Jie Ke, Shenzhen Grubbs Institute and Department of Chemistry, Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Small Molecule Drug Discovery and Synthesis, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Catalysis, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen 518055, Guangdong, China. E-mail: kej@mail.sustech.edu.cn

Abstract

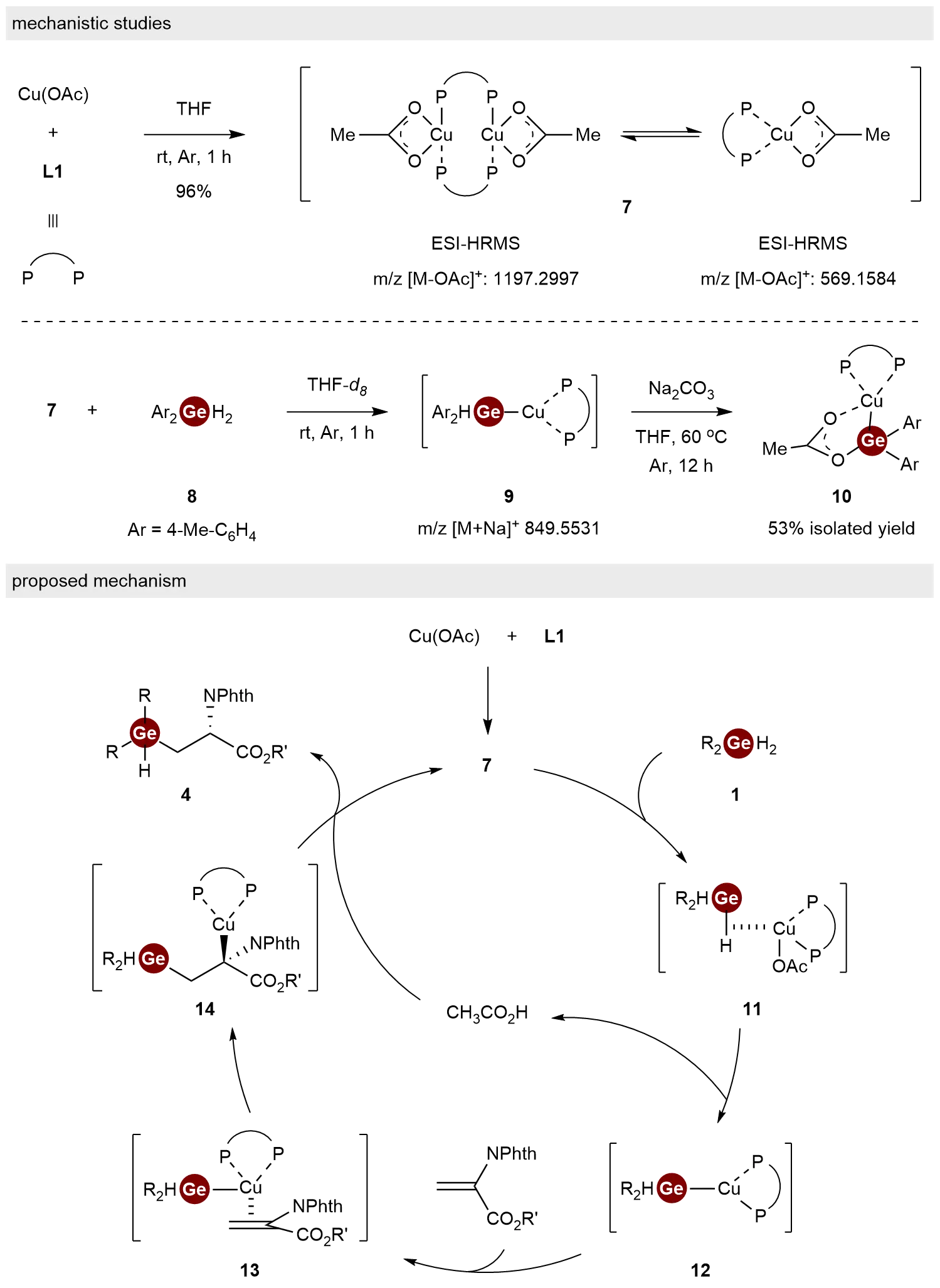

Chiral organogermanes hold great potential as bioisosteres in medicinal chemistry and functional materials, yet their development has long been hindered by a scarcity of efficient synthetic strategies. This review offers a comprehensive overview of recent advances in the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of chiral organogermanes, highlighting a shift from traditional resolution methods toward asymmetric catalytic approaches. The content is organized into three main categories: (i) synthesis of C-stereogenic germanes, (ii) synthesis of Ge-stereogenic germanes, and (iii) synthesis of other chiral germanes, including planar, inherent, and axially chiral types. Key synthetic methodologies are systematically examined, such as enantioselective alkene hydrofunctionalization, carbene insertion, coupling reactions, and [2+2+2] cycloaddition, utilizing a variety of catalytic systems ranging from transition metals (Rh, Cu, Ni, Co) and Lewis acids to engineered metalloenzymes. Particular emphasis is placed on the mechanistic insights and ligand design principles that enable stereochemical control in these transformations. We hope this review will inspire chemists working in related areas and contribute to the future advancement of this field.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

1. Introduction

Chiral molecules play a significant role in the areas of pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and functional materials. While asymmetric synthetic methodologies for carbon stereogenic centers have matured, the catalytic, enantioselective creation of architectures centered on heavier Group 14 elements, particularly germanium, remains an underexplored frontier. Germanium possesses unique physical and chemical attributes, including a larger atomic radius (122 pm) and lower electronegativity (χp = 2.01) compared to carbon, coupled with enhanced stability and lipophilicity relative to silicon. These attributes make organogermanes promising candidates as bioisosteres of carbon and silicon in biological studies[1-3] and as functional components in materials science[4-7]. Despite many studies on organo-germanium compounds in recent years[8-10], the known methods toward optically active organogermanes remain limited[11].

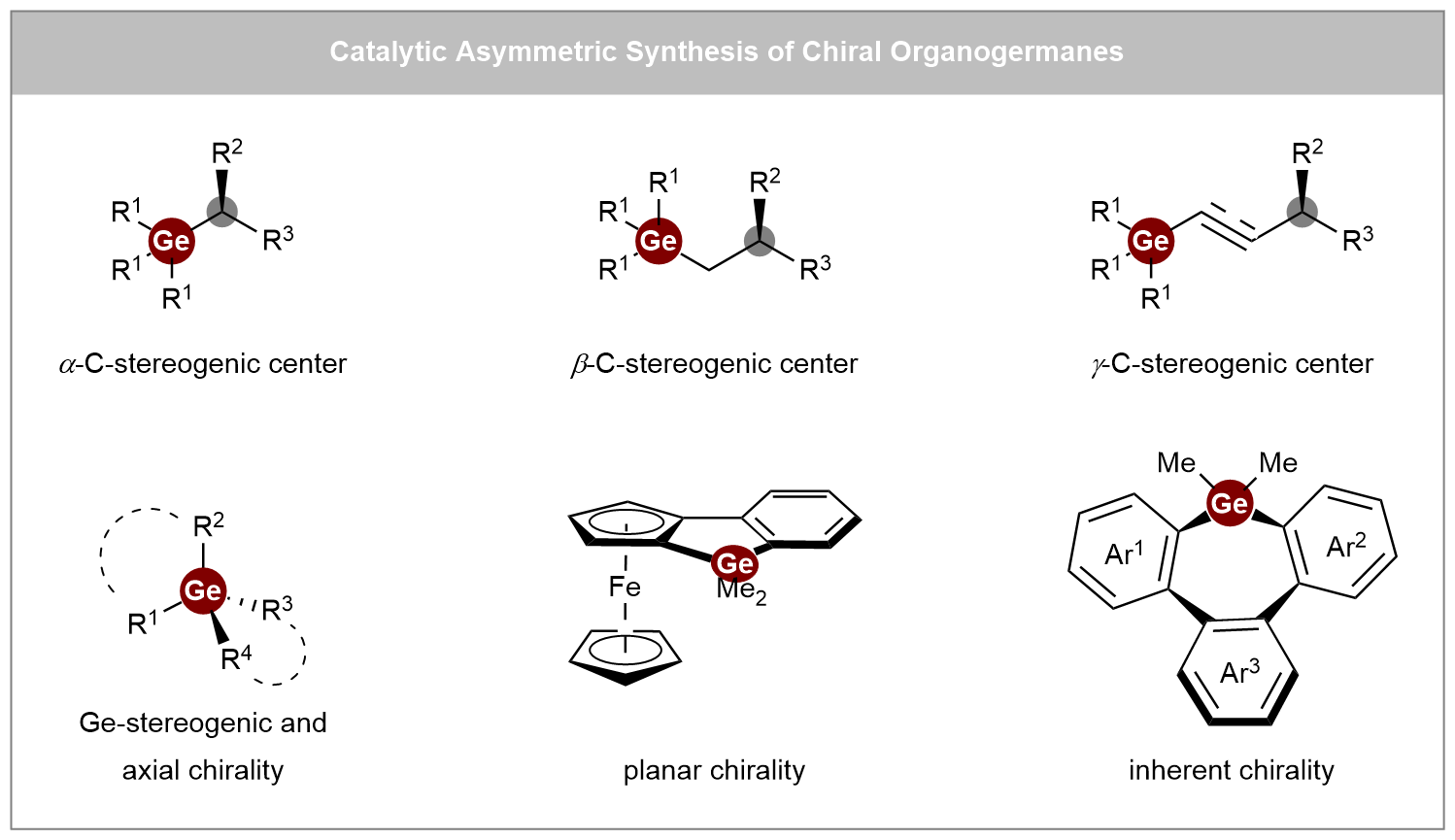

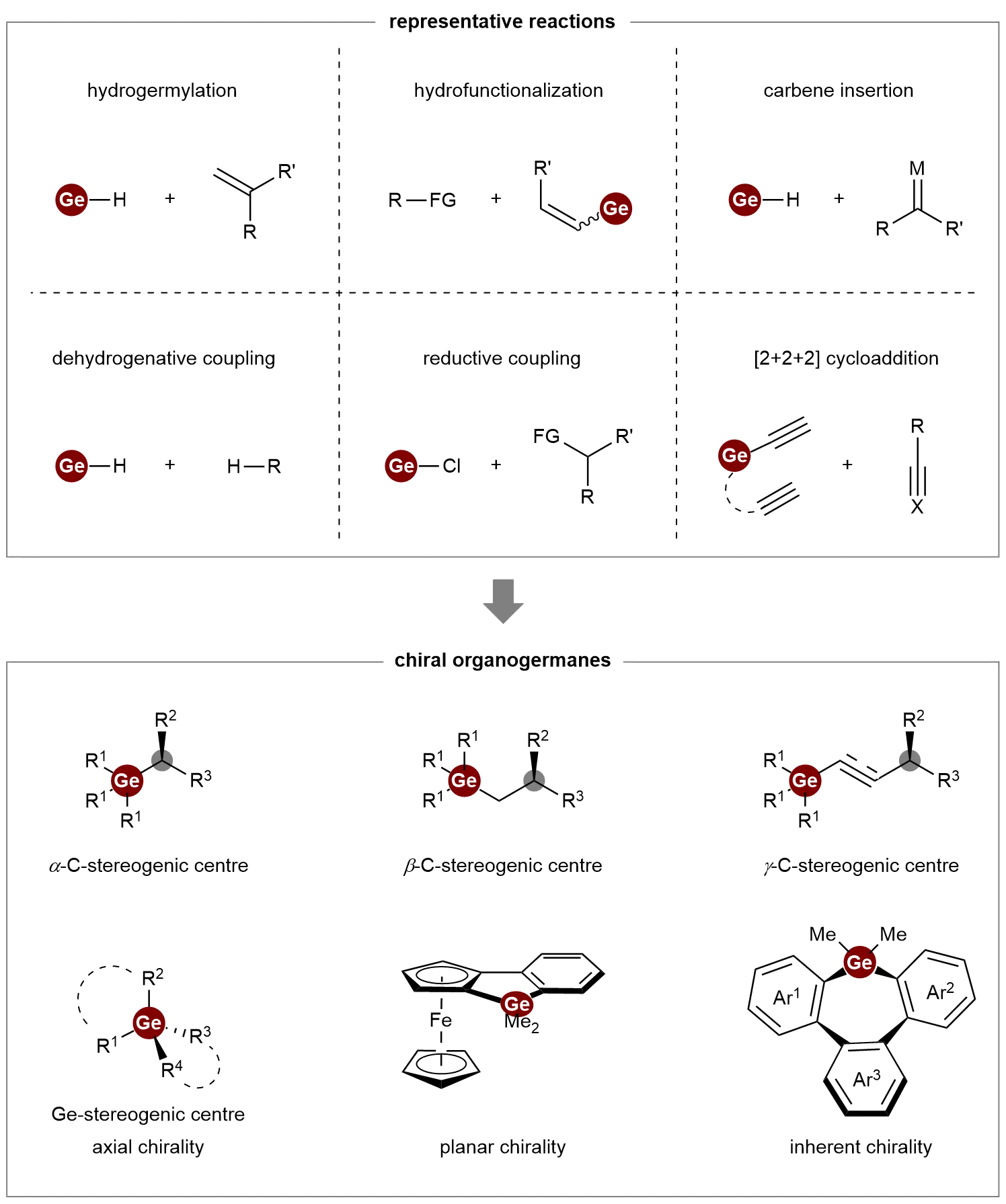

Traditional access to enantiopure organogermanes relied on resolution techniques or stoichiometric chiral auxiliaries, approaches that are inefficient and limited in scope[12,13]. Recent years have witnessed a transformative shift with the emergence of catalytic strategies. Notable advances include transition-metal-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogermylation of alkenes, hydrofunctionalization of vinylgermanes, carbene insertion into Ge–H bonds, dehydrogenative and reductive couplings, and [2+2+2] cycloadditions, all of which collectively enable efficient construction of chiral organogermanes. These catalytic breakthroughs have unlocked access to a full spectrum of chiral germanes, ranging from C- and Ge-stereocentric to planar, inherent, and axially chiral systems (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Representative reactions for the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of chiral organogermanes.

This review provides a comprehensive survey of recent advances in the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of chiral organogermanes, systematically organized into three sections based on the nature of the stereogenic element: (i) synthesis of C-stereogenic germanes, (ii) synthesis of Ge-stereogenic germanes, and (iii) synthesis of other chiral germane types—including planar, inherent, and axially chiral systems. The article concludes with an outlook on persisting challenges and promising future directions, offering perspectives on potential trends in this rapidly evolving research field.

2. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of C-Stereogenic Germanes

The catalytic asymmetric synthesis of chiral organogermanes has to date primarily focused on the stereocontrol at carbon centers. To provide a clear and systematic overview of this progress, the following sections are organized according to key reaction types: alkene hydrofunctionalization, carbene insertion, and coupling reactions.

2.1 Alkene hydrofunctionalization

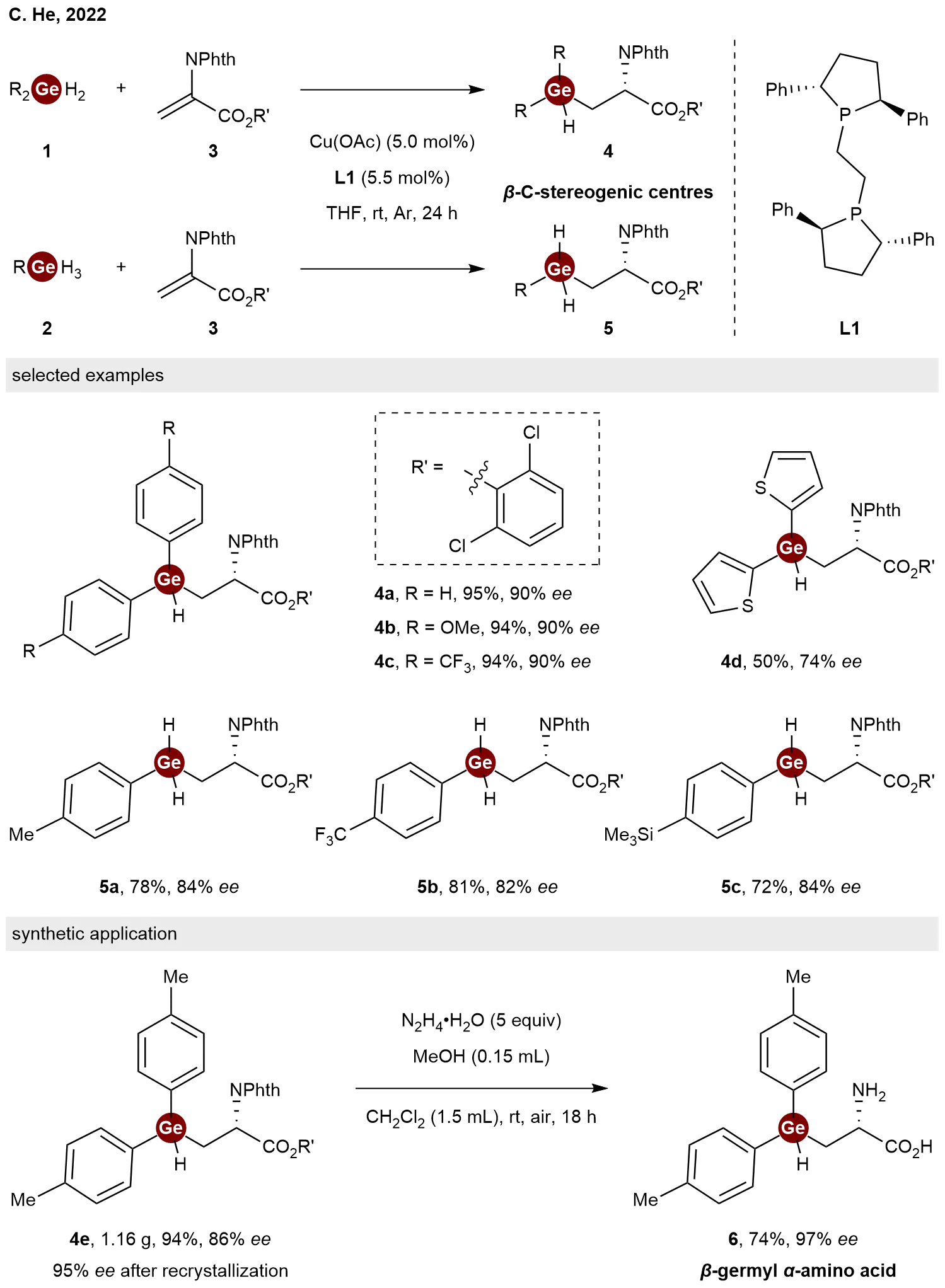

Hydrogermylation of alkenes represents one of the most straightforward and atom-economic approaches for the construction of organogermanium compounds[14]. Despite considerable progress in hydrogermylation methodologies over the past decades, achieving an enantioselective variant has remained a formidable challenge. In 2022, He and co-workers achieved a breakthrough by reporting a copper-catalyzed enantioselective intermolecular hydrogermylation of dehydroalanines 3 with dihydrogermanes 1 and trihydrogermanes 2[15]. By employing a catalytic system consisting of Cu(OAc) and the chiral bisphosphine ligand (S,S)-Ph-BPE L1, this process gave access to a variety of chiral β-germyl α-amino acid derivatives 4 and 5 in decent yields with good to excellent enantioselectivities (Scheme 2). This work represents the first example of a catalytic enantioselective hydrogermylation of alkenes. To underscore the synthetic utility of the method, the authors demonstrated that hydrazine mediated deprotection of product 4e yielded the fully deprotected β-germyl α-amino acid 6 without erosion of enantiopurity, highlighting the robustness of the stereocenter under the reaction conditions.

Scheme 2. Copper-catalyzed enantioselective hydrogermylation of dehydroalanines with dihydrogermanes and trihydrogermanes.

To investigate the reaction mechanism of this hydrogermylation process, a series of experimental studies were conducted (Scheme 3). Initially, the stoichiometric reaction of Cu(OAc) with L1 yielded complex 7 in 96% isolated yield. Analysis by 1H NMR, 31P NMR, X-ray crystallography, and ESI-HRMS revealed that there were two components (dimer and monomer) in complex 7. Subsequent ESI-HRMS monitoring of the reaction between complex 7 and dihydrogermane 8 indicated the formation of a [Cu–Ge] species 9, which was subsequently trapped and structurally characterized by X-ray crystallography as the stabilized complex 10. Notably, this behavior contrasts with previously reported reactions of Cu complexes with hydrosilanes, which typically lead to the formation of [Cu–H] species[16]. On the basis of these findings, a plausible catalytic cycle was proposed: First, the reaction between Cu(OAc) and L1 generated the active catalytic species complex 7. Then, coordination between dihydrogermanes 1 and complex 7 formed complex 11, followed by the formation of [Cu–Ge] species 12 with the release of CH3CO2H. Next, the coordination and nucleophilic addition of complex 12 to dehydroalanine occurred, producing complexes 13 and 14 subsequently. Finally, the protonation of intermediate 14 by CH3CO2H afforded the desired product 4 and regenerates complex 7, thereby completing the catalytic cycle.

Scheme 3. Mechanistic studies and proposed mechanism for the hydrogermylation of dehydroalanines with dihydrogermanes.

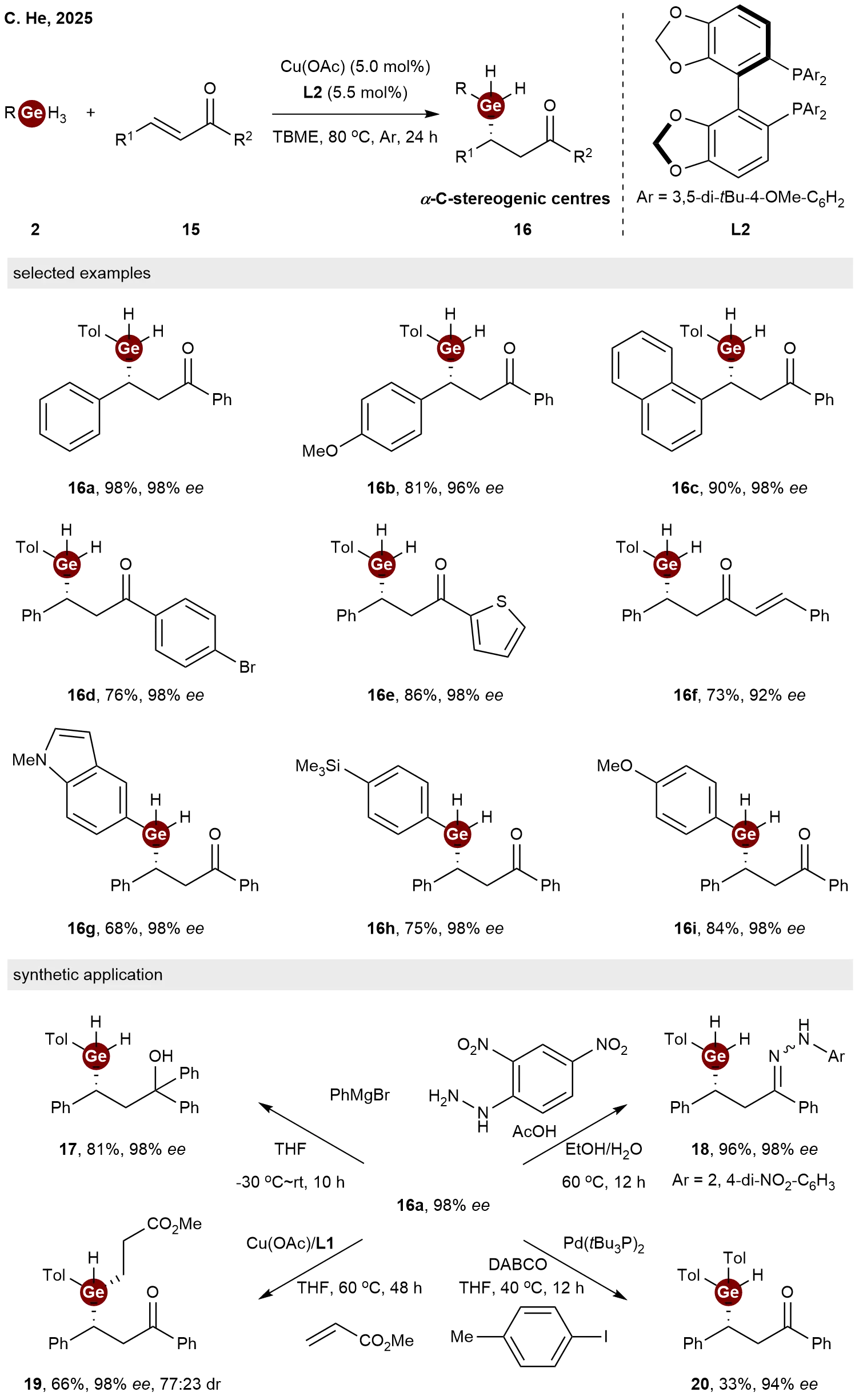

Based on their previous success in the asymmetric hydrogermylation for the synthesis of β-C-stereogenic germanes, in 2025, He and co-workers expanded this strategy to the synthesis of α-C-stereogenic germanes[17]. Utilizing Cu(OAc) as the catalyst and

Scheme 4. Copper-catalyzed enantioselective hydrogermylation of α,β-unsaturated compounds with trihydrogermanes.

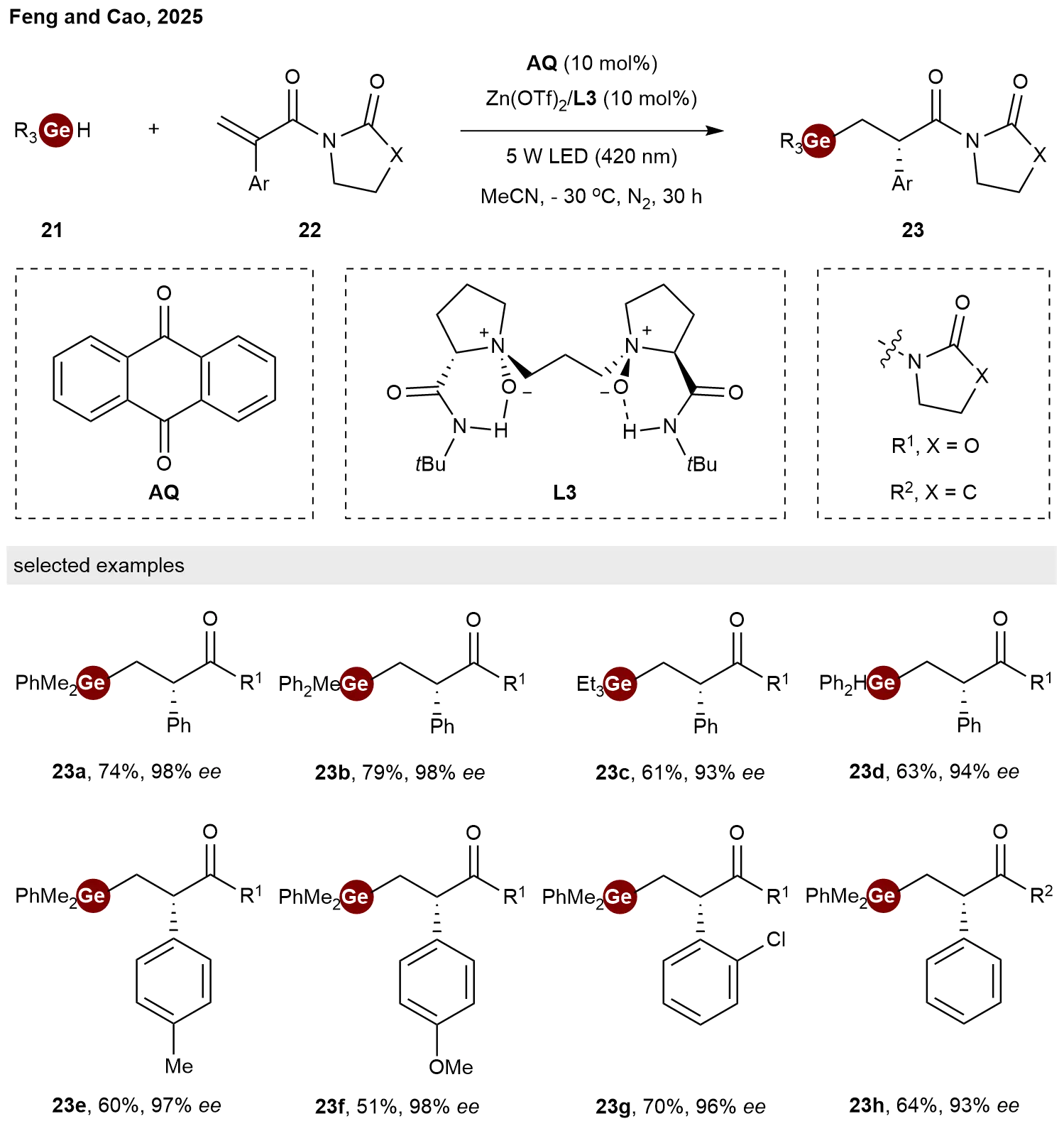

In addition to transition-metal catalysis, chiral Lewis acid catalysis also serves as an effective approach for asymmetric hydrogermylation reactions. Taking advantage of the unique chiral N,N′-dioxide ligand[18], in 2025, Chen and co-workers reported a synergistic catalytic strategy for enantioselective hydrogermylation of α,β-unsaturated amides 22 with germanes 21[19]. This system integrates anthraquinone (AQ) as a dual-functional photocatalyst with a chiral Lewis acid catalyst derived from Zn(OTf)2 and ligand L3. This approach demonstrates broad substrate scope. A variety of chiral organogermanes 23 bearing α-C-stereogenic centers were afforded in high yields with good chemo-, regio and enantioselectivities (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5. Enantioselective hydrogermylation of α,β-unsaturated amides mediated by synergistic HAT photocatalyst and chiral Lewis acid. HAT: hydrogen atom transfer.

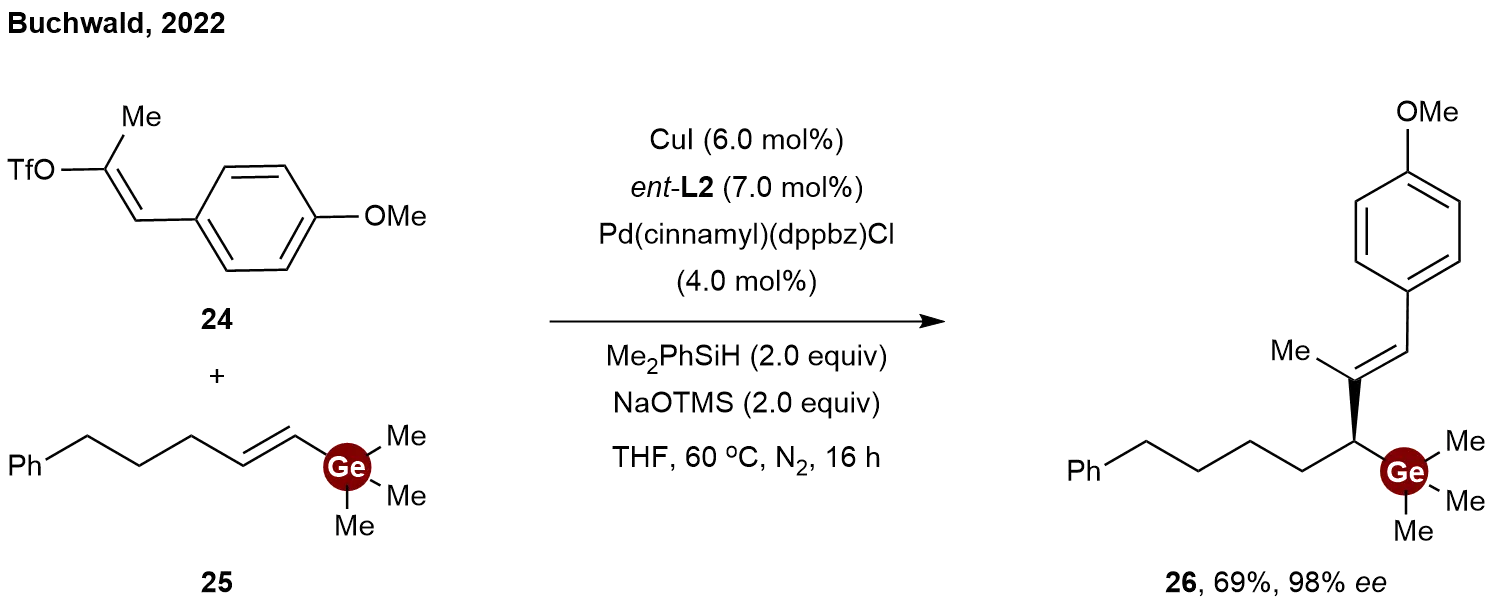

Diverging from the aforementioned hydrogermylation strategies centered on Ge–H bond activation, alternative hydrofunctionalization of vinylgermanes has also been developed. In these transformations, the germanium moiety does not participate in bond cleavage, remaining intact throughout the bond-forming process. In 2022, Buchwald and co-workers disclosed a protocol for the asymmetric synthesis of α-stereogenic allyl metalloids via dual CuH- and Pd-catalyzed hydroalkenylation[20]. Although the study primarily focused on silicon and boron substrates, its applicability was successfully extended to organogermanium chemistry. Under optimized conditions employing CuI/ent-L2 and Pd(cinnamyl)(dppbz)Cl as dual catalysts, the enantioselective hydroalkenylation of vinylgermane 25 with enol triflate 24 afforded the chiral organogermane 26 in 69% yield with 98% ee (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6. Enantioselective hydroalkenylation of vinyl germane with enol sulfonate via dual copper hydride- and palladium-catalysis.

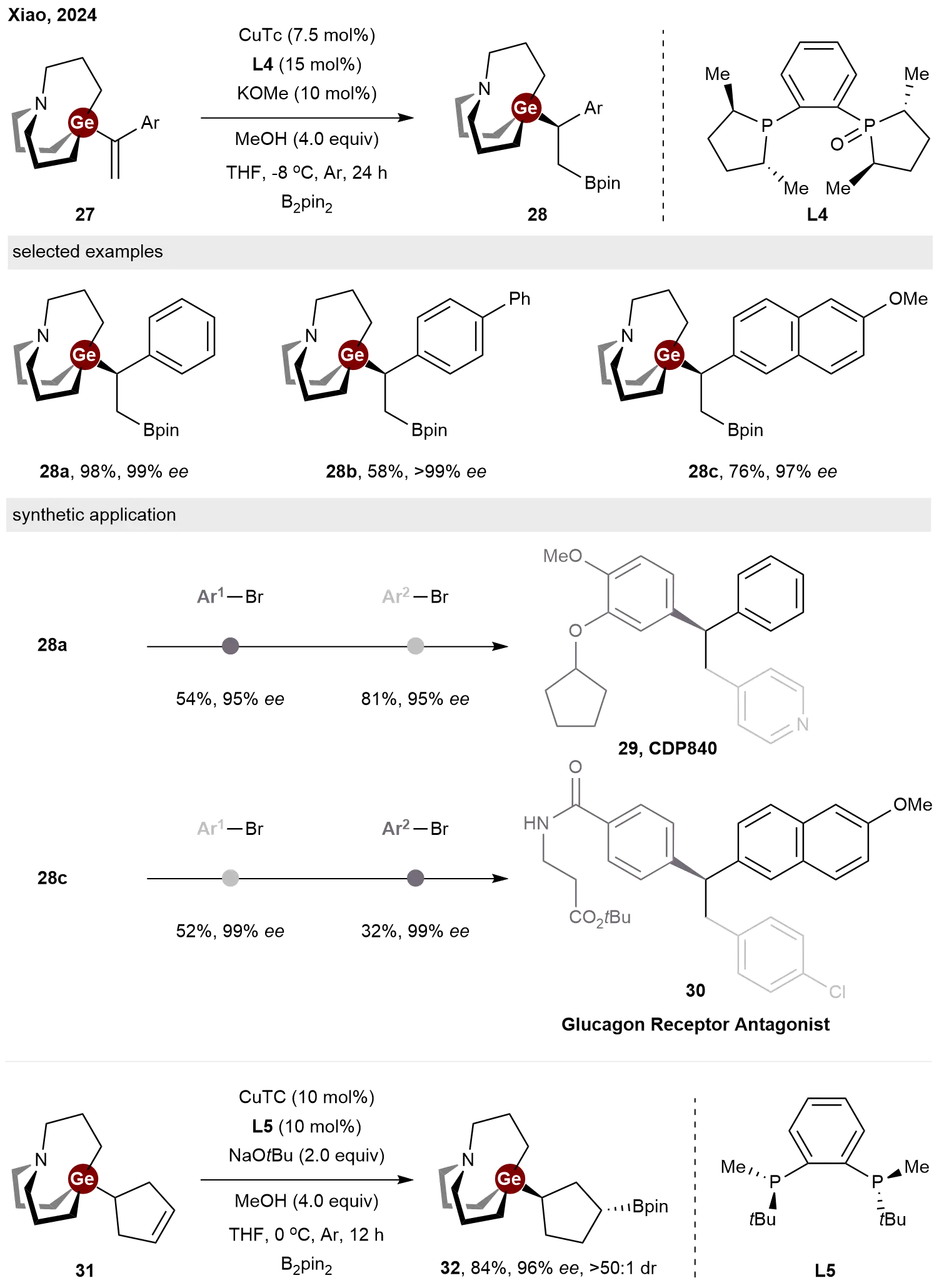

In 2024, Xiao and co-workers reported a copper-catalyzed enantioselective hydroboration of vinylgermanes[21]. In this study, carbagermatrane-containing alkenes 27 underwent hydroboration in the presence of the CuTc/L4 catalyst, yielding target products 28 in moderate to good yields and excellent enantioselectivities (Scheme 7). These sp3-Ge/B bimetallic modules demonstrated remarkable orthogonal cross-coupling selectivity under different Pd-catalyzed conditions. For example, enantioenriched 29 and 30 can be readily prepared via -Ge/-B iterative cross-coupling sequence or -B/-Ge iterative cross-coupling sequence from 28a and 28c. They also expanded this asymmetric hydroborylation strategy to cyclopent-3-ene-1-carbagermatrane 31. This allowed rapid access to highly enantioenriched cyclopentyl-Ge/B module 32, which may serve as a useful building block for the construction of valuable 3D cyclopentyl molecules.

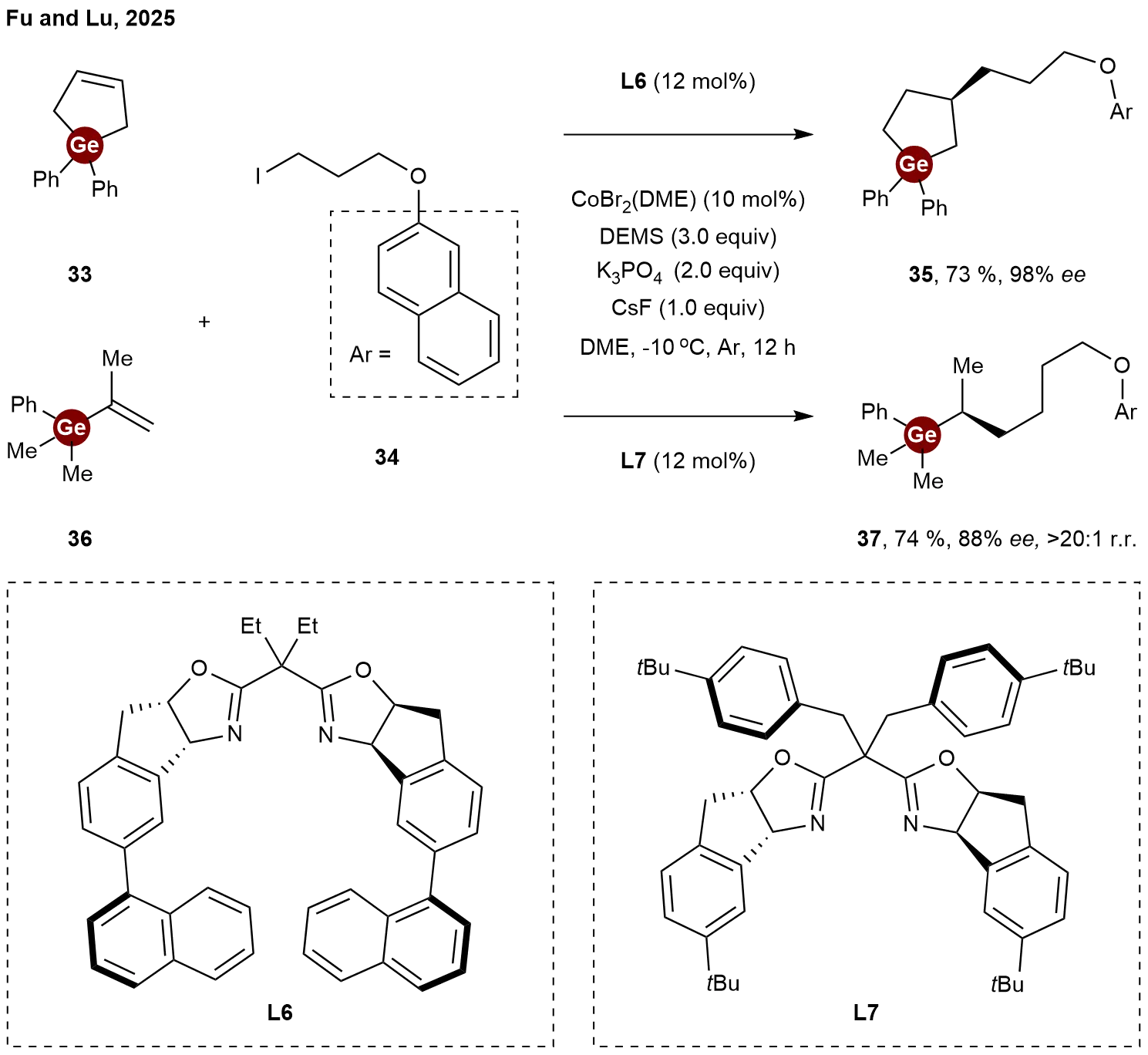

In 2025, Fu and Lu achieved the extension of their well-established cobalt-catalyzed alkene hydroalkylation strategies[22] to the synthesis of chiral organogermanium compounds[23]. They showcased the versatility of their catalytic platform by successfully extending it to germanium-containing alkenes. Employing the chiral bisoxazoline ligand L6, the hydroalkylation of

Scheme 8. Cobalt-catalyzed enantioselective hydroalkylation of germacyclopent-3-enes and vinylgermaniums.

In summary, the catalytic strategies for asymmetric alkene hydrofunctionalization differ in mechanism and scope. For hydrogermylation, the copper-catalyzed system proceeds via a key Cu–Ge intermediate, while the photocatalytic/chiral Lewis acid system likely involves a germyl radical pathway. However, both catalytic systems are currently effective only for electron-deficient alkenes, and extending these methodologies to unactivated alkenes represents an important future direction. On the other hand, for the hydrofunctionalization of vinylgermanes, reported methods have so far been limited to hydroalkenylation, hydroboration, and hydroalkylation. Other potentially valuable transformations such as hydrosilylation and hydroamination remain undeveloped and warrant further investigation.

2.2 Carbene insertion

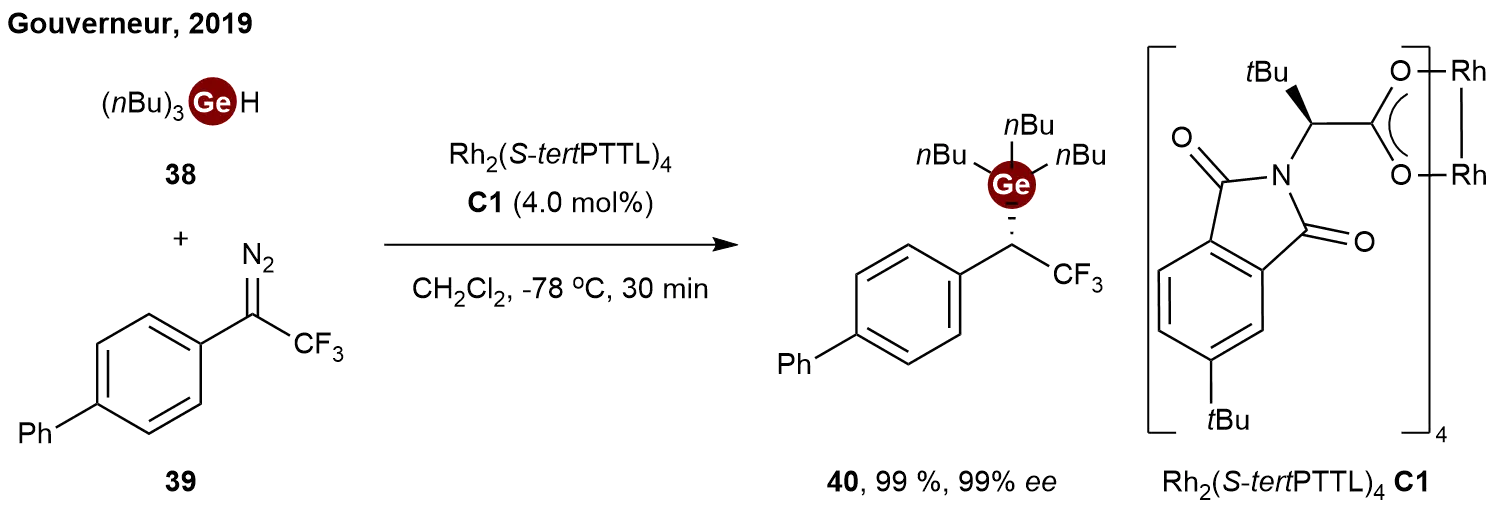

Carbene insertion into heteroatom–hydrogen (X–H) bonds is a powerful method for constructing carbon–heteroatom bonds[24,25]. While asymmetric insertions into Si–H and B–H bonds are well-established[26,27], the corresponding transformation with Ge–H bonds had remained unexplored. To bridge this gap, in 2019, Gouverneur and co-workers disclosed a rhodium-catalyzed asymmetric carbene insertion strategy, primarily focusing on tin hydrides (Sn–H) while successfully extending it to germanium substrates[28]. To access bench-stable chiral α-trifluoromethylated derivatives, the authors employed the sterically demanding dirhodium catalyst C1 to mediate the reaction between aryl-substituted 2,2,2-trifluorodiazoethane 39 and tributylgermane 38. Notably, when conducted at

Scheme 9. Rhodium-catalyzed enantioselective insertion of trifluorodiazoethanes into germanium hydrides.

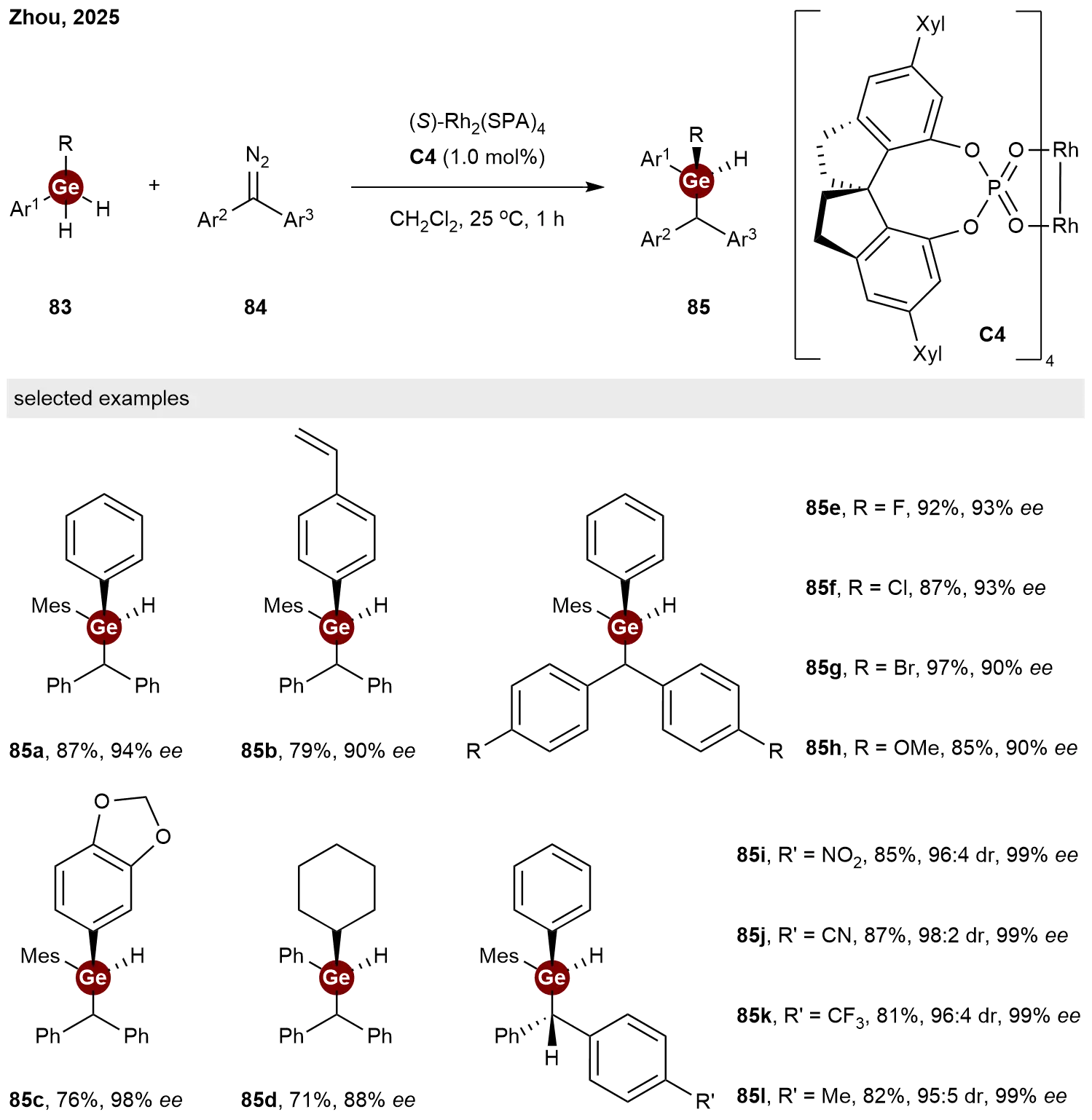

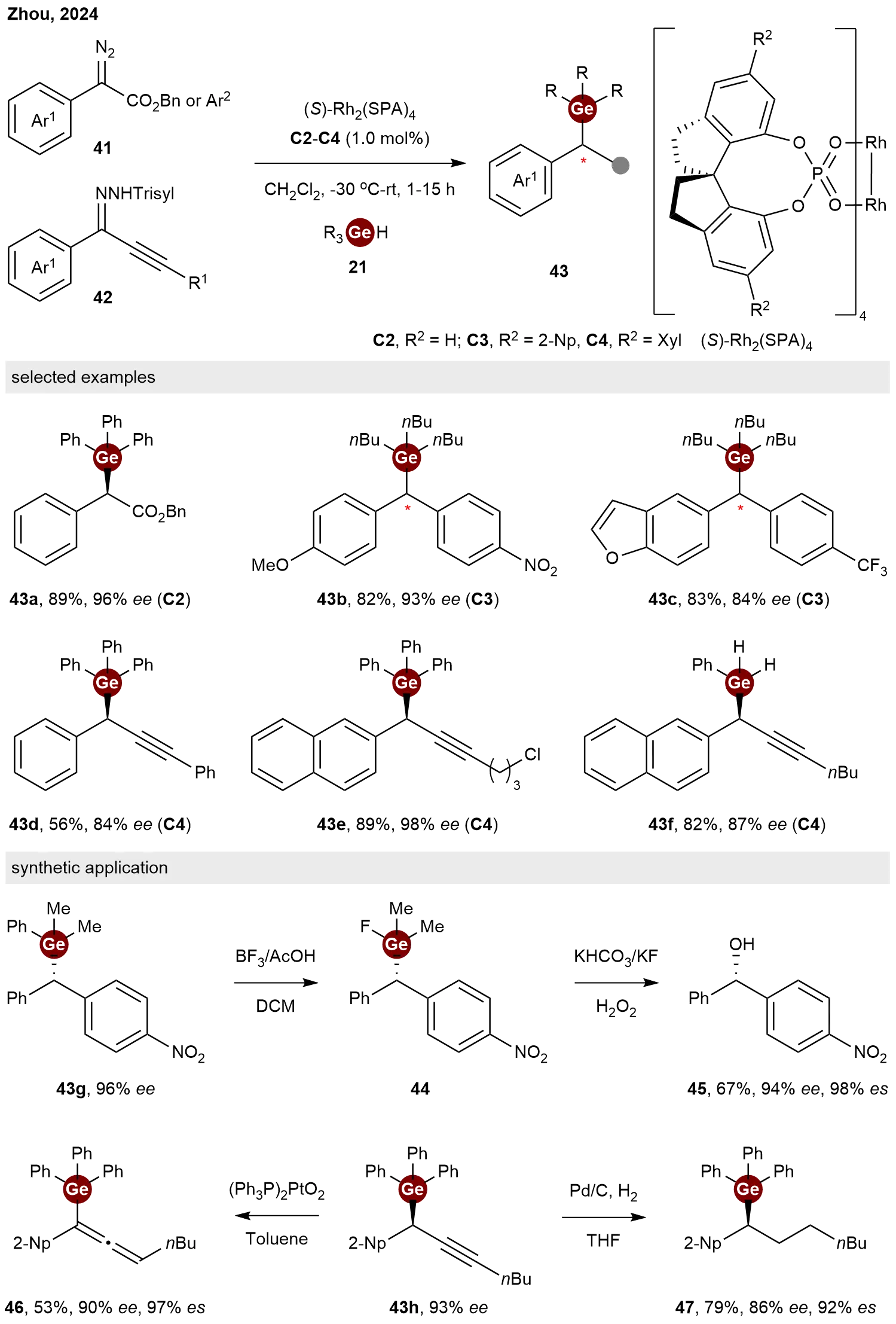

In 2024, Zhou and co-workers established a general and highly enantioselective strategy for carbene insertion into Ge–H bonds[29], leveraging their expertise in asymmetric Si–H and B–H insertions[30-31]. Utilizing the rigid chiral spiro dirhodium phosphate catalysts

Scheme 10. Rhodium-catalyzed enantioselective C–Ge bond formation by carbene insertion.

To elucidate the reaction mechanism, they studied the kinetic isotope effect (KIE) in the reactions of carbene precursor 48 and 50 with nBu3GeH or nBu3GeD (Scheme 11). The KIEs of the reactions were 1.0 and 1.6, respectively, suggesting that C–Ge bond formation may not be the rate-limiting step. Based on the results, they proposed a mechanism for the Ge–H bond insertion. The catalytic cycle commences with the coordination of the diazo substrate 41 or 42 to the chiral dirhodium catalyst, forming adduct 52. Subsequent nitrogen extrusion via transition state 53 generates the reactive rhodium-carbene species 54. The electrophilic carbene intermediate 54 undergoes a concerted, irreversible insertion into the Ge–H bond via a three-center transition state 55. DFT calculations further elucidated the origin of stereocontrol, revealing that the excellent enantioselectivity stems from destabilizing steric repulsion between the catalyst ligand and the substrate in the unfavorable transition state, thereby energetically favoring the formation of the chiral organogermane 43.

Scheme 11. Mechanistic studies and proposed mechanism for the Ge–H bond insertion reaction.

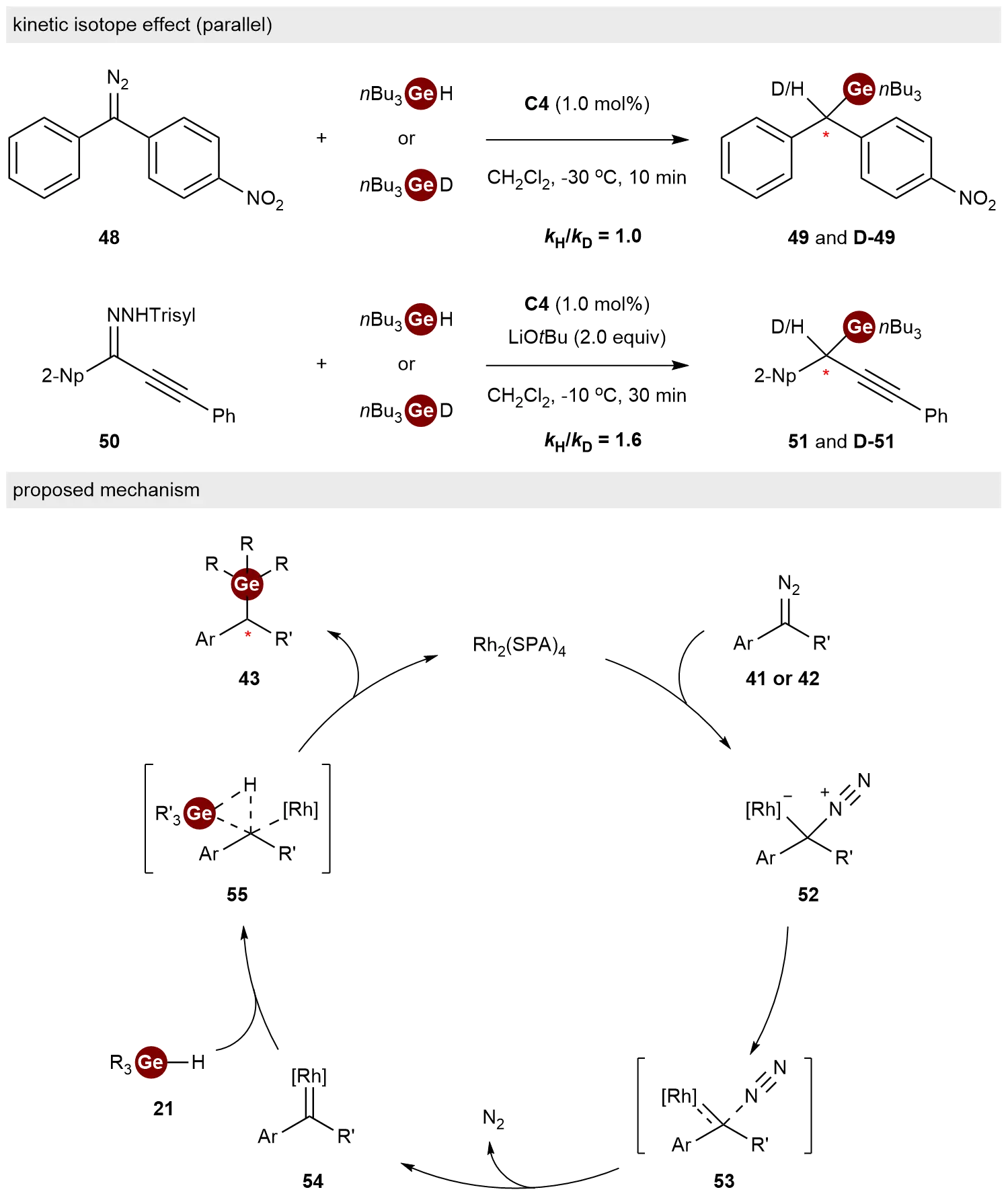

In 2025, Wang and co-workers demonstrated the good performance of chiral spirosilacycle ligands in the Cu-catalyzed asymmetric carbene insertion into Ge–H bonds[32]. Enabled by newly developed C2-symmetrical bisoxazoline ligands L8, the reaction of various

Scheme 12. Copper-catalyzed enantioselective carbene insertion into Ge−H bonds enabled by SPSiBox ligand.

A comparison of the mechanistic studies by Zhou’s and Wang’s groups reveals a unified stereocontrol model for asymmetric carbene insertion into Ge–H bonds, despite their distinct catalytic systems. Both works identify steric repulsion as the decisive factor governing enantioselectivity, as confirmed by DFT calculations. The key difference lies in the source of this repulsion. In Zhou’s chiral dirhodium system, enantiocontrol arises primarily from repulsion between the bulky chiral ligand scaffold and the substituents on the carbene precursor. In contrast, Wang’s copper/SPSiBox system relies on a more localized clash between a specific ligand alkyl group and the substituents on the germanium center. These findings collectively demonstrate that constructing a tailored chiral pocket to differentially destabilize one transition state through steric interactions is a general strategy across diverse catalyst platforms.

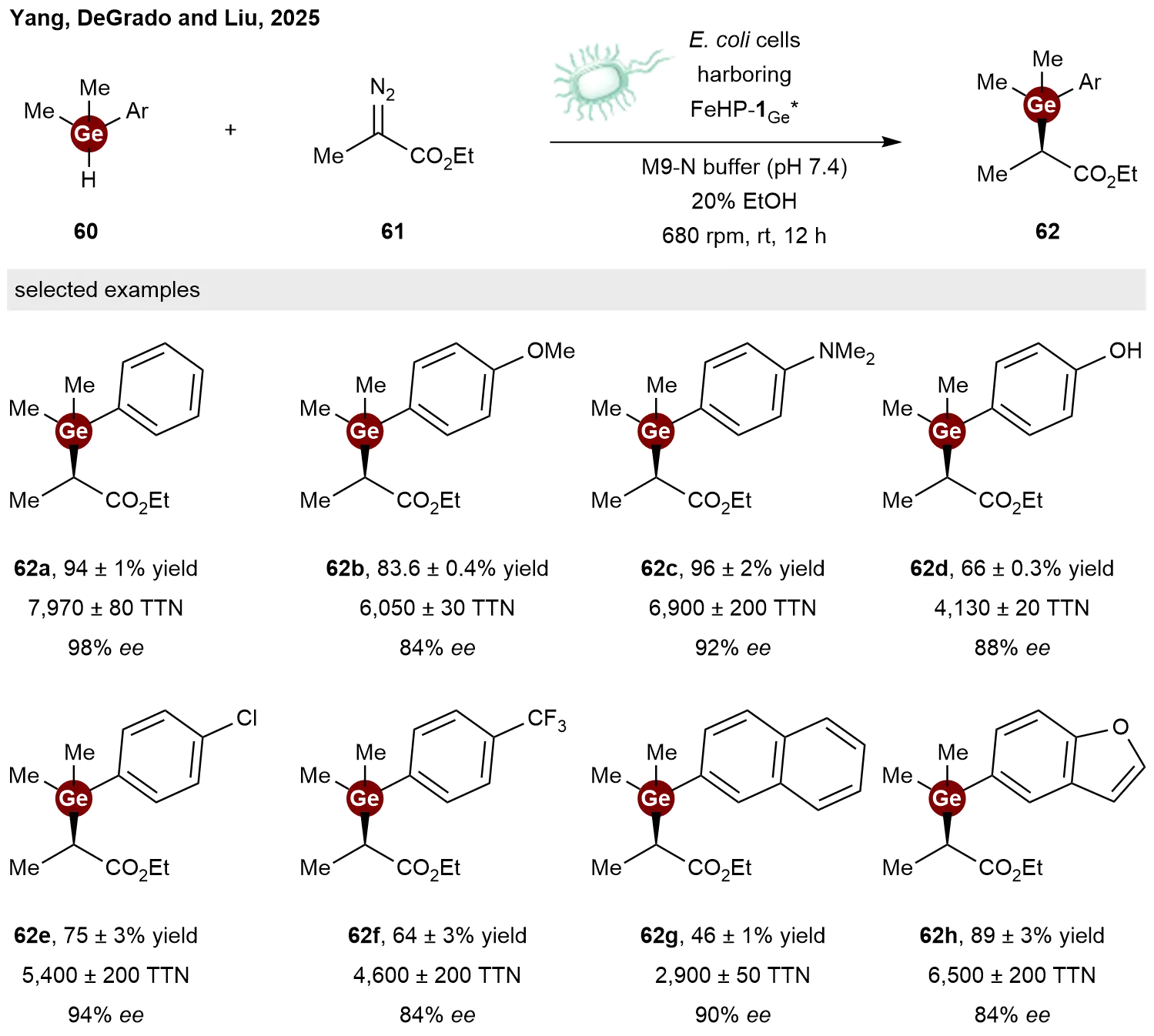

Over the past decade, de novo designed protein catalysts have shown considerable potential to advance the field of biological catalysis, attracting increasing attention toward enzyme engineering. Notably, a range of stereoselective catalytic reactions that are not found in nature have been developed. The representative examples are the pioneering work by Arnold, which demonstrated that engineered natural hemoproteins can catalyze Si–H and B–H insertion reactions[33,34]. Recently, Huang and co-workers reported the de novo design and directed evolution of helical bundle proteins as enantioselective catalysts for germylation via Ge–H insertion[35]. Addressing the specific challenge of controlling the earlier and more flexible transition state inherent to this transformation, the authors synergized de novo protein design with directed evolution to engineer a heme-binding helical bundle protein catalyst,

2.3 Coupling reactions

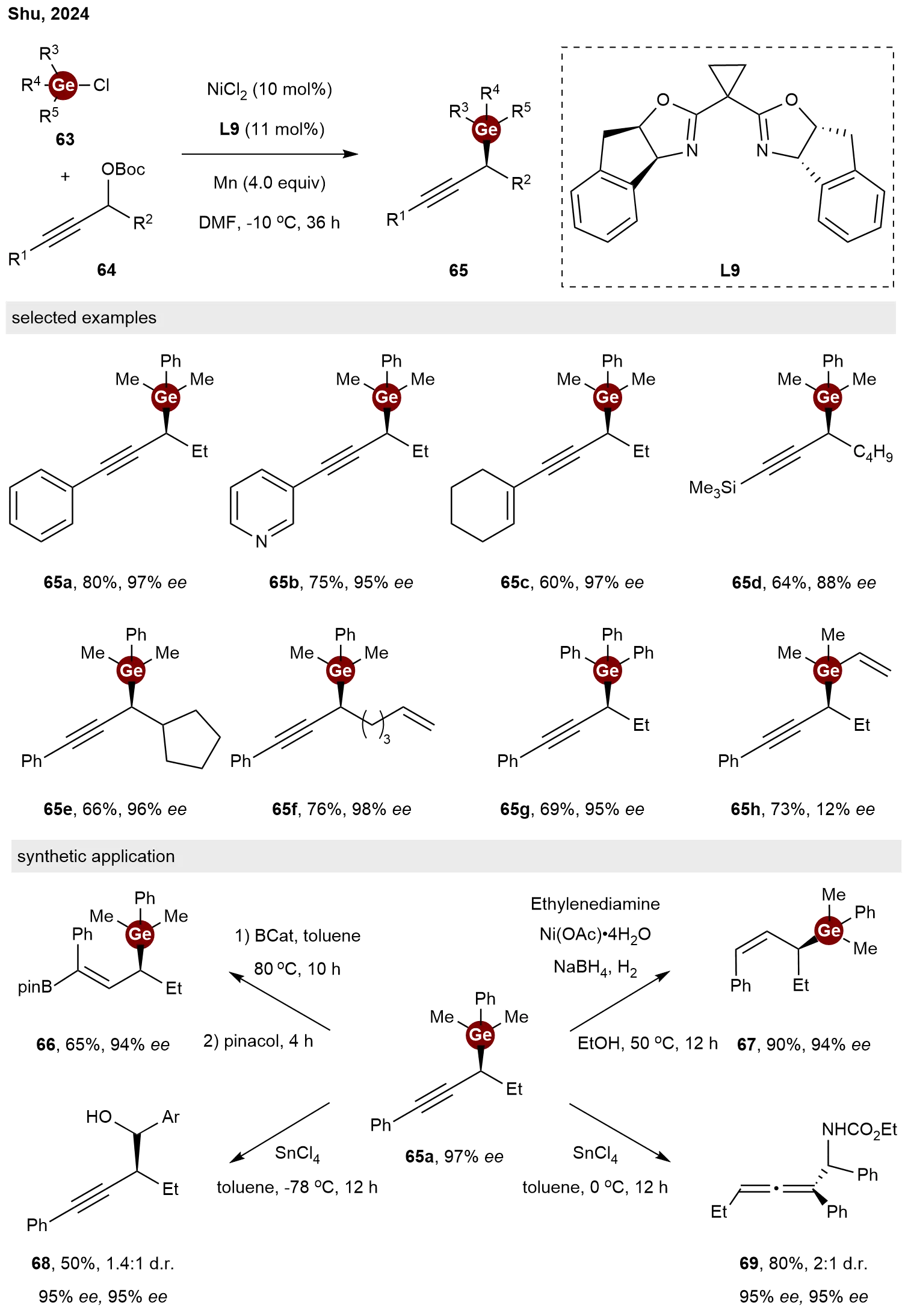

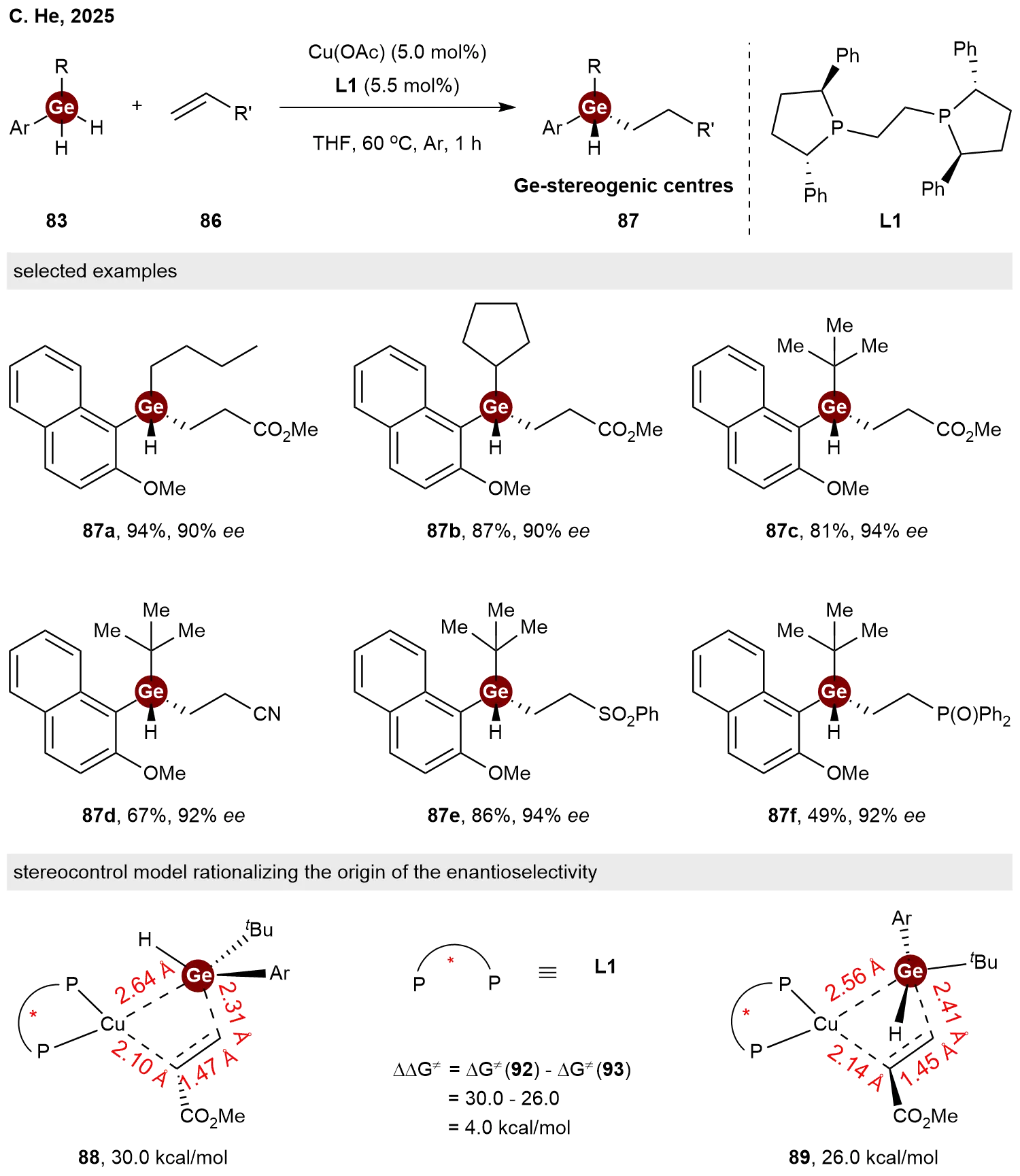

Enantioconvergent cross-electrophile coupling has emerged as a powerful technique for constructing chiral molecules and has witnessed rapid advancement in recent years[36-39]. Current approaches to stereochemical control predominantly rely on redox-active substrates, such as alkyl halides, which can be readily activated into carbon radicals for subsequent interaction with coordinated metals. Achieving stereoconvergent coupling with non-redox-active and stable alcohol derivatives is synthetically attractive but has remained largely underdeveloped. In 2024, Shu and co-workers explored a nickel-catalyzed stereoconvergent coupling of

Scheme 14. Nickel-catalyzed enantioconvergent and regioselective reductive coupling of propargylic esters with chlorogermane.

To gain insight into the mechanism of this process, a radical clock experiment was conducted (Scheme 15, top). Under standard conditions, the reaction of cyclopropyl substrate syn-70 with 63a resulted in the ring expanded product 73 at 43% yield with a Z:E ratio of 2:1. This result is consistent with a radical ring-opening/closing process via intermediates 71 and 72. Based on these experimental results and relevant literature precedents, a catalytic cycle was proposed (Scheme 15, bottom). Initially, propargylic ester 64 reacts with Ni(0), followed by reduction with Mn, to generate propargylic Ni(I) species 75. Subsequent oxidative addition of 75 to chlorogermane 63 yields Ni(III) complex 76. Reversible homolytic cleavage of the Ni–C bond in 76, followed by recombination between the resulting Ge–Ni(II)X species and the propargyl radical via intermediate 77, produces enantioenriched complex 78. Finally, stereospecific reductive elimination from 78 delivers the desired chiral product 65.

Scheme 15. Mechanistic studies and proposed mechanism for the reductive C−Ge coupling.

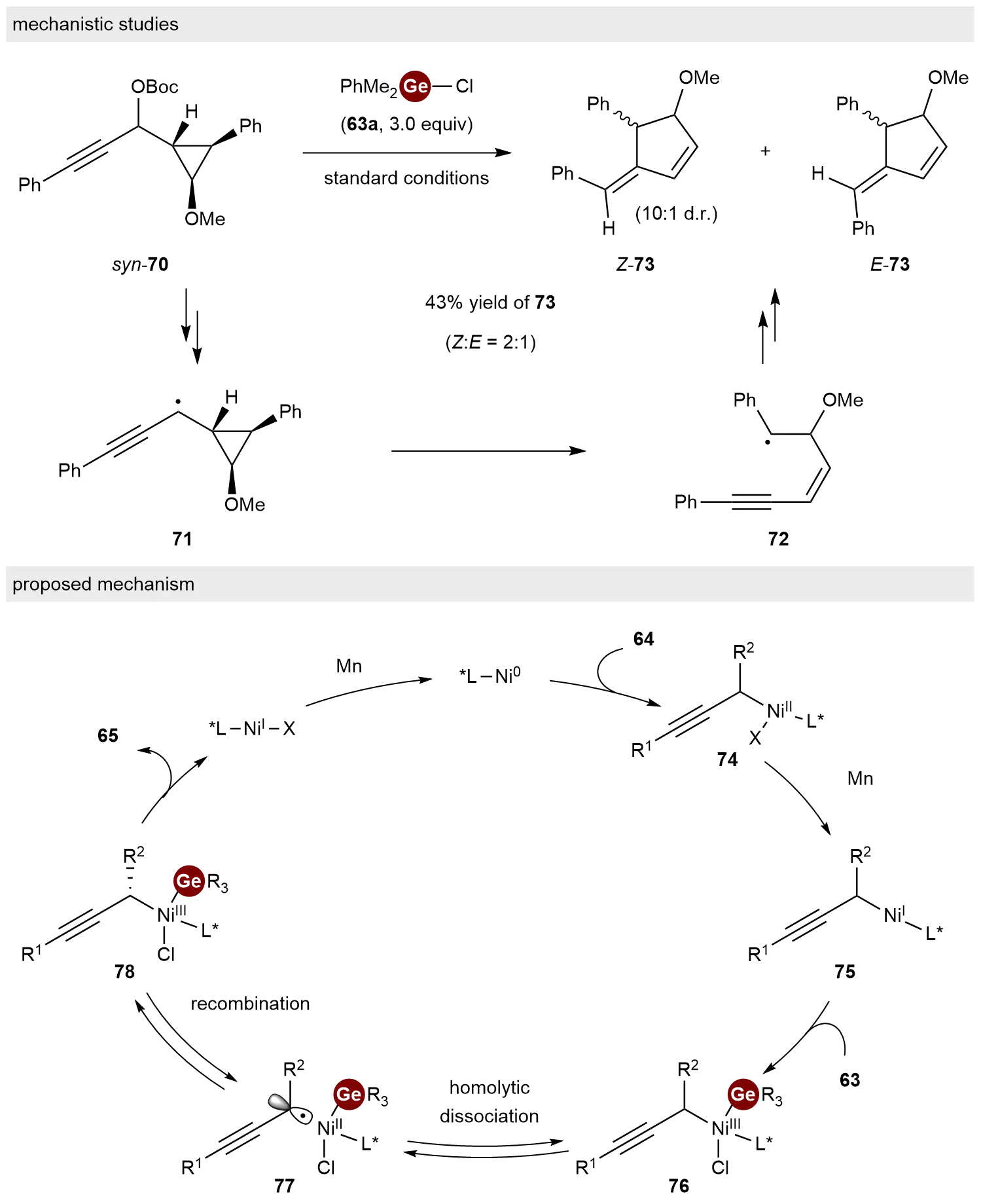

In addition to the aforementioned asymmetric C–Ge coupling approach for synthesizing C-stereogenic germanes, an alternative strategy involves the asymmetric C–C coupling between germylated allylic electrophiles and alkyl nucleophiles. In 2023, Oestreich and co-workers developed a nickel-catalyzed enantio- and regioconvergent cross-coupling of regioisomeric mixtures of racemic germylated allylic electrophiles 79 with alkylzinc reagents[41]. The success of this method relies on a newly designed

Scheme 16. Nickel-catalyzed enantio- and regioconvergent C(sp3)−C(sp3) cross-coupling of germylated allylic electrophiles.

The nickel-catalyzed asymmetric coupling methods discussed herein, including stereoconvergent reductive cross-coupling and enantio- and regioconvergent C–C coupling, provide efficient routes to chiral germanes. Despite these advances, significant challenges and opportunities remain in this field. Currently, the substrate scope is largely confined to activated electrophiles, such as propargylic and allylic derivatives. Expanding these methodologies to encompass less activated or simpler electrophiles would substantially broaden their synthetic leverage and practical utility. Furthermore, the development of catalytic asymmetric intermolecular dehydrogenative Ge–H/X–H couplings remains an underexplored yet promising avenue for the direct construction of Ge–stereogenic centers.

3. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Ge-Stereogenic Germanes

The construction of germanium-stereogenic centers represents a frontier in main-group stereochemistry. Unlike carbon chirality, where precursors are abundant, accessing Ge-stereogenic compounds typically requires the desymmetrization of prochiral substrates or complex resolution steps. Recent years have seen the development of elegant catalytic strategies to address this challenge, focusing on the desymmetrization of dihydrogermanes and tetraorganogermanes.

3.1 Desymmetrization of dihydrogermanes

Building upon their earlier success with C-stereogenic germanes, Zhou and co-workers recently achieved the construction of

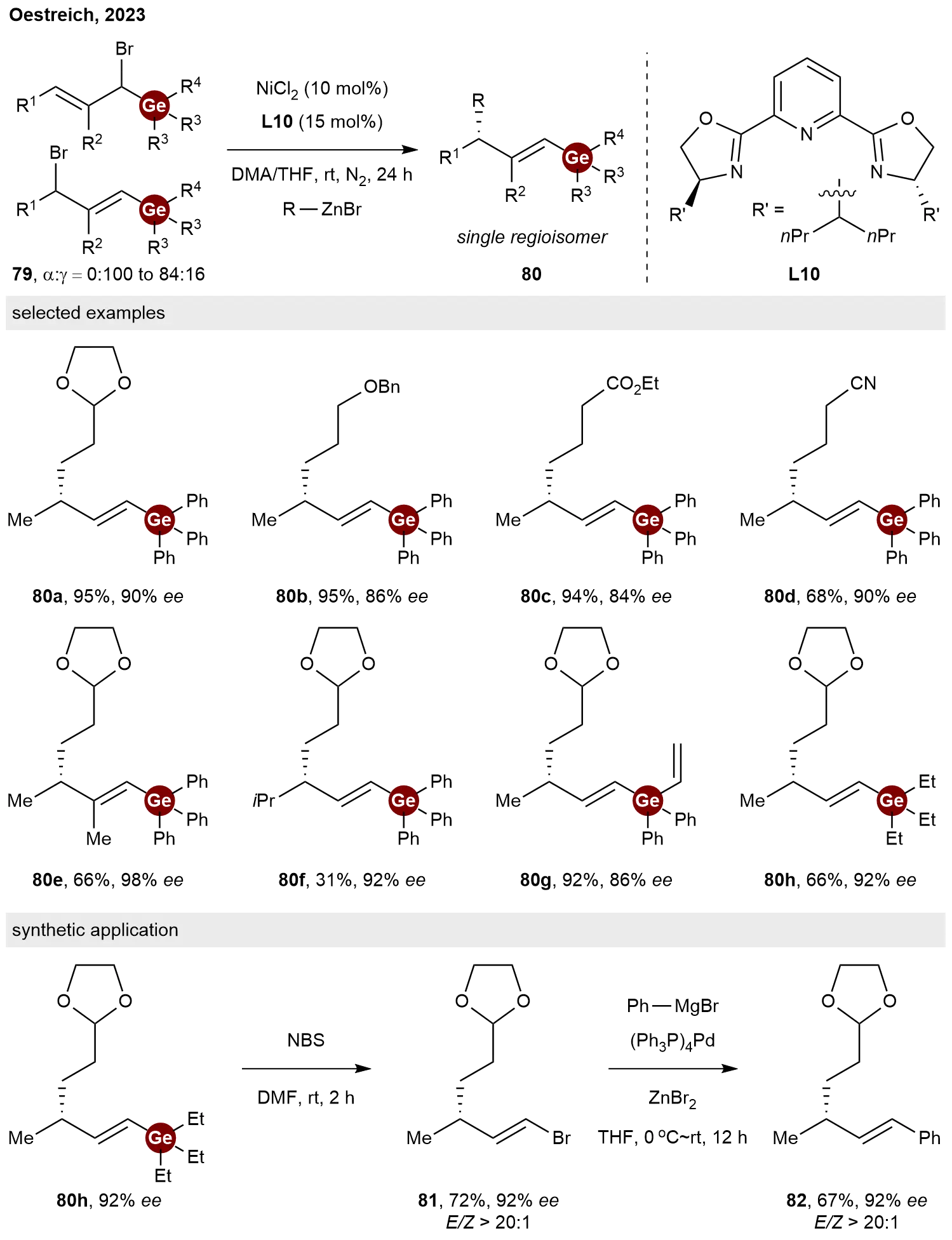

Following the development of synthetic routes to α- and β-C-stereogenic germanes, C. He and co-workers have successfully extended the asymmetric hydrogermylation strategy to the construction of Ge-stereogenic germanes[17]. Employing a catalytic system of Cu(OAc) and the chiral ligand (S,S)-Ph-BPE L1, they achieved the desymmetric hydrogermylation of activated alkenes 86 with prochiral dihydrogermanes 83 in THF at 60 °C (Scheme 18). This protocol featured a broad substrate scope, furnishing the desired chiral germanes 87 in high yields with good to excellent enantioselectivities. DFT calculations elucidated the origin of the enantioselectivity, indicating that the reaction proceeds via the nucleophilic addition of an in situ generated [Cu–Ge] intermediate to the alkene. As illustrated in the stereocontrol model, the transition state leading to the major enantiomer 89 (26.0 kcal/mol) is energetically favored by 4.0 kcal/mol over the minor pathway 88 (30.0 kcal/mol). This preference is ascribed to the minimized steric repulsion between the ligand framework and the substituents on the germanium atom in the favored transition state.

Scheme 18. Copper-catalyzed enantioselective hydrogermylation of activated alkenes with dihydrogermanes.

3.2 Desymmetrization of tetraorganogermanes

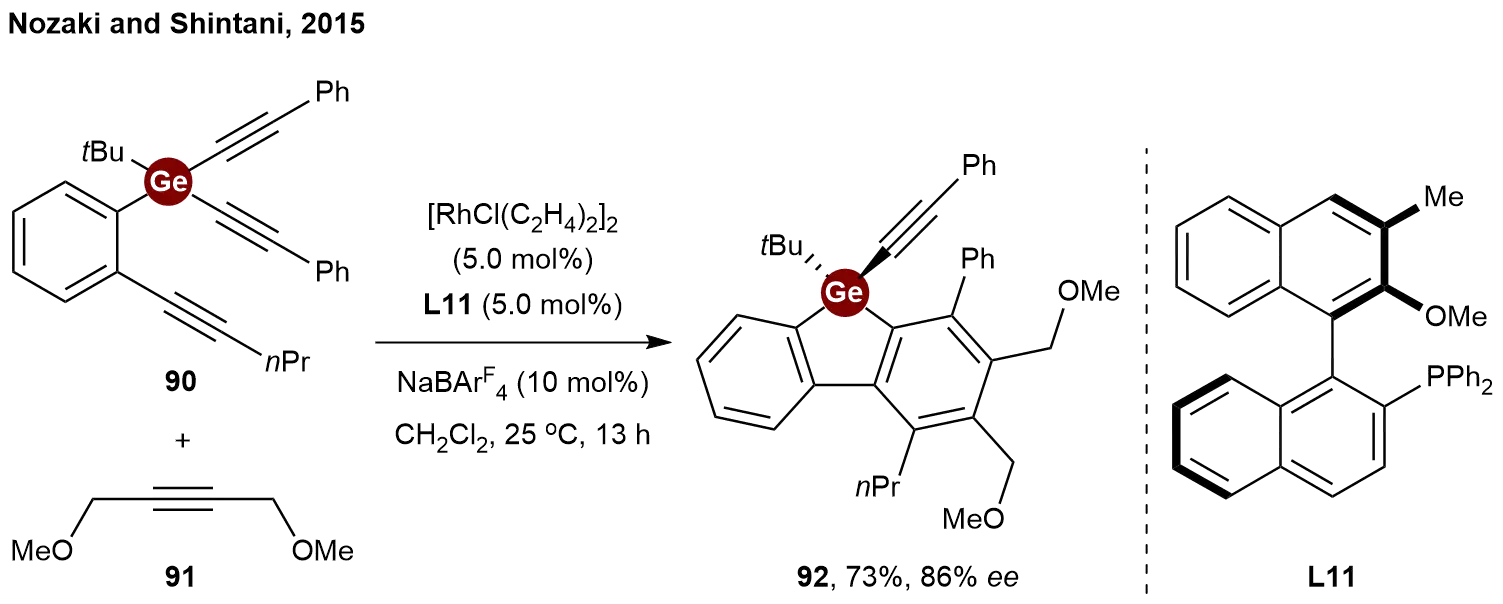

The pioneering example of transition-metal-catalyzed desymmetrization of tetraorganogermanes was reported by Nozaki and Shintani in 2015[43]. By extending the rhodium-catalyzed [2+2+2] cycloaddition strategy to heavier group 14 elements, they achieved the desymmetrization of germanium-containing triyne 90 with alkyne 91 by using the axially chiral monophosphine ligand L11

Scheme 19. Rhodium-catalyzed enantioselective [2+2+2] cycloaddition of germanium-containing prochiral triynes.

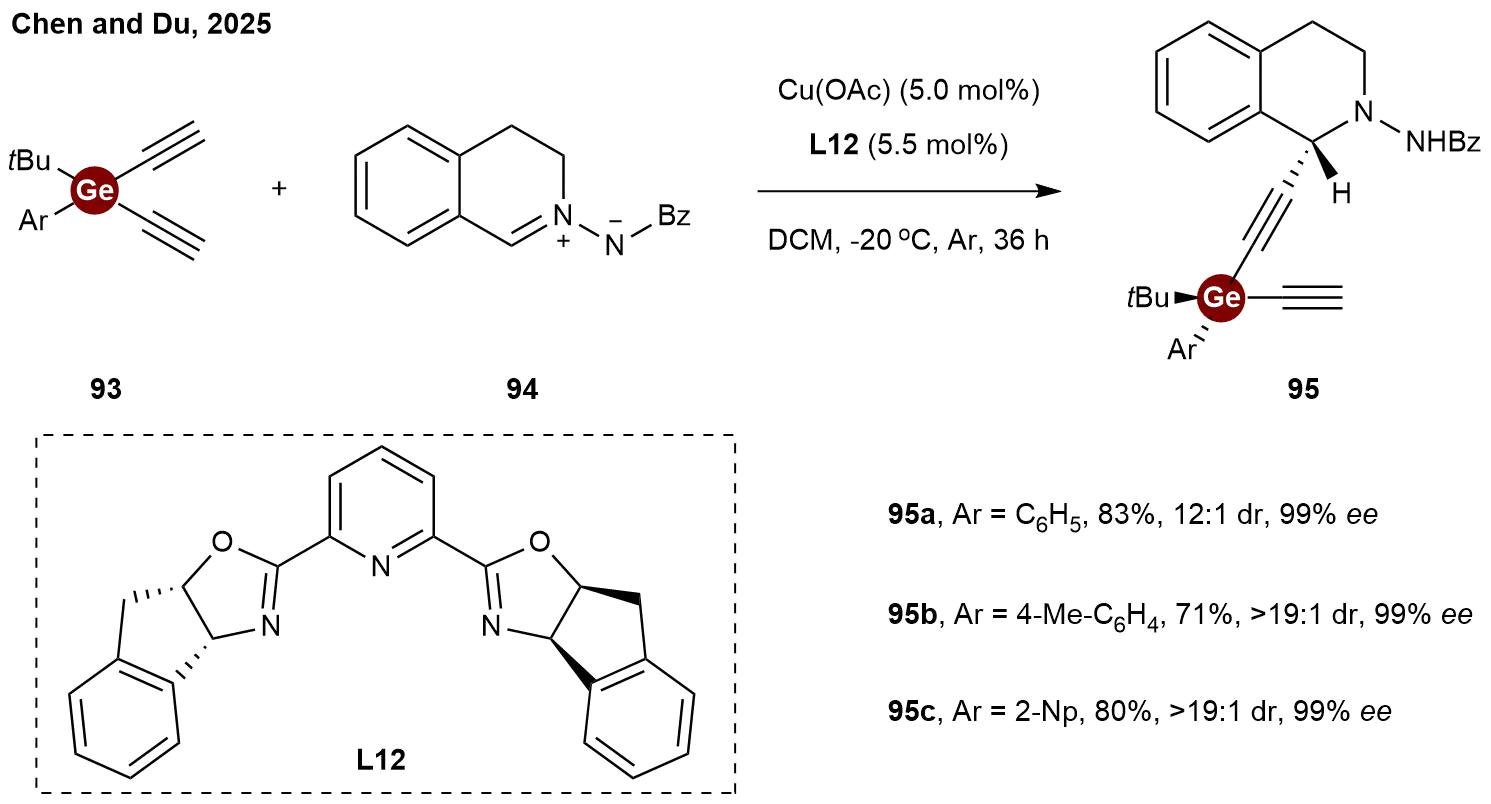

The installation of distant stereogenic centers (such as 1,4-positioned centers) in acyclic systems remains a formidable challenge. In 2025, Chen and Du reported a copper-catalyzed asymmetric alkynylation of C, N-cyclic azomethine imine 94 with dialkynylgermanes 93 (Scheme 20)[44]. This methodology afforded enantioenriched propargylic germanes 95 with high diastereo- and enantioselectivities. This sequential asymmetric deprotonation-alkynylation approach, mediated by a single chiral catalyst, offers a reliable and efficient method for the diastereo- and enantioselective synthesis of products featuring conventionally difficult-to-access rectilinear

Scheme 20. Copper-catalyzed asymmetric alkynylation of C,N-cyclic azomethine imine with dialkynylgermanes.

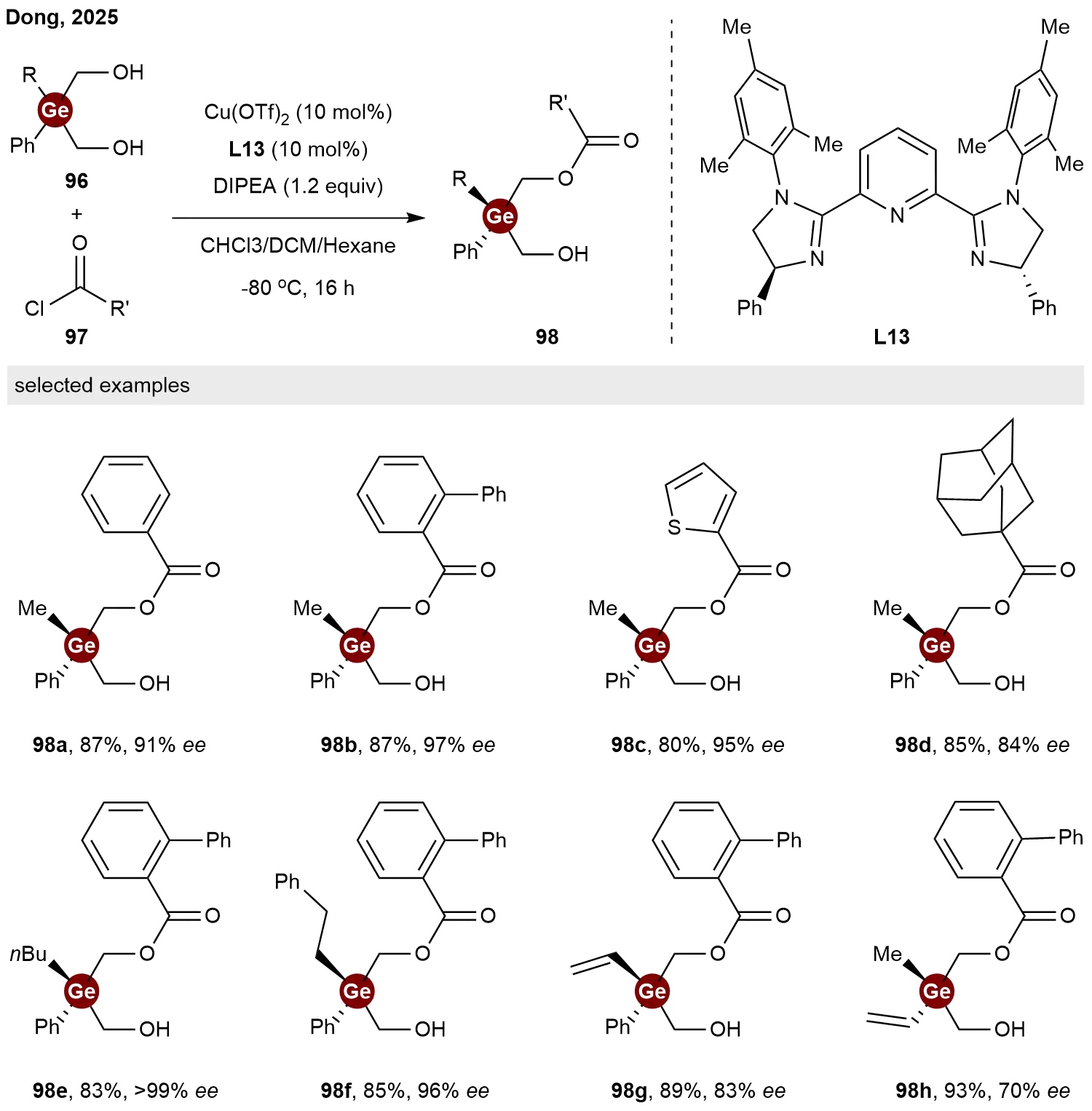

In addition to constructing Ge-stereogenic centers through the desymmetrization of germanium-containing bis-alkynes, germanium-based 1,3-diols have also been demonstrated to serve as viable prochiral substrates. In 2025, Dong and co-workers reported a copper-catalyzed desymmetrization of diols to access chiral germanium centers[45]. Employing a pyridine-bisimidazoline L13 as the chiral ligand and acyl chlorides 97 as acylating agents, the hydroxyl groups of diol substrate 96 were selectively

As noted in Section 3, the current catalytic desymmetrization strategies for constructing Ge-stereocenters largely rely on germanes bearing bulky substituents. The development of methods applicable to simpler dihydrogermanes and tetraorganogermanes remains a challenging but highly desirable goal. Addressing this limitation will likely require the design of new chiral ligands and catalytic systems.

4. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Other Chiral Germanes

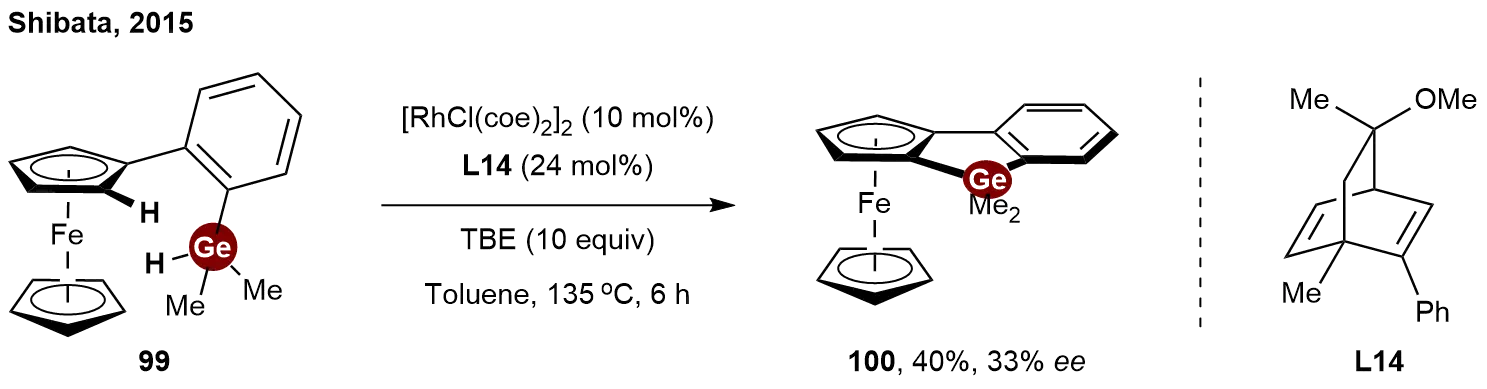

In recent years, the asymmetric catalytic synthesis of other chiral germanes has also been reported. Parallel to the reports by Takai and He on the enantioselective synthesis of silicon-bridged planar-chiral ferrocenes in 2015[46,47], Shibata and co-workers independently disclosed a similar rhodium-catalyzed intramolecular dehydrogenative coupling strategy[48]. Notably, while concurrent studies focused predominantly on silylation, they successfully expanded the scope of this methodology to the heavier congener, germanium. By using a Rh/chiral diene L14 catalyst with tert-butyl ethylene (TBE) as a hydrogen acceptor, the intramolecular C–H/Ge–H dehydrogenative coupling of 2-(dimethylhydrogermyl) phenylferrocene 99 proceeded to afford benzogermoloferrocene 100 in 40% yield with 33% ee

Scheme 22. Rhodium-catalyzed enantioselective intramolecular C−H germylation toward planar-chiral benzogermoloferrocene.

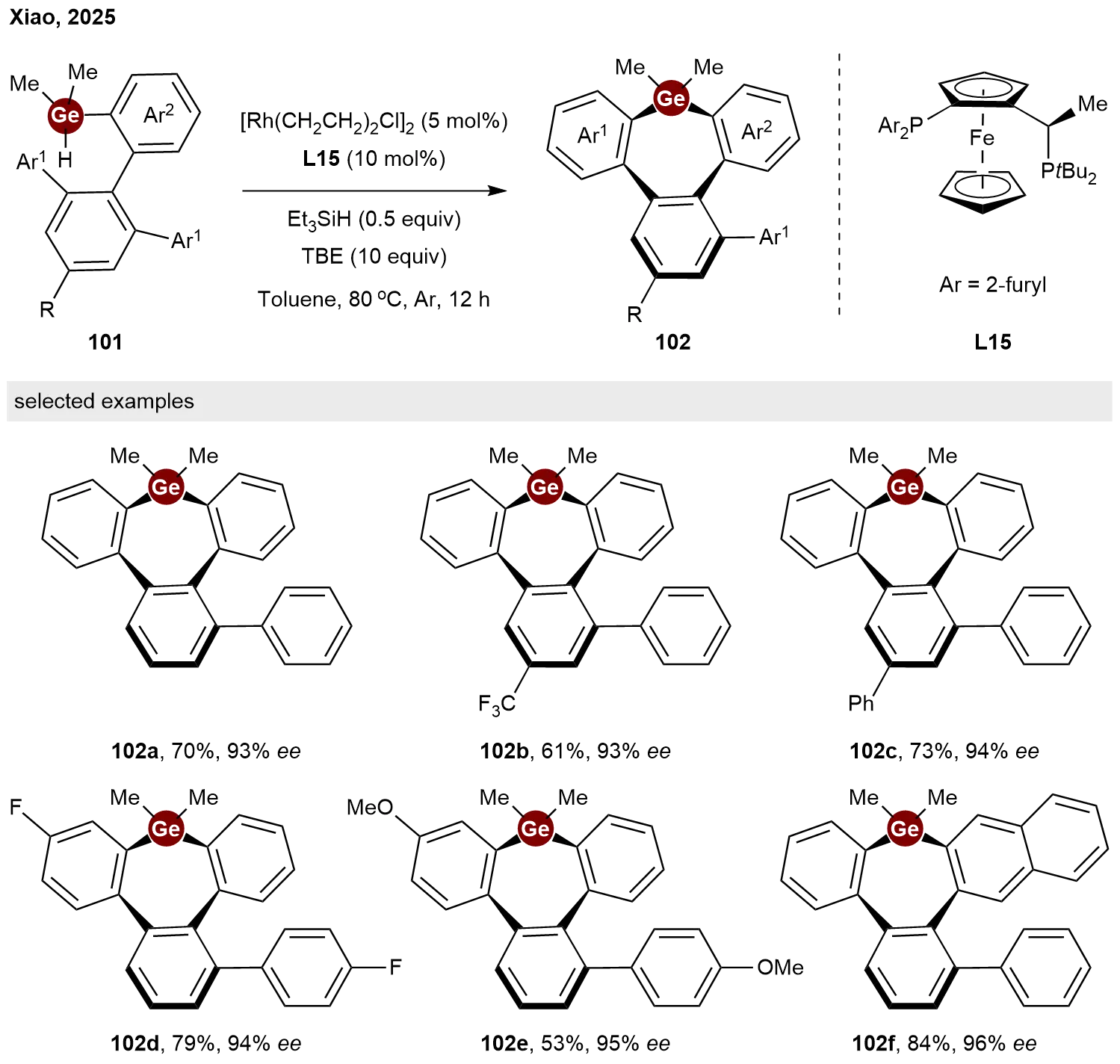

Recently, Xiao and co-workers extended the rhodium-catalyzed enantioselective intramolecular C–H/Ge–H dehydrogenative coupling strategy to the synthesis of inherently chiral germanes[49]. Employing the chiral Josiphos-type ligand L15, a series of inherently chiral tribenzogermepins 102 were successfully synthesized via this intramolecular asymmetric C–H germylation of hydrogermane precursors 101 in moderate to high yields with excellent stereoselectivity (Scheme 23).

Scheme 23. Rhodium-catalyzed enantioselective intramolecular C−H germylation toward inherently chiral germepins.

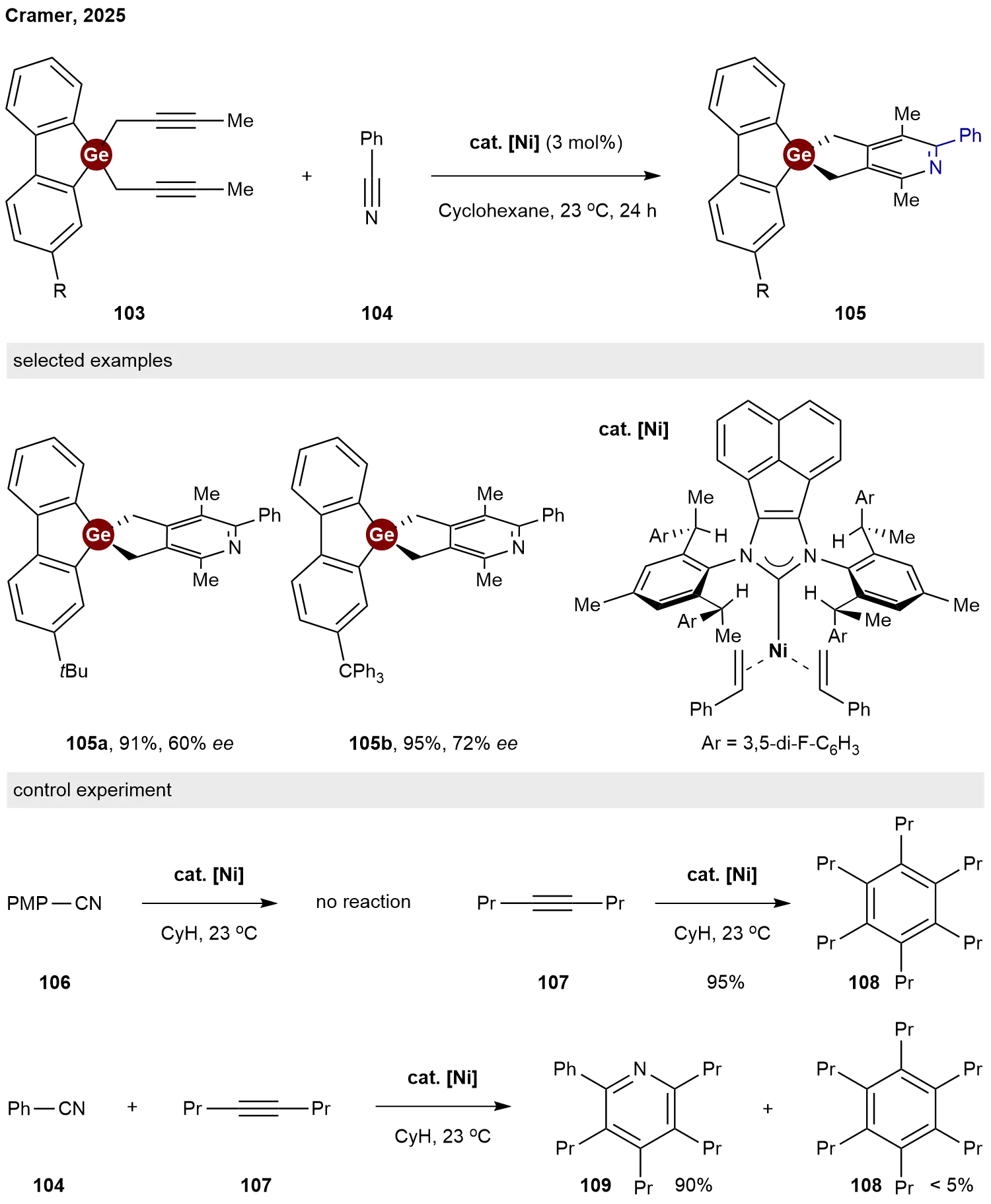

In 2025, Cramer and co-workers reported a unified strategy for the construction of chiral spirocyclic skeletons via nickel-catalyzed enantioselective hetero [2+2+2] cycloaddition[50]. A chiral designer Ni(0) N-heterocyclic carbene complex cat. [Ni] enables the required long-range enantioinduction. After demonstrating its broad utility for synthesizing carbon- and boron-centered spirocycles, they successfully extended this protocol to the chiral spirogermanium center. When dialkynylgermanes 103 and benzonitrile 104 were selected as substrates for this hetero [2+2+2] cycloaddition, the target spiro germafluorene 105a and 105b were obtained in 91% and 93% yields with 60% and 72% ee, respectively (Scheme 24). To shed some light on the reaction mechanism, some control experiments were conducted. No reaction occurred between precatalyst cat. [Ni] and p-methoxybenzonitrile 106, indicating that nickel has a stronger affinity for styrene than nitrile and that coordination of the nitrile is contingent following ligand exchange of styrene with alkyne substrate. In the absence of a nitrile, cat. [Ni] cleanly catalyzed trimerization of alkyne 107 to afford 108 in 95% yield; however, the formation of pyridine 109 is largely favored in its presence. This indicates that pyridine formation proceeds much faster than cyclotrimerization of alkyne. These experimental results support that the reaction proceeds by a heterocoupling mechanism in which one of the alkynes and the nitrile link together first.

Scheme 24. Nickel-catalyzed enantioselective hetero [2+2+2] cycloaddition for construction of spiro germafluorene.

5. Conclusion and Perspective

This review has summarized recent advances in the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of chiral organogermanes, including the construction of C-stereogenic and Ge-stereogenic centers, as well as planar, inherent, and axial chiral organogermanes. Despite these achievements, several challenges and opportunities for improvement remain. First, the range of methodologies for constructing Ge-stereogenic centers is still relatively narrow, and the substrates are also largely limited to germanes bearing bulky substituents. The development of novel approaches would significantly expand structural diversity and enhance synthetic practicality, such as in intermolecular asymmetric Ge–H/X–H dehydrogenative coupling reactions. Second, achieving the synthesis of complex architectures bearing multiple stereogenic centers represents a formidable next frontier, demanding innovative catalytic strategies to control both enantioselectivity and diastereoselectivity simultaneously. Third, in-depth mechanistic studies are essential to understand the stereocontrol processes, thereby guiding the rational design of chiral catalysts. Fourth, the practical utility of these chiral organogermanes, for example, as chiral ligands or functional materials, requires more systematic investigation to fully demonstrate their unique value.

In conclusion, while established methods provide access to certain chiral organogermanes, the field presents clear opportunities for future development. Addressing the current limitations in reaction methodology, mechanistic understanding, and functional exploration will be key to advancing the chemistry and utility of chiral organogermanium compounds.

Authors contribution

Liu S: Investigation, writing-original draft, visualization.

Ke J: Project administration, methodology, writing-review & editing.

He C: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

We are grateful for financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22271134), Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Catalysis (No. 2020B121201002), Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission (No. RCJC20221008092723013 and No. JCYJ20230807093104009).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

2. Menchikov LG, Ignatenko MA. Biological activity of organogermanium compounds (a review). Pharm Chem J. 2013;46(11):635-638.[DOI]

-

7. Xiang X, Zhou Z, Wu X, Ni Z, Gai L, Xiao X, et al. Novel germoles and their ladder-type derivatives: Modular synthesis, luminescence tuning, and electroluminescence. CCS Chem. 2022;4(12):3798-3808.[DOI]

-

8. Ke J, Chen D, Ren LQ, Zu B, Li B, He C. Transition-metal-catalyzed C–Ge coupling reactions. Org Chem Front. 2024;11(22):6558-6572.[DOI]

-

10. Tu JL, Huang B. Catalytic construction of C(sp3)–Ge bonds: Recent advances and future perspectives. Adv Synth Catal. 2024;366(22):4618-4633.[DOI]

-

12. Corriu RJP, Moreau JJE. Stereospecific route to asymmetric vinylgermanes: Hydrogermylation of phenylacetylene catalysed by rhodium and platinum complexes. J Chem Soc D. 1971(15);812.[DOI]

-

13. Nanjo M, Maehara M, Ushida Y, Awamura Y, Mochida K. Convenient access to optically active silyl- and germyllithiums: Synthesis, absolute structure, and reactivity. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46(51):8945-8947.[DOI]

-

14. Zhao Z, Zhang F, Wang D, Deng L. Advances in transition-metal-catalyzed hydrogermylation of alkenes and alkynes. Chin J Chem. 2023;41(22):3063-3081.[DOI]

-

15. Lin W, You L, Yuan W, He C. Cu-catalyzed enantioselective hydrogermylation: Asymmetric synthesis of unnatural β-germyl α-amino acids. ACS Catal. 2022;12(23):14592-14600.[DOI]

-

17. Lin W, Ren LQ, Chen D, Han X, Zhang L, Chen Z, et al. Cu-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogermylation towards C- and Ge-stereogenic germanes. CCS Chem. 2025;7(4):1157-1167.[DOI]

-

23. Hu X, Wang C, Yu L, Tong YZ, Li Z, Li Y, et al. Modular construction of α- or β-stereogenic organosilanes and organogermanes via enantioselective alkene hydroalkylation. Nat Synth. 2025;4(11):1442-1452.[DOI]

-

25. Bergstrom BD, Nickerson LA, Shaw JT, Souza LW. Transition metal catalyzed insertion reactions with donor/donor carbenes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2021;60(13):6864-6878.[DOI]

-

26. Huang MY, Zhu SF. Catalytic reactions for enantioselective transfers of donor-substituted carbenes. Chem Catal. 2022;2(11):3112-3139.[DOI]

-

28. Hyde S, Veliks J, Ascough DMH, Szpera R, Paton RS, Gouverneur V. Enantioselective rhodium-catalysed insertion of trifluorodiazoethanes into tin hydrides. Tetrahedron. 2019;75(1):17-25.[DOI]

-

29. Han AC, Zhang XG, Yang LL, Pan JB, Zou HN, Li ML, et al. Rhodium-catalyzed enantioselective C−Ge bond formation by carbene insertion: Efficient access to chiral organogermanes. Chem Catal. 2024;4(1):100826.[DOI]

-

37. Lucas EL, Jarvo ER. Stereospecific and stereoconvergent cross-couplings between alkyl electrophiles. Nat Rev Chem. 2017;1:65.[DOI]

-

39. Gao Z, Liu L, Gu QS, Liu XY. Enantioconvergent cyclopropyl radical C−C coupling. Trends Chem. 2024;6(12):786-787.[DOI]

-

40. Han GY, Su PF, Pan QQ, Liu XY, Shu XZ. Enantioconvergent and regioselective reductive coupling of propargylic esters with chlorogermanes by nickel catalysis. Nat Catal. 2024;7(1):12-20.[DOI]

-

44. Zheng JL, Yuan WH, Zheng HW, Du W, Chen YC. Diastereoselective and enantioselective construction of 1, 4-nonadjacent alkyne-tethered products through CuI-promoted deprotonation and addition of terminal alkynes. Org Chem Front. 2025;12(23):6407-6414.[DOI]

-

50. Cao YX, Chauvin AS, Tong S, Alama L, Cramer N. Accessing carbon, boron and germanium spiro stereocentres in a unified catalytic enantioselective approach. Nat Catal. 2025;8(6):569-578.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite