Abstract

Solid waste generation from industrial production and construction activities has increased sharply in recent years. Improper disposal and abandonment of solid waste have led to significant resource loss and pose serious risks to soil, water, and air quality. As a result, incorporating solid waste into concrete production presents a promising strategy to reduce environmental pressure and promote sustainable development. This review investigates the feasibility and performance of various solid waste materials, such as fly ash, limestone powder, stone sludge, silica fume, waste glass, rubber particles, and recycled concrete sand, that are incorporated into 3D printed concrete (3DPC). These materials demonstrate the potential to enhance rheological behavior, mechanical strength, interfacial bonding, and dimensional stability of printable composites. Additionally, their incorporation reduces carbon emissions, diverts waste from landfills, and promotes resource circularity. The benefits and limitations of solid waste are critically evaluated, including printability challenges arising from particle morphology and water absorption. The review emphasizes the need for standardized cost-effectiveness analysis frameworks to quantify economic and environmental balance. Finally, this study highlights the importance of optimizing mix design, surface treatment techniques, and large-scale production strategies to enable widespread adoption of waste-based 3DPC in sustainable construction.

Keywords

1. Introduction

3D printed concrete (3DPC) represents a nascent digital construction technology that fabricates cementitious structures through automated layer-by-layer extrusion without formwork[1,2]. Compared to traditional casting, 3DPC eliminates the need for conventional formwork and manual labor, offering greater freedom in architectural design, improved material efficiency, and enhanced construction automation[3,4]. Depending on the construction scenario and printer system, 3DPC is implemented in several forms, which include component prefabrication, continuous layer-wise construction, and printing of reusable molds to assist cast work[5]. Each method offers distinct advantages in speed, design flexibility, and material usage[6]. For instance, prefabrication improves quality control and repeatability, while onsite printing reduces transportation costs and supports large-scale integrated construction[7]. The flexibility of 3DPC allows for faster project delivery, reduced labor dependency, and precise execution of geometrically complex designs[8,9].

However, industrial development remains one of the largest contributors to environmental degradation[10,11]. The construction industry produces massive amounts of solid waste and contributes to global carbon dioxide emissions exceeding 5%[12]. Cement manufacturing, a resource-heavy and energy-demanding process, leads to significant greenhouse gas emissions[13]. As global solid waste production is projected to hit 3.4 billion tons by 2050, sustainable and low-carbon construction practices are urgently needed[14]. Therefore, the effective utilization of solid waste as alternative raw materials in concrete is no longer optional but essential for achieving environmental and resource sustainability in future construction.

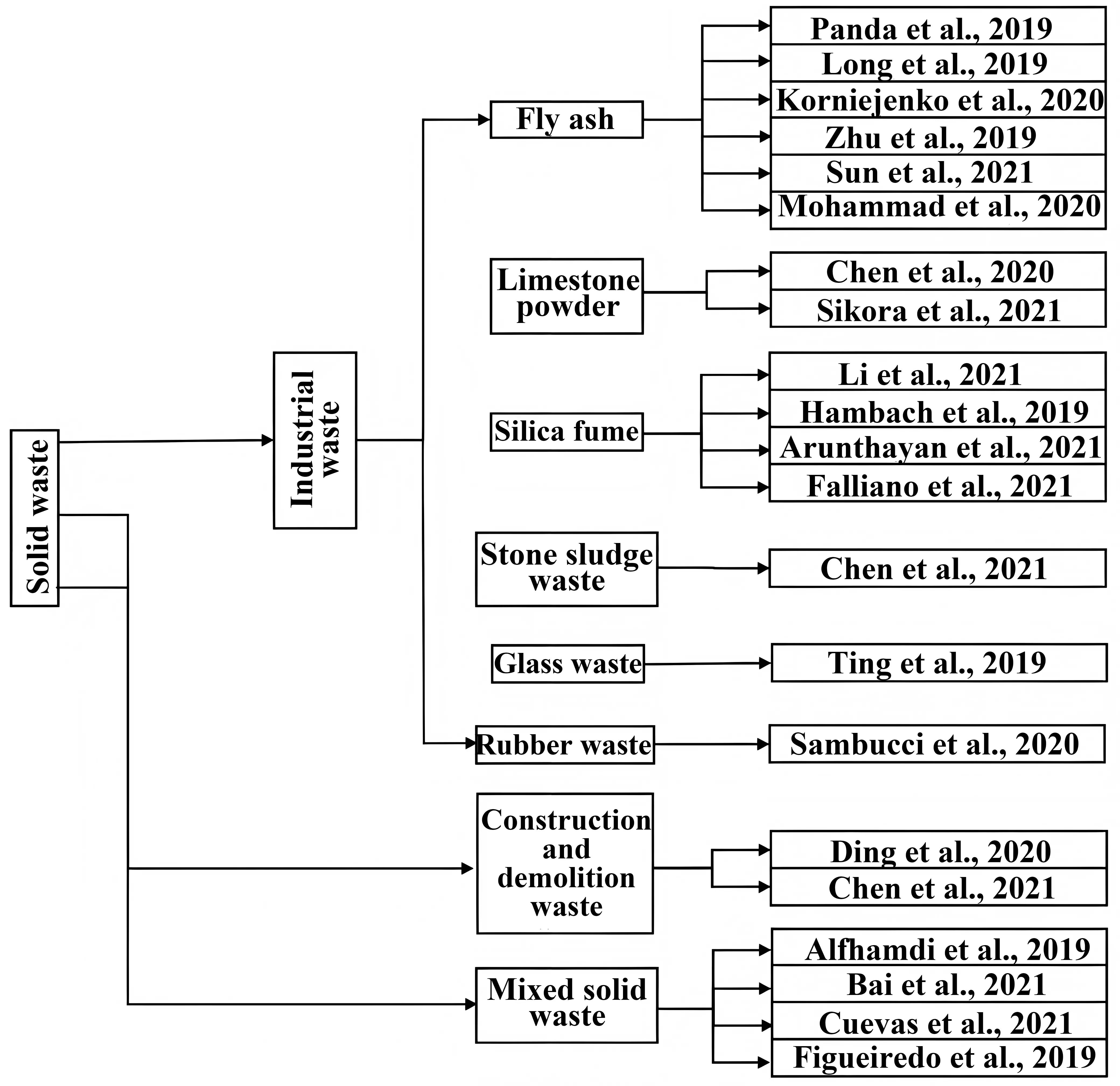

3DPC provides a potential solution to the above challenges by facilitating the recycling of solid waste materials in printed concrete. Examples of recyclable material include ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS)[15-18], silica fume (SF)[19-21], limestone powder (LP)[22-25], fly ash (FA)[26-29], stone sludge waste[30-32], slag[33-36], tailings[37-39], rubber waste[40-43], and glass waste (GW)[44-46], which are studied as partial replacements for cement and aggregates. These materials possess pozzolanic and filler properties, and their proper incorporation improves workability, buildability, early strength, and environmental performance[47,48]. The use of solid waste serves to curtail natural resource depletion, while concurrently diverting landfill-bound waste streams and mitigating the carbon footprint of printed concrete[49,50]. Additionally, concrete waste, such as coarse or fine aggregates generated during industrial development, is used in printed composites. Figure 1 illustrates the representative categories of various solid wastes applied in 3DPC.

Figure 1. The representative categories of various solid wastes used in 3DPC. 3DPC: 3D printed concrete.

This review aims to summarize the current research progress in 3D printing solid waste concrete and introduce the classification, sources, and material characteristics of typical wastes. The impacts of solid waste materials on rheological behavior, printability, and mechanical strength are discussed, along with their potential in developing functional concrete with properties such as lightweight performance, conductivity, and enhanced durability. The review explores engineering applications, key challenges in layer adhesion and long-term performance, and future directions for intelligent design and material optimization. By systematically examining material, structural, and environmental aspects, this review provides insight into the sustainable transformation of concrete through digital manufacturing.

2. Industrial Wastes

2.1 Fly ash

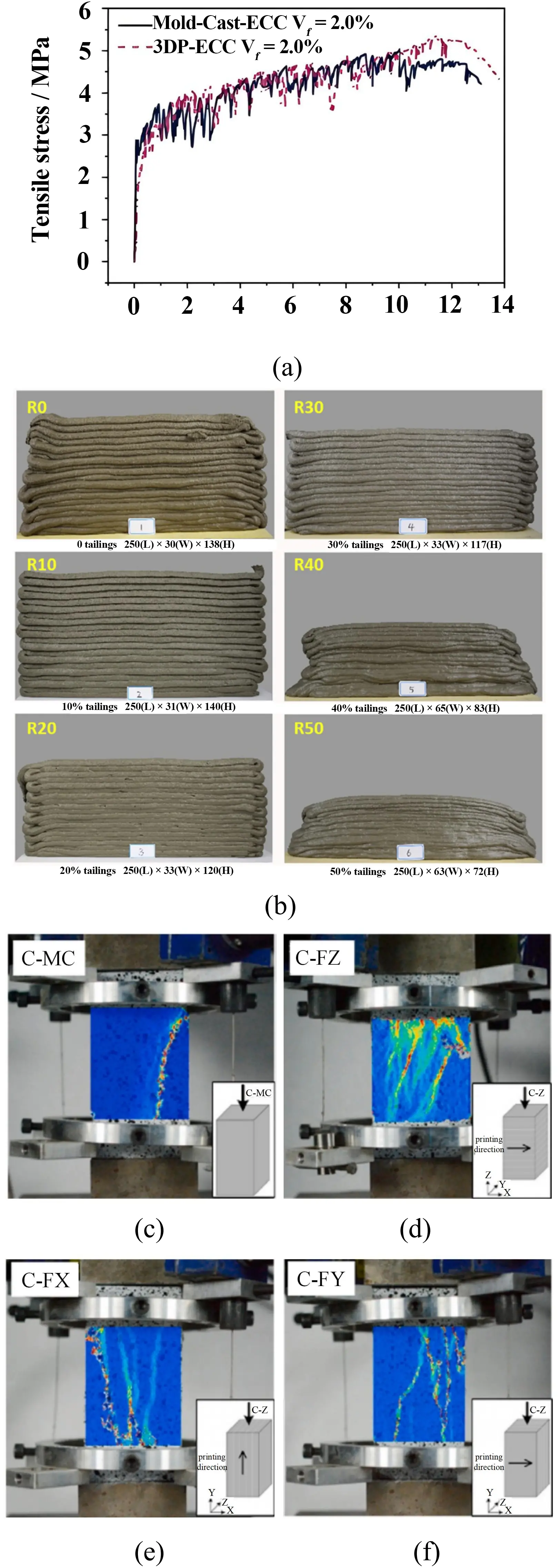

FA, a residual byproduct resulting from coal-fired generation processes, has emerged as a focal point in 3DPC research[51]. Due to its fine spherical particles and high specific surface area, FA contributes to flow behavior by reducing internal friction and hydration heat, which is beneficial for maintaining buildability and controlling early shrinkage[52]. FA participates in pozzolanic reactions, consuming calcium hydroxide and forming additional calcium silicate hydrate phases, which densify the microstructure and improve both early-age and long-term mechanical performance. Figure 2 presents a series of experimental results, microstructural observations, and schematic diagrams related to 3DPC incorporating FA. Table 1 presents the mechanical properties obtained with different FA contents and ratios of W/B and B/A. Panda et al. reported that substituting 70% of the cementitious phase with FA achieves a static yield stress magnitude of 4.8 kPa[71]. Long et al. discovered that adding FA to printed specimens increased the yield stress to 1,200 Pa and allowed for layer heights of up to 18 mm because FA increased the plastic viscosity of the mortar[57]. Figure 1c,d,e,f illustrates the crack morphologies of mold-cast specimens and 3D printed specimens with a FA dosage of 604 kg/m3 under compression.

Figure 2. (a) The tensile strain comparison of Mold-Cast-ECC and 3DPC-ECC[53]; (b) Copper tailing incorporated built-up structures at twenty filament layers. Republished with permission from[54]; (c) Crack patterns of mold-cast specimens; (d-f) 3D printed rubber aggregate incorporated specimens in multiple directions under compression. Republished with permission from[55]. 3DPC: 3D printed concrete; ECC: cementitious composites.

| Elements | Element contents | W/B | B/A | Fc (MPa) | Ff (MPa) | Ft (MPa) | Ref. |

| FA | 5 wt% | 0.55 | 0.91 | 54 | 8 | [56] | |

| FA | 54 wt% | 0.35 | 0.5 | 45 | 7.5 | [57] | |

| Incinerator FA | 7.5 wt% | 0.4 | 0.66 | 70 | [58] | ||

| FA | 10 wt% | 0.5 | 0.33 | 90 | 7 | [59] | |

| FA | 50 wt% | 0.67 | 47 | 7.4 | [60] | ||

| FA/Polyvinyl alcohol fiber | 11 wt%/2 vol% | 0.47 | 2 | 30 | 6.5 | [61] | |

| FA/Polyethylene fiber | 34 wt%/2 vol% | 0.28 | 2.5 | 47 | 19 | 5.7 | [53] |

| FA | 12 wt% | 0.28 | 0.75 | 50 | 30 | [62] | |

| LP | 7 | 0.3 | 0.67 | 45 | [63] | ||

| LP | 5 | 0.3 | 0.67 | 40 | |||

| LP | 20 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 80 | [64] | ||

| SF/Glass fiber | 16 wt%/1 vol% | 0.24 | 1 | 88 | 11 | [65] | |

| SF/Gasalt fiber | 16 wt%/1 vol% | 0.24 | 1 | 85 | 8 | ||

| SF/Carbon fiber | 21 wt%/3 vol% | 0.3 | 0.67 | 84 | 120 | [66] | |

| SF/Carbon fiber | 21 wt%/1 vol% | 0.3 | 0.67 | 82 | 29 | ||

| SF/Glass fiber | 21 wt%/1 vol% | 0.3 | 0.67 | 84 | 12 | ||

| SF/Polyvinyl alcohol fibers | 3 wt%/1 vol% | 0.27 | 2.7 | 55 | 7 | [67] | |

| SF/Steel fibers | 14 wt%/2 vol% | 0.16 | 1 | 153 | 40 | [68] | |

| SF/Steel fibers | 14 wt%/2 vol% | 0.16 | 1 | 144 | 72 | [69] | |

| SF/Foam | 5 wt%/28 wt% | 0.35 | 1 | 27 | [70] |

Ff: flexural performance; Ft: tensile property; Fc: compressive performance; B/A: binder-aggregate proportion; W/B: water-binder proportion; FA: fly ash; LP: limestone powder; SF: silica fume.

From a mechanical perspective, incorporating FA in printed composites has demonstrated improvements in both early and late strength[72]. Various studies reported that appropriate dosages of FA not only improved static yield stress and printing layer height but also maintained desirable compressive performance[73]. To illustrate, Korniejenko et al. utilized 54% FA as a binding constituent in formulating 3D-printed composites, yielding a sample exhibiting a compressive strength of 45 MPa[74]. Soltan and Li introduced 39% FA into engineered cementitious composites (ECC) to improve tensile ductility[61]. Compared to conventionally cast specimens, the printed ECC samples exhibited a 300% increase in tensile strain capacity. Furthermore, Zhu et al. investigated the combined effects of sulfoaluminate cement and FA in ECC[53]. Researchers developed an industrial waste-based printable ECC that demonstrated a remarkable tensile strain capacity of 11.4%, as shown in Figure 2a. The printed composites achieved superior mechanical performance, with a compressive strength of 47 MPa and a flexural strength of 19 MPa.

In the development of 3D printed lightweight composites, FA is a promising additive for enhancing both mechanical performance and structural efficiency. Due to its low density, FA contributes to reducing the weight of printed components and maintaining adequate strength[75]. Sun et al. produced lightweight 3D printed samples containing FA, achieving a compressive strength of 37.5 MPa with a reduced density of 1,464 kg/m3[75]. Similarly, Mohammad et al. showed that incorporating 12 % FA into the composite matrix yielded a flexural and compressive performance of 30 and 50 MPa, respectively[62]. These findings confirm that FA enhances the buildability and mechanical stability of lightweight 3D printed components, supporting broader applications in sustainable construction systems.

2.2 Limestone powder

LP, produced through the calcination of calcium carbonate-rich minerals, has become a common additive in 3DPC due to its availability and performance-enhancing potential[22]. The inclusion of LP in fresh mortar mixtures reduces slump, which facilitates layer retention and improves shape stability during the extrusion process[76]. LP boosts early-age mechanical performance, that is attributed to the promotion of cement hydration kinetics. Chen et al. found that 3DPC incorporating LP achieves a 7-day compressive strength of 42 MPa, indicating strong early mechanical development after printing[76]. However, to avoid adverse thermal effects due to the high reactivity between LP and water, Chen et al. found the optimal replacement rate of LP to be 7% and confirmed the compressive strength close to 45 MPa[63].

Recent investigations have explored the possibility of using higher LP content while controlling particle size distribution to mitigate excessive heat generation. Sikora et al., incorporating 20% LP with a two-particle size, attained 80 MPa compressive strength[64]. These findings indicate that with proper dosage regulation and particle optimization, LP serves as a viable partial binder in 3DPC, supporting potential adoption in large-scale printed structural elements. Table 1 lists the mechanical properties obtained with different LP contents and ratios of W/B and B/A.

2.3 Silica fume

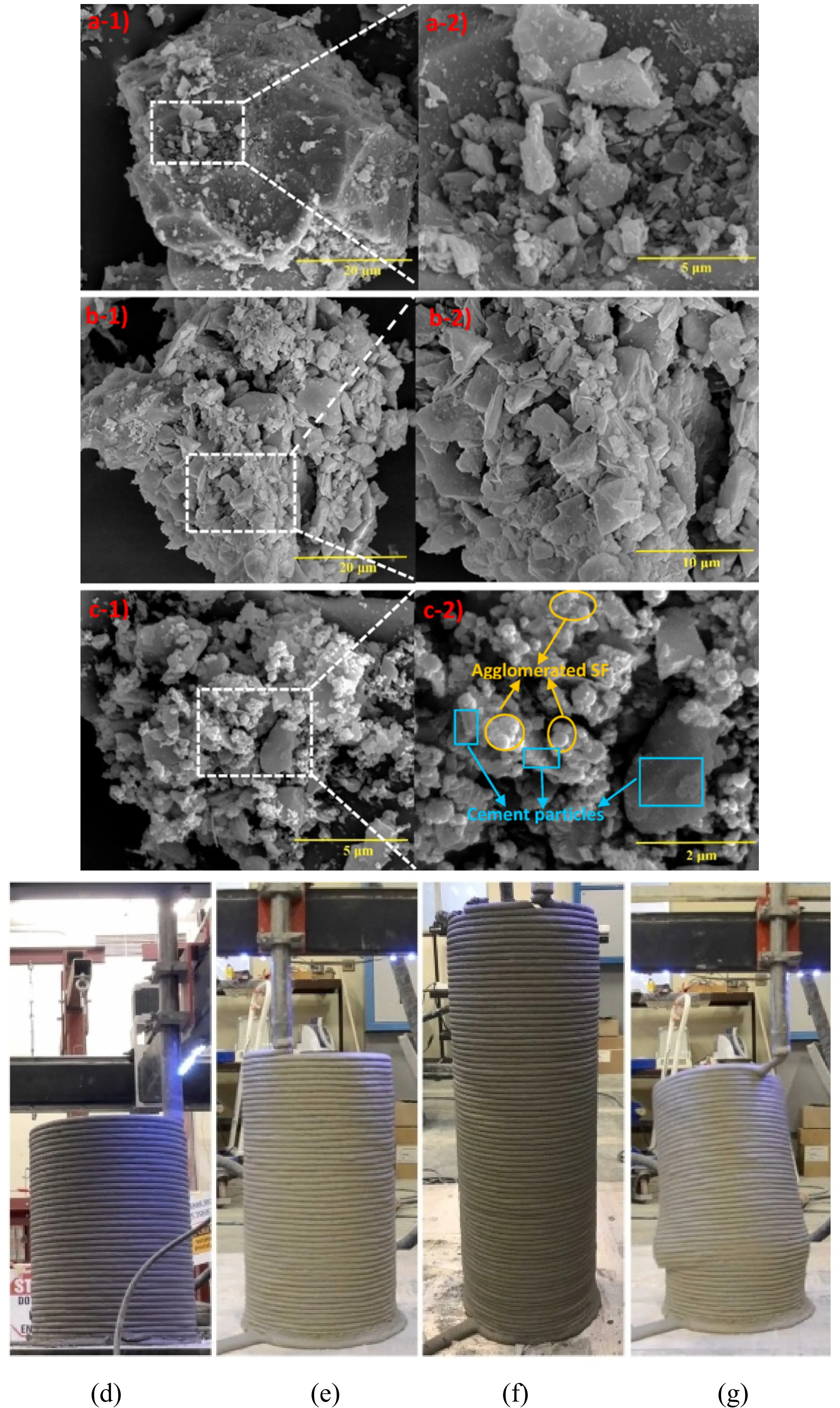

SF, a by-product of industrial ferrosilicon production, is recognized for its pozzolanic activity and particle packing effect, presenting both mechanical enhancement and durability benefits in 3DPC[77]. When incorporated as a supplementary cementitious material, SF effectively densifies the matrix, enhances interfacial bonding, and accelerates hydration reactions, thereby improving the early-stage and long-term strength of printed composites[78,79]. Figure 3 shows a schematic diagram of the printability experiments and microstructure of 3DPC with FA incorporated.

Figure 3. (a) The influence of foam concrete on particle packing effect about foam concrete in the control group; (b) Foam concrete with 0.12% hydroxypropyl methylcellulose; (c) Foam concrete with 6% SF. Republished with permission from[70]; (d) The Circular hollow column printing of 50%FA10%SF mixture; (e) 40%FA20%MK60 Mix; (f) 60%GGBS mixture; (g) Column failure of 40%FA20%MK60 Mix[80]. SF: silica fume; FA: fly ash; MK: metakaolin; GGBS: ground granulated blast furnace slag.

The utilization of SF in fiber-reinforced cementitious composites (FRCC) for 3DPC exhibits remarkable performance gains. Li et al. discovered that 16% SF attained 85 MPa compressive strength in FRCC specimens[65]. Hambach et al. revealed that the incorporation of SF and fibers led to a 1400% increase in flexural strength of printed composites[66]. At the same time, Zhang and Aslani demonstrated that SF enhanced mechanical properties, achieving a 28-day compressive strength of 55 MPa and a 50% improvement in flexural strength[67].

In ultra-high-performance FRCC, SF plays a critical role in achieving compressive strength exceeding 150 MPa while reducing the requirement for steel fiber length. Arunothayan et al. found that adding 14% SF into ultra-high-performance FRCC resulted in 40 MPa flexural performance and 152.5 MPa compressive performance, and enhanced the flexural strength to 72 MPa through the addition of 6mm-long steel fibers[68,69].

Finally, the integration of SF into lightweight foamed concrete enables the reduction of ordinary Portland cement while maintaining thermal insulation and mechanical performance[81]. Falliano et al. reported that SF additions improved compressive strength by 25% and reduced thermal conductivity to 0.125 W/mK due to refined pore structures[82,83]. Characterized by a dry unit weight of 400 kg/m3, SF-modified foamed composites demonstrated excellent extrudability and stability[83]. Furthermore, Liu et al. incorporated SF into 3D printed foamed concrete, resulting in substantial enhancements in mechanical performance, with the static yield stress reaching 7,000 Pa[70]. Figure 3a,b,c show the microstructure of the mixture with hydroxypropyl methylcellulose and SF added, which further explains the reason for the improved mechanical properties. Colyn et al. investigated the effects of using FA, SF, GGBS, and metakaolin (MK) as alternative binders on the pumpability, extrudability, and buildability of 3DPC[80]. As shown in Figure 3d,e,f,g, three mixed binder samples (50% FA with 10% SF, 40% FA with 20% MK, and 60% GGBS) were designed to meet the required rheological properties for 3D printing. The three mixtures achieved 28-day compressive strengths ranging from 31 to 55 MPa and elastic moduli between 29 and 37 GPa. Thus, the addition of SF improves mechanical performance and durability, and supports superior workability and structural integrity in 3D printed fiber-reinforced and lightweight foam. Table 1 lists the mechanical performance obtained with different SF contents and ratios of W/B and B/A.

2.4 Stone sludge waste

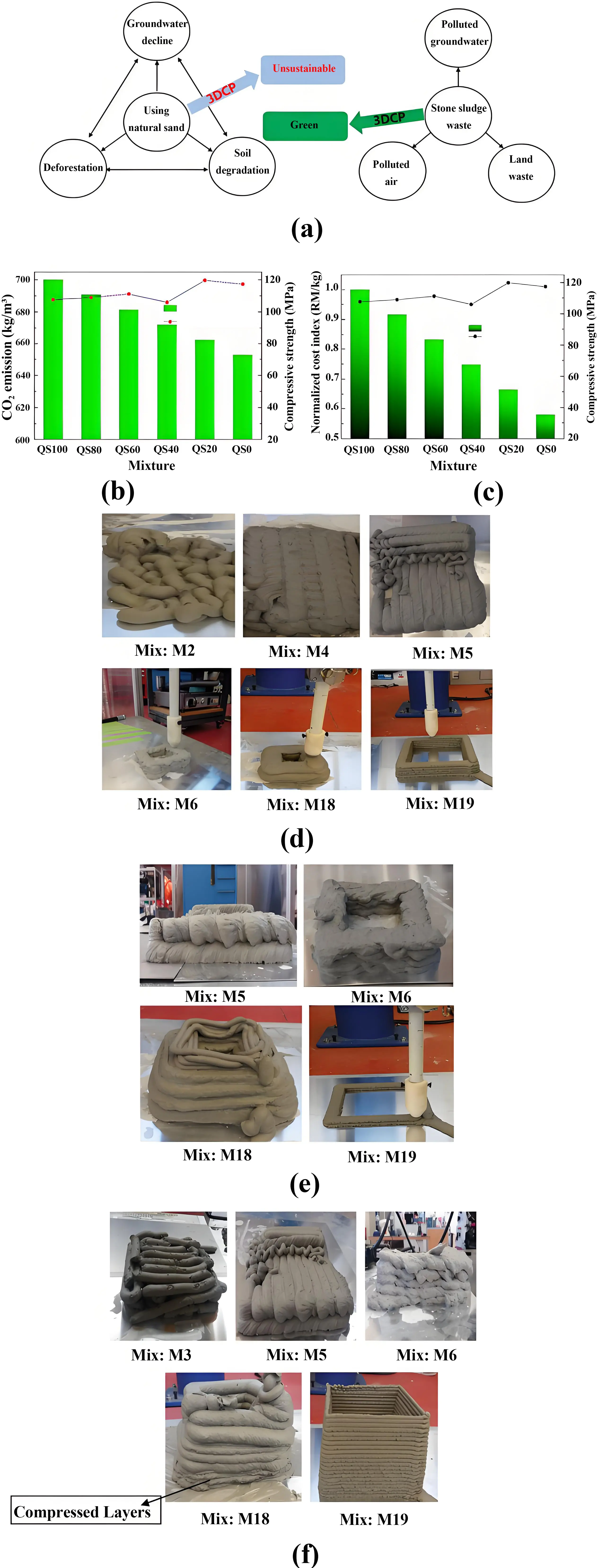

Stone sludge waste, including basalt, marble, and granite dust, represents a prevalent by-product of stone processing industries[84]. The excessive accumulation of fine particulate waste has raised environmental concerns, particularly about soil degradation and groundwater contamination[85]. Figure 4a illustrates the environmental benefits of substituting natural sand with stone-mud waste in 3DPC. As a sustainable solution, researchers utilized stone sludge waste to replace sand in 3DPC applications to enhance mechanical properties without compromising the integrity of the printed structure[31]. The fine particle size and high pozzolanic potential of stone sludge contribute to improved particle packing, reduced porosity, and enhanced interfacial transition zone (ITZ) density, which collectively improve early-age strength and printability. Figure 4 focuses on describing the environmental benefits, mechanical properties, and printability of mixtures incorporating stone sludge waste. For example, Chen et al. revealed that incorporating 39% of two-size basalt dust in 3DPC resulted in a 65 MPa compressive performance[89]. The fine particle size and high pozzolanic reactivity of basalt dust facilitate early-age hydration and densify the ITZ, leading to superior mechanical development. Moreover, marble and granite dusts, due to favorable mineral compositions and particle morphologies, contribute to improved printability and buildability of fresh mixtures, addressing common challenges in extrusion-based 3D printing[90]. Annappa et al. evaluated six distinct mortar formulations incorporating varying proportions of stone sludge and chemical admixtures to assess printability[88]. As illustrated in Figure 4d,e,f, the experimental results demonstrate the feasibility of utilizing stone sludge in printing applications, with the printed specimens exhibiting satisfactory surface uniformity and structural integrity.

Figure 4. (a) Green benefits of replacing natural sand with stone sludge waste in printed concrete[86]; (b) CO2 emission; (c) Relative material price of the mixture with varying content of stone sludge waste and compressive strength at 28 days (QS100, QS80, QS60, QS40, QS20, and QS0 represent 100%, 80%, 60%, 40%, 20%, 0% quartz sand in experimental groups, respectively). Republished with permission from[87]; (d) Extrusions of mixes; (e) Shape retention of mixes; (f) Buildability of mixes. Republished with permission from[88]. 3DPC: 3D printed concrete.

In addition to mechanical benefits, Yang et al. reported that the 100% replacement of quartz sand with stone sludge waste showed substantial environmental gains, including a 42% reduction in material costs and a 6.8% decrease in CO2 emissions[87]. These advantages underscore the potential of stone sludge waste as a multifunctional raw material in 3DPC for the development of ultra-high-performance, eco-efficient construction components.

2.5 Glass waste

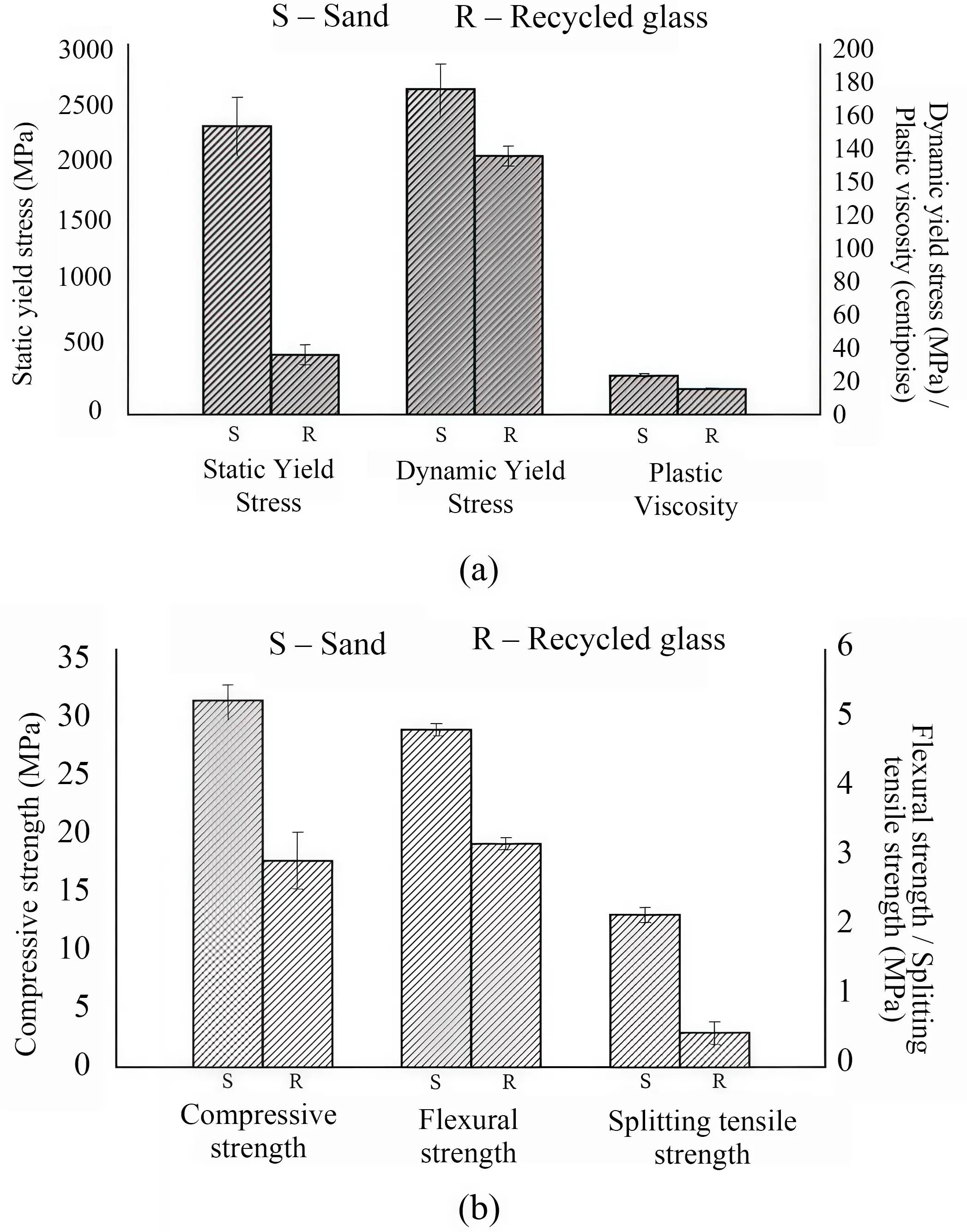

GW, including soda-lime, borosilicate, and vitreous silica glass, is generated from glass manufacturing and post-consumer products. To mitigate the overuse of natural sand, GW is introduced as an alternative fine aggregate in cementitious composites[91]. The inert properties of GW reduce permeability and enhance the durability of 3DPC[92,93]. Due to its smooth surface and low water absorption, GW improves workability and reduces the water demand of mixtures, thereby enhancing flowability and interlayer bonding[94]. Zainab et al. explored the replacement of sand with 10%, 15%, and 20% GW and found that 20% GW, the 28-day flexural and compressive strengths increased by 10.99% and 4.23%, respectively[95]. However, excessive GW not only gradually diminishes the mechanical improvement but also exerts a negative impact due to the angular particle shape of GW. Ting et al. discovered that 100% recycled glass aggregate showed superior extrudability and structural performance compared to conventional river sand composites, achieving 18 MPa in flexural tests[94]. Figure 5 illustrates the rheological properties and mechanical properties of mixtures with sand replaced by soda-lime glass aggregate. These findings suggest that the rational design of GW dosage is essential to achieve superior print quality and to construct lightweight 3D-printed elements.

Figure 5. (a) Rheological properties of the river sand and recycled glass; (b) Mechanical properties of the river sand and recycled glass. Republished with permission from[94].

2.6 Rubber waste

Rubber waste, derived from discarded tires and rubber products, presents an effective alternative to natural aggregate in 3D printed cementitious composites[96,97]. The low density and elastic nature of rubber particles contribute to lightweight mixtures with improved impact resistance and crack-bridging capability, while their hydrophobic surface reduces water absorption and enhances durability in aggressive environments[98-100]. In 3DPC, rubber aggregates mitigate the environmental impacts of rubber incineration and contribute to material lightweighting[101,102]. Sambucci et al. introduced 0-1 mm and 2-4 mm rubber waste aggregates into 3DPC, resulting in a 23.83% reduction in bulk density while maintaining superior mechanical anisotropy and overall strength performance[103]. With a 3% addition, the printed specimen demonstrated superior cracking behavior and a notable increase in compressive strength from 39 to 46 MPa[55]. These results demonstrate the potential of rubber waste to produce low-density and mechanically optimized 3DPC, highlighting its value in developing resource-efficient and structurally reliable construction materials.

3. Construction and Demolition Waste

Recycled concrete derived from construction and demolition activities, has emerged as a key alternative to natural aggregates in 3DPC applications[104]. Due to its abundance and low cost, construction and demolition waste (CDW) is adopted in printed structural elements, floor components, and pavement layers[105]. Inherent characteristics of CDW, such as high water absorption and rough surface texture, influence the rheological behavior of mixtures and the interfacial bonding performance of fresh mixes[106,107]. As a result, printed mixtures incorporating recycled concrete sand and aggregate exhibit higher static yield stress and improved buildability compared to conventional sand.

Research has shown that partial replacement of natural coarse aggregate with concrete waste can improve mechanical and durability performance[108]. Ding et al. reported that 20% recycled concrete sand enhanced compressive strength by 50%, and 6% recycled sand improved the compressive performance to 30 MPa[109,110]. Furthermore, Ding et al. and Chen et al. demonstrated that 20% recycled concrete aggregate(RCA) in 3DPC achieved favorable mechanical performance, with a flexural strength of 13 MPa[111,112].

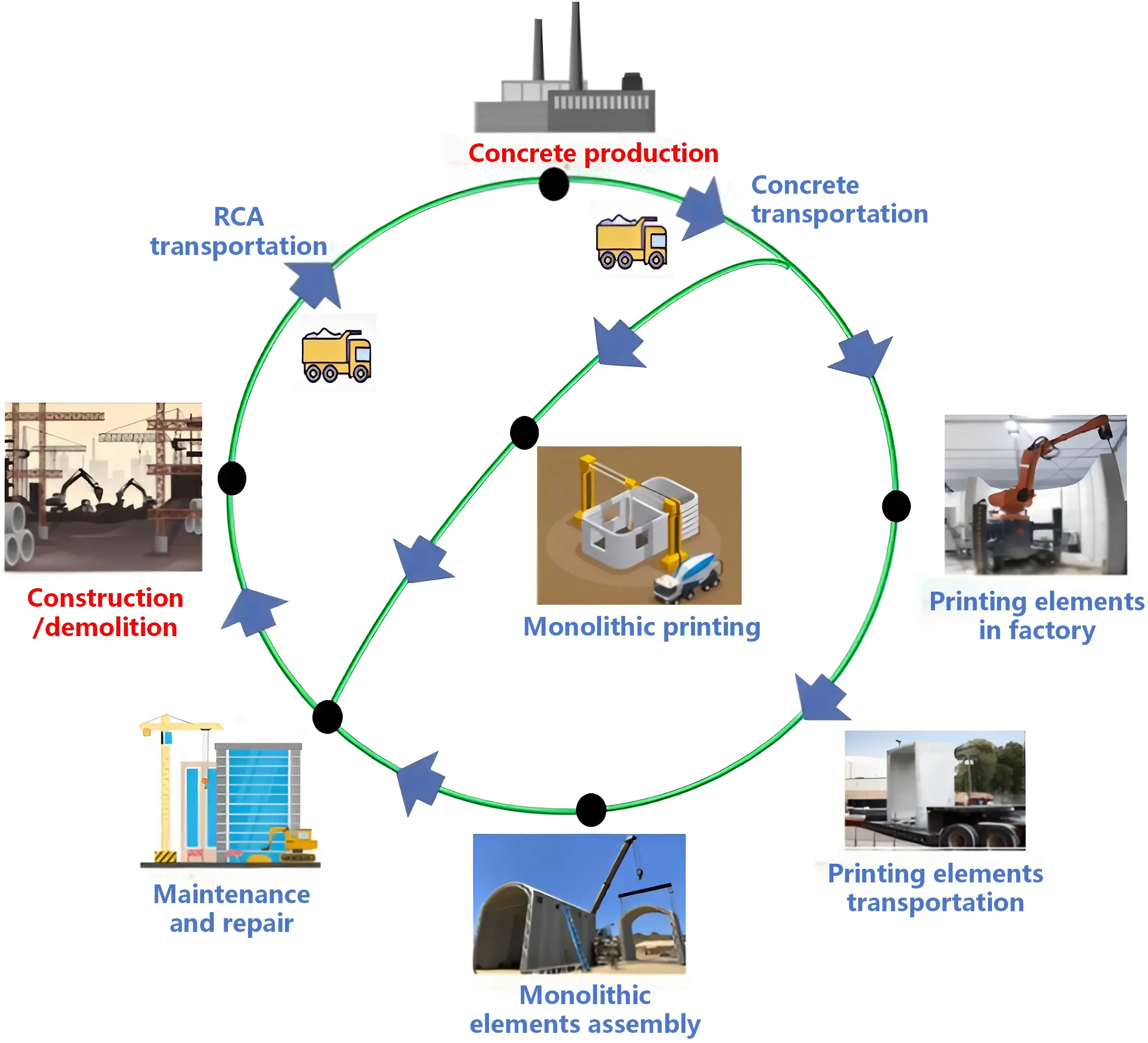

Beyond mechanical benefits, the circular utilization of CDW in 3DPC aligns with the principles of sustainable construction[113]. Figure 6 illustrates the recovered application of recycled materials in 3DPC. The closed-loop cycle from demolition to material recovery and recycling provides a pathway to reduce the carbon footprint, conserve raw materials, and lower landfill pressure. As the use of recycled concrete waste in technology matures, large-scale 3DPC systems present practical feasibility for prefabricated components and monolithic construction. The alignment between environmental goals and material performance suggests that CDW in 3DPC will continue to expand in academic research and industrial practice.

Figure 6. The recovered application of recycled materials in 3DPC[86]. 3DPC: 3D printed concrete.

4. Mixed Solid Waste

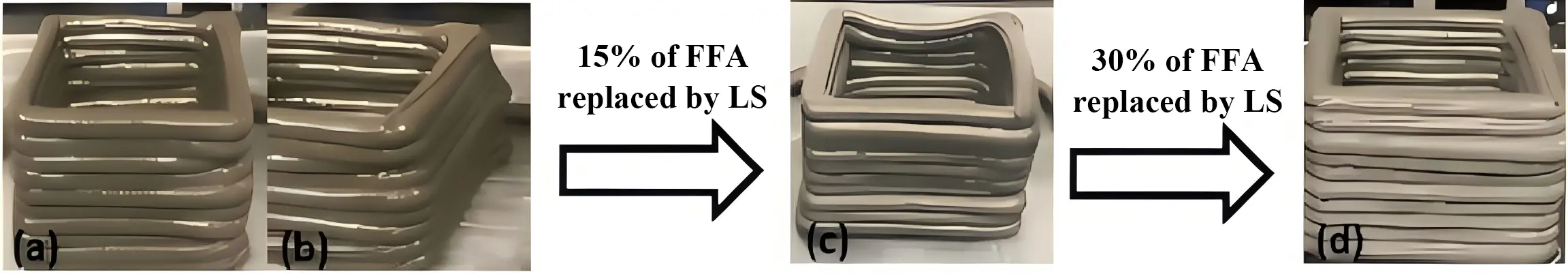

The combined incorporation of mixed solid waste into 3DPC offers a strategically viable approach to enhance overall material performance through complementary interactions between different waste characteristics. This synergy not only improves particle packing and rheological behavior but also optimizes mechanical properties and sustainability outcomes, moving beyond the limitations of single-waste systems. For instance, FA improves extrudability and flowability due to its spherical particle morphology, while LP contributes to early-age strength development and buildability through its filling effect and hydration acceleration. In terms of printability, Alghamdi et al. utilized 15% fine LP to replace FA, addressing deformation issues at printed corners caused by excessive cohesion[114]. In comparison to the mixtures shown in Figure 7a,b, the incorporation of 15% limestone improved consistency and water retention. However, as illustrated in Figure 7c, the print quality remained unsatisfactory. To achieve satisfactory extrudability and buildability, they further increased the limestone content to 30% and adjusted the liquid-binder ratio to 0.27. Similarly, Bai et al. demonstrated that a mixture of desert sand, SF, ceramic particles, and RCA increased the printable 40-layer height from 50 to 400 mm, which is higher than that of individual waste added cementitious material[115]. In addition, Cuevas et al. reported that incorporating LP, basalt dust, and glass aggregates not only enhanced mechanical properties (compressive strength increased from 35 to 40 MPa compared to individual aggregate samples) but also reduced thermal conductivity and density[116].

Figure 7. Hollow cubic geometries printed with FA-based binders activated by 10% NaOH: (a) and (b) 100% class F FA; (c) 15% limestone replaced by limestone; (d) 30% limestone replaced by limestone[114]. FA: fly ash.

The integration of mixed solid waste has also led to substantial gains in mechanical performance. Ma et al. showed that the FA and SF-based concrete, combined with aligned fiber orientation, enabled printed FRCC to achieve a compressive strength of 40 MPa[117]. Panda et al. printed geopolymer concrete with 35 MPa compressive strength by replacing 100% cement with FA, SF, and slag[118]. In foamed concrete systems, Cho et al. reported a compressive strength of 31 MPa with the incorporation of FA and SF[119]. Moreover, studies by Figueiredo et al., Chaves Figueiredo et al., and Weng et al. concluded that 3D printable ECC containing FA and SF achieved high compressive strength (65 MPa) and static yield stress (3,289 Pa)[120-122]. A summary of the mechanical properties of mixed solid waste-based composites is provided in Table 2.

| Elements | Element contents | W/B | B/A | Fc (MPa) | Ff (MPa) | Ft (MPa) | Ref. |

| FA/SF/Slag | 19 wt%/2 wt%/4 wt% | 0.43 | 35 | [118] | |||

| FA/SF/Basalt fiber | 8 wt%/4 wt%/0.7 wt% | 0.27 | 0.84 | 40 | 6.5 | 5.5 | [123] |

| GBFS/LP/Polyvinyl alcohol fiber | 29 wt%/41 wt%/2 vol% | 0.29 | 6.2 | 45 | 4 | [121] | |

| GBFS/LP/Polyvinyl alcohol fiber | 29 wt%/40 wt%/1 vol% | 0.29 | 6.2 | 48 | 8 | ||

| SF/FA/ Polyvinyl alcohol fiber | 0.5 wt%/56 wt%/1 vol% | 0.28 | 2 | 65 | 9 | [122] | |

| FA/SF/Foam | 33 wt%/3 wt%/1 wt% | 0.28 | 10 | 31 | 4 | [124] | |

| LP/Basalt dust/GW | 18 wt%/12 wt%/12 wt% | 0.37 | 0.44 | 40 | 8.5 | [116] | |

| LP/Basalt dust | 18 wt%/24 wt% | 0.35 | 0.44 | 38 | 8 | ||

| LP/GW | 18 wt%/24 wt% | 0.38 | 0.44 | 35 | 7.5 |

FA: fly ash; SF: silica fume; GBFS: ground blast furnace slag; LP: limestone powder; GW: glass waste.

The strategic incorporation of mixed solid waste in 3DPC not only improves printability but also enhances mechanical properties while supporting cement reduction and sustainability goals. Future work should focus on optimizing composite formulations to balance multiple properties and maximize the synergistic use of diverse waste in digital manufacturing.

5. Overall Evaluation and Cost-Effectiveness Perspective

5.1 Performance benefits and key conclusions

5.1.1 Printability and performance impact of solid waste in 3DPC

The preceding discussion highlights that various industrial and construction-derived waste materials demonstrate high compatibility with 3DPC technology. These materials confer a synergistic enhancement to both the fresh-state rheology and the hardened-state mechanical properties. The intrinsic link between process-induced morphology and material performance is a cornerstone of advanced 3DPC mix design. This section provides a synthesis of these findings by highlighting the common mechanisms through which solid wastes influence printability and mechanical performance.

The incorporation of supplementary cementitious materials, such as FA and SF, exemplifies the synergy. FA functions as a rheological modifier, reducing interparticle friction and enhancing extrudability and flowability[125]. In contrast, SF increases the thixotropy and static yield stress of the mixture, which is critical for ensuring high shape retention and buildability immediately after deposition[126]. Both FA and SF participate in pozzolanic reactions, consuming portlandite and generating additional calcium silicate hydrate phases[127]. SF and FA, combined with their micro-filler effect, lead to a densified microstructural matrix, a refined pore structure, and a strengthened ITZ[128]. The macroscopic manifestation of this microstructural refinement is the development of robust early-age strength and superior interlayer bond strength, thereby mitigating the anisotropic mechanical behavior inherent to the layer-wise deposition process.

The strategic use of waste-derived aggregates further advances the solid waste material performance design. Glass-based aggregates, characterized by low water absorption and a smooth surface, facilitate excellent flowability, while GW’s inherent rigidity contributes to increased compressive and flexural strength[129]. Conversely, rubber aggregates reduce the composite's ultimate compressive strength due to their distinct functional property[130]. However, rubber enhances fracture energy, crack resistance, and overall ductility by providing an energy-dissipating mechanism within the brittle cementitious matrix[131]. Furthermore, stone sludge waste not only enhances packing density, water retention, and buildability, but its potential pozzolanic activity can contribute to long-term strength development[132].

Overall, solid waste materials affect 3DPC through shared rheological mechanisms and microstructural modifications, and their appropriate incorporation can enhance printability and mechanical performance, aligning with sustainable material objectives.

5.1.2 Environmental sustainability and economic prospects

In addition to the performance advantages, the incorporation of solid waste materials into 3DPC presents compelling environmental and economic advantages, positioning it as a key enabler for sustainable construction.

From an environmental perspective, the utilization of wastes such as FA, SF, and recycled aggregates decreases the demand for virgin raw materials, thereby conserving natural resources and minimizing the environmental degradation associated with quarrying and mining[133,134]. More significantly, this method diverts substantial volumes of industrial and construction debris from landfills, addressing critical waste management challenges and mitigating associated soil and groundwater contamination risks[135]. A paramount benefit is the substantial reduction in the embodied carbon of the printing process. The partial replacement of ordinary Portland cement (a major contributor to global CO2 emissions) reduces the emissions from the production of natural aggregate and lowers the overall carbon footprint of 3DPC[136,137]. Sabău et al. reported that replacing 25% of cement with FA reduced Global Warming Potential (GWP) by 8-17% compared with a sample (323-332 kg CO2-eq) containing only ordinary Portland cement and natural aggregates[138]. Other studies similarly show that GWP is governed by cement content and decreases with higher FA substitution[139,140]. Nair et al. demonstrated that incorporating FA, GGBS, and SF to partially replace cement, together with recycled fine aggregates, reduced ordinary Portland cement content by 35%[141]. This optimized mix achieved a 32.15% reduction in GWP (from 3,252.02 to 2,206.37 kg CO2-eq), a 30.49% reduction in cumulative energy demand (from 38,062.75 to 26,456.32 MJ), and a 30.46% decrease in fossil resource depletion. Rohl et al. found that replacing natural aggregates with 30% recycled aggregates, slag, bottom ash, or GW resulted in varied environmental impacts, with 30% waste-glass aggregate yielding GWP and air pollution values of 118.56% to 220.61% of the control mix[142]. Therefore, preliminary life cycle assessment studies corroborate that waste-based 3DPC mixes exhibit a notably lower GWP compared to conventional concrete mixes.

Economically, the use of solid wastes leads to considerable material cost savings. Locally sourced waste streams are available at low and negative costs, reducing expenditures on cement and natural aggregates[143]. This enhances the cost-effectiveness of 3DPC projects, particularly in regions where traditional materials are scarce and expensive. For example, Ohemeng et al. reported that the long-term production cost of coarse RCA is approximately 40% lower than that of natural aggregate, while offering about 97% greater environmental benefits[144]. However, a comprehensive life cycle cost analysis is imperative to fully understand the economic balance. The analysis must account for potential upstream costs, including waste collection, transportation, and processing, as well as potential investments in chemical admixtures to ensure consistent printability. Furthermore, the resource circularity achieved by transforming waste into valuable construction materials enhances supply chain resilience and aligns with the principles of a circular economy, providing long-term economic stability.

In conclusion, the strategic integration of solid wastes into 3DPC advances environmental sustainability by reducing resource consumption and embodied carbon. At the same time, it establishes a foundation for improved economic viability through material cost savings and circular resource flows.

5.2 Current challenges and technical bottlenecks of waste incorporation in 3DPC

5.2.1 Inherent variability of waste materials

The heterogeneous nature of solid wastes poses fundamental challenges to material consistency. Variations in chemical composition, particle size distribution, and morphological characteristics across different waste sources directly impact the rheological and mechanical properties of 3DPC mixtures. This variability complicates the development of standardized mix designs and impedes the precise control essential for reproducible printing outcomes. Furthermore, potential contamination from associated waste streams and the current absence of comprehensive classification frameworks further exacerbate these issues, undermining quality assurance protocols and hindering reliable industrial-scale applications.

5.2.2 Process compatibility and long-term performance

The incorporation of waste materials introduces complex interactions that affect both fresh-state behavior and hardened-state performance. The elevated water demand of highly porous waste particulates, such as recycled concrete fines, alters the hydration process and narrows the critical printability window[145,146]. Simultaneously, the smooth surface topology of glass aggregates and the compliant nature of rubber particles create suboptimal interfaces within the cementitious matrix, resulting in compromised interlayer adhesion and mechanical anisotropy[147]. These microstructural deficiencies may accelerate degradation mechanisms, including increased susceptibility to shrinkage cracking, reduced resistance to environmental stressors, and questionable long-term durability.

5.2.3 Uncertain economic viability

Despite growing attention to sustainability and material circularity, limited research has evaluated the economic benefits of waste incorporation in 3DPC. Waste-based mixtures demonstrate cost-effective reductions in cement and natural aggregates. However, few studies have assessed the full life-cycle implications, including transportation, processing, and pre-treatment of waste materials[141].

A comprehensive cost-benefit analysis framework is needed to compare waste-modified 3DPC with conventional alternatives. This framework accounts for material procurement costs, print process efficiency, structural performance over the service life, and environmental benefits quantified through carbon pricing. By presenting economic data alongside mechanical and durability outcomes, stakeholders can better understand the balance and make decisions for practical implementation.

5.2.4 Lack of industry standards and specifications

A significant barrier to the widespread adoption of concrete waste from 3D printing is the lack of unified industry standards and regulatory frameworks. Currently, there are no comprehensive guidelines for the pretreatment of solid wastes (washing, grinding, and chemical activation) to ensure consistent quality and performance. Similarly, standardized performance evaluation indicators specific to 3DPC containing waste materials are lacking, including criteria for printability, early-age strength development, interlayer bonding, and long-term durability. The establishment of such standards is essential to ensure material reliability, facilitate quality control, and support certification processes for industrial applications.

5.2.5 Technical obstacles to large-scale production

Scaling up waste-incorporated 3DPC from laboratory to industrial production faces several technical hurdles. Raw material stability control remains challenging due to the inherent variability of waste streams, which can affect the consistency of fresh and hardened properties. Furthermore, printing equipment adaptability is a key concern: existing extrusion systems may not be optimized for handling mixtures with high waste content, irregular particle shapes, or altered rheology. Issues such as nozzle clogging, layer adhesion inconsistency, and printing speed limitations need to be addressed through equipment modification or the development of waste-tailored printing systems. Integrated solutions combining material design, process control, and equipment innovation are required to achieve reliable, large-scale production of waste-based 3DPC.

5.3 Future research directions and pathways

5.3.1 Intelligent material design and processing

The inherent complexity and variability of waste-based mixtures necessitate a shift from empirical methods to data-driven approaches. Future research should prioritize the development of machine learning and artificial intelligence frameworks that model the complex relationships between waste characteristics, mix proportions, rheological properties, and final performance[148,149]. This will achieve the inverse design of optimal mixtures tailored for specific printing requirements. Concurrently, advanced processing techniques, such as targeted surface functionalization of waste particles and the synthesis of tailored chemical admixtures, are crucial to enhance compatibility, improve interfacial bonding, and provide precise control over the printability window.

5.3.2 Multi-material printing and functional integration

Moving beyond homogeneous single-material printing is key to creating high-value, functional components. Research should explore multi-material 3D printing technologies that allow for the strategic placement of different wastes within a single component. For instance, high-strength waste composites (steel slag) can be deposited in load-bearing zones, while lightweight or insulating wastes (rubber, foamed glass) can be used in infill sections. This approach is applied to fabricate specialized structures such as acoustic barriers with sound-absorbing rubber cores and durable external shells, and building façades with integrated thermal insulation[150,151]. This functional integration significantly enhances the practical applicability and economic value of waste-based 3DPC.

5.3.3 Promoting industrialization and ecosystem development

Transitioning waste-based 3DPC from laboratory research to industrial application demands coordinated progress in both technical capabilities and supporting infrastructure. Key priorities involve establishing standardized classification frameworks for waste feedstocks and defining quantitative performance metrics for printing processes. Comprehensive life cycle assessment and life cycle cost analyses quantify environmental impacts and economic viability, generating critical data to support regulatory approval and attract investment[152,153]. Technologically, integrated production systems must incorporate in-line material processing, continuous quality monitoring, and closed-loop printing control to achieve the reliability and scale required for commercial adoption. These coordinated advances in standardization, economic validation, and production technology will collectively accelerate the formation of a robust ecosystem for waste-based 3DPC.

6. Concluding Remarks

The incorporation of solid waste into 3DPC presents remarkable potential in addressing both performance optimization and sustainability concerns. A wide range of industrial and construction wastes is introduced into the printable cementitious system, improving rheological performance, mechanical strength, and buildability while reducing the demand for virgin resources. However, the widespread adoption of 3D printing technology requires coordinated progress across materials, equipment, standards, and economics.

1) Waste-based 3DPC demonstrates material compatibility and performance benefits, including improved compressive strength, reduced cracking risk, and enhanced interlayer bonding. Pozzolanic additives, lightweight aggregates, and recycled sands contribute synergistically to fresh- and hardened-state properties. However, challenges such as inconsistent quality, variable particle shapes, and high water demand require stricter mix design control.

2) Printing outcomes are tied to the performance of solid waste, including chemical reactivity, surface texture, and particle size distribution. These parameters significantly affect flowability, extrusion continuity, and early-age strength. Tailored processing methods (grinding, sieving, and surface treatment) are adopted to improve compatibility with extrusion systems.

3) Despite evident environmental advantages, most existing studies lack a comprehensive economic evaluation. Future research should integrate cost-effectiveness analysis and life cycle assessment to quantify trade-offs between waste treatment costs, processing energy, and material savings. These methods serve to clarify the practical value of waste incorporation in 3DPC.

4) Standardization and process innovation are necessary for broader adoption. To accelerate commercial implementation, it is essential to establish guidelines for waste classification, dosage thresholds, and printer-material interaction. At the same time, real-time monitoring and adaptive control systems should be integrated into the printing workflow to ensure quality and repeatability.

Authors contribution

Sun J: Conceptualization, supervision, visualization.

Wang H: Writing-original draft, writing-review & editing, methodology, formal analysis.

Zhang Y: Methodology, data curation, visualization.

Liu H: Formal analysis, writing-review & editing, conceptualization.

Zhang M: Visualization, writing-review & editing, conceptualization.

Conflicts of interest

Junbo Sun is the Executive Chief Editor of Journal of Building Design and Environment. Xiangyu Wang is the Editor-in-Chief of the journal. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Nadi M, Majdoubi H, Haddaji Y, Bili O, Chahid M, Oumam M, et al. 23-Digital fabrication processes for cementitious materials using three-dimensional 3D printing technologies. In: Khan AH, Akhtar MN, Bani-Hani KA, editors. Recent developments and innovations in the sustainable production of concrete. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2025. p. 595-620.[DOI]

-

2. Zhang J, Wang J, Dong S, Yu X, Han B. A review of the current progress and application of 3D printed concrete. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2019;125:105533.[DOI]

-

3. Mechtcherine V, Grafe J, Nerella VN, Spaniol E, Hertel M, Füssel U. 3D-printed steel reinforcement for digital concrete construction–Manufacture, mechanical properties and bond behaviour. Constr Build Mater. 2018;179:125-137.[DOI]

-

4. Jipa A, Dillenburger B. 3D printed formwork for concrete: State-of-the-art, opportunities, challenges, and applications. 3D Print Addit Manuf. 2022;9(2):84-107.[DOI]

-

5. Quah TKN, Tay YWD, Lim JH, Tan MJ, Wong TN, Li KHH. Concrete 3D printing: Process parameters for process control, monitoring and diagnosis in automation and construction. Mathematics. 2023;11(6):1499.[DOI]

-

6. Xiao J, Ji G, Zhang Y, Ma G, Mechtcherine V, Pan J, et al. Large-scale 3D printing concrete technology: Current status and future opportunities. Cem Concr Compos. 2021;122:104115.[DOI]

-

7. Kantaros A, Zacharia P, Drosos C, Papoutsidakis M, Pallis E, Ganetsos T. Smart infrastructure and additive manufacturing: Synergies, advantages, and limitations. Appl Sci. 2025;15(7):3719.[DOI]

-

8. Mishra SK, Snehal K, Das BB, Chandrasekaran R, Barbhuiya S. From printing to performance: A review on 3D concrete printing processes, materials, and life cycle assessment. J Build Pathol Rehabil. 2025;10(2):117.[DOI]

-

9. Ramírez EG, Orobio A, Campaña W. Crucial aspects on planning construction projects using extrusion-based 3D printing technologies. SSRN: 4970655 [Preprint]. 2024.[DOI]

-

10. Destek MA, Hossain MR, Khan Z. Premature deindustrialization and environmental degradation. Gondwana Res. 2024;127:199-210.[DOI]

-

11. Sui Y. Analyzing the impact of industrial growth and agricultural development on environmental degradation in South and East Asia. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023;30(57):121090-121106.[DOI]

-

12. Liu Y, Qin H, Gao P, Yang Y, Hong L, Zhan B, et al. Overview of waste generation and carbon emissions in the construction industry. In: Wang L, Guo B, Ma B, editors. Wastes to low-carbon construction materials. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2025. p. 3-27.[DOI]

-

13. Küfeoğlu S. Industrial process emissions. In: Küfeoğlu S, editor. Net zero: Decarbonizing the global economies. Amsterdam: Springer; 2024. p. 341-414.[DOI]

-

14. Peng X, Jiang Y, Chen Z, Osman AI, Farghali M, Rooney DW, et al. Recycling municipal, agricultural and industrial waste into energy, fertilizers, food and construction materials, and economic feasibility: A review. Environ Chem Lett. 2023;21(2):765-801.[DOI]

-

15. Zhao Y, Gao Y, Chen G, Li S, Singh A, Luo X, et al. Development of low-carbon materials from GGBS and clay brick powder for 3D concrete printing. Constr Build Mater. 2023;383:131232.[DOI]

-

16. Rahmat NF, Ali N, Abdullah SR, Abdul Hamid NA, Salleh N, Shahidan S. Fresh properties and flexural strength of 3D printing sustainable concrete containing GGBS as partial cement replacement. IOP Conf Ser: Earth Environ Sci. 2023;1205(1):012042.[DOI]

-

17. Si W, Hopkins B, Khan M, McNally C. Towards sustainable mortar: Optimising Sika-Fibre dosage in ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS) and silica fume blends for 3D concrete printing. Buildings. 2025;15(19):3436.[DOI]

-

18. Suryanto B, Higgins J, Aitken MW, Tambusay A, Suprobo P. Developments in Portland cement/GGBS binders for 3D printing applications: Material calibration and structural testing. Constr Build Mater. 2023;407:133561.[DOI]

-

19. Thajeel MM, Kopecskó K, Balázs GL. Enhancing printability of 3D printed concrete by using metakaolin and silica fume. Struct Concr. 2025.[DOI]

-

20. Xue JC, Wang WC, Lee MG, Huang CY. Development of sustainable 3D printing concrete materials: Impact of natural minerals and wastes at high replacement ratios. J Build Eng. 2025;113:114020.[DOI]

-

21. Liu C, Chen Y, Xiong Y, Jia L, Ma L, Wang X, et al. Influence of HPMC and SF on buildability of 3D printing foam concrete: From water state and flocculation point of view. Compos Part B Eng. 2022;242:110075.[DOI]

-

22. Wang XY. Optimal mix design of low-CO2 blended concrete with limestone powder. Constr Build Mater. 2020;263:121006.[DOI]

-

23. Yang H, Che Y, Shi M. Influences of calcium carbonate nanoparticles on the workability and strength of 3D printing cementitious materials containing limestone powder. J Build Eng. 2021;44:102976.[DOI]

-

24. Jia Z, Kong L, Jia L, Ma L, Chen Y, Zhang Y. Printability and mechanical properties of 3D printing ultra-high performance concrete incorporating limestone powder. Constr Build Mater. 2024;426:136195.[DOI]

-

25. Dey D, Srinivas D, Boddepalli U, Panda B, Gandhi ISR, Sitharam TG. 3D printability of ternary Portland cement mixes containing fly ash and limestone. Mater Today Proc. 2022;70:195-200.[DOI]

-

26. Luo S, Jin W, Wu W, Zhang K. Rheological and mechanical properties of polyformaldehyde fiber reinforced 3D-printed high-strength concrete with the addition of fly ash. J Build Eng. 2024;98:111387.[DOI]

-

27. Varela H, Barluenga G, Perrot A. Extrusion and structural build-up of 3D printing cement pastes with fly ash, nanoclays and VMAs. Cem Concr Compos. 2023;142:105217.[DOI]

-

28. Taqa AA, Mohsen MO, Aburumman MO, Naji K, Taha R, Senouci A. Nano-fly ash and clay for 3D-Printing concrete buildings: A fundamental study of rheological, mechanical and microstructural properties. J Build Eng. 2024;92:109718.[DOI]

-

29. Liu X, Wang N, Zhang Y, Ma G. Optimization of printing precision and mechanical property for powder-based 3D printed magnesium phosphate cement using fly ash. Cem Concr Compos. 2024;148:105482.[DOI]

-

30. Scioti A, Fabbrocino F, Fatiguso F. Sustainable production of building blocks by reusing stone waste sludge. Appl Sci. 2025;15(9):5031.[DOI]

-

31. Shen K, Ding T, Cai C, Xiao J, Xiao X, Liang W. Feasibility analysis of 3D printed concrete with sludge incineration slag: Mechanical properties and environmental impacts. Constr Build Mater. 2024;449:138521.[DOI]

-

32. Ding T, Shen K, Cai C, Xiao J, Xiao X, Liang W. 3Dprinted concrete with sewage sludge ash: Fresh and hardened properties. Cem Concr Compos. 2024;148:105475.[DOI]

-

33. Yu Q, Zhu B, Li X, Meng L, Cai J, Zhang Y, et al. Investigation of the rheological and mechanical properties of 3D printed eco-friendly concrete with steel slag. J Build Eng. 2023;72:106621.[DOI]

-

34. Ma G, Yan Y, Zhang M, Sanjayan J. Effect of steel slag on 3D concrete printing of geopolymer with quaternary binders. Ceram Int. 2022;48(18):26233-26247.[DOI]

-

35. Dvorkin L, Marchuk V, Hager I, Maroszek M. Design of cement–slag concrete composition for 3D printing. Energies. 2022;15(13):4610.[DOI]

-

36. Wu M, Wang Z, Chen Y, Zhu M, Yu Q. Effect of steel slag on rheological and mechanical properties of sulfoaluminate cement-based sustainable 3D printing concrete. J Build Eng. 2024;98:111345.[DOI]

-

37. Singh A, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Sun J, Xu X, Li Y, et al. Utilization of antimony tailings in fiber-reinforced 3D printed concrete: A sustainable approach for construction materials. Constr Build Mater. 2023;408:133689.[DOI]

-

38. Zhou L, Gou M, Zhang H. Investigation on the applicability of bauxite tailings as fine aggregate to prepare 3D printing mortar. Constr Build Mater. 2023;364:129904.[DOI]

-

39. Yuan S, Duan D, Sun J, Yu Y, Wang Y, Huang B, et al. Mechanical, alkali excitation, hydrothermal enhancement of 3D printed concrete incorporated with antimony tailings. Constr Build Mater. 2024;443:137610.[DOI]

-

40. Carvalho IC, Melo ARS, Melo CDR, Brito MS, Chaves AR, Babadopulos LFAL, et al. Evaluation of the effect of rubber waste particles on the rheological and mechanical properties of cementitious materials for 3D printing. Constr Build Mater. 2024;411:134377.[DOI]

-

41. Liu J, Setunge S, Tran P. 3D concrete printing with cement-coated recycled crumb rubber: Compressive and microstructural properties. Constr Build Mater. 2022;347:128507.[DOI]

-

42. Sun J, Zhang Y, Wu Q, Wang Y, Liu H, Zhao H, et al. 3D printed concrete incorporating waste rubber: Anisotropic properties and environmental impact analysis. J Mater Res Technol. 2024;33:2773-2784.[DOI]

-

43. Xiong B, Nie P, Liu H, Li X, Li Z, Jin W, et al. Optimization of fiber reinforced lightweight rubber concrete mix design for 3D printing. J Build Eng. 2024;88:109105.[DOI]

-

44. Sheng Z, Zhu B, Cai J, Han J, Zhang Y, Pan J. Influence of waste glass powder on printability and mechanical properties of 3D printing geopolymer concrete. Dev Built Environ. 2024;20:100541.[DOI]

-

45. Li J, Singh A, Zhao Y, Sun J, Tam VWY, Xiao J. Enhancing thermo-mechanical and moisture properties of 3D-printed concrete through recycled ultra-fine waste glass powder. J Clean Prod. 2024;480:144121.[DOI]

-

46. Ramakrishnan S, Pasupathy K, Manalo AC, Sanjayan J. Rheological, mechanical and fire resistance performance of waste glass activated geopolymers for concrete 3D printing. J Sustain Cem-Based Mater. 2025;14(11):2294-2309.[DOI]

-

47. Liu CH, Hung C. Reutilization of solid wastes to improve the hydromechanical and mechanical behaviors of soils—a state-of-the-art review. Sustain Environ Res. 2023;33(1):17.[DOI]

-

48. Wei J, Wei J, Huang Q, Zainal Abidin SMIBS, Zou Z. Mechanism and engineering characteristics of expansive soil reinforced by industrial solid waste: A review. Buildings. 2023;13(4):1001.[DOI]

-

49. Hou H, Su L, Guo D, Xu H. Resource utilization of solid waste for the collaborative reduction of pollution and carbon emissions: Case study of fly ash. J Clean Prod. 2023;383:135449.[DOI]

-

50. Ren C, Wang W, Yao Y, Wu S, Qamar , Yao X. Complementary use of industrial solid wastes to produce green materials and their role in CO2 reduction. J Clean Prod. 2020;252:119840.[DOI]

-

51. Maroszek M, Rudziewicz M, Hebda M. Recycled components in 3D concrete printing mixes: A review. Materials. 2025;18(19):4517.[DOI]

-

52. Tao JL, Lin C, Luo QL, Long WJ, Zheng SY, Hong CY. Leveraging internal curing effect of fly ash cenosphere for alleviating autogenous shrinkage in 3D printing. Constr Build Mater. 2022;346:128247.[DOI]

-

53. Zhu B, Pan J, Nematollahi B, Zhou Z, Zhang Y, Sanjayan J. Development of 3D printable engineered cementitious composites with ultra-high tensile ductility for digital construction. Mater Des. 2019;181:108088.[DOI]

-

54. Ma G, Li Z, Wang L. Printable properties of cementitious material containing copper tailings for extrusion based 3D printing. Constr Build Mater. 2018;162:613-627.[DOI]

-

55. Ye J, Cui C, Yu J, Yu K, Xiao J. Fresh and anisotropic-mechanical properties of 3D printable ultra-high ductile concrete with crumb rubber. Compos Part B Eng. 2021;211:108639.[DOI]

-

56. Papachristoforou M, Mitsopoulos V, Stefanidou M. Use of by-products for partial replacement of 3D printed concrete constituents; rheology, strength and shrinkage performance. Fract Struct Integr. 2019;13(50):526-536.[DOI]

-

57. Long WJ, Tao JL, Lin C, Gu Y, Mei L, Duan HB, et al. Rheology and buildability of sustainable cement-based composites containing micro-crystalline cellulose for 3D-printing. J Clean Prod. 2019;239:118054.[DOI]

-

58. Rehman AU, Lee SM, Kim JH. Use of municipal solid waste incineration ash in 3D printable concrete. Process Saf Environ Prot. 2020;142:219-228.[DOI]

-

59. Inozemtcev A, Korolev E, Qui DT. Study of mineral additives for cement materials for 3D-printing in construction. IOP Conf Ser: Mater Sci Eng. 2018;365(3):032009.[DOI]

-

60. Nematollahi B, Xia M, Sanjayan J, Vijay P. Effect of type of fiber on inter-layer bond and flexural strengths of extrusion-based 3D printed geopolymer. Mater Sci Forum. 2018;939:155-162.[DOI]

-

61. Soltan DG, Li VC. A self-reinforced cementitious composite for building-scale 3D printing. Cem Concr Compos. 2018;90:1-13.[DOI]

-

62. Mohammad M, Masad E, Seers T, Al-Ghamdi SG. High-performance light-weight concrete for 3D printing. In: Bos FP, Lucas SS, Wolfs RJM, Salet TAM, editors. Second RILEM International Conference on Concrete and Digital Fabrication; 2020 Jul 6-8; Eindhoven, Netherlands. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 459-467.[DOI]

-

63. Chen Y, Li Z, Figueiredo SC, Çopuroğlu O, Veer F, Schlangen E. Limestone and calcined clay-based sustainable cementitious materials for 3D concrete printing: A fundamental study of extrudability and early-age strength development. Appl Sci. 2019;9(9):1809.[DOI]

-

64. Sikora P, Chung SY, Liard M, Lootens D, Dorn T, Kamm PH, et al. The effects of nanosilica on the fresh and hardened properties of 3D printable mortars. Constr Build Mater. 2021;281:122574.[DOI]

-

65. Li LG, Xiao BF, Fang ZQ, Xiong Z, Chu SH, Kwan AKH. Feasibility of glass/basalt fiber reinforced seawater coral sand mortar for 3D printing. Addit Manuf. 2021;37:101684.[DOI]

-

66. Hambach M, Rutzen M, Volkmer D. Properties of 3D-printed fiber-reinforced Portland cement paste. In: Sanjayan JG, Nazari A, Nematollahi B, editors. 3D concrete printing technology. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2019. p. 73-113.[DOI]

-

67. Zhang Y, Aslani F. Development of fibre reinforced engineered cementitious composite using polyvinyl alcohol fibre and activated carbon powder for 3D concrete printing. Constr Build Mater. 2021;303:124453.[DOI]

-

68. Arunothayan AR, Nematollahi B, Ranade R, Bong SH, Sanjayan JG, Khayat KH. Fiber orientation effects on ultra-high performance concrete formed by 3D printing. Cem Concr Res. 2021;143:106384.[DOI]

-

69. Arunothayan AR, Nematollahi B, Ranade R, Bong SH, Sanjayan J. Development of 3D-printable ultra-high performance fiber-reinforced concrete for digital construction. Constr Build Mater. 2020;257:119546.[DOI]

-

70. Liu C, Wang X, Chen Y, Zhang C, Ma L, Deng Z, et al. Influence of hydroxypropyl methylcellulose and silica fume on stability, rheological properties, and printability of 3D printing foam concrete. Cem Concr Compos. 2021;122:104158.[DOI]

-

71. Panda B, Ruan S, Unluer C, Tan MJ. Improving the 3D printability of high volume fly ash mixtures via the use of nano attapulgite clay. Compos Part B Eng. 2019;165:75-83.[DOI]

-

72. Panda B, Unluer C, Tan MJ. Investigation of the rheology and strength of geopolymer mixtures for extrusion-based 3D printing. Cem Concr Compos. 2018;94:307-314.[DOI]

-

73. Xu Z, Zhang D, Li H, Sun X, Zhao K, Wang Y. Effect of FA and GGBFS on compressive strength, rheology, and printing properties of cement-based 3D printing material. Constr Build Mater. 2022;339:127685.[DOI]

-

74. Korniejenko K, Łach M, Chou SY, Lin WT, Cheng A, Hebdowska-Krupa M, et al. Mechanical properties of short fiber-reinforced geopolymers made by casted and 3D printing methods: A comparative study. Materials. 2020;13(3):579.[DOI]

-

75. Sun J, Aslani F, Lu J, Wang L, Huang Y, Ma G. Fibre-reinforced lightweight engineered cementitious composites for 3D concrete printing. Ceram Int. 2021;47(19):27107-27121.[DOI]

-

76. Chen Y, Figueiredo SC, Li Z, Chang Z, Jansen K, Çopuroğlu O, et al. Improving printability of limestone-calcined clay-based cementitious materials by using viscosity-modifying admixture. Cem Concr Res. 2020;132:106040.[DOI]

-

77. González-Fonteboa B, Martínez-Abella F, Martínez-Lage I, Eiras-López J. Structural shear behaviour of recycled concrete with silica fume. Constr Build Mater. 2009;23(11):3406-3410.[DOI]

-

78. Siddique R. Utilization of silica fume in concrete: Review of hardened properties. Res Conserv Recycl. 2011;55(11):923-932.[DOI]

-

79. Weng Y, Lu B, Li M, Liu Z, Tan MJ, Qian S. Empirical models to predict rheological properties of fiber reinforced cementitious composites for 3D printing. Constr Build Mater. 2018;189:676-685.[DOI]

-

80. Colyn M, van Zijl G, Babafemi AJ. Fresh and strength properties of 3D printable concrete mixtures utilising a high volume of sustainable alternative binders. Constr Build Mater. 2024;419:135474.[DOI]

-

81. Amran YHM, Farzadnia N, Abang Ali AA. Properties and applications of foamed concrete; a review. Constr Build Mater. 2015;101:990-1005.[DOI]

-

82. Falliano D, Gugliandolo E, De Domenico D, Ricciardi G. Experimental investigation on the mechanical strength and thermal conductivity of extrudable foamed concrete and preliminary views on its potential application in 3D printed multilayer insulating panels. In: Wangler T, Flatt RJ, editors. First RILEM International Conference on Concrete and Digital Fabrication–Digital Concrete 2018; 2018 Sep 10-12; Zurich, Switzerland. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 277-286.[DOI]

-

83. Falliano D, De Domenico D, Ricciardi G, Gugliandolo E. 3D-printable lightweight foamed concrete and comparison with classical foamed concrete in terms of fresh state properties and mechanical strength. Constr Build Mater. 2020;254:119271.[DOI]

-

84. Hameed MS, Sekar A. Properties of green concrete containing quarry rock dust and marble sludge powder as fine aggregate. ARPN J Eng Appl Sci. 2009;4(4):83-89. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/M-Hameed-3/publication/237647736.pdf

-

85. Hameed MS, Sekar ASS, Balamurugan L, Saraswathy V. Self-compacting concrete using Marble Sludge Powder and Crushed Rock Dust. KSCE J Civ Eng. 2012;16(6):980-988.[DOI]

-

86. Zhao H, Wang Y, Liu X, Wang X, Chen Z, Lei Z, et al. Review on solid wastes incorporated cementitious material using 3D concrete printing technology. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2024;21:e03676.[DOI]

-

87. Yang R, Yu R, Shui Z, Gao X, Xiao X, Fan D, et al. Feasibility analysis of treating recycled rock dust as an environmentally friendly alternative material in Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC). J Clean Prod. 2020;258:120673.[DOI]

-

88. Annappa V, Gaspar F, Mateus A, Vitorino J. 3D printing for construction using stone sludge. In: Rodrigues H, Gaspar F, Fernandes P, Mateus A, editors. Sustainability and automation in smart constructions. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. p. 121-130.[DOI]

-

89. Chen Y, Zhang Y, Pang B, Liu Z, Liu G. Extrusion-based 3D printing concrete with coarse aggregate: Printability and direction-dependent mechanical performance. Constr Build Mater. 2021;296:123624.[DOI]

-

90. Hojati M, Nazarian S, Duarte JP, Radlinska A, Ashrafi N, Craveiro F, et al. 3D printing of concrete: A continuous exploration of mix design and printing process. In: Proceedings of the 42nd IAHS World Congress–The housing for the dignity of mankind; 2018 Apr 10-13; Naples, Italy. Naples: Giapeto; 2018. p. 10-13. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325076823_3D_Printing_of_Concrete_a_Continuous_Exploration_of_Mix_Design_and_Printing_Process

-

91. Tan KH, Du H. Use of waste glass as sand in mortar: Part I–Fresh, mechanical and durability properties. Cem Concr Compos. 2013;35(1):109-117.[DOI]

-

92. Taha B, Nounu G. Properties of concrete contains mixed colour waste recycled glass as sand and cement replacement. Constr Build Mater. 2008;22(5):713-720.[DOI]

-

93. Sun J, Wang Y, Liu S, Dehghani A, Xiang X, Wei J, et al. RETRACTED: Mechanical, chemical and hydrothermal activation for waste glass reinforced cement. Constr Build Mater. 2021;301:124361.[DOI]

-

94. Ting GHA, Tay YWD, Qian Y, Tan MJ. Utilization of recycled glass for 3D concrete printing: Rheological and mechanical properties. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag. 2019;21(4):994-1003.[DOI]

-

95. Ismail ZZ, Al-Hashmi EA. Recycling of waste glass as a partial replacement for fine aggregate in concrete. Waste Manag. 2009;29(2):655-659.[DOI]

-

96. Ross DE. Use of waste tyres in a circular economy. Waste Manag Res. 2020;38(1):1-3.[DOI]

-

97. Aslani F, Sun J, Huang G. Mechanical behavior of fiber-reinforced self-compacting rubberized concrete exposed to elevated temperatures. J Mater Civ Eng. 2019;31(12):04019302.[DOI]

-

98. Li B, Huo B, Cao R, Wang S, Zhang Y. Sulfate resistance of steam cured ferronickel slag blended cement mortar. Cem Concr Compos. 2019;96:204-211.[DOI]

-

99. Huo B, Li B, Chen C, Zhang Y. Surface etching and early age hydration mechanisms of steel slag powder with formic acid. Constr Build Mater. 2021;280:122500.[DOI]

-

100. Roychand R, Gravina RJ, Zhuge Y, Ma X, Youssf O, Mills JE. A comprehensive review on the mechanical properties of waste tire rubber concrete. Constr Build Mater. 2020;237:117651.[DOI]

-

101. Sambucci M, Valente M. Thermal insulation performance optimization of hollow bricks made up of 3D printable rubber-cement mortars: Material properties and FEM-based modelling. IOP Conf Ser: Mater Sci Eng. 2021;1044(1):012001.[DOI]

-

102. Adesina AY, Zainelabdeen IH, Dalhat MA, Mohammed AS, Sorour AA, Al-Badour FA. Influence of micronized waste tire rubber on the mechanical and tribological properties of epoxy composite coatings. Tribol Int. 2020;146:106244.[DOI]

-

103. Sambucci M, Marini D, Sibai A, Valente M. Preliminary mechanical analysis of rubber-cement composites suitable for additive process construction. J Compos Sci. 2020;4(3):120.[DOI]

-

104. Wang Y, Sun J, Wang X, Huang B, Xu S, Shang J, et al. Environmental and economic evaluation of a prefabricated 3D-printed structural units using recycled aggregates from construction and demolition waste: A case study in China. Energy Build. 2025;347:116405.[DOI]

-

105. Han Y, Yang Z, Ding T, Xiao J. Environmental and economic assessment on 3D printed buildings with recycled concrete. J Clean Prod. 2021;278:123884.[DOI]

-

106. Medina C, Zhu W, Howind T, Frías M, Sánchez de Rojas MI. Effect of the constituents (asphalt, clay materials, floating particles and fines) of construction and demolition waste on the properties of recycled concretes. Constr Build Mater. 2015;79:22-33.[DOI]

-

107. Saiz Martínez P, Ferrández D, Melane-Lavado A, Zaragoza-Benzal A. Characterization of three types of recycled aggregates from different construction and demolition waste: An experimental study for waste management. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4):3709.[DOI]

-

108. Ghorbani S, Sharifi S, Ghorbani S, Tam VWY, de Brito J, Kurda R. Effect of crushed concrete waste’s maximum size as partial replacement of natural coarse aggregate on the mechanical and durability properties of concrete. Res Conserv Recycl. 2019;149:664-673.[DOI]

-

109. Ding T, Xiao J, Qin F, Duan Z. Mechanical behavior of 3D printed mortar with recycled sand at early ages. Constr Build Mater. 2020;248:118654.[DOI]

-

110. Ding T, Xiao J, Zou S, Wang Y. Hardened properties of layered 3D printed concrete with recycled sand. Cem Concr Compos. 2020;113:103724.[DOI]

-

111. Ding T, Xiao J, Zou S, Yu J. Flexural properties of 3D printed fibre-reinforced concrete with recycled sand. Constr Build Mater. 2021;288:123077.[DOI]

-

112. Chen F, Zhong Y, Gao X, Jin Z, Wang E, Zhu F, et al. Non-uniform model of relationship between surface strain and rust expansion force of reinforced concrete. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):8741.[DOI]

-

113. Sakhare V, Khairnar N, Dahatonde U, Mashalkar S. Review on sustainability in 3D concrete printing: Focus on waste utilization and life cycle assessment. Asian J Civ Eng. 2025;26(9):3589-3605.[DOI]

-

114. Alghamdi H, Nair SAO, Neithalath N. Insights into material design, extrusion rheology, and properties of 3D-printable alkali-activated fly ash-based binders. Mater Des. 2019;167:107634.[DOI]

-

115. Bai G, Wang L, Ma G, Sanjayan J, Bai M. 3D printing eco-friendly concrete containing under-utilised and waste solids as aggregates. Cem Concr Compos. 2021;120:104037.[DOI]

-

116. Cuevas K, Chougan M, Martin F, Ghaffar SH, Stephan D, Sikora P. 3D printable lightweight cementitious composites with incorporated waste glass aggregates and expanded microspheres–Rheological, thermal and mechanical properties. J Build Eng. 2021;44:102718.[DOI]

-

117. Ma H, Li Z. Multi-aggregate approach for modeling interfacial transition zone in concrete. ACI Mater J. 2014;111(2):189-200.[DOI]

-

118. Panda B, Mohamed NAN, Tan MJ. Effect of 3D printing on mechanical properties of fly ash-based inorganic geopolymer. In: Taha MMR, editor. International Congress on Polymers in Concrete (ICPIC 2018); 2018 Apr 29-May 1; Washington, USA. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 509-515.[DOI]

-

119. Cho S, van Rooyen A, Kearsley E, van Zijl G. Foam stability of 3D printable foamed concrete. J Build Eng. 2022;47:103884.[DOI]

-

120. Figueiredo SC, Romero Rodríguez C, Ahmed ZY, Bos DH, Xu Y, Salet TM, et al. An approach to develop printable strain hardening cementitious composites. Mater Des. 2019;169:107651.[DOI]

-

121. Figueiredo SC, Romero Rodríguez C, Ahmed ZY, Bos DH, Xu Y, Salet TM, et al. Mechanical behavior of printed strain hardening cementitious composites. Materials. 2020;13(10):2253.[DOI]

-

122. Weng Y, Li M, Liu Z, Lao W, Lu B, Zhang D, et al. Printability and fire performance of a developed 3D printable fibre reinforced cementitious composites under elevated temperatures. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2019;14(3):284-292.[DOI]

-

123. Ma G, Li Z, Wang L, Wang F, Sanjayan J. Mechanical anisotropy of aligned fiber reinforced composite for extrusion-based 3D printing. Constr Build Mater. 2019;202:770-783.[DOI]

-

124. Cho S. Rheo-mechanics and foam stability of 3D printable foamed concrete with nanoparticle incorporation [dissertation]. Stellenbosch: Stellenbosch University; 2021.[DOI]

-

125. Xu K, Yang J, He H, Wei J, Zhu Y. Influences of additives on the rheological properties of cement composites: A review of material impacts. Materials. 2025;18(8):1753.[DOI]

-

126. Şahin HG, Mardani A, Beytekin HE. Effect of silica fume utilization on structural build-up, mechanical and dimensional stability performance of fiber-reinforced 3D printable concrete. Polymers. 2024;16(4):556.[DOI]

-

127. Weng JK, Langan BW, Ward MA. Pozzolanic reaction in portland cement, silica fume, and fly ash mixtures. Can J Civ Eng. 1997;24(5):754-760.[DOI]

-

128. Lei X, Wang B, Xie Y, He Z. Performance and microstructure evaluation of self-compacting UHPC containing silica fume and fly ash. J Sustain Cem-Based Mater. 2025;14(12):2572-2584.[DOI]

-

129. Naik GB, Nakkeeran G, Roy D. Recycling glass waste into concrete aggregates: Enhancing mechanical properties and sustainability. Asian J Civ Eng. 2025;26(1):1-19.[DOI]

-

130. Benazzouk A, Mezreb K, Doyen G, Goullieux A, Quéneudec M. Effect of rubber aggregates on the physico-mechanical behaviour of cement-rubber composites-influence of the alveolar texture of rubber aggregates. Cem Concr Compos. 2003;25(7):711-720.[DOI]

-

131. Alshaeer H, Amran M, Rezzoug A, Murali G, Makul N, Al-Yaari M, et al. Recent trends in rubberized and non-rubberized ultra-high performance geopolymer concrete for sustainable construction: A review. Rev Adv Mater Sci. 2025;64(1):20250127.[DOI]

-

132. Hao N, Song Y, Wang Z, He C, Ruan S. Utilization of silt, sludge, and industrial waste residues in building materials: A review. J Appl Biomater Funct Mater. 2022;20:22808000221114709.[DOI]

-

133. Irshidat M, Cabibihan JJ, Fadli F, Al-Ramahi S, Saadeh M. Waste materials utilization in 3D printable concrete for sustainable construction applications: A review. Emergent Mater. 2025;8(3):1357-1379.[DOI]

-

134. Ren C, Hua D, Bai Y, Wu S, Yao Y, Wang W. Preparation and 3D printing building application of sulfoaluminate cementitious material using industrial solid waste. J Clean Prod. 2022;363:132597.[DOI]

-

135. Ogidi OI, Izah SC. Water contamination by municipal solid wastes and sustainable management strategies. In: Izah SC, Ogwu MC, Loukas A, Hamidifar H, editors. Water crises and sustainable management in the Global South. Cham: Springer; 2024. p. 313-339.[DOI]

-

136. Capêto AP, Jesus M, Uribe BEB, Guimarães AS, Oliveira ALS. Building a greener future: Advancing concrete production sustainability and the thermal properties of 3D-printed mortars. Buildings. 2024;14(5):1323.[DOI]

-

137. Singh N, Colangelo F, Farina I. Sustainable non-conventional concrete 3D printing—a review. Sustainability. 2023;15(13):10121.[DOI]

-

138. Sabău M, Bompa DV, Silva LFO. Comparative carbon emission assessments of recycled and natural aggregate concrete: Environmental influence of cement content. Geosci Front. 2021;12(6):101235.[DOI]

-

139. Tošić N, Marinković S, Dašić T, Stanić M. Multicriteria optimization of natural and recycled aggregate concrete for structural use. J Clean Prod. 2015;87:766-776.[DOI]

-

140. Braga AM, Silvestre JD, de Brito J. Compared environmental and economic impact from cradle to gate of concrete with natural and recycled coarse aggregates. J Clean Prod. 2017;162:529-543.[DOI]

-

141. Nair SR, Nagarajan P, Thampi SG, Das S, Rajesh P. Life cycle-based sustainability assessment of optimized 3D printable concrete mixes incorporating SCMs and recycled aggregates. Results Eng. 2025;28:108002.[DOI]

-

142. Roh S, Kim R, Park WJ, Ban H. Environmental evaluation of concrete containing recycled and by-product aggregates based on life cycle assessment. Appl Sci. 2020;10(21):7503.[DOI]

-

143. Siddique R. Use of municipal solid waste ash in concrete. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2010;55(2):83-91.[DOI]

-

144. Ohemeng EA, Ekolu SO. Comparative analysis on costs and benefits of producing natural and recycled concrete aggregates: A South African case study. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2020;13:e00450.[DOI]

-

145. Gao Y, Lalevée J, Simon-Masseron A. An overview on 3D printing of structured porous materials and their applications. Adv Mater Technol. 2023;8(17):2300377.[DOI]

-

146. Lin Y, Yan J, Sun M, Tang B, Han X. Effects of waste glass powder on printability, hydration and microstructure of 3D printing concrete. J Build Eng. 2025;112:113882.[DOI]

-

147. Zhuang Z, Xu F, Ye J, Hu N, Jiang L, Weng Y. A comprehensive review of sustainable materials and toolpath optimization in 3D concrete printing. npj Mater Sustain. 2024;2(1):12.[DOI]

-

148. Uddin MA, Sobuz MHR, Kabbo MKI, Tilak MKC, Lal R, Reza MS, et al. Predicting the mechanical performance of industrial waste incorporated sustainable concrete using hybrid machine learning modeling and parametric analyses. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):26330.[DOI]

-

149. Prasittisopin L. Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) in sustainable concrete construction: Review, trend and gap analyses. J Asian Archit Build Eng. 2025.[DOI]

-

150. Wilk-Jakubowski JL, Kuchcinski A, Pawlik L, Wilk-Jakubowski G. Advanced sound insulating materials: An analysis of material types and properties. Appl Sci. 2025;15(11):6156.[DOI]

-

151. Fediuk R, Amran M, Vatin N, Vasilev Y, Lesovik V, Ozbakkaloglu T. Acoustic properties of innovative concretes: A review. Materials. 2021;14(2):398.[DOI]

-

152. França WT, Barros MV, Salvador R, de Francisco AC, Moreira MT, Piekarski CM. Integrating life cycle assessment and life cycle cost: A review of environmental-economic studies. Int J Life Cycle Assess. 2021;26(2):244-274.[DOI]

-

153. Petrillo A, De Felice F, Jannelli E, Autorino C, Minutillo M, Lavadera AL. Life cycle assessment (LCA) and life cycle cost (LCC) analysis model for a stand-alone hybrid renewable energy system. Renew Energy. 2016;95:337-355.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite