Abstract

This perspective reframes human–robot interaction (HRI) through extended reality (XR), arguing that virtual robots powered by large foundation models (FMs) can serve as cognitively grounded, empathic agents. Unlike physical robots, XR-native agents are unbound by hardware constraints and can be instantiated, adapted, and scaled on demand, while still affording embodiment and co-presence. We synthesize work across XR, HRI, and cognitive AI to show how such agents can support safety-critical scenarios, socially and cognitively empathic interaction across domains, and extend physical capabilities with XR and AI integration. We then discuss how multimodal large FMs (e.g., large language models, large vision models, and vision-language models) enable context-aware reasoning, affect-sensitive situations, and long-term adaptation, positioning virtual robots as cognitive and empathic mediators rather than mere simulation assets. At the same time, we highlight challenges and potential risks, including overtrust, cultural and representational bias, privacy concerns around biometric sensing, and data governance and transparency. The paper concludes by outlining a research agenda for human-centered, ethically grounded XR agents, emphasizing multi-layered evaluation frameworks, multi-user ecosystems, mixed virtual–physical embodiment, and societal and ethical design practices to envision XR-based virtual agents powered by FMs as reshaping future HRI into a more efficient and adaptive paradigm.

Keywords

1. Introduction

As robotics has prospered in recent years, intelligent robots have been more integrated into everyday lives[1]. In particular, human–robot interaction (HRI) has become a crucial field by intertwining humans with robots in human-centric environments[2]. However, HRI has traditionally been rooted in the constraints of the physical world, prioritizing mechanical safety, real-time control, and spatial coordination between humans and embodied machines. These systems have yielded significant advances in domains such as manufacturing, logistics, and assistive robotics[3-6], yet they remain bounded by several practical limitations, such as the cost of hardware, the risks of human–machine co-location, and the inflexibility of physical deployment in rapidly dynamic or hazardous environments[7,8].

Meanwhile, extended reality (XR), an umbrella term encompassing virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR), has matured into a powerful paradigm for immersive interactions, multimodal interaction, and elevated cognition in the field of general human-computer interaction (HCI) over the past decades[9]. By incorporating virtual information visualized either in a complete virtual world or the real-world, XR offers not only visual-spatial fidelity but also the capacity for dynamic feedback,

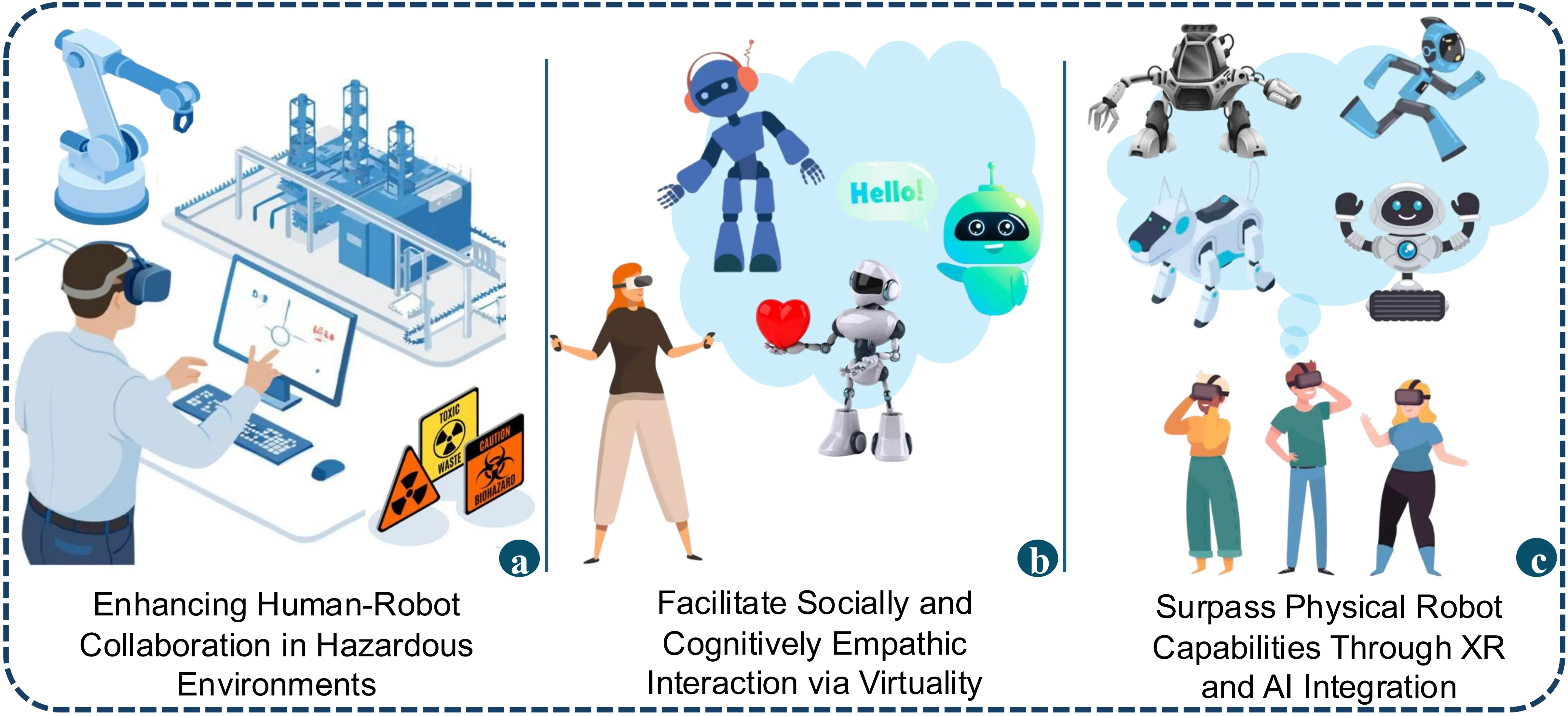

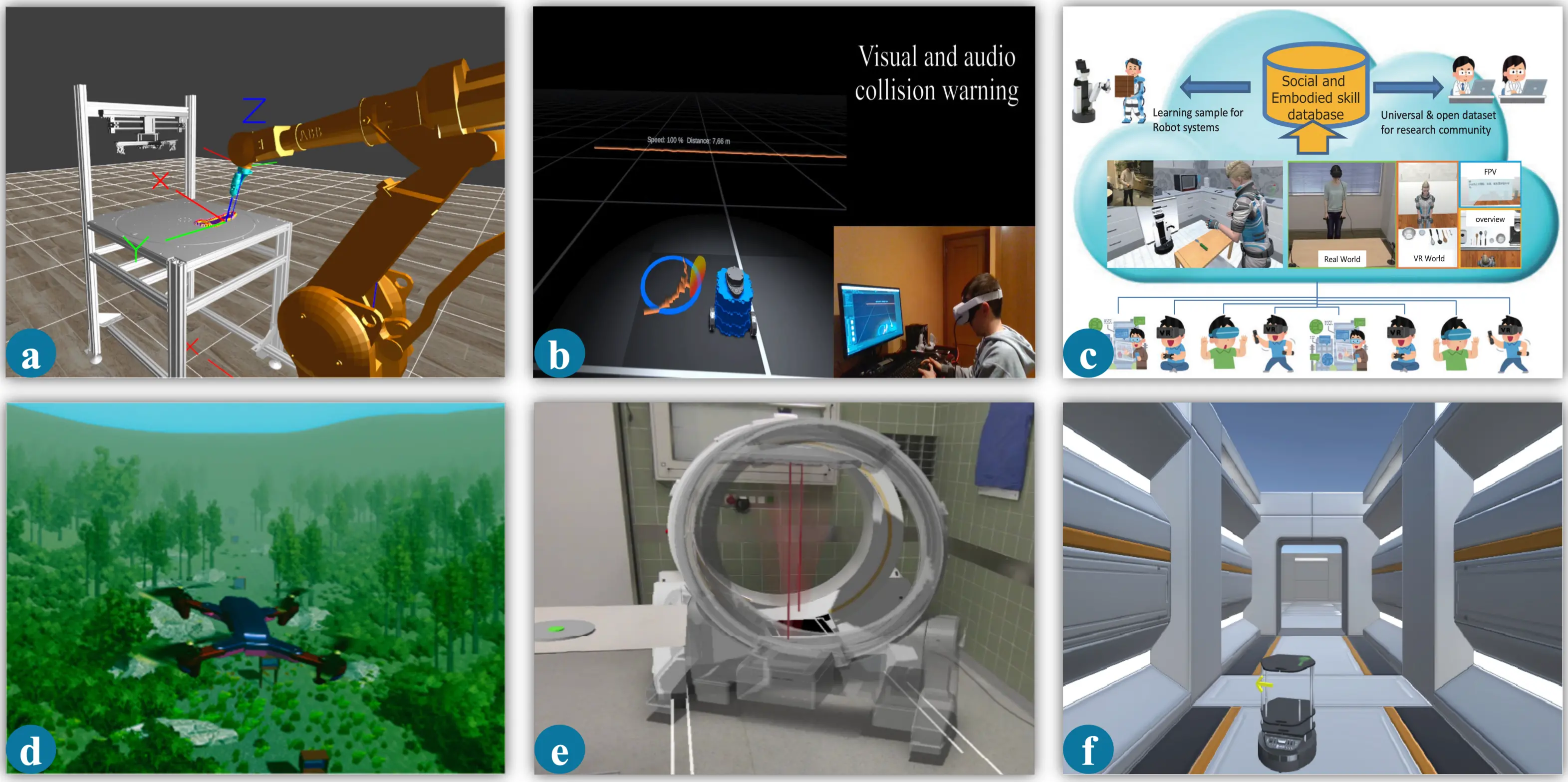

Figure 1. Representative examples of interacting with XR-based virtual robots across different domains, illustrating the breadth of mechanisms that motivate this paper’s focus. (a) Virtual robot arm in VR enabling safe task execution without physical co-location[12]; (b) Virtual mobile robot in VR with motion details visualized to improve situational awareness[13]; (c) Virtual humanoid robot in VR supporting social skill learning[14]; (d) Virtual aerial robot (drone) in VR for teleoperation and training in environments where physical deployment is impractical[15]; (e) Virtual medical robot in AR/MR where the visualization supports context-aware guidance and safer clinical workflow understanding[16];(f) Virtual mobile robot in the format of AR/MR visualization to support shared scene coordination and spatial understanding[17]. XR: extended reality; VR: virtual reality; AR: augmented reality; MR: mixed reality.

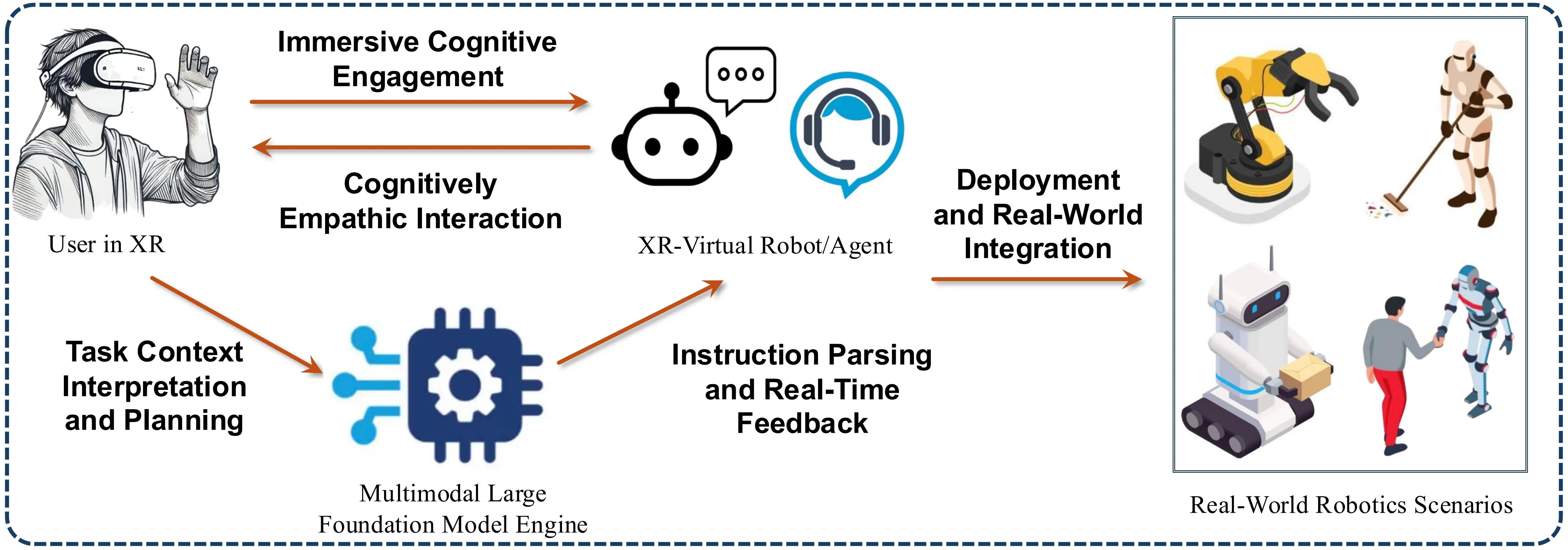

In parallel, we are witnessing an unprecedented shift in artificial intelligence (AI) through the development of large foundation models (FMs)[18], particularly large language models (LLMs), large vision models (LVMs), and vision–language models (VLMs), that endow agents with context-aware reasoning, conversational competence, and multimodal perception[19-21]. When integrated with HRI, these models enable the creation of more smooth interactions between humans and robots due to algorithmic advancements, for example, in communicating robot intent or learning from human feedback[22,23]. When coupled with XR, the involvement of virtual elements would lead to another potential approach for interaction[24]. For instance, intelligent virtual robots, which are agents that inhabit immersive spaces, can understand user intent and adaptively respond through natural language, gaze, gesture, or other inputs[25-29].

The virtual robots are more than plain visualizations or surrogates[16,30] of corresponding physical systems. Besides serving as virtual counterparts, they also represent a new category of cognitive agent capable of participating in collaborative tasks, simulating empathic engagement, and supporting experiential learning without the material constraints of conventional robotics. In industrial training scenarios, for example, XR-based robots have been shown to improve domain task performance, user experience, and procedural safety awareness[31,32]. In specific therapeutic and educational contexts, socially responsive virtual agents powered by LLMs are already being explored as scalable tools for mental health interventions, language acquisition, and neurodiverse engagement[33,34]. This evolution of immersive media technology and cognitive AI, alongside the intersection between them, encourages us to reflect: while the traditional robotic paradigm emphasized physical manipulation, like grasping, moving, and executing, more emerging paradigms emphasize co-presence and the co-construction of tasks through immersive interactions[35,36] with the engagement of virtual elements[37-39]. This shift reframes HRI from a primarily mechanical interface to a socio-cognitive encounter mediated by technology.

By witnessing the current landscape of interacting with virtual robots through the lens of XR-generated autonomous and adaptive agents that reside entirely within immersive environments, we argue that in the future, such virtual agentic loops will offer not only practical benefits—safety, scalability, and cognitive adaptability—but also open new directions for understanding human–machine interaction as a fundamentally relational process. We explore how humans engage with these virtual robots as social, instructional, and empathic partners across diverse domains, such as industrial safety training, education, therapeutic interventions, collaborative design, etc. By narrowing the scope to XR-native agents, we are able to examine the unique affordances and challenges inherent in this paradigm: embodiment without physical form, presence without mass, and cognition unconstrained by mechanical limitations. This framing also enables us to explore how emerging AI models (e.g., LLMs, VLMs) can endow these agents with contextual awareness, responsiveness, and the capacity for long-term adaptation. By synthesizing developments across XR, HRI, and large-scale FMs, we articulate a research agenda for the next generation of empathic and ethically grounded virtual robotics.

1.1 Positioning

This paper investigates the interaction between humans and intelligent virtual robots that exist entirely within XR environments. Unlike conventional literature reviews such as work[40] identifying the methodologies of XR in HRI, or work[41] discerning the interaction modalities for XR in HRI, in this paper, we position virtual robots as embodied, agentic entities, either humanoid or

Figure 2. Conceptual interaction framework for XR-native virtual robots powered by multimodal FMs. User inputs in XR (e.g., speech, gesture, and contextual cues) are interpreted by an FM engine (e.g., LLM/VLM) for task-aware understanding, instruction parsing, and response generation; the XR-native virtual robots deliver

1.2 Terminology disambiguation

To reduce ambiguity, we use the following terms consistently throughout the paper. We use robot to denote an embodied robotic system in the physical world (i.e., with sensors/actuators), and agent as a general term for an entity that perceives, reasons, and acts within an environment. virtual robot (our focus): a robot-like virtual agent that exists entirely within XR and is not dependent on a physical robot for its embodiment or behavior (although it may optionally be informed by external data). When referring to this entity, we primarily use virtual robot (or XR-native/XR-powered/XR-based virtual robot or similar) and avoid using robot alone where confusion could arise.

1.3 How does HRI with XR-native virtual robots differ from physical robot

Traditional HRI assumes a physically embodied robot whose interaction is constrained by mass, force, sensing placement, actuation limits, and co-location risks; as a result, much of HRI centers on mechanical safety, real-time control, and physical task feasibility. In contrast, XR-native virtual robots are embodied through perceptual and interaction cues rather than material form, and their action space is programmable rather than physically limited. This could result in a significant transition by unleashing the interaction paradigm from physical mass constraints. Table 1 summarizes the main differences between the two interaction formats and motivates why XR-powered virtual agents can enable different forms of HRI rather than merely simulating physical robots.

| Dimension | Traditional HRI With Physical Robots | HRI with XR-native Virtual Robots |

| Embodiment | Material body with mass anchored in physical space | Perceptual virtual embodiment without material form |

| Main Safety Concern | Physical harm (collision, force, impact) and workspace certification | Cognitive or psychological harm with substantially reduced physical hazard |

| Main Evaluation Mechanism | Task performance in physical world and safety metrics | (Co-)presence, empathy, and cognitive workload |

HRI: human–robot interaction; XR: extended reality.

2. Current Advancements of HRI with XR and FMs

The intersection of XR and HRI has witnessed rapid growth in recent years, driven by advances in immersive technologies, intelligent agent architectures, and the democratization of AI models. Across both industrial and academic settings, XR platforms are increasingly being used to simulate robot behavior, mediate collaboration, and enable safer, more personalized forms of interaction. In this section, we examine recent related works to provide an argument-driven synthesis to motivate our Perspective’s central focus: XR-native virtual robots, when coupled with FMs, can unlock interactions that are (i) safer, (ii) smarter, and (iii) more empathic and emotionally intelligent. Accordingly, we discuss representative prior works by: (1) Safety-Aware XR for Human–Robot Collaboration; and (2) Cognitive and Empathic Virtual Robots: Large FMs with XR with specific sub-domains aligned with our pivotal concerns.

2.1 Safety-aware XR for human–robot collaboration

The use of XR (mostly VR and AR) has gained considerable traction in enabling safety-aware human–robot collaboration (HRC), especially in industrial, high-risk, or mission-critical domains. XR systems enable the development of virtual elements or digital twins of physical robots that support users in visualizing robot behaviors, simulating hazardous tasks, and reducing physical risks during planning and training phases.

2.1.1 Visualizing robot behavior for hazardousness

Multiple studies emphasize the power of XR to make robot behavior more transparent and predictable through visual overlays and real-time cues. Enayati et al.[32] propose a human-in-the-loop XR system to visualize robot trajectories and operational zones. Similarly, MR interfaces evaluated by study[42] use audio–visual cues to render dynamic hazard zones, increasing user awareness. Works[30,43,44] explore AR projections or visualizations of robot motion intent or predicted paths, improving perceived safety, interaction naturalness, and reducing ambiguity during close-range collaborations with robots. Digital twins are increasingly used to visualize risk and monitor remote systems. As shown in works[45-47], synchronizing virtual and physical robots allows users to anticipate unsafe interactions and maintain awareness during shared-space operations. There are several literature reviews[40,48,49] which further highlight the role of digital twins and virtual agents in visualizing context and enhancing transparency.

2.1.2 Training and planning with simulated XR

XR-based training tools have demonstrated strong potential in improving procedural safety and knowledge retention in HRI[50-52]. Dianatfar et al.[31] show how VR welding simulations lead to increased user confidence and task proficiency. Similar systems[53] offer immersive environments where users engage with simplified navigation alongside robot behavior. Surve et al.[54] enabled HRI training to be conducted in photorealistic simulated environments, using XR wearables with virtual underwater robots before deployment in real-world scenarios where safety could be at risk. Virtual laboratories, allowing for reproducible and controlled studies of HRC under complex psychological and ergonomic conditions[55,56], were developed for enhanced interaction safety. For example, study[57] examines how robot motion affects human posture and stress using VR-based observation, while another[58] combined AR with haptic feedback to reduce cognitive load during robot-assisted surgical situations. For task planning, some systems help reduce planning errors and allow iterative testing without physical execution, such as study[59] which provided AR interfaces to preview and adjust robotic motion paths, or study[60] which offered a virtual robot in AR for high-level requests before accurate motion planning. For industrial assembly contexts, AR-based tools assist in human-robot alignment and workflow optimization[61,62] for improved task efficacy.

2.1.3 Remote and distributed safety-aware HRI

Remote interaction with robots or robotic teleoperation through XR is also gaining prominence[63-66]. Previous studies[67,68] combine XR and networked control for distributed robot supervision. Through immersive visualizations and overlays from VR and AR, users retain situational awareness and control without excessive direct physical presence in adaptive teleoperation, where intuitive visual, audio, or mid-air feedback[69,70] is accompanied.

2.1.4 Adaptive, accessible, and inclusive XR-HRI

Despite broad applicability, many XR-HRI systems still lack adaptability or emotional responsiveness. Some reviews[40,48] highlighted that most implementations are tailored to single-user setups or rigid scenarios. Recent works have begun to address these gaps through individualized or personalized safety concerns and adaptive communication modeling[71,72]. XR is also proving to be a

In summary, XR-based robot systems using additional visualized virtual elements contribute significantly to safety-aware HRI/HRC by enabling informative visualizations, safe training environments, and more intuitive interactions. Moving forward, research should continue to explore adaptive, intelligent, and inclusive XR interfaces to fully realize the potential of virtual robotic collaboration in complex and dynamic settings.

2.2 Cognitive and empathic virtual robots: large FMs with XR

The rise of large FMs during past years is enabling a new generation of cognitive and empathic norms of both advanced robotic and HRI loops. No longer limited to passive interfaces or scripted responses, virtual agents embedded in XR environments can now engage in contextual reasoning, adapt behavior in real time, and respond empathetically to users due to generative AI.

2.2.1 FMs as cognitive engines in XR-HRI

Numerous recently developed platforms and frameworks integrate LLMs into XR to support spatially and semantically grounded communications with agents. CUIfy[76] demonstrates an open-source pipeline for embedding LLM-powered conversational agents in Unity XR environments, minimizing latencies during interactions. Konenkov et al.[77] combine VR with VLMs, enabling reduction in task completion time and elevation in user comfort. Afzal et al.[78] highlighted that LLMs with XR facilitate situational awareness while underlining ethical considerations. Li et al.[79] showed that foundational VLMs can make robotic control more flexible while being a cost-effective and easy-to-use solution. Synthetically, study[80] explored a GPT-based human-robot teaching through VR settings, which showed the functionality of simulated virtual robots powered by FMs.

2.2.2 Empathic and emotionally aware virtual robots

Empathy-focused HRI is a growing priority in XR systems. The review[81] detailed how LLMs facilitate emotion recognition, conversational nuance, and contextual understanding in HRI. Social cues, such as haptics are also simulated in XR. For example, a study[82] presented a haptic-enhanced VR handshake system with visual cues to enhance social presence for robotic partnership. Another study[55] enabled empathetic testing of prosthetic interaction through a safe virtual laboratory. Understanding user stress, posture, and motion in XR has also been studied for adaptive and empathic robot control and interaction[56,57]. Notably, some

2.2.3 Human-centered and multimodal interaction

To support human-centered core, while retaining trustworthy and intuitive virtual agents in XR-based HRI, several works have proposed distinct taxonomies and design principles. These include the virtual element design taxonomy[88], the dedicated AR-HRI classification[84], and the key characteristics of robots[89], which help researchers build user-centered, expressive, and empathic agentic interactions. Design-oriented XR systems[90-93] explore proxemics, social communication, and information exchange, facilitating emotionally intelligent design of HRI systems. In terms of interaction modalities, gesture and non-verbal input are critical components of empathic HRI. Gesture recognition in VR[94] and multimodal input[95] via wearable MR[25] enable virtual robots to interpret user intent and adjust behavior dynamically.

In summary, human-centered, cognitive, and empathic virtual robots especially powered by FMs are transforming XR into a

3. Future Scenarios of XR-Enhanced Virtual Robot Interaction

By revisiting the current research and application status of XR-based HRI, as well as the surge of large foundational models, the next generation of XR-enabled virtual robots will go beyond mere simulation and visualization[96]. These virtual robots are envisioned to be developed with agentic empathy[97] to become different roles, such as adaptive collaborators and companions capable of reasoning, teaching, and responding to user needs across a range of real-world tasks. We outline here three forward-looking domains where virtual robots could deliver transformative impact, while the three corresponding scenarios are shown in Figure 3.

3.1 Enhancing industrial collaboration in hazardous environments

Industrial domains such as manufacturing, construction, biochemical processing, and emergency cases frequently involve hazardous conditions that challenge conventional human–robot co-presence[37,98]. Safety concerns, limited visibility, high-risk machinery, and unstable environments often preclude direct interaction with physical robots. XR technologies offer a transformative alternative: by simulating immersive digital twins of real-world operations, workers can engage with virtual counterparts of industrial robots to rehearse procedures, calibrate workflows, and develop collaborative pipelines with mitigating physical risks.

Within these environments, users can interactively visualize safety-critical zones, explore dynamic task trajectories, and manipulate virtual robots with high fidelity to their real-world equivalents[99]. VR is particularly effective for simulating chaotic or unpredictable scenarios where physical testing is impractical. In such settings, virtual robots that are programmed with behaviors modeled after their physical counterparts can provide users with realistic and repeatable task rehearsals that improve coordination and situational awareness[100,101].

AR or MR expand these capabilities into real-time field operations[102]. For example, through optical see-through head-mounted displays, users can view superimposed virtual robots aligned with their physical environments, enabling spatially accurate remote teleoperation[103-105]. This is especially valuable in mobile robotics deployed in the onsite hazardousness-aware situations, where AR overlays allow for user interaction and monitoring at a safe distance, while maintaining functional continuity with on-site deployments.

By integrating real-time sensory feedback and AI-driven reasoning (e.g., via LLMs), these virtual agents adaptively interpret human intent and respond to dynamic conditions. More than functional simulators, they serve as communicative intermediaries for visualizing robot intent, forecasting motion paths, and modeling shared control frameworks. Such transparency builds user trust, reduces cognitive load, and fosters safer, more effective collaboration during both training and live operations[106-108]. As such,

Illustrative vignette: FM-based virtual robot assistance in hazardous environment with XR. Consider a hazardous maintenance task (e.g., in welding or chemical processing) where standing next to an operating robot is highly risky. However, in VR, the team is able to rehearse the entire process in a virtually identical workspace, where the robot’s planned motions and prohibited areas are visualized clearly to help operators understand where it is safe to stand and how the robot will move[30,32,42,43,45,47]. When an FM is integrated into the pipeline, it can anticipate the virtual robot’s next actions and explain the reasons behind them (e.g., why it slows down or pauses), answer “what happens if I do this” questions during rehearsal, and proactively highlight risky situations with timely safety reminders (e.g., if the operator is too close to the hazard)[76,78]. Overall, the virtual setup reduces exposure during training and makes robot behavior easier to anticipate during real-world deployment.

3.2 Empowering socially and cognitively empathic interaction via virtual humanoid robots

In social, healthcare, and educational contexts, humanoid robots are increasingly deployed to support therapy, rehabilitation, companionship, and interactive learning[109-112]. However in numerous cases, physical platforms remain expensive, difficult to adapt, and are often limited in their range of emotional expression. Virtual humanoid robots in XR alleviate many of these constraints by existing as fully programmable, reconfigurable avatars that can be tailored to individual users and scenarios. Within immersive environments, these agents can inhabit shared spaces with users, maintain functionality, modulate input signals such as voice and posture, and enact subtle social cues, practically achieving a richer empathic interaction than many current physical

The integration of large FMs further amplifies these capabilities. By combining LLMs, LVMs, and VLMs, virtual agents can interpret multimodal input such as speech, gaze, audios, facial expression, and gesture, and respond in a manner that is contextually appropriate and emotionally attuned. In VR, fully immersive environments populated with such agents can be used to rehearse or remaster challenging social situations, practice turn-taking with more empathy[114,115]. The game-like learning experiences in VR with virtual robots can reward mutual collaboration and facilitate curiosity, improving overall learning efficiency in educational cases[116]. In AR, virtual companionship robots can be overlaid onto ordinary environments, functioning as “always-available” conversational partners who accompany users in need through mentally therapeutic exercises[117]. By enabling empathic conversations with target users, without the physical constraints of moving and operating hardware, virtual empathic agents can more effectively facilitate communicative interaction[118-120].

These virtual companions are particularly well-suited for supporting heterogeneous user groups, ranging from language learners who benefit from personalized tutoring to patients undergoing exposure therapy for anxiety or mental trauma. Because their forms and behavior are reconfigurable, virtual robots can be adapted to different cultures, age groups, and appearance preferences without redesigning hardware. Their consistent and programmable empathy make them promising supports for vulnerable populations, including children on the autism phase or older adults experiencing cognitive decline. As AI-driven virtual agents continue to advance in empathy modeling and affective reasoning[121-123], XR systems may increasingly sustain relationships that are practically meaningful, while dynamically adapting to users’ emotional states and evolving alongside therapeutic or educational goals.

Illustrative vignette: XR-native humanoid coaching with affective adaptation. Consider a VR (or AR) coaching or therapy session where a virtual humanoid robot helps a user practice a skill (e.g., coping with anxiety or learning a routine). Unlike scripted agents which reply merely to certain keywords, an FM-driven virtual humanoid robot can hold a natural, multi-turn conversation and adjust what it says based on what the user has already shared and what is happening in the context[33,34,81]. Since the interaction happens in XR, the agent can also respond to simple and observable cues, such as long pauses and user emotional changes, by slowing the pace, offering more empathy, and giving the user more space rather than pushing forward[56,57,82,83]. The empathic advantage is evident: with FM integration, the virtual robots can adapt to users’ affect in real-time without requiring the actuation on physical robots, and they can be easily personalized in appearance and interaction style for different users and contexts without changing any hardware.

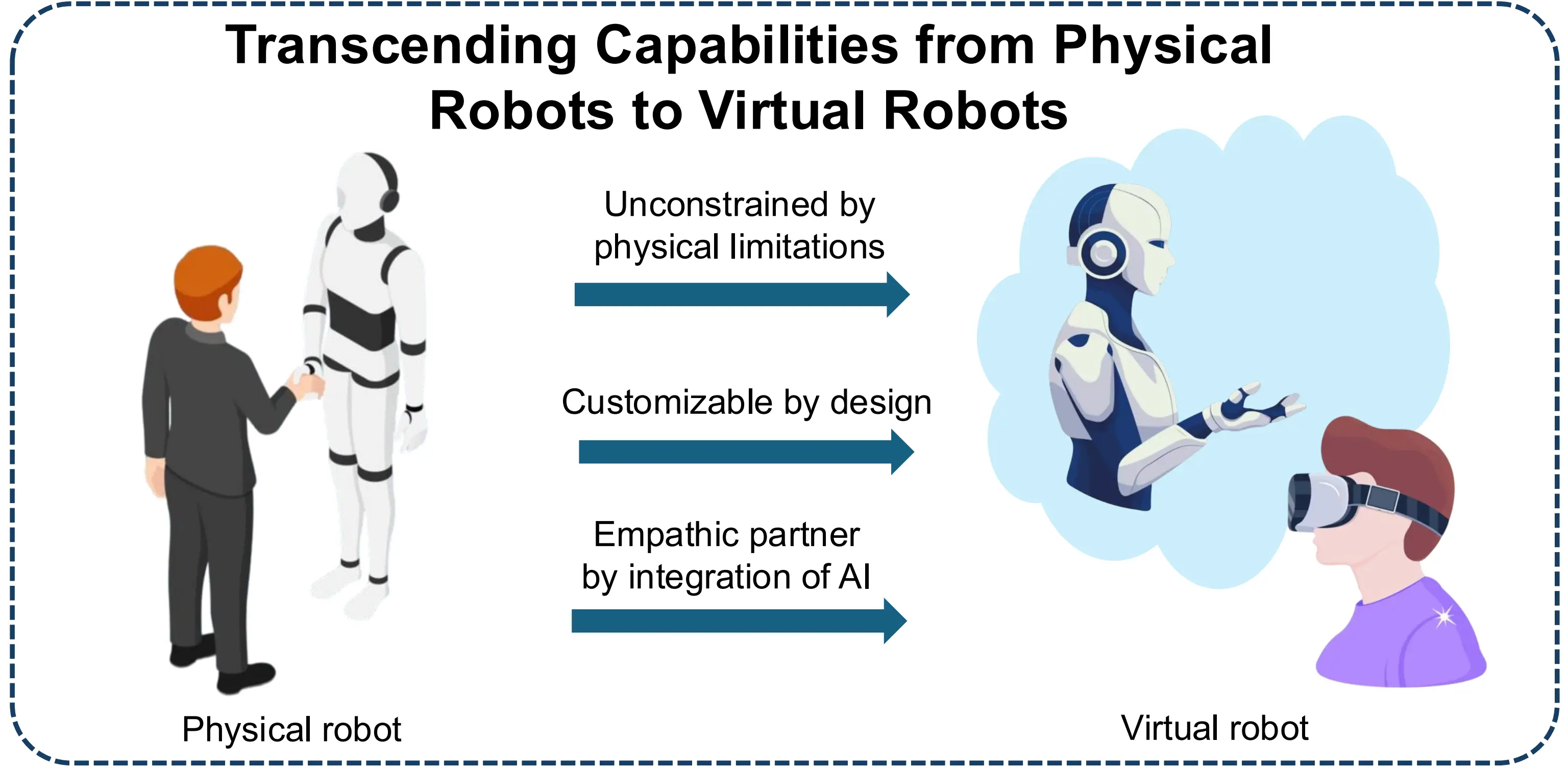

3.3 Surpassing physical robot capabilities through XR and AI integration

Another revolutionary implication of XR-based virtual robots is envisioned to be their ability to transcend the limitations of physical embodiments[124,125]. Unconstrained by friction, mass, structural rigidity, or mechanical complexity, virtual agents are not bound to a single physical body or configuration[96]; they can transform roles instantaneously, adapt behaviors dynamically, and evolve across time and contexts. In VR environments, while the entire surroundings can be constructed virtually with immersion, designers are allowed either to mirror existing physical robots in appearance and shape or to create entirely novel embodiments tailored to specific interaction goals[126,127]. Locomotion, morphology, and other functions are therefore determined by the design intent customized for concrete needs rather than hardware feasibility. In AR and MR, similar principles apply: virtual counterpart robots or purely virtual agentic avatars can be anchored into the physical environment[128-131], moving and interacting according to the programmability that does not need to comply with the same constraints as physical robots.

These agents can seamlessly shift roles from tutor to collaborator to supervisor and beyond without the need for physical redesign, complex reconfiguration, or new hardware deployments. Through integration with LLMs or multimodal VLMs, they acquire the capacity to bear multi-turn dialogues, reason over task contexts, and anticipate user needs at a high level of abstraction[77]. Such abilities position XR-native robots as empathic mediators unconstrained by physical hardware: they not only deliver instructions and guidance but also co-construct knowledge within specific contexts while sidestepping the limitations imposed by physical embodiments[132-134]. In this sense, virtual robots act as adaptive, empathic partners that extend and complement human

Figure 4. XR virtual agentic robots surpass physical capabilities. XR: extended reality.

Illustrative vignette: Reconfigurable XR-native robot that exceeds physical embodiment constraints. Consider a participatory design session where the users’ needs shift over time: first they want a quick demonstration, then they switch to a different task, and finally they want a step-by-step guidance while trying it themselves. In the physical world, this could require multiple platforms

4. Discussion

After synthesizing representative works in Section 2 and articulating three envisioned future scenarios in Section 3. In this section, we consolidate our arguments by (i) discussing the advantages brought by virtual embodiment and how this embodiment and

4.1 Virtual embodiment and user presence

Although virtual robots lack physical mass, they are not disembodied abstractions. In XR, virtual embodiment is achieved through consistent visual appearance, coherent spatial behavior, and responsiveness that aligns with human expectations for social interaction[135,136]. Studies of MR hazard visualization and robot collaboration show that gaze synchrony, joint attention cues, and predictable proximity dynamics can substantially enhance users’ sense of safety, control, and shared situational awareness. Work on avatar responsiveness and motion timing similarly suggests that even relatively simple agents can evoke strong impressions of

However, this form of embodiment remains partial. The lack of rich haptic and tactile feedback limits the kinds of tasks that can be trained purely in XR, particularly those requiring fine manipulation, force sensing, or shared physical contact. Emerging haptic overlays and pseudo-physical resistance may narrow this gap, but they also introduce new layers of technical complexity and potential sensory mismatch. Designing virtual embodiment thus becomes a balancing act: providing sufficient realism to support user trust, learning, and empathy, without promising physical capabilities that the virtual environment cannot reliably deliver.

4.2 Toward next generation interaction with virtuality

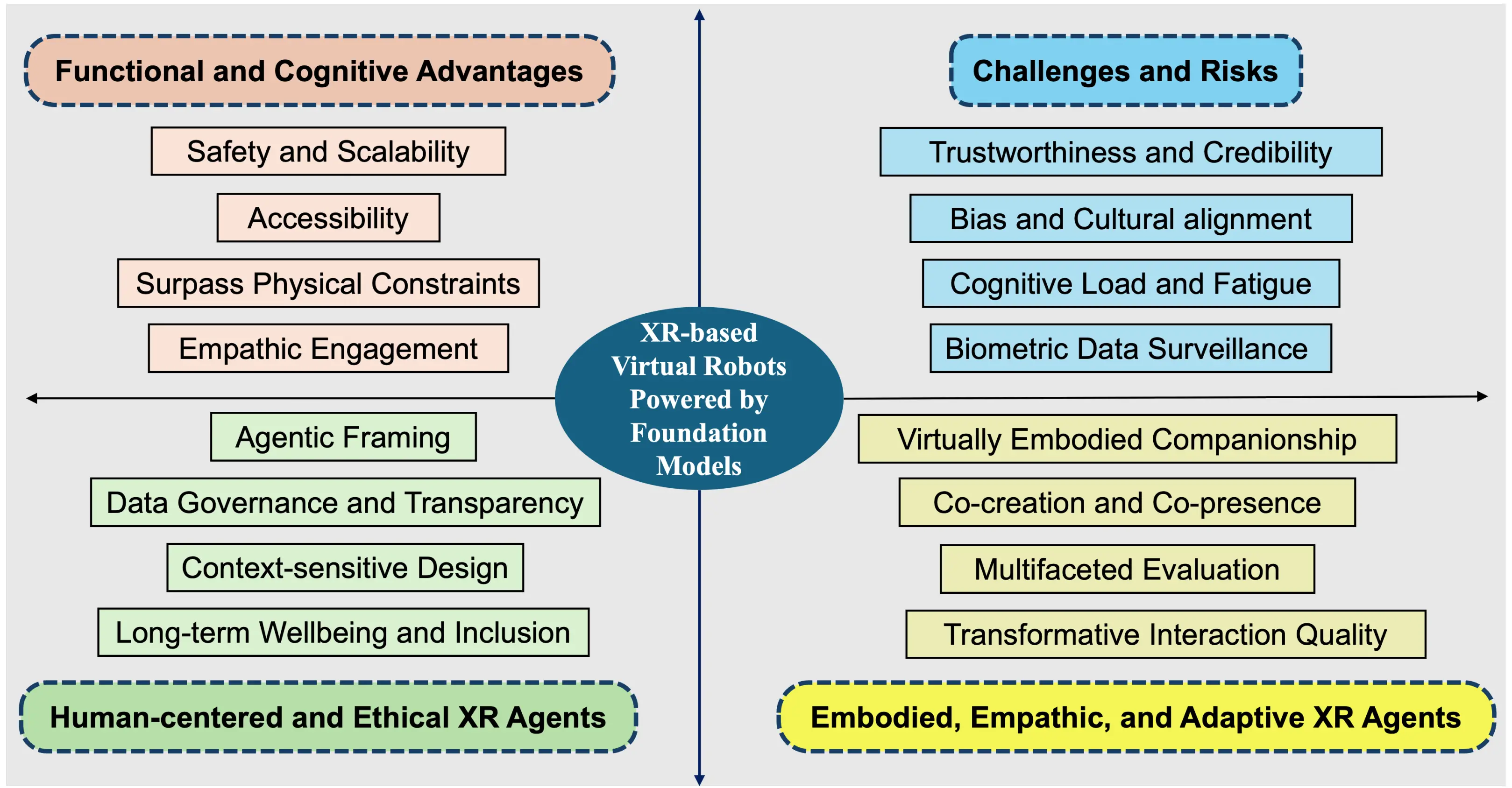

To reframe the next generation of effective interactions between humans and virtual robots with XR, large FMs are expected to be employed for endowing virtual agents with situational awareness[138-141]. This enables new forms of physical–virtual interaction but also introduces challenges and risks. Building on the instantiation of the three future scenarios before, we propose four aspects towards effective next generation interaction of human-virtual robot synergy, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5. A new form of XR-based virtual robots powered by FMs. The upper left highlights functional and cognitive advantages, while the upper right summarizes key challenges. The lower bands illustrate two complementary design trajectories: human-centered and ethical XR agents (left) and embodied, empathic, and adaptive

4.2.1 Functional and cognitive advantages

The integration of XR with AI-powered virtual robots offers advantages that are not merely incremental extensions of traditional HRI, but qualitatively new affordances. Functionally, safety and scalability are the most immediate benefits: hazardous, rare, or

On the cognitive side, XR-native agents supported by LLMs and VLMs can provide context-aware assistance that goes beyond scripted interaction[77,80,81]. Because the agent has access to the shared virtual scene and to ongoing user input, it can explain intent, adapt guidance to the user’s current state, and adjust interaction pacing in real time[43-45]. This supports empathic engagement in a practical way: the system can shift from a neutral, task-focused mode to a more supportive and reassuring mode when the user appears confused or stressed, which is difficult to achieve reliably with many physical platforms due to sensing and actuation

4.2.2 Potential challenges and risks

The same characteristics that make XR-based virtual robots powered by large FMs compelling also introduce significant risks: XR and FM integration with high immersion increases perceived realism and social presence, while FM-driven interaction can appear confident and socially fluent even when it is uncertain, biased, or misaligned with the user’s needs.

Trustworthiness and credibility are the most immediate concerns. FM-driven agents can generate persuasive explanations and recommendations that sound coherent while being incorrect, incomplete, or poorly grounded[34,81]. In XR, where users may experience a virtual robot as a co-present partner, this fluency can amplify overtrust: users may follow guidance because it feels competent and empathic, not because it is verifiably correct[30,44,49]. The risk is especially pronounced in safety training, clinical support, and education, where an erroneous suggestion delivered with high confidence may translate into unsafe actions, misplaced reliance, or inappropriate decisions[31,58]. For XR-native virtual robots, a key challenge is therefore not only “making the agent smarter”, but helping users calibrate reliance through clear boundaries, uncertainty communication, and interaction designs that privilege justifiable guidance[47,88].

Bias and cultural alignment constitute another critical, but often less visible risk. Because virtual robots in XR are embodied through appearance, gaze behavior, proxemics, and conversational style, bias can be expressed not only in language but also in social behavior[84]. Models trained on unreliable or biased data may inadvertently reproduce stereotypes, misinterpret culturally specific gestures, or privilege certain communication styles over others[34,81]. When such biases are encapsulated in smart or empathic manners, they can be harder to notice and may subtly shape users’ sense of belonging and legitimacy in the interaction[83,92,93]. This makes cultural alignment an HRI problem as much as a model problem: the system must be designed and evaluated for diversity and inclusion, with attention to how embodiment and interaction choices coincide with social norms[88].

Cognitive load and fatigue are practical risks that may be intensified by FM-driven interaction. XR already imposes perceptual and attentional demands; prolonged exposure can lead to motion sickness, eye strain, and attentional exhaustion[10]. Adding an

Finally, biometric data surveillance and the associated governance concerns are inherently tied to XR. Many XR systems rely on gaze tracking, head and hand motion, voice, and sometimes facial expression analysis for interaction and personalization[25,28]. Even when collected for benign purposes, such signals can enable sensitive inference (e.g., stress, attention, and impairments)[56,57]. Without careful design, governance, and transparency, these issues raise concerns about privacy, consent, and accessibility[48,78]. The practicality and fairness of deploying XR-powered virtual robots to target groups therefore remains an open question, especially in domains such as healthcare and pediatric care where trust and vulnerability are heightened[109,111]. Addressing this requires clearer privacy statements and transparency about what and why it is needed, and how it is governed.

4.2.3 Toward human-centered and ethical XR agents

The emergence of XR-based virtual robots powered by FMs introduces a new form of agency, autonomy, and perceived authenticity in HCI. As these agents begin to mirror human social cues, such as maintaining eye contact, modulating voice, and mirroring posture, they encourage users to treat them as intentional partners rather than mere tools[28,97]. This blurring of boundaries raises practical questions for designers and practitioners: How should such agents be framed and introduced to users? How can we ensure that the data used for pre-training and adaptation is curated, documented, and governed in ethically robust and trustworthy ways[34,48]

Agentic framing concerns how the system is introduced and what users are encouraged to believe about the agent’s competence and intent. Because XR embodiment can make a virtual robot feel socially present, users may interpret it as an intentional partner and attribute authority to it[10,49]. A human-centered framing therefore requires explicit boundary setting: the system should disclose when it is FM-driven, what it is designed to do, what it is designed not to do, and how uncertainty should be interpreted[78,81]. The aim is not to reduce engagement, but to support appropriate reliance and prevent users from confusing social fluency with verified capability.

Data governance and transparency are central because XR interaction often relies on multimodal sensing. Ethical deployment requires clarity about what is sensed (e.g., gaze, voice, motion), why it is needed, and whether it is used for personalization or model improvement[25,28,48]. Consent must be acquired with granularity, and users should be able to disable sensitive modalities without losing basic access to the system[48]. More broadly, governance should align with data minimization and purpose limitation: only the data required for the stated function should be collected, retention should be bounded, and secondary use should be constrained and monitored.

Context-sensitive design recognizes that “appropriate” embodiment and autonomy vary by domains and populations. In therapy and education, for example, highly anthropomorphic behavior may increase engagement for some users while increasing the risk of over-attachment for others[109,112]. Similarly, official workplace deployments raise distinct concerns compared to home companionship, and pediatric settings differ from adult settings in both vulnerability and consent to a large extent[48,111]. As a result, ethical design should be calibrated to the specific settings: the level of anthropomorphism, initiative, persuasion, and personalization should be chosen in relation to the contexts and the users’ agency, rather than harnessing universal design defaults.

Finally, long-term wellbeing and inclusion require thinking about out-of-the-box usability. XR-based agents can shape habits, expectations of social interaction, and patterns of reliance over time, especially for users who interact frequently or who are vulnerable (children, older adults, users with cognitive impairments). Human-centered design therefore needs longitudinal attention to whether these systems support dignity, independence, and psychological safety[40,97,112]. In practice, this means designing for accessibility concerns, evaluating differential impacts across user groups, and ensuring that personalization supports long-term wellbeing and inclusion instead of only pursuing short-term task performance or technical novelty[73-75].

4.2.4 Toward embodied, empathic, and adaptive XR agents

These concerns and opportunities point toward a reconceptualization of robots—from purely physical tools to relational, cognitively and emotionally engaged virtual partners. In XR, virtual robots do not primarily manipulate the physical world; instead, they shape users’ attention, scaffold their understanding, and participate in the co-construction of tasks and meanings[92,93]. Their value lies in adaptive dialogue, emotional resonance, and the ability to inhabit shared virtual spaces in which roles, perspectives, and interaction scripts can be fluid and negotiable, supporting virtually embodied companionship that is experienced as socially situated rather than merely functional[10,97,126].

Designing for this paradigm demands new forms of co-creation and evaluation. On the design side, achieving meaningful co-creation and co-presence requires XR–HRI systems to be developed through interdisciplinary collaboration that includes not only HCI and AI researchers, but also domain experts such as clinicians, educators, and accessibility specialists, together with end users

Reframing virtual robots as relational entities rather than passive tools shifts the focus of innovation from mechanical capability to transformative interaction quality. It requires asking not only what robots can do, but how they make people feel, what forms of understanding they enable, and whose needs they foreground or neglect[97,112]. By making the interaction empirical, ethical, and collaborative, the transformative potential of XR-based HRI with virtual robots is most likely to be realized.

5. Future Research Agenda

To ensure that XR-based virtual robots evolve in ethically responsible and socially beneficial ways, several research priorities can be pursued in the coming years. Building on the perspectives outlined in this paper, we highlight four potential research directions.

5.1 Evaluation frameworks for trust, empathy, and transferability

Existing XR–HRI evaluations often foreground usability or task performance but rarely capture the affective, relational, and longitudinal dimensions that are central to XR-native virtual robots. Future work should therefore develop multilayered evaluation frameworks that address at least three questions: (i) how users calibrate trust in agents that may be communicatively fluent but epistemically unstable; (ii) how empathic relationships and perceived psychological safety emerge and are maintained over time; and (iii) how learning and behavioral patterns acquired in virtual settings transfer to physical contexts.

Such frameworks will likely need to incorporate and coordinate behavioral, physiological, and self-report measures. Transferability studies are particularly underdeveloped in XR-HRI works: it remains unclear when and how competencies developed with XR-native virtual robots can be generalized into interactions with physical robots or human teammates in real-world conditions. Addressing these gaps will require controlled virtuality-to-physicality experiments, longitudinal field deployments, and shared benchmarks that allow comparison across systems and domains.

5.2 Multi-agent and multi-user interactions

Real-world collaboration rarely occurs in dyads; it typically involves heterogeneous groups of humans and agents coordinating under uncertainty. Yet, most XR–HRI prototypes still assume a single user and a homogeneous agent or agent group. Next-generation platforms should therefore support synchronous, parallel interaction among multiple users and multiple virtual robots, with roles and behaviors that adapt dynamically over time. This calls for mechanisms that enable flexible role allocation and reallocation between humans and agents, and for systematic research on how such roles are negotiated and transformed—how participants shift between leader, peer, tutor, and observer, and how these dynamics shape system accountability, perceived empathy, and inclusion. Understanding and deliberately designing for these emergent, multi-party interaction patterns will be crucial for safe, equitable, and effective XR-mediated teamwork.

5.3 Societal and ethical design

As XR-based virtual robots might flourish in schools, clinics, workplaces, and homes, they will not only reflect but also participate in shaping social norms, expectations, and mutual relations. Future research must therefore move beyond ad hoc “ethics checklists” and toward empirically grounded, participatory approaches to socio-technical design. A first priority is the detection, characterization, and mitigation of bias in both reasoning processes and actual embodiments. This includes examining how cultural, gendered, racialized, or ability-related cues are encoded in appearance, voice, posture, and interaction style, and how these cues influence user trust, identification, and perceived legitimacy.

Second, the extensive biometric sensing often involved in XR (eye tracking, facial expression analysis, posture and gesture monitoring, and voice sentiment inference) demands consent frameworks and data governance models that are legible to

5.4 Mixed embodiment and XR–physical integration

Finally, the integration of XR-native agents with physical robots presents an important, yet comparatively underexplored frontier. XR can function as a cognitive and social twin of physical systems, providing a training and interaction layer that mirrors

Research in this area must examine how consistency, continuity, and synchronization are maintained across modalities, including: When does divergence between virtual and physical behavior support learning and creativity? When does it undermine trust or induce negative awareness? How should haptic overlays, audio cues, and other multisensory feedback be orchestrated so that transitions between virtual and physical embodiments remain intelligible and safe? Addressing these questions will require joint advances in control, interface design, perception, and systematic evaluation, as well as careful consideration of where hybrid systems are most appropriate versus where purely virtual or purely physical approaches suffice.

6. Conclusion and Outlook

Virtual robots in XR mark a significant evolution in the broader spectrum of HRI. More than simulations or visualization tools, these agents can act as collaborative partners, capable of learning from users, adapting to context, and engaging across cognitive, emotional, and spatial dimensions through the state-of-the-art large FMs. They offer safer environments for training and exploration, richer and more flexible educational and therapeutic experiences, and new spaces for participatory design and experimentation that are not constrained by the limits of physical hardware.

In this paper, we have argued that virtual robots in XR should be understood not only as technical artifacts, but as relational and cultural ones. They mediate how people learn, work, and relate to one another, and thus must be designed and evaluated with attention to empathy, inclusion, and long-term wellbeing. We call on researchers, designers, practitioners, and policymakers to treat XR-native virtual robots as part of a broader socio-technical ecosystem: one that spans AI, HRI, XR, ethics, accessibility, and domain expertise. By approaching these systems as sites of interdisciplinary co-creation, rather than as isolated engineering projects, we can better ensure that their evolution is aligned with human values and diverse forms of flourishing. The future of virtual robots, like our own, will be shaped by the commitments we adopt and the infrastructures we build in the present.

At the same time, this potential is inseparable from responsibility. Without appropriate design and governance, XR-based virtual robots with large FMs may inadvertently reproduce existing inequities, foster less transparency, or blur the boundaries in certain aspects. As XR technologies mature and FMs grow more capable and autonomous, we are approaching a decisive juncture: whether virtual robots will amplify human cognition, compassion, and creativity, or raise bias, erode agency, and normalize intrusive sensing will depend on choices made now.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge that authors made limited use of generative AI tools for language polishing only.

Authors contribution

Zhang Y: Conceptualization, resources, writing-original draft.

Ma Y: Resources.

Kragic D: Supervision.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2026.

References

-

1. Xia H, Zhang Y, Rajabi N, Taleb F, Yang Q, Kragic D, et al. Shaping high-performance wearable robots for human motor and sensory reconstruction and enhancement. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1760.[DOI]

-

2. Zhang Y, Ma Y, Kragic D. Vision beyond boundaries: An initial design space of domain-specific large vision models in human-robot interaction. In: Dingler T, Salim F, Koelle M, van Berkel N, Waycott J, editors. Adjunct Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Mobile Human-Computer Interaction; 2024 Sep 30-Oct 3; Melbourne, Australia. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2024. p. 1-8.[DOI]

-

3. Ringwald M, Theben P, Gerlinger K, Hedrich A, Klein B. How should your assistive robot look like? A scoping review on embodiment for assistive robots. J Intell Rob Syst. 2023;107(1):12.[DOI]

-

4. Karabegović I, Karabegović E, Mahmić M, Husak E. The application of service robots for logistics in manufacturing processes. Adv Prod Eng Manag. 2015;10(4):185-194.[DOI]

-

5. Schmitt F, Piccin O, Barbé L, Bayle B. Soft robots manufacturing: A review. Front Robot AI. 2018;5:84.[DOI]

-

6. Zhang Y, Rajabi N, Taleb F, Matviienko A, Ma Y, Björkman M, et al. Mind meets robots: A review of EEG-based brain-robot interaction systems. Int J Hum. 2025;41(20):12784-12815.[DOI]

-

7. Trevelyan J, Hamel WR, Kang SC. Robotics in hazardous applications. In: Siciliano B, Khatib O, editors. Springer handbook of robotics. Cham: Springer; 2016. p. 1521-1548.[DOI]

-

8. Willemse CJ, Toet A, van Erp JB. Affective and behavioral responses to robot-initiated social touch: Toward understanding the opportunities and limitations of physical contact in human–robot interaction. Front ICT. 2017;4:12.[DOI]

-

9. Zhang Y, Nowak A, Xuan Y, Romanowski A, Fjeld M. See or hear? Exploring the effect of visual/audio hints and gaze-assisted instant post-task feedback for visual search tasks in AR. In: 2023 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR); 2023 Oct 16-20; Sydney, Australia. Piscataway: IEEE; 2023. p. 1113-1122.[DOI]

-

10. Kim D, Jo D. Effects on co-presence of a virtual human: A comparison of display and interaction types. Electronics. 2022;11(3):367.[DOI]

-

11. Lee H. A unified conceptual model of immersive experience in extended reality. Comput Hum Behav Rep. 2025;18:100663.[DOI]

-

12. Román-Ibáñez V, Pujol-López FA, Mora-Mora H, Pertegal-Felices ML, Jimeno-Morenilla A. A low-cost immersive virtual reality system for teaching robotic manipulators programming. Sustainability. 2018;10(4):1102.[DOI]

-

13. Solanes JE, Muñoz A, Gracia L, Tornero J. Virtual reality-based interface for advanced assisted mobile robot teleoperation. Appl Sci. 2022;12(12):6071.[DOI]

-

14. Inamura T. Digital twin of experience for human–robot collaboration through virtual reality. Int J Autom Technol. 2023;17(3):284-291.[DOI]

-

15. Covaciu F, Iordan AE. Control of a drone in virtual reality using MEMS sensor technology and machine learning. Micromachines. 2022;13(4):521.[DOI]

-

16. Plümer JH, Yu K, Eck U, Kalkofen D, Steininger P, Navab N, et al. XR prototyping of mixed reality visualizations: Compensating interaction latency for a medical imaging robot. In: 2024 IEEE International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality (ISMAR); 2024 Oct 21-25; Bellevue, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2024. p. 1-10.[DOI]

-

17. Cleaver A, Tang D, Chen V, Sinapov J. HAVEN: A unity-based virtual robot environment to showcase HRI-based augmented reality. arXiv:2011.03464 [Preprint]. 2020.[DOI]

-

18. Awais M, Naseer M, Khan S, Anwer RM, Cholakkal H, Shah M, et al. Foundation models defining a new era in vision: A survey and outlook. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2025;47(4):2245-2264.[DOI]

-

19. Lu P, Bansal H, Xia T, Liu J, Li C, Hajishirzi H, et al. MathVista: Evaluating mathematical reasoning of foundation models in visual contexts. arXiv:2310.02255 [Preprint]. 2023.[DOI]

-

20. Li C, Gan Z, Yang Z, Yang J, Li L, Wang L, et al. Multimodal foundation models: From specialists to general-purpose assistants. Found Trends Comput Graph Vis. 2024;16:1-214.[DOI]

-

21. Ma Y, Nordberg OE, Zhang Y, Rongve A, Bachinski M, Fjeld M. Understanding dementia speech: Towards an adaptive voice assistant for enhanced communication. In: Companion Proceedings of the16th ACM SIGCHI Symposium on Engineering Interactive Computing Systems. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2024. p. 15-21.[DOI]

-

22. Lin J, Ma Z, Gomez R, Nakamura K, He B, Li G. A review on interactive reinforcement learning from human social feedback. IEEE Access. 2020;8:120757-120765.[DOI]

-

23. Kupcsik A, Hsu D, Lee WS. Learning dynamic robot-to-human object handover from human feedback. In: Bicchi A, Burgard W, editors. Robotics research. Cham: Springer; 2017. p. 161-176.[DOI]

-

24. Nowak A, Zhang Y, Romanowski A, Fjeld M. Augmented reality with industrial process tomography: To support complex data analysis in 3D space. In: Adjunct Proceedings of the 2021 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing and Proceedings of the 2021 ACM International Symposium on Wearable Computers; 2021 Sep 21-26; USA. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2021. p. 56-58.[DOI]

-

25. Park KB, Choi SH, Lee JY, Ghasemi Y, Mohammed M, Jeong H. Hands-free human–robot interaction using multimodal gestures and deep learning in wearable mixed reality. IEEE Access. 2021;9:55448-55464.[DOI]

-

26. Qi J, Ma L, Cui Z, Yu Y. Computer vision-based hand gesture recognition for human-robot interaction: A review. Complex Intell Syst. 2024;10(1):1581-1606.[DOI]

-

27. Lynch C, Wahid A, Tompson J, Ding T, Betker J, Baruch R, et al. Interactive language: Talking to robots in real time. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2024.[DOI]

-

28. Ruhland K, Peters CE, Andrist S, Badler JB, Badler NI, Gleicher M, et al. A review of eye gaze in virtual agents, social robotics and HCI: Behaviour generation, user interaction and perception. Computer Graph Forum. 2015;34(6):299-326.[DOI]

-

29. Zhang Y, Kassem K, Gong Z, Mo F, Ma Y, Kirjavainen E, et al. Human-centered AI technologies in human-robot interaction for social settings. In: Matviienko A, Niess J, Kosch T, editors. Proceedings of the International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia; 2024 Dec 1-4; Stockholm, Sweden. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2024. p. 501-505.[DOI]

-

30. Walker ME, Hedayati H, Szafir D. Robot teleoperation with augmented reality virtual surrogates. In: 2019 14th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI); 2019 March 11-14; Daegu, Korea (South). Piscataway: IEEE; 2019. p. 202-210.[DOI]

-

31. Dianatfar M, Pöysäri S, Latokartano J, Siltala N, Lanz M. Virtual reality-based safety training in human-robot collaboration scenario: User experiences testing. AIP Conf Proc. 2024;2989(1):020002.[DOI]

-

32. Karpichev Y, Charter T, Hong J, Soufi Enayati AM, Honari H, Tamizi MG, et al. Extended reality for enhanced human-robot collaboration: A human-in-the-loop approach. In: 2024 33rd IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (ROMAN); 2024 Aug 26-30; Pasadena, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2024. p. 1991-1998.[DOI]

-

33. Zhang B, Soh H. Large language models as zero-shot human models for human-robot interaction. In: 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2023 Oct 1-5; Detroit, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2023. p. 7961-7968.[DOI]

-

34. Wang J, Shi E, Hu H, Ma C, Liu Y, Wang X, et al. Large language models for robotics: Opportunities, challenges, and perspectives. J Autom Intell. 2025;4(1):52-64.[DOI]

-

35. Duguleana M, Barbuceanu FG, Mogan G. Evaluating human-robot interaction during a manipulation experiment conducted in immersive virtual reality. In: Shumaker R, editor. Virtual and mixed reality-new trends. Heidelberg: Springer; 2011. p. 164-173.[DOI]

-

36. Zhang Y, Xuan Y, Yadav R, Omrani A, Fjeld M. Playing with data: An augmented reality approach to interact with visualizations of industrial process tomography. In: Abdelnour Nocera J, Kristín Lárusdóttir M, Petrie H, Piccinno A, Winckler M, editors. Human-computer interaction–INTERACT 2023. Cham: Springer; 2023. p. 123-144.[DOI]

-

37. Weistroffer V, Paljic A, Fuchs P, Hugues O, Chodacki JP, Ligot P, et al. Assessing the acceptability of human-robot co-presence on assembly lines: A comparison between actual situations and their virtual reality counterparts. In: The 23rd IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication; 2014 Aug 25-29; Edinburgh, UK. Piscataway: IEEE; 2014. p. 377-384.[DOI]

-

38. Bayro A, Ghasemi Y, Jeong H. Subjective and objective analyses of collaboration and co-presence in a virtual reality remote environment. In: 2022 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW); 2022 Mar 12-16; Christchurch, New Zealand. Piscataway: IEEE; 2022. p. 485-487.[DOI]

-

39. Zhang Y, Nowak A, Romanowski A, Fjeld M. An initial exploration of visual cues in head-mounted display augmented reality for book searching. In. p. 273-275.[DOI]

-

40. Wang X, Shen L, Lee LH. A systematic review of XR-enabled remote human-robot interaction systems. ACM Comput Surv. 2025;57(11):1-37.[DOI]

-

41. Tanaka Y, Ruiz CM. Immersive technologies for remote human-robot interaction: A systematic literature review. Eur J Emerg Comput Vis Nat Lang Process. 2024;1(1):1-20. Available from: https://parthenonfrontiers.com/index.php/ejecvnlp/article/view/74

-

42. San Martin A, Kildal J, Lazkano E. Mixed reality representation of hazard zones while collaborating with a robot: Sense of control over own safety. Virtual Real. 2025;29(1):43.[DOI]

-

43. Bolano G, Juelg C, Roennau A, Dillmann R. Transparent robot behavior using augmented reality in close human-robot interaction. In: 2019 28th IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN); 2019 Oct 14-18; New Delhi, India. Piscataway: IEEE; 2019. p. 1-7.[DOI]

-

44. Walker M, Hedayati H, Lee J, Szafir D. Communicating robot motion intent with augmented reality. In: 2018 13th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI); 2018 Mar 5-8; Chicago, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2018. p. 316-324. Available from: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9473546

-

45. Ahmad Malik A, Brem A. Digital twins for collaborative robots: A case study in human-robot interaction. Robot Comput Integr Manuf. 2021;68:102092.[DOI]

-

46. Xie J, Liu Y, Wang X, Fang S, Liu S. A new XR-based human‐robot collaboration assembly system based on industrial metaverse. J Manuf Syst. 2024;74:949-964.[DOI]

-

47. Choi SH, Park KB, Roh DH, Lee JY, Ghasemi Y, Jeong H. An XR-based approach to safe human-robot collaboration. In: 2022 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW); 2022 Mar 12-16; Christchurch, New Zealand. Piscataway: IEEE; 2022. p. 481-482.[DOI]

-

48. Pan M, Wong MO, Lam CC, Pan W. Integrating extended reality and robotics in construction: A critical review. Adv Eng Inform. 2024;62:102795.[DOI]

-

49. Green SA, Billinghurst M, Chen X, Chase JG. Human robot collaboration: An augmented reality approach—a literature review and analysis. In: ASME 2007 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference; 2007 Sep 4-7; Las Vegas, USA. New York: ASME; 2007. p. 117-126.[DOI]

-

50. Duguleana M, Barbuceanu FG, Mogan G. Evaluating human-robot interaction during a manipulation experiment conducted in immersive virtual reality. In: Shumaker R, editor. Virtual and mixed reality-new trends. Heidelberg: Springer; 2011. p. 164-173.[DOI]

-

51. Higgins P, Kebe GY, Berlier A, Darvish K, Engel D, Ferraro F, et al. Towards making virtual human-robot interaction a reality. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Virtual, Augmented, and Mixed-Reality for Human-Robot Interactions (VAM-HRI); 2020 Mar 23; Cambridge, UK. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2021. Available from: https://vam-hri.github.io/previous/2021/papers/10_towards_making_virtual_human_robot_interaction_a_reality.pdf

-

52. Murnane M, Higgins P, Saraf M, Ferraro F, Matuszek C, Engel D. A simulator for human-robot interaction in virtual reality. In: 2021 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW); 2021 Mar 27-Apr 1; Lisbon, Portugal. Piscataway: IEEE; 2021. p. 470-471.[DOI]

-

53. Arntz A, Helgert A, Straßmann C, Eimler SC. Enhancing human-robot interaction research by using a virtual reality lab approach. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and eXtended and Virtual Reality (AIxVR); 2024 Jan 17-19; Los Angeles, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2024. p. 340-344.[DOI]

-

54. Surve S, Guo J, Menezes JC, Tate C, Jin Y, Walker J, et al. UnRealTHASC–a cyber-physical XR testbed for underwater real-time human autonomous systems collaboration. In: 2024 33rd IEEE International Conference on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (ROMAN); 2024 Aug 26-30; Pasadena, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2024. p. 196-203.[DOI]

-

55. Bustamante S, Peters J, Scholkopf B, Grosse-Wentrup M, Jayaram V. ArmSym: A virtual human–robot interaction laboratory for assistive robotics. IEEE Trans Human-Mach Syst. 2021;51(6):568-577.[DOI]

-

56. Villani V, Capelli B, Sabattini L. Use of virtual reality for the evaluation of human-robot interaction systems in complex scenarios. In: 2018 27th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN); 2018 Aug 27-31; Nanjing, China. Piscataway: IEEE; 2018. p. 422-427.[DOI]

-

57. Fratczak P, Goh YM, Kinnell P, Soltoggio A, Justham L. Understanding human behaviour in industrial human-robot interaction by means of virtual reality. In: Proceedings of the Halfway to the Future Symposium 2019 Nov 19-20; Nottingham, United Kingdom. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2019. p. 1-7.[DOI]

-

58. Yamamoto T, Abolhassani N, Jung S, Okamura AM, Judkins TN. Augmented reality and haptic interfaces for robot-assisted surgery. Int J Med Robot Comput Assist Surg. 2012;8(1):45-56.[DOI]

-

59. Fang HC, Ong SK, Nee AYC. A novel augmented reality-based interface for robot path planning. Int J Interact Des Manuf (IJIDeM). 2014;8(1):33-42.[DOI]

-

60. Hernández JD, Sobti S, Sciola A, Moll M, Kavraki LE. Increasing robot autonomy via motion planning and an augmented reality interface. IEEE Robot Autom Lett. 2020;5(2):1017-1023.[DOI]

-

61. Kousi N, Stoubos C, Gkournelos C, Michalos G, Makris S. Enabling Human Robot Interaction in flexible robotic assembly lines: An Augmented Reality based software suite. Procedia CIRP. 2019;81:1429-1434.[DOI]

-

62. Michalos G, Karagiannis P, Makris S, Tokçalar Ö, Chryssolouris G. Augmented reality (AR) applications for supporting human-robot interactive cooperation. Procedia CIRP. 2016;41:370-375.[DOI]

-

63. Milgram P, Zhai S, Drascic D, Grodski J. Applications of augmented reality for human-robot communication. In: Proceedings of 1993 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS ‘93); 1993 Jul 26-30; Yokohama, Japan. Piscataway: IEEE; 1993. p. 1467-1472.[DOI]

-

64. Malý I, Sedláček D, Leitão P. Augmented reality experiments with industrial robot in industry 4.0 environment. In: 2016 IEEE 14th International Conference on Industrial Informatics (INDIN); 2016 Jul 19-21; Poitiers, France. Piscataway: IEEE; 2016. p. 176-181.[DOI]

-

65. Ostanin M, Yagfarov R, Devitt D, Akhmetzyanov A, Klimchik A. Multi robots interactive control using mixed reality. Int J Prod Res. 2021;59(23):7126-7138.[DOI]

-

66. Fang B, Ding W, Sun F, Shan J, Wang X, Wang C, et al. Brain–computer interface integrated with augmented reality for human–robot interaction. IEEE Trans Cogn Dev Syst. 2023;15(4):1702-1711.[DOI]

-

67. Guhl J, Hügle J, Krüger J. Enabling human-robot-interaction via virtual and augmented reality in distributed control systems. Procedia CIRP. 2018;76:167-170.[DOI]

-

68. Wang X, Guo S, Xu Z, Zhang Z, Sun Z, Xu Y. A robotic teleoperation system enhanced by augmented reality for natural human-robot interaction. Cyborg Bionic Syst. 2024;5:0098.[DOI]

-

69. Bischoff R, Kazi A. Perspectives on augmented reality based human-robot interaction with industrial robots. In: 2004 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2004 Sep 28-Oct 2; Sendai, Japan. Piscataway: IEEE; 2004. p. 3226-3231.[DOI]

-

70. Hedayati H, Walker M, Szafir D. Improving collocated robot teleoperation with augmented reality. In: Proceedings of the 2018 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction; 2018 March 5-8; Chicago, USA. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2018. p. 78-86.[DOI]

-

71. Choi SH, Park KB, Roh DH, Lee JY, Mohammed M, Ghasemi Y, et al. An integrated mixed reality system for safety-aware human-robot collaboration using deep learning and digital twin generation. Robot Comput Integr Manuf. 2022;73:102258.[DOI]

-

72. Li C, Zheng P, Yin Y, Pang YM, Huo S. An AR-assisted Deep Reinforcement Learning-based approach towards mutual-cognitive safe human-robot interaction. Robot Comput Integr Manuf. 2023;80:102471.[DOI]

-

73. Chacko SM, Kapila V. An augmented reality interface for human-robot interaction in unconstrained environments. In: 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2019 Nov 3-8; Macau, China. Piscataway: IEEE; 2019. p. 3222-3228.[DOI]

-

74. Ostanin M, Yagfarov R, Klimchik A. Interactive robots control using mixed reality. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2019;52(13):695-700.[DOI]

-

75. Manring L, Pederson J, Potts D, Boardman B, Mascarenas D, Harden T, et al. Augmented reality for interactive robot control. In: Dervilis N, editor. Special topics in structural dynamics & experimental techniques, volume 5. Cham: Springer; 2020. p. 11-18.[DOI]

-

76. Buldu KB, Özdel S, Lau KHC, Wang M, Saad D, Schönborn S, et al. CUIfy the XR: An open-source package to embed LLM-powered conversational agents in XR. In: 2025 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and eXtended and Virtual Reality (AIxVR); 2025 Jan 27-29; Lisbon, Portugal. Piscataway: IEEE; 2025. p. 192-197.[DOI]

-

77. Konenkov M, Lykov A, Trinitatova D, Tsetserukou D. VR-GPT: Visual language model for intelligent virtual reality applications. arXiv:2405.11537 [Preprint]. 2024.[DOI]

-

78. Afzal MZ, Ali SA, Stricker D, Eisert P, Hilsmann A, Perez-Marcos D, et al. Next generation XR systems: Large language models meet augmented and virtual reality. IEEE Comput Grap Appl. 2025;45(1):43-55.[DOI]

-

79. Li X, Liu M, Zhang H, Yu C, Xu J, Wu H, et al. Vision-language foundation models as effective robot imitators. arXiv:2311.01378 [Preprint]. 2023.[DOI]

-

80. Lakhnati Y, Pascher M, Gerken J. Exploring a GPT-based large language model for variable autonomy in a VR-based human-robot teaming simulation. Front Robot AI. 2024;11:1347538.[DOI]

-

81. Zhang C, Chen J, Li J, Peng Y, Mao Z. Large language models for human–robot interaction: A review. Biomim Intell Robot. 2023;3(4):100131.[DOI]

-

82. Wang Z, Giannopoulos E, Slater M, Peer A. Handshake: Realistic human-robot interaction in haptic enhanced virtual reality. Presence. 2011;20(4):371-392.[DOI]

-

83. Wang I, Smith J, Ruiz J. Exploring virtual agents for augmented reality. In: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2019 May 4-9; Glasgow, UK. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2019. p. 1-12.[DOI]

-

84. Suzuki R, Karim A, Xia T, Hedayati H, Marquardt N. Augmented reality and robotics: A survey and taxonomy for AR-enhanced human-robot interaction and robotic interfaces. In: CHI conference on human factors in computing systems; 2022 Apr 29-May 5; New Orleans, USA. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2022. p. 1-33.[DOI]

-

85. Lee YK, Jung Y, Kang G, Hahn S. Developing social robots with empathetic non-verbal cues using large language models. arXiv:2308.16529 [Preprint]. 2023.[DOI]

-

86. Darwesh L, Singh J, Marian M, Alexa E, Hindriks K, Baraka K. Exploring the effect of robotic embodiment and empathetic tone of LLMs on empathy elicitation. In: Social robotics. 16th International Conference, ICSR + AI 2024; 2024 Oct 23-26; Odense, Denmark. Singapore: Springer; 2024. p. 1-11.[DOI]

-

87. Chen X, Ge J, Dai H, Zhou Q, Feng Q, Hu J, et al. Empathyagent: Can embodied agents conduct empathetic actions? arXiv:2503.16545 [Preprint]. 2025.[DOI]

-

88. Walker M, Phung T, Chakraborti T, Williams T, Szafir D. Virtual, augmented, and mixed reality for human-robot interaction: A survey and virtual design element taxonomy. ACM Trans Hum-Robot Interact. 2023;12(4):1-39.[DOI]

-

89. Groechel TR, Walker ME, Chang CT, Rosen E, Forde JZ. A tool for organizing key characteristics of virtual, augmented, and mixed reality for human–robot interaction systems: Synthesizing VAM-HRI trends and takeaways. IEEE Robot Automat Mag. 2022;29(1):35-44.[DOI]

-

90. Peters C, Yang F, Saikia H, Li C, Skantze G. Towards the use of mixed reality for hri design via virtual robots. In: 1st International Workshop on Virtual, Augmented, and Mixed Reality for HRI (VAM-HRI); 2020 Mar 23; Cambridge, UK. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2020. Available from: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1507485/FULLTEXT01.pdf

-

91. Wang N, Pynadath DV, Unnikrishnan KV, Shankar S, Merchant C. Intelligent agents for virtual simulation of human-robot interaction. In: Shumaker R, Lackey S, editors. Virtual, augmented and mixed reality. Cham: Springer; 2015. p. 228-239.[DOI]

-

92. Szafir D. Mediating human-robot interactions with virtual, augmented, and mixed reality. In: Chen JYC, Fragomeni G, editors. Virtual, augmented and mixed reality. Applications and case studies. Cham: Springer; 2019. p. 124-149.[DOI]

-

93. Qiu S, Liu H, Zhang Z, Zhu Y, Zhu SC. Human-robot interaction in a shared augmented reality workspace. In: 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS); 2021 Oct 24-Jan 24; Las Vegas, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2020. p. 11413-11418.[DOI]

-

94. Sabbella SR, Kaszuba S, Leotta F, Nardi D. Virtual reality applications for enhancing human-robot interaction: A gesture recognition perspective. In: Proceedings of the 23rd ACM International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents; 2023 Sep 19-22; Würzburg, Germany. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2023. p. 1-4.[DOI]

-

95. Arntz A, Eimler SC, Hoppe HU. “The robot-arm talks back to me”-human perception of augmented human-robot collaboration in virtual reality. In: 2020 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality (AIVR); 2020 Dec 14-18; Utrecht, Netherlands. Piscataway: IEEE; 2020. p. 307-312.[DOI]

-

96. Zhang Y, Omrani A, Yadav R, Fjeld M. Supporting visualization analysis in industrial process tomography by using augmented reality-a case study of an industrial microwave drying system. Sensors. 2021;21(19):6515.[DOI]

-

97. Paiva A, Leite I, Boukricha H, Wachsmuth I. Empathy in virtual agents and robots: A survey. ACM Trans Interact Intell Syst. 2017;7(3):1-40.[DOI]

-

98. Zhao S. Toward a taxonomy of copresence. Presence. 2003;12(5):445-455.[DOI]

-

99. Szczurek KA, Prades RM, Matheson E, Rodriguez-Nogueira J, Di Castro M. Multimodal multi-user mixed reality human–robot interface for remote operations in hazardous environments. IEEE Access. 2023;11:17305-17333.[DOI]

-

100. Simaan N, Taylor RH, Choset H. Intelligent surgical robots with situational awareness. Mech Eng. 2015;137(9):S3-S6.[DOI]

-

101. Roldán JJ, Peña-Tapia E, Martín-Barrio A, Olivares-Méndez MA, Del Cerro J, Barrientos A. Multi-robot interfaces and operator situational awareness: Study of the impact of immersion and prediction. Sensors. 2017;17(8):1720.[DOI]

-

102. Zhang Y, Nowak A, Rao G, Romanowski A, Fjeld M. Is industrial tomography ready for augmented reality? A need-finding study of how augmented reality can be adopted by industrial tomography experts. In: Chen JYC, Fragomeni G, editors. Virtual, augmented and mixed reality. Cham: Springer; 2023. p. 523-535.[DOI]

-

103. Van Haastregt J, Welle MC, Zhang Y, Kragic D. Puppeteer your robot: Augmented reality leader-follower teleoperation. In: 2024 IEEE-RAS 23rd International Conference on Humanoid Robots (Humanoids); 2024 Nov 22-24; Nancy, France. Piscataway: IEEE; 2024. p. 1019-1026.[DOI]

-

104. Zhang Y, Orthmann B, Welle MC, Van Haastregt J, Kragic D. LLM-driven augmented reality puppeteer: Controller-free voice-commanded robot teleoperation. In: Coman A, Vasilache S, editors. Social computing and social media. Cham: Springer; 2025. p. 97-112.[DOI]

-

105. Zhang Y, Orthmann B, Ji S, Welle M, Van Haastregt J, Kragic D. Multimodal “puppeteer”: Exploring robot teleoperation via virtual counterpart with LLM-driven voice and gesture interaction in augmented reality. arXiv:2506.13189 [Preprint]. 2025.[DOI]

-

106. Kim CY, Lee CP, Mutlu B. Understanding large-language model (LLM)-powered human-robot interaction. In: Proceedings of the 2024 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction; 2024 Mar 11-15; Boulder, USA. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2024. p. 371-380.[DOI]

-

107. Kawaharazuka K, Matsushima T, Gambardella A, Guo J, Paxton C, Zeng A. Real-world robot applications of foundation models: A review. Adv Robot. 2024;38(18):1232-1254.[DOI]

-

108. Costa GM, Petry MR, Moreira AP. Augmented reality for human-robot collaboration and cooperation in industrial applications: A systematic literature review. Sensors. 2022;22(7):2725.[DOI]

-

109. Robins B, Dautenhahn K, Te Boekhorst R, Billard A. Robotic assistants in therapy and education of children with autism: Can a small humanoid robot help encourage social interaction skills? Univ Access Inf Soc. 2005;4(2):105-120.[DOI]

-

110. Shamsuddin S, Yussof H, Ismail L, Hanapiah FA, Mohamed S, Ali Piah H, et al. Initial response of autistic children in human-robot interaction therapy with humanoid robot NAO. In: 2012 IEEE 8th International Colloquium on Signal Processing and Its Applications; 2012 Mar 23-25; Malacca, Malaysia. Piscataway: IEEE; 2012. p. 188-193.[DOI]

-

111. Mohebbi A. Human-robot interaction in rehabilitation and assistance: A review. Curr Robot Rep. 2020;1(3):131-144.[DOI]

-

112. Leite I, Pereira A, Mascarenhas S, Martinho C, Prada R, Paiva A. The influence of empathy in human–robot relations. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2013;71(3):250-260.[DOI]

-

113. Baytas MA, Çay D, Zhang Y, Obaid M, Yantaç AE, Fjeld M. The design of social drones: A review of studies on autonomous flyers in inhabited environments. In: Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2019 May 4-9; Glasgow, UK. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2019. p. 1-13.[DOI]

-

114. Shin D. Empathy and embodied experience in virtual environment: To what extent can virtual reality stimulate empathy and embodied experience? Comput Hum Behav. 2018;78:64-73.[DOI]

-

115. Rueda J, Lara F. Virtual reality and empathy enhancement: Ethical aspects. Front Robot AI. 2020;7:506984.[DOI]

-

116. Lv N, Gong J. The application of virtual reality technology in the efficiency optimisation of students’ online interactive learning. Int J Contin Eng Educ Life Long Learn. 2022;32(1):35.[DOI]

-

117. Zhang Y, Ma Y, Fu D, Portales SZ, Fjeld M, Kragic D. Personalizing emotion-aware conversational agents? Exploring user traits-driven conversational strategies for enhanced interaction. arXiv:2511.06954 [Preprint]. 2025.[DOI]

-

118. Nakazawa A, Iwamoto M, Kurazume R, Nunoi M, Kobayashi M, Honda M. Augmented reality-based affective training for improving care communication skill and empathy. PLoS One. 2023;18(7):e0288175.[DOI]

-

119. Billinghurst M. Using augmented reality to create empathic experiences. In: Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces; 2014 Feb 24-27; Haifa, Israel. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2014. p. 5-6.[DOI]

-

120. Ma Y, Zhang Y, Bachinski M, Fjeld M. Emotion-aware voice assistants: Design, implementation, and preliminary insights. In: Proceedings of the Eleventh International Symposium of Chinese CHI; 2023 Nov 13-16; Denpasar, Indonesia. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2023. p. 527-532.[DOI]

-

121. Sorin V, Brin D, Barash Y, Konen E, Charney A, Nadkarni G, et al. Large language models and empathy: Systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2024;26:e52597.[DOI]

-

122. Hasan M, Ozel C, Potter S, Hoque E. SAPIEN: Affective virtual agents powered by large language models. In: 2023 11th International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction Workshops and Demos (ACIIW); 2023 Sep 10-13; Cambridge, USA. Piscataway: IEEE; 2023. p. 1-3.[DOI]

-

123. Shih MT, Hsu MY, Lee SC. Empathy-GPT: Leveraging large language models to enhance emotional empathy and user engagement in embodied conversational agents. In. p. 1-3.[DOI]

-

124. Lee KM, Jung Y, Kim J, Kim SR. Are physically embodied social agents better than disembodied social agents? The effects of physical embodiment, tactile interaction, and people’s loneliness in human–robot interaction. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2006;64(10):962-973.[DOI]

-

125. Wainer J, Feil-seifer DJ, Shell DA, Mataric MJ. The role of physical embodiment in human-robot interaction. In: ROMAN 2006-the 15th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication; 2006 Sep 6-8; Hatfield, UK. Piscataway: IEEE; 2006. p. 117-122.[DOI]

-

126. Kilteni K, Groten R, Slater M. The sense of embodiment in virtual reality. Presence Teleop Virt Environ. 2012;21(4):373-387.[DOI]

-