Abstract

Aims: Users’ empathy towards artificial agents can be influenced by the agent’s expression of emotion. To date, most studies have used a Wizard of Oz design or manually programmed agents’ expressions. This study investigated whether autonomously animated emotional expression and neural voices could increase user empathy towards a Virtual Human.

Methods: 158 adults participated in an online experiment, where they watched videos of six emotional stories generated by ChatGPT. For each story, participants were randomly assigned to a virtual human (VH) called Carina, telling the story with either (1) autonomous expressive or non-expressive animation, and (2) a neural or standard text-to-speech (TTS) voice. After each story, participants rated how well the animation and voice matched the story, and their cognitive, affective, and subjective empathy towards Carina were evaluated. Qualitative data were collected on how well participants thought Carina expressed emotion.

Results: Autonomous emotional expression enhanced the alignment between the animation and voice, and improved subjective, cognitive, and affective empathy. The standard voice was rated as matching the fear and sad stories better, the sad animation was better, creating greater subjective and cognitive empathy for the sad story. Trait empathy and ratings of how well the animation and voice matched the story predicted subjective empathy. Qualitative analysis revealed that the animation conveyed emotions more effectively than the voice, and emotional expression was associated with increased empathy.

Conclusion: Autonomous emotional animation of VHs can improve empathy towards AI-generated stories. Further research is needed on voices that can dynamically change to express different emotions.

Keywords

1. Introduction

The current landscape of embodied conversational agents is rapidly evolving. Before the advent of large language models, agents’ scripts were all pre-written by human programmers; now agents’ speech can be generated by large language models, meaning conversations can flow more smoothly and responses can be more tailored. Another change has been in agents’ expression of facial emotions; in the past, these were predefined by programmers, whereas now agents’ expressions can be automatically generated in real-time. A third change has been the development of more natural-sounding artificial voices, known as neural voices. To date, little research has examined whether automatically generated language, emotional expressions, and neural voices are perceived as accurately matching the agent’s intended emotional state. If there is a perceived mismatch between the agent’s channels of emotional expression (i.e. its spoken words, voice, body gestures and facial expressions), users may not be able to feel empathy towards the agent, which can negatively affect the relationship between agents and humans. This study aimed to address this gap.

The key contribution of this paper is to test user perceptions of a humanlike agent designed to autonomously express nonverbal behaviours that match the content of its speech, using neural and standard voices. The study examines the impact of combining the output of large language models, synthetic voices, autonomous expressions of facial emotions and gestures on users’ empathy for six different emotions. A user study was conducted with 158 adults who evaluate emotional stories that randomly differ in non-verbal animation and voice. The next part of the introduction focuses on related work, describing the background and rationale for the study, as well as its aims and scope, research questions, and hypotheses. It sets the context for the study and outlines its importance in the field.

2. Related Work

2.1 Definition of empathy

Empathy is commonly defined as ‘understanding others emotionally’ and has both cognitive and affective components[1]. Affective empathy refers to the emotions people feel in response to others’ emotions, whereas cognitive empathy refers to the ability to understand others’ emotions. Research suggests that empathy has a neurobiological basis[2]. More empathetic people tend to have greater unconscious mimicry of the postures, mannerisms, and facial expressions of others, and the same motor and sensory areas are activated in the brain.

Empathy is vital in both interpersonal relations and societal roles because it enables emotions to be shared and promotes prosocial behaviour[2]. Observing pain in others often motivates compassion and helping behaviour, which promotes the survival of species. Empathy is crucial in healthcare, where empathy comprises not just understanding, but also expressing that understanding and acting therapeutically. Teaching enhanced empathy skills to healthcare professionals can improve patient satisfaction[3]. In health, these skills are referred to as clinical empathy.

2.2 Empathy towards artificial agents

Clinical empathy skills have been applied to a model of social robotics, in which verbal and non-verbal communication are key components[4]. Verbal behaviours (humour, self-disclosure, tone of voice) and non-verbal behaviours (eye gaze, body posture, facial expressions, gestures) by both humans and robots can improve empathy and impact outcomes[5]. Similarly, both verbal and non-verbal communication skills can enhance rapport and relationship quality in interactions with embodied conversational agents[6].

Empathy is increasingly studied and applied in social robotics, and it has been argued that robots must have both cognitive and affective empathy to avoid sociopathic behaviour[7]. There are now conceptual empathy models for conversational AI systems[8]. Research has investigated both robots’ and virtual agents’ empathy towards humans, as well as humans’ empathy towards robots and virtual agents[9]. Outcomes are more favourable for participants interacting with more empathetic agents (e.g., users like the agent more). To date, computational expression of empathy has largely been achieved through facial expressions, head and mouth movements, and verbal statements that have been programmed manually. Applications have included games, healthcare, story narration, bullying, and intercultural training.

Feelings of empathy towards artificial agents can be influenced by how they are treated. For example, research suggests that people feel more negative emotions after watching videos of robots being treated violently compared to when they are treated affectionately[10]. Empathy towards robots can also be affected by the robot’s appearance, with more human-like social robots evoking more empathy when mistreated[11].

Several previous studies have examined the role of emotional expression in robots and agents as storytellers. One study used manual emotional tagging of the story to generate the display of emotions by the robot and virtual agent[12]. It found evidence of listeners’ empathy towards the agent through their facial expressions in response to the story, although the study did not examine voices. Another study found that empathy was stronger towards a robot telling a story in the first person compared to the third person[13]. Other work has shown that robot facial expressions that were manually programmed to be congruent with its story enhance listeners’ immersion into the story and robot likability compared to incongruent expressions[14]. In that study, congruent facial expressions also improved users’ perceptions of the vocal tone, even though it was identical between conditions.

A major limitation of research in empathetic agent interactions to date is the use of Wizard of Oz and predefined behaviours, and it is imperative to build fully autonomous empathetic agents[15]. Wizard of Oz studies are limited because they require a human to operate the agent. In many real-world circumstances, this is not practical. Furthermore, Wizard of Oz studies do not reveal any insights into the capabilities of real agents.

Only a handful of studies have been published using automated facial expressions in robots and agents; some have used mapping of human facial expressions for copying, and others have used the context of the conversation[16]. Automated gesture generation software includes rule-based, statistical, and machine-learning generative models[17,18]. These models have been employed on robots and virtual agents, mostly for talks and presentations[19]. Recent work created a virtual human that used a large model and embedded personality, mood, and attitudes, along with emotional facial expressions. The system was demonstrated to elicit differences in users’ valence (but not arousal) for five emotional states[20].

2.3 Agent voice

Research has demonstrated that an agent’s voice is very important in human-robot interaction. Humanlike, happy and empathetic voices with high pitch are preferred, and the match between agent appearance and voice is important[21]. Technical progress has been made in the synthesis of natural and empathetic voices. People prefer an empathetic voice compared to a standard voice when it is performed by an actor and deployed on a robot[22]. Furthermore, when a synthesized version of the empathetic voice was used, participants preferred this over the standard synthetic voice, and rated it as more empathetic[23]. There are 8 emotional voices available on Microsoft Azure Neural Text to Speech, including cheerful, angry, terrified and sad[24]. Similarly, Amazon has developed neural voices which are designed to be more natural in a number of languages[25].

Neural text-to-speech is an emerging and burgeoning topic, and evaluative studies combining it with gestures in storytelling are lacking. Neural text-to-speech systems utilise neural networks to convert text into speech, thereby enhancing the quality and naturalness of the resulting speech compared to traditional methods[26]. However, research in this space is limited to date. Related research has examined the use of natural (human) versus synthetic speech and gestures in an embodied conversational agent with positive, negative, or neutral emotions, finding that natural speech and gestures produced a higher speech-gesture match, as well as greater likeability and anthropomorphism[27]. However, this did not examine neural versus standard synthetic voices.

2.4 Aims and scope

The aim of this paper was to evaluate an autonomous agent to see if its verbal and non-verbal expression could elicit empathy. The agent used in this study was a virtual human created by Soul Machines Ltd (soulmachines.com, Auckland, New Zealand). These artificial intelligence (AI) assistants use live neural networks when interacting with people to make classifications of their emotional state, and respond using speech, facial expressions, and body gestures. Their own speech and emotional expressions can be manually programmed, but they can also be autonomous. Large language models and advanced AI techniques have enhanced the ability to autonomously generate language along with matching gestures and facial expressions. An advantage of using this agent is its high degree of realism and ability to display detailed facial expressions and gestures, as well as to choose different voices.

Agents generated by Soul Machines Ltd generate real-time gesturing. Emotional gestures are based on the emotional content of the agent’s words (facial expressions, head tilts); symbolic gestures are based on the meaning of the words (such as opening the arms out wide when talking about ‘everybody’); and beat gestures are based on the rhythm of the speech (e.g., an arm ‘beats’ for emphasis on each word). Animations drive the mouth, lips, and facial muscles aligned with the audio and phonemes. The head and neck move in line with the audio. Iconic gestures are based on the meaning of the speech context, for example, showing a heart sign when talking about passion or dedication. This real-time gesturing combines all the techniques for the face and body to create synchronised and human-like behaviour.

This study used a voice, an agent, and an LLM using commercially available software. This makes them relevant experimental research platforms that readers can use to replicate and extend this work. The Soul Machines platform has the advantage of displaying much more detailed humanlike expressions and small movements than commonly used platforms in storytelling research, such as Nao, e.g.,[28] allowing richer and more nuanced gestures to be investigated for effects on empathy.

2.5 Research questions

It is critical to test whether people think that autonomously generated facial expressions and body gestures match the emotional content of a virtual human’s speech. If the matching is not suitable, this may impair the ability of the user to relate to the agent. It’s also important to test whether people think that neural voices match speech content better than standard voices, and whether this differs by the emotional content of the speech. More natural agent voices may increase people’s empathy towards an agent. Furthermore, it’s crucial to investigate whether users are better able to identify the agent’s emotions (cognitive empathy) and share the agent’s emotions (affective empathy) when these techniques are added. Questions also remain as to whether trait empathy predicts subjective empathy towards virtual humans, and how much the match of voice and animation to the story can contribute to empathy over and above trait levels. Therefore, this study aimed to answer the following research questions:

RQ1. Do autonomous gestures and facial expressions enhance affective, cognitive and subjective empathy towards a storytelling agent compared to a non-expressive condition?

RQ2. Do neural voices enhance affective, cognitive, and subjective empathy towards a storytelling agent compared to a standard voice?

RQ3. Is subjective empathy enhanced when people think the animation and voice better match (animation matching and voice matching) the stories, after controlling for trait empathy?

RQ4. Which cues inform the users’ understanding of the virtual human’s emotional expression, as assessed through qualitative analysis?

The hypotheses were that autonomous emotionally expressive animation and neural voices would increase empathy (affective, cognitive and subjective) towards the virtual human’s stories compared to the non-expressive animation and standard voice. It was also hypothesised that subjective empathy would be enhanced when the voice and face were rated as matching the stories better. A qualitative question was included to provide a rich data set and contribute to the development of a conceptual model.

3. Methods

Twelve emotional stories were generated using ChatGPT with the prompt “Can you tell me a very brief x story about a person in first person perspective in less than 80 words?”. Two stories were generated for each emotion; x was replaced with sad, happy, scary, angry, surprising, or disgusting. As a manipulation check, the 12 stories were printed and rated by 16 participants for how sad, happy, scary, angry, disgusting, and surprising the stories were, from 1 (not at all) to 10 (extremely). These 16 participants were different from the participants who watched the videos in the next part of the study. The six stories with the highest corresponding emotional ratings were chosen for the study and are listed in Table 1 along with their ratings.

| Emotion | Narrative stimulus | Manipulation check (M ± SD) |

| Anger | Fury consumed me as I faced betrayal, a friend turned foe. The lies and deceit sliced through my trust like a dagger. How could they? Rage ignited a fire within, burning bridges we once crossed. Their apologies fell on deaf ears, for the damage was irreparable. I vowed to rise above the hurt, leaving them to dwell in the ashes of my broken loyalty. The anger fueled my determination to rebuild, stronger and wiser, without their toxic presence. | 8.88 ± 2.45 |

| Disgust | As I explored the abandoned basement, I stepped on something squishy. Looking down, horror engulfed me—it was a decaying rat. The repulsive stench filled the air, making my stomach churn. Unable to bear it, I ran upstairs, battling waves of nausea. The image haunted me for days, a reminder of the revolting encounter with death and decay. | 8.75 ± 1.98 |

| Happy | Sunlight danced through the leaves as I walked hand in hand with my partner. We reached the hilltop, where a breathtaking sunset painted the sky with vibrant hues. Heart pounding, I got down on one knee, and with tears of joy, asked for forever. Their “yes” echoed through the valley, sealing our love beneath the canvas of the setting sun. Time seemed to stand still as we embraced, knowing this was the start of an extraordinary journey together. | 9.31 ± 1.20 |

| Sad | In the hospital room, I held her fragile hand, watching life slip away. Memories of laughter and love flooded my mind, but the reality of losing her was unbearable. “Please don’t leave”, I begged, tears streaming down my face. Her soft smile comforted me, as if saying goodbye without words. In that moment, my heart shattered, and I knew life would never be the same without her. | 9.44 ± 1.15 |

| Fear | In the haunted house, shadows writhed with eerie life. My heart raced as creaks echoed through the halls, footsteps not my own. A chilling whisper brushed my ear, and unseen hands grazed my skin. Panic swirled in my mind, urging me to flee, but an invisible force locked the doors. The walls seemed to close in, and I knew I wasn’t alone. Terrified, I searched for an escape, praying I’d survive the night in this malevolent labyrinth. | 9.13 ± 1.54 |

| Surprise | As I opened the old chest in the attic, my heart skipped a beat. Amongst forgotten belongings, I found a letter addressed to me. Confused, I read words penned by a long-lost relative, revealing a hidden inheritance. Astonishment washed over me as I learned I was the heir to an extraordinary estate. The news was a delightful shock, opening doors to a new life I never knew awaited. With anticipation, I embraced the unexpected journey ahead, forever changed by the surprising revelation. | 9.13 ± 1.45 |

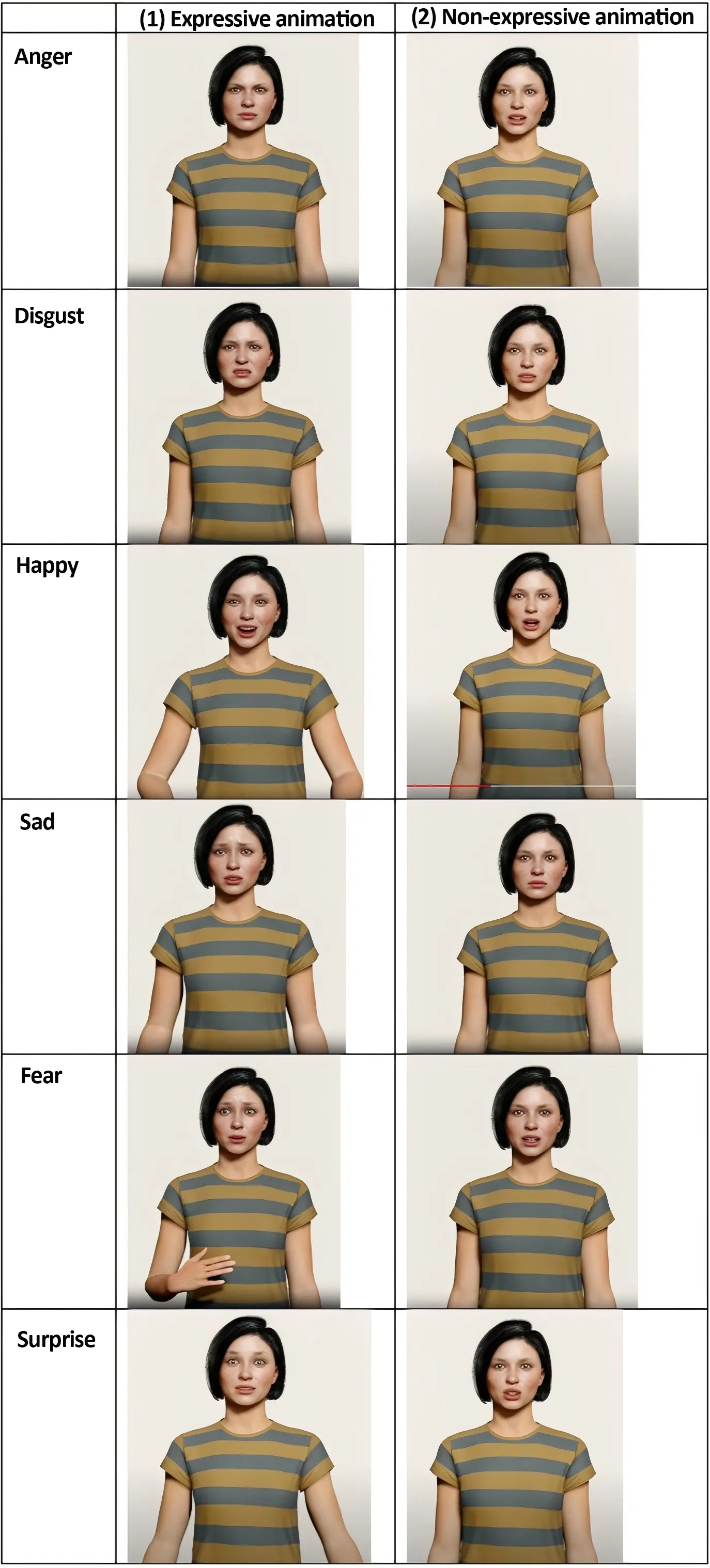

Four videos of a virtual human (Carina) telling each story were created with Soul Machines software, using: (1) expressive animation and neural voice; (2) expressive animation and standard voice; (3) non-expressive animation and neural voice; and (4) non-expressive animation and standard voice. Each video ranged in length from 25 seconds (disgust) to 33 seconds (anger). Figure 1 shows example images of Carina for each story in the expressive and non-expressive animation styles. The Supplementary materials provide links to each video.

Figure 1. Images of the virtual human Carina telling each story with expressive animation and non-expressive autonomous animation.

Soul Machines uses a Natural Language Processing classifier to analyse the character’s speech content and adds a chosen style of gesturing and facial expressions in real-time. For the expressive animation conditions, the style ‘Friendly’ was chosen with the function ‘react to negative speech and face’ was turned on. The ‘Friendly’ style is described as relatable, kind, even-tempered, empathetic, and loves greeting others with a warm smile. The settings for ‘Friendly’ are moderate to high happiness and sensitivity, and moderate on energy and formality. The non-expressive animation was created with the ‘Frosty’ style with the option ‘react to negative speech and face’ turned off. ‘Frosty’ is described as tense, suspicious, cold, private, and may appear aloof. The settings are very low on energy and happiness, high on formality, and moderate to low on sensitivity. The neural voice was Amazon Neural Text to Speech Amy Female UK, and the standard voice was Amazon Standard Text to Speech (TTS) Amy Female UK. Standard TTS concatenates phonemes of recorded speech, whereas neural TTS converts a sequence of phonemes to spectrograms to produce more natural sounding speech.

One hundred and fifty-eight participants were recruited from Prolific (prolific.com), an online research platform. The inclusion criteria were adults aged over 16 years, living in the UK, with English fluency. The sample size was calculated using G*Power, with a power of .80, an alpha of .05, and an expected effect size of f = .30, based on previous findings[14]. Each participant was paid 1.75 British Pounds to complete a survey that took about 12 minutes.

Participants completed a baseline questionnaire to assess age, gender, ethnicity, education, and trait empathy using the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (empathic concern subscale)[29]. This subscale has 7 items rated from 1 (does not describe me well) to 5 (describes me well) and was chosen because it was related to greater hesitation to strike a robot in previous work (i.e. it was related to empathy behaviour towards a robot) whereas the other subscales were not[30]. Cronbach’s alpha was .86. Higher scores indicate higher empathy.

Participants were then shown one version of each of the videos for each emotion at random (seeing six videos in total). After watching each story, the appropriateness of the animation and voice for each story was assessed by asking participants how much they agreed t with the statement that Carina’s facial expressions and body gestures matched what she said, using a 5-point Likert scale with response anchors (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”). Another item asked whether the emotion of Carina’s voice matched what she said using the same response scale.

To assess cognitive empathy, participants were asked to rate how they thought Carina felt in the story from 1 (not at all) to 10 (extremely) for happy, sad, scared, disgusted, angry, and surprised. To assess affective empathy, participants rated how they felt on the same scales. For subjective empathy, participants were asked to rate how empathetic they felt towards Carina’s story on scale from 1 = “not at all” to 10 “completely”[31]. These measures were custom items, which were created for the study. These items were chosen to minimise participant burden and increase specificity.

Lastly, participants were asked, “Overall, please comment on how well you think Carina expressed her emotions in the stories?” They were provided a blank box in which to respond. Participants’ answers were copied into an Excel file and analysed with thematic analysis. This involved six steps. First, all the answers were read for familiarisation. Next, keywords were selected to identify recurring patterns. Third, codes were generated alongside the participants’ answers to identify elements related to the research questions. In the fourth step, themes were generated by grouping the codes into meaningful patterns and relationships, offering insights into participants’ experiences. The themes were reviewed, defined, and named[32]. The sixth step involved generating a conceptual model. An inductive approach was employed, aiming to develop theories from the data. One researcher generated the codes and themes, and another researcher then checked and validated these codes and themes. There were no disagreements.

Quantitative data were analysed using SPSS version 28. Six 2 by 2 factorial ANOVAs were conducted with bootstrapping to test main and interaction effects of the animation and voice conditions. There was no missing data. Hierarchical linear regression was then conducted to see whether perceived matching of the voice and animation predicted subjective empathy after controlling for empathic concern in the first step.

This study was approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee, number UAHPEC23402. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

4. Results

4.1 Sample characteristics

The participants were 87 males, 68 females, and 3 transgender/gender non-conforming participants. The mean age was 43.46 years (SD = 14.59). There was a range of education levels: 40 had high school or less, 20 had a trade certificate, 77 had an undergraduate degree, and 21 had a postgraduate degree. 117 participants were identified as white British or Irish (74%), 20 as black British, Caribbean or African (13%), and 21 as another ethnicity (13%). Mean empathic concern at baseline was 22.65/30 (SD = 4.45).

4.2 Factorial ANOVA for expressive/non-expressive animation and neural/standard voice conditions

Table 2 shows the results of the hypothesis testing. The results indicate that the expressive animations improved ratings of how well the animations and voice matched every emotional story, compared to the non-expressive animations.

| Story | Outcome | Expressive Animation | Non-expressive Animation | F value | ||||

| Neural Voice | Standard Voice | Neural Voice | Standard Voice | Animation | Voice | Interaction | ||

| Anger | Animation matched | 3.67 | 3.58 | 2.66 | 2.12 | 45.08** | 2.72 | 1.52 |

| Voice matched | 3.15 | 2.97 | 2.36 | 2.23 | 12.63** | 0.27 | 0.85 | |

| Subjective empathy | 5.51 | 5.69 | 4.56 | 4.17 | 6.31* | 0.04 | 0.33 | |

| Cognitive empathy (Carina anger) | 6.77 | 6.79 | 6.24 | 4.56 | 10.47** | 3.77 | 4.01* | |

| Affective empathy (Participant anger) | 2.72 | 3.2 | 2.44 | 1.95 | 5.44* | 0.99 | 0.14 | |

| Disgust | Animation matched | 3.7 | 4.02 | 2.21 | 2.25 | 93.52*** | 1.17 | 0.71 |

| Voice matched | 2.85 | 3.02 | 2.29 | 2.37 | 9.47** | 0.67 | 0.052 | |

| Subjective empathy | 5.52 | 5.52 | 4.66 | 4.37 | 4.35* | 0.09 | 0.09 | |

| Cognitive empathy (Carina disgust) | 7.72 | 8.15 | 5.42 | 5.75 | 33.71** | 0.87 | 0.01 | |

| Affective empathy (Participant disgust) | 4.65 | 5.02 | 3.58 | 3.27 | 11.53** | 0.93 | 0.41 | |

| Happy | Animation matched | 4.12 | 3.77 | 1.97 | 2.07 | 159.36*** | 0.65 | 2.22 |

| Voice matched | 3.42 | 3.05 | 2.33 | 2.26 | 25.12** | 2 | 0.43 | |

| Empathy | 5.27 | 5.35 | 4.22 | 4.87 | 2.76 | 0.61 | 0.38 | |

| Cognitive empathy (Carina happy) | 8.27 | 7.7 | 5 | 5.81 | 43.04*** | 0.09 | 3.12 | |

| Affective empathy (Participant happy) | 4.05 | 4.7 | 3.2 | 3.76 | 5.03* | 0.13 | 0.91 | |

| Sad | Animation matched | 3.4 | 3.12 | 2 | 2.5 | 41.58*** | 8.44* | 0.01 |

| Voice matched | 2.72 | 3.07 | 2.12 | 2.58 | 8.01** | 6.46* | 0.07 | |

| Subjective empathy | 5.85 | 7.21 | 6.17 | 6.97 | 0.01 | 4.55* | 0.32 | |

| Cognitive empathy (Carina sad) | 5.76 | 7.43 | 5.47 | 6.86 | 1.09 | 13.75** | 0.87 | |

| Affective empathy (Participant sad) | 4.65 | 4.6 | 4.27 | 4.71 | 1.21 | 3.72 | 0.72 | |

| Fear | Animation matched | 3.07 | 3.4 | 2 | 2.2 | 43.83*** | 2.39 | 0.12 |

| Voice matched | 2.47 | 2.95 | 1.69 | 2.2 | 18.18*** | 7.87* | 0.01 | |

| Subjective empathy | 4.42 | 4.42 | 2.56 | 3.97 | 2.09 | 0.65 | 0.65 | |

| Cognitive empathy (Carina fear) | 6.3 | 6.7 | 4.35 | 5.38 | 14.25*** | 2.73 | 0.53 | |

| Affective empathy (Participant fear) | 2.35 | 2.3 | 2.05 | 2.2 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.01 | |

| Surprise | Animation matched | 3.61 | 3.71 | 1.92 | 2.09 | 103.28*** | 0.72 | 0.05 |

| Voice matched | 3.46 | 2.97 | 2.31 | 2.36 | 20.31*** | 0.27 | 0.16 | |

| Subjective empathy | 5.02 | 4.48 | 3.82 | 4.36 | 2.06 | 0 | 1.37 | |

| Cognitive empathy (Carina surprised) | 7.49 | 6.59 | 5.43 | 5.48 | 13.43*** | 0.97 | 1.22 | |

| Affective empathy (Participant surprised) | 4.12 | 3 | 3.1 | 3.39 | 0.65 | 1.14 | 3.25 | |

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The presence of expressive animations was also associated with increased subjective empathy towards the virtual human (VH) during the anger and disgust stories; increased ratings of the VH’s emotion for the anger, disgust, happy, fear, and surprise stories (cognitive empathy); and increased participants’ own emotions for the anger, disgust, and happy stories (affective empathy).

On the other hand, the voice condition only had significant effects for the sad and fear stories. In the sad story, the standard voice was rated as matching the animation and voice in the story better, was rated higher for subjective empathy with Carina, and Carina was rated as more sad (cognitive empathy). Similarly, the standard voice was rated as matching the fear story better.

There was only one interaction effect; the standard voice with non-expressive animation was associated with the lowest rating of perceived anger in Carina (cognitive empathy).

4.3 Regressions for effects of trait empathy, perceived matching of animation and voice on subjective empathy

For the anger story, empathic concern predicted 15% of the variance in subjective empathy towards the agent in the first step of the regression, F(1,156) = 27.23, p < .001, R2 = .15. In the second step of the regression, an additional 20% of the variance in subjective empathy was explained by ratings of the match of the face and voice to the story, over and above empathic concern, Fchange(2,154) = 24.07, R2 = .35. In the final model, both empathic concern and ratings of the voice matching the anger story were significant predictors.

In the first step of the regression for the disgust story, empathic concern predicted 13% of the variance in subjective empathy, F(1,156) = 23.35, p < .001, R2 = .13. In the second step, an additional 25% of the variance was explained by the ratings of the match of the face and voice to the story, Fchange(2,154) = 31.23, R2 = .38. In the final model, empathic concern, ratings of the voice matching the story, and ratings of the animation matching the story were all significant predictors.

For the fear story, the first step of the regression showed empathic concern predicted 11% of the variance in subjective empathy, F(1,156) = 19.17, p < .001, R2 = .11. An additional 25% of the variance was explained by the match of the face and voice to the story, Fchange(2,154) = 30.93, R2 = .36, in the second step of the regression. In the final model, empathic concern and ratings of the voice matching the fear story were significant predictors.

In the first step of the regression for the happy story, empathic concern predicted 10% of the variance in subjective empathy, F(1,156) = 17.13, p < .001, R2 = .10. In the second step, an additional 22% of the variance was explained by ratings of the match of the face and voice to the story, Fchange(2,154) = 24.70, R2 = .32. In the final model, empathic concern and ratings of the voice matching the happy story were significant predictors.

For the sad story, the first step showed that empathic concern predicted 14% of the variance in subjective empathy, F(1,156) = 25.32, p < .001, R2 = .14. An additional 16% of the variance was explained by ratings of the match of the face and voice to the story, Fchange(2,154) = 17.47, R2 = .30, in the second step. In the final model, empathic concern and ratings of the voice matching the sad story were significant predictors.

For the surprise story, the first step of the regression showed that empathic concern predicted 11% of the variance in subjective empathy, F(1,156) = 18.48, p < .001, R2 = .11. In the second step, an additional 19% of the variance was explained by ratings of the match of the face and voice to the story, Fchange(2,154) = 20.76, R2 = .30. In the final model, empathic concern and ratings of the voice matching the surprise story were significant predictors.

4.4 Qualitative results

Four themes were identified. The first theme illustrated a mixed experience for participants due to the different amounts of expression in each video. The second theme focused on how emotions were expressed through voice, face, and gestures, which were further broken down into four subthemes, as detailed below. The third theme related to the words of the stories, and the fourth theme centred on empathy and how people related to Carina’s stories.

4.4.1 Theme 1: a mixed experience

It was clear that participants could distinguish between the videos with emotional expression and those without. For example, “Carina’s reactions felt and looked expressionless in half of the videos I viewed, and in the other half, her expressions seemed to be legitimate regarding the scenarios she illustrated” (participant 20). “Some videos were more expressive than others.” (participant 158).

4.4.2 Theme 2: emotional expression

This theme describes how people perceived emotions in the face, gestures, and voice, and had three subthemes. The first sub-theme was that the voice was expressionless and monotone. Some quotes for this theme are: “The voice often lacked emotion” (participant 17); “The tone of her speaking was flat and emotionless” (participant 28). The second subtheme was that the face and gestures were better, which helped create empathy: “I think the vocal intonation stayed (sic) pretty similar in all the videos i.e. mechanical and monotone, however the facial reactions and body language were more nuanced to the circumstances, that gave a different feel to the story and therefore my reactions changed ever so slightly in each scenario” (participant 1); “I think her voice sounded robotic and emotionless and didn’t change throughout as you’d expect, but there were some facial triggers which matched what she was saying in some instances” (participant 8).

Breaking down comments about the gestures in more detail, some participants said that the emotional expressions in her face matched her words and aided emotional expression, whereas others thought her facial expressions were hard to read. One participant said that Carina’s eyes were enough to convey the scared emotion without other gestures “The cold look was eerie enough to sell the story”. Some people suggested that the body gestures (arm and head) made a big difference, made her come alive, and kept the attention of the audience. Others thought the gestures were unnatural or did not match the stories, or that the arms should move more. Finally, one participant commented that the symbolic gesture of waving goodbye to someone who was dying was not appropriate.

A third subtheme was the overall impression of the emotional expressions, and this varied greatly between participants. For example, “She expressed them extremely well. She was almost perfect” (participant 157); “I thought the different expressions fit well with what she was saying in general” (participant 113); “fairly well” (participant 64); “I didn’t think they were expressed very well” (participant 115); “quite poorly, she remained neutral” (participant 85). The fourth subtheme related to how lifelike and humanlike she was, e.g., “very well, very lifelike” (participant 35); “As the videos progressed, it became more realistic” (participant 135); “Very well, it felt quite humanlike” (participant 21).

4.4.3 Theme 3: the words

This theme related to how the words and stories themselves were perceived. Some people felt the words were good, whereas others felt they could have been better. e.g., “…the words were better than the expressions” (participant 33); “Words used were too flowery or OTT (over the top)” (participant 99); “Verbally Carina expressed her emotions well; she used good vocabulary and sentence structure” (participant 155); “Her choice of words wandered (sic) into the verbosity and weirdness - very unnatural for emotional situations” (participant 127); “It was good, but I felt I was listening to Carina reading a story rather than telling me about her experiences” (participant 72).

4.4.4 Theme 4: empathy

This theme describes how people felt towards Carina and her stories. Some felt empathy and others felt she lacked empathy. For example, “…would occasionally have some moments of emotion which made me feel a bit more empathy towards her” (participant 46); “She expressed them to the point where I could feel what she was feeling, but I feel like there could be a bit more enthusiasm and emotion in her voice to empathise with certain words or how she feels, but it was easy to understand how she was feeling” (participant 26); “The whole thing lacked empathy or enthusiasm and was machine like” (participant 13); “The expressions are too smooth and don’t really replicate human emotion so much as imitate it. I find it uncanny.” (participant 24); “Her voice never changed to match the tone of the story she was telling, and most of her facial expressions and gestures were either non-existent or over the top. I found her very hard to relate to” (participant 24). “Very well, the content of each video changed some, I don’t know if her tone did, but her expressions changed, her eyes, the delivery of content, she got a little excited, I think placing myself in these scenarios may have altered my perception. My own feelings seen in her ...” (participant 133).

4.5 Conceptual model

Overall, the qualitative analysis showed a wide range of experiences, which may reflect that people saw different combinations of videos. There was a consistent theme that the voice was expressionless and did not relate to the stories; many felt that the facial expressions were better. Empathy was most commonly noted when people could see her emotional expressions. Some people felt that the stories were more about others than about Carina’s own experiences, and the words were unnatural. The data inform a conceptual model in which users employ a range of cues to infer agents’ emotions, which include their voice, gestures, facial expressions, and words. Users found it difficult to feel empathy when emotional expression was lacking or too mechanical.

5. Discussion

This study adds to previous research by investigating the effects of an artificial agent’s animation and voice on user empathy for different emotional stories. The main contributions of this study are that it investigated the effects of autonomous emotional animation (rather than Wizard of Oz or manual labelling) and employed both quantitative and qualitative methods. This helped to combat the limitations of previous work[15]. The stories themselves were generated by AI, which adds a further autonomous component. The findings provide insights into how humans react to AI generated stories and autonomous emotional expressions in agents. The inclusion of measures for different types of empathy (affective, cognitive and subjective) is a further strength. The study investigated six different emotional stories so that effects could be studied by emotion type. Triangulation was used by collecting both quantitative and qualitative data.

In terms of research question 1, the results showed that people felt greater empathy towards a virtual human with autonomous expressive animation compared to a non-expressive animation. Specifically, people were better able to recognise emotions when expressive animation was used in every story except the sad story (cognitive empathy). Participants’ feelings of emotion after the anger, disgust, and happy stories were also enhanced by expressive animation (affective empathy). The animation also increased subjective ratings of empathy for the anger and disgust stories.

The slight differences in results for the different emotional stories may be due to several factors. First, the stories differed in how much they contained other emotions and the strength of the emotional content. For example, the surprise story included words relating to joy as well as surprise, and the sad story contained the words ‘smile’ and ‘comfort’. Second, the ability of the digital human to portray different emotions on her face and through body gestures might differ. Third, some gestures may have been inappropriate to the context, e.g., saying “goodbye” in the sad story was accompanied by a big wave gesture. Last, the content of some of the stories may have resonated with people better than others. Recent research has found greater empathy towards human-written stories than AI-written stories[33].

In terms of research question 2, there was no evidence that the neural voice enhanced empathy towards a virtual agent in the storytelling scenario. In fact, the agent’s voice had the greatest effect on the sad story, where, contrary to hypotheses, the standard voice was rated as matching the story better. The standard voice improved ratings of whether the animation matched the sad story, created greater subjective empathy towards Carina, and greater perceptions of Carina as sad. The standard voice was also rated as matching the fear story better. Although not statistically significant, the standard voice had a slightly higher mean for matching the disgust story than the neural voice. The reason might be that the neural voice had a higher and more variable pitch, and the standard voice was flatter. A flat voice may be better suited to sad and scary stories. Previous research has shown that when reading aloud sad and happy book excerpts, readers’ voice pitch tends to be higher for happy text, and pitch variability tends to be lower for sad excerpts[34]. Together, these results suggest that the neural voice used in the study still struggled with the dynamic prosody required for emotional storytelling.

The finding that expressive animation affected how both the animation and the voice were perceived supports previous research and extends it to autonomous animation rather than manual[14]. To the best of our knowledge, the finding that the voice affects how a sad animation is perceived is novel for TTS voices. Previous work found that voice alone was sufficient to convey emotions compared to an agent plus voice for three of four emotions in a learning context[35]. However, the voice in that study was human, and the animations were based on human recordings.

For research question 3, trait empathy was a predictor of subjective empathy towards the virtual human across all stories. Above the trait level, how well people perceived that the voice and animations matched the stories further predicted subjective empathy. The coefficients demonstrated that ratings of voice matching were a consistently significant predictor for all the stories, whereas ratings of animation matching were only significant for the disgusting story. This suggests that the perceptions of the agent’s voice are critical to subjective empathy.

The qualitative findings add to the quantitative results by showing that most people thought that the virtual human’s voice did not express her emotions well, and that the animations were more expressive. There was wide variation, with some people saying she was very good at expressing emotions and others saying she was poor. Those who reported empathy towards her tended to comment on being able to identify or feel her emotions in some of her stories and relate to them. Most people did not comment on the stories that were generated by ChatGPT, although a few commented that the words were strange, unnatural, or over the top. The conceptual model informs theories of the importance of verbal and non-verbal cues to emotional expression and empathy towards artificial agents. One cannot ignore any of the components (face, gestures, voice, and words), because when one of these is misaligned, it affects the development of empathy. This aligns with a proposed Empathy-GPT system, which builds embodied conversational agents with empathic capacity[36].

5.1 Limitations

This study has several limitations. It was performed with people from the UK, and the results may not generalise to other countries. Furthermore, the virtual human appeared as a white female, which introduces potential cultural and gender biases. The universality of the results across different ethnic backgrounds and cultural understandings remains unverified. Further research could test virtual humans with male, or gender neutral, or different ethnic appearances, or with physical robots. This study chose to show people all the stories with a random combination of conditions. Future work could perform a similar study in which the participants are randomised to see all stories with the same combination of animation and voice, and explore effects on other outcomes. Another limitation was that the study had limited interactivity; however, this is not dissimilar to other published storytelling studies[37]. Participants watched pre-recorded videos, and therefore the results may not generalise to more interactive conversational AI scenarios. Future research could be performed using a more interactive approach. Soul Machines software can analyse the emotional content of the user’s face and speech, and can produce facial expressions in reaction to the user. Adding interactivity would complicate the research because the agent’s expressions would be driven not only by the agent’s own words but also by the facial reactions of each individual user. An interactive study would be a very interesting next step, but this study is a necessary first approach. Additionally, future research could investigate TTS voices that can dynamically adjust pitch and tone in response to the emotional content of spoken words. A further limitation is that the six stories may differ in linguistic complexity emotional intensity, which may potentially confound emotion-specific results; this variation was not controlled for. Finally, facial expressions and body gestures were studied together because the software automatically combines them. It may be useful in future research to test these variables separately to investigate their individual contributions to empathy.

5.2 Implications

It is impractical to pre-program the emotional expression of artificial agents in long-term, evolving relationships in real-world applications. This study provides evidence that the automatic generation of emotional expressions can enhance humans’ perceptions of emotions and empathy towards agents. Agents that can create natural-sounding conversations, with detectable and suitable facial expressions of emotion and gestures, as well as a matching vocal tone, will facilitate more empathetic interactions. The work adds to previous research demonstrating the feasibility and potential to deploy virtual humans in practical applications, such as business, healthcare, and education[20].

6. Conclusion

Autonomously generated expressive animation can improve cognitive, affective, and subjective empathy towards virtual humans compared to neutral expressions. Manual emotional markup may no longer be necessary to program robots and virtual humans to portray emotions through facial expressions and gestures. Some neural voices may not be as effective as standard voices for portraying emotions such as sadness and fear, as the neural voices’ higher pitch and greater pitch variation do not accurately match these emotions. Despite the voices being rated poorly for emotional expression, matching the voice to the story was important for subjective empathy, over and above trait empathy.

Supplementary materials

The supplementary material for this article is available at: Supplementary materials.

Authors contribution

Broadbent E: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, writing-original draft.

Yang S: Investigation, methodology, project administration, software, writing-review & editing.

Loveys K: Conceptualization, methodology, writing-review & editing.

Verma R: Methodology, software, visualization, writing-review & editing.

Sagar M: Conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, resources, software, writing-review & editing.

Conflicts of interest

Mark Sagar is the co-founder and former CEO of Soul Machines Ltd., Kate Loveys is a former employee of Soul Machines Ltd., and Elizabeth Broadbent is a former consultant to Soul Machines Ltd. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was approved the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee, number UAHPEC23402.

Consent to participate

All participants gave consent to participate, and were informed about the study purpose, procedures, risks and benefits.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding

None.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Jami PY, Walker DI, Mansouri B. Interaction of empathy and culture: A review. Curr Psychol. 2024;43(4):2965-2980.[DOI]

-

2. Riess H. The science of empathy. J Patient Exp. 2017;4(2):74-77.[DOI]

-

3. Keshtkar L, Madigan CD, Ward A, Ahmed S, Tanna V, Rahman I, et al. The effect of practitioner empathy on patient satisfaction: A systematic review of randomized trials. Ann Intern Med. 2024;177(2):196-209.[DOI]

-

4. Broadbent E, Johanson D, Shah J. A new model to enhance robot-patient communication: Applying insights from the medical world. In: International Conference on Social Robotics; 2018 Nov 28-30; Qingdao, China. Cham: Springer; 2018. p. 308-317.[DOI]

-

5. Johanson DL, Ahn HS, Broadbent E. Improving interactions with healthcare robots: A review of communication behaviours in social and healthcare contexts. Int J Soc Robot. 2021;13(8):1835-1850.[DOI]

-

6. Loveys K, Sebaratnam G, Sagar M, Broadbent E. The effect of design features on relationship quality with embodied conversational agents: A systematic review. Int J Soc Robot. 2020;12(6):1293-1312.[DOI]

-

7. Christov-Moore L, Reggente N, Vaccaro A, Schoeller F, Pluimer B, Douglas PK, et al. Preventing antisocial robots: A pathway to artificial empathy. Sci Robot. 2023;8(80):eabq3658.[DOI]

-

8. Raamkumar AS, Yang Y. Empathetic conversational systems: A review of current advances, gaps, and opportunities. IEEE Trans Affect Comput. 2022;14(4):2722-2739.[DOI]

-

9. Park S, Whang M. Empathy in human-robot interaction: Designing for social robots. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3):1889.[DOI]

-

10. Rosenthal-Von der Pütten AM, Schulte FP, Eimler SC, Sobieraj S, Hoffmann L, Maderwald S, et al. Investigations on empathy towards humans and robots using fMRI. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;33:201-212.[DOI]

-

11. Mattiassi AD, Sarrica M, Cavallo F, Fortunati L. Degrees of empathy: Humans’ empathy toward humans, animals, robots and objects. In: Casiddu N, Porfirione C, Monteriù A, Cavallo F, editors. Ambient assisted living. Cham: Springer; 2017. p. 101-113.[DOI]

-

12. Costa S, Brunete A, Bae BC, Mavridis N. Emotional storytelling using virtual and robotic agents. Int J Humanoid Robot. 2018;15(03):1850006.[DOI]

-

13. Spitale M, Okamoto S, Gupta M, Xi H, Matarić MJ. Socially assistive robots as storytellers that elicit empathy. ACM Trans Hum-Robot Interact. 2022;11(4):1-29.[DOI]

-

14. Appel M, Lugrin B, Kühle M, Heindl C. The emotional robotic storyteller: On the influence of affect congruency on narrative transportation, robot perception, and persuasion. Comput Hum Behav. 2021;120:106749.[DOI]

-

15. Paiva A, Leite I, Boukricha H, Wachsmuth I. Empathy in virtual agents and robots: A survey. ACM Trans Interact Intell Syst. 2017;7(3):1-40.[DOI]

-

16. Rawal N, Stock-Homburg RM. Facial emotion expressions in human–robot interaction: A survey. Int J Soc Robot. 2022;14(7):1583-1604.[DOI]

-

17. Ferstl Y, Neff M, McDonnell R. ExpressGesture: Expressive gesture generation from speech through database matching. Comput Animat Virtual Worlds. 2021;32(3-4):e2016.[DOI]

-

18. Nyatsanga S, Kucherenko T, Ahuja C, Henter GE, Neff M. A comprehensive review of data-driven co-speech gesture generation. Comput Graph Forum. 2023;42(2):569-596.[DOI]

-

19. Liu Y, Mohammadi G, Song Y, Johal W. Speech-based gesture generation for robots and embodied agents: A scoping review. In: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Human-Agent Interaction; 2021 Nov 09-11; Virtual Event, Japan. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2021. p. 31-38.[DOI]

-

20. Llanes-Jurado J, Gómez-Zaragozá L, Minissi ME, Alcañiz M, Marín-Morales J. Developing conversational virtual humans for social emotion elicitation based on large language models. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;246:123261.[DOI]

-

21. Seaborn K, Miyake NP, Pennefather P, Otake-Matsuura M. Voice in human–agent interaction: A survey. ACM Comput Surv. 2021;54(4):1-43.[DOI]

-

22. James J, Watson CI, MacDonald B. Artificial empathy in social robots: An analysis of emotions in speech. In: 2018 27th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication (RO-MAN); Aug 27-31; Nanjing, China. Piscataway: IEEE; 2018. p. 632-637.[DOI]

-

23. James J, Balamurali B, Watson CI, MacDonald B. Empathetic speech synthesis and testing for healthcare robots. Int J Soc Robot. 2021;13(8):2119-2137.[DOI]

-

24. Beatman A. Announcing new voices and emotions to Azure Neural Text to Speech. Redmond: Microsoft Azure; 2022. Available from: https://azure.microsoft.com/en-us/blog/announcing-new-voices-and-emotions-to-azure-neural-text-to-speech/

-

25. Yun C. A new generative engine and three voices are now generally available on Amazon Polly. Seattle: Amazon Web Services; 2024. Available from: https://aws.amazon.com/cn/blogs/aws/a-new-generative-engine-and-three-voices-are-now-generally-available-on-amazon-polly/

-

26. Tan X. Neural text-to-speech synthesis. In: O’Sullivan B, Wooldridge M, editors. Artificial intelligence: Foundations, theory, and algorithms. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2023.[DOI]

-

27. Du H, Chhatre K, Peters C, Keegan B, McDonnell R, Ennis C. Synthetically expressive: Evaluating gesture and voice for emotion and empathy in VR and 2D scenarios. In: Proceedings of the 25th ACM International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents; 2025 Sep 16-19; Berlin, Germany. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2025. p. 1-10.[DOI]

-

28. Velentza AM, Fachantidis N, Pliasa S. Which one? Choosing favorite robot after different styles of storytelling and robots’ conversation. Front Robot AI. 2021;8:700005.[DOI]

-

29. Davis M. A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog Sel Doc Psychol. 1980;10:85. Available from: https://www.uv.es/friasnav/Davis_1980.pdf

-

30. Darling K, Nandy P, Breazeal C. Empathic concern and the effect of stories in human-robot interaction. In: 2015 24th IEEE international symposium on robot and human interactive communication (RO-MAN); 2015 Aug31-Sep 04; Kobe, Japan. Piscataway: IEEE; 2015. p. 770-775.[DOI]

-

31. Jauniaux J, Tessier MH, Regueiro S, Chouchou F, Fortin-Côté A, Jackson PL. Emotion regulation of others’ positive and negative emotions is related to distinct patterns of heart rate variability and situational empathy. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0244427.[DOI]

-

32. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101.[DOI]

-

33. Shen J, DiPaola D, Ali S, Sap M, Park HW, Breazeal C. Empathy toward artificial intelligence versus human experiences and the role of transparency in mental health and social support chatbot design: Comparative study. JMIR Ment Health. 2024;11:e62679.[DOI]

-

34. Stolarski Ł. Pitch patterns in vocal expression of ‘happiness’ and ‘sadness’ in the reading aloud of prose on the basis of selected audiobooks. Res Lang. 2015;13(2):140-161.[DOI]

-

35. Lawson AP, Mayer RE. The power of voice to convey emotion in multimedia instructional messages. Int J Artif Intell Educ. 2022;32(4):971-990.[DOI]

-

36. Shih MT, Hsu MY, Lee SC. Empathy-GPT: Leveraging large language models to enhance emotional empathy and user engagement in embodied conversational agents. In: Adjunct Proceedings of the 37th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology; 2024 Oct 13-16; Pittsburgh, USA. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2024. p. 1-3.[DOI]

-

37. Steinhaeusser SC, Piller R, Lugrin B. Combining emotional gestures, sound effects, and background music for robotic storytelling-effects on storytelling experience, emotion induction, and robot perception. In: Proceedings of the 2024 ACM/IEEE international conference on human-robot interaction; 2024 Mar 11-15; Boulder, USA. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2024. p. 687-696.[DOI]

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026. This is an Open Access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Publisher’s Note

Share And Cite