Abstract

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common degenerative joint disease driven by synovial inflammation and immune dysregulation, especially in the knee joint. Macrophages play a key role in innate immunity and can differentiate into pro-inflammatory M1 or anti-inflammatory M2 phenotypes, which have a significant impact on the progression of OA. Electrospun nanofiber membranes, as a promising biomaterial, can regulate the polarization of macrophages towards the M2 phenotype, thereby reducing inflammation and promoting tissue repair. This article systematically reviews the immune microenvironment of OA, the mechanism of macrophage polarization, and the role of nanofiber membranes in the treatment of OA. In conclusion, the continuous development of nanofiber membrane technology will greatly change the future of OA treatment and provide more effective and efficient solutions for patients.

Keywords

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a highly prevalent disease; the disease process not only involves joint cartilage but also the entire joint, including changes in the proximal bone of the joint, synovium, joint capsule, ligaments, and surrounding muscles of the joint[1]. OA is prone to cause severe personal pain and disability, being the most common cause of restricted activity in adults and a major cause of deformity among the elderly population. With the global trend of population aging and the prevalence of obesity, OA has also become an increasingly common disease, exerting a broad impact on most health outcomes worldwide[2]. Obesity and joint injury, as strong evidence of risk factors for OA, call for increased efforts at both clinical and public health levels to mitigate these risks[3].

The specific pathogenesis of OA remains incompletely elucidated, and current therapeutic strategies are predominantly aimed at symptom alleviation and disease progression delay rather than curative intervention[4]. These approaches primarily encompass pharmacological management, physical therapy, and surgical procedures. In early-stage OA, conservative measures such as controlled physical activity, weight reduction, and the administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are commonly employed to mitigate clinical symptoms. For patients with advanced OA, who often present with substantial articular cartilage degeneration, intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid or corticosteroids may provide transient symptomatic relief. Ultimately, end-stage disease frequently necessitates surgical intervention, including joint replacement arthroplasty. Nevertheless, these existing treatments are largely palliative and fail to modify the underlying pathological processes, thereby imposing significant limitations on long-term patient function and quality of life[5].

OA is a major global source of pain, disability, and socioeconomic burden. The epidemiology of this disease is complex and multifactorial, including genetic, biological, and biomechanical factors as well as joint-specific etiological factors[6]. Globally, in 2020, 595 million people suffered from OA, equivalent to 7.6% of the global population[4]. From 1990 to 2019, the number of people affected worldwide increased by 48%, and by 2019, OA had become the 15th leading cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) globally, accounting for 2% of total global DALYs[7]. The 2020s to 2030s were designated by the World Health Organization as the Decade of Healthy Aging, and OA is one of the primary contributors to disability among them[8]. OA is the third fastest-growing disability-related health condition after diabetes and dementia in terms of prevalence[9]. If current trends continue, we estimate that by 2050, nearly 1 billion people will suffer from some form of OA[8].

In the United States, osteoarthritis constitutes the most common form of arthritis, with a prevalence of around 24% among adults[10]. Between 2010 and 2012, physician-diagnosed arthritis affected 52.5 million U.S. adults, constituting 22.7% of the adult population. Among them, 22.7 million (9.8%) reported arthritis-attributable activity limitations. It is projected that by 2040, the prevalence of diagnosed arthritis will surge by 49%, affecting 78.4 million adults (25.9% of the population). Concurrently, those with activity limitations are expected to increase by 52%, totaling 34.6 million individuals (11.4% of adults)[11]. The age-standardized incidence rate in China increased from 377.93 per 100,000 in 1990 to 406.42 per 100,000 in 2021[12]. In a four-year national longitudinal analysis and follow-up by Ren et al., the cumulative incidence rate of knee OA in middle-aged and elderly adults in China was 8.5%; the incidence rate in women (11.2%) was higher than in men (5.6%)[13,14]. Based on two UK national electronic health record databases (Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) Aurum and CPRD GOLD) from 2000 to 2019, the annual average percentage change in OA prevalence was 2.8% (95% CI: 2.5 to 3.2) in Aurum, indicating an upward trend, while it was -2.9% (95% CI: -3.9 to -1.9) in GOLD, reflecting a decline. Specifically, in Aurum, the annual consultation prevalence rose from 26.86 per 1,000 person-years in 2005 to 29.15 in 2019. In contrast, in GOLD, it decreased from 23.08 per 1,000 person-years in 2004 to 16.70 in 2012, further dropping to 12.82 by 2016, and remained relatively stable thereafter[15]. Prieto-Alhambra et al., in their study of adults aged ≥ 40 years in Catalonia, Spain, found that individuals with a history of hand OA had a significantly increased risk of developing hip and knee OA. Similarly, a prior history of knee OA was linked to a higher risk of subsequent hip OA. Notably, these associations remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, and body mass index[16,17].

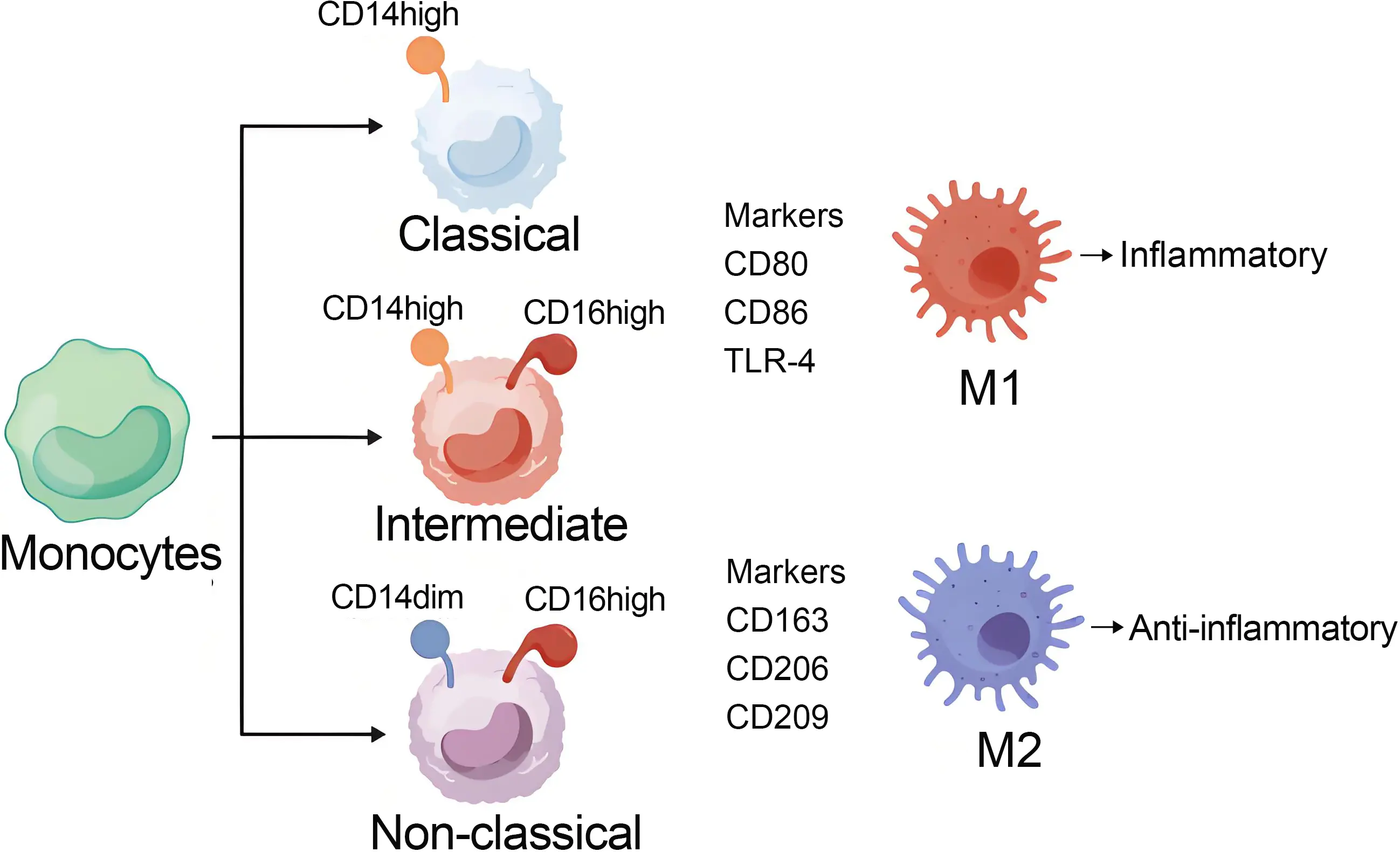

Monocytes are classified into three subgroups: classical monocytes characterized by high CD14 expression, intermediate monocytes with moderate CD14 expression, and non-classical monocytes exhibiting low CD14 and high CD16 expression. Classical monocytes predominantly differentiate into pro-inflammatory macrophages and osteoclasts, contributing to synovial inflammation and bone erosion. Intermediate monocytes mainly give rise to pro-inflammatory macrophages, which further exacerbate tissue inflammation. In contrast, non-classical monocytes primarily differentiate into anti-inflammatory macrophages, which facilitate phagocytosis and promote the resolution of inflammation[18]. Among them, macrophages are central players in the pathogenesis of OA, and their activation phenotypes have been extensively investigated. Numerous studies indicate that macrophages can dynamically switch between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory states in response to local microenvironmental cues. Macrophages can be divided into two subtypes: activated macrophages (M1) and another alternatively activated macrophage (M2). Typically, M1 is a pro-inflammatory cell, while M2 plays the opposite role in the inflammatory process. The conversion of macrophages from M1 to M2 under inflammatory stimulation is called macrophage polarization, and this conversion is involved in the pathophysiological processes of various diseases (such as tumors[19,20], liver diseases[21,22], rheumatoid arthritis[18], infection[23], and OA)[24]. M1 macrophages can induce inflammation, while M2 macrophages suppress inflammation. The imbalance between these two types of macrophages can significantly affect disease progression[25]. The intermediate monocyte subset primarily differentiates into pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages[18]. M1 macrophages, or classically activated macrophages, are participants in antibacterial and pro-inflammatory responses and are activated upon stimulation by type 1 helper T cells[24]. Under stimulation by factors including lipopolysaccharide, interferon-α, IL-12, and IL-23, resting macrophages (M0) polarize toward a pro-inflammatory M1-like phenotype. M1 macrophages are characterized by specific surface biomarkers, predominantly TLR-4 CD80, and CD86[25]. The M2 macrophage phenotype is generally considered an anti-inflammatory phenotype. However, the M2 macrophage phenotype can be further divided into several other phenotypes: M2a, M2b, M2c, and M2d[25-27]. The polarization of macrophages toward the M2 phenotype is primarily driven by factors such as cytokines (e.g., IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, IL-34), TGF-β, prostaglandin E2, glucocorticoids, and growth factors including VEGF, EGF, and M-CSF, as well as vitamin D3[28], while the main markers of M2 are CD163, CD206, CD209, etc.[25].

M2a macrophages are recognized for their roles in wound healing and allergic responses, as well as for their ability to suppress inflammation and promote the stabilization of angiogenesis[29]. M2a macrophages are recognized as anti-inflammatory mediators involved in tissue remodeling. Furthermore, recombinant PRG4 has been shown to reduce the expression and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in TLR2-stimulated M2a macrophages[30,31]. M2b macrophages function as regulatory cells with immunomodulatory activity, primarily by releasing anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-1RA to support Th2 responses. However, they also express pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α, reflecting a dual cytokine profile. Unlike M2a macrophages, M2b macrophages do not promote extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition in inflammatory arthritis[31,32]. M2c macrophages are characterized by their high phagocytic capacity, serving as key phagocytes for the clearance of apoptotic cells and cellular debris. This function is associated with the upregulation of phagocytosis-related genes and surface markers such as CD163 and MARCO[33]. Furthermore, M2c macrophages exhibit strong anti-inflammatory activity, marked by the expression of CD206 and CD163 and the release of high levels of IL-10 and TGF-β[34]. Notably, TGF-β also confers regenerative properties to M2c macrophages, supporting cartilage and bone repair[35]. M2d macrophages play a dual role in mediating inflammation resolution and promoting angiogenesis[31]. In these cells, the IL-10 signaling pathway can be activated by stimuli such as IL-6, TLR ligands, and A2 adenosine receptor agonists[36]. IL-10 exerts its anti-inflammatory effects primarily by inhibiting the MAPK pathway, thereby attenuating excessive pro-inflammatory responses. Additionally, IL-10 suppresses the synthesis of key pro-inflammatory mediators, including IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, GM-CSF, and TNF-α, and this collectively supports mucosal and epithelial healing and facilitates the resolution of inflammation[37].

We have summarized the differentiation process of the aforementioned monocytes in Figure 1.

Electrospinning provides a versatile and efficient method for producing nanofibers with high specific surface area, tunable porosity, and excellent mechanical properties, making them suitable for applications ranging from filtration and sensors to tissue engineering and energy storage. A particularly promising and emerging application lies in the development of smart nanofiber membrane systems for controlled drug delivery[38].

These electrospun nanofibers can be engineered into biomimetic, stimuli-responsive drug delivery platforms capable of releasing therapeutic agents in a controlled manner in response to external triggers such as temperature, pH, light, or electric/magnetic fields. By mimicking both the structural and functional aspects of biological systems, these intelligent nanofiber membranes act as on-demand drug release depots, offering enhanced precision, reproducibility, and responsiveness in therapeutic substance delivery[39].

Nanofibers are primarily composed of various polymer types, and their size or diameter depends on the polymer type, manufacturing technology, and design specifications. Raw materials include polymers, ceramics, small molecules, and their blends[40]. Nano-cellulose materials are typically divided into three major categories: nanofibrillated cellulose, also known as microcellulose or cellulose nanofibers, cellulose nanocrystals, also known as nanocrystalline cellulose or cellulose nanorods; and bacterial cellulose, also known as microbial cellulose. The classification depends on the source and size of the nano-cellulose material[41]. In recent years, various high-performance, multi-functional nanofiber membranes have been successfully manufactured from nano-cellulose through different methods. The manufacturing of nanofiber membranes involves various manufacturing technologies, including electrospinning, phase separation, physical manufacturing, and chemical synthesis[40]. Among these, electrospinning technology is the most mainstream method for preparing nanofiber membranes and is widely used in the treatment of various diseases. With continuous technological development, electrospinning has evolved from a single-fluid blending process to include coaxial, side-by-side, emulsion, triaxial, multi-nozzle, portable, and near-field[40]. These technologies produce nanofibers with high porosity, interconnectedness, and flexibility, making them highly suitable for targeted treatment of various disease conditions, including cancer, bacterial infections, bone OA, and wound healing.

Nanofiber membrane-based immunomodulation for OA faces several major bottlenecks. These include achieving spatiotemporally precise control over macrophage polarization cues within the dynamic joint microenvironment, ensuring long-term stability and effective bio-integration of the membranes under chronic inflammatory conditions, and designing responsive systems capable of addressing the complex, multifactorial pathology of OA. Substantial controversies persist in macrophage polarization research. Key debates center on the functional plasticity and heterogeneity of macrophage phenotypes that extend beyond the simplistic M1/M2 dichotomy, such as the distinct roles of M2a, M2b, M2c, and M2d subsets, as well as the relative contributions of tissue-resident versus monocyte-derived macrophages to disease progression.

This review aims to address the knowledge gap concerning how nanofiber membranes can be optimally designed to precisely modulate macrophage polarization within the osteoarthritic joint for therapeutic benefit. It further seeks to outline strategies to overcome the aforementioned bottlenecks and navigate key biological controversies, thereby providing a material-centric roadmap for next-generation immunomodulatory strategies in OA.

Relevant literature for this review was identified via a comprehensive search of the PubMed database from January, 2015 to December, 2025. The search strategy utilized the following Boolean logic: the keywords used for the search included osteoarthritis, macrophage polarization, nanofiber membrane, M1, and M2. Inclusion criteria comprised original research articles, preclinical studies, clinical trials, and systematic reviews specifically focused on the role of nanofiber membranes in modulating macrophage phenotypes (M1/M2) within the context of OA therapy. Exclusion criteria included conference abstracts, case reports, editorials, non-peer-reviewed publications, and studies published before 2015 or in languages other than English. To ensure completeness, the reference lists of key articles were manually screened for additional relevant sources.

2. Macrophage Polarization

Macrophages play a crucial role in innate immunity and exhibit high plasticity[42,43]. Macrophages are distributed throughout multiple components of the joint, such as the bone marrow, ligaments, synovium, adipose tissue, subchondral bone, etc. Under physiological conditions, they help maintain joint homeostasis by phagocytosing pathogens and clearing aged tissue debris. In OA, however, abnormal macrophage activation can contribute to joint destruction. Substantial evidence supports the important role of macrophages in the progression of OA. An imbalance in the M1/M2 ratio is significantly associated with the severity of OA[44]. Sun et al. demonstrated that in OA synovium, the population of F4/80-positive cells, a general macrophage marker, was significantly elevated, along with an increased proportion of cells expressing the M1-associated markers inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and CD80[45]. This suggests that the occurrence of OA is closely related to M1 polarization. LIU et al. found through histological analysis of human samples and single-cell RNA sequencing of mouse models that in OA synovial macrophages, macrophage PGAM5 significantly increased; specifically inhibiting PGAM5 in macrophages can re-polarize M1 macrophages to M2 macrophages, which significantly alleviates OA symptoms[46]. The manifestations of OA can be modulated through the regulation of M1/M2 macrophage polarization. As a low-frequency, low-intensity physical modality, low-intensity pulsed ultrasound has been shown to reduce the proportion of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages while promoting an increase in anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages within the joint synovium[47]. Kinetinoid (KIN) suppressed the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, thereby facilitating the polarization of macrophages from the M1 to the M2 phenotype. Furthermore, KIN enhanced the functional activity of M2 macrophages by upregulating the expression of M2-specific markers[48]. Quercetin alleviates OA symptoms via multiple pathways, which involve inhibiting the Akt/STAT6 signaling axis, reducing the expression of inflammatory mediators (such as iNOS, COX-2, MMP-13, and ADAMTS-4), reversing cartilage matrix degradation induced by IL-1β, and promoting the polarization of synovial macrophages toward the M2 phenotype[49]. Other chemical synthetic compounds, such as dexamethasone, pravastatin and other statin drugs, and rapamycin also have the effect of altering the M1/M2 ratio to improve the progression of OA[47].

Macrophages, as the “main regulators” of inflammation, play a central role in the development and improvement of OA and fibrosis in hands, feet, hips, and knee joints. They can exhibit different pro-inflammatory and anti- inflammatory phenotypes based on the signals received from the environment, and these phenotypes are influenced by various endogenous and exogenous factors[50].

3. Application of Nanofiber Membrane in OA

Electrospun nanofibers have gained attention as potential matrices for the treatment of OA because of their high degree of ECM mimicry, which supports chondrocyte migration, adhesion, and proliferation[51]. The mechanisms by which nanofiber membranes function on the synovium (anti-inflammatory) versus on the cartilage surface (repair) differ and correspond to distinct macrophage states. The current treatment outcomes for OA are not entirely satisfactory. Since OA is accompanied by changes in pH values within the inflammatory microenvironment, pH-responsive drug delivery systems (DDS) have been widely applied in the treatment of OA. Wang et al. prepared a PCL/PEG-Nar nanofiber membrane using electrospinning technology, as a pH-responsive DDS, for the treatment of OA. This nanofiber membrane system continuously releases Nar with anti-inflammatory effects to alleviate the severity of OA[52]. Wu et al. also prepared an intelligent ROS-responsive polylactic acid (PLA)/PEGDA-EDT@rGO-Fucoxanthin (PPGF) nanofiber membrane as a DDS for OA treatment that promoted the formation of effective drug concentrations and improved the treatment efficiency of OA[53]. Arslan et al. prepared a hybrid nanofiber membrane, HA/K-PA hybrid membrane, to promote the protection of cartilage tissue in OA. Their results indicated that the hybrid nanofiber scaffold provided a potential platform for treating OA[54]. We also summarized the applications of other types of nanofiber membranes in OA, as shown in Table 1.

| Nanofiber Membrane | Preparation Method | Experimental Subjects and Joints | Average Diameter | Advantage | Year | References |

| PCL/PEG-Nar | electrospinning | SD rats’ knee joints | 503 ± 169 nm | It promotes chondrocyte proliferation, downregulates inflammatory genes, upregulates chondrogenic genes, reduces cartilage damage, and restores a smooth articular surface. | 2022 | Wang et al.[52] |

| PPGF | electrospinning | Rat knee joint | 365.3 ± 58 nm | Its ROS-responsive and sustained drug release properties, combined with low cytotoxicity, mitigate IL-1β-induced inflammation and protect cartilage viability. | 2022 | Wu et al.[53] |

| PCL-lignin50 | electrospinning | New Zealand rabbit’s right knee | 224 ± 68 nm | It protects chondrocytes against oxidative stress, inhibits H2O2-induced oxidative damage and autophagy-mediated stress, suppresses inflammatory factors, and reduces MMP-13 and IL-6 levels by 52.28% and 63.20%, respectively. | 2019 | Liang et al.[55] |

| HA/K-PA hybrid membrane. | nitial electrostatic | Sprague-Dawley Rats’ Knee Joint | / | Biocompatible, stable, mechanically robust, and injectable, it preserves cartilage structure and function. | 2018 | Arslan et al.[54] |

OA: osteoarthritis; SD: Sprague–Dawley; PPGF: PLA/PEGDA-EDT@rGO-Fucoxanthin; ROS: reactive oxygen species; HA, hyaluronic acid; IL: interleukin.

4. The Effects of Different Nanofiber Membranes on M1M2 and Their Impact on OA

We searched PubMed for articles with keywords such as nanofiber membranes, M1, and M2 to understand how different nanofiber membranes influence the polarization and ratio changes of M1/M2, as well as their anti-inflammatory or pro-inflammatory effects on inflammation and their applications in various diseases, as shown in Table 2.

| Nanofiber membrane | Preparation method | The pathway of influence | Affected cells | Effect | References |

| TPG/PLGA/PCL | Electrospinning | PI3K/AKT and NF-kB | Inhibit the transformation of RAW264.7 cells into M1 cells | Anti-inflammatory | [56] |

| PCLHAp/MTA containing RvD2 | Electrospinning | Reduce the production of IL-1β and TNF-α | M1 | Anti-inflammatory | [57] |

| PLA/SCS/PDA-GS | Electrospinning and evaporation | Reduced the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 | Regulate the transformation of macrophages into M2 type | Anti-inflammatory | [58] |

| P@PCH | Double-layer electrospinning | Increased the expression of CD206 significantly | Regulate the transformation of macrophages into M2 type | Anti-inflammatory | [59] |

| HMF scaffold | Template-assisted electrospinning | IL-4 and IL-10 | Regulate the transformation of macrophages into M2 type | Anti-inflammatory | [60] |

| PLA/Gel-CS-IBU | Electrospinning combined with freeze-drying method | The expression of pro-inflammatory genes TNFA and IL-1b is low, while the expression of anti-inflammatory genes IL-10 and IL-4 is high | Regulate the polarization of macrophages to an anti-inflammatory phenotype | Anti-inflammatory | [61] |

| PCL/AM Composite Membrane | Electrospinning | Increase the expression of IL-10 and IL13 to inhibit the expression of IL-6 and TNF-α | Regulate the transformation of macrophages into M2 type | Anti-inflammatory | [62] |

| PFKU | Hydrogel and electrospinning | / | Induce macrophages to polarize towards M2 phenotype | Anti-inflammatory | [63] |

| M-sheet | Electrospun nanofiber laminated redox membrane | The expression of iNOS significantly decreased, while the level of CD206-positive cells increased | Induce macrophages to polarize towards M2 phenotype | Anti-inflammatory | [64] |

P@PCH: PCL@PVA/COS/HMB-Ca; HMF: hierarchical-structured mineralized nanofiber; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; IL: interleukin.

5. Compatibility

Currently, attempts at tissue regeneration using synthetic and decellularized biomaterials are often partially hindered by the innate immune response at the implantation or transplantation site, with a strong inflammatory reaction. This can ultimately lead to tissue fibrosis, negatively impacting tissue development, and function[65]. Another unresolved challenge is finding semi-permeable materials with excellent biocompatibility to counteract the tissue reaction that threatens the encapsulated cells. As a semi-permeable immune isolation membrane, nanofiber structures mimic the topological features of the natural ECM. Specifically, electrospinning technology can produce fiber matrices with controllable structural properties by simply adjusting process parameters, including fiber diameter, pore size, and thickness. Wang et al. demonstrated that, compared to microfiber membranes, electrospun nanofibers induce only a slight foreign body reaction, and the activation of macrophage cells is also not significant. Therefore, nanofiber membranes can be used as a new category of semi-permeable materials for cell transplantation and immune isolation with excellent biocompatibility[66]. This result has also been confirmed by many peers. Ma et al. used NIH 3T3 fibroblasts to evaluate the biocompatibility of the PLA/SCS/PDA-GS membrane, confirming that fibroblasts proliferate stably on the membrane[61]. Han et al. used flow cytometry to confirm that the nTPG/PLGA/PCL membrane serves as a good biocompatible support surface for cell growth and is biologically safe[56]. He et al. cultured two cell lines, RAW 264.7 and HaCaT, on electrospun membranes for 24 hours, and their survival rates were both over 90%; these results indicate that the P/G-CS-OI membrane has good cell compatibility[67]. Taken together, these findings further confirm that the prepared electrospun nanofiber membranes exhibit good biocompatibility, suggesting their potential in wound healing intervention and delaying the progression of OA.

6. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

OA, as a complex disease characterized by progressive cartilage degeneration, synovial inflammation, and osteophyte formation, has seen its treatment evolve from mere mechanical support and symptom relief to a new stage of modulating the immune microenvironment and promoting in situ regeneration. In this paradigm shift, the plasticity of macrophages and their M1/M2 polarization balance have been identified as key hubs in regulating OA inflammation and tissue repair. Nanofiber membranes, with their biomimetic topological structure of the ECM, precisely tunable physicochemical properties, and efficient delivery of bioactive factors, provide an unprecedented platform for precise regulation of macrophage polarization in the joint cavity. Studies show that nanofiber membranes can effectively convert pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages into anti-inflammatory and reparative M2 macrophages, demonstrating excellent cartilage protection and repair potential in OA animal models.

Strategies for immunomodulation using nanofiber membranes have successfully combined biomaterial science with immunological engineering, opening up a highly attractive new avenue for OA treatment and representing the future direction of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine in the field of OA therapy.

To advance nanofiber membrane-based OA therapies, strategic insights can be drawn from established cartilage repair platforms. 3D-printed scaffolds exemplify precise structural and mechanical customization through layer-by-layer fabrication[68], an approach that could guide the design of zonally graded or patient-specific nanofiber architectures. Meanwhile, hydrogel systems offer exceptional cytocompatibility, injectability, and sustained bioactive molecule release[69], highlighting the potential for developing hybrid membrane-hydrogel composites to enhance cell delivery, integration, and minimally invasive deployment.

Incorporating these advantages, structural programmability from 3D printing and functional adaptability from hydrogels could yield next-generation nanofiber membranes with improved biomimetic, mechanical, and translational properties. Future work may focus on integrating multi-material electrospinning with volumetric printing or formulating injectable nanofiber-reinforced hydrogels to synergize immunomodulation with structural cartilage regeneration.

Although the prospects for using nanofiber membranes to modulate macrophage polarization in treating OA are promising, this technology still faces a series of key challenges and directions that urgently need exploration: (1) Long-term safety and efficacy evaluation: Most current research is limited to short-term animal models. There is an urgent need to validate the long-term safety and sustained efficacy of this strategy in large animal models. (2) In-depth optimization of material properties requires a systematic screening of optimal material parameter combinations to achieve the best immunomodulatory effects and ensure good integration with and degradation matching to the host tissue. (3) Intelligence and precise regulation, future research needs to develop more “intelligent” nanofiber systems capable of responding to specific biomarkers in the OA lesion microenvironment (such as pH, reactive oxygen species levels, and specific enzyme concentrations) to achieve on-demand, controllable release of polarization-inducing factors. This will avoid desensitization or side effects caused by continuous stimulation, enabling more precise time-controlled regulation. (4) Achieving precise anatomical positioning and secure, long-term fixation of nanofiber membranes within the spatially constrained and dynamic joint cavity, while concurrently ensuring the sustained local release of bioactive factors to maintain therapeutic immunomodulatory efficacy. (5) Strategically coordinating the degradation kinetics of the nanofiber membranes with the pathological timeline of OA. This ensures that the scaffold provides mechanical and biological support during the critical inflammatory and early repair phases, followed by timely clearance to facilitate native tissue integration and avoid long-term interference. (6) Conducting comprehensive long-term biosafety evaluations is paramount. This necessitates rigorous assessment of potential local adverse reactions (e.g., chronic synovitis, abnormal tissue fibrosis), systematic evaluation of systemic toxicity, and close monitoring of immunogenicity. Each of these interconnected challenges demands dedicated and in-depth investigation through robust preclinical models to ensure clinical translatability.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that DeepSeek-V3.2 was used only for language polishing during the preparation of this manuscript. AI was not used to generate any academic content, including figures, tables, or other materials. The authors take all responsibilities for the final content.

Authors contribution

Xu G: Conceptualization, methodology, supervision, project administration, writing-review & editing.

Wang X: Methodology, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Bliddal H. Definition, patologi og patogenese af artrose. Ugeskrift for Læger. 2020;182:V06200477. Available from: https://ugeskriftet.dk/videnskab

-

2. Jiang T, Su S, Tian R, Jiao Y, Zheng S, Liu T, et al. Immunoregulatory orchestrations in osteoarthritis and mesenchymal stromal cells for therapy. J Orthop Transl. 2025;55:38-54.[DOI]

-

3. Cao F, Xu Z, Li XX, Fu ZY, Han RY, Zhang JL, et al. Trends and cross-country inequalities in the global burden of osteoarthritis, 1990–2019: A population-based study. Ageing Res Rev. 2024;99:102382.[DOI]

-

4. Su S, Tian R, Jiao Y, Zheng S, Liang S, Liu T, et al. Ubiquitination and deubiquitination: Implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of osteoarthritis. J Orthop Transl. 2024;49:156-166.[DOI]

-

5. Liu W, Guo NY, Wang JQ, Xu BB. Osteoarthritis: Mechanisms and therapeutic advances. MedComm. 2025;6(8):e70290.[DOI]

-

6. Wang D, Liu W, Venkatesan JK, Madry H, Cucchiarini M. Therapeutic controlled release strategies for human osteoarthritis. Adv Healthc Mater. 2025;14(2):2402737.[DOI]

-

7. Hunter DJ, March L, Chew M. Osteoarthritis in 2020 and beyond: A Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396:1711-1712.[DOI]

-

8. Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990-2020 and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023;5(9):e508-e522.[DOI]

-

9. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403(10440):2133-2161.[DOI]

-

10. Abdullah Y, Olubowale OO, Hackshaw KV. Racial disparities in osteoarthritis: Prevalence, presentation, and management in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. 2025;117(1):55-60.[DOI]

-

11. Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA, Weiss J, Brunner R, Mishra NK, Ding M, et al. Cardiovascular disease, bone fracture, and all-cause mortality risks among postmenopausal women by arthritis and veteran status: A multistate markov transition analysis. Geroscience. 2025;47(3):4169-4186.[DOI]

-

12. Li M, Xia Q, Nie Q, Ding L, Huang Z, Jiang Z. Burden of knee osteoarthritis in China and globally: 1990–2045. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2025;26(1):582.[DOI]

-

13. Ren Y, Hu J, Tan J, Tang X, Li Q, Yang H, et al. Incidence and risk factors of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis among the Chinese population: Analysis from a nationwide longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1491.[DOI]

-

14. Hu S, Li Y, Zhang X, Alkhatatbeh T, Wang W. Increasing burden of osteoarthritis in China: Trends and projections from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Med Sci Monit. 2024;30:e942626.[DOI]

-

15. Yu D, Missen M, Jordan KP, Edwards JJ, Bailey J, Wilkie R, et al. Trends in the annual consultation incidence and prevalence of low back pain and osteoarthritis in England from 2000 to 2019: Comparative estimates from two clinical practice databases. Clin Epidemiol. 2022;14:179-189.[DOI]

-

16. Liu X, Zheng Y, Li H, Ma Y, Cao R, Zheng Z, et al. The role of metabolites in the progression of osteoarthritis: Mechanisms and advances in therapy. J Orthop Translat. 2025;50:56-70.[DOI]

-

17. Prieto-Alhambra D, Judge A, Javaid MK, Cooper C, Diez-Perez A, Arden NK. Incidence and risk factors for clinically diagnosed knee, hip and hand osteoarthritis: Influences of age, gender and osteoarthritis affecting other joints. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(9):1659-1664.[DOI]

-

18. Cutolo M, Campitiello R, Gotelli E, Soldano S. The role of M1/M2 macrophage polarization in rheumatoid arthritis synovitis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:867260.[DOI]

-

19. Xu C, Chen J, Tan M, Tan Q. The role of macrophage polarization in ovarian cancer: From molecular mechanism to therapeutic potentials. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1543096.[DOI]

-

20. Boutilier AJ, Elsawa SF. Macrophage polarization states in the tumor microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(13):6995.[DOI]

-

21. Jeon S, Jeon Y, Lim JY, Kim Y, Cha B, Kim W. Emerging regulatory mechanisms and functions of biomolecular condensates: Implications for therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10(1):4.[DOI]

-

22. Wang C, Ma C, Gong L, Guo Y, Fu K, Zhang Y, et al. Macrophage polarization and its role in liver disease. Front Immunol. 2021;12:803037.[DOI]

-

23. Mège JL, Mehraj V, Capo C. Macrophage polarization and bacterial infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2011;24(3):230-234.[DOI]

-

24. Yuan Z, Jiang D, Yang M, Tao J, Hu X, Yang X, et al. Emerging roles of macrophage polarization in osteoarthritis: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Orthop Surg. 2024;16(3):532-550.[DOI]

-

25. Luo M, Zhao F, Cheng H, Su M, Wang Y. Macrophage polarization: An important role in inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1352946.[DOI]

-

26. Funes SC, Rios M, Escobar-Vera J, Kalergis AM. Implications of macrophage polarization in autoimmunity. Immunology. 2018;154(2):186-195.[DOI]

-

27. Muñoz J, Akhavan NS, Mullins AP, Arjmandi BH. Macrophage polarization and osteoporosis: A review. Nutrients. 2020;12(10):2999.[DOI]

-

28. Kerneur C, Cano CE, Olive D. Major pathways involved in macrophage polarization in cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1026954.[DOI]

-

29. Bianchini R, Roth-Walter F, Ohradanova-Repic A, Flicker S, Hufnagl K, Fischer MB, et al. IgG4 drives M2a macrophages to a regulatory M2b-like phenotype: Potential implication in immune tolerance. Allergy. 2019;74(3):483-494.[DOI]

-

30. Qadri M, Jay GD, Zhang LX, Schmidt TA, Totonchy J, Elsaid KA. Proteoglycan-4 is an essential regulator of synovial macrophage polarization and inflammatory macrophage joint infiltration. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23(1):241.[DOI]

-

31. Kulakova K, Lawal TR, McCarthy E, Floudas A. The contribution of macrophage plasticity to inflammatory arthritis and their potential as therapeutic targets. Cells. 2024;13(18):1586.[DOI]

-

32. Huang S, Yue Y, Feng K, Huang X, Li H, Hou J, et al. Conditioned medium from M2b macrophages modulates the proliferation, migration, and apoptosis of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells by deregulating the PI3K/Akt/FoxO3a pathway. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9110.[DOI]

-

33. Lurier EB, Dalton D, Dampier W, Raman P, Nassiri S, Ferraro NM, et al. Transcriptome analysis of IL-10-stimulated (M2c) macrophages by next-generation sequencing. Immunobiology. 2017;222(7):847-856.[DOI]

-

34. Wang Q, Sudan K, Schmoeckel E, Kost BP, Kuhn C, Vattai A, et al. CCL22-polarized TAMs to M2a macrophages in cervical cancer in vitro model. Cells. 2022;11(13):2027.[DOI]

-

35. Yang J, Zhang X, Chen J, Heng BC, Jiang Y, Hu X, et al. Macrophages promote cartilage regeneration in a time- and phenotype-dependent manner. J Cell Physiol. 2022;237(4):2258-2270.[DOI]

-

36. Rőszer T. Understanding the mysterious M2 macrophage through activation markers and effector mechanisms. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:816460.[DOI]

-

37. Lai W, Xian C, Chen M, Luo D, Zheng J, Zhao S, et al. Single-cell and bulk transcriptomics reveals M2d macrophages as a potential therapeutic strategy for mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;121:110509.[DOI]

-

38. Xu C, Tan J, Li Y. Application of electrospun nanofiber-based electrochemical sensors in food safety. Molecules. 2024;29(18):4412.[DOI]

-

39. Chen M, Li YF, Besenbacher F. Electrospun nanofibers-mediated on-demand drug release. Adv Healthc Mater. 2014;3(11):1721-1732.[DOI]

-

40. Han Y, Wei H, Ding Q, Ding C, Zhang S. Advances in electrospun nanofiber membranes for dermatological applications: A review. Molecules. 2024;29(17):4271.[DOI]

-

41. Hua K, Ålander E, Lindström T, Mihranyan A, Strømme M, Ferraz N. Surface chemistry of nanocellulose fibers directs monocyte/macrophage response. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16(9):2787-2795.[DOI]

-

42. Liu M, Wu C, Wu C, Zhou Z, Fang R, Liu C, et al. Immune cells differentiation in osteoarthritic cartilage damage: Friends or foes? Front Immunol. 2025;16:1545284.[DOI]

-

43. Yao H, Tian A, Ma J, Ma X. [Effect of mechanical stimuli on physicochemical properties of joint fluid in osteoarthritis]. Chin J Repar Reconstr Surg. 2025;39(7):903-911.[DOI]

-

44. Zhang Y, Ji Q. Macrophage polarization in osteoarthritis progression: A promising therapeutic target. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2023;11:1269724.[DOI]

-

45. Sun Z, Liu Q, Lv Z, Li J, Xu X, Sun H, et al. Targeting macrophagic SHP2 for ameliorating osteoarthritis via TLR signaling. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12(7):3073-3084.[DOI]

-

46. Liu Y, Hao R, Lv J, Yuan J, Wang X, Xu C, et al. Targeted knockdown of PGAM5 in synovial macrophages efficiently alleviates osteoarthritis. Bone Res. 2024;12(1):15.[DOI]

-

47. Sun Y, Zuo Z, Kuang Y. An emerging target in the battle against osteoarthritis: Macrophage polarization. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(22):8513.[DOI]

-

48. Zhou F, Mei J, Han X, Li H, Yang S, Wang M, et al. Kinsenoside attenuates osteoarthritis by repolarizing macrophages through inactivating NK-κB/mapk signaling and protecting chondrocytes. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2019;9(5):973-985.[DOI]

-

49. Hu Y, Gui Z, Zhou Y, Xia L, Lin K, Xu Y. Quercetin alleviates rat osteoarthritis by inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis of chondrocytes, modulating synovial macrophages polarization to M2 macrophages. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;145:146-160.[DOI]

-

50. Pemmari A, Moilanen E. Macrophage and chondrocyte phenotypes in inflammation. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2024;135(5):537-549.[DOI]

-

51. Plath AMS, de Lima PHC, Amicone A, Bissacco EG, Mosayebi M, Berton SBR, et al. Toward low-friction and high-adhesion solutions: Emerging strategies for nanofibrous scaffolds in articular cartilage engineering. Biomater Adv. 2025;169:214129.[DOI]

-

52. Wang Z, Zhong Y, He S, Liang R, Liao C, Zheng L, et al. Application of the pH-responsive PCL/PEG-Nar nanofiber membrane in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10:859442.[DOI]

-

53. Wu J, Qin Z, Jiang X, Fang D, Lu Z, Zheng L, et al. ROS-responsive PPGF nanofiber membrane as a drug delivery system for long-term drug release in attenuation of osteoarthritis. NPJ Regen Med. 2022;7(1):66.[DOI]

-

54. Arslan E, Sardan Ekiz M, Eren Cimenci C, Can N, Gemci MH, Ozkan H, et al. Protective therapeutic effects of peptide nanofiber and hyaluronic acid hybrid membrane in in vivo osteoarthritis model. Acta Biomater. 2018;73:263-274.[DOI]

-

55. Liang R, Zhao J, Li B, Cai P, Loh XJ, Xu C, et al. Implantable and degradable antioxidant poly(ε-caprolactone)-lignin nanofiber membrane for effective osteoarthritis treatment. Biomaterials. 2020;230:119601.[DOI]

-

56. Han X, Wang F, Ma Y, Lv X, Zhang K, Wang Y, et al. TPG-functionalized PLGA/PCL nanofiber membrane facilitates periodontal tissue regeneration by modulating macrophages polarization via suppressing PI3K/AKT and NF-κB signaling pathways. Mater Today Bio. 2024;26:101036.[DOI]

-

57. Sheela S, AlGhalban FM, Khalil KA, Gopinath VK. The potential of resolvin D2 loaded hydroxyapatite/mineral trioxide aggregate electrospun membranes to downregulate Interleukin 1 beta and tumor necrosis factor alpha in human dental pulp stem cells and macrophages co-cultures. Clin Oral Investig. 2025;29(7):346.[DOI]

-

58. Yu H, Li Y, Pan Y, Wang H, Wang W, Ren X, et al. Multifunctional porous poly (L-lactic acid) nanofiber membranes with enhanced anti-inflammation, angiogenesis and antibacterial properties for diabetic wound healing. J Nanobiotechnology. 2023;21(1):110.[DOI]

-

59. Wang S, Li C, Chen S, Jia W, Liu L, Liu Y, et al. Multifunctional bilayer nanofibrous membrane enhances periodontal regeneration via mesenchymal stem cell recruitment and macrophage polarization. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;273:132924.[DOI]

-

60. He Y, Tian M, Li X, Hou J, Chen S, Yang G, et al. A hierarchical-structured mineralized nanofiber scaffold with osteoimmunomodulatory and osteoinductive functions for enhanced alveolar bone regeneration. Adv Healthc Mater. 2022;11(3):e2102236.[DOI]

-

61. Ma Q, Liu J, Tang R, Liu Z, Wu J. Chitosan and ibuprofen functionalized electrospun nanofiber membrane modulates inflammatory response and promotes full-thickness abdominal wall repair. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;321:146380.[DOI]

-

62. Liu C, Liu D, Zhang X, Hui L, Zhao L. Nanofibrous polycaprolactone/amniotic membrane facilitates peripheral nerve regeneration by promoting macrophage polarization and regulating inflammatory microenvironment. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023;121:110507.[DOI]

-

63. Cao W, Peng S, Yao Y, Xie J, Li S, Tu C, et al. A nanofibrous membrane loaded with doxycycline and printed with conductive hydrogel strips promotes diabetic wound healing in vivo. Acta Biomater. 2022;152:60-73.[DOI]

-

64. Kim JU, Ko J, Kim YS, Jung M, Jang MH, An YH, et al. Electrical stimulating redox membrane incorporated with PVA/gelatin nanofiber for diabetic wound healing. Adv Healthc Mater. 2024;13(27):e2400170.[DOI]

-

65. Bury MI, Fuller NJ, Meisner JW, Hofer MD, Webber MJ, Chow LW, et al. The promotion of functional urinary bladder regeneration using anti-inflammatory nanofibers. Biomaterials. 2014;35(34):9311-9321.[DOI]

-

66. Wang K, Hou WD, Wang X, Han C, Vuletic I, Su N, et al. Overcoming foreign-body reaction through nanotopography: Biocompatibility and immunoisolation properties of a nanofibrous membrane. Biomaterials. 2016;102:249-258.[DOI]

-

67. He J, Zhou S, Wang J, Sun B, Ni D, Wu J, et al. Anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative electrospun nanofiber membrane promotes diabetic wound healing via macrophage modulation. J Nanobiotechnology. 2024;22(1):116.[DOI]

-

68. Li B, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Wang W, Yang F, Wei Q, et al. Mimicking DOUGONG brackets orchestrate regulating inflammation and mechanical stimuli for osteochondral regeneration using 3D printing. Interdiscip Med. 2025.[DOI]

-

69. Liao Z, Lian R, Zhao S, Yang J, Deng Z, Wu D, et al. Activation of endogenous latent transforming growth factor β1 with the ascorbic acid-ferric chloride system for osteoarthritis treatment and osteochondral repair. Interdiscip Med. 2025;3(5):e70055.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite