Abstract

Asymmetric hydrogenation is an efficient tool for rapid synthesis of a diverse range of chiral compounds with high yields and excellent enantioselectivities. Chiral 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-quinoline is a valuable building block for organic synthesis and has been widely used in the synthesis of bioactive molecules and chiral ligands. Herein, we report an improved iridium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-methylquinoline on a hundred-gram scale for efficient synthesis of chiral 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline with up to 91.4% ee value and an 80,000 turnover number. Optically pure 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline could be obtained in high yields through recrystallization or chemical resolution with the tartaric acid derivative (L)-DMTA.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

1. Introduction

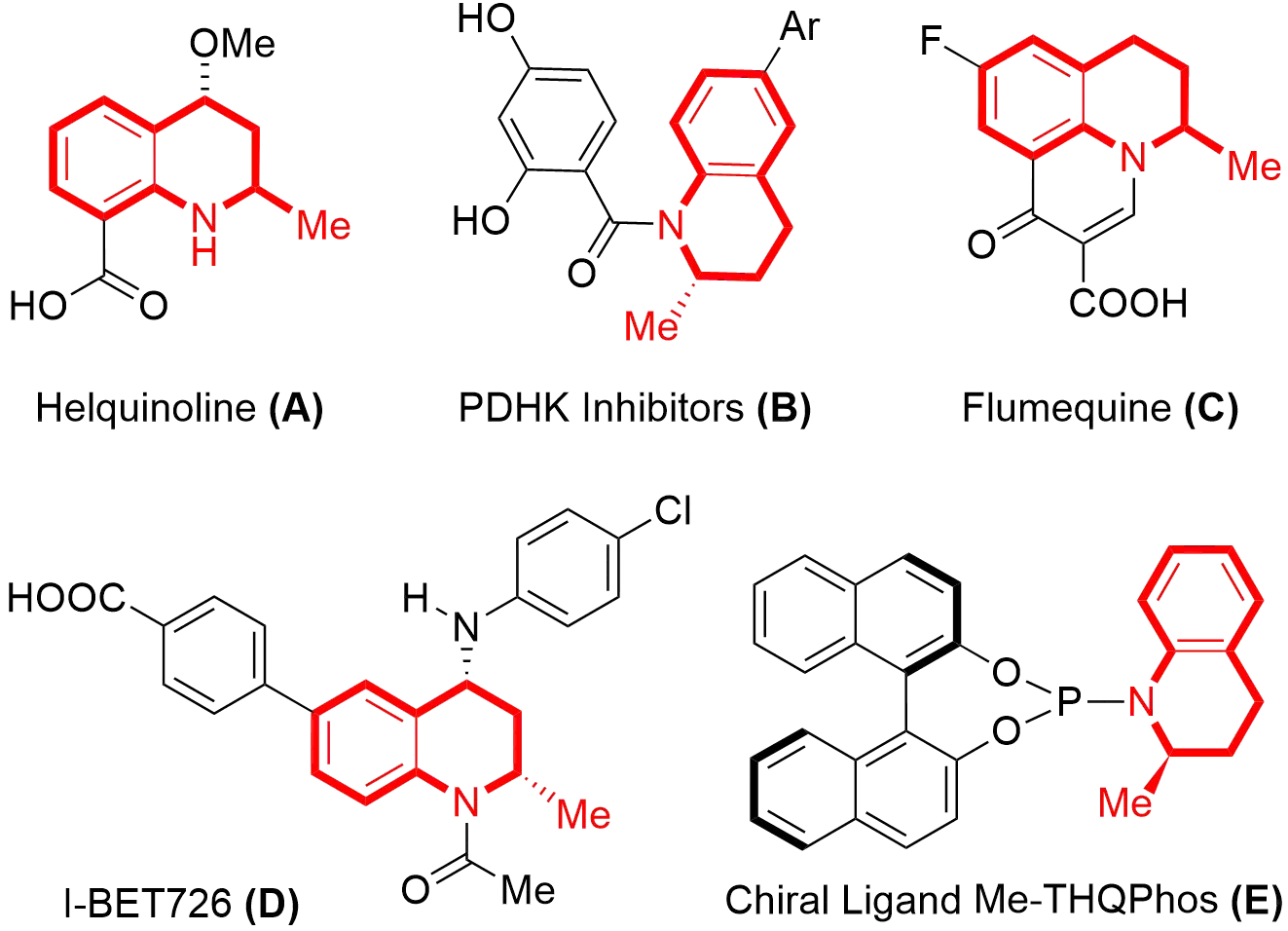

2-Methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline is an important nitrogen-containing heterocycle skeleton that widely exists in natural products and a variety of molecules with pharmacological activities (Figure 1)[1-5]. For example, Helquinoline (A) is a natural product isolated from the North Sea bacterium isolate Hel-1 that is used as an antibiotic[1]. The pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDHK) inhibitors (B) are PDHK inhibitors and are used to study the role of PDHK in cancer[2]. Flumequine (C), a second generation of synthetic quinolone veterinary antibacterial drugs, shows powerful effects on bacterial diseases in animals[3]. The I-BET726 (D) has been approved as a potent and selective inhibitor of the bromodomain and extra terminal domain, and has anti-inflammatory effects[4]. The privileged chiral phosphoramidite ligand Me-THQPhos E, originally developed by You’s group, was found to be an efficient chiral ligand in metal-catalyzed allylic substitution and asymmetric Friedel-Crafts reactions[5].

Figure 1. Representative molecules containing 2-Methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline Motifs. PDHK: pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase.

Given the importance of chiral 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline, some catalytic asymmetric methodologies have been developed. The early research mainly focused on catalytic cascade reactions with readily available simple starting materials. For example, Gong’s group developed a tandem hydroamination/asymmetric transfer hydrogenation reaction that transformed 2-(2-propynyl)aniline derivatives into tetrahydroquinolines with excellent enantioselectivity under tandem catalysis by Au and chiral phosphoric acid[6]. Zhao and co-workers developed an enantioselective synthesis of tetrahydroquinolines through a borrowing hydrogen method under the cooperative catalysis of an achiral iridium complex and chiral phosphoric acid[7]. Satyanarayana’s group reported the facile synthesis of chiral tetrahydroquinolines through regio- and asymmetric iridium-catalyzed allylic amination and a hydro-boration/intramolecular Suzuki-Miyaura coupling sequence[8]. In recent years, Yang reported the synthesis of tetrahydroquinoline through a relay visible-light-mediated cyclization/Brønsted acid-catalyzed asymmetric transfer hydrogenation[9].

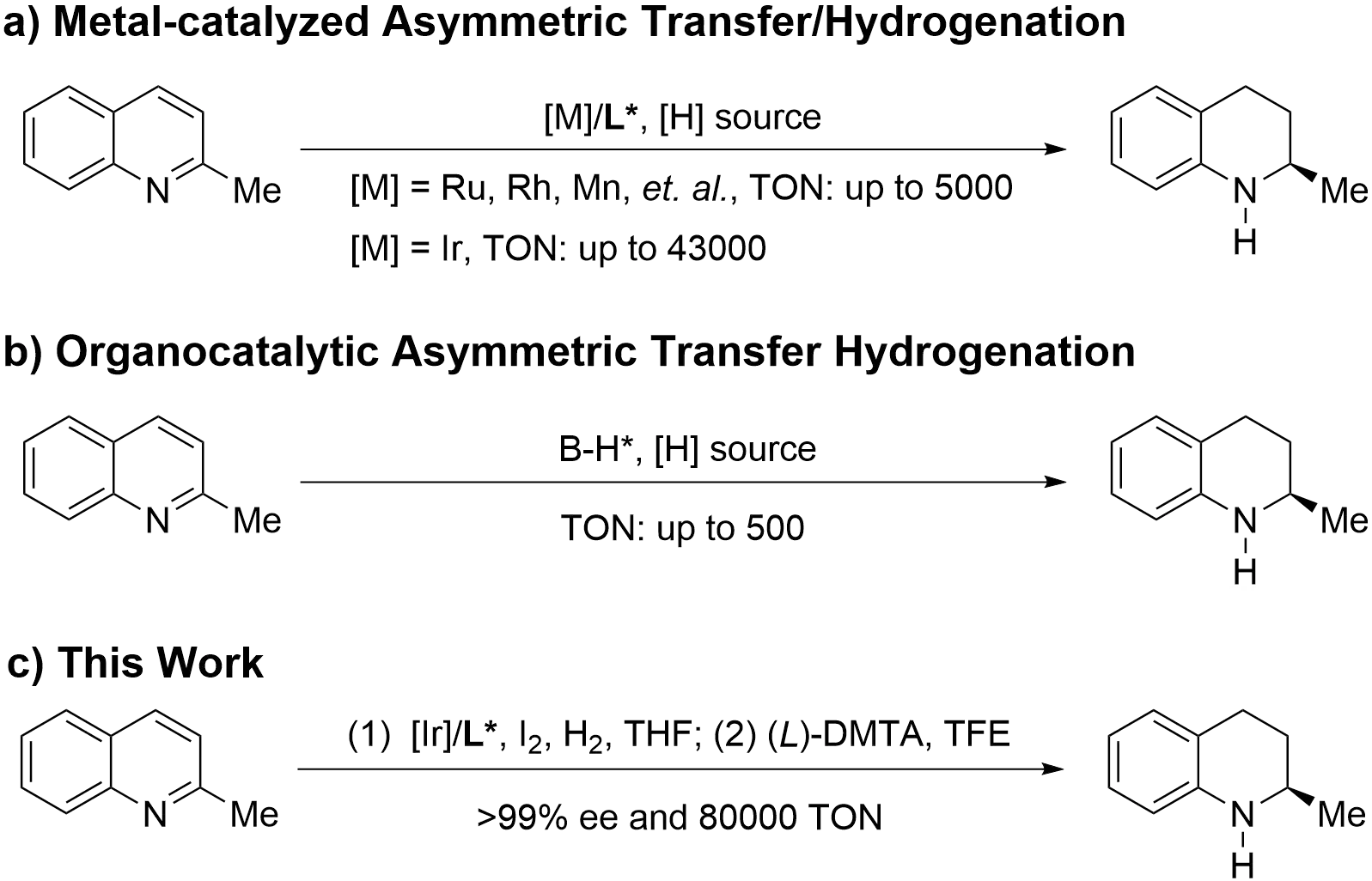

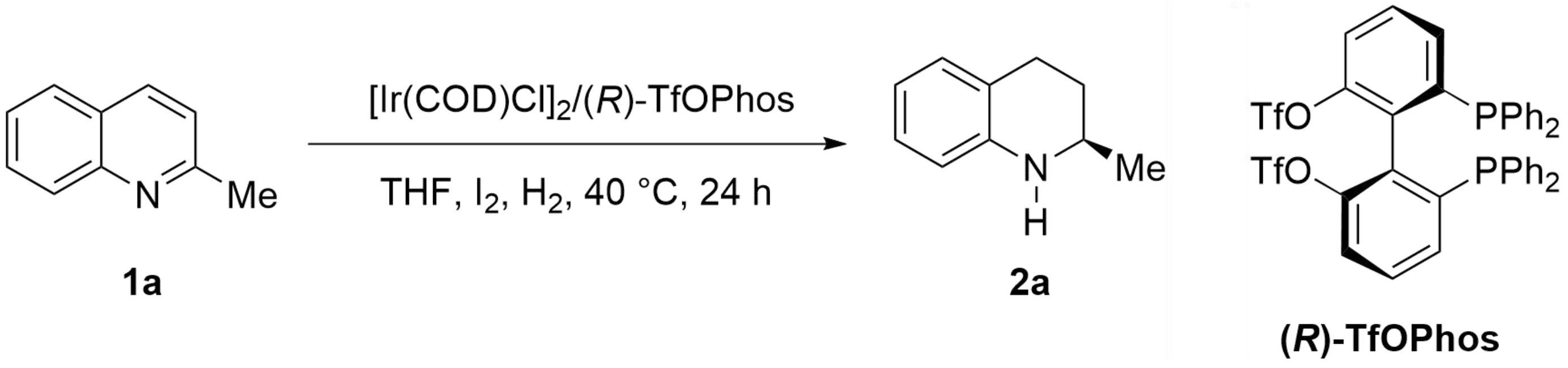

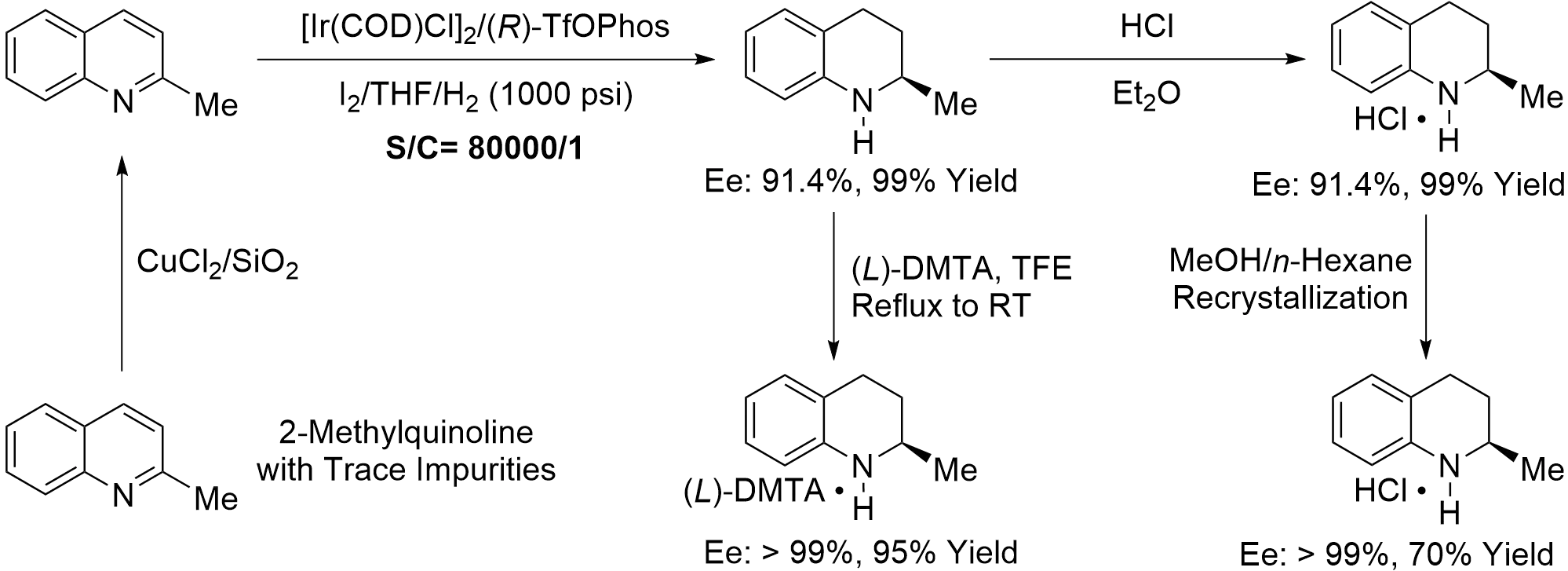

In addition, asymmetric hydrogenation of commercially available 2-methylquinoline is regarded as one of the most effective ways to synthesize optically active 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (Scheme 1a)[10]. In 2003, Zhou’s group pioneered the use of an iridium catalyst bearing an axially chiral bisphosphine ligand that, in combination with iodine as an additive, afforded the chiral 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline with 94% ee (S/C = 200, 700 psi hydrogen gas, room temperature, 24 hours)[11]. Subsequently, Chan[12,13], Reetz[14], Mashima[15], Liang[16] and other groups[17] used a variety of chiral ligands with iridium catalysts and also achieved the asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-methylquinoline under S/C = 50-500. Notably, Fan and Xu’s group reported iridium-catalyzed hydrogenation of 2-methylquinoline with the chiral bisphosphine ligands G2DenBINAP[18], DifluorPhos[19] and P-Phos[20], up to 43,000 of turnover number (TON) was obtained for dendritic G2DenBINAP[18], which was ascribed to the dendrimer effect that inhibited deactivation. Apart from the iridium catalyst system, other transition metal catalytic systems have also been screened. In 2008, Chan reported a Ru/Ts-dpen in [BMIM]PF6 (BMIM = 1-n-butyl-3-methylimidazolium) for enantioselective hydrogenation of 2-methylquinoline with S/C = 100/1[21]. Next, Fan also realized asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-methylquinoline with 5,000 TON using chiral cationic Ru(II) complexes[22]. In 2009, Xiao reported the first Rh-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-methylquinoline with water as the solvent (S/C = 200/1)[23]. In 2016, Zhang reported a strong Brønsted acid promoted asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-methylquinoline by a chiral Rh-thiourea phosphine complex with 200 TON and 99% ee[24]. In 2021, Liu’s group developed an earth-abundant manganese-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-methylquinoline and achieved 3840 TON and 93% ee[25]. Recently, Nagorny[26], Sun[27], Nie[28], Zhang[29] and others[30] have also realized metal-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-methylquinoline with moderate reactivities (S/C = 20-10,000). Organocatalytic asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of 2-methylquinoline has also been reported by Rueping[31], Du[32], Bhanage[33], Qin[34], and other groups[17], giving low catalytic efficiency (TON = 20-500, Scheme 1b). Although many kinds of catalytic systems have been developed for asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-methylquinoline, the low turnover numbers and expensive catalysts make them difficult to apply in practical production. As an important pharmaceutical intermediate and organic building block, chiral 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline holds promising application prospects. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop an economical and efficient method for its scale-up production.

Scheme 1. Catalytic asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-methylquinoline. TON: turnover number; THF: tetrahydrofuran; TFE: 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol.

In the past two decades, our group has been committed to the asymmetric hydrogenation of heteroaro-matic compounds including pyridines[35], isoquinolines[36], quinolines[37], indoles[38], and pyrimidines[39]. With our continuous efforts to develop practical asymmetric hydrogenation, we aim to establish a scalable process for enantiopure 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline at the hectogram scale. Herein, we describe the realization of an efficient, sustainable, and scalable asymmetric hydrogenation process for the production of chiral 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline under a very low catalyst loading. Through simple recrystallization or chemical resolution, the target molecule with > 99% optical purity could be obtained in high yield (Scheme 1c).

2. Experimental Section

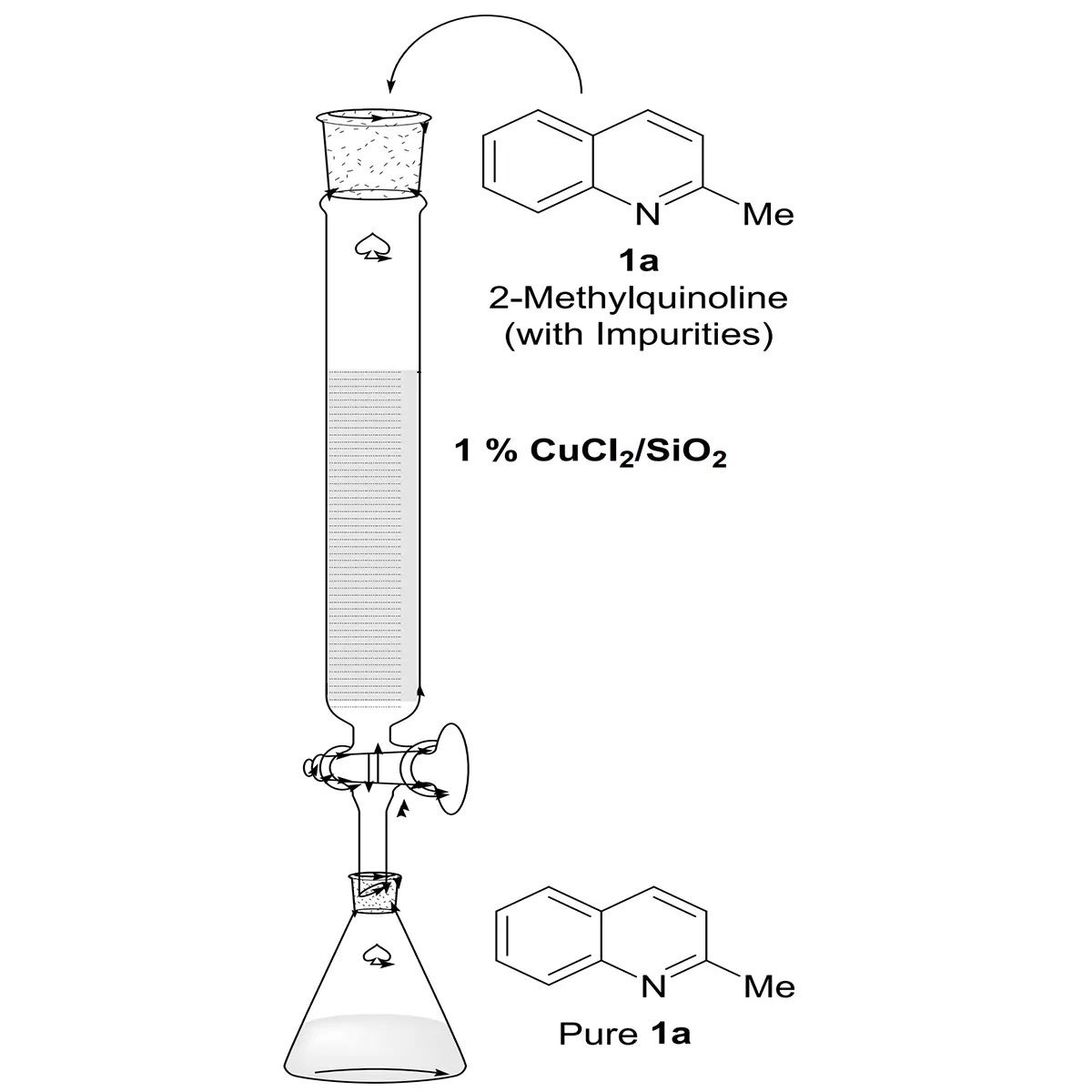

General Considerations: Commercially available solvents and reagents were used as received. 2-Methyl-quinoline could be suitable after adsorption purification through a silica gel column doped with 1% copper(II) chloride. 1H NMR, 13C NMR and 19F NMR spectra were recorded at room temperature in CDCl3 on a 400 MHz instrument with TMS as the internal standard. Enantiomeric excess was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis using the chiral column described below in detail. Optical rotations were measured by a polarimeter. Flash column chromatography was performed on silica gel (200-300 mesh). The heat source for all heating reactions was an oil bath.

2.1 Iridium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation

Iridium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of 2-Methylquinoline 1a. In a nitrogen-filled glovebox, a mixture of [Ir(COD)Cl]2 (14.7 mg, 21.9 μmol) and (R)-6,6'-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1'-biphenyl-2,2'-diylbis (trifluoromethylsulfonate) ((R)-TfOPhos, 43.0 mg, 52.5 μmol) in tetrahydrofuran (THF) (24 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 30 minutes to give the chiral catalyst solution. Then, the above solution was transferred to a 2 L autoclave in which the additive iodine (1.110 g, 4.38 mmol), THF (560 mL) and 2-methyl-quinoline 1a (250.3 g, 1.75 mol) had been added. The autoclave was then charged with hydrogen gas (1,000 psi) and stirred at 50 °C for 30 hours (Note: hydrogen gas was continuously supplemented to keep the reaction pressure at 1,000 psi). After carefully releasing hydrogen gas, the reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was washed with sodium thiosulfate solution (3.0 M, 100 mL) and extracted three times with ethyl acetate (100 mL × 3). The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford 256.1 g of hydrogenation product (R)-2a in 99% yield with 91.4% ee. Known compound[22], Rf = 0.75 (hexanes/ethyl acetate = 5/1), 91.4% ee, [> 99% ee, [α]20D = + 91.4 (c 2.00, CHCl3)], [lit[22]: 99% ee, [α]RTD = + 84.3 (c 0.20, CHCl3)]. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.99-6.93 (m, 2H), 6.64-6.56 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.50-6.43 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 3.69 (brs, 1H), 3.44-3.35 (m, 1H), 2.88-2.79 (m, 1H), 2.76-2.68 (m, 1H), 1.96-1.89 (m, 1H), 1.64-1.53 (m, 1H), 1.20 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 144.8, 129.3, 126.7, 121.1, 117.0, 114.0, 47.2, 30.2, 26.6, 22.7. HPLC: Chiralcel OJ-H, 254 nm, 30 °C, n-Hexane/i-PrOH = 95/5, flow = 1.0 mL/min, retention time 10.8 min and 11.9 min (major).

Iridium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of 6-Fluoro-2-methylquinoline 1b. In a nitrogen-filled glovebox, a mixture of [Ir(COD)Cl]2 (2.0 mg, 3.0 μmol) and (R)-6,6'-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1'-biphenyl-2,2'-diylbis (trifluoromethylsulfonate) ((R)-TfOPhos, 5.9 mg, 7.2 μmol) in THF (4.0 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 30 minutes to give the chiral catalyst solution. Then, the above solution was transferred to a 300 mL autoclave in which the additive iodine (152 mg, 0.6 mmol), THF (36 mL) and 6-fluoro-2-methylquinoline 1b (19.34 g, 0.12 mol) had been added. The autoclave was then charged with hydrogen gas (1,000 psi) and stirred at 40 °C for 63 hours (Note: Hydrogen gas was continuously supplemented to keep the reaction pressure at 1,000 psi). After carefully releasing hydrogen gas, the reaction mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was washed with sodium thiosulfate solution (3.0 M, 10 mL) and extracted three times with ethyl acetate (30 mL × 3). The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford 19.71 g of product 2b in 99% yield and 91.4% ee. Known compound[22], Rf = 0.75 (hexanes/ethyl acetate = 5/1), 91.4% ee, [α]20D = + 81.8 (c 2.00, CHCl3), [lit[22]: 98% ee, [α]RTD = + 80.3 (c 0.19, CHCl3)]. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.75-6.61 (m, 2H), 6.46-6.34 (m, 1H), 3.56 (d, J = 59.2 Hz, 1H), 3.40-3.29 (m, 1H), 2.89-2.75 (m, 1H), 2.73-2.66 (m, 1H), 1.96-1.87 (m, 1H), 1.62-1.49 (m, 1H), 1.23-1.18 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 156.7, 154.4, 141.0, 122.5, 122.4, 115.5, 115.3, 114.8, 114.7, 113.3, 113.0, 47.3, 29.9, 26.7, 22.5. 19F NMR (376 MHz, CDCl3) δ -128.34. HPLC: Chiralcel OJ-H, 254 nm, 30 °C, n-Hexane/i-PrOH = 98.5/1.5, flow = 1.0 mL/min, retention time 11.1 min and 11.6 min (major).

2.2 Recrystallization of 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline hydrochloride

Typical Procedure. Under an ice bath, 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline 2a (80.0 g, 0.544 mol, 91.4% ee), and diethyl ether (400 mL) were added to a 1,000 mL round-bottomed flask, equipped with a mechanical stirring bar. Hydrogen chloride in 1,4-dioxane solution (4.0 M, 136 mL, 0.544 mol) was added dropwise, and the mixture was stirred for 1.5 hours. Then, the crude mixture was filtered over Buchner funnel, and the residue was washed with ethyl ether (50 mL × 3), The residue was collected and dried under vacuum to afford 99.9 gram of white solid 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline hydrochloride (3).

A 500 mL round-bottom flask was charged with 99.9 gram of the above compound 3 (91.4% ee) and 120 mL of methanol. An additional 24 mL of methanol was added dropwise under reflux until complete dissolution. Subsequently, n-hexane (20 mL) was introduced. The solution was allowed to stand overnight. The precipitated solid was collected by filtration, washed with chilled methanol, and dried under vacuum to afford 70.1 g of white solid 3’ in 70% yield and 99.4% ee. (Note: the optical purity was determined by the analysis of 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline after neutralization with sodium carbonate.)

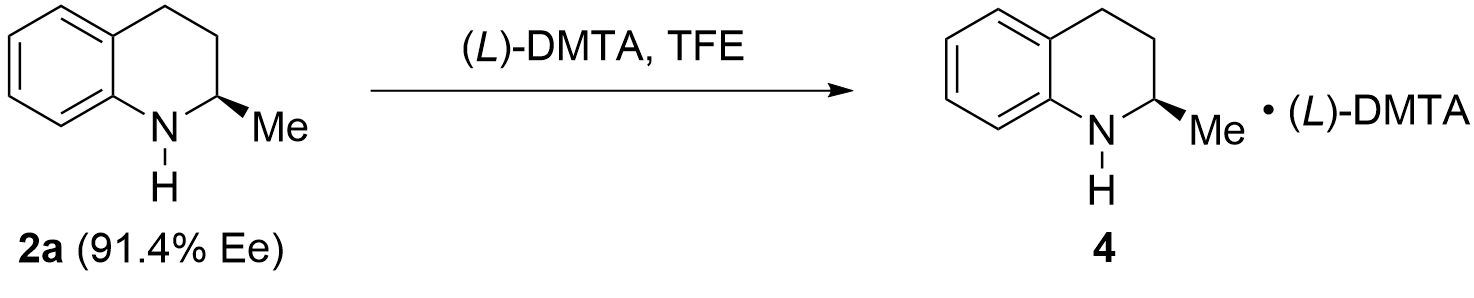

2.3 Resolution with (L)-DMTA

Resolution of 2-Methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline with (L)-DMTA. (L)-DMTA (653.9 g, 1.563 mol) and solvent trifluoroethanol (2.67 L) were added to a round-bottom flask. A solution of 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline 2a (230.1 g, 1.563 mol, 91.4% ee) in trifluoroethanol (382 mL) was added dropwise under reflux. After the addition was completed, the mixture was stirred for 5 hours. Heating was stopped, and the solution was allowed to cool naturally to room temperature with continued stirring for 12 to 15 hours. The resulting mixture was filtered, and the solid was washed with cold trifluoroethanol (2 × 100 mL) and dried under vacuum to afford 842.2 g of powdered solid product 4 in 95% yield and 99.3% ee. (Note: the optical purity was determined by the HPLC analysis of 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline after neutralization with sodium carbonate.)

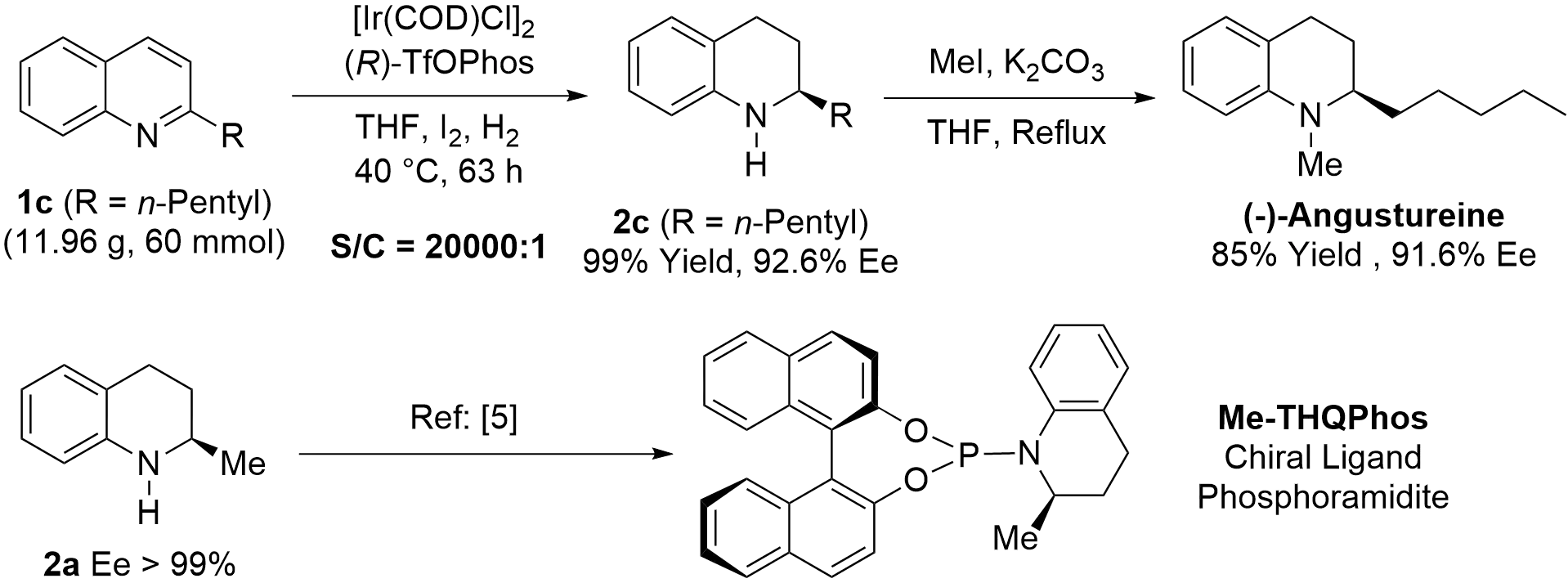

2.4 Enantioselective synthesis of Alkaloid (-)-Angustureine

In a nitrogen-filled glovebox, a mixture of [Ir(COD)Cl]2 (2.0 mg, 3.0 μmol) and (R)-TfOPhos, (5.9 mg, 7.2 μmol) in THF (2 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 30 minutes to give the chiral catalyst solution. Then, the above solution was transferred to a 300 mL autoclave in which additive iodine (152.0 mg, 0.6 mmol), THF (20 mL) and 2-n-pentylquinoline (11.96 g, 60 mmol) had been added. The autoclave was then charged with hydrogen gas (1,000 psi) and stirred at 40 °C for 63 hours. After carefully releasing hydrogen gas, the mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was washed with sodium thiosulfate solution (3.0 M, 10 mL) and extracted three times with ethyl acetate (15 mL x 3). The combined organic layers were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure to give 12.11 g of chiral reductive product (R)-2-n-pentyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2c) in 99% yield and 92.6% ee. Known compound[11], Rf = 0.70 (hexanes/ethyl acetate = 20/1), 92.6% ee. [α]20D = + 72.6 (c 1.05, CHCl3), [lit[11]: 83% ee, [α]20D = + 44.8 (c 1.00, CHCl3)]. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.94 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 6.60 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.51-6.46 (m, 1H), 3.90 (s, 1H), 3.28-3.18 (m, 1H), 2.86-2.66 (m, 2H), 2.00-1.91 (m, 1H), 1.65-1.26 (m, 9H), 0.94-0.87 (m, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 144.5, 129.3, 126.7, 121.6, 117.1, 114.2, 51.7, 36.6, 32.0, 28.1, 26.4, 25.5, 22.7, 14.1. HPLC: Chiralcel OJ-H, 254 nm, 30 °C, n-Hexane/i-PrOH = 95/5, flow = 0.5 mL/min, retention time 13.0 min (minor) and 14.0 min (major).

To a solution of (+)-2c (11.93 g, 59 mmol) and K2CO3 (32.60 g, 236 mmol) in THF (400 mL), MeI (21.00 g, 148 mmol) was added under N2 atmosphere. After the reaction mixture was refluxed for 10 h, the reaction was quenched by water. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2 (20 mL x 3) and the combined organic layers were washed with brine and dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. After removal of the solvent, the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel to afford (-)-Angustureine as pale-yellow oil with 85% yield and 91.6% ee. Known compound,[11] Rf = 0.75 (hexanes/ethyl acetate = 20/1), 91.6% ee. [α]20D = -7.16 (c 1.69, CHCl3), [lit[11]: 94% ee, [α]15D = -6.70 (c 1.00, CHCl3)]. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.07 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 6.64-6.47 (m, 2H), 3.27-3.18 (m, 1H), 2.92 (s, 3H), 2.85-2.73 (m, 1H), 2.70-2.59 (m, 1H), 1.93-1.85 (m, 2H), 1.65-1.55 (m, 1H), 1.49-1.14 (m, 7H), 0.89 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 145.4, 128.7, 127.1, 121.8, 115.2, 110.4, 59.0, 38.0, 32.1, 31.2, 25.8, 24.4, 23.6, 22.7, 14.1. HPLC: Chiralcel OJ-H, 254 nm, 30 °C, n-Hexane/i-PrOH = 95/5, flow = 0.5 mL/min, retention time 8.4 min (major) and 9.2 min (minor).

3. Results and Discussion

In our previous work, we designed and synthesized the electron-deficient chiral bisphosphine ligand (R)-TfOPhos and applied it in asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-methylquinoline with a TON = 14,600, delivering the desired product 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline with 95% ee value[40], which proved the superiority of the chiral ligand (R)-TfOPhos as an electron-deficient ligand in iridium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of quinoline derivatives. So, this chiral ligand was used here to further optimize the reaction parameters such as the additive iodine amount, solvent, hydrogen pressure, and reaction temperature, the detailed experimental results were listed in Table 1.

| Entry | 1a (g) | S/C | I2 (mg) | THF (mL) | H2 (psi) | Convn (%)a | TON | Ee (%)b |

| 1 | 8.58 | 20,000/1 | 76 | 12 | 400 | > 99 | 20,000 | 91.8 |

| 2 | 17.16 | 40,000/1 | 76 | 24 | 400 | 80 | 32,000 | 91.8 |

| 3 | 21.45 | 50,000/1 | 76 | 30 | 400 | 75 | 37,400 | 92.2 |

| 4 | 21.45 | 50,000/1 | 38 | 30 | 400 | 42 | 21,200 | 91.8 |

| 5 | 21.45 | 50,000/1 | 114 | 30 | 400 | 81 | 40,650 | 92.3 |

| 6 | 21.45 | 50,000/1 | 152 | 30 | 400 | 84 | 42,000 | 92.5 |

| 7 | 21.45 | 50,000/1 | 152 | 21 | 400 | 71 | 35,500 | 92.1 |

| 8 | 21.45 | 50,000/1 | 152 | 38 | 400 | 94 | 47,000 | 92.5 |

| 9 | 21.45 | 50,000/1 | 152 | 50 | 400 | > 99 | 50,000 | 92.8 |

| 10 | 25.74 | 60,000/1 | 152 | 60 | 600 | 92 | 55,200 | 92.6 |

| 11 | 25.74 | 60,000/1 | 152 | 60 | 800 | > 99 | 60,000 | 92.8 |

| 12 | 34.32 | 80,000/1 | 152 | 80 | 1,000 | 83 | 66,400 | 92.5 |

| 13c | 34.32 | 80,000/1 | 152 | 80 | 1,000 | > 99 | 80,000 | 91.8 |

| 14d | 34.32 | 80,000/1 | 152 | 80 | 1,000 | > 99 | 80,000 | 90.8 |

| 15c | 42.90 | 100,000/1 | 152 | 100 | 1,000 | 86 | 86,000 | 91.7 |

| 16c,e | 42.90 | 100,000/1 | 152 | 100 | 1,000 | 89 | 89,000 | 91.8 |

a: Determined by 1H NMR; b: Determined by HPLC with chiral column; c: Reaction at 50 °C; d: Reaction at 60 °C; e: The substrate 2-methylquinoline was degassed through freeze-thaw; TON: turnover number; THF: tetrahydrofuran; HPLC: high-performance liquid chromatography.

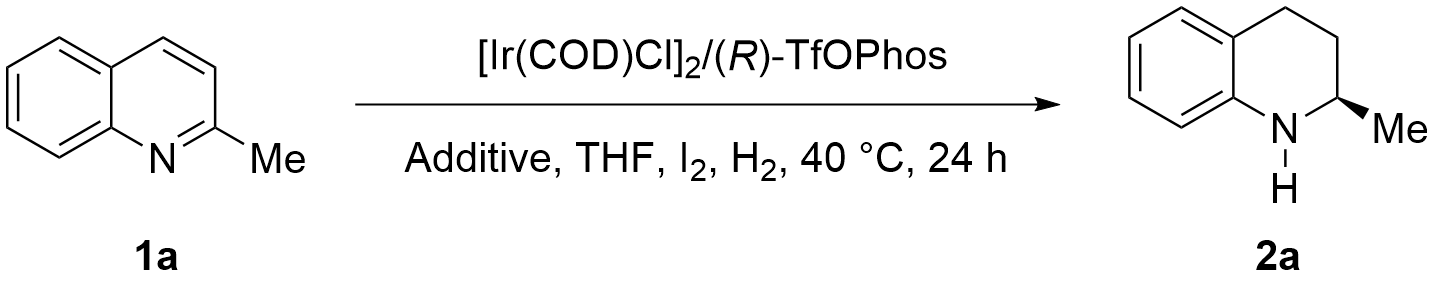

First, the hydrogenation was conducted under 40 °C, S/C = 20,000/1, full conversion was observed (Table 1, entry 1). When the amount of substrate was further increased to S/C = 40,000/1, 80% conversion (TON of 32,000) could be achieved (entry 2). Then the S/C was increased to 50,000/1, giving the product with 75% conversion and 92% ee (entry 3). Next, the amount of iodine was investigated under this condition, and it was found that the reduced iodine resulted in lower yield, and slightly increased yield was obtained when the amount of iodine added was doubled (entries 4-6). Then, the amount of solvent was investigated (entries 7-9), and the conversion was improved from 71% to > 99% with the increase of solvent volume. The TON increased from 50,000 to 66,400 when the hydrogen pressure was raised to 1,000 psi (entries 10-12). Considering both the economy and safety, the solvent volume and the hydrogen pressure were not further increased. Finally, the reaction temperature was investigated and found that although higher temperature could promote the reaction activity, a slightly decreased ee value was observed (entries 13-14). When the S/C was further increased to 100,000/1, 86,000 TON was obtained (entry 15). Considering that the chiral iridium catalyst might be sensitive to oxygen gas, the residual oxygen was removed from the solvent through freeze-thaw before it was used with an S/C of 100,000/1 (entry 16). There was no significant improvement in the reactivity, which indicated that the iridium catalyst system is tolerant to trace amounts of oxygen gas. So, the optimal conditions were established for the subsequent amplification: S/C/I2 = 80,000/1/200, concentration 3 mol/L, H2 (1,000 psi), 50 °C.

However, a phenomenon was observed where the reactivity of 2-methylquinoline from different manufacturers varied greatly under S/C = 40,000:1 (Table 2, entry 1), which was attributed to trace amounts of impurities in the 2-methylquinoline poisoning the chiral catalyst. Initially, we tried to remove the impurities through distillation, which did not produce any improvement. Next, additives (FeCl3, Cu(OTf)2, CoCl2, ZnCl2) were added to the reaction system to form complexes with the impurities to avoid catalyst deactivation (entries 2-5), and the reactivity increased to 71% while the optical purity remained when CoCl2 was used as the additive (entry 4). Although the reactivity improved significantly, the result was not yet satisfactory. Therefore, we tried to remove the impurities through salting with alkyl halides, but lower reactivities were also observed (entries 6, 7). Since additives did not yield the desired results, an adsorption purification method was employed using a silica gel column doped with copper(II) chloride, which effectively improved the reactivity of the raw material without erosion of the enantioselectivity (S/C = 80,000:1, 92.1% ee) (Figure 2).

| Entry | Additive | Convn (%)a | Ee (%)b |

| 1 | none | 5.7 | -- |

| 2 | FeCl3 | 62 | 92.8 |

| 3 | Cu(OTf)2 | 70 | 92.6 |

| 4 | CoCl2 | 71 | 92.7 |

| 5 | ZnCl2 | 63 | 92.7 |

| 6c | MeI | 54 | 92.5 |

| 7c | EtI | 18 | 91.9 |

1a: (17.16 g, 120 mmol), [Ir(COD)Cl]2 (2.0 mg, 3 μmol), (R)-TfOPhos (5.9 mg, 7.2 μmol), I2 (76 mg, 0.3 mmol), Additive (0.12 mmol), THF (24 mL), H2 (400 psi), 40 °C, 24 h, S/C = 40,000:1; a: Determined by 1H NMR; b: Determined by HPLC with chiral column; c: Additive (0.6 mmol); THF: tetrahydrofuran; HPLC: high-performance liquid chromatography.

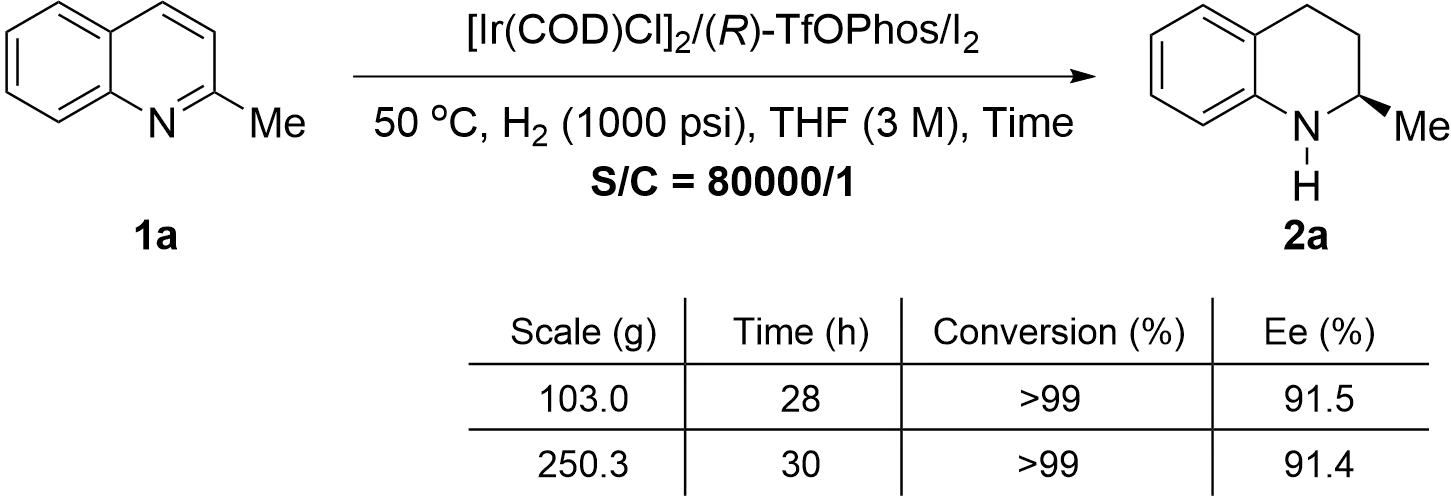

With the optimal conditions in hand, the current process was scaled up with a low catalyst loading of S/C = 80,000/1. The process was conducted on 103.0 g and 250.3 g scales, respectively. To our delight, identical enantioselectivities and catalytic activity were observed in the asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-methylquinoline on a hundred-gram scale (Scheme 2), which demonstrated the potential for further industrial application.

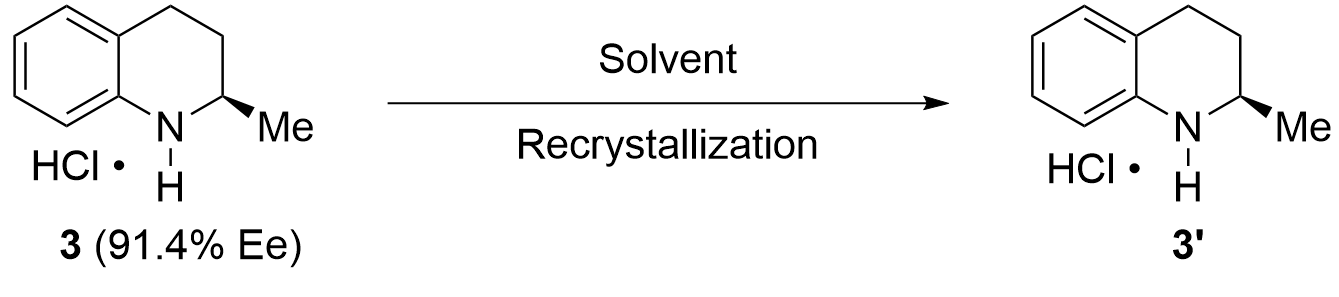

Considering that the 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline with 91.4% optical purity was not suitable for the synthesis of chiral ligands and biologically active molecules, we turned our attention to explore recrystallization to upgrade the optical purity. First, the raw material was converted into hydrochloride salt with hydrogen chloride 1,4-dioxane solution, followed by careful selection of the recrystallization solvent. Dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, and acetone failed to provide satisfactory yields and ee values. An 85% yield and 97.8% ee were obtained when ethanol was used as the solvent (Table 3, entry 1). So, other alcohol solvents were investigated (entries 2, 3). It was gratifying that the product could achieve 99.5% ee when methanol was used as the solvent, albeit with 49% yield. To improve the yield, we next investigated a mixed solvent of n-hexane and methanol for recrystallization, and found that as the proportion of n-hexane increased, the yield significantly improved. When the ratio of methanol to hexane was 8:1, 72% yield and 99.5% ee were achieved (entry 4). Further increasing the n-hexane amount resulted in a lower 98.2% ee (entry 5), so a mixture ratio of 8:1 was selected and this ratio was further validated by repeating the experiments on larger scales of 50 g and 100 g, respectively (entries 6, 7).

| Entry | 3 (g) | Solvent (mL) | Yield (%)a | Ee (%)b |

| 1 | 5.00 | EtOH (9) | 85 | 97.8 |

| 2 | 5.00 | iPrOH (9) | 89 | 94.9 |

| 3 | 5.00 | MeOH (6) | 49 | 99.5 |

| 4 | 20.00 | MeOH (24) + n-Hexane (3) | 72 | 99.5 |

| 5 | 20.00 | MeOH (24) + n-Hexane (5) | 79 | 98.2 |

| 6 | 50.00 | MeOH (63) + n-Hexane (11) | 72 | 99.2 |

| 7 | 100.0 | MeOH (134) + n-Hexane (20) | 70 | 99.4 |

a: Determined by 1H NMR; b: Determined by HPLC with chiral column; HPLC: high-performance liquid chromatography.

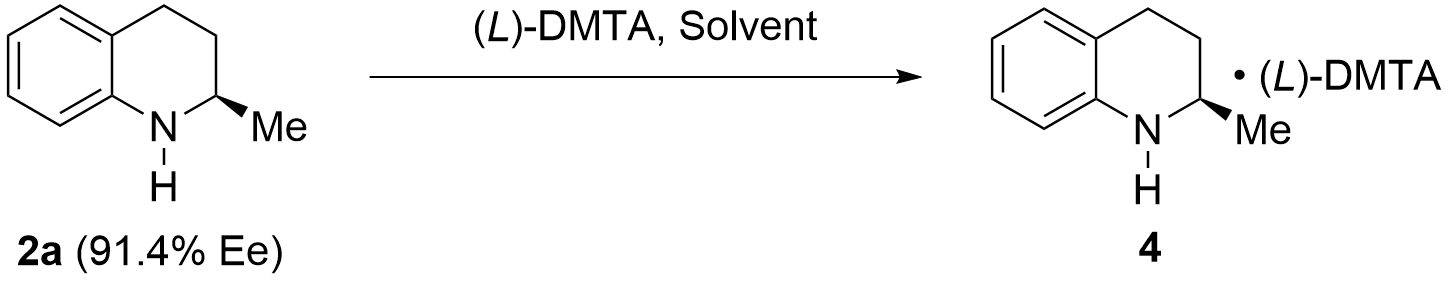

Although we succeeded in upgrading the optical purity through recrystallization, the solvent ratio for each recrystallization was not entirely determined. In addition, the yield of the recrystallization was also unsatisfactory, which urged us to further explore the new process.

Although chemical resolution is not considered as an economic method to obtain optically pure products, it is a good solution to improve the optical purity of the hydrogenative product here. Through extensive screening of resolving agents, we applied di-(p-methoxybenzoyl)-L-(-)-tartaric acid ((L)-DMTA) for the chemical resolution of 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline. This procedure was further investigated as shown in Table 4. 97.8% ee was obtained in methanol (Table 4, entry 1). Next, the generally used solvents such as ethanol and acetone were screened, affording moderate yields and ee values, respectively (entries 2, 3). To our delight, 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol (TFE) delivered the best result in terms of yield and optical purity (entry 4, 93% yield, 98.7% ee).

| Entry | Solvent | Yield (%)b | Ee (%)c |

| 1 | MeOH | 82 | 97.8 |

| 2 | EtOH | 88 | 95.3 |

| 3 | Acetone | 71 | 97.7 |

| 4 | TFE | 93 | 98.7 |

Conditionsa: 2a (7.35 g), (L)-DMTA (1 eq.); b: Determined by 1H NMR; c: Determined by HPLC; HPLC: high-performance liquid chromatography; TFE: 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol.

With the optimal resolution conditions in hand, gradient amplification of the chemical resolution experiments was performed, and it was found that a 97% yield and 99.0% ee were obtained when the resolution was conducted on a 30.14 g scale (Table 5, entry 1). Next, the resolution was performed on 105.0 g and 200.0 g scales, respectively, and the satisfactory results could still be obtained (entries 2, 3). Although chemical resolution gave high yield and optical purity, the expensive trifluoroethanol was a challenge for large-scale production. Based on this, we conducted solvent recovery and reuse experiments. Over 95% of trifluoroethanol could be recovered by distillation, and the recovered solvent was used for resolution, achieving the same yield and optical purity (entry 4). According to the methods described in the literature, (L)-DMTA could also be recycled[41], which significantly reduced the resolution cost.

| Entry | 2a (g) | TFE (mL) | Yield (%) | Ee (%)a |

| 1 | 30.14 | 400 | 97 | 99.0 |

| 2 | 105.0 | 1,400 | 95 | 99.3 |

| 3 | 200.0 | 2,650 | 95 | 99.3 |

| 4b | 230.0 | 3,050 | 95 | 99.3 |

a: Determined by HPLC with chiral column; b: Recovered solvent 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol was used; TFE: 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol; HPLC: high-performance liquid chromatography.

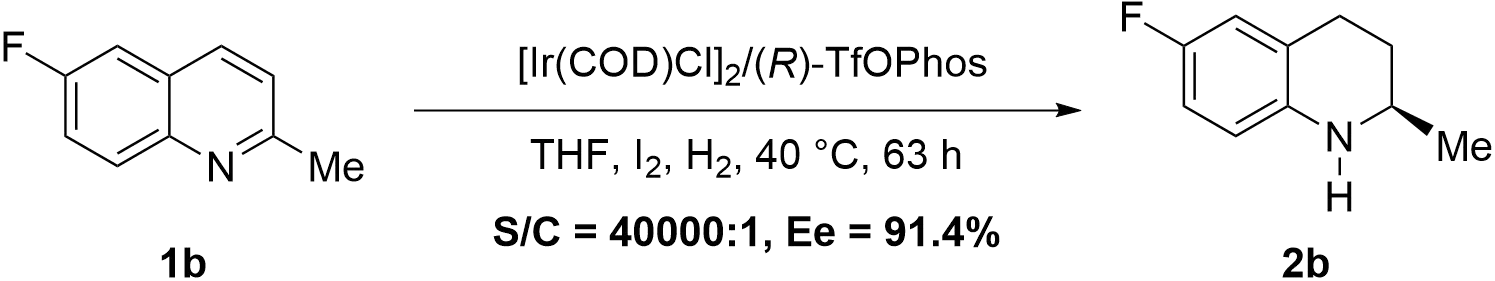

Flumequine is a veterinary drug widely used in livestock, poultry, and aquaculture. Considering that the core skeleton of Flumequine is 6-fluoro-2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline[3], and based on the aforementioned work, we further applied this catalytic system to the synthesis of chiral 6-fluoro-2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline. After minor optimization, the reaction achieved full conversion at S/C = 40,000/1, affording the product with 91.4% ee and 99% yield (Scheme 3). The optically pure Flumequine could be obtained according to the reported procedure[3].

Scheme 3. Asymmetric hydrogenation of 6-fluoro-2-methylquinoline. THF: tetrahydrofuran.

This methodology was applied to the total synthesis of tetrahydroquinoline alkaloid (-)-Angustureine on a decagram scale. First, asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-pentylquinoline (1c) gave the key intermediate 2c with 92.6% ee and 99% yield with 20,000 TON. Next, N-methylation of intermediate 2c was conducted to give the tetrahydroquinoline alkaloid (-)-Angustureine with 85% yield and 91.6% ee (Scheme 4). Chiral 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2a) could also be used for the synthesis of chiral privileged phosphoramidite ligand Me-THQPhos according to the method developed from the You’s group[5].

Scheme 4. Synthesis of alkaloid (-)-angustureine and chiral ligand Me-THQPhos. THF: tetrahydrofuran.

4. Conclusion

In summary, an improved protocol for hundred-gram scale asymmetric hydrogenation of aromatic 2-methylquinoline was developed using the chiral iridium/(R)-TfOPhos catalyst, with up to 80,000 TON, 91.4% enantioselectivity, and 99% yield (Scheme 5). The current process enables facile production of 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline and 6-fluoro-2-methyltetrahydroquinoline with high optical purity. Further chemical resolution using (L)-DMTA as the resolving reagent and TFE as the solvent produced the optically pure (R)-2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline with 95% yield and > 99% ee, which has the potential for industrial production.

Scheme 5. Synthesis of chiral 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline. TFE: 2,2,2-trifluoroethanol; THF: tetrahydrofuran.

Supplementary materials

The supplementary material for this article is available at: Supplementary materials.

Authors contribution

Jing H: Investigation, data curation, formal analysis, writing-original draft.

Yu CB, Zhou YG: Conceptualization, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Yong-Gui Zhou is an Editorial Board Member of Chiral Chemistry. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

Financial support from National Natural Science Foundation of China (22471264) and Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP I202442), Chinese Academy of Sciences is acknowledged.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Asolkar RN, Schröder D, Heckmann R, Lang S, Wagner-Döbler I, Laatsch H. Helquinoline, a new tetrahydroquinoline antibiotic from Janibacter limosus Hel 1. J Antibiot. 2004;57(1):17-23.[DOI]

-

2. Brough PA, Baker L, Bedford S, Brown K, Chavda S, Chell V, et al. Application of off-rate screening in the identification of novel pan-isoform inhibitors of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase. J Med Chem. 2017;60(6):2271-2286.[DOI]

-

3. Bálint J, Egri G, Fogassy E, Böcskei Z, Simon K, Gajáry A, et al. Synthesis, absolute configuration and intermediates of 9-fluoro-6,7-dihydro-5-methyl-1-oxo-1H,5H-benzo[i,j]quinolizine-2-carboxylic acid (flumequine). Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 1999;10(6):1079-1087.[DOI]

-

4. Gosmini R, Nguyen VL, Toum J, Simon C, Brusq JM, Krysa G, et al. The discovery of I-BET726 (GSK1324726A), a potent tetrahydroquinoline ApoA1 up-regulator and selective BET bromodomain inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2014;57(19):8111-8131.[DOI]

-

5. Liu WB, He H, Dai LX, You SL. Synthesis of 2-methylindoline and 2-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline-derived phosphoramidites and their applications in iridium-catalyzed allylic alkylation of indoles. Synthesis. 2009;2009(12):2076-2082.[DOI]

-

6. Han ZY, Xiao H, Chen XH, Gong LZ. Consecutive intramolecular hydroamination/asymmetric transfer hydrogenation under relay catalysis of an achiral gold complex/chiral Brønsted acid binary system. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(26):9182-9183.[DOI]

-

7. Lim CS, Quach TT, Zhao Y. Enantioselective synthesis of tetrahydroquinolines by borrowing hydrogen methodology: Cooperative catalysis by an achiral iridacycle and a chiral phosphoric acid. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56(25):7176-7180.[DOI]

-

8. Satyanarayana G, Pflästerer D, Helmchen G. Enantioselective syntheses of tetrahydroquinolines based on iridium-catalyzed allylic substitutions: Total syntheses of (+)-angustureine and (–)-cuspareine. Eur J Org Chem. 2011;2011(34):6877-6886.[DOI]

-

9. Xiong W, Li S, Fu B, Wang J, Wang QA, Yang W. Visible-light induction/Brønsted acid catalysis in relay for the enantioselective synthesis of tetrahydroquinolines. Org Lett. 2019;21(11):4173-4176.[DOI]

-

10. Zhou YG. Asymmetric hydrogenation of heteroaromatic compounds. Acc Chem Res. 2007;40(12):1357-1366.[DOI]

-

11. Wang WB, Lu SM, Yang PY, Han XW, Zhou YG. Highly enantioselective iridium-catalyzed hydrogenation of heteroaromatic compounds, quinolines. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(35):10536-10537.[DOI]

-

12. Xu L, Lam KH, Ji J, Wu J, Fan QH, Lo WH, et al. Air-stable Ir-(P-Phos) complex for highly enantioselective hydrogenation of quinolines and their immobilization in poly(ethylene glycol) dimethyl ether (DMPEG). Chem Commun. 2005.[DOI]

-

13. Lam KH, Xu L, Feng L, Fan QH, Lam FL, Lo Wh, et al. Highly enantioselective iridium-catalyzed hydrogenation of quinoline derivatives using chiral phosphinite H8-BINAPO. Adv Synth Catal. 2005;347(14):1755-1758.[DOI]

-

14. Reetz MT, Li X. Asymmetric hydrogenation of quinolines catalyzed by iridium complexes of BINOL-derived diphosphonites. Chem Commun. 2006.[DOI]

-

15. Deport C, Buchotte M, Abecassis K, Tadaoka H, Ayad T, Ohshima T, et al. Novel Ir-SYNPHOS® and Ir-DIFLUOROPHOS® catalysts for asymmetric hydrogenation of quinolines. Synlett. 2007;2007(17):2743-2747.[DOI]

-

16. Gou FR, Li W, Zhang X, Liang YM. Iridium-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of quinoline derivatives with C3*-Tunephos. Adv Synth Catal. 2010;352(14):2441-2444.[DOI]

-

17. (a) Kim AN, Stoltz BM. Recent advances in homogeneous catalysts for the asymmetric hydrogenation of heteroarenes. ACS Catal. 2020;10(23):13834-13851.[DOI](b) Cabré A, Verdaguer X, Riera A. Recent advances in the enantioselective synthesis of chiral amines via transition metal-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation. Chem Rev. 2022;122(1):269-339.[DOI](c) Gao B, Han Z, Meng W, Feng X, Du H. Asymmetric reduction of quinolines: A competition between enantioselective transfer hydrogenation and racemic borane catalysis. J Org Chem. 2023;88(5):3335-3339.[DOI](d) Varga B, Buna L, Vincze D, Holczbauer T, Mátravölgyi B, Fogassy E, et al. Enantioseparation of P-stereogenic 1-adamantyl arylthiophosphonates and their stereospecific transformation to 1-adamantyl aryl-H-phosphinates. Molecules. 2023;28(4):1584-1598.[DOI](e) Karthick M, Someshwar N, Mariappan CR, Ramasubbu A, Ramanathan CR. Chiral 3,3'-diaroyl BINOL phosphoric acids: Syntheses and evaluation in asymmetric transfer hydrogenation, photophysical, and electrochemical studies. Org Biomol Chem. 2025;23(13):3112-3125.[DOI]

-

18. Wang ZJ, Deng GJ, Li Y, He YM, Tang WJ, Fan QH. Enantioselective hydrogenation of quinolines catalyzed by Ir(BINAP)-cored dendrimers: Dramatic enhancement of catalytic activity. Org Lett. 2007;9(7):1243-1246.[DOI]

-

19. Tang W, Sun Y, Lijin X, Wang T, Qinghua F, Lam KH, et al. Highly efficient and enantioselective hydrogenation of quinolines and pyridines with Ir-Difluorphos catalyst. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8(15):3464-3471.[DOI]

-

20. Tang WJ, Tan J, Xu LJ, Lam KH, Fan QH, Chan ASC. Highly enantioselective hydrogenation of quinoline and pyridine derivatives with iridium-(P-Phos) catalyst. Adv Synth Catal. 2010;352(6):1055-1062.[DOI]

-

21. Zhou H, Li Z, Wang Z, Wang T, Xu L, He Y, et al. Hydrogenation of quinolines using a recyclable phosphine-free chiral cationic ruthenium catalyst: Enhancement of catalyst stability and selectivity in an ionic liquid. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47(44):8464-8467.[DOI]

-

22. Wang T, Zhuo LG, Li Z, Chen F, Ding Z, He Y, et al. Highly enantioselective hydrogenation of quinolines using phosphine-free chiral cationic ruthenium catalysts: Scope, mechanism, and origin of enantioselectivity. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133(25):9878-9891.[DOI]

-

23. Wang C, Li C, Wu X, Pettman A, Xiao J. PH-regulated asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of quinolines in water. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48(35):6524-6528.[DOI]

-

24. Wen J, Tan R, Liu S, Zhao Q, Zhang X. Strong Brønsted acid promoted asymmetric hydrogenation of isoquinolines and quinolines catalyzed by a Rh-thiourea chiral phosphine complex via anion binding. Chem Sci. 2016;7(5):3047-3051.[DOI]

-

25. Liu C, Wang M, Liu S, Wang Y, Peng Y, Lan Y, et al. Manganese-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of quinolines enabled by π-π interaction. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2021;60(10):5108-5113.[DOI]

-

26. Sun S, Nagorny P. Exploration of chiral diastereomeric spiroketal (SPIROL)-based phosphinite ligands in asymmetric hydrogenation of heterocycles. Chem Commun. 2020;56(60):8432-8435.[DOI]

-

27. Qi H, Wang L, Sun Q, Sun W. Asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of quinoline derivatives catalyzed by chiral iridium-imidazoline complex in water. Mol Catal. 2022;532:112715.[DOI]

-

28. Li B, Zhou G, Zhang D, Yao L, Li M, Yang G, et al. Spiro-Josiphos ligands for the Ir-catalyzed asymmetric synthesis of chiral amines under hydrogenation conditions. Org Lett. 2024;26(10):2097-2102.[DOI]

-

29. Zhang F, Chen GQ, Zhang X. Design and synthesis of diphosphine ligands based on the chiral biindolyl scaffold and their application in transition-metal catalysis. Org Lett. 2024;26(8):1623-1628.[DOI]

-

30. (a) Wang Z, Chen L, Mao G, Wang C. Simple manganese carbonyl catalyzed hydrogenation of quinolines and imines. Chin Chem Lett. 2020;31(7):1890-1894.[DOI](b) Vermaak V, Vosloo HCM, Swarts AJ. Fast and efficient nickel(II)-catalysed transfer hydrogenation of quinolines with ammonia borane. Adv Synth Catal. 2020;362(24):5788-5793.[DOI](c) Han Z, Liu G, Yang X, Dong XQ, Zhang X. Enantiodivergent synthesis of chiral tetrahydroquinoline derivatives via Ir-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation: Solvent-dependent enantioselective control and mechanistic investigations. ACS Catal. 2021;11(12):7281-7291.[DOI](d) Zhu M, Tian H, Chen S, Xue W, Wang Y, Lu H, et al. Homogeneous cobalt catalyzed reductive formylation of N-heteroarenes with formic acid. J Catal. 2022;416:170-175.[DOI](e) Mao W, Song D, Guo J, Zhang K, Zheng C, Lin J, et al. Manganese-catalyzed asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of quinolines in water using ammonia borane as a hydrogen source. Green Chem. 2024;26(10):5933-5939.[DOI](f) Wen Y, Cabré A, Benet-Buchholz J, Riera A, Verdaguer X. Chiral cnn pincer Ir(III)-H complexes. Transient ligand and counterion influences in the asymmetric hydrogenation of imines and quinolines. Dalton Trans. 2025;54(26):10246-10253.[DOI]

-

31. Rueping M, Antonchick AP, Theissmann T. A highly enantioselective Brønsted acid catalyzed cascade reaction: Organocatalytic transfer hydrogenation of quinolines and their application in the synthesis of alkaloids. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45(22):3683-3686.[DOI]

-

32. Guo QS, Du DM, Xu J. The development of double axially chiral phosphoric acids and their catalytic transfer hydrogenation of quinolines. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47(4):759-762.[DOI]

-

33. More GV, Bhanage BM. Chiral phosphoric acid catalyzed asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of quinolines in a sustainable solvent. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2015;26(20):1174-1179.[DOI]

-

34. Zhao J, Shi X, Tan S, Li Y, Li R, Zhang B, et al. Aporphinol-derived chiral phosphoric acids: Synthesis and catalytic performance. Org Lett. 2025;27(17):4463-4468.[DOI]

-

35. Chen MW, Ji Y, Wang J, Chen QA, Shi L, Zhou YG. Asymmetric hydrogenation of isoquinolines and pyridines using hydrogen halide generated in situ as activator. Org Lett. 2017;19(18):4988-4991.[DOI]

-

36. Lu SM, Wang YQ, Han XW, Zhou YG. Asymmetric hydrogenation of quinolines and isoquinolines activated by chloroformates. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45(14):2260-2263.[DOI]

-

37. Wang J, Chen MW, Ji Y, Hu SB, Zhou YG. Kinetic resolution of axially chiral 5- or 8-substituted quinolines via asymmetric transfer hydrogenation. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(33):10413-10416.[DOI]

-

38. Duan Y, Li L, Chen MW, Yu CB, Fan HJ, Zhou YG. Homogenous Pd-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation of unprotected indoles: Scope and mechanistic studies. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(21):7688-7700.[DOI]

-

39. Feng GS, Chen MW, Shi L, Zhou YG. Facile synthesis of chiral cyclic ureas through hydrogenation of 2-hydroxypyrimidine/pyrimidin-2(1H)-one tautomers. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2018;57(20):5853-5857.[DOI]

-

40. Zhang DY, Wang DS, Wang MC, Yu CB, Gao K, Zhou YG. Synthesis of electronically deficient atropisomeric bisphosphine ligands and their application in asymmetric hydrogenation of quinolines. Synthesis. 2011;2011(17):2796-2802.[DOI]

-

41. Zhang ZG, Cheng YT, inventors. Method for Recovering and Recycling L-Tartaric Acid. China patent CN 102503810. 2014 May 21.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite