Lihui Yuwen, State Key Laboratory of Flexible Electronics (LoFE) & Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Smart Biomaterials and Theranostic Technology, Institute of Advanced Materials (IAM), Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Nanjing 210023, Jiangsu, China. E-mail: iamlhyuwen@njupt.edu.cn

Abstract

Pathological calcification is typically regarded as a pathological endpoint, representing the abnormal deposition of calcium salts in tissues. With the continuous advancement of research, scientists have explored novel therapeutic strategies involving the induced calcification of tumor cells, demonstrating its potential therapeutic capabilities. Recently, a pioneering study on the use of induced calcification to treat bacterial infections has been reported. This commentary first introduces the classification, etiology, and treatment of pathological calcification. Then, the antibacterial effects of induced calcification therapy through the delicately designed antibacterial agent against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are generally demonstrated and discussed. The underlying mechanism of induced calcification for the treatment of chronic lung infections and chronic osteomyelitis caused by MRSA is revealed from the perspectives of bacterial energy metabolism and immune modulation. At the end of this commentary, challenges and future directions for induced calcification therapy are also briefly presented.

Keywords

1. Introduction

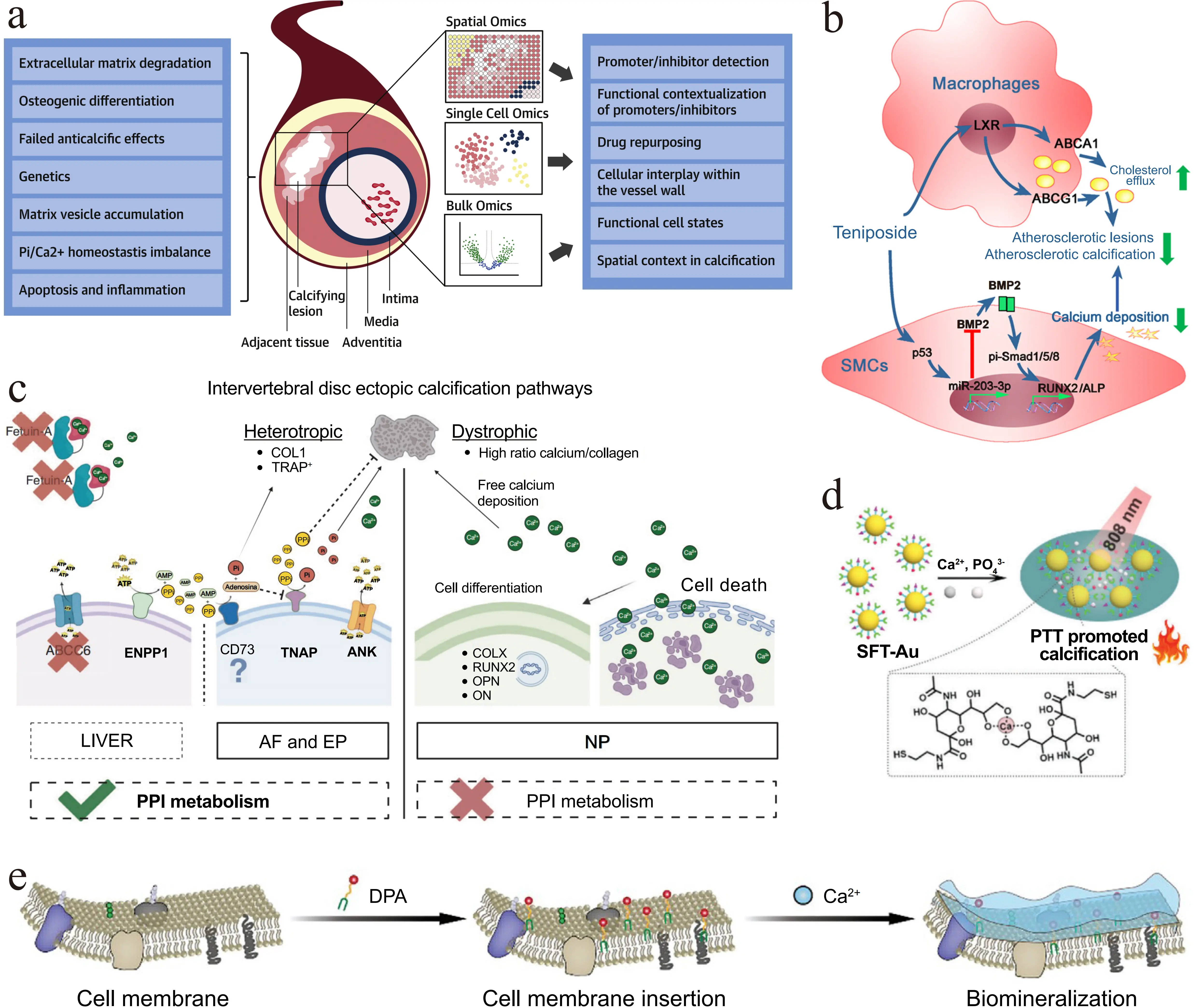

Pathological calcification refers to the abnormal deposition of calcium salts in human tissues[1]. Records of this phenomenon date back to the 16th century when Donatus first described prostatic calcification[2,3]. With the development of X-ray imaging in the late 19th century, tissue calcifications appearing as high-density shadows were systematically identified in clinical practice. Since the 20th century, advances in histology, pathology, and modern imaging techniques have enabled detailed documentation of calcification patterns in various organs. The causes of calcification are varied and can be broadly grouped into two categories based on the association with infection: non-infection-related calcification and infection-related calcification. Non-infection-related calcification results from factors such as elevated blood calcium levels (due to metabolic disorders), tissue damage, or congenital anomalies. Typical examples include arterial intimal calcification[4,5] (Figure 1a,b) and ectopic calcification of intervertebral discs[6] (Figure 1c). Infection-related calcification involves pathogens, such as bacteria, viruses, or parasites, which induce tissue infection or necrosis, a process that subsequently alters the microenvironment and causes abnormal calcium salt deposition. Examples include calcification in pulmonary tuberculosis and diabetic foot infections[9-11].

Figure 1. Mechanisms of calcification formation and calcification-related therapeutic strategies. (a) Arterial intimal calcification[4]; (b) Mechanisms of teniposide in inhibiting atherosclerosis and vascular calcification[5]; (c) Primary pathways of extradiscal calcification[6]; (d) Calcification-dependent photothermal therapy for treating tumors. Republished with permission from[7]; (e) Treatment of osteosarcoma via a versatile polymer-induced calcification approach. Republished with permission from[8]. LXR: liver X receptor; BMP2: bone morphogenetic protein 2; ABCA1: ATP-binding cassette transporter A1; ABCG1: ATP-binding cassette transporter G1; SMCs: smooth muscle cells; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ABCC6: ATP binding cassette subfamily C member 6; ENPP1: ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1; COL: collagen; TRAP: tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase; TNAP: tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase; ANK: ankylosis gene; AF: annulus fibrosus; EP: endplate; PPI: inorganic pyrophosphate; PTT: photothermal therapy; SFT-Au: surface-functionalized gold nanoparticles; DPA: DSPE-PEG-ALN.

Pathological calcification typically requires different treatment approaches based on its type, location, and severity. Benign calcifications (e.g., those from pulmonary tuberculosis or traumatic tissue calcification) exhibit excellent biocompatibility and lack malignant potential. If they do not compress surrounding tissues or impair organ function, regular imaging follow-up is sufficient, and no specific intervention is required. If the calcifications pose a significant risk of progression (e.g., intracranial calcification, cardiac valve calcification), pharmacological or surgical intervention should be implemented[12].

Pathological calcification may also provide a basis for a promising novel therapeutic strategy for various diseases. Researchers have found that the process of encapsulation and repair of necrotic tissues in tuberculosis patients is accompanied by abnormal deposition of calcium salts, leading to the formation of calcifications. Late-stage calcified tuberculous lesions exhibit low permeability, which helps limit the spread of the pathogen[13,14]. Therefore, simulating the calcification process to form localized barriers holds promise for treating diseases such as tumors. Chang et al. synthesized SFT-Au via surface modification of gold nanoparticles with sialic acid, folic acid, and triphenylphosphine[7]. SFT-Au specifically targets tumor mitochondria and mediates calcium enrichment. Upon irradiation with 808 nm light, the calcium-dependent photothermal conversion accelerates intratumoral calcification and disrupts cellular energy metabolism, enhancing therapeutic efficacy against colorectal cancer (Figure 1d). Jiang et al. fabricated the nanoplatform DPA using 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine, polyethylene glycol, and alendronate as the functional components[8]. By inserting into the cell membrane and promoting calcium enrichment, DPA induces calcification while suppressing osteoclast activity, thus mitigating bone destruction in osteosarcoma models (Figure 1e).

Bacterial infectious diseases pose a long-term and serious threat to human life and health[15,16]. In recent years, bacterial resistance has grown progressively critical, posing a significant challenge to global public health[17]. Traditional antibiotic therapy not only struggles to eradicate drug-resistant bacteria but may also exacerbate the development of bacterial resistance. The development cycle for new antibiotics spans over a decade and involves substantial costs, with their pace of advancement significantly lagging behind the progression of bacterial resistance[18,19]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop efficient novel antibacterial strategies. The above relevant studies have confirmed that the calcification mechanism can serve as a potential therapeutic strategy for tumor treatment. Thus, if calcification can be induced on bacterial surfaces and form dense calcified layers, can the recalcitrant drug-resistant bacterial infections be effectively eliminated?

2. Induced Calcification Therapy for Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) Infection

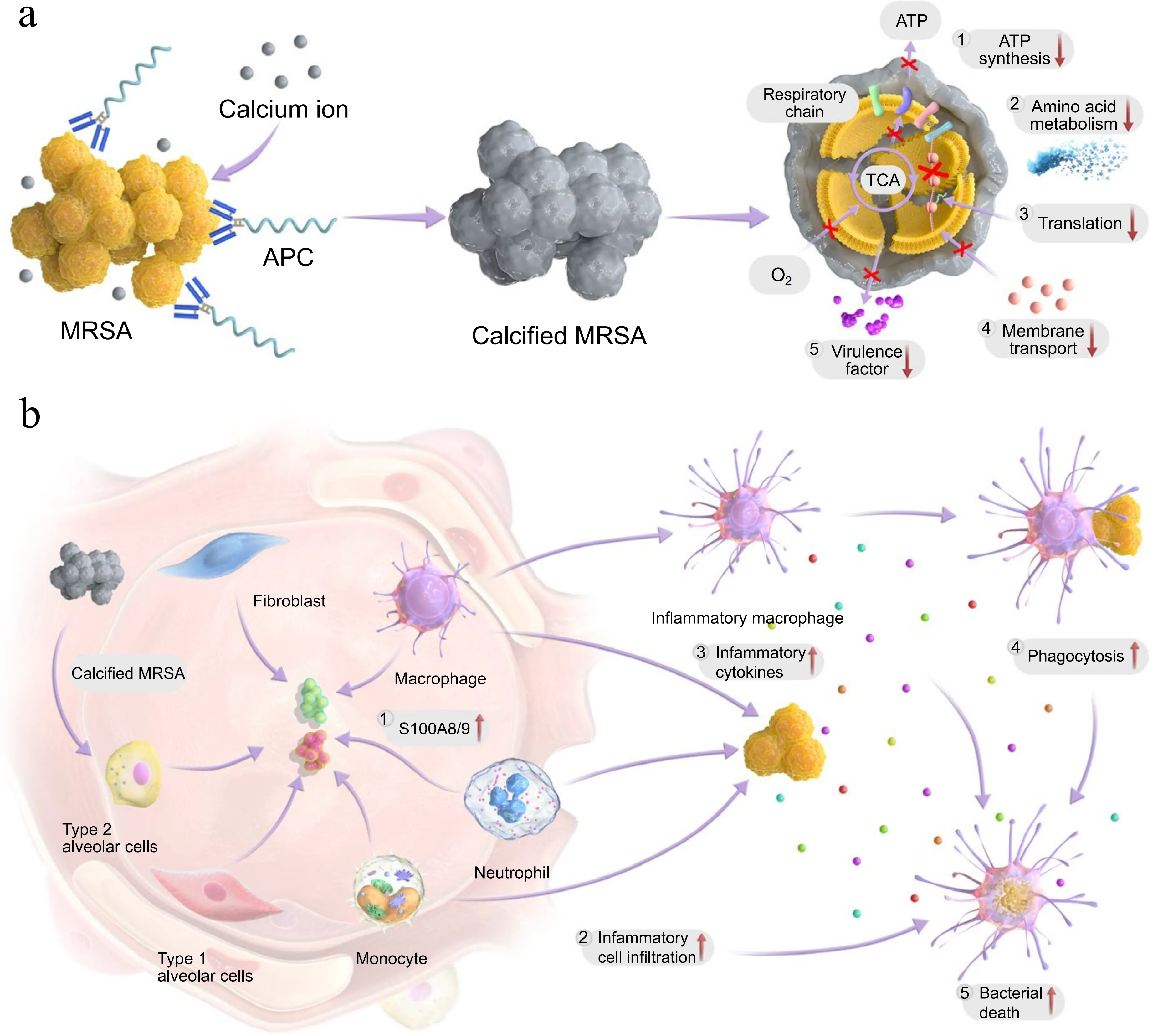

To explore calcification as an antibacterial strategy, Zhang et al. developed a calcification-based antibacterial agent for the treatment of MRSA infections[20]. They conjugated the antigen-binding fragment of the monoclonal antibody targeting wall-teichoic acid (WTA) to polysialic acid (PSA), forming an antibody-PSA conjugate (APC). APC specifically targets the cell wall of MRSA and induces the formation of a calcified shell on its surface. On one hand, the calcified shell hinders bacterial energy metabolism and key metabolic pathways, while inhibiting MRSA virulence factors, quorum sensing, and two-component systems, thereby reducing its pathogenicity (Figure 2a). On the other hand, calcified MRSA can induce the activation of inflammatory macrophages, upregulate the expression of inflammatory cytokines, and promote cell infiltration, thereby enhancing the host’s antibacterial immune response (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Schematic of APC for treating MRSA infection. (a) APC induces the calcification of MRSA and inactivates bacteria by various routes; (b) Calcified MRSA boosts innate immunity and synergizes with the antibacterial effect of APC. Republished with permission from[20]. APC: antibody-PSA conjugate; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; ATP: adenosine triphosphate.

The researchers employed multiple methods to systematically evaluate the calcium enrichment effect of APC on the surface of MRSA, and the results indicated that APC and Ca2+ can form calcified crystals around bacteria, thus confirming the formation of calcified shells. In vitro experiments demonstrated that APC significantly reduced the activity of MRSA through colony-forming unit (CFU) plating assays and live/dead staining experiments. In addition, APC demonstrated the ability to inhibit MRSA biofilm formation and disrupt preformed biofilm structures.

To investigate the fundamental antibacterial mechanism of APC, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) was employed to analyze the gene profiles of MRSA co-treated with APC and Ca2+. RNA-seq results showed that the genes related to energy metabolism, including those involved in ATP metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, and gluconeogenesis (e.g., atpA, atpD, tpiA), were significantly downregulated in the calcified group. The expression of genes encoding virulence factors (e.g., esxA, hlg, spa), as well as genes involved in quorum sensing and two-component system was also significantly downregulated, thus confirming the inhibitory effect of calcification on metabolic and virulence pathways at the gene level. In addition, metabolomics analysis showed that 242 metabolites were downregulated in the calcified group, including key metabolites of energy metabolism (e.g., ATP precursor, NAD+, TCA cycle intermediates), and the intracellular ATP level and NAD+/NADH ratio of MRSA were significantly reduced, further confirming the inhibitory effect of calcification on energy metabolism.

The above results indicate that APC can inhibit the growth and metabolism of MRSA by inducing bacterial calcification. In mouse models of chronic pneumonia and chronic osteomyelitis, APC treatment reduced bacterial load at the infection site, improved survival rates, and ameliorated pathological changes at the site of infection. The number of MRSA in the lungs and bone marrow of mice, as determined by CFU plating assays, was significantly reduced, with diminished inflammatory responses in lung tissue and bone. Additionally, distinct calcifications were observed in the lungs. Furthermore, APC enhanced the host’s innate immune response, activated macrophages, and promoted the chemotaxis of inflammatory cells and the release of inflammatory cytokines. Biosafety evaluation showed that APC had a satisfactory safety profile.

To investigate the impact of bacterial calcification on the immune microenvironment of the host, the researchers performed single-cell RNA sequencing analysis on all cells in the lungs of mice. The APC group exhibited significantly higher pro-inflammatory scores than the control group, with significantly upregulated gene expression of S100a8 and S100a9. The researchers further evaluated the effect of bacterial calcification on immune cells through in vitro experiments. By co-culturing mouse alveolar macrophages (MH-S) with fixed calcified MRSA, a significant increase in the proportions of CD80 and CD86 was observed, and the levels of TNF, CXCL1, CXCL2, IL-6, and TLR4 in the cell culture supernatant were significantly elevated. Following stimulation of MH-S by calcified bacteria, the phagocytic ability of MH-S was significantly enhanced. The knockout of S100a8 and S100a9 abolished the above differences, indicating that calcified bacteria activated macrophages by upregulating the expression of S100a8 and S100a9, enhancing their phagocytosis and the release of inflammatory factors, thereby promoting the immune response of inflammatory cells.

3. Conclusion

The antibacterial strategy of inducing bacterial calcification achieves physical encapsulation by forming a calcified outer shell, and further blocks multiple core pathways of MRSA, including energy metabolism, substance synthesis, quorum sensing, transmembrane transport, and virulence factor secretion, thereby generating a global metabolic inhibition effect. Concurrently, the calcified bacteria act as immunomodulators that activate the host’s innate immune response, thereby achieving a synergistic antibacterial effect. Compared with existing non-antibiotic approaches such as metal ion toxicity, nanomaterial-mediated physical disruption, metabolic inhibition, and immune modulation, this strategy exhibits more robust antibacterial efficacy by combining the global metabolic inhibition triggered by physical encapsulation with immune modulation in a synergistic manner. This study breaks through traditional understandings of pathological calcification processes, extends the application of pathological calcification processes to the treatment of bacterial infections, and opens new avenues for research on combating drug-resistant bacterial infections.

4. Challenges and Future Directions

The clinical translation of induced calcification therapy still faces several challenges, primarily regarding the drug application, dosage regimens, and biosafety. APC exerts its antibacterial activity by targeting the WTA within the cell wall of MRSA, yet it lacks generality against other drug-resistant bacteria without WTA (e.g., Gram-negative bacteria) and intracellular bacteria. Without precise targeting capability, this therapy may fail to achieve desired antibacterial efficacy and could even induce unintended calcification or other off-target adverse effects. As a result, expanding the antibacterial spectrum of induced calcification therapy is still required. In addition, the high dose of APC used in this study may trigger the immune response and increase the risk of immunogenicity. Moreover, the local calcium deposition in tissues by induced calcification may trigger adverse effects on surrounding tissues and organs. Induced calcification, when deposited long-term within tissues, may progressively lead to stiffening of blood vessel walls or other localized fibrosis, thereby increasing the risk of potential complications. Simultaneously, structural rupture of a calcified lesion could further induce thrombosis, thereby triggering adverse effects such as myocardial infarction and stroke. During tissue repair processes, calcification may induce abnormal cross-linking of the extracellular matrix, forming irreversible fibrosis that subsequently impacts organ structure and function. Also, calcified structures may compress surrounding blood vessels and nerves, causing local tissue dysfunction and chronic pain. Therefore, in vivo long-term systemic biosafety may be the most concerning issue of the induced calcification therapy, and further experimental evaluation in large-animal models is needed.

Future research on induced calcification therapy should further optimize the rational design of calcification agents, develop targeted delivery carriers, deepen the understanding of the mechanisms of action, prevent damage to non-target tissues, expand the range of indications, explore combination therapy approaches, and so on. Additionally, it is necessary to advance preclinical trials, enhance drug safety assessments, and promote the clinical translation of induced calcification therapy.

Authors contribution

Zhang C: Writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Zhang H: Writing-review & editing.

Zhang Q, Yuwen L: Supervision, project administration, funding acquisition, conceptualization, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Lihui Yuwen is an Editorial Board Member of BME Horizon. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22375101).

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Vidavsky N, Kunitake J, Estroff LA. Multiple pathways for pathological calcification in the human body. Adv Healthc Mater. 2021;10(4):e2001271.[DOI]

-

2. Fox M. The natural history and significance of stone formation in the prostate gland. J Urol. 1963;89:716-727.[DOI]

-

3. Hyun JS. Clinical significance of prostatic calculi: A review. World J Mens Health. 2018;36(1):15-21.[DOI]

-

4. Lanzer P, Hannan FM, Lanzer JD, Janzen J, Raggi P, Furniss D, et al. Medial arterial calcification: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78(11):1145-1165.[DOI]

-

5. Liu L, Zeng P, Yang X, Duan Y, Zhang W, Ma C, et al. Inhibition of vascular calcification: A new antiatherogenic mechanism of Topo II (DNA topoisomerase II) inhibitors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2018;38(10):2382-2395.[DOI]

-

6. Novais EJ, Narayanan R, Canseco JA, van de Wetering K, Kepler CK, Hilibrand AS, et al. A new perspective on intervertebral disc calcification-from bench to bedside. Bone Res. 2024;12(1):3.[DOI]

-

7. Chang X, Tang X, Liu J, Zhu Z, Mu W, Tang W, et al. Precise starving therapy via physiologically dependent photothermal conversion promoted mitochondrial calcification based on multi-functional gold nanoparticles for effective tumor treatment. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33(35):2303596.[DOI]

-

8. Jiang Z, Liu Y, Shi R, Feng X, Xu W, Zhuang X, et al. Versatile polymer-initiating biomineralization for tumor blockade therapy. Adv Mater. 2022;34(19):e2110094.[DOI]

-

9. Guzman RJ, Bian A, Shintani A, Stein CM. Association of foot ulcer with tibial artery calcification is independent of peripheral occlusive disease in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99(3):281-286.[DOI]

-

10. Reed RM, Amoroso A, Hashmi S, Kligerman S, Shuldiner AR, Mitchell BD, et al. Calcified granulomatous disease: Occupational associations and lack of familial aggregation. Lung. 2014;192(6):841-847.[DOI]

-

11. Yedgarian N, Agopian J, Flaig B, Hajjar F, Karapetyan A, Murthy K, et al. The intricate process of calcification in granuloma formation and the complications following M. tuberculosis infection. Biomolecules. 2025;15(7):1036.[DOI]

-

12. Jain H, Goyal A, Khan A, Khan NU, Jain J, Chopra S, et al. Insights into calcific aortic valve stenosis: A comprehensive overview of the disease and advancing treatment strategies. Ann Med Surg. 2024;86(6):3577-3590.[DOI]

-

13. Lenaerts A, Barry CE, Dartois V. Heterogeneity in tuberculosis pathology, microenvironments and therapeutic responses. Immunol Rev. 2015;264(1):288-307.[DOI]

-

14. Urbanowski ME, Ordonez AA, Ruiz-Bedoya CA, Jain SK, Bishai WR. Cavitary tuberculosis: The gateway of disease transmission. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6):e117-e128.[DOI]

-

15. Lu L, Qiu S, Li W, Gong H, Zhang Q, Yuwen L, et al. Ultrasound-responsive multifunctional nanodroplets for enhanced biofilm penetration and synergistic sonodynamic/gas therapy of bacterial implant infections. Nano Res. 2025;18(12):94908166.[DOI]

-

16. Yuwen L, Xu F, Zhang C, Lu L, Liu Y, Li X, et al. Manganese carbonate-gold schottky heterostructure nanosonosensitizer with enhanced sonodynamic effect and pH-responsive degradation for effective treatment of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm infection. Chem Eng J. 2025;515:163945.[DOI]

-

17. Zeng Z, Li Y, Deng K, Zou D, Liu L, Guo B, et al. Thermal-cascade multifunctional therapeutic systems for remotely controlled synergistic treatment of drug-resistant bacterial infections. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(18):2311315.[DOI]

-

18. Brüssow H. The antibiotic resistance crisis and the development of new antibiotics. Microb Biotechnol. 2024;17(7):e14510.[DOI]

-

19. GBD 2019 Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2022;400(10369):2221-2248.[DOI]

-

20. Zhang W, Liu L, Zhang Q, Lu H, Li A, Huang Y, et al. Inducing bacterial calcification for systematic treatment and immunomodulation against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Biotechnol. 2025.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite