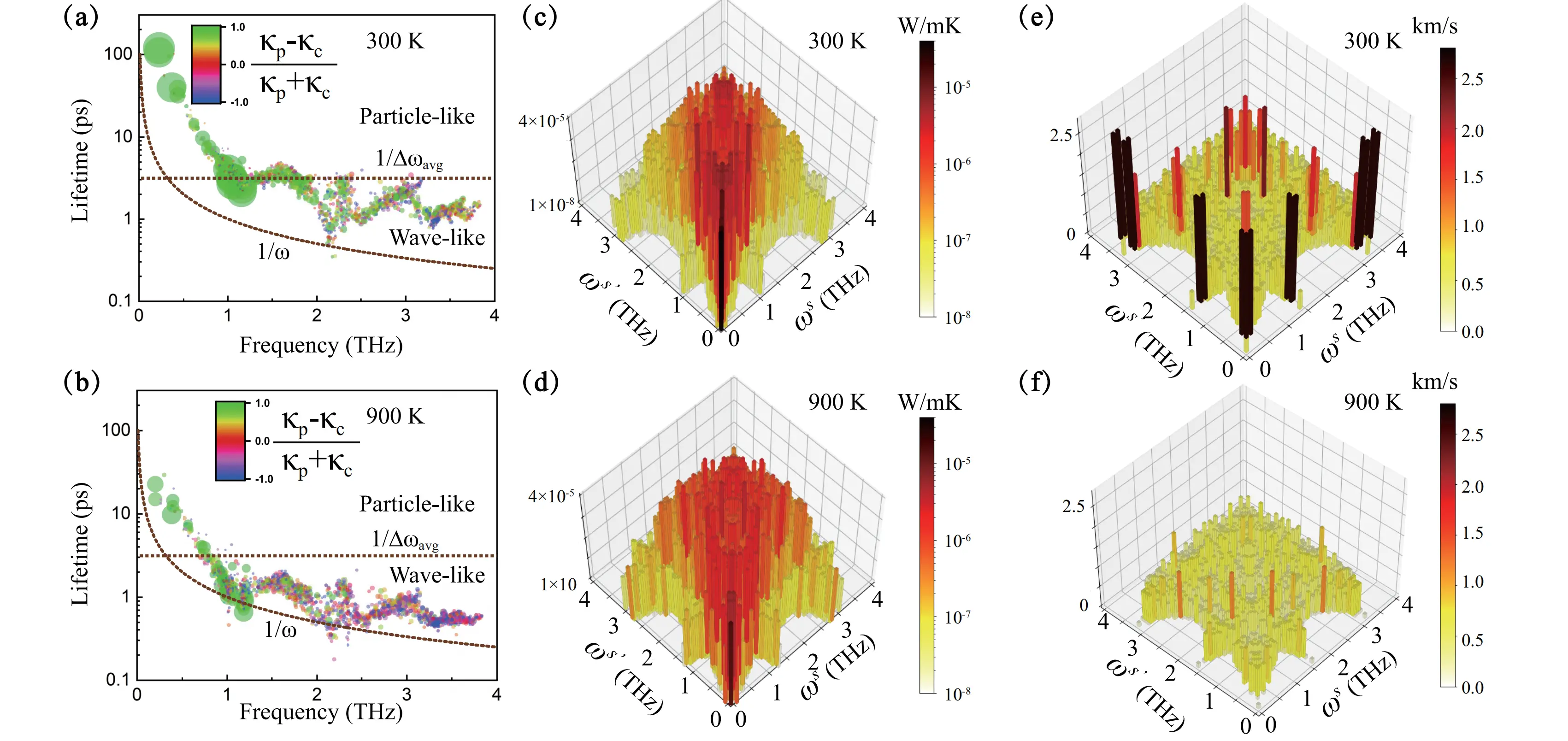

Figure 5a,b presents the phonon lifetime distribution as a function of frequency at 300 K and 900 K, respectively, with the scatter point area proportional to each mode’s contribution to κL and color-coded by transport mechanism (green for particle-like κp, blue for glass-like κc). At 300 K (Figure 5a), most phonons lie above the Wigner limit, indicating dominant particle-like thermal transport. The rattling-induced flat phonon branches create a dense population of modes near the Ioffe-Regel limit, suggesting emerging wave-like characteristics.

Figure 5. Phonon lifetime versus frequency at (a) 300 K and (b) 900 K, with scatter point areas proportional to their contribution to κL (green: particle-like κp, blue: glass-like κc). The Wigner limit

With increasing temperature to 900 K (Figure 5b), enhanced phonon-phonon scattering reduces lifetimes, causing a significant portion of modes to shift into the region between Wigner and Ioffe-Regel limits, where wave-like tunneling becomes important. This transition explains the temperature-induced enhancement of κc shown in Figure 3.

The origin of wave-like thermal transport is further analyzed in Figure 5c,d, which displays the resolved κc contributions from different phonon pairs at 300 K and 900 K. The strong diagonal features confirm that phonon pairs with small frequency differences

To understand the role of interbranch coupling, Figure 5e,f presents the interbranch phonon group velocity

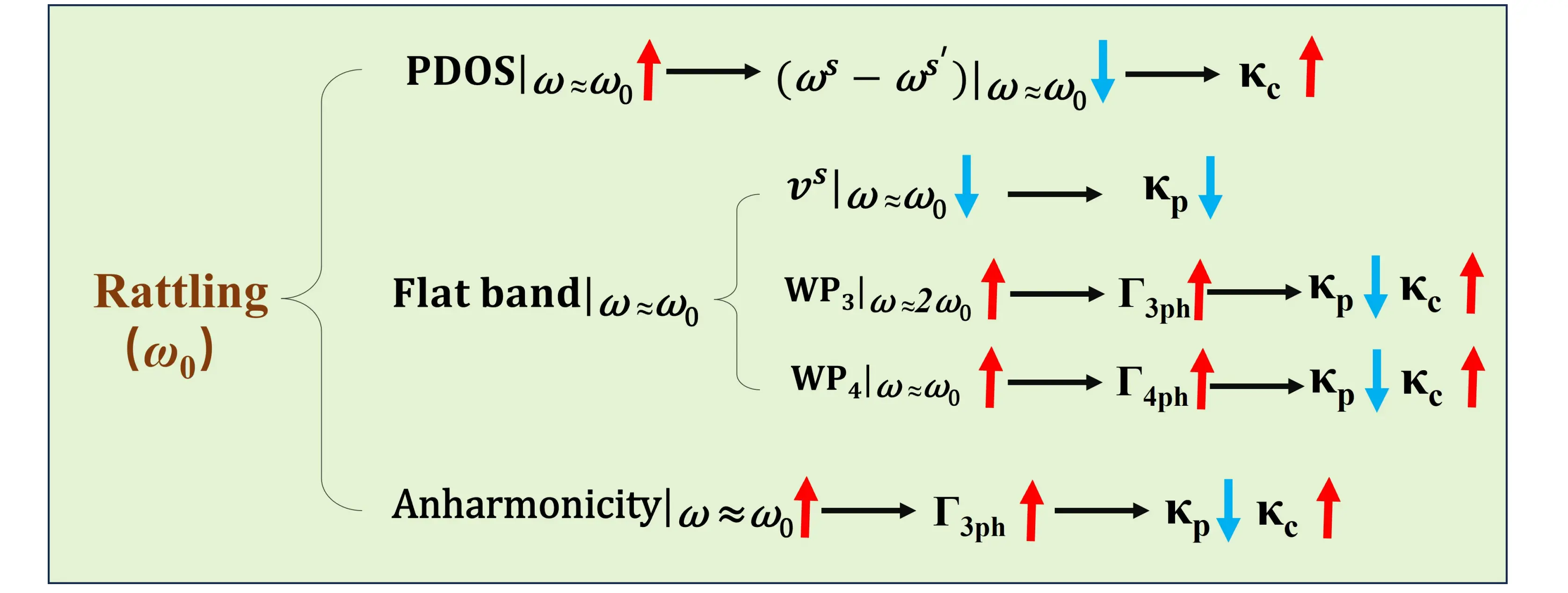

Figure 6 systematically demonstrates how rattling modes at ω0 influence thermal transport through three distinct mechanisms: (1) The dense phonon spectrum near ω0 generates large phonon density of states, where small frequency differences

Figure 6. Schematic illustration of rattling mode effects at ω0 on phonon scattering and thermal transport.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that metallic rattling of weakly bonded Hg atoms in Sr2HgSn effectively suppresses particle-like thermal conductivity (κp) while enhancing wave-like conduction (κc). Through force-constant modulation and frequency-resolved analysis, we establish that rattling-induced flat phonon bands simultaneously intensify three- and four-phonon scattering and promote phonon mode hybridization, leading to a frequency-selective crossover between κp and κc. The resulting competition between suppressed particle-like transport and enhanced wave-like tunneling yields a weak temperature dependence of total lattice thermal conductivity. These findings highlight rattling as a tunable mechanism for dual control of phonon scattering and coherence, offering a design strategy for advanced thermoelectric materials.

Acknowledgements

AI tools were used solely for language editing and polishing of the manuscript. The authors take full responsibility for the integrity, accuracy, and originality of the content.

Authors contribution

Wu Y: Data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing-original draft.

Liu Y, Shang L: Investigation, validation.

Zeng S: Formal analysis, software, writing-review & editing.

Liu C: Resources, supervision, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials could be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Funding

This work is supported by Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants Nos. 12304038, 52206092, 12204402), Outstanding Youth Foundation Project of Jiangsu Province (BK20250035), National Key R&D Program of China (Grants No. 2024YFF0508900), and Big Data Computing Center of Southeast University and the Center for Fundamental and Interdisciplinary Sciences of Southeast University.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Jana MK, Pal K, Warankar A, Mandal P, Waghmare UV, Biswas K. Intrinsic rattler-induced low thermal conductivity in zintl type TlInTe2. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139(12):4350-4353.[DOI]

-

2. Di Lucente E, Simoncelli M, Marzari N. Crossover from Boltzmann to Wigner thermal transport in thermoelectric skutterudites. Phys Rev Res. 2023;5(3):033125.[DOI]

-

3. Christensen M, Abrahamsen AB, Christensen NB, Juranyi F, Andersen NH, Lefmann K, et al. Avoided crossing of rattler modes in thermoelectric materials. Nat Mater. 2008;7(10):811-815.[DOI]

-

4. Tadano T, Gohda Y, Tsuneyuki S. Impact of rattlers on thermal conductivity of a thermoelectric clathrate: A first-principles study. Phys Rev Lett. 2015;114(9):095501.[DOI]

-

5. Dutta M, Samanta M, Ghosh T, Voneshen DJ, Biswas K. Evidence of highly anharmonic soft lattice vibrations in a zintl rattler. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2021;60(8):4259-4265.[DOI]

-

6. Lin H, Tan G, Shen JN, Hao S, Wu LM, Calta N, et al. Concerted rattling in CsAg5Te3 leading to ultralow thermal conductivity and high thermoelectric performance. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55(38):11431-11436.[DOI]

-

7. Li J, Hu W, Yang J. High-throughput screening of rattling-induced ultralow lattice thermal conductivity in semiconductors. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144(10):4448-4456.[DOI]

-

8. Yue T, Zhao Y, Ni J, Meng S, Dai Z. Strong quartic anharmonicity, ultralow thermal conductivity, high band degeneracy and good thermoelectric performance in Na2TlSb. npj Comput Mater. 2023;9(1):17.[DOI]

-

9. Wang W, Dai Z, Wang X, Zhong Q, Zhao Y, Meng S. Low lattice thermal conductivity and high figure of merit in n-type doped full-Heusler compounds X2YAu (X = Sr, Ba; Y = as, Sb). Int J Energy Res. 2021;45(15):20949-20958.[DOI]

-

10. Wang SF, Zhang ZG, Wang BT, Zhang JR, Wang FW. Intrinsic ultralow lattice thermal conductivity in the full-heusler compound Ba2AgSb. Phys Rev Appl. 2022;17(3):034023.[DOI]

-

11. Garmroudi F, Parzer M, Mori T, Pustogow A, Bauer E. Thermoelectric transport in Ru2TiSi full-Heusler compounds. PRX Energy. 2025;4(1):013010.[DOI]

-

12. Sergueev I, Glazyrin K, Kantor I, McGuire MA, Chumakov AI, Klobes B, et al. Quenching rattling modes in skutterudites with pressure. Phys Rev B. 2015;91(22):224304.[DOI]

-

13. Sales BC, Mandrus D, Williams RK. Filled skutterudite antimonides: A new class of thermoelectric materials. Science. 1996;272(5266):1325-1328.[DOI]

-

14. Li W, Mingo N. Ultralow lattice thermal conductivity of the fully filled skutterudite YbFe4Sb12 due to the flat avoided-crossing filler modes. Phys Rev B. 2015;91(14):144304.[DOI]

-

15. Feng T, Lindsay L, Ruan X. Four-phonon scattering significantly reduces intrinsic thermal conductivity of solids. Phys Rev B. 2017;96(16):161201.[DOI]

-

16. Ji L, Huang A, Huo Y, Ding Y, Zeng S, Wu Y, et al. Influence of four-phonon scattering and wavelike phonon tunneling effects on the thermal transport properties of TlBiSe2. Phys Rev B. 2024;109(21):214307.[DOI]

-

17. Li Y, Chen J, Lu C, Fukui H, Yu X, Li C, et al. Multiphonon interaction and thermal conductivity in half-Heusler LuNiBi. Phys Rev B. 2024;109(17):174302.[DOI]

-

18. Ouyang N, Zeng Z, Wang C, Wang Q, Chen Y. Role of high-order lattice anharmonicity in the phonon thermal transport of silver halide AgX (X = Cl, Br, I). Phys Rev B. 2023;108(17):174302.[DOI]

-

19. Zhang Y, Frauenheim T, Dumitrică T, Tong Z. Lonesome Ag atoms drive ultralow thermal conductivity in argyrodite Ag8SnSe6. PRX Energy. 2025;4(1):013012.[DOI]

-

20. Ouyang N, Shen D, Wang C, Cheng R, Wang Q, Chen Y. Positive temperature-dependent thermal conductivity induced by wavelike phonons in complex Ag-based argyrodites. Phys Rev B. 2025;111(6):064307.[DOI]

-

21. Wu Y, Ji J, Ding Y, Yang J, Zhou L. Ultralow lattice thermal conductivity and large glass-like contribution in Cs3Bi2I6Cl3: Rattling atoms and p-band electrons driven dynamic rotation. Adv Sci. 2024;11(42):2406380.[DOI]

-

22. Kresse G, Furthmüller J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys Rev B. 1996;54(16):11169-11186.[DOI]

-

23. Perdew JP, Ruzsinszky A, Csonka GI, Vydrov OA, Scuseria GE, Constantin LA, et al. Restoring the density-gradient expansion for exchange in solids and surfaces. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;100(13):136406.[DOI]

-

24. Hellman O, Abrikosov IA. Temperature-dependent effective third-order interatomic force constants from first principles. Phys Rev B. 2013;88(14):144301.[DOI]

-

25. Li W, Carrete J, Katcho NA, Mingo N. ShengBTE: A solver of the Boltzmann transport equation for phonons. Comput Phys Commun. 2014;185(6):1747-1758.[DOI]

-

26. Han Z, Yang X, Li W, Feng T, Ruan X. FourPhonon: An extension module to ShengBTE for computing four-phonon scattering rates and thermal conductivity. Comput Phys Commun. 2022;270:108179.[DOI]

-

27. Guo Z, Han Z, Feng D, Lin G, Ruan X. Sampling-accelerated prediction of phonon scattering rates for converged thermal conductivity and radiative properties. npj Comput Mater. 2024;10(1):31.[DOI]

-

28. Wu Y, Huang A, Ji L, Ji J, Ding Y, Zhou L. Origin of intrinsically low lattice thermal conductivity in solids. J Phys Chem Lett. 2024;15(46):11525-11537.[DOI]

-

29. Thakur S, Giri A. Origin of ultralow thermal conductivity in metal halide perovskites. ACS Appl Mater. 2023;15(22):26755-26765.[DOI]

-

30. Moyal JE. Quantum mechanics as a statistical theory. Math Proc Cambridge Philos Soc. 1949;45(1):99-124.[DOI]

-

31. Simoncelli M, Marzari N, Mauri F. Unified theory of thermal transport in crystals and glasses. Nat Phys. 2019;15(8):809-813.[DOI]

-

32. Simoncelli M, Marzari N, Mauri F. Wigner formulation of thermal transport in solids. Phys Rev X. 2022;12(4):041011.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite