Abstract

Adrenaline hydrochloride is an indispensable drug in clinical emergencies, effective at alleviating critical conditions such as weak pulse and respiratory distress. However, the catechol moiety in its molecular structure is prone to oxidation, leading to drug degradation, reduced efficacy, and a short half-life. These inherent limitations significantly restrict its broader clinical application. To address this challenge, this study constructed an intelligent microneedle patch designed to stabilize drugs. We first grafted 3-aminophenylboronic acid onto silk fibroin via 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide/N-hydroxysuccinimide coupling chemistry. This design enables the formation of reversible boronic ester bonds between phenylboronic acid and the catechol structure of adrenaline, effectively shielding the oxidation-sensitive sites and significantly enhancing the drug’s storage stability. Upon insertion into the skin, the microneedles encounter the physiological environment where glucose competitively binds to the phenylboronic acid, triggering the cleavage of the boronic ester bonds and resulting in the on-demand release of adrenaline. A cumulative drug release rate of approximately 60% was achieved over 24 hours. This study proposes a novel “protection-release” dual-functional design, offering a new strategy for the efficient delivery and stabilized storage of catechol-containing drugs. This approach holds significant promise for applications in emergency medicine and the long-term storage of pharmaceuticals.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Adrenaline hydrochloride (AD) serves as a definitive emergency medication for critical conditions such as bradycardia, hypotension, and respiratory distress[1,2]. Its broad therapeutic efficacy and vital physiological role render it clinically irreplaceable. However, the clinical utility of AD is substantially limited by its inherent chemical instability. In the absence of protective excipients, the solid-state powder is susceptible to oxidative degradation, a process markedly accelerated in neutral to alkaline aqueous environments. These stability issues present significant challenges throughout the drug’s lifecycle, from storage and transport to its reliable administration in clinical settings[3,4]. Furthermore, the extremely short in vivo half-life of AD (approximately 2-3 minutes) significantly restricts its ability to sustain therapeutic efficacy[5]. Currently, it is primarily administered via intravenous, intramuscular, or subcutaneous injections[6], while these methods ensure rapid onset of action[7], they entail significant drawbacks, including the requirement for professional administration, pronounced pain, and the risk of local tissue injury[8].

Nebulized inhalation serves as an alternative route for adrenaline administration. However, its efficacy is substantially limited by low pulmonary deposition, with only 1-6% of the nebulized dose effectively reaching the lung tissue[9]. This results in poor systemic bioavailability and consequently suboptimal therapeutic outcomes. Therefore, developing delivery strategies that enhance bioavailability and enable sustained drug release is of significant importance. Microneedles (MNs) offer a promising solution for transdermal drug delivery. They effectively penetrate the stratum corneum without stimulating underlying nerves[10]. This approach not only bypasses gastrointestinal degradation and first-pass metabolism but also minimizes pain and tissue damage. Consequently, MNs can significantly improve drug bioavailability and enhance patient compliance[11-13].

Silk fibroin (SF), a natural polymeric protein derived from silkworm silk, has garnered significant attention in biomedical applications[14,15] due to its exceptional mechanical strength[16,17], tunable biodegradability[18,19], excellent biocompatibility[20,21], and low immunogenicity[22,23]. SF-based materials exhibit outstanding biocompatibility and controllable biodegradability, enabling their fabrication into diverse formats such as thin films[24-26], fibers[27,28], hydrogels[29,30], and three-dimensional porous scaffolds[31,32], facilitating their adaptation to various biomedical requirements. In transdermal drug delivery systems, SF-based MNs demonstrate remarkable advantages. Their optimal mechanical properties enable effective penetration through the stratum corneum, creating microchannels that provide an ideal pathway for drug transport[33,34]. The formation of stable β-sheet structures within SF endows the MNs with enhanced mechanical strength[35] and moisture resistance[36]. This inherent property ensures that the MNs maintain their structural integrity without softening or collapsing when penetrating the hydrated skin environment. Furthermore, SF exhibits excellent film-forming capacity and drug-loading capability, enabling the incorporation of diverse active ingredients. The drug release profile can be precisely modulated by adjusting parameters such as crystallinity[37,38] and concentration[39]. Compared to conventional MN materials like hyaluronic acid and polyvinyl alcohol, SF exhibits a superior capacity to preserve the stability of biomacromolecules, including proteins and peptides, under high-temperature or long-term storage conditions[40]. This characteristic renders it particularly suitable for the delivery of sensitive drugs.

However, SF exhibits inherent limitations in providing antioxidant protection for small-molecule drugs such as AD. Unlike mechanisms stabilizing biomacromolecules, SF lacks specific binding sites, and its hydrophilic matrix cannot provide effective steric and electron shielding for the catechol structure in AD, making it difficult to withstand oxidative attacks. This limitation forms the core starting point of our study. To specifically address this issue, we introduced phenylboronic acid (PBA) to chemically graft SF. Our aim was to achieve specific stabilization and protection of AD’s oxidation-prone sites through the dynamic covalent bond formed between the two compounds.

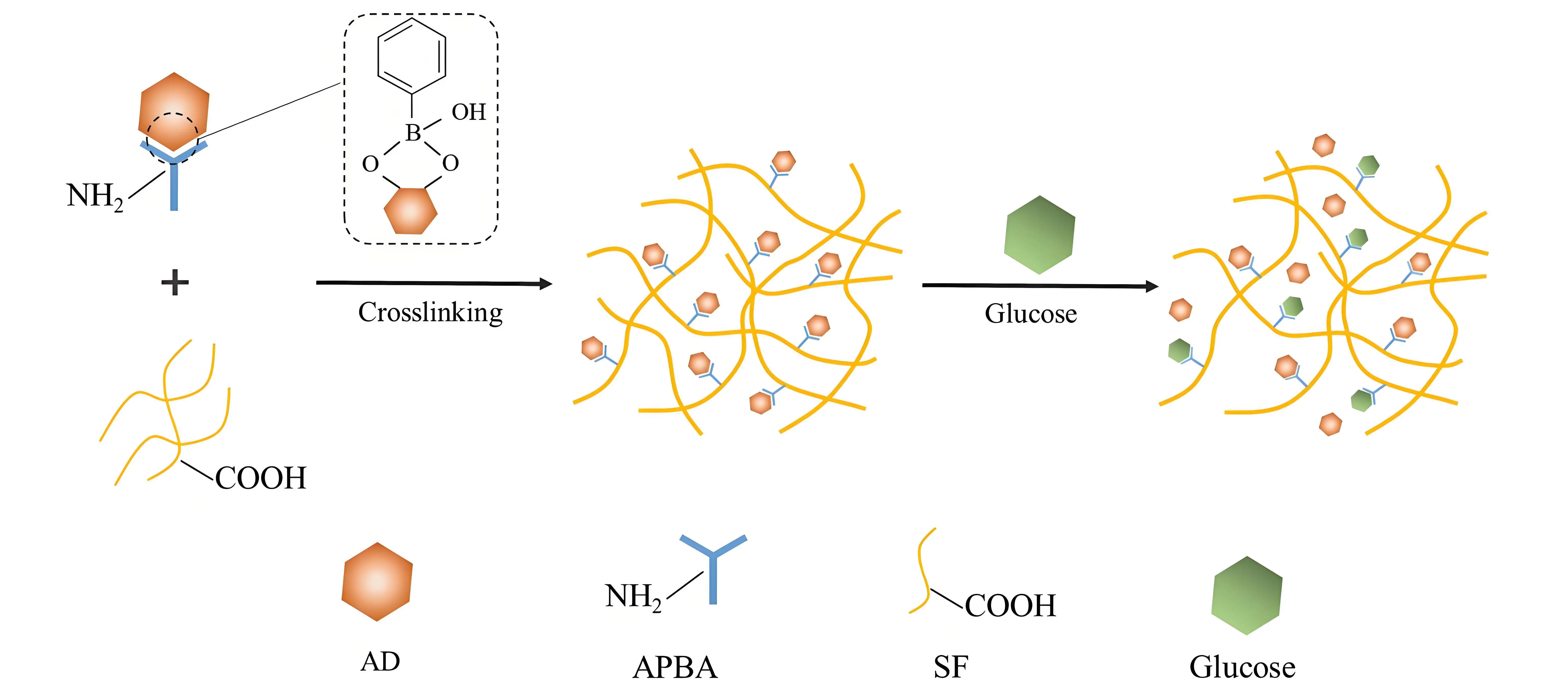

As shown in Figure 1, the boronic acid group of PBA can specifically react with the two adjacent hydroxyl groups in the catechol structure of AD, forming reversible five- or six-membered cyclic boronate esters[41,42]. This covalent linkage effectively immobilizes and protects AD from oxidative degradation during storage and transit. Upon MNs insertion into the skin, glucose present in the tissue fluid competes with AD for binding to PBA. Owing to the higher affinity of PBA for the cis-diol structure in glucose, the boronic ester bond is cleaved, enabling controlled drug release[43]. This approach not only protects AD from degradation but also enables its sustained release. Consequently, it improves bioavailability, enhances therapeutic efficacy, and reduces the required drug dosage, demonstrating significant potential for biomedical applications.

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of the glucose-responsive release of AD based on dynamic boronic ester bonds formed in the APBA-grafted SF system. AD: adrenaline hydrochloride; APBA: 3-Aminophenylboronic acid; SF: silk fibroin.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

Fresh Bombyx mori silkworm cocoons were supplied by Shaoxing Shenglai Biotechnology Co., Ltd. 3-Aminophenylboronic acid (APBA) was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Concentrated nitric acid and sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) were obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. AD, sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3), and N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) were acquired from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) was sourced from Kemiao Biochemical Co., Ltd. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was provided by Yonghua Chemical Co., Ltd. Lithium bromide (LiBr) was supplied by Tiancheng Chemical Co., Ltd. Dialysis membranes (molecular weight cut-off: 8-14 kDa and 3.5 kDa) were procured from Shanghai Yepu Bio-Technology Co., Ltd.

2.2 Preparation of SF solution

SF solution was prepared from Bombyx mori cocoons according to a previously reported method[44], with the specific procedure illustrated in Figure 2a. Briefly, 80 g of finely cut cocoons were boiled in 4 L of an aqueous solution containing 0.3 wt% Na2CO3 and 0.1 wt% NaHCO3 at 100 °C for 30 min. This degumming step, involving thorough rinsing and rubbing, was repeated three times to ensure complete sericin removal. The resulting SF fibers were rinsed extensively with deionized water and dried to a constant weight in a 60 °C oven. Subsequently, 15 g of the dried SF fibers were completely dissolved in a 9.3 M LiBr solution under continuous stirring for 1 h. Finally, the SF solution was filtered through gauze to remove impurities, aliquoted, and stored at 4 °C for further use.

Figure 2. Process flow diagrams. (a) Preparation of SF solution; (b) Synthesis of PBA-SF conjugate; (c) Fabrication of MNs. SF: silk fibroin; PBA-SF: 3-APBA -modified SF; MNs: microneedles; APBA: 3-Aminophenylboronic acid; NHS: N-hydroxysuccinimide; EDC: 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide; LiBr: lithium bromide.

2.3 Synthesis of 3-APBA -modified SF (PBA-SF)

The modification of silk fibroin with APBA was performed as illustrated in Figure 2b. The SF solution prepared in Section 2.2 was diluted to concentrations of 100 mg/mL and 50 mg/mL, respectively, and cooled to 1-2 °C in an ice bath. A 14 mg/mL APBA solution was added dropwise to each SF solution with gentle stirring, yielding final molar ratios of APBA amino groups to SF carboxyl groups of 1:1, 10:1, and 20:1, which corresponded to final SF concentrations of 50 mg/mL and 25 mg/mL. Subsequently, NHS (2.5 wt% relative to SF mass) and EDC (5 wt% relative to SF mass) were introduced, and the reaction proceeded for 3 h under continuous shaking in the ice bath. After completion, the reaction mixture was transferred into a dialysis membrane (MWCO: 8-14 kDa) and dialyzed against deionized water at 4 °C for 3 days. The dialyzed solution was then filtered and centrifuged to collect the product. The resulting solution was further concentrated using a dialysis membrane (MWCO: 3.5 kDa) immersed in a 10% polyethylene glycol solution for 6 h. The final PBA-SF solution was collected, its mass concentration (wt%) determined, and stored at 4 °C for further use.

2.4 Characterization of PBA-SF

A 5 mL aliquot of the PBA-SF solution was treated with concentrated nitric acid and digested using a microwave digestion system to decompose the silk fibroin matrix. After complete digestion and evaporation of the residual nitric acid, the sample was diluted to 10 mL with deionized water. The boron content was quantified by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES; Vista-MPX, Agilent Technologies, USA) at a wavelength of 249 nm. This measurement confirmed the successful grafting of APBA onto SF by detecting the incorporated boron element, enabling subsequent calculation of the grafting efficiency.

2.5 Fabrication of different MNs

The MNs fabrication process is illustrated in Figure 2c. Briefly, 6 mL of the precursor solution was cast onto a polydimethylsiloxane MN mold and placed in a vacuum desiccator to remove entrapped air bubbles. The mold was then dried under constant temperature and humidity conditions (25 °C, 55% RH), followed by demolding to obtain the final MNs.

Preparation of APBA solution: APBA was directly dissolved in a 50% DMSO aqueous solution to obtain a concentration of 14 mg/mL.

Preparation of AD solution: AD was dissolved in deionized water to achieve a concentration of 1 mg/mL.

Fabrication of AD-loaded SF MNs (SF@MNs): A predetermined volume of the as-prepared AD solution was blended uniformly with the SF solution. The mixture was then processed according to the general MN fabrication procedure described above. The resulting drug loading per MN patch was 13 μg.

Fabrication of AD-loaded blended MNs (PBA/SF@MNs): A predetermined volume of the as-prepared AD solution, APBA solution, and SF solution was mixed directly at a specific ratio. The mixture was then processed following the general MN fabrication procedure described in Section 2.5. The resulting drug loading per MN patch was 13 μg.

Fabrication of AD-loaded grafted MNs (PBA-SF@MNs): The as-prepared AD solution was added dropwise to the PBA-SF solution under gentle stirring, achieving final concentrations of 25 mg/mL for PBA-SF and 0.1 mg/mL for AD in the mixture. The resulting solution was used as the precursor and processed according to the standard MN fabrication protocol. The drug loading per MN patch was controlled at 13 μg.

2.6 Morphological characterization of PBA-SF@MNs

The MNs were examined under a stereo optical microscope (DFC-420, Leica Microsystems, USA) to observe the surface morphology of the silk fibroin-based MNs. Images of the MN arrays were captured to document their structural integrity and needle morphology. The needle length was measured based on the recorded images and annotated accordingly.

2.7 Analysis of the aggregated structure of PBA-SF@MNs

2.7.1 Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

A small segment was carefully excised from the MN patch prepared following the method in Section 2.5 and compared with pristine SF MNs. The sample was placed on the stage of an FTIR spectrometer (VERTEX, Bruker, Germany) and pressed firmly against the crystal using a rotating pressure head to ensure intimate contact. FTIR spectra were acquired in ATR mode over a wavenumber range of 600 cm-1 to 3000 cm-1 with 32 scans per measurement.

2.7.2 Wide-angle X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The treated MN sample was cut, ground into a fine powder, and uniformly pressed into a quartz sample holder. Measurements were performed using an automated intelligent X-ray diffractometer (D8 Advance, Bruker, Germany) under the following conditions: current of 35 mA, voltage of 40 kV (stable without fluctuation), scanning speed of 8 °/min, and a 2θ range of 5-45°.

2.8 Mechanical properties of PBA-SF@MNs

Individual MNs were carefully excised from the MN array and mounted vertically on the flat stage of a texture analyzer (TMS-PRO, Food Technology Corporation, USA) with the needle tip facing upward. The fracture force was measured under the following conditions: pre-load force of 0.05 N, load cell capacity of 25 N, 80% compression strain, and a probe descent rate of 10 mm/min.

2.9 Dissolution and swelling properties of different MNs

The swelling ratio and mass loss of the MNs were determined using a gravimetric method. A MN sample prepared as described in Section 2.5 was weighed to obtain its initial mass (M0). The sample was then immersed in PBS at a bath ratio of 1:100 (w/v) and incubated in a shaking water bath at 37 °C for 24 h. After incubation, the MN sample was removed, rinsed gently with deionized water, and blotted dry with absorbent paper to remove surface moisture before recording the wet mass (M1). The sample was subsequently dried in an oven at 105 °C until a constant mass was achieved, which was recorded as M2. The swelling ratio and mass loss were calculated using the following Equations (1) and (2), respectively:

Where M0 is the initial mass of the MN, M1 is the mass of the MN after swelling, N is the solid content ratio of the MN (calculated as the ratio of the mass after drying at 105 °C to constant weight to the initial mass).

2.10 Dissolution of APBA from MNs

The PBA/SF@MNs and PBA-SF@MNs prepared according to Section 2.5 were placed in centrifuge tubes containing 0.01 M PBS solution and incubated in a constant-temperature shaking water bath at 37 °C for 24 h. Samples (5 mL) were collected at predetermined time intervals (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h), with an equal volume of fresh PBS replenished after each sampling to maintain a constant volume. The fluorescence intensity of APBA in the collected samples was immediately measured using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Horiba Fluoromax-4, HORIBA Jobin Yvon) at an excitation wavelength of 295 nm and an emission wavelength of 728 nm, with both slit widths set at 5 nm. The cumulative release percentage of APBA from the MNs was calculated using the following Equation (3):

Where R (%) is the cumulative release percentage of APBA from the MNs; V is the total volume of the release medium (mL); Vi is each sampling volume (5 mL); Cn and Ci are the concentrations of APBA (μg/mL) in the release medium at the n-th and i-th sampling points, respectively; and M is the initial mass of PBA loaded in the MNs (μg).

2.10 In vitro release of different MNs

2.10.1 Release performance in PBS solution

Fresh and intact frog skin was selected for the in vitro drug release study[45]. The prepared PBA-SF@MNs were inserted into the frog skin, and 12 mL of 0.01 M PBS solution was added to the diffusion chamber. The system was maintained at 37 °C with agitation at 300 rpm. Samples (5 mL) were collected at specified time points (0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h), and an equal volume of fresh PBS was replenished after each sampling to maintain a constant total volume. The concentration of released AD was immediately determined using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (Horiba Fluoromax-4, HORIBA Jobin Yvon) with excitation and emission wavelengths set at 280 nm and 315 nm, respectively, and slit widths of 5 nm.

The cumulative drug release rate from the MNs in vitro was calculated using the following Equation (4):

Where Q (%) is the cumulative transdermal drug release rate from the MNs; V is the volume of the solution in the release chamber (mL); Vi is the volume of each sample withdrawal (5 mL); Cn and Ci are the drug concentrations (μg/mL) in the release chamber at the n-th and i-th sampling time points, respectively; and M is the total drug loading amount (μg).

The drug release rate of the MNs in vitro was calculated using the following Equation (5):

Where S is the transdermal drug release rate of the MNs (μg/cm2·h); Qn and Qn-1 are the cumulative drug release rates at the n-th and (n-1)-th sampling points, respectively; Tn is the time interval between the n-th and (n-1)-th sampling events (h); and M is the total drug loading amount (μg).

2.10.2 Release performance in glucose solutions with different concentrations

The experimental procedure followed the method described in Section 2.10.1, except that the solution in the diffusion chamber was replaced with glucose solutions at different concentrations: 400 mg/mL (high concentration), 200 mg/mL (normal concentration), and 100 mg/mL (low concentration). The cumulative drug release rate and release kinetics of the MNs were compared across these glucose concentrations.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Effect of PBA on AD stability

As shown in Figure 3, the drug-loaded film prepared by blending AD solution with SF solution exhibited a distinct yellow-to-dark discoloration after 72 hours of storage at room temperature, indicating significant oxidation of the drug under ambient conditions. In contrast, the film fabricated from a mixture of SF and APBA with the same amount of AD showed no obvious color change under identical storage conditions. This result demonstrates that the phenylboronic acid group in APBA can form stable boronic ester bonds with the catechol structure of AD, effectively shielding the drug from ambient oxygen and thereby significantly suppressing its oxidation.

Figure 3. Comparative images of drug-loaded films prepared from different solutions after 72 h of storage at room temperature. (a) SF-APBA mixed solution; (b) SF solution. SF: silk fibroin; APBA: 3-Aminophenylboronic acid.

3.2 Characterization of PBA-SF and grafting efficiency calculation

The SF molecule contains various amino acid residues[46,47]. Specifically, the side-chain carboxyl groups of glutamic acid and aspartic acid can undergo an amidation reaction with the amino group (-NH2) of APBA, enabling the grafting modification of SF to obtain SF molecules containing boronic acid groups. As illustrated in Figure 1b, EDC and NHS were employed to activate the -COOH groups on the SF side chains. The subsequent amidation reaction grafted APBA onto the SF side chains, yielding PBA-SF.

Based on the SMRT sequencing of long repetitive sequences[48], the SF heavy chain and P25 chain contain 28 and 24 glutamic acid residues, and 9 and 15 aspartic acid residues, respectively. By summing the data from each chain, it can be concluded that each SF molecule possesses a total of 76 carboxyl groups, which serve as potential grafting sites. While no boron (B) element was detected in pure SF solution, after grafting reactions performed with varying molar ratios of APBA in different SF concentrations via EDC/NHS chemistry, the B concentration in the resulting mixture was quantified by ICP analysis. The grafting efficiency of PBA onto SF is calculated using the following Equation (6):

Where CB is the boron content measured by ICP (μg/mL), C0 is the concentration of SF in the solution (μg/mL), MB is the relative atomic mass of boron, and M0 is the molecular weight of SF.

As shown in Table 1, higher amounts of added APBA led to increased boron content in the mixed solution after grafting, accompanied by a notable improvement in grafting efficiency. However, when the molar ratio of -COOH to -NH2 was increased from 1:10 to 1:20, the grafting efficiency only rose slightly from 1.62% to 1.95%, indicating that the grafting reaction was approaching saturation. Moreover, at the 1:20 ratio, excessive APBA addition caused severe gelation of the SF solution, which hindered subsequent processing. Therefore, the optimal grafting conditions were determined as an SF concentration of 50 mg/mL and a -COOH to -NH2 molar ratio of 1:10, yielding a grafting efficiency of 1.62% ± 0.35%.

| Sample | Concentration of SF(mg/mL) | n(-COOH): n(-NH2) | Concentration of Boron (μg/mL) | Grafting Rate (%) |

| APBA1@SF50 | 50 | 1:1 | 0.35 ± 0.022 | 0.97 ± 0.016 |

| APBA10@SF50 | 50 | 1:10 | 0.58 ± 0.064 | 1.62 ± 0.038 |

| APBA20@SF50 | 50 | 1:20 | 0.70 ± 0.047 | 1.95 ± 0.025 |

| APBA1@SF25 | 25 | 1:1 | 0.20 ± 0.017 | 0.77 ± 0.012 |

| APBA10@SF25 | 25 | 1:10 | 0.39 ± 0.034 | 1.50 ± 0.029 |

| APBA20@SF25 | 25 | 1:20 | 0.49 ± 0.056 | 1.88 ± 0.042 |

APBA: 3-Aminophenylboronic acid; SF: silk fibroin.

Based on this grafting system, the molar ratio of APBA to AD was further controlled at 1:1. Under the optimal grafting conditions (1:10 -COOH to -NH2 ratio and 1.62% grafting efficiency), the calculated drug loading in the resulting MNs was 13 μg.

3.3 Morphology of PBA-SF@MNs

Figure 4 shows the macroscopic morphology of the prepared MNs. It can be observed that the MNs fabricated by the casting method exhibit complete structural integrity, excellent conformity with the mold cavities, uniform needle height, and intact needle tips. The individual needles measure approximately 450 μm in length, 200 μm in base diameter, and are arranged with an inter-needle spacing of 500 μm.

3.4 Aggregated structure of different MNs

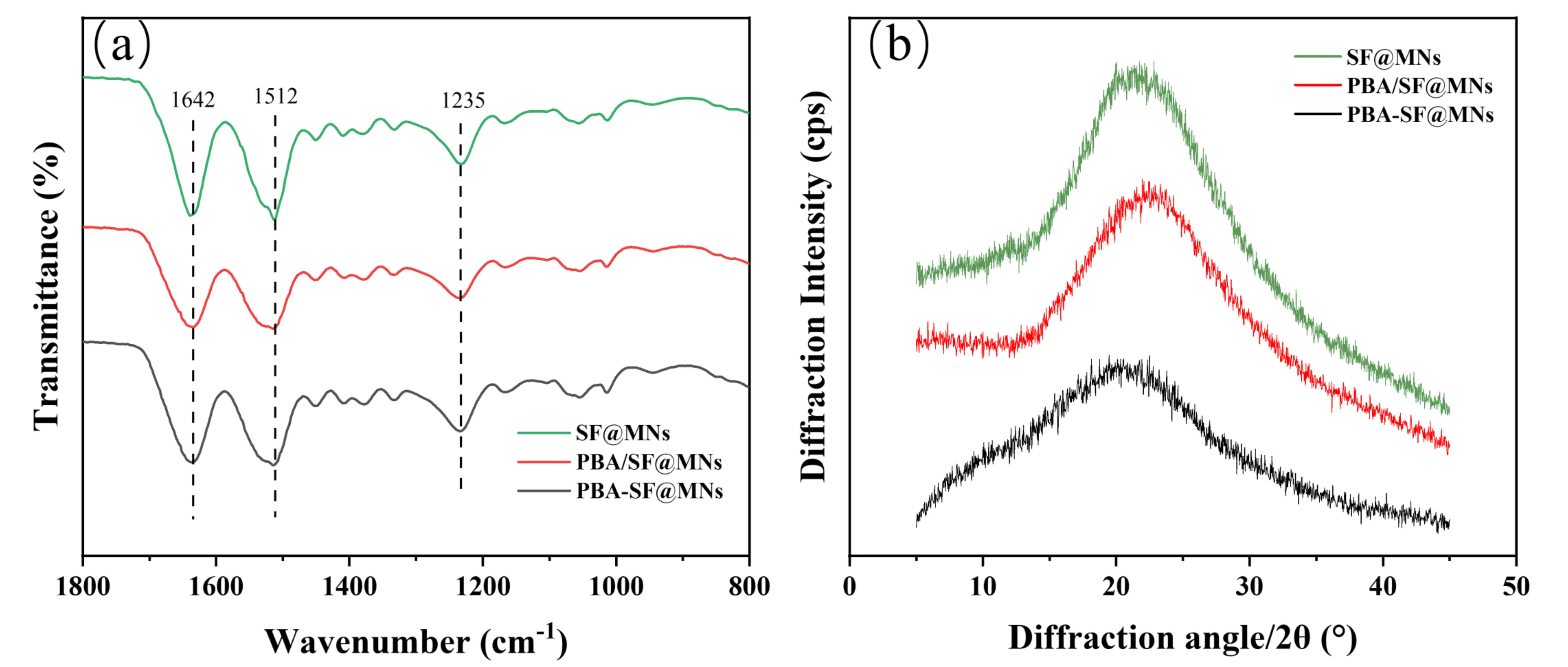

To investigate whether APBA affects the microstructure of silk fibroin-based MNs, SF@MNs, PBA/SF@MNs, and PBA-SF@MNs prepared according to Section 2.5 were compared using FTIR and XRD. As shown in Figure 5a, the characteristic FTIR peaks of SF are located at 1642 cm-1, 1512 cm-1, and 1235 cm-1, corresponding to amide I, amide II, and amide III bands, respectively, indicating a conformation dominated by random coils[49-51]. In both grafted and blended samples, the positions of these characteristic peaks show no significant shifts, suggesting that the grafting reaction did not alter the secondary structure of SF, which maintained its original random coil conformation.

Figure 5. Aggregated structure of SF-based MNs. (a) FTIR spectra; (b) X-ray diffraction patterns. SF: silk fibroin; MNs: microneedles; FTIR: fourier transform infrared; PBA/SF@MNs: AD-loaded blended MNs; PBA-SF@MNs: AD-loaded grafted MNs; SF@MNs: AD-loaded SF MNs.

The XRD results further support this conclusion. As shown in Figure 5b, the XRD pattern of pure SF exhibits a broad “bread-like” peak, indicating a predominantly amorphous structure without significant crystallization[52]. Both the grafted PBA-SF@MNs and blended PBA/SF@MNs show XRD curves nearly identical to that of pure SF, with no emerging sharp diffraction peaks. This confirms that the introduction of APBA did not induce the formation of new crystalline regions in SF, nor did it alter its inherent amorphous structural characteristics.

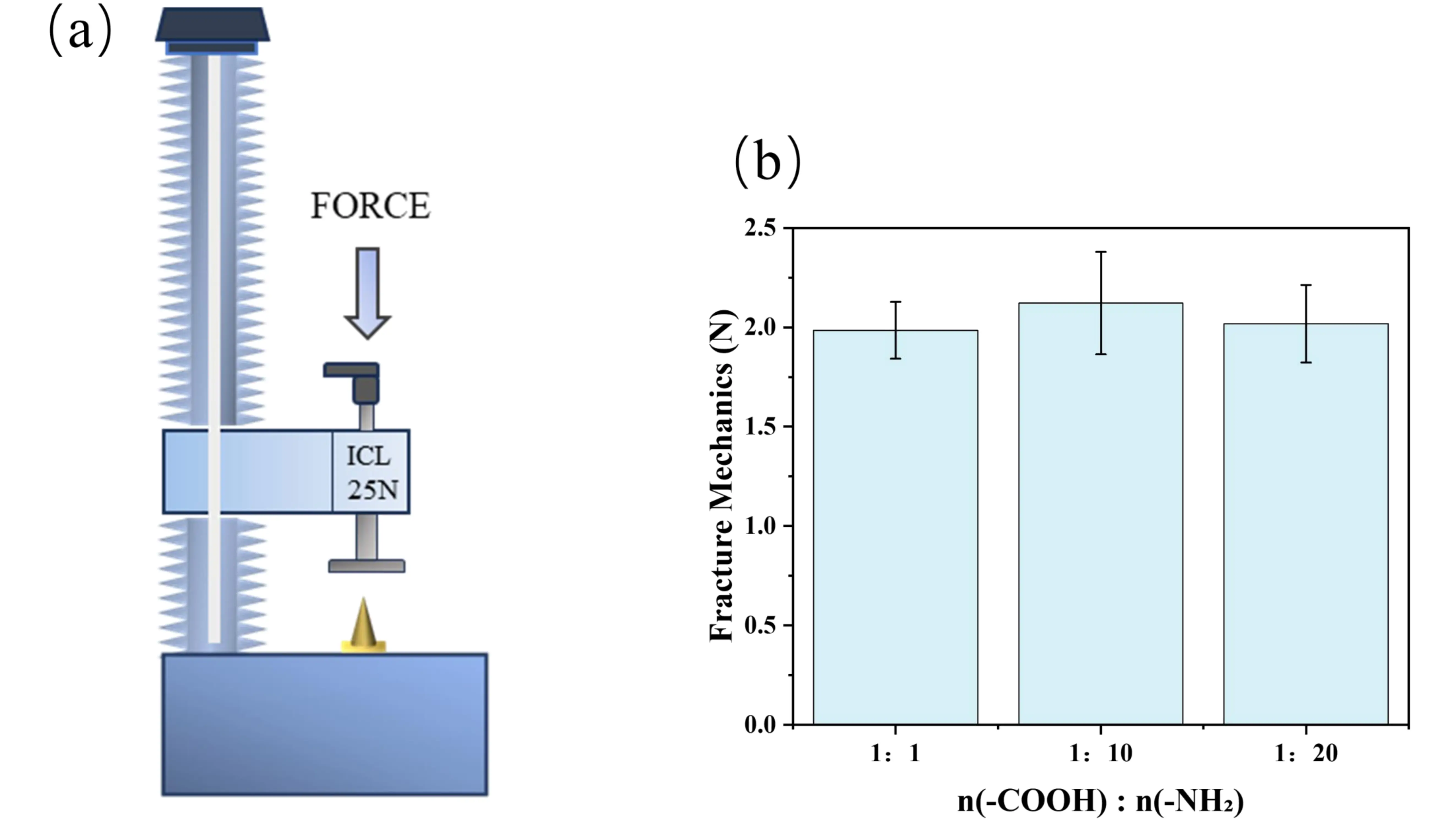

3.5 Mechanical properties of different MNs

The mechanical properties of a single microneedle are shown in Figure 6a. Studies have shown that the critical force required for a single MN to successfully penetrate the human stratum corneum is approximately 0.08 N[53]; in practical applications, the insertion force per needle typically needs to be in the range of 0.1-3 N to ensure effective skin penetration by MN arrays. As shown in Figure 6b, the compressive strengths of MNs prepared with -COOH to -NH2 molar ratios of 1:1, 1:10, and 1:20 were 1.98 ± 0.14 N, 2.12 ± 0.26 N, and 2.02 ± 0.19 N, respectively. All MN samples exhibited excellent mechanical properties. During compression testing, the MNs demonstrated stable mechanical responses without structural fracture or failure, indicating sufficient mechanical strength to withstand external loads. This mechanical performance ensures that the MNs can effectively penetrate the stratum corneum in practical applications and maintain structural integrity throughout the drug delivery process, providing reliable mechanical support for efficient drug delivery. The test results confirm that all prepared MNs meet the basic mechanical strength requirements for transdermal drug delivery systems.

Figure 6. Mechanical characterization of individual MNs. (a) Schematic diagram of the texture analyzer test setup; (b) Compressive strength of different MNs formulations. MNs: microneedles.

Based on comprehensive consideration of mechanical properties and grafting efficiency, n(-COOH): n(-NH2) = 1:10 was determined to be the optimal process parameter for preparing grafted MNs.

3.6 Dissolution and swelling properties of different MNs

As shown in Table 2, the PBA-SF@MNs exhibited a swelling ratio of 132.9 ± 2.61%, indicating excellent water absorption and expansion capacity, which is conducive to drug release. Furthermore, the mass loss of PBA-SF@MNs was only 4.71 ± 0.87%. This characteristic suggests that the chemical cross-linking bonds formed between APBA and SF create a stable three-dimensional network, which allows water penetration and swelling while effectively preventing the dissolution and loss of silk fibroin molecules in aqueous environments. In contrast, PBA/SF@MNs underwent severe structural disintegration in water, with a mass loss as high as 58.0 ± 1.72%, indicating that more than half of the silk fibroin matrix dissolved. Since only weak intermolecular interactions exist between SF and APBA in the blended system, the unmodified SF molecular chains rapidly dissolved upon contact with water, leading to the complete destruction of the MN structure. During sampling, the MN arrays were observed to deform, soften, and even disintegrate entirely, making it impossible to accurately measure their swelling ratio.

| Sample | Swelling Ratio (%) | Dissolution Ratio (%) |

| PBA/SF@MNs | Cannot be measured | 58.0 ± 1.72 |

| PBA-SF@MNs | 132.9 ± 2.61 | 4.71 ± 0.87 |

MNs: microneedles; SF: silk fibroin; PBA/SF@MNs: AD-loaded blended MNs; PBA-SF@MNs: AD-loaded grafted MNs.

The chemical grafting strategy demonstrates significant advantages in constructing stable and efficient MNs-based drug delivery systems. By establishing a covalent cross-linking network between APBA and SF, this approach successfully addresses the rapid dissolution and structural disintegration issues observed in physically blended MNs. This network structure maintains favorable swelling capacity while effectively minimizing matrix material loss, thereby providing a solid foundation for controlled drug release.

Based on these findings, the grafted MN system was selected for subsequent in-depth evaluation of in vitro drug release behavior to further explore its potential as a transdermal drug delivery carrier.

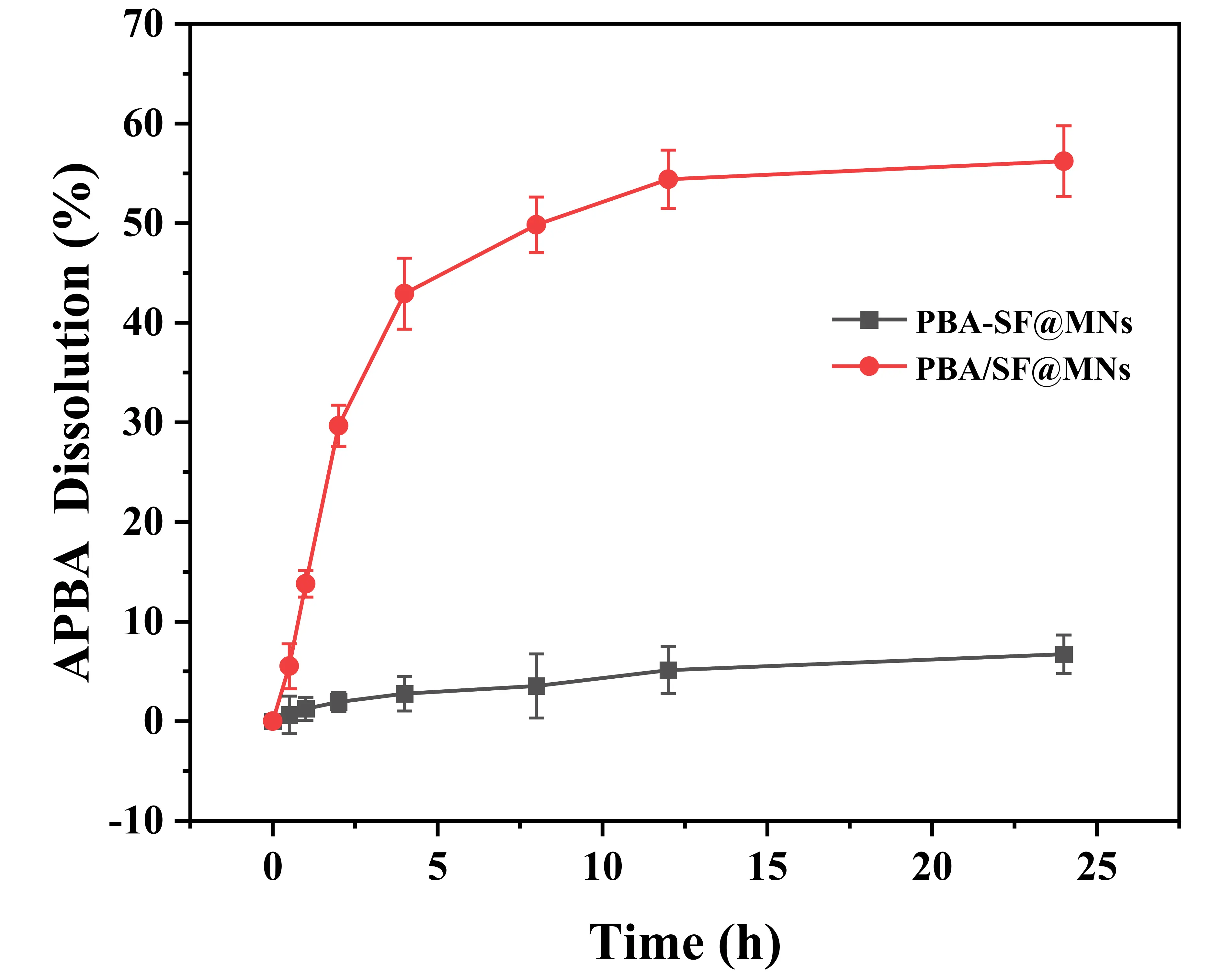

3.7 Dissolution of APBA from MNs

The PBA/SF@MNs and PBA-SF@MNs prepared according to Section 2.5 were placed in centrifuge tubes containing 0.01 M PBS solution and incubated in a constant-temperature shaking water bath at 37 °C for 24 h. Samples (5 mL) were collected at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h, with an equal volume of fresh PBS replenished after each sampling to maintain a constant total volume. The fluorescence intensity of the samples was measured using a fluorescence spectrophotometer at excitation and emission wavelengths of 295 nm and 728 nm, respectively. The dissolution of APBA from the MNs was then calculated.

As shown in Figure 7, the dissolution of APBA from PBA/SF@MNs over 24 h was 56.22 ± 3.55%, significantly higher than that of PBA-SF@MNs (6.72 ± 1.94%). This result can be attributed to the fact that APBA in PBA/SF@MNs, being physically blended with SF, may remain in a free form and be released along with the drug, potentially entering the body. It is important to note that direct skin contact with or inhalation of APBA dust can cause irritation and may pose health risks. In contrast, in PBA-SF@MNs, APBA is covalently grafted onto the SF backbone, forming stable chemical bonds. During use, only the reversible boronic ester bonds dissociate to release the drug, while APBA remains firmly anchored within the MN matrix and does not enter the body, thereby avoiding potential toxicity. These findings demonstrate that the grafted PBA-SF@MNs exhibit enhanced safety and stability.

Figure 7. APBA dissolution from the MNs. APBA: 3-Aminophenylboronic acid; MNs: microneedles; PBA/SF@MNs: AD-loaded blended MNs; PBA-SF@MNs: AD-loaded grafted MNs; SF: silk fibroin.

3.8 In vitro drug release performance of MNs in different solutions

3.8.1 Drug release performance of different MNs in PBS solution

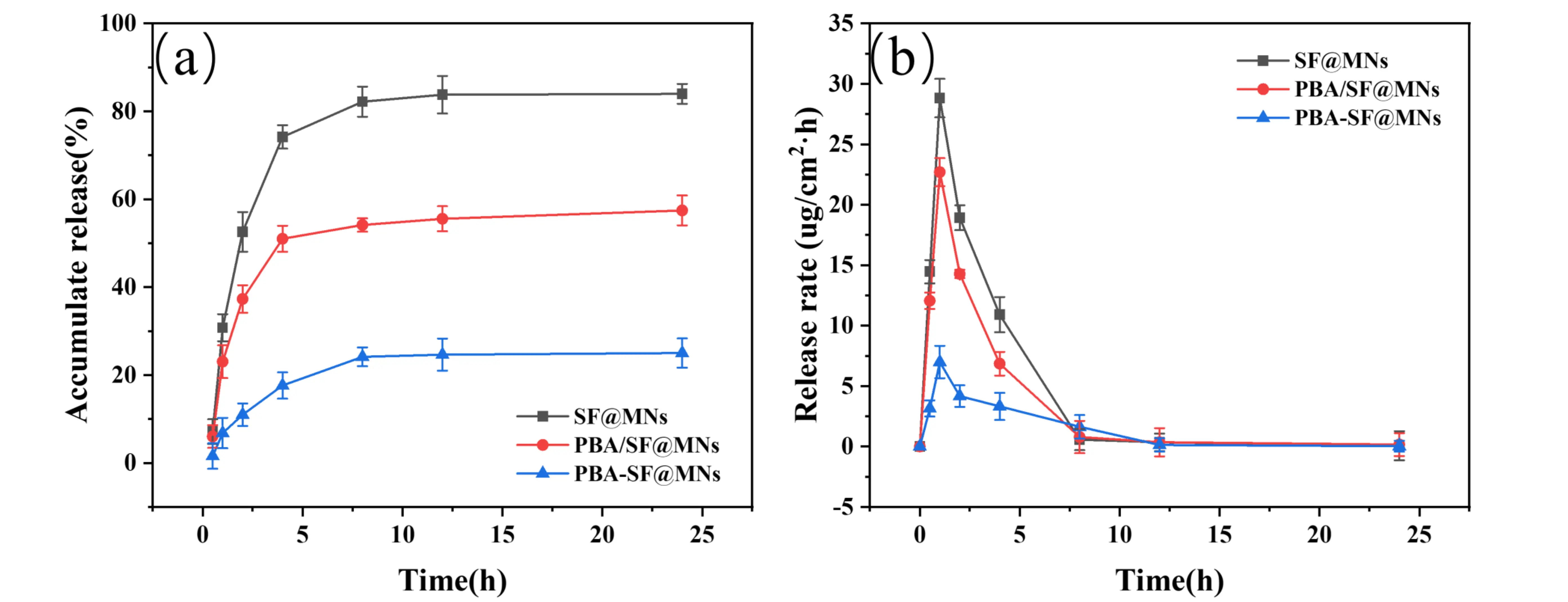

The pure SF@MNs, PBA/SF@MNs, and PBA-SF@MNs were prepared according to the method described in Section 2.5. Based on the analytical results from Section 3.1, the drug loading in all MNs was set at 13 μg. As shown in Figure 8a,b, the cumulative release rate and release rate of AD from PBA/SF@MNs, PBA-SF@MNs, and SF@MNs in PBS solution were compared. SF@MNs are soluble MNs that degrade and dissolve in PBS solution, causing the encapsulated drug to lose its barrier rapidly and resulting in a rapid, burst-release diffusion. The drug release rate of SF@MNs peaked at 1 h (47.24 ± 1.59 μg/cm2·h), with a cumulative release rate exceeding 50% within 2 h and nearly complete release (83.99 ± 2.26%) within 24 h. Although these MNs can achieve rapid drug release, they are unable to provide sustained and controlled drug delivery.

Figure 8. Drug release performance of different MNs in PBS solution. (a) Cumulative drug release rate of SF@MNs, PBA/SF@MNs, and PBA-SF@MNs; (b) Drug release rate of SF@MNs, PBA/SF@MNs, and PBA-SF@MNs. MNs: microneedles; SF: silk fibroin; PBA/SF@MNs: AD-loaded blended MNs; PBA-SF@MNs: AD-loaded grafted MNs; SF@MNs: AD-loaded SF MNs.

The drug release behavior of the PBA/SF@MNs reflects the combined effect of two competing mechanisms. On the one hand, the dynamic boronic ester bonds formed between APBA and AD remain relatively stable in PBS, contributing to a certain retention effect that delays drug release. On the other hand, the absence of covalent cross-linking between SF and APBA results in a matrix structure primarily held by weak physical interactions. Upon contact with an aqueous medium, the rapid dissolution of the SF matrix dominates the early release phase, generating abundant pores and channels that not only facilitate rapid drug diffusion but also disrupt the stable microenvironment required for boronic ester bond maintenance. Consequently, a notable release rate peak (22.69 ± 1.16 μg/cm2·h) was observed at 1 h, though the final cumulative release (57.45 ± 3.14%) remained lower than that of pure SF MNs. These results indicate that while the presence of dynamic covalent bonds can partially retard drug release, it cannot fully counteract the burst release caused by the disintegration of the physical matrix structure.

In contrast, the PBA-SF@MNs exhibited a diffusion-controlled release mechanism dominated by a cross-linked network. The amide bonds formed between SF and APBA via EDC/NHS chemistry established a stable and durable three-dimensional covalent network. This structure not only endowed the MNs with excellent mechanical properties and structural integrity, allowing them to maintain their morphology in PBS for an extended period without the dissolution observed in the other two types of MNs, but also significantly increased the resistance to drug diffusion. Drug molecules must navigate through the pores within the cross-linked network to be released. Although dynamic boronic ester bonds between APBA and AD are also present inside, their dissociation is suppressed in the neutral PBS environment, further restricting drug diffusion. The synergistic effect of these two factors resulted in a consistently low drug release rate, with a cumulative release of only 25.02 ± 3.32% over 24 hours.

3.8.2 Effect of glucose concentration on in vitro drug release from MNs

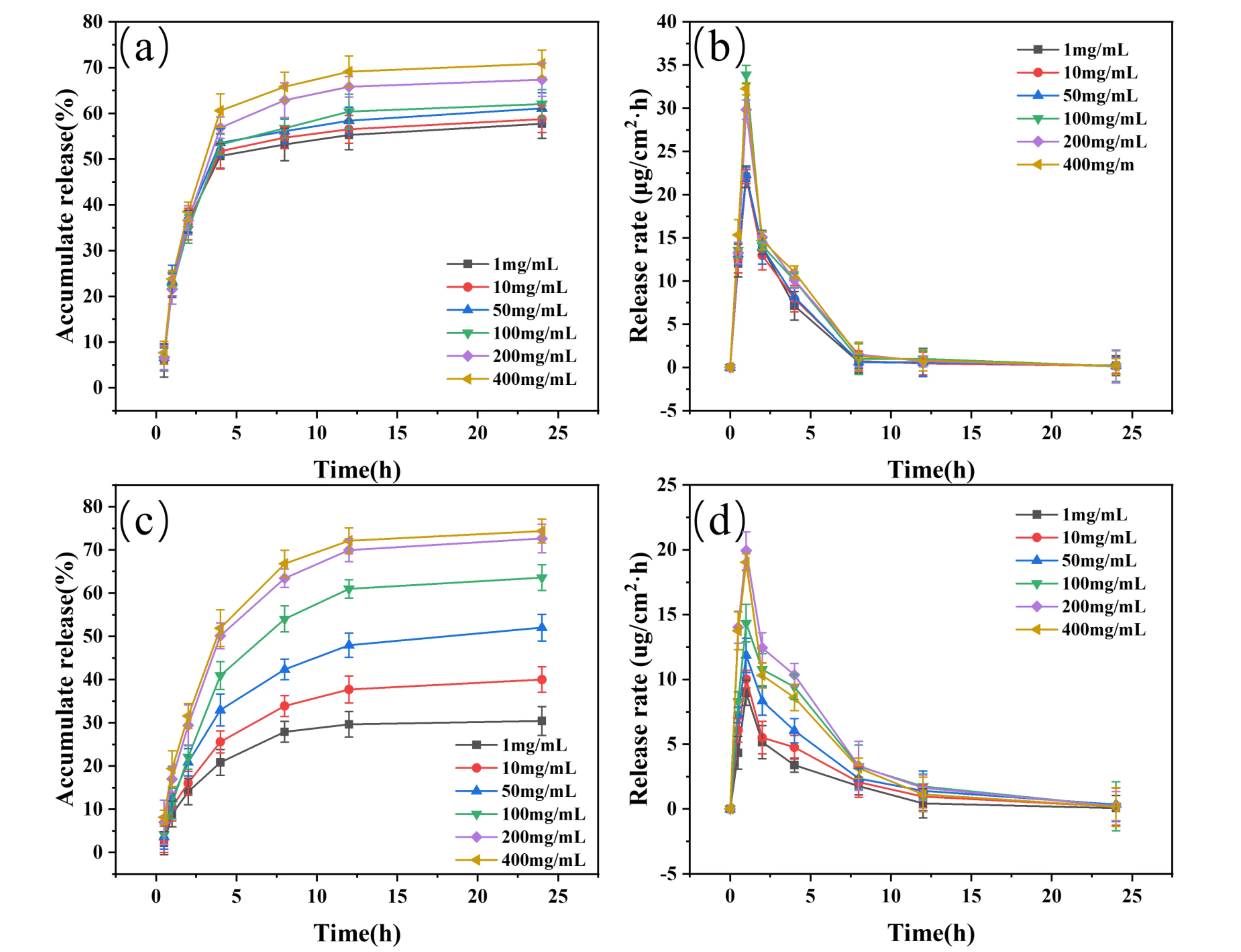

To investigate the effect of glucose concentration on the stability of boronic ester bonds, this study systematically compared the drug release behaviors of PBA/SF@MNs and PBA-SF@MNs in glucose solutions at different concentrations (1, 10, 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg/mL). The selected concentration range covers clinically relevant blood glucose levels: 100 mg/mL (5.6 mM) corresponds to normal fasting levels, 200 mg/mL (11.1 mM) represents typical postprandial or controlled diabetic ranges, while 400 mg/mL (22.2 mM) simulates severe hyperglycemic states. This range spans scenarios from low to high concentrations, thoroughly validating the system’s glucose-competitive drug release capability and its reliability as a stimulus-response platform.

As shown in Figure 9a, PBA/SF@MNs exhibited a burst release–dominated pattern across all glucose concentrations. The cumulative release rates of PBA/SF@MNs at 24 hours were 57.72 ± 3.17%, 58.74 ± 2.94%, 61.11 ± 3.40%, 62.04 ± 3.11%, 67.37 ± 3.62%, and 70.87 ± 2.97% in glucose solutions of 1, 10, 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg/mL, respectively. In all cases, the cumulative release exceeded 50% within the first 4 hours, and the 24-hour cumulative release gradually increased from 57.72 ± 3.17% (1 mg/mL) to 70.87 ± 2.97% (400 mg/mL). This phenomenon can be primarily attributed to the lack of a stable three-dimensional network in its physically blended structure. The MNs rapidly undergo partial dissolution and structural damage in the solution environment, leading to rapid drug release through diffusion channels. Meanwhile, as shown in Figure 9b, the maximum drug release rates of PBA/SF@MNs in glucose solutions with concentrations of 1, 10, 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg/mL were 22.06 ± 1.24 μg/cm2·h, 22.08 ± 0.82 μg/cm2·h, 22.29 ± 0.80 μg/cm2·h, 33.89 ± 1.08 μg/cm2·h, 29.84 ± 1.13 μg/cm2·h, and 32.26 ± 0.69 μg/cm2·h, respectively. Although the maximum release rate increased with rising glucose concentration (from 22.06 ± 1.24 μg/cm2·h to 32.26 ± 0.69 μg/cm2·h), indicating competitive binding between glucose and the drug for boronic acid sites, some APBA may be lost due to physical entrapment and dissolution with SF, resulting in a limited number of boronic acid sites actually available for glucose response. Furthermore, due to the inherent structural instability of the non-crosslinked SF, this system cannot achieve long-term controlled drug release.

Figure 9. Drug release performance of MNs in glucose solutions with different concentrations. (a-b) Cumulative release rate and release rate of PBA/SF@MNs in glucose solutions (1-400 mg/mL); (c-d) Cumulative release rate and release rate of PBA-SF@MNs in glucose solutions (1-400 mg/mL). MNs: microneedles; SF: silk fibroin; PBA/SF@MNs: AD-loaded blended MNs; PBA-SF@MNs: AD-loaded grafted MNs.

In contrast, PBA-SF@MNs exhibited significantly different release characteristics and glucose-competitive behavior. As shown in Figure 9c, the cumulative drug release rates of PBA-SF@MNs in glucose solutions with concentrations of 1, 10, 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg/mL were 30.42 ± 3.35%, 40.00 ± 2.96%, 52.02 ± 3.07%, 63.59 ± 2.97%, 72.64 ± 3.32%, and 74.36 ± 2.76%, respectively. The 24-hour cumulative release demonstrated a clear concentration-dependent gradient, increasing from 30.42 ± 3.35% (1 mg/mL) to 74.36 ± 2.76% (400 mg/mL), indicating high sensitivity of the internal boronic ester bonds to glucose concentration. This is consistent with the well-established competitive binding mechanism between glucose and catechol derivatives for phenylboronic acid, where glucose exhibits higher affinity for the boronic acid moiety under physiological conditions[54]. Furthermore, under low glucose concentrations (1-50 mg/mL), the cumulative release of PBA-SF@MNs was consistently lower than that of PBA/SF@MNs under the same conditions, further confirming that its release behavior is primarily governed by chemical bond dissociation rather than matrix disintegration. Within the stable cross-linked network (with a mass loss of only 4.7 ± 0.87% over 24 hours), APBA is covalently anchored to the SF backbone, ensuring efficient utilization of boronic acid sites. Glucose molecules freely diffuse into the network and compete with the drug for binding to these boronic acid sites. In addition, as shown in Figure 9d, the maximum drug release rates of PBA-SF@MNs in glucose solutions of 1, 10, 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg/mL were 8.97 ± 0.97 μg/cm2·h, 10.02 ± 0.67 μg/cm2·h, 11.86 ± 1.32 μg/cm2·h, 14.34 ± 1.45 μg/cm2·h, 19.93 ± 1.46 μg/cm2·h, and 19.04 ± 0.89 μg/cm2·h, respectively. These values were significantly lower than those of the blended group and were sustained beyond 8 hours, demonstrating excellent prolonged release capability, which can be attributed to the controlled dissociation of boronic ester bonds in response to glucose concentration[55].

This study successfully constructed an innovative “protect-release” dual-function MN system by chemically grafting phenylboronic acid onto sericin. This system design directly addresses the core challenge of stabilizing easily oxidized catecholamine drugs such as epinephrine. Its outstanding performance is primarily attributed to the stable three-dimensional covalent cross-linked network formed during the grafting process. This structure achieves two critical and interrelated functions: First, covalent anchoring of APBA to the fibroin backbone significantly reduces its dissolution rate (from 56.22% to 6.72%), thereby eliminating potential biosafety risks from free APBA. Second, it establishes a dual-mode controlled-release mechanism, the cross-linked hydrogel matrix itself forms a physical diffusion barrier, slowing drug migration. Simultaneously, immobilized phenylboronic acid groups provide specific binding sites to form reversible borate ester bonds with the drug. Release kinetics are thus dual-regulated by diffusion through the gel network and bond dissociation dynamics. This mechanism is robustly validated by the system’s glucose-responsive concentration-dependent release curve, glucose exerts its effect through a competitive binding pathway.

However, this study still has certain limitations: the current data are primarily based on ex vivo skin models and buffer solutions, and have not yet been validated in complex in vivo physiological microenvironments for drug release behavior, long-term biocompatibility, and pharmacodynamic effects. Additionally, the platform’s applicability to other easily oxidized drugs requires further investigation. Future work will focus on in vivo evaluation and platform expansion to advance its translation toward clinical application.

4. Conclusion

This study successfully developed a novel MN drug delivery system (PBA-SF@MNs) based on the chemical grafting of silk fibroin and 3-aminophenylboronic acid, aiming to enhance the stability and sustained release of catechol-containing drugs. Compared to PBA/SF@MNs, the PBA-SF@MNs demonstrated significantly superior performance: a mass loss of less than 5%, with the formed dense network effectively preventing drug oxidation. Through the specific binding of boronic ester bonds, controlled and sustained drug release was achieved. The study also confirmed the glucose-responsive behavior of the MN system. Within a glucose concentration range of 1-400 mg/mL, the 24-hour cumulative release of the MNs increased from 30.42% to 74.36%, showing clear concentration dependence.

This SF-based MN system innovatively leverages the dynamic reversibility of boronic ester bonds, ensuring drug stability during storage and transportation while enabling effective release upon application. The chemical grafting strategy provides an ideal protective environment for oxidation-prone catechol-containing drugs, significantly improving their storage stability and bioavailability. This approach offers a new solution for the transdermal delivery of oxidation-sensitive drugs and holds substantial application value in the field of drug stability protection.

Authors contribution

Cao Y: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft.

Chen Y: Conceptualization, methodology.

Wang H: Conceptualization, visualization.

Tan G: Writing-review & editing.

Lu S: Writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51973144) and the Priority Academic Program Development (PAPD) of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions for Textile Engineering in Soochow University.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Dribin TE, Waserman S, Turner PJ. Who needs epinephrine? Anaphylaxis, autoinjectors, and parachutes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2023;11:1036-1046.[DOI]

-

2. Ghanayem NS, Yee L, Nelson T, Wong S, Gordon JB, Marcdante K, et al. Stability of dopamine and epinephrine solutions up to 84 hours. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2001;2(4):315-317.[DOI]

-

3. Carr RR, Decarie D, Ensom MH. Stability of epinephrine at standard concentrations. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2014;67(3):197-202.[DOI]

-

4. Heradstveit BE, Sunde GA, Asbjørnsen H, Aalvik R, Wentzel-Larsen T, Heltne JK. Pharmacokinetics of epinephrine during cardiac arrest: A pilot study. Resuscitation. 2023;193:110025.[DOI]

-

5. Ebisawa M, Muraro A, Worm M, Katelaris CH, Pouessel G, Ring J, et al. Optimizing adrenaline administration in anaphylaxis: Clinical practice considerations and safety insights. Clin Transl Allergy. 2025;15(8):e70085.[DOI]

-

6. Li C, Wan L, Luo J, Jiang M, Wang K. Advances in subcutaneous delivery systems of biomacromolecular agents for diabetes treatment. Int J Nanomedicine. 2021;16:1261-1280.[DOI]

-

7. Zhao R, Lu Z, Yang J, Zhang L, Li Y, Zhang X. Drug delivery system in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:880.[DOI]

-

8. Wang B, Wang L, Yang Q, Zhang Y, Qinglai T, Yang X, et al. Pulmonary inhalation for disease treatment: Basic research and clinical translations. Mater Today Bio. 2024;25:100966.[DOI]

-

9. Qi Z, Yan Z, Tan G, Jia T, Geng Y, Shao H, et al. Silk fibroin microneedles for transdermal drug delivery: Where do we stand and how far can we proceed? Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(2):355.[DOI]

-

10. Yin Z, Kuang D, Wang S, Zheng Z, Yadavalli VK, Lu S. Swellable silk fibroin microneedles for transdermal drug delivery. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;106:48-56.[DOI]

-

11. Indermun S, Luttge R, Choonara YE, Kumar P, du Toit LC, Modi G, et al. Current advances in the fabrication of microneedles for transdermal delivery. J Control Release. 2014;185:130-138.[DOI]

-

12. Zhao J, Xu G, Yao X, Zhou H, Lyu B, Pei S, et al. Microneedle-based insulin transdermal delivery system: Current status and translation challenges. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2022;12(10):2403-2427.[DOI]

-

13. De Giorgio G, Matera B, Vurro D, Manfredi E, Galstyan V, Tarabella G, et al. Silk fibroin materials: Biomedical applications and perspectives. Bioengineering. 2024;11(2):167.[DOI]

-

14. Wani SUD, Gautam SP, Qadrie ZL, Gangadharappa HV. Silk fibroin as a natural polymeric based bio-material for tissue engineering and drug delivery systems-A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;163:2145-2161.[DOI]

-

15. Bitar L, Isella B, Bertella F, Vasconcelos BC, Harings J, Kopp A, et al. Sustainable bombyx mori’s silk fibroin for biomedical applications as a molecular biotechnology challenge: A review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;264(1):130374.[DOI]

-

16. Zhao Y, Zhu ZS, Guan J, Wu SJ. Processing, mechanical properties and bio-applications of silk fibroin-based high-strength hydrogels. Acta Biomater. 2021;125:57-71.[DOI]

-

17. Chen K, Li Y, Li Y, Pan W, Tan G. Silk fibroin combined with electrospinning as a promising strategy for tissue regeneration. Macromol Biosci. 2023;23(2):e2200380.[DOI]

-

18. Wen DL, Sun DH, Huang P, Huang W, Su M, Wang Y, et al. Recent progress in silk fibroin-based flexible electronics. Microsyst Nanoeng. 2021;7:35.[DOI]

-

19. Zhang Y, Jian Y, Jiang X, Li X, Wu X, Zhong J, et al. Stepwise degradable PGA-SF core-shell electrospinning scaffold with superior tenacity in wetting regime for promoting bone regeneration. Mater Today Bio. 2024;26:101023.[DOI]

-

20. Lujerdean C, Baci GM, Cucu AA, Dezmirean DS. The contribution of silk fibroin in biomedical engineering. Insects. 2022;13(3):286.[DOI]

-

21. Zhang Y, Sun T, Jiang C. Biomacromolecules as carriers in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2018;8(1):34-50.[DOI]

-

22. Rockwood DN, Preda RC, Yücel T, Wang X, Lovett ML, Kaplan DL. Materials fabrication from Bombyx mori silk fibroin. Nat Protoc. 2011;6(10):1612-1631.[DOI]

-

23. Srivastava CM, Purwar R, Kannaujia R, Sharma D. Flexible silk fibroin films for wound dressing. Fibers Polym. 2015;16(5):1020-1030.[DOI]

-

24. Jiang C, Wang X, Gunawidjaja R, Lin YH, Gupta MK, Kaplan DL, et al. Mechanical properties of robust ultrathin silk fibroin films. Adv Funct Mater. 2007;17(13):2229-2237.[DOI]

-

25. Huang Y, Bailey K, Wang S, Feng X. Silk fibroin films for potential applications in controlled release. React Funct Polym. 2017;116:57-68.[DOI]

-

26. Frydrych M, Greenhalgh A, Vollrath F. Artificial spinning of natural silk threads. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):15428.[DOI]

-

27. Peng Q, Zhang Y, Lu L, Shao H, Qin K, Hu X, et al. Recombinant spider silk from aqueous solutions via a bio-inspired microfluidic chip. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36473.[DOI]

-

28. Wang HY, Zhang YQ. Processing silk hydrogel and its applications in biomedical materials. Biotechnol Prog. 2015;31(3):630-640.[DOI]

-

29. Zheng H, Zuo B. Functional silk fibroin hydrogels: Preparation, properties and applications. J Mater Chem B. 2021;9(5):1238-1258.[DOI]

-

30. Wu H, Lin K, Zhao C, Wang X. Silk fibroin scaffolds: A promising candidate for bone regeneration. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:1054379.[DOI]

-

31. Zhang X, Baughman CB, Kaplan DL. In vitro evaluation of electrospun silk fibroin scaffolds for vascular cell growth. Biomaterials. 2008;29(14):2217-2227.[DOI]

-

32. Yao X, Zou S, Fan S, Niu Q, Zhang Y. Bioinspired silk fibroin materials: From silk building blocks extraction and reconstruction to advanced biomedical applications. Mater Today Bio. 2022;16:100381.[DOI]

-

33. Li Y, Ju XJ, Fu H, Zhou CH, Gao Y, Wang J, et al. Composite separable microneedles for transdermal delivery and controlled release of salmon calcitonin for osteoporosis therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(1):638-650.[DOI]

-

34. Ruan S, Zhang Y, Feng N. Microneedle-mediated transdermal nanodelivery systems: A review. Biomater Sci. 2021;9(24):8065-8089.[DOI]

-

35. Song Y, Hu C, Wang Z, Wang L. Silk-based wearable devices for health monitoring and medical treatment. iScience. 2024;27(5):109604.[DOI]

-

36. Johari N, Khodaei A, Samadikuchaksaraei A, Reis RL, Kundu SC, Moroni L. Ancient fibrous biomaterials from silkworm protein fibroin and spider silk blends: Biomechanical patterns. Acta Biomater. 2022;153:38-67.[DOI]

-

37. Hu X, Shmelev K, Sun L, Gil ES, Park SH, Cebe P, et al. Regulation of silk material structure by temperature-controlled water vapor annealing. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12(5):1686-1696.[DOI]

-

38. Li X, Fan Q, Zhang Q, Yan S, You R. Freezing-induced silk I crystallization of silk fibroin. CrystEngComm. 2020;22(22):3884-3890.[DOI]

-

39. Yavuz B, Chambre L, Kaplan DL. Extended release formulations using silk proteins for controlled delivery of therapeutics. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2019;16(7):741-756.[DOI]

-

40. Zhu M, Liu Y, Jiang F, Cao J, Kundu SC, Lu S. Combined silk fibroin microneedles for insulin delivery. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2020;6(6):3422-3429.[DOI]

-

41. Yang B, Lv Y, Zhu JY, Han YT, Jia HZ, Chen WH, et al. A pH-responsive drug nanovehicle constructed by reversible attachment of cholesterol to PEGylated poly(L-lysine) via catechol–boronic acid ester formation. Acta Biomater. 2014;10(8):3686-3695.[DOI]

-

42. Mu J, Ding X, Song Y, Mi B, Fang X, Chen B, et al. ROS-responsive microneedle patches enable peri-lacrimal gland therapeutic administration for long-acting therapy of sjögren’s syndrome-related dry eye. Adv Sci. 2025;12(16):e2409562.[DOI]

-

43. Liu L, Ma Z, Han Q, Meng W, Ye H, Zhang T, et al. Phenylboronic ester-bridged chitosan/myricetin nanomicelle for penetrating the endothelial barrier and regulating macrophage polarization and inflammation against ischemic diseases. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2023;9(7):4311-4327.[DOI]

-

44. Tao X, Jiang F, Cheng K, Qi Z, Yadavalli VK, Lu S. Synthesis of pH and glucose responsive silk fibroin hydrogels. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(13):7107.[DOI]

-

45. Haslam IS, Roubos EW, Mangoni ML, Yoshizato K, Vaudry H, Kloepper JE, et al. From frog integument to human skin: Dermatological perspectives from frog skin biology. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2014;89(3):618-655.[DOI]

-

46. Kyte J, Doolittle RF. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157(1):105-132.[DOI]

-

47. Ma Y, Canup BSB, Tong X, Dai F, Xiao B. Multi-responsive silk fibroin-based nanoparticles for drug delivery. Front Chem. 2020;8:585077.[DOI]

-

48. Lu W, Ma S, Sun L, Zhang T, Wang X, Feng M, et al. Combined CRISP toolkits reveal the domestication landscape and function of the ultra-long and highly repetitive silk genes. Acta Biomater. 2023;158:190-202.[DOI]

-

49. Bai S, Zhang X, Lu Q, Sheng W, Liu L, Dong B, et al. Reversible hydrogel–solution system of silk with high beta-sheet content. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15(8):3044-3051.[DOI]

-

50. Lee KJ, Park SH, Lee JY, Joo HC, Jang EH, Youn YN, et al. Perivascular biodegradable microneedle cuff for reduction of neointima formation after vascular injury. J Control Release. 2014;192:174-181.[DOI]

-

51. Ming J, Li M, Han Y, Chen Y, Li H, Zuo B, et al. Novel two-step method to form silk fibroin fibrous hydrogel. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2016;59:185-192.[DOI]

-

52. Li M, Lu S, Wu Z, Yan H, Mo J, Wang L. Study on porous silk fibroin materials. I. J Appl Polym Sci. 2001;79(12):2185-2191.[DOI]

-

53. Davis SP, Landis BJ, Adams ZH, Allen MG, Prausnitz MR. Insertion of microneedles into skin: Measurement and prediction of insertion force and needle fracture force. J Biomech. 2004;37(8):1155-1163.[DOI]

-

54. Liu Y, Yang X, Wu K, Feng J, Zhang X, Li A, et al. Skin-inspired and self-regulated hydrophobic hydrogel for diabetic wound therapy. Adv Mater. 2025;37(16):e2414989.[DOI]

-

55. Xie H, Wang Z, Wang R, Chen Q, Yu A, Lu A. Self-healing, injectable hydrogel dressing for monitoring and therapy of diabetic wound. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(36):2401209.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite