Yuqiang Zeng, School of Microelectronics, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen 518005, Guangdong, China; State Key Laboratory of Quantum Functional Materials, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen 518055, Guangdong, China; Shenzhen Key Lab for Phononics and Intelligent Thermal Materials, Shenzhen 518055, Guangdong, China. E-mail: zengyq@sustech.edu.cn

Abstract

The high integration density of modern energy and information devices often results in high power density and intense heat flux. Depending on the operating and optimal temperature range of the device, heat must be either effectively dissipated or retained. Precise regulation of heat flow is essential for the advancement of next-generation energy and information technologies. Dynamic heat flow control and nonlinear thermal transport open new avenues for developing smart battery thermal management systems, solid-state refrigeration devices, and thermal logic elements analogous to electronic circuits. Due to their unique capability to actively modulate heat transfer and exhibit thermal rectification behavior, thermal switches and thermal diodes have shown great potential in managing heat and/or maintaining thermal stability beyond the limits of conventional passive thermal materials and devices. Here, we review recent progress in the design principles, fundamental mechanisms, and applications of thermal switches and thermal diodes for energy and information technologies, and evaluate their potential for practical deployment. Furthermore, we discuss the emerging demands in these sectors and provide future perspectives to inspire applied research toward solving real engineering challenges.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

1. Introduction

The push for higher integration density in modern energy and information technologies, spanning electric vehicles[1,2], grid-scale storage[3,4], microprocessors[5], and edge computing devices[6], has driven device power densities and local heat fluxes to unprecedented levels. Depending on the device’s operating and optimal temperatures, heat must be dissipated rapidly to avoid overheating in certain scenarios, whereas in others heat should be retained or redirected to maintain optimal operating windows for performance and lifetime. The inherent limitation of traditional passive thermal materials and solutions in responsiveness and spatial/temporal selectivity has spurred growing interest in active and nonlinear thermal control elements capable of dynamically routing, modulating, and rectifying heat fluxes. For example, traditional heat sinks, thermal interface/insulation materials, and heat pipes are designed solely for heat dissipation or insulation, and thus lack the adaptive thermal regulation capabilities needed for all-climate operation.

Two main classes of devices have attracted particular attention: thermal switches (i.e., elements whose thermal conductance can be actively or passively toggled between low and high states) and thermal diodes/rectifiers (i.e., structures that conduct heat preferentially in one direction). For high on/off ratios or rectification factors not attainable in homogeneous passive materials, a range of physical mechanisms have been exploited, including contact/noncontact mechanical actuation[7], phase-change-driven conductivity contrast (e.g., VO2)[8], electrochemical modulation[9], near-field radiative effects[10,11], and geometry/material engineering[12]. Mechanically actuated thermal switches provide large ON/OFF conductance contrasts suitable for macroscopic and aerospace applications; solid-state regulators based on phase-change materials and electrochemical modulation offer fast, reversible tuning for thermal exchange; and radiative or photonic devices, including near-field modulators and emissivity switches, enable contactless heat control and transistor-like functionality. These advances collectively pave the way for integrating thermal switching and rectification into energy and information systems such as battery thermal management, building energy saving, solid-state refrigeration, and on-chip thermal regulation. Further, the emerging nonlinearity in thermal circuits draws a direct analogy to electronic switches, diodes, and transistors, enabling new thermal circuit functionalities, e.g., thermal logic and thermal memory.

Despite these achievements, the gap between proof-of-concept demonstrations and system-level deployment remains significant. Many devices sacrifice scalability and durability for high performance[13-15], while most studies emphasize individual performance metrics (e.g., rectification ratio, response time) under idealized conditions[16-18]. Systematic evaluations under realistic environments, as well as integration studies with existing architectures, are still limited. Bridging this gap requires application-driven research focused on scalable manufacturing, multi-physics reliability testing, and system co-design. Promising directions encompass cell-level thermal routing for batteries, solid-state refrigeration based on cascaded thermal diodes, and caloritronic logic architectures for information processing, requiring coordinated efforts across materials science, device engineering, and thermal systems design.

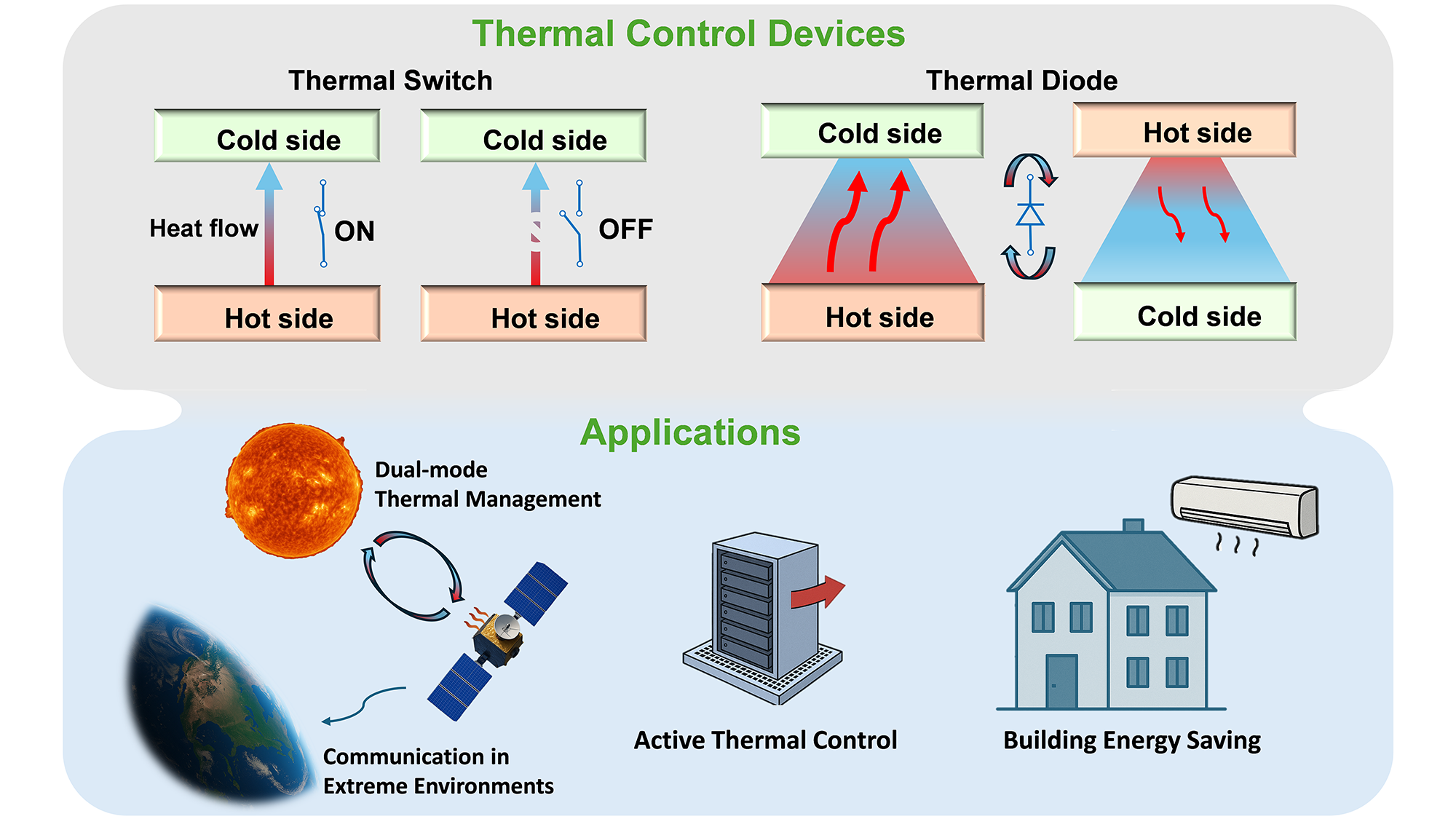

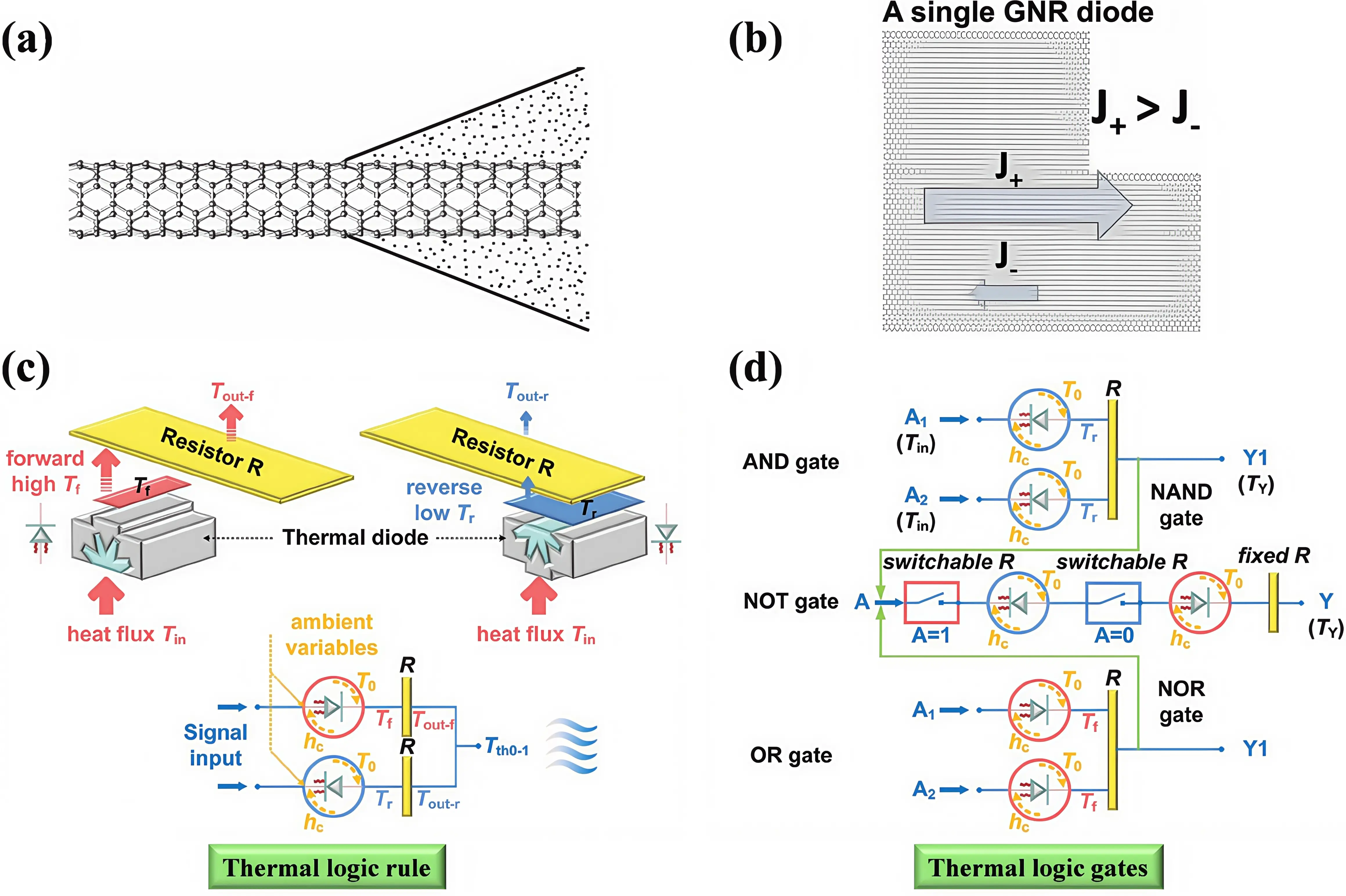

As an application-oriented review (Figure 1), we summarize recent advances in thermal switches and thermal diodes that are relevant to energy (Section 2) and information (Section 3) technologies, emphasizing their underlying mechanisms, device architectures, and key performance metrics such as switch ratio, rectification ratio, response speed, and durability. Representative demonstrations are discussed across contact-based, phase-change, electrochemical, and radiative approaches, with a critical evaluation of their respective advantages and practical limitations. Finally, we outline future research opportunities in scalable fabrication, multi-physics reliability assessment, and system-level co-design, aiming to bridge the gap between laboratory-scale prototypes and practical thermal control units for next-generation energy and information systems.

Figure 1. Overview of thermal switches and diodes for energy and information technologies. SMA: shape memory alloy; TR: thermal runaway; EFETT: electric field-effect thermal transistor; NTM: NanoThermoMechanical.

2. Applications in Energy Technology

Thermal switch or rectification is critical for the efficiency and/or safety of energy usage[19]. For example, the retention or dissipation of battery heat at harsh (low or high) ambient temperatures requires adaptive thermal regulation[20]. Thermal switches offer this flexibility by dynamically toggling between heat dissipation (at high temperatures) and insulation (at low temperatures). Elastocaloric cooling systems similarly demand fast and efficient heat flow modulation; integrating rapid thermal switching can significantly improve heat pumping and operating frequency compared to traditional fluid-based systems[21]. In buildings, large diurnal and seasonal thermal variations call for envelope technologies (e.g., dynamic insulation and thermal-switching panels) that intelligently shift between radiative cooling and solar heat gain depending on weather conditions[22]. These application scenarios all involve highly variable thermal environments and therefore require tunable, multimodal pathways for heat transfer. Relying solely on thermal diodes is often insufficient due to their one-way conduction constraint. Traditional manually actuated switches, combining movable mechanical structures with diode-like elements, provide only limited practicality due to their bulky design, limited tunability, and constrained integration.

2.1 Battery thermal management

In recent years, the global new energy sector, especially the electric vehicle industry, has witnessed rapid expansion[23]. From vehicle platforms to grid-scale storage, electrochemical energy systems now serve as a critical foundation of sustainable energy infrastructure[24,25]. However, lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) operate optimally only within a narrow temperature range (15-35 °C)[26]. Deviations from this range accelerate degradation and can trigger thermal runaway (TR), with severe safety and economic consequences[27]. The safety and functionality of battery packs under extreme temperatures have become critical metrics. Battery thermal management aims to maintain cell temperatures within the desired range, enhancing power capability and lifetime while preventing TR. Conventional strategies combine heating in cold environments with cooling under high loads or ambient temperatures[28-33], yet single-state designs struggle to handle both regimes, particularly under transient or geographically variable climates. Thermal switches provide tunable thermal states for all-climate management by actively modulating heat transport in response to external stimuli or operating states, providing high thermal conductance for rapid heat dissipation and low conductance for heat retention[34]. Furthermore, this enables asymmetric charge-discharge temperatures desirable for fast charging: rapidly elevating temperature to boost battery kinetics during charge, then switching to efficient cooling to mitigate the temperature rise and degradation. We thus identify thermal switches as a central enabler for adaptive, application-aware battery thermal management under real-world operating conditions.

2.1.1 Charge-discharge performance optimization

The charge-discharge behavior of LIBs is highly sensitive to temperature. At low temperatures (typically below 15 °C), reduced electrolyte ionic conductivity impedes Li-ion transport and slows intercalation kinetics at the anode[35]. This transport limitation triggers lithium plating during charging, which accelerates capacity degradation and long-term performance decline[36]. At elevated temperatures (typically above 35 °C), accelerated molecular motion drives electrolyte decomposition and other parasitic reactions, leading to irreversible active lithium loss and performance degradation[37,38]. Since annual ambient temperatures in most regions exceed the narrow 15-35 °C window optimal for batteries, thermal management systems capable of both efficient high-temperature cooling and low-temperature heating are essential. A further, yet often overlooked, opportunity for reversible thermal switching lies in fast-charging thermal management. Zeng et al.[39] showed that retaining heat during fast charging, followed by active cooling, can achieve a cycle lifetime comparable to that of slow charging. Thus, thermal-switch-enabled battery management has gained increasing attention for improving performance and safety under extreme temperatures, as discussed below according to different switching mechanisms.

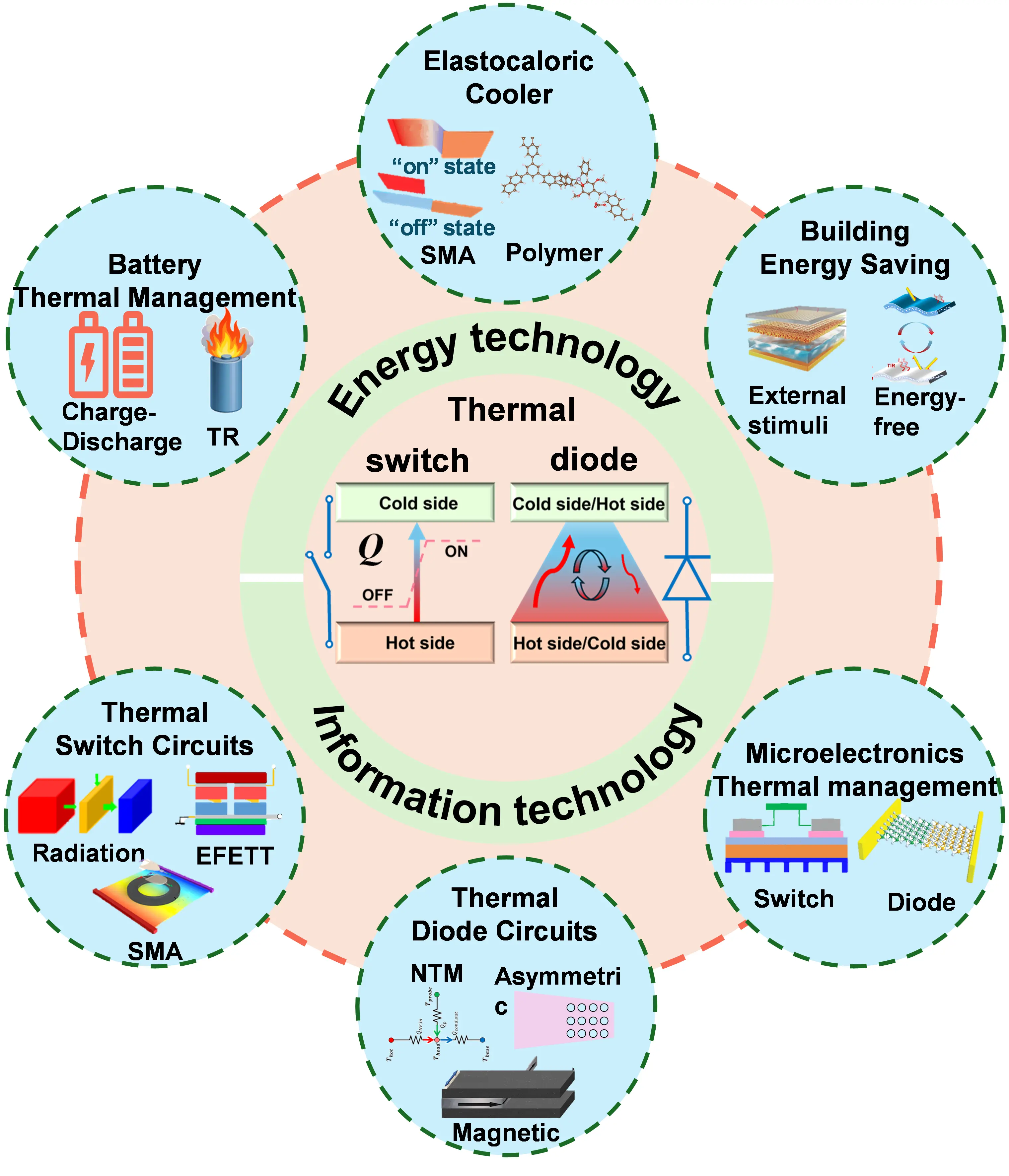

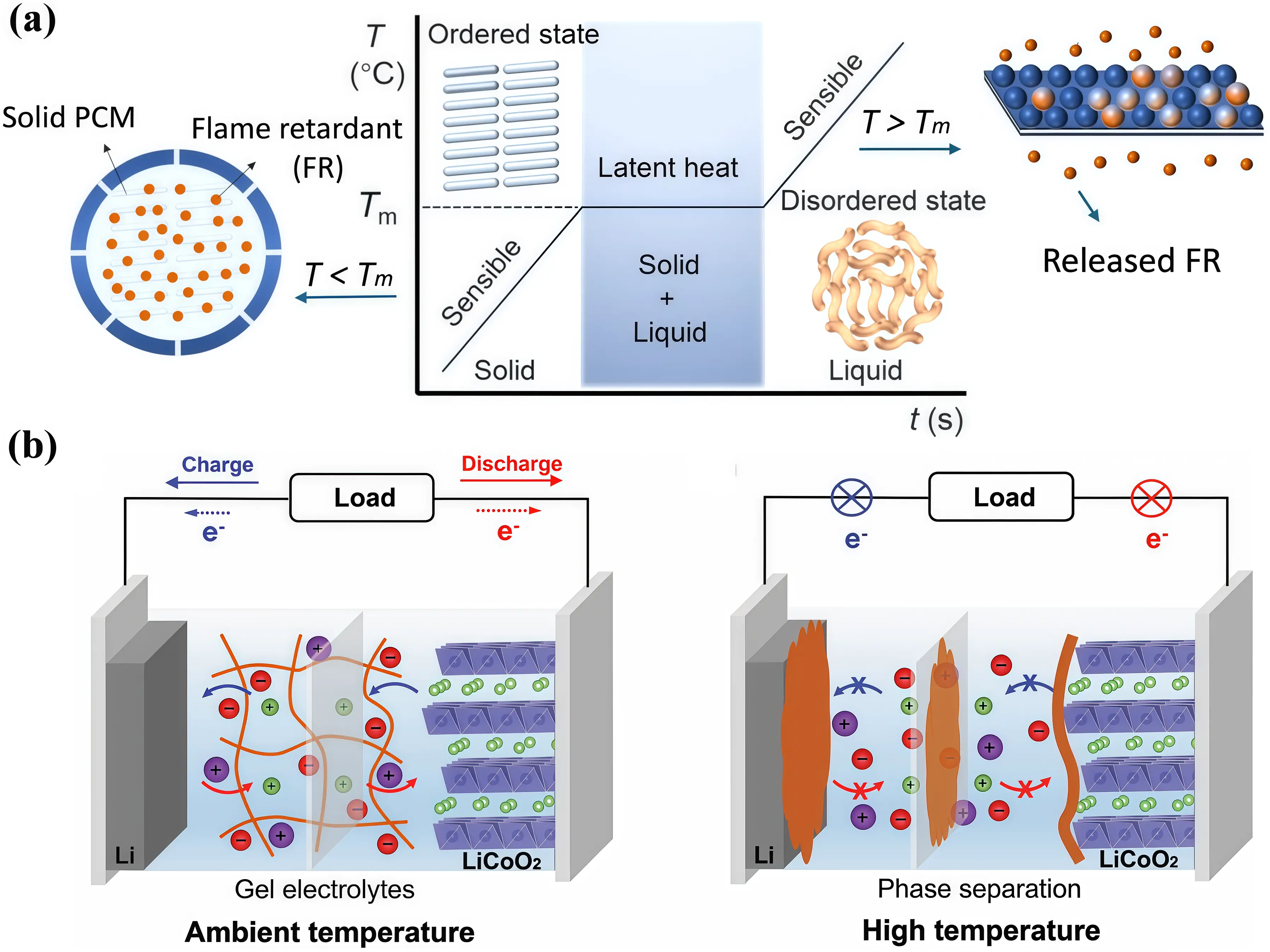

Compressible carbon-based thermal switches: Porous graphene foam composites exhibit high elastic compressibility, enabling compression-tunable heat transport. Under high compressive strain, pore collapse forms continuous conduction pathways, facilitating efficient heat dissipation; when released, air-filled pores suppress heat flow[20]. Building on this concept, Yu et al.[40] developed a continuously tunable thermal switch using carbon nanotubes and aerogel (Figure 2a). Thermal conductance is modulated by compression-induced microstructural rearrangement, and the process is highly reversible, maintaining performance after ~3,000 cycles. Applied to cylindrical LIBs, the switch effectively mitigates battery temperature fluctuations under varying ambient conditions. Even at -24 °C, it can maintain battery operating temperature within 20-40 °C, thereby enhancing discharge performance. Cheng et al.[41] reported a graphene aerogel showing a 3.3-fold reduction in thermal resistance under 80% compressive strain, while in the uncompressed state, batteries at low temperature exhibited a 26% increase in discharge capacity. However, carbon-based composites suffer from low “on-state” thermal conductivity (~1 W/m-K), limiting high-temperature heat dissipation, and their complex fabrication hinders large-scale deployment.

Figure 2. (a) Compressible carbon-based thermal switch. Reproduced with permission from[40]; (b) Phase-change-driven thermal switch. T is temperature (K), and R represents thermal resistance (K/W). Reproduced with permission from[44]; (c) A potential pack-level design for active thermal switching. Republished with permission from[39].

Phase-change-driven thermal switches: Compared with aerogel-based composites, phase change materials (PCMs) provide broader thermal regulation through latent heat storage and temperature-triggered property changes[42,43]. As shown in Figure 2b, PCM-based thermal switches maintain low thermal conductivity at low ambient temperatures to reduce heat loss, and switch to high thermal conductivity at elevated temperatures to enhance heat dissipation. The flowing liquid phase further promotes convective heat transfer, aiding battery cooling to optimal operating temperatures[44]. Wang et al.[45] exploited phase-change–induced volumetric expansion to modulate coolant flow, tuning overall thermal transport and reducing cyclic temperature excursions in batteries. Despite these advantages, PCM-based thermal switches are constrained by the fixed phase transition temperature and provide limited thermal insulation at low temperatures.

Shape-memory-alloy-driven thermal switches: The phase-change-induced actuation of shape-memory alloys (SMAs) can create or break thermal contact between heat conductors, thereby modulating interfacial thermal resistance. Hao et al.[46] designed an SMA-based switch that detaches the battery from the heat sink at low temperatures for battery heat retention. Using only the cell self-heating, this switch increased battery capacity by roughly threefold at -20 °C. Li et al.[13] extended this design to the pack level, demonstrating excellent thermal regulation capability. In addition, Zeng et al.[39] proposed an extreme fast-charging strategy that combines cell self-heating with active thermal switching. They constructed a mechanical thermal switch prototype based on SMA wires integrated with a cold plate, achieving a thermal switching ratio of approximately ON/OFF ≈ 10. More importantly, the work considers system-level design; the switch is completely non-intrusive and does not require any modification of the cell, so the same thermal modulation strategy can be implemented at the module or pack level simply by controlling the contact and gap between the cold plate and the cells (Figure 2c).

Table 1 summarizes the key performance metrics and practical characteristics of representative thermal switches for battery thermal management. Note that the switching ratio of SMA-based thermal switches is based on interfacial thermal conductance because they control interfacial contact, while other thermal switch types are typically evaluated in terms of thermal conductivity. From the comparison, SMA-based thermal switches exhibit both high switching ratios and fast response speeds, while other approaches are limited by switching ratio, response time, and/or maximum thermal conductance. In terms of technology readiness level (TRL), these thermal switches have not yet reached the level (TRL > 5) required for practical applications. We evaluated the total cost range of these thermal switches under current laboratory conditions, including raw material, processing and assembling costs. Comparative analysis shows that, despite their respective advantages, existing thermal switches are not yet mature for practical deployment.

| Types | Switching ratio | ResponseTime (min) | Maximum Thermal Conductivity/Conductance | TRL | Cost Range(USD/m2) | Ref |

| Compressible carbon-based thermal switches | 43 3.3 | 6.8~12.6 - | 1.29 W/m-K 2.3 W/m-K | 3-4 3-4 | 200~800 200~500 | [40] [41] |

| Phase-change-driven thermal switches | 15.4 ~50 | ~3 2~10 | 0.59 W/m-K 1.03 W/m-K | 4-5 3-4 | 80~200 360~700 | [44] [45] |

| SMA-driven thermal switches | ~2,000 10.4 174.7 | 0.2 - 0.1 | 2,340 W/m2-K ~180 W/m2-K ~6,300 W/m2-K | 4-5 5-6 4 | 20~60 10~40 100~250 | [46] [39] [13] |

SMA: shape memory alloy; TRL: technology readiness level.

2.1.2 TR mitigation

Considerable effort has focused on mitigating TR in LIBs at elevated temperatures[47-50]. However, high temperature is not the only trigger; aging, overcharging, mechanical abuse, and other abnormal conditions can also initiate TR. Suppressing TR propagation, by restricting heat and gas transfer from the initiating cell to its neighbors, is as vital as preventing its onset. Systems must both enhance tolerance for adverse conditions[51] and delay or block TR propagation for safety response time[52]. Given the severe consequences of TR[53], thermal switches for safety applications can be broadly categorized as irreversible or reversible, depending on their protection mechanisms.

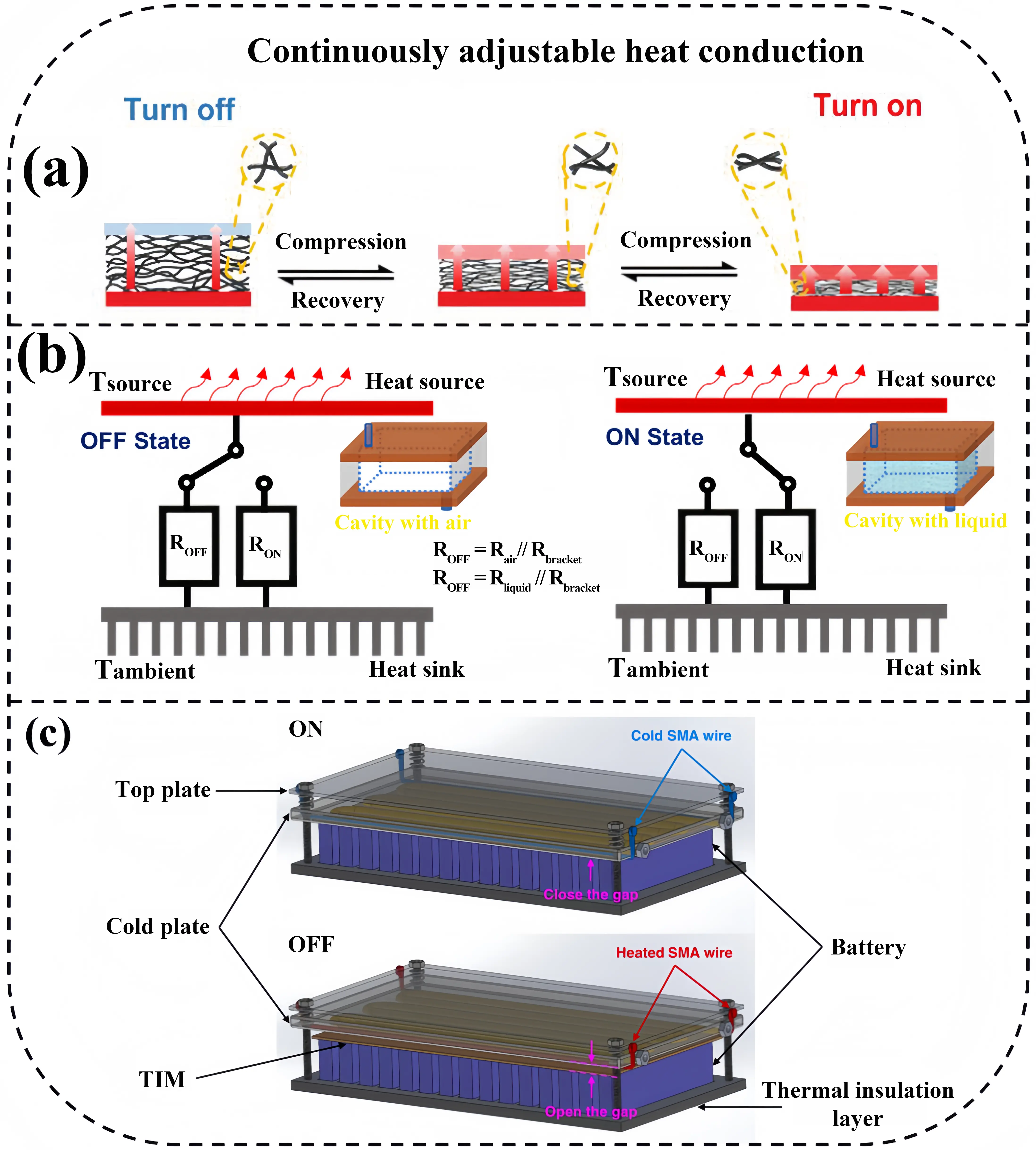

Irreversible thermal switches: Liu et al.[54] developed a thermally responsive composite separator by depositing ceramic SiO2 microcapsules onto a commercial polyolefin film (Figure 3a). Each microcapsule, fabricated via vacuum impregnation, contains PCM and a flame retardant. The PCM absorbs excess heat to moderate temperature rise, while the flame retardant is released above a critical temperature, reducing the risk of TR. Wang et al.[19] designed a thermal switch that rapidly transitions to a thermally insulating state at 100 °C. In TR tests, it maintained effective heat dissipation under normal operation but blocked heat transfer at high temperatures, preventing cell-to-cell propagation and mitigating venting or explosion. Future improvements should aim to incorporate low-temperature insulation and enhance cost-effectiveness for broader applicability.

Reversible thermal switches: Reversible, stimulus-responsive thermal switches offer flexible protection against TR. Certain electrolytes that undergo thermally triggered sol-gel transitions can suppress ion transport[55-57], but these systems typically suffer substantial capacity loss after only ~10 cycles. To address this, Liu et al.[58] developed a gel electrolyte (Figure 3b) that precipitates polymer uniformly onto the electrode and separator surfaces above 110 °C, blocking Li-ion intercalation and interrupting TR escalation. This electrolyte sustained 100 thermal cycles without measurable performance degradation. Beyond gels, Lu et al.[59] reported an ionic liquid crystal electrolyte with excellent reversible switching. The smectic ionic liquid crystal, composed of [C14Mim][BF4] and LiBF4, exhibits ionic conductivity of 10-4~10-3 S/cm. In its crystal phase, charge/discharge is effectively suppressed, while returning to the higher-mobility phase restores normal operation, enabling temperature-adaptive and reversible regulation at the cell level.

2.2 Elastocaloric cooler

With ongoing global warming and rising cooling demand, air conditioning currently accounts for ~17% of global electricity consumption, and conventional vapor-compression refrigerants are predominantly high-global-warming-potential materials[60]. For carbon neutrality, there is an urgent need for environmentally sustainable alternatives. Solid-state cooling based on the elastocaloric effect of SMAs and elastic polymers has attracted increasing attention due to zero greenhouse gas emissions and high energy efficiency.

Recent efforts have focused on developing novel materials and device architectures to overcome the limited cooling capacity of elastocaloric systems and enable practical applications. Thermal switches or diodes can control heat flow direction, reduce backflow, and enhance unidirectional heat transport. This strategy simplifies complex thermofluidic systems and improves overall thermal management efficiency.

In caloric cooling studies, thermal switches have been integrated via simulations or experiments. Resende et al.[61] modeled a solid-state electrocaloric cooler using thermoelectric switches to regulate heat flow between the electrocaloric material and the heat source/sink. The switches generate a Peltier effect under applied current, thermally isolating the electrocaloric material during polarization/depolarization and maintaining directional heat flow. Simulations indicate a coefficient of performance (COP) > 1 under a 6 K temperature span. In magnetocaloric cooling, Klinar et al.[62] proposed a ferrofluid thermal switch to control heat flow: theoretical calculations predict a 1.12 K system temperature difference, demonstrating the potential of thermal switches for optimizing caloric cooling systems.

2.2.1 SMA based elastocaloric cooler

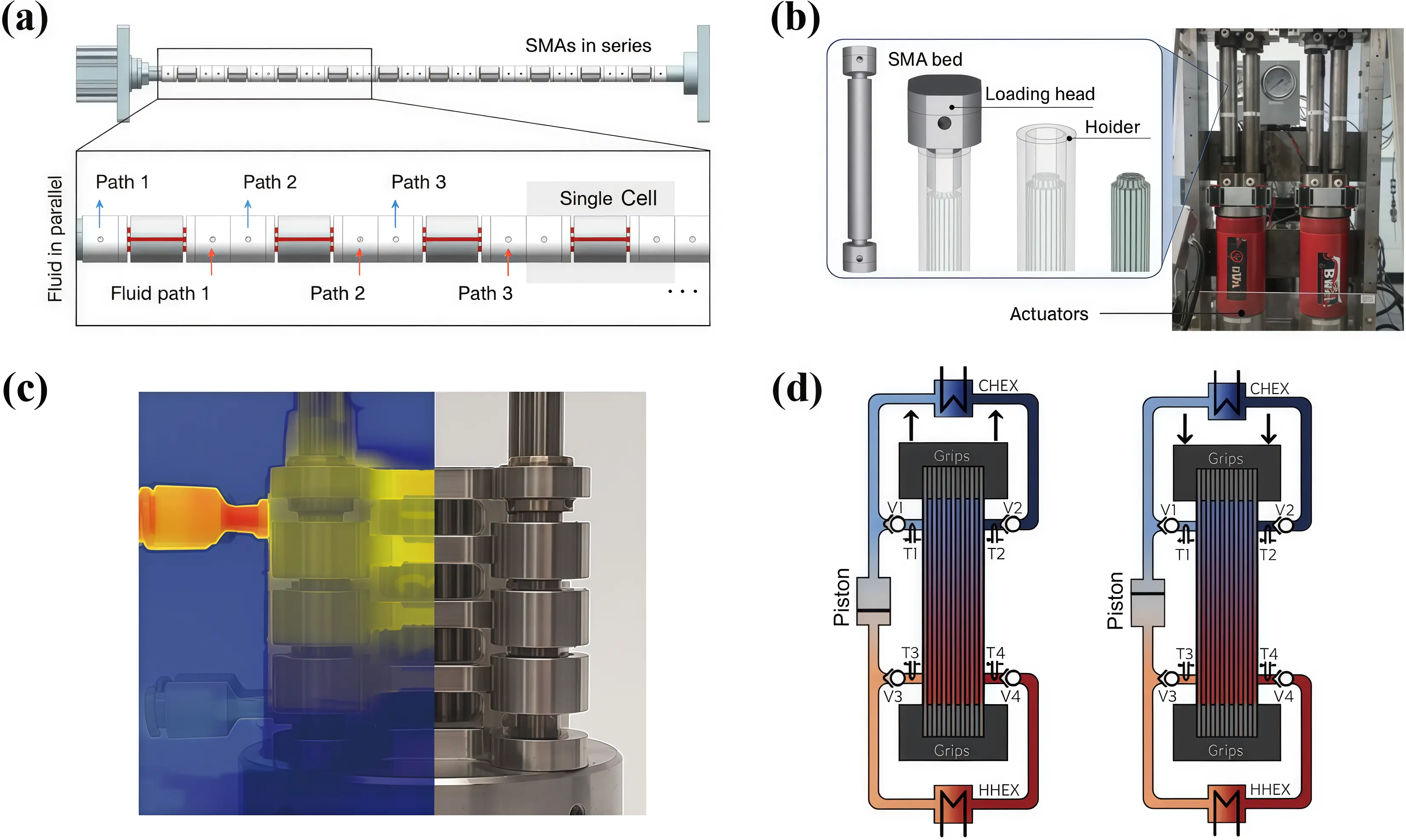

Current SMA-based elastocaloric coolers often employ loading/unloading of NiTi alloys. Zhou et al.[63] proposed a multi-cell architecture featuring a “material-in-series, fluid-in-parallel” design, connecting ten elastocaloric units in series along the loading direction, each comprising multiple thin-walled NiTi tubes (Figure 4a). This hybrid serial-parallel configuration increases specific cooling power and enables stable high-frequency operation. The thin-walled NiTi tubes provide a high surface-area-to-volume ratio, enhancing heat exchange efficiency with the working fluid. Graphene-based nanofluids further increase the thermal conductivity by ~50% compared to pure water, leading to a specific cooling power of 12.3 W/g and total cooling power of 1,284 W at 3.5 Hz. Qian et al.[64] developed a multi-mode elastocaloric thermal regeneration system capable of switching between the active regeneration mode and the maximum utilization mode through precise control of valve operation sequences (Figure 4b). In active regeneration mode, optimized fluid flow achieves a larger temperature span, while maximum utilization mode prioritizes higher cooling power via increased fluid displacement. The system demonstrated a maximum cooling power of 260 W and a maximum temperature span of 22.5 K, though the system-level COP remained modest at 1.03, below some magnetocaloric cooling systems. Ahčin et al.[65] designed a shell-and-tube elastocaloric regenerator with optimized NiTi tube arrangements and fluid flow distribution (Figure 4c). The regenerator achieved a maximum temperature span of 31.3 K in heating mode and delivered over 60 W of cooling or heating power in cooling mode. Furthermore, the system demonstrated excellent durability with > 300,000 operating cycles under stresses up to 825 MPa. Tušek et al.[66] further constructed a porous-structured elastocaloric regenerator, achieving a maximum temperature span of 15.3 K, specific heating power up to 800 W/kg, and COP as high as 7 (Figure 4d).

Figure 4. (a) The multi-cell elastocaloric architecture in which SMAs are compressed in series and the fluid paths are independent and parallel. Republished with permission from[63]; (b) A photo of the central part of the multimode elastocaloric cooling system. Republished with permission from[64]; (c) Photo of the actual regenerator. Republished with permission from[65]; (d) Loading-the length of the regenerator is increased causing the martensitic transformation. Republished with permission from[66]. SMA: shape memory alloy; CHEX: cold heat exchanger; HHEX: hot heat exchanger.

In NiTi-based cooling systems, specialized loading heads are essential for stress application. However, their mechanical complexity and added thermal mass introduce parasitic losses, reducing system COP and complicating fabrication[67]. Recent studies have focused on minimizing the loading head volume relative to its structural limit, thereby reducing ineffective heat capacity and preserving effective cooling output.

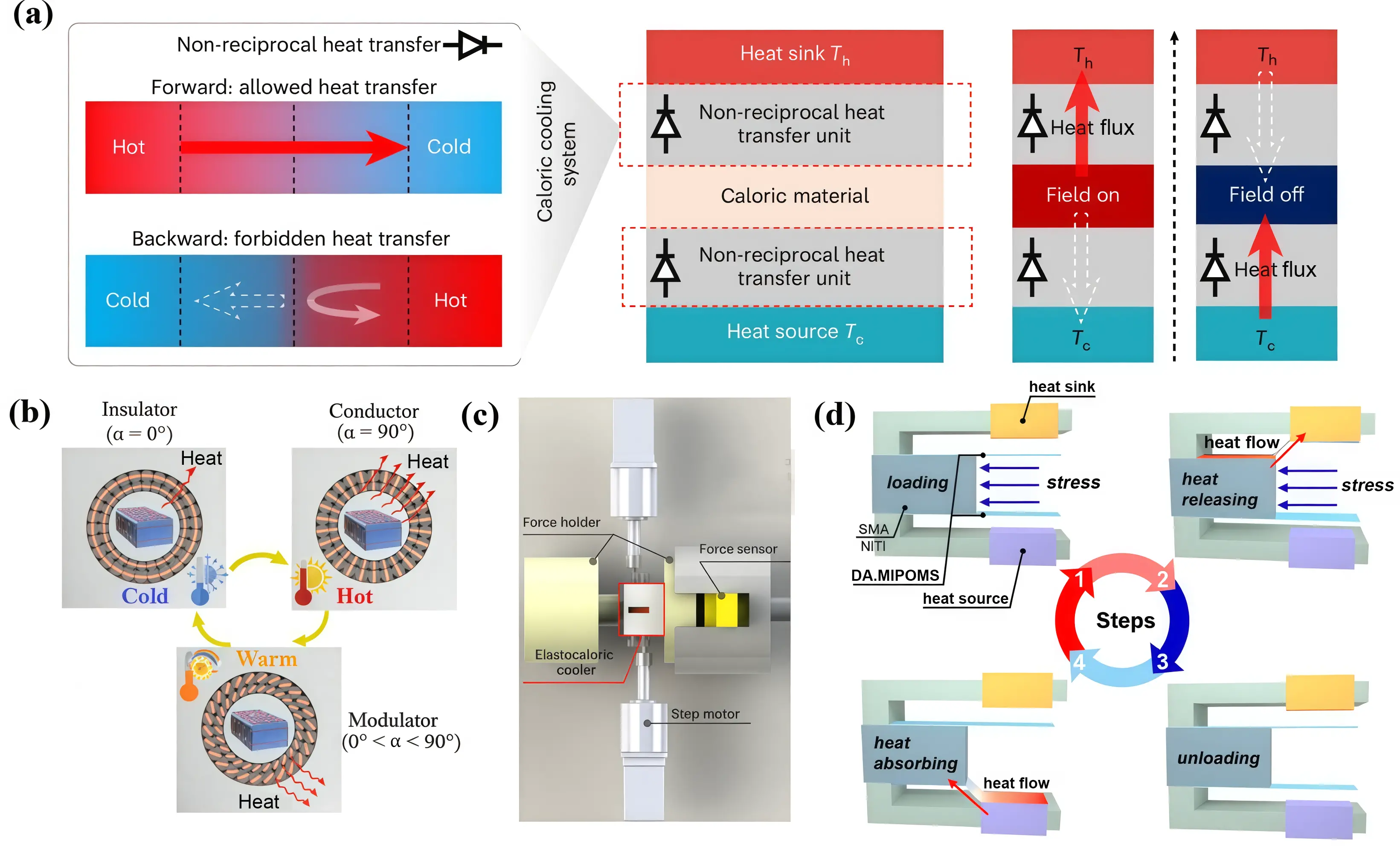

Integrating thermal switch/diode units into elastocaloric coolers for unidirectional heat flow control offers broad application potential. Figure 5a shows a caloric cooling system based on a non-reciprocal heat transfer unit[68]. Such non-reciprocal transport enables heat flow only along a prescribed temperature gradient and suppresses heat transfer when the gradient is reversed. Chen et al.[69] pioneered a multifunctional thermal metamaterial device based on solid composites, featuring a “sandwich” structure (polystyrene/copper/polystyrene) with rotatable units (Figure 5b). Rotation of these units allows continuous tuning of thermal conductivity from 1.95 to 12.69 W/m-K, achieving a thermal rectification ratio of 6.5. This enables multiple functions within a single device, including thermal cloaking, and concentration.

Figure 5. (a) One-way heat transfer based on an ideal thermal switch. The non-reciprocal heat transfer unit replaced by thermal diode only permits directional heat flow according to the operational requirements. Republished with permission from[68]; (b) Heat flow regulation by dynamically adjusting the sandwich structure of the metamaterial. Republished with permission from[69]; (c) Integration between the thermal switch unit and the elastocaloric cooling component. Republished with permission from[68]; (d) Heat exchange process in the all-solid-state elastocaloric cooling system integrated with thermal switches, comprising four key steps: stress loading, heat release, stress unloading, and heat absorption. Republished with permission from[70]. SMA: shape memory alloy; PDMS: polydimethylsiloxane.

Based on this, Zhang et al.[68] integrated these metamaterial units as core switching components with elastocaloric material and a heat source/sink to construct an all-solid-state cooling prototype (Figure 5c). An external stepper motor drives a gear set to rotate the switch units simultaneously, adjusting effective thermal conductivity. Unlike traditional solid-state devices, the switch maintains stable contact with components, enabling efficient heat flow regulation without periodic mechanical contact and separation. This prototype achieved a temperature span of 4.3 K and a high cooling heat flux of 242.8 mW/cm2, alongside an ultra-long fatigue life exceeding 2 million cycles. Although mechanically driven switches perform well, their drive systems limit miniaturization and integration. To address this, Luo et al.[70] developed a magnetic field-driven thermal switch based on a flexible thermal interface material, achieving a switching ratio of 22 via magnetic deformation control (Figure 5d). Integration into an elastocaloric cooler demonstrates a compact solution for heat flow control.

2.2.2 Polymer based elastocaloric cooler

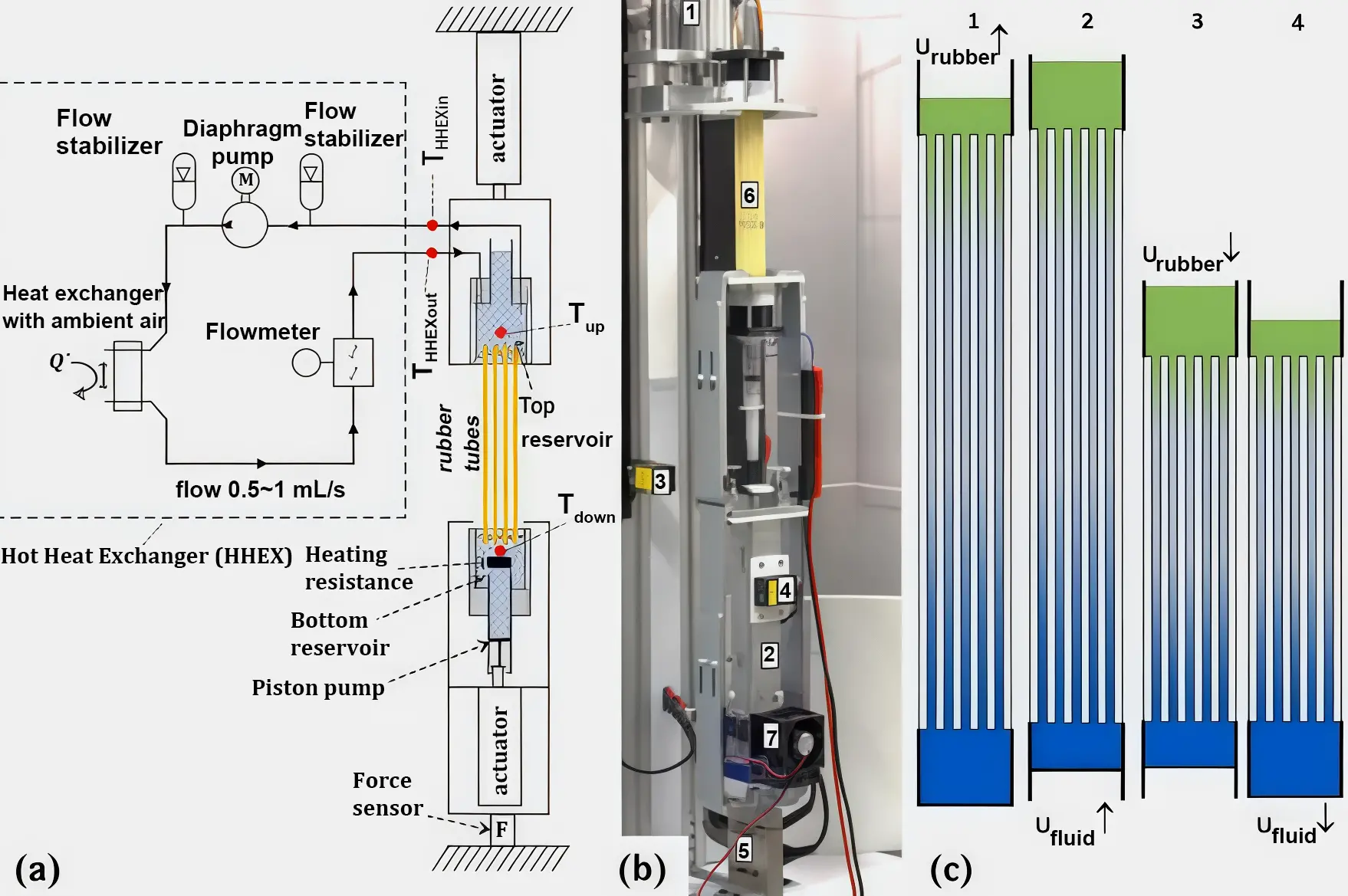

Polymer-based elastocaloric coolers require large material deformations. For example, thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) fibers with a diameter of 1.7 mm must be stretched to 400% strain or twisted to 1.0 turn/mm for a temperature drop of ~3 K[71]. Due to the high strain and low thermal conductivity of polymers, stretching requires a water flow volume tens of times greater than the polymer to ensure rapid convective heat transfer (Figure 6)[72]. Twisting generates intense friction with sealing components, leading to seal wear and potential fluid leakage. These challenges hinder the use of fluid-based heat transfer in polymer elastocaloric coolers, limiting their integration and miniaturization.

Figure 6. (a) The schematic diagram; (b) Device photograph; (c) Operation principle of polymer based elastocaloric coolers. Republished with permission from[72].

Carina et al.[73] eliminated the fluid heat transfer module by using a small-capacity electric motor to move the polymer (Figure 7). This ensures contact with the heat sink and heat source during loading and unloading respectively, thereby circumventing sealing issues. Their experiments highlighted the potential of thermal diodes and switches for integration and miniaturization of elastocaloric coolers. Replacing the motor with a passive thermal diode or programmed thermal switch could maintain close contact with the heat source and sink, reducing contact resistance and preventing thermal and/or mechanical shocks[74,75]. Moreover, since TPU is a common 3D printed thermal interface material, its integration with thermal diodes and switches opens opportunities for thermal management in power electronics[76,77].

Figure 7. Elastocaloric cooler’s operation principle using electric motor designed by Carina et al. Republished with permission from[73].

Currently, research on elastocaloric coolers mainly focuses on SMA- and polymer-based types. Based on these studies, we have summarized the performance metrics of both cooler types in Table 2, including temperature span, maximum cooling power, and COP. SMA-based coolers primarily use NiTi alloys, while polymer-based coolers employ natural rubber, styrene-ethylene-butylene-styrene, and other highly elastic materials. Both types show comparable temperature spans and COPs. SMA-based types achieve higher cooling power than polymer-based types, but incur higher material and/or manufacturing costs. Moreover, SMA-based thermal switches offer higher thermal conductivity and a wider range of thermal conductivity regulation than polymer-based switches[69,72]. In contrast, polymer-based thermal switches provide better mechanical tolerance and fatigue resistance. Advances in polymer-metal composites with high thermal conductivity, mechanical flexibility, and long-term durability could greatly facilitate practical elastocaloric cooler implementation. Despite progress, research on thermal switches in elastocaloric systems remains at an early stage. In particular, the use of temperature-driven passive thermal switches/diodes has yet to be fully explored. This represents an important future research direction for improving system efficiency and reliability.

| Device Prototype | Temperature Span (K) | Maximum Cooling Power (W) | COP | Raw Material Price (USD/kg) | Ref |

| NiTi | 5 | 553.3 | 3.3 | 150 | [63] |

| NiTiFe | 9.4 | 0.05 | 3.1 | 600 | [78] |

| TiNiCuCo | 12.6 | 0.12 | 4.3 | - | [79] |

| Natural rubber balloon | 7.9 | 0.88 | 4.7 | 2 | [80] |

| Natural rubber tube | 8.3 | 1.5 | 6 | 2 | [72] |

| Natural rubber foil | 4 | 0.12 | 4.7 | 2 | [73] |

| SEBS | 5.2 | 4.6 | 9.3 | 3 | [81] |

| Graphene/SEBS | 3.7 | 2.5 | 8.3 | - | [82] |

SMA: shape memory alloy; COP: coefficient of performance; SEBS: styrene-ethylene-butylene-styrene.

2.3 Building energy saving

Buildings remain a major energy and emission source. In China, building operations accounted for ~22% of total energy use and 21.7% of carbon emissions in 2024, largely from heating and cooling[83]. Conventional single-mode thermal materials, designed solely for heating or cooling[84], cannot accommodate year-round climate variability and often cause energy waste. In contrast, smart dual-mode materials that dynamically regulate heat transfer in response to outdoor conditions offer greater potential for building energy savings[85]. Accordingly, this section examines two classes of thermal switches for building energy savings: actively controlled systems requiring external energy input and passive systems enabling self-regulated switching.

2.3.1 Actively controlled thermal switches

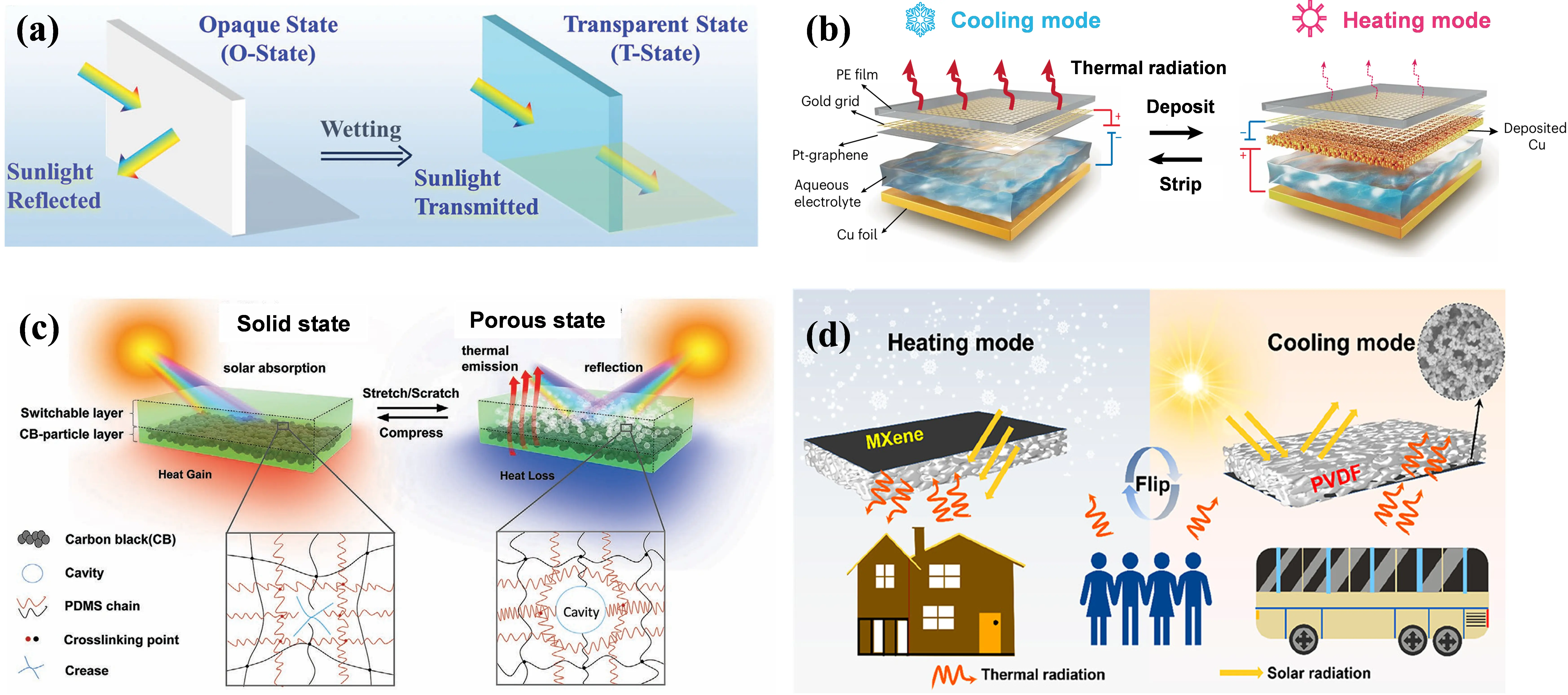

Reversible wettability-based thermal switches: Porous polymer coatings that combine strong solar reflectance with high mid-infrared emissivity are efficient radiative coolers[86,87]. Mandal et al.[14] proposed a reversible approach in which liquids such as alcohol or water wet the radiative surface, and achieved a visible-transmittance swing of up to 0.8 by switching it between optically transparent and opaque states. Scalability remains a key requirement for building applications. Given its short growth cycle, scalable production, and environmental friendliness, bacterial cellulose shows significant promise for radiative cooling applications. Shi et al.[88] reported a biosynthetic bacterial cellulose-based material that modulates solar transmittance from 4.7% (opaque) to 70% (transparent) upon wetting (Figure 8a).

Figure 8. (a) Wetting-induced switchable solar transmittance. Republished with permission from[88]; (b) Electrochromic thermal switch. The device can be tuned between the heating mode (Cu-deposited, right) and the cooling mode (Cu-stripped, left). Republished with permission from[92]; (c) Bilayer structure consisting of a switchable silicone top layer and carbon black particle embedded bottom layer and its cooling and heating mechanism. Republished with permission from[94]; (d) Dual-mode film at heating (left) and cooling (right) mode by flipping. Republished with permission from[96].

Electrochromic thermal switches: Electrochromic materials reversibly change color and transparency under an applied voltage, enabling active control of radiative heat exchange[89]. When integrated into walls, roofs, or glazing, such switches can reduce annual heating and cooling loads by dynamically regulating indoor–outdoor thermal exchange[90]. Zhao et al.[91] demonstrated a switchable solar reflectance from 0.17 to 0.89 via reversible silver electrodeposition on glass; climate simulations across 15 U.S. cities predicted up to ~23% reductions in annual heating, ventilating, and air conditioning (HVAC) energy use. To reduce cost and expand tunability, Sui et al.[92] achieved an emissivity modulation range of 0.07-0.92 through bias-controlled copper deposition and stripping on graphene-based ultra-wideband transparent conductive electrodes (Figure 8b). Such a device switches the system between heating (high infrared reflectivity) and cooling (high emissivity) states. Similarly, WO3/VO2 thin-film structures enable three distinct optical states via voltage-driven lithium-ion intercalation/deintercalation, allowing independent regulation of radiative heat exchange[93].

Strain-induced thermal switches: Strain-induced switching can be achieved using bilayer structures that combine a porous silicone layer with a carbon-black absorber (Figure 8c)[94]. Under tensile strain, collapse of the porous network yields a transparent, high-transmittance state, while strain release restores the porous, highly reflective structure, achieving reflectivity up to 0.93. Li et al.[95] further proposed a flexible thermoplastic film with continuously tunable reflectivity enabled by reversible stretching. Although promising for scalable production, applying controlled strain across building-scale surfaces requires dedicated mechanical systems, and the associated fabrication and operational energy costs are non-negligible.

Manually flipped thermal switches: Another strategy employs manual flipping to alternate between heating and cooling modes (Figure 8d). Shi et al.[96] deposited a high-solar-absorptivity MXene coating on one side of a porous PVDF film with high solar reflectance. In cold conditions, the MXene side faces outward for solar heating; in hot conditions, flipping the film exposes the PVDF side for radiative cooling. Ly et al.[97] demonstrated dual-mode flipping based on asymmetric photonic structures. However, implementing such flipping over large building surfaces remains challenging, motivating the development of simple, energy-free thermal switches that operate without external actuators.

2.3.2 Passive thermal switches

Thermal switches often rely on external stimuli for active regulation, adding energy consumption and system complexity. In contrast, adaptive thermal regulation is promising for building energy savings[98,99]. For example, passive thermochromic materials can vary their radiative properties with ambient temperature without external energy input[100].

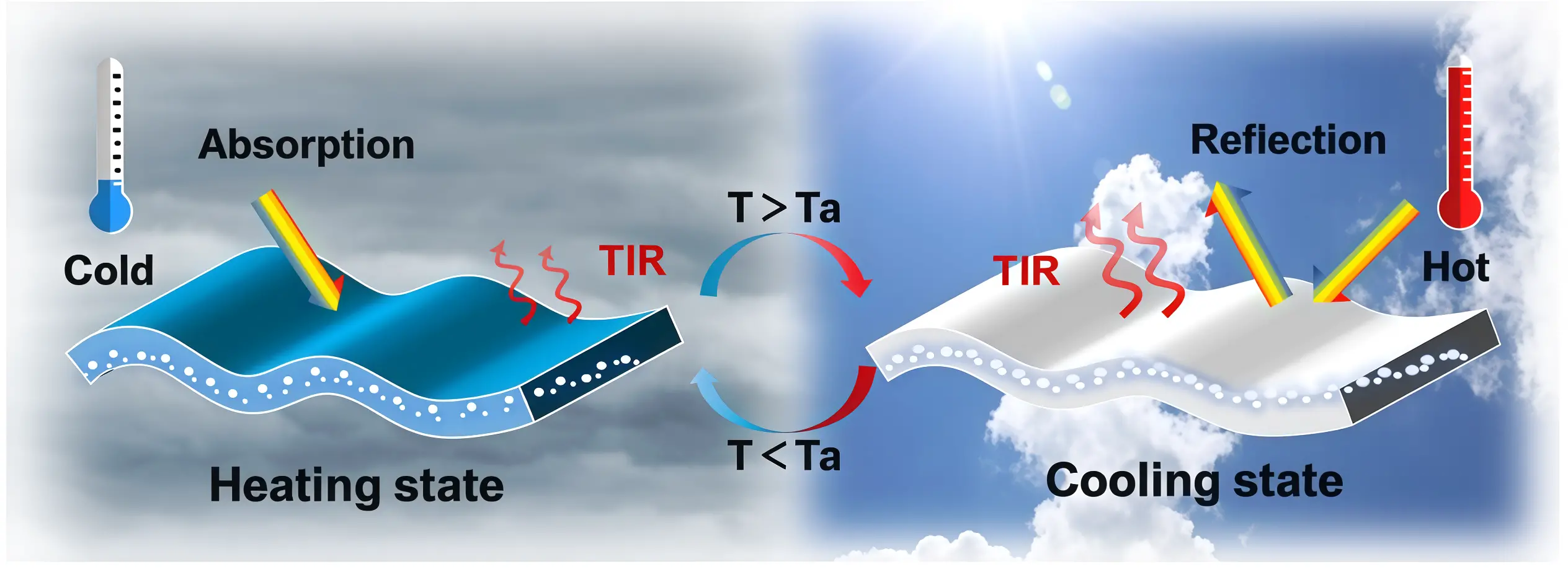

Recent advances have demonstrated environmentally benign, large-area temperature-responsive radiative materials fabricated via scalable processes[101,102]. Cellulose-based passive radiative cooling materials, in particular, show strong potential for large-area adaptive thermal management. For instance, the heterogeneous cellulose coating developed by Zhou et al.[102] induces multistage scattering of incident light, with solar reflectivity of 0.92 and emissivity of 0.93 at high temperatures. Concurrently, chromogenic molecules form and disrupt conjugated regions, enabling visible-light modulation of 0.6 and automatic switching to a heating mode at low temperatures (Figure 9). Tungsten-doped vanadium dioxide (W-VO2) remains another candidate for dynamic radiative thermal management, modulating infrared radiation purely via thermal excitation[103]. Nevertheless, synthesizing high-quality crystalline W-VO2 thin films remains challenging.

Figure 9. Working principle of the self-adaptive thermal management coating. Republished with permission from[102]. TIR: total internal reflection.

Therefore, with its passive and temperature-responsive radiative thermal management that operates without external energy input or active control, this approach offers significant potential to reduce building energy consumption and advance sustainable energy solutions for mitigating global climate challenges. However, a critical, yet often overlooked, issue for thermochromic and temperature-adaptive radiative materials is durability under extreme climatic conditions. Long-term exposure to UV radiation, large daily temperature swings (-20 to 40 °C), and repeated freeze-thaw cycles can induce microcracking, delamination, or chemical degradation of the active layer and its encapsulants. Recent studies[101-103] evaluating performance under real outdoor scenarios have demonstrated improvements in both cyclic stability and processing scale over hundreds of hours of accelerated weathering tests. However, systematic outdoor aging data spanning multiple years remain scarce. Addressing this durability gap represents a critical avenue for advancing building thermal management devices towards practical engineering applications.

3. Applications in Information Technology

With the rapid advancement of electronic information technologies, from 5G infrastructure to quantum processors and highly integrated microchips, modern information processing has become increasingly dependent on electrical power. Thermal logic circuits offer a compelling computing paradigm in certain conditions[104]. In the short term, thermal logic is unlikely to compete with CMOS electronics for general-purpose computing due to its limited switching frequency, relatively large footprint, and higher energy dissipation per operation. In fact, its unique value may lie in extreme environments where conventional CMOS electronics cannot operate reliably, as well as in niche scenarios where heat itself serves as the information carrier. One promising direction is embedded, fail-safe control in harsh environments, such as high-temperature reactors, combustion systems, or space and nuclear applications, where conventional electronics suffer from radiation damage or thermal failure. In these settings, thermal logic elements that autonomously route or block heat could enable simple protection functions without external power or complex electronic circuitry. Early work by Koller et al.[105] demonstrated reversible thermal logic by constructing CMOS-like architectures and basic logic functions, highlighting its potential for low-energy computing. For decades, research on thermal information processing has remained largely conceptual. More recently, Wang et al.[106] proposed phonon-based computing elements, including thermal repeaters and Boolean logic gates, strengthening the theoretical framework for heat-based computation. Progress in thermal switches[107,108] and diodes[109-113] has since begun translating these concepts toward practical, complex thermal logic systems.

Meanwhile, continuous scaling of microelectronics has pushed on-chip heat flux densities beyond 1,000 W/cm2, resulting in severe localized overheating that degrades reliability and accelerates failure[114,115]. Microprocessors in portable electronics experience rapid temperature spikes under high load[116,117], while power semiconductors undergo large, high-frequency junction-temperature oscillations during switching[118]. Such dynamic heat-flux fluctuations are increasingly difficult to manage with conventional passive components such as thermal interface materials[119,120] and cold plates[121]. Thermal switches and diodes are thus being explored as next-generation solutions, attenuating heat-flow noise and mitigating phonon nonequilibrium at the micro/nanoscale to stabilize thermal environments and enhance signal integrity in advanced electronics[122].

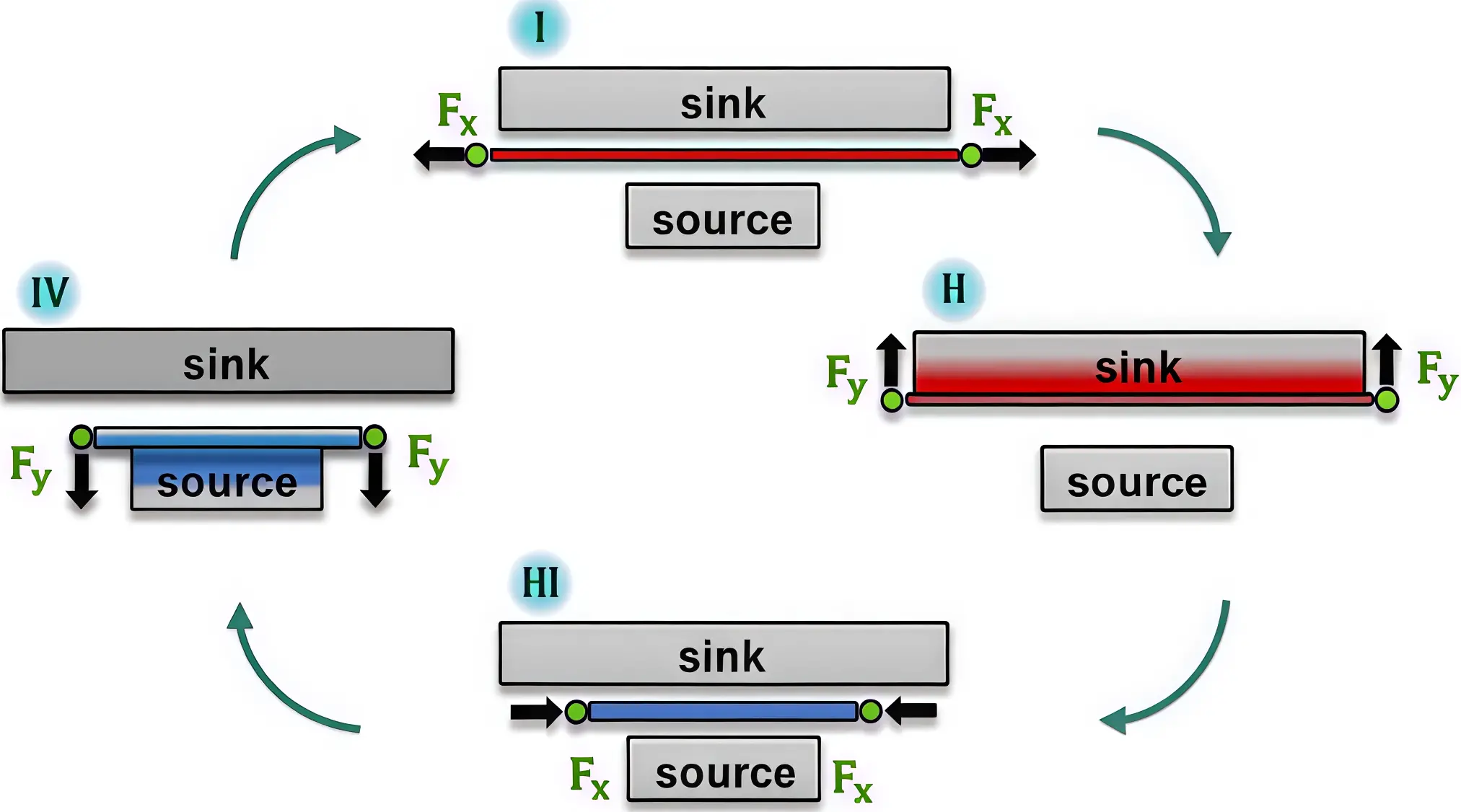

3.1 Thermal switch circuits

This section focuses on thermal circuits that employ thermal switches as functional units. The operational principle of thermal switch-based logic is to encode logical states (“0” and “1”) through reversible transitions in thermal transport properties triggered by external stimuli. Representative control mechanisms include: (i) temperature- and gap-dependent radiative modulation via emissivity or near-/far-field coupling, (ii) electrostatic or electrochemical regulation of thermal conductivity, and (iii) thermo-mechanically induced switching of thermal contact. Accordingly, we review modeling frameworks and recent experimental progress in three archetypal platforms: radiative thermal switches, electric field-effect thermal switches, and shape-memory-alloy-actuated thermal switches.

3.1.1 Radiation thermal switches

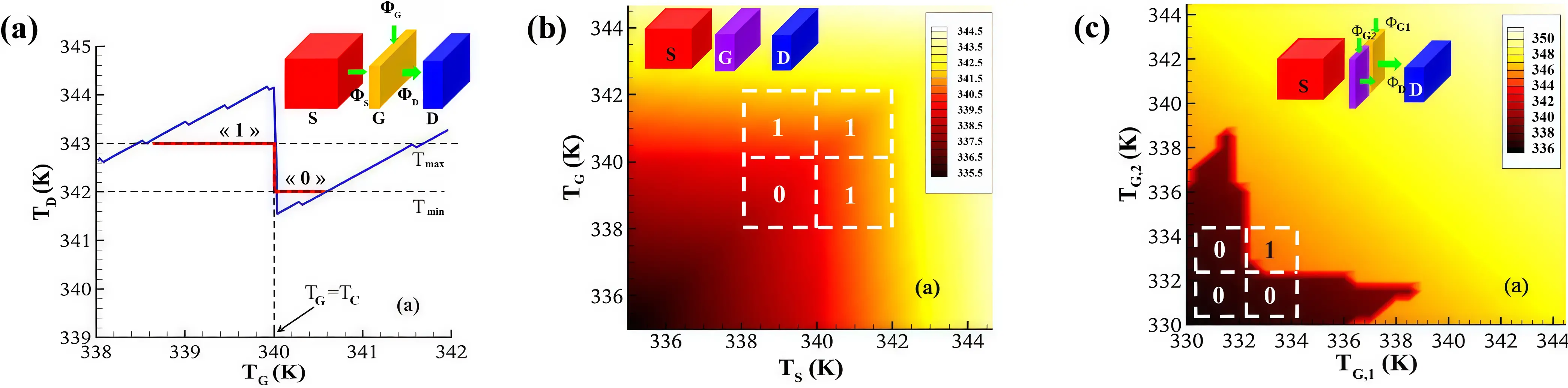

Early progress on radiative thermal switch circuits was largely simulation-based. Ben-Abdallah et al.[123] exploited the abrupt change in VO2 emissivity at its transition temperature to implement a control layer for state switching, and simulated NOT, OR, and AND gates using VO2/SiO2 stacks (Figure 10). While these models demonstrate Boolean functionality, their simplified geometries and idealized assumptions pose hurdles for practical realization (e.g., biasing, parasitic heat paths, and fabrication tolerances). Boolean algebra formed the foundation of modern computing based on electronic devices. Similarly, ensuring the operational stability and robustness of Boolean operations is of particular importance in thermal logic computing. In this spirit, Paolucci et al.[124] constructed a functionally complete thermal logic architecture through the synergy between temperature-biased superconducting quantum-interference proximity transistors and temperature-biased normal-metal-ferromagnetic-insulator-superconductor tunnel junctions, which can even achieve a switching frequency of GHz in the temperature range below 3 K.

Figure 10. Thermal radiation logic gates. (a) NOT gate made with a three-layer SiO2/VO2/SiO2 structure. Where Φ is radiative energy flux; (b) OR gate made with VO2/VO2/SiO2; (c) AND gate made with SO2/double SiO2/VO2. Republished with permission from[123].

These theoretical explorations establish the feasibility of information processing via controlled heat flow, motivating design and testing of more complex logic. Kathmann et al.[125] theoretically surveyed a broader logic set—NOT, OR, NOR, AND, and NAND—implemented by near-field radiative switching among VO2, SiO2, and SiC nanoparticles, laying the groundwork for scalable thermal circuits. Moving from theory to experiment, Li et al.[126] realized a far-field radiative thermal transistor (Figure 11a), analogous to an electronic field-effect transistor: a phase-change “gate” layer is placed between two thermal emitters held at distinct temperatures TS and TD, separated by a gap much larger than the thermal wavelength. By biasing the gate temperature TG around the PCM’s transition using integrated heaters, the radiative heat fluxes QS (source-gate) and QD (gate-drain) are switched, modulated, and even amplified. Figure 11b shows the prototype experimental setup. This first laboratory demonstration of a radiative thermal switch underscores a path toward low-power thermal signal processing and intelligent sensing based on radiative heat-flux control.

In addition, Zhang et al.[127] innovatively proposed a reconfigurable structure with a rotatable gate, as shown in Figure 11c. In this design, the source has the highest temperature, while the temperatures of drain 1 and drain 2 are lower than that of the source; the central terminal is the rotatable gate. The gate is divided into three parts, namely Gs, G1, and G2. By altering the phase-change materials of the first and second layers of the gate, thermal transistors with different thermal properties can be obtained for the design of thermal logic gates. Accordingly, this structure can achieve eight logical combinations using only two phase-change materials (VO2 and germanium-antimony-tellurium, GST) and three gate surfaces. When expanded to five phase-change materials and five gate surfaces, it can even realize up to 24.8 × 109 distinct configurations. Such a vast design space significantly enhances the potential of thermal computing and promotes the development of non-electronic, energy-efficient thermal logic computing systems.

3.1.2 Electric field-effect thermal switches

In metals and semiconductors, heat is transported predominantly by electrons and phonons. An applied electric field can modulate electron transport and electron-phonon scattering, thereby tuning thermal conductivity. For instance, antiferroelectric PbZrO3 thin films exhibit field-induced lattice transitions with abrupt changes in thermal conductivity[17]. Electric-field-regulated thermal switches thus offer large switching ratios, fast response, and cycling stability, making them attractive building blocks for high-performance thermal logic circuits.

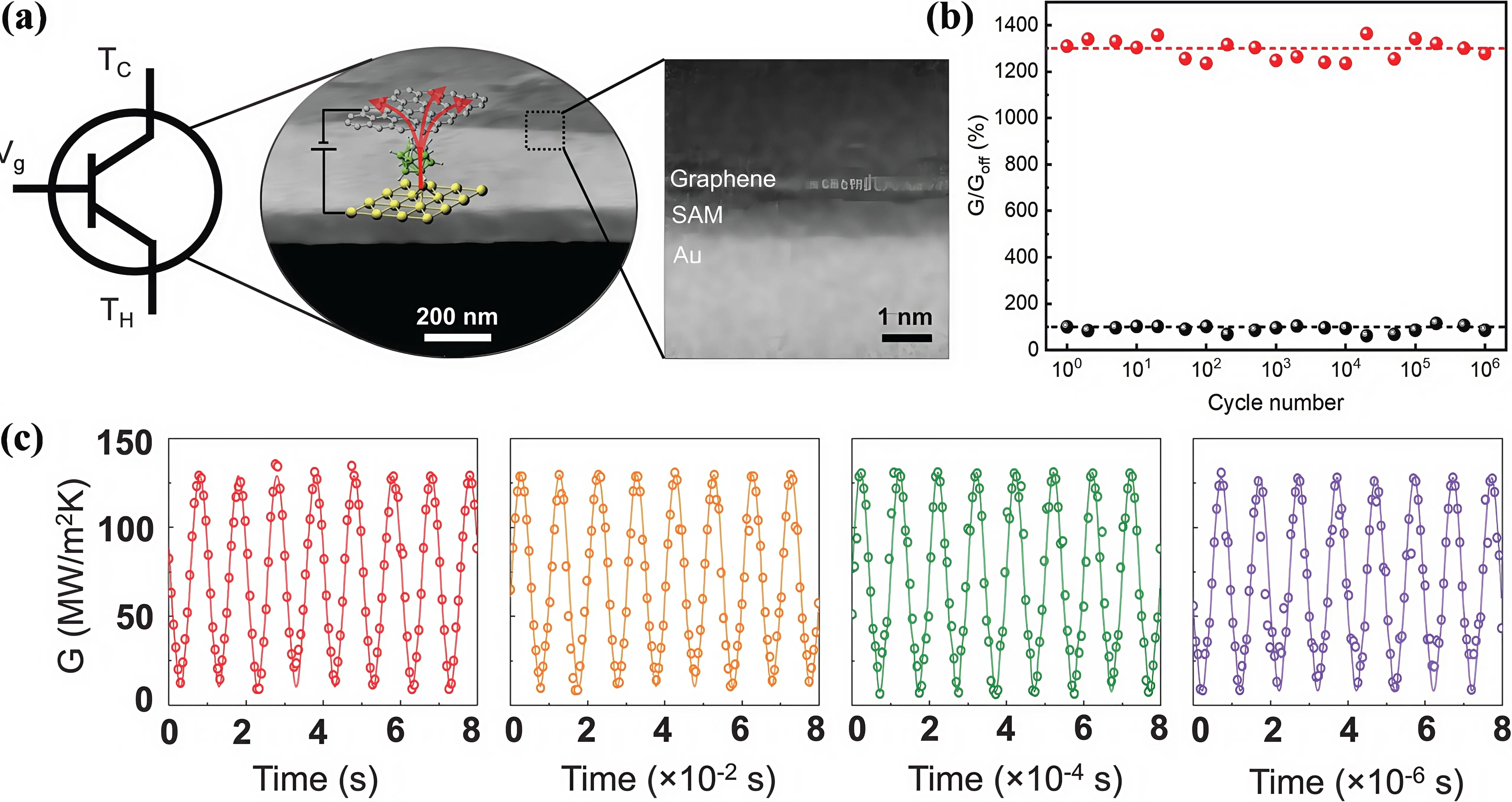

Li et al.[128] realized a three-terminal, field-effect thermal switch using a self-assembled molecular (SAM) layer sandwiched between a bottom Au electrode and a top monolayer graphene, as illustrated in Figure 12a. As observed from the scanning electron microscope (SEM), the bottom layer is gold, the top layer is monolayer graphene, and the middle layer consists of a SAM layer of carboranethiol cage molecules. Gate bias modulates the S-Au bond strength within carboranethiol cages, reversibly tuning interfacial thermal conductance. As shown in Figure 12b,c, the thermal switch delivers a switching ratio of 13 with stable, rapid response, enabling precise heat-flux control for logic operations. Prior to this, Wei et al.[129] simulated electrically gated thermal transport and attributed the conductivity change to field-driven charge-density redistribution that alters electron-phonon coupling. Field-effect is a commonly used method for resistance modulation, and heat carriers also exhibit a fast response to field-effect[128,129]. It can be anticipated that materials modulated by field-effect can be applied to heat current control in thermal circuits as they have been in electronic ones.

Figure 12. Device design and performance tests of the self-assembled molecular thermal switch. (a) Conceptual illustration and tilted top-view SEM image of the three-terminal thermal device; (b) Reversibility test of electrical gating between ± 2.5 V on cycling measurements of the thermal device up to 106 times. Red and black dashed guidelines indicate ratios of 1,300% and 100%, respectively. The value of Goff is 10 MW/m2-K; (c) Experimental data of thermal conductance (circles) in response to gate fields with different frequencies, plotted together with sine function waves of 1 Hz, 100 Hz, 10 kHz, and 1 MHz (solid lines). Republished with permission from[128].

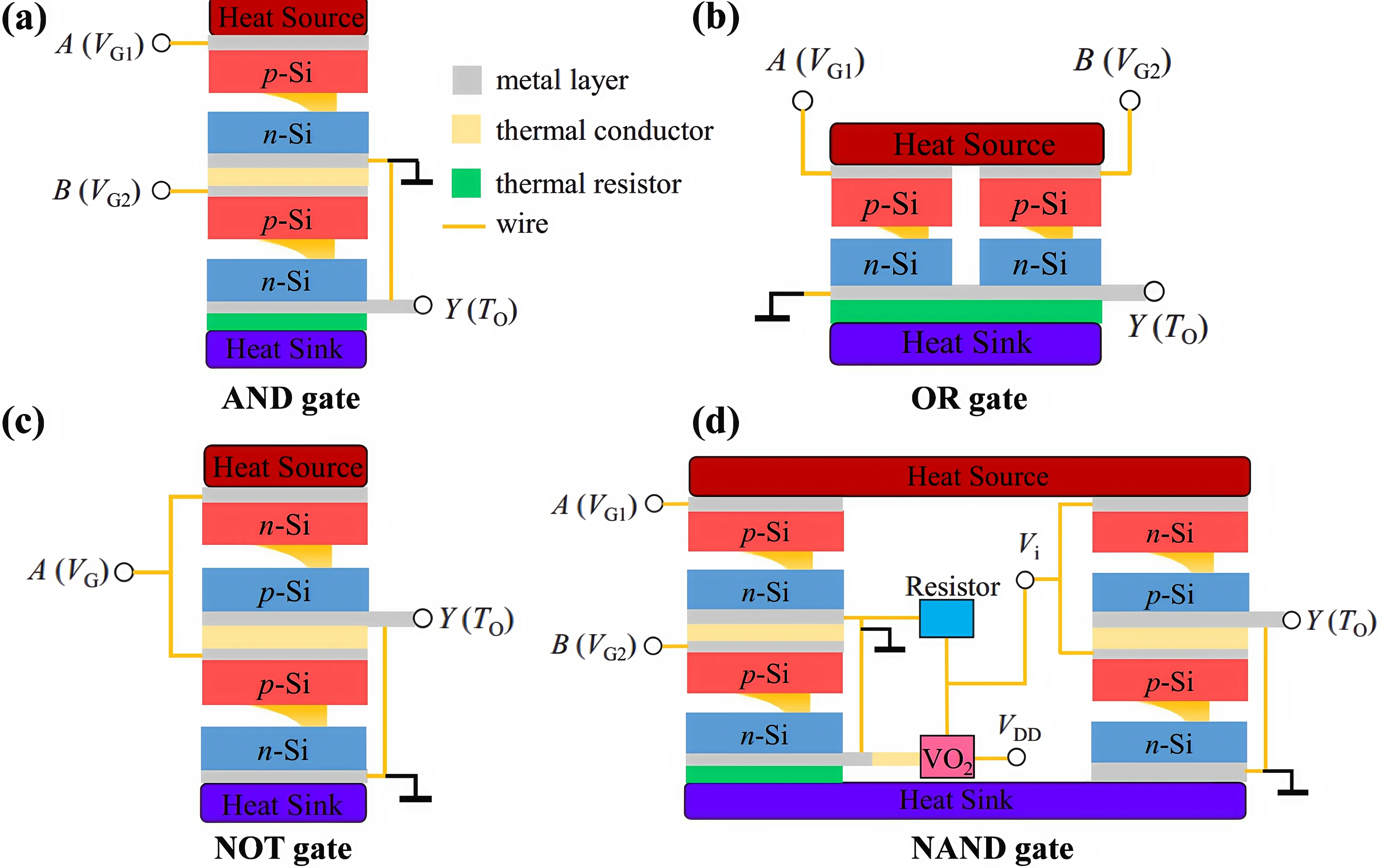

Xu et al.[130] introduced an electric field-effect thermal transistor for constructing complex thermal logic. A gate bias redistributes holes in the source and electrons in the drain, thereby modulating radiative heat flux. Under different combinations of the photonic p-n junction, arbitrary thermal logic gates such as AND, OR, and NOT can be constructed (Figure 13a,b,c). The series and parallel connections between different logic gates can be easily extended to more complex thermal circuits in Figure 13d. The device exhibits millisecond-scale response and a modulation factor up to 6.88, without relying on exotic materials or intricate architectures, underscoring its value for thermal information processing. Relative to the far-field radiative transistor of Figure 11a, the electrically controlled thermal transistor greatly simplifies the structure of logic gates, which is conducive to device packaging and integration.

Figure 13. Configuration of electric-field-effect thermal logic gates. (a) AND; (b) OR; (c) NOT; (d) NAND. The output temperature TO as a function of the input voltage VG. The metal layer and the thermal conductors are used to transfer potential and temperature, respectively. Republished with permission from[130].

3.1.3 SMA-based thermal switches

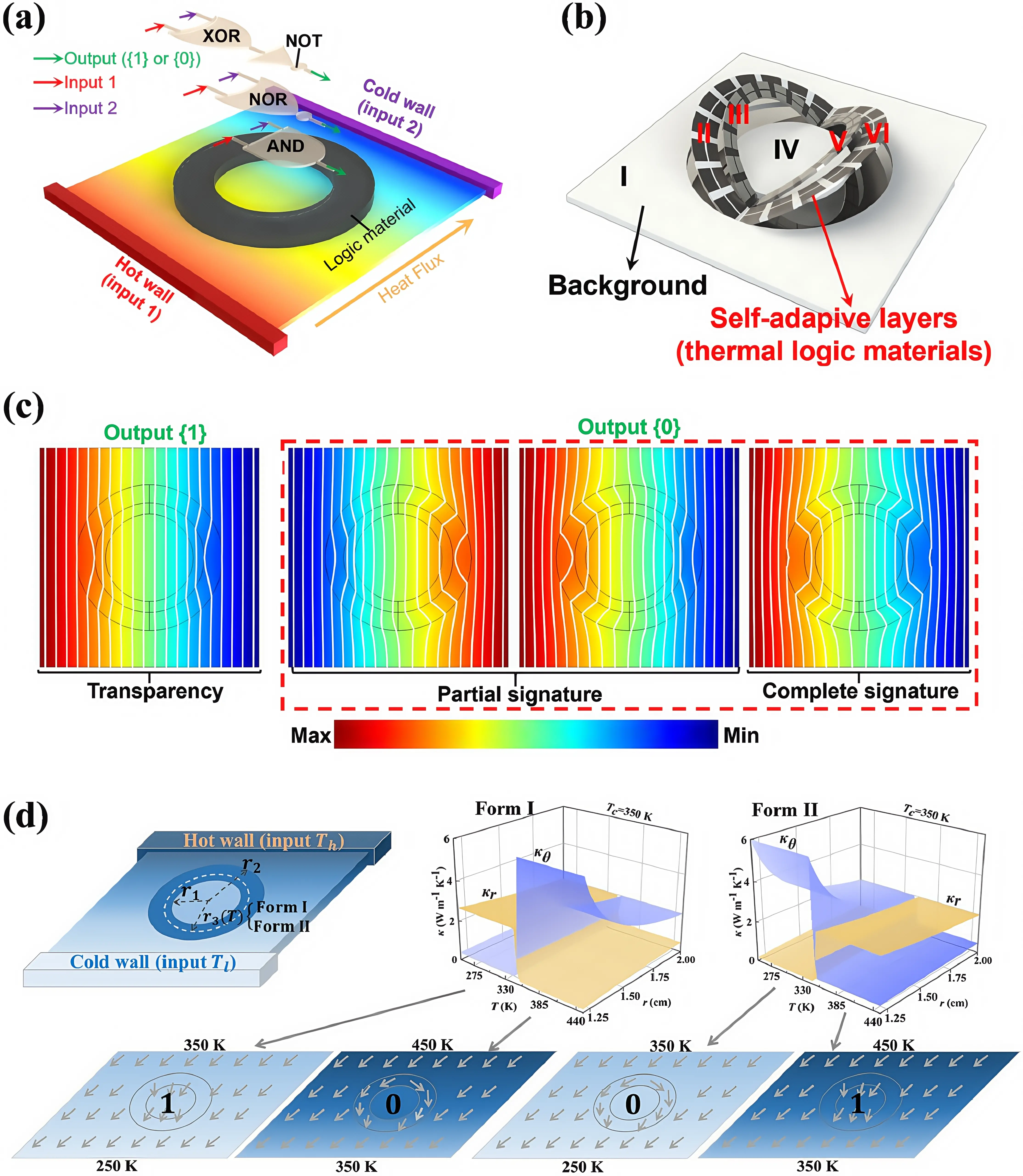

SMAs enable thermally triggered structural reconfiguration and conductivity modulation, making them promising candidates for thermal logic operations. Zhou et al.[131] proposed a thermal logic paradigm that integrates SMA components with conventional media to construct AND, NOR, and coupled XOR-NOT logic gates (Figure 14a). As shown in Figure 14b, the device consists of background (regions I and IV) and inner/outer functional SMA components (regions II-III and V-VI). Logic states are encoded through the contrast of heat-flux distributions: a thermally transparent state with minimal perturbation corresponds to logic “1”, while significant redistribution yields logic “0” (Figure 14c). The switching behavior originates from SMA’s temperature-dependent thermal conductivity and shape transformation. This strategy demonstrates a new thermal information encoding method rooted in self-adaptive thermal transport.

Figure 14. Thermal switch logic gates enabled by SMAs. (a) SMA-assisted thermal logic concept with input temperatures and heat-flow-defined outputs. Republished with permission from[131]; (b) Device architecture for logic operation implementation. Republished with permission from[131]; (c) Output mapping: thermal transparency (“1”) vs. thermal signatures (“0”). Republished with permission from[131]; (d) Programmable thermal encoder using two oppositely switching domains. Republished with permission from[132]. SMAs: shape memory alloys.

Building on similar concepts, Lei et al.[132] developed a programmable thermal encoder using switchable cloak–concentrator elements (Figure 14d). Their simplified architecture consists of two functional domains (Form I and II), which output binary states through reversible switching of anisotropic heat-diffusion behavior. Compared with earlier demonstrations[131,133,134], this approach enables more robust thermal signal discrimination and highlights the feasibility of heat-flow-based encoding for future thermal information processing systems.

3.2 Thermal diode circuits

Beyond thermal-switch-based logic, the intrinsic heat-flow directionality of thermal diodes enables thermal information transmission and storage without electrical carriers.

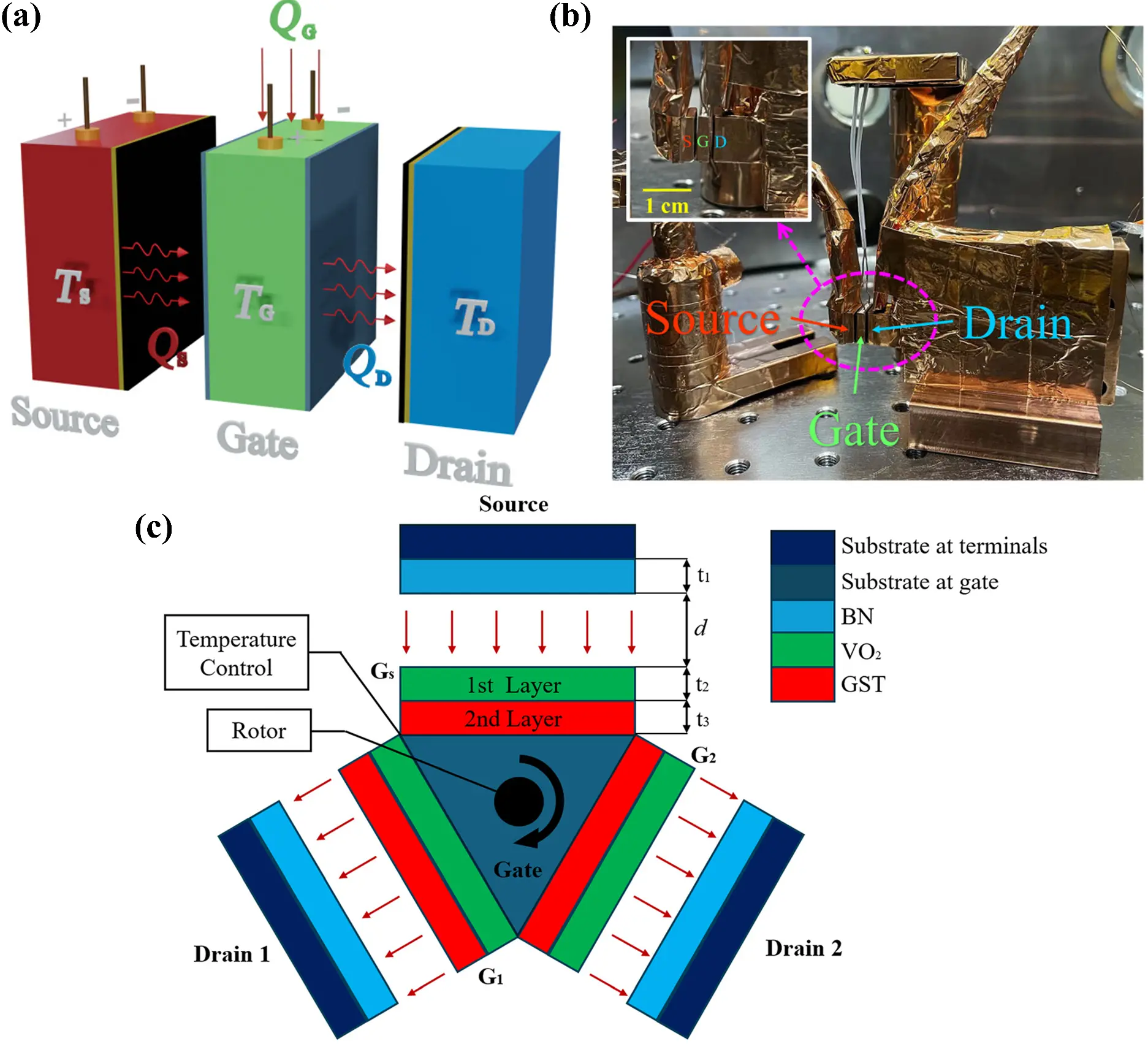

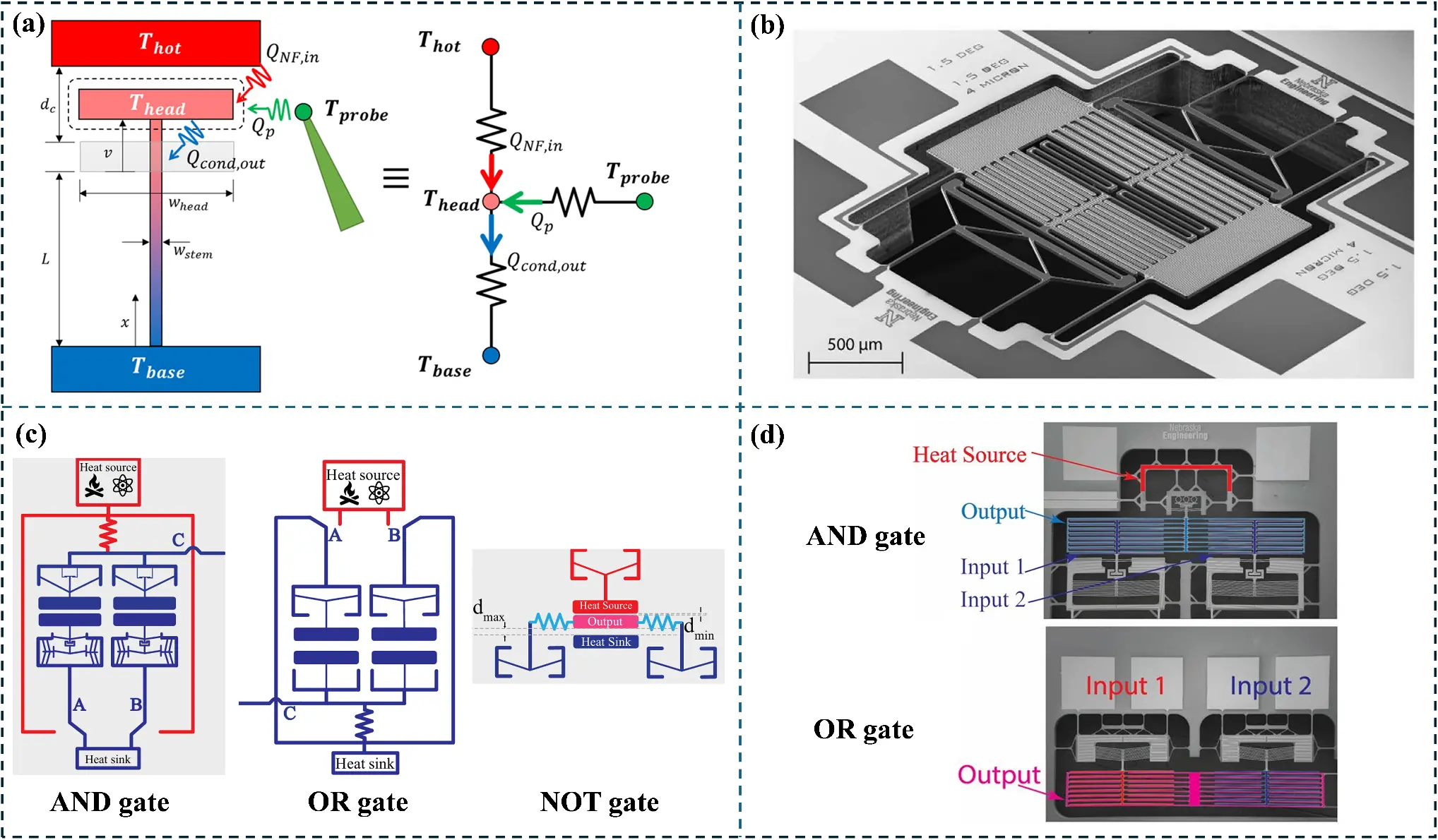

3.2.1 NanoThermoMechanical (NTM) diodes

Conventional electronic memories deteriorate in extreme thermal or electromagnetic conditions, driving interest in NanoElectroMechanical memory devices[135,136]. However, their reliance on electrical actuation and semiconductor properties makes them still susceptible to external interference[137-139]. To address this limitation, Elzouka et al.[138] introduced an NTM memory that processes information purely through heat. The operating principle leverages negative differential thermal resistance arising from thermomechanical deformation and near-field radiative coupling (Figure 15a). Based on this mechanism, they fabricated an NTM thermal diode (Figure 15b) showing ~5.3% rectification at 600 K[140], demonstrating strong potential for heat-based information technology under extreme conditions.

Figure 15. (a) NTM memory device layout and equivalent thermal circuit. The memory device consists of two terminals (base and head). The head is initially separated from the hot terminal by a distance dc. QNF,in denotes the near-field radiative heat input to the head, while Qcond;out represents the heat loss from the head through thermal conduction. Republished with permission from[138]; (b) SEM image of the proof-of-concept microdevice. Republished with permission from[140]; (c) Diagrams of NTM thermal logic AND, OR, and NOT gate. Republished with permission from[104]; (d) SEM images of AND and OR gate. Republished with permission from[141]. NTM: NanoThermoMechanical; SEM: scanning electron microscope.

Hamed et al.[104] further constructed AND, OR, and NOT gates using NTM diodes and thermal transistors (Figure 15c). For AND and OR, two diodes link inputs (A, B) to the output (C), where Tmax and Tmin encode logic “1” and “0”, respectively. Logic inversion is achieved through a thermal transistor. Later experimental work confirmed logic operation stability at high temperatures[141]; SEM images of the AND/OR prototypes are shown in Figure 15d. Overall, NTM diodes provide a promising avenue for radiation-immune, high-temperature thermal logic systems, advancing computation in harsh environments where electronics fail.

3.2.2 Asymmetric-structure thermal diodes

In addition to diodes relying on asymmetric temperature dependence or radiative transport, geometric and material asymmetry alone can also induce thermal rectification[142]. A key advantage of such diodes is that they operate without external control stimuli, making them well suited for integrated thermal logic[143-145]. Chang et al.[146] demonstrated this concept by coating carbon and boron nitride nanotubes with amorphous layers, producing axially mass-graded nanostructures (Figure 16a). Crystalline-amorphous contrasts introduce nonlinear phonon scattering, enabling enhanced nanoscale rectification through boundary-dominated heat transport. Similarly, Pal et al.[147] realized a thermal AND gate using a graphene nanoribbon diode, where asymmetric geometry yields directional phonon scattering and thus direction-dependent heat flux (Figure 16b). Prior studies in this field typically relied on fixed asymmetric geometries[148-150] or heterogeneous low-dimensional fillers[151-153], but such methods inherently lack dynamic tunability, limiting their versatility in reconfigurable thermal circuits.

Figure 16. (a) Amorphous material (black dots) on a nanotube (lattice structure). Republished with permission from[146]; (b) A single GNR diode is shown with heat currents J+ and J-. Here, J+ > J-, which indicates that the GNR diode prefers heat current to flow from the wider to the narrower terminal. Republished with permission from[147]; (c) and (d) Thermal circuits design based on rectifiable conductive thermal diodes and resistors. Republished with permission from[154]. GNR: graphene nanoribbon.

To overcome this limitation, Li et al.[154] introduced an experimentally validated thermal diode based on a tree-like eutectic gallium-indium printed PLA interface, offering dual-mode and switchable heat-flow regulation (Figure 16c). Based on this criterion, they fabricated basic (AND, OR, NOT) and compound (NAND, NOR) thermal logic gates (Figure 16d). These diodes provide high scalability, enabling complex thermal logic architectures through cascading and arrayed configurations. As such, asymmetric-structure thermal diodes represent a promising building block for fully passive thermal information processing, advancing the practical engineering of thermal computing systems.

3.2.3 Magnetic thermal diodes

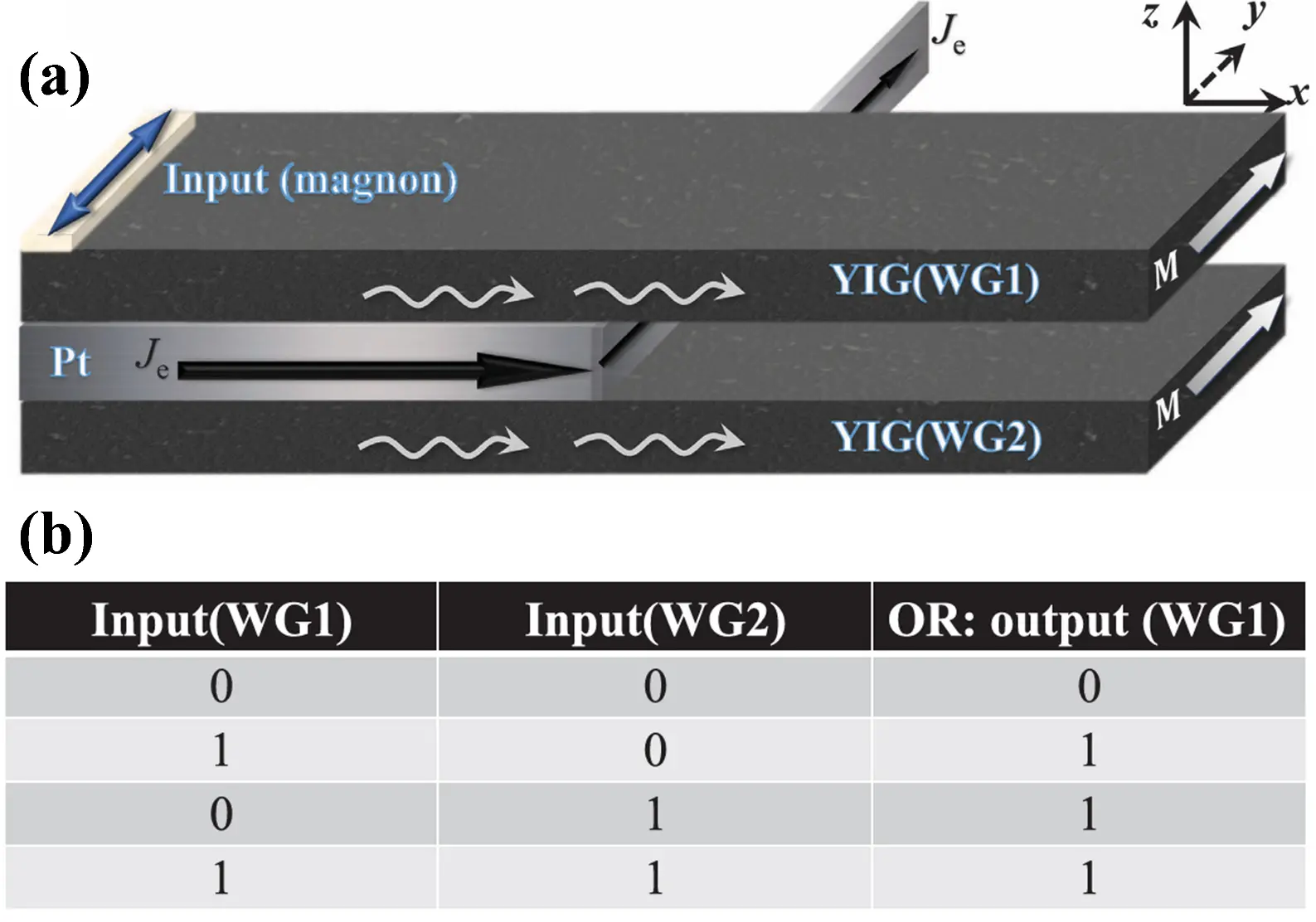

Magnons and spinons, magnetic quasiparticles in magnetic materials, can transport energy analogously to electrons and phonons[155]. As a result, magnonic currents enable energy transfer and information processing, and magnetic logic circuitry has already been experimentally demonstrated[156]. In certain ferromagnets such as yttrium iron garnet (YIG), applying a magnetic field suppresses electron- and phonon-mediated heat conduction, allowing heat transport to be dominated and precisely controlled by magnons[157]. Additionally, strong magnon-phonon coupling gives rise to nonlinear and temperature-dependent magnonic thermal conductivity[158,159]. These advances establish a basis for magnon-driven thermal signal transmission and point toward magnon-based thermal computing. However, new mechanisms must be developed to achieve robust and reconfigurable magnonic logic operations.

Recent work shows that parity-time (PT) symmetry near its phase transition can induce highly nonlinear magnetothermal behavior with properties such as amplified thermal excitations, enhanced perturbation sensitivity, and intrinsic nonreciprocity[160,161]. Leveraging these effects, Wang et al.[162] proposed an experimental framework for a PT-symmetric magnetothermal diode (Figure 17a), where YIG serves as two insulating magnetic waveguides separated by a charge-carrying spacer with strong spin-orbit coupling. Applying a current Je in the Pt layer generates spin Hall torques that damp magnons in one waveguide and amplify them in the other, producing PT-symmetry-induced nonreciprocal heat flow and enabling diode-like directional control. The logic “OR” operation can be realized in the heat diode structure, as shown in Figure 17b. This work demonstrates a new strategy for thermal logic device design by leveraging PT-symmetry critical points to amplify and manipulate thermal information.

Figure 17. (a) Magnetically excited thermal diode structure; (b) The OR logic gate operation table. Republished with permission from[162]. YIG: yttrium iron garnet.

3.3 Microelectronics thermal management

Electrical signals continue to dominate information transmission in the modern era. Here, we review recent advances in microelectronics, specifically thermal switches and diodes, highlighting their rapid thermal response and high rectification capabilities, and offering new perspectives for the design of microelectronic thermal management systems.

3.3.1 Thermal switch solutions

In recent years, extensive theoretical and experimental efforts have explored diverse thermal switch mechanisms, including electrochemical[163-166], strain-induced[20,167,168], and other approaches[169-171], aiming to achieve higher switching ratios and faster response times. Here, we focus on the application of thermal switches in microelectronic thermal management, highlighting their potential for dynamic and high-performance thermal control.

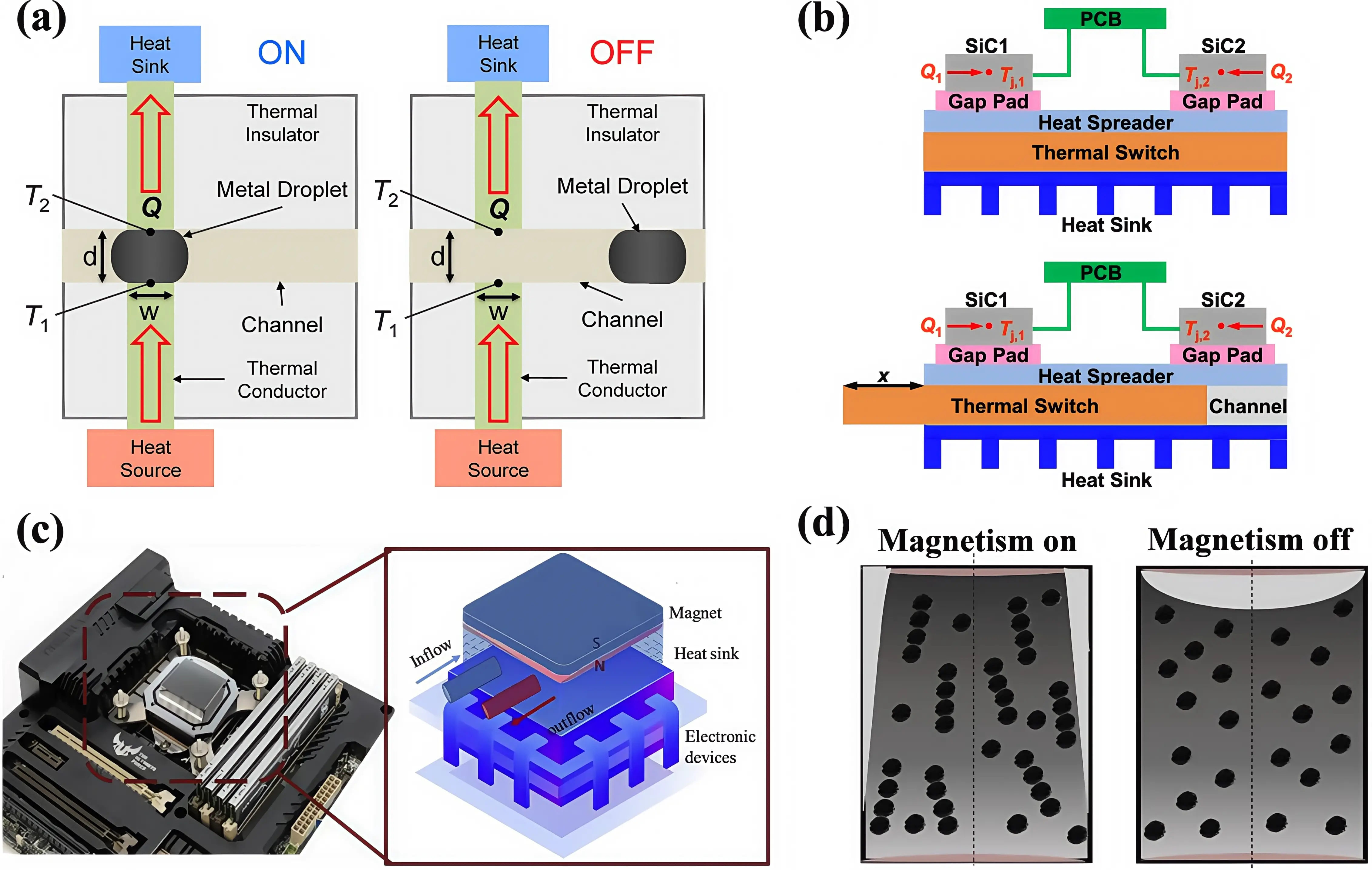

Analogous to electrical switches, active heat-path modulation can be realized by altering the bridging medium between two thermal conductors. Yang et al.[172,173] developed a millimeter-scale liquid-metal thermal switch (Figure 18a) in which a droplet bridges a gap in the ON state (1.83 W at 6 °C) and is replaced by low-conductivity vapor in the OFF state (1.45 W at 42 °C), achieving an ultrahigh switching ratio of 71.3 and enabling uniform temperature distribution and improved microelectronic reliability. Extending this concept, they implemented a solid-state contact thermal switch using a stainless-steel spreader and movable copper plate within a dual-device SiC power module (Figure 18b)[174]. By repositioning the plate, the devices achieve quasi-isothermal operation under 4.7 W dissipation, improving thermal stability in heterogeneous integration. However, the added interfacial resistance limits heat dissipation efficiency, posing challenges under high heat flux densities (> 1,000 W/cm2).

Figure 18. (a) Thermal switch showing the on state with the liquid metal droplet bridging the heat source and sink and off state with liquid metal removed from the channel. Republished with permission from[172]; (b) Solid heat spreader thermal switch integrated with two SiC devices when Cu thermal switch resides in the air channel and is moved to position x along the channel. Republished with permission from[174]; (c) Experimental setup photograph of microelectronic components for heat dissipation. Republished with permission from[177]; (d) Nano-magnetic chain occurs under magnetic field (on) and disappears without magnetic field (off). Republished with permission from[177]. PCB: printed circuit board.

Beyond movable elements, magnetically actuated thermal switches (MATS) offer a contactless approach by tuning thermal transport via magnetic field intensity[175,176]. Shi et al.[177] integrated Fe3O4-based MATS into microelectronic components, forming conductive paths through nanoparticle aggregation (“needle-like protuberances”) at 30 mT (Figure 18c,d). Similarly, Andrade et al.[178] dispersed MnFe2O4 nanoparticles in a low-viscosity ethylene glycol–water solution, achieving enhanced switching ratios and faster response due to high saturation magnetization and reduced fluid resistance. Magnetic materials enable this functionality because their thermal transport depends on magnetization-mediated scattering among magnons, electrons, and phonons[158,179,180]. These advances demonstrate the versatility of thermal switches, from droplet-based and solid-state designs to magnetically tunable systems, in dynamic thermal regulation of microelectronics.

3.3.2 Thermal diode solutions

Thermal diodes, which enable directional heat conduction, have been widely investigated for microelectronic thermal management, including low-temperature quantum devices and wide-range thermal regulation[181]. Unlike thermal switches, diodes achieve unidirectional heat transport without requiring external control[182].

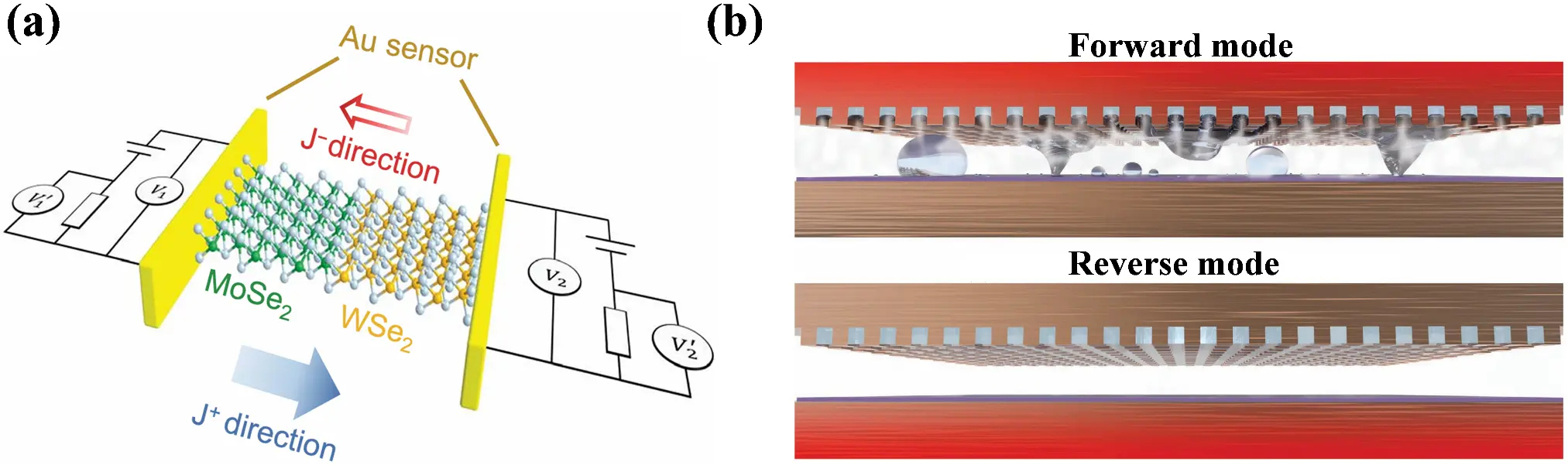

At ultralow temperatures, self-heating from electron transport can generate nanoscale temperature gradients that obscure target signals[183-185]. To address this, Maria et al.[186] fabricated a hybrid thermal diode comprising metals, insulating layers, and superconducting electrodes, achieving a rectification ratio of 140 at 150 mK, demonstrating effective cryogenic thermal control and noise mitigation. Similarly, in 2D lateral heterostructures, intrinsic differences in interface thermal transmittance yield strong rectification even at low temperatures[187,188]; e.g., a monolayer MoSe2/WSe2 heterostructure exhibits up to 96% rectification due to asymmetric phonon transport and localization (Figure 19a)[189]. Bulk heterostructures, such as Fe-doped NiS/Al2O3 junctions, also show significant rectification, with a ratio of 1.8 at 50 K[190-193].

Figure 19. (a) Thermal measurement circuit for the MoSe2-WSe2 heterostructure. The blue solid arrow represents the high thermal conductivity direction J+ from MoSe2 to WSe2, while the red hollow arrow represents the low thermal conductivity direction J- from WSe2 to MoSe2. Republished with permission from[189]; (b) Forward and reverse mode. Republished with permission from[203].

In conventional high-power devices, the temperature gaps of hotspots can exceed 100 K[194], necessitating diodes capable of operating over wide temperature ranges. Doped Si and VO2 systems achieve rectification exceeding 50% with ~140 nm gaps and 70 K temperature differences[195], though radiative heat flux remains limited (< 1 W/cm2) for high-power dissipation[196]. Shape-memory-alloy-based diodes have demonstrated significant temperature reductions, e.g., 36.3 K in chip-scale atomic clocks[197]. Liquid-vapor phase-change diodes offer higher forward heat flux and stronger rectification. Traditional heat-pipe diodes, with asymmetric geometries, rely on gravity and thus function in a single orientation[198]. Jumping-droplet diodes overcome this limitation via coalescence-induced droplet ejection between superhydrophobic and superhydrophilic surfaces, enabling gravity-independent operation[199,200]. Wang et al.[201] systematically studied the effects of gap size, coolant mass, filling ratio, and external electric fields on droplet diode performance, revealing that applied fields can modulate heat transfer. To enhance robustness, Tsukamoto et al.[202] replaced fragile nanostructures with smooth hydrophobic condensers. Edalatpour et al.[203] reported a bridging-droplet design (Figure 19b) capable of high-flux directional transport. Droplets evaporate from a superhydrophilic copper plate, condense on a hydrophobic plate, and bridge back to the evaporator, thereby sustaining efficient thermal rectification.

In summary, thermal function devices for microelectronics are mostly demonstrated on custom test chips or simple heater structures. Their compatibility with mainstream microelectronic packaging flows is a central bottleneck toward real use.

First, materials and process windows must align with standard assembly steps. Any switch or diode placed between the chip and heat spreader must withstand solder reflow (typically 220-260 °C), underfill curing, and lid attachment without losing its microstructure or phase-change functionality. VO2 and other oxide films are promising because they can be deposited as back end of line (BEOL) compatible layers on Si or Cu[204]. However, their crystallization often requires annealing near or above the BEOL thermal budget, and they must remain electrically insulated while providing a low-resistance thermal path. Liquid-metal and magnetofluidic thermal switches[172,177], in contrast, are assembled at low temperatures but demand robust encapsulation and barrier layers that are compatible with Cu, Al, Ni, and common solders, while exhibiting low outgassing under vacuum and temperature cycling.

Second, form factor and mechanical reliability are tightly constrained. Most microelectronic packages tolerate only a few tens of micrometers of additional z-height and minimal extra thermal interface resistance. Many laboratory devices rely on millimeter-scale channels, reservoirs, or external magnets that cannot fit within a power-module housing. Additionally, coefficient of thermal expansion mismatch between functional layers and Cu/Si must be managed to prevent delamination or crack growth under thousands of power cycles.

Experimentally, only a subset of works has moved beyond simple test protocols to package-relevant demonstrators, e.g., liquid-metal thermal switch embedded in lids and mounted on heater chips that emulate realistic hotspot power densities[172], and microfluidic routing layers integrated in interposers for 2.5D/3D stacks[177]. These prototypes generally follow standard reflow and underfill processes, and their thermal cycling tests (102-103 cycles) suggest that the additional interfaces can maintain low contact resistance if appropriate metallization and surface preparation are applied. Nevertheless, long-term reliability data under combined thermo-mechanical and electromagnetic stress remain scarce.

Overall, thermal functional devices demonstrate impressive performance but only partially align with industrial packaging practices. The integration with microelectronics will be critical for translating these devices from laboratory demonstrations to practical applications.

4. Existing Challenges and Emerging Applications

Despite advances in thermal switching and rectification, a substantial gap remains between laboratory prototypes and practical deployment. Most devices are still at the proof-of-concept stage, with integration, scalability, and reliability challenges. Here, we evaluate these challenges and discuss potential applications of thermal switches and diodes in spacecraft and personal thermal management.

4.1 Practical challenges for thermal switches and diodes

Although significant progress has been made in thermal switches and diodes, most devices remain at the proof-of-concept stage, and key technical and integration challenges must be addressed for practical deployment. From a technology-readiness perspective, the vast majority of reported thermal switches and diodes remain at the component or device level. Typical demonstrations involve single interfaces, millimeter to centimeter scale samples, or highly idealized test rigs (e.g., VO2 thin films[103,205], liquid metals in microchannels[172,173], magnetofluidic pillars[177,178]). In fact, practical systems, such as battery modules, power-electronic converters, building envelopes, spacecraft radiators, and wearable devices, span length scales from centimeters to meters. They face tightly coupled constraints on mass, volume, power consumption, safety, and cost. Bridging this gap requires not only scaling up the active materials or interfaces but also co-designing packaging, interconnects, control strategies, and system architectures.

Manufacturability and scalability: Conventional thermal solutions benefit from mature, highly scalable fabrication processes, like compact heat sinks and densely embedded heat pipes. In contrast, integrating and packaging multiple thermal switches or diodes adds complexity[205]. Further, fabrication of micro- and nanoscale switches/diodes requires advanced techniques, such as high-quality thin-film deposition (such as VO2) and electron-beam lithography for nano-gaps[205], which are feasible at the lab scale but difficult to reproduce with high yield in mass production. At the system level, additional challenges arise from assembling, including the risk of parasitic thermal shortcuts, excessive contact resistance, and/or increased thermal mass. Consequently, strategies or devices that perform well at small scales may lose effectiveness when scaled to the square-meter areas required for building envelopes, spacecraft radiators, battery packs, and elastocaloric coolers.

Performance validation in real conditions: Most studies have been conducted under idealized conditions[172,174,189] or with switches tested in isolation[17,128,206]. In actual electronic systems, the practical effectiveness of these devices could be limited by complex thermal environments with multiple heat sources, fluctuating power loads, and variable ambient conditions. Thus, integrating prototypes into functional platforms, such as GPU modules or power converters under realistic duty cycles, is essential to benchmark their true system-level impact. Laboratory characterization often focuses on steady-state or slowly varying boundary conditions, whereas the heat loads in practical systems are transient and spatially non-uniform. For a thermal diode with a high rectification ratio under a fixed temperature bias, its benefit is still unclear when integrated into processors with migrating hotspots or battery modules with highly non-uniform heat generation during fast charging. Similarly, thermal switches in spacecraft must be evaluated under realistic orbital day-night cycles, accounting for combined radiative, conductive, and mechanical perturbations. For elastocaloric coolers, an ideal thermal switch should combine long-term cyclability, system-level integrability, and high on-state thermal conductance with a large on/off ratio. Translating laboratory performance into practical gains thus requires device-in-system testing under representative duty cycles, as well as multi-physics models that capture electrical, mechanical, and control interactions.

Reliability and longevity: Commercial deployment requires devices to endure tens to hundreds of millions of switching cycles or thousands of thermal cycles under realistic operating conditions, including temperature, humidity, and mechanical stresses[207]. While some VO2-based switches have survived ~108 thermal cycles[208], comprehensive reliability validation to industry standards remains largely unreported, hindering adoption in high-reliability sectors like aerospace or automotive.

Economic and practical considerations: Finally, new thermal management technologies must demonstrate clear cost-benefit advantages. Currently, adding thermal switches or diodes may be more expensive and riskier than using slightly larger heat sinks, more aggressive fans, or liquid cooling solutions. How to reduce costs is a problem that all industries need to address.

Practically, the dominant scaling bottlenecks differ across application domains: 1) Battery thermal management. Maximizing the switching ratio is a lower priority than safety, manufacturability, compatibility with existing cell and module designs, non-flammability, and reproducible interfacial quality. Although significant progress has been made in thermal safety[19] and management technologies[13,39,54], balancing these requirements remains challenging. There is an urgent need for advanced thermal management solutions that enable heat retention at low temperatures, dissipation at high temperatures, and suppression of TR propagation under extreme conditions. 2) Building application. Building envelopes require low actuation energy, material cost, and multi-year outdoor durability. Most existing studies[88,94] focus on large-scale material fabrication, while comparatively less attention is paid to actuation operability and long-term durability testing. Durability tests under harsher environments will be essential for advancing practical engineering applications. 3) Information processing. Thermal logic circuits, proposed as alternatives to conventional microelectronics under extreme conditions, prioritize high switching ratios and speed over operational longevity for short-duration applications or proof-of-concept studies. In contrast, microelectronic systems emphasize extreme heat-flux handling, minimal added thermal resistance, and full compatibility with standard packaging processes such as solder reflow, underfill, and lid attach. Understanding these sector-specific trade-offs helps guide the selection of thermal switches for each application.

These challenges vary in importance across industries, reflecting the distinct priority requirements of each sector. In battery thermal management, preventing cell overheating and TR propagation is critical, which requires rapid thermal switch response under extreme conditions. Elastocaloric cooling emphasizes high cooling capacity and power density, while building management focuses on reducing annual energy consumption and costs. Thermal logic circuits aim to achieve stable signal transmission in specific scenarios, such as strong electromagnetic interference. For microelectronic thermal management, increasing the thermal budget and adopting miniaturized designs within existing packaging systems are essential. Successful applications must align with the practical needs of each industry. To support the selection of thermal switching devices and the identification of optimal technical routes, we have systematically compiled the performance metrics of thermal switches and diodes based on different mechanisms, as summarized in Table 3.

| Thermal Control Mechanism | Switching ratio/Thermal Rectification Coefficient | Operating Temperature Range (°C) | Actuation Energy Consumption | Durability (Cycles) | Ref |

| Compressible carbon-based thermal switch | 43 | 25~120 | - | > 1,000 | [40] |

| Phase-change-driven thermal switch | 15.4 | 25~60 | > 100 mW | - | [44] |

| SMA-driven thermal switch | 10 | -30~45 | 10 mW | > 1,000 | [39] |

| Polymer based thermal switch | 9.7 | 5~25 | > 100 mW | > 30,000 | [72] |

| Reversible wettability thermal switch | 14.9 | 0~40 | - | - | [88] |

| Electrochromic thermal switch | 13.1 | -20~50 | 0.18% HVAC | 1,800 | [92] |

| Manually flipped thermal switch | 8.3 | -5~35 | - | - | [96] |

| Thermochromic thermal switch | - | -20~50 | 0 | - | [102] |

| Radiation Thermal Switch | 5~10 | 60~80 | - | - | [123] |

| NTM thermal diode | 10~100 | > 25 | - | - | [138] |

| Asymmetric-structure thermal diode | 5.8 | 30~70 | 0 | - | [154] |

| Magnetic thermal diode | > 10 | ~25 | - | - | [162] |

| Liquid-metal thermal switch | > 10 | 25~100 | - | 10~100 | [177] |

| Bridging-droplet thermal diode | > 10 | 25~200 | 0 | > 10 | [203] |

SMA: shape memory alloy; NTM: NanoThermoMechanical; HVAC: heating, ventilating, and air conditioning.

4.2 Emerging opportunities: spacecraft and personal thermal management

4.2.1 spacecraft thermal management

Aerospace systems for communications, navigation, and scientific observation increasingly rely on highly integrated, high-power electronics[209]. Operating in microgravity with alternating solar exposure, deep-space cold, and intense radiation, these devices experience extreme thermal swings[210]. Conventional thermal control technologies, such as heat pipes, often struggle to balance the high temperatures under direct sunlight with the extreme cold on shadowed surfaces[211]. Thermal switches and diodes address this challenge by enabling precise, on-demand heat flux regulation and thermal isolation, that aligns closely with spacecraft requirements.

Although switching strategies for spacecraft thermal management were explored over two decades ago[212-214], many early approaches suffered from vacuum incompatibility, high actuation energy, or limited radiating area. Spacecraft operate in high vacuum, where convection is negligible and radiation becomes the dominant heat transfer mode. Moreover, components experience extreme temperature excursions (roughly 200 to 400 K in low-Earth orbit) and harsh environments, including particle radiation and atomic oxygen erosion. These factors impose stringent requirements on thermal switches and diodes: chemical stability under extreme temperatures, stable optical properties under radiation, minimal mass and volume addition, and reliable operation through tens of thousands of orbital day-night cycles.

More recently, Ueno et al.[215] demonstrated an active thermal radiation control device using an array of voltage-driven thermal switches with nanogap-enhanced near-field radiation, achieving a switching ratio of 28.5, a radiation-area ratio of 61%, and low-power operation. Since thermal radiation is the primary heat rejection pathway in space, tunable emittance is crucial. In their thermal resistance analysis, the temperature range of the heat dissipation surface is 300~400 K, while the ambient temperature is 3~300 K, resulting in a maximum temperature gradient of 400 K. They also accounted for strong vibrations during rocket launch and intense radiation in the aerospace environment.

Xu et al.[216] applied a voltage-controlled tunable-emittance coating to a heat sink, achieving an effective emittance range exceeding 0.7 relative to 3 K deep space. The device operated within a temperature range of 240~360 K, which is more stringent than typical near-Earth orbit conditions. However, environmental reliability factors, such as radiation aging and oxidation resistance, have not been evaluated.

Complementarily, Hou et al.[217] developed a dual-mode thermal management system based on a temperature-responsive asymmetric shape-memory Janus array, which adaptively switches between thermal insulation and radiative cooling modes, with corresponding infrared emissivity of 0.04 and 0.9 in high-vacuum conditions. They considered two orbital scenarios (Earth and Venus), as solar radiation near Venus is approximately twice that near Earth. This study demonstrated the adaptive switching capability of the device under low and high heat fluxes. Meanwhile, environmental stability was evaluated through cyclic shape memory tests and accelerated UV irradiation tests.