Abstract

Cholesteric liquid crystal polymer network (CLCN) patterns composed of oppositely handed helical structures are attractive for anti-counterfeiting. Different areas can be observed under the circularly polarized light with opposite handedness. However, achieving precise control over the reflection band wavelengths of CLCN patterns using photochromic cholesteric liquid crystals (CLCs) remains a significant challenge. Herein, we synthesized a chiral cyanostilbene derivative that demonstrated significant modulation of its helical twisting power upon 365 nm ultraviolet (UV) irradiation. When incorporated into CLC mixtures, this additive enabled precise control over both the handedness and reflection wavelength of the resulting CLCN patterns within seconds under UV exposure. The system allowed for the preparation of colorful CLCN patterns through in-situ photopolymerization. These findings demonstrate that the developed CLC mixtures are well-suited for high-throughput fabrication of CLCN patterns on industrial coating lines.

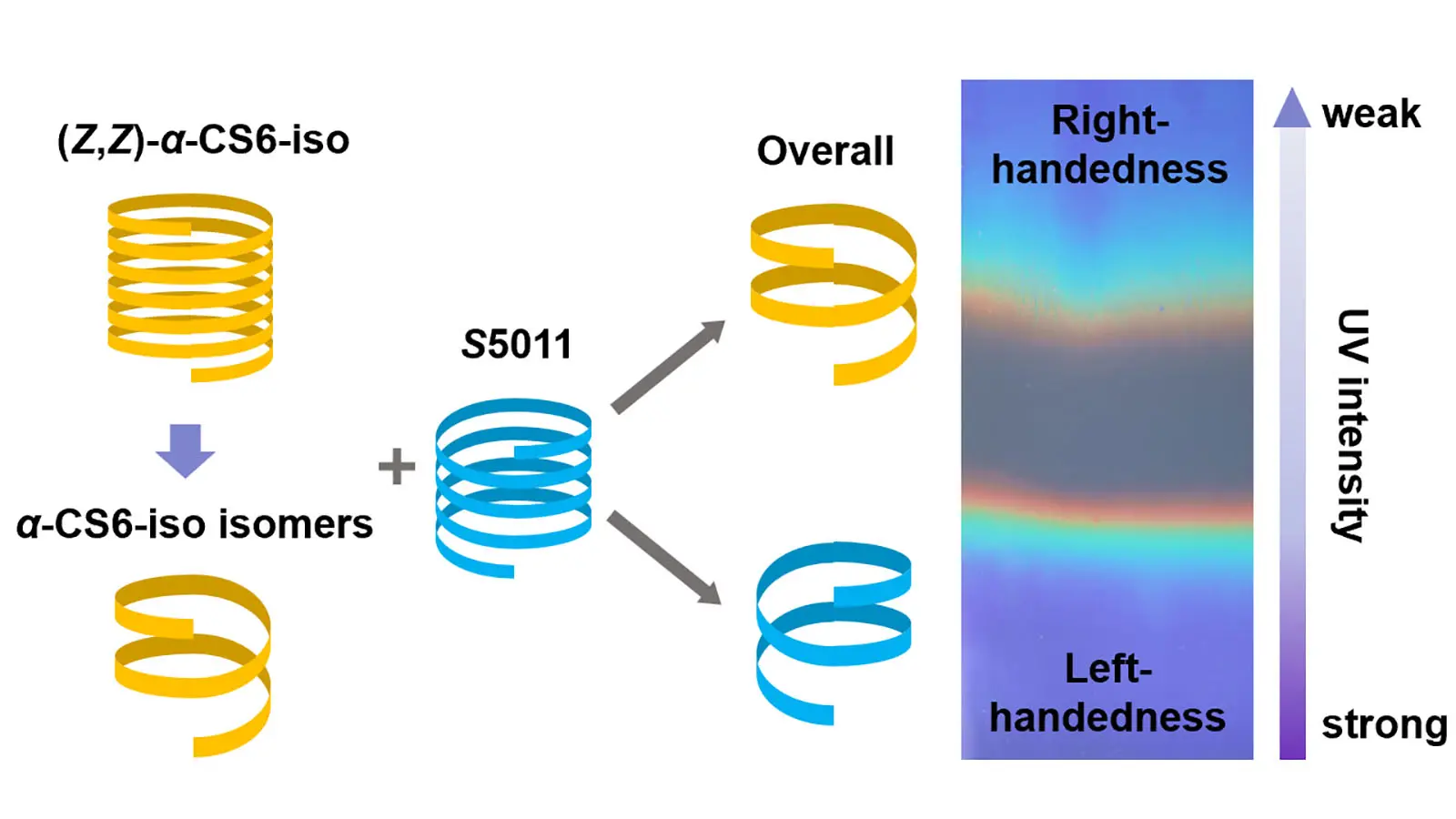

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

1. Introduction

Color is a crucial element in nature[1,2]. The diverse colors allow plants to selectively absorb light of different wavelengths, while animals can utilize them for camouflage and self-protection[3-5]. Among these, pigment color determined by chemical pigments and structural color determined by the microscopic structure of the substance's surface or interior are the two primary causes of color[6]. Typically, structural colors exhibit higher saturation and brightness, and are more responsive to environmental stimuli, making them commonly used in functional materials[7]. Photonic crystals are materials exhibiting structural colors[8,9]. Among them, the cholesteric liquid crystals (CLC) derive their structural color from its periodically helical structure. The reflection band wavelength (λ) of the CLC system follows Bragg’s law, as described by the equation:

CLCs have demonstrated extensive applications in various fields, including reflective display technologies, high-density optical data storage, tunable optical filters, and advanced information encryption systems[12-21]. By introducing functional groups or chemicals with different characteristics into the CLCs, photochromic, thermochromic, mechanically, or humidity responsive CLCs have been prepared, which have been applied as smart sensors[22-28]. For decoration and anti-counterfeiting, optical masking, screen printing, inkjet printing, 3D printing, gravure and flexographic printing techniques have been applied for the preparation of patterned CLC polymer network (CLCN) films through in-situ photopolymerization of CLCs[29-32]. The optical mask can cause CLCs to undergo varying degrees of photochromism in different areas, or enable thermochromic liquid crystals to polymerize in an area-selective under temperature control. However, since it is difficult to control the polymerization temperature on coating lines, it is hard to prepare patterned CLCN films on a large-scale using thermochromic CLCs. For controlling the structural colors of photochromic LCs, the intensity and irradiation time of the light for photochromism should be precisely controlled.

The photochromic liquid crystals are generally prepared by adding photoisomerizable chiral additives to nematic liquid crystals[33-38]. The helical twisting power (HTP) values of the chiral additives can be quantitatively controlled by the light dose. At present, common photoreactive chiral dopants are mainly prepared by introducing photoreactive functional groups. These chiral additives are generally derived from azobenzene[39-42], cinnamate[43,44] and cyanostilbene[45]. Azobenzenes can undergo reversible changes in their cis- and trans-isomers under the light with different wavelengths[39-42]. Due to the high activation energy barrier between the Z-type and E-type of cinnamates, it is difficult for them to undergo reversible molecular configurational changes[43,44]. The cyanostilbene compounds not only exhibit reversible Z-type and E-type changes, but also have attracted much attention from researchers due to their fluorescence emission properties[45-49].

Herein, a cyanostilbene-based chiral additive, α-CS6-iso, was synthesized. The CLCs prepared using it can reach the photostationary state (PSS) within several seconds. By controlling the concentration of α-CS6-iso, patterned CLCN films with precisely controlled reflection bands can be obtained. Due to the significantly large change in the HTP value of α-CS6-iso upon 365 nm ultraviolet (UV) light irradiation, handedness invertible CLC mixtures were prepared. The CLCN patterns, composed of both left- and right-handed helical structures, were successfully fabricated. Complementary images were observed when viewed through left- and right-handed circular polarizers. These patterns are particularly well-suited for decorative and anti-counterfeiting applications.

2. Experimental Section

2.1 Materials and instruments

CA-Acrylate and rubbing-oriented PET film were provided by Wuxi Shengcai Optical Sci. & Tech. Co., Ltd. (China). Cyclopentanone was purchased from Chinasun Specialty Products Co., Ltd., and ethyl acetate was obtained from Shanghai Lingfeng Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. E7 was sourced from Yantai Xianhua Technology Group Co., Ltd., while C6M and S5011 were acquired from Nanjing Sanjiang New Materials Development Co., Ltd. Methyl p-cyanomethylbenzoate and isosorbide were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Additional reagents, including 1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-3-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDCI), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), Irgacure 907, 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)acetonitrile, potassium hydroxide, potassium carbonate, 1-bromohexane, and cyclohexanone, were obtained from Shanghai Aladdin Biochem. Techn. Co., Ltd. Solvents such as methanol, acetonitrile, ethanol, hydrochloric acid, acetone, ethyl acetate, CDCl₃, and tetrahydrofuran (THF) were procured from Shanghai Lingfeng Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Photomasks were fabricated by printing patterns onto PET substrates using a laser printer (HP LaserJet P1007, China).

The FT-IR spectra were performed on a Nicolet 6700 spectrometer at 2.0 cm-1 resolution by averaging over 32 scans. UV-vis spectra were taken using the UV-vis spectrophotometer (UV-1900i, Japan). Error limits were estimated as follows: wavelength, ± 1 nm; transmittance, ± 0.1 %. The POM images of the target compounds were taken using a CPV-900C polarization microscope fitted with a Linkam LTS420 hot stage. The FE-SEM images were obtained using a Hitachi S-4800 operating (Ibaraki prefecture, Japan) at 5.0 kV. The MINHIO 4012-20 UV curing machine composed of a high-pressure Hg lamp (280-450 nm, 1.0 kW) and a conveyer belt was produced by MINHIO Intelligent Equipment Co., Ltd (Shenzhen, China). The UV LED series equipment (UVSF81T, 400 mW cm-2, output power) was produced by FUTANSI Electronic Technology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). The ZF-7A portable UV lamp was produced by Guanghao Analytical Instrument Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

2.2 Synthesis of α-CS6-iso

A mixture of p-hydroxybenzaldehyde (12.12 g, 100 mmol), 1-bromohexane (24.76 g, 150 mmol), K₂CO₃ (24.88 g, 180 mmol), and 500 mL of acetone was stirred at 50 °C for 24 h. After filtration, the solvent was removed in vacuum, and the residue was purified by column chromatography (petroleum ether as eluent) to afford the intermediate. This intermediate (12.38 g, 60 mmol) was dissolved in 300 mL of THF, and a solution of methyl p-cyanomethylbenzoate (8.76 g, 50 mmol) in 100 mL of EtOH containing KOH (7.0 g, 120 mmol) was added at 50 °C. After 24 h, the reaction mixture was acidified to pH 1.0 with 11.9 M HCl aq. solution. The precipitated solid was filtered, and the solvent was removed in vacuum. The crude product was purified by recrystallization from methanol to yield the desired product. The obtained powder (7.69 g, 22 mmol), isosorbide (1.46 g, 10 mmol), EDCI (5.37 g, 28 mmol), and DMAP (0.24 g, 2.0 mmol) were dissolved in 200 mL of THF at 30 °C under nitrogen. After 24 h, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the crude product was purified by recrystallization from an acetone/methanol mixture, yielding a light-yellow solid (3.37 g, 41.6% yield). m.p.: 176.3 °C. [α]D20 = -208.2° (c = 0.5, CHCl3). FT-IR vmax: 2925, 2862, 2365, 2337, 2218, 1718, 1584, 1512, 1472, 1415, 1350, 1312, 1263, 1182, 1112, 1096, 1063, 1019, 966, 853, 831, 772 and 693 cm-1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, Chloroform-d): δ = 8.07 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 8.00 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.85 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.0 Hz, 4H), 7.71-7.63 (m, 4H), 7.50 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 2H), 6.91 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H), 5.47-5.36 (m, 2H), 5.03 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H), 4.65 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 4.08-3.94 (m, 8H), 1.78-1.70 (m, 4H), 1.45-1.37 (m, 4H), 1.32-1.25 (m, 8H), 0.88-0.82 (m, 6H) ppm. MS m/z (rel. int.): 831.512 ([M+Na]+, 100). Elemental analysis: calculated (for C50H52N2O8): C 74.24%, H 6.48%, found: C 74.09%, H 6.63%.

2.3 Preparation of the structurally colored CLCN films by changing the α-CS6-iso concentration

A typical preparation procedure was shown as follows. The LC242/α-CS6-iso/Irgacure 907 (w/w/w, 92.5/4.5/3.0) mixture was dissolved in a cyclohexanone/ethyl acetate (v/v, 4:1) solvent mixture to achieve a 20 wt% solid content. The resulting solution was coated onto a rubbing-oriented PET film using a 20 μm Mayer bar to control the film thickness. The coated film was then dried at 120 °C for 2.0 min to remove the solvents, followed by annealing at 70 °C for 2.0 min. The CLCN film was finally prepared by irradiating the mixture with a high-pressure Hg lamp (1.0 kW) at 25 °C for 10 s. Films with varying α-CS6-iso concentrations were prepared by adjusting the initial composition.

2.4 Preparation of the structurally colored CLCN films by changing the photoisomerization time

A typical preparation procedure was shown as follows. The C6M/α-CS6-iso/CA-Acrylate/Irgacure 907 (91.0/2.4/3.6/3.2, w/w/w/w) mixture was coated on the surface of a PET film as above. It was then irradiated under the 365 nm LED lamp (24 mW cm-2) at 70 °C for 3.0 s. Finally, the CLCN film was prepared through the photopolymerization as described above. The other CLCN films were prepared by changing the 365 nm UV light irradiation time or the CA-Acrylate/α-CS6-iso weight ratio.

2.5 Preparation of the patterned CLCN film using inkjet printing

Three C6M/α-CS6-iso/CA-Acrylate/Irgacure 907 mixtures were prepared using the Mc1~Mc3 mixtures in Table S1, respectively, which were dissolved in the mixture of cyclohexanone and ethyl acetate (v/v, 4/1) with a solid content of 20 wt%. Then, the solutions were printed on the PET substrate using the inkjet printer. The solvents were removed at 70.0 °C for 1.0 min. After irradiation under the LED lamp (24 mW cm-2) at 70 °C for 5.0 s, the CLCN film was prepared under the irradiation of the high-pressure Hg lamp at 25 °C for 10 s.

2.6 Preparation of the CLCN film with two rainbow pattern

The C6M/α-CS6-iso/S5011/Irgacure 907 (w/w/w/w, 82.4/11.0/3.4/3.2) was coated on the surface of a PET film as above. Then, the CLC mixture was irradiated using the portable UV lamp with a tilt angle for 30 s at 70 °C. Finally, the CLCN film was prepared under the irradiation of the high-pressure Hg lamp at 25 °C for 10 s.

2.7 Preparation of the patterned CLCN films through handedness inversion

A typical preparation procedure was shown as follows. A mixture of C6M/α-CS6-iso/S5011/Irgacure 907 (w/w/w/w, 82.4/11.0/3.4/3.2) was coated onto a PET film as described previously. The coated film was then exposed to an LED lamp (24 mW cm-2) at 70 °C for 10 s through a photomask. After removing the photomask, the patterned film was further irradiated under the high-pressure Hg lamp at 25 °C for 10.0 s. Two additional CLCN patterns were fabricated using mixtures with weight ratios of 85.3/8.8/2.7/3.2 and 87.0/7.5/2.3/3.2, respectively, while varying the photomask design.

3. Results and Discussion

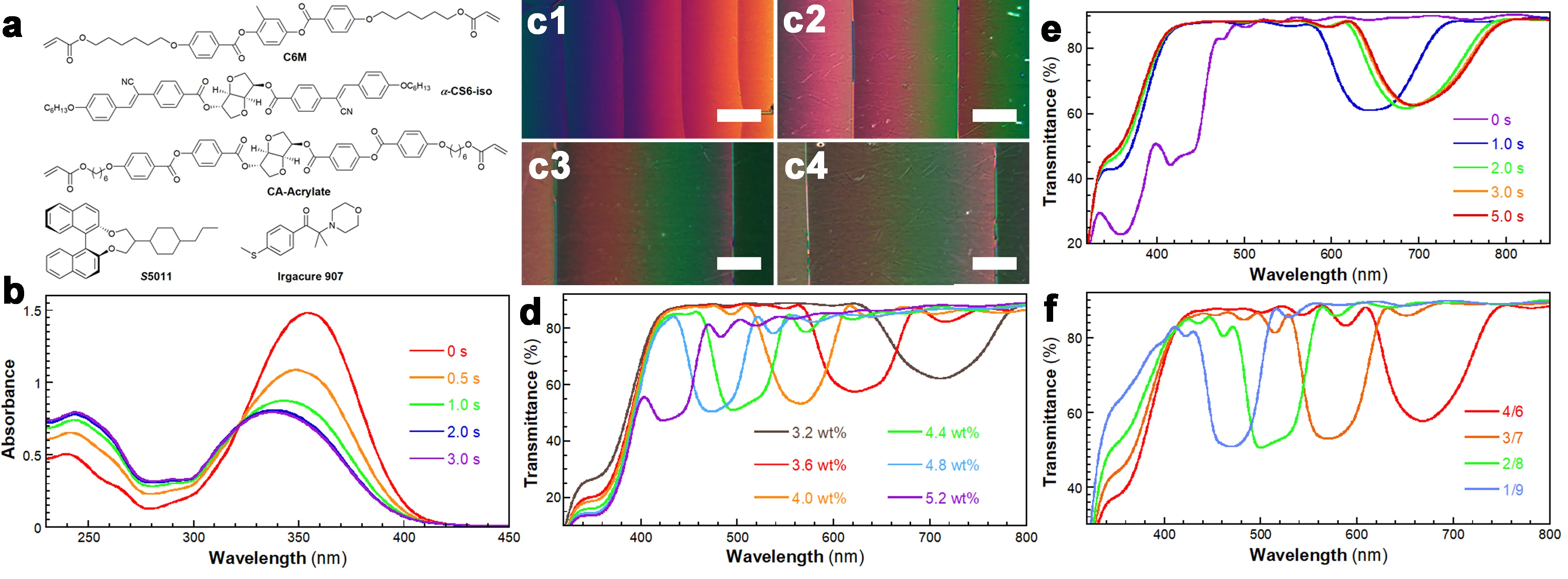

The chemical structures of the compounds used for preparing CLCN films are shown in Figure 1a. C6M shows a phase transition sequence of Cr 85.0 °C N 120.0 °C I[50]. It has been widely employed in fabricating CLCN and polymer-stabilized cholesteric liquid crystal films via photopolymerization[51]. Irgacure 907 is a photoinitiator containing a tertiary amino group[52]. S5011 and CA-Acrylate can induce the formation of left- and right-handed cholesteric structures, respectively[53]. α-CS6-iso is a chiral dopant synthesized from isosorbide and cyanostilbene, which imparts chirality and photoisomerization properties to the molecule (Scheme S1). The melting point and [α]D20 are 176.3 °C. and -208.2° (c = 0.5, CHCl3), respectively. α-CS6-iso undergoes photoisomerization under 365 nm UV light (24 mW cm-2) irradiation (Figure 1b). For an α-CS6-iso solution (2.3 × 10-5 M in CH2Cl2), an absorption band at 354 nm (25 °C) was attributed to the π–π* transition of the Z-form cyanostilbene group[54]. Upon 365 nm UV irradiation (24 mW cm-2), the intensity of this band decreased gradually, while the absorption at 249 nm increased, reaching a PSS in ~3.0 s. An isosbestic point was observed at 321 nm. The solid-state fluorescence spectra of α-CS6-iso and its photoisomer mixture (prepared by evaporating CH2Cl2 post-irradiation) showed emission bands at 530 nm and 508 nm, respectively (Figure S1). The HTP of α-CS6-iso was studied using the Cano’s Wedge method. In an α-CS6-iso/E7 mixture (w/w, 1.0/99.0), the HTP value decreased from 42.8 to 12.2 μm-1 after 60 s of irradiation with a low-pressure mercury lamp (80 W) at 25 °C (Figure 1c1,c2,c3,c4). The photoswitching of α-CS6-iso was studied using a portable UV lamp (254 nm) and an LED UV lamp (365 nm, 40 mW cm-2) at the concentration of 3.0 × 10-5 M in CH2Cl2 (Figure S2). The solution was cyclically irradiated with 365 nm UV light for 5.0 s and 254 nm UV light for 5.0 min. It was found that the cis-configuration could be partially recovered by the 254 nm UV light.

Figure 1. (a) Chemical structures of the compounds; (b) UV–vis spectra of α-CS6-iso in CH2Cl2 (2.3 × 10-5 M) taken at 25.0 °C and under the UV light irradiation, POM images of the α-CS6-iso/E7 (w/w, 1.0/99.0) mixture in (c1) its initial state and after UV irradiation for (c2) 10 s; (c3) 30 s and (c4) 60 s in a wedge-shaped cell (scale bar, 50 μm), UV–vis spectra of (d) the CLCN films prepared using the Ma1~Ma6 mixtures, (e) the Mb1 mixture taken at different UV light irradiation times, and (f) the CLCN films prepared using the Mb1~Mb4 mixtures. UV: ultraviolet; POM: polarized optical microscopy; CLCN: cholesteric liquid crystal polymer network.

A series of CLC mixtures, Ma1~Ma6, were prepared by varying the concentration of α-CS6-iso (Table S1). The formation of the cholesteric structure was confirmed by polarized optical microscopy (POM), which revealed a distinct oily streak texture at 70.0 °C (Figure S3). Subsequently, CLCN films with tunable structural colors were fabricated by irradiating the mixtures with a high-pressure mercury lamp (1.0 kW) for 10.0 s at 25.0 °C. As the α-CS6-iso concentration decreased from 5.2 to 3.2 wt%, the reflection band of the CLCN films exhibited a significant redshift from 421 nm to 711 nm (Figure 1d). The structural color changed from purple to red, and then to colorless (Figure S4). The field-emission scanning electron microscopy image of the CLCN film prepared with 3.2 wt% of α-CS6-iso is presented in Figure S5. The film had a thickness of approximately 3.1 μm and a helical pitch of 476 nm. Based on these parameters, the average refractive index of the CLCN film was calculated to be about 1.49.

To precisely control the reflection band of the CLC mixture both before and after photochromism within the visible light range, a non-photoisomerizable chiral additive, CA-Acrylate, was incorporated into the CLC mixture, with the total concentration of CA-Acrylate and α-CS6-iso maintained at 6.0 wt%. The Mb1 mixture exhibited a reflection band at 430 nm (Figure 1e and Table S1). Upon exposure to 365 nm UV light (24 mW cm-2), the PSS was achieved within 3.0 s, accompanied by a redshift of the reflection band to 695 nm (Figure 1e). This photochromic process was significantly faster than previously reported; tens of minutes or at least 25 s are needed for reaching the PSS[55]. The fast response of the photochromism presented here is proposed to be driven by the low barrier of the cis-trans conformational transition[55]. Furthermore, the reflection band wavelength of the CLC mixture could be precisely tuned after photochromism, making it highly suitable for fabricating CLCN patterns on coating lines.

To separately control the photochromism and photopolymerization steps, a series of CLCN films were prepared using the Mb1~Mb4 mixtures through a two-step approach (Table S1). The POM images of these mixtures indicated a cholesteric structure (Figure S6). In the first step, photochromism was performed under 365 nm UV light (24 mW cm-2) for 3.0 s at 70.0 °C. The second step involved photopolymerization under a high-pressure Hg lamp for 10 s at 25 °C. By decreasing the α-CS6-iso/CA-Acrylate weight ratio from 4/6 to 1/9, the reflection band wavelength was tuned from 668 nm to 470 nm (Figure 1f). Concurrently, the absorption band intensity at 365 nm gradually diminished with a reduction in the α-CS6-iso concentration. For comparison, a one-step approach was also employed. Direct photopolymerization of the Mb1 mixture under the high-pressure Hg lamp for 10 s resulted in a CLCN film with a reflection band at 412 nm (Figure S7). This blueshift compared to the CLC mixture was attributed to the volume shrinkage induced by polymerization. After polymerization, the intensity of the absorption band at 359 nm decreased, indicating the photoisomerization of α-CS6-iso. Hence, upon irradiation with the high-pressure Hg lamp, photopolymerization and photoisomerization were carried out simultaneously. However, due to the high viscosity of the CLC mixture at a lower temperature, the isomerized α-CS6-iso did not have enough time to change the helical pitch[38].

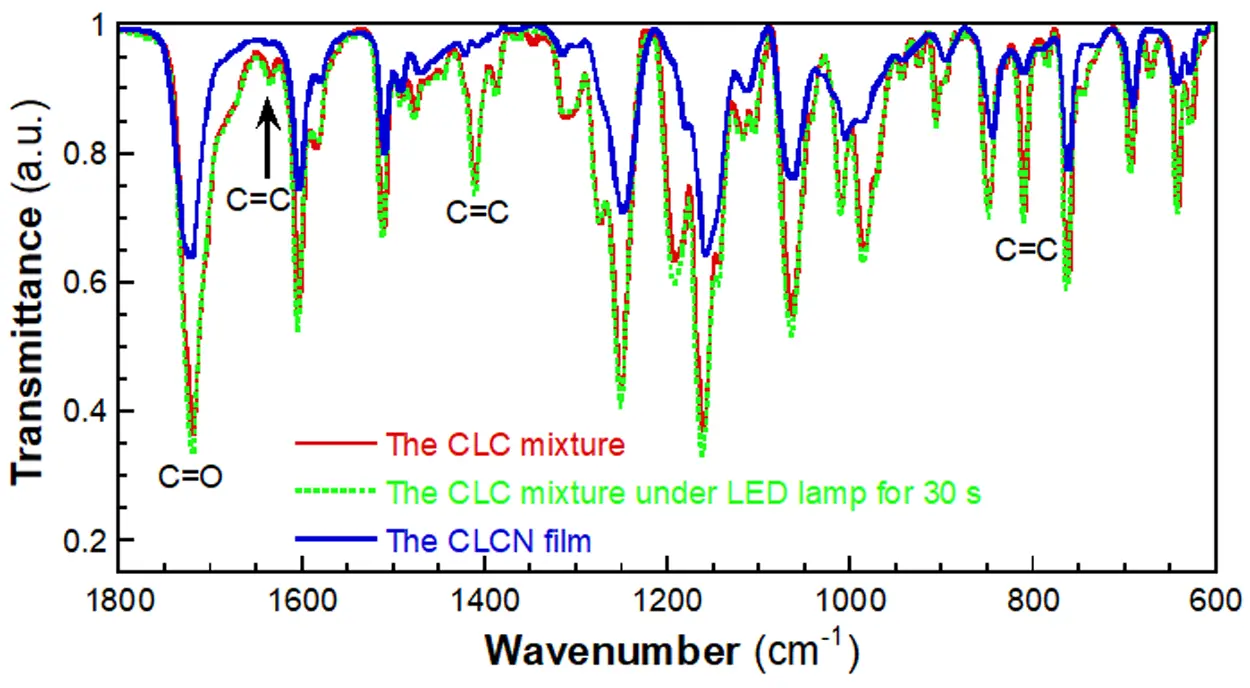

To better understand the two-step approach, FT-IR spectra were recorded during the preparation process of a CLCN film. For the CLC mixture shown above, three characteristic absorption bands were observed at 1636, 1411, and 810 cm-1, respectively, which are the characteristic bands of the C=C bond of the acrylate group (Figure 2)[32]. Upon exposure to 365 nm UV light, the intensities of these bands remained unchanged, confirming that the photochromic process did not affect the acrylate groups. However, after irradiation with the high-pressure Hg lamp, the intensities of these bands decreased significantly, indicating the successful polymerization of the acrylate groups.

Figure 2. FT-IR spectra taken during the CLCN film preparation process. FT-IR: ; CLCN: cholesteric liquid crystal polymer network.

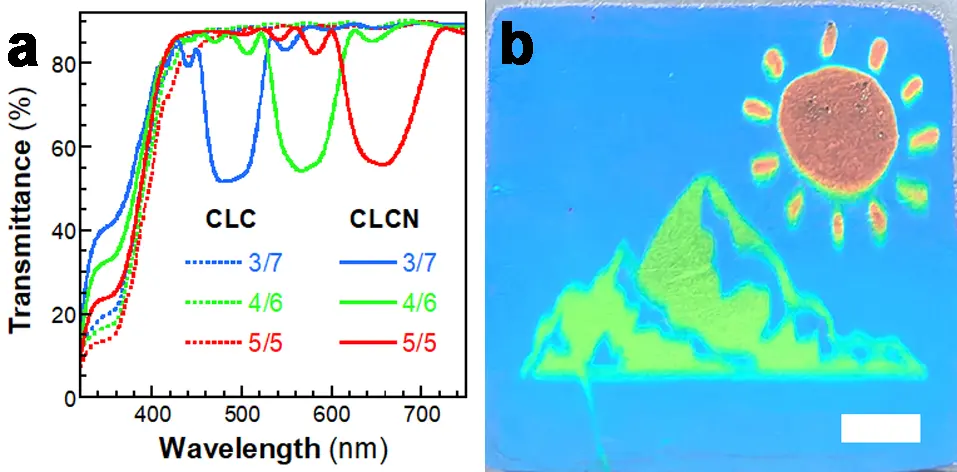

Furthermore, three CLC mixtures were prepared with α-CS6-iso/CA-Acrylate weight ratios of 3/7, 4/6, and 5/5 (Mc1~Mc3 in Table S1), respectively, while maintaining a total chiral dopant concentration of 7.0 wt%. Due to the high concentration, the helical pitches of these mixtures should be very short, and the reflection bands should be located within the UV region. Thus, all these CLC mixtures appeared colorless (Figure 3a). However, after undergoing the photoisomerization of α-CS6-iso, the helical pitches of the CLC mixtures increased. Then, the structural colors were able to be observed by the naked eye. The Mc1, Mc2 and Mc3 mixtures showed blue, green and red structural colors, respectively. After photopolymerization, the structural colors of the CLC mixtures were fixed, and the obtained CLCN films also exhibited blue, green, and red structural colors, respectively (Figure 3b). A colorless CLC pattern was first prepared using these mixtures as inks on a PET film substrate through inkjet printing. Subsequently, a full-color CLCN pattern was successfully fabricated through the two-step preparation approach. This demonstrates that the photochromic CLC mixtures developed in this study are highly suitable for applications in information storage and encryption.

Figure 3. (a) UV–vis spectra of the CLC mixtures and CLCN films prepared using the Mc1~Mc3 mixtures and (b) photograph of the CLCN pattern produced by inkjet printing (scale bar, 1.0 cm). CLC: cholesteric liquid crystal; CLCN: cholesteric liquid crystal polymer network; UV: ultraviolet.

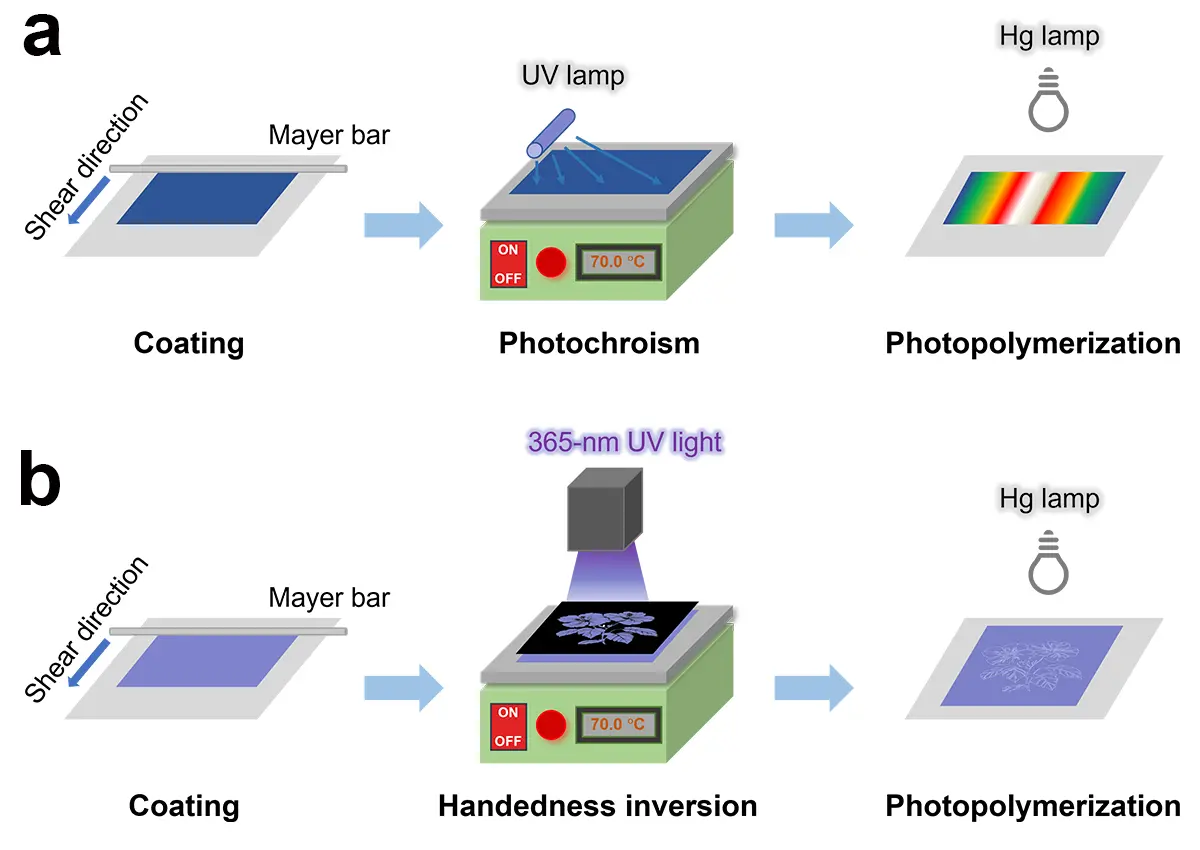

It has been reported that the non-photoisomerizable chiral additive S5011 can induce the formation of a left-handed helical supramolecular structure[53]. For the Md1 mixture (Table S1), a clear oily streak texture was observed in the POM image at 70 °C, confirming a planar cholesteric structure (Figure S8a). Upon irradiation of the CLC mixture with a low-pressure mercury lamp (80 W) for 20, 25, 30, and 60 s (Figure S8b,c,d,e), the textures evolved sequentially from finger-print to pseudo-isotropic, back to finger-print, and finally to oily streak. This texture evolution is attributed to the gradual decrease in the HTP of α-CS6-iso under UV irradiation, which caused a handedness inversion of the CLC mixture from right- to left-handedness. Based on this handedness inversion phenomenon, a CLCN film featuring dual rainbow patterns was successfully prepared using the Me1 mixture (Figure 4 and Table S1). During the photochromism step, the portable 365 nm UV lamp was tilted relative to the CLC film at an angle of 30°, and the distance between the lamp and the CLC film was about 3.0 cm, resulting in non-uniform irradiation doses across different areas of the film (Scheme 1a). This controlled irradiation approach enabled the creation of complex CLCN patterns. The demonstrated capability of this CLC mixture to produce intricate, color-tunable patterns makes it particularly attractive for applications in decorative and anti-counterfeiting technologies.

Figure 4. Photograph of the CLCN film with two rainbow patterns (scale bar, 1.0 cm). CLCN: cholesteric liquid crystal polymer network.

Scheme 1. Schematic representation of the preparation processes of the CLCN films with (a) two rainbow patterns and (b) a flower pattern. CLCN: cholesteric liquid crystal polymer network.

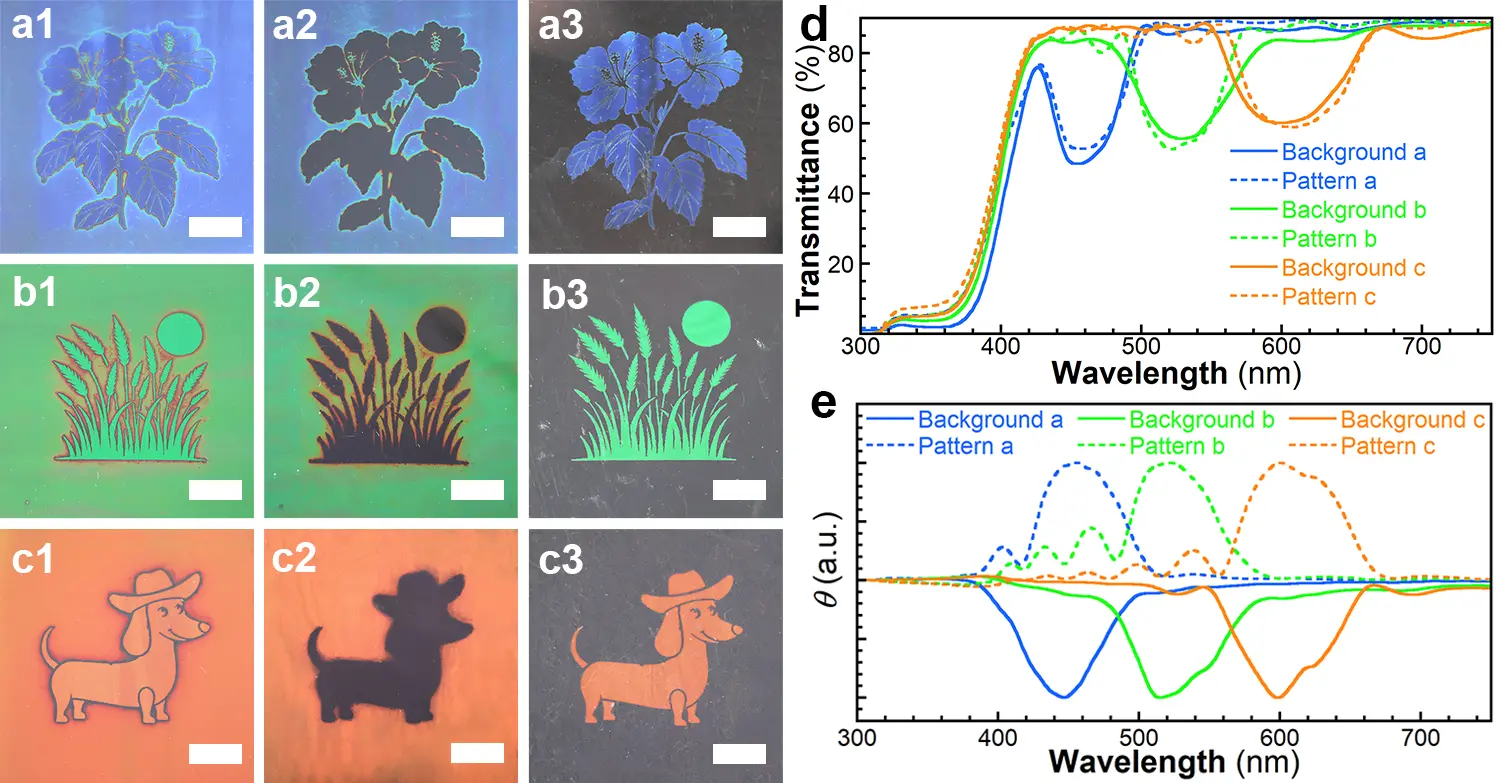

To prepare CLCN patterns composed of both left- and right-handed helical structures, the Me1, Me2 and Me3 mixtures were prepared by changing the concentrations of the chiral additives (Figure 5a1,b1,c1, and Table S1). These mixtures exhibited orange, green, and blue structural colors, respectively. During the photoisomerization step, the CLC mixtures were irradiated through different photomasks at 70.0 °C (Scheme 1b). Notably, for the mixture with a blue structural color, the uncovered area underwent a distinct color transition from blue to red, then to colorless, and back to red, finally returning to blue within 10 s of irradiation. After removing the photomask and performing photopolymerization, the structural colors were permanently fixed (Figure 5a1). Complementary images were observed when viewed through left-handed (Figure 5a2,b2,c2) and right-handed (Figure 5a3,b3,c3) circular polarizers, confirming that the background and pattern regions reflected right- and left-handed circularly polarized light, respectively. The UV–vis spectra of the backgrounds and patterns (Figure 5d) showed nearly identical reflection band wavelengths, while the circular dichroism (CD) spectra (Figure 5e) revealed opposite handedness between the two regions. This demonstrates the successful fabrication of CLCN patterns with dual-handed helical structures, achieved by precisely controlling the photoisomerization process. Weak multi-bands were also observed in the UV–vis and CD spectra, which were proposed to originate from the higher order Bragg reflections[56].

Figure 5. Photographs of the CLCN patterns taken under (a1, b1, c1) the natural light, through the (a2, b2, c2) left- and (a3, b3, c3) right-handed circular polarizers (scale bar, 1.0 cm); (d) UV–vis and (e) CD spectra of different areas of the CLCN patterns. CLCN: cholesteric liquid crystal polymer network; UV: ultraviolet; CD: circular dichroism.

3. Conclusions

A photochromic CLC mixture was prepared using a photoisomerizable chiral additive containing the α-cyanostilbene group. Remarkably, the photochromic response exhibited an ultra-fast rate under 365 nm UV light (24 mW cm-2) at 70.0 °C, with the reflection band stabilizing within seconds. This rapid response makes the CLC mixture highly suitable for fabricating colorful CLCN patterns on coating lines. Furthermore, patterned CLCN films featuring both left- and right-handed helical supramolecular structures were successfully prepared using handedness-invertible CLC mixtures. The demonstrated properties of these CLC mixtures, including ultra-fast photochromism, precise wavelength control, and handedness inversion, make them particularly promising for information encryption applications. Additionally, the patterned CLCN films show great potential for decorative and anti-counterfeiting purposes, as they can produce complex and color-tunable patterns.

Supplementary materials

The supplementary material for this article is available at: Supplementary materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support from the Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Advanced Functional Polymer Design and Application, the Jiangsu Engineering Laboratory of Novel Functional Polymeric Materials, and the Key Laboratory of Polymeric Materials Design and Synthesis for Biomedical Function.

Authors contribution

Liu X: Data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing-original draft.

Li Y: Methodology, Funding acquisition.

Liu W: Supervision, writing-review & editing.

Yang Y: Conceptualization, project administration, funding acquisition, resources, supervision, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data and materials could be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52273212).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Klymchenko AS. Solvatochromic and fluorogenic dyes as environment-sensitive probes: design and biological applications. Acc Chem Res. 2017;50(2):366-375.[DOI]

-

2. Kulyk O, Rocard L, Maggini L, Bonifazi D. Synthetic strategies tailoring colors in multichromophoric organic nanostructures. Chem Soc Rev. 2020;49(23):8400-8424.[DOI]

-

3. Zhang P, de Haan LT, Debije MG, Schenning APHJ. Liquid crystal-based structural color actuators. Light Sci Appl. 2022;11(1):248.[DOI]

-

4. Lee GH, Choi TM, Kim B, Han SH, Lee JM, Kim SH. Chameleon-inspired mechanochromic photonic films composed of non-close-packed colloidal arrays. ACS Nano. 2017;11(11):11350-11357.[DOI]

-

5. Zi J, Yu X, Li Y, Hu X, Xu C, Wang X, et al. Coloration strategies in peacock feathers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U. A. 2003;100(22):12576-12578.[DOI]

-

6. Xu CT, Liu BH, Peng C, Chen QM, Chen P, Sun PZ. Heliconical cholesterics endows spatial phase modulator with an electrically customizable working band. Adv Optical Mater. 2022;10(19):2201088.[DOI]

-

7. Cullen DK, Xu Y, Reneer DV, Browne KD, Geddes JW, Yang S, et al. Color changing photonic crystals detect blast exposure. NeuroImage. 2011;54:S37-S44.[DOI]

-

8. Mulder DJ, Schenning APHJ, Bastiaansen CWM. Chiral-nematic liquid crystals as one dimensional photonic materials in optical sensors. J Mater Chem C. 2014;2(33):6695-6705.[DOI]

-

9. Wang M, Zou C, Sun J, Zhang LY, Wang L, Xiao JM, et al. Asymmetric tunable photonic bandgaps in self-organized 3D nanostructure of polymer-stabilized blue phase I modulated by voltage polarity. Adv Funct Mater. 2017;27(46):1702261.[DOI]

-

10. Chang CK, Bastiaansen CMW, Broer DJ, Kuo HL. Alcohol-responsive, hydrogen-bonded, cholesteric liquid-crystal networks. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22(13):2855-2859.[DOI]

-

11. Zhang W, Froyen AAF, Schenning APHJ, Zhou G, Debije MG, de Haan LT. Temperature-responsive photonic devices based on cholesteric liquid crystals. Adv Photonics Res. 2021;2(7):2100016.[DOI]

-

12. Broer DJ, Lub J, Mol GN. Wide-band reflective polarizers from cholesteric polymer networks with a pitch gradient. Nature. 1995;378(6556):467-469.[DOI]

-

13. Mitov M. Cholesteric liquid crystals with a broad light reflection band. Adv Mater. 2012;24(47):6260-6276.[DOI]

-

14. Herze , N , Guneysu H, Davies DJD, Yildirim D, Vaccaro AR, Broer DJ, et al. Printable optical sensors based on h-bonded supramolecular cholesteric liquid crystal networks. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(18):7608-7611.[DOI]

-

15. Yin S, Ge S, Li X, Zhao Y, Ma H, Sun Y. Recyclable cholesteric phase liquid crystal device for detecting storage temperature failure. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(23):35302-35310.[DOI]

-

16. Noh KG, Park SY. Biosensor array of interpenetrating polymer network with photonic film templated from reactive cholesteric liquid crystal and enzyme-immobilized hydrogel polymer. Adv Funct Mater. 2018;28(22):1707562.[DOI]

-

17. Myung DB, Hussain S, Park SY. Photonic calcium and humidity array sensor prepared with reactive cholesteric liquid crystal mesogens. Sens Actuators B chem. 2019;298:126894.[DOI]

-

18. Lee YH, Chen H, Martinez R, Sun Y, Pang S, Wu ST. Multi-image plane display based on polymer-stabilized cholesteric texture. In: SID Symposium Digest of Technical Papers. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2017. p. 760-762.[DOI]

-

19. Zhang P, Kragt AJJ, Schenning APHJ, de Haan LT, Zhou G. An easily coatable temperature responsive cholesteric liquid crystal oligomer for making structural color patterns. J Mater Chem C. 2018;6(27):7184-7187.[DOI]

-

20. Zhang P, Shi XY, Schenning APHJ, Zhou G, de Haan LT. A patterned mechanochromic photonic polymer for reversible image reveal. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2020;7(3):1901878.[DOI]

-

21. Hong W, Yuan Z, Chen X. Structuralcolor materials for optical anticounterfeiting. Small. 2020;16(16):1907626.[DOI]

-

22. Moirangthem M, Scheers AF, Schenning APHJ. A full color photonic polymer, rewritable with a liquid crystal ink. Chem Commun. 2018;54(35):4425-4428.[DOI]

-

23. Lub J, Nijssen WPM, Wegh RT, Vogels JPA, Ferrer A. Synthesis and properties of photoisomerizable derivatives of isosorbide and their use in cholesteric filters. Adv Funct Mater. 2005;15(12):1961-1972.[DOI]

-

24. Sun J, Yu L, Wang L, Li C, Yang Z, He W, et al. Optical intensity-driven reversible photonic bandgaps in self-organized helical superstructures with handedness inversion. J Mater Chem C. 2017;5(15):3678-3683.[DOI]

-

25. van Delden RA, van Gelder MB, Huck NPM, Feringa BL. Controlling the color of cholesteric liquid-crystalline films by photoirradiation of a chiroptical molecular switch used as dopant. Adv Funct Mater. 2003;13(4):319-324.[DOI]

-

26. Bao J, Wang Z, Shen C, Huang R, Song C, Li Z, et al. Freestanding helical nanostructured chiro-photonic crystal film and anticounterfeiting label enabled by a cholesterol-grafted light-driven molecular motor. Small Methods. 2022;6(5):2200269.[DOI]

-

27. de Castro LDC, Lub J, Oliveira Jr ON, Schenning APHJ. Mechanochromic displays based on photoswitchable cholesteric liquid crystal elastomers. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2025;64(1):e202413559.[DOI]

-

28. Relaix S, Mitov M. Polymer-stabilized cholesteric liquid crystals with a double helical handedness: influence of an ultraviolet light absorber on the characteristics of the circularly polarised reflection band. Liq Cryst. 2008;35(8):1037-1042.[DOI]

-

29. Zhang M, Zhao J, Yao Z, Liu W, Li Y, Yang Y. A hyper-reflective cholesteric liquid crystal polymer network with double layers. New J Chem. 2023;47(37):17261-17266.[DOI]

-

30. Zhang Z, Wang C, Wang Q, Zhao Y, Shang L. Cholesteric cellulose liquid crystal ink for three-dimensional structural coloration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2022;119(23):e2204113119.[DOI]

-

31. Guo Y, Zhao J, Wu L, Liu W, Li Y, Yang Y. Structural colored epoxy resin patterns prepared using thermochromic epoxy liquid crystal mixtures. New J Chem. 2024;48(10):4598-4605.[DOI]

-

32. Wang T, Zhao J, Wu L, Liu W, Li Y, Yang Y. Polymer network film with double reflection bands prepared using a thermochromic cholesteric liquid crystal mixture. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024;16(14):18001-18007.[DOI]

-

33. Feringa BL, van Delden RA, Koumura N, Geertsema EM. Chiroptical molecular switches. Chem Rev. 2000;100(5):1789-1816.[DOI]

-

34. Bandara HMD, Burdette SC. Photoisomerization in different classes of azobenzene. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41(5):1809-1825.[DOI]

-

35. Irie M. Diarylethenes for memories and switches. Chem Rev. 2000;100(5):1685-1716.[DOI]

-

36. Pieraccini S, Gottarelli G, Labruto R, Masiero S, Pandoli O, Spada GP. The control of the cholesteric pitch by some azo photochemical chiral switches. Chem Eur J. 2004;10(22):5632-5639.[DOI]

-

37. Wang H, Tang Y, Krishna Bisoyi H, Li Q. Reversible handedness inversion and circularly polarized light reflection tuning in self‐organized helical superstructures using visible‐light‐driven macrocyclic chiral switches. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2023;62(8):e202216600.[DOI]

-

38. Li Z, Zhao J, Wu L, Li Y, Liu W, Yang Y. Large-area preparation of rainbow cholesteric liquid crystal polymer network films using a photoisomerizable chiral dopant. Liq Cryst. 2024;51(11):1933-1941.[DOI]

-

39. Wang L, Urbas AM, Li Q. Nature-inspired emerging chiral liquid crystal nanostructures: from molecular self-assembly to DNA mesophase and nanocolloids. Adv Mater. 2020;32(41):1801335.[DOI]

-

40. Ryabchun A, Sakhno O, Stumpe J, Bobrovsky A. Full-polymer cholesteric composites for transmission and reflection holographic gratings. Adv Opt Mater. 2017;5(17):1700314.[DOI]

-

41. Lee YH, Wang L, Yang H, Wu ST. Photo-induced handedness inversion with opposite-handed cholesteric liquid crystal. Opt Express. 2015;23(17):22658-22666.[DOI]

-

42. Kang W, Tang Y, Meng X, Lin S, Zhang X, Guo J, et al. A photo- and thermo-driven azoarene-based circularly polarized luminescence molecular switch in a liquid crystal host. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2023;62(48):e202311486.[DOI]

-

43. Dadivanyan N, Bobrovsky A, Shibaev V. Photo-optical properties of photopolymerizable cholesteric compositions. Colloid Polym Sci. 2007;285(6):681-686.[DOI]

-

44. Chien CC, Liu JH. Optical behaviours of cholesteric liquid-crystalline polyester composites with various chiral photochromic dopants. Langmuir. 2015;31(49):13410-13419.[DOI]

-

45. Zhang J, Zhang S, Liu J, Ren Y, Chen J, Hu W, et al. Simultaneous or independent programming and reconfiguration of structural and fluorescent information in multi-stimuli-responsive liquid crystalline polymer film. Chem Eng J. 2025;505:159583.[DOI]

-

46. Koo J, Jang J, Oh M, Kim M, Hyeong J, Lim SI, et al. Cyanostilbene‐based AIEgen smart film: optical switching by engineering molecular packing structure and molecular conformation through thermal and photoinduced monotropic phase transition. Adv Optical Mater. 2022;10(11):2200405.[DOI]

-

47. Koo J, Jang J, Kim M, Hyeong J, Yu D, Rim M, et al. Molecular engineering for chiroptical smart paints: photo‐tunable and polymerizable helical nanostructures by cyanostilbene‐based reactive mesogens. Adv Optical Mater. 2023;11(6):2202707.[DOI]

-

48. Liu Z, Guo G, Liao J, Yuan Y, Zhang H. Manipulated and improved photoinduced deformation property of photoresponsive liquid crystal elastomers by copolymerization. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2022;43(6):2100717.[DOI]

-

49. Zhu G, Liu Z, Bisoyi H, Li Q. Controllable versatility in a single molecular system from photoisomerization to photocyclization. Adv Optical Mater. 2023;12(7):2301908.[DOI]

-

50. Broer DJ, Heynderickx I. Three dimensionally ordered polymer networks with a helicoidal structure. Macromolecules. 1990;23(9):2474-2477.[DOI]

-

51. Seo W, Haines CS, Kim H, Park CL, Kim SH, Park S, et al. Azobenzene-functionalized semicrystalline liquid crystal elastomer springs for underwater soft robotic actuators. Small. 2025;21(8):2406493.[DOI]

-

52. Ligon SC, Husár B, Wutzel H, Holman R, Liska R. Strategies to reduce oxygen Inhibition in photoinduced polymerization. Chem Rev. 2014;114(1):557-589.[DOI]

-

53. Ma Z, Han S, Li Y, Liu W, Yang Y. Precise control of the wavelengths of the reflection bands of the cholesteric liquid crystal polymer network patterns. ACS Appl Polym Mater. 2025;7(12):7999-8006.[DOI]

-

54. Cao XJ, Li W, Li J, Zou L, Liu XW, Ren XK, et al. Controlling the balance of photoluminescence and photothermal effect in cyanostilbene‐based luminescent liquid crystals. Chin J Chem. 2022;40(8):902-910.[DOI]

-

55. Tian J, He Y, Li J, Wei J, Li G, Guo J. Fast, real-time, in situ monitoring of solar ultraviolet radiation using sunlight-driven photoresponsive liquid crystals. Adv Optical Mater. 2018;6(6):1701337.[DOI]

-

56. Christou MA, Papanicolaou NC, Polycarpou AC. Modeling the reflection from cholesteric liquid crystals using modal analysis and mode matching. Phys Rev E. 2012;85:031702.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite