Abstract

Developing mild and sustainable strategies for the synthesis of complex molecules is a pivotal yet challenging goal in modern synthesis. While cobalt catalysis offers a sustainable alternative to noble metals, achieving such transformations at room temperature remains elusive. Herein, we report a cobalt-catalyzed aerobic oxidative asymmetric formal cycloaddition involving C(sp2)–H bond activation of benzamides with unactivated alkynes at room temperature using air as the oxidant. For challenging low-activity substrates, reaction efficiency is enhanced via a photoinduced catalytic cycle. Mechanistic and substrate scope studies indicate that substrate reactivity is influenced by electronic and steric effects.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

1. Introduction

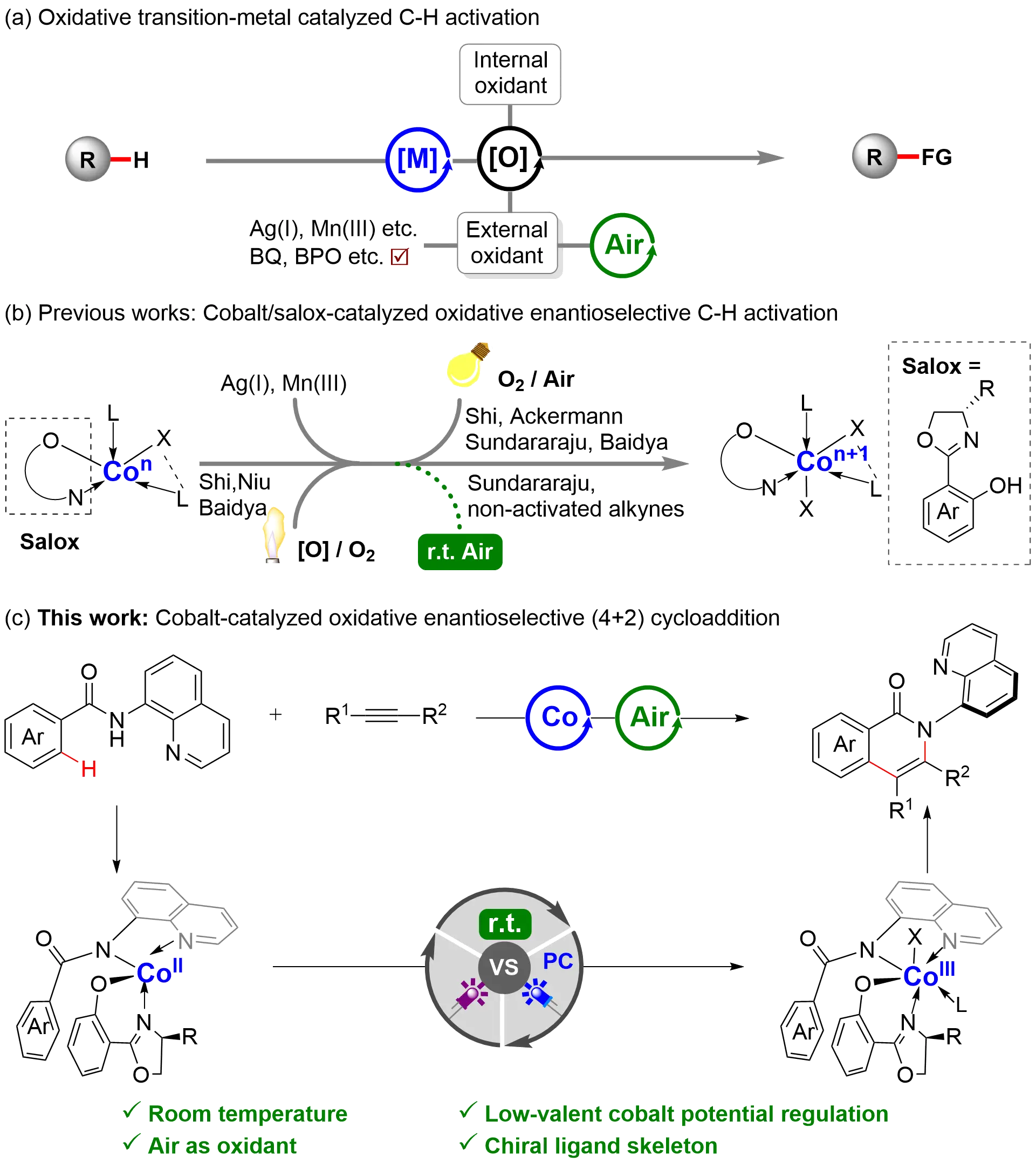

Constructing molecular complexity with high efficiency under mild and environmentally friendly conditions is a central pursuit in synthetic chemistry[1,2]. Transition-metal-catalyzed oxidative C–H functionalization stands as a direct route for this purpose[3,4], yet it often depends on stoichiometric oxidants, such as Ag(I), Mn(III), oxone, or organic peroxides, to regenerate the active catalyst

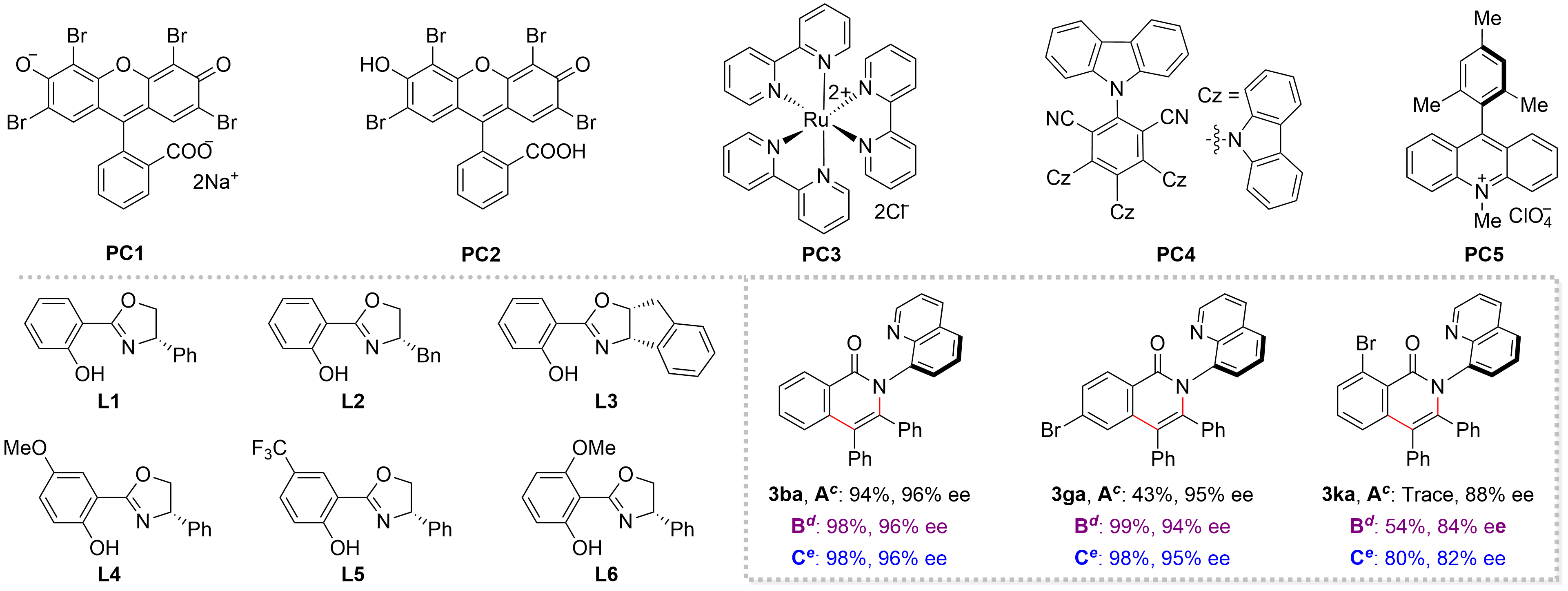

Figure 1. Design plan: cobalt-catalyzed oxidative enantioselective formal (4+2) cycloaddition.

Transition-metal-catalyzed asymmetric C–H functionalization has emerged as a direct and powerful strategy for constructing chiral molecules[18-20]. Among the various metals explored, earth-abundant and low-toxicity cobalt has demonstrated unique reactivity in C–H activation[21-24]. Since Yoshikai’s seminal 2014 report on the cobalt-catalyzed enantioselective C(sp2)–H intramolecular hydroacylation[25], significant advances have been witnessed in enantioselective cobalt catalysis. They are enabled by diverse chiral ligand systems, including phosphines[26,27], carboxylic acids[28-30], cyclopentadienyl ligands[31,32], and N-heterocyclic carbenes[33]. Notably, salicyloxazoline (Salox)-based ligands, originally developed by Bolm, have recently emerged as a privileged scaffold in this field (Figure 1b)[34]. While these systems have achieved substantial progress in enantioselective C(sp2)–H functionalization[35-40], they typically rely on stoichiometric oxidants and often require elevated temperatures. A critical step toward sustainability was taken by Niu in 2022[41], who successfully utilized oxygen gas to re-oxidize Co(I) to Co(III) in an asymmetric C–H activation, albeit under heating. More recently, photoirradiation strategies by Shi[42,43], Ackermann[44,45], Sundararaju[46], and Baidya[47] have demonstrated that light can activate O2 for this oxidation, enabling transformations like indole dearomatization. More recently, Sundararaju[48] reported an elegant room-temperature, air-activated strategy for the construction of distal 1,3-C−N diaxes using indole-containing active alkynes. Inspired by these works, we questioned whether the catalytic cycle in asymmetric cobalt-catalyzed C–H activation could be driven by air at room temperature using non-activated alkynes. We hypothesized that coordinating an electron-rich ligand could lower the oxidation potential of the low-valent cobalt intermediate, facilitating its re-oxidation by air without external energy input (Figure 1c). Herein, building on our longstanding interest in photoinduced asymmetric cobalt catalysis[49-53], we report an efficient,

2. Experimental/Methods

Under air, Co(NO3)2·6H2O (0.02 mmol, 5.82 mg), L4 (0.015 mmol, 8.08 mg), and 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP, 2 mL) were added to a 10 mL vial. After stirring at room temperature (rt) for 2 h, corresponding substrate 1 (0.2 mmol), alkyne 2 (0.3 mmol), PC5 (1.64 mg, 0.004 mmol), and PivONa (49.9 mg, 0.4 mmol) were added to the resulting mixture. The mixture was stirred at rt under 5 W blue light-emitting diodes (LEDs) for approximately 48 h. The concentrated reaction residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (3:1-1.5:1) as eluent to give the corresponding product 3.

3. Results and Discussion

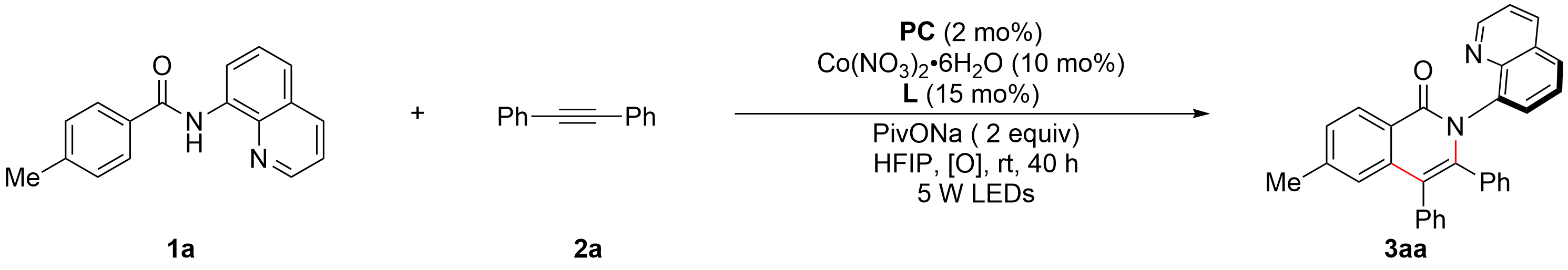

Initially, we investigated the reaction of 4-methyl-N-(quinolin-8-yl)benzamide 1a with diphenylacetylene 2a as the model substrates

| Entry | PC | Light | Oxidant | L | Yield (%) | ee (%) |

| 1 | PC1b | 5 W white LEDs | O2 | L1 | 46 | 90 |

| 2 | PC2b | 5 W white LEDs | O2 | L1 | 51 | 89 |

| 3 | PC3 | 5 W white LEDs | O2 | L1 | 14 | 85 |

| 4 | PC4 | 5 W blue LEDs | O2 | L1 | 30 | 85 |

| 5 | PC5 | 5 W blue LEDs | O2 | L1 | 86 | 89 |

| 6 | PC5 | 5 W blue LEDs | Air | L1 | 85 | 89 |

| 7 | PC5 | 5 W blue LEDs | Air | L2 | 95 | 61 |

| 8 | PC5 | 5 W blue LEDs | Air | L3 | 85 | 67 |

| 9 | PC5 | 5 W blue LEDs | Air | L4 | 94 | 95 |

| 10 | PC5 | 5 W blue LEDs | Air | L5 | 87 | 82 |

| 11 | PC5 | 5 W blue LEDs | Air | L6 | 67 | 75 |

| 12 | - | 5 W purple LEDs | Air | L4 | 94 | 96 |

| 13 | - | No light | Air | L4 | 93 | 96 |

a: 1a (0.1 mmol), 2a (0.15 1mmol), PC (2 mol%), Co(NO3)2·6H2O (10 mol%), L (15 mol%), PivONa (2 equiv) in HFIP (1 mL) under O2 at rt for 40 h. Yields were determined using

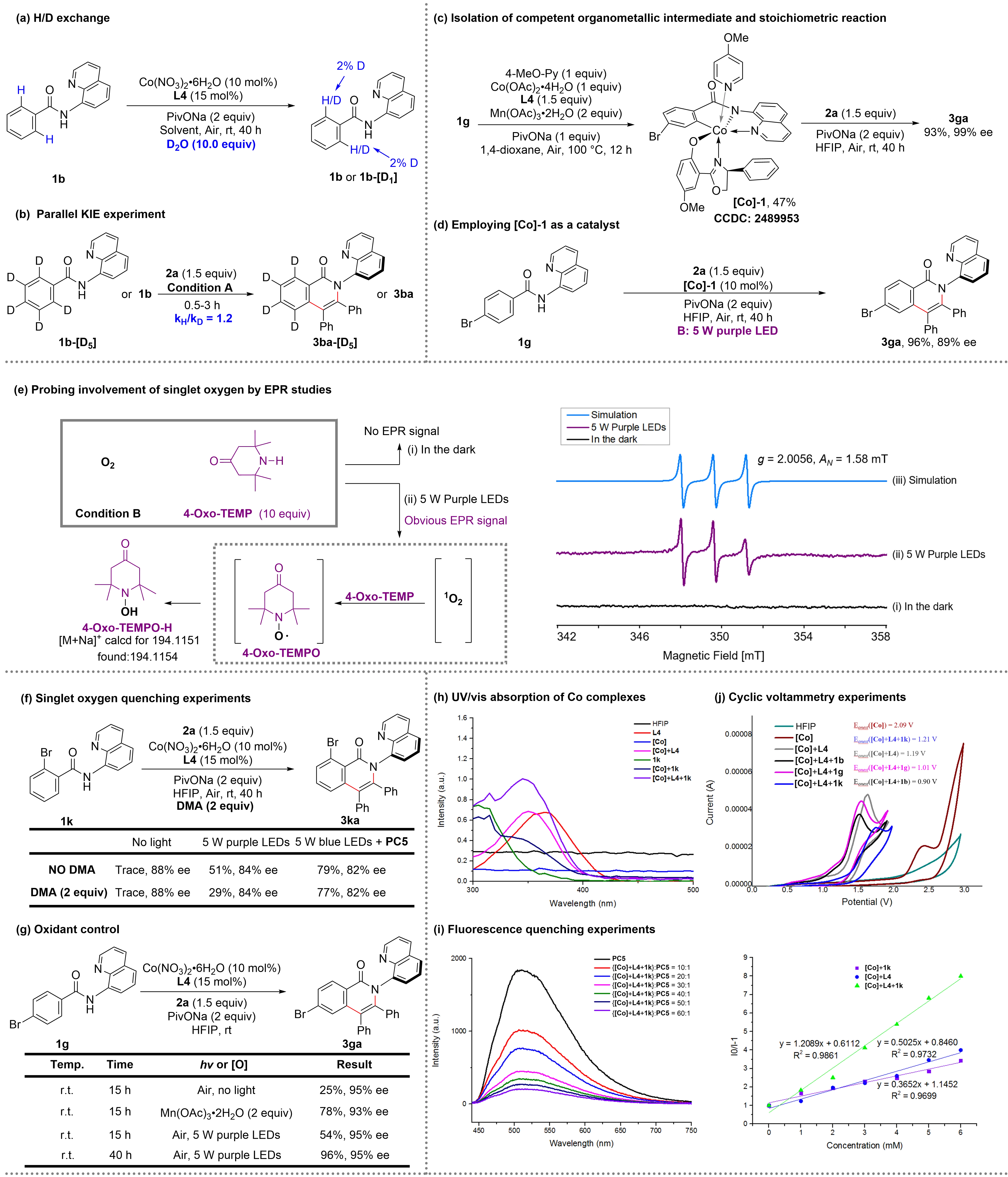

Subsequently, a series of mechanistic experiments was carried out to rationalize the way photocatalysis works and to understand the explicit role of the light (Figure 2). First, H/D exchange experiments were performed with 1b/D2O in the absence of both alkynes, PC5 and light, and it was found that the recovered 1b was hardly deuterated at the ortho-positions of the phenyl ring (Figure 2a). This indicates that the cleavage of the C–H bond is irreversible. Second, the parallel kinetic isotope effect (KIE, kH/kD = 1.2) was then evaluated, suggesting that C–H bond cleavage may not be involved in the rate-determining step (Figure 2b). Third, employing the cobaltacycle intermediate [Co]-1 in a stoichiometric reaction with alkynes can give the desired cycloadduct 3ga in 93% yield with 99% ee (Figure 2c). Under catalytic conditions, [Co]-1 delivered 3ga in 96% yield with 89% ee (Figure 2d). Both experiments indicate that the chiral ligand chelated Co(III) species [Co]-1 might be involved in the catalytic cycle. The structure of [Co]-1 was confirmed by X-ray diffraction (CCDC: 2489953).

Figure 2. Mechanistic experiments. [Co], Co(NO3)2·H2O. DMA, 9,10-dimethylanthracene.

To gain a more mechanistic understanding, we performed electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) studies with

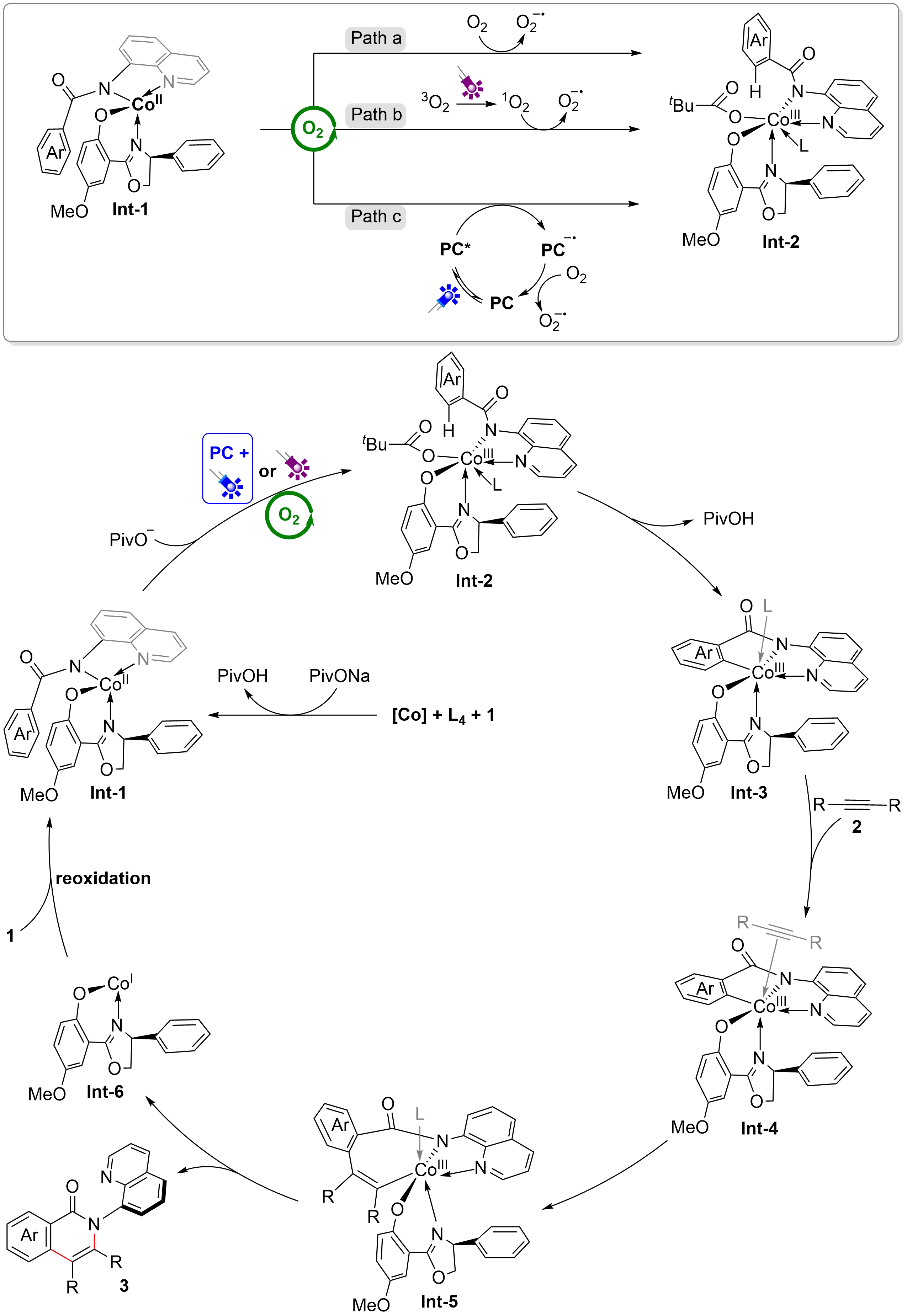

Combined with the three sets of conditions and detailed experimental results required in the reaction, three distinct mechanistic pathways were proposed in the process of oxidative regeneration of cobalt(III) Int-2 (Figure 3). In the conditions without both PC and light, the reaction undergoes path a: the cobalt(II) intermediate Int-1 was oxidized directly by oxygen to the cobalt(III) intermediate Int-2, releasing the superoxide anion O2•-. In the conditions of 5 W purple LEDs without PC, the reaction undergoes path b: the ground state oxygen (3O2) was excited by purple light to afford the singlet oxygen (1O2), and then the cobalt(II) intermediate Int-1 was oxidized by the singlet oxygen (1O2) to the cobalt(III) intermediate Int-2, accompanied by the release of superoxide anion O2•−. In the conditions of 5 W blue LEDs and PC, the reaction undergoes path c: the ground state PC reaches an excited state (PC*) under irradiation with blue LED, which is subsequently quenched by cobalt (II) Int-1 in a reductive process via a SET pathway and forms PC•-. The oxidation of

Based on the mechanistic studies and related literature, a plausible mechanism was proposed (Figure 3). Firstly, cobalt(II) salt coordinates with L4 and substrate 1 to generate the cobalt(II) intermediate Int-1, which is oxidized to the cobalt(III) Int-2 by oxygen in the air. Notably, this process may need to be facilitated by direct photoexcitation and photoredox catalysis, considering the different electrical properties and steric hindrances of the substrates. Subsequently, carboxylate-assisted C–H activation led to the five-membered cobaltacycle intermediate Int-3, which undergoes ligand exchange with alkynes 2 to give the intermediate Int-4. Then, the migratory insertion of C–Co(III) bond of alkynes 2 affords the seven-membered cobaltacycle intermediate Int-5. Finally, the reductive elimination of Int-5 leads to chiral product 3, releasing the cobalt(I) intermediate Int-6, which could be easily re-oxidized to the cobalt(II) intermediate Int-1 under aerobic conditions.

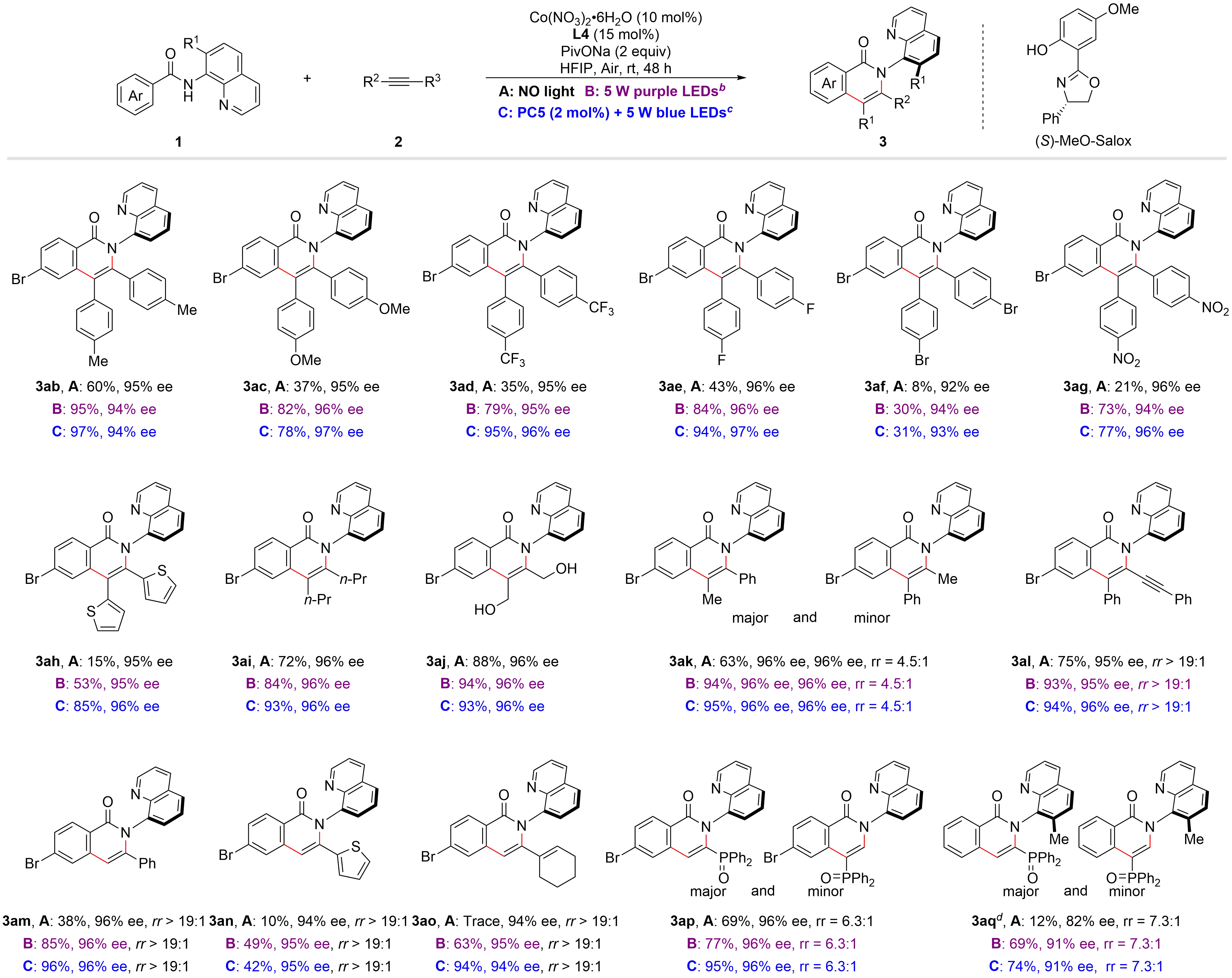

After determining the optimal reaction conditions and plausible mechanism, we began to investigate the substrate scope of this asymmetric oxidative [4+2] cycloaddition under three different reaction conditions (Figure 4). Electron-donating substituted diarylacetylenes (3ab, 3ac) gave the desired products with reduced yields under the conditions without both PC5 and light, and the irradiation with a 5 W purple LEDs was necessary in order to ensure a good yield. Electron-withdrawing substituted diarylacetylenes

Figure 4. The scope of alkynes. a: 1 (0.2 mmol), 2 (0.3 mmol), Co(NO3)2•H2O (10 mol%), L4 (15 mol%), PivONa (2 equiv) in HFIP (2 mL) under air at rt for 48 h, isolated yields;

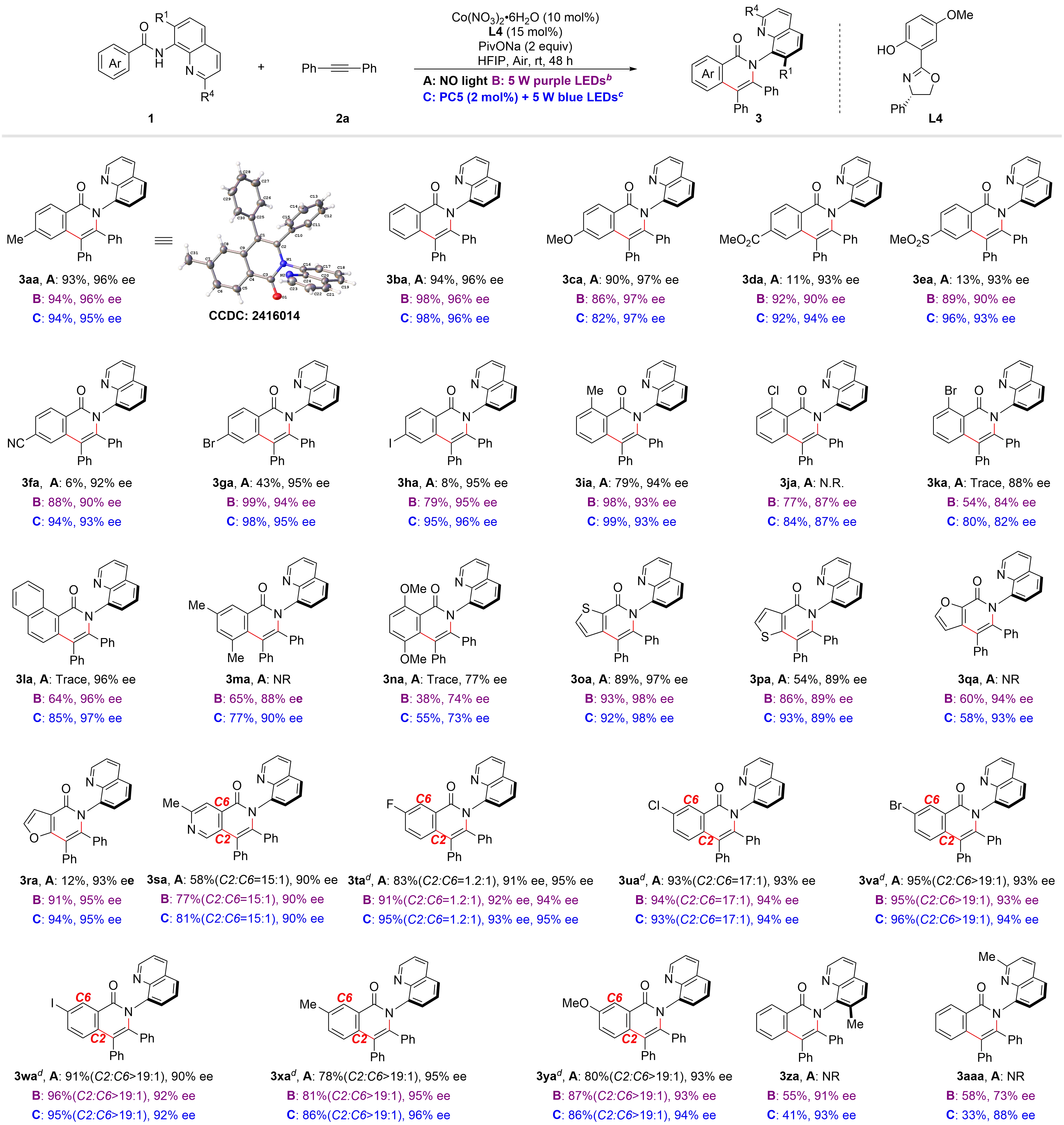

We next turned our attention to determining the scope of arylamides that are amenable to asymmetric cyclization reaction under the three sets of conditions (Figure 5). A range of amide groups containing electron-neutral or -rich substituents at the para-position, such as Me, H, OMe, could be employed as suitable substrates, and the corresponding products (3aa-3ca) were all produced in good to excellent yields (82-98%) with high enantioselectivity (96-97% ee) under the three sets of conditions. However, the analogous reaction with electron-deficient substituents at the para-position, such as CO2Me (3da), SO2Me (3ea), CN (3fa), Br (3ga), and I (3ia), was less effective under the conditions without both PC5 and light, and irradiation with a 5 W purple LEDs was needed to ensure good yields. Ortho-substituted Br, Cl, 1-naphthyl, and 3,5-/2,4-di-substituted (3ja-3na) benzamide derivatives did not react or had only trace yields without both PC5 and light. Again, the yield can be increased by irradiation with a 5 W purple LED, and the replacement of a 5 W blue LEDs and PC5 led to better results. Remarkably, 2-thienylamide (3oa) and the introduction of an electron-rich group (Me, 3ia) at the 2-position of the benzamide are well tolerated under the three sets of conditions. Heterocyclic amides, including 3-thienyl (3pa), 2-furanyl (3qa), 3-furanyl (3ra), and ortho-substituted pyridine (3sa) were subsequently reacted, with inferior results obtained without both PC5 and light, but irradiation with a 5 W purple LEDs often resulted in significantly enhanced yields. Benzamides bearing electron-deficient (F, Cl, Br, I), or electron-rich (Me, OMe) substituents in the meta-position reacted efficiently with 2a to give the corresponding product 3ta−3ya in good to excellent yields (78-96% yield) and high enantioselectivity (90-96% ee) under the three sets of conditions. The regioselectivity (C2 or C6) was entirely determined by the size of the steric hindrance of the substituent group. The steric hindrance may weaken the coordination between N-atom and the cobalt center and reduce the electron density of the low-valent cobalt intermediate. Additionally, the 2-position (3za) or 7-position(3aaa) methyl substitution on quinoline also leads to a decrease in enantioselectivity. The absolute stereochemistry of 3aa was established by X-ray diffraction (CCDC: 2416014).

Figure 5. The scope of arylamides. a: 1 (0.2 mmol), 2 (0.3 mmol), Co(NO3)2·H2O (10 mol%), L4 (15 mol%), PivONa (2 equiv) in HFIP (2 mL) under air at rt for 48 h, isolated yields; b: under 5 W purple LED; c: Using PC5 (2 mol%), 5 W blue LED; d: 36 h. LED: light-emitting diode; HFIP: 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol.

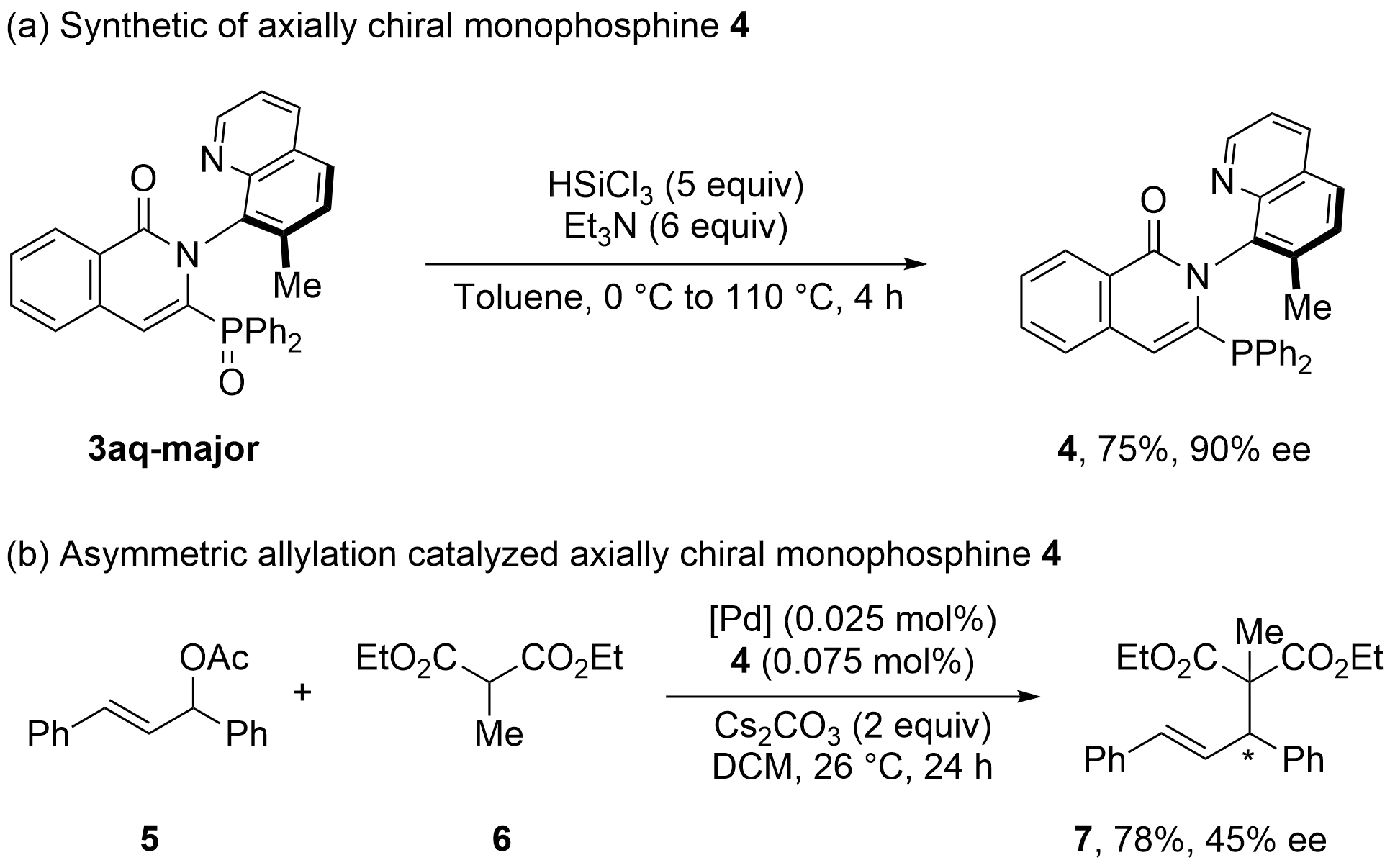

Product 3aq-major could be smoothly transformed to C–N axially chiral monophosphine compound 4 with high enantioselectivity by using HSiCl3 (Figure 6a). Notably, the compound 4 could act as a potential chiral ligand for the palladium-catalyzed asymmetric

4. Conclusion

In summary, we have developed a Co-catalyzed asymmetric aerobic oxidative C(sp2)–H bond activation/[4+2] cycloaddition. The reactions proceed under room temperature with air as an oxidant, and provided an efficient and highly enantioselective method for the assembly of axially chiral isoquinolinones. Light irradiation can increase the yield of lowly active substrates by activating oxygen. Preliminary experiments indicate that this axially chiral skeleton is a promising chiral ligand for Pd-catalyzed asymmetric reactions. Substrate studies and mechanistic experiments reveal a correlation between substrate activity and its substituent electrical properties and steric hindrance. We believe that this work provides an unprecedentedly mild and sustainable new strategy for transition metal catalyzed asymmetric aerobic oxidation.

Supplementary materials

The supplementary material for this article is available at: Supplementary materials.

Acknowledgement

We thank Prof. Jia-Rong Chen, Prof. Zhihan Zhang, and many other group members for helpful discussions.

Authors contributions

Wang LN: Investigation, writing-original draft.

Fu YLT: Writing-review & editing.

Liao CY: Investigation, Resources.

Xiao WJ: Methodology, writing-review & editing.

Lu LQ: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Data availability statement

The data supporting this article have been included as part of the Supplementary Information. Crystallographic data for (3aa, [Co]-1) has been deposited at under (2416014, 2489953) and can be obtained from [URL of data record, format https://doi.org/DOI].

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 92256301, 22471089, and 22271113), and the National Key R & D Program of China (Grant Nos. 2023YFA1507203 and 2024YFA1509700).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Zhang G, Bian C, Lei A. Advances in visible-light-mediated oxidative coupling reactions. Chin J Catal. 2015;36(9):1428-1439.[DOI]

-

2. Cannalire R, Pelliccia S, Sancineto L, Novellino E, Tron GC, Giustiniano M. Visible light photocatalysis in the late-stage functionalization of pharmaceutically relevant compounds. Chem Soc Rev. 2021;50(2):766-897.[DOI]

-

3. Yang Y, Lan J, You J. Oxidative C–H/C–H coupling reactions between two (hetero)arenes. Chem Rev. 2017;117(13):8787-8863.[DOI]

-

4. Rogge T, Kaplaneris N, Chatani N, Kim J, Chang S, Punji B, et al. C–H activation. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2021;1:43.[DOI]

-

5. Shi Z, Zhang C, Tang C, Jiao N. Recent advances in transition-metal catalyzed reactions using molecular oxygen as the oxidant. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41(8):3381-3430.[DOI]

-

6. Bryliakov KP. Catalytic asymmetric oxygenations with the environmentally benign oxidants H2O2 and O2. Chem Rev. 2017;117(17):11406-11459.[DOI]

-

7. Kananovich D, Elek GZ, Lopp M, Borovkov V. Aerobic oxidations in asymmetric synthesis: Catalytic strategies and recent developments. Front Chem. 2021;9:614944.[DOI]

-

8. Chen G, Shao P, Niu X, Wu LZ, Zhang T. Innovative and sustainable approaches to aerobic oxidation reactions for organics upgrading. CCS Chem. 2025;7(5):1272-1288.[DOI]

-

9. Sun X, Li X, Song S, Zhu Y, Liang YF, Jiao N. Mn-catalyzed highly efficient aerobic oxidative hydroxyazidation of olefins: A direct approach to β-azido alcohols. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(18):6059-6066.[DOI]

-

10. Yu Y, Xia Z, Wu Q, Liu D, Yu L, Xiao Y, et al. Direct synthesis of benzoxazinones via Cp*Co(III)-catalyzed C–H activation and annulation of sulfoxonium ylides with dioxazolones. Chin Chem Lett. 2021;32(3):1263-1266.[DOI]

-

11. Uchida T, Katsuki T. Green asymmetric oxidation using air as oxidant. J Synth Org Chem Jpn. 2013;71(11):1126-1135.[DOI]

-

12. Goicoechea L, Losada P, Mascareñas JL, Gulías M. Palladium-catalyzed enantioselective C–H arylations and alkenylations of 2-aminobiaryls with atmospheric air as the sole oxidant. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2025;64(20):e202425512.[DOI]

-

13. Ikariya T, Kuwata S, Kayaki Y. Aerobic oxidation with bifunctional molecular catalysts. Pure Appl Chem. 2010;82(7):1471-1483.[DOI]

-

14. Koya S, Nishioka Y, Mizoguchi H, Uchida T, Katsuki T. Asymmetric epoxidation of conjugated olefins with dioxygen. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51(33):8243-8246.[DOI]

-

15. Mizoguchi H, Uchida T, Katsuki T. Ruthenium-catalyzed oxidative kinetic resolution of unactivated and activated secondary alcohols with air as the hydrogen acceptor at room temperature. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53(12):3178-3182.[DOI]

-

16. Maji B, Yamamoto H. Asymmetric synthesis of tertiary α-hydroxy phosphonic acid derivatives under aerobic oxidation conditions. Synlett. 2015;26(11):1528-1532.[DOI]

-

17. Verdhi LK, Fridman N, Szpilman AM. Copper- and chiral nitroxide-catalyzed oxidative kinetic resolution of axially chiral N-arylpyrroles. Org Lett. 2022;24(28):5078-5083.[DOI]

-

18. Newton CG, Wang SG, Oliveira CC, Cramer N. Catalytic enantioselective transformations involving C–H bond cleavage by transition-metal complexes. Chem Rev. 2017;117(13):8908-8976.[DOI]

-

19. Achar TK, Maiti S, Jana S, Maiti D. Transition-metal-catalyzed enantioselective C(sp2)–H bond functionalization. ACS Catal. 2020;10(23):13748-13793.[DOI]

-

20. Wang Q, Liu CX, Gu Q, You SL. Chiral CpxRh complexes for C–H functionalization reactions. Sci Bull. 2021;66(3):210-213.[DOI]

-

21. Yoshikai N. Cobalt-catalyzed asymmetric C–H functionalization. In: Maiti D, editor. Handbook of C–H Functionalization. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2022. p. 1-19.[DOI]

-

22. Gao K, Yoshikai N. Low-valent cobalt catalysis: New opportunities for C–H functionalization. Acc Chem Res. 2014;47(4):1208-1219.[DOI]

-

23. Moselage M, Li J, Ackermann L. Cobalt-catalyzed C–H activation. ACS Catal. 2016;6(2):498-525.[DOI]

-

24. Zheng Y, Zheng C, Gu Q, You SL. Enantioselective C–H functionalization reactions enabled by cobalt catalysis. Chem Catal. 2022;2(11):2965-2985.[DOI]

-

25. Yang J, Yoshikai N. Cobalt-catalyzed enantioselective intramolecular hydroacylation of ketones and olefins. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136(48):16748-16751.[DOI]

-

26. Whyte A, Torelli A, Mirabi B, Prieto L, Rodríguez JF, Lautens M. Cobalt-catalyzed enantioselective hydroarylation of 1,6-enynes. J Am Chem Soc. 2020;142(20):9510-9517.[DOI]

-

27. Ghosh KK, RajanBabu TV. Ligand effects in carboxylic ester- and aldehyde-assisted β-C–H activation in regiodivergent and enantioselective cycloisomerization–hydroalkenylation and cycloisomerization–hydroarylation, and [2+2+2]-cycloadditions of 1,6-enynes. J Am Chem Soc. 2024;146(27):18753-18770.[DOI]

-

28. Pesciaioli F, Dhawa U, Oliveira JCA, Yin R, John M, Ackermann L. Enantioselective cobalt(III)-catalyzed C–H activation enabled by chiral carboxylic acid cooperation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2018;57(47):15425-15429.[DOI]

-

29. Fukagawa S, Kato Y, Tanaka R, Kojima M, Yoshino T, Matsunaga S. Enantioselective C(sp3)–H amidation of thioamides catalyzed by a cobalt(III)/chiral carboxylic acid hybrid system. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58(4):1153-1157.[DOI]

-

30. Liu YH, Xie PP, Liu L, Fan J, Zhang ZZ, Hong X, et al. Cp*Co(III)-catalyzed enantioselective hydroarylation of unactivated terminal alkenes via C–H activation. J Am Chem Soc. 2021;143(45):19112-19120.[DOI]

-

31. Ozols K, Jang YS, Cramer N. Chiral cyclopentadienyl cobalt(III) complexes enable highly enantioselective 3d-metal-catalyzed C–H functionalizations. J Am Chem Soc. 2019;141(14):5675-5680.[DOI]

-

32. Ozols K, Onodera S, Woźniak Ł, Cramer N. Cobalt(III)-catalyzed enantioselective intermolecular carboamination by C–H functionalization. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2021;60(2):655-659.[DOI]

-

33. Jacob N, Zaid Y, Oliveira JCA, Ackermann L, Wencel-Delord J. Cobalt-catalyzed enantioselective C–H arylation of indoles. J Am Chem Soc. 2022;144(2):798-806.[DOI]

-

34. Bolm C, Weickhardt K, Zehnder M, Ranff T. Synthesis of optically active bis(2-oxazolines): crystal structure of a 1,2-bis(2-oxazolinyl)benzene·ZnCl₂ complex. Chem Ber. 1991;124(5):1173-1180.[DOI]

-

35. Garai B, Das A, Vineet Kumar D, Sundararaju B. Enantioselective C–H bond functionalization under Co(III)-catalysis. Chem Commun. 2024;60:3354-3369.[DOI]

-

36. Yao QJ, Shi BF. Cobalt(III)-catalyzed enantioselective C–H functionalization: ligand innovation and reaction development. Acc Chem Res. 2025;58(6):971-990.[DOI]

-

37. Yang T, Zhang Y, Dou Y, Yang D, Niu JL. Earth-abundant cobalt-catalyzed enantioselective C–H functionalizations. Sci China Chem. 2025.[DOI]

-

38. Yao QJ, Chen JH, Song H, Huang FR, Shi BF. Cobalt/Salox-catalyzed enantioselective C–H functionalization of arylphosphinamides. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2022;61(25):e202202892.[DOI]

-

39. von Münchow T, Dana S, Xu Y, Yuan B, Ackermann L. Enantioselective electrochemical cobalt-catalyzed aryl C–H activation reactions. Science. 2023;379:1036-1042.[DOI]

-

40. Wu X, Tian Q, Ge J, Liu Y, Li Z, Zhang J, et al. Cobalt-catalyzed regio-, diastereo-, and enantioselective C–H annulation of aminoquinoline amides with internal alkynes for the construction of diaxes. Chin J Chem. 2025;43(20):2669-2676.[DOI]

-

41. Si XJ, Yang D, Sun MC, Wei D, Song MP, Niu JL. Atroposelective isoquinolinone synthesis through cobalt-catalysed C–H activation and annulation. Nat Synth. 2022;1(9):709-718.[DOI]

-

42. Teng MY, Liu DY, Mao SY, Wu X, Chen JH, Zhong MY, et al. Asymmetric dearomatization of indoles through cobalt-catalyzed enantioselective C–H functionalization enabled by photocatalysis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2024;63(40):e202407640.[DOI]

-

43. Qian PF, Zhou G, Hu JH, Wang BJ, Jiang AL, Zhou T, et al. Asymmetric synthesis of chiral calix[4]arenes with both inherent and axial chirality via cobalt-catalyzed enantioselective intermolecular C–H annulation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2024;63(52):e202412459.[DOI]

-

44. Xu Y, Lin Y, Homölle SL, Oliveira JCA, Ackermann L. Enantioselective cobaltaphotoredox-catalyzed C–H activation. J Am Chem Soc. 2024;146(34):24105-24113.[DOI]

-

45. Xu Y, Pandit NK, Meraviglia S, Boos P, Stark PAM, Surke M, et al. Stereocontrolled construction of multi-chiral [2.2]paracyclophanes via cobaltaphotoredox dual catalysis. ACS Catal. 2025;15(13):11716-11725.[DOI]

-

46. Das A, Kumaran S, Sankar RHS, Premkumar JR, Sundararaju B. A dual cobalt-photoredox catalytic approach for asymmetric dearomatization of indoles with aryl amides via C–H activation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2024;63(40):e202406195.[DOI]

-

47. Koner M, Ballav N, Varma AJ, Ghosh S, Mondal T, Kuniyil R, et al. Multifaceted photocatalysis enables cobalt-catalyzed enantioselective C–H activation and APEX reaction for C–N axially chiral molecules. Chem Sci. 2025;16(41):19296-19303.[DOI]

-

48. Das A, Kumaran S, Maity P, Premkumar JR, Sundararaju B. Cobalt-catalyzed enantioselective and diastereodivergent construction of C–N atropisomers. J Am Chem Soc. 2025;147(30):26226-26237.[DOI]

-

49. Lu FD, Chen J, Jiang X, Chen JR, Lu LQ, Xiao WJ. Recent advances in transition-metal-catalysed asymmetric coupling reactions with light intervention. Chem Soc Rev. 2021;50(22):12808-12843.[DOI]

-

50. Jiang X, Han X, Lu FD, Lu LQ, Zuo Z, Xiao WJ. Stereocontrol strategies in asymmetric organic photochemical synthesis. CCS Chem. 2025;7(6):1567-1602.[DOI]

-

51. Zhang K, Lu LQ, Jia Y, Wang Y, Lu FD, Pan F, et al. Exploration of chiral cobalt catalyst for visible-light-induced enantioselective radical conjugate addition. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2019;58(38):13375-13379.[DOI]

-

52. Jiang X, Xiong W, Deng S, Lu FD, Jia Y, Yang Q, et al. Construction of axial chirality via asymmetric radical trapping by cobalt under visible light. Nat Catal. 2022;5(9):788-797.[DOI]

-

53. He XK, Lu LQ, Yuan BR, Luo JL, Cheng Y, Xiao WJ. Desymmetrization–addition reaction of cyclopropenes to imines via synergistic photoredox and cobalt catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2024;146(28):18892-18898.[DOI]

-

54. Rosenthal I, Krishna CM, Yang GC, Kondo T, Riesz P. A new approach for EPR detection of hydroxyl radicals by reaction with sterically hindered cyclic amines and oxygen. FEBS Lett. 1987;222(1):75-78.[DOI]

-

55. Wandt J, Jakes P, Granwehr J, Gasteiger HA, Eichel RA. Singlet oxygen formation during the charging process of an aprotic lithium–oxygen battery. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;128(24):7006-7009.[DOI]

-

56. Winternheimer DJ, Merlic CA. Alkoxydienes via copper-promoted couplings: Utilizing an alkyne effect. Org Lett. 2010;12(11):2508-2510.[DOI]

-

57. Nishida M, Fujii S, Aoki T, Hayakawa Y, Muramatsu H, Morita T. Synthesis and polymerization of ethynylthiophenes and ethynylfurans containing trifluoromethyl groups. J Fluorine Chem. 1990;46(3):445-459.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite