Abstract

Integrating Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage technology into concrete additive manufacturing represents an innovative pathway for achieving carbon emission reduction in the construction industry, while simultaneously offering effective solutions to critical challenges such as insufficient early-age strength and weak interlayer bonding in printed components. Bibliometric analysis reveals that this interdisciplinary field is experiencing a period of exponential growth, with research hotspots rapidly shifting from fundamental 3D printing process exploration to the synergistic optimization of material properties utilizing accelerated carbonation and carbon dioxide sequestration technologies. This review systematically elucidates the mechanisms of carbon mineralization curing, with a particular focus on analyzing three key process pathways: fresh state carbon mineralization, synchronous carbon sequestration during printing, and post-printing carbonation curing. Furthermore, the synergistic enhancement mechanisms of material strategies, including supplementary cementitious materials and carbonated recycled aggregates, are discussed. On this basis, the review identifies core challenges regarding curing uniformity, narrow process windows, and the absence of long-term durability research, and subsequently outlines future development directions such as intelligent closed-loop control and integrated structure-material-process design.

Keywords

1. Introduction

In the global context of combating climate change, the construction industry has come under intense scrutiny due to its substantial carbon footprint. The construction and operation of buildings account for more than one-third of global energy consumption and

As a pivotal technological strategy for realizing the vision of global carbon neutrality, Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) aims to physically or chemically capture carbon dioxide and either convert it into high-value-added products or permanently sequester it geologically[8,9]. In particular, the carbon sequestration pathway based on mineralization principles is capable of transforming gaseous greenhouse gases into thermodynamically stable solid carbonates. This mechanism provides a robust theoretical foundation for the low-carbon reshaping of traditional building materials[10-12]. Deeply integrating this technological system into the fields of intelligent construction and novel building materials not only aligns with the industry trend driven by the synergy of smart construction and green development but also enables concrete, traditionally a major carbon source, to potentially be transformed into a carbon sink carrier possessing active carbon absorption capabilities. This transformation opens a new technological dimension for the sustainable development of the construction industry at a macro level, while simultaneously providing new opportunities to address the material performance challenges currently facing additive manufacturing[13-15].

In recent years, concrete additive manufacturing has garnered increasing attention as a pivotal technological pathway for transforming traditional construction methodologies. Among the various techniques, 3D printed concrete (3DPC) is regarded as a critical approach for revolutionizing conventional construction practices due to its formwork-free nature, high material utilization efficiency, geometric freedom, and digital construction potential[16-19]. Therefore, 3DPC, as the representative technology of concrete additive manufacturing, forms the primary focus of this review. However, the practical engineering application of this technology remains constrained by critical scientific and technical challenges, including the dual requirements of rapid shaping and stable

To address the aforementioned technical bottlenecks, the utilization of carbon mineralization curing technology for performance regulation of cementitious systems has emerged as a significant research direction. The reaction of CO2 with hydration products and unhydrated clinker generates stable carbonates, which significantly enhances early-age strength and accelerates the structural build-up process. This mechanism precisely satisfies the stringent requirements of 3DPC for rapid shaping and stable load-bearing while simultaneously endowing the concrete system with carbon sequestration potential. Crucially, the layer-by-layer stacking process of 3DPC results in concentrated porosity at the interlayer interfaces, while the formwork-free characteristic results in a substantially larger surface area exposed to the atmosphere[26-28]. Such a structural configuration provides ideal conditions for efficient CO2 penetration and rapid reaction, thereby offering a distinct process-material coupling advantage in accelerated carbonation compared to traditionally cast concrete.

Current research on the integration of CCUS process systems within 3DPC has established several distinct technical routes. These encompass utilizing CO2 during the fresh state to regulate rheological behavior for rapid structural stabilization, achieving

In light of this background, this review systematically summarizes the latest research progress on CCUS processes in concrete additive manufacturing. It analyzes the subject from the perspectives of material reaction mechanisms, process coupling strategies, microstructural regulation, and macro-performance evolution, while also discussing the critical challenges and potential development directions facing the field. This work aims to provide a reference for constructing high-performance, low-carbon, and even carbon-negative concrete additive manufacturing systems, thereby offering technical support for the future development of intelligent construction and sustainable infrastructure.

2. Bibliometric Statistical Analysis

2.1 Data retrieval and screening

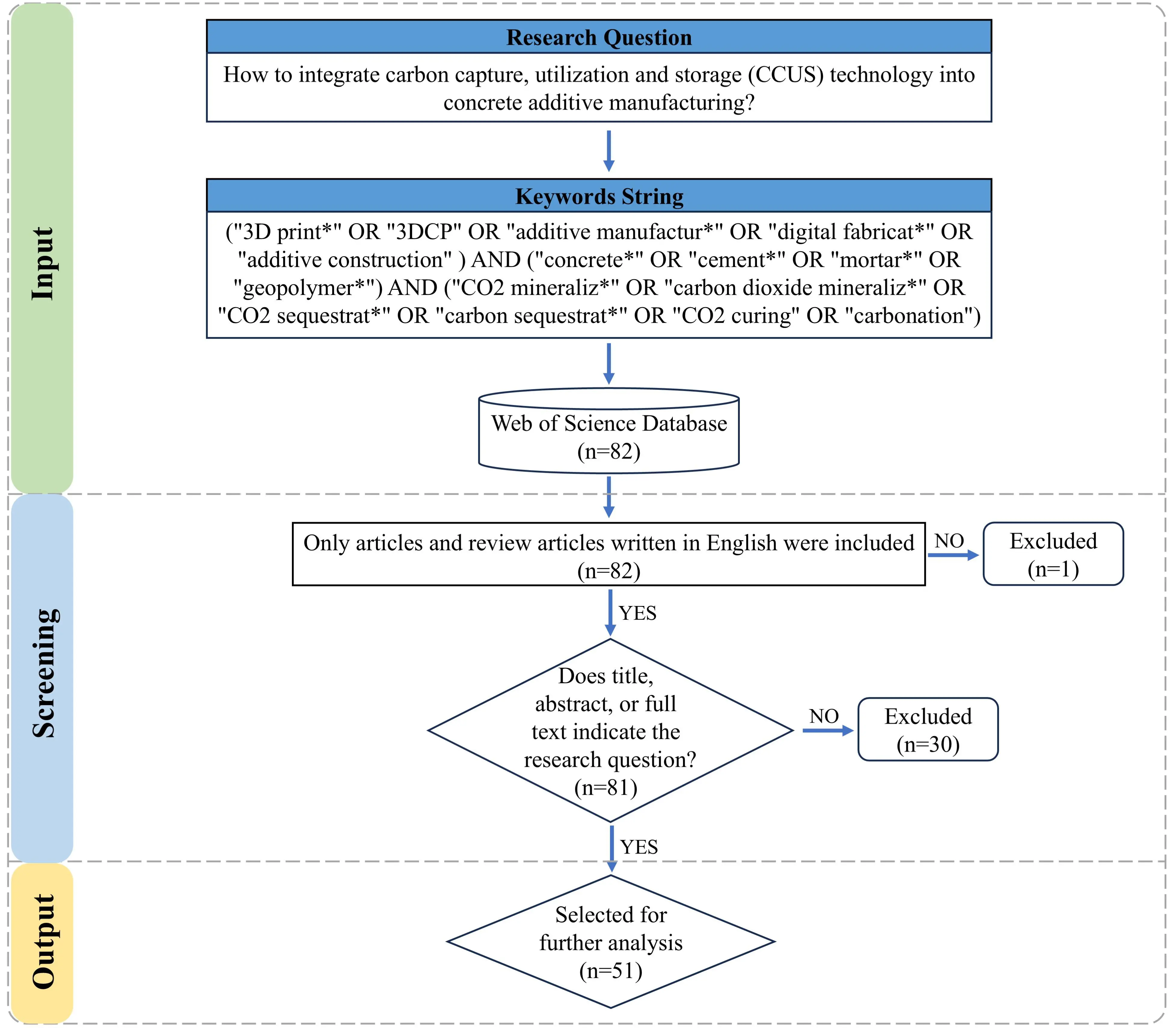

To systematically delineate the current research landscape of CCUS technology within concrete additive manufacturing, this review is grounded in the core research question: “How to integrate CCUS technology into concrete additive manufacturing?”. The formulation of this question established a definitive direction for the subsequent systematic literature retrieval and screening. Guided by this research objective, the keyword string was constructed as follows: (“3D print*” OR “3DCP” OR “additive manufactur*” OR “digital fabricat*” OR “additive construction”) AND (“concrete*” OR “cement*” OR “mortar*” OR “geopolymer*”) AND (“CO2 mineraliz*” OR “carbon dioxide mineraliz*” OR “CO2 sequestrat*” OR “carbon sequestrat*” OR “CO2 curing” OR “carbonation”). Employing this string, a literature search was conducted within the Web of Science Core Collection database, yielding an initial corpus of 82 relevant documents. As illustrated in the literature screening flowchart in Figure 1, these documents underwent a multi-stage evaluation. Initially, non-English literature was excluded, and document types were restricted to journal articles and reviews, resulting in 81 remaining papers. Subsequently, through a meticulous examination of titles, abstracts, and full-text contents to assess their close alignment with the core research question, 30 non-pertinent documents were further excluded. Ultimately, 51 highly relevant papers were selected to serve as the analytical foundation for this review.

2.2 Analytical tools

To conduct a systematic bibliometric analysis of this research domain, VOSviewer software (version 1.6.20) was employed as the core analytical instrument, being a widely recognized tool for constructing and visualizing bibliometric networks[29-31]. Specifically, the robust text mining and keyword co-occurrence analysis functionalities of the software were leveraged to extract high-frequency terms from the titles, abstracts, and keywords of the 51 selected core documents. The software initially constructs a co-occurrence matrix, which is subsequently transformed into a distance-based visualization map via the “VOS mapping technique”. This spatial arrangement ensures that keywords sharing tighter conceptual correlations are positioned in closer proximity, while clustering algorithms are applied to identify distinct thematic communities. To facilitate an accurate interpretation of the keyword

2.3 Results

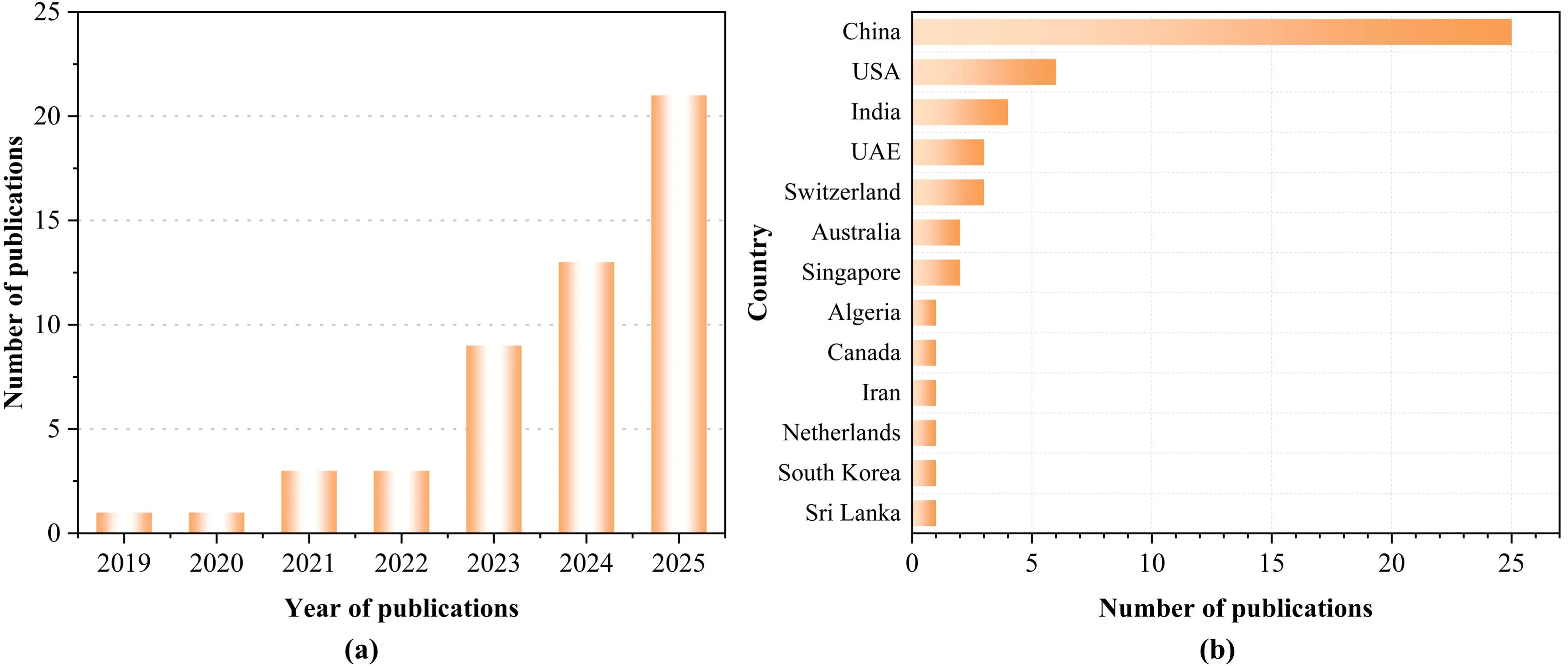

An analysis of the distribution of publication years, as illustrated in Figure 2a, clearly demonstrates an accelerating growth trend in research concerning CCUS technologies within concrete additive manufacturing. The period from 2019 to 2021 can be regarded as an initial exploratory phase, characterized by an average annual publication volume of approximately two papers. Since 2022, publication output has increased significantly, with the three-year span from 2022 to 2024 yielding a total of 25 papers and an average of over eight articles per year. It is particularly noteworthy that the statistics for 2025, covering only up to November, have already reached 21 papers, a figure that far exceeds the annual total of any preceding year. This upward trajectory indicates that academic interest in the synergy between CCUS technology and additive manufacturing processes is rising rapidly. This surge is primarily attributed to the urgent global demand for carbon neutrality and the consequent emphasis on low-carbon construction technologies. The potential of this synergy lies in its capacity not only to utilize and sequester CO2 as a resource but also to simultaneously resolve technical bottlenecks in concrete additive manufacturing related to early-age strength and interlayer bonding performance.

Figure 2. (a) Number of papers obtained from literature selection criteria; (b) Number of publications by country/region.

In terms of national and regional contributions, as depicted in Figure 2b, research output exhibits a high degree of geographical concentration. China makes a particularly prominent contribution to this field, having published 25 papers, which accounts for 49.0% of the total. This dominance profoundly reflects the high priority and substantial investment dedicated to this interdisciplinary frontier by China, driven by the dual national strategies of Intelligent Construction and Carbon Neutrality. The USA serves as the second-largest contributor, publishing 6 papers (11.8%), followed by India at 7.8%. Furthermore, the active engagement of nations such as the UAE, Switzerland, Australia, and Singapore indicates that this research direction is not confined to specific regions but has instead emerged as a global topic of common interest among both developed and major emerging economies. This underscores a broad consensus regarding the immense potential of this field in driving the future of sustainable construction.

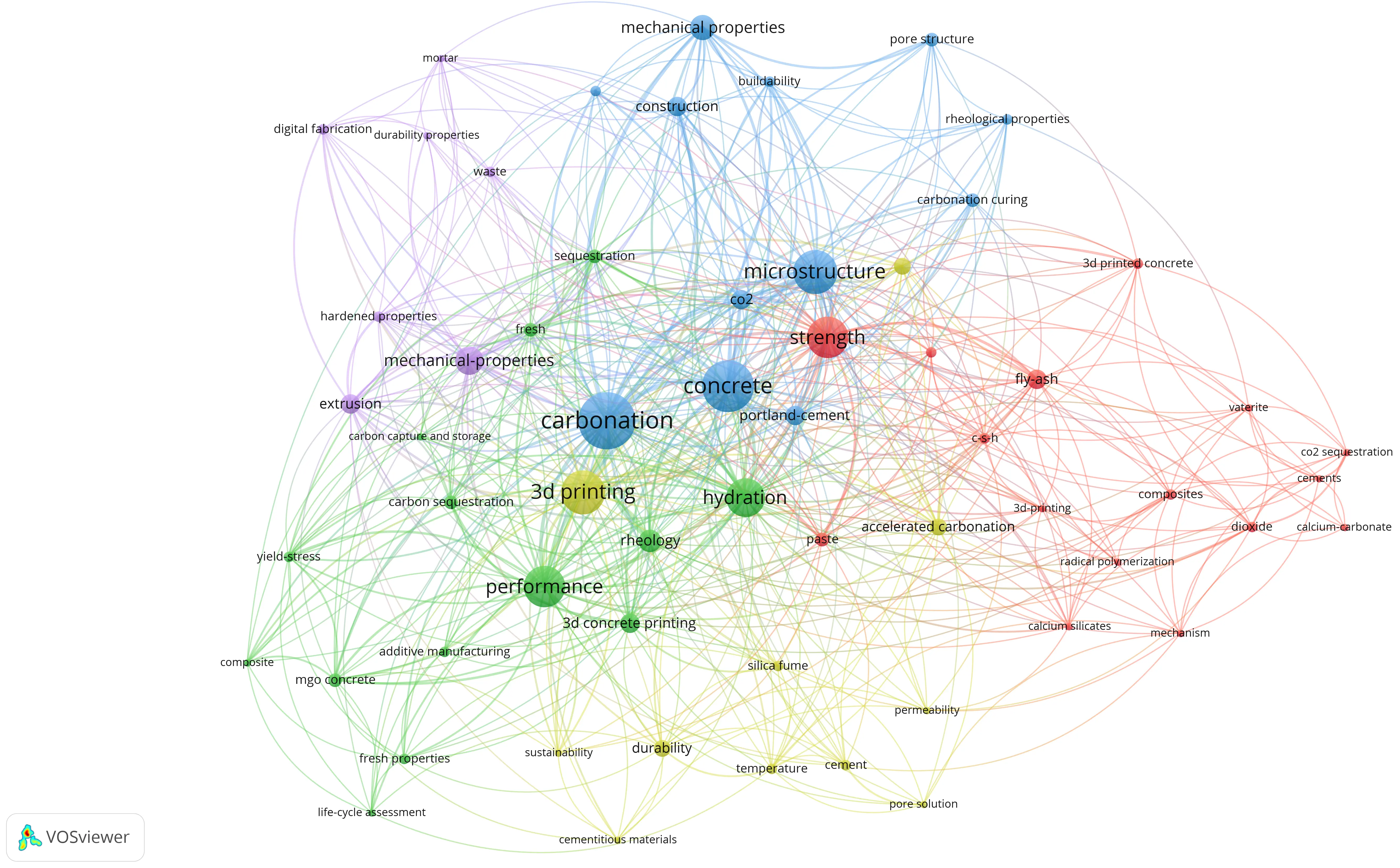

To further elucidate the research hotspots, knowledge structure, and thematic evolution of this field, this study employed bibliometric methods to conduct a co-occurrence analysis and visualization of keywords from the selected literature using VOSviewer software, as shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5. The keyword co-occurrence network map in Figure 3 delineates the research hotspots into three primary thematic clusters. The red cluster represents fundamental research in materials science, centered on “concrete”, “strength”, and “Portland cement”, while encompassing terms such as “fly ash”, “C-S-H”, and “accelerated carbonation”. This composition reflects that researchers are devoting efforts to exploring the mechanisms by which accelerated carbonation influences the chemical reactions and strength development of 3DPC cementitious systems. The green cluster focuses on the process and application dimensions, with “performance”, “3D concrete printing”, and “rheology” as the core, and includes terms like “fresh properties”, “sustainability”, and “additive manufacturing”. This indicates that this direction concentrates on how the introduction of CO2 regulates the printability of the material and ultimately achieves sustainable construction performance goals. The blue cluster constitutes the community most closely aligned with the theme of this review. Characterized by the dual cores of “carbonation” and “3D printing”, it tightly connects mechanistic keywords such as “CO2”, “sequestration”, and “carbon capture and storage” with process and outcome-related keywords like “extrusion” and “mechanical-properties”. This suggests that this thematic community represents the research pathway of applying CO2 curing as a functional technology in situ during the printing process to enhance performance. Situated at the center of the map between these clusters, keywords such as “microstructure” and “strength” serve as critical bridges connecting the red material cluster and the blue mechanism cluster, while the term “rheology” connects the green process cluster, highlighting that maintaining material printability while introducing CO2 remains a key challenge facing this interdisciplinary field.

Figure 4. Overlay visualization showing the temporal evolution of keywords using VOSviewer.

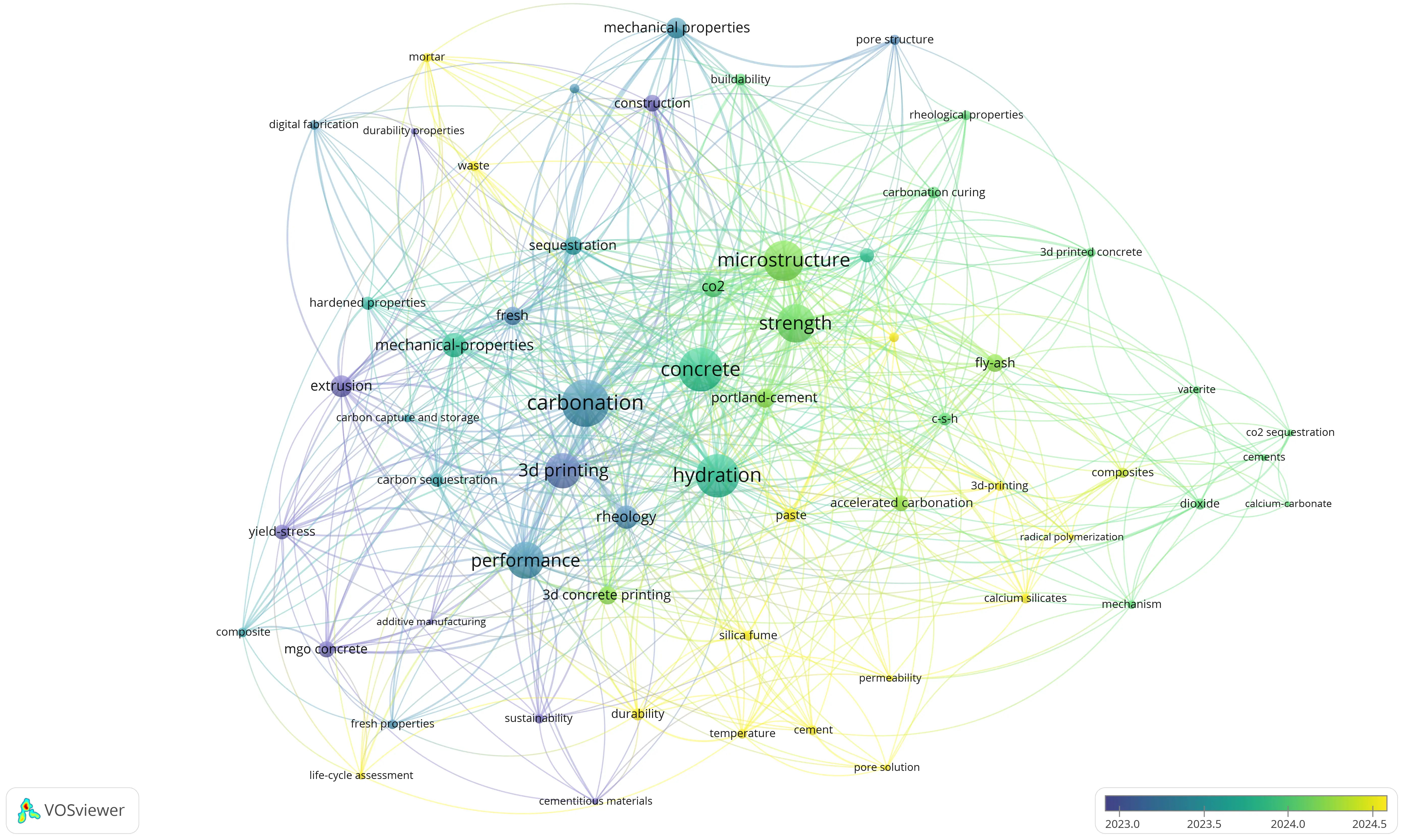

The keyword co-occurrence overlay visualization in Figure 4 intuitively illustrates the evolutionary trends of the research frontiers. Foundational terms such as “hydration” and “3D printing” appear in earlier blue or green hues, indicating they constitute the research basis of the field. Conversely, keywords directly related to the theme of this review, particularly “accelerated carbonation”, “CO2 sequestration”, and specific carbonation products like “vaterite” and “calcium carbonate”, all appear in the most recent yellow hues. This distinct temporal evolutionary path indicates that research in this domain is rapidly shifting from the exploration of basic concrete additive manufacturing processes toward utilizing advanced carbon capture and mineralization technologies to synergistically enhance material performance and carbon sequestration efficiency. This implies that the deep integration of CCUS technology and concrete additive manufacturing is a development direction with immense potential. The density visualization map in Figure 5 further corroborates this assessment. High-density hotspot regions in the map are clearly concentrated on keywords including “carbonation”, “3D printing”, “concrete”, “microstructure”, “strength”, and “performance”. This demonstrates that the central focus of current research lies in exploring the integration of carbonation technology with concrete additive manufacturing processes, with the primary research objectives being the regulation of microstructure and the optimization of macro-performance and strength, which aligns closely with the theme of this review.

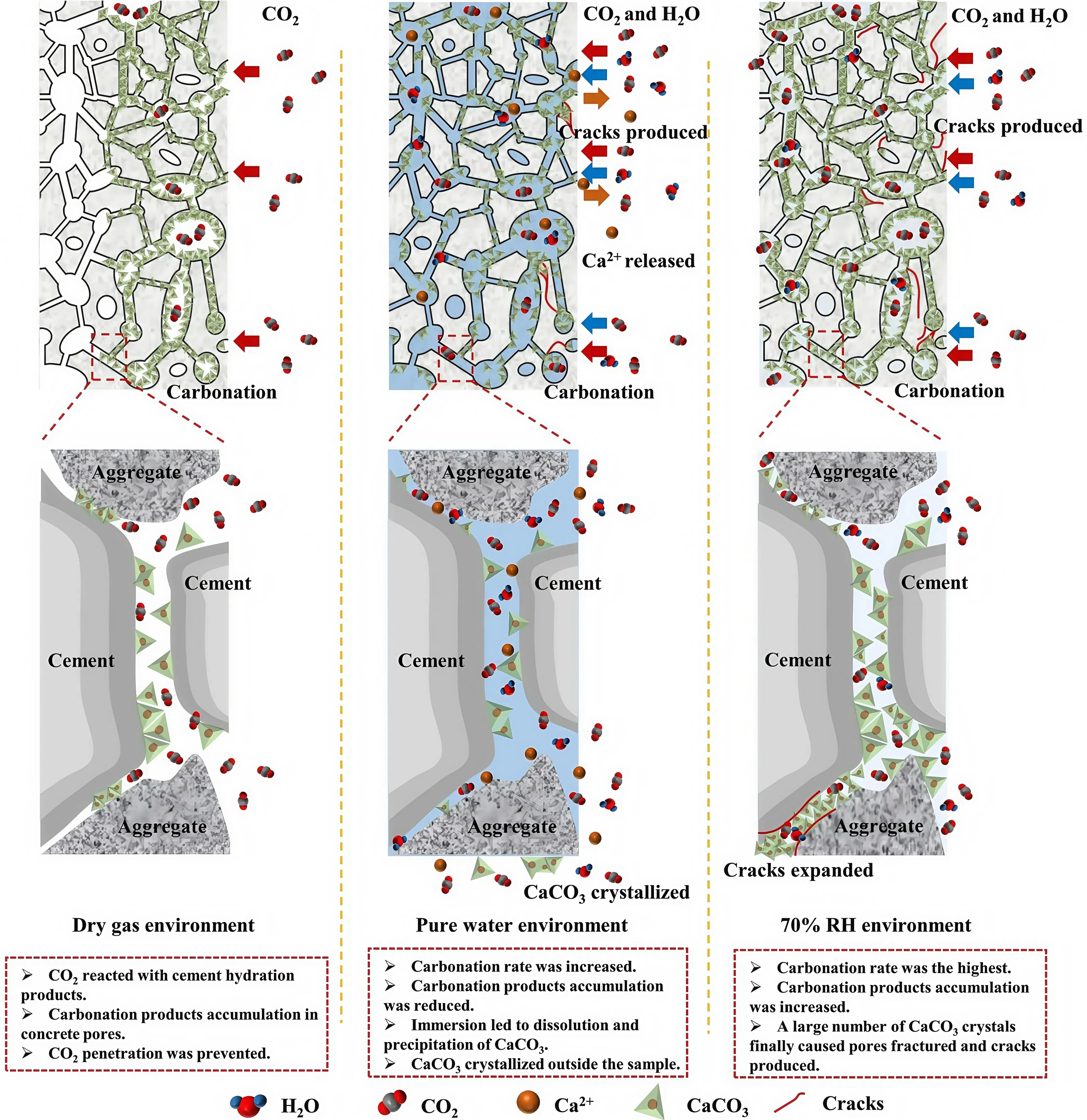

3. CO2 Curing Mechanism

The carbon curing of 3DPC fundamentally leverages the carbon mineralization process within CCUS technology as a reaction driving force, promoting the rapid formation of a solidified matrix with substantial strength in the cementitious material system within an extremely short timeframe. This mechanism not only achieves mineralized carbon sequestration but also effectively addresses the stringent requirements imposed by the 3D printing process on the early-age properties of concrete. This carbon sequestration process involves complex multiphase chemical reactions, where the gaseous carbon source dissolves into the pore solution to form carbonic acid (H2CO3), significantly lowering the pH value and providing the necessary chemical environment for subsequent ionic reactions[34]. In this acidic environment, Ca(OH)2 is rapidly consumed, precipitating solid-phase calcium carbonate (CaCO3)[35-37]. These products, initially appearing as metastable vaterite or aragonite, subsequently transform into stable calcite[38-40], filling the interstitial spaces between particles to constitute the initial consolidation network. As illustrated in Figure 6, this microstructural evolution is highly dependent on environmental humidity. Optimal humidity facilitates deep CO2 penetration and induces efficient pore filling by crystals to achieve matrix densification. Conversely, the micro-cracking features presented in the figure serve as a visual warning regarding the risk of expansive damage caused by excessive carbonation[41]. This further corroborates the necessity of precisely regulating the reaction window in the 3D printing process to balance strength enhancement with structural integrity. Simultaneously, H2CO3 attacks the calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel, prompting the leaching of calcium ions to combine with carbonate ions and form CaCO3. Consequently, the silicate chains within the C-S-H structure re-polymerize, transforming into silica gel with a lower Ca/Si ratio[42-45].

Figure 6. Schematic diagram of the carbonation mechanism and microstructural evolution model of concrete under different humidity environments. Republished with permission from[41].

However, for 3D printing, a process that pursues instantaneous solidification, the most decisive mechanism is the direct carbon mineralization pathway. In this process, the carbon utilization aspect of CCUS technology involves the direct reaction of CO2 with the surfaces of unhydrated tricalcium silicate (C3S) and dicalcium silicate (C2S) clinker mineral particles, generating CaCO3 and early-age C-S-H in situ[46-48]. In traditionally water-cured concrete, this is a relatively slow, late-stage process[49-51]; however, within the

4. Carbon Curing Processes in Concrete Additive Manufacturing

4.1 Fresh state carbon mineralization

To address the buildability challenges inherent to 3DPC, in situ rheological control has emerged as a critical technological pathway. Among the various approaches, carbon mineralization in the fresh state exhibits immense potential. This strategy utilizes CO2 as a chemical trigger, injecting it into the fresh mortar via secondary mixing prior to printing to achieve an on-demand transformation of material properties.

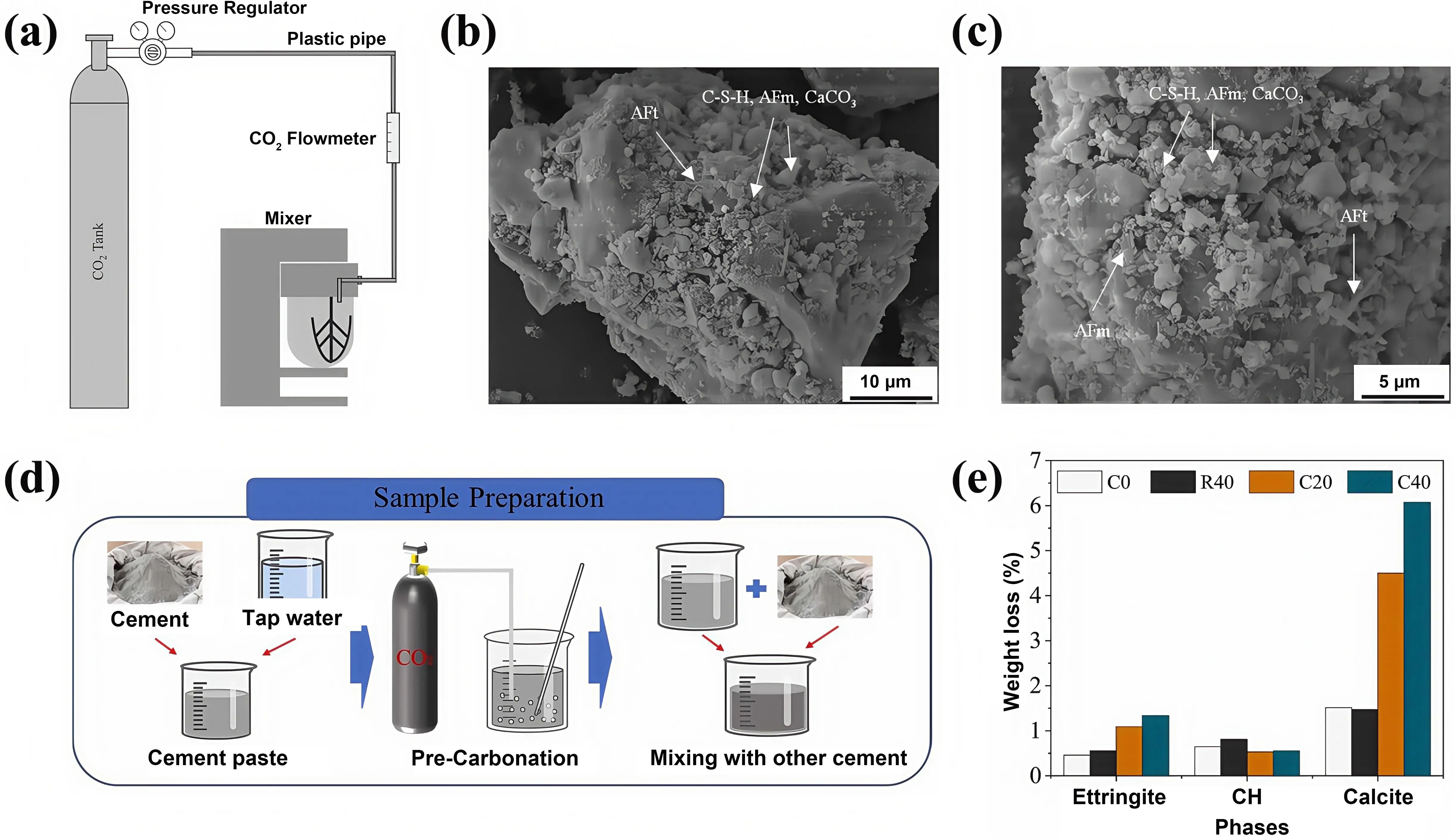

Li et al.[52] utilized the apparatus illustrated in Figure 7a to continuously inject CO2 gas at a flow rate of 10 L/min into mortar that had undergone 4 minutes of conventional mixing. With increasing CO2 mixing duration, the flowability of the mortar declined significantly, and the setting time was drastically shortened. Following 240 seconds of CO2 mixing, the fluidity of the 3DPC decreased by 13% compared to the control group, while the final setting time was reduced by 40%. The injected CO2 reacted rapidly with calcium ions and hydration products within the paste, generating solid-phase CaCO3 and carboaluminates, as shown in Figure 7b,c. This process altered the surface morphology of the cement particles and induced flocculation, thereby causing the static yield stress of the 3DPC to escalate sharply within a short period. This rapid evolution of rheological properties induced by CO2 mixing resulted in a significant enhancement in the buildability of the 3DPC. The uncarbonated control group collapsed upon reaching a printing height of 11 layers, whereas the 3DPC treated with secondary CO2 mixing stably exceeded 50 layers without observable deformation.

Figure 7. (a) Schematic diagram of the experimental setup. Republished with permission from[52]; (b)-(c) Micro-morphology of the carbonated group immediately after mixing (0 h) and after 1 h, illustrating the in-situ generation and packing densification process of granular calcium carbonate and carboaluminates. Republished with permission from[52]; (d) Schematic diagram of the process flow. Republished with permission from[53]; (e) Quantitative phase analysis showing a significant increase in calcite generation with extending carbonation time. Republished with permission from[53].

In a different approach, Qian et al.[53] proposed a stepwise mixing pre-carbonation process, as depicted in Figure 7d. In this method, 50% of the cement was initially mixed with water to prepare a base slurry, which was subjected to carbonation pretreatment for a specific duration via a micro-bubble diffuser, followed by the addition of the remaining cement to complete the final mixing. This process flow substantially intensified the carbon capture capability of the material. Quantitative phase analysis results (Figure 7e) revealed that after 40 minutes of treatment, the calcite content within the paste surged by 301% compared to the uncarbonated control. This result substantiates that the staged introduction of CO2 effectively drives the conversion of gas into stable sub-micron carbonate particles, thereby significantly elevating the mineralization and sequestration capacity of the material. Consequently, this provides a crucial theoretical and practical foundation for additive manufacturing technologies like 3DPC that necessitate precise rheological regulation.

Building on this foundation, the introduction of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) into the material system can yield significant synergistic enhancements when combined with CO2 mixing. The micro- and sub-micron scale particles of silica fume[54] provide abundant active sites for the heterogeneous nucleation of carbonate products, thereby substantially accelerating the carbon mineralization reaction process. As illustrated in Figure 8a,b,c, with the silica fume dosage increasing from 0% to 5%, there is a significant enrichment of granular carbonation products, such as mono-carboaluminate, generated on the surface of the paste particles. Driven by the synergy between CO2 and silica fume, the buildability of 3DPC is further amplified; the maximum number of printable layers surged from 13 layers using CO2 alone to over 33 layers, far surpassing the efficacy achievable by solitary CO2 mixing. The elucidation of this synergistic mechanism offers a novel technical pathway for optimizing the performance of 3DPC. However, the efficacy of this technology is highly sensitive to the CO2 injection dosage. An insufficient dosage fails to achieve the anticipated carbon mineralization modification, whereas an excessive dosage exerts a detrimental impact on the flowability of the paste

Figure 8. (a) Carbonated group without silica fume; (b) Carbonated group with 2% silica fume; (c) Carbonated group with 5% silica fume; Flowability changes of mortars with different silica fume dosages (0%, 1%, 2%, 5%) under different CO2 mixing times (d) and flow rates (e); (f) DTG curves of paste groups after carbonation. Republished with permission from[54]. DTG: thermogravimetric analysis.

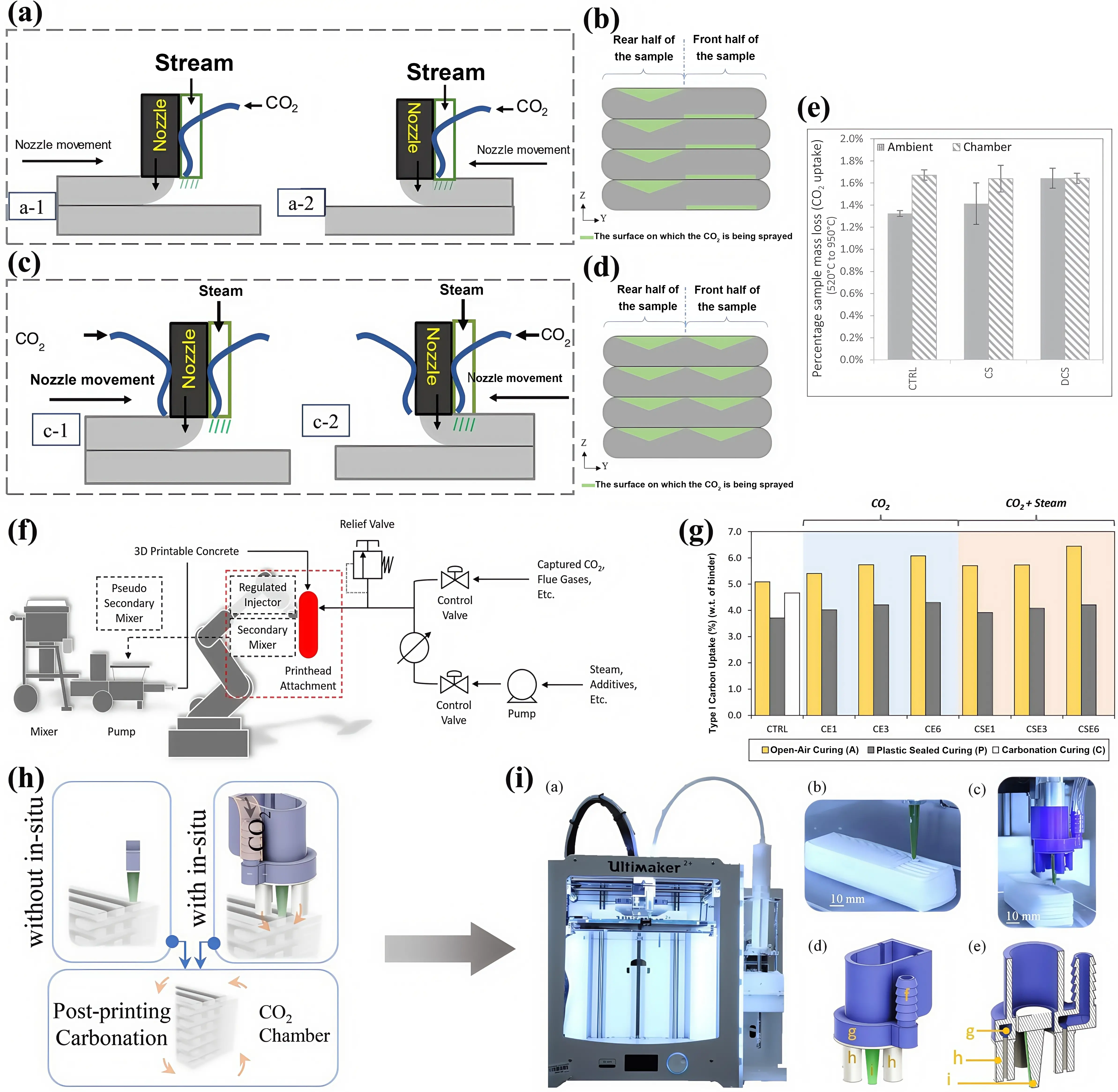

4.2 Synchronous carbon sequestration during printing

The layer-by-layer construction characteristic of 3D printing technology offers unique temporal windows and spatial advantages for CCUS technology. Compared to the fresh state carbon mineralization strategy, synchronous carbon sequestration technology during printing is capable of fully exploiting the transient state of material extrusion and deposition by triggering an immediate carbonation reaction through the real-time introduction of CO2. This process not only maximizes carbon sequestration efficiency at the critical moment of high material reactivity but also enhances interlayer bonding and structural stability through rapidly generated carbonation products. Based on the contact method between CO2 and the printing material, this process is primarily categorized into two types, namely post-extrusion surface carbonation and pre-extrusion carbonation.

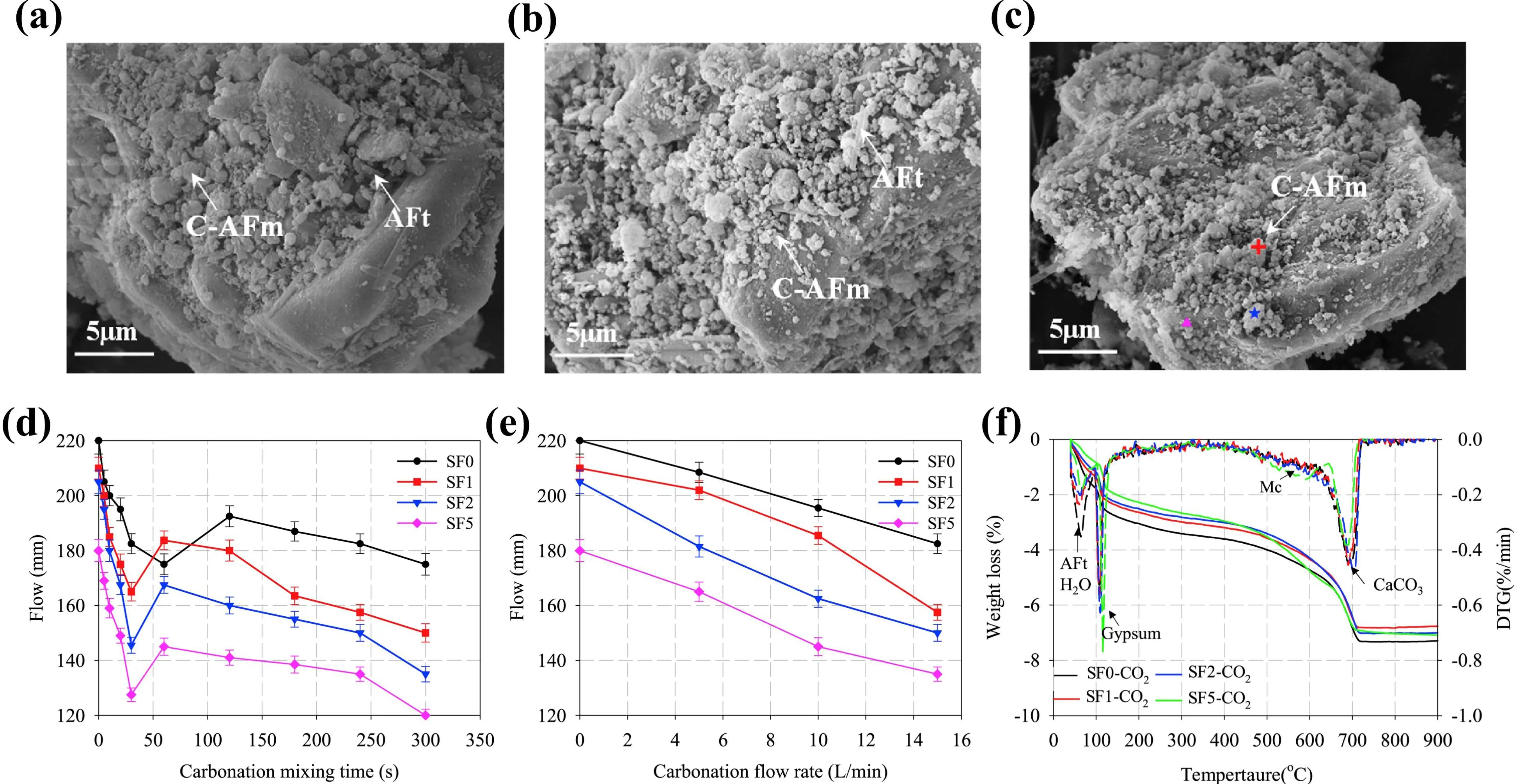

The post-extrusion surface carbonation process involves mounting nozzles alongside the printhead to spray CO2 gas directly onto the surface of the freshly deposited 3DPC filaments. Early research by Tay et al.[55] revealed that spraying pressurized CO2 gas onto the surface of each layer during the printing process increased the carbon uptake of the 3DPC by 15% compared to control samples. However, the “blowing effect” of high-pressure CO2 gas caused physical damage to the moist concrete filaments, leading to material loss and the formation of interlayer defects, thereby reducing mechanical strength. To address this issue, researchers explored a synergistic CO2 and steam spraying process[55], wherein synchronous steam injection not only promoted carbonation through hydrothermal conditions but also mitigated the drying and bonding issues caused by gas impact. Subsequently, addressing the issue of uneven coverage associated with single-jet spraying, Tay et al.[56] compared unidirectional spraying (Figure 9a,b) with a bidirectional spraying process (Figure 9c,d); the bidirectional design effectively eliminated gas coverage blind spots on the rear of the filaments. Test results from Figure 9e further confirmed that, compared to the control and unidirectional groups, the bidirectional spraying system significantly enhanced calcium carbonate generation under ambient curing, ultimately resulting in a CaCO3 content approximately 24% higher than that of the control group. Despite these advancements, this technology still struggles to completely avoid increased porosity and interfacial delamination induced by gas impact.

Figure 9. (a)-(b) Schematic diagram of the CS setup and coverage area[56]; (c)-(d) Schematic diagram of the DCS setup and coverage area[56]; (e) Comparison of carbon uptake among the CTRL, CS, and DCS groups[56]; (f) Schematic diagram of the two-step extrusion system[57]; (g) Comparison of volumetric carbon uptake among the CTRL, CE, and CSE groups[57]; (h) Schematic of the in-situ carbonation strategy[58]; (i) Customized four-pronged diffusion nozzle and printing equipment[58]. CS: unidirectional CO2 spraying; DCS: bidirectional CO2 spraying; CTRL: control; CE: CO2-only exposure; CSE: steam-CO2 synergistic exposure.

To overcome the potential damage to material structural integrity caused by post-extrusion surface carbonation, the pre-extrusion carbonation process was proposed. Lim et al.[57] developed an innovative two-step extrusion system, as shown in Figure 9f, which integrates a secondary mixer at the printhead. This system directly injects and forcibly mixes CO2 and steam into the flowing material at the moment the 3DPC is extruded. This approach aims to achieve more uniform volumetric carbonation rather than merely a surface reaction. Research has found that this technology achieves positive synergistic enhancements in both carbon capture and mechanical performance. As evidenced in Figure 9g, compared to traditional accelerated carbonation in a closed chamber, the volumetric carbon uptake increased by 38.2%. Simultaneously, the in situ generated nano-scale CaCO3 particles accelerated early hydration, thereby exerting a positive influence on the final performance of the material.

Furthermore, synchronous carbon sequestration during printing exerts a significant positive influence on the rheological properties and printability of the material. On one hand, the pre-extrusion injection research by Lim et al.[57] demonstrates that the injection of CO2 enhances the thixotropy of the paste. Simultaneously, the rapid early-age carbonation reaction endows the material with

Synchronous carbon sequestration during printing represents a highly promising in situ curing technology; however, its efficacy is heavily contingent upon the specific technical pathway employed. Post-extrusion surface carbonation demonstrates significant effectiveness in promoting surface carbon sequestration, yet the physical impingement of high-pressure gas on the printed filaments requires cautious management. This method yields maximum advantage when combined with porous structural designs and

4.3 Post-printing carbonation curing

Post-printing carbonation curing currently stands as the most widely implemented carbonation process in 3DPC. This process typically involves placing the components into a specific CO2 environment for accelerated curing after the printing construction is completed. This approach aims not only to enhance the mechanical properties of the components, particularly early-age strength and the weak interlayer bonding, through carbonation reaction products[59-61], but also serves as an effective CO2 sequestration method that contributes to reducing the carbon footprint of the material[62,63].

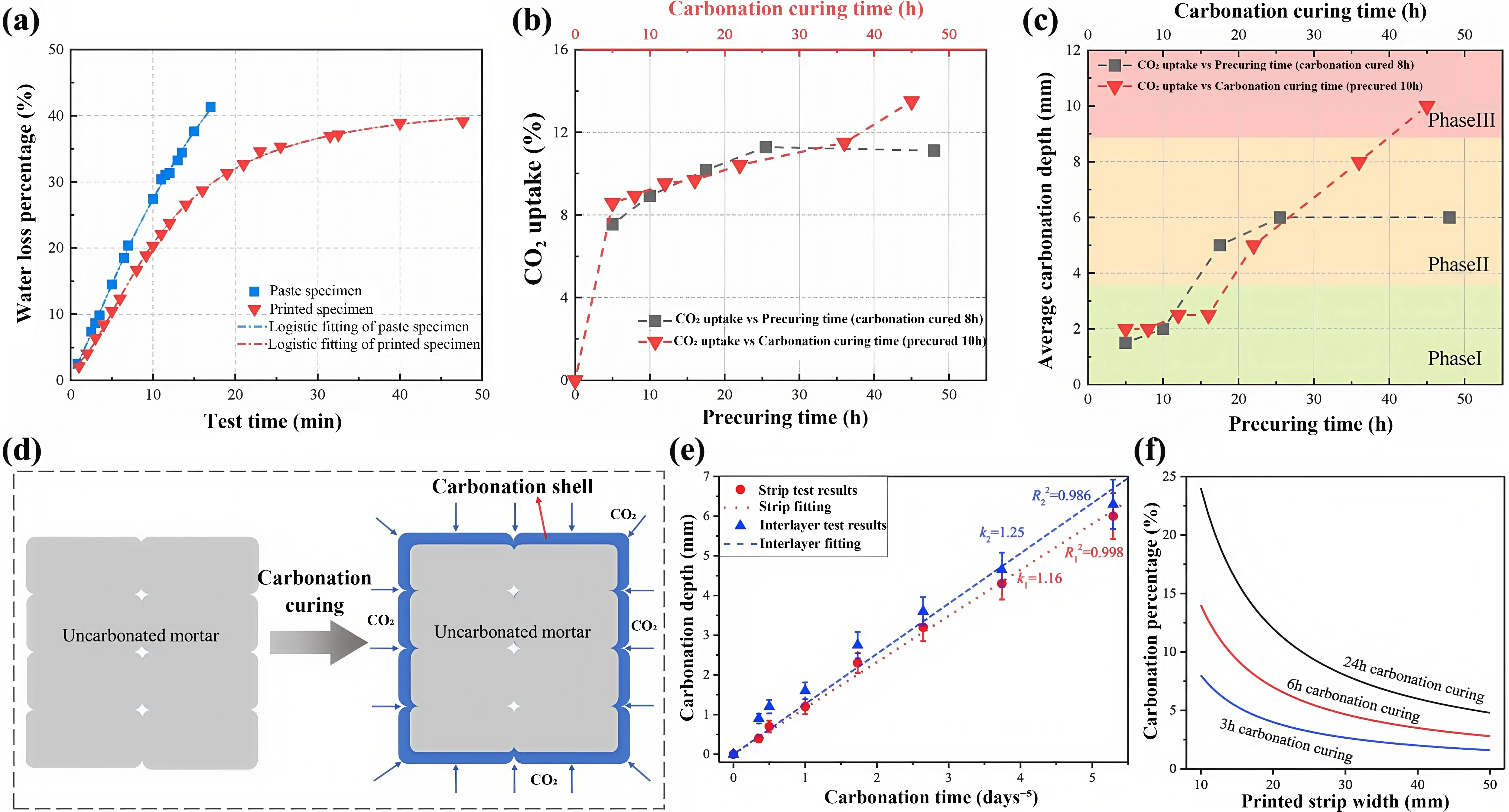

The efficacy of the post-printing process relies heavily on the precise regulation of the curing regime, specifically the synergistic matching of the pre-curing, carbonation, and subsequent curing phases. The primary critical step in the post-treatment process is pre-curing or pre-drying. Fresh 3DPC materials possess a high moisture content immediately after printing, and excessive water can block pore channels, thereby impeding the transport and diffusion of CO2 gas[64]. Consequently, it is imperative to achieve an “optimal moisture content” for the component through pre-curing (Figure 10a). Research indicates that the pre-curing duration is closely correlated with optimal mechanical performance and CO2 uptake. A study by Han et al.[64] focusing on ordinary Portland cement (OPC)-based 3DPC revealed that with the extension of pre-curing time, both CO2 uptake and carbonation depth exhibited a trend of rapid initial growth followed by stabilization (Figure 10b,c). Among the tested durations, a pre-curing time of 10 to 17.5 hours, corresponding to a water loss rate of approximately 20%, was identified as the ideal choice for achieving optimal early strength. For other binder systems, such as γ-C2S-based[59] and magnesium slag-based[65] printing materials, the optimal pre-drying water-to-solid ratio (w/s) was determined to be around 0.08. However, excessive pre-curing is not beneficial. Over-drying results in a lack of sufficient liquid water within the pores to dissolve CO2 and leach calcium ions, thereby inhibiting the progress of the carbonation reaction. Simultaneously, excessive moisture loss exerts adverse effects on subsequent hydration reactions, potentially leading to a reduction in late-age strength[64].

Figure 10. (a) Variation of water loss percentage of 3DPC specimens with drying time. Republished with permission from[64]; (b) Variation of CO2 uptake with pre-curing time and carbonation curing time, showing the existence of an optimal window. Republished with permission from[64]; (c) Promoting effect of pre-curing time on carbonation depth. Republished with permission from[64]; (d) Schematic of the “carbonation shell” effect, illustrating the blocking mechanism of the external dense carbonation layer against internal moisture transport and reaction. Republished with permission from[60]; (e) Evolutionary comparison of carbonation depths between printed strips and interlayer regions, confirming faster interlayer penetration. Republished with permission from[60]; (f) Influence of printed strip width on overall carbonation percentage, showing the highest carbonation efficiency for the 10 mm narrow strip. Republished with permission from[60]. 3DPC: 3D printed concrete.

Upon reaching the optimal moisture content, the components are transferred to a carbonation chamber for accelerated curing. Process parameters during this phase, such as CO2 concentration, pressure, and curing duration, play a decisive role in the final performance[64,66]. Notably, excessively prolonged carbonation times may have detrimental effects on mechanical properties. Although extending the carbonation duration typically increases total CO2 uptake, multiple studies indicate the existence of an optimal duration. For OPC-based materials, a carbonation time of 12 to 16 hours maximizes early strength, whereas carbonation exceeding 22 hours leads to a decline in late-age strength compared to standard curing or results in no significant improvement[64]. This phenomenon is attributed to the formation of a dense “carbonation shell” caused by over-carbonation, which hinders the infiltration of water into the component interior during the subsequent curing stage, thereby inhibiting the long-term hydration reaction of the unhydrated cement core (Figure 10d)[60]. Furthermore, in specific binder systems such as calcium sulphoaluminate cement-based engineered cementitious composite, the carbonation process may decompose hydration products that are critical to performance, such as ettringite, leading to a decrease in flexural performance[62]. Therefore, the post-treatment process must balance the instantaneous gain from the carbonation reaction with long-term hydration development to achieve an optimal solution for

In summary, these three process pathways present distinct technical trade-offs. Fresh state carbon mineralization effectively regulates rheology to improve buildability, but excessive carbonation can compromise material extrudability. Synchronous carbon sequestration enables real-time performance enhancement, although high-pressure gas injection risks physical damage to the printed filaments. Post-printing carbonation curing provides the most significant improvement in mechanical properties and interlayer bonding, yet its effectiveness is limited by carbonation depth and the necessity of specific pre-curing regimes. Therefore, selecting the appropriate strategy tailored to specific engineering scenarios is essential to balance printability, early-age stability, and long-term performance.

5. Mechanical Performance Regulation Mechanisms via CO2 Curing in 3DPC

5.1 Ordinary cementitious materials

Systems utilizing OPC as the core binder constitute the foundation of concrete additive manufacturing applications. The

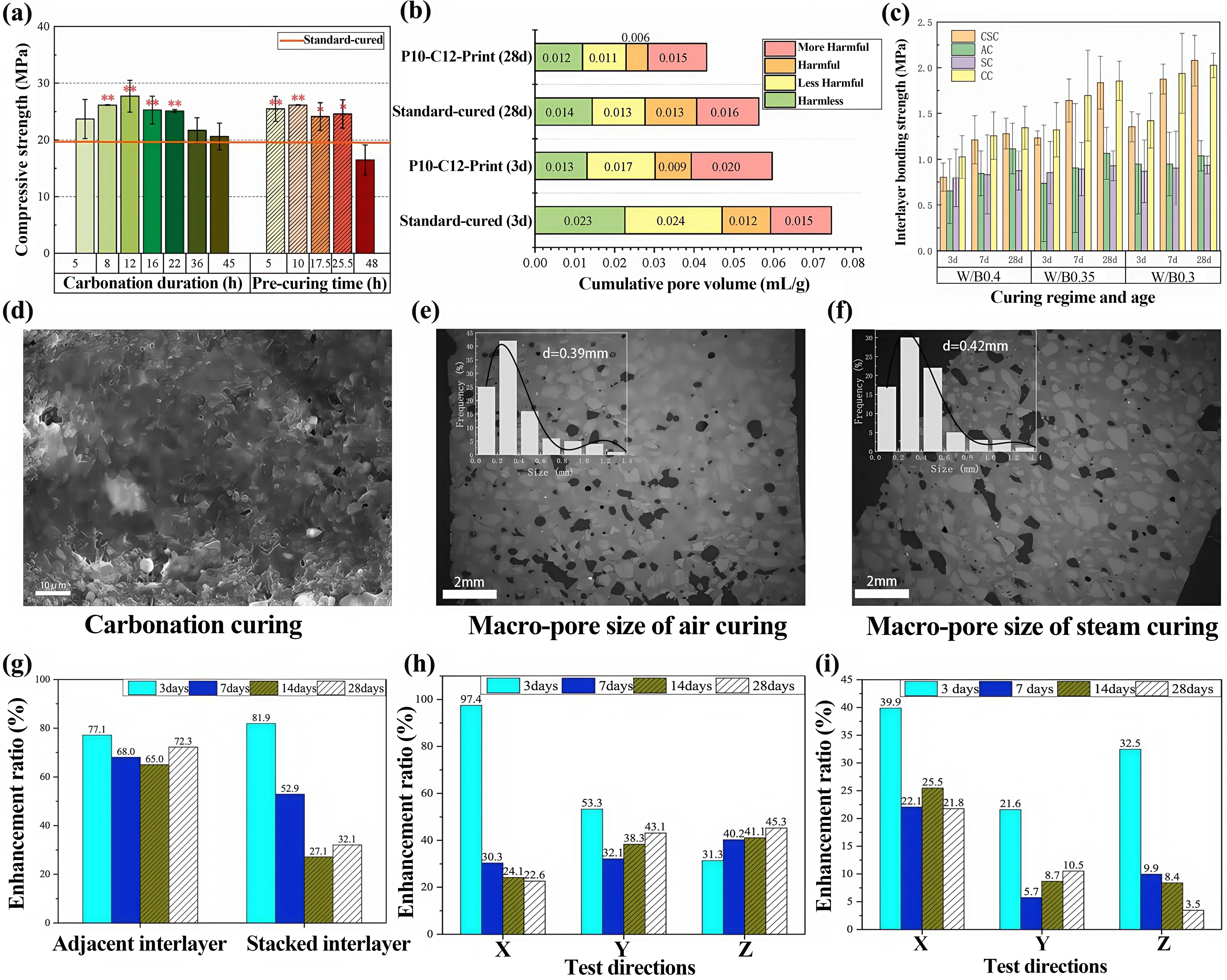

The enhancement of mechanical properties in 3DPC by this technology is particularly profound at early ages. An appropriate carbonation curing regime can achieve a compressive strength increment of up to 39.9% at 3 days (Figure 11a)[64]. This strengthening effect relies heavily on the optimization of curing process parameters, implying the existence of an optimal curing window. Both insufficient and excessive durations of pre-curing and carbonation are detrimental to strength development. Ideal pre-curing aims to achieve an optimal water loss rate to facilitate CO2 diffusion. Conversely, excessive carbonation, such as that exceeding 22 hours, may lead to strength reduction due to the excessive consumption of hydration precursors and the hindrance of late-age hydration[64]. As the curing age increases, the enhancing effect of CO2 curing on late-age strength diminishes.

Figure 11. (a) Influence of carbonation duration and pre-curing time on early-age compressive strength[64]; (b) Evolution of pore volume and size distribution pre- and

Specifically, the inherently loose and porous nature of the 3DPC interlayer transition zone provides ideal permeation channels for CO2 gas, enabling carbonation products to effectively fill mesopores and macropores smaller than 200 nm, thereby significantly reducing porosity and the volume fraction of harmful pores (Figure 11b)[64]. This improvement in pore structure is directly reflected in the comparison of macroscopic interlayer performance. Li et al.[61] found that compared to standard curing, air curing, and steam curing, the interlayer bond strength after carbonation curing exhibited significant advantages at all ages (Figure 11c). Carbonation curing forms a dense skeletal and shell structure around interfacial pores (Figure 11d), whereas samples under air curing (Figure 11e) and steam curing (Figure 11f) retain numerous macropore defects and loose structures at the interface due to poor hydration environments, which explains the degradation of their interlayer strength.

Research by Wang et al.[60] further quantified the targeted enhancement effect of carbonation curing on weak links. At an age of

In summary, carbon mineralization serves as an effective strategy for regulating the mechanical properties of OPC-based 3DPC. By generating calcium carbonate fillers in situ within the material, particularly at the loose interlayer interfaces, this technology significantly enhances early compressive, tensile, and interlayer bond strengths. This targeted reinforcement of weak links holds positive significance for ameliorating the anisotropy issues of the material.

5.2 Supplementary cementitious materials

SCMs play a pivotal role in the carbon sequestration systems of 3DPC, exerting a significant influence on the development of mechanical properties during the carbonation process through their unique chemical compositions and reactivity.

As a highly reactive SCM, silica fume exhibits a unique synergistic strengthening effect on the mechanical properties of 3DPC during the carbon sequestration process. Research by Hao et al.[54] revealed that the incorporation of silica fume could significantly amplify the beneficial effects of fresh state carbon mineralization technology on mechanical properties. This is primarily attributed to silica fume particles serving as nucleation sites that promote the formation of CaCO3 and monocarboaluminate during the mixing process, thereby improving the early strength development of 3DPC. The study indicates that under identical carbonation conditions, the compressive strength of specimens containing silica fume is significantly higher than that of the control group without silica fume, a trend that is particularly pronounced at early ages. Furthermore, silica fume not only functions within OPC systems but also plays a critical physical role in certain novel cementitious material systems. In a printable paste system based on γ-C2S developed by

The impact of high-volume SCM replacement strategies on the mechanical properties of 3DPC exhibits complex variation patterns. Research by Srinivas et al.[73] indicates that when OPC is replaced by high volumes, specifically 60% to 75%, of SCMs such as silica fume, limestone powder, and rice husk ash, mechanical performance is compromised to a certain extent; compressive strength decreases by up to 14%, and flexural strength decreases by 36%. Nevertheless, the mechanical properties of these high-volume SCM systems are significantly enhanced through carbonation treatment. It was observed that while carbonation curing enhances material strength by facilitating CaCO3 formation and refining the pore structure, this increment is insufficient to fully offset the mechanical performance deficit resulting from high-volume replacement relative to pure cement systems. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the lower CO2 buffering capacity of high-volume SCM systems, combined with a carbonation mechanism that relies more heavily on the decalcification of C-S-H gel. Such a process may induce pore coarsening, thereby limiting the ultimate improvement in mechanical properties.

The mechanisms by which different types of SCMs influence mechanical properties during the carbonation process exhibit significant differences. A review by Von Greve-Dierfeld et al.[74] demonstrates that in cementitious materials containing SCMs such as slag, fly ash, silica fume, metakaolin, or limestone, the decalcification and recrystallization of C-S-H gel during carbonation alter the pore structure and compactness of the material, consequently affecting compressive and flexural strengths. In slag-containing cement pastes[75], a substantial portion of calcium remains sequestered within the unhydrated fraction of the slag during the carbonation process. This distinct reaction mechanism causes slag-containing systems to exhibit mechanical property development patterns that differ from those of OPC during carbon curing. Research by Saillio et al.[75] further confirms that the presence of diverse SCMs significantly alters carbonation depth and the distribution of carbonation products, thereby influencing the final mechanical properties.

5.3 Fine aggregates

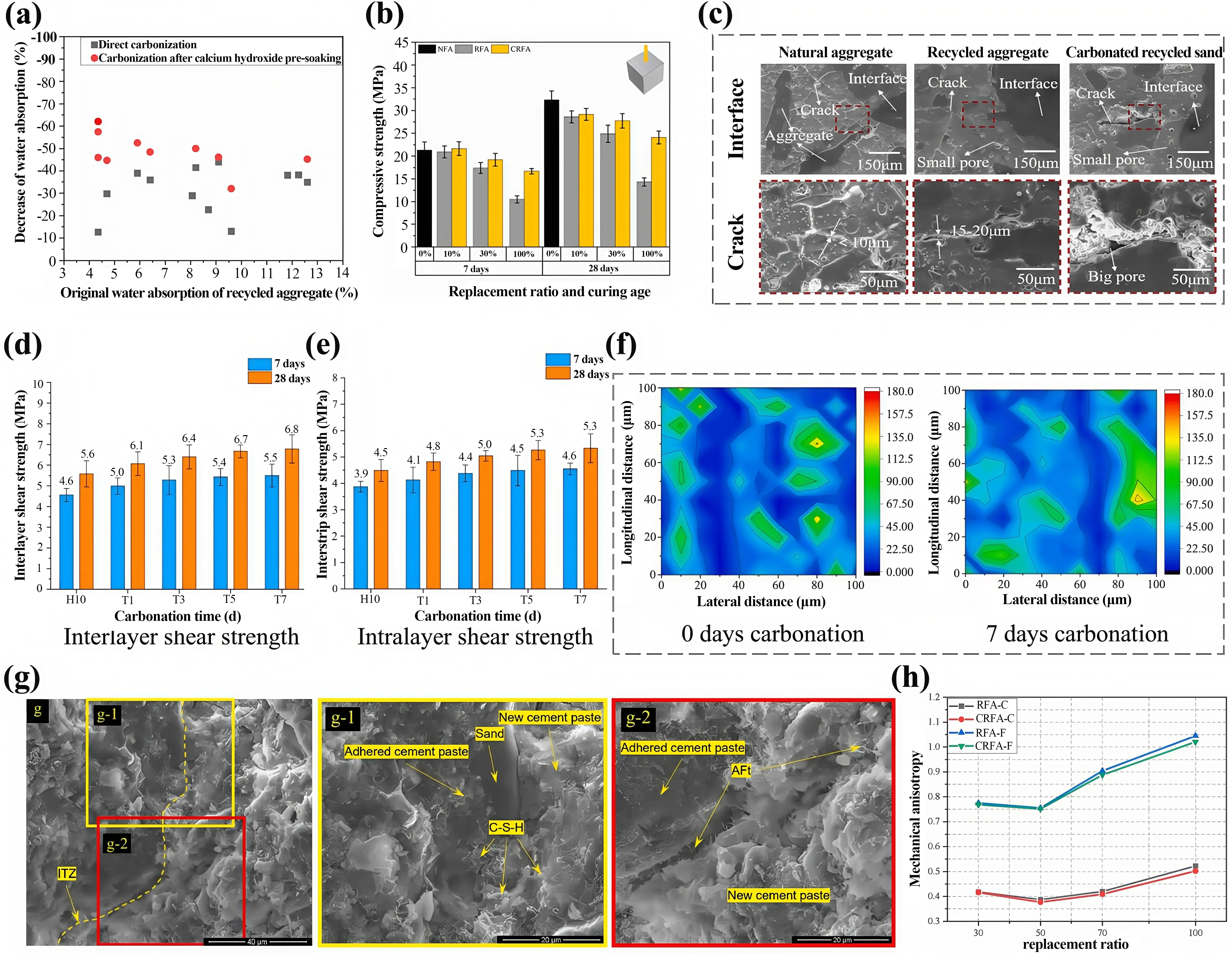

Substituting natural river sand with recycled fine aggregate (RFA) in 3DPC is a key measure to promote the circular economy in the construction industry[76-78]. However, RFA possesses defects such as high water absorption, low strength, and high angularity due to the porous old cement mortar adhered to its surface, which severely debilitates the workability of 3DPC as well as its mechanical properties and durability of the hardened body[79-81]. To address this issue, carbonation pretreatment has been proven to be an efficient and environmentally friendly modification method. Its mechanism lies in the dissolution of CO2 into the pore water on the RFA surface to form carbonic acid, that reacts with Ca(OH)2 and C-S-H gel in the attached mortar to generate dense calcite crystals which fill surface micro-cracks and pores, thereby reducing water absorption and enhancing compactness and strength[82,83]. To further intensify this effect, Ding et al.[82] innovatively adopted a composite method of “saturated calcium hydroxide solution

Figure 12. (a) Improvement effect of pre-soaking carbonation on RFA water absorption. Republished with permission from[82]; (b) Compressive strength of 3DPC in different directions at 100% CRFA replacement ratio. Republished with permission from[83]; (c) Influence of different aggregates on micro-cracks at the interlayer interface. Republished with permission from[84]; (d) Effect of aggregate carbonation duration on interlayer shear strength. Republished with permission from[85]; (e) Effect of aggregate carbonation duration on intralayer shear strength. Republished with permission from[85]; (f) Comparison of nano-indentation modulus distribution in the interfacial region after 0 and 7 days of carbonation. Republished with permission from[85]; (g) Micro-morphology of hydration products in the CRFA interfacial transition zone. Republished with permission from[83]; (h) Influence of CRFA content on mechanical anisotropy coefficients of 3DPC. Republished with permission from[82]. RFA: recycled fine aggregate;

The application of carbonated recycled fine aggregate (CRFA) in 3DPC can significantly enhance the mechanical properties after hardening. Sun et al.[83] found that when natural sand was replaced by 100% CRFA, the 28-day Z-axis compressive strength of 3DPC increased by 68.5% compared to the control group using natural sand (Figure 12b). In addition, carbonation pretreatment not only improved the aggregate itself but also strengthened the weakest interlayer interface in the 3D printed structure. Research by

In addition, the incorporation of CRFA exhibits positive effects on the early-age performance and mechanical anisotropy of 3DPC.

5.4 Coarse aggregates

The introduction of coarse aggregate into 3DPC is a key step in advancing it from mortar systems to concrete applications, yet it faces challenges such as nozzle blockage, aggregate segregation, and aggravated mechanical anisotropy, and potential durability

This deeply modified carbonated recycled aggregate (CRCA) brought fundamental improvements to the mechanical properties of 3DPC, particularly regarding anisotropy. Systematic research by Tong et al.[94] indicated that while the mechanical properties of printed bodies showed a declining trend with increasing RCA replacement rates, performance fully recovered after carbonation modification. Crucially, under the limiting condition of 100% RCA replacement, compared to printed bodies using unmodified RCA, the compressive strength of specimens incorporating CRCA increased by 24.71%, 19.38%, and 23.26% in the X, Y, and Z directions, respectively. Similarly, their flexural strength and splitting tensile strength showed significant improvements in all directions. This series of data forcefully proves that carbonation modification of RCA not only enhances the absolute strength of the material but, more importantly, significantly narrows the gap in mechanical properties between different directions. This effectively alleviates the anisotropy problem of 3D printed structures, which is vital for the safety and reliability of printed load-bearing components.

From the perspective of microstructural evolution, this improvement in macro-performance is fully explained. Through X-ray computed tomography technology, researchers were able to non-destructively observe the internal pore structure of the printed body. The results showed that the incorporation of CRCA could significantly optimize the internal pore defects of 3D printed RCA concrete, reduce the overall porosity, and improve the pore size distribution[94]. The strengthening mechanism is twofold. The physical properties of the modified RCA itself (such as reduced water absorption and decreased crushing index) provided a

6. Technical Challenges and Limiting Factors

The integration of concrete additive manufacturing with CCUS technologies faces fundamental challenges rooted in materials science and process control in practice. At its core, the rapid carbonation mechanism exacerbates the intrinsic rheological paradox within the concrete additive manufacturing process. Specifically, the process necessitates high flowability during the pumping and extrusion phases to ensure smooth transport, yet demands the immediate acquisition of high yield stress post-extrusion to resist self-weight and subsequent layer loads, thereby maintaining geometric stability[95-97]. Although the carbon mineralization process generates rigid CaCO3 via rapid carbonation reactions, significantly enhancing early-age strength and shape retention of deposited layers, this vigorous surface chemical reaction drastically curtails the open time window available for forming effective interlayer bonds. The rapidly formed dense calcium carbonate layer physically obstructs interlayer interdiffusion and chemical bonding, predisposing the interface to the formation of weak zones. This phenomenon, coupled with the distinct pore defect distribution inherent to the printing process[98], serves as the primary driver of significant mechanical anisotropy within the structure.

This extreme emphasis on early-age performance is clearly corroborated by the bibliometric analysis presented in Section 2.3. The keyword density visualization (Figure 5) reveals that “strength” and “performance” constitute absolute research hotspots, exhibiting tight linkages with “carbonation” and “3D printing”. Conversely, nodes related to “durability” are situated at the periphery of the

Current preliminary research suggests that carbonation processes primarily enhance the durability of 3DPC by densifying the microstructure, forming dense protective layers, and repairing interlayer defects. Regarding resistance to erosion and permeability, the synchronous carbon sequestration during the printing process generates a dense calcium carbonate protective layer in situ on the surface of printed strips, which aids in reducing gas permeability and hindering chloride ion ingress[55]. Both fresh state carbon mineralization and post-printing carbonation curing fill the matrix pores via calcium carbonate precipitation, thereby reducing the volume of harmful pores and refining the pore size distribution[52,64]. For the weak interlayer regions, carbonation curing effectively ameliorates the loose interfacial structures resulting from drying or steam curing environments[61]. In particular, the introduction of a C2S-based CO2-activated interlayer enhancer can facilitate the in-situ mineralization of calcium carbonate and silica gel, effectively filling interlayer voids and lowering porosity, thus significantly elevating interlayer compactness and impermeability[67]. However, carbonation exerts potential adverse effects on shrinkage and expansion behavior and long-term performance. On one hand, while densifying the matrix, carbonation may induce a slight increase in drying shrinkage[52]; furthermore, in engineered cementitious composites that rely on ettringite to generate micro-expansion for shrinkage compensation, carbonation can decompose ettringite, thereby weakening its expansive performance and increasing the risk of cracking[62]. On the other hand, excessive carbonation curing can form a dense “carbonation shell” on the surface, obstructing moisture migration to the interior and consequently inhibiting the subsequent hydration reaction of unhydrated cement, which is unfavorable for the sustained development of late-age

The aforementioned contradictions at the material level directly translate into complexity in process control and uncertainty in mechanical performance. To ensure structural stability while preventing the formation of weak interlayer planes, material deposition and carbon sequestration processes must achieve precise spatiotemporal synchronization at the millisecond level, rendering the process window extremely narrow. Any deviation in control may lead to over-carbonation. In this scenario, excessive CO2 exposure prematurely consumes active cementitious components, such as C3S and C2S, which are essential for long-term strength development, and strips away necessary moisture. This inhibits subsequent hydration reactions, ultimately resulting in components that, despite possessing high early strength, exhibit stagnant or even regressive long-term mechanical property growth. Furthermore, carbonation curing is fundamentally a surface-to-interior diffusion-controlled process, which inevitably results in

7. Development Trends and Technical Outlook

To address the aforementioned challenges, future development trends are propelling this technology toward maturity through systematic synergistic innovation in materials, processes, and design. The bibliometric analysis map in Section 2.3 (Figure 3) provides a clear roadmap for these trends. In terms of materials, although nodes such as “geopolymer” have appeared in the map, their volume remains small, and they are situated at the periphery of the network. This presages a shift in research focus from the current red cluster centered on “portland cement” toward exploring the integration of low-carbon cementitious materials with carbon mineralization technologies.

Current research demonstrates a clear technological evolution in 3D printed low-carbon cementitious materials. Regarding the resource utilization of construction and industrial wastes, materials such as recycled clay brick powder[99,100] and incineration bottom ash[101] have been successfully modified to reduce embodied carbon without compromising printability. Subsequently, research has advanced toward the precise design of alternative binder systems tailored for 3D printing. This encompasses not only limestone calcined clay cement optimized for extrudability[102,103], but also geopolymer concrete modified for large-scale applications[104], as well as one-part geopolymers designed to further minimize carbon footprints[105,106]. Moreover, reactive magnesium oxide-based

Regarding process control, intelligent closed-loop control is an inevitable trajectory. Although the term “intelligent” has not yet become a hotspot in the current map, the “digital fabrication” node in the green cluster already underscores the significance of process control. Future efforts must integrate multi-modal sensor arrays encompassing vision, thermal imaging, and pressure, and employ artificial intelligence algorithms to analyze real-time data, thereby achieving dynamic modulation of process parameters. This intelligent closed-loop system is pivotal for coping with material and environmental variations, transcending the narrow process window, and ensuring the stability of printing quality. To further validate the long-term reliability of printed components, future research must prioritize quantifying critical durability indicators, particularly chloride ingress resistance to verify the efficacy of microstructure densification, and long-term shrinkage and expansion behavior to assess the risks of cracking.

These technological advancements will ultimately be maximized through an integrated design-material-process approach. The geometric freedom endowed by concrete additive manufacturing makes it possible to design and manufacture structures with complex topological morphologies, such as triply periodic minimal surfaces[110] or helical surfaces[111]. Such structures, while substantially reducing material consumption, leverage their exceptionally high specific surface area to transform the carbon sequestration process from a slow, diffusion-dominated process into an efficient, convection-driven process, significantly elevating carbon capture efficiency and economic viability. By synergizing low-carbon materials, efficient intelligent curing processes, and extreme structural optimization design, future buildings are expected to achieve carbon-negative emissions, transitioning from being primary carbon sources to long-term carbon sinks. From a broader perspective, the combination of this technology with in-situ resource utilization provides key technical support for extraterrestrial construction in extreme environments, such as the Moon, by utilizing local CO2-rich atmospheres, serving as a fundamental cornerstone for sustainable deep space exploration.

8. Conclusions

This review has systematically summarized the process pathways, regulation mechanisms, and development frontiers of CCUS technologies in concrete additive manufacturing. Research indicates that integrating CCUS technology with 3D printing processes is not only an effective means to enhance the performance of printed components and resolve technical bottlenecks, but also provides an innovative pathway for achieving carbon sequestration and carbon-negative construction within the building industry. Based on the analysis presented herein, the main conclusions are summarized as follows:

(1) Bibliometric analysis demonstrates an accelerating growth trend in this field, with research focus shifting from basic printing processes to synergistic optimization via carbon sequestration. While current studies concentrate on “strength” and “performance”, “durability” remains peripheral, highlighting a significant knowledge gap in long-term serviceability research.

(2) Three technical routes are established. Fresh state carbon mineralization regulates rheology to enhance buildability. Synchronous carbon sequestration favors pre-extrusion injection over post-extrusion spraying to avoid physical damage and ensure uniformity. Post-printing carbonation curing relies on pre-drying to control the optimal moisture content for effective CO2 diffusion.

(3) Carbonation curing enhances early-age properties and ameliorates anisotropy by generating calcium carbonate to fill pores, specifically achieving a targeted enhancement of weak interlayer interfaces. Experimental results show that at 3 days, curing increased stacked layer bond strength by 81.9% and X-direction splitting tensile strength by 97.4%.

(4) Supplementary cementitious materials and recycled aggregates exhibit synergistic effects. Silica fume provides nucleation sites to accelerate mineralization. Carbonation pretreatment modifies RFA by forming dense calcite crystals; notably, using 100% carbonated RFA increased 28-day Z-axis compressive strength by 68.5% compared to natural sand controls.

(5) The field faces bottlenecks regarding curing uniformity and narrow process windows. Future directions include intelligent

Authors contribution

Liu L: Investigation, writing-original draft.

Liu H: Methodology, writing-original draft, funding acquisition.

Ma R: Data curation, visualization.

Wang Z: Conceptualization, analysis.

Wang Z: Supervision.

Liu C: Conceptualization, project administration, supervision, funding acquisition.

Conflicts of interest

Chao Liu is an Editorial Board Member of Journal of Building Design and Environment. Huawei Liu is a Youth Editorial Board Member of Journal of Building Design and Environment. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52178251, Grant No. 62276207), the National Natural Science Foundation of China Youth Fund (Grant No. 52408289), the Technology Innovation Guidance Program of Shaanxi Province (Grant No. 2023GXLH-049), Shaanxi Provincial Natural Science Basic Research Program (Grant No. 2025JC-YBMS-550), Qinchuangyuan’s “Scientist and Engineer” Team Building of Shaanxi Province (Grant No. 2023KXJ-242), and the Special Research Program for Local Service of Shaanxi Province (Grant No. 23JC047).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Ahmed Ali K, Ahmad MI, Yusup Y. Issues, impacts, and mitigations of carbon dioxide emissions in the building sector. Sustainability. 2020;12(18):7427.[DOI]

-

2. Chen L, Huang L, Hua J, Chen Z, Wei L, Osman AI, et al. Green construction for low-carbon cities: A review. Environ Chem Lett. 2023;21(3):1627-1657.[DOI]

-

3. Röck M, Saade MRM, Balouktsi M, Rasmussen FN, Birgisdottir H, Frischknecht R, et al. Embodied GHG emissions of buildings–The hidden challenge for effective climate change mitigation. Appl Energy. 2020;258:114107.[DOI]

-

4. Andrew RM. Global CO2 emissions from cement production, 1928–2018. Earth Syst Sci Data. 2019;11(4):1675-1710.[DOI]

-

5. Chaudhury R, Sharma U, Thapliyal P, Singh L. Low-CO2 emission strategies to achieve net zero target in cement sector. J Clean Prod. 2023;417:137466.[DOI]

-

6. Shah IH, Miller SA, Jiang D, Myers RJ. Cement substitution with secondary materials can reduce annual global CO2 emissions by up to 1.3 gigatons. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):5758.[DOI]

-

7. Winnefeld F, Leemann A, German A, Lothenbach B. CO2 storage in cement and concrete by mineral carbonation. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2022;38:100672.[DOI]

-

8. Davoodi S, Al-Shargabi M, Wood DA, Rukavishnikov VS, Minaev KM. Review of technological progress in carbon dioxide capture, storage, and utilization. Gas Sci Eng. 2023;117:205070.[DOI]

-

9. Chen S, Liu J, Zhang Q, Teng F, McLellan BC. A critical review on deployment planning and risk analysis of carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) toward carbon neutrality. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2022;167:112537.[DOI]

-

10. Jiang T, Cui K, Chang J. Development of low-carbon cement: Carbonation of compounded C2S by β-C2S and γ-C2S. Cem Concr Compos. 2023;139:105071.[DOI]

-

11. Woodall CM, McQueen N, Pilorgé H, Wilcox J. Utilization of mineral carbonation products: Current state and potential. Greenh Gases Sci Technol. 2019;9(6):1096-1113.[DOI]

-

12. Snæbjörnsdóttir SÓ, Sigfússon B, Marieni C, Goldberg D, Gislason SR, Oelkers EH. Carbon dioxide storage through mineral carbonation. Nat Rev Earth Environ. 2020;1(2):90-102.[DOI]

-

13. Vijayan DS, Gopalaswamy S, Sivasuriyan A, Koda E, Sitek W, Vaverková MD, et al. Advances and applications of carbon capture, utilization, and storage in civil engineering: A comprehensive review. Energies. 2024;17(23):6046.[DOI]

-

14. Lin Q, Zhang X, Wang T, Zheng C, Gao X. Technical perspective of carbon capture, utilization, and storage. Engineering. 2022;14:27-32.[DOI]

-

15. Li N, Mo L, Unluer C. Emerging CO2 utilization technologies for construction materials: A review. J CO Util. 2022;65:102237.[DOI]

-

16. Batikha M, Jotangia R, Baaj MY, Mousleh I. 3D concrete printing for sustainable and economical construction: A comparative study. Autom Constr. 2022;134:104087.[DOI]

-

17. Hassan A, Alomayri T, Noaman MF, Zhang C. 3D printed concrete for sustainable construction: A review of mechanical properties and environmental impact. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2025;32(5):2713-2743.[DOI]

-

18. Ahmed GH. A review of “3D concrete printing”: Materials and process characterization, economic considerations and environmental sustainability. J Build Eng. 2023;66:105863.[DOI]

-

19. Khan SA, Koç M, Al-Ghamdi SG. Sustainability assessment, potentials and challenges of 3D printed concrete structures: A systematic review for built environmental applications. J Clean Prod. 2021;303:127027.[DOI]

-

20. Tu H, Wei Z, Bahrami A, Ben Kahla N, Ahmad A, Özkılıç YO. Recent advancements and future trends in 3D concrete printing using waste materials. Dev Built Environ. 2023;16:100187.[DOI]

-

21. Nguyen-Van V, Li S, Liu J, Nguyen K, Tran P. Modelling of 3D concrete printing process: A perspective on material and structural simulations. Addit Manuf. 2023;61:103333.[DOI]

-

22. Ding T, Xiao J, Mechtcherine V. Microstructure and mechanical properties of interlayer regions in extrusion-based 3D printed concrete: A critical review. Cem Concr Compos. 2023;141:105154.[DOI]

-

23. Nodehi M, Aguayo F, Nodehi SE, Gholampour A, Ozbakkaloglu T, Gencel O. Durability properties of 3D printed concrete (3DPC). Autom Constr. 2022;142:104479.[DOI]

-

24. Liu C, Liang Z, Liu H, Wu Y, Zhang Y, Bai G. Seismic performance of 3D printed reinforced concrete walls: Experimental study and numerical simulation. Eng Struct. 2025;333:120176.[DOI]

-

25. Liu H, Wang Y, Zhu C, Wu Y, Liu C, He C, et al. Design of 3D printed concrete masonry for wall structures: Mechanical behavior and strength calculation methods under various loads. Eng Struct. 2025;325:119374.[DOI]

-

26. Chen Y, Zhang Y, Xie Y, Zhang Z, Banthia N. Unraveling pore structure alternations in 3D-printed geopolymer concrete and corresponding impacts on macro-properties. Addit Manuf. 2022;59:103137.[DOI]

-

27. Şahin HG, Mardani A. Mechanical properties, durability performance and interlayer adhesion of 3DPC mixtures: A state-of-the-art review. Struct Concr. 2023;24(4):5481-5505.[DOI]

-

28. Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Yang L, Liu G, Chen Y, Yu S, et al. Hardened properties and durability of large-scale 3D printed cement-based materials. Mater Struct. 2021;54(1):45.[DOI]

-

29. Moral Muñoz JA, Herrera-Viedma E, Santisteban Espejo AL, Cobo Martín MJ. Software tools for conducting bibliometric analysis in science: An up-to-date review. El Prof Inf. 2020;29(1):1699-2407.[DOI]

-

30. Donthu N, Kumar S, Mukherjee D, Pandey N, Lim WM. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J Bus Res. 2021;133:285-296.[DOI]

-

31. Van Eck N, Waltman L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics. 2010;84(2):523-538.[DOI]

-

32. van Eck NJ, Waltman L. Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics. 2017;111(2):1053-1070.[DOI]

-

33. Kirby A. Exploratory bibliometrics: Using VOSviewer as a preliminary research tool. Publications. 2023;11(1):10.[DOI]

-

34. Liu B, Qin J, Shi J, Jiang J, Wu X, He Z. New perspectives on utilization of CO2 sequestration technologies in cement-based materials. Constr Build Mater. 2021;272:121660.[DOI]

-

35. Song B, Hu X, Pang SD, Du H, Ke G, Shi C. Effect of early CO2 curing on the chloride induced steel bars corrosion in cement mortars. J Sustain Cem-Based Mater. 2024;13(7):1063-1078.[DOI]

-

36. Liu L, Ji Y, Gao F, Zhang L, Zhang Z, Liu X. Study on high-efficiency CO2 absorption by fresh cement paste. Constr Build Mater. 2021;270:121364.[DOI]

-

37. Monkman S, Lee BEJ, Grandfield K, MacDonald M, Raki L. The impacts of in-situ carbonate seeding on the early hydration of tricalcium silicate. Cem Concr Res. 2020;136:106179.[DOI]

-

38. Zhao D, Williams JM, Hou P, Moment AJ, Kawashima S. Stabilizing mechanisms of metastable vaterite in cement systems. Cem Concr Res. 2024;178:107441.[DOI]

-

39. Park J, Seo J, Park S, Cho A, Lee HK. Phase profiling of carbonation-cured calcium sulfoaluminate cement. Cem Concr Res. 2025;189:107776.[DOI]

-

40. Zhou Q, Meawad A, Wang W, Noguchi T. Stabilization of metastable calcium carbonate polymorphs on the surface of recycled cement paste particles: A two-step carbonation approach without chemical additives. Cem Concr Compos. 2025;155:105829.[DOI]

-

41. Xue Q, Zhang L, Mei K, Wang L, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Evolution of structural and mechanical properties of concrete exposed to high concentration CO2. Constr Build Mater. 2022;343:128077.[DOI]

-

42. Fu X, Guerini A, Zampini D, Rotta Loria AF. Storing CO2 while strengthening concrete by carbonating its cement in suspension. Commun Mater. 2024;5(1):109.[DOI]

-

43. De Weerdt K, Plusquellec G, Belda Revert A, Geiker MR, Lothenbach B. Effect of carbonation on the pore solution of mortar. Cem Concr Res. 2019;118:38-56.[DOI]

-

44. Ma Y, Li W, Jin M, Liu J, Zhang J, Huang J, et al. Influences of leaching on the composition, structure and morphology of calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) with different Ca/Si ratios. J Build Eng. 2022;58:105017.[DOI]

-

45. Zajac M, Irbe L, Bullerjahn F, Hilbig H, Ben Haha M. Mechanisms of carbonation hydration hardening in Portland cements. Cem Concr Res. 2022;152:106687.[DOI]

-

46. Monkman S, MacDonald M, Hooton RD, Sandberg P. Properties and durability of concrete produced using CO2 as an accelerating admixture. Cem Concr Compos. 2016;74:218-224.[DOI]

-

47. Monkman S, Kenward PA, Dipple G, MacDonald M, Raudsepp M. Activation of cement hydration with carbon dioxide. J Sustain Cem-Based Mater. 2018;7(3):160-181.[DOI]

-

48. Kopitha K, Rajeev P, Sanjayan J, Elakneswaran Y. CO2 sequestration and low carbon strategies in 3D printed concrete. J Build Eng. 2025;99:111653.[DOI]

-

49. Li L, Wu M. An overview of utilizing CO2 for accelerated carbonation treatment in the concrete industry. J CO Util. 2022;60:102000.[DOI]

-

50. Meng D, Unluer C, Yang EH, Qian S. Carbon sequestration and utilization in cement-based materials and potential impacts on durability of structural concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2022;361:129610.[DOI]

-

51. Zajac M, Maruyama I, Iizuka A, Skibsted J. Enforced carbonation of cementitious materials. Cem Concr Res. 2023;174:107285.[DOI]

-

52. Li L, Hao L, Li X, Xiao J, Zhang S, Poon CS. Development of CO2-integrated 3D printing concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2023;409:134233.[DOI]

-

53. Qian X, Chen J, Jia C, Fang Y, Li M, Yang H, et al. Improving the rheological performance of cement-based materials via pre-carbonated cement slurry. Constr Build Mater. 2025;490:142507.[DOI]

-

54. Lucen H, Long L, Shipeng Z, Huanghua Z, Jianzhuang X, Chi Sun P. The synergistic effect of greenhouse gas CO2 and silica fume on the properties of 3D printed mortar. Compos B Eng. 2024;271:111188.[DOI]

-

55. Tay YWD, Lim SG, Phua SLB, Tan MJ, Fadhel BA, Amr IT. Exploring carbon sequestration potential through 3D concrete printing. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2023;18(1):e2277347.[DOI]

-

56. Tay YWD, Lim SG, Fadhel BA, Amr IT, Bamagain RA, Al-Hunaidy AS, et al. Potential of carbon dioxide spraying on the properties of 3D concrete printed structures. Carbon Capture Sci Technol. 2024;13:100256.[DOI]

-

57. Lim SG, Tay YWD, Paul SC, Lee J, Amr IT, Fadhel BA, et al. Carbon capture and sequestration with in-situ CO2 and steam integrated 3D concrete printing.Carbon Capture Sci Technol. 2024;13:100306.[DOI]

-

58. Ralston N, Gupta S, Moini R. 3D-printing of architected calcium silicate binders with enhanced and in-situ carbonation. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2024;19(1):e2350768.[DOI]

-

59. Zhong K, Liu Z, Wang F. Development of CO2 curable 3D printing materials. Addit Manuf. 2023;65:103442.[DOI]

-

60. Wang D, Xiao J, Sun B, Zhang S, Poon CS. Mechanical properties of 3D printed mortar cured by CO2. Cem Concr Compos. 2023;139:105009.[DOI]

-

61. Li Q, Gao X, Su A, Lu X. Interlayer adhesion strength of 3D-printed cement-based materials exposed to varying curing conditions. J Build Eng. 2023;74:106825.[DOI]

-

62. Zhou W, Zhu H, Hu WH, Wollaston R, Li VC. Low-carbon, expansive engineered cementitious composites (ECC) in the context of 3D printing. Cem Concr Compos. 2024;148:105473.[DOI]

-

63. Zhong K, Huang K, Liu Z, Wang F, Hu S. CO2-driven additive manufacturing of sustainable steel slag mortars. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2024;12(29):10919-10932.[DOI]

-

64. Han X, Yan J, Huo Y, Chen T. Effect of carbonation curing regime on 3D printed concrete: Compressive strength, CO2 uptake, and characterization. J Build Eng. 2024;98:111341.[DOI]

-

65. Zhong K, Huang S, Liu Z, Wang F, Hu S, Zhang W. CO2 absorbing 3D printable mixtures for magnesium slag valorization. Constr Build Mater. 2024;436:136894.[DOI]

-

66. Douba A, Badjatya P, Kawashima S. Enhancing carbonation and strength of MgO cement through 3D printing. Constr Build Mater. 2022;328:126867.[DOI]

-

67. Lucen H, Hanxiong L, Huanghua Z, Shipeng Z, Jianzhuang X, Sun PC. Development of CO2-activated interface enhancer to improve the interlayer properties of 3D-printed concrete. Cem Concr Compos. 2025;162:106122.[DOI]

-

68. van den Heever M, du Plessis A, Kruger J, van Zijl G. Evaluating the effects of porosity on the mechanical properties of extrusion-based 3D printed concrete. Cem Concr Res. 2022;153:106695.[DOI]

-

69. Jiang Y, Gao P, Adhikari S, Yao X, Zhou H, Liu Y. Studies on the mechanical properties of interlayer interlocking 3D printed concrete based on a novel nozzle. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2025;22:e04193.[DOI]

-

70. Marchment T, Sanjayan J, Xia M. Method of enhancing interlayer bond strength in construction scale 3D printing with mortar by effective bond area amplification. Mater Des. 2019;169:107684.[DOI]

-

71. He L, Chow WT, Li H. Effects of interlayer notch and shear stress on interlayer strength of 3D printed cement paste. Addit Manuf. 2020;36:101390.[DOI]

-

72. Rahul AV, Santhanam M, Meena H, Ghani Z. Mechanical characterization of 3D printable concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2019;227:116710.[DOI]

-

73. Srinivas D, Panda B, Suraneni P, Sitharam TG. Influence of mixture composition and carbonation curing on properties of sustainable 3D printable mortars. J Clean Prod. 2025;492:144894.[DOI]

-

74. von Greve-Dierfeld S, Lothenbach B, Vollpracht A, Wu B, Huet B, Andrade C, et al. Understanding the carbonation of concrete with supplementary cementitious materials: A critical review by RILEM TC 281-CCC. Mater Struct. 2020;53(6):136.[DOI]

-

75. Saillio M, Baroghel-Bouny V, Pradelle S, Bertin M, Vincent J, d’Espinose de Lacaillerie JB. Effect of supplementary cementitious materials on carbonation of cement pastes. Cem Concr Res. 2021;142:106358.[DOI]

-

76. Xiao J, Zou S, Ding T, Duan Z, Liu Q. Fiber-reinforced mortar with 100% recycled fine aggregates: A cleaner perspective on 3D printing. J Clean Prod. 2021;319:128720.[DOI]

-

77. Pepe M, Lombardi R, Lima C, Paolillo B, Martinelli E. Experimental evidence on the possible use of fine concrete and brick recycled aggregates for 3D printed cement-based mixtures. Materials. 2025;18(3):583.[DOI]

-

78. Chandru U, Bahurudeen A, Senthilkumar R. Systematic comparison of different recycled fine aggregates from construction and demolition wastes in OPC concrete and PPC concrete. J Build Eng. 2023;75:106768.[DOI]

-

79. Ding T, Xiao J, Qin F, Duan Z. Mechanical behavior of 3D printed mortar with recycled sand at early ages. Constr Build Mater. 2020;248:118654.[DOI]

-

80. Tao Y, Zhang Y, Mohan MK, Dai X, Ren Q, Rahul A. Waste-derived aggregates in 3D printable concrete: Current insights and future perspectives. Mater Rep Solidwaste Ecomater. 2025;1:9520013.[DOI]

-

81. De Vlieger J, Boehme L, Blaakmeer J, Li J. Buildability assessment of mortar with fine recycled aggregates for 3D printing. Constr Build Mater. 2023;367:130313.[DOI]

-

82. Ding Y, Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Zhang M, Tong J, Zhu L, et al. Impact of pre-soaked lime water carbonized recycled fine aggregate on mechanical properties and pore structure of 3D printed mortar. J Build Eng. 2024;89:109190.[DOI]

-

83. Sun B, Zeng Q, Wang D, Zhao W. Sustainable 3D printed mortar with CO2 pretreated recycled fine aggregates. Cem Concr Compos. 2022;134:104800.[DOI]

-

84. Liu Q, Tang H, Chen K, Peng B, Sun C, Singh A, et al. Utilizing CO2 to improve plastic shrinkage and mechanical properties of 3D printed mortar made with recycled fine aggregates. Constr Build Mater. 2024;433:136546.[DOI]

-

85. Luo S, Li W, Cai Y, Zhang K. Effects of carbonated recycled sand on the interfacial bonding performance of 3D printed cement-based material. J Build Eng. 2025;99:111551.[DOI]

-

86. Butkute K, Vaitkevicius V, Sinka M, Augonis A, Korjakins A. Influence of carbonated bottom slag Granules in 3D concrete printing. Materials. 2023;16(11):4045.[DOI]

-

87. Wang H, Shen W, Sun X, Song X, Lin X. Influences of particle size on the performance of 3D printed coarse aggregate concrete: Experiment, microstructure, and mechanism analysis. Constr Build Mater. 2025;463:140059.[DOI]

-

88. Warsi SBF, Srinivas D, Panda B, Biswas P. Investigating the impact of coarse aggregate dosage on the mechanical performance of 3D printable concrete. Innov Infrastruct Solut. 2023;9(1):5.[DOI]

-

89. Yu S, Du H, Sanjayan J. Aggregate-bed 3D concrete printing with cement paste binder. Cem Concr Res. 2020;136:106169.[DOI]

-

90. Liu H, Tao Y, Zhu C, Liu C, Wang Y, Yun J, et al. 3D printed concrete with recycled coarse aggregate: Freeze–thaw resistance assessment and damage mechanisms. Cem Concr Res. 2026;200:108095.[DOI]

-

91. Rahul AV, Mohan MK, De Schutter G, Van Tittelboom K. 3D printable concrete with natural and recycled coarse aggregates: Rheological, mechanical and shrinkage behaviour. Cem Concr Compos. 2022;125:104311.[DOI]

-

92. Wu Y, Liu C, Liu H, Zhang Z, He C, Liu S, et al. Study on the rheology and buildability of 3D printed concrete with recycled coarse aggregates. J Build Eng. 2021;42:103030.[DOI]

-

93. Liu C, Zhang Y, Liu H, Wu Y, Yu S, He C, et al. Interlayer reinforced 3D printed concrete with recycled coarse aggregate: Shear properties and enhancement methods. Addit Manuf. 2024;94:104507.[DOI]

-

94. Tong J, Ding Y, Lv X, Ning W. Effect of carbonated recycled coarse aggregates on the mechanical properties of 3D printed recycled concrete. J Build Eng. 2023;80:107959.[DOI]

-

95. Sanjayan JG, Jayathilakage R, Rajeev P. Vibration induced active rheology control for 3D concrete printing. Cem Concr Res. 2021;140:106293.[DOI]

-

96. Tay YWD, Qian Y, Tan MJ. Printability region for 3D concrete printing using slump and slump flow test. Compos Part B Eng. 2019;174:106968.[DOI]

-

97. Paritala S, Singaram KK, Bathina I, Khan MA, Jyosyula SKR. Rheology and pumpability of mix suitable for extrusion-based concrete 3D printing–A review. Constr Build Mater. 2023;402:132962.[DOI]

-

98. Liu H, Liu C, Zhang Y, Bai G. Bonding properties between 3D printed coarse aggregate concrete and rebar based on interface structural characteristics. Addit Manuf. 2023;78:103893.[DOI]

-

99. Zhang C, Jia Z, Luo Z, Deng Z, Wang Z, Chen C, et al. Printability and pore structure of 3D printing low carbon concrete using recycled clay brick powder with various particle features. J Sustain Cem-Based Mater. 2023;12(7):808-817.[DOI]

-

100. Zhao Y, Gao Y, Chen G, Li S, Singh A, Luo X, et al. Development of low-carbon materials from GGBS and clay brick powder for 3D concrete printing. Constr Build Mater. 2023;383:131232.[DOI]

-

101. Ye J, Teng F, Yu J, Yu S, Du H, Zhang D, et al. Development of 3D printable engineered cementitious composites with incineration bottom ash (IBA) for sustainable and digital construction. J Clean Prod. 2023;422:138639.[DOI]

-

102. Chen Y, Li Z, Chaves Figueiredo S, Çopuroğlu O, Veer F, Schlangen E. Limestone and calcined clay-based sustainable cementitious materials for 3D concrete printing: A fundamental study of extrudability and early-age strength development. Appl Sci. 2019;9(9):1809.[DOI]

-

103. Ibrahim KA, van Zijl GPAG, Babafemi AJ. Influence of limestone calcined clay cement on properties of 3D printed concrete for sustainable construction. J Build Eng. 2023;69:106186.[DOI]

-

104. Chen Y, Xia K, Jia Z, Gao Y, Zhang Z, Zhang Y. Extending applicability of 3D-printable geopolymer to large-scale printing scenario via combination of sodium carbonate and nano-silica. Cem Concr Compos. 2024;145:105322.[DOI]

-

105. Al-Noaimat YA, Ghaffar SH, Chougan M, Al-Kheetan MJ. A review of 3D printing low-carbon concrete with one-part geopolymer: Engineering, environmental and economic feasibility. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2023;18:e01818.[DOI]

-

106. Panda B, Singh GVPB, Unluer C, Tan MJ. Synthesis and characterization of one-part geopolymers for extrusion based 3D concrete printing. J Clean Prod. 2019;220:610-619.[DOI]

-

107. Khalil A, Wang X, Celik K. 3D printable magnesium oxide concrete: Towards sustainable modern architecture. Addit Manuf. 2020;33:101145.[DOI]

-

108. Chen M, Li L, Wang J, Huang Y, Wang S, Zhao P, et al. Rheological parameters and building time of 3D printing sulphoaluminate cement paste modified by retarder and diatomite. Constr Build Mater. 2020;234:117391.[DOI]

-

109. Zhao Z, Chen M, Zhong X, Huang Y, Yang L, Zhao P, et al. Effects of bentonite, diatomite and metakaolin on the rheological behavior of 3D printed magnesium potassium phosphate cement composites. Addit Manuf. 2021;46:102184.[DOI]

-

110. Yu KH, Teng T, Nah SH, Chai H, Zhi Y, Wang KY, et al. 3D concrete printing of triply periodic minimum surfaces for enhanced carbon capture and storage. Adv Funct Mater. 2025;2509259.[DOI]

-

111. Posani M, Voney V, Odaglia P, Du Y, Komkova A, Brumaud C, et al. Low-carbon indoor humidity regulation via 3D-printed superhygroscopic building components. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):425.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite