Yun-Shen Chan, Guangzhou National Laboratory, Guangzhou International Bio Island, Guangzhou 510005, Guangdong, China. E-mail: chan_yunshen@gzlab.ac.cn

Abstract

Wingless/Integrated (WNT) signaling is a central pathway governing tissue morphogenesis, stem cell maintenance, and regeneration. However, its therapeutic translation has been hindered by challenges in delivering stable and active WNT ligands over long distances to target tissues and organs. Recent advances in exosome engineering offer a new solution to this problem by delivering WNT ligands via engineered exosomes, dual-ligand vesicles to achieve robust and sustained activation of WNT signaling both in vitro and in vivo. This perspective highlights how such dual-ligand exosomes overcome the biochemical and delivery barriers of WNT activation, promote liver regeneration under diverse conditions, including acute, chronic, and aging-associated injuries, and establish a conceptual framework for next-generation regenerative therapeutics. These findings mark a pivotal step toward reprogramming tissue homeostasis and rejuvenation through bioengineered signaling vesicles.

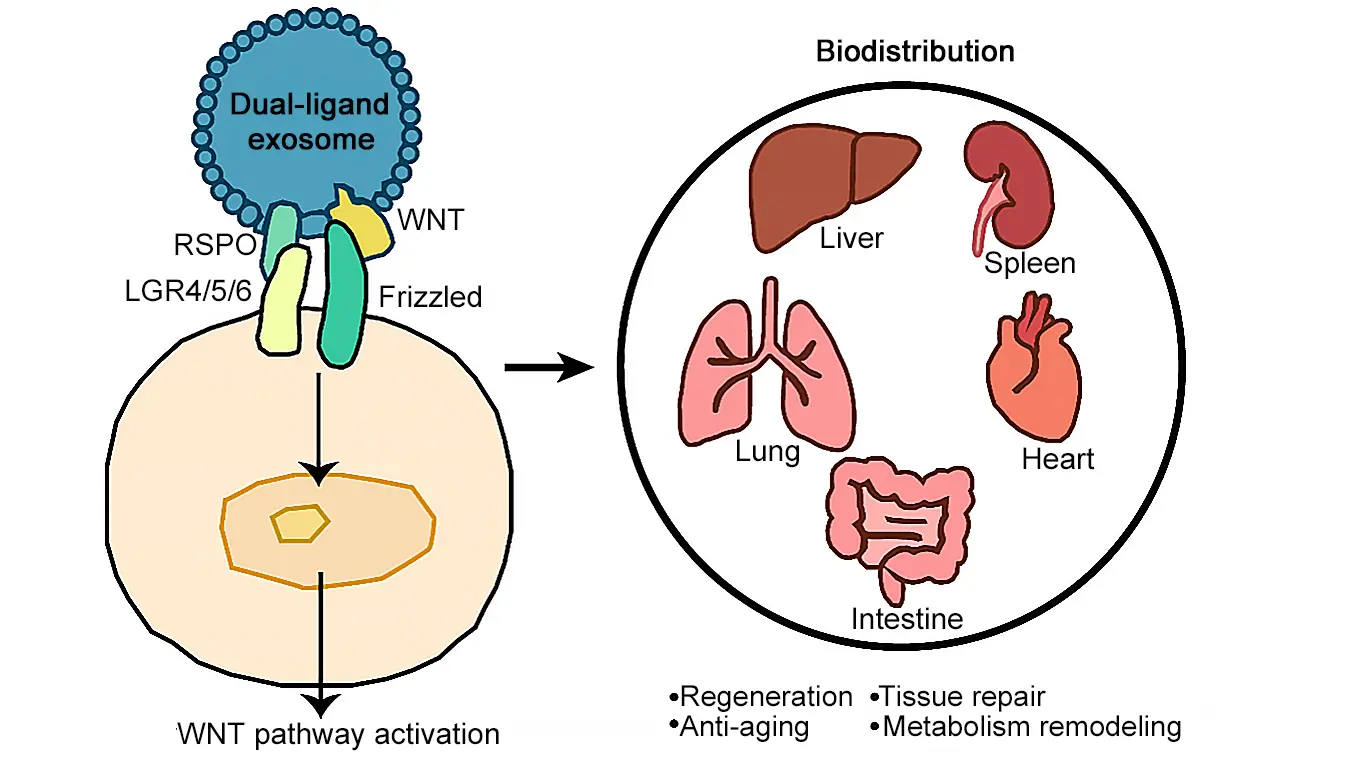

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

1. Introduction

Wingless/Integrated (WNT) signaling has long been recognized as a central regulator of tissue morphogenesis and regeneration, orchestrating stem cell fate and organ patterning throughout development and adulthood[1,2]. However, despite decades of study, the translational potential of WNT activation remains largely untapped. The major bottleneck lies not in our understanding of the pathway’s molecular intricacies, but in the challenge of delivering functional WNT ligands to target tissues in vivo. Recent advances in exosome engineering have opened an unprecedented opportunity to overcome this barrier. By delivering WNT ligands via engineered exosomes, Yang et al. used dual-ligand vesicles to achieve robust and sustained activation of WNT signaling both in vitro and in vivo to treat different types of liver injury[3].

1.1 The unfulfilled promise of WNT in regenerative medicine

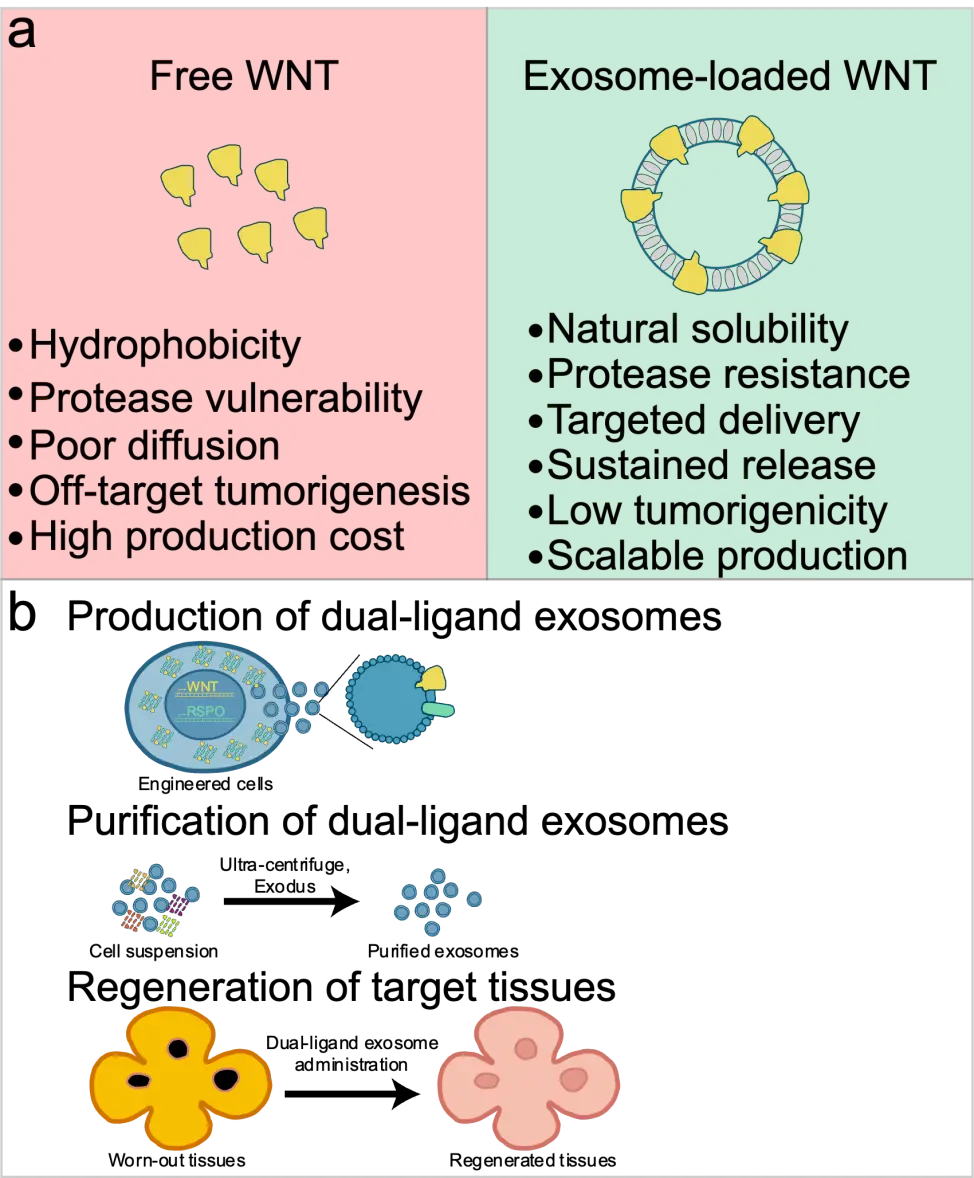

The liver’s remarkable regenerative capacity provides an ideal context for exploring WNT-based therapies. Following injury or partial hepatectomy, canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling is rapidly and transiently activated, driving hepatocyte proliferation and tissue reconstruction[4,5]. However, attempts to therapeutically harness this pathway have faced persistent limitations. Small-molecule activators, such as glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta inhibitors (e.g., CHIR99021), can induce strong canonical WNT activation but do so indiscriminately, often resulting in off-target effects and toxicity[6]. In contrast, recombinant WNT proteins, despite their ligand-receptor specificity, are notoriously difficult to purify and stabilize due to their lipid modification and hydrophobicity[7]. Thus, a fundamental translational gap persists between mechanistic insight and clinical application. A delivery platform capable of preserving the biochemical integrity of WNT ligands and targeting them to specific tissues could bridge this gap (Figure 1a).

Figure 1. Advantages of using exosomes for WNT delivery. (a) Comparison between free WNT protein and exosome-loaded WNT; (b) Schematics illustrating the generation of exosomes for targeted tissue regeneration. WNT: Wingless/Integrated.

1.2 Exosomes as nature’s nanocarriers for morphogen transport

Exosomes are nano-sized extracellular vesicles that are secreted by cells and naturally carry proteins, RNAs, and lipids that function as intercellular messengers[8,9]. Their biocompatibility, circulatory stability, and low immunogenicity make them ideal therapeutic vehicles[10-12]. Intriguingly, endogenous WNT ligands have been observed on exosome membranes in both Drosophila and mammalian systems, indicating a conserved mechanism for lipid-modified morphogen dissemination[13]. Building on this concept, engineered exosomes that actively load WNT and R-spondin (RSPO) proteins provide a biologically inspired delivery system. By embedding the WNT ligand–loading machinery (e.g., Wntless (WLS)) and co-expressing specific ligands, Yang et al. have achieved stable encapsulation and secretion of bioactive exosomes (Figure 1b).

Engineered WNT exosomes represent a conceptual shift from earlier WNT delivery strategies that relied largely on passive encapsulation or bolus administration of recombinant ligands. By harnessing WLS, this system enables active and efficient loading of WNT proteins onto exosomes, overcoming the long-standing challenges imposed by WNT hydrophobicity and instability. Notably, this approach allows modular presentation of any of the 19 WNT family members, offering an unprecedented level of control over pathway specificity. Previous studies have not reported exosome-based delivery of RSPOs. Beyond WNT ligands themselves, this work has expanded this platform to include the full R-spondin family (RSPO1–4), introducing a previously unexplored dimension of WNT signal amplification via exosome-based delivery. The integration of WNT and RSPO within a single exosome further elevates this strategy, enabling coordinated pathway activation that exceeds the efficacy of simple ligand co-administration. Together, these advances redefine exosomes as programmable signaling units rather than passive carriers and point toward a future in which rationally designed WNT–RSPO exosomes can be tailored for tissue-specific regeneration and therapeutic precision.

1.3 Regulating hepatic differentiation and proliferation

The engineered exosomes surpass the activity of both single ligand and pharmacological activators. In human hepatic progenitor cells, they promote efficient differentiation toward hepatocyte lineages, partly by activating the peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor alpha signaling pathway, a metabolic regulator newly implicated in liver progenitor differentiation. Moreover, by culturing adult liver organoids, Yang et al. demonstrated that the engineered WNT exosomes activated mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling to promote hepatocyte proliferation, whereas the WNT agonist CHIR99021 failed to elicit a similar effect.

1.4 Regeneration beyond repair

In murine models, the engineered WNT exosomes robustly activate WNT signaling in Axin2+ and Cyp2e1+ hepatocytes around the central vein and stimulate hepatocyte proliferation. This activity restores liver zonation and enhances regeneration after various insults, including acute injury, chronic fibrosis, and aging-associated tissue changes. Notably, their treatment not only restored hepatocyte regeneration and metabolic functions, but also attenuated cell death, inflammation, fibrosis, and aging-related phenotypes.

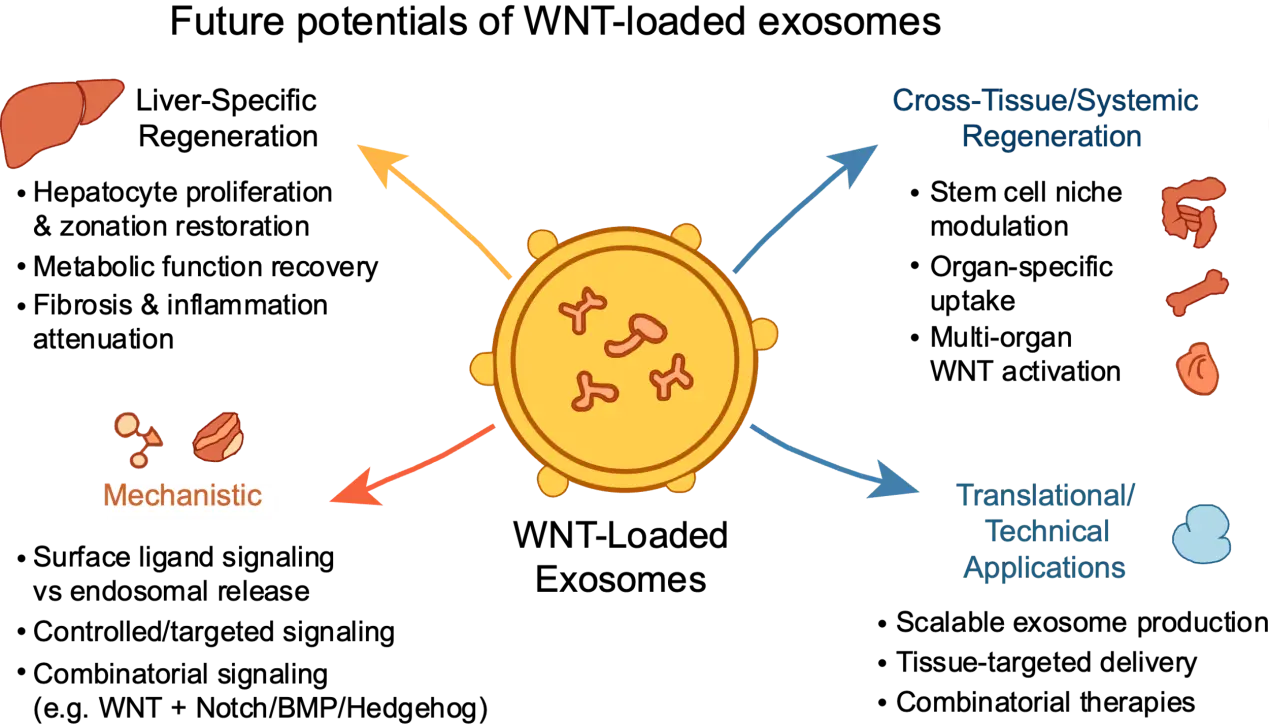

1.5 Toward systemic and cross-tissue regeneration

WNT-loaded exosomes are poised to achieve much more in the future, with possibilities that reach far beyond existing applications (Figure 2). Although the work of Yang et al. primarily focused on liver regeneration following injury, the restoration of hepatocyte metabolic functions (e.g., glucose metabolism, fat metabolism, cholesterol metabolism, and drug metabolism) observed in their study suggests broader applications for treating liver metabolic disorders, such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease or metabolic hepatopathies. Similarly, WNT signaling has been implicated in metabolic regulation (e.g., adipogenesis in adipose tissue and amino acid metabolism in liver cancer) in various contexts[14,15], yet its precise contribution to hepatocyte metabolic reprogramming remains incompletely understood. These findings underscore the need for systematic investigations to delineate how WNT pathway activation coordinates both proliferative and metabolic programs in liver cells, and whether this modulation can be therapeutically harnessed to reverse metabolic dysfunctions in chronic liver diseases.

Figure 2. Multifaceted potential of WNT-loaded exosomes in regeneration, mechanistic studies, and translational development. WNT: Wingless/Integrated.

Beyond hepatology, the implications of engineered WNT exosomes extend to systemic and cross-tissue regeneration. The WNT signaling pathway constitutes core components of stem cell niches across multiple organs, including the intestines, bones, muscles, and skin[16], suggesting that the principles demonstrated in liver repair may be generalizable. Notably, Yang et al. reported that the engineered WNT exosomes could be taken up not only by the liver but also displayed marked enrichment in the spleen, lung, heart, kidney, and intestine, where they effectively activated WNT signaling. This widespread biodistribution opens the possibility of using engineered exosomes as a platform for multi-organ regenerative therapy. Importantly, long-term administration did not produce detectable adverse effects in these organs for up to six months, except for mild intestinal hyperplasia, and circulating WNT levels became undetectable within ~1 h, indicating limited systemic exposure and predominant hepatic uptake, which is consistent with previous studies[17]. These data suggest a favorable preliminary safety profile, although WNT activation in extra-hepatic tissues may still exert context-dependent effects, potentially beneficial in regenerative settings such as the lungs[18], but is also associated with risks when aberrantly sustained[3]. Further studies are needed to define these cross-tissue responses and fully assess systemic safety. Refining exosome formulations through surface engineering or ligand display could enable tissue-specific targeting, increasing both efficacy and safety. Moreover, the concept of exosomes carrying rationally designed combinations of signaling ligands, for instance, WNT in combination with Notch, bone morphogenetic proteins, or Hedgehog modulators, may allow the creation of synthetic morphogen systems. Such systems would provide a controllable platform for dissecting inter-pathway crosstalk, programming specific cell fates, and guiding tissue repair in adult organs. Together, these findings point to a new paradigm in regenerative medicine, where exosome-based approaches could be fine-tuned for organ-specific repair, functional restoration, and the modulation of systemic tissue networks.

1.6 Challenges and future outlook

While these advances highlight the exciting regenerative potential of engineered WNT exosomes across multiple tissues, they also raise important questions regarding the precise mechanisms, delivery dynamics, and safety considerations that must be addressed to fully realize their therapeutic potential.

Although engineered WNT exosomes have shown substantial potential for in vivo treatment of liver injury, the precise mechanisms underlying their therapeutic effects remain unclear. For instance, while WNT signaling reportedly activates stellate cells, how periodic WNT dosing reverses the fibrogenic phenotype in chronic disease is yet to be fully understood. Mechanistically, the exact mode of signaling activation, whether via exosome fusion, receptor presentation, or endosomal release, has yet to be fully elucidated. Yang et al. also observed loss of WNT signaling activity after removal of surface-bound WNT ligand, highlighting the importance of surface-bound WNT ligands for signaling transduction. Surface-presented WNT on exosomes engages receptors directly at the plasma membrane, providing rapid and spatially restricted signaling, whereas endosomal release may prolong signaling and broaden target-cell range. Understanding the dominant mechanism would help to predict tissue specificity.

Beyond mechanistic uncertainties, several technical and translational hurdles remain. Scalable and reproducible production of engineered exosomes is a significant hurdle, as current isolation and purification methods often yield variable quantities and qualities of vesicles. Batch-to-batch heterogeneity in vesicle populations, including differences in size, cargo composition, and surface markers, can affect both efficacy and safety, complicating standardization for preclinical and clinical studies. Recent work shows that optimized upstream culture systems, such as perfusion or batch-refeed bioreactors, can stabilize EV output and maintain consistent vesicle subpopulations over extended production periods[19]. In addition, standardized downstream purification methods such as size-exclusion chromatography and microfluidic-based isolation improve purity and reproducibility compared to ultracentrifugation[19,20]. Capricor Therapeutics has initiated a first in-human Phase I trial of its StealthX™ exosome-based vaccine, supported by a scalable and standardized manufacturing framework. Additionally, the biodistribution, pharmacokinetics, and immunological interactions of engineered exosomes in other animal models, and, ultimately, in clinical trials require thorough characterization. Optimizing delivery routes, dosing regimens, and formulation strategies will be crucial to maximizing bioavailability and target specificity. Potential off-target WNT activation can be minimized through tissue-targeted exosomes, controlled dosing, local administration, and preclinical monitoring for abnormal proliferation or tumorigenesis. Potential risks of systemic WNT activation can be mitigated by several complementary strategies, such as engineering exosome surfaces for tissue-specific targeting (e.g., organ-selective peptides or antibodies), minimizing systemic exposure via local administration or low-dose regimens, and using controllable or transient activation systems (e.g., switchable ligands or degradable displays). Rigorous preclinical evaluation, including biodistribution, dose-response, immunogenicity, and long-term tumorigenicity studies, is essential to define safe windows for therapeutic use. Together, these technical and translational considerations highlight the complexity of advancing engineered exosomes from bench to bedside.

From a regulatory perspective, frameworks for exosome-based biologics are still emerging. Establishing standardized potency assays, reference materials, and quality control pipelines will be critical for clinical translation. Finally, combining exosome therapy with complementary strategies, such as organoid implantation or biomaterial scaffolds, may further enhance regenerative outcomes and improve therapeutic efficacy. Biomaterial carriers (e.g., injectable hydrogels, electrospun nanofibers, 3D-printed scaffolds, or bioengineering platelets) provide sustained, local release of exosomes and mechanical support that enhances tissue integration and angiogenesis, improving outcomes in cardiac, bone, and cartilage repair, and potentially type I diabetes amelioration[21-25]. Likewise, organoids co-delivered with exosome preparations or engineered to secrete therapeutic EVs can better reconstitute tissue architecture and local paracrine signaling, accelerating functional regeneration[26-28].

2. Conclusion

The advent of dual-ligand exosomes represents a transformative advance in regenerative medicine. By restoring the combinatorial complexity of WNT signaling, these engineered exosomes enable targeted activation of tissue repair pathways. Their demonstrated capacity to reverse liver injury and ameliorate aging-associated phenotypes highlights the potential of a new class of programmable regenerative biologics. Beyond liver repair, the principles underlying exosome engineering may be extended to other organs and tissues, offering a versatile platform for systemic regeneration.

As synthetic biology, nanotechnology, and stem cell engineering converge, we are entering an era in which the fundamental language of intercellular communication can be rewritten. This convergence allows precise modulation of cellular behavior, controlled activation of signaling networks, and tailored orchestration of tissue regeneration. Looking forward, continued optimization of exosome design, delivery, and combinatorial ligand programming will be crucial to translate these innovations from bench to bedside, ultimately paving the way for regenerative therapies that not only repair but also rejuvenate adult tissues.

Authors contribution

Yang L: Writing–original draft, writing–review & editing.

Wang S: Writing–original draft.

Chan YS: Writing–review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Lingyan Yang is an Editorial Board Member of BME Horizon. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82370053 to Lingyan Yang) and Guangzhou National Laboratory Fund (Grant No.MP-GZNL2025C02009-01 to Yun-Shen Chan).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149(6):1192-1205.[DOI]

-

2. Nusse R, Clevers H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling, disease, and emerging therapeutic modalities. Cell. 2017;169(6):985-999.[DOI]

-

3. .Yang L, Wang S, Qiao Z, Liu Y, Wang X, Liu L, et al. Dual-ligand engineered exosome regulates WNT signaling activation to promote liver repair and regeneration. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):9019.[DOI]

-

4. Pu W, Zhu H, Zhang M, Pikiolek M, Ercan C, Li J, et al. Bipotent transitional liver progenitor cells contribute to liver regeneration. Nat Genet. 2023;55(4):651-664.[DOI]

-

5. Xu J, Guo P, Hao S, Shangguan S, Shi Q, Volpe G, et al. A spatiotemporal atlas of mouse liver homeostasis and regeneration. Nat Genet. 2024;56(5):953-969.[DOI]

-

6. Sato N, Meijer L, Skaltsounis L, Greengard P, Brivanlou AH. Maintenance of pluripotency in human and mouse embryonic stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling by a pharmacological GSK-3-specific inhibitor. Nat Med. 2004;10(1):55-63.[DOI]

-

7. Willert K, Brown JD, Danenberg E, Duncan AW, Weissman IL, Reya T, et al Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature. 2003;423(6938):448-452.[DOI]

-

8. Jeppesen DK, Fenix AM, Franklin JL, Higginbotham JN, Zhang Q, Zimmerman LJ, et al. Reassessment of exosome composition. Cell. 2019;177(2):428-445.[DOI]

-

9. Kim S, Kim YK, Kim S, Choi YS, Lee I, Joo H, et al. Dual-mode action of scalable, high-quality engineered stem cell-derived SIRPα-extracellular vesicles for treating acute liver failure. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):1903.[DOI]

-

10. Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367(6478):eaau6977.[DOI]

-

11. Fusco C, De Rosa G, Spatocco I, Vitiello E, Procaccini C, Frigè C, et al. Extracellular vesicles as human therapeutics: A scoping review of the literature. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024;13(5):e12433.[DOI]

-

12. Shi Y, Zheng Z, Wang W, Hu H. Harnessing the therapeutic potential of bacterial extracellular vesicles via functional peptides. Interdiscip Med. 2025;3(4):e20240125.[DOI]

-

13. Gross JC, Chaudhary V, Bartscherer K, Boutros M. Active Wnt proteins are secreted on exosomes. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14(10):1036-1045.[DOI]

-

14. Yang Loureiro Z, Joyce S, DeSouza T, Solivan-Rivera J, Desai A, Skritakis P, et al. Wnt signaling preserves progenitor cell multipotency during adipose tissue development. Nat Metab. 2023;5(6):1014-1028.[DOI]

-

15. Nakagawa S, Yamaguchi K, Takane K, Tabata S, Ikenoue T, Furukawa Y. Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates amino acid metabolism through the suppression of CEBPA and FOXA1 in liver cancer cells. Commun Biol. 2024;7(1):510.[DOI]

-

16. Clevers H, Loh KM, Nusse R. An integral program for tissue renewal and regeneration: Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Science. 2014;346(6205):1248012.[DOI]

-

17. Du W, Chen C, Liu Y, Quan H, Xu M, Liu J, et al A combined “eat me/don’t eat me” strategy based on exosome for acute liver injury treatment. Cell Rep Med. 2025;6(4):102033.[DOI]

-

18. Shen S, Wang P, Wu P, Huang P, Chi T, Xu W, et al. CasRx-based Wnt activation promotes alveolar regeneration while ameliorating pulmonary fibrosis in a mouse model of lung injury. Mol Ther. 2024;32(11):3974-3989.[DOI]

-

19. Paganini C, Boyce H, Libort G, Arosio P. High-yield production of extracellular vesicle subpopulations with constant quality using batch-refeed cultures. Adv Healthc Mater. 2023;12(8):2202232.[DOI]

-

20. Takov K, Yellon DM, Davidson SM. Comparison of small extracellular vesicles isolated from plasma by ultracentrifugation or size-exclusion chromatography: yield, purity and functional potential. J Extracell Vesicles. 2019;8(1):1560809.[DOI]

-

21. Amini H, Namjoo AR, Narmi MT, Mardi N, Narimani S, Naturi O, et al. Exosome-bearing hydrogels and cardiac tissue regeneration. Biomater Res. 2023;27(1):99.[DOI]

-

22. Lu Y, Mai Z, Cui L, Zhao X. Engineering exosomes and biomaterial-assisted exosomes as therapeutic carriers for bone regeneration. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14(1):55.[DOI]

-

23. Hu W, Wang W, Chen Z, Chen Y, Wang Z. Engineered exosomes and composite biomaterials for tissue regeneration. Theranostics. 2024;14(5):2099-2126.[DOI]

-

24. Lv Z, Xu J, Cai X, Wang Y, Yang X, Wang H, et al. Exosome-integrated biomaterials: A paradigm in musculoskeletal regeneration. Cell Rep Phys Sci. 2025;6(10):102892.[DOI]

-

25. Ma Y, Meng F, Lin Z, Chen Y, Lan T, Yang Z, et al. Bioengineering platelets presenting PD-L1, Galectin-9 and BTLA to ameliorate type 1 diabetes. Adv Sci. 2025;12(16):2501139.[DOI]

-

26. Liu H, Su J. Organoid extracellular vesicle-based therapeutic strategies for bone therapy. Biomater Transl. 2023;4(4):199-212.[DOI]

-

27. Qian J, Lu E, Xiang H, Ding P, Wang Z, Lin Z, et al. GelMA loaded with exosomes from human minor salivary gland organoids enhances wound healing by inducing macrophage polarization. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22(1):550.[DOI]

-

28. Ye L, Li S, Bi G, Li B, Cai Z, Jin M, et al. Exosomes from intestinal epithelial cells promote hepatic differentiation of liver progenitor cells in gut-liver-on-a-chip models. Adv Sci. 2025;12(32):e17478.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite