Abstract

It has been extensively shown that Building Information Modelling (BIM) improves project performance, which is impacted by various critical performance factors of BIM project (CPFs-BP). However, it has become a difficult problem in theory and practice to determine the most important CPFs-BP impacting BIM project performance (BPP) at various life-cycle stages. In light of this information gap, the goal of this study is to identify the most important CPFs-BP and identify the stages at which BIM can be applied to enhance BPP through specific

Keywords

1. Introduction

Low productivity and efficiency have become typical throughout the building project lifecycle[1]. Building information modelling (BIM) has emerged as a potential approach for creating realistic virtual models and supporting project operations throughout the project’s lifecycle[2,3]. BIM, a digital technology that allows for the creation of accurate virtual models and supports additional activities in the project delivery process[2], is a digital representation used to plan, design, control, and maintain facilities. It has changed the traditional ways that project participants define their roles[4] and collaborate, and it has enabled teams to manage projects using a model-based cooperative approach[5]. BIM improves BIM project performance (BPP) in the following ways: cost savings and high returns[6], faster delivery[7], safety, higher quality[8], fewer document errors and rework[9], perceived facility quality, and better decision-making[10]. However, the extent to which BIM improves project performance varies greatly between projects, frequently due to variances in implementation, stakeholder engagement, or organizational norms.

While BIM has been demonstrated to improve project performance, it can also have a negative influence on BPP, such as increased in-construction requests for information (RFIs), increased change order costs, and increased punch list expenses[11], among other things. Worse, BPP is linked to certain project stakeholders and stages. For example, a failure to uncover design mistakes and RFIs prior to construction may be due to an overreliance on BIM software and insufficient cooperation between suppliers and

BPP originates from the dynamic interaction of these CPFs-BP. Owners, contractors, designers, and BIM consultants all use BIM differently depending on their goals and roles, and project stages influence the impact of these actions. Owners want to finish a project within a particular timetable, budget, and specifications[5]. They recognize the significant potential advantage of employing BIM technology[17], since they may benefit the most from using a facility model and its inherent knowledge of the facility’s lifecycle[18]. Contractors aim to make the highest possible profit from the project[5] and consider themselves as the party that benefitted most from BIM technology[6], as they perceive the top project benefits of BIM to be reduced errors and omissions, collaboration with owners and design firms, reduced rework, reduced construction cost, better cost control and predictability, and reduced overall project duration[19]. Designers use BIM to reduce document errors, improve workflows, and support coordination during construction[20]. Designers consider the reduction in design revisions to be the most significant benefit of BIM[6]. Although owners recognize the high potential value of using BIM, many are unsure about which stage of BPP to improve over the lifecycle[21]. Understanding how CPFs and BPP interact is therefore critical for increasing BIM utilization and project outcomes across the lifecycle.

Recent studies have investigated BPP using a variety of approaches, but no study has developed a phase-based approach to predict and improve BPP considering multiple CPFs-BP. Besides, few quantitative studies have attempted to clarify the complex relationships between the project stages and CPFs-BP. Therefore, this study answers two research questions: 1) At what point in the project lifecycle might the use of BIM technology increase BPP? 2) How to increase BPP? To fill a research need, this study will identify

To accomplish this, a complex network technique is used to describe CPFs-BP as interconnected nodes, allowing for systematic and quantitative identification of significant elements and interaction analysis. By taking this approach, the study not only broadens our understanding of how CPFs and BP interact to affect BPP, but it also offers project managers actionable insights to optimize BIM deployment and project outcomes. In doing so, the study adds to both the academic literature on BIM performance and the practical decision-making process in building project management.

2. Literature Review

2.1 BPP

BPP can encompass several critical items such as cost, rework, project schedule, stakeholder satisfaction, facility

As shown in Table 1, a list of 17 CPFs-BP and their explanations are given based on an extensive literature review, and they are classified into three groups: BIM technology (CPFs-BP1–8), stakeholder competitiveness (CPFs-BP9–12), and stakeholder interaction (CPFs-BP13–17). Nonetheless, few studies have considered how BIM adoption might improve project performance by precisely controlling a series of key factors. Therefore, one of the research objectives is to determine the principal CPFs-BP in accordance

| CPFs-BP | Description |

| Functionality of BIM tools(CPFs-BP1) | It is essential to confirm what BIM tools need to be adopted to help deliver expected BIM uses[14]. Despite the software vendor’s claim of access to wonderful functions, the usability of new advanced technology is subject to how users define and implement it in practice[13]. |

| Compatibility of BIM tools(CPFs-BP2) | It measures the convenience and evaluates the received outcomes or products when people adopt different tools and standards resulting in different model formats and levels of details[4]. In addition, interoperability problems between BIM models and other project management software packages, as well as those among various engineering information, still trouble practitioners[27-29]. |

| Diversity of BIM application areas(CPFs-BP3) | BIM uses include five generic categories: (1) architectural design, engineering system design, (2) MEP coordination/conflict detection, (3) two-dimensional (2D) documentation, three-dimensional (3D) detailing, and four-dimensional (4D) scheduling, and (4) facility management[20]. Other areas such as BIM/GIS overlapping, energy simulation, and sustainability analysis are also influential on project objectives[14]. |

| BIM quality(CPFs-BP4) | It refers to how well a BIM model fulfils the requirements. Liu et al.[13] offered some detailed metrics, including the ratio of the warnings to objects, criticality of warnings, consistency of 3D model and 2D references, and analytical reporting quality (the structural analysis quality, daylighting simulation report quality, energy simulation report quality, etc.). |

| BIM accuracy(CPFs-BP5) | It refers to how precisely the BIM model reflects the physical conditions of projects, i.e., how closely the BIM’s geometry/data represents as-built conditions in the field. Quantity takeoff accuracy, discrepancies between models, average number of generic objects per assembly, and constructability, can jointly depict BIM |

| BIM usefulness(CPFs-BP6) | It refers to how useful the model information and geometry is over the project lifecycle. Some variables might be how often the model is accessed for different purposes, ease of construction documentation creation, and reliability of model data for end-user during operation and maintenance[4]. |

| BIM economy(CPFs-BP7) | It refers to whether it is constructed in the most cost and time-efficient manner, which is also related to how fast a BIM is developed on average[4]. It may involve a high initial investment in BIM projects[30], expensive cost for design changes, and financial support for infrastructure[29,31]. |

| BIM Institutional Environment(CPFs-BP8) | It refers to the regulatory system formed by BIM-related standards and technical requirements, organizational rules and requirements, and policy and legal issues to ensure BIM implementation within the project context[32]. An institutional environment within a BIM-based project is required to facilitate BIM governance and ensure collaborative working among project teams[32]. |

| Capability of stakeholders’ organizations(CPFs-BP9) | It includes competency of individual stakeholders, capability and maturity of AECO organizations, maturity of using BIM technology and workflows[6]. Lack of BIM knowledge in the team members is to the disadvantage of BIM adoption[33]. |

| Stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities(CPFs-BP10) | The best practices of BIM include clear roles and responsibilities in BIM affairs within the coordination |

| Organizations’ adaptability to changes(CPFs-BP11) | Different organizations should develop adaptability to changes, which enables participants to fit in the exchange environment quickly and obtain mutual benefits, and then improve their overall performance[1]. |

| Inter-organization leadership(CPFs-BP12) | It refers to the relative leadership between project stakeholders and leaders can complete the work collaboratively, rather than solely face the challenges of restructuring projects organizationally[4]. For example, when design errors occur in the clash detection, or the unreasonable schedule is discovered in the visualization roam, it is hard to be corrected because of the ambiguous power relationship[13]. |

| Stakeholders’ involvement(CPFs-BP13) | It emphasizes to what degree and how much time the stakeholders are involved in delivering BIM uses[14,34]. It is critical in BEP for successful BIM implementation[35]. |

| Contract(CPFs-BP14) | A correct and matching contract should be constructed because proper contract management will positively influence project performance[16]. It works as a measure to improve BIM collaboration and reduce subsequent disputes[36]. |

| Inter-organizational trust(CPFs-BP15) | A firm expects that its partner will not behave opportunistically and allows firms to exchange information and share responsibilities for decision making[29]. Trust relationships inspire the diffusion of valuable knowledge and innovations, which lessens opportunism and contributes to project performance[37]. |

| Inter-organization communication(CPFs-BP16) | It facilitates different organizations from different backgrounds to exchange knowledge and frequently[1]. Consequently, project players can amplify their efforts. Positive behaviours can improve project performance, such as resolving problems collaboratively, working harmoniously, and engaging in mutual support[7,11,36]. |

| Information exchange (CPFs-BP17) | Frequent information exchange is the basic element of cooperation and shows more effects on project performance due to the enormous information applied to BIM models[1]. |

CPFs-BP: critical performance factors of BIM project; BIM: Building Information Modelling; MEP: mechanical, electrical, and plumbing; AECO: architecture, engineering, construction, and operation; BEP: BIM Execution Planning.

2.2 Methods of BPP research

Diverse qualitative and quantitative methodologies have been used to investigate the influence and optimization mechanisms of BPP. Qualitative analysis includes surveys[16], interviews[38], contract-based models[37], and so on. Celoza et al.[16] surveyed the industry on BIM practices and evaluated the impact of BIM-related contract practices on project performance; Chen et al.[38] conducted qualitative interviews to understand how the performance indicators are influenced by the use of BIM; and Lee et al.[37] proposed an integrative trust-based functional contracting model that describes how trust can enhance BPP in engineering, procurement.

Other methods aim to quantify the relation between BIM implementation and project performance, such as the partial least squares structural equation modelling[5], dynamic model[39], benchmarking models[13,40,41], and Bayesian network models[42]. Tang et al.[1] explored the direct relationship between BIM implementation and the performance of off-site manufacturing projects using the partial least-squares structural equation modelling; by the same technique, Lee et al.[5] analyzed joint contract–function effects on BIM-enabled EPC project performance; Zoghi et al.[39] developed a system dynamics model to evaluate the social performance of

2.3 Complex network theory

To address the relationship between CPFs-BP and project stages, complex network theory is applied in this study, which is a research paradigm for modeling and visualizing diverse complex systems. On the one hand, a complex network can evolve over time and space and can undergo change. Typically, nodes or connecting edges can be added or removed to alter the network structure. It is possible to abstract the connection between various project stages and CPFs-BP into a complicated network. On the other hand, it has been challenging to investigate large-scale network interactions using mathematical analytic techniques, including the “network” at various stages of the project and the “network” between CPFs-BP. However, the complex network theory derived from graph theory can address this issue. Complex network analysis is more appropriate than other methods in this study because it has a tendency to solve the issues, such as comparing the state of constituent parts, forming alliances between constituent elements, and information sharing and transfer among constituent elements.

Complex network theory is thus applied by visualizing the relation as an intuitive 2-mode network. Moreover, the theory has been widely used in identifying critical factors and quantifying relations between homogeneous or heterogeneous nodes. A single type of node (e.g., people, risks) can form a 1-mode network, such as the study in He et al.[43], which is the current research focus. Two types of nodes can constitute a 2-mode network (also known as bipartite network)[44], such as the study in Wu et al.[45], where no direct link exists between homogeneous nodes. Among all parameters, maximum matching is one algorithm particularly used to deal with

The current BPP research mainly focuses on the evaluation of BPP, and the methods used are mainly statistical methods or system theory based on causality[48]. However, in fact, a concept of “interaction” has been produced in the process of researching the phased performance of BIM projects, which is difficult to research using quantitative analysis tools[49]. Few studies have used complex network theory to improve BPP at life-cycle stages. Complex network analysis could be used to solve problems such as comparing constituent element status, forming alliances among constituent elements, and transmitting and sharing information among constituent parts. As a result, developing an all-stage BPP relationship research model based on the network method may address the bottleneck in effective prediction and improvement of BPP in practice. Compared with existing evaluation frameworks, such as structural equation modeling (SEM) and Bayesian networks, the proposed network–polynomial approach offers complementary strengths. SEM mainly models linear and predefined causal relationships, while Bayesian networks rely on prior probability assumptions. In contrast, complex-network analysis captures multi-directional interactions among CPFs-BP, and polynomial functions allow for nonlinear stage-based prediction of BPP. Together, this approach provides a flexible way to explore dynamic relationships across life-cycle stages.

In this study, complex network analysis is used to address specific challenges in BPP, such as quantifying interactions between

3. Methodology

To ensure that the identification of CPFs-BP was systematic and replicable, a content analysis approach was adopted. Firstly,

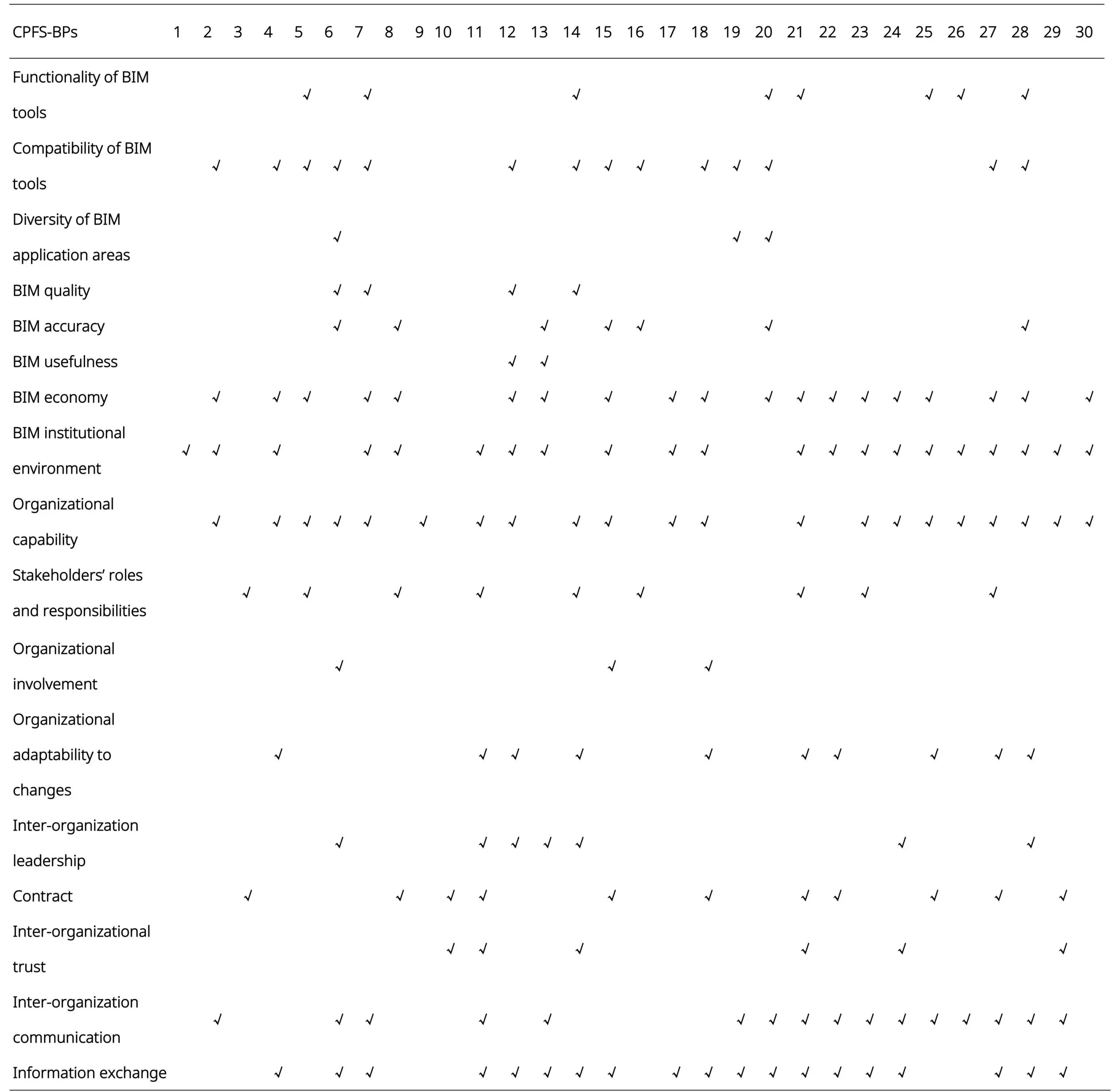

Figure 1. List of CPFs-BP occurrences frequency on literature review. 1[50], 2[51], 3[16], 4[52], 5[14], 6[53], 7[54], 8[55], 9[21], 10[30], 11[56], 12[30], 13[57], 14[13], 15[31], 16[58], 17[59], 18[60], 19[61], 20[62], 21[63], 22[1], 23[23], 24[64], 25[65], 26[66], 27[67], 28[68], 29[69], 30[70]. CPFs-BP: critical performance factors of BIM project; BIM: Building Information Modelling.

Only factors that occurred more than five times in the literature were kept from the original list of thirty to guarantee that the chosen CPFs-BP were well-known, pertinent, and significant for further study. This frequency-based threshold was selected to minimize the inclusion of infrequently reported or marginally significant features while striking a balance between comprehensiveness and practical usefulness. As a result, the final set of 17 CPFs-BP offers a solid, representative, and trustworthy basis for the ensuing complicated network modelling, assessment, and identification of critical elements affecting BPP throughout various life-cycle stages.

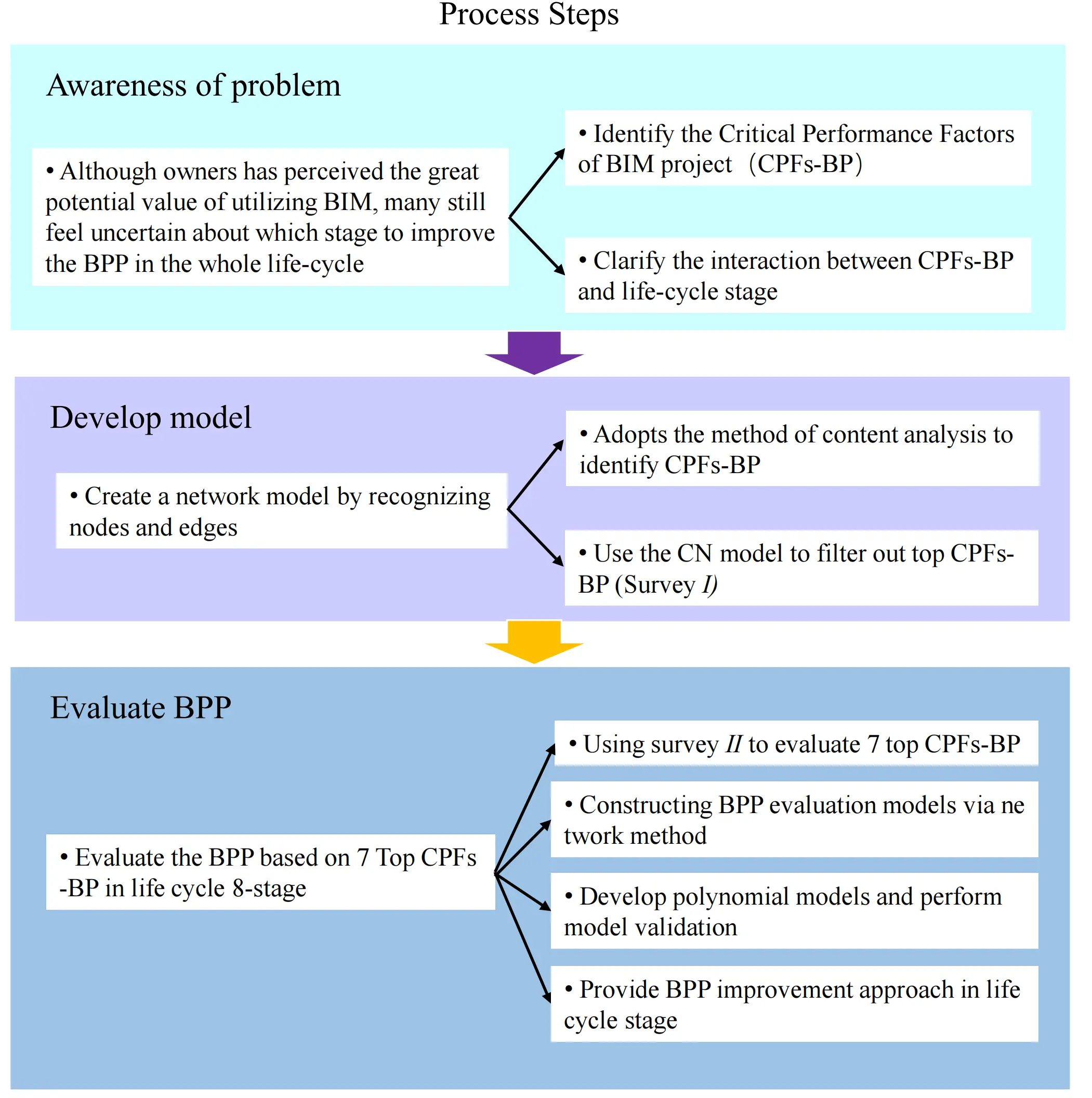

Then, combining descriptive analysis and complex network theory, the top seven CPFs-BP among the 17 were identified, and the relationship between project stages and CPFs-BP was discovered using literature review and data collected from Survey I. Survey I was designed to identify the most influential CPFs-BP and explore their interactions with different project life-cycle stages. Following that, by analysing the parameters of the established two-dimensional two-mode heterogeneous network model, this study explained the interaction between CPFs-BP and life-cycle stages. Subsequently, Survey II was used to evaluate the top seven CPFs-BP along with network analysis. Survey II aimed to evaluate the impact of these top seven CPFs-BP on BPP and predict improvement strategies by quantifying their contributions at each project stage. Finally, a total of 56 BPP evaluation models were constructed, corresponding to the top seven CPFs-BP across the eight project life-cycle stages. Refer to Figure 2 for the research design and methodological workflow. Developing these models allows for a detailed, stage-specific assessment of each factor’s contribution to BPP, facilitating the identification of critical stages and providing a quantitative basis for targeted improvement strategies.

Figure 2. Research design and process steps. CPFs-BP: critical performance factors of BIM project; BPP: BIM project performance; BIM: Building Information Modelling.

4. Determining Top Seven CPFs-BP

4.1 Survey I

With three parts contained in the Survey I, Part A consisted of seven questions gathering the respondents’ information, such as the details of BIM-related experience, including the organization type, the number of BIM personnel, participant’s professions and working experience in BIM projects, and the characteristics of BIM projects (i.e., type, figure, and investment nature). Part B was devised to measure the positive influence of 17 CPFs-BP in eight project stages. The five-point Likert scale was used in this survey, with “1” referring to very low and “5” referring to very high. Finally, Part C set out to collect comments supplying additional ways to enhance BPP.

4.2 Data collection

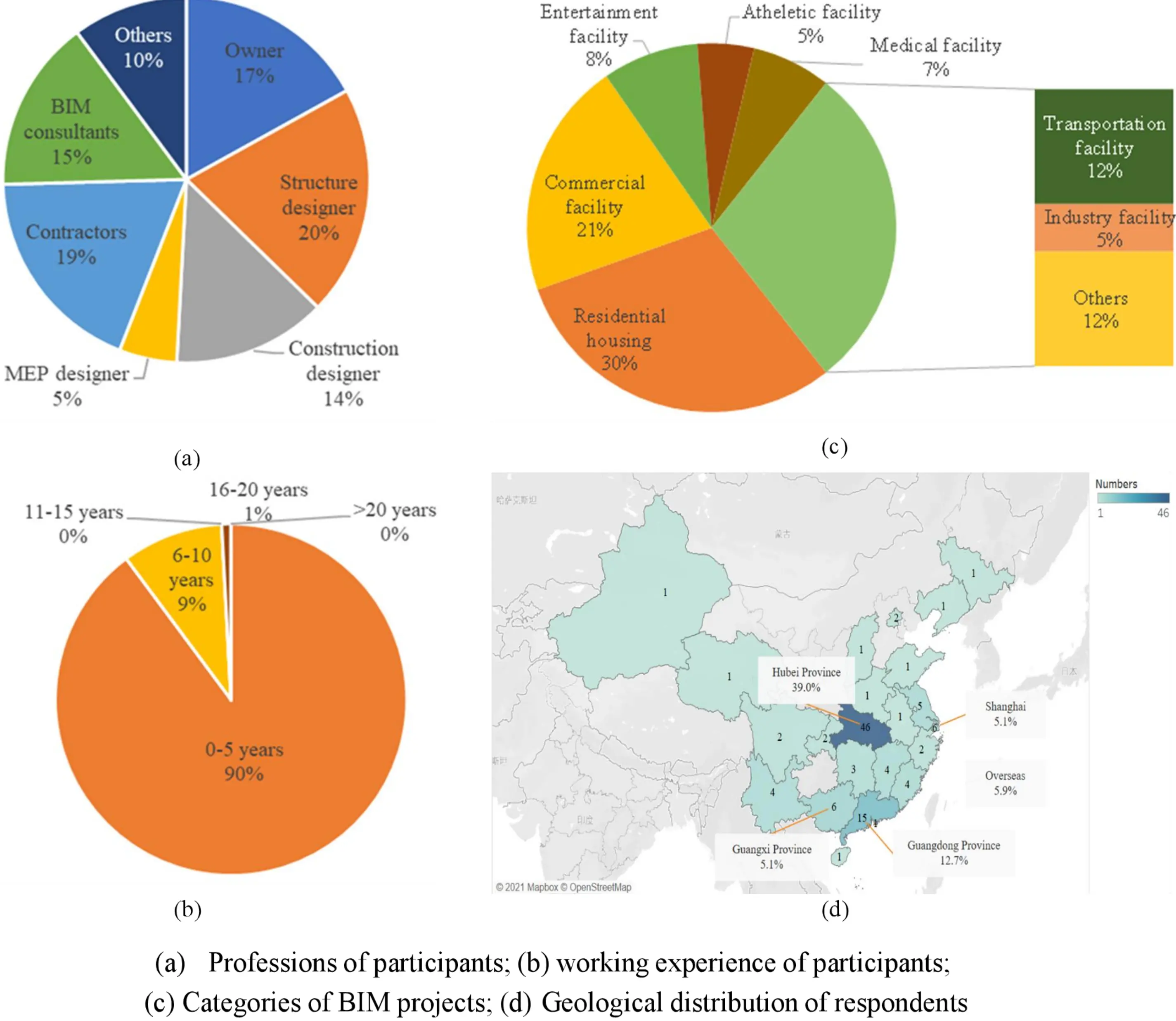

The population of Survey I refers to those who have BIM-related working experience, and the participants were specifically selected via a stratified sampling strategy. Delivered by e-mail, LinkedIn, and hard copy, a total of 200 questionnaires were then sent out to various large-scale organizations in AEC industry, compromising owners, designers, contractors, BIM consultants, academic researchers, and other practitioners. Under such standards, 118 responses were refined, meaning a valid response rate of 59%. Despite the limitation of sample size, the response rate was relatively acceptable compared to other similar studies including 34% in Ozorhon and Karahan[59], 31.6% in He et al.[43], and 23.48% in Ma et al.[29]. Figure 3 summarizes the relevant information collected in part A of the questionnaire.

Figure 3. Relevant information collected in part A, Survey I. BIM: Building Information Modelling.

In addition, Table 2 summarizes BIM-related information about the respondents. First, BIM was widely applied to all kinds of projects, mainly in residential housing (30%) and commercial facilities (21%). Also, 82.2% of respondents reported that BIM projects had attained government funding. This evidence exactly reflects the present-day megatrend that politics is positively promoting the digital transformation in AEC industry. However, the strategic moves, especially in China, had insufficient influence on BIM adoption. As seen in Table 2, 54% of survey organizations own less than 5 BIM staff, and 66.1% of respondents have participated in no more than five BIM projects, indicating that BIM practices in China are likely to be stagnated and vulnerable to face the industry transformation by digital technologies.

| Category | Subcategory | Percentage | Category | Subcategory | Percentage |

| Organization type | Owner | 19% | BIM personnel | 0-5 | 54% |

| Designers | 24% | 6-10 | 17% | ||

| Contractors | 23% | 11-15 | 5% | ||

| BIM consultants | 3% | 20 | 4% | ||

| Academics | 23% | > 20 | 20% | ||

| Others | 8% | ||||

| Project type | Residential housing | 30% | BIM project quantity | 0-5 | 66.1% |

| Commercial facility | 21% | 6-10 | 11.0% | ||

| Entertainment facility | 8% | 11-15 | 4.2% | ||

| Athletic facility | 5% | 20 | 3.4% | ||

| Medical facility | 7% | > 20 | 15.3% | ||

| Transportation facility | 12% | ||||

| Industry facility | 5% | ||||

| Others | 12% |

BIM: Building Information Modelling.

4.3 Statistical analysis

Four main statistical parameters were measured in the section using a Likert-scale method, as shown in Table 3: average mean, relative importance index (RII), normalized value (NV), and Cronbach’s alpha (α). Cronbach’s alpha was adopted to assess the reliability of survey data, and its value ranged from 0 to 1. According to Kazado et al.[71], an acceptable α score commonly varies from 0.70 to 0.95. With the same threshold, Gunduz and Abdi[72] believed it is also supportable if α ≤ 0.99. Tested by SPSS25.0, the α of 0.944 within the whole survey sample indicated high reliability of questionnaire survey, and the fact that α of each CSF was below 0.944 proved strong inner consistency of all scales.

| No. | CPFs-BP | Rank | Mean | NV | RII | Cronbach’s alpha | |

| Top 7 CPFs-BP | CPFs-BP5 | BIM accuracy | 1 | 3.601 | 1.000 | 0.721 | 0.926 |

| CPFs-BP17 | Information exchange | 2 | 3.569 | 0.856 | 0.713 | 0.924 | |

| CPFs-BP6 | BIM usefulness | 3 | 3.545 | 0.750 | 0.709 | 0.922 | |

| CPFs-BP4 | BIM quality | 4 | 3.521 | 0.644 | 0.704 | 0.921 | |

| CPFs-BP9 | Capability of stakeholders’ organizations | 5 | 3.510 | 0.594 | 0.702 | 0.932 | |

| CPFs-BP8 | BIM Institutional Environment | 6 | 3.498 | 0.539 | 0.699 | 0.921 | |

| CPFs-BP16 | Inter-organization communication | 7 | 3.493 | 0.517 | 0.699 | 0.931 | |

| CPFs-BP14 | Contract | 8 | 3.478 | 0.450 | 0.696 | 0.929 | |

| CPFs-BP7 | BIM economy | 9 | 3.475 | 0.439 | 0.695 | 0.918 | |

| CPFs-BP15 | Inter-organizational trust | 10 | 3.456 | 0.356 | 0.691 | 0.941 | |

| CPFs-BP11 | Stakeholders’ involvement | 11 | 3.448 | 0.317 | 0.690 | 0.915 | |

| CPFs-BP2 | Compatibility of BIM tools | 12 | 3.441 | 0.289 | 0.688 | 0.926 | |

| CPFs-BP13 | Inter-organization leadership | 13 | 3.434 | 0.256 | 0.687 | 0.927 | |

| CPFs-BP3 | Diversity of BIM application areas | 14 | 3.406 | 0.133 | 0.681 | 0.927 | |

| CPFs-BP12 | Organizations’ adaptability to changes | 15 | 3.386 | 0.044 | 0.678 | 0.94 | |

| CPFs-BP1 | Functionality of BIM tools | 16 | 3.380 | 0.017 | 0.676 | 0.894 | |

| CPFs-BP10 | Stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities | 17 | 3.376 | 0.000 | 0.675 | 0.931 |

Mean: mean value of statistics; NV: normalized value; RII: relative independence index (an indicator used to measure the independence between feature variables and sample label variables); Cronbach’s alpha is a parameter of the reliability of a scale or test; CPFs-BP: critical performance factors of BIM project; BIM: Building Information Modelling.

Admittedly, scads of research have already offered several statistical treatments to rank factors’ importance, generally including mean scores[29,65], NV[56], and RII[72], etc. However, it is partial to choose one method of ranking factors in most studies, thus the optimal way is to conduct rank analysis by multiple methods. Therefore, this study might yield two situations, including consistent rank analysis or conflicting rank results. As for the latter situation, it is reasonable that a factor ranked prior to another in any criteria is more critical, which is commensurate with a multi-objective optimization problem. A significant volume of statistical data requires an original processing style in order to improve decision-making power, insight finding, and process optimization skills. Table 3 provides the respective value of mean, NV, and RII. Results of RII analysis were greatly consistent with those of the others, saving more steps to correct the potential conflicting rank results. The reduction from 17 initial CPFs-BP to 7 principal factors was performed using network-parameter–based criteria. For each lifecycle subnetwork, degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and weighted interaction frequency were computed. Factors that consistently ranked in the top quartile across all stages were retained as principal CPFs-BP.

Moreover, previous studies assume that variables with an NV above 0.5 could be viewed as important factors[56]. At this point, the top seven CPFs-BP were obtained, including CPFS-BP5 (BIM accuracy), CPFS-BP17 (Information exchange), CPFS-BP6 (BIM usefulness), CPFS-BP4 (BIM quality), CPFS-BP9 (Capability of stakeholders’ organizations), CPFS-BP8 (BIM Institutional Environment), and

4.4 Network analysis

Previous analysis had revealed insights about BPP hinging on top seven CPFs-BP, while those statistical methods confront a formidable challenge in exploring the relation between project stages and the CPFs-BP, not least in visualization. Thus, complex network tools such as Gephi were used to shape the complex network of project (CNP) stages and CPFs-BP via network parameters as explained in Table 4.

| Parameters | Explanation |

| Network density | A proportion of potential connections to the actual ones. |

| Network diameter | The maximum shortest paths between any pair of nodes. |

| Average path length | The average distance of all node pairs. |

| Degree | The sum of links for a node. |

| Betweenness centrality | Measuring the times when a node lies on the shortest path between other node pairs. |

| Closeness centrality | Scoring each node’s closeness to the others in the network. |

| Authority and hub | Deciding which node has control over the network. |

| Page rank | Finding influential nodes whose reach extends beyond direct connections. |

| Eigenvector centrality | Indicating a strong influence over other nodes in the network. |

| Weighted degree | Summer the weight of links of one node. |

| Modularity class | Detect a group of nodes with similar traits and close relationships. |

To visualize complex network, project stages over the whole lifecycle are defined as project proposal (P1), feasibility study (P2), concept design (P3), construction documents design (P4), project bidding (P5), construction (P6), completion (P7), and operation and maintenance (P8). First, the global characteristics of CNP can be understood through three related parameters including network diameter (2), average path length (1.467), and network density (0.533). According to Sahoo et al.[73], normal network density is about 0.034 and far lower than that of CNP.

Six measurements are generally used to gauge node function and reveal the individual characteristics, namely degree, closeness centrality, betweenness centrality, authority, hub, and page rank. However, data results failed to differentiate the role of complex network nodes and instead classified the nodes into two explicit groups: project stages and CPFs-BP. Therefore, an additional three parameters were used to make up for this dysfunctional phenomenon, referring to the eigenvector centrality, weighted degree, and modularity class as described in Table 5.

| Label | Eigenvector centrality | Weighted degree | Modularity class |

| CPFS-BP5 | 0.386 | 28.81 | 1 |

| CPFS-BP17 | 0.382 | 28.55 | 0 |

| CPFS-BP6 | 0.379 | 28.36 | 2 |

| CPFS-BP4 | 0.377 | 28.17 | 0 |

| CPFS-BP9 | 0.375 | 28.08 | 2 |

| CPFS-BP8 | 0.374 | 27.98 | 0 |

| CPFS-BP16 | 0.373 | 27.94 | 0 |

| P6 | 0.382 | 26.77 | 1 |

| P4 | 0.379 | 26.6 | 2 |

| P8 | 0.359 | 25.18 | 2 |

| P3 | 0.356 | 24.97 | 0 |

| P7 | 0.355 | 24.88 | 0 |

| P5 | 0.354 | 24.8 | 0 |

| P2 | 0.324 | 22.7 | 0 |

| P1 | 0.314 | 21.99 | 0 |

Eigenvector centrality refer to a network parameter, which mainly measures the influence of a node in the network; Weighted degree refers to the sum of the weights of all edges associated with this node; Modularity class is a metric parameter of the network, used to measure the strength of the network divided into modules (or groups, clusters or communities); CPFs-BP: critical performance factors of BIM project.

The results of eigenvector centrality and weighted degree are consistent with statistical results. The study also shows that the construction stage (P6) has a more significant impact on BIM projects, followed by the construction document design stage (P4), operation/maintenance (P8), concept design (P3), completion (P7), project bidding (P5), feasibility study (P2), and project proposal (P1). Regarding network modularization, research also provides some clues about which nodes belong to the same community according to the modularity class given in Table 5.

Figure 4 shows the network visualization result. Figure 4 offers a clear picture modularized by Gephi, which has three colorized communities: purple nodes (P1, P2, P3, P5, P7, CPFs-BP4, CPFs-BP8, CPFs-BP16, and CPFs-BP17) in Community 1, green nodes (P6 and CPFs-BP5) in Community 2, and orange nodes (P4, P8, CPFs-BP6, and CPFs-BP9) in Community 3. For the other stages, Community 1 brings four relevant aspects together, including project quality, institutional environment, inter-organization communication, and information exchange. Community 2 indicates that practitioners should raise awareness of BIM accuracy, particularly in the construction process. Community 3 highlights the prominent importance of BIM usefulness and the capability of organizations in the construction document design and operation/maintenance stage. This step pinpointed that information exchange and

Figure 4. Network visualization by Gephi. CPFs-BP: critical performance factors of BIM project.

5. Predicting BPP

5.1 Survey II

Survey II was undertaken to predict BPP using the top seven CPFs-BP. The purpose of Survey II was to find the stages and ways to improve BPP by improving the contributions of participants at various project stages. In the previous part of this paper, the seven CPFs-BP and eight project stages were sorted according to the average and complex network parameters, and the specific weights of the CPFS-BP and project stages could be calculated; moreover, the interaction between CPFs-BP and project stages revealed ways to improve BPP, so the interaction weights were obtained by multiplication and sorted. In addition, this study summarizes three communities and seven node pairs, respectively, revealing the interaction between CPFs-BP and stages from a network perspective.

5.2 Data collection

The questionnaire consisted of five sections involving (1) respondents’ profiles, incorporating the same questions as Survey I;

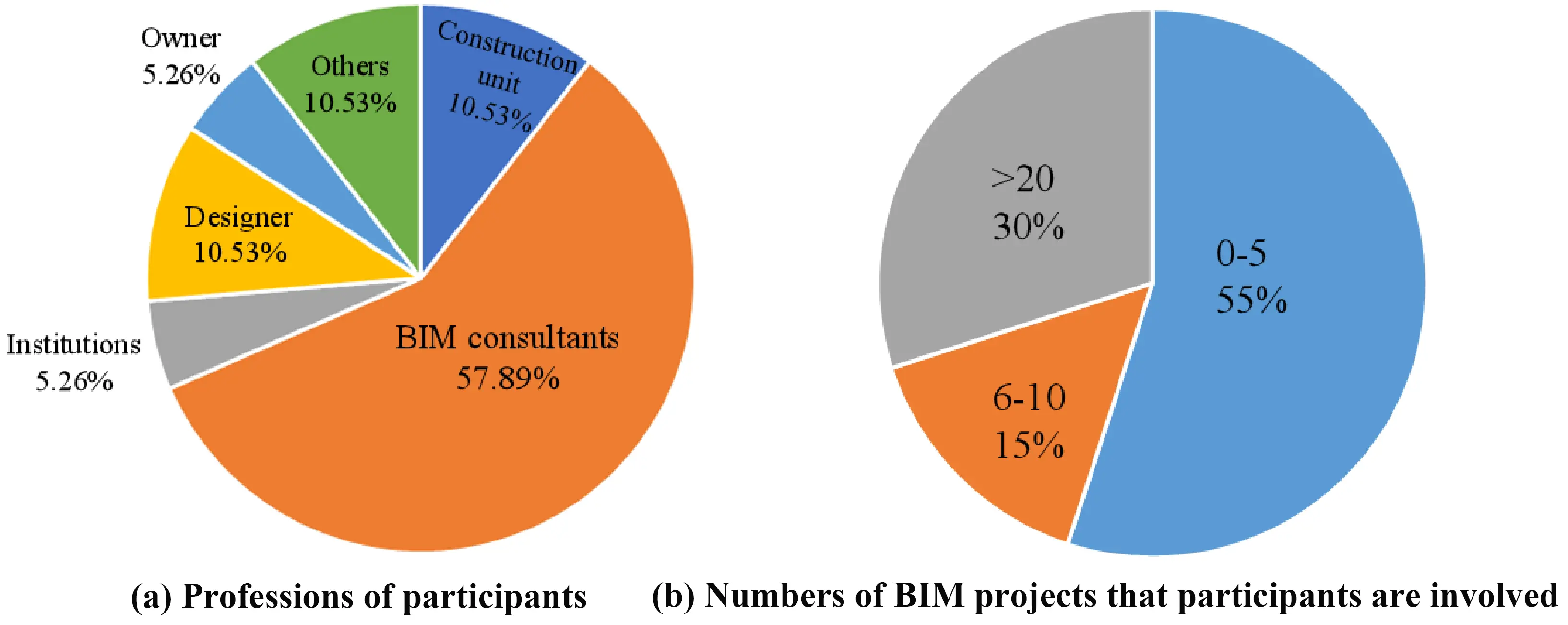

Before the survey, an interview attended by five academic professionals was conducted to collect suggestions and comments concerning the design of the initial questionnaire. Subsequently, the revised questionnaires were specifically sent to 20 experts, including three clients, six designers, five contractors, and six BIM consultants. All experts consulted were highly knowledgeable, having either more than 20 years of BIM-related experience or having participated for more than five years on BIM projects. Figure 5 shows the relevant details collected in Survey II, Part A.

Figure 5. Relevant details collected from Survey II. BIM: Building Information Modelling.

Here, a five-point Likert scale was adopted to gauge the three variables in eight project stages. As determined by SPSS25.0, the α of collected data was larger than 0.7, with a value of 0.973, showing high reliability of received responses.

5.3 Developing polynomial models

To proceed in the research, the Curve Fitting Toolbox in MATLAB R2021a was adopted to establish fifth-order polynomial models, which achieved the best fitness in predictive data analytics of this study among any other numerical techniques, such as splines, interpolation, and smoothing. Based on the least square method, polynomial curve fitting (polyfit) is an approach in mathematical modelling used to determine a function that is the best fit for a set of data points. A polynomial function with three variables was utilized in each fitting of this study. The three variables have been coded according to eight project stages as shown in Table 6. For instance, DP1 refers to the degree of BIM adoption in the stage of project proposal, C4P1 means the degree to which BIM models meet the project requirements in the stage of project proposal, and BP1 shows BPP in the current stage (P1).

| Project stages | The degree of BIM adoption | CPFs-BP’s performance | BPP |

| P1 | DP1 | Cn*P1 | BP1 |

| P2 | DP2 | Cn*P2 | BP2 |

| P3 | DP3 | Cn*P3 | BP3 |

| P4 | DP4 | Cn*P4 | BP4 |

| P5 | DP5 | Cn*P5 | BP5 |

| P6 | DP6 | Cn*P6 | BP6 |

| P7 | DP7 | Cn*P7 | BP7 |

| P8 | DP8 | Cn*P8 | BP8 |

Cn*: CPFS-BP4/CPFS-BP5/CPFS-BP6/CPFS-BP8/CPFS-BP9/CPFS-BP16/CPFS-BP17; DPj refers to the degree of BIM adoption in the stage Pj; CiPj means the degree to which BIM models reach the project requirements in Pj; BPj shows the comprehensive performance of BIM projects in Pj; CPFs-BP: critical performance factors of BIM project;

Therefore, a total of 56 groups of data sets, made up of seven CPFs-BP and eight project stages, were fitted, resulting in 56 3D figures and 56 groups of corresponding coefficients returned by MATLAB R2021a. The figures and coefficients have been given in

5.4 Model validation

Generally, three types of parameters are considered to justify the accuracy and efficiency of polynomial fitness. These include the coefficient of determination (R-square), adjusted R-square (adj R-square), and root mean square error (RMSE). RMSE is defined as the standard deviation of the residuals and is applied to verify the experimental results of prediction. The type and goodness of fit are shown in Table 7. In addition to R-square, adjusted R-square, and RMSE, two supplementary checks were performed to ensure model robustness. A 10-fold cross-validation showed that the testing RMSE values were consistent with those in Table 7, indicating that the polynomial models were not overfitted. A simple sensitivity analysis, conducted by varying each CPFs-BP input by ± 10-20%, further confirmed the numerical stability of model outputs. Polynomial orders from two to six were compared, and the fifth-order model was selected because it provided the best balance between fit quality and stability.

| Fit name | R-square | Adj R-square | RMSE | Fit name | R-square | Adj R-square | RMSE |

| CPFs-BP4-P1 | 0.999496 | 0.999495 | 0.023599 | CPFs-BP8-P5 | 0.999478 | 0.999477 | 0.04036 |

| CPFs-BP4-P2 | 0.996906 | 0.9969 | 0.05891 | CPFs-BP8-P6 | 0.999549 | 0.999548 | 0.02044 |

| CPFs-BP4-P3 | 0.999845 | 0.999845 | 0.01068 | CPFs-BP8-P7 | 0.998383 | 0.99838 | 0.032219 |

| CPFs-BP4-P4 | 0.999319 | 0.999318 | 0.012933 | CPFs-BP8-P8 | 0.997736 | 0.997732 | 0.051862 |

| CPFs-BP4-P5 | 0.999471 | 0.99947 | 0.03191 | CPFs-BP9-P1 | 0.999767 | 0.999766 | 0.014243 |

| CPFs-BP4-P6 | 0.999757 | 0.999757 | 0.012014 | CPFs-BP9-P2 | 0.999942 | 0.999942 | 0.137127 |

| CPFs-BP4-P7 | 0.994808 | 0.994797 | 0.082831 | CPFs-BP9-P3 | 0.999548 | 0.999547 | 0.023872 |

| CPFs-BP4-P8 | 0.999029 | 0.999028 | 0.051042 | CPFs-BP9-P4 | 0.999866 | 0.999865 | 0.013661 |

| CPFs-BP5-P1 | 0.999405 | 0.999404 | 0.028635 | CPFs-BP9-P5 | 0.999146 | 0.999145 | 0.023736 |

| CPFs-BP5-P2 | 0.999125 | 0.999123 | 0.454019 | CPFs-BP9-P6 | 0.999988 | 0.999988 | 0.080903 |

| CPFs-BP5-P3 | 0.999177 | 0.999175 | 0.038792 | CPFs-BP9-P7 | 0.999813 | 0.999812 | 0.046238 |

| CPFs-BP5-P4 | 0.999902 | 0.999902 | 0.013063 | CPFs-BP9-P8 | 0.999923 | 0.999923 | 0.049514 |

| CPFs-BP5-P5 | 0.996426 | 0.996419 | 0.052880 | CPFs-BP16-P1 | 0.999651 | 0.999651 | 0.026626 |

| CPFs-BP5-P6 | 0.999694 | 0.999694 | 0.025248 | CPFs-BP16-P2 | 0.999918 | 0.999918 | 0.193996 |

| CPFs-BP5-P7 | 0.999716 | 0.999716 | 0.051792 | CPFs-BP16-P3 | 0.999931 | 0.999931 | 0.069683 |

| CPFs-BP5-P8 | 0.998971 | 0.998969 | 0.048497 | CPFs-BP16-P4 | 0.999745 | 0.999744 | 0.019628 |

| CPFs-BP6-P1 | 0.999152 | 0.999150 | 0.025117 | CPFs-BP16-P5 | 0.99934 | 0.999339 | 0.028572 |

| CPFs-BP6-P2 | 0.999936 | 0.999936 | 0.108458 | CPFs-BP16-P6 | 0.99826 | 0.998256 | 0.034108 |

| CPFs-BP6-P3 | 0.996899 | 0.996892 | 0.052604 | CPFs-BP16-P7 | 0.999361 | 0.999359 | 0.027598 |

| CPFs-BP6-P4 | 0.999678 | 0.999677 | 0.016998 | CPFs-BP16-P8 | 0.99987 | 0.99987 | 0.062313 |

| CPFs-BP6-P5 | 0.999844 | 0.999844 | 0.026899 | CPFs-BP17-P1 | 0.999887 | 0.999886 | 0.055023 |

| CPFs-BP6-P6 | 0.999738 | 0.999737 | 0.011156 | CPFs-BP17-P2 | 0.999899 | 0.999899 | 0.221988 |

| CPFs-BP6-P7 | 0.999818 | 0.999818 | 0.024947 | CPFs-BP17-P3 | 0.999874 | 0.999873 | 0.014696 |

| CPFs-BP6-P8 | 0.999407 | 0.999406 | 0.045328 | CPFs-BP17-P4 | 0.999897 | 0.999897 | 0.071657 |

| CPFs-BP8-P1 | 0.996432 | 0.996425 | 0.053101 | CPFs-BP17-P5 | 0.995771 | 0.995762 | 0.042451 |

| CPFs-BP8-P2 | 0.999915 | 0.999915 | 0.226017 | CPFs-BP17-P6 | 0.999775 | 0.999774 | 0.018643 |

| CPFs-BP8-P3 | 0.999446 | 0.999445 | 0.019004 | CPFs-BP17-P7 | 0.999544 | 0.999543 | 0.04295 |

| CPFs-BP8-P4 | 0.999368 | 0.999397 | 0.016889 | CPFs-BP17-P8 | 0.999562 | 0.999391 | 0.062456 |

CPFs-BP: critical performance factors of BIM project; RMSE: root mean square error.

5.5 Selecting a BPP improvement approach

Based on the interaction weights of stages and performance factors from complex network analysis, the results of BPP improvement approach selection are shown in Table 8.

| Top CPFs-BP | Stage | Rank result | Top CPFs-BP | Stage | Rank result | ||

| CPFs-BP5 | P6 | 0.019737 | CPFs-BP16 | P3 | 0.017782 | ||

| CPFs-BP6 | P6 | 0.019379 | CPFs-BP8 | P7 | 0.017773 | ||

| CPFs-BP6 | P4 | 0.019242 | CPFs-BP9 | P5 | 0.017766 | ||

| CPFs-BP9 | P4 | 0.019039 | CPFs-BP16 | P7 | 0.017725 | ||

| CPFs-BP5 | P3 | 0.018402 | CPFs-BP8 | P5 | 0.017719 | ||

| CPFs-BP5 | P7 | 0.018343 | CPFs-BP16 | P5 | 0.017672 | ||

| CPFs-BP5 | P5 | 0.018288 | CPFs-BP5 | P2 | 0.016738 | ||

| CPFs-BP6 | P8 | 0.018220 | CPFs-BP17 | P2 | 0.016565 | ||

| CPFs-BP17 | P3 | 0.018211 | CPFs-BP6 | P2 | 0.016435 | ||

| CPFs-BP17 | P7 | 0.018153 | CPFs-BP4 | P2 | 0.016348 | ||

| CPFs-BP4 | P8 | 0.018124 | CPFs-BP9 | P2 | 0.016261 | ||

| CPFs-BP17 | P5 | 0.018098 | CPFs-BP5 | P1 | 0.016218 | ||

| CPFs-BP9 | P8 | 0.018028 | CPFs-BP8 | P2 | 0.016218 | ||

| CPFs-BP6 | P7 | 0.018010 | CPFs-BP16 | P2 | 0.016175 | ||

| CPFs-BP4 | P3 | 0.017973 | CPFs-BP17 | P1 | 0.016050 | ||

| CPFs-BP6 | P5 | 0.017956 | CPFs-BP6 | P1 | 0.015924 | ||

| CPFs-BP4 | P7 | 0.017915 | CPFs-BP4 | P1 | 0.015840 | ||

| CPFs-BP9 | P3 | 0.017878 | CPFs-BP9 | P1 | 0.015756 | ||

| CPFs-BP4 | P5 | 0.017861 | CPFs-BP8 | P1 | 0.015714 | ||

| CPFs-BP8 | P3 | 0.017830 | CPFs-BP16 | P1 | 0.015672 | ||

| CPFs-BP9 | P7 | 0.017820 | |||||

BPP: BIM project performance; CPFs-BP: critical performance factors of BIM project.

From the results in the first and last rows of Table 8, it can be seen that improving the accuracy of BIM (CPFs-BP5) at the construction stage (P6) was the best way to improve BPP. The stage with the lowest BPP was the project proposal stage (P1), in which it is not advisable to carry out inter-organizational communication (CPFs-BP16). The value of BIM technology in the construction stage was mainly reflected in accuracy, visualization, and high efficiency. BIM accuracy is a factor linked to the deviation between contracts/documents and actual records, and compromises geometric accuracy evaluated in the construction stage[74]. Faultless BIM models can help decrease the intricacy of projects and result in higher user satisfaction.

In addition, Table 8 shows that the BPP improvement mainly falls in the design stage (P4) and construction stage (P6); while the entire project proposal stage (P1) and feasibility study stage (P2) are not beneficial to BPP. This finding reminds decision-makers to grasp the effective timing in the process of carrying out BIM projects.

6. Discussion

6.1 Specific improvement approach

Derived from Table 8, five additional BPP improvement approaches were chosen by the results of weight ranking, Gephi modularization, and maximum matching, including CPFs-BP9 in P4, CPFs-BP5 in P7, CPFs-BP16 in P3, CPFs-BP8 in P5, and CPFs-BP17 in P2. The first path (CPFs-BP9 in P4) argues for the attention of stakeholders in BIM projects to address their BIM capabilities or competency, particularly during the stage of construction document design, because subtle design errors can have a significant negative impact on project performance. To boost BIM capability, major stakeholders can enrich their understanding of BIM with reference to technology, staff experience, usability, exhaustive use requirements, and deliverable evaluation[17]. Then, it will be much easier to evaluate the functioning of the degree of BIM adoption and CPFs-BP9, which helps predict and calculate project performance via the polynomial function in Stage 2.

Another path (CPFs-BP5 in P7) reminds practitioners and researchers of focusing on ensuring accurate BIM models when delivering projects. Existing research mainly emphasizes BIM models in the design and construction stages and ignores verification of differences between models and physical conditions in post-construction stages. Similar to an analysis of the optimal path

The third path (CPFs-BP16 in P3) emphasizes the importance of inter-organization communication in the concept design stage. Generally prepared by owners, designers, or BIM consultants, concept drawings comprise much precious information, such as cost and schedule estimates, equipment plot plans, and building layouts[75]. Therefore, patiently shaping consensus on BIM models is necessary for designers and others to adapt to ever-changing conditions/data due to complex interaction[76], and to prevent design deficiency[77]. Two critical elements found to promote inter-organization communication include mature and transparent BIM implementation and integrated teams[53]. Overall, it should be noted that further research into this path is required to predict BPP more accurately, particularly as it refers to effective improvements and quantitative evaluation of communication.

Additional reasonable paths (CPFs-BP8 in P5) show the close connection between the BIM institutional environment and the project bidding process. BIM technology is applied to gain effective cost management from the owners’ perspective at the project bidding stage, where contractors may encounter intense competition to deliver BIM models that are as accurate as possible[78]. Successful BIM models must be in line with the content of the institutional environment, which consists of industry standards and technical needs, policy and regulations, and organizational rules[32].

BIM models have been regarded as useful platforms for information sharing that provide services for project stakeholders, especially in the design and construction stages. Thus, the underappreciated path (CPFs-BP 17 in P2), despite a low ranking of interactive weight, discovers the neglected fact that effective information exchange is valuable to feasibility studies. As suggested by

6.2 BPP improvement in the top seven CPFs-BP

A growing interest in BIM adoption has promoted remarkable research into diverse areas. This study develops quantified improve approach of BPP, considering the degree of BIM adoption and the seven top CPFs-BP over the project lifecycle. The most effective way for major stakeholders is to pay more attention to improve BIM model accuracy at the construction stage. Interestingly, three special optimization paths were detected through multiple views of interactive weight, modularization results and maximum matching results by Gephi. Specifically, project stakeholders need to raise concerns about the capabilities of stakeholder’s organizations in designing construction documents, BIM accuracy in the completion stage, inter-organization communication in concept design, the BIM institutional environment in project bidding, and information exchange in feasibility studies.

BIM accuracy refers to how precisely the BIM reflects the physical real-world conditions of a project, i.e., how closely the BIM’s geometry/data represents as-built conditions in the field. Quantity takeoff accuracy, discrepancies between each discipline’s models, average number of generic objects per assembly, and constructability (i.e., the ability to construct from the model) are able to jointly depict BIM accuracy[13]. Many studies have pointed out that cooperation is closely related to project performance, and frequent information exchange is the basic element of cooperation[1]. BIM usefulness refers to how useful the model information and geometry are over the project lifecycle. Some variables to measure this might be how often the model is accessed for different purposes, ease of construction documentation creation, and reliability of model data for end users during operation and maintenance (i.e., how reliable data extracted from the model is)[13]. BIM quality refers to how well a BIM fulfills desired requirements. Liu et al.[4] offered some detailed metrics, including the ratio of number of warnings to number of objects, criticality of warnings (some warnings are more critical than others; e.g., a warning related to a column is more critical than that of a door), consistency of 3D model and 2D references (i.e., number of errors in reference to 2D deliverables), and analytical reporting quality (structural analysis quality, day lighting simulation report quality, energy simulation report quality, etc.).Organizational competitive capability includes competency of individual stakeholders, capability and maturity of architecture, engineering, construction, and operation (AECO) organizations, and maturity of using BIM technology and workflows[6]. These core objectives are to facilitate AECO stakeholders in the successful delivery of BIM projects. Lack of BIM knowledge among team members leads to the disadvantage of BIM adoption[33]. BIM Institutional Environment refers to the regulatory system formed by BIM-related standards and technical requirements, organizational rules and requirements, and policy and legal issues to ensure BIM implementation within the project context[32]. An institutional environment within a BIM-based project is required to facilitate BIM governance and ensure collaborative working among project teams[32]. In addition, Lee et al.[5] argued that inter-organizational trust may influence the effect of joint-contract functions on project performance. Inter-organizational trust is a firm’s expectation that another firm will not behave opportunistically.

The dominance of specific CPFs-BP at particular stages can be explained by the functional needs of each life-cycle phase. Stakeholder capability (CPFs-BP9) becomes critical during construction document design because modeling quality relies heavily on organizational competence. BIM accuracy (CPFs-BP5) is most influential in the completion stage, where as-built verification determines project outcomes. Communication (CPFs-BP16) and information exchange (CPFs-BP17) are essential during conceptual design and feasibility studies, as early coordination shapes subsequent decisions. The BIM institutional environment (CPFs-BP8) has a greater impact during bidding because standards and regulations directly guide model requirements.

These findings align with previous studies emphasizing BIM accuracy, organizational competency, and inter-organizational communication as critical factors for project performance[74,82-84]. While the survey data mostly represent Chinese AEC projects, the fundamental principles are likely to apply across locations and project types, as long as the local institutional environment, stakeholder capabilities, and project scale are properly recognized.

More importantly, the most distinctive finding of this study is that BIM-enabled project performance improvement does not rely solely on the most highly weighted CPFs-BP, but rather on a set of stage-specific and sometimes underappreciated improvement paths identified through complex network analysis. Unlike prior studies that primarily rank critical factors based on overall importance or frequency, this study integrates interactive weight analysis, modularization, and maximum matching to reveal how specific CPFs-BP exert dominant influence at particular life-cycle stages.

7. Conclusion and Recommendations

Growing interest in BIM applications has spurred ground-breaking research in various fields, including CPFs-BP identification and BPP improvement. This study determined seven principal CPFs-BP by both statistical analysis and complex network analysis, quantified and illustrated the connections between CPFs-BP and life-cycle stages, and developed models of BPP prediction and approaches of BPP improvement. In summary, this study developed a unique methodology to predict and improve BPP based on complex networks and polynomial models, i.e., identifying at which stage BPP may be improved.

Remarkably, the manuscript finds interesting conclusions using different interactive weight views. In particular, stakeholders in BIM projects should pay attention to 5 matching results: Capability of stakeholders’ organizations (CPFs-BP9) in the project proposal

The findings of this study have important policy implications for both governmental and organizational decision-making in the AEC industry. Policymakers can improve BIM adoption and project performance by highlighting crucial CPFs-BP and their impact at various stages of the project. Nonetheless, the study has limitations, such as a sample drawn mostly from China and an emphasis on large-scale projects, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. To improve practical applicability, future research could extend this framework to other geographies and project types, incorporate other CPFs-BP, and evaluate the prediction and improvement models using longitudinal case studies.

Supplementary materials

The supplementary material for this article is available at: Supplementary materials.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank all the interviewees for taking the time to participate in the interviews; their cooperation and friendly attitude played a crucial role in the successful completion of this study.

Authors contribution

Yang L: Writing-review & editing, visualization, methodology, formal analysis, conceptualization.

Hu X: Writing-original draft, visualization, methodology, data curation.

Zhao X: Writing-review & editing, validation, supervision.

Conflicts of interest

Xianbo Zhao is an Editorial Board Member of Journal of Building Design and Environment. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study involved voluntary participation of professionals through anonymous questionnaires. According to institutional guidelines, formal ethical approval was not required.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data and models generated and used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This research was supported by Hubei Provincial Science and Technology Key Project under Grant 2023BAA007.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025.

References

-

1. Tang X, Chong HY, Zhang W. Relationship between BIM implementation and performance of OSM projects. J Manag Eng. 2019;35(5):04019019.[DOI]

-

2. Oraee M, Hosseini MR, Edwards DJ, Li H, Papadonikolaki E, Cao D. Collaboration barriers in BIM-based construction networks: A conceptual model. Int J Proj Manag. 2019;37(6):839-854.[DOI]

-

3. Won J, Lee G. How to tell if a BIM project is successful: A goal-driven approach. Autom Constr. 2016;69:34-43.[DOI]

-

4. Liu Y, van Nederveen S, Hertogh M. Understanding effects of BIM on collaborative design and construction: An empirical study in China. Int J Proj Manag. 2017;35(4):686-698.[DOI]

-

5. Lee CY, Chong HY, Li Q, Wang X. Joint contract–function effects on BIM-enabled EPC project performance. J Constr Eng Manag. 2020;146(3):04020008.[DOI]

-

6. Hossain M, Abbott ELS, Chileshe N, Zuo J. Lifecycle BIM adoption factors in construction projects: A multi-level analysis. Build Environ. 2022;214.[DOI]

-

7. Abdirad H. Metric-based BIM implementation assessment: A review of research and practice. Arch Eng Des Manag. 2017;13(1):52-78.[DOI]

-

8. Habibnezhad M, Puckett J, Jebelli H, Karji A, Fardhosseini MS, Asadi S. Neurophysiological testing for assessing construction workers’ task performance at virtual height. Automat Constr. 2020;113:103143.[DOI]

-

9. Troiani E, Mahamadu AM, Manu P, Kissi E, Aigbavboa C, Oti A. Macro-maturity factors and their influence on micro-level BIM implementation within design firms in italy. Arch Eng Des Manag. 2020;16(3):209-226.[DOI]

-

10. Franz B, Leicht R, Molenaar K, Messner J. Impact of team integration and group cohesion on project delivery performance. J Constr Eng Manag. 2017;143(1):04016088.[DOI]

-

11. Hu X, Chen, Y. Impact of BIM on project performance. In: Proceedings of the 2023 European Conference on Computing in Construction and the 40th International CIB W78 Conference; 2023 Jul 10-12; Heraklion, Greece. Heraklion: European Council on Computing in Construction (EC3); 2023.[DOI]

-

12. Hwang BG, Zhao X, Yang KW. Effect of BIM on rework in construction projects in Singapore: Status quo, magnitude, impact, and strategies. J Constr Eng Manag. 2019;145(2):04018125.[DOI]

-

13. Liu R, Du J, Issa RRA, Giel B. BIM cloud score: Building information model and modeling performance benchmarking. J Constr Eng Manag. 2017;143(4):04016109.[DOI]

-

14. Badrinath AC, Hsieh SH. Empirical approach to identify operational critical success factors for BIM projects. J Constr Eng Manag. 2019;145(3):04018140.[DOI]

-

15. Ma P, Zhang S, Hua Y, Zhang J. Behavioral perspective on BIM postadoption in construction organizations. J Manag Eng. 2020;36(1):04019036.[DOI]

-

16. Celoza A, Leite F, de Oliveira DP. Impact of BIM-related contract factors on project performance. J Leg Aff Disput Resolut Eng Constr. 2021;13(3):04521011.[DOI]

-

17. Giel BK, Mayo G, Issa RRA. BIM use and requirements among building owners. In: Issa RRA, Olbina S, editors. Building information modeling. Reston: ASCE; 2015. p. 255-277.

-

18. Das K, Khursheed S, Paul VK. The impact of BIM on project time and cost: Insights from case studies. Discov Mater. 2025;5(1):25.[DOI]

-

19. Cao D, Li H, Wang G, Luo X, Tan D. Relationship network structure and organizational competitiveness: Evidence from BIM implementation practices in the construction industry. J Manag Eng. 2018;34(3):04018005.[DOI]

-

20. Franz B, Messner J. Evaluating the impact of building information modeling on project performance. J Comput Civ Eng. 2019;33(3):04019015.[DOI]

-

21. Giel B, Issa RRA. Framework for evaluating the BIM competencies of facility owners. J Manag Eng. 2016;32(1):04015024.[DOI]

-

22. Yuan J, Li X, Ke Y, Xu W, Xu Z, Skibnewski M. Developing a building information modeling–based performance management system for public–private partnerships. Eng Constr Archit Manag. 2020;27(8):1727-1762.[DOI]

-

23. Ma X, Chan APC, Li Y, Zhang B, Xiong F. Critical strategies for enhancing BIM implementation in AEC projects: Perspectives from chinese practitioners. J Constr Eng Manag. 2020;146(2):05019019.[DOI]

-

24. Van Tam N, Quoc Toan N, Phong VV, Durdyev S. Impact of BIM-related factors affecting construction project performance. Int J Build Pathol Adapt. 2021;41(2):454-475.[DOI]

-

25. Han X, Feng Y, Hou L, Wei L. Analysis on the BIM application in the whole life cycle of railway engineering. In: Zhai, W, Wang KCP, editors. ICRT 2017: Railway development, operations, and maintenance (Proceedings of the First International Conference on Rail Transportation 2017); Jul 10-12; Chengdu, China. Reston: ASCE; 2017. p. 331-338.[DOI]

-

26. Luo L, Yan Z, Yang D, Xie J, Wu G. BIM application in the whole life cycle of construction projects in China. In: Shane JS, Madson KM, Mo Y, Poleacovschi C, Sturgill Jr RE, editors. Construction research congress. Reston: ASCE; 2018. p. 189-197.[DOI]

-

27. Korpela J, Miettinen R, Salmikivi T, Ihalainen J. The challenges and potentials of utilizing building information modelling in facility management: The case of the Center for Properties and Facilities of the University of Helsinki. Constr Manag Econ. 2015;33(1):3-17.[DOI]

-

28. Ozturk GB. Interoperability in building information modeling for AECO/FM industry. Autom Constr. 2020;113:103122.[DOI]

-

29. Ma X, Darko A, Chan APC, Wang R, Zhang B. An empirical analysis of barriers to building information modelling (BIM) implementation in construction projects: Evidence from the Chinese context. Int J Constr Manag. 2022;22(16):3119-3127.[DOI]

-

30. Liao L, Teo EAL, Li L, Zhao X, Wu G. Reducing non-value-adding BIM implementation activities for building projects in Singapore: Leading causes. J Manag Eng. 2021;37(3):05021003.[DOI]

-

31. Lee J, Ahn Y, Lee S. Post-handover defect risk profile of residential buildings using loss distribution approach. J Manag Eng. 2020;36(4):04020021.[DOI]

-

32. Ma X, Xiong F, Olawumi TO, Dong N, Chan APC. Conceptual framework and roadmap approach for integrating BIM into lifecycle project management. J Manag Eng. 2018;34(6):05018011.[DOI]

-

33. Kassem M, Kelly G, Dawood N, Serginson M, Lockley S. BIM in facilities management applications: A case study of a large university complex. Built Environ Proj Asset Manag. 2015;5(3):261-277.[DOI]

-

34. Sacks R, Bloch T, Katz M, Yosef R. Automating design review with artificial intelligence and BIM: State of the art and research framework. In: Cho YK, Leite F, Behzadan A, Wang C, editors. Computing in civil engineering 2019. ASCE International Conference on Computing in Civil Engineering 2019; 2019 Jun 17-19; Atlanta, Georgia. Reston: ASCE; 2019. p. 353-360.[DOI]

-

35. Daoud AO, Oke AE, Singh AK, Famakin IO, Abdel Aziz KM, Olayemi TM. Exploring the building information modelling benefits for sustainable construction using PLS-SEM. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):35781.[DOI]

-

36. Marinho A, Couto J, Teixeira J. Relational contracting and its combination with the BIM methodology in mitigating asymmetric information problems in construction projects. J Civ Eng Manag. 2021;27(4):217-229.[DOI]

-

37. Lee CY, Chong HY, Wang X. Enhancing BIM performance in EPC projects through integrative trust-based functional contracting model. J Constr Eng Manag. 2018;144(7):06018002.[DOI]

-

38. Chen Y, John D, Cox RF. Qualitatively exploring the impact of BIM on construction performance. In: Wang Y, Zhu Y, Shen GQP, Al-Hussein M, editors. ICCREM 2018: Innovative technology and intelligent construction (Proceedings of the International Conference on Construction and Real Estate Management 2018); 2018 Aug 09-10, Charleston, USA. Reston: ASCE; 2018. p. 60-71.[DOI]

-

39. Zoghi M, Lee D, Kim S. A computational simulation model for assessing social performance of BIM implementations in construction projects. J Comput Des Eng. 2021;8(2):799-811.[DOI]

-

40. Du J, Liu R, Issa RRA. BIM cloud score: Benchmarking BIM performance. J Constr Eng Manag. 2014;140(11):04014054.[DOI]

-

41. Zhao X, Tang L, Zhang L. Digital transformation in construction: A systematic review focusing on BIM-driven practices. Autom Constr. 2021;130:103845.[DOI]

-

42. Chen F, Liu Y. Innovation performance study on the construction safety of urban subway engineering based on bayesian network: A case study of BIM innovation project. J Appl Sci Eng. 2015;18(3):233-244.[DOI]

-

43. He N, Li Y, Li H, Liu Z, Zhang C. Critical factors to achieve sustainability of public-private partnership projects in the water sector: A stakeholder-oriented network perspective. Complexity. 2020;2020(1):8895980.[DOI]

-

44. Lu W, Chen K, Chang R, Li H. Examining the influence of BIM capability on construction firms’ performance: Evidence from China. J Manag Eng. 2020;36(1):05019011.[DOI]

-

45. Wu G, Qiang G, Zuo J, Zhao X, Chang R. What are the key indicators of mega sustainable construction projects? —A stakeholder-network perspective. Sustainability. 2018;10(8):2939.[DOI]

-

46. Blum N. Maximum matching in general graphs without explicit consideration of blossoms revisited. ArXiv: 1509.04927 [Preprint]. 2015.[DOI]

-

47. Lee CY, Chong HY. Influence of prior ties on trust and contract functions for BIM-enabled EPC megaproject performance. J Constr Eng Manag. 2021;147(7):04021057.[DOI]

-

48. Li Y, Sun H, Li D, Song J, Ding R. Effects of digital technology adoption on sustainability performance in construction projects: The mediating role of stakeholder collaboration. J Manag Eng. 2022;38(3):04022016.[DOI]

-

49. Liu T, Chong HY, Zhang W, Lee CY, Tang X. Effects of contractual and relational governances on BIM collaboration and implementation for project performance improvement. J Constr Eng Manag. 2022;148(6):04022029.[DOI]

-

50. Ahankoob A, Abbasnejad B, Wong PSP. The support of continuous information flow through building information modeling (BIM). In: Chaari F, Gherardini F, Ivanov V, Haddar M, editors. Lecture notes in mechanical engineering. Singapore: Springer; 2020. p. 125-137.[DOI]

-

51. Awwad KA, Shibani A, Ghostin M. Exploring the critical success factors influencing BIM level 2 implementation in the UK construction industry: The case of SMEs. Int J Constr Manag. 2022;22(10):1894-1901.[DOI]

-

52. Fotsing C, Menadjou N, Bobda C. Iterative closest point for accurate plane detection in unorganized point clouds. Autom Constr. 2021;125:103610.[DOI]

-

53. Alsulamy W, Rezgui Y, Li H. Exploring the influence of organisational culture on BIM adoption: Case studies from the UK construction industry. Eng Constr Archit Manag. 2020;27(6):1437-1459.

-

54. Faisal Shehzad HM, Binti Ibrahim R, Yusof AF, Khaidzir KAM, Shawkat S, Ahmad S. Recent developments of BIM adoption based on categorization, identification and factors: A systematic literature review. Int J Constr Manag. 2022;22(15):3001-3013.[DOI]

-

55. Ghaffarianhoseini A, Tookey J, Ghaffarianhoseini A, Naismith N, Azhar S, Efimova O, et al. Building information modelling (BIM) uptake: Clear benefits, understanding its implementation, risks and challenges. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;75:1046-1053.[DOI]

-

56. Liao L, Teo EAL. Organizational change perspective on people management in BIM implementation in building projects. J Manag Eng. 2018;34(3):04018008.[DOI]

-

57. Wang J, Chen D, Zhu M, Sun Y. Risk assessment for musculoskeletal disorders based on the characteristics of work posture. Autom Constr. 2021;131:103921.[DOI]

-

58. Morlhon R, Pellerin R, Bourgault M. Building information modeling implementation through maturity evaluation and critical success factors management. Procedia Technol. 2014;16:1126-1134.[DOI]

-

59. Ozorhon B, Karahan U. Critical success factors of building information modeling implementation. J Manag Eng. 2017;33(3):04016054.[DOI]

-

60. Alreshidi E, Mourshed M, Rezgui Y. Factors for effective BIM governance. J Build Eng. 2017;10:89-101.[DOI]

-

61. Walasek D, Barszcz A. Analysis of the adoption rate of building information modeling [BIM] and its return on investment [ROI]. Procedia Eng. 2017;172:1227-1234.[DOI]

-

62. Antwi-Afari MF, Li H, Pärn EA, Edwards DJ. Critical success factors for implementing building information modelling (BIM): A longitudinal review. Autom Constr. 2018;91:100-110.[DOI]

-

63. Charef R, Emmitt S, Alaka H, Fouchal F. Building information modelling adoption in the european union: An overview. J Build Eng. 2019;25:100777.[DOI]

-

64. Mellado F, Lou ECW. Building information modelling, lean and sustainability: An integration framework to promote performance improvements in the construction industry. Sustain Cities Soc. 2020;61:102355.[DOI]

-

65. Belay S, Goedert J, Woldesenbet A, Rokooei S. Enhancing BIM implementation in the Ethiopian public construction sector: An empirical study. Cogent Eng. 2021;8(1):1886476.[DOI]

-

66. Van Tam N, Diep TN, Quoc Toan N, Le Dinh Quy N. Factors affecting adoption of building information modeling in construction projects: A case of Vietnam. Cogent Bus Manag. 2021;8(1):1918848.[DOI]

-

67. Olanrewaju OI, Kineber AF, Chileshe N, Edwards DJ. Modelling the relationship between building information modelling (BIM) implementation barriers, usage and awareness on building project lifecycle. Build Environ. 2022;207:108556.[DOI]

-

68. Phang TCH, Chen C, Tiong RLK. New model for identifying critical success factors influencing BIM adoption from precast concrete manufacturers’ view. J Constr Eng Manag. 2020;146(4):04020014.[DOI]

-

69. de Brito DM, de Andrade Marques Ferreira E, Bastos Costa D. Framework for building information modeling adoption based on critical success factors from brazilian public organizations. J Constr Eng Manag. 2021;147(7):05021004.[DOI]

-

70. Le Y, Zhang X, Liu M. Study on influencing factors of BIM adoption in China’s construction industry based on FA-SEM model. In: ICCREM 2019: Innovative construction project management and construction industrialization. International Conference on Construction and Real Estate Management (ICCREM 2019); 2019 May 21-24; Banff Alberta, Canada. Reston: ASCE; 2019. p. 93-100.[DOI]

-

71. Liu Y, Wang X, Wang D. How leaders and coworkers affect construction workers’ safety behavior: An integrative perspective. J Constr Eng Manag. 2021;147(12):04021176.[DOI]

-

72. Gunduz M, Abdi EA. Motivational factors and challenges of cooperative partnerships between contractors in the construction industry. J Manag Eng. 2020;36(4):04020018.[DOI]

-

73. Motamedi A, Hammad A, Asen Y. Knowledge-assisted BIM-based visual analytics for failure root cause detection in facilities management. Autom Constr. 2014;43:73-83.[DOI]

-

74. Jiang H, Cui Z, Yin H, Yang Z. BIM performance, project complexity, and user satisfaction: A QCA study of 39 cases. Adv Civil Eng. 2021;2021(1):6654851.[DOI]

-

75. El-Reedy M A. Engineering management. In: El-Reedy M A, editor. Onshore structural design calculations. Amsterdam: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2017. p. 1-12.

-

76. Taghizadeh K, Alizadeh M, Roushan TY. Cooperative game theory solution to design liability assignment issues in BIM projects. J Constr Eng Manag. 2021;147(9):04021103.[DOI]

-

77. Koo HJ, O’Connor JT. Building information modeling as a tool for prevention of design defects. Constr Innov. 2021;22(4):870-890.[DOI]

-

78. Attarzadeh M, Nath T, Tiong RLK. Identifying key factors for building information modelling adoption in Singapore. Proc Inst Civ Eng Manag Procure Law. 2015;168(5):220-231.[DOI]

-

79. Che Ibrahim CKI, Mohamad Sabri NA, Belayutham S, Mahamadu A. Exploring behavioural factors for information sharing in BIM projects in the Malaysian construction industry. Built Environ Proj Asset Manag. 2018;9(1):15-28.[DOI]

-

80. Ahn E, Kim M. BIM awareness and acceptance by architecture students in Asia. J Asian Archit Build Eng. 2016;15(3):419-424.[DOI]

-

81. Aka A, Iji J, Isa RB, Bamgbade AA. Assessing the relationships between underlying strategies for effective building information modeling (BIM) implementation in Nigeria construction industry. Archit Eng Des Manag. 2021;17(5-6):434-446.[DOI]

-

82. Hosseini MR, Pärn EA, Edwards DJ, Papadonikolaki E, Oraee M. Roadmap to mature BIM use in Australian SMEs: Competitive dynamics perspective. J Manag Eng. 2018;34(5):05018008.[DOI]

-

83. Jallow AS, Wu Y, Evangelista A. BIM adoption in facilities management: A review and future research directions. J Facil Manag. 2022;20(3):451-473.[DOI]

-

84. Khanzadi M, Sheikhkhoshkar M, Banihashemi S. BIM applications toward key performance indicators of construction projects in Iran. Int J Constr Manag. 2020;20(4):305-320.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2025. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite