Abstract

Bacterial infections caused by biomaterials represent a significant challenge in the clinical management of implants. Implant infections not only lead to surgical failure, prolong patient hospital stays, and increase healthcare costs, but may also trigger severe complications and even pose a threat to the patient’s life. Research on antimicrobial materials for metal implant surfaces holds significant importance. By developing antimicrobial coatings for implant surfaces or utilizing inherently antimicrobial metallic materials, bacterial adhesion and growth on implant surfaces can be effectively suppressed, thereby reducing infection rates and improving the success rate of implant surgeries. Simultaneously, the development of antimicrobial materials also contributes to advancing medical materials science, offering new approaches and methodologies for antimicrobial design in other medical devices. This holds broad application prospects and significant socioeconomic benefits.

Keywords

1. Introduction

With the rapid advancement of modern medical technology, metal implants are increasingly being used across numerous medical fields such as orthopedics, dentistry, and cardiovascular medicine, significantly improving patient treatment and physical recovery. In orthopedics, metal implants are used in procedures such as fracture fixation and joint replacement to help patients restore normal skeletal function and improve their quality of life[1]. In the field of dentistry, metal implants such as dental implants provide effective restorative solutions for patients with missing teeth, improving both chewing function and aesthetic appearance[2]. In the field of cardiovascular medicine, implants such as metal stents can expand narrowed or blocked blood vessels, restoring blood flow and saving patients’ lives[3]. However, implant-related infections have long been a major challenge in clinical treatment, severely impacting patients’ health and quality of life. According to relevant research statistics, the additional medical costs incurred globally each year due to infections from metal implants amount to billions of dollars, with the number of infection cases showing an upward trend year by year[4]. In orthopedic joint replacement surgery, the incidence of prosthetic joint infection has been reported to range from 2% to 34% across different studies[5]. In specific high-risk groups, such as patients undergoing tumor prosthesis replacement, infection rates may be higher[5]. Following spinal internal fixation surgery, the incidence of surgical site infection can reach between 7% and 20%. Once these infections occur, treatment proves extremely challenging[6]. The formation of bacterial biofilms on implant surfaces enables bacteria to evade the body’s immune system and develop resistance to antibiotics, resulting in suboptimal outcomes with conventional treatments[7]. Complex infections typically require comprehensive treatment involving multiple surgical debridements, prolonged antibiotic therapy, and even implant replacement. Despite these interventions, outcomes remain unsatisfactory, leaving patients to endure significant suffering and financial strain[8,9].

In order to effectively solve the problem of metal implant infection, the development of metal implant surface materials with antimicrobial properties has become a current research hotspot in the field of biomedical engineering. Wu et al.[10] analyzed the antibacterial effects of copper-doped titanium and titanium alloys, concluding that copper addition exhibits promising antibacterial potential while offering advantages such as biocompatibility and safety. Xiang et al.[11] systematically analyzed research progress on antimicrobial implant materials for bone infections from 2019 to 2025 by classifying antimicrobial materials, providing a framework for understanding antimicrobial strategies across different matrix materials. Yang et al.[12] comprehensively reviewed biodegradable zinc-based metallic materials, examining the degradation behavior, biofunctionality, and mechanical properties of zinc alloys. They emphasized the unique advantages of zinc alloys in biodegradability, antimicrobial activity, and osteogenic promotion. However, the above reviews are limited to single antimicrobial strategies or individual antimicrobial elements, lacking a systematic integration and comparison of multiple antimicrobial strategies and mechanisms.

This paper aims to focus on and conduct an in-depth analysis of the principal categories of antimicrobial materials for metal implant surfaces that have attracted concentrated research attention and demonstrate significant application potential. In terms of material selection, this paper focuses on silver, copper, and zinc-based inorganic antimicrobial materials, alongside representative organic antimicrobial materials such as quaternary ammonium salts and chitosan derivatives, along with their composite systems. This selection is primarily based on two criteria: firstly, research prominence and maturity. These materials have been most extensively reported in recent academic literature and experimental studies, with their antimicrobial efficacy and mechanisms relatively well-validated. Secondly, clinical translation potential. Compared to other exploratory materials, the aforementioned substances demonstrate clearer clinical application prospects in terms of safety, processability, and compatibility with existing implant technologies. By systematically organizing and comparing the classification, properties, mechanisms of action, and research case studies of these key materials, this paper aims to elucidate the advantages and limitations of different strategies. It seeks to consolidate current mainstream antimicrobial design approaches, thereby providing clearer scientific guidance for selecting antimicrobial implants tailored to specific clinical needs. Furthermore, it offers a basis for refining future research directions in novel material development.

2. Types of Antimicrobial Materials for Metal Implant Surfaces

Antimicrobial materials may be categorized according to their chemical composition and origin into inorganic antimicrobial materials, organic antimicrobial materials, and composite antimicrobial materials. The classification and properties of antimicrobial materials are shown in Table 1.

| Dimensional Characteristics | Inorganic Antibacterial Materials | Organic Antimicrobial Material | Composite Antimicrobial Material |

| Core Antimicrobial Mechanism | 1. Slow-release of metal ions (e.g., Ag+, Cu2+, Zn2+): binds to bacterial proteins/enzymes and disrupts their functions. 2. Photocatalysis (e.g., TiO2, ZnO): generates reactive oxygen species to oxidize and decompose bacteria. 3. Physical contact (e.g., nano ZnO): Penetrates cell membranes. | 1. Chemical action: destroy cell membrane/wall. 2. Penetration: binds to intracellular components (such as proteins and nucleic acids) and interferes with metabolism. | Collaborative/multi-mechanism action: • The combination of the durability of inorganic materials and the wide spectrum and high efficiency of organic materials. • Extend the time of action by carrier-controlled release. • Multi-target attack reduces the risk of drug resistance. |

| Key Advantages | • Excellent durability and heat resistance, long-lasting. • High safety and low toxicity. • Good stability and not easily decomposed. | • Fast action, high antibacterial efficiency. • Broad spectrum antibacterial, a variety of types. • Easy to process, easy to synthesize and modify. | • Synergistic efficiency, better performance than a single component. • Overcome the limitations of a single material. • The function is highly customizable. |

| Main Limitations | • Slow to take effect (ion release type). • The antibacterial spectrum may be limited (non-photo-catalytic type). • Higher cost (e.g. silver). • Color changes may occur (e.g. silver ion oxidation). | • Poor heat resistance, may decompose. • Shorter life span, volatile or decomposable. • May cause drug resistance. • Some varieties are highly toxic. | • The preparation process is more complex. • Costs may be higher. • Compatibility and stability between components are key challenges. |

| Typical Representative | Zeolite, nano titanium dioxide, zinc oxide, copper compounds | Quaternary ammonium salts, triclosan, parabens, chitosan | Silver/polymer composites, photocatalyst/support composites, chitosan/metal nanoparticle composites |

The ‘Typical Representative’ listed in this table represents materials that have been extensively studied, possess well-defined mechanisms, and demonstrate significant application potential within the field of biomaterials. Selection criteria encompassed their representative antibacterial efficacy, typical mechanisms of action, and frequency of appearance in relevant reviews and research. The aim is to elucidate category characteristics rather than provide an exhaustive list of all materials.

2.1 Inorganic antimicrobial materials

Inorganic antimicrobial materials are composed of inorganic carriers combined with antimicrobial transition metal ions such as Ag and Cu, along with oxides like TiO2 and ZnO2, to create materials with antimicrobial properties[13]. While metal ions exhibit antibacterial properties, most are also toxic. However, trace amounts of Ag, Cu, and Zn are beneficial to humans yet harmful to microorganisms. Consequently, Ag-based, Cu-based, and Zn-based inorganic antibacterial materials are currently the focus of extensive research and application. Table 2 summarizes representative inorganic antibacterial coatings and their characteristics.

| Material Type | Core Antibacterial Component/Form | Common Preparation/Introduction Methods | Key Antibacterial Mechanisms | Representative Research & Application Cases | References |

| Silver-Based Materials | Ag+, AgNPs | Ion implantation, magnetron sputtering, anodic oxidation loading, sol-gel method | Ag+ binds to sulfhydryl groups of bacterial enzymes/proteins, disrupting energy metabolism; induces ROS generation; physically penetrates membranes. | Silver zeolite exhibits potent bactericidal activity (> 90%) against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. | [14-16] |

| Copper-Based Materials | Cu2+, CuO, Cu alloying | Plasma spraying, electrochemical deposition, alloy melting, PVD | Cu2+ triggers Fenton-like reactions to generate reactive oxygen species; disrupts membrane integrity; interferes with the respiratory chain. | PVD-prepared copper oxide coatings achieved a 99.19% kill rate against Escherichia coli and 95.03% against Staphylococcus aureus. | [17,18] |

| Zinc-Based Materials | Zn2+, ZnO | MAO, hydrothermal method, ALD | Zn2+ disrupts membrane permeability; ZnO photocatalysis generates ROS; nano-ZnO physically pierces cell membranes. | ZnO coating effectively inhibits the formation of Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms. | [19,20] |

| Photocatalytic Materials | TiO2, ZnO (nanostructured) | Anodic oxidation, hydrothermal method, sol-gel method | Under light illumination, electron-hole pairs are generated, leading to the production of ·OH and other ROS that oxidize bacterial components. | Under UV light, TiO2 nanotube arrays demonstrate significant antibacterial effects against oral pathogenic bacteria. | [13,21] |

AgNPs: Ag nanoparticles; PVD: physical vapor deposition; MAO: micro-arc oxidation; ALD: atomic layer deposition; ·OH: hydroxyl radicals; ROS: reactive oxygen species; UV: ultraviolet.

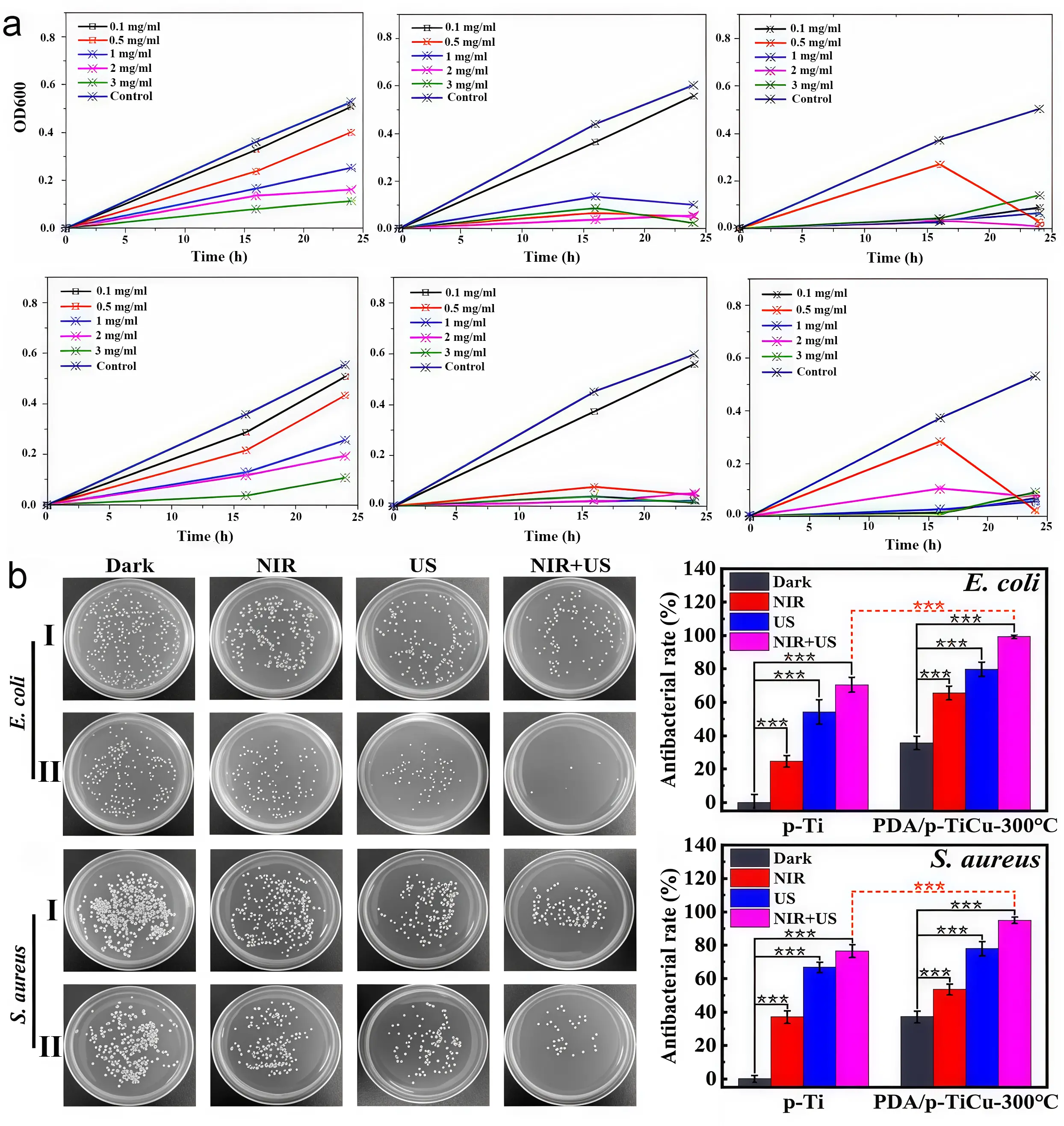

Silver possesses unique physical antibacterial properties and stands as a representative inorganic antibacterial agent, with its antibacterial activity stemming from positively charged silver ions[22]. Silver ions attract negatively charged bacteria through Coulombic forces. Upon accumulation, they disrupt the cell wall and penetrate the cell interior, causing protein coagulation and protease inactivation to inhibit microbial reproduction. Additionally, they generate atomic oxygen to enhance antimicrobial efficacy[14,23,24]. Among metallic implants, silver-based antimicrobial materials such as silver zeolite and silver-impregnated activated carbon have been extensively researched and applied. Silver zeolite is a composite material formed by loading silver ions onto the porous structure of zeolite through methods like ion exchange[25]. The silver ions released from silver zeolite bind to biomolecules within bacteria, such as proteins and nucleic acids, disrupting their normal physiological functions and thereby achieving antibacterial effects[15,26,27]. Perla et al.[16] reported that silver zeolite exhibits significant inhibitory effects against common implant infection pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli, achieving an antibacterial rate as high as 90% (Figure 1a). Silver activated carbon is produced by loading silver onto the surface or into the pores of activated carbon. The loading capacity of activated carbon not only enables the aggregation of bacteria and their metabolites, but also provides abundant loading sites for silver ions[28,29]. Silver activated carbon achieves antibacterial effects in metal implants through the synergistic action of adsorption and silver ion antibacterial activity[30,31].

Zinc oxide has a unique antibacterial mechanism. It releases zinc ions that bind to proteins on the cell membrane of bacteria, disrupting the structure and function of the cell membrane and causing the bacteria to die[19,32]. Research has shown that zinc oxide coatings have good antibacterial effects on Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and other bacteria, and that their antibacterial performance is related to factors such as coating thickness and crystallinity (Figure 1a)[16]. Copper oxide exerts its antibacterial effect by releasing copper ions. Copper ions are highly oxidative and can react with active groups within bacterial cells, causing protein denaturation and inactivation. They can also interfere with electron transport in the respiratory chain, disrupting energy metabolism[17,33,34]. In the application of metal implants, Chi et al.[18] discovered that copper oxide can form antimicrobial coatings on implant surfaces via methods such as physical vapor deposition and electroless plating, achieving outstanding broad-spectrum bactericidal efficacy against Escherichia coli (99.19% killing) and Staphylococcus aureus (95.03% killing) (Figure 1b).

The primary advantages of inorganic antimicrobial materials lie in their high durability, excellent thermal stability, and relatively high safety profile[35]. However, their drawbacks are equally evident, particularly with regard to silver-based materials. Although no clinically significant bacterial resistance to silver ions has yet been observed, comparable to that seen with traditional antibiotics, prolonged or inappropriate use may indeed trigger adaptive responses in bacteria. A study has found that Escherichia coli, when exposed to low concentrations of nanosilver over an extended period, evolved enhanced resistance to oxidative damage and acid tolerance[36]. Concurrently, inorganic antimicrobial materials commonly suffer from high production costs, slow onset of antimicrobial efficacy, and potential biotoxicity. Their antimicrobial efficiency is heavily dependent on the release rate of metal ions, which can decline sharply in dry conditions or organic environments. Furthermore, prolonged use may lead to the development of microbial resistance. These factors collectively constrain their broader application[37].

2.2 Organic antimicrobial materials

Organic antimicrobial materials are diverse in type, primarily acting through chemical mechanisms to disrupt bacterial cell membranes or interfere with intracellular metabolism. For systematic exposition, they may be categorized according to chemical structure and origin, with the principal categories and characteristics outlined in Table 3.

| Category | Representative Substances | Mechanism of Action | Application Examples on Metal Implant Surfaces | References |

| Cationic Polymers | QAS, quaternary phosphonium salts, polycations (e.g., polylysine) | Positively charged; adsorb to and disrupt negatively charged bacterial cell membranes via electrostatic interactions, leading to content leakage. | SLA/PQCS/OGA coating grafted with polyquaternary ammonium salt on titanium surfaces, achieving 96%-98% inhibition rates against Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum. | [38,39] |

| Natural Polymers and Their Derivatives | Chitosan, gelatin, hyaluronic acid (modified for antimicrobial properties) | Good biocompatibility and biodegradability. Chitosan is positively charged and causes membrane damage; can be further quaternized for enhanced efficacy. | Chitosan-casein phosphopeptide coating on cobalt-chromium alloy provides antimicrobial function. Imidazole-modified quaternized chitosan exhibits enhanced antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. | [40,41] |

| Small-Molecule Organic Antimicrobial Agents | CHX, triclosan, vanillin derivatives | Low molecular weight, facilitating diffusion and penetration; often immobilized on surfaces via covalent bonding or physical encapsulation. | Vanillin derivative coatings show > 90% antibacterial rates against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Chlorhexidine covalently coupled to titanium surfaces prevents early bacterial adhesion. | [42,43] |

| Bioactive Molecules | AMPs (e.g., LL-37), enzymes (e.g., lysozyme) | Diverse mechanisms (membrane disruption, targeting intracellular components); low tendency to induce resistance; good biocompatibility. | Antimicrobial peptide LL-37 can inhibit biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli at sub-inhibitory concentrations. | [44] |

QAS: quaternary ammonium salts; CHX: chlorhexidine; AMPs: antimicrobial peptides.

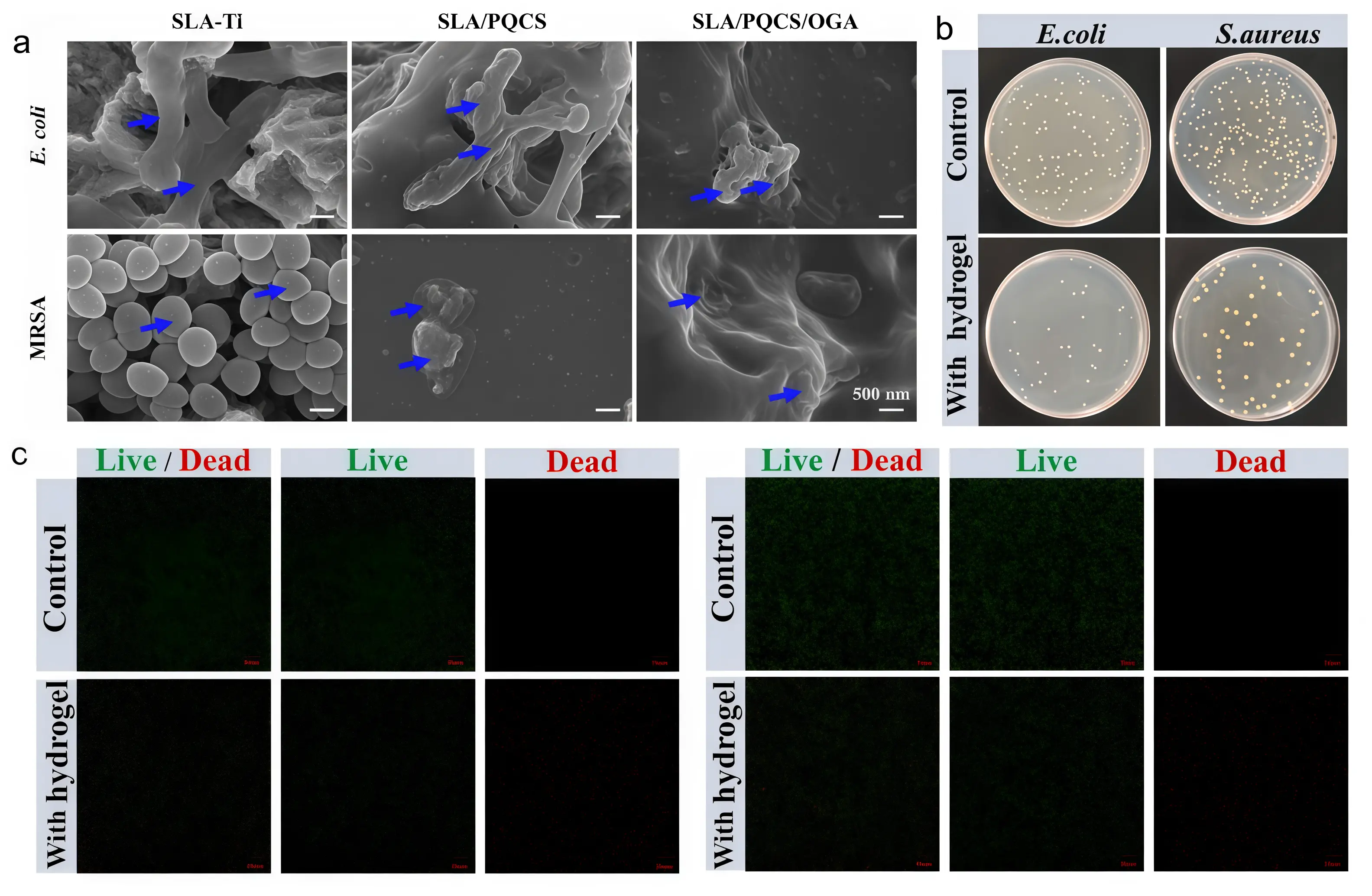

Quaternary ammonium salts represent the most extensively researched and widely applied class of antimicrobial materials within the field of organic antimicrobial substances[45,46]. Quaternary ammonium salt antimicrobial materials demonstrate significant advantages in the field of metal implants due to their unique antibacterial properties[47]. Quaternary ammonium salt coatings are a prime example of such materials, and their application on metal implants offers a novel approach to addressing implant infections. Quaternary ammonium salts are cationic polymers containing positively charged quaternary ammonium cations in their molecular structure. After forming a polyquaternary ammonium salt coating on the surface of metal implants, the quaternary ammonium cations within the coating exert electrostatic attraction toward negatively charged groups on bacterial cell membranes. This enables polyquaternary ammonium salt molecules to tightly adsorb onto bacterial surfaces, thereby disrupting bacterial cell membranes, causing protein denaturation, or destroying cellular structures[38,48]. Polyquaternium-based coatings are widely used in clinical settings. In certain dental implant applications, these coatings rapidly inhibit the adhesion of oral bacteria to the implant surface during the initial post-implantation period, thereby creating a favorable microenvironment for osseointegration. Chen et al.[39] developed a polyquaternary ammonium salt coating (SLA/PQCS/OGA coating) exhibiting potent antibacterial activity. Following 24-hour co-culture with Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum, colony count analysis revealed inhibition rates of 96% and 98% respectively against these pathogens (Figure 2a).

Figure 2. (a) Antibacterial activity of polyquaternary ammonium salts against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. Republished with permission from[39]; (b and c) Antibacterial performance testing of vanillin-based antibacterial materials against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus strains, and bacterial live/dead staining. Republished with permission from[42].

In addition to quaternary ammonium antimicrobial agents, various organic antimicrobial materials such as vanillin derivatives, acyl anilines, and chitosan also hold potential for application in metallic implants. Vanillin-based antimicrobial materials contain active groups such as phenolic hydroxyl groups and aldehyde groups, which can disrupt bacterial cell membranes, inhibit bacterial growth, and prevent biofilm formation[49] Sun et al.[42] found that composite materials coated with vanillin derivatives had an antibacterial rate of over 90% against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus, which is conducive to the integration of implants with surrounding tissues (Figure 2b,c). Acylaniline antimicrobial agents inhibit bacterial metabolism by binding to biomolecules within bacterial cells. When loaded onto nanoparticles and coated onto metal implant surfaces, they form composite antimicrobial coatings. In vitro experiments demonstrate strong inhibitory effects against multiple bacteria, coupled with excellent biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity. Barbour et al. covalently coupled chlorhexidine to a titanium surface and found it prevented early bacterial adhesion[43]. Mohd Daud et al. found that immobilized polydopamine coatings inhibited both Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-negative Escherichia coli[50]. Maria et al.[51] demonstrated that gentamicin combined with calcium sulfate/hydroxyapatite effectively inhibits the adhesion of Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa to implant surfaces. This treatment disrupts biofilm formation on implants, prevents peri-implant infections, and simultaneously promotes bone regeneration. Ma et al.[40] synthesized and studied three chitosan derivatives bearing imidazole rings. The results demonstrated that quaternized chitosan exhibits synergistic effects with imidazole groups, exhibiting superior antioxidant, antifungal, and antibacterial properties compared to native chitosan. These derivatives can serve as drug delivery materials to achieve antioxidant and antibacterial objectives. Qin et al.[41] found that chitosan-casein phosphopeptide coatings can provide antibacterial efficacy for cobalt-based orthopedic implants. Catheterin is a relatively popular class of antimicrobial peptides, among which human catheterin LL-37 is in the spotlight. Research indicates that LL-37 exhibits anti-biofilm activity against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli isolated from urinary tracts. Even at concentrations as low as one-sixteenth of its minimum inhibitory concentration against free bacteria, it suppresses biofilm formation, thereby eliminating the bacteria[44].

The primary advantages of organic antimicrobial materials lie in their highly effective, broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties and rapid action, coupled with good water solubility and the ease of imparting durable antimicrobial functionality through chemical modification[52]. However, their drawbacks are also significant. For instance, quaternary ammonium compounds may induce microbial resistance with prolonged use. Their antimicrobial efficacy is highly susceptible to environmental factors such as pH levels, and they exhibit relatively poor chemical stability. Furthermore, their effectiveness against certain persistent microorganisms is limited, and high concentrations may pose potential toxicity to human cells[53]. Future research should focus on further optimizing the preparation process of the material to enhance its stability and antimicrobial persistence, thereby better meeting clinical needs[54].

2.3 Composite antimicrobial materials

Composite antimicrobial materials represent a novel class of composite developed from organic and inorganic antimicrobial materials[55]. Composite antimicrobial materials overcome the limitations of single inorganic or organic antimicrobial materials by combining the inherent antimicrobial properties of inorganic materials with the antimicrobial components of organic materials[56]. Based on the nature of the composite components, they can primarily be categorized into inorganic-inorganic composites, inorganic-organic composites, and organic-organic composites, with representative systems shown in Table 4.

| Composite Type | Material Composition Examples | Design Purpose & Synergistic Mechanism | Preparation Methods | Performance Advantages | References |

| Inorganic-Organic Composite | Silver nanoparticles/chitosan coating; Antibiotic-loaded mesoporous silica/polymer coating | Synergistic Antibacterial Action: Inorganic components (e.g., Ag+) provide long-term antibacterial effect, while organic components (e.g. chitosan) enhance adhesion, biocompatibility, and contact-killing. Controlled Release: Organic matrices or inorganic carriers regulate the release kinetics of antibacterial agents. | LbL assembly, co-deposition, dip-coating & cross-linking | Combines high efficiency with long-lasting antibacterial activity; Improved biocompatibility; Reduced toxicity of single components. | [57-59] |

| Inorganic-Inorganic Composite | Cu/Zn co-doped calcium phosphate coating; Ag-doped zinc oxide/graphene composite | Ionic Synergy: Different metal ions (e.g. Cu2+ and Zn2+) exert multi-target antibacterial effects. Structure-Function Synergy: e.g., Combining photocatalytic materials with conductive carriers enhances ROS generation efficiency. | Co-sputtering, composite electrodeposition, sol-gel co-synthesis | Broad-spectrum and potent antibacterial activity; May improve coating mechanical stability and osteogenic activity. | [60-62] |

| Organic-Organic/Multifunctional Composite | Co-immobilized quaternary ammonium salts-antimicrobial peptide coating; Dual-function antibacterial-anti-inflammatory molecular coating | Mechanistic Synergy & Functionalization: Combines rapid membrane disruption (quaternary ammonium salts) with intracellular action less prone to resistance (antimicrobial peptides). Integrates antibacterial and immunomodulatory functions. | Chemical grafting, blending & coating, biomimetic immobilization | Reduces risk of drug resistance; Endows materials with multiple biological functions (antibacterial, osteogenic, anti-inflammatory). | [63-65] |

LbL: layer-by-layer; ROS: reactive oxygen species.

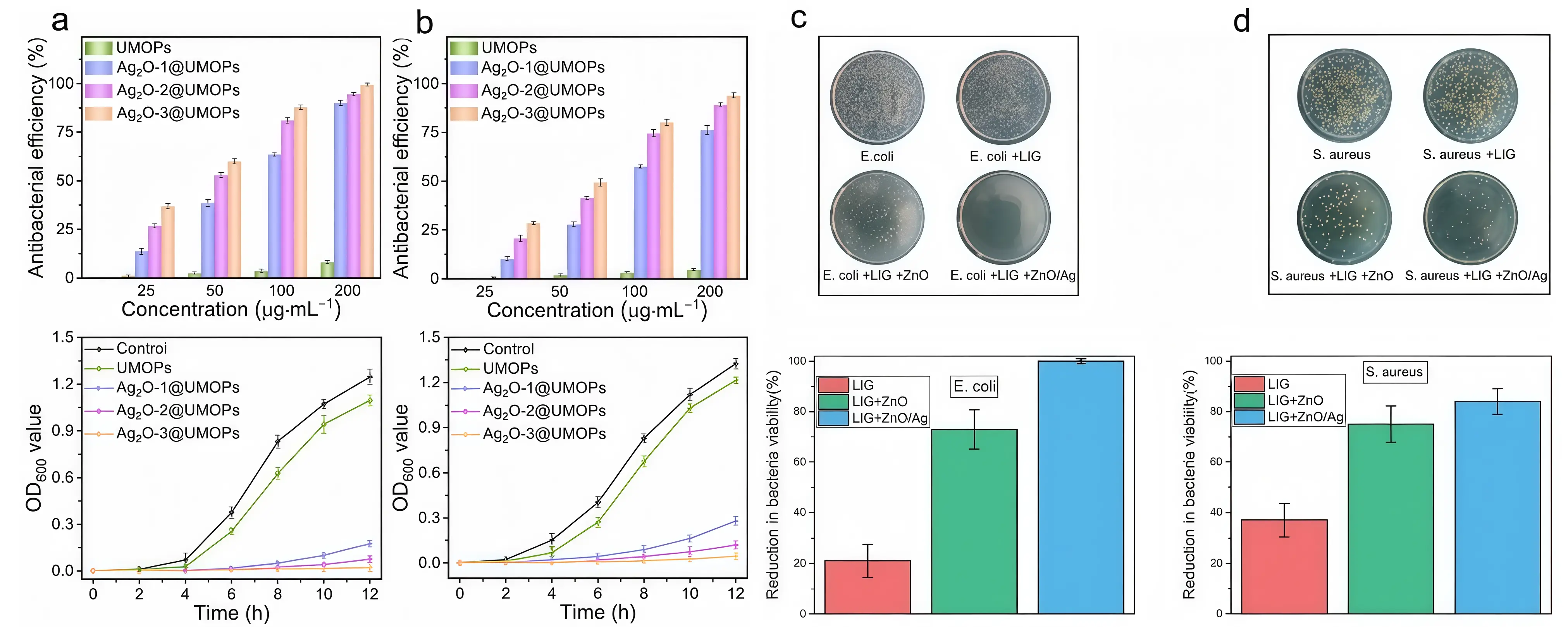

Inorganic-organic composite antimicrobial materials ingeniously combine the stability and long-lasting antimicrobial properties of inorganic materials with the excellent biocompatibility and specificity of organic materials, demonstrating outstanding synergistic antimicrobial advantages and holding immense application potential in the field of metal implants[66,67]. Taking silver-organic compound composites as an example, silver ions effectively inhibit the growth and reproduction of various bacteria due to their potent broad-spectrum antibacterial properties. Meanwhile, organic compounds interact with receptors on the bacterial surface through specific molecular structures, enhancing the material’s affinity and targeting ability toward bacteria[57,68]. Zhang et al.[58] found that silver nanoparticles inhibit the growth of Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus by releasing silver ions and inducing oxidative stress through reactive oxygen species (ROS), achieving an antibacterial rate exceeding 95% (Figure 3a,b). In dental implant studies, implants coated with this compound exhibited potent bactericidal activity during the early phase (12 and 24 hours post-seeding) and maintained sustained antimicrobial efficacy in subsequent stages (1 to 2 weeks) as silver ions were gradually depleted[69].

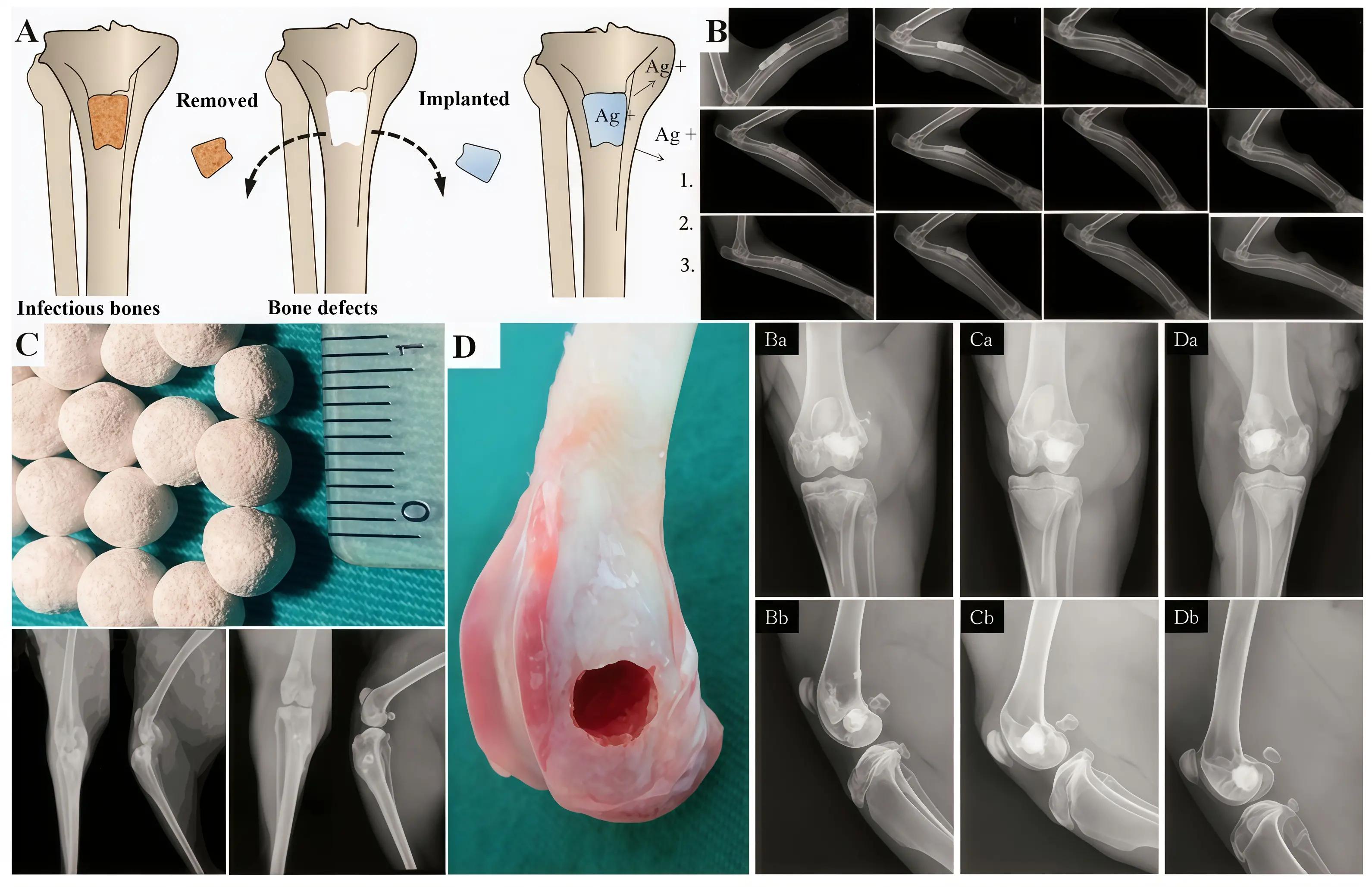

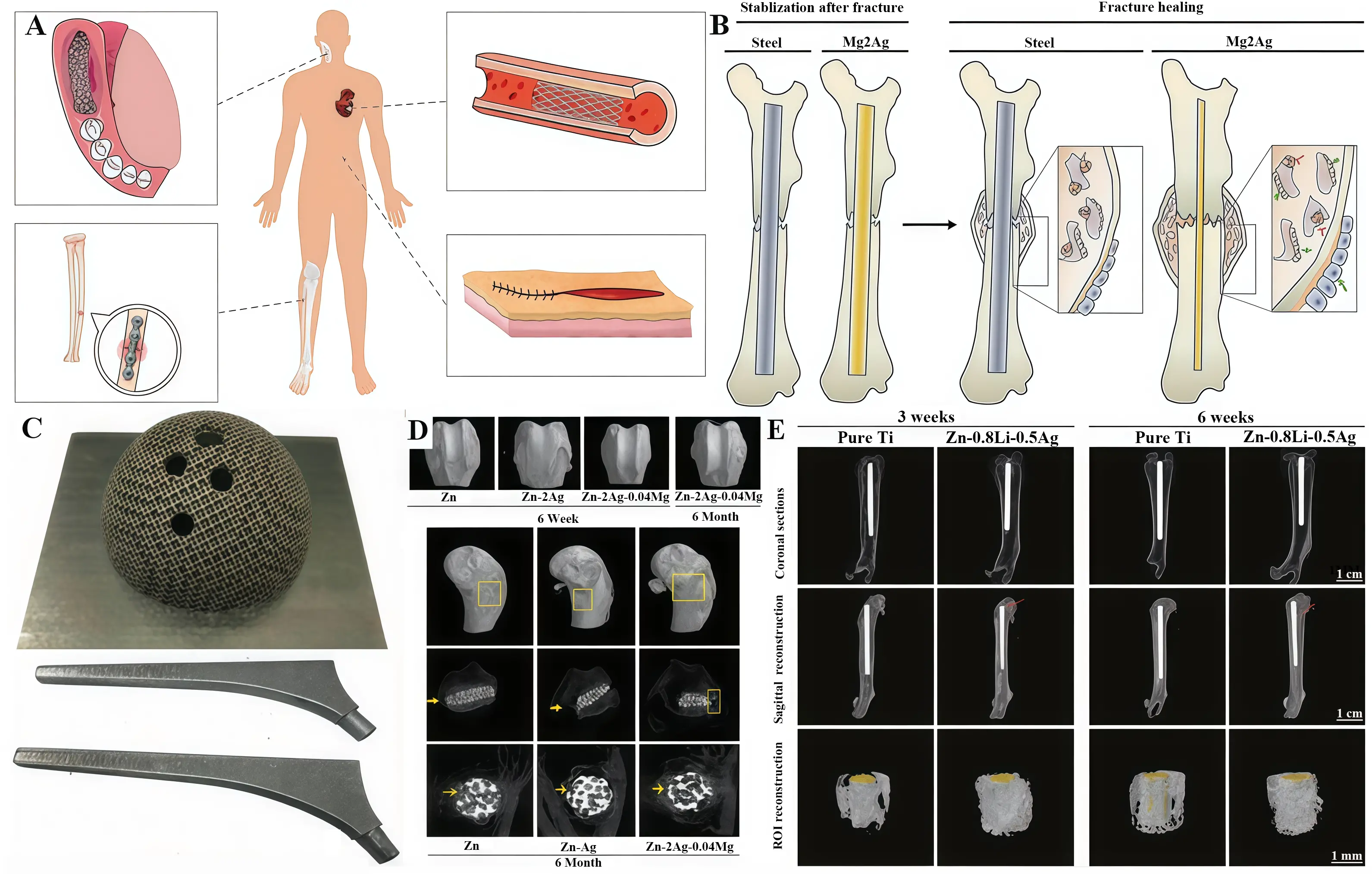

Inorganic-inorganic composite antimicrobial materials enhance overall antimicrobial performance by combining two or more inorganic antimicrobial materials, thereby fully leveraging the advantages of each component. Wang et al.[60] prepared a hydroxyapatite/copper nanocomposite coating on a titanium surface using pulsed electrochemical deposition. Experimental results demonstrated that this material exhibits an antibacterial rate as high as 97%. Li et al.[20] incorporated zinc ions into the hydroxyapatite lattice by partially replacing calcium ions. They found that coating samples with higher zinc ion concentrations significantly inhibited the growth of Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria while exhibiting excellent biocompatibility. Wolf et al.[61] synthesized a copper/zinc/calcium phosphate composite coating via electrochemical deposition. The results indicated that the highest antibacterial efficacy was achieved when both copper and zinc ion concentrations were maximized. Wang et al.[62] found that integrating silver-doped zinc oxide nanocrystals onto laser-induced graphene surfaces significantly suppressed the growth of Staphylococcus aureus (inhibition rate 84%) and Escherichia coli (inhibition rate approaching 100%) (Figure 3c,d). The incorporation of silver into bioceramics enhances their antibacterial properties and bioactivity, offering significant application potential. Various types of bioceramics have been developed for use in multiple fields, including dentistry, orthopedics, and trauma repair[70] (Figure 4). Moreover, the formability and malleability of silver with other metals enable the fabrication of implants that can be personalized to meet the patient’s requirements[70] (Figure 5).

Figure 4. (A) Nano-hydroxyapatite combined with Ag-containing polyurethane for treating chronic osteomyelitis of tibia in rabbits with bone defects; (B) Silver-loaded coral hydroxyapatite-based scaffold for infected segmental defects of the radius in rabbits. Reproduced with permission; (C) Ag doped CaP based ceramic beads for the treatment of osteomyelitis; (D) AgNPs doped porous β-TCP for biological applications. Republished with permission from[70]. AgNPs: Ag nanoparticles; TCP: tricalcium phosphate.

Figure 5. (A) Zn-Ag alloys for application in humans; (B) Mg2Ag intramedullary nail promotes fracture recovery in mice; (C) 3D printed acetabular cup and femoral prosthesis based on Zr60.14 Cu22.31 Fe4.85 Al9.7 Ag3; (D) Zn-Ag-Mg alloys for femoral bone defects in rabbits; (E) Zn-Li-Ag alloys implants for MRSA-induced rat osteomyelitis. Republished with permission from[70]. MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Organic-organic composite antimicrobial materials are created by combining different types of organic antimicrobial materials to achieve complementary advantages[71]. Combining quaternary ammonium salt antimicrobial materials with vanillin antimicrobial materials integrates the strong cationic antimicrobial action of quaternary ammonium salts with the biocompatibility and antioxidant properties of vanillin, not only enhancing antimicrobial efficacy but also reducing oxidative stress reactions in the tissues surrounding the implant[63,72]. In the application of metal implants, organic-organic composite antibacterial materials can be attached to the surface of implants through physical blending, chemical grafting, and other methods to form coatings with good antibacterial properties and biocompatibility[73,74]. Ashbaugh et al.[64] developed a polymeric nanofiber coating for the tailored release of combination antimicrobial agents from various metal implants or prostheses, thereby effectively reducing biofilm-associated infections in patients.

Composite antimicrobial materials achieve synergistic enhancement, broad-spectrum efficacy, and reduced risk of microbial resistance by combining different antimicrobial components[75]. However, they also have some inherent drawbacks, such as typically more complex preparation processes and higher costs. Additionally, interference between different components may occur, and the long-term stability and biosafety of certain materials require further research and validation[76]. Future research should delve into the composite mechanisms and optimize preparation processes to advance the practical application of these composite antimicrobial materials in the field of metal implants[59].

3. Materials Antimicrobial Mechanism of Antimicrobial Materials

3.1 Mechanism of metal ion release

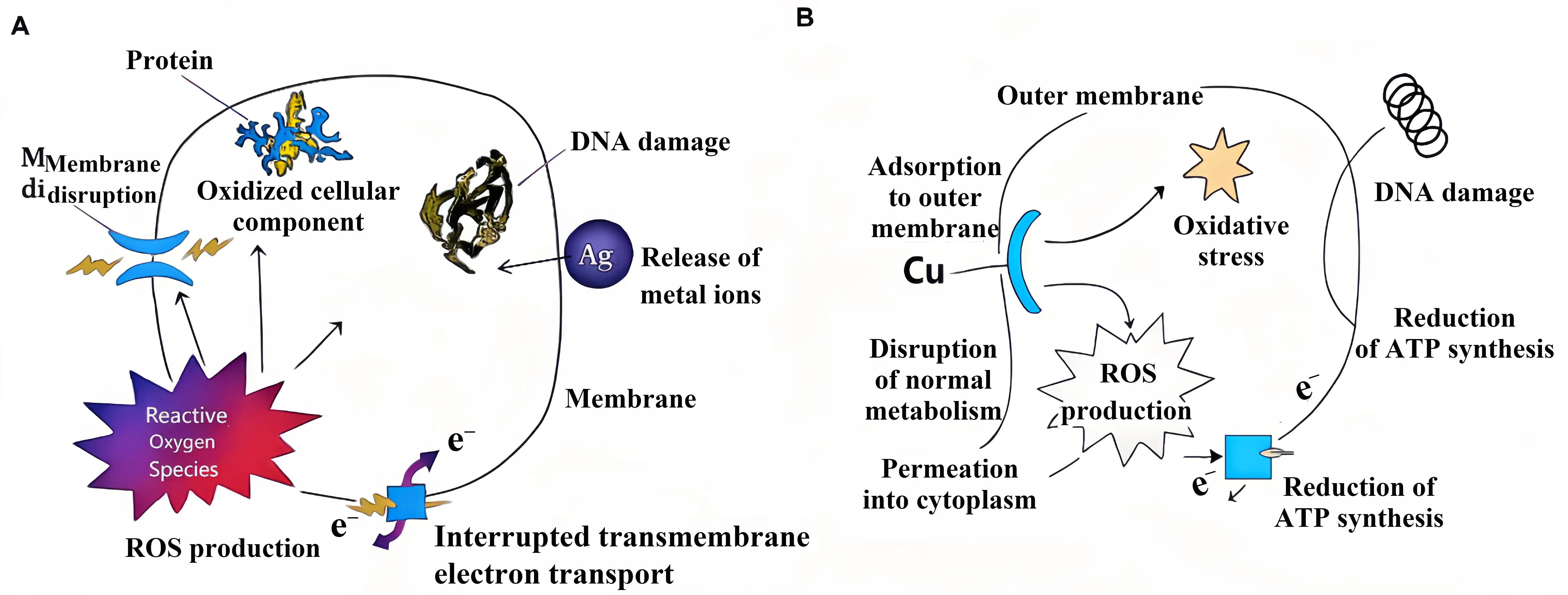

The release of metal ions is one of the key mechanisms by which antimicrobial materials exert their antibacterial effects, with copper and silver ions demonstrating particularly pronounced activity. When antimicrobial materials containing copper or silver ions come into contact with bacteria, ions are released from the material surface. The specific antibacterial mechanism is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6. (A) Silver ion antibacterial mechanism diagram; (B) Copper ion antibacterial mechanism diagram. ROS: reactive oxygen species; ATP: Adenosine Triphosphate.

The antibacterial mechanism of silver ions primarily involves physical disruption and biochemical interference. Firstly, silver ions adsorb to and penetrate bacterial cell membranes via electrostatic interactions, causing structural damage and increased permeability. This leads to leakage of cellular contents and cell lysis. Once within the cell, silver ions bind to multiple critical biomolecules. They react with the sulphhydryl groups (-SH) of enzyme proteins, inhibiting their activity and disrupting energy metabolism. Concurrently, silver ions can incorporate into bacterial DNA molecules, interfering with replication and transcription processes and causing genetic damage. Furthermore, silver ions induce the production of ROS within the cell, triggering oxidative stress that further degrades cellular components such as proteins and lipids[77]. Even at low concentrations, silver ions can significantly inhibit bacterial growth and reproduction, and at sufficient concentrations, bacteria will die[78,79].

The bactericidal mechanism of copper ions is similar. They can bind to bacterial cell membrane proteins and lipids, disrupting the integrity and permeability of the cell membrane and causing the leakage of intracellular substances. At the same time, copper ions have a high redox potential and participate in redox reactions to produce a large number of ROS, which attack bacterial biomolecules, causing protein denaturation, DNA fragmentation, and lipid peroxidation, thereby damaging and killing bacteria[80-82]. Research has found that in environments containing copper ions, the antioxidant defense system of bacteria is disrupted, placing them in a state of oxidative stress and accelerating their death.

3.2 Physical destruction mechanism

Physical disruption represents the most direct mode of action for antimicrobial materials, primarily achieved through mechanisms such as nanostructured puncturing and membrane integrity disruption. Research indicates that numerous nanomaterials possess sharp edges or specific surface topologies capable of physically compromising the integrity of bacterial cell membranes[83,84]. For instance, Fe3O4@C@Cu2O nanocomposites can directly damage bacterial cell walls upon contact, leading to leakage of cellular contents and thereby achieving highly efficient bactericidal effects[21]. Scanning electron microscopy observations clearly reveal that the bacterial cell walls treated with this material exhibit significant indentations, ruptures, and even complete disintegration.

Polymeric materials with surface-grafted quaternary ammonium salts achieve antibacterial effects through two steps: electrostatic adsorption and cell wall dissolution. First, positively charged quaternary ammonium salts rapidly adsorb bacteria via electrostatic interactions with negatively charged bacterial membranes. Subsequently, the cell walls are gradually dissolved, ultimately leading to bacterial death[63,85,86]. The microbial oxygen consumption assay confirmed that this process initially proceeded primarily through adsorption, shifting predominantly to killing in the later stages, representing a continuous transition from rapid to slow rates.

3.3 Mechanism of chemical oxidation

The chemical oxidation mechanism is the core mode of action for photocatalytic antibacterial materials, primarily causing oxidative damage to bacteria by generating ROS. ROS include hydroxyl radicals (·OH), superoxide anion (O2·-), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). These highly reactive chemical species can non-selectively oxidize vital biomolecules on bacterial cell membranes, such as lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids—leading to structural disruption and functional loss[21,52]. Research has revealed that Fe3O4@C@Cu2O nanocomposites can generate ROS via electron-hole pairs under illumination, achieving bactericidal rates of 98.45% against Escherichia coli and 90.58% against Staphylococcus aureus[21]. Electron paramagnetic resonance testing directly detected ·OH signals, confirming the presence of ROS and their dominant role in the antibacterial process[87,88].

3.4 Multi-mechanism synergistic antibacterial action

Most highly effective antimicrobial materials exert their antibacterial effects through multiple synergistic mechanisms rather than relying on a single mechanism. For example, when silver nanoparticles are combined with photothermal therapy, Ag ions interfere with the respiratory chain, while elevated temperatures further disrupt bacterial protein folding, resulting in a synergistic lethal effect[89]. Near-infrared light triggers Ag ion release or ROS generation, enabling deep tissue penetration and on-demand activation of multiple mechanisms to minimize damage to healthy tissues[90]. This multi-mechanism synergistic strategy not only significantly enhances antimicrobial efficacy but, more importantly, makes it difficult for bacteria to simultaneously develop multiple resistance mechanisms, thereby effectively delaying the emergence of drug resistance.

4. Analysis of The Current State of Research

In recent years, countries around the world have achieved fruitful results in the research and application of antibacterial materials on the surfaces of metal implants. As a leading country in the field of biomedicine, the United States has invested heavily in the research and development of antimicrobial materials. A research team at Johns Hopkins University has developed a new type of nanostructured antimicrobial coating. This coating utilizes nanoscale topological structures on the surface of titanium alloys to significantly reduce the adhesion of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli on implant surfaces through physical interactions, thereby minimizing the risk of infection[64]. Researchers at Harvard University are focusing on developing smart antimicrobial materials. These materials can intelligently regulate the release of antimicrobial agents based on environmental signals around the implant, such as inflammatory factor concentrations and bacterial metabolites, to achieve precise antimicrobial effects[91].

Europe also has its own unique strengths in the field of antimicrobial materials research. Researchers at University College London have developed a novel photoactive antimicrobial material that exhibits antimicrobial activity both under light and in dark environments. This material combines dyes such as crystal violet and methylene blue with gold nanoparticles, which are then attached to a silicone rubber surface through a specialized processing technique. Under standard hospital fluorescent lighting, it can kill bacteria within 3-6 hours, even in dark environments without light exposure, it can kill bacteria within 3-18 hours[92]. This material offers a new solution for reducing hospital-acquired infections and holds great potential for future applications.

China has also made significant progress in the research of antimicrobial materials for metal implant surfaces. A research team from the Shanghai Institute of Ceramics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, has proposed a novel antibacterial approach termed the “dual-functional microbattery effect” This innovation involves simultaneously introducing inert antibacterial metals and active bone-promoting metals onto a titanium surface to construct a “dual-functional microbattery” The cathodic hydrogen evolution reaction within this microbattery disrupts bacterial energy metabolism[93]. This method not only achieves antibacterial functionality but also activates the osteogenic pathway regulated by integrin in rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells, promoting bone integration, thereby providing a new direction for the development of “antibacterial and osteogenic” implant devices.

5. Challenges Ahead

5.1 Balance between antimicrobial efficacy and biocompatibility

5.1.1 Potential toxicity of antimicrobial agents to human cells

In the research and application of antimicrobial materials on the surface of metal implants, the potential toxicity of antimicrobial agents to human cells is a critical issue that cannot be ignored, as it directly affects the long-term safety of implants and the health of patients[94,95]. While some antimicrobial agents can effectively inhibit bacterial growth, they may have adverse effects on human cells. Take silver ions, for example, which are widely used as antimicrobial agents. At higher concentrations, silver ions may interfere with physiological processes such as metabolism, proliferation, and differentiation in human cells. Relevant studies have shown that high concentrations of silver ions can inhibit cellular respiration, impair mitochondrial function, and consequently lead to insufficient energy supply to cells, thereby affecting their normal physiological activities[96]. Silver ions may also bind to biomolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids within cells, altering their structure and function and negatively impacting key processes such as genetic information transfer and protein synthesis[97].

Some organic antimicrobial agents also pose potential cytotoxicity issues. Certain quaternary ammonium antimicrobial agents may disrupt the structure and function of human cell membranes at certain concentrations, leading to increased membrane permeability, leakage of intracellular substances, and subsequent impairment of normal cellular physiological functions[98]. At high doses, vanillin-based antimicrobial agents may interfere with the antioxidant system of cells, leading to increased levels of oxidative stress within cells and causing oxidative damage to cells[99,100]. These potential cytotoxic issues not only affect the normal function of cells surrounding the implant, but may also trigger inflammatory responses, affecting the integration of the implant with surrounding tissues and reducing the success rate of implant surgery[101]. Long-term exposure to cytotoxic antimicrobial agents may also pose potential hazards to the human immune system, nervous system, and other systems, increasing health risks for patients.

5.1.2 How to improve biocompatibility while maintaining antimicrobial performance

To enhance biocompatibility while maintaining antimicrobial efficacy, a variety of optimization strategies may be employed. In selecting antimicrobial agents, priority should be given to those with excellent biocompatibility, such as antimicrobial peptides. These are small-molecule peptides produced by living organisms that specifically disrupt bacterial cell membranes to exert their bactericidal effect, while exhibiting low cytotoxicity towards human cells. Research indicates that they possess potent inhibitory activity against common pathogenic bacteria, coupled with extremely low toxicity towards human fibroblasts and endothelial cells[102]. Adjusting the concentration of antimicrobial agents is an important strategy for balancing antimicrobial activity and biocompatibility. Taking silver ion antimicrobial agents as an example, studies have found that at concentrations of 1-10μg/mL, they exhibit significant bacterial inhibitory activity while causing minimal cytotoxicity to human cells[103]. Modifying the surface of metal implants is an effective means of improving biocompatibility. Modifying the surface of implants with bioactive molecules such as collagen and chitosan can enhance biocompatibility and cell affinity, promote cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation, and synergize with antimicrobial agents to enhance antimicrobial effects[104].

5.2 Bacterial resistance issues

5.2.1 Mechanisms of bacterial resistance to antimicrobial materials

The process by which bacteria develop resistance to antimicrobial materials is complex and involves multiple mechanisms, with gene mutations and efflux pump mechanisms being particularly critical. Gene mutations are a key factor, as bacterial genomes are highly variable and may undergo mutations under the selective pressure of antimicrobial materials, altering their physiological structure and function to develop resistance. For example, genes encoding enzymes involved in bacterial cell wall synthesis or DNA gyrase may undergo mutations[105]. In terms of efflux pump mechanisms, various efflux pumps within bacterial cells can recognize and bind to antimicrobial substances, expelling them outside the cell to reduce intracellular concentrations and thereby conferring resistance. For example, the NorA efflux pump in Staphylococcus aureus can expel fluoroquinolone antibiotics[106]. In addition, bacteria can develop resistance by altering metabolic pathways or producing inactivating enzymes, such as altering metabolic pathways to reduce dependence on the target site, or producing β-lactamases that hydrolyze the β-lactam ring of β-lactam antibiotics, rendering them inactive[107].

5.2.2 Strategies for addressing bacterial resistance

To design antimicrobial metallic implants that minimize the risk of antibiotic resistance, current strategies no longer rely on traditional antibiotics but instead harness the inherent physical and chemical properties of materials to combat microorganisms. Among these, multi-mechanism synergistic antimicrobial action, precision targeting and localized delivery, and immunomodulation represent the most promising approaches capable of fundamentally reducing the risk of resistance.

Multi-mechanism synergistic antibacterial action is achieved by constructing functional coatings on implant surfaces that combine multiple antimicrobial substances (such as host defense peptides and metal ions), simultaneously eliminating bacteria through diverse pathways including disruption of bacterial cell membranes and induction of oxidative stress[65]. This multi-targeted approach makes it difficult for bacteria to develop complete resistance[108]. For instance, coating magnesium alloy implants with a polycaprolactone layer incorporating the host defense peptide Caerin 1.9 not only demonstrates sustained antibacterial efficacy against Staphylococcus aureus but also exhibits excellent biocompatibility and promotes osseointegration[65]. Precision targeting and localized delivery utilize nanocarriers (such as polycaprolactone nanospheres) or specific antibodies to achieve precise targeting and controlled local release of antimicrobial agents. This approach not only enhances drug concentration at infection sites and facilitates efficient penetration of biofilms, but also avoids systemic toxicity. It reduces bacterial exposure to sublethal doses, thereby diminishing selective pressure for resistance development. Research indicates that antibiotic-loaded nanocarriers exhibit enhanced antibacterial activity against drug-resistant bacteria and can inhibit biofilm formation[109]. Novel implant materials not only exhibit direct bactericidal properties but also eliminate bacteria through immunomodulatory mechanisms. For instance, titanium surfaces doped with specific metal ions can regulate macrophage polarization towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype, thereby promoting osteogenesis[65]. A more advanced strategy involves designing materials that guide the human immune system to eliminate bacteria, such as by inducing calcification on bacterial surfaces to activate macrophages and enhance their ability to clear pathogens[110].

5.3 Material stability and durability

5.3.1 Stability of antimicrobial materials in the body environment

The complex nature of the internal environment poses multiple challenges to the stability of antimicrobial materials on the surfaces of metallic implants. The body contains abundant biomolecules such as proteins, enzymes, and polysaccharides that can interact with the surface of antimicrobial materials, altering their structure. Proteins may adsorb onto the surface of antimicrobial materials, forming a protein layer that alters surface charge distribution and chemical composition. This impedes the release of antimicrobial agents, thereby diminishing antimicrobial efficacy. For instance, in solutions containing bovine serum albumin, silver-based antimicrobial materials exhibit reduced silver ion release rates and weakened antimicrobial effects[111]. The dynamic changes in the body’s acid-base environment and redox conditions can affect the stability of antimicrobial materials. Differences in pH and redox potential between various tissues and organs can induce chemical reactions within the composition of antimicrobial materials, leading to alterations in their structure and properties, which in turn affect their antimicrobial efficacy[112,113]. Furthermore, microorganisms within the body may interact with antimicrobial materials, thereby affecting their stability. Microorganisms adhere to and proliferate on antimicrobial material surfaces, forming biofilms that impair the release of antimicrobial agents and diminish their efficacy[114]. Once Staphylococcus aureus forms a biofilm on the surface of silver-loaded antimicrobial materials, it impedes the diffusion of silver ions, thereby reducing the bactericidal efficacy against bacteria within the biofilm[115].

5.3.2 Methods for improving material durability

Improving material preparation processes and selecting appropriate carriers are key methods for enhancing the durability of antimicrobial materials. In terms of material preparation processes, taking nanostructure regulation technology as an example, precise control of the size, shape, and surface properties of silver nanoparticles is crucial when preparing silver-based antimicrobial materials. Spherical silver nanoparticles with sizes ranging from 20 to 50 nm exhibit higher stability and antimicrobial activity. Optimizing the preparation process and performing surface modification can prevent agglomeration and enhance durability[116]. In terms of carrier selection, biodegradable polymers such as poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) can be used as carriers to achieve slow release of antimicrobial agents and prolong antimicrobial activity. Loading antimicrobial agents onto PLGA microspheres coated on the surface of metal implants, and optimizing their preparation process and composition, allows them to remain stable in vivo and continuously release antimicrobial agents for weeks or even months. Compared with traditional methods of directly coating antimicrobial agents, this approach significantly improves the durability of antimicrobial materials, reduces sudden release, and lowers potential toxicity[117].

5.4 How to prioritize factors such as biocompatibility, bacterial resistance and material durability

When selecting antimicrobial materials for specific clinical applications (such as orthopedic implants and dental implants), it is essential to achieve a long-term functional equilibrium within complex physiological environments. Biocompatibility remains the primary prerequisite, with materials required to ensure that no adverse reactions occur during prolonged coexistence with host tissues[118]. Building upon this foundation, the assessment of antimicrobial performance should shift from static broad-spectrum activity towards dynamic durability and anti-biofilm capability. The focus should be on the material’s surface efficacy in resisting bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation during prolonged service, rather than solely pursuing rapid initial bactericidal activity[119]. In terms of priority, a dynamic phased strategy should be adopted. During the initial implantation phase, broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties and biocompatibility are paramount to prevent early infections. For instance, silver films deposited using HiPIMS technology can achieve potent antimicrobial effects without cytotoxicity, even under extremely thin conditions[120]. In the medium to long term, material durability and osteogenic potential become critical indicators, as successful osseointegration serves as a natural barrier against microbial colonization. For instance, multifunctional CFRPEEK implants, through composite design, enhance antimicrobial effects while promoting bone integration[121]. Therefore, the ideal antimicrobial material does not seek to maximize any single property in isolation, but rather strives to achieve optimal synergy among competing factors such as biocompatibility, antimicrobial efficacy, and osteoconductive capacity.

6. Analysis of the Limitations of Various Antimicrobial Materials

6.1 Limitations of inorganic antimicrobial materials

Although inorganic antimicrobial materials such as silver, copper and zinc offer advantages including excellent durability and high thermal stability, their inherent limitations significantly constrain their clinical application prospects. The primary issue lies in the conflict between antimicrobial efficacy and biological toxicity. Their antibacterial activity is highly dependent on the sustained release of metal ions, while the effective bactericidal concentration window often approaches or exceeds the toxicity threshold for mammalian cells[122,123]. For instance, while silver ions inhibit bacterial growth, they may also interfere with mitochondrial function, induce cellular oxidative stress, and even cause DNA damage. High local concentrations are detrimental to osseointegration around implants[124,125]. This represents microbial adaptation rather than classical drug resistance. While prolonged exposure to sublethal doses is unlikely to generate plasmid-mediated resistance genes, it may prompt bacteria to enhance antioxidant defenses through genetic mutation, activate efflux pumps, or form more resilient biofilms, thereby diminishing the material’s long-term efficacy[126,127]. Moreover, their antimicrobial efficacy is significantly constrained by environmental factors. Within protein-rich bodily fluids, ion release channels are prone to blockage, causing activity to decline sharply due to ‘biofouling’[128]. Finally, from an application perspective, most inorganic materials involve complex preparation processes and high costs, coupled with insufficient bonding strength to substrates, posing a risk of coating delamination. This further limits their reliability[129].

6.2 Limitations of organic antimicrobial materials

Organic antimicrobial materials, represented by quaternary ammonium salts, chitosan, and antimicrobial peptides, whilst possessing advantages such as rapid action and ease of modification, also exhibit significant and systemic limitations. The most prominent challenge is the development of resistance. Particularly concerning quaternary ammonium cationic antimicrobial agents, their singular mechanism of membrane disruption renders bacteria highly susceptible to developing adaptive resistance through altering membrane lipid composition, enhancing efflux pump expression, or forming protective biofilms. Prolonged use may consequently lead to a significant decline in efficacy[130-132]. Secondly, the materials exhibit insufficient stability and durability. Most organic molecules are chemically unstable within the body’s complex physiological environment (such as specific pH levels and enzymatic degradation), rendering them prone to degradation or inactivation. This impedes the sustained maintenance of antimicrobial functionality over extended periods[133]. Thirdly, they exhibit high environmental sensitivity. Their antimicrobial efficacy is frequently influenced by local pH levels and ionic strength, with performance potentially fluctuating in acidic or high-protein environments within infection sites[134,135]. Moreover, the boundaries of biocompatibility are blurred. Certain organic antimicrobial agents (such as some biguanides and high-concentration quaternary ammonium salts) exhibit membrane-dissolving effects on host cells or may induce inflammatory responses at concentrations effective for antimicrobial activity. Striking a balance between promoting tissue integration and achieving potent bactericidal effects proves challenging[136]. These factors collectively cast doubt on their reliability as a long-lasting antimicrobial coating for implant surfaces.

6.3 Limitations of composite antimicrobial materials

Composite antimicrobial materials are designed to achieve synergistic effects, yet their complex architecture introduces novel systemic limitations. Firstly, technical bottlenecks lie in the compatibility and stability between components. The interfacial bonding strength between inorganic and organic constituents, the alignment of differing release kinetics, and phase separation issues during prolonged service impose stringent demands on preparation techniques, directly impacting coating uniformity and reliability[122]. Secondly, the introduction of multiple components introduces the risk of unpredictable interactions. Adverse chemical reactions may occur between components, or they may interfere with each other’s release kinetics. Not all combinations yield a synergistic effect where ‘1 + 1 > 2’; sometimes, antagonistic effects or unexpected toxicity may even arise[137]. Thirdly, the long-term biocompatibility of the material remains uncertain. Composite systems may introduce novel degradation products with more complex toxicological effects; mismatched long-term release kinetics among components could result in early-stage toxicity risks or subsequent gaps in protection[138]. Finally, there are challenges of cost and standardization. The complex preparation process inevitably leads to high production costs and difficulties in maintaining batch-to-batch consistency, presenting significant obstacles to large-scale clinical translation and standardized manufacturing[139]. Therefore, the full realization of composite materials’ advantages is highly dependent on precise, controllable design and manufacturing processes, and currently remains at a stage requiring extensive optimization and validation.

7. Development Trends

7.1 Research and development directions for new antimicrobial materials

7.1.1 Intelligent responsive antimicrobial materials

Smart responsive antimicrobial materials can respond to external environmental stimuli or bacterial metabolites, precisely regulating their antimicrobial function, making them one of the hot topics in research. Thermosensitive antimicrobial materials adjust their antimicrobial activity in response to changes in body temperature. Antimicrobial materials based on thermosensitive polymers undergo structural changes in their polymer molecules when body temperature rises, exposing antimicrobial groups. During infection, the inflammation-induced temperature increase leads to strong antimicrobial activity, while under normal conditions, the antimicrobial activity is low to minimize the impact on normal cells[140].

pH-sensitive antimicrobial materials activate their antimicrobial function in response to changes in pH levels in different parts of the body. Infected areas tend to be acidic due to bacterial metabolism, and these materials can sense such changes and inhibit bacteria by releasing antimicrobial agents. Researchers have developed pH-responsive polymer antimicrobial coatings that protonate and release antimicrobial agents when the environmental pH is below normal levels, demonstrating excellent antimicrobial performance[141]. In addition, there are also smart antimicrobial materials that respond to stimuli such as light, electricity, and salt. Light-responsive materials generate ROS or undergo structural changes under specific light irradiation to achieve antimicrobial effects, offering advantages in applications requiring precise control of the antimicrobial area and timing[142]. Electrically responsive types regulate the release of antimicrobial agents through an external electric field, while salt-sensitive types adjust antimicrobial activity according to changes in ion concentration within the body, adapting to complex physiological environments[143].

Intelligent responsive antimicrobial materials face a series of substantial challenges in advancing towards clinical application, with their technology readiness level generally remaining low. Firstly, the complexity and long-term stability of materials represent critical bottlenecks. Whether multi-component dynamic response systems can maintain response accuracy, reproducibility, and functional durability within the intricate physiological environment of the body, including protein adsorption, ionic changes, mechanical loading, and prolonged degradation, remains insufficiently validated[144]. Secondly, the risks to biological safety cannot be overlooked. The dynamic changes and degradation products of smart materials may trigger unpredictable immune responses or local/systemic toxicity, with a severe lack of long-term biocompatibility data[108,145]. Moreover, large-scale production and quality control pose significant challenges. The complex synthesis processes, precise control of nanostructures, and achieving batch-to-batch consistency represent major obstacles hindering the transition from laboratory-scale to industrial-scale production, resulting in high costs[146]. Finally, the regulatory approval pathway remains unclear. The existing medical device regulatory framework primarily addresses static products with stable functionality. For such “dynamic” or “programmable” smart materials, there is a lack of explicit safety and efficacy evaluation criteria alongside long-term regulatory strategies, significantly increasing the uncertainty and duration of their clinical translation[147]. Therefore, future research must shift from mere functional demonstrations toward addressing these core challenges in engineering and clinical translation, including simplifying material design, establishing reliable in vivo long-term evaluation models, and actively engaging in regulatory science dialogue.

7.1.2 Biomimetic antibacterial materials

Bio-inspired antimicrobial materials are designed and prepared by mimicking the antimicrobial mechanisms of biological surfaces, offering a new approach to addressing infections associated with metal implants. Many organisms in nature possess natural antimicrobial properties. For example, the nanoscale columnar structures on insect wings can physically disrupt bacterial cell membranes, while the micro- and nano-scale structures and low surface energy of lotus leaves confer superhydrophobicity, and they also contain antimicrobial active substances that inhibit bacterial growth[148].

Inspired by this, researchers have developed biomimetic antimicrobial materials. One approach involves constructing nanoscale columnar structures similar to insect wings on the surface of the material. Using micro-nano fabrication technology, nanocolumn arrays are prepared on the surface of metal implants, with parameters that can be precisely controlled. The surfaces of nanocolumns with specific dimensions and spacing exhibit significant antimicrobial activity against common pathogenic bacteria[149]. Secondly, by mimicking the dual properties of lotus leaves, which are superhydrophobic and antibacterial, low surface energy substances are modified on the surface of metal implants and micro-nano structures are constructed to prepare superhydrophobic surfaces. Antibacterial agents can also be loaded to enhance the antibacterial effect. For example, an antibacterial coating with superhydrophobic micro-nano structures loaded with silver nanoparticles on stainless steel implants has shown good and lasting antibacterial performance against various bacteria in vitro experiments[150].

The development of biomimetic antimicrobial materials also faces numerous challenges. The primary challenge lies in the long-term maintenance of structure and function. Under conditions such as mechanical friction during implant surgery, tissue ingrowth, and prolonged immersion in bodily fluids, biomimetic micro- and nanostructures are highly susceptible to structural wear, degradation, or clogging. This leads to a rapid decline in their superior physical antibacterial properties[151,152]. Secondly, the conflict between biocompatibility and functionality has become increasingly apparent. For instance, low-surface-energy chemicals introduced to achieve superhydrophobicity may hinder host cell adhesion and spreading, thereby compromising osseointegration. While sharp nanostructures effectively eliminate bacteria, they may also inflict physical damage on surrounding healthy tissue cells or trigger chronic inflammatory responses[153,154]. Moreover, the complexity and reproducibility of manufacturing processes present significant challenges for industrialization. There remains a lack of mature industrial solutions for achieving large-scale, low-cost, and highly consistent fabrication of precise biomimetic structures on the surfaces of complex three-dimensional implant geometries[155]. Future research and development must place greater emphasis on integrating biomimetic principles with clinical utility, striving to develop biomimetic strategies that are more stable within the in vivo environment and compatible with tissue regeneration processes, rather than merely pursuing complex structural imitations.

7.2 Interdisciplinary integration

7.2.1 Combination of materials science and medicine

The deep integration of materials science and medicine has driven the development of antimicrobial materials for metal implants. From a medical perspective, orthopedic surgeons expect implants to be resistant to infection and to fuse with bone tissue to promote bone regeneration. This requires antimicrobial materials to have both antimicrobial properties and biological activity to support osteoblast adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation.

To meet clinical needs, materials scientists carefully control the composition and structure of materials. In terms of composition, they select appropriate antimicrobial agents and bioactive components for combination, such as combining silver ions with calcium and phosphorus elements to prepare multifunctional antimicrobial materials. For titanium alloy implants, they use magnetron sputtering technology to prepare composite coatings containing silver and calcium phosphate, which have an antimicrobial rate of over 95% and can promote osteoblast proliferation and differentiation, thereby improving the bonding strength between the implant and bone tissue[156]. In terms of structural design, special structures such as nanostructures and porous structures are constructed to optimize performance. Nanostructures increase the specific surface area, enhance the loading capacity and release efficiency of antimicrobial agents, and improve interaction with cells. Porous structures facilitate the penetration of nutrients and cells, promoting tissue growth and repair. For example, the preparation of a nanoporous silver coating can rapidly release silver ions to inhibit bacteria, provide space for cell growth, and enhance the integration capacity of the implant with surrounding tissues[157].

At present, the depth of this interdisciplinary integration between materials science and medicine remains to be enhanced. Much current research still remains at the preliminary stage of ‘material preparation followed by in vitro performance evaluation’, presenting a significant gap compared with the complex in vivo pathophysiological environment[158]. Future research requires the development of more advanced in vitro models (such as dynamic fluid models, co-culture models incorporating multiple cell types, and biofilm models) alongside more relevant animal infection models. These models will simulate the interactions between the human immune system, metabolic activity, and microbial communities with implanted materials[159-161]. Furthermore, clinicians and materials scientists must collaborate earlier and more frequently to incorporate practical clinical constraints—such as surgical feasibility, imaging compatibility, and revision surgery difficulty—into the initial design criteria for materials[139].

7.2.2 Integration with nanotechnology, biotechnology, etc.

Nanotechnology and biotechnology have significant advantages in the research and development of antimicrobial materials. The advantages of nanotechnology are as follows: first, it enhances antimicrobial performance. For example, nanosilver has a small particle size (1-100 nm) and a large specific surface area, which allows silver ions to be released quickly, thereby enhancing the antimicrobial effect. The minimum inhibitory concentration of 20 nm nanosilver particles against Staphylococcus aureus is more than 50% lower than that of ordinary silver ions[162]. Secondly, precise loading and release control of antimicrobial agents can be achieved through nanocarrier technology, enabling slow and sustained release of antimicrobial agents. For example, silver-loaded nanocapsules can slowly release silver ions in the body, providing sustained antimicrobial activity for several weeks, and their surfaces can be modified to impart targeting properties. In the field of biotechnology, genetic engineering techniques can be used to develop novel antimicrobial materials by introducing antimicrobial substance genes into host cells. For instance, antimicrobial peptide genes can be introduced into Escherichia coli and immobilized on the surface of metal implants to inhibit bacterial growth[163]. Immunological technology combines immunologically active substances with antimicrobial materials, such as fixing antibodies to the surface of metal implants to activate immune cells, thereby achieving active immune defense and reducing the risk of implant infection[164].

The integration of antimicrobial materials with nanotechnology and biotechnology presents equally formidable challenges. The biodistribution and long-term fate of nanomaterials constitute significant safety concerns, with their potential systemic toxicity, accumulation within organs, and clearance pathways requiring urgent systematic investigation[165]. Maintaining the stability and activity of bioactive molecules presents another challenge, as these molecules may become inactivated after immobilization on material surfaces or within in vivo environments. Moreover, their large-scale production and immobilization incur substantial costs. Compounding this complexity, the convergence of multiple technologies heightens regulatory intricacies, potentially placing products within the overlapping regulatory domains of pharmaceuticals, biological products, and medical devices, thereby confronting more formidable approval challenges[138]. Therefore, future convergence research must concurrently undertake rigorous biosafety evaluations and scalability assessments, while actively exploring regulatory science pathways tailored to the characteristics of composite products.

8. Conclusions and Outlook

This study provides a systematic review of the types, antimicrobial mechanisms, research progress, existing challenges, and future trends of antimicrobial materials for metal implant surfaces. In terms of material types, inorganic, organic and composite antimicrobial materials all exhibit distinctive antibacterial properties. Their mechanisms of action primarily encompass ion release, physical disruption of cellular structures, and chemical oxidation-based sterilization. Research developments both domestically and internationally have made significant strides. Notable achievements have been made in areas such as nano-antibacterial coatings and intelligent antimicrobial materials internationally; domestically, important breakthroughs have been realized in antibacterial designs utilizing the ‘dual-function microbattery effect’, antibacterial titanium-copper alloys, and mesoporous silica coatings. However, the development of this field still faces a series of challenges. Firstly, there is the difficult balance between antimicrobial efficacy and biocompatibility; the potential cytotoxicity of antimicrobial agents must be addressed through optimizing their types, concentrations, and surface modifications. Secondly, the issue of bacterial resistance is becoming increasingly severe, necessitating the development of new mechanism materials or the adoption of strategies such as combination therapy. Thirdly, the stability and durability of materials within the complex in vivo environment are insufficient, requiring enhancement through process improvements and carrier optimization.

Future research into antimicrobial materials for metal implant surfaces will continue to advance. Smart responsive materials aim to enable on-demand activation and precise control of antimicrobial functions, such as developing coatings responsive to near-infrared light or the pH of the infection microenvironment. These coatings would release antimicrobial agents only upon external triggering or detection of bacterial infection, thereby achieving highly effective sterilization while minimizing damage to healthy tissue and the risk of developing resistance. Bionic antimicrobial materials enhance antibacterial performance by mimicking biological surface structures and mechanisms. Multidisciplinary integration serves as the core driving force for advancement. Materials science and medicine must closely align with clinical requirements, simulating the human physiological environment to develop novel implant materials that combine antimicrobial properties, biocompatibility, and mechanical performance. Nanotechnology requires precise control over material dimensions, shapes, and surface properties to achieve efficient loading and sustained release of antimicrobial agents. Biotechnology, meanwhile, must endow materials with functions such as immune modulation and tissue repair, promoting harmonious symbiosis between implants and surrounding tissues.

With the acceleration of global aging and people’s pursuit of a healthy quality of life, the market demand for metal implants will continue to grow. Antimicrobial materials, as a key factor in enhancing the safety and efficacy of implants, will play a vital role across multiple fields including orthopedics, dentistry, and cardiovascular medicine, delivering improved treatment experiences and recovery outcomes for patients. In the future, research and application of antimicrobial materials on metal implant surfaces will continue to revolutionize the field of biomedical engineering and make significant contributions to human health.

Authors contribution

Wang J: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft.

Shao L: Conceptualization, methodology.

Zhang Z: Conceptualization, visualization.

Huang K, Yang C: Writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Chengliang Yang is an Editorial Board Member of BME Horizon. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Guangxi Key Laboratory of basic and translational research of Bone and Joint Degenerative Diseases, China (Grant No. 21-220-06).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Lee SH, Kiapour A, Stoeckl BD, Zhang EY, Begley MR, Oldham J, et al. Therapeutic implants: Mechanobiologic enhancement of osteogenic, angiogenic, and myogenic responses in human mesenchymal stem cells on 3D-printed titanium truss. Adv Healthc Mater. 2025;14(27):e2501856.[DOI]

-

2. Abdo VL, Vieira-Silva IF, Dias BMF, de Arruda JAA, Barreiros ID, Sampaio AA, et al. Success and survival of titanium surface modification on dental implant osseointegration: A systematic review. Br Dent J. 2025;239(8):571-577.[DOI]

-

3. Zhang W, Gao X, Zhang H, Sun G, Zhang G, Li X, et al. Maglev-fabricated long and biodegradable stent for interventional treatment of peripheral vessels. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7903.[DOI]

-

4. Al-Suhaimi EA, Cabrera-Fuentes HA, AlJafary M, Sharma I, Kotb E, Alharbi G, et al. Next-generation nanotechnology strategies for infection-resistant and bio-integrative implants. J Drug Deliv Sci Tec. 2026;115:107686.[DOI]

-

5. Bulut HI, Okay E, Kanay E, Batibay SG, Ozkan K. Comparative effectiveness of silver-coated implants in periprosthetic infection prevention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop. 2025;61:133-139.[DOI]

-

6. Leggi L, Terzi S, Sartori M, Salamanna F, Boriani L, Asunis E, et al. First clinical evidence about the use of a new silver-coated titanium alloy instrumentation to counteract surgical site infection at the spine level. J Funct Biomater. 2025;16(1):30.[DOI]

-

7. Kreve S, Reis ACD. Bacterial adhesion to biomaterials: What regulates this attachment? A review. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2021;57:85-96.[DOI]

-

8. Davidson DJ, Spratt D, Liddle AD. Implant materials and prosthetic joint infection: The battle with the biofilm. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4(11):633-639.[DOI]

-

9. Craig J, Fuchs T, Jenks M, Fleetwood K, Franz D, Iff J, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the additional benefit of local prophylactic antibiotic therapy for infection rates in open tibia fractures treated with intramedullary nailing. Int Orthop. 2014;38(5):1025-1030.[DOI]

-

10. Wu Y, Zhou H, Zeng Y, Xie H, Ma D, Wang Z, et al. Recent advances in copper-doped titanium implants. Materials. 2022;15(7):2342.[DOI]

-

11. Xiang B, Jiang J, Wang H, Song L. Research progress of implantable materials in antibacterial treatment of bone infection. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2025;13:1586898.[DOI]

-

12. Yang H, Huang H, Li S, Qin Y, Wen P, Qu X, et al. Biodegradable zinc-based metallic materials: Mechanisms, properties, and applications. Prog Mater Sci. 2026;157:101584.[DOI]

-

13. She P, Li S, Li X, Rao H, Men X, Qin JS. Photocatalytic antibacterial agents based on inorganic semiconductor nanomaterials: A review. Nanoscale. 2024;16(10):4961-4973.[DOI]

-

14. Teymourinia H, Amiri O, Salavati-Niasari M. Synthesis and characterization of cotton-silver-graphene quantum dots (cotton/Ag/GQDs) nanocomposite as a new antibacterial nanopad. Chemosphere. 2021;267:129293.[DOI]

-

15. Li S, Wang Q, Yu H, Ben T, Xu H, Zhang J, et al. Preparation of effective Ag-loaded zeolite antibacterial materials by solid phase ionic exchange method. J Porous Mater. 2018;25(6):1797-1804.[DOI]

-