Abstract

When focusing on enhancing specificity, selectivity, and reproducibility of a powerful transducer, such as graphene-based field effect transistors (gFETs), the surface architecture is nearly as important as the bioreceptor, and plays a pivotal role, especially for sensing in complex real-world media. Maximizing analyte-receptor binding efficiency and boosting signal transduction require careful consideration of the charge and size of the bioreceptor and the implementation of strategies for bioreceptor configuration optimization, and concepts to prevent non-specific binding. Antifouling strategies for gFETs commonly include the integration of polyethylene glycol or creating barriers against unwanted proteins and molecules via the formation of functional coatings on the device surface. Recently, special approaches have been proposed, such as coating graphene with co-polymers or hydrogels. This perspective article will discuss how the unique properties of these materials can be leveraged to improve gFET sensor sensitivity, selectivity, and performance towards protein biomarkers.

Keywords

1. Introduction

The growing interest in straightforward yet sensitive and selective biomarker detection technology, particularly in complex media, has sparked substantial interest in original nanoelectronics. Field effect transistors (FETs), operating by means of an electrical field which modulates charge carriers across a semiconducting sensing channel, have been exploited for analyte-receptor interaction for more than 30 years[1]. There is a great diversity of FET-based biosensors, with key variations originating from the materials used in the transistor channel, the gate architecture, and the way signal transduction is achieved. Graphene-based field effect transistors (gFETs) have proven to be particularly well-adapted for biomarker sensing, due to the exceptional electronic and chemical characteristics of graphene, such as high surface area (~2,630 m2·g-1), large charge carrier mobility (~200,000 cm2·V-1·s-1), and enhanced electrical conductivity (~104 S·cm-1). Graphene’s outstanding electronic properties originate from electron confinement and a lack of interlayer interactions resulting in a high signal-to-noise ratio. Being a zero-bandgap semiconductor that exhibits an ambipolar field-effect allows electron and hole conduction. This unique two-channel transport of graphene can complicate gFET operation but offers distinct sensing advantages, like higher sensitivity at the charge neutrality point, called the Dirac point. As the position of the Dirac point (VDirac) can be precisely measured, shifts in VDirac can be used for quantifying biomarkers without the need for external labels in a highly simplified and cost-effective manner[2-4]. The other advantage of graphene, as compared to other nanostructures in FET-based sensors design, is related to its biocompatibility, necessary to maintain the activity of bioreceptors. Additionally, owing to its two-dimensional structure, each carbon in graphene is directly exposed to biological recognition events occurring at the surface, thereby enhancing the sensitivity of graphene-based biosensors. While early gFET biosensors focused on DNA hybridization studies[5], their application field has expanded to biomarkers such as glucose, bacteria, viruses and a range of protein biomarkers[6-10]. In 2010, Ohno et al. reported one of the first gFET sensors for the detection of immunoglobulin E[11]. The construction of the gEFT is based on this work -like in many others- on the wet transfer of graphene synthesized by chemical vapor deposition (CVD)[12]. This process involves a polymer, typically polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), to support and protect graphene sheets. The metal catalyst beneath the graphene is then etched away, after which the PMMA/graphene film is transferred onto the sensor substrate. Finally, the PMMA layer is removed to leave the graphene on the target substrate. The process of transferring CVD graphene from the copper or nickel catalyst to a substrate is complex and time-consuming, often leaving behind residues that make the binding of bioreceptors to the graphene surface challenging[12-14].

A simple and cost-effective fabrication approach is the direct deposition of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) nanoflakes on a substrate to form a rGO-based FET transducer[15,16]. The disadvantages of rGO-FETs are the random distribution of rGO flakes, which can lead to less predictable surface architecture and compromise reproducibility. In addition, the higher defect density of rGO reduces carrier mobility, which results in less steep charge transfer characteristics and often lower sensitivity due to a weaker signal. Nevertheless, rGO-FET platforms have allowed for the femtomolar sensing of the PSA/α-1-antichymotrypsin complex, a prostate cancer biomarker[17], or NT-proBNP, a heart failure biomarker in saliva[18]. Despite advancements in the field, gFETs still struggle to accurately detect protein biomarkers in complex biological media such as blood, urine or saliva[3], as outlined in Table 1.

| Limitations | Strategies to circumvent limitations | |

| Selectivity | Basal planes of pristine graphene surfaces are chemically inert | - Implementation of covalent and non-covalent surface modifications. - Covalent approaches can disrupt its unique electronic properties. |

| Sensitivity | At low biomarker concentrations, the sensor’s response can be overwhelmed by electrical noise, leading to reduced sensitivity | Sample pre-concentration via: - Use of microfluidics. - Signal amplification. |

| Stability | FET sensors can suffer from drift of their electrical properties over time, particularly when exposed to liquid environments or during storage. This drift affects the long-term reliability of the sensor. | Coating with a protective passivation layer to shield against moisture and other atmospheric contaminants. |

| Non-specific binding | Graphene has a strong affinity for proteins via π–π stacking and hydrophobic interactions. In real-world samples, like blood or urine, many proteins are present and can thus bind to the graphene surface, leading to false signals and reduced accuracy. | Implementation of anti-fouling strategies that consider the need for bioreceptor integration and Debye length limitations. |

| Debye screening | Reduced Debye length limits the sensing distance of gFETs to the immediate surface (0.1 M solution equals to 0.8 nm sensing field). | Surface modification with PEG, hydrogels, co-polymers. Channel morphology alterations. Electronic tuning. Reduction of biorecognition size. |

| Reproducibility | Precisely controlling graphene’s structure and electronic properties leads to poor device-to-device and batch-to-batch variability. | Use of graphene arrays and negative control subarrays |

gFETs: graphene field effect transistors; PEG: polyethylene glycol.

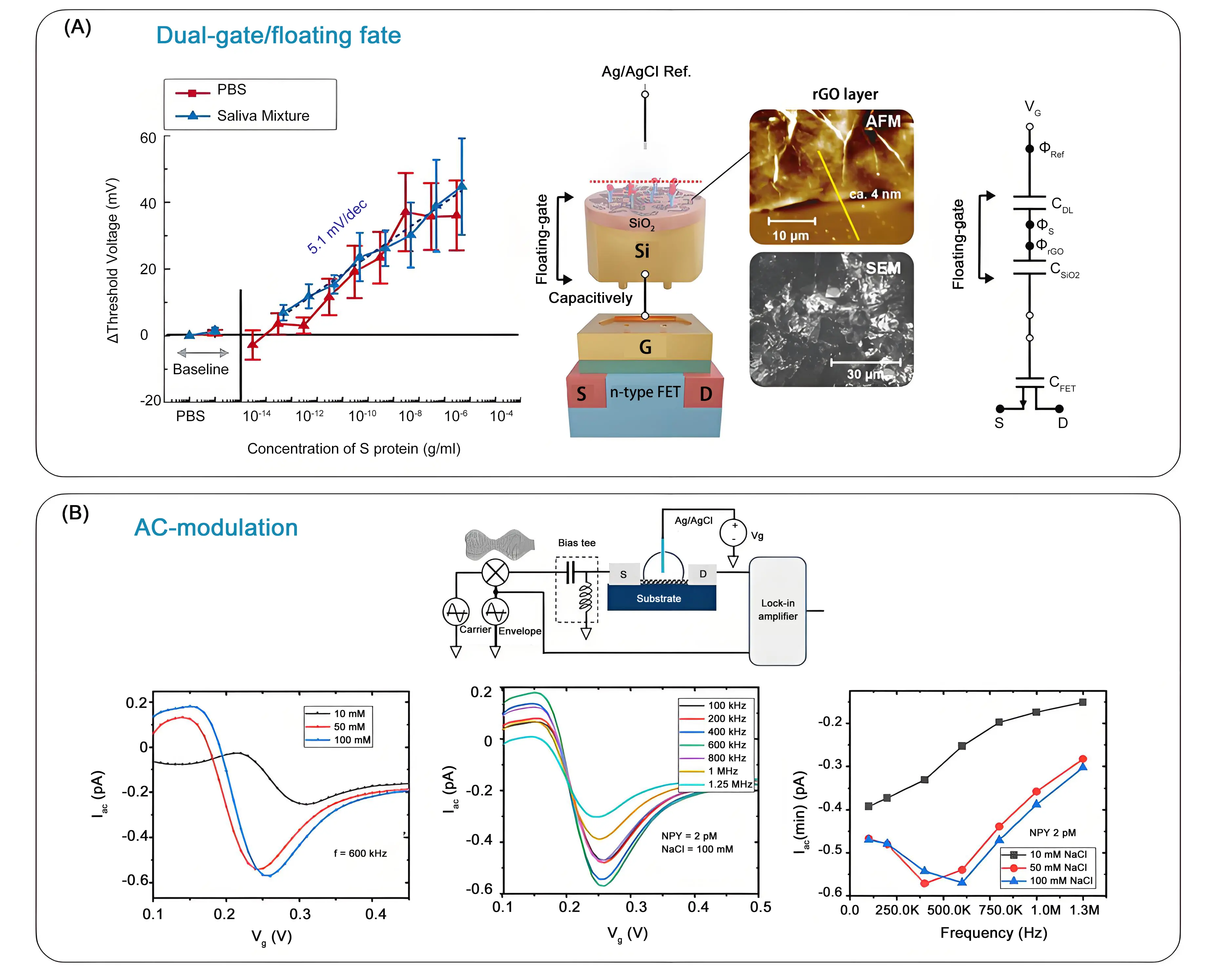

A common challenge is that many blood and saliva-based biomarkers are present at very low concentrations, often below the limit of detection (LoD) and limit of quantification (LoQ) of numerous bio-gFETs. Sensitivity enhancement can be achieved through architectural design, such as dual-gate configuration[19] (Figure 1), or through optimizing the operating points via adjusting the gate voltage (VG) to operate the gFET in a more sensitive regime. External and chemical amplifications can be considered, as in any other biosensor system, but this comes at the cost of increased complexity. Similarly, improving the signal-to-noise ratio using a closed configuration, such as microfluidics, can enhance detection efficiency, but comes at the cost of a bulkier setup. While numerous reports have underlined that femtomolar concentrations can be detected with gFETs, in most cases, these were recorded in non-physiological solutions with low ionic strength, under which Debye screening effects can be neglected. The ionic strength of biological fluids is typically greater than 0.1 M, corresponding to a theoretical Debye length of about 0.8 nm. This shielding effect prevents the electric field of the target biomolecules from reaching the graphene channel surface and modulating its conductivity, thus reducing the measurable electrical signal (source-drain current variation). As a result, the gFET’s ability to detect charged molecules, especially larger ones, is severely hindered, leading to decreased reliability in relevant biological applications. Various approaches to mitigate or overcome these hurdles have been explored[10,20-22] and will be discussed in the upcoming sections.

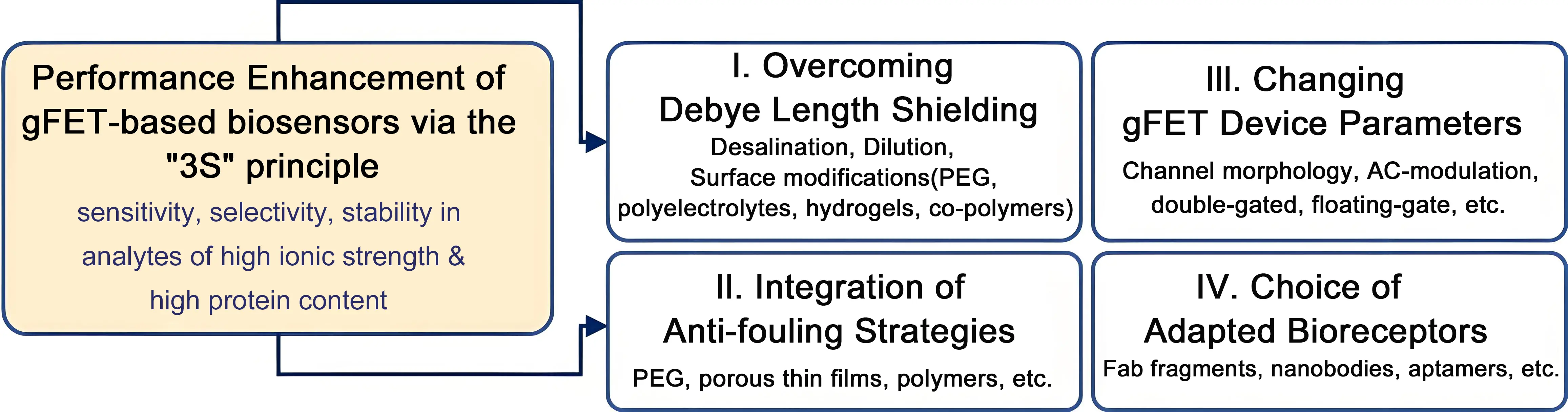

Figure 1. Approaches to be considered to enhance the performance of gFET-based sensing of protein biomarkers under physiological conditions: I. Overcoming limitations related to Debye screening effects in high ionic strength solutions, such as blood, serum or saliva, through desalination, dilution and surface chemistry strategies; II. Integration of antifouling layers to limit non-specific binding events and increase background signals; III. Considering alternative gFET configurations next to the widely used liquid-gated ones, such as dual-gate and floating gates as well, as the use of AC-modulation rather than DC-modes of analysis; IV. Considering antibody alternatives, such as antibody fragments, nanobodies, DNA and PNA aptamers and peptides, to detect protein-binding events. Integration of these bioreceptors in an oriented manner with adapted surface chemistry. gFET: graphene field effect transistor; PEG: polyethylene glycol; PNA: peptide nucleic acid; AC: alternating current; DC: direct current.

The aromatic nature of graphene also makes it prone to protein adsorption, owing to the strong π–π stacking interactions between the aromatic rings of graphene and the aromatic amino acid residues (phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan) present in proteins[23]. This interaction is a major driving force in the non-specific adsorption of blood-based proteins on the graphene surface, alongside other forces such as hydrophobic, van der Waals, and electrostatic interactions. Anti-fouling strategies are essential for sensing in unprocessed blood[14], especially for point-of-care devices like gFETs, because blood contains proteins and cells that are able to non-specifically adsorb onto the sensor surface, causing signal interference and inaccurate readings. Implementing anti-fouling measures is crucial to ensure the accuracy and reliability of these diagnostic tools.

A major hurdle in developing practical gFET-based clinical devices is the lack of sufficient data on the reproducibility of a large number of sensors under real-world conditions, despite their potential for ultra-sensitive detection. While laboratory-based tests have exhibited promising results, the high variability of gFET responses across different chips and within a large array is a significant challenge that needs to be overcome for clinical application, where chip-to-chip uniformity and consistency are critical for reliable results. Recently, Yin et al.[24] emphasized the advantage of graphene arrays and the use of negative control subarrays for achieving meaningful detection of biomarkers in clinical samples. The stability of gFET devices over time remains the major hurdle. Low-cost and low-temperature sol-gel-based passivation layers have been poised to increase gFET stability[25].

This perspective article will outline some of the more recent concepts, including surface chemistry, device engineering and architecture-related strategies, developed to overcome the current limitations of gFETs when it comes to ultrasensitive and selective protein sensing under physiological conditions. The perspective article is divided into several key sections, starting with the presentation of the specific aspects of the sensing mechanism, followed by a revision of the meaning of sensitivity and selectivity and their interconnection with the LoD and LoQ for gFET actuators. Following this, the review delves into current developments to improve sensitivity and selectivity for protein sensing in complex analytes, focusing on examples from the recent literature.

2. Operation Mechanism of Field-Effect Transistors

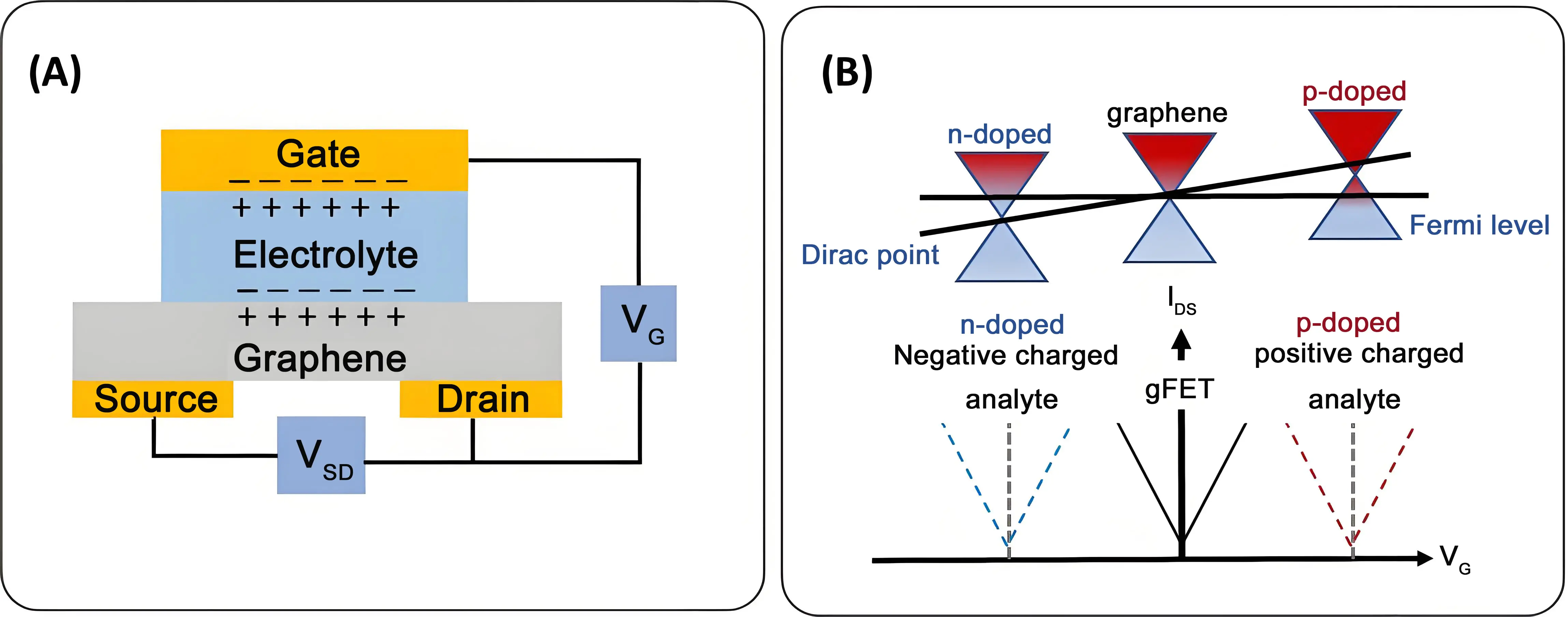

A standard FET is a voltage-controlled semiconductor device that uses an electric field generated by applying a potential to the gate (VG) to modulate the conductivity of a semiconductor channel, thereby controlling the current flow between the Source and Drain (IDS). A gFET is a unique type of FET, where the properties of graphene, such as high carrier mobility and tunable carrier density, are exploited as the semiconducting material. Figure 2A schematically outlines the commonly used liquid-gated gFET configuration, where an electrolyte solution and an immersed reference electrode act as the gate terminal. Electron transport in this zero-bandgap semimetal is governed by the Dirac relation, where electrons and holes can travel at high Fermi velocities. These extraordinary charge carrier transport capabilities of graphene endow gFETs with a transfer characteristic, where the potential difference between the graphene channel and the gate electrode governs the carrier density and the type of carriers within the channel. Application of large positive and negative gate voltages modulates the current between the source and drain by either attracting (accumulating) or repelling (depleting) charge carriers (electrons or holes) in the graphene channel. This creates two branches of the transfer characteristics that are separated by the charge neutrality point at the Dirac voltage (VDirac), where IDS reaches its minimum (Figure 2B)[4,26,27]. The detection principle of gFETs is based on variations of different electrical indicators (VDirac, IDS, transconductance) upon biomolecular interactions with surface-immobilized bioreceptors and provides highly sensitive, label-free detection.

Figure 2. Operation principle of a graphene-based field effect transistor: (A) Schematic illustration of liquid-gated gFET widely used for protein sensing. When applying a voltage to the reference electrode, the gate, ions in the electrolyte migrate to form an EDL at the interface with the semiconductor channel, graphene. This EDL electrostatically gates the channel; (B) Variation of the device transfer curves in different doping processes. If negative charges are transferred to graphene, n-type doping is enhanced, resulting in a more negative shift of VDirac. Transferring positive charges modulates graphene by p-type doping, leading to a more positive shift of VDirac. EDL: electrical double layer; gFET: graphene field effect transistors.

3. Selectivity, Sensitivity, and Limit of Detection

Selectivity is the ability of a gFET to detect a specific target without interference from other substances. The key to selectivity is the biological recognition element, which can be an antibody, aptamer, or enzyme that specifically binds to the target analyte. Antibody- and nanobody-based gFETs[14,28], often named immunosensors, are distinct from aptamer-based gFETs[10,29] or enzymatic gFETs[30], primarily due to fundamental differences in their biorecognition elements: chemical nature (protein vs. nucleic acid vs. enzyme), stability, size, production methods, and sensing mechanism.

Sensitivity (S) (Equation 1) in biosensors refers to the signal change (Δy) per unit of the measured analyte (Δx), mostly reflecting the change in the analyte concentration. In a gFET, the variation of the output signal is typically due to a change in drain current (ΔID), a shift of the Dirac point (ΔVDirac), or a variation in drain-source current at a fixed gate voltage (ΔIDS)[31].

According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, sensitivity is defined as the slope of the calibration curve (Figure 3), representing the ratio of the change in output to the change in input signal. It corresponds to the ability of the gFET to respond to changes in analyte concentration, with units such as A/mM or V/mM. Sensitivity can be improved in different ways, notably using nanomaterials, which increase surface area, or via signal amplification using catalysts or other amplification approaches[32].

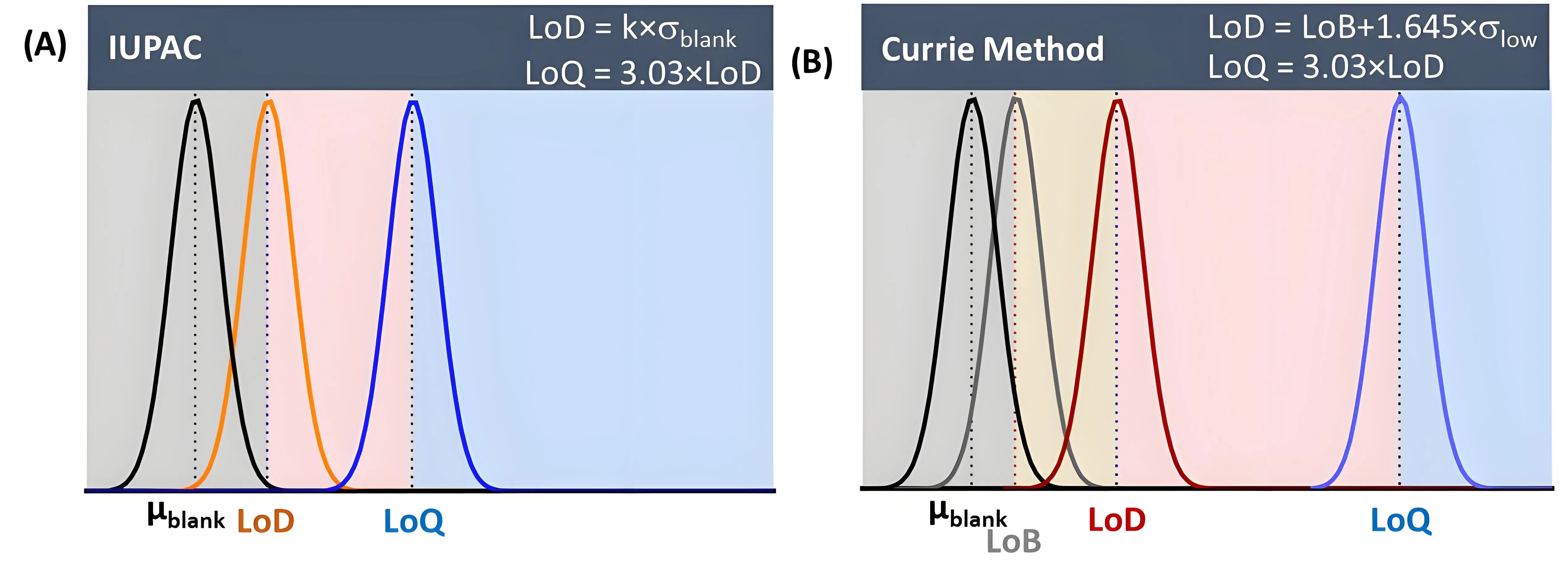

Figure 3. Comparison of two methods for the determination of the LoD and interlink to LoQ: (A) The IUPAC approach; (B) Currie method based on a “well-known” blank value. LoD: limit of detection; LoQ: limit of quantification.

Sensitivity is directly related to the LoD, which is the lowest concentration that can be detected, and the LoQ, the lowest concentration that can be reliably quantified. Most gFET sensor-related studies note the LoD as the sensitivity level rather than the sensitivity, as defined in equation 1. Reliable detection requires that the signal from the target analyte be distinctly greater than the random fluctuation of the background noise. Various methods use a statistical threshold, often based on the signal-to-noise ratio[33], to define this minimum reliable detection level. A commonly used criterion for determining the LoD is a signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1 (Equation 2).

where k is the confidence factor typically set to 3.3 (99% confidence level), and σblank is the standard deviation of the blank (Equation 1). While this approach is common and practical, especially when a good calibration curve is available, a more comprehensive method is to calculate the LoD as the limit of blank (LoB)[34,35] plus 1.645 times the standard deviation of a low concentration of sample (σlow), according to Equations 3-4.

with

with μblank being the mean response of blank samples and σblank the standard deviation of the blank. This method ensures the LoD is statistically separated from the blank signal, as it explicitly accounts for the background signal from blank samples before considering the low-concentration sample and is preferred by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institutes.

The LoD is the lowest concentration that can be detected, though not necessarily quantified. The LoQ is the lowest concentration that can be quantified reliably. A common criterion formula (Equation 5):

Sensitivity is directly related to the LoD, which is the lowest concentration that can be detected, and the LoQ, the lowest concentration that can be reliably quantified. Most gFET sensor-related studies note the LoD as the sensitivity level rather than the sensitivity, as defined in equation 1. Reliable detection requires that the signal from the target analyte be distinctly greater than the random fluctuation of the background noise. Various methods use a statistical threshold, often based on the signal-to-noise ratio[33], to define this minimum reliable detection level. A commonly used criterion for determining the LoD is a signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1 (Equation 2).

4. Methods to Improve gFET Sensitivity for Protein Analysis in Complex Media

Different options are sought after for improving the sensitivity of current gFET devices, with reducing Debye shielding effects so that the binding events fall within the Debye length, which is probably the most classical concept (Figure 1). Increasing the Debye length can be achieved by diluting the solution, disrupting the stable formation of the electrical double layer, or using desalting strategies[10,16,36]. Other methods for overcoming Debye length limitations include refining surface functionalization using polymers and hydrogels[9,20], and applying three-dimensional (3D) graphene frameworks[22]. Building a 3D graphene structure helps not only to overcome Debye length limitations but also provides more active sites for bioreceptor binding, leading to a sensor with a wider dynamic range and tuned sensitivity.

4.1 Breakthrough approaches to increase Debye screening length

The Debye shielding effect arises from the formation of an electrical double layer (EDL) at the interface between the graphene sensing channel and the electrolyte. When graphene is in contact with an electrolyte, ions in the solution redistribute near the surface, creating an electrical double layer capacitance (CEDL), which generates a local electric field. This field creates a shielding layer that screens the charges on the graphene channel. The distance over which this shielding occurs is the Debye length, λD (Equation 6), which effectively measures the thickness of the electrical double layer

where ϵr is the relative permittivity of the electrolyte, ϵ0 the permittivity of free space, I the ionic strength of the electrolyte, T the absolute temperature, NA the Avogadro number, kb the Boltzmann constant, and e the elementary charge. As λD is inversely proportional to T, increasing the solution temperature will increase λD, as thermal motion of ions in solution takes place and ion diffusion is enhanced, weakening the shielding effect on charge. This strategy is, however, of limited use in the case of gFET-based protein sensing, as these biological analytes are temperature sensitive and can undergo denaturation or lose activity. An increase in temperature is generally correlated with an increase in noise, which negatively affects detection accuracy.

4.1.1 Ion depletion to overcome Debye length shielding

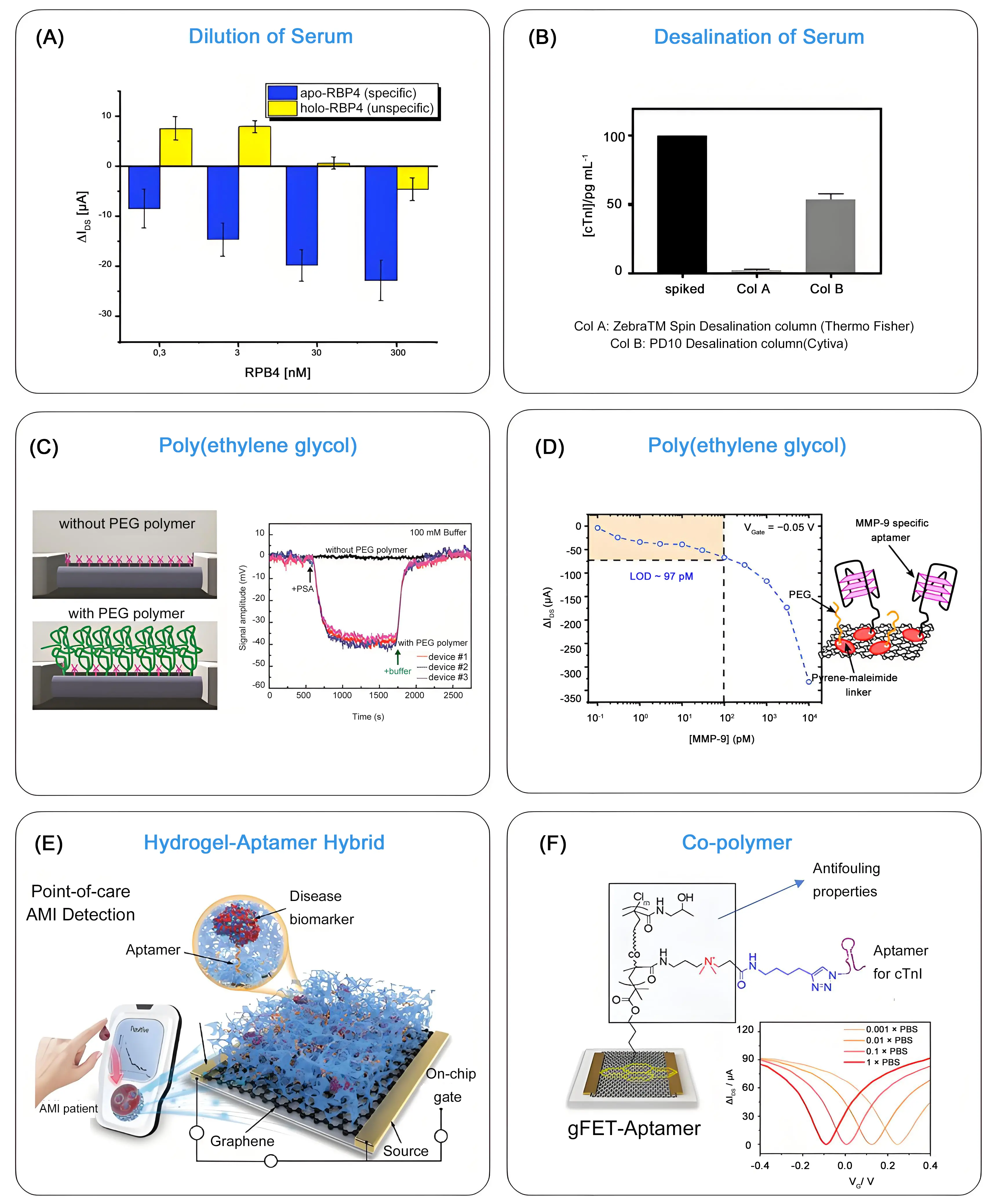

Ion depletion is an effective strategy to enhance the sensor performance in high-ionic-strength solutions. By reducing the local ionic concentration through dilution or desalination, the Debye length is increased, allowing target molecules to interact more efficiently with the sensor surface, improving sensitivity and signal reliability in complex biological or environmental media. Since blood salt concentration is normally in the range of 130-150 mM (λD ≈ 0.8 nm), dilution of a blood sample becomes a necessity for sensing. This approach was recently applied by Kissmann et al.[16] for the sensing of apo and holo retinol-binding protein 4 in blood plasma using a rGO-FET, where 10% human plasma was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before analysis (Figure 4A). However, dilution is not ideal for any analytical purposes, as it increases experimental uncertainty and makes detection in the low concentration range highly inaccurate.

Figure 4. Dilution, desalting and PEG-functionalization of gFET surface to overcome Debye shielding: (A) Difference in drain-source current (IDS) recorded at a fixed gate voltage of VG = 0.4 V upon addition of increasing concentrations of RBP4. Republished with permission from[16]; (B) Comparison of two different desalting columns for HS spiked with cTnI (100 pg mL-1). Column B dilutes cTnI by half while lowering the salt concentration of the solution, whereas column A retains almost all cTnI. Therefore, Column A is not suitable for reducing the ionic strength of HS for subsequent protein sensing. Republished with permission from[10]; (C) Implementation of PEG modification of the silicon nanowire surface for increasing the Debye screening length and sensing of PSA in 0.1 M ionic strength medium. Republished with permission from[37]; (D) Use of MMP-9 aptamer/PEG modified gFET for sensing of MMP-9: gFET current response as a function of MMP-9 concentration for VG= -0.05 V. Republished with permission from[39]; (E) Functionalization of a gFET actuator by a 3D hydrogel-aptamer structure exhibiting high antifouling properties which led to monitoring of cTnI down to lower nanomolar range in whole blood. Republished with permission from[43]; (F) Leveraging the properties of the zwitterionic co-polymer composed of HPMAA and CBMAA in the form of a pyrene-tagged poly[HPMAA-co-CBMAA] for sensing in blood droplets. ΔIDS - VG transfer curves of gFET-co-polymer in PBS of different concentrations showing preserved ambipolar behavior and stable Dirac point position across low to high ionic strength media. Republished with permission from[20]. PEG: polyethylene glycol; gFET: graphene-based field effect transistor; HS: human serum; PSA: prostate-specific antigen; HPMAA: N-(2-hydroxypropyl) methacrylamide; CBMAA: carboxy betaine methacrylamide; PBS: phosphate-buffered saline.

Desalting of human plasma is another reported strategy for protein sensing using gFETs[10]. Desalination of human serum, spiked with 100 pg mL-1 cTnI, through a D10 Desalting Column from Cytiva led to salt removal; however, this process diluted the cTnI by half. Out of the 100 pg mL-1 added to human serum, 51 pg mL-1 were recovered according to ELISA as well as gFET measurements, in agreement with the column specifications (Figure 4B). This approach allowed the evaluation of 15 clinical samples from patients with different troponin levels. While desalting columns are excellent for removing salts and performing buffer exchanges, they are limited for analytical purposes because they can selectively remove or retain compounds depending on their size and properties. This makes them unsuitable for a comprehensive analysis of complex samples.

4.1.2 Surface modification with polyethylene glycol (PEG) and polyelectrolyte multilayers

PEG and polyelectrolyte multilayers can modulate λD by altering the physical environment (dielectric constant and ion density) in which electrostatic screening occurs. PEG layers can create dense, hydrated environments that physically limit the volume available for mobile ions to occupy. In polyelectrolyte multilayers specifically, the entropic cost of confining ions within the polymer matrix leads to a reduction in local ion concentration compared to the bulk solution. The presence of high-volume fractions of polymers, such as PEG or polyelectrolytes, further changes the effective dielectric permittivity (εr) within the film. Since λD ≈(εr/I)1/2, with I being the ionic strength, reducing the available water content effectively alters the screening environment. Dense PEG or polyelectrolyte multilayer coatings can increase the effective λD by up to an order of magnitude as the field emanating from surface charges is not immediately screened by a high density of mobile ions

4.1.2.1 Surface modification with PEG

Integration of PEG into gFETs was demonstrated by Gao et al. in 2015 and 2016, which allowed for the sensing of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) over a linear range of 1-1,000 nM in 0.1 M phosphate buffer[37,38]. In their first work, PEG- and (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES)-modified silicon nanowire (SiNW) device chips were used for the real-time detection of PSA, with a sensitivity of ~10 nM in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (Figure 4C). In the follow-up work, a gFET construct was considered, where PSA specificity was obtained by first adsorbing pyrene butyric acid via π–π stacking onto graphene surface to introduce functional carboxyl groups, followed by covalent coupling of different ratios of amine-terminated 10 kDa PEG/amine-terminated DNA aptamer, as a specific protein receptor. This allowed the detection of PSA already at ~1 nM in 0.1 M phosphate buffer.

A comparable approach was used by some of us for the construction of a MMP-9 specific gFET sensor[39]. In this work, a maleimide carrying pyrene ligand (PMAL) was immobilized onto the graphene sensing channel, followed by covalent anchoring of a cysteine-carrying MMP-9 specific aptamer and thiol-(PEG)4-methyl ligand (Figure 4D). The LoD of the sensor toward MMP-9 in concentrated buffer conditions (1 × MOPS/1 mM CaCl2) was 97 pM, surprisingly three times lower than that recorded in lower ionic strength solutions. An improved aptamer/protein binding under high ionic strength conditions was put forward. When tested in wound fluids, with ionic strength reaching 0.2 M in some cases (due to a complex mix of salts), the LoD increased to 478 pM for MMP-9, suggesting that PEG moieties do not allow for the full screening of charges in complex, high ionic strength media. Very recently, a similar surface engineering strategy was implemented for the detection of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in undiluted medium. This aptamer-based gFET biosensor implemented a biomolecule-permeable polyethylene glycol (PEG) isolation layer and achieved a LoD of 0.13 pM for TNF-α and 0.20 pM for IL-6[40].

4.1.2.2 Surface modification with polyelectrolytes

Next to PEG chains, a polyelectrolyte multilayer film, made from poly(diallyldimethylammonium) chloride and poly(styrene sulfonate) sodium salt (PDADMA/PSS), was investigated for rGO-gFET modification via layer-by-layer assembly, owing to its ability to increase the Debye length up to 9.6 nm[41]. The formed polyanion/polycation structure resulted in charge overcompensation and led to variations of the surface potential at the polyelectrolyte/solution interface. The polyelectrolyte film generated a low ion concentration inside the formed ionic polymer membrane, implying that the Debye length inside the membrane is different from the that in the solution. While this concept has been extended to other layer-by-layer assemblies, notably enzyme-loaded polyelectrolyte multilayers for sensing small molecules, such as urea[41], no extension to protein sensing on gFETs has been made so far. This would require the fabrication of antibody- or aptamer-polyelectrolyte multilayer assemblies, as already shown using electrochemical sensors for lysozyme detection.

4.2 Integration of anti-fouling layers

The natural physiological environment contains a high concentration of proteins and other biomolecules at a level of up to tens of mg mL-1. This overwhelming background causes significant nonspecific adsorption and false-signal transduction on FETs. This is particularly a serious issue for gFETs, as graphene is known to establish strong interactions with biomolecules through π–π stacking, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatic interactions. More than 50% of blood serum consists of human serum albumin, which signifies its role as a dominant source of false signal generation. Co-polymers and hydrogels integrated with gFETs have demonstrated their ability to mitigate challenges associated with sensing in high-ionic strength physiological fluids without the need for preprocessing, while also reducing nonspecific binding between graphene and nontarget biological compounds. To this end, Bay et al.[42] prepared a functional hydrogel through the copolymerization of PEG linker/enzyme and polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA) in the presence of Eosin Y as a photo-initiator to trigger covalent cross-linking and gelation. This hydrogel was applied as a gate in gFETs for the real-time, label-free enzymatic sensing of Penicillin G.

The possibility of rapid and ultra-sensitive screening of acute myocardial infarctions via elevation of blood-derived troponin dates back to 2022[22]. The concept is based on the modification of the graphene sensing channel with a mixed solution that contains a gel stock of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide and an acrydite-modified cTnI aptamer. The hydrogel-aptamer hybrid exhibited nano- and micro-holes with self-filtration capacity for analytes such as cTnI, allowing a LoD of 28.1 ag mL-1 in whole blood to be reached (Figure 4E). This enabled the identification of patient samples within possible acute myocardial infarctions within 5 min, with an accuracy rate of over 94%.

Our team presented more recently the interest of a zwitterionic diblock co-polymer, poly[HPMAA-co-CBMAA], combining poly[N-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide] and poly[carboxybetaine methacrylamide], with pyrene-based surface anchors in the terminal block to allow its immobilization on the graphene surface (Figure 4F)[20]. The co-polymer-functionalized gFET preserved well-defined ambipolar behavior and a stable Dirac point position across low to high ionic strength media, underscoring the co-polymer’s capacity to restructure the local electrical double layer and mitigate electrostatic screening at the graphene interface. In parallel, the poly[HPMAA-co-CBMAA] modified gFET displayed excellent anti-fouling properties when immersed for 2 h in whole blood, which remained even after the covalent conjugation of DNA-aptamers. This allowed sensing in unprocessed blood samples in an easy manner, with a LoD ofabout 1 pg mL-1, well within the clinically relevant cTnI range for myocardial injury diagnostics.

4.3 From change of channel morphology to device alterations and electrical field modulation

Computational and theoretical analyses predict that the curvature of sensing materials significantly affects Debye screening, particularly influencing the Debye volume near the surface[44]. Specifically, Debye screening is weaker near concave regions of nanowire sensors, such as the concave corners formed between nanowires and their substrate, which leads to an increased Debye volume compared to convex surfaces. This hypothesis inspired the use of crumpled single-layer graphene to effectively increase the Debye length, which allowed for the sensing of miRNA in human serum samples with a LoD of 20 aM[45]. The shrinkage properties of a plastic sheet were used for the formation of a crumpled gFET, which was employed for the sensing of adenosine triphosphate in human serum down to 10 aM[46]. More recently, a crumpled gFET sensor functionalized with L-polylysine was proposed, which allowed the sensing of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) with high sensitivity, by recognizing its papain-like cysteine protease (PLpro) [47].

Dual-gate FETs have proven their ability to overcome the Debye length issues in biosensing by using capacitive coupling between two gates to enhance sensitivity[48], even though these sensing architectures have not been applied to proteins so far. Extended gate, also called (remote) floating gate gFETs, have been proposed[49,50], where the base transducer is a classical gFET (the control gate), whereas sensing is performed on the extension that connects to the control gate. The bioreceptors are immobilized on this external gate, which has the advantage that the gFET channel is not in direct contact with the analyte. This configuration results in higher stability and enables sensing in physiological fluids with high selectivity. Juang et al. proposed a remote floating gate FET using rGO as a sensing gate to eliminate device-to-device variations and to sense the presence of the spike proteins (S1) of SARS-CoV-2 in saliva (Figure 5A)[50]. In this configuration, rGO was electrically isolated by an insulator and capacitively connected to an external gate. The rGO sensing membrane was highly sensitive to potential changes at the interface occurring when the S1 protein binds to the neutralizing antibodies modified rGO. Following the change in threshold voltage, a LoD of 500 fg mL-1 was achieved Figure 5A)[50].

Figure 5. From use of polymers/hydrogels to channel morphology modulation of gFETs for sensing under physiological conditions: (A) Schematic image and equivalent circuit of the remote floating gate FET together with ΔVth upon binding of S-protein to neutralizing antibody-functionalized rGO in an artificial saliva mixture. Republished with permission from[50]; (B) Carrier frequency (30 kHz - 1 MHz, amplitude = 50 mV) is amplitude modulated by a fixed reference signal (envelope,1.43 kHz and amplitude depth of 50) and fed into the source electrode of the gFET through a bias tree. VG is applied to the gate electrode (Ag/AgCl wire), immersed in electrolyte. The alternating mixing current from the drain terminal is measured by using a lock-in amplifier. Current modulation as a function of salt concentration (carrier frequency = 600 kHz) and carrier-frequency-dependent transfer curves of a gFET device for NPY = 2 pM and a fixed salt concentration of 100 mM, together with plots of minimum current for various salt concentrations as a function of the carrier frequency of AC voltage. Republished with permission from[51]. gFETs: graphene field effect transistors; rGO: reduced graphene oxide; AC: alternating current.

A different approach used high-frequency alternating current (AC) to weaken the Debye shielding effect by preventing ions from forming a stable EDL, thereby reducing the screening of the electric field[51,52]. The use of AC-mode gFET for the sensing of the neuropeptide-Y, a key stress biomarker, in artificial sweat at physiologically relevant ionic concentrations resulted in an ultralow detection limit of 2 aM with a dynamic range of 10 orders of magnitude[51]. In contrast to the DC-mode, in the AC-mode of sensing, the sensor response increases proportionally to the ionic strength of the electrolyte and can be further modulated by tuning the carrier frequency of the applied AC voltage (Figure 5B). This approach has not been widely developed yet, most likely because the use of high-frequency AC increases circuit complexity, production cost, and power consumption, which is unfavorable for miniaturized and portable devices, thereby limiting their application scenarios.

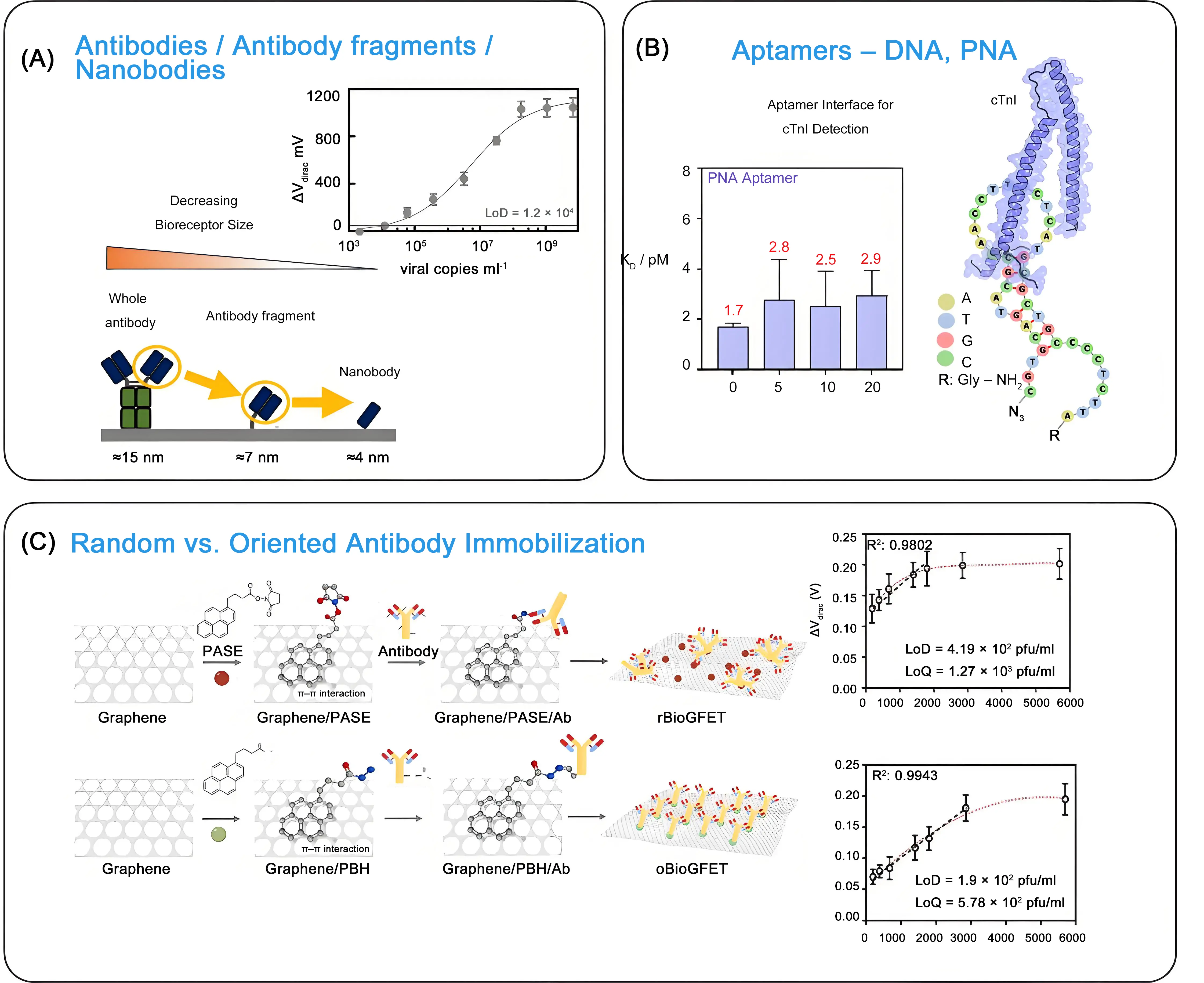

4.4 Reduction of biorecognition element size

Replacing full-sized antibodies (about 150 kDa), which are about 12-14 nm in width and 2-6 nm in height, with antibody fragments, single-domain antibodies (also called nanobodies), aptamers or peptides as bioreceptors is a successful strategy to improve the sensitivity of gFET sensing. These smaller bioreceptors (Figure 6A), like nanobodies (which are about 12-15 kDa and ~2.5 × 4 nm), can bind to targets that are difficult for antibodies to reach, potentially exposing more active sites for binding. A greater number of smaller nanobodies can also generally be immobilized on gFET transducers compared to full-size antibodies, increasing the overall number of binding sites available for target molecules and leading to stronger signals. Additionally, smaller receptors exist in the electrostatic field defined by the Debye length of their surrounding solution. The other interest in using antibody fragments, such as nanobodies, is linked to their greater thermal and pH stability than conventional antibodies, making them more robust during storage. One of the first examples is the work by Okamoto et al., dating back to 2012[53], where the antigen-binding fragment (Fab) of an antibody, obtained by cleaving the antibody by enzymatic digestion, was applied for protein sensing. This concept was more recently applied for the detection of hepatitis E virus ORF2 antigens using a gFET functionalized by co-immobilization of PEG and nanobodies[28]. A similar approach was adopted by some of us for the sensing of SARS-CoV-2 via the S1 envelope protein. Using an S1-specific nanoClamp ligand[54], a LoD of about 1.2 × 104 viral copies mL-1 was recorded. Furthermore, implementation of recognition scaffolds such as nanobodies adds to the aspect of cost-effectiveness of such sensing interfaces, since they can be routinely produced much more easily by recombinant microbial systems (bacteria or yeast) at much lower cost in comparison to monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)[55].

Figure 6. Bioreceptor considerations: (A) Size change upon replacing full-sized antibodies by antibody fragments and nanobodies together with gFET-nanoCLAMP-based titration of SARS-CoV-2 (unpublished results); (B) Predicted secondary structure of PNA investigated towards cTnI biomarker sensing and change of dissociation constant upon incubation with increasing concentrations of DNase-I. Republished with permission from[58]; (C) Strategies employed for random and oriented immobilization of anti-Spike protein Ab on graphene surface using either PASE or PBH as bifunctional linker together with dose-dependent response curves for SARS-CoV-2 in VTM solutions. Republished with permission from[59]. gFET: graphene field effect transistor; SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; PNA: peptide nucleic acid; Ab: antibodies; PASE: 1-pyrenebutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester; PBH: 1-pyrenebutyric hydrazide; VTM: Virus Transport Medium.

Aptamers, notably DNA aptamers, have been the most widely integrated bioreceptors in gFET-based protein biomarker sensing platforms[10,16,20,56,57]. Their use over antibodies is motivated by their superior chemical stability, low cost, ease of production, and structural tunability. Additionally, their small size positions binding events extremely close to the FET surface, within the Debye screening length, which enhances sensor sensitivity.

Short protein fragments, such as peptides or elaborated peptide-based architectures, could also be promising biological recognition elements for integration with gFET sensors. Peptides are relatively easy and cost-effective to synthesize chemically, allowing for consistent production and modification. Their small size facilitates direct functionalization and dense packing on the graphene surface, which is crucial for maximizing sensitivity in gFET devices. Rationally designed peptides based on a motif sequence in olfactory receptors, when integrated into gFETs, showed sensing capability for odorants such as limonene, menthol and methyl salicylate[60]. The molecular detection of proteins by peptide-modified gFETs still remains underdeveloped, even though their interest as sensing probes and for preventing non-specific protein adsorption was already demonstrated in 2014[61].

5. Strategies for Enhancing gFET Selectivity for Protein Sensing

As pointed out by Sun et al. recently, the performance of gFET biosensors underlines the “3S” principle- stability, sensitivity and specificity[4]. Selectivity, alongside sensitivity, remains a paramount indicator of sensor performance, dictating the reliability and accuracy of the data. Improving the selectivity of a biosensor often leads to high sensitivity by ensuring that the sensor primarily detects the target analyte and minimizes interference.

5.1 Bioreceptor considerations

The core of a biosensor’s selectivity lies in its bioreceptor, which can range from antibodies to antibody fragments, nanobodies, and aptamers (Figure 6A). Aptamer-based gFETs are widely exploited in the literature. However, the DNA aptamers’ negatively charged phosphate backbones are a challenge for charge-based biosensors, such as gFETs. Their vulnerability to degradation by nucleases and their performance limitations in biological samples, due to ionic strength and pH, have in addition often been put forward as the main disadvantage for aptamer-based gFET sensing. Peptide nucleic acid (PNA)-based aptamers, in which the phosphate backbone is replaced with a neutral amide-bonded one, allow to minimizing electrostatic interactions between the bioreceptor and the sensing matrix and enabling efficient target capture. We recently demonstrated that the use of PNA-based aptamers could represent potential next-generation bioreceptors for gFET-based protein biomarkers’ sensing[10,29], compared to their DNA aptamer counterparts (Figure 6B). Owing to their backbone, PNAs also exhibited higher stability against DNase I.

5.2 Surface Chemistry considerations

Controlling the orientation of bioreceptors on the surface of gFET has proven essential to optimize biorecognition, improve assay reproducibility, and increase sensitivity. Lozano-Chamizo et al.[59] produced antibody-directed and antibody-randomized gFETs (Figure 6C) by functionalizing the graphene surface through different biochemical reactions. For random bioreceptor immobilization, 1-pyrenebutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (PASE) was used, while 1-pyrenebutyric hydrazide (PBH) promoted oriented antibody linkage. The oriented antibodies against the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 exhibited significantly enhanced reproducibility and responsiveness, with a LoD for SARS-CoV-2 reaching 4.19 × 102 pfu mL-1, indicating more than twice the detection sensitivity of non-oriented antibody-modified gFET.

5.3 Device and system-level considerations

In addition, device- and system-level strategies can enhance the overall selectivity of the sensor. Specifically structured DNA probes, notable Y-shaped and tetrahedral DNA aptamers, when linked with gFET-based sensing, have been shown to decrease the risk of nonspecific binding[62,63]. While demonstrated for nucleic acid sensing, such approaches might be of equal interest for protein sensing on gFETs.

Incorporating gFET sensors into microfluidic systems facilitates the separation of target molecules and allows for specific wash steps to be integrated into the analytical workflow to remove non-specifically bound molecules, thus improving assay reliability.

The use of differential measurement design in the form of a dual-channel gFET, where the graphene channel is functionalized with Tween 80 to form a passivation layer, effectively eliminates false response signals caused by unwanted background interferences in the biofluid, thereby enhancing sensor specificity[64].

6. Perspectives Concerning Commercialization and Clinical Translation of Protein Sensing Using gFET Technologies

The different laboratory-scale technological advancements mainly focused on performance improvements. Numerous technical strategies have been proposed (Table 2) to achieve highly sensitive and selective sensing of protein biomarkers by gFETs under physiologically relevant conditions. The market translation of gFETs remains limited even in 2026, as little effort has been undertaken on how to scale up the current complex laboratory-based designs of gFETs for mass production. While simplified methods based on reduced graphene oxide rather than CVD graphene are exploited with a good degree of success for reaching low sensitivity, the diversity in the quality of rGO flakes used, characterized by parameters like carbon/oxygen ratio and conductivity, remains a significant hurdle for mass production of rGO-based FETs.

| Strategy | Advantage | Disadvantage |

| Dilution of blood/serum sample with low ionic strength buffer | simple | Increases experimental uncertainty Makes detection in the low concentration range highly inaccurate |

| Desalination of blood/serum sample via columns | simple | Analyte is strongly diluted during the process |

| Integration of PEG onto gFET | PEG linkers are commercially available Well-accepted strategy | PEG linkers are expensive Exhibit short-term stability, as they can degrade over extended periods, particularly in demanding environments like biological fluids |

| Integration of polyelectrolyte multilayer films onto gFET | Commercial products | Upscale limitationsIntegration of bioreceptors challenging |

| Co-polymers and/or hydrogels | Excellent anti-fouling character and stability | Synthesis is required as they are not commercially available |

| Crumpled single-layer graphene | High specific surface area with enhanced sensing capabilities | Limitation in upscaling Reproducibility limitations |

| Remote floating gate | Device reliability Operational flexibility | Increased device size Potential signal interference |

| AC modulation | Enhanced stability in complex media | Increased circuit complexity, production cost, and power consumption |

| Nanobodies as bioreceptors | Small size High stability Ability to target unique epitopes Relatively cheap | Need to be designed for a targeted application Requires immunization of Llama or other Camelids |

| Aptamers as bioreceptors | Reversible folding with large conformational changes upon analyte binding Effective Production No animals needed | SELEX process is time-consuming (weeks to months) and may not always yield an optimal binder for every target. Aptamer folding and binding affinity are highly dependent on specific salt concentrations Susceptibility to nucleases: degradation |

gFETs: graphene field effect transistors; PEG: polyethylene glycol; AC: alternating current.

Industrial reports of the last year, however, highlight a critical shift toward addressing large-scale fabrication barriers for gFETs, with manufacturers increasingly adopting automated, industrially compatible technologies to resolve consistency, quality, and cost issues. CVD technology now enables continuous, large-area graphene film production via roll-to-roll transfer or the direct growth of graphene on insulating wafers[65,66]. Production is concentrating in regions with mature semiconductor ecosystems, notably China, South Korea, and the U.S., to leverage existing infrastructure and reduce input costs. The U.S. company Paragraf is one of the leaders in the use of graphene-based electronic sensors[67]. Its capability to mass-produce graphene-based electronic components using standard semiconductor processes opens the possibility for the practical application of graphene-based biosensors across a range of markets and use cases. Likewise, the U.S. based biotech company IdentifySensors, developer of graphene-based biosensors, has announced plans to commercialize the “Check4” platform, a digital multiplex system for the rapid detection of cancers, viruses, and bacteria[68].

Next to the gFET device itself, one of the next major leaps in the field revolves around the implementation of more stable and cost-effective recognition scaffolds. The key advantage of integrating nanobodies rather than antibodies into gFET constructs remains limited to some research works. As nanobodies can be produced economically and on a large scale using prokaryotic expression systems (like E. coli), and have increased stability compared to antibodies, with the same ability to target unique protein epitopes (Table 2), they are ideal for PoC diagnostics. Their limited use in gFET sensing is related to availability constraints, as they first need to be generated. The process starts with immunization of Llamas or other Camelids to create an immune library, where the nanobody genes are then identified, amplified, and inserted into a microbial host for large-scale, cost-effective production. Successful collaboration of molecular biologists and biotechnologists with gFET engineers and sensor developers is required, which faces several challenges, including communication barriers, technical integration issues between biological and engineering components, and difficulties in aligning project goals. Engineers focus on reliability and scalability in production, while biologists focus on performance and function in complex biological matrices, which can be difficult to reconcile at large scales. For any clinical translation, prototyping such proof-of-concept devices is crucial for advancing gFET biosensor development before wider clinical studies can be envisioned.

7. Conclusion

Despite the promising potential of graphene-based field effect transistors (gFETs), several limitations persist that hinder their widespread clinical application and commercial viability. Industrial advancements to overcome technical limitations have been reported recently, with routine sensing in biological fluids remaining a big challenge due to the limited stability and reliability of gFETs. While a number of strategies have been designed to overcome the Debye screening length limitation of gFET sensors (Table 2), correcting interference factors in gFET sensing data in complex media and data standardization processes remain constraints to be addressed for translating laboratory-based prototypes into commercially viable biosensing platforms. Accounting for physiological lags, individual variability, and low analyte concentrations in biofluids can be addressed by machine learning approaches as well as the use of multiplexed sensors with reference channels. Machine learning algorithms can analyze complex, time-series data to model and predict actual analyte concentrations despite individual variations and are particularly effective at correcting for noise at low concentrations.

As an emerging sensing technology, anticipated to become a backbone for future diagnostics, long-term sensor stability needs to be further addressed adequately. This requires robust, scalable immobilization methods for innovative bioreceptors to minimize drift and improve bioreceptor retention. The ease of pyrene-based chemistry makes it well-suited for gFET modifications in a single-step protocol, notably when pyrene-labeled bioreceptors are considered.

The fitness of gFET as a PoC device needs further consideration around user convenience. Portability in PoC sensors has reached a critical milestone with the integration of gFETs within wearable and/or implantable technologies. Core challenges like biofouling and sensitivity are supplemented in wearable devices with sensor biocompatibility, longevity, power consumption, and stability of integrated power management systems. While graphene is inherently biocompatible, long-term implantation might trigger host responses, including fibrosis, chronic inflammation, and oxidative degradation. As gFETs are highly sensitive to their environment, they are prone to signal drift and interference from human movement. Achieving stable, high signal-to-noise ratios requires advanced skin-conformal interfaces and robust signal processing to filter out physiological “noise”. Developing efficient, miniaturized power sources remains a primary obstacle. The need for frequent battery charging has also driven interest in alternative energy harvesting and self-powered systems. gFET sensors can, for example, be made self-powdered by generating piezoelectric currents through bending and deformation, by integrating ferroelectric materials, or by combining with other energy sources such as solar power.

When considering wearable gFETs, continuous monitoring of biomarker levels becomes of top importance. Active sensor reset mechanisms that enable real-time, continuous monitoring of protein biomarkers, analogous to small analytes, are crucial for high-frequency measurements. Application of external stimuli, such as high-frequency oscillations, to accelerate the dissociation of bioreceptor-protein interaction, which allows the sensor to be ready for the next measurement within a minute and prevents saturation, remains not widely exploited, but is essential for applications like real-time inflammation monitoring in patients.

While the modification of gFETs with cutting-edge materials like MXene, black phosphorus, and the use of smart responsive materials (e.g., temperature-sensitive/photo-responsive hydrogels) might help to overcome some of the current sensing limitations, the resulting complex architectures are generally considered ill-suited for widespread clinical use, notably due to significant stability issues in physiological environments[69]. Perseverance, together with new ideas and visions, will shape the future of gFET biosensing of proteins.

Authors ontribution

Szunerits S: Conceptualization, visualization, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing, project administration, funding acquisition.

Yesupatham MS: Conceptualization, validation, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Bagale R, Hambli A: Writing-review & editing.

Sahu S: Validation, visualization, writing-review & editing.

Ritzenthaler C: Writing-review & editing, funding acquisition.

Amiri M, Kissmann AK, Rosenau F: Writing-review & editing.

Boukherroub R: Validation, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

Financial support from the Gesellschaft für Forschungsförderung (GFF) of Lower Austria under Grant No. FTI23-G-0001, entitled “Double stranded RNA analysis using an innovative biosensor-integrated nanopore sequencing approach” (SensNanopore) is acknowledged. This work was further supported by the ANR under project ANR-22-CE35-0012 (“VDOSAGE”) and by the FLAG-ERA grant “G-Virals” (Grant No. FLAG-ERA III/2023/808/G-Virals). Additional financial support was provided by the Fédération Française de Cardiologie (FFC) through the CardioBreath project.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Bergveld P. A critical-evaluation of direct electrical protein-detection methods. Biosens Bioelectron. 1991;6(1):55-72.[DOI]

-

2. Krishnan SK, Nataraj N, Meyyappan M, Pal U. Graphene-based field-effect transistors in biosensing and neural interfacing applications: Recent advances and prospects. Anal Chem. 2023;95(5):2590-2622.[DOI]

-

3. Zhou Y, Feng T, Li Y, Ao X, Liang S, Yang X, et al. Recent Recent advances in enhancing the sensitivity of biosensors based on field effect transistors. Adv Electron Mater. 2025;11(7):2400712.[DOI]

-

4. Sun M, Zhang C, Lu S, Mahmood S, Wang J, Sun C, et al. Recent advances in graphene field-effect transistor toward biological detection. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(44):2405471.[DOI]

-

5. Mohanty N, Berry V. Graphene-based single-bacterium resolution biodevice and DNA transistor: Interfacing graphene derivatives with nanoscale and microscale biocomponents. Nano Lett. 2008;8(12):4469-4476.[DOI]

-

6. Kim J, Kim M, Lee MS, Kim K, Ji S, Kim YT, et al. Wearable smart sensor systems integrated on soft contact lenses for wireless ocular diagnostics. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):14997.[DOI]

-

7. Wang L, Wang X, Wu Y, Guo M, Gu C, Dai C, et al. Rapid and ultrasensitive electromechanical detection of ions, biomolecules and SARS-CoV-2 RNA in unamplified samples. Nat Biomed Eng. 2022;6(3):276-285.[DOI]

-

8. Wang Z, Hao Z, Yu S, De Moraes CG, Suh LH, Zhao X, et al. An ultraflexible and stretchable aptameric graphene nanosensor for biomarker detection and monitoring. Adv Funct Mater. 2019;29(44):1905202.[DOI]

-

9. Li J, Liu J, Wei C, Liu X, Lin S, Wu C. Hydrogel-gated mxene-graphene field-effect transistor for selective detection and screening of SARS-CoV-2 and E. coli bacteria. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2025;17(2):2871-2883.[DOI]

-

10. Rodrigues T, Mishyn V, Leroux YR, Butruille L, Woitrain E, Barras A, et al. Highly performing graphene-based field effect transistor for the differentiation between mild-moderate-severe myocardial injury. Nano Today. 2022;43:101391.[DOI]

-

11. Ohno Y, Maehashi K, Matsumoto K. Label-free biosensors based on aptamer-modified graphene field-effect transistors. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(51):18012-18013.[DOI]

-

12. Mishyn V, Rodrigues T, Leroux YR, Aspermair P, Happy H, Bintinger J, et al. Controlled covalent functionalization of a graphene-channel of a field effect transistor as an ideal platform for (bio) sensing applications. Nanoscale Horiz. 2021;6.[DOI]

-

13. Mishyn V, Hugo A, Rodrigues T, Aspermair P, Happy H, Marques L, et al. The holy grail of pyrene-based surface ligands on the sensitivity of graphene-based field effect transistors. Sens Diagn. 2022;1(2):235-244.[DOI]

-

14. Boukherroub R, Szunerits S. The future of nanotechnology-driven electrochemical and electrical point-of-care devices and diagnostic tests. Anual Rev Anal Chem. 2024;17.[DOI]

-

15. Aspermair P, Mishyn V, Bintinger J, Happy H, Bagga K, Subramanian P, et al. Reduced graphene oxide–based field effect transistors for the detection of E7 protein of human papillomavirus in saliva. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2021;413(3):779-787.[DOI]

-

16. Kissmann AK, Andersson J, Bozdogan A, Amann V, Krämer M, Xing H, et al. Polyclonal aptamer libraries as binding entities on a graphene FET based biosensor for the discrimination of apo- and holo-retinol binding protein 4. Nanoscale Horiz. 2022;7(7).[DOI]

-

17. Kim DJ, Sohn IY, Jung JH, Yoon OJ, Lee NE, Park JS. Reduced graphene oxide field-effect transistor for label-free femtomolar protein detection. Biosens Bioelectron. 2013;41:621-626.[DOI]

-

18. Jarić S, Kudriavtseva A, Nekrasov N, Orlov AV, Komarov IA, Barsukov LA, et al. Femtomolar detection of the heart failure biomarker NT-proBNP in artificial saliva using an immersible liquid-gated aptasensor with reduced graphene oxide. Microchim J. 2024;196:109611.[DOI]

-

19. Kammarchedu V, Asgharian H, Chenani H, Ebrahimi A. Active dual-gated graphene transistors for low-noise, drift-stable, and tunable chemical sensing. arXiv:2509.04137v1 [Preprint]. 2025.[DOI]

-

20. Bagale R, Yesupatham MS, Hambli A, Sahu S, Ritzenthaler C, Amiri M, et al. Point-of-care applicability of graphene-based field effect transistors upon modification with a pyrene-tagged antifouling copolymer: Application for ctni sensing in blood. ACS Sens. 2025;10(9):7072-7083.[DOI]

-

21. Nakatsuka N, Yang KA, Abendroth JM, Cheung KM, Xu X, Yang H, et al. Aptamer–field-effect transistors overcome debye length limitations for small-molecule sensing. Science. 2018;362(6412):319-324.[DOI]

-

22. Wang Z, Hao Z, Yang C, Wang H, Huang C, Zhao X, et al. Ultra-sensitive and rapid screening of acute myocardial infarction using 3D-affinity graphene biosensor. Cell Rep Phys Sci. 2022;3:100855.[DOI]

-

23. Gu Z, Yang Z, Wang L, Zhou H, Jimenez-Cruz CA, Zhou R. The role of basic residues in the adsorption of blood proteins onto the graphene surface. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):10873.[DOI]

-

24. Yin T, Xu L, Gil B, Merali N, Sokolikova MS, Gaboriau DCA, et al. Graphene sensor arrays for rapid and accurate detection of pancreatic cancer exosomes in patients’ blood plasma samples. ACS Nano. 2023;17(15):14619-14631.[DOI]

-

25. Premsai N. Process yield and device stability in sol-gel alumina passivation layer-based GFETs. IEEE Trans Electron Devices. 2023;70(9):4928-4934.[DOI]

-

26. Dai C, Kong D, Chen C, Liu Y, Wei D. Graphene transistors for in vitro detection of health biomarkers. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33(31):2301948.[DOI]

-

27. Sun M, Wang S, Liang Y, Wang C, Zhang Y, Liu H, et al. Flexible graphene field-effect transistors and their application in flexible biomedical sensing. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024;17(1):34.[DOI]

-

28. Giménez E, Arce LP, Piccinini E, Brancher JM, Piccinini JM, Marmisollé WA, et al. Digital detection of hepatitis E antigen tailored for multiple genotypes using graphene transistors functionalized with nanobodies: End-to-end test development and optimization. Biosens Bioelectron. 2026;292:118085.[DOI]

-

29. Rodrigues T, Curti F, Leroux YR, Barras A, Pagneux Q, Happy H, et al. Discovery of a Peptide Nucleic Acid (PNA) aptamer for cardiac troponin I: Substituting DNA with neutral PNA maintains picomolar affinity and improves performances for electronic sensing with graphene field-effect transistors (gFET). Nano Today. 2023;50:101840.[DOI]

-

30. Khodadadian E, Mirsian S, Shashaani S, Parvizi M, Khodadadian A, Knees P, et al. A Bayesian inversion supervised learning framework for the enzyme activity in graphene field-effect transistors. Mach Learn Appl. 2025;21:100718.[DOI]

-

31. Szunerits S, Rodrigues T, Bagale R, Happy H, Boukherroub R, Knoll W. Graphene-based field-effect transistors for biosensing: Where is the field heading to? Anal Bioanal Chem. 2024;416(9):2137-2150.[DOI]

-

32. Peveler WJ, Yazdani M, Rotello VM. Selectivity and specificity: Pros and cons in sensing. ACS Sens. 2016;1(11):1282-1285.[DOI]

-

33. Pan L, Shrestha S, Taylor N, Nie W, Cao LR. Determination of X-ray detection limit and applications in perovskite X-ray detectors. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5258.[DOI]

-

34. Armbruster DA, Pry T. Limit of blank, limit of detection and limit of quantitation. Clin Biochem Rev. 2008;29.[PubMed]

-

35. Sankar K, Kuzmanović U, Schaus SE, Galagan JE, Grinstaff MW. Strategy, design, and fabrication of electrochemical biosensors: A tutorial. ACS Sens. 2024;9(5):2254-2274.[DOI]

-

36. Kesler V, Murmann B, Soh HT. Going beyond the debye length: Overcoming charge screening limitations in next-generation bioelectronic sensors. ACS Nano. 2020;14(12):16194-16201.[DOI]

-

37. Gao N, Zhou W, Jiang X, Hong G, Fu TM, Lieber CM. General strategy for biodetection in high ionic strength solutions using transistor-based nanoelectronic sensors. Nano Lett. 2015;15(3):2143-2148.[DOI]

-

38. Gao N, Gao T, Yang X, Dai X, Zhou W, Zhang A, et al. Specific detection of biomolecules in physiological solutions using graphene transistor biosensors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2016;113(51):14633-14638.[DOI]

-

39. Hugo A, Rodrigues T, Mader JK, Knoll W, Bouchiat V, Boukherroub R, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase sensing in wound fluids: Are graphene-based field effect transistors a viable alternative? Biosens Bioelectron X. 2023;13:100305.[DOI]

-

40. Wang Z, Dai W, Zhang Z, Wang H. Aptamer-based graphene field-effect transistor biosensor for cytokine detection in undiluted physiological media for cervical carcinoma diagnosis. Biosensors. 2025;15:138.[DOI]

-

41. Piccinini E, Bliem C, Reiner-Rozman C, Battaglini F, Azzaroni O, Knoll W. Enzyme-polyelectrolyte multilayer assemblies on reduced graphene oxide field-effect transistors for biosensing applications. Biosens Bioelectron. 2017;92:661-667.[DOI]

-

42. Bay HH, Vo R, Dai X, Hsu HH, Mo Z, Cao S, et al. Hydrogel gate graphene field-effect transistors as multiplexed biosensors. Nano Lett. 2019;19(4):2620-2626.[DOI]

-

43. Zhu J, Tao J, Yan W, Song W. Pathways toward wearable and high-performance sensors based on hydrogels: Toughening networks and conductive networks. Nat Sci Rev. 2023;10:nwad180.[DOI]

-

44. Shoorideh K, Chui CO. On the origin of enhanced sensitivity in nanoscale FET-based biosensors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 2014;111(14):5111-5116.[DOI]

-

45. Hwang MT, Heiranian M, Kim Y, You S, Leem J, Taqieddin A, et al. Ultrasensitive detection of nucleic acids using deformed graphene channel field effect biosensors. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1543.[DOI]

-

46. Ding Y, Li C, Tian M, Wang J, Wang Z, Lin X, et al. Overcoming Debye length limitations: Three-dimensional wrinkled graphene field-effect transistor for ultra-sensitive adenosine triphosphate detection. Front Phys. 2023;18(5):53301.[DOI]

-

47. Xu S, Tian M, Li C, Liu G, Wang J, Yan T, et al. Using a crumpled graphene field-effect transistor for ultrasensitive SARS-CoV-2 detection via its papain-like protease. Chem Eng J. 2025;505:159386.[DOI]

-

48. Bhatt D, Panda S. Dual-gate ion-sensitive field-effect transistors: A review. Electrochem Sci Adv. 2022;2(6):e2100195.[DOI]

-

49. Sheibani S, Capua L, Kamaei S, Akbari SSA, Zhang J, Guerin H, et al. Extended gate field-effect-transistor for sensing cortisol stress hormone. Commun Mater. 2021;2(1):10.[DOI]

-

50. Jang HJ, Sui X, Zhuang W, Huang X, Chen M, Cai X, et al. Remote floating-gate field-effect transistor with 2-dimensional reduced graphene oxide sensing layer for reliable detection of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(21):24187-24196.[DOI]

-

51. Sarker BK, Shrestha R, Singh KM, Lombardi J, An R, Islam A, et al. Label-free neuropeptide detection beyond the debye length limit. ACS Nano. 2023;17(21):20968-20978.[DOI]

-

52. Gil B, Anastasova S, Lo B. Graphene field-effect transistors array for detection of liquid conductivities in the physiological range through novel time-multiplexed impedance measurements. Carbon. 2022;193:394-403.[DOI]

-

53. Okamoto S, Ohno Y, Maehashi K, Inoue K, Matsumoto K. Immunosensors based on graphene field-effect transistors fabricated using antigen-binding fragment. Jpn J Appl Phys. 2012;51(6S):06FD08.[DOI]

-

54. Pagneux Q, Garnier N, Fabregue M, Sharkaoui S, Mazzoli S, Engelmann I, et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 and intranasal protection of mice with a nanoCLAMP antibody mimetic. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2024;7(3):757-770.[DOI]

-

55. Verma V, Sinha N, Raja A. Nanoscale warriors against viral invaders: A comprehensive review of Nanobodies as potential antiviral therapeutics. mAbs. 2025;17(1):2486390.[DOI]

-

56. Bagale R, Sahu S, Basini F, Filipiak MS, Montaigne D, Ritzenthaler C, et al. Making field effect transistor measurements accessible to electrochemists and biologists. J Solid State Electrochem. 2025;29(6):2385-2394.[DOI]

-

57. Chen Y, Kong D, Qiu L, Wu Y, Dai C, Luo S, et al. Artificial nucleotide aptamer-based field-effect transistor for ultrasensitive detection of hepatoma exosomes. Anal Chem. 2022;95.[DOI]

-

58. Basini F, Hambli A, Sahu S, Bagale R, Yesupatham MS, Ritzenthaler C, et al. PNA aptamer-based bioreceptors for cardiac biomarker (cTnI) detection: Insight into the structural and stability-related aspects. Nano Today. 2026;67:102957.[DOI]

-

59. Lozano-Chamizo L, Márquez C, Marciello M, Galdon JC, de la Fuente-Zapico E, Martinez-Mazón P, et al. High enhancement of sensitivity and reproducibility in label-free SARS-CoV-2 detection with graphene field-effect transistor sensors through precise surface biofunctionalization control. Biosens Bioelectron. 2024;250:116040.[DOI]

-

60. Homma C, Tsukiiwa M, Noguchi H, Tanaka M, Okochi M, Tomizawa H, et al. Designable peptides on graphene field-effect transistors for selective detection of odor molecules. Biosens Bioelectron. 2023;224:115047.[DOI]

-

61. Khatayevich D, Page T, Gresswell C, Hayamizu Y, Grady W, Sarikaya M. Selective detection of target proteins by peptide-enabled graphene biosensor. Small. 2014;10(8):1505-1513.[DOI]

-

62. Wang X, Kong D, Guo M, Wang L, Gu C, Dai C, et al. Rapid SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid testing and pooled assay by tetrahedral DNA nanostructure transistor. Nano Lett. 2021;21(22):9450-9457.[DOI]

-

63. Kong D, Wang X, Gu C, Guo M, Wang Y, Ai Z, et al. Direct SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid detection by Y-Shaped DNA dual-probe transistor assay. J Am Chem Soc. 2021;143(41):17004-17014.[DOI]

-

64. Hao Z, Luo Y, Huang C, Wang Z, Song G, Pan Y, et al. An intelligent graphene-based biosensing device for cytokine storm syndrome biomarkers detection in human biofluids. Small. 2021;17(29):2101508.[DOI]

-

65. Fang Y, Zhou K, Wei W, Zhang J, Sun J. Recent advances in batch production of transfer-free graphene. Nanoscale. 2024;16(22):10522-10532.[DOI]

-

66. Ullah S, Yang X, Ta HQ, Hasan M, Bachmatiuk A, Tokarska K, et al. Graphene transfer methods: A review. Nano Res. 2021;14(11):3756-3772.[DOI]

-

67. Paragraf. Biosensors [Internet]. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20230601054915/https://paragraf.com/diagnostics/

-

68. Graphene-Info [Internet]. 2025 Nov [cited 2026 Jul 01]. Available from: HYPERLINK "https://www.graphene-info.com/archive/202511?page=1" https://www.graphene-info.com/archive/202511?page=1

-

69. Mostafavi E, Iravani S. Mxene-graphene composites: A perspective on biomedical potentials. Nano-Micro Lett. 2022;14(1):130.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite