Abstract

The increasing digitalization of the construction industry is reshaping how professionals are trained and educated. As a key component of construction education, traditional site visits provide students with valuable first-hand exposure to real-world construction environments. However, despite their educational value, such visits present multiple challenges, including scheduling difficulties, limited site capacity, health and safety restrictions, induction requirements, and high logistical costs. In recent years, Virtual Reality (VR) has offered new opportunities to deliver remote, realistic, and interactive site experiences that replicate the authenticity of on-site learning without requiring physical presence. Previous studies have primarily focused on fully computer-generated VR environments developed using platforms such as Unity or Unreal Engine. While these models offer flexibility and interactivity, they often lack the contextual realism of actual construction sites. Addressing this gap, the present study designed and developed a VR immersive construction site experience tailored to the Australian construction industry, built from 111 high-resolution 360° panoramas captured at a real construction site. The system architecture was developed using an incremental development approach to manage complexity, refine functions, and ensure continuous feedback. Drawing on insights from a systematic literature review, the system architecture specifically targeted barriers to VR adoption in construction education. The resulting prototype was evaluated by 31 students, revealing positive perceptions across all key constructs, with mean scores of 4.31 for usefulness, 4.30 for ease of use, and 4.28 for learning impact (five-point Likert scale). This study represents a pioneer exploration in establishing a scalable and educationally aligned framework for VR-based construction learning. Future development stages will focus on expanding the system to cover diverse project types, integrating adaptive learning features, and linking it with learning management systems to enhance engagement and learning analytics.

Keywords

1. Introduction

The construction industry is undergoing rapid digital transformation, driven by advances in Building Information Modelling (BIM), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and immersive technologies. These innovations are reshaping not only how projects are designed and delivered but also how future professionals in the construction industry are educated and trained. As a traditional and essential component of construction education, site visits are typically organized a few times throughout a degree program, providing students with valuable exposure to real-world projects and construction processes[1,2]. While physical site visits remain a valuable experiential learning method, many active sites restrict student access due to occupational health and safety requirements, tight construction schedules, or contractual obligations[3]. Additionally, financial constraints, weather conditions, and geographical distance further limit the frequency and inclusivity of site-based learning opportunities[4], preventing students from observing diverse construction stages, methods, and work environments. Consequently, many graduates complete their studies with limited practical understanding of on-site operations and insufficient exposure to digital tools and processes increasingly used in modern construction practice. These challenges highlight the growing need for supplementary approaches that can replicate the authenticity and educational value of real-site experiences while promoting inclusivity, flexibility, and safety in construction education.

In recent years, the rapid advancement of virtual reality (VR) technology has created new opportunities for immersive learning in construction education. As a computer-generated environment, VR allows users to be fully immersed in a three-dimensional digital space that can be explored and interacted with in real time[5]. Within a VR environment, users can move freely, observe spaces from multiple viewpoints, and engage with virtual objects or embedded information overlays, creating an experience that closely replicates on-site exploration. VR environments can be broadly categorized into two main types: those that are fully computer-generated and those created through 360-degree image or video capture of real-world settings. Fully computer-generated environments, typically developed using platforms such as Unity or Unreal Engine, provide a high degree of control, customization, and interactivity. In contrast, 360-degree captured environments, created using panoramic cameras, provide photorealistic representations of actual construction sites, enhancing realism and authenticity. Although they generally offer lower levels of interactivity, they can be developed more efficiently and are particularly well suited to educational scenarios that prioritize realism, accessibility, and contextual understanding.

Previous studies have demonstrated the potential of VR in construction education, showing that it enables learners to explore construction sites virtually, safely, and repeatedly, at their own pace, without disrupting real-world operations. However, most existing applications have relied on fully computer-generated environments. For example, Wang and Hsu[2] proposed a VR-based system for construction site planning using the Unity game engine, allowing students to navigate simulated worksites and interact with individual building components in real time. Similarly, Abotaleb et al.[6] and Sun et al.[7] developed virtual construction site simulations in Unity that allowed students to engage with potentially hazardous scenarios in a risk-free environment, thereby strengthening their understanding of safety procedures and site operations. Despite these advances, fully computer-generated environments often lack the authentic visual and contextual richness of real construction settings[8]. In contrast, the use of 360-degree immersive environments has been explored far less extensively in construction education. Compared with fully modelled simulations, 360-degree approaches provide greater realism, shorter development time, lower technical and computational requirements, and significantly reduced costs[9]. They are also easier to deploy, update, and scale, making them a practical and sustainable alternative for educational applications. Most importantly, because they capture real construction conditions, 360-degree environments can significantly enhance authenticity and contextual understanding, making them particularly suitable for construction education, where exposure to real-world environments is essential for developing practical knowledge and spatial awareness.

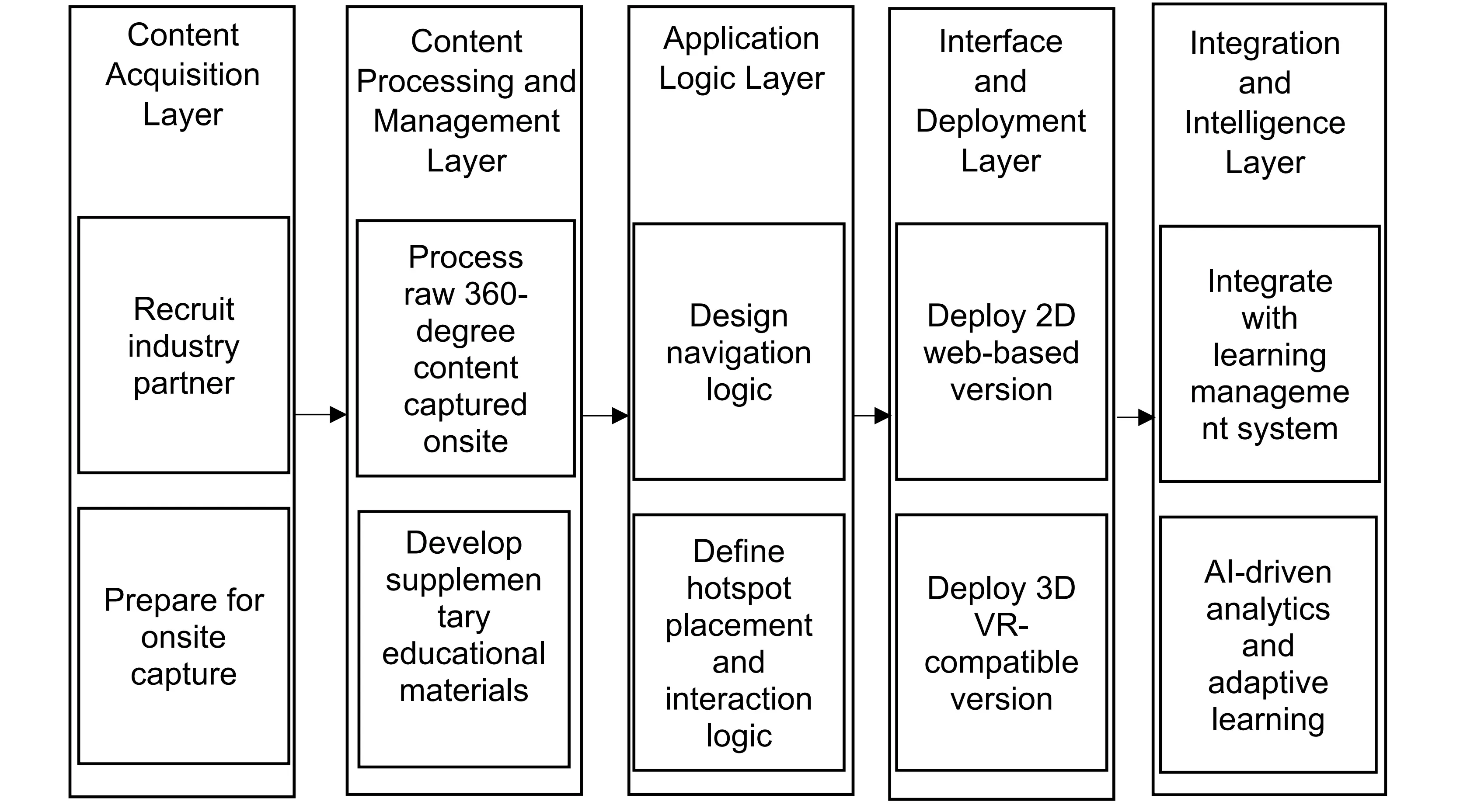

To address this gap, this study aims to design and develop a VR immersive construction site experience tailored to the Australian construction industry using an incremental development approach. This method facilitated early testing and feedback, reduced development risks, and allowed for flexible integration of new features based on user input[10]. This study seeks to address two research questions: 1) what the key challenges are in adopting VR for construction education, and 2) how system design can be structured to address these identified challenges. The first research question is answered through a systematic literature review that identifies the barriers to VR adoption in construction education. The second research question is addressed through the design and development of a five-layer system architecture comprising content acquisition, content processing and management, application logic, interface and deployment, and integration and intelligence. A prototype was subsequently developed and evaluated through two user evaluation workshops to examine participants’ perceptions of usefulness, usability, and learning impact, providing empirical insights to guide future refinement and system enhancement. The findings of this research contribute to the development of an educationally aligned and scalable framework for VR-based construction learning, supporting broader initiatives in digital transformation and immersive education within the Australian construction industry.

2. Challenges in VR Adoption in Construction Education

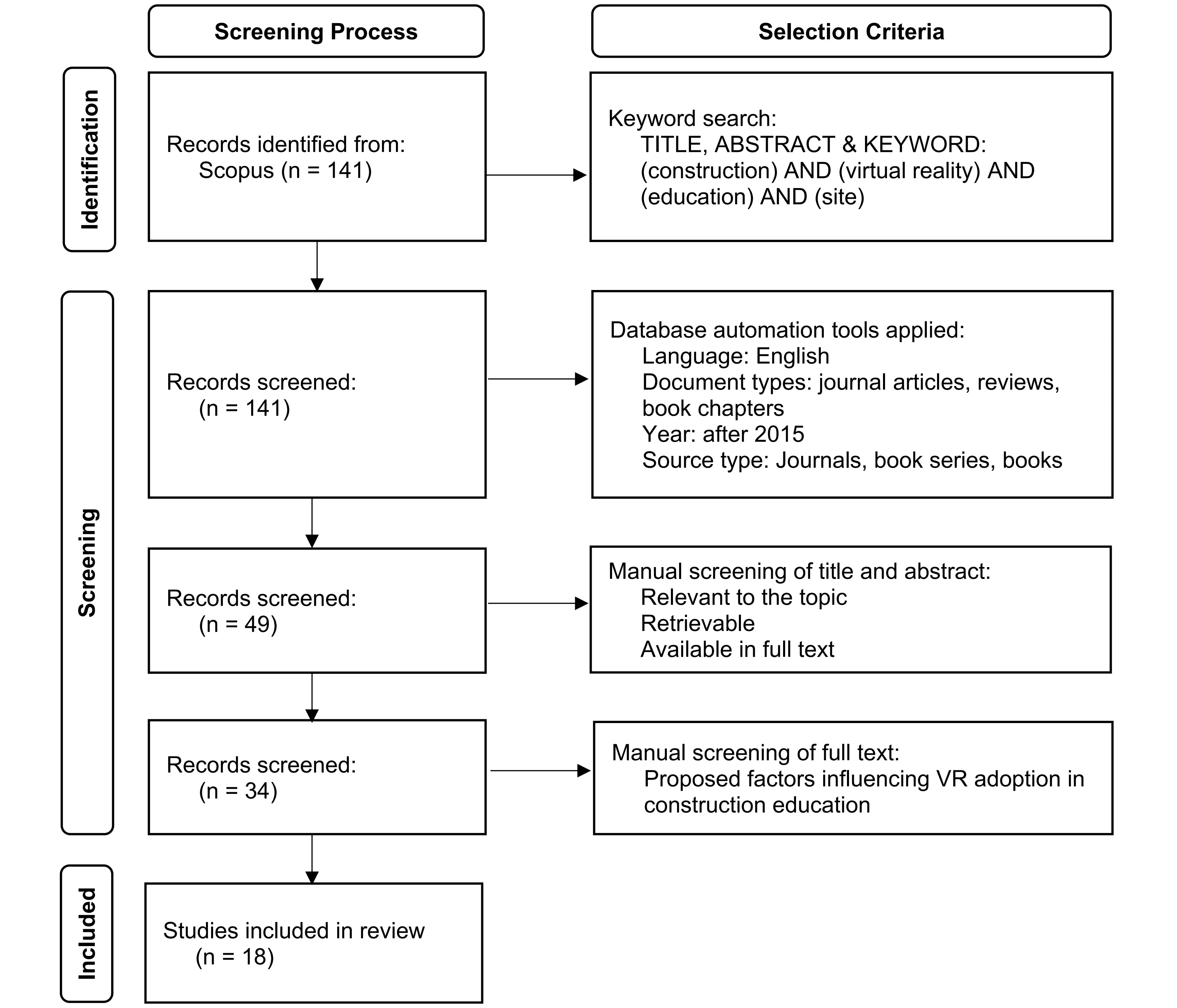

Before developing the system architecture of the VR construction site tour, a systematic literature review was conducted to identify the key challenges associated with VR adoption in construction education. The findings from this review informed the architectural design of the system, ensuring that each layer was strategically structured to address the identified barriers. The challenges extracted from the literature formed the theoretical foundation for the system’s design framework, guiding decisions related to usability, pedagogical integration, and technological scalability. As a widely recognized research method, a systematic literature review enables the systematic identification, evaluation, and synthesis of existing studies on a defined topic[11]. The thematic synthesis approach was employed in this study, which allowed the categorization of findings into recurrent themes and the extraction of actionable insights for system design. To ensure transparency, reproducibility, and methodological rigor, the review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses approach. The full selection and screening process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

The literature search was conducted using Scopus, selected for its comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed publications in construction management, engineering, and education. The search query, “construction” AND “virtual reality” AND “education” AND “site”, initially retrieved 141 records. A two-stage screening process was then applied. The first round used Scopus’s filtering tools to include only English-language journal articles, reviews, or book chapters published after 2015, reducing the dataset to 49 records. In the second round, titles and abstracts were manually screened for relevance to VR adoption in construction education, after which 34 papers were retained for full-text review. Following detailed assessment, 18 studies were included in the final synthesis. This number is consistent with the scope of prior systematic reviews in the construction management field[12,13]. The selected papers were analyzed using thematic analysis in Lumivero NVivo 14, which facilitated efficient data organization, coding, and theme development[14]. Each paper was reviewed manually, and descriptive codes were assigned to text segments that reflected key factors influencing the adoption of VR in construction education, as summarized in Table 1. As the coding process progressed, codes with similar or overlapping meanings were merged to reduce redundancy and improve clarity.

| Challenges | Papers | |||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |

| Technical complexity | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||

| Curriculum integration | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Potential user discomfort | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||||

| Ethical considerations | X | X | ||||||||||||||||

| Learning curve for students | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| Realism and accuracy issues | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||||

| User acceptance and perspective | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| Budgetary requirement | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| Ref. | [23] | [20] | [2] | [5] | [7] | [26] | [6] | [18] | [1] | [19] | [25] | [22] | [21] | [15] | [24] | [17] | [27] | [16] |

Across the 18 studies, experimental designs were most commonly used to compare VR-based learning with traditional instructional approaches, particularly in areas such as safety training, site planning, plan reading, and problem-solving skills. In contrast, case studies primarily focus on the design, development, and classroom deployment of VR systems. Only two studies adopted review-based approaches to synthesize existing evidence, examining topics of accreditation alignment and emerging educational trends related to VR. Survey and interview-based methods are used by most studies to capture learner and educator perceptions, usability considerations, and stakeholder informed risk scenarios. In terms of contextual settings, all studies are situated within higher education, with a strong focus on undergraduate and postgraduate programs in civil engineering, construction management, architecture, and related built environment disciplines. Few studies extend beyond academic settings to include industry contexts, such as construction workers, safety managers, and experienced professionals, particularly within safety and technology focused training scenarios.

By conducting thematic analysis, eight key challenges were identified. The learning curve for students was the most cited challenge in the reviewed studies, particularly for students with limited prior exposure to VR technology. For instance, Eiris et al.[15] reported that many students initially struggled to interact effectively within VR environments, which motivated their experimental evaluation of 360-degree panoramic virtual site visits supported by virtual humans. By providing guided interactions and familiar site representations, their study demonstrated how system design can reduce cognitive load and support learner acclimatisation to immersive environments. Similarly, Sun et al.[7] addressed learning curve related adoption challenges through the design of RoboSite, a Unity-based immersive virtual site visit platform. By embedding structured interactions and contextualised learning scenarios, the system enabled learners to engage with complex concepts such as four-legged robots in construction without requiring advanced VR expertise, thereby lowering barriers to initial adoption. Maghool et al.[16] likewise responded to usability and learning curve challenges in immersive learning by developing Learning Architectural Details Using Virtual Reality Technology, an Unreal Engine based VR application that emphasised intuitive interaction with architectural details. The study showed that simplifying user interaction and focusing on task specific immersion supported effective learning, suggesting that careful system design can help overcome early adoption challenges associated with VR technologies.

Another frequently reported barrier was the technical complexity of VR development, which requires specialized skills and interdisciplinary collaboration. For example, Walker et al.[17] highlighted the importance of cooperation between educators and technical developers to ensure that VR systems are both pedagogically sound and technically functional. Their case study documented the use of panoramic stereoscopic VR images captured during a campus library construction project, demonstrating that while the approach supported experiential, discovery based, and situated learning, its successful implementation relied on substantial technical coordination and development effort. Similar technical demands were evident in Chen et al.[18], who conducted an experimental study using Autodesk Revit and Iris VR to support undergraduate design review and construction site planning tasks within a virtual environment. The study evaluated student performance through task success rates in realistic underground design and site layout scenarios, illustrating how the integration of building information modelling and VR introduces additional technical complexity that can act as a barrier to widespread adoption. Likewise, Eiris et al.[19] developed the iVisit Collaborate platform using Unity 3D and Photon to enable multi-user 360-degree virtual site visits with virtual humans. While the system effectively supported collaborative problem solving through augmented spatiotemporal contexts and real time interaction affordances, its development required advanced programming skills and networking capabilities. Budgetary constraints were another commonly reported barrier. Implementing VR in education often demands substantial investment in compatible hardware, software licenses, and ongoing maintenance. As presented by Kuncoro et al.[20], a case study employed Unity to develop an earthquake resistant construction model for civil engineering education. While the VR application effectively supported immersive visualization of seismic design principles, the study highlighted the cost associated with specialized development tools and VR compatible infrastructure as a practical challenge for broader implementation. Also, the literature review by Adinyira et al.[21] examined emerging trends in construction education, training, and employment with a focus on experiential learning and virtual reality. Their analysis emphasized workforce development needs while also identifying financial constraints as a key factor restricting the widespread integration of VR technologies within educational institutions.

Curriculum integration posed an additional challenge, as embedding VR activities meaningfully into existing course structures requires careful alignment with learning outcomes, teaching objectives, and assessment frameworks. For instance, Seo et al.[22] conducted a case study that combined interviews and VR development to create a safety education system reflecting real world electrical construction site risks. By immersing learners in realistic safety scenarios derived from actual accident cases, the study sought to align VR activities with established safety training objectives and curricular requirements. Additionally, Díaz-Durán[23] developed an Unreal-based VR model representing a confined masonry building to support civil engineering undergraduates in exploring construction techniques, structural elements, and building components. The use of interactive site exploration and material manipulation was explicitly designed to align learning activities with formal curriculum requirements, including compliance with Mexican construction codes. Moreover, Terentyeva et al.[24] conducted a survey-based study incorporating focus groups with teachers and students to examine the integration of virtual construction sites within construction education programs. Their findings proposed effectiveness criteria and pedagogical guidelines to support curriculum alignment, digital skills development, and knowledge management.

User acceptance also emerged as a significant issue. Some students perceived VR as a form of entertainment rather than a legitimate educational tool, which reduced the perceived academic value of the experience. As noted by Abotaleb et al.[6], such perceptions were observed in their experimental research, which proposed a fully immersive and interactive VR safety training model grounded in experiential learning principles. Developed using Unity and C#, the system demonstrated significant improvements in students’ hazard identification and mitigation skills compared with traditional training methods, indicating that well-structured pedagogical design can help shift learner perceptions and enhance acceptance. Similarly, Wang and Hsu[2] conducted an experimental study developing an immersive VR-based education system using Unity and Revit to simulate construction site planning for undergraduate students. By integrating animations, interface text, and instructional images to teach facility configuration and safety regulations, the system aimed to reinforce VR’s instructional purpose and improve user acceptance through guided learning. In addition, Elgamal et al.[5] conducted a systematic literature review examining how VR has been used to support construction education accreditation aligned with Accreditation for Construction Education Student Learning Outcomes. While the review identified strong coverage of technical and experiential learning outcomes, it also highlighted limited application in areas requiring human interaction, quantitative analysis, and construction management tools, which may affect broader acceptance among educators and institutions.

The realism and accuracy of virtual environments were another source of concern. When tours were created entirely using simulation software such as BIM or Unity, they often lacked the authenticity of real-world construction sites, diminishing their instructional impact. For instance, Sun et al.[1] conducted an experimental study that developed a collaborative virtual learning environment using Mozilla Hubs to support plan reading activities for construction management students. While the VR environment enhanced social presence and collaborative learning compared with Zoom-based instruction, the study also highlighted the limitations of abstracted or simplified virtual representations when conveying the complexity of real construction contexts. In response to concerns regarding realism, Shojaei et al.[25] conducted an experimental study investigating the use of immersive video formats, including 360-degree video, 180-degree stereoscopic video, and flat video, in construction management education. Students reported more positive learning experiences and demonstrated a clear preference for head mounted displays over traditional screens, suggesting that higher levels of visual realism and environmental fidelity can enhance learner engagement and perceived authenticity.

Furthermore, several studies reported user discomfort, including motion sickness, dizziness, and disorientation. These physical discomforts can negatively affect learner engagement and limit the duration and frequency of VR use. Cheng et al.[26] highlighted this issue through an experimental study that developed a semi-immersive 360-degree VR training environment to educate construction professionals about drone applications and safety. By employing a semi-immersive approach rather than fully interactive VR, the system aimed to reduce sensory overload and mitigate discomfort while retaining key immersive benefits. The results demonstrated significant improvements in safety related knowledge and confirmed the usability of 360-degree VR as an effective training delivery platform.

Finally, a small number of studies raised ethical considerations related to data privacy and user consent, especially when recording user interactions or storing performance data. For example, Pham et al.[27] conducted an experimental study that developed a web-based panoramic VR safety education system for building construction students, integrating lesson delivery, practical experience, and knowledge assessment modules based on real construction site scenarios. While the system demonstrated educational effectiveness, it also highlighted the need for clear protocols regarding user consent, data handling, and ethical governance when deploying VR platforms that track learner behavior. These findings suggest that ethical considerations, although less frequently discussed, represent an important factor influencing institutional acceptance and the responsible implementation of VR in construction education.

These identified challenges collectively informed the system architecture design of this study, ensuring that each layer was strategically structured to address and mitigate these barriers through targeted technical and pedagogical solutions.

3. System Architecture Design

A system architecture defines the high-level structure of a system, outlining its key components and the interactions among them to achieve the desired functions and performance outcomes[28]. For this study, the proposed architecture is organized into five interconnected layers: (1) content acquisition layer, (2) content processing and management layer, (3) application logic layer, (4) interface and deployment layer, and (5) integration and intelligence layer. Each layer performs a distinct role within the system while collectively forming an integrated framework that supports scalability, adaptability, and user engagement. Building upon previous studies, this system architecture design directly addresses the key barriers to VR adoption identified through the systematic literature review (as presented in Table 1). Figure 2 presents the overall system architecture.

3.1 Content acquisition layer

The content acquisition layer forms the foundation of the immersive system, responsible for capturing high-quality visual and auditory data from real construction sites to ensure realism and contextual accuracy. The process began with the recruitment of an industry partner, a main contractor within the Australian construction industry, whose active project provides authentic environments for educational and training purposes. Prior to any data collection, an information sheet and consent form were distributed to outline project objectives, data usage, and ethical safeguards. Collaborative arrangements are then established to ensure safe on-site shooting, compliance with workplace regulations, and coordination with site operations.

A key design feature of this layer is its systematic capture planning process, as recommended by Loddo[29], which involves reviewing architectural drawings and floor plans to determine optimal shooting points before fieldwork. This pre-design stage ensures comprehensive spatial coverage and pedagogical relevance, targeting areas that demonstrate key construction activities and sequencing. The shooting plan specifies camera positions, orientations, and time schedules that align with site access availability and safety protocols. The proposed shooting period is typically arranged in consultation with the contractor to minimize disruption, such as during off-peak hours or non-critical work periods.

This layer directly targets two major challenges in VR adoption identified in the literature: realism and accuracy, and user acceptance and perspective. To enhance realism and visual fidelity, the system employs professional 360-degree cameras together with a structured capture protocol that ensures consistent lighting, exposure, camera height, and frame alignment across all scenes. In contrast to the commonly used approach of creating fully computer-generated environments in platforms such as Unity[2] or Revit[30], this method enables learners to experience a construction site exactly as it existed at a specific point in time. This level of authenticity strengthens contextual understanding and exposes students to the natural imperfections, constraints, and situational conditions of an active worksite, elements that are difficult to model accurately and are often cited as valuable learning moments in construction education.

Moreover, VR adoption is often hindered because students perceive fully modelled VR environments as “too artificial” or “game-like”, which reduces their sense of academic value and realism[6]. The use of photorealistic 360-degree imagery directly addresses this concern by presenting the site in its genuine, unaltered form. This improves the perceived credibility of the VR experience and helps students view the tour as an authentic learning resource rather than a simulated fantasy. Capturing real-world details such as surface imperfections, incomplete formwork, temporary structural supports, exposed reinforcement, and active construction layouts further enhances perceived usefulness, as these conditions mirror what learners would encounter during a real site visit.

3.2 Content processing and management layer

The content processing and management layer is designed to process the raw materials captured on site while incorporating structured learning resources that enhance industry relevance. This layer consists of two components. The first component focuses on processing the raw 360° content, including stitching, stabilization, and optimization of the panoramic imagery and videos to ensure smooth visual continuity and spatial accuracy. Each processed scene is submitted through an approval workflow with the collaborating industry partner to confirm the technical correctness and site safety representation before integration into the system. The second component focuses on developing supplementary educational materials that contextualize the immersive visuals within the context of the Australian construction industry. This involves preparing concise scripts that explain major structural and service elements, as well as broader aspects such as safety procedures, site logistics, and compliance with Australian construction regulations and standards. These scripts are recorded as audio narrations and paired with explanatory videos, diagrams, and reference images to deepen conceptual understanding. Storytelling may also be incorporated, as highlighted by Wen and Gheisari[31], to enhance learner engagement and contextual understanding. The content created in this layer is stored within a central resource hub and is triggered by the hotspots governed by the application logic layer.

This layer addresses two key challenges identified in the literature: budgetary requirements and ethical considerations. From a cost-management perspective, this layer was designed to support an incremental development approach, allowing additional features, panoramas, and learning materials to be incorporated progressively as resources become available. This approach avoids the high upfront costs typically associated with fully modelled VR environments and ensures that the system can grow sustainably over time. By structuring content into modular units, such as individual panoramas, audio explanations, video clips, and hotspot annotations, the system enables the research team to update or expand the VR experience without reconstructing the entire environment, thereby reducing long-term financial and technical burden.

Ethical considerations are also embedded directly into this layer. All captured panoramas and associated materials undergo a review and approval process with the industry partner prior to inclusion in the VR tour. Consent is formally obtained for filming, and the partner is given the opportunity to verify that the content does not reveal sensitive information, operational details, or identifiable workers. When necessary, face blurring, signage masking, and other privacy-preserving techniques can be applied during the processing stage to safeguard confidentiality and meet organizational and legal requirements. This structured workflow ensures that the VR content not only adheres to ethical and privacy expectations but also maintains the integrity and professionalism required for use in formal construction education settings.

3.3 Application logic layer

The application logic layer defines the functional behavior of the system, serving as the bridge between content management and user interaction. It governs how users navigate, explore, and interact within the virtual environment. The layer is designed around a structured hotspot logic, initially mapped using the building’s floor plan to ensure spatial coherence and intuitive movement flow. The navigation pathway begins at the main entrance and progresses through key construction zones such as structural areas, service rooms, and fit-out sections. Each hotspot functions as an interactive trigger that activates scene transitions and dynamically displays the learning content created in the content processing and management layer, including audio narrations, explanatory videos, annotated images, and textual descriptions of site components. The logic ensures that these educational materials are contextually presented at the precise location where each construction element appears.

The navigation framework supports both guided tours and free exploration, providing flexibility for different learning styles. In guided mode, users follow a step-by-step sequence designed to mirror real construction workflows, while in exploration mode, they can freely select hotspots to access detailed explanations. Pop-up instructions, visual cues, and progress indicators are embedded to provide real-time scaffolding, easing navigation for first-time users. System parameters such as camera speed, field of view, and transition timing remain flexible for adjustment in future development stages, allowing continuous refinement based on user feedback or evolving technological capabilities.

This layer responds to two key challenges in VR adoption: technical complexity and the learning curve for students. Compared with fully computer-generated environments, which require extensive 3D modelling, programming expertise, and continuous debugging, this design significantly simplifies the development process. Using 360-degree panoramas as the foundation reduces the need for complex coding while still enabling rich interactivity through the integration of hotspots, directional transitions, audio overlays, and embedded multimedia. This approach maintains flexibility, as additional hotspots or scene customizations can be added incrementally without the technical overhead associated with traditional game-engine development.

The layer also reduces the learning curve for students by prioritizing intuitive navigation and interaction design. The movement logic is structured in a manner similar to Google Street View, allowing users to navigate through the site by following clear visual cues and directional arrows. This familiar interaction model supports rapid user adaptation, even for students with no prior experience using VR systems. By linking panoramas in logical sequences that mimic real site movement and by incorporating consistent iconography, the application logic ensures that learners can focus on understanding construction processes rather than on overcoming technological barriers.

3.4 Interface and deployment layer

The interface and deployment layer delivers the visual and interactive front end of the system, enabling users to access and experience a virtual construction environment. It provides a user interface (UI) designed for clarity, responsiveness, and accessibility, incorporating intuitive navigation controls, an interactive floor map, and a radar indicator to help users identify their position and orientation within the building. The interface supports two operational modes: a 2D web-based version that can be accessed through a standard browser for convenience and inclusivity, and a fully immersive 3D version compatible with VR headsets and controllers, allowing users to explore the environment with enhanced spatial perception. The system is hosted online to facilitate remote access, ensuring scalability for institutional use and future integration with learning management systems (LMS).

This layer targets the challenge of potential user discomfort, which is frequently reported in VR adoption studies. To support diverse comfort levels, the system provides two deployment options: a fully immersive 3D VR version and a more accessible 2D web-based version. The 3D version enables customized motion controls, fixed reference points, and minimal-transition navigation, all of which help reduce motion sickness, dizziness, and visual fatigue. For users who are sensitive to immersive environments or unable to tolerate extended headset use, the 2D version offers a practical alternative that preserves the learning content while eliminating the physical discomfort associated with head-mounted displays. This dual-version deployment expands accessibility and ensures that users can engage with the site content in a manner that aligns with their comfort levels and technological constraints. Additionally, hosting the tour online allows both versions to be accessed across a range of devices, supporting flexible usage in classroom, laboratory, and remote learning environments.

3.5 Integration and intelligence layer

The integration and intelligence layer was designed to connect the immersive environment with external learning and analytical systems. This layer enables integration with institutional LMSs, such as Moodle, Blackboard, and Canvas, supporting seamless incorporation of VR-based learning activities into existing curricula. In addition, usage data and learner interactions, including time spent in specific zones, hotspots accessed, and completion of guided tours, can be tracked to evaluate engagement and learning outcomes. AI-driven analytics and adaptive learning are also supported, where user behavior data can be analyzed to identify common learning patterns, knowledge gaps, or usability issues. These insights inform iterative system refinement, generating data-driven feedback loops that support continuous improvement and personalization of the learning experience.

This layer addresses the challenge of curriculum integration, which is widely noted in the literature as a key barrier to the effective adoption of VR in construction education. This layer provides the foundation for linking the VR tour with LMSs, enabling the VR experience to be embedded directly within structured teaching modules, weekly activities, or assessment tasks. Through LMS integration, educators will be able to track student engagement, access usage analytics, and align VR interactions with specific learning outcomes or accreditation requirements. This layer also establishes the potential for adaptive learning features, such as automated feedback, in-tour quizzes, and AI-driven prompts tailored to individual learner progress. These capabilities will support stronger alignment between immersive learning activities and formal curriculum design, ensuring that the VR tour functions not as a stand-alone digital tool but as a pedagogically meaningful component of construction education. As the system evolves, this layer will enable deeper integration of data analytics, personalized learning pathways, and competency-based tracking, thereby enhancing both instructional value and long-term scalability.

4. Prototype Development

After the system architecture design was finalized, a prototype was developed to demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed framework. As an early-stage implementation, the primary aim of this prototype was to validate the system design and evaluate its usability in an educational context. The target audience was limited to students enrolled in built environment programs, particularly those with little or no prior site experience. Key components outlined in the system architecture were successfully implemented, while certain advanced features were reserved for future development stages.

4.1 Content acquisition layer

An industry partnership was established through the University of New South Wales (UNSW) Women in Construction Project, which facilitated access to an active construction site for content acquisition. Following a series of consultations with the partner, a 12-storey healthcare facility was selected as the pilot site. The project comprised two basement levels and a total gross floor area exceeding 100,000 m2, delivered under a design and construction contract. Key structural and construction features included deep basement excavation, piled foundations, a reinforced concrete frame, and the application of jump-form construction techniques for constructing the building’s structural core. In agreement with the industry partner, five representative floors, Basement 2, Ground Floor, Level 6, Level 9, and the Roof, were approved for on-site capture. These floors were at varying stages of completion, offering the opportunity to document different phases of the construction process and present a comprehensive learning experience. Table 2 summarizes the intended use and construction status at the time of filming for each selected floor.

| Level | Intended Use | Construction Status at Filming |

| Basement 2 | Serves as the main logistics hub | Internal fit-out in progress |

| Ground | Acts as the main Entry and outdoor area | Fit-out underway for lobby |

| Level 6 | Provides inpatient care | Prior to internal room construction |

| Level 9 | Houses essential mechanical and engineering systems | Table formwork in place |

| Roof | Supports installation of solar panels | Concrete slab to be completed |

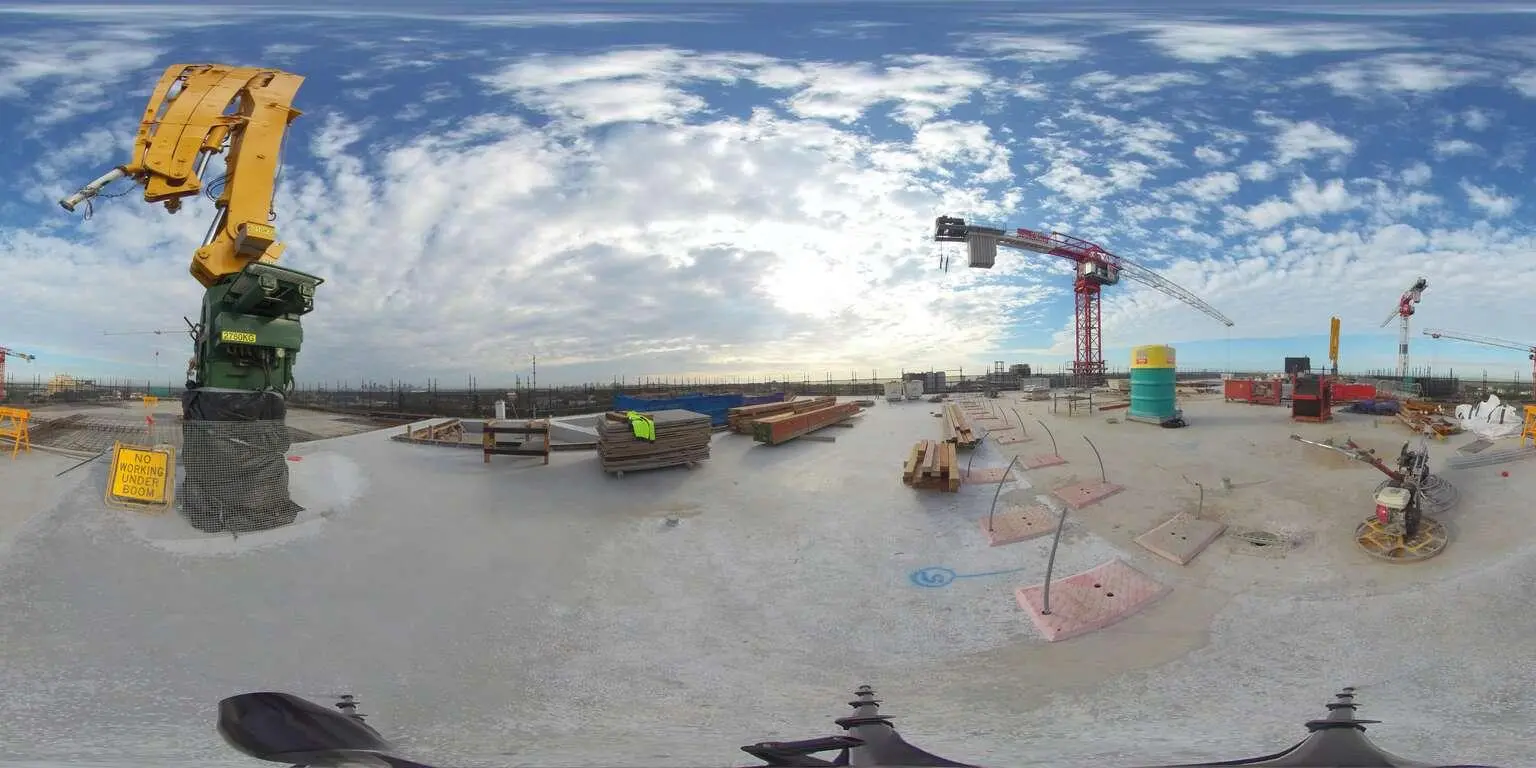

The filming was conducted approximately 18 months after the commencement of the main works on the healthcare facility project, by which time the piling, excavation, and primary structural works had been completed, providing a safe and stable environment for recording. Floor plans were supplied in advance by the industry partner, enabling the research team to systematically plan shooting positions across the selected floors. To capture high-quality 360° images and videos, an Insta360 Pro camera mounted on a tripod was used. The on-site filming took place on a Saturday, as requested by the industry partner, to minimize workforce interruption and maintain a controlled environment. Prior to filming, all members of the research team completed a full on-site safety induction by a site officer to ensure compliance with emergency procedures and site protocols, and personal protective equipment (PPE) was worn throughout. To protect worker privacy, the industry partner requested that no personnel be included in the panoramas. The process lasted approximately five hours, during which a total of 111 high-resolution 360° panoramas were captured.

4.2 Content processing and management layer

Following the completion of the on-site shoot, the captured videos and images were first stitched and rendered using Insta360 Studio, producing seamless panoramic visuals suitable for immersive display. The dataset was then cleaned to remove duplicate photographs (n = 3) and unclear or low-quality images (n = 2). The remaining panoramas were submitted to the industry partner for review and verification, ensuring that the visual representations accurately reflected construction details and safety conditions. Based on the industry partner’s feedback, several panoramas were excluded, resulting in a final dataset of 71 panoramas: 8 from Basement 2, 13 from the Ground Floor, 20 from Level 6, 13 from Level 9, and 17 from the Roof. Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 present the panoramas used.

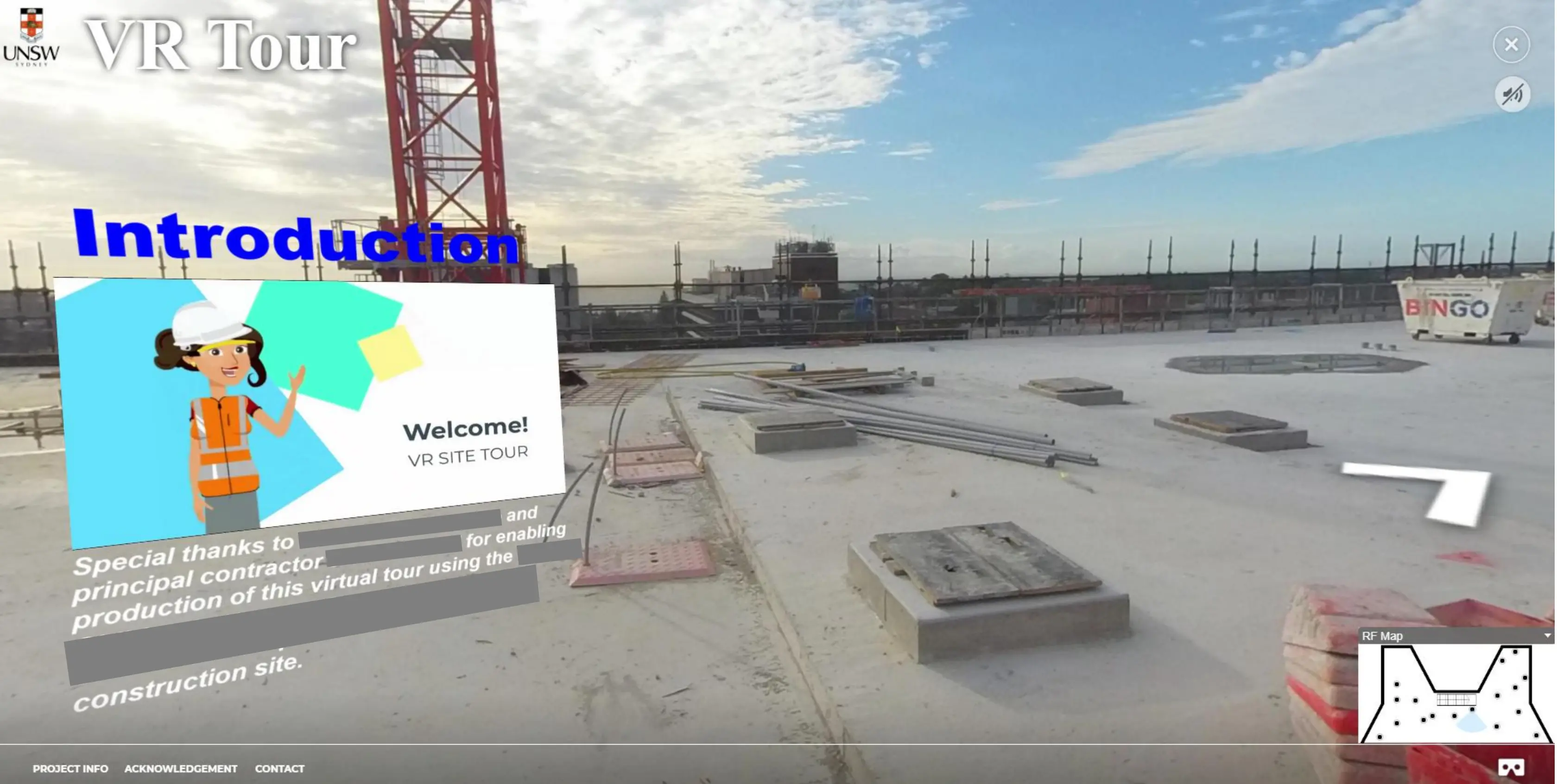

In accordance with the system architecture design, supplementary learning materials were created to enhance educational value and contextual understanding. An introductory video was produced to help users quickly understand how to navigate the VR environment, outlining the purpose of the tour, system functions, and safety considerations. For each included panorama, key construction elements were identified and annotated with audio explanations, resulting in 60 annotated site features across the tour. Scripts were drafted to provide concise overviews of these components, each lasting less than one minute. The voiceovers were generated using EaseUS Voice Over software to ensure consistent tone and clarity across all narrations. To complement the audio guidance, additional explanatory videos and images were embedded to highlight technical details, materials, and construction methods. The accuracy and clarity of all educational content were independently reviewed and verified by two senior academics from the Construction Management program at the university. Table 3 summarizes the construction elements annotated on each floor and their associated learning content.

| Level | Number of elements | Items highlighted |

| Basement 2 | 7 | Loading dock; TMV box; Drywall; Air conditioning duct; Cable caddy; Electrical lead stand; Plant room |

| Ground | 12 | Toolbox; Air return duct; Flat steel; Air supply duct; Mobile scissor lift; Electric cables; Ladder; Change room; Wet paint; Portable buildings |

| Level 6 | 13 | Shoring towers; Stressing pans; Loading platform; Scaffolding planks; Safety nets; Protection mesh; Scaffolding; Temporary power; Portable concrete mixer; Pallet jack; Spider crane; Lift shaft protection cage; Table form |

| Level 9 | 8 | Steel columns; Storage; Access mesh; Nurse station; Hoist; Emergency lights; Exit sign; Floor plan |

| Roof | 20 | Tower crane; Nurse station; Void; Penetration; Timber; Concrete pump; Trowelling machine; Safety sign; Storage; Guardrail; Scaffolding; Post-tensioning anchorage; Concrete reinforcement mesh; Marks on slab; Hose; Air compressor; Bubbler; Portable toilet; Rubbish bin; Drainage |

TMV: Thermostatic Mixing Valve.

4.3 Application logic layer

Following the finalization of the visual and educational content, the application logic layer was developed to define the interactive structure and navigation behavior of the virtual tour. This layer determines how users move between panoramas, access learning materials, and experience spatial continuity within the virtual environment. The commercial software 3DVista Pro was selected as the development engine due to its robust functionality and compatibility with both 2D and VR modes[32]. In this implementation, a slight modification was made from the original system architecture design: the tour begins at the roof level, providing a bright and engaging entry point, and then progresses downward through Level 9, Level 6, the Ground Floor, and Basement 2, following a top-to-bottom navigation sequence.

To simulate realistic movement through the construction site, panoramas were interconnected through interactive hotspots, designed as directional arrows that indicate the next viewpoint. These arrows were strategically positioned based on the site layout and user perspective, allowing intuitive navigation and preserving spatial orientation. To improve visibility and engagement, each navigation arrow featured an animated Graphics Interchange Format icon, displaying a looping directional motion that clearly signaled the transition to the next scene. When users click on an icon, the system triggers a seamless transition or activates the corresponding multimedia element, replicating the experience of walking through the site. Additionally, audio narrations, explanatory videos, and doorway introductions were embedded as interactive hotspots within each panorama. When activated, these icons trigger the associated content generated in the content processing and management layer, allowing users to listen to contextual explanations, view supplementary videos, or explore specific construction components in detail. This logic ensures that educational materials are spatially and contextually linked, enhancing both comprehension and engagement. Collectively, the application logic layer transforms static visuals into an interactive and pedagogically guided virtual learning experience, maintaining flexibility for future expansion and adaptive content updates. Table 4 presents the icons used for navigation arrows, audio narrations, videos, and doorway introductions.

| Icon | Purpose | Image |

| Audio | Plays short audio narration explaining a construction element |  |

| Video | Opens an embedded video providing additional explanation |   |

| Door Entry | Indicates a transition to a room |  |

| Turn Left | Guides user to turn left and move to the next panorama in that direction |  |

| Turn Right | Guides user to turn right and move to the next panorama in that direction |  |

| Go Straight | Guides user to move forward to the next viewpoint, simulating physical site movement |  |

4.4 Interface and deployment layer

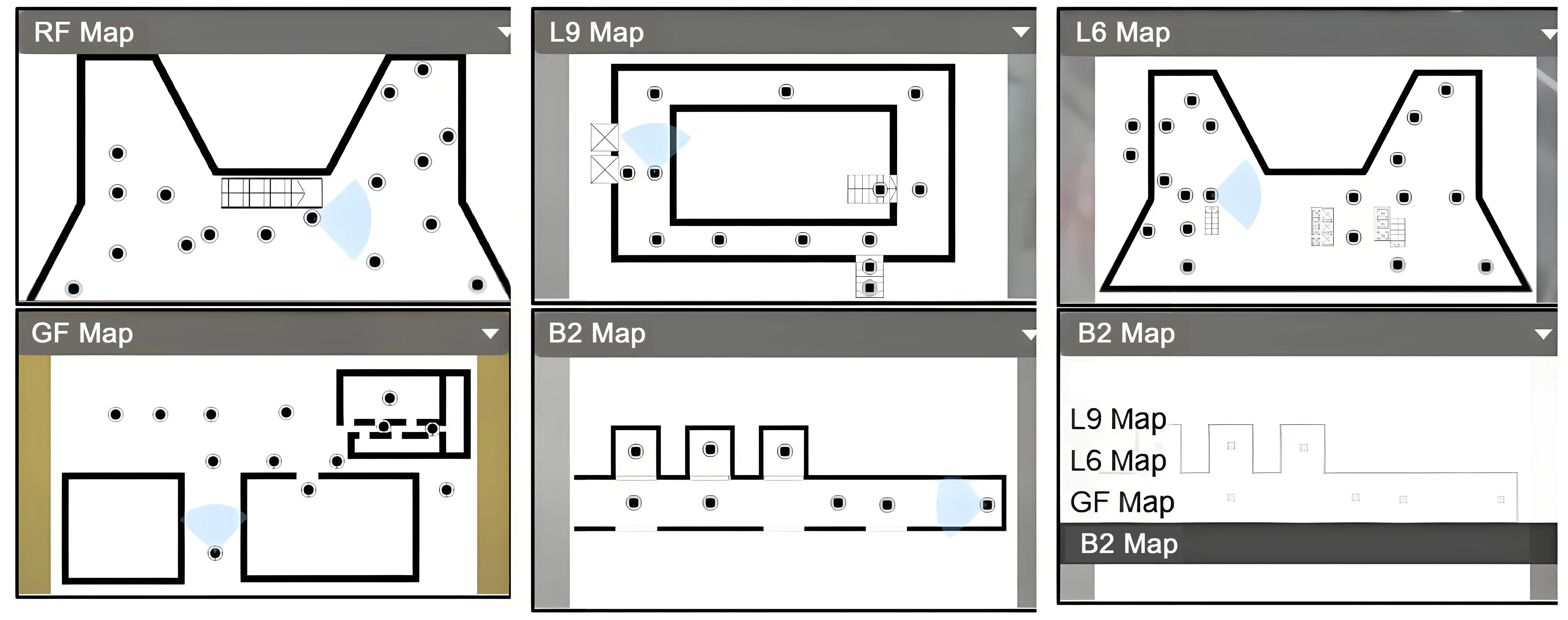

Following the system architecture design, the interface and deployment layer was developed to deliver the interactive user interface. To support intuitive navigation, an interactive floor map was embedded for each level of the building. Owing to the complexity of the original architectural drawings, the maps were simplified to enhance readability and user comprehension. Each panoramic viewpoint was represented on the map with clickable markers, allowing users to identify their position and navigate directly between locations. A radar function was integrated to display the user’s current orientation within the virtual environment, ensuring spatial awareness during exploration. In addition, a dropdown menu enabled users to switch between floors seamlessly without returning to the main interface. Figure 8 illustrates the design of the interactive floor maps and the dropdown navigation interface.

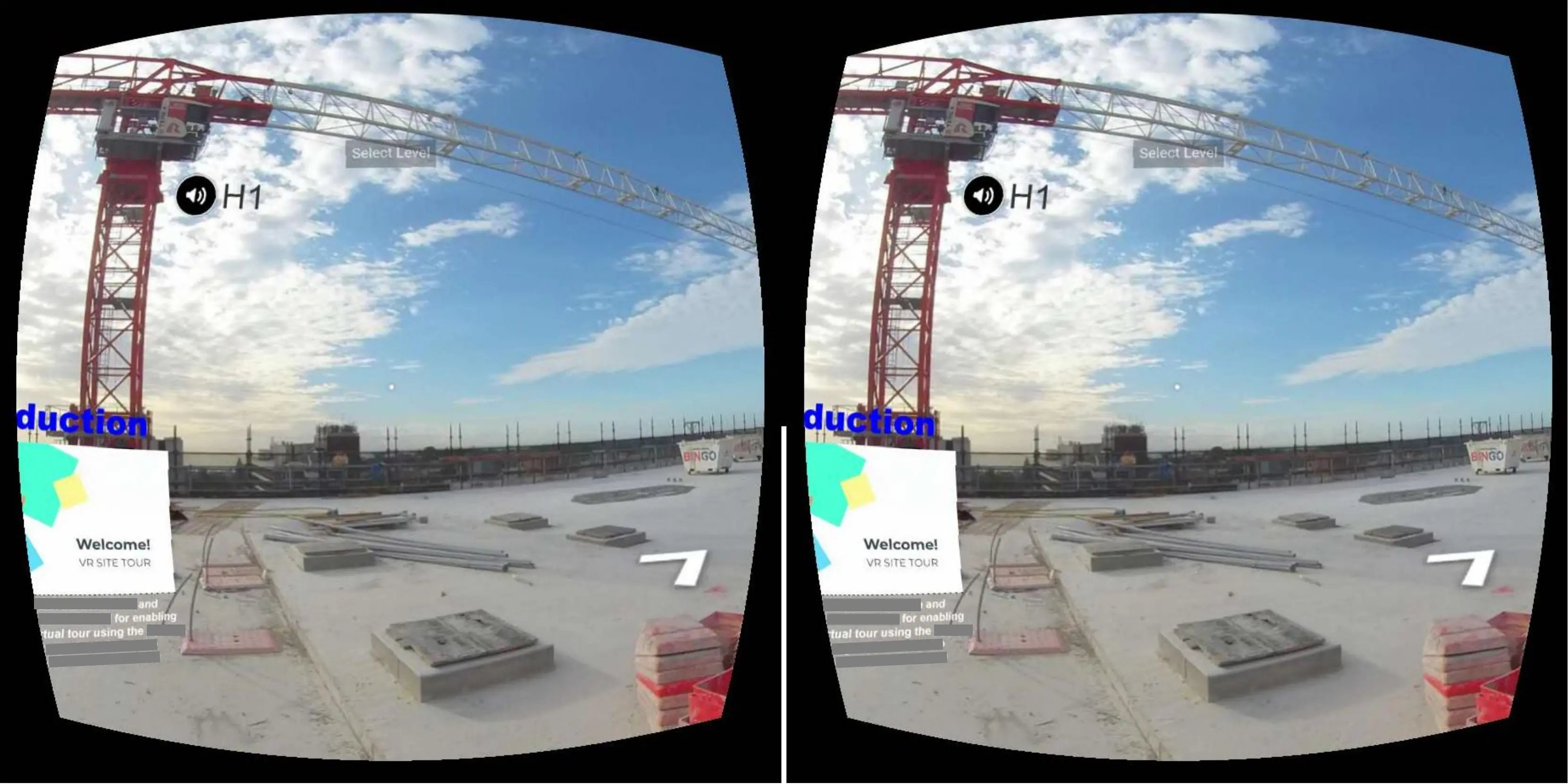

The prototype was deployed in two accessible formats: a 2D web-based version (Figure 9) and a 3D immersive VR version (Figure 10). Each serves distinct pedagogical and technical purposes. The 2D version prioritizes accessibility and convenience, allowing users to explore the construction site through standard web browsers without requiring specialized hardware. This version is particularly suitable for classroom demonstrations or remote learning contexts. The 3D version, in contrast, provides a high-fidelity immersive experience, enabling users equipped with VR-compatible devices, such as head-mounted displays, to perceive spatial depth, scale, and proximity with greater realism. Both versions are browser-based and hosted on a cloud server, ensuring ease of access, scalability, and maintenance across different institutional settings. This dual-deployment approach maximizes inclusivity and learning flexibility, catering to users with varying levels of technological capability and access to VR equipment.

4.5 Integration and intelligence layer

The integration and intelligence layer, as outlined in the system architecture, was not implemented in the current prototype due to additional technical and resource requirements. This layer is intended to enable future integration with LMSs such as Moodle, Blackboard, or Canvas, allowing the system to record user engagement metrics, learning progress, and assessment outcomes. It will also support the incorporation of AI-driven analytics and adaptive learning mechanisms, enabling the system to analyse user behaviour, identify common challenges, and provide personalised feedback or recommendations. Implementing this layer will require secure data exchange protocols, user consent mechanisms, and compatibility with institutional IT infrastructure. These features were beyond the scope of the initial prototype but are planned for inclusion in future development stages, where the system will evolve from a stand-alone immersive experience into an intelligent, data-informed educational platform capable of supporting continuous learning analytics and curriculum integration.

5. Prototype Performance Analysis

Following internal testing, two rounds of user evaluation workshops were organized at the university to assess usefulness, ease of use, and the impact of the VR prototype. University-wide email invitations and promotional posters were distributed to recruit participants from both undergraduate and postgraduate cohorts across the School of Built Environment. Each workshop commenced with a 15-minute introductory presentation delivered by the research team, outlining the objectives of the study and demonstrating how to navigate the VR tour. This was followed by a 45-minute self-directed exploration session, during which participants interacted freely with the prototype using Meta Quest 3 headset. Upon completion, participants were invited to complete a user feedback questionnaire designed to capture both quantitative and qualitative insights into their experience. The questionnaire consisted of demographic questions, ten five-point Likert-scale items, and four open-ended questions.

A total of 42 students participated in the workshops. All questionnaire responses were screened for completeness and validity prior to analysis. Incomplete submissions (n = 3), responses with missing demographic data (n = 5), and careless responses, identified as those with uniform answers across all items (n = 3), were excluded. The final dataset comprised 31 valid responses, which provided a sufficient basis for descriptive analysis. Although the sample size was relatively small, it met the assumptions of the Central Limit Theorem, which posits that when the sample size exceeds approximately 30, the sampling distribution of the mean can be considered approximately normal[33].

Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, while qualitative feedback from open-ended questions was analyzed through manual coding to identify recurring themes and improvement suggestions. Nearly half of the participants (45%) were aged between 26 and 30 years, with 74% identifying as female. Most participants (81%) reported no prior work experience in the Australian construction industry. Table 5 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the user participants.

| Demographics | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

| Gender | Male | 8 | 26% |

| Female | 23 | 74% | |

| Age | 18-25 years old | 11 | 35% |

| 26-30 years old | 14 | 45% | |

| 31-35 years old | 6 | 19% | |

| Employment in the Construction Industry in Australia | No experience | 25 | 81% |

| 1-2 years | 3 | 10% | |

| 3-4 years | 2 | 6% | |

| Current Degree Education | Bachelor's degree | 11 | 35% |

| Master’s degree | 20 | 65% | |

| Previous experienced a VR simulation or 360° tour? | No | 22 | 71% |

| Yes | 9 | 29% | |

| Previous physically visited a construction site before? | No | 10 | 32% |

| Yes | 21 | 68% |

VR: Virtual Reality.

The quantitative section of the questionnaire comprised ten Likert-scale items, each rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), designed to evaluate participants’ perceptions of the VR prototype across three key constructs: usefulness, ease of use, and impact.

Usefulness was defined as the extent to which users believed that the VR tour provided relevant, engaging, and educationally meaningful learning experiences. Three items measuring this construct were adapted from Venkatesh and Bala[34], originally part of the Technology Acceptance Model, which has been widely applied in educational technology research.

Ease of use referred to the degree to which users found the system intuitive, user-friendly, and easy to navigate. Four items were also adapted from Venkatesh and Bala[34].

Learning Impact captured participants’ perceptions of the extent to which the VR tour influenced their understanding of construction practices, improved their learning experience, and enhanced awareness of industry roles. Three items were adapted from Le et al.[35].

Table 6 presents the descriptive statistics, including the mean scores, standard deviations, and Cronbach’s alpha values for each construct. The results indicate generally favorable perceptions across all statements, suggesting that participants viewed the prototype as both educationally valuable and technically effective in supporting learning within the context of construction education.

| Factor | Statement | Mean | Standard Deviation |

| Usefulness Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.79 | 1. The VR tour enhanced my understanding of a construction site. | 4.29 | 0.12 |

| 2. The VR tour felt more engaging than traditional classroom or lecture-based learning. | 4.42 | 0.11 | |

| 3. The hotspots within the VR tour provided valuable insights into construction components. | 4.23 | 0.12 | |

| Ease of Use Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.76 | 4. The VR tour was easy to access and operate. | 4.52 | 0.10 |

| 5. Navigation within the VR tour was intuitive. | 4.29 | 0.14 | |

| 6. The VR tour met my expectations. | 4.19 | 0.15 | |

| 7. I was able to focus on the experience without being distracted by the technology. | 4.19 | 0.13 | |

| Learning Impact Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.81 | 8. The VR environment felt realistic and gave me a sense of being on-site. | 4.35 | 0.14 |

| 9. The VR tour increased my learning in understanding construction site environments. | 4.19 | 0.13 | |

| 10. The experience motivated me to learn more about construction projects. | 4.29 | 0.16 |

VR: Virtual Reality.

The survey results were also used to evaluate the effectiveness of the developed system in addressing the key challenges associated with VR adoption in construction education. The three survey items related to perceived usefulness received an average score of 4.31 out of 5, suggesting strong user acceptance and positive learner perceptions. Most students agreed that the VR tour enhanced their understanding of construction sites, was more engaging than traditional classroom or lecture-based learning, and that the embedded hotspots provided valuable insights into construction components. Ease of use was evaluated through four survey items, which achieved an average score of 4.30, indicating that the system effectively addressed challenges related to technical complexity and the learning curve for students. Participants reported that the VR tour was easy to access and operate, navigation was intuitive, the experience met their expectations, and they were able to focus on learning without being distracted by the technology. In terms of learning impact, three survey items achieved an average score of 4.28, highlighting the system’s ability to address challenges related to realism and accuracy. Students noted that the VR environment felt realistic and provided a strong sense of being on site, enhanced their understanding of construction site environments, and motivated further interest in construction projects.

User discomfort was reported by approximately 20 percent of participants, with only minor symptoms noted. This finding indicates an overall acceptable level of physical comfort while also highlighting opportunities for further refinement, which are discussed in the future development roadmap. Ethical considerations were explicitly addressed in this study through close collaboration with the industry partner and adherence to a structured approval process. Budgetary constraints continued to influence the scope of the study, as the production of high-quality educational content, particularly videos, required considerable time and resources. However, compared with fully computer-generated environments that rely on detailed 3D modelling and high-performance computing, the proposed approach required substantially lower development costs. Although the system architecture explicitly considers curriculum integration, this layer was not implemented at the current stage of development. Nevertheless, student feedback indicated strong interest in formal integration with course structures, providing confidence and direction for future development and implementation of this functionality.

6. Future Improvement Roadmap

The questionnaire survey also gathered user input to inform the future improvement roadmap of the VR prototype. This section of the survey included three multiple-choice questions with optional free-text responses and one open-ended question designed to collect qualitative feedback on desired enhancements. Responses to the multiple-choice items were categorized by frequency of occurrence, as summarized in Table 7, to identify the most commonly suggested improvement areas. In addition, six participants provided detailed free-text comments, offering constructive recommendations for refining the system.

| Questions | Options | Frequency | Percentage |

| Were there any parts of the VR tour that could be improved? | Audio quality | 11 | 35% |

| Clarity and placement of hotspots | 10 | 32% | |

| Wearing comfort | 6 | 19% | |

| Additional hotspots | 6 | 19% | |

| Loading speed | 5 | 16% | |

| Video quality | 1 | 3% | |

| What features or content would you like to see added to the VR tour? | Time-lapse of construction progress | 19 | 61% |

| Safety training scenarios | 16 | 52% | |

| Guided tour option | 10 | 32% | |

| Interactive quizzes | 6 | 19% |

VR: Virtual Reality.

Regarding the existing features of the prototype, the most frequently mentioned area for improvement was audio quality. This limitation arose because the current version uses generated voiceovers rather than professional human narration, primarily due to budget constraints. For future iterations, audio quality could be improved by hiring professional voice actors to record the narrations or by leveraging advanced large language models capable of producing more natural and expressive AI-generated speech, as recommended by Cui et al.[36]. Also, over 30% of participants suggested enhancing the clarity and placement of hotspots. The current prototype contains 60 interactive hotspots, which some users found difficult to locate, particularly because the virtual tour covers a large spatial area with multiple levels and viewpoints. One potential solution is to standardize hotspot placement with consistent visual cues or highlight active hotspots through subtle animation or colour contrast. Additionally, around 20% of participants recommended including more hotspots to enrich interactivity. This will require careful consideration of visual balance and user visibility to avoid cognitive overload. For example, additional hotspot types, such as text pop-ups, photographic comparisons, or embedded 3D models, could be introduced to illustrate construction sequences or material details more effectively. As highlighted by Lai[37], multimodal hotspot design enhances engagement and supports diverse learning preferences, reinforcing this direction for future development. Moreover, wearing comfort was mentioned by approximately 20% of participants, reflecting known ergonomic limitations of VR technology[38]. In future development stages, additional measures could be implemented to further improve user comfort and accessibility. For example, the system could incorporate adjustable movement speeds, shorter scene transitions, or stabilized camera viewpoints to reduce motion-induced discomfort. Incorporating seated viewing modes and introducing user calibration tools, such as interpupillary distance, brightness, and focal depth adjustments, based on individual preferences could further enhance comfort and accommodate varying tolerance levels. Lastly, loading speed was raised by about 16% of participants. Performance issues were primarily attributed to internet connectivity and the large file size of panoramic images, resulting in minor delays of up to five seconds when loading new scenes. Although this did not significantly affect overall usability, even short delays can reduce immersion. To improve performance, future versions could incorporate pre-loading mechanisms or local download options that allow users to access tours offline. Alternatively, cloud-based content optimization and adaptive streaming could dynamically adjust image resolution based on connection speed. One participant also commented on video quality, which may have been influenced by viewing settings or improper headset calibration. Future development stages will explore higher-resolution video rendering and automated display adjustment to maintain visual consistency across different devices.

When asked which additional features or content participants would like to see incorporated in future versions of the prototype, the most frequently mentioned request was the inclusion of a time-lapse feature to demonstrate construction progress over time. To implement this functionality, the same construction zones would need to be captured from identical camera positions at multiple time intervals, allowing users to visually compare and understand how the site evolves across different stages. This feature would be particularly valuable for educational purposes, as it could reduce the need for repeated on-site visits while still offering insights into the sequencing and duration of key construction activities[3]. Another commonly suggested addition, raised by more than half of the participants, was the inclusion of safety training scenarios. Given that safety is a critical component of construction education and professional practice, VR provides an ideal platform for simulating high-risk situations in a safe, controlled environment[39]. For example, future versions could incorporate interactive modules demonstrating hazard identification, PPE requirements, or emergency response procedures. Such scenarios would not only enhance engagement but also strengthen students’ understanding of the safety culture within the construction industry. Furthermore, over 30% of participants expressed interest in a guided tour mode, which was also proposed in the original system architecture design. A guided mode could help address users’ difficulty in locating hotspots while providing instructors with greater control over the learning sequence, ensuring that all educational content is covered consistently during class demonstrations. Although this feature was not implemented in the current prototype due to time constraints, it remains a key focus for the next development stage. In addition, consistent with the integration and intelligence layer of the system architecture, several participants also recommended introducing interactive learning activities aligned with course outcomes, such as quizzes or reflection prompts embedded within the virtual environment. For instance, users could answer short scenario-based questions at specific hotspots to reinforce learning or receive immediate feedback.

Qualitative comments suggested further enhancing interactivity by “showing how machinery operates,” “simulating the excavator’s interior view,” or “adding sustainability-related features.” These suggestions could be achieved through animated 3D simulations, contextual pop-ups, or embedded multimedia displays, offering richer insights into construction processes and sustainable design practices. Last but not least, one participant also proposed incorporating additional user control options, such as captions for audio narration, adjustable audio levels, and screen brightness controls, which would improve accessibility and inclusivity, particularly for neurodivergent learners or those with sensory sensitivities. Future iterations will therefore prioritize customisable interface settings to support diverse learning needs, aligning with universal design for learning principles[40]. These requests for additional interactivity reflect a known limitation of panoramic image-based VR systems, in which users can only experience scenes from fixed capture locations, thereby restricting first-person navigation and limiting the range of possible interactions. Despite this limitation, panoramic VR offers notable advantages in visual realism when compared with fully computer-generated environments developed using platforms such as Revit or Unity, particularly in its ability to capture the complexity and authenticity of real construction sites. Recent advances in 3D capture technologies have created new opportunities to further enhance realism and interactivity in construction related VR applications. For instance, point-cloud-based VR systems can enable more flexible spatial exploration, allow users to navigate environments with greater freedom, and support interaction with detailed geometric representations of site conditions[41]. Such approaches have the potential to improve experiential learning by combining high levels of realism with increased interactivity. However, their adoption is currently constrained by ethical considerations related to data sensitivity and privacy, as well as higher costs associated with data capture, processing, and hardware requirements. Nevertheless, future studies may benefit from exploring hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of panoramic VR while selectively integrating advanced 3D capture technologies to enhance interactivity without substantially increasing costs or ethical risk.

7. Conclusion

This study presented the design and development of a VR construction site tour tailored to the Australian construction industry, developed using an incremental development approach. The proposed system architecture comprises five interconnected layers, content acquisition, content processing and management, application logic, interface and visualization, and integration and intelligence, designed to support future scalability and functional expansion. The system architecture design was strategically informed by a systematic literature review that identified key challenges in VR adoption within construction education, including technical complexity, curriculum integration, potential user discomfort, ethical considerations, learning curve for students, realism and accuracy issues, user acceptance, and budgetary constraints. Following the design phase, a prototype was developed and evaluated through two rounds of user workshops. The evaluation results demonstrated consistently positive user perceptions, with mean ratings of 4.31 for usefulness, 4.30 for ease of use, and 4.28 for impact on a five-point Likert scale. Notably, many participants reported that the VR tour provided an engaging, realistic, and accessible learning experience, particularly beneficial for students with limited exposure to real construction sites. These findings reinforce the prototype’s practical potential to complement traditional teaching and site-based learning, offering an innovative digital tool that enhances understanding of construction processes and professional contexts.

This study has several limitations that present opportunities for future development. First, the prototype represents an early-stage implementation focused on a single project type, a healthcare facility, which may limit the generalizability of findings to other construction contexts. Differences in construction processes, site conditions, regulatory requirements, and risk profiles across sectors such as residential, commercial, and infrastructure projects may influence how VR-based learning systems are experienced and adopted. Future development stages could therefore expand the content base to include a wider range of project types, enabling users to engage with diverse construction environments, methodologies, and safety scenarios. Second, the sample size for user evaluation was restricted to students from a single university and exhibited a gender imbalance, with 74 percent of participants identifying as female. This distribution may influence the transferability of the findings, as gender-related differences in prior exposure to technology, learning preferences, or perceptions of VR may affect user responses. Future studies should broaden participant recruitment to include students from multiple institutions, with more balanced gender representation, as well as industry practitioners, educators, and apprentices. Such diversification would support more robust validation of the system’s applicability across different user groups and learning contexts. Third, the evaluation relied primarily on self-reported perceptions, which may introduce response bias, as participants’ ratings may be influenced by subjective impressions. To capture changes in knowledge or skill development, future evaluations could incorporate more objective assessment methods, such as pre- and post-knowledge tests or task-based performance metrics. In addition, future work could include a comparative evaluation by contrasting learning outcomes between students who experience the VR tour and those who participate in traditional site visits or use alternative digital learning resources. Such comparative analysis would help demonstrate the relative effectiveness of the VR system and provide stronger empirical support for its educational value. Fourth, the current prototype was designed primarily for desktop and VR-headset use. Its usability and performance on mobile or tablet devices remain untested. Future iterations will aim to achieve cross-platform compatibility, improving accessibility and enabling flexible use in both formal classroom and remote learning settings. Finally, certain components of the proposed system architecture, particularly the integration and intelligence layer, were not yet implemented due to resource constraints. The next stage of development will focus on implementing this layer by enabling integration with LMSs and implementing AI-driven analytics for tracking learner engagement, adaptive feedback, and performance monitoring. These planned enhancements align with broader Construction 4.0 trends that emphasize digitalization, data centric workflows, and intelligent systems across the construction lifecycle. The integration of analytics and data-driven feedback mechanisms could also pave the way toward digital twin-enabled learning environments, where virtual representations can be dynamically linked with real world construction data to support training and simulation. In doing so, this work establishes a foundation for future research and development at the intersection of immersive technologies, artificial intelligence, and digital transformation in construction education.

Acknowledge

Grammarly was used solely as a proofreading tool to correct typographical errors, spelling, grammar, and punctuation. It was not used to generate research ideas, interpret data, develop arguments, write original content, or influence the intellectual contribution of this work. All research design, analysis, interpretation, and conclusions are entirely the authors’ own.

Authors contribution

Yan D: Conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, software, visualization, writing-original draft, writing-review & editing.

Wang CC: Funding acquation, supervision, writing-review & editing.

Sunindijo RY: Funding acquation, supervision, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the University Human Research Ethics Committee at UNSW under Human Ethics Reference Number HC230268.

Consent to participate

Informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. Participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, potential risks, and anticipated benefits before providing their consent. Participation was voluntary, and participants were advised that they could withdraw from the study at any time without penalty or consequence.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to ethical and confidentiality constraints but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

This study was supported by the UNSW Women in Construction project (RG220780), which is funded by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet’s Office for Women, under the Australian Government’s Women’s Leadership and Development Program.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Sun Y, Albeaino G, Gheisari M, Eiris R. Online site visits using virtual collaborative spaces: A plan-reading activity on a digital building site. Adv Eng Inform. 2022;53:101667.[DOI]

-

2. Wang KC, Hsu LY. Effectiveness of an immersive Vr system for construction site planning education. KSCE J Civ Eng. 2024;28(5):1622-1634.[DOI]

-

3. Shojaei A, Ly R, Rokooei S, Mahdavian A, Al-Bayati A. Virtual site visits in Construction Management education: A practical alternative to physical site visits. J Inf Technol Constr. 2023;28:692-710.[DOI]

-

4. Eiris Pereira R, Gheisari M. Site visit application in construction education: A descriptive study of faculty members. Int J Constr Educ Res. 2019;15(2):83-99.[DOI]

-

5. Elgamal S, Ayer S, Parrish K. A review of vr in undergraduate construction education and training: Unveiling the opportunities to address content areas from ACCE’s Student Learning Outcomes (SLOs). Int J Constr Educ Res. 2025;21(3):408-432.[DOI]

-

6. Abotaleb I, Hosny O, Nassar K, Bader S, Elrifaee M, Ibrahim S, et al. An interactive virtual reality model for enhancing safety training in construction education. Comput Appl Eng Educ. 2023;31(2):324-345.[DOI]

-

7. Sun Y, Gheisari M, Jeelani I. Robosite: An educational virtual site visit featuring the safe integration of four-legged robots in construction. J Constr Eng Manag. 2024;150(10):04024126.[DOI]

-

8. Asad MM, Naz A, Churi P, Tahanzadeh MM. Virtual reality as pedagogical tool to enhance experiential learning: A systematic literature review. Educ Res Int. 2021;2021(1):7061623.[DOI]

-

9. Eiris R, Gheisari M, Esmaeili B. Desktop-based safety training using 360-degree panorama and static virtual reality techniques: A comparative experimental study. Autom Constr. 2020;109:102969.[DOI]

-

10. Petersen K, Wohlin C. The effect of moving from a plan-driven to an incremental software development approach with agile practices. Empir Software Eng. 2010;15(6):654-693.[DOI]

-

11. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45.[DOI]

-

12. Sawsan RM.A systematic literature review on construction management productivity enhancement by utilizing business information modeling. Eng Technol Appl Sci Res. 2024;14(2):13702-13705.[DOI]

-

13. Abd Aziz N, Rahim FA, Aziz NM. Systematic literature review on communication in construction project management: Issues among project participants. J Surv Constr Prop. 2022;13:52-70.[DOI]

-

14. Allsop DB, Chelladurai JM, Kimball ER, Marks LD, Hendricks JJ. Qualitative methods with nvivo software: A practical guide for analyzing qualitative data. Psych. 2022;4(2):142-159.[DOI]

-

15. Eiris R, Wen J, Gheisari M. Ivisit – practicing problem-solving in 360-degree panoramic site visits led by virtual humans. Autom Constr. 2021;128:103754.[DOI]

-

16. Maghool SA, Moeini SH, Arefazar Y. An educational application based on virtual reality technology for learning architectural details: Challenges and benefits. Archnet-IJAR. 2018;12(3):246.[DOI]

-

17. Walker J, Towey D, Pike M, Kapogiannis G, Elamin A, Wei R. Developing a pedagogical photoreal virtual environment to teach civil engineering. Interact Technol Smart Educ. 2020;17(3):303-321.[DOI]

-

18. Chen X, Li S, Li G, Xue B, Liu B, Fang Y, et al. Effects of building information modeling prior knowledge on applying virtual reality in construction education: Lessons from a comparison study. J Comput Des Eng. 2023;10(5):2036-2048.[DOI]

-

19. Eiris R, Wen J, Gheisari M. Ivisit-collaborate: Collaborative problem-solving in multiuser 360-degree panoramic site visits. Comput Educ. 2022;177:104365.[DOI]

-